The Project Gutenberg eBook of Half hours on the quarter deck, by Anonymous

Title: Half hours on the quarter deck

The Spanish Armada to Sir Cloudesley Shovel 1670

Author: Anonymous

Release Date: September 30, 2022 [eBook #69077]

Language: English

Produced by: Juliet Sutherland, Charlie Howard, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

THE HALF HOUR LIBRARY.

TRAVEL, NATURE, AND SCIENCE.

Handsomely bound, very fully Illustrated, 2s. 6d. each;

gilt edges, 3s.

Half Hours in the Holy Land.

Travels in Egypt, Palestine, and Syria.

By Norman Macleod.

Half Hours in the Far North.

Life amid Snow and Ice.

Half Hours in the Wide West.

Over Mountains, Rivers, and Prairies.

Half Hours in the Far South.

The People and Scenery of the Tropics.

Half Hours in the Far East.

Among the People and Wonders of India.

Half Hours with a Naturalist.

Rambles near the Seashore.

By the Rev. J. G. Wood.

Half Hours in the Deep.

The Nature and Wealth of the Sea.

Half Hours in the Tiny World.

Wonders of Insect Life.

Half Hours in Woods and Wilds.

Adventures of Sport and Travel.

Half Hours in Air and Sky.

Marvels of the Universe.

Half Hours Underground.

Volcanoes, Mines, and Caves.

By Charles Kingsley and others.

Half Hours at Sea.

Stories of Voyage, Adventure, and Wreck.

Half Hours in Many Lands.

Arctic, Torrid, and Temperate.

Half Hours in Field and Forest.

Chapters in Natural History.

By the Rev. J. G. Wood.

Half Hours on the Quarter-Deck.

Half Hours in Early Naval Adventure.

Frontispiece.]

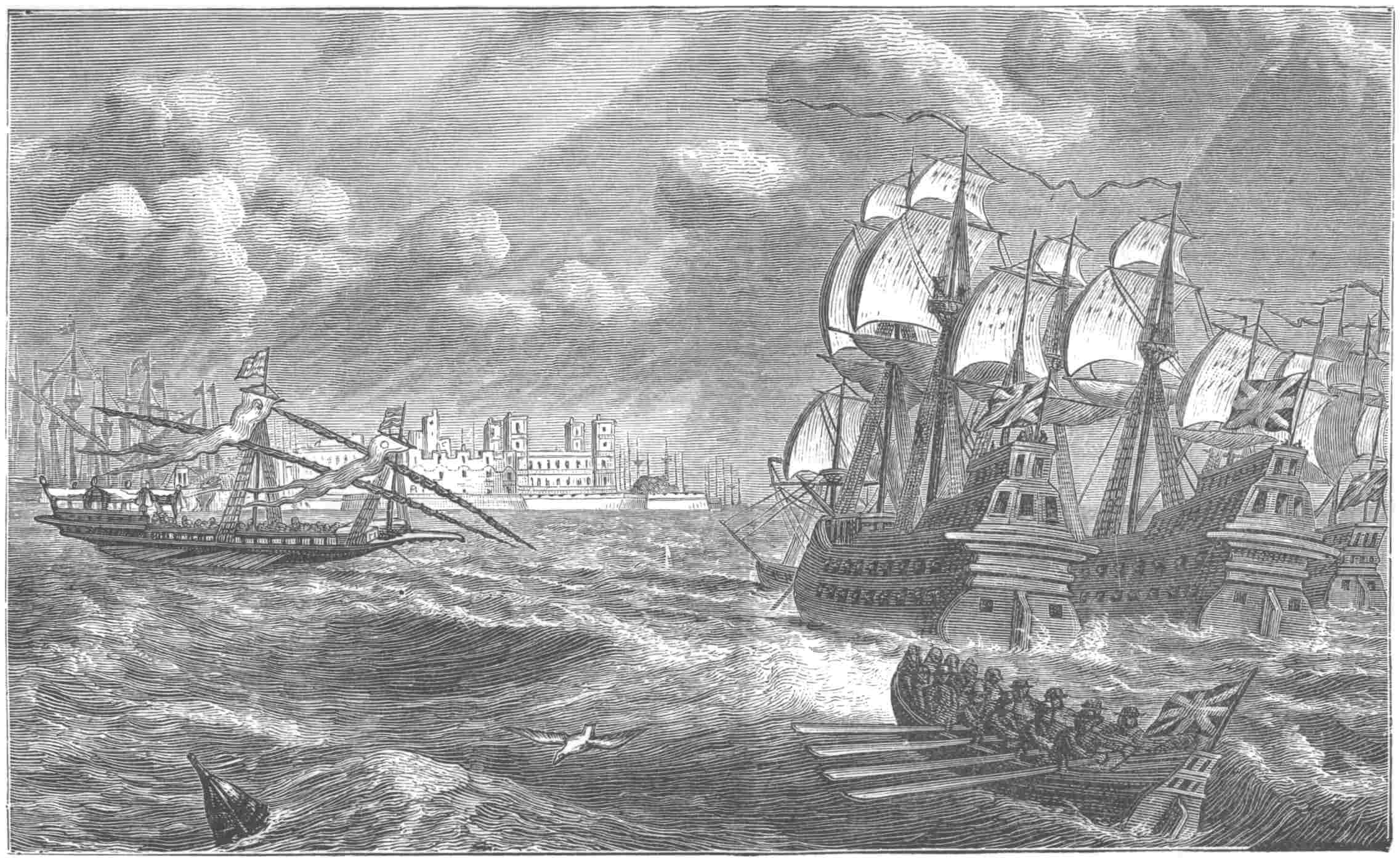

SIR FRANCIS DRAKE CALLS ON HIS COMRADES TO “PLAY OUT THE MATCH, FOR THERE IS PLENTY OF TIME TO DO SO, AND TO BEAT THE SPANIARDS TOO.”

THE HALF HOUR LIBRARY

OF TRAVEL, NATURE, AND SCIENCE

FOR YOUNG READERS

HALF HOURS ON

THE QUARTER-DECK

The Spanish Armada to Sir Cloudesley Shovel

1670

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS

London

JAMES NISBET & CO. LIMITED

21 Berners Street, W.

1899

vii

This is the second of a series of books on a subject of the greatest interest to all young Englishmen—the Naval History of England. To the sea England owes its greatness, and the Anglo-Saxon race its possession of such large portions of the earth. Two-thirds of the surface of our globe are covered with water, and the nations that have the chief command of the seas must naturally have immense power in the world. There is nothing more marvellous in the last century, great as has been the progress in all directions, than the birth of new nations in distant parts of the earth, sprung from our own people, and speaking our own language. England and America bid fair to encompass the world with their influence; because, centuries ago, England became, throughviii the bravery and endurance of her sailors, the chief ocean power.

From the earliest times, the command of the sea was eagerly sought after. The Phœnicians, occupying a position of much importance as a commercial centre between the great regions of Asia on the east and the countries surrounding the Mediterranean on the west, made rapid progress in navigation. The large ships they sent to Tarshish were unequalled for size and speed. Their vessels effected wonderful things in bringing together the varied treasures of distant countries. They used the sea rather for commerce, and the sending forth of colonists through whom they might extend their trade, than for purposes of conquest. With the Romans, who succeeded them in the command of the sea, especially after the fall of Carthage, the sea was a war-path, and the subjugation of the world was the paramount idea, although the vessels brought treasures from all parts to enrich the imperial city. The Anglo-Saxons have used the seas, both east and west, as the Phœnicians used the Mediterranean, forix the extension of commerce and the planting of colonies, but also, as the Romans, for the subjugation and civilisation of great empires.

There is a great interest in observing the progress of events for a century after the opening up of the great world by Columbus and others of the same period. It seemed for a time as if Spain and Portugal were to conquer and possess most of the magnificent territories discovered; France seemed also likely to have a fair portion; but England, almost nowhere at first, gradually led the way. This was due chiefly to the wonderful feats and endurance and bravery of her sailors. One country after another fell under our influence, till the great continent of America in all its northern parts became peopled by the Anglo-Saxon race—which has, in later periods, similarly spread over Australia and New Zealand.

With the growth of the maritime power of England is associated a splendid array of heroic names, and many of the humblest sailors were equal in bravery to their renowned commanders. No history is more intensely interesting thanx that of the daring perils and triumphs of heroic seamen. The heroes, who have distinguished themselves in the history and growth of the British Navy, furnish a gallery and galaxy, bewildering in extent; the events of pith and moment, in which they have been prominent actors, present fields too vast to be fully traversed; they can only be touched at salient points.

