Far below a sudden flash appeared, and a pair of Hop soldiers toppled off the invisible ladder....

No name in human speech was black

enough for the man who was surrendering

Earth to the aliens ... but Everson

knew that the only way to keep his

world from slavery was to link it to the

invaders—with a cosmic ball and chain!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Super Science Stories May 1950.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

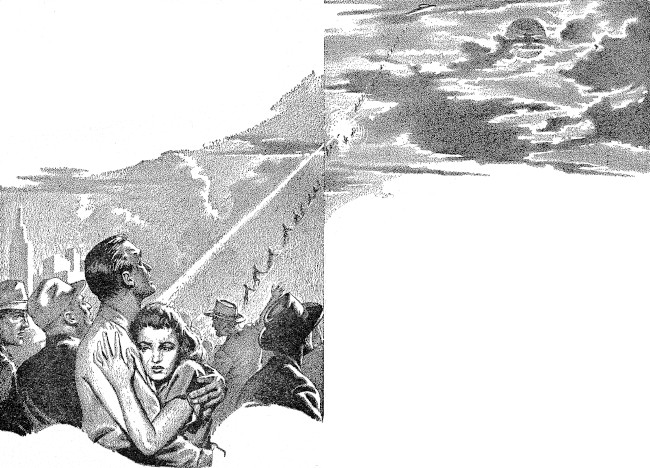

George Everson descended hastily from the air liner, and the flying steps of a street escalator carried him up into the Star Building, but not before the crowd surging behind the fence a hundred yards away had caught sight of him. How they recognized him in the growing dusk he didn't know. His gray hair and mustache, the sensitive lines of his face were unobtrusive, anonymous—but recognize him they did. Probably hate had sharpened their vision, for the chorus of yells that overtook him was fierce. It was clear enough that they didn't like traitors.

He smiled wearily, knowing, without pausing to make sure, that his hand-picked guards were keeping them in check, and dropped wearily into a convenient desk chair. As it headed for his office, he switched on the visor, and his secretary's anxious face met his eyes. "We've been expecting you, Mr. Everson."

"Any messages?"

"A great many of them, sir."

"What do they say about the surrender?" he asked.

"Most of them are protests, sir. Official resignations—"

"The resignees have been replaced, according to plan?"

"Naturally, Mr. Everson."

"And they are proceeding to carry out the surrender, as ordered?"

"Well, not quite. A few said they couldn't stomach it, Mr. Everson. They resigned too."

"See that they are replaced with names selected from List C. The surrender must go through."

"Yes, Mr. Everson."

His secretary—herself a replacement of the man who had been with him for ten years—seemed to wait for him to go on, but he only nodded curtly and switched off. There were other people to see and talk to, but suddenly he felt it impossible to face them, to stare into their eyes. He let the chair carry him silently, and once in his office, he turned on the door lock to insure privacy. Then he stared out through the transparent wall at the spectacle the heavens offered.

Off the right, not far above the horizon, hung the Hop planet-fortress, from which he had just come. A bit smaller than the moon in apparent diameter, it was actually larger than Jupiter, and had several times that planet's mass.

From an anti-grav chamber, he had seen only one tiny corner of its vast surface, but that single vision had been enough to convince him that he had been correct. The Hops, in their countless numbers, were unconquerable, and the human race, despite all its weapons, had no choice but to surrender unconditionally.

The Hop Supreme Three had observed all the customary formalities. They had signed the agreement for humane treatment of the surrendering race, and given their most solemn promises to live up to the agreement in every detail; although from what he had seen of them, Everson knew that their idea of what was humane differed from his. He knew also that they signed agreements merely to break them, as they had broken the one on Neptune, and that when they broke this one the human race might very well be exterminated. But, as he had been telling himself time and again these last five days, he had no choice.

He had, by dint of superhuman effort, managed to persuade the majority of his Council of that, and only two members had resigned. Public opposition had been more violent and outspoken, with here and there some firebrand calling for a war of defense to the death. But he had pointed out as coolly as he could, in one System-wide speech after another, that the war would be to their death. Resistance was one thing, suicide another. The opposition had been disorganized, if not overcome, and the surrender was now going on. His present task was to speed it up as much as he could, and for that he would have to see and talk to the numerous individuals whose calls were waiting.

