THE DAVID.

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Michelangelo, by Edward C. Strutt

Title: Michelangelo

Author: Edward C. Strutt

Release Date: November 6, 2022 [eBook #69303]

Language: English

Produced by: Al Haines

Bell's Miniature Series of Painters

BY

EDWARD C. STRUTT

LONDON

GEORGE BELL & SONS

1908

First Published, January, 1904.

Reprinted, 1908.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHRONOLOGY OF THE ARTIST'S LIFE

LIST OF THE ARTIST'S CHIEF WORKS IN PUBLIC GALLERIES

"Carte Michelangiolescheinedite." Milano, 1865.

"Vita di Michelangelo Buonarroti," by A. Condivi. Pisa, 1823.

"Michelangelo," by H. Knackfuss. Berlin, 1895.

"Michel Ange," by E. Ollivier. Paris, 1892.

"The Lives and Works of Michelangelo and Raphael," by Quatremere de Quincy.

"Michelangelo," by L. von Scheffler. 1892.

"Michelangiolo in Rom, 1508-1512," by A. Springer. Leipzig, 1875.

"Life and works of M. A. Buonarroti," by Charles Heath Wilson. London, 1876.

"Life of Michelangelo Buonarroti," by John Addington Symonds. London, 1893.

"Michelangelo Buonarroti," by Sir Charles Holroyd. London, 1903.

"An account of the drawings by Raphael and Michelangelo in the University Galleries of Oxford," by Sir J. C. Robinson.

"Michael Angelo," by Lord Ronald Sutherland Gower. London, 1903.

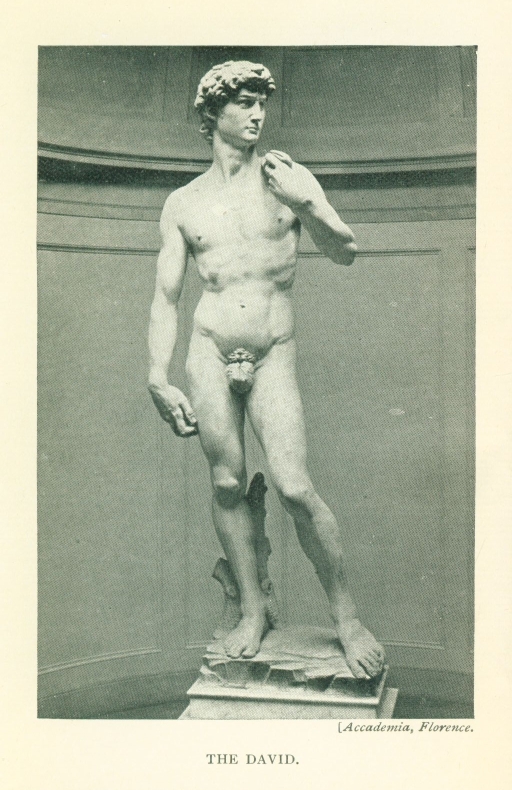

THE DAVID Accademia, Florence, Frontispiece

PORTRAIT OF MICHELANGELO Uffizi Gallery, Florence

THE CREATION OF MAN Sistine Chapel, Vatican, Rome

TOMB OF LORENZO DE' MEDICI New Sacristy, San Lorenzo, Florence

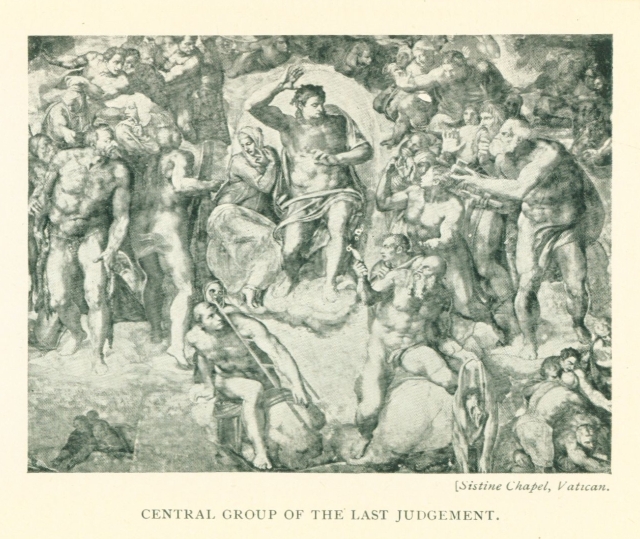

CENTRAL GROUP OF THE LAST JUDGMENT Sistine Chapel, Vatican, Rome

THE MADONNA DELLA PIETÀ St. Peter's, Rome

THE HOLY FAMILY Uffizi Gallery, Florence

THE MOSES San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome

1475. Born at Caprese.

1488. Is apprenticed to Domenico Ghirlandajo.

1489-92. Studies sculpture under the patronage of Lorenzo il Magnifico.

1504. Enters into competition with Leonardo da Vinci.

1505. Goes to Rome at the invitation of Pope Julius II.

1508. Begins painting ceiling of Sistine Chapel.

1512. Completes it.

1521. Commences Medicean Tombs in San Lorenzo.

1529. Fortifies Florence against Charles V.

1535-41. Paints Last Judgment.

1547. Begins building Cupola of St. Peter's.

1564. Dies in Rome.

In the quaintly written diary of Messer Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, a well-to-do Florentine citizen, the following entry, dated March 6th, 1475, may still be found: "To-day there was born unto me a male child, whom I have named Michelagnolo.[1] He saw the light at Caprese, whereof I am Podestà, on Monday morning, 6th March, between four and five o'clock, and on the 8th of the same month he was baptized in the church of San Giovanni." Messer Lodovico had been appointed Podestà, or Governor, of Chiusi and Caprese in the Casentino by Lorenzo de Medici only a few months before penning this memorandum, so that, by a strange caprice of fate, it was here, in the little town overshadowed by the rugged Sasso della Verna, hallowed by the ecstatic visions of St. Francis of Assisi, and not in Florence, in the Athens of the Italian Renaissance, where resurrected Paganism ran riot and triumphed, that the longest and most glorious career in the history of art and of human endeavour began.

[1] This is the archaic form of angelo. The name is also sometimes spelt Michelangiolo, but I have thought it advisable to adopt the modern and more generally accepted Michelangelo.

Vasari and Condivi, Michelangelo's pupils and enthusiastic biographers, maintain that the Buonarroti family was closely related to the great house of the Counts of Canossa, a conviction fully shared, curiously enough, by the artist himself, who rather prided himself on his aristocratic connection. But recent genealogical researches have proved beyond all doubt that, although of gentle birth (both his father and his mother, Madonna Francesca di Miniato Del Sera, coming of ancient Florentine stock), Michelangelo could not in reality lay claim to even distant ties of kinship with the Canossa family.

On the expiration of his term of office as Podestà of Caprese, which extended little over a year, Messer Lodovico returned with his family to Settignano, the picturesque little village built on a vine-clad slope overlooking Florence, where, in an old-fashioned mansion nestling among olive trees and surrounded by a well-cultivated podere, many generations of the Buonarroti had lived and died. Before leaving Caprese, however, the proud father had the child's horoscope cast, and greatly did he rejoice when the astrologer announced that a singularly lucky combination of the planets had presided over the birth of his boy, who was destined "to perform wonders with his mind and with his hands," a prophecy which was amply fulfilled.

FIRST FLORENTINE PERIOD

The removal of the Buonarroti family to Settignano, the little village almost exclusively inhabited by stonemasons and workers in marble, exercised a most decisive influence on the child's future career. Indeed, Michelangelo himself used to say half jestingly, that as he had been given out to nurse to a stonemason's wife, the mania for sculpture must have entered his blood together with the milk which he had sucked as a babe. A mallet and a chisel and bits of marble were the only toys that the infant Michelangelo cared for, and it is recorded of him that when he grew up to be a sturdy boy of ten he could use his tools almost as skilfully as his foster-father himself. He soon became more ambitious, and would pass whole hours with chalk and charcoal, trying to copy the marble figures and ornaments plentifully strewn about.

For it was a busy time at Settignano, whose hundreds of stone-carvers were hardly able to cope with the numerous commissions which poured in upon them from the merchant princes of Florence, anxious to rival Lorenzo the Magnificent in the building and decoration of splendid palaces. A spirited drawing of a faun by Michelangelo's boyish hand may still be seen on a wall of the Buonarroti Villa.

