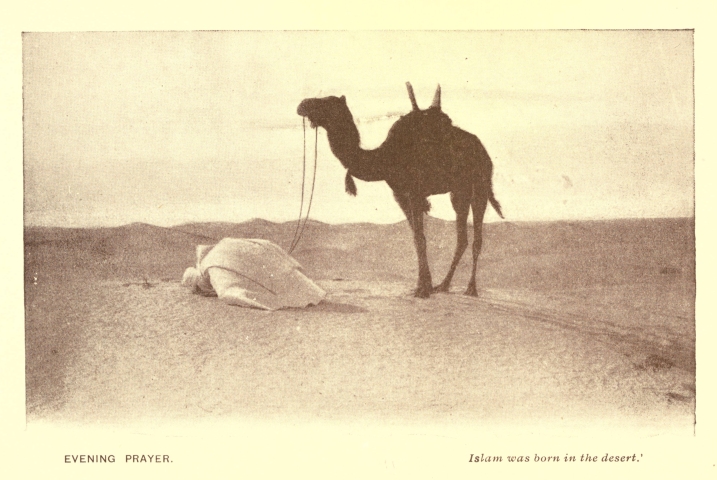

EVENING PRAYER.

'Islam was born in the desert.'

The Project Gutenberg eBook of The story of Islam, by Theodore R. W. Lunt

Title: The story of Islam

Author: Theodore R. W. Lunt

Release Date: October 31, 2022 [eBook #69276]

Language: English

Produced by: Al Haines

EVENING PRAYER.

'Islam was born in the desert.'

BY

THEODORE R. W. LUNT

GENERAL SECRETARY, NATIONAL LAYMEN'S

MISSIONARY MOVEMENT

(FORMERLY EDUCATIONAL SECRETARY, CHURCH

MISSIONARY SOCIETY)

THIRD EDITION (REVISED)

LONDON

UNITED COUNCIL FOR MISSIONARY EDUCATION

CATHEDRAL HOUSE, 8 PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C.

1909. First Edition.

1911. Second Edition.

1916. Third Edition (Revised).

Dedicated

to the Public Schoolboys

of Great Britain, who

have a Big Part yet to play

in shaping the Future

Story of Islam

In the Same Series

THE SECRET OF THE RAJ

BY

BASIL MATHEWS, M.A.

Price 1/6, post free

From all Missionary Societies

TO THIRD EDITION

It has been strange indeed to revise this book in barracks, amid efforts to learn to fire big guns—possibly against the Turks. And yet this necessity which lies upon us Englishmen to-day only emphasizes afresh the importance of our trying to understand the real problem of Islam.

When the war is over, Islam will remain. Whatever state of disorganization it may be in and whatever its centre, it will still tower up before us gaunt and shadowed as one of the most difficult problems of civilization and as the great reproach of the Christian Church.

We can do nothing to help Moslems, or to solve their problem, unless we know something of their story and have tried to understand the power and fascination of their rugged simple creed.

Those of us who are called to fight—for honourable necessity—have the lesser task {vi} though it be costly. The real opportunity will lie with those who come after—with those, in fact, who are at school to-day. Their task will be not to destroy but to build, to dream holy dreams of a great World Kingdom of Love and Gentleness and Truth and Purity and Honour, and to consecrate their lives to the One from Whom and through Whom alone these things can come.

THEO. R. W. LUNT.

R.F.A. MESS, BEDFORD BARRACKS,

EDINBURGH, January 1916.

CONTENTS

CHAP.

II. Early Manhood

IV. Life in Mecca

V. The Unsheathing of the Sword

VII. Islam's Success

VIII. Islam's Failure

XI. Islam and the Church of Christ

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Evening Prayer ... Frontispiece

'Islam was born in the desert.'

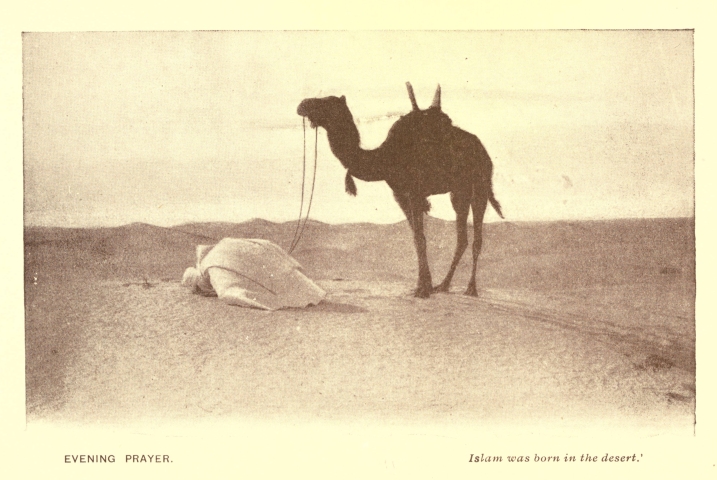

The Kaaba at Mecca

'Recognized as the religious centre of all Arabia.'

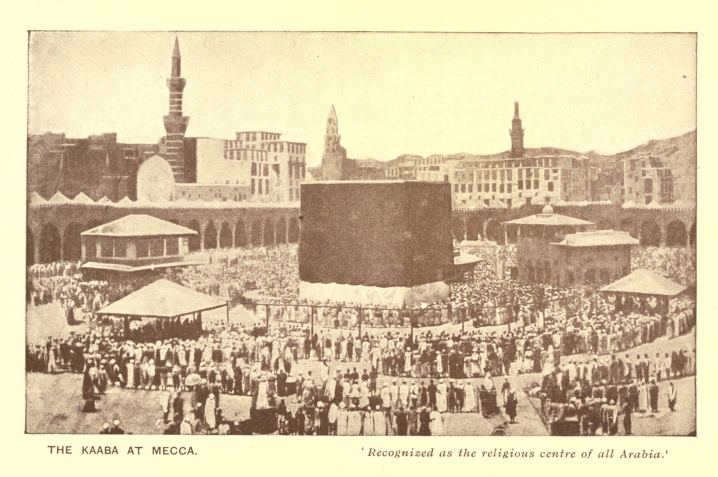

A Camel Merchant

'Mohammed's fame spread along every caravan route of Arabia.'

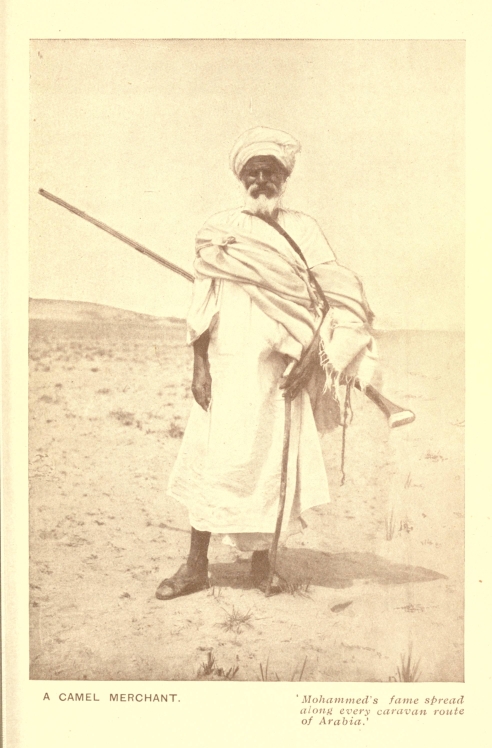

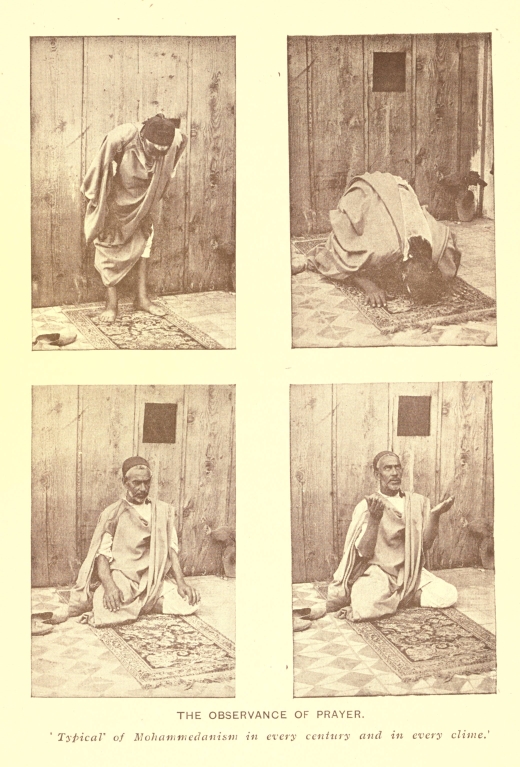

The Observance of Prayer

'Typical of Mohammedanism in every century and in every clime.'

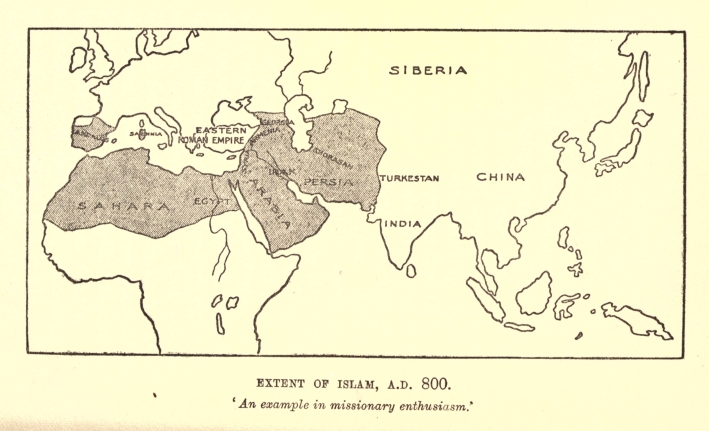

The Extent of Islam, 800 A.D. (map)

'An example in missionary enthusiasm.'

