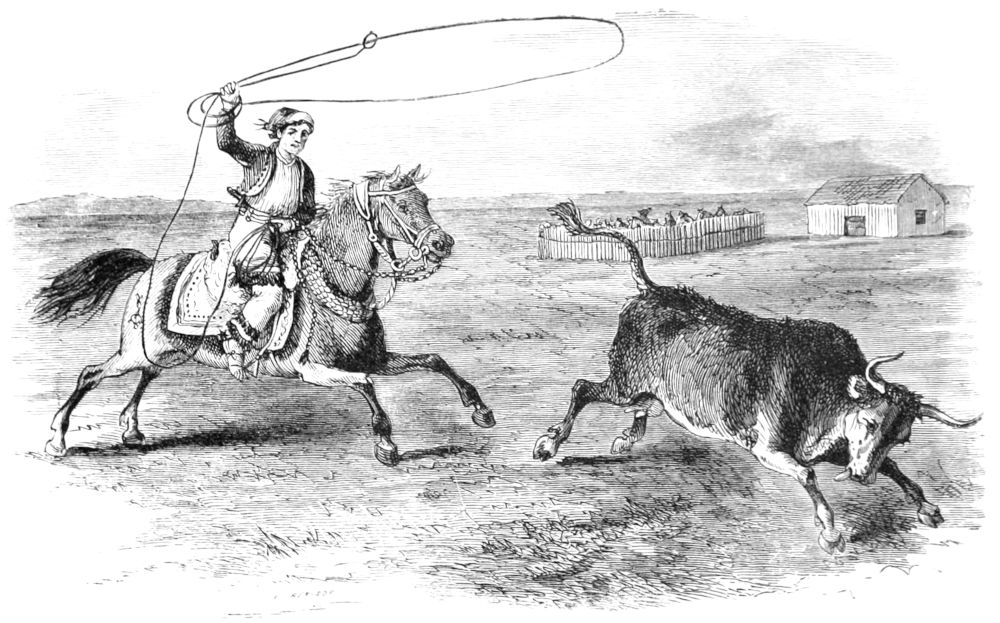

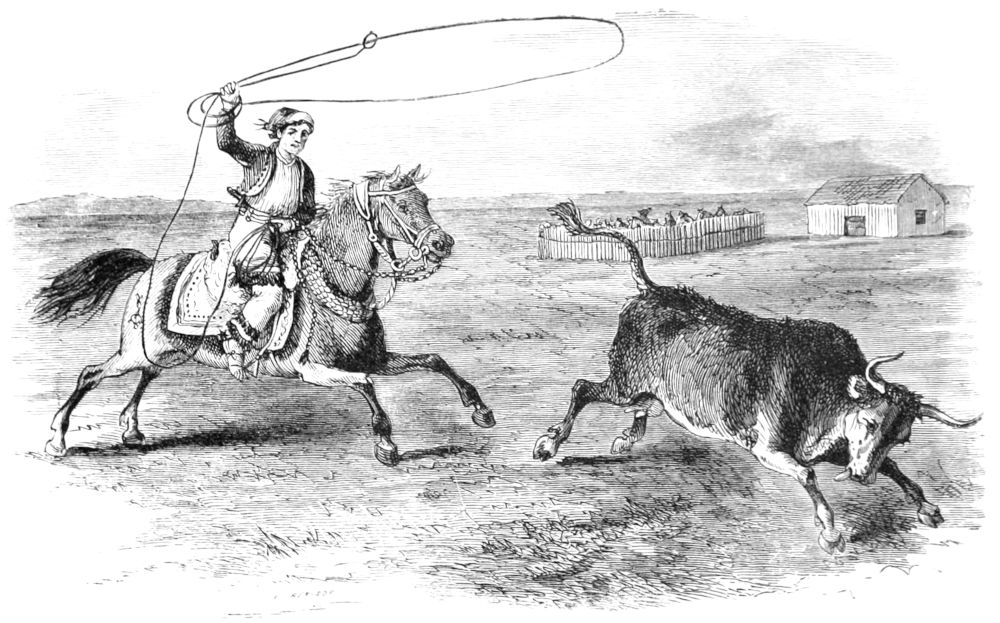

Throwing the Lasso.

[Pg 1]

A

THOUSAND MILES’ WALK

ACROSS

SOUTH AMERICA.

BY

NATHANIEL H. BISHOP.

WITH AN INTRODUCTION

BY

EDWARD A. SAMUELS, Esq.,

AUTHOR OF “ORNITHOLOGY AND OÖLOGY OF NEW ENGLAND,”

ETC., ETC.

THIRD EDITION, ILLUSTRATED.

BOSTON:

LEE AND SHEPARD, PUBLISHERS.

NEW YORK:

LEE, SHEPARD AND DILLINGHAM.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1868, by

LEE AND SHEPARD,

In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

STEREOTYPED AT THE

BOSTON STEREOTYPE FOUNDRY,

No. 19 Spring Lane.

TO

PROFESSOR SPENCER F. BAIRD,

ASSISTANT SEC’Y OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION,

This Work is Dedicated,

AS A TOKEN OF SINCERE REGARD,

BY HIS FRIEND,

THE AUTHOR.

When, a few weeks since, I saw my little book of South American travels issued from the press, I supposed that my connection with it had ended. My publishers now ask for a preface to a second edition. I take this occasion to express my thanks for the very kind manner in which my boyish descriptions of a boy’s travels have been received by the public and the press. I can only wish that my book had been more worthy of the liberal patronage and the generous praise which have been bestowed upon it.

If I had followed my own inclinations, I should have given my narrative a thorough revision, and thus have corrected some of the crudeness of my first literary effort. To this revision, however, my publishers objected, on the ground that it would raise the suspicion of genuineness as to these being the travelling observations[Pg 2] of a lad seventeen years of age, and impair also the freshness of the narrative. My book has therefore been given to the public with but slight alterations from the original draft.

I should have been glad to have made the story of my travels more fruitful in scientific results. But I had no instruments for making accurate observations, and had not the opportunity to preserve and transport many objects of natural history for comparison and verification. Such observations as I have made on topics relating to natural history, during my wandering on the inhospitable Pampas of South America, if they are superficial, I have sought to make them at least truthful.

Nathaniel H. Bishop.

Oxycoccus Plantation,

Mannahawkin, N. J.

[Pg 3]

In placing this little volume before the public, a few words, regarding the manner in which the incidents and material composing it were acquired, may be of interest to the reader.

The young gentleman who made the pedestrian trip, of which this forms the narrative, was a native of Massachusetts. I had missed him from his accustomed place for some time, but was ignorant of his contemplated journey, or even that he had gone away, until my attention was called to the following paragraph in the columns of the Boston Daily Advertiser of January 12, 1856, from its Chilian correspondent:—

“Valparaiso, November 27, 1855.

“There arrived here, a few days since, a young man belonging to Medford, Mass., who has walked across the Pampas and Cordilleras, more than a thousand miles, unable to speak the language, and with an astonishingly small amount of money.

“So much for a Yankee.”

My friend was but seventeen years of age when he entered upon his difficult undertaking; but by dint of[Pg 4] perseverance, backed by an enthusiastic love for nature, he accomplished a task that would have seemed insurmountable to many older and more experienced than himself. To use the language of Dr. Brewer, the able author of the Oölogy of North America, he was “a young and enthusiastic naturalist, whose zeal in the study of Natural History prompted him, alone, unaided, and at the risk of his life, to explore the arid plains of South America, while yet a mere lad in years and stature, though his observations there exhibit the close and careful study of maturer years.”

The young traveller started on his journey of upwards of twelve thousand miles, by sea and land, with a cash capital of forty-five dollars, and returned home with fifty; thus proving to those who wish to see the world that energy, industry, and economy are as potent to assist them in their efforts as unlimited wealth.

On his return, I requested him to furnish me with an account of his journey; this he has been unable to do, from press of business, until recently, when he gave me a copy of his journal, which, in a slightly revised form, is now published.

Edward A. Samuels.

[Pg 5]

| Page | |

|---|---|

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PASSAGE OF THE RIVER PLATA. | |

| The Bark M.—First Glimpses of Life in the Forecastle.—An old Salt, and forecastle Etiquette.—A self-constituted Guardian.—Another old Salt, and how he spliced the Main-brace.—Farewell to Boston.—The Passage.—The tropical Seas.—The Rocks of St. Paul’s, and their Natural History.—First Visit of the Pampero.—The “Doctor’s” poetical Effusions. | 11 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| IN THE RIVER PLATA. | |

| We enter the River Plata.—Land.—Montevideo.—Another Pampero.—Effects of the Hurricane.—Its Season.—We arrive at the outer Roads at Buenos Ayres. | 30 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| BUENOS AYRES—THE PROVINCE AND CITY. | |

| Letters from Home.—A Visit to the City.—Its Population.—Thistle Forests.—Agricultural Resources.—Public Edifices of Buenos Ayres.—Improvements.—Soil and Water.—Slavery and its History.—Don[Pg 6] D. F. Sarmiento.—Paper Currency.—General Rosas and his cruel Tyranny. | 35 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| VISIT TO THE TIGRE AND BANDA ORIENTAL. | |

| A new Acquaintance.—Preparations for a Journey.—The Departure.—The Cochero and his Vehicle.—Residence of the late President.—Agriculture.—Fuel.—San Fernando.—Mr. Hopkins and United States and Paraguay Navigation Company.—Yerba.—We leave the Tigre.—Arrival at the Banda Oriental.—Wild Dogs.—Estancia.—Departure for the Las Vacas River.—A Revelation.—An Ignis Fatuus.—Estancia House, and Cattle Farm.—The Proprietor at Home.—Inhospitable Reception.—The Peons.—Insulting Treatment.—An Irishman and his Opinions.—We reach the River.—Gold Prospects.—We return to the Tigre.—My Companion’s Fate. | 49 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| ASCENDING THE PLATA AND PARANÁ. | |

| Rosario.—Departure from the Tigre.—A Dialogue.—I visit the M.—The Irish Barrister’s Son.—I return to the City.—Leave Buenos Ayres.—Banks of the River.—El Rosario.—Schools, &c.—Enterprise of the People.—Diligences.—The Press.—Vigilantes.—Paraná.—Its Position.—Bank.—Railroad and its Prospects. | 68 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| A VISIT TO THE PAMPA COUNTRY. | |