xi

| CHAP. | WILLIAM, JOHN, AND RICHARD HAWKINS. | PAGE |

| I. | THREE GENERATIONS OF ADVENTURERS, | 1 |

| CHARLES HOWARD, BARON OF EFFINGHAM, AFTERWARDS EARL OF NOTTINGHAM. | ||

| II. | “BORN TO SERVE AND SAVE HIS COUNTRY,” | 37 |

| SIR MARTIN FROBISHER, NAVIGATOR, DISCOVERER, AND COMBATANT. | ||

| III. | THE FIRST ENGLISH DISCOVERER OF GREENLAND, | 47 |

| THOMAS CAVENDISH, GENTLEMAN ADVENTURER. | ||

| IV. | THE SECOND ENGLISHMAN WHO CIRCUMNAVIGATED THE GLOBE, | 57 |

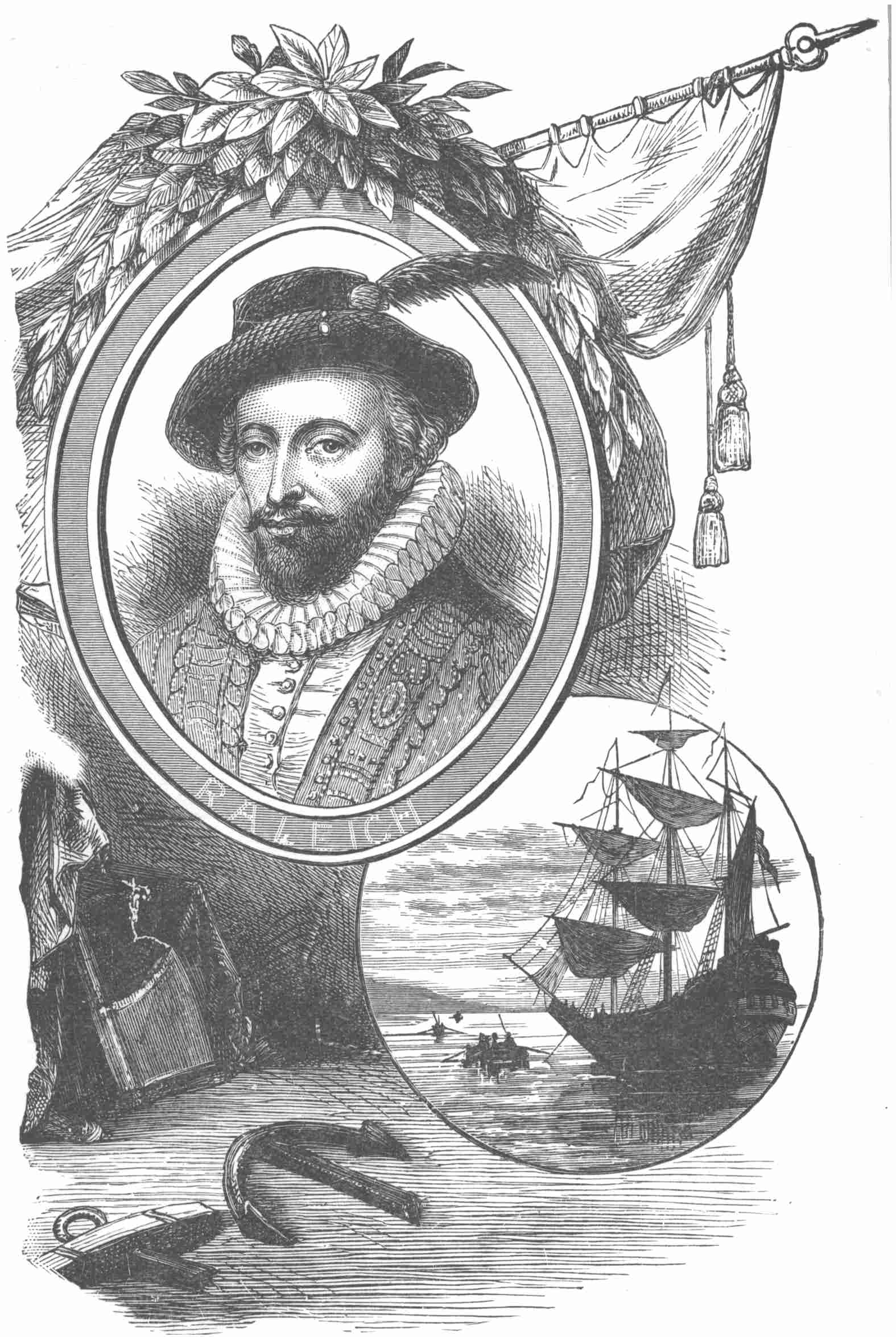

| SIR WALTER RALEIGH, QUEEN ELIZABETH’S FAVOURITE MINISTER. | ||

| V. | AMERICAN COLONISATION SCHEMES, | 83 |

| SIR WALTER RALEIGH, SAILOR, SCHOLAR, POET. | ||

| VI. | NAVAL EXPEDITIONS—TRIAL AND EXECUTION, | 130 |

| THE PLANTING OF THE GREAT AMERICAN COLONIES. | ||

| VII. | “TO FRAME SUCH JUST AND EQUAL LAWS AS SHALL BE MOST CONVENIENT,” | 173 |

| OLIVER CROMWELL AND THE SEA-POWER OF ENGLAND. | ||

| VIII. | A LONG INTERVAL IN NAVAL WARFARE ENDED, | 181xii |

| ROBERT BLAKE, THE GREAT ADMIRAL OF THE COMMONWEALTH. | ||

| IX. | HE ACHIEVED FOR ENGLAND THE TITLE, NEVER SINCE DISPUTED, OF “MISTRESS OF THE SEA,” | 186 |

| GEORGE MONK, K.G., DUKE OF ALBEMARLE. | ||

| X. | THE FRIEND OF CROMWELL, AND THE RESTORER OF CHARLES II., | 230 |

| EDWARD MONTAGU, EARL OF SANDWICH. | ||

| XI. | NAVAL CONFLICT BETWEEN THE ENGLISH AND THE DUTCH, | 253 |

| PRINCE RUPERT, NAVAL AND MILITARY COMMANDER. | ||

| XII. | THE DUTCH DISCOVER ENGLISH COURAGE TO BE INVINCIBLE, | 290 |

| SIR EDWIN SPRAGGE, ONE BORN TO COMMAND. | ||

| XIII. | THE DUTCH AVOW SUCH FIERCE FIGHTING NEVER TO HAVE BEEN SEEN, | 315 |

| SIR THOMAS ALLEN. | ||

| XIV. | THE PROMOTED PRIVATEER, | 334 |

| SIR JOHN HARMAN. | ||

| XV. | “BOLD AS A LION, BUT ALSO WISE AND WARY,” | 343 |

| ADMIRAL BENBOW. | ||

| XVI. | THE KING SAID, “WE MUST SPARE OUR BEAUX, AND SEND HONEST BENBOW,” | 346 |

| SIR CLOUDESLEY SHOVEL. | ||

| XVII. | THE SHOEMAKER WHO ROSE TO BE REAR-ADMIRAL OF ENGLAND, | 359 |

xiii

| PAGE | |

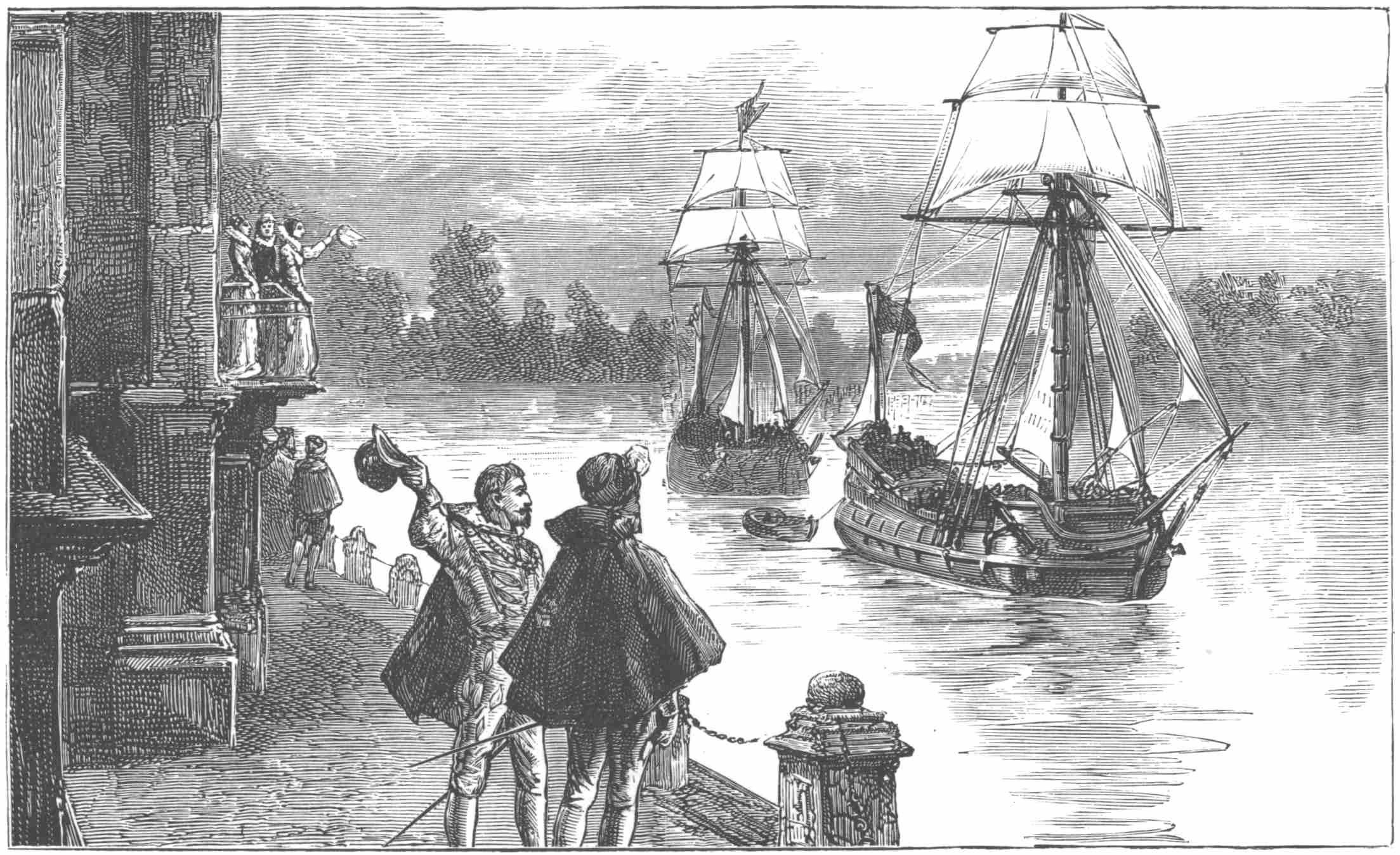

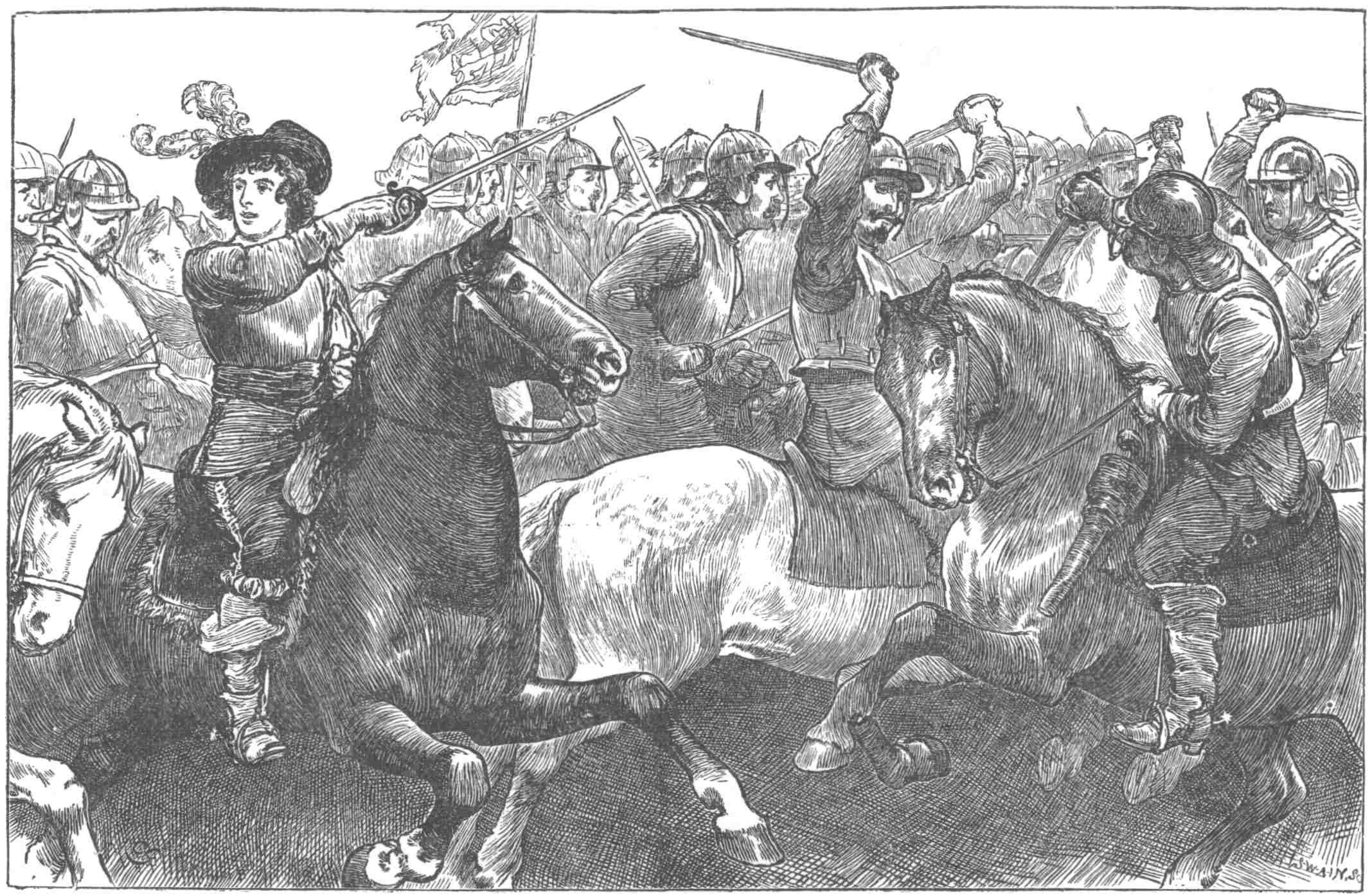

| SIR FRANCIS DRAKE CALLING ON HIS COMRADES TO PLAY OUT THE MATCH, AND TO BEAT THE SPANIARDS TOO, | Frontispiece |

| SIR JOHN HAWKINS, | 3 |

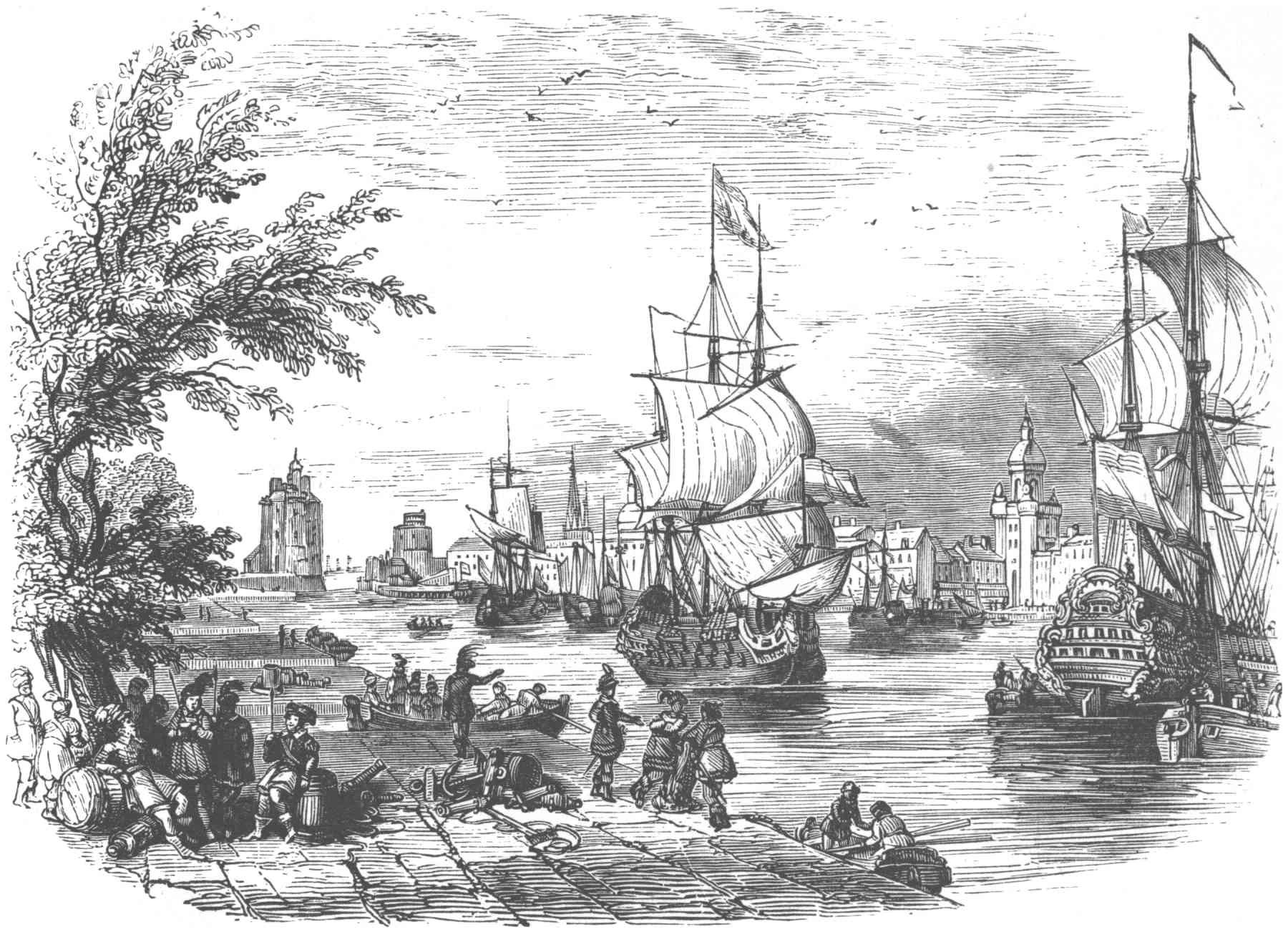

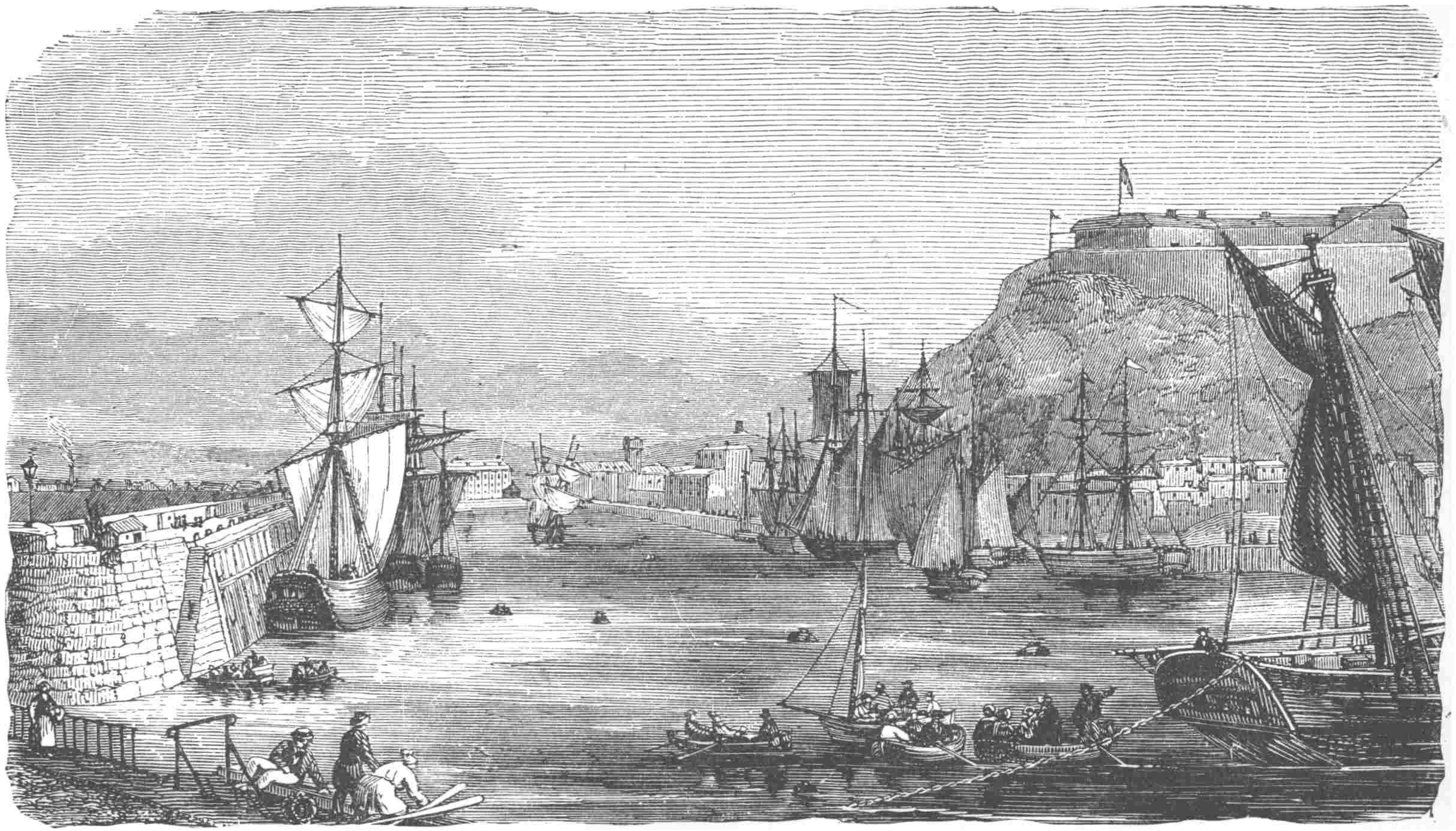

| ROCHELLE, | 11 |

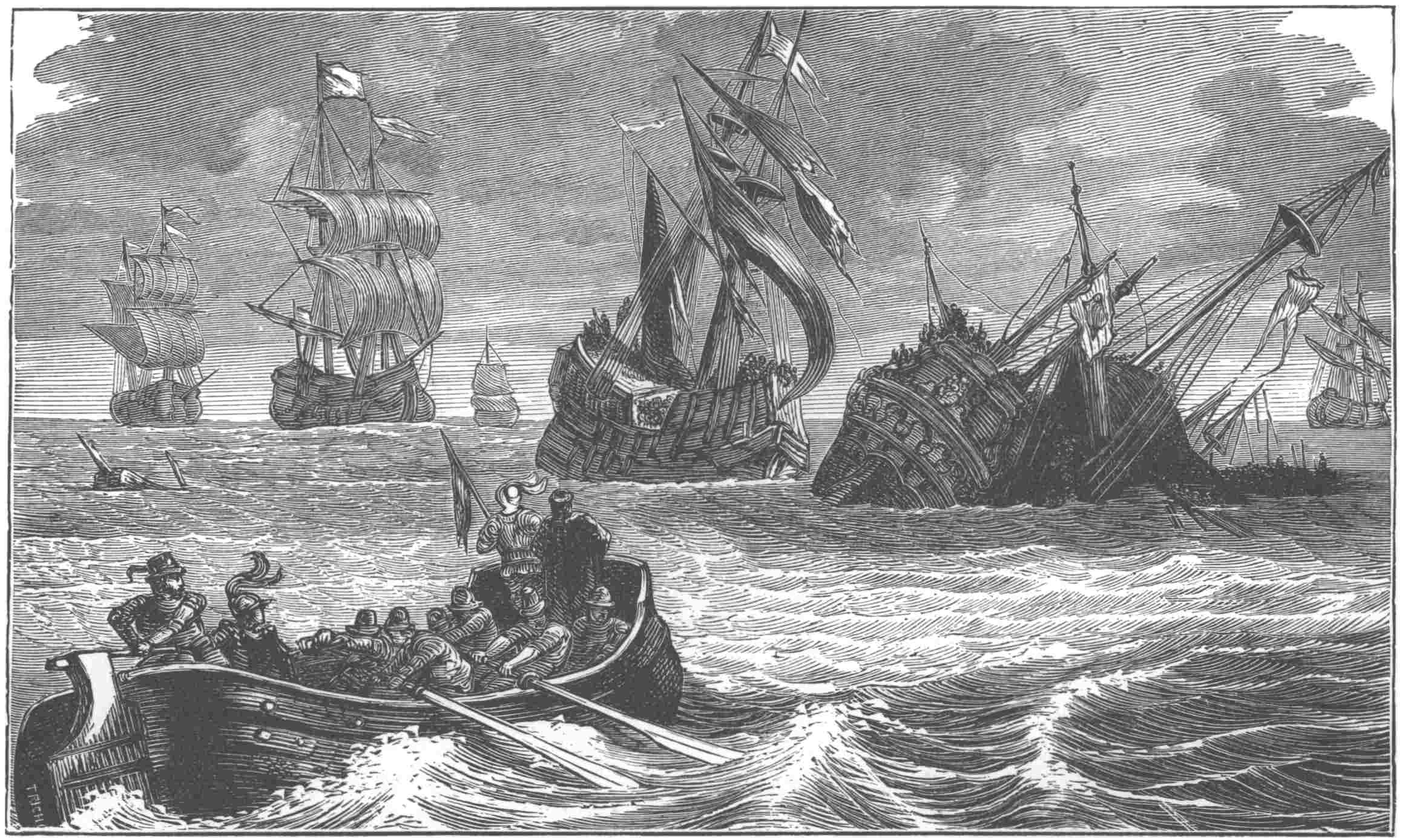

| SIR JOHN HAWKINS PURSUING THE SHIPS OF THE ARMADA, | 19 |

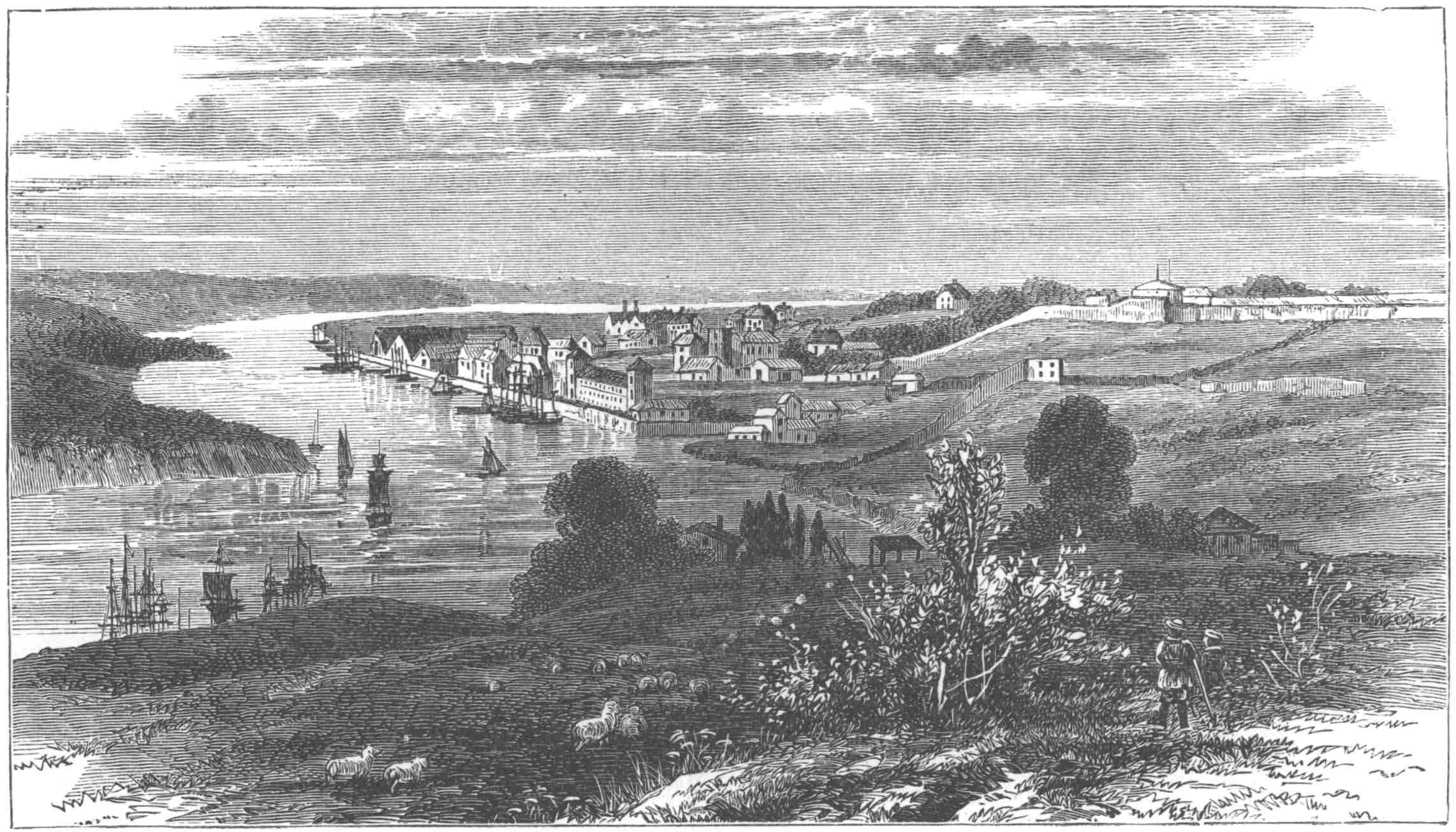

| CHATHAM EARLY IN THE 17TH CENTURY, | 25 |

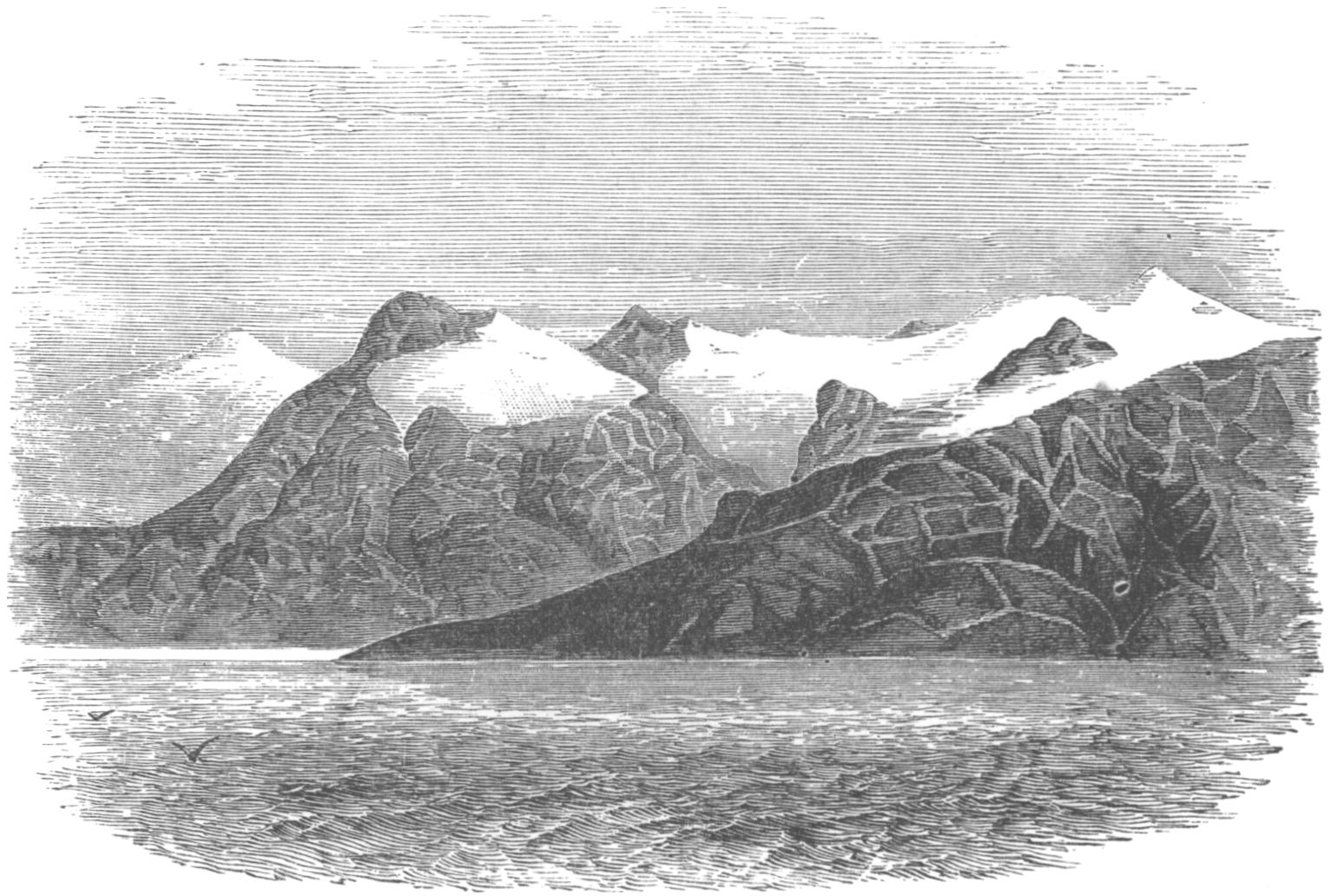

| MOUNTAINS AND GLACIERS IN THE STRAITS OF MAGELLAN, | 33 |

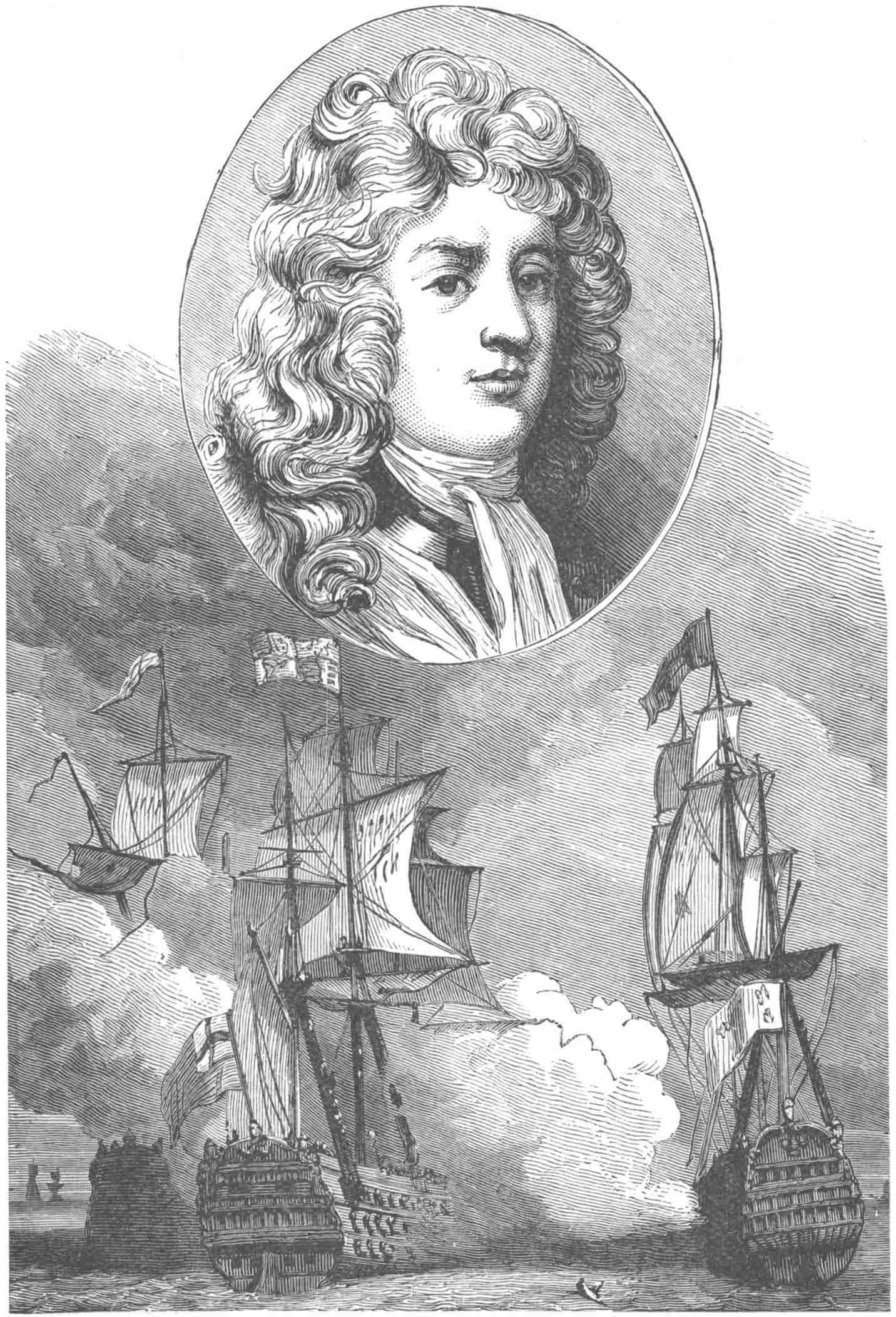

| EARL OF EFFINGHAM, | 38 |

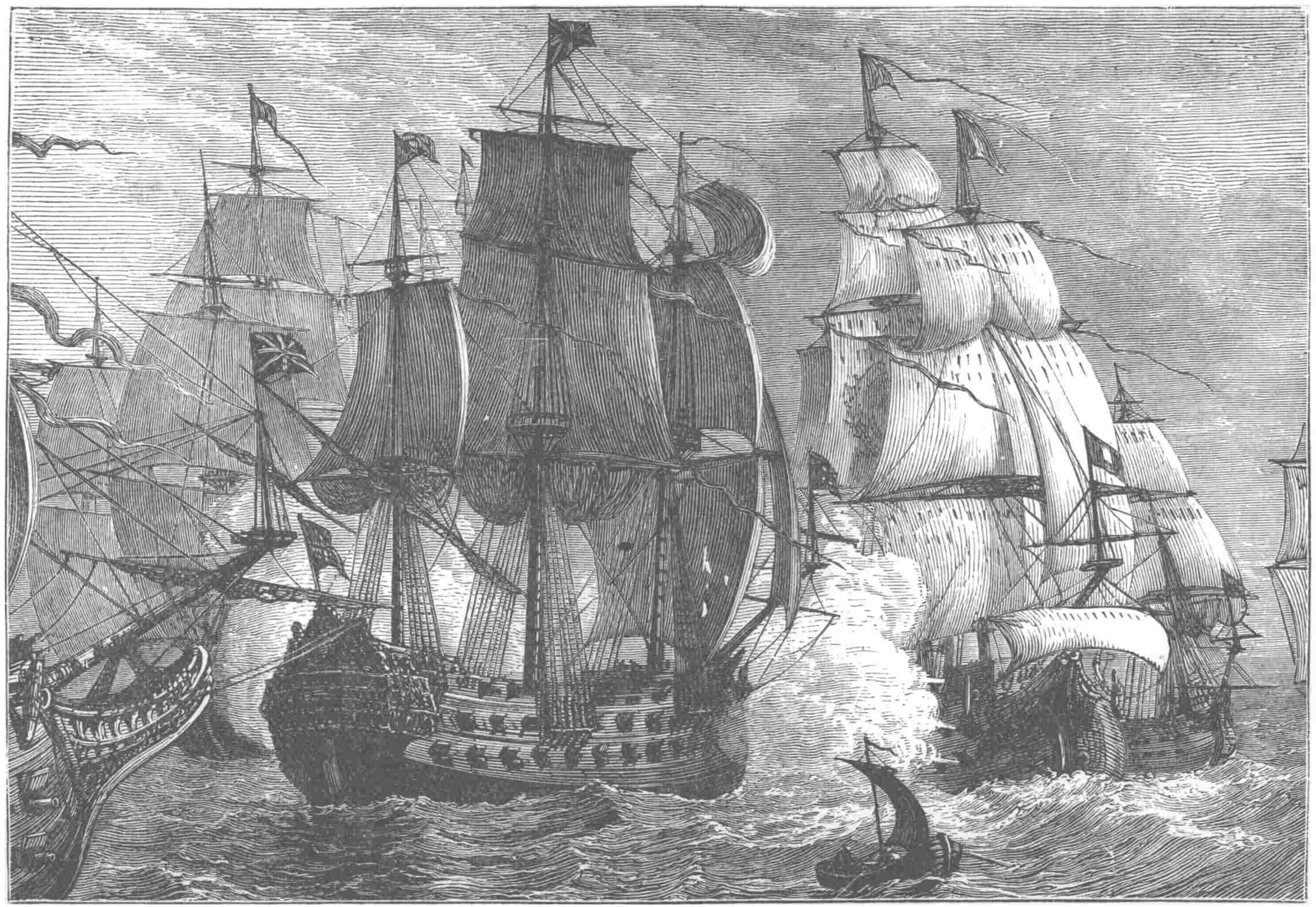

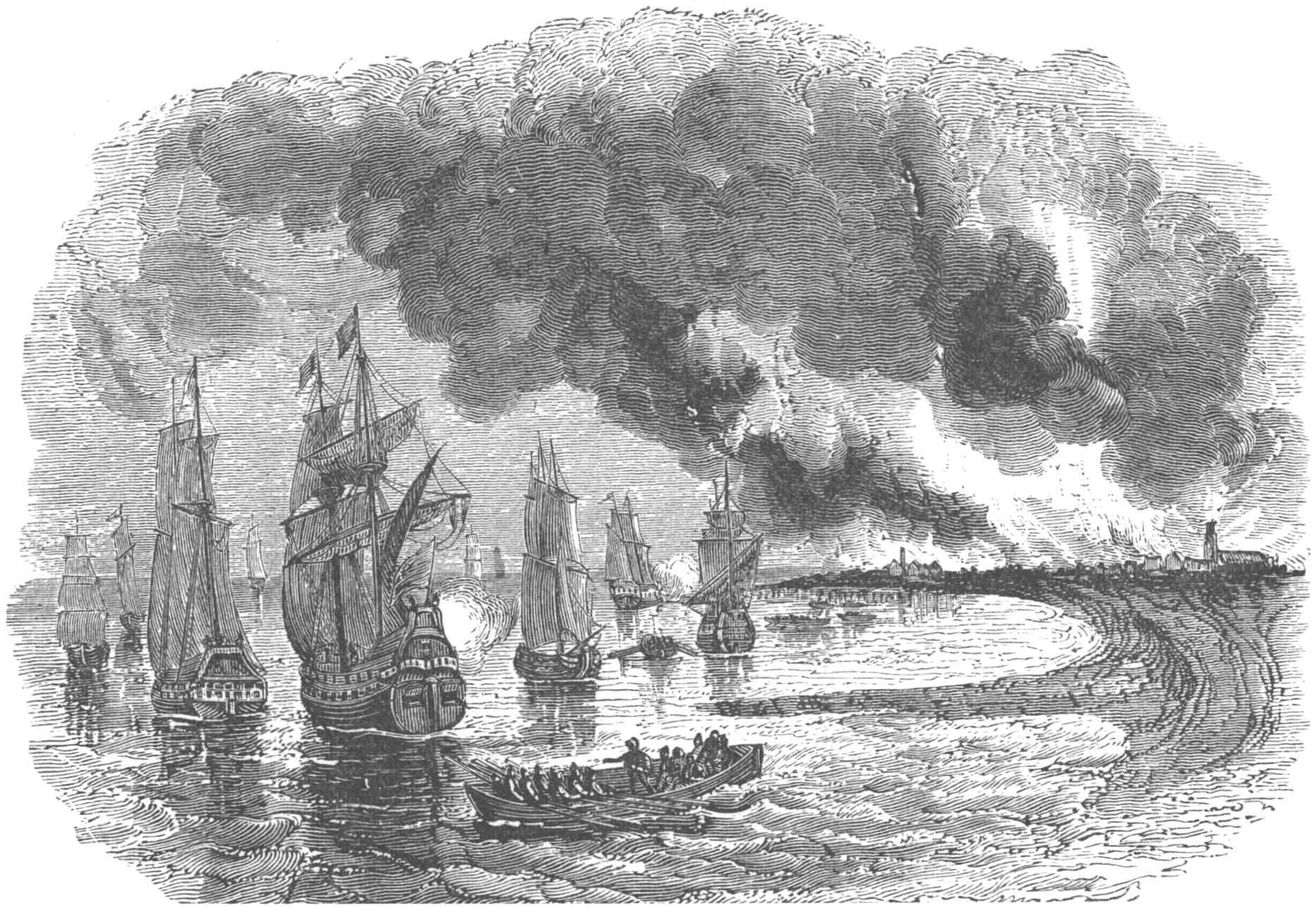

| LORD HOWARD DEFEATING A SPANISH FLEET, | 43 |

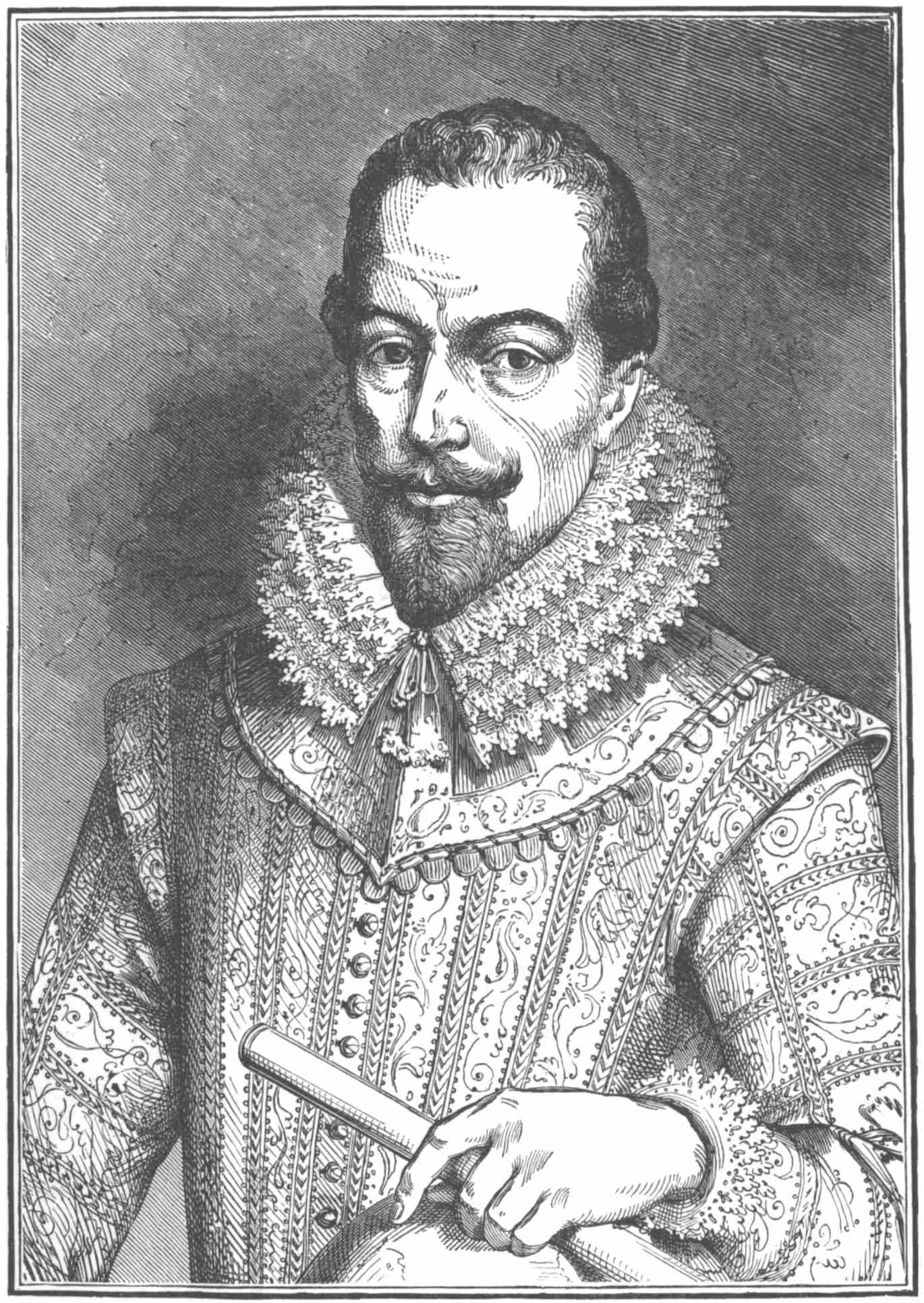

| SIR MARTIN FROBISHER, | 49 |

| SIR MARTIN FROBISHER PASSING GREENWICH, | 53 |

| THOMAS CAVENDISH, | 59 |

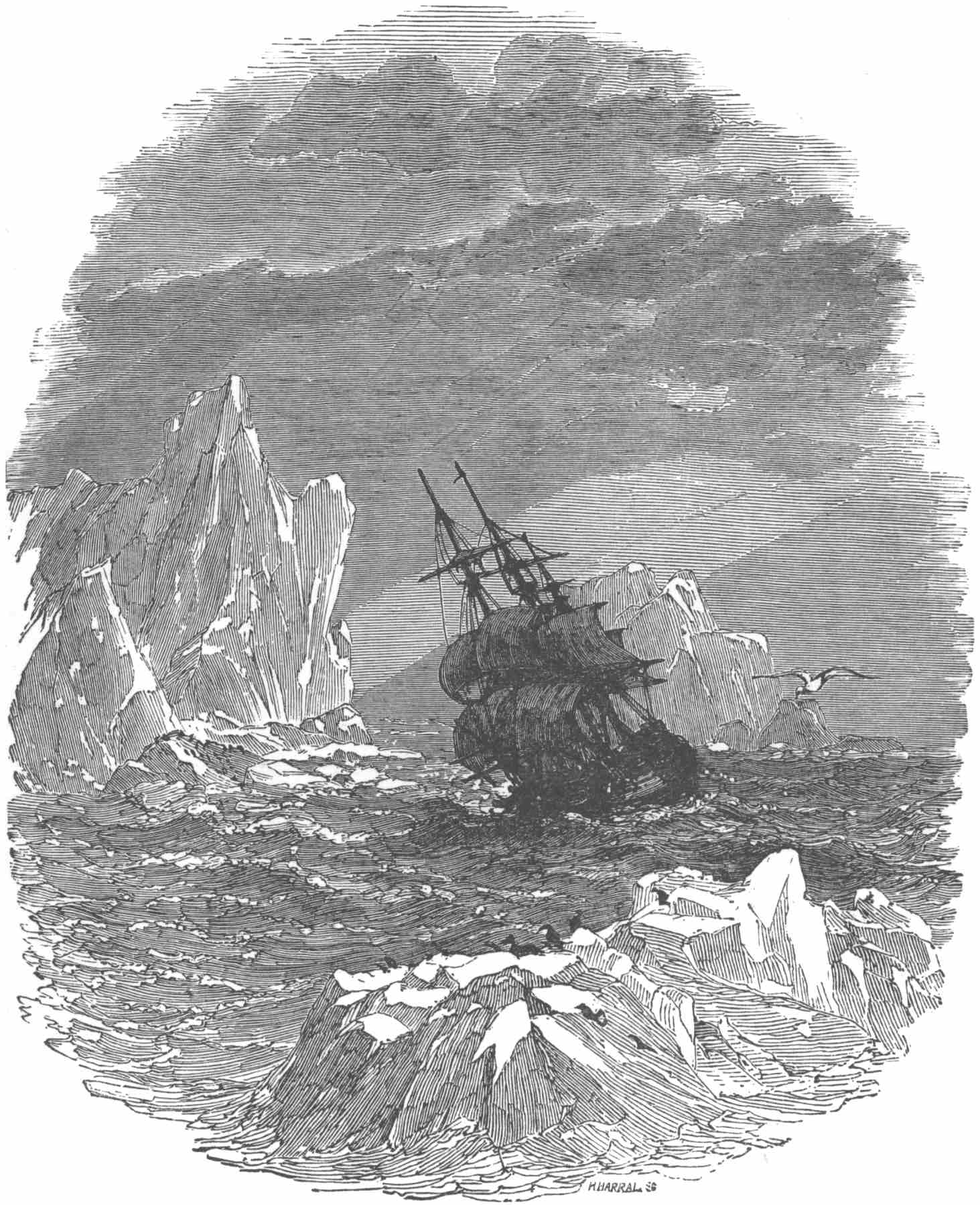

| PERILOUS POSITION IN THE STRAITS OF MAGELLAN, | 67 |

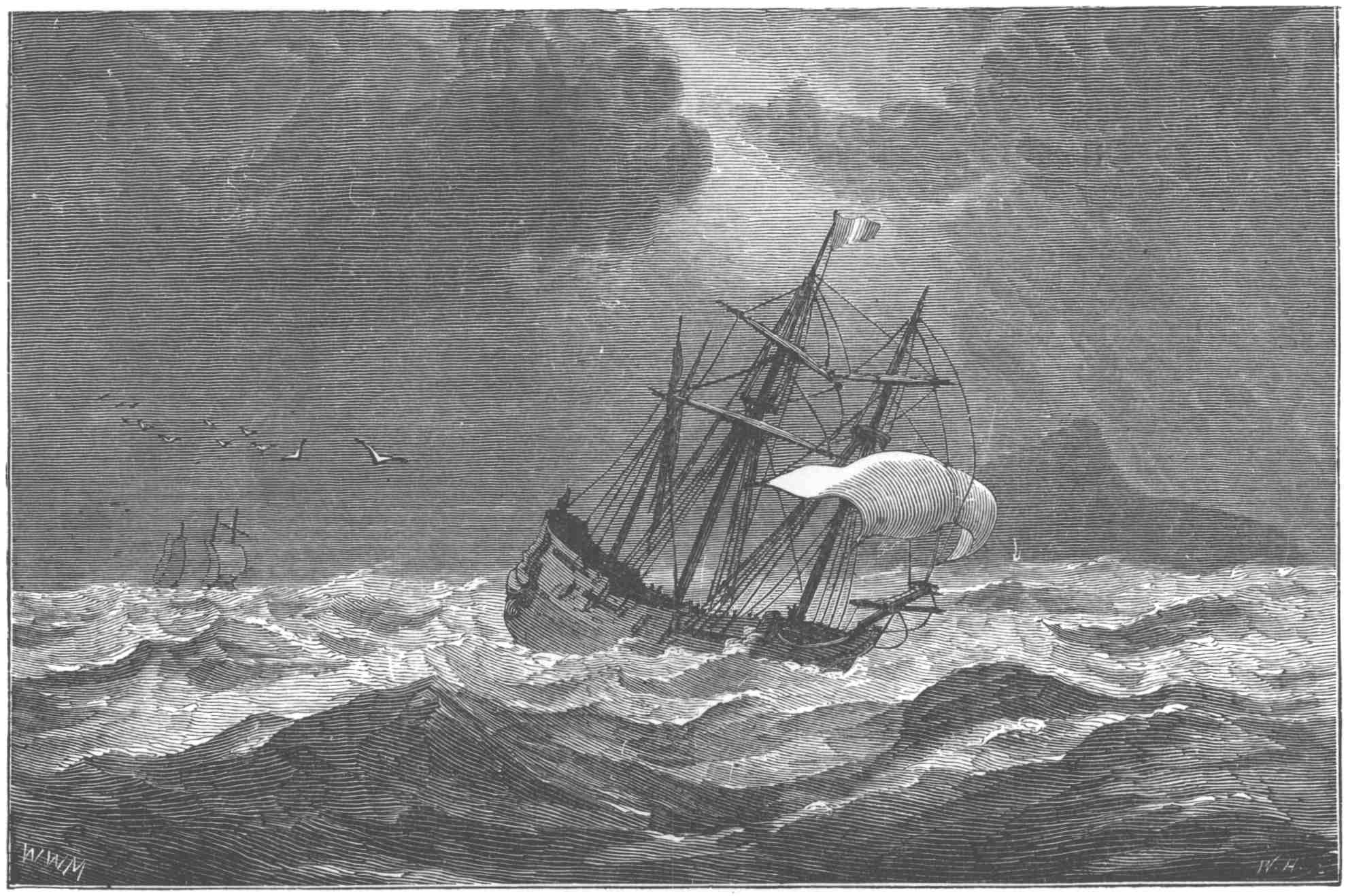

| ROUNDING THE CAPE DE BUENA ESPERANÇA, | 75 |

| SIR WALTER RALEIGH, | 85 |

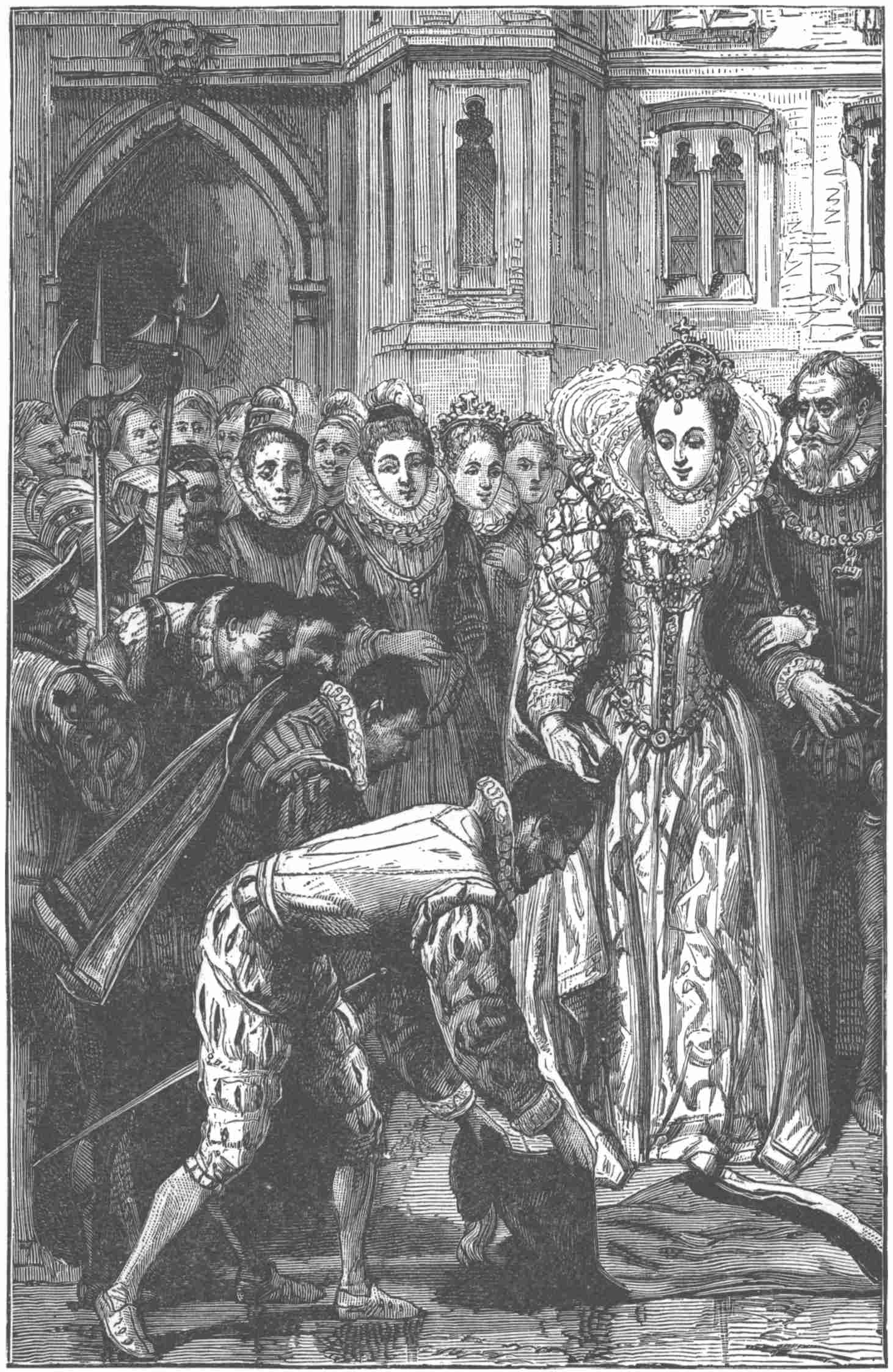

| RALEIGH SPREADING OUT HIS CLOAK TO PROTECT THE QUEEN’S FEET FROM THE MUD, | 93 |

| EDMUND SPENSER, AUTHOR OF THE “FAERIE QUEENE,” | 103 |

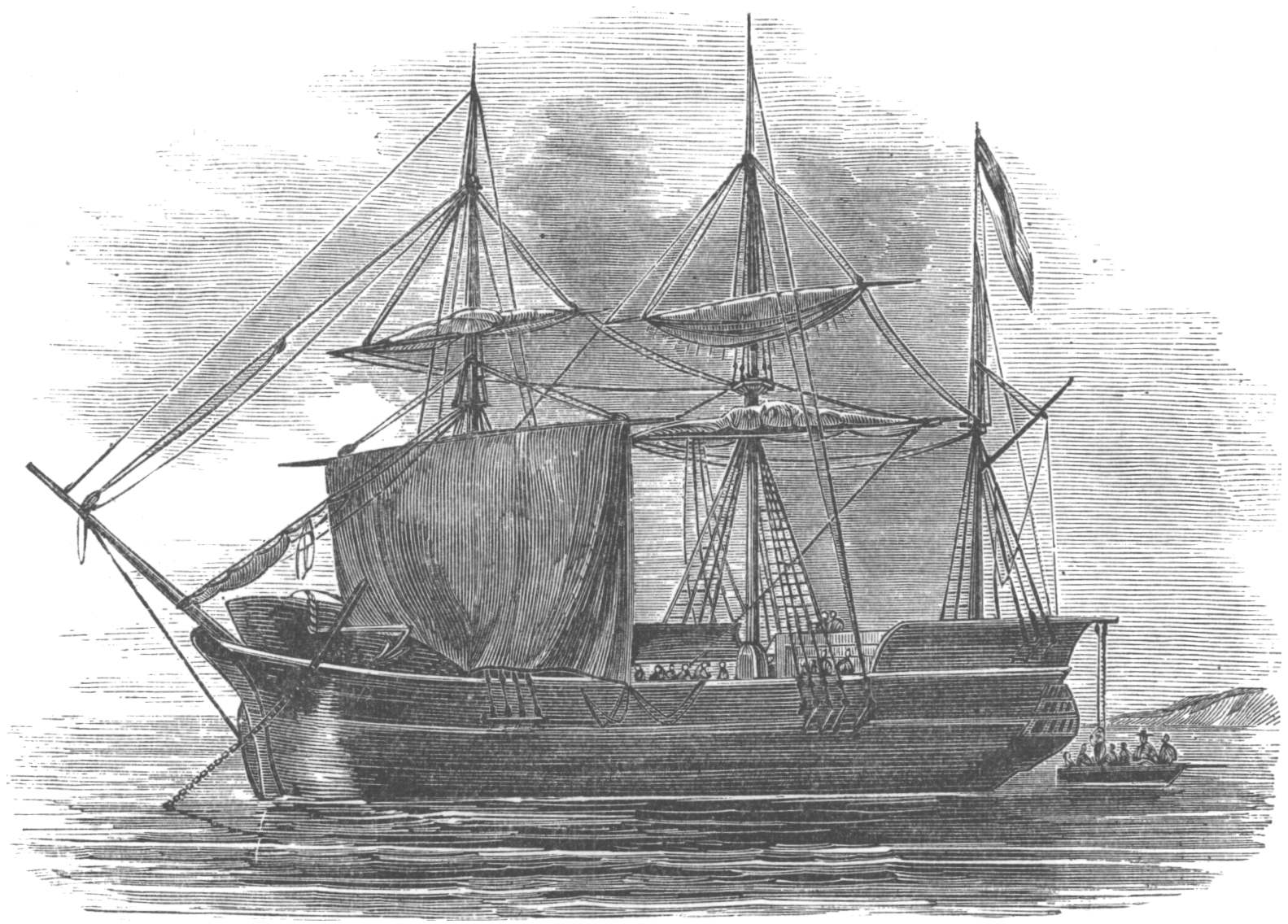

| THE MADRE DE DIOS, | 111 |

| RALEIGH ON THE ORINOCO RIVER, | 121 |

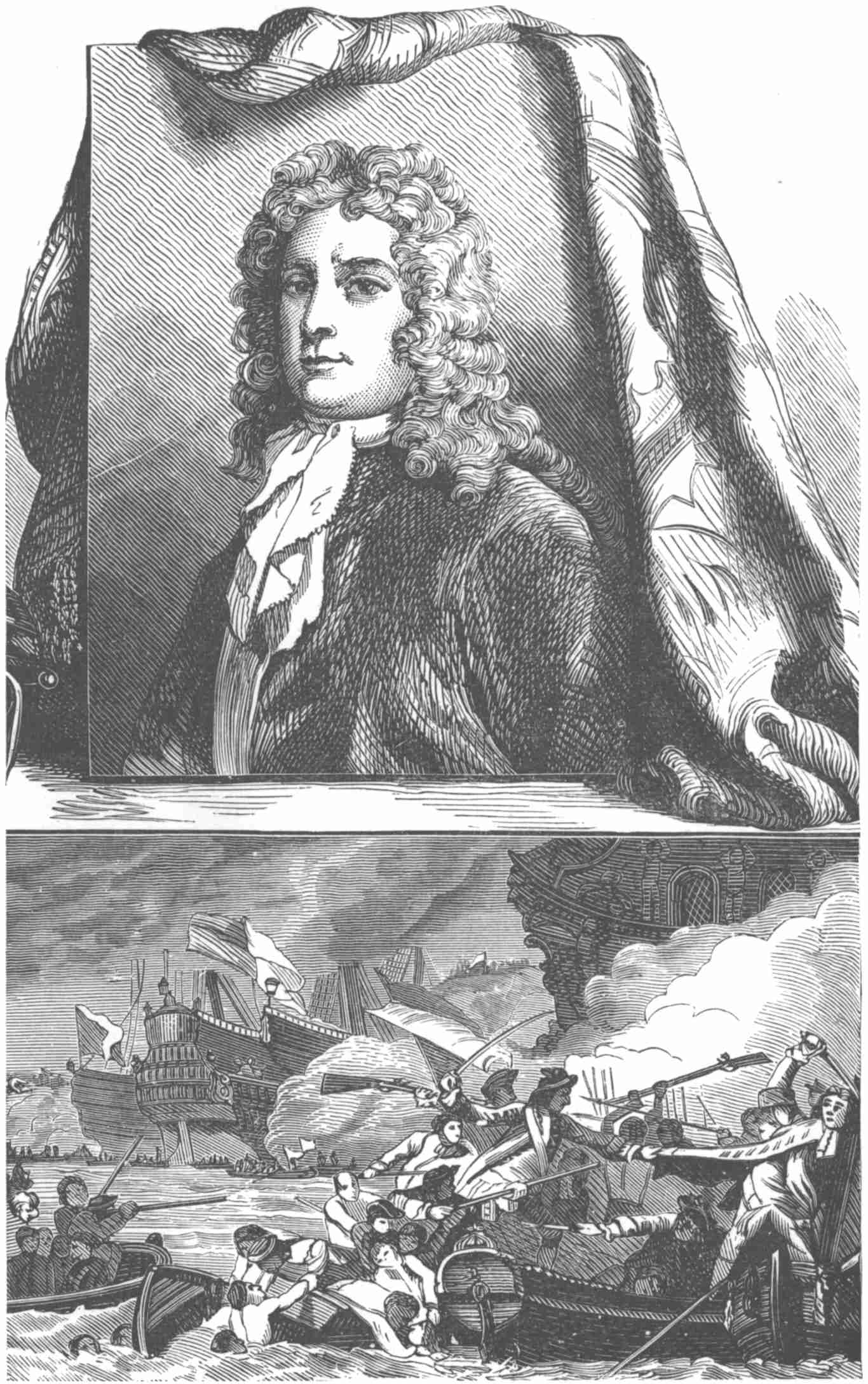

| RALEIGH AS SAILOR, SCHOLAR, POET, | 131 |

| ENGLISH FLEET BEFORE CADIZ, | 139 |

| ST. HELIERS, JERSEY, | 149 |

| SIR WALTER RALEIGH CONFINED IN THE TOWER, | 157 |

| LORD FRANCIS BACON, | 167xiv |

| THE MAYFLOWER, | 175 |

| OLIVER CROMWELL, | 183 |

| ADMIRAL BLAKE, | 193 |

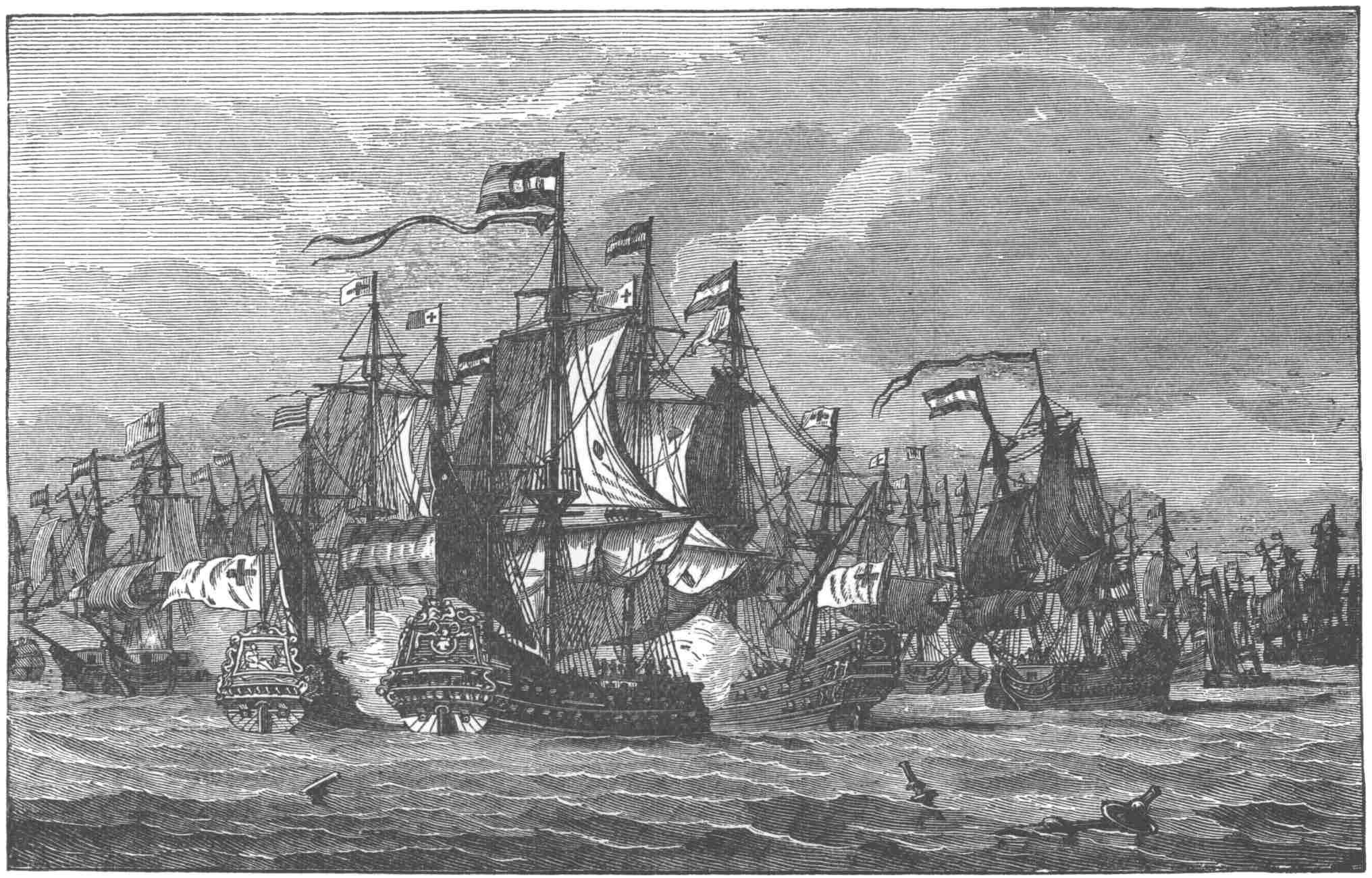

| BATTLE BETWEEN BLAKE AND VAN TROMP, | 203 |

| ADMIRAL VAN TROMP, | 213 |

| THE DEATH OF ADMIRAL BLAKE, | 225 |

| GENERAL MONK, | 233 |

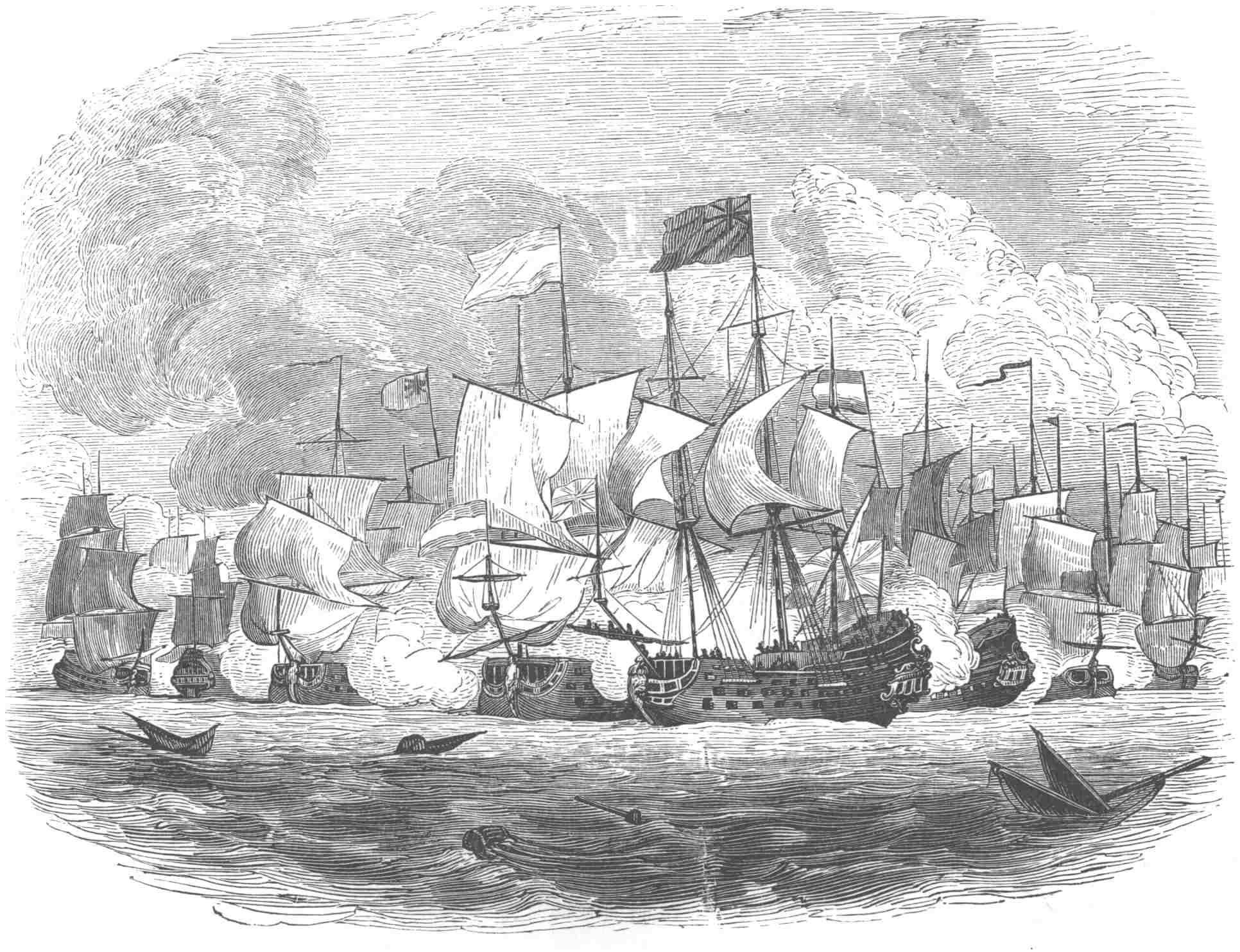

| DEFEAT OF THE DUTCH FLEET BY MONK, | 241 |

| SEA FIGHT WITH THE DUTCH, | 249 |

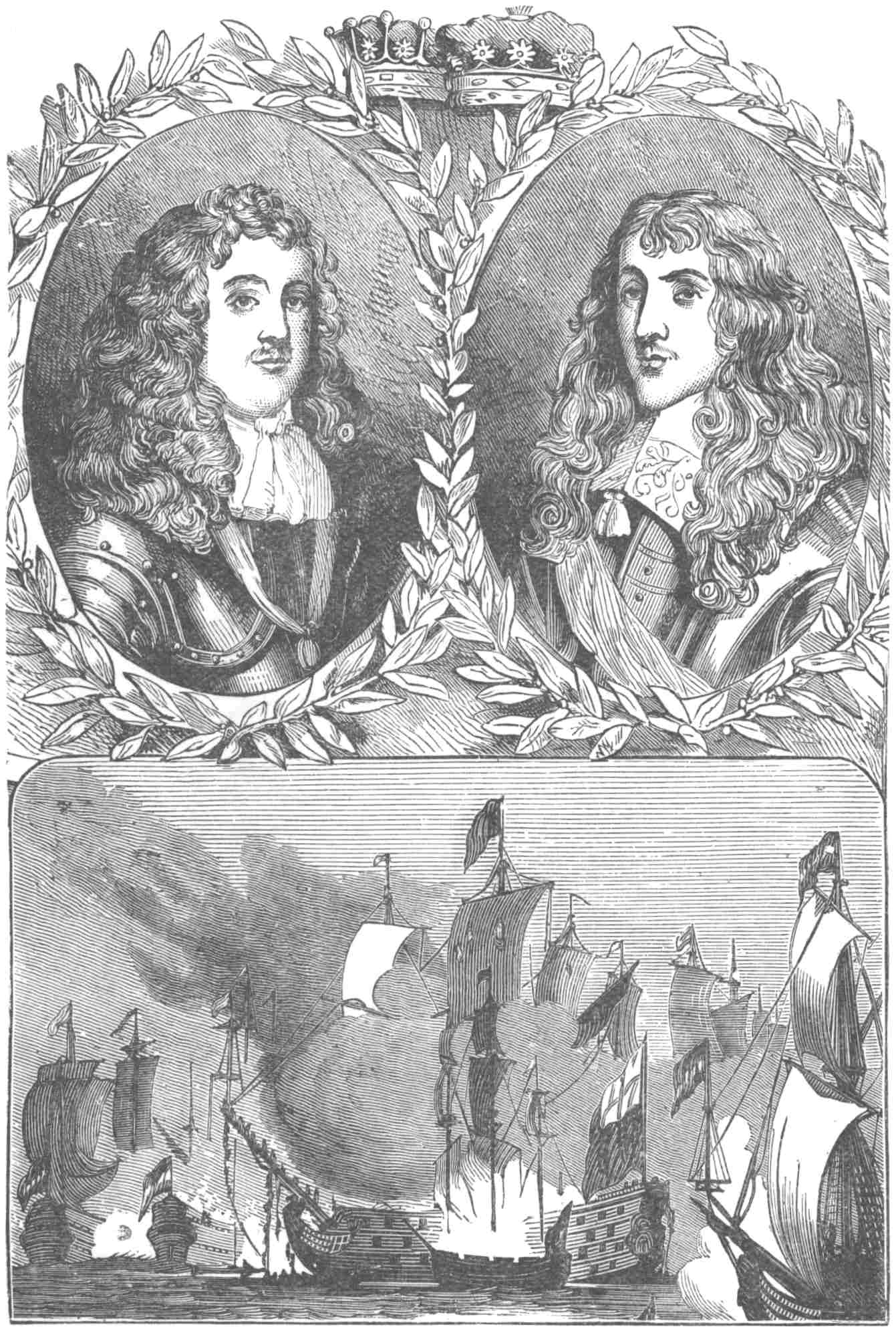

| EARL OF SANDWICH, DUKE OF YORK—BATTLE OF SOUTHWOLD OR SOLE BAY, | 257 |

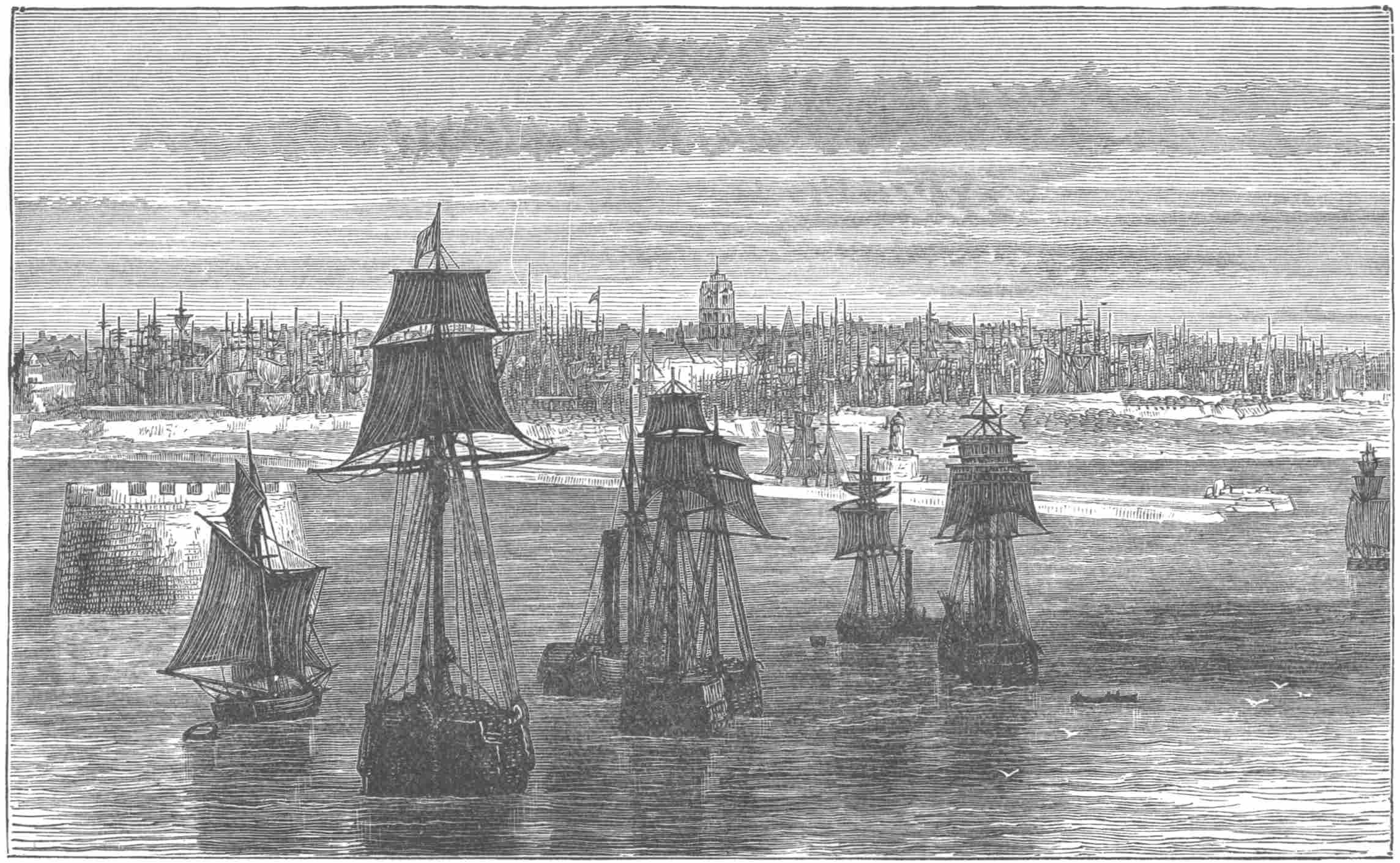

| DUNKIRK, | 265 |

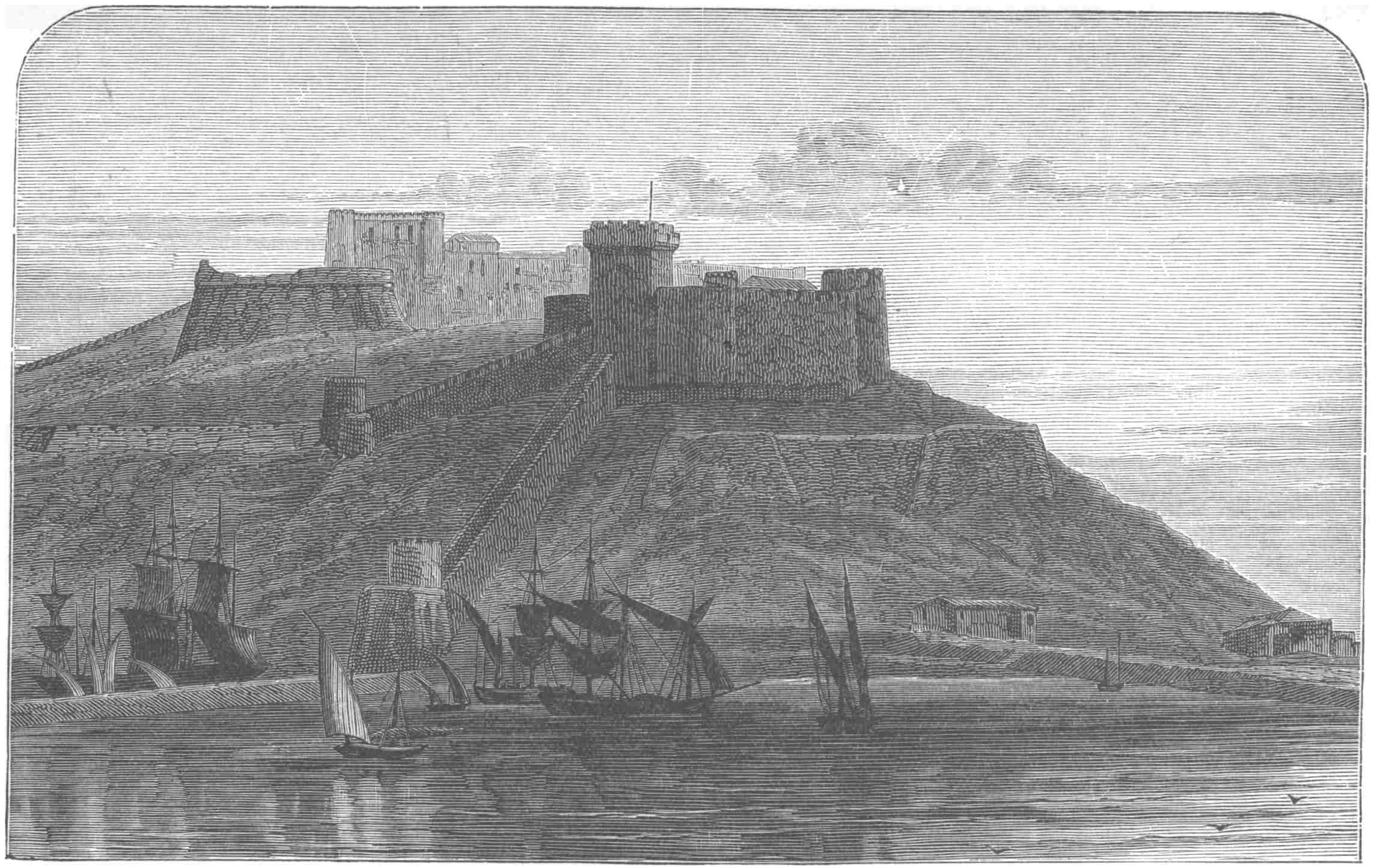

| CASTLE OF TANGIERS, | 273 |

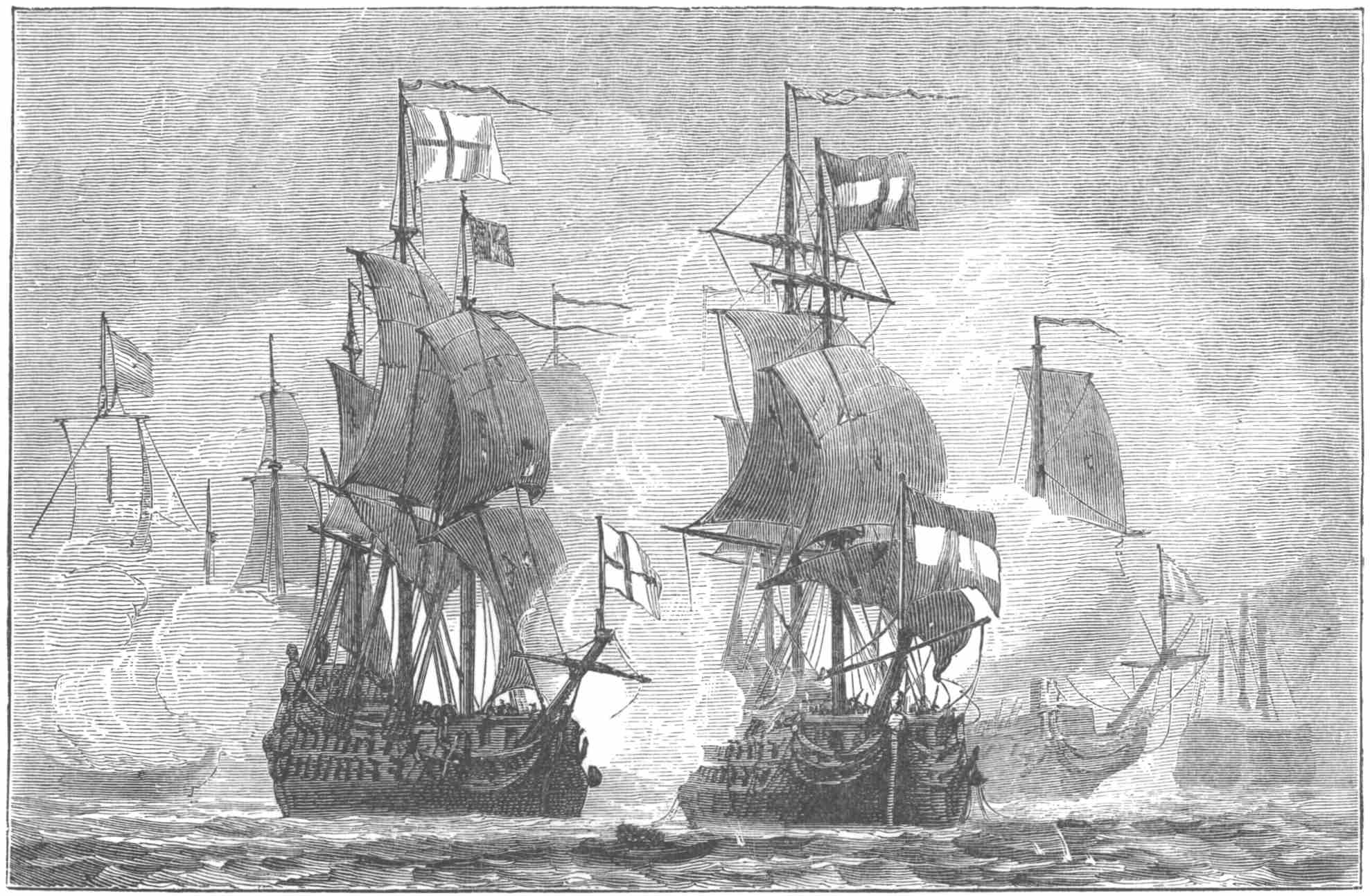

