The Project Gutenberg eBook of Prehistoric villages, castles, and towers of southwestern Colorado, by Jesse Walter Fewkes

Title: Prehistoric villages, castles, and towers of southwestern Colorado

Author: Jesse Walter Fewkes

Release Date: November 9, 2022 [eBook #69319]

Language: English

Produced by: The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

BULLETIN 70

BY

J. WALTER FEWKES

WASHINGTON

GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE

1919

LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL

Sir: I have the honor to transmit the accompanying manuscript, entitled “Prehistoric Villages, Castles, and Towers of Southwestern Colorado,” by J. Walter Fewkes, and to recommend its publication, subject to your approval, as Bulletin 70 of this Bureau.

Very respectfully,

Dr. Charles D. Walcott,

Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution.

| Page | |

| Introduction | 9 |

| Historical | 10 |

| Classification | 14 |

| Villages | 16 |

| Rectangular ruins of the pure type | 16 |

| Surouaro | 16 |

| Goodman Point Ruin | 17 |

| Johnson Ruin | 18 |

| Bug Mesa Ruin | 19 |

| Mitchell Spring Ruin | 19 |

| Mud Spring (Burkhardt) Ruin | 20 |

| Ruin with semicircular core | 22 |

| Wolley Ranch Ruin | 22 |

| Blanchard Ruin | 23 |

| Ruins at Aztec Spring | 23 |

| Great open-air ruins south and southwest | |

| of Dove Creek post office | 28 |

| Squaw Point Ruin | 28 |

| Acmen Ruin | 29 |

| Oak Spring House | 29 |

| Ruin in Ruin Canyon | 30 |

| Cannonball Ruin | 30 |

| Circular ruins with peripheral compartments | 31 |

| Wood Canyon Ruins | 32 |

| Butte Ruin | 32 |

| Emerson Ruin | 33 |

| Escalante Ruin | 36 |

| Cliff-dwellings | 37 |

| Cliff-dwellings in Sand Canyon | 38 |

| Double cliff-house | 38 |

| Scaffold in Sand Canyon | 38 |

| Unit type houses in caves | 39 |

| Cliff-houses in Lost Canyon | 40 |

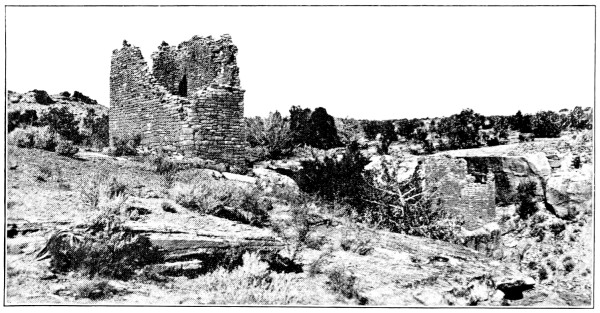

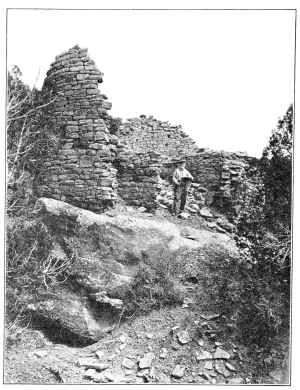

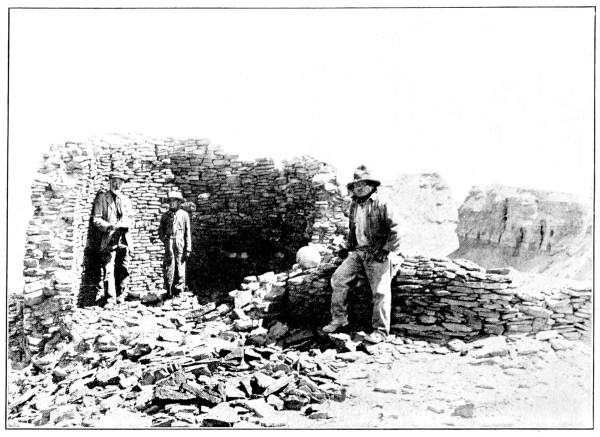

| Great houses and towers | 40 |

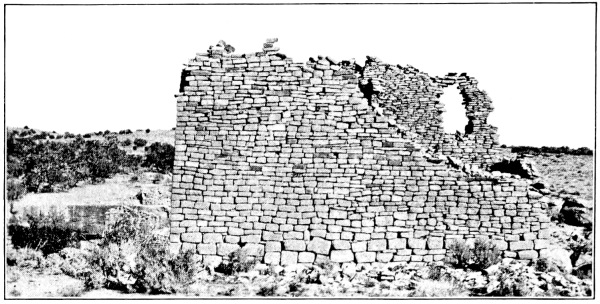

| Masonry | 40 |

| Structure of towers | 42 |

| Hovenweep district | 44 |

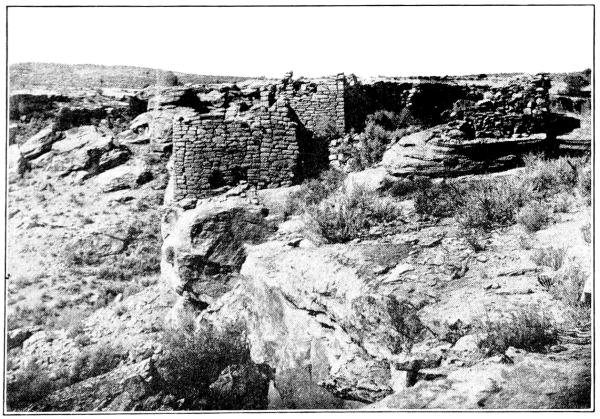

| Ruin Canyon | 44 |

| Square Tower Canyon | 45 |

| Classification of ruins in Square Tower Canyon | 46 |

| Hovenweep House (Ruin 1) | 46 |

| Hovenweep Castle | 47 |

| Western section of Hovenweep Castle | 47 |

| Eastern section of Hovenweep Castle | 48 |

| Ruin 3 | 48 |

| Ruin 4 | 49 |

| Ruin 5 | 49 |

| Ruin 6 | 49 |

| Eroded bowlder house (Ruin 7) | 49 |

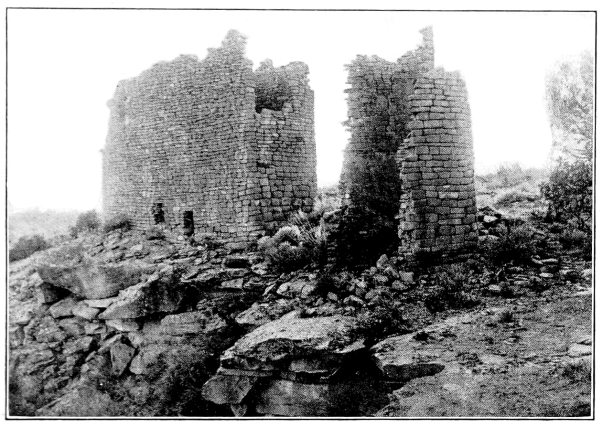

| Twin Towers (Ruin 8) | 50 |

| Ruin 9 | 50 |

| Unit type House (Ruin 10) | 50 |

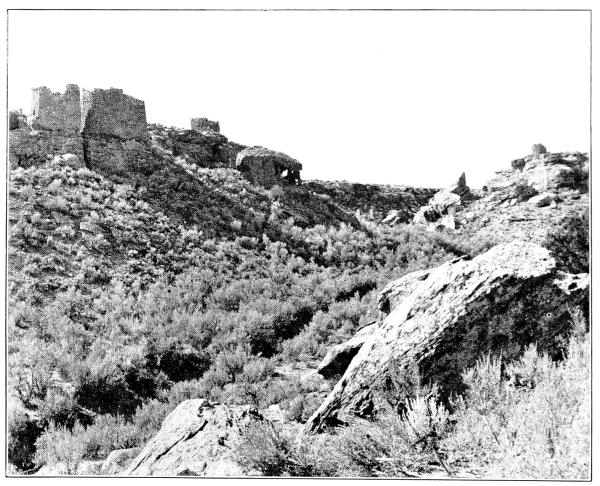

