One by one, forty of the Earth's greatest

scientists vanished into that world beyond the

universe—until one man, doomed by its fatal

rays, carried humanity's last hope back the

blinding, twisted corridors that led through—

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Super Science Stories May 1950.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

CHAPTER ONE

The Shape of Danger

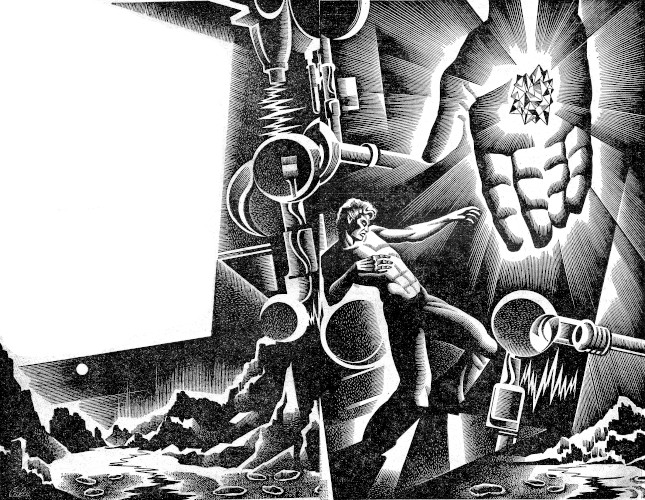

They looked at the crystal in horror.

It was the horror of the serpent, or of the Gorgon's head. They were fascinated; in that moment not one of them could have torn his gaze away. All work ceased. The noises in the concrete-walled room died until the whish of breathing and the thumping of hearts could be heard.

Then panic caught them, and fought against training. Panic cried, Run! and training said, Remove yourself quickly.

With the motion-saving efficiency of the emergency drill, each man turned from his position and walked rapidly towards whichever exit was nearest.

Actually, they could not outrun the danger any more than one can duck a rifle bullet or outrace the atomic bomb. But they went, five men and one woman, out through the zigzag corridors towards a mirage of safety.

One man remained.

Dave Crandall stepped forward and picked the crystal from its place in the evaporation dish. He turned, doused hand and crystal under a faucet, and then dropped the crystal on an anvil. He hit it with a heavy hammer. Anvil and crystal rang musically, and the crystal rebounded and flew through the air unharmed.

Cursing under his breath, Dave Crandall darted, picked it up again, and looked around wildly.

There were vats of acid handy; an electronic furnace glowed white-hot through its slit; a tunnel gaped unexcitingly but in its depths were the invisible radiations of the atomic pile. None of these would work soon enough.

Dave turned to the desk. He flipped open the end of the pneumatic message tube and popped the crystal into the chamber. There was the whroooom! of pumped air, a few tinkles as the crystal hit the sides of the tube on its way down.

Then from somewhere outside the concrete-walled room came the awesome blast. The wave-front traveled down the zigzag passages and Dave thought he could almost see it. The roar deafened him.

Dave went out through the zigzag passage.

A mile across the plain, a billowing white cloud was rising.

Claverly greeted Dave. Claverly was a bit shaken, and more than a little abashed. "The relay station," he said, pointing at the rising cloud.

"Oh?" remarked Crandall. He asked, frowning, "Anybody in there?"

"No."

Crandall smiled wryly. "That's a relief," he said. "But I didn't have time to ask where that tube went. I might have blown up the administration building."

Claverly laughed. "About all you've done is to cut a large hole in the coast-to-coast pneumo," he said. "No jury in the world would convict you."

DeLieb came around from the other side of the building. "There," he said, "but for the Grace of God—" pointing at the billowing pillar of smoke. "Thanks, Dave. This makes you unique, you know."

"Unique?"

"You are the only living man who has seen one of those devils' rocks in operation."

"We were all there," objected Dave, "and how about the Manhattan Crystal?"

"In the first place, the Manhattan Crystal is furnishing New York with electrical power—from a generating plant twenty miles outside New York, telemeter-controlled, and completely unattended. Montrose and Crowley and their associates who first made the crystal went up trying to reproduce it at Brookhaven. So did Brookhaven. Harvard, Purdue, Caltech, and Argonne went up trying to make one, too."

"But you were there, too, and you've seen it."

DeLieb nodded. "It is a six-sided crystal about three inches long, with a pyramidal point at either end, and about three-quarters of an inch across the hexagonal flats. It is clear with a trace of blue tint. So much we know, Dave. But what shape was it when you tossed it into the tube?"

"Cubical, and full of flashing red glints," said Dave.

"And why were we suddenly scared bright green?"

"Because it began to change shape before our eyes," said Dave.

"And it was still fluid when we—left."

"I think so," said Dave uncertainly.

DeLieb turned and went into the laboratory again, with the others following. He inspected the anvil and straightened up with a wry smile. There was the dent on the soft iron, made by the crystal under Dave's blow. "That," said DeLieb, "is the impact of a hexagonal crystal slightly distorted. A hexagonal form half-changed to a cubical shape. So, Dave Crandall, you are the only man alive to have seen such a crystal. Who knows the shape of the Manhattan Crystal by now?"

Steps clicked along the other zigzags. Phelps came in through one. "No hits," he said, "one run, and the only error was shutting off the cross-country pneumo. Tough. But the country got along without the shipment of short-lived radioisotopes before and it'll have to do without them again until they get the tube put together. Nice going, Crandall."

Behind him was Jane Nolan—Doctor Jane Nolan. Like her colleagues, Jane Nolan was often quoted in texts, had made several contributions to science, and was an authority on several subjects. She was not a beautiful woman; but her quiet air sometimes permitted a rather interesting personality to show through. Men forgot her mature thirty years and her lack of breath-taking beauty and dated her; then found themselves at once intrigued by her personality and completely baffled by her quick mind—and then went elsewhere in search of wide-eyed pulchritude.

Deep interest or honest admiration often lighted up her face and made it handsome if not beautiful. She looked very attractive now as she went to Crandall.

"That was brave," she said.

"Self-preservation," he said.

"We have that too," she replied with a slight smile. "And we also know that we cannot outrun that sort of thing. But we ran."

He smiled at her cheerfully. "I'm not a scientist," he said. "I'm just a newspaperman, remember? Perhaps I'm just too ignorant to realize the degree of danger."

Jane Nolan shook her head. "You've either seen the remains or pictures of them, of the other labs that failed. You know—"

"Look," he chuckled, "let's put it this way. We were dead ducks anyway. The devil himself couldn't have outrun that explosion without jet assistance." He turned to Claverly, "If I'd had any sense, I wouldn't have tried to smash it. I should have known that belting it with a hammer wouldn't have stopped it—if anything, it should have hastened the explosion."

"I hardly think so," said Claverly thoughtfully. "Remember that the crystal is not an explosive in itself. Or so we believe. Anyway—"

"Anyway, thanks to Dave, we still have our lab," said Jane. "Let's get back to work."

