The Project Gutenberg eBook of Travels in Western Africa, vol. II (of 2), by John Duncan

Title: Travels in Western Africa, vol. II (of 2)

Author: John Duncan

Release Date: October 18, 2022 [eBook #69179]

Language: English

Produced by: The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

From a Sketch by Duncan. Hullmandel & Walton Lithographers.

MODE OF EXECUTION AT DAHOMY. THE BLOOD DRINKER WAITING WITH HIS

CALABASH TO DRINK THE BLOOD.

[Pg iii]

1845 & 1846,

COMPRISING

A JOURNEY FROM WHYDAH, THROUGH THE KINGDOM OF DAHOMEY, TO ADOFOODIA, IN THE INTERIOR.

BY JOHN DUNCAN,

LATE OF THE FIRST LIFE GUARDS, AND ONE OF THE

LATE NIGER EXPEDITION.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. II.

LONDON:

RICHARD BENTLEY, NEW BURLINGTON STREET,

Publisher in Ordinary to Her Majesty.

1847.

LONDON:

R. CLAY, PRINTER, BREAD STREET HILL.

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| CHAPTER I. | |

| The Zafidah Mountains—Zoogah—Reception by the Caboceer—Bamay—Its Market—Curiosity of the People—Population—The Davity Mountains—Daragow—Qualifications for a Caboceer—The River Zoa, or Lagos—Its wooded Banks—Ferry—Superstition—Water-lilies—The Plain set on fire to destroy the Shea-butter Tree, &c.—Valley of Dimodicea-takoo—Kootokpway—Gbowelley Mountain—Romantic Scenery—Hospitable Reception—The Mahees—Their total Defeat by the Dahomans—Ascent of the Mountain—Ruins of a Town—Skeletons of the Slain—Soil—Twisted Rock—Mineral Springs—Agbowa—Herds of Cattle—Paweea, its healthy Situation—Palaver with the Caboceer—Description of him—His Hospitality—The Markets—Guinea Corn—Natives good Farmers—Cloth Manufacture—Native Loom—Hardware—Hyæna Trap—Admiration of my Sword—Review of native Soldiers—Population. | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| The Caboceer’s Kindness to my Servant—Presents—Names of Caboceer, &c.—Granite Mountains—Tanks—The Adita—Soil—The Tawee—Mountains—Grain and Vegetables—The Zoglogbo Mountain—Reception by the Caboceer of Zoglogbo—Ascent[Pg iv] of the Mountain—Cotton-trees—Mountain-pass—Singular Situation of the Town—Houses—Dahoman Political Agent—Probable Origin of the Mountain—Kpaloko Mountain—Ignorance, assumed or real, of the neighbouring Country by the Natives—The Dabadab Mountains—Superstition—Singular Method of conveying Cattle—Cruelty to the Brute Creation—Difficult Descent—Agriculture and Manufactures—Height of the Mountains—Death of Three Kings at Zoglogbo—Names of the Caboceer, &c.—Reception at Baffo—Costume of Caboceer and his Wife—His Principal Wives—Beautiful Birds—Gigantic Trees—Parasitical Plants—Singular Tree—Soil—Grain, Fruits, &c.—Cattle—Market-day, and Bustle of the Caboceer—Goods exposed for Sale—Rival Caboceers—Game—Pigeon-trap—Trial of Skill—Dog poisoned—Increasing Illness of my Servant—The Caboceer’s principal Cook | 27 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The River Loto—Jokao Mountain—Jetta—Reception by the Caboceer—Ruins of the old Town of Kpaloko—Its curious Formation—Its former Importance on account of its Manufactures—Desolating Effects of War—Attachment of the Natives to particular Spots—Natural Tanks in the Mountains—Mount Koliko—Precipitous Granite Rock—Similarity to Scottish Scenery—The Nanamie—Laow, and the Laow Mountain—Kossieklanan Cascade—Tamargee Mountains—Mineral Spring—Mount Koglo—Insulting Conduct of the Caboceer—Whagba—Caboceer’s Hospitality—the Town—Inhabitants—Kindness of Athrimy, the Caboceer of Teo—War-Dance—Drunkenness—Names of the Caboceer, &c.—Game—Curious Pigeons—An Incident—Absurd Notion—Departure from Whagba—Names of the Caboceer, &c.—Hospitality of the Caboceers of Laow and Massey—Beautiful Valley—Impregnable Position—The Caboceer of Kpaloko—Grandeur of the Scene—Jeka Houssoo—The Dabadab Mountains—Difficulty in obtaining Information—Resolve to leave my Attendants—My Scheme—Departure—Zafoora—Soil, Grain, Trees, Plants, &c.—Shea-butter used for Lamps | 55[Pg v] |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Zafoora—Terror of the Natives—Cold Reception by the King—My Disappointment—Exorbitant Charge—Unpleasant Position—Palaver with the King—Scene of the Defeat of the Dahomans—Inhospitality—The Shea-butter, and other Trees—The Gwbasso—Prevalent Diseases—Soil—The Velvet Tamarind—Wearisome Journey—Akwaba—Cold Reception by the Caboceer—His Disappointment—Slave Trade—Hard Bargain—Manufacture of Indigo—Hardware—The Ziffa—King Chosee and his Cavalry—Their Hostile Attitude—Moment of Danger—Result of a Firm Demeanour—Respect shown by the King and Natives—Enter Koma with a Band of Music—Kind Reception—Introduction to the King’s Wives—Palaver with the King—The Niger known here as the Joleeba—Presents to the King—Babakanda—Exorbitant Charges for Provisions—Manufactures—Ginger, Rice, &c.—Seka—Bustle of the Caboceer—Slave Market—Trade Monopolized by the Caboceer—The Kolla-nut—Honey—Peto—Palaver with the Caboceer—Soil—Assofoodah—Hostile Reception—Palaver—Ridiculous Confusion—Inhospitality | 80 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Inhospitality—Good Fortune—Soil—Mahomedan Town—Hymn of Welcome—The Natives, their Curiosity, &c.—Manufactures, &c.—The Crown-bird domesticated—Quampanissa—Market Day—Curiosity of the Natives—A Cranery—Market Constables, their Functions—Singular Musical Instrument—A Palaver with the Caboceer—Bidassoa—Mishap—A Bivouac—Reception by the Caboceer—Palm Wine freely taken by Mahomedans—Superstition of the Natives—Grain Stores—Manufactures—Buffaloes—Fruit Trees—Horses, their market price here—Cattle—Elephants—Manufactures—Game—Method of Drying Venison—Trees, Shrubs, Grasses, &c.—Kosow—Terror of the Native Females—Appearance of the Caboceer—Palaver—Presents to the Caboceer—His Harem—Swim across the River Ofo—Its Width, &c.—The Town of Kasso-Kano—Slave-Market—The Women—Neighbouring Hills—Iron—Antimony—Native System of smelting Ore—Native Furnace and Bellows—Roguery—Bivouac | 108[Pg vi] |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Peculiar Breed of Dogs—The Town of Zabakano—Market Day—Native Manufactures—Domestic Slaves—Palm Oil—Joleeba, or Niger—Horses make part of the Family—Pelican Nest—Pigeons—Kindness of the Gadadoo—Pigeon Shooting—Palaver with the Gadadoo—Population—Mounted Soldiers—Character of the Scenery—Grooba—Manufactures—The Town of Sagbo—Drilling System general here—Two sorts of Rice—Received by the Gadadoo with great Pomp—Palaver—Dromedary and Elephant—Prevalent Diseases—The Town of Jakee—Reception—Ancient Custom—Breakfast of the Natives—Manufactures—Terror of the Natives—Chalybeate Springs—The River Jenoo—The Land Tortoise—Interesting Panorama—The Town of Kallakandi—Reception by the Sheik—Palaver—Band of Musicians—Peculiar Instruments—Manufactures, &c.—Slave Market—Horses—Laws—Cruel Punishment—Population—Attack on a Boa-Constrictor—Manufactures—Deer—Method of Preserving Meat and Fish—Trap for Wild Animals—Town of Ongo—Reception by the Caboceer—Interesting Aspect of the Country | 136 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Ongo—Weariness of my Attendants—Bivouac—Alarm of my Horse at the Neighbourhood of Wild Beasts—Terror of the Natives—Their Kindness—Establishment for Mahomedan Converts—Singular Custom—My Anxiety to find Terrasso-weea, who had been present at the Death of Mungo Park—Loss of my Sand-glass—Its Construction—Adofoodia—The Market-Place—Reception by the King—Interview with Terrasso-weea—Ceremony of welcoming me—His Stores—Discovery of an Old Acquaintance—Narrative of his Adventures—Terrasso-weea’s House—His Wives—Inquire of him Particulars of the Fate of Mungo Park—His Relation of the Death of that Intrepid Traveller—Terrasso-weea an Eye Witness of it—Park’s Property seized by the King—His Despotic Character—Flight of Terrasso-weea—My Palaver with the King—Hospitality of the Merchant—Information obtained respecting Timbuctoo—Market of Adofoodia | 163[Pg vii] |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Return to Baffo—Anxiety of my Caboceer—Rejoicings for my Return—Our March—Fine Plain—Plants—Neutral Ground—Natives of the Dassa Mountains—Agriculture—The Annagoos, dangerous Enemies—Poisoned Arrows—Poisonous Plants—Alarm of my Attendants on my plucking it—Fatal Effects of this Plant and Dread of it by the Natives—Number of the Natives Blind, supposed to be the result of it—Unsuccessful Attack on them by the Dahomans—Spiral Rocks—Hostile Demeanour of the Natives—They follow us with Menaces—Some Account of these Mountaineers and of the Dassa Mountains—The Blue Eagle—Cataracts—Beautiful Plain—One of my Cases of Rum broken by a Carrier—Twisted Marble of Variegated Colours—Path covered with Pepper-trees—Monkeys—Logazohy—Mayho’s Town—The Caboceer—The Merchants—Their Names—Carelessness with respect to Fire—Visit of the Caboceer | 190 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Enter Logazohy in Regimentals—Received by the Caboceer, attended by his Soldiers—Singular Mode of Dancing—Native Jester—Description of the Town—Corn Mills—Presents from Fetish-women—Agriculture—Prevalent Diseases—A disgusting Case of Leprosy—Quarrel among my Carriers—My Illness—The Damadomy—Trees, Shrubs—The Agbado—Rapid Construction of a Suspension Bridge by my Dahoman Guards—Savalu—Reception by the Caboceer—Picturesque Situation of the Town—Caboceer’s House—His Wives—His Jester—My Illness | 210 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Importance of the Caboceer of Savalu—Curiosity of the natives—State Constables—Military Dance—Introduction to the Fetish-women—Manufactures—Crane-shooting—Present by Fetish-women—Hospitality of the Caboceer—His Name and those of[Pg viii] his Head Men—Wild Grapes—The Zoka—Shrubs—Swim across the Zoka—Mode of Transporting my Luggage—Difficulty in getting my Horse across—Fearlessness of the Dahoman Female Carriers—Bad Roads—Jallakoo—Reception by the Caboceer—My Illness—Appear in Regimentals before the Caboceer—Concern evinced on account of my Illness—Description of the Town—Agriculture—Caboceer’s Name and those of his Head Men—Presents to the Caboceer | 229 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| My continued Illness—The Koffo—The Langhbo—Bivouac—Keep Sentinel—Shea-butter Trees—Springs impregnated with Iron—Gijah—Poverty of the Caboceer—Hospitality of Atihoh, the Merchant—Doko—Met by the Avoga of Whydah—Etiquette with regard to the Time of entering a Town—Enter Abomey—My Servant Maurice takes to his Bed—Sudden Change in the Temperature—Visit to the King—His Gratification at my safe Return—My Conversation with his Majesty—His Views with regard to the Slave Trade—His Desire to cede Whydah to the English Government—Dictates a Letter to me to that effect—His costly Tobes—Singular Piece of Patch-Work | 253 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Conversation with the King of Dahomey continued—Visit Coomassie, another Palace of the King—Great Number of Human Skulls—Skulls of Kings taken in Battle—Death-drums—Peculiarity of Skulls—Craniums of the Fellattahs—Skulls of Rival Kings—Criminal Case heard by the King, and his Award—Death of my Servant Maurice—Regret of the King—Christian Burial of my Servant—The King’s Kindness to me—My increasing Illness and Depression of Spirits—Method of Procuring Food in the Bush by the Dahoman Soldiers—My Alarm at the Dangerous State of my Wound—Make Preparations to amputate my Limb—My Recovery—My Last Conversation with the King—The King’s Presents to the Queen of England—Present from him to her Majesty of a Native Girl—Escorted[Pg ix] out of Abomey, and Departure for Whydah—Absurd Custom—Canamina—Ahgrimah—My Pigeons from the Kong Mountains—Non-Arrival of some of my Carriers—Punishment awarded them for their Roguery on their Arrival | 273 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Akpway—Superstition of the Natives—Singular proceeding of my Bullock-Drivers—Arrival at Whydah—Kind Reception by Don Francisco de Suza—Kindness of all the Merchants—Parting Interview with M. de Suza—Sail for Cape Coast—Terror of the Mahee Girl (presented to the Queen) at the Roughness of the Sea—Arrival at Cape Coast—Kindness of Mr. Hutton—Dr. Lilley—Recover from my Fever—Kindness of the Wesleyan Missionaries—General Character of Africans—Hints with regard to Educating them—Observations on the Manners and Customs of the Dahoman, Mahee, and Fellattah Countries—Enlightened Conduct of the King of Dahomey—The Dahomans—Trade of Dahomey—Paganism—The Mahees—The Kong Mountains—Sail for England | 293 |