Messer Lodovico did everything in his power to discourage these marked artistic tendencies, and in order the better to uproot what he regarded as a worthless inclination, he sent the boy to a grammar-school in Florence, away from the dangerous milieu of Settignano, with its unceasing din of hammer and chisel on reverberating marble, which was sweet music to Michelangelo's ear. But although Maestro Francesco da Urbino, to whose care Messer Lodovico had entrusted his son, frequently had recourse to the most persuasive and forcible arguments, they were entirely lost on young Michelangelo, who had instinctively drifted into the company of the garzoni and pupils of leading Florentine artists, and sadly neglected his books in order to devote himself with growing enthusiasm to the study of art.

Amongst his new friends was Francesco Granacci, a pupil of Domenico Ghirlandajo, who often lent him drawings to copy, and took him to his master's bottega whenever any work was going forward from which he might learn. "So powerfully," says Condivi, "did these sights move Michelangelo, that he altogether abandoned letters; so that his father, who held art in contempt, often beat him severely for it." But it soon became apparent that blows and persuasion were equally unavailing, and Messer Lodovico finally gave up the hopeless struggle, apprenticing his thirteen-year-old son on April 1st, 1488, to Domenico and David Ghirlandajo, reputed the best painters of the time in Florence. Although a mere child, Michelangelo was evidently already able to make himself useful in the studio, for instead of paying a certain sum for his apprenticeship, as was usually the case, it was stipulated that he should receive twenty-four florins, about £8 12s., during the three years of its duration.

Michelangelo's first picture was a strikingly faithful copy of Martin Schongauer's famous Temptation of St. Antony, which he painted with a realistic force considered wonderful for a child of his age. A number of anecdotes illustrative of the precocity of the boy's genius, are related by Condivi and by Vasari. "Michelangelo," says the latter, "grew in power and character so rapidly that Domenico was astonished seeing him do things quite extraordinary in a youth, for he not only surpassed the other students, but often equalled the work done by his master. It happened that Domenico was working in the great chapel of Santa Maria Novella, and one day when he was out Michelangelo set himself to draw from nature the scaffolding, the tables with all the materials of the art, and some of the young men at work. Presently Domenico returned, and saw Michelangelo's drawing. He was astonished, saying 'this boy knows more than I do;' and he was stupefied by this style and new realism; 'a gift from heaven to a child of such tender years.'"

Michelangelo derived very little advantage from his apprenticeship to Domenico Ghirlandajo, who was actually jealous of his pupil and gave him little or no assistance in his studies. He may have picked up some practical knowledge, however, transferring cartoons for his master in the church of Santa Maria Novella, painting draperies and ornaments, mixing colours for fresco painting, and generally fulfilling the rather menial duties which fell to the lot of an artist's apprentice in those days. The boy had no fixed plan or method of study, but devoted himself principally to drawing, in which he soon acquired a boldness and security of line never attained by his master, whose faulty cartoons Michelangelo often had the courage to correct.

It was in the gardens of the Medici at San Marco, where Lorenzo the Magnificent had collected many antique statues and decorative sculptures, that Michelangelo finally discovered his real artistic vocation, and here he would spend many hours every day, assimilating the Hellenic spirit which emanated from the masterpieces before him.

Lorenzo's principal object in establishing a museum of antique sculpture at San Marco had been to raise Florentine sculpture from the state of comparative neglect into which it had fallen since the death of Donatello. He therefore appointed one Bertoldo, who had been foreman of Donatello's workshop, keeper of the collection, with a special commission to encourage and instruct the young men who studied there. But there was evidently a great lack of students, for Lorenzo had recourse to Domenico Ghirlandajo, requesting him to select from his pupils those he considered the most promising, and send them to work in the garden of San Marco. Domenico, nothing loth to get rid of his two most ambitious apprentices, selected Francesco Granacci and Michelangelo, and it was thus that the latter came under the influence of Donatello's school. Of Bertoldo, who must be considered Michelangelo's first instructor in the art of sculpture, and who doubtless had a great share in shaping his genius, very little is known beyond Vasari's statement that "although he was old and could not work, he was none the less an able and highly reputed artist." The magnificent pulpits of San Lorenzo, begun by Donatello and completed by Bertoldo, amply suffice to confirm Vasari's eulogistic estimate.

Under such a master Michelangelo made rapid progress, and by his first attempt at sculpture, a mask of a grinning Faun, attracted the attention of Lorenzo the Magnificent, who took the keenest interest in the art school which he had founded. So struck was Lorenzo with the boy's genius, that he prevailed upon Messer Lodovico, not without the greatest difficulty, to entrust the talented young sculptor to his care. Vasari tells us that "he gave Michelangelo a good room in his own house with all that he needed, treating him like a son, with a seat at his table, which was frequented every day by noblemen and men of great importance."

Michelangelo's daily companions at this hospitable board were such men as Pico della Mirandola, surnamed "the prince of wisdom," Marsilio Ficino, the expounder of Plato, and the poets Luigi Pulci and Angelo Poliziano. It was the latter who suggested the subject of Michelangelo's first important work, a bas-relief, now in the Casa Buonarroti, representing the Battle of the Centaurs and Lapithae. It is a singularly powerful composition, conceived and carried out with a freedom and originality little short of miraculous in a boy of fifteen. The struggling groups of combatants, instinct with life and energy, the masterful treatment of anatomical problems, and the already profound knowledge of the human frame, reveal the future author of the Last Judgment.

Michelangelo himself, when at the height of his artistic greatness, used to say that he had never quite fulfilled the splendid promise contained in this youthful work of his. Apart from its intrinsic merit, this bas-relief is interesting as illustrating Michelangelo's complete independence from the school and methods of Donatello. His bold and original genius had sought inspiration directly from the antique, and the Battle of the Centaurs and Lapithae might easily be taken for a fragment from some Roman sarcophagus. In view of these very pronounced characteristics, it is difficult to understand why another bas-relief, also in the Casa Buonarroti, representing a seated Madonna with the Infant Jesus, and chiefly notable for its almost servile imitation of Donatello's manner, should be ascribed by most critics to this same period. Indeed, the execution and design of this Madonna and Child are so inferior as to render it a work of extremely doubtful authenticity.

Although he applied himself principally to the study of sculpture, Michelangelo continued to devote many hours every day to drawing, and, like most young artists of his age, he drew and studied assiduously in the Brancacci Chapel of the Church of the Carmine, containing the famous frescoes of Masaccio and his followers. Conscious of his own superiority, Michelangelo was, it appears, in the habit of frankly criticizing the work of his fellow-students in the Brancacci Chapel, and one of these, named Piero Torrigiani, a brutal and proud fellow, got so angry one day that he hit Michelangelo a formidable blow on the nose, breaking the cartilage and disfiguring his critic for life. For this act of temper Torrigiani was banished from Florence, but it is pleasant to know that Michelangelo successfully interceded with Lorenzo on behalf of the man who had assaulted him.

Michelangelo had just completed the Battle of the Centaurs and Lapithae when he lost his best friend and munificent patron, to whom he had become deeply attached. On April 8th, 1492, Lorenzo the Magnificent died at Careggi, sincerely mourned, not only in Florence, but throughout Italy. The generous encouragement which he gave to art and letters, the power and splendour which he bestowed on Florence in exchange for her lost liberty, more as an infatuated lover dowering a wayward bride than as a conqueror imposing his will, the consummate ability displayed in his diplomatic dealings with the other Italian States, these were the principal merits which justified the proud title of Il Magnifico, conferred on him by his contemporaries, and which caused Lorenzo's death to be regarded as a public calamity throughout Italy.

So much grief, says Condivi, did Michelangelo feel for his patron's death, that for some time he was quite unable to work. He left the Medicean palace, which had been his home during three years, and returned to his father's house. But his love for art was stronger than his grief, and after a few weeks, when he was himself again, he bought a large piece of marble that had for many years been exposed to the wind and rain, and carved a Hercules out of it. This statue was placed in the Strozzi Palace, where it stood until the siege of Florence in 1530, when Giovanni Battista della Palla bought it and sent it into France as a gift to King Francis I. It has unfortunately been lost.

At this time Michelangelo applied himself most diligently to the study of anatomy, a profound knowledge of which is apparent in all his subsequent works. He was indebted to the Prior of Santo Spirito for many kindnesses, amongst others for the use of a room where he dissected the subjects, for the most part executed criminals, which the Prior placed at his disposal. "Nothing," says Condivi, "could have given Michelangelo more pleasure, and this was the beginning of his anatomical studies, which he followed until he had completely mastered the secrets of the human frame."

