The Project Gutenberg eBook of The island of the stairs, by Cyrus Townsend Brady

Title: The island of the stairs

Author: Cyrus Townsend Brady

Illustrator: The Kinneys

Release Date: October 10, 2022 [eBook #69130]

Language: English

Produced by: Emmanuel Ackerman, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

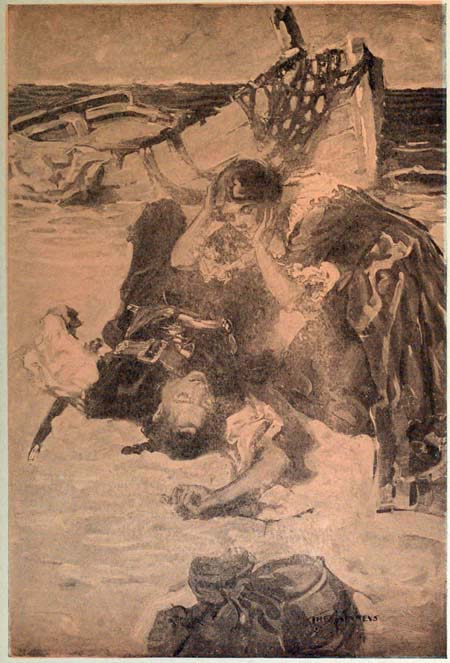

The Flight from the Place of Horror

The

Island of the Stairs

By CYRUS TOWNSEND BRADY

Author of “The Island of Regeneration,” “As the

Sparks Fly Upward,” “The West Wind,” Etc.

With Four Illustrations By

THE KINNEYS

A. L BURT COMPANY, PUBLISHERS

114-120 East Twenty-third Street - - New York

Published by Arrangement with A. C. McClurg & Company

Copyright

A. C. McCLURG & CO.

1913

Published November, 1913

Copyrighted in Great Britain

This story is affectionately

dedicated to my far-off adventurous

Brother-in-law,

E. S. BARRETT

In order to safeguard the reputation of that worthy seaman and most gallant gentleman who writes this memoir, the editor thereof deems it proper to call attention to the fact that Master Hampdon has described accurately the Island of Mangaia of the Cook, or Hervey, group in the South Seas. It is still completely encircled by the unbroken barrier reef, over which the natives ride in their light canoes. The stairs still exist despite the earthquake to which Master Hampdon refers—and other upheavals which may have followed—and are still traversed by the feet of curious, if infrequent, visitors. For the rest, such altars and platforms as he and his little lady found still abound in the South Seas. Also on Easter Island, and on others, too, such statues of the grotesque and hideous “Stone Goddes” as he describes may be seen. Who made them and why, as well as when they were put there, are as much mysteries today as they were when, in that far-off time, Master Hampdon and his lady sailed those then unknown seas in that brave little barque The Rose of Devon.

C. T. B.

Mount Vernon, N. Y.

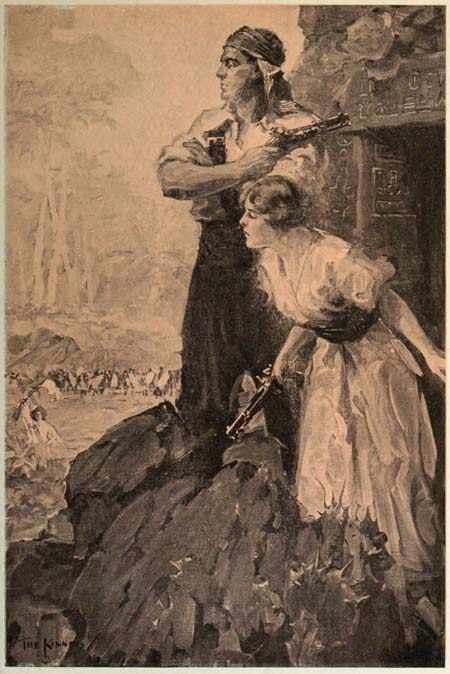

| The flight from the place of horror | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| “The treasure is thereabouts” | 122 |

| Then she bent over me | 190 |

| She had stepped out by my side | 290 |

THE ISLAND OF THE

STAIRS

I CANNOT say that I was greatly surprised when I stumbled across the body of Sir Geoffrey in the spinney, which is not for a moment meant to convey the impression that I was not shocked. Many times before that morning in my long and adventurous life I had, as I have often since, seen many people die in all sorts of sudden and dreadful ways, in all parts of the globe, too. And in some cases where the sufferer was past hope and the suffering great, I have prayed for the good mercy of a quick end; but never, even under such circumstances, have I been able to look upon death philosophically, at least afterwards. The shock is always there. It always will be, I imagine; indeed I would not[2] have it otherwise. I hope never to be indifferent to the passing of that strange mysterious thing we call life. But I digress.

Truth to tell, I had expected that Sir Geoffrey would come to some such sad end, therefore, I repeat that I was not surprised; but as I stood over him in the gray dawn, looking down upon him lying so quietly on his back with the handsome, silver-mounted, ivory-handled dueling pistol, with which he had killed himself, still clasped in his right hand, I was fascinated with horror. I was younger then and not so accustomed to sudden death as I have become since so many years and so much hard service have passed over my head.

And this was in a large measure a personal loss. At least I felt it so for Mistress Lucy’s sake, and for my own, too. Sir Geoffrey had been my ideal of the fine gentleman of his time. I liked him much. He had often honored me with notice and generally spoke me fair and pleasantly.

In his situation some men would have blown out their brains—and there would have been a singular appositeness in the action in his case—but[3] Sir Geoffrey had carefully put his bullet through his heart. It was less disfiguring and brutal, less hard on those left behind, less troublesome, more gentlemanly! I divined that was his thought. He was ever considerate in small matters.

The red stain that had welled over the fine ruffled linen, otherwise spotless, of his shirt and the powder marks and burns still visible thereon in spite of the dried blood, all indicated clearly what had happened. The pistol was a short one, heavy in build, made for close work, else he could never have used it so effectively. For the rest, he was clad in his richest and best apparel. His sword lay underneath him, the diamond-studded hilt protruding. He must have fallen lightly, gently, I thought, because his body lay easily on its back and his dress was not greatly disturbed.

I guessed that he was glad enough, after all, that the end had come, for his countenance had not that look of pain, or horror, or fear upon it, which I have so often seen on the face of the dead. His features were calm and composed. Evidently he had not been dead long. I remember[4] the first thing I did was to reach down and gently close his eyes. I shall never forget them to my dying day. They were dreadfully staring. As I bent over him for this purpose I noticed that he had something in his left hand. That hand was resting lightly by the hilt of his sword as if he had stood with his left hand on his sword in that gallant defiant position which I had often enough seen him assume, when he pressed the trigger with his right hand. As he had fallen, his hand had been lifted a little away from the sword and in his fingers there was a paper. A nearer look showed it to be an envelope. I drew it away and, glancing at it, saw that it was addressed to Mistress Lucy. Thrusting it in the pocket of my coat, I rose to my feet.

At that instant I heard steps and voices. Now I had nothing on earth to fear from anybody. The death of Sir Geoffrey was too obviously a suicide for anyone to accuse me, even if there had been any reason whatever for bringing me under suspicion. The letter which I carried in my pocket addressed to Mistress Lucy would undoubtedly explain everything there[5] was to explain. Something, however, moved me to seek concealment. I am a sailor, as you will find out, and act quickly in an emergency by a sort of instinct. On the sea men have little time for reflection. The crisis is frequently upon one with little or no warning, and generally it must needs be met on the instant and without deliberation.

Sir Geoffrey lay on the side of the path which ran through the spinney and beyond him the coppice thickened. The path twisted and turned. From the sound of the footsteps, I judged that men were coming along it. I instantly stepped across the body and concealed myself behind a tree trunk in the leafy foliage of the undergrowth. I could see without being seen, and hear as well.

The approaching footsteps might belong to some of the gamekeepers, to a stray poacher, to some of the servants of the castle, or to someone who, like myself, had been abroad in the gray dawn and had been attracted to the spot by the sound of the shot, although they approached over leisurely for that. I was prepared for any of these things but I did not expect that any of[6] the guests of the castle would make their appearance at that hour. The footsteps stopped. Two men, one of whom had been pointed out to me as Baron Luftdon in the lead followed by another who was strange to me, suddenly appeared. A voice which I recognized as the baron’s at once exclaimed in awe-struck tones:

“By gad, he’s done it!”