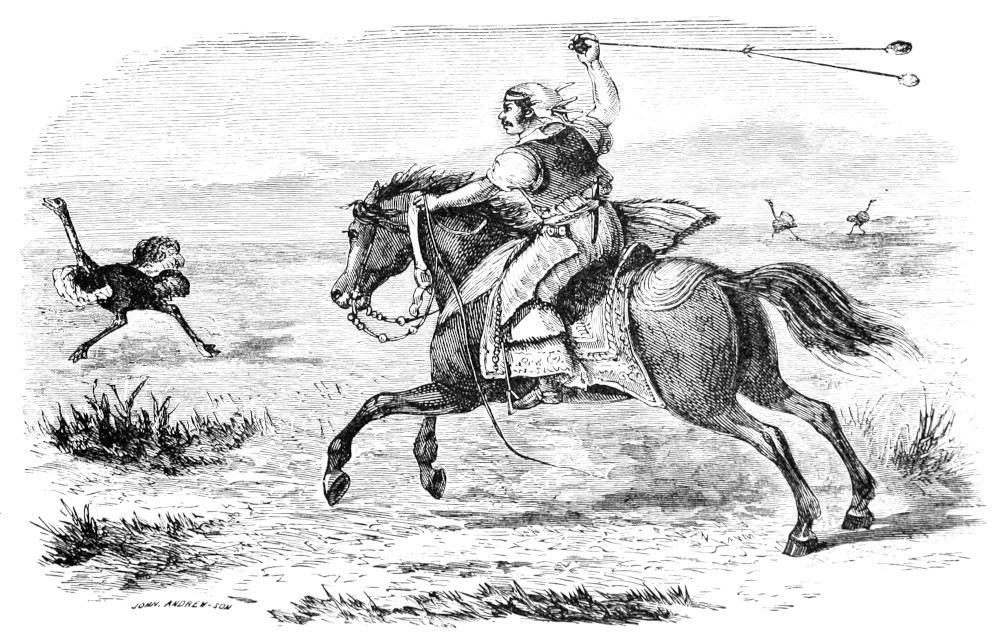

| A new Acquaintance.—An Invitation.—We set out upon the Plains.—Incidents of the Journey.—A Pampa Lord.—We visit his Mansion.—The House and its Inmates.—Cattle.—Niata Breed.—Ostriches. Riding a wild Colt.—Trial of Horses.—The Boliadores.—Estancia Life.—The Gauchos.—Duties on the Cattle Farm.—Feast Days and Aguardiente.—Customs of the Gauchos.—Training Colts.—The Herdsman’s Dress. | 76[Pg 7] |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| LIFE ON THE PAMPAS. | |

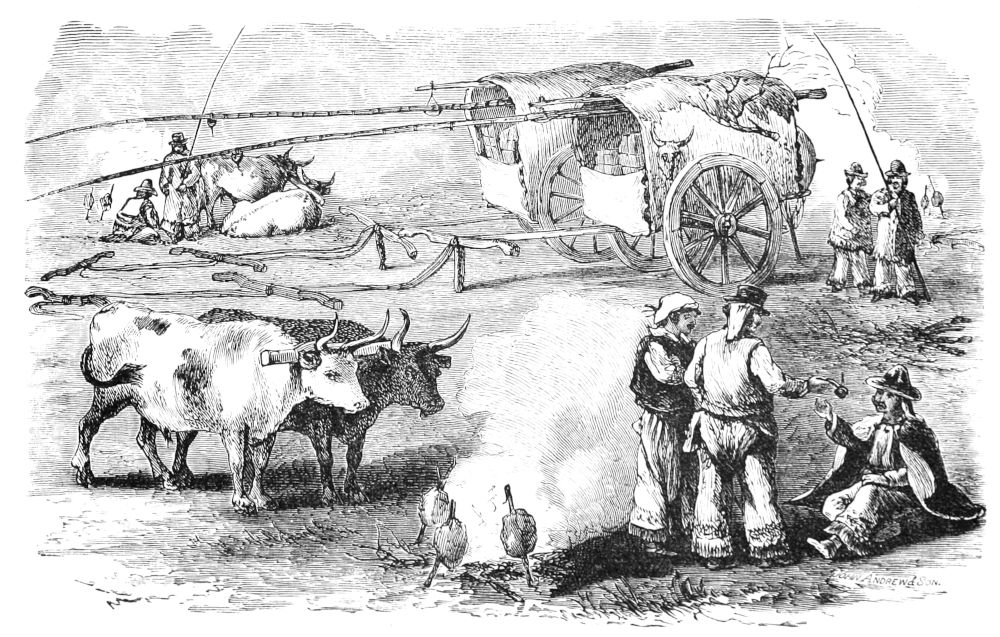

| Don José and my new Guardian.—Preparations for Departure.—Pampa Carts.—Method of driving Oxen.—Fresh Meat.—A Santa.—Farewell to Rosario.—The Caravan.—A Halt.—Novel Mode of Cooking.—First Lesson in Gaucho Etiquette.—A Name.—Habits of the Bizcacha.—Burrowing Owls.—First Night in the Pampas. | 101 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| LIFE ON THE PAMPAS—CONTINUED. | |

| A new Dress.—Riding a Ram.—Deer.—Parrots.—Mirages.—A Troop of Carts.—A Pantana.—Grass on fire.—Another Caravan.—Armadillos.—Guardia de la Esquina.—A sad Story.—Irreverence of the Peons.—Cabeza del Tigre.—Indian Attack.—Saladillo.—I visit a Rancho.—Punta del Sauce.—Its Inhabitants.—A geographical Dispute.—La Reduccion.—Paso Durazno.—Cerro Moro in the distance.—Indian female Spies. | 117 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| FROM RIO QUARTO TO CERRO MORO. | |

| Rio Quarto.—Indian Incursions.—A novel Method of charging a Cannon.—Scarcity of Bread.—A Bath.—The Peons’ Objection to Bathing.—Ox brain Soup.—A mule Troop.—The Madrina.—Armadillos.—Their Habits.—A Caravan from Mendoza.—Bread and Ovens.—Preparations for a hungry Time.—A Prostration. | 136 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| FROM RIO QUARTO TO CERRO MORO—CONTINUED. | |

| Prospects and Experiences.—The Peons’ dislike for the “Gringo.”—Fear of Dr. Carmel.—Little Juan.—Suspicious Movements.—Sympathy of the China Women.—Intrigue.—The Breakfast.—Don Manuel lacks Etiquette.—Sickness.—A Dream. | 152[Pg 8] |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| SAN LUIS AND THE SALINE DESERT. | |

| Don Manuel the Capataz.—His Services as Baqueano.—A Mendoza Troop of Carts.—Approach to the “Interior Town.”—Appearance of San Luis de la Punta.—The Governor.—Indian Troubles.—A Captive.—Indian Attack.—Treatment of Foreigners.—On the Travesia.—Watering Places.—Cacti.—Cochineal.—Condiments.—Saline Mineral.—Its Properties and Analysis by Dr. A. A. Hayes.—Conjectures as to its Origin. | 165 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| ON THE TRAVESIA. | |

| We cross the Desaguadero.—Artificial Canals.—La Paz.—Results of Irrigation.—View of the Andes.—An Invitation to Dinner.—Gormandizing of the Peons.—Santa Rosa.—Goats.—Alto Verde.—Camp on the Road.—A Bath.—Goitre.—Preparations for entering Mendoza.—The little China.—Arrogance of the Santiagueños.—Plants of the Travesia.—Dwellings.—A Dialogue.—We enter the Town.—An English Doctor.—Cool Treatment.—Circo Olympico.—A Visit to Plaza Nueva. | 182 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| MENDOZA. | |

| A Disappointment.—Mendoza.—The Alameda.—The Governor.—Houses, Churches, &c.—Doings of the Priests.—The Confessionals.—Padre A.—Madcap young Ladies.—Musical Bells.—Theatre.—Inhabitants.—The Goitre.—San Vicente.—School Library.—Newspaper and Press of Vansice.—Celebration of the 25th of May.—Soldiers.—Circus Performers.—Arrival of Indians from the South.—Veracity of the Cacique.—The Correo and his Men.—Casuchas.—Snow Travel.—A new Character Introduced.—Destruction of the City.—Departure for San Juan.—The consuming Lake.—Fishes.—Arrival at San Juan. | 195[Pg 9] |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| A WINTER IN SAN JUAN. | |

