The Project Gutenberg eBook of Women in white raiment, by John Lemley

Title: Women in white raiment

Author: John Lemley

Release Date: October 1, 2022 [eBook #69085]

Language: English

Produced by: Juliet Sutherland, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

BY

JOHN LEMLEY,

EDITOR OF

THE ZION’S WATCHMAN,

AND AUTHOR OF

“The Christ Lifted Up,” “Land of Sacred Story,”

“Wonders of Grace,” “Personal

Recollections,” Etc.

“They shall walk with me in white; for they shall be worthy, ... and shall be clothed in white raiment.”—Rev. iii: 4, 5.

THE FIRST EDITION.

Albany, New York,

1899.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1898, by

JOHN LEMLEY,

in the office of the Librarian at Washington.

All Rights Reserved.

CHARLES VAN BENTHUYSEN & SONS,

Printers, Electrotypers and Binders,

ALBANY, N. Y.

| INTRODUCTORY. | |

| Women Owe their Elevation to the Bible—The Condition of Women in Heathen Lands Contrasted with the Condition of Women in Bible Lands—God’s Thought of Woman in the Creation—Her Rights Under the Hebrew Economy—Christ’s Tenderness Towards Womanhood—Blessing Others. | 7-19 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| The Paradise Home in Eden. | |

| Man’s First Home a Garden—Eve the Isha—The Scene of the Temptation—Hiding from God—Refusing to Confess, Judgment is Pronounced—The Sad Results of Sin—Eve Believed the Promise. | 21-35 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Womanhood in the Patriarchal Age. | |

| Sarah the Beautiful Princess—Her Faith Tested—The Mistake of Her Life—Her Lovely Character—Rebekah—An Oriental Wooing—Eliezer’s Prayer—The Bride’s Answer—Meeting Isaac—A Mother’s Love for Her Son—Jacob’s Flight—Rebekah, the Beautiful Shepherdess—Seven Years’ Service for Her—Laban’s Deception—Leah, the Tender-Eyed—Human Favorites—Divinely Honored—Rachel’s Tomb the First Monument to Human Love. | 36-70 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Womanhood During the Egyptian Bondage and in the Desert of Sinai. | |

| Jochebed—Her Remarkable Courage—Thonoris—Her Compassion—Heroic Labors Seemingly Unrewarded—Zipporah, the Midianite Shepherdess—Glorifying Daily Labor—At a Wayside Inn—Miriam—Her Song of Triumph at the Red Sea—Her Affliction at Hazeroth—An Eventful Life. | 71-89 |

| CHAPTER IV.[4] | |

| Womanhood During the Conquest and the Theocracy, or Rule of the Judges. | |

| Rahab—Great Grace for Great Sinners—The Fall of Jericho—The Covenant Remembered—Deborah—Her Remarkable Courage—Sisera’s Iron Chariots Broken—The Daughter of Jephthah—Her Loving Devotion and Sacrifice—The Story of Naomi—Orpah’s Kiss—The Loving Ruth—Gleaning Among the Reapers—Her Rich Reward—Hannah—Her Consecration—Yearly Visits to Shiloh—Stitching Beautiful Thoughts into Samuel’s Coat—Her Beautiful Life. | 90-117 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Womanhood During the Reign of the Kings. | |

| Abigail—Churlish Nabal—Chivalrous Appreciation—David’s Messengers—Saul’s Daughters—His Treachery—Michal’s Stratagem—Rizpah—Her Heroic Endurance and Loving Fidelity—The Queen of Sheba—Her Visit to Jerusalem—The Glory and Wisdom of Solomon—The Half Not Told—The Queen’s Royal Gifts. | 118-137 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Womanhood in the Time of the Prophets and During the Captivity. | |

| The Wicked Jezebel—The Widow of Sarepta—The Tishbite at the City Gate—His Strange Request—The Widow’s Unfaltering Obedience—An Appeal to Elisha—A Pot of Oil—The Widow’s Wonderful Faith—The Rich Woman of Shunem—Her Modest Life—Barley Harvest—A Ride to Carmel in the Glare of the Sun—Esther—Her Beautiful Traits of Character—Crowned as Queen—Pleading for the Life of Her People—Found Favor with the King. | 138-161 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Womanhood in the Time of the Saviour’s Nativity. | |

| An Angel by the Altar of Incense—His Message—An Israelitish Home—In the Spirit of Elijah—The Desert Teacher—The Annunciation—The Visit of Mary to Elizabeth—Mary’s [5] Magnificat—Journey to Bethlehem—The Nativity—Home Life in Nazareth—After Scenes in Mary’s Life—Her Residence and Death at Ephesus—The Prophetess Anna—Her Waiting for Redemption in Jerusalem—The Lesson of Her Pure and Beautiful Life. | 162-189 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Womanhood During our Lord’s Galilean Ministry. | |

| Christ and Womanhood—Noontide at Jacob’s Well—The Lord’s Wonderful Tact—Fields White to the Harvest—An Uninvited Guest at Simon’s Feast—Cold Hospitality—A Concise Parable—Forgiving Sin—A Street Scene—Humble Confession—Most Gracious Words—Coast of Tyre and Sidon—Syro-Phœnician Woman—Strangely Tested—Her Humility—Went Away Blessed. | 190-222 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Womanhood During Our Lord’s Judean Ministry. | |

| The Sisters of Bethany—Their Characteristics—Not Good, But Best Gifts—The Extravagance of Love—Salome’s Strange Request—Her Fidelity—Joanna—The Poor Widow’s Gift—How Estimated—The Saviour’s Words of Peace. | 223-244 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Womanhood During the Apostolic Ministry. | |

| Tabitha—Glorified Her Needle—The Results of Little Acts—Lydia—Her Humility—Philip’s Four Daughters—Phœbe—Priscilla—Eunice—Lois— Eudia—Syntyche—Hulda—The Hebrew Maid—Tamar—Mothers of Great Men—The Author of the Bible Woman’s Best Friend. | 245-266 |