“Yes,” drawled the other, whose cold blooded calmness was in marked contrast with the unwonted excitement of the first speaker, “I rather expected it.”

“Here’s a pretty affair,” said the first man.

“Oh, I don’t know,” said the second indifferently, “it might be worse.”

“Worse for him? Great heavens, man, he’s dead!”

“Worse for us.”

“What d’ ye mean? I don’t understand.”

“Well, for instance, he might have shot himself before we—ah—plucked him.”

“Oh, I see,” returned my lord with a rather askant glance at his companion, for which I almost respected him for the moment.

The two stepped a little nearer. The first[7] speaker, Lord Luftdon, one of the young bloods who had been having high carouse with Sir Geoffrey for the past week at the castle, bent over him.

“There’s no doubt about his being dead, I suppose?” he asked after a brief inspection.

“Good gad, no,” replied the second man with a contemptuous laugh. “Where are your wits, man? He must have held the muzzle of the pistol close to his breast. See how his shirt is burned and powder blackened. He must have died instantly.”

“I suppose you are right.”

“Well,” continued the drawler nonchalantly—as for me I hated them both but the latter speaker the more if possible, for reasons which you will presently understand—“this relieves me greatly.”

“What do you mean?”

“You are very stupid this morning, mon ami,” returned the other, gracefully taking a pinch of snuff and laughing again with that horrible indifference to the dead man who had been his host and friend.

“After such a night as we had, to come thus[8] suddenly upon—this—’tis enough to unsettle any man,” muttered Luftdon apologetically.

“Pooh, pooh! man, you’re nervous.”

“Well, I don’t know how it relieves you. And after all’s said and done, Wilberforce was a gentleman, a good player and a gallant loser, and I liked him.”

“Exactly, I liked him too, well enough. And he lost his all like a gentleman.”

“And you got it, at least most of it.”

“Patience, my friend, you had your share, you know,” returned the other with his damnable composure.

“I don’t know but I’d give it back to have poor old Geoff with us once again,” retorted Luftdon with some heat.

“That is a perfectly foolish statement, my buck,” returned the other, philosophically taking snuff. “Somebody was bound to get it; Wilberforce has been going the pace for years; we happened to be in at the death, that’s all.”

“Well, how does it relieve you, then? Do you think Wilberforce would have attempted to get you to support him?”

The drawler laughed.

[9]“Of course not, this”—he pointed to the dead body—“is proof enough of the spirit that was in him; but of course, I cannot marry the girl now.”

“You can’t?”

“Certainly not. Her father a bankrupt and a suicide—”

“But the castle and this park?”

“Mortgaged up to the hilt. Speaking of hilts—” he stooped down and daintily avoiding contact with the corpse, drew from the scabbard the diamond-hilted sword—“this belongs to me. It’s worth taking. You remember he staked it last night on the last deal.”

“Good God, man,” protested the first speaker, “don’t take the man’s sword away. Let him lie with his weapons like a gentleman.”

“Tut, tut, you grow scrupulous, it seems. We will provide him a cheaper badge of his knighthood, if necessary,” returned the other lightly.

“And about the girl?”

“’Tis all off.”

“You will have some trouble breaking your engagement with her, I am thinking.”

“Not I. To do her justice, the wench has[10] the spirit of her father. A whisper that I am—er—disinclined to the match will be quite sufficient.”

“Aye, but who will give her that whisper?”

“We will arrange that some way. Truth to tell, I am rather tired of the minx, she bores me with her high airs. She does not know that she is penniless and disgraced. And as for her good looks—’tis a country beauty after all.”

“Poor girl—” began Luftdon, whose face, though bloated and flushed and seamed with the outward and visible evidences of his evil life, still showed some signs of human kindness.

At that point I intervened. I could bear no more. When they spake so slightingly of my little mistress it was more than I could stand. I burst out of the brush and stood before them—mad, enraged all through me. I will admit that I lacked the composure and breeding of that precious pair. What I had heard had filled me with as hot an indignation as ever possessed the soul of man, and with every moment the fire of my resentment burned higher and more furiously. They started back at my sudden appearance, in some little discomfiture, from which he[11] of the slower speech the more speedily recovered. He was the greater man, and eke the greater villain. The younger, the one with the red face, looked some of the discomposure he felt. The other presently leered at me in a deliberate and well intentioned insulting way and began:

“Now who may you be, my man, and what may you want?”

“Who I may be matters nothing,” said I, “but what I want matters a great deal.”

“Ah! And what is it that you want that matters so much?”

“In the first place, that sword.”

“This?” asked the sneering man, holding Sir Geoffrey’s handsome weapon lightly by the blade and smiling contemptuously at me.

“That,” answered I with equal scorn.

I am accustomed to move quickly as well as to think quickly, and before he knew it, I had it by the hilt and but that he released the blade instantly I would have cut his hand as I withdrew it. He swung round and clapped his hand on his own sword, a fierce oath breaking from his lips, his face black as a thundercloud.

[12]“Don’t draw that little spit of yours,” I said, “or I will be under the necessity of breaking your back.”

I towered above both of them and I have no doubt that I could have made good my boast. Yet, to do him justice, the man had the courage of his race and station. He faced me undaunted, his hand on his sword hilt.

“Would you rob me of mine own, Sirrah?” he asked more calmly if not less irritatingly.

“I might do so, and with justice,” I replied. “You had no hesitation in robbing the living or the dead.”

“Zounds!” cried the other man, touched on the raw of a guilty conscience apparently, “’twas in fair play. We risked each what we had and Sir Geoffrey lost.”

“Yes, I see,” I replied. “Having paid you with everything else, and possessing nothing beside, he had to throw away his life in the end. I heard what you said. You wonder how Mistress Wilberforce is to learn the situation—you who have doubtless once borne the reputation of a man of honor! You wonder who is to tell her that you discard her. I will.”

[13]“That is good, well thought of, yokel,” said the drawler with amazing assurance, and keeping his temper in a way that increased mine, “I could not have wished it better. As for your reflections upon me they interest me not at all. You are doubtless some servant of the house—”

“I am no man’s servant,” I interrupted in some heat.

“Somebody born on the place who probably cherishes a peasant’s humble admiration for the lady of the manor,” he continued.

I displayed the red ensign in my weather-beaten cheeks at this. I never was good at the dissimulation that goes on in polite society and I never could control my color for all I am bronzed with the wind and spray of all the seas, to say nothing of tropic suns.

“Ah,” he laughed sneeringly, taking keen note of my confusion, “see the red banner of confession in the brute’s face, Lord Luftdon.”

“I see it, of course,” said the other, whose frowning face was far redder than my own, though from drink—“but I must confess that personally I don’t like the allusion.”

“That for your likes, Luftdon,” cried the other[14] as contemptuous of his companion as of me apparently. “Tell her, my man, tell her. Tell her that she is a beggar and her father a suicide, and that I have all her property without her. She can go to your arms or those of any other she fancies. She is not meet for the Duke of Arcester.”

So this was Arcester! I had heard of him, as I had of Luftdon, two of the most debauched, unprincipled rakes, idlers, fortune hunters, gamblers, men-about-town, in all England. But of the two he bore much the worse reputation. Indeed, no one in that day surpassed him in baseness and villainy. But that he was a duke, he had been branded, jailed, or even hanged long since in England. But I cared nothing for his dukedom. As he spoke thus slightingly of my lady, I stepped closer to him and struck him with the palm of my hand. I suppose a gentleman would have tapped him lightly but not being of that degree I struck hard across the face, not so hard as I might have, to be sure, for I could doubtless have killed him, but hard enough to make him reel and stagger. His sword was out on the moment but before he could make a pass I[15] wrenched it from him, broke the blade over my knee and hurled the two pieces into the coppice.

“I can match you with swords,” said I, coolly enough now that the issue was made and the battle about to be joined. “I have fought with men, not popinjays, in my day, all over the world, and I know the use of the weapon; but I would not demean myself, being an honest man though no gentleman, much less a duke, by crossing blades with such a ruffian.”

“By God!” cried the duke furiously, “I will have you flogged and flung into the mill pond, I will clap you in jail, I will—”

“You will do nothing of the sort,” said I, composedly. “There is no man on the estate who would not take my part against you, especially when I repeat what you have said about Mistress Lucy. They love her and they loved him. With all his drink and extravagance he was a good master and you have been a bad friend.”

