[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Startling Stories, March 1948.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

CHAPTER I

Contact!

The bit of whitish substance fluoresced, which of course was quite natural. It also vibrated very faintly, which was unnatural. At least, this property had not been known previously—which is really saying little since the material had been compounded from artificial radioisotopes from the big piles. All too little was known about such items and the fact that this one was vibrating ever so faintly whenever the electron beam struck it was interesting both from a scientific and a lay curiosity standpoint.

Ed Bronson blinked a bit and decided that he had made some mistake. It had ceased to vibrate.

Ed cracked the experimental tube and removed the irregular lump. It had been hoped to produce a more brilliant and higher-contrast phosphor for television screens. But if it was going to vibrate—

Ed inserted the lump of phosphor back in the tube, pumped it and restarted the whole gear.

It vibrated again, ever so faintly, against the bottom of the glass. Bronson listened carefully, his engineer's mind trying to identify the sound. It was not the sixteen kilocycle sweep circuit—not the one that scanned the face of the television tube, because this was not a complete set-up and there was no scanning energy necessary. It was vaguely familiar.

It came and it went, that faint vibration. Sometimes it rattled violently, other times it purred gently. Always very faintly of course—for the term 'violently' means only by comparison.

Ed adjusted the field strength of the focusing magnet about the neck of the tube and the vibration strengthened to a noticeable degree. He juggled the controls but found he had hit the maximum or optimum response.

There was something about it.... It was like human whisperings too faint to be understood but not too faint to be unheard. Like the bloop-bleep of a leaky faucet that seems to be saying things about you just too quietly to be really understood. Like the imagined whisperings heard by the paranoiac....

Ed laughed. Hearing things!

Like hades he was hearing things. It was really there. The lump of phosphor moved a perceptible amount as a peak of rattle passed. And yet....

Ed Bronson uncoiled his wiry six feet from the chair and cracked the seal on the tube again. He lifted the top and squinted at the crystalline whiteness that had been rattling so maddeningly.

He went to a cupboard at the end of his laboratory and rummaged among small boxes that stood on one shelf—no two boxes seeming to be of the same size. The upshot of this rummaging was that Bronson had to spend some time repiling the boxes after he had found the contact microphone he was seeking. Eventually, however, Ed Bronson was repumping the tube.

Inside was the crystal phosphor and fastened to it was a sensitive contact microphone.

Once more Bronson keyed the switches, adjusted focus, and intensity. Then, from the speaker of the amplifier connected to the contact microphone, there came a cacophony of noise, howling whistles, deep-throated hums, and a horde of middle-register tones. Not music, and far from it. Just random—somethings.

Yet in the background, barely audible as such but most definitely identifiable, was the voice of a woman.

Any speaker would have ceased had she known her efforts were thus wasted. It was indistinguishable and unintelligible save for a scattered word here and there, which was unmistakably in English. Ed Bronson thought that it was like trying to eavesdrop on a conversation in a boiler factory.

He wondered what radio program he had tapped in on. He turned his radio on, and scanned the bands, even listening to the weaker stations—which, of course were far from being as ragged as this, regardless of their weakness—but came to the conclusion that there was nothing on the air that corresponded to the voice of the woman that emerged from his kinescope testing tube.

Bronson noted with questing interest that occasionally one or more of the interfering hoots, sirens and honks would cease for a moment or two. So also did the woman's voice. Ed prayed that when sufficient interference would cease, the woman would not choose that moment to cease also. He wanted to know more about this. There was more to it than met the eye.

If he could identify the speaker he might be able to establish a means of communication. Location was also important. Furthermore, if this were telephone or radio, he had a new means of receiving both. If it were telephone and it worked on any or all, Ed Bronson had a gadget that would make him the bane of all lovers of secrecy—including espionage agents, who, of course, hate penetration of their own little conclaves as deeply as they try to penetrate others'.

He—well, if it were radio he was intercepting he had nothing as interesting as a telephone tapping gadget. But....

The tones dropped in volume. A shrill whistle that made vicious interference with his hearing suddenly keyed off like the turning off of a light. A booming roar ceased also and others of less importance dropped or died. The cumulative effect of this was to permit the woman's voice to come through.

It was not the perfect voice of a magnificent contralto reproduced on the finest radio gear but a cool, clear contralto, transmitted by cheap, shoddy equipment and received on something both obsolete and inefficient.

Yet is was a woman's voice. And, with the luck of the patient scientist, she was saying, "... home? It's at Thirteen forty-seven Vermont Street, Postal Zone Eleven...."

And that was the first complete reception Ed Bronson heard. For, with the completion of the message, the cacophony of hoots, keenings and sirens blasted forth like a mad, insane symphony.

"I live at Thirteen forty-eight Vermont," shouted Bronson. "Across the street!"

He charged out, raced across the street and pressed the doorbell. He waited a moment and an elderly man came to the door.

"I'm Ed Bronson," explained he.

"I know you," snapped the other man. "Always gumming up my radio with your fool experiments. What do you want?"

"Is your daughter using the telephone?" he asked.

"She ain't home."

"Your wife?"

"She's with Regina."

"Well, was some woman using the—"

"Look, Bronson, I ain't got no women here when my wife ain't, see? Now what's your idea, huh?"

Bronson looked apologetic. This was Mr. Lewis McManner and both he and his family were the kind of people—one of which seems to live on every block—who chase robins from the front yard, call the police for ball-playing boys and manage to maintain an immaculate house because it never has a good chance to get cluttered with people.

"I've been working on an idea," he told McManner, "and I seem to have picked up someone who claimed that her address was Thirteen forty-seven Vermont Street."

"You'd think this was the only Vermont Street in the world!" snorted McManner, slamming the door.

Bronson turned from the front door and retraced his steps. Despite his disappointment, he could not help but grin at himself. After all, how many 1347 Vermont Streets might there be between Puget Sound and Key West? And, were he to try mailing each a letter, someone would most certainly object loudly enough to cause Ed Bronson to explain that he had heard a woman's voice mention the number and that he wanted to meet her. He could visualize the psychiatric ward looming to receive him while they tapped his knees and inspected his brain to find out whether he was safe to let loose without a muzzle.

Yet Bronson sobered soon enough. He was an engineer. He knew that what had been done once could be done again. Perhaps the way to get in touch with this woman was to try to tap back. At least he could listen to everything she said in the hope that she would repeat other information.

With a prayer Bronson separated a sizable hunk of the phosphor to work upon, while the other "sang." He breathed no sigh of relief until he had half of the original phosphor back in the tube with the works completely covered, as before, by the mad mass of meaningless hoots and catcalls. Then he went to work on the other piece. He did have a parallel set-up right on the same bench. There was something about this....

During the hours that followed there were three breaks in the whistlings. The first produced only the words "nature of the situation—" The second time the woman said, "—something must be done, of course, but you tell me what. I—" which also left Bronson completely in the dark. The third time, she said "—so this part of the Carlson family is going to bed!"

After which there was no woman's voice riding along with the myriad of sounds. They were as before, like a radio that has gone off the air, leaving an increased racket of background noise. It was maddening and futile.

All he had to show for her hours of telephoning was her name. Carlson.

All he had to do was to get the telephone directories of all the cities in the United States of America and perhaps Canada, then run through the listings of 'Carlson' until he hit one that lived on 1347 Vermont Street.

It might as well have been 'Smith' as far as running them down went. He could try Central City. After all, he could easily have made an error in listening.

But that was futile. Bronson sought the entire list of Carlsons and found none who lived on Vermont Street or any phonetic variation. Grumbling and baffled, he returned to his labors.

That, at least, proved more profitable. It was midnight when Bronson discovered that tapping one of the bits of phosphor caused a response in the other when they were energized by the electron bombardment from the television tube works.

From that point to vibrating the hunk of phosphor with the adapted insides of an old earphone and getting a response, took another hour of whittling, filing and working. He discarded that method of modulation two hours later when he discovered that an audio modulation of the electron stream in the kinescope tube produced the same effect.

Then, dead tired, Ed Bronson went to bed. He'd have called the woman right then and there had she been handy, but she had gone.

Bronson was truly beat. Had he stopped to think about it he would have known that something big was in the wind. For he was tapping no telephones. He had accidentally discovered some sort of communication receiving principle and had then devised a transmitter.

His first thought on the following morning was to try the receiver. She was there, all right, and so was a hooting cry of the dissonant pipe-organings.

