By William Johnston

Author of "Tom Graham, V.C.," "With the Rhodesian Horse," etc.

With

Coloured Illustrations

by

Lancelot Speed

COLLINS' CLEAR-TYPE PRESS

LONDON, GLASGOW, AND NEW YORK

CONTENTS

CHAP.

I. JACK LOVAT

II. A BOER LAAGER

III. FRINGED WITH FIRE

IV. MR. LOVAT'S ADVENTURE

V. DIAMOND VALLEY

VI. A CAPE REBEL

VII. A WEIRD ADVENTURE

VIII. THE AMBUSH

IX. THE RESCUE

X. THE FARM RECAPTURED

XI. DIAMONDS GALORE

THE KOPJE FARM

Those stirring times are days of the past, and the unsheathed sword has given place to the ploughshare, but weird pictures of bloodshed among man and beast are indelibly impressed on Jack Lovat's brain, and his dreams of to-day are often linked with the scenes enacted during the "White Men's War" beneath the glittering Southern Cross.

Jack Lovat was not a Colonial bred and born, for his boyhood had been passed amid the peaceful surroundings of a Highland sheep farm in dear old Scotland. Mr. Lovat, Jack's father, had been a laird of substantial means, and was descended from a line of ancestors in whose veins coursed a strain of royal blood; but bad times came, and Jack, instead of proceeding to Loretto, took passage as a member of the Lovat family, in a Castle liner bound for Cape Town.

Jack was seventeen at the time our story opens. Rather above the middle height, he was broad, and his bronzed features testified to his three years' sojourn on the South African veldt.

The Kaffirs on his father's ostrich farm, near Orangefontein, had dubbed him "The Strong-armed Baas," only a month later than his advent to the holding locally known as "The Kopje Farm."

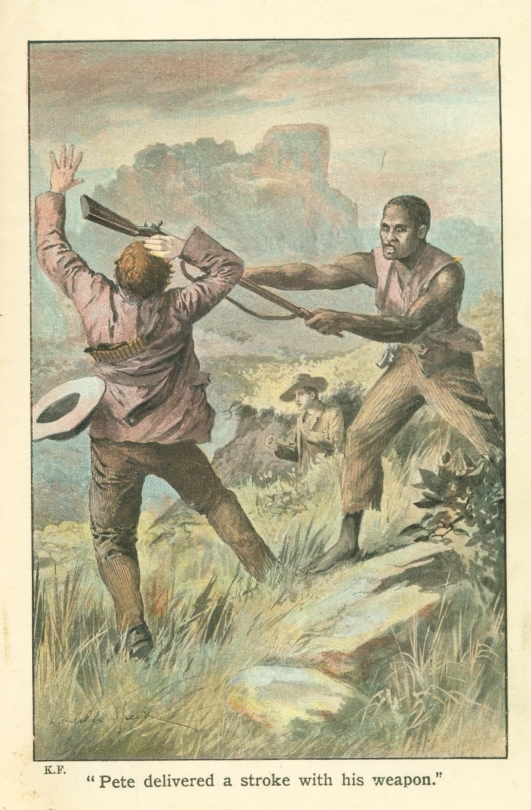

Pete, the Kaffir who acted as native foreman to Mr. Lovat, declared that "Baas Jack" could fell the biggest ox ever inspanned in a Cape waggon, which of course was an exaggeration of a very bad type, but to which statement Pete and the other "boys" employed on the estate pinned implicit faith.

The dogs of war had been let loose in South Africa, but Orangefontein had not been troubled as yet. Ladysmith, Kimberley, and gallant little tin-roofed Mafeking had been besieged and relieved, but round the homes of the settlers near Ookiep and Orangefontein tranquillity reigned.

On the outbreak of hostilities, Jack Lovat had begged his father to allow him to join a Colonial mounted corps, but Mr. Lovat withheld his permission.

"No, boy," said the ostrich farmer; "we will defend our home to the last, and I can't spare you; so say no more about it. It will be quite time for us to take up arms when the Boers come round here." So Jack, with a somewhat bad grace, had to rest content, and busy himself with attending to the ostriches and the big fruit farm on the bank of the Zak River.

One afternoon during the African winter, Jack and Pete were engaged in rounding up the ostriches. Mr. Lovat had left early in the morning for Springbokfontein. He had driven over to the town in a light Cape cart, in whose shafts was Bessie—a favourite mare, foaled on the farm, and belonging to Mary Lovat, Jack's sister.

Bessie was known to be the fastest roadster in the district, and was as playful as a kitten, and never was a horse better loved than was Bessie by Mary Lovat.

The ostrich farmer had promised Mrs. Lovat that he would be home soon after midday, and it was now four hours past that time; so Jack was naturally anxious.

In a cowhide portmanteau Mr. Lovat had taken five hundred sovereigns, intended for deposit in Springbokfontein Bank. The town guard in Springbokfontein was exceptionally strong, and Mr. Lovat, after much discussion with his wife and Jack, had decided to deposit the gold for safe keeping in the bank, instead of, as Mrs. Lovat at first suggested, hiding it in some carefully marked spot on the kopje, in case of the advent of the Boers.

The ostriches having been penned up in Cromarty Kraal—so called from his mother's maiden name—Jack turned to Pete and said, "My father is late. I hope he is all right."

"De baas will come in his own good time," observed Pete; "he will be able to take good care ob himself. Dere be no Boers about here."

"I should like to see some of them come," said Jack, with a laugh. "I think we could give a good account of them. Let me see," and the young settler began to count on his fingers; "there's you, Pete, and Saul, Moses, Jethro, Simon, Zacchary, Daniel, Obadiah, and I must not forget Pat, besides my father and self. That makes eleven, doesn't it? With the rifles and ammunition we got from Port Nolloth, and inside our strong walls, we could keep a commando at bay."

Jack's enthusiasm began to rise, and he went on: "I hope some of the beggars do come down upon us. I want to try my rifle upon something better than springbok and hartebeeste. What say you, Pete?"

A broad grin spread over the Kaffir's face, as he replied, "I dunno, Baas Jack. I no want a Mauser bullet through my skin. All de same, baas, if de time eber comes, Pete will be found ready to lay down his life for de baas, missis, little missie, an' you."

"Bravo, Pete! spoken like a man!" cried Jack, who nearly so far forgot himself as to shake hands with the Kaffir. "And now, Pete, let us go round and see what the boys are doing."

Kopje Farm well deserved its appellation, for it stood on the middle spur of a high, flat-topped range of hills. The building had been erected many years before by a Dutch settler, when trouble was rife with the Bantus, and its thick stone walls, loopholed here and there, gave it the appearance of a fort. Around the dwelling-house ran a wall of stone, some six feet in height and correspondingly thick, which had continuations to the ostrich kraal, where the birds were penned at night.

Jack found that the "boys" had finished their task of fastening up the ostriches committed to their charge, and were standing in a group, chattering in their guttural Kaffir tongue. A few yards away was Pat O'Neill, an Irishman hailing from the wilds of Connaught, who had followed the fortunes of the Lovat family as general factotum from the day the Scotch laird had landed in the colony.

Jack's quick eye glanced at the Kaffirs, after which he strode towards the place where Pat was standing contemplatively smoking a short black duddeen. Pat on seeing his young master approach, came instantly to the salute; for the Connemara man, twenty years before, had formed one of the glorious defenders of Rorke's Drift.

"Where is Saul?" inquired Jack of the Irishman.

"He has gone on an errand for the mistress, sorr," answered Pat. "One of Master Butler's children down the valley is laid up wid fever, an' the mistress, who is good to every one, has sent some cooling medicine for the poor thing, which will do it good, please God. Has the master returned from Springbokfontein?"

"He has not arrived yet, Pat," answered Jack.

"Then I shall be mighty glad when I see him," observed the Irishman.

"Things are all right, Pat," said Jack, forcing a laugh.

"They may be, and may not be, sorr," remarked Pat. "Zacchary has just told me that a commando of Boers under the daring leader, Christian Uys, is trekking this way. The last time the Boers were heard of they were in the Upper Zak River district. How in the world these niggers get news, sorr, is more than Pat O'Neill, late corporal in the ould 24th Regiment, can understand. Shall I saddle up and go to meet the master, sorr?"

"Not a bad idea, Pat. Just wait a moment until I see mother;" and Jack went inside the farmhouse, where he found Mrs. Lovat peering through a window at the long winding road leading down the valley towards Springbokfontein.

Hearing footsteps, Mrs. Lovat turned round, and seeing Jack, said, "I'm dreadfully anxious about your father, Jack. I cannot understand why he has not returned. It is so unlike him to disappoint me."

"He'll be all right, mother," observed Jack cheerfully. "Very probably he has met some one he has not seen for a time. He is sure to be here before nightfall. Did he take any lamps? I was busy branding an ostrich when he went away."

