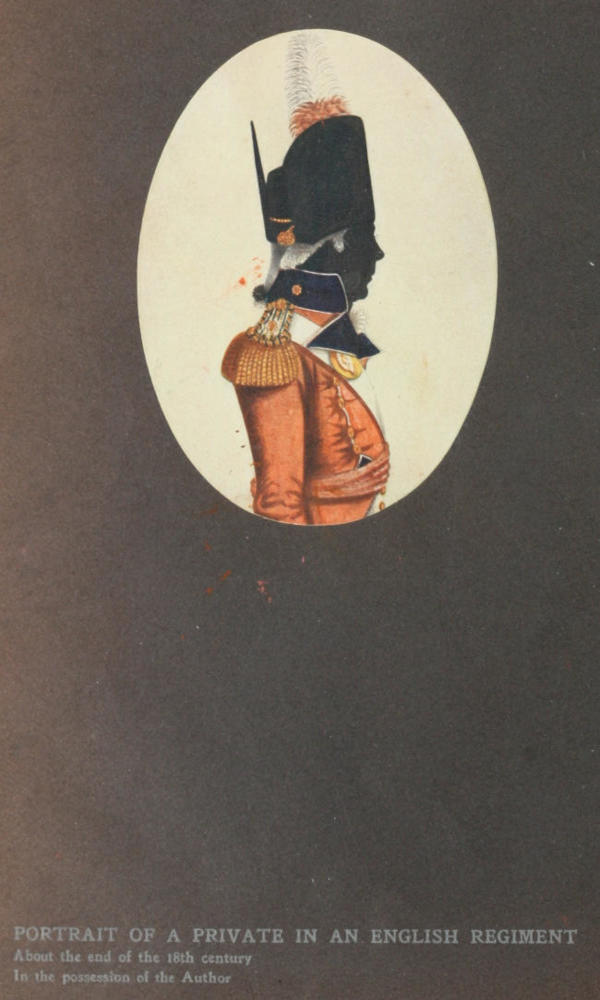

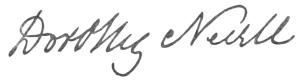

PORTRAIT OF A PRIVATE IN AN ENGLISH REGIMENT

About the end of the 18th century

In the possession of the Author

The Project Gutenberg eBook of The history of silhouettes, by Emily Nevill Jackson

Title: The history of silhouettes

Author: Emily Nevill Jackson

Contributor: Dorothy Nevill

Release Date: October 30, 2022 [eBook #69273]

Language: English

Produced by: MWS and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

PORTRAIT OF A PRIVATE IN AN ENGLISH REGIMENT

About the end of the 18th century

In the possession of the Author

The History

of Silhouettes

BY

E. NEVILL JACKSON

London:

THE CONNOISSEUR

1911

All rights reserved

Copyright by E. Nevill Jackson in the United States of America, 1911.

Amongst my reminiscences of personal belongings and the charm of old portraiture, none has given me greater pleasure than the silhouette of bygone days.

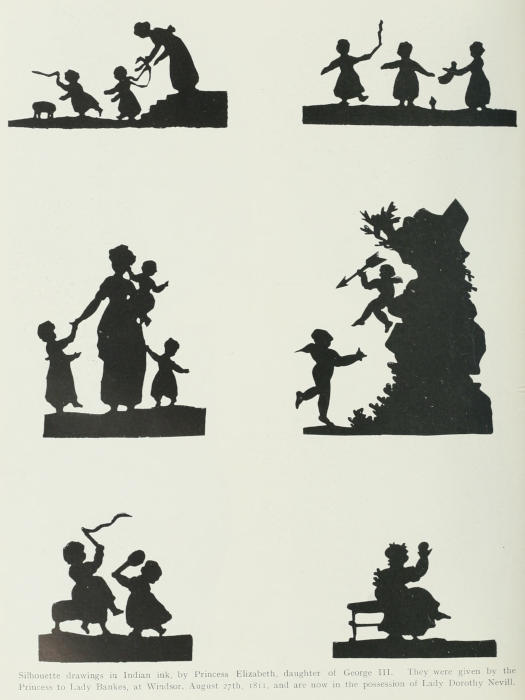

The souvenir, sometimes cut by gifted amateurs, was exchanged amongst friends in my early days as the photograph is to-day. We had many at Wolterton, our Norfolk home, and the picture of my grandmother, Lady Orford, and the cuttings of Princess Elizabeth are amongst my treasured possessions.

I remember Mr. Guest collected silhouettes, and had some fine examples of the work of Miers (who lived near Exeter Change), of Rosenberg, and of Field.

Mr. Guest was a very good judge of such things, having, by many years of collecting, perfected a naturally cultured sense of art. Like myself, he had learnt much from Mr. Pollard.

Lady Evelyn Cobbold shewed me three silhouettes of Mr. Cobbold, his father, and his grandfather, all perfect portraits, and very interesting.

| PAGE | |

| Preface | 1 |

| Chapter I. Black Profile Portraiture, its place in Art, Literature and Social Life | 3 |

| Chapter II. The Coming of the Silhouette and its Passing | 13 |

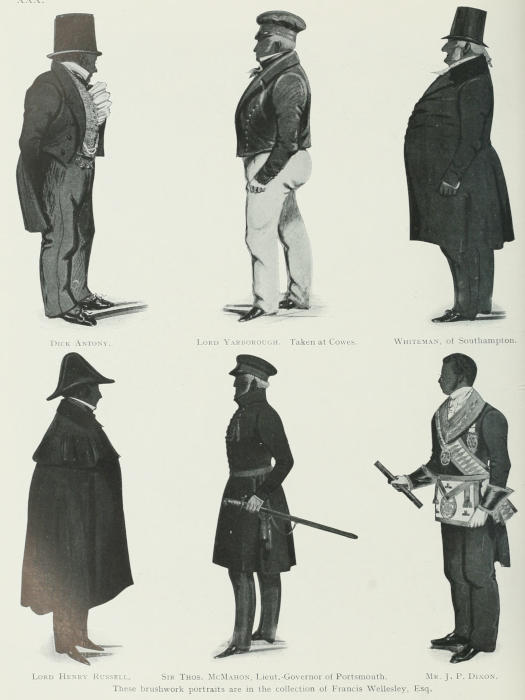

| Chapter III. Processes: (1) Brushwork | 20 |

| Chapter IV. Processes: (2) Shadowgraphy and Mechanical Aids | 35 |

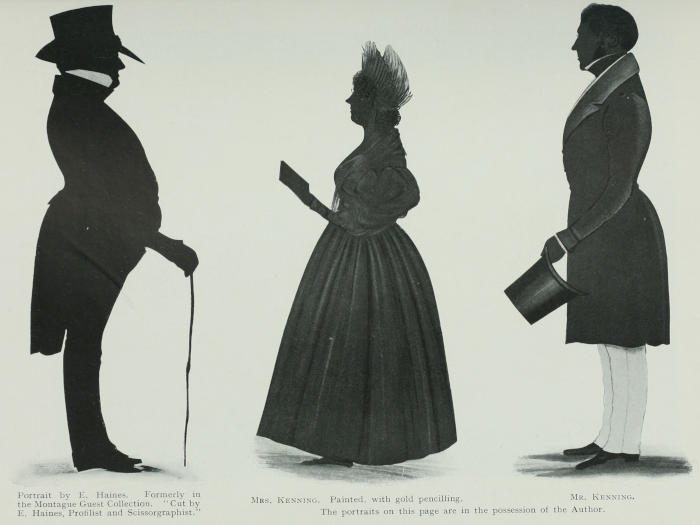

| Chapter V. Processes: (3) Freehand Scissor-work | 47 |

| Chapter VI. August Edouart and His Book | 59 |

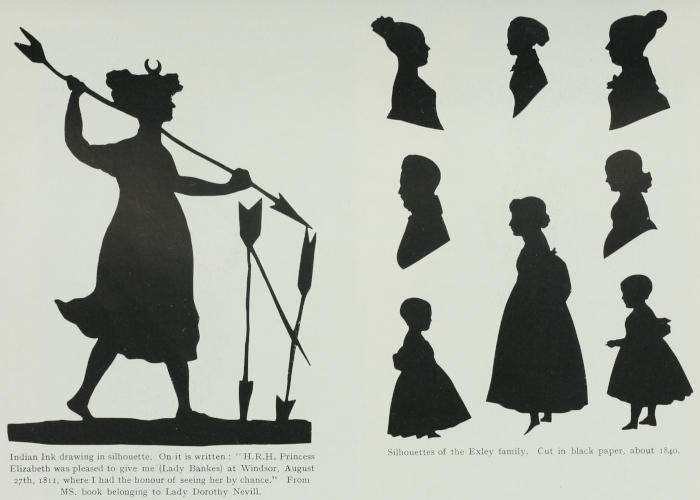

| Chapter VII. Scrap-Books. A Royal Cutter and Her Work | 73 |

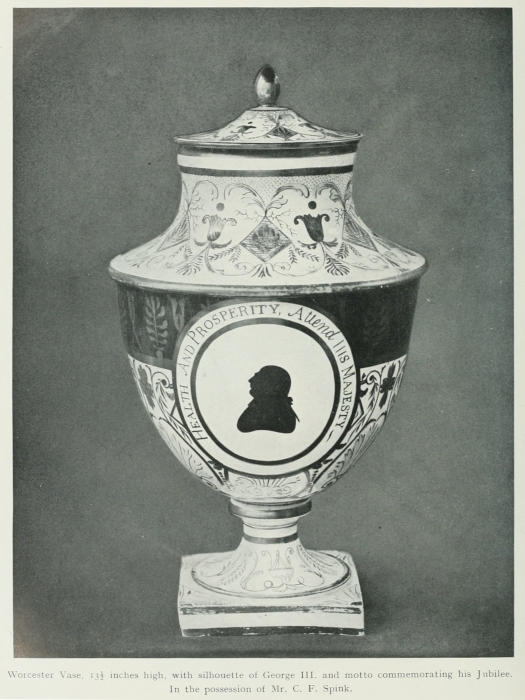

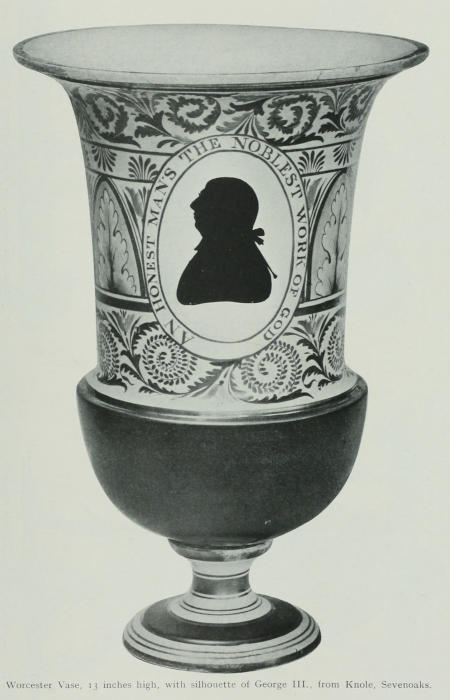

| Chapter VIII. Silhouette Decoration on Porcelain and Glass—The Silhouette Theatre | 81 |

| Alphabetical List of Silhouettists, Makers of Silhouette Mounts and others connected with the Craft | 87 |

