"'FOUND THEM HIDIN' DOWN THE FORE-HOLD, SIR.'" p. 26.

"'FOUND THEM HIDIN' DOWN THE FORE-HOLD, SIR.'" p. 26.

BY

HAROLD BINDLOSS.

Author of "In the Niger Country," "The Concession Hunters,"

"Ainslie's Ju-ju" etc.

WITH EIGHT ILLUSTRATIONS.

TORONTO:

THE MUSSON BOOK COMPANY,

LIMITED.

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER

II.—IN COLLISION

III.—THE STOLEN CATTLE

SUNSHINE AND SNOW.

It was a December day, the great day of all the year to Charley Gordon and the boys of Firdene School, which stands in a deep, green valley of the North Country, for the last term's work was done. That very morning the prizes had been given away, and on the following one they would depart homewards for their Christmas holiday. Charley had come out first in many subjects, besides winning a special certificate for all-round excellence, and had read his prize essay to a gathering of all his comrades and some of their parents in the great stone hall which had once formed part of an ancient abbey. The prize distribution at Firdene was generally well attended.

Even now, as he ran first in the paper-chase, he could remember the mass of faces turned towards him, and the clapping of hands, though it hurt him to see his elder brother Arthur, who stood among the guests, watching him, he thought, sadly. Arthur was an officer of artillery, as he too hoped to be, and since their father and mother died had been his only guardian, while Charley was never tired of singing his praises to less fortunate companions who had not an army officer for a brother. Still—when everybody called, 'Bravo!' and he blushed and felt uncomfortable when one old lady said, "What a pretty boy!"—Arthur only said very quietly, "You have done well, Charley."

In the afternoon there was always a paper-chase, with prizes for the two hares if not caught, or the first two hounds that overtook them, and all the athletes of Firdene practised for it. Charley ran well, and now with the empty bag which had held the torn paper fluttering behind his shoulders he did his best, a comrade panting at his heels, and several of the fastest hounds somewhere two or three fields behind, while not far ahead a high ridge of furzy down shut off the dip into Firdene valley. Although it was winter, a gentle south-west wind blew up channel soft to the breath, while, as the daylight faded a white mist rolled up from the valley, and the rush through the damp air brought the blood mantling under the runner's skin. He was a clean-limbed, vigorous English boy, with muscles suppled and strengthened by many a swim from the pebble beach and exercise in the open air; for they were taught at Firdene that a healthy body means a healthy mind, and that laziness and uncleanliness, with the habits they breed, formed a millstone which might hang about a boy's neck during the rest of his life. So, very few among them slunk off into the fir-woods to smoke, as unfortunately some school-boys do, and, when caught red-handed it was bad for those who did; while it was currently reported that the head of the school once checked an indignant parent who complained about her son getting kicked at football and tearing his clothes in the paper-chase: "Madam, you should be thankful you boy takes an innocent pleasure in these desirable things," he said. "If he doesn't lose his temper, a few kicks may even be good for him."

Charley, however, had his failings, and one of them was a conviction that only the best of everything was good enough for him. In itself this was not very wrong, but in trying to get it he sometimes forgot what others were entitled to; and, because he was generally successful, there began to grow up within him a dangerous vanity. Many a vain boy finds when he has left the school he lorded over that in the outside world busy men are sometimes uncivil to presumptuous striplings, and then the discovery that he is a very insignificant person pains him. Still, he did all that lay before him thoroughly; and now, dressed in the Firdene football jersey with a crimson band round shoulders and breast, and the neatest of cricket shoes, he ran his hardest, swinging light-footed across the long meadows, through the dead leaves that rustled beside a copse, and then over stiff-ploughed furrows that sadly soiled his shoes, towards the brook which crossed a hollow. He halted a moment on the short turf beside it, for the stream ran fast and high, and while he did so the clumsy red-haired boy behind him came lumbering up.

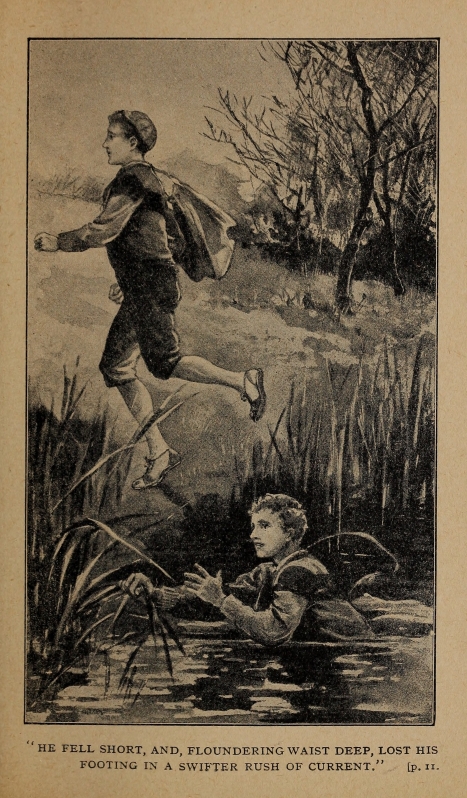

"We're caught; I can't jump it!" gasped the latter, looking ruefully at the wide stretch of muddy water which eddied and gurgled among the rotting flags. "No scent left for them to follow, so they'll head us off!"

"Don't be a muff, Baxter!" said Charley, moving backwards, as the hounds behind, catching sight of them, set up a triumphant cry. "I can; follow me;" and, with a rapid quickening of short steps, he set himself at the leap, while Baxter looked on and envied him. Then the lithe form shot out into mid-air, landed lightly on the ball of the feet; and, never looking behind him, Charley went springily up the opposite slope of the hollow.

"Might have waited for me!" said Baxter, as, setting his teeth, he also hurled himself at the leap; but he fell short, and, floundering waist-deep, lost his footing in a swifter rush of current; then clawing at the rushes and willow branches, was swept towards a deeper pool—and Baxter could not swim. But the hounds were close upon their heels; and Pierce, the foremost, was prompt of action when he saw what had happened.

"HE FELL SHORT, AND, FLOUNDERING WAIST DEEP,

LOST HIS FOOTING IN A SWIFTER RUSH OF CURRENT."

"Go on, you behind there! Come with me, Maxwell; we must get him out!" he shouted, and throwing his chance of the prize away, leapt boldly into the water. There was another splash close by and, when Pierce grabbed the floundering Baxter, his comrade helped him, so that presently they dragged the unfortunate lad out upon the bank, spluttering and very wet, but not much the worse for his ducking. "It was mean of Gordon major; he ought to have seen you across," Maxwell said. "But, of course, that wouldn't strike him. The worst of Gordon is that he thinks such a lot of himself."

Meantime Charley, remembering nothing but that he was first, ran on alone, brushing with a sharp crackle through yellow tufts of withered fern, or winding among the prickly furze on the edge of the down. He had trained hard for that race, and the boy, or man either, who will deny himself superfluous food, rise on raw cold mornings for an icy bath, and in other ways try to keep his body subject to his mind, for the benefit of both, is entitled to rejoice in the strength that comes from it. Training can, of course, be over-done, but it teaches self-restraint, and those who think too much of their food and comforts can never grow brave and strong. But Pierce and Maxwell had done so, too, and they did not forget everything but the prize. So, with head flung proudly back, and the damp air whipping his clear red cheeks, Charley swept down the side of the valley, while the grey walls of Firdene rose higher ahead. The last stretch was a long meadow with a tall hedge at the end of it, beyond which he could see a number of grown-up people as well as boys waiting to witness the finish; and, glancing behind him, Charley slackened his stride and let the hounds draw up a little. He had an audience, and would show them what he could do. Then the others saw him, and a shouting began.

"Gordon's home first! Well done, Charley! No, he's pumped out; the hounds are coming through the gate. A last spurt, Charley, before they catch you!"

Sixty yards behind came the pursuers, panting heavily,—forty—thirty, and there was a roar of voices, for the great hedge, with the steep fall behind it, lay close ahead; while someone shouted above all the rest in warning, "Round by the gap, Gordon—you'll never do it!"