"Yes, he trimmed the lamps and put them on before he set out," answered Mrs. Lovat. "I was rather surprised, as I thought he would not need them."

"These South African roads are not good, and people are delayed sometimes," said Jack. "Pat is going down the road to meet him, so cheer up, mother. Where is Mary?"

"She has a bad headache, Jack, and is lying down on the couch in the dining-room," replied Mrs. Lovat. "I do wish this time of dreadful uncertainty was over. It seems to be wearing my life out."

"I should like to take part in the war, mother," said Jack. "I sometimes get tired of the humdrum life we lead. Why didn't dad allow me to join the Scouts Mr. Driscoll raised when the war broke out? I can fight as well as any man, and I know I can shoot straight."

"Jack!"

"I did not mean to hurt your feelings, mother; but if any Boers come here to harm you or Mary, they will have a bad time of it, so long as I can stand on my feet or hold a rifle."

Tears came into gentle Mrs. Lovat's eyes, as she replied, "The war spirit is a dreadful thing, Jack. It seems a crime in this twentieth century for men to be so anxious to imbrue their hands in their fellow-creatures' blood. I am always saying, 'Lord! how long?'"

"Well, all I can say, mother, is that if any Boers try to take Kopje Farm, while I can handle my rifle, they will stand a chance of being winged for their pains," observed Jack. "No Boers come here unless I am disabled and can't stop them. I am going now to tell Pat to saddle up and give a look-out for dad;" and saying this, he strode out of the apartment and walked to where Pat was still standing staring at the road leading to Springbokfontein.

"Pat!"

"Yes, sorr," answered the Irishman, coming to attention; "I'm at your service, sorr."

"Put the saddle on Cawdor and gallop down the road. If you should happen to meet father, you need not say that I sent you. You understand?"

"I know your meaning perfectly well, sorr," replied Pat; and the honest fellow walked to the stables, where he saddled Cawdor, a beautiful Arab, which Mr. Lovat had purchased at Worcester a year before, while on his ostrich-selling peregrinations.

Jack looked attentively at Pat's preparations. The Irishman spent some time in examining the saddlery, paying special attention to the girths, and being apparently satisfied with his inspection, he mounted.

"You have forgotten your rifle," said Jack. "You had better take it with you."

"I've got a barker, sorr," observed Pat, with a laugh, tapping his hip-pocket. "An officer of the ould corps gave it me many years ago, an' we've not parted company yet."

"Wait here till I return," said Jack authoritatively; and the settler's son went back to the house.

Jack proceeded straight to a storeroom where Mr. Lovat was in the habit of keeping his rifles and ammunition. He selected a weapon of the Lee-Enfield pattern, and took down a bandolier which was hanging on a peg. The bandolier was empty, but Jack broke open an ammunition box and filled the pockets of the belt with cartridges, after which he returned to Pat.

"Here, take these, Pat," said Jack, handing up the rifle and bandolier, which the Irishman took. The latter slung the belt over his shoulder, and, at Jack's suggestion, filled the magazine of the rifle.

"Well, good-bye, sorr," said Pat, and the next moment Cawdor was proceeding at a canter down the mountain road.

An hour passed, still no signs of Mr. Lovat or Pat, and Jack's anxiety increased. The ostrich farmer was a man of his word, and Jack began to fear that something was wrong, but he kept a cheerful face in front of his mother and Mary.

They were sitting in the dining-room, partaking of tea, when a tap was heard on the half-open door. Jack instantly rose to his feet and went outside. In the hall stood Pete. The Kaffir did not speak, but beckoned with his forefinger, and then passed through a door leading to a back yard.

Jack followed, and when outside, said, "Well, Pete, what is it?"

"Baas Jack," exclaimed Pete, "I dunno, but something is wrong. Come!" and the native walked rapidly round to the front of the house, Jack following in wonderment.

"Look, baas," said the Kaffir, "what does that mean?" and he pointed to what appeared to be a moving spot on the veldt.

Jack gazed long and earnestly. "Why, it is a horse without a rider!" he exclaimed at last.

Kaffirs are noted for their keenness of vision, and shading his eyes with his right hand, Pete observed, "The horse is coming dis way, Baas Jack."

Pete was right. Nearer and nearer came the flying quadruped, until at last the stirrups from an empty saddle could be seen swaying backwards and forwards.

Jack's breath came thick and fast. The horse in a mad gallop was approaching them.

"Baas Jack," cried Pete, "it is Bessie!"

And so it proved. A few moments later, Mary's pet, the beautiful creature Mr. Lovat had driven to Springbokfontein that morning in the Cape cart, galloped up, covered with foam and blood!

Bessie was trembling in every limb, but she whinnied gently as Jack patted her neck. On Bessie's back was a Boer saddle. A sudden fear descended on Jack Lovat, and mentally he asked the question, "What has happened to father?"

The mare was bleeding from a wound in the right shoulder, evidently caused by a bullet.

"Take her round to the stables, Pete," said Jack. "I will join you presently." Saying this, he went into the house. He met Mrs. Lovat coming out of the dining-room, and she at once accosted him.

"What is the matter, Jack? I heard the noise of hoofs just now. Is it your father who has returned?"

"No, he has not come yet, mother," answered Jack. "You must finish your tea. Pete wants me round at the stables. I shall be back presently;" and he went out again, but Mrs. Lovat followed him.

Pete was busily engaged in rubbing down the mare, and when Mrs. Lovat caught a glimpse of the blood on the poor creature's hide, she cried out, "Why, Jack, it is Bessie! Where is your father?" and the settler's wife burst into a flood of tears.

"You are in the way just now, mother," said Jack gently. "Go inside, until I have seen to Bessie. Something, I am afraid, has happened. The poor thing is in great pain, and I must do what I can to relieve it. Do go inside, please, mother. I will come to you presently."'

Mrs. Lovat, whose vivid imagination had conjured up all kinds of evils, obeyed Jack, and returned to the house.

Now Jack Lovat's sterling qualities of coolness and resource began to be displayed. With the skill of an experienced veterinary surgeon, he examined Bessie's wound, and then carefully washed away the coagulated blood. A gaping orifice an inch in diameter in the animal's shoulder told Jack that it was a gunshot wound and that it had been caused by a Mauser expanding bullet.

The "boys" had gathered round, all anxious to help; but Jack would allow no other hands than those of himself and Pete to touch the mare, so the Kaffirs drew back, and stood whispering among themselves.

Suddenly a clattering noise was heard, and before the "boys" could get out of the way, Pat O'Neill, mounted on Cawdor, whose chest and flanks were foam-flecked, was on the top of them, sending Zacchary and Moses tumbling to the ground.

The Irishman was bareheaded, and the arteries in his temples stood out like whipcord. He pulled Cawdor up, and dismounted. Jack, with wildly dilated eyes, queried, "What is the matter, Pat? Have you seen father?"

"No, sorr," gasped the faithful Irishman, "I haven't seen the master; but a Boer commando—bad luck to them!—is making straight for us. And I'm afraid, sorr, it will be a bad job for all of us. Their scouts are close at hand even now. You'll fight, sorr?"

"Yes, we will all fight, Pat," answered Jack proudly. "Boys, all at once to the storeroom. Pete, take Bessie into the stable and give her some water and a feed of corn. I'm sorry for mother and Mary, but it can't be helped. No surrender to the Boers!"

And Jack Lovat, although only a lad, and suffering under dire apprehension, began his preparations for the defence of the Kopje Farm.

His worthy henchman, Pat O'Neill, had often detailed to him the story of the glorious defence of Rorke's Drift, where a few Britishers, many of whom were sick and wounded, for hours, amid flames and death-dealing bullets, had held at bay the flower of savage Tshingwayo's command.

"Master Jack," said Pat, as Mr. Lovat's son stopped for a moment in his work, "we will hould the place for the sake of the missis an' Miss Mary, an' please the Almighty, I hope wid the same results as we had at the Drift on the Buffalo River, when eight Victoria Crosses were won in one night."

"We will hold it to the last, Pat," responded Jack quietly. "My father has had to work hard for all he has, and the Boers shan't take it from him while my finger can pull a trigger;" and Jack Lovat meant every word he said.

Eleven miles north-west of Orangefontein, and an almost equal distance from Springbokfontein, a party of Boers were laagered. They were Free Staters, with a sprinkling of Hollanders and renegade Britons—the latter, few in number, having at one time served with the English colours, and owing to their misdeeds, had deserted or been drummed out of the British army.

Nearly all were in rags, for that ubiquitous cavalry leader, General French, had not allowed them a minute's rest, but had hurried and harried them hither and thither, until the majority of the burghers had grown sick and tired of the guerilla warfare, and wished for the end to come.

Their portable possessions—and indeed the latter could not be otherwise than portable—were stowed away in a few light Cape carts.