| PAGE. | |

| The Accepted Offering | 31 |

| Jacob’s Struggle at the Jabbok | 67 |

| The Israelites in Bondage | 73 |

| Moses Rescued from the Nile | 75 |

| Miriam’s Song of Triumph | 84 |

| The Fall of Jericho | 95 |

| Ruth, the Faithful Friend | 108 |

| The Beautiful Abigail Meeting David | 121 |

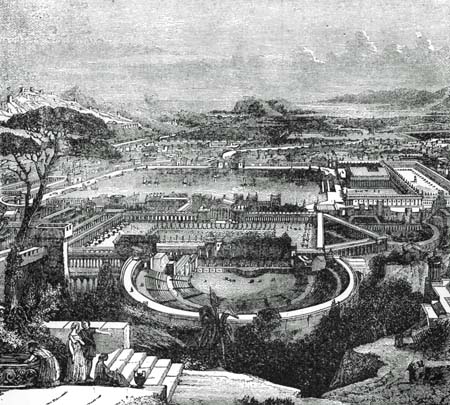

| Solomon’s Merchant Ships | 130 |

| The Queen of Sheba | 133 |

| Hadassah in the Persian Court | 153 |

| Esther Pleading for Her People | 157 |

| The Angel’s Message | 164 |

| The Ministry at Ephesus | 181 |

| Anna, the Prophetess | 185 |

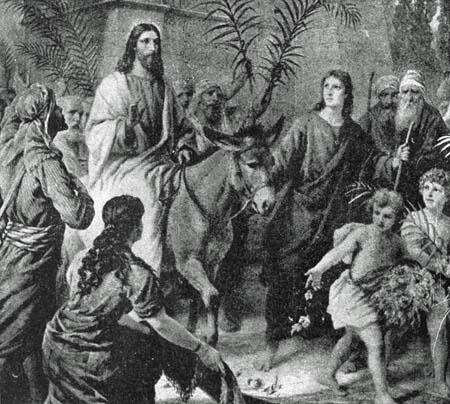

| Christ and Womanhood | 193 |

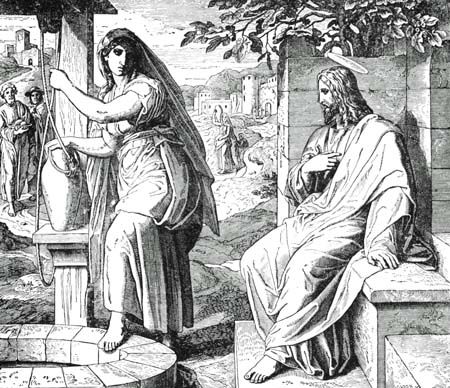

| The Noontide Hour at Jacob’s Well | 198 |

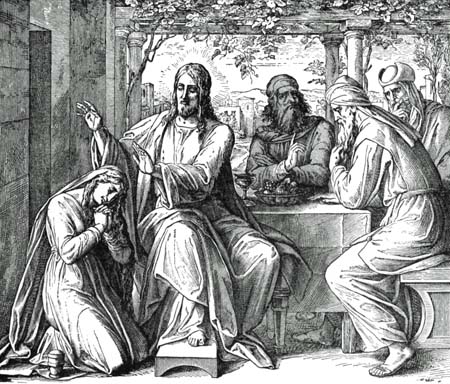

| The Uninvited Guest | 208 |

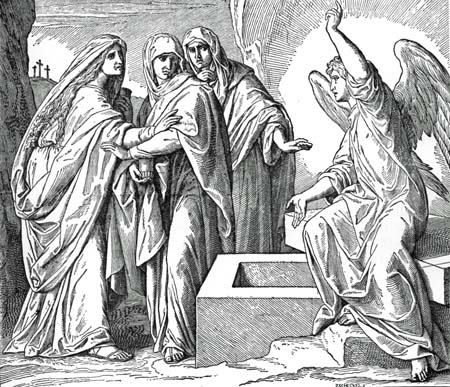

| Seeking the Living Among the Dead | 237 |

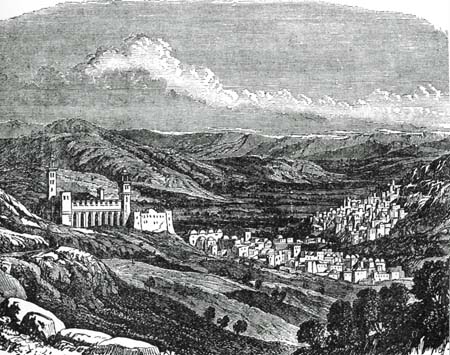

| The City by the Anghista | 253 |

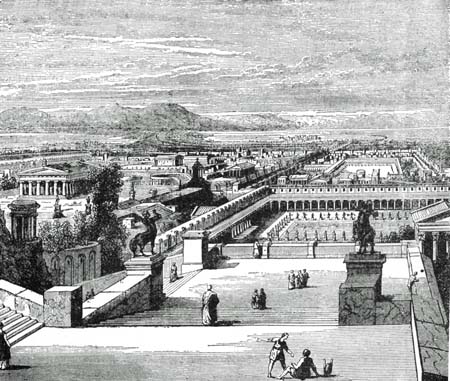

| Corinth, the Gate of the Peloponnesus | 260 |

It has long been in our mind to write this book, in which we seek to set forth the beautiful lives of representative women of the Bible. There has been much written about prophets, kings and priests, about our Lord and His Apostles, about scenes, of different types of character, customs and manners of Oriental life, but so far as we know, nothing has been written about the womanhood of the Bible. We believe a study of these lovely Princesses of God will be both profitable and instructive.

That we may have a suitable background for our pen pictures of these Daughters in Israel, and also, by way of contrast, show what the Bible has done for womanhood, let us briefly take a glance into countries where the Bible has been a sealed book, for the position of women among the Hebrews has always afforded a pleasing contrast with that of their heathen sisters. The position of Jewish women is just what we would expect among a people who were indebted for their laws to the Creator.

It has always been Satan’s shrewdest trick to degrade motherhood, and to cause her to be treated with contempt, knowing that she it is who stands at the fountain head of the race, and her hand always shapes the life and forms the civilization, hence the universal oppression of womanhood in all heathen lands.

The effect of religion (for all nations worship something) upon the people affords overwhelming evidence of its origin. In all heathen lands the people are exceedingly religious. In India alone they worship 360,000,000 gods, but they know nothing about morality. Their religion offers no light in life and no hope in death. The condition of women in India is indescribable. If a man speaks of his wife he never says[8] “wife,” but “family”; and if away, he never speaks of going home, but he is going to his house. There is no home life, as we look upon it, in all that heathen land. Women are considered by the Hindus as a thing that exists solely for their use. She is given away like a lifeless thing to the man who is to be her husband, but who does not consider her his equal. He is commanded by his religion to “enjoy her without attachment,” and never to love her or put his confidence in her. Some women are set apart religiously for the use of the men of all classes and castes. They are consecrated and “married” to the idols in the temples, and are brought up from their girlhood to live as prostitutes. Hindoo sacred law reaches its climax of cruelty and degradation in the rules it lays down for the control of a woman after her husband has died. She may be young and beautiful, she may belong to a wealthy and powerful family; it matters not; custom is as relentless as death in its weight of woe to crush her completely down.

One of the Hindoo sacred books says: “It is unlawful for any man to take a jewelless woman,” whose eyes are like the weeping cavi-flower; being deprived of her beloved husband, she is like a body deprived of the spirit. She may have only been a betrothed infant or a child of a few years. It makes no difference. The Shasters teach that if a widow burns herself alive on the funeral pile of her husband, even though he had killed a Brahmin, that most heinous of deeds, she expiates the crime. For long centuries widows have been a literal burnt offering for the redemption of husbands.

Another law is laid down after the following fashion: “On the death of their attached husbands, women must eat but once a day, must eschew betel and a spread mattress, must sleep on the ground, and continue to practice rigid mortification. Women who have put off glittering jewels of gold must discharge with alacrity the duties of devotion, and neglecting their persons, must feed on herbs and roots, so as barely to sustain life within the body. Let not a widow ever pronounce the name of another man.”

[9]There are, in India, twenty-three millions of widows, of these fourteen thousand are baby widows under four years of age, and sixty thousand girl widows between five and nine years of age. Nearly one-fourth of the whole number of widows are young. Besides, there are many millions of deserted wives, whose condition is as bad, and in some cases worse, than that of the widows. The lives of many millions of these poor women are made so miserable that they prefer death to life, and thousands commit suicide yearly.

And all these helpless women have never heard the message of salvation from God’s Holy Word.

It so happens in these days of missionary work among the heathen that now and then the light of the Gospel finds its way into these benighted hearts. Such was the case of a Brahmin widow, who had lived in the home of her uncle, but, for a fancied offence, was beaten and turned into the street naked. She was a woman of commanding manner and appearance, such as few suffering widows possess. She was tall, elegant of bearing, and attractive. Her story, in short, is this: “I was married when only five years of age. I soon became a widow, and then my father and mother took care of me, though I was kept secure in their home. My father and mother died, and since I was fifteen years of age I have been with their relatives, who let me work in the fields and earn an honorable living. Then my mother’s own brother came along, and persuaded me to come to his house. I hoped for kindness, but I have been their slave from that day.”

When asked whether she had been led astray, she replied, “I might have been, and sat with jewels on my neck and arms, with a frontlet on my brow, and gems would have bedecked my ears had I yielded to the machinations of my uncle and the desires of his friends to betray me into a life of glittering slavery! Because I would not, I am in rags, and now turned homeless into the streets.”

Such is the suffering of women in India. And the saddest of all is, the only heaven they look for after this world, is a[10] place where they can be their husband’s servants. Sad and terrible is their state!

The condition of womanhood in China is but little better. In fact she is unwelcome at her birth. If she is suffered to live, she is subjected to inhuman foot-binding. The feet are supposed to merit the poetical name of “golden lilies.” But how sad it is to discover that such a result is produced by indescribable torture, and that the part of the foot that is not seen is nothing but a mass of distorted or broken bones!

This binding process commences when the girl is about six years old. There is a Chinese proverb that says, “For every pair of bound feet has been shed a kong full of tears.” And yet, the most important part of a Chinese girl’s dress is her tiny shoe of colored silk or satin, most tastefully embroidered, with bright painted heels just peeping beneath the neat pantalets. Missionary ladies tell us how they themselves have seen three strong women holding a little girl by force to compel her to submit to this awful torture. It is not an uncommon thing for a mother to get up in the night and beat a poor child of seven or eight for keeping her awake by her stifled sobs from the terrible pain produced by the bandages. Through the weary summer days, instead of romping and enjoying the fresh air and sports with brothers, the poor little girl will lie, restless with fever, upon her little couch, and when the cold nights of winter come, she is afraid to wrap her limbs in any covering, else they grow warm and the suffering becomes more intense.

At last the much desired smallness is obtained, the feet are deformed for life and she is greatly admired by all her friends. If she is not betrothed until she is ten or more years of age, one of the first questions is, “What is the length of her feet?” Three inches is the correct length of the fashionable shoe, but some are only two.