But Charley only clenched his hands, and quickened his stride as the hounds came on hot-foot to catch him. Some of them spread out to bar the way to a gap where the thorns were thinner, and Charley smiled a little to himself, knowing that by doing so they were throwing their chance away. He had fixed his eyes upon a spot straight before him, where hazel branches, which would bend easily under anyone who had the courage to charge them, grew tall and slender. So a few seconds later a great shout went up as the slim figure went flying at, what appeared to be, the stiffest part of the barrier. The lad rose gallantly, and some of the watchers held their breath, expecting to see him come down head-foremost, but there was a crash of yielding branches and rustle of withered leaves, and breaking through he descended lightly through eight feet of air into the hollow below. Then while several of the hounds tore their skins and jerseys as they struggled amid the thorns, and the rest trotted beaten round by the gap, he came on at an easy stride with a red gash on one leg. There were deafening cheers when he halted breathless at the goal, and a burly country gentleman clapped his shoulder as he said, "Well done, my lad; well done! My word, sir, there's good pluck in him! Where did you leave my big, slow-moving son?"

But the head of the school only nodded stiffly, as if he were not altogether pleased, and looked grim when, after he asked, "Where is Baxter?" Charley, answered smiling, "I left him in the Willow Brook, sir."

Then the tail of the hunt came up with Baxter; and there was more cheering when the prizes were handed to the winners; while, after Charley had changed his clothes, he was told that the head master wanted to see him. He found him in his study, a grey-haired man with a keen, close-shaven face, which looked softer than usual under the light of a shaded lamp.

"Sit down, Gordon," he commenced, gravely. "Your brother has important news for you, and you must try to meet it courageously. You are leaving Firdene to-morrow, and I hope you will do your work in the world as thoroughly as you have done it here. But I want you to remember that the best men do not work for the mere sake of the prizes, that is, the money or fame it brings. They call the latter—you will learn why some day—playing to the gallery, and strong, brave men despise it. For instance, you ran and jumped well, but would you have taken the last dangerous leap if there had been no one to see you? You won the prize, but I would sooner have handed it to Pierce or Maxwell, who gave up their chance to help poor Baxter. You will remember that neither the prize nor the applause are, after all, very important, and the main thing is to do your work well, won't you? Now, go, bear your troubles bravely. Do your best, as I think you have always tried to do, and some day we hope Firdene will be proud of you."

He shook the boy's hand, and Charley went out abashed to have tea with his brother Arthur in a quaint old-English hostelry. This was all part of a long-expected treat, but Charley felt he would hardly enjoy it now, while the master's words and his brother's looks in the morning had left him with an uneasy feeling that there was trouble at hand. Arthur was like him in face, with fair hair and honest grey eyes, and he stood on the hearth-rug, looking at him, the boy fancied, half-pityingly. "I was glad to see you do so well, Charley," he said; "but I almost wish I had made a blacksmith or a carpenter of you. I am afraid you will be sorry to hear that you can't be a soldier as you hoped to. How would you like to turn farmer instead?"

Then, as the boy stared at him with puzzled eyes he laid a hand on his shoulder saying, "Charley, the bank has failed, and nearly all our money has been lost. I have left the army, and nothing remains but for you and little Reggie to begin life working for a few shillings weekly in some big English town, or go out with me to seek our fortune in another country. There are too many poor people in this one already. You remember what I told you about my visit to Canada? Well, now we have very little money left, I have decided to try farming on the prairie. You would like to live in the open air and drive your own oxen and horses, wouldn't you? At least, it would be better than licking postage stamps or copying letters all day in a dingy office."

The boy's first feeling was that somebody had cruelly injured him. His one desire had been to become a soldier, and he had often pictured himself leading his company of red-coated men. Now, however, all that was gone; he was perhaps poorer than Evans, whom he had once laughed at for coming back each term with fresh patches on his well-worn clothes. He might even have to wear old clothes, too, and it all seemed hard and unfair, but his master's words had left their mark, and he remembered that Arthur, who only seemed sorry for him, had also lost everything, and said, very slowly—

"I would like it far better than living in a big smoky town. Little Reggie is fond of cattle and horses, too—but I had set my heart on being an army officer."

"That's right!" said his brother Arthur. "We can't often get what we like. Perhaps it wouldn't be good for us if we did, and I am sorry for you. Still, you will learn to ride, and shoot, and plough, and there are such things as coyotes and antelopes to hunt if there are no more buffalo. Oh, yes, you'll like it famously. However, it's the day before the holidays. Sit down, forget everything unpleasant, think of the saddles and guns and snow-shoes, and enjoy your tea."

Charley did his best to be cheerful, and finally grew keenly interested in his brother's stories about the prairie; while, when he walked back to the school afterwards, the future seemed brighter, and he told an admiring audience what he was going to do. Some of the listeners, however, laughed when Maxwell said—

"You'll have to clean out stables and hen-houses, Charley, and black your own boots—if you wear any—and you won't like that, you know. Fancy Gordon major plucking a fowl or combing the tail of a mule. That's the worst of setting one's self up to be particular."

He went home with Arthur and his younger brother Reggie next day, and it was a somewhat silent journey, while he remembered how he had long looked forward to it. Then for four months he lived on a farm in the bleak hill country, where he got up long before daylight, even when there was bitter frost, and learned to do many disagreeable but very useful things, until at last the spring came and one afternoon he stood, with Arthur and Reggie, on the deck of a great steamer hauling out of dock at Liverpool. Steam roared aloft from her escape pipe, the winches clattered, and the deck was like a fair with swarming passengers, while he heard his brother say to a tall, soldierly man who shook his hand when the warning bell rang——

"Yes, I feel it. I'm about the only friend these youngsters have in the world, and it's a heavy responsibility. However, it seems the only thing we can do, and for their sake I must make the best of it. I can't thank your wife too much for taking care of my sister. We shall have a hard time at the beginning, but as soon as possible I will send for her."

The bell rang again, ropes were let go, and, with the screw throbbing in time to the big engines which pounded below, the steamer forged out slowly into the tide that raced seaward down the Mersey. There was a storm of voices, a great waving of hats, and an answering cheer from the watchers ashore. Then the faces grew blurred and hazy, poorly-dressed women sat down and cried, and the men talked thickly, while for some reason, Charley, who had neither father nor mother to leave behind, felt his breath come faster and something dim his eyes. It was only then, when he was leaving it for ever, he learned how much he loved his native country. Presently the dock wall faded behind them too, rolling, red-painted lightships, each with a big lantern at her mast-head, slid by, and the steamer commenced to lift her bows leisurely out of boiling white froth as she met the long heave of the open sea, and rolled westwards into a great half-circle of clear, transparent blue. But by-and-by the blue changed to crimson low down on the horizon, and there were smears of red fire on the sea as the sun dipped like a burning coal beneath it; after which the twinkling stars came out one by one, and the night wind sang songs in the rigging as the tall black masts lurched to and fro. From one of them a reeling shaft of light zig-zagged across the sky.

Charley found it made him faint and dizzy to watch them, and, after staring at a trembling streamer of brightness that flickered up from a lighthouse near the Isle of Man, he suddenly lost all interest in everything, and crawled away below, where he lay groaning with sea-sickness. His room smelt nastily, and presently grew suffocating; he could scarcely keep himself within his berth, and somebody was making unpleasant noises in the one below him. But though he did not think so at the time, that sickness did him no harm, because Charley had rather too good an opinion of himself; and if anyone, man or boy, wants to find out what a cowardly wretch he is, he cannot do better than make himself sea-sick. Still, though their throbbing added to the torture of his aching head, the big engines steadily pounded on, and swinging like a pendulum until the cabin floor seemed to rise up on end beneath him, for there was a fresh breeze now, the steamer, hurling the white seas apart before her bows, rolled north and west towards the rock-bound coast of Ireland. Charley, however, would have felt thankful for his comfortable room, had he seen the crowded steerage, where sea-sick emigrants who could not get into their berths rolled up and down together among their clattering pots and pans. An ocean voyage on a large steamer is not always nice at the beginning, and third-class passengers had not much comfort then.

On the second afternoon, after calling in Lough Foyle for Irish emigrants, the vessel steamed out into the Atlantic, past the great cliffs of Donegal. Charley leaned feebly against the bulwarks watching the rainbows that flickered in the spray each time the bows dipped into a great blue ridge of water. Then he watched the tall masts swing across the sky, and the bleak Irish hills grow dimmer behind them, after which his eyes wandered curiously across the swarming passengers. They were men of all nations, though most of them were evidently the struggling poor, while a few days earlier he might have glanced indifferently, or even with disgust at their toil-stained garments and careworn faces. Now he could sympathise with them, for he had learned what it costs to leave one's mother country, and that it is not easy, even when there is only want and hardship at home, to leave all one loves behind and go out with a brave heart to seek better fortune in the new lands across the sea.

