The Project Gutenberg eBook of International cartoons of the War, by H. Pearl Adam

Title: International cartoons of the War

Editor: H. Pearl Adam

Release Date: October 7, 2022 [eBook #69107]

Language: English

Produced by: Brian Coe, Brian Wilsden and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

[Pg i]

[Pg ii]

[Pg iii]

[Pg iv]

[Pg v]

THE HISTORIAN who, a couple of centuries hence, tries to get at the real kernel of the great War, will find himself overwhelmed with material, buried under evidence, like the great authority on Penguinia. Every doubtful point will be clearly and irrefutably decided for him in at least seven different ways. A burning sense of conviction may be his, but he will not be sure which conviction it is. The lot of the historian has changed for the worse since the days of Herodotus. It no longer suffices for an account of a battle to be possible if not probable, marvellous if not possible, for it to rank as history; mankind chose to start on the thorny quest of Truth, and is now beginning to see that in every affair there are exactly as many Truths as there are actors.

When the war broke out in August, 1914, the curious art of conveying a knowledge of thoughts and fact between two or more human organisms, the only art or appliance which man has really invented without referring to Nature—the art of writing—was resorted to on every hand. An unprecedented crop of war books began to sprout from the blood-fertilized fields of Flanders. Men might safely exclaim: "Mine enemy hath written a book"; they had perforce to add: "And so hath each of my friends." They poured from the Press, little books and big, sober and hysterical, speculative and emotional. After them came the sedate polychromatic procession of Government literature. Along with them flowed the swift and multitudinous efforts of journalism. And in a very short time began those strange enterprises, at once droll and portentous, the Serial Histories of the War.

What the great historian will make of all this when his time comes to correlate it, it is difficult to say. If he feel conscientiously bound to consult contemporary evidence, there is little hope for him, unless he takes the bold step of writing a historical novel out of his inner consciousness instead.

[Pg vi]

But there will be at least one unfailing guide for him. The very increase

in mechanical processes which contributes to his undoing in the matter of

books, will come to his aid with regard to pictures. Every great event

since the invention of mechanical reproductive processes has produced its

due reflection in the mirror of the artist. The crude old broadsheets told

their tale of the Napoleonic wars more vividly than any historian could;

and the present struggle, while it slew nearly every other art for the time

being, worked up to fever-pitch the output of pictorial comment. In

France, where this form of expression has always been popular, an unexampled

flood of cartoon and caricature poured from artists both celebrated

and unknown. Other countries followed suit, in proportion to their

national liking for prints; and the evidence supplied by this mass of international

material is as direct and reliable as anyone need demand.

II.

THE VALUE of the contemporary cartoon is very great; for it deals almost entirely with what people are feeling, in distinction to what they are doing. It uses their deeds as a mere background to their emotions, and it is only the emotions which count. What the soldier feels, the sailor, the mother at home, the man in the street—these are the really important things, for it is these things which are the causes of events. If enough ordinary people want peace at any price, the Governments of all the States in the world will be powerless to wage war one moment longer; if enough ordinary people consider their honour involved in fighting to a finish, emperors and kings and presidents and trade unions and the N.C.C. will united be unable to break the smallest twig from the olive.

The material of the cartoonist is drawn from sources useless to the writer, or at best, of only ephemeral utility. A chance-heard remark, the expression of a face seen in the street, the glances turned on a wounded man as he hobbles by on his stick, the ineptitude of a comment on the day's news—these are the media by which the cartoonist conveys his view of what his country feels. And he has this advantage over the writer—that a well-done drawing is a volume in itself; in one glance the eye has absorbed the background which a tedious explanation is necessary to convey in [Pg vii] words, and is free to take in the essential meaning of the drawing. A picture appeals as directly to the eye as does a sunset, or as food to the stomach, or a soft bed to the tired body. It uses a natural sense, not a cultivated faculty.

Cartoons are meant for the man in the street; they are meant to tell a story, to convey some feeling or idea rather than to be an artistic rendering of an object or collection of objects. Therefore artistic canons apply to them in this limited sense—that while the great cartoonist may and must be as big an artist as he can, he must first of all remember that he has to explain himself and his subjects, or he ceases to be a cartoonist at all. A Futurist Forain, a Cubist Raemaekers, are inconceivable because they would be quite useless as cartoonists, whatever they were as artists.

The artistic value of the cartoons issued in all countries—and in some

cases it is very great—is a matter for future discussion. It is of no present

importance. What is of some actual value is a comparison between the

cartoons of the various countries, for they show with unfailing accuracy the

trend of public opinion. From the human point of view this comparison

is invaluable to the student of humanity in the present upheaval. From

the cheap postcard to the twopenny broadsheet, from the most commonplace

poster to the finest lithograph, each has its place. To collect these

things is not only very interesting, but most enlightening; the national

spirit and the national moods of each country are unmistakably portrayed,

and the crudest production takes rank with the best as a human document.

III.

THE GOOD cause has always produced the good cartoonist—witness the Napoleonic wars, when England rejoiced in Gillray and Rowlandson, while France had no topical draughtsman of any outstanding merit. So far as one can tell, this is very much the case with the present war. At any rate, the good cause has produced its good men, and, judging by what one can manage to see of German caricature, they have no mind of any large calibre at work on cartoons. This is, perhaps, because the greater part of the German drawings I have seen are intended to rouse hatred, scorn, and anger. Clever they certainly are, but too many of them are spiritually [Pg viii] debased. The best are those directed against England, which are dedicated to hatred, a passion greater than scorn or anger, and consequently more elevating in its effects. Otherwise the German cartoonist has not distinguished himself, in the sense that the war has not raised him above himself.

This can certainly not be said of France, where a crowd of new men have appeared, and where the well-known draughtsmen of pre-war days have been roused to unprecedented excellence by their emotions. At least one of them, M. Forain, has made history with his pencil. There came a time, when the first excitement had died away, when the victory of the Marne had for months been followed by stagnation—stagnation in victory, progress in casualties—a time when no news ever came, when Paris was left in a kind of twilight of suspense and endurance, when the economic pinch began to be acutely felt, when bereaved wives and mothers were told in the morning that their loved ones "were gloriously dead for their country," and read at night that "there is nothing to report on the front; the night was calm." And for just a moment the human need and sorrow of the individual cried louder than the pride of country. "It's very long, this war!" "What I want to know is, how much more do they expect us to endure?" "Could defeat be worse than war?" and even the sinister "if we win," were phrases that crept into conversation. It was hardly to be wondered at. France had expended so much energy on her magnificent effort in August, '14, when her very babies bore themselves proudly and with self-control, that she was bound to feel the reaction.

It did not last long, and it was Forain who swept it away by a dose of strong tonic. He drew two French privates in a trench, snow and hail and shrapnel raining round them, in conditions as bad as the most anxious mother's nightmare could have pictured them. And one says: "If only they hold out!" The other, with a look of great surprise, enquires: "Who?" "Those civilians!" In a week that drawing was historic, and civilian France, with a blush and a laugh, had pulled herself together. M. Forain does not care to have his drawings reproduced, or this famous cartoon would have been included in this book.

Nor, unfortunately, will M. Jean Véber have his cartoons reproduced [Pg ix] till after the war, which deprives us of that Napoleon of his, standing on his own tomb and crying "Vive l'Angleterre," which created such a stir on both sides of the Channel. "La Brûte est Lâchée," by the same artist, is one of the most impressive drawings France has produced since the war. Published so early as September, '14, it represents the Prussian monster, madness and fury in his face, starting out like an unleashed animal on his career of destruction.

This print was the first to indicate the enormous boom in war-drawings which has characterized Paris. Published at 5 francs, it was within a few months unobtainable under 500. Collectors took the hint, and the drawings of Forain, Steinlen, and other well-known artists were eagerly sought after, and rose to very high premiums. The character of the prints changed; with the exception of M. Véber's series, the greater part of the drawings published outside magazines and newspapers had been cheap, ranging from threepence to two francs each, and including some publications of deliberately naïve construction and crude colours, others which achieved without deliberation a startling likeness to the old broadsheets with their childlike simplicity. Postcards and prints fairly flooded Paris in the first few months of the war, but since the collector appeared on the scene in his dozens the cheaper publications have been displaced by more ambitious works that range up to a hundred francs each, and have crowded out the smaller artist, the smaller print-seller, and the smaller collector.

This variety of output has been increased by the publication of many illustrated war-papers in Paris, such as Le Mot, l'Europe Anti-Prussienne, l'Anti-Boche, A la Baïonnette, war editions of already established papers, and a crop of crude halfpenny papers, printed after the Epinal manner, and greatly used by children and the very low classes. A coloured history of the war, of extraordinary naïveté, issued in penny sheets, was intended for use in schools, but achieved an additional success in hospitals, where the thin sheet was easily held and folded, and the incidents depicted roused the liveliest interest among the wounded.

In the whole of this output it is difficult to find any sign of wavering in the national spirit of France. Once the civilians had decided to hold [Pg x] out, there could be no other stumbling-block. Naturally, in such a range of drawings, there are many that drop into brutality on the one hand, vulgarity on the other; but the overwhelming majority breathe a spirit of calm, determined endurance, with a ready laugh for hardships, a sly dig at politicians, and no little irony at the expense of their own weaknesses and foibles. Very often, so often as to set the key for the whole, the note is heroic, sometimes grimly so. There is none of the splenetic fury of the German drawings about the majority of the French ones; the Germans are ridiculed and hated, it is true, but the spirit is more steady and less spiteful—it rests on an emotion which for forty-five years has been a religion to the Frenchman.

The English cartoons are as different as possible from both the French and the German. We have no separately published prints, our postcards have been few, vulgar, and negligible; our cartoonists are really only offered the pages of newspapers and magazines in which to exert their influence over us. And there cannot be two questions as to that influence—it is the influence of good humour. The French mistake it sometimes for indifference, but the English know better. The Germans say they mistake it for frivolity, but they so foam at the mouth about it that one suspects them of glimpsing the spirit behind the smile. The grim note of Steinlen and Forain is almost wholly wanting from English cartoons. The Kaiser, who is a devil in France, is merely making an unholy fool of himself in England; the Crown-Prince, a mass of vice in Paris, is "an awful silly blighter" in London. Will Dyson, the young artist of whom Australia has such reason to be proud, is our grimmest product, and even he lets the Prussian off more easily than do the French artists. Because, after all, don't you know, we're going to thrash the brutes, but there's no need to make a fuss about it, hang it all. Let us have our pipe and our grin, and let us keep to those till the end. For the Lord's sake don't let us have any heroics—those are for doing, not for showing. That is the attitude which one finds over and over again in English drawings; not contempt of danger, so much as a serene determination to grin at it and have no fuss.

Punch has come out brilliantly in this particular. Allowed by tradition [Pg xi] to have two heroic cartoons a week, the rest of his pages are dedicated to the god of laughter. Germany reads Punch with stupefaction. What, we not only laugh at the Germans, we laugh more at the English! Extraordinary, sinister, effete, degenerate race! It is true, we laugh at ourselves far more than at anybody else—and very often it is for that painful but cogent reason, that we may not weep. Perhaps at the front they laugh wholeheartedly at Punch; at home it is a different laugh that greets Tommy in his imperturbable good-humour. In the midst of a hell of fire, Tommy says that what with the beastly Belgian tobacco and the blooming French matches, this'll be the death of him. Sitting on the edge of a trench which consists of nothing but mud and water, in a fearful downpour, he remarks that he pities the poor fellows at home—the London streets must be something awful! And on a dozen other occasions he has expressed that cheery soul of his, in a way as charming as it is moving.

As for the Germans, perhaps Mr. Punch reached his happiest moment when he gave us the German family "enjoying its morning hate." A French paper copied that with enjoyment tinged with bewilderment, since the idiomatic "morning hate" was beyond the French editor, who published it merely as "a study of a German family at breakfast time". The Germans have not published it at all.

Nothing more light-hearted and good-humoured than Mr. Heath Robinson's fantastic inventions (such as the Tatcho bomb) could be found—unless perhaps, in the inimitable "Big and Little Willie" of Mr. Haselden, which have given pleasure to countless people, at the front and at home, and have caused howls of Majestätsbeleidigungisch laughter in German trenches, when Tommy has been so kind as to throw a copy over.

England has never taken cartoons so seriously as has France, nor has she a public for separate topical prints; but she has done as much as she can, for her war cartoons accurately express her mind, and that is their real function and constitutes their real value.

Neutral countries have had to be careful in some ways; it is difficult to find any interesting war-prints or postcards on sale there. What there are [Pg xii] are rather insipid, at any rate to the Allied mind. But in individual newspapers and periodicals the struggle has raged fiercely by pen and pencil, pro-Ally or pro-German. Mr. Robert Carter, for instance, in his drawings in the New York Evening Sun, has spoken with no uncertain voice, as one of his cartoons in this book will witness. Spain has had more pro-Ally cartoons than one might have expected, Scandinavia has been very discreet—Italy never was, even before she came in.