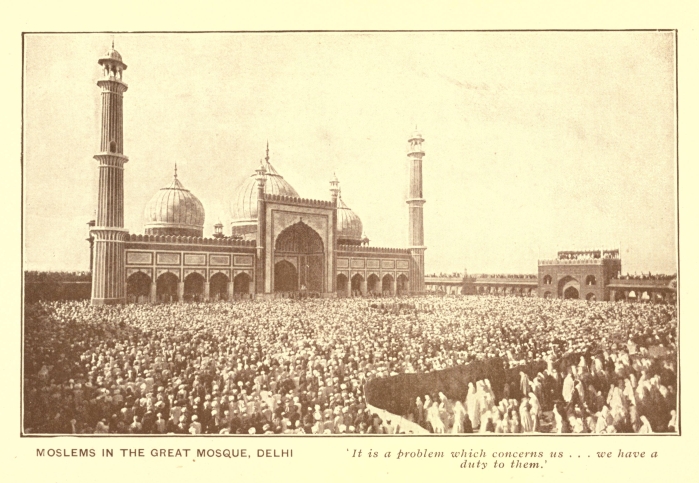

Moslems in the Great Mosque, Delhi

'It is a problem which concerns us, ... we have a duty to them.'

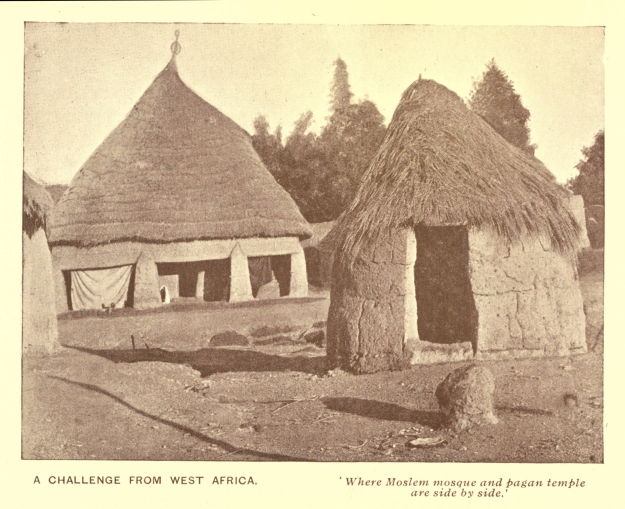

A Challenge from West Africa

'Where Moslem mosque and pagan temple are side by side.'

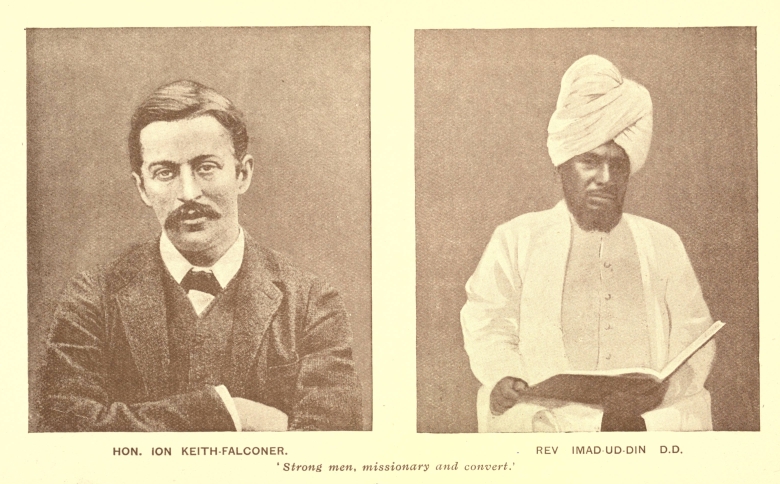

Hon. Ion Keith-Falconer and Dr. Imad-ud-Din

'Strong men, missionary and convert.'

Moslem Boy-Faces (Tunis)

'What have we Christians that we can say to them?'

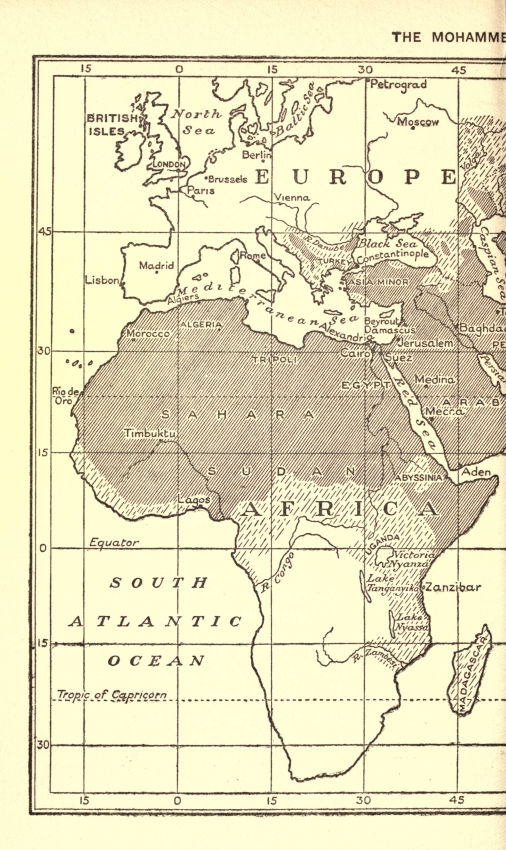

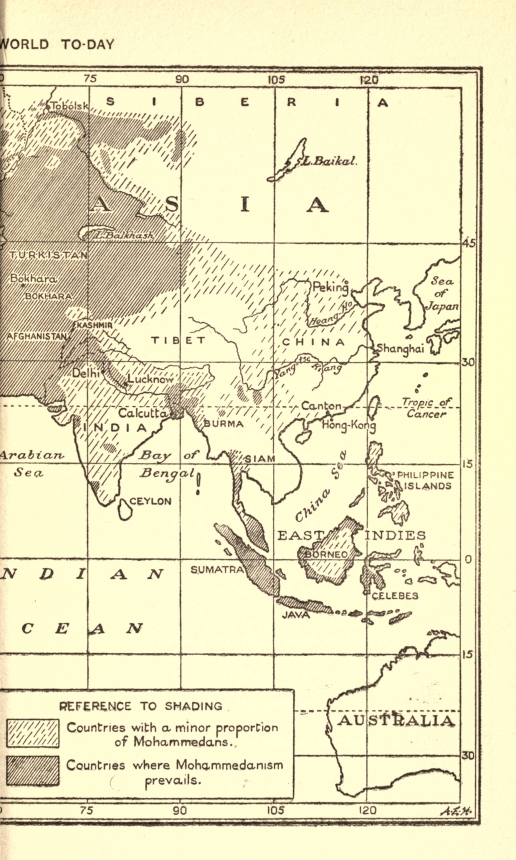

The Mohammedan World To-day (map)

THE STORY OF ISLAM

'The boy is father of the man.'

'Islam was born in the desert.'

EDWIN ARNOLD.

Mecca.

Close to the focus of three great continents, where East meets West and North meets South, Asia almost touching both Africa and Europe, lies the great unknown country of Arabia, the 'Land of the Desert.'

The long, low coast-line of its western shore is familiar enough to all who travel to the East. About seventy miles behind that coast lies a wild chain of desert mountains. Here, in a valley snuggling among massive peaks, is an Arab town, a kind of mountain fastness, lying in an amphitheatre of rugged hills.

It marks the spot, so the Arab legend runs, where long years ago Hagar the {2} bondwoman laid her son, parched and dying of a desert thirst, while she drew away out of reach of his cries, and 'lifted up her voice and wept.' Here, too, is the well from which she filled her bottle and gave the lad to drink, reverenced to-day by all good Arabs as the sacred well of Zemzem.

Mohammed's Birth 570 A.D.

In this town of Mecca there lived in the year 570 A.D. a young Arab widow mother. She had not been married long when her husband Abdallah joined a caravan on a long trading journey up to Syria. On his way back he sickened of some desert fever and died, and a son was born to her after the father's death. The child's grandfather was a person of considerable importance, the patriarchal head of the ruling clan, the Koreish. He took the boy in his arms and went to the sacred temple of Mecca, and gave thanks to God. The child was named Mohammed.

Childhood.

His mother was poor, but she was of noble family; and so, according to the custom of Arab aristocracy, the child was not nursed at home but entrusted to the care of a woman of one of the wild wandering tribes of the desert for his first five {3} years. The boy's earliest recollections must have been of wild Bedouin life, in which he grew strong and robust in frame, trained in the pure speech and free manners of the desert. For little more than a year he returned to his mother and his home, but at the age of seven his mother died, and he was left an orphan. He was old enough to feel her loss very deeply, and also the desolation of his orphan state. The shadow overcast his life and turned his thoughts to melancholy. His grandfather, Abd al Muttalib, was an old man now, and Mohammed was his favourite grandson. He took the lad to his own home and was more than ordinarily kind to him; yet Mohammed never forgot his mother, nor the sorrow of her death. No doubt it did much to make him the pensive, meditative man he afterwards became—anyhow it set him thinking.

When he was eight years old the boy's heart was again wounded by the death of his kind grandfather and guardian. With him he had lived in the proudest home in Mecca, for Abd al Muttalib had been a kind of hereditary 'lord mayor' of the town, whose special duty it was to take {4} charge of the Temple and the Holy Well, and to care for the many pilgrims that came to visit them. Now the 'clan' was left without its proper head, and Mohammed was given into the charge of his uncle, Abu Talib.

Education.

There was little ordinary 'schooling' for the Arabs of those days, except for the favoured few, and Mohammed, fatherless, motherless, and now grandfatherless, was not among these. Probably he never even learned to write. His school was the schooling of the desert and the caravan; he was to become his uncle's 'handy-man,' and for the present the best thing he could do was to go and help in looking after the camels and sheep which his uncle kept on the slopes of Mount Arafat.

