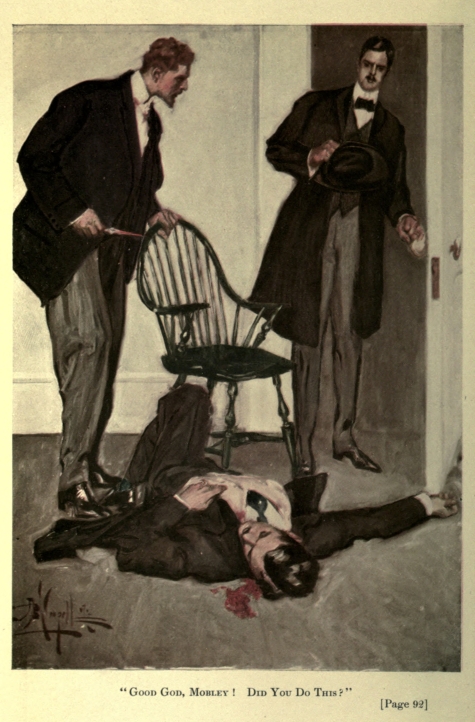

"Good God, Morbley! Did You Do This?" Page 92

The Project Gutenberg eBook of The silver blade, by Charles Edmonds Walk

Title: The silver blade

The true chronicle of a double mystery

Author: Charles Edmonds Walk

Release Date: October 6, 2022 [eBook #69106]

Language: English

Produced by: Al Haines

"Good God, Morbley! Did You Do This?" Page 92

THE TRUE CHRONICLE OF A

DOUBLE MYSTERY

BY

CHARLES EDMONDS WALK

WITH FIVE ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOR

BY A. B. WENZELL

CHICAGO

A. C. McCLURG & CO.

1908

COPYRIGHT

A. C. McCLURG & Co.

1906

Published March 18, 1908

Entered at Stationers' Hall, London, Eng.

All Rights Reserved.

The Lakeside Press

R. R. DONNELLY & SONS COMPANY

CHICAGO

TO THE MEMORY OF MY BROTHER

GEORGE EDWARD WALK

WHOSE INTEREST IN THE GROWTH OF THIS STORY

WAS NOT THE LEAST INCENTIVE

TO ITS COMPLETION

CONTENTS

BOOK I. A DUPLEX PROBLEM

CHAPTER

I. Exit Señor de Sanchez

II. The First Problem Develops

III. A Search for Clues

IV. Mr. Converse Appears as Chorus

V. A Telegram from Mexico

VI. The Inquest

VII. The Verdict

VIII. Cherchez la Femme

IX. The Second Problem

X. Footprints

XI. A Burnt Fragment

XII. A Door is Opened

BOOK II. CHARLOTTE FAIRCHILD

I. Miss Charlotte Waits in the Hall

II. Miss Charlotte Entertains a Caller

III. "Paquita—What Do You Spell?"

IV. Miss Charlotte Becomes a Factor

V. A Decision and a Letter

VI. Faint Rays from Strange Sources

VII. A Voice in the Night

VIII. The Coroner's Coup

IX. The Light Brightens—and Dims

BOOK III. SLADE'S BLESSING

I. Opening Ways

II. Fairchild Redivivus

III. "The Thunderbolt Has Fallen"

IV. Some Loose Ends

V. Mr. Slade Resigns

VI. An Arrest

VII. "Slade's Blessing"

BOOK IV. THE DANCER AND THE MOUNTEBANK

I. "That Is Paquita"

II. The Serpent Strikes

III. Which Is the Last

ILLUSTRATIONS

"Good God, Mobley! Did you do this?" ... Frontispiece

Joyce was herself a mystery, an enigma, as inscrutable as "Paquita"

LIST OF CHARACTERS

GEN. PEYTON WESTBROOK, a gentleman of the Old South.

MRS. WESTBROOK, his wife.

DR. MOBLEY WESTBROOK, their son.

JOYCE, Mobley's sister.

MRS. ELINOR FAIRCHILD, a widow of fallen fortunes.

CLAY, her son.

"MISS CHARLOTTE," Clay's sister.

JOHN CONVERSE, Captain of Detectives.

MR. MOUNTJOY, the District Attorney.

MR. MERKEL, the Coroner.

J. HOWARD LYNDEN, a cotton-broker.

SENOR JUAN DE VARGAS Y ESCOLADO, otherwise known

as Señor Vargas, a Mexican capitalist.

WILLIAM SLADE, an abstracter of titles.

ABRAM FOLLETT, a dealer in worn-out utilities.

ROBERT NETTLETON, a lawyer.

FERDINAND HOWE, a banker.

HARRY MCCALEB }

SEPTIMUS ADAMS } serving under Capt. Converse.

SAM }

JOE } faithful servants.

MELISSA }

POLLY ANN }

THE PLACE: A City in the South.

TIME: The Present.

Is this a dagger which I see before me,

The handle toward my hand?

—MACBETH.

THE SILVER BLADE

BOOK I—A DUPLEX PROBLEM

About six o'clock on an evening in the early part of a recent November, the drowsy quiet sometimes pervading police headquarters was rudely broken by the precipitate entrance of a young man, who made his way hurriedly to the door marked, in neat gilt letters, "CHIEF OF POLICE."

In addition to the reserve squad, whose vigil never ends, many other officers were present in the lazy transition stage between going on and going off duty. The attention of them all was immediately attracted to the stranger, and held by his extraordinary manner, from the instant he became visible in the flickering gas-lights until he finally disappeared.

In the first place, he was not such a one as usually comes to the city-hall basement, either voluntarily or when haled hither by one of the law's myrmidons; for he was fashionably, even fastidiously, attired, with a marked preciosity of manner which would have been even more noticeable under ordinary conditions.

But it was not over any idiosyncrasy of apparel or customary detail of personality that the aroused curiosity of the officers lingered. Inured as they were to uncommon and surprising events, they were nevertheless startled by this young man's advent, and greatly interested in his extreme discomposure. It was obvious to the most casual glance that he was the victim of a fright so potent that it possessed him to the complete exclusion of every other feeling, made him oblivious of the scrutiny to which he was subjected, and drove him blindly to the commission of some idea fixed by the terror which mastered him. And there was one other still more powerful emotion depicted in his pallid, twitching countenance: a horror unspeakable.

Looking neither to the right nor the left, the stranger walked directly to the Chief of Police just as that official was in the act of closing and locking his office door for the night. The latter looked up inquiringly, and, struck at once by the young man's appearance, asked with sudden sharpness:

"What's the matter? What has happened?"

The young man, his wild regard fastened on the Chief, tried to answer; but he was incapable of speech, and the effort resulted only in a queer, gasping sound.

With the directness of a man accustomed to prompt action, the Chief of Police opened his door once more, and guided the young man into the smaller room beyond. The visitor, dazed by his emotions and unable to respond to any suggestion less forceful than the actual pressure of the persuasive hand on his arm, probably would have remained indefinitely motionless on the threshold before any customary invitation to enter.

The Chief struck a match and ignited a gas-jet above a big roll-top desk. The action, simple in itself, seemed to loose the young man's faculty of speech; just as the official turned, he darted suddenly forward, grasped the other's arm, and began incontinently:

"Murder! Murder has been done!" The words had the effect of a cry, although uttered in a hoarse whisper.

"Murder, I tell you. Come with me at once; don't delay." He shook the Chief's arm excitedly, and strove to draw him toward the door.

"Hurry! Hurry! For God's sake, hurry!"

The Chief of Police easily disengaged his imprisoned arm.

"There, there .... sit down there," said he, in a tone he might have used to calm a terrified child. "You are upset. Sit there awhile and try to collect yourself. Come; make an effort. Pull yourself together and tell me about it."

"But the murderer!" the young man went on, still with high excitement, but unconsciously sinking back into the chair under the gentle pressure of the Chief's hand. "The murderer will escape! Great Heavens, man! even now he may be assaulting the doctor—Mobley—do you hear me?—he may have killed him! Send officers—go yourself—anything but to sit here idle. Come!" He made as if to rise again; but the other pressed him back.

"Steady," said the Chief quietly. "Mobley? Do you mean Doctor Mobley Westbrook? Has he been murdered?"