Holland remains, and well has she shown that she still possesses that spirit of resistance to the oppressor which dictated the pages of her superb history. Small in size, in a geographical position of great danger, her economic interests very largely identified with the welfare of Germany, Holland might have been excused for holding her peace. Everyone knew that German influence was, and is, very important in Holland; that the Netherlands reek with German espionage, and that method of commercial penetration which is one of Prussia's most valued weapons. Yet none of these things sufficed to silence the Dutch love of liberty and hatred of oppression. A band of Dutch cartoonists, hot with indignation, took the bit between their teeth, and ran away with their pencils, their papers, their public, and, if their startled Government is right, very nearly with Dutch neutrality. Anyone who has watched Dutch drawings must have been impressed by the fire of the pro-Ally artists, Braakensiek, Albert Hahn, Peter van den Hem, and Lazrom. Neutrality is too pale for them.

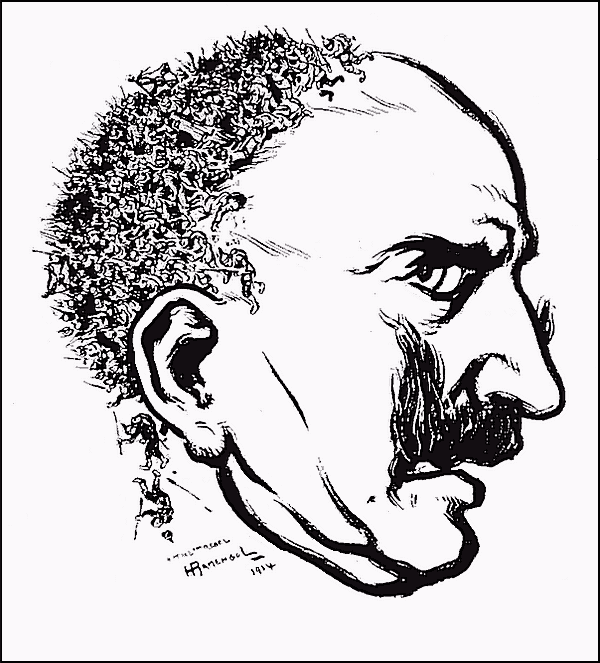

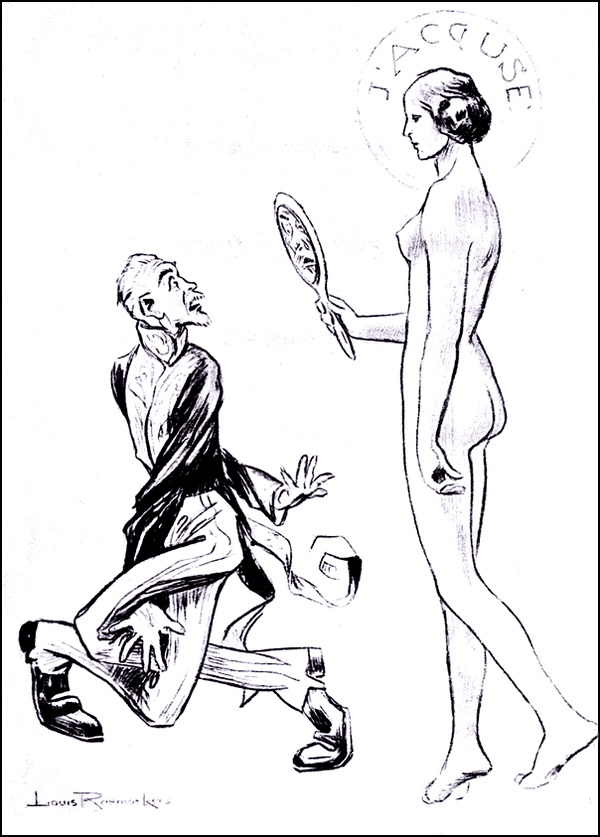

And, of course, there is Louis Raemaekers. Only a neutral could have done what he has done; but it might not have been done at all had not Raemaekers arisen with his accusing pencil. In his work the war takes on its right colour, as something far above international hatreds or the struggle of policies, far above even a battle for the welfare of peoples whose interests are opposed. It appears in its right aspect, as a spiritual conflict, more deadly, more earnest, more vital, than any revolution or reformation or war since that struggle in which proud Lucifer fell. This is every man's war, the world's war, the war of God and devil. And, taking this heroic view of it, Raemaekers has stepped into the rôle of Tragedy, which is "to arouse pity and terror, and the noble movements of the soul." His [Pg xiii] "Prisoners" and "Barbed Wire" (Plates XXII. and XXIII.) show well his detached, tragic quality. There are many of his drawings which are too dreadful to be contemplated for long—"Slow Gas Poisoning," the German thief trampling in blood that drops from his heavy sack, the professor and the devil leering delightedly into each other's eyes. But after such horrors one comes always back to the exquisite tenderness which is the real distinguishing characteristic of Raemaekers. The young German soldier who writes home that "our cemeteries now stretch nearly to the sea" is as tenderly drawn as are the widows of Belgium. The tenderness of strength is the heart of the tragic spirit, the heart that bleeds for suffering and weakness, the heart that grows hot for injustice and wrong. It is this spirit, with its heart of tenderness, that has made the fame of Raemaekers. It is not comfortable nor pleasant to be roused to the tragic sentiments, but it is right that we should; and had the Allies needed any reassurance as to the nature of the reason for which they fight, Raemaekers' work would have supplied it. The good cause has found its good artist, and he is all the stronger because he is a neutral. Like Truth in the cartoon with which this book closes, he has held up the mirror to the Prussian, and we can see, Germany can see, the whole world can see, what kind of soul is reflected therein.

I.

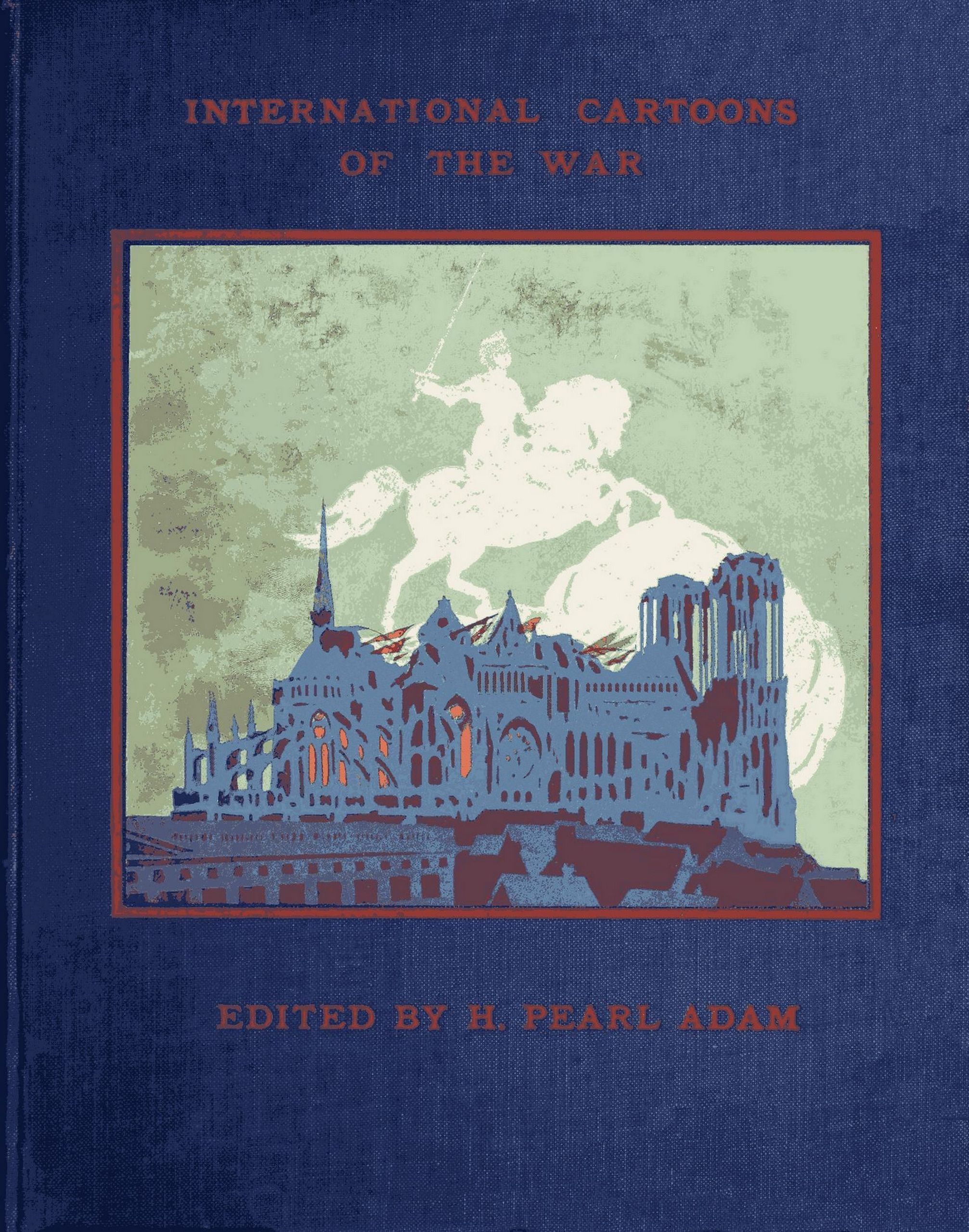

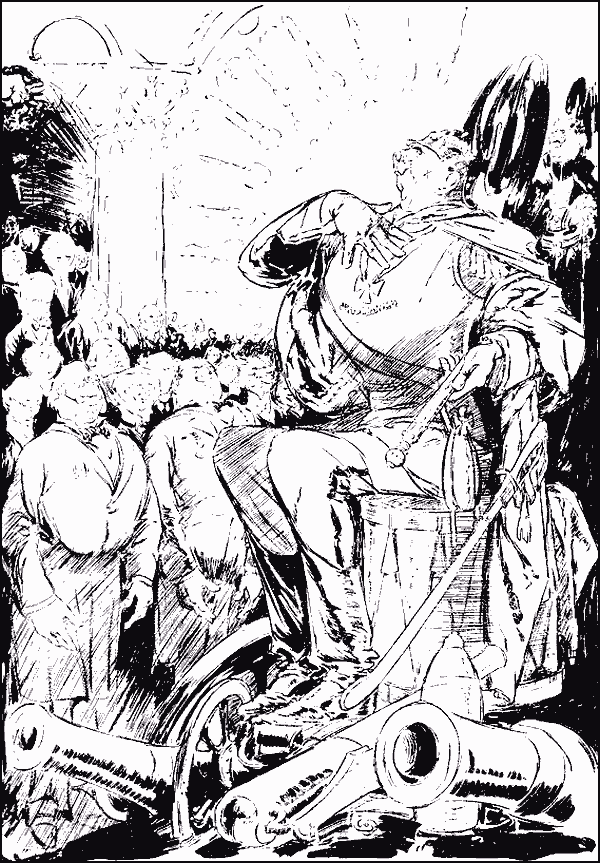

The famous cartoon by F. H. Townsend, "Bravo Belgium," fitly appears as the frontispiece to this book. It is reprinted from Punch by permission of the Proprietors.

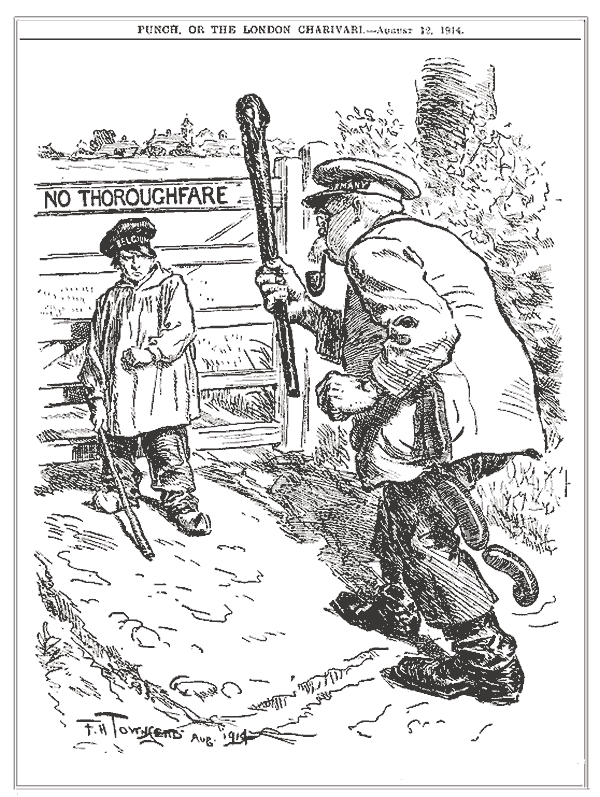

II.

REHABILITATED!

Germany (to her Professor):

"What if we do not fulfil our promises—the whole world must now admiringly confess we are men of honour—we fulfil our threats!"

By Will Dyson. First published in The Nation, May 15, 1915.

III.

AUDIENCE.

Prussianism. "... And Poets, Professors, Instructors of the Young, let it be Your divine labour to quicken our Germany with a hate of England so vast, so holy, so unappeasable, that WE need fear no more the danger of her hating US."

By Will Dyson. First published in The Nation, May 8, 1915.

IV.