| Stronghold House (Ruin 11) | 51 |

| Ruins in Holly Canyon | 52 |

| Ruin A, Great House, Hackberry Castle | 52 |

| Towers [C and D] | 52 |

| Holly House | 53 |

| Ruins in Hackberry Canyon | 53 |

| Horseshoe House | 53 |

| Towers in the Main Yellow Jacket Canyon | 54 |

| Davis Tower | 55 |

| Lion (Littrell) Tower | 55 |

| McLean Basin | 55 |

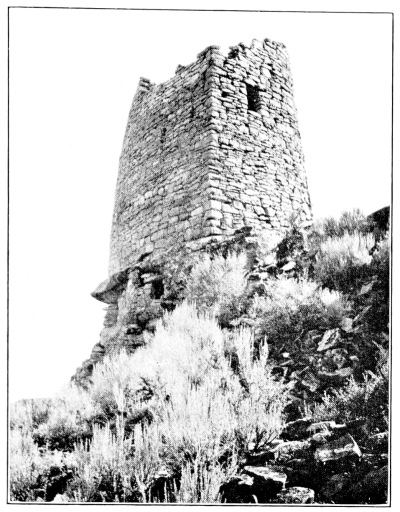

| Tower in Sand Canyon | 57 |

| Towers in Road (Wickyup) Canyon | 57 |

| Towers of the Mancos | 58 |

| Holmes Tower | 58 |

| Towers on the Mancos River below the bridge | 59 |

| Tower A | 59 |

| Tower B | 59 |

| Megalithic and slab house ruins at McElmo Bluff | 60 |

| Grass Mesa Cemetery | 64 |

| Reservoirs | 64 |

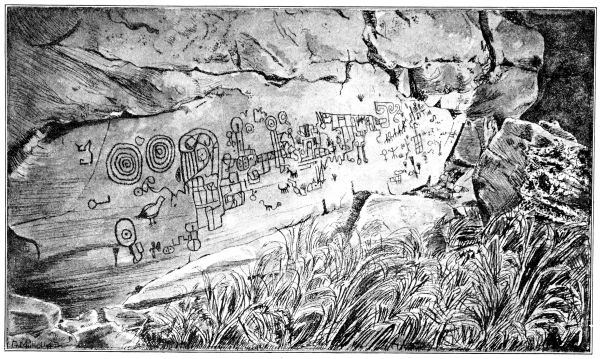

| Pictographs | 65 |

| Minor antiquities | 66 |

| Historic remains | 68 |

| Conclusions | 68 |

| Index | 77 |

| PLATES | ||

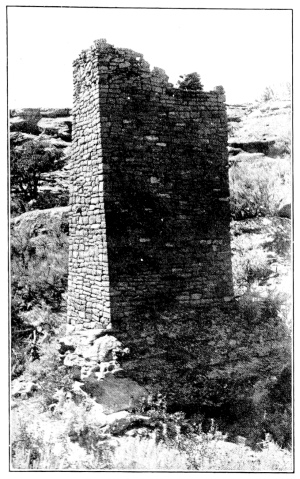

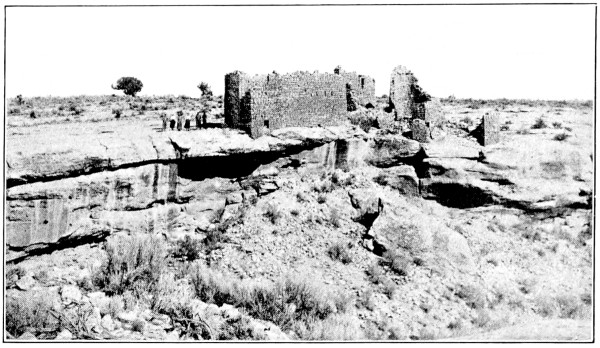

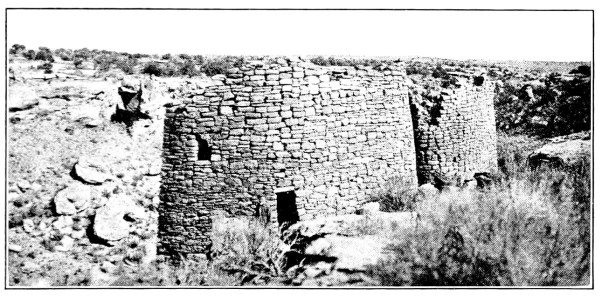

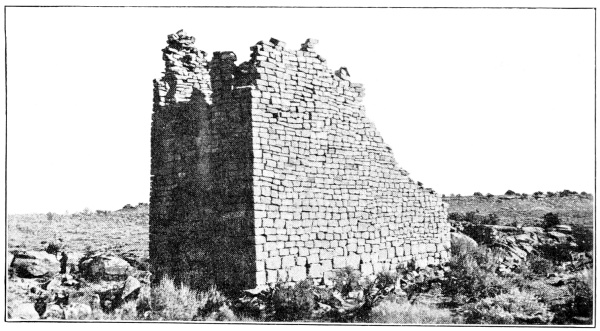

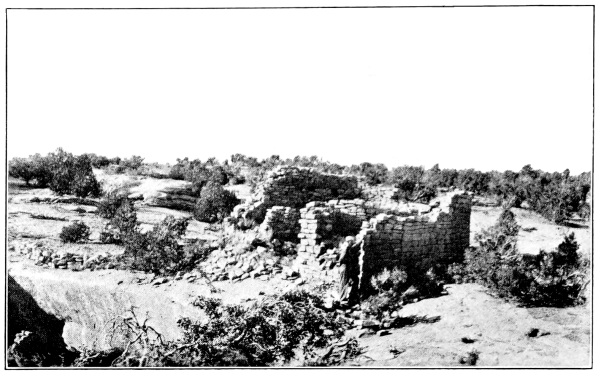

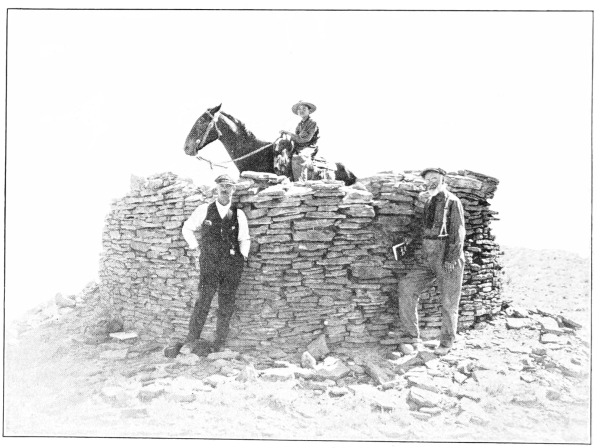

| 1. | a, | Butte Ruin. |

| b, | Aztec Spring Ruin. | |

| c, | Surouaro, Yellow Jacket Spring Ruin. | |

| 2. | a, | Blanchard Ruin. |

| b, | Blanchard Ruin, Mound 2. | |

| c, | Surouaro, Yellow Jacket Spring Ruin. | |

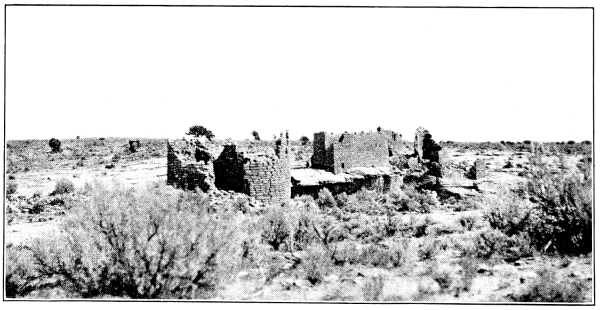

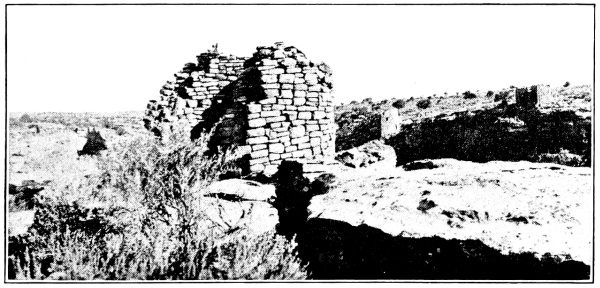

| 3. | a, | Acmen Ruin. |

| b, | Mud Spring Ruin. | |

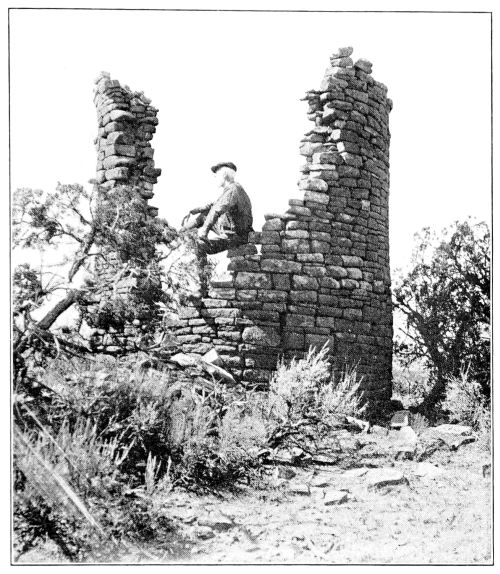

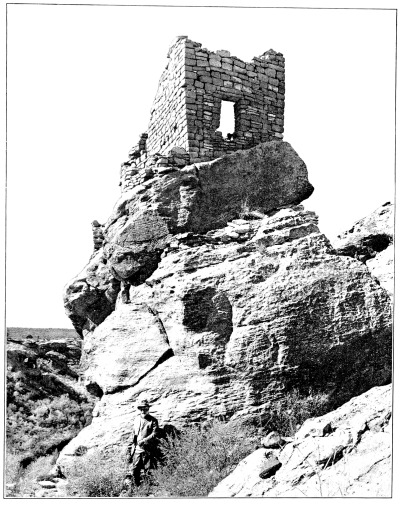

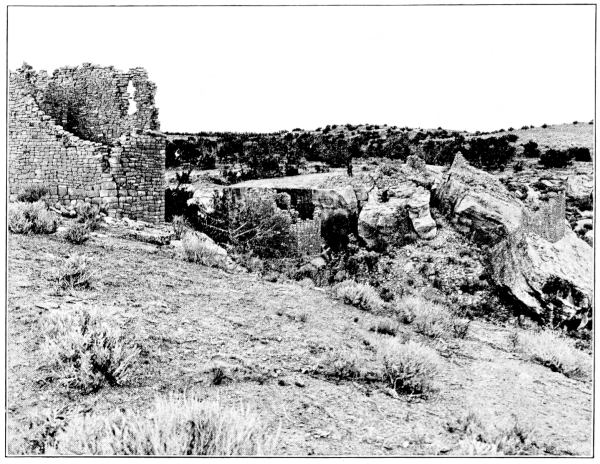

| 4. | a, | Building on rock pinnacle, near Stone Arch, Sand Canyon. |

| b, | Stone Arch, Sand Canyon. | |

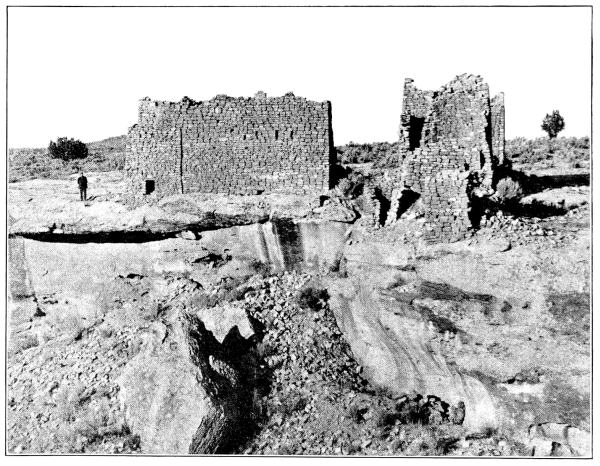

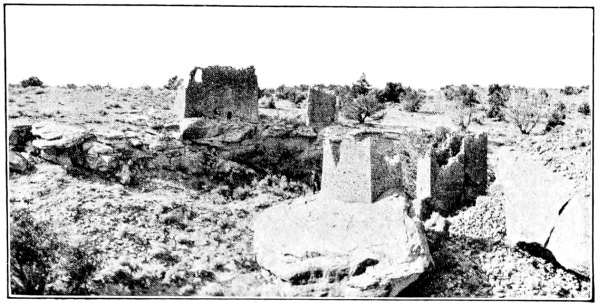

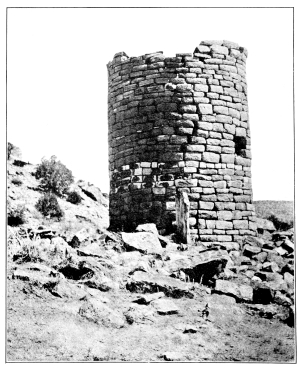

| 5. | a, | Tower in Sand Canyon. |

| b, | Unit type House in Sand Canyon. | |

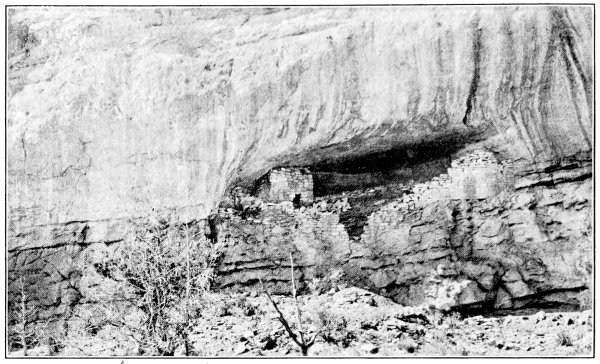

| 6. | a, | Stone Arch House, Sand Canyon. |

| b, | Cliff-house, showing broken corner. | |

| 7. | a, | Scaffold in Sand Canyon. |

| b, | Storage cist in Mancos Valley. | |

| c, | Pictographs near Unit type House in cave. | |

| 8. | Double cliff-dwelling, Sand Canyon. | |

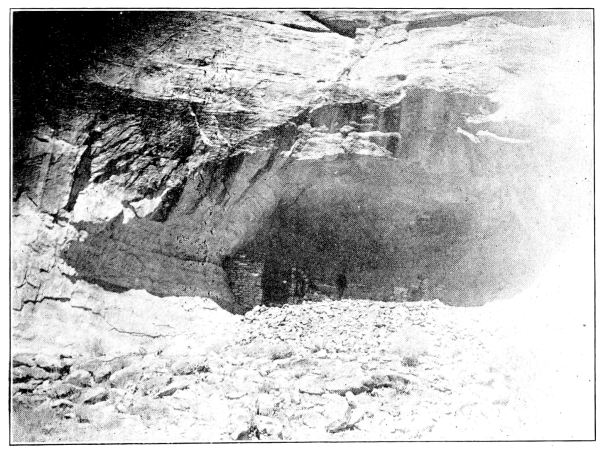

| 9. | a, | Cliff-dwelling under Horseshoe Ruin. |

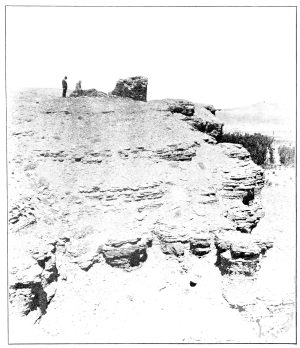

| b, | Cliff-dwelling, Ruin Canyon. | |

| 10. | a, | Kiva of cliff ruin, Lost Canyon. |

| b, | Cliff ruin, Lost Canyon. | |

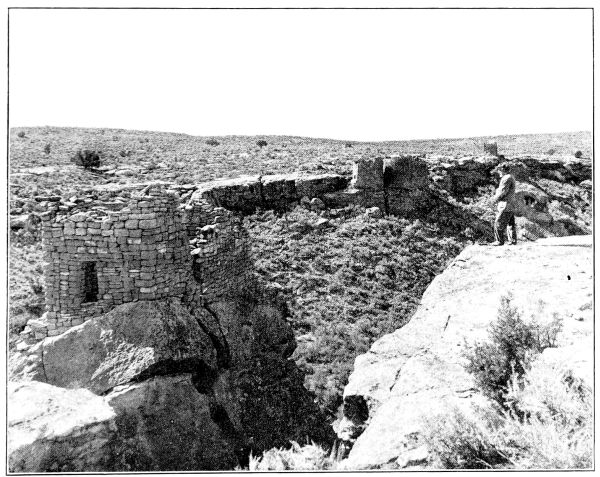

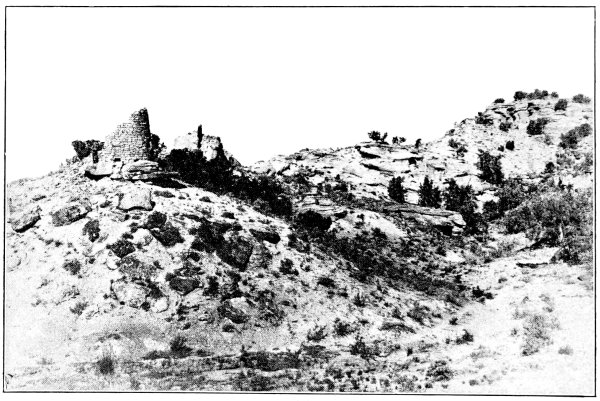

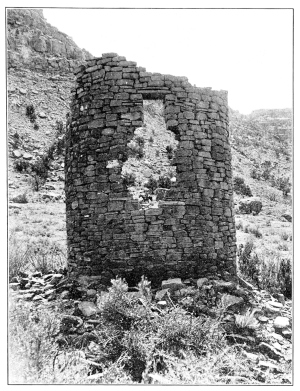

| 11. | a, | Square Tower in Square Tower Canyon. |

| b, | Tower in McLean Basin. | |

| c, | Ruin in Hill Canyon, Utah. | |