[Pg x]

[Pg xi]

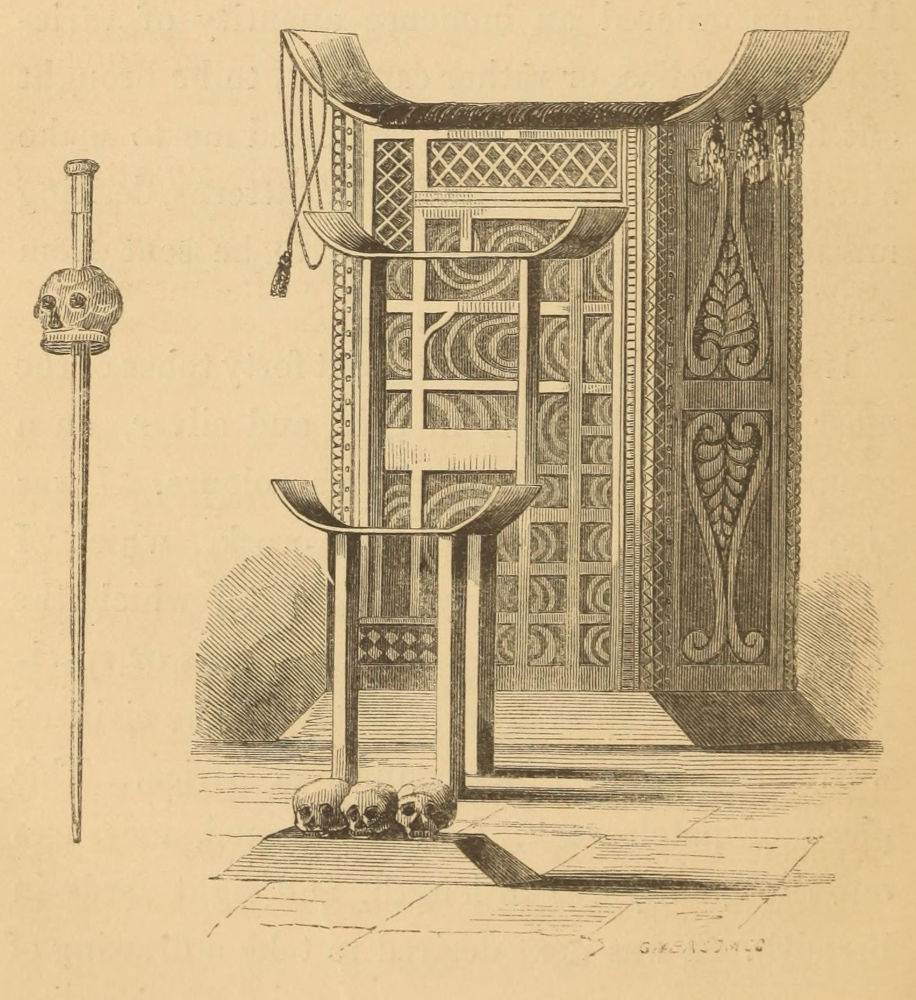

| Mode of Execution at Dahomey | To face the Title. |

| The Kong Mountains, in the Neighbourhood of Logazohy | p. 219 |

| Wood Cuts. | |

| State Chair of the King of Dahomey | 272 |

| The King’s Staff | 272 |

[Pg xii]

TRAVELS

IN

WESTERN AFRICA.