Dave shook his head. There was no point in arguing with them. They called him brave. Nuts! Nine great laboratories had gone skyward with their complement of scientists, trying to reproduce the fabulous Manhattan Crystal which was now furnishing the city of New York with electrical power. And with the deadly record of nine to nothing against them, the scientists continued to try. Theirs was the true bravery. It was a deadly experiment, and one that was not permitted—

Dave looked startled. "I thought the government insisted that these experiments be run by telemeter control?"

"They are."

"Then what in the hell were we doing here?" demanded Crandall.

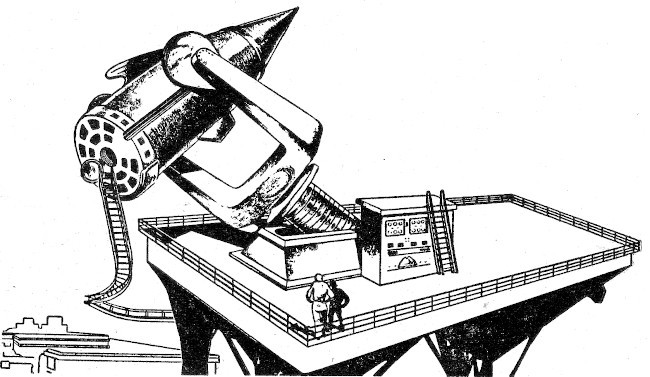

"The crystal," said Claverly, "was developed last week. We'd done everything but taste it by telemeter. It had been tested chemically, electrically, mechanically, atomically, physically and about any other way you can think of. We've had it white-hot and down to a half-degree Kelvin. We've dropped it, hit it, subjected it to electrostatic and electromagnetic fields, dunked it in everything from aqua to zerone, looked at it and through it, bombarded it with every radiation possible from the pile, and let it sit on a glass-topped platform to meditate. We believed it was safe; that we'd been successful. We came in to hook it up and test its power output, like the Manhattan Crystal. You came along."

Dave nodded. The message in his pocket told him that Merion Laboratory had successfully created a replica of the Manhattan Crystal and if he so desired, he could be present at its testing.

He said slowly, "It seems as if there might be something important here."

"What?"

"I hate to suggest it; it sounds silly."

"So do a lot of things," said Claverly. "Go on."

"I'm out of my depth here," said Dave. "But I've read of the so-called human aura. The sort of thing that gives certain gardeners a 'green thumb' and makes other men capable of curing a headache by merely rubbing the head with the fingertips. Is this sort of thing merely superstition or has it any basis in fact?"

Claverly frowned. "We don't like to answer such questions," he said. "But I'm being honest with you, Dave. The reason we don't like to answer is that we are not too certain. The best answer is maybe, and who knows?"

"So the crystal sat here and took all sorts of radiation, treatment, investigation, and the like. Then when the group of us assemble, blooey!"

Claverly looked at Dave. "What do you suggest?"

"I suggest that the crystal be worked on by one person at a time. Perhaps there's a critical mass of life-force—?"

"Sounds fantastic. You'll keep this out of your paper, Dave?"

"You bet—until we prove it. I don't want to sound any crazier than I am." He looked around. "I'm going to file a yarn on the explosion," he said. "Where's a typewriter and a telephone?"

Claverly said, "Jane, you show him. The rest of us will mix another batch and make us a new crystal. Then—" He left it unfinished.

Jane Nolan nodded. "Come on, Dave."

She led him to one of the jeeps that the laboratory crew used, and they started back towards the main collection of buildings.

"Dave, I like you."

Dave blinked. She laughed. "Does my directness bother you?"

"Not exactly. But—"

"It's caused me a lot of grief in the past; it's one of the reasons why I've never been a howling social success. However, saying and doing what I think makes a fine physicist out of me."

"That I believe," said Dave. The jeep drew up to one of the buildings. "Now," he said, "where's that typer?"

"In the office. Or better, we have a few empties; maybe you'd like to use one until you go back to Chicago?"

"That would be good," he told her. "I'm going to stay right here until you folks get this problem solved—or go up taking Merion Laboratory with you. Maybe," he said cheerfully, "I'll be able to use your typer to write the description of that, but it's unlikely."

Jane faced him as he climbed out of the jeep. "We've got a job to do. I know it sounds like a chunk of lousy script, but the bunch of us are devoted to the job of increasing human knowledge. So we're ready to accept the danger. But there's no reason why you should risk your hide. You can write from here and be safe."

"I wouldn't miss the fun for anything," he said. "When will the new crystal be ready?"

"Tomorrow morning."

Jane climbed out after him. "I'll arrange for that office," she said. "Come on."

From the window of his office Dave Crandall watched Jane drive off in her jeep. Then he turned to the desk and put through a long-distance telephone call.

"Meteridge speaking."

"Dave Crandall, doc."

"Yes, David. How're things going?"

"About the same."

"Fine. Keep the chin up."

"Doc—there's nothing can be done?"

"Five years ago we could have—"

"I couldn't see it."

Meteridge swore. "And now, like everybody else, you've changed your mind too late?"

"No, doc. I haven't changed my mind. I just wish it had been different."

"So do we all. But five years ago—"

"I know. I know. Five years ago you could have given me twenty years more, but it meant staying on my backside for the whole route. I took six years of active life in favor of twenty years as a total loss. I'd do it again."

"I suppose you would. So would I, to tell you the truth."

Dave chuckled. "So I just called to tell you the usual. I'm okay and feeling no pain."

"Good. Keep me informed. And when you start feeling the pangs, let me know. We can give you some relief."

They hung up and Dave, deliberately putting the thought out of his mind, went to work on his news story. It was the sort of thing that a stable man does not dwell upon; within him, burning at his vitals, was a fission fragment. Dispersed, it was. Too widespread for a single removal; years and years of almost continuous operations and convalescence would remove the danger, but it would leave Crandall abed most of his active life.

He—and Doctor Meteridge—knew that he had been no hero when he stayed behind with the crystal. At the worst it had meant an instant death; at the best, saving the lives of other people. What could Dave lose?

Nothing but a forfeited life.

CHAPTER TWO

The Crystal Phantoms

"Now," said Claverly, peering through the television hookup that brought him an image of the crystal, "we are ready." His voice came over the speaker tinnily.

"It's been checked?"

"Definitely. We're all ready."

DeLieb manipulated the controls as the rest of them watched through the large projection screen. Clawed arms came from the side of the screen and picked the crystal out of the dish. They carried it over to the mouth of a pneumatic tube, where it was dropped into a carrier. There was a whoosh! and the carrier disappeared.

The scene on the television screen switched abruptly to Claverly, who opened the end of the tube and removed the crystal. He held it up for them to see.

