The Project Gutenberg eBook of Memorials of old Derbyshire, by J. Charles Cox

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online

at

www.gutenberg.org. If you

are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the

country where you are located before using this eBook.

Title: Memorials of old Derbyshire

Author: J. Charles Cox

Release Date: September 20, 2022 [eBook #69017]

Language: English

Produced by: Tim Lindell, Chris Jordan, George Peabody Library (Johns Hopkins University) and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MEMORIALS OF OLD DERBYSHIRE ***

Memorials of Old Derbyshire

Memorials of the Counties of England

General Editor: Rev. P. H. Ditchfield, M.A., F.S.A.

Memorials

of

Old Derbyshire

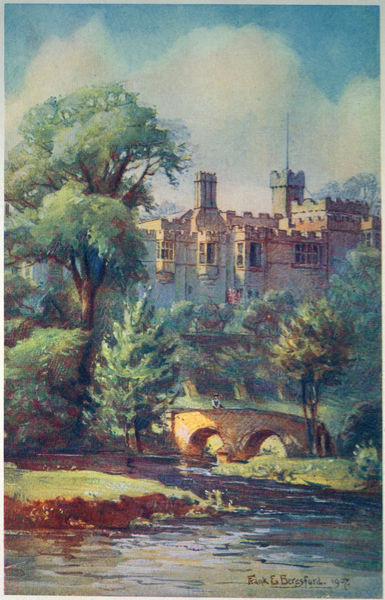

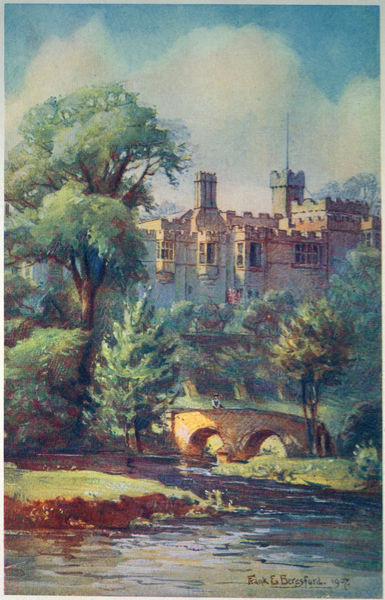

Haddon Hall:

“Dorothy Vernon’s Bridge.”

From a water-colour sketch by

Mr. Frank E. Beresford.

MEMORIALS

OF

OLD DERBYSHIRE

EDITED BY

Rev. J. CHARLES COX, LL.D., F.S.A.

Author of

“Churches of Derbyshire” (4 vols.),

“Three Centuries of Derbyshire Annals” (2 vols.),

“How to write the History of a Parish,”

“Royal Forests of England,”

“English Church Furniture,” etc., etc.

Editor of “The Reliquary”

With many Illustrations

LONDON

Bemrose and Sons Limited, 4 Snow Hill, E.C.

AND DERBY

1907

[All Rights Reserved]

TO

THE RIGHT HONOURABLE

SPENCER COMPTON CAVENDISH,

K.G., F.R.S., D.C.L., LL.D.,

EIGHTH DUKE OF DEVONSHIRE,

CHANCELLOR OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE,

AND LORD-LIEUTENANT OF DERBYSHIRE,

THESE MEMORIALS ARE,

BY KIND PERMISSION,

INSCRIBED

[vii]

PREFACE

It has been a great pleasure to accept the request of

the General Editor of this Memorial Series to edit

a volume on my native county of Derby. In proportion

to its size and population, more has been written

and printed on Derbyshire than on any other English

county. But in these days, when, year by year, the national

stores of information in Chancery Lane are becoming

better arranged and more fully calendared, when there is

more generous access to muniments in private possession,

and when the spirit of critical archæology is becoming more

and more systematised, there is no sign whatever that

the history of the county is in any way near exhaustion.

Nor will that be the case even when the four great

volumes of the Victoria County History are completed.

So abundant are the historical records of Derbyshire,

and so rich are the archæological remains, that there

would be no difficulty, I think, in the speedy production

of a companion volume to this of equal interest and of

as much originality, should the General Editor and the

publishers desire such a sequel. I say this as an apology

for omissions of which I am fully conscious; and, as

it is, the publishers have kindly allowed the present[viii]

pages to exceed in number those of any other volume

of the series.

There is one sad subject in connection with the

production of this work—I allude to the death of that

distinguished antiquary, the late Earl of Liverpool. Many

years ago, in the “seventies” of last century, it was

owing to his suggestion and friendly encouragement that

I first undertook and persevered in the attempt to write

on all the old churches of Derbyshire; and when he

was known as Mr. Cecil Foljambe, we often visited

together such churches as Tideswell, Bakewell, and

Chesterfield. Immediately the idea of this volume had

been formed, I wrote to Lord Liverpool, and at once

received his cordial assent to prepare an article on the

Foljambe monuments of the county. In the course of

his letter he wrote:—“I accept your proposal all the

more willingly as I have recently unearthed certain strong

confirmatory evidence as to the two Tideswell effigies,

claimed of late years to belong to the De Bower family,

and rashly lettered, being in reality Foljambes” (see

p. 103). We exchanged several letters on the subject,

then his health began to fail, and he begged me to

undertake the work, promising to revise it carefully and

to give additional matter; but, alas! death intervened

before even this could be accomplished.

All the articles between these covers have been

specially written, and for the most part specially

illustrated for the book, with one exception, namely, the

delightfully vivid chapter by Sir George R. Sitwell, on

the country life of a Derbyshire squire of the seventeenth[ix]

century. To almost all the readers of the book, this

essay will also be entirely novel. It is reproduced, in a

somewhat abbreviated form, by the writer’s kind and

ready permission, from the introductory chapter to Sir

George Sitwell’s privately issued Letters of the Sitwells

and Sacheverells, of which only twenty-five copies were

printed.

My most grateful thanks are due to each of the

contributors for their valuable papers, as well as to those

who have supplied photographs, or who have loaned

prints or drawings. It would be invidious for me to

particularize where there has been so much ready kindness

in contributing the elements of this Olla Podrida.

In arranging this book, it may be well to state that

no effort whatever has been made to produce a kind of

history of the shire inpetto, which would, in my opinion,

be a great mistake in a work of this character and

intention. Each essay stands by itself; all that I have

done, in addition to my own contributions, is to arrange

them in a kind of rough chronological order.

J. Charles Cox.

Longton Avenue,

Sydenham,

November, 1907.

[xi]

CONTENTS

| Page |

| Historic Derbyshire |

By Rev. J. Charles Cox, LL.D., F.S.A. |

1 |

| Prehistoric Burials |

By John Ward, F.S.A. |

39 |

| Prehistoric Stone Circles |

By W. F. Andrew, F.S.A. |

70 |

| Swarkeston Bridge |

By W. Smithard |

89 |

| Derbyshire Monuments to the Family of Foljambe |

By Rev. J. Charles Cox, LL.D., F.S.A. |

97 |

| Repton: Its Abbey, Church, Priory and School |

By Rev. F. C. Hipkins, M.A., F.S.A. |

114 |

| The Old Homes of the County |

By J. A. Gotch, F.S.A. |

133 |

| Wingfield Manor House in Peace and War |

By G. Le Blanc-Smith |

146 |

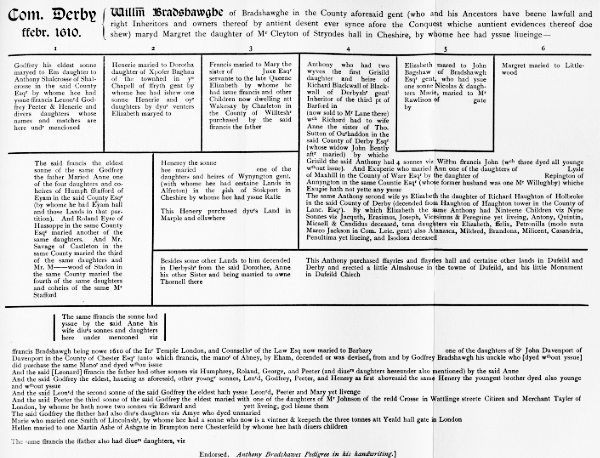

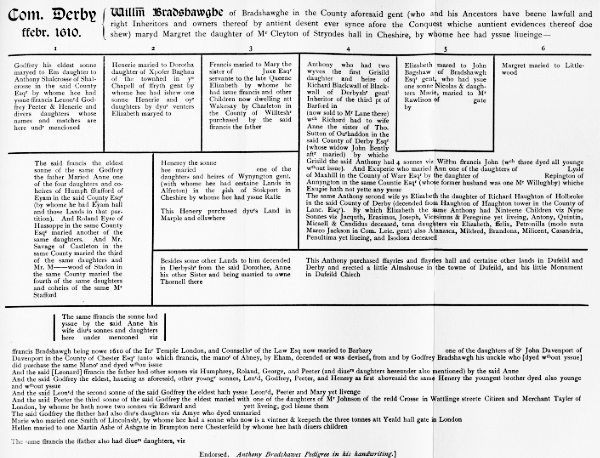

| Bradshaw and the Bradshawes |

By C. E. B. Bowles, M.A. |

164 |

| Offerton Hall |

By S. O. Addy, M.A. |

192 |

| Roods, Screens and Lofts in Derbyshire Churches |

By Aymer Vallance, F.S.A. |

200 |

| Plans of the Peak Forest |

By Rev. J. Charles Cox, LL.D., F.S.A. |

281 |

| Old Country Life in the Seventeenth Century |

By Sir George R. Sitwell, Bart., F.S.A. |

307 |

| Derbyshire Folk-Lore |

By S. O. Addy, M.A. |

346 |

| Jedediah Strutt |

By the Hon. F. Strutt |

371 |

| Index |

| 385 |

[xiii]

PLATE ILLUSTRATIONS

Haddon Hall: “Dorothy Vernon’s Bridge”

(From a water-colour Sketch by Mr. Frank E. Beresford) |

Frontispiece |

| Facing Page |

Melbourne Castle

(Survey, temp. Elizabeth) |

14 |

Wingfield Manor

(From a Drawing by Colonel Machell, 1785) |

20 |

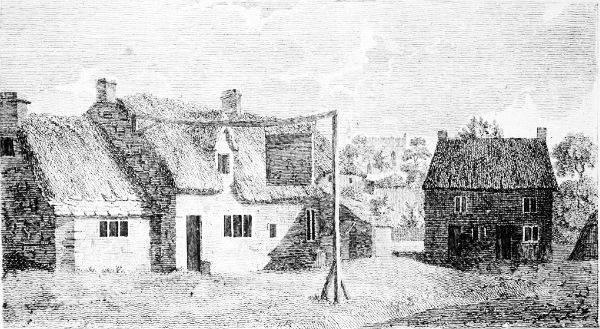

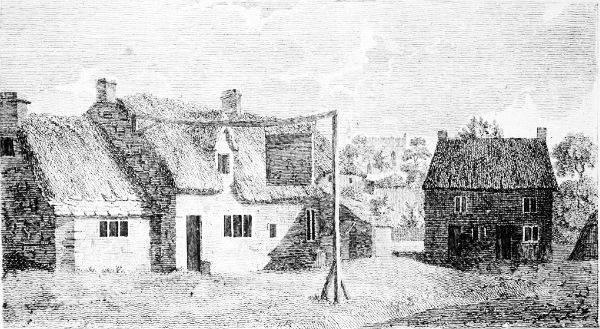

Revolution House at Whittington

(From “Gentleman’s Magazine,” 1810) |

32 |

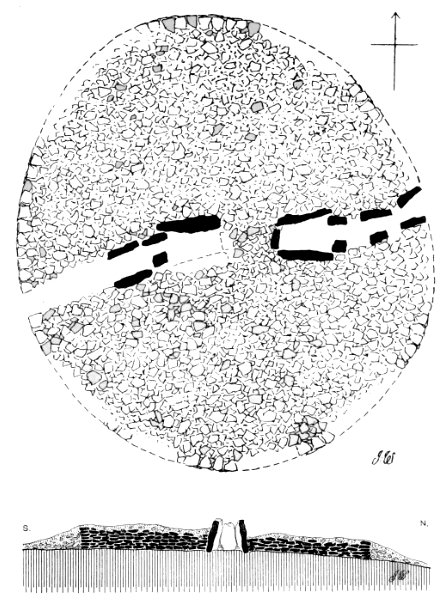

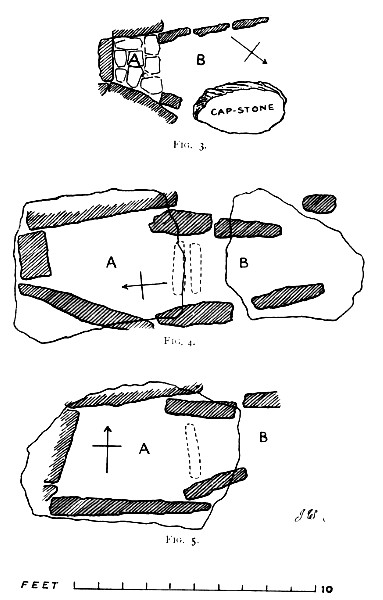

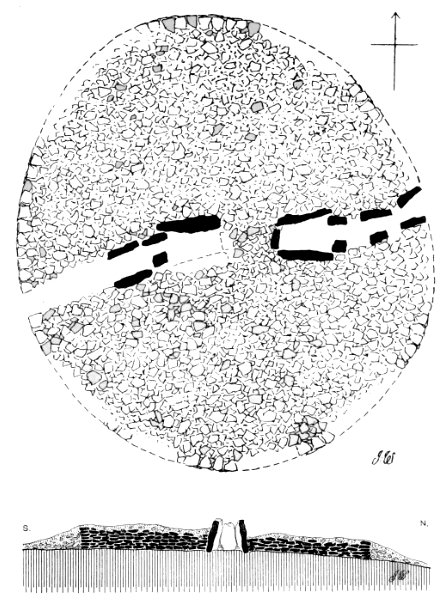

Plan and Section of Chambered Tumulus, Five Wells, Derbyshire

(From Drawings by John Ward) |

42 |

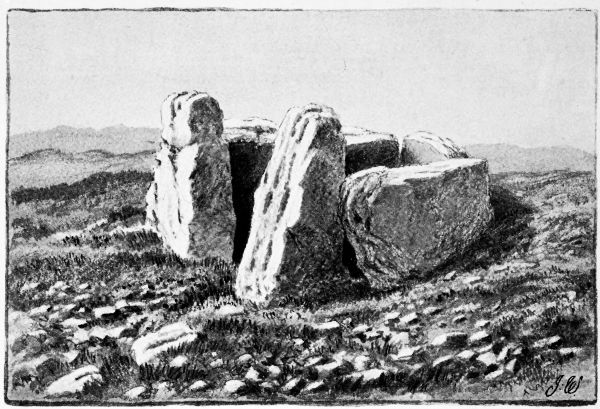

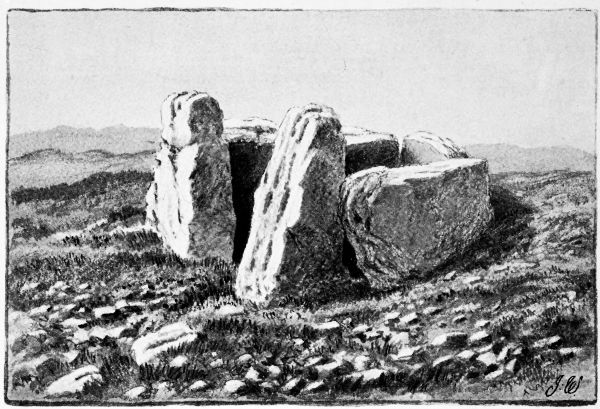

East Chamber at Five Wells. View from the North-East

(From a Sketch by John Ward) |

44 |

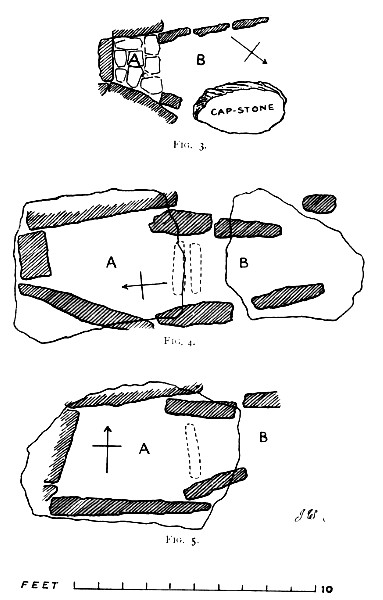

Plans of “Chambers” at Harborough Rocks and Mininglow, Derbyshire

(From Drawings by John Ward) |

46 |

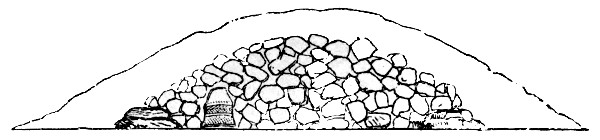

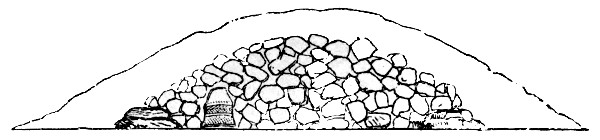

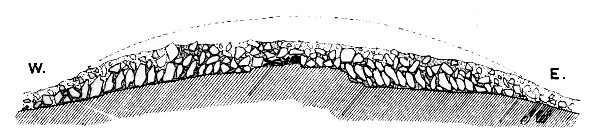

Section of Barrow at Flaxdale, near Youlgreave

(From wood-cut by Llewellynn Jewitt) |

50 |

| Section of Barrow at Grinlow, near Buxton |

50 |

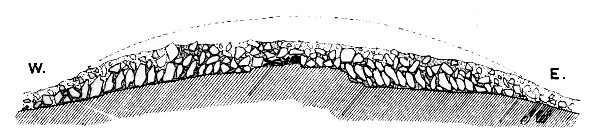

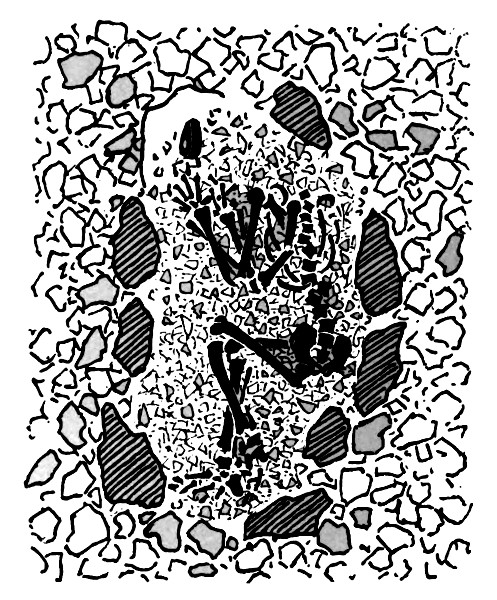

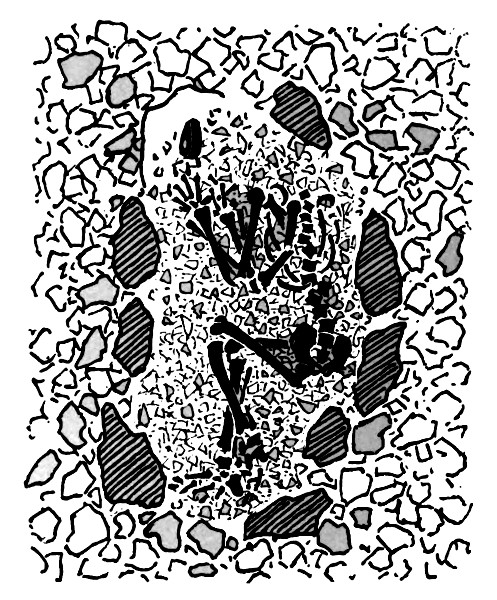

Plan of Burial at Thirkelow, near Buxton

(From Drawings by John Ward) |

50 |

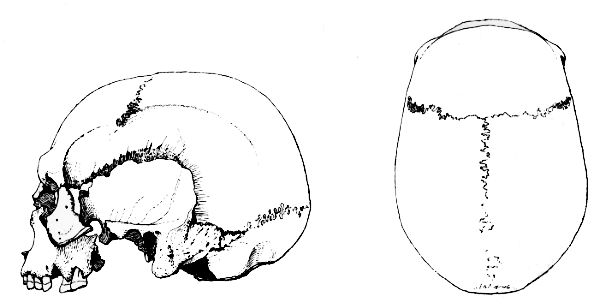

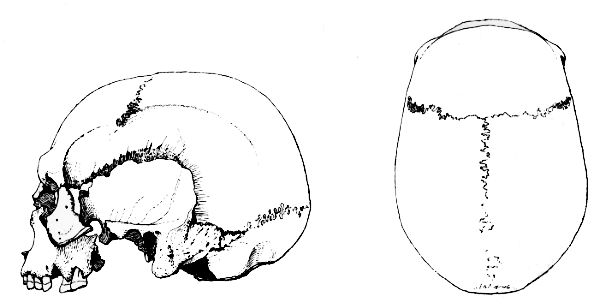

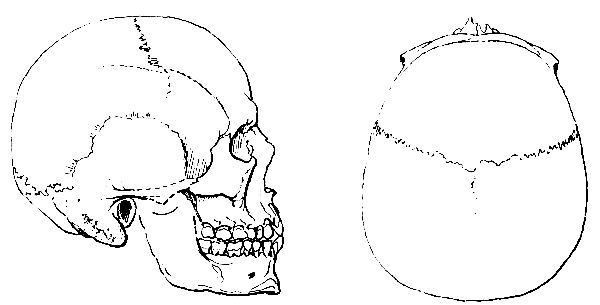

Dolichocephalic Skull from “Chamber” at Harborough Rocks.

