The Project Gutenberg eBook of Land of play, by Sara Tawney Lefferts

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online

at

www.gutenberg.org. If you

are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the

country where you are located before using this eBook.

Title: Land of play

Verses, rhymes, stories

Editor: Sara Tawney Lefferts

Illustrators: M. L. Kirk

Florence England Nosworthy

Release Date: November 6, 2022 [eBook #69302]

Language: English

Produced by: Juliet Sutherland and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LAND OF PLAY ***

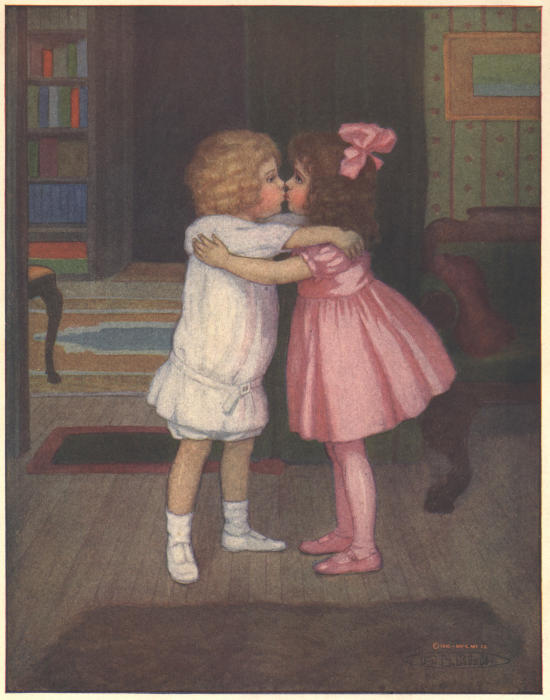

THEIR FIRST KISS

Land of Play

Verses—Rhymes—Stories

Selected by

Sara Tawney Lefferts

Illustrated by

M. L. Kirk & Florence England Nosworthy

New York

Cupples & Leon Company

Copyright, 1911, by

CUPPLES & LEON COMPANY

Printed in U.S.A.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Acknowledgment is due the following publishers and authors, for

their courteous permission to use material on which they hold copyright:

Houghton, Mifflin & Co., for permission to use “Hiawatha’s Childhood,”

“The Heights by Great Men Reached,” by Henry W. Longfellow;

“Barefoot Boy,” by John G. Whittier; “Chippy Chirio,” by John Burroughs;

“What the Winds Bring,” by Edmund Clarence Stedman;

“Fable,” “Duty,” by Emerson; “The Brown Thrush,” by Lucy Larcom;

“April,” by Alice Cary.

The Century Co., for permission to use “The Little Elf,” by John

Kendrick Bangs.

Small, Maynard & Co., for permission to use “The Tax Gatherer,”

by John B. Tabb.

Harper & Brothers, for permission to use “A Child’s Laughter,”

from The Poetical Works of Algernon Charles Swinburne.

Little, Brown & Co., for permission to use “The Swallow,” “There’s

Nothing Like the Rose,” by Christina G. Rossetti; “Boys and Girls,” by

Louisa M. Alcott.

Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Co., for permission to use “Follow Me,”

by Eliza Lee Follen.

New England Publishing Co., for permission to use “Our Mother,”

from The American Primary Teacher.

The Reilly & Britton Co., for permission to use “The Christmas

Stocking,” by L. Frank Baum (copy. 1905).

Sarah J. Day, for permission to use “Buttercups,” from “Mayflowers

to Mistletoe” (G. P. Putnam’s Sons).

Kate Upson Clark, for permission to use “Charlie’s Story,” “Marjorie’s

Bath,” “Good Listening.”

Good Housekeeping Magazine, for permission to use “A Dutch

Lullaby,” “A Dutch Winter,” by Ella Broes van Heekeren.

Newson & Co., for permission to reprint “A Story of Washington.”

Charles Scribner’s Sons, for permission to use “Extremes,” by James

Whitcomb Riley, from “The Book of Joyous Children”; “My Ship

and I,” “The Little Land,” from “A Child’s Garden of Verses,” by

Robert Louis Stevenson, and “The Duel,” by Eugene Field.

I have just to shut my eyes

To go sailing through the skies—

To go sailing far away

To the pleasant Land of Play.

—Robert Louis Stevenson.

Knowing how much good books are enjoyed by those who

travel through what Stevenson calls “The Land of Play,” it

has been a pleasure to select from the verse and prose of our

best writers, old and new, the contents of this pictured volume

for “The Little People,” and perchance for some older traveller

who may wish to be,—

“A sailor on the rain-pool sea,

A climber in the clover tree;

And just come back a sleepy-head,

Late at night to go to bed.”

—S. T. L.

HIE AWAY.

Hie away, hie away!

Over bank and over brae,

Where the copsewood is the greenest,

Where the fountains glisten sheenest,

Where the lady fern grows strongest,

Where the morning dew lies longest,

Over bank and over brae,

Hie away, hie away!

—Sir Walter Scott.

CHARLIE’S STORY.

I was sitting in the twilight,

With my Charlie on my knee,—

Little two-year-old, forever

Teasing, “Talk a ’tory p’ease to me.”

“Now,” I said, “talk me a ’tory.”

“Well,” all smiles,—“now, I will ’mence.

Mamma, I did see a kitty,—

Great—big—kitty,—on the fence.”

Mamma smiles. Five little fingers

Cover up her laughing lips.

“Is ’oo laughing?” “Yes,” I tell him,

But I kiss the finger-tips;

And I beg him tell another.

“Well,” reflectively, “I’ll ’mence.

Mamma, I did see a doggie,—

Great—big—doggie,—on the fence.”

“Rather similar,—your stories,—

Aren’t they, dear?” A sober look

Swept across the pretty forehead;

Then he sudden courage took.

“But I know a nice, new ’tory,—

’Plendid mamma! Hear me ’mence.

Mamma, I did see a elfunt,—

Great—big—elfunt,—on a fence.”

—Kate Upson Clark.

Old King Cole.

Old King Cole

Was a merry old soul,

And a merry old soul was he;

He called for his pipe,

And he called for his bowl,

And he called for his fiddlers three.

Every fiddler, he had a fiddle,

And a very fine fiddle had he;

Twee tweedle dee, tweedle dee, went the fiddlers.

Oh, there’s none so rare,

As can compare

With King Cole and his fiddlers three!

Rub-a-Dub-Dub.

Rub-a-dub-dub,

Three men in a tub,

And who do you think they be?

The butcher, the baker,

The candlestick-maker;

Turn ’em out, knaves all three!

There Was a Little Man.

There was a little man, and he had a little gun,

And his bullets were made of lead, lead, lead;

He went to the brook, and saw a little duck,

And shot it through the head, head, head.

He carried it home to his old wife Joan,

And bade her a fire to make, make, make,

To roast the little duck he had shot in the brook,

And he’d go and fetch the drake, drake, drake.

Fiddle-de-dee.

Fiddle-de-dee, fiddle-de-dee,

The fly shall marry the humble-bee,

They went to the church, and married was she,

The fly has married the humble-bee.

SEVEN TIMES ONE.

There’s no dew left on the daisies and clover,

There’s no rain left in heaven;

I’ve said my “seven times” over and over—

Seven times one are seven.

I am old! so old I can write a letter;

My birthday lessons are done;

The lambs play always, they know no better;

They are only one time one.

Oh, moon! in the night I have seen you sailing,

And shining so round and low;

You were bright! Ah, bright! but your light is failing;

You are nothing now but a bow.

You Moon! have you done something wrong in heaven,

That God has hidden your face?

I hope if you have, you will soon be forgiven,

And shine again in your place.

O, velvet Bee! you’re a dusty fellow,

You’ve powdered your legs with gold;

O, brave marsh Mary-buds, rich and yellow!

Give me your money to hold.

O, Columbine! open your folded wrapper

Where two twin turtle-doves dwell;

O, Cuckoo-pint! toll me the purple clapper,

That hangs in your clear green bell.

And show me your nest with the young ones in it—

I will not steal them away;

I am old! you must trust me, Linnet, Linnet—

I am seven times one to-day.

—Jean Ingelow.

GOING INTO BREECHES.

Joy to Philip! he this day

Has his long coats cast away,

And (the childish season gone)

Put the manly breeches on.

Sashes, frocks, to those that need ’em,

Philip’s limbs have got their freedom—

He can run, or he can ride,

And do twenty things beside.

Which his petticoats forbade;

Is he not a happy lad?

Baste-the-bear he now may play at;

Leap-frog, foot-ball sport away at;

Show his skill and strength at cricket,

Mark his distance, pitch his wicket;

Run about in winter’s snow

Till his cheeks and fingers glow;

Climb a tree or scale a wall,

Without any fear to fall.