"No-no-no," in a burst of exasperation. "It was—it was—I mean—good God, what do I mean? It—it happened in his office."

The Chief regarded him for a moment with eyes that were mere pin-points of light.

"You are Mr. J. Howard Lynden, are you not?" he presently asked. The other nodded a quick affirmative. "I thought so," he continued. "Who is the murderer? Who has been murdered?—or has any murder been done? You don't make yourself clear."

Lynden twisted nervously upon his chair. "Heavens! you do not doubt me?" he cried. "Why, Mobley's office is like a shambles. It's horrible!—horrible! Mobley—Doctor Westbrook, that is—was standing right over the dying man with—with—" He checked himself abruptly, as an expression of horror deepened in his pale countenance.

Since the introduction of Doctor Mobley Westbrook's name, the Chief of Police was paying closer attention to the incoherent recital; he regarded the young man gravely, and evidently concluded that the situation was serious enough to warrant some initiative on his own part. He was accustomed to panic-stricken people who intruded thus unceremoniously upon him, and experience had taught him that, oftener than not, the circumstances were far from warranting the excitement.

Concerning his present visitor, he was aware, in a general way, that the young man was well known about town, the inheritor of a considerable fortune from his father, and that his name figured prominently as a leader of cotillons, on the links of the Country Club, and among the names of the many others who formed the society set of the city.

But all these qualifications did not supply the force so conspicuously absent from Mr. Lynden's personality, lacking which his perturbation was not very impressive. He was not at all bad looking: he was even handsome in a way; but the Chief of Police, as he looked, could not help remarking that a more resolute man would have been less the slave of his emotions in a situation like the present. While the young man sat drumming with nervous fingers on the arms of his chair, the Chief pressed a button beneath his desk, whereupon the door was almost immediately opened by an officer, who, without entering, respectfully awaited his superior's commands.

To him the Chief said, "If Converse is in, tell him to come to my office;" and as the door closed, "I want Captain Converse to hear this," he explained to Lynden; "it seems to be a matter for his department."

The two had not long to wait. A man entered, cast a piercing glance at the visitor, and took his stand at a corner of the roll-top desk, waiting with an air of deferential attention. He was a man of physique so immense—with such a breadth of shoulders and absence of neck—that his more than average height was much disguised. Above all, he was one whose appearance must attract attention in any gathering of his kind; for even as Lynden seemed to lack those desirable traits, so force and resolution flowed from this man's rugged personality, making their influence felt subtly and insistently. His air of quiet composure was evocative of confidence. Endowed with the impassiveness of an Indian, one could hardly imagine him excited or agitated in any circumstances.

The Chief recognized his presence with a brief nod, and at once addressed Lynden:

"Repeat what you have told me; see if you can't make it plainer."

The visitor recounted the bare facts in a more connected manner. "But I was so shocked," he supplemented, "that I am afraid I can't make myself intelligible. The facts explain nothing to my mind further than that an atrocious murder has been committed, that the victim is still lying in Doctor Westbrook's office, and that no one seems to know who is responsible for the deed."

"You say the man was stabbed?" queried the Chief.

"Yes," was the reply; "stabbed in the throat."

"But I fail to understand," the Chief frowned. "Do you mean to say that a man was stabbed in the presence of Doctor Westbrook, and that he knows nothing about it?"

"No—no. It seems to have occurred in the hall just outside Mobley's door; the man fell through the door into the office, Mobley said. I don't know—I am so confused." Which last statement he confirmed by at once becoming involved in a wild incoherency of utterance.

After he had quieted somewhat, he sat trembling for a moment, suddenly bursting forth again:

"Wait!" he cried, his face lighting. "I forgot to say there was another man present in Doctor Westbrook's office—a stranger to me. I never saw him before."

"And he?"

"Just like Mobley and myself, he appeared to be overcome by the shocking occurrence."

The Chief of Police plainly showed his perplexity. "According to your statement—the man who was killed—will you repeat his name?"

"De Sanchez. General Westbrook's friend, Alberto de Sanchez."

"According to your statement he was bleeding profusely. Had the weapon been withdrawn from the wound?"

The young man evinced unaccountable hesitancy. He moved uneasily, and glanced from his questioner to the impassive figure standing at a corner of the desk. This man, called Converse, had taken no part in the talk; he stood silent and motionless, seemingly paying no heed to what was going forward; but now he shot a swift glance at Lynden, whose nervousness measurably increased. That look was remarkable in a way: the eyes, steely gray, were in themselves without expression; they failed, however, to veil an intentness and concentration of mind which disclosed beyond a doubt that their owner was abnormally alive to every detail of speech and manner; they could not hide a power of will lying behind their quick regard, which mocked deception, and Mr. Lynden shuddered. Instantly the brief glance was withdrawn; but the young man, if such had been his intention, attempted no liberties with the truth. The confusion with which he now spoke, however, suggested strongly that the thought had entered his mind, although he may not have entertained it there.

"I—I—I would rather that you, or some officer, accompany me to Mobley's office," he faltered. "I consider it rather unfair, in my condition, to press me further. I wouldn't for the world present anything in a false light. I feel that the situation is not only serious, but extremely delicate."

"It is that," the Chief agreed, emphatically. "For that very reason you must tell all you know. Now, why should you hesitate in regard to the weapon? Come now, what about it?"

"Well, sir, I answer you under protest; remember, I did not see the blow struck."

"Sure?"

The young man nearly sprang from his chair. The interruption, a penetrating, sibilant bullet of speech, came from the massive figure of Mr. Converse; again that shrewd regard was fastened on him, and the sweat started from his brow.

"No!" he cried, explosively; "I did not. By George, how nervous I am!—but I think half-truths should not be told. No one is less capable of perpetrating such a deed than Mobley Westbrook. Why, you know the man!" He appealed with feverish eagerness to the two figures now sternly confronting him. "Every one knows Mobley Westbrook's character; would he do such a thing?"

"But come to the point—come to the point, man!" the Chief demanded, rapping sharply upon the desk with his knuckles. "What of the weapon—was it a knife—sword—axe—hatchet? Where was it?"

"Well, Mobley had some kind of a—blade, a—dagger in his hand; but—"

"Ah! And standing over a man whose very life-blood is ebbing away beneath his eyes!" The Chief's manner was politely ironical, and struck the young man cold. "You must admit that you portray an astonishing set of circumstances to surround a man not only innocent but ignorant of an offence," concluded the official, pointedly.

Lynden indeed started from his chair. "I knew it! I knew it!" cried he, wildly. "I knew you would put such a construction upon my words; now, damn it! I'll not say another word. Go—go! Go and see for yourselves how wrong you are!"

The Chief of Police ignored this vehement advice. Instead, he curtly admonished Lynden to remain a few moments where he was; and leaving the wretched news-bearer alone with his own reflections, he and Converse withdrew from the room.

After a minute or two the Chief returned. "I have sent for a carriage," said he. "As soon as it arrives I must request you to accompany Captain Converse to Doctor Westbrook's offices; are you willing to do that?" He awaited the reply with an interest mingled with doubt of what its probable tenor might be; when the young man acquiesced with an alacrity and relief obviously sincere, his doubt merely grew. He contemplated Lynden an instant longer, and with a curt nod, seated himself at his desk again.

Almost at once, however, the large figure of the Captain—or plain Mr. Converse, as he much preferred to be known—appeared in the doorway.

"Come!" he whispered; and the whisper rasped upon Lynden's nerves. Confound the man! was he afraid he would betray some momentous secret, so that he did not talk like other people? Nevertheless, he arose and followed him,—under the heavy stone arches, shrouded with gloom in the flickering gas-light, out into the cool night air and into a waiting hack. Two other men followed close behind, and entered a second hack; immediately the two vehicles, one behind the other, were going at full speed in the direction of Doctor Westbrook's offices.

Under the soothing influence of rubber tires spinning easily over the smooth asphalt, the young man was fast regaining his lost composure. He was so rapt in his own thoughts that for a time he quite forgot his still companion, and presently he laughed—mirthlessly, but a laugh signifying sudden relief. Quite as suddenly it was checked, as he met the inquiring, probing glance of his vis-à-vis.

"It is astonishing that I never thought of it before," he explained, in an embarrassed way. "That other man—the stranger—can set Mobley right in an instant. Do you think Doctor Westbrook could have done it?"