The Arabs.

Who were these Arabs from whom Mohammed sprang and among whom he lived? They were cousins of another mighty race, the Jews, their neighbours, for both traced their descent from Abraham—the Jews through Isaac and Jacob, the Arabs through Ishmael, and also through Esau who married the daughter of Ishmael. In a marvellous way have the Arabs all through their history been fulfilling the old prophecy of the sons of {5} Ishmael: 'He shall be as a wild ass among men: his hand shall be against every man and every man's hand against him, and he shall dwell in the presence of his brethren.'[1] How better could we describe the Arab to-day? The description was equally true in the days of Mohammed. Customs and ways of men change slowly in the East when they change at all, and the Arab all through history has clung to the wandering and warlike habits of his patriarch Ishmael, and follows the same rude, natural mode of life which existed in Arabia then.

The wild ass among men—independent, haughty, hater of towns, dweller in the wilderness, untameable;[2] it is a description that stirs our blood. The Arab roves through boundless deserts in wild and unfettered freedom, despising a 'civilized' life, scorning its comforts, proud and haughty in mien and character, the one untameable race of all the world.

In such a race was Mohammed born. True, the Arabs were not all Bedouins of the desert. Towns had sprung up where caravan routes crossed, or where rich wells {6} and springs attracted a constant stream of shepherds and camel drivers, or more often around some spot consecrated by tradition as holy ground, and by custom as a place of pilgrimage.

Mohammed's Shepherd Life.

Mohammed was a child of the town—a Hadesi—but he was a child of the desert too. For the town dwellers of Arabia were also her travelling merchants, and, as in Joseph's time, they were known in distant countries as men of merchandise and caravan. Like many a seer and patriarch of old he spent some years in shepherd life among the Bedouins who tended Abu Talib's camels and sheep on the slopes of Mount Arafat. It was a wild, open, and lonely life, such as has developed the thoughtfulness and strong self-reliance of many another man. Long, hot days under the burning tropical sun, with the responsibility of valuable flocks to be protected and fed, could not but train his powers of observation. Long, still nights beneath the innumerable stars of a rainless sky would develop a deep wondering thoughtfulness in a boy already inclined to melancholy and meditation, and naturally taciturn.

Mohammed visits Foreign Lands.

When he was twelve years old there came to Mohammed the chance of visiting foreign places. Abu Talib proposed joining a caravan that was going to Syria where he had business to transact. As the caravan was about to start and Abu Talib was mounting his camel, Mohammed, overcome by the prospect of a long separation, clung to his uncle, begging to be allowed to join the party. For some months he served as his uncle's caravan boy. He had never before been far away from home, and the long journey through the desert northwards must have strongly impressed his mind. 'The imagination of the people had filled the solitudes, as has been the case in all lands, with supernatural inhabitants, monstrous and malignant, the genii or djinns of the Arabian Nights. The horror of loneliness, either in the night or in the equally silent noontide, found expression in mysterious tales and legends haunting every hill and vale of the regions through which he passed.'

Mohammed meets Christians.

The caravan bivouaced wherever there was water, preferably in any town or trading centre. Round the camp fire in the evening the boy would hear much {8} that was strange and new. At Mecca he had heard but little of the Jews and their religion, and less of the Christians; but there were many Jewish settlements on this road up north, and at least a few outposts of the Christian Church. Christian preachers of the Syrian Church preached in the big centres, and we are told that Abu Talib's caravan was at one time entertained by Buhaira, a Christian monk.

In some of the places where the caravan encamped they found settled Christian communities with churches and crosses and pictures, and other symbols of the Faith. Mohammed would hear how these same rites were practised in the centre of world-power—his attention would be arrested by the fact that the great Emperor owed allegiance to the Gospel. He saw, too, how everywhere the Christians were respected as men of learning.

But what was the Christian teaching he would hear? Alas! the Church of Christ was rent by factions, and false teaching prevailed, at any rate in the East. The simplicity which had characterised the Church in the earlier days when Christians were oppressed and {9} persecuted had passed away; as one of their own historians put it, 'the World had entered the Church.' Christ Jesus had no longer the pre-eminence; instead of a rich consciousness of His glory and beauty and power, the minds of Christians were full of theories about Him and of strange and false ideas of God. The Talmud and the Apocryphal Gospels, with their crude, strange myths, were set beside the Bible, and truth and falsehood were dangerously intertwined. Many had ceased to believe in JESUS as indeed the Son of God. Some deified the Virgin Mary, giving her a place in the Trinity; to them Jehovah was no longer the God of the universe but of the Jews only.

'In all probability Mohammed never heard a word of the New Testament; the pages of the Korân bear silent testimony to the shameful fact that the only way in which the Christianity of that time and place reached Mohammed was through the false Gospels.'[3]

Even in these early days Mohammed would ponder these things and sift them in his mind, and if at this time he had {10} longings and aspirations for a purer and higher religion than the star worship and crude idolatry of his countrymen, it need not surprise us that such Christianity, overlaid with myths and fables, and confused by the worship of saints and images, failed to satisfy his longings or to fulfil his aspirations.

In later days, when Mohammed had become the founder of a new religion and the ruler of a mighty Empire, and was acclaimed the Prophet of God, Moslem writers began to weave strange and unworldly incidents and miraculous signs into the account of his journey—indeed, into all the stories of his boyhood. Angel wings sheltered him from the noontide heat, and withered trees were clothed with leaves to give him shade, and a strange fire is said to have played about his head, marking him as the future Prophet of God. In reality the long journey seems to have been uneventful enough.

THE KAABA AT MECCA.

'Recognized as the religious centre of all Arabia.'

Yet on his return he would look on Mecca with opened eyes.

The Kaaba.

We can picture Mohammed going sadly back to the worship of the Kaaba and {11} the religion of Arabia. The Kaaba was a small and simple building, almost a cube as the name implies, about 27 feet square and 34 feet high. Originally it had been the local sanctuary of the Koreish tribe and contained only one image, that of Hobal, their tribal god. Long before Mohammed's days, however, images of the local deities of other tribes had been set up beside Hobal, until it was a veritable pantheon, and was recognised as the religious centre of all Arabia.

The 'Black Stone.'

The Kaaba's chief claim to this distinction lay in the famous 'Black Stone' of Mecca, which, encircled with a band of silver, was built into its outer wall four feet from the ground.

This stone is described as about six inches by eight inches in size, of a reddish-black colour, stained by sin, so the Arabs say, and dotted with coloured crystals. Its history is shrouded in mystery and myth, but Mohammed was taught to look upon it as one of the stones of Paradise brought to earth by the angel Gabriel. Probably it was an aerolite. Then, as now, it was regarded by all true Arabs as man's most sacred possession, and was the object of {12} pilgrimage to Arabs of all clans, and from even the most distant parts, that they might touch or kiss it.

An Arab Legend.

The story of the Kaaba is no less mysterious and wonderful. Originally built to guard or mark a sacred spot connected in Arabian legend with the story of Ishmael, its true history has been enshrouded and obscured in a cloud of myths. According to the inventive genius of Arabian writers it was first constructed in heaven 2000 years before the creation of the world, and Adam erected a replica on earth exactly below the spot its perfect model occupies in heaven. At the Flood the sacred building was destroyed, and God is said to have instructed Abraham to journey from Syria to rebuild it with the help of Hagar and Ishmael.

The Religion of Arabia.

How uncouth and far behind the times it all seemed! The Jews had their Prophet and law-giver Moses, the Nazarenes looked to Jesus, the Persian magicians quoted Zoroaster, even Abyssinia was a homogeneous kingdom owning allegiance to the Gospel. Every nation had its revelation and its Book;—Arabia had none at all, no open vision, no Prophet, {13} nothing certain. It was but a tangle of tribes and clans with hardly any cohesion at all. Each clan was a law to itself, a separate unit, in competition with all other clans, and the law of the blood-feud tyrannized everywhere. Such a social organization was calculated to ensure the maximum of confusion with the minimum of achievement. Mohammed could not but contrast it all with the definiteness, strenuousness, and order of the political and social organizations which he had seen abroad. There could be no law, for there was no ruler; no justice, for there was no supreme authority; no progress, for there was no plan.

QUESTIONS ON CHAPTER I

1. What is known of Mohammed's parents and grandparents?

2. Describe Mohammed's education. What part of it did him most good?

3. Describe the Arab race.

4. Wherein lay the chief interest of Mohammed's caravan journeys? To what countries would he go?

5. Describe the Kaaba, and the worship of Arabia in olden days.

[1] Gen. xvi. 12.

[2] Job xxxix. 5-8.

[3] J. M. Arnold, Christianity and Islam, p. 32.

'The future comes not from before to meet us, but streams up from behind over our heads.'—RAHEL LEVIN.

Mohammed's First Fighting.

So the years passed on, and Mohammed grew from boyhood to youth, fair of character and of honourable bearing among his fellow citizens. Though he shunned the coarser sins and licentious practices of the city he could no longer as a young Meccan hold aloof from the civil and social life of his day. When he was about twenty he received 'his baptism of fire,' and fought in his first battle. The Koreish were at war with a neighbouring tribe. The cause of the war was insignificant enough, but it is typical of the slight causes of the blood-feuds of that day.

At certain seasons of the year it was the custom of the tribes to gather at the larger towns for fairs. Of these the most important was the sacred Fair of {15} Ukaz, a large market town not far from Mecca.

A Blood-feud.

It was at one of these annual Ukaz fairs that the trouble arose. An arrogant Koreish poet had been boastfully vaunting the superiority of his tribe, and was struck by a zealot of the Hawazin tribe. A story got about that a Hawazin girl had been ill-treated by some Koreish maidens. A certain man of the Koreish was unable to pay a debt to a man of the Hawazin tribe. Arab blood boiled hot. The Hawazin creditor thereupon seated himself in a conspicuous place in the market with a monkey by his side, and proclaimed to all who passed by, in the true Eastern language of figure of speech: 'If you will give me another such ape, I will give you in exchange my claim on...' naming the debtor, with his full pedigree, back to Kinana, an ancestor of the Koreish. This he kept vociferating to the intense annoyance of the Kinana, till one of them drew his sword and cut off the monkey's head. In an instant the whole Hawazin and Kinana tribes were embroiled in bloody strife.