| ACTION BETWEEN THE EARL OF SANDWICH AND ADMIRAL DE RUYTER, | 283 |

| PRINCE RUPERT AT EDGEHILL, | 293 |

| DEFEAT OF THE DUTCH OFF LOWESTOFT, | 301 |

| ADRIAN DE RUYTER, | 309 |

| THE DUTCH FLEET CAPTURES SHEERNESS, | 319 |

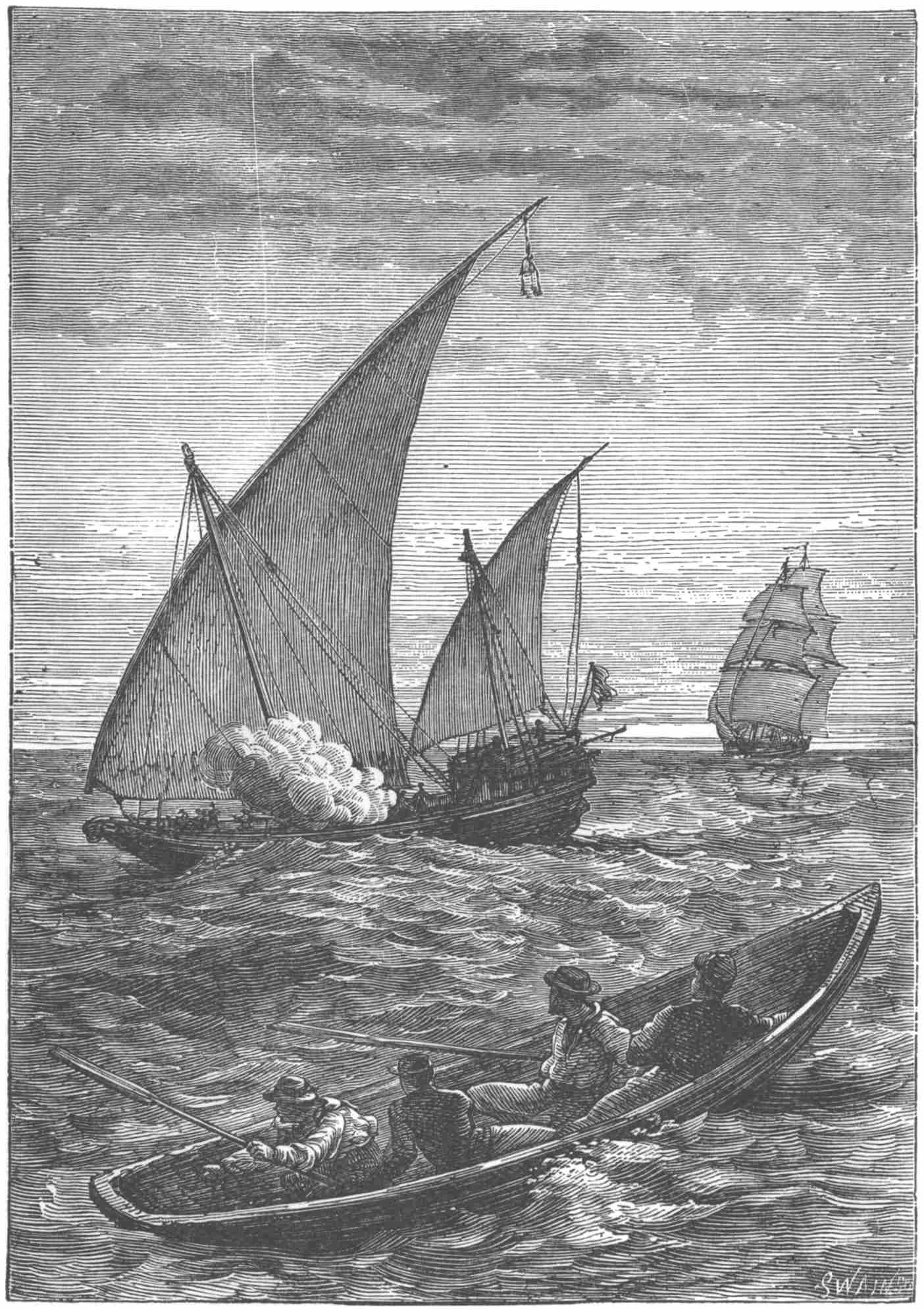

| ATTACKING A PIRATE OFF ALGIERS, | 329 |

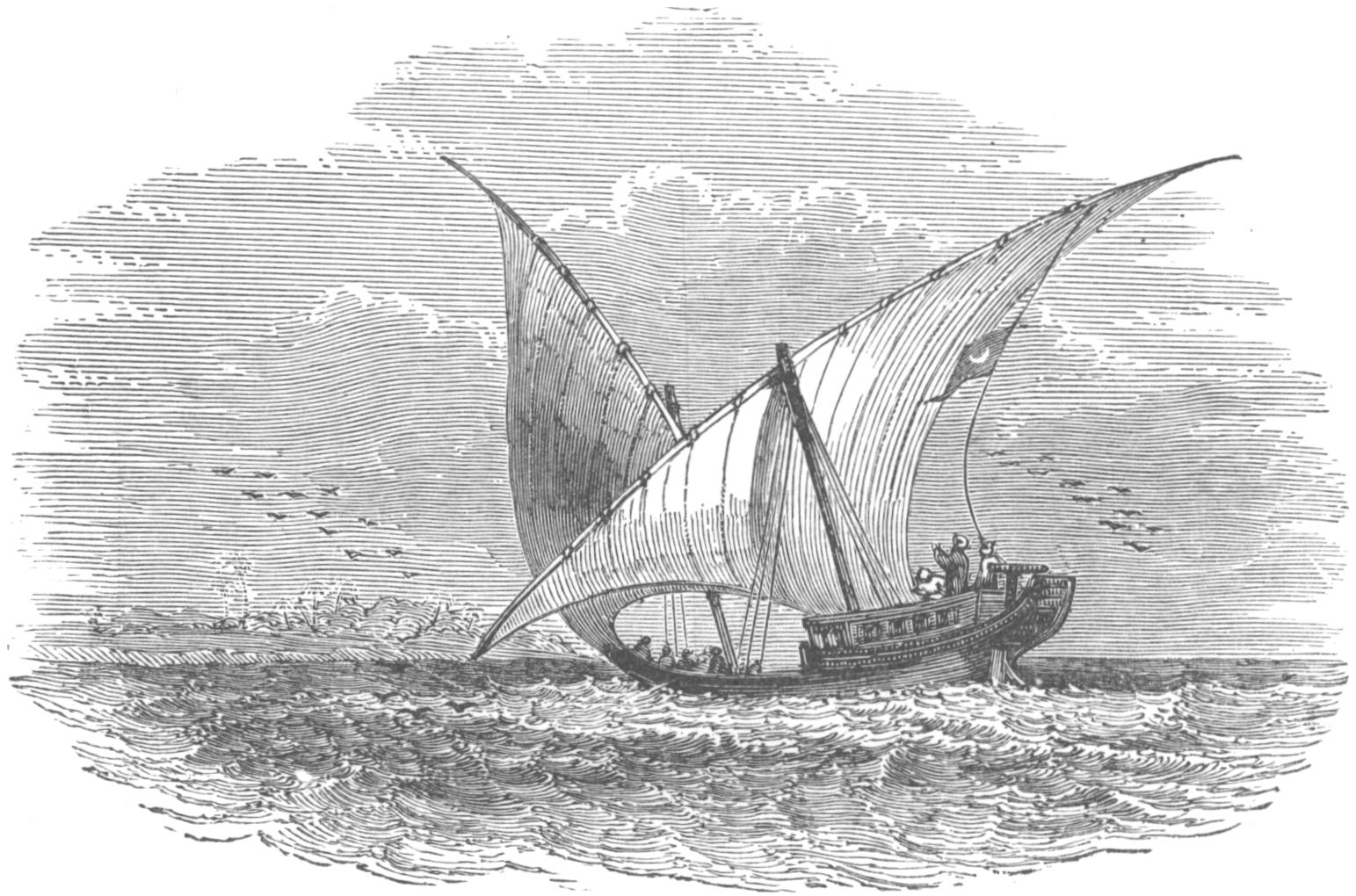

| AN ALGERINE CORSAIR, | 339 |

| ADMIRAL BENBOW, | 351 |

| SIR CLOUDESLEY SHOVEL, | 361 |

| CARRICKFERGUS CASTLE, | 369 |

1

The proclivities of parents are not uniformly manifested in their children, and the rule of “Like father, like son” has its exceptions. The three generations of the Hawkins’ family, who distinguished themselves as maritime adventurers in the reign of Henry VIII. and Queen Elizabeth, while differing in character, disposition, and attainments at divers points, were in common governed by a ruling passion—love of the sea, and choice of it as a road to fame and fortune.

William Hawkins, Esq., of Tavistock, was a man of2 much property, acquired by inheritance, but chiefly by his good fortune as a successful naval adventurer. He was regarded with great favour by King Henry VIII. About the year 1530 he fitted up a ship of 250 tons burthen, which he named the Paul of Plymouth, and in which he made three voyages to Brazil, touching also at the coast of Guinea to buy or capture human beings,—to make merchandise of them. He was probably the first English adventurer that engaged in this horrible traffic. Old chroniclers coolly record the fact that he traded successfully and most profitably in “slaves, gold, and elephants’ teeth.” Brazil was in those days under a quite different government to that of the enlightened ex-Emperor Dom Pedro, or of the Republic that has recently succeeded him. Its rulers were savage Indian chiefs, with whom Hawkins was signally successful in ingratiating himself. On the occasion of his second visit to the country, so complete was the confidence reposed in him by these native princes, that one of them consented to return with him to England, Hawkins leaving Martin Cockram of Plymouth, one of his crew, as a hostage for the safe return of the prince. The personal adornments of this aboriginal grandee were of a remarkable character. According to Hakluyt’s account, “In his cheeks were holes, made according to the savage manner, and therein small bones were planted, standing an inch out from the surface, which in his country was looked on as evidence5 of great bravery. He had another hole in his lower lip, wherein was set a precious stone about the bigness of a pea. All his apparel, behaviour, and gestures were very strange to the beholders,” as may easily be believed. After remaining in England for about a year, during which time the distinguished foreigner was a repeated visitor at the court of Henry VIII., who was a warm patron of Hawkins, the adventurer embarked to return to Brazil. Unhappily, the Indian prince died on the passage, which naturally occasioned serious apprehensions in Hawkins’ mind. He was sorry for the death of his fellow-voyager, but more concerned on account of poor Cockram, the hostage, whose life, he feared, was imperilled by the death of the savage, for whose safe return he had been left as security. The confiding barbarians, however, disappointed his fears; they accepted, without doubt or hesitation, his account of the circumstances of the chief’s death, and his assurance that all that was possible to skill and care had been done to save his life. The friendly intercourse between Hawkins and the natives continued; they traded freely upon mutually satisfactory terms, and Hawkins returned to England freighted with a valuable cargo. He was greatly enriched by his successive voyages to the West Indies and Brazil, and at a mature age retired from active life, in the enjoyment of the fortune he had amassed by his skill and courage as a seaman, his wisdom and astuteness as a merchant, his enterprise,6 fortitude, perseverance, and other qualities and characteristics that distinguish most men who get on in the world.