Side and Top Views

(From Drawings by John Ward) |

52 |

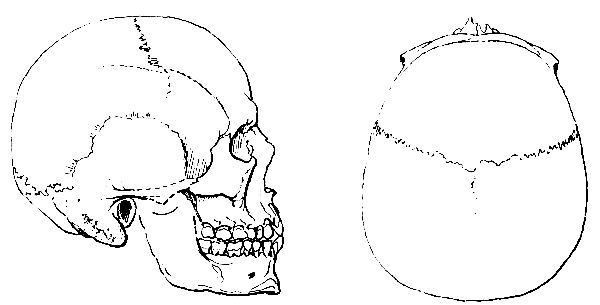

Brachycephalic Skull from Grinlow. Side and Top Views

(From Drawings by John Ward) |

54 |

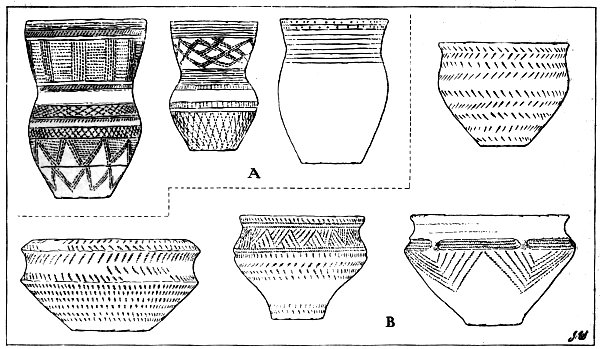

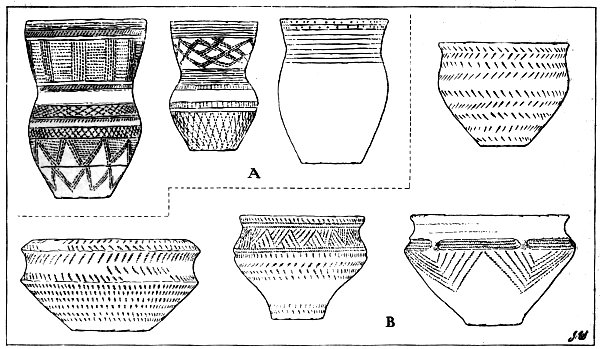

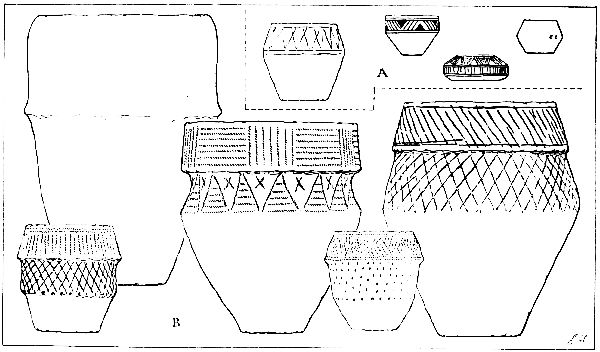

Typical Examples of Bronze Age Burial Vessels, Derbyshire

(From Drawings by John Ward) |

56 |

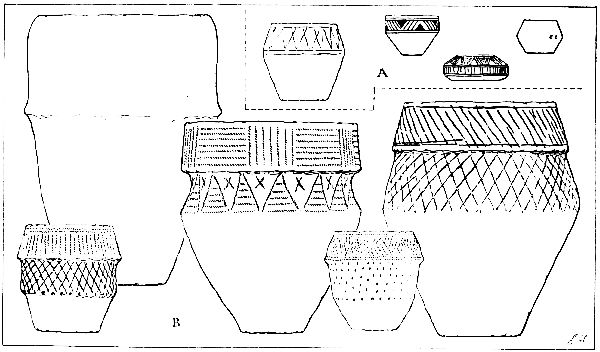

Typical Examples of Bronze Age Burial Vessels, Derbyshire

(From Drawings by John Ward) |

58 |

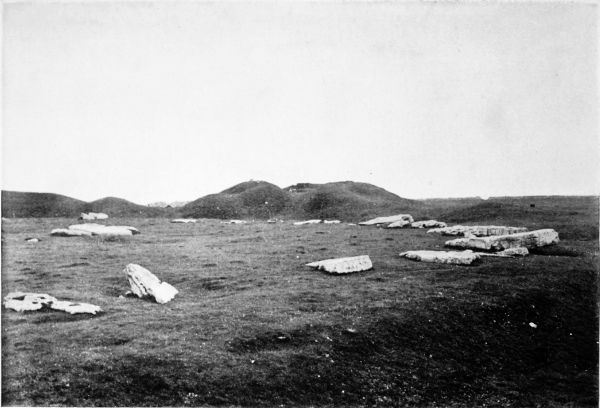

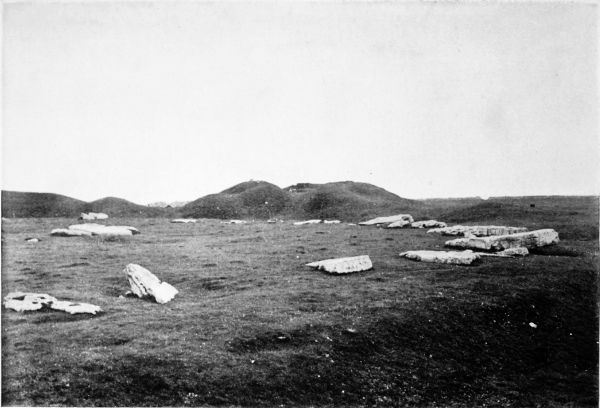

Arbor Low: General View of the Southern Half

(From a Photograph in possession of the Derbyshire Archæological Society) |

70 |

Arbor Low: General View of the Southern and Western Part

(From an Original lent by the Derbyshire Archæological Society) |

80 |

Swarkeston Bridge

(From a Photograph by Frank W. Smithard) |

90 |

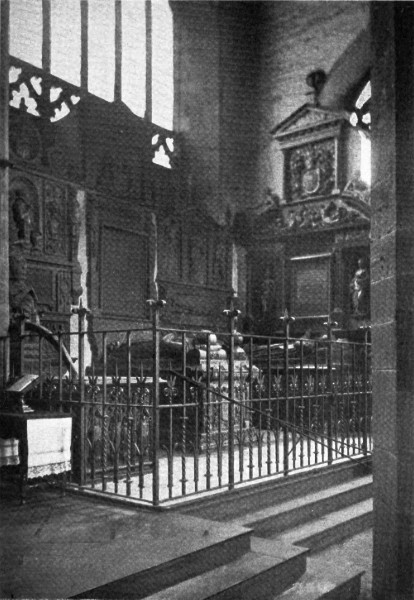

Tideswell Church: The Chancel

(From a Photograph by F. Chapman, Tideswell) |

102[xiv] |

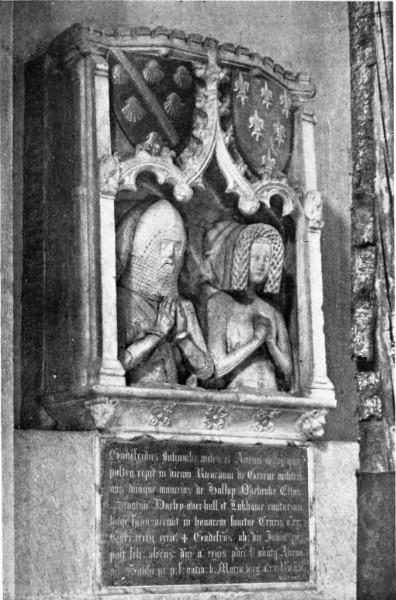

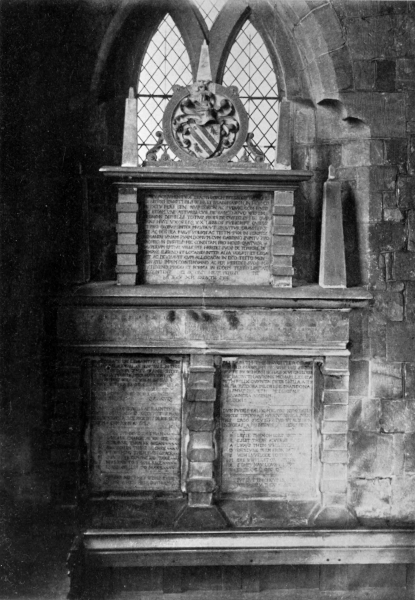

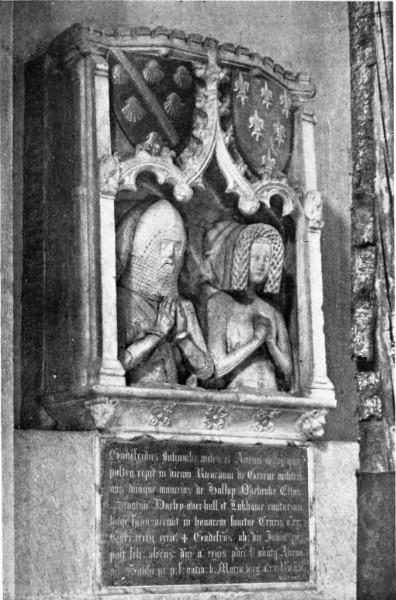

Bakewell Church: Foljambe Monument

(From a Photograph by Guy Le Blanc-Smith) |

106 |

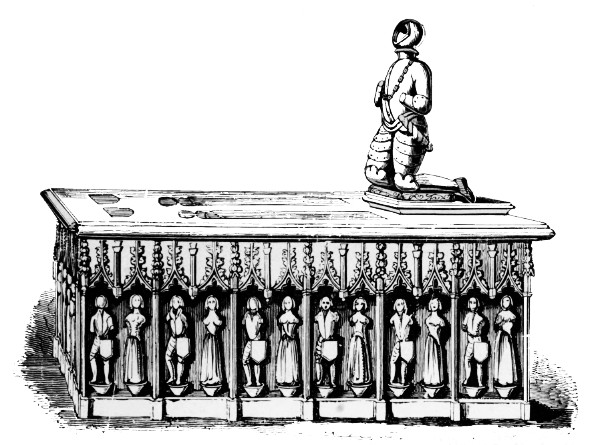

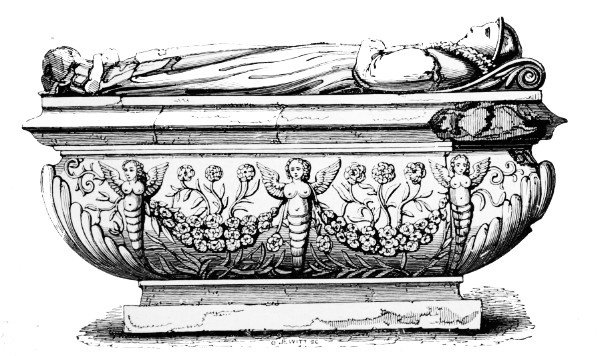

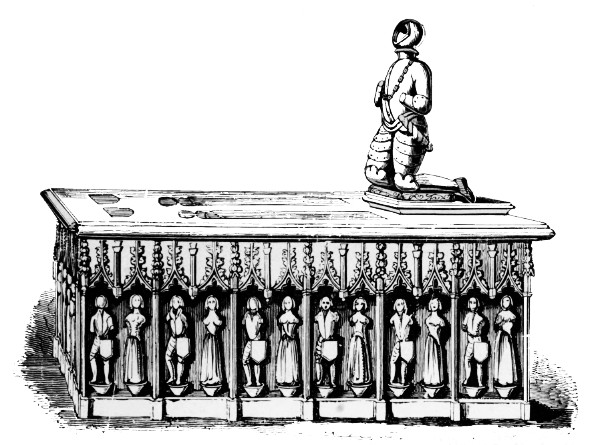

Tomb of Henry Foljambe, 1510, and Kneeling Figure of Sir

Thomas Foljambe, 1604; Tomb of Godfrey Foljambe, 1594

(From Originals (1839) lent by Mr. Jaques) |

108 |

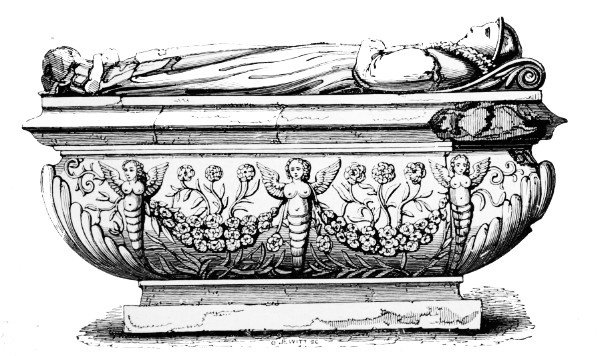

Chesterfield Church: Foljambe Chapel

(From a Photograph by J. H. Gaunt, Chesterfield) |

110 |

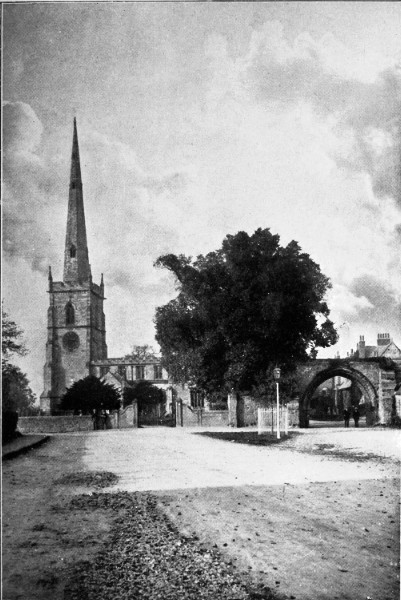

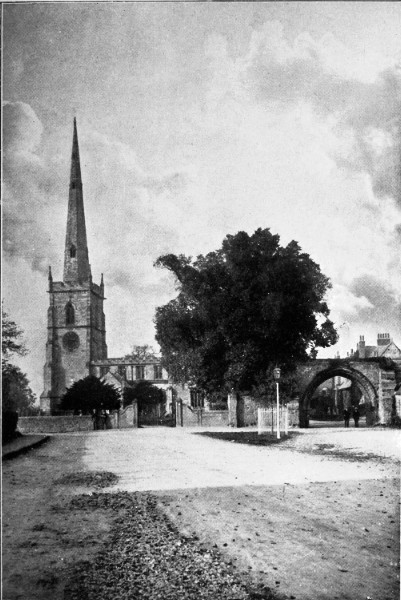

Repton: Parish Church and Priory Gateway

(From a Photograph by Rev. F. C. Hipkins) |

114 |

Repton Church: Saxon Crypt

(From a Photograph by Rev. F. C. Hipkins) |

118 |

Repton: The Priory Gateway and School

(From a Photograph lent by Rev. F. C. Hipkins) |

124 |

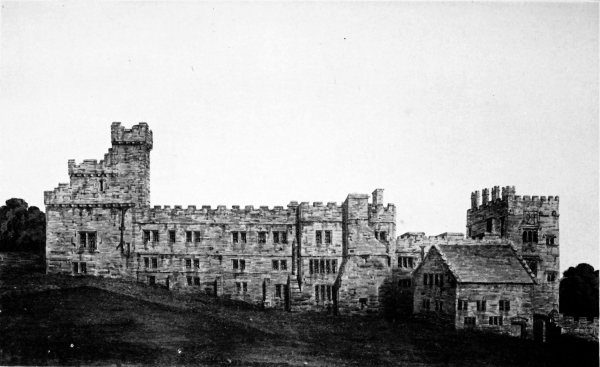

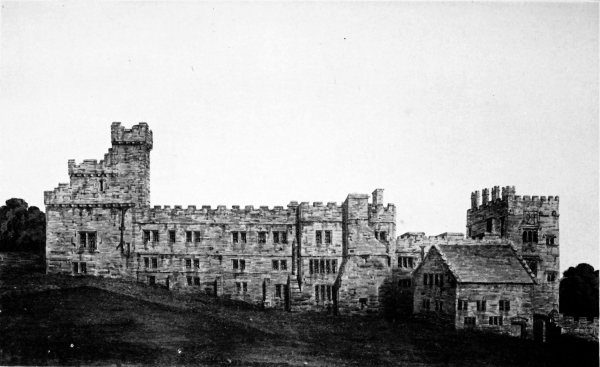

The Castle of the Peak

(From a Photograph by R. Keene & Co.) |

134 |

Bolsover Castle: “La Gallerie”

(From Sir W. Cavendish’s “Treatise on Horsemanship”) |

136 |

| Haddon Hall (North View, 1812) |

138 |

| Haddon Hall (North View, circa 1825) |

140 |

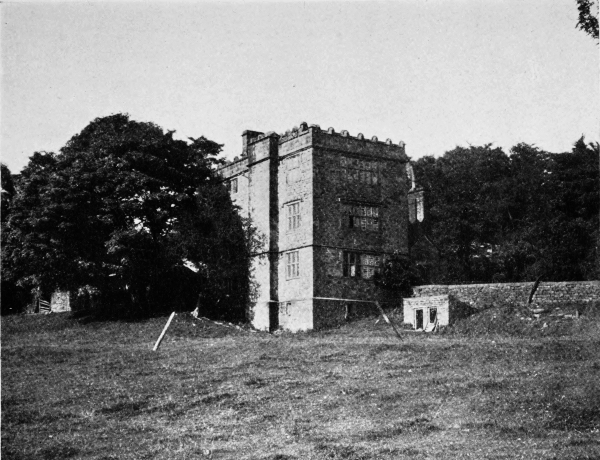

Snitterton Hall

(From a Photograph by R. Keene & Co.) |

142 |

North Lees Hall; Foremark Hall (Garden Front)