| Bibliography | 117 |

| Index | LXXIII |

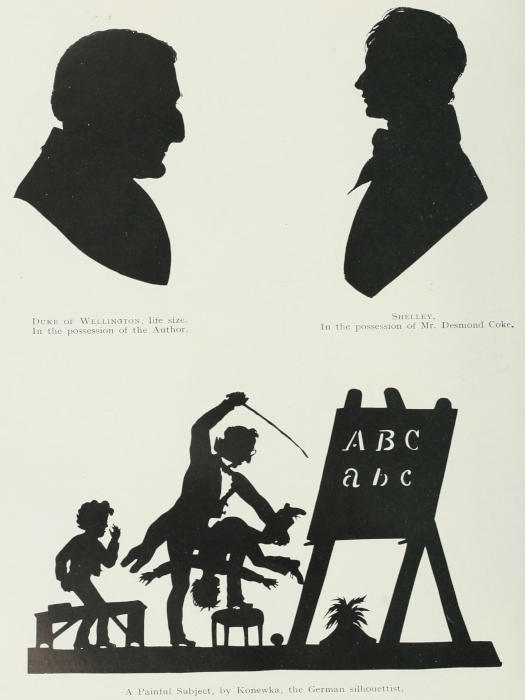

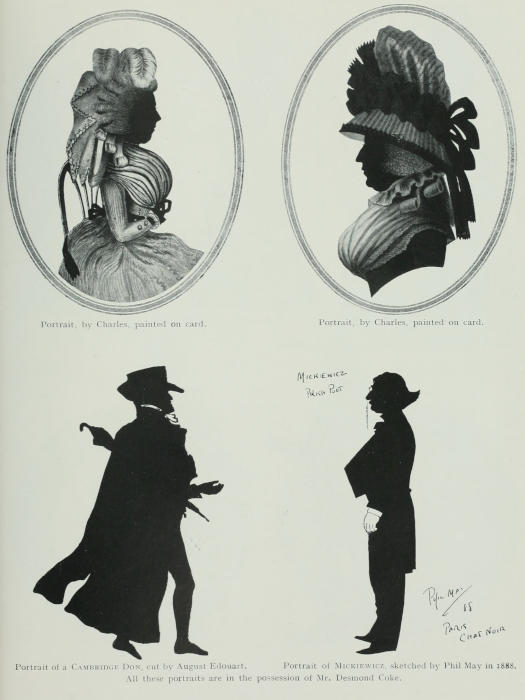

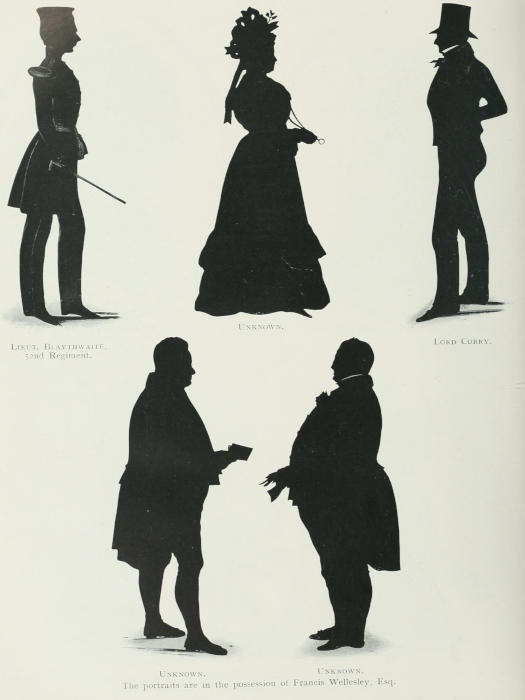

| Portrait of a Private in an English Regiment | Frontispiece |

| Facing Page | |

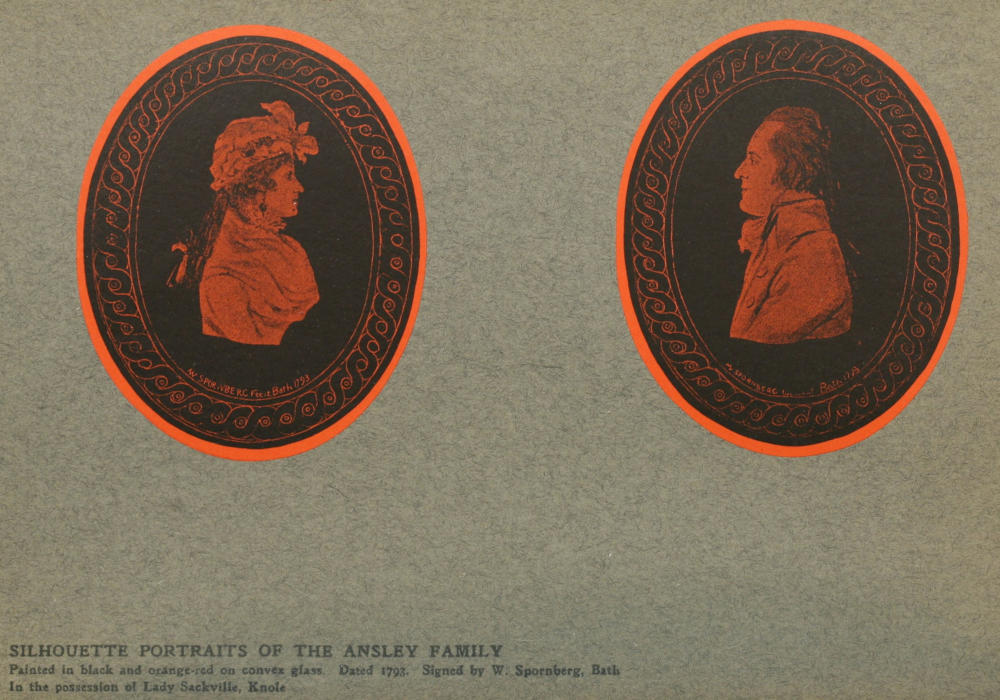

| Silhouette Portraits of the Ansley Family | 1 |

| Painted in black and orange-red on convex glass | |

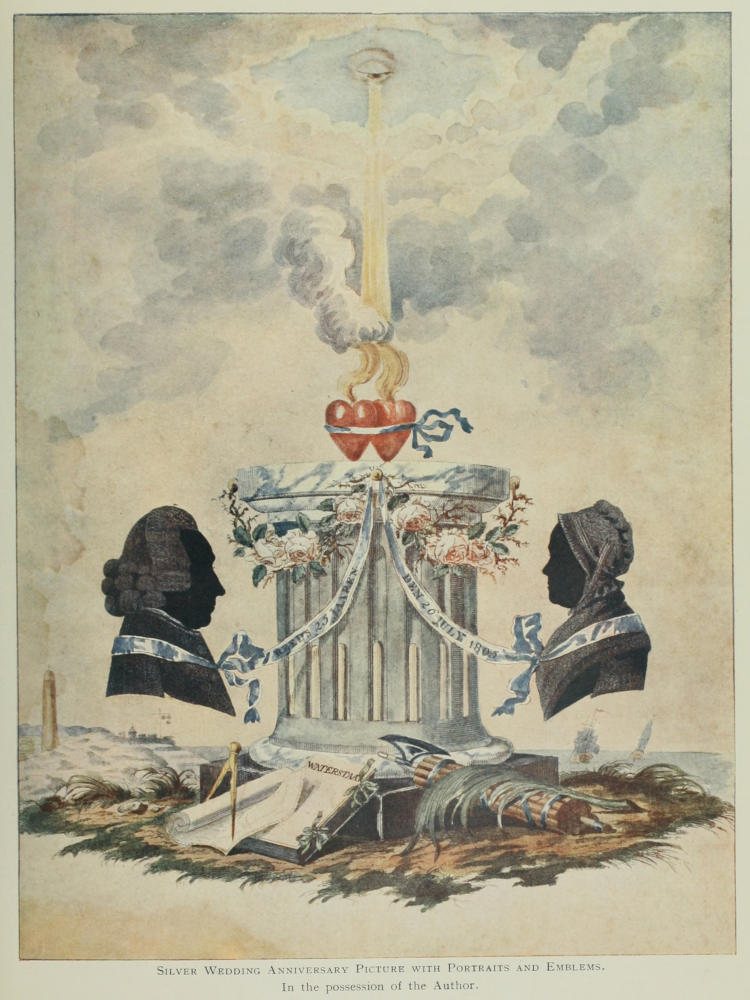

| Silver Wedding Anniversary Picture | 16 |

| With portraits and emblems | |

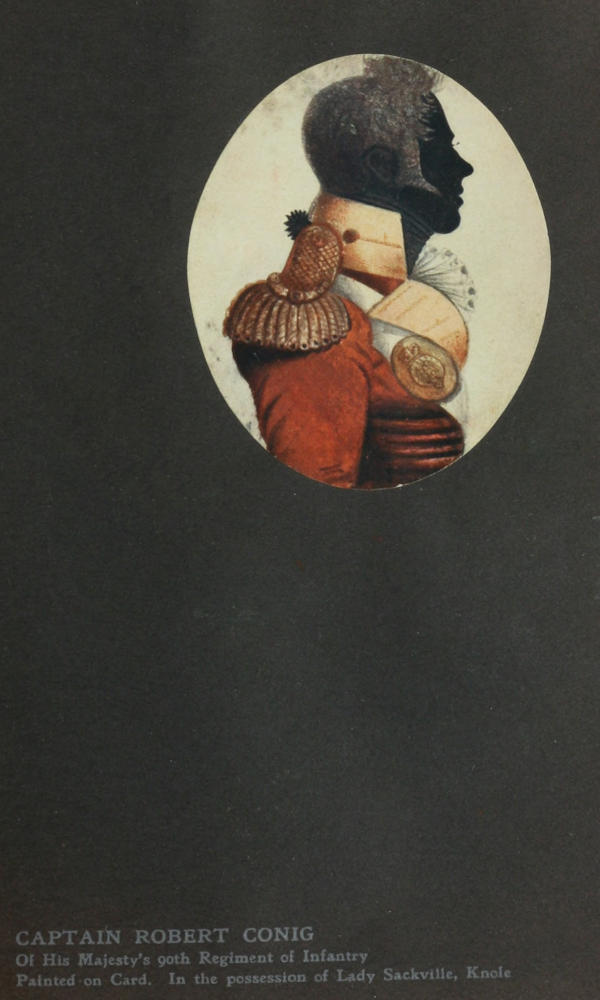

| Captain Robert Conig | 32 |

| Of H.M. 90th Regiment of Infantry | |

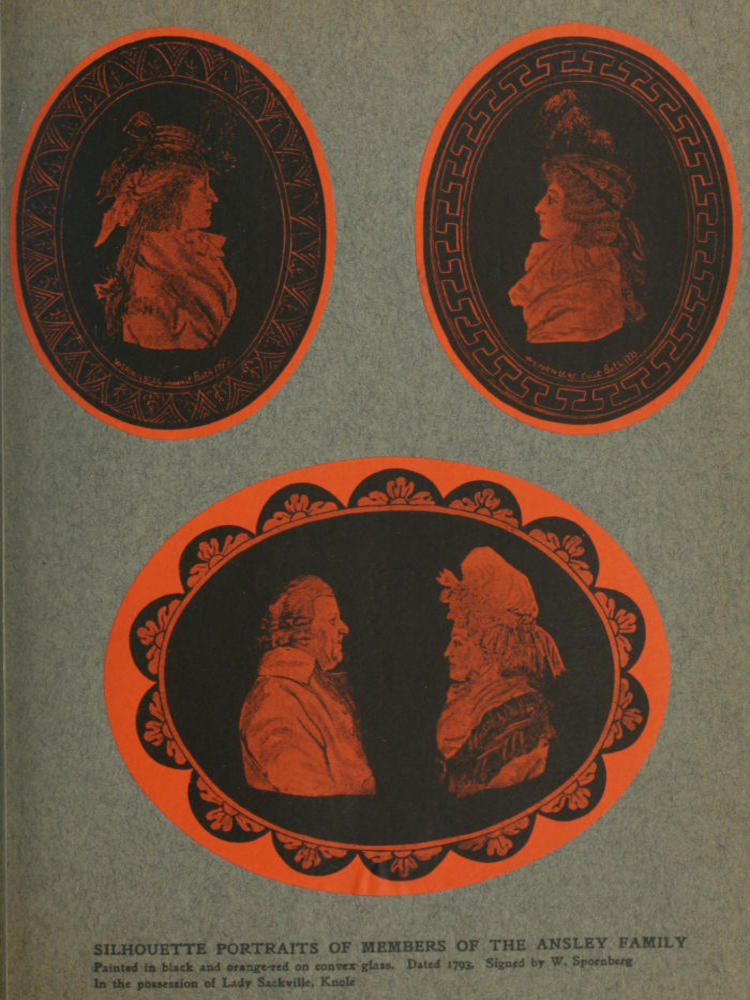

| Silhouette Portraits of Members of the Ansley Family | 48 |

| Painted in black and orange-red on convex glass | |

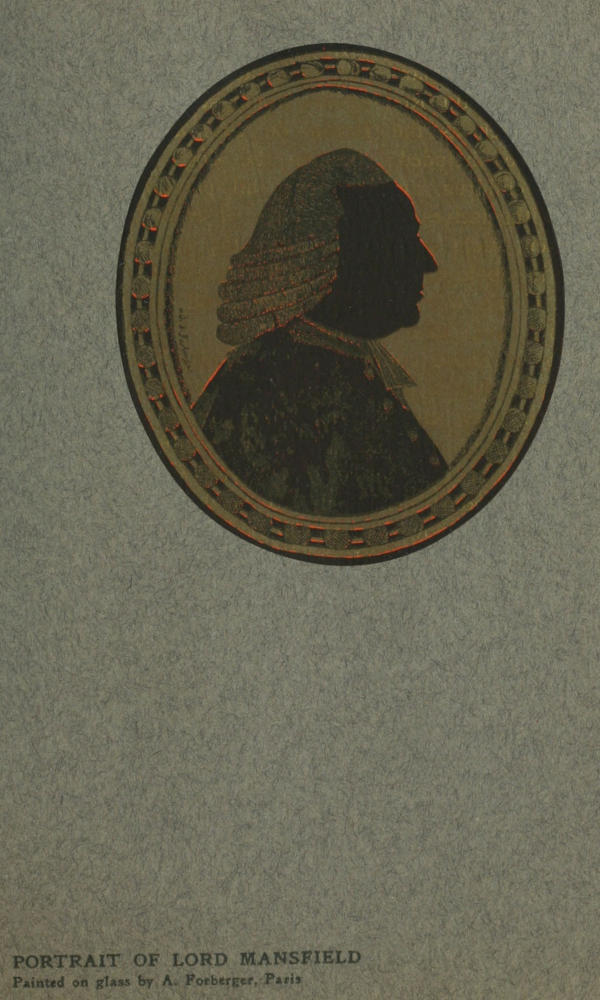

| Portrait of Lord Mansfield | 64 |

| Painted in black and gold on glass | |

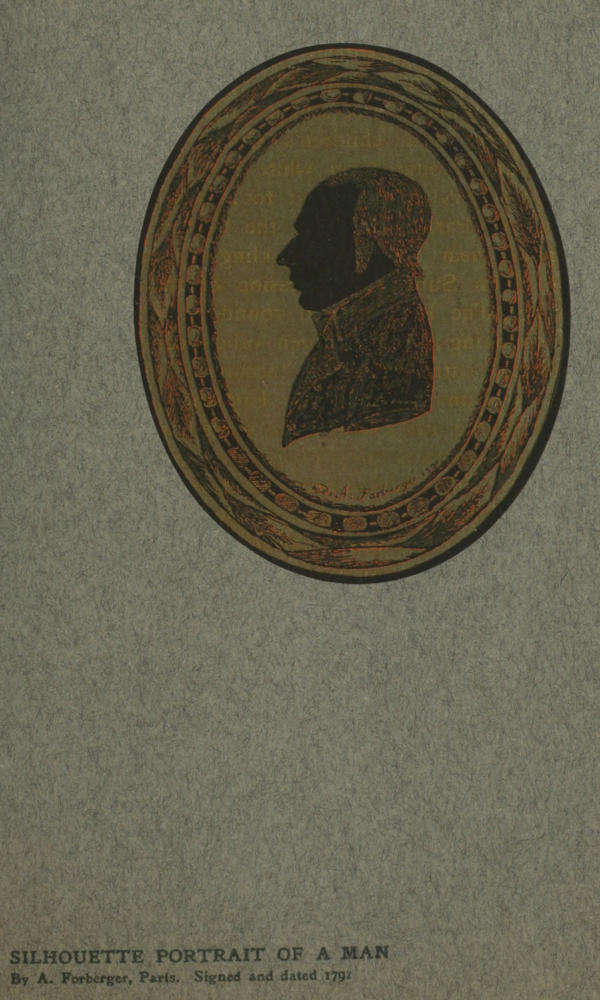

| Silhouette Portrait of a Man | 80 |

| Painted in black and gold on glass | |

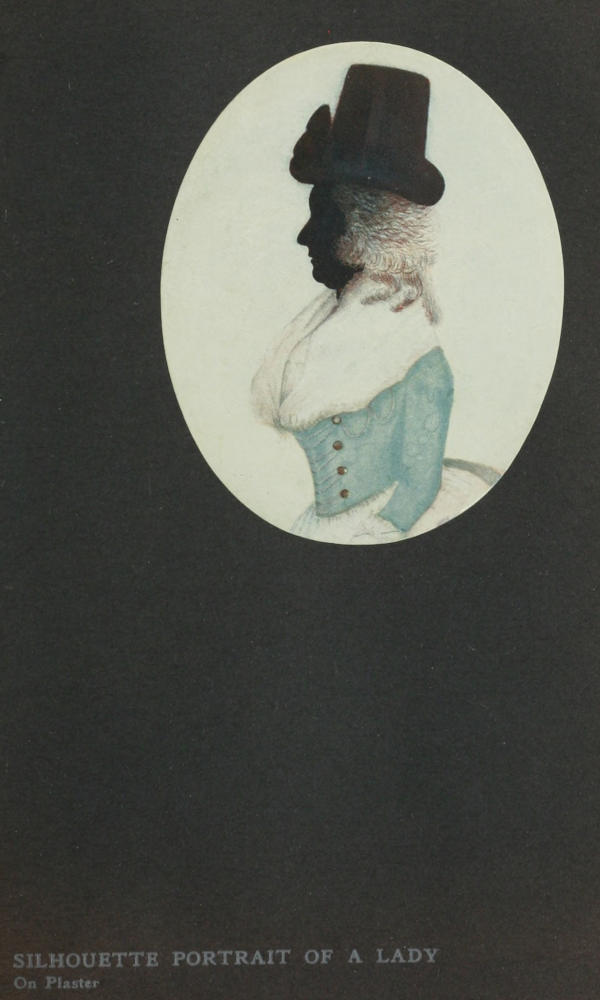

| Silhouette Portrait of a Lady | 96 |

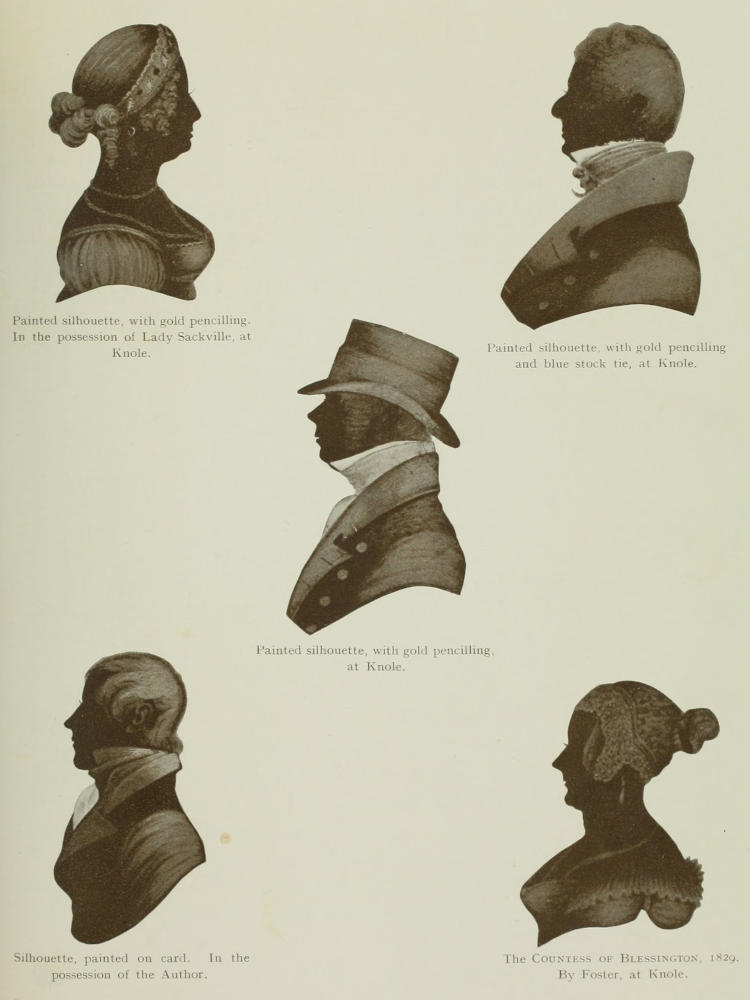

| Painted Silhouettes | 112 |

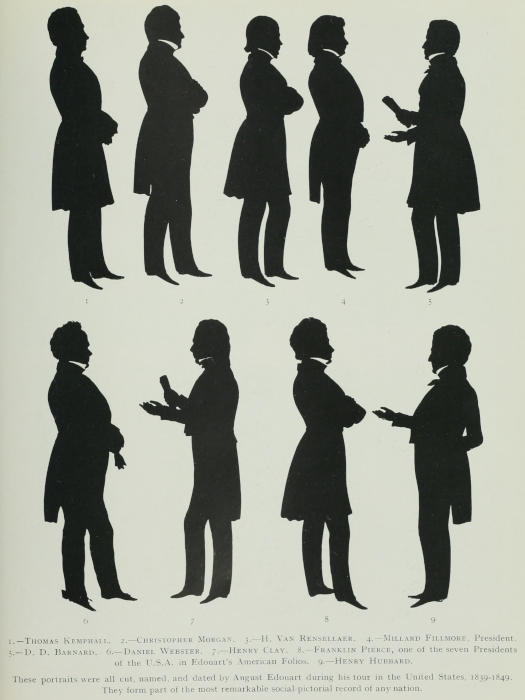

| Illustrations in Monochrome | I to LXXII |

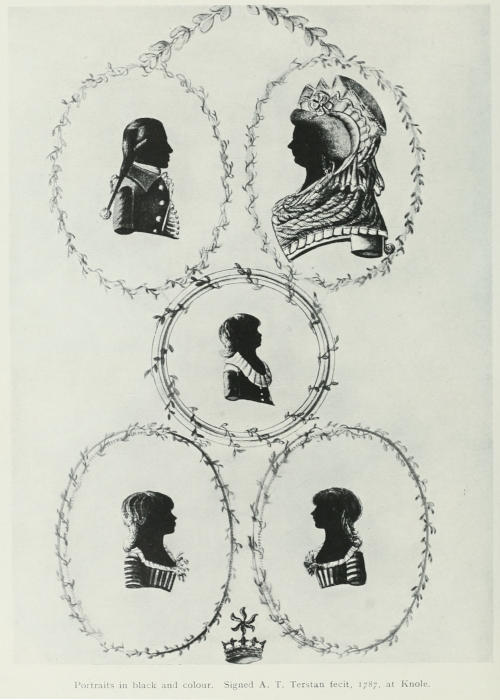

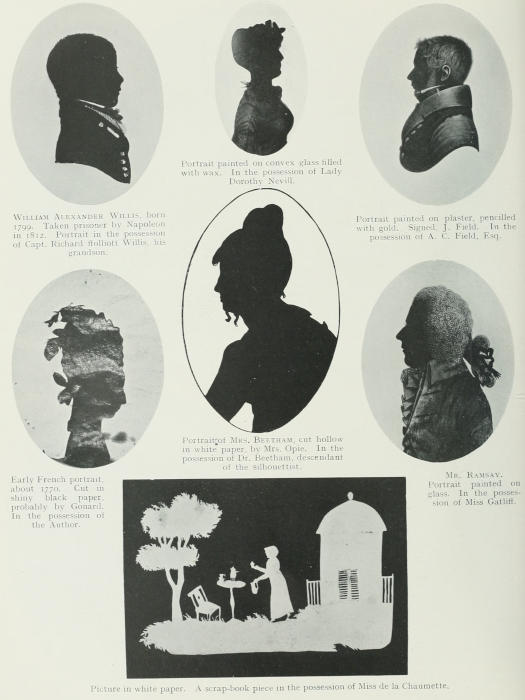

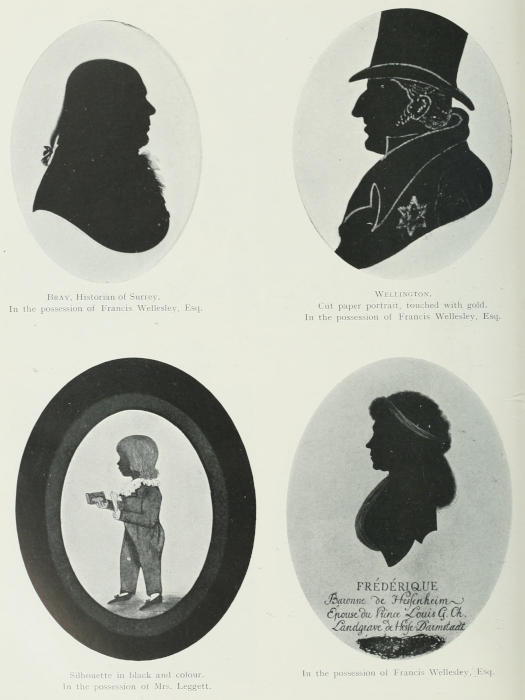

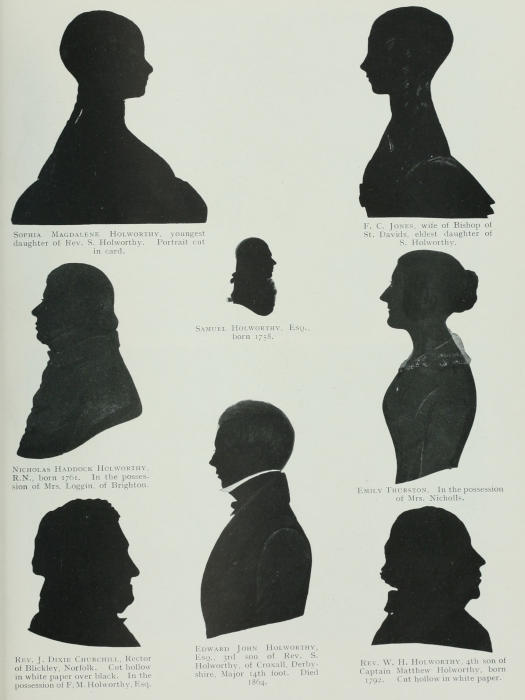

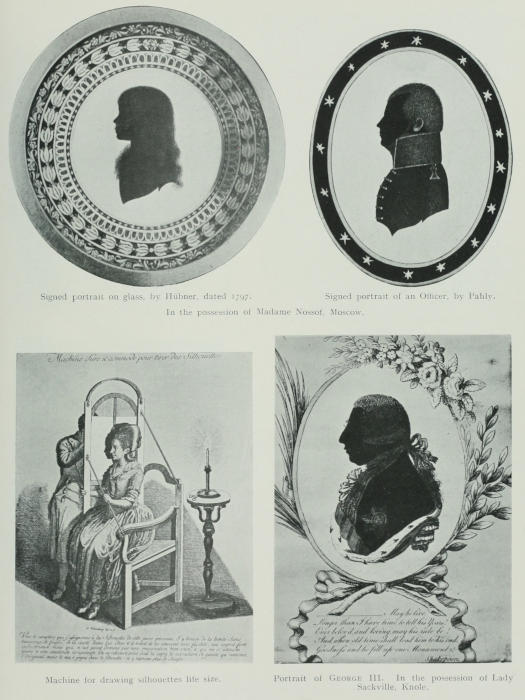

SILHOUETTE PORTRAITS OF THE ANSLEY FAMILY

Painted in black and orange-red on convex glass. Dated 1793. Signed by W. Spornberg, Bath

In the possession of Lady Sackville, Knole

It has not been easy to gather up the threads of history concerning an art and handicraft long fallen into desuetude. Amongst the few who still work at black profile portraiture, none has been found who is cognisant of the traditions, nor who has any knowledge of the complex processes by means of which the fine eighteenth-century work was accomplished.