Presently there was a commotion about the forward hatch, and a seaman appeared, dragging two unkempt urchins out from the black hole in the deck. One was still flecked with bits of the dirty newspapers he had wrapped about him to keep out the cold when he and his companion crawled down the slippery ladder, and hid themselves among the cargo, before the steamer sailed. He looked about ten years old, and was dressed in very thin, ragged clothes, as he had been all the bitter winter, during which he hawked papers up and down the seaport town; while the other, who seemed older, grasped one of the boxes of wax-lights he sold in Liverpool. It was empty now, for he had struck the matches to keep the rats away. Huge rats swarm in many steamers' holds.

"They can't drown'd us or send us to prison, can they, Tom?" asked the younger lad, shivering, and the other flung back his head as he answered—

"Not they! There ain't no prisons in Canady. My, ain't all this wonnerful! Never you mind for nothin', and look straight at the Capt'in, Jim. I've heard as all sailors is soft-'earted, an' p'r'aps he'll be good to us."

"Found them hiding down the fore-hold, sir," said the seaman; and an officer nodded, answering, "Take them to the skipper." Then the pair were led aft by two big seamen, while eight hundred passengers stared at them.

Some of the women were pitiful, and a very poor one, fishing two oranges out of the bundle she never lost sight of by night or day, and now sat upon, thrust them into the younger lad's hand. The pair had pinched, blue faces, and shivered in the breeze, for it had been very dark and cold in the hold, and they had had very little to eat as they crouched there on the hard railway iron, which groaned as the steamer rolled.

It struck Charley that he was not so very unfortunate, and had much to be thankful for, as he watched them.

About the time when the seamen found the stowaways hiding in the hold, Arthur Gordon sat in the Captain's room, and he afterwards told Charley what happened. He was chatting with the Purser when someone rapped at the door, and a sailor entering explained how he came across two boys, covered with damp newspapers, crouching in a corner among the cargo of railway iron.

"What do you mean by hiding in my ship?" asked the Captain sternly as they were led in. "Tell me your names, where you live, and just what brought you here. Don't you know I could send you to prison for trying to steal a passage without paying your fare?

"I'm Tom," said the eldest, trying to hide the thin blue knees that peeped through his ragged clothes, with a wondering look at the luxurious room, "and this is Jim. Ain't got no other names. We lives with Jim's mother in a cellar. She sewed sacks, an' was very kind to us. Gives us what she had, an' it wasn't very much. Then she dies, and the workhouse buries her—what was it, Jim?"

"'Flammation, the doctor said, but I think it was starvin'. There was a month when she had nothink hardly to eat," answered Jim, gulping down something in his throat; and the Captain added more gently, "Go on, my lad, what did you do then?"

"Then," said Tom boldly, "we lives where we could, under arches an' sheds, dodgin' the police—Jim he sells papers, I sells matches—until we saw them plackgards on the emigration offices. 'Free homes in Canady. Free land. Work and plenty for everyone,' all printed in big red letters, an' we says, 'There's room for us two somewhere in that good country.' So we clubs our tradin' money—four shillin' it was—spends sixpence on purvisions, an' hides among the cargo, where the rats nearly eat us. We'll give you the rest for our passage, sir, an' when we gets rich some day we'll pay you some more. We're not cheats, but honest traders, sir."

The Purser solemnly stretched out his hand for the bundle of coppers in a dirty rag. Arthur Gordon, who was too kindly a gentleman to hurt anybody's feelings, tried not to smile when the ragged urchin called himself a trader, and the Captain, who asked a few more questions, pressed a bell button as he said, "H'm; it was very wrong of you. Still, we're not going to hang you. Steward, take these young rascals forward, and feed them in the steerage—they look as if they wanted it. Hunt out some of my old things, and ask the stewardess to double them until they fit. Those clothes are a disgrace to humanity. Now, my lads, you'll have to work for your passage, and I've got my eye on you. By the way, steward, don't forget to wash them, whatever you do!"

Tom touched his grimy forehead, Jim stared blankly, and the Captain, who had boys of his own, said as they went out, "Poor little beggars!—it's a hard world for such as them. I like that eldest lad; there's spirit in him. What are you going to do with that money, Purser?"

The Purser laughed as he answered, "Make the saloon passengers add to it, and give it to the lads when they land. I'll tell them the story at dinner to-day"; while Arthur Gordon said, "I'm only a poor man, but will you put this in for me?" When he told his brother he also said, "So you see, Charley, there are folks very much worse off than you," and Charley agreed with him.

For six days the steamer sped westwards across a great circle of blue, and Charley thought he would never grow tired of the measured dip of the long deck, the wash of broken waves, and all the new wonders of the sea; while little Reggie would sit wrapped up for hours with an unread book upon his knee, and say at times, "I never dreamt of anything like this. It's just glorious."

Then she ran into the bank fog which lies heavy and thick on the waters where, near Newfoundland, the ocean grows shallow and the great cod feed on the sands below. The sun went out, and there was grey dimness all day, while the oily sea heaved in slow green levels, and a ringing of bells came out of the vapour as the ship crept at half speed through the fishing fleet. The anxious Captain never left his bridge, two men kept lookout above the bows, and now and then, with a roar of her whistle, a steamer they could not see went by, while sometimes the frightened emigrants shouted, as a great iron hull rushed past half visible through the thick white curtain. A fog is perhaps the worst of all dangers at sea, and there is generally fog off Newfoundland, where too many poor fishermen lose their lives through collision annually. One dismal afternoon was fading into night, when Charley, leaning over the rails, watched the mist slide past. Arthur stood near talking to Miss Armadale, a young lady who lived in the part of Canada they were going to, and the two stowaways sat under a lifeboat close by.

"I'm so glad you brought me, Tom," he heard one of them say. "We're partners in everythin', an' we're goin' to make our fortune in Canady. It's lots better than starvin' an' dodgin' the p'licemen where we come from. Hullo, there's another steamer comin'."

A great screech came ringing out of the fog, their steamer's whistle answered it with a hoarse bellow like an angry cow, and then a deep boom deafened them. "A mailboat bound for England, an' a cargo steamer somewhere. This fog's just thick with vessels," said a passing seaman.

Then the tinkle of a bell rose up through the engine-room skylights, the machinery beat more slowly, and between the roar of the whistles Charley heard one of the urchins say, "That's our ship a-callin' to tell them which way she's going. They talk to each other with the whistles. Wouldn't it be awful, Tom, if one came smashin' into us when we're almost at Canady? I've been countin' the hours till we get there."

Tom did not answer, for just then a seaman on the look-out cried, "Steamer's green light broad on our port bow, sir!" and after an answering shout from the bridge, called again as if alarmed, "She's openin' up her red." Then the deck trembled beneath them as the big engines were turned backwards to stop the ship. But it was too late, and Charley felt his heart beat wildly, as a clamour of frightened voices commenced, and after a shrill screech of a whistle the great bow of another steamer swept out of the fog. It looked huge and awful, forging resistless through the black water, which boiled with a drowsy roar about the rusty iron. He could see the tall funnel behind it, and a blink of coloured lights, then his ears were deafened by a thundering rush of steam, and eight hundred passengers were floundering and shouting all over the deck. Next he staggered backwards, for there was a heavy shock, and amid a horrible grinding the other vessel drove along their rail, crunching in the iron like cardboard, and tearing the boats away, while Arthur, shouting, "Stand clear of the wreckage, Charley!" thrust the lady beside him as far back as he could.

The ship rolled sideways and back again, as vessels in collision generally do, throwing the passengers down in heaps, and the screams of terrified women were louder than the roar of escaping steam. Men leapt from vessel to vessel, which in cases of panic even trained seamen will, some fell into the sea, and others fought and trampled on each other to be the first to reach the uninjured boats, where two bare-headed mates and a few sailors swinging heavy ashwood bars, struck down the boldest of them. A collision at sea is terrifying, and sometimes strong men, brought suddenly, without warning, face to face with death, act like frightened children, while there is an end of all sense and order when once blind fear takes hold of a crowd.

The shouting, rending of iron, and smashing of wood grew louder; somebody switched on an electric light for working cargo by, and as the sudden glare beat down upon the pale faces and struggling figures about the crowded deck, Charley saw the big lifeboat close by him hurled up on one end. His brother sprang in front of the lady who stood near him, and shouted to the urchins,

"Jump clear, Tom! Crawl this way, Jim, before it falls and crushes both of you!"