John Hawkins, the second son of William Hawkins of Plymouth above referred to, was born at Plymouth about the year 1520. His elementary education was followed up in his early youth by assiduous study of mathematics and navigation. Early in life he made voyages to Spain and Portugal, and to the Canary Islands—the latter being considered a rather formidable undertaking in those days. In his early life he so diligently applied himself to his duties, and acquitted himself so successfully in their discharge, as to achieve a good reputation, and soon after the accession of Queen Elizabeth, an appointment in her navy, as an officer of consideration. It is stated concerning him, that as a young man he had engaging manners, and that at the Canaries, to which he had made several trips, “he had, by his tenderness and humanity, made himself very much beloved,” and had acquired a knowledge of the slave trade, and of the mighty profits which even in those days resulted from the sale of negroes in the West Indies. These glowing accounts of a quick road to riches fired the ambition of the tender and humane adventurer.

In 1562, when he had acquired much experience as a seaman, and was at the best of his manhood’s years, he projected a great slave-trading expedition. His design was to obtain subscriptions from the most eminent7 London traders and other wealthy persons, to provide and equip an adventure squadron. He proposed to proceed first to Guinea for a cargo of slaves, to be procured by barter, purchase, capture, or in any other way,—and the cheaper the better. With his freight of slaves, his design was to proceed to Hispaniola, Porto Rico, and other Spanish islands, and there to sell the slaves for money, or barter them in exchange for sugar, hides, silver, and other produce. He readily obtained, as his partners in this unscrupulous project, Sir William Lodge, Sir William Winter, Mr. Bromson, and his (Hawkins’) father-in-law, Mr. Gunson. The squadron consisted of the Solomon, of 120 tons, Hawkins, commander; the Swallow, of 100 tons, captain, Thomas Hampton; and the Jonas, a bark of 40 tons. The three vessels carried in all one hundred men. The squadron sailed in October 1562, and touched first at Teneriffe, from which they proceeded on to Guinea, where landing, “by money, and where that failed, by the sword,” Hawkins acquired three hundred negroes to be sold as slaves. These he disposed of at enormous profits at Hispaniola and others of the Spanish settlements, and returned to England,—to the enrichment, as the result of his “famous voyage,” of himself and his unscrupulous co-proprietors.

“Nothing succeeds like success.” There was now no difficulty in obtaining abundant support, in money and8 men, for further adventure, on the same lines. Slave-trading was proved to be a paying pursuit, and then as now, those who hasted to be rich were not fastidious, as to the moral aspect and nature of the quickest method. Another expedition was determined upon, and on a larger scale. Hawkins, the successful conductor of the expedition, was highly popular. As eminent engineers have taken in gentlemen apprentices in more modern times, Captain Hawkins was beset with applications to take in gentlemen apprentices to the art and mystery of slave-trade buccaneering. Among the youngsters entrusted to his tutelage were several who afterwards achieved distinction in the Royal Navy, including Mr. John Chester, son of Sir Wm. Chester, afterwards a captain in the navy; Anthony Parkhurst, who became a leading man in Bristol, and turned out an enterprising adventurer; John Sparkes, an able writer on maritime enterprises, who gave a graphic account of Hawkins’ second expedition, which Sparkes had accompanied as an apprentice.

The squadron in the second expedition comprised the Jesus of Lubeck, of 700 tons, a queen’s ship, Hawkins, commander; the Solomon; and two barques, the Tiger and the Swallow. The expedition sailed from Plymouth on the 18th October 1564. The first endeavour of the adventurers was to reach the coast of Guinea, for the nefarious purpose of man-stealing, as before. An9 incident, that occurred on the day after the squadron left Teneriffe, reflects credit on Hawkins in showing his paternal care for the lives of his crew, although he held the lives of Guinea negroes of little account, and in exhibiting also his skill as a seaman. The pinnace of his own ship, with two men in it, was capsized, and the upturned boat, with the two men struggling in the water, was dropped out of sight, before sail could be taken in. Hawkins ordered the jolly-boat to be let down and manned by twenty-four able-bodied seamen, to whose leading man he gave steering directions. After a long and stiff pull, the pinnace, with the two men riding astride on the keel, was sighted, and their rescue effected.