[Pg 1]

The Zafidah Mountains—Zoogah—Reception by the Caboceer—Bamay—Its Market—Curiosity of the People—Population—The Davity Mountains—Daragow—Qualifications for a Caboceer—The River Zoa, or Lagos—Its wooded Banks—Ferry—Superstition—Water-lilies—The Plain set on Fire to destroy the Shea-butter Tree, &c.—Valley of Dimodicea-takoo—Kootokpway—Gbowelley Mountain—Romantic Scenery—Hospitable Reception—The Mahees—Their total Defeat by the Dahomans—Ascent of the Mountain—Ruins of a Town—Skeletons of the Slain—Soil—Twisted Rock—Mineral Springs—Agbowa—Herds of Cattle—Paweea, its healthy Situation—Palaver with the Caboceer—Description of him—His Hospitality—The Markets—Guinea Corn—Natives good Farmers—Cloth Manufacture—Native Loom—Hardware—Hyæna Trap—Admiration of my Sword—Review of native Soldiers—Population.

July 11th.—We marched from Setta at 8 A.M., the first high land bearing from the north side of the town N. 25° E., and named the Zafidah mountains,[Pg 2] distant about twelve miles. These mountains form the western extremity of a range, running as far to the eastward as the eye can reach. The path led directly to these mountains, and the surrounding country was of a beautiful champaign character, studded at considerable intervals with trees of various descriptions.

About half a mile from Setta, and journeying N.E., we crossed a fine brook with a waterfall. The bed of the brook was of granite or quartz, in immense detached blocks, the brook running eastward. Close to this ford is a small kroom, called Zoogah; and although we had come so short a distance the old patriarch or caboceer had provided plenty of provisions for myself and private servants, with water and peto. The poor man also presented me with several fowls. He told me that the people of his small town had made a subscription and purchased these fowls to offer to me, but were ashamed to make so trifling a present, although they were anxious to show their good feeling towards the King’s white stranger. He had told them what I had said at Setta to the old woman (for he was present on that occasion) who presented me with the two eggs. The kindness shown towards me now formed a perfect[Pg 3] contrast to that which I had experienced on the coast, where the character and disposition of the people are vile. I gave the caboceer some needles and thimbles, with directions to distribute them amongst his people.

At four miles from this place we arrived at a small kroom of about three hundred inhabitants, called Bamay. Here is a good market, which is held weekly: it happened to be held on this day. The caboceer was waiting in the market-place to receive us, in all his grandeur. Here we had plenty of good water and provisions. The caboceer seemed highly delighted at receiving a visit from a white man, and introduced me to all his head men and principal wives. The people assembled in the market-place all came running, pushing each other aside, with eager curiosity to obtain a sight of me. In the market, which is shaded with large trees, called by Europeans the umbrella-tree, they were selling cloth of the country, of various colours in stripe; kao (saltpetre in its original state) which is found in the mountains; different sorts of grain produced in the country; tobacco, and pipes made at Badagry, much resembling the head of the German pipe, but of red clay; shalots and vegetables[Pg 4] of various sorts for soups, and also manioc or cassada-root ready cooked; with yams, plantains, and bananas, oranges, limes, pine-apples, cashu nuts, kolla or goora nuts, indigo and pepper; snuff is also sold here. Butcher’s meat is exposed for sale early in the morning, but if it be not sold quickly it is cooked in the market-place, to prevent putrefaction. Sheep and goats are sold in the market, but, singular enough, I never saw a live bullock in the market in any part of Africa, except at Tangiers. Fowls and eggs, and agricultural implements of various descriptions, are also sold in all the markets of any magnitude in this part of the country. Here the land is well cultivated, and the crops are very good.

This kroom contains about six hundred inhabitants, who are evidently of a different tribe to the people of Whydah. They are much better formed and more nimble, and apparently more capable of enduring fatigue than the natives on the coast. After distributing some small presents and some rum to the caboceer, we resumed our journey.

At ten miles distant, and bearing (magnetic) E.S.E. the Davity mountains are seen. These mountains form a range extending from east to[Pg 5] west, for a distance of about twelve miles, and are separated by a narrow plain from another range of mountains, distant about two miles. Both ranges are of conical or hogback character. At the distance of four miles and a half we reached Daragow, a small kroom of about three hundred inhabitants. Here we were welcomed by the caboceer, whose name was Badykpwa, a fine stout old man of about fifty-five years of age.

The necessary qualifications for a caboceer in nearly all the kingdoms and petty states of Western and Central Africa, are, that he should be tall and stout; a beard is also indispensable. In many African kingdoms, indeed, rank is estimated by the length and thickness of the beard.

At six miles we reached the banks of the river Zoa, here forty yards wide and seven feet deep. It is very muddy, for it is now the rainy season. Large blocks of granite rise above the surface; the bed of the river consists of a drab-coloured sand. The current is about two miles per hour, running (magnetic) E.S.E. The banks are thirty feet deep, and wooded on each bank with trees of gigantic size, whose enormous roots extend in all directions. The greater number of these roots run along the surface, in most cases crossing[Pg 6] and re-crossing each other, presenting the appearance of network. Their trunks are buttressed all round, somewhat like the cotton-tree. At about eight feet from the ground the buttresses, which so far are straight, break off in different directions, crossing each other around the trunk, like a number of large serpents wattled across each other. I did not observe any trees of the same description at a distance from the rivers.

At this ferry we found a large canoe, which is left here for the use of passengers. By order of the king of Dahomey, all traders carrying goods are exempt from paying fees for crossing. Here we were detained for some time, the canoe not being capable of conveying more than ten persons without luggage at a time. I remained till all the party had been ferried over, except the caboceer, or captain, and the other principal officers of my suite. When we embarked, the captain begged me to sit in the bottom of the canoe with my face towards the stern, so that in crossing I was conveyed backwards. When I remonstrated with him on the absurdity of doing so, he declared it to be “bad fetish” for any great man in crossing water to look in the direction he is proceeding, assuring me also that he was answerable[Pg 7] for my safety, and that should anything of an unpleasant nature happen to me he should be severely punished, or if any thing should occur to my personal injury he should lose his head. When I found the poor fellow, who was under these restrictions, felt distressed at the observations I had made, I readily assented to all his instructions and directions. My little horse swam across, tied to the canoe, which materially assisted us in getting it across.

This river is the same as the river Lagos at Badagry on the coast, although here called the Zoa; but the same thing occurs all over Africa where I have yet been. I am also informed that this same river has two other distinct names, between this place and the place where it takes the name of Lagos, which fully accounts for many supposed errors of our travellers, as well as many errors in fact.

Our party having now all safely crossed the river, we immediately resumed our journey amongst thickets of underwood scarcely passable, the bushes having closed in and across the path, and joined over the narrow sheep-track for such it really was. After travelling half a mile, the path became more open, and we suddenly came upon a small lake or pond, apparently[Pg 8] of stagnant water, with the delicate water-lily sprinkled over its surface. The sight of these beautiful flowers, coming upon us so unexpectedly, created a very pleasing sensation, for they were exactly the same as the water-lily of England.

The country now opened, and the path, clear of bush, became less irksome to the traveller. I observed here that the grass had been recently burnt, and inquiring of my guide the reason of it, was informed that the whole surface was set on fire twice annually, to the extent of many square miles. This is done for the double purpose of destroying the reptiles and insects, as well as the decayed vegetable, and also to annihilate the vegetative powers of the shea butter-tree, which grows here in great abundance. At seven miles the path changed its direction to the eastward. The land was level, but exhibited no cultivation, nor any appearance of human habitation. At eight miles and a half a valley opened upon us on a gentle slope, with a brook running to the eastward.

At ten miles we crossed another valley of greater depth, called by my guide, Dimodicea-takoo. On each side of the path were numerous aloes of various descriptions. The aloes which have a mark on the leaves like a partridge’s wing, were[Pg 9] at this time in seed. My servant Maurice now begun to complain very much of pain in his head and loins, and seemed quite exhausted, although he had ridden my horse ever since I had crossed the Zoa.

At twelve miles and a half we crossed another valley and brook, running eastward, named Kootokpway. At thirteen miles and a half we reached a stupendous mountain, called Gbowelley. Here the path suddenly changed to NN.W., passing near to the base of the mountain, which forms the western extremity of a range of less magnitude than this. At its foot, and at its western extremity, is a small kroom, of about two hundred inhabitants. It is very pleasantly situated on the plain or division between Gbowelley and another chain, or rather crescent of mountains, at a few miles farther to the westward, commanding a view of high mountains to the northward. This sudden and delightful change seemed to inspire all of us with fresh animation and spirits; for though we had passed over several tracts of country partaking somewhat of the character of hills, we were now almost on a sudden directly amidst a number of stupendous mountains of great magnitude and singularity of character, at once romantic and pleasing. The old caboceer was warned of our[Pg 10] approach by the noise of our drums, and was close to the path awaiting our arrival with plenty of kankie, water, and peto for our refreshment, which were very acceptable to all of us: for my own part, I felt quite prepared for a hearty meal, without scrutinizing it. Here the air felt refreshing and pure, and rushed in a current between the mountains.