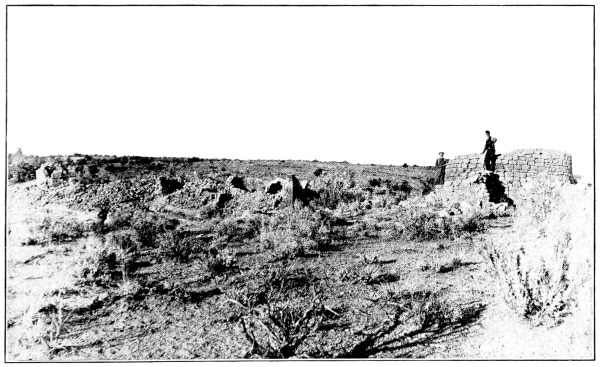

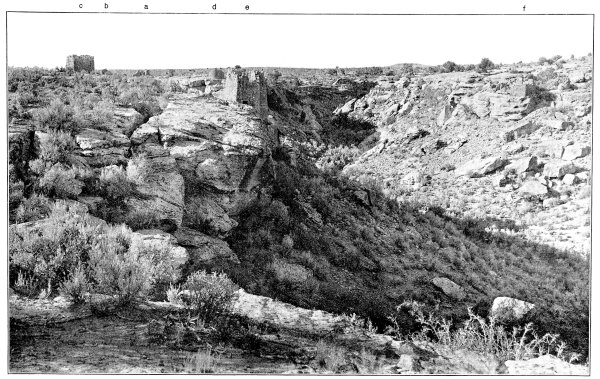

| 12. | Head of South Fork, Square Tower Canyon. | |

| 13. | North Fork of Square Tower Canyon, looking west. | |

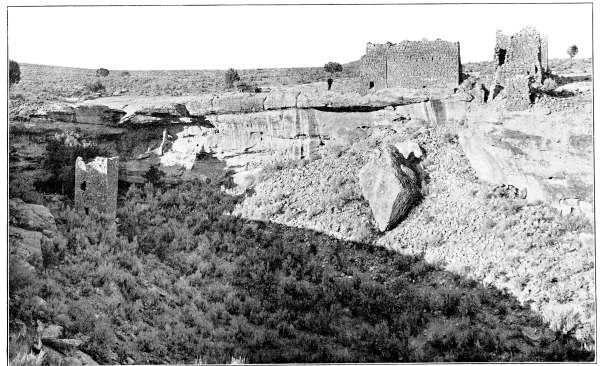

| 14. | a, | Hovenweep House and Hovenweep Castle, from the south. |

| b, | Hovenweep Castle, from the west. | |

| c, | Hovenweep Castle, from the south. | |

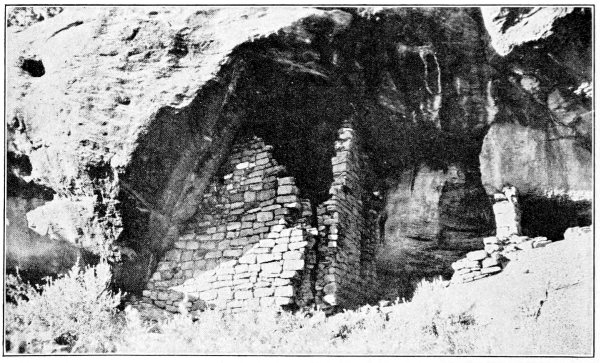

| 15. | a, | West end of Twin Tower, showing small cliff-house. |

| b, | Twin Towers, Square Tower Canyon, from the south. | |

| c, | Tower 4, junction of North and South Forks, Square Tower Canyon. | |

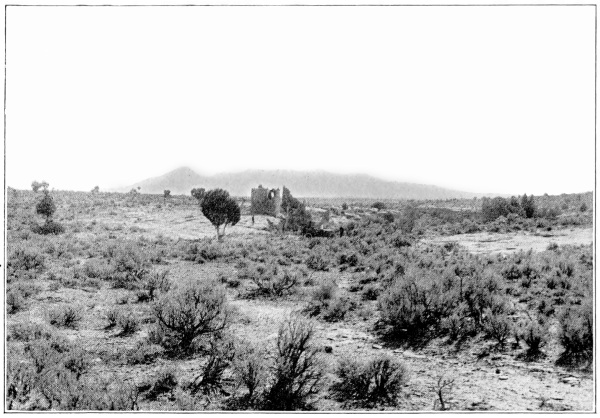

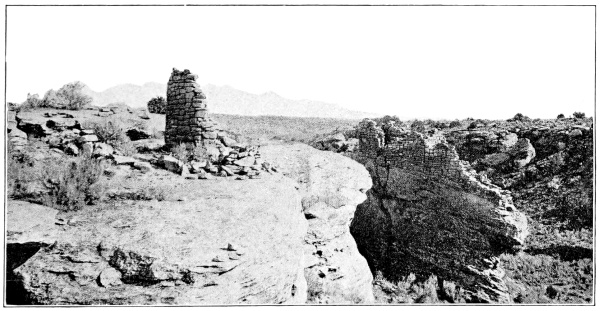

| 16. | a, | Hovenweep Castle, with Sleeping Ute Mountain, South Fork, Square Tower Canyon. |

| b, | Entrance to South Fork, Square Tower Canyon. | |

| 17. | Stronghold House, Square Tower Canyon. | |

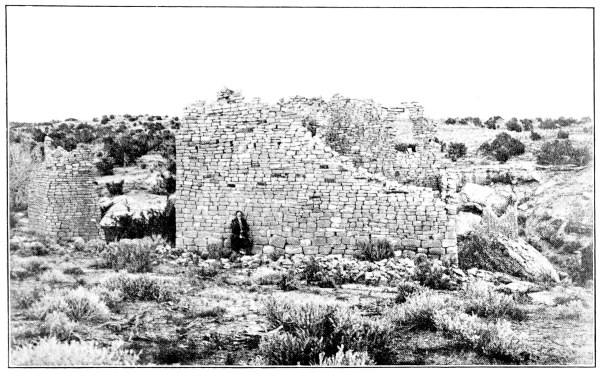

| 18. | a, | Head of Holly Canyon. |

| b, | South side of Hovenweep Castle, Square Tower Canyon. | |

| 19. | a, | Holly Canyon group, from the east. |

| b, | Great House at head of Holly Canyon, from the north. | |

| c, | Unit type Ruin, from the east. | |

| 20. | a, | Great House at head of Holly Canyon, from the south. |

| b, | Ruin B at head of Holly Canyon, from the west. | |

| c, | Great House at head of Holly Canyon. | |

| 21. | a, | Great House, Holly Canyon. |

| b, | Stronghold House and Twin Towers, Square Tower Canyon. | |

| 22. | a, | Hovenweep Castle. |

| b, | Southern part of Cannonball Ruin, McElmo Canyon. | |

| 23. | a, | Square tower with rounded corners, Holly Canyon. |

| b, | Holly Tower in Holly Canyon. | |

| c, | Horseshoe House. | |

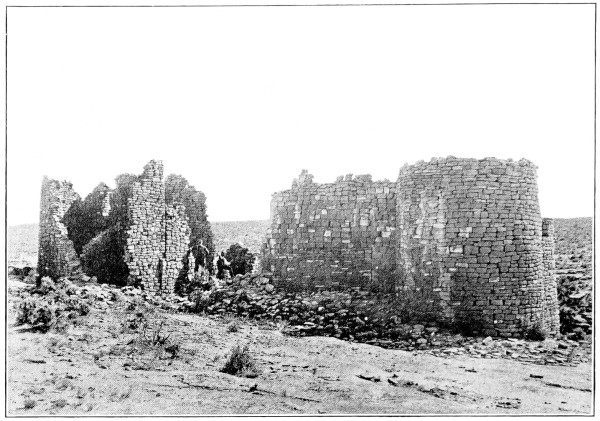

| 24. | a, | Horseshoe Ruin. |

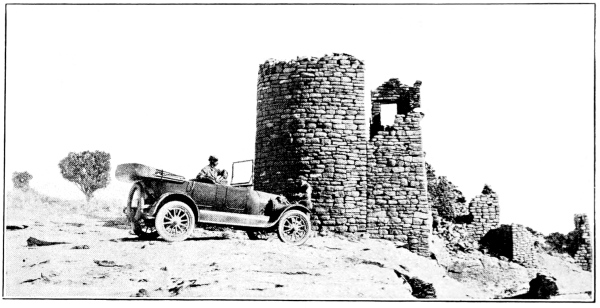

| b, | Bowlder Castle, Road (Wickyup) Canyon. | |

| 25. | a, | Closed doorway in Bowlder Castle, Road (Wickyup) Canyon. |

| b, | Broken-down round tower, Square Tower Canyon. | |

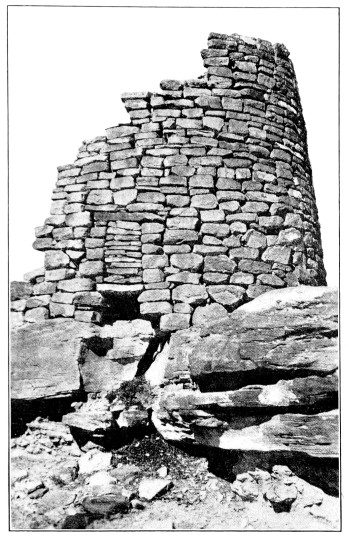

| 26. | a, | North side of tower, Square Tower Canyon. |

| b, | D-shaped tower near Davis ranch, Yellow Jacket Canyon. | |

| c, | Model of towers in McLean Basin. | |

| 27. | Round tower and D-shaped tower in McLean Basin. | |

| 28. | a, | D-shaped tower in McLean Basin, showing cross section of wall. |

| b, | Round tower in McLean Basin, showing standing stone slab. | |

| 29. | a, | Holmes Tower, Mancos Canyon. |

| b, | Lion Tower, Yellow Jacket Canyon. | |

| 30. | a, | Tower above cavate storehouses, Mancos Canyon, below bridge. |

| b, | Tower on mesa between eroded cliffs and bridge over Mancos Canyon, on Cortez Ship-rock Road. | |

