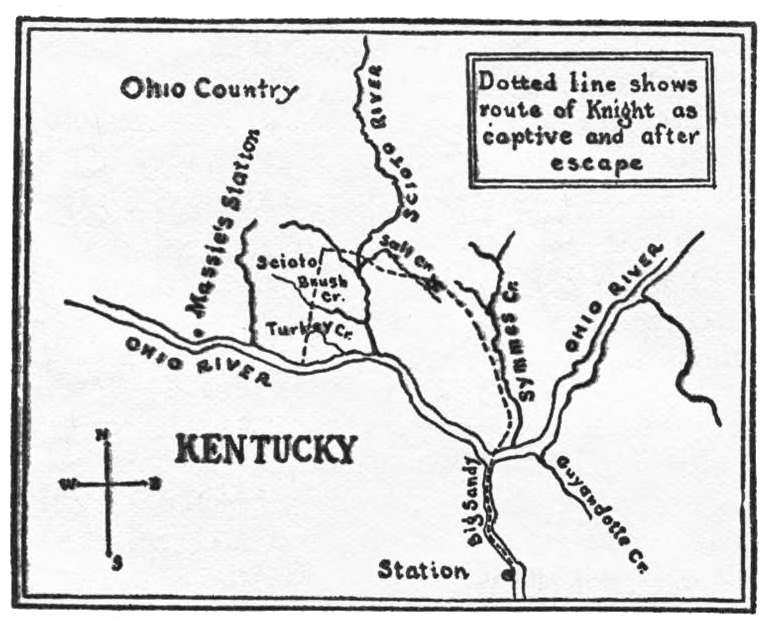

From the moment he was made captive near the station on the Big Sandy, the Virginian began looking for an opportunity to escape. He was ferociously angry at himself for venturing outside the station against the advice of the small garrison. Recently arrived from Richmond, he had presumed to know more about red men than did the border people. He had insisted the Indians had abandoned the siege after losing three warriors and having two wounded. And within easy gunshot of the stockade he had been jumped by the Wyandots and hustled away. His captors were from the Lower Sandusky village. Throughout the journey down the Sandy and up the Ohio to the Guyandotte Crossing he had nursed his resentment against the Indians and himself. In the back of his mind was the hope he would find an opportunity to break clear before crossing to the Indian shore. But the Guyandotte was reached and the Ohio was crossed without a minute of carelessness on the part of the raiders. At night the Virginian slept as best he could with a rawhide thong around his waist, from which lines were attached to the waist of a warrior on each side. In addition to this precaution his feet and hands were tied. When canoes were abandoned for forest travel his hands were tied at his back and he was led along by a length of rawhide around his neck. He fell and bruised himself. He was hauled through bushes and was scratched by briers from head to waist. At times the cord tightened, and he was all but strangled.

The leader of the Wyandots was a short, thick-set man. Unlike his followers he wore no paint on his face and his countenance was agreeable and very intelligent. His only attempt at adornment was the red stripe following the backbone from the nape of his neck to his waist. All of his men were similarly painted and in addition were grotesque and frightful because of the patterns masking their faces. The raid had been a failure, and the warriors were in an evil mood. The chief realized that his popularity as a leader would quickly wane did he encounter one more defeat, yet he treated the prisoner kindly once a camp was made. In person he saw to it that the Virginian had water and meat. This consideration led the prisoner to believe that at the worst he would be held in some red village until he could be ransomed.

After he reached the Indian shore several ambitious young men remained behind and did not rejoin the band until the evening of the second day. They brought in two scalps and one prisoner. The chief rejoiced greatly. He would be credited with victory by a slight margin. The horrid proofs of the tragedy were danced with much enthusiasm that evening.

When he found himself by the prisoner the Virginian asked for details.

“We was took by surprize while setting traps for beaver and otter,” the man explained in a monotonous voice. “I’m Abner Bryant. There was the three of us, Ben an’ Tom Durgin an’ me. Ben ’lowed he could make a fire-hole in a clump of willers that no Injun could see. Well, both the Durgins are dead.”

He was a thin, dried-out wisp of a man whose head was thinly frosted by a round number of years. He spoke without emotion, as one who is weary. His acceptance of his capture and the death of his friends smacked of fatalism. The incident was closed and did not interest him. However, he was curious enough to inquire—

“Who might you be?”