But the effort of pressing a button which would bring their faces opposite his own was more than he could manage. And then, to his relief, he found an excuse for putting off the painful task. A bell tinkled musically, and his secretary's voice said softly, "Mr. Arthur Everson, sir."

His son entered and stood regarding him silently. Arthur's hair was black, and with his young, clean-shaven face he lacked the aspect of official dignity which the gray mustache gave his father. But he had the same sensitive features, and under his eyes there were hollows sunk deep by the tension and sleeplessness of the past week. He said finally, "Have a nice trip, dad?"

"Not nice. Interesting."

"Something like my life now. Did you know that I'm afraid to go out into the streets?"

"You have your guards."

"I don't mean that. I don't dare to look people in the eye."

"You'll get over it."

"I'm afraid not," said Arthur. "I'll never get over being the son of a traitor. At first, when I heard of the plans for surrender, I thought they were intended as a maneuver, to throw the Hops off their guard. I never believed that you could intend them seriously."

"The Hops aren't to be thrown off their guard so easily. Don't you know anything about them?"

"I know a great deal. I've seen several of your secret reports."

Everson frowned. "How did you get at those?"

"Never mind that. I wanted to know if a military defense was possible. On the basis of those reports, I think it was. But you didn't have the courage to undertake it."

"It isn't a question of courage. In the first place, we'd have been slightly out-numbered."

"That wouldn't have mattered. There's a human population of six billion on Earth, four billion on the other planets. The Hops were estimated to number a hundred billion in all—"

"That is inaccurate," said his father, with that weariness which never seemed to leave him in these days. "That was the first, very wild estimate. We've corrected it since. The Hops number ten trillion. And they regard most of their number as expendable."

"They can't be so many."

"They can. They are. Which reports did you see, Arthur?"

"The entire first series. A one to A seven."

"Then since you know that much, perhaps I'd better fill you in with some more recently obtained information. To begin with, their name is officially Maletes, which can be translated roughly as The Big Men. The designation may seem strange to you. But it fits much better than that stupidly patronizing 'Hop O' My Thumb', which some bright journalist called the first one he saw, and which has since become their usual name among us. There's nothing elfin or pixielike about them, and on their own planet, compared to the other animal life, they're really big.

"Moreover, they're heavy. The adults average no more than ten inches high, but they run to about forty pounds. They're as strong as human beings, not to speak of being quicker and more active. Pit a wildcat against an unarmed man, and what chance do you think the man has? Well, a Hop is more dangerous than a wildcat, even without taking into consideration his superior intelligence."

"You're exaggerating, dad."

"No. I saw an exhibition on their planet. They put several Hop fighters against their own native animals, as well as against several specimens they had captured on outer planets. In every case but one the Hop came out the victor. The sole exception was a Jovian strom, a kind of lizard, and that managed a draw not so much because it was twice the Hop's size as because it's the fastest-moving creature in the System."

"But we wouldn't be fighting without weapons."

"They'd have the advantage there too. Their weapons are better than ours. In nuclear physics and biological warfare, they're ahead of us. Not too far ahead, I'll admit. Give us a hundred years—possibly even fifty—and we'd be up to them. But we haven't those fifty years, and there's no way of stalling them that long."

"How about psychological weapons?"

"No chance. We couldn't get close enough to make a beginning. They're aware of the danger, and they've taken precautions against it."

"They'd have to come to us. They'd have to attack—"

"Good Lord, Arthur, don't you see that if they did, they'd have a still greater advantage? The moment they close in on us, and nuclear weapons are out, we don't stand a chance. As individuals they're too small to make good targets, and too tenacious to be easily killed even if they are hit."

"And they have no weaknesses?"

The bell tinkled again, and the secretary's voice said, "I'm sorry, Mr. Everson, but there's a report that requires your attention. With regard to the surrender on Venus—"

"Go ahead."

He listened, and at the end, said simply, "Have McReady take Mauvernon's place. The plans are ready for him. Tell him to carry them through as they stand." He turned to face his son again.

"I asked if they had no weaknesses, dad."

"Several. But none that we can take advantage of at the moment. Don't think our decision to surrender was an easy one, Arthur. During the entire period of negotiation, we've had our spies out. We've managed, with difficulty, to learn a few things about them.