| At San Juan.—Wet and dry Winters.—Don Guillermo Buenaparte.—Visit to Causete.—I become a Miller.—Natural History.—The Mill.—New Characters.—The Scenery.—A curious Lot.—Inhabitants of San Juan.—The Town.—Trade and Productions.—Agricultural Tools.—Irrigation.—Don José the Penitent. | 216 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| A WINTER IN SAN JUAN—CONTINUED. | |

| A Mine.—A new Acquaintance.—An Account of the Prowess of a Diablo.—His Dress.—Horse’s Trappings.—The Rastreador.—His Skill.—A Translation from Sarmiento. | 229 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| VIENTE DE ZONDA. | |

| Regarding the Zonda Wind.—Miers’s Opinion.—Courses of the Zondas.—A Wind of long Duration.—South Wind.—Speculations upon the Starting-point of the Zondas. | 239 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| ADVENTURES OF DON GUILLERMO BUENAPARTE. | |

| Don Guillermo relates his Adventures.—Leaves New Bedford.—Deserts his Ship for another.—Rock of Dunda.—Terrapin Island.—Sufferings and Escape from the Place.—Marquesas Islands.—Leaves the Vessel.—Life among the Cannibals.—Cruel Fate of his Companions.—Settles down to Marquesan Life.—A Ship.—Escape of Don Guillermo.—Other Adventures.—Leaves Chili.—Additional Remarks. | 245[Pg 10] |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| CROSSING THE ANDES. | |

| Preparations for leaving San Juan.—I leave the Mill.—The Post House—The Minister and his friendly Offer.—The Flecha.—El Durazno.—The Hut and its Occupants.—The Binchuca.—A bloodless Battle.—El Sequion.—Chinas.—A Troop of Mules, and a Night with the Capataz.—Up the Valley.—A Hut and a pretty Señorita.—An elevated Plain.—Camp.—Sunrise in the Andes.—The Road to Uspallata.—Don Fernando.—An Invitation.—Farewell to Uspallata.—Indian Structures.—A sad Tale.—Cueste de la Catedral.—La Punta de las Vacas. | 277 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| CROSSING THE ANDES—CONTINUED. | |

| Descent of the Andes.—Baqueano Mule.—Waiting for the Snow to crust over.—Strange Scenery.—Below the Snow.—Another Snow-Hut.—A Drift.—Travellers from Chili.—Preparations for ascending the Cordillera.—Remedy for the Puna.—A hard Road.—On the Cumbre. | 296 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| FROM THE ANDES TO THE PACIFIC. | |

| Passage down the Valley.—Eyes of Water.—The Chilians and their Characteristics.—San Rosa.—A Chilian Welcome.—A Feast.—The River Aconcagua.—Quillota.—At Valparaiso.—Departure for Home. | 305 |

[Pg 11]

A THOUSAND MILES’ WALK.

One cold November morning, in compliance with previous orders, I reported myself ready for duty at the shipping office of Messrs. S. and K., Commercial Street, Boston, and having received, as is customary, one month’s wages in advance, proceeded with my baggage to Battery Wharf, at the foot of which lay the bark M., destined to be my future home for many weeks. As but one of the crew had already gone on board, I had ample leisure for examining the vessel, on board of which I was to receive my first lessons in practical seamanship, and to endure privations hitherto happily unknown to me. The M. was not prepossessing in appearance, and I confess that her model did not give a favorable idea of her sailing qualities: vessels, like horses, have peculiar external points by which their virtues may be judged, and their speed determined. As I gazed upon her long, straight sides, square bows, and box-like hull, it seemed to me that her builders must have mistaken her ends; for, certes, had her spars been reversed, she would have made[Pg 12] better progress by sailing stern foremost. Some knowing ones, who have since examined this specimen of marine architecture of twenty years ago, have sustained my suspicion that the M. belonged to that enduring fleet of cruisers, now scattered over the great deep, which were originally built in the State of Maine, of which report is made that “these vessels are built by the mile, and sawed off according to the length ordered by the buyer.”

The mate, who was occupied in receiving live stock,—i. e., two young pigs,—ordered me to stow my things “for’ard;” an order somewhat difficult to comply with, as the forecastle was well filled with firewood, ropes, blocks, swabs, and the various other articles used on shipboard.

I crawled down the dark passage, and was feeling about to discover the dimensions of a sailor’s home, doubting, meanwhile, whether, in reality, this narrow hole could be the abode intended for human beings, when suddenly a gruff voice called down to me, “Come, youngster, bear a hand! Make yourself lively! We must clean out this shop before the crew come down; stir yourself, and pass me up the pieces.” Obeying these peremptory commands, I applied myself to work, and in an hour’s time my companion declared the place “ship-shape, and fit for sailors.” I would remark, en passant, that this declaration was made in the face of the fact that mould and dust covered the timbers and boards, and cockroaches filled the many crevices. “But,” said my companion, with a philosophical air, “if the place were carpeted, and lighted with a fine lamp, the fellows would be the[Pg 13] more dissatisfied; the better treated they are, the worse they growl.” At the time I inwardly dissented from the truth of this remark; but subsequent experiences taught me the old salt was right.

As I had been of service in removing all the lumber, I thought to repay myself by securing a good bunk, and therefore chose an upper one. After I had given it a thorough cleaning, and had carefully stowed away my mattress and blanket, one of the new crew entered the forecastle, and, on noticing my labors, at once removed my bed, and placed his own in its place, remarking, at the same time, that it was a highly impolite and lubberly action for an understrapper to “bunk down where he didn’t belong; upper bunks were men’s bunks; lower ones, boys’.” Although I pleaded ignorance of the etiquette of the forecastle, and selected another resting place, my shipmate continued his lecture on the rules of the sea, and hinted at the future “rope’s-endings from the little man aft,” as he called the mate, in store for me.

During his harangue two or three of my old schoolfellows came aboard, and, on visiting my quarters, remarked upon the poor accommodations and filthiness to which I was to be doomed; upon which remark the old tar broke out with, “And so this is a young gentleman going to sea for the first time? O, ho! All right. I’ll be his guardian, and keep an eye on him when he’s aloft, and, to start fair, if my opinion was asked, I’d say we’d better go up the wharf, and splice the matter over a social glass.” At this hint, so delicately conveyed, we gave the fellow a sum sufficient to allay his thirst, had it been never so great, and he[Pg 14] at once took leave of us, only to return, however, in a few minutes, declaring that he had lost every cent, at the same time reiterating his offer to become my friend for a consideration.

The noise of the tow-boat now called us on deck, where we found a perfect Babel of confusion, caused by the throng of porters, boarding-house runners, idlers, and sailors’ friends, who were giving and receiving advice in quantities to last until the vessel returned to her port. About this time I was touched on the shoulder by a rough-looking personage in a sailor’s dress, who took me aside, and inquired if I really intended going to sea. “Because,” said he, “if you are, let me give you a bit of advice. I’m an old shell, and can steer my trick as well as the next one; and as we’re to be shipmates, and you’re young, all you’ve got to do is to stick close to me, and I’ll larn yer all the moves.” After showing so kind an interest in my affairs, he hinted, like the other man, that there was “still time enough to step up to the house, and splice the main brace.” As I was ignorant of this point in seamanship, I handed him some money, that he might perform it alone, when he disappeared. I saw nothing more of him for the next half hour; and it was only when the vessel was about moving off that he staggered over the rail, to all appearances well braced; and as he expressed a desire to handle all on board, from the “old man” (the captain) “in the cabin to the doctor” (cook) “in the galley,” I concluded that his splicing had received especial attention, and that his strands would not unravel for several hours to come.

These scenes on board of the M., while getting[Pg 15] under way, were comparatively tame to others that I have since witnessed on other vessels. I have known men to be carried on board ship by boarding-house keepers, who had enticed them into their dens of infamy, and who had drugged them so powerfully that they did not recover their senses until the vessel had left the port. In this manner, fathers of families, mechanics, tradesmen, and other persons wholly unfitted for a sea life have been carried off, unknown by their friends. When full consciousness returned to the unhappy victims, they sought the officers for an explanation, when I have seen them so beaten and kicked, that in apprehension for their lives, they bowed in submission to a tyranny worse than that of slavery itself.

After lying for more than twenty-four hours, wind-bound, in the outer harbor, all hands were called before daylight, and though the mercury stood but a few degrees above the freezing point, the decks were washed down; after which operation the anchor was weighed, and we set sail out upon the bosom of the broad Atlantic. When we were fairly under way, we were set to work stowing away chains and ropes, securing the water casks upon deck, lashing the anchors upon the rail; then a short breathing spell was allowed us. While looking to windward, an old sailor, with whom I had commenced a friendship, which I was determined to strengthen, said, “Here, boy: do you see that land, there? It is the last you will see until we drop anchor in the River Plata.” I gazed long upon it. It was Cape Cod. Its white sand-hills looked cold and drear as the sea beat against their bases, some of which were[Pg 16] smooth and sloping, others steep and gullied by the rains. An hour after this the breeze freshened, the light sails were taken in, and the topsails double-reefed; and as the sea ran higher, and our little vessel grew proportionally uneasy, I began to experience the uncomfortable nausea and dizziness of seasickness, which, added to the repulsive smell and closeness of the forecastle, completely overcame my fortitude, when retiring to my bunk I tried to make myself comfortable.