But this has respect only to those girl-babies who are suffered to live. The horrors of heathenism permits the new-born girl baby to be disposed of. There is outside the city walls of Fuchan, China, a structure of stone without doors, but[11] with two window-like openings. This well-known and frequently visited building is the baby tower—not a day nursery for the care of the infants of the poor, not an orphanage where the little waifs are clothed and fed and educated, but a place where girl-babies can be thrown and left to die. In larger cities, such as Pekin, carts pass through the streets at an early hour of the day and gather up the babies abandoned to the streets by their inhuman parents.

Women in the common walks of life are the slaves of their husbands. The wife rises early in the morning, does the housework for the day, and prepares the morning meal for her husband, who always eats it by himself while she serves. Having finished her own meal, after her husband has eaten his, she cleans up the dishes, and then hastens to the fields to toil all day under a burning sun. The husband, meanwhile, spends the day in sleeping, or gambling, or when opportunity occurs, in thieving or marauding. Sometimes, frequently indeed, the women are carried off by other tribes while out in the fields, and are only released at a price, varying with the excellencies of the woman in question. And yet, if any one were to offer to relieve these women of their work, their offer would be rejected, for this life of toil is what they have been brought up to and trained in, and they know of nothing better. They especially like to be in the fields by themselves, for then they are alone, and are free from the hated presence of man (curiously enough they are said to hate their men), and surely no one would grudge them their liberty.

In dark Africa, where lives one-sixth of the heathen population of the globe, human sacrifice is something awful. And the saddest of all is, the victims are mostly from the ranks of women. Of the languages and dialects, five hundred have never been reduced to writing. What scenes of horrors are locked up in oblivion among these wild tribes of that dark land. Almost daily, the numerous wives of the rulers, as they die, are buried alive in their graves, being compelled to hold the dead bodies of their husbands on their[12] laps, until they themselves are relieved by death. The witch doctors annually slay thousands of innocent women. Among the Masai, a woman has a market value equal to five glass beads, while a cow is worth ten of the same.

Woman’s life in the harem of the Mohammedan is but little better. The code of morals is a very loose one, and the degradation of women beyond our pen to describe. The women of the harems are divided into three classes: The Rhadines, or legitimate wives. The Ikbals, or favorites, out of whose ranks the Rhadines are chosen, and Ghienzdes or “women who are pleasing to the eye of their lord,” and who have the chance to advance to the rank of Ikbals. If the wife of a Turkoman asks his permission to go, and he says, “go,” without adding, “come back,” they are divorced. If he becomes dissatisfied with the most trifling acts of his wife, and tears the veil from her face, that constitutes a divorce. In the streets, if a husband meets one of his numerous wives, he never recognizes her, or ever introduces her to a male friend. A Mohammedan never inquires after the female portion of the household of his friend. The system is full of cruelty and despotism. In Mohammedan countries women suffer from the low opinion held of them by men. The prophet said: “I stood at the gates of hell, and lo! most of its inhabitants were women!” And yet, strange to say, while the religion of Islam denies that woman has a soul, it teaches a sensual paradise.

In fact, in all nations where the Bible is unknown, woman is the slave of man’s lust. She is a drudge or a toy, whose reign is as short-lived as her personal charms. She may not be trusted out of sight of her guardians, though the masculine members of the family are anything but choice in their associations. Indeed, in some countries a woman can not visit even her own mother without being carried in a palanquin or guarded by slaves.

One of the strangest, saddest sights we ever saw was at Mersina, in the Levant. Passing a field one day there were six native women (noble in form and of beautiful olive complexion)[13] hoeing what looked to be cucumbers, while a step or two in their rear stood a negro, a full-blooded Nubian, with a long stick, like an ox-goad, in his hand, evidently their master.

In Ceylon, when it was proposed by a missionary to teach women to read, one native said to another, “What do you think that man is talking about? He wants to teach the women to read! He’ll be wanting to teach the cows next!”

Such is the disrespect in which women are held by heathen people. Five words describe the biography of women in all lands where the Bible is not known: Unwelcomed at birth; untaught in childhood; uncherished in widowhood; unprotected in old age; unlamented when dead.

Such, in brief, is the treatment of womanhood in lands where the Bible is a sealed book, and truly, in comparison with their heathen sisters, women living under the blessed teachings of Christianity are “clothed in white raiment.”

But, perhaps, we ought not to think it so very strange that men who dishonor God, and who want Him blotted out of their thoughts, should abuse God’s best gift to man. This much we know, that God created man in His own image, in the image of God created He him; male and female created He them. And God blessed them, and God said unto them, “Have dominion over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.” When the Pharisees, in their malignity, framed the question, “Is it lawful for a man to put away his wife for every cause?”—a problem beset with many difficulties, our Lord very promptly asked a counter question, “What did Moses command you?” Instead of entering into their vexed question, He appeals at once to the law and the testimony, and requires them to recite the provision made by Moses for such cases; not as settling the difficulties, but as presenting the true status quaestionis, which was not what the Scribes taught or the Pharisees practiced, but what Moses meant and God permitted. They said, “Moses suffered to write a bill of divorcement, and to put her away.” Quickly[14] Jesus replied, “For the hardness of your heart he wrote you this precept.” The substance of our Saviour’s answer was, Moses gave you no positive command in the case; he would not make a law directly opposite to the law of God; but Moses saw the wantonness and wickedness of your hearts, that you would turn away your wives without any just and warrantable cause; and to restrain your extravagancies of cruelty to your wives, or disorderly turning of them off upon any occasion, he made a law that none should put away his wife but upon a legal cognizance of the cause and giving her a bill of divorce. “From the beginning,” that is, in the very act of creation, God embodied the idea of equality. Capricious divorce is a violation of natural law.

What a beautiful picture Solomon gives us of womanhood. “Her price,” he says, “is far above rubies. The heart of her husband doth safely trust in her, so that he shall have no need of spoil. She will do him good and not evil all the days of her life. She seeketh wool, and flax, and worketh willingly with her hands.” After the grace of God in the soul, a good wife, one planned on the Divine model, is the Lord’s best gift. To the husband who has such a woman to stand at the head of his home, nothing can measure her value. His heart rests safely in her integrity. He has no need to add to his wealth by spoils, for she will do him good and not evil all the days of his life. She is industrious. She not only works into comfort the wool and flax that are at hand; she seeks to add to her store from the outside world. She does not ask to be kept in idleness. She worketh willingly with her hands. Not content to be a consumer, she becomes a producer. Not satisfied with home production, she brings suitable comforts and luxuries from afar into her home. She is careful in the use of her time. She is not feebly self-indulgent. She riseth while it is yet night to look after her domestic affairs. She is a business woman, knowing the laws that underlie the rise and fall of real estate. She considereth a field, and buyeth it. Then with her hands she planteth a vineyard.

[15]She does not produce inferior goods, neither is she cheated in a bargain. She perceiveth that her merchandise is good. She loves to share her husband’s business burdens, that he may share her society; and they twain are one in service and one in recreation. Like our Lord, she delights not to be ministered unto, but to minister. She is benevolent. Being a recognized producer, she has the luxury of giving of her own means to the poor. She provides well for her household, keeping her dependents in comfort, and even in luxury. As the Revised Version puts it, “She maketh herself carpets of tapestry.” Her own clothing is of the best.

The husband of such a wife has the gentle manners that belong with such a home, and he can but succeed in life. He is known and honored among the best in the land. As her business grows, her products become finer and more expensive; and as she puts them upon the market, her profits increase. This woman is clothed with strength and honor. She has no anxiety about the future. She knows that though her beauty may fade, and her social charms become a thing of the past, her strength and honor will become richer and more glorious as the years go by. “In her tongue is the law of kindness.” She is too busy with her own affairs to look after those of her neighbors. In heathen countries it is a great disgrace for a woman’s voice to be heard in the presence of men. Where women are held back from the real interests that concern them and for which they have so often proved themselves fully qualified, what else could take up their active minds but the pettiness of gossip?

Such are the beautiful tributes paid to women by Solomon, the wisest of men. Nor are the prophets behind in acknowledging the worth and quality of women. Eight hundred years before the Christian era, the prophet Joel wrote, “And it shall come to pass in the last days, saith God, I will pour out of my Spirit upon all flesh: and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, and your young men shall see visions, and your old men shall dream dreams: and on my servants and on my handmaidens I will pour out in those[16] days of my Spirit; and they shall prophesy.” In the Christian dispensation, the daughters as well as the sons were to be filled with the Spirit of God, and the Spirit would use their lips in the declaration of His truth as certainly as the lips of men, and Paul defined prophecy to be speaking “unto men to edification, and exhortation, and comfort.” It has been one of the devices of the evil one to padlock the lips of that half of the race who are most loyal to God and who have the most helpful knowledge of human nature.