“Harry Knight. A fool. Knew more’n my elders at the station on the Big Sandy,” was the bitter reply. “We got three of them. Then I had to go outside the stockade to prove I knew it all and that the Injuns had gone. Now I s’pose I’ve got to put in a winter in some filthy village.”

Bryant eyed him in mild surprize and asked—

“Know their lingo?”

Knight shook his head impatiently.

“No sense to their jabber. The leader treats me well. I think he likes me.”

Bryant pursed his thin lips and glanced appraisingly at the well-knit figure of the younger man and decided.

“You oughter last three days. They’ll manage to keep you alive for two, anyway.”

“Keep me alive?” repeated Knight. “But I ain’t sick. Bruised and scratched—”

Bryant broke in:

“Young man, you’n me will be painted black once we git to the Lower Sandusky village. Better they treat us now, the worse they’ll treat us when we make the village. I won’t need much killing. But you’re younger an’ stronger. You’ll be stubborn an’ die hard. I’m nigh to eighty. Forty-odd year ago they’d had a rare time with me. My pride would a held me up. Now they won’t git much fun out of my dying.”

“Merciful heavens!” hoarsely whispered Knight, and he turned to stare at the leaping, gesticulating figures circling the scalp poles.

The older man casually explained:

“Of course I tried to git killed along with Ben an’ Tom. Didn’t have no luck. Chief there is Cap’n Jimmy, his white name. Red name’s Little Beaver. If you see the slimmest chance for ducking out, grab it. Don’t make over your back track. Strike west an’ lose yourself. If you live to hit the Scioto, travel southwest to the Ohio and follow it down to Massie’s Station.[1] As a fact you’ll prob’ly be overhauled mighty sharp an’ sudden. But that’s all right if they don’t take you alive. That’s the prime p’int I always tried to ding into our settlers. Never be took alive. Now see me! Trussed up like this! ’Low I’ll raise the chief’s dander. Sometimes you can git them mad enough to swing an ax and cheat themselves out of the torture.”

He threw back his head and in the Huron dialect loudly called out:

“Ho! Ho! They say a chief runs back whipped from a red path. They say he throws away his warriors like a foolish man. Has a wolf stepped over his gun and spoiled his medicine? His young men break away and bring two scalps. Where are the scalps Little Beaver has taken?”

The chief stared at him ferociously. A man near-by reached forward and struck him across the mouth.

Bryant philosophically remarked:

“Well, it didn’t work that time. Mebbe next time.”

A man brought water in a kettle and held it up for Knight to drink, but gave the old man none. The latter mused:

“Still treating you like a brother. But wait.”

“I’ll not wait. I’ll try to escape the first time my hands and feet are untied,” muttered the Virginian.

Because of their two wounded men and the loot taken from two cabins on the Sandy the band covered not more than a dozen miles a day. During the three days they traveled up Symmes Creek Bryant was loaded with plunder while Knight was compelled to carry nothing. He gladly would have shouldered the old man’s burden, but the later explained:

“Best this way. If you git a glimmer of a chance to scoot you’ll need all your strength. I couldn’t make a race of it if I had half a mile start. I’ve lived my years an’ I’ve sent a sizable number of them on ahead of me.” He paused and lifted his head the better to watch two men busy with something on the opposite side of the small fire. Then he was whispering, “They’re fixing black paint.”

“Black paint!” gasped Knight. “You said I’d be painted black.”

“Not yet. They’ll keep you to show at the village. Got to make some showing to offset the men he’s lost. The women folks would be mad if a prisoner wasn’t fetched in. Here they come. Keep a bold face.”

Two men briskly advanced bearing a bowl taken from some settler’s cabin. This was filled with a rough paste made from charcoal and water. The other Wyandots gathered around to witness the ceremony. A man released Bryant’s legs and jerked him roughly to his feet.

The old man belligerently demanded:

“Are you women to be afraid of a man about to talk with ghosts? Untie my hands. You are young and foolish men. You do not know how to paint a man who will do you great honor by the way he will die. Are you afraid?”

The Indians approved of this sturdy bearing. He was old, just a shell of a man, but his heart was strong. Little Beaver said:

“He will die very brave. Let him paint himself.”