The old caboceer was of commanding figure, about five feet ten inches in height, of pleasing countenance, and of quick and intelligent manner. He was a native of Dahomey, and in great confidence with the King. He took pleasure in boasting that he had seen me at Dahomey during the custom or holiday, having been invited to the latter place purposely to receive orders from his Majesty respecting my treatment when I should arrive in the Mahee country. He had despatched orderlies to every town occupied by a caboceer, to deliver the King’s orders respecting me. It was now that my suppositions were realized respecting the kindness shown me on my journey, viz. that the King had given orders as to every particular, however trifling, respecting my treatment and the presents I was to receive. The caboceer is named Hah, and the old man was sent here from Dahomey at the time of its surrender to the Dahomans.

[Pg 11]

The inhabitants of these mountains are called Mahees, and occupy part of the country of that name. They made a determined resistance against the Dahomans, and held out for seven moons, or months, having possession of the mountains, and concealing themselves in the fissures and caves, advancing and retreating in turn according to circumstances. Though their numbers were great, yet the caution and skill of their besiegers prevailed; for they had the advantage of good firearms, and were able to avail themselves of the crops and cattle on the plains at the base of the mountains. The Dahomans always choose the harvest season for besieging a mountain; and although the steepness of these mountains renders the ascent of a besieging army impossible, they can so entirely blockade the occupants from all communication with the plain, as soon either to starve them to death, or compel them to surrender to their enemies, at discretion.

These mountaineers never think of reserving any of their corn or other produce as stores, so that they invariably become an easy prey, though in this country they can raise four crops in the year. The Mahees use the bow and arrow, the King of Dahomey forbidding the transport of firearms through his kingdom from the coast. The[Pg 12] old caboceer and my guide both informed me, that, during the seven months’ war in Gbowelley and the neighbouring mountains to the eastward, four hundred caboceers were killed, so that, allowing only a proportion of one hundred individuals to each caboceer, at least forty thousand men must have perished.

After a great deal of remonstrance and persuasion with the caboceer and my captain, a promise was given that I should be allowed to examine the mountain, but upon condition that I would take my shoes off, so that I should incur less risk in climbing up the steep fissures, which are not wide enough to admit of more than one man in width. The old caboceer took the lead in ascending, giving me his hand the whole of the way up; and my own caboceer kept close behind me, fearing lest I might slip. In our ascent I observed many very large cotton-trees in the fissures, with scarcely any soil to support them. Monkeys were very numerous amongst the branches.

After gaining the top, in a sort of hollow or basin, on one side of the dome-shaped summit, were the remains apparently of a large town. This place was truly the picture of desolation, and the ravages of war and famine presented themselves on all sides. Hundreds of human[Pg 13] skulls, of different sizes, were still to be seen; as also the skulls of sheep, goats, and oxen. No doubt the latter named animals had been used as food by the people whose remains we saw around us, the greater part of whom had been starved to death rather than surrender. Many of the soldiers of my guard had been on service during this siege, and described the scene on ascending as of the most awful description. The bodies of the dead in a putrid state were, it appears, mixed with those who were still alive, but unable to move; many were wounded with bullets, whose limbs were rotting off and covered with vermin;[1] and the air was so pestiferous, that many of the Dahomans died from its effects. The vultures tore the bodies of the poor wounded people, even while they were yet alive. In many of the small fissures I observed the remains of various domestic quadrupeds, together with human bones, very probably carried there by the vulture or eagle, also natives of this mountain, as well as the common fox, the panther, and large hyæna, or patakoo, the name given to it by the natives.

[Pg 14]

This mountain is formed by horizontal beds about forty feet deep, composed of gneiss or granite, each bed differing in quality from another in the proportions of feltspar and mica. It rises at an angle of 23°. All the mountains in this neighbourhood rise abruptly, and are very steep,—in fact, on some sides, they are nearly perpendicular, the plain in most cases being truly level to the very base of the mountains.

After descending, and returning to the place where I left my party refreshing themselves, I found many of them in a partial state of intoxication, from too freely indulging in the use of the peto. My poor man Maurice, induced by a high state of fever, had attempted to allay his thirst by copiously partaking of the same liquor. After giving some small presents to the caboceer and principal people, we resumed our journey. Just as we began our march, the rain descended in torrents. Fortunately, while at Whydah, I had made myself a waterproof cloak, which I now gave to my poor white man, who seemed a little revived after his rest and the stimulating effects of the peto. He proposed walking; but I knew that his revival was only temporary, and compelled him to ride.

The path was now very deeply worn with the[Pg 15] heavy rains, a stream pouring down and washing all the soil from amongst the stones, leaving only the iron stone or ore, which rendered walking very unpleasant. The country was level, with the exception of a gentle declivity in the direction in which we were now proceeding (NN.W.). The plain at intervals was studded with large and small blocks of granite, some round, others angular, but the foundation chiefly iron, which I have observed in many places, only covered with a thin surface of vegetable soil of a loamy nature. The surface of the iron is quite smooth, and resembles our pavement of asphalte in London. In some places the iron rock is entirely bare, and has every appearance of having run to its own level while in a state of fusion.

The soil now changed to a rich sand and clay, very productive. I observed some fine specimens of the twisted rock, but without any mica in its composition, being more compact and solid than the composition of the last-named mountain, and of a similar character to marble, of blue, black, and white mixture. Here we were again met by the caboceer and a number of his people, belonging to a small kroom at some considerable distance from the path. They brought us plenty of kankie and peto. We again stopped for some time,[Pg 16] and made inquiry respecting the neighbourhood, but I invariably found it impossible to obtain any information respecting any other locality than their own immediate vicinity, unless from some of the travelling merchants. After giving a small present, which is always necessary on such occasions, we resumed our journey. Close to the path were several mineral springs, powerfully impregnated with iron. These springs are permanent. This country is beautifully watered, having a great many springs of various qualities, and numerous small brooks.

The rains are more regular here than near the coast, and thunder is much less frequent. No doubt the extreme fertility of the soil in this locality is attributable to the good supply of water from the regular rains and springs, for four crops of corn I was told are obtained in one year.

At nineteen miles and a half, bearing or direction of the path, we changed to east, and crossed the brook Halee, which runs eastward, with water sufficient to propel machinery of any ordinary power. At twenty miles and a half, Mount Weesee, bearing west, and Lusee to the east. At twenty-one miles we came upon a brook called Agbowa, with abundance of water. Here the land is well cultivated. This is the first place in Africa where[Pg 17] I have observed the use of manure in agriculture. Some Guinea corn, which is planted in drill, measured ten feet in height, the maize about eight feet. Here are large herds of very fine cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs; the Guinea fowl and common domestic fowl, as well as partridges of great size, are also abundant. The turtle-dove abounds here, as in most other places in the vicinity of towns and villages.

At twenty-one miles and a half we arrived at Paweea, a very large town, composed chiefly of low square huts, very neat and clean, with several large markets. At the entrance of the town we were met by the caboceer and his soldiers, part of whom were armed with muskets, and accoutred in the same manner as my own guard; the rest were armed with the bow and arrow. Paweea is well situated, and commands a view of the surrounding country to a great distance. The atmosphere is much clearer here than on the coast, or even at Abomey, so that the surrounding mountains are very distinctly observable, and minor objects perfectly seen at a very considerable distance, in comparison with the coast.

The caboceer, and his principal attendants and men of office, led us into the principal market-place within the walls, which is held under several[Pg 18] large trees, covering about three quarters of an acre. Here we seated ourselves, and the usual complimentary palaver of welcoming the King’s stranger to the town of Paweea followed, and a large calabash of water was offered to me, after it had been tasted. Then the rum was passed round amongst all my people. After this indispensable ceremony was concluded, we were directed to my lodgings, which were not far distant.

The houses here are superior to those of many other towns, consequently I had comfortable quarters for myself and people. The caboceer was a fine, stout, square-built man, and very agreeable both in person and manner, but with a very singularly-formed head above the temples, narrowing acutely to the upper part of the skull. This gave his head the appearance of having been squeezed or pressed. He seemed, however, possessed of more than the ordinary sense of his countrymen, and appeared to be in every way anxious to accommodate and please us. Plenty of excellent provisions were soon brought to my apartments for myself and people.

After we had finished our meal, the caboceer and several of the principal members of his retinue came to spend an hour with us. Upon this occasion I ordered some rum to be unpacked and[Pg 19] distributed amongst them. I was much gratified to find the caboceer enter so fully into conversation, and make so many shrewd inquiries respecting England, our manufactures and laws. He also seemed very communicative, and willing to give me every information in his power respecting his own country. He had been in command during the late war, and had of course travelled a considerable distance beyond his own locality.

In this town peto is made entirely from the Guinea corn, not as on the coast, from the maize or Indian corn. It is a very agreeable liquor, and less sweet than that made from the Indian corn. After conversing about two hours, the caboceer withdrew, to allow me to repose, which was very agreeable to me, for I was very tired.