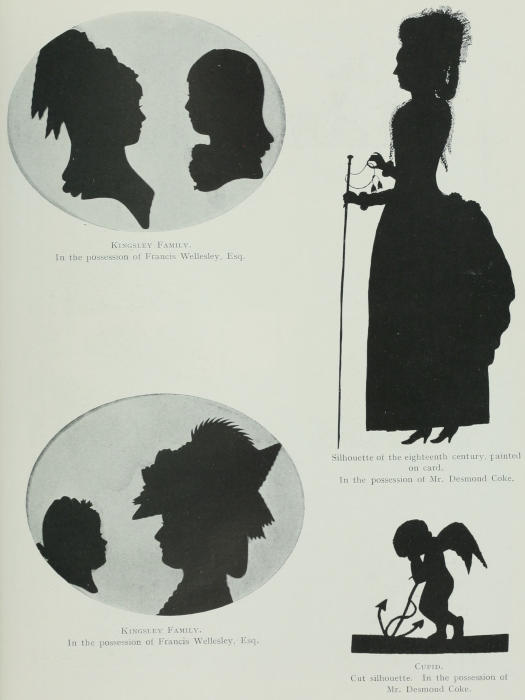

My sincere thanks are due to Mrs. Head, Mrs. Whitmore, Madame Nossof, Mrs. Wadmore, Mrs. Lea Carson (of Philadelphia), Mrs. Whetridge, Mr. Francis Wellesley, Mr. H. Palmer, Mr. Desmond Coke, Mr. Holworthy, Captain Pringle, Mr. H. Terrell (of Boston), Mr. Laurence Park, Dr. Beetham (descendant of Mrs. Beetham, the fine eighteenth-century silhouettist), Mr. J. A. Field, for the interesting series of portraits painted by his great-grandfather, and many others, who, possessing silhouettes, have allowed me to visit and make a study of their collections or have sent specimens for examination. Without their courtesy, and that of many others who gave me facilities for studying some thousands of specimens and advertisements, it would have been impossible to write this book. A subject on which there exists no written history, and which has hitherto received scant attention, requires much research amongst a large number of examples, amongst old newspaper matter, contemporary social history, and the trade labels of the silhouettists, for its faithful record.

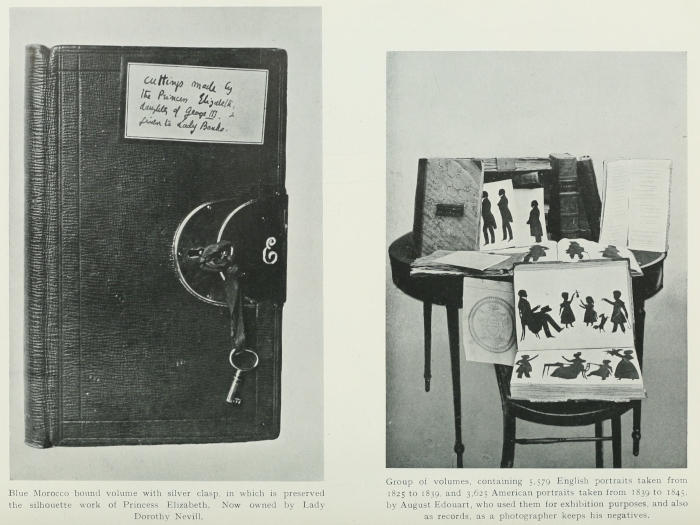

More especially I am grateful to those who have kindly permitted me to reproduce their silhouettes, thus making clear to art lovers, and those who take pleasure in the curio, how manifold are the charms of family treasure, which would not otherwise have been available for study. To Herr Julius[2] Leisching, Director Erzerzog Rainer Museum, I am indebted for information concerning silhouettists of Germany and Austria contained in his memorandums of the Industrial Museum; to Sir Sidney Colvin, Keeper of the Prints in the British Museum; to Mr. C. J. Holmes, Director of the National Portrait Gallery; to Mr. T. Corsan Morton, of the National Galleries of Scotland; to Mr. D. E. Roberts, of the Library of Congress, Washington, for access to special collections; to Mr. Horace Cox and Mr. T. P. O’Connor, with regard to pictures under their control in the “Collector” and the Magazine; to Lady Dorothy Nevill, for placing at my disposal the beautiful silhouette work of Princess Elizabeth, daughter of George III.; to Lady Sackville, for allowing me to study the silhouettes of Knole, and to reproduce some of the silhouette porcelain in her possession.

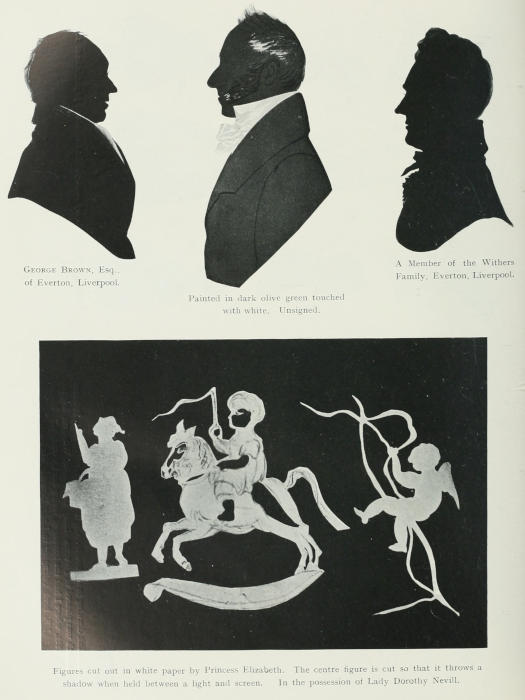

If fresh interest is kindled in the graceful art of the silhouettist, and the names of some little known artists are rescued from oblivion, my pleasant task will not have been in vain. Perhaps those who read these pages will find a charm and wistfulness in the shadow portrait. Beauty is not alone recorded by the brush of great artists, but also by minor workers. Gainsborough painted portraits of beautiful women at Bath, and Charles and Spornberg worked at their shades in the same street; the same clients visited both studios. The silhouette, poor relation of the miniature, the forerunner of Daguerre, shows the Belle of Cheltenham, or the Dandy of Bath and the Wells, appealing and dainty in shadowland, while the laughter of the shadow children echoes ghost-like as we note their toys and sports; they flit across the pages, they cast a shadow, and are gone.

E. J.

Oak Lodge, Sidcup.

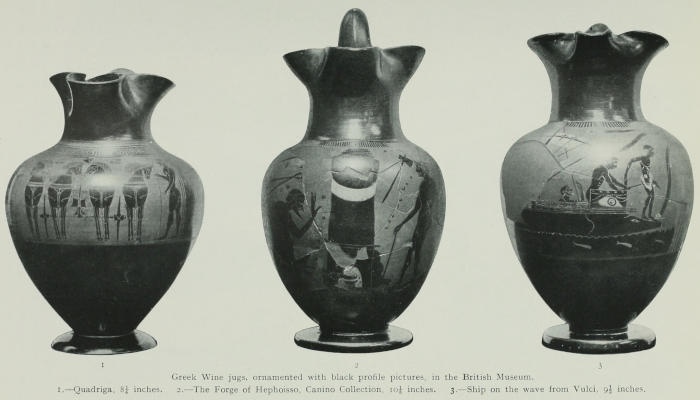

Figures in black profile join hands round the wine-cups and oil-jars made by Etruscan potters; in silhouette men are armed to battle, women weave cloth and grind corn, children play at ball and knuckle-bones, life-like in shadow.

There is a pageant of profile portraiture on the mummy cases and frescoed tombs of ancient Egypt. Strange peoples are shown in outline as they lived; they go to war, they marry, their children play, the ritual of their Book of the Dead is pictured in profile three thousand years before the Christian era.

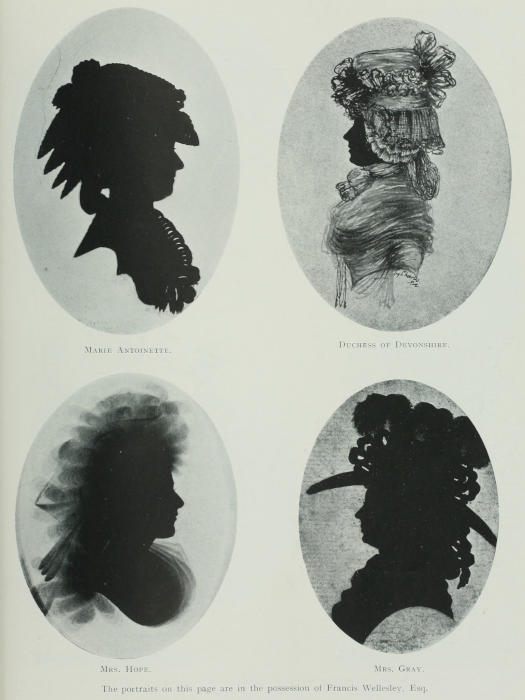

These flat and unsubstantial ghost figures come to us down the ages. From those mystic times when Crates of Sicyon, Philocles of Egypt, and Cleanthes of Corinth first worked in monochrome, there is an unbroken tale of men and women who have lived, loved, hated, and triumphed—Pharaohs and their slaves, Greek gods, and athletes; a French king, a murdered queen; Napoleon and his generals; statesmen and politicians; Goëthe, Beethoven, Burns, Wellington, Dickens, Washington, Harrison, Scott, and ten thousand others down to the present day. They come as colourless ghosts, relics of bygone men and women, shadows caught and held, while the realities have flitted across life’s stage and vanished.

Old Omar Khayâm, “King of the Wise,” in the twelfth century knew

He had not been busied with winning knowledge without seeing the deep significance of the shadow portrait. The familiar figure of the showman whose lantern displays the black moving figures in the midnight streets of Teheran appealed to him with vital force. He uses the shadow picture constantly as a simile in his matchless quatrains—

The subtle appeal of the silhouette is inevitably associated with death, in its legendary origin. Filled with joyous anticipation, thrilling with the thought of the woman he would soon hold in his arms, a lover returned after a short absence to find that his betrothed was dead; he rushed into the death chamber, maddened with grief, to look his last on the face of his beloved before it should be hidden from him for ever. There on the wall the shadow of the dead woman’s features appeared in perfect outline, for a taper at the head of the bier cast the shadow. With reverent hand the man traced the portrait, which he believed to have been specially sent as consolation.

There are other variants of the story. The Greek legend attributes the invention of painting to the daughter of Dibutades. Knowing that the passion of her lover was waning, she furtively sketched his shadow on the wall as he stood with the sun behind him. We are not told if this delicate way of indicating that even a shadow outline can be made permanent by a sufficiently determined young woman was of any use in making the love of the inconstant swain indelible.

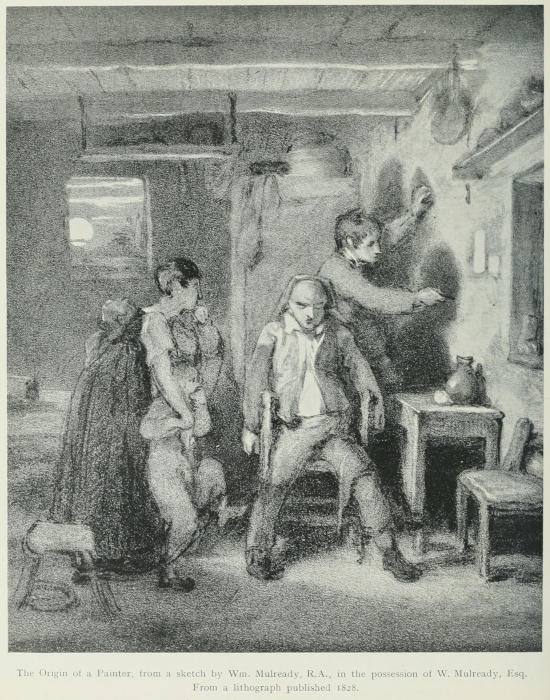

Many artists have illustrated different phases of the basic idea as to the shadow having first suggested portraiture. Le Brunyn, Schenan, B. West, R.A., and Mulready are some of them.

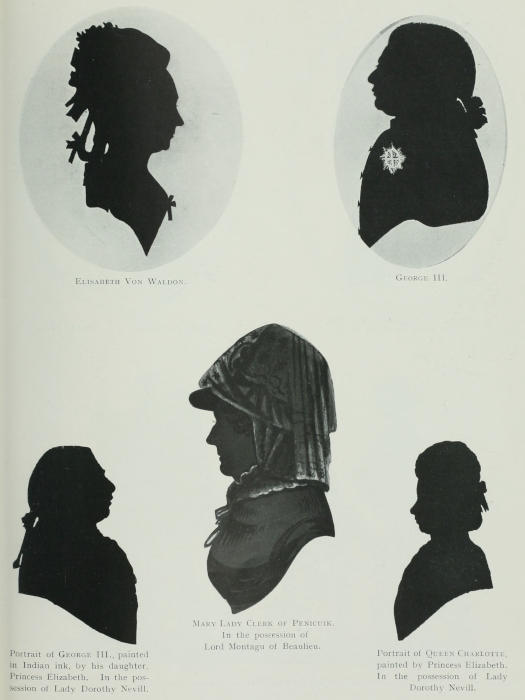

We make no apology for studying the history of this art of[5] the silhouettist in its latter-day manifestations. At its best, black profile portraiture is a thing of real beauty, almost worthy to take its place with the best miniature painting; at its worst, it is a quaintly appealing handicraft, revealing the fashions and foibles, the intimate domestic life and conventions of its day. It was executed by so many distinguished amateurs, from Etienne de Silhouette himself to Queen Charlotte and Princess Elizabeth of England, that few social histories or collections of letters of the eighteenth century fail to show how its strange chequer fitted into the fashionable life of the period.

Surely it is high time the art of black profile portraiture had a historian of its own and the great masters of silhouette portraiture were rescued from oblivion. Shadows are impalpable things which fade away almost before we are aware of their existence.

Year by year accident and the ravages of time lessen the number of these fragile curios; the beautiful portraits on ivory and glass, being the most fragile, are the first to go. Already it is not easy to find good examples in their original frames complete with convex glass and trade label of the artist pasted on the back. Mutilated examples with cracked wax filling or plaster paintings, chipped and incomplete, are still to be found; but even these have often been reframed, or have been broken open to renew glass or back, and so the trade label has been lost. The searcher who hopes to be successful in his quest has now to go very far afield, unless he be satisfied with the paper pictures of indifferent quality, interesting perhaps on account of the identity of the sitter or the fame of the cutter, but very far from equalling in beauty the best work of the masters in black profile portraiture. Some enthusiasts maintain that the least artistic profile shadow portrait has a curious individuality which redeems it from overwhelming ugliness; certainly the infinite variety of[6] the processes and the fresh and vigorous outlines in unexpected media give a charm to the portrait in monochrome.

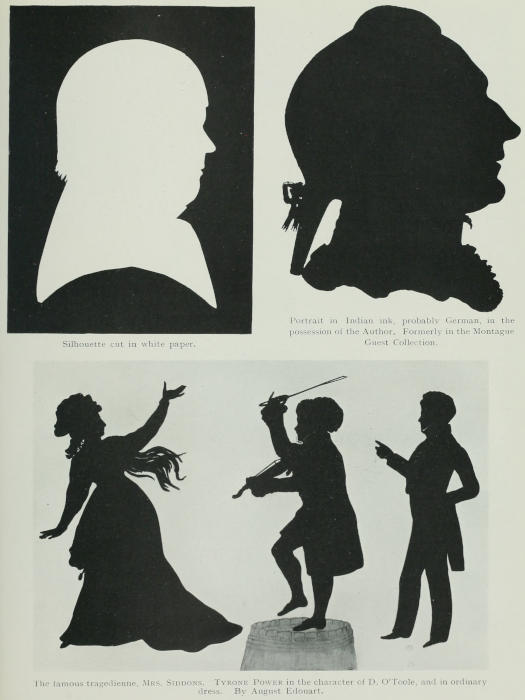

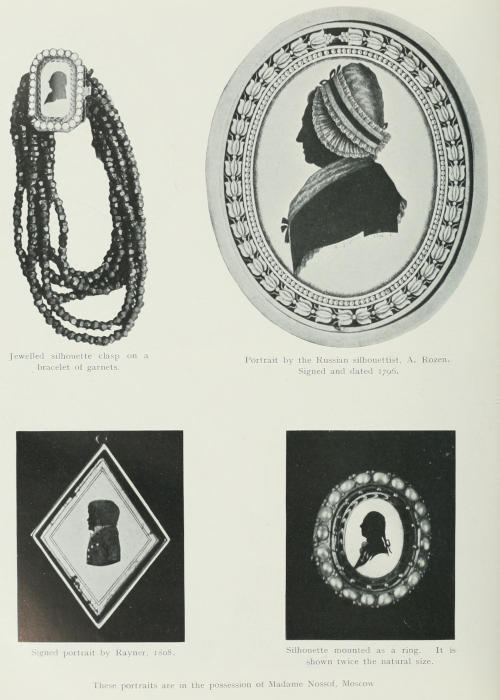

There is no sequence in the production of the different types. Some of the earliest specimens were cut in paper, for Mrs. Pyburg is said to have cut out the portraits of William and Mary in 1699; and certainly some of the beauties of Versailles were cut by Gonard in paper; the mid-Victorians worked in paper, and there are still a few cutters busy with their scissors. Glass, ivory, and plaster, oil-painting, smoke-staining, and Indian ink, all were used one by one or together. There is no evolution and gradual development to trace in the art and craft of the silhouettist; the pictures come before us like the shadows that they are, each process appearing and disappearing. Sometimes the same man worked in half a dozen different processes, using now one and now another, according to the taste or purse of the sitter, or guided by his own judgment as to the suitability of his subject for this or that medium of expression. The miniature shades for mounting in rings, brooches, scarf-pins, and pendants were not done exclusively by a few men, as one might surmise from their rarity; they were painted with the delicacy of a miniaturist by many of the silhouettists, who usually painted silhouettes of ordinary size. These jewel shadows are now very difficult to find, and it is probable no such collection as that of the late Mr. Montague Guest will ever come into the market again.