"So here we are," said Claverly. "The crystal and myself, removed from the critical mass of human radiation—if that means anything. Watch me closely. I am going to test this crystal for power output."

Claverly turned aside and clamped the crystal in a holder. He turned away, then, and—

There was a flash that filled the telescreen. It did not blind the onlookers, for the total output of the projection system would not furnish so much light. But the flash at the transmitting end paralyzed the orthicon, and once the phosphor of the receiving tube ceased to glow, the screen went dark. The orthicon at the far end of the line was no longer working. There was no roar of sound from the speaker. Just an electric crackle, and then the hiss of the live circuit.

"Gone!" said DeLieb explosively.

Phelps turned from the mounted telescope and said, "I saw a flicker from the windows, but the building is still there."

"Then it didn't blow," said Jane Nolan.

Crandall caught a faint flicker on the telescreen. The bare highlights were there, just coming up above the black level. "Claverly!" said Dave.

They turned. The tall scientist was visible, standing still as they had seen him before. Motionless, like a strobo-flashed picture.

Dave raced down, out of the building and into the parked jeep. He shoved the jeep into gear and took off with a roar. His tires threw dust as he raced across the intervening three miles to the remote laboratory.

Claverly was there. A phantom Claverly; a three-dimensional image, unmistakable as the man himself. Transparent, however; the bricks of the far wall could be distinguished through it.

The image was fading, but so very gradually that Dave had to watch carefully to be certain.

"The crystal is still here," said Dave. "It seems unchanged."

"We see," replied DeLieb. "The video is working again."

"So—what was Claverly's next move to be?"

"Wait!" cried Jane. "Be careful; Claverly—"

"Someone has to do it," said Dave. "If you'll give me directions—?"

Phelps shook his head at the rest and said: "Dave, if we could manipulate that thing from here through these last few motions, Claverly wouldn't have been there."

"Forgot that," said Dave unhappily. "So now what?"

"I'm coming over. You leave."

"Check—but don't like it."

Dave was less than a thousand yards away from the building when Phelps entered. His jeep was not equipped with radio or telephone so he did not know what went on. All he knew was a swift burst of brightness, perceptible against the bright sky. Dave stopped the jeep in half its length and turned it to go racing back.

Phelps was there, too. A phantom image standing near the image of Claverly, but apparently more solid. Claverly was fading; Phelps was a fresh image.

"Same damned thing!" cried Crandall into the microphone.

"I'm coming—" started DeLieb, but Dave stopped him with a firm "No!"

Then he ran the jeep back to the main buildings, thinking furiously. By the time he arrived, he had an idea....

"This is no random thing," he said. "This is malicious."

"Malicious?" asked Jane. "What do you mean?"

"How many nuclear laboratories have we lost, trying to reproduce this crystal?"

"Nine."

"And how many top-flight scientists?"

"Almost forty."

"The forty we can least afford to lose," added Dave. "Can you think of an easier way to sap the scientific strength of a country than to give it something that performs miracles—and also kills?"

"Ah," said Jane, shaking her head. "But there's a hole in that reasoning. No one gave us anything. We discovered the Manhattan Crystal by accident—in a restricted laboratory and under the most rigid supervision."

"Accident, hell! No doubt a young and innocent mouse thinks it's an accident when he finds a piece of cheese. The crystal is the cheese—and the trap. Kids, we're being taken for a ride. Give 'em a chance to lop off a gang of you and a lab at the same time and they do it. Give them no chance to get the lab, and they'll wait to get a scientist. Offer 'em a cluck of a newsman, of no scientific learning, and they wait until they have a chance at an important scientist. The crystal is still there."

"I'll go—"

"DeLieb, sit still. Claverly went, Phelps went. You go, and the next will be Nolan or Howes."

"So what do you suggest?"

"I'm no scientist. Teach me what to do. I'll do it."

"You'll die."

"I'll prove a point," said Dave. "And I won't die! I'll prove to you that anybody but a top scientist can tinker all day with that thing without danger. If you think I'm wrong, remember that I was there once and came back. Now—what do I do?"

Howes laughed bitterly. "If that were as simple as winding an alarm clock or grinding the valves on a gas engine, we'd have no problem, Dave."

"You can tell me the motions; you can tell me what to do. You can coach me at the job, and with training—hell, fellers, you don't have to know organic chemistry to mix a cake and men have performed operations with a jackknife at sea, with directions by radio. I'm checked out in a B-108, and any man who can keep his eyes on seventy meters, a hundred and twelve switches, forty levers, sixty-seven pushbuttons, and drive the damned thing with his free hand at the same time ought to be able to learn whatever this job requires." He looked around him. "And in the meantime, we'll let that crystal sit there and simmer, waiting for a nice, ripe physicist to come and get stuck!"

"It will take days," said Jane thoughtfully.

"Better days than lives," said Dave sharply.

"Okay," said DeLieb. "You certainly can do no harm. You may do some good. We'll try it your way."

For the next ninety-six hours, Dave Crandall got a total of nine hours of sleep. He worked in another replica of the remote lab, using similar instruments. He had not the foggiest notion of what he was doing, but he learned the manual dexterity necessary to do it. He didn't know what the meters meant, but he learned how to read them. He couldn't understand why he must do thus and so when such and such a meter read to a certain value, but he learned that, too. He became a trained human primate, an animal who knew that four raps plus four raps equalled eight raps; a chimpanzee trained to drive an automobile.

Not that Dave was ignorant, unintelligent, or untutored. Dave was college, postgrad, and a writer. Dave knew as much present-day science as any layman. He wrote science articles for his paper, was constantly exposed to science, and a lot of it took. But this science was as far beyond the kind he knew as the jet plane is beyond the Wright Brothers' original model.

Then DeLieb told him, "Dave, you're ready."

"Let's go."

"Not tonight."

"Why waste time?"

"You're tired. I'm tired. We're all tired, if you want to finish the conjugation. Tonight we loaf and rest and get a full night's sleep. Tomorrow we work. This is the royal edict."

"I vote yea," laughed Jane Nolan. "Come, ambitious one. On nine hours' sleep in four days, you should be easy to handle."

Dave shrugged. DeLieb looked askance. "Jane, if you take him dancing, we'll all kill you."

"You wouldn't have to," she said. "I'd be dead already. No, I'm taking Dave out to the farm where he can see stars and breathe fresh air, and loaf on long grass."

Jane's mother, forewarned, piled the dinner table high, and Dave was fed to the bursting point. They walked under the stars, afterwards, and then sprawled on the long grass, looking at the sky.

"You're quite a guy, Dave," said Jane.

"Probably the only one of my kind in existence," he said solemnly. "Most men have eight eyes, you know. I've only got two."

"Blue, aren't they?"

"Brown," he corrected. "All two of them."

"They're blue."

"Brown."

"Dave, I'm a qualified observer and I recall them as blue!"

"Wishful thinking. Probably your first love had blue eyes."