The poor hunted savages sometimes sold their lives and liberties dearly to their Christian captors. In one of his raids upon the coast of Africa in this expedition, the taking of ten negroes cost Hawkins six of his best men killed, and twenty-seven wounded. The Rev. Mr. Hakluyt—affected with obliquity of moral vision it may be—deliberately observes concerning Captain Hawkins and this disaster, that “his countenance remained unclouded, and though he was naturally a man of compassion, he made very light of his loss, that others might not take it to heart.” A very large profit was realised by this expedition, “a full cargo of very rich commodities” having been collected in the trading with Jamaica, Cuba, and other West Indian islands. On the return voyage10 another incident occurred illustrative of Captain Hawkins’ punctilious regard to honesty in other directions than that of negroes—having property rights in their own lives and liberties. When off Newfoundland, which seemed to be rather round circle sailing on their way home, the commander fell in with two French fishing vessels. Hawkins’ squadron had run very short of provisions. They boarded the Frenchmen, and, without leave asked or obtained, helped themselves to as much of their stock of provisions, as they thought would serve for the remainder of the voyage home. To the amazement as much as the satisfaction of the Frenchmen, Hawkins paid honourably for the salt junk and biscuits thus appropriated.

The squadron arrived at Padstow, Cornwall, on the 20th September 1565. The idea of the brotherhood of man had not in that age been formulated, and Hawkins was honoured for his achievements, in establishing a new and lucrative branch of trade. Heraldic honours were conferred upon him by Clarencieux, king at arms, who granted him, as an appropriate crest, “a demi-moor bound with a cord or chain.”

In 1567 Hawkins sailed in charge of an expedition for the relief of the French Protestants at Rochelle. This object was satisfactorily effected, and he proceeded to prepare for a third voyage to the West Indies. Before this expedition sailed, Hawkins, while off Cativater waiting 13the queen’s orders, had an opportunity, of which he made12 prompt and spirited use, for vindicating the honours of the queen’s flag. A Spanish fleet of fifty sail, bound for Flanders, passed comparatively near to the coast, and in sight of Hawkins’ squadron, without saluting by lowering their top-sails, and taking in their flags. Hawkins ordered a shot to be fired across the bows of the leading ship. No notice was taken of this, whereupon he ordered another to be fired, that would make its mark. The second shot went through the hull of the admiral, whereupon the Spaniards struck sail and came to an anchor. The Spanish general sent a messenger to demand the meaning of this hostile demonstration. Hawkins would not accept the message, or even permit the messenger to come on board. On the Spanish general sending again, Hawkins sent him the explanation that he had not paid the reverence due to the queen, that his coming in force without doing so was suspicious; and he concluded his reply by ordering the Spanish general to sheer off, or he would be treated as an enemy. On coming together, and further parley, Hawkins and the Spaniard arrived at an amicable understanding, and concluded their conferences in reconciliation feasts and convivialities, on board and on shore.

The new expedition sailed on the 2nd October 1567. The squadron consisted of the Jesus of Lubeck, the Minion, and four other ships. As before, the adventurers made first for Guinea, the favourite gathering-ground for the14 inhuman traffic, and collected there a crowd of five hundred negroes, the hapless victims of their cupidity. The greater number of these they disposed of at splendid prices, in money or produce, in Spanish America. Touching at Rio Del Hacha, to Hawkins’ indignant surprise, the governor, believing it to be within his right, refused to trade with him. Such arrogance was not to be submitted to, and Hawkins landed a storming party, who assaulted and took the town, which, if it did not exactly make things pleasant, compelled submission, and, for the invading adventurers, a profitable trade. Having made the most he could of Hacha, Hawkins next proceeded to Carthagena, where he disposed, at good prices, of the remainder of the five hundred slaves.