It is surprising that artists of the Cinquecento should have enjoyed privileges for practically studying anatomy which were denied to physicians. When the famous Dr. Hunter saw Leonardo da Vinci's anatomical drawings and their descriptions, preserved in the library of George III., he discovered with astonishment that the artist had been a deep student, "and was at that time the best anatomist in the world." Michelangelo, as Vasari tells us, "dissected many dead bodies, zealously studying anatomy," whereas Cortesius, professor of anatomy at Bologna, who wrote a century later, complains that he was prevented finishing a treatise on "Practical Anatomy" in consequence of having only been able twice to dissect a human body in the course of twenty-four years. To please his friend the Prior, Michelangelo carved a crucifix in wood, a little under life size, which was placed over the high altar of the church of Santo Spirito, but which has since been lost.

Piero de' Medici, the Magnifico's son and successor, had inherited none of his father's brilliant qualities. He was proud and insolent, and his coarse tastes and manners soon lost him that popularity which had been Lorenzo's stepping-stone to greatness. Michelangelo, who had been his companion as a boy, and whom he persuaded to accept his hospitality, was ill at ease in the house of a Prince who could so far insult the sensitive artist as to boast that he had two remarkable men in his establishment, Michelangelo and a certain Spanish groom remarkable for his athletic prowess, thus placing both on the same level.

Too proud to tolerate such treatment, and foreseeing Piero's approaching fall, Michelangelo left Florence early in the year 1494 and went first to Venice, where he failed to find employment, and thence to Bologna. Here he was hospitably received by a gentleman named Messer Gian Francesco Aldovrandi, who not only paid a fine of fifty Bolognese lire to which the impecunious young sculptor had been condemned for having neglected to provide himself with a passport, but invited him to his house and honoured him highly, "delighting in his genius, and every evening he made him read something from Dante or from Petrarca, or now and then from Boccaccio, until he fell asleep."

While staying with Aldovrandi, and thanks to his recommendation, Michelangelo completed an unfinished statue of San Petronio in the church of San Domenico and carved a statuette of a kneeling angel holding a candlestick for the arca or shrine of the saint, begun by Nicolò di Bari. It is a beautiful and highly finished work, which was greatly admired and for which he received thirty ducats. His success aroused the fierce jealousy of the Bolognese sculptors, and it was under fear of personal violence from the native craftsmen, who accused him of taking the bread out of their mouths, that Michelangelo hastily left Bologna in the spring of 1495 and returned to Florence.

In November of the preceding year Piero de' Medici had had to fly from the city over whose destinies he was so unfit to preside, and when Michelangelo returned to Florence he found that Savonarola had established a popular government. The fiery Dominican, with his inspired eloquence, his ascetic fervour and an energy bordering upon violence, was exactly a man after Michelangelo's heart, and Savonarola's impassioned and gloomy appeals made an indelible impression upon him. The Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel might almost be regarded as a pictorial rendering of one of the terrible frate's sermons.

Although only twenty years of age, Michelangelo, of whom it has been said "that he was never young," was made a member of the General Council of Citizens. But his political duties did not take up much of his time, for to this period must be ascribed the statue of a youthful St. John the Baptist, executed for Lorenzo di Pier Francesco, a cousin of the exiled Medici, and now in the Berlin Museum. It is a charming but somewhat effeminate figure, differing strangely from the powerful and rugged style to which we are accustomed in Michelangelo's works. Lorenzo, however, was delighted with it and became a staunch friend and admirer of the young sculptor, whose studio he frequently visited. On one occasion he found Michelangelo at work on a Sleeping Cupid so perfectly modelled and conceived in a spirit so truly Hellenic, as to appear a masterpiece of antique art. Lorenzo suggested that Michelangelo should make it look as if it had been buried under the earth for many centuries, so that the statue, being taken for a genuine antique, would sell much better, and the artist, more out of professional pride than in hopes of gain, followed his friend's suggestion. The Sleeping Cupid was sent to Rome, where Raffaelo Riario, Cardinal di San Giorgio, bought it as an antique for two hundred ducats, an evidence not so much of the Cardinal's ignorance as of Michelangelo's careful study of classical art.

This work was indirectly the cause of Michelangelo's first coming to Rome, for the Cardinal having discovered that his Cupid had been made in Florence was at first very angry at having been fooled, and insisted on the dealer, Baldassare del Milanese, taking back the statue and refunding the two hundred ducats (of which sum, by the way, Michelangelo had only received thirty ducats), but when his anger had subsided, the prelate, who was a liberal patron of art, shrewdly concluded that a sculptor who could so well imitate the antique was worth encouraging, and he forthwith despatched one of his gentlemen to Florence for the express purpose of discovering the mysterious forger and bringing him to Rome.

The Cardinal's emissary, after much fruitless search, chanced upon Michelangelo in his studio, and was so struck with the masterful manner in which the young sculptor made a pen-drawing of a hand in his presence, that he began to cross-examine him discreetly about his other works, and gradually learned all the story of the Cupid. Michelangelo, who longed to see Rome, which his visitor extolled as the widest field for an artist to study and to show his genius in, readily consented to leave Florence. In fact it appears that he was not very popular among his fellow-citizens owing to his former intimacy with the exiled Medici, and so, towards the end of June, 1496, he set foot in Rome for the first time. As to the Sleeping Cupid, nothing is known about its fate beyond the fact that it fell into the hands of Cesare Borgia at the sack of Urbino in 1592, and was by him presented to the Marchioness of Mantua, who in acknowledging the gift describes it as "without a peer among the works of modern times."

Michelangelo was greatly disappointed in his hopes of obtaining lucrative employment from Cardinal Riario. Indeed, the only work which he did during the first few weeks of his sojourn consisted in a cartoon for a Saint Francis receiving the Stigmata, to be painted by the Cardinal's barber! Fortunately for the young artist a wealthy Roman gentleman, Messer Jacopo Galli, came to his rescue, commissioning a Bacchus, which is now in the National Museum at Florence, and a Cupid, believed by some to be the statue now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, South Kensington. Of all Michelangelo's works, this Bacchus is certainly the most realistic and least dignified, representing as it does a youth in the first stage of intoxication, holding a cup in his right hand and in his left a bunch of grapes, from which a mischievous little Satyr is slily helping himself.

The statue was greatly admired in Rome and was the means of bringing Michelangelo to the notice of the French king's envoy in Rome, Cardinal De la Groslaye de Villiers, who commissioned him to carve a marble group of Our Lady holding the dead Christ in her arms, for the price of four hundred and fifty golden ducats. The contract, dated August 26th, 1498, is still preserved in the Archivio Buonarroti, and concludes with these words: "And I, Jacopo Gallo, promise to his Most Reverend Lordship that the said Michelangelo will furnish the said work within one year, and that it shall be the most beautiful work in marble which Rome to-day can show, and that no master of our days shall be able to produce a better." We shall see, when describing this magnificent group, that Jacopo's boast and promise were more than justified.

While in Rome, Michelangelo kept up an active correspondence with Messer Lodovico, who, it appears, found himself in great financial straits at this time. Being a most dutiful and affectionate son, the young sculptor sent every available scudo of his money to succour his father and his three younger brothers, namely Buonarroto, born in 1477, whom he placed in the Arte della Seta; Giovan Simone, born in 1479, who led a vagabond life and was a source of continual trouble, and Sigismondo, born in 1481, who became a soldier. The letters which Michelangelo, in the midst of his artistic labours, found time to write home, full of tender solicitude and good advice and invariably containing a remittance, give us a touching insight into the beautiful and disinterested character which lay hidden underneath his stern and decidedly unattractive exterior.

He lived not only very economically, but penuriously, in order the better to help his family, and it appears that his health suffered not a little from these privations. His father heard of it, and wrote a letter, dated December 19th, 1500, in which these passages occur: "Economy is good, but above all do not be penurious; live moderately and do not stint yourself, and avoid hardships, because in your art, if you fall ill (which God forbid), you are a lost man. Above all things, never wash; have yourself rubbed down, but never wash!"

When Michelangelo returned to Florence in the spring of 1501, the fame of the great works which he had accomplished in Rome had already preceded him, and he was generally admitted to be the first sculptor of the day. Commissions came pouring in upon him, including one from Cardinal Francesco Piccolomini, who afterwards became Pope Pius III., for fifteen statues of saints to adorn the Piccolomini Chapel in the Duomo of Siena.