Immediately he regretted the question, for it entailed hearkening to that uncomfortable hissing voice. It was Mr. Converse's misfortune that, properly speaking, he had no voice at all. His entire speech was a series of sibilant utterances, wonderfully distinct and possessed of remarkable carrying power when one considered their quality. It is likely that he was sensitive about his vocal defect, since he was known as a silent, taciturn man among his confrères. On certain rare occasions, however,—under, for example, the spur of an inflexible purpose or the influence of a sympathetic nature,—it was also known that he could wax eloquent; his forceful individuality supplied, in a large measure, the place of a normal, flexible voice.

The head of the detective department might have been anywhere between forty and sixty years of age, so far as one could gather from his huge frame and stolid countenance. His hair was gray, and thinning slightly at the temples; but behind his illegible exterior there reposed a vigor and a reserve of power—revealed now and then, as in the lightning-like glance cast at Lynden in the Chief's office—which could not be reconciled with age. He was, in fact, fifty-two.

His face was full and round, smooth-shaven, expressionless—such a visage as one associates with some old sea-dog; a countenance that has long been subjected to the hardening processes of wind and weather. As the young man waited for a reply, the immovable features underwent a curious change; the mouth gradually assumed a pucker, as though the facial muscles were inelastic and unused to such exercise; his right eyebrow lifted, which, as the other remained motionless, was made all the more noticeable,—the effect being an expression of inquiry and speculation that seemed ludicrously out of place. Lynden became familiar with this queer transformation later on; he learned to associate it with the futility of seeking to penetrate the wall of reserve which ever surrounded this unusual man, and perceived that it came and went as a sort of involuntary warning to place least trust in his frankest confidences. Now it introduced the response to his question, "Do you think Doctor Westbrook could have done it?"

"The Doctor is a strong, vigorous man, isn't he? I don't see why he couldn't."

"My dear sir," Lynden anxiously expostulated, "you don't know Mobley Westbrook, or you never could entertain such a thought."

"Pardon me," said Mr. Converse, carelessly, "the thought seems to be your own; I was simply giving you the first fact that occurred to me, to justify your opinion. I have formed none myself."

"You interpret my words strangely."

"No; your silence."

The young man, with another shudder, drew back to the corner of the vehicle farthest from his companion.

The receding lights outside followed the carriage in squares of diminishing illumination, which, shining through the window, made strange play of light and shadow over that inscrutable visage. All at once it became deeply portentous to Lynden; as if by sudden divination he became possessed of a conviction that it was destined to take a high place in his affairs,—signifying, perhaps, the controlling influence in a strange drama, the first scene of which was now upon the boards.

"It is very remarkable," the Captain mused, presently, as if the episode were too much for him.

Lynden started from his reverie.

"Yes," he murmured, not meeting the other's eye. "Yes; it is very remarkable." Both lapsed into a silence that continued until the end of the ride.

As the vehicle proceeds, a few words about those whose names have been mentioned, together with some others who will figure in this narrative, will give a better idea of the importance of the tragedy, the ill tidings of which Lynden had been the bearer.

Both by reason of recognized ability in his profession and of his high family connections, Doctor Mobley Westbrook was leader of the medical fraternity in the city of his birth and residence. He was still youthful in spite of his thirty-five years; democratic in his tastes, immensely popular in every class of society, and for these reasons considerably at odds with his father.

Notwithstanding his popularity, his single excursion into politics had only shown his unfitness for the national game; a circumstance mentioned here because later on he is to have it brought back to him in a manner both forcible and disagreeable.

Singularly enough,—for from another and altogether different sentiment the General himself was popular,—General Westbrook was known to hold his son in some disfavor because he was so well and universally esteemed. His exclusive nature could not brook the physician's democratic inclinations; it made the latter an alien. The General did not understand it, and what he could not understand he disliked.

The two personalities were remarkably divergent in every way. General Peyton Westbrook was an exaggerated type of the old-school Southern gentleman. Strikingly handsome, elegant in appearance, his erect and rigid bearing, together with a falcon-like glance suggested a stature which one in describing would be likely to pronounce tall when in reality it was not much over five feet. His graceful slenderness added considerably to the illusion. His hair was white, his features cameo-like—aristocratic, and stamped with the overweening family pride, to which, with him, every other human emotion was subservient.

It is probable that his presence and name were better known in every part of the State than those of any other living man. For the class which he represented was that noble body of patricians—handsome and recklessly brave men, and beautiful, high-minded women—who have given the world criterions by which human excellence and human weakness alike may be measured; and his position was a personal hobby, persistently and consistently ridden.

Of his standing he was perhaps pardonably proud. Besides his social position and that of his wife, who had been a Shepardson, and of his lovely daughter, Joyce, he had fought gallantly, if not brilliantly, through the war between the States; but he was just narrow-minded enough to allow his pride and egoism to exclude the rest of humanity.

There was but one uniting link between Mobley and his father and mother—the latter even more distant and unapproachable than her spouse—and that was the daughter and sister, Joyce. Whatever their differences, the family was held together by affection for this beautiful girl.

The love that bound Joyce and Mobley was deep and abiding. It is not surprising, then, when the question of his sister's marriage became gossip, that Mobley should have taken a stand on the subject which brought about a final and complete rupture from his father and mother. The name with which his sister's had been linked was no other than that of this same Alberto de Sanchez, who now lay dead, with a ghastly knife-wound in his throat, in the Doctor's own office.

James Howard Lynden—or "Jim," as Doctor Westbrook called him—had long been on intimate terms with the Westbrook family. And it was he who now accompanied the silent Mr. Converse through a small but curious group gathered about the entrance leading to the Doctor's office; the first stage of an intermingling of interests widely diverse; the bringing together of lives as far asunder as the stars.

Doctor Westbrook's offices were in the Nettleton Building in Court Street. It and its neighbor on the east, the Field Building, were of that solid old style of structure devoted to business, which knew not the elevator nor steam heat, nor any of the many devices that enter into the complexities, and often questionable conveniences, of the modern office edifice. They were not, and never had been, of an imposing appearance, boasting as they did only three stories; but they were nevertheless the blue-bloods among the city's commercial houses, preserving their exclusive position amidst the newer generation of garish sky-scrapers which rudely intercepted the vision on every hand.

The occupants of these monuments of the old regime were in full accord with their habitations,—solid, conservative, and even aristocratic. As often as not a modest sign—if it could be deciphered at all—notified the visitor that behind certain doors could be found "Harvey Nettleton, Estate of," or, "Richard Fairchild, Estate of," or some name equally well known, and associated with a glory that had departed. In most instances, well might the present owners of those family names cry "Ichabod!" for they had long since ceased to have any interest in the estates other than the shadowy interests which lie in memories and vain regrets.

As Mr. Lynden and his taciturn companion passed through the Nettleton Building entrance, where the curious little throng was restrained by the presence of a couple of mute policemen, the Captain's entire manner underwent a complete and sudden transformation; his expressionless countenance remained wooden, but into his eyes there arrived an intentness and brightness entirely absent from them before; his rather lethargic and apparently purposeless movements giving way to a brisk mode of proceeding which one would hardly have expected from his cumbrous frame. His demeanor was become at once alert and wary, and he had little to say to Lynden.

It was now night outside, and the stairs were faintly illuminated by the single incandescent lamp which hung at their head in the hall of the second story. The sole indication that Mr. Converse was striving to allow nothing to escape his observation was the quickness with which he stooped, when near the top, and picked something from the stairs—something too small for Lynden to catch even a glimpse of—which, whatever it was, the Captain scrutinized intently a moment, and, without comment, dropped into the large pocket-book he brought forth from an inside pocket. The two continued on their way until they reached Doctor Westbrook's office.

Everything was as Lynden had left it, save for the fact that Doctor Westbrook, and the stranger mentioned by the young man, had been joined by several other persons.

One was a swarthy, lean man, whose face was pitted by small-pox, and whose rather dull eyes remained expressionless behind a pair of gold-rimmed pince-nez. He was standing aloof from the others, and seemed to be taking only languid interest in what was going forward. Occasionally he coughed in a manner that told much to the physician's trained ear; save for this, he remained silent. Mr. Merkel, the coroner, and a uniformed policeman were also present.