Bronson shrugged and fired up his transmitting gadget. "Miss Carlson!" he called into the microphone. "Calling Miss Carlson of Thirteen forty-seven Vermont Street. Can you hear me?"

Then he listened.

Her voice paused briefly, took a new tone, but was still covered by the whinings.

"Miss Carlson, this is Ed Bronson. I cannot hear you clearly because of much interference. If you can hear me, make a lilting rill with your voice. This I can distinguish among the many stable-toned notes that are coming in at the time."

The voice rilled up and down several times. Then there was considerable speech which Bronson could not understand.

The upshot of this, however, was a gradual shutting down of the hootings and honkings until the receiver was clear. Then her voice came through again.

"Mr. Bronson. I have requested silence for one minute. Where are you?"

"Thirteen forty-eight Vermont Street, Central City Eleven."

"That is across the street," she said.

"Perhaps," he answered.

"Well, it is," she said. "Unless we're in different Central Cities."

"Central City, New Mexico, eighteen miles from Albuquerque?"

"That's it. But we have little time, really, because we didn't get the clear as soon as we asked for it. They hung over a bit—the commercials, I mean."

"Commercials?" he asked. Dumfounded, he began to wonder. Commercial, in radio parlance, meant any transmitter on the air for commercial purpose and the presupposition that this system of communications must be quite well known.

How then had Ed Bronson, an electronics engineer, managed to live through the commercialization of an entirely new field of communications?

"The commercial laboratories," she said.

"Oh? Then this is a laboratory experiment?"

"More than that—"

Bronson heard with dismay the first thin whistle resume.

He interrupted.

"Miss Carlson," he pleaded quickly, "we're going to be cut off again. Meet me on the corner of Vermont and Thirteenth, please?"

"Yes but—"

That was all. The keening, piping howl came with ear-shattering loudness once more.

Bronson turned off his gear and headed for the corner of Vermont and 13th. Let 'em hoot and howl.

He'd speak to the girl in person!

An hour later, Ed Bronson still stood there, leaning disconsolately against a lamp post in the bright daylight. A ring of cigarette butts surrounded his feet.

Whatever it was it was important and he, Bronson, had the key. All he had to do was to find the door!

Bronson returned home. The trouble—one of them, anyway—was that his amplifier was a high fidelity affair, capable of flat transmission of sounds as far as the human ear could hear.

That made for good music and that's what the amplifier had been built for.

So Bronson went home determined to build a series of sharp filters. First he would curtail the band-width of the amplifier until it peaked around eight hundred cycles per second, near the musical note 'A' one octave above the standard Concert Pitch 'A'.

Then he would build a set of sharply-tuned filters that would cut 'holes' in the remaining spectrum where the tonal interferences came. It would make her speech less natural but far more intelligible.

Bronson needed more evidence before he did anything serious about it.

It was nearing five o'clock in the morning before he finished his job, and started to listen once more.

CHAPTER II

The Red Sky

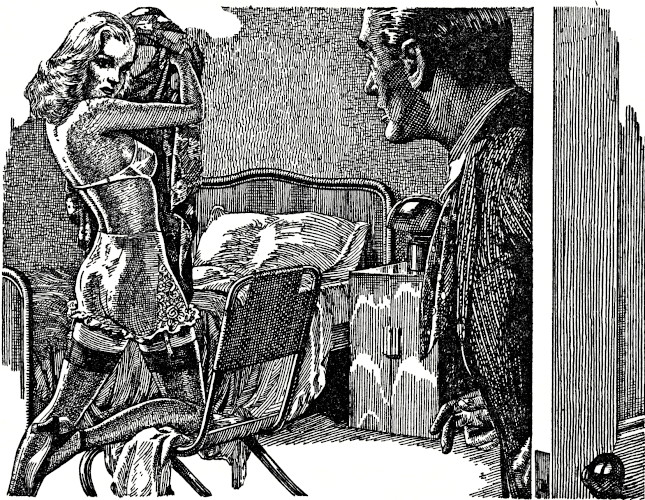

The girl turned from the window, where the bright sky silhouetted her slender figure.

"How do I know where he is?" she snapped.

"Now look, Virginia," objected one of the men in the room, "there's no point in getting angry. We must know."

"I know you must, Peter," she returned. "I agree. But I don't know. Do you understand that? I don't know!"

Peter Moray shrugged. "Anybody capable of building a space resonator must have enough training to have known about it in the first place."

John Cauldron spoke sharply, "You went out to the corner as suggested?"

"I did. He did not appear. After I returned I watched at regular intervals. No one came. Also I listened carefully as you suggested. He hasn't been calling—hasn't called since about eleven o'clock this morning."

Peter Moray smiled. "Yesterday morning," he corrected.

"Don't be funny. You're the ones that have kept me up all night asking fool questions over and over."

"They're not fool questions, Virginia."

"Any question repeated too often becomes a fool question," she replied.

Cauldron spoke heavily. "We're not cross-examining you, Virginia. Please believe that. We ask and ask and ask because it may be that something might have been said that sounds trivial, but may make large sense."

The girl shrugged. "You're entitled to try," she said. She passed a hand across her face wearily. "You've heard and reheard our conversation as verbatim as I recall it. And it was an experience I will not forget easily."

"Agreed," said Moray, walking to the west window and looking out. "I guess we're all overkeyed."

Cauldron grumbled a bit. "There have been a lot of strange things happening," he said. "This isn't the first."

Virginia smiled wanly but it was Cauldron who spoke next after a short pause. "And at five-thirty in the morning, everything begins to get somewhat distorted from a mental standpoint."

Moray turned from the brightness of the sky and mumbled something about life's lowest ebb occurring just before dawn.

Then he added, "Why did this mess have to happen? Blast it, everybody that knew swore up and down that the possibility was nil."

"Not nil enough," said Cauldron.

"No," agreed Virginia. "But that's life."

Moray slammed his fist down on the window-sill and swore. "That's life," he echoed in a mocking tone. "Well, I don't like it!"

"Who does?" demanded Cauldron quietly.

"Can't you face facts?" snapped Moray. "Do you realize that we haven't much time left? And what are we doing about it? Where are we? Nowhere, or no further along than we were thirty years ago—exactly thirty years ago. It's July sixteenth right now, and that's—"

"You're talking like a fool, Moray," said Virginia. "Have you ever stopped to think that those of us who do not rant and rave and worry ourselves into ulcers may have faced the fact, and find it ungood? Well, there are those of us who will do what we can. There's little sense in worrying about conditions—all it does is remove you from your highest efficiency.

"When something is awry you do something to correct it if you can. If you cannot you pigeonhole it until such a time as you can solve it. Not forget it, never for a moment. But there's no sense in dragging a worry back and forth across the floor until it is draining your life's blood. As for that out there, I didn't do it."

"Good for you, Virginia," applauded Cauldron.

"No," snapped Moray. "You didn't. You were not born at that time. But you can't fold your hands and accept it—nor can you say that it is none of your business!"

"There's always suicide," said Virginia Carlson.

A clock in the lower part of the house chimed once, marking the hour of five-thirty.

Moray returned to the window and looked at the sky, west. "At five-thirty in the morning of July sixteenth," he said, "one hundred and twenty miles southeast of Albuquerque, in a remote section of the Alamogordo air base, a group of scientists released the first atomic fire. Thirty years later," he finished bitterly, "we have a perpetual sunrise!"

On the laboratory table, the receiver rattled loudly. They turned, as one.

"Look," snapped Cauldron quickly, "if that is this Ed Bronson character, get in touch with him. We can use any technician we can get our hands on. Any man with a brain might well hold the key to that living cancer out there that is burning up the very earth."

"I'll put my chances on a space rocket," replied Peter Moray.

"I'd rather stop that fire out there."

"Why?" demanded Moray.

"Where would you go?" snapped Cauldron angrily. "There isn't a planet fit for human occupation and you know it. You'll either put it out or we'll all die. Not a chance for escape in any other way."

"I—"

"Shut up, while Virginia answers Bronson. He's having interference trouble—you'll make it no easier."

From the speaker was coming Ed Bronson's voice, calling for Miss Carlson and requesting an answer, for he had filters installed that eliminated the whistlings.

Cauldron jabbed Moray with an elbow. "He's a right bright fellow," he observed in a whisper.

Virginia Carlson spoke into the microphone. "You're right on the big moment," she told Bronson.

"Big moment?" he replied.