“And who would believe you?” queried the duke, whose anger was at a frightful height in being thus braved and insulted. In his agitation he tore at his neckcloth and almost frothed at the mouth like a man in a fit—I doubt he had[16] ever been so spoken to before. “’Twould be your word against mine, you dog, and—”

“For the matter of that, my word will not be uncorroborated,” I interrupted swiftly.

“What d’ ye mean, curse you?”

“This gentleman—”

“By gad,” said Lord Luftdon, decisively, responding to my appeal more bravely than I had thought, “you are right to appeal to me and you were right to strike Arcester. ’Fore God, I’m sorry for the girl and for Sir Geoffrey and ashamed for my—my—friend.”

“Would you turn against me in this?” asked the duke, surprised at this amazing defection.

“I certainly would,” answered the other with dogged courage.

“God!” whispered his grace hotly, fumbling at the empty sheath, “I wish I had my sword. I’d run the two of you through!”

“There is Sir Geoffrey’s sword,” said Lord Luftdon, who did not lack courage, it seemed, clutching his own blade as he spoke and making as if to draw it.

“No,” said I, master of the situation as I meant to be, “there shall be no more fighting[17] over the dead body of Sir Geoffrey. You and Lord Luftdon can settle your differences elsewhere. I am glad for his promise to tell the truth in case you attempt to carry out your threat and I am just as grateful as if it had been necessary.”

“On second thought, there will be no further settlement,” said Luftdon, regaining his coolness and thrusting back into its scabbard his half-drawn blade. “His grace and I are in too many things to make a permanent difference between us possible.”

“I thought so,” I replied.

“By gad,” laughed Luftdon, “I like your spirit, lad. Who are you, what are you?”

“The late gardener’s son.”

“Do they breed such as you down here in these gardens?”

“As to that, I know not, my lord. I am a sailor. I have commanded my own ship and made my own fortune. I come back here between cruises because I am devoted to—”

“The woman!” sneered the duke, and I marveled at the temerity of the man, seeing that I could have choked him to death with one hand.

[18]“Mention her name again,” I cried, “and you will lie beside your victim yonder!”

“Right,” said Luftdon approvingly.

“I come back here because I am fond of the old place. Lord Luftdon, it is my home. My people have served the Wilberforces for generations. Their forebears and mine lie together in the churchyard around the hill yonder. You can’t understand devotion like that,” said I, turning to the duke, “and ’tis not necessary that you should.”

“And indeed what is necessary for me, pray?” he sneered.

“That you and Lord Luftdon leave the place at once.”

“Without speech with my lady?”

“Without speech with anyone. There is a good inn at the village. I will take it upon myself to see that your servants pack your mails and follow you there at once.”

“I will not be ordered about like this,” protested the duke blusteringly.

“Oh, yes you will,” said Luftdon. “The advice he gives is good. We have nothing more to do here.”

[19]“No,” said I bitterly, “you have done about all that you can. The man is dead but the woman’s heart will not be broke because of you. Now go.”

“If I had a weapon,” said Arcester slowly, shooting at me a baleful and envenomed glance, “I believe I would even send one of his faithful retainers to accompany Sir Geoffrey.”

I never saw a man who was more furiously angry, baffled, humiliated than he. As for me, I was glad of his rage. If I had known any way to make him more angry and humiliated I confess I would have followed it.

“Don’t be a fool, Arcester,” said the other; “you’ve got everything you wanted in this game and ’tis only just that you should pay a little for it. What’s your name, my man?”

“Never mind what it is.”

“Are you ashamed of it?”

“Hampdon!”

“Master Hampdon, you may not be a gentleman,” said Luftdon, “but by gad, you are a man, and here’s my hand on ’t.”

He had played a man’s part, so I clasped it.

“You will be embracing him next, inviting[20] him to your club, I suppose,” said Arcester in mocking contempt.

“No,” said Luftdon, sarcastically, “he would not be congenial company for you and me, neither would we be for him. He seems to be an honest man. Let’s go.”

And so they went down the path, leaving me not greatly relishing my triumph, for now I had to tell Mistress Lucy all that had happened. I had to say the words that would tell of the loss in one fell moment of her father, of her property, and of her lover. I was greatly puzzled what to say and how to say it, for Mistress Lucy Wilberforce was no easy person to deal with at best.

THE path from the spinney to the ancient castle which antedated King Henry VIII, and which in its older parts goes much farther back into the past, led through the park full of noble oaks and beeches, many of them older even than the ancient and honorable family which now, alas, bade fair to lose them all forever. As I trudged over it with lagging footsteps, misliking my duty more and more as the necessity for discharging it drew closer, I caught a glint of rapidly moving color on the long driveway that led from the lodge to the steps of the hall. The scarlet of my lady’s riding coat as she galloped up the tree bordered road, it was that attracted my attention. I quickened my pace and we arrived at the steps leading up to the terrace at the same instant. She was alone, for she had either chosen to ride unaccompanied, as was her frequent custom, or else, being the[22] better mounted, she had left her groom far behind.

I stood silent before her with that curious dumbness I generally experience—even at this day—when first entering her presence, while she drew rein sharply. She was a little thing compared to me, small compared even to the average woman, but in one sense she was the biggest thing I had ever confronted. No burly shipmaster had ever impressed me so, not even when I was a raw boy on my first cruise. I actually looked upon her with a feeling of—well, shall I say awe?—mingled with other emotions which I would not have breathed to a soul. The chance hit by the Duke of Arcester had brought the color to my cheek and it takes something definite and apposite to bring the color to a bronzed, weather-beaten cheek like mine, which has been thrust into the face of wintry seas and exposed to tropical suns all over the globe. That is the way I thought of her. I was almost afraid of her! I, who feared nothing else on land or sea! What she thought of me was of little moment to her.

It was Mistress Lucy’s regular habit to take a[23] morning gallop every day. It was that usual custom that caused her to look so fresh and young and beautiful, that put the color in her cheek and the sparkle in her eye. Although she had left her father playing hard late the night before when she had gone to bed, there had been nothing in that to cause her to intermit her practice. Poor girl, she had left her father doing that more nights than she could remember in her short life, and I suppose she had become used to it, to a certain extent, at any rate.

She nodded carelessly, yet kindly to me. It was her habit, that careless kindness. When she was a little girl and I had been a great boy we had played together familiarly enough—children caring little for distinctions of rank, I have observed—but that habit was long since abandoned. Then she looked about for her groom. The steps that led to the terrace were deserted. Sir Geoffrey of late had grown slack in the administration of affairs on account of his troubles, therefore no attendant was at hand. Like master, like man! I suspected that the servants had kept late hours, too. Indeed they probably plundered Sir Geoffrey in every way and he,[24] seeing that all was gone or going, perhaps shut his eyes to their peculations. They might as well get what was left as his creditors. Mistress Lucy after that first nod stared at me frowning.

“Master Hampdon,” she said at last, “since nobody else seems to be about, suppose you attempt the task.”

She loosed her little foot from the stirrup and thrust it out toward me. I am nothing of a horseman. I was very early sent off to sea and I have a sailor’s awkwardness with horses. Naturally I did not know how a lady should be dismounted from her horse. I had never attempted the thing and I did not recall ever to have seen it done, otherwise I might have managed, for I am quick enough at mechanical things; but her desire was obvious and I must accomplish it the best I could. I stepped over to her, disregarding her outthrust foot, for all its prettiness, seized her about the waist with both hands, lifted her bodily from the saddle and set her down gently on the gravel. She looked at me very queerly and gave a faint shriek when her weight came upon my arms.[25] Indeed, I have no doubt that I held her tightly enough through the air.

“I dare say there is not a man among my father’s friends or mine, who could have done that, Master Hampdon,” said she, smiling up at me a little and looking flushed and excited.

“’Tis no great feat,” said I stupidly enough, “I have lifted bigger—”

“Women!” flashed out Mistress Lucy slightly frowning.

“Things,” I replied.

“It amazes me,” she said. “I have never been dismounted that way before. However, I remember you always were stronger than most men, even as a boy. There seem to be no grooms about, the place is wretchedly served. Will you take my horse to the stables?” she asked me.

There was a certain flattery to me in that request. If I had not shown her how strong I was, in all probability she would have thrown me the bridle and with a nod toward the stables to indicate her wishes would have left me without a word. Now it was different. I took the bridle, not intending, however, to take the horse around, not because I disdained to do her any[26] service but because I had other duties to discharge more important than the care of horses.