Aside from all these high social and spiritual relations of the Hebrew women, they had a legal status. The rights of the Jewish wife were carefully guarded. Her husband was not allowed to go to war for a year after they were married; and though the eastern institution of polygamy was not utterly prohibited, yet it was so restricted that it must not in any way invade the rights and privileges of the wife. If a husband became jealous of his wife’s fidelity, the legal presumptions were all in her favor. The husband was not allowed to inflict summary punishment; but she was subjected to an ordeal which could by no possibility work injury to her, unless through the guilt of her own conscience or the interposition of divine Providence.

As a mother, the Jewish woman must be honored by her children. As a daughter, she had rights and an inheritance. If the wife or daughter uttered rash and foolish vows, the husband or father had a right to disannul them, provided he did it from the day it came to his knowledge. Even the Gentile woman taken captive by a young Israelite warrior must have been surprised to receive treatment so strangely different from that received by captives in her own country, or even among modern nations who profess to be civilized. Her captor could not offer her an insult; she must be taken, not to a prison, but to his home, where she must neither be abused nor outraged, but treated with patient consideration; and she could not be taken, even as a wife, until a full month had elapsed, during which he might secure her affections or reconsider his determination. And if after her marriage she[17] was discontented and made herself disagreeable, she could never again be held as a servant, but must be allowed to go free. Widows, who in heathen lands have been degraded and sometimes murdered or burned, were to be treated with the utmost tenderness. They shared in the tithes, and were admitted to the public festivities. They had a right to glean in the fields and gather up the forgotten sheaves, to gather which the owner was not allowed to go back. Injustice against widows was treated with fearful punishment. “Thou shalt not take the widow’s raiment to pledge” (Deut. xxiv, 17), was a benevolent law which can not be paralleled in any modern code. The command to lend to an Israelite in his poverty was imperative, but no pledge of raiment could be exacted from a widow.

Thus in a variety of ways was the Lord pleased to manifest his kindness and compassion for the fatherless and the widow, and in consequence womanhood was honored and honorable in the Jewish nation, beyond anything known in the heathen world. From the vile and degrading orgies of heathenism the women of Israel were exempt. They feared the Lord, and at his hand received blessings and mercies without number.

Thus it is seen that Hebrew women had rare privileges. They tower like desert palms above the women in pagan lands. In her home she is honored and respected. In India a woman eats her first and last meal with her husband on her wedding day. In the Hebrew home her children are like “olive plants” round her table. In China they may kill their little daughters by the thousands. She has legal rights in her Hebrew home. In all Mohammedan lands a man has the same power over the life of his wife that he has over the life of his horse.

What makes this difference? We answer, It is God’s thought of womanhood, for there was nothing in the Hebrew men to bring about such thoughtful consideration. There were periods in the history of the Hebrew nation when they departed from God, and sank into the vices of the heathens[18] around them. It was during these periods that womanhood was degraded to that of their pagan sisters. There were times when the Hebrews had taken on heathen manners to such an extent as to regard it a disgrace for a rabbi to recognize his wife if he met her on the street. It was commonly said that he was a fool who attempted the religious instruction of a woman, and the words of the law had better be burned than given to a woman.

So it was not Hebrew manhood that saved the daughters of Israel from the suicidal injustice practiced among the heathens, but the sure Word of God. Under its wise provisions and recognized equality they became prophetesses, leaders of armies, and judges. And they taught a pure morality, trained their children according to principles of justice and righteousness, and lived in expectation and hope of the coming of the Messiah in whom all the nations of the earth were to be blessed.

And above all, Christ was the true Friend of womanhood. No teacher in any age of the world or in any land ever taught woman as He did, when He came that glorious morning to Jacob’s well, or in the house of Simon the Pharisee, when the sin-stained woman of the street, who had unobserved entered the banquet hall, and taken up her position at the feet of Jesus, and there poured out the great sorrow of her heart in a paroxysm of humble and grateful love, and bathed His feet with her tears, and wiped them with the hair of her head, anointing them also with ointment, when He personally addressed her and said, “Thy sins are forgiven.” How beautiful is all this, and how grandly these women showed their gratitude and appreciation by following Him and ministering unto “Him of their substance.” They were last at the cross and first at the tomb, and first to publish the Saviour’s resurrection.

From that day to this, women owe their spiritual elevation and their opportunities of usefulness to the recognition Christ gave them in His ministry. In all places untouched by Christian light they are not sure that they have souls. Where[19] the light shines clearly they have equal rights with the men by whose side they are privileged to labor for God’s glory. This being so, how ought they to love God, and in every way possible, spread the light of Christianity through all the earth. We would say to every woman who loves her Lord, the field is wide enough, and opportunities present themselves in every passing hour, therefore, if you have a message which will help and bless some struggling soul heavenward, tell it.

With these brief, introductory words, we come to our subject proper. And should you, dear woman, whom we seek to glorify in the following pages, be blessed and comforted in the unfolding of God’s love towards womanhood, and your own faith take a firmer hold upon the Father’s thought of you, do not, after reading this book, put it away in your book-case, but place it in the hands of some tempted, discouraged, struggling soul, and thereby let others become sharers of the same helpful words, and, possibly, in so doing, you may not only save precious souls, but add many stars to your own crown of life.

As ever, respectfully,

THE AUTHOR.

Albany, N. Y.

[20]

WOMEN IN WHITE RAIMENT.

Man’s First Home a Garden—Eve the Isha—The Scene of the Temptation—Hiding from God—Refusing to Confess, Judgment is Pronounced—The Sad Results of Sin—Eve Believed the Promise.

Perhaps there never lived a woman who has been “talked about” so much as this first woman in White Raiment, for who has not said, If Eve had not been beguiled into a violation of the one commandment by partaking of the fruit of the forbidden tree, we would all be as happy and sinless as was she and her husband before that act of disobedience. But we shall miss the great lesson Eve’s experience intended to convey if we fail to recognize that God put humanity on probation, and the fact of the first temptation is the symbol of every temptation; the fact of the first fall is the symbol of every transgression; the great mistake that lay in the first sin is the symbol of every effect of sin.

After the Lord God had formed man, we read that He “planted a garden eastward in Eden; and there He put the man.” What pen could describe the garden of the Lord’s planting? There were splashing fountains. There were woodbine, and honeysuckles, and morning-glories climbing over the wall, and daisies, and buttercups, and strawberries in the grass. There were paths with mountain mosses, bordered with pearls and diamonds. Here and there cooling streams sparkled in the sunlight or made sweet music as they fell over ledges and rippled away under the overstretching shadows of palm trees or fig orchards, and their[22] threads of silver finally lost amid the fruitage of orange groves. Trees and shrubs of infinite variety added their beauty to the many picturesque scenes everywhere spread out. In the midst of the overhanging foliage were all the bright birds of heaven, and they stirred the air with infinite chirp and carol. Never since have such skies looked down through such leaves into such waters. Never has river wave had such curve and sheen and bank as adorned the Pison, the Havilah, the Gihon and the Hiddekel, even the pebbles being bdellium and onyx stone. What fruits, with no curculio to sting the rind! What flowers, with no slug to gnaw the root! What atmosphere, with no frost to chill and with no heat to consume! Bright colors tangled in the grass. Perfume filled the air. Music thrilled the sky. Great scenes of gladness and love and joy spread out in every direction.

We know not how long, perhaps ever since this man had been created in the “image” of his God, he had wandered through this Eden home, had watched the brilliant pageantry of wings and scales and clouds, and may have noticed that the robins fly the air in twos, and that the fish swim the waters in twos, and that the lions walk the fields in twos, and as he saw the merry, abounding life of his subject creatures, every one perfectly fitted to its environment, and each mated with another of the same instincts and methods of living, he felt the isolation of his own self-involved being, and, possibly, a shadow of loneliness may have crept into his face, and God saw it. And so He said, “It is not good that the man should be alone.” So “He caused a deep sleep to fall upon Adam,” as if by allegory to teach all ages that the greatest of earthly blessings is sound sleep.

When he awoke, a most beautiful being, the crowning glory of creation, stood beside him, looking at him with heaven in her eyes, her exquisite form draped with perfect feminine grace and strength. As Adam looked into the face of this immaculate daughter of God, this Woman in White Raiment, he said, “This is now bone of my bones, and flesh[23] of my flesh. She shall be called Woman” (Hebrew Isha), because God had clothed in separate flesh the gentler and more conscientious part of Adam’s nature, that it might share the work and bliss of Paradise.