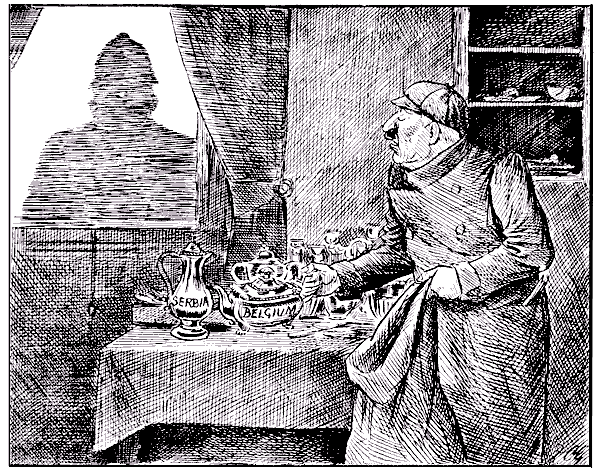

THE BAFFLED BURGLAR.

The Burglar: "I've got the swag, but strafe that copper! I can't get away with it, and there's no food in that beastly cupboard!"

By "F. C. G." First published in the Westminster Gazette, February 11, 1916.

V.

This very Haseldenian page speaks for itself.

By permission of the Editor of the Daily Mirror.

VI.

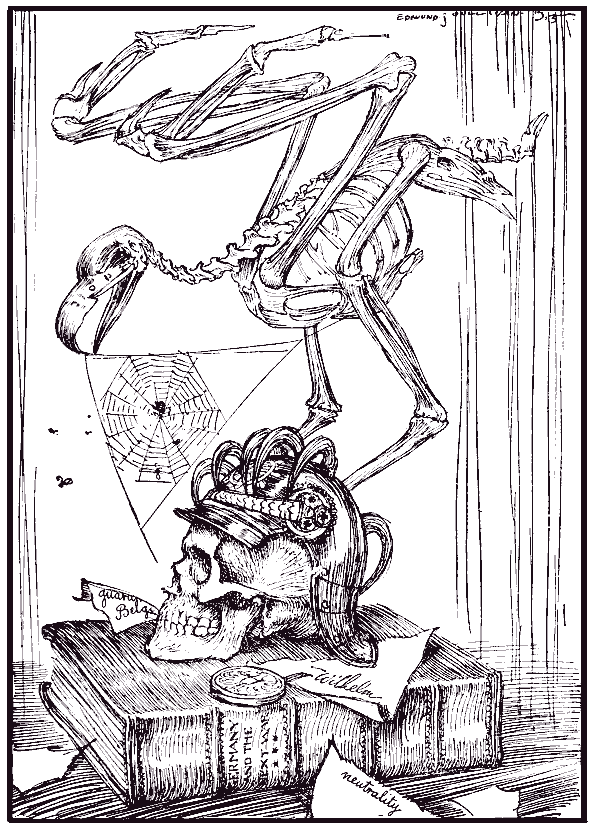

IMPERIALISMUS.

Under this laconic title Mr. E. J. Sullivan shows us a museum specimen of that extinct monster "The German Eagle."

Reproduced from "The Kaiser's Garland," by permission of Mr. William Heinemann.

VII.

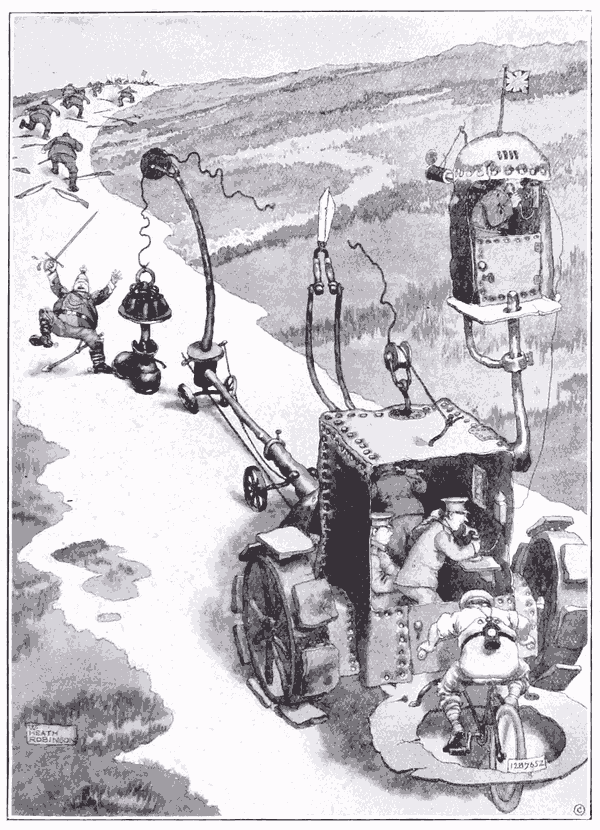

Mr. W. Heath Robinson's well-known series entitled "Rejected by the Inventions Board," is typical of the irresponsible sense of fun which English People seem able to retain even in war-time. Here we see an excellent idea put into action: "The Armoured Corn-Crusher for treading on the Enemy's Toes."

Reproduced from The Sketch of Jan. 5, 1916.

VIII.

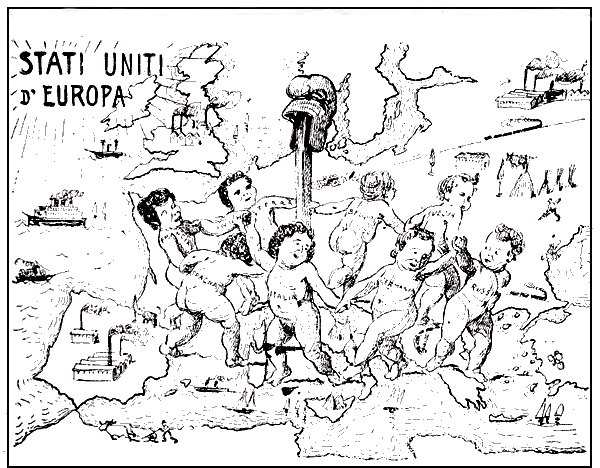

This is what the Auckland Observer thought of floating mines, in the first few months of the war. Those were the days before submarine warfare put even mines in the shade for wanton cruelty and stupid destructiveness.

IX.

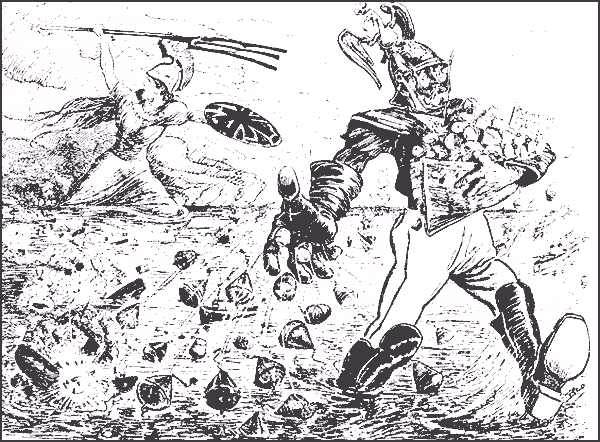

There were few pro-German cartoons in Italy, even before she came in with the Allies. Now and then her artists took a cynical and detached attitude towards the awful struggle in the north, but for the most part their drawings left no doubt as to where their sympathies lay, as may be judged by this and the two following cartoons. This first is from the Turin Numero. Musini shows the Germans paving the ruined streets of Flanders with the material most plentifully to hand.

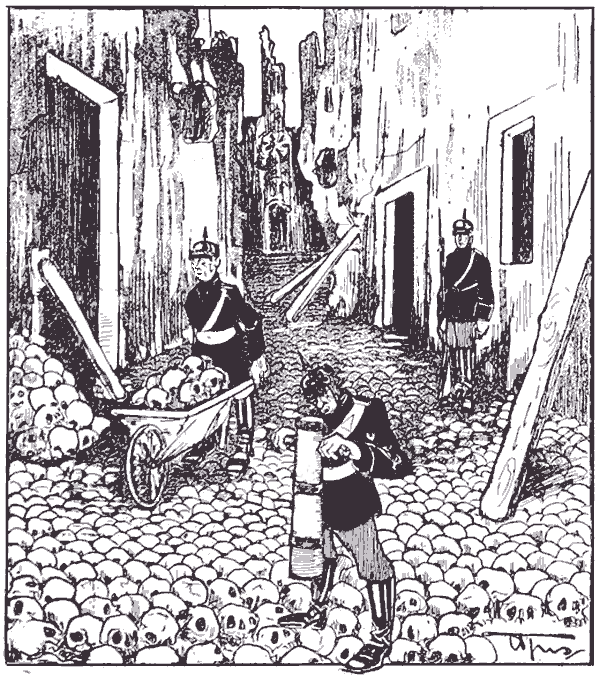

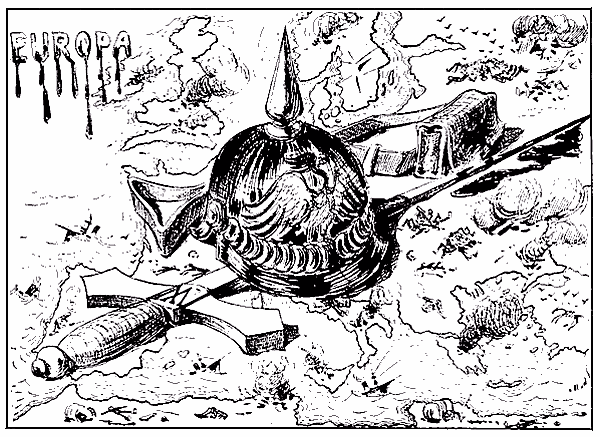

X. & XI.

In these allegorical sketches, published by l'Uomo di Pietra, of Milan, the artist pictures the results to Europe should Germany and should the Allies win. Under the Prussian sword and helmet the whole continent lies burning and bleeding; around the Phrygian cap of liberty her merry and obviously well-nourished children play over her prosperous lands, amid commerce-laden seas.

XII. & XIII.

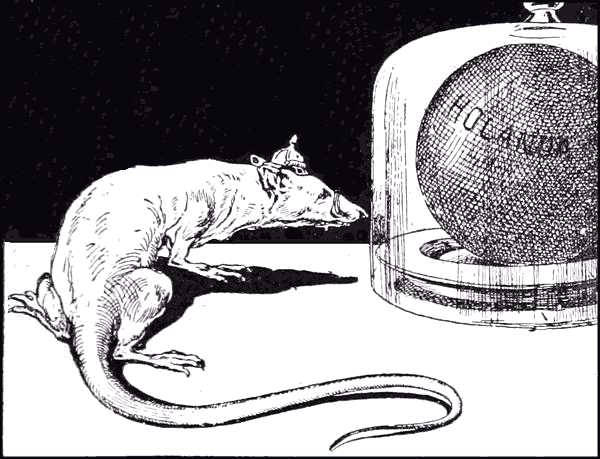

The Argentine is a long way off—further than Washington—and might have been pardoned if she had looked with detached philosophy upon the deeds of Germany. Her attitude, however, leaves much to be desired from the point of view of Berlin. Whether as a rat coveting the good Dutch cheese, or as "the Monster" taking what he wants from helpless Belgium, the German does not cut a good figure in the Critica, of Buenos-Ayres.

XIV.

The neutrality of these three drawings is distinctly open to question. "The Order of the Iron Cross" is from Life, of New York.

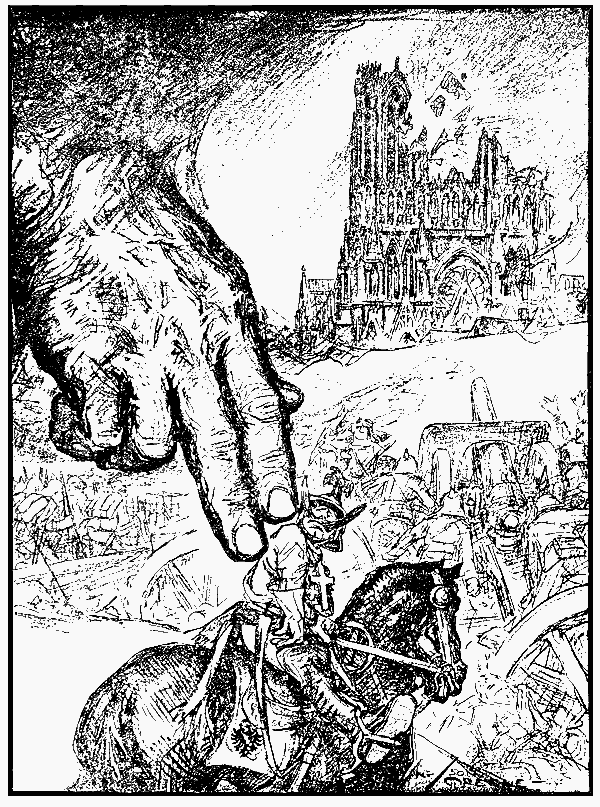

XV.

"The Hand of God," by Nelson Greene. One of the best known American cartoons since the war.

From Puck, of New York.

XVI.

Mr. Robert Carter's drawings for the New York Evening Sun have acquired a reputation in Europe since the war. This is one of the best, which appeared on January 18, 1916.