“Have you seen my father this morning?” she asked as I paused before her and then, not giving me time to answer, looked up at the sun. “But of course not,” she continued, a little bitterly, “he probably only went to bed an hour or two since and ’tis not his habit to rise so early as you and I.”

As luck would have it, while she spoke a sleepy groom chanced to come round the house. I flung the reins to him, bade him take the horse away and turned to my lady.

“Madam,” said I, my voice thickening and choking, “as it happens, I have seen your noble father this morning.”

There was something in my voice and manner, great stupid fool that I was, that instantly apprised her that something was wrong. With one swift step she was by my side.

“Where?”

“In the spinney.”

“When?”

“But just now.”

“What does he there at this hour?”

[27]“Nothing.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Sir Geoffrey—” I began racking my brains, utterly at loss what to say next and how to convey the awful tidings.

She made a sudden step or two in my direction, then turned toward the coppice, her suspicions fully aroused.

But now I ventured upon a familiarity, that is, I turned with her and caught her by the arm before she could take a step.

“I will see him myself,” she began resolutely.

“Madam,” said I swiftly, “you cannot.”

“Master Hampdon,” she said, “something dreadful has happened.”

I nodded.

This was breaking it gently with a vengeance, but what could I do? She always did twist me around her little finger and I was always more or less helpless before her. I admit that. I am still, for that matter, although she will not have it so.

“What is it? Is my father—what is he doing in the spinney? He never rises at this hour.”

“Mistress Wilberforce,” I said, “you come of[28] a brave stock and the time for your courage is now.”

“Is my father dead?” she asked, after a sudden, awful stillness.

I nodded while she stared at me like one possessed.

“Killed in a duel?” she whispered. I shook my head.

“Would to God I could think so,” I replied.

“You mean that he was—murdered?”

“Mistress,” said I bluntly, seeing no other way, “he died by his own hand.”

“Oh, my God!” she cried, clapping her hands to her face and reeling back.

I caught her about the waist. She had no knowledge that she was held or supported, of course; all her interest and attention were elsewhere. She did not weep or give way otherwise. She was a marvelous woman and her self-mastery and control amazed me, for I knew how she had loved her father.

“When? Why?” she gasped out.

“I was early awake and abroad,” I answered—and I did not tell her it was my habit to see her gallop off for that morning ride, for even a[29] glimpse of her was worth much to me—“and I heard a shot in the spinney. I hurried there and found Sir Geoffrey—”

“Dead?”

“Stone dead, mistress, with a bullet in his heart.”

“Let us go to him.”

“No,” said I, and I marveled to find myself assuming the direction as if I had been on the deck of my own ship, “that you cannot. It is no sight for your eyes now. I was coming to the castle to tell you and to send the servants to fetch—him. Meanwhile, do you go into the hall and summon your women and—”

“I will do what you say, Master Hampdon,” she whispered, very small, very forlorn, very despairing. “My father, oh, my good, kind father!”

She turned, and I still supporting her, we mounted the steps of the terrace. Suddenly she stopped, freed herself, and faced me.

“Lord Luftdon and the Duke of Arcester,” she explained, “they are staying at the castle; they must be notified.”

“Madam,” said I, “they already know it.”

[30]“And why then have they left the duty of telling me to you? Where are they? Summon them at once.”

“They are gone,” I blurted out, all my rage at the duke reviving on the instant.

“Gone!”

“Having won everything from Sir Geoffrey they have left him alone in his death,” I retorted bitterly.

“Impossible!”

“I ordered them off the place,” I said bluntly.

“You!” she flashed out imperiously. “And who gave you the power to dismiss my—my father’s friends?”

“I heard what they said, being close hid myself in the coppice.”

“And what said they?”

“It concerned you, mistress.”

“The Duke of Arcester,” she promptly began, “is my betrothed husband. I will hear no calumny against him.”

“Madam,” I said, keenly aware that I had made no charges yet and wondering at her thought, “your engagement is broken.”

“Broken!” she cried in amaze.

[31]“The duke declared himself to his friend to be too poor to marry the penniless child of a—disgraced man—his words, not mine, believe me.”

The awful death of her beloved father had been shock enough to her, but with this insult added I thought she would have swooned dead away. She turned so white and reeled so that I caught her again. I even shook her while I cried roughly,

“You must not give way.”

“It is a lie, a dastardly lie!” she panted out at last.

“It is God’s truth,” said I. “He repudiates you.”

“No man could be so base,” she persisted, “he swore that he loved me.”

“I would it were otherwise, madam, but he is gone, leaving that message for you.”

“And he made you his messenger?”

“I volunteered.”

“Why? Why?”

“Because he is a low coward.”

“And you stood by and let him insult me, your patron’s daughter, your mistress?”

[32]Now so far as that went, I had got mightily little out of the late Sir Geoffrey’s patronage, but whatever duty I could compass I would gladly pay the little lady who stood before me.

“Mistress, you misjudge me. He had taken Sir Geoffrey’s sword, saying that he had won it with everything else. I took it from him. When he said those words about you I struck him across the face, no light blow, I assure you. When he grasped his own sword I wrenched it away from him, broke it, and cast it away. You may find the broken pieces in the spinney. I told him that you were meet for his betters and that you were well rid of him, and bade him begone.”

“In that,” she said in a certain strained way, “you acted as a loyal servitor of the house and I thank you.”

“I am to give orders to have his baggage sent to the inn at once,” said I.

“And Lord Luftdon?”

“He came to your defense as if he were still the gentleman he had once been. But he goes hence with his friend. His baggage will also follow him.”

[33]“I will attend to that for them both,” said Mistress Lucy, growing strangely and firmly resolved again, and even I could guess the tremendous constraint she put upon herself. “Enough of Arcester. I am well rid of him and of his companion. Summon the servants to bring my father’s body to the castle. I suppose the crowner will have to be notified.”

“Yes,” said I. “I will see to that myself.”

“Of all my friends,” said she piteously, almost giving way, “you seem to be the only one left me, Master Hampdon.”

“I have been your faithful servant always, Mistress Lucy,” I answered as I ushered her into the hall.

I DELIVERED my little mistress to her woman who came at my call, and then I summoned the steward and butler and told them what had happened. In a moment all was confusion. But presently they brought the body of Sir Geoffrey back to the castle which was no longer his. As the duke had said, it was mortgaged to its full value. The unfortunate baronet had gambled away everything in his possession, the family jewels, the heirlooms of his daughter, and even the property that had been left to her by her dead mother, of which he was trustee. Everything that he could get his hands on had been sacrificed to his passion for play.

Following the inquest, and after a due interval to show a decent respect for the dead, there was a great funeral, of course, during which what little ready money there was available was of necessity spent. The gentry came for miles[35] around, even Luftdon was there in the background, although Arcester had the decency to keep away. I was there, too, finding my place among the upper servants of the household. Although I was in no sense a servant of the house, being a free and independent sailorman and my own master, still I found no place else to stand. I was glad that I had taken that position for I happened to be immediately back of Mistress Lucy. From under her veil she shot a forlorn, grateful look at me as she came in, as if she felt I was the only real friend she had in that great assemblage of the gentry of the county and the tenants and dependents of the estate.

Sir Geoffrey, except Mistress Lucy, was the last of his race. The brave, fine old stock had at last been reduced to this one slender slip of a girl. Kith or kin, save of the most distant, she had none. Nor did she enjoy a wide acquaintance. She had never been formally introduced to society. Sir Geoffrey had loved her and had been kind enough to her in his careless, magnificent way, but she had been left much alone since the death of her mother some years[36] before, and she had grown up under the care of a succession of wandering and ill-paid governesses and tutors. The neighboring gentry had assembled for the funeral with much show of sympathy but in my heart I knew that Mistress Lucy felt very much alone and I rather gloried in the position which made me, humble though I was, her friend. Well, she could count upon me to the death, I proudly said to myself. She would find I was always devoted to her and I solemnly consecrated myself anew to her service in her loneliness and bereavement.

The show and parade were over soon enough. The parson’s final words of committal were said. We left Sir Geoffrey in his place in the churchyard and went back to the hall, after which the company began to disperse. I had nothing to do at the time. No one paid any attention to me. I held myself above the servants and the gentry held themselves above me. I wandered into the hall and stood waiting. No one spoke to me save Lord Luftdon, who expressed a heart-felt regret that he had had anything to do with the final plundering of the unfortunate[37] baronet, which in a measure had brought about this sorry ending to his career.

“You seem to be a man of sense, Master Hampdon,” he whispered, drawing me apart, after it was all over, “and I noticed the way Mistress Wilberforce looked at you when she first came in.”