How long that first married pair lived in Paradise we are not informed. The story of their disastrous disobedience is given in as few words as possible. Eve may have sauntered out one beautiful morning and as she looked up at the fruit of the various trees of the garden must have recognized “the tree of the knowledge of good and evil,” and doubtless she had heard Adam say that this was the forbidden tree, and possibly may have cautioned her, “For,” said he, the Lord had said, “in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die.” As she looked up at the tree and saw the beautiful fruit hanging on the branches, she may have admired its bright, fresh color without any thought of evil in her heart. It is the characteristic of woman to admire the beautiful. Indeed her finer feelings can better appreciate than man, the blendings of color and shadings that combine to give expression to the beautiful.

But it was Satan’s moment. We do not know how long he had been in hiding among the recesses of the garden waiting for just such an opportunity. Quickly he entered a serpent, which, it is declared, “was more subtle than any beast of the field,” and came up to Eve as she admired the tree and its fruit, and in most questioning surprise said, “Yea hath God said, Ye shall not eat of every tree of the garden?” The query is very cautiously made, expressing great surprise: Yea, truly, can it be possible? The query, with its questioning surprise, had in it now a yes, and now a no, according to the connection. This is the first striking feature in the beginning of the temptation. The temptation of Christ, in the wilderness, was very similar to this. Satan twice challenged our Lord on the point of his divine Sonship: “If thou be the Son of God.” As if he had said, “You claim to be the Son of God, I doubt it, and challenge the claim. If you are, prove it by doing what I suggest.”[24] This was also a blow at the confession of God Himself, “This is My beloved Son.” So here, Satan, in the most cautious manner, would excite doubt in the mind of Eve. Then the expression also aims to awaken mistrust at the goodness and wisdom of God, and so weaken the force of the temptation. As if he had said, “What, not eat of every tree of the garden? I doubt it. Such a prohibition seems unreasonable.”

Here Eve would assure the tempter that she was not mistaken in regard to the prohibition. “We may eat of the fruit of the trees of the garden. But of the fruit of the tree which is in the midst of the garden, God hath said, Ye shall not eat of it, neither shall ye touch it, lest ye die.” Notice the Italic words are added by Eve to the command of God concerning the tree. No doubt, as she stood there admiring the tree, the monitor of her heart kept saying, “Don’t touch it, don’t touch it,” and, in her guileless simplicity, she adds the words to the prohibition. And yet by this very addition does her first wavering disguise itself under the form of an overdoing obedience. The first failure is her not observing the point of the temptation, and allowing herself to be drawn into an argument with the tempter; the second, that she makes the prohibition stronger than it really is, and thus lets it appear that to her, too, the prohibition seems too strict; the third that she weakens the prohibition by reducing it to the lesser caution. God had said, “Thou shalt surely die.” She reduces it to “lest ye die,” thus making the motive of obedience to be predominantly the fear of death.

Her tempter, who could quote Scripture to our Lord in his second temptation, after he had failed in the first, was quick to take up the woman’s rendering of the prohibition, and makes answer, “Ye shall not surely die!” What an advance over the first suggestion, “Yea, hath God said.” No doubt he had noted her wavering, and, instead of turning promptly away from the author of her wavering, saw her disposed to inform him of what God had said concerning this “tree of the knowledge of good and evil,” and he promptly steps out from the area of cautious craft into that of a reckless denial[25] of the truth of God’s prohibition, and a malicious suspicion of its object. Eve had not repeated the words of the prohibition, and of the penalty, in its double or intensive form, but Satan repeats it, in blasphemous mockery, as though he had heard it in some other way, and stoutly denies the truth of the threatening, that is, the doubt becomes unbelief.

The way, however, is not prepared for the unbelief without first arousing a feeling of distrust in respect to God’s love, His righteousness, and even His power. So the tempter denies all evil consequences as arising from the forbidden enjoyment, whilst, on the contrary, he promises the best and most glorious results from the same. “Instead of your eyes closing in death,” he said, “they shall be opened.” The tempter would have the woman believe that, in eating of the fruit, she would become wonderfully enlightened, and, at the same time, raised to a divine glory—“shall be as gods, knowing good and evil.” And so, in like manner, is every sin a false and senseless belief in the salutary effects of sin.

We tremble for Eve at this point of her interview with her tempter. It is an awful moment, a moment in which her own happiness and that of her husband’s and all the generations of earth are in the balances.

“And when the woman saw.” She was now looking at the tree and its fruit from a far different standpoint from that in the morning. She beheld it now with a look made false by the distorted application of God’s prohibition by her tempter. In fact, she had become enchanted by the distorted construction put upon God’s plain commandment. The satanic promises seemed to have driven the threatening of that prohibition out of her thought. Now she beholds the tree with other eyes. Three times, it is said, how charming the tree appeared to her.

But where has Adam been all this time? Doubtless he was busy with his duties, for God had set him “to dress and to keep” the garden in which he had been placed. He may have seen Eve passing down one of the beautiful paths of the garden in her morning walk, beguiled by the splash of[26] the fountains, the song of the birds, and the beauty of the flowers at her feet. He may have observed her stay longer than usual, and so turned aside from his duties to see what had become of her, and following down the path over which he had last seen her disappear among the trees and shrubbery of the garden, soon came to the place where “the tree of the knowledge of good and evil” stood, and then, from the lips of his own pure, sweet wife, learned what had taken place. Possibly she was holding the very fruit of which she had said, “neither shall ye touch it,” in her hands, admiring its beauty and wondering how it tasted. And, while examining the fruit, she told her husband what had passed between her and her tempter, and as she finished her story she said, “I do not think there can be any harm in my just breaking the rind of it, to see how it looks inside.” Prompted by womanly curiosity, she broke open the fruit, and, before she was really conscious, she “did eat!” “Why, how nice!” she exclaimed, at the same time handing the other half to her husband. As a good gardener, he would naturally share the curiosity of his wife to taste this fruit, “and he did eat!”

The next statement we have, “And the eyes of them both were opened.” But how were they opened? Each of them had two good eyes before eating the fruit; in fact, Eve had been admiring the fruit as it hung among the branches of the tree, and as she had turned it over in her hands. Before they tasted they saw with their natural eyes. Now they see with a higher knowledge of sense—there is added a con-sense—a conscience or self-consciousness. In the relation between the antecedent here and what followed there evidently lies a terrible irony. The promise of the tempter becomes half fulfilled, though, indeed, in a sadly different sense from what they had supposed. They had attained, in consequence, to a moral insight. Self-consciousness was awakened with their knowledge of right and wrong, good and evil. It belongs to the very beginning of moral cognition and development.

[27]How strange it all is. Eden full of trees, fruits of every kind, luscious and satisfying, but, excited by false and wicked statements in respect to the prohibition of the fruit of one tree, she straightway desires to taste for herself, and that curiosity blasted her and blasted all nations. And thousands in every generation, inspired by unhealthful inquisitiveness, have tried to look through the keyhole of God’s mysteries—mysteries that were barred and bolted from all human inspection—and they have wrenched their whole moral nature out of joint by trying to pluck fruit from branches beyond their reach.

We may also learn that fruits which are sweet to the taste may afterward produce great agony. Forbidden fruit for Eve was so pleasant she invited her husband also to take of it; but her banishment from paradise and years of sorrow and wretchedness and woe paid for that luxury.

Sometimes people plead for just one indulgence in sin. There can be no harm to go to this or that forbidden place just once. Doubtless that one Edenic transgression did not seem to be much, but it struck a blow which to this day makes the earth stagger. To find out the consequences of that one sin you would have to compel the world to throw open all its prison doors and display the crime, throw open all its hospitals and display the disease, throw open all the insane asylums and show the wretchedness, open all the sepulchres and show the dead, open all the doors of the lost world and show the damned. That one Edenic transgression stretched chords of misery across the heart of the world and struck them with dolorous wailing, and it has seated the plagues upon the air and the shipwrecks upon the tempest, and fastened, like a leech, famine to the heart of the sick and dying nations. Beautiful at the start, horrible at the last. Oh, how many have experienced it! Beware of entertaining temptations to first sins! Turn away and flee for thy life to the sure and only Refuge—Christ Jesus.

In the cool of the day, as the evening hours drew on, Adam and Eve “heard the voice of the Lord God walking[28] in the garden.” They were used to hearing that voice walking in the garden in the cool of the day. Eden had become a dear spot to the heart of their Father, and doubtless He often came down to converse with them. So now He seeks companionship with the majestic human masterpieces of His creation. And why should he not?