The trouble was patched up at the time, {16} but only to burst forth into a fiercer fury a few years later, when a spiteful murder supplied more serious cause of offence. Then the fierce fire of tribal hatred was unquenchable, and the whole country was embroiled in a war which lasted for four years, with short truces and respites, and ended at last in the Koreish agreeing to pay blood money in the shape of hostages for the Hawazins they had slain.

Into some, at least, of the battles of this war, Mohammed, then in his teens, accompanied his uncle. He seems to have played no conspicuous or glorious part, and even in later days, when he referred to it, it was without enthusiasm or pride. Perhaps he discharged some arrows at the enemy—more likely he acted as attendant to his uncle, collecting arrows and handing them to him to shoot. Indeed, neither then nor at any later period of his career was Mohammed distinguished for his physical courage or martial daring.

Mohammed's Appearance.

Let us now introduce ourselves to our hero himself. His face has taken the set features of manhood, and we may safely apply to him the picture left by his contemporaries of the man as they knew him, {17} and as in later years they bowed beneath his influence and power. He was no Saul in stature, though perhaps above the average height; yet in his countenance there was much that we are accustomed to expect in a leader of men. A Napoleonic nose, a head too big for the body, flowing jet black locks, falling on either side of his face, intense, gleaming black eyes, slightly bloodshot, an ample beard and moustache covering a rather sensuous mouth must have given him a striking and commanding appearance. His skin was slightly fairer than that of most Arabs, with a faint tinge of blue. Across his ample forehead ran a prominent vein, of which much is said, and which used to swell and throb when he was angry. Yet, withal, his face could have its gentler moods; he could be kindly when he would, and to the end he was a lover of children.

His Manner of Life.

Such was his outward appearance; we have some records, too, of his manner of life among his fellow-citizens in Mecca—records which show no trace of the man that was to be; he was respected but undistinguished. From early manhood they named him Al Amin—'The Faithful,'—and he seems to have been regarded by {18} his fellow-citizens as a solid, dependable, brotherly, genuine man. Passionate and unrestrained, yet a serious, sincere, character, capable of real amiability, and with a good laugh in him withal.

Fair of Ukas.

Year by year would come fresh stimulus to his active mind. With his fellow-citizens he went regularly to the annual fair at Ukaz, probably on business as well as pleasure bent. This fair was indeed one of the few institutions of Arabia which could well be called 'national.' Thither during two sacred months of truce the many scattered tribes gathered. It was the 'Olympia' of Arabia. The rivalry was not the rivalry of discus and javelin, but of poetry and eloquence. Ukaz was, indeed, the press, the stage, the pulpit, the parliament, and the 'Academie Française' of the Arab people. It was the focus of all the literature of Arabia. Thither resorted the poets of these rival clans and tribes, to a literary congress without formal judges but with unbounded influence. And because it was the centre of emulation for Arab poets, it was also a kind of annual review of Bedouin virtues and Arabian religion. For it was in poetry {19} that the Arab—as indeed man all the world over—expressed his highest thoughts.

At these fairs a strange assortment of religious opinions would be found. There would be Christian preachers, probably of many rival factions, each not only proclaiming his 'gospel' but disclaiming all the others, Jews and Sabæans, Zoroastrians and Hanîfites, each with complete systems of religion. The orators of each Arab tribe, too, vied with one another in acclaiming the superior powers and merits of their own tribal gods, their own sacred spot or relics, and their particular superstitious traditions.

Was there Hope of a United Arabia?

Though the discords were so great and the causes of friction so numerous, these discordant notes were sounding a kind of harmony in the peaceful rivalries of a national fair. For in the long years of history it was seldom that the peace of the fairs was seriously broken, or the two months' truce for attending them violated, or the sacred spots of a tribe desecrated by bloodshed. How was this? There was no central government, no punitive authority other than that of the tribe which was in the ascendant at the time, {20} or the strongest combination of clans allied for the moment by some common interest. It was not in the government that hope for the future lay.

The Possibilities of the Arabs.

(a) Germ of Belief in One Supreme God.

Was it in religion? At the bottom of all mythologies, at the back of the rudest superstitions and crudest idolatries the whole world over, there are fragments of truth. And in Arabia, lying so close to the countries of God's earliest revelation to mankind, we should expect yet more than this. Long centuries before, the Book of Job had been written in Arabia; Moses spent forty years there, leading a Bedouin life in charge of the flocks of his father-in-law; and Jethro, high priest of Midian as he was, had prepared burnt-offerings and sacrifices for the one true God, confessing, 'Now I know that the LORD is greater than all gods.' The Queen of Sheba journeying from the South to see the wisdom of Solomon may have taken back with her fragments of the truth.

The wonder is that these sparks of light had never burst into the flame of worship of the one true God. Instead they were all but extinguished; none but a thoughtful {21} man would recognise behind the gross fetishism, and the thousand petty gods of the Arab tribes, acknowledgment of the ancient belief in one supreme Deity. Yet there it was, as history proves. And Mohammed saw it.

(b) Common Ancestry. (c) Common Tongue.

There were two other common elements which all Arabia shared: a common ancestry giving them very marked national characteristics and a strong Arabian sentiment or patriotism; and a common tongue spoken (with some variation of dialect) by Bedouin and Hadesi all through that vast land of desert.[1] These were both assets of great value in Mohammed's future schemes. Whether as yet he recognized their possibilities we do not know. Anyhow he was no agitator. After all who was he? Only his uncle's dependent.

Mohammed's First Marriage.

As a rule in the East men marry young, but Mohammed was an exception, At twenty-five marriage and love came to him rather than were sought by him, and they were the making of his life. For there is no doubt that his wife Khadîjah deserves to rank among the great women of history. During her {22} lifetime her great and strong influence upon Mohammed kept him from stumbling where afterwards he fell, and as she was a woman of considerable wealth, marriage very greatly altered her husband's material and social position.

It happened in this wise. Abu Talib, finding his own family increasing faster than his ability to provide for them, bethought him of setting his nephew to earn a livelihood for himself, and addressed him in these words:

'I am, as thou knowest, a man of small substance, and truly the times deal hardly with me. Now there is a caravan of thine own tribe about to start for Syria, and Khadîjah needeth men of our tribe to send forth with her merchandise. If thou wert to offer thyself she would readily accept thy services.'

To which Mohammed very respectfully replied: 'Be it so as thou hast said.'

This sent Abu Talib off to visit Khadîjah.

'We hear that thou hast engaged such an one for two camels, and we should not be content that my nephew's hire were less than four.' To this she replied:

'Hadst thou asked this thing for one {23} of a distant or alien tribe, I would have granted it: how much rather now that thou askest it for a near relative and friend?'

So the matter was settled, and Mohammed went in charge of the caravan. His sagacity and shrewdness carried him prosperously through the undertaking, and when with the caravan he retraced his steps it was with a balance of barter goods more than usually in his favour.

Mohammed's Wooing.

It is quite a pretty picture, this, of old-time romance, albeit Khadîjah was fifteen years the senior. She is sitting on the roof surrounded by her maidens, on the watch for the earliest glimpse of the caravan, when a single camel is seen approaching, the rider of which is soon recognized as Mohammed, who has ridden ahead of the caravan to bear his news as quickly as possible. And so, travel-stained, yet flushed with his first success, he is conducted up to the presence of his mistress. 'She was delighted at all she heard: but there was a charm in the dark and pensive eyes, in the noble features, and the graceful form of her assiduous agent which pleased her even {24} more than her good fortune.' And when she had dismissed him with ample wages she did not forget him. Mohammed, too, was heart-whole no longer, and became melancholic and broody.

The ways of love are the same all the world over and in all times, but its etiquettes and customs vary. And in those days things in Arabia were not as they are with us to-day, nor as they are now in the East, where, by a strange irony, owing to the very system which Mohammed inaugurated, women are the mere chattels of men, and know no such liberty as that which brought him his best fortune in his young days.

For it was Khadîjah that played the first move in the game of courtship, and she played it with a woman's adroitness and discernment. Her sister was her accomplice.

'What is it, O Mohammed, which hindereth thee from marriage?'

'I have nothing in my hands wherewith I might marry,' was his very sensible reply.

'But if haply that difficulty were removed and thou wert invited to espouse {25} a beautiful and wealthy lady of noble birth—wouldest thou not desire to have her?'

'And who might that be?' said Mohammed, warming to her questions.

'It is Khadîjah.'

'But how might I attain unto her?' asked Mohammed.

'Let that be my care,' was the reassuring answer.

That was sufficient for him, and the sister returned to Khadîjah, who then lost no time in sending an open message to Mohammed appointing a time when they should meet. Within the year they were married with Arab ceremony by Khadîjah's aged cousin, Warakah, who blessed the union in homely Bedouin language, declaring that Mohammed was 'a camel whose nose would not be struck.'

With Mohammed's marriage to Khadîjah, his opportunity, if he were looking for one, would seem to have come. Free from his uncle's patronage, freed, too, from the carping cares of straitened circumstances, or the necessity of working long hours at some small task to earn his daily bread, he had passed to a position of {26} ease and affluence. Henceforth he led no camels or he led his own. He was free to shape his life as he would, while his wealth and new position made him one of the leading men of Mecca.

Now, if he had great thoughts, was the time to make them known; now, if he felt disquieted about the gross idolatry of the people, was his chance to bear witness against it; now, if he wanted to revolutionize the old-world life of Mecca, he had his vantage ground from which to do so. But instead, during those fifteen years, from twenty-five to forty, so full and strenuous in the life of most men of action, Mohammed played no conspicuous part,—the years passed by, and on none did he write his name.