July 12th.—Early in the morning a messenger arrived from the caboceer with his cane, which he presented to me with his master’s compliments, desiring to know if I were quite well, and how I slept. Soon after the messenger had left me, the caboceer came, preceding his commissariat train, with an immense quantity of provision in large and small calabashes, containing beef, pork, mutton, fowl, kankie, dabadab, and a delicious dish made from a vegetable called occro, which when boiled forms a gelatinous substance, and is very[Pg 20] strengthening. This dish is seasoned with palm oil and pepper. The provisions in all amounted to twenty bushels. The good old caboceer of Gbowelley, whom we left yesterday, sent some of his people after us this morning with a present of one goat, three fowls, and a large calabash of kankie. This was an acknowledgment for some presents, which I had given to him when I left him. The carriers and messengers were quite delighted when I presented each of them with some needles and thimbles, and returned home rejoicing.

After breakfast, the caboceer wished me to walk round his town with him—seeming anxious to gratify his people with a glimpse or sight of the King’s stranger. This was just what I wished, as I was anxious to acquire as much information as possible during the short time I had to spare. Accordingly we visited the markets, which were well supplied with provisions and articles of manufacture. I noticed amongst other things some English chequered handkerchiefs. Native cloth, of various quality and colours, was exposed for sale. Kaom, or saltpetre, is very abundant in the Kong mountains, and is sold in the markets in all the towns in the vicinity. It is used as medicine, and, as in England, is much in requisition for cattle. Deer skins of various[Pg 21] species are sold in the market, also nuts of various sorts, as well as different kinds of beans and peas. Ginger is very abundant in this neighbourhood, and is sold at about eight-pence per Winchester bushel. The corn is now nearly ripe, and some of the Guinea corn is as much as ten feet high, so that the town is entirely concealed until the fence, which invariably encloses the African towns on the plain, is passed. The prickly bush at Abomey is planted like a double hedge round the town, and is about ten yards wide, so that to a European it would seem a matter of impossibility ever to break through it. The female soldiers of Dahomey, however, as I have already mentioned, are capable of taking one of these towns with apparently little trouble.

The owners of the numerous herds of cattle keep them in folds or pens in the town, and the dung is preserved for manure. They are excellent farmers, even in this remote part, where they never can have had intercourse with any civilized being. They also manufacture very good cloth, although their method is certainly tedious, the thread being spun by the distaff, and their loom being of a very simple construction, though upon the same principle as our linen looms in England. Their web is necessarily narrow, not[Pg 22] exceeding six inches. As they have not yet found out the use of the shuttle, they merely hand the reel through the shade from one side to the other in putting in the weft; and instead of treadles to set the foot upon, they use two loops, which are suspended from the treadles, into which they put their big toes, which act upon the same principle as the treadle. The warp is not rolled round a beam, as in our looms, but kept at its extreme length, and the farther end is made fast to a large stone or heavy substance, which is gradually drawn towards the weaver as he progresses in his work.

Iron is very good in this neighbourhood, and is worked with considerable skill. Their implements for agricultural purposes are much superior to those manufactured nearer the coast. Sweet potatoes, yams, and manioc or cassada, are cultivated here with great success.

The different articles sold in the market are nearly the same as I have already mentioned at Whydah. I was amused upon being shown a patakoo or large hyæna trap, from the simplicity of its construction. It is about twenty feet long and two feet broad. The walls are thick and strong. The trap is constructed upon the same principle as some of those used in England for catching various sorts of vermin without destroying or injuring[Pg 23] them. A goat or young kid is placed in a cage in the trap, at the farthest extremity from the entrance, and the hyæna, or panther, (whichever may happen to pass,) is attracted by the bleating of the kid. Upon entering the trap, it must step on a board with a string attached, the other end of which is connected with a trigger which suspends a sliding door. Upon the trigger being pulled, the sliding door immediately drops and incloses the animal. It is then sometimes maimed or baited with dogs.

Dinner-time had now arrived, and we returned to our quarters, when it was soon afterwards brought in, and consisted of one large hog, three goats, sixteen fowls, and a fine bullock, all which were served up in excellent style, with plenty of dabadab and kankie, and round balls of cakes made with meal and palm oil, baked or roasted together with abundance of peto.

After dinner, the caboceer expressed a desire to see me in uniform, and wished also that the ceremony of receiving me on entering his town should be repeated as the King’s stranger, similar to my reception on the previous evening. This requisition was not very agreeable to me, as my white man Maurice was still very ill and in low spirits. However, I prepared myself soon after dinner, and[Pg 24] mounted my little charger. The caboceer examined my horse and accoutrements very minutely, as also my appointments. My sword, large knife, as they called it, excited much admiration from its brightness, and above all, for its pliability in bending and again resuming its original form. Their short swords are made of iron, but have no spring in them. He next examined my double-barrelled gun, and seemed much astonished at the percussion caps, believing that the cap alone was also the charge, no doubt from its loud report. After explaining it to him, he seemed much gratified.

We then proceeded out of the town, one half of my guard in front, and the other in my rear, with the caboceer’s soldiers in rear of the whole, one half of whom were armed with bows and arrows. After proceeding about half a mile from the town into an open piece of ground not planted with corn, the soldiers commenced a review and sham fight, which, although it did not display any great complication of manœuvres, was interesting from the quickness of their motions, and significant gestures.

After the review was over, we returned to the market-place, when all my soldiers commenced dancing. This was kept up alternately by my[Pg 25] guard, and the soldiers belonging to the town. In this country each caboceer invariably keeps a clown or jester, many of whom are clever and amusing on account of their ready wit. After the dance, which lasted about two hours, I gave each of the party some rum, which is always expected on such occasions. I then retired to my quarters, accompanied by the caboceer, who seemed very anxious to maintain a friendly conversation, evidently with a view to obtain information on general topics. He remained till a late hour, when he retired to his home, leaving me once more to enjoy my own reflections upon what I had seen, and to take notes for my Journal.

The town of Paweea contains about sixteen thousand inhabitants. They seem rather an industrious race in comparison with those near the coast. Here, as well as in most other towns in the neighbourhood, the mechanic is very much esteemed on account of his craft, but especially the blacksmith, who in their own language is called a cunning man, ranking next to the fetish-man or priest. The soil round this place is a rich sandy loam, and the land well watered, consequently, the crops are abundant, and the people are in the enjoyment of plenty, with but little labour. They seem a very happy race, and[Pg 26] well satisfied with their present government and laws, which, previous to their subjection to the King of Dahomey, were arbitrary and cruel in the extreme. This town has two strong gates on the south-east and north-west sides, which are closed at sunset, and guarded by soldiers or watchmen, who take that duty in turn.

[1] This may appear an exaggeration, but I assure my readers, that I have had a large quantity taken from a very severe wound I received when in the Niger expedition. Dr. Williams and Dr. Thompson can corroborate my assertion. The African fly blows live maggots instead of eggs.

[Pg 27]

The Caboceer’s Kindness to my Servant—Presents—Names of Caboceer, &c.—Granite Mountains—Tanks—The Aditay—Soil—The Tawee—Mountains—Grain and Vegetables—The Zoglogbo Mountain—Reception by the Caboceer of Zoglogbo—Ascent of the Mountain—Cotton-trees—Mountain-pass—Singular Situation of the Town—Houses—Dahoman Political Agent—Probable Origin of the Mountain—Kpaloko Mountain—Ignorance, assumed or real, of the Neighbouring Country by the Natives—The Dabadab Mountains—Superstition—Singular Method of conveying Cattle—Cruelty to the Brute Creation—Difficult Descent—Agriculture and Manufactures—Height of the Mountains—Death of Three Kings at Zoglogbo—Names of the Caboceer, &c.—Reception at Baffo—Costume of Caboceer and his Wife—His Principal Wives—Beautiful Birds—Gigantic Trees—Parasitical Plants—Singular Tree—Soil—Grain, Fruits, &c.—Cattle—Market-day, and Bustle of the Caboceer—Goods exposed for Sale—Rival Caboceers—Game—Pigeon-trap—Trial of Skill—Dog poisoned—Increasing Illness of my Servant—The Caboceer’s principal Cook.

Sunday, July 13th.—Early in the morning the caboceer again sent me plenty of provisions for myself and people, and showed great kindness to Maurice, my white servant, using every means to induce him to partake of some food, bringing amongst other dishes one made of meal[Pg 28] and water boiled together, sweetened with honey, and about the consistence of thin gruel. This composition is used as we do tea in England, but is of course much more substantial. I relished it very much. My poor servant also partook of a considerable portion, but he could not rally, having lost all the courage of which he had so often boasted. The caboceer then desired us to proceed again to the market-place, where we found two fine bullocks tied to a tree; one was a present to the King of Dahomey, and the other to myself.