Jane lit a match and held it over him for an instant. "Blue," she said.

"Are you going to believe your eyes or what I tell you?" he demanded.

"My eyes," she said. "Just because I happen to think you're quite special, I don't necessarily believe everything you say."

"What's so special? I'm just an ordinary sort of guy. Most of the things I learned in school haven't been much use to me. I drink too much and smoke too much, go to church far too little—if at all—and have no immediate hope for mankind."

"You're an idealist."

"No cigar. Cynic, yes. But idealist—?"

"You are," she said. "You are also some sort of human dynamo. You come as a newspaperman to report on our doings and end up marching yourself into danger and almost running the research group."

"Think of the story I'll be able to write," he said.

"And if you don't—?"

He laughed. "I'm in no danger," he said.

"I hope you aren't."

"Better me than someone who might be able to solve this thing."

"I don't think so."

"I'm no loss to civilization, Jane."

"That's your fault," she told him, half-angry. "You could be a great asset if you'd only try."

"And what form of attempt does this require?"

"Stop playing cynic. We don't need people to tell civilization that it has a dirty back yard or a few rotten beams in the cellar. What we need is a few men with ideals to tell us how to clean up the yard and how to bolster the rotten stringers. Set your sights on some goal, and then settle down to work for it."

Dave groaned. "How do you start settling down after thirty-five years of hell-raising?"

"Do you want to know?"

"I've often wanted to know."

"Get married, Dave."

"Who'd have me?"

"I would. Marry me, Dave."

"Lord, no!" he exploded.

"I expected a refusal," she said softly. "I didn't expect quite such a vigorous rejection."

"I'm not rejecting you," he said earnestly. "You're a fine woman, Jane."

"Who was she?" Jane asked.

"She? Who?"

"The girl that broke your heart."

Dave laughed. "I'm not carrying any torch," he told her. He leaned on one elbow and looked down at her. The starlight was faint, but he could see her well enough. "In fact, Jane, under other circumstances I might get quite soft-headed about you."

"Then why not?"

He flopped back and stared at the sky. "Jane, you've accused me of being brave. This is damned foolishness. I'm not brave. I've got about six months to live, and I'm told the end will not be pleasant. I'd prefer to go black in a hurry, doing something that couldn't be done by a man with his life ahead of him. That isn't bravery; it's just cutting clean the end of a well-frayed rope."

"Who says so?" demanded Jane.

"The famous Dr. Thomas Meteridge."

"He might be wrong."

Crandall chuckled. "He's seldom wrong. Fact is, Jane, I've to kick off in six months, otherwise Old Doc Meteridge is a quack and a charlatan."

"He may be wrong."

Dave found her hand and held it over his side. "Feel warm? That's a collection of fission products, tossing all sorts of junk around."

After a moment she said, "Some men wait for death complacently; some spend their remaining time roistering; and Dave Crandall spends his time doing dangerous jobs for humanity. Now tell me that you're not an idealist, Dave."

"I—"

"Oh, stop arguing," she said. She still held the hand that had pressed hers over his side. Now Jane caught it in a hard grip and pulled, rolling him towards her. She met him halfway, missed his lips on the first try, and then made contact as her free arm went around his shoulders. Dave's was a startled response at first.

"Who's arguing?" he asked after a moment. He added his free arm to the embrace and held her to him.

The stars above them whirled a quarter way across the sky—unnoticed.

CHAPTER THREE

The Other World

Crandall awoke to the faint sounds of farm life and spent a few sleepy moments wondering where he was. The low of a cow, the creak of a windmill, and the bustle of activity in another part of the house; the sigh of a free wind and the whisper of leaves—none of these were indigenous to his normal habitat and it annoyed him until the sleep left him and he recalled.

Days of hard work and too little sleep, the relaxation of the farm for an evening. Jane. Jane!

Crandall swore mildly. He became introspective and carefully analyzed his feelings, even though he knew that he was hopelessly incapable of coming to an honest solution about himself. His glands and his intellect were at wide variance. He had no right to ask for nor could he offer love.

Dave growled at himself and climbed out of bed. A cool shower helped; he was glad that the Nolan farm was not of the older variety. Here at least was farm life with almost every comfort of urban living. He dressed and then went down the stairs slowly.

"Sleepyhead," Jane called as she saw him. "It's nearly nine o'clock."

"Middle of the night," he said.

"Dad and Mom have been up for hours."

"And you?"

"Positively minutes." Jane came to him, face upraised. He kissed her and momentarily forgot his troubles.

But it all ended too soon. Breakfast was leisurely, and then they were off, back to Merion.

They arrived at the laboratory in an hour, and then the bustle of activity herded Dave's introspective feelings out of his mind.

He discovered that the night of relaxation had sharpened his mind. He ran through the program once more in the remote lab, and then they announced that he was ready to try the real thing.

Dave went to the jeep. Jane followed.

"Dave—be careful."

"As possible," he agreed. He kissed her and then started off towards the remote lab that still held the crystal clamped in the electrodes.

They wanted physicists, huh? He'd show them, whoever they were. He'd fox them. The trick was completely incomprehensible, but however they did it, it was as neat a program of treachery as had been invented in all history. In an earlier day the enemy went for the leaders, the generals and the admirals and the kings and emperors. Now it was the engineers and physicists, for it was science that carried victory. The most brilliant military strategist was a mere cork bobbing on the rim of a whirlpool if he were not equipped with the latest and best that could come from applied physics.

But Dave was not a physicist. He was just a scribbler of articles, an occasional writer of fiction. So Dave was not the man they wanted. Let them sit and chew their fingernails while he, a zero quantity as far as they were concerned, toyed with the crystal. It wouldn't be practical to waste the crystal on him, any more than it was practical to hurl a can of SPAM[1] at a convoy escort.

Dave arrived at the remote lab and went to work. They checked him through the video and the sound channel both ways, and then Dave turned toward the crystal.

"The power," he said, "is being built up, as you can hear in the background, the generators are groaning a bit under the initial heavy load. The—ah—gaussmeter is rising up the scale. It occurs to me that the boys on the other side of this might well be chewing their fingernails at the moment. If I've got this thing figured right, they can see into this lab and know me and who I am—and possibly what I am doing. Maybe they've even figured out the why of it.

"Now, the next item is something I've been keeping quiet about. I doubt that they can read minds, but I'm pretty sure they can hear us and watch us. So I've kept quiet until now.

"As Dr. Thomas Meteridge can tell you, I've been given about six months to live. So I have nothing to lose, especially if I can prove a point. I've claimed stoutly that they aren't interested in anything but physicists, and that a tyro would be safe out here. But it's still possible that I was wrong.

"As you'll note, I've already got farther than either Claverly or Phelps. I think that if I kept my mouth shut now, I'd be allowed to finish the job. But—I think I have a clue to the identity of the enemy, and the method they're using to destroy our top scientific talent!"