| 31. | a, | Tower above cavate storehouses, Mancos Canyon, below bridge. |

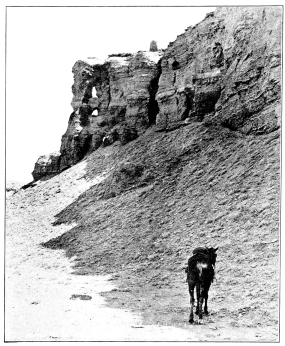

| b, | Eroded shale formation in which are small walled cavate storehouses. | |

| 32. | a, | Reservoir near Picket corral, showing retaining wall. |

| b, | Kiva, Unit type House, Square Tower Canyon. | |

| 33. | Pictographs, Yellow Jacket Canyon. | |

| TEXT FIGURES | ||

| Page | ||

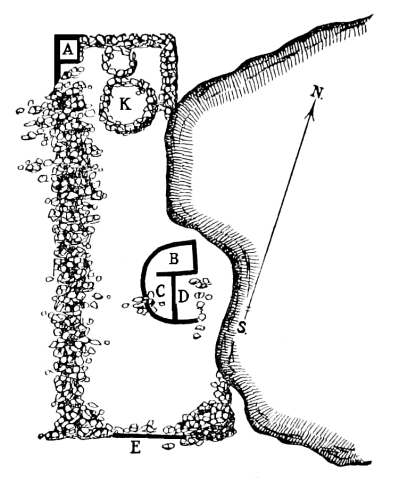

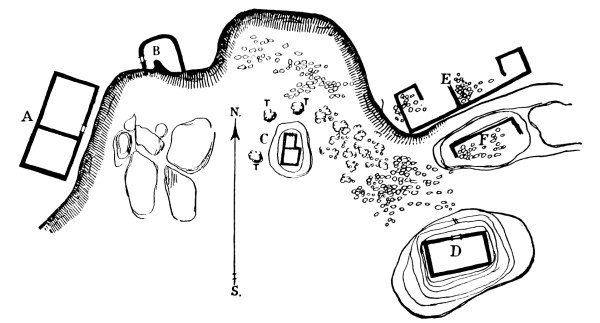

| 1. | Ground plan of Aztec Spring Ruin | 26 |

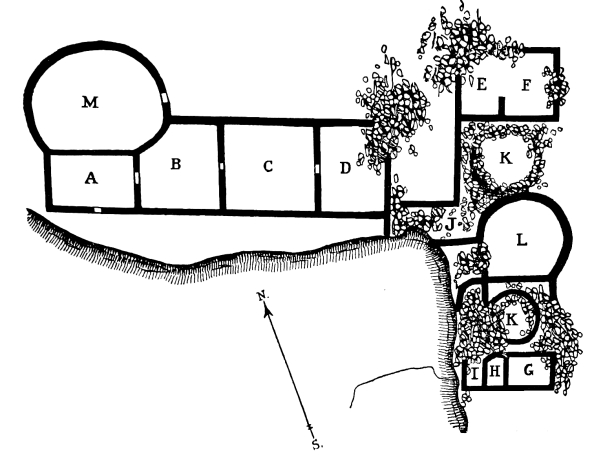

| 2. | Ground plan of Wood Canyon Ruin | 32 |

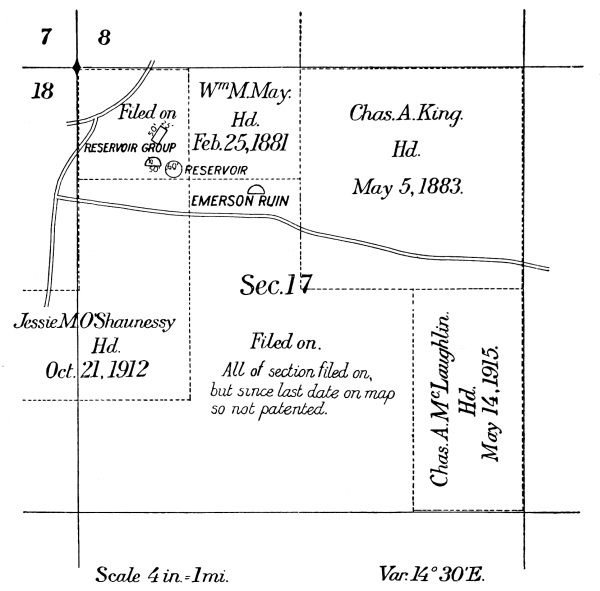

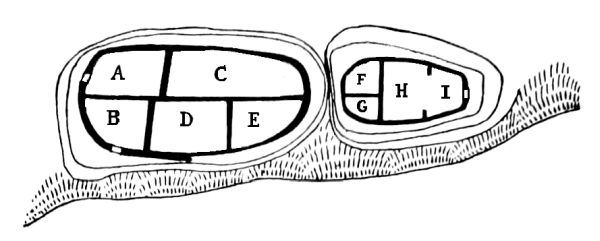

| 3. | Metes and bounds of Emerson Ruin | 34 |

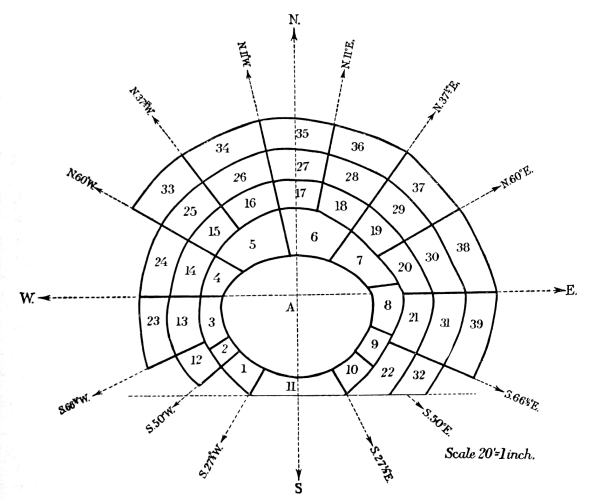

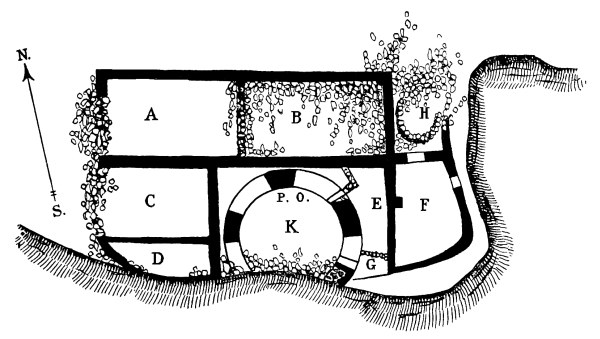

| 4. | Schematic ground plan of Emerson Ruin | 35 |

| 5. | Ground plan of Unit type House in cave | 39 |

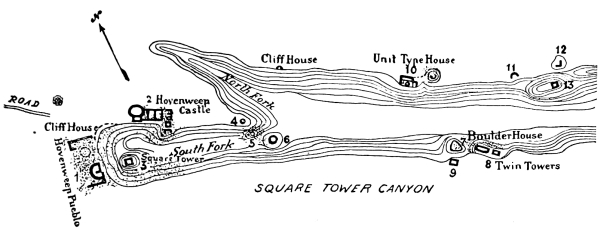

| 6. | Square Tower Canyon | 45 |

| 7. | Ground plan of Hovenweep House | 46 |

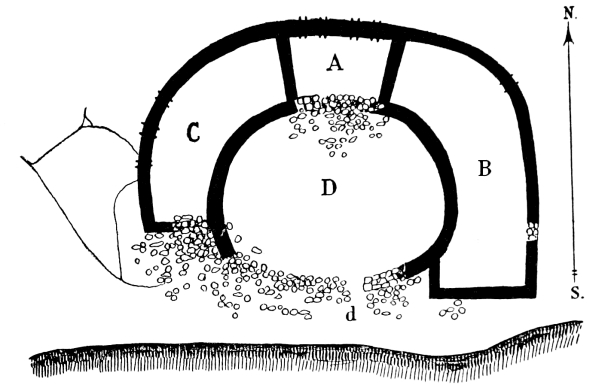

| 8. | Ground plan of Hovenweep Castle | 47 |

| 9. | Ground plan of Twin Towers | 50 |

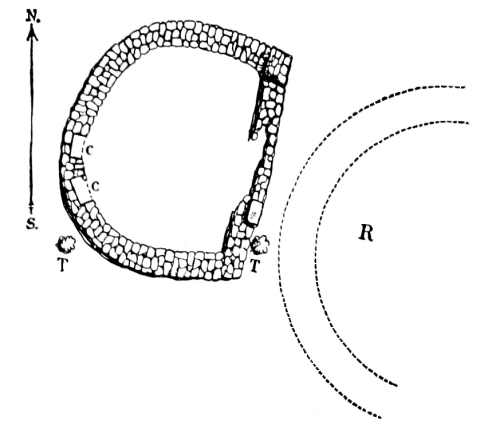

| 10. | Ground plan of Unit type House | 51 |

| 11. | Holly Canyon Ruins | 52 |

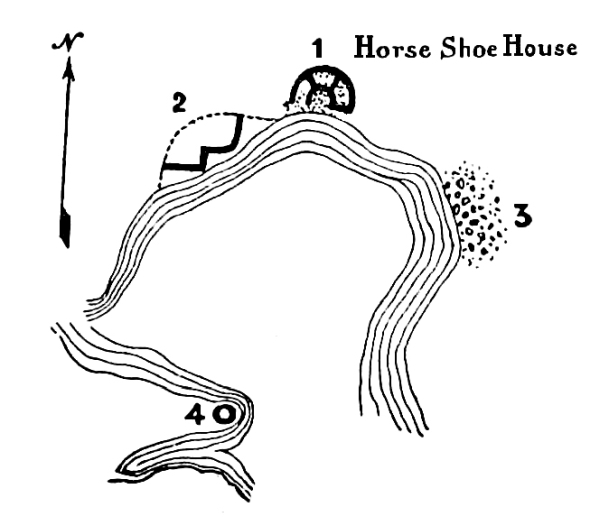

| 12. | Horseshoe (Hackberry) Canyon | 53 |

| 13. | Ground plan of Horseshoe House | 54 |

| 14. | Ground plan of Davis Ruin | 55 |

| 15. | Ground plan of Lion House | 55 |

| 16. | Ground plan of ruin with towers in McLean Basin | 56 |

| 17. | Doorway in Round Tower, McLean Basin | 57 |

| 18. | Megalithic stone inclosure, McElmo Bluff | 61 |

[Pg 9]

PREHISTORIC VILLAGES, CASTLES, AND

TOWERS OF SOUTHWESTERN

COLORADO

By J. Walter Fewkes

The science of archeology has contributed to our knowledge some of the most fascinating chapters in culture history, for it has brought to light, from the night of the past, periods of human development hitherto unrecorded. As the paleontologist through his method has revealed faunas whose like were formerly unknown to the naturalist, the archeologist by the use of the same method of research has resurrected extinct phases of culture that have attained a high development and declined before recorded history began. No achievements in American anthropology are more striking than those that, from a study of human buildings and artifacts antedating the historic period, reveal the existence of an advanced prehistoric culture of man in America.

The evidences of a phase of culture that had developed and was on the decline before the interior of North America was explored by Europeans are nowhere better shown than in southwestern Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah, the domain of the Cliff-dwellers, or the cradle of the Pueblos. There flourished on what is now called the Mesa Verde National Park, in prehistoric times, a characteristic culture unlike that of any region in the United States. This culture reached its apogee and declined before the historic epoch, but did not perish before it had left an influence extending over a wide territory, which persisted into modern times. Through the researches of archeologists the nature of this culture is now emerging into full view; but much material yet remains awaiting investigation before it can be adequately understood. The purpose of this article is to call attention to new observations bearing upon its interpretation made by the author, under the auspices of the Bureau of American Ethnology, on brief trips to Colorado and Utah in 1917 and 1918.

The peculiar cliff-dwellings and open-air villages of the Mesa Verde are here shown to be typical of those found over a region many miles in extent. They indicate a distinct culture area, which is easily distinguished from others where similar buildings do not exist, but not [Pg 10] as readily separated from that of adjacent regions where the buildings are superficially similar but structurally different. In order to distinguish it from its neighbors and determine its horizon, we must become familiar with certain architectural characteristics. As our knowledge of the character of buildings in this area is incomplete, the intention of the author is to define the several different types of buildings that characterize it.