This and more must now be done,

Now the breeches are put on.

—Charles and Mary Lamb.

MR. PEGGOTTY’S HOUSE.

I had known Mr. Peggotty’s quaint house very well in

my childhood, and I am sure I could not have been more

charmed with it if it had been Aladdin’s palace, roc’s egg and

all. It was an old black barge or boat, high and dry on Yarmouth

sands, with an iron funnel sticking out of it for a chimney.

There was a delightful door cut in the side, and it was

roofed in, and there were little windows in it. It was beautifully

clean, and as tidy as possible. There were some lockers

and boxes, and there was a table, and there was a Dutch clock,

and there was a chest of drawers, and there was a tea-tray with

a painting on it, and the tray was kept from tumbling down by

a Bible, and the tray if it had tumbled down, would have

Smashed a quantity of cups and saucers and a tea-pot that were

grouped around the book.

On the walls were colored pictures of Abraham in red

going to sacrifice Isaac in blue, and of Daniel in yellow being

cast into a den of roaring green lions. Over the little mantleshelf

was a picture of the “Sarah Jane” lugger, built at Sunderland,

with a real little wooden stern stuck on it—a work

of Art combining composition with carpentry, which I had regarded

in my childhood as one of the most enviable possessions

the world could afford.

—Charles Dickens.

From the author’s condensation of David Copperfield.

Buff says Buff.

Buff says Buff to all his men,

And I say Buff to you again;

Buff neither laughs nor smiles,

But carries his face

With a very good grace,

And passes the stick to the very next place!

Hark, hark! the Dogs do Bark!

Hark, hark!

The dogs do bark,

The beggars are coming to town;

Some in rags,

Some in jags,

And some in velvet gowns.

APRIL.

The wild and windy March once more

Has closed his gates of sleep,

And given us back our April time,

So fickle and so sweet.

Now blighting with our fears—our hopes,

Now kindling hopes with fears—

Now softly weeping through the smiles,

Now smiling through the tears.

—Alice Cary.

THE TABLE AND THE CHAIR.

I.

Said the Table to the Chair,

“You can hardly be aware,

How I suffer from the heat,

And from chilblains on my feet.

If we took a little walk,

We might have a little talk;

Pray let us take the air,”

Said the Table to the Chair.

II.

Said the Chair unto the Table,

“Now you know we are not able:

How foolishly you talk,

When you know we cannot walk!”

Said the Table with a sigh,

“It can do no harm to try.

I’ve as many legs as you:

Why can’t we walk on two?”

III.

So they both went slowly down,

And walked about the town,

With a cheerful bumpy sound,

As they toddled round and round;

And everybody cried,

As they hastened to their side,

“See! the Table and the Chair!”

IV.

But in going down an alley,

To a castle in a valley,

They completely lost their way,

And wandered all the day;

Till, to see them safely back,

They paid a Ducky-quack,

And a Beetle, and a Mouse,

Who took them to their house.

V.

Then they whispered to each other,

“O, delightful little brother,

What a lovely walk we’ve taken!

Let us dine on beans and bacon.”

So the Ducky and the leetle

Browny-Mousy and the Beetle

Dined, and danced upon their heads

Till they toddled to their beds.

—Edward Lear.

Tom, Tom.

Tom, Tom, the piper’s son,

Stole a pig and away he run!

The pig was eat, and Tom was beat,

And Tom went roaring down the street.

Eye Winker, Tom Tinker.

Eye winker,

Tom tinker,

Nose dropper,

Mouth eater,

Chin chopper,

Chin chopper.

THE BRAVE BROTHER.

I was scared almost to death

When I heard my sister Beth

Screeching loud and crying.

But I ran and took a stick,

And I tell you, pretty quick,

I had taught our goose a trick,

And had sent him flying.

Girls are always frightened stiff,

Just as sister Beth was, if

That cross, ugly gander

Flies across the garden fence.

And they always will commence

Screaming,—’stead of having sense

And showing out some dander.

I made believe, with all my might,

He was a dragon, dressed in white,

With his fiery red mouth grinning,—

Like that one mother read about,

That old St. George marched forth and fought,

And beat and killed him out and out

Almost in the beginning.

And once I heard my father say,

“It’s pretty sure to be the way,

When you’re awful frightened,

If you fight till you’re ’most dead,

Bravely, you’ll come out ahead;”

But sister told me mother said,

“You might,—and then you mightn’t!”

—Lillian Howard Cort.

You’d scarce expect one of my age

To speak in public or on the stage;

And if I chance to fall below

Demosthenes or Cicero,

Don’t view me with a critic’s eye,

But pass my imperfections by.

Large streams from little fountains flow,

Tall oaks from little acorns grow.

—David Everett.

THERE’S NOTHING LIKE THE ROSE.

The lily has an air,

And the snowdrop a grace,

And the sweet-pea a way,

And the heart’s-ease a face—

Yet there’s nothing like the rose

When it blows.

—Christina G. Rossetti.

A CONTEST BETWEEN NOSE AND EYES

Between Nose and Eyes a strange contest arose.

The spectacles set them unhappily wrong;

The point in dispute was, as all the world knows,

To which the sad spectacles ought to belong.

So Tongue was the lawyer and argued the cause

With a great deal of skill, and a wig full of learning;

While Chief-Baron Ear sat to balance the laws,

So famed for his talent in nicely discerning.

“In behalf of the Nose it will quickly appear,

And your lordship,” he said, “will undoubtedly find

That the Nose has had spectacles always in wear,

Which amounts to possession time out of mind.”

Then holding the spectacles up to the Court—

“Your lordship observes they are made with a straddle,

As wide as the ridge of the Nose is; in short,

Designed to sit close to it, just like a saddle.

“Again, would your lordship a moment suppose

(’Tis a case that has happened, and may be again),

That the visage or countenance had not a nose,

Pray who would, or who could, wear spectacles then?

“On the whole it appears, and my argument shows,

With a reasoning the Court will never condemn,

That the spectacles plainly were made for the Nose,

And the Nose was as plainly intended for them.”

Then shifting his side (as a lawyer knows how),

He pleaded again in behalf of the Eyes;

But what were his arguments few people know,

For the Court did not think they were equally wise.

So his lordship decreed with a brave solemn tone,

Decisive and clear, without one if or but—

“That whenever the Nose put his spectacles on,

By daylight or candlelight—Eyes should be shut!”

—William Cowper.

To err is human, to forgive divine.

—Alexander Pope.

The man that hails you Tom or Jack,

And proves by thumping on your back,

His sense of your great merit,

Is such a friend that one had need

Be very much his friend, indeed,

To pardon or to bear it.

—William Cowper.

Out in the Cold.

The Old Woman and Her Pig.

An old woman was sweeping her house, and she

found a little crooked sixpence. “What,” said she, “shall

I do with this little sixpence? I will go to market, and

buy a little pig.” As she was coming home, she came

to a stile; the piggy would not go over the stile.

She went a little farther, and she met a dog. So

she said to the dog—

“Dog, dog, bite pig;

Piggy won’t get over the stile;

And I shan’t get home to-night.”

But the dog would not.

She went a little farther, and she met a stick. So

she said—

“Stick, stick, beat dog;

Dog won’t bite pig;

Piggy won’t get over the stile;

And I shan’t get home to-night.”

But the stick would not. She

went a little farther, and she met a fire. So she said—

“Fire, fire, burn stick;

Stick won’t beat dog;

Dog won’t bite pig;

Piggy won’t get over the stile;

And I shan’t get home to-night.”

But the fire would not.

She went a little farther, and she met some water.

So she said—

“Water, water, quench fire;

Fire won’t burn stick;” etc.

But the water would not.

She went a little farther, and she met an ox. So

she said—

“Ox, ox, drink water;

Water won’t quench fire;” etc.

But the ox would not.

She went a little farther, and she met a butcher.

So she said—

“Butcher, butcher, kill ox;

Ox won’t drink water;” etc.

But the butcher would not. She went a little

farther, and she met a rope. So she said—

“Rope, rope, hang butcher;

Butcher won’t kill ox;” etc.

But the rope would not. She went a little farther,

and she met a rat. So she said—

“Rat, rat, gnaw rope;

Rope won’t hang butcher;” etc.

But the rat would not.

She went a little farther, and

she met a cat. So she said—

“Cat, cat, kill rat;

Rat won’t gnaw rope;” etc.

But the cat said to her, “If you will go to yonder

cow, and fetch me a saucer of milk, I will kill the rat.”