But he completely neglected this work in order to devote himself with characteristic ardour to a more congenial task, that of carving a colossal statue of David out of a huge block of marble which had been previously spoiled by an inferior artist and abandoned as useless in the Opera del Duomo. Surmounting the enormous technical difficulties which he had to contend with, Michelangelo succeeded, after nearly two years of hard work, in evolving from the crippled block of marble one of the greatest masterpieces of modern art.

On the 14th of May, 1504, Il Gigante, as it was called by the Florentines, left Michelangelo's workshop and was dragged with much difficulty to the Piazza della Signoria, where it stood until the year 1873, when it was removed to the hall of the Accademia delle Belle Arti. It has fortunately suffered very little from its exposure in the mild Florentine air, but the left arm was shattered by a stone during the tumults of 1527. The broken pieces were carefully collected, however, by Vasari and a young sculptor, Cecchino De' Rossi, who restored the arm in 1543. Another giant David in bronze was commissioned to Michelangelo in 1502 by the Republic, who wished to make a present of it to a French statesman, Florimond Robertet, but although this work is known to have remained for more than a hundred years in the château of Bury, near Blois, it has since disappeared.

While wrestling with the difficulties of his David, Michelangelo found time to accomplish many other important works, including two marble tondi in bas-relief, the first of which is now in the National Museum at Florence and the other in the Royal Academy, London. Both represent the Madonna and Child with the Infant St. John, and although lacking in finish they deserve to rank among the finest of Michelangelo's works. The composition is beautiful and simple, the modelling bold and the expression of the Madonna singularly noble and striking.

In April, 1503, Michelangelo was commissioned by the Operai of the Duomo to carve out of Carrara marble twelve colossal statues of the Apostles, one to be finished each year, and a workshop was specially built for the sculptor in the Borgo Pinti, but the contract could not be carried out, the unfinished St. Matthew, now in the courtyard of the Accademia, in Florence, being the only work which resulted from this commission: "And in order not altogether to give up painting," says Condivi, "he executed a round panel of Our Lady for Messer Agnolo Doni, a Florentine citizen, for which he received seventy ducats." This tondo, representing The Holy Family, with nude figures in the background, is now in the Uffizi Gallery, and apart from its originality and artistic merit, it is especially interesting as being the only easel picture which may be attributed with absolute certainty to Michelangelo.

In August, 1504, Michelangelo was commissioned by his friend and protector, Piero Soderini, Gonfaloniere of the Republic, to decorate a wall in the Sala del Gran Consiglio in the Palazzo Vecchio, a most flattering compliment to the young artist, as Leonardo da Vinci, then at the height of his fame, was already engaged in preparing cartoons for the opposite wall. Leonardo's designs represented the famous Fight for the Standard, an episode of the battle of Anghiari, fought in 1440, when the Florentines defeated Niccolò Piccinino. Michelangelo selected for his subject an episode in the war with Pisa, which gave him an opportunity to display his wonderful draughtsmanship and his profound knowledge of the human frame.

Benvenuto Cellini, who copied the cartoon in 1513, just before its mysterious disappearance, describes it as follows: "Michelangelo portrayed a number of foot soldiers who, the season being summer, had gone to bathe in the Arno. He drew them at the moment the alarm is sounded, and the men, all naked, rush to arms. So splendid is their action that nothing survives of ancient or of modern art which touches the same lofty point of excellence; and, as I have already said, the design of the great Leonardo was itself most admirably beautiful. These two cartoons stood, one in the Palace of the Medici, the other in the hall of the Pope. So long as they remained intact they were the school of the world. Though the divine Michelangelo in later life finished that great chapel of Pope Julius, he never rose halfway to the same pitch of power; his genius never afterwards attained to the force of those first studies."

Leonardo, after having begun painting a group of horsemen on the wall, abandoned the task with characteristic fickleness, and Michelangelo having been summoned to Rome in the beginning of 1505 by Pope Julius II., left his work unfinished. It is said that a worthless rival named Baccio Bandinelli, envious of Michelangelo's greatness, destroyed the famous cartoon of Pisa. A sketch of the whole composition may be seen in the Albertina Gallery at Vienna, but perhaps the most complete copy of the cartoon is the monochrome painting belonging to the Earl of Leicester, at Holkham Hall.

THE TRAGEDY OF THE TOMB

Michelangelo little suspected when he left Florence that he was bidding adieu for ever to his happiness and peace of mind. Hitherto he had had to deal with generous tyrants, such as the Medici, with rivals whose envy was shorn of dangers by their cowardice, and with a protector such as Piero Soderini, whom Machiavelli taunted with being a weakling only fit for the Limbo of Infants. It was not until he came to Rome that he was brought face to face with a man blessed or cursed with indomitable energy, boundless ambition and a morbid restlessness which was probably the resultant of these two forces. Both Julius II. and Michelangelo were what their contemporaries called uomini terribili, proud, passionate, given to sudden bursts of fury, yet generous withal and truly great. For two such men to live together in uninterrupted peace and goodwill would have been a sheer impossibility.

After some months of hesitation, Julius II. finally decided upon the best way of employing Michelangelo's talents. He resolved to have a magnificent monument erected during his lifetime, and confided the task to the young sculptor. In an incredibly short time Michelangelo prepared his great design, which pleased the Pope so much that he at once sent him to Carrara to quarry the necessary marble. During the eight months which he spent at Carrara, Michelangelo blocked out two of the figures for the tomb, so anxious was he to begin his colossal work.

In November Michelangelo returned to Rome, where a house and spacious workshop were as signed to him near the Vatican, and in January, 1506, most of the marble, which had come by water, was spread all over the Piazza of St. Peter's: "This immense quantity of marble," says Condivi, "was the admiration of all and a joy to the Pope, who heaped immeasurable favours upon Michelangelo, and was so interested in his work that he ordered a drawbridge to be thrown across from the Corridore to the rooms of Michelangelo, by which he might visit him in private."

Michelangelo's original project of the tomb subsequently underwent so many modifications and reductions, that Condivi's account of what the monument should have been is deeply interesting: "The tomb was to have had four faces, two of eighteen braccia, that served for the flanks, so that it was to be a square and a half in plan. All round about the outside were niches for statues, and between niche and niche terminal figures; to these were bound other statues, like prisoners, upon certain square plinths, rising from the ground and projecting from the monument. They represented the liberal arts, each with her symbol, denoting that, like Pope Julius, all the virtues were the prisoners of Death, because they would never find such favour and encouragement as he gave them. Above these ran the cornice that tied all the work together. On its plane were four great statues; one of these, the Moses, may be seen in San Pietro ad Vincula. So the work mounted upward until it ended in a plane. Upon it were two angels who supported an arc; one appeared to be smiling as though he rejoiced that the soul of the Pope had been received amongst the blessed spirits, the other wept, as if sad that the world had been deprived of such a man. Above one end was the entrance to the sepulchre in a small chamber, built like a temple; in the middle was a marble sarcophagus, where the body of the Pope was to be buried; everything worked out with marvellous art. Briefly, more than forty statues went to the whole work, not counting the subjects in mezzo rilievo to be cast in bronze, all appropriate in their stories and proclaiming the acts of this great Pontiff."

As the monument would have covered an area of about 34½ feet by 23 feet, the church of St. Peter, although restored by Nicholas V., was found to be too small to contain it, and Julius II. decided to rebuild the whole church on a more magnificent scale, after designs prepared by Bramante.

The eager enthusiasm with which Michelangelo attacked his colossal task was not destined to last long. One day a quantity of marble arrived from Carrara, and Michelangelo, desiring at once to pay the freight and porterage, went to ask the Pope for money, but found his Holiness occupied. He paid the men out of his own pocket, but when he returned on several succeeding days he found access to the Vatican more difficult than usual, and finally learned that the Pope had given orders that he should not be admitted. Julius II., always entangled in warlike adventures, was evidently short of money and could not or would not pay Michelangelo at the time. The proud and short-tempered sculptor flew into a passion, and exclaiming that "henceforward the Pope must look for him elsewhere if he wanted him," took horse at once and returned to Florence, vainly pursued by five messengers from the Pope.

It was thus that the gigantic work on which he had set his heart was interrupted for the first time, and the curtain rose on the first act of that "tragedy of the tomb," as Condivi appropriately calls it, by which the rest of Michelangelo's life was darkened.

He had no sooner arrived in Florence than he received an imperative order from the Pope to return immediately to Rome under pain of his displeasure, but Michelangelo's blood was up, and he disregarded alike the threats of the Pope and the exhortations of Piero Soderini, who was greatly embarrassed, having received three official Briefs from Julius II., demanding that the artist should be sent back either by fair means or by force. Fearing actual violence, Michelangelo had made up his mind to go to Constantinople, but the Gonfaloniere dissuaded him, saying "that it was better to die with the Pope than to live with the Turk."