After going through the usual compliments on either side, we marched on our journey till we came to the gates on the north-east of the town, where several of the principal officers of the staff of the caboceer’s household approached him, apparently in great anxiety, whispering something to the caboceer. After this, the captain of my guard communicated to me that the caboceer of Paweea begged that I would honour himself and head men so far, as to enter their names in my book. This is, in all places in the Dahoman kingdom, considered the highest honour that can possibly be conferred upon them. To this request I readily acceded; and in a short time[Pg 29] had all their names registered in my fetish-book, as they called it. After entering the names, as given by the caboceer’s principal officer, I was very shrewdly asked to call each individual by their name, as this was considered a puzzler for me; but when they found that I called the roll correctly, they all seemed surprised and delighted. A report to the same effect soon spread over the greater part of the Mahee country. We now took our final departure from the town of Paweea.

I here record the names of the head men according to my Journal:—

| Caboceer’s name | Terrasso-Weea. |

| 1st Head man | Adah. |

| 2d do. | Chaaoulong. |

| 4th do. | Daowdie. |

| 5th do. | Avamagbadjo. |

| 6th Head Musician | Hawsoo-Agwee.[2] |

The names of Mayho’s traders from Abomey, who treated myself and people with provisions and peto at Paweea[3] were:—

Tossau.

Yakie.

Bowka.

Adassie.

Howta.

Kossau.

Nookodoo.

[Pg 30]

We now passed through the gate, which is very strong. The walls of the town are very thick, and are composed of reddish-coloured clay. Close to the gates is the weekly market-place, held under several large trees, which afford a grateful shade from the sun, as well as a temporary protection from the rain. In the whole of the Mahee country which I have yet visited, I find that the weekly markets are held without the walls, to prevent as much as possible strangers entering the town. The daily markets are seldom attended by any except their own people, principally for a mutual exchange of goods of native manufacture.

About nine A.M. we recommenced our journey, the path bearing N.E., and at one mile N. 35° E. I noticed the chain of mountains running N.E. and S.W., distant about four miles, and bearing north from Paweea. The country round, however, is level, and studded with palm and other trees. In the distance, the immense blocks of granite appeared stratified, or divided into perpendicular sections, but upon a nearer approach were found to be only marks left by the running down of the water which accumulates in naturally formed basins or tanks on the tops, apparently formed by the heavy rains acting powerfully on the softer[Pg 31] parts of the rock. From the excessive heat, this water soon becomes foul, and the first succeeding rains cause an overflow, marking the rock in dark streaks, and giving it the appearance I have stated.

At a mile and a half, bearing north, the soil became gravelly, studded with trees. At two miles and a half, bearing again north, we crossed the brook Aditay, running eastward, over a rocky bottom of blue granite. This beautiful clear stream is, on an average, during the season only two feet deep and six wide. It is a permanent stream, capable of propelling machinery. At three miles and a half, the bearing changed to E. N. E., with clear springs, impregnated with iron. The temperature was 64° Fahrenheit. The land is still level, and the soil of the dark colour of decayed vegetation. At five miles we crossed the river Tawee, running east. This river is wider than the last, with a gravelly bed; current less rapid, but also capable of turning machinery.

At seven miles I observed two mountains of considerable magnitude, and very picturesque, distant from the path two miles, and bearing N. 35° W. The land is beautifully cultivated along the foot of the mountains. The drilling system is followed here with the corn, both in the Dahoman[Pg 32] and Mahee countries, and with all sorts of grain, as well as with the sweet potato; but yams are planted in mounds about three feet in height, of a conical form. In this part, however, the yams are inferior generally to those grown on the coast, being what are called water-yams, which are much softer than those found near Whydah. Four different sorts of maize, or Indian corn, are grown here, the smallest of which produces four crops in twelve months. The Guinea corn is also very abundant, as well as another grain which grows about the same height. This grain very much resembles mustard-seed.

At ten miles, we arrived at the foot of the mountain of Zoglogbo, a splendid specimen, although not more than eighteen hundred feet high on the south-east side. We halted at a small kroom at its foot, in the market-place, where I changed my dress at the desire of the captain of my guard, and put on my regimentals to receive the caboceer of Zoglogbo. I had scarcely finished, when he arrived with his retinue. He is a remarkably fine old man, apparently about sixty years of age, and of a very venerable appearance. He is nearly six feet high, and altogether of a noble and graceful figure. He approached within about five yards of the place where I was seated,[Pg 33] by the side of the caboceer or captain of my guard, when, before speaking a word, he, together with his head men and attendants, prostrated themselves, throwing dust on their heads, and rubbing their arms with the same. My own caboceer next prostrated himself, going through similar forms of humility. Both parties afterwards remained on their knees, and delivered the King’s message respecting the King’s stranger, as they constantly called me. We then drank water with each other, previous to the introduction of rum, of which our new and venerable friend Kpatchie seemed very fond.

We now proceeded to ascend the mountain by a narrow fissure or fracture nearly perpendicular, passing in our ascent many very large cotton-trees, dispersed irregularly in the different crevices of the rock. Numbers of large monkeys of different species were playing amongst the boughs, but they were rather wild, being hunted for their flesh, which is used here for food. The passage up the side of the mountain is so narrow, as only to admit of one man passing at a time, and very steep and difficult, on account of the many blocks of stone which impede the ascent. It would have been impossible for me to ascend with my shoes on, had not the old caboceer of the mountain[Pg 34] walked in front and given me his hand, and another person pushed at my back, as occasion required.

After a somewhat toilsome though romantic journey, we arrived at the gates of the town, which were of very thick planks of seven inches, strongly barred with iron. After passing the gates the path was much easier and not so steep, from the fissure not being filled so high, so that the top of the fissure was far above the head, apparently above twenty yards. After passing a little distance farther we came upon the town, which is situated in a basin, or crater, formed in the centre of the top of the mountain. Round the outer edge of this immense basin are thrown tremendous blocks of various sizes, underneath which many houses are built. Although these blocks are placed on each other in such a tottering position, the houses in the centre of the town are erected with considerable taste and regularity. The residences of the principal merchants and influential members of the town are built in the form of squares or quadrangles, which are occupied by their wives, which are frequently very numerous, as well as their families. Their slaves also occupy a part of the buildings, and are treated as well as their own families. Indeed, as I have[Pg 35] already observed, they work together in cultivating the fields, or any other domestic employment.

The caboceer led us to a tolerably good house with every necessary utensil for our use. Many presents of various descriptions were brought to me, the old caboceer seeming much pleased at the kindness of his people to the King’s stranger. His own kindness and attention were unbounded, as well as those of his principal attendant, a young man of rank from Dahomey, and the handsomest and most intelligent African I had ever met. The King of Dahomey displays great sagacity in sending Dahomans to the frontiers between the Mahees, Yarriba, and Fellattahs. These men, although acting as principal attendants to chiefs or caboceers of the subdued Mahees, are nothing more nor less than political spies, the upper rank of such persons preventing any combination or alliance dangerous to the power of the King of Dahomey, although generally the Mahees seem very much pleased with their present government and new laws.

After we had established ourselves in our quarters, we were supplied with plenty of peto and clean water to drink, and the caboceer sat down and enjoyed himself with us, often expressing his gratification at being visited by the King’s stranger. In a short time large quantities of provision were brought for us, and as usual ready[Pg 36] cooked. Being rather hungry, we made a pretty hearty meal, and afterwards were again joined by the old caboceer, and several of the merchants or traders from Abomey, who presented me with a large quantity of peto.

It now commenced a very heavy rain, consequently we were obliged to content ourselves with remaining in the house, and conversing upon different topics respecting England and Africa. I found while conversing on the state and government of Dahomey, a certain backwardness in their replies, unless through my own caboceer. Whether this arose from a want of knowledge on the subject, or in compliance with orders given to refer such questions to the caboceer of my guard, I am unable to decide, but should suppose that this latter was the fact. During the evening the caboceer partook too much of the peto and rum, accompanied with large quantities of snuff, which he administered alternately to his mouth and nose. Several persons were admitted and introduced to me by him. My poor servant Maurice, although I had given him my horse the whole of the day’s journey, was now quite knocked up, and extremely low in spirits. After spending a tolerably comfortable evening my friends departed, and I went to rest for the night.