"The Hops have come out of another galaxy. For a great many centuries they've been able to move their entire planet, to attach it as a temporary satellite to some star, and to release it again, without expending too much energy, when conditions became unfavorable for a longer stay.

"Wherever they have come across a planet suitable for Hop habitation, they've left sizable colonies. But they've never run across anything as good as their original home.

"They were originally about three feet high. They've been deliberately bred to diminish their size, so that more of them might be supported at a given standard of nutrition. But overpopulation has always been a problem nonetheless, and has driven them on continually to look for new planets. That's why they're so interested in our system."

"And that," said Arthur, "is also why, once we've handed over everything we have, they'll exterminate us, and proceed to colonize as if they had never signed an agreement."

"Possibly."

"You say that very calmly, dad. As if the extinction of the race meant nothing to you."

"Because we have no choice. However, I was going to tell you about their weaknesses. These derive from their lack of height. As the Hops shrank in size from generation to generation, they became shorter-lived. At present, they live on an average only five of our years, of which at most three can be considered years of maturity, with full adult powers.

"They might have done something about it originally by changing the direction of their own evolution. But the shorter their lives, the less pressing the problem of overpopulation. And at a time when they were engaged in continual wars, they preferred to have replacements made as quickly as possible—which meant a shorter period of infancy, and again a shorter total life.

"Their ability to mature quickly also made for greater vigor as soldiers, and involved no lengthy old age during which the injured veterans had to be taken care of. Later on, when the process had gone further than they liked, they tried to reverse it, and couldn't. It was biologically difficult, and politically impossible. It would have intensified all the problems of overpopulation, and started a civil war. They're stuck with their five-year lives.

"The consequences have been tremendous. During the three years of adulthood it is no longer possible to master any reasonably broad and complicated field of knowledge, let alone advance it. Despite their application of what had previously been learned in psychology, and their attempt to substitute machine calculation for brainwork as much as possible, they are no longer able to train any large body of research scientists. Instead of developing, their science has deteriorated. Entire branches they had formerly mastered have now been relegated to the museums and libraries. They don't have time for philosophy or logic, or other such luxuries. All their science is, one way or another, military science. They hang desperately onto that."

"And this deterioration is continuing?"

"Steadily. It would take us a hundred years to reach their present attainments in military nucleonics and biologics. But they're going backward as rapidly as we move forward. That's why I told you before that fifty years might be enough."

"And we don't have the fifty years."

"Not even a reasonable fraction of it. That's why we can't take advantage of the weaknesses we've discovered. Remember that they're physically more vigorous than we are, and intellectually just as alert. They can see through any tricks we try. They lack merely sufficient time for each individual to accumulate a sizable and coherent body of knowledge which has been tested in practice."

"There must be some way—"

"When you think of it, let me know," said the older man, suddenly curt. He stood up, as if the recital of the hopeless story had renewed his energy. "At present, I have to see to it that the surrender is carried out."

"I still think that you're merely trying to rationalize an act of treason." Arthur's voice was choked, and tears filled his eyes. "Do you ever stop to think of the place that men like Arnold and Quisling hold in human history? When I think that your name will join theirs, that it will be even more infamous than theirs, I feel like killing myself."

The older Everson laughed, rather harshly. "If I'm right, I'm no traitor. If you're right, there will be no human race, and no human history to record my name. Don't be such a child, Arthur, and don't try to make history's decisions for it. Now get out, and let me work."

For a time after his son left, Everson worked steadily. The surrender wasn't going as smoothly as he would have liked. Even those who had accepted the numerous vacant posts had no heart in the work, and whether through carelessness or through deliberate sabotage, many of the minor points of the agreement with the Hops were in danger of being violated. If Everson could help it, there were going to be no violations that would give the Hops an excuse to use military force. He checked over the details of what was being done in the asteroid belt, and found, as he had suspected would happen, that the largest asteroid base of all had been left out of the list to be turned over to the Hops.

He spoke personally to the governor of the Asteroid Group. "Clayton? Ever hear of Base AZ?"

"Of course, Mr. Everson."

"So have the Hops. They're very sensitive, and I'd hate to upset them by pretending that it doesn't exist. Turn it over to a Hop crew, and see that it's brought directly to their planet."