The Bear: "Glad to see you out again."

Kaiser: "I feel better myself!"

XVII.

"The Austro-German Alliance," as seen by an artist of the Jiji Shimpo of Tokio.

XVIII.

THE GAME OF CHESS.

"He alone can decide how the game shall end."

(De Roskam, of Maëstricht).

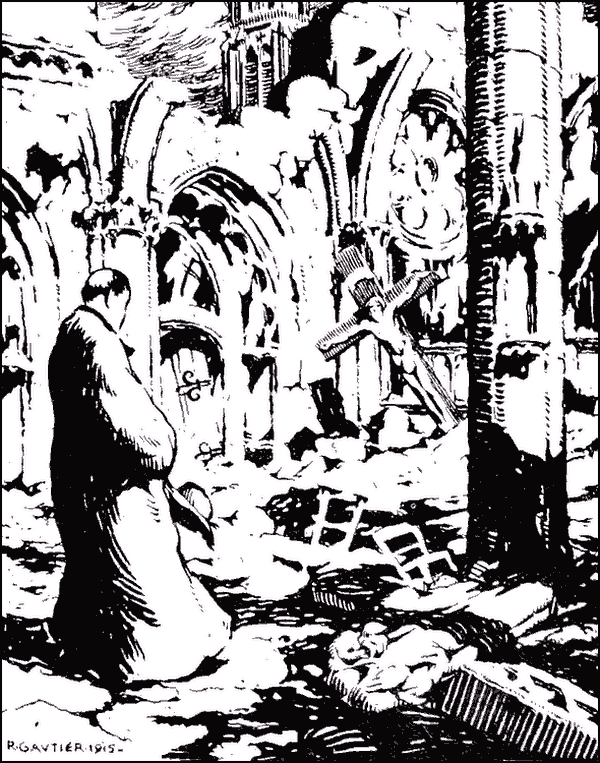

XIX.

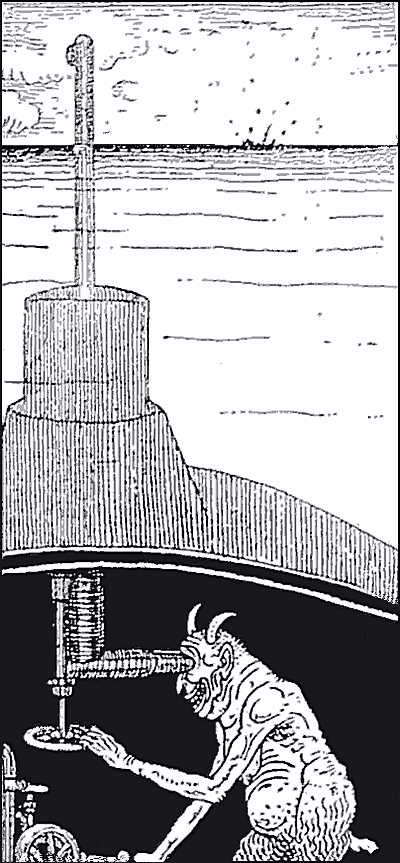

IN THE SUBMARINE.

XX.

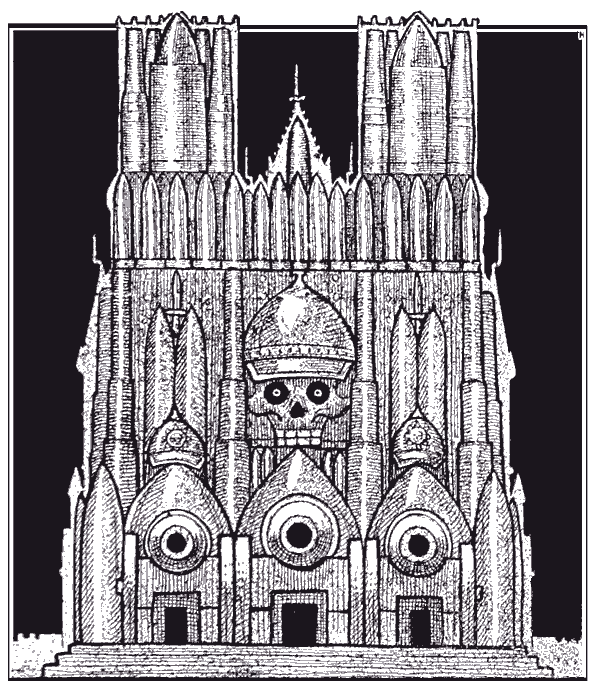

"TWENTIETH CENTURY MONUMENTAL STYLE."

Suggestion by M. Albert Hahn, in De Notenkraker, of Amsterdam, for the rebuilding of Rheims Cathedral after the war, in a style more conformable to Kultur than the Gothic.

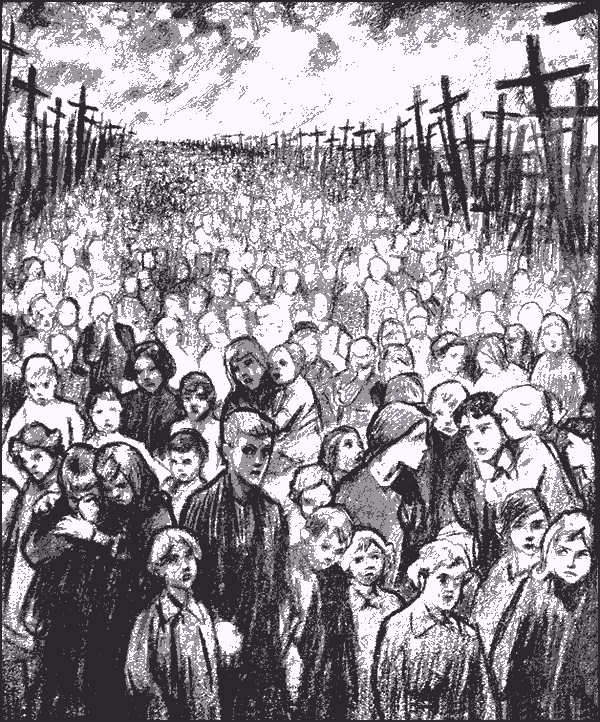

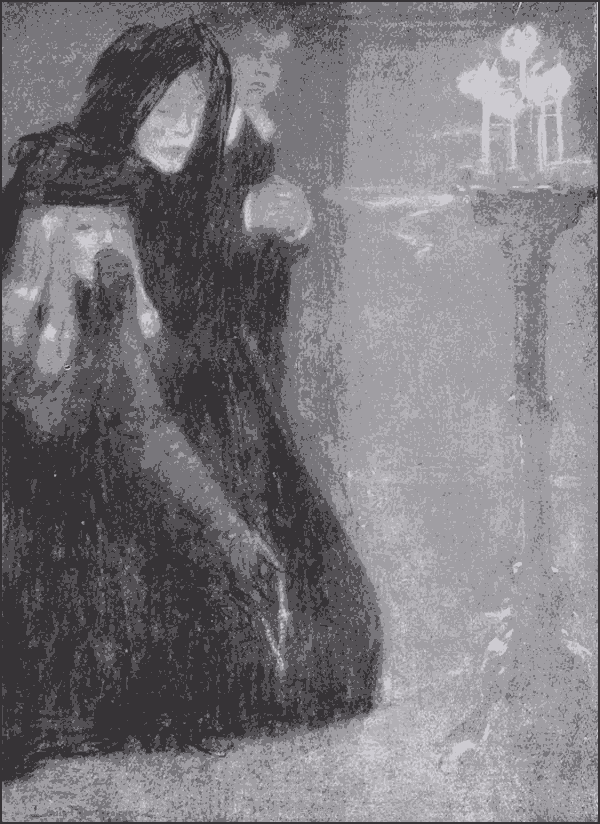

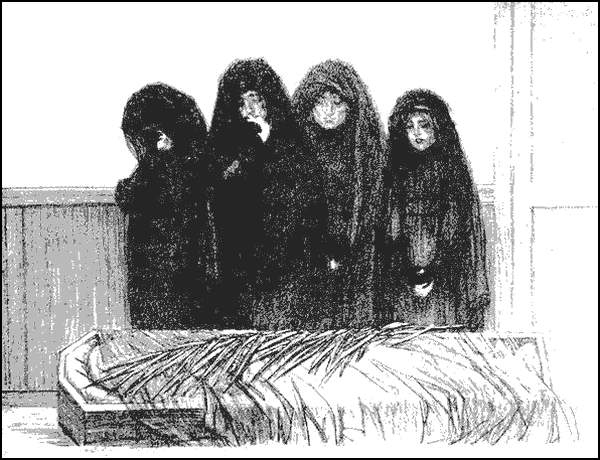

XXI.

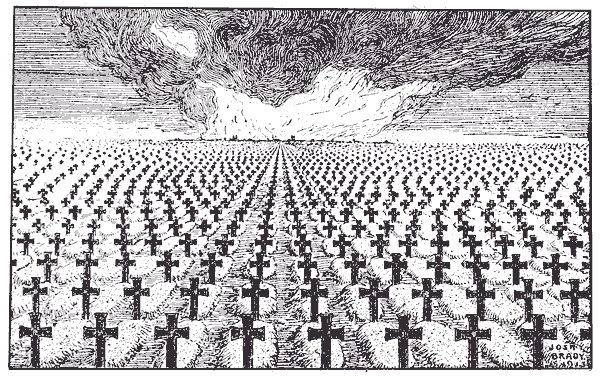

"KREUZLAND! KREUZLAND ÜBER ALLES!"

By Louis Raemaekers.

This is the third and last of a powerful series of three drawings of the sorrows of Belgium—"The Mothers," "The Widows," and "The Children." This and the three following drawings were among those which appeared in the Amsterdam Telegraaf, and carried the fame of M. Raemaekers almost instantaneously over the world. They are reproduced here by permission of the Proprietors of Land and Water.

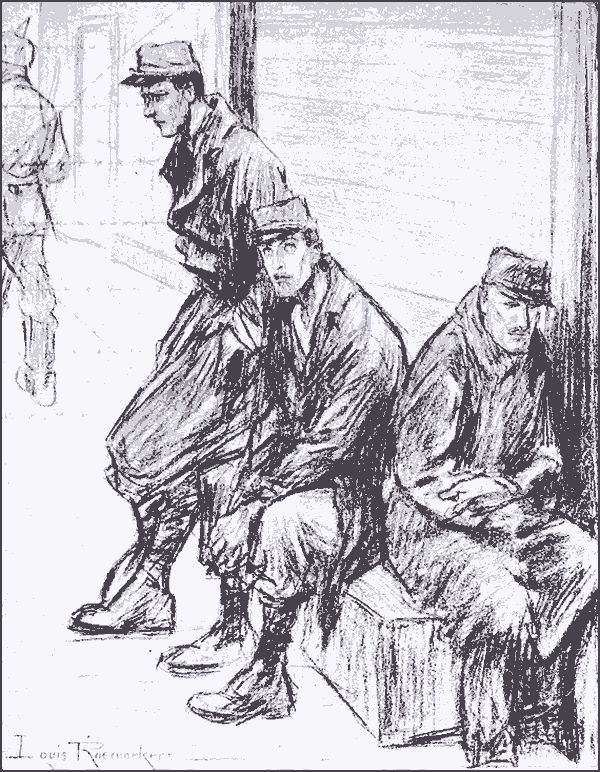

XXII.

PRISONERS. "HUNGER AND MISERY."

By Louis Raemaekers.

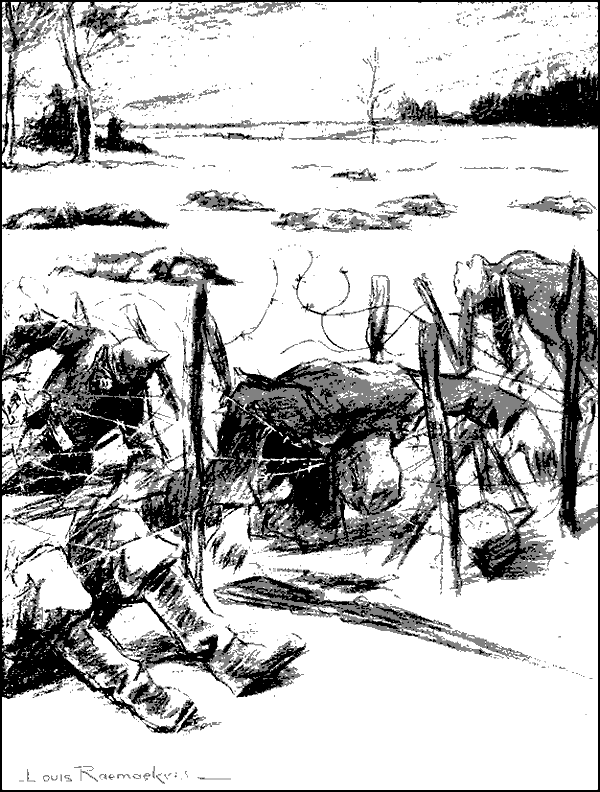

XXIII.

"BARBED WIRE."

By Louis Raemaekers.

Barbed wire figures in both these drawings, widely-different as they are. It has a special significance, used as a background to two such contrasting aspects of war.