Rebuilding of the Kaaba.

Of many incidents recovered by Mohammedan historians in later days from the scrap-heap of small provincial history, and filled by them with portent and meaning, one at least is worth recalling. It reveals a touch of that capacity for manipulating men and circumstances which contributed so largely to Mohammed's power in later days.

When he was in his thirty-fifth year, one {27} of those sudden, sweeping floods to which all mountain districts are liable swept through Mecca, and struck the Kaaba, tearing a hole in the wall, damaging the contents, and imperilling the roof. To the superstitious Meccans it was a portentous omen, and they waited expectantly for some dread visitation of the wrath of the gods whose shrine had been thus desecrated. As time passed and no calamity befell them, and less superstitious, or less reverent thieves took advantage of its insecure condition to pillage the shrine and plunder the sacred relics, the leading men of Mecca met in solemn conclave and decided that the Kaaba must be rebuilt. News reached them of a Grecian ship wrecked on the Red Sea shores not very far away. The timbers of the broken ship were bought, and her Greek captain, who had some reputation as an architect, was requisitioned to direct the building. The work was entered upon with great trepidation, but when once the ruined walls had been taken down without any visitation upon the workmen or the town, the work of rebuilding was eagerly begun, and the various clans of the Koreish vied with one another for what {28} they began to think the gods might after all consider zeal of religion and not sacrilege.

The tribes of the Koreish were divided into four parties, to each of which one wall was assigned; stones of grey granite from the neighbouring hills were carried on the citizens' heads; soon the walls began to assume their old familiar shape, and all went harmoniously.

When the walls had grown to about four feet high, a new difficulty arose. They had reached the place where the sacred Black Stone must be masoned in, in its accustomed place, in the outside of the wall near the door. Who should have the honour of laying this heaven-given stone, reverenced from time immemorial by all true Arabs? It was a puzzling question and a contentious question, too, where there was no king, nor even a prince with a special genius—as, of course, all princes have—for laying stones, nor was there any sacred order of priest or patriarch to whom appeal could be made—not even a cabinet minister!

It was settled thus. As they stood beside the wall disputing for the honour, the oldest citizen arose and said:

'O Koreish, hearken unto me! My advice is {29} that the man who chanceth first to enter the court of the Kaaba by yonder gate, he shall be chosen either to decide the difference among you, or himself to place the stone.'

The proposal was readily passed by acclamation, and they waited the issue. Presently Mohammed was seen approaching, and all unknowing he entered the chosen door. Calm and self-possessed he rose to the occasion. Taking off his mantle, he spread it on the ground and placed the stone thereon.

'Now,' he said, 'let one from each of your four divisions come forward and raise a corner of this mantle.'

Four chiefs approached, and, holding each a corner, raised the stone to the proper level, and Mohammed with his own hand guided it to its place.

The difficulty was solved and the walls were soon completed, and the roof put on—'of fifteen rafters resting upon six central pillars.' The Kaaba was complete once more, though it is doubtful whether the same respect and veneration could ever again be commanded by gods who had allowed a river to break up their sanctuary, and men to handle and restore it.

New Forces at work in Mecca.

Beyond the confines of Arabia two mighty Empires were throbbing with the activities of strenuous life, and the back-waters of quiet Mecca could not remain undisturbed.

A Meccan caravan expedition penetrated into the heart of Persia with record success; the spirit of enterprise was awake, and new-world thoughts came into the old-world city. The growth of a small but influential religious party called the Hanîfahs, led by the aged Warakah, Khadîjah's cousin, had struck at the roots of idolatry, and raised the cry of 'Back to Abraham and his simple worship of the one true God.' This told of a deepening thought and growing dissatisfaction with the gross idolatry and superstition which had hitherto done duty for religion in Mecca.

By these currents Mohammed's outward life was apparently as untouched as that of any other average citizen. Professor Davidson used to say that in youth men get their visions, and see the glory of the sun upon the distant mountains of life's horizon, and the rest of life is but a following—often through the darkness—towards the light seen in {31} youth. If it were so with Mohammed he gave little evidence of all that was passing in his mind. He lived a domestic life with Khadîjah and a now growing family of children, of whom he was very fond. Every evening he performed idolatrous rites in his home, and he named at any rate some of his children after heathen deities. He filled his place, no doubt, as a wealthy, and therefore leading citizen of Mecca, but beyond that he was known as a retiring, thoughtful man, who preferred the seclusion and quiet of home life to the rush and scramble of the market and the rostrum.

Who would have thought that this man would mightily affect the destiny and history of the whole human race, that he would be the founder of an Empire which within a hundred years would hold sway from Cadiz to Bokhara, would annihilate the Empire of Persia and lay siege to Byzantium?

Who would have thought that twelve hundred years after, this man's name, coupled with that of the Almighty, would be invoked in prayer by just over two hundred millions of mankind, and proclaimed {32} from ten thousand minarets: 'There is no God but God: Mohammed is the Apostle of God'?

How was it? Why was it?

QUESTIONS ON CHAPTER II

1. What is a blood-feud? Illustrate your answer. How far is the system good which gives rise to blood-feuds?

2. Comment on Mohammed's appearance. In what ways was it an index to his character?

3. Describe the Fair of Ukaz. What was the use of it?

4. What hope existed of the Arabs becoming a united nation?

5. How did Mohammed's marriage come about? What effect did it have upon his life?

[1] The area of Arabia about equals that of India.

'We must be as courteous to a man as to a picture, which we are willing to give the advantage of a good light.'—EMERSON.

Mohammed's first 'Revelation.'

We come now to the event in Mohammed's life about which there has been both the keenest investigation and bitterest controversy. Scholars have elaborated very different theories about the 'method' of Mohammed's inspiration, partly because of its true importance as the crisis and turning-point of his life, and partly because men used to think that the understanding of it was the key to the reading of Mohammed's character. Without troubling ourselves with the various conflicting theories, we shall confine ourselves to what is sufficiently difficult—brushing aside all fancies and excrescences with which the records are garnished, we shall tell as nearly as possible what happened, or at any rate give Mohammed's account of it.

Scene on Mount Hira.

It was Mohammed's custom—one not uncommon in Arabia at that time—to retire for a fixed season each year to the seclusion of the rocks and ravines which encircled Mecca. One of these in particular, a cave in Mount Hira, was a favourite resort—a wild, bleak, barren spot, in harmony with troubled heart and wounded spirit. And some suras (i.e. chapters) of the Korân, almost certainly composed at this time, reveal an intensity of anguish and also a growing sense of the reality of God—the following for example:

'By the rushing panting steeds,

Striking fire with flashing hoof,

That scour the land at early morn;

And, darkening it with dust,

Cleave thereby the enemy:

Verily man is to his Lord ungrateful,

And he himself is witness of it:

Verily he is keen after this World's good.

Ah! witteth he not that when what is in the

graves shall be brought forth,

And that which is in men's breasts laid bare:—

Verily in that day shall the Lord be well

informed of them.'

To this cave Mohammed had come with his trusted wife, in his fortieth year, to {35} spend the month Ramadân in undisturbed meditation; in wrestling, we may believe, with his own heart, and in contemplating the eternal problem of the world's sin and sorrow. There, in the midst of prayers and supplications, the light of revelation seemed suddenly to burst upon him.

It was midnight in the cave when a glorious angel appeared first in the sky, then approached within two bow-shots' length, holding a silken cloth written all over. The angel roused him from sleep and bade him 'Read.' 'But I am not a reader,' Mohammed replied. Thrice was the injunction repeated, the third time in these words:

'Read, in the name of the Lord who created,

Created man from a clot of blood.

Read, for the Lord is the most beneficent,

He hath taught the use of the pen;

He hath taught man that which he knoweth not.'

Then Mohammed repeated the words to himself, and they were 'written upon his heart.' Then, we are told, he went to the door of the cave, and remained standing there till again there appeared his heavenly visitant, 'in the form of a man, with wings, {36} and with his feet upon the horizon,' and saluted him: 'Mohammed, thou art the Prophet of God, and I am Gabriel.'

Trembling and overstrung, Mohammed returned to Khadîjah, and nestling close beside her like a frightened child related what had passed.

'Cover me, cover me,' he said. 'I fear for my soul.' She covered him with a mantle and comforted him, saying:

'Rejoice: God will not put you to shame; thou art so kind to thy relations, sincere in thy words, afraid of no trouble to serve thy neighbour, supporting the poor, given to hospitality, and defending the truth.'

The visitations occurred several times, and each time they were accompanied by violent physical effects upon Mohammed. 'He was angry if anyone looked upon him: his face was covered with foam, his eyes were closed and sometimes he roared like a camel.'

Even the faithful Khadîjah began to have her fears. Demon possession is a common idea in the East. 'Could it be that her exemplary husband was the victim of the wrath of some genius of evil?' She consulted her cousin, Warakah, {37} the sage and savant. His answer was wholly satisfactory, for he exclaimed:

'Holy! holy! by Him in Whose hand Warakah's soul is, if thou has told me the truth, then the Greatest Namus (nomos=law) has come to him which also appeared to Moses, and he is the Prophet of this nation. Tell him to be content.'

Still her fears were not allayed, and a test was proposed. She reasoned thus: 'If it is an evil spirit which visits my husband, it will not be ashamed in the presence of an unveiled woman, but if the spirit is good he will surely be too modest to remain.' So with elaborate ritual the test was laid. Mohammed was to summon her when next his visitant appeared, and she was to take off her veil; should the spirit depart, she would know him for a good spirit. The visitant fully vindicated himself, disappearing from Mohammed's sight at the appearance of an unveiled woman; he never was visible to Khadîjah, From that day onwards, through storm, and shine, darkness and light, contumely ridicule, and persecution, Khadîjah never doubted, never wavered in complete confidence in her husband and his message.

Days of Darkness.