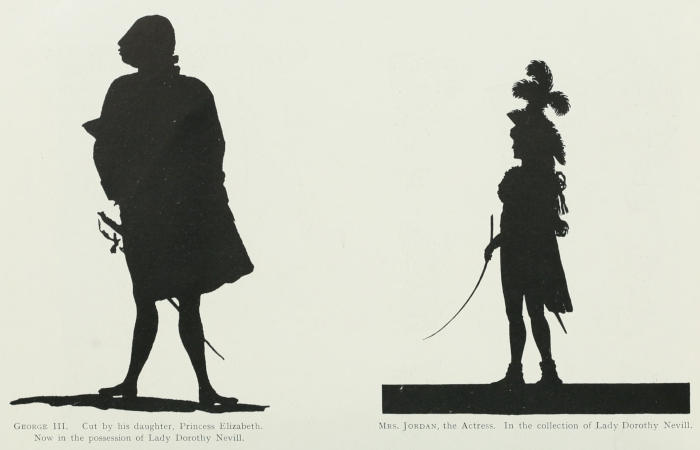

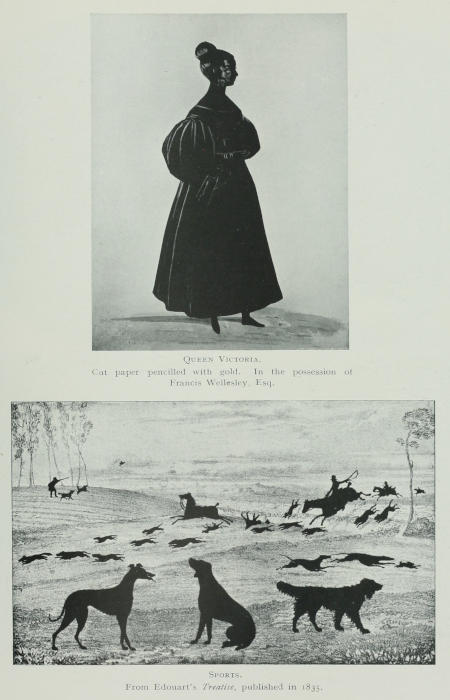

Into the lives of great personages, such as Goëthe, Napoleon, our English kings, queens, and princesses, the silhouette creeps with colourless persistence; there is no escaping it. Goëthe writes letters to his mother, and to Lavater, being touched with enthusiasm for the silhouette and its uses by the zealous Zürich minister. The poet cut a few himself. Napoleon presents glass profile portraits of himself in black on gold tinsel ground to[7] his generals. Princess Elizabeth, daughter of George III., is a famous scissor-woman, and many are the pictures she cut, not only of her father, mother, and sisters, but also of trees, birds and flowers, rural scenes, cupids, and cupid groups.

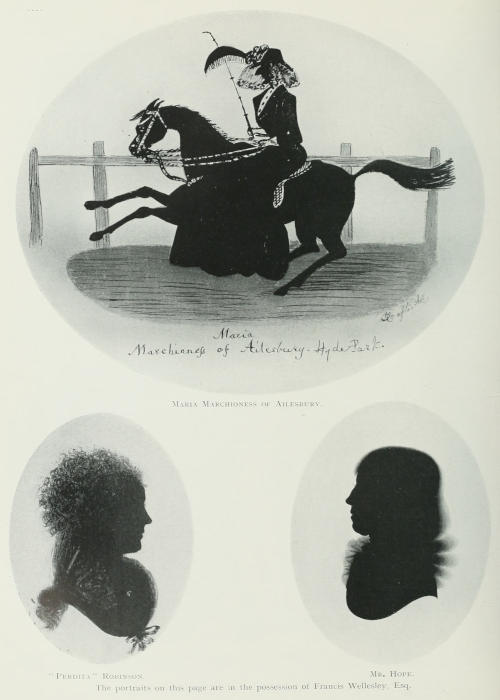

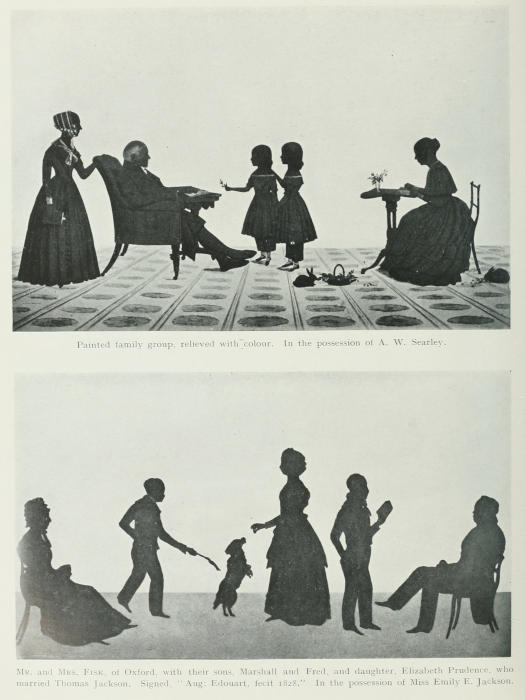

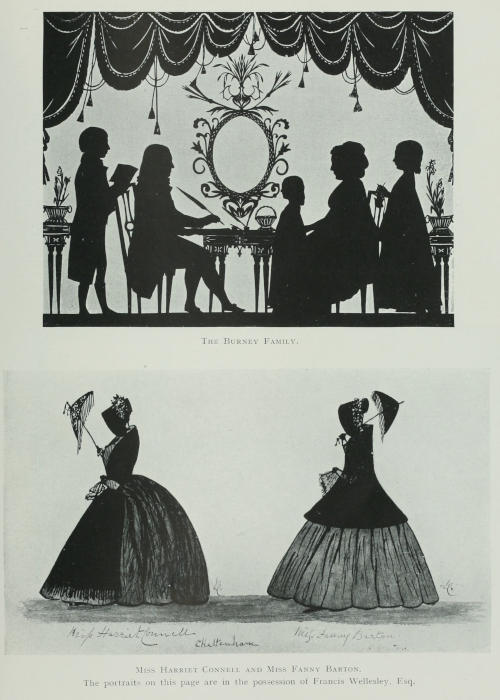

Fanny Burney delights in the black portraits; all the Burney family are grouped together. She records her visits to the silhouettist Charles, when her attendance on the Queen as Maid of Honour was over. This portrait shows the famous creator of “Evelina” to be sprightly indeed; her delicate profile is well set off with curled and powdered hair, lace ruffle, and beribboned hat, whose tilt must surely have been learnt at Versailles.

Pepys lived too early to have his shadow taken. We feel sure the old coxcomb would have had a dozen of himself, mighty fine in new clothes, and perchance, if in generous mood, a single one of his wife in her old ones. [My father’s profile, cut in paper, is spoken of by Bulwer Lytton in “The Caxtons,” in the second volume.]

Horace Walpole, in his letter to Sir Horace Mann, written in 1761, desires him to thank the Duchess of Grafton on his behalf for the découpure of herself, this being, he explains in a note, “her figure cut out in card by M. Herbert, of Geneva, who was famous in that art.” This allusion at this early date again indicates that the cut silhouette was the earliest, as it certainly is the last survival, of the art. The scissor-type, it is still called by the old inhabitants of Suffolk, who well remember the visits of the itinerant artists.

Strange confusion has arisen in the minds of many admirers of silhouettes on account of the name. Black profile portraiture was practised long before Etienne de Silhouette economised in the public finance department of Louis XV., and the wits of the day nicknamed “silhouette” whatever was cheap and common.

In Swift’s “Miscellanies,” ed. 1745, vol. x., page 204, is a whole series of poems (full of the most eccentric rhymes) on silhouette portraits, e.g.:—

“On Dan Jackson’s Picture Cut in Paper.”

Swift, “Miscellanies,” vol. x., p. 205.

Another.

Swift, “Miscellanies,” vol. x., p. 206.

Another.

Now, Swift died in 1745, and may be said to have died to literature some years earlier. Silhouette’s cheese-paring economy was, we are told, induced by the deficit entailed “by the ruinous war of 1756,” consequently it could not have been before 1760 that his name would have become synonymous with cheapness. We thus have evidence that the art was in use at the least twenty years before his name could have been applied to it; and it does not at all appear that it was new then, as Mrs. Pyburg cut William and Mary’s portrait out of black paper in 1699. This nomenclature must, therefore, have been caused by his adoption of it as a pastime, and not by the reason given by I. D’Israeli and the Dict. Hist. This is an instance of how easily false derivations may be published even within so short a time of the events for which they profess to account.

A very slight study of silhouettes shows how characteristic is the pose of many of the old black profile portraits. In the shadow of George III., do we not see the embodiment of Lord Rosebery’s inimitable description, “the German Princelet of his day,” and in Pitt’s silhouette, with its “damned long, obstinate upper lip,” as his royal master so vigorously described it, there is the very ego of the man who was premier at twenty-five.

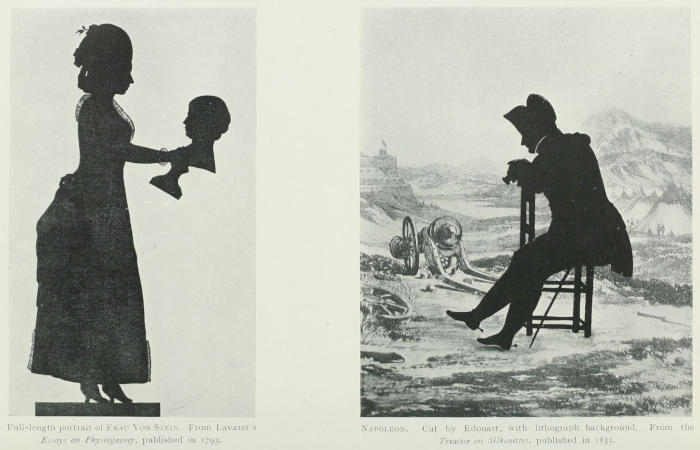

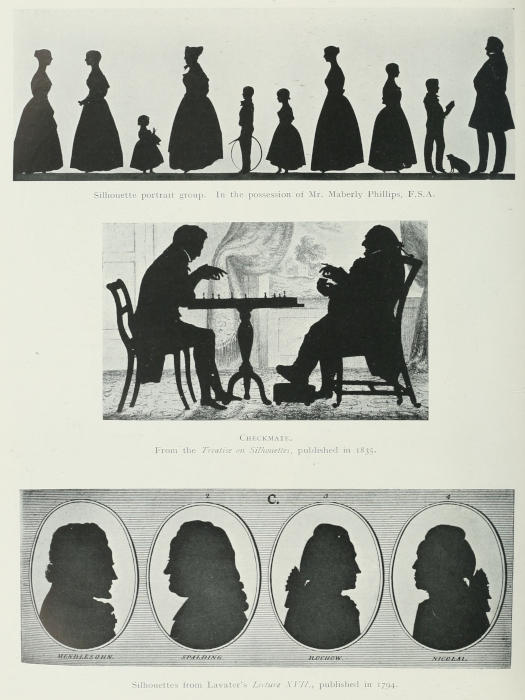

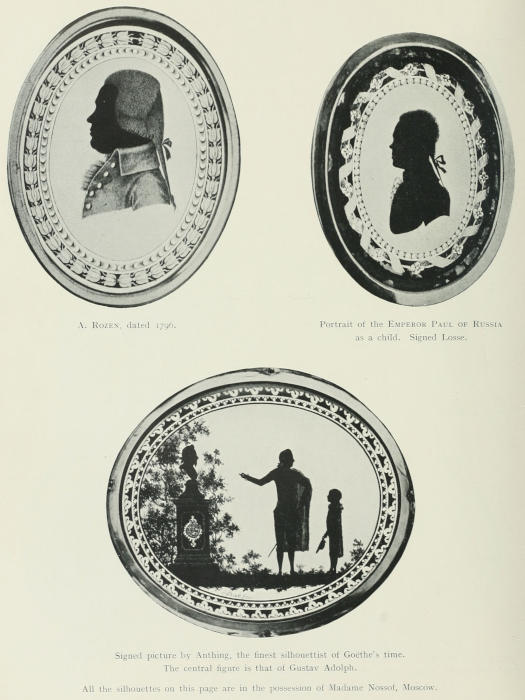

Goëthe’s letters to his mother are full of allusions to the[10] novel portraiture which had been brought to his notice by Lavater, the Zürich divine, whose essay on Physiognomy, written for the promotion of the knowledge and love of mankind, is still read in Germany. The edition of 1794 is before us, and shows hundreds of silhouette drawings, for he wrote of the importance of reading character from people’s faces, and used the silhouette for this purpose. Thus the shadow portrait, once the amusement of amateurs, now began to have scientific significance.

Goëthe testifies that Lavater wished all the world to co-operate with him, and he arrived at Goëthe’s house on June 23rd, 1774, not only to take portraits of the young genius, but also of his parents. A year later Goëthe implores Lavater in a letter, “I beg you will destroy the family picture of us; it is frightful. You do credit neither to yourself nor us. Get my father’s cut out and use him as a vignette, for he is good. You can do what you like with my head too, but my mother must not stand there like that!”

An amusing sequel to this is that when, in the third volume of the “Physiognomy,” the councillor’s portrait appeared, but not that of Goëthe’s mother, she was much annoyed, and said that Lavater evidently did not think her face worthy to appear. The matter rankled, for in 1807 she had her head examined by Dr. Gall, “to find out if the great qualities of her son had, by any chance, been passed on to her.”

This much discussed silhouette of Goëthe’s mother is illustrated in “Goëthe’s Mother,” by Dr. Karl Heinemann, and fuller accounts of the poet’s attitude towards the silhouettists of his day, and the instructive and exciting deductions from their work, will be found further on in our volume.

In a letter from Fräulein von Göchhausen to Frau Rath—we use the translation of Mr. A. S. Gibb—the delight in the novel[11] portraiture is shown, and incidentally the vivacity of the writer:—

“Weimar, the 27th December, 1781.

“I am sure, dearest mother, that you in your life have had many and varied joys; but whether you know any such joy as you have given me on Christmas Day, at least I wish it you! Your silhouette, so like! of such an excellent, dear, beloved woman! in such a costly, pretty, and stylish setting; and your letter—O your dear letter!—could I only say how indescribably admirable the letter is! Enough, dearest mother: from all my exclamations there is, alas, nothing further to be learned than that I am half out of my wits with excessive joy. The first day Goëthe had much to bear from me, for I almost ate him up. By monstrous good luck there was on that joyous day a grand dinner at the Duchess’s, and nearly half the town was assembled. I could, therefore, produce at once my splendid present (which will not so soon come off my so-called swan-like neck); and there was a questioning and a glancing at the beautiful novelty, and I was thoroughly wild, and people thought I must have had a gift of clear quicksilver.[1]

“Dearest woman, how shall I thank you! how ever deserve so much goodness—so without all desert and worthiness on my part! In return, I can, alas! do nothing, except to go on in my old jog-trot—love, honour, and obey you my life long. Amen!

“L. Göchhausen.”

[1] This seems a strange expression; but at that time, when anyone showed a restless activity, they would say that someone had given them quicksilver.

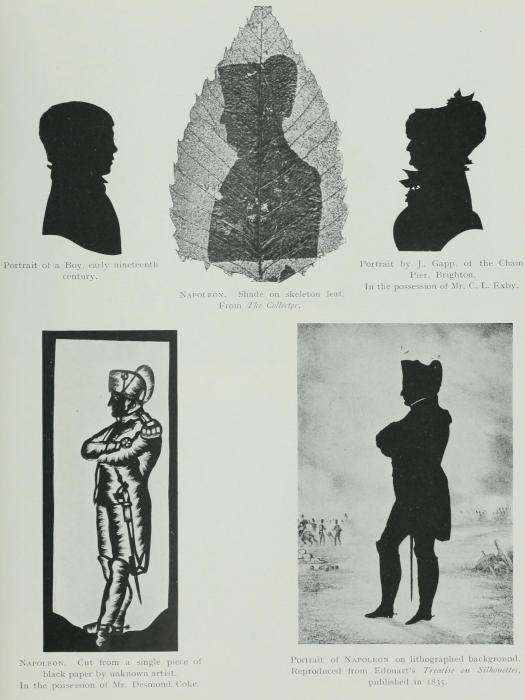

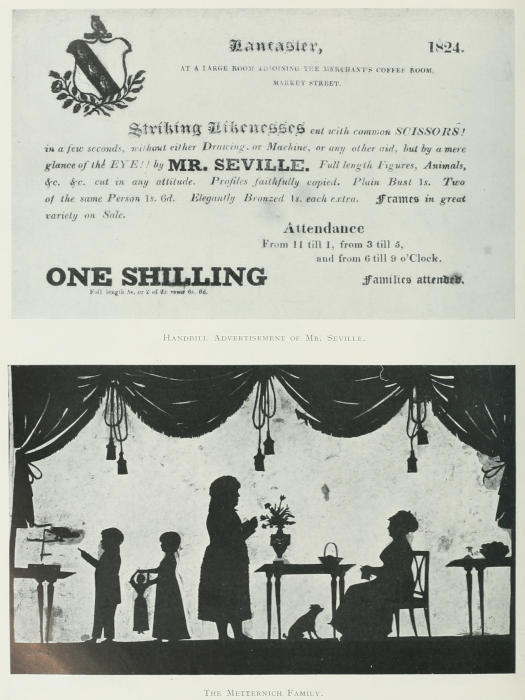

Later the craft of the silhouettist fell into disrepute when it had become part of the curriculum of young ladies’ schools; unskilful artists itinerated, pursuing their craft in booths and at fairs—one in the Thames Tunnel, several on the Chain Pier at Brighton. At street corners magic figures, with concealed workers, were used to entice the unwilling with mystery. Even Sam Weller, in his inimitable letter to Mary, laughs at the methods of the “profeel macheen.”

“So I take the privilidge of the day, Mary, my dear—as the gen’l’m’n in difficulties did ven he valked out of a Sunday—to tell you that the first and only time I see you your likeness was took on my hart in much quicker time and brighter colours than ever a likeness was took by the profeel macheen (wich p’raps you may have heerd on, Mary, my dear), altho’ it does finish a portrait and put the frame and glass on complete, with a hook on the end to hang it up by, and all in two minutes and a quarter.”

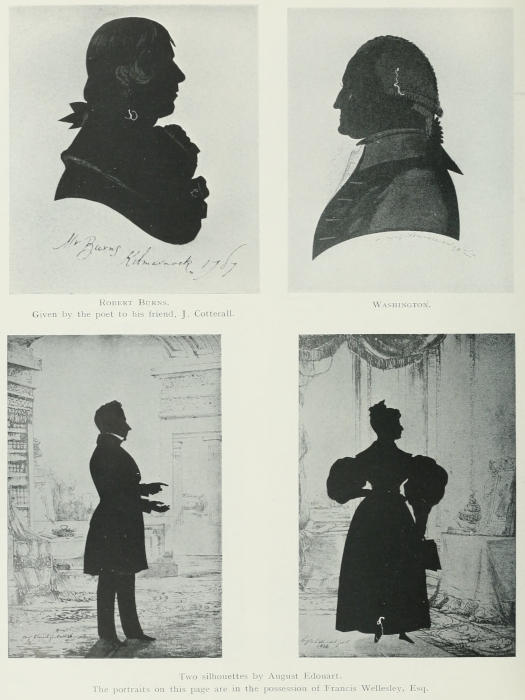

Such is the story, in brief, of the silhouette. Sometimes we see in it a little social document, elevated by fortuitous circumstances or scarcity of other pictorial record to historical value. As in the case of Robert Burns’s portrait, by J. Miers, and that of his brother, Gilbert Burns, by Howie, in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, at all times it is passively charming. Surely we need not scorn this step-sister of photography—this poor relation of the art world. In the words of Seraphim, when, in 1771, he flung wide the doors of his Shadow Theatre at Versailles—

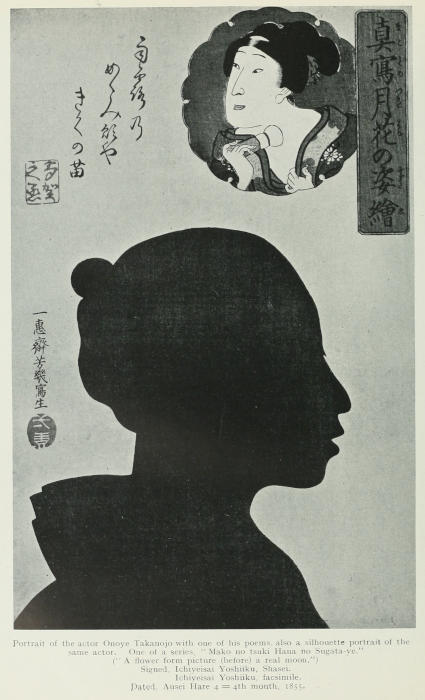

There is a simplicity in the silhouette picture which brings it nearer to the Japanese print in its effect upon the mind than any other expression in art. All our attention is concentrated on outline, and in consequence there is a directness and vigour in the likeness which are lacking in more complex studies. Some Japanese artists, recognising this peculiar quality in the black profile portrait, supplement a conventionally drawn coloured portrait with a silhouette.