XXIV.

"OUR FATHER WHICH ART IN HEAVEN."

By Louis Raemaekers.

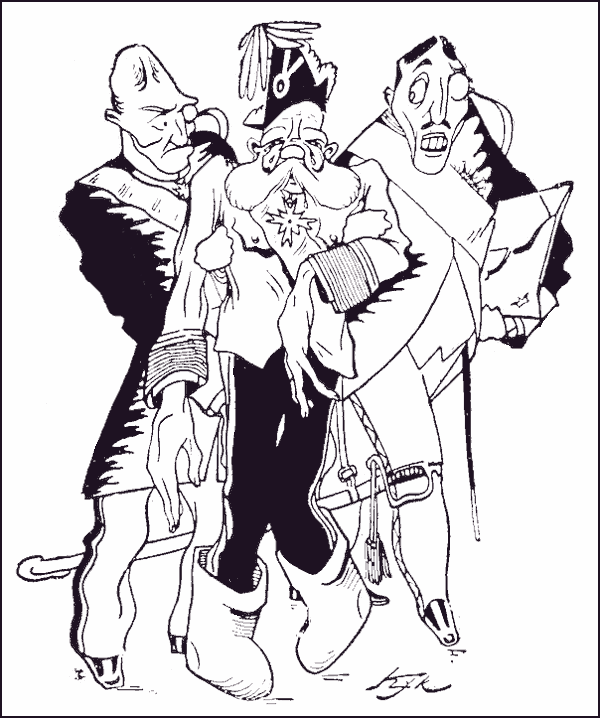

XXV.

Franz Joseph departs to the Front to cheer his Troops. But will he get there?

XXVI.

"THE WEAKLING."

Nobody could congratulate Mother Turk and Father Ferdinand on the son (Turco-Bulgar Agreement) Doctor Kaiser has just helped into the world. It would hardly be tactful for the closest friend to hazard a statement that it favoured either parent.

XXVII.

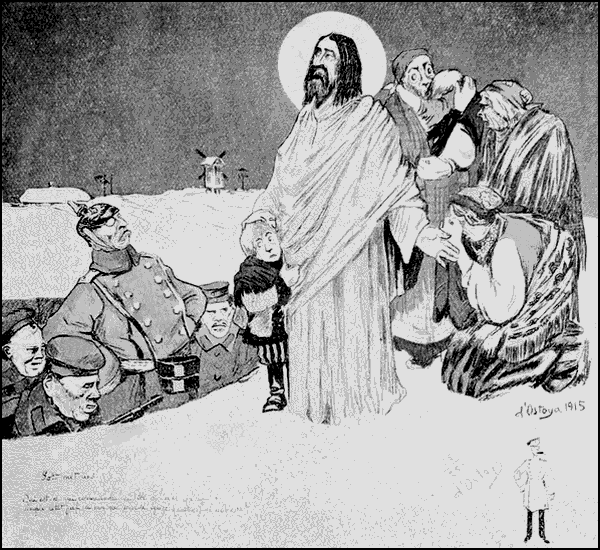

M. d'Ostoya, the well-known Polish artist, has published in Paris, during the war, a very strong series of drawings, both in colour and in black. Of this series the two shown here are among the best-contrasted.

Says the Prussian Officer: "Who is it who commands here? You, a simple little Jew, or I—who have thirteen quarterings of nobility?"

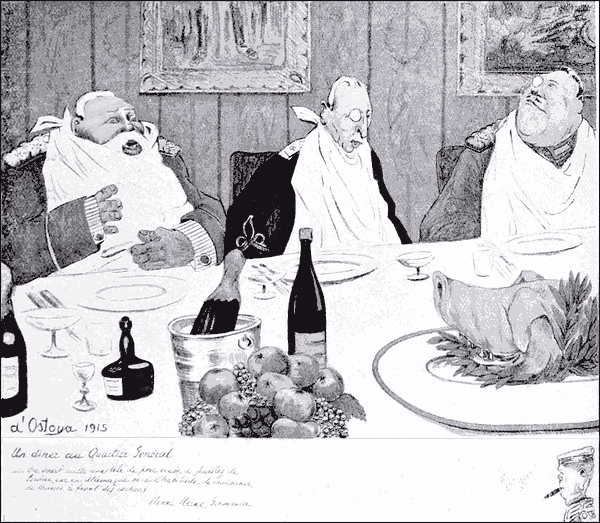

XXVIII.

A DINNER AT HEADQUARTERS.

"A pig's head was also served, ornamented with laurel-leaves—for in Germany it is customary to crown pigs with laurel."

Heinrich Heine, Germania.

Henri Heine, Germania

XXIX.

Poulbot is the interpreter of French childhood, and in that capacity his pencil, before August 1914, had given infinite pleasure. But pleasure ceased to be a very important pre-occupation in August, 1914, and even Poulbot's sympathetic pencil lent itself to horror as easily as to mirth.

This drawing appeared in l'Anti-Boche, of Paris.

"Don't be frightened, kill her—I've got hold of her," runs the legend.

XXX.

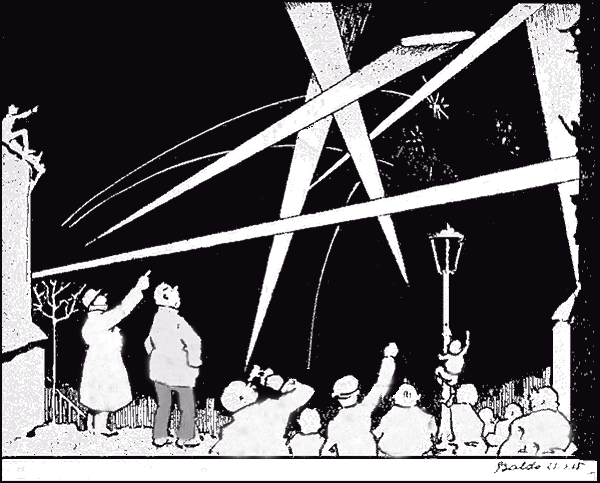

When the Zeppelins first came to Paris, public interest was immense, and children were wakened that they might not miss the sight. This drawing by Baldo from l'Anti-Boche, is not at all exaggerated.

"It looks like a sausage!"

"Oh, no!" cries the child, "if it had been a sausage the Boches would have eaten it long ago."

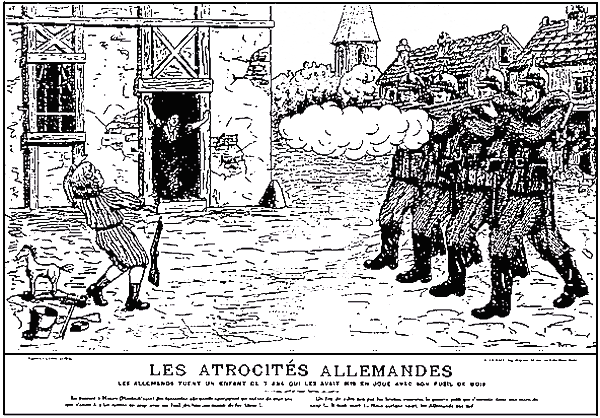

XXXI.

THE GERMAN ATROCITIES.

This was one of the earliest coloured prints published in Paris during the war, and formed part of a cheap series, issued at a few sous each, and printed in colours the most brilliant and most naïve. The little boy of seven who was shot for levelling his wooden gun in play at the German invaders was a very favourite theme with all French artists, from Véber downwards. The incident is alleged to have taken place in the village of Magny, Alsace.

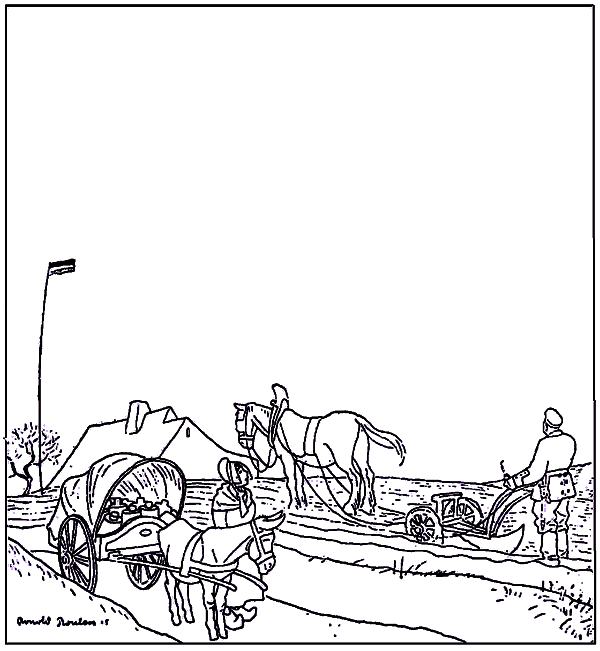

XXXII.

A drawing by Armengol, from Le Rire Rouge, Paris. "Retreat from the Front" (Le Front se Degarnit).

XXXIII.

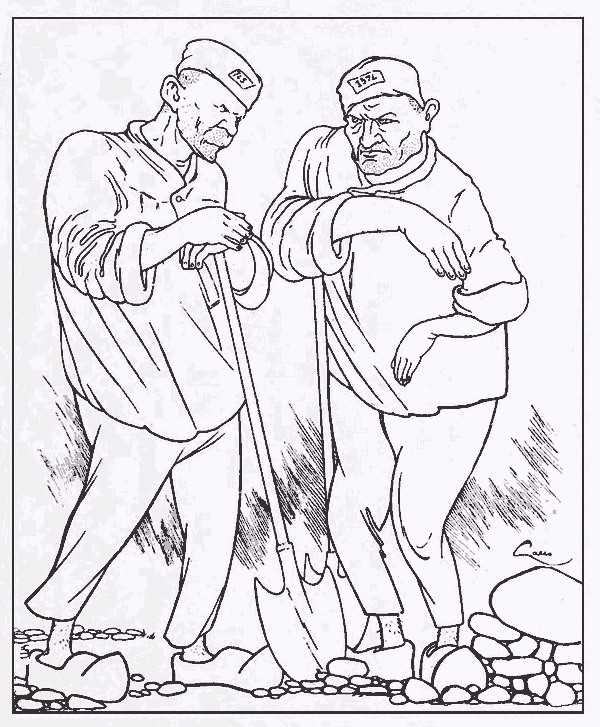

IN THE BAGNIO.

By Gallo.

"What did you do?"

"I killed my mother. And you?"

"I was Emperor of Germany."

(Reproduction of a drawing in A la

Baïonnette, Paris.)

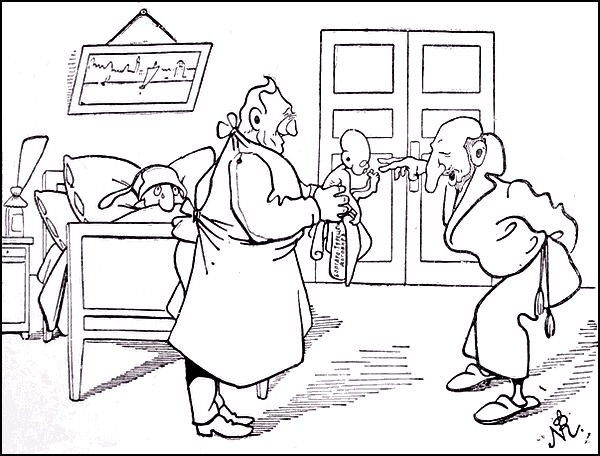

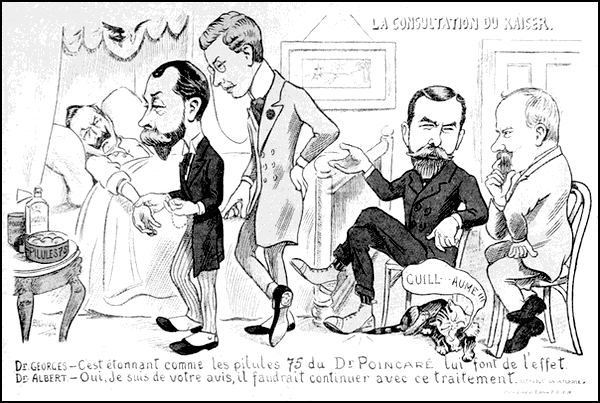

XXXIV.

THE CONSULTATION ON THE KAISER.

Dr. George: It is astonishing how effective are the "75" pills of Dr. Poincaré.

Dr. Albert: Yes, I agree with you; the treatment should be continued.

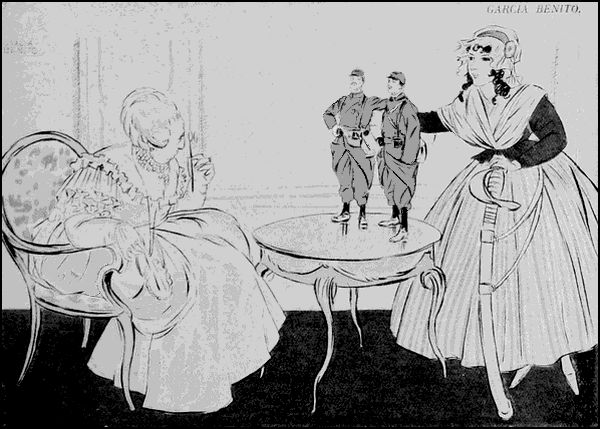

XXXV.