Ammunition was scarce, and had to be husbanded with the greatest care, while food could only be procured with much difficulty from the scattered farmsteads among the mountains of the Langeberg Range.

A Boer of immense stature, holding in his right hand a formidable sjambok, was leaning against the wheel of one of the carts. He was a magnificent specimen of physical manhood, and the privations that for two long years he had uncomplainingly endured had only served to increase his tremendous muscular strength.

His bronzed and deeply marked features showed a strength of will and determination rare even in that race of obstinate men, the Boers of South Africa.

An immense beard swept his breast, the hair composing it being streaked with gray. When Christian Uys first shouldered his rifle on the outbreak of hostilities he was, comparatively speaking, a young man, but under the sombre folds of the flag of war he had grown prematurely aged and gray.

A young burgher passing with a led horse, with a limping gait, arrested his attention, and awoke him from the train of gloomy reveries he was indulging in.

"Ah, Van Donnop," said the commandant, "I wish to speak to you. What is the matter with your horse?"

The burgher whom he addressed was a sprightly young fellow of nineteen, strongly made, and as agile as the springbok he had hunted from youth upwards.

"It is lame, Commandant," answered the youth. "One of its pasterns is split. I do not think it will be able to travel farther. And my favourite horse, too. I am very sorry, for it has been mine since it was a foal."

"I too am sorry, Piet," said the officer in a sympathising tone of voice. "We are greatly in need of horses."

The commandant stooped down and examined the horse's hoofs, after which he looked up and remarked in a grave tone of voice, "A bad case, Piet. The poor brute must be killed."

A crimson flush surged up into the face of the young burgher, and he exclaimed excitedly, "Do not ask me to kill her, Commandant! She was my mother's gift to me when I was sixteen. I am hoping to leave her at my father's farm and obtain another mount in her place."

A look of pity crept into the commandant's face as he gazed at the boy.

"Ah, I forgot, Van Donnop," said the Boer leader; "you are now in your native parts. How long have you served in my commando?"

The young burgher thought for a moment, and then answered, "From three months before we beat the rooineks at Koorn Spruit, near the Waterworks. Let me see, that is now going on for two years. You will allow me to keep the mare, Commandant?" Van Donnop asked beseechingly.

"But how will you travel?" asked Uys.

"I am fleet of foot, and do not mind the hardship," pleaded the lad. "If I may only keep my horse, I shall be happy. She is part of myself;" and Piet's voice faltered as he went on, "She who gave me the mare is dead."

Piet stroked the finely arched neck of the mare, and the gentle creature rubbed its tawny muzzle against the young burgher's cheek.

"We shall see," said the commandant at last. "By the way, you and your brother Jan know this countryside well. If we are to reach Port Nolloth, we must have more mounts. Do you know any likely place where we can replenish our stock of horses?"

"There is one farm where many horses are kept—at least there used to be, when I was at home."

"And where is that?" asked the commandant. "To whom does the farm belong?"

"To a settler named Lovat," answered Piet.

"One of our race?" interrogated the commandant.

"He is opposed to us," replied Piet; "his name is a foreign one. He is a Scotch settler who breeds many horses and ostriches."

"Has he helped the rooineks?" queried Uys, and a frown passed over his face.

"He does not sympathise with us, Commandant," answered Piet, "but I do not think he has favoured one side or the other. I believe he is entirely taken up with looking after his ostriches."

"And you can guide us to this farm?" asked the commandant. "Possibly he may have some spare nags."

Piet Van Donnop evidently did not like the suggested commission, and the commandant, noting this, went on: "We must have some mounts, Piet, or the rooineks will catch us. If that happens, I'm afraid our fate will be a sorry one. A regiment of Lancers—the men who cut up the Transvaalers at Elandslaagte—as well as several troops of New Zealanders are on our track, and without fresh horses we shall stand an almost sure chance of capture."

"You will not harm Mr. Lovat or his family?" asked Piet.

A smile played for a moment on the commandant's stern features, then he said, "Not at all, Piet. Why should we? I'm afraid your heart is concerned in the matter. But of course we must have what we require, and very few questions asked into the bargain."

"I will guide you, then," said the young burgher. "I may keep my horse, Commandant?"

"We shall see in the morning, boy," was the only reply vouchsafed by the Boer leader; and Piet moved on, leading his lame horse.

Taking out an immense pipe from one of his pockets, Christian Uys filled it with leaf tobacco, lit up, and began to smoke.

The commandant was evidently in a tender mood, for his thoughts were in distant Winburg, where his wife and the children left to him were being sheltered in a concentration camp, created by his arch-enemies, the British.

His was a strange compound of human nature. At times generous and kind, at others he was fierce, implacable, and relentless. Like his famous leader, General Joubert, at the outset he had realised that the struggle in which his country had engaged was a hopeless one, but with the obstinacy characteristic of his race, when once his hand was put to the plough, there was no turning back.

Christian Uys had already lost three sons in the war. His youngest, a boy of fifteen, and the flower of the commandant's family, had been shot in the stomach at Senekal. The brave boy hid his wound and continued on the march, although a trail of blood marked the path along which he rode, until he fell exhausted from his saddle, and with his dying breath, and a look of intense love in his eyes, said, "Father, I can fight no more, I am done." These were the brave lad's last words, and like others on both sides, yielded up his spirit for the cause in which he thought he was righteously fighting.

An older brother had been with the fierce Cronje in the honeycombed banks of the Modder, amidst the brown sulphurous smoke of bursting lyddite shells, and while bringing water for a wounded comrade from the polluted stream, had been struck squarely in the chest by a Lee-Enfield bullet, and had fallen on his face, never to rise again.

The last to die was the oldest boy of the family. A delicate youth at the best, he had gone on commando with his father when the vierkeleur was first hoisted in the field. For several months he had fought and roughed it with the rest, until foul enteric seized him, and the ranks of the Boer army knew him no more. He found a last resting-place in a shallow grave on the veldt, not many miles from his birthplace.

Christian Uys woke up from his reverie and took a stroll round the laager. Here was Jan Steen, once a well-to-do jeweller of Winburg, who before war broke out was always immaculately dressed, with ample starched shirt front and bejewelled fingers; there Van Sterck, the learned medico of the same town. Neither had had a change of raiment for months, and both looked correspondingly miserable. Yonder stood Louis Bredon, the dandy of Harrismith, now a veritable scarecrow in trousers made of sacking on which the address of a large milling concern in Johannesburg was branded in staring black letters. Bredon, like the rest of the commando, was weary of the daily trekking, discomfort, and misery incidental to warfare, and his mind was wandering back to the time when he used to walk down the shady side of Harrismith's main street, the cynosure of the belles of the Free State town.

"You look discontented, Bredon," said Uys. "I am afraid you are like most of my burghers. We cannot give in now, after we have endured so much. There has not been sufficient fighting of late to keep up your martial spirit. We want horses, Bredon, and they must be obtained, if we are to reach Port Nolloth. Otherwise we had better surrender."

"I have no objection, Commandant," replied Bredon somewhat brusquely. "I've had enough of the war. We ought never to have been drawn into it."

"You speak like a patriot," observed Uys sarcastically. "I undergo the same hardships as other burghers. You have suffered nothing as yet. In what respect have you endured more than the rest of us?"

Bredon hung down his head in a sheepish manner and remained silent.

"I am finding a cure for your melancholy and dissatisfaction, Bredon. I am detaching a portion of the commando for the duty of securing a fresh supply of horses. Van Donnop is acting as guide to the farmstead of a settler named Lovat. You will form one of the commandeering party;" and Uys passed on.

"To think," muttered the commandant, "fellows such as Bredon were the most eager at the outset, and now they begin to whine when a little hardship has to be borne! My poor Christian, Louis, and Wilhelm were formed of different stuff."

Christian Uys came up to a man who was busily engaged in cleaning his Mauser. The burgher laid down his rifle as the commandant approached.

"Eloff," began Uys, "I want you to pick a dozen good men of the commando. Before morning I must have half a score of horses. Piet Van Donnop knows a farm where they can be obtained, and will guide you to it."

Paul Eloff was a man built in the same herculean mould as his leader, Christian Uys, and he looked at the commandant keenly.

"We shall want more, Commandant," said Eloff; "a dozen will scarcely suffice. Let me see," and the Boer began counting rapidly on his fingers, after which he added, "Yes, quite a dozen, Commandant. The spare led horses were taken as mounts yesterday. We must reach Port Nolloth, or we shall be cut off by the rooineks."

"You will muster the burghers, then, Eloff," said Uys. "Bring them round to the commissariat waggon within half an hour, and do not forget Van Donnop. Although a boy, his heart is good."

"I will not fail, Commandant," replied Eloff, picking up his rifle and recommencing the cleansing process.