He paused. "Of course, I could be bluffing. But I don't think they can afford to take that chance. So, in a minute, when I start to tell you what I think I know, they'll have to decide...."

"Dave," cried Jane, "what chance have you got?"

"A fair chance," he said. "We've got them spread nicely across the horns of a dilemma. If they do grab me, it will prove that there's an enemy alien at work. If they don't grab me, I'll solve their secret—"

As the crystal flashed, he vanished....

The crystal flashed pearly-white. Again it paralyzed the orthicon and crackled in the loudspeaker. It blinded Dave momentarily, but he shouted, "I'm still here!"

He heard a cry from the far end of the sound system. It faded rapidly.

As his eyesight returned, Dave looked around curiously. The laboratory was still around him, but it had the same semi-ghostly appearance that Claverly and Phelps had had. Of the images of the two physicists Dave could see nothing. They had been there, faintly visible, when he had gone in. Now they were gone. Dave looked at the workbench. He passed a hand through it. He stamped on the floor and found that he was stamping through the floor; he was actually standing on a semi-smooth surface a few inches below it.

"Damn!" he swore. He looked around. The concrete walls of the building were heavy and thick; he could not see clearly through them. He walked forward, hands outstretched, and saw his hands enter the wall. He walked through the wall, and felt a slight resistance, as though he were walking through water. He burst through the far side and the released pressure pitched him headlong.

Once outside, Dave looked around. In the ghostly distance he could see the main laboratory building and the jeep bearing Jane, DeLieb, and Howes. They came to the building and Dave ran to meet them.

"I'm here," he called. He screamed it. He yelled at the top of his voice. Jane walked through him. Her face was broken, tears filled her eyes, and Dave tried desperately to get her attention. But she walked through him and went on. They went in the door; Dave walked back through the phantom wall and met them inside.

"Dave!" cried Jane. She ran across the room and reached—then recoiled, her face twisted in horror.

"Like Claverly, like Phelps," she whispered.

"Like hell!" yelled Dave. "Dammitall, I'm here!"

"Gone!" said Jane.

"I'm not gone!" snapped Dave. But a still voice inside him said that he was. He looked carefully at the place Jane watched with horror-filled eyes. He could see nothing. Then he went to Jane and peered into her eyes. The pupils were clear. Dave snorted. If he could not see the image of himself that Jane saw, there was no reason why he could see a possible reflection of that image in her pupils.

"So he proved it," said DeLieb.

"And so we continue, knowing that something or someone is maliciously attacking us," said Howes.

"It's mine," said Jane in a flat voice.

"No—" said DeLieb.

"I want to follow him," she said.

"Don't be a fool!" yelled Dave.

He ran to the crystal and slapped at it. It hurt. With a glad cry, Dave pried at it with his fingers. The clamping electrodes held it firm—and he could not touch them, for they were as thin and tenuous as the concrete wall through which he had walked. Only the crystal was solid both there and here.

Dave smiled sourly. If he was dead, then this was a fine psychological hell. Here he was watching friends and a loved one marching into deadly danger, listening to their grief and their dangerous plans, while he was completely helpless to guide them.

He felt the crystal move slightly under his straining fingers. Wrapping a handkerchief about his fist, Dave punched at the crystal. It gave—or on the other side, the clamping electrodes gave. At any rate, it was loose.

He hit it again and jarred it.

"The crystal!" cried Jane. "It's moving!"

"Blow-up!" yelled DeLieb.

But this time there was no panic. Howes cut the energizing power with a flick of his hands across the toggle switches. DeLieb clamped down on the electrodes with a hand and spun the wingnuts that held it with the other. Jane Nolan grabbed at the crystal as it came free and turned to the pneumatic delivery tube.

But Dave reached out a hand and snatched it from her.

Jane cried in pain and fear, and watched the crystal make three long swoops towards the concrete wall—Dave had grabbed it and started to run outside. The crystal was wrenched from his fingers as he went through the wall. It fell to the floor, and all three physicists swooped down upon it.

Jane came up with it and popped it into the pneumatic tube.

It rattled thrice and was gone, racing down the tube end over end, visible to Dave as it raced out of reach.

"It wants physicists," breathed DeLieb.

"But it's gone now."

"And so is Dave," cried Jane.

"Dammit," snapped Dave. Then he gave up, because he knew the utter futility of trying to make them hear him.

But there was a way!

The crystal extended through both worlds. All Dave had to do was to get the crystal and use it as a stylus against some surface in the other world.

He turned to follow the pneumatic tube towards the place where the crystal had gone. He was not more than a hundred yards down the length of the tube when the sky blinded him from a couple of miles away, and then the air roared, and then when vision returned he could see a pillar of white smoke billowing skyward. They had destroyed the crystal!

Dave stopped to think.

Clearly, the exploding crystal was as dangerous on this side as it was on the other. That meant that no one could stand close by and watch the thing to be sure of which physicists they got—unless they used some sort of television hookup.

So Dave retraced his steps to the laboratory and inspected it. He saw nothing, and so began to feel his way through the walls of the building. He became engrossed in this job; it was both interesting and a bit terrifying to go walking through walls and feeling along the insides of beams and rafters. The building was a sort of thick phantom. Not only were the walls transparent, but the pipe lines, electrical wiring, nails, and other normally hidden bits of construction were visible within them. And walking along the length of a wall with a shoulder on either side, one in one room and one in the other, was disconcerting as well as amusing.

The heavy concrete-block walls, set up for radiation barriers, were wider than Crandall's shoulder-spread, and he could walk through their length completely enclosed in the hard concrete. Here it was eerie, too, for encased in the concrete were electrical wires and pipes, to Dave no heavier than the concrete through which he walked, but none the less clearly visible.

So Dave inspected the remote lab, walking down the walls and through the pipes and wires that stretched through the house like a spider's web, and he saw no evidence of espionage—

—until he caught his throat under a wire that should have been as tenuous as the others, but which almost throttled him.

Dave bounded back, clutching at his throat and swearing soundly.

Then he realized!

And forgetting his throat, Dave followed the wire to one of the remote video and audio sets. He pulled it aside—and it split into two complete sets! There were two television cameras, identical in every way, one in Dave's world, one in the everyday world, placed in perfect register!

His proof!

His friends had gone; obviously back to their laboratory to prepare another crystal. Here he could get one: their next one. Then he could communicate with them and start planning a counter-offensive.

Dave looked across the plain towards the main laboratory building, and shrugged. If he had a crystal now, all he could do would be to let them know he was alive and on the job, but had no information. On the other hand, he had fouled up the television camera in the remote lab, and it seemed likely that there would be a repairman coming along to see what was wrong.

Just where Claverly and Phelps were in this mess Dave didn't know. But he assumed that soon after their projection into this cockeyed half-world, the enemy had come along to collect them both.