So away went the old woman to the cow, and said—

“Cow, cow, give me a saucer of milk;

Cat won’t kill rat;” etc.

But the cow said to her, “If you will go to yonder

haymakers, and fetch me a wisp of hay, I’ll give you

the milk.” So away went the old woman to the haymakers,

and said—

“Haymakers, give me a wisp of hay;

Cow won’t give me milk;” etc.

But the haymakers said to her, “If you will go to

yonder stream, and fetch us a bucket of water, we’ll give

you the hay.” So away the old woman went; but when

she got to the stream, she found the bucket was full

of holes. So she covered the bottom with pebbles, and

then filled the bucket with water, and away she went

back with it to the haymakers; and they gave her a

wisp of hay. As soon as the cow had eaten the hay,

she gave the old woman the milk; and away she went

with it in a saucer to the cat. As soon as the cat had

lapped up the milk—

The cat began to kill the rat;

The rat began to gnaw the rope;

The rope began to hang the butcher;

The butcher began to kill the ox;

The ox began to drink the water;

The water began to quench the fire;

The fire began to burn the stick;

The stick began to beat the dog;

The dog began to bite the pig;

The little pig in a fright jumped over the stile;

And so the old woman got home that night.

As Tommy Snooks.

As Tommy Snooks and Bessy Brooks

Were walking out one Sunday,

Says Tommy Snooks to Bessy Brooks,

“To-morrow will be Monday.”

As Tittymouse sat.

As Tittymouse sat in the witty to spin,

Pussy came to her and bid her good e’en.

“Oh, what are you doing, my little ’oman?”

“A-spinning a doublet for my gude man.”

“Then shall I come to thee and wind up thy thread?”

“Oh, no, Mr. Puss, you will bite off my head.”

THE BROWN THRUSH.

There’s a merry brown thrush sitting up in the tree.

He’s singing to me! He’s singing to me!

And what does he say, little girl, little boy?

“Oh, the world’s running over with joy!

Don’t you hear? Don’t you see?

Hush! Look! In my tree

I’m as happy as happy can be!”

And the brown thrush keeps singing, “A nest do you see

And five eggs, hid by me in the juniper?

Don’t meddle! Don’t touch! little girl, little boy,

Or the world will lose some of its joy!

Now I’m glad! Now I’m free!

And I always shall be,

If you never bring sorrow to me.”

So the merry brown thrush sings away in the tree,

To you and to me, to you and to me;

And he sings all the day, little girl, little boy,

“O, the world’s running over with joy!”

But long it won’t be,

Don’t you know? Don’t you see?

Unless we’re as good as can be.

—Lucy Larcom.

The best doctors in the world are Doctor Diet, Doctor

Quiet, and Doctor Merryman.

—Dean Swift.

OUR MOTHER.

Hundreds of stars in the pretty sky,

Hundreds of shells in the shore together,

Hundreds of birds that go singing by,

Hundreds of birds in the sunny weather.

Hundreds of dew drops to greet the dawn,

Hundreds of bees in the purple clover,

Hundreds of butterflys on the lawn,

But only one mother the wide world over.

—Unknown.

A LOBSTER QUADRILLE.

“Will you walk a little faster?” said a whiting to a snail,

“There’s a porpoise close behind us, and he’s treading on my tail.”

See how eagerly the lobsters and the turtles all advance!

They are waiting on the shingle—will you come and join the dance?

Will you, won’t you, will you, won’t you, will you join the dance?

Will you, won’t you, will you, won’t you, won’t you join the dance?

“You can really have no notion how delightful it will be

When they take us up and throw us, with the lobsters, out to sea!”

But the snail replied, “Too far, too far!” and gave a look askance—

Said he thanked the whiting kindly, but he would not join the dance.

Would not, could not, would not, could not, would not join the dance.

Would not, could not, would not, could not, would not join the dance.

“What matters it how far we go?” his scaly friend replied,

“There is another shore, you know, upon the other side.”

The further off from England, the nearer is to France—

Then turn not pale, beloved snail, but come and join the dance.

Will you, won’t you, will you, won’t you, will you join the dance?

Will you, won’t you, will you, won’t you, won’t you join the dance?

—Lewis Carroll.

THE TAX-GATHERER.

“And pray, who are you?”

Said the violet blue

To the Bee, with surprise

At his wonderful size,

In her eye-glass of dew.

“I, madam,” quoth he,

“Am a publican Bee,

Collecting the tax

Of honey and wax.

Have you nothing for me?”

—John B. Tabb.

Blessings on thee, little man,

Barefoot boy with cheek of tan!

With thy turned-up pantaloons,

And thy merry whistled tunes;

With thy red lips, redder still

Kissed by strawberries on the hill;

With the sunshine on thy face,

Through thy torn brims jaunty grace:

From my heart I give thee joy—

I was once a barefoot boy!

Prince thou art—the grown-up man

Only is republican.

Let the million-dollared ride!

Barefoot, trudging at his side,

Thou hast more than he can buy

In the reach of ear and eye—

Outward sunshine, inward joy:

Blessings on thee, barefoot boy!

O, for boyhood’s painless play,

Sleep that wakes in laughing day,

Health that mocks the doctor’s rules,

Knowledge never learned of schools,

Of the wild bees’ morning chase,

Of the wild-flower’s time and place,

Flight of fowl and habitude

Of the tenants of the wood;

How the tortoise bears his shell,

How the woodchuck digs his cell

And the ground-mole sinks his well;

How the robin feeds her young,

How the oriole’s nest is hung;

Where the whitest lilies blow,

Where the freshest berries grow,

Where the groundnut trails its vine,

Where the wood-grapes’ clusters shine;

Of the black wasp’s cunning way,

Mason of his walls of clay,

And the architectural plans

Of gray hornet artisans!

For eschewing books and tasks,

Nature answers all he asks;

Hand in hand with her he walks,

Face to face with her he talks,

Part and parcel of her joy—

Blessings on the barefoot boy.

O, for boyhood’s time of June,

Crowding years in one brief moon,

When all things I heard or saw,

Me, their master, waited, for

I was rich in flowers and trees,

Humming birds and honey-bees;

For my sport the squirrel played,

Plied the snouted mole his spade;

For my taste the blackberry cone

Purpled over hedge and stone;

Laughed the brook for my delight,

Through the day and through the night,

Whispering at the garden wall,

Talked with me from fall to fall;

Mine the sand-rimmed pickerel pond,

Mine the walnut slopes beyond,

Mine, on bending orchard trees,

Apples of Hesperides!

Still as my horizon grew,

Larger grew my riches, too;

All the world I saw and knew

Seemed a complex Chinese toy,

Fashioned for a barefoot boy!

O, for festal dainties spread,

Like my bowl of milk and bread—

Pewter spoon and bowl of wood,

On the door-stone, gray and rude—

O’er me like a regal tent,

Cloudy-ribbed, the sunset bent,

Purple-curtained, fringed with gold,

Looped in many a wind-swung fold;

While for music came the play

Of the pied frogs’ orchestra;

And, to light the noisy choir,

Lit the fly his lamps of fire.

I was monarch; pomp and joy

Waited on the barefoot boy!

Cheerily, then, my little man,

Live and laugh, as boyhood can!

Though the flinty slopes be hard,

Stubble-speared the new-mown sward,

Every morn shall lead thee through

Fresh baptisms of the dew;

Every evening from thy feet

Shall the cool wind kiss the heat:

All too soon these feet must hide

In the prison cells of pride,

Lose the freedom of the sod,

Like a colt’s for work be shod,

Made to tread the mills of toil,

Up and down in ceaseless moil:

Happy if their track be found

Never on forbidden ground;

Happy if they sink not in

Quick and treacherous sands of sin:

Ah! that thou couldst know thy joy,

Ere it passes, barefoot boy!

—John Greenleaf Whittier.

A STORY OF WASHINGTON.

During the Revolutionary War, the corporal of a little

band of soldiers was giving orders about a heavy beam which

they were trying to raise to the top of the wall. It was almost

too heavy for them, and the voice of the corporal was often

heard shouting, “Heave away! There it goes! Heave ho!”

A man in citizen’s clothes was passing, and asked the corporal

why he did not help them. Very much astonished, the

corporal replied, with the pomp of an emperor, “Sir, I am a

corporal!”

“You are, are you?” replied the stranger; “I was not

aware of that,” and taking off his hat he bowed, saying, “I ask

your pardon, Mr. Corporal.”

Upon this he put his shoulder to the beam and pulled

until the sweat stood on his forehead. When the beam was

right, he turned to the corporal, saying, “Mr. Corporal, when

you have another such job and have not men enough, send

for your commander-in-chief, and I shall gladly come to help

you a second time.”