“What do you mean?” I asked hotly, not liking to hear her name on his lips, and especially resenting what I thought was a reflection upon her.

“Nothing but the best,” he answered equably. “I have still unspent some of the proceeds of our last bout at the table with her father that could be conveyed to the lady, and—”

“She would burn her hand off rather than accept anything,” said I promptly.

“But, man, I wish to—” he persisted.

“It is not to be thought of.”

“You speak with authority?” he asked, looking at me strangely.

“I have known her from a child,” said I, “and her father before her. It is not in the breed to take favors, and—”

“But this is—er—restitution.”

[38]“Did you win it fairly?” I asked.

“By God,” he answered, clapping his hand to his sword, “if another had asked me that I would have had him out.”

“Your answer?” I persisted, undaunted by his fierceness.

He smiled, his sudden heat dying out apparently as he realized how foolish it was to quarrel with me and discovered the meaning of my question.

“Of course we won it fairly. Sir Geoffrey was the most reckless and even the most foolish gambler I ever played with. We took advantage of that, but there was no cheating, Master Hampdon, no, on my honor, as I am a gentleman.”

“Under the circumstances then,” said I, “there is nothing further to be said.”

“But what will the poor girl do?” he demanded.

I shook my head. I did not know how to answer that question for I did not know what she would do. Nevertheless I was not a little touched and pleased with his interest and desire. Surely the man had some good in him still.[39] Association with such a scoundrel as Arcester had not yet wholly ruined him.

“You should have thought of this before,” said I.

“Yes, I suppose so,” he admitted rather woefully.

“It is too late to make reparation now, although the wish does you honor, my lord.”

“Well, Hampdon, if you have a chance to tell her what I wanted,” he said, “please do. I should do it myself,” he continued, “only since her repudiation by that blackguard Arcester she will not admit me to speech. By gad—” he looked over at her where she stood in the doorway going through the dreary process of bidding farewell to the guests after the funeral meal that had followed the interment, “by gad, if I were a bit younger and not so confoundedly in debt I would marry the woman myself.”

“She is meet for a better man, my lord,” said I, exactly as I had answered the duke.

He looked at me curiously for a moment and then laughed loudly.

“Doubtless,” he said, “you may tell her that, too.”

[40]With that he turned on his heel and walked away and I saw no more of him. I stood idle on the terrace until the last of the gentry had gone. As before, I did not know just what to do or just where to go. My position was most anomalous. I wanted to be of service, but how to offer myself without intrusion, I could not readily discover. It was my lady herself who solved the problem.

“Master Hampdon,” she began wearily, “will you come into the house? Master Ficklin, the lawyer, is here, waiting to go over my father’s papers with me. You have stood by me manfully, your people and my people have been—” she stopped a moment, “friends,” she added with kindly condescension, “for five hundred years. I have no one else with whom to counsel. Come with me.”

Sir Geoffrey’s will, as Master Ficklin read it, was a simple affair. It left everything of which he died possessed to his daughter. Unfortunately, he died possessed of nothing; the document was mere waste paper. Everything was mortgaged, every family portrait, even. Mistress Lucy appeared to have no legal right to[41] anything in or out of the castle apparently, save the clothes she wore.

“Sir Geoffrey,” said Master Ficklin, endeavoring to put a good face on the matter, “was well meaning—most well meaning. Not only did he play high and long at the gaming table but he speculated also, for he was always trusting to recoup himself; in which event doubtless there would have been a handsome patrimony for his daughter.”

“You may spare me any encomiums of my father, Master Ficklin,” said Mistress Lucy very haughtily; “I knew his devotion and affection better than anyone possibly could.”

In her mind there was no double meaning to these brave words she uttered so quickly, although I listened amazed. To rob his daughter of her all in the indulgence of a wicked passion for gaming and speculation was no great evidence of devotion or affection, I thought. However, Master Ficklin was only putting the best face upon a sorry matter, and for that I honored him, for all my mistress’ haughty and imperious manner.

“The point is, however,” she continued, as[42] Master Ficklin bowed deferentially toward her, “that I have nothing.”

“Nothing from your father, madam,” answered the man of law.

“But my mother’s estate?”

“I regret to say,” said Master Ficklin, “that most of it has been converted into money and—er—lost by your father. Strictly speaking he had no—er—legal right to dispose of your property and we might recover by suits at law from those—”

“I gave him the right,” interrupted Mistress Lucy quickly.

She had never given him any such right, of course, but she was jealous for the honor of her father and the family and I could only admire her action, although the plain, blunt truth ever appeals to me, let it hurt whom it may.

“In that case, there is nothing to be said or done,” returned the old attorney, who knew the facts as well as I.

“I forget,” she went on, “just how much of my mother’s property was devoted to—to our needs, by my father and myself.”

“There is left in my hands, madam, a matter[43] of some two thousand pounds out at interest which you, being now of full age—”

“I was eighteen on my last birthday.”

“Exactly, so that the two thousand is at your present disposal.”

“In what shape is it?”

“It is invested in consols.”

“Can they be realized upon?”

“Instantly.”

“To advantage?”

“Most certainly.”

“I thank you, Master Ficklin, for your provident care of my little fortune. It is most unexpected,” she faltered, almost overwhelmed at the sudden realization that she was not altogether a pauper.

“Believe me, Mistress Lucy, it is a happiness to do anything for you,” said the old attorney, rising and gathering up his papers, and bowing low before her. “My father, and his father before him served the estates of the Wilberforces, and for how many generations back I know not. You may command me in everything. A temporary loan, or—”

“Thank you, Master Ficklin,” said Mistress[44] Lucy, “you touch me greatly, but I need nothing at present. My father made me an allowance and generally paid it. It was a generous one; living alone as I did I could not spend it all. I have a few hundred pounds in my own name at the bank, and with that for temporary use and my mother’s legacy I shall lack nothing.”

“But where will you live, Mistress Lucy?”

“It matters little,” she answered listlessly.

“My sister and I,” said the old attorney, “live alone in the county town. The house is large. If you would accept our hospitality until your future is decided we should be vastly honored.”

“Master Ficklin—” began my lady.

“I know that the accommodations are poor,” interrupted the attorney hastily, “and we are humble folk, but—”

“I accept your kindly proffer most thankfully,” was her prompt reply. “I have been invited to various homes here and there in the county, but those who invited me have sought to convey a favor to me by their courtesy and I prefer to go to you.”

“Good,” said Master Ficklin briskly. “That is settled then. No one has either a legal or[45] a moral claim to your clothes or personal belongings or such jewelry as you have been accustomed to wear or have in your possession. You may pack everything of that sort and take away with you any little keepsake. In fact, I am empowered by those who held the mortgage to tell you that the pictures of your father or mother or anything strictly personal they waive their claim to.”

“Thank you,” said Mistress Lucy, “I shall take but small advantage of their generosity.”

“I know that,” answered Master Ficklin, “and now I will return to the town. If you will be ready about six o’clock—” it was then about two—“I will return and fetch you to our home.”

“I shall be ready. Good-by.”

The little lawyer bent over her hand and left the room. I had sat dumb and silent during the whole interview, although I had listened to everything with the deepest interest. As usual it was she who broke the silence when we were alone again.

“Master Hampdon,” she began, “to what a sorry pass am I reduced! What shall I do now?”

[46]“My lady,” said I, “the sorriest part of the pass to which you have been brought is that you have in me such a poor counselor, a rough sailor, but one who would, nevertheless, give his heart’s blood to promote your welfare, or do you any service.”

Now as I said that I laid my hand on the breast of my coat and as I bent awkwardly enough toward her—I could not even bow as gracefully as the little attorney just departed—I felt the paper which I had taken from Sir Geoffrey’s hand and which I had entirely forgot in the hurry and confusion of the days that had followed his death. I stood covered with surprise and shame at my careless forgetfulness, and stared at her.

“What is it?” she asked, instantly noting my amaze.

“I am a fool, madam, a blundering fool,” said I, drawing forth the paper. “Here is a letter addressed to you which I should have delivered at once,” I continued extending it toward her.

“To me? From whom?” she asked.

“Your father.”

[47]“My father!” she exclaimed.

“Yes, I took it from his dead hand that morning and thrust it into the breast of my coat and forgot it until this very moment. It may be vital to your future, my carelessness may have lost you—”

“It can lose me nothing,” said the girl with unwonted gentleness. I looked for her to rate me sharply, as I deserved, for my forgetfulness, but she was in another mood. “I can read it now with more composure and understanding than before,” she went on.