Dave blinked at a sudden fantastic thought: would the flashing of a crystal send him back to his own world, or toss him along into another one?

An interesting thought—to be pursued later. Right this moment the thing to do was to lie doggo until the enemy arrived to take Dave in tow. This time, instead of a baffled scientist, they were attempting to catch a gent who was more interested in being alive than in figuring out where he was.

Had Dave been a pure scientist, he would have been amazed and baffled by this half-world. The whys and wherefores would have bothered him to the exclusion of other considerations, and he would have been standing there trying to figure it all out when the enemy came along to collect him. Instead, Dave was still alive, or felt that he was, and that was enough for him. Someone else could figure out how and why; his was the line of action; so long as he was able, he was going to continue to live and fight.

So when the helicopter dropped down out of the sky near the remote laboratory and disgorged a man carrying a rifle, Dave, the quarry, was sprawled behind a slight ridge in the half-world's terrain, watching through a cleft in the stone outcrop.

CHAPTER FOUR

The Struggle for Earth

The man with the rifle prowled around the ship, looking carefully out across the plains.

Then, angrily, he turned and said something at the door of the helicopter, and a second head appeared. There was a short discussion that Dave could not hear, and then the second man came out carrying a tool kit and headed for the lab. The first man got back into the helicopter and took off towards the main building.

Dave nodded. It was reasonable to suppose that Claverly, and then Phelps, after finding themselves in this half-world alone, had gone back to the main laboratory to see if they could raise the attention of their friends. Dave himself could have been expected to follow, running after the jeep that had taken the others back to their lab. The hunter expected to find Dave wandering disconsolately around the other lab.

When the helicopter had disappeared, Dave arose and scuttled across the plain towards the building he had left. He felt like a battleship on a clear ocean in broad daylight trying to slink unseen behind an enemy, but there seemed no way to avoid it. At any rate, the workman was paying no attention to his surroundings.

Within the walls of the laboratory, the workman was unlimbering his tool kit. He was an efficient workman. It was his job to repair the television camera and it was his cohort's job to track down and dispose of Dave.

He went to work on this basis and ignored the possibility that Dave might be stalking him—until Dave came silently up behind him and kicked the small sectional ladder out from beneath the workman's feet. Dave's fist came plunging through the windmill of flying arms and legs and connected solidly beneath the workman's ear. Startled, off-balance, and then slugged, the workman came to earth with a dull thud and sprawled motionless. Dave snarled and made doubly sure with a thrusting heel-kick against the workman's jaw and throat. The workman was not the first man to die from such a kick.

Then, in a matter of minutes, Dave was wearing the dead workman's shirt and trousers and was plying the tools on the television camera deftly. Dave had not wrecked the thing, he had just swung his weight against its moorings and displaced it. The problem was simple, and was handled by a couple of adjustable end-wrenches. It could have been done by sheer strength, but not with the desired precision. So Dave loosened the nuts that held the flexible couplings and slid the camera back into its original perfect registry with the camera in the real world. He was tightening the nuts again when he heard the helicopter returning.

Dave stooped and packed the tools back in the kit, folded the collapsible ladder and stowed it atop the tools, and then stood up and waved at the pilot.

The helicopter landed. The pilot got out and called, "Have you seen him?"

This was in a foreign tongue that Dave understood, and could speak acceptably.

"He jumped me," called Dave, pointing with his toe at the inert figure on the floor beside him.

The pilot looked and scowled. "Dead?"

"No!" grunted Dave, turning his back on the pilot, who was approaching. He scooped up the tool kit with his left hand and walked rapidly to get out of range of whatever loudspeaker system the enemy had in the laboratory. He strode thirty feet towards the pilot, who also came towards Dave about the same distance. Then—

"You're not—"

"Up!" snapped Dave, dropping the tool kit and pulling the captured revolver out of its holster.

The pilot snarled and made a side-swinging fadeaway motion, bringing the rifle up from its under-arm position. The pilot fired and the slug snapped past Dave's head. Dave fired and winged the pilot in the right shoulder, spinning the man around and dropping him to the ground.

Then Dave raced forward, made a long leap, and landed, kicking the rifle away with one heel and planting the toe of the other foot cruelly in the armpit of the wounded shoulder.

Pain crazed the pilot and he writhed on the ground, half-conscious. When he came to, Dave had his knees and ankles trussed with friction tape and was winding his free arm against his body with more tape.

The pilot mouthed some unprintables.

"Shut up!" snapped Dave.

"Bah!"

Dave backhanded the pilot across the face. The face writhed in pain and the eyes half-closed again. Dave tore the sleeve from the shirt and bound the bullet wound crudely.

"Now," he said harshly, "you'll live if you behave. It ain't painless, but you'll live—if you want to."

"You can't get away with this."

"No?"

"We'll get you sooner or later—"

"Think you'll live to see it?"

"Yes."

"You're wrong again, chum."

"Bah! We know your kind, all of you. Self-centered and egotistical, not one of you would care to die for his fellow man. We—"

Dave snorted scornfully. "During the last time we got in a scrap to prove that we're not as sloppy as you think, I took on a load of fission products. I don't much care whether you kill me quick right now or whether you let me die six months from now. I'm a dead man anyway. But in the meantime, little pawn of the superstate, I might be able to foul you up because I have nothing to be afraid of—but failure!" Dave let that sink in, although he doubted whether it made much impression. Then he demanded, "What do you know about this?"

"Nothing."

Dave joggled the wounded arm. "Are you certain?"

"You can't torture it out of me," said the pilot between gritted teeth.

"Maybe I can scare it out of you," said Dave. He stood up and lifted the pilot by hooking his left hand under the windings of tape. He dragged the man along the ground to the helicopter and slung him into the passenger's seat. Then Dave went around and climbed into the pilot seat and wound up the motor. He snapped off the radio and inspected the dashboard carefully to be sure that all radiating equipment was dead; he did not wish to be followed by any direction-finding equipment.

Then he drove the helicopter for two solid hours north until he came to a piney forest. He dropped the ship slantwise through the forest for a mile and came to earth in a little glade. The wheels of the 'copter rested on the half-world surface a few inches below the apparent ground.

"Now, my friend, I'm going to show you a few things that may prove to you that we're not as stupid as you think. For one thing, I, an unarmed man in a strange world, have succeeded in killing one of your buddies, wounding you, and making off with your helicopter. I've succeeded in escaping to a place where it may be difficult—if possible at all—to find us. Third, I've established the fact that you are not carrying any means of communicating to the real world on this 'copter."

"Oh, brilliant," said the pilot.

"It was," nodded Dave. "You see, we're a bunch of mechanical geniuses, which you've always admitted. So I postulate some sort of mechanical linkage through these devil's crystals of yours. A pencil, perhaps, with the barrel in one world and the magazine in the other world, coupled between them with a bushing made of a crystal. Maybe a radio set with bushings in the dials, and a crystal between the this-world diaphragm and the real-world electrical element. But if we were carrying anything of that nature I'd have felt resistance as we passed down through this forest. So—?"