(From Photographs by J. A. Gotch, F.S.A.) |

144 |

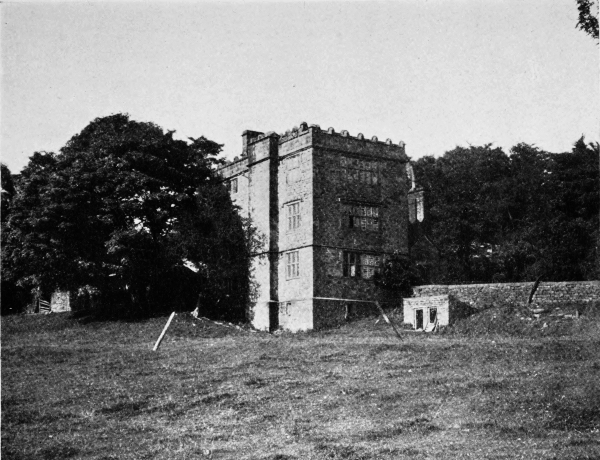

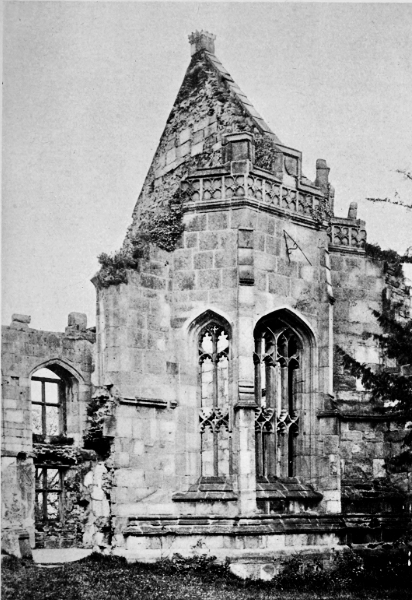

The Tower, and Rooms occupied by Mary Stuart, Wingfield

(From a Photograph by Guy Le Blanc-Smith) |

146 |

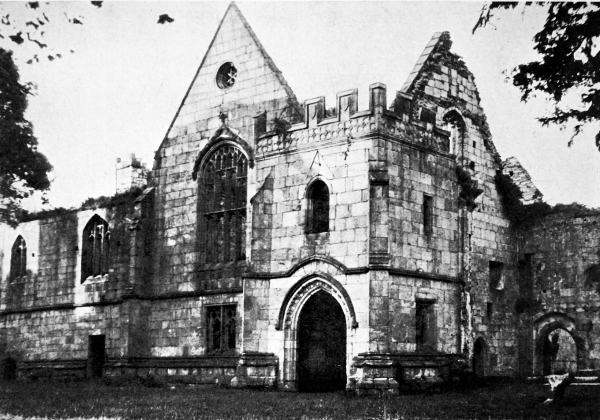

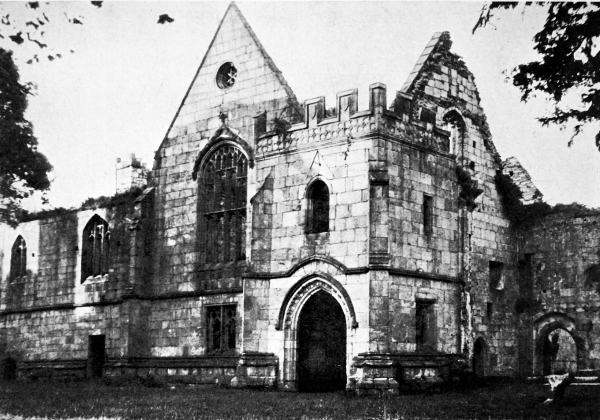

The Porch of Banqueting Hall, Wingfield

(From a Photograph by Guy Le Blanc-Smith) |

152 |

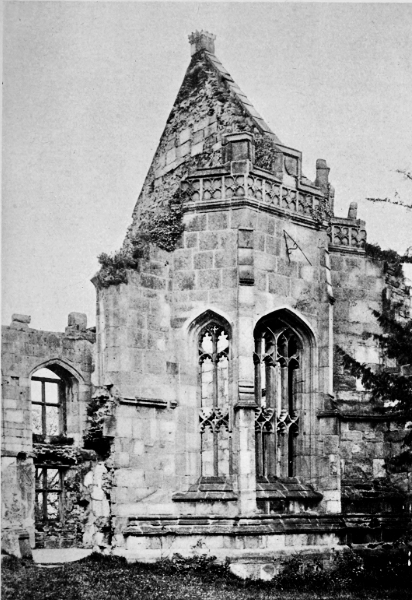

The Window in the Banqueting Hall, Wingfield

(From a Photograph by Guy Le Blanc-Smith) |

156 |

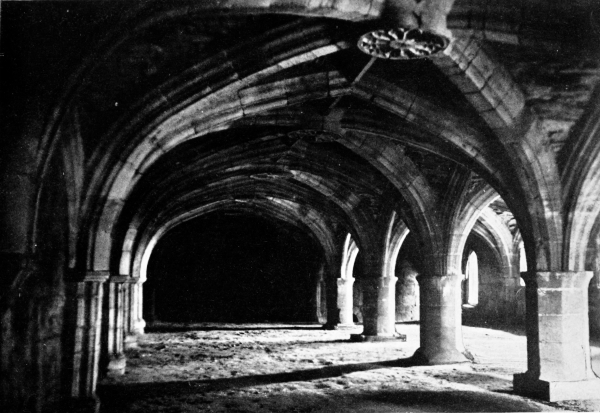

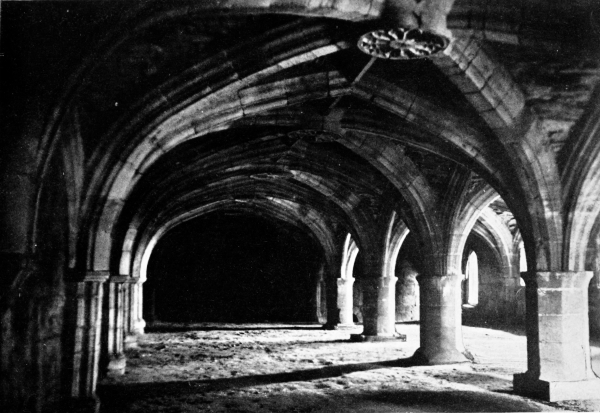

The Undercroft, Wingfield

(From a Photograph by Guy Le Blanc-Smith) |

162 |

Bradshawe Hall

(From a Photograph by C. E. B. Bowles) |

164 |

John Bradshawe, Serjeant-at-Law

(From an Original lent by C. E. B. Bowles) |

174 |

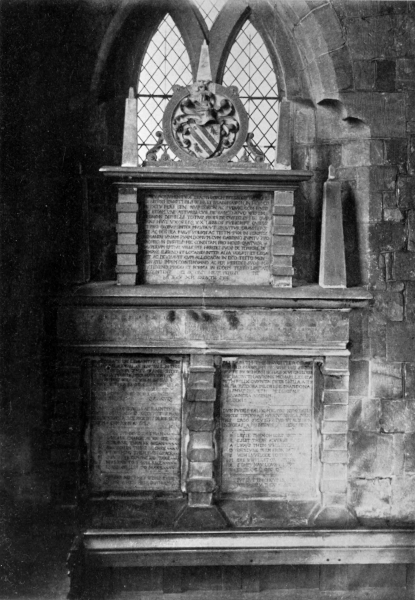

Duffield Church: Monument of Anthony Bradshawe

(From a Photograph by R. Keene & Co.) |

178 |

Bradshawe Hall: Detail of Gateway

(From a Photograph by C. E. B. Bowles) |

188 |

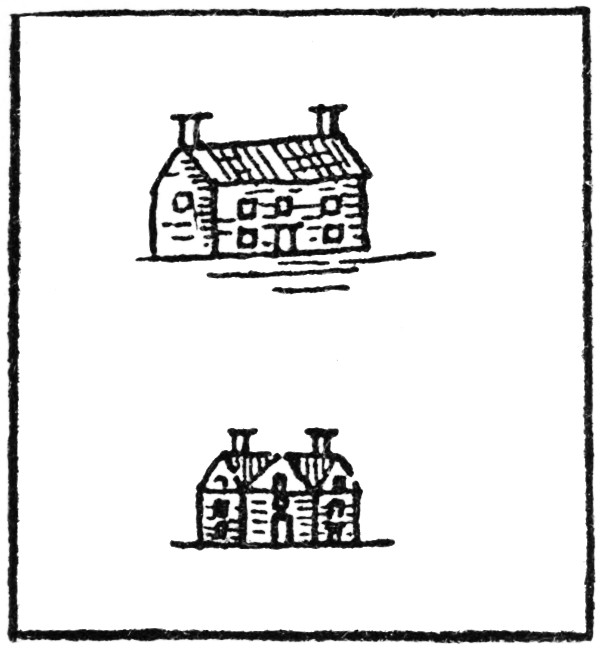

Offerton Hall (Front and Back Views)