In the meantime, Julius II., after subduing Perugia, had entered Bologna in triumph on November 11th, 1506, and he had not been many days in the town before he despatched another urgent message to the Signoria asking for Michelangelo to be sent to him. The artist finally gave in, and proceeded to Bologna, armed with a most flattering letter from the Signoria, but feeling "like a man with a halter round his neck." His misgivings, however, were unfounded, for Julius II., who was only too glad to have won his artist back, welcomed Michelangelo most cordially and commissioned him to make a great portrait statue of him in bronze, to be placed in front of the church of San Petronio. And thus were these two men, who had so many points in common that they regarded each other with mutual fear, like giants conscious of their strength, reconciled for the time.

The Pope returned to Rome in very good spirits, leaving Michelangelo in Bologna to finish the colossal statue, which was only completed on February 21st, 1508, after much hard work and many disappointments, chiefly caused by the ignorance of the bronze-founder, who cast it faultily. It is greatly to be regretted that this work, which cost Michelangelo over a year of unremitting labour, should have been destroyed in 1511, when the Bentivogli returned to Bologna and drove out the Papal Legate. A huge cannon, ironically called La Giulia, was cast out of the broken fragments. Michelangelo, having completed his task, hurried back to Florence, and three days after his arrival Messer Lodovico emancipated his son from parental control, as we learn from a document dated March 13th, 1508.

It appears that Michelangelo intended to settle down for several years in his native city in order to decorate the Sala del Consiglio, for which he was to receive three thousand ducats, and to carry out other important commissions, including that of twelve statues of the Apostles for Santa Maria del Fiore, but "his Medusa," as he called Julius II., would not suffer him to remain in peace, and summoned him to Rome.

THE SISTINE CHAPEL

The artist obeyed, hoping that the Pope would allow him to go on with the tomb, but, during his absence, Michelangelo's rivals had persuaded Julius II. that it was unlucky to have a monument erected during his lifetime, and that it would be much better to set Michelangelo to work on the vault of the Sistine Chapel.

This they did maliciously, because they never suspected that Michelangelo was as great a painter as he was a sculptor, and hoped that he would prove himself inferior to the task, and thus lose the Pontiff's favour. "All the disagreements which I have had with Pope Julius," wrote Michelangelo to Marco Vigerio, "have been brought about by the envy of Bramante and of Raphael of Urbino," who were the cause that his monument was not finished during his lifetime. Bitter, unscrupulous rivalry was the leper-spot that marked the Italian Renaissance, especially at the Papal Court.

Michelangelo would gladly have declined the commission, for which he considered himself unfit, but, seeing the Pope's obstinacy, he reluctantly set to work on May 10th, 1508. The difficulties which he had to surmount were enormous, but he was not a man to be frightened by obstacles, however formidable. Knowing little or nothing of the technicalities of fresco painting, Michelangelo at first called six Florentine painters to his aid, including his old friends Francesco Granacci and Giuliano Bugiardini. But he was too exacting, and aimed at an ideal of perfection which his assistants could never attain, so that in January, 1509, he sent them all away, and destroying the work done by them, shut himself alone in the chapel to wrestle single-handed with his gigantic task.

The result fully justified his confidence in his own powers. To attempt an adequate description of the vault of the Sistine Chapel in this little book would be a hopeless task. The stupendous frescoes which adorn it, although described in hundreds of volumes, still afford material for much original study and research, but we must here content ourselves with a mere enumeration of the principal motives which go to make up this grand pictorial symphony.

Michelangelo chose for his subject the Story of the Creation, the Fall of Man, the Flood, and the Second Entry of Sin into the World, illustrated by a series of nine compositions on the central space of the ceiling. Twenty magnificent nude figures, representing Athletes, decorate the corners of these central compositions, and support bronze medallions held in place by oak garlands and draperies. The shape of the ceiling is what is commonly called a barrel vaulting resting on lunettes, six to the length and two to the width of the building. The second part of the decoration demonstrates the need for a scheme of Salvation, promised by the Prophets and Sibyls, whose majestic figures are painted alternately in the triangular spaces between the lunettes, in the lower part of which is a series of wonderful groups representing the ancestors of Christ.

Michelangelo, although engaged on a great pictorial work, never considered himself as anything but a sculptor, and followed in painting the same systems that he would have adopted in his own art. Sir Charles Holroyd, in his recent most valuable contribution to Michelangelesque literature, very justly remarks: "When Pope Julius prevented Michelangelo from going on with his beloved project of the tomb and made him paint the vault, the master set to work to produce a similar conception to the tomb in a painted form. The vault became a great temple of painted marble and painted sculptures raised in mid air above the walls of the chapel. The cornices and pilasters are of simple Renaissance architecture, the only ornaments he allowed himself to use being similar to those he would have used as a sculptor. Acorns, the family device of the della Rovere, rams' skulls, and scallop shells, and the one theme of decoration that Michelangelo always delighted in—the human figure. The Prophets and Sibyls took the positions occupied by the principal figures designed for the tomb, like the great statue of Moses. The Athletes at the corner of the ribs of the roof were in place of the bound captives, two of which are now in the Louvre, and the nine histories of the Creation and the Flood fill the panels like the bronze reliefs of the tomb."

Michelangelo must have toiled with almost superhuman energy at his great work. In a letter to his favourite brother, Buonarroto, dated October 17th, 1509, he writes: "I live here in great distress and with the greatest fatigue of body, and have not a friend of any sort, and do not want one, and have not even enough time to eat necessary food." This is not surprising when we remember that as early as the 1st of November, 1509, the first and most important part of this colossal work, which comprises three hundred and ninety-four figures, the majority ten feet high, was exposed to view, and greatly admired by the Pope, who, being vehement by nature and impatient of delay, insisted upon having it uncovered, although it was still incomplete.

Such was the impatience of Julius II. that on one occasion he threatened to have Michelangelo thrown down off the scaffolding if he did not hasten the completion of the work, and even went so far as to strike the artist with a stick. Thus urged, Michelangelo uncovered his work on the 1st of November, 1512, although he used to say in after years that he had been prevented by the hurry of the Pope from finishing it as he would have wished. "Michelangelo's fame and the expectation they had of him," says Condivi, "drew the whole of Rome to the chapel, whither the Pope also rushed, even before the dust raised by the taking down the scaffolding had settled."

SECOND FLORENTINE PERIOD

Julius II. died on February 21st, 1513, four months after the completion of the great work with which his name will remain as indelibly associated as that of Michelangelo. Shortly before his death he had ordered that the tomb which Michelangelo had begun should be finished, and had instructed his nephew, Cardinal Aginense, and Cardinal Santi Quattro, to see that everything should be carried out according to the original designs. But his executors, finding the project far too grand and expensive, had it altered, so that Michelangelo began all over again.

He set to work with great energy and goodwill, determined to finish the monument now that its completion appeared to him almost as a sacred debt to the memory of his dead patron. But the strange fatality that presided over the tragedy of the tomb again interfered. Cardinal Giovanni de' Medici, who had been Michelangelo's friend and fellow-pupil at the Medicean Court, succeeded Julius II. on the pontifical throne and assumed the name of Leo X. No sooner were the magnificent festivities over with which he celebrated his accession, than he sent for Michelangelo and ordered him to proceed to Florence to ornament the façade of San Lorenzo with sculpture and marble work. It was in vain that Michelangelo protested, saying that he was bound by contract to finish the tomb before undertaking any other commission, for Leo X. was as self-willed and imperious as his predecessor, and "in this fashion," says Condivi, "Michelangelo left the tomb and betook himself weeping to Florence."

It is not surprising that the artist should have wept tears of bitter disappointment, for we learn from a letter to his brother Buonarroto, dated June 15th, 1515, that at this time not only had he completed the Moses and the Captives in marble, but the panels in relief were ready for casting. Had he been left in peace, Michelangelo would certainly have finished the monument to Pope Julius in its modified form in half the time which he wasted quarrying marble from Carrara and Pietrasanta for the façade of San Lorenzo. For over two years Michelangelo was engaged in the tedious work of roadmaking and quarrying. In August, 1518, he wrote: "I must be very patient until the mountains are tamed and the men are mastered. Then we shall get on more quickly. But what I have promised, that will I do by some means, and I will make the most beautiful thing that has ever been done in Italy if God helps me."