"Ah!" exclaimed Mr. Merkel to Converse as he and his companion appeared. "So they have sent you, have they? How fortunate! how exceedingly fortunate! This, gentlemen," he continued, addressing the other occupants of the room, "is Captain Converse. He will pardon me, I know, if I add—the great detective. Nothing has been disturbed, Captain, nothing has been disturbed. You will find everything just as I did. It is a bad business, a bad business."

Mr. Merkel was fussy, important, and wholly incompetent; and the Captain was so accustomed to his repetitions of phrases that were not, to say the least, pregnant with meaning, that he ignored them and turned to an inspection of the dead man.

The body lay just as it had fallen. Somebody had placed a handkerchief over the face, a covering that also hid an ugly wound in the throat. Mr. Converse stooped and removed this, and began a minute but rapid examination of the still form. It reposed in the Doctor's reception-room, close to the wall, partially on its back and partially on its right side. The right arm was extended, the fingers of that hand still in a position as though upon the point of grasping something. Curved naturally across the breast, the left arm suggested restful slumber rather than death by violence; but whatever the eyes had last looked upon, before the film dimmed their lustre, it had stamped upon the handsome features an indelible expression of mingled terror and horror, which one could scarcely regard without an inward tremor of something very like fear. It was an expression likely to remain disagreeably in the memory for a long time.

A search of the dead man's pockets revealed nothing unusual, except that, in a petty way, he had been a violator of the law; for the first thing Mr. Converse drew forth was a nickel-plated, pearl-handled revolver of 32-caliber. The remainder consisted of a number of letters, all relating to business matters; two long envelopes, evidently but recently sealed, and addressed simply, "El Señor Juan de Vargas"; a purse containing money; a gold watch; a fountain pen, and pencil; two memorandum books; a silver match-box; a pouch of dark tobacco, and brown cigarette papers; a handkerchief; a penknife; a bunch of keys,—these were all.

When these effects were inventoried, while Mr. Merkel was assorting them at Doctor Westbrook's writing-table, the dark man with the pince-nez stepped forward. All eyes were turned toward him, excepting, apparently, those of Converse, which continued to give the body and the reception-room floor their attention.

"Pardon, señores," said the dark man, bestowing a bow upon the entire group, and ending it at the Coroner; "is there anything addressed to Juan Vargas, or Juan de Vargas? I am he."

Mr. Merkel looked at him sternly, and held up the two long envelopes.

"I see the name of Vargas—er—ah—inscribed on these. Are you Mr. Vargas?"

The other remained unmoved, replying simply, "I am Juan de Vargas."

"What connection have you with the deceased gentleman?" continued the Coroner, without relaxing in the least the sternness of his look. "Can you tell us anything of this affair?"

Señor de Vargas shrugged his shoulders. "Nothing, señores; I lament that I cannot. The contents of the envelopes should tell you about the extent of our connection; they contain but a deed, some shares of stock, no more. Señor de Sanchez would have delivered them to me to-night. Open them by all means."

The man's eyes, dull and unmoving, continued to regard Mr. Merkel. Had he been discussing the weather his tones could have been no more dispassionate.

The Coroner tore open the envelopes, and, as the man had said, one contained a deed, conveying certain land to Juan Sebastian de Vargas y Escolado, the notary's certificate showing it had been signed and acknowledged that very day before Clay Fairchild. Alberto de Sanchez had made the transfer. The other envelope disclosed a certificate for one thousand shares of stock in the Paquita Gold Mining and Milling Company, also made over to Señor Vargas in due form. The papers told no more.

"Good!" exclaimed Señor de Vargas. "We agreed yesterday, and I have made the first payment of ten thousand dollars for myself and associates. I was but awaiting the deed and the stock."

At this juncture Doctor Westbrook interposed:

"I happen to know that this gentleman is Señor de Vargas," said he. "He called here with—with Señor de Sanchez last evening. I have heard something of this deal between the two, and I believe it represents the occasion of this gentleman's presence in the city at this time."

Señor de Vargas acknowledged this speech with a grave "Gracias, señor." Turning to Mr. Merkel again, "I hope there will not be much delay?" he queried, mildly, with a certain precision of enunciation that alone marked him of an un-English-speaking race.

Since he had comprehended the magnitude of the transaction as disclosed by the deed and certificates, and after Doctor Westbrook's interposition, the Coroner's manner toward the Mexican had noticeably altered.

"No more than necessary," he replied deferentially; "no more than necessary, sir. I am sorry, but these papers will have to remain among the deceased's other effects until after the inquest, anyhow. Mr. Mountjoy, our district attorney, is the proper authority for you to see."

"Good!" returned the Mexican. "I desire not for my humble affairs to stand in the path of justice." Bowing once more, he returned to his former position away from the others.

Converse suddenly passed over to the Coroner, and laid a bloody dagger upon the table. Its silver blade, crimsoned in part, was grewsome and startling beneath the bright glare of the shaded incandescent lamp. Mr. Merkel involuntarily drew back his hands, the strange gentleman who had been with the Doctor since the tragedy visibly shuddered, and for an instant—the smallest portion of a second—the dull eyes of Señor Vargas took on a strange light, as though the pupils had all at once distended, allowing a glimpse to the uttermost depths, then became dull again. It was like the abrupt opening and closing of a shutter. Otherwise his features did not change, nor did he move. The more phlegmatic policeman looked upon the little weapon without apparent emotion; the Doctor and Howard Lynden with none at all.

However, as the Captain placed it upon the table his eyes took in every occupant of the room in one rapid sweeping glance, only to drop as he stooped and whispered to the Coroner, who there upon nodded and turned to the waiting group.

"Now, gentlemen," said he, "this is not the inquest, of course; but let us hear what you have to say about this. You first, Doctor Westbrook; you first."

"What I can tell you will seem much less than it should," the Doctor returned. "It was about five o'clock, and I was sitting at my table—there, where you are now. I had just finished a letter to no other than Señor de Sanchez himself."

"Is this it?" the Coroner interrupted, extending a letter to the speaker. Doctor Westbrook replied affirmatively, and proceeded with his recital.

"I had just completed and blotted it, and was preparing to address the envelope, when I heard footsteps in the hall. I paused, with the pen in my hand, and listened, for I was expecting Señor de Sanchez to call at my office this evening, though not so early, and I imagined the footsteps might be his. As I listened, I noted that my door was not quite shut, and the footfalls advanced steadily down the hall, approaching my office. When immediately outside the door, and while I was looking up expectant of the caller's entrance, they ceased abruptly. There was a slight sound of scraping on the floor of the hall, as though the man—whom I could not then see—were endeavoring to rub something from his shoe-sole on the boards, or had slipped slightly; without the slightest warning, his whole weight plunged against the door. It was thrown violently open by the impact, and I was horrified to behold Señor de Sanchez stagger through, his right hand extended in front of him, as if groping for support. As he crossed the threshold he lurched to his right and struck the wall, along which he slid to the floor, just as you now see him."

During his relation of these particulars, the Doctor's manner was perfectly cool and collected. The next incident fairly electrified his intent listeners.

"As he was falling," he continued, "I noticed the dagger handle protruding from the left side of his throat."

"Is this the one?"

It was Converse's sibilant whisper which now rudely broke into the recital. At the same time he thrust the silver blade close to the other's face.

Doctor Westbrook at first merely glanced at the weapon; but something about it evidently caught and held his attention, and an emotion vastly different from mere recognition overspread his countenance; it was astonishment, pure and simple.

"God bless my soul!" he gasped, in extreme amazement; "that is mine—my paper-knife—and I did not recognize it! What does this mean?" He sat with his eyes glued upon it, the centre of a dumfounded group. The Captain continued a moment to hold it forward, his gaze fixed inscrutably upon the physician's puzzled and bewildered countenance.

Presently Converse drew the weapon slowly back again, and replaced it upon the table.

"So that is yours?" the Coroner soberly asked.

"It is," replied the Doctor; "and I did not recognize it until this minute. How did it—why—" he began vaguely; but Merkel interrupted.

"Well," said he, with a wave of the hand that seemed to dispose of all complications, "it will be time enough for questions when you have finished."