"Sure. Thirty years ago today—this moment."

"Yeah?" drawled Bronson. "And what happened?"

Peter Moray looked at John Cauldron. "Tell me," he snapped, "what kind of man could live to maturity and not know Alamogordo?"

"I don't know. I can't imagine," replied John Cauldron. "But maybe—just maybe—it is the answer we've been seeking."

Ed Bronson shook his head though he knew that the girl could not see him. He had not heard Moray or Cauldron mention Alamogordo. He repeated his query.

"And what happened?"

Virginia Carlson told him, "Thirty years ago, at Alamogordo, the scientists first released the energy from the atom."

"Oh," he replied. "I didn't know it was marked on the calendar as a holiday."

"Holiday?" exploded Virginia.

"Well?"

"That atomic fire is still burning!" snapped Virginia.

"Oh, no!"

"Well, I'm within a hundred and thirty miles of it," she replied, "and I can see it out of the window."

"Where the dickens are you?" he asked.

"You know my address," she replied.

"Yes," he agreed. "And I went there and got pushed in the face for my trouble."

"And the people who live at your address are named Carrington, not Bronson."

"How old are you?" asked Bronson.

"Twenty-five—why?"

"Look," he said, "if that atomic fire is running out there, then how did the World War Two end?"

"They brought high officials over to see the awful pillar of fire. They didn't tell them that the atomic flame would eventually eat the earth—so surrender was a matter of expediency. Once the shooting was over all the earth turned at once to the job of putting it out. You know that."

"Nope," he replied. "It worked—as did the others at Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and two at Bikini Atoll."

"Hiro—and what was at Bikini Atoll?" demanded the girl.

"Tests—Operation Crossroads."

"Tests!" exploded Virginia. "And none of them started atomic fires in the earth itself?"

"Nope."

"Then you tell me what happened?"

"I don't know."

"You're not psycho?" asked Virginia.

"Not that I know of," he replied with a chuckle. "Though—as Pontius Pilate is credited with having said—'What is truth?'"

"Hmmm. I cannot deny your right to state truth as you see it, Bronson, but be it remembered that practically every human born since the atomic fire is a mutation of some sort or another."

"So what does that make me?"

"You might be some sort of brain mutation—don't ask what kind—one who does not recognize the truth."

"All I know is what I read in the papers, what I see in the moving pictures, and how I feel at the moment. Also, I am no mutation. I was exactly one year old when Alamogordo took place, even supposing that it did take off with radiations that might have mutated the germ plasm."

"Well, it did."

"According to you it did," replied Bronson.

"May I repeat your own statement to yourself?" she told him. "All I know—et cetera."

"Okay," he said. "And granting that our separate tales are true, then what?"

Virginia mentioned a few items of history. Both then got their own history books and started to compare closely. They agreed on everything up to the moment of the atomic bomb at Alamogordo.

And at that moment, the histories diverged.

"Nature," said Ed Bronson, "must have been perplexed. So she took both roadways. One in which the earth is engulfed with atomic flame and one in which the thing worked."

"What do we do next?" asked Virginia.

"We get in touch with the respective authorities of our worlds," said Bronson. "Alone we can do little. Together we can do something to aid you."

"Tomorrow night at seven, then?" asked Virginia.

"Right."

The contact was broken.

"And there," said Peter Moray, "is our answer!"

CHAPTER III

Earth Three

Harry Maddox turned from his laboratory table as the tall, dark man entered. Maddox greeted the taller man obsequiously, but the other's reply was curt.

"They've done it, you say?" asked Kingston.

"They've done it," replied Maddox gloatingly.

"That proves it then," replied Kingston with interest. "Though it has always been a common enough theory."

"Within the past thirty-six hours," said Maddox, "there have been two transmissions. The latter one is now going on. Want to hear it?"

"Not particularly," replied Kingston. "It will be recorded for my leisure."

"Yes," nodded Maddox. His nod was toward a rather attractive girl, who was riding herd on a large wire recorder. From time to time she would reach out and adjust the volume of the recording. Over long blond hair she wore earphones to monitor the conversation directly. Kingston made a mental note that he could trust Maddox to adorn his laboratory and workshop with the most attractive human decor that he could find.

Instead of commenting on this he smiled in amusement and continued to speak. "Rather dramatic, isn't it?"

Maddox nodded. "Thirty years to the moment. That Alamogordo affair had three possibilities. It could either have gone off normally—it could have started an atomic fire in the earth—or it could have fizzled. And so, thirty years later, the three temporal possibilities are meeting."

"No, my dear Maddox," said Kingston with the air of a savant correcting a student who was not too careful of his facts. "Just two of them. We sit by—remember?"

"I know," said Maddox, rebuffed.

"Remember—and never for a moment forget—that the possibility of the Alamogordo bomb starting an atomic fire in the earth was a remote possibility. That means that the tensors which maintain that line of temporal advancement are very shaky.

"Time, you know, consists of following the Laws of Least Reaction, which simply means that in any reaction wherein a number of possibilities occur, that which will happen with the least energy will take place. This is statistically true, and need not hold for specific instances.

"Now," Kingston went on, enjoying his role of lecturer even though Maddox fiddled impatiently because he knew it all beforehand—and besides, the blonde was half-listening, though alert on her recording job. "Be it always remembered that the chances of the Alamogordo Bomb being a fizzle were as remote as the other case.

"Ergo, Maddox, our own world hangs on a slender thread of reality. We have as much need to escape from this time-slot as they whose earth is burning with atomic fire. For only in the time-slot where the Alamogordo Bomb behaved according to principle are the time-tensors heavy enough to maintain it."

"Yes, your Excellency," replied Maddox.

Kingston nodded. "You are a lucky fellow, Maddox. I came as soon as I could get away. I shall remain here until we can go through and take over."

"Sir, a question." Maddox knew that he must use deference at least until Kingston climbed down from his tall horse. "What happens when, as and if they start an atomic fire in Earth One?"

"They cannot, save by sheer chance of almost impossible mathematical odds," said Kingston. "Besides, they hope to move in—or will as soon as they learn the truth. No man burns the home he hopes to own in the near future."

"But what will happen?" asked Maddox. "That expectation is far too deep for me to follow."

"Men—all men—are inclined to feel sorry for the trapped," said Kingston. "In some cultures their sorrow is shown by killing the trapped to remove them from their misery. In other cultures, the trapped are aided even though they may eventually turn against their liberators. Once the truth is known to both worlds, those who are in Earth One will be moved to aid the trapped ones in Earth Two.

"We shall aid them as we did before by transmitting to Earth One more samples of the space-resonant radioisotope to contaminate their scientific works. There will be a gaudy search for them once the truth is known, you know. Anyway, those on Earth One will undoubtedly admit the trapped ones from Earth Two."

Maddox shrugged. "No dice, yet."

"Don't be stupid. Those on Earth Two are a race faced with death. They'll send through their mutants, their death-dealing types first. That will decimate Earth One and leave Earth One in the hands of Earth Two. Follow?"

"So far, yes. But where do we come in?"

"We come in shortly. Ninety percent of those remaining on Earth Two are mutants from the atomic fire or considerably older than thirty. The ninety are almost certain to be—if not sterile—then not cross-fertile with the rest of the mutant race. Each will have gone mutant in some fashion different from his fellow.

"All we need do then is to sit and wait until the race dies out—another thirty or forty years. Or, better, depending on the circumstances following the eventual battle, we go to war. We shall win, for our people have not lost much. At any rate we're permitting Earth Two to do our cleaning-up for us."

"Unless—" began Maddox, then paused. He knew that if he advanced a theory unasked it would be scorned. However, were he to make some leading statement and then disavow it unuttered Kingston would demand that he complete it whether he thought it right or wrong.

Kingston did, which was an excellent proof of the theory that it is a good thing to know the nature of your fellow man. "Unless what?" demanded Kingston.

"It was but an idle thought. Who fights more fiercely—he who has lost his home and fights for another or he who protects himself from the one who would dispossess him?"

Kingston laughed nastily. "Little difference," he said. "This is rigged so that no matter what, a fight will ensue. It is always easy to lick the survivor of a tough battle."

Maddox shrugged. "Just remember that you're not fighting aliens, but you—our—own kind!"

Kingston nodded. "That," he said succinctly, "is why I know them so well."

Cauldron looked at his watch. "Two hours," he said. "Time enough?"