In Europe, during the last decade of the eighteenth century, the time was ripe for some popular outlet for the newly awakened interest in the old Greek classical method, for the recently excavated wonders revealed at Pæstum and Pompeii had appealed strongly to the popular taste, causing Greek purity of line and simplicity to dominate all ornament.

There was a natural rebound towards simplicity after the over-gorgeous detail in all domestic decoration under Le Roi Soleil, though exuberance survived for many years; the Greek influence may be traced from the latter half of the eighteenth century. Gradually the rococo absurdities disappeared; purity of line came back to architecture, and was manifested in furniture, in damask, brocade, and all ornamental expression, until at the beginning of the nineteenth century the mode in building design, decoration and dress was of the First Empire, and that is pure Greek.

The silhouette was another answer to the demand which gave us the reliefs after the antique which Flaxman and Josiah Wedgwood supplied.

At first these paper portraits must have seemed grotesquely cheap and ineffective to men to whom portraiture had hitherto meant a painting on canvas or panel, a delicate miniature, or an enamel of Limoges; but economy was in the air, the palmy days of reckless expenditure on personal matters by the few were over. Marie Antoinette was soon to wear India muslin instead of costly hand-made lace—very soon she might not even wear her own head; the gorgeously painted equipages of the Martin Brothers would give way to the less costly tumbrils. The days of fustian and the proletariat were coming; paper portraits instead of painting; then the apothecary picture-man, as Ruskin calls the photographer Daguerre.

The silhouette was the pioneer of cheap portraiture, which is now so great a factor in modern life. No wonder that, like all pioneers, the shadow portrait was made the butt of the wits.

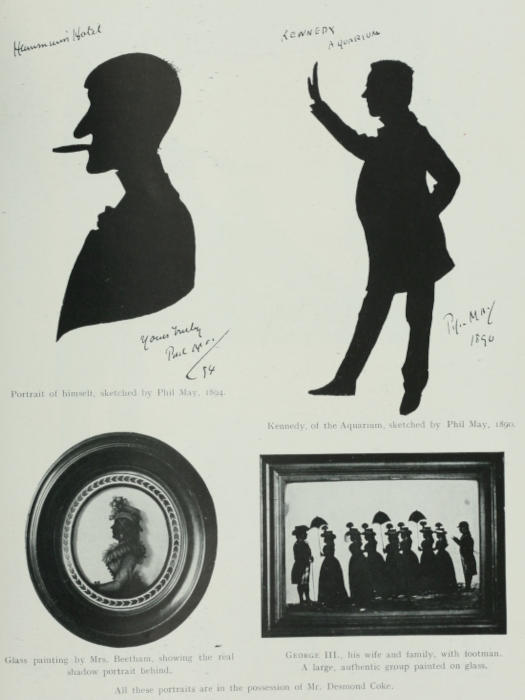

Born in France, flourishing greatly in Germany, the silhouette soon reached England, and penetrated to the middle class, through the upper classes and court circles, the first English cut portrait that we can find record of being the cut silhouette of William and Mary in 1699. Then, while such men as Gonard were working in France, some of our best English exponents came to the fore. Miers, first of Leeds, then of London, painted generally in unrelieved black on plaster or ivory; John Field, his partner for thirty-five years, whose studio was thronged at 11, Strand, close to the old Northumberland House, which has now given way to Northumberland Avenue. Mrs. Beetham painted in shadowgraphy with exquisite skill, some of her jewel portraits rivalling the finest miniatures in quality. Charles, of 130, Strand, worked in Indian ink with pen on card, and produced such beautiful work that his trade description, “the first Profilist in England,” may well be excused.

It is interesting to note the very varied nomenclature of this art[15] of black profile portraiture. H. Gibb and many others, besides Charles, call themselves Profilists.

Skiagraphy is used early.

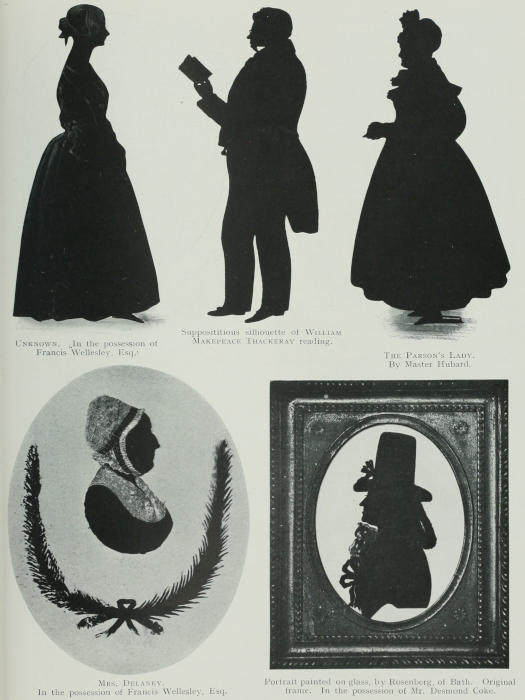

The fashionable Shade is mentioned by half a dozen diarists and social writers of the eighteenth century, and was in more common use early in the nineteenth century. Horace Walpole gives us Découpure. Scissargraphist is used by Haines, of Brighton; in rural districts in Suffolk silhouettes are still called Scissartypes, quite regardless of whether the picture is of cut black paper or done with brush or pencil. Hubard, of Kensington and American fame, calls himself a Papyrologist, and his art that of Papyrolomia. In the Art Journal, 1853, p. 140, we read Papyrography is the title given to the art of cutting pictures in black paper.

Shadowgraphy was frequently used by the artists who took the portrait in shadow with or without the patent chair and wax candle so carefully described by Lavater, while some silhouettists are content to describe themselves as artists.

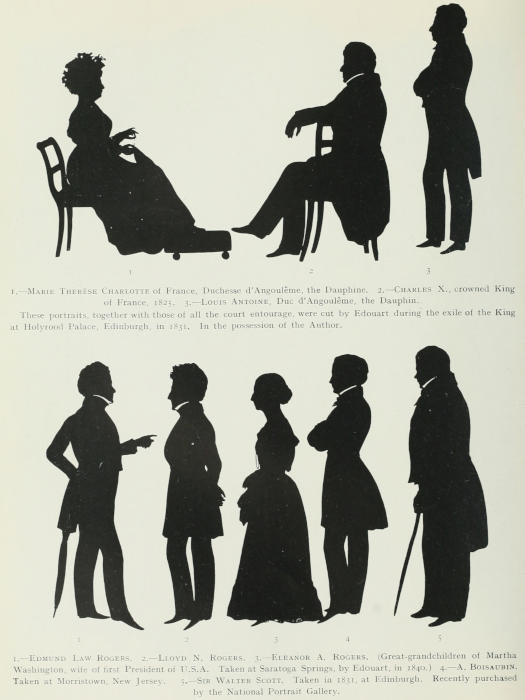

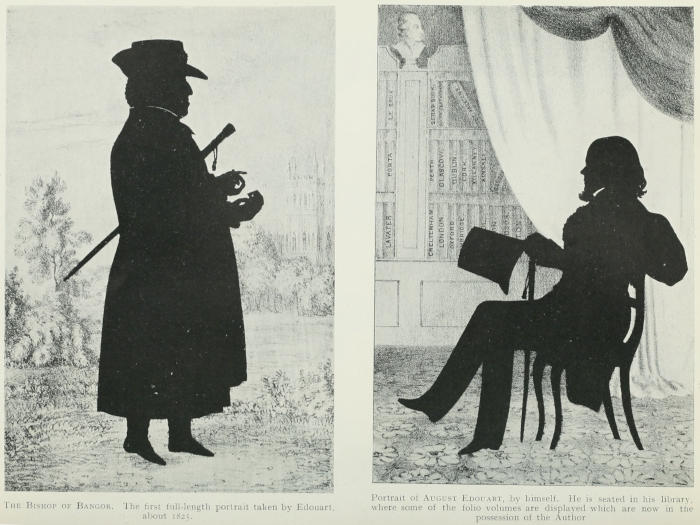

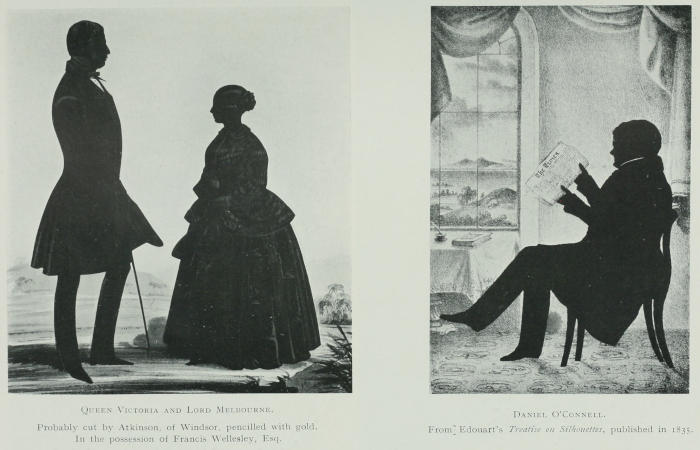

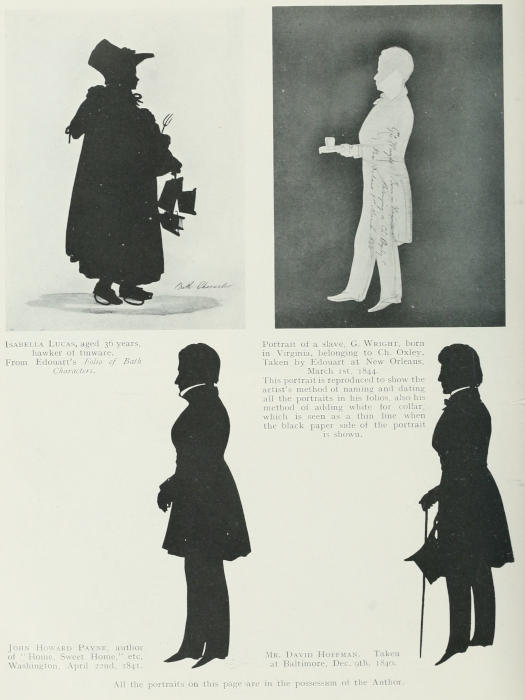

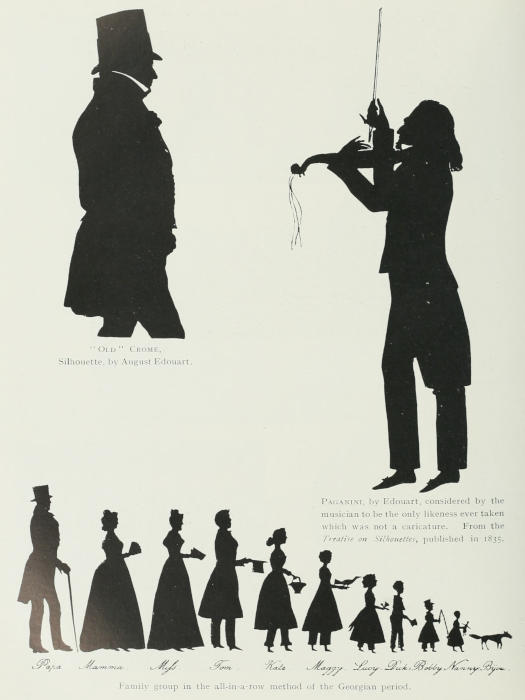

It was August Edouart, the Frenchman, who, wishing to emphasize the superiority of his methods over the machine-made shadows of his day, first used the words silhouette and silhouettist, or silhouetteur, in England. So great a novelty were these names that Edouart relates in his treatise how visitors constantly came to his salon to obtain the new silhouette portrait, and retired disappointed when they found it was only the familiar black shade which was offered to them.

Not only has there been much confusion in the popular mind with regard to the name of the silhouette, but also on account of the many different processes, and mixture of processes, used in their execution. Many silhouettists, as we have said, used several different ways of gaining the desired result. Mrs. Beetham, for example, painted exquisitely on ivory and plaster,[16] with and without gold; she also cut out black paper, pasted it on card, and finished the edges with softening lines of paint on the background. This artist also painted on plaster and also on glass, so that very considerable study is required in order to judge unsigned examples.

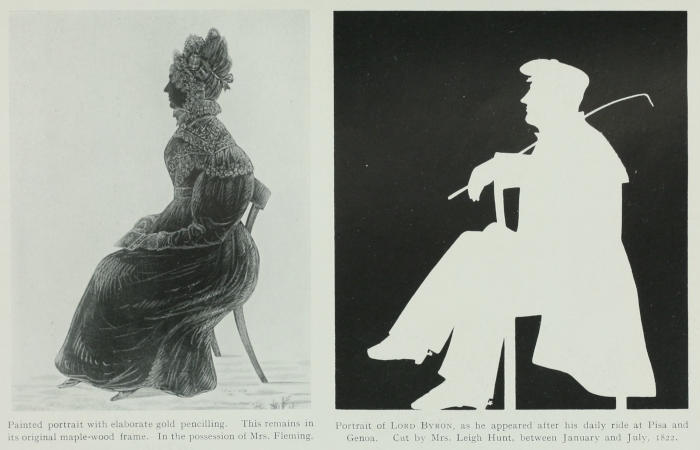

Occasionally the whole process in silhouette cutting is reversed, and not only is a white paper portrait mounted on black, as in Mrs. Leigh Hunt’s silhouette of Byron, but the portrait is cut as a hole in a sheet of paper, and, on placing black paper, silk, or velvet at the back, the portrait outline is seen. The author owns an interesting silhouette locket in this manner, but examples are rare in England, though there are several at the Congressional Library at Washington.

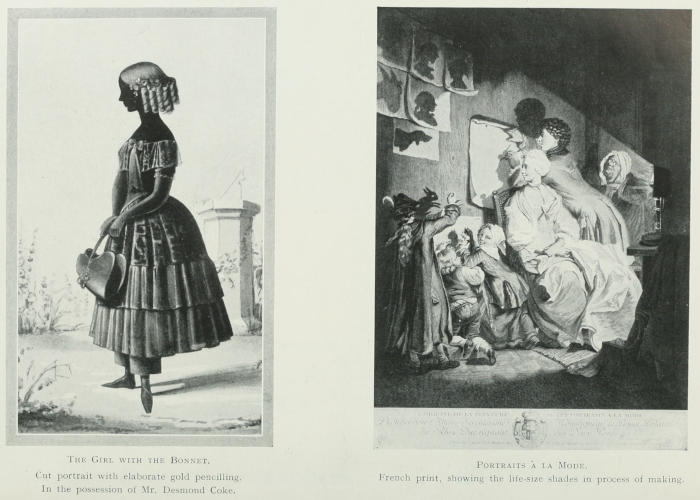

Shadow portraits began to receive popular attention about 1770. At this date a picture was painted by J. C. Schenan (1740-1806), who also worked under the name of Johann Eleazar Zeisig.

The picture, which was extremely popular, was called “L’Origine de la peinture ou les portraits à la mode.” This showed a modern version of the old Greek legend. A lady, in a modish cap and deshabille, is having her shade outlined by a youth who holds a paper against the wall. This is the first hint at the movable picture which can be executed in one place and hung elsewhere; hitherto the wall or ground itself has been in place of the canvas. Two children are in the foreground, one holds up the cat while the other wields the pencil; another child makes a rabbit shadow with his fingers. Against the wall are many shadow pictures, all life-size, including one of a man, a dog, and a donkey. The dedication of the engraving of this picture runs thus: “Dediée à Son Altesse Serenissime Monseigneur le Prince Paladin du Rhin Duc regnant des Deux Ponts.”

Silver Wedding Anniversary Picture with Portraits and Emblems.

In the possession of the Author.

A century before, Frances Chauveau engraved a picture by C. le Brunyn which shows the traces of a shadow portrait on the wall. The figures are in classical dress—the woman steadies her subject with one hand while she pencils the shadow with the other. A winged love superintends the process.

The popularity of such pictures was easily accounted for. Those whose accuracy of vision and skill of hand were insufficient to achieve the fashionable freehand scissor-work, saw in this tracing method an easy way of making the black profile portraits.

The tracing of shadow pictures was considered to be of Greek origin, and the enthusiasm for any art of Greek origin was assured, and the amateurs prospered.

The inevitable book of instruction for amateurs appeared in 1779 in Germany, “Directions for silhouette drawing, and the art of reducing them, together with an introduction dealing with their physiognomical use.” It must be remembered, in its early days silhouetting was supposed to be the handmaid of scientific research, and it was very many years before the artists in black portraiture threw off this pose in connection with their work. This book is published by Römhild, Leipzig.

Another little book of 258 pages, with eleven copper-plate illustrations, is now very rare, dated 1780; it was published by Philip Heinrich Perrenon, bookseller, of Münster. Rules are given, advice as to materials, the reduction of portraits, their finish, ornamentation, etc. Processes on glass, in relief, etc., are described.

Pantographs and other mechanical processes were invented, the names of such things varying from the high-sounding parallelogrammum delineatorium to the “monkey” indispensable for silhouette artists. Other books are described more fully in our chapters on the processes.

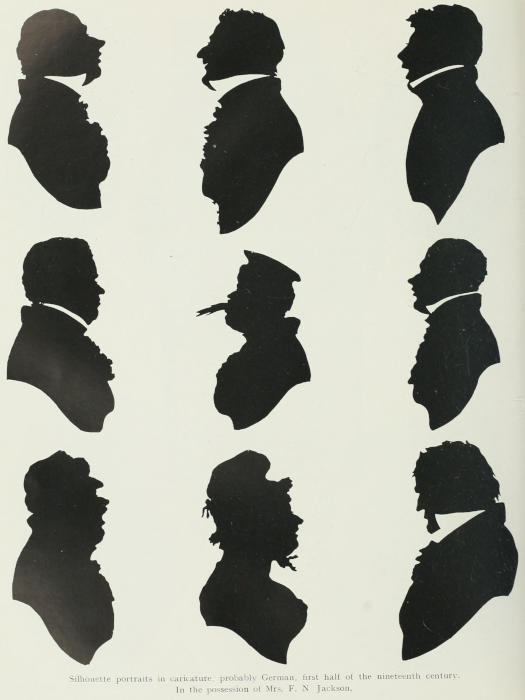

The silhouette mania affected the engravers of the day; black portraits in copper-plate appeared, and were used to illustrate histories and biographies. Also domestic scenes, with elaborate backgrounds, such as the death of the Empress Marie Theresa, which occurred in 1780. This was to be had of Loeschen Köhl, of Vienna, in the High Market, No. 488. It appeared in “An Almanack for the year 1786,” with fifty-three silhouettes, published by Loeschen Köhl.