[Pg 37]

July 14th.—Early in the morning the caboceer again visited me, to pay me the customary morning compliment, and in about an hour after he had retired breakfast was sent ready cooked, as usual, for myself and soldiers. After breakfast we walked round the town, which is of great beauty. From the quantities of fused iron-stone thrown indiscriminately amongst the immense blocks of granite, it would appear that the centre of the mountain had at some remote period been thrown up by some volcanic irruption. Zoglogbo forms the N.E. extreme of a range of mountains running N.E. and S.W. and is the highest of that range. The grain of the granite is much larger than that of most of the rocks of the other mountains. On the north-eastern extremity, and on the top of the rock, are several tanks nearly filled with water, for it is now the rainy season. These tanks are formed by nature, and are found to be of great advantage, both for the people and the cattle, which, to my great surprise, I found in and about the town, though the ascent from the plain is so difficult, that I was obliged to leave my horse at the bottom at one of the towns. The fracture, extending entirely across the mountain, forms two passes, adjoining which is a town on each side. I found upon inquiry, that a cow and bull had[Pg 38] been carried up into the mountain, and their offspring preserved, and that only very lately they had begun to kill them. The cattle live upon leaves and branches of different shrubs and stunted trees.

After examining the town we went to the highest pinnacle of Zoglogbo, where we obtained a very pleasant view of the surrounding country. At four miles distant, and bearing north-east, is seen the beautiful and gigantic block of granite, two thousand five hundred feet high, named Kpaloko; and as far as the eye can reach to the eastward are three mountains of a conical form, all of which are of the same shape and height. I asked the caboceer the name of these mountains, but he denied all knowledge of them, either by name or otherwise. I then asked several of my soldiers, from whom I received a similar reply. It seemed to me very singular, that a man should live during his whole life so near any remarkable spot without knowing something of the place, or even its name; but from a communication I received from a Mahomedan priest at Abomey, I was convinced that the distant mountains were the Dabadab Mountains, from the resemblance of their shape to a dumpling made from the Indian corn-meal so called. After measuring the height[Pg 39] by the boiling-point thermometer, we descended the rock, which was quite smooth on the slope, so that it would be impossible for any person to keep his footing with shoes on. But my friend Kpatchie paid every attention to me, both during my ascent and descent, ordering one of his principal attendants to take one of my arms, while he himself took the other.

The people here are, like all other Africans, very superstitious. When I was taking the bearings of the different mountains, and measuring the distances, they seemed very uneasy, but as the King had given orders that I was to be permitted to use my own discretion in all things, it was useless to object to anything I thought proper to do. After descending this steep mountain, we visited the principal market-place, where the caboceer had ordered two fine bullocks to be brought; one of them I was to deliver to the King as a present, and the other was presented to myself; and the old caboceer forwarded both animals all the way to Abomey, to be there for me on my return. The manner in which they carry cattle is singular. They tie the feet of the animal together, and run a long palm pole between the legs, and thus carry the poor animals with their backs downwards, each end of the pole resting on the head of the carriers.[Pg 40] Six men are generally appointed to carry one bullock, who relieve one another in turns. It would seem impossible, to those unacquainted with African cattle, for two men to carry one bullock; but it must be remembered that the African ox is very small in comparison with English oxen.

The natives have no sympathy or feeling for the lower animals. They throw the animal down when they get tired, with its back on the rough gravel, so that if they have a long journey to perform, the flesh is cut to the bone, and the death of the poor animal often ensues from such usage.

After we had received the presents from the caboceer, several of the merchants from Abomey presented me with goats and fowls, which kindness I of course acknowledged by making presents of some trifling articles of European manufacture. We now got ourselves ready for our march to the town of Baffo, which is only a few miles distant; my excellent old friend, Kpatchie, and his whole retinue, with a guard of honour, accompanying me.

Our descent was by the fissure on the opposite side of the mountain to that which we had ascended, and was equally difficult. However, my friend kept close to me, rendering me every requisite assistance in our perilous descent. At the[Pg 41] foot of the mountain we entered another town of considerable size. Here I found my horse, which had been brought round to be in readiness for me. I remained some time in this town to ascertain their system of agriculture and their manufactures, which I found superior to any thing nearer the coast, except in Abomey and in Whydah. They consist of cloth, iron, knit nightcaps, mats, baskets, and a curious sort of girdle composed of different-coloured grasses, neatly fringed at each end, resembling the sashes worn by our infantry officers. All sorts of agricultural implements are also manufactured here in a superior style, as likewise earthen pots and pipes.

The northernmost of the four conical mountains I have mentioned measures from the top of Kpaloko 18° 7ʹ towards N.E. when the observer is placed on the N.E. end of Zoglogbo, and Kpaloko bears N.E., distant by observation from Zoglogbo 12°, and the back bearing of Gbowelley S.E. Zoglogbo is much famed in the Mahee country for having been the place of refuge for three moons of three kings, who led their combined armies to the plains of Paweea, where they were met by the Dahoman army, commanded by the King, who destroyed the whole of the combined armies of the kingdoms of Eyo, or Yarriba, and Annagoo, and a[Pg 42] kingdom in the Mahee country in the adjoining Mountains of Kong.

These three kings declared war against the King of Dahomey, and threatened also to make his head a balance to a distaff; but the army of Dahomey, being well armed with muskets, although much inferior in numbers, totally destroyed the combined armies; and the three kings fled to Zoglogbo, where the Dahoman army followed them, and blockaded the passes, so that all supplies were entirely cut off, and in three moons the whole were compelled to surrender at discretion. These three kings were beheaded, and their heads used for a similar purpose to that which they had threatened the King of Dahomey with.

The head man of this town is Kpatchie’s principal attendant. Kpatchie is caboceer, or king, of all the towns and krooms in and round the mountain of Zoglogbo. The principal men’s names in Zoglogbo are as follows:—

1. Kpatchie.[4]

2. Bleedjado.

3. Annagoonoo.

4. Dawie.

5. Dyenyho.

6. Dosou say Footoh.

7. Zayso avarahoo.

8. Bayo Bozway.

9. Dogano.[5]

10. Mapossay.[6]

11. Awenoo.[7]

12. Bokava.

13. Dogwhay, the Caboceer’s wife.

14. Adoo, the Caboceer’s son.

[Pg 43]

12 P.M.—We now continued our march from this town to Baffo, bearing west from this place, and at three miles and a half arrived there. We were met about half way by the caboceer of Baffo and his principal wife, attended by a guard of honour, some of whom were armed with bows and arrows, and others with muskets, with which they kept up a constant irregular fire the whole of the way as we passed along. The caboceer and his wife were covered with ornaments, principally of cowries, fixed to leather, made of goatskin, and coloured blue and red, and about the width of the reins of a riding bridle, so that they were equipped similar to our Hussar officers’ horses. This caboceer is a very quick, active, and shrewd man; proud and foppish, moreover, and very jealous of my fine old friend, Kpatchie, who accompanied me to Baffo.

Shortly after our arrival in that town, we were, as usual, supplied with provision, ready cooked, to the amount of eighty dishes, composed of goats, pigs, and Guinea fowls. We were visited by the caboceer’s principal wives, who drank each a glass of rum with us. This is customary with all visitors of note or rank, but they always drink water with each other first. My old friend Kpatchie remained with me till he got intoxicated,[Pg 44] when I advised him to return home, which recommendation he immediately adopted.

In the evening I went out to observe the neighbourhood of the town, taking my gun with me, when, just after passing through the gates, a crow flew over us, which I shot. This caused great amusement, as the natives of this place are not expert with the gun. The crows are very large here, but of the same colour as the smaller ones on the coast, black, with white breast. In this place I observed several beautiful birds, many of which were on their passage, for nearly all the tropical birds of Africa are migratory.

We visited another small town, about half a mile west of Baffo, very pleasantly situated at the foot of the steep mountain of Logbo, the rocks of which at a short distance appear to hang over the town. The town of Baffo is similarly situated, and is ornamented with a great variety of trees of gigantic size. The highest of these are the silk cotton-trees; sycamore and a species of ash are also abundant here. The acacias are very large, and at this season in full blossom. Many beautiful parasitical plants hang from the large trees and rocks; and the clematis and jessamine fill the air with their luxurious odour. A tree resembling the drooping ash is very abundant,[Pg 45] bearing a very delicious fruit, like a yellow plum, which hang in bunches very similar to the grape. The fruit is very delicious, though there is very little flesh on the stone, which is porous, and yields to the bite of the teeth like a piece of cork, but is considerably harder.

This is the first place in which I have yet been, since my journey commenced, which reminds me of my native country. Here, for the first time the large branches of the different trees are in gentle motion, caused by the considerable current of air or light wind passing along the steep mountain-side, forming a very agreeable contrast to what is nearly always experienced in Central Africa, by the suffocating, heated atmosphere, where no motion is perceptible except during a tornado. I cannot express with what satisfaction and delight I sat me down on the end of a ruined wall of a hut, to embrace the luxury to which I had for many months been a stranger. Here solitude and loneliness even were pleasing. In my lonely reverie, my recollections were carried unimpeded over wastes of waters back to my native land, and perhaps to happier days, before Care had ploughed her furrows on my brow.