(From Photographs by S. O. Addy, M.A.) |

192[xv] |

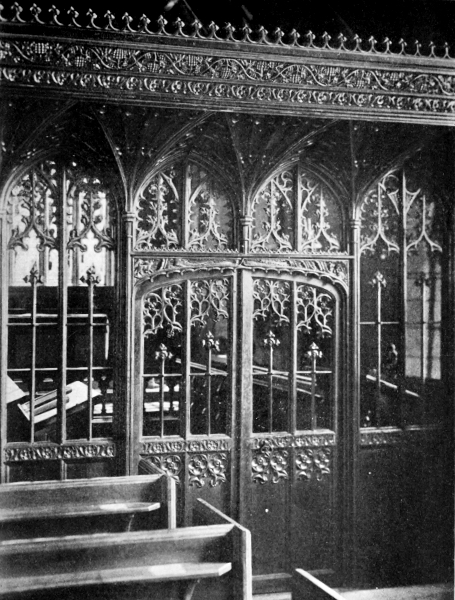

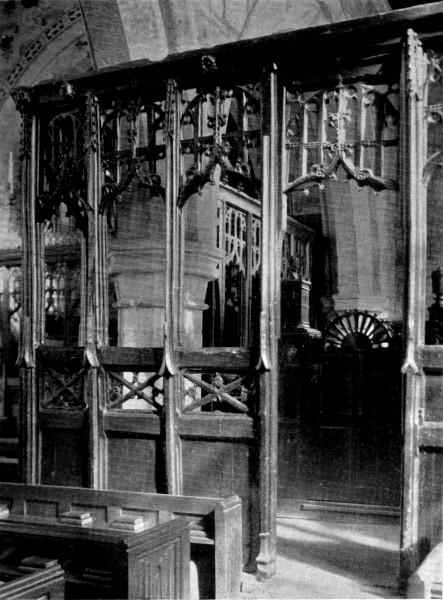

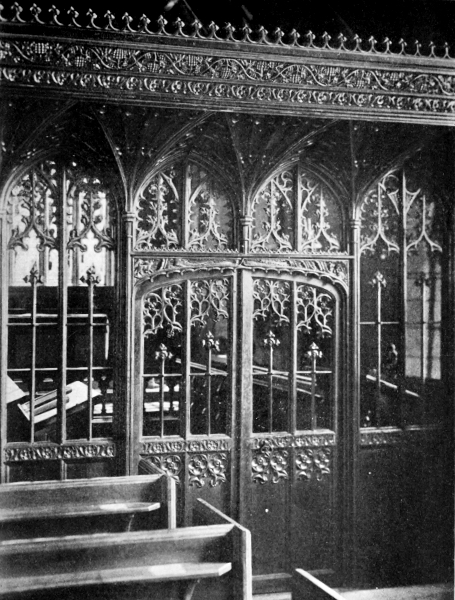

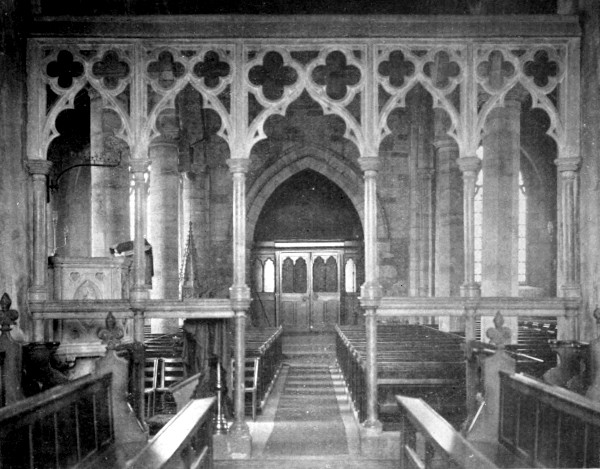

Fenny Bentley Church: Rood-Screen

(From a Photograph by Aymer Vallance) |

200 |

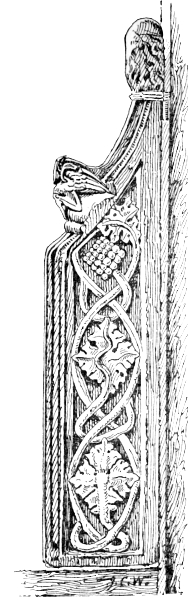

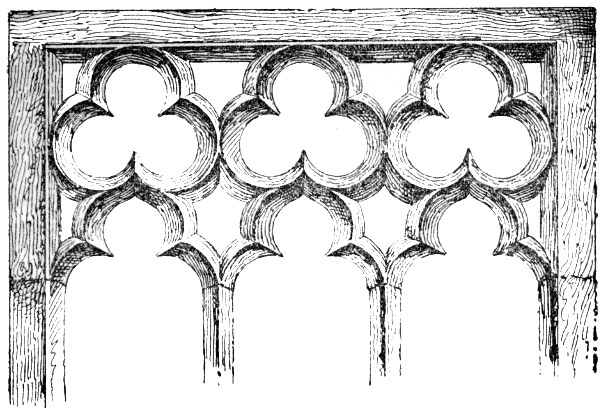

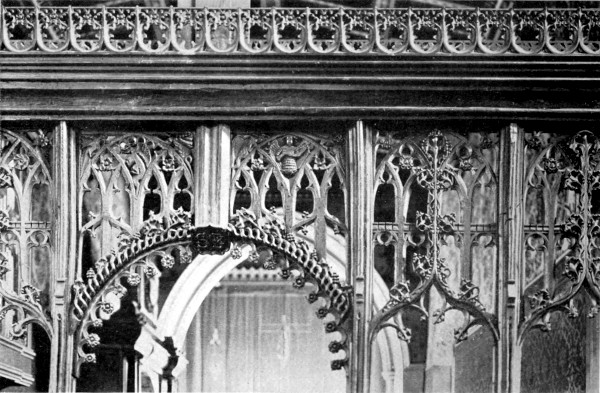

Chaddesden Church: Detail of Rood-Screen from the Chancel

(From a Sketch by Aymer Vallance) |

206 |

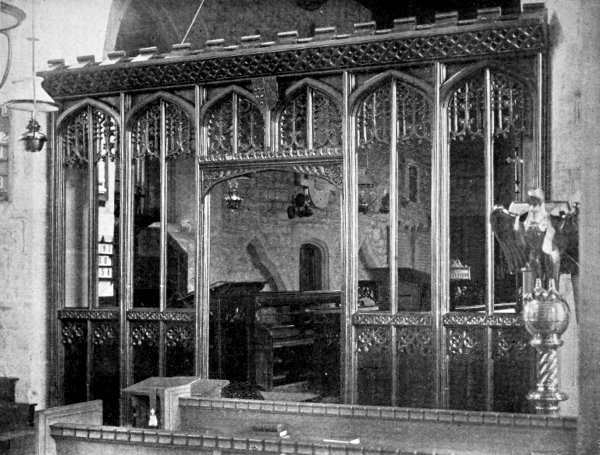

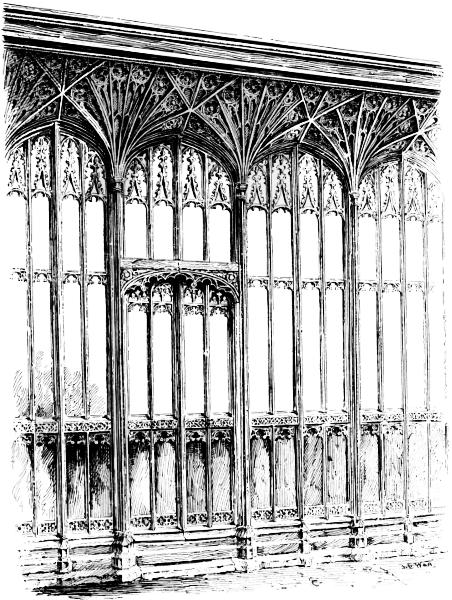

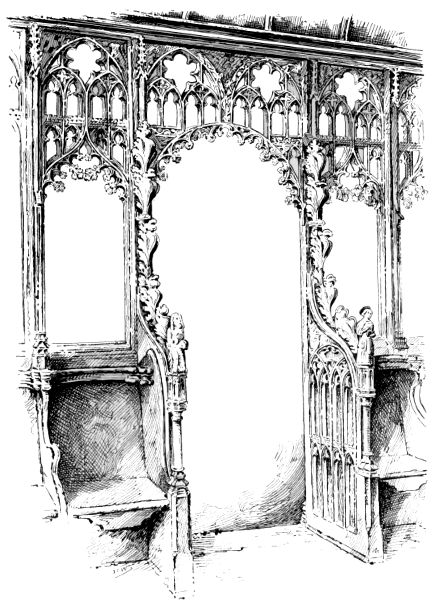

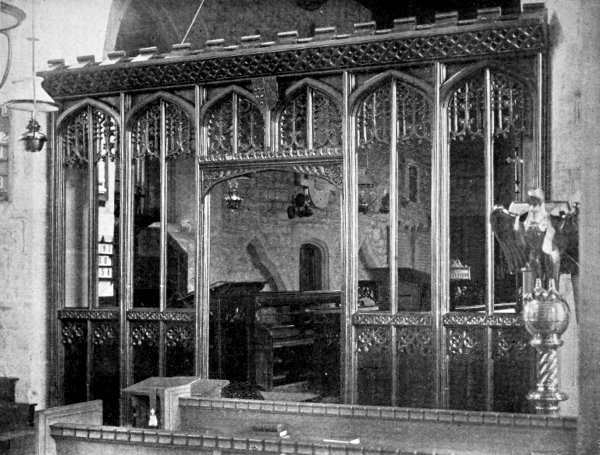

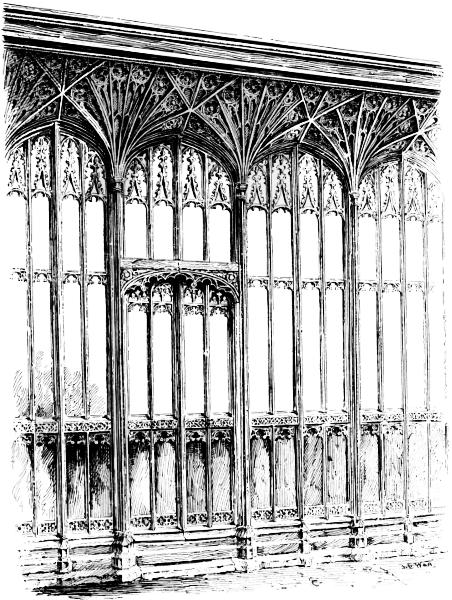

Elvaston Church: Parclose Screen in the South Aisle

(From a Photograph by Aymer Vallance) |

210 |

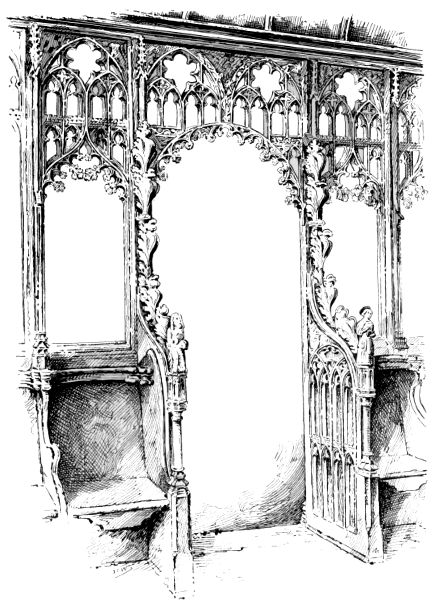

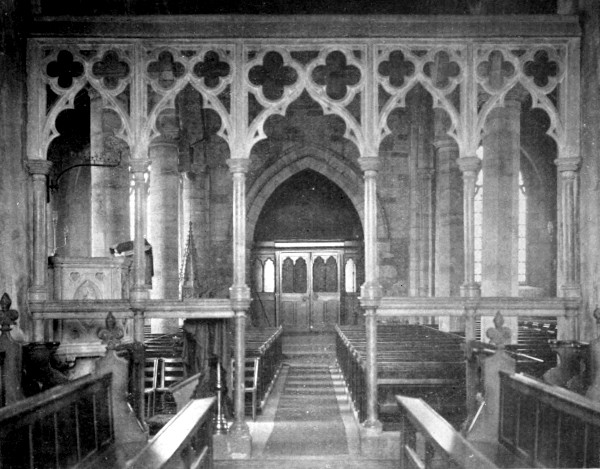

Ilkeston Church: Stone Rood-Screen, from the Chancel

(From a Photograph by Aymer Vallance) |

212 |

| Chelmorton Church: Southern Half of Stone Rood-Screen |

214 |

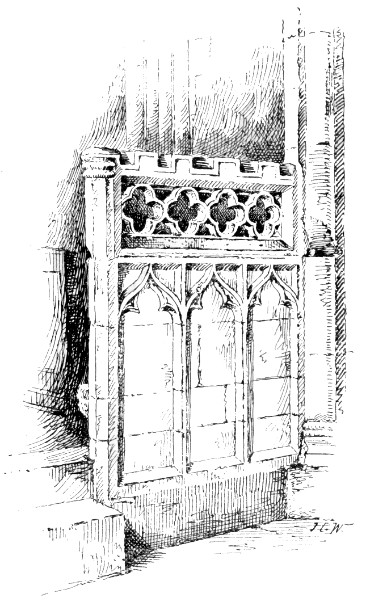

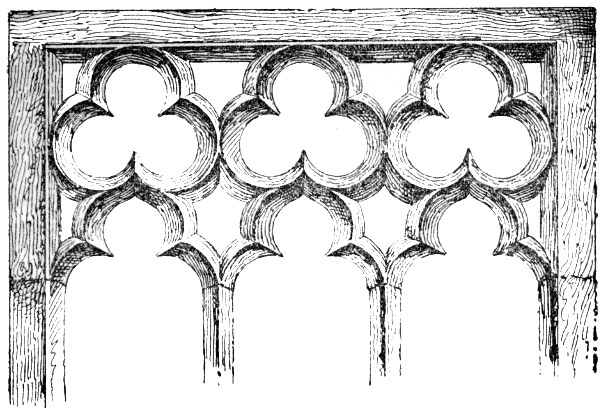

Darley Dale Church: Detail of Stone Parclose

(From Sketches by J. Charles Wall) |

214 |

Elvaston Church: Detail of Rood-Screen

(From a Photograph by Aymer Vallance) |

220 |

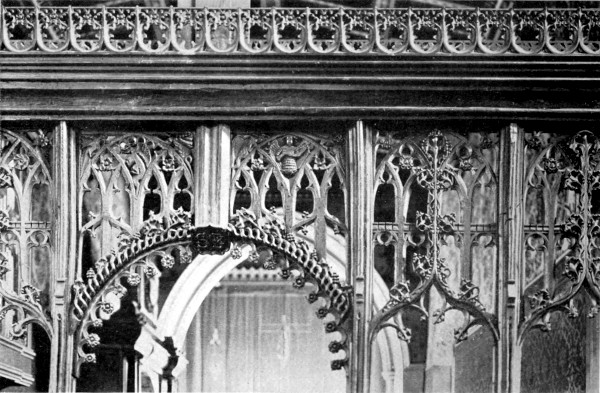

Chesterfield Church: Detail of Screen in the North Transept,

formerly the Rood-Screen

(From a Photograph by Aymer Vallance) |

222 |

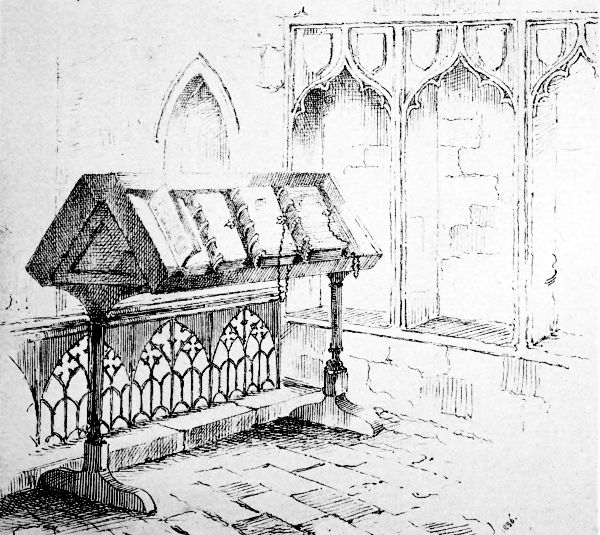

Wingerworth Church: Base of the Rood-Loft

(From a Photograph by Aymer Vallance) |

228 |

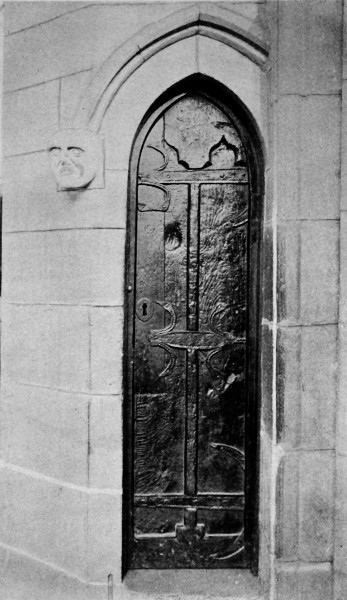

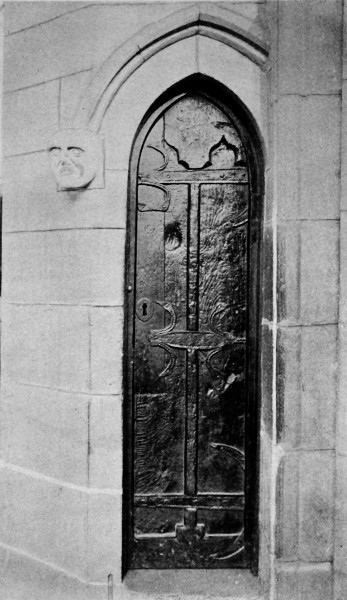

Ashbourne Church: Door leading to the Rood-Stair

(From a Photograph by Aymer Vallance) |

234 |

Ashover Church: Rood-Screen

(From a Photograph by Aymer Vallance) |

252 |

| Breadsall Church: Detail of Rood-Screen in process of Restoration |

256 |

Breadsall Church: Showing the Remains of the Rood-Screen in 1856

(From Photographs by Aymer Vallance) |

256 |

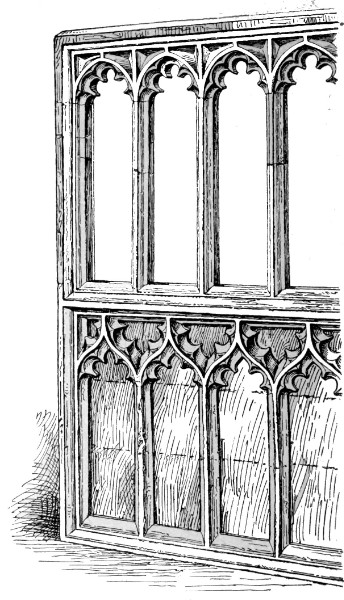

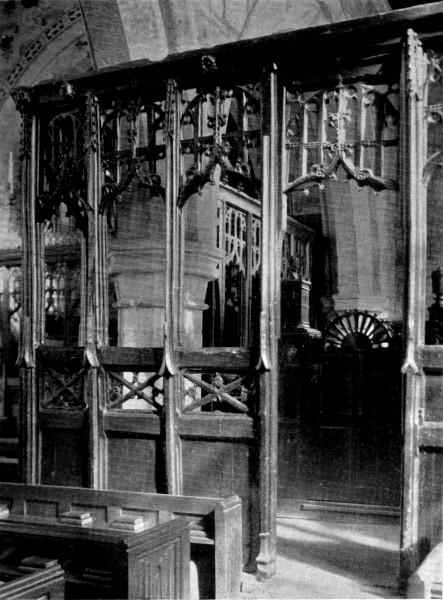

Chesterfield Church: Part of Parclose Screen in South Transept

(From a Sketch by J. Charles Wall) |

260 |

Elvaston Church: Rood-Screen (restored)

(From a Photograph by Aymer Vallance) |

264 |

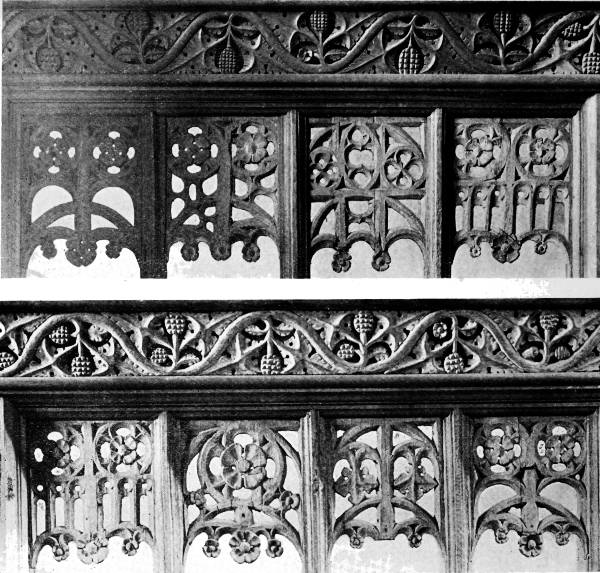

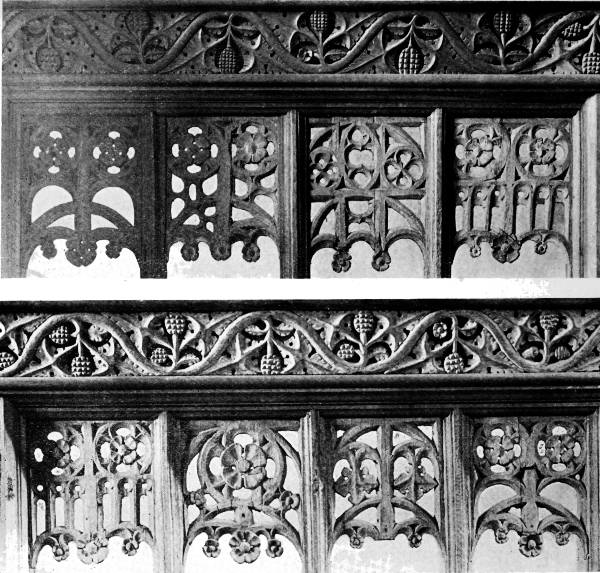

Kirk Langley Church: Detail from Parcloses of North and

South Aisles

(From a Photograph by Aymer Vallance) |

270 |

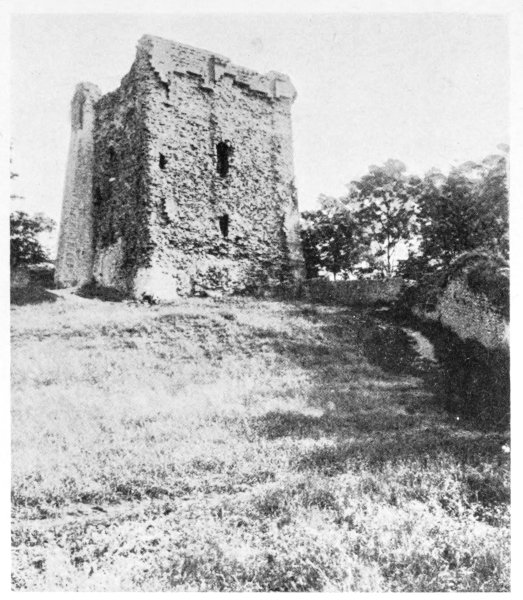

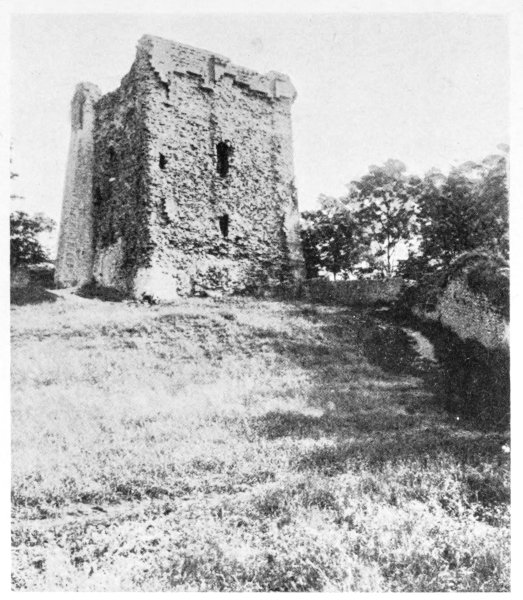

| The Keep: Peverel Castle |

362 |

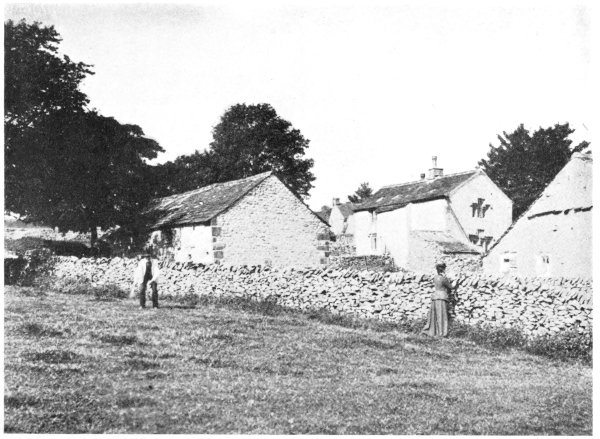

Little Hucklow: Folk Collector’s Summer House

(From Photographs by S. O. Addy, M.A.) |

362 |

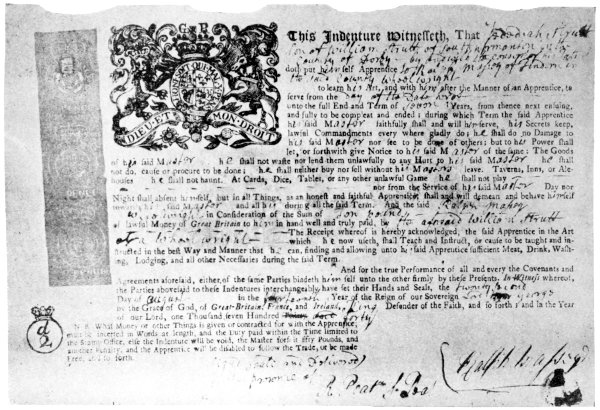

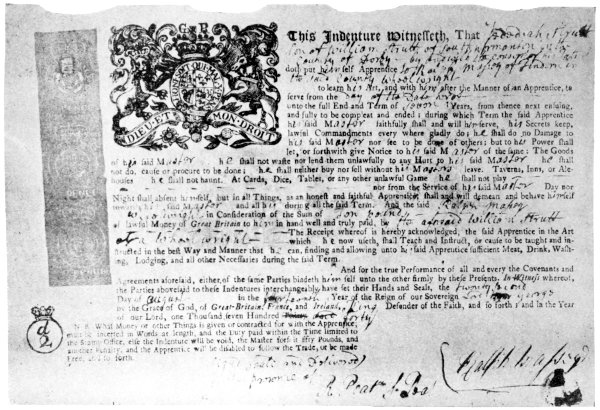

Apprenticeship Indenture of Jedediah Strutt, 1740

(From the Original lent by Hon. F. Strutt) |

372 |

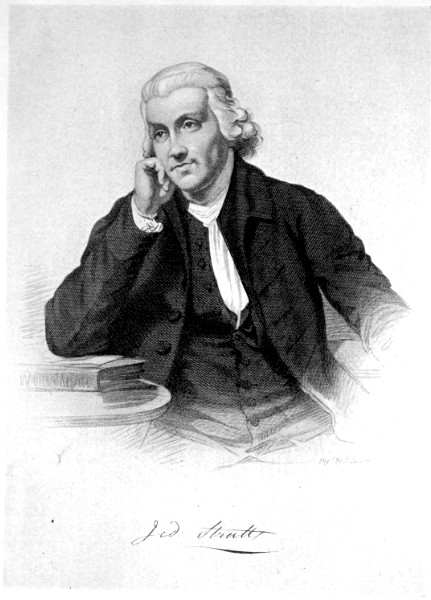

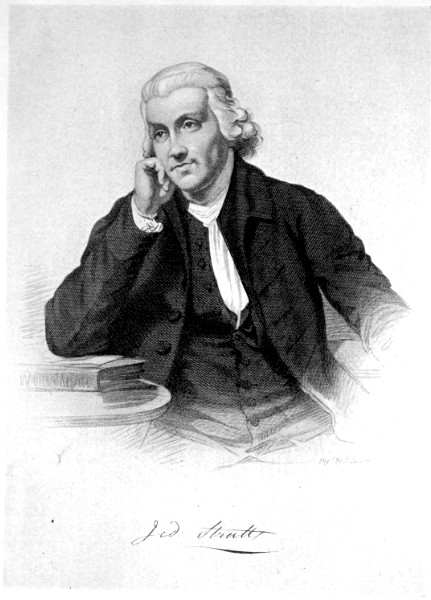

Jedediah Strutt

(From Original Painting by Joseph Wright, c. 1785) |

382 |

[xvi]