"Why don't you kill me and forget it all?" asked the pilot.

"I am compassionate, sympathetic. A lover of mine enemy. When smitten upon one cheek, I turn the other cheek for a second wallop. Since you've had only one wallop, I'm keeping you alive so you can get that busted wing back in shape for the second smiting. But you see," added Dave as he saw a wave of pain pass over the pilot, "the book doesn't fill in the gap between the smiting of the first cheek and the offering of the second. Elsewhere in the same book—and a long way in front of that—you find references to the taking of an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth. You and your gang of hotshots have been responsible for the deaths of a lot of fine men, killed with no warning.

"So," finished Dave, hard-voiced, "maybe you'd like to learn what goes on when a mild-mannered gent like myself gets mad?"

Dave reached across the pilot's body, grasped the wounded arm and joggled it sharply. The pilot cried out in pain and beads of sweat popped out on his face.

"Talk, damn you!" Dave twisted the arm again.

"Where are you running this game from?"

No answer—and another twist of the arm.

"How do you blow up the crystals?"

The pilot's eyes closed and he breathed heavily.

"Possum!" said Dave, slapping the pilot across the face. There was no response, so he fumbled under the seat and found a water flask. He threw a small handful into the pilot's face. "There isn't much of this here," he said, "and I doubt that there's any water we can drink on this half-world. Wounded men get thirsty, don't they, chum?"

The pilot opened his eyes and groaned, "Water—"

"Talk!"

"I don't know anything."

"Then you're no good to me alive!" snapped Dave.

The pilot sat up a bit. Dave twisted the arm again. "Don't!" pleaded the pilot.

"Then talk!" snapped Dave again. "You got into this world the same as I did, but by choice. How do we get out again?"

"There's—no way out."

"Baloney."

The pilot screamed in pain. "No—I swear it!"

"How does the Manhattan Crystal furnish power for New York?"

"I don't know."

"It's transmission of power, isn't it?" demanded Dave, jerking the wounded arm again.

"I—"

"Good. That's what I thought. Transmission from one crystal to another. They blow them up the same way?"

The pilot nodded, weakly.

"So we don't manufacture the crystals in the nuclear laboratories. You and your gang deliver them like Santa Claus, coming down the chimney!"

The pilot nodded again.

"Now—where is this thing run from?"

The pilot shook his head. Dave snapped the arm sharply and the pilot screamed. He screamed a name.

"There's no way back?"

"No," groaned the pilot.

Dave let him go. "No way of communicating with the real world from here?"

"No."

"Do you know where we are?"

"Interstitial time."

"What?" roared Dave angrily.

The pilot winced. "I'm told," he gasped, "that time moves in quanta, like energy. We're—between two quanta of time."

Dave frowned thoughtfully. The expression, "out of phase" came to mind, and he decided that the half-world was displaced, out of phase in time, moving behind one peak of the "real world" and before the next. He remembered seeing a series of synchronizing pulses depicted on an oscilloscope; a series of rectangular waves, square-sided and flat-topped, rising from the baseline sharply. Like the cross-section of a row of piano keys, the separation between pulses very narrow compared to the width of the flat top. This half-world, he supposed, moved along in the separation.

"Where is Claverly—and Phelps?"

"I don't know. Another crew captured them and took them back."

"I think that's about enough," said Dave. "I think we can take it from here."

"And what are you going to do with me?"

Dave grinned, "We'll make a sporting proposition out of this, superman. You'll be the bait for a trap. If the trap springs on me, you'll win. If the trap springs on you, well, that's just too damned bad!"

"You can't trap us!"

"No? You told me I couldn't get anything out of you, either. So just watch!"

Dave lifted the 'copter once more and drove, at headlong pace, back to Merion. He hovered thirty feet above the pseudo-ground, less than half a mile from the main building, and then cut the engine and let the helicopter drop. For good measure, he tilted it sidewise. The ship landed with a jarring crash that crumpled the landing gear and folded one of the rotor blades down. The hull crumpled in on one side, and a litter of broken glass and some splinters of metal spread out across the earth. Dave completed the picture by kicking out the fore window and strewing the ground around the ship with the gear from the various tool boxes and compartments.

He found a first-aid kit. He charged a hypo needle with a healthy slug of sedative and placed it handy.

Then he sat back and waited.

An hour passed; two, three, and darkness began to fall. Dave switched on the landing lights of the 'copter, and then with a vicious smile he kicked one of them loose so that its beam cut the ground askew, illuminating the litter on the ground.

Two hours after dark he was rewarded by the distant sound of another helicopter. Dave went to work vigorously. He clipped the pilot across the jaw, dazing him. He shoved the needle home and discharged the sedative into the pilot's body. Then he cut the tape and shoved the feebly-struggling body half out through the fore window, being callously rough so that the pilot's face and shoulders were slightly cut by the broken glass.

The pilot, roused a bit by the pain, waved at the oncoming helicopter, trying to warn it off. Instead, the other pilot dropped rapidly towards the wreck.

It landed a hundred feet away and two men dropped to the ground and came running.

"What happened?" cried the foremost.

"Wreck," groaned Crandall, inside the ship.

He took careful aim with the pilot's rifle and fired, twice. Both men dropped in their tracks.

Leaping over them, Dave went to their helicopter and climbed in. He snapped the radio switch and said, "We're back, reporting."

"What happened, M-22?" the speaker answered tinnily, and Dave cheered himself for guessing correctly that the other pilot or observer had reported before investigating.

"Complete wreck," he said shortly.

"The men?"

"Dead."

"You're certain, M-22?"

"I am."

"What was the waving, then?"

"Piece of canvas. I thought it was one of them. The light, you know."

"Ah, yes. Over there it is dark. All right, proceed as directed and return to this wreck once the crystal is placed!"

"Check. M-22 signing off."

Dave snapped off the radio and rummaged about in the helicopter. He found the crystal, packed neatly in an aluminum box in the compartment below the dash.

Now to find something to write upon. Nothing he had available would suffice. And if he took the crystal into the laboratory to write upon a wall, the video cameras would see him and the enemy would blow the crystal up, and himself with it. There was—

Jane!

Dave grinned happily. He lifted the 'copter and drove it madly across the plain, following the ghostly road he recalled so well, until he came to the farmhouse of the Nolan family. Shamelessly, Dave lifted the 'copter around the farmhouse, peering into the windows until he located Jane's bedroom. He took the crystal from its packing and forced it through the window screen. Then he took the whole helicopter in through the house until he was sitting beside her bed. He tapped her shoulder with the crystal until she awoke.

"Uh—what?" she gasped, rubbing the sleep from her eyes.

She snapped on the light and sat up in bed.