The corporal was thunderstruck. It was Washington.

There Was a Fat Man of Bombay.

There was a fat man of Bombay,

Who was smoking one sunshiny day,

When a bird, called a snipe,

Flew away with his pipe,

Which vexed the fat man of Bombay.

Sing a Song of Sixpence.

Sing a song of sixpence,

A pocket full of rye;

Four and twenty blackbirds

Baked in a pie;

When the pie was opened,

The birds began to sing;

Was not that a dainty dish

To set before the king?

The king was in the parlour

Counting, out his money;

The queen was in the kitchen,

Eating bread and honey;

The maid was in the garden,

Hanging out the clothes;

There came a little blackbird,

And snipped off her nose.

EPITAPH ON A FREE BUT TAME REDBREAST.

These are not dewdrops, these are tears,

And tears by Sally shed,

For absent Robin, who she fears,

With too much cause, is dead.

One morn he came not to her hand

As he was wont to come,

And, on her finger perch’d, to stand

Picking his breakfast crumb.

Alarm’d, she called him, and perplex’d,

She sought him, but in vain;

That day he came not, nor the next,

Nor ever came again.

She therefore raised him here a tomb,

Though where he fell, or how,

None knows, so secret was his doom,

Nor where he moulders now.

Had half a score of coxcombs died

In social Robin’s stead,

Poor Sally’s tears had soon been dried

Or haply never shed.

But Bob was neither rudely bold

Nor spiritlessly tame;

Nor was, like theirs, his bosom cold,

But always in a flame.

—William Cowper.

SLOTH MAKES ALL THINGS DIFFICULT.

Sloth makes all things difficult; but Industry, all easy;

and he that rises late must trot all day, and shall scarce overtake

his business at night; while Laziness travels so slowly that

Poverty soon overtakes him.

—Benjamin Franklin.

The year’s at the Spring,

The day’s at the morn;

Morning’s at seven;

The hillside’s dew-pearled;

The lark’s on the wing;

The snail’s on the thorn;

God’s in His heaven—

All’s right with the world!

—Robert Browning.

Humpty Dumpty.

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall.

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall;

Threescore men and threescore more

Cannot place Humpty Dumpty as he was before.

Hot-Cross Buns!

Hot-cross buns!

Hot-cross buns!

One a penny, two a penny,

Hot-cross buns!

Hot-cross buns!

Hot-cross buns!

If ye have no daughters,

Give them to your sons.

MY BLUE-EYED BABY BOY.

You ask me why I’m smiling so,

When every stock and bond is low;

Why my heart seems full, and running o’er with joy.

Can’t you guess the reason, say?

I am sure ’tis plain as day—

I’ve been romping with my blue-eyed baby boy.

Though I faint beneath my cares,

And my wheat seems full of tares,

I can still have fullest peace without alloy;

For in the twilight gloam,

I shall hasten to my home,

And be greeted by my blue-eyed baby boy.

Let the morbid fellow groan,

In a melancholy tone,

Seeing only thorns and thistles that annoy;

Missing all the roses nigh,

And not once suspecting why—

He has never had a blue-eyed baby boy.

—Ellen Brannan Tawney.

The Nursery Express.

PLAYING TABLEAUX.

Mother dressed us up for tableaux,

Little Cousin Lu and me;

And I heard the people saying,

We were cute as we could be!

Maybe Lu looked rather pretty,

But a boy dressed up like that,

With a great long coat around him,

And his Father’s new silk hat,

Feels like running off and hiding;

And I would have done it, too,

If I hadn’t promised Mother,

I would be as good as Lu.

Lu was dressed in shining satin,

With a veil fixed on her head,

Just like Aunt Lucille last summer,

When she married Uncle Ned.

But I mean to marry Mother,

When I’ve grown up big and strong;

I was six years old last Sunday,

So it won’t take very long.

When I told her all about it,

She just laughed and shook her head,

“When you’re quite grown up, my laddie,

You’ll ask someone else instead.”

—Lillian Howard Cork.

Old Mother Hubbard.

Old Mother Hubbard

Went to the cupboard,

To get her poor dog a bone;

But when she came there,

The cupboard was bare,

And so the poor dog had none.

She went to the baker’s

To buy him some bread;

But when she came back,

The poor dog was dead.

She went to the joiner’s

To buy him a coffin;

But when she came back,

The poor dog was laughing.

She took a clean dish

To get him some tripe;

But when she came back,

He was smoking his pipe.

She went to the fishmonger’s

To buy him some fish;

And when she came back,

He was licking the dish.

She went to the ale-house

To get him some beer;

But when she came back,

The dog sat in a chair.

She went to the tavern

For white wine and red;

But when she came back,

The dog stood on his head.

She went to the hatter’s

To buy him a hat;

But when she came back,

He was feeding the cat.

She went to the barber’s

To buy him a wig;

But when she came back,

He was dancing a jig.

She went to the fruiterer’s

To buy him some fruit;

But when she came back,

He was playing the flute.

She went to the tailor’s

To buy him a coat;

But when she came back,

He was riding a goat.

She went to the cobbler’s

To buy him some shoes;

But when she came back,

He was reading the news.

She went to the seamstress

To buy him some linen;

But when she came back,

The dog was spinning.

She went to the hosier’s

To buy him some hose;

But when she came back,

He was dressed in his clothes.

The dame made a curtsey,

The dog made a bow;

The dame said, “Your servant,”

The dog said, “Bow, wow.”

This wonderful Dog

Was Dame Hubbard’s delight;

He could sing, he could dance,

He could read, he could write.

She gave him rich dainties

Whenever he fed,

And erected a monument

When he was dead.

Here am I.

Here am I, little jumping Joan.

When nobody’s with me, I’m always alone.

Hurly, Burly.

Hurly, burly, trumpet trase,

The cow was in the market-place.

Some goes far, and some goes near,

But where shall this poor henchman steer?

I Went up One Pair of Stairs.

1. I went up one pair of stairs. Just like me.

2. I went up two pair of stairs. Just like me.

3. I went into a room. Just like me.

4. I looked out of a window. Just like me.

5. And there I saw a monkey. Just like me.

Elsie Marley.

Elsie Marley has grown so fine

She won’t get up to feed the swine;

She lies in bed till half-past nine—

Ay! truly she doth take her time.

WHAT DOES LITTLE BIRDIE SAY?

What does little birdie say,

In her nest at peep of day?

“Let me fly,” says little birdie,

“Mother, let me fly away.”

Birdie, rest a little longer,

Till the little wings are stronger.

So she rests a little longer,

Then she flies away.

What does little baby say,

In her bed at peep of day?

Baby says, like little birdie,

“Let me rise and fly away.”

Baby, sleep a little longer,

Till the little limbs are stronger.

If she sleeps a little longer,

Baby, too shall fly away.

—Alfred, Lord Tennyson.

Whatever is worth doing at all, is worth doing well.

—Lord Chesterfield.

THE RAINBOW.

My heart leaps up when I behold

A rainbow in the sky;

So was it when my life began,

So is it now I am a man,

So be it when I shall grow old,

Or let me die!

The child is father of the man;

And I could wish my days to be

Bound each to each by natural piety.

—William Wordsworth.

Hey! Diddle, Diddle.

Hey! diddle, diddle, the cat and the fiddle,

The cow jumped over the moon;

The little dog laughed to see such sport,

And the dish ran away with the spoon.

Little Jack Jingle.

Little Jack Jingle,

He used to live single;

But when he got tired of this kind of life,

He left off being single, and lived with his wife.

Cock Robin Got Up Early.

Cock Robin got up early

At the break of day,

And went to Jenny’s window,

To sing a roundelay.

He sang Cock Robin’s Love

To the pretty Jenny Wren,

And when he got unto the end,

Then he began again.

Pussy-cat, Pussy-cat.

Pussy-cat, pussy-cat, where have you been?

“I’ve been up to London to look at the Queen.”

Pussy-cat, pussy-cat, what did you there?

“I frightened a little mouse under the chair.”

SPRING SONG.

Spring comes hither,

Buds the rose;

Roses wither,

Sweet Spring goes.

Summer soars,—

Wide-winged day;

White light pours,

Flies away.

Soft winds blow,

Westward born;

Onward go,

Toward the morn.

—George Eliot.

Millions for defense, but not one cent for tribute.

—C. C. Pinckney.

DUTY.

So nigh is grandeur to our dust,

So near is God to man;

When Duty whispers low, “Thou Must,”

The youth replies, “I can.”

—Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Dickory, Dickory, Dock.

Dickory, dickory, dock,

The mouse ran up the clock,

The clock struck one,

The mouse ran down;

Hickory, dickory, dock.