"De Sanchez was falling," resumed the Doctor after a moment's reflection, "when I noticed the dagger handle. The body had scarcely touched the floor before I had stooped and wrenched the blade from the wound. It did not come easily; it required a severe tug to loosen it, and the withdrawal of the blade was followed by such a gush of blood that I knew some important artery must be severed. The man's death was practically instantaneous. After I had extracted the blade I had no time to render him any further service; I simply stood dumfounded until Jim—Mr. Lynden—grasped my arm and shook me."

"But, Doctor Westbrook," insisted Mr. Merkel, "was there no one else in the hall? Did you hear no other footsteps? Didn't you see or hear some one else when the door was thrust wide open? Surely the murderer couldn't have left so quickly without attracting the attention of some one of you. It is simply incredible." He grasped the arms of his chair, leaning forward in his eagerness, his heavy countenance overshadowed with perplexity.

As the Doctor started to reply, Converse glanced sharply toward him; when Lynden's name was presently mentioned, shifting his scrutiny to that gentleman.

"I must say no to all those questions," was the Doctor's reply. "I saw nobody but De Sanchez. I heard nothing but his footsteps, and the noise he made in collapsing through this door. Ask Jim Lynden, there; he was in the hall at the time; he followed so closely behind De Sanchez that he arrived here before the man died."

Lynden merely shook his head, hopelessly, as if he had no vocabulary to express himself. The Coroner was impressed by the young man's mien, and after regarding him a moment with a scowl, turned again to Doctor Westbrook.

"Was any one else present, Doctor?" he asked.

The physician's face was suddenly illumined.

"Yes; why, certainly. Howe!" he exclaimed. "Howe, where were you?"

The man, who apparently had been a stranger to everybody in the room, now advanced.

"I was in there—your laboratory—looking into the light-well."

Converse noiselessly disappeared into the room indicated, returning in a few seconds to eye the stranger with increased interest.

"And who are you, if I may ask?" bluntly demanded the Coroner.

"My name is Ferdinand Howe, sir," the stranger replied, with dignity. "My home is in Bruceville, Georgia, and I am in your city on business for the bank of which I happen to be the cashier. Doctor Westbrook and I are old college-mates, and I know about as much of this affair as he has told you; that is to say, I was there—the other side of that partition in the laboratory—when the murdered man fell where you now see him. The first intimation I had that anything was amiss was when the outside door crashed open and the body fell to the floor. I ran into this room, saw the man gasp twice, and then lie motionless. I never saw him, and never heard of him, before this night. That is all."

Mr. Howe appeared to be about the Doctor's age, and was a fair type of the American man of business. He was well groomed, clean, and possessed of a clear, steady eye.

"And you saw and heard no one else?" Mr. Merkel persisted.

Howe shook his head. "No, sir; no one. There was not the slightest thing to indicate—"

He stopped. He shot a swift, startled glance at Doctor Westbrook; but the Doctor remained unconscious of it, evidently absorbed in his own cogitations. Mr. Converse's eyes watched the speaker through mere slits, so nearly closed were they; but a gleam came from between the contracted lids that might have betrayed a quickened interest somewhere in the depths of his big frame.

"No," concluded Howe presently, in tones measurably subdued; "I neither saw nor heard anybody else, but—" With compressed lips he indicated by a nod the form on the floor. "You must remember," he concluded, "I was in the next room, looking out the window into the light-well."

Converse looked quickly from the speaker to Lynden. That young man was staring strangely at Howe, evidently impressed by something unusual in his concluding words.

Suddenly the young man caught Converse's intent look, and his own eyes lowered. Next they shifted to Doctor Westbrook, at whom he continued to look in a moody silence.

The Coroner, apparently more and more at sea, stared first at one and then another of the room's occupants, at the partition which separated the reception-room from the laboratory, and lastly through the open doorway into the hall. The most extreme of the different points were not over six feet apart; and for three men—wide awake and in full possession of their faculties—to be so close to such a crime and know nothing of it until it was all over! How could human ingenuity supply an explanation for so incongruous a circumstance? Had the man committed suicide? The most cursory examination of the wound demonstrated beyond doubt that, however else it might have been inflicted, Alberto de Sanchez was incapable of having administered it himself.

Meanwhile the Captain was moving from one to another of the group, his whisper barely audible, but persistent and pervading the entire room. Occasionally he made a brief memorandum upon an envelope,—cabalistic marks which no one but himself could have deciphered. Then the whisper again for a moment, followed by a deferential lowering of his gray head as he hearkened to the reply. Had one been observing him closely he would have noticed that the circle of inquiry gradually narrowed. The policeman he paid no attention to at all; he was soon through with Señor Vargas; but from Lynden he passed to Howe; next to Doctor Westbrook; and from one to another of the last three, as a word from one suggested a new inquiry to be asked of another. His movements were silent, his manner unobtrusive, distracting no attention from Mr. Merkel and his investigation. Now and then he paused and stared contemplatively into vacancy for a moment, with the odd lifting of his right eyebrow, and with his mouth thoughtfully pursed; but the mask of his countenance told nothing, and only once did he include the whole group with a question. It was after he had been whispering quietly for some minutes with Howe.

"Who can give me young Mr. Fairchild's address? You, Doctor?" he asked.

"Clay?" Dr. Westbrook returned. "Yes. It is close to the terminus of the Washington Heights car line. The conductor can direct you to it; the houses are not numbered out there."

Converse nodded, and chose a slip of paper from the table. After looking at it, first on one side and then on the other, it apparently did not suit his purpose; for he subjected another bit of paper to a similar scrutiny before pencilling a hurried line thereon, although he did not replace the first slip. The note he handed to the policeman with a whispered word, and the policeman instantly quitted the room. Had one still been observing Mr. Converse he would have seen him abstractedly place the first bit of paper in his waistcoat pocket.

Well, it seemed that no one present could throw additional light upon the manner of Señor de Sanchez's death. Mr. Merkel arose from his chair at the Doctor's table, and looked a pointed inquiry at the Captain, who responded by a short negative shake of his head. As if relieved of a distasteful responsibility, the Coroner said:

"Such of you as desire to go may do so. Captain Converse and I will have to look about a bit. He must have an opportunity to apply his wonderful skill, gentlemen; and you will all be notified of the inquest; you will be duly notified..... Doctor Westbrook, I will send a wagon for the body," he concluded. "Good-night, gentlemen." He turned to the table again, and to a contemplation of the dead man's personal effects, as though picking out an answer to this latest riddle propounded by death.

Whatever of restraint had been upon the group, it was released by the Coroner's words, and each member showed it in his own way. Ferdinand Howe instantly advanced to Doctor Westbrook, and, smiling, held out his hand.

"Well, Mobley," said he, as they grasped hands, "this is a regrettable affair. It has been a shocking interruption to my visit; a visit which I now suppose will be indefinitely extended. If I can be of service, don't hesitate to call upon me. I shall be at the hotel any time I am wanted. Good-night." And he quitted the room.

Next, Señor Vargas bowed before the Doctor, saying in a low, conventional tone:

"My sympathies, Señor Doctor, that anything so deplorable should have occurred in your apartments." He turned to the Coroner:

"Don Alberto was a fellow-countryman," he went on; "he had many relatives and friends, by whom he was much beloved. But Mexico is far away, señor, and should there be any delay in communicating with those relatives or those friends, it is I, his countryman, upon whom you should call. Upon my own responsibility I request that every attention be accorded the body, and that no expense be considered. I also will be at—what you call la posado?—the 'otel. I thank you for your courtesy."

His departure left, besides the Captain and Mr. Merkel, only Howard Lynden and the Doctor; as the door closed behind the Mexican, the Doctor said:

"Now, then, we here are all about equally interested; if you have any idea how this dreadful crime was committed, pray enlighten us. Surely even vulgar curiosity is pardonable under the circumstances." He looked inquiringly from the Coroner to Mr. Converse.

The latter made no remark, but watched the Doctor steadily, while Mr. Merkel dubiously shook his head, and replied:

"It seems as though we scarcely had made a beginning yet. We shall be obliged to go much farther, Doctor—much farther."

"I will begin right now, then," Converse whispered. "Mr. Lynden, you can help me if you will."

All four were in the act of emerging from the room, when the Captain, as though an idea had just occurred to him, turned suddenly and touched Doctor Westbrook upon the arm.