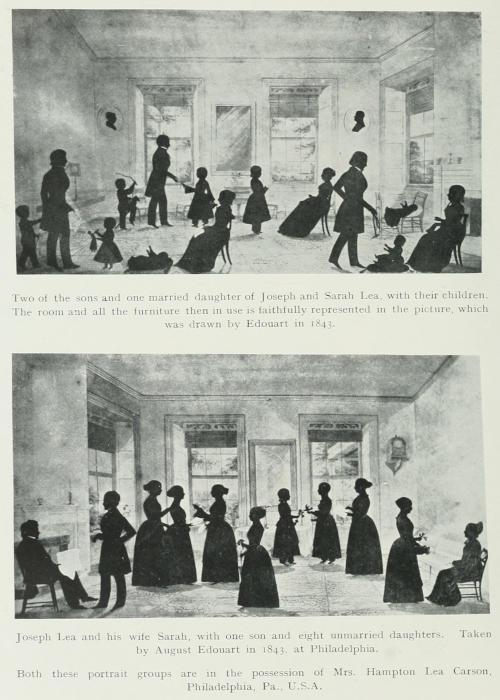

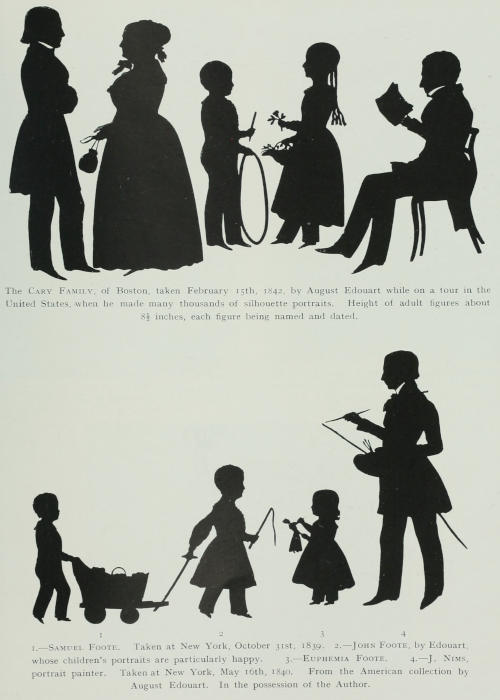

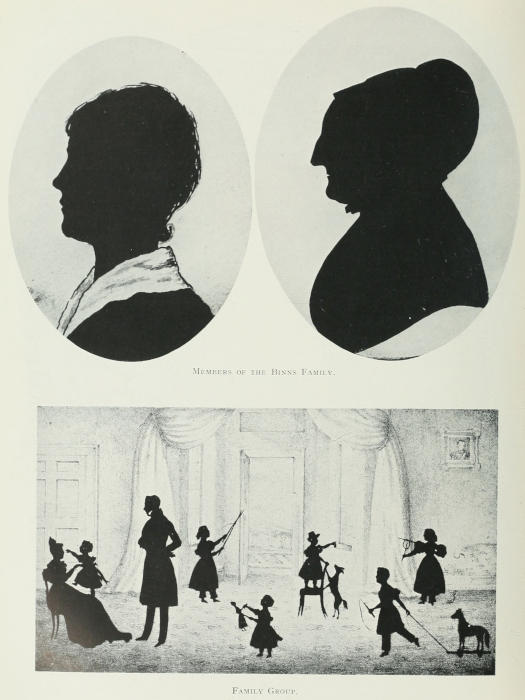

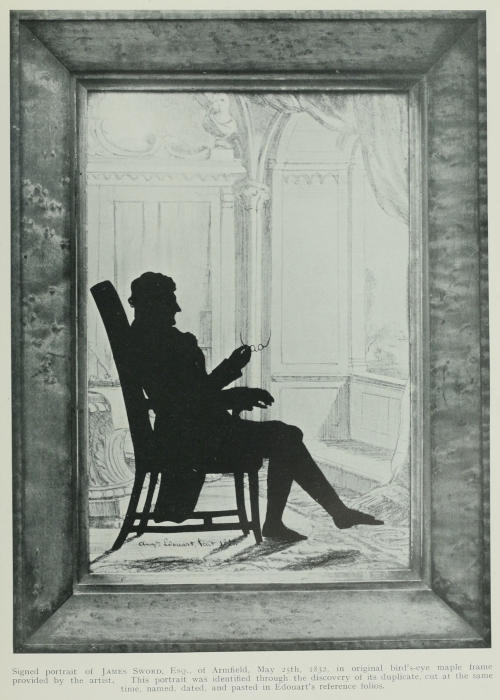

Large engraved silhouette pictures also appeared, and were sold separately, such as the Festivity on the Prater. Another variety now in the Höhenzollern Museum in Berlin shows Friedrich Wilhelm II., with his wife, four sons, and three daughters, walking in a garden. This picture is painted on glass, and is mounted on a red ground. Later, August Edouart achieved elaborate pictures, such as a skirmish of cavalry or sports. His figures were entirely scissor-work—and extraordinarily clever. The black portraits were mounted on drawn or lithographed backgrounds.

Many English books of a biographical nature were entirely illustrated with portraits in silhouette, notably, “The Warrington Worthies,” by James Kendrick, M.D., published in 1854 by Longman Brown, London; “Hints, designed to promote Beneficence, Temperance, and Medical Science,” by J. C. Lettsom, published in 1801, by J. Mawman. In the second volume of this work there are nine fine silhouette portraits.

In the memoir of Hannah Kilham, by her daughter-in-law, published by Darton Harvey, London, 1837, there is a beautiful silhouette portrait. Field, of the firm of Miers & Field, notifies on his trade label that he cuts silhouettes suitable for “frontispieces in literary work.”

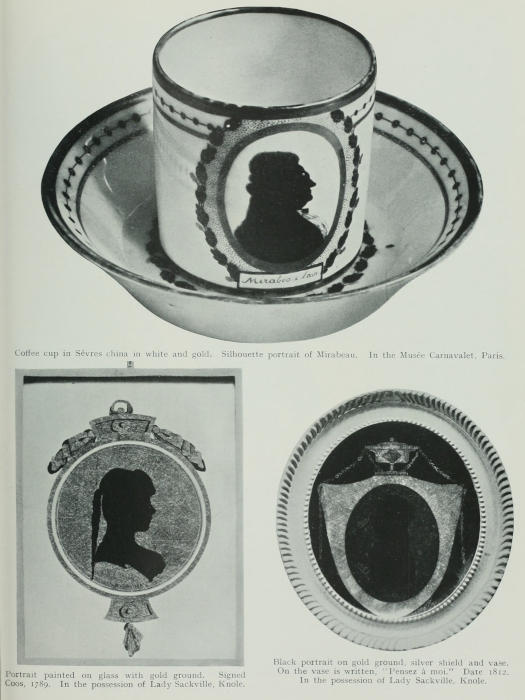

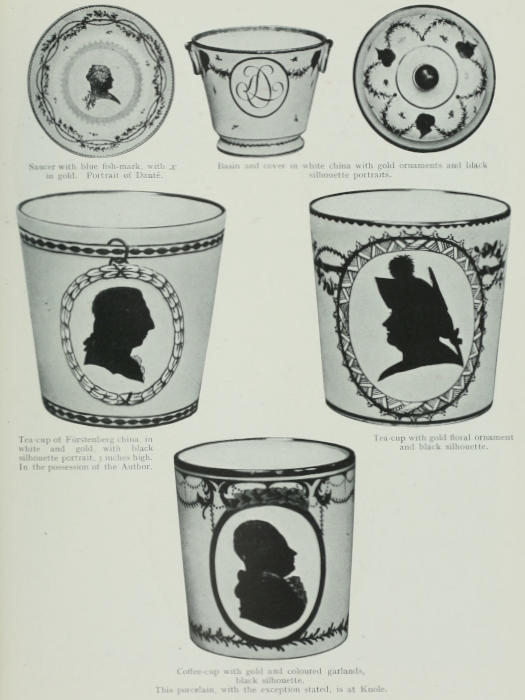

In the porcelain factories of England and Germany silhouette pictures were used for the ornamentation of gift-pieces, and also[19] for souvenir examples. In connection with such factories we may mention that a cup was made on which Dr. Wall, of Worcester fame, is painted in silhouette, and at the museum belonging to the Meissen factory, sixteen miles from Dresden, there is a portrait of Johannis Joachim Kändler, born 1706, King’s Court Commissioner and model master at the Royal porcelain factory. Rare and interesting specimens of silhouette porcelain are dealt with in a separate chapter. In glass, too, silhouette portraits were etched in gold leaf and in black on glass, which was then enclosed in another transparent layer of glass for protection.

The taste for the silhouette spread its glamour over many arts; it became vitiated on account of unskilled and inartistic work, and may be said to have fallen into disrepute in the early days of Queen Victoria.

It was then that the art of Miers and Field, Gibb and Charles, fell into the hands of unworthy exponents, whose works partake of the ineptitude of so much of the early Victorian art. There are silhouette portraits of the second quarter of the nineteenth century and later, which are amusing because of their vitality, interesting because of the people whom they portray, or because of a quaint bygone fashion; but with the exception of the work of Edouart, which stands alone on account of its superb technique, they are as a rule no longer examples which connoisseurs sincerely admire for their beauty. On the production of the real treasures of black portraiture the curtain was rung down about 1850. At that date the pageant of shadow pictures since the days of black outline on Etruscan vases ceased to be hauntingly beautiful, mystic, alluring; its subtle appeal was over.

Research regarding the processes by which the shadow portraiture was produced, results in a baffling amount of material. Besides the professional silhouettists, who worked on definite lines of their own, or who used several of the processes from time to time according to the wishes of the sitter and the purpose for which the portrait was intended, there was a very large number of amateur workers who used any materials that came to hand and any process or mixture of processes which seemed good to them for gaining the desired result.

The silhouette portrait produced by the brush on ivory, card, or plaster is not necessarily the highest type, although it approaches most nearly to the work of the miniature painter, for the technique of one or two of the cutters, such as Edouart, is so fine that it lifts this humbler process on to the highest plane. Many miniature painters of the eighteenth century worked alternately in black profile portraiture and colour. Silhouettes thus done are, in fact, original profile portraits in monochrome; the process employed for producing them has nothing to do with scissor or penknife cutting.

Those who know only the picture of more or less shiny black paper stuck on card by inferior cutters of the early and mid Victorian era, are apt to consider the silhouette beneath contempt from the artistic point of view; but the collector who has studied fine examples, and who knows many processes, understands that each variety has its special charm, and that many have an individuality and dignity which raise them to a very high level.

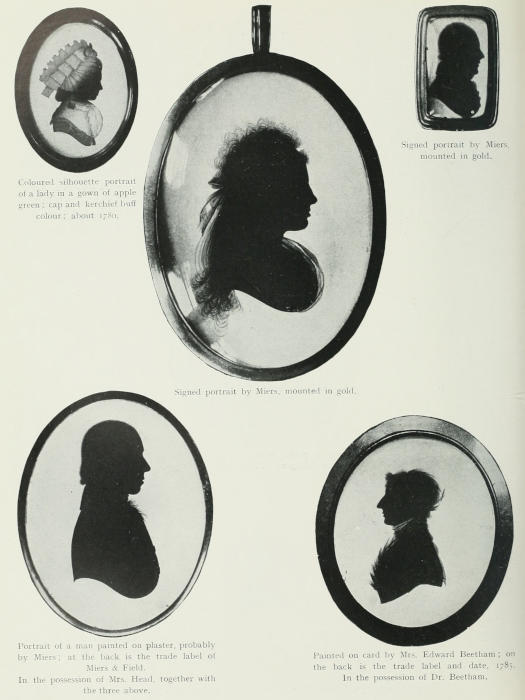

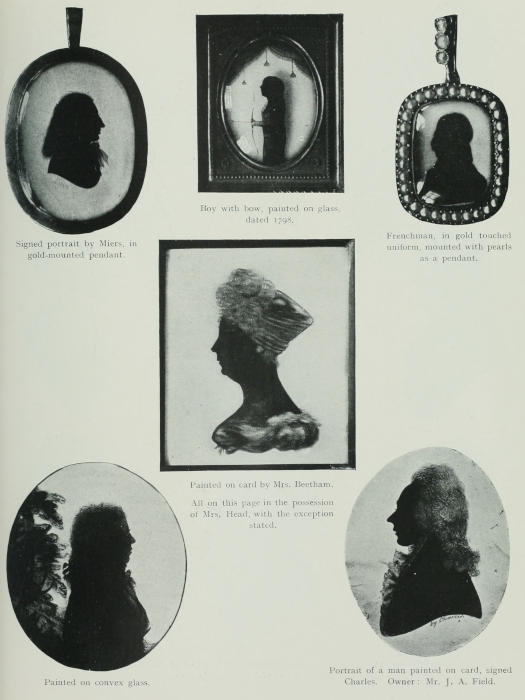

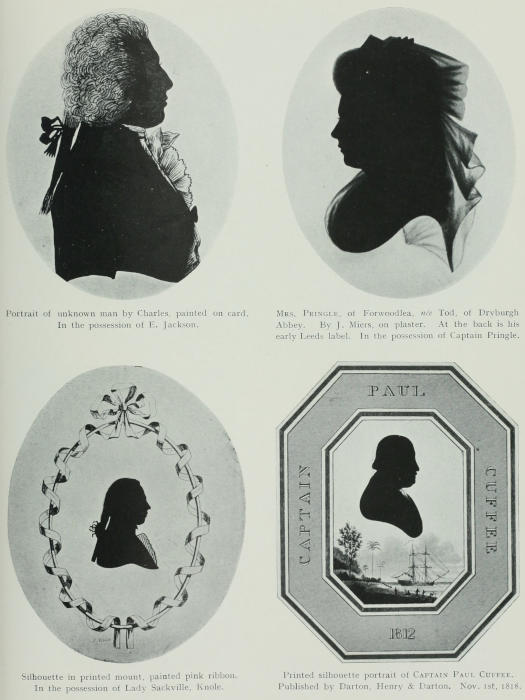

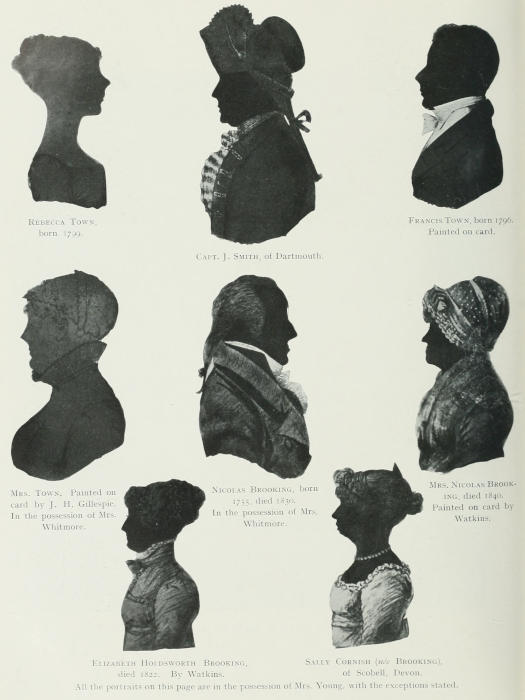

John Miers, whose silhouette of Robert Burns is in the National Portrait Gallery of Edinburgh, worked at Leeds, and afterwards had headquarters in the Strand, opposite Exeter Change, where he was in partnership for many years with John Field, another silhouettist, whose work is of very fine quality. On most of Miers’ work he is described as “late of Leeds.” His early business label in Leeds is extremely rare. It is on a fine portrait of a man which lies before us. This is painted on plaster, and, like nearly all his early work, is untouched with gold.

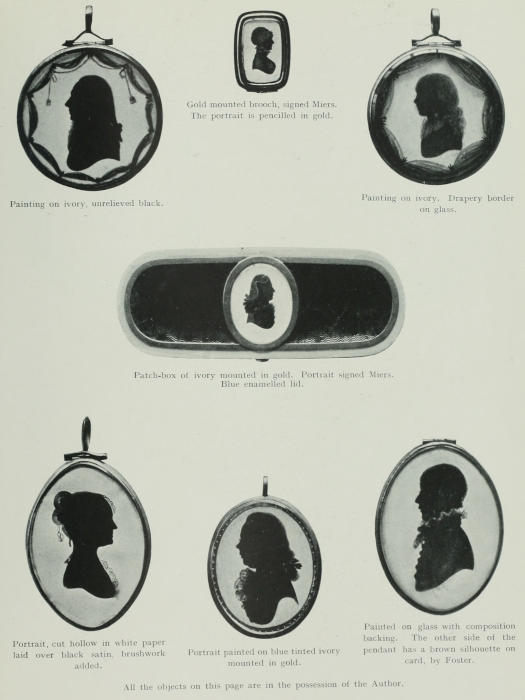

Miers did an enormous amount of work on plaster and ivory, in the usual 2½ to 3 inch oval size, as well as the inch to half-inch size for mounting in rings, brooches, and pins. These latter are frequently signed “Miers,” sometimes “Miers and Field.” On a fine portrait by Field, during the time of the partnership with Miers, there is an advertisement on the back; the partners set forth the announcement at this period that they

“Execute their long approved Profile Likenesses in a superior style of elegance and with that unequalled degree of accuracy as to retain the most animated resemblance and character, given in the minute sizes of Rings, Brooches, Lockets, etc. (Time of Sitting not exceeding five minutes.) Messrs. Miers & Field preserve all the original shades by which they can at any period furnish copies without the necessity of sitting again.”

In the London Directory of 1792 John Miers’ name is first mentioned as “Profilist and Jeweller, 111, Strand”; in 1817, in the London Directory, “Miers & Son, Profilists and Jewellers”; ten years later, in Kent’s London Directory, 1827, “Miers & Field, Profilists and Jewellers”; and in the London Directory of the same date, “Profile Painters and Jewellers.”

Miers is frequently called the Cosway of silhouettists. This name is correctly suggestive in a double sense, for not only was he amongst the most charming and successful exponents of his art, as was Cosway, but his methods and brushwork on[22] ivory were, with well-defined limitations, identical with those of the miniaturist.

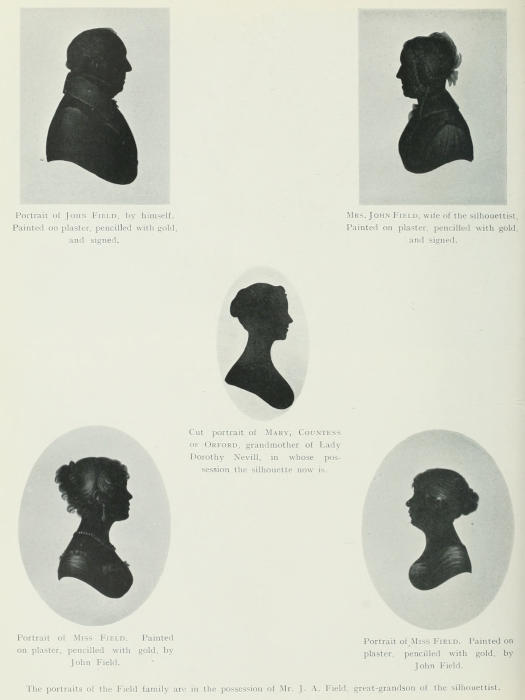

We are able to reproduce the portrait of John Field, the partner of Miers, through the courtesy of his great-grandson. This silhouette was done by himself, and that of his wife is a companion picture. Portraits also of his two daughters, Sophie, afterwards Mrs. Webster, and her sister, who married E. J. Parris, the artist who decorated the dome of St. Paul’s, are amongst an interesting collection belonging to the Field family. All these are painted on plaster, and beautified with exquisite pencilling in gold. The muslin cap and dainty neck frills of the artist’s wife are handled with great skill. Field’s shop was next door to Northumberland House, No. 11, Strand, and here he amassed a very substantial fortune. He usually had several apprentices, both male and female, in his studio, and his brother being a skilled frame-maker, the Field frames, in black papier-mâché and brass mounts, are very dainty, while the jewel work in gold and pinchbeck is always suitable and sometimes beautiful. After many years the partnership between Miers and Field was dissolved, as a cloud seems to have settled on the life of the former artist, and we have not been able to find details of his latter years.

Mrs. Beetham also painted in unrelieved black on ivory or plaster, and connoisseurs are divided in opinion as to whether her work should not bear the palm instead of that of Miers. Examples are much more rare. Her label on the portrait of a woman in cambric stock and ruffle runs thus:—

“Profiles in Miniature by

Mrs. Beetham,

No. 27, Fleet Street.

1785.”

Sometimes Mrs. Beetham cut black paper, and used a little brushwork in the more delicate hair outlines, softening the hard[23] paper line. This artist excels not only in the delicacy of her profile portraits, but also in the way in which she depicts, with the very limited materials at her command, the texture of hair, gauze, and ribbon ornaments.