For Mohammed there were yet many searchings of heart. He found himself unable to summon his visitor, or to command hours of inspiration at his will. Three years, it is said, he waited for another revelation, staggering in uncertainty and doubt and darkness, driven sometimes to the brink of despair, saved from suicide once at least only by the intervention of his wife. Light seemed to struggle with darkness in his soul, but gradually certain grand verities stood out clear. 'God, the sole Creator, Ruler, Judge of men and angels; the hopeless wretchedness of his people sunk in darkness and idolatry; Heaven and hell, the Resurrection, Judgment, the Recompense of good and evil in the World to come.' We can gather something of the sombre realities he saw, and something of the conviction with which they came to him from some of the suras written at the time:

'That which striketh! what is it which striketh?

And what shall certify thee what the striking is?

The day on which mankind shall be like moths scattered abroad,

{39}

And the mountains like wool of divers colours carded;

Then, as for him whose balances are heavy, he

shall enter into bliss;

And as for him whose balances are light, the

pit shall be his dwelling-place.

And what shall certify thee what is the pit? a raging fire!'

The One God.

One great eternal truth alone stood out before him, 'Lâ ilāha illâ 'llâhu.' 'There is no God but God.' Surely the discovering of this great truth raised him high above all Arabia. 'There is no God but God'—he had discovered it, it had been revealed to him—surely, surely he was the favoured one, the Prophet of God; yes, The Prophet of God. It all seemed to stand together, and he set it in one sentence, Lâ ilāha illâ 'llâhu; Muhammadur rasûlu 'llâh.' 'There is no God but God: Mohammed is the Apostle of God,' and so it stood for his creed, and the creed he taught, and it stands to-day as the creed of 200,000,000 of our fellow-men.

Early Followers of Mohammed.

There was another, too, besides Khadîjah who from the first followed Mohammed's fortunes with unwavering faith, a man who is truly said to have saved Islam twice. He was a personal friend of {40} Mohammed's, a popular but unimportant fellow-citizen of Mecca, by name Abu Bakr. Through these early trying years he was the propagandist of the new creed, and won to his friend's side the first little circle of Islam's converts. Years afterwards it was he who, as the first Caliph, took the white banner from his dying master's hands, raised it aloft again, and rallied fortunes that seemed shattered by the master's death.

With these two we must group another—a man of different type and a very different story—Zaid, a slave whom Khadîjah had bought some years before and presented to Mohammed,—this man proved himself a faithful friend in darker days.

The little group was but a poor token of the mighty armies Mohammed would ere long lead. Yet unquestionably a conviction grows infinitely the moment another believes in it; and these three did believe with all their hearts. Progress was slow at first; Mohammed wished to keep the matter as dark as possible, and those who knew of this teacher and his little band of disciples regarded them as a small secret society, more or less {41} harmless—after all, there were other secret societies in Arabia at that time.

In the first three years there were not more than forty converts, won chiefly by Abu Bakr's assiduous work. It is much easier to persuade people to believe in someone else than to persuade them to believe in yourself. Abu Bakr saw this, and right loyally did he play his part. These forty were mostly from the lower ranks of society, including slaves and outcasts, who found here something of a brotherhood and a fraternal generosity, if not a community of goods. As in another small society in a Grecian city five hundred years before, 'not many wise men after the flesh, not many mighty, not many noble' were called in those days.

Mohammed's 'Revelations.'

Meanwhile the seasons of 'revelation' had returned, and as time went on Mohammed was able to summon them at will. Each time the visitation was accompanied, as before, by mysterious physical symptoms and weird bodily contortions. 'His countenance was troubled; he would turn deadly pale or glowing red. He would cover himself with a blanket. He fell to the ground like one intoxicated; foam {42} would appear at his mouth; on the coldest day the perspiration would pour from his forehead. Sometimes he would hear the coming of the revelation like the ringing of a bell.' Sometimes the inspiration would come in true dreams or 'suggestions of the heart'; more often it was Gabriel, once even it was said to be God Himself speaking to him from behind a curtain. But when it was over he spoke his 'suras' which his hearers laid to heart, and afterwards noted down, and so the Korân (or Recitation) was compiled. As a modern Asian quaintly puts it: 'The heart of Mohammed was the Sinai where he received the revelation, and his tablets of stone were the hearts of true believers.'

But as Mohammed claimed that these physical seizures which he underwent in times of revelation were evidences of the reality of his divine commission, it was natural that men's thoughts should stray in search of other explanations thereof. His friends remembered that as a boy he had some sort of fit; others recollected seizures of the kind; and men of science and learning since, unwilling to ascribe the {43} origin of the Korân to fits of epilepsy, have shown how in such constitutions there do lie rich but dangerous strains of high emotion, and how a hysterical disposition is not inconsistent with strength of will and a high and lofty purpose. It is an obvious danger for such a nature possessing great thoughts to become possessed by them and be carried beyond the depth where man may walk with sure and certain tread.

Mohammed's Public Avowal.

After three years of these intermittent revelations, and quiet work and conference with his secret society, Mohammed felt prepared to take the big step of his life,—to come out and openly declare himself the Prophet of Arabia and preach his doctrines. He was the less afraid, perhaps, to do so because he held that, except for the all-important claim of his own Prophetship, he taught no new doctrine at all. Historians and scholars since have abundantly shown that all he taught was there before, hidden, indeed, and scattered, without coherence or cohesion, but there nevertheless. Covered with fable and distorted by superstition, it was part of Arabia's sub-consciousness.

Tradition tells how the Prophet took {44} his stand on Al Safa, a hill outside Mecca, and summoned the Koreish. They were followed by the Meccan mob, and to the whole assembly Mohammed preached his first public sermon. The truths, indeed, awoke an echo in their hearts; they could not gainsay them. But this was not truth as a cold cinder raked out from the past and from their national consciousness, but truth living, burning,—truth on fire. They had heard of Allah before. Here was a man to whom Allah was a reality, so great a reality that there could be no other god but Him. They would not have denied that there was a life beyond the grave. Here was a man to whom God's universe was an awful fact; who, as he poured forth his invective, seemed to have himself gazed upon the flaming fires of hell; to him there was a world of difference between heaven and hell and the paths that lead to each. Then, like some unexpected cataract, he would burst into tumultuous rhapsodies charged with thrilling words of conviction and fervid aspiration, insisting again on the realities of life, the certainty of the Judgment, the peril of the soul,—the soul of one believer outweighs {45} all earthly kingdoms. They could no more ignore this preaching than ignore the pealing of the thunder.

The Effect on Mecca.

Mecca was stirred to its depths. What! Was this man who had grown up among on them indeed sent by God to overthrow their sacred Kaaba, to tell them that the gods they worshipped were no gods at all, but wood and stone? Their ancestors had worshipped these same gods for centuries before them. Had not they themselves prayed to Uzza and to Lât, and had they not instances of answers to their prayers?

Besides, if idolatry were a crime, what became of the prestige of Mecca? Where, indeed, was their own livelihood? Like the silver-smiths of Ephesus they saw the axe laid at the root of their prosperity. Mecca owed its pre-eminence above all the cities of Arabia to its guardianship of the sacred shrine. For that reason, too, it was the one city which no Arab dared attack: its people reaped a great benefit from its central mart and a rich harvest from the pilgrims, besides a heavy tribute from the tribes. It was no wonder, then, that the Prophet's denunciations of their {46} idols, his exposures of the grossness of their worship, lashed the Koreish into fury.

Abu Talib, now the head of the clan, expostulated, and sought to bring Mohammed to reason, and begged him to renounce the task he had undertaken, but he was obdurate. 'O, my uncle, if they placed the sun on my right hand and the moon on my left, to force me to renounce my work, verily I would not desist therefrom until God made manifest His Cause, or I perished in the attempt.' There was no persuading a man like that, although it is recorded that in the course of the interview he burst into tears.

Something had happened in Mecca which Mecca could not hide.

QUESTIONS ON CHAPTER III

1. Describe Mohammed's surroundings at the time of his first 'revelation.'

2. Give three possible explanations of Mohammed's 'inspiration.' Can all three be partly true?

3. What is the Mohammedan Creed? Can you account for Mohammed's belief in it?

4. Who were the earliest converts?

5. How did further 'revelations' come to Mohammed? Why did he claim them to be divine? When did he first publicly proclaim his message?

'We would know the world—not to censure, not to boast ourselves, but that sympathy may be wider and wider.'—LYNCH.

Mohammed's Position as Prophet in Mecca.

Mohammed had now crossed the Rubicon. He had taken the decisive step of his career. To turn back was impossible. Islam was no longer a secret society. The issues at stake were clear both to Mohammed and to the men of Mecca, and they opposed his attack upon their shrine with a bitterness reinforced by a kind of patriotism. Mohammed himself was inviolable through the protection of Abu Talib, but an incessant petty persecution was maintained against his converts. As the opposition increased so did Mohammed's teaching grow in positiveness, and his violent vituperations increase in fury. 'Whoso obeyeth not God and His Prophet, to him verily is {48} the fire of hell.' Mohammed was never meek, and when assailed and contradicted his cheeks blazed fury, while his lips poured forth a torrent of curses upon his enemies.

The advantage of secrecy during the first few years had been great; it had saved the cause from being crushed at the outset. Ridicule and contempt can more easily be borne where some hundred persons are involved. Mohammed made his public début not in the rôle of an eccentric sage but as the leader of a party, a force to be reckoned with; and soon his fame spread along every caravan route of Arabia.

A CAMEL MERCHANT.

'Mohammed's fame spread along every caravan route of Arabia.'