"THE SACRED UNION."

By Garcia Benito.

The Marchioness: "Dear me—in uniform one can't tell mine from yours!"

XXXVI.

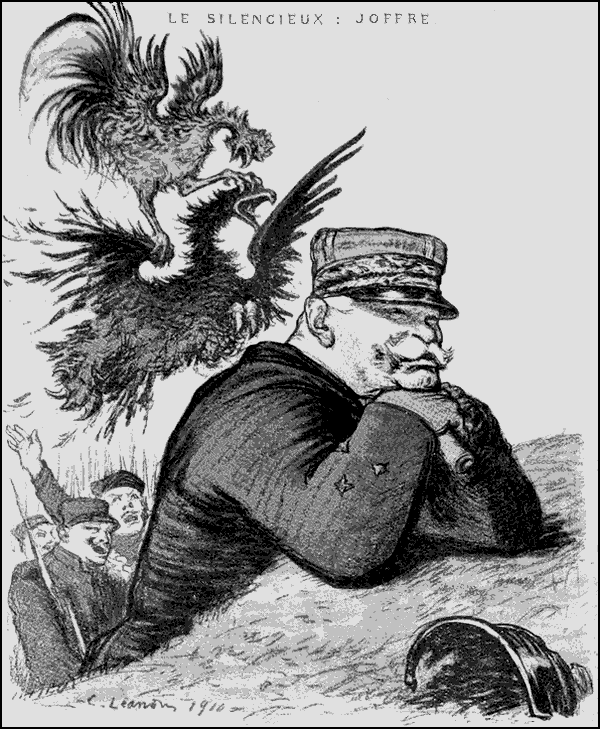

"THE SILENT ONE"—JOFFRE.

By Leandre, the allegorical cartoonist, in Le Rire Rouge, Paris.

The reputation for silence enjoyed by General Joffre is better-founded than is always the case with the reputed characteristics of great men. In the course of being shaved at a Paris barber's recently, an English client was told that General Joffre had for fifteen years been a regular customer at the shop. "And what sort of person is he really?" "I don't know, sir—he never said anything!"

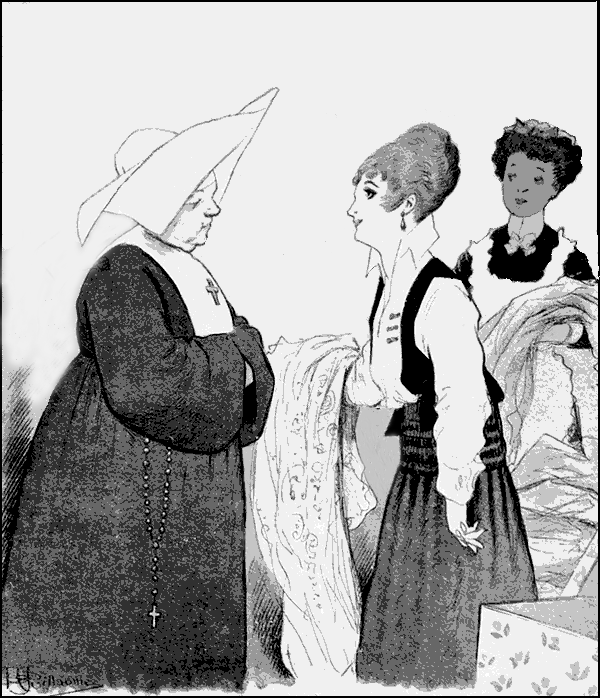

XXXVII.

French satire has not devoted itself entirely to our enemies, but has been frequently turned on France. There are comedy and irony, perhaps even pathos, in Albert Guillaume's cartoon in Le Rire Rouge of the fair and probably frail lady who replies to the Sister of Mercy's request for clothes for the refugees: "Certainly, Sister. Françoise, bring me my pink dress with silver sequins. Do you mind it's being slit up at one side, Sister? It does rather date it."

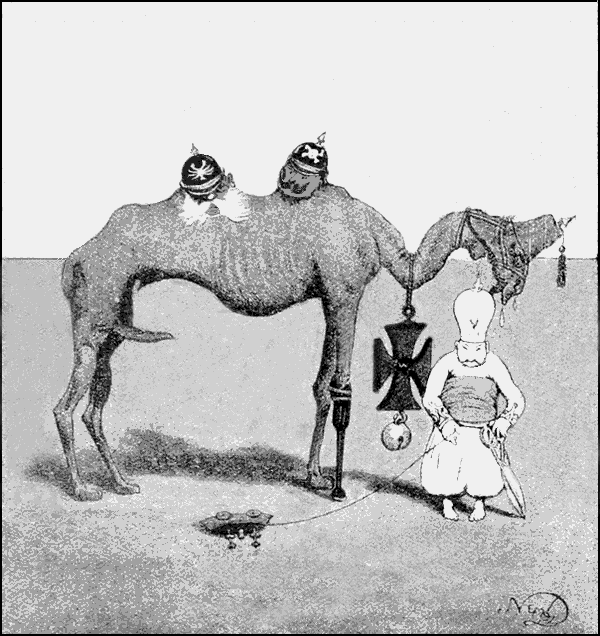

XXXVIII.

THE SICK MAN'S BURDEN.

The Two-Hunned Camel [Le Chameau à Deux Boches].

From Le Rire Rouge.

XXXIX.

AT THE GATES OF THE VATICAN.

"Open! Open! It is unhappy Belgium!"

The Pope's neutrality was not popular in France, even before he refused to pronounce an opinion on the violation of Belgium, as "that had happened in his predecessor's time." Many people consider that by this attitude the Vatican lost a priceless opportunity of re-capturing France. It is significant that this moving cartoon, from Le Rire Rouge, is signed: "A. Willette, Catholique."

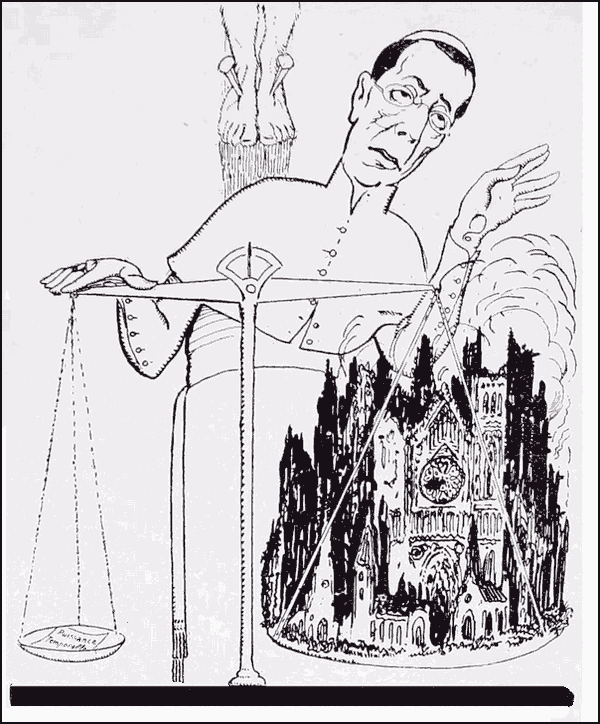

XL.

"The Pope says...."

By Grandjouan (Le Rire Rouge).

XLI.

GOTT MIT UNS.

"What would they have left Him if He had not been with them?"

Le Rire Rouge.

XLII. & XLIII.

Steinlen was once known best for his black cats—thin, rather wicked cats, prowling and hungry, and with inscrutable thoughts of their own. His fame grew, his scope widened and deepened, but never had he probed so deep nor risen so high as he has done since the war took him from his observation of social traits and concentrated him on the nobler aspects of mankind—and especially womankind. These two drawings are from a series which they worthily represent: "National Aid" and "Glory."

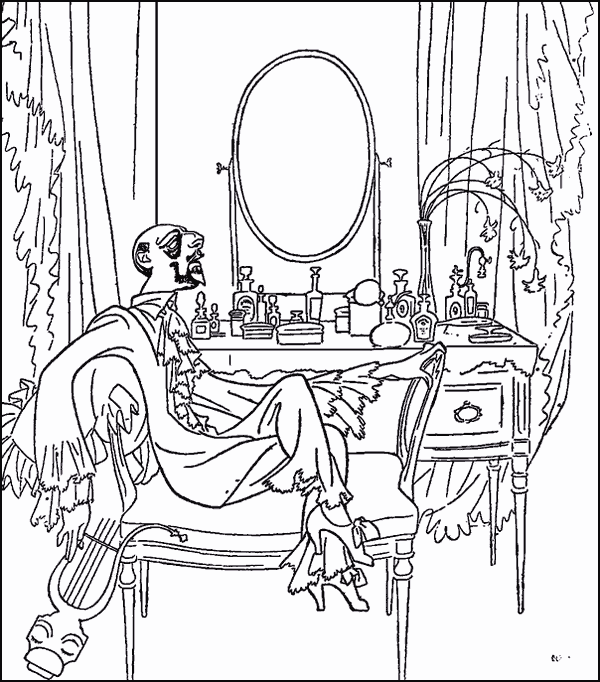

XLIV.

KAISER BONNOT, by H. A. Ibels.

The war has not obliterated so completely the life that went before it, that we have forgotten the Motor Bandits, headed by Bonnot, who terrorised Paris by their audacity for many weeks. Had this drawing not been a likeness of the Kaiser it would still have been a wonderful delineation of the apache, his reckless soul showing through every inch of his stealthy body.

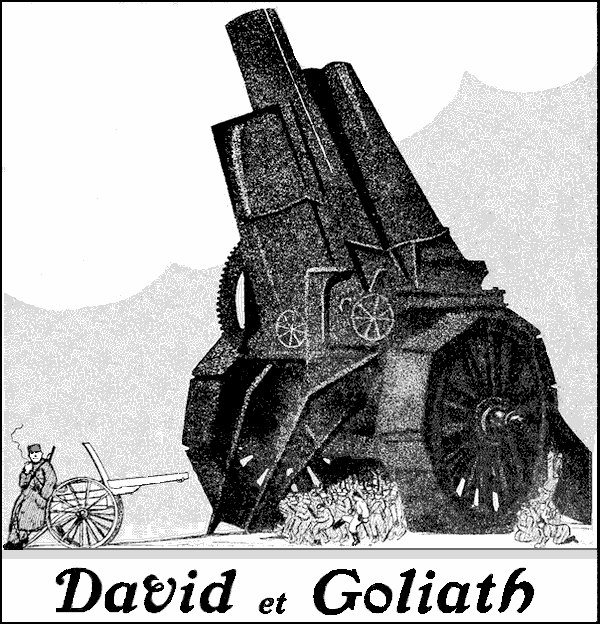

XLV.

DAVID AND GOLIATH, by Paul Iribe.

This drawing formed the cover of the first number of Le Mot, a short-lived but most interesting penny paper published in Paris during the war.

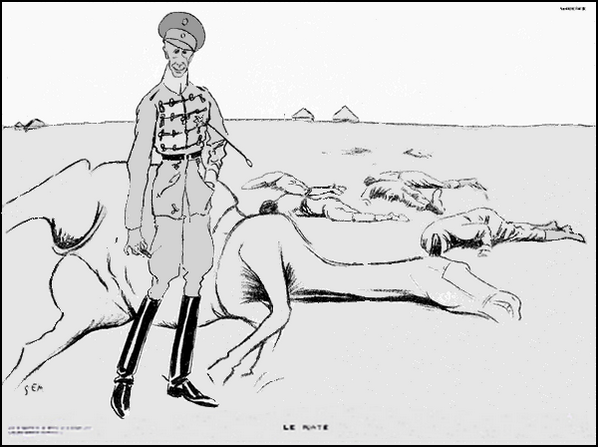

XLVI.

THE FAILURE, by Sem.

"After the Battle of the Marne, more than 50,000 German corpses were counted"—(The Papers).

Le Mot.

(LES JOURNAUX).

(A Franco-Russian Drawing.)

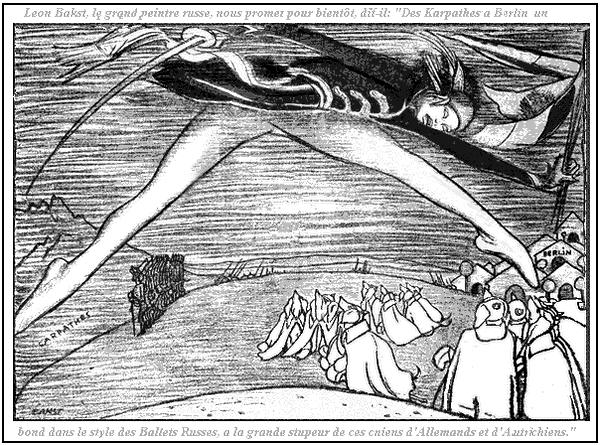

XLVII.

This drawing by Bakst, which appeared in Le Mot, bears the following legend:

"Leon Bakst, the great Russian painter, promises very soon, he says: From the Carpathians to Berlin a bound in the style of the Russian ballets, to the great stupefaction of those hounds of Germans and Austrians."