The adventurers were now (September 1568) in good condition for returning home with riches, leaving honours out of consideration, but the time had passed for their having their own will and way. Plain sailing in smooth seas was over with them; storm and trouble, and struggle for dear life, awaited them. Shortly after leaving Carthagena the squadron was overtaken by violent storms, and for refuge they made, as well as they could, for St. John de Ulloa, in the Gulf of Mexico. While in the harbour, the Spanish fleet came up in force, and was about to enter. Hawkins was in an awkward position. He liked not the Spaniards, and would fain have given their vastly superior force a wide berth. He tried what15 diplomacy would do. He sent a message to the viceroy that the English were there only for provisions, for which they would pay, and he asked the good offices of the viceroy, for the preservation of an honourable peace. The terms proposed by Hawkins were assented to, and hostages for the observance of the conditions were exchanged. But he was dealing with deceivers. On Thursday, September 23rd, he noticed great activity in the carrying of ammunition to the Spanish ships, and that a great many men were joining the ships from the shore. He sent to the viceroy demanding the meaning of all this, and had fair promises sent back in return. Again Hawkins sent Robert Barret, master of the Jesus, who knew the Spanish language, to demand whether it was not true that a large number of men were concealed in a 900-ton ship that lay next to the Minion, and why it was that the guns of the Spanish fleet were all pointed at the English ships. The viceroy answered this demand by ordering Barret into irons, and directing the trumpet to sound a charge. At this time Hawkins was at dinner in his cabin with a treacherous guest, Don Augustine de Villa Nueva, who had accepted the rôle of Hawkins’ assassin. John Chamberlain, of Hawkins’ bodyguard, detected the dagger up the traitor’s sleeve, denounced him, and had him cared for. Going on deck, Hawkins found the English attacked on all sides; an overpowering crowd of enemies from the great Spanish ship alongside was16 pouring into the Minion. With a loud voice he shouted, “God and St. George! Fall upon those traitors, and rescue the Minion!” His men eagerly answered the call, leaped out of the Jesus into the Minion, and made short work with the enemy, slaughtering them wholesale, and driving out the remnant. Having cleared the Minion of the enemy, they did equally effective service with the ship’s guns; they sent a shot into the Spanish vice-admiral’s ship that, probably from piercing the powder-room, blew up the ship and three hundred men with it. On the other hand, all the Englishmen who happened to be on shore were cut off, except three who escaped by swimming from shore to their ships. The English were overmatched to an enormous extent, by the fleet and the attack from the shore. The Spaniards took the Swallow, and burnt the Angel. The Jesus had the fore-mast cut down by a shot, and the main-mast shattered. The Spaniards set fire to two of their own ships, with which they bore down upon the Jesus, with the desire of setting it on fire. In dire extremity, and to avert the calamity of having their ship burnt, the crew, without orders, cut the cables and put to sea; they returned, however, to take Hawkins on board. The English ships suffered greatly by the shots from the shore, as well as from the fleet, but inflicted, considering the disparity in strength of the combatants, much greater damage than they sustained. The ships of the Spanish admiral and vice-admiral were17 both disabled,—the latter destroyed; four other Spanish ships were sunk or burnt. Of the Spanish fighting men,—fifteen hundred in number at the commencement of the battle,—five hundred and forty, or more than a third, were killed or wounded. The Jesus and the Minion fought themselves clear of the Spaniards, but the former was so much damaged as to be unmanageable, and the Minion, with Hawkins and most of his men on board, and the Judith, of 50 tons, were the only ships that escaped. The sanguinary action lasted from noon until evening. The wreckage to such an extent of Hawkins’ fleet involved, of course, a heavy deduction from his fortune.