Mohammed now set up with some state and dignity in a central position in the 'House of Al Arkam,' still famous throughout the Moslem world as 'The House of Islam.' The house was put at his disposal by one of his richer early converts. Here the Prophet held meetings of his followers, received enquirers, and held audiences of pilgrims and others who pressed upon him. At these audiences Mohammed played the Prophet's part to perfection; he wore a veil, and assumed a benign and patriarchal {49} manner. When he shook hands he would not withdraw his first, nor would he remove his searching gaze till the other turned away. His toilet, according to all accounts, was very elaborate; every night he painted his eyebrows, and he was strongly scented with perfume. Arab-like, he allowed his hair to grow long till it fell upon his shoulders, and when it began to turn grey he dyed it. He possessed the power of winning confidence at slight acquaintance, though it is said that new converts returned often from their first audience not only with a feeling of awe and chill, but of dislike. The stories of these meetings and interviews show us the kind of rugged earnestness of the man, and at the same time the motives to which he appealed in winning men's allegiance.

Mohammed's Preaching.

One day, as he sat with the men of Mecca in the common meeting-place around the Kaaba, a certain Utba, whose younger brother had recently joined the new Faith, sat down beside him and said:

'O son of my friend, you are a man eminent both for your great qualities and for your noble birth. Although you have {50} thrown the country into turmoil, created strife among families, outraged our gods, and taxed our forefathers and wise men with impiety and error, yet would we deal kindly with you. Listen to the offers I have to make to you, and consider whether it would not be well for you to accept them.'

Mohammed bade him speak on, and he said:

'Son of my friend, if it is wealth you seek, we will join together to give you greater riches than any man of the Koreish has possessed. If ambition move you, we will make you our chief, and do nothing save by your command. If you are under the power of an evil spirit which seems to haunt and dominate you so that you cannot shake off its yoke, then we will call in skilful physicians, and give them much gold that they may cure you.'

'Have you said all?' said Mohammed; and then, hearing that all had been said, he poured forth on his amazed listener the 41st chapter of the Korân:

'This is a revelation from the most Merciful: a book whereof the verses are distinctly explained, an Arabic Korân, {51} for the instruction of people who understand.... It is revealed unto me that your God is one God.... This is the disposition of the mighty, the wise God. If the Meccans withdraw from these instructions, say, I denounce unto you a sudden destruction.... The unbelievers say, Hearken not unto this Korân; but use vain discourse during the reading thereof, that ye may overcome the voice of the reader by your scoffs and laughter. Wherefore we will surely cause the unbelievers to taste a grievous punishment.... This shall be the reward of the enemies of God, namely, hell fire; therein is prepared for them an everlasting abode, as a reward for that they have wittingly rejected our signs.... Say, what think ye? If the Korân be from God, and ye believe not therein, who will lie under a greater error than he who dissenteth widely therefrom? ... Is it not sufficient for thee that thy Lord is witness of all things?'

Conversion of Ali.

Another time we hear him preaching publicly in a different strain: 'I know no man in the land of Arabia who can lay before his kinsfolk a more excellent offer than that which I now make to you. {52} I offer you the happiness of this world, and of that which is to come. God Almighty hath commanded me to call mankind unto Him. Who, therefore, among you will second me in that work, and thereby become my brother, my vice-regent, my Khalifa (successor)?'

In the audience that day was his young cousin, Ali, Abu Talib's son, whom Mohammed had adopted shortly after his marriage with Kadijah, and this sermon is said to have been the cause of his conversion.

'I, O Apostle of God, will be thy minister,' he exclaimed; 'I will knock out the teeth, tear out the eyes, rip up the bellies, and cut off the legs of all who shall dare to oppose thee.' Then in the presence of all the assembly the prophet embraced him, exclaiming, 'This is my brother, my deputy, my Khalifa: hear him and obey him.' In such manner did this Peter of Islam receive his commission.

Conversion of Omar.

There is one other story of this time which must be told. Its central figure is that of the man who later on succeeded Abu Bakr as second Caliph, who captured Jerusalem and Alexandria and conquered {53} Persia, and ruled an Empire as wide as that of Rome. He left for ever the stamp of his dauntless spirit upon Islam.

He was one of Mohammed's bitterest opponents and was engaged in elaborating a plot upon the Prophet's life, when he heard that his own brother-in-law and sister were secret converts. His wrath was aroused and he proceeded at once to their house. As he drew near he heard the low murmur of reading.

'What sound was that I heard just now?' he demanded in his rage.

'Nothing,' they replied, as many have done before and since.

'Nay,' he said with an oath, 'I hear that ye are renegades.'

'But, O Omar, may there not be truth in another religion than thine?' The argument ended in a free fight in which the woman was injured. Then at last Omar showed some signs of manhood; shamed by her bleeding head, he suggested by way of compensation that he would read the paper.

The sister persisted: 'None but the pure may touch it.'

Then Omar arose and washed himself {54} and took the paper; it was the twentieth sura, and he read it. His mood completely changed, and when he had finished its perusal he said:

'How excellent are these words and gracious.' The brother-in-law was not slow to follow up the opportunity.

'O Omar, I trust that the Lord hath verily set thee apart for himself in answer to his Prophet; it was but yesterday I heard him praying thus: "Strengthen Islam, O God, by Abu Jahl or by Omar.'" That completed the work of conversion, and Omar proceeded boldly to the house of Al Arkam and greeted Mohammed with these words:

'Verily I testify thou art the Prophet of God.'

Filled with delight the Prophet cried aloud, 'Allah Akbar,' God is most great. Henceforth Omar was a staunch follower, of whom Mohammed one day said: 'If Satan were to meet Omar, Satan would get out of his way.'

Persecution.

So there were added to the converts men of very varying types, not outcasts only now, but men of wealth, of learning, and of social position. As Mohammed {55} grew stronger, opposition to him increased. At one time a price was set upon his head, and those of his followers who were not protected by influential patrons were persecuted and boycotted in the town.

Mohammed was by no means without consideration for his followers. The persecution and violence, which befell especially the slave portion of his adherents, pressed upon him heavily. In the fifth year of his teaching he advised a large party of them to seek refuge with the Christian King of Abyssinia: 'Yonder,' pointing to the west, 'lieth a country wherein no one is wronged—a land of righteousness. Depart thither and remain until it pleaseth the Lord to open your way before you.' A strange step, it seems to us, when we reflect upon the usage he and his successors meted out to Christians in a few years' time. It reads not unlike a story of Huguenot refugees of later days. The Koreish sent their envoys to beg the King not to harbour the enemies of their country, who had forsaken the religion of their fathers, and were preaching another 'different alike from ours and from that of the King.' The Moslem representatives refused to prostrate {56} themselves, as the custom was, saying boldly: 'By our Prophet's command we prostrate ourselves only before the one true God.'

The Koreish set forth their case. Then, with that most convincing rhetoric of simple, personal narration, the Moslems declared how they had once been idolaters till it pleased Allah to send them his message through his apostle, 'a man of noble birth and blameless life, who has shown us by infallible signs proof of his mission, and has taught us to cast away idols, and to worship the only true God. He has commanded us to abstain from all sin, to keep faith, to observe the times of fasting and prayer ... to follow after virtue. Therefore do our enemies persecute us, and therefore have we, by our Prophet's command, sought refuge and protection in the King's country.' We are told that the King and his bishops were melted to tears. They offered the exiles a safe asylum.

Mohammed's attempted Compromise, c. 615 A.D.

In spite of the growth in the number of his followers, Mohammed was much exercised just at this time by the failure of his mission: the fate of Islam seemed to be {57} hanging in the balance, and once at least he allowed himself to be betrayed into the path of compromise. He was preaching one day in his accustomed place before the Kaaba, and he recited the fifty-third sura:

'By the star when it falleth your companion erreth not, neither is he misled, nor speaketh he from lust.... One taught him who is mighty in power. Have ye considered Al Lât and Al Uzza and Manât, the third with them? These are the exalted maidens, and verily their intercession may be hoped for.'

The Koreish were as much delighted as astonished. This was their doctrine. When he ended his sura with: 'Wherefore bow down before God and serve Him,' the whole assembly obeyed. The new popularity, however, disquieted him, and he was man enough to see there could be no sound building upon such a compromise. Besides, too, the very heart of his message—the unity of God—was gone. Accordingly, a few days later he publicly retracted the verse, ascribing the words to Satan. Afterwards Mohammed dubbed Uzza and Lât 'names invented by your fathers, for which Allah has given no authority.' It was the first time, but not {58} the last, that he went back upon revelations which in the most solemn words he had ascribed to God Himself. But in the circumstances his recantation was the act of a strong man, and a brave one, for he knew that the storm would break out with greater fury than before. Surely, unless Mohammed found some hope in his own heart through these long years of struggle, his courage must have failed.

Death of Khadîjah and of Abu Talib.

In the tenth year of his mission the Prophet suffered two grievous losses in the death of his faithful wife Khadîjah, and his life-long protector Abu Talib. Mohammed is said to have tried unsuccessfully to get his dying uncle to pronounce the Islamic confession. He, therefore, was doomed to hell, and the utmost that his nephew could procure for him was that while others would be in a lake of fire, he should be only in a pool! The Prophet assured Khadîjah, on her death-bed, that she, with the Virgin Mary, Potiphar's wife, and 'Kulthum, Moses' sister,' should be with him in Paradise.

When men recover quickly from a loss, unworthy souls are all too quick to say that they don't feel it. And yet one cannot {59} suppress an exclamation of surprise and shame when we find that within two or three months of the death of the noble Khadîjah, the wife, friend, and adviser of Mohammed, he was married to another widow, by name Saudah, and had betrothed himself also to Ayesha, the seven-year-old child of Abu Bakr. Yet in these two months of pain and darkness and apparent hopelessness Mohammed had set forth upon an expedition which, for sheer pluck and determination, is hardly rivalled in the story of his life. A solitary man, despised and rejected in his own city, he went forth to try to plant his teaching in another. As it turned out, his choice was an unhappy one, for he was quickly mobbed and driven forth, and Taif proved in future years the last city of Arabia to hold out against the new Faith.

Mohammed's Failure to impress Mecca.

For six years or nearly seven Mohammed had been patiently seeking to make an impression on Mecca. A very mixed band of about a hundred converts of no particular influence was the result. There was no turn of public opinion in his favour. The outlook was dark, when a gleam of hope shot across his path.