In less than the stipulated time, Eloff with his picked burghers stood before the commandant, each man at his horse's head.

Christian Uys called Eloff aside and whispered, "Do you think you are sufficiently strong for the purpose in hand?"

"I should make the patrol fifty strong, Commandant," answered Eloff. "You are remaining in laager, I suppose, until we return?"

"That is my intention, Eloff," answered Uys. "Van Donnop informed me that the Kopje Farm—this Scotch settler's residence—is some eight miles from here. You will keep a sharp look-out for the rooineks, Eloff, and not be caught napping?"

A smile spread over Eloff's face as he answered, "When I am found asleep, Commandant, I shall not return to tell the tale. We have got to the end of our tether, and I am longing to have one more go at the rooineks. After that, well—oblivion."

"It is a bad cause we have started on, Eloff," said Uys. "It is as General Joubert foretold at the beginning, we are fighting in a lost cause. How can we hope to stand against a mighty Power like England, which has millions of gold and men without number? Bah! we were a race of fools to be led by the nose. President Kruger, who commenced the war, basely deserted us. But I must not speak of this. It is horses we want, and horses we must have."

Paul Eloff quickly mustered the additional burghers required, and in sections of fours the motley cavalcade trekked towards the Kopje Farm.

Eloff and Van Donnop rode at the head of the slender force, and the former turning to the young Dutchman, said, "This is a rough country, Van Donnop. You spent most of your life here?"

"Until I went on commando," answered Piet. "I shall be glad when I can get back to my father's farm. Those were happy days, Eloff."

"You know the farmstead whither we are bound," inquired Eloff, "and the people as well, I suppose?"

"Perfectly," answered Piet.

"And what about the owner? Is he a fighting man? Shall we have much trouble?"

"Mr. Lovat is quiet enough," replied Piet. "He has a son named Jack, a dare-devil sort of boy, who will show fight, I think, but possibly he may be on commando with the rooineks."

"Any Kaffirs kept on the farm?" queried Eloff.

"There used to be many," answered Van Donnop. "I do not wish any harshness to be used towards Mr. Lovat. He used to be very kind to me before I went on commando. The horses will be paid for, I suppose?"

Eloff laughed outright as he replied, "Van Donnop, I don't think a single gold piece can be found in the pockets of the whole commando. My instructions are to take what we require—as civilly, of course, as possible. The account will be paid when the vierkeleur flies not over the Transvaal and Orange Free State only, but over the whole of the Cape. A receipt for the horses, of course, will be given."

The Boers, who had been travelling through a series of dongas, now debouched into a fairly open country.

Eloff halted his men, and after looking ahead, turned to Van Donnop.

"You have a pair of field glasses, Van Donnop, allow me to look through them."

Piet handed the glasses to Eloff, who placed them to his eyes.

"There is a farmhouse, Van Donnop, on a kopje some four miles ahead," said Eloff; "is it the home of this Mr. Lovat?"

"That is where Mr. Lovat used to live," replied Piet; "things have changed much lately."

"A big place for a farmstead," observed Eloff. "This Mr. Lovat must be rich."

"He is said to be fairly wealthy," answered Piet. "He was a nobleman in his own country, so I have heard it said."

"And the house lower down the valley, to whom does that belong?" queried Eloff. "Take the glasses, Van Donnop, then you will see what I mean. Over there;" and the Boer pointed with his index finger in a certain direction.

"That is Jagger's Farm," said Piet, after a glance through the glasses. "No horses can be obtained there. The farm has not been occupied for years."

"We will march straight on the place, Van Donnop, rest a while, and then move on to—what is the name of the place, Piet?"

"The Kopje Farm," replied the young Dutchman. "Someone is driving a Cape cart towards Jagger's Farm, Eloff."

"Right you are, Van Donnop. Give me the glasses again," said Eloff.

Eloff peered through the instrument for a moment, after which he ordered half a dozen burghers to gallop rapidly towards Jagger's Farm, in order to intercept the solitary passenger in the Cape cart, while he and his remaining fellow-countrymen dismounted and awaited events.

Kopje was singularly well situated for defence. From the rising ground behind the house, no attack could be made by mounted men, as it was strewn with big boulders of rock, and interlaced with dongas, which though not deep, presented insuperable difficulties to an enemy manoeuvring on horseback.

The ostrich kraals—which were in reality one long rambling building—commanded the country from which the only attack by mounted men could be made, and the ground in front was open.

On receipt of Pat's intelligence, Jack went to his mother and told her the news brought by the Irishman. He insisted upon her as well as Mary remaining inside the house, and would not listen to her suggestion that if the Boers were really advancing upon the farmstead, they should be allowed to take whatever they pleased, on condition they harmed none of its inmates.

"No, mother," said Jack firmly; "I have always been obedient, but any Boer who dares to enter Kopje Farm without an invitation from me will have a bullet from my rifle through him before he can say 'Jack Robinson'! Please say no more, mother. Father is not here, and may be dead, but if he is all right I could never look him in the face again if I did not show fight. Stay inside with Mary, and do not venture out until I come for you. I must go to the 'boys' now, as time is precious;" and saying this, Jack went across to the ostrich kraal, where the Kaffir servants were assembled.

The sun was within half an hour of setting, and the light was good enough to enable our hero—for such Jack Lovat will prove to be before we bid him adieu—to distinguish a body of horsemen moving in an oblique direction across the veldt. Pat had stabled Cawdor, and stood awaiting orders from Jack.

"We must have the rifles and ammunition from the storeroom, Pat," said Jack, "and quick must be the word. Kindly look after the boys, Pat. Zacchary, Pete, and the lot of you, go and bring the rifles; and don't forget, Pete, to bring a hammer. One moment, Pat; a couple of lanterns will be needed, as well as some matches."

Strange it is that fighting blood is transmitted from generation to generation, but so it proved in Jack Lovat's case. An ancestor of his had suffered death on Culloden field for what he considered his duty towards the unfortunate race of Stuarts, and Jack was prepared to lay down his life in the defence of the Kopje Farm.

In the excitement of the moment he forgot about his father's possible peril. His thoughts were concentrated on the question, "Can I strike a blow for the honour of the old country?" Jack had not gone through a course of metaphysics or logic. He was simply a lad, made a man before his time perhaps, and yearning for an outlet through which a vast flood of pent-up patriotism could be poured.

Pat and the "boys," in almost less time than it takes to relate, transferred the arms to the ostrich kraal. The weapons were in splendid order. Jack Lovat had seen to that. Many hours he had spent in cleaning the rifles, always hoping, boylike, that some day they would come in handy, when the Boers put in an appearance.

The ungainly-looking ostriches, penned in spaces of rectangular form, craned their far-stretching necks, all the while uttering the grunt peculiar to the birds, dubbed by naturalists Struthio Camelus.

A passage, four feet in width, ran between the inner walls of the kraal and the high hurdles forming the temporary home of the ostriches. Four feet above the flagged floor of the kraal were loopholes, and these presently had the barrels of rifles protruding from them.

A couple of thousand rounds of ammunition, in boxes holding one hundred each, were placed in handy positions, and Pete with much dexterity knocked off the lids of the boxes, thus exposing the little nickel-plated messengers of death.

Each "boy" was given a rifle, and by the way the magazines were charged it was evident that the weapons had been handled before.

Pat, who was peering through a loophole, cried out, "The beggars are coming, sorr, an' they're more than fifty strong."

Jack, who was engaged in inspecting the "boys'" rifles, at once went up to Pat.

"How far off do you make them now, Pat?" he asked.

"Bedad! they seem to be only five hundred yards away," answered the Irishman. But Pat was wrong in his conjecture, and Pete at once corrected him.

"Dey be quite a mile from de farm, Baas Jack," said the Kaffir. "De eyes ob white men do not see right—at least not in dis country."

A peep through a loophole told Jack that Pete's estimate was a correct one. The South African atmosphere is so clear that distance seems annihilated on the veldt.

Jack addressed a few words to the defenders of the farm. "Boys," he began, "before long we may be in a tight hole. I am going to run the show for what it is worth. It shall never be said that Christian Uys and his men took Kopje Farm without a shot being fired. You boys, of course, know what it will mean if any of you are captured with arms in your hands. A sjambokking first, and possibly after that a Mauser bullet through the head. We must have no white-flag business here. If any of you boys don't care to fight, there is time for you to get away over the kopje. Pat and I mean to stay here till the last."

"We stay with the baas as well," said Pete emphatically; and in Kaffir fashion the whole of the "boys" held up their right hands, extending the index finger in a significant manner.

"Thanks," returned Jack. "And now to business!"

The eyes of the Kaffirs were fixed on something behind Jack, and the latter noting this, turned quickly round. To his great surprise, his eyes fell upon the figures of his mother and Mary.

"This is no place for you, mother," said Jack. "You must return to the house. It is quite safe there."