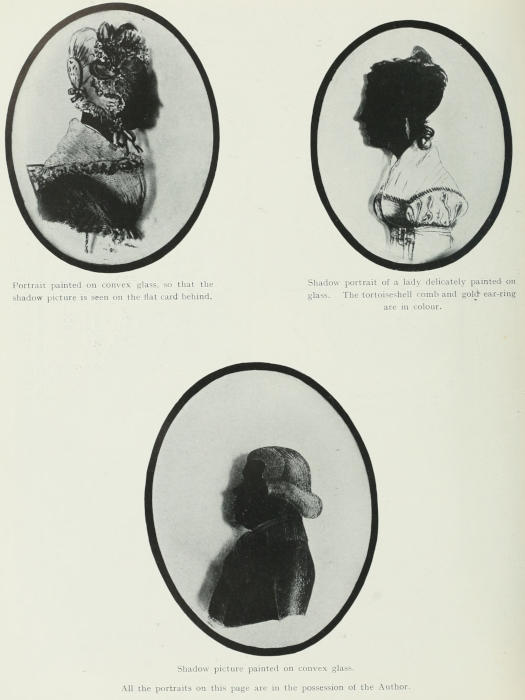

A third process employed by Mrs. Beetham was the painting on glass of flat or convex shape. The painting was done on the back of the glass, and usually a backing of wax or plaster was placed to preserve the portrait. As a consequence of this filling of wax, many of these old pictures have suffered severely from extremes of temperature, cold shrinking the wax and causing disfiguring cracks, and heat, when the portraits were hung on the chimney wall, as they so frequently were, being no less disastrous.

Occasionally a shade painted on convex glass is found with a flat composition card or plaster background, upon which, standing away behind the rounded glass on which the portrait is painted, a beautiful shadow is cast by the painting.

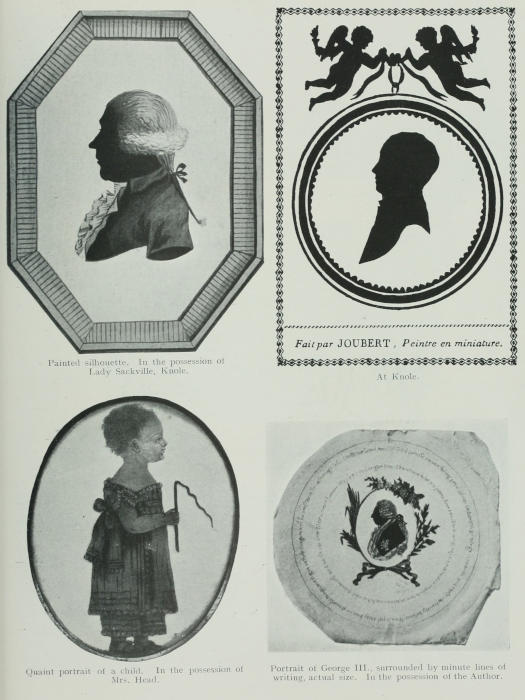

This is perhaps one of the loveliest embodiments of the miniature shadow portrait, created independently of all shadow tracing, for the portrait is simply painted on the inside of a convex glass; yet the shade is there, dainty, alluring, created through the workings of one of nature’s laws; the brushwork becomes of secondary importance, and nature’s shadow the likeness. Rosenberg of Bath (1825-69), whose son was an associate of the Old Water-Colour Society, was a proficient in this process. His advertisement is quaintly worded in the small card found pasted on the back of his framed specimens:—

“Begs leave to inform the Nobility

And Gentry that he takes most striking

Likenesses in Profile, which he Paints

On Glass in imitation of Stone.

Prices from 7s. 6d. Family pieces,

Whole Lengths in different Attitudes.

N.B. Likenesses for Rings, Lockets,

Trinkets, and Snuff-boxes.”

This unusual allusion to imitation on stone is doubtless written to attract those who, cognisant of the recent discoveries in Pæstum and Herculaneum, were on the alert for portraiture in profile and ready to patronise an art which was well in accordance with the return to Greek feeling in matters artistic.

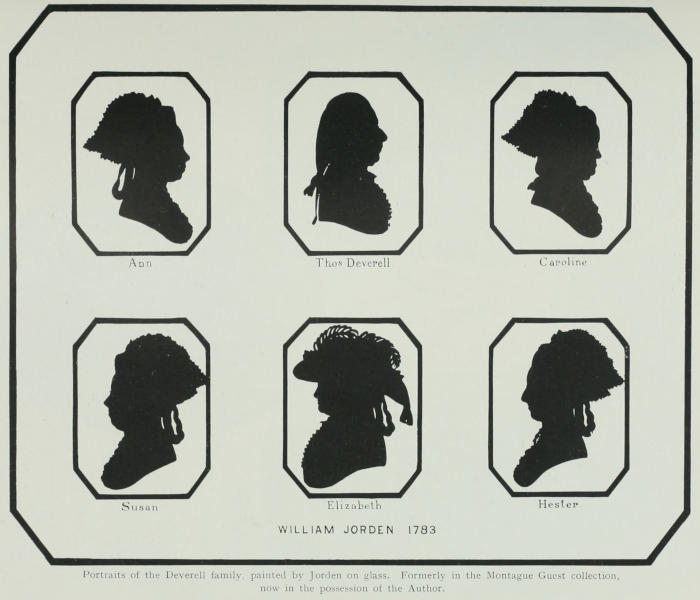

Another type of glass painting was executed by W. Jorden, who in 1783 painted the portraits of the Deverell family. These six fine examples show Thomas Deverell in ribbon-tied wig and shirt frill, Ann, Caroline, Susan, Elizabeth, and Hester; they were formerly in the collection of Mr. Montague Guest, and were sold for a large price at Christie’s. The work of Jorden differs considerably from the glass painting of other profilists, as he used flat glass instead of the convex, and his work is extremely bold and without detail, except in outline. He does not depend on any shadow casting for his charm in the work. Examples by Jorden are exceedingly rare.

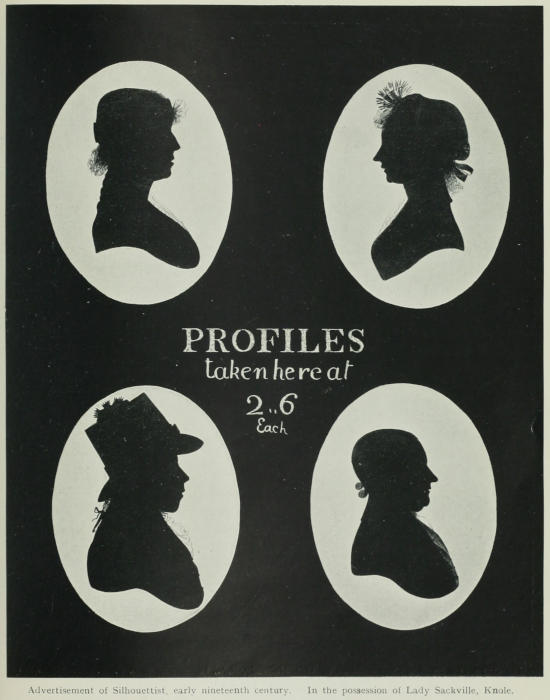

A. Charles was another profilist of the eighteenth century, whose work has extraordinary charm. He used Indian ink and fine line together with the solid black work. Sometimes examples are to be found where the draperies and dress are in colour. A good specimen in the original wood oval frame, in the possession of Mr. Rowson, has a trade label on the back as follows:—

“Profiles taken in a new method by A. Charles, No. 130, opposite the Lyceum, Strand. The original miniaturist on glass, and the only one who can take them in whole length by a pentagraph. They are also worked on paper and ivory, from 2s. 6d. to £4 4s. They have long met the approval of the first people and deemed above comparison.

“N.B.—Drawing taught.”

Glass portraits were executed with a mixture of carbon made with pine-soot and beer, which gives an intense blackness. The process was sometimes inverted, and the flat or convex glass having been blackened with pine-smoke all over, the outline of[25] the head or figure was then drawn in with a sharp point and the blackness removed, except where it served as the filling of the outlined objects to be silhouetted.

The back of such a portrait was then treated in one of the several different ways—gold leaf or gold tinsel paper was placed over the back, and was as a rule covered with a thin layer of wax, so that, looked at from the front, the silhouette portrait stood out from a gold ground; or, if the blacking process had been reversed, the gold portrait showed on a black ground.

Sometimes silver leaf was used instead of gold, and occasionally, as in the Forberger memorial picture in the Wellesley collection, and in a fine, small example at Knole, both gold and silver are used in the same picture.

In the Graz Museum in Germany there is a beautiful head of a youth painted on glass. A pyramid-like building also figures in the picture, both gold and silver foil being used as background.

We have seen gold-backed silhouette portraits showing profiles which, like the old puzzle pictures popular at the same period, are hard to decipher. Thus an urn is made the central feature of the picture, but the outline, varying slightly on either side, gives the profile of a man and his wife. Such quaint conceits were popular at the time. George III. and Queen Charlotte, or his successor and Queen Caroline, are sometimes the subject of such freakish portraiture in silhouette; this method in black and white survives to the present day.

The richness of the gold-leaf background made this variation of the profile portrait especially suitable for jewels. Lockets, brooches, and pins are the most usual form; these may be set in gold or in carved pinchbeck. Occasionally a tiny silhouette picture is in pearl framing, or an ornamental one of paste.

The silhouette rings are most frequently in the marquise[26] setting; it was not unusual for a bequest to be made for profile portrait memorial rings. Occasionally some apt motto was engraved inside, such as, “Il ne reste que l’ombre.” The ethereal shadow picture seems to have specially appealed to the sentimental of the eighteenth century as a suitable reminder after death.

In the Wellesley collection there is a charming patch-box with three gold-backed profile portraits set in a row. None measures more than half an inch across; the faces are those of three lovely women. Another example is of a fine silhouette portrait of somewhat larger size, set in the lid of a small, round black lacquer snuff-box.

A mirror case was exhibited at the Silhouette Exhibition held in Maehren, Germany, in 1906, which had, on one side, the head and shoulders of a woman painted in black on glass. This was mounted on a yellow ground.

Finer than either of these is a patch-box in ivory, set in gold, with gold hinges and snap. In the centre is a gold set profile portrait of a man, signed by Miers; on either side there are beautiful panels of blue enamel. Doubtless this was a well-thought-out gift of a devoted admirer to the lady-love whose patches were to be held in this artistic box. A tiny oblong looking-glass is set in the inside of the lid to facilitate the adjustment of the beauty spots.

It is in work for the embellishment of such dainty things as these that the art of the profilist touches its highest point in minute work. Those who had the opportunity of examining the marvellous collection of the late Mr. Montague Guest can judge how these rare gems are not only beautiful in themselves, but speak of the illusive charm of the eighteenth century more eloquently than many other more costly bibelots.

The dainty sentimentality of a gold ring set with the shadow[27] of a beautiful woman, or the scarf-pin with the shade of a friend; a locket with the unsubstantial reflection of a child’s face; who can resist the colourless appeal of so unobtrusive a jewel, which is yet one of such rich association and rare beauty?

The method most usual for profile portraits in minute size is the painting with Indian ink on ivory or plaster. We have seen these as small as a pea, but this is unusual; they are generally double that size for rings, or, for lockets and brooches, larger still.

J. Miers must have painted many of these jewels. Amongst the examples we have examined, some are plain black, probably of early date; some pencilled with gold. This process we cannot help surmising to have been a concession on the part of the artist to the popular demand which came early in the nineteenth century. In two signed examples, in the possession of the author, one is plain black—a man’s head, with tied queue wig and high stock with ruffle; the other, a woman exquisitely pencilled in gold, a lawn cap of Quaker shape on her head, a folded kerchief crossing her breast. Both are signed.

Authentic examples by Mrs. Beetham are rare, for she seldom signed her work; but there is a quality in them which usually proclaims their authorship. The nervous delicacy of the work equals that of Miers: the manipulation of accessories excels it when she is at her best.

These silhouette jewels, of fine quality, are very rare, and are much sought after. Unfortunately, like so many of our beautiful and artistic treasures, the boundless wealth of America is absorbing many good examples. Is it possible that a frame containing about forty of the finest examples of Field’s work went to America before the collection came up for public inspection in the auction room, when the Guest collection was dispersed?

A variant of the shadow portrait, painted on glass, shows a blue, rose, or green coloured paper or coloured foil taking the place of the gold or silver leaf ground. A beautiful locket in the Wellesley collection demonstrates the charm of this method to perfection. It is probably French.

In a book of instructions for the amateur silhouettists of Germany, published in Frankfurt and Leipzig by Philip Heinrich Perrenon, bookseller, of Münster, 1780, we are told: “One can use tinfoil for the ornamentation of silhouettes for hanging. When the glass is turned round, the places where the tinfoil is form a sort of mirror. If the background be black and the portrait the mirror, the effect is pretty, but it is as contrary to nature as a white shadow. It is best to have the ground of looking-glass, and to blacken or colour the silhouette.”

One of the earliest silhouettists was François Gonard, a Frenchman, whose processes seem to have been very varied. Unlike most of the early shade-makers, he did not make a speciality of any particular process. His profile portraits were painted on ivory and plaster, and were occasionally cut out in paper and engraved on copper for reproduction; in fact, he seems to have practised every kind of profile portraiture.

Born at St. Germain in 1756, he was taught copper engraving at Rouen, and was specially clever in reducing copper-plate engravings. In the Manuel de l’amateur d’estampes, Joubert relates having seen a plan of St. Petersburg engraved in minute size by Gonard, who had reduced it from one of much larger size. This brings us to the pantograph.

In Le Journal de Paris, 1788, Le Sieur Gonard, who is called a dissenateur physionomiste, announces that he is in a position to take silhouette portraits quicker than any other artist. He will make these for 24 sols each, but he will not make less than two for each person. The price of those of minute[29] size, suitable for mounting, as boxes, lockets, and rings, is £3. He also announces silhouettes à l’Anglaise; these have the dress and head-dress added, and the price is £6 each, whether they be on ivory for wearing as an ornament or on paper to be framed. Whether the paper is scissor-work—the profile cut out of black paper—or the black drawing is made on paper, we are not told. For this latter type a sitting of one minute only was necessary, and the following day the portrait was finished.

Another process, which he describes as silhouette colorée, can also be done. These seem to have been more like miniatures; they cost £12, and a three-minute sitting was required. The portrait was finished on the next day but one.

Gonard’s address is given as the Palais Royal, under arch No. 166, on the side of the Rue des bons Enfants, and he describes how a lantern shall be lit each evening to facilitate the finding of his salon on dark nights. The lantern had silhouettes on it, as a sign for the footmen bringing carriages.

One cannot help imagining the scene when gay aristocrats, with powdered heads and dainty brocades, drove up to have their pictures taken in the fashionable mode, and beaux, with lace cravats and wigs, trod the floors of the studio with steps as firm as they might be three years hence when mounting the steps of the guillotine. How many of those beauties of the court of Louis XVI. were left when the terrors of the Revolution were past? How many of the pathetic little paper shadows have come down to us, fragile, indeed, but outliving the doomed originals by a century and a half?

As would be imagined, Gonard used elaborately engraved mounts to add to the grace of his portraits, and occasionally he used relief in white, grey, or colour in the execution of the portrait.

The view that the shadow portrait should remain a shadow[30] always in black is held by one of the most prolific of all silhouettists, Edouart, whose work is fully described in the chapter on Freehand Scissor-work. In deploring the decline of the public taste for shadow portraiture, he says in his treatise on Silhouette Likenesses:—“As something was wanting to revive the expiring taste of the public for these black shades, some of the manufacturers introduced the system of bronzing the hair and dress. To what species of extravagant harlequinade this gave rise, the public is sufficiently aware. I cannot avoid making my observations concerning profile likenesses taken by patent machines, which possess sometimes all the various colours of the rainbow: for example, every day there is to be seen in the shops this kind of profile, with gold hair drawn on them, coral earrings, blue necklaces, white frills, green dress, and yellow waistband, etc. Is it not ridiculous to see such harlequinades? The face, being quite black, forms such a contrast that everyone looks like a negro! I cannot understand how persons can have so bad and, I may say, a childish taste! Very often those likenesses are brought to me to have copies made of them, and it is with the greatest trouble I am able to make them understand that it is quite unnatural; and that, taking a silhouette, which is the facsimile of a shade, it is unnecessary for its effect to bedizen it with colours.

“I would not be surprised that by-and-by those negro faces will have blue or brown eyes, rosy lips and cheeks; which, I am sure, would have a more striking appearance for those who are fond of such bigarrades.

“It must be observed that the representation of a shade can only be executed by an outline; that all that is in dress is only perceived by the outward delineation; consequently, all other inward additions produce a contrary effect of the appearance of a shade.

“Here it may be said that every one has not the same taste; some like colour which others dislike; some find ugly what others find beautiful; and, in fact, des gouts et colours on ne peut pas disputer. But every artist or real connoisseur will allow with me that when nature is to be imitated, the least deviation from it destroys what is intended to be represented.”

Edouart concludes with some severe remarks. “It is a pity that artists, in whatever line they profess, should give way to those fantastic whims, and execute works against all rules; for if they would employ their time in proper studies, and try to show the absurdity of encouraging whatever deviates from the true line of nature, they would improve themselves, and in time would derive greater benefit than in executing things which only bring scorn and ridicule from people of discernment.”

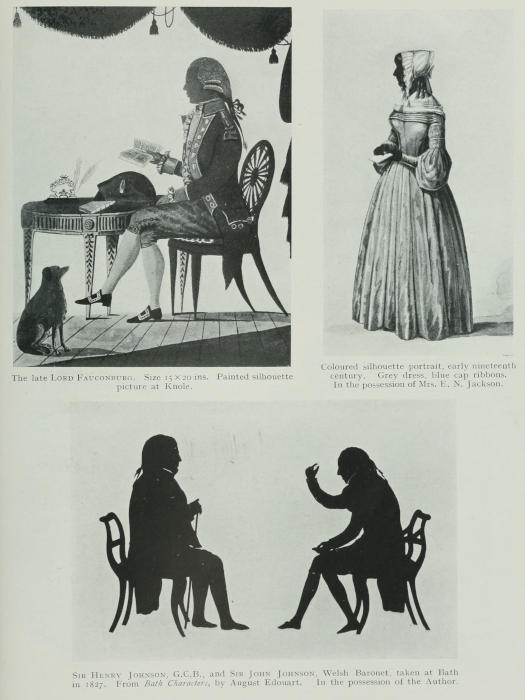

Despite the opinion of Edouart, with which most connoisseurs of the present day heartily agree, much silhouette work was finished in colour. We have before us a delicately painted lady of the Early Victorian period. She wears a grey dress with graceful pleated sleeves, a deep embroidered muslin collar, and the most bewitching cap tied with blue ribbons. Her face and hands only are shadow black. The delightful ringlets of the period are marked in gold, and she is writing in a note-book with a gold pencil, quite a blue-stocking occupation for a lady of that period. In the collection of Dr. A. Figdor, Vienna, there is an elaborate picture of a mother with a young child on her knee; two elder children and her husband complete the group. Only the heads in this group are black. Again, Professor Paul Naumann, of Dresden, owns the silhouette of a Moor. The clothing is brightly coloured, the head alone black. Every collector will find he has some examples where colour has been used to relieve the black of the card, ivory, or glass painting.

It must be remembered that this was the time of glass pictures of the ordinary coloured type, and this glass painting—Églomisé, as the process is called by the learned Dr. Leisching—would naturally influence the minds of the profile portrait painter on glass. So it came about that the two allied crafts gradually overlapped in ideas, and method and points of colour began to appear in uniform or other parts of the picture where colour would obviously add interest of a historical or sentimental character to the silhouette portrait, and in the glass picture of saint or Bible history. The glaring colours hitherto used to appeal to the popular taste began to be modified, and examples are found where the figures are all in black, the background alone being coloured; so that the glass picture is to all intents and purposes a silhouette on a coloured ground.