Virginia looked concerned. "He didn't state whether he'd been asleep lately," she said.

"Unless he's a complete screwball, he'll work days and sleep nights," observed Moray. "Even supposing he works at home, he'll be arising about noon at the latest and hitting the hay about three-odd. Excepting when something was really in the fire like this receiver of his. I predict that he hit the sheets after we closed and is now pounding the pillow at a fine rate of speed."

Virginia smiled uncertainly, turning back from her communicating equipment. "He doesn't answer," she said.

"Can you locate his phosphor?" demanded Cauldron.

"I have."

"Then try," snapped Moray. "Aid! Help!" he sneered, "We're in the way of losing our very lives, and what we need, we take!"

Cauldron nodded. "Moray—you first. If Bronson is still in evidence clip him. If not we'll go ahead and do whatever is necessary. We can't take too long. After all—"

Moray nodded. "Ready, Virginia?"

"Ready."

Virginia worked over another bit of equipment in her laboratory. Moray walked over easily, smoking a last cigarette leisurely until Virginia turned to him.

"The focal volumes are resonant," she said. Then Moray seated himself in the chair before the equipment and, as Virginia started the machine, it began to transmit Pete Moray from one world to the other.

It was not especially spectacular. No flashing lights or flowing aurae of color. Moray's body, still breathing, still living, began to be less solid. At one time Moray lit another cigarette.

A bit of the cigarette smoke entered Ed Bronson's laboratory. The amount was that percentage of the transmission that had been accomplished.

There, before the big kinescope tube in Bronson's laboratory, the air was beginning to show the vague outlines of a figure, seated on a chair. This figure thickened gradually as the random atoms in Moray's body passed over.

A half hour passed and Virginia told Cauldron that the transmission should be about half complete. Moray's body could be seen through faintly—not that any of the internal organs were visible but as if he were a wraith.

Then the halfway point came. The floor in Bronson's laboratory was lower than the floor in Virginia Carlson's laboratory—with respect to their transmitters and receivers—and Moray and his chair dropped several feet on both sides. Moray seemed to be unmindful of the fact that the hard floor of Virginia's laboratory was about where his stomach was.

A half hour later, there was little of Moray left on Earth Two. Most of him was on Earth One!

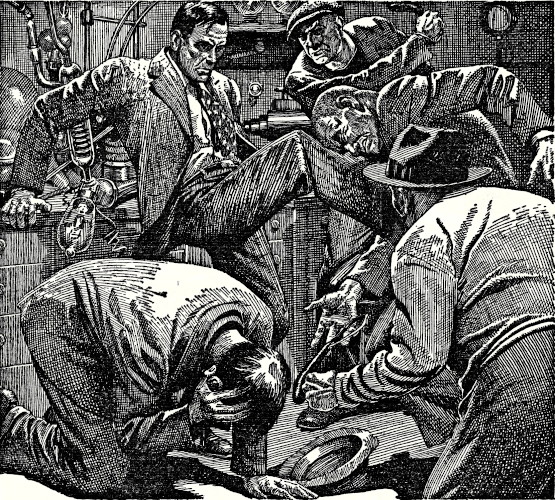

As the final molecules came through the space resonator Moray heard a noise. Frantic, he turned to see but could do nothing until the last of him was complete. The noise resolved itself to footsteps, and then the door opened and Ed Bronson strode in.

"Smoke—" he mumbled sleepily, then, "—who the heck are you!"

Moray was complete. He leaped to his feet and clipped Bronson viciously with the side of his hand. Bronson dropped, stunned, dazed, but not unconscious. Deftly, Moray found a roll of tape, bound Bronson's ankles and wrists, slapped a bit of tape across his mouth.

"Aid?" sneered Moray. "Promise us aid, all right. Fifty years will pass while the idea is being thrashed out in Congress or in whatever international organization there is here. Behave, Bronson, and you'll live. Help us—understand? If you don't it's—" Moray drew a forefinger across his throat.

Another figure started to form—vague and indistinct—and Moray lifted the taped man across his shoulders, carried him upstairs, dumped him across his bed and left him there.

When he returned to the laboratory, Virginia was beginning to solidify. Moray seated himself and waited, smoking Bronson's cigarettes and fortifying himself with a drink of Bronson's liquor. Moray smiled, but his humor was bitter.

How to marshal an army? It took an hour to get one person through—to pass the six or seven million still living in Earth Three would at this rate take six or seven million hours—a mere eight hundred years if you didn't bother with the extra leap-year days or take Christmas off.

Time passed slowly and it was the full hour before Virginia came through completely and arose from her chair.

"Collect Bronson or kill him?" she asked.

"I should have killed him," said Moray.

"Not at all," replied Virginia. "Even though this is quite similar to our world remember that thirty years of time separate us—and thirty years each of divergent development. We need someone to show us our way around."

Moray shrugged. "He might guess about this factor?"

Virginia shook her head. "No," she said with finality. "He's just beginning to think about the space resonator. Look at that pile of haywire junk! He's downright dumbfounded at the idea of communicating over a lump of electron-bombarded radioisotopic compound.

"To consider the transmission of matter from one volume of focus to another is an idea beyond concept. And—no doubt—radioisotopes aren't dished out as easily here as they are back there."

"Here, there, whither?" grinned Moray. "Let's call this Earth One because it is going to be here long after Earth Two has dissolved in atomic flame."

"Okay. So we've got this station first. We've got to get enough radioisotopic phosphor passed around Earth One to make wholesale passage possible. You run this station, Moray, and I'll stand by to act as a front."

Moray looked at Virginia closely. Slender, blonde and possessed of an ethereal and almost violent beauty, her personality and looks could and would forestall much idle questioning. He nodded.

"You keep out of sight of Friend Bronson," he said. "It might be handy to have you for a—a face card."

Virginia grinned....

Ed Bronson had a splitting headache and a crying pain in every muscle. He had been lying motionless. It was all he could do against the adhesive-taping job done by Peter Moray. His tongue was thick and furry and his very soul cried for water. He could make no sound for the tape covered his mouth.

Angrily, and resentfully, Bronson's temper flared. He set his muscles against the tape about his wrists and strained. He tried the tape about his ankles. Both were wound many times with the heavy tape which would not be torn.

A twisting strain succeeded only in abrading his skin until the flesh was raw and bleeding. With fading hope he prayed that the blood would soften the tape and thought about rubbing himself raw even more so that the further flow of blood might aid.

He gave that up when he saw that the tape was of the waterproof variety. All the soaking in the world would do little good.

He rolled from the bed onto the floor, easing the thud by dropping taped feet first and then angling to knees, turning to land on his buttocks and then unfolding as gently as he knew how. He made it with no undue effort. Then he rolled across the floor to the door and, turning, he caught the hinge-butt under the tape at his wrists where tape and wrists made a small triangle.

After many minutes, Bronson succeeded in weakening the tape and then, hooking the tape firmly over the hinge, he tore it loose. To remove the tape from his mouth and from his ankles was but a moment's work and then Ed Bronson was free to act!

Quietly, he dressed. Then, using the utmost stealth, he stole down the stairs and out onto the street. It was midmorning.

Nodding amicably to Lewis McManner, who scowled back across the street, Ed Bronson headed for police headquarters.

CHAPTER IV

"What Fools—"

Ed Bronson thought it out on his way to the police station. Man was an impossible mixture of altruism and selfishness. Man was inclined to give freely to those who were needy—but would fight like fury to withhold the very smallest of his possessions from the avaricious grasp of those who would wrest them from him by force.

As a world requiring pity, aid and mercy, every effort would be bent towards that end, even to the job of making room for them in an already crowded world. But they had entered like bank robbers or claim jumpers. Their own world lost, they intended to abandon it, pirating any other world they could.

The brotherhood of man collapsed at that point and became a brotherhood of hate. Tolerance and mercy and willingness to offer succor must be forgotten when the needy become vicious. Biting the hand that feeds is an old platitude which still holds true.

So Ed Bronson knew that, regardless of their wretched situation, they must be stopped. This was invasion with capital letters. Even though many of them must be direct descendants of people in this world, invasion meant war! Even worse than civil war was the brother against brother, man against man, war of survival.

They—and Ed Bronson paused. 'They' was an indefinite term. 'They' should have some nomenclature for purposes of identification. Were the invasion from another planet, 'they' would have a name.

Were it merely an earthly war, country against country or political clan against political clan, both sides would have names. But here was a case where it would be one earth, one world, against another world—identical save for a trick in time that had split them apart.