About five o’clock in the afternoon all hands were mustered upon the quarter-deck, and the watches chosen. To my satisfaction I was selected by the mate, and had the further gratification of finding that old Manuel, my friend, had also been chosen for our watch—a result which evidently delighted him as much as myself. Ours was the larboard watch, and remained upon deck, while the captain’s, or starboard watch, went below. The duties of sea life had now fairly commenced.

The two hours that followed, from six to eight, were passed in a pleasant conversation with the old Frenchman, Manuel. He informed me that he had his eye on the moves of the crew, and he concluded that there was but one sailor on board: it was left to my sagacity to infer that he meant himself.

Two of the crew, who had shipped as ordinary seamen, were ignorant of the duties for which they had contracted, and each man in the forecastle had shipped as an American-born citizen, with protection papers received from the Custom House, which legally asserted him as such. These papers they had obtained[Pg 17] from their boarding-house masters, who had purchased them at twenty-five cents each, and had retailed them to their foreign customers at seventy-five cents apiece. Of this American crew, two were Germans, or Dutchmen (an appellation given by sailors to all persons from the north of Europe), one of unknown parentage, who could only speak a few words of English, two Irishmen, one Englishman, another who swore point blank to being a native-born citizen of the States, an old mariner from Bordeaux, and myself. The law that makes it the duty of a captain to take with his crew a certain proportion of native-born Americans, had surely not been complied with here. To one of our crew I cannot do otherwise than devote a few lines.

The “doctor,” or cook, had already introduced himself, and informed us in a short and patriotic speech, delivered at the galley door, that he would confess that his father was a distinguished Irish barrister, and that he himself possessed no little share of notoriety in the old country. He had once been taken by a celebrated duchess, as she rode past in her carriage, for a son of the Marquis of B. His amusing vanity drew many expressions of contempt from the tars, who pronounced him to be “an idle Irish thief,” which only served to make him wax more warm in his assumptions of gentility. He was interrupted in the midst of a high-flown harangue by the loud squealing of the pigs, which squealing reminded him that his duties must not be neglected for the purpose of edifying a crowd of ignorant tars.

Our watch lasted until eight bells, when I went below, but had very little appetite for supper—a meal[Pg 18] consisting of salt beef, biscuits, and a fluid which the cook called tea, although, on trial, I was sadly puzzled to know how it could merit such an appellation.

Of the three weeks which followed this first experience of nautical life and its miseries, I can say but little, as I labored during this period under the exhausting effects of seasickness, which reduced me to such a degree of weakness that I once fainted on the flying jib-boom, from which position of peril I was rescued and brought in by my friend Manuel. But this distressing malady wore away, and at last became altogether a memory of the past. Despite hard fare and labor, I not only recovered my lost flesh, but grew rugged and hearty, and, moreover, became tolerably familiar with the duties of a life at sea.

I have alluded to our cook, and to his ineffable conceit, mock sentimentality, and Hibernian fertility of invention.

It was his opinion that the “low-lived fellows” on board ought to feel highly honored by the presence in their midst of at least one gentleman—a title which he continually arrogated to himself. I am sorry to say, that as a cook he was not “a success.” He cared very little about the quality of the food he served to us; and its preparation was usually a subordinate consideration, with him, to the indulgence of his master passion,—the perusal of highly-colored novels,—to which he devoted every possible moment.

In the hope of improving my wretched diet, I applied myself to the study of this man’s character, and, having soon discovered his assailable point, supplied him with some works of fiction more entrancing than[Pg 19] any he had hitherto possessed. I bought them just before our leaving home, thinking that perhaps some such an opportunity might offer for making a friendship with some of my messmates. His delight at receiving them was extreme; and I received in exchange for my favors many a dish that added a zest to my food, which it had hitherto altogether lacked.

Whenever I wished to be entertained with some marvellous account of “life in the highest circles of Great Britain,” I had only to request from the sympathetic cook a passage or two from his eventful life. It was his constant lament that he had never kept a dialogue (diary) of his travels, which, according to his account, must have surpassed those of most mortals in adventure and interesting incidents.

Of our crew, his countryman, the “boy Jim,” was his favorite. This Jim was the red-shirted sailor who had promised to instruct me in all the “moves” of an experienced salt, before we had left the wharf at Boston. A very few days of our voyage, however, served to prove, that he not only had no claim to the title of “old salt,” but also that he had never learned to “steer a trick at the wheel.” The first order that he received from one of the mates was, “Boy Jim, lay aloft there, and slush down the foretop-gallant and royal masts!” Seizing a tar bucket, and pointing aloft, he exclaimed, “Shure, sir, and which of them sticks is it that ye mane?” thus laying bare his ignorance of all nautical matters, and bringing on himself the ridicule of the whole ship’s crew.

As with head winds we slowly drew near the variables, or horse latitudes, rainy weather, accompanied[Pg 20] by squalls of wind, commenced, and for twenty-one days and nights we were wet to the skin: clothes, bedding, all were saturated from the effects of a leaky deck; and it was a common occurrence to find, on awakening from slumber, a respectable stream of water descending into the close and crowded forecastle. When on deck our oil clothes did not protect us, for from our having worked in them constantly, the oil coating had worn off: so, at the end of a watch, we wrung out our under garments, and turned into our narrow bunks, where we quickly fell asleep, and forgot our miseries and troubles, until we were aroused to them by the gruff voice of some sailor of the other watch, shouting down the companion-way, “Ay—you—Lar-bowlines—ahoy—there; eight—bells! Lay up here, bullies, and get your duff.” Or, perhaps, “Do those fellows down there ever intend to relieve the watch!” exclaimed in no pleasant tones by the captain of the other watch.

The rainy season was succeeded by as delightful weather as we could have desired. A fair wind sprang up a few days before crossing the line, and with straining canvas we sped on towards Buenos Ayres. The days passed pleasantly, and our duties became light and agreeable. Enjoyable as were these tranquil days, the nights were still lovelier in those latitudes. The moon seemed to shine with an unwontedly pure and spiritual light, and with a brightness known only to the clear atmosphere of the tropics.

As we glided along, night after night, under a firmament studded with countless lights, and over a broad expanse ruffled with short, dark waves curling crisply[Pg 21] into foam, I could hardly conceive a scene of more quiet beauty. Standing upon the forecastle deck, a glorious vision frequently met our gaze: a phosphorescent light gleamed beneath the bows, and streamed along the sides and in the vessel’s wake, looking like a train of liquid gems to the imaginative observer. If we looked aloft to the white canvas of our wide-spread sails, we seemed borne along by some gigantic bird, of which the sails were the powerful wings, to the distant horizon, in which were the Southern Cross and other larger constellations, burning, like beacon lamps, leading us on to our destined port.

During these days and nights our attention was not unfrequently attracted to the dwellers in the deep, which were constantly sporting around us. Schools of black-fish and porpoises continually crossed our track; and large numbers of flying-fish often shot across our bows, sometimes leaving at our mercy a few stragglers upon the decks.

Upon such nights as I have described, when acting as lookout by the windlass bits, old Manuel frequently came to my side, and conversed upon the various topics connected with his past life, which had been an eventful one. He was born in Bordeaux. His mother died when he was an infant, leaving him to the care of his father, who owned and commanded a small vessel engaged in the coasting trade.

While very young, Manuel preferred playing about the streets of his native city, and hiding, with other boys, among the vines which covered his father’s dwelling, to following any plan of education proposed by his father. Under the direction of an uncle, however,[Pg 22] he attended school when nine years old, and learned to read and write during the two succeeding years. So rapid was his progress, that the uncle, who was wealthy, offered to defray his expenses if he would fit himself for the university; but Manuel preferred following the fortunes of his father for a season, and accordingly sailed with him along the coasts of France and Spain. But the voyage was not destined to be a pleasant one. The boy was continually offending his father, who was a cold and unlovable man; and one afternoon, while performing certain antics upon the main-topsail-yard-arm, the old gentleman called him down, and rewarded his exertions with a lusty application of the end of the main sheet, which rope’s-ending was not to Manuel’s taste. He availed himself of the first opportunity, deserted the vessel, and joined a fine ship sailing to Havana. Before reaching Cuba he had become acquainted with the ropes, and not wishing to return to his parent until time had soothed his outraged feelings, he left the ship, and became a destitute wanderer in a foreign land. He was at that time twelve years of age. Being led into bad company, he joined a slaver, bound for the west coast of Africa. The galota in which he sailed reached the Rio Congo, and received on board nine hundred negroes, nearly all of whom were landed safely in Cuba. His wages, as boy, amounted to fifty dollars per month; but, though engaged in so profitable an undertaking, his sense of right caused him to leave his unprincipled associates, and to seek employment elsewhere. Since that time he had served beneath the flag of nearly every maritime nation, and had also fought in the China wars.[Pg 23] For thirteen years he had sailed from Boston and New York, choosing the American republic as his adopted country, for which he was willing, as he declared, to shed his best blood, should necessity require.

While conversing with Manuel, one morning before sunrise, I was surprised by his suddenly jumping to his feet and scanning the horizon. At length he exclaimed, “There is a sight you may never see again. I have crossed the line many times in this longitude, but never beheld that before to-day!” At this moment the mate, who had been keeping a long lookout, disappeared below, returning in a moment with the captain. Looking in the direction pointed out by the old sailor, I discerned far away to the south-south-east, broken water; and, as the daylight advanced, we were soon able to distinguish two detached and rugged rocks, rising out of the sea, together with many smaller peaks rising out of the water around them. One of these bore a striking resemblance to a sugar-loaf. This group was the St. Paul’s Rocks. When first seen they appeared dark and drear; but, as our vessel approached them, we discovered that the excrements of myriads of sea-fowl, with which they were covered, had made them of a glistening white, presenting a strange appearance, not wholly devoid of the picturesque. Here, at no less a distance than five hundred and forty miles from the continent of South America, these peaks, the summits of mountains whose bases are planted in unfathomed depths, arise.