"Yes, Mr. Everson," said Clayton dully.

During the night, his wife visored the Star Building. All through the period of the negotiations she had said nothing, but the long years of living together had enabled Everson to guess her thoughts, and he knew that she shared Arthur's views that everyone responsible for turning Earth over to the Hops was guilty of treason—and that she made an exception only in the case of her husband.

What would have been an act of betrayal in someone else was only a mistake in judgment in George Everson, and this despite the fact that for almost thirty years she had maintained proudly that her husband never made mistakes.

She had deliberately involved herself in a tangle of face-saving inconsistencies for which he was deeply grateful. If she had turned against him as Arthur had done, and as even his own brothers had done, his life would have been altogether intolerable.

Even as it was, he was none too happy at her expression. "George," she said, from a distance of two thousand miles, "the Hops are arriving. Have you seen them?"

"I can get a direct military view. Just a moment."

A touch of one of the buttons on his desk brought the picture to the military screen in front of him. The sun was just rising, and in the early dawn, the Hop craft was barely visible as it hovered high overhead. Occasional glints from something in the air revealed that they had let down a transparent ladder. Down this ladder were climbing rows of Hops, perceptible only as tiny dots near the top, becoming larger as they neared the ground. To the onlookers from below it seemed as if the Hops were climbing down out of the sky on thin air.

"I have the picture, Ada. They're the occupation crew."

"They're going to govern our own district?"

"That's right," he said gruffly.

"There aren't many of them, George. And we have a large military force near-by. If you gave the word, we could wipe them out."

He said wearily, "If you knew how many times that suggestion has been made to me! No, Ada, there's no chance of that. Both the local commander and his subordinates are tested men. I am not giving the word, and they will not take it from anyone else."

"You have to give it personally? Isn't that unusual?"

"Decidedly unusual. But I'm taking no chances of betrayal. As I've repeated time and again, I want the surrender to go off smoothly."

She nodded slowly. "That has become clear enough. You're working all night?"

It was his turn to nod.

"Try to rest for a while, darling. And have something to eat."

"I won't starve, Ada. Good night."

The screen became blank, and he turned to stare once more at the military visor, still exhibiting the arrival of the Hop occupation crew. From somewhere, far below, a sudden flash appeared, and a pair of Hop soldiers seemed to lose their grip on the air and toppled off the invisible ladder. The others froze in their places.

Far below a sudden flash appeared, and a pair of Hop soldiers toppled off the invisible ladder....

But retribution against the unseen sharpshooter was rapid. Not the Hop ship, but a small Earth craft flashed into view from the side and swooped down, its guns blazing. A building shattered in the lower part of the screen. And the Hop troops resumed their descent.

A few hours later, Venus was the scene of a more serious incident. Here a whole garrison rose in revolt, armed with modern weapons, and well trained in their use. Everson turned aside from everything else to take personal part in the crushing of this revolt. The angry troops fought savagely, but had no chance from the beginning. The loyal forces were concentrated against them in overwhelming strength within an hour, and they threw in everything they had. Half a day of fierce fighting saw the collapse of the desperate gamble.

Through these and other revolts that followed, thought Everson sardonically, no more than ten Hop soldiers were lost. Everson had suggested that System troops would be more effective in crushing a rebellion of their own people, and the Hop authorities had agreed.

Late in the day the Hop Supreme Three contacted Everson. He studied them in his visor, three elflike creatures whose eyes twinkled as merrily as if they had been genuine elves. To judge from first appearances alone, the journalist who had originally christened them hadn't done so badly. They did have the sharp leprechaun ears and the leathery skin of authentic gnomes, born of a marriage of different mythologies. It was not until you got a good all-around look that you became aware of features that no genuine elves or gnomes would have tolerated in themselves. The third eye near the top of the forehead, the fourth on the back of the head, the antenna-like third pair of arms that was ordinarily folded in back and unfolded only in moments of excitement, the ugly and apparently useless patch of blue skin below the neck, visible above the loose clothes they wore—all these testified to a race of creatures that had not been dreamed of in human folklore.

The Spokesman waited for Everson, and as became the representative of an inferior race, the latter bowed humbly and said, "Greetings."

"Greetings. We have heard excellent reports of you."