There Was an Old Man.

There was an old man,

And he had a calf,

And that’s half;

He took him out of the stall,

And put him on the wall,

And that’s all.

PLAYING MOTHER—A MONOLOGUE.

Now, dollie, dear, you have been here

For a long time, almost a year,

And we have played with one another—

That you were baby, I was mother.

Now let us change about, I pray,

And you be mother for to-day.

Now you must go to town, you say!

Then tell me, ’fore you go away,

A lot of things I must not do,

And point your finger at me, too,

This way: Now don’t climb up on chairs,

And don’t go tumblin’ down the stairs;

Don’t tease your little sister, dear,

And don’t do anything that’s queer.

Don’t say “I won’t” to Auntie Bee—

What is it you are telling me?

You won’t say “Don’t” to me to-day?

Well, then, how can I disobey?

I wish my truly mother could

Make it so easy to be good!

—Sara Tawney Lefferts.

The heights by great men reached and kept

Were not attained by sudden flight,

But they while their companions slept

Were toiling upward in the night.

—Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

There Was a Little Girl.

There was a little girl who wore a little hood,

And a curl down the middle of her forehead;

When she was good, she was very, very good,

But when she was bad, she was horrid.

Ladybird, Ladybird, Fly Away Home.

Ladybird, ladybird, fly away home,

Thy house is on fire, thy children all gone,

All but one, and her name is Ann,

And she crept under the pudding-pan.

Curly Locks! Curly Locks!

Curly locks! curly locks! wilt thou be mine?

Thou shalt not wash dishes, nor yet feed the swine;

But sit on a cushion and sew a fine seam,

And feed upon strawberries, sugar, and cream!

Little Bob Snooks.

Little Bob Snooks was fond of his books,

And loved by his usher and master;

But naughty Jack Spry, he got a black eye,

And carries his nose in a plaster.

FOLLOW ME.

Children go

To and fro,

In a merry, pretty row,

Footsteps light,

Faces bright;

’Tis a happy sight.

Swiftly turning round and round,

Never look upon the ground;

Follow me,

Full of glee,

Singing merrily.

Work is done,

Play’s begun;

Now we have our laugh and fun;

Happy days,

Pretty plays,

And no naughty ways.

Holding fast each other’s hand,

We’re a happy little band;

Follow me,

Full of glee,

Singing merrily.

Birds are free,

So are we;

And we live as happily.

Work we do,

Study too,

For we learn “Twice two;”

Then we laugh, and dance, and sing,

Gay as larks upon the wing;

Follow me,

Full of glee,

Singing merrily.

—Eliza Lee Follen.

To Make Your Candles Last.

To make your candles last for aye,

You wives and maids give ear-o!

To put ’em out’s the only way,

Says honest John Boldero.

Tommy Trot.

Tommy Trot, a man of law,

Sold his bed and lay upon straw;

Sold the straw and slept on grass;

To buy his wife a looking-glass.

There Were Two Blackbirds.

There were two blackbirds

Sitting on a hill,

The one named Jack,

She other named Jill;

Fly away, Jack!

Fly away, Jill!

Come again, Jack!

Come again, Jill!

There Was an Old Man.

There was an old man of Tobago,

Who lived on rice gruel and sago;

Till much to his bliss,

His physician said this,—

“To a leg, sir, of mutton you may go.”

Mary Had a Little Lamb.

Mary had a little lamb,

Its fleece was white as snow;

And everywhere that Mary went,

The lamb was sure to go.

He followed her to school one day;

That was against the rule;

It made the children laugh and play

To see a lamb at school.

And so the teacher turned him out,

But still he lingered near,

And waited patiently about

Till Mary did appear.

Then he ran to her, and laid

His head upon her arm,

As if he said, “I’m not afraid—

You’ll keep me from all harm.”

“What makes the lamb love Mary so?”

The eager children cry.

“Oh, Mary loves the lamb, you know,”

The teacher did reply.

And you each gentle animal

In confidence may bind,

And make them follow at your will,

If you are only kind.

A MODEST WIT.

A supercilious nabob of the East—

Haughty, being great—purse-proud, being rich—

A governor, or general, at the least,

I have forgotten which—

Had in his family a humble youth,

Who went from England in his patron’s suit,

An unassuming boy, in truth

A lad of decent parts, and good repute.

This youth had sense and spirit;

But yet with all his sense,

Excessive diffidence

Obscured his merit.

One day, at table, flushed with pride and wine,

His Honor, proudly free, severely merry,

Conceived it would be vastly fine

To crack a joke upon his secretary.

“Young man,” he said, “by what art, craft, or trade,

Did your good father gain a livelihood?”—

“He was a saddler, sir,” Modestus said,

“And in his time was reckon’d good.”

“A saddler, eh! and taught you Greek,

Instead of teaching you to sew!

Pray why did not your father make

A saddler, sir, of you?”

Each parasite, then, as in duty bound,

The joke applauded, and the laugh went round.

At length Modestus, bowing low,

Said (craving pardon, if too free he made),

“Sir, by your leave, I fain would know

Your father’s trade!”

“My father’s trade! by heaven that’s too bad!

My father’s trade? Why, blockhead, are you mad?

My father, sir, did never stoop so low—

He was a gentleman, I’d have you know.”

“Excuse the liberty I take,”

Modestus said, with archness on his brow,

“Pray, why did not your father make

A gentleman of you?”

—Selleck Osborne.

Truth is the highest thing that man may keep.

—Geoffrey Chaucer.

LITTLE THINGS.

Little drops of water,

Little grains of sand,

Make the mighty ocean

And the pleasant land.

Thus the little minutes,

Humble though they be,

Make the mighty ages

Of eternity.

—Ebenezer Cobham Brewer.

THE BOY WHO NEVER TOLD A LIE.

Once there was a little boy,

With curly hair and pleasant eye—

A boy who always told the truth,

And never, never told a lie.

And when he trotted off to school,

The children all about would cry,

“There goes the curly-headed boy—

The boy that never tells a lie.”

And everybody loved him so,

Because he always told the truth,

That every day, as he grew up,

’Twas said, “There goes the honest youth.”

—Anonymous.

Saw, Sacradown.

See, saw, sacradown,

Which is the way to London town?

One foot up, the other foot down,

And that is the way to London town.

Little Boy Blue.

Little Boy Blue, come blow up your horn,

The sheep’s in the meadow, the cow’s in the corn;

Where’s the little boy that tends the sheep?

He’s under the haycock, fast asleep.

Go wake him, go wake him. Oh! no, not I;

For if I wake him, he’ll certainly cry.

Once I Saw a Little Bird.

Once I saw a little bird

Come hop, hop, hop;

So I cried, “Little bird,

Will you stop, stop, stop?”

And was going to the window

To say, “How do you do?”

But he shook his little tail,

And far away he flew.

See, see, what shall I see?

A horse’s head where his tail should be?

Jack and Jill.

Jack and Jill went up the hill,

To fetch a pail of water;

Jack fell down, and broke his crown,

And Jill came tumbling after.

Dame, Get Up, and Bake Your Pies.

Dame, get up and bake your pies,

Bake your pies, bake your pies,

Dame, get up and bake your pies,

On Christmas-day in the morning.

Dame, what makes your maidens lie,

Maidens lie, maidens lie;

Dame, what makes your maidens lie,

On Christmas-day in the morning?

Dame, what makes your ducks to die,

Ducks to die, ducks to die;

Dame, what makes your ducks to die,

On Christmas-day in the morning?

Their wings are cut, and they cannot fly,

Cannot fly, cannot fly;

Their wings are cut, and they cannot fly,

On Christmas-day in the morning.

Willy, Willy Wilkin.

Willy, Willy Wilkin

Kissed the maids a-milking,

Fa, la, la!

And with his merry daffing,

He set them all a-laughing,

Ha, ha, ha!

Thirty Days Hath September.

Thirty days hath September,

April, June, and November;

February has twenty-eight alone,

All the rest have thirty-one,

Excepting leap-year—that’s the time

When February’s days are twenty-nine.

Come, Dance a Jig.

Come, dance a jig

To my granny’s pig,

With a raudy, rowdy, dowdy;

Come, dance a jig

To my granny’s pig,

And pussy-cat shall crowdy.

March Winds.

March winds and April showers

Bring forth many flowers.

IT TAKES TWO TO MAKE A QUARREL

THE FROG AND THE OX.

“Oh, father,” said a little frog to a big frog, sitting by

the side of a pool, “I have seen such a terrible monster! It was

as big as a mountain, with horns on its head. It had a long tail,

and hoofs divided in two.”