The rocks lie in longitude twenty-nine degrees fifteen minutes west, and are only fifty-eight miles north of the equator. The highest peak rises but fifty feet[Pg 24] above the sea, and is not more than three quarters of a mile in circumference.

These isolated rocks have been visited by a few persons only. Darwin, the naturalist, made a thorough investigation into their natural history. Among birds, the booby gannet and noddy tern were found; both species being very tame, depositing their eggs and rearing their young in great numbers. Darwin, in his account of the tenants of these rocky islets, observes, “It was amusing to watch how quickly a large and active crab (Grapsus), which inhabits the crevices of the rocks, stole the fish from the side of the nest, as soon as we had disturbed the parent birds. Sir W. Symonds, one of the few persons who have landed here, informs me that he saw these crabs dragging even the young birds out of the nests, and devouring them. Not a single plant, nor even lichen, grows on this islet; yet it is inhabited by several insects and spiders. The following list completes, I believe, the terrestrial fauna: A fly (Olfersia), living on the booby, and a tick, which must have come here as a parasite on the birds; a small brown moth, belonging to a genus that feeds on feathers; a beetle (Quedius), and a wood-louse from beneath the dung; and, lastly, numerous spiders, which, I suppose, prey on these small attendants and scavengers of the water-fowl.”

I afterwards met, among the many roving characters with whom the traveller becomes acquainted, a person, who, in his younger days, had been engaged not only in privateering, but also in the lucrative, though inhuman, slave traffic. He knew of many instances when slavers and freebooters had been obliged to visit St.[Pg 25] Paul’s from necessity, not only for the purpose of securing the rain-water that is caught in the cavities and depressions in the rock, but also to procure a supply of the fish which play about the islets in large schools, or, more properly, perhaps, shoals, or schules.

Although our vessel was built before the age of clippers, and consequently made slow progress through the water, St. Paul’s was far astern by ten o’clock. A fresh breeze sprang up, and, as it continued fair, we were wafted along smoothly day after day towards our destined port.

At length the sudden changes of the atmosphere, and careful consultations of the officers, and admonitions “to keep a bright lookout ahead,” warned the forecastle hands that we were nearing the Rio Plata, the great River of Silver, whose broad mouth we were soon to enter, there to gaze upon the shores of another continent.

The nights seemed cooler, and the beautiful appearance of the heavens, as the sun, with a broader disk, sank beneath the western horizon, particularly attracted our attention. As it slowly disappeared, clouds of many varied hues gathered above it like heavy drapery, as if to conceal its flight; while others, taking the form of long ranges of mountains, with here and there a tall peak towering up into the clearer firmament, presented a panorama of exquisite beauty and grandeur. But all evenings were not of this description. Sometimes the heavens darkened, and for two or three hours not a breath of air moved the murky atmosphere. Long, dark swells came rolling towards us from the south-east, sure indicators of the distant pampero, the hurricane[Pg 26] of La Plata. When these swells were visible, the crew at once became active: every light sail was snugly furled, and the topsails double reefed, for our captain was a prudent man, who had sailed long enough in these latitudes to know the fearful devastation that is often occasioned by the pampero. Before our voyage terminated we had an opportunity to appreciate this trait in his seamanship.

One afternoon, when within four or five days’ sail of the mouth of the Plata, the sky became overcast with murky clouds, while the distant thunder and lightning in the south-west warned us of the proximity of the hurricane. “All hands” were called and we hurried to our stations; but before everything could be made snug aloft, a fierce shower of hail descended, pelting us mercilessly; and glad enough we were to get below, at four bells, to supper. The wind increased, and blew very hard for an hour or more, when it became calmer; but still the heavy sea came rolling towards us, making our stout bark toss and pitch about as if old Neptune were irritated at her sluggish ways. We congratulated ourselves at our easy escape from the pampero, but we should have remembered the old saying, “Never shout until you are out of the wood.”

As we were below, discussing various subjects, we were joined by the cook, who descended the ladder, requesting the loan of a novel, declaring that he was dying by inches of the “onwy.” “Get out of this, you and your trash!” shouted an old tar: “this is no place for distinguished characters.”

But the “doctor” did not appear to be disconcerted[Pg 27] in the least at this rude salutation and reference to his pretensions.

“Ah, boys!” he exclaimed, with a touch of sentimentality, “how can ye be so boistherous? Here we are, every hour dhrawing nearer and nearer to that mighty river which runs past Buenos Ayres; and does not the thought of it inspire ye with romantic feelings? As for meeself, I can scarce slape at night for the ecstatic thoughts that crowd me brain. Ye may all laugh,” he continued, as some of the sailors interrupted him with a boisterous laugh, “but it does not alter the case in the laste, for it is thrue. To-night, when I was standing in the galley, the thought came to me, that perhaps the boy here,” pointing to myself, “would like a few stanzas of poetry for his dialogue (diary), which he is keeping; so I, in my mind, composed a few lines, which, if he wants, I will recite to him.”

At this, some of the sailors exclaimed, “Get out of this, for a dirty sea-cook as you are, and don’t attempt to spoil sensible people.”

I, however, said that I would be pleased to receive his stanzas, and, preparing my pencil and paper, wrote down the following lines as he recited them, together with the interpolations and remarks of the sailors. Striking a beatific attitude, the poet began:—

“I saw her; yes, I saw her.”

Old Salt (gruffly). “What if you did? If she saw you, she sickened, I dare swear!”

The Doctor (continuing).

“Tripping along so gayly,

With mantilla fluttering in the wind.”

[Pg 28]

Old Salt 2d. “Shaking in the wind’s eye, in a squall.”

The Doctor.

“Eyes like a dove’s in mildness,

Or an eagle’s in its wildness.”

Old Salt 1st. “More like a hen’s with one chicken.”

Old Salt 3d. “Or a sick rooster with one tail-feather.”

The Doctor.

“Smiles they were sweet,

Lips together did meet.”

Old Salt 1st (dubiously). “Lips together did meet? I wonder, mateys, if she wasn’t smacking them after a glass of grog?”

The Doctor.

“Clamors of war and terrible drums,

Noise of trumpets and the hum of tongues,

Can frighten the timid, but not her;

For brave as a lion, dauntless as fire,

She’s ruled by love, and not by ire.”

Here some of the sailors pretended to faint; others reeled off to their bunks, saying that the doctor’s poetry was “worse than his duff, and that wasn’t fit to give a measly hog;” while one old follow ascended to the deck, declaring that he “couldn’t sleep after hearing such blasted nonsense, until he had taken a salt junk emetic.”

The doctor would have continued his poetry, notwithstanding the ridicule of the “low, ignorant fellows,” as he called them; but he was interrupted by the voice[Pg 29] of the mate, calling down to the cook to “doctor the binnacle lamp,” when the poet hurried up the companion-way, leaving me to turn in, and dream of

“Lips that together did meet,

Clamors of wars, and terrible drums,”

until the man at the wheel struck eight bells.

[Pg 30]

At length the day for making preparations for nearing land arrived. One fine afternoon the order was given to have everything ready for entering the river. All hands were kept on deck, and every one manifested an unusual readiness to work. The lashings were cut adrift from the anchors; the chain drawn out of the locker, and overhauled upon the deck; and the other matters attended to, which are not to be neglected on a ship about coming to an anchorage. Towards night, the changing color of the water, which in the deep ocean is of a dark blue, but which had now become of a greenish tinge, told us of the proximity of land.

At sunrise of the next morning, the cry of, “Land on the starboard bow!” awoke me from a sound slumber. Hurrying on deck, I was able to discover a faint streak of red in the distant horizon, which a sailor declared to be “the loom of the land;” and by eight o’clock the low shores of the Uruguayan republic were distinctly visible from our deck, and the monotony of our sea life was at an end.

As it was necessary to take a pilot on board, we were obliged to first make Montevideo, the great seaport of the Banda Oriental, or Uruguayan republic, which[Pg 31] country, as most of my readers are doubtless aware, was formerly a constant bone of contention between Buenos Ayres and Brazil, but is now independent of both, and according to all accounts promises to become the greatest producer of wool of the South American republics.

A light breeze wafted us past the rocky isle of Flores to Montevideo, where, about dusk, we dropped anchor at a distance of three miles from the shore.

While aloft, I had time to observe that a conical mountain, with smooth sides, and crowned by an old fort, was connected with the main land by a peninsula, in such a manner that a fine bay was formed, where a large fleet of vessels were lying at anchor. The fort on the mount showed a light, four hundred and seventy-five feet above the level of the sea. The town lies on the opposite side of the bay, to the eastward of the mountain, from which fact it derives its name.

By the time the sails were furled, and several additional ranges of chain overhauled, night came on, and the anchor watch was set, with orders to call the mate if it lightened in the south-west, the region of pamperos.