She saw the crystal, apparently floating before her eyes, and she jumped with fright. Then Dave took the 'copter close to the wall. He scratched in the plaster:

Jane. This is Dave!

"Dave!" she breathed.

Yes! It was hard on the plaster, but necessary.

"You can hear me?"

Dave pointed to the "Yes" with the crystal.

"You can see me?"

Again came the point. And Jane hurriedly wrapped herself in the sheet and blushed. Then she threw away the sheet and said. "It seems that this is no time for modesty, Dave."

He tapped the printed "Yes" once again as Jane reached for her dressing gown and slipped into it.

"What do you want?" she asked.

Carbon paper, he wrote on the wall.

Jane disappeared, and Dave smiled at the scribbling on the wall. Its disjointed message was bearing fruit. But what could one make out of:

Jane. This is Dave!

Yes!

Carbon paper.

Nothing but the safety of America!

Instead of carbon paper, Jane brought a "Magic Slate", one of those wax-based tablets covered with a celluloid sheet that can be written on with a stylus and then erased by lifting the celluloid. It was better than carbon paper, and Dave cheered to himself at her brain-work.

"What is that?" she asked.

This crystal is the one the enemy was bringing to Merion Laboratory to replace the one they blew up in the safety-dump yesterday, he wrote.

"Where are you?"

I am in some sort of interspace between time quanta. Your guess is better than mine.

"Who is the enemy?"

Dave wrote it out, and then added the rest of the details.

"What shall I do?"

Stop them—somehow.

"How can I stop them?" wailed Jane.

Call President Morgan. You can do that, he wrote. Let the President put a stop to it!

Jane nodded and went to the telephone. Dave followed. I'm putting this crystal in Merion, he said. I've been away too long—they will be getting suspicious.

"Dave," cried Jane, helplessly looking for him. It was hard on Dave, for he knew what she wanted and was unable to stand where her eyes were trying to focus. He gave up and watched her eyes look aside and through him, unable to help her see him as he could see her. "Dave," she cried plaintively, "come back to me!"

When I can, he promised.

Jane waved the pad. "I have that in writing," she said. Her face showed it to be a hard try at humor.

Dave tapped her gently on the forehead with the crystal, and then it took off in a long swoop towards the window as he left. He did not know, but he assumed that a certain amount of time must be permitted the placers of those crystals since the operator could not open a door, nor must he permit the crystal to be seen floating through a busy corridor. How much of this grace period he had left he did not know, but he wanted the crystal placed under the eye of the television cameras of the enemy before they became suspicious.

The crystal was a deadly thing under any circumstances, but now it was like a gallon tin of nitroglycerine; Jane, knowing the facts, would keep people out of its sphere of death.

Meanwhile, as Dave drove the helicopter towards Merion, the avalanche of action that he had initiated was rolling higher and higher.

A common, garden-variety citizen of no especial degree of public acclaim is normally supposed to be able to shake the President by the hand and/or complain about the weather or the administration, or taxes, or anything. It has never been determined just what might happen if Peter Doakes, of South Burlap, Idaho, became possessed of vital information that must be handed to the President within the hour. Without a doubt the country would be blown sky-high by the time Mr. Doakes succeeded in proving to ninety-odd undersecretaries that he had something truly important and was not a crank or a crackpot. But Dr. Jane Nolan of Merion Atomic Laboratory had both a name and a reputation, and when she placed her call to the White House, it took her exactly twelve minutes to convince the powers that be that she had something vital to discuss with President Morgan. Four minutes later, the President had been awakened and was on the telephone. It took another fifteen minutes for Jane to tell her story.

Then the President haled a pompous little man out of bed and made him stand at the telephone while the President of the United States gave the Foreign Ambassador a bit of the Official What-For, and began explaining that it was not necessary for Congress to convene in order for the United States to rise and defend herself against a sneak attack from a Foreign Power, and that under the Circumstances, the President was going to present the Foreign Power with a fine collection of American Military Secrets, and that the first of these Gifts would be presented within the hour unless the Foreign Power surrendered first.

The President had a few other suggestions regarding the Return, unharmed, of a couple of American Scientists, and the well-being of a certain American Newspaperman, and some other items of mutual interest, and Furthermore, Mister Ambassador—

Dave Crandall flew his helicopter towards Merion, wondering how things were going. His job was done. He, too, was finished. There was no return. Not that Dave felt any great urge to return; doubtless there was something he could find to do in this half-world that would let him go on working. He would have to contact them and have them ship him groceries, cigarettes, and water. But there were many things that a man could do here.

He thought about Jane, and his heart softened for a moment. This was just as well, however. She would forget him, while he had no future worth thinking about. Only hard work, partly because he liked activity, partly because it kept him from brooding about the date of his certain death.

A wonderful woman, Jane Nolan; one not to be hurt by fate's little tricks. But so long as he was here, she—

The crystal he had in his pocket flashed brilliantly, penetrating the cloth and lighting up the cabin of the helicopter. At once, Dave felt the hard matter of the seat grow tenuous, and there was a bare instant of sliding resistance, like the feeling of plunging a foot into the shifting sand of a beach. Then the helicopter disappeared and Dave felt himself falling.

"Damned unmitigated liar!" growled Dave. Then he crashed into a tree and lost consciousness.

Dave meant the pilot who swore that there was no return to the real world.

He opened his eyes and groaned. He tried to move and found that he could not. He might as well be covered up to the eyebrows in concrete.

He looked around and saw a crowd of people watching him.

"Welcome home."

"But—?"

"I owe you an apology." Dave looked and saw President Morgan.

"Apology?"

"I got too tough with them. They flashed you back while you were flying the helicopter. You're banged up a little."

"Nothing that can't be repaired," said Doctor Meteridge cheerfully. "A beautiful case. Fractures of the tibia, fibula, radius and ulna on one side, humerus and clavicle on the other. Bruises and a couple of abrasions. Nothing serious."

"David," said President Morgan, "a grateful people is waiting for your convalescence so that we can show you our appreciation."

"Yes," said Jane. "Get well. We all have plans for you!"

Dave tried to shake his head. "No, Jane. Doc'll tell you. Six months—"

"You can't escape me that easily," said Jane. "While you're all neatly immobilized in that plaster cast, we are using their machine to separate out the widespread specks of fission products that were killing you. Just a matter of tuning critically so that it will send certain isotopes into the half-world instead of the whole human being. So by the time you get off your back, we'll have you healthy again and then, Dave Crandall, just you think up another excuse!"

"Pick on a guy when he's down," grumbled Dave. He was laughing, then, but the room blurred through the tears in his eyes.

[1] For Self Propelled Atomic Missile: a humorous contraction used in a novel, "Murder of the U.S.A.," by Will F. Jenkins, shortly after World War II. When self-propelled guided missiles came into being, General Lansdowne conferred Jenkins' appellation upon them and the name has remained.—G.O.S.