“Tush, child, tush,” said the old frog, “that was only

Farmer White’s ox. I can easily make myself as big; just you

see.” And he blew himself out. “Was he as big as that?” he

asked.

“Oh, much bigger than that,” said the young frog.

Again the old frog blew himself out, and asked the young

one if the ox was as big.

“Bigger, father,” was the reply, “much bigger.”

Then the old frog took a very deep breath, and blew and

swelled, and swelled and blew—until he burst!

Chippy, chippy, chirio,

Chippy, chippy, chirio,

Not a man in Dario,

Can catch a chippy, chippy chirio.

—John Burroughs.

A CHILD’S LAUGHTER.

All the bells of heaven may ring,

All the birds of heaven may sing,

All the wells on earth may spring,

All the winds on earth may bring

All sweet sounds together;

Sweeter far than all things heard,

Hand of harper, tone of bird,

Sound of woods at sundown stirred,

Welling water’s winsome word,

Wind in warm, wan weather.

One thing yet there is that none

Hearing, ere its chime be done,

Knows not well the sweetest one

Heard of man beneath the sun,

Hoped in heaven hereafter;

Soft and strong and loud and light,

Very sound of very light,

Heard from morning’s rosiest height,

When the soul of all delight

Fills a child’s clear laughter.

Golden bells of welcome rolled

Never forth such note, nor told

Hours so blithe in tones so bold,

As the radiant month of gold

Here that rings forth heaven.

If the golden-crested wren

Were a nightingale—why, then

Something seen and heard of men

Might be half as sweet as when

Laughs a child of seven.

—Algernon Charles Swinburne.

THE BOY AND THE SHEEP.

“Lazy sheep, pray tell me why

In the pleasant field you lie,

Eating grass and daisies white,

From the morning till the night:

Everything can something do;

But what kind of use are you?”

“Nay, my little master, nay;

Do not serve me so, I pray!

Don’t you see the wool that grows

On my back to make you clothes?

Cold, ah, very cold you’d be,

If you had not wool from me.

“True, it seems a pleasant thing

Nipping daisies in the spring;

But what chilly nights I pass

On the cold and dewy grass,

Or pick my scanty dinner where

All the ground is brown and bare!

“Then the farmer comes at last,

When the merry spring is past;

Cuts my wooly fleece away,

For your coat in wintry day.

Little master, this is why

In the pleasant fields I lie.”

—Ann Taylor.

There Was an Old Woman.

There was an old woman she lived in a shoe,

She had so many children she didn’t know what to do;

She gave them some broth without any bread;

She whipped them all soundly, and put them to bed.

Oh, the Little Rusty, Dusty, Rusty Miller.

Oh, the little rusty, dusty, rusty miller!

I’ll not change my wife for either gold or siller.

Four-and-Twenty Tailors.

Four-and-twenty tailors went to kill a snail,

The best man among them durst not touch her tail;

She put out her horns like a little Kyloe cow—

Run, tailors, run, or she’ll kill you all e’en now.

When I Was a Little Girl.

When I was a little girl, I washed my mammy’s dishes;

Now I am a great girl, I roll in golden riches.

Three Little Kittens.

Three little kittens lost their mittens,

And they began to cry:

“O mother dear we very much fear

That we have lost our mittens.”

“Lost your mittens, you naughty kittens!

Then you shall have no pie.”

“Mee-ow, mee-ow, mee-ow,

And we can have no pie,

Mee-ow, mee-ow, mee-ow!”

Little Tommy Tucker.

Little Tommy Tucker

Sings for his supper;

What shall he eat?

White bread and butter,

How shall he cut it

Without e’er a knife?

How will he be married

Without e’er a wife?

DO YOU KNOW HOW MANY STARS?

Do you know how many stars

There are shining in the sky?

Do you know how many clouds

Ev’ry day go floating by?

God in heaven has counted all,

He would miss one should it fall.

Do you know how many children

Go to little beds at night,

And without a care or sorrow,

Wake up in the morning light?

God in heaven each name can tell,

Loves you too and loves you well.

—From the German.

A VIOLET BANK.

I know a bank where the wild thyme blows,

Where ox-lips and the nodding violet grows;

Quite over-canopied with luscious woodbine,

With sweet musk roses and with eglantine.

—William Shakespeare.

A BLADE OF GRASS.

Gather a single blade of grass, and examine for a minute

its narrow sword-shaped strip of fluted green. Nothing, as it

seems, is there of notable goodness or beauty. A very little

strength, and a very little tallness, and a few delicate long

lines meeting in a point—not a perfect point, either, but blunt

and unfinished—by no means a creditable or apparently much-cared-for

example of Nature’s workmanship, made only to be

trodden on to-day, and to-morrow to be cast into the oven; and

a little pale hollow stalk, feeble and flaccid, leading down to

the dull brown fibers of roots.

And yet think of it well, and judge whether of all the

gorgeous flowers that beam in summer air, and of all the strong

and goodly trees, pleasant to the eyes or good for food—stately

palm and pine, strong ash and oak, scented citron, burdened

vine—there be any by man so deeply loved, by God so highly

graced, as that narrow point of feeble green.

—John Ruskin (Modern Painters).

’Tis education forms the common mind

Just as the twig is bent, the tree’s inclined.

—Alexander Pope.

GOOD-NIGHT AND GOOD-MORNING.

A fair little girl sat under the tree

Sewing as long as her eyes could see;

Then smoothed her work and folded it right,

And said, “Dear work, good-night, good-night!”

Such a number of rooks came over her head

Crying, “Caw, caw!” on their way to bed;

She said as she watched their curious flight,

“Little black things, good-night, good-night!”

The horses neighed, and the oxen lowed;

The sheep’s “Bleat, bleat!” came over the road,

All seeming to say with a quiet delight,

“Good little girl, good-night, good-night!”

She did not say to the sun, “Good-night!”

Though she saw him there like a ball of light;

For she knew he had God’s own time to keep

All over the world, and never could sleep.

The tall, pink Fox-glove bowed his head—

The violets curtesied, and went to bed;

And good little Lucy tied up her hair

And said, on her knees, her favorite prayer.

And while on her pillow she softly lay,

She knew nothing more till again it was day,

And all things said to the beautiful sun,

“Good-morning, good-morning! our work is begun.”

—Lord Houghton.

Sing, Sing! What Shall I Sing?

Sing, sing! what shall I sing?

The cat has eat the pudding-string!

Do, do! what shall I do?

The cat has bit it quite in two.

Pease-Pudding Hot.

Pease-pudding hot,

Pease-pudding cold,

Pease-pudding in the pot,

Nine days old.

Some like it hot,

Some like it cold,

Some like it in the pot,

Nine days old.

Peter, Peter, Pumpkin-eater.

Peter, Peter, pumpkin-eater,

Had a wife, and couldn’t keep her;

He put her in a pumpkin-shell,

And there he kept her very well.

Peter, Peter, pumpkin-eater,

Had another and didn’t love her;

Peter learned to read and spell,

And then he loved her very well.

The Farmyard.

Waiting to be Hired.

Little Miss Muffet.

Little Miss Muffet

Sat on a tuffet,

Eating of curds and whey;

There came a spider,

And sat down beside her,

And frightened Miss Muffet away.

My Lady Wind, my Lady Wind.

My Lady Wind, my Lady Wind,

Went round about the house to find

A chink to get her foot in.

She tried the key-hole in the door,

She tried the crevice in the floor,

And drove the chimney soot in.

And then one night when it was dark

She blew up such a tiny spark,

That all the house was bothered:

From it she raised up such a flame,

As flamed away to Belting Lane,

And White Cross folks were smothered.

And thus when once, my little dears,

A whisper reaches itching ears,

The same will come, you’ll find:

Take my advice, restrain the tongue,

Remember what old Nurse has sung

Of busy Lady Wind!

What is the Rhyme for Porringer?

What is the rhyme for porringer?

The king he had a daughter fair,

And gave the Prince of Orange her.

The Queen of Hearts.

The queen of hearts

She made some tarts,

All on a summer’s day;

The knave of hearts

He stole those tarts,

And with them ran away.

The king of hearts

Called for those tarts,

And beat the knave full sore;

The knave of hearts

Brought back those tarts,

And said he’d ne’er steal more.

Where Are You Going, My Pretty Maid?

“Where are you going, my pretty maid?”

“I’m going a-milking, sir,” she said.

“May I go with you, my pretty maid?”

“You’re kindly welcome, sir,” she said.

“What is your father, my pretty maid?”

“My father’s a farmer, sir,” she said.

“What is your fortune, my pretty maid?”

“My face is my fortune, sir,” she said.

“Then I can’t marry you, my pretty maid!”

“Nobody asked you, sir,” she said.

Here We Go Up, Up, Up.