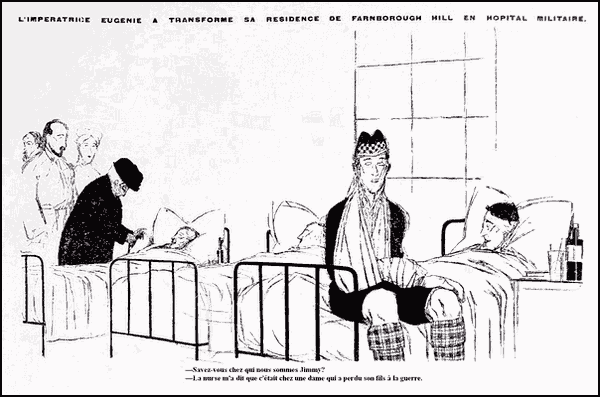

XLVIII.

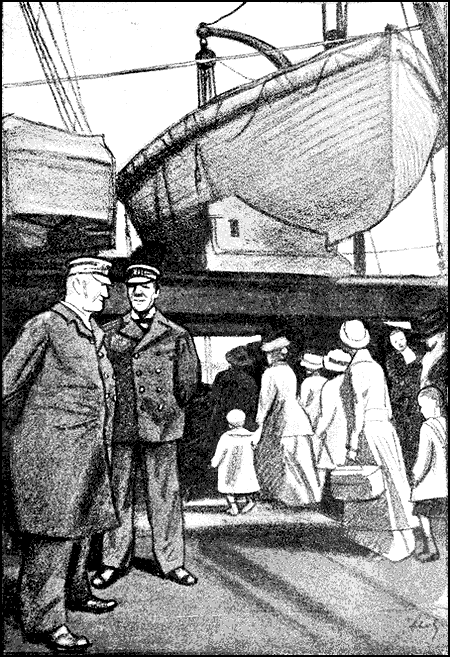

The Empress Eugènie has turned her house into a military hospital.

"Do you know where we are, Jimmy?"

"The nurse told me that it's the house of a lady

who has lost her son in the war."

From Le Mot.

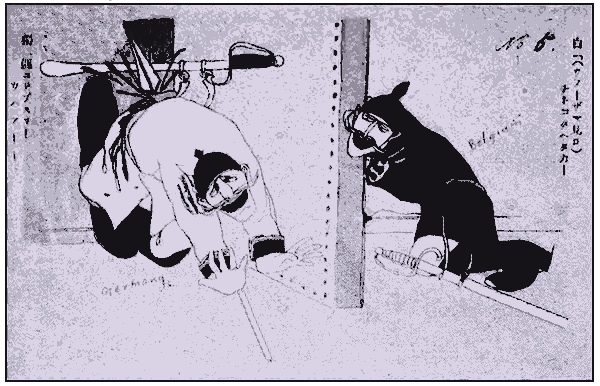

XLIX.

THE HOSTAGES, by A. Hermann-Paul.

L.

A Japanese postcard, on the resistance of Belgium to Germany. This is a characteristic production, with the legend in Japanese, and was not published for the Western market. The English names and number were written on it by the purchaser in Japan.

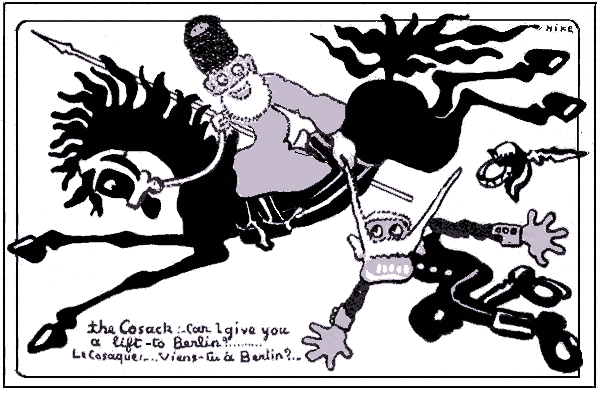

LI.

This spirited and delightful postcard by Niké, one of a series which foreran his book of soldiers (almost the only wholesome war-book for children), was published as early as August, 1914, before the victory of the Marne. Looking at its breezy outlines, and at the merry colours of the original, it is difficult to believe that it was drawn and printed at a time when all the printers were mobilised, and makeshift workmen formed the only labour.

LII.

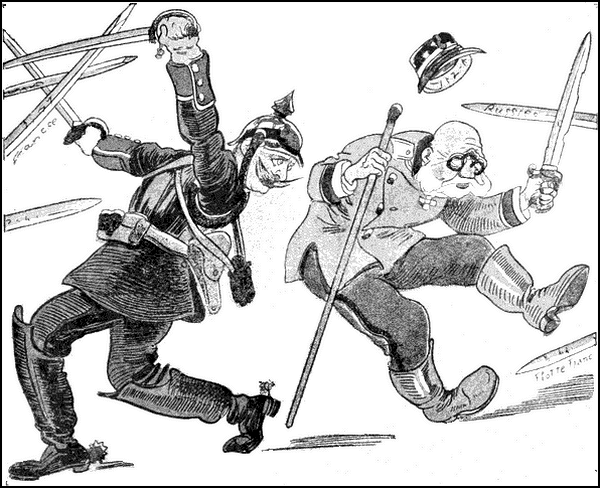

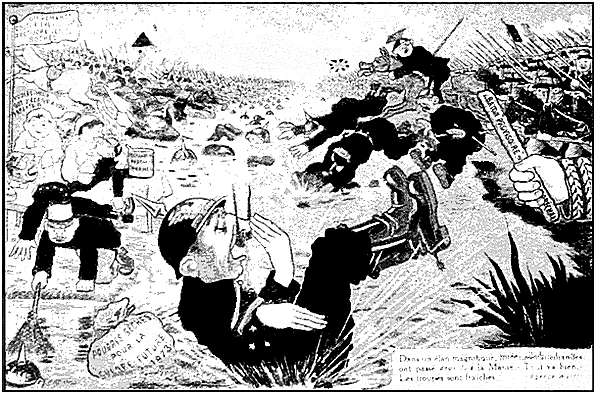

THE BATTLE OF THE MARNE.

"In a magnificent rush the German armies have twice passed the Marne. All goes well. The troops are fresh."—Wolff.

Collection of 6 cards of the firm Bouveret, Le Mans.

LIII.

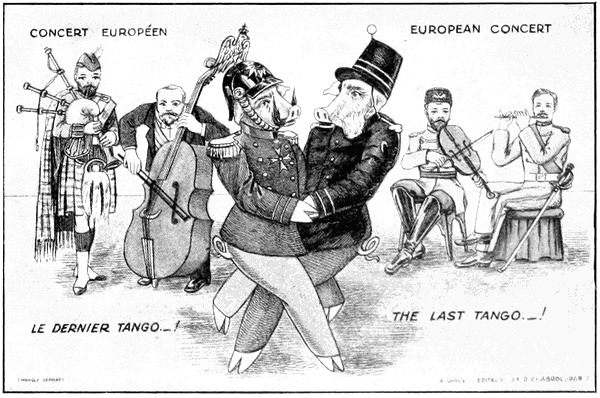

THE LAST TANGO.

L. Dalvy, 50 Bd. de Strasbourg, Paris.

It is not easy to come by copies of the German papers,

as the Trade-with-the-Enemy Act frowns upon such commerce.

Happily, there are neutral countries, through

whose agency something may be done. This and the

following six pages are devoted to German Cartoons, from

Simplicissimus, the famous Munich illustrated paper. They

are very clever, very mordant, very amusing, and always at

their best when directed against England.

LIV.

THE LUSITANIA.

"Isn't it madness, to take so many women and

children in a munition transport?"

"On the contrary; by this means, when the

ship goes to the devil, the world will be raging

against Germany."

And it was!

LV.

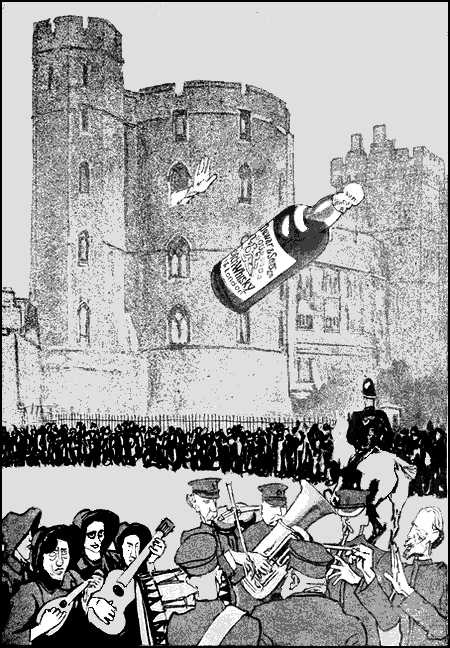

EARNEST TIMES IN WINDSOR CASTLE.

"To the noisy applause of the Salvation Army, King George banishes the Devil Alcohol."

The castle is not very life-like, but the bottle is—the free advertisement should be worth something, even in war-time.

LVI.

D'Annunzio: "At any rate, I am sure of being immortal in the heart of my creditors."

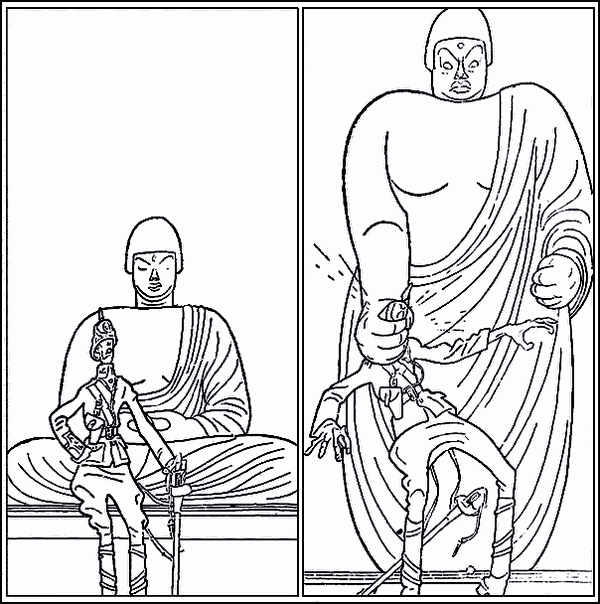

LVII.

WHEN BUDDHA WAKES.

This is a typical example of the view taken of the British soldier by the German artist—that he is extremely long, extremely thin, and extremely ugly. He is not here, however, smoking the usual pipe.

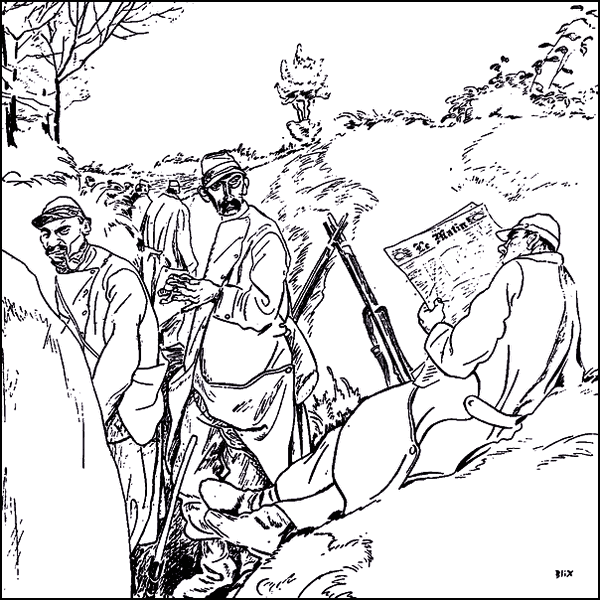

LVIII.

APACHES IN THE TRENCHES.

"Paris without light and without police! That does make a man homesick!"

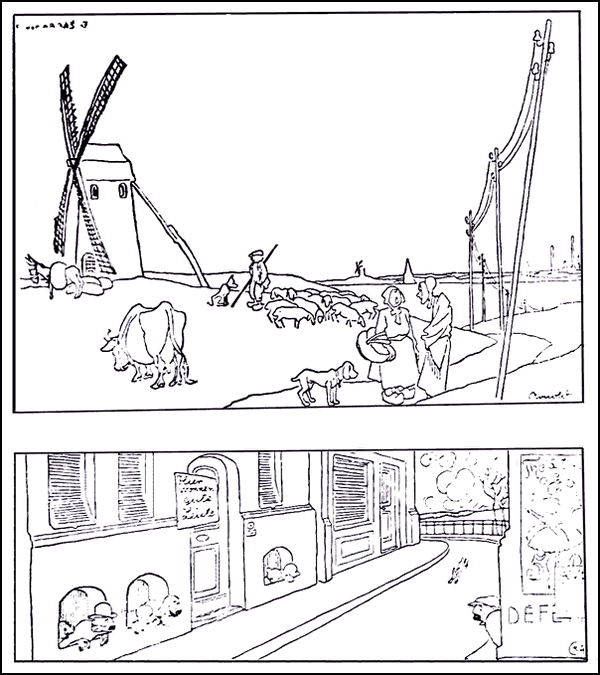

LIX.

THE MOOD IN FRANCE.