His wrist thongs were unfastened and his hunting-shirt was removed. He rubbed his hands and arms briskly to stimulate circulation. One young man stood behind him and the man holding the dish was before him. With much deliberation he took the fragment of pounded bark, serving as a brush, and began smearing the mixture over his scrawny chest. Little Beaver looked on approvingly.

Wild of gaze, Knight watched the old man calmly decorate himself for the fire. Bryant slowly drew a spiral and informed the interested watchers:

“This is a smoke medicine. It will keep me from choking.”

Those in the background edged closer, ever keen to learn about new medicines. Little Beaver grimly suggested—

“Let the white man draw a medicine that will keep the fire from burning.”

“He will do that after the smoke medicine is finished,” quietly assured the old man. “Let Little Beaver watch closely and learn about strong medicines. I heard an owl in the woods telling the ghost of my grandfather that Little Beaver’s medicine is sick, or asleep.”

Knight understood nothing of this exchange but felt the drama of it. The chief was now glaring malevolently and all were watching the prisoner with the greatest interest. Despite his terrible plight the younger man found himself likening the curious, expectant Indians to inquisitive little children. The comparison was grotesque, yet it persisted. The old man finished the smoke-spiral and held the dripping bark-brush high and sharply called out:

“Look! Look! With sharp eyes and see a strong medicine!”

The gaze of all was lifted to watch the brush, now slowly describing a small circle. With incredible quickness the thin claw-like hand shot forward and plucked a skinning-knife from a Wyandot’s belt and almost with the same movement thrust it deep between the man’s bare ribs. Simultaneously the brush was smeared across the face of the next nearest man. It was done and the prisoner was leaping toward the dusky woods before an Indian could make a move. Then Little Beaver threw up his gun and fired just as the prisoner was making cover.

Yelling like wolves, men raced after the fugitive. Knight huskily exclaimed aloud—

“He got clear!”

The old man had worked most cunningly. He had “got clear”—clear of the stake and the flaying knives, and never again could he suffer hurt. Bryant felt nauseated as the chief returned to the fire, carrying the yellowish white scalp.

There was no rejoicing over this trophy. Little Beaver respectfully placed it on the fire and directed that the dead warrior be hidden in the ground, or a hollow log, and that the camp be shifted a few miles. It was not a good place for Wyandot men to tarry in. The white man’s medicine was about the little opening. It had saved him from the smoke and the coals, even as he had claimed that it would. He had died painlessly and had cheated his captors. He was a very wise old man, and his ghost even now was laughing at them. Around red camp-fires he would be spoken of with great respect.

The camp was moved two miles to a creek.[2] The men were gloomy and dispirited. A strong medicine had worked against success on this path. Once the men decided Little Beaver’s medicine was responsible his following would fall off. None sensed this more quickly than the chief himself. Like his men he was in a gloomy state of mind when he took to his blankets. With his belt of rawhide around his waist Knight slept by snatches. Each time he woke up he was overwhelmed by his awful plight. It was so inexorable; so inescapable. The darkness was thinning when the first warrior rolled out and threw dry fuel on the fire. Knight’s appearance plainly revealed his state of mind. Unlike Bryant he could not make-believe.

His guards rose and unfastened the thongs running from their waists to the prisoner’s waist. His feet were untied and he was helped to stand. The men were courteous, even gentle, but now he knew all this was deliberately planned to increase his suffering. He held out his hands for one of the men to unfasten. The Indians had no fear that he could escape; and did he try his disappointment would be their joy. One of his guards released the thong and Knight rubbed his hands and wrists smartly. As he did this he looked for a possible avenue of escape.

The Indians’ guns were resting against a pole which was supported by two crotched sticks. If he attempted to run in that direction he would find but few between him and the timber, as almost all the men were around the kettle. But pursuit would be made by the warriors near the guns, which they could snatch up and use with deadly effect before he could reach cover. Had it been broad daylight he might have elected to attempt that course, and to count it success if he was shot off his feet. He had supposed all hope had left him. Now the gloomy woods, just beyond the fire, invited him to make it a race. If he took this direction he must win his way through and around the bulk of the warriors. But if he reached the growth they either would pursue him unarmed, or else lose time in running back across the opening to get guns.