Bronson needed a name and he needed it quickly. He reasoned and came to the conclusion that the 'other world' should be called Earth Two because it was not long for living. Once it was destroyed by its own fire this world would revert to being 'the' earth. Until such a time as differentiation became unnecessary he would call the two worlds Earth One and Earth Two.

Thus, independently, did the people of three almost identical earths arrive at the same conclusion. Earth One was the original, where the Alamogordo Experiment had been successful. Earth Two was where the million-to-one chance of starting an all-consuming atomic fire had actually happened. Earth Three was where the Alamogordo Experiment had failed.

Ed Bronson and the folk from Earth Two were still to learn of Earth Three and it was only sheer reasoning that made all three systems of nomenclature congruent.

So by the time Ed Bronson located the police department he was prepared to give a coherent story. He asked for the captain in charge.

"Cap'n Norris is busy," grumped the desk sergeant. "What's the matter?"

"My home is being invaded and—"

"Well, you don't need the captain for that," snapped the sergeant. "Joe! Eddie! Get the wagon and go with this here—what's your name, mister?—and see that the guys that broke into his place are canned!"

"I'm Ed Bronson," explained Ed. "But—"

"That's all right," grunted the sergeant. "Joe and Eddie'll take care of you!"

"But you don't understand," said Ed patiently. "These are invaders from another world."

"Invaders from—what?" asked the sergeant, doing a double take.

"They're just the beginning," said Ed. "If you manage to grab them others will be coming."

"Eddie—Joe! Forget it. This is a Number Seven deal."

Joe and Eddie looked at Ed Bronson with an odd glint in their eyes. The sergeant looked down across the desk and said, "Now, Mr. Bronson, suppose you come with me to the captain's office and we'll talk to him."

"That's fine," said Bronson. "You see, I'm not sure of what to do about it all."

"Captain Norris will be able to help you," said the sergeant. "This way."

He came from behind his desk and led Ed Bronson to the hallway door. He opened the door and stepped back, permitting Ed to go first. Ed found himself in a short hallway and started down it uncertainly. The sergeant followed him until he reached the proper door.

"In there, Mr. Bronson," he said.

Bronson did not make particular note of the fact that the desk sergeant had at no time been with his back to Ed. He opened the door and found himself facing an elderly wise-looking man who had the appearance of having seen, heard, and experienced, either first-hand or vicariously, every item of trouble, grief and sin in the list.

"Captain Norris, this is Mr. Bronson. He has a bit of trouble. Thought you'd best hear about it."

"Sit down, Mr. Bronson, and tell me about it," replied Captain Norris easily.

"Well, sir, in the first place, I am an electronics specialist. It's—"

"A scientist of some sort, is that it?"

Ed nodded. "Most of us shy away from the name 'scientist' but that's about it," he said. "So you're a scientist?" smiled Norris.

"Yes. And I was experimenting on a bit of radioisotopic phosphor, hoping to make a better, more brilliant television picture."

"Has this all got to do with the people who are breaking into your home?" asked Norris.

"Yes. That's how they got in."

"I see. Then go ahead. No, Sergeant Foster, you stay because you may have to do something about this and it is best that you get your story first hand. It'll save time. Now, Mr. Bronson?"

"Well, under the combined forces of the magnetic field and the electronic bombardment the phosphor vibrated. I half recognized the vibration. It was like a very faint whisper in another room that you can't quite understand—but you know that someone is whispering.

"So I went to work on the phosphor and used a contact microphone on it, and got in touch with some woman, who gave her address as across the street from my home. When I went over there, I discovered that it couldn't possibly be correct. Later I refined the thing a bit and learned that her name was Carlson. Then I built a means of talking back to her, and I learned that she was not on this world at all. It was—"

"Not on this earth—but talking American?" demanded Norris.

"Yes."

"Do go on," said Captain Norris, putting down his pipe and leaning forward a bit.

"Well, you see, Captain Norris, there were some of the Manhattan Project physicists who believed that there was a chance that the atomic explosion might be strong enough to start a fission train in the earth itself. In other words, they were afraid of setting the earth on fire atomically. This was a possibility, and it seems that we now have two worlds, each following the natural chain of events pursuant to the two different possibilities."

"Very interesting, Mr. Bronson. Please go on. There must be more."

"After learning this, we decided to do what we could to alleviate the difficulty. I went to bed. In the night—or rather while I was asleep, they used some means or other to pass through from one world to the other and one of them clipped me and taped me up. He told me that they were going to move in on us—to displace us. I escaped and came here. Something must be done!"

"Indeed! Something must be done indeed," replied Captain Norris.

Bronson took a deep breath, and said, "I'm glad that I had this chance. It was a heavy weight on my mind, knowing that this was happening and I was the only one in the whole world that knew the truth."

Captain Norris nodded. "I trust that you are feeling all right now?"

"Of course."

"We'd better get you to a doctor, Mr. Bronson. Those wrists look inflamed."

Bronson looked down at them. "Now that this affair is in the hands of authority," he said, "I think I can take time off to see a doctor."

"We'll take you to our doctor," said Captain Norris.

"I have my own," said Bronson.

"We—insist!"

"But—"

Norris smiled genially. "You'll like our doctor," he said. "He's such a nice congenial fellow. Everybody likes him. Now—"

"What is this?" demanded Bronson.

"Take it easy," said the captain, "it's just routine. Everybody who gets hurt in the course of committing a crime or being victimized in such is always treated by the official medical department. Just a matter of establishing legal medical evidence, that's all. Now relax, Mr. Bronson, and come along. I'll have the boys take you to the hospital."

"Hos—?"

"Routine. The doctor works for us, Mr. Bronson. Therefore he has no office hours. Logical?"

Joe and Eddie treated Ed Bronson to a wild ride through the city streets with the siren on full. They slid to a stop in front of a squat, dirty limestone building and they escorted him in—convoyed him in, to be exact, for one went in front and one followed up the rear.

"I am Doctor Mason," said a white-clad man, meeting them in the corridor of the building. "Captain Norris told me you'd be coming."

"Just abraded skin, doctor," said Ed, showing the doctor his wrists.

"We'll take care of that instanter," smiled Doctor Mason. "Meanwhile, what's this tale you were telling Norris? Something about hearing voices? Threatening voices?"

Bronson recoiled a bit.

"Now, relax," said Mason.

"Do you think I'm crazy?" asked Bronson sharply.

"Of course not. You're not crazy, my boy. Just tell me—"

"You—"

"My friend, the symptoms of paranoia are simple and easy to determine. The hushed voices, in the earlier stages, merely talk about the victim. In a later stage the voices threaten. In still a later state the hushed voices take physical being and all too often it is someone entirely innocent of any malice.

"Now this tale of people from another world, Mr. Bronson, must be faced for what it is. You are not crazy, my boy. Merely ill—no worse than a bad cold or influenza, for instance. But you are ill and you must be treated."

"Treated?" exploded Bronson angrily. "Treated—for an imagined mental ailment when the earth itself is in danger of being invaded?"

"The earth is not in danger," said the psychiatrist firmly. "And—"

"I will not be—"

"Violent, too," said Mason with a solemn shake of his head. "Normally, we try to gain the patient's confidence. But in advanced cases of paranoia, they will resent even altruism. Everything is suspected of plot. Now, Mr. Bronson, whether you believe that this is for your own good or not, you're coming with me. Will you come quietly or shall I have some orderlies bring you?"

Bronson shook his head and turned to go. He walked into the waiting arms of Joe and Eddie, who subdued him easily because they were well trained in the art of handling men. Mason waved them on, and Bronson walked with both arms in hammerlock behind him. He could either walk or have both arms dislocated at the shoulder.

Mason spoke to the policemen. "The thing that makes psychiatry tough is that the patient likes himself the way he is—just as all men do, really—and resents bitterly any suggestion that his personality be changed."

"What do you intend to do?" asked Joe.

"Electro-therapy," said the doctor in a decisive tone.

Bronson writhed in both physical and mental anguish. He, the only man on earth that realized the danger, being dog-walked into a cell—accused of the crime of warning the earth of its fate! Outnumbered, overpowered and disbelieved!

CHAPTER V

Head Start

Leader Kingston shook his head. "Bronson is dangerous to us," he said.

Maddox nodded. "If his tale is believed Earth One will arm against invasion."