When, in 1915, there was brought to light on the Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, the mysterious structure, Sun Temple, the author recalled well-known descriptions of towers and other related buildings that have been recorded from other localities in southwestern Colorado and Utah. The published descriptions of these structures did not seem to him adequate for comparisons, and he planned an examination of these great houses and towers, hoping to gather new data that would shed some light on his interpretation of Sun Temple. During the field work in 1917, thanks to an allotment from the Bureau of American Ethnology for that purpose, he undertook a reconnoissance in the McElmo district, where similar buildings are found and where he believed cultural relatives of the former inhabitants of Mesa Verde once lived. In 1918 he extended his field work still farther. He investigated ruins as far as the western tributaries of the Yellow Jacket Canyon, penetrating a short distance beyond the Colorado border into Utah. The object of the following pages is to make known the more important results of this visit, and interpret the evidence they present as a contribution to our knowledge of the extension in prehistoric times of the Mesa Verde culture area.

Attention was first publicly called, about 40 years ago (1875-1877), by Messrs. Jackson,[1] Holmes, Morgan, and others, to some of the ruins here considered. It is difficult to identify all of the ruins mentioned or described by these pioneers. Their “Hovenweep Castle” is supposed to lie in about the center of the district here considered, possibly on Square Tower (Ruin) Canyon, although the large castellated building[2] in Holly Canyon would also fulfill conditions equally well. Their “Pueblo” may have been situated on the McElmo near the mouth of Yellow Jacket Canyon. Early writers rather vaguely refer to a cluster of castles and towers as situated some distance from the “Burial Place,” which is readily identified on the promontory at the mouth of the McElmo, as probably those in Square Tower (Ruin) Canyon, but the [Pg 11] cluster may be either at Square Tower or Holly Canyon, both of which are about the same distance from this site. As “Pueblo” is not indicated on the map accompanying the Hayden report, the sites of rock shelters “some 7 miles from ‘Pueblo’ and 3 miles from the McElmo” remain doubtful. The author retains the name “Hovenweep Castle” for the ruin in Square Tower Canyon.

In his account of ruins in the region visited, Prof. W. H. Holmes[3] considers several other ruins, as “the triple-walled tower” (here called Mud Spring village, p. 20), ruins at Aztec Spring (p. 23), cliff-dwellings and towers of the San Juan and Mancos, the “slab cysts” or burial places on the Dolores, and the promontory at the junction of the Hovenweep and McElmo (p. 60). The best preserved towers and castellated buildings which his article considers occur on the San Juan and Mancos Canyons, districts on the periphery of the region covered by this account.

These pioneer reports of Jackson and Holmes not only called attention to a new archeological field, but also introduced to the archeologist several new types of prehistoric American architecture of which nothing was previously known. They have been repeatedly quoted and are still constantly referred to by writers on southwestern archeology.

Although Jackson made many photographs of the castles and towers of the Hovenweep, none of these were published in his reports, possibly because halftone methods of reproduction were then unknown. The illustrations that appear in the text of early reports are mainly reproductions of sketches. These reports, in which the discovery of the tower type of architecture and its adjacent cliff-dwellings were announced, should thus rightly rank as the first important steps in the scientific investigations of the stone-house builders of this district of our Southwest; although the allied “Casas Grandes” or great houses of the Chaco had been described a few years before by Gregg, Stimpson, and others.

We have, in addition to these pioneer reports, several magazine articles of about the same date, the material for which was largely drawn from them. One of the most important newspaper articles of that date was written by Mr. Ernest Ingersoll, published in the New York Tribune, and another, of anonymous authorship, is to be found in the Century Magazine for the year 1877. New forms of towers and castellated buildings were added in these accounts to those of the earlier authors.

One of the most important contributions to the antiquities of the region about Mesa Verde was made by the veteran ethnologist, Morgan, who published notes contributed by Mr. Mitchell on a cluster of mounds [Pg 12] near his ranch. As no name was given this village it is here called the Mitchell Spring Village. Morgan likewise mentions the ruin at Mud Spring and a tower in the ruin near his spring. Professor Newberry was the first author to affix the name Surouaro to a ruin situated at the head of the Yellow Jacket Canyon.

Several of these ruins were described and figured by Mr. Warren K. Moorehead as “The Great Ruins of Upper McElmo Creek” in the Illustrated American for July 9, 1892, the sixth of a series of articles under a general title “In search of a Lost Race.” He gives descriptions of a “cave shelter” found near Twin Towers, Square Tower in “Ruin Canyon,” a building (Hovenweep Castle), and the tower at the junction of the North and South Forks of Ruin Canyon. This paper is accompanied by a map of Ruin Canyon by Mr. Cowen. In Moorehead’s discussion of these remains, individual towers and other ruins are designated by capital letters, A-V, to some of which are also affixed the names “Hollow Boulder,” “Twin Towers,” “Square Tower,” etc. Details of structure and measurements of the more striking buildings and a discussion of certain features of structure, some of which will be considered later under individual ruins, are likewise given.

The most important general article yet published on the prehistoric remains of the region here considered is by Dr. T. Mitchell Prudden,[4] who also mentions several of the ruins here treated. His most important contribution is a description of what he calls the “unit type,” which he recognized as a fundamental structural feature in the pueblos of this region. He also showed that the kiva in Montezuma Valley villages is identical with that of cliff-dwellings in the Mesa Verde, and emphasized, as an important feature, the union of the tower and the pueblo, a characteristic of the highest form of pueblo architecture.

Doctor Prudden has followed his comprehensive paper above mentioned with an account[5] of the excavation of one of the mounds at Mitchell Spring in which he adds to our knowledge of the structure of his “unit type.”

In “A Further Study of Prehistoric Small House Ruins in the San Juan Watershed,”[6] Doctor Prudden has furnished important additional data which shows the uniformity of the unit type over a large area of the San Juan drainage.

The following among other prehistoric remains in the district mentioned or described by Doctor Prudden are covered by the author’s reconnoissance: [Pg 13]

The following towers can be identified from his figures:[7]

1. “Square building opposite mouth of Dawson Creek.” Prudden, pl. xviii, fig. 2. (This building is not square, but semicircular.)

2. Cannonball Ruin. Prudden, pl. xxi [xxii].

3. “Small tower-like structure ... at the head of Ruin Canyon, in the Yellow Jacket group.” Prudden, pl. xxiii, fig. 2. (This building is not in Ruin Canyon, but in Holly Canyon.)

4. “Tower ... about the head of Ruin Canyon.” Prudden, pl. xxiii, fig. 1. (This is the most eastern of the Twin Towers, but not about the head of the canyon.)

5. Sand Canyon Tower. Prudden, pl. xxiv, fig. 2.

Although mainly devoted to descriptions of the cliff-houses of the Mesa Verde, Baron G. Nordenskiöld’s “Cliff-Dwellers of the Mesa Verde” discusses in so broad a manner the relationship of pueblo ruins and cliff-houses that no student can overlook this epoch-making work. In fact, Nordenskiöld laid the foundations for subsequent students of pueblo morphology, although some of his comparisons and generalizations were premature because based on imperfect observations which have been superseded by later investigations.

The partial excavation of the excellent ruin at the head of Cannonball Canyon by S. G. Morley[8] sheds considerable light on the morphology of prehistoric buildings in the McElmo district. Unfortunately no attempt was made by him to repair the walls of this ruin for permanent preservation, but it is not too late still to prevent their further destruction and preserve them for future students and visitors. Morley’s description of the buildings is accompanied by good photographs and a ground plan. He brought to light in this ruin examples of the characteristic unit type kiva. [Pg 14]

The latest work on the McElmo Ruins, one part of which has already appeared, is a joint contribution by Morley and Kidder.[9] In this publication accurate dimensions and sites of ruins in the McElmo and Square Ruin Canyons are given, with other instructive data. Morley and Kidder have designated the ruins by Arabic numbers, and in a few instances by names. The author has preserved these numbers so far as possible in his account.

The following ruins in Ruin Canyon and neighboring district covered by this reconnoissance are described by Morley and Kidder:

The pueblos and cave dwellings of the “Pivotal group” (those on or near the promontory at the junction of the McElmo and Yellow Jacket Canyons) were also studied by the authors.

Almost the whole article by Morley and Kidder, which the editor announces will be completed in a future number of “El Palacio,” is devoted to descriptions of buildings[10] in Ruin and Road (Wickyup) Canyons and the ruins of the “Pivotal group” at the base of a promontory between the junction of the Yellow Jacket and McElmo.

In the classification by Morley and Kidder and the majority of writers, sites rather than structural features are adopted as a basis although all recognized that large cliff-dwellings like Cliff Palace are practically pueblos built in caves. In the following classification more attention is directed to differences in structure than to situation, notwithstanding the latter is convenient for descriptive purposes.

1. Villages or clusters of houses, each having the form of the pure pueblo type. The essential feature of the pure type is a compact pueblo, [Pg 15] containing one or more unit types, circular kivas of characteristic form, surrounded by rectangular rooms. These units, single or consolidated, may be grouped in clusters, as Mitchell Spring or Aztec Spring Ruins; the clusters may be fused into a large building, as at Aztec or in the community buildings on Chaco Canyon.

2. Cliff-houses. These morphologically belong to the same pure type as pueblos; their sites in natural caves are insufficient to separate them from open-sky buildings.

3. Towers and great houses. These buildings occur united to cliff-dwellings or pueblos, but more often they are isolated.

4. Rooms with walls made of megaliths or small stone slabs set on edge.

In reports on the excavation of Far View House[11] on the Mesa Verde, the author called attention to clusters of mounds indicating ruined buildings in the neighborhood of Mummy Lake, a little more than 4 miles from Spruce-tree House. This cluster he considers a village; Far View House, excavated from one of the mounds, is regarded as a prehistoric pueblo of the pure type. The forms of other buildings covered by the remaining mounds of the Mummy Lake site are unknown, but it is probable that they will be found to resemble Far View House, or that all members of the village have similar forms.

This grouping of small pueblos into villages at Mummy Lake on the Mesa Verde is also a distinctive feature of ruins in the Montezuma Valley and McElmo district. In these villages one or more of the component houses may be larger and more conspicuous, dominating all the others, as at Goodman Point, or at Aztec Spring. The houses composing the village at Mud Spring were about the same size, but at Wolley Ranch Ruin only one mound remains, evidently the largest, the smaller having disappeared.

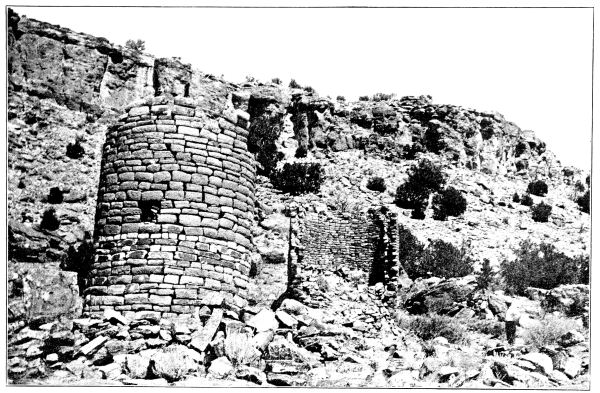

The third group, towers and great houses, includes buildings of oval, circular, semicircular, and rectangular shapes. Morphologically speaking, they do not present structural features of pueblos, for they are not terraced, neither have they specialized circular ceremonial rooms, kivas with vaulted roofs surrounded by rectangular rooms, or other essential features of the pueblo type. The group contains buildings which are sometimes consolidated with cliff-houses and pueblos, but are often independent of them. In this type are included castellated buildings in the Mancos, Yellow Jacket, McElmo, and the numerous northern tributary canyons of the San Juan. [Pg 16]

As the word is used in this report, a village is a cluster of houses separated from each other, each building constructed on the same plan, viz, a circular ceremonial room or kiva with mural banquettes and pilasters for the support of a vaulted roof, inclosed in rectangular rooms. When there is one kiva and surrounding angular rooms we adopt the name “unit type.” When, as in the larger mounds, there are indications of several kivas or unit types consolidated—the size being in direct proportion to the number—we speak of the building as belonging to the “pure type.” Doctor Prudden, who first pointed out the characteristics of the “unit type,”[12] has shown its wide distribution in the McElmo district. The Mummy Lake village has 16 mounds indicating houses. Far View House, one of these houses, is made up of an aggregation of four unit types and hence belongs to the author’s “pure type.”