"By the way, Doctor," he whispered, close to that gentleman's ear, "I notice you have several penholders on your table; are you particularly partial to any one of them? No, no, don't stop; go on."

The Doctor turned a surprised visage to his questioner.

"Why, yes, since you have mentioned it. I always use the black celluloid holder. Why?"

"It is just an idea of mine; I took a particular fancy to that holder..... And have you had occasion to put a new point in it lately?"

Doctor Westbrook now did stop. He frowned heavily as he pondered a moment, while the Captain watched him steadily.

"Yes," he presently said. "I placed a new pen-point in it this evening. I found the other broken—bent—quite useless."

"Thank you, thank you," Mr. Converse said, hastily. "Good-night, Doctor Westbrook."

While the Doctor and Mr. Merkel continued on out of the building, Converse devoted his attention to the hall window which opened into the light-well. There he stood until the others had disappeared; whereupon he and Lynden reëntered the Doctor's office.

By running a board partition down the centre of the room nearest the hall, Doctor Westbrook had by the simplest means given himself a place of reception; one where his patients could wait while he was engaged in the room overlooking Court Street, there being still another for his drugs and medicines.

There was not much wasted space in the laboratory. Against the walls stood cases filled with bottles of many sizes and colors, and other cases displaying glittering, sinister instruments; in one corner stood a carboy of distilled water, and by the window, opening into the light-well, stood the table where the Doctor compounded such prescriptions as he did not send to a regular apothecary.

The light-well opened like a chasm between the Field and Nettleton buildings; its bottom, on a level with the second-story floors, was of heavy semi-opaque glass, so that such rays of light as were not diverted into the windows on the one hand or the other found a way to the shop space on the ground floor. At present an arc lamp beneath this skylight suffused a soft and mellow radiance throughout the entire light-well.

Mr. Converse let himself down to a narrow ledge bordering the skylight, and with an injunction to the young man to wait, made his way around it to a window diagonally opposite, which the latter recognized as belonging to the offices of Petty & Carlton, attorneys, in the Field Building. Here the Captain drew himself up with remarkable agility, and disappeared through the window. All the windows letting into the light-well were open, the watcher was noticing, when his attention was attracted by Mr. Converse's sharp whisper.

"Stand where you are a few minutes, Mr. Lynden," said he. "I want to experiment a bit, and I shall call on you for a report presently."

He lowered himself to the ledge again, passed over to Nettleton Building side, and to the hall window of the latter. There he stooped and scrutinized the ledge intently, and next the window-sill; after which, with a little spring, he raised himself to the window, and crawled through it into the hall.

A sudden quiet fell,—a quiet unbroken by any sound. Standing there alone in the gloom, one undoubtedly would have been impressed by the blank, staring windows that were like wide and lidless eyes; and as he looked, Lynden seemed to become sensible of a feeling of dread at the awfulness of the crime which had been committed so near at hand, for he shuddered visibly, as if the windows had some purpose in staring,—as if they were in reality eyes that still retained some expression of their horror at a deed witnessed but a moment since.

Noting the alacrity with which Converse let his heavy frame in and out of windows, a spectator might fancy it an easy matter for one lurking in the light-well to do likewise, at the ripe moment strike a swift blow, and then leap back again.

But whatever the current of Lynden's meditations, it was abruptly diverted. He fell to listening intently. The door between the hall and the reception-room was being slowly and cautiously opened; still slowly and with an apparent effort to occasion no betraying noise, some one advanced on tiptoe into the room. The young man faced deliberately about until he could see the door in the partition, and waited. Toward it the almost silent footfalls were moving; presently there appeared at the aperture the expressionless face of Mr. Converse, who, when he perceived Lynden's startled attitude, gave utterance to a low chuckle.

"I was not endeavoring to frighten you, Mr. Lynden," said he; "I was simply trying a little experiment. When did you first hear me?"

"I heard the door open, and next, you tiptoeing across the room. I did not know what to think." He was pale and trembling.

"Not another sound? No footsteps in the hall? Nothing of that kind?"

Lynden shook his head. "No; the first thing I heard was the door opening," he repeated.

"Well," continued the Captain, reflectively, pursing his mouth, and lifting his right eyebrow at the young man, "I don't believe anybody could have made less noise than I did in there"—he nodded his head toward the partition—"nor more than I made in the hall. And you heard nothing until the door began to open—h-m-m!" He looked around the laboratory,—at the shelves of bottles, at the partition not reaching quite to the ceiling; he stepped to the window, and, leaning out, contemplated the hall window. "It's confoundedly queer," he concluded.

"What is?"

"Why, the way noises act here. You know, that man—Mr. Ferdinand Howe—was standing at this window, and heard nothing in the hall. I almost believe, if the deceased had been shot instead of stabbed he would not have heard it..... But let us have a look at the other side of the hall.... Let me see," he went on, in a meditative way, "Room 4; that must be Mr. Nettleton's private office; as my friend Mr. Follett would say,—his 'lair.' He has no use for lawyers." He pushed open the door directly opposite the Doctor's suite.

The room was large and had three windows opening into the light-well. Through these windows sufficient light from the arc lamp beneath the skylight found its way to cause the furnishings to loom shadowy and ghost-like in a sort of feeble twilight, and to make it easy to find an incandescent lamp, which Mr. Converse turned on, illuminating the apartment with a brighter and more cheerful radiance. He surveyed the room, and looked at Lynden.

"I suppose," said he, "the door has not been locked this evening?"

The young man merely shook his head. For some reason since passing to this side of the hall, he had become strangely taciturn, though he watched the Captain's every movement eagerly, and cast many furtive glances toward the denser shadows.

Converse, knelt and examined the floor closely on either side of the door. Lynden's nerves were at such a tension that he actually started at a whispered ejaculation from the Captain as he picked up a tiny hairpin,—the kind a woman would have specified as "invisible."

So, then, there had been some one behind this door—and that one a woman!

Why should this circumstance affect Lynden so strangely? for it would seem that, in the undisturbed stillness of these deserted chambers, there was a potent, disquieting influence which kept him in a qui vive of nervous expectancy,—an invisible something in the atmosphere of the place filling him with an apprehensive dread. It was really remarkable that his observant companion did not notice his agitation; and still it was difficult to imagine how he could, for he was crossing the floor in a crouching attitude, apparently directing his entire attention to the floor with a concentration that permitted no individual thread of the heavy carpet to escape his earnest scrutiny.

Mr. Nettleton was a lawyer, and he occupied two rooms, both of which opened directly into the hall. The two men were now in the one that the lawyer used as his consultation room, and the course being pursued by Mr. Converse would soon take him to the connecting door between the two offices. Arriving at that point, he stood erect and paused a moment, plunged in thought. He said nothing, and seemingly had become oblivious of his companion's attendance.

Just to the left of the connecting door, and in the general office, stood the desk occupied during business hours by Clay Fairchild. Above this desk was another incandescent light, which the Captain lighted, after which he took up whatever trail he had been following so closely, at the exact point where he had left it, continuing, in a stooping posture, to the hall door of the general office. From the point where he had picked up the hairpin, immediately within the entrance to Room 4, he had pursued a course away from the hall, through the connecting door to Room 5, and back again toward the hall to the hall entrance of the latter room,—the whole forming, roughly, an arc, the chord of which was the hall.

At the door of Room 5 he stood upright once more, and the young man became aware all at once that he was being eyed quizzically.

"Look!" the Captain whispered. Stooping again, he pointed to the heavy ply of the moquette carpet.

For a moment Lynden could descry nothing unusual; his heart was thumping in a manner for which he could assign no reason; but when the Captain traced an outline with his thumbnail, he could see quite distinctly the imprint of a small, partial footprint, such as a woman's French heel might make.

"That appears at just two other places," Converse continued; "at the entrance to Room 4, where I found the hairpin, and just inside this room; and there, beyond that desk, near the connecting door. They were made by a woman who stood a while at the first door, and who then, I believe,—though I can't be positive,—tiptoed to the connecting door, where she paused again for a while. She either tiptoed between those points, or stood for a time; the marks wouldn't have remained had she walked directly through the two rooms."

Lynden stared at the tiny impression—so faint that nobody else would ever have remarked it—and seemingly sought to frame a reply that he could voice naturally.