"Correct. Properly to save us trouble the invasion must take place against small armed odds. Otherwise, instead of our finding a world decimated and wearied by war, we'll find a world with its wits sharpened and its anger high."

Maddox turned the focus knob to readjust the image that had fuzzed a bit because of a varying line voltage. He pointed to Bronson's image, struggling against the policemen.

"He's in a fix right now," he said.

Kingston nodded dubiously. "But he'll not remain there," he said. "Bronson is suspected of being paranoid right now. Any man coming to high authority with such an unbelievable tale of alien entities or time-divided worlds would be suspected of insanity. But before anybody tries to cure him, they will give him their most extensive tests to prove or disprove his sanity.

"It is a fundamental principle that no man need be subjected to treatments or cure that needs them not. It is a violation of human integrity to attempt to cure a man of delusions who has no instability. Therefore they will apply the last word in checks and tests and discover that Bronson is not insane.

"Once they discover his stability they will admit the shadow of a doubt. Only the completely insane will not admit their error or possibility of error. An honestly sane man will admit—however grudgingly—the possibility of anything, even to alien entities and split time-continua."

"Then—?"

"Then let them listen but once to his flanged-up space resonator. His is a fine spectacle, you admit—about as neat and as efficient as the First Radio Receiver. On such, many people are making many transmissions of all sorts. Obviously, Maddox, the state of the art is higher than the technical efficiency of Bronson's gadget which to men of science will mean that there is something to Bronson's story. Follow?"

Maddox nodded. "The men who know will have sufficient knowledge to evaluate the negative evidence. They know of no such technique."

"Exactly," nodded Kingston. "Precisely. This we must stop!"

"This we can stop," said Maddox.

"How?" demanded Kingston sharply.

Maddox made a wry grin. "Watch," he said. He turned to the kinescope screen once more and watched Ed Bronson prowling the lonely cell....

For the thirtieth time, Ed Bronson paced his tiny cell. It was hopeless. Everything mobile was too large and soft to use as tool or weapon—for either egress or self-destruction. His clothing had been removed forcibly and Ed Bronson seethed angrily, dressed in only his skin.

He realized that he had been a fool. Had he been less violent he might not be so well incarcerated. He should have known that no amount of physical struggle would get him anything. After all he had striven against greater numbers of men who were all trained in the art of handling men possessed of the strength of the insane.

Bronson had only the strength of the indignant, which was far from the unreasonable power of the insane. With the use of a small amount of foresight, Ed Bronson knew that he might have been in a room less bare, perhaps one in which the door had not been bolted, barred and locked.

Bronson, it must be told, was not aware of the fact that the men who held him were also used to prisoners possessed of the cunning of the insane. No amount of cajolery, honest protest, supine acquiescence or willing aid would have made them do other than lock, bolt and bar his door.

What Bronson needed was a friend....

Maddox smiled with grim humor. "We cannot silence him now."

Kingston nodded, his face clearing of its slight frown. "Good man," he breathed.

"Nor," said Maddox, looking at the cell depicted on the kinescope tube, "can we aid him to escape."

"To kill him inside of that room would most certainly prove to them that enough of his tale is true to make them suspicious. Even to open that room and let him out will prove to them that there is more than the agency of a single man at work."

"In other, terser words," grunted Maddox, "he has placed himself in a position where he has life insurance—only in the name of Earth Three."

"And you see to it that he stays alive, suspect and helpless!" snapped Kingston.

"That I shall do," nodded Maddox. "That I shall do!"

"Unless, of course, he is threatened by death with both killer and motive indigenous—or apparently so—to Earth One."

Peter Moray turned to Virginia Carlson and shook his head. "Won't work," he said.

"Why not?" she asked.

Moray explained. His explanation was almost identical to that of Kingston and Maddox. To hurl a man into an asylum for hallucination is all well and good. To protect society, for any number of reasons all directed at the protection of society, from the maniac or to protect the maniac from society is sound.

Yet no man can be incarcerated very long if he is sane and wants to get out. It is as difficult for a sane man to fake insanity as it is for an insane man to fake insanity.

"So what do we do now?" asked Virginia.

"We should have eliminated him at once," snapped Moray. "Confound it, I was sleeping. I thought he might be useful."

"You were wrong," she said. "It seems to me that we might as well give him the works. I'll go down and see that he is taken care of."

Peter Moray nodded. Bronson had seen Moray but had never seen Virginia. In fact, Bronson knew only Virginia's last name. That was a help. Also, Virginia was a very good looking young woman and the power of a beautiful woman who speaks with certainty is great. She was also a capable calculator and could plan her campaign as she went along. Moray nodded, and Virginia headed for the asylum.

In her handbag, Virginia carried a small automatic. Bronson was a threat. The threat must be eliminated. The lover's quarrel perhaps or, better, he was in the asylum for paranoia. Why not have him attack her? Self-defense is a good alibi and her story would be strengthened by the doctor's decision. She smiled cryptically.

Supposing she were convicted of murder in the first degree and sentenced to the gas chamber? By the time the trial came to its end, the invasion would be ready and the first act of the men of Earth Two would be to rescue Virginia from her cell. She had everything to gain, nothing to lose by acting—and there was an entire world dependent upon her.

Confidently Virginia opened the door of Bronson's house and headed down the street. It was her first venture outside along the ways of Earth One.

In the morning, from her home, there were two lights in the sky, one a disc rising in the east, one a blinding glare that rendered the disc ineffective. Albuquerque never really knew night nor had it during the course of Virginia Carlson's life. Here, however, there was but the shining sun and Virginia found the streets a bit sheltered, shadowed, compared to the streets of her home.

But—the thought came to her—this was her home! She walked along the same street as the one she lived on. She looked across the street from Bronson's front steps and saw her own number there. It was a different house but none the less it was her number. It was sandwiched between two other houses whose outlines and architecture she recognized.

The street light was there, recognizable, though this one was not the remaining remnant of the pre-Alamogordo era. The one in her Albuquerque had not been used in the course of her life, though it had not been removed.

The street-car line was still on the next corner, and the cars that ran might have been the same—could they have been? Interested, Virginia waited until one came along and, though she could not be certain, it seemed the same.

It was a matter of interest to find out whether the same cars plied the same tracks in two different time streams. This seemed at once paradoxical and quite possible, for Virginia had seen both her own street address with a new house on the location, and the houses on either side which were older than Alamogordo and recognizable.

Virginia walked on slowly, a number of things running through her mind. Even though the city seemed the same, there was quite a difference. The population was thick here, not thinned out by radiation-sterility. The people were smiling and unafraid. On no face was that look of stark wonder and fear that never left the faces of the people of Earth Two even though they had been born and bred under the blinding light of the Alamogordo Blow-up.

Nor were there the mutants.

That was what made the most difference. In her life and counted among her friends were strange biological forms, often unhuman. There was, for instance, a fellow called Thomas Lincoln whose eyes grew on stalks and was quite a man at work on large machinery because he could see deep within the machine without having to rely on mirrors or the sense of touch.

His eyes, when extended, could either assume the proper distance for perspective, could narrow or widen the angle of perspective—and his mind, trained over the years, made due allowance so that he knew and accepted these differences.

There was Greene, the man whose hands had a palm on either side and whose fingers could bend to make a fist on either the inside or the outside of the arm. This might seem good, but it presented a lack of firmness. Greene's hands were far weaker than Harrison's, whose hands had but three fingers with twin thumbs on either side, making the hand symmetrical.

Her girl-friend, Edna, secreted pure metal instead of pigment and her skin and hair had a metallic sheen that was rather beautiful. In a strong light, Edna's skin and hair were almost luminous, like iridescent paint. There was the fellow that lived on the corner—Virginia never knew his name—who had a double knee and elbow. This made for physical instability.

There were others. Some were interesting from functional standpoints, some were interesting from banal standpoints. Others were just horrible and many were viciously dangerous. But many of them were her friends. Virginia had grown up without one iota of prejudice regarding the shape of a man's body, the color of his skin, or the nationality of his father. For in a life where few men were as simply mutated as to have a mere skin coloration, all of the former prejudices were so minor in the face of the acceptance of the more violent differences that to accept the latter meant complete disregard of the former.

This world contrasted sharply with Virginia's world. To see people walking freely in the streets, pursuing their normal life, was puzzling. Virginia, born in the glare of Alamogordo, under a culture that had devoted itself completely to one main idea or to the secondary or tertiary support of those who pursued that idea, this freedom was inexplicable.