She tore open the envelope as she spoke and drew forth a letter, unfolded it, and there dropped from it a little piece of parchment which I instantly picked up and extended to her. But she was so engrossed in the letter that she did not see my action and paid no attention to my outstretched hand.

UNDER the circumstances, therefore, and without a thought that my action might be considered a possible violation of confidence, I looked at the parchment I held in my hand. It was evidently the half of a larger sheet which had been torn in two. The right half was in my possession. A glance showed me that it was a part of a rudely-drawn map, apparently of an island, although, lacking the other half, of that I could not be quite certain. Being a seafaring man, I was familiar with maps and charts of all sorts but I must admit that I had never seen a map that looked exactly like that one. It was lettered in characters which were very old and quaint, and some figures in the upper right-hand corner appeared to indicate a longitude. The outlines of the map and the letters and figures were all very dim and faded and a longer and[49] closer inspection than I could give it then would be needed to show just what they were.

My lady’s letter was a short one, for she looked up from it presently, her eyes filled with tears, the first I had seen there, and for that reason I was glad she could enjoy this relief. I suppose the fact that she was so alone and had no one else induced her to confide in me. At any rate, she extended the paper to me.

“Read it,” she said. “’Tis my father’s last word to me.”

I took it from her and this is what I read:—

My Dear Lucy:

As an ancient King of France once said, everything is lost but honor, and that trembles in the balance. I have speculated, gambled, tempted fortune; first because I loved it and at last hoping to win for you. But everything has gone wrong. You are penniless, even your mother’s fortune, of which she foolishly made me trustee, has followed my own. Master Ficklin may save something from the wreck. I hope so. I can do no more and perhaps, nay certainly, the best thing I can do for you is to leave you. May God help you since I cannot.

Your shamed and unhappy father,

Geoffrey Wilberforce.

Post Scriptum: The last thing that I possess is this[50] scrap of parchment. It has been handed down from father to son for five generations. The tradition of it is lost, but there has always been attached to it a singular value. Perhaps some day the missing part may turn up. There used to be a little image with it, but that has disappeared, too. At any rate, of all that I once had, this alone is left. Should you marry and have children pass it to them, a foolish request, but I am moved to make it as my father made it to me.

G. W.

I read it slowly. It was not a brave man’s letter. I liked Sir Geoffrey less then than ever before. Some of the ancient awe and reverence I felt for the family went out of my heart then. Well, the man was dead, and there was no use dwelling on that any longer. I handed the letter back to Mistress Lucy without comment. As she took it I extended the parchment in the other hand.

“Here,” said I, “is the enclosure to which your father refers. It seems to be a chart or map but in its torn condition it is of but little use.”

She took it listlessly, but as her glance fell upon it her face brightened.

“Why!” she exclaimed, brushing aside her[51] tears, “I, myself, have the other half and also the image.”

I stared at her stupidly, not in the least taking in her meaning and she evidently resented my dullness.

“I have the other half of the parchment, the missing portion of the map, and the little idol, I tell you,” she urged.

“You don’t mean to say—” I began in amazement.

“Yes,” she interrupted, “they came to me from my mother. When she died five years ago she gave them to me with much the same account as my father writes. I have never shown them to anyone, never mentioned the circumstances, even.”

“Why not?” I asked.

“I scarcely know. The torn map was valueless. I attached no special importance to the hideous little image. But now, now—”

“It is a miracle,” I said, “that the two pieces should have come together in your hands.”

“I don’t yet understand what it all means,” she said, “but—”

“Meanwhile,” said I, “may I respectfully[52] suggest that you get the other piece and the idol or image and let me look at them? I know something about such matters.”

“You!” she flashed out in one of those sudden changes of mood, sometimes so delightful and sometimes the reverse.

“I am a seafaring man, as you know, Mistress,” said I humbly, “and I have seen many strange gods in different parts of the world. Also I am accustomed to study maps and charts. Perhaps this may contain information vital to your fortunes which I can decipher more easily than another.”

She nodded and went rapidly out of the room. In a few moments she came back with another piece of parchment and a little stone figure, which I glanced at and laid aside for the moment, fixing my attention on the parchments. I placed them side by side and the torn and jagged edges fitted into each other perfectly. I had laid them on a table and bent over them in great excitement, excitement on my part caused by her proximity rather than by the faded, yellow sheepskin.

“It is an island!” she exclaimed.

[53]“Yes,” said I.

“Where is it?” she asked.

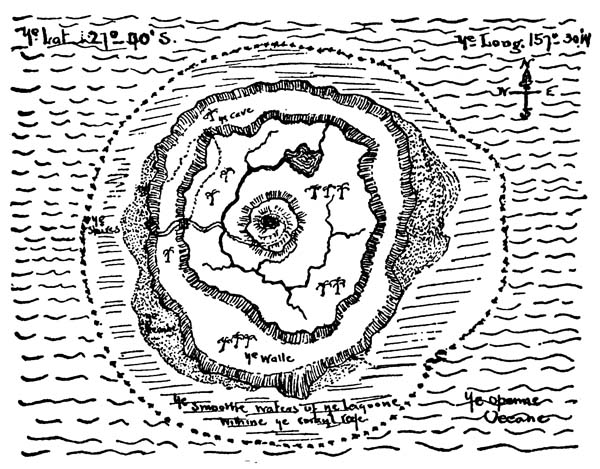

I pointed with my huge index finger to the figures in the upper left-hand corner and the upper right-hand corner marked respectively latitude and longitude.

“That will tell us exactly.”

“And you can find it?”

“If it be there, where the figures say it is, I can, as easily as I can find the park gate yonder.”

She looked at me with a certain amount of awe. Evidently the nice possibilities of the art of navigation had not been brought to her attention. I went up several degrees in her respect it seemed because I knew something she did not. Well, she was to find out that I knew many things that she did not—but I must not boast.

“Why, that is wonderful!” she exclaimed.

“Not at all. It is done by seamen every day.”

“Have you ever been there?”

“No,” said I, “I have crossed the South Seas several times but I have never chanced upon that[54] island or in fact sailed anywhere near that latitude or longitude.”

“But you know where it is?”

“Exactly, and if I had my great chart of the South Seas here, I could put my finger upon it and show it to you.”

“What,” she asked, pointing with her own dainty finger in her turn, “is that ring around the island?”

“That will be a coral reef, I take it. They usually are broken at some point so that ships can sail within, but here is a complete circle enclosing the island. There seems to be no entrance anywhere. ’Tis unusual and most strange.”

“Perhaps the man that drew the map made a mistake.”

“I think not. The map has been made by a seafaring man, that is plain.”

“I see, and the island itself is a circle,” she said, bending to inspect it more closely.

“Yes,” said I, “and it is like no island that I have ever seen, for here be two great rings like a gigantic wall and a hill or something of the sort in the middle.” I bent lower over it in[55] my turn. My eyes are unusually keen and I saw words written on the outside of the island proper and between it and the coral reef. “See,” said I, “the words ‘ye stairs’!”

“Stairs!” exclaimed the girl in amazement, “did you ever see stairs on such an island?”

“No, I have not. But these may only be some natural means of ascent.”

“It is most strange and meaningless,” she said.

“Not so, my lady,” I said, “these torn halves of the map have not been preserved through generations and handed down from father to son, or daughter, so carefully unless there be some meaning attached to them. What do you know about it? Forgive the presumption of my inquiry, but in this matter perhaps I can be of more service to you than I could be in anything else.”

“You have been a faithful, devoted servitor, Master Hampdon,” she said, “and I have no hesitation in telling you all I know. My mother and father were distantly related, that is they were descendants in the fifth generation from two brothers.”

“Exactly,” said I, “your father’s note says this[56] piece of parchment has been in possession of his family for five generations and evidently the other was in the possession of your mother’s people for the same time.”

“Why, that must be so,” said the girl amazed, “indeed, I think you are very acute to have reasoned it out.”

“I have but anticipated your own reflections, I am sure,” said I. “Who was the father of these two brothers?”

She thought a moment.

“Sir Philip Wilberforce was his name. He was—”

“A sailor!” I exclaimed on a venture.

“You have guessed rightly; he voyaged in distant seas in Queen Elizabeth’s time. It is reported that he was one of the first who went around the world after Sir Francis Drake showed all Englishmen the way.”

“Exactly,” I cried, “we are on the right track now. What further?”