The stern of the steamer which struck them was level with Charley now, and it was one of her iron davits which had caught the boat. He saw Tom the stowaway drag the younger lad to his feet, and calling, "Jump for the other ship! We're sinkin'!" thrust him from the broken rail. The younger lad jumped and clutched the davit, and then, just as the boat fell crushed in, Tom sprang across the widening gulf, caught something and held on by one hand; after which, as the two vessels drove clear at last, there was a heavy splash in the sea, and Charley saw only one small clinging figure where two had been before. Then this one loosed its hold and dropped into the dark water, too, while Charley, who, in his excitement, only remembered he could swim, was running towards the rail, when Arthur hurled him aside. "You would only drown yourself. Stay here; I'm going to get him!" he cried.

After this Arthur leapt out into the darkness, and Charley grew faint and sick, remembering the thrashing screw, whose iron blades might cut any swimmer to pieces, while presently a cry came down from the bridge, "The steamer only struck us a glancing blow. If you'll stand fast and keep quiet you'll all be safe enough. Lower away the two starboard lifeboats, Mr. Davies."

There was a clatter of blocks as two boats on the uninjured side sank down into the sea, men dropped into them, and the other vessel was lost in the fog, while faint shouts rose from the water, and a heavy silence followed when the pounding engines stopped.

Charley felt his throat dry up, and his fingers would tremble as he pictured his brother swimming somewhere in that icy water under the fog, and he felt glad when Miss Armadale placed a hand on his shoulder. She looked at him compassionately, though he could see she was trembling, too, as she said, "Your brother is a very brave man, and I feel sure he will save them. There! Isn't that a splash of oars coming? You must not be over anxious, the boats will find him."

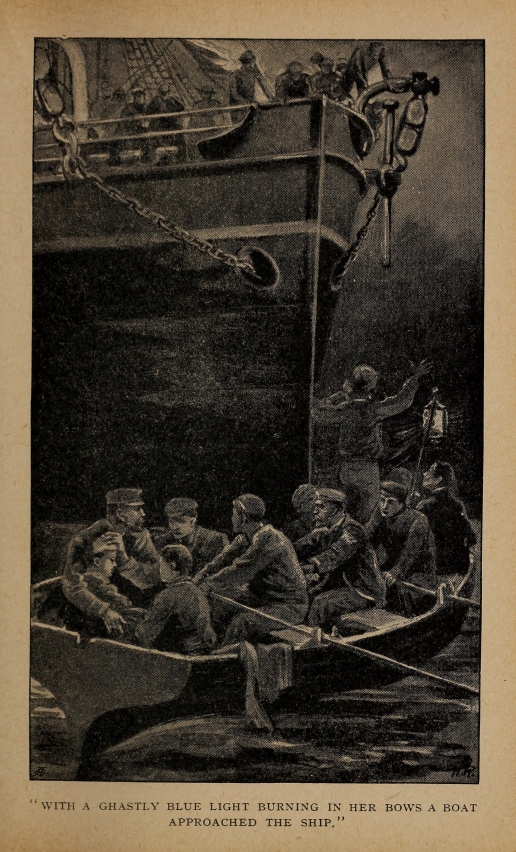

Charley took comfort. He felt proud of Arthur, and drawing himself up stood beside the lady, as he thought, protectingly, for what seemed an endless time, until a cheery shout came out of the clammy mist, "I think we have got them all, sir."

Then, with a ghastly blue light burning in her bows a boat approached the ship, and hurrying his companion to the rail Charley shouted with delight as he saw his brother in the stern. The second boat also came surging towards them, and while wet objects were helped up the steamer's side a man scrambled to the bridge, and again the Captain's voice came down, "The other ship has her bows badly crushed, but she can get back to Halifax. Our vessel seems only damaged above water level, and we're going on again soon."

"WITH A GHASTLY BLUE LIGHT BURNING IN HER BOWS

A BOAT APPROACHED THE SHIP."

A hoarse cheer went up from the passengers, who were comforted by the news, and Charley laughed excitedly, though his voice was thick as, hurling hurried questions at him, he grasped Arthur's arm. Still he remembered hearing Miss Armadale say, "I am thankful to see you back safe again. It was very gallantly done, and I hope you will allow me to congratulate you on more than your escape."

"I have often swum much farther for amusement; there were several boats about, and the only thing that troubled me was the cold," said Arthur gently; and the lady smiled at him curiously as, seeing her own friends at last, she turned away.

The stowaways were helped up next, and the ship's doctor bent over Jim, who lay limply in a seaman's arm with a red gash across his forehead.

"Take this little fellow to the surgery; he's badly hurt," he said; "see the rest get into warm blankets, steward, and they won't be much the worse. When I've time I'll physic you according to your deserts, but it's a pity the worst dose I've got won't teach you sense. When you had a comfortable ship under you whatever must you jump into that cold water for? This Company's vessels are not built to sink."

For an hour the steamer's boats rowed through the fog, burning blue lights; and then, as she went on again, Arthur explained that the other vessel had only struck them slantwise in passing, though several passengers were missing. He also said that he found the two urchins clinging to a piece of the boat, for Tom, who could swim, had somehow got his comrade there. He helped one lad on to the wreck, and then held the other up against it until a boat came and took them off—"just in time," he added simply. Arthur, as his brother knew, never said much about his own doings, and there was no need for him to do so, because a meritorious action speaks for itself, while by and by he went away to talk to Miss Armadale, who seemed very pleased to see him.

Next morning Arthur went into the surgery and found Jim lying, with his white face half-hidden by bandages, on a cot in it. The purser and doctor sat there, looking very grave, and the former said, "When Tom fell from the rail what made you jump in? You couldn't do any good—you said you couldn't swim, you know." Jim stared at the speaker, as though puzzled, before answering, "We was partners in everythin,' Tom an' me, an' when he lets go, of course, I let go too."

"I see," said the purser. "There is more in that answer than I daresay you guess. I wonder if, among all my friends, anyone would do as much for me. You want to see your partner? Well"—he glanced at the surgeon, who nodded—"I'll bring him to you."

He had not far to go, for Tom was crouching against the bulkhead just outside the door, as he had done most of the night, while when he came in, the doctor whispered, "I am afraid he is very ill, and you must not excite him. Sit still, and don't talk much; he is not always quite sensible."

The lad clenched one thin hand, his lips quivered, but he walked in very quietly, and there was only a dimness in his eyes as he touched the clammy fingers the other stretched out towards him, while a low voice said, "We was true partners an' I wanted you. I know I'm very bad, though they won't say so, an' perhaps you'll go on to Canady without me. It's a very good land, Tom; plenty for everyone—them plackgards said so. No more cold, an' no more starvin'. We was cold an' hungry often yonder, but there's good times coming for you an' me. We're goin' to a better country."

"Hush!" said the doctor. "He's getting light headed again"; and Tom, who tried not to choke, said, "I'll be quiet as a mouse, sir, if you'll only let me stay with him. I know he'd like to feel me near him."

Then the purser coughed a little, and Tom sat very still, holding his comrade's hand, until the other sank into a restless doze, while, when the doctor went out with Arthur, he said, "He hasn't any chance, poor little fellow. Got badly crushed somehow, and he's sinking fast. There is nothing I can do."

The doctor was right, for Jim died a few hours later, still holding his partner's hand, and lay in state in the wheelhouse, a little hunger-pinched figure out of which an heroic soul had gone, wrapped round in the broad red folds of his country's flag. "He's better off," said the purser, who came out bare-headed. "As he said, there's neither hunger nor cold now for him, and, sail-maker, we'll let him keep the flag. He won the right to wear it by his fidelity."

Charley long remembered the solemn scene which followed at the changing of the watch, when eight hundred passengers, most of them bare-headed, stood very silent about the deck, and a little roll of canvas with the red flag wrapped about it lay on a grating at the rail. Clear sunlight shone down on the white and crimson crosses that covered the dead waif's breast, for the clammy fog had gone, and the brass clasps of the book a clergyman read from flashed dazzlingly. Then someone on the watch raised a beckoning hand, and, as the throbbing engines stopped, the solemn words came clearly through the sudden hush. The grating tilted, there was a splash in the dark blue water, and the steamer went on again, leaving Jim the newspaper seller, who had given his life for his comrade, to rest with many another sprung from the same fearless race, far down in the icy depths, until the sea gives up her dead.