He thought it out and made his decision inside a few seconds of deliberation. The very idea of attempting to do something gave him physical strength. He advanced toward the kettles. Little Beaver followed and overtook him as he halted as if waiting for his breakfast. The chief patted him on the shoulder. Knight met the smoldering gaze and smiled and nodded his head. The Indians averted their gaze to hide their amusement. The white man was believing them to be friendly. With a final pat Little Beaver dropped his hand to his side. Knight’s hard fist, starting from his hip, came up with terrific force under the chief’s chin and fairly lifted him off his feet. Then with a leap, and a jump to one side, and a left-handed smash in the face of a man he could not dodge, he was bursting through the fringe of bushes and plunging into the gloomy woods.

The complete surprize of it all dazed the warriors some seconds. Then they followed their first impulse, to run down and recapture their man. As they took the woods, whooping and howling, and armed only with their knives and axes, Knight fought against panic and even slowed his gait to prevent a collision with the faintly outlined trees. One of the warriors yelled for the men to secure their guns. Some ran back to do this. It was too dark for those pressing the chase to pick up the trail, and quite to his amazement Knight found himself on the bank of the creek. The infuriated yells and howls suddenly ceased and Knight at once imagined the foe were all but upon him. Still he practised enough self-control to slip into the icy waters of the creek and noiselessly make his way to the opposite bank.

He started at right angles from the stream and soon came to a long, sloping ridge, where there was more light. Up and along the ridge he ran until it did seem as if his pounding heart would burst.

For the first time he ventured to look back. He could discover no signs of pursuit, but he realized he must now sacrifice speed for cunning. Once the light strengthened, the Indians would pick up his trail and follow it at a run. He walked on ledges whenever possible. He took care not to break off twigs and small branches in passing through bush-dotted openings. He was young and in excellent physical condition. He was spurred on by the fear of something worse than death. He kept his back to the sun, and he chased after the sun. Late in the afternoon he came to a stream he knew must be the Scioto.[3]

He did not believe he could lift one foot ahead of the other, but fear told him he must place the river between him and his enemies. On the western bank he told himself he had done all that mortal could; and, flogged on by thoughts of Little Beaver’s terrible rage, he walked with staggering steps into the sunset.

With the first light he was continuing his flight and fought pains and aches for several miles before his legs limbered up. Two hours after sunrise he killed a squirrel with a rock and ate the scanty meat raw. Fortunately his mind focused on the fear behind him and he did not take time to realize he might run into another band of Indians at any moment. He entered the rugged hills around Sunfish creek. He was determined to use every hour of light for travel, and fear served as food and drink in keeping him going. Traveling south, he crossed Scioto Brush and Turkey Creek; and everything seemed unreal. Another night and day, and he halted and stared stupidly when he beheld a broad river, which, he knew, must be the Ohio. He was ten miles below the mouth of the Scioto. He had no idea of how and when he had rested, of the meager food of nuts and raw squirrel meat. But he did know he was gazing on the Ohio and the Kentucky shore beyond. His problem now was to cross the river although it was very possible that would mean from pan to fire. He remembered poor Bryant’s advice to make for Massie’s Station, but he had no idea whether he was above or below it. Nor did he know how much time had elapsed since he struck Little Beaver and escaped from the Salt Creek camp.

He crawled into a thicket of bushes as a befuddling sense of helplessness swept over him. His clothing consisted of a few rags. His moccasins were worn out. His feet and limbs and chest were scratched and torn by the wildness of his flight. As he stared at his poor feet he discovered he was weeping. He fought down the weakness, and was startled into lively perception by a slight splashing noise in the current above his hiding-place. As it sounded at regular intervals and appeared to be drawing nearer he forced his way closer to the bank to stare down through the tangled growth.

He felt as if he were suffocating when he beheld a man in a canoe. The man was dressed like one of the Long Hunters who lighted the Kentucky fire.

“Take me off! Save me!” Knight hysterically called out.

The canoe swerved in to the bank and out of sight.

“I’m a white man! Save me!” he repeated. As he received no response he cried again and again to the same effect.

“Who are you?” asked a curious voice behind him.