“It is in my mind,” she said, “that Geoffrey and Oliver, his sons, quarreled over his property after his death, and—”

“There you have it. They divided his fortune[57] and tore the parchment apart, it being thought valuable for some reason, and each kept half,” I returned confidently.

“That is the tradition as regards the fortune, and it may account for the parchment,” she admitted in admiration of my conclusion, though indeed it was an easy one to draw.

“What next, madam?”

“The families drifted apart and gradually died out until Sir Geoffrey and my mother were alone left of their respective lines, and without knowing the relationship at the time they met and married, and I—” she faltered and put her hand over her face—“am the only one left of the family, of either branch.”

“Now here,” said I devoutly, for I fully believed what I said, “are the workings of Divine Providence. The parchment came from old Sir Philip, it was torn apart by his sons, and the pieces came not together until in you the ancient lines were united.”

“Yes, but what does it mean?” she asked turning to the table again.

As she did so the sleeves of her dress caught the parchment and separated the two pieces.[58] One of them fell to the floor face downward. I picked it up.

“Why, there is writing on it!” I exclaimed.

“So there is. I had forgotten that. It was unintelligible to me and, in fact, I put it in my jewel case and forgot about it.”

“And the image?”

“It was so hideous and so repellent I thrust it into a drawer of my cabinet and forgot it too.”

“Let’s put the two pieces together and take them to the light and see if we cannot decipher it,” said I. “Mistress Wilberforce,” I continued, “I have a sailor’s premonition that we are on the track of something that may greatly better your fortunes.”

There was no table near the window but I spread the two pieces of parchment on my two broad hands, from which you can get an idea of how large they were. The writing was dim and faded with age. It seemed to have been done with some sharp pointed instrument which cut into the sheepskin, and where the ink which had been used had faded, the scratches still remained. This that follows is what I made out.[59] I have reproduced exactly the old spelling and capitalization, and for your further illumination I have copied as best I could the map, or chart, upon the other side, so you can easily comprehend the story of our adventures upon it as I am now endeavoring to relate them. Of course my memory may be at fault in some particulars, but if so they are unimportant. As for the image, I can never forget its grinning, malign, evil hideousness, no, not to my dying day.

In ye yeare of oure Lorde 1595, I, Philip Wilberforce, Bt., of ye countie of Devon, being ye captaine of ye good shippe Scourge of Malice, didde take ye grate Spanish Galleon Nuestra Senora de la Concepcion after a bloudie encountre, wherein mine own shippe was sunke. Ye lading of ye galleon was worthe muche monaie, milliones of pounds esterling, I take yt. Withe manie jewelles and stones of price, pieces of eight and bullione, together with silkes and spicerie. Being blowne to ye southe and weste manie days in a grate tempeste, ye galleon was caste awaye on Ye Islande of ye Staires. Wee landed ye tresor and hidde yt in ye walle. Alle my menne being in ye ende dead ye natives came over ye seas from ye other Islandes in their grate cannos and tooke me, being like a madde manne. Godde mercifullie preserving my life, I escaped frome themm and at last am comme safe intoe mine own sweet lande of Englande once[60] more. Toe finde ye mouthe of ye tresor cave, take a bearing alonge ye southe of ye three Goddes on ye Altar of Skulles on ye middel hille of ye islande. Where ye line strykes ye bigge knicke in ye walle withe ye talle palmme tree bee three hoales. Climbe ye stones. Enter ye centre one. Yt. is there. Lette him that wille seek and finde. Here bee two of ye littel goddes I picked uppe and fetched awaye. Ye others are lyke onlie muche larger.

I spelt out the letters slowly, deciphering the quaint, faint writing with difficulty. Mistress Lucy drew near to me, bending over the parchment closely, following my efforts, indeed anticipating them with her quicker eye. Her[61] presence was a distraction to me, yet I was so glad to have her near me that I wished the parchment letter as long as this story I am writing bids fair to be. Well, we finished it at last.

Then I turned to the table in the center of the room where I had left the image. I stooped over it, picked it up and brought it to the light. It was a head, with the neck and the top of the shoulders showing, mounted on a pedestal roughly cut in imitation masonry. It was made of some hard pinkish stone like granite. There was no skill or nicety in its carving; it was rough and rude, inexpressibly so, and the marks of the chisel, or whatever the tool with which it had been carved, were quite apparent here and there; and yet years of exposure to wind and weather had smoothed it off in part. The evil face was long and the dog teeth fell over the protruding lip in a peculiarly brutal and ferocious way. There was sort of a crown on the head, the eyes were sightless, and the whole expression was revolting and beastly.

What kind of people made and what kind of people worshiped such a god I wondered. I was not surprised that my little mistress had[62] hid it away, nor that the one that came down through Sir Geoffrey’s line had been lost. If I had possessed it, I would have destroyed it long since. It fairly radiated evil, and the contrast between my lady’s face, all sweetness, purity, and light and this hideous image was the more marked. She has since confessed that she drew the same contrast between it and what she was pleased to call my brave and honest countenance! But of that more anon. We stared from the image to the parchment and then looked wonderingly at each other.

There was much in the letter, of course, that we could not possibly understand. We could only comprehend it fully if we were lucky enough to stand beneath “ye Stone Goddes,” of which I held a sample in my hand, on the island itself. Still the general purport was sufficiently clear. Sir Philip Wilberforce had evidently concealed a very considerable treasure there. If we could find it our fortunes would be made, or hers rather, for I swear I never thought of myself at all.

“Think you,” my little mistress began at last, her pale face flushing for the first time, her[63] bosom heaving quickly, “that the treasure may still be there watched over by those awful gods?”

She glanced at the image I still held in my hand as she spoke.

“Who can tell?” I answered. “I am probably as familiar with the South Seas and their islands as any sailor; which is not saying a very great deal, for there are thousands of islands in those unknown seas which have never been visited by man, by white men, that is, or by any race which preserves records. I have never heard even a rumor of the Island of the Stairs, yet it would seem to be sufficiently different from all other islands to have been published abroad if it had been discovered. Its latitude and longitude place it in unfrequented seas among others peopled by races of savage cannibals. I think it not at all unlikely that it may have remained unvisited by any who would appreciate the value of the treasure since Sir Philip’s day.”

“But would such treasure last so long?”

“Stored in a cave, gold and silver and jewels would last forever. Everything else would have rotted away probably.”

[64]“It says to the value of millions of pounds, you notice,” she repeated thoughtfully, pointing to the parchment again.

“Aye,” I answered, “there is nothing unusual or unbelievable in that; the cargoes of those old Spanish galleons ran up into the millions often, I have read.”

“How could we get there?” she asked.

“If you had a ship,” said I, “well commanded and found and manned you could reach the spot without difficulty.”

“How much would it cost?”

Well, I quickly and roughly estimated in my mind the necessary outlay. Such a vessel as she would require might be bought for perhaps twenty-five hundred or three thousand pounds; provisioning, outfitting, together with the pay of the officers and the crew, would require perhaps from fifteen hundred to two thousand five hundred pounds more, or a total of between five and six thousand pounds. And she had but two!

I was about to tell her the prohibitive truth when the solution of the problem suddenly came to me. In one way or another I had been a[65] fortunate voyager and I had saved up or earned by trading and one or two adventures in which I had taken part, something over four thousand pounds, which was safely lodged to my credit in a London bank. Her fortune was two thousand pounds. Alone she could do nothing, together we could accomplish it. I had no right to put the suggestion in her mind, but I did it.

“I should think,” I said slowly, “that two thousand pounds would be ample to cover everything.”

“Ah,” she said triumphantly, “exactly the sum that Master Ficklin said was left of my mother’s fortune.”

“Yes,” said I, and then I added in duty bound, “but you surely would not be so foolish, Mistress Wilberforce, as to risk your all in this wild goose chase?”

“If you were in my position, Master Hampdon, what would you do?” she asked pointedly.

“I am a man,” I answered, “accustomed to shift for myself. I might take a risk which I would not advise you to essay.”

“I must shift for myself, too,” she said, her eyes sparkling. The Goddess Fortune which[66] had ruined her father was evidently jogging her elbow. “Indeed, I shall take the chance,” she persisted. “I am resolved upon it.”

“But you could easily live on two thousand pounds for a long while,” I urged, against my wish, for I was keen to go treasure hunting with her for a shipmate.

“Not such life as I crave. If I cannot have enough for my desires I would be no worse off had I nothing.”