Afterwards the bright rays seemed to grow warmer, and that evening there was a shout from the passengers as the long-expected shore rose before them, a faint blurr of greyness broad across the blood-red sunset. Some laughed excitedly, some looked serious, and Charley felt a thrill of hope and eagerness, while he saw that Tom's eyes were red, as, looking forward over the dipping bows, he caught through a mist of tears his first glimpse of the promised land. But he did not reach it either destitute or friendless, for the purser had told his story well, and the rag that had been full of pennies was heavy with golden coin now, while a kind Canadian promised to find work for him, and in due time he and Charley met again.

During the next five days Charley and Reggie had much to interest them, as the long train went clattering through old Quebec, then out across the meadows and orchards of fertile Ontario, past many a prosperous wooden town, until it rolled into a region of rock and forest. Then there were frothing rivers, lonely lakes, black pinewoods, and a few Indian teppees to stare at, until, with a beat of wheels ringing back from the granite rock, it thundered along the shores of Lake Superior. Afterwards there were more rivers and forests before these were left behind in turn, and clanking through Winnipeg city they ran past groves of willows out into the great open prairie, and Charley knew they were getting near their future home.

On taking up a map of Canada, anyone may see that north of the United States boundary a wide stretch of level country runs west from Winnipeg towards the Rocky Mountains, and this is the great prairie. You will notice it is divided into Manitoba, Assiniboia, and Alberta, but there is not very much difference between them, except that men rear cattle and horses at its western end, which is higher and undulating, and grow wheat in the more level east. It is more than twice as large as Great Britain and part of it was once the bottom of an inland sea. Now, it is one great stretch of grass that grows in most places just above one's ankles, and in others to the waist, while this grass, growing and rotting for many centuries, has left a thick black mould which is perhaps the richest wheat-soil in the world. You will remember that Nature does nothing in a hurry, and except in parts of the unhealthy tropics where they die of fever, seldom allows men to eat in idleness; so here, though there is nearly always sunshine, there are also such things as droughts which starve the cattle, and frosts that shrivel the grain, so that the farmers have never a very easy time. It is very hot and bright in summer, and bitterly cold during the winter, when part of the prairie lies sheeted for months together under frozen snow.

There are few rich men in it, but there are still fewer very poor; while health, independence, and content are very much better than riches, and the settlers grow strong and fearless because they own their own land, and work hard under clear sunshine in the open air. Therefore, though they sometimes lose their crops and cattle, they face their troubles cheerfully, perhaps because the laborious life they lead strengthens the best that is in them. But you will say you want a story, and not a lesson in geography, of which you get enough at school.

Arthur Gordon built his homestead on the Assiniboian prairie, mostly of slender birch-logs and sods, because he was too wise to waste what money he had left on sawn timber. He also built a sod stable and barn; and being clever enough to realise how little he knew, which some men as well as boys are not, hired a grim old Scotchman, Peter Mackenzie, to advise and help him. Meantime he bought two big working oxen, a few cattle, a team of horses, a heavy breaker-plough to rip up the matted sod, harrows, a light waggon, and a seeder to sow the grain, besides a binder which would both cut and tie the sheaves. Then finding he had very little money left, he at once proceeded to plough for his first crop, while Charley always remembered the day they drove the first furrow.

There was a straggling wood of slender birches behind them, a clear blue sky above, and on every other side a great white waste of grass dotted by sloos, or lakes of melted snow, which would dry up in summer. Still, a breadth of yellow stubble ran across it where another man had raised a crop. They slept in the barn because the house was not finished yet, and Charley, whose clothes now showed more than signs of wear, was lighting fires with a bundle of old newspapers among the stubble. The warm wind caught them, and with a loud crackling a red blaze raced across one part of it, while he ran to and fro lighting those which had gone out again, until he was sooty all over. Next he led his brother's oxen, tapping them with a stick, while Arthur laughed when the heavy breaker-plough which tore a long furrow through the snow-bleached sod zig-zagged awkwardly, or the oxen stopped dead as its share struck some soil still frozen beneath the surface. Afterwards, old Peter let him have the lines, and clutching the handles of the lighter plough he turned up the mould where the stubble had been; and so with an hour's rest at noonday, when he had to wade deep into a sloo after the oxen, the work went on until the stars were blinking down upon the prairie. At first Charley lost his patience with the slow moving beasts, especially when they ran into water too deep for him and would not come out, while he wet himself all over trying to make them.

It was the same every day. They rose at five in the morning, worked hard, lived plainly, until at last both ploughing and sowing were done, and, leaving the grain to the care of the kindly earth, they resumed the house-building. Meantime a tender flush of green crept across the prairie, the silver birches in the bluff put out their whispering leaves, and it grew hotter day by day. The mosquitoes came down in millions, and bit them until sometimes their faces were so swollen that they could hardly see; little gophers like squirrels scurried among the tender grain; while the coyotes, which are the wolves of the grassland, howled on moonlit nights along the edge of the prairie. Then there was hay to cut for winter, and Charley drove the tinkling mower through the long grass of the sloos, and rode home under the moon on a waggon piled high with dry white trusses which smelt of peppermint. Also he grew strong of limb and cheerful, and learned it was not beneath him to clean out either the stable or chicken-house, and that it was better to have sometimes very dirty hands than keep them clean by idleness, though the sharp-tongued Peter saw he had little chance of this. Sometimes he grew angry with Peter.

Then it happened that one day, when the tall wheat grew yellow towards the harvest, Arthur sent him to count their half-wild cattle which wandered at will across the prairie. He rode out in the early morning with a Marlin rifle slung across his shoulders, feeling proud of himself, but though he swept the prairie until noon there was no sign of the beasts. It grew blazing hot, he was tired and thirsty, but he still rode on until he discovered by the trampled grasses and dints of hoofs that not only had a drove of cattle passed that way, but that several horsemen accompanied them. Then he patted the bronco's neck and turned back for home, swinging through a dust cloud across the long levels which had grown white again, and towards dusk dropped stiffly from the lathered horse, while, when grimed with dust and perspiration he told his story, old Peter said, "Ay; I was partly expectin' this. The Rustlers have lifted our beasts for us."

Now a little time earlier a very bad state of things existed across the American border, where the rich owners of many head of stock—the Cattle Barons they were called—tried to drive the poor men off their small plots of land. In return, the poor men burnt the others' homesteads, and shot some of the greediest, while afterwards very cruel deeds were done by either side, until when there was peace at last, bands of desperate men who had lost everything wandered about the country, robbing where they could, and it was some of these Peter meant when he said the Rustlers.

So when Charley added, "I think they must have taken Caryll's beasts as well!" Arthur, whose face grew stern, said sharply, "If they once get them across the border it means ruin, for the money I hope to get for those cattle must keep us through the winter. Get into the saddle; we'll ride over to Caryll's. I'll borrow another horse, and meet you, Peter."

Slinging his rifle he mounted the bronco barebacked, and while little Reggie watched them enviously they rode out at full gallop under the starlight with the dust whirling up behind them, Charley's horse stumbling now and then. It was five miles to Caryll's homestead, and they found him sitting on the doorstep, a big, good-humoured Ontario man, who said gravely, "If they've lit out with my cattle they might have taken the farm as well. Well, it's a long way to the American border, and we might come up with them; cattle travel slow. I should say somebody will get hurt if we do."

"Mayn't I come?" asked Charley, and while Arthur hesitated, Caryll, who noticed the longing in the boy's eyes, laughed, as he said, "Bring him along. If you're raising him to the prairie he may as well see the rough side of it; and if you want to teach a dog to hold fast, you must begin when he's a pup. I'm a peaceful man myself if other folks will let me—but I don't lie down while they put on big boots to tramp on me."

Caryll found fresh horses, and brought a young Blackfoot Indian called Coyote too, while after meeting Peter they pressed on fast until Charley showed them the trail of the cattle. After that he rode like one in a dream, almost falling asleep in the saddle; while at last, when the red sun leapt up, and Caryll said they must rest, dropping, aching all over, from the horse, he fell asleep in earnest. It was in the heat of afternoon he awoke, and Arthur said that Coyote reported the stolen cattle were not very far ahead, and when night came they hoped to recover them. "You see, if they once crossed the border while we went collecting help, the beasts would be corned beef in Chicago before we took up the trail again," said Caryll. "So we're going quietly to steal them back again. There are six thieving Rustlers with them, big, bad, hard men, but I figure somehow we'll come out ahead of them."