Of this type is the picture at the Francesco Carolinum Museum at Linz, where eight musicians in uniform are shown in black in the chapel. There is a good deal of wreath and ribbon decoration, and two small curtained windows are in the background.

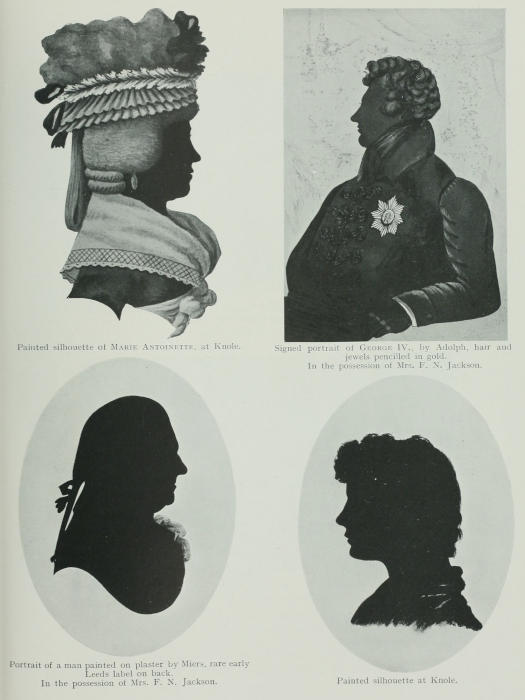

An important example of the black glass painting on coloured ground is the picture on a red ground in the Berlin Museum. Other red and black silhouette works are owned by Lady Sackville, who has an extraordinarily interesting collection of the Ansley family, painted by Spornberg in 1793. Each portrait is signed and dated, the address of the artist, No. 5, Lower Church Street, Bath, being given on one. These pictures are painted on convex glass in black; the background, outlines of the face, dress, hair, and elaborate wigs, caps and hats, together with the eyes, and slight shading, being painted in black. Over the whole an orange red paint is then worked in at the back, so that one sees from the front the red bust figure shown in black lines on the black background.

CAPTAIN ROBERT CONIG

Of His Majesty’s 90th Regiment of Infantry

Painted on Card. In the possession of Lady Sackville, Knole

Coloured grounds are very rarely found in connection with English silhouette work. One, in the possession of the author, is of a boy’s head finely painted on ivory; the background is tinted blue, the whole mounted in a chased gold locket of the period, early eighteenth century.

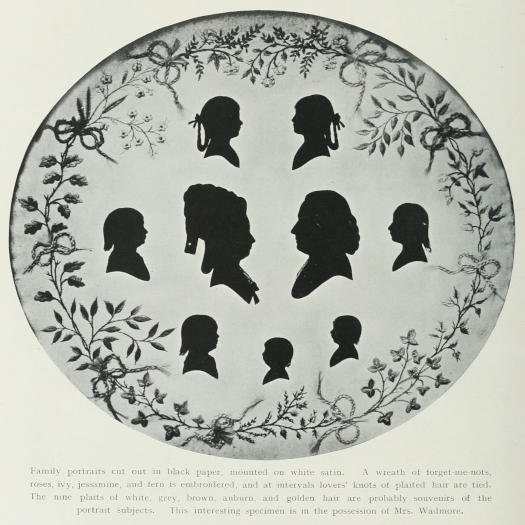

Abroad, especially in Germany, we constantly find coloured backgrounds and coloured cardboard mounts, with or without wreaths or other ornamental frames.

In the catalogue of the Silhouette and Miniature Exhibition held at Brünn from April 22nd to May 20th, 1906, there was much work of the kind:—

The silhouette numbered 67. Head and shoulders of a young man. Silhouette painted on glass on a brown ground. At the back the letters A. J. L.

No. 77. Round lacquer box with head and shoulders of a man in silhouette on a yellow ground, gold glass mount. Owner: R. Blümel, Vienna.

No. 99. Head of an officer, silhouette, painted on glass, blue ground.

No. 106. Lady walking, silhouette on glass, blue ground.

No. 26. Gentleman sitting at a writing-table, painted on glass, yellow silk background. French, Louis XVI.

No. 127. Lady sitting at a table, companion picture.

Other silk-mounted pictures are numbered 154.

Elise Herger (née V. Pige) and the Countess Chotek, both painted on glass and mounted on silk.

No. 159. Two female and two male heads, probably members of the noble family of Belcredi, silhouettes, cut out of paper and mounted on mother-of-pearl, 1800.

No. 184. In this there is a fresh variety of mounting. The head and shoulders of a man in painted silhouette, on glass; this shows up over white paper. Above this portrait, within the same[34] frame, is a semicircle of nine female figures in silhouette over blue foil; completing the circle is a gold laurel branch. This example is signed “Fecit Schmid, Vienna, 1796.”

Schmid, of Vienna, seems to have constantly used coloured backgrounds. A fine drawing by him, on glass, of Sophie Landgravine Fürstenberg, 1787-1800, is mounted on green; this was painted in 1800. It is an interesting specimen, as it is one of the rare examples of silhouette work in which human hair is used. At the back there is a landscape drawing in silhouette, on glass. The brook in the sylvan scene is put in with the waved lines of hair. It is remarkable that Edouart, who was a skilled worker in human and animal hair before he was a silhouette cutter, never combined the two crafts.

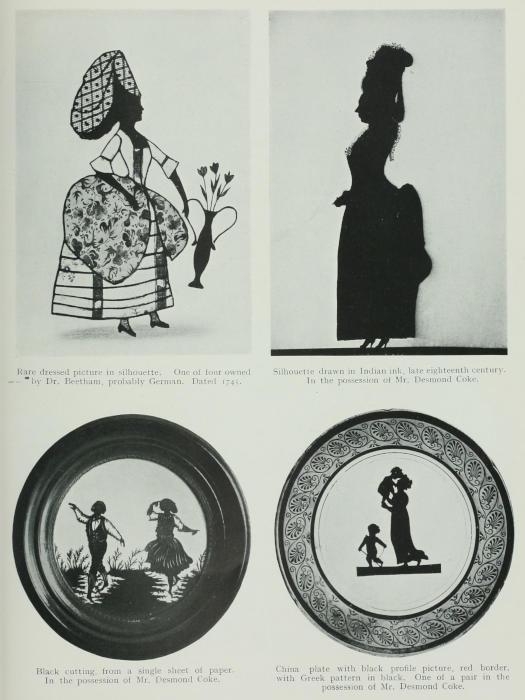

A strange variant of the dressed picture must be mentioned in connection with silhouettes where colour and exotic processes are employed. In four examples in the possession of Dr. Beetham, descendant of Mrs. Beetham, the fine silhouette painter, of 27, Fleet Street, the face, hair, arms, hands, and neck are cut out of black paper. The vase, in the example illustrated, is also in black, in this case, as in the less rare dressed engravings of the same period. The dress of the figure is made up of deftly arranged scraps of material. The head-dress is of spotted black, outlined by narrow bands of black paper; the bodice and skirt are of linen, with purple bands; the outstanding paniers are of faded scarlet flowered cotton; the flowers in the vase are painted, being outlined in gold. There are also dressed silhouettes in the possession of the Beck family. These show the Quaker dress in folded material with the black silhouette. All these examples are probably the work of clever amateurs.

Up to this point we have discussed only those processes which entail hand drawing with pen, pencil, or brush, which are undoubtedly an attractive type of the shadow picture, whether they are executed on ivory, plaster, or paper; their backing with wax, gold, or silver leaf tinsel, on coloured paper makes accidental varieties of the one type.

Any of these processes require a good deal of artistic training, even if the shade is used as a guide, for unless there is skill in catching a likeness, or delicacy and charm in drawing, black portraiture has nothing whatever to recommend it. However the silhouette is executed, the mechanical appliances play so important a part in nearly all the processes that they need a chapter to themselves. In order to popularise the black portrait, some means of achieving it was required which could be used by persons without talent or artistic training.

It was here that shadowgraphy came to the fore. Even the most ignorant in art work could trace a shadow when thrown upon white paper on a wall or specially made screen, and if the full life-size were considered too large, the Singe, pantograph, or other contrivance could reduce its size; then only scissors were required, and the silhouette-by-machinery maker felt himself to be as gifted as the black portrait painter, or the freehand scissor-cutter, whose work we describe in another chapter.

Etienne de Silhouette, born in 1709, amused himself with the craze of the day. His craft, belonging essentially to this section of mechanical execution, deserves special mention, not[36] because he invented the black profile portrait, for they were made sixty years before he was born, but because his name was given to it in derision, and has stuck to it ever since. Being finance minister, he was supposed to be a promoter of the fine arts, but such was his economy, or meanness, that artists styled his paper pictures “portraits à la silhouette,” a name synonymous with paltry effort and cheapness. This did not, however, deter people from patronising the silhouette artists, nor of attempting, themselves, to achieve the machine-made variety of the fashionable black portrait.

In the Journal Officiel, published in Paris, August 29th, 1869, we read:—“Le Chateau de Berg sur Marne fut construit en 1759 par Etienne de Silhouette ... une des principales distractions de se seigneur consistait à tracer une ligne autour d’un visage, afin d’en avoir le profil dessiné sur le mur: plusieurs salles de son chateau avaient les murailles couvertes de ses sortes de dessins que l’on appelle des silhouettes du nom de leur auteur de nomination que est toujours resté.”

In the seventeenth century, dillettantism was an obsession with the leisured classes. The tendency of the time towards Greek art, as has been indicated in another chapter, helped to popularise the scissor-work of this type of shadow portraiture, and it became a fashionable craze. Though the cutting out with scissors and penknife sometimes took the form of landscape groups and small whole figures, the profile alone in small, though not miniature size, proved the most fascinating branch of scissor-work, and survived the longest in the favour of amateurs, because the purely mechanical shadow tracing required no skill, and inevitably gave a life-like likeness if traced with reasonable care.

There were several methods of securing steadiness on the part of the sitter and the best result as to arrangement of[37] candle-light essential to the success of the portrait. Lavater, who believed so sincerely in the infallibility of the silhouette as an assistance in his physiognomical studies, gives elaborate directions as to how to obtain the best results. He says in Lecture XVI. (we spare our readers the long observations on silhouettes):—

“It may be of use to point out the best method of taking this species of portraits.

“That which has hitherto been pursued is liable to many inconveniences. The person who wants to have his portrait drawn is too incommodiously seated to preserve a perfectly immovable position; the drawer is obliged to change his place; he is in a constrained attitude, which often conceals from him a part of the shade. The apparatus is neither sufficiently simple nor sufficiently commodious, and, by some means or other, derangement must, to a certain degree, be the consequence.

“This will happen when a chair is employed expressly adapted to this operation, and constructed in such a manner as to give a steady support to the head and to the whole body. The shade ought to be reflected on fine paper, well oiled and very dry, which must be placed behind a glass, perfectly clear and polished, fixed in the back of the chair. Behind this glass the designer is seated; with one hand he lays hold of the frame, and with the other guides the pencil. The glass, which is set in a movable frame, may be raised or lowered at pleasure; both must slope at bottom, and this part of the frame ought firmly to rest on the shoulder of the person whose silhouette is going to be taken.

“Toward the middle of the glass, is fixed a bar of wood or iron furnished with a cushion to serve as a support, and which the drawer directs as he pleases by means of a handle half an inch long.

“Take the assistance of a solar microscope, and you will succeed still better in catching the outlines; the design also will be more correct....

“There are faces which will not allow of the most trifling alteration in the silhouette, or strengthen or weaken the outline but a single hair’s-breadth, and it is no longer the portrait you intended; it is one quite new, and of character essentially different.”

In this work of silhouette-making and physiognomical study, Lavater wished the whole world to co-operate with him, as Goëthe testified. On a long journey down the Rhine, he had the portraits taken by his draughtsman, Schmoll, of a great number of important people. This served the secondary purpose of interesting his sitters in his work. He also asked artists to send him drawings for his purpose, and wrote much on the physiognomical character of the figures in the pictures of such artists as Raphael and Vandyck.

Goëthe was intensely interested, and there is much of his correspondence extant on the subject. Enthusiastic at first, his zeal seems to have waned. On June 23rd, 1774, Lavater arrived at Goëthe’s house with Schmoll, and portraits were taken of the author of “The Sorrows of Werther,” and of his parents.

A year later, in August, 1775, Goëthe writes, imploring Lavater, “I beg you will destroy the family picture of us; it is frightful. You do credit neither to yourself nor to us. Get my father cut out, and use him as a vignette, for he is good. I do entreat of you to do this; you can do what you like with my head too, but my mother must not be recorded like that.”

An amusing sequel to this correspondence is that when the third volume of Lavater’s “Physiognomy” appeared containing[39] her husband’s portrait alone, the councillor’s wife was extremely offended, and says that evidently the author did not think her face worthy to appear.

A scrap-book full of these machine- and scissor-made silhouettes, with copious notes made by Lavater on the character of the sitters, judged by the shadow portraits, is one of the chief treasures in the collection of Mr. Wellesley, and forms an important item in silhouette history in its use for scientific purposes.

A machine for the use of amateurs is owned by Dr. Beetham, descendant of Mrs. Edward Beetham, the clever silhouettist of Fleet Street. This machine for taking silhouettes is a box about the size of a cigar box. One end has a lens glued into a sliding block or frame for focusing purposes. A piece of looking-glass reflects the object on to a piece of frosted glass on the top of the box. The subject is drawn from this reduced shadow.

There were others besides Lavater who published advice as to the best way of taking silhouettes.

In “A Detailed Treatise on Silhouettes: their Drawing, Reduction, Ornamentation and Reproduction,” published in 1780, the author, after many allusions to prisma, cylinder, pyramid, cone, the sun and moon, and perpendicular and horizontal lines, gives indispensable rules for the silhouetteur:—

1. The surface on which the shadow is made must be upright.

2. It must be parallel with the head of the sitter.

3. The imaginary line running from the centre of the flame to the middle of the profile must be horizontal with the surface on which the shadow is to be cast.

4. The light must be as far from the head as possible, but the surface for drawing on must be as near the head as possible.

As will be seen from the print taken from Lavater’s book, these rules were fairly accurately carried out in the chair depicted. Practical hints are also given in the treatise as to paper, light, pencils, etc. Great stress is laid on the importance of obtaining paper large enough for the drawing of the enormous modern head-dress of women, for which, sometimes, two pieces were put together. We have seen interesting examples of this, where the paper is actually joined together with the thin old-fashioned pins of the period, and life-size heads, executed in black paper, in a country house in Sussex.

“A wax light is better than tallow or suet,” this careful mentor continues, “as there is nothing so harmful as a flare, which makes the shadow tremble. If one cannot obtain a wax candle, and must use a lamp, let it be dressed with olive oil. Coughing, sneezing, or laughing are to be avoided, as such movements put the shadow out of place.”

The reduction of shadow portraits so taken is then described at length, and by various methods, “as the physiognomical expression is more piquant in a reduced silhouette.” “The best of these mechanical reducers is the Stork’s Beak or Monkey (this is our present-day pantograph), which consists of two triangles so joined by hinges that they resemble a movable square, which is fixed at one point of the base of the drawing, while a point of the larger triangle follows the outline of the life-size silhouette. A pencil attached to the smaller triangle traces the same outline smaller and with perfect accuracy. By repeating these reductions, silhouettes may be made in brooch and locket size.”

“With regard to the ornamentation and finish of the silhouette portrait, black paint should be used.” We presume this would be for the fine lines of the hair, which are sometimes added to the background after paper-cut silhouettes are[41] mounted. Chinese or Indian ink is advised, or pine-soot, mixed with brandy, gum, or beer.

Advice is also given as to painting round the paper outline: the paint should be put on from the pencil outline towards the centre. The anonymous author suggests that two portraits should be cut at once; the first to be stuck into the family album, the second to be hung upon the wall.

For such decorative purposes elaborate instructions are given. “Take a nice clear sun-glass and clean it with powdered chalk and clean linen to remove all grease and dirt. Cover this glass on one side with finely powdered white lead mixed with a little gum-water. When this is dry take the silhouette, which has been cut out of strong paper, place it on the powdered surface, and trace round the outline with a needle; remove the silhouette, and scrape away all the white within the drawn line. Thus one obtains a transparent silhouette, which can be turned into a black one by laying a piece of black velvet at the back of the glass, or if not velvet, fine black cloth or taffeta or paper.”

This silhouette recipe maker also suggests that the cut-out black silhouettes can be stuck on to the glass with Venetian turpentine, and the glass then treated with the white covering; or one can use tinfoil, which forms a mirror.

This brings us back to the background treatment for painted silhouettes without the aid of shadowgraphy and scissor-work, so that we need not repeat the various kinds.

In this remarkable book, which is in the possession of Professor Dr. Th. Slettner (Münich), and for a description of which we are indebted to Herr Julius Leisching, a further description of silhouette-making is given:—“By sticking together three or four sheets of paper and working at the back with a polishing steel, one can actually make a profile portrait in slight[42] relief out of a cut-out silhouette in white paper, ‘giving it the appearance of a marble tablet or a plaster cast done by a sculptor,’” adds this enthusiast.

A treatise on this method exists in English, entitled “Papyro-Plastics; or the Art of Modelling in Paper, with Directions to cut, fold, join, and paint the same,” with eight plates, published in the first quarter of the nineteenth century.

Mention is also made of silhouettes in enamel on copper for snuff-boxes, lockets, and rings, and the black profile portraits on porcelain in the German volume.

Finally, the author praises a process by which, by means of a stencil, one can make one hundred copies a minute, and the reproduction of the silhouette portrait by woodcut and copper-plate impressions.

A second book appeared simultaneously, if not immediately before the treatise. It was published by Römhild at Leipzig, and in the following year (1780) Philip Heinrich Perrenon brought out a third, which is called “Description of Bon Magic; or the Art of Reduplicating Silhouettes easily and surely.”

The principal process is one which the author describes as “so simple that every woman who can make silhouettes can practise it as well as the best artist.”

“Take a piece of flat tin, polish it on one side, put the drawing on it and cut out the tin accordingly, and the form is obtained. Rub this form on the side to be printed off on a flat stone with sand. Damp some paper, and make a black mixture out of linseed oil and pine-soot. Make a pair of balls of horsehair covered with sheepskin. Get a small piece of hat felt. Blacken the shape or form with the black mixture put on with the horsehair ball; place it on the table, and over it, on the blackened side, the damp paper, on this a few sheets of waste paper and then the felt. Now nothing but the[43] press is required; this consists of a rolling-pin, which can be made by any turner. Roll it over, and when the paper is taken away the silhouette, en Bon Magic, appears printed off.”

Illustrations of various implements are given, besides a simple pantograph for reducing the life-size shadow. Many pantographs are mentioned in connection with silhouette work. It is probable the earliest one was invented by Christopher Scheiner, a Jesuit, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, and was called the parallelogrammum delineatorium.

We meet it again in England, where mercifully its name is shortened, and it is interesting to see that it is a woman who applies for protection of her invention. The abridgment of her specification runs thus:—

Patents for Inventions.

Abridgments of Specifications.

Artists’ Instruments and Materials.

1618-1866.

A.D. 1775, June 24.—No. 1100.

Harrington, Sarah.—“A new and curious method of taking and reducing shadows, with appendages and apparatus never before known or used in the above art, for the purpose of taking likenesses, furniture, and decorations, either the internal or external part of rooms, buildings, &c., in miniature.” The person whose likeness is to be taken is placed so “as to procure his or her shadow to the best advantage, either by the rays of the sun received through an aperture into a darkened room, or by illuminating the room.” The face is then brought “directly opposite the light, so that the shadow may be reflected through a glass (or transparent paper);” the glass is movable in a frame “so as to fix it on a level direction with the head of the person.” The outline of the shadow is then traced with a pencil, &c., after which it is “reduced to a miniature size by an instrument called a pentagrapher.”