"Wonderful! Wonderful!" was all he said, but in tones so low that they were scarcely louder than Mr. Converse's whisper.

The latter now turned to the rest of the room. Swiftly, but apparently permitting not the least article to escape his observation, he made the circuit of the apartment, and finally paused at Clay Fairchild's desk. Almost instantly his eyes singled out one from among the mass of papers which littered it. This he carefully folded, and placed, with the article he had picked up on the stairway, which Lynden had been unable to see, in the capacious pocketbook. He seemed reluctant to leave this desk; after he had turned away he paused and cast another look at it, sniffing as one striving to locate the source of a faint odor. Lynden paused too; he glanced hurriedly from right to left, his brow lined, his expression troubled and perplexed.

At length they returned to Mr. Nettleton's private office, which was subjected to as close and thorough an examination as had been the room just quitted. Only one thing seemed especially to hold Converse's attention, and that was the space beneath the lawyer's desk. Here he got down to his hands and knees, and struck no less than five matches in an effort to obtain a better light. Whether the dusty space told him anything Lynden could not determine.

They passed back into the hall again. Converse walked directly to the entrance of Suite 2, immediately adjoining Doctor Westbrook's offices, on the side nearest the stairway. A small card pasted on the ground glass of this door bore the words "To Let." Converse ignited another match, in the added light of which he examined the door-knob. His companion observed him touch it with the tip of a finger, and shake his head, as if something incomprehensible had all at once presented itself.

"Does the janitor sleep in the building?" the Captain inquired after a moment; when the young man nodded affirmatively, he added: "Can you get the keys of this floor for me? It will save some time and trouble, and I want to finish before the reporters come."

"Certainly. His room is in the third story."

Converse watched him until he disappeared around the corner toward the stairway, and straightway did something very strange. With the silence and speed of a cat he made his way back to Fairchild's desk. Over this he bent and smelt the papers which lay there. But that would not do. Hastily he tried the top right-hand drawer. It was unlocked—as were all the other drawers—and opened easily. That for which he was searching was not there, either. He turned rapidly to another drawer, and another, and another, until every drawer in the desk had been opened and closed again, its contents having been hastily but thoroughly gone over; and still the object of this hurried search was not found. Quickly he glanced from side to side. To the left of the desk was a waste-paper basket, which had not been recently emptied, and over this he inhaled deeply, as one would drink in the fragrance of a rose. He thrust a hand among the debris of papers, and in a moment drew forth a dainty lace handkerchief, to which clung the unmistakable odor of stephanotis. Again the capacious pocket-book; and when Lynden returned with the keys the Captain was contemplating the door-knob of Suite 2 with unabated interest.

Lynden sniffed as the other ran over the key-tags in a search for No. 2.

"What is that perfume?" he demanded sharply.

"Ah, do you like that, now?" rejoined Converse, with the first display of enthusiasm he had yet shown. "That is an odor I am very partial to, and hope to have more of—if I can find where this came from."

The young man moistened his lips, and his eyes turned away from the other's steady look.

Converse now had the door to No. 2 open, but he did not enter this room. It needed only the match he now struck to disclose layer upon layer of dust, the undisturbed accumulation of months.

"Now, then," said he, as he closed and locked the door again, "back to the light-well for a minute or two, and I am through."

He let himself out of the hall window, and made another circuit of the ledge around the skylight. The light-well was more or less a catch-all for the windows opening into it; it therefore contained many scraps of paper, every one of which he glanced at before casting it aside. Only one thing here seemed to interest him,—something he picked up far out on the skylight and scrutinized. Lynden was afforded another glimpse of the pocket-book.

"What is it?" he asked.

"A cigarette butt," was the reply; "interesting only because it is the second one of the same kind I have found to-night."

Presently, when he announced that he had finished, Lynden said it had fallen to them to turn out the lights and lock the doors, as the negro janitor was too frightened to venture into the second story that night. This was soon accomplished, and the two had turned to depart, when both abruptly stopped. A light had flashed forth through the ground glass of Room 6.

"What room is that?" asked Converse; for the door was bare of significance excepting for the single figure "6," now standing out boldly against the light behind.

"The record and abstract room of the Guaranty Trust Company," was the reply. "He must have come in while you were in the light-well."

"He? Who?" Converse queried bluntly.

Both were standing as they had paused when the light first surprised them, and Lynden turned to his interlocutor with some surprise at the quickening eagerness of his tone, but he answered merely:

"Slade,—William Slade; he prepares the company's abstracts of title, you know."

Converse's manner became completely impersonal again. "Can you find some excuse for knocking?" he asked. "Would you mind doing so? I should like to have a glimpse of him."

"Not at all; if I can make him hear. He's quite deaf."

Lynden, after knocking once perfunctorily, did not wait for a summons to enter. He immediately threw the door wide open, crying, without much show of deference:

"Hello, Mr. Slade! You work late to-night."

A little, dingy, dreary figure of a man, perched on a high stool, and bending over a huge canvas-bound volume, slowly raised his head, and gazed at his unceremonious callers with the vacant look that one sees in the eyes of deaf people who have not heard distinctly. His smooth-shaven face was like leather, shot and crisscrossed with a network of fine wrinkles. Almost on the tip of his nose he was balancing a pair of steel-rimmed spectacles, and the eyes which now looked over them were remarkably bright and sparkling, like a mouse's, conveying to the casual glance an alertness which they did not actually possess.

"Howard Lynden, close the door," was the odd creature's greeting, in a voice hoarse and rasping. The sharp little eyes shifted to the Captain, and back to Lynden again. There was no cordiality in either his tone or manner.

The young man took a step forward, laid his hand upon the tall desk at which the little man was seated, raised his voice and asked, "Did you know there had been a murder committed on this floor this evening?"

"Murder?" querulously, and with no show of interest. "Murder?"

"Yes; murder. The man died in Doctor Westbrook's office—stabbed."

Without displaying the least curiosity at so unexpected, so sensational an announcement, Mr. Slade slowly wagged his head, saying only, "I heard nothing of it." He dipped his pen into the ink-well, with an air of dismissing his callers and the subject alike.

"I saw your light, and just dropped in to learn if you knew of it," Lynden concluded, as he followed the Captain toward the hall. Lowering his voice, and addressing the latter, "Is there anything else?" he inquired; at once the wrinkled, meagre visage and twinkling eyes became suspicious and alert.

"What is that?" demanded Slade, with obvious mistrust.

"Nothing," the young man returned shortly. "Good-night."

Mr. Slade's parchment-like countenance again bent over the big volume, and his pen flew industriously. It was startling, when the door had nearly closed, to have the rasping voice come after them with the suddenness of an explosion.

"Howard Lynden!" it cried. That gentleman, surprised, thrust his head back into the room.

With pen poised in hand, with spectacles still balanced near the tip of his thin nose, the ill-favored mask of Slade's countenance was again confronting the detective and his companion.

"What time was that murder?" asked the abstracter.

"At five o'clock," Lynden rejoined, he and the Captain again advancing into the room.

"And the murdered man?"

"General Westbrook's friend, Señor de Sanchez."

The little eyes turned once more quickly to the Captain and back to Lynden as he asked the next question:

"Ah! And who was—the—murderer?" He spoke deliberately, his harsh voice lowering itself strangely.

"That the police would very much like to know."

Again the little eyes shifted to Mr. Converse.

"An officer?" inquired Slade.

The Captain nodded. Slade's brusque manner returned; dropping his eyes to his work once more, he said, with an air of finality:

"I am sorry, gentlemen, I can tell you nothing. This is my first intelligence that a crime had been committed. Good-night. Howard Lynden, close the door tightly after you."

When the two were once more in the hall the Captain said, "Mr. Slade developed a mighty sudden interest."

"Yes," returned his companion; "a queer bird—irascible, and touchy about his deafness. His father was an overseer, you know," as though this fully accounted for Mr. Slade's undesirable qualities. "But his curiosity got the better of him that time; he couldn't let us go without finding out more."

"He and I would have some difficulty in getting along together without a sign language," remarked Mr. Converse, dryly.