Starting once more they rode circuitously, following the hollows between each higher roll of grass, while Coyote the Indian went scouting before them until long after the stars were out. Then leaving the horses tethered behind them, they crept on hands and knees towards the edge of a ravine which wound steeply through the edge of a plateau, and Charley never forgot what he saw, when, at a whisper from Caryll they lay still among the grass. A few willows clothed the sides of the declivity, and a herd of long-horned cattle moved restlessly below, while a fire blazed redly among a clump of dew-damped bushes. Tethered horses stood beside it, and lower down white mist filled a deeper hollow. Beyond this, where the steep sides fell away, a dim stretch of grass faded into the distance, and the stars were pale overhead.

"Can't do nothin' by force," said Caryll. "They're armed, every man, an' watchin' too. So we'll wait 'til they get sleepy, and then stampede the herd on them. Guess I'm a peaceful person and don't want a rifle bullet in me if I can help it. It's not nice when it goes in, and it hurts worse to get it out."

After that, there was silence, and Charley, lying flat on his chest, could feel his heart beating as he breathed the scent of wild peppermint and the smell of hot earth drinking in the dew. The cattle were uneasy, and at times surged to and fro, bellowing, a dusky mass of tossing horns, with white vapour rising from it, while now and then a black shape rose up from the shadows and growled at them. Once, too, Charley nearly cried out when with the red light on him he saw a big bearded man, who balanced a rifle, staring up at the head of the ravine; then remembering that, if only because of the firelight, the man could not see those who watched him. Meantime Coyote was very busy tying together bunches of dry grass, or crawling snake-like into the ravine; after which there was a fresh disturbance among the cattle, and Caryll said they were mad with thirst and it would not take much to stampede or start them racing across the prairie in mad panic.

Slowly the glimmer of firelight died, and at last Caryll whispered it was time to commence, for the beasts were moving towards them. So Coyote was sent for the horses, and Arthur said, "Keep in the rear, Charley, and take care of yourself. You are growing a big lad now, and it's only fitting you should learn the rough work as well as the smooth, but I would sooner lose the farm and everything on it than that any injury should happen to you."

"I will be careful," said Charley, for his brother's voice trembled; then Coyote came up with the horses, while hardly had he mounted than a hoarse voice cried out below,

"Who's there? Stand fast before we plug a bullet into you."

But it was too late, for a dark figure rose up among the cattle with a bunch of blazing grasses in its hand, Caryll charged into the ravine waving another, and Arthur fired his repeating rifle into the air. This was sufficient, for the cattle were untamed creatures which ran wild about the prairie three parts of every year, and lowering its head one burnt and frightened steer bolted furiously down the ravine. The others followed it, and next moment the narrow hollow was filled with a thunder of hoofs, while, scarcely hearing the rifle bullet that hummed above his head, Charley swayed in his saddle as his half-broken bronco swept down the slope at a flying gallop. Coyote was yelling like a whole pack of wolves on the other flank of the herd, scattering blazing grass among them; Caryll roared himself hoarse close beside; and riding just clear of the beasts ahead, Arthur Gordon's soldierly figure rushed through the darkness. The ground sloped steeply, the beasts were madly afraid, and in that condition there is nothing that can turn a stampeding herd.

Dwarf willows rose up before the excited lad, and there was a great crackle of branches as the horse broke through, while some of them lashed him like a whip. Tangled tussocks of tall grass ripped apart and were whirled up by the battering hoofs, and Charley knew that he would probably break his neck or leg if the beast blundered into a badger hole. Still, he drove his heels against the horse's lathered flanks, for the sight below and the touch of the cool night wind that screamed past him set his blood bounding. He had once longed to be a soldier, but this was as exhilarating as galloping the guns into action or a charge of cavalry.

Where all the Rustlers went to he never knew, though staring ahead through the whirled-up dust, he fancied he saw one human figure running for life before the sea of tossing heads and horns; then with a smashing of bushes the herd charged through the camp, and he could dimly see riderless horses that had broken their tethers galloping among them. Caryll and Coyote had laid their plans well, for the thieves had no time to mount before the cattle were upon them. Next Charley felt a sudden cold sickness as the running figure disappeared, and he wondered if the herd had charged straight over the fallen man. But he forgot it in the exultation that followed the mad, headlong rush, until an object which might have been a man, came blundering as though to cut him off, down one side of the ravine. Instinctively he bent low over his horse's mane, and it was well he did so, for there was a red flash before him and the ringing of a rifle. Then, remembering he had no time to unsling his own weapon, and that the other man's was probably a repeater, he struck the horse with his heels and drove him straight at his enemy. There was no choice left him but to defend himself or be shot, and all these thieves could shoot well, so, though Charley set his teeth together and determined to do the former, he was conscious of a painful cold sinking under his belt. There was a heavy thud, and a shock; and he lurched backwards in the saddle. Something, or somebody rolled over among the grasses; and he was flying on again, while Caryll's shout rang in his ears, "A good beginning for the pup!"

They left the ravine behind at last; the herd ran straight out across the dim prairie, and Caryll let them run, for he said, "The more grass they put between themselves an' the Rustlers the better. They're tough, bad men, an' they'll follow us presently when they find their horses, though I guess it may take them all night to do it. When you once start them broncos they don't know how to stop."

It was afternoon next day, and the herd could travel no further, when dusty and aching they lay hidden among the willows which fringed another ravine. Below, the cattle waded in the cool water of a creek which wandered through the hollow, or lay contentedly among the lush grasses, while on the farther side the prairie stretched towards the horizon in a succession of swelling ridges. All the party were very silent, for they knew the thieves were following their trail, while Arthur's eyes grew anxious as he watched the shadows lengthen, creeping, black and cool, across the dusty grass. They were safe while daylight lasted, but the rifles would be useless in the dark, and they had desperate men to deal with who were not afraid of murder. Presently a tall man in a blue shirt, holding a heavy rifle, rode out from behind a rise across the hollow, and looking about him from under his broad ragged hat, drew near the ravine. He shouted when he saw the cattle, and several more similar ruffians, also mounted, appeared behind. Then, standing up in his stirrups with reckless bravado, he called, "Come out from where you're skulking like Jack rabbits in your lairs, an' we'll made a deal with you. Give us up them cattle, an' we'll let you go. Try to hold them, an' we'll most certainly make an end of every one of you. We're genuine ontamed Rustlers, and don't you forget it! Crawlin' up like sneak-thieves in the dark—I'm ashamed of you!"

"PRESENTLY A TALL MAN, HOLDING A HEAVY RIFLE, RODE OUT."

Arthur was rising from the bushes, when Caryll pulled him down. "Guess he's been drinking somethin' stronger than creek water," he said. "You don't know their little ways like I do, an' if you show yourself, the rest might shoot you. I'm a peaceful man, if I can, but losin' a horse may scare them. That's an easy mark, Peter."

"Go back," roared Arthur, "before we fire on you! If you want the cattle come and take them," and quick as thought an answering bullet hummed through the bushes, close above the speaker's head.

Meantime, old Peter stretched himself out full-length, with his left elbow buried in the mould, and his legs crossed behind him, while his eye ran down the blue rifle-barrel. "I'm no sayin' it's difficult," he answered. "One hunner yards, an' a clear light! Where will I take him—the puir beast, I mean? I'm thinkin' it's a painful necessity."

"Where you can," said Arthur, "only do it mercifully. As you say, it's a painful necessity," and for a few moments Charley held his breath, as, snapping down the rear-sight, Peter cuddled his cheek against the stock of his rifle. Then the muzzle tilted, there was a spitting of red flame, a ringing report, and man and horse went down together. The man got up again, shaking his fist in the air, and ran back after his comrades, while the beast lay still, and Peter said grimly, "I'm sorry for the horse, but it will be a lesson to them."

After that, there was a very anxious waiting, for each of the watchers knew their enemies would steal on them through the dark, and Charley felt that anything would be better than this cruel suspense, until suddenly, with a great beat of hoofs, the Rustlers swept out straight as a crow flies across the prairie. "I might get one at long range if I wasn't a peaceful man," said Caryll, longingly; but Arthur Gordon broke in, "No; we had a right to defend our lives and property, but they're in full flight now. Why, I don't know."

"I'm thinkin' it's time," said Peter, with a dry laugh. "The North-West Police are after them. Where did ye put they glasses? Oh, ay, ye can see the troopers' horses just topping the rise. I ken the big sergeant on the black charger; it's my second cousin. Ride ye, Donald—ride!"