But, passing strange! instead of running to Him out of their Eden home, as doubtless they had been wont to do, “Adam and his wife hid themselves from the presence of the Lord God amongst the trees of the garden.” This act, no doubt, was prompted by self-consciousness and the shame and guilt which it brought. So we clearly see that sin separates from God. They had pronounced judgment upon their transgression by their very conduct. Instead of meeting God as they had been doing, a feeling of distrust and servile fear entered their hearts, and a sense of the loss of their spiritual purity, together with the false notion that they can hide themselves from God. And so it has come to pass that ever since the first transgression men have been hiding from God, running away from his presence.

“And the Lord God called unto Adam, and said unto him, Where art thou?” The Lord is the first to break the silence; the first to seek erring humanity. Not for His own sake does God direct this inquiry, for He knew where Adam was, but that Adam might take courage and open his mouth in confession—it was an invitation to tell the whole sad story. But, instead, he multiplies the difficulties by his answer, “I was afraid, because I was naked.” That is to say, Adam, instead of confessing the sin, sought to hide behind its consequences, and his disobedience behind his feeling of shame. His answer to the interrogation is far from the real cause of the change that had come over his conduct, which was sin, and made his consciousness of nakedness to be the reason. To still make Adam see the true reason for his hiding, God farther asked, “Hast thou eaten of the tree whereof I commanded thee that thou shouldst not eat?” Observe this question is so framed as to[29] contain in it the eating and the tree from which he ate, and could have been answered with, “Yes!” How easy God made it for Adam to confess. But, alas! How far from it. He answered, “The woman whom thou gavest unto me, she gave me of the tree and I did eat.” How deep the root of sin had taken hold upon Adam’s heart. What does he say in this answer? Why this, he acknowledged the guilt, but indirectly charges God as the author of the calamity. Eve is referred to as “the woman” who is the author of his sin, and, since she was given to him by the hand of the Lord, therefore it is the Lord’s fault, for if He had not given her to Adam, he would not have partaken of the forbidden tree! How passing strange is all this. And yet that is just what men are doing after six thousand years of experience with sin. Instead of breaking away from it, they say, God put it before them, and they could not resist the temptation to sin. The loss of love that comes out in this interposing of the wife is, moreover, particularly observable in this, that he grudges to call her Eve (Isha—married) or my wife.

Failing to return unto God by way of confession, the Lord next deals with Adam in judgment. “Cursed is the ground for thy sake ... thorns also and thistles shall it bring forth to thee.” The very soil he had been sent to cultivate, and to carry forward in a normal unfolding, to imperishable life and spiritual glory, is now cursed for his sake, and therewith changed to that of hostility to him. Referring to the curse upon mankind, in consequence of the fall, Hugh MacMillan has called attention to the remarkable fact that weeds, the curse of the cultivator, accompany civilization. “There is one peculiarity about weeds which is very remarkable,” says this writer, “namely, that they only appear on ground which either by cultivation or for some other purpose, has been disturbed by man. They are never found truly wild, in woods or hills, or uncultivated wastes far away from human dwellings. They never grow on virgin soil, where human beings have never been. No weeds exist in those parts of the earth that are uninhabited, or[30] where man is only a passing visitant.” And what is true of mother earth is in a sense true of the human heart. The youthful mind no sooner awakes to thought and reason, than it gives evidence of abundance of weeds. In surprise the mother asks where the little one has learned disobedience and questions how so young a mind can assert such strong opposition to wholesome discipline.

And now, lest a worse calamity should fall on Adam and his wife, by stretching forth their hands “and take also of the tree of life, and eat, and live forever,” God “drove out the man” from Eden, and placed “cherubims, and a flaming sword which turned every way, to keep the way of the tree of life.” The act of driving Adam and Eve out of Eden has always been looked upon as a harsh measure. If, however, we stop to reflect what awful consequences would have followed the rash act of eating of the tree of life, we shall see that it was an act of mercy. For, after placing himself under the law of sin, what endless sorrow would have come upon the race, if men could not be removed by death. Think of such human monsters as history has time and again produced. Men and women degraded by thousands of years in sin would indeed be dangerous characters. So God cut off this possibility by guarding the tree of life.

But there came a great change over all life. Beasts that before were harmless and full of play put forth claw and sting and tooth and tusk. Birds whet their beak for prey, clouds troop in the sky, sharp thorns shoot up through the soft grass, blastings are on the leaves. All the chords of that great harmony are snapped. Upon the brightest home this world ever saw our first parents turned their back and led forth on a path of sorrow the broken-hearted myriads of a ruined race.[31]

THE ACCEPTED OFFERING.

When Eve looked into the face of her first-born, she remembered the words of the Lord, in His judgment upon Satan, “I will put enmity between thee and the woman, and between thy seed and her seed; it shalt bruise thy head and thou shalt bruise his heel,” and, misunderstanding the meaning of the promise, she called him Cain, meaning, “I have gotten a man from the Lord,” mistaking him for the Redeemer. But how bitter must have been her disappointment as she saw the child grow up, saw his characteristics manifest themselves in acts of hatefulness and revenge. However, but little is said of Cain and his younger brother Abel, until they bring their offerings to the Lord. We read that Abel was a “keeper of sheep,” and Cain was a “tiller of the ground.” While it is not stated, we must believe[32] these brothers knew what was, and what was not, an acceptable offering to the Lord, that Cain could easily have exchanged his fruits of the soil for a lamb of Abel’s flock. Evidently Cain was lacking in that fine moral insight which would lead him to have respect as to the nature of the sacrifice necessary to atone for sin. There must be the shed blood of the victim, for, “without shedding of blood,” there is no remission. Either Cain did not regard himself a sinner, or, if he did, he thought one sacrifice as good as another, and so he brings “of the fruit of the ground an offering unto the Lord.” God could not accept this act of disobedience. Because his offering was rejected, and seeing Abel’s offering accepted, Cain rose up and slew his brother. He failed to shed the blood of a lamb for his sin, but was quick to shed the blood of his brother, and thereby add to his sin. But what a crushing blow was this to the hopes of the mother heart who had supposed that her first-born was the promised “seed.” How she must have broken down under her sorrow, as she saw the blood dripping from Cain’s fingers, and that, too, the blood of his own brother. And sadder still as she looked upon the face of death for the first time. However she might have understood the lying words of her tempter, “Ye shall not surely die,” she now sees in the lifeless body of her second child, the awful reality of death. And when the first grave was made, how she must have daily wept over the precious mound, not only over this her first experience in bitter bereavement, but also over the circumstances under which it was brought about, and as she plants the flowers on the tomb, she fancies she hears the blood of the innocent victim continually crying unto heaven to be avenged. Oh, the bitter, bitter fruits of disobedience, who can know to what misery they bring us?

And then also observe Cain’s conduct in this awful crime. God’s arraignment of this fratricide was analogous to that of Adam and Eve. But Cain evades every acknowledgment of it. He not only tells a barefaced falsehood, but in a most impudent manner asks, “Am I my brother’s keeper?”[33] What a fearful advance on the timid explanations of Adam’s transgression as he spoke to the Lord out of his hiding place. How men should tremble at the very thought of sin.

But the sorrowing Eve took heart once more in the birth of Seth, “for,” said she, “God hath appointed another seed instead of Abel.” So hope in the heart, like the perpetual altar fires in the sacrifices of the temple, seemed to sing a sweet song of comfort, and every child born seemed to outweigh the bitter disappointments in the realization of the promised Redeemer.

With this hope in the heart of Eve, and this beautiful language upon her lips, the Scripture account closes. How long she lived after the birth of Seth we are not informed, but of this we are assured, she believed God in His promise of the Messiah. That she misunderstood when that promise was to be realized, is quite evident, but there is every reason to believe she died in the faith of its ultimate realization, for she judged God to be righteous in the promise.

What is the lesson the loss of Paradise has for us? Plainly this: The perverted use of things good in themselves. Eve saw that the tree was pleasant to the eyes. From that day to this there have been women who would throw their health, their home happiness, their chance of training their children for God, their life, their honor, their hope of heaven, into a cauldron out of which might be brought something pleasant to the eyes. Eyes are good, useful and necessary, but we need to make a covenant with them not to see more than is good for our souls.