"But what does this mean, Jack?" asked Mrs. Lovat, pointing to the ammunition boxes and rifles. "This will be death to someone. My dear boy, pray do be careful."

"All right, mother," said Jack, with a laugh. "I'll be more than careful. But you must go back to the house. You will only be in the way here."

"I am almost distracted, Jack. Your father may be dead;" and Mrs. Lovat broke into a paroxysm of tears. "This cruel war is killing me. Why cannot things be settled without recourse to bloodshed?"

Had Mrs. Lovat passed through the same experiences as many settlers' wives in Natal and the northern parts of Cape Colony, the exclamation might have been a justifiable one. As it was, the black wings of Azrael, the Angel of Death, were beginning to flap over the Kopje Farm, and the ostrich farmer's wife, whose nature was a curious compound of kindness, fear, credulity, and misgiving, began to show signs of fainting.

Not so Mary Lovat. Although only a girl in her early teens, she possessed a large share of her brother Jack's mental and moral courage, and she came up and whispered in Jack's ear, "Mother will go back to the house with me, but I should so much like to stay here."

Pat O'Neill ended Mary's whispering somewhat abruptly, but quietly. He had been patrolling the rough ground outside the Kopje Farm, and coming inside the walled enclosure, walked swiftly up to Jack.

"The Boers are near at hand, sorr," he whispered. "What is the missis doing here? This is no place for ladies. Shall I take them across to the house?"

The next moment, Mrs. Lovat and Mary, escorted by Pat and Moses, were passing under the shelter of the dry stone wall to the farmhouse, and Moses, who had his rifle and a supply of ammunition with him, was told to stay with the "missis" until he was sent for.

Having seen the two ladies seated in the dining-room, with Moses acting as their guard, Pat returned at breakneck speed to the kraal, where he found Jack examining the approaching horsemen attentively through a pair of field glasses.

The twilight of South Africa is of short duration, but the light was still good.

"They are Boers," said Jack, handing the glasses to his faithful henchman. "Just give a look, Pat, and tell me, if you can, how many there are, and what distance they are now from the farm."

Pat placed the binocular to his optics and gazed for a moment down the valley, after which he spoke.

"Right you are, sorr; they're Boers sure enough, and well within half a mile av us. About fifty or more, I should say, sorr, an' a big fellow in front is houlding a white flag. You saw the chap, sorr, the man on the gray horse. Now they have halted, and, bedad, the man is coming forrard. See for yourself, sorr;" and the worthy Irishman handed back the glasses to his young master.

It took but a moment to convince Jack that Pat was right, and that a Boer was approaching under a flag of truce.

"Inside at once, Pat!" our hero cried; and the pair entered the kraal.

"Man the loopholes, boys!" said Jack; and the Kaffirs, whose rifle magazines were charged, stood to their posts. Nine murderous-looking small-bore rifles were instantly pointed down the valley.

The man on the gray horse had halted a couple of hundred paces in front of the party of horsemen, as though undecided what to do.

"I'll interview him, sorr," said Pat, whose place was next to Jack Lovat. "I'll go and see what the rascal wants."

"I was thinking about the same thing myself," observed Jack. "Maybe it will be the best thing that can be done. No, you must not take your rifle; and put that bandolier off, Pat."

"All right, sorr. I'm anyhow for an aisy life. An' conscience," replied the brave Irishman, "I've got the barker, sorr, if things come to the worst. Then I can go, Master Jack?"

"Certainly, Pat; just slip down and see what the thieving rascals want. But remember, we have no remounts at Kopje Farm for them."

"I understand, sorr," said Pat; and the ex-soldier walked boldly out of the kraal to the spot where the individual on the gray horse had halted.

Pat, whose stride was none of the shortest, made rapid tracks towards the solitary horseman, whose left hand grasped a short stick to the end of which was attached a white handkerchief, while the right supported the barrel of a Mauser rifle, the butt end of which rested on his thigh.

"Halt!" cried the horseman in perfect English, as Pat came up. "Who and what are you?"

"That is my business," answered Pat. "I will put a more pertinent question to you. Long-whiskers! who an' what are you, an' what do you mane by disturbing honest folk in these lonely parts?"

"Have you any horses at the farmstead just ahead?" asked the stranger. "This is a part of Christian Uys's commando, and we want a few Boer ponies badly."

"You said Boer ponies?" said Pat interrogatively.

"I spoke plainly enough, I think," answered the Boer. "We are in need of a few horses, which the British Government will pay for. We will give a receipt for them."

"The master has some grand nags," said Pat, "but av course he will want payment for them. Can you pay on the nail?"

The Boer, who was not by any means a bad-looking man of about fifty, laughed outright at Pat's insouciance.

The Irishman went on: "Will the paper hould good if the master lets you have them?"

"When the vierkeleur flies over the whole of South Africa, your master will be paid in good gold, and that will be before many months are over," replied the Boer.

"And if the master does not care to part with the animals?" inquired Pat.

"We'll take them, of course," replied the Boer. "We are tired of bloodshed, but we have won the day; the rooineks can't deny that fact. You see the burghers behind me? Well, we are some of the fellows who cut up your crack regiments at Sanna's Post."

"Then I may return an' tell the master that you'll pay for the nags?" asked Pat.

"Certainly, but don't be long about it," replied the Boer; "and tell your employer's son—for the master of the house is not at home, and won't be to-night—that any attempt at double-dealing will be harshly dealt with. Within ten minutes from now we will advance upon the farm, and if necessary, take by force all we require."

Pat needed no further telling, but strolled back to the farmstead, wondering all the time whether a Boer bullet would lay him flat on the veldt or not.

The orange tints glimmering above the mountains were beginning to fade into a light purplish gray as Pat walked into the ostrich kraal.

Jack, naturally enough, was awaiting his return with some anxiety.

"They are Boers, Pat?" queried Jack.

"Boers, sure enough," responded Pat, "an' they've come to commandeer the horses. The chap wid the white flag says they will pay for them when the Boer flag waves over this heathen part av the world."

"That is enough for me," said Jack, after he had listened to Pat's brief narration. "We will wait until we see them on the move towards us. After that, they can look to themselves."

The minutes seemed long, but at last, through the dim twilight, the Boer on the gray horse was seen waving his flag, as though beckoning his fellow-burghers to advance.

On seeing this, Jack Lovat elevated his rifle, pulled the trigger, and the bullet went whistling high over the heads of the Boers.

The commando instantly halted, and the advanced Boer rode quickly back to his comrades.

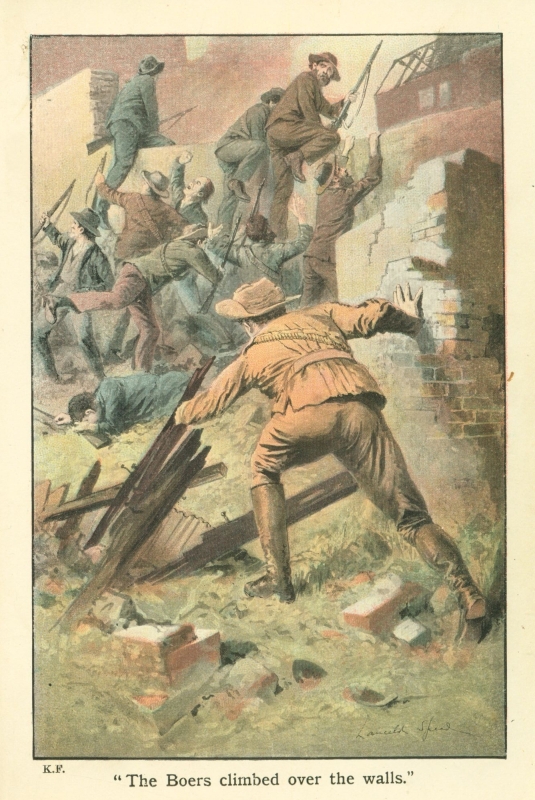

The burghers opened out in wide formation, and dismounting, poured in a volley. The majority of the bullets splashed against the rough stones forming the wall of the ostrich kraal.

"Now, boys," cried Jack, "that is just what I wanted. Take a careful, steady aim. Don't fire too wildly, and let every one select his man. There is yet enough light to see them by. Take the word from me."

Instantly the muzzles of nine rifles peeped through as many loopholes, and Jack gave the word, "Fire!"

The reports rang out as one, and the defenders of the farm could see that some of their shots had taken effect, for a couple of Boer horses broke loose, and with clattering hoofs came galloping towards the ostrich kraal. A desultory fire came from the Boers, but as yet no bullets had entered the loopholes.

"Empty your magazines," cried Jack, "but wait for my orders. Now, boys, one, two, three," and at each successive number a tiny horizontal sheet of flame shot from the loopholes.