My watch was from nine to ten: when I was relieved, I went below with a light heart, and “turned in” to my bunk, with the prospect of unbroken rest. It was perhaps an hour later that I was awakened by the confused sounds on deck, caused by the “letting go” the second anchor, and the loud calling down the companion-way for “all hands on deck.” Hurrying above, we found that a pampero had struck the vessel, which was moving through the water at the rate of at[Pg 32] least four miles an hour before the force of the hurricane. When the second anchor became fast, however, the vessel’s course was checked, she swung around, broadside to the wind, and held her ground. The force of the wind striking our backs was so great that we were obliged to take shelter beneath the bulwarks to recover our breath.

The darkness was intense, save when flashes of lightning illumined every headland along the coast, and threw out in bold relief the mountain and its castle. But duty called us from the protection of the bulwarks to the chain lockers. Vainly, however, did the officers vociferate their commands; not a word could we understand; but we instinctively laid hold of the chain, and, guided by flashes of lightning, paid out many fathoms. Hardly had we accomplished our object in giving scope to the cable, when a noise like thunder announced that one of the sails, the main spencer, had broken adrift, and in an instant it beat and clattered across the quarter-deck. From side to side it tore, cutting the rigging to pieces, with the block at its clew. Half an hour’s labor was ineffectual in securing the sail, though ends of braces were strongly passed around it; it continually broke loose, tumbling upon the deck all the men who were clinging to it, and we might have labored much longer, had not Manuel crawled aloft, and cut the sail adrift, by coming down the jack-stay, knife in hand.

The spencer had not been securely fastened before from between the harness-casks, the mizzen staysail, which had been carefully furled, seemed endowed with life, for in an instant it ran up its stay like a bird, and was at once torn to shreds.

[Pg 33]

At this point the prospect was fair for a wreck. The captain brought an axe on deck to prepare for the last resort. But such a fierce wind fortunately could not last long; its own force must prove exhaustive: it soon came only in gusts, and two hours later it had greatly subsided.

The scene now around us challenged our attention; and, until morning, I leaned across the rail, completely engrossed with the many curious phenomena before me.

The air was filled with electrical flashes, which at times rendered the tall mount plainly visible, and brought out the spars of the fleet in the bay in weird-like prominence against the gloomy background.

The fort on the height seemed clothed with flame, while the short, quick waves around the vessel gleamed with phosphorescent light. The pampero had struck the vessel during the watch succeeding mine, and the man on duty became so frightened that he did not call the mate. Luckily, that officer discovered the true state of affairs in time to prevent a serious disaster.

The dawn of the following morning revealed a sight such as might be expected after so violent a hurricane. In one part of the harbor were two vessels, whose crews were hard at work in clearing them from the entanglement of their rigging, which was completely wrecked.

Close by lay two others, with their topmasts gone, and in the distance were many others in a similar condition; while from the town came floating logs, boxes, barrels, and other lumber in great quantities, telling of the havoc of the pampero.

The effect of the wind was even felt to a greater extent farther up the river, where some fifteen or twenty[Pg 34] small vessels were capsized, and many of the crews drowned.

A new and beautiful English bark, that had left her anchorage for Buenos Ayres the night before, we saw two days afterwards; but she was nothing but a dismantled hulk, with only the stump of her mizzenmast left: every spar had been blown away, and one of her men killed by a falling mast.

Though the pampero season generally lasts from March to September, this wind is likely to blow at any time; and a careful captain will always be prepared for it. The state of the mercury in his barometer, together with the appearance of the heavens in the south-west, must be carefully watched. These winds, coming from the cold summits of the Andes, sweep first across an undulating, then a flat country; and, meeting no obstacle to break their force, do great damage to the settlements about Buenos Ayres, as well as to the shipping in the River Plata, and are felt many miles out to sea.

The River Plata, at its entrance, between Cape St. Mary on the north coast, and Cape St. Antonio on the south, is one hundred and seventy miles; and we can see that the pampero, in traversing this broad channel, has a most unobstructed course.

At noon a pilot came aboard, bearing a letter from the owner’s agent; and at about eleven o’clock the following night we hove up both anchors, and, with a fine breeze, sailed up the river. Thirty-six hours later, we dropped anchor in the outer roads of Buenos Ayres, seven or eight miles from the city, whose plastered dwellings and lofty cathedral were plainly seen from the decks of our vessel.

[Pg 35]

For a whole month I was obliged to remain by the vessel, awaiting the arrival of the orders that were to set me free. During this period, to prepare the vessel for a long stay, the lighter spars were sent down, the flying jib-boom sent in, sails unbent, &c. The tides in the River Plata are governed by the wind, and have no regularity in rising; the current of the river is at the rate of three miles per hour. Vessels drawing above eleven feet of water remain in the outer roads, while smaller craft can approach within two or three miles of the city; all of these discharge and receive their cargoes by the assistance of lighters, generally schooner-rigged, and principally manned by foreigners,—chiefly French, Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese.

At last, about the 20th of February, a Boston vessel entered the river, bringing letters from home, and I was gratified by the information from the captain, that, after seeing the American consul, who had received orders to discharge me from duty, I should be at liberty to depart on my long pedestrian journey. I went ashore at the earliest opportunity, and at once called upon Colonel Joseph Graham, the American consul,[Pg 36] who received me with great kindness, but condemned my intention of crossing, alone, so wild a country, with the people and language of which I had no acquaintance; he, however, furnished me with the necessary papers of protection, together with letters of introduction to various persons in the interior. During my stay in the consul’s office Dr. Henry Kennedy, a young North American physician, came in, and although a stranger to me, presented me, after a few minutes’ conversation, with a letter of introduction to Mr. G—n, a resident of Rosario. This act of kindness towards a stranger proved the generous character of Dr. Kennedy, and it is with a feeling of gratitude that I recall his name here. I was now my own master, and at once went about the city in search of information relative to crossing the country.

The consul and one or two other parties had given me the names of persons to whom I was to apply for the necessary information to guide me in my journey. I was surprised, however, to find that the foreign merchants knew so little of the interior; for, after several days’ inquiry, the principal fact that I learned was, that to cross the pampas on foot it would be necessary to accompany one of the troops of carts that carried merchandise to the other provinces, as otherwise I would find it impossible to obtain food or to follow the right trail. One of my informants was a stout little Irish gentleman, who quoted a message sent to Sir Woodbine Parish, by a gentleman who crossed the country several years before; and as his description is almost true of the Buenos Ayrean, or southern road across the pampas, I will present it here. He said,[Pg 37] “The country is more uninteresting than any I ever travelled over, in any quarter of the globe. I should divide it into five regions; first, that of thistles, inhabited by owls and biscachas; second, that of grass, where you meet with deer, ostriches, and the screaming, horned plover; third, the region of swamps and morasses, only fit for frogs; fourth, that of stones and ravines, where I expected every moment to be upset; and, last, that of ashes and thorny shrubs, the refuge of the tarantula and binchuco, or giant-bug.

“And now,” continued the little Irishman, “I ask leave to put you a question. How many days can you conveniently go without water?”

“Two or three, perhaps,” I replied.

“Well, then, you will never last to cross the plains,” was his encouraging answer; “for, mark you, a merchant of this city crossed last summer, and went without water for twenty-one days. I think you had better return to America, and give up travelling for information.”

Such were the stories—some true, and many, like that of the Irishman, utterly fabulous—that were told me by the different individuals upon whom I called during my short stay in Buenos Ayres. In the course of my inquiries I learned that a train of wagons would shortly leave Rosario, a small town upon the River Paraná, about two hundred miles north of Buenos Ayres, for Mendoza, a town situated at the base of the Andes, and I resolved to visit the place in time to catch the caravan. A steamboat plied between the city of Buenos Ayres and Rosario, but as it was not to sail for a fortnight, I had ample time for surveying the adjacent country, and even for[Pg 38] making a flying visit across the Plata to the Banda Oriental.

The State of Buenos Ayres usually monopolizes the attention of visitors to the region which is known as the Argentine Confederation, on account of her favorable situation on the seaboard, her possession of the only maritime port in the vast confederacy, and the predominating influence which these advantages have secured to her in peace as well as in war. The state contains an area of fifty-two thousand square miles, and is, consequently, but little larger than the State of New York. Her population, according to an estimate formed some ten years since, amounted to some three hundred and twenty thousand souls; of whom one hundred and twenty thousand are inhabitants of the city, while the remainder are sparsely distributed over the extensive plains that commence a few miles from the coast, and, running inland, stretch across and far beyond the limits of the state. The population of the city itself is composed of a great variety of types and colors, among which, however, the whites are rapidly predominating; as every year introduces new blood from Europe and North America, while parties interested are doing their best, in connection with the government, to divert a portion of the Irish immigration from the United Slates towards their own province. The government furnishes immigrants with land free of charge, but an extortionate price is not unfrequently paid, in the end, for a farm.

The study of the mixed races which inhabit, not only this province, but also the entire region between the Paraná and the Cordillera, has as yet received but[Pg 39] little attention from the student of ethnology. The lines of demarcation, however, between race and race, are clear and distinct; and the future ethnographer of this region will have no difficulty in tracing the population, through its intermediate stages of gauchos, zambas, mestizos, etc., to its origin with the immigration from Old Spain and other European countries, and to the aboriginal and negro stocks.

Throughout the state the soil is richly alluvial to a depth of two or more feet, beneath which lies a stratum of clay, differing in kind and quality according to its location. Thus strata of white, yellow, and red clays have been discovered in different regions of the same province, furnishing the population with abundant material for the manufacture of tiles, bricks, and innumerable articles of pottery.