ILLUSTRATIONS IN TEXT

| |

Page |

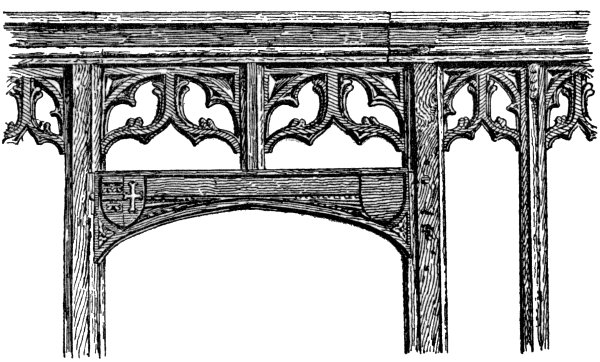

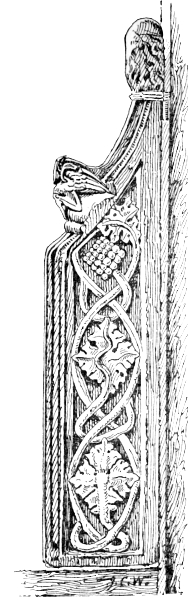

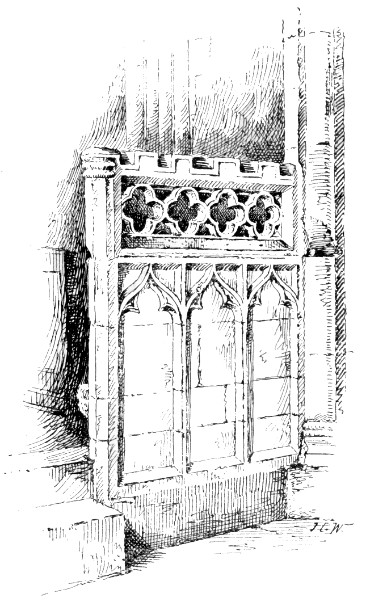

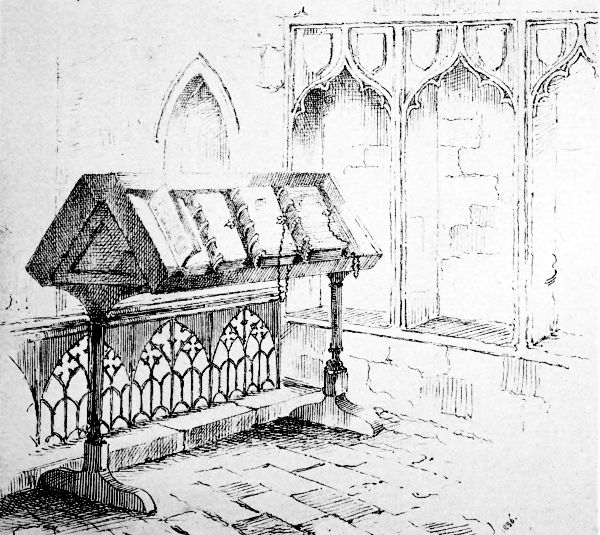

Norbury Church: Stall End attached to Jamb of Rood-Screen

(From a Sketch by Aymer Vallance) |

206 |

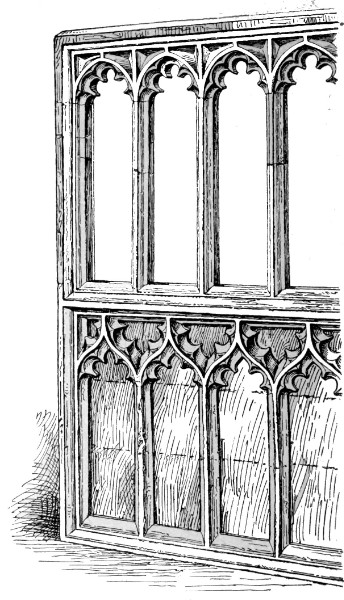

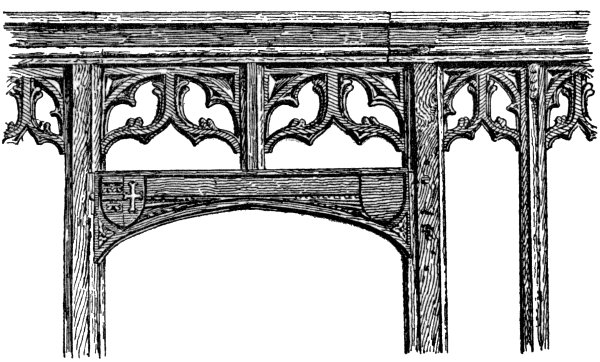

Kirk Langley Church: Detail of former Rood-Screen in Oak

(From a Sketch by Aymer Vallance) |

217 |

Brackenfield: Detail of Oak Rood-Screen

(From a Sketch by Aymer Vallance) |

255 |

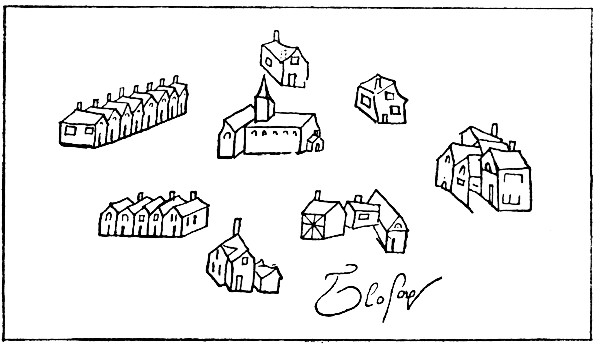

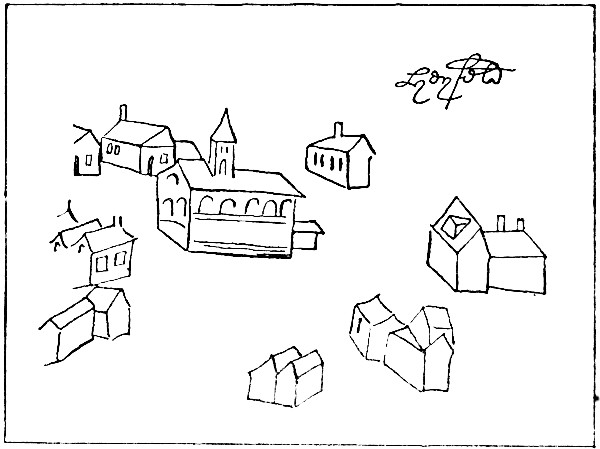

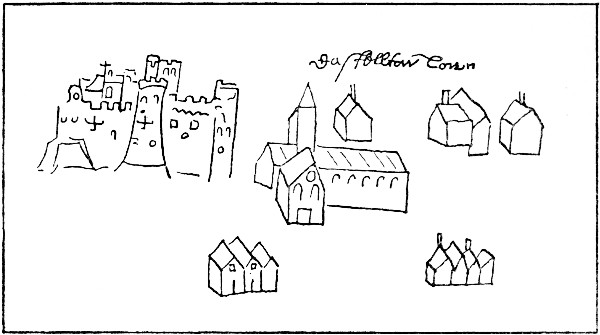

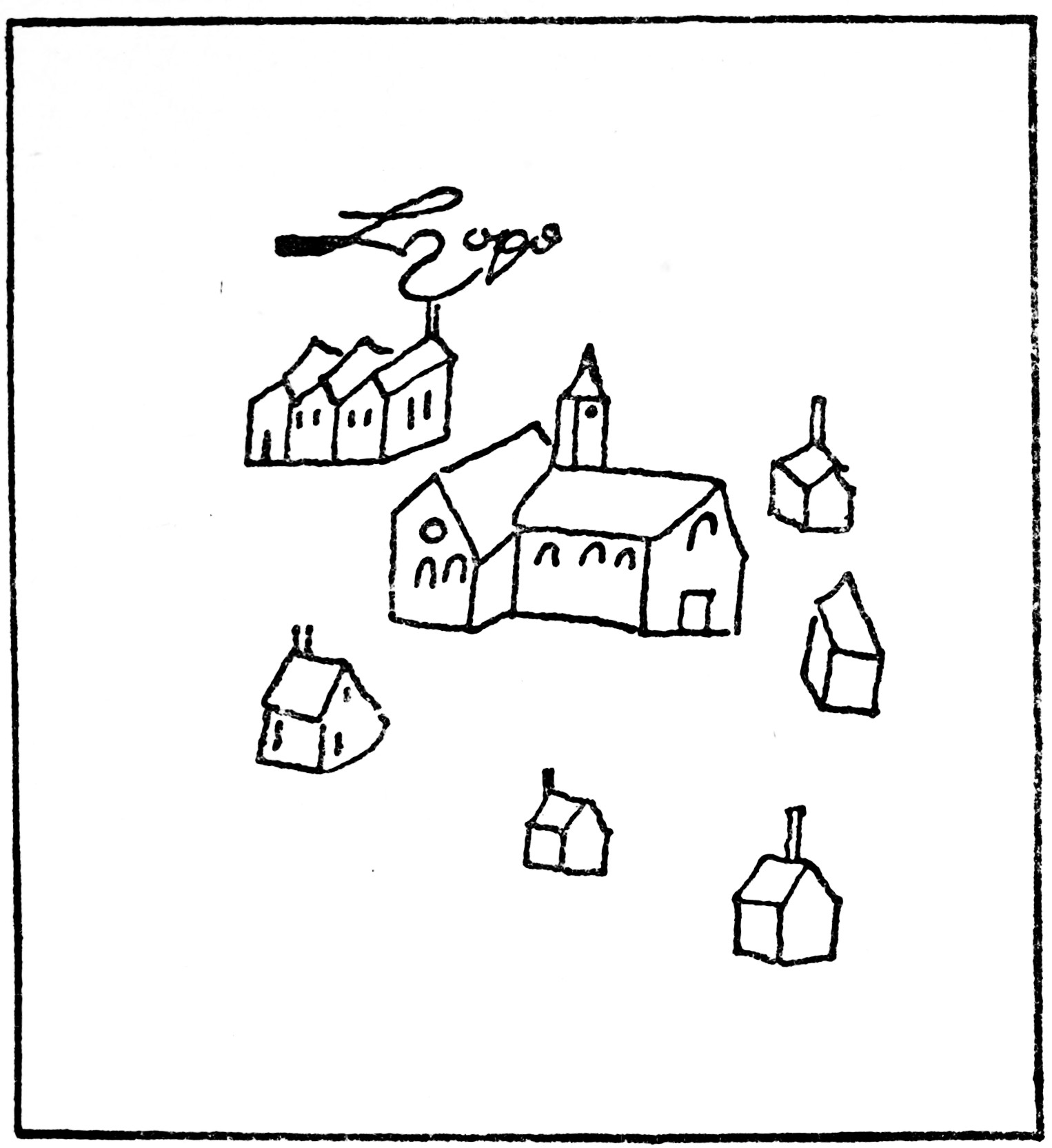

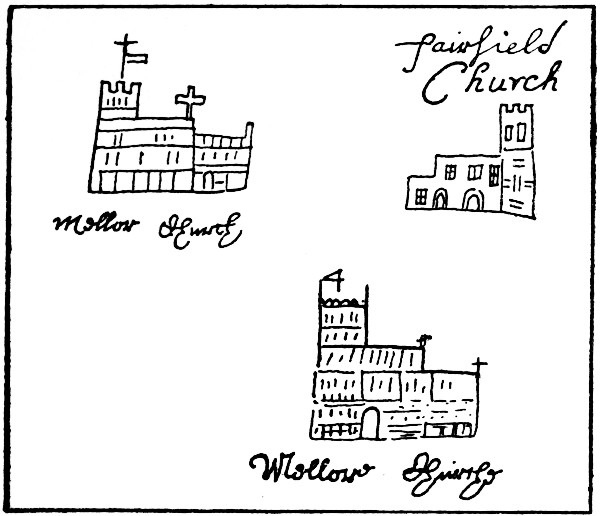

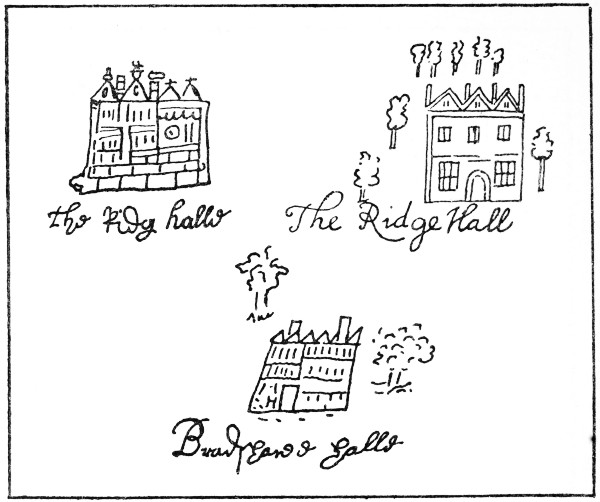

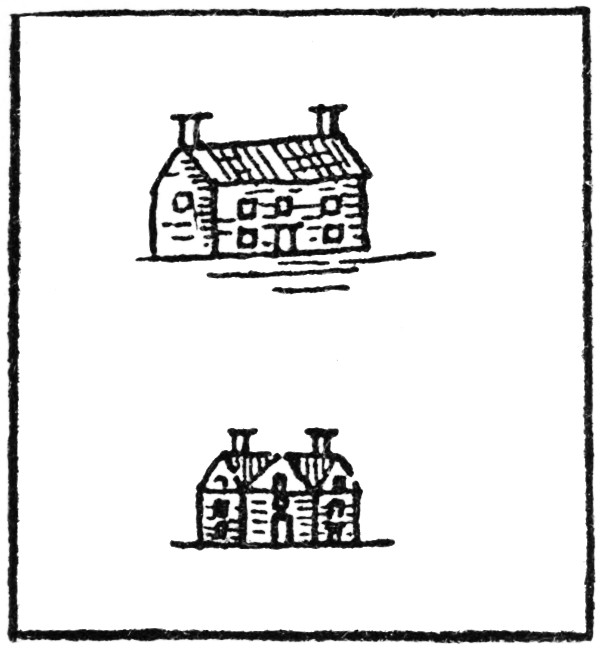

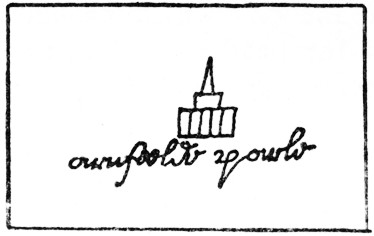

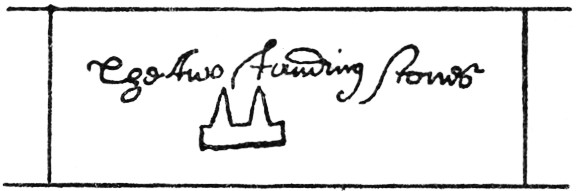

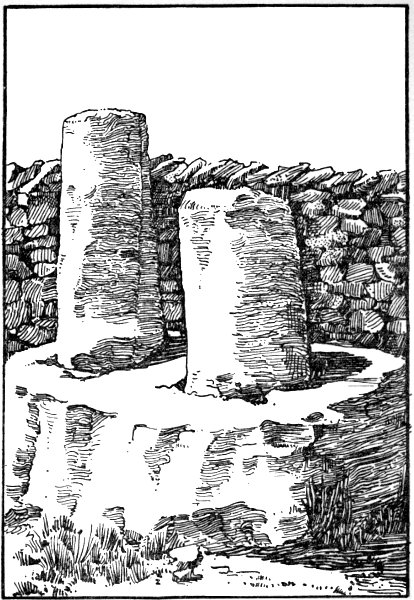

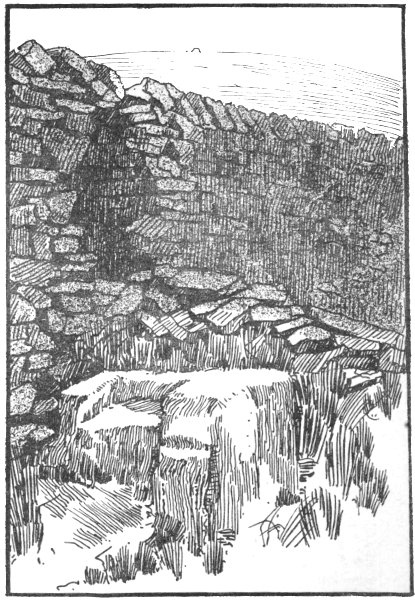

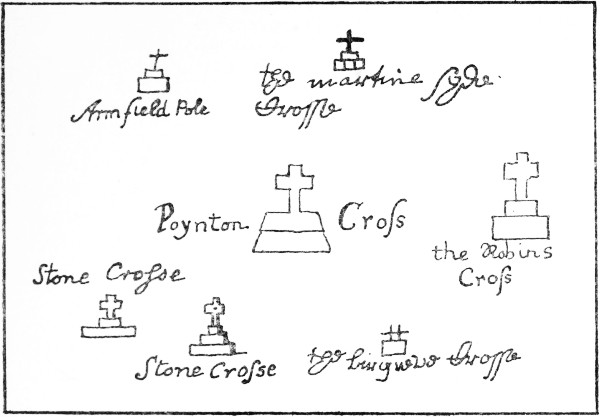

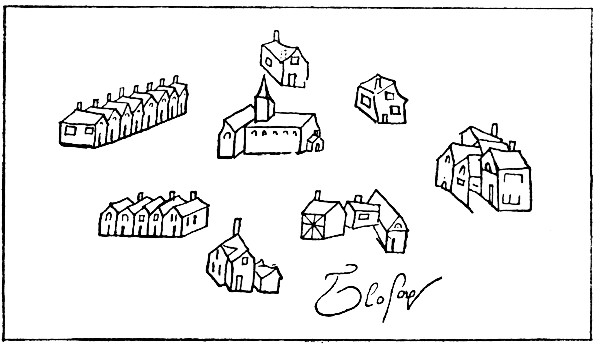

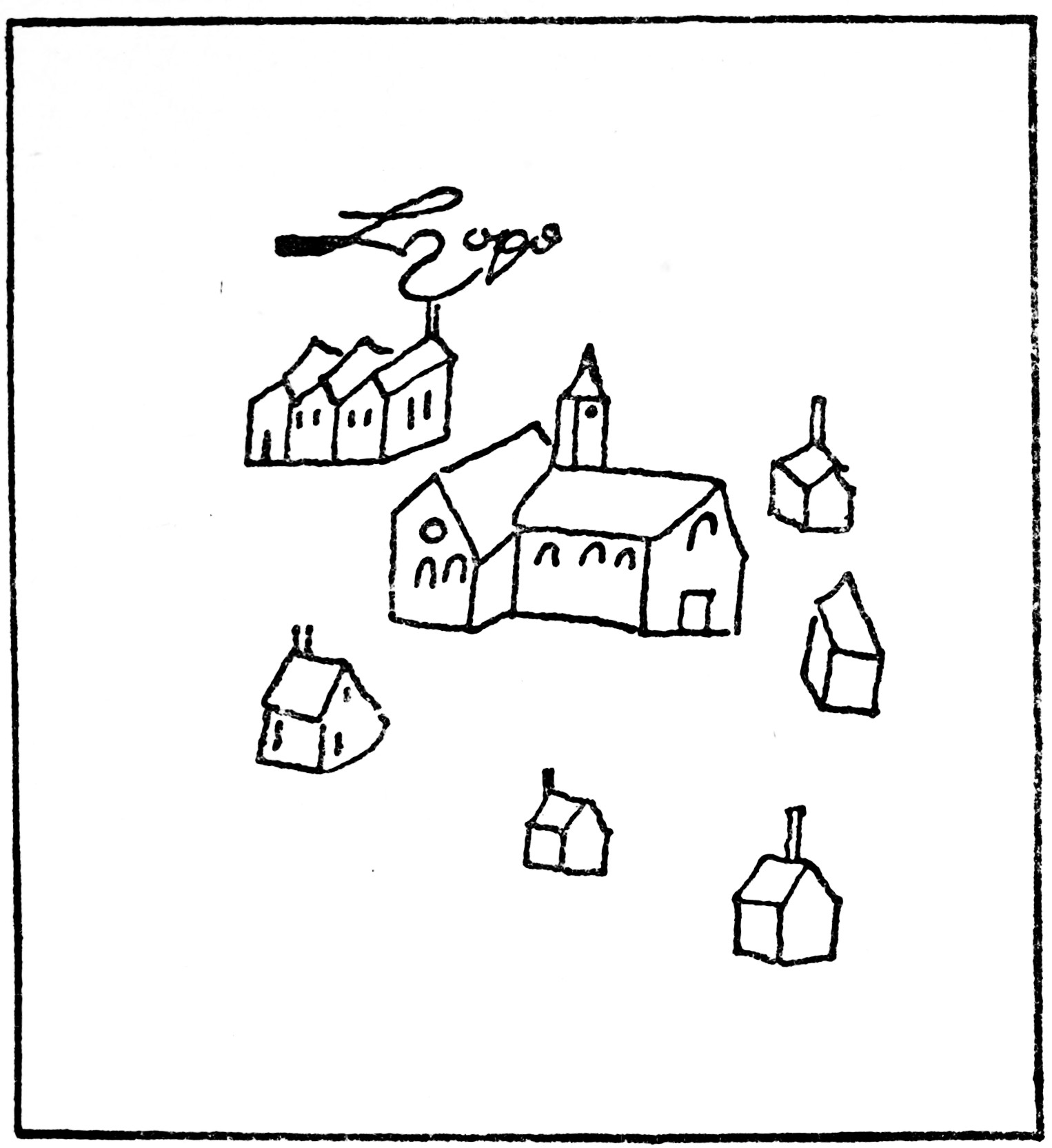

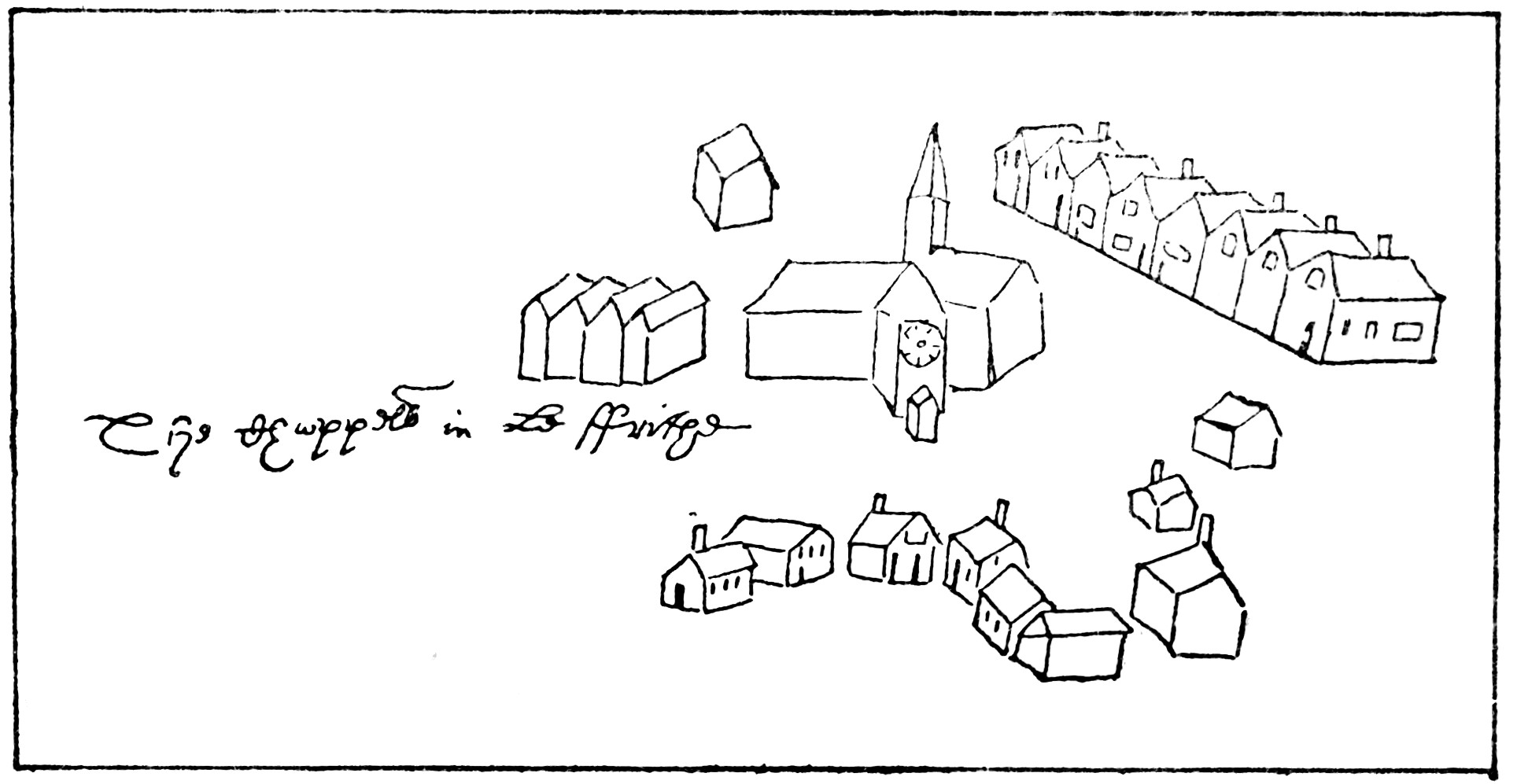

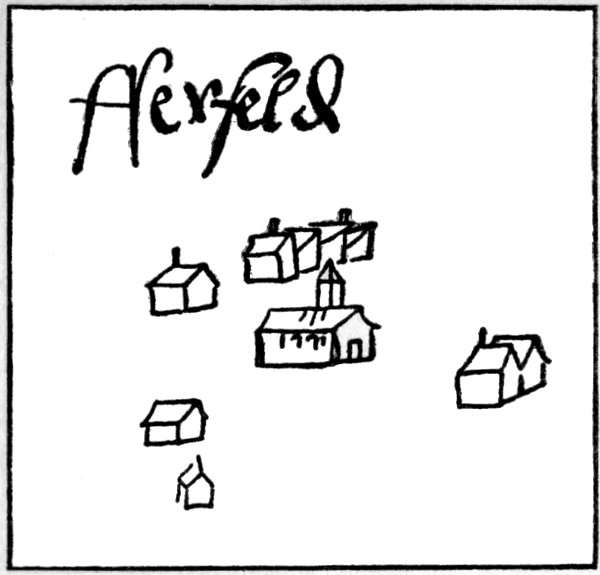

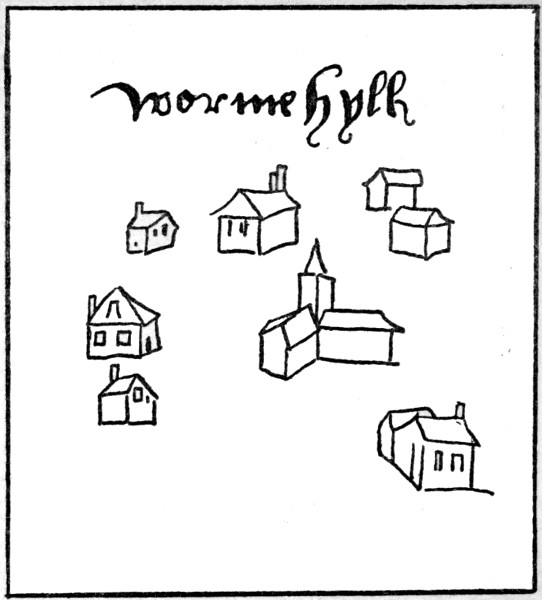

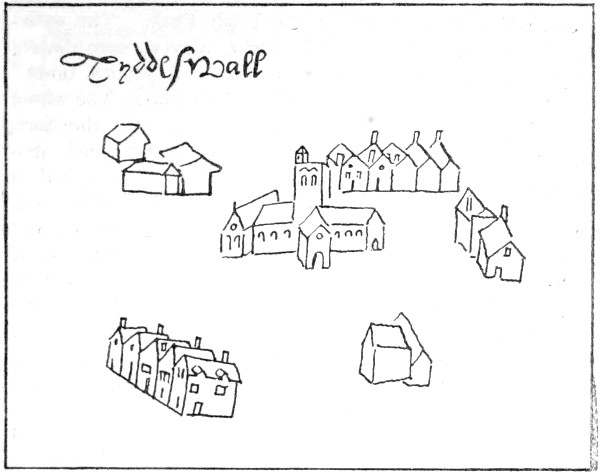

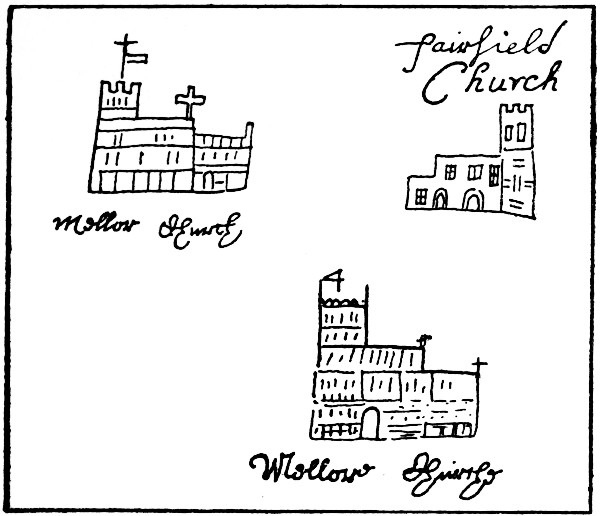

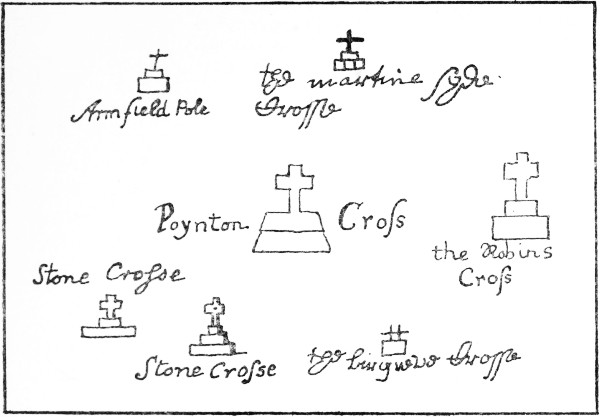

| Plans of the Peak Forest:— | |

| Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 |

283–291 |

| "10, 11, 12 |

293–295 |

| "13, 14 |

298 |

| No. 15 |

300 |

| "16 |

302 |

| "17 |

305 |

| (Nos. 15 and 16 Drawings by M. E. Purser; remainder by V. M. Machell Cox.) |

Country Gentlemen on the London Road

(From Loggan’s “Oxford,” 1675) |

311 |

Arrival of a Guest at a Country House

(From “Le Nouveau Theatre de la Grande Bretagne,” 1724) |

318 |

A Ball at an Assembly Room

(From a Broadsheet, c. 1700) |

320 |

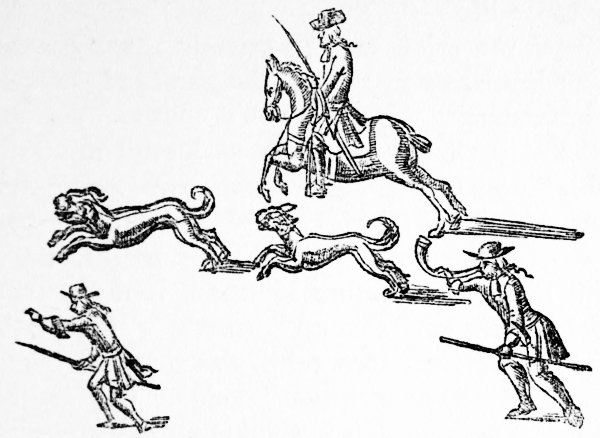

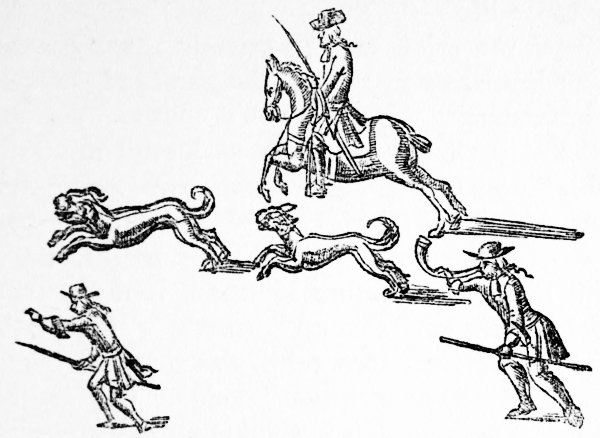

Stag-Hunting

(From Chauncy’s “Hertfordshire,” 1700) |

329 |

Acquaintances meeting in London

(From “Le Nouveau Theatre de la Grande Bretagne,” 1724) |

336 |

Guest arriving on Horseback

(From “Le Nouveau Theatre de la Grande Bretagne,” 1724) |

341 |

A Gentleman and his Servant on the Road

(From Loggan’s “Oxford,” 1675) |

345 |

[1]

HISTORIC DERBYSHIRE

By Rev. J. Charles Cox, LL.D., F.S.A.

After making due allowance for a natural

prejudice in favour of the county of one’s

birth and early associations, it may, I think, be

reasonably maintained that the comparatively

small shire of Derby not only contains within its limits

most exceptionally wild, beautiful and varied scenery,

but that its social and political history is exceedingly

diversified and full of interest. In all, too, that pertains

to almost every branch of archæology, Derbyshire is well

able to hold its own with any other county that could

be named.

The proofs of the residence of early man in the

district are afforded by the considerable variety of

remains that have been discovered in the bone caves of

the High Peak near Buxton, in those of the high lands

above Wirksworth, and more especially in the Creswell

caves on the verge of Nottinghamshire. In Grant Allen’s

remarkable and generally accurate book on the beginnings

of county history throughout England, a singular blunder

is made with regard to Derbyshire; it is there stated that

this county “was almost uninhabited until long after the

English settlement of Britain, with the solitary exception

of a few isolated Roman stations.” Archæology, however,

puts such a statement as this to complete rout.

Difficult as it is to understand how such large bands of

savage men were able to maintain themselves in so wild[2]

a district, it is the fact that the Peak of Derbyshire was,

so to speak, thickly populated by prehistoric tribes.

A glance at the map of prehistoric remains, given in

the first volume of the Victoria History of the County of

Derby, to illustrate Mr. Ward’s article, will at once show

that the whole of that part of North Derbyshire which

extends from Ashbourne to Chapel-en-le-Frith on the

west, from thence to Derwent Chapel on the north, and

then southward through Hathersage and Winster back

again to Ashbourne, is peppered all over with the red

symbols that betoken the barrows or lows which were

the burial places of our forefathers during the neolithic

and subsequent ages. Round Stanton-in-the-Peak and

Hathersage the barrows, circles and other early remains

occur with such frequency that it is difficult to mark even

small dots on the map without them running into each

other.

When the Romans held Derbyshire they had five

chief stations in the county, namely, at Little Chester,

near Derby; at Brough, near Hope; at Buxton; at

Melandra Castle, on the verge of Cheshire; and near

Wirksworth. The chief Roman road, termed Ryknield

Street, entered the county at Monksbridge, between

Repton and Egginton; crossing the Derwent by Derby

to Little Chester, the road proceeded to Chesterfield, and

thence into Yorkshire. Another road crossed the south

of the county, entering Derbyshire on the east near

Sawley, and passing through Little Chester to Rocester,

in Staffordshire. A whole group of other roads radiated

throughout the Peak from Buxton as a centre.

Doubtless one of the chief reasons why the Romans

were so determined to occupy, after a military fashion,

the north of the county was because of the lead mining

which they so actively pursued. The chief district of

this lead mining extended between Wirksworth on the

south and Castleton on the north. Between these two

places groups of disused mines appear with frequency.[3]

Most of those that have been closely examined yield

obvious traces of having been worked by our conquerors.

Six pigs of inscribed Roman lead have been found in

the county. One of them bears the name of Hadrian

(A.D. 117–138). The probabilities, however, are strong that

the Roman miners were at work in this county half a

century earlier, for there is evidence of lead working in

western Yorkshire in A.D. 81, and it is most unlikely that

mining began in that part of Yorkshire before Derbyshire

had been touched.

It is scarcely possible to exaggerate the interest and

importance pertaining to Dr. Haverfield’s article on

Romano-British Derbyshire, as set forth in the first

volume of the Victoria History of the county.

When the Romans left this county at the dawn of

the fifth century, the first English or Saxon settlement

speedily followed. The north of Derbyshire formed the

southern extremity of that long range of broken primary

hills—termed the Pennine Chain—which extended from

the Cheviots down to the district long known as Peakland

or the Peak. As the Romans withdrew, Peakland seems

to have been overrun by hordes of the Picts; but when

the pagan English settled in Northumbria a new element

of strife was introduced which affected the line of

Pennine Hills from end to end. This range became a

boundary between two hostile races dissimilar in habits,

tongue and creed. The older British race, Christianized

to a considerable extent, took up their position on the

western side, and also held their own in certain parts of

the actual dividing ridge.

It seems likely that the Peakland, for about 150 years

after the first coming of the English—and possibly

other parts to the east and south afterwards known under

the common name of Derbyshire—was retained by the

Celts, or Welsh, after the same fashion as they undoubtedly

held the districts round the modern town of

Leeds.

[4]

With the opening of the seventh century substantial

historic data begin. Ethelfrith, the last pagan king of

Northumbria, crossed the southern end of the Pennine

Chain in 603, and by a notable victory at Chester

extended, as Bede tells us, the dominions of the English

to the Mersey and the Dee. The actual conquest of Peakland

probably soon followed. Mr. Grant Allen’s supposition

that it was never actually overrun by a military

force, but that the scanty numbers of the Welsh were by

degrees absorbed into the surrounding English population,

may, however, be the true explanation. The general

story of English place-names shows that the majority of

our hill and river names are earlier than the English occupation;

but in North Derbyshire there is not a single

river or hill that does not bear a Welsh name, whilst not

a few of the homestead names have a like origin, and

even words of Cymric etymology still linger in the fast

disappearing dialect.

It is of interest to remember that those Mercians who

settled from time to time in small groups throughout the

wilder parts of Derbyshire bore the local name of

Pecsaete, that is to say, settlers in the Peak; so that the

future county, as Mr. Allen remarks, narrowly escaped

being styled Pecsetshire, after the fashion of Dorsetshire

or Somersetshire.

In the development and Christianising of the widespread

Mercian kingdom, South Derbyshire played a

very considerable part. Repton, on the banks of the

Trent, is mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in the

year 755 in the account of the slaying of Ethelbald, the

Mercian king. The same Chronicle also records the visit

of the devastating Danes to Repton in 874, when they

made that town their winter quarters. The founding of

an abbey at Repton early in the seventh century, and

the same place becoming the first seat of the Mercian

bishopric from 654 to 667, is dealt with in another part

of this volume and need not be named further in this sketch.

[5]

The Peak seems to have known of no widespread

Saxon or English settlement until after the eruption of

the Danes. It is also to the Danes that the town of

Derby owes its present name, and the importance which

gave its title to the surrounding shire. When the

marauding Scandinavian bands overran the kingdoms of

Northumbria and Mercia, the value of the Derbyshire lead

soon attracted their attention. Hence they established

themselves strongly and built a fort at Northworthy (the

earlier name for Derby), whence the valley of the Derwent

branched off in different directions to the lead-mining

districts. It was the common practice of the Danes to

change the names of the places where they settled;

Northworthy was to them an unmeaning term now that

settlements of importance had been pushed on much

further northward. Deoraby, or the settlement near the

deer, was clearly suggested by the close propinquity of

the great forests. There is no part of the county where

the place and field names are of greater interest than in

the Ecclesbourne valley, which leads up from Duffield

to Wirksworth. The intermingling of Norse names shows

that at least two distinct streams of colonists pushed

their way to this valuable mining centre.

In the north-eastern portion of Mercia, five of these

Scandinavian hosts, each under its own earl, made a

definite settlement; they became known as the Five

Burghs, and formed a kind of rude confederacy. In this

way Derby became linked in government with Nottingham,

Stamford, Lincoln and Leicester. This combination,

however, had not long been made before Ethelfleda, the

Lady of the Mercians, the sister of Alfred the Great,

began to win back her dominions from these pagan

Norsemen, building border forts at Tamworth and

Stafford. Derby was stormed by Ethelfleda in 918, after

fierce fighting, and this victory secured for her for a

time the shire as well as the town itself. Six years later