While villages similar to the Mummy Lake group, in the valleys near Mesa Verde, have individual variations, the essential features are the same, as will appear in the following descriptions of Surouaro, and ruins at Goodman Point, Mud Spring, Aztec Spring, and Mitchell Spring. Commonly, in these villages, one mound predominates in size over the others, and while rectangular in form, has generally circular depressions on the surface, recalling conditions at Far View mound before excavation. These mounds indicate large buildings in blocks, made up of many unit forms of the pure type, united into compact structures. One large dominant member of the village recalls those ruins where the village is consolidated into one community pueblo. The separation of mounds in the village and their concentration in the community house may be of chronological importance, although the relative age of the simple and composite forms can not at present be determined; but it is important to recognize that the units of construction in villages and community buildings are identical.

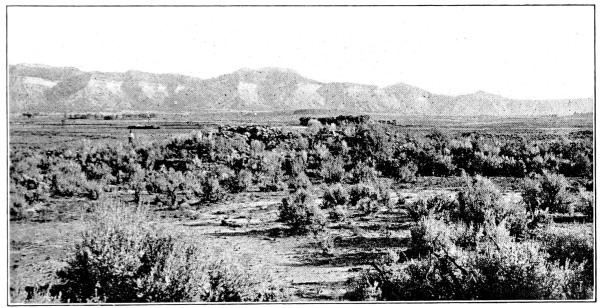

The cluster of mounds formerly called Surouaro, now known as Yellow Jacket Spring Ruin, is situated near the head of the canyon of the same name to the left of the Monticello road, 14 miles west of Dolores. This village (pls. 1, c; 2, c) contains both large and small houses of the pure pueblo type, covering an area somewhat less than the Mummy Lake group, on the Mesa Verde. The arrangement of mounds in clusters naturally recalls the Galisteo and Jemez districts, New Mexico, [Pg 17] where, however, the arrangement of the mounds and the structure of each is different. The individual houses in a Mesa Verde or Yellow Jacket village were not so grouped as to inclose a rectangular court, but were irregularly distributed with intervals of considerable size between them.[13]

The largest mound in the Surouaro village, shown in plate 1, c, corresponds with the so-called “Upper House” of Aztec Spring Ruin, but is much larger than Far View or any other single mound in the Mummy Lake village.

Surouaro was one of the first ruins in this region described by American explorers, attention having been first called to it by Professor Newberry,[14] whose description follows: “Surouaro is the name of a ruined town which must have once contained a population of several thousands. The name is said to be of Indian (Utah) origin, and to signify desolation, and certainly no better could have been selected.... The houses are, many of them, large, and all built of stone, hammer dressed on the exposed faces. Fragments of pottery are exceedingly common, though like the buildings, showing great age.... The remains of metates (corn mills) are abundant about the ruins. The ruins of several large reservoirs, built of masonry, may be seen at Surouaro, and there are traces of acequias which led to them, through which water was brought, perhaps from a great distance.”

This ruin is a cluster of small mounds surrounding larger ones, recalling the arrangement at Aztec Spring. They naturally fall into two groups which from their direction or relation to the adjacent spring may be called the south and north sections.

The most important mound of the south section, Block A, measures 74 feet on the north, 79 feet on the south, and 76 feet on the west side. This large mound corresponds morphologically to the “Upper House” at Aztec Spring (fig. 1, A). About it there are arranged at intervals, mainly on the north and east sides, other smaller mounds generally indicating rectangular buildings. The southeast angle of the largest is connected by a low wall with one of the smaller mounds, forming an enclosure called a court, whose northern border is the rim of the canyon just above the spring. A determination of the detailed architectural features of the building [Pg 18] buried under Block A is not possible, as none of its walls stand above the mass of fallen stones, but it is evident, from circular depressions and fragments of straight walls that appear over the surface of the mound, that the rooms were of two kinds, rectangular forms, or dwellings, and circular chambers, or kivas. This mound resembles Far View House on the Mesa Verde before excavation.

A large circular depression, 56 feet in diameter, is situated in the midst of the largest mounds. A unique feature of this depression, recognized and described by Doctor Prudden, are four piles of stones, regularly arranged on the floor. The author adopts the suggestion that this area was once roofed and served as a central circular kiva, necessitating a roof of such dimensions that four masonry pillars served for its support. The mound measures about 15 feet in height, and has large trees growing on its surface, offering evidence of a considerable age. Several other rooms are indicated by circular surface depressions, but their relation to the rectangular rooms can be determined only by excavation.

This ruin, to which the author was conducted by Mr. C. K. Davis, is about 4 miles west of the Goodman Point Ruin near Mr. Johnson’s ranch house, in section 12, township 36, range 18. It is said to be situated at the head of Sand Canyon, a tributary of the McElmo, and is one of the largest ruins visited. The remains of former houses skirt the rim of the canyon head for fully half a mile, forming a continuous series of mounds in which can be traced towers, great houses, and other types of buildings, and numerous depressions indicating sunken kivas. The walls of these buildings were, however, so tumbled down that little now remains above ground save piles of stones in which tops of buried walls may still be detected, but not without some difficulty. In a cave under the “mesa rim” there is a small cliff-house in the walls of which extremities of the original wooden rafters still remain in place.

In an open clearing, about 3 miles south and west of Mr. J. W. Fulk’s house, Renaraye post office, there is a small ruin of rectangular form, the ground plan of which shows two rectangular sections of different sizes, joined at one angle. The largest section measures approximately 20 by 50 feet. It consists of low rooms surrounding two circular depressions, possibly kivas. Although constructed on a small scale, this section reminds one of the Upper House of Aztec Spring Ruin. The smaller section, which also has a rectangular form, has remains of high rooms on opposite sides and low walls on the remaining sides. In the enclosed area there is a circular depression or reservoir, corresponding with the reservoir of the Lower House at Aztec Spring Ruin. [Pg 19]

The author was guided by Mr. H. S. Merchant to a village ruin, one of the largest visited, situated a few miles from his ranch house. This village is about 10 miles due south of the store at the head of Dove Creek, and consists of several large mounds, each about 500 feet long, arranged parallel to each other, and numerous isolated smaller mounds. Not far from this large ruin there is a prehistoric reservoir estimated as covering about 4 acres. Many circular depressions, indicated kivas, and lines of stones showed tops of buried rectangular rooms. Excavations in a small mound near this ruin were conducted by Doctor Prudden.[15]

The canyon which heads near the corral on the road to Merchant’s house revealed no evidence of prehistoric dwellings.

This ruin takes its name from the earliest known description of it by Morgan,[16] which was compiled from notes by Mr. Mitchell, one of the early settlers in Montezuma Valley. Morgan’s account is as follows:

“Near Mr. Mitchell’s ranch, and within a space of less than a mile square, are the ruins of nine pueblo houses of moderate size. They are built of sandstone intermixed with cobblestone and adobe mortar. They are now in a very ruinous condition, without standing walls in any part of them above the rubbish. The largest of the number is marked No. 1 in the plan, figure 44, of which the outline of the original structure is still discernible. It is 94 feet in length and 47 feet in depth, and shows the remains of a stone wall in front inclosing a small court about 15 feet wide. The mass of material over some parts of this structure is 10 or 12 feet deep. There are, no doubt, rooms with a portion of the walls still standing covered with rubbish, the removal of which would reveal a considerable portion of the original ground plan.”

The author paid a short visit to the Mitchell Spring village and by means of Morgan’s sketch map was able to identify without difficulty the nine mounds and tower he represents. The village at Mitchell Spring differs from that at Mud Spring and at Aztec Spring mainly in the small size and diffuse distribution of the component mounds and an absence of any one mound larger than the remainder. It had, however, a round tower, but unlike that at Mud Spring village, this structure is not united to one of the houses. The addition of towers to pueblos, as pointed out by Doctor Prudden[17] several years ago, marks the highest development of pueblo architecture as shown not only in open-air villages but also in some of the large cliff pueblos, like Cliff Palace. Isolated towers are as a rule earlier in construction. [Pg 20]

The unit type mound uncovered by Doctor Prudden is one of the most instructive examples of this type in Montezuma Canyon, but the author in subsequent pages will call attention to the existence of the same type in Square Tower Canyon. All of these pueblos probably have kivas of the pure type, practically the same in structure as Far View House on the Mesa Verde National Park.

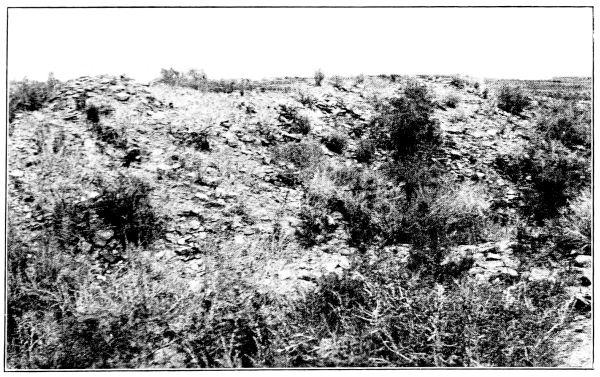

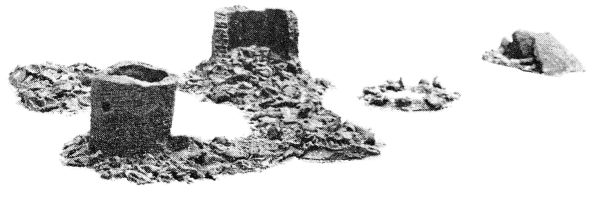

The collection of mounds (pl. 3, b), sometimes called Burkhardt Ruin, situated at Mud Spring, belongs to the McElmo series. This ruin, in which is the “triple-walled tower” of Holmes, for uniformity with Mitchell Spring Ruin and Aztec Spring Ruin, is named after a neighboring spring. Like these, it is a cluster of mounds forming a village which covers a considerable area. The arroyo on which it is situated opens into the McElmo, and is about 7 miles southwest from Cortez, at a point where the road enters the McElmo Canyon.

The extension of the area covered by the Mud Spring mounds is east-west, the largest mounds being those on the east. These latter are separated from the remainder, or those on the west, by a shallow, narrow gulch. There are two towers united to the western section overlooking the spring, the following description of one of which, with a sketch of the ground plan, is given by Holmes.[18]

“The circular structures or towers have been built, in the usual manner, of roughly hewn stone, and rank among the very best specimens of this ancient architecture. The great tower is especially noticeable.... In dimensions it is almost identical with the great tower of the Rio Mancos. The walls are traceable nearly all the way round, and the space between the two outer ones, which is about 5 feet in width, contains 14 apartments or cells. The walls about one of these cells are still standing to the height of 12 feet; but the interior can not be examined on account of the rubbish which fills it to the top. No openings are noticeable in the circular walls, but doorways seem to have been made to communicate between the apartments; one is preserved at d.... This tower stands back about 100 feet from the edge of the mesa near the border of the village. The smaller tower, b, stands forward on a point that overlooks the shallow gulch; it is 15 feet in diameter; the walls are 3½ feet thick and 5 feet high on the outside. Beneath this ruin, in a little side gulch, are the remains of a wall 12 feet high and 20 inches thick.... The apartments number nearly a hundred, and seem, generally, to have been rectangular. They are not, however, of uniform size, and certainly not arranged in regular order.” [Pg 21]

Morgan[19] gives the following description of the same ruin which seems to the author to be the Mud Creek village:

“Four miles westerly [from Mitchell ranch], near the ranch of Mr. Shirt, are the ruins of another large stone pueblo, together with an Indian cemetery, where each grave is marked by a border of flat stones set level with the ground in the form of a parallelogram 8 feet by 4 feet. Near the cluster of nine pueblos shown in the figure are found strewn on the ground numerous fragments of pottery of high grade in the ornamentation, and small arrowheads of flint, quartz, and chalcedony delicately formed, and small knife blades with convex and serrated edges in considerable numbers.