"I have tried to carry out all that I promised."

"You have done even better than we expected. When do you think the surrender will be complete?"

He made a rapid mental calculation.

"In thirty-seven Large Vibration Units."

With no permanent sun of their own, the Hops based their time standards on the frequency of atomic vibrations. The thirty-seven Large Units were equivalent to about thirty hours. By that time, all the planned surrenders would have gone through on schedule, and the human race would be at the mercy of the Hops.

"We congratulate you on your fidelity to your word. You shall receive a suitable reward."

What, he wondered, did they regard as "suitable"? To kill him first, after they had no further use for him, and thus to spare him the sight of the extermination of his race? Or to keep him alive until the bitter end, to grant him a few extra hours of painful existence, in return for an act of betrayal on so grand a scale that their own history had never seen its like?

He couldn't possibly guess, but he said simply, and still humbly, "I await your generous gift."

The Three grimaced. Presumably, that was their equivalent of an amused smile. Then the Spokesman said, "One important surrender is yet incomplete. That of the Pleasure Planet."

"I shall attend to that myself."

"Good. And we shall attend personally to your reward."

He would have said impertinently, if he had dared, that this act of virtue would be its own reward, but it would have been stupid to lose control of his tongue at this late stage. So he merely bowed humbly, and the next moment they had broken contact. He returned to his work.

But during the day something happened that he had not expected. His wife arrived, and neither his secretary nor any of the guards dared keep her out. She came into his office quietly.

"I want to be near you at the end, George," she told him.

"It's good to have you near, Ada. But I have no time to spare."

"I won't take up any of your time. I merely want to sit near you and watch you."

Then she fell silent again, and he went about his work once more. In the afternoon he dozed off, and only when the bell rang and he awoke with a start did he realize that she had adjusted a pillow at his head so that he might sleep more comfortably. Not until evening did she interrupt him, and then in order to get him to eat a meal she had ordered.

He ate without tasting the food, but the few minutes of intermission did him good. He said gratefully, "Thank you, dear. Without your thoughtfulness I don't know what would become of me."

"The same thing that will become of all of us, George.... I hear that you are surrendering the Pleasure Planet."

"Yes. There it is."

Through the transparent walls of the room they could see in the sky a luminous dot that moved slowly in the direction of the Hop planet.

"After all that it has cost us, George, doesn't it hurt you to give it up?"

He nodded slowly. Whatever else might be returned to them, the Pleasure Planet would be gone forever. He recalled now the years of planning for a vacation spot that would be capable of serving the entire System; he recalled the two decades during which they had swept up asteroids and interplanetary meteor swarms for raw material, and then the decade following, in which the surface of the new planet had first been blasted into shape, and then swept and ordered, landscaped and built upon until it had become the pride of the System. It was Everson's task merely to turn it over to the Hops.

"George." She was biting her lips. "You know that I'm not going to be able to live through this."

"You may change your mind, dear."

"No, darling, I can't live with the horrible thoughts that keep running through my mind. You know how much I've always loved and admired you, and now, after what you've done—" She fumbled in her purse and brought out a tiny metal rod. "I'm going to shoot myself."

He stared at her gravely. "Not now. Wait, dear."

"Through this agony? Why prolong it?"

"Because I need you." It was the most effective argument he could have used. "You know that I won't be able to live without you. Wait till I finish my work. And then, if you haven't changed your mind, shoot me along with yourself."

"I couldn't—"

"I can." He took the tiny weapon away from her. "When I have turned the Pleasure Planet finally over to the Hops, and given a few more orders, my work will be done. If you still want to die after that, I'll shoot you and myself." He looked into her eyes. "I promise, you, dear. And even the Hops know that I carry out my promises," he added bitterly.

He took her in his arms and kissed her, the weapon still in his right hand. Then he put it in a drawer of his desk, and returned to his work.

The minutes passed slowly. He looked up, startled, as the excited voice of his secretary came to him, without the warning bell that should have preceded it. "Mr. Everson! There's been a massacre! The Hops—they've slaughtered thousands! It was completely unprovoked—"

The tiny dot of the Pleasure Planet was almost touching the circumference of the Hop stronghold. He sighed, and dropped his pen.

"They're not even waiting," said Ada, in a choked voice.