After she saw, she “desired.” This would seem to imply that the real source of all sin is in the spirit of our own desires. The last of the Ten Commandments strikes down to the very tap-root of all evil, “Thou shalt not covet.” All sin commences with the kindling of desire. The apostle James gives us the pedigree, “Every man is tempted when he is turned away of his own lust and enticed; then, when lust and desire hath conceived, it bringeth forth sin, and[34] sin, when it is finished, bringeth forth death.” The secret of victory, therefore, is not to allow the mind and heart to dwell for a moment upon any forbidden thing. The whole modern life is terribly fitted to stimulate unholy desire. The little child is taught from infancy to covet the vain and glittering attractions of the world—dress, equipage, pleasure, praise, fashion, display and a thousand worldly allurements. The city bill boards are covered with nude harlots. There are no less than 200,000 houses for these social outcasts in our fair land. These open gateways to immorality, where the virtue of the nation is ground out, are not only guarded by police force, but young girls by the 100,000 a year are stolen from country homes by the paid agents, and sold into these open dens of vice and crime, where these poor girls die in a short time, the average length of this life of sin being only five years. And still the people have not a word to say for the suppression of these crime-breeding dens of vice, but legalize and protect them by law to the ruin of our homes. These are the things that are eating out the spiritual life of the nation, and for that reason many do not want to retain the thought of God in their hearts. Hence the responsibilities of life are pressing upon us. As you have seen the child trundling its little hoop by touching it on both sides alternately to keep it from either extreme, so God teaches us both with warning and with promise, as our spiritual condition requires. Sometimes it is warning we need, and He shouts in our ear the solemn admonition, as a mother would cry to her babe in wild alarm if in danger of falling over the precipice. But, again, when we are in danger of being too much depressed, He speaks to us with notes of encouragement and promise, and tells us there is no real danger of our failing utterly, and that He will never suffer us to be tempted above what we are able. And so we hear Him saying on one hand, “Let him that thinketh he standeth take heed lest he fall;” but immediately after adding on the other side, “God is faithful, who will not suffer you to be tempted above that ye are able, but will,[35] with the temptation, make a way of escape that ye may be able to bear it.”

We are also impressed with the influence woman has for good or evil. What we need as a nation is consecrated womanhood. When at last we come to calculate the forces that decide the destiny of nations, it will be found that the mightiest and grandest influence came from home, where the wife cheered up despondency and fatigue and sorrow by her own sympathy, and the mother trained her child for heaven, starting the little feet on the path to the celestial city, and the sisters, by their gentleness, refined the manners of the brother, and the daughters were diligent in their kindness to the aged, throwing wreaths of blessing on the road that led father and mother down the steep of years. God bless our homes. And may the home on earth be the vestibule of our home in heaven.

Sarah the Beautiful Princess—Her Faith Tested—The Mistake of Her Life—Her Lovely Character—Rebekah—An Oriental Wooing—Eliezer’s Prayer—The Bride’s Answer—Meeting Isaac—A Mother’s Love for Her Son—Jacob’s Flight—Rebekah, the Beautiful Shepherdess—Seven Years’ Service for Her—Laban’s Deception—Leah, the Tender-Eyed—Human Favorites—Divinely Honored—Rachel’s Tomb the First Monument to Human Love.

From the prominence given to Eve in connection with the temptation and the overwhelming disasters which followed the loss of the Eden home in Paradise, we are surprised the Sacred historian passes over a period of about two thousand years without giving us any record of women. The names of good men are mentioned. Enoch walked before God for over three hundred years, and the walk was such a perfect one, and it pleased God so well, that He translated Enoch. Noah also “found grace in the eyes of the Lord,” and he was “a just man and perfect in his generations,” and “walked with God,” doubtless as Enoch had done. No doubt there were others who lived clean, pure lives. Of this number was Lamech, the father of Noah, for he was comforted in the birth of his son, saying, he “shall comfort us concerning our work and toil of our hands, because of the ground which the Lord hath cursed.” Surely such men must have had good mothers to train them, and good wives for companions. But nothing is said about these women that walked in White Raiment in that dark and sinful age, when “all flesh had corrupted his way upon the earth,” until Sarah, the fair wife of Abraham, is reached.

We find this beautiful princess willing to leave her home and her people in the land of Ur of the Chaldees and journey[37] for more than a thousand miles to the land of Canaan. However, this journey was not a continuous one, for a long stop was made at Haran, in Mesopotamia, perhaps half way between Ur and Palestine.

Of her birth and parentage we have no certain account in Scripture. In Gen. xx, 12, Abraham speaks of her as “his sister, the daughter of the same father, but not the daughter of the same mother.” The Hebrew tradition is that Sarai is the same as Iscah, the daughter of Haran. This tradition is not improbable in itself, and certainly supplies the account of the descent of the mother of the chosen race.

The change of her name from Sarai to Sarah was made on the establishment of the covenant of circumcision between Abraham and God, and signifies “princess,” for she was to be the royal ancestress of “all families of the earth.”

The beautiful fidelity of this noble woman is shown in her willingness to accompany her husband in all the wanderings of his life. Her home in Mesopotamia was gladly and willingly exchanged for a tent, and that tent was often taken down and set up during the nomadic life which formed the basis of the patriarchal age. God intended to set forth in Abraham not only the thought that here man has no continuing city, but also the life of faith. And this faith of Abraham is distinguished from the faith of the pious ancestors in this, that he obtained and held the promises of salvation, not only for himself, but for his family; and from the Mosaic system, by the fact that it expressly held the promised blessing in the seed of Abraham, as a blessing for all people. But this faith had not only to be developed, but also tested. It is beautiful to read that Abraham believed God, but his faith when he went down into Egypt was far from that when he went “into the land of Moriah” to offer up Isaac. Nothing is plainer in the Bible than that a man’s faith is not a matter of indifference. He can not be disobedient to God’s calls, and yet go to heaven when he dies. This is not an arbitrary decision. There is and must be an adequate ground for it. The rejection of God’s dealings with us is as[38] clear a proof of moral depravity, as inability to see the light of the sun at noon is a proof of blindness.

Now let us look at a few of these testings or trials of faith that came into the life of this woman in White Raiment, this princess in Israel. She was asked to give up her native land. How dear the fatherland is to the heart, only those who have passed through the experience can realize. This was not all. She was asked to give up her kindred. To move away from all the associations of childhood and youth, requires a brave heart. But she was also asked to give up her home, and what is dearer to a woman’s heart than her home? We have no doubt Sarah’s home by the beautiful streams that flow down from the high table-lands of Armenia into the rich valleys of Mesopotamia, was a lovely one, and to exchange it for tent-life was a brave sacrifice. Her love to God must have been deep and constant.

After a long, weary journey through the desert sands, the land of promise is finally reached, only to find it afflicted with a famine. How often Sarah must have longed for one look out over the fig orchards, the olive yards and waving grain fields ripening in the summer’s sun of her native Mesopotamia, as she looked out over the barren hills, burned-up fields, and dried-up water courses of Palestine. Night after night, Abraham’s tent is pitched, only to be taken down in the morning, in quest of pasturage for their herds and flocks, until the wilderness in the southern extremity of Canaan is reached. How all this must have tested their faith. Had they not mistaken the call of God? Is it possible that this parched land is the land of promise? How disappointments and failures test our faith, and the heart of poor Sarah must have been sorely tried.

But there was yet another test, and a humiliating one at that, and it seems to look as if their united faith was wavering. She was a beautiful woman, and they were now upon the very borders of Egypt, and there was no other alternative but to perish with famine or to go down into the land of the Pharaohs. Both Abraham and Sarah seemed to realize[39] the hazard they were running, for, possibly, the bloom and beauty of Sarah’s face might cost Abraham’s life. So they agreed between them that Sarah should say that she was his sister, lest he should be killed. The declaration was not false. She was his half-sister, but it was not the whole truth, and it would seem, from their present conduct, that their faith, tested by the famine, was now wavering, for, why not appeal their cause to God, instead of taking it into their own hands? The reason for resorting to this deception was, if she was regarded as his wife, an Egyptian could only obtain her, when he had first murdered her husband. But if she was his sister, then there was a hope that she might be won from her brother by loving attentions and costly gifts, or, if her beauty came to the notice of Pharaoh she would be taken to his harem by arbitrary methods. They had not reasoned in vain. The princes of the land saw her, “and commended her before Pharaoh,” and “Sarah was taken into Pharaoh’s house.”

It is hard for us to understand what a trial of her faith this harem life must have been to the pure-minded Sarah. How often her mind must have gone out over the stretches of desert wastes to her own land abounding with streams and fertility. And to be conscious that the charms of her person were the centre of attraction in the court of Egypt.

But all this time God’s eye was a witness to all that was passing. When we get to the end of self, He always comes to our rescue—our extremity is His opportunity. In her resided the religious disposition in the highest measure, and just at a time when the nations appeared about to sink into heathenism, hence her faith must be saved to the race, so “the Lord plagued Pharaoh with great plagues,” that is to say, God administered “blow on blow,” and these were of such a nature as to guard Sarah from injury. At length the ruler of the land, whose heart does not seem to be hardened like the later kings, concludes that his punishment is for the sake of Sarah, and restores her to Abraham.