Edward the Elder, Ethelfleda’s brother, advanced against[6]

the Danes through Nottingham, penetrating into Peakland

as far as Bakewell, where he built a fort. In 941–2

King Edmund finally freed the Five Burghs and all

Mercia from Danish rule.

The establishment of a mint at Derby during the

reign of Athelstan (924–940) is a clear evidence of the

advance of civilisation. Coins minted at Derby are also

extant of the reigns of Edgar, Edward II., Ethelred II.,

Canute, Harold I., Edward the Confessor, and Harold II.

The division of Derbyshire among the conquering Normans,

together with the social conditions of the times, so

far as they can be gathered from the entries in the Domesday

Survey, have been admirably treated of at length

in the recently issued opening volume of the Victoria

History, to which reference has already been made. The

number of manors held by the Conqueror in this county

was very considerable. He derived his Derbyshire

possessions from three sources. In the first instance he

succeeded his predecessor, the Confessor, in a great group

of manors that stretched without a break across the

county in a north-easterly direction from Ashbourne to

the Yorkshire borders near Sheffield. The second division

of the Kings’ land consisted of the forfeited estates

of Edwin, the late earl of the shire, and grandson of

Earl Leofric of Mercia. These lay in a widespread group

along the Trent south of Derby, and included Repton,

so famous in earlier Mercian history. In the north of

the county the King also secured a very considerable

number of manors which had belonged to various holders,

such as Eyam and Stony Middleton, Chatsworth and

Walton, and a considerable group round Glossop.

There were two ecclesiastical tenants-in-chief in the

county, namely, the Bishop of the diocese, who held

Sawley with Long Eaton, and the manor of Bupton in

Longford parish, and the Abbot of Burton-on-Trent, who

held the great manor of Mickleover and several others

which nearly adjoined the Abbey on the Derbyshire side.

[7]

By far the largest Derbyshire landholder was Henry

de Ferrers, lord of Longueville in Normandy, whose son

in 1136 became the first Earl of Derby. He held over

ninety manors in this county, but the head of his barony,

where his chief castle was, lay just outside the border of

Derbyshire, at Tutbury. Just a few of the smaller landholders

seem to have been Englishmen, confirmed in their

rights by the Conqueror. In one case it can be definitely

said that an Englishman not only held land at the time

of the survey, under Henry de Ferrers, but became the

ancestor of a family which continued for centuries to

hold of Ferrers’ successors. This was “Elfin,” who held

Brailsford, Osmaston, Lower Thurvaston, and part of

Bupton. During the reigns of William the Conqueror

and his two sons, Rufus and Henry, genuine historical

particulars relative to the county are almost entirely

absent. When persistent civil war raged for so long a

time over the greater part of England during Stephen’s

reign, Derbyshire was but little disturbed, for the leading

men of the county adhered loyally to the King and held

its several fortresses on his behalf. In the great Battle

of the Standard, fought against the Scots at Northallerton

in 1138, Derbyshire played the leading part in winning

the victory; its chief credit being due to the valour of

the Peakites under Robert Ferrers. Ralph Alselin and

William Peveril, two other Derbyshire chieftains, were

also among the successful leaders of the battle.

Peak Castle, built by William Peveril in the days of

the Conqueror, passed to the Crown in 1115 on the forfeiture

of his son’s estates. The Pipe Roll of 1157 shows

an entry, repeated annually for a long term of years, of

a payment of four pound, ten shillings, and two watchmen,

and the porter of the Peak Castle. In that year

Henry II. received the submission of Malcolm, King of

Scotland, within the walls of this castle. There are

records of other visits made to this castle by Henry II.

in 1158 and 1164.

[8]

In this reign a variety of interesting particulars relative

to the castles of Bolsover and the Peak can be

gleaned from the Pipe Rolls, particularly with regard to

their provisioning, garrisoning and repairing between

1172 and 1176, during the time of the rising of the Barons.

Richard I., at the beginning of his reign, gave the castles

of the Peak and Bolsover to his brother John, who

succeeded to the throne in 1199. In 1200, King John

was at Derby and Bolsover in March, and at Melbourne

in November. This restless King’s visits to the county

were frequent throughout his reign, and included a

sojourn at Horsley Castle in 1209. During this turbulent

reign Derbyshire was again fortunate in escaping any

material share of civil warfare. The party of the Barons

gained but little support, for the three notable fortresses

of Castleton, Bolsover and Horsley were held for the

King with but slight intermission.

In any historic survey of Derbyshire, however brief,

it must not be forgotten that the Normans, for the convenience

of civil administration, linked together this

county and Nottinghamshire, giving precedence in some

respects to the latter. The Assizes, for instance, up to

the reign of Henry III., were held only at Nottingham,

and the one county gaol for the two shires was in the

same town. From the beginning of the reign of

Henry III. up to the time of Elizabeth, the Assizes were

held alternately at the two county towns. During the

whole of this period there was but one sheriff for the

two shires; it was not until 1566 that they each possessed

a sheriff of their own.

Derbyshire possessed a fourth great fortress, which

has generally been overlooked; it does not appear on the

Pipe Rolls, as it was never held by the Crown. Duffield

was a convenient centre for the great Derbyshire possessions

of Henry de Ferrers. The castle at this place

stood on an eminence commanding an important ford of

the Derwent, at the entrance of the valley that led to[9]

Wirksworth with its lead mines, and hence forwards to

the High Peak. Here was erected in early Norman days

(as we know from the long-buried remains) a prodigiously

strong and massive keep. William, Earl Ferrers,

was a stalwart supporter of Henry III. until his death,

but his grandson, Robert de Ferrers, soon after he came

of age, in 1260, threw himself with ardour into the

baronial war against the King. Eventually he was overcome

when fighting with his allies at Chesterfield in

1266. Ferrers was taken prisoner, and his life spared;

but all his lands, castles, and tenements were confiscated

to the crown, and conveyed by Henry to his son Edmund,

who was afterwards created Earl of Lancaster. It would

be at this period that Duffield Castle was demolished.

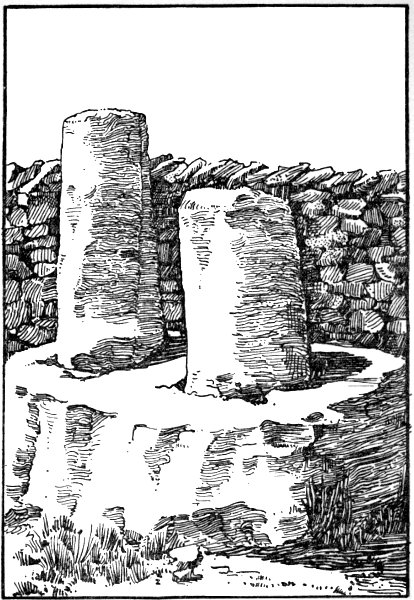

The foundations of this castle were accidentally discovered

in 1886. The lower part of the walls of a great

rectangular keep, 95 feet by 93 feet, were brought to

light, the walls averaging 16 feet in thickness. These

measurements show that Duffield Castle far exceeded in

magnitude any other Norman keep, with the single exception

of the Tower of London.

Before taking the next step in this sketch of the

political history of the county, it will be well to go back

a little in the account of the great Derbyshire family of

Ferrers, with special reference to their connection with the

Peak Forest. William de Ferrers, the fourth Earl of Derby,

was bailiff of the Honour of the Peak from 1216 to 1222.

It was charged against him that during that time he had

in conjunction with others taken upwards of 2,000 head of

deer without warrant. At the Forest Pleas held in 1251,

five years after the Earl’s death, formal presentments as

to these offences were made, when Richard Curzon was

fined the then great sum of £40 as one of the late Earl’s

accomplices, and other county gentlemen in smaller

amounts. But much more serious matters occurred in

the wild region of the Peak later on in the reign of

Henry III., when the transgressor was Robert de Ferrers,[10]

the grandson of the Earl just mentioned. The Pleas of

the Forest were generally held at long and somewhat

fitful intervals. It was not until September, 1285, that

these pleas were again held at Derby, when all the

offences committed during the thirty-four years that had

passed since the last eyre were presented by the forest

officials. By far the gravest charge at this eyre was that

made against the last Earl of Derby (of the first creation),

who died in 1278. It was charged against Robert de

Ferrers that on three separate occasions, in July, August

and September, 1264, he had hunted in the forest, with a

great company of knights and others, and had on these

occasions taken 130 head of red deer, and had driven a still

greater number far away. These illicit hunting affrays were

evidently made on a great scale, for thirty-eight persons

are named in the presentment, and there were many others,

besides the Earl himself, who were dead before the eyre

was held. Others, too, were not summoned because they

were mere servants of the Earl. Eight out of the thirty-eight

were knights, and it is not a little remarkable that

hardly any of those who joined in the forest affrays were

of Derbyshire families; they came from such counties as

Warwick, Leicestershire, Lancashire, Yorkshire, Cambridgeshire,

etc. Reading between the lines, though it is

not mentioned in the presentments—the originals of

which can be studied at the Public Record Office—it

becomes clear that these incursions into a royal forest

must have been animated by something deeper than a love

for wholesale poaching. In May, 1264, the battle of

Lewes was fought, when the King’s forces were defeated

by those of the barons. For two or three years from that

date, as an old chronicler has it, “there was grievous

perturbation in the centre of the realm,” in which Derbyshire

must have pre-eminently shared, for the youthful

Earl Robert was one of the hottest partisans of the

barons. There can be no reasonable doubt that these

three raids on the Peak Forest in the months immediately[11]

following the battle of Lewes, were undertaken by Robert

de Ferrers and his allies, issuing probably from his great

manor house at Hartington, much more to show contempt

for the King’s forest and preserves, and to get booty

and food for his men-at-arms, than for any purposes of

sport.

It is interesting to note that in April, 1264, Henry III.

came into Derbyshire, and lodged for a time at the castle

of the Peak after the subjection of Nottingham.

Definite Parliamentary rule began in England under

Edward I. No Derbyshire writs are extant for the

Parliaments of 1283, 1290 or 1294. The first Parliamentary

return extant for Derbyshire names Henry de

Kniveton and Giles de Meynell as summoned to attend

the Parliament at Westminster in November, 1295. The

county representatives in 1297 were Robert Dethick and

Thomas Foljambe; in 1298, Henry de Brailsford and

Henry Fitzherbert, and in 1299 Jeffrey de Gresley and

Robert de Frecheville. John de la Cornere and Ralph de

Makeney represented the borough of Derby in 1295. The

maintenance of the knights of the shire when attending

Parliament, as well as their travelling expenses, were

paid by the county. The scale of payment per day in

the fourteenth century varied from 3s. 4d. to 5s., whilst

the payment of the borough members varied from 20d.

to 2s. a day.