The men of Yathreb.

It was the time of the yearly pilgrimage: Mohammed happened on a group of men more open-eared than those of Mecca.

He asked the city whence they came.

'We come from Yathreb,' they said.

'Ah,' said he, 'the city of the Jews. Why not sit ye down a little with me and I will speak with you?'

In the conversation which ensued Mohammed was both learner and teacher; expounding his doctrines, he at the same time sounded the possibilities of Yathreb for his cause. The Jews, as all men knew, looked for a prophet to come; the Arab population of Yathreb were not bigoted idolaters. 'What a different reception they would give my teaching,' thought Mohammed, and further inquiries only strengthened his belief. 'This man, if he could rule our quarrelling tribes, might bring us peace and wealth once more,' so thought the men of Yathreb. For Yathreb, although it was in one of the richest valleys, and a veritable garden of Arabia, was torn with civil strife, and was plunged in poverty and distress. They were as much pleased as Mohammed. {61} There seemed possibilities here, but there was need of caution.

The First Pledge of Acaba.

A year of uncertainty and doubt followed for Mohammed. But when at the ensuing pilgrimage he sought the spot appointed for secret conclave with his Yathreb friends, a narrow, sheltered glen not far from Mecca, his fears vanished. Twelve citizens of note and influence in Yathreb were ready there to pledge their faith to Mohammed thus:

'We will not worship any but one God: we will not steal, neither will we commit adultery, nor kill our children; we will not slander in any wise, nor will we disobey the Prophet in anything that is right.'

It was a mild pledge by the side of what Mohammed demanded later, and because there was no mention of the sword it was afterwards styled 'The Pledge of Women.' But it served for the present, and Mohammed assured them:

'If ye fulfil the pledge, Paradise shall be your reward.'

With statesmanlike restraint Mohammed was content to wait another anxious year.

The twelve were now committed to his {62} cause; he could count on their zeal to propagate the new teaching and prepare Yathreb for his coming.

The Second Pledge of Acaba.

A year later, at the time of the next pilgrimage, Mohammed, without attendant, stands at the appointed trysting-place. It is midnight, for the utmost secrecy is necessary, and they assemble 'waking not the sleeper nor tarrying for the absent'; not twelve but seventy men prepared to pledge their troth this time in no doubtful words. Yathreb, they report, is honeycombed with the new teaching; a royal welcome awaits the Prophet; they were prepared to see it through.

'Our resolution is unshaken. Our lives are at the Prophet's service.' 'Stretch out thy hand, O Prophet.' And one by one, with solemn Eastern ritual, the seventy struck their hands thereon in token of their pledge.

It only remained now to remove the faithful in small parties to Yathreb, and then for the Prophet and Abu Bakr to follow with as much secrecy and as little disturbance as possible. For in the eyes of the men of Mecca this was not merely a change of residence but a transfer of {63} allegiance—they might even call it sedition.

The Hegira, of Flight to Medina, 622 A.D.

Abu Bakr was eager to set off, but still the Prophet lingered, waiting, perhaps, till his followers were all gone; perhaps for some favourable omen (for he was superstitious to the last); perhaps dreading the long, toilsome, dangerous journey, or, as he said, waiting till it was revealed that the time was come. Two swift camels were bought and kept on high feed in readiness; money in portable form was prepared; a guide, accustomed to the devious tracks of the desert, was hired.

At last the night arrived. Stealing through a back window, they escaped unobserved through a southern suburb in the opposite direction to Yathreb, and after some hours' wandering, took refuge in a cave near the summit of Mount Tûr.

They lay in hiding while Mecca raised the hue and cry.

Miracles and legends cluster around that cave and hide its Prophet. Branches sprouted in the night and hemmed it in on every side, and wild pigeons lodged upon them. A spider wove its web across the entrance. Once again Islam hung in {64} the balance. Glancing upwards at a crevice through which the morning light began to break, Abu Bakr whispered:

'What if one were to look through the chink and see us underneath his feet?'

'Think not thus, Abu Bakr,' the Prophet replied; 'we are two, but God is in the midst, a third.'

Meanwhile scouts had been sent in every direction; but at last, opining that Mohammed had escaped towards Yathreb by the fleetness of his camel, they desisted. Then the fugitives came forth, and set out for their desert journey of four hundred miles.

They were not quite 'out of the wood' yet. They met a scout returning from the search. A Bedouin encampment where they sought food held elements of danger. But at length they reached the garden outskirts of Yathreb, to be known henceforth as El Medina—'The City'—'The City of the Prophet.' For several days the town had been in eager and excited expectation of its illustrious visitor. Still, with his unrivalled restraint, Mohammed waited for four days to recover from the effects of his journey. On a Friday he made his state entry amid the cheers of {65} the populace, preached them a sermon of religious exhortation and eulogy of the new Faith, and in the midst of a circle of one hundred believers, conducted before all the people the first great Mohammedan 'Friday Service.' It was in the year of our era 622 Anno Domini, henceforth the 'First year of Islam,' the year of the 'Hegira,' or 'departure,' the Flight of Mohammed from Mecca to Medina.

Ten years of brave struggle, lonely leadership, and self-restraint do not diminish dignity: Mohammed rode into Medina in all things fulfilling the highest Oriental idea of the true king.

QUESTIONS ON CHAPTER IV

1. What were the advantages of keeping the Faith secret for some years? Was it right?

2. Describe Mohammed's mode of life in Mecca. Was it suitable?

3. Give an account of the conversion of some one convert.

4. Is persecution good or bad for a religion? How far did Mohammed and his followers suffer?

5. To what do you attribute Mohammed's failure to make his way at Mecca? What circumstances led to the flight to Medina? Was this flight a good thing?

'Too oft religion has the mother been,

Of impious act and criminal.'

LUCRITIUS.

As Al Caswa, the favourite camel, swung slowly with loose rein through the streets of Medina, allowed by her master to choose the place where he should alight, she bore him not only to a new home but to new circumstances, and to a new act in the drama of his life.

Mohammed's Claim.

There is nothing to show that Mohammed was ever a man of great foresight, or that he saw in the distance a clear, guiding star towards which he shaped his course. Indeed, the constantly changing and contradicting suras of the Korân show how his views were altered and modified from time to time. He was pre-eminently a man of the present, who understood how to deal with present circumstances and make them serve his ends. How would he act now {67} that his chance had come? He had claimed to be a Prophet, nay The Prophet of God. In Mecca he had been a preacher and a warner only. Was that all it meant? The new opportunities of Medina made him face the claim.

He had started with a two-clause creed, 'There is no God but God: Mohammed is the Prophet of God.' But he lost the emphasis on God, and with that he lost his balance. 'Mohammed is the Prophet of God'—that was the clause men resisted most. That was what drove him to persecute the Jews—when he no longer needed their friendship—more harshly than he persecuted others.

Moreover, what did this claim involve? What did it mean in Medina—this city without a visible head or any central authority—to be the Prophet of God? What was its meaning for Mecca, where he had defied the many idols of the Kaaba? What was his relation to Arabia? What was Arabia's relation to him? Obviously 'the man who determined the fate of the Kaaba must ipso facto be the chief of the nation and remodel its entire structure.' Who would gainsay the Prophet of God?

First Year in Medina: Institution of Religious Observances.

Meanwhile he must not go too fast, and so Mohammed 'with the stolid patience which in Europe belongs only to the greatest, and in Asia to everybody,' waited the year in peace—he spent it, in fact, making his own domestic arrangements, strengthening his own position, organizing the practice of the Faith. The empty plot of ground at which Al Caswa halted was bought, and upon it arose the first Mohammedan mosque. Beside it were built two cottages, one for Saudah, the wife whom he had married within a few weeks of Khadîjah's death, and the other for Ayesha, the child of Abu Bakr, only nine years of age, whom he now took as a second wife.

THE OBSERVANCE OF PRAYER.

'Typical of Mohammedanism in every century and in every clime.'

The mosque was the first visible centre of Islam. As it rose he built, too, the pillars of Mohammedan religious practice, on which Islam has rested ever since. Friday was established as the day of assembly when he preached himself to the people of Medina from a pulpit built of tamarisk trees, by the outside wall of the mosque. The duty of ceremonial washing (lustration as it was called) as a preliminary to prayer was enjoined, and {69} most typical of Mohammedanism in every century and in every clime, the observance of prayer at five stated times in the day. The prayers, accompanied by a series of four genuflections, were to be said facing originally towards Jerusalem and later towards Mecca. These prayers soon became the habit of 'the faithful.' To-day they are said in all the great mosques of the East. They are recited along every trade route of the Sahara and Soudan where the Arab drives his lonely caravan; they are used by saint and ascetic, brigand and slave-dealer alike—wherever men call themselves after the name of the Prophet.

But none of these provisions so well illustrate Mohammed's judgment and his æsthetic sense as his institution of the call to prayer by the human voice, and not by Jewish trumpet or Christian bell. It is said that the suggestion came from Omar. He communicated it to the Prophet, who cleverly replied that a special revelation to that effect had just been given him. Anyhow, the negro slave, Bilâl, was soon shouting the call from the highest turret in Medina, and the weird music of the muezzin's voice from myriads of minarets {70} still floats across the air from Cape Verde to Muscat, from Suez to Nankin, summoning one out of every seven of the entire human race to worship five times a day. 'God is most great! I witness that there is no God but God, and Mohammed is the Apostle of God! Come to prayer! Come to salvation! God is most great! There is no God but God!' At dawn is added the very human reminder, 'Prayer is better than sleep!'

Mohammed's Followers in Mecca.

Such were the religious observances of Islam, together with legal almsgiving, the duty of the jihad, or holy war, the reconsecrating of the old Arab fasting month of Ramadân, and a few solemn feasts. Mohammed added nothing in later years except that most meritorious of acts—a pilgrimage to Mecca.