Yells of rage could be heard from the Boers, mingled with groans, after which the sounds of galloping hoofs were borne on the night air, followed by complete silence.

It was now quite dark, and after waiting, it must be said somewhat anxiously for several minutes for a renewal of the attack, Jack ordered Pat to light the lanterns, and the Irishman instantly obeyed, and showed himself an adept at the work.

Carefully shading the lighted match, so that no stray rays of light could creep through the loopholes, Pat lit the lanterns, when the whinnying of horses outside attracted Jack's attention.

"Remain here, Pat," said Jack. "I'm going across to the house, to give a look to my mother and sister. Keep a sharp look-out while I am gone, in case the beggars come back."

Saying this, Jack walked out into the darkness, and the next moment stumbled against a horse. He, however, walked swiftly towards the house, and found Moses, rifle in hand, guarding the hall. Jack had taken the precaution of shouting out as he approached, for he by no means relished the idea of a bullet being planted between his ribs.

Mrs. Lovat and Mary were still in the dining-room, and as Jack entered, the former exclaimed, "What is the meaning of all this firing, Jack?"

"It means, mother, that if there had been no firing, the Boers would before now have emptied our stables. We have beaten them off, I think."

"Has anyone been hurt?" inquired Mrs. Lovat nervously.

"Not on our side, mother," replied Jack, with a laugh; "as far as the Boers are concerned, I do not know. If any harm has happened to father, then I hope we have killed the lot of them. Moses is still on guard, mother; you need have no fear. I shall be back presently;" and he walked out of the room.

Moses, whose white teeth gleamed as Jack passed him, said, "Dings are all right, Baas Jack. I will see dat no Boers come in here to frighten de missis an' de little missie."

"Quite right, Moses," observed Jack cheerfully. "Give the beggars beans if they come."

"I'll do dat, baas," replied the grinning Kaffir.

An hour later the moon, which was on the wane, would creep over the kopje, and give the defenders of the farm a chance to locate their now unseen assailants.

A deep silence hung over the place, and Jack groped his way along the wall leading to the ostrich kraal. Pat evidently knew his work, for the place was in darkness.

Suddenly a challenge rang out: "Is that you, sorr?"

The speaker was Pat, whom Jack found outside the kraal, holding a couple of horses.

"All right, Pat," answered Jack. "The Boers seem to have departed."

"Then I'll take these nags inside, sorr, an' have a look at them. The poor things are trembling all over their bodies down to their fetlocks."

Jack entered the kraal, followed by Pat, dragging the dumb brutes behind him.

"A light here, Pete," said Jack; and the Kaffir foreman brought a shielded lantern. Jack turned on the light, and by its aid examined the horses.

By the saddlery on the animals, he came to the conclusion that the horses had a couple of hours before formed part of the equipment of Christian Uys's commando, and a patch of clotted blood on the saddle and off stirrup of one of the horses told its own tale.

"Bring the light a little closer, Pat. I want to see the——"

Jack Lovat never finished the sentence, for a fierce fusillade was directed at the kraal from the immediate outside, and Zacchary, who was standing leaning on the butt of his rifle with his head on a level with a porthole, tumbled over—never to rise again, for a Mauser bullet had found its billet in the unfortunate Kaffir's head.

"To the loopholes, boys!" cried Jack; and the defenders replied with a will to the fire of the unseen enemy. For half an hour a constant fusillade was kept up, but without further loss to the defenders of the kraal, after which the Boer fire ceased.

Their attempt to storm the kraal had failed. Very tenderly Jack Lovat and Pat carried the stricken Zacchary to a corner of the kraal, and covered the dead body with some empty mealie sacks, after which Jack paid another visit to the house, where he found his mother and Mary quite safe.

A couple of hours were spent by Jack and Pat in reconnoitring, but all traces of the Boers had vanished, with the exception of a dead horse, which evidently had been wounded and managed to crawl towards the farm, where it had dropped down and died.

About two o'clock in the morning a sheet of flame, accompanied by the reports of many rifles, was seen far down the valley.

"They have come up with some Britishers, Pat," said Jack.

"By the powers!" observed the Irishman, "they seem to be hard at work. I would give something to be there."

For some minutes the firing lasted, then ceased, and shortly afterwards the sound of horses' hoofs could be heard coming up the valley.

Jack and his followers instantly manned the loopholes, but the strangers came steadily on.

"Shall I challenge them, sorr?" asked Pat; and without waiting for a reply, the brave Irishman passed out of the kraal, and with a stentorian voice called out, "Halt! who comes there?" at the same time levelling his rifle at the approaching figures.

"It is I, Pat!" shouted the master of the Kopje Farm; and the next moment Mr. Lovat had Jack in his arms, exclaiming, "It was a near shave, Jack, but I am glad I am able to see you all once more."

Mrs. Lovat and Mary were delighted beyond measure at Mr. Lovat's return, and with much trembling listened to the account of his adventures since he left the Kopje Farm on the previous morning.

Little did Mr. Lovat dream of the adventures he would pass through that morning as he drove away from Kopje Farm in the direction of Springbokfontein. Bessie was in good condition, and trotted swiftly between the shafts of the Cape cart, and the crisp air exhilarated man and beast.

When a couple of miles from home, he met an acquaintance riding a Cape pony, and pulled up to pass the time of day.

"Well, Mr. Bassett," said the ostrich farmer, "any news of the Boers?"

Mr. Bassett—a sturdy, thick-set man of middle age, who during his lifetime had tried his hand at nearly every kind of occupation, and now combined the office of land valuer with that of gold prospector—replied, "I've just come from Springbokfontein, Mr. Lovat, and rumours are flying thick and fast about Christian Uys being in the neighbourhood with a commando. This Uys is a very daring fellow, and has proved himself to be a most capable leader. Their stock of horses, I suppose, is getting low, and naturally enough the Boers want to replenish their store."

"Certainly," observed Mr. Lovat. "I suppose the town guard at Springbokfontein are on the alert?"

"Not half of them are to be trusted," replied Mr. Bassett grimly, "for I am afraid several of them are rebels at heart. You have left things all right up at the Kopje Farm, I hope?"

"Any Boers calling there will get a warm reception, I can assure you," replied Mr. Lovat, with a laugh. "I think that my son and the 'boys' will be able to give a good account of themselves, if they are interfered with. But I must be getting along, as I wish to be back by noon. Good-morning, Mr. Bassett;" and the ostrich farmer flicked Bessie with his whip.

The mare darted forward with a quick motion, and in a short time Mr. Lovat came to Jagger's Farm, the ruined building half way between the Kopje Farm and Springbokfontein.

The country was wild in the extreme. The road ran between a range of kopjes, at the bases of which were watercourses, dry in summer, but at times during the winter months raging torrents.

Jagger's Farm had an unenviable notoriety, several white men having been murdered in its vicinity. The building was surrounded by a roughly-built stone wall, which in many places was in a state of ruin.

The roadway was strewn with boulders of rock, and Mr. Lovat had to descend from his perch in the cart for the purpose of leading Bessie along the stony roadway.

The ostrich farmer was holding Bessie's head, for the mare made a stumble, when a harsh voice called out in Dutch, "Halt!"

To Mr. Lovat's dismay, he perceived six unkempt and fierce-looking men with heads and shoulders appearing above the farm wall, and the more ominous sight of a row of rifles pointed at him.

A couple of the Boers, for such they were, leaped over the wall and ran towards Mr. Lovat. The latter halted. The nature of the road and the murderous-looking Mausers dispelled any idea of escape, so grasping Bessie's reins tightly with his left hand, he faced the strangers, and said, "What do you want?"

"Your mare," answered one of the Boers in English.

"I won't sell her," said Mr. Lovat decisively. "She is not to be bought at any price. Allow me to pass, please."

A loud laugh burst from the Boers, the remaining three having joined their fellows in the roadway.

"Commandant Christian Uys requires the service of your horse. You will receive payment for it when the war is over," was the response Mr. Lovat received.

A couple of Boers sprang to the mare's head, evidently with the intention of unharnessing Bessie.

Grasping the handle of his whip, Mr. Lovat brought the butt end down with force upon the head of the Boer who had just spoken, and the Dutchman stumbled and fell in the roadway.

The next moment the ostrich farmer was lying senseless on the ground, having been knocked down by a blow from a clubbed rifle.

First came a vision of many-coloured stars, then oblivion; and the world for the time being was a blank to Mr. Lovat.

When he came to his senses, he found himself lying in the farmyard. His arms and wrists had been securely fastened behind his back, while his ankles were also tied. The Cape cart was standing close to where he lay, but the mare was gone.

Then his thoughts turned to the bag of gold, and though dazed and suffering from a violent headache, a remembrance of his encounter with the Boers flashed through his mind, and he gave vent to a heavy groan.