"I thought we'd be spared this."

"Spared! They meant to slaughter us from the beginning, and you only made things easier for them!"

He tried to put his arm around her, but she shook it off. "You knew what would happen, George. I've seen too much—"

It was only out of a corner of his eye that he saw her hand steal into the desk drawer and come out with the weapon.

He leaped at her, twisting her arm with brutal efficiency. She cried out as she dropped the weapon, and then she covered her eyes, the tears flowing freely at last.

And it was at that moment that everything happened.

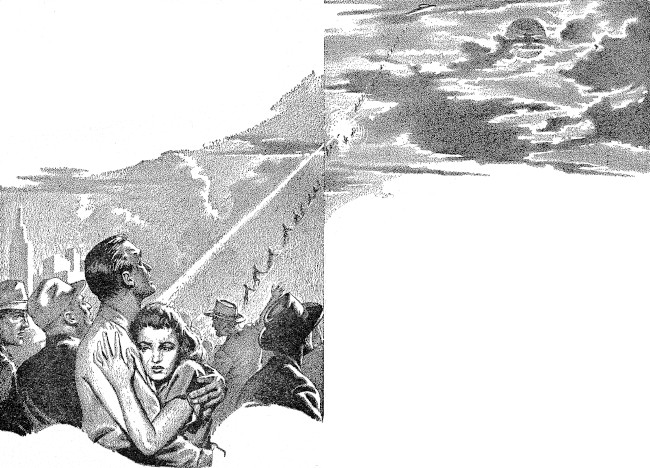

A blaze of light spread across the heavens from the Hop planet. It blotted out the moon and dazzled their eyes in one blinding flash. And then it was gone, and when their dazed eyes could see again, they saw that where there had been the Hop planet was nothing.

Everson leaped to his row of visors.

"We were right!" he shouted excitedly. "My God, how right we were!" And his fingers trembled as they swept across one button after another.

"Clayton!" he barked. "Wipe out the Hop occupation troops in your sector. No, I haven't gone crazy. You have the equipment to do it with. Go ahead and do it. They won't get reinforcements. Djervas, get rid of the Hop troops in Sector C. Zalmette, Goran, Halkim—"

He spoke so rapidly that the names became a blur of sound. But the orders were clear enough, and from the reports that began to come in, it was clear also that they were being carried out.

Arthur came into the office. He had been near the Star Building when it happened, and tears were streaming down his face. "The people are crying in the streets," he said huskily. "All the announcers on all the communication systems seem to have gone crazy. But it's hard to believe. What happened, Dad? A nuclear explosion?"

"There wasn't any explosion."

"But we saw it with our own eyes!"

"You don't know what you saw. That wasn't an explosion, it was a collapse. Remember, Arthur, what I told you of Hop science? That they had neglected what they regarded as theoretical and useless branches?"

"You say their planet collapsed?"

"Yes, that's the clue. It was calculated long ago that when the mass of a body exceeded a certain maximum, the force of gravity would overcome those structural forces that tended to maintain the existence of ordinary types of matter. Ordinary molecules would collapse, and even atoms and nuclei, as we know them, would be unable to maintain their separate existence. The whole mass would fall into a single, compact, giant molecule."

"I seem to remember something we were taught in school. Vaguely, though."

"Yes, it's a commonplace to us now. But the twentieth century astrophysicists were tremendously excited by their discovery at first, although their original calculations were considerably off the mark, as far as the mass required was concerned. We've fixed a more accurate figure since then.

"Through the course of millennia, as a result of conquest and loot, the mass of their planet grew. Our astronomers calculated that it wasn't far from its critical collapse mass. And so as we couldn't hope to win in a direct struggle, our own hope was to build up that mass until the collapse actually took place. That's why we were in such a hurry to send them our heaviest equipment."

His wife said painfully, "And you couldn't have let me know—not even hinted—"

"No, dear. We couldn't afford to take any chances. Not even the members of the Council were informed."

Arthur said, in a voice he couldn't control, "And all the time, everyone was calling you a traitor—even I. How can you ever forgive us?"

"No forgiveness is necessary. That was a necessary part of the plan, which helped convince the Hops that we had nothing up our sleeves." He put his arms around his wife, and then said sharply, "Come, Arthur, don't you collapse!"