“This is an immense ruin with small portions of the walls still standing, particularly of the round tower of stone of three concentric walls, incorporated in the structure, and a few chambers in the north end of the main building. The round tower is still standing nearly to the height of the first story. In its present condition it was impossible to make a ground plan showing the several chambers, or to determine with certainty which side was the front of the structure, assuming that it was constructed in the terraced form.... The Round Tower is the most singular feature in this structure. While it resembles the ordinary estufa, common to all these structures, it differs from them in having three concentric walls. No doorways are visible in the portion still standing, consequently it must have been entered through the roof, in which respect it agrees with the ordinary estufa. The inner chamber is about 20 feet in diameter, and the spaces between the encircling walls are about 2 feet each; the walls are about 2 feet in thickness, and were laid up mainly with stones about 4 inches square, and, for the most part, in courses. There is a similar round tower, having but two concentric walls, at the head of the McElmo Canyon, and near the ranch of Mr. Mitchell [Mitchell Ruin].”

As the name Mud Spring is locally known to the natives, especially to employees of livery stables and garages, the ruin is here called Mud Spring. The tower and the other circular buildings are united to other rooms as in similar groups of mounds. The presence of surface depressions, thought to indicate circular kivas,[20] shows that the Mud Spring mounds are remains of a village of the same type as the Mummy Lake group, but with towers united to the largest mounds.

The time the author could give to his visit to the Mud Spring Ruin (pl. 3, b) was too limited to survey it, but he noticed in addition to the two circular buildings already recorded, a large mound situated on the west side of the gulch, and numerous small mounds on the east [Pg 22] side of the same, each apparently with a central depression like a kiva. All these mounds have been more or less mutilated by indiscriminate digging, but many mounds, still untouched, remain to be excavated before we can form an adequate conception of the group. The “triple-walled tower” is now in such a condition that the author could not determine whether it was formerly circular or D-shaped; the “small tower” is in even worse condition and its previous form could not be made out. The Mud Spring mounds cover a much larger area than descriptions or ground plans thus far published would indicate.

Originally Mud Spring Ruin consisted of a cluster of pueblos of various sizes, each probably with a circular kiva and rectangular rooms, combined with one or more towers at present too much dilapidated to determine architectural details without excavations. Like the other clusters of pueblos in the McElmo and Montezuma Valley, the cemetery near Mud Spring Ruin has suffered considerably from pothunters, but there still remain many standing walls that are well preserved.

This ruin is situated on the San Juan about 3 miles below the sandy bed of the mouth of the Montezuma, on a bluff 50 feet above the river. The ground plan by Jackson[21] indicates a building shaped like a trapezoid, 158 feet on the northeast side, 120 on the southeast, and 32 on the northwest side. The southwest side is broken midway by a reentering area at the rim of the bluff over the river.

In the center of this trapezoidal structure there is represented a series of rooms arranged like those of Horseshoe House, but composed of a half-circular chamber surrounded by seven rooms between two concentric circular walls. Thus far the homology to Horseshoe House is close but beyond this series of rooms, following out the trapezoidal form, at least five other rooms appear on the ground plan. The position of these recalls the walls arranged around the tower at Mud Spring village. In other words, the ruin resembles Horseshoe House, but has in addition rectangular rooms added on three sides, forming an angular building. So far as the author’s information goes, no other ruin of exactly this type, which recalls Sun Temple, has been described by other observers.

Wolley Ranch Ruin, situated 10 miles south of Dolores, is one of the largest mounds near Cortez. There are evidences of the former existence of a cluster of mounds at this place, only one of which now remains. This is covered with bushes, rendering it difficult to trace the bounding walls. [Pg 23]

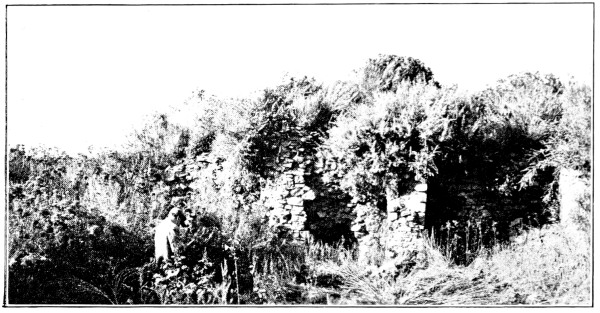

Several years ago private parties constructed at Manitou, near Colorado Springs, a cliff-dwelling on the combined plan of Spruce-tree House and Cliff Palace. The rocks used for that purpose were transported from a large mound on the Blanchard ranch near Lebanon, in the Montezuma Valley, at the head of Hartman’s draw, about 6 miles south of Dolores. Two mounds (pl. 2, a, b), about three-quarters of a mile apart, are all that now remain of a considerable village; the other smaller mounds, reported by pioneer settlers, have long since been leveled by cultivation. As both of these mounds have been extensively dug into to obtain stones, the walls that remain standing show much mutilation. The present condition of the largest Blanchard mound, as seen from its southwest angle, is shown in plate 2, b. About half of the mound, now covered with a growth of bushes, still remains entire, exposing walls of fine masonry, on its south side. The rooms in the buried buildings are hard to make out on account of this covering of vegetation and accumulated débris; but the central depressions, supposed to be kivas, almost always present in the middle of mounds in this district, show that the structure of Blanchard Ruin follows the pure type.

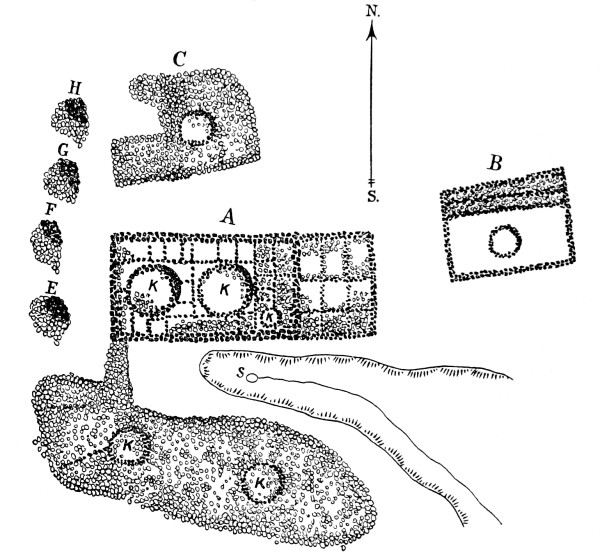

The mounds at Aztec Spring (pl. 1, b), situated on the eastern flank of Ute Mountain, at a site looking across the valley to the west end of Mesa Verde, were described forty years ago by W. W. Jackson[22] and Prof. W. H. Holmes.[23] The descriptions given by both these pioneers are quoted at length for the reason that subsequent authors have added little from direct observation since that time, notwithstanding they have been constantly referred to and the illustrations reproduced.

As a result of a short visit, the author is able to add the few following notes on the Aztec Spring mounds. The ruin is a village consisting of a cluster of unit pueblos of the pure type in various stages of consolidation. No excavations were made, but the surface indications point to the conclusion that the different mounds indicate that these pueblos have different shapes and sizes.

The author’s observations differ in several unimportant particulars from those of previous writers, and while it is not his intention to describe in detail the Aztec Spring village he will call attention to certain features it shares with other villages in the Montezuma Valley. [Pg 24]

The best, almost the only accounts of this village are the following taken from the descriptions by Jackson and Holmes published in 1877. Mr. Jackson gives the following description:[24]

“Immediately adjoining the spring, on the right, as we face it from below, is the ruin of a great massive structure [Upper House?] of some kind, about 100 feet square in exterior dimensions; a portion only of the wall upon the northern face remaining in its original position. The débris of the ruin now forms a great mound of crumbling rock, from 12 to 20 feet in height, overgrown with artemisia, but showing clearly, however, its rectangular structure, adjusted approximately to the four points of the compass. Inside this square is a circle, about 60 feet in diameter, deeply depressed in the center. The space between the square and the circle appeared, upon a hasty examination, to have been filled in solidly with a sort of rubble-masonry. Cross-walls were noticed in two places; but whether they were to strengthen the walls or divided apartments could only be conjectured. That portion of the outer wall remaining standing is some 40 feet in length and 15 in height. The stones were dressed to a uniform size and finish. Upon the same level as this ruin, and extending back some distance, were grouped line after line of foundations and mounds, the great mass of which is of stone but not one remaining upon another.... Below the above group, some 200 yards distant, and communicating by indistinct lines of débris, is another great wall, inclosing a space of about 200 feet square [Lower House?].... This better preserved portion is some 50 feet in length, 7 or 8 feet in height, and 20 feet thick, the two exterior surfaces of well-dressed and evenly laid courses, and the center packed in solidly with rubble-masonry, looking entirely different from those rooms which had been filled with débris, though it is difficult to assign any reason for its being so massively constructed.... The town built about this spring is nearly a square mile in extent, the larger and more enduring buildings in the center, while all about are scattered and grouped the remnants of smaller structures, comprising the suburbs.”

The description by Professor Holmes[25] is more detailed and accompanied by a ground plan, and is quoted below:

“The site of the spring I found, but without the least appearance of water. The depression formerly occupied by it is near the center of a large mass of ruins, similar to the group [Mud Spring village] last described, but having a rectangular instead of a circular building as the chief and central structure. This I have called the upper house in the plate, and a large walled enclosure a little lower on the slope I have for the sake of distinction called the lower house. [Pg 25]

“These ruins form the most imposing pile of masonry yet [1875] found in Colorado. The whole group covers an area about 480,000 square feet, and has an average depth of from 3 to 4 feet. This would give in the vicinity of 1,500,000 solid feet of stonework. The stone used is chiefly of the fossiliferous limestone that outcrop along the base of the Mesa Verde a mile or more away, and its transportation to this place has doubtless been a great work for a people so totally without facilities.

“The upper house is rectangular, measuring 80 feet by 100 feet, and is built with the cardinal points to within a few degrees. The pile is from 12 to 15 feet in height, and its massiveness suggests an original height at least twice as great. The plan is somewhat difficult to make out on account of the very great quantity of débris.

“The walls seem to have been double, with a space 7 feet between; a number of cross-walls at regular intervals indicate that this space has been divided into apartments, as seen in the plan.

“The walls are 26 inches thick, and are built of roughly dressed stones, which were probably laid in mortar, as in other cases.

“The enclosed space, which is somewhat depressed, has two lines of débris, probably the remains of partition-walls, separating it into three apartments, a, b, c [note]. Enclosing this great house is a network of fallen walls, so completely reduced that none of the stones seem to remain in place; and I am at a loss to determine whether they mark the site of a cluster of irregular apartments, having low, loosely built walls, or whether they are the remains of some imposing adobe structure built after the manner of the ruined pueblos of the Rio Chaco.

“Two well-defined circular enclosures or estufas [kivas] are situated in the midst of the southern wing of the ruin. The upper one, A, is on the opposite side of the spring from the great house, is 60 feet in diameter, and is surrounded by a low stone wall. West of the house is a small open court, which seems to have had a gateway opening out to the west, through the surrounding walls.

“The lower house is 200 feet in length by 180 in width, and its walls vary 15 degrees from the cardinal points. The northern wall, a, is double and contains a row of eight apartments about 7 feet in width by 24 in length. The walls of the other sides are low, and seem to have served simply to enclose the great court, near the center of which is a large walled depression (estufa B).”

The number of buildings that composed the Aztec Spring village (fig. 1) when it was inhabited can not be exactly estimated, but as indicated by the largest mound, the most important block of rooms exceeds in size any at Mitchell Spring Ruin. While this village also covered more ground than that at Mud Spring, it shows no evidence of added towers, a [Pg 26] prominent feature of the largest mound of the latter. Two sections (fig. 1, A, B) may be distinguished in the arrangement of mounds in the village; one may be known as the western and the other as the eastern division.