Soon after the accession of Edward I., inquiries were

made into the various abuses that had arisen during the

latter part of the turbulent reign of his predecessor.

A considerable number of official irregularities and illegalities

were brought to light in this county, including

both the imprisoning and undue releasing from prison

at the Castle of the Peak.

Edward I. visited Derbyshire in 1275, tarrying both

at Ashbourne and Tideswell, when on his way to North

Wales. In the subjugation of Wales, various of the great

landholders of Derbyshire, with their tenants, took a[12]

prominent part; among them were William de Ferrers,

William de Bardolf, Henry de Grey, Edward Deincourt,

John de Musard, and Nicholas de Segrave.

Between 1290 and 1293 the King was frequently in

the county, coming on more than one occasion for sport

amongst the fallow deer of Duffield Frith, at the forest

lodge of Ravensdale. Derbyshire was closely concerned

in the long dispute as to the succession to the Crown of

Scotland, of which Edward I. was made arbitrator in

1291. His decision was in favour of John Balliol, who

was most intimately connected with this county. Balliol

held for a time the custody of the Peak, with the Honour

of Peveril; he was lord of the manors of Hollington and

Creswell; and he had served as joint sheriff of the

counties of Derby and Nottingham from 1261 to 1264.

All the leading men of Derbyshire were engaged from

time to time in the prolonged wars with Scotland which

resulted in the deposition of Balliol in 1296. This

county had its share in the discreditable honours that

Edward II. showered on his favourite, Piers Gaveston,

for early in the reign he held the custody of the High

Peak. In 1322 the Scotch forces entered into alliance

with those of the rebel Earls of Lancaster and Hereford.

After fierce fighting at the bridge of Burton-on-Trent,

the royalists crossed the river by a ford and drove

Lancaster’s forces before them into Yorkshire. During

the retreat Derbyshire suffered severely. The King, with

several of his ministers, tarried for a few days at Derby;

from thence he visited Codnor Castle, which was held by

one of his ardent supporters, Richard, Lord Grey.

Edward II. also, on several different occasions, sojourned

at the lodge of Ravensdale, amid the beautiful parks of

Duffield Forest.

In the various wars of the reign of Edward III.

Derbyshire was often called upon to supply forces for

the hastily raised armies of the King. The number of

men levied on several occasions in this county were[13]

considerably in excess of its due proportion when

compared with neighbouring shires, either in acreage

or population. This may, we suppose, be taken as

a compliment to the valour of the county, and it is by

no means improbable that the hardy lead miners of the

north of the county would furnish better men, and

perhaps more capable archers, than were to be found

in purely agricultural districts. Early in 1333, when

the Scots were making great preparations for invasion,

John de Twyford and Nicholas de Longford were

appointed Commissioners of Array for Derbyshire, to

call out and have in readiness for the field all men

between sixteen and sixty years of age. Soon afterwards

they received a definite warrant to send to the front

five hundred archers and two hundred light horsemen

from within the county. Derbyshire archers to the number

of six hundred set forth for Scotland in 1344, and

there were frequent levies of them during this reign to

proceed to France. Derbyshire, however, considering the

fame of its archers and the fighting-men of the Peak,

took but a small part in the French campaign of 1346–7,

which resulted in the crowning triumph of Crecy and

the fall of Calais. The reason for this was that only

those counties that were citra Trent received summonses

to take part in the French expedition; the forces of

Derbyshire, Yorkshire, and other northern counties were

kept at home for fear of aggression from Scotland.

There were, however, a sprinkling of Derbyshire men in

the ranks of the English at Crecy, including Sir John

Curzon, Nicholas de Longford, and Anker de Frecheville.

The wide-spread revolt of the peasantry was the great

feature of the reign of Richard II.; but Derbyshire,

together with most of the west midlands, remained unaffected

by these serious disturbances, in which the miners,

at all events, had no inclination to take part.

Henry IV. was not unfrequently in Derbyshire in

connection with the rebellious movements of that much-troubled[14]

reign. In the summer of 1402 the King tarried

for some little time at the small town of Tideswell in

a secluded district of the Peak, issuing from thence a

variety of orders to sheriffs and other officials as to the

military preparations against the Welsh. When sojourning

about the same time at the royal hunting lodge

at Ravensdale, he dispatched thence orders for hastening

resistance against serious Scotch invasion.

In the following year, when the Percys and their

followers suddenly raised the standard of revolt, the

King hastened to Derby with all the forces he could

gather. After waiting there a few days to rally the

musters, he proceeded through Burton-on-Trent to

Shrewsbury, where a terrible battle was fought on

July 20th. Early that morning, before the fray began,

Henry knighted several of the gallant esquires of Derbyshire.

Of these Sir Walter Blount, who bore the King’s

standard, Sir John Cokayne, and Sir Nicholas Longford

were slain in the fight, whilst Sir Thomas Wendesley died

soon afterwards of the wounds he had received. It is

not a little interesting to note that the last three of these

Derbyshire knights, who held their honour for so brief

a period, have their effigies still extant in fair preservation

in the respective churches of Ashbourne, Longford, and

Bakewell; the fourth, Sir Walter Blount, was buried, in

acordance with his will, at Newark. Of the 4,500 men

slain or grievously wounded on the King’s side in the

Battle of Shrewsbury, a large proportion must have been

Derbyshire men. It was, perhaps, out of compliment to

this county that Henry, when the fray was over, proceeded

yet again to Derby before going north to York

to receive the Earl of Northumberland’s submission.

It was under Henry V. that the memorable Battle of

Agincourt was fought on October 25th, 1415. In this

battle the county played a prominent part. Richard,

Lord Grey of Codnor, was at the head of a large contingent

of Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire retainers and[15]

tenants. The list of horsemen under him begins with

two Derbyshire knights—Sir John Grey and Sir Edward

Foljambe, and it also includes such well-known county

names as Cokayne, Strelley, FitzHerbert, and Curzon.

Another contingent of Derbyshire men was in the retinue

of Philip Leach, of Chatsworth, whilst an important

command was held by Thomas Beresford, of Fenny

Bentley, as recorded on his monument in that church.

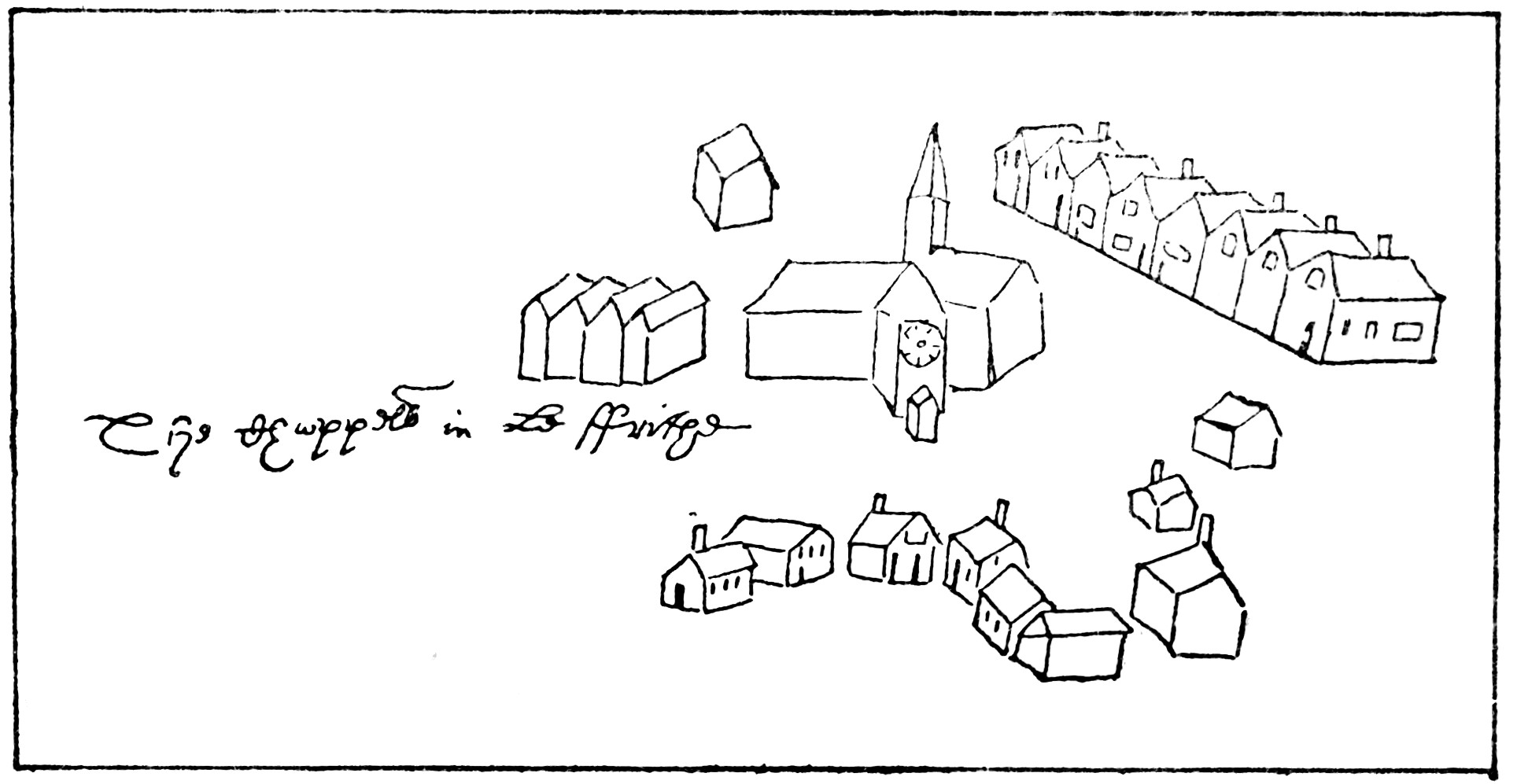

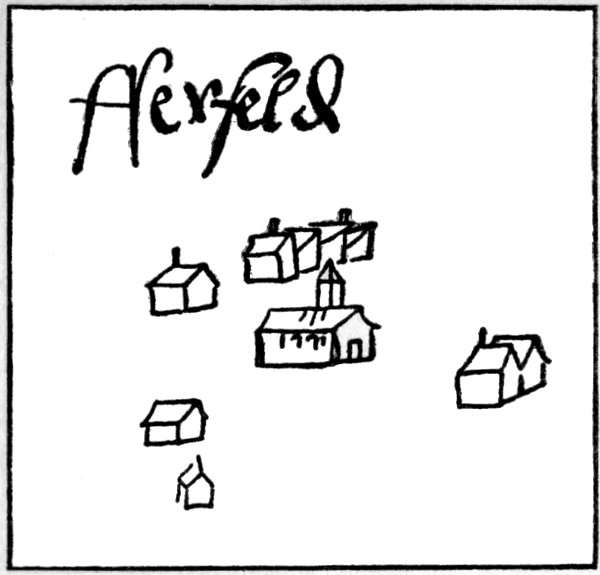

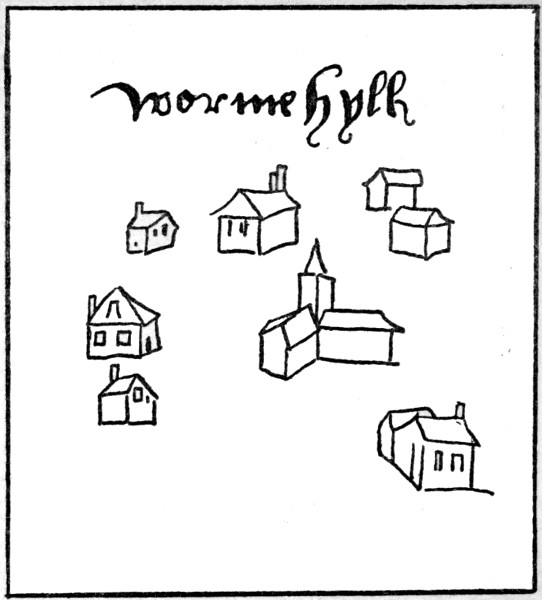

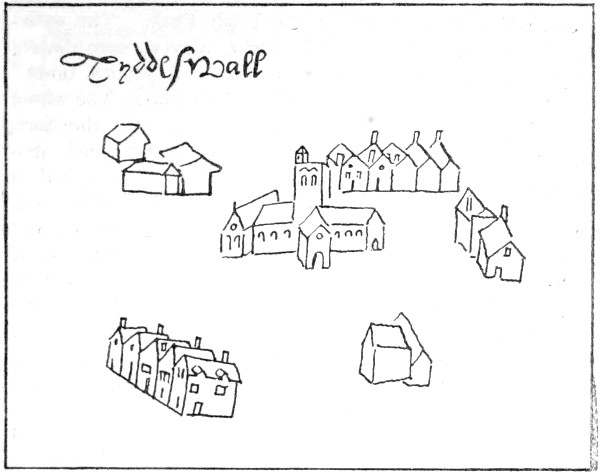

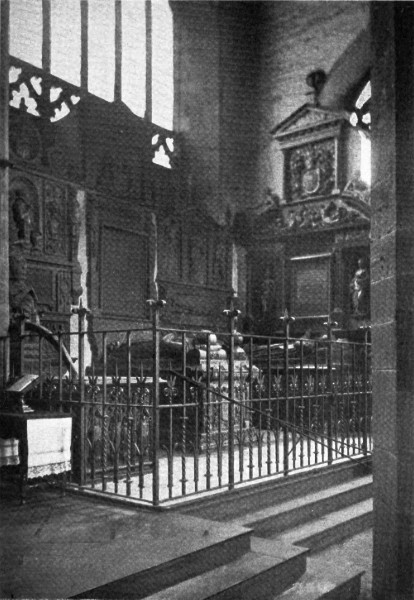

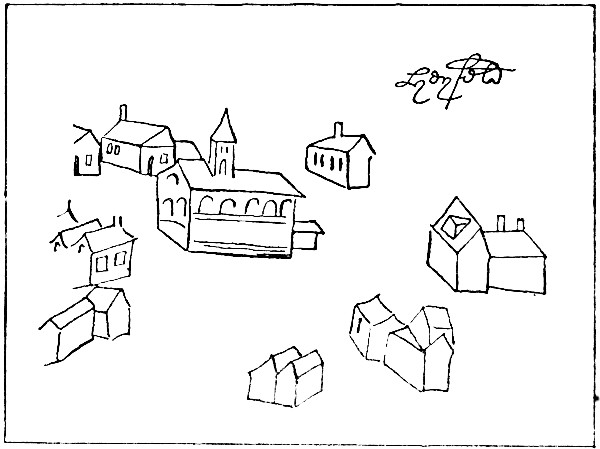

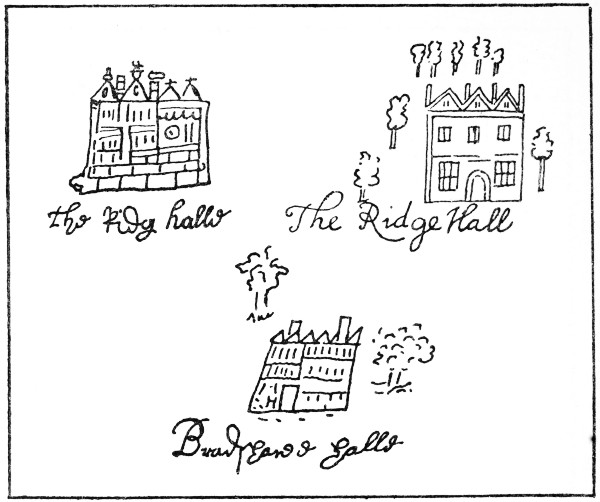

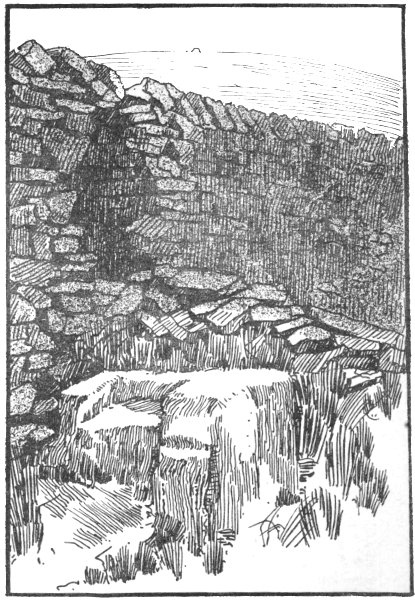

MELBORN CASTLE

in the County of DERBY.

Formerly a Royal Mansion, now in Ruins; where John Duke of Bourbon taken Prisoner by K: Henry Vth.

in the Battle of Agincourt (Ano. 1414.) was kept Nineteen Years in Custody of Nicholas Montgomery

the Younger; he was released by K: Henry VIth.

This Draught is made from a Survey now in the Dutchy office of Lancaster,

taken in the Reign of Q: Elizabeth. Sumptibus, Soc: Ant: Lond: 1733.

The notable triumph of Agincourt must have been

long held in remembrance in Derbyshire, for the midland

fortress of Melbourne Castle was selected as the place

of imprisonment for the most notable prisoner taken on

that field of French disaster. John, Duke of Bourbon,

was confined at Melbourne for nineteen years; at first

under the custody of Sir Ralph Shirley, one of the leaders

in the fight, and afterwards in the charge of Nicholas

Montgomery the younger.

In the deplorable Wars of the Roses, between the

Lancastrians and the Yorkists, which extended over thirty

years from 1455 to 1485, Derbyshire men took no small

part, now on one side, now on the other, whilst occasionally

they were found in the ranks of both parties.

A commission issued in December, 1461, to Sir William

Chaworth, Richard Willoughby, and the Sheriff of

Derbyshire, illustrates the disturbed condition of the

county in the beginning of the reign of Edward IV.

These commissioners were ordered to arrest John Cokayne,

of Ashbourne, who is represented as wandering about in

various parts of the county with others, killing and

spoiling the King’s subjects, and to bring him before the

King in council.

A manuscript list of the “names of the captayns and

pety captayns wyth the bagges, in the standerds of the

army and vantgard of the king’s lefftenant enterying

into Fraunce the xvj day of June,” 1513, begins with

George, Earl of Shrewsbury, the King’s lieutenant of the

vanguard, who bore on his standard “goulles and sabull[16]

a talbot sylver passant and shaffrons gold”; the Derbyshire

banneret, Sir Henry Sacheverell, with John Bradburne

for his petty captain, bearing “goulles a gett buk

sylver.” Other Derbyshire gentlemen who were captains in

this array, each having his petty captain and his

“bagges” (badges) or arms as borne on his standard,

were:—Robert Barley with John Parker, Nicholas Fitzherbert

with John Ireton, Sir John Leek with Thomas

Leek his brother, Sir Thomas Cokayne with Robert

Cokayne, Sir William Gresley with John Gresley, Sir

Gylbert Talbot the younger with Humphrey Butler,

Robert Lynaker with George Palmer, Thomas Twyford

with Roger Rolleston, Sir John Zouch (of Codnor) with

Dave Zouch (his brother), Arthur Eyre with Thomas

Eyre (his brother), Ralph Leach and John Curzon (of

Croxall) with Edward Cumberford.

In addition to all these Derbyshire gentlemen,

William Vernon bore the banner of St. George, John

Leach the banner of the lieutenant’s arms, and Thomas

Rolleston the standard of the talbot and chevrons.

Derbyshire considerably preponderated in this army of

the vanguard, there being twelve companies from that

county. Shropshire had nine companies, Staffordshire

eight, Nottinghamshire six, and Leicestershire and

Cheshire two each; five other counties only furnished a

single company.

Into the grievous question of the cruel way in which

the monasteries were suppressed by Henry VIII. it is

not proposed here to enter, even after the briefest fashion.

It may, however, be remarked that although the county

had no religious houses of first importance within its

limits—the most noteworthy being the Premonstratensian

Abbeys of white canons at Dale and Beauchief, and

the houses of black or Austin canons at Darley Abbey

and Repton Priory—the amount of landed estates, both

large and small, held throughout Derbyshire under

abbeys or priories situated in other shires, was very[17]

considerable. If there is one social or economic fact that

is thoroughly established in connection with this great

upheaval, whose main object was to secure pelf for the

Crown, it is that the condition of the monastic tenantry

was far better than that of those under often changing

secular rule.

The sternest possible measures were taken to suppress

the least disaffection shown against the policy of dissolution.

Lives were lost, even of those in high position up

and down the country, on the merest hearsay evidence of

having indulged in private talk against the King’s policy.

At the time when Henry and his Court were seriously

alarmed by the Lincolnshire rising on behalf of the

smaller monasteries, lists were drawn up on October 7th,

1536, of the names of noblemen and gentlemen to whom

it was proposed to write, under privy seal, requiring their

aid with men and horses fit for war. The Derbyshire

names on this list were: the Lord Steward, Lord Talbot,

Sir Henry Sacheverell, Matthew Kniveton, Sir Godfrey

Foljambe (Sheriff), Roland Babington, and Francis

Cokayne. The rising was, however, so summarily suppressed

that there was no necessity for the calling out of

any general array.

There are full particulars extant of the Derbyshire

musters for April, 1539, giving the exact number under

each parish of archers with horses and harness, of billmen

with horses and harness, and also of unharnessed archers

and billmen. The total for the various hundreds of the

county, including the town of Derby, reached the total

of 4,510.