In Virginia's world, there were two classes of people—those who worked directly on the problem of saving their world in one way or another and those who worked to support those who worked on the problem. Farmers produced so much, by law. Book dealers sold so many kinds of books, produced by printers and publishers who did exactly what was needed and no more. Entertainment and relaxation was far from spontaneous.

People did not collect at random and throw a party on the spur of the moment nor could one decide to go out and buy a magazine and read it instead of cleaning out the basement. Though it was admitted as such, it was an emergency dictatorship, with the Alamogordo Blow-up as main dictator. Regulation was the order of the years.

Earth One was, to Virginia, completely unregulated. Women walked along the streets idly, looking in windows and smiling at men. The sign "Bar" intrigued Virginia. She was no stranger to the potable qualities of alcohol, but the concept of an establishment directed at the sole idea of selling drinks had not occurred to her.

This—recall—was Virginia's first experience in living in a world not harassed by fear.

She paused at a window showing an assortment of dresses on well-made forms. In her world, Virginia was a good-looking woman and dressed as well as the next.

In contrast to a world where much time and energy was directed at luxury instead of the sheer, vicious necessity driven of hope and despair—in a world where the accolade of young womanhood is to be permitted her first trip to mother's beauty salon and thereafter make obeisance regularly—Virginia, a beauty in her own world, knew that here she was as conspicuous as a tall telephone pole in a snowbound prairie.

She knew because the window before which she stood reflected her own hand-made dress against the luxurious mannequin inside the window.

Moray had been correct in his assumption that a beautiful woman could get away with more than a plain one. His only mistake was in not judging alien demands for grooming. And yet it was not a true mistake. It was rooted in sheer ignorance.

Virginia wondered. Money? Coinage does not change very often. But the few coins she had in her bag would not cover the two figures to the left of the decimal point—iffing and providing that they were still good.

There was, on her right hand, her mother's diamond. On her left wrist was a wristwatch of quite ancient vintage—Virginia automatically called it "Pre-Blast"—which might bring a few dollars.

Virginia turned from the window and went across the street to a pawnshop. She emerged with a handful of greenbacks, re-crossed the street and entered the ladies' shop. With satisfaction Virginia noted a beautician's place next door and, though rather questioning of the nefarious arts that might go on behind the curtains, Virginia was determined to compete with her contemporary girl-friends on an even basis—perhaps with a fair head start!

CHAPTER VI

Sprung by the Foe

John Cauldron made contact with Peter Moray shortly after Virginia had gone. Moray, busy with the details at hand, had not given much time to thinking out the course of the future. Besides, it was Moray's business to act upon orders from above. His was not the planner's lot.

"What's cooking?" he asked Cauldron.

"We're putting on a security silence on the space resonators," replied Cauldron.

"Why?"

"Whether they think Bronson insane or not, whether he lives or dies, we must see that there are as many bits of radioisotopic phosphor in Earth One as possible."

"Yes, but—"

"Bronson may be judged insane. However, give him a chance and he will demonstrate the space resonator. If he should pick up an Earth Two broadcast or even a molecular pattern it will lend weight to his tale. On the other hand, Bronson will be given credit—sane or otherwise—for the invention of a new level of communication.

"When it becomes known that gross matter can be shipped across space with the same scientific concept people will rush madly to develop and build delivery sets."

"I get it."

"Sure," replied Cauldron. "It's easy enough. Tell Virginia—"

"She's gone already. She left to take care of Bronson."

"Oh blast! Look, Moray, how are people dressed there?"

"Why—I wouldn't know. Bronson was in pajamas when I intercepted him and it's just barely morning now. I've not really been out yet."

"You should have taken time to get Virginia fixed up as close to one of the women of this world as possible."

"Why?"

"Because she'll be less conspicuous," said Bronson. "If they get to peering into Bronson's mind they'll come to the conclusion that he isn't as mad as his tale sounds. Give them one overly-conspicuous character to look at and they will definitely begin to think loud thoughts."

"Well, why shouldn't Virginia get along?" demanded Moray.

"You're a young squirt," snapped Cauldron shortly. "You weren't around before the blow-up. You haven't the vaguest idea of how much time and hard money was spent by women on the luxury of appearing beautiful. That has been curtailed on Earth Two by necessity and emergency. But I'll bet a tall hat that they are still shelling out plenty there. Is there a telephone book handy?"

"Yeah," said Moray.

"Then crack it to the classified section and tell me how many pages there are of beauty shops, beauty salons, beauticians, or whatever they're called."

Silence ensued for several minutes and then Peter Moray returned and gave Cauldron the answer.

"You see?" replied Cauldron. "You have no idea of how life is lived when there is no cause for fear."

"So—"

"So I'd feel better if Virginia were heading for that place in something better than a hand-made dress of reclaimed cloth, a self-done hairdo and flat-heeled slippers. Besides," he chuckled wryly, "it would help her morale no end."

Harry Maddox turned from the hapless spectacle of Ed Bronson and shrugged. "He's safe," he said. "Now what?..."

"They've gone into a security silence," said Kingston. "As we expected."

"Then our friend Bronson is no longer needed?"

"Nope. They'll get along without him, now. What worries me is that the psychiatrist may get to work on Bronson long enough to establish a reasonable doubt in their minds."

"Even so," said Maddox thoughtfully, "we're stuck. Supposing we were to kill him? It's obviously impossible in that room. It is equally impossible for him to escape nor can we arrange it."

"What we need is a person who might be quite willing to murder Bronson in cold blood for the sake of murder itself—or even better, for some mundane motive."

"What about the characters from Earth Two?" suggested Maddox.

"Let's find 'em," snapped Kingston, apparently struck with an idea.

Maddox had little trouble in locating Moray. He looked in on Peter Moray for a moment, and then went in search of Virginia. Virginia, apparently, had disappeared.

It was quite impossible to search every possible place in Albuquerque for a glimpse of Virginia and, after covering the pathway to and from Bronson's cottage to the police station and thence to the police hospital, Maddox gave up and returned to Moray, who had stopped speaking to Cauldron. As Moray turned away from the equipment, the telephone rang, and he went to it, wondering.

Moray lifted the phone and said, gingerly, "Yes? This is the Brons—"

"Moray! This is Virginia. I'm going to dig Bronson out of the clink and bring him home. You hide or at least lie low. Follow?"

"Where are you?"

Virginia named an address.

Kingston snapped, "Get that address—quick. Know where it is?"

"Heck," drawled Maddox insolently, "This is the same Albuquerque. Sure I know the address."

The video screen showed a blur, and settled on the showroom of a ladies' apparel shop. Virginia was just hanging up the telephone and Maddox whistled.

"Knockout," he said succinctly.

"She got the works," grinned Kingston. "Thanks to her we can watch."

"Well," said Maddox thoughtfully, "there goes your party with murderous intent, and quite worldly too."

Kingston nodded. "That automatic in her bag isn't an unaccustomed weapon," he said thoughtfully. "And she can and will claim attack. Self defense...."

Clad in a printed silk that graced her svelte body caressingly, with the sheerest of hose, the seams of which ran die-true down from the hem of her dress to her sandal-shod, tiny feet, Virginia Carlson of Earth Two was well on her way to being the most fetching woman in three worlds. Her hair had been coiffed to perfection and her face had been made up by an expert.

Virginia looked soft and sweet and perfect. She was a sight that made men turn to watch but not to whistle because she radiated some quality that rendered the wolf-whistle a definite insult.

Then, patting the automatic confidently, Virginia turned down along the street once more and headed for the police hospital. Though she could not know it, the plane of focus of the video resonator followed her. Maddox and Kingston were watching her as she went.

"Once this is finished," thought Virginia, "I shall enjoy living like this!"

Her feet, unaccustomed to dancing, did a pointless little step. Her eyes sparkled, iris wide even in the morning sunshine, for Earth One had no eternal light in the sky to keep a dazzling brightness day and night. She pirouetted once and the sleek silk frock whirled and clung to her legs. As she stopped, the weight of the automatic in her bag hit her and reminded her of a job to be done before all this could be hers.

Bronson must be stopped—somehow!

Virginia knew how.

With a fetching smile on her face Virginia entered the police hospital and asked for the police physician. Doctor Mason came and was a bit set back by the obviously high quality of his caller.

"You're—?"

"Virginia Wells. I'm a friend of Mr. Bronson."