The cattle thieves were evidently off in a very great hurry, for Charley could see them driving home their spurred heels into their horses' sides, or lashing them with the long hide bridles savagely. They had good reason to be, for when they grew smaller far down on the white levels, Gordon's party stood up and cheered, as a detachment of mounted police raced by. They were very bold horsemen, each one as well drilled as any cavalry soldier, and when, with a great pounding of hoofs and jingle of steel, they dashed at headlong gallop past the ravine, the leader on the big black charger waved a hand to Peter. As Charley learned subsequently, the sergeant, hearing of the Rustlers, had called at their homestead, and after listening to Reggie's story, rode his hardest on their trail. Then the police also vanished over the rim of the prairie and there was silence again, for, leaving Coyote to watch, the rest sank into well-earned slumber, and it was midnight before they started on their homeward journey. It ended safely, and they learned presently that two of the desperadoes who had lost their horses were caught, while the rest got away.

A few weeks later the binders were driven through the crop, and Arthur was glad when the harvest was over to find that, though frosts had spoiled a little, his first year's yield of wheat and oats would pay expenses. Charley rode with him beside the loaded waggons, piled high with sacks of corn, one bitter day when the snow-dust was already whirling across the prairie, thirty miles to the railway, and both felt grateful when that evening they watched the long freight-train lurch out across the white-sprinkled wilderness bearing their, and others' grain to the markets in Winnipeg. The fruitful earth now sinking into its winter sleep had repaid them for their labour, and they could rest, too, while, because no man can work for himself alone, they had helped to send the poor in England the cheap food they badly needed. Next day, Arthur also made a journey by passenger train, while, when Charley rode home alone he wondered if his brother had gone to see their friend of the steamer, Miss Armadale, who lived not very far away, and then wisely decided it was no business of his if he had done so.

Winter came, and Charley learned to use the heavy axe, which added to the breadth of his shoulders, as he whirled it round his head hewing birch-logs for fuel in the bluff. The stove glowed red hot by night and day, and they slept under rugs of skin in an upper room through which its iron chimney ran, for all the way across that great lonely land, from Hudson's Bay to the River Missouri, winter is nearly Arctic on the prairie. Then there were long sleigh rides over the snow to the little railway town for provisions—for the men who work like giants acquire gigantic appetites—and cosy evenings spent beside the stove, when their sister Alice, who had come out from England to keep house, read to them.

Frost flowers crusted the windows, and outside the coyotes howled as they sought shelter in the birch-bluff from the bitter cold, but it was very snug and warm within.

Winter passed, as even the longest winters do, and the bleached grasses peeped out through the melting snow, turned green for a few weeks and grew white again early in the hot summer; but Arthur Gordon lost his crop that year.

A few nights of autumn frost shrivelled up the grain. Still he and Charley only worked the harder, hoping for better fortune, and breaking more land to make up for the loss next season, though sometimes Alice sighed as she noticed the troubled look in her brother's eyes when he turned over his accounts. If a crop fails on the prairie the settler and his family must live very sparingly during the following year, and two bad harvests may ruin him altogether.

Winter came round once more, and one afternoon Charley and his brother stood dressed in long skin coats in the unpaved streets of a railway town. Frost and sun had tanned their faces almost to the colour of oak, and their frames were nearly as strong, for it is not in soft warm climates where life is easy that white men thrive best. Biting cold and sturdy labour harden instead of weaken them. The shingled roofs were white above them, and beyond the tall elevators where the wheat is stored, a lonely wilderness, which had a curious blue-white glimmer, stretched back towards the grey horizon with little huffs of snow dust racing across it. Presently Arthur raised his fur cap when they passed a store, in which one could purchase everything, from tinned provisions or a necktie, to a plough. A lady muffled in splendid furs sat inside a sleigh at its door, and Charley blushed with pleasure when she smiled at him graciously. This was Miss Armadale, their friend of the steamer, who lived with her father at Barholm Grange, one of the largest farms in that part of Canada. Arthur lingered a moment beside the sleigh, and then bowed, as another sleigh passed him slowly, when he walked away.

There were two people in it, and one, a grim-faced old man whom Charley knew was Colonel Armadale, stared straight at his brother without noticing him, after which Charley heard him say to his younger companion, who tried to hide a smile, "Settler Gordon has shown considerable presumption, and I have warned Lilian not to encourage him. The last time he came I tried to make it plain that it was blind foolishness for a man like, him with three hundred poor acres, and a few half-starved cattle, to grow interested in my daughter." Then he called out, "Send your bill along, storekeeper, and if you charge as much for your rubbish as you did last time, I'll start a store of my own. My hogs won't eat some of the decayed tin goods you palm off on me. Lilian, come on when you're ready and overtake us at the crossing. Our sleigh is loaded, and I don't like the signs of the weather."

Charley felt hot and angry, and he noticed the store-keeper frowned, though he answered nothing, for Colonel Armadale was the richest and worst-tempered man in all that district, while Arthur, who had set his lips tight, sighed as the loaded sleigh moved out and grew smaller across the prairie. Presently Lilian Armadale followed, and the store-keeper said, "A nice, quiet man to talk to, he is; guess one would never think that sweet-tempered girl was the daughter of yonder surly old bear. Wants to marry her to the man with him—some British relative. But she doesn't like him, the boys were saying. He's not much to look at any way, even if he is rich. Well, you just hold on; Miss Armadale is worth it, and those over-fed horses of his will break old Cast-iron's neck for him some day, and except Miss Lily nobody will be sorry. Say, has it struck you a blizzard's coming along?"

"If I ever hear you talk in that way again there will be trouble between you and me," was Arthur's sharp answer. "Charley, you had better ride on—there are signs of a snowstorm—and if I don't catch you before you reach the crossing, make straight for home. When will those things be ready, store-keeper?"

Charley was glad to obey, for he was chilled all through, and so by and by there were four moving specks upon the prairie, hidden from one another by the low rises which looked at a distance like the waves of a frozen sea. It was bitterly cold, and puffs of icy wind hurled stinging white crystals into his half-frozen face, until he drew down the flaps of his fur cap to meet his big collar. The horse did its best, for there are times when dumb beasts are wiser than men, and it knew a snowstorm was coming, so the hoofs hurled up the dusty snow, while the clumps of dwarf willows which rushed past showed how fast they were travelling. Then there was only a great level desolation which looked as if no one had lived in it since the beginning of the world, until at last he reached the straggling woods which marked the crossing.

Here again the prairie rolled in broken rises; it was a little warmer in the shelter of the trees, and Charley checked his horse when he found Miss Armadale holding her impatient team under the edge of a big ravine. Prairie streams generally run in a hollow like a deep railway cutting, and this one was larger than usual, while the little river which flowed through the bottom was not hard frozen yet, for winter had just begun and the trees sheltered it. Still, looking down between the scattered silver-barked birches which clothed the slope on either side, he could see the glimmer of black ice below, and, because the narrow trail bent to make the descent less steep, a rough log bridge without a parapet, some distance to the right.

"Did you see my father on the way?" asked the lady; and when Charley answered, "No," she added, "Perhaps he passed me behind the long ridge, though I don't think so. You know, the one with the sledge trail on both sides of it. I'm afraid there's a big storm coming. Where is your brother, Charley?"

She stood up in the sleigh looking back across the prairie, and Charley thought she was even prettier than his sister Alice, while there was something he liked in her voice and kindly eyes, and he felt it would be a pleasure to do anything for her. But nothing moved on the prairie except the whirling drifts, for the wind, which grew even colder, was fast rising now, while already daylight was fading, and the birches moaned eerily. Then he grew suddenly afraid, because there are times when even strong men realise their feebleness before the great powers of nature, and he knew that it often means death to be caught in the rush of a blizzard on the open prairie. The horses knew it, too, for the sleigh team snorted, while Miss Armadale shivered as she said, "I dare not wait any longer. Tell your brother to make for the Grange; you will never get home in time. No—I am forgetting—he must not come." Then, with a heightened colour in her cheeks, and a curious ring in her voice, she added, "Yes—you will bring him. It might cost his life to cross the prairie to-night."

There was a patter of hoofs behind them, but even as Charley turned round, the sleigh-team bolted, and leaving the narrow trail, charged headlong down the slope. Then Charley, remembering that the half-frozen river would not bear the weight of that load, urged his own horse after them. Miss Armadale stood upright, clenching the reins, her slight figure swaying before him among the scattered trees, which fortunately grew well apart, but the team were going their own way, the straightest to the bottom, and he shuddered when the sleigh drove crashing against a trunk. Even if the vehicle was not wrecked before it reached it, the muddy creek, like most prairie streams, was deep. But though the fur-robed figure sank down suddenly the sleigh went on as though uninjured, while Charley shouted, "Try to turn them towards the bridge. I am coming to help you."