As to the various religious changes in the reigns of

Henry VIII., Edward VI., Mary, and Elizabeth, which

affected Derbyshire as much as any other part of the

kingdom, it is not proposed here to enter. Suffice it to say

that their distinguishing feature under Elizabeth, which

was also continued throughout the greater part of the

seventeenth century, was the fierce persecution and ruinous[18]

fining directed against the recusants of the Roman

obedience. The reason for the pre-eminence of Derbyshire

in this respect arose from two facts: firstly, that some of the

most influential of the old Derbyshire families, such as the

Fitzherberts and the Eyres, remained steadfast to the unreformed

faith; and, secondly, that the wild districts of

the Peak afforded so many places of shelter to those

recusants of this and the neighbouring counties who desired

to escape the rigorous search of Elizabeth’s pursuivants.

Throughout the long reign of Elizabeth, the county

musters were under frequent survey. A few months

before the reign began, the old local militia, with its scale

of arms (including bows and arrows) as revised in 1285,

which had continued for more than four centuries in

accordance with the scheme laid down by Henry II., came

to an end. The old Assize of Arms had long been found

unsuitable to the advance in the art of war. Eventually

an Act of Parliament of Philip and Mary “for the having

of horse armour and weapon,” which provided that after

May 1st, 1558, everyone who had an estate of inheritance

of the value of £1,000 or above was to keep at his own

cost six horses meet for demi-lances (heavy cavalry), and

ten horses meet for light horsemen, with the requisite

harness and weapons; also 40 corselets for pikemen,

40 Almayne rivettes (flexible German armour), 40 pikes,

30 longbows, 30 sheaves of arrows, 30 steel caps, 20 black

bills or halberds, 20 hand-guns, and 20 morions or light

open helms. A sliding scale followed, making due

provision for what was required from those having lands

of various values down to £10, and these last had to

find a longbow, a sheaf of arrows, a steel cap, and a

black bill. Another section of the Act provided that the

inhabitants of every town, parish, or hamlet, other than

those who were already charged in proportion to their

landed property, were to find and maintain at their own

charges such harness and weapons as might be appointed

by the commissioners of the musters.

[19]

Within a few months of Elizabeth’s accession, this

new legislation was tested by calling out the general

muster throughout the kingdom, and by obtaining returns

of the number in equipment from each county. The long,

interesting return for Derbyshire, dated March 9th,

1558–9, is extant; it is signed by seven justices—George

Vernon, Humphrey Bradbourne, Henry Vernon, Francis

Curzon, John Frances, Gilbert Thacker, and Richard Pole.

Every hundred and township is set forth in detail, both

as to the arms and the men. There was only one

landowner of sufficient wealth in the county to be called

upon to provide all that was requisite for a heavy

horseman; but there were ten light horsemen. The total

of “the able Footemen harnissed and unharnissed”

amounted to 1,211, namely, 56 harnessed archers, 135

harnessed billmen, 236 unharnessed archers, and 784

unharnessed billmen.

A second full certificate of the able men, arms, and

weapons throughout the county was forwarded ten years

later to the council. With this return a letter was

forwarded signed by the Earl of Shrewsbury as lord-lieutenant,

as well as by his deputies. A noteworthy

paragraph in this letter shows that Derbyshire was not

taking kindly to the general substitution of explosive

weapons in the place of archery which was then in

progress.

“Touching thorders prescribed for thexercise of harquebuziers, the

truthe is this shire doth not aptlie serve theretoe for we have very few

harquebuziers & they placed so farre from market townes as they shuld

nott come to a day of exercise above the nombre of six, & yet their travell

further than in the time for the same is prescribed. Indeed we have

good plenty of archers & therefore in our generall musters wee thought it

best to appoint many of them to be furnished accordingly & nowe if we

shuld make a new charge the countrey undoubledy wuld think themselves

oversore burdened.”

The Earl of Shrewsbury received orders in November,

1569, to raise the whole force of Derbyshire and[20]

Nottinghamshire, and to proceed against the Earls of

Northumberland and Westmoreland, “now in rebellion.”

It would be wearisome in a sketch of this character to

note the various incidents, which can be gleaned from

both the public records and the county muniments, as

to the several occasions on which the Derbyshire musters

were called out when there was no immediate necessity

for their use.

The considerable part that this county played

in the safeguarding of Elizabeth’s unhappy prisoner,

Mary, Queen of Scots, during her repeated sojourns at

Wingfield Manor House, together with her visits to

Chatsworth and Buxton, are fully dealt with in another

paper in this volume. It may, however, be here remarked

that the deplorable execution of Mary, in 1587, and the

way in which the youthful Babington had so rashly

conspired in her favour, made a great impression upon

this county, and caused the Council as well as the local

authorities to redouble their precautions. Not only was

a certain local undercurrent stirred up in Derbyshire

through the Fotheringay execution, but it also had the

result of hastening the hostilities of Philip of Spain and

other of Elizabeth’s external enemies. There was in

consequence at this period frequent exercise of the county

forces. The Earl of Shrewsbury’s gout prevented his

taking any active part, and the work was chiefly supervised

by his brother-in-law, John Manners, the senior of the

deputy-lieutenants. A certificate of the musters, as viewed

by Manners in November, 1587, shows that there were

400 “selected bands armed and prest for present service”;

these bands were divided into 160 “shot,” 80 pikemen,

80 billmen, and 80 archers. It is interesting here to

note the remarkable way in which the musket had gained

ascendancy over the bow in fourteen years. In addition

to the selected 400, Manners returned 1,300 men who

were available in times of need, namely, 300 for shot,

300 for pikes, 360 for bills, 200 for bows, 80 as carpenters[21]

and wheelwrights, and 60 as smiths. The mounted forces

consisted of 9 demi-lances and 178 light-horse.

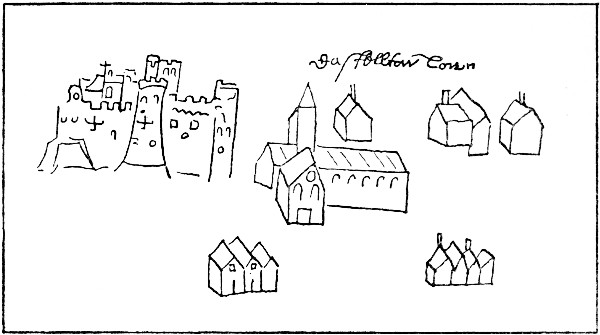

Wingfield Manor.

(From an Indian Ink Drawing by Colonel Machell, 7th August, 1785.)

This return, large as it was, was not, however, a

complete one for the whole county, for none of the musters

from the hundred of Scarsdale were allowed to be present

for fear of infection. A grievous attack of the plague

was then raging at Chesterfield and several of the adjacent

parishes. The severity of what is termed in the parish

register “the great plague of Chesterfield” may be

gathered from the fact that the deaths of that town in

June, 1587, were fifty-four, in July fifty-two, and yet the

average deaths in Chesterfield for several years about that

period were only three a month.

Although Derbyshire was perhaps further removed

from the sea-coast than any other county, the threatened

approach of the great Spanish Armada appears to have

made almost as much stir as in the sea-board counties.

The gentlemen of the county consented to greatly increase

the number of lances and light-horse, provided that such

action should not be taken as a precedent; and they

further promised to provide an addition of 400 to the

number of unmounted troops. The old earl wrote a

brave letter to his sovereign, assuring her that the

gentlemen of Derbyshire were both ready and well

affected, and that, as for himself, the threatened invasion

was making him young again, “though lame in body,

yet was he lusty in heart to lead her greatest enemy one

blow, and to live and die in her service.”

The signal defeat of Spain brought for some years

general peace and quiet throughout the kingdom. The

musters in Derbyshire and elsewhere were but rarely called

out, save in the winter of 1598–9, when renewed threats

from Spain caused Sir Humphrey Ferrers, the most active

of the Derbyshire deputy-lieutenants, to view the musters

of the various hundreds.

Quite irrespective of the part played by the general

musters during this reign in preparation for possible[22]

emergencies, there was much stir and excitement in the

county, accompanied, no doubt, by a great deal of misery,

consequent upon the repeated call for troops to take part

in the subjection of Ireland. The levies of troops for

Ireland were almost ceaseless during the last quarter of

the sixteenth century. It has usually been understood by

historians that these raw troops came mainly from

Lancashire and Cheshire; but the Belvoir manuscripts,

supported by the Acts of the Privy Council and local

muniments, show that Derbyshire—possibly as a compliment

to her bravery—was being constantly called upon

to supply men for these expeditions entirely out of

proportion to the limited area and population of the

county. It is not surprising to find that these forcibly

impressed levies, utterly untrained in military matters,

and suffering severely from poor clothing, insufficient food,

the dampness of the climate, and frequent infectious

disease, perished in large numbers before they could attain

to any proficiency. When the Earl of Essex was granted

special powers in 1573 to suppress the Irish rebellion,

Derbyshire had to submit to the impressment of a hundred

men, and a complaint was lodged at the sessions that

some of the best lead-miners had been taken for that

purpose. The whole story of these forced levies, of the

difficulty of conveying them to the ports of Lancashire

and Cheshire, of their frequent desertions both en route

and even when they had crossed the seas, of the poorness

of the weapons and equipments with which they were

supplied by the swindling contractors of the day, is a most

sorry and sordid tale. Nor could these Derbyshire troops

have presented, even when first called out, a particularly

attractive or uniform appearance, for the Belvoir

manuscripts tell us that they were to be provided, in

addition to convenient hose and doublet, “with a cassock

of motley and other sea-green colour or russet.”

There was much nervousness with regard to Derbyshire

when Elizabeth was on her deathbed, in March, 1682–3.[23]

The council were alarmed lest attempts should be made

to remove Lady Arabella Stuart (who had a certain kind

of claim to the throne) by violence from the custody of

her grandmother, the old Countess of Shrewsbury, better

known as Bess of Hardwick. They dispatched Sir Henry

Brounker in haste with a warrant to all the Derbyshire

lieutenants, justices, and constables, to give him all

assistance in guarding Arabella, and in the suppression

of every form of disorder and riot. On March 25th, Sir

Henry met a large body of the deputy-lieutenants and

justices at North Wingfield, a short distance from Hardwick

Hall, when it was arranged that there should at present

be no general view of the musters, but that the constables

were to see that the armour was in readiness, and to

take other precautions. But whilst they were thus

debating, death removed Elizabeth, and on the following

day James I. was quietly proclaimed King at Derby

without any trace of remonstrance.

Early in the reign of James I. the nature of the

general musters or local militia was considerably changed,

but their special services were never really needed during

the time he was on the throne. In 1624, when James

was unhappily persuaded to give authority to the Duke

of Buckingham to raise 10,000 men in England to proceed

to the Palatinate, this county had some share in the general

misfortune. Out of the great disorderly rabble collected

by impressment at Dover, half of whom died in the overcrowded

vessels from the plague ere they could even be

landed, Derbyshire contributed 150 men. These troops

from the centre of England were allowed 8d. a day whilst

marching to Dover, and they were expected to make at

least twelve miles daily. It is probable that James was

at Derby in August, 1609, when making a progress from

Nottingham to Tutbury Castle. He was certainly in the

county towards the close of his life, during the summer

progress of 1624. On August 10th the King was at

Welbeck, when he knighted two Derbyshire gentlemen,[24]

Sir John Fitzherbert of Norbury, and Sir John Fitzherbert

of Tissington. In the following week he stopped two

nights at Derby with Prince Charles, proceeding thence

in the following week to Tutbury. In the latter place

he knighted Sir Edward Vernon, of Sudbury.

In no other county in the whole of England is the

evidence more clear or detailed than in Derbyshire as

to the ill-advised proceedings in the opening part of the

reign of Charles I., which eventually brought about the

misfortunes of the great Civil War. The methods of

raising funds for the Crown after an irregular fashion

by way of benevolences and loans, was no new invention

of this ill-fated Stuart King. Such exactions, though

contrary to statute, were resorted to by Henry VII. in

1491, when he took a “benevolence” from the more

wealthy folk for his popular incursion into France.

Henry VIII. made like cause for an “aimable graunte”

in 1528 and in 1548. Elizabeth appears to have always

expected and received valuable “gifts” of money or

plate during her progresses, and numerous “loans”

demanded and obtained from Derbyshire gentlemen by

that Queen were considerable, and a frequent cause of

friction when it was found that they were scarcely ever

repaid. Charles I., however, was so foolishly advised as

to begin his reign by pressing for definite sums, which

were ridiculously termed “free gifts.” Derbyshire was

practically unanimous in its refusal to the demand.

The courts of four of the hundreds duly met in 1626,

and declined to pay a single farthing “otherwise than

by way of Parliament.” The Derbyshire justices met in

session on July 18th, and forwarded to the council the

answers from all the hundreds. The first signature to

this reply was that of the Earl of Devonshire, and in

the whole county only £20 4s. was subscribed.

Two years later the King’s consent was obtained to

the Petition of Rights, and thus benevolences or forced

loans were put an end to in most explicit terms. The[25]

next expedient, however, for raising money without

Parliament was still more foolish. A well recognised

method for getting together a navy in actual time of war,

namely, by issuing ship-writs, had become established in

Plantagenet days, and proved of great service to Elizabeth

in resisting the Armada. There were also later precedents

of 1618 and 1626, but in every one of these cases ship-writs

were only served on seaports, and were never issued

save for immediate warlike enterprise. The ship-writs,

however, of 1634 were served when there was no war

or fear of attack; and in the following year the grievance

was intensified by serving writs on inland as well as

maritime counties and towns. Under the writs of 1635,

the small county of Derbyshire was called upon to pay

the great sum of £3,500—£90 of which was to be

contributed by the clergy. Many in the county actively

resisted. Sir John Stanhope, of Elvaston, flatly declined

to pay a farthing, was put under arrest, taken before

the council in London, and his goods distrained. A third

ship-writ reached Derbyshire in 1636, but the sheriff

could only raise £700, and that with much difficulty. A

fourth writ in October of the same year, again demanding

£3,500, was served on the new sheriff, Sir John Harper.

Resistance was general. The King was compelled in 1640

to summon the “Long Parliament,” which speedily declared

all the late proceedings touching ship money to be illegal

and void. To this the King consented; but it was too

late, the mischief was done.

Charles I., in the earlier part of his reign, was on

three occasions the guest of the Earl of Newcastle at

Bolsover Castle. The record visit of the three was in

1633, when he was accompanied by his Queen. The

entertainment, as Lord Clarendon has it, was “very

prodigious and most stupendous.” The expenses for

hospitality on this occasion reached the huge total of

£15,000; it was during the visit that Ben Jonson’s masque

of Love’s Welcome was performed.

[26]

In 1635 Charles I. visited Derby, and slept at the

Great House in the market-place. The corporation and

townsmen had very good reason to remember this visit,

for they gave the Duke of Newcastle for the King a fat

ox, a calf, six fat sheep, and a purse of gold to enable

him to keep hospitality, with a further present to the

Elector Palatine of twenty broad pieces. The King further

improved the occasion by “borrowing” £300 off the

corporation in addition to his gifts, as well as all the

small arms in possession of the town. At the end of

the Scottish War in August, 1641, Charles I. passed

through Derbyshire, and was again at the county town

on the eleventh of August, when he made Sir John Curzon,

of Kedleston, and Sir Francis Rodes, of Barlborough,

baronets.

The great Civil War began in the summer of 1642

with the raising of the Royal Standard at Nottingham.

The registers of All Saints, the great church of the county

town, have the following brief chronicle of this dramatic

incident: “the 22 of this August errectum fuit

Notinghamiæ Vexillum Regale.—Matt. xii. 25.” The

vicar, Dr. Edward Wilmot, who made the entry, was a

staunch Royalist, and probably employed the Latin tongue

knowing full well the general tendency of the opinions

of the townsmen. When the news reached Derby, the

response was meagre. Hutton, the historian, tells us

that about twenty Derby men marched to Nottingham and

entered the King’s service. On September 13th the King

marched with his army from Nottingham to Derby, but

only made one day’s stay in the town, pushing on from

thence to Shrewsbury. Within a few months practically

the whole of the counties of Derby, Leicester, Stafford,

Northampton, and Warwick were united in an association

against the King.

Sir John Gell, of Hopton, at once came to the fore

as the local energetic supporter of Parliamentary

Government, obtaining a commission as colonel from[27]

the Earl of Essex. After rousing the county both at

Chesterfield and Wirksworth, he marched with a small

force to Derby, which he entered on the thirty-first of

October, 1642, where he was joined by one of the leading

gentlemen of the south of the shire—Sir George Gresley.

It would take far more space than can here be afforded

to give even the barest outline of the ups and downs

of the sad civil strife that raged throughout Derbyshire,

for the most part in favour of the Commonwealth, for

the next few years. It must suffice to state that

the county, apparently owing to its central position,

suffered more in various ways, both in loss of men and

property of all descriptions, than any other part of the

whole of England. Wingfield Manor House, Bolsover

Castle, and such great houses as Chatsworth, Tissington,

Sutton, and Staveley, were held first by one side and

then by the other; whilst important garrisons at places

so near to the county boundaries as Welbeck, Tutbury,

and Nottingham, contributed to constant raids over the

parts of Derbyshire within easy reach.

In 1645 the plight of Derbyshire was most deplorable,

through the frequent marches and counter-marches of the

hostile forces through its limits; for, although the

Parliament held its own throughout the county during

the prolonged struggle, the Royalists now and again

gained the victory in a skirmish, and succeeded in

maintaining their hold in well-garrisoned places for a few

months at a time. Both sides, also, found it essential

in their campaigns to cross the county in various directions.

In August of this year Sir George Gresley and others

wrote to the Speaker as to the miserable condition of

the county, which had been successively afflicted by the

armies of Newcastle, the Queen, Prince Rupert, Goring,

and others, who had freely raided from even the poorest

of the people during their transits. The enemy, he stated,

had lost all their Derbyshire garrisons, but they had been

taken by force and at a great charge to the county.[28]

Several garrisons on the confines of the county, such

as Newark, Tutbury, and Welbeck, still had power and

means to levy contributions on the adjacent parts of

Derbyshire, and to ruin those who denied them. Moreover,

the Scotch army had been for a time very chargeable

to the county, for they not only claimed free quarters,

but supplied themselves with what horses they required.

And now, to crown all, the King’s army had passed through,

and made spoil of a great part of the county. Some of

the Parliament forces had come to their help, and more

were daily expected; but all of them would at least

have free quarters, and the owners of the very few horses

left in Derbyshire had now small hope of retaining them.

The House of Commons was asked to grant them the

excise of the town and county for the present maintenance

of their own soldiers.

It must also be remembered in estimating the share

that Derbyshire had in this momentous conflict, that it

has not only to be gauged from what went on within her

borders, but from the prominent share which Derbyshire

forces took in the battles and skirmishes that took place

in other parts of the kingdom. At the very outset of the

struggle, Derbyshire troops played an important part

round Lichfield and in other parts of Staffordshire.

During the winter of 1644–5, Gell’s forces from this county

were busy about Newark, and also in Cheshire. In

the spring of the latter year they were engaged before

Tutbury Castle; and in July, 1648, Derbyshire horse

played an important part in the Parliamentary victory

at Willoughby, Nottinghamshire.

In this same month the Derbyshire committee were

ordered to send sixty of their horse to Pontefract to

help in the siege, and to join in the resistance to the

invasion from Scotland. On August 18th came the rout

of the great army of the Scots, under the Duke of

Hamilton, at Preston. The defeated cavaliers disbanded

themselves in Derbyshire, dispersing in all directions.[29]

Considerable numbers of the Scotch infantry were

gradually arrested, having vainly endeavoured to conceal

themselves amid the hills and dales of the wild Peak

district. One of the most terrible episodes of the strife

in the Midlands occurred in the then large church of

Chapel-en-le-Frith. A vast number of the Scotch

prisoners were crowded into the church, with the shocking

result thus curtly entered in the registers:—

“1648 Sept: 11. There came to this town of Scots army, led by the

Duke of Hambleton & squandered by Colonell Lord Cromwell sent

hither prisoners from Stopford under the conduct of Marshall Edward

Matthews, said to be 1500 in number put into ye church Sept: 14. They

went away Sept: 30 following. There were buried of them before the

rest went away 44 persons, & more buried Oct. 2 who were not able to

march, & the same thyt died by the way before they came to Cheshire

10 & more.”

Space must be found for a far less tragic incident

that occurred in connection with another Derbyshire

church in the south of the county earlier in this strife.

When the Royalists were making a special effort to regain

their hold on Wingfield Manor, Colonel Eyre, with his

regiment of 200 men, marching from Staffordshire, passed

the night in the church of Boyleston. Major Saunders,

a local Derbyshire leader on the Parliament side, heard

of this night encampment, and with a small troop of horse

surrounded the church, and raising a simultaneous shout

at all the windows and doors demanded the instant

surrender of all the Royalists under pain of immediate

fire. Colonel Eyre’s men, startled from their sleep, were

compelled to surrender; they were ordered to come out

one by one through the small priest’s door on the south

side of the chancel, and as each stepped forth he was

seized and stripped of his arms—“and soe,” wrote Major

Saunders, “we took men, collours, and all without loss

of one man on either side.”

As to the general sympathy of this shire with the

Commonwealth proceedings, even after the execution of[30]

the King, the Commission of the Peace in 1650 shows

how large a proportion of the old county gentlemen

were content to accept commissions at the hands of the

new rulers. It includes such names as Sir Francis Burdett,