After leaving St. John de Ulloa, the adventurers suffered great privations. Their design to replenish their failing stock of provisions had been frustrated, and Hawkins was now threatened with mutiny among the crew, because of the famine that seemed imminent, and which he was powerless to avert. They entered a creek in the Bay of Mexico, at the mouth of the river Tampico. A number of the men demanded to be left on shore, declaring that they would rather be on shore to eat dogs and cats, parrots, rats, and monkeys, than remain on board to starve to death. “Four score and sixteen” men thus elected to be left on shore. Job Hortop, one of the crew, who left a narrative of the voyage, states that Hawkins counselled the men he was leaving to “serve God and love one another, and courteously bade them a18 sorrowful farewell.” On the return voyage, Hawkins and the remnant with him, sustained great hardships and privations. At Vigo, where he touched, he met with some English ships, from which he was able to obtain, by arrangement, twelve stout seamen, to assist his reduced and enfeebled crew, in the working of his ships for the remainder of the homeward voyage. He sailed from Vigo on the 20th January 1569, and reached Mount’s Bay, Cornwall, on the 25th of the same month. Thus ended his third eventful and disastrous expedition to El Dorado.

The poor fellows, left on shore in Mexico, entered upon a terrible campaign of danger and suffering. The first party of Indians that the castaways fell in with, slaughtered a number of them, but on discovering that they were not Spaniards, whom the Indians hated inveterately, spared the remainder, and directed them to the port of Tampico. It is recorded of two of their number, Richard Brown and Richard Twide, that they performed the wonderful feat, under such cruel disadvantages and difficulties, of marching across the North American continent from Mexico to Nova Scotia,—from which they were brought home in a French ship. Others of the wanderers fell into the hands of the Spaniards, who sent some of them prisoners to Mexico, and others to Spain, where, by sentence of the Holy Inquisition, some were burnt to death, and others consigned for long terms21 to imprisonment. Miles Philips, one of the crew, reached England, after many perilous adventures and hair-breadth ’scapes, in 1582. Job Hortop and John Bone were sentenced to imprisonment for ten years. Hortop, after twenty-three years’ absence from England, spent in Hawkins’ fleet, and in wanderings, imprisonment, and divers perils, reached home in 1590, and wrote an interesting account of the voyage, and of his personal adventures.

In his last expedition Hawkins had returned with impaired fortune, but without dishonour. He had, indeed, added to the lustre of England, and to his personal renown, by the skill and valour he had displayed in the affair of St. John de Ulloa,—in which the glory was his, and infamy attached to the treacherous Spaniards, whose immense superiority in strength should have enabled them to extinguish their enemy, instead of being beaten by him. In recognition of his valour, Hawkins was granted by Clarencieux, king at arms, further heraldic honours, in an augmentation of his arms; he was also appointed Treasurer to the Navy, an office of great honour and profit.

Hawkins’ next great public service was rendered, as commander of Her Majesty’s ship Victory, in the actions against the Spanish Armada in 1588. The commanders of the English squadrons in the Armada actions and pursuit were the Lord High Admiral, and Sir Francis Drake,22 and Sir John Hawkins, rear-admiral. Sir John was knighted by the Lord High Admiral for his distinguished services; as was also Sir Martin Frobisher. Sir John Hawkins shared largely in the dangers and honours of the actions, and, in the pursuit of the Spaniards, he rendered extraordinarily active and successful service, for which he was particularly commended by Queen Elizabeth.

In 1590 Sir John Hawkins, in conjunction with Sir Martin Frobisher,—each with a squadron of fifty ships,—was sent to harass the Spanish coast, and to intercept and capture, if possible, the Plate fleet. Suspecting this intention, the Spanish king contrived to convey intelligence to India, ordering the fleet to winter there, instead of coming home. Hawkins and Frobisher cruised about for six or seven months, with no more definite result than humiliating Spain, and detracting from its dignity and influence as a naval power.

Sir John Hawkins was next appointed in a joint expedition against Spain with Sir Francis Drake. The design of the expedition, which sailed from Plymouth on the 28th August 1595, was to burn Nombre-de-Dios, and to march thence overland to Panama, and appropriate there the Spanish treasure from Peru. The design proved abortive, partly from tempestuous weather, but partly also from disagreement between the commanders. On the 30th October, at a short distance from Dominica, the Francis, a bark of 35 tons, the sternmost of Sir23 John Hawkins’ fleet,—and a long way in the rear of the others,—was fallen in with by a squadron of five Spanish frigates, and captured. This misfortune, in conjunction with other depressing circumstances, and the hopelessness of the enterprise, so much affected Sir John Hawkins as to cause his death on the 21st November 1595—of a broken heart, it was believed.

The expeditions of Sir John Hawkins to the West Indies, his services in connection with the Spanish Armada, his joint expeditions with Frobisher and Drake, fall far short of filling up the story of his life, or the measure of his usefulness as a public man. Of his home life they tell nothing.

Sir John was twice married, and was three times elected a member of Parliament, twice for Plymouth. He was a wise, liberal, and powerful friend and supporter of the British Navy. He munificently provided, at Chatham, an hospital for poor and distressed sailors. The “Chest” at Chatham was instituted by Sir John Hawkins and Sir Francis Drake,—being a provident fund, formed from voluntary deductions from sailors’ pay, applied to the relief of disabled and indigent comrades. Sir John Hawkins was the author and promoter of many beneficial rules and regulations for the government of the navy. He was an accomplished mathematician, a skilful navigator, a courageous combatant; as Treasurer of the Navy he proved an able administrator; and to these24 qualities he added the enterprising spirit of a merchant prince,—he and his brother William being joint owners at one time of a fleet of thirty good stout ships. It was said of him by a contemporary that he had been graceful in youth, and that he was grave and reverend in advanced life. He was a man of great sagacity, unflinching courage, sound judgment, and cool presence of mind, submissive to authority, courteous to his peers, affable and amiable to his men, by whom he was much beloved. His active life embraced a period of forty-eight years, during which he, for longer or shorter periods, acted as a commander at sea, including twenty-two years, during which he held the office of Treasurer of the Navy.

Richard Hawkins, of the third generation of eminent navigators, and son of Sir John Hawkins, was born at Plymouth about the year 1570. He had a strong predilection for naval service, and when only a lad in his teens had the command of a vessel, and was vice-admiral of a small squadron commanded by his uncle, William Hawkins, Esq., of Plymouth, that was employed in a “private expedition” to the West Indies—really to “pick and steal” what they could from the Spaniards. He had an early opportunity of showing his courage and confidence in his own powers. The captain of one of the ships of the fleet, the Bonner, complained that his ship was not seaworthy, and recommended that his crew and himself should be shifted into a better ship, and that the27 Bonner should be sunk. Young Hawkins protested against the sacrifice of the ship, and offered, if a good crew were allowed him, to carry the Bonner through the cruise, and then home. His success would, of course, have disgraced the captain, who withdrew his recommendation, and remained in his ship,—which justified young Hawkins’ protest by continuing seaworthy for many years.

In 1588 young Hawkins was captain of the queen’s ship Swallow, which suffered most of any in the actions with the Spanish Armada. A fire arrow that had been hid in a sail, burnt a hole in the beak-head of the Swallow. Richard afterwards wrote an able account of the actions, with a judicious criticism and defence of the strategy of the Earl of Nottingham, Lord High Admiral,—in not laying the Spaniards aboard. This Hawkins held would have been a dangerous course, from the greater height of the Spanish ships, and from their having an army on board. By keeping clear, the English ships could also take advantage of wind and tide for manœuvring round the enemy. He held that, by lying alongside of the Spaniards they would have risked defeat, and that the free movement and fighting gave them a better chance of humiliating the enemy.

In 1590 Richard Hawkins commanded the Crane, of 200 tons, in the expedition of his father and Sir Martin Frobisher against Spain. The commander of the Crane did excellent service in the pursuit of the Spanish28 squadron employed in carrying relief to the forces in Brittany; and afterwards he so harassed the Spaniards at the Azores, as to incite the merchants there to curse the Spanish ministers who had brought about (or permitted) a war with such a powerful enemy as England.

On returning from this expedition, Hawkins commenced preparations for a bold buccaneering project against Spain. He built a ship of 350 tons, to which his mother-in-law—who had assisted with funds—obstinately persisted in giving the ominous name of the Repentance. Richard Hawkins could not stand this name, and sold the ship to his father. The Repentance, in spite of the name, did excellent service, and had very good fortune. On return from an expedition, while lying at Deptford, the Repentance was surveyed by the queen, who rowed round the ship in her barge, and graciously—acting probably upon a hint from Sir John or his son Richard—re-named it the Dainty, whereupon Richard bought back the ship from his father for service in his projected great expedition. His plan included, in addition to plundering the Spaniards, visits to Japan, the Moluccas, the Philippines, passage through the Straits of Magellan, and return by the Cape of Good Hope. His ambitious prospectus secured the admiration and approval of the greatest men of the time, including the lord high admiral, Sir R. Cecil, Sir Walter Raleigh, etc. On the 8th of April 1593, the Dainty dropped down the river to29 Gravesend, and on the 26th arrived at Plymouth, where severe misfortune overtook the little squadron, consisting of the Dainty, the Hawk, and the Fancy,—all of them the property of Richard Hawkins, or of the Hawkins family. A tempest arose in which the Dainty sprang her main-mast, and the Fancy was driven ashore and knocked to pieces before the owner’s eyes. This misfortune magnified the fears, and intensified the tender entreaties, of his young wife that he would abandon the perilous enterprise,—but he was not to be dissuaded. He said that there were “so many eyes upon the ball, that he felt bound to dance on, even though he might only be able to hop at last.”

On the 12th June 1593, Hawkins left Plymouth Sound, with his tiny squadron of the Dainty and tender. Before the end of the month he arrived at Madeira, and on the 3rd July passed the Canaries, and shortly after the Cape de Verd Islands, all well, and without anything notable occurring to the squadron. Later, however, when nearing the coast of Brazil, scurvy of a malignant type broke out among the crew. Hawkins gave close attention to the men stricken, personally superintended their treatment, and made notes,—from which he afterwards wrote an elaborate paper on the disease, its causes, nature, and cure. At a short distance south of the Equator he put in to a Brazilian port for provisions. He sent a courteous letter, written in Latin,30 to the governor, stating that he was in command of an English ship, that he had met with contrary winds, and desired provisions, for which he would gladly pay. The governor replied that their monarchs were at war, and he could not supply his wants, but he politely gave him three days to do his best and depart. The three days’ grace were promptly taken advantage of to lay in a supply of oranges and other fruit, when he again sailed southward. On the 20th November he arrived at the Island of St. Ann, 20° 30’ south latitude, where—the provisions and stores having been taken out of the Hawk—that vessel was burned. He touched at other parts of the coast for provisions and water. Hawkins had a difficult part to play in dealing with his crew, who were impatient for plunder. Robert Tharlton, who commanded the Fairy, and who had proved a traitor to Captain Thomas Cavendish, in the La Plata, drew off a number of the men, with whom he deserted before they reached the Straits of Magellan. Notwithstanding the discouragement of Tharlton’s treachery and desertion, Hawkins courageously proceeded with his hazardous enterprise. Sailing along the coast of Patagonia, he gave names to several places, amongst others to Hawkins’ Maiden Land,—because discovered by himself in the reign of a maiden queen.

In the course of his voyage southward, he made a prize of a Portuguese ship. He found it to be the31 property of an old knight who was on board, on his way to Angola, as governor. The old gentleman made a piteous appeal to Hawkins, pleading that he had invested his all in the ship and its cargo, and that the loss of it would be his utter ruin. His petition was successful, and Hawkins let him go. On the 10th February he reached the Straits of Magellan, and, passing through, emerged into the South Pacific Ocean on the 29th March 1594. This was the sixth passage of the straits—the third by an Englishman. He wrote an excellent account of the passage through the straits, which he pronounced navigable during the whole year, but the most favourable—or, it should rather perhaps be put, the least unfavourable—seasons for the at best unpleasant voyage were the months of November, December, and January. On the 19th April he anchored for a short time under the Isle of Mocha. Resuming his voyage along the coast of Chili, he encountered, in the so-called Pacific Ocean, a violent storm, that lasted without intermission for ten days. His men were becoming desperately impatient, and they insisted that they should attempt to take everything floating that they sighted. Every vessel in those waters, they believed, had gold or silver in them. At Valparaiso they took four ships, much against Hawkins’ wish. He exercised discrimination, and wished to reserve their strength, and prevent alarm on shore, by waiting till a prize worth32 taking came in their way. They got from the prizes an abundant supply of provisions, but very little gold, and only trifling ransoms for the prisoners. The small amount taken added greatly to Hawkins’ difficulties and embarrassments. His bold buccaneers demanded that the third part of the treasure should, according to contract, be given up to them,—then and there. He resisted the demand, urged that they could not expend anything profitably here and now, and that they would only gamble with their shares, which would probably lead to quarrels and the ruin of the expedition. It was at last agreed that the treasure should be placed in a chest with three locks,—one key to be held by Hawkins, one by the master, and the third by a representative appointed by the men.

Arriving at Ariquipa, Hawkins ascertained by some means that Don Garcia Hurtado de Mendoza, Viceroy of Peru, had received intelligence of his being off the coast, and had sent out a squadron of six vessels to capture him. Hawkins had in the Dainty, and in a little Indian vessel he had taken, and which he had fitted up as a pinnace, a combined crew of seventy-five men and boys—a lamentably small force to resist a well-manned squadron of six men-of-war ships. About the middle of May the Spanish squadron was sighted near Civite. Hawkins, who was to windward, stood out to sea. The Spanish ships, under the command of Don33 Bertrand de Castro, followed. The wind freshened greatly; the Spanish admiral lost his main-mast, the vice-admiral split his main-sail, and the rear-admiral’s main-yard tumbled down. The Spaniards were thrown into utter confusion, and Hawkins escaped. On34 returning to port with his damaged ships, and without the diminutive enemy he had gone out to capture, De Castro and the other commanders were received with humiliating and exasperating derision. De Castro’s earnest petition to be allowed to go to sea again was granted, and he sailed with two ships and a pinnace,—all fully manned with picked men. On the 20th June the Spanish squadron came in sight. Hawkins’ ungovernable crew would have him chase everything they sighted; they would have it that the armed cruisers were the Peruvian plate fleet, laden with the treasure for which they had come, and for which they had so long toiled and waited. They were soon undeceived by the Spanish attack, which they met with dogged bravery. The Spanish ships were manned by about thirteen hundred of the best men in the service,—and it seems marvellous that Hawkins and his bull-dogs could have stood out so long. The fight lasted for two whole days and part of a third. Hawkins had received six wounds, two of them dangerous, and was at last completely disabled. Besides the killed, there were forty of his men wounded, and his ship was sinking. On the afternoon of 22nd June, this was his deplorable plight:—the whole of his sails were rent, the masts shattered, eight feet of water in the hold, and the pumps rent and useless; scarcely a single unwounded man was left in the ship, and all were so fatigued that they could not stand.35 Helpless as was their plight, and desperate their condition, Hawkins was able to obtain honourable conditions of surrender, namely, that himself and all on board should have a free passage to England, as soon as possible. De Castro swore by his knighthood that the conditions would be faithfully observed, in token of which he sent his glove to Hawkins, and took possession of the shattered Dainty, without inflicting the slightest humiliation on his brave fallen enemy, or permitting his crew to express triumph over them. On the 9th July, the Spanish squadron, with Hawkins on board De Castro’s ship, arrived at Panama, which was brilliantly illuminated in celebration of the “famous victory.” Despatches, to allay apprehensions concerning the terrible enemy, were sent off to the viceroys of New Spain and Peru. Hawkins was allowed to send letters home to his father and other friends, and to the queen. From Don Bertrand, Hawkins learned that the King of Spain had received from England full and minute particulars, concerning the strength and equipment of Hawkins’ little squadron before it sailed, showing that the King of Spain had spies in England. The Dainty prize was repaired and re-named the Visitation, because surrendered on the day of the feast of the blessed Virgin. Hawkins was long kept in captivity. He was for two years in Peru and adjacent provinces, and was then sent to Europe and kept a prisoner at Seville and Madrid. His release was claimed36 on the ground of Don Bertrand’s knightly pledge, but the reply was given that he had received his authority from the Viceroy of Peru, not from the King of Spain, upon whom his engagement was not binding. The Count de Miranda, President of the Council, however, at last gave judgment, that the promise of a Spanish general in the king’s name should be kept, and Hawkins was set at liberty, and returned to England.

During his captivity he wrote a detailed account of his voyage, entitled The Observations of Richard Hawkins, Knight, in his Voyage into the South Sea, 1593. It was published in London in 1622, the year in which Hawkins died of apoplexy,—at somewhere near fifty years of age.

Sir Richard Hawkins possessed powers that fitted him for great achievements. With resources at command, and a fitting field for their use, corresponding with his courage and ability, he would have distinguished himself by mighty deeds. His ill-fated voyage to the South Sea was like the light cavalry charge at Balaclava—it was magnificent, but it was not war!

37

Queen Elizabeth has been magniloquently designated the Restorer of England’s Naval Power and Sovereign of the Northern Seas. Under her sovereignty Lord Charles Howard wielded supreme authority worthily and well, on behalf of his country, during that naval demonstration, which may be regarded as the most important, in its design and results, of any that the world has known. Lord Charles was High Admiral of England during the period of the inception, the proud departure, the baleful course, and the doleful return to Spain, of the “most happy and invincible Armada,” or rather—what was left of it.

38

Charles Howard, elder son of the Earl of Effingham, was born in the year 1536, in the reign of Henry VIII. Charles served under his father, who was Lord Admiral to Mary, in several expeditions. He did duty as an envoy to Charles IX. of France on his accession. He served as a general of horse in the army headed by Warwick, against the Earls of Northumberland and Westmoreland, and, as a courtier, he rendered various other services, not calling for particular notice. In 1572 he39 succeeded his father, and in 1573 was made a Knight of the Garter. On the death of the Earl of Lincoln, in 1585, the queen appointed Lord Charles, High Admiral. This appointment gave great satisfaction to all ranks, and was especially gratifying to seamen,—with whom Lord Charles was highly popular.

Philip of Spain employed all the art he was possessed of to obtain ascendency over Elizabeth, as he had done over her infatuated sister Mary, and—irrespective of law, if any existed to the contrary—was more than willing to marry his “deceased wife’s sister,” but Elizabeth would neither marry, nor take orders from him, which exasperated Philip greatly. His religious fanaticism and the influence of the Jesuits made him determined to punish the queen and ruin her country. With this amiable intention the great Armada was prepared. It consisted of 130 ships, of an aggregate of about 60,000 tons. It was armed with 2630 pieces of cannon, and carried 30,000 men, including 124 volunteers,—the flower of the Spanish nobility and gentry,—and 180 monks. Twelve of the greatest ships were named after the twelve apostles.

The English fleet was put under the command of Lord Howard, with Sir Francis Drake for his vice-admiral, and Sir John Hawkins for his rear-admiral. Lord Henry Seymour, with Count Nassau, cruised on the coast of Flanders, to watch the movements of the40 Duke of Parma, who purposed, it was believed, to form a junction with the Spanish Armada, or to aid it, by making a separate descent upon England.

The threatened invasion stirred the kingdom to the highest pitch of patriotic fervour. The city of London advanced large sums of money for the national service. Requisitioned to provide 15 ships and 5000 men, the city fathers promptly provided 30 ships and 10,000 men.

The Armada encountered a violent storm, at almost the commencement of the voyage northwards, and had to put back. The rumour was current in England that the great expedition was hopelessly shattered. Lord Howard consequently received, through Walsingham, Secretary of State, instructions to send four of his largest ships into port. The admiral doubted the safety of this course, and willingly engaged to keep the ships out, at his own charge. He bore away towards Spain, and soon obtained such intelligence, as confirmed him in the opinion he had formed, and fully justified the course he had adopted.

On the 19th July, Fleming, a Scottish pirate, who plied his vocation in the Channel and the approaches thereto, sailed into Plymouth in hot haste, with the intelligence that the Armada was at hand. This pirate did, for once at least in his life, an honest and incalculably important day’s work. An ancient historian41 estimates it so highly as to say that “this man was, in reality, the cause of the absolute ruin of the Spaniards; for the preservation of the English was undoubtedly owing to his providential discovery of the enemy.” At the request of Lord Admiral Howard, the queen afterwards granted a pardon to Fleming for his past offences, and awarded him a pension for the timely service he had rendered to the nation.

“And then,” says Dr. Collier, “was played on the Hoe at Plymouth that game of bowls, which fixes itself like a picture on the memory,—the faint, hazy blue of the July sky, arching over sun-baked land and glittering sea; the group of captains on the grass, peak-bearded and befrilled, in the fashion of Elizabeth’s day; the gleaming wings of Fleming’s little bark skimming the green waters like a seagull, on her way to Plymouth harbour with the weightiest news. She touches the rude pier; the skipper makes hastily for the Hoe, and tells how that morning he saw the giant hulls off the Cornish coast, and how he has with difficulty escaped by the fleetness of his ship. The breathless silence changes to a storm of tongues; but the resolute man who loaded the Golden Hind with Spanish pesos, and ploughed the waves of every ocean round the globe, calls on his comrades to ‘play out the match, for there is plenty of time to do so, and to beat the Spaniards too.’ It is Drake who speaks. The game is resumed, and played42 to the last shot. Then begin preparations for a mightier game. The nation’s life is at stake. Out of Plymouth, along every road, men spur as for life, and every headland and mountain peak shoots up its red tongue of warning flame.”