He had evidently warmed to his work, and it is melancholy to think that Fate again interposed to prevent its completion. Giuliano de' Medici, the Pope's only brother, and Lorenzo, his nephew, having died at this time, Leo X. ordered Michelangelo to interrupt the façade of San Lorenzo and to build a new sacristy in which he proposed to erect a monument to their memory. The document exonerating Michelangelo from all duties and obligations in connection with the façade is dated March 10th, 1520.

Michelangelo only now found time to carry out a commission which he had received seven years previously from a Roman gentleman, Metello Vari, namely a nude statue of Christ bearing the cross. It was finished in the summer of 1521 and sent to Rome, the extremities being left in rough to prevent their being broken during the journey. Pietro Urbino accompanied the statue to Rome, with orders to complete it, and very nearly spoiled it by his careless and inferior workmanship. The Risen Christ, now in the church of the Minerva, is one of the most noble and majestic of religious statues in existence; the torso and arms are particularly fine, but the hands and feet, which were spoiled by Urbino, are stumpy and defective.

Leo X.'s pontificate, which, although short, was one of the most glorious and eventful in the history of art, came to an abrupt conclusion on December 1st, 1521. By a strange irony of fate, the magnificent patron of art and letters was succeeded by a pious and simple-minded Dutch prelate, who regarded statues as pagan idols, and said that the Sistine Chapel was "nothing but a room full of naked people." There is little doubt that he secretly longed to have it whitewashed. Fortunately for art and artists, his pontificate was of brief duration, and in 1523 Cardinal Giulio de' Medici was elected in his stead, under the name of Clement VII.

In the following year Michelangelo finished the new sacristy of San Lorenzo, and immediately set to work on the Medicean tombs. But he was constantly worried and interrupted by new commissions from the Pope, who wanted him, among other things, to build a library in which to place the famous collection of books and manuscripts begun by Cosimo de' Medici: "I cannot work at one thing with my hands and at another with my brain!" exclaimed the artist in despair. Nevertheless he undertook to build the library, and carried on both works at the same time, constantly urged on by Pope Clement, who wrote to him in an autograph letter: "Thou knowest that Popes have no long lives, and we cannot yearn more than we do to behold the chapel with the tombs of our kinsmen, and so also the library."

These were troublous times for Italy. After the disastrous battle of Pavia, in which he had lost everything "except honour," Francis I. concluded with the Sforza of Milan, with Venice, Florence, and Pope Clement VII. a league against Charles V., which proved fatal to all who took part in it. In 1527, a rabble of German and Spanish soldiers of fortune, led by the renegade Connétable de Bourbon, took and pillaged Rome, and the Pope himself was besieged in the Castle of Saint Angelo for nine months. The Florentines availed themselves of this opportunity to shake off the despotic yoke of the Medici, but two years later, Charles V. concluded the peace of Barcelona with Clement VII., one of the conditions being that he should re-establish the Medicean rule in Florence. But the citizens would not give up their newly-acquired liberty without a struggle, and prepared for a desperate resistance. Michelangelo was appointed Commissary-General of defence, and showed himself worthy of the confidence placed in him by his fellow-citizens.

It was in a great measure due to the skill with which he fortified the town, and more especially the hill of San Miniato, that Florence was enabled to withstand the attacks of the Imperial troops for twelve months. But the treachery of Malatesta Baglioni, who commanded the troops of the Republic, paralyzed the efforts of Michelangelo and of its other brave defenders, and in August, 1530, the city fell. Alessandro de' Medici returned in triumph to Florence, and would certainly have beheaded Michelangelo, who only saved himself by hiding in the bell-tower of San Nicolò beyond the Arno, until the first fury of his enemies was over.

In spite of his important military duties, Michelangelo continued working at the Medicean tombs during the siege, and also painted a panel picture, representing Leda and the Swan, originally intended for the Duke of Ferrara, but which he afterwards gave to his pupil Antonio Mini, together with many cartoons and drawings, that he might dower two sisters with the proceeds. It was sold to the King of France and hung at Fontainebleau until the time of Louis XIII., one of whose ministers ordered it to be destroyed as an improper picture. According to another version, however, it was only hidden, and afterwards brought to England. The Leda and the Swan now in the National Gallery is regarded by some as the damaged and much restored original of Michelangelo's famous picture. Clement VII.'s anger soon abated, and Michelangelo was able to return to his work, thanks chiefly to the kind offices of Baccio Valori, the Papal envoy in Florence, to whom the sculptor presented, out of gratitude, the fine statue of Apollo, now in the National Museum at Florence.

The Medicean tombs progressed but slowly, for all this time Michelangelo was worried almost to death by the Duke of Urbino, a nephew of Julius II., who insisted upon his finishing the famous tomb, while Clement VII., on the other hand, threatened the artist with excommunication if he neglected his work in the new sacristy for anything else. Probably the first statue to be finished was the beautiful Madonna suckling the Child Jesus, represented as a strong boy straddling across her knee. It is one of Michelangelo's noblest works, possessing all the majestic simplicity of his earlier Madonnas enhanced by greater power.

To give an adequate description of the tombs of Giuliano and Lorenzo de' Medici would be impossible within the narrow limits of this little book. Suffice it to say that the princes are represented in the garb of ancient warriors, each seated in a niche above a sarcophagus, on which two allegorical figures recline. Lorenzo appears to be plunged in sorrowful meditation; at his feet recline the colossal statues of Evening, represented by a powerful male figure, apparently on the point of falling asleep, and Dawn, symbolized by a beautiful young woman in the act of awaking, not to joy and hope, but to another day of sorrow. The beauty of this last figure cannot be described; it is such as the imagination of the ancient Greeks might have endowed a goddess with. The statue of Dawn was finished in 1531, soon after the fall of Florence and the return of the Medici, and there is little doubt that Michelangelo intended his mournful figures to express sorrow at the loss of Florentine liberty, rather than at the death of the two young princes. The same idea is evident in the tomb of Giuliano, with the two figures of Night, symbolized by a sleeping woman of singular beauty and power, and Day, a vigorous bearded giant just rising to his work and looking over his shoulder as if dazzled by the glare of the rising sun. Although the head of Day is unfinished, it is a striking example of how Michelangelo was able to give life and expression to his work from the first stroke of his chisel.

THE LAST JUDGMENT

In 1534 Michelangelo left Florence for the last time. His proud and independent spirit was unable to tolerate Alessandro's petty tyranny. The unfinished bust of Brutus, now in the Bargello, a vigorous and striking piece of work, is another proof of his intense longing for liberty. On arriving in Rome he found that Clement VII. had died two days previously, and that Paul III., Farnese, had been elected Pope.

Michelangelo had finally come to an understanding with the executors of Julius II., the agreement being that he should make a tomb with one façade only, using the marbles already carved for the quadrangular tomb and supplying six statues from his own hand, the rest of the work to be completed by other artists under his supervision. He therefore hoped to finish the tomb which had embittered thirty years of his life, but once more he was doomed to disappointment, for Paul III. immediately appointed him chief architect, sculptor and painter of the Vatican, with a pension of 1,200 golden crowns, and ordered him to carry out a commission which Clement VII. had given him shortly before his death. It was no less a task than to paint the end wall of the Sistine Chapel. Prayers and remonstrance were alike unavailing, and the doors of the Sistine closed once more upon the master, not to be opened again until the Christmas of 1541, when his Last Judgment was uncovered "to the admiration of Rome and of the whole world."

Thirty years earlier Michelangelo had depicted the Creation on the vault of this same chapel; he now took for his subject the final doom of all things created. The colossal work which cost him eight years' labour is a magnificent but almost terrifying pictorial rendering of the Dies Irae, the Day of Wrath, when "even the just shall not feel secure." Awe and terror are equally apparent among the spirits of the blessed crowding round the dread Judge, and on the despairing countenances of the condemned souls dragged down by hideous demons towards the infernal river, where Charon in his boat "beckons to them with eyes of fire and beats the delaying souls with uplifted oar." The rendering of the subject is thoroughly Dantesque, and very different from the conventional treatment of the same theme by all preceding artists. The composition, however, and indeed several individual groups and figures, remind us forcibly of the Campo Santo at Pisa.

Although all true artists received this work with enthusiasm, as Vasari says, and came from every part of Italy to study it, Michelangelo's enemies, including Pietro Aretino, the most immoral writer of his age, criticised it as a highly improper painting, because most of the figures were nude. So incensed was Michelangelo at this that he revenged himself by painting one of his critics, Messer Biagio da Cesena, as Minos surrounded by a crowd of devils. Some years later Paul IV. obtained Michelangelo's consent to partly drape most of the figures, and the work was done with commendable discretion by Daniele da Volterra, who thereby earned the nickname of Il Braghettone, or the breeches-maker.