The farmyard was covered with rough veldt grass, which made his couch a less painful one than it would have otherwise been. A bundle of dirty, discarded Boer clothing lay beside him, and in the vehicle was a roughly made hamper, which was not there when he left home.

He thought about his wife, Mary, and Jack, and imagined their anxiety at his non-return. He tried to move, but was unable to do so, while the pain in his head was almost insufferable.

The sun climbed higher in the heavens, and its fierce rays beat upon his bare head. His physical pain grew greater, but the acuteness of his mind-suffering lessened, and at last he again relapsed into unconsciousness.

Then Mr. Lovat was brought to himself by some one shaking him.

The ostrich farmer looked up in a dazed sort of way, and the sight of a bronzed and stalwart Colonial trooper clad in khaki, and wearing a couple of bandoliers, met his gaze.

"What is the meaning of this?" asked the trooper. "Ah! I see you are wounded. You are a Britisher, of course?"

In a few words, Mr. Lovat told the story of his capture, and the Colonial drawing out a clasp knife, cut the cords with which Mr. Lovat's arms and ankles were bound, after which the Irregular helped the farmer to his feet.

A little pool of semi-coagulated blood lay where his head had rested, and the trooper noticing the settler's pallid face, drew out a small flask containing brandy, and insisted on his taking a drink. The spirit revived Mr. Lovat, and he made a search for the bag containing the gold, but, alas! it too was gone.

While he was engaged in ruefully surveying the cart, the trooper was joined by half a dozen comrades, who had been busy searching the farm premises.

"Hullo, Morton!" said one of the troopers, addressing the Irregular who had released Mr. Lovat. "What is the matter?"

"This gentleman has evidently been held up by a party of Boers belonging to Christian Uys's commando," replied Morton. "The rascals have looted him of a bag containing five hundred sovereigns."

"Great Scot! that is what I call a haul," exclaimed a young trooper. "I didn't think there was so much money to be found in this blessed country. Give me New Zealand in preference to this wilderness."

"We're Auckland Rangers," explained Trooper Morton to Mr. Lovat, "and are on the track of Christian Uys, one of the best leaders the Boers possess. He is on the look-out for horses and stores, I think, and although we have been dogging his commando for some days we have not been able to come up with them. Ah! here come our other fellows."

A party of horsemen in files of four came clattering along the stony road, and presently halted at the entrance to the farmyard. The troopers were about thirty in number—hardy, stalwart young Maorilanders—commanded by Major Salkeld, a Colonial who had done splendid service during the siege of Wepener.

The troop had several spare horses with them, and after Morton had explained the situation to his officer, Mr. Lovat was offered a mount, which he gladly accepted.

The horses were given a feed, and the troopers snatched a hasty meal of bully beef and biscuit. During the repast Mr. Lovat detailed a few facts concerning his farm and the surrounding country to Major Salkeld, and it was settled that the party should proceed in the direction of the Kopje Farm. Possibly they might come across the marauders and be able to restore Mr. Lovat's lost property to him.

The harness belonging to the Cape cart had been wantonly hacked, so that the idea of the vehicle's removal had to be abandoned.

Kopje Farm lay a good distance up the valley, and before the little force had proceeded a mile, Major Salkeld called a halt.

Trooper Morton's quick eye had detected a body of horsemen defiling through a donga about a mile away on the New Zealander's left flank. Morton, who was acting as scout, at once returned and reported the fact to his officer, who instantly placed his field glass to his eyes. The major looked long and earnestly, then handing his binocular to Morton, said, "Just give a glance through these, and tell me what you make of them."

The scout applied the glasses, after which he handed them back to the major, saying, "They are Boers, sir, without doubt."

"And how many do you make of them?" inquired the officer.

"About forty, I should say, sir," answered the trooper. "They have a couple of led horses with them as well."

Major Salkeld turned to Mr. Lovat, who had been riding by his side, and pointing to the donga, asked, "Where does the bridle-path leading to the donga terminate, Mr. Lovat?"

"It runs up to a settler's farm, some seven or eight miles from here," replied Mr. Lovat. "The settler is a Dutchman named Van Donnop, and it is said that his three sons are on commando with the rebels."

"Ah!" muttered the major, "just so; and these fellows doubtless are making tracks for this farm to re-equip and get a fresh supply of ammunition and stores. I am sorry that we cannot see you home, but duty is always duty, and the exigencies of the service demand that when we get on the track of the Boers we must follow them up."

"I am going with you, if I may," said Mr. Lovat. "Possibly these fellows have my five hundred pounds, and I can hardly afford to lose that."

"I am afraid, my dear sir, that you have said good-bye to your gold," said the major. "However, if you care to accompany us, you can do so. You are looking better now than when I saw you first. I suppose you can shoot?"

"There are not many settlers who can't," answered Mr. Lovat, with a touch of dignity in the tones of his voice.

"I mean no offence," said the major. "Do you feel strong enough to go with us?"

"I'm all right now," replied the settler. "My head is somewhat sore, and the muscles of my neck a little stiff, but I would rather go on with you, sir."

"Very good, you shall," said the officer. Turning to Morton, he continued, "We have a spare rifle?"

"Half a dozen, sir," answered the trooper. "I have an extra one with me, which Mr. Lovat can have, if he understands the mechanism."

"Then kindly hand it over," said the major.

Turning again to the settler, the officer continued, "Luckily you have not been much troubled in these parts, but I'm afraid you soon will be. The Boers are getting short of ammunition, and these roving bands of burghers are merely the advanced guard of a bigger force of Boers. The supply of ammunition has been stopped through Lorenzo Marquess, and the burghers are making their way to Port Nolloth, and other places on the west coast, where contraband stuff in the shape of rifles and cartridges are to be had in plenty. I suppose the majority of the settlers about here are loyal?"

"I'm afraid I can't answer that question entirely in the affirmative. I know that I am, and all living in the Kopje Farm are loyal subjects of the King. Many young men have disappeared from the district, and I saw signs of the coming storm long before it burst."

"What! even in this remote part?" asked the Colonial officer.

"A couple of years before the war broke out, Boer emissaries went about from place to place, ostensibly as pedlars, but I am certain they were secret agents of the Transvaal Republic," answered Mr. Lovat.

The major addressed a few words to his men. They were brief and to the point:—

"Boys," he began, "I have no doubt that we are on the track of Christian Uys, and I sincerely trust we shall be able to lay him by the heels. Perhaps this is part of his commando in front of us. Be careful with your ammunition, for we have none to spare. Don't waste it. I hope to be in Springbokfontein to-morrow when the regiment arrives; but in the evening we must harry the enemy, who I am pleased to say have on the whole proved honourable men. The day after to-morrow I promise you a couple of days' rest. Then we move on to Port Nolloth. Now, boys, a fairly good pace, but don't blow your horses."

The road, however, was so difficult that there was no prospect of the latter occurrence happening. The troopers could only proceed in double file, and the men were compelled to assume an oblong formation, which would have formed a splendid target for an enemy armed with Mausers or light field guns.

Morton, the most daring man in the Auckland Rangers, was well in front when a "Phit!" "Phit!" followed by a fusillade, caused him to halt.

The New Zealanders had been discovered by the enemy, who by this time had passed out of view. The bullets went whistling over the heads of the Colonials, who, on the order of Major Salkeld, retired to the shelter of a small donga, some two hundred yards in their rear.

Every fourth man was detailed to lead his own and three comrades' horses to a watercourse naturally protected by immense boulders of quartz.

Ten dismounted troopers were next ordered by the major to creep forward to the position they had just left, while the rest of the unencumbered advanced one hundred yards and flung themselves on the ground.

Mr. Lovat, savage at the loss of his gold, begged the officer to allow him to form one of the advanced party, and the major readily acceded to his request.

The ostrich farmer declared that he was all right,—the pain in his head had left him,—and Morton having glanced approval, Major Salkeld consented, and the eleven Imperialists crept forward on hands and knees towards the spot they had just vacated.

The sun was on the point of dropping below the western horizon, and in half an hour's time darkness would cover the veldt, so there was no time to be lost if the Boers were to be captured.

The long, low buildings which constituted Van Donnop's farmstead could be plainly seen, but the Boers had disappeared within a donga. Their approach to the farm, however, would be covered by the troopers' fire, and Morton and his fellow-Colonials waited impatiently for the enemy to emerge from the donga.

Presently a couple of Boers dashed across the space intervening between the donga and the farm.

Two shots rang out, and thin wreaths of bluish-tinted vapour hung round the muzzles of the rifles wielded by Mr. Lovat and Trooper Morton.

"Got him!" ejaculated the latter, as one of the Boers threw up his arms and fell from the horse. The animal, relieved of its burden, galloped wildly towards the farmstead.

The second Boer, on seeing his fellow-burgher fall, wheeled his horse quickly round and dashed furiously for the shelter of the donga.