For nearly two hundred miles west of the La Plata, the soil produces a luxuriant growth of herbage, which is choked, however, in many places, by extensive forests of gigantic thistles, which grow to such a height that men, passing through them on horseback, are hidden by the lofty stems. So heavy is this growth that, at times, the thistle fields are impassable to man, and serve to the wild animals of the pampas as an undisturbed lair. These thistles are fired, from time to time, by the gauchos; after the ground that they covered has been burnt over, a fine sweet crop of grass starts up, upon which the cattle feed luxuriantly.

A native author, of eminent accuracy, who has carefully studied the statistics and resources of the province of Buenos Ayres, has published the following estimate of the value of real estate and other property in the country, in 1855:—

[Pg 40]

State of Buenos Ayres, its Extent, Value, &c

| Fifty-two thousand miles of uncultivated lands, at $1000 per square mile, | $52,000,000 |

| Six million head of cattle, at $6 per head, | 36,000,000 |

| Three million mares, at $1 per head, | 3,000,000 |

| Five million sheep, at $1 per head, | 5,000,000 |

| Half a million swine, at $1 per head, | 500,000 |

| Houses, &c., in the country, | 10,000,000 |

| Total value, | $106,500,000 |

The following statement, derived from the Buenos Ayres Custom House, for the first six months of 1854, may serve as a means of estimating the number of horned cattle in the state:—

| Hides exported in six months, 1854, | 759,968 |

| Deduct quantity received from the provinces, | 121,166 |

| Total exports of Buenos Ayres hides, in six months, | 638,802 |

| Add a corresponding six months’ exports for balance of the year, | 638,802 |

| Estimated export for 1854, | 1,277,604 |

The following were some of the agricultural productions of Buenos Ayres in 1854, as computed by Señor Maezo:—

| Wheat, | 200,000 fanezas. |

| Maize and barley, | 70,000 ” |

| Potatoes, | 60,000 ” |

The faneza is nearly equal to four English imperial bushels, or to 2218.192 cubic inches.

[Pg 41]

Of late years the value of provisions, hides, tallow, and horns has been greatly enhanced.

I am informed that under the government of General Rosas, the price of beef was fixed by law at fifteen cents per arroba (twenty-five pounds), and that the severest punishment was inflicted for any attempt to evade or infringe upon the regulation. The price of beef during my stay in the province was never less than sixty cents per arroba.

Frequent revolutions have naturally hindered, in a very great degree, the development of the resources of this province. Since 1810-11 it has been subjected to continual and sudden changes of government: at one moment, as it were, attempting to form the cornerstone of a vast confederation, in a short time the scene of the wildest anarchy, and soon prostrate under one of the most grinding despotisms that the nineteenth century has beheld.

Buenos Ayres, the richest and most powerful of the provinces of La Plata, holds herself aloof from the remainder, preferring a state of isolation, through dislike for President Urquiza, to joining with her sister states in laying the foundation of a strong and permanent confederacy. Her import and export duties, together with port charges, stamps, direct taxes, &c., constitute a considerable revenue; and these resources would, undoubtedly, give her a powerful influence over the other states should she finally become a part of the Argentine Confederation. Though a coolness, almost amounting to ill-will, is manifested by the people of Buenos Ayres towards those of the neighborhood provinces, a treaty has been lately signed by the two[Pg 42] governments, in which each promises aid and assistance to the other in case of attack from a neighboring or foreign power. It is evident, from their careful movements, that all the La Plata states stand in dread of their grasping and powerful neighbor—the empire of Brazil.

The city of Buenos Ayres is laid out in the usual Spanish-American manner—in squares, measuring one hundred and fifty yards upon a side; the streets, of course, cross each other at right angles, and run due north and south, east and west. They are regular throughout, but are very roughly paved. With some exceptions the dwellings are of but one story in height, and are built of brick, overlaid with a white plaster, which gives them a very neat appearance; but the heavy iron gratings with which every window is protected detract not a little from the beauty of the dwellings; and a stranger unaccustomed to Spanish architecture may readily, at the first sight of these forbidding gratings, believe himself among the prisons of the city. The roofs are covered with oval or square tiles.

Buenos Ayres is rich in public institutions. Her theatres and places of public resort are eight in number, besides the governor’s mansion, the House of Representatives, and the Casa de Justicia, or Hall of Justice. Besides these may be enumerated the Tribunal of Commerce, the Inspection of Arms, the Artillery Arsenal, the Ecclesiastical Seminary, the Museum of Natural History, Public Library, Custom House, Mint, Bank, and Jail.

The treatment of the inmates of the latter institution[Pg 43] secures for them a degree of comfort far less than that which is reached in our own reformatory institutions.

In addition to the public buildings enumerated above, there are also suites of rooms occupied by the Ecclesiastical Court, the General Archives, Topographical Department, Statistical Department, Medical Academy, Historical Institute, etc.

The citizens of Buenos Ayres have well provided for the unfortunate. Besides granting licenses to mendicants, and allowing them to go from door to door on horseback, the municipality has established an asylum for orphans and a foundling hospital.

Besides the cathedral, there are thirteen Catholic churches, two monasteries, and three convents. There are two hospitals, one for males, the other for females; but these institutions have neither the conveniences nor skilful physicians which those of more enlightened or longer established countries possess. There are also three foreign hospitals, supported by the English, French, and Italian governments.

The plazas, or public squares, are nine or ten in number; one of them is overlooked by the lofty cathedral and by the Casa de Justicia, and contains a monument, erected in commemoration of past events of national importance, and especially of the Declaration of Independence from the mother country.

Many improvements have been made in the city in late years, chief among which is the new brick seawall, of considerable height, protecting the town from damage by high tides of the river.

From this wall, projecting into the stream, there was in process of construction at the time of my arrival a[Pg 44] mole or wharf, of great length, which has since been completed, enabling small vessels and lighters to discharge their cargoes unassisted by the clumsy carts that formerly were the sole means of communication with the shore. The piles that support this wharf are pointed with iron, a precaution rendered necessary by the peculiarly hard formation of the river bed at this locality.

As the soil is impregnated with nitrate of potash, the well and other water is rendered unfit for table use. The wealthier citizens have deep cisterns at their residences, in which rain water is preserved; but the poorer classes have no other beverage than the river water, which is carried around the city in barrels, upon horses and mules, and retailed at a moderate price.

Slavery, which existed in these regions in a mild form until 1813, was, during that year, abolished by law. The system never assumed, in point of fact, that form which existed in our own republic, but was so lenient that the slaves were treated rather as children, or favorite servants, than as merely so much property.

Its gradual extinction set in many years before the period of legislation upon the subject. During the struggle for independence, the slave frequently fought side by side with his master, and manifested an equal anxiety with him to be liberated from the dominion of Spain. In consideration of services rendered during these patriotic struggles, and from a conviction that the system was far from beneficial to a newly-organized republic, the slaves were emancipated, and their descendants now form a valuable and active class, retaining[Pg 45] little of the indolence usually ascribed to the unfortunate races from which they sprung.

During the ascendency of Rosas, the negro population was devotedly attached to Doña Mañuelita, his celebrated daughter, and their influence with her was almost boundless. It is related that in 1840, while an attack by Lavalle was momentarily expected, a young man from the town of San Juan was in Buenos Ayres, and was forbidden, under pain of death, to leave the city. An aged negress, who had, in former years, been in the service of his family, happened to recognize him, and learned his anxiety to depart. “All right, my friend!” she said; “I will go at once, and get you a passport.” “Impossible!” exclaimed the young man. “Not at all,” replied the negress. “La Señorita Mañuelita will not deny it to me.”

In a quarter of an hour she brought a passport, signed by Rosas, enjoining his mercenaries to oppose no hinderance to the bearer’s departure.

Thus gained over by petty favors from the all-powerful dictator, the negroes formed a corps of zealous spies and adherents of Rosas, whose secret observations were carried on in the very midst of the families whom he suspected. They also formed a brigade of excellent troops, on whose fidelity he was able to rely at all times.

Don Domingo F. Sarmiento, from one of whose works the above anecdote is derived, is one of the most enlightened patriots and philosophers of South America. He is a native of San Juan, a town in the interior of the Confederation, but has travelled extensively in Europe and the United States, and was for[Pg 46] many years a resident of Chili, whither he was banished by Rosas in 1840. He has done much by his writings to advance a practical knowledge both of the principles of agriculture and of education in his native country, and is earnestly endeavoring to secure the cooperation of the government and legislature of Buenos Ayres in the advancement of those sciences. He desires to see some portion of the European emigration diverted from the United States to Buenos Ayres, the government of which province, indeed, offers land freely to all who will settle in the interior; and he has recently published, among other valuable works, a treatise on agriculture and education, entitled “Plan combinado de Educacion comun, Silvicultura e Industria Pastoril,” especially designed for the province of Buenos Ayres. He is also translating into Spanish the writings of Adams, Jefferson, and others of our early statesmen, which we may hope will enlighten the Spanish republics of South America on a subject that they seem at best to very imperfectly understand.

A word concerning the currency of this province, and I will dismiss it from the reader’s attention. Rosas, before he was driven from power, established a paper currency, which, being of small nominal value, was intended to supply the place of coin. These bills were struck off with the value of from one to several hundred pesos stamped upon them. But their value fluctuated to such an extent, that while at one time one Spanish dollar could purchase twenty pesos, a few weeks later not eight could be obtained with the same sum. At the present time a peso is valued at four or five cents of our money.