The two were near the foot of the stairs, but they were not destined to leave the building without another interruption. A man came precipitately, though noiselessly, in at the entrance, who, when he observed they were descending, stopped short and awaited their approach at the foot of the stairs. He was one of the two men who had followed them from headquarters, and he now, after touching his hat respectfully to Mr. Converse, looked askance at Lynden. The Captain, with a nod of apology to the young man, drew the newcomer to one side.

"Well, Adams?" said he.

"We found Mr. Fairchild's all right," the man whispered; "but Mr. Fairchild was not there. He has not returned from the office, and his sister and mother are very anxious. The mother is something of an invalid—didn't see her at all. Talked with the sister, who seemed, anyhow, to be the head. Pretended to want a notary and quizzed her, but she could tell me nothing. I don't believe horses could draw anything from her if she didn't want to tell. Captain Converse, sir, she had an eye that looked right into me all the time I was talking, and I know she thought I was lying when I said I wanted a notary." The man showed two rows of glistening white teeth in an unpleasant grin. "I did want a notary, but she didn't know I was so particular about which one. But I don't believe she knows where he is. I left Barton to watch the house, and I came on to report."

"Very good."

"And what shall I do now?"

"Keep your eye on this man here with me until I can send you relief; I shall keep Barton watching the house."

The manner of the man called Adams was both stealthy and ingratiating; his visage seemed unable to rid itself of a perpetual smile, which, taken with a pair of crafty, shifting eyes, gave him a sinister appearance. During the entire time he and Mr. Converse were talking, he kept looking past the latter at Lynden; and that this surreptitious espionage was extremely unpleasant was made manifest by the young man's growing uneasiness.

Still smiling, shooting a last rapid glance at Lynden, he departed as abruptly and noiselessly as he had come.

Converse turned to his companion, fixing him with a steely eye; and what he said seemed unaccountably to agitate the young man.

"I wish to remind you that you are a very important witness in this affair. I shall venture a hint and a word of advice: if you are not more circumspect on the witness-stand than you have been to-night, you will have a mighty bad hour; if you are contemplating a trip from the city, why—change your mind." With a curt "Good-night," he left Lynden speechless in the doorway of the Nettleton Building.

Lynden remained motionless many minutes. When he at last produced a cigarette from his pocket, the cupped hands holding the lighted match trembled so he had difficulty in igniting it. Abruptly he started away in a direction opposite that taken by the huge figure of the Captain.

Behind him moved a shadow so stealthily, its outlines so dim, that it was scarcely to be distinguished from the surrounding night.

Early the next morning Mr. Mountjoy, the district attorney, and the Coroner were seated in the former's office with a flat desk between them. Upon this set forth in orderly array, were the letters, papers, and other personal effects gleaned from the pockets of the dead man; dominating the whole was the sinister and grewsome little silver blade,—Doctor Westbrook's paper-knife.

The regard of both officials rested upon it as they meditated and waited for the Captain.

Remove those bloodstains and the weapon became a dainty toy, but withal a dangerous one. The point was like a needle's, and terminated a slender, tapering blade, silver-like in its brightly polished steel, two-edged, and of indubitable fineness. The guard, a solid piece of beautifully engraved gold, was shaped somewhat like a Cupid's bow, while the hilt, of silver, was decorated with an intricate, graceful pattern of chasing, inlaid with gold, and surrounding a scroll upon which was engraved in script the single word:

Paquita

The chasing, in addition to being an exquisite work of art, possessed also the utility of supplying an excellent purchase for any hand grasping it.

And what hand was upon that pretty hilt when last it was held in anger? Whose fingers had tightened slowly over the dainty feminine name, as the unsuspecting victim approached? Did "Paquita" contain a hidden charm—some invisible potency—to guide the hand to its hideous, self-appointed task?

Alas, if it could but tell! If, instead of the prænomen, redolent as it was of fresh maiden innocence, the scroll had borne some word pointing to the assassin! And yet, after all, could it be possible that the momentous intelligence actually was there, and only human eyes were blind? If such be the case, it will require a vision more than human to seek it out and read what is there written. Surely; for the weapon bore no other mark or testimony.

The District Attorney's voice disturbed the quiet.

"It is an amazing thing," said he, in a speculative tone, "what a nice tangle this case is beginning to promise. Relate the bare facts, as we know them, to any disinterested person, and he would instantly say that Mobley Westbrook committed the deed. To be suddenly come upon, a smoking dagger in your hand—standing over a dying man—the provocation supplying a motive—and all that—h-m-m! pretty bad."

But Mr. Mount joy the next instant laughed in a way that signified it to be the height of absurdity to think of Doctor Westbrook as a murderer.

"There is not a phase or side of the man's character," he continued, "with which the crime can be made to fit. I can more easily imagine Mobley Westbrook—but of course I know him so well that personal bias influences me largely in his favor. It would require evidence quite conclusive, though, to move me to proceed against him. It's queer, anyhow, a family of their quiet, humdrum respectability being mixed with an affair of this nature, even remotely; there is more behind it than we now imagine; and I believe there will be plenty of work for one John Converse."

As if this colloquy had been a scene on a stage, and the two last words a cue, the door opened, and the Captain of detectives himself entered. He walked to the desk with manner quiet and deferential, gravely returning the salutations of the two officials seated there.

"Here's John to speak for himself," said the Coroner.

"Theseus has come to lead us from this labyrinth of mystery," laughed Mr. Mountjoy. "Silent and enigmatical servant of Destiny, who knows what momentous knowledge is hidden behind that impassive exterior? John, are you ready to point the stern and unrelenting finger of denunciation at the guilty wretch, and say, 'Thou art the man!'?"

But the Captain did not respond to the lawyer's bantering humor. Instead, he seated himself on one side of the table, remarking merely:

"Gentlemen, this is a very serious case."

"Serious!" cried the District Attorney, his mood in no wise changing. "Serious? which is but one method of informing us that there has been a dearth of clues." He suddenly leaned forward, rested his elbows upon the table, and interlocked his slender fingers. "Come, John, what have you discovered?" he concluded more soberly.

CAPTAIN CONVERSE WAS ENDOWED WITH THE IMPASSIVENESS

OF AN INDIAN, NOR COULD ONE IMAGINE HIM AGITATED

IN ANY CIRCUMSTANCES.

For answer Mr. Converse drew forth his large and well-worn pocket-book, from which he took one by one, and laid upon the desk, two slips of paper, a small hairpin, two half-consumed cigarettes—the paper of which was a dark brown, like butcher's wrapping-papers—and lastly, a dainty bit of cambric and lace, to which clung a delicate odor of stephanotis,—a lady's handkerchief.

Mr. Merkel adjusted his spectacles; the District Attorney became wholly serious; and together they bent over the grotesque assortment, staring as though the mystery might be disclosed then and there.

Presently both sat back in their chairs, and turned expectantly to Converse.

"Well, sir," he began gravely, "I believe we must look to a certain lady for a detailed account of her connection with this case."

"A woman!" ejaculated the lawyer. "Well, I am not surprised; it could not promise much without a woman—no more than that affair of the Garden could have been without Eve.... And do you know who she is?"

Mr. Converse raised a protesting hand.

"No," said he; "not yet. But a woman was in Mr. Nettleton's offices so close to the time the crime was committed that her presence is quite the most important factor at present—that, and Clay Fairchild's disappearance."

Both listeners showed their astonishment.

"So that young Fairchild has disappeared, has he?" remarked Mr. Merkel. "I always thought he was a steady sort of chap. But you can never tell about these young fellows, especially when they get tangled with a woman. I wonder who she is?" he added, musingly, and colored when Mr. Mountjoy laughed.

"That is just a puzzling feature of the thing," the Captain resumed. "I have had no trouble in securing a complete record of the young man's private life, and it proves to be unexceptionably clean. No woman figures in it to any great extent. Young Fairchild is very poor; but he is the head of one of these old families here, and is on a footing with people like the Westbrooks, the Nettletons, and their class, that a great many with more money can't boast of. He is one of 'the quality'; and though his poverty prevents him from figuring at all in society, he is nevertheless a frequent visitor in many of the best homes in the city."

"Aye, I know those Fairchilds," said Mr. Mountjoy, nodding his head slowly; "fine old stock, but dropped from sight since Dick, the scamp, went smash. There's a girl, too, isn't there? Mother an invalid? Thought so. Proceed, John."