[40]After Abraham had separated from Lot, the Lord again appeared unto him, at which time Abraham complained for the want of an heir. So the Lord leads Abraham out of his tent, under the heavens as seen by night, and in that land of blue skies, the night heavens are beautiful indeed. God had promised at first one natural heir, but now the countless stars which he sees, should both represent the innumerable seed which should spring from this one heir, and at the same time be a warrant for his faith.

At this point the human element again seeks to aid in bringing about the realization of the divine promise. The childless state of Abraham’s house was its great sorrow, and the more so, since it was in perpetual opposition to the calling, destination, and faith of Abraham, and was a constant trial of his faith. Sarah herself, doubtless, came gradually more and more, on account of her barrenness, to appear as a hindrance to the fulfillment of the divine promise, and as Abraham had already fixed his eye upon his head servant, Eliezer of Damascus, so now Sarah fixes her eye upon her head maid, Hagar the Egyptian. It must be this maid not only had mental gifts which qualified her for the prominent place she occupied in the household, but also inward participation in the faith of her mistress. So Hagar is substituted, for, in the substitution, Sarah hopes to carry forward the divine purpose of the family. In this she certainly practiced an act of heroic self-denial, but still, in her womanly excitement, anticipated her destiny as Eve had done, and carried even Abraham away with her alluring hope. Though she greatly erred in this effort to assist God in bringing in the realization of the promise, and thereby revealed a lack of faith in the divine appointments, yet we have here a beautiful exhibition of her heroic self-denial even in her error. Perhaps, viewed from the human standpoint, we should here bring into our narrative also, the fact, that they had been already ten years in Canaan, and Sarah was now seventy-five years of age, waiting in vain for the heir, through whom the great blessing was to come to all the families of the earth.

[41]However, in all this, Sarah, the noble generous hearted, had not counted upon the conduct Hagar would assume in her new relation. As an Egyptian, Hagar seemed to have regarded herself as second wife, instead of recognizing her subordination to her mistress. This subordination seems to have been assumed by Abraham, and hence the apparent indifference probably was the source of Sarah’s sense of injury, when she exclaimed, “My wrong be upon thee.” She felt that Abraham ought to have redressed her wrong—ought to have seen and rebuked the insolence of the maid. Beyond a doubt, looking at the pride and insolence of Hagar, from Sarah’s standpoint, it was very trying. The Hebrews regarded barrenness as a great evil and a divine punishment, while fruitfulness was held as a great good and a divine blessing. The unfruitful Hannah received the like treatment with Sarah, from the second wife of Elkanah. It is still thus, to-day, in eastern lands. With almost the tenderness of Elkanah to the sorrowing Hannah, Abraham says, “Behold the maid is in thy hand.” He regards Hagar still as the servant, and the one who fulfills the part of Sarah. But now the overbent bow flies back with violence. This is the back stroke of her own eager, overstrained course. Sarah now turns and deals harshly with Hagar. How precisely, we are not told. Doubtless, through the harsh thrusting her back into the mere position and service of a slave. But Hagar, it appears, would not submit to such treatment. She, perhaps, believed that she had grown above such a position, and fled from the presence of Sarah.

What need was there for Sarah to learn the lesson of the patience of faith. God had promised her great honors and blessings. There was in her nature much that needed toning up by the grace of patience, and God would take his own best time in developing her life. Her haste to anticipate the blessing promised, not only delayed its realization, but brought sorrow to her own heart, and untold trouble to her posterity, for Ishmael’s hand has been “against every man, and every man’s hand against him.” The Ishmaelites,[42] it is said, “dwelt from Havilah unto Shur,” and it is certain that they stretched in very early times across the desert to the Persian Gulf, peopled the north and west of the Arabian peninsula, and eventually formed the chief element of the Arab nation, which has proved to be a living fountain of humanity whose streams for thousands of years have poured themselves far and wide. Its tribes are found in all the borders of Asia, in the East Indies, in all Northern Africa, along the whole Indian Ocean down to Molucca, they are spread along the coast to Mozambique, and their caravans cross India to China. These wandering hordes of the desert have always and still lead a robber life. They justify themselves in it, upon the ground of the hard treatment of Ishmael, their father, who, driven out of his paternal inheritance, received the desert for his possession, with the permission to take whatever he could find. Mohammed is in the line of Ishmael, and the followers of Islam, in their pride and delusion, claim that the rights of primogeniture belong to Ishmael instead of Isaac, and assert their right to lands and goods, so far as it pleases them. Vengeance for blood rules in them, and the innocent have often fallen victims to their horrible massacres. So that the disaster which overtook the race in this premature anticipation of divine Providence is second only to the disaster that overtook Eve in the temptation and the loss of Paradise. Could Sarah have foreseen all the sad consequences of her unseemly haste to pluck the unripened promise God meant to give her, she certainly would have cultivated the patience of faith.

But the years passed on—fifteen of them nearly—since the child Ishmael had been in the home of the patriarch, and the visit of the angels under the Oaks in the plain of Mamre. During this time God had once more renewed his promise to Abraham, and also the rite of circumcision had been established, and, doubtless, the symbolical purification of Abraham and his house, opened the way for the friendly appearance of Jehovah in the persons of the angels, or men, as the patriarch at first thought them to be, as he looked up,[43] while seated in his tent door through the heat of the noontide hours.

When he saw the angels, “he ran to meet them,” and, it seems, instantly recognized among the three the one whom he addressed as the Lord, and who afterwards was clearly distinguished from the two accompanying angels. “If now,” Abraham asks, “I have found favor in Thy sight, pass not away.” This cordial invitation, while it has in it the marked hospitality of Orientals, to the inner consciousness of Abraham it had a deeper meaning, the covenant relation between himself and Jehovah, that is, he hopes this relation is still continued. His humble and pressing invitation, his zealous preparations, his modest description of the meal, his standing by to serve those who were eating, are picturesque traits of the life of faith as it here reveals itself, in an exemplary hospitality. This is the custom still in Eastern lands, and is referred to by our Lord in that passage where He speaks of His second coming, and shall find His people watching, for He will “make them to sit down to meat, and will come forth and serve them” (Luke xii, 37), and seems to be one of the countless instances where, in the web of the Holy Scriptures, the golden threads of the Old Testament are interwoven with those of the New, and form, as it were, one whole. And the fact that this beautiful custom of hospitality is still observed among the Bedouins, as we can speak from personal knowledge, is remarkable, and impresses us with the thought that the covenant blessings, like some sweet, heavenly fruitage, refuses to be lost out of the lives of that ancient people.

The meal having been served in this beautiful Oriental manner, the Lord asks, “Where is Sarah?” Abraham made answer, “Behold, in the tent.” Then the Angel of the Lord, not only renews the promise, but that it should be fully realized in the birth of Isaac within a year. Sarah, behind the tent door, hears this unqualified assurance, but, viewing it from nature’s standpoint, rendered doubly improbable from her life-long barrenness, “laughed within herself.”[44] We can not regard this as a laugh of unbelief, or the scoff of doubt, as some do, but as a laugh falling short in her conception of God. The thing which was impossible according to the established laws of nature, her faith had not yet grasped as being possible with God. But the Lord, nevertheless, observed Sarah’s laugh, and this divine hearing on the part of the Angel of the Lord, startled her, and had its part in the strengthening of her faith. It prepared the way for the question, “Is anything too hard for the Lord?” To her own mind one thing, namely, that she should be a mother at ninety years of age, seemed too hard. And so the question had to do with this very thought, and must be settled on the side of her faith. And she grandly and heroically asserted her belief that nothing, not even the seeming insurmountable obstacle which nature interposed, was too great for God to overcome, and her faith was strengthened, for we read, “through faith Sarah received strength to conceive seed, and was delivered of a child when she was past age, because she judged Him faithful who had promised” (Heb. xi, 11). The trial of her patience of faith was a long struggle. It took twenty-five years to bring her up to the point where her faith could grasp the truth that nothing was too hard for the Lord to perform. But this blessed woman at length stood in right relation to God, for, without faith, be it observed, it is impossible to please God, or to receive anything at His hands.

In due time Isaac was born. It was the great event in Sarah’s life. As the mother looked down into the face of the son of her bosom she breaks forth in an exultant song of thankfulness, not unlike that of Mary, the blessed virgin. The little song of Sarah, it has beautifully been said, is the first cradle hymn. Our Lord reveals the profoundest source of this joy, when, in addressing the Pharisees, who held Abraham to be their father, said, “Your father Abraham rejoiced to see my day.” Sarah, in the birth of Isaac, is the ancestress of Christ. Spiritually viewed, the birthday of Isaac becomes the door or entrance of the day of Christ,[45] and the day of Christ the background of the birthday of Isaac.