“But it is a long chance,” I persisted, “upon which to risk your all.”

“Master Hampdon,” she said solemnly, “the fact of the separation of those two pieces of parchment for a century and a half, and the fact that they come together in me, one half received from each of the dead who in neither case knew of the existence of the other half, the fact that I am Sir Philip Wilberforce’s last descendant through both the original heirs—see you not something providential in all this?”

“A strange coincidence,” I admitted.

“More than that,” she protested.

Well, I was arguing against my wishes and from a sense of duty, so I at last gave way.[67] After all, the treasure might be there. If so, it was hers and it would be a shame not to get it. The pulse of adventure leaped in my veins.

“So be it,” I said.

“Will you help me to make my arrangements, you are accustomed to the sea, and—”

“I will do more than that,” said I, “with your gracious permission I will go with you.”

“To the island?”

“To the end of the world,” I replied, whereat she stared at me a moment, then looked away.

She extended her hand to me and I tried to kiss it like a gentleman. I made, no doubt, a blundering effort, but at least it was that of an honest man.

“I must go and get ready to go to Master Ficklin’s in the town,” she said softly. “You know the house.”

I nodded.

“Come to me there tomorrow and we will talk further about the project.”

“Can I be of any other service?”

“Not now,” she answered, “you have been of great service already. I shall not forget it.”

[68]And so I turned and walked out of the hall, leaving her standing there for the last time, at least so we thought, the last little descendant of a brave race. But you never can tell what the future will bring forth. I little dreamed that she and I were to stand there again some day under quite different circumstances. It is a good thing for me that I did not dream that dream then. It would have turned my head if I had.

WHEN we broached the subject of our treasure hunting expedition to Master Ficklin the next day at his house, he would not hear of it. He examined the parchment with interest, but pooh-poohed the tale because, forsooth, it had no legal standing and was couched in the language of the sea rather than in the dry verbiage of the law. He pointed out that he had only succeeded in saving this last two thousand pounds of my lady’s fortune because he had skillfully concealed its existence from Sir Geoffrey, foreseeing that all that he could come at would be recklessly flung away in the baronet’s mad battle with fortune. He felt, he admitted to us, some compunctions of conscience about having hidden this little remainder from his friend and patron, and then he pleaded artfully that as he had gone against his sense of right for the sake of preserving this money, his[70] wishes as to the spending of it ought to be respected, especially when they concerned so intimately the welfare of my lady; for, he asked pertinently, what would happen to her when all was gone and she had found no treasure, the very existence of which he affected to disbelieve?

A very hard-headed, practical person was Master Ficklin. He was not cut out for an adventurer, that was patent. Still his statements and propositions were entitled to the highest consideration. His arguments, indeed, appealed to my better judgment and I seconded them to the best of my ability in spite of my own desires. I was born with a roving spirit, and in my own blood ran something of the gambling strain, and the longer I dwelt upon possible treasure the more alluring grew the prospect of searching for it, and the more certain I became that it was there. It is so easy to persuade ourselves of what we wish.

Besides, even if there were no treasure, I luxuriated in spirit at the thought of the long months’ intimate companionship at sea with my Little Mistress. It is true she already honored me with her friendship, but in no other way[71] could I hope to enjoy much of her society in the future. She was too young and too beautiful for obscurity. Sooner or later true men would love her, the gay world would seek her out, she would enter upon her proper station again, and then where would I be? Selfish! Aye, but I am frankly telling the truth in these rambling recollections, even to my own discredit, though my lady will not have it so.

But I had stern ideas of duty, too, and Master Ficklin’s good sense ever appealed to me. Yet when did mere good sense serve to persuade a woman against her wish? My lady would fain challenge fortune on her own account. She was of age and what she had left was absolutely in her control, but had she been but sixteen I make no doubt she would have had her way. She has ever had that way and ever will have it, so far as I am concerned. Worthy Master Ficklin has gone to his well-earned rest these many years as I write, but I am quite warranted, I am sure, in saying the same thing for him.

Well, the end of it was she made over her two thousand pounds to me without requiring me to give any bond, which Master Ficklin would fain[72] have insisted upon. This would have been embarrassing indeed for me for my bond would have been my own capital which I was going to embark in the enterprise in secret. I had saved up that money with no one knows what foolish dreams. I now realized these dreams possibly would come to nought. Well, what difference? I had no one dependent upon me, brother or sister I had never been blessed with, and father and mother were both dead long since. I was alone in the world. What need had I for the money?

I could always get a berth on a good ship as mate, or perhaps as master, for which I was fully qualified; and I could always earn enough for my needs and to spare. Let her have it whose need was great and whose desire was greater.

I might have bargained for a share of the treasure did we find any, but I scorned to do it. I would fain give all and expect nothing. There was a certain salve to my pride in becoming a benefactor to the woman I—But I must not anticipate in my story, trouble came soon enough, as you shall see.

[73]At any rate, not being in too great a hurry, although I was constantly urged to action by my lady, who could scarce possess her soul in patience before she began her treasure hunting once she was resolved upon it, I looked about a good deal in order to get just what I wanted. Finally from a merchant of Plymouth I purchased a stout little ship of three hundred and fifty tons burden called The Rose of Devon, which had been engaged in the West Indian and the American colonial trade. The name caught my fancy, too, for was not my Little Mistress the Rose of Devon herself? You that read may laugh at me for my posying thought if you will; I care not, for it is true.

It was my first design to have gone as master of her myself and my lady would fain have had it so, but after reflection I decided it were better to have a much older man than I to command so long as she went as passenger, so I engaged a worthy seaman, one Samuel Matthews, old enough to be my father, with whom I had often sailed, in fact the man under whom I made my first cruise. I did engage myself as mate, however, and I even tried to induce Master Ficklin[74] and his sister to go with us, whereat that worthy couple held up their hands in horror, preferring the one his musty parchments and suits at law, and the other her well ordered house and spacious garden. I was not sorry for their decision. I wanted to be alone on that ship with Mistress Wilberforce, with what vague idea or aspiration I dared not admit even to myself.

It seemed proper, in venturing among islands filled according to common report with savage peoples, to make ready for fighting; therefore, after consulting with Captain Matthews, whom I fully acquainted with the entire project in all its details, I shipped a crew of thirty men and I provided in the equipment plenty of muskets, pistols, and cutlasses with the necessary powder and ball and, in addition, a small brass cannon which I mounted on the forecastle. Nor did our cargo lack means for friendly trading and barter among the natives should such be found practicable.

Naturally, the unusualness of these preparations attracted some little attention and although Captain Matthews and I kept the destination of the ship and the purpose of the cruise strictly[75] private, we were overwhelmed with applications from adventurous men who desired to make the voyage, surmising that it was after treasure of some sort and that it would be vastly different from the monotony of an ordinary merchant trading cruise. Clearance papers were got out for the South Seas, which added the touch of romance that those waters always have, for an appeal.

Being so engaged with these larger matters, perforce I left the work of signing on a crew to Captain Matthews. He had as boatswain a veteran seaman named Pimball in whom he placed great confidence. He was a villainous looking man with a white scar running from his left eye across his cheek, caused by a cut he had received in some fight, and the line of white showing against the bronzed, weather-beaten cheek he sported, did not improve his appearance. But that he was a prime seaman was evident. Captain Matthews reposed much trust in him, somewhat to my surprise, for I was not prepossessed by his appearance, but the contrary. In answer to my objections he pointed out that many a man’s looks belied his character, and although[76] Pimball was certainly ugly, he was undoubtedly able. He had cruised several voyages with Captain Matthews and had always shown himself both experienced and dependable, so I let it go and he and Pimball selected the rest of the crew. It had been better for us in the end if I had got rid of the man as I wished. Or would it? Well, it would certainly have been better for Master Pimball and his friends.

To anticipate, when we boarded the ship I liked the crew not much better than the boatswain. I will say this for them, however, that a smarter, quicker set of seamen never hauled on brace or lay out on yardarm. It was not their skill or strength or courage that I misliked, no man could fault that, but they were not the sort of men I would have sought for a ship of my own; and the presence of my lady and her maid, a worthy woman, a long time servant at the castle, who had elected to follow her fortunes, perhaps made me unduly timorous; yet I was not unusually or extremely apprehensive. I had a sublime confidence in my own ability to deal with any man or any group of men. I had no doubt that Captain Matthews and I would[77] be able to master them and bend their wills to ours at the cost of a few hard words backed by a ready rope’s end or a well-used marlinspike or belaying pin.