He turned in frantic haste and beheld the man, his rifle across his left arm. The man had landed and mounted the bank and gained the rear of the fugitive’s position without being heard.

In a recital that was almost incoherent Knight told his story. The man relaxed and rested the butt of his rifle on the ground. As Knight ceased talking the other squatted on his heels and checked off.

“You’re Virginny. Catched at the Big Sandy station. White man, named Bryant, was fetched in and got hisself killed. You busted loose. Injuns chasing you. That right?”

“Yes, yes. And we must be going. Set me across, will you?”

“You forgot to say what band of Injuns was it,” prompted the man.

“Little Beaver and his Wyandots. Cap’n Jimmy, the whites call him. Poor Bryant told me. Chief has red stripe up and down his back.”

“That’s Little Beaver. All his men have red stripes till they quit his band. My name’s Kinsty. I’d like to obleege you. Too much risk. If Little Beaver is on your trail he’d cross into Kentucky quicker’n scat to overhaul you.”

“Good heavens! You’re a white man. You don’t refuse to help me?” pleaded Knight.

“I’m just saying I ain’t going to cross to t’other shore and run the risk of having a Wyandot or Shawnee ax sunk in my head. There’s a better way. Twenty-five miles down stream, by the Injun path, is Massie’s Station. It’s a bit longer by water. Know anybody there?”

“No one. Not a soul.”

“Makes no difference. They’ll be glad to take you in.”

“If you won’t go with me then set me on the path. I must get somewhere that’ll be safe to close my eyes in, and sleep.”

“I’ll lead you there,” assured Kinsty.

“Then let’s get into your canoe and start now.”

Kinsty shook his head.

“Safer to foller the Injun path. Whose your folks back in Virginny?”

Knight got to his feet and hurriedly told the names of his people. Kinsty worked inland and struck into the old trail. As he walked along in the lead he seemed hungry to be told things and asked many questions about Knight’s home life, his friends, and the like. Knight patiently answered the queries, as he had learned this was a characteristic of isolated people. The first four questions a traveler would be asked at a frontier cabin would be: “What’s your name? Where you from? Where you going? What’s your business?”

Knight talked until weary, and finally complained:

“Can’t we push forward faster? Seems like we was holding back.”

“No hurry so long’s we got to make one camp. Can’t do it on a stretch. Least-ways, you can’t. Won’t do to git tuckered out. You must be good for a long run if jumped by Injuns. You say you can’t speak nary a word of red lingo?”

“Not a word.”

Kinsty halted and stared at Knight thoughtfully. Then he announced:

“’Low you’re all right and are the man you say you be. But at the first I had a sneaking notion you might be Greeby.”

“The monster who lives with Indians from choice and kills his own people?” exclaimed Knight in a horrified tone. For the renegade’s infamous acts had been rehearsed at the Big Sandy station although the man seldom ventured that far up river.

“Now I know you’re all right,” chuckled Kinsty. “Only a man who’s all right could speak in that way. It was your scratched legs and arms that made me suspicious. Your calling like you did was the first thing to make me suspicious. Greeby is a master hand for yelling from the shore for some one to save his pelt by setting him across the river. Some say he’ll wade out in the water and pray to be took off.”

“I’m what I look. A poor, helpless man in need of a friend. Why do we halt? I have many hours of energy left in me if there’s a safe bed at the end of the journey.”

“You think so but you’d go kerflummox first thing you know. You got to have victuals. We can’t git through tonight anyway. We’ll camp here off the trail and I’ll shoot something and make a soup. With a full stomach and some sound sleep you’ll go through to Massie’s mighty fine.”

“If you think best,” sighed Knight. “How far is it to the station?”

“Twenty miles,” replied Kinsty.

“Bout sixteen miles,” corrected a voice from the bushes.

Kinsty exclaimed under his breath and dropped on one knee and cocked his rifle. Knight warned:

“It’s all right. It’s a white voice.”

“It’s all right after we look him over,” growled Kinsty. “Stranger, whoever you be, show yourself. Both hands up and empty.”

A man stepped into the path between the two men, his arms raised, one holding a long Kentucky rifle. He said: “Here I be. Had to fetch the old gun along. Think I was red?”

“I knew you was white. But keep your hands up. Knight, lift up his hunting-shirt so we can have a peek at his back.”