Unfortunately the smoke from the altar candles and censers, and the dust of centuries have darkened and almost completely destroyed the original colour of this fresco; ominous cracks have also appeared in several places, but it is to be hoped that time will spare one of the greatest masterpieces of modern art for many centuries to come.

No sooner had Michelangelo finished the Last Judgment, than Paul III. set him to work on the side walls of the chapel which Antonio da San Gallo had just completed, and which is now known as the Cappella Paolina. Michelangelo was nearly seventy years old at this time, and fresco painting over a large surface is a fatiguing task even for a young man, but the veteran artist obeyed, and in 1549 he completed what was to be his last pictorial work, the two frescoes representing the Conversion of St. Paul and the Martyrdom of St. Peter.

The composition of these pictures is as masterly as ever, and the drawing, especially in the fore-shortened figures, faultless, but for the first time we are aware of something cold and unnatural, very different from the glorious life and power with which the frescoes of the Sistine literally glow. Michelangelo was getting old, and even his Titanic frame could not withstand the insidious attacks of time. He was seventy-five years of age when he carried these frescoes to completion, and he himself confessed to Vasari that he did so "with great effort and fatigue." Nevertheless he found sufficient time and strength to complete the famous monument of Pope Julius II. during the intervals of his fresco painting, and in 1545 the tragedy of the tomb finally came to an end.

It must have been with feelings of mingled relief and bitterness that Michelangelo surveyed the much modified tomb in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli. The mighty design which had fired his youthful ambition forty years previously had dwindled down to a comparatively unimposing monument, but everybody will agree with Condivi when he says that "although botched and patched up, it is the most worthy monument to be found in Rome, or perhaps in the world; if for nothing else, at least for the three statues that are by the hand of the master." Of the central figure, representing Moses, we shall have occasion to speak later on; the remaining statues by Michelangelo to which Condivi alludes are two female figures of rare beauty, representing Active and Contemplative Life. The rest of the tomb was finished by Raffaello da Montelupo and by other assistants under the master's supervision.

Having, as best he could, fulfilled his sacred pledge to the memory of Julius II., Michelangelo appeared to consider his artistic career as practically at an end. He was always inclined to sadness, but a cloud of deeper melancholy seemed to settle over him, and like Titian, Tintoretto, and other artists who attained to great old age, he turned his thoughts almost exclusively to religious speculation. In one of his sonnets he beautifully expresses the yearning for peace and rest which had taken possession of his storm-tossed soul:

Painting nor sculpture now can lull to rest

My soul, that turns to His great love on high,

Whose arms to clasp us on the Cross were spread.[2]

[2] "The Sonnets of Michelangelo." By J. A. Symonds, No. lxv.

Henceforward he regarded his art as a devotional exercise more than anything else. The unfinished marble group of the Deposition, now in the Duomo at Florence, and which he intended should be placed over his tomb, was carved by the master during these years of serene preparation for his approaching end.

Throughout his long and laborious career, devoted to the threefold worship of God, art and his country, Michelangelo had constantly refused to think of other ties, remarking that he had "espoused the affectionate fantasy which makes of art an idol." From some of his sonnets, however, it would appear that while at the court of Lorenzo the Magnificent he had secretly cherished a deep and hopeless passion for the beautiful Luigia de' Medici, who died in 1494. Forty years were to elapse ere in his heart, yet youthful at the approach of age, another woman, and she the first of her era, Vittoria Colonna, occupied the place left vacant by Luigia de' Medici. The friendship between these two lofty spirits, based upon mutual admiration and esteem, is one of the most beautiful romances in history, and inspired Michelangelo with some of his finest poems. It was brought to a close in 1547 by Vittoria Colonna's death, which left Michelangelo "dazed as one bereft of sense." "Nothing," says Condivi, "grieved him so much in after years as that when he went to see her on her death-bed he did not kiss her on the brow or face, as he did kiss her hand."

ST. PETER'S

It will be remembered that Pope Julius II. had ordered Bramante to rebuild the church of St. Peter's on a more magnificent scale, in order that his tomb should derive additional grandeur from its stately surroundings. Bramante was succeeded by Raphael, Peruzzi and Antonio da Sangallo, and when the latter died in October, 1546, Paul III. conferred the post of architect-in-chief upon Michelangelo. But the aged master at first refused, saying that architecture was not his art, and it was only when the Pope issued a peremptory motu proprio that he set to work, on condition that he should receive no payment for his services.

Michelangelo returned to Bramante's original design of the Greek cross, which had undergone considerable alterations, his object being to erect a perfectly symmetrical building in such a manner that its dominant feature, both from within and without, should be the cupola. He began by demolishing most of Sangallo's work, and severely putting a stop to all jobbery, thereby creating a number of enemies who did all in their power to have him removed from his post. But Julius III., who succeeded Paul III. in 1549, had implicit faith in Michelangelo, and the colossal work proceeded so rapidly, in spite of intrigues and opposition, that in 1557 the great cupola was commenced.

The master was now unable, owing to his extreme old age, to personally superintend the building, so that he constructed a wooden model, still preserved at the Vatican, after which his assistants carried on the work. From the window of his house Michelangelo used to watch for hours together the huge cupola slowly rounding itself against the sky, and wondered, perhaps, in how many years after his death it would be finished. The evening of Michelangelo's long life was saddened by the loss of nearly all who were near and dear to him. His two remaining brothers (for Buonarroto had died of the plague in 1528) passed away in Florence, and the only representative of the family, besides the aged artist, was his nephew Leonardo, only son of his favourite brother, Buonarroto. Although a confirmed bachelor himself, Michelangelo prevailed upon his nephew to marry, and Leonardo became the head of the still existing branch of the Buonarroti family. Another terrible loss to Michelangelo was the death of his faithful servant Francesco Urbino, of whom he wrote to Vasari: "While Urbino living kept me alive, in dying he has taught me to die, not unwillingly, but rather with a desire for death. The better part of me has gone with him, and nothing is left to me now but endless sorrow."

In spite of old age, illness and afflictions, Michelangelo's last years were perhaps the busiest of a life of uninterrupted work. To this period must be attributed the plan for the improvements upon the Capitol; the design for the church of San Giovanni del Fiorentini; the drawing for the monument to Giangiacomo de' Medici which Leone Leoni erected in the Milan Cathedral; the plans for the conversion of the Baths of Diocletian into the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli, and a number of other drawings and sketches for palaces, statues, monuments, which other artists carried out. He found time for all these things while actively superintending the construction of St. Peter's, and yet his restless spirit was not satisfied. In a beautiful sonnet, beginning with the words

Giunto è gia' il corso della vita mia,

he laments the loss of his former creative power, and says that he has already felt the pangs of one death, while another is fast approaching. Nothing could be more pathetic than the spectacle of this strong creative spirit, already imprisoned in the iron embrace of death, yet struggling, like a Laocoon, against inevitable dissolution. Although nearly ninety years of age, Michelangelo would still walk abroad in all weathers, taking no precaution whatever. On February 14th, 1564, a friend of the master, Tiberio Calcagni, met him in the street on foot. It was raining hard, and Calcagni affectionately upbraided the old man for going about in such weather: "Leave me alone," cried Michelangelo fiercely, "I am ill, and cannot find rest anywhere."

He spent the next four days in an armchair near the fire, not complaining of any particular suffering, "quite composed and fully conscious," as Diomede Leoni wrote to Leonardo, "but oppressed with continual drowsiness." In order to shake it off, the brave old man tried to mount his horse and go for a ride, but he was too weak. Without a word he sat down again in his armchair, and on the afternoon of February 18th, 1564, a little before five o'clock, Michelangelo peacefully breathed his last. "He made his will in three words," says Vasari, "committing his soul into the hands of God, his body to the earth, and his goods to his nearest relatives."

Leonardo arrived in Rome three days after his uncle's death. He had some difficulty in fulfilling Michelangelo's wish to be buried in his native town, as the Romans, who had conferred the citizenship on the artist, would not allow his body to be removed. At last the remains were smuggled out of Rome in a bale of merchandise and conveyed to Florence, where they were buried with great pomp and solemnity in the church of Santa Croce. For some unaccountable reason the group of the Pietà which Michelangelo had intended for his monument, was not placed over his tomb. The present very ugly monument was designed by Vasari at Leonardo's request. It bears the following inscription:

D. O. M.

Michaeli Angelo BONAROTIO

Vetusta . Simoniorum . Familia

Sculptori . Pictori . et . Architecto

Fama . Omnibus . notissimo

Leonardus . patruo . Amantiss . et . de . se . optime . merito

Translatis . Roma . ejus . ossibus . atque . in . hoc . templo

Majorum . suorum . sepulcro . conditis

Cohortante. Seren. Cosmo. Med. Magno. Etrur. Duce. p. c.