"Indeed? A peculiar case, Miss Wells," he observed gravely.

"Not at all," she said with a smile. "Mr. Bronson, as a hobby, has been writing fiction and we got into an argument as to whether high authority could hear a rather bizarre tale without thinking the story teller was insane. I won."

"So that's it," grunted Doctor Mason. "He sounded sincere enough to me."

Virginia shrugged shapely shoulders and hurled at him the dazzle of her smile. "After all," she said in an entrancing contralto, "he is a successful author even though he doesn't work at it one hundred percent of the time. He should be able to concoct a story that would hold water, and he should be convincing. Why, that's his business!"

"Um."

Mason left the office for a moment and came back with Bronson at his heels—dressed.

Virginia gave Bronson a warning look and then laughed at him. "Like spending the night in the clink, Ed?" she asked brightly.

"No!" he snapped.

"You needn't have," she said with a smile. "All you had to do was tell them the truth. Why, they'd have thrown Orson Welles into jail for the Martian Invasion if he hadn't been famous."

Bronson started. The Orson Welles affair had taken place a long time ago—before either of them were born, in fact. This rather glorious girl was trying to tell him something.

"Yeah," he drawled, stalling for time.

"All right, so you lost," she told him. "And now, if you don't have to stay here for playing pranks, we can go on home and write it up."

Bronson looked at Mason. Mason shrugged. "What's the pitch?" he asked. "As for me, no—we don't want you though I'd like to have you reprimanded for wasting time."

"Come to think of it, Doctor Mason, how should a man try to tell high authority of some impending form of outrageous doom?" asked Virginia.

"Why—" stammered Doctor Mason, "I—"

"Yes," snapped Bronson angrily. "Tell us!"

"Why?"

"Because," said Virginia, sweetly, "some day someone is really going to come up with invaders from outer space or some other unbelievable little item and, while the big bright brass is psychoanalyzing the discoverer, the invasion or the doom will take place."

"Why—I'm—"

"Forget it, Mason," said Bronson. Then, because he was completely unaware of his visitor's name or anything else about her save that she knew something that prompted her to aid him, Bronson turned to the girl and held out an elbow.

"May I escort you home, Madame Pompadour?"

Virginia smiled at him with exaggerated enticement. "Only if you want to be Benjamin Franklin, dear."

Doctor Mason stood up and hurled the door open angrily. "Get the devil out of here!" he snapped. He was still looking for a fine vocabulary when they left. Once outside and on the street beyond, Ed Bronson paused.

"Now," he said seriously, "what in the name of eternal sin is this?"

"I had to get you out of there," she said. "I'm glad you are sharp enough to follow suit."

"You can be glad that Mason did not choose to question me about you," snapped Bronson. "I'd have denied you deeply."

"All a part of your tale to convince," she smiled. "I'd have forced it into the open—forced Mason to let us meet. Then we'd make out."

"Fine, fine," he said with a bitter grin. "Just tell me what the score is right now."

"I happen to know that you are right," she told him.

"But—"

She nodded. She explained at length that she had been tinkering in her cellar and had come in with something that had permitted her to hear his half of the initial discussion with the girl named Carlson.

She paused at that point and grinned at him. "Just to keep the record clear," she said, "I'm Virginia Wells."

"Well, Miss Wells, I'm grateful. But what does a girl like you find interesting in tinkering in the cellar?"

"You call me Virginia like everybody else," she told him. "As for tinkering in the cellars, when has a woman's appeal anything to do with the liking for science—and furthermore I might even resent the phrase 'like you' that was hurled at me. Do you think anybody that looks like this must necessarily be completely vacant above the ears?"

Bronson smiled. "Not every girl," he said with a sour smile. "But the percentage assays high."

Virginia took a deep breath. Thin though her story was, he'd accepted it for the nonce.

"Where do we go from here?" he asked. "I want to reason this thing out."

Virginia smiled tolerantly. "My equipment isn't very good," she said. "I'd like to see yours."

Bronson smiled. For hours he had been itching to show someone the equipment and this was his chance. He was going to take the opportunity regardless of where the chance came. Virginia had known that too!

The girl tucked a slender hand into the crook of his elbow. "Let's go," she said with a bright smile.

Bronson nodded and they started toward his home.

He walked easily, she thought, neither too fast nor too slowly. His stride seemed to coincide with hers so that the periods of out-of-step walking were minimized. They were not nonexistent, for Ed Bronson was a tall, long-legged man and, though Virginia's legs were long and slender, she was not so tall as Ed Bronson by seven inches.

"I might suggest," said Bronson thoughtfully, "that we can do a bit of talking while we collect us some lunch. Me—I'm hungry."

Virginia paused. Visiting a restaurant was another thing that was seldom done on Earth Two, excepting by those who found it essential. This she viewed as another luxury and she wanted to try it. On the other hand, she had too thin a story prepared regarding her 'experiments' with the space-resonant crystals of radioisotopic phosphor, of her listening to Bronson and his subsequent rescue from the asylum.

Yet—Virginia shrugged slightly—she could probably handle this. Besides, she could learn more of Earth One were she to visit with Bronson.

Virginia nodded and smiled at him. Bronson paused in mid-stride and turned toward a small restaurant he knew. Inwardly he chuckled to himself. It was not always that a woman rescuer, fellow scientist and friend-indeed was so very delectable. Bronson was proud to have such a woman in his company.

CHAPTER VII

Transfer Arranged

The automatic computer in the laboratory of atomic physics at the New Mexico University on Earth Three was a vast thing that encompassed many acres of wiring, tubes and memory-storage circuits.

It had been working silently—save for an occasional click—for an hour, which was a pointed commentary on the depth of the problem presented to it, since its usual time of operation was startling in its brevity. It was, without a doubt, the great-great-grandfather of all automatic computers and even it was forced to mull over the problem.

Leader Kingston and Harry Maddox lounged before the massive control board, smoking and watching Virginia and Bronson on a small remote-presentation kinescope.

Finally the machine emitted a series of typewriter-like clicks and a sheet of paper emerged from the slot. It bore a complex equation that Maddox took and pored over.

Kingston waited quietly, for he knew that Maddox was far more capable than he at interpreting the equations. Any interference would interrupt Maddox, ruin his train of thought and require more time in the long run.

Finally Maddox looked up and smiled.

"It seems so," he said.

"There is no definite proof?" demanded Kingston.

"Time and the future are both based upon the laws of probability," replied Maddox. "That these three worlds do exist side by side by side in time is certain—that they might have existed at any time before they did start was a matter of probability. Anything is probable, you know. That we live is a most certain probability, yet that we will continue to live is less certain."

"You're talking in circles," snapped Kingston. "Get to the point!"

"Sorry, I must sound vague. You see, Leader, I've been thinking about this for some time and therefore I am inclined to think over the well-worn thought-trails swiftly and in considerable elision. However, according to this equation, the fact is this. The spatial continuum is strained by the unnatural presence of three congruent pathways through the present time.

"As we know, only the most probable of these will continue to exist. That—unfortunately—is Earth One. The Alamogordo experiment on Earth One was the most probable, of course. Obviously Earth Two is destined to die soon, leaving but Earths One and Three.

"But," continued Maddox thoughtfully, "we have posed the problem and the machine here reasons that we are correct."

"Then we need not undergo all the strife in order to survive!"

"Obviously not. Once the pathways through time are no longer strained by multiple existences the strain will cease. In other words, once we—Earth Three—are the only true survivor the strain will cease and there will be no fear of our demise."

"Then all we need do is to eliminate One and Two—and then," Kingston grinned, "Earth Three becomes the only one?"

"Three becomes One," nodded Maddox. "Now—"

"Now we figure out a means of destroying Earth One utterly."

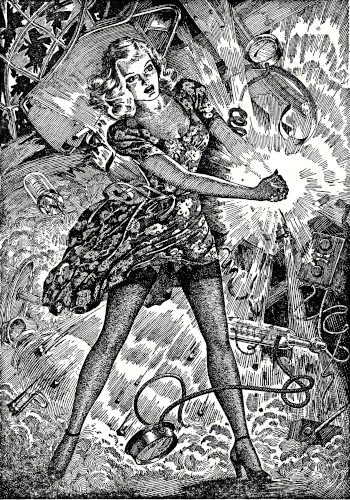

"Simple," said Maddox. "All we need do is to rotate a bit of the core of the Alamogordo Blow-up from Earth Two to Earth One."