Here in this beautiful though lonely spot, I could not help thinking how much gratification[Pg 46] I should have felt had any of my old friends and associates in England been present, to whom I might have expressed my gratification. My poor servant Maurice was now getting worse, and obliged to lie down immediately he arrived at Baffo.

I found the land well cultivated, and the crops very luxuriant. The Indian corn here produces a crop four times in the year; the Guinea corn, twice only. Fruits of various descriptions are also abundant; tamarinds of two different species, the velvet tamarind and long pod, both grow in abundance: the yellow fig, of excellent flavour, and green grapes are also plentiful. There are two species of cashu with fruit, much larger than I have seen on the coast. The kolla-nut is abundant here, as also several species of the under-ground nut, some about the size of a walnut.

Cattle are of a superior breed here, being very square and clean in the legs, but very small. Sheep and goats are considerably more numerous than nearer the coast, but no horses are bred in this part of the country, consequently the natives were very timid in approaching my animal. The country around is well watered by some considerable streams, which run eastward. The waters are of different qualities, some streams[Pg 47] being impregnated with iron, others with magnesia. Pipe-clay is abundant in some of the valleys.

After two hours’ range in the neighbourhood of these two towns, I returned with my party and found the caboceer of the town awaiting us. He was, no doubt, anxious to taste again the contents of my liquor-case, which, unfortunately, was but scantily stored, as far as regards variety, but I had plenty of the common American trade rum, which I brought with me from the coast. This is the only drink used by the natives, excepting peto.

I gave the caboceer a good bumper or two, which he seemed to relish very much. He seemed extremely anxious to excel in politeness; but he assumed a little too much civility to reconcile me to him as an honest man. However, I spent the evening tolerably comfortable till a late hour, when we retired to rest. Maurice was still very ill, although the fever was subdued, but now diarrhœa succeeded, and his spirits were very low; I, therefore, made up my mind to remain a day or two till I should see whether any alteration took place in him.

July 15th.—Early in the morning the caboceer came to pay his morning compliments and to drink a glass of rum previous to sending me breakfast. The old man seemed all in a bustle, this being the[Pg 48] principal market-day in Baffo; and he is allowed still to maintain an ancient custom, which existed here previous to the subjection of the Mahee country, of monopolizing the whole trade of the place to himself. In consequence of this, he was busily employed in watching his young wives, who kept stalls, or hawked their goods in the market-place, many of whom I believe possessed very little personal interest in their divided spouse’s profits, but, in order to render theft impracticable, he placed all his youngest wives in the most conspicuous parts of the market-place, and himself occupied a position which commanded a view of the whole scene. The older or more trustworthy wives were permitted to use their own discretion as to their choice of carrying their goods round the different parts of the town. The principal or favourite wives dole out the portions of goods allotted to each individual to sell, but it often occurs that they are sold at even a higher price than designed by the owner, particularly when strangers are the purchasers. Of course the extra charge is appropriated by the individual seller.

The articles sold in the market are much the same as those exposed for sale in Whydah, which I have previously enumerated, with the exception of European manufactured goods: these, however,[Pg 49] are very limited, tobacco and rum being the principal articles. In addition to these, I only observed a few very common plaid cotton handkerchiefs. Good cloth is manufactured here, and sold in the market, but manufacture even seems to be monopolized by the caboceer of Baffo, for, on my treating with a weaver for the purchase of a piece of cloth, he was obliged to consult the caboceer whether he might dispose of it at the price I offered him, which, after some higgling, was agreed to. The whole of the inhabitants of this town are literally slaves, but live in peace and plenty ever since their subjection to the King of Dahomey.

About eleven o’clock, my friend, Kpatchie, and his young Dahoman attendant, came again to visit me, bringing with him about thirty persons, carrying provisions for myself and people. This act of kindness proceeded, undoubtedly, from his own generosity, independent of the order of the King. The old gentleman seemed delighted at having an opportunity of testifying his good feelings towards a white man, but this kindness on his part seemed to create a considerable degree of jealousy between the two caboceers, Agassadoo and Kpatchie, so much so that high words ensued.

Although no preparation was made for our[Pg 50] dinner, for I had remained at Baffo one day longer than was expected by the King, I was amused with the contemptuous manner exhibited towards Agassadoo by my venerable friend. He begged me not to rely on any of his (Agassadoo’s) promises, as he was only a man of words, and of too much palaver to be good. This certainly was correct, but the wordy war soon terminated, Kpatchie being senior, and principal caboceer of the range of mountains on which Baffo is situated.

A reconciliation having been effected, I honoured them both by inviting them to dine with me, which was the first time I had ever done so since I had left Abomey. This seemed to give great satisfaction to both parties, and their differences seemed mutually forgotten. After dinner we went out shooting. I shot several birds of various descriptions on the top of the steep rock, which almost overhangs Baffo. I observed a great number of small animals, somewhat like the rabbits of Great Britain. When I expressed a great wish to ascend the pass, which is very steep and dangerous, I was strongly dissuaded from attempting it, it being declared to be quite impracticable, except to some of the most daring of the huntsmen. I was consequently obliged to satisfy[Pg 51] myself with remaining at the foot to pursue my sport.

Game is very plentiful here, such as Guinea-fowl of various species, some jet-black and very large, others of a lighter colour, some horned and others not. Partridges are large and abundant; the male of one species is armed with four spurs, two upon each leg, nearly three-quarters of an inch apart, and in length according to their age. Pigeons of various sorts are also abundant, but the most numerous is the turtle-dove, which is here more domesticated than any other, except the common house-pigeon. The turtle-doves always take up their resting-place in towns or villages. The wood-pigeon is also abundant, but very wild. I observed another species, of a green and yellow colour, with a red ring round the neck about half an inch in diameter, and without feathers, the surface much resembling morocco leather. The natives have a very efficient mode of trapping these pigeons.

A little circumstance took place here, perhaps not unworthy of narration, respecting one of the last-named pigeons. This pigeon had been caught in a trap, and one of my young soldiers, anxious to elevate himself in my estimation, caught a pigeon, and, in order to make it appear that he[Pg 52] had shot it, destroyed part of the head before presenting it to me, but of course I was quite aware that this was not true. This was the same young man who had on a former occasion, as I have previously related, procured a Guinea-fowl, and made a hole through the neck, declaring that, although he always used ball, he shot his birds through the neck. I now set him a task which gave him a damper. Taking a small piece of white paper, wetting it, and sticking it on the side of a rock, at twenty yards distance, I asked him to shoot at that mark; which he did, but it was nowhere near the paper. This very much chagrined not only himself, but the whole of his companions, who declared that the bullet had tumbled out before firing. I determined, however, to prove to him that it was not so easy a matter as he supposed to deceive an Englishman, and therefore gave him another chance, by shooting at the same piece of paper stuck against a palm-tree. This he also missed, as well as the tree. The caboceer seemed much annoyed lest I should consider the huntsman a fair specimen of their skill. He therefore desired me to shoot, thinking probably that I might be an equally bad shot; but I was fortunate enough to hit part of the paper, and of course the bullet entered the tree, which created some considerable[Pg 53] surprise amongst the soldiers who accompanied me.

Upon our return to the town we found a fine dog lying on the ground, apparently just killed. He was very much swollen, particularly one of his fore-legs. I made inquiry of the owner respecting the cause of its death, and was told that, while visiting his farm at some short distance on the plain, a large snake came in contact with the dog, and in the conflict bit the dog in the fore-arm. The venom caused death in about a quarter of an hour afterwards. The dog died within two hundred yards of its home. Serpents are said to be very numerous and extremely venomous here, but I have not seen any of the serpent tribe since I left Whydah.

Upon my return to my quarters I found my servant Maurice apparently worse, and in very low spirits. He had hitherto expressed a wish not to be left, but to proceed with me on my journey. This, of course, in his present state, it would have been folly to allow him to do. I proposed, therefore, that if he were not much better in the morning, to leave him a few days, till I returned from the town of Whagba, for which place I intended to march. This the poor fellow consented to. He was now suffering much[Pg 54] from dysentery, and his illness had every appearance of terminating fatally.

In the evening I was visited by one of the caboceer’s wives, who was introduced to me as the principal cook, and who had presided at the cooking of my food. This, of course, was a very broad hint that I should not forget her when distributing presents. Several of the caboceer’s younger wives, who seemed very anxious to flirt when an opportunity presented itself, came to make inquiry after the health of my servant, but their real motive was to obtain a glass of rum, for they knew that I had arranged to depart on the following morning. The caboceer, Agassadoo, importuned for every thing that met his eye, though he took special care not to do so when the caboceer or captain of my guard was present.

[2] I found this man was a native of Houssa, which accounts for his surname.

[3] The inhabitants of Paweea are about three thousand.

[4] Caboceer.

[5] Brother to the caboceer.

[6] Commander-in-chief of the soldiers.

[7] Second in command of the soldiers.

[Pg 55]