Knight stared stupidly. The man good-naturedly requested: “Don’t waste time. This gun’s gitting heavy.” Then to Kinsty, “Just what you looking for, mister?”

“A red stripe up and down your back, Mister,” growled Kinsty.

The stranger laughed and exclaimed: “Beats all natur’ how every one you meet you sort of think may be that skunk Greeby. Go ahead, younker. My name’s Daniels. Been in the bush so long my back ain’t very clean, mebbe. But you’ll find no red stripe.”

Knight stepped behind the stranger and pulled up the hunting-shirt. The back was that of a very muscular man. Daniels, without being told, slowly turned around, and Kinsty dropped the butt of his gun to the ground and barked—

“All right. But I don’t take no chances with a strange white man this far down the Ohio, on either the Injun or the Kentucky shore.”

Daniels chuckled as if it were a good joke. Then he silently surveyed Knight for a bit and briskly decided:

“Feller’s half starved. Been running his legs off. Hide barked and scratched most tarnal. He oughter eat and sleep.”

“Just what I was telling him,” agreed Kinsty. “He’s most bodacious to be pushing through to Massie’s Station.”

“Safe here for the night as he’d be at Massie’s. What with Greeby and the Girtys and the Shawnees, the station is fair beset.”

“If they ain’t strongly forted he shouldn’t go there,” said Kinsty.

“They can stand off the Injuns if white renegades don’t lend a hand and play some new deviltry. If Gineral Sinclair ’arned a lesson from Gineral Harmar’s defeat last year we’ll have peace along this river. If he gits a red ax in the head it’ll keep on being death to any one planting corn north of this river. And I’m afraid for Sinclair. Little Turtle and his Miamis are ag’in him as they was ag’in Harmar,” said Daniels.

“I don’t think this country will ever be safe for whites,” sighed Knight. “I feel faint. Wish I could eat and sleep and cross into Kentucky and make back to Richmond. I’m mortal tired of the border.”

“Make a fire and I’ll fetch in some small game,” said Daniels. “After we’ve et and rested we’ll see what fits the young man’s case best.”

He slipped into the growth and Kinsty scooped a shallow hole one side of the path and started a small blaze, feeding it with small pieces of bark until he had a deep bed of coals. Daniels came in with a turkey and some pigeons. He had knocked them over with his ax. The meat was quickly put to roasting.

Knight discovered he was ravenously hungry. He could not wait for the meat to be cooked through. He snatched a turkey leg and ate like a wolf.

“Take your time and don’t wolf it in chunks,” advised Daniels.

After they had finished and covered the fire-hole with branches and dirt, with two small apertures for air, Daniels jumped to his feet and announced he would scout for a bit. Kinsty said nothing until the stranger had withdrawn; then he leaned forward and whispered—

“Wish I knew more ’bout him.”

Knight shivered at this suggestion that all might not be right with Daniels.

“He’s a white man. He didn’t have any red stripe on his back. Could he be one of the Girtys?”

“Not Simon. I seen Simon once. May be George. I’m just as skeered of him as I be of Simon.”

Knight’s nerves were unstrung. He groaned and complained, “I thought I’d be all right if I could live to reach the river. Now it looks worse’n it did when I was knocking Little Beaver off his feet. What shall we do? I’m fair wore out just from being afraid of what may happen.”

Kinsty frowned at the threads of smoke escaping from the fire-hole vents, and after a while replied:

“We’ve got to make sure. He may be honest as we be. But till we know we don’t want him behind us, nor scouting off one side. See here: only sensible thing for us to do is to take him to Massie’s. If folks there say he’s all right no harm’s done.”

Knight sadly exclaimed:

“Just let me git out of this country! I vow I’ll stay east of the mountains if I ever get back there.”

“Few miles more won’t make much difference,” consoled Kinsty. “If we can s’prize that feller and tie his hands and take him down stream we’ll soon know if he’s all right.”

“He seems to be a pleasant sort of man,” said Knight, now speaking more hopefully.

Kinsty laughed silently.