The sorrows and sufferings of the crowd of Spaniards noble and ignoble, of the nine score holy fathers, and the two thousand galley slaves, who left the Tagus in glee and grandeur, in the “happy Armada,” with a great design,—but really to serve no higher purpose, as things turned out, than to provide, in their doomed persons, a series of banquets for the carnivorous fishes in British waters,—need not be dwelt upon here, being referred to elsewhere.

As commander-in-chief, it was universally felt and admitted that Lord Charles Howard acquitted himself with sound judgment, consummate skill, and unfaltering courage. The queen acknowledged his merits, the indebtedness of the nation to the lord high admiral, and her sense of his magnanimity and prudence, in the most expressive terms. In 1596 he was advanced to the title and dignity of Earl of Nottingham, his patent of nobility containing the declaration, “that by the victory obtained anno 1588, he did secure the kingdom of England from the invasion of Spain, and other impending dangers; and did also, in conjunction with our dear cousin, Robert, Earl of Essex, seize by force the45 Isle and the strongly fortified castle of Cadiz, in the farthest part of Spain; and did likewise rout and entirely defeat another fleet of the King of Spain, prepared in that port against this kingdom.” On entering the House of Peers, the Earl of Nottingham was received with extraordinary expressions and demonstrations of honourable regard.

In 1599, circumstances of delicacy and difficulty again called for the services of the Earl of Nottingham. Spain meditated another invasion. The Earl of Essex in Ireland had entangled affairs, had left his post there, and had rebelliously fortified himself in his house in London. The Earl of Nottingham succeeded in bringing the contumacious earl to a state of quietude, if not of reason, and had the encomium pronounced upon him by the queen, that he seemed to have been born “to serve and to save his country.” He was invested with the unusual and almost unlimited authority of Lord Lieutenant General of all England; he was also appointed one of the commissioners for executing the office of Earl-Marshal. On her death-bed the queen made known to the earl her desire as to the succession,—an unequivocal proof of her regard and confidence,—the disclosure having been entreated in vain by her most favoured ministers.

The accession of James did not impede the fortunes of the Earl of Nottingham; he was appointed Lord High Steward, to assist at the coronation; and afterwards46 commissioned to the most brilliant embassy—to the court of Philip III. of Spain—that the country had ever sent forth. During his stay at the Spanish court, the dignified splendour that characterised the Embassy commanded the admiration and respect of the court and people; and at his departure, Philip made him presents of the estimated value of about £20,000,—thereby exciting the jealousy and displeasure of the far from magnanimous James I. Popularity and influence, enjoyed or exercised independently of himself, were distasteful and offensive to his ungenerous nature. James frequently reminded his nobles at court “that they were there, as little vessels sailing round the master ship; whereas they were in the country so many great ships each riding majestically on its own stream.”

The earl had his enemies, but he regained the confidence of the king, and in 1613 assisted at the marriage of the Princess Elizabeth with Frederick, the Elector Palatine. His last naval service was to command the squadron that escorted the princess to Flushing. The infirmities of age having disqualified him for discharging the onerous duties of the office, he resigned his post of lord high admiral, after a lengthened term of honourable and effective service. The distinguished career of this eminent public man came to a calm and honourable close on the nth December 1624—the earl having reached the advanced age of eighty-eight years.

47

Martin Frobisher had no “lineage” to boast of; he was of the people. His parents, who had respectable connections, are supposed to have come from North Wales to the neighbourhood of Normanton, Yorkshire, where he was born about the year 1535. Frobisher seems to have taken to the sea from natural inclination. He is said to have been bred to the sea, but had reached the prime of life—about forty years of age—before he came into public notice as a mariner. He must have been a man of mark, and possessed of qualities that commanded confidence. His mother had a brother in London, Sir John York, to whom young Frobisher was sent, and by whom he was probably assisted.

48

In 1554 he sailed to Guinea in a small squadron of merchant ships under the command of Captain John Lock, and in 1561 had worked his way up to the command of a ship. In 1571 he was employed in superintending the building of a ship at Plymouth, that was intended to be employed against Ireland. For years he had been scheming, planning, and striving to obtain means for an expedition in search of a North-West passage from England to “far Cathay.” He was at last so far successful as to get together an amusingly small squadron for such a daring project. He was placed in command of the Gabriel and the Michael, two small barques of 20 tons each, and a pinnace of 10 tons, with crews of thirty-five men all told, wherewith to encounter the unknown perils of the Arctic seas. Captain Matthew Kindersley was associated with him in the adventure. The expedition sailed from Gravesend on the 7th June 1576, and proceeded northwards by way of the Shetland Islands. The pinnace was lost on the voyage, and the other vessels narrowly escaped wreck in the violent weather encountered off the coast of Greenland, of which Frobisher was the first English discoverer. He reached Labrador 28th July, and effected a landing on Hall’s Island, at the mouth of the bay that bears Frobisher’s name. At Butcher’s Island, where he afterwards landed, five of the crew were captured by the natives, and were never again seen. The adventurers51 took on board samples of earth,—with bright specks supposed to be gold. Compared with subsequent Arctic expeditions, this was a small affair in length of voyage and time occupied,—the mariners reaching home on the 9th October.

Practical mineralogy was in its infancy in those days, and the supposed auriferous earth excited great expectations, but no attempt seems to have been made to find out whether it was or was not what it seemed. Pending analysis, the expedition was considered so far satisfactory and successful, and a Cathay Company was straightway formed under a charter from the Crown. Another expedition was determined upon; the queen lent a ship of 200 tons, and subscribed £1000; Frobisher was appointed High Admiral of all lands and seas he might discover, and was empowered to sail in every direction except east. The squadron consisted of the queen’s ship, the Aid, the Gabriel, and the Michael of last year’s voyage, with pinnaces and boats, and a crew of one hundred and twenty men. The squadron sailed 28th May 1577, and arrived off Greenland in July. More of the supposed precious earth was shipped, and certain inhospitable shores were taken possession of in the queen’s name, but no very notable discoveries were made. An unsuccessful search was made after the five men lost in the previous expedition. The Aid arrived home at Milford Haven on 22nd August, and the52 others later,—one at Yarmouth, and others at Bristol. Although no results had been obtained from the “ore,” yet another and much larger expedition was planned. Frobisher was honoured with the thanks of the queen, who showed great interest in the expeditions. The new fleet consisted of thirteen vessels of various kinds, including two queen’s ships of 400 and 200 tons, with one hundred and fifty men and one hundred and twenty pioneers. For the other ships there was an aggregate crew of two hundred and fifty men. The squadron sailed from Harwich on the 31st May 1578, and reached Greenland 19th June, and Frobisher Bay about a month later. A considerable amount of hitherto unexplored area of land and water was roughly surveyed in this voyage, including a sail of sixty miles up Hudson’s Strait, and more would probably have been done, but for dissensions and discontent among the crews. A vast quantity of the golden (?) earth was shipped, and the expedition returned to England, which was reached in October.

Frobisher’s next public employment was of a different character. In command of the Primrose, he accompanied Drake’s expedition to the West Indies in 1585, and shared in the rich booty of which the Spaniards were spoiled during that cruise. In 1588 Frobisher held a high command, and with his ship, the Triumph, rendered distinguished service in the actions with the55 Spanish Armada. The Triumph was the largest ship in the English fleet, being of about 1000 tons burthen, or the same as the floating wonder of Henry VIII., the Henry Grace à Dieu,—but not so heavily armed. The Henry carried no fewer than one hundred and forty-one guns, whereas the Triumph was armed with only sixty-eight guns. Frobisher proved well worthy of his important command. For his skilful and courageous service, in the series of actions against the Armada, he received the well-earned honour of knighthood, at the hands of the lord high admiral. In 1591 he commanded a small fleet that cruised on the coast of Spain, with hostile and plundering designs. He burned one rich galleon in the course of this cruise, and captured and brought home another. Having got the prize safely disposed of, the gallant old hero answered a summons from the court of Cupid, and, after a short courtship, he led the fair daughter of Lord Wentworth to the altar. The following year, however, he was again afloat in command of a cruising fleet, as successor to Sir Walter Raleigh, who had been recalled.

One of the most important and brilliant actions, among the many in which Sir Martin had taken a leading part, was his next, and, alas! his last,—the taking of Brest from the Spaniards. The place was strong, well armed, and stubbornly defended, with obstinate valour. Sir Martin first attacked from the sea, but, impetuous56 and impatient, was dissatisfied with the result of his cannonade, and, landing his blue-jackets, headed them in a desperate storming assault, which compelled the surrender of the garrison. The surrender cost the assailants a heavy price in the lives of many brave heroes, Sir Martin Frobisher himself, their gallant leader, receiving a musket ball in his side. His wound was unskilfully treated, and he died from its effects at Plymouth two days after the action,—22nd November 1594. His body was conveyed to London, and interred at St. Giles’s, Cripplegate.

Sir Martin Frobisher was a man of great and varied capabilities as a navigator and commander; enthusiastic, enterprising, skilful, manly, and of dauntless valour, but rather rough and despotic, and not possessed of the polished manners, airs, and graces that adorn carpet knights and make men shine in courts.

57

In the time of Queen Elizabeth it was not unusual for men of the highest rank to devote their private fortunes and their personal services to the advancement of what were considered national interests, with the tacit understanding that the adventurers should consider themselves at liberty to engage in operations fitted to serve their own private interests, concurrently with those of the State. The morals of the time were somewhat lax, and “sea divinity,” as Fuller terms it, was taken to sanction extraordinary transactions in the appropriation and treatment of property, especially such as was owned by the State or the subjects of Spain. To spoil the Spaniards by all and every possible means, seems to58 have been esteemed an object of honourable and patriotic enterprise, in which Sir Francis Drake distinguished himself, as he did also by much nobler and more disinterested service. Thomas Cavendish was a contemporary of Drake, and in his wake plundered the Spaniards, and he also followed him in circumnavigating the globe,—the second Englishman who achieved that feat.

Thomas was a descendant of Sir William Cavendish; he was born at the family mansion, Trimley, Suffolk, about the year 1560. His father died while he was still a minor. Trimley, his birthplace, is situate on the river Orwell, below Ipswich. The locality in which he spent his early days probably induced a liking for the sea.

In April 1585, Cavendish accompanied Sir Richard Grenville in an expedition to Virginia, its object being the establishment of a colony as designed by Sir Walter Raleigh. The colony was a failure, and Drake, as we have related in another place, subsequently brought home the emigrants sent out to form it. Cavendish accompanied the expedition in a ship that had been equipped at his own cost, and acquired considerable nautical experience in the course of the voyage.

On his return to England, Cavendish applied such means as he could command to the equipment of a small squadron with which to commence business as a61 buccaneer. He diligently got together all the existing maps and charts accessible, and, through the influence of Lord Hunsdon, he was so fortunate as to obtain a queen’s commission. The “flag-ship” of Cavendish, admiral and commander, was the Desire, of only 120 tons burthen; the others were, the Content, of 60 tons, and the Hugh Gallant, a barque of 40 tons. The crews consisted of 123 officers, sailors, and soldiers, all told. The expedition sailed from Plymouth on the 21st July 1586. The squadron first touched at Sierra Leone, where they landed, and plundered and burned the town. Having obtained supplies of water, fish, and lemons, the squadron sailed for the coast of America, and reached in 48° S. a harbour on the coast of Patagonia, in which they anchored, and which, in honour of the admiral’s ship, they named Port Desire. Here the crews were enabled to make an agreeable change in the ship’s dietary, by slaughtering the sea-lions and the penguins that abounded on the coast; the flesh of the young sea-lions, after a long course of salt junk, seemed to the sailors equal to lamb or mutton. Towards the end of December the squadron sailed southward for Magellan’s Straits, which were entered on the 6th January 1587. At a short distance from the entrance, lights were seen from the north shore that were supposed to be signals, and on the morning following a boat was sent off for information. Unmistakable signs were made, as the62 shore was approached, by three men waving such substitutes as they could find for flags. It was found that they were the wretched survivors of one of the colonies that the Spaniards had attempted to plant, in order to intercept Drake on his expected return, and to prevent, in the future, any buccaneer from ravaging the coast as he had done. The crops of the perishing colonists had all failed; they were constantly harassed by the natives, subject to unspeakable hardships; out of four hundred men and thirty women landed by Pedro Sarmiento, about seven years before Cavendish’s visit, only fifteen men and three women survived. He offered the poor creatures a passage to Peru. They at first hesitated to trust themselves with the English heretic, but, after brief reflection on the misery and hopelessness of their situation, eagerly accepted the offer,—but unhappily too late. A favourable wind sprang up, of which Cavendish took advantage, and set sail. Concern for the safety of his crew, desire to escape as speedily as possible from the perilous navigation of the Straits, and probably eagerness to make a beginning with the real objects of the expedition—the acquisition of plunder—overbore any pity he may have felt for the wretched colonists, whose heartless abandonment to hopeless misery attached shame and infamy to the Spanish Government responsible for sending them thither, rather than to the bold buccaneer, with no humanitarian pretensions, who had come upon them63 accidentally. He brought off one Spaniard, Tomé Hernandez, who wrote an account of the colony.

On the 24th of February the squadron emerged from the Straits and sailed northwards, reaching the island of Mocha about the middle of March, but not before the little ships had been much knocked about, by weather of extreme violence. The crews landed at several points, and laid the natives under contribution for provisions. They were mistaken for Spaniards, and were in some cases received with undisguised hatred, in others with servility. On the 30th they anchored in the Bay of Quintero, to the north of Valparaiso, which was passed by mistake, without being “tapped.” Notice of the appearance of the suspicious squadron seems to have reached some of the authorities. Hernandez, the Spaniard, was sent ashore to confer with them. On returning, he reported that the English might have what provisions they required. Remaining for a time at their anchorage here, parties were sent ashore for water and such provisions as could be obtained. In one of these visits, the men were suddenly attacked by a party of two hundred horsemen, who cut off, and took prisoners, twelve of the Englishmen. Six of the English prisoners were executed at Santiago as pirates, although, as has been said, with somewhat arrogant indignation, “they sailed with the queen’s commission, and the English were not at open war with Spain.”

64

Putting again to sea, the adventurers captured near Arica a vessel laden with Spanish treasure. The cargo was appropriated, and the ship—re-named the George—attached to the squadron. Several other small vessels were taken and burned. One of these from Santiago had been despatched to the viceroy, with the intelligence that an English squadron was upon the coast. Before they were taken, they threw the despatches overboard, and Cavendish resorted to the revolting expedient of torture, to extort their contents from his captives. The mode of torture employed was the “thumbikins,” an instrument in which the thumb, by screw or lever power, could be crushed into shapeless pulp. Having got what information he could wring out of his prisoners, Cavendish burned the vessel and took the crew with him. One of them was a Greek pilot, who knew the coast of Chili, and might be useful. After a visit to a small town where supplies were obtained—not by purchase—of bread, wine, poultry, fruit, etc., and some small prizes taken, the adventurers proceeded to Paita, where they landed on the 20th May. The town, consisting of about two hundred houses, was regularly built and very clean. The inhabitants were driven out, and the town burned to the ground. Cavendish would not allow his men to carry away as much as they could, as he expected they would need a free hand to resist a probable attack. After wrecking the town and burning a ship in the65 harbour, the squadron again sailed northwards, and anchored in the harbour of the island of Puna. The Indian chief, who lived in a luxuriously furnished palace, surrounded by beautiful gardens, and the other inhabitants had fled, carrying as many of their valuables with them as possible. The English visitors sank a Spanish ship of 250 tons that was in the harbour, burned down a fine large church, and brought away the bells.

On the 2nd June, before weighing anchor at Puna, a party of Cavendish’s men, strolling about and foraging, was suddenly attacked by about one hundred armed Spaniards. Seven of the Englishmen were killed, three were made prisoners, two were drowned, and eight escaped. To avenge this attack, Cavendish landed with as powerful a force as he could muster, drove out the Spaniards, burned the town and four ships that were building; he also destroyed the gardens and orchards, and committed as much havoc generally as was in his power. Again proceeding northwards to Rio Dolce, he sent some Indian captives ashore, and sank the Hugh Gallant, the crew of which he needed for the manning of the other two ships. On the 9th July a new ship of 120 tons was taken; the sails and ropes were appropriated, and the ship burned. A Frenchman, taken in this vessel, gave valuable information respecting a Manilla ship, then expected from the66 Philippines. The record of the proceedings of the squadron continues most inglorious, including the burning of the town, the church, and the custom-house of Guatulco; the burning of two new ships at Puerto de Navidad; capturing three Spanish families, a carpenter, a Portuguese, and a few Indians,—the carpenter and the Portuguese only being kept for present and future use. On the 12th September the adventurers reached the island of St. Andrew, where a store of wood and of dried and salted wild-fowl was laid in, and the sailors, failing other supply, had a fresh meat change in cooking the iguanas, which were found more palatable, than inviting in appearance. Towards the end of September the fleet put into the Bay of Mazattan, where the ships were careened, and water was taken in. During October the fleet cruised, in wait for the expected prize, not far wide of Cape St. Lucas. On the 4th November a sail was sighted, which proved to be the Santa Anna, which was overtaken after some hours’ chase, and promptly attacked. The Spaniards resisted with determination and courage, although they had no more effective means of defence than stones, which they hurled at the boarders, from behind such defective shelters as they could improvise. Two separate accounts of the action have been preserved, both written by adventurers who were present. After receiving a volley of stones from the defenders, one 69narrator proceeds: “We new-trimmed our sails and67 fitted every man his furniture, and gave them a fresh encounter with our great ordnance, and also with our small-shot, raking them through and through, to the killing and wounding of many of their men. Their captain, still like a valiant man with his company, stood very stoutly in close fights, not yielding as yet. Our general, encouraging his men afresh, with the whole voice of trumpets, gave them the other encounter with our great ordnance and all our small-shot, to the great discouragement of our enemies,—raking them through in divers places, killing and wounding many of their men. They being thus discouraged and spoiled, and their ship being in hazard of sinking by reason of the great shot which were made, whereof some were made under water, within five or six hours’ fight, sent out a flag of truce, and parleyed for mercy, desiring our general to save their lives and take their goods, and that they would presently yield. Our general, of his goodness, promised them mercy, and called to them to strike their sails, and to hoist out their boat and come on board; which news they were full glad to hear of, and presently struck their sails and hoisted out their boat, and one of their chief merchants came on board unto our general, and, falling down upon his knees, offered to have kissed our general’s feet, and craved mercy.” It is satisfactory that this craven submission was not made by the commander of the Santa Anna, who must have been a noble hero to70 stand out, almost without arms of any kind, against the “great ordnance and small-shot” of his enemy for five or six hours. The narrator proceeds: “Our general graciously pardoned both him and the rest, upon promise of their true-dealing(!) with him and his company concerning such riches as were in the ship, and sent for their captain and pilot, who, at their coming, used the like duty and reverence as the former did. The general, out of his great mercy and humanity, promised their lives and good usage.”

Cavendish and his crews must have been getting rather disgusted with their hard and bitter experiences up to the time they fell in with the Santa Anna. They were about sixteen months out from Plymouth; had been much knocked about; had destroyed a great deal of property, but had acquired very little. The Santa Anna compensated for all their hardships and disappointments. It was a ship of 700 tons burthen, the property of the King of Spain, and carried one of the richest cargoes that had ever floated up to that time. It had on board 122,000 pesos of gold, i.e. as many ounces of the precious metal, with a cargo of the finest silks, satins, damasks, wine, preserved fruits, musk, spices, etc. The ship carried a large number of passengers, with the most luxurious provision for their accommodation and comfort. The captors entered with alacrity upon the unrestrained enjoyment of luxuries such71 as many of them had never known before. Cavendish carried his prize into a bay within Cape St. Lucas, where he landed the crew and passengers,—about one hundred and ninety in all. He allowed them a supply of water, a part of the ship’s stores, some wine, and the sails of the dismantled prize to construct tents for shelter. He gave arms to the men to enable them to defend their company against the natives. He also allowed them some planks wherewith to build a raft, or such craft as they might be able to construct for their conveyance to the mainland. Among the passengers were two Japanese youths, both of whom could read and write their own language. There were also three boys from Manilla, one of whom, on the return of the expedition to England, was presented to the Countess of Essex,—such an attendant being at that time considered evidence of almost regal life and splendour. These youths, with a Portuguese who had been in Canton, the Philippines, and Japan, with a Spanish pilot, Cavendish took with him.