Ann. Sal. M. D. LXX

Vixit. Ann. LXXXVIII. M. XI. D. XV.

Other monuments to Michelangelo exist in the church of the Santissimi Apostoli at Rome, and on the hill of San Miniato, overlooking Florence, which he so bravely defended. But the noblest monument of Michelangelo the artist are his undying works, and the highest praise of Michelangelo the man and the Christian is contained in these simple words of a contemporary, Scipione Ammirato, "During the ninety years of his life, and in spite of numberless temptations, Michelangelo never did or said anything that was not pure and great."

In the history of Art, Michelangelo stands isolated, a colossal figure looming terrible and majestic, a Titan towering far above the sons of men. Yet his was an age of giants. When Michelangelo came before the world the glorious tide of the Renaissance was still rising; sculpture and architecture had been brought to an unprecedented degree of excellence by such men as Lorenzo Ghiberti, Donatello and Brunelleschi, and following in Masaccio's footsteps, a host of great painters had successfully striven to renovate and perfect their art until it culminated in a Raphael. Leonardo da Vinci was already famous before Michelangelo had touched chisel or brush, but neither Leonardo's encyclopaedic achievements nor Raphael's meteorlike career can be regarded as the ultimate expression, the high-water mark of the Italian Renaissance.

In Michelangelo we behold the giant embodiment of the true spirit of that wonderful period, the synthesis of its various forms of beauty and perfection, the final manifestation of its aesthetic possibilities. When Art first shook off the trammels of mediaevalism, she was content to worship at the shrine of Truth; with Botticelli and Leonardo she passed into vague regions of poetry. Raphael touched a more human note, often soaring to sublime harmonies: with Michelangelo the Renaissance reached its fullest development, attaining to a spiritual height, an almost superhuman loftiness hitherto undreamt of. Other men had excelled in painting, in sculpture, or in architecture before him, but Michelangelo was the first to attain perfection in every branch of Art, and such was his strong creative individuality that he left nothing to which he applied himself at the same stage where he had found it, bringing every manifestation of Art to the highest degree of perfection of which it was capable, and crowning all with that glorious aureola of spiritual grandeur which is the most awe-inspiring characteristic of his works.

We have said that Michelangelo stands alone. Of other artists it is easy to trace the aesthetic derivation, but he is the product of no school, the result of no external influence. Michelangelo, the most perfect emanation of the Renaissance, came before an astonished world like Minerva leaping from the head of Jove, all armed and beautiful in her strength and wisdom.

Although he lived in an age when tradition was almost an artistic canon, and when the pupil felt in duty bound to follow his master's methods, even his early works reveal a singular originality and freedom from all imitative tendencies. Take for instance his Battle of the Centaurs and Lapithae, which he carved when working under Bertoldo at the court of Lorenzo the Magnificent: it has nothing in common with the school of Donatello, but is instinct with the spirit of antique art, showing that the young sculptor derived infinitely more profit from the close study of the antique masterpieces which Lorenzo had collected in the gardens of San Marco than from Bertoldo's precepts. That he succeeded in mastering the style and manner of the ancients to perfection is proved by such works as the Sleeping Cupid, now unfortunately lost, but which was bought by Cardinal Riario as an antique, and was the cause of Michelangelo's first coming to Rome; the Bacchus, hardly inferior to the Dancing Faun of the Capitol, and the beautiful statues of the Medicean tombs, which might easily be mistaken for the work of a Greek chisel.

It is certain that during the first years of his long sojourn in Rome he gave himself up enthusiastically to the study of its ancient monuments and works of art. When the famous group of the Laocoon was discovered in 1506, Michelangelo greeted it as a "miracle of art," affirming that the only statue worthy of being compared with it was the torso of Hercules, which he was never tired of drawing, and evidently had before his mind when painting the magnificent ignudi of the Sistine Chapel. In the Wicar Museum at Lille there are several copies by Michelangelo of various decorative motives in the Baths of Titus, showing how deeply he studied ancient art even in minor details. But he was far from being a servile imitator; indeed his powerful originality is never so strikingly manifest as in those of his masterpieces which appear to be conceived in a purely classical spirit.

Although deeply religious, even to the point of regarding his art, especially during the latter part of his life, more as a devotional exercise than as a stepping-stone to glory, Michelangelo had one essential point in common with Pagan artists, namely, a boundless and reverent cult for beauty in all its forms, and especially in its highest and most wonderful manifestation, the human frame. "He loved the beauty of the human body," says Condivi, "as one who best understands it, and likewise every beautiful thing—a beautiful horse, a beautiful dog, a beautiful country, a beautiful plant, and every place and thing beautiful and rare after its kind, admiring them all with a marvellous love; thus choosing beauty in nature as the bees gather honey from the flowers, and using it afterwards in his works." In one of his sonnets Michelangelo thus expressed his highest idea of beauty—man created in the image of God:

Nor hath God deigned to show Himself elsewhere

More clearly than in human forms sublime,

Which, since they image Him, alone I love.[1]

[1] J. A. Symonds, "The Sonnets of Michelangelo and Campanella," n. lvi. p. 90.

It is certain that he studied anatomy far more deeply than any of his contemporaries, not excluding Leonardo da Vinci, and devoted so much time to dissecting that "it turned his stomach so that he could neither eat nor drink with benefit. Nevertheless," adds Condivi, "he did not give up until he was so learned and rich in such knowledge that he intended to write a treatise on the movements of the human body, its aspect, and concerning the bones, with an ingenious theory of his own, devised after long practice."

Michelangelo has been accused by some critics, not wholly without reason, of having somewhat ostentatiously availed himself of his anatomical knowledge. In some figures of his Last Judgment, for instance, the muscular masses, the bones and tendons and other anatomical details are hardly concealed by the skin, as if he had painted from the subject on the dissecting-table rather than from the living model. The result is undoubtedly striking and terrible, and we may even hazard the conjecture that the master purposely exaggerated his efforts in a picture representing the final resuscitation of the flesh, the awesome reconstruction and starting back into life of bodies long since reduced to dust. This "stupendous defect," if such it may be called, is far more apparent in Michelangelo's frescoes than in his works of sculpture.

Having taken the human frame as the highest possible standard of beauty, Michelangelo made use of it in all his works not only as the principal theme, but as a decorative element. The ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, with its magnificent nude Athletes and allegorical figures, is the apotheosis of the human frame as the noblest means of decoration. By introducing nude figures in his tondo of the Holy Family and by his powerful but utterly unconventional treatment of the angels and saints in the Last Judgment, Michelangelo once more affirmed his faith in the beauty and purity of the "human form divine" as a decorative element of religious art. He went even further, for in a letter to Cardinal Ridolfo da Carpi, which he wrote when engaged on the construction of St. Peter's, Michelangelo hazards the strange theory that the study of the human figure is indispensable not only to sculptors and painters, but to architects as well: "For it is very certain that the members of architecture depend upon the members of man. Who is not a good master of the figure, and especially of anatomy, cannot understand it."

Michelangelo's system of working was as powerful and original as his art. Before he began a statue he could already discern the finished masterpiece lurking within the rough-hewn block of marble, which he would attack with reckless assurance, great splinters flying in all directions as he feverishly cut away the waste stone, and saw the figure spring slowly into life under his magic chisel. A contemporary, writing in 1550, when Michelangelo, then seventy-five years of age, was carving the Pietà which he intended for his tomb, thus describes the master at his work: "I have seen him, although over seventy years of age and no longer strong, cut away more splinters from a block of very hard marble in fifteen minutes than three young men could have done in a couple of hours, and with such fierce recklessness that I thought the whole work must fall to pieces. For he knocked off splinters the size of a hand, following the line of his figures so closely, that the slightest mistake would have irreparably spoilt the whole group."

In one of his finest sonnets Michelangelo mentions this wonderful gift of the true artist to penetrate dull marble and to perceive, as through a veil, the perfect work of art within:

Non ha l' ottimo artista alcun concetto

Ch' un marmo solo in se' non circoscriva

Col suo soverchio; e solo a quello arriva

La mano che ubbidisce all' intelletto.