Then he muttered, “Pleasant? Yes, they can be that. A white man who lives with Injuns from ch’ice can be lots of things. They can wade into the river, with what looks to be blood on their face and arms, and beg for a keel-boat to swing in toward the bank and pick ’em up. No end to the traps they can set. Why, when you first called out I was sure you was bait for the trap that might snag me. Even when I see you, your legs’n arms all scratched and torn, I thought you was fixed up that way to fool me.”

“That’s why you kept pestering me about my folks and friends?”

“Zactly. Trying to catch you in a lie, but you rung true. Now, this is what we must do. I’ll jump this feller and git the drop. You ties his hands behind him when I give the word. We’ll take him through to Massie’s. If he’s all right he won’t feel hard for the way we’ve used him. If he’s a bad one Massie’s men will settle him.”

The plan repelled Knight, but he could think of nothing better. He bowed his head in agreement.

Kinsty stirred uneasily and whispered:

“We got to have light. He could kill both of us in this darkness. Light to see to work by.”

He tore the cover off the fire-hole and threw in dry branches and piled on dead limbs until he had a companionable blaze which brightly lighted the small opening where they had camped. In a short time careless steps sounded in the woods and soon Daniels burst through into the light and harshly demanded:

“What be you trying to do? Call down on us all the northwest tribes?”

“No danger,” replied Kinsty. “Younker was in a bad way along of the darkness.”

Daniels squatted on his heels, his rifle on the ground beside him. On the opposite side of the fire Kinsty sat cross-legged, his rifle across his knees.

Knight held his breath as he discovered the two men were staring at each other fixedly. He was positive that Daniels had overheard, or had guessed their plan.

Kinsty slowly leaned back and commenced swinging the long barrel of his gun toward the fire. Then with breath-taking quickness the squatting figure straightened out and was flying through the flames to land on Kinsty before the latter could straighten out his legs. Kinsty’s rifle went off, the bullet passing close to Knight’s head and causing him to cry out wildly.

“Hit him!” gasped Kinsty.

Knight moved around the fire, but the interlocked figures were rolling and twisting so rapidly he had no opportunity to land a blow without running the risk of hitting the wrong man. He shuddered as he caught the flash of the firelight on two knife blades. Each man had drawn his long butcher-knife, and they grunted loudly as they endeavored to give mortal wounds. They revolved, a blur of arms and legs, out of the zone of light and crashed into the edge of the growth. Then sounded a loud groan.

Knight came out of his stupor and sprang to the rifles and snatched up Kinsty’s weapon and stood desperately at bay as a figure emerged from the darkness.

With gaping mouth he leaned forward to discover which had survived the terrible duel. The figure entered the light. It was Daniels.

“You’ve killed him!” yelled Knight. “Put up your hands! Drop that knife!”

The man threw the knife to the ground and picked up a burning faggot. Then he commanded:

“Follow me and take a peek at your friend, who was so cur’ous to see my back.” Waving the torch to keep it alive he strode to the edge of the growth. Knight followed, the rifle cocked. Swinging the torch down in a half circle the man invited, “Take a look. What d’ye see?”

The two had torn the clothing almost from each other in their desperate fight. Kinsty, with his hunting-shirt ripped from hem to collar, was lying on his face. A red stripe extended the length of his spine.

Straightening up the man continued:

“Knew him the second I see him. But he didn’t know me. He’s one of Little Beaver’s white Injuns. He’s Greeby.”

Knight nearly collapsed.

“Greeby the renegade! Why did he ask about my folks, my home, so many questions about everything?” he cried.

“So’s he could pass off for you where your folks was known and you wa’n’t. Now we’ll pick up a canoe I had hid along here somewheres and cross to t’other shore.”

“He was taking me to Massie’s station tomorrow!”

“He was taking your ha’r back to Little Beaver, leaving you dead where he cooked your supper. No more talk. Take his gun, powder horn ’n’ knife.”

“Not the knife,” shuddered Knight. “Can you find your canoe in the dark?”

“Why not? It ain’t run away. Come, hurry. This light may fetch a parcel of Injuns on our backs.”

“Lord knows I’m grateful, Daniels—”

“Boone. Dan’l Boone. Didn’t want to give my name to Greeby till I had a fair chance in a fight. Told him when we was scuffing on the ground. S’prized him so mightily I got home with the knife.”

Transcriber’s Note: This story appeared in the November 23, 1926 issue of Adventure magazine.