(a) Behind the German lines.

(b) Behind the French lines.

LX.

THE MOOD IN FLANDERS.

"Is that an enemy aeroplane, Madeleine?"

"No, Fritz; it isn't an enemy, its a German!"

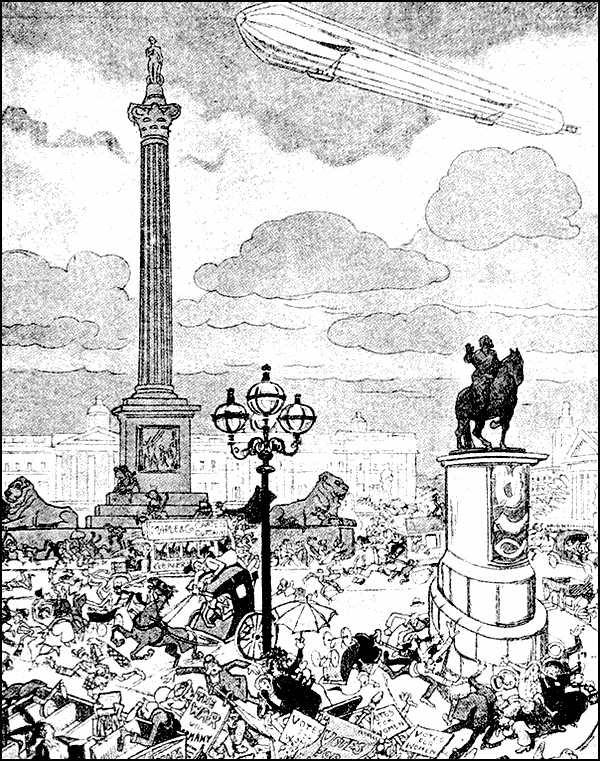

LXI.

A ZEPPELIN OVER TRAFALGAR SQUARE.

Free advertisement appears again here—Otherwise, the cab-horse and King Charles are the striking features.

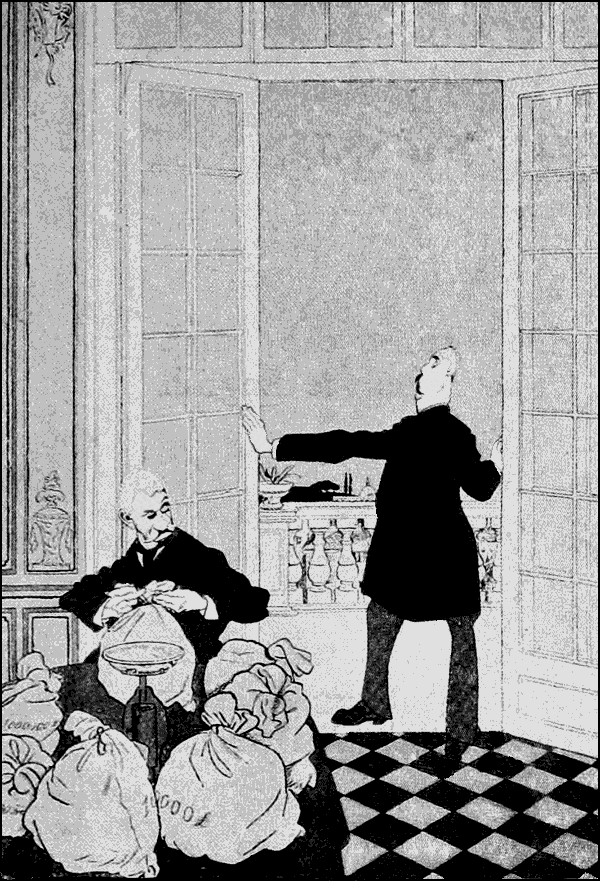

LXII.

SONNINO AND SALANDRA.

"Now we've got the money, Herr Colleague, you can summon the Italian people to its great historical mission."

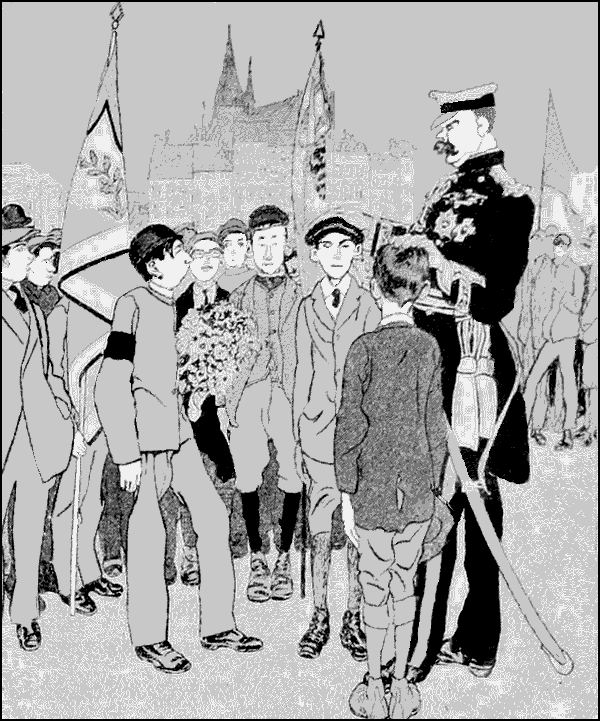

LXIII.

KITCHENER AND FRANCE'S RECRUITS.

"Only have patience, boys, and you shall yet fight for England. We will keep the war on long enough for that."

LXIV.

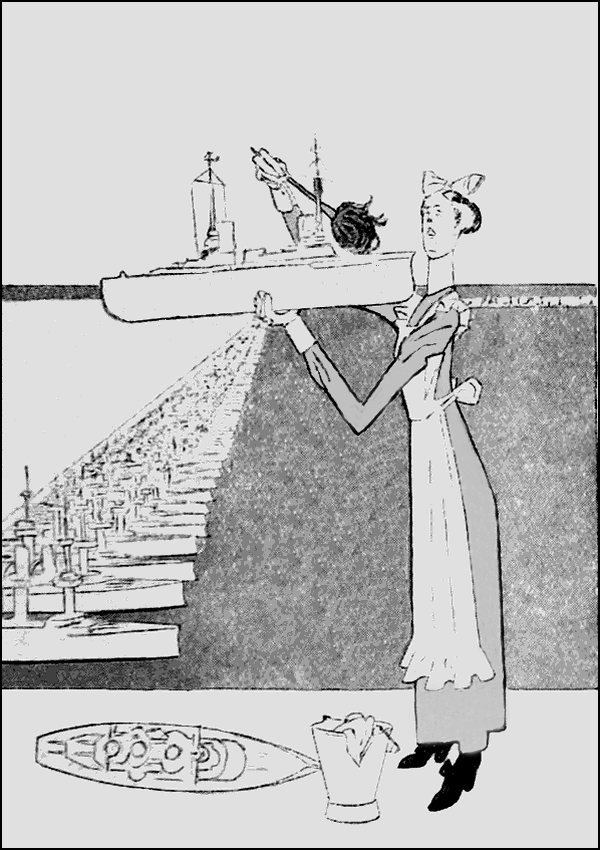

BRITANNIA THE HOUSEKEEPER, TO THE FLEET:

"I must dust you nicely every week, so that you may be as good as new when peace is concluded."

LXV.

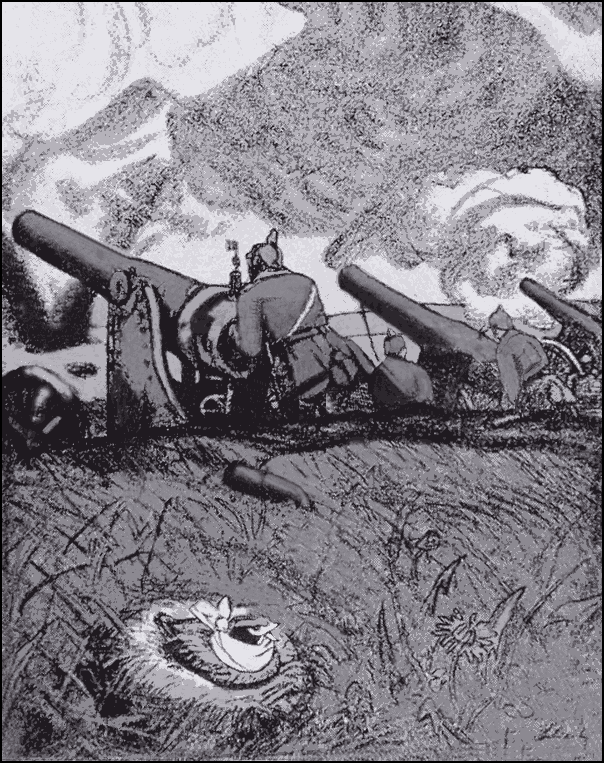

THE POOR LARK.

"I give it up, trying to sing against the guns! I'm completely hoarse already."

LXVI.

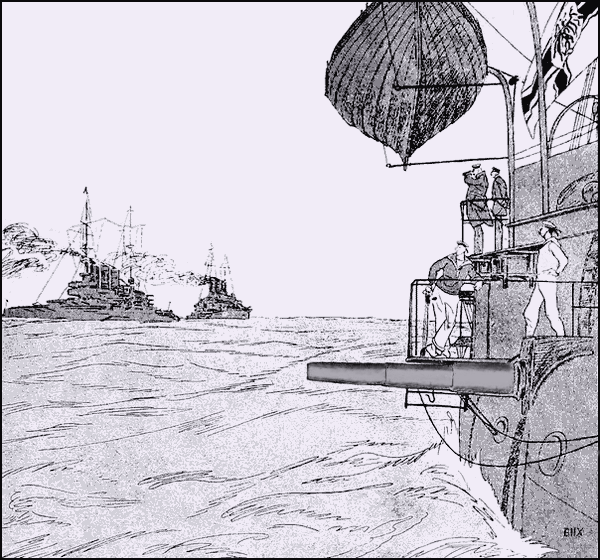

ENGLISH TACTICS.

"Only two Dreadnoughts against one small cruiser—it will take a lot to make the English attack!"

LXVII.

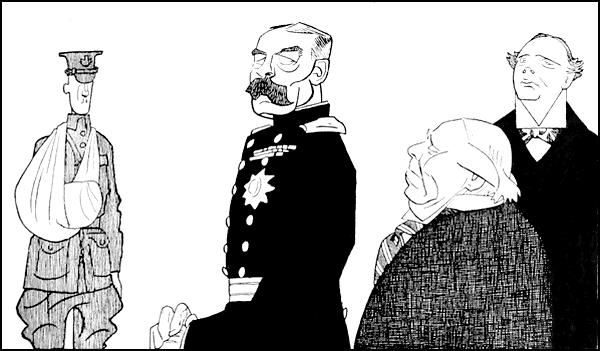

LORD KITCHENER DISTORTS THE EVIDENCE.

"This man says that the Germans treat their wounded prisoners well. But you see, Sir, that they have tortured him so terribly that he has lost his senses."

Better caricatures than these one could not ask to see. Tommy comes off worse than anyone else, and even for him his ear and his breeches have been rendered characteristically.

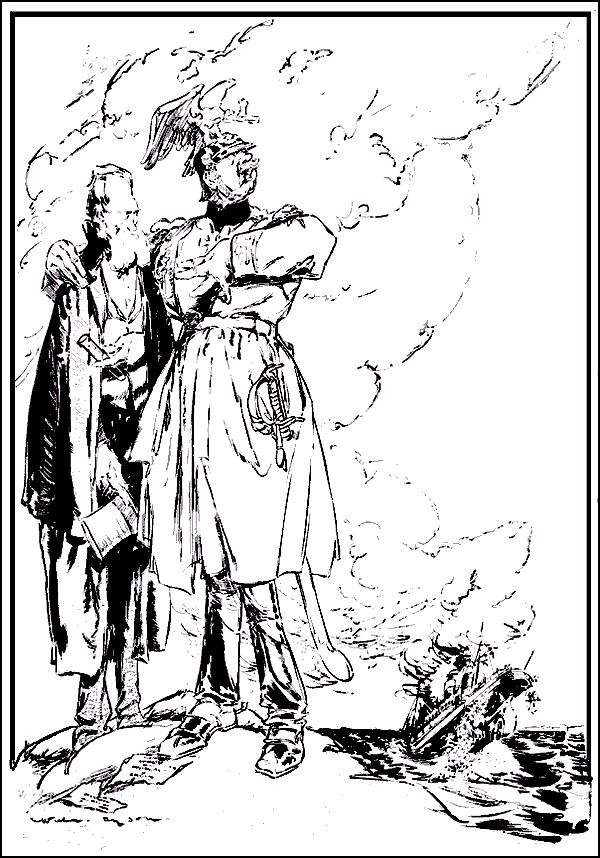

LXVIII.

THE TRUTH.

By Louis Raemaekers.

By permission of the proprietors of Land and Water.

PRINTED BY

THE STRAND ENGRAVING CO., LTD.,

MARTLETT COURT, BOW STREET,

LONDON, W.C.

Transcriber's Notes.

1. Introduction and Illustrations XXI to XXIV: The spelling of the name "Louis Raemakers", corrected to "Louis Raemaekers".

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.