A dozen leaden messengers of death whistled around him, but he and his steed passed through them unharmed.

With the exception of a solitary shot, no fire came in reply to the troopers' fusillade, and Morton waved to the remainder of the troop to come up, which the latter did.

A consultation was held between Major Salkeld and Morton, and it was eventually decided to await the darkness which would descend on the veldt. Under its cover an advance would be made on the farm.

Just as the last streaks of yellow light were fading into a mass of purplish gray, Morton begged his major to allow him to creep forward in the direction of the farm for the purpose of reconnoitring, and the officer assented.

Slinging his rifle behind his back, the scout slowly edged his way to where the stricken Boer lay on the veldt. The Free Stater was dead, for a couple of bullets had pierced his brain.

He was a rough-looking man with unkempt hair and beard, and the daring trooper, still prostrate, turned him over and coolly began to search his pockets.

Morton abstracted several documents, which he thrust into an inner pocket of his khaki tunic, after which he retraced his way to his comrades, still crawling on his hands and knees.

He handed the papers to Major Salkeld, who determined to advance at once on Van Donnop's farmstead. In answer to an interrogation from his superior, Morton explained that he had not seen any Boers except the dead one, and that the Dutch settler's farm betrayed no sign of life.

Ten minutes later, the New Zealanders were drawn up in front of the farm buildings, and Morton, always the first to volunteer for any hazardous duty, went straight to the front door of the house and began hammering with the butt of his rifle upon its stout panels.

Footsteps could be heard in the passage, and a voice called out in Dutch, "Who is there?"

"Open the door instantly," commanded Morton brusquely, "or I'll blow it in."

The door was unfastened by a man of immense girth of chest. His physiognomy showed his Dutch extraction.

"What do you want?" demanded the farmer gruffly. This time he spoke in English.

Morton in reply gave a shrill whistle, and the next moment a dozen troopers crowded into the wide passage, Major Salkeld being at their head.

"Now, then, Mynheer—whatever your name is, we want to have a look at the stores you have concealed in this building," began the major. "I shall also be glad to learn something about the whereabouts of Christian Uys and his commando."

"I know nothing about them," answered Van Donnop, for such he was.

"You can tell some other person that tale," observed Major Salkeld, with a laugh. "You have some food in the house, I suppose?"

Van Donnop looked at the speaker with a surly expression on his face.

"Oh, we shall pay for everything we consume," continued the officer. "Look sharp, my man;" and Van Donnop with bad grace led the way to a large kitchen, in which half a dozen Kaffirs, evidently farm hands, were seated round a log fire.

Food was supplied to the troopers, as well as forage for their horses, after which the premises were thoroughly searched for concealed arms; but the hunt proved fruitless. After paying for the supplies, the major and his troopers rested for a couple of hours.

Sounds of rifle-firing away to the west were heard, and soon after midnight the New Zealanders, accompanied by Mr. Lovat, set out for the Kopje Farm, and all earnestly hoped they would come across their brave and stubborn enemy.

And so they did; but with the exception of a few desultory shots fired at an uncertain range, and without any casualties on their side, Major Salkeld and his troopers, as related in the last chapter, arrived on the scene where Jack Lovat and his handful of Kaffirs had so bravely defended his father's farmstead.

Jack Lovat was warmly congratulated by the New Zealanders on their arrival at the Kopje Farm, and the ostrich farmer naturally felt proud of his son.

The return of Bessie was described by Jack, and Trooper Morton said he had no doubt whatever that the animal which had bolted when its Boer rider was shot by Trooper Morton and Mr. Lovat was none other than the gallant little mare.

As soon as daylight broke, the Colonials, headed by Mr. Lovat, Jack, and Pete, examined the country in front of the ostrich kraal to a distance of a thousand paces.

Three dead Boers and two horses were found stretched on the veldt, and Jack Lovat had no difficulty in identifying the body of Jan Van Donnop, one of the sons of the Dutch settler of that name.

Jan and his brothers, Piet and Stephanus, had mysteriously disappeared from the neighbourhood soon after the outbreak of hostilities, and their father had given it out that the lads had gone to reside at East London with a relative in order to learn the trade of milling.

Mr. Lovat made a more important discovery. Attached to the saddle of a dead horse was the cowhide bag which the previous morning had contained his five hundred sovereigns, but which, alas! was now empty.

The pockets of the dead Boers revealed no traces of the lost gold, and Morton remarked, "I'm afraid, Mr. Lovat, you have said good-bye to the coin. None of these men are leaders."

Mr. Lovat was examining the features of one of the dead men, and without heeding the Colonial's remark, he said, "This fellow is the man who commandeered Bessie."

With the aid of pickaxes and spades, a trench was made by the New Zealanders, and the stricken Boers and their horses were decently interred, Jack Lovat taking charge of several mementos belonging to Jan Van Donnop.

Jack was possessed of a humane nature, and being far from illiterate and possessing a cosmopolitan turn of mind, he had not the racial prejudices so largely predominant during the awful struggle in South Africa which commenced at the end of the nineteenth century.

Morton had taken intuitively to Jack, and after the interment he whispered in the lad's ear, "Why don't you join us? The war is not half over yet, and there is sure to be a lot of fighting. Ask your father to allow you to come with us."

"I'm afraid he won't," answered Jack. "I wanted to join Driscoll's Scouts, but he refused, and I believe I have learned the first duty of a soldier."

"And pray, what is that?" queried the trooper.

"Why, obedience," replied Jack. "I owe that duty to my father, who is most kind to me. Besides, I hardly think it would be right for me to leave mother and Mary just now. Mary is my sister. You saw her when your fellows came here."

"Well, all I can say, youngster, is that you are a brick and no mistake," said the trooper enthusiastically. "What did you feel like when the Boers came up? Timid?"

"Hardly," remarked Jack laconically. "I was only sorry that they didn't try to storm in broad daylight. I mean about noon, say."

The trooper laughed outright at Jack's bold statement, and said, "Well, I thought we New Zealanders were a cool set of fellows, but you ostrich people take the cake."

The pair were approaching the Kopje Farm, bringing up the rear-guard, when Jack turned and asked, "You have been a soldier all your life, haven't you?"

The trooper laughed as he replied, "Oh dear no; I'm a working jeweller by trade, and when at home am engaged by a large firm in Auckland. When the mother country called for men, I volunteered for service in South Africa. Why do you ask the question, my lad?"

"I thought you had always been a soldier, for you look so like one," answered Jack; and Morton felt a trifle elated, for what man or boy exists who does not inwardly relish a small modicum of flattery?

"You have nothing in the shape of diamonds, I suppose, in this part of the country?" queried the trooper. "I have examined the clay in several dongas as we came along, and from what I know of mineralogy, I should say that diamonds are to be found in this district."

"Crystals are common enough about here," answered Jack. "I have a collection which I will show you when we reach the farm. Among the pebbles are several fine garnets and amethysts. One of our 'boys,' Pete by name, picked up a stone, which he found embedded in a sort of bluish clay only a fortnight ago. It is too dull, however, for a diamond."

During the few minutes occupied in the return to the farm, Morton thought deeply about what Jack had told him. He was a thorough patriot, but since he had been in South Africa his mind had dwelt largely on diamonds, for exaggerated accounts of the mineral resources of the veldt had reached New Zealand.

Mr. Lovat was a thoughtful man, and since the beginning of the war had laid up big supplies of eatables in the shape of hams, bacon, preserved meats, and tins of jam and marmalade.

It seemed as though the Kopje Farm had been designedly prepared for a siege, for in the big storeroom at the back of the house were provisions calculated by Mr. Lovat to last at least twelve months, and these were being added to.

The major determined to allow his men a few hours' rest, and the horses were off-saddled and given a good feed of corn, Jack Lovat paying particular attention to Morton's mare, which was a magnificent creature nearly seventeen hands high, and noted for its swiftness and sureness of foot.

Jack conducted his newly-made friend round the ostrich kraal, and explained the various operations connected with the hatching of eggs and the plucking of the birds' plumage, and the trooper evinced great interest in the young settler's narration.

The remains of poor Zacchary, the "boy" who was shot at the loophole, had been reverently interred, and Jack and his friend were standing alone beside the mound of freshly turned earth, when the latter observed, "Oh, by the way, Jack, I would very much like to have a look at that stone you spoke to me about."

"You mean the pebble Pete gave to me?" asked Jack.

"Yes, I think that is the nigger's name," replied Morton.

To the trooper's great surprise, Jack instantly fired up. "No, that won't do; we don't call our 'boys' niggers. They are our 'boys,' and faithful ones they are, too."

The New Zealander smiled at Jack's impetuosity, and remarked, "A very good trait in your character. Only we have seen so many Kaffirs since we have been in the country that all nice distinctions are washed out, and we call the blacks generally 'niggers,'—not a very gentlemanly expression, I admit."