Here we go up, up, up,

And here we go down, down, downy,

And here we go backwards and forwards,

And here we go round, round, roundy.

Oh, Dear! What Can the Matter Be?

Oh, dear! what can the matter be?

Two old women got up an apple-tree;

One came down,

And the other stayed till Saturday.

For Every Evil Under the Sun.

For every evil under the sun,

There is a remedy, or there is none.

If there be one, try and find it,

If there be none, never mind it.

MY FATHER WAS A FARMER.

My father was a farmer, upon the Garrick border, O,

And carefully he bred me in decency and order, O;

He bade me act a manly part, though I had ne’er a farthing, O—

For without an honest, manly heart, no man was worth regarding, O.

—Robert Burns.

HIAWATHA’S CHILDHOOD.

From “The Song of Hiawatha.”

At the door on summer evenings

Sat the little Hiawatha;

Heard the whispering of the pine-trees,

Heard the lapping of the water,

Sounds of music, words of wonder;

“Minne-wawa!” said the pine trees,

“Mudway-aushka!” said the water.

Saw the firefly, Wah-wah-taysee,

Flitting through the dusk of evening

With the twinkle of his candle

Lighting up the brakes and bushes,

And he sang the song of children,

Sang the song Nokomis taught him:

“Wah-wah-taysee, little firefly.

Little, flitting, white-fire insect,

Little, dancing, white-fire creature,

Light me with your little candle,

Ere upon my bed I lay me,

Ere in sleep I close my eyelids!”

Forth into the forest straightway

All alone walked Hiawatha

Proudly, with his bow and arrows;

And the birds sang round him, o’er him,

“Do not shoot us, Hiawatha!”

Sang the robin, the Opechee,

Sang the bluebird, the Owaissa,

“Do not shoot us, Hiawatha!”

Up the oak-tree, close beside him,

Sprang the squirrel, Adjidaumo,

In and out among the branches,

Coughed, and chattered from the oak-tree,

Laughed, and said between his laughing,

“Do not shoot me, Hiawatha!”

But he heeded not, nor heard them,

For his thoughts were with the red deer;

On their tracks his eyes were fastened,

Leading downward to the river,

To the ford across the river,

And as one in slumber walked he.

—Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

They are never alone that are accompanied with noblest

thoughts.

—Sir Philip Sidney.

As I was Going to St. Ives.

As I was going to St. Ives,

I met a man with seven wives,

Every wife had seven sacks,

Every sack had seven cats,

Every cat had seven kits—

Kits, cats, sacks, and wives,

How many were there going to St. Ives?

(One.)

Merry are the Bells.

Merry are the bells, and merry would they ring,

Merry was myself, and merry could I sing;

With a merry ding-dong, happy, gay, and free,

And a merry sing-song, happy let us be!

Waddle goes your gait, and hollow are your hose,

Noddle goes your pate, and purple is your nose;

Merry is your sing-song, happy, gay, and free,

With a merry ding-dong, happy let us be!

Merry have we met, and merry have we been,

Merry let us part, and merry meet again;

With our merry sing-song, happy, gay, and free,

And a merry ding-dong, happy let us be!

AMERICA.

My country, ’tis of thee,

Sweet land of liberty,

Of thee I sing;

Land where my fathers died,

Land of the Pilgrim’s pride;

From every mountain side,

Let freedom ring.

My native country, thee—

Land of the noble free—

Thy name I love;

I love thy rocks and rills,

Thy woods and templed hills;

My heart with rapture thrills,

Like that above.

Let music swell the breeze,

And ring from all the trees

Sweet freedom’s song;

Let mortal tongues awake;

Let all that breathe partake;

Let rocks their silence break—

The sound prolong.

Our father’s God, to Thee,

Author of liberty,

To Thee we sing;

Long may our land be bright

With freedom’s holy light:

Protect us by Thy might,

Great God, our King.

—Samuel Francis Smith.

THE NATIONAL FLAG.

There is the national flag! He must be cold, indeed, who

can look upon its folds rippling in the breeze without pride of

country. If he be in a foreign land the flag is companionship

and country itself, with all its endearments. It has been

called “a floating piece of poetry,” and yet I know not if it

have greater beauty than other ensigns. Its highest beauty

is in what it symbolizes. It is because it represents all, that

all gaze at it with delight and reverence. It is a piece of bunting

lifted in the air, but it speaks sublimely, and every part has

a voice. Its stripes of alternate red and white proclaim the

original union of thirteen states to maintain the Declaration

of Independence. Its stars of white in a field of blue proclaim

that union of States constituting our national constellation,

which receives a new star with every state. The two together

signify union, past and present. The very colors have a

language which was officially recognized by our fathers.

White is for purity, red for valor, blue for justice; and all together,

bunting, stars, stripes, and colors, blazing in the sky,

make the flag of our country—to be cherished by all our hearts,

to be upheld by all our hands.

—Charles Sumner.

MARJORIE’S BATH.

(Marjorie)

The water is cold, it makes me cry.

(Mother)

It will be warmer by and by.

(Marjorie)

A crab is hid deep in the sand below!

(Mother)

Then he cannot bite you dear, I know.

(Marjorie)

If you will let me paddle and play

I’ll try and swim some other day.

(Mother)

But the sea will be cold to-morrow, too,—

And the crab will be always biting you.

(Marjorie)

The big waves scare me, mother dear,

And make me feel so cold and queer.

If you’ll let me run on the sand and play,

I’ll find pretty shells for you, to-day.

—Helen Lee Sargent.

BLIND MAN’S BUFF.

Harry, Charlie, Grace and May,

Playing Blind-man’s-buff one day,

Running here and running there,

Falling over stool and chair.

Strange how Charlie right away

Caught them, ’till his cousin May

Saw him peek, and cried, “No fair,

Charlie boy, how do you dare.”

Charlie hung his head in shame,

Ran and left them to their game,

Hid himself behind the door

For at least an hour or more.

So I’m sure it did not pay

Charlie boy to peek that way,

In playing games of any kind

Honesty is best you’ll find.

—Ella Broes van Heekeren.

The noblest mind the best contentment has.

—Edmund Spenser.

The Death and Burial of Cock Robin.

Who killed Cock Robin?

“I,” said the Sparrow,

“With my bow and arrow

I killed Cock Robin.”

This is the Sparrow,

With his bow and arrow.

Who saw him die?

“I,” said the Fly,

“With my little eye,

And I saw him die.”

This is the little Fly,

Who saw Cock Robin die.

Who caught his blood?

“I,” said the Fish,

“With my little dish,

And I caught his blood.”

This is the Fish

That held the dish.

Who made his shroud?

“I,” said the Beetle,

“With my little needle,

And I made his shroud.”

This is the Beetle,

With his thread and needle.

Who shall dig his grave?

“I,” said the Owl,

“With my spade and show’l,

And I’ll dig his grave.”

This is the Owl,

With his spade and show’l.

Who’ll be the parson?

“I,” said the Rook,

“With my little book,

And I’ll be the parson.”

This is the Rook,

Reading the book.

Who’ll be the clerk?

“I,” said the Lark,

“If it’s not in the dark,

And I’ll be the clerk.”

This is the Lark,

Saying “Amen” like a clerk.

Who’ll carry him to the grave?

“I,” said the Kite,

“If ’tis not in the night,

And I’ll carry him to his grave.”

This is the Kite,

About to take flight.

Who’ll carry the link?

“I,” said the Linnet,

“I’ll fetch it in a minute,

And I’ll carry the link.”

This is the Linnet,

And a link with fire in it.

Who’ll be the chief mourner?

“I,” said the Dove,

“I mourn for my love,

And I’ll be chief mourner.”

This is the Dove,

Who Cock Robin did love.

Who’ll sing a psalm?

“I,” said the Thrush,

As she sat in a bush,

“And I’ll sing a psalm.”

This is the Thrush,

Singing psalms from a bush.

And who’ll toll the bell?

“I,” said the Bull,

“Because I can pull;”

And so, Cock Robin, farewell.

LONDON BRIDGE.

How many a bridge in London-Town,

In by-gone years has fallen down!

And little children every day

Are building bridges the self-same way.

They may use wrought iron and steel and try

To make them strong, but by and by

You’ll hear the wild alarming cry:

“London bridge is falling down,

Falling down, falling down!

London bridge is falling down,

My fair lady!”

—Sara Tawney Lefferts.

Truth is the highest thing that man can keep.

—Geoffrey Chaucer.

THE SWALLOW.

Fly away, fly away over the sea,

Sun-loving swallow, for summer is done;

Come again, come again, come back to me,

Bringing the Summer and bringing the sun.