He drove his horse at a willow bush, and the beast went through it with a bound; birch-twigs lashed his face like whips, and once a branch struck his forehead so that it bled, while jumbled all together the trunks rushed past. But he was overtaking the sleigh, and old Peter had taught him to ride half-broken broncos without either stirrups or saddle, holding on by his knees. This was painful, and sometimes dangerous work, but few things worth having can be got easily, and the skill he had acquired so hardly was very useful now, for without it he would never have come safely down that steep, tree-cumbered descent.

The wind screamed past him, there was a haze of falling snow, and as he dashed by he saw for a moment the drawn, white face of the lady in the sleigh. Then bending down he clutched at, and gripped the reins close in to the bit beside one horse's head, and afterwards saw nothing clearly. There was only an uncertain vision of flying trees, a mad thunder of hoofs, and the sleigh lurching behind him like a ship at sea. It bounced clear of the earth in places, while the black ice streaked with snow seemed rushing towards them from below. White powder rose in clouds from about the hissing steel runners and, mingling with the steam of the horses, filled his staring eyes. Then a mounted figure shot out from among the trees, swayed sideways in the saddle by the other horse's head, and his brother's voice rang out——

"Hold fast for your life, Lilly; you cannot turn them now! It won't bear us all. Charley—let go!"

"HE CLUTCHED AT AND GRIPPED ONE HORSE'S HEAD,

AND AFTERWARDS SAW NOTHING CLEARLY"

Charley, who had learned the useful lesson of swift obedience, loosed his hold, and struggled for a few moments to rein in his horse; then, trembling with excitement, watched the sleigh charge on down the slope towards the river. He knew Arthur was trusting that the pace they travelled at would carry them across before the ice broke through. He watched the sleigh shoot out from the bank, then there was a sharp crackle, and he caught his breath as Arthur's floundering horse disappeared from view. It had struck a weaker place, or stumbled, and the treacherous slippery covering had yielded beneath it. But his brother, flinging himself from the saddle, had already clutched the sleigh, and Charley shouted with relief when he saw him stand up in it grasping the reins, while a few seconds later the team crashed through the willows by the water's edge on the farther side, and drew clear of the dangerous ice. Charley felt almost dizzy now the crisis had passed, for he knew the horses could not run away up the opposite slope.

Then the snow thickened, there was a roaring among the branches, and the daylight went out, while when he reached the river he could hardly see the hole in the ice under which the current had doubtless sucked the unfortunate horse. He crossed by the bridge, but the whole air was filled with driving snow, while broken twigs were hurled about him by the sudden gale, and when he reached the level there was only thick whirling whiteness ahead. It filled his eyes and nostrils, deadened his hearing, and almost took his breath away; he could not even see the trees, and let the horse go its own way until it nearly walked into what looked like a white bear and was a man on foot. By the voice he recognised Colonel Armadale's companion, who shouted——

"Where is the team that ran away? We could see you from a distance."

"I don't know," said Charley. "Haven't seen them for ten minutes. More to the right, I think;" and the other, grasping his horse's bridle, said, "Come back, and tell him," while by-and-by they reached a sleigh in which an upright figure sat sheeted with snow. He guessed it must be Colonel Armadale.

Then the old man said, in a tone that seemed less sharp than usual, though the roar of the gale prevented the lad from hearing plainly, "You are young Gordon, are you not? My daughter would have been drowned long before we could have reached the ravine—we crossed before her somehow—but for your brother's good sense and gallantry. Not seen them since? It's hardly surprising. Let your horse go, and get into the sleigh. No, Lawrence—come back, d'you hear?"

The other man appeared to demur, saying something which sounded like, "I must try to find them, sir," but Colonel Armadale turned upon him angrily.

"Come back, you idiot!" he repeated. "Nobody could find them, and even if you could your extra weight would hamper them unnecessarily. Your brother should know the prairie well, eh, Gordon?"

"Yes, sir," said Charley, who felt bitter against the speaker for his rudeness to Arthur, "but I'm going straight home and won't get in."

"Get in at once!" said Colonel Armadale. "You would be frozen stiff long before you reached your home. Lily's team can find their own way to the stables; these western horses are like pigeons—that is, if your brother has the sense to let them. We can do nothing but trust our own to do the same, and it's considerably safer under the sleigh robes than it is in the saddle. Let them go, Lawrence. We have not a minute to lose."

Charley loosed his horse, which followed the sleigh; and then for what seemed ages the beasts blundered through a whirling cloud of snow that grew thicker and thicker, while the awful cold chilled the lad to the backbone. Still, he knew Colonel Armadale was right, and protected by the thick robes, he could just keep alive, though he would certainly have frozen in the saddle. But, at last, when he could hardly either speak or see, a dim brightness flickered ahead, voices hailed them, and he fell half-fainting over the threshold into the glare of a great fire that burned in the log-built hall of Barholm Grange. Someone who took his skin coat away brought him hot coffee and food, and when he had eaten and grown accustomed to the temperature, the grim, white-haired colonel made him sit beside the stove in a big hide-covered chair. Still, there was an unusually gentle look in his stern eyes now, and presently Charley, whose head was swimming, found him talking to him confidentially, until the colonel said abruptly, "So your brother was an officer—what made him start farming without capital on the prairie?"

Charley explained at some length as well as he could, and when he had finished the old man said, "H'm, I see. Well, he has been a good brother and done his duty to you. Never suspected he had so much in him, and that he held Her Majesty's Commission is news to me. At least, he is a courageous gentleman, and I am indebted to both of you."

After this he paced fiercely to and fro, while the icy wind howled about the building, shaking it until the logs it was made of trembled, and its wooden roofing shingles strained and clattered overhead. Thicker and thicker, with a heavy thudding the snow drove against the double windows, until it seemed that nothing living could escape destruction upon the open prairie. So presently Charley, who felt his strength returning, said——

"I can sit still no longer. You must please lend me a horse, sir, and I will go to look for them."

"Sit down again," answered the Colonel. "Ay, you have learned obedience. Do you think that if there was any small chance of finding them I would loiter here while my only daughter struggles in peril of her life somewhere out there in this awful snow? There are times, my lad, when the boldest man is helpless, and your brother's only hope is to trust the instinct given as a compensation to every dumb beast. No, we can only wait, and to wait with patience is considerably harder than doing risky things, as you will find some day."

After that the time passed very slowly, and the storm grew, if possible, fiercer, until somebody shouted, and they stood holding the great door open in the hall, and staring, with eyes that watered, into the maze of whirling drift outside. The snow blew along, fine as powder, in blinding clouds like smoke.

"Thank heaven!" said Colonel Armadale, as dim shapes, which might have been either beasts or men, loomed out through the whiteness. He ran forward holding up a lantern, Charley followed, and was immediately blown headlong into a drift, while when he scrambled out of it Arthur staggered past. He was crusted with the wind-packed powder into a formless object, and reeled blindly into the hall with a burden, which afterwards transpired to be Lilian Armadale, who had fainted in his arms. Then Charley slipped out of the way, for everyone was busy doing something for the two nearly frozen travellers, while, when Arthur appeared later in borrowed garments, Colonel Armadale met him with outstretched hands.

"You have done me a great service—a service I can never repay; and you are very welcome to Barholme," he said. "We must try to be better friends than we have been—in the future."

Charley thought the last words hardly explained the position, for he considered that nobody could have called Colonel Armadale's previous conduct friendly at all, but he was glad when his brother took the outstretched hand, for the older man's lips trembled under his long moustache. Then he was led into a snug matchboarded room, and sank into a deep sleep which lasted ten hours on end. They stayed at the Grange all the next day, and Arthur afterwards told Charley that Miss Armadale would have spoiled him altogether had he stayed any longer; then, after a friendly parting with the colonel, they rode home again, while as their horses picked their way through the drifts Arthur said, "Charley, I am afraid I have given way to foolish pride. Colonel Armadale wanted to pay me for the horse I lost, and I would not let him. It was worse than foolish, when we have Alice and Reggie to think of, and have lost all the crop."

"I am glad you did it," said the lad, flinging back his head. "It would look too much like being paid for kindness, and even if we are poor I couldn't have taken the money." Then he sighed, for he noticed his brother's face grew care-worn, and guessed that the thought of the coming year troubled him. But Arthur only said, half-aloud, "It was foolish; I had no right to refuse. Still, bad luck can't last for ever, and it may all come right some day."