[Pg 47]

It is said that the president, having put this currency into circulation, realized thousands of dollars from it by monopolizing the money market, and causing the paper to rise or depreciate at his pleasure. I have seen a four-real piece coined by him, or by order of his government (which amounted to the same thing), with these words stamped upon it: “Eterno Rosas” (Eternal Rosas). This man was, in every sense of the word, a tyrant—cool, calculating, and selfish; possessed of a degree of cunning and penetration, that aided him in discovering his most secret enemies. Ruthless in the execution of his designs, he spared neither age nor sex; even the venerable mayor, his earliest friend, his more than father, was murdered in cold blood by a party of masorgueros (men of the Masorca, or club, a band of butchers and assassins, on whom Rosas relied for the perpetuation of his reign of terror), at the bidding of their atrocious chief.

In a work published at Montevideo, in 1845, by Don José Rivera Indarte, a native of Buenos Ayres, he gives the following estimate of the numbers who died through the hatred or caprice of Rosas: Poisoned, 4; executed with the sword, 3765; shot, 1393; assassinated, 722,—total, 5884. Add this to the numbers slain in battle, and those executed by military orders, at a moderate computation 16,520, we have 22,404 victims. If we deduct from this—allowing some latitude for the prejudices of Señor Indarte—one third for exaggeration, we still have 14,936,—a fearful aggregate of victims to the ambition of a Gaucho chief.

But his career has ended; the exiled patriots have returned from Brazil and Chili, and in place of his[Pg 48] there exists another, and, it is to be hoped, a better, government. He was at one time the absolute ruler of his country; and his long and cruel reign has left an effect upon its inhabitants which many years of wise legislation alone can eradicate.

[Pg 49]

The steamer in which I expected to embark for Rosario, on the Paraná River, would not sail from Buenos Ayres for ten days or a fortnight, and I began to look around me for some occupation, by means of which I might become more acquainted with the localities about the city. I was eager to visit the gaucho in his home upon the pampas; and when a young man, who had just arrived from New York, invited me to accompany him across the Plata to the Republic of Uruguay, I did not wait for a second invitation, but accepted his offer upon the spot.

I knew nothing more of this young man than that he had come to Buenos Ayres recommended to the first merchant of the place; but that his purpose for the visit was a secret one, I did not at the time suspect. He prepared himself for the journey by simply providing himself with a large blanket, a revolver pistol, and a sounding-rod. The first two articles seemed rational enough; but the rod, which he carried as a cane, required an explanation.

We received from a countryman a letter of introduction to Edward Hopkins, Esq., who was about to sail in the “Asuncion” for the north side of the river. This[Pg 50] gentleman was at the River Tigre, twenty-one miles from Buenos Ayres, and acted as agent for the United States and Paraguay Navigation Company. As there was no other way for crossing the Plata to the particular part of the coast where my friend wished to land, he decided to visit the Tigre, and embark in the Asuncion.

Having bargained for seats with the driver of the diligence that ran between Buenos Ayres and the village of San Fernando, near the Tigre, we set out one fine morning, accompanied by a native gentleman, who spoke English imperfectly.

Our cochero was a conceited fellow, and felt the dignity of office to an unnecessary degree. We had no little amusement during our journey with him in watching the phases of his character: once, when the cart of a milkman became entangled in the harness of our horses, he became so laughable in his wounded pride and impotent rage, that we had difficulty in restraining our faces to a decently sober appearance. As we became disentangled, and drove on, he, in the midst of a volley of carrambas, denounced all cartmen who had the impudence to cross the track of the mail-coach. And such, in fact, his vehicle was; but, as we noticed that the contents of the mail, instead of being confined in a mail-bag, or other suitable receptacle, were scattered here and there in various corners of the coach, some tucked beneath the cushions, and others lying under our feet, the opinion that we formed of the native postal arrangements was not of the highest.

For nearly a league we passed over a Macadamized road, shaded here and there by willows that ran along[Pg 51] the river. We soon passed the deserted quinta of General Rosas. The house was built upon arches, the materials being brick and plaster. Around it were artificial groves, and little lakes and canals of water.

To the right of the house, on the side nearest the city, were numerous little brick buildings, where the tyrant quartered his troops. The situation was very beautiful, and the surroundings altogether were interesting.

Farther on were casas (houses) of country gentlemen, with orchards of peach, olive, and quince, which, with the foliage of many varieties of shrubs, made the prospect on all sides most beautiful.

If a well-regulated estate particularly attracted our attention, we universally found, on inquiry, that its owner was a foreigner, whom the cochero dignified by the low word gringo, which is equivalent to “paddy” in our own language; and in this estimation, I afterwards found, our countrymen and all strangers are held by the indolent and treacherous country people.

Wheat, potatoes, onions, beans, tomatoes, &c., thrive wonderfully upon the farms; and, if the whole agricultural department were in foreign hands, the country, with its fine climate, and rich and easily-worked lands, could produce almost every kind of vegetable. With the exception of a few English and Scotch, the French from the Basque provinces are the most energetic and thrifty farmers. In a few instances the Yankee plough has been used with great success, in place of the miserable wooden one of the natives.

We met large covered wagons carrying produce to the city, and troops of mules and donkeys freighted[Pg 52] with thistles, in bundles, to heat the ovens of the bakers; also others with peach and willow trees, which had been raised for firewood, an article bringing a good price, on account of its scarcity.

As we approached the Tigre and Las Conchas, we found that the country is undulating; but beyond the line of the latter, it stretches out into the pampas as far as the vision can reach.

The diligence entered San Fernando about noon; we found it a little town, surrounded with fruit trees left to the care of nature, the people being satisfied with her products without wasting time in laboring to improve them.

Two miles distant was the River Tigre, which empties its waters into the wide Plata; towards the river we directed our steps, and we arrived in time to dine with Edward Hopkins, Esq., the gentleman whom we had come to visit.

Mr. Hopkins, who has acted as our consul in Paraguay, and as agent for the United States and Paraguay Navigation Company, invited us aboard the little steamer Asuncion, which had been put together at this place a short time before.

This company had been formed in the United States for the purpose of opening commercial intercourse with Paraguay, a country that had, under the dictator Francia, excluded foreigners. Lopez, its present ruler, had been on very intimate terms with our countryman, Mr. H.; and, taking advantage of this intimacy, and the president’s friendly feeling towards the United States, the above company was formed; and it soon sent out from Providence, R. I., a clipper schooner of[Pg 53] beautiful mould, containing, in pieces, a small steamer and “hoop boat,” with their appropriate crews, carpenters, millwrights, &c.

The schooner was damaged in the Tigre; but her cargo was landed, and the Asuncion put together, and sent up the Paraná to Paraguay. A cigar manufactory, employing three hundred native girls, was set on foot, a colony formed, and the steamer was to run between that country and Buenos Ayres, when an event occurred that blasted the prospects of the North Americans. A brother of Mr. Hopkins was stopped in the street for some trivial cause (probably galloping his horse) by a vigilante, whose language was insulting, whereupon difficulty ensued. As representative of his government, Mr. Hopkins interfered; and then followed the expulsion of our countrymen from the unexplored and little-known Paraguay. The United States steamer Water Witch, then lying in the Plata, ascended the river, and was fired upon from a fortification; several balls lodged in her hull, and one man was killed. The Water Witch destroyed the structure, and retired down the river to Montevideo, while the company’s men settled at the Tigre until matters could be adjusted. The Asuncion was then engaged in carrying sheep across to the Banda Oriental, the country on the north shores of the Plata, which is known on some maps as Uruguay.

San Fernando, in conjunction with the Tigre, is the watering-place of the ton of Buenos Ayres, many of whom pass the summer in the village. The next day after our arrival was passed in pleasant conversation with our countryman, and during the evening a large[Pg 54] party of ladies and gentlemen sailed down the river to two islands covered with groves of peach trees, where they took maté (tea), and danced La Samba Cueca, to the music of the guitar. I did not accompany them; for, having met a young man whose desire for travel had caused him to leave home, we passed the night wandering among the willows on the banks of the stream, and at an early hour on the following morning retired to rest as the piano frog was chanting his reveillé.

This was a spot where the naturalist would love to dwell. Above our heads sang many curious birds, and around us were still more curious insects.

On the neighboring church of Las Conchas, the carpentero built its oven-like nest, and parrots filled the air with their cries, while the mocking-bird rattled out his medley as in our own country.

As strangers, we were cordially received by the natives who occupied the houses close at hand, and many were the matés (cups of Paraguay tea) we took, because the pretty señoritas informed us that their language and maté were inseparable, and not until the foreigner became addicted to its use could he ride a horse, throw the lasso, learn the language, or win a fair maid.

I have already alluded to the yerba, sometimes called yerba maté, from which the Paraguay tea is made.

It is to South America what the tea of China is to Europe and the United States; nor are its qualities very greatly different from those of the Asiatic herb.

The yerba trees grow in forests, called yerbales, on the rivers of Paraguay, and attain a considerable size.

[Pg 55]

At the time of gathering, a party of peons are sent into the forest, who collect the branches, sprigs, and leaves in vast piles, which are afterwards thoroughly scorched. This being accomplished, the leaves and twigs are packed in a raw hide, which contracts as it dries, compressing the yerba into an almost solid mass. In this condition it is sent to market.