—Christina G. Rossetti.

BUTTERCUPS.

The buttercups with shining face

Smile upward as I pass.

They seem to lighten all the place

Like sunshine in the grass.

And though not glad nor gay was I

When first they came in view;

I find when I have passed them by,

That I am smiling, too.

—Sarah F. Day.

As I Was Going o’er Westminster Bridge.

As I was going o’er Westminster Bridge,

I met with a Westminster scholar;

He pulled off his cap an’ drew off his glove,

And wished me a very good morrow.

What is his name?

Margery Mutton-pie.

Margery Mutton-pie and Johnny Bo-peep,

They met together in Gracechurch-street;

In and out, in and out, over the way,

Oh! says Johnny, ’tis chop-nose day.

Simple Simon Met a Pieman.

Simple Simon met a pieman

Going to the fair;

Says Simple Simon to the pieman,

“Let me taste your ware.”

Says the pieman to Simple Simon,

“Show me first your penny;”

Says Simple Simon to the pieman,

“Indeed, I have not any.”

Simple Simon went a-fishing

For to catch a whale;

All the water he had got

Was in his mother’s pail.

Simple Simon went to look

If plums grew on a thistle;

He pricked his fingers very much,

Which made poor Simon whistle.

FABLE.

The mountain and the squirrel

Had a quarrel,

And the former called the latter “Little Prig.”

Bun replied:

“You are doubtless very big;

But all sorts of things and weather

Must be taken in together

To make up a year

And a sphere;

And I think it no disgrace

To occupy my place.

If I am not so large as you,

You are not so small as I,

And not half so spry.

I’ll not deny you make

A very pretty squirrel track;

Talents differ; all is well and wisely put;

If I cannot carry forests on my back

Neither can you crack a nut!”

—Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Solomon Grundy.

Solomon Grundy,

Born on a Monday,

Christened on Tuesday,

Married on Wednesday,

Took ill on Thursday,

Worse on Friday,

Died on Saturday,

Buried on Sunday.

This is the end

Of Solomon Grundy.

Baa, Baa, Black Sheep.

Baa, baa, black sheep,

Have you any wool?

Yes, marry, have I,

Three bags full;

One for my master,

And one for my dame,

But none for the little boy

Who cries in the lane.

Bell-Horses, Bell-Horses.

Bell-Horses, bell-horses,

What time of day?

One o’clock, two o’clock,

Off and away.

THE FIELD MOUSE AND THE TOWN MOUSE.

A Field Mouse had a friend who lived in a house in town.

Now the Town Mouse was asked by the Field Mouse to dine

with him, and out he went and sat down to a meal of corn and

wheat.

“Do you know, my friend,” said he, “that you live a mere

ant’s life out here? Why, I have all kinds of things at home;

come and enjoy them.”

So the two set off for town, and there the Town Mouse

showed his beans and meal, his dates, too; his cheese and fruit

and honey. And as the Field Mouse ate, drank, and was

merry, he thought how rich his friend was and how poor he was.

But as they ate, a man all at once opened the door, and the

mice were in such fear that they ran into a crack.

Then when they would eat some nice figs, in came a maid

to get a pot of honey or a bit of cheese; and when they saw her,

they hid in a hole.

Then the Field Mouse would eat no more, but said to the

Town Mouse: “Do as you like, my good friend; eat all you

want, have your fill of good things, but you are always in fear

of your life. As for me, poor Mouse, who have only corn and

wheat, I will live on at home, in no fear of any one.”

—Aesop.

A DUTCH WINTER.

The windmills of Holland are silent and stilled,

Their whirling has ceased, for their long arms are chilled.

The ice-prisoned boats are hung with a lace

Of Flemish design of most delicate grace.

While the watchman calls out, with a voice like a bell,

The time by the tower, and adds, “All is well.”

The tulips are hid ’neath a rug of soft white,

They’re dreaming of spring, and the sun warm and bright.

The rollicking lads, with the lassies in wake,

Sweep by on their ice skates of old Friesian make,

While the watchman calls out, with a voice like a bell,

The time by the tower, and adds, “All is well.”

In the land of the windmills, the stars one by one

Slowly people the heavens, for night has begun.

The rosy-cheeked babies, in nightcap and gown,

Are asleep in their cradles with curtains hung down,

While the watchman calls out with a voice like a bell,

The time by the tower, and adds, “All is well.”

—Ella Broes van Heekeren.

He that complies against his will

Is of the same opinion still.

—Samuel Butler.

IF I WERE A COBBLER.

If I were a cobbler, I would make it my pride

The best of all cobblers to be;

If I were a tinker, no tinker beside

Should mend an old kettle like me.

THANKSGIVING DAY.

Over the river and through the wood,

To grandfather’s house we go;

The horse knows the way

To carry the sleigh

Through the white and drifted snow.

Over the river and through the wood—

Oh, how the wind does blow!

It stings the toes

And bites the nose,

As over the ground we go.

Over the river and through the wood,

To have a first-rate play.

Hear the bells ring,

“Ting-a-ling-ding!”

Hurrah for Thanksgiving Day!

Over the river and through the wood,

Trot fast, my dapple-gray!

Spring over the ground,

Like a hunting hound!

For this is Thanksgiving Day.

Over the river and through the wood,

And straight through the barn-yard gate.

We seem to go

Extremely slow—

It is so hard to wait!

Over the river and through the wood—

Now grandmother’s cap I spy!

Hurrah for the fun!

Is the pudding done?

Hurrah for the pumpkin pie!

—Lydia Maria Child.

HALLUCINATIONS.

He thought he saw an Elephant,

That practiced on a fife.

He looked again, and found it was

A letter from his wife.

“At length I realize,” he said,

“The bitterness of life!”

He thought he saw a Buffalo,

Upon the chimney piece.

He looked again, and found it was

His sister’s husband’s niece.

“Unless you leave this house,” he said,

“I’ll send for the police!”

He thought he saw a Rattlesnake,

That questioned him in Greek.

He looked again, and found it was

The middle of next week.

“The one thing I regret,” he said,

“Is that it cannot speak!”

He thought he saw a Banker’s Clerk,

Descending from the ’bus.

He looked again, and found it was

A hippopotamus.

“If this should stay to dine,” he said,

“There won’t be much for us.”

—Lewis Carroll.

LET US HAVE FAITH.

Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that

faith let us to the end dare to do our duty as we understand it.

—Abraham Lincoln.

LUCY’S BALLOON.

Little Donald was one day taken by his father to see the

circus procession. His little sister Lucy was obliged to stay

at home. While they were standing on the sidewalk, the

father bought two balloons, saying, “One of these is for you,

Donald, and the other we will take home to Lucy.” On account

of the dense crowd, the father was carrying the balloons,

holding them high above his head, when suddenly one of them

exploded. Donald looked at it in dismay for a moment. Then

his little face brightened, and he said cheerfully, “It’s too bad

that Lucy’s balloon is spoiled, but I will let her play with mine

sometimes.”

—Kate Upson Clark.

London Bridge is Broken Down.

London Bridge is broken down,

Dance o’er my lady Lee;

London Bridge is broken down,

With a gay lady.

How shall we build it up again?

Dance o’er my lady Lee;

How shall we build it up again?

With a gay lady.

Silver and gold will be stole away,

Dance o’er my lady Lee;

Silver and gold will be stole away,

With a gay lady.

Build it up again with iron and steel,

Dance o’er my lady Lee;

Build it up with iron and steel,

With a gay lady.

Iron and steel will bend and bow,

Dance o’er my lady Lee;

Iron and steel will bend and bow,

With a gay lady.

Build it up with wood and clay,

Dance o’er my lady Lee;

Build it up with wood and clay,

With a gay lady.

Wood and clay will wash away,

Dance o’er my lady Lee;

Wood and clay will wash away,

With a gay lady.

Build it up with stone so strong,

Dance o’er my lady Lee;

Huzza! ’twill last for ages long,

With a gay lady.

See a Pin and Pick It Up.

See a pin and pick up,

All the day you’ll have good luck;

See a pin and let it lay,

Bad luck you’ll have all the day!

Pussy-Cat, Wussy-Cat.

Pussy-cat, wussy-cat, with a white foot,

When is your wedding? for I’ll come to ’t.

The beer’s to brew, the bread’s to bake.

Pussy-cat, pussy-cat, don’t be too late.

The Man in the Wilderness.

The man in the wilderness asked me,

How many strawberries grew in the sea.

I answered him, as I thought good,

As many red herrings as grew in the wood.

Poor Dog Bright.

Poor Dog Bright

Ran off with all his might,

Because the cat was after him—

Poor Dog Bright!

Poor Cat Fright

Ran off with all her might,