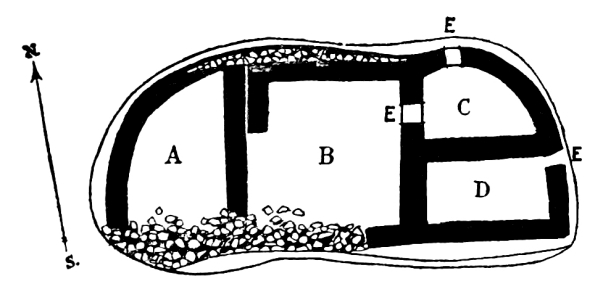

Fig. 1.—Ground plan of Aztec Spring Ruin.

The highest and most conspicuous mound of the western section (A) is referred to by Professor Holmes as the “Upper House.” Surface characteristics now indicate that this is the remains of a compact rectangular building, with circular kivas and domiciliary rooms of different shapes, the arrangement of which can not be determined without extensive excavations. The plan of this pueblo published by Holmes[26] shows two large and one small depression, indicating peripheral rectangular chambers surrounded by walls of rectangular rooms.

The author interprets the depressions, K, as kivas, but supposes that they were not rectangular as figured by Holmes, but circular, surrounded on all four sides by square secular chambers, the “Upper House” being formed by the consolidation of several units of the pure [Pg 27] pueblo type. Although Aztec Spring Ruin is now much mutilated and its walls difficult to trace, the surface indications, aided by comparative studies of the rooms, show that Holmes’ “a,” “b,” and “c,” now shown by depressions, are circular, subterranean kivas. They are the same kind of chambers as the circular depressions in the mounds on the south side of the spring. The height of the mound called “Upper House” indicates that the building had more than one story on the west and north sides, and that a series of rooms one story high with accompanying circular depressions existed on the east side.

The “Upper House” is only one of several pueblos composing the western cluster of the Aztec Spring village. Its proximity to the source of water may in part account for its predominant size, but there are evidences of several other mounds (E-H) in its neighborhood, also remains of pueblos. Those on the north (C) and west sides (E-H) are small and separated from it by intervals sometimes called courts. The most extensive accumulation of rooms next the “Upper House” is situated across the draw in which the spring lies, south of the “Upper House” cluster already considered. The aggregation of houses near the “Upper House” is mainly composed of low rectangular buildings among which are recognized scattered circular depressions indicating kivas. The largest of these buildings is indicated by the mound on the south rim of the draw, where we can make out remains of a number of circular depressions or kivas (K), as if several unit forms fused together; on the north and west sides of the spring there are small, low mounds, unconnected, also suggesting several similar unit forms. The most densely populated part of the village at Aztec Spring, as indicated by the size of the mounds clustered on the rim around the head of the draw, is above the spring, on the northwest and south sides.

There remains to be mentioned the eastern annex (B) of the Aztec Spring village, the most striking remains of which is a rectangular inclosure called “Lower House,” situated east of the spring and lower down the draw, or at a lower level than the section already considered. The type of this structure, which undoubtedly belonged to the same village, is different from that already described. It resembles a reservoir rather than a kiva, inclosed by a low rectangular wall, with rows of rooms on the north side. The court of the “Lower House” measures 218 feet. The wall on the east, south, and west sides is only a few feet high and is narrow; that on the north is broader and higher, evidently the remains of rooms, overlooking the inclosed area.

Perhaps the most enigmatical structures in the vicinity of Aztec Spring village are situated on a low mesa south of the mounds, a few hundred feet away. These are circular depressions without accompanying mounds, [Pg 28] one of which was excavated a few years ago to the depth of 12 feet; on the south there was discovered a well-made wall of a circular opening, now visible, by which there was a communication through a horizontal tunnel with the open air. The author was informed that this tunnel is artificial and that one of the workmen crawled through it to its opening in the side of a bank many yards distant.

No attempt was made to get the exact dimensions of the component houses at Aztec Spring, as the walls are now concealed in the mounds, and measurements can only be approximations if obtained from surface indications without excavation. The sketch plan here introduced (fig. 1) is schematic, but although not claimed as accurate, may serve to convey a better idea of the relation of the two great structures and their annexed buildings than any previously advanced.

The author saw no ruined prehistoric village in the Montezuma Valley that so stirred his enthusiasm to properly excavate and repair as that at Aztec Spring,[27] notwithstanding it has been considerably dug over for commercial purposes.

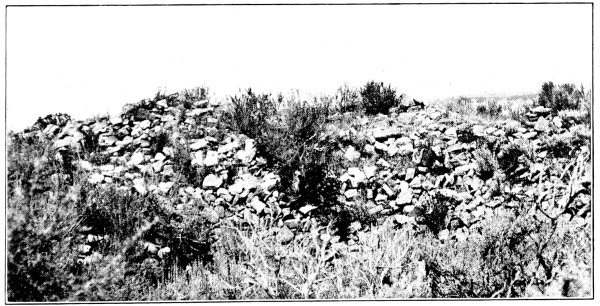

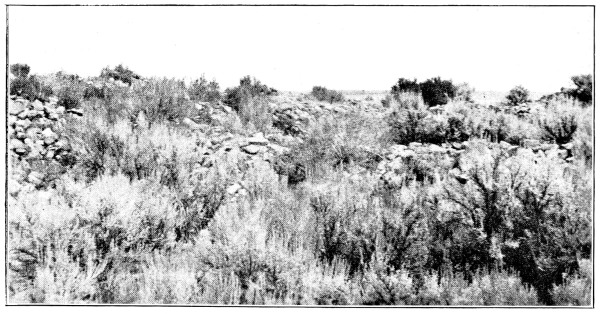

In the region south and southwest of Dove Creek there are several large pueblo ruins, indicated by mounds formed of trimmed stone, eolean sand, and clay from plastering, which have certain characters in common. Each mound is a large heap of stones (pl. 3, a) near which is a depression or reservoir, with smaller heaps which in different ruins show the small buildings of the unit type. These clusters or villages are somewhat modified in form by the configuration of the mesa surface. The larger have rectangular forms regularly disposed in blocks with passageways between them or are without any definite arrangement.

This large ruin, which has been described by Doctor Prudden as Squaw Point Ruin and as Pierson Lake Ruin, was visited by the author, who has little to add to this description. One of the small heaps of stone or mounds has been excavated and its structure found to conform with the definition of the unit type. The subterranean communication between one of the rectangular rooms and the kiva could be well seen at the time of the author’s visit and recalls the feature pointed out by him in some of the kivas of Spruce-tree House. The large reservoir and the great ruin are noteworthy features of the Squaw Point settlement.

It seems to the author that the large block of buildings is simply a congeries of unit types the structure of one of which is indicated by [Pg 29] the small buildings excavated by Doctor Prudden, and that structurally there is the same condition in it as in the pueblo ruins of Montezuma Valley, a conclusion to which the several artifacts mentioned and figured by Doctor Prudden also point.

The same holds true of Bug Point Ruin, a few miles away, also excavated and described by Doctor Prudden. Here also excavation of a small mound shows the unit type, and while no one has yet opened the larger mound or pueblo, superficial evidences indicate that it also is a complex of many unit types joined together. Until more facts are available the relative age of the small unit types as compared to the large pueblo can not be definitely stated, but there is little reason to doubt that they are contemporaneous, and nothing to support the belief that they do not indicate the same culture.

Following the Old Bluff Road and leaving it about 5 miles west of Acmen post office, one comes to a low canyon beyond Pigge ranch. The heaps of stone or large mounds cover an area of about 10 acres, the largest being about 15 feet high. East of this is a circular depression surrounded by stones, indicating either a reservoir or a ruined building.

The top of the highest mound (pl. 3, a)—no walls stand above the surface—is depressed like mounds of the Mummy Lake group on the Mesa Verde. This depression probably indicates a circular kiva embedded in square walls, the masonry of which so far as can be judged superficially is not very fine. There are many smaller mounds in the vicinity and evidences of cemeteries on the south, east, and west sides, where there are evidences of desultory digging; fragments of pottery are numerous.

These mounds indicate a considerable village which would well repay excavation, as shown by the numerous specimens of corrugated, black and white, and red pottery in the Pigge collection, made in a small mound near the Pigge ranch.

The specimens in this collection present few features different from those indicated by the fragments of pottery picked up on the larger mounds a mile west of the site where they were excavated. They are the same as shards from the mounds in the McElmo region.

About 15 miles southwest of Dove Creek on Monument Canyon there is a good spring called Oak Spring, near which are several piles of stones indicating former buildings, the largest of which, about a quarter of a mile away, has a central depression with surrounding walls now covered with rock or buried in soil or blown sand. Very large piñon trees grow [Pg 30] on top of the highest walls of this ruin, the general features of which recall those at Bug Spring, though their size is considerably less. In the surface of rock above the spring there are numerous potholes of small size. One of these, 4 feet deep and about 18 feet in diameter, is almost perfectly circular and has some signs of having been deepened artificially. It holds water much of the time and was undoubtedly a source of water supply to the aborigines, as it now is to stock in that neighborhood.

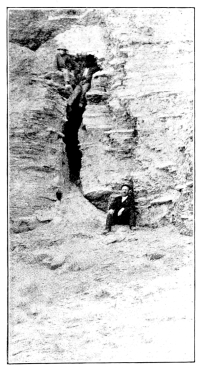

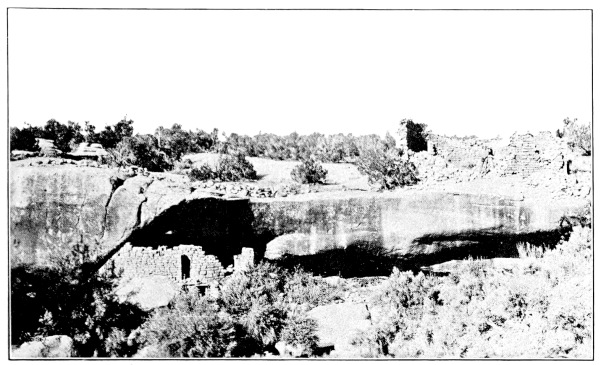

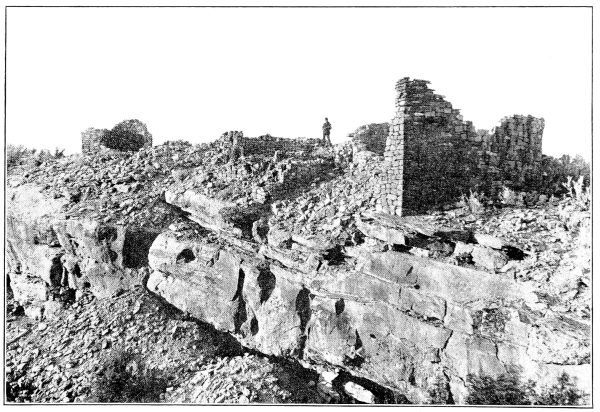

One of the large rim-rock ruins may be seen on the left bank of Ruin Canyon in full view from the Old Bluff Road. The ruin is an immense pile of stones perched on the very edge of the rim, with no walls standing above the surface. The most striking feature of this ruin is the cliff-house below, the walls and entrance into which are visible from the road (pl. 9, b). It is readily accessible and one of the largest in the country. On either side of the Old Bluff Road from Ruin Canyon to the “Aztec Reservoir” small piles of stone mark the sites of many former buildings of the one-house type which can readily be seen, especially in the sagebrush clearings as the road descends to the Picket corral, the reservoirs, and the McElmo Canyon.

One of the most instructive ruins of the McElmo Canyon region is situated at the head of Cannonball Canyon, a short distance across the mesa north of the McElmo, at a point nearly opposite the store. This ruin is made up of two separate pueblos facing each other, one of which is known as the northern, the other as the southern pueblo (pl. 22, b). Both show castellated chambers and towers, one of which is situated at the bottom of the canyon. The southern pueblo was excavated a few years ago by Mr. S. G. Morley, who published an excellent plan and a good description of it, and made several suggestions regarding additions of new rooms to the kivas which are valuable. Its walls were not protected and are rapidly deteriorating.

This pueblo, as pointed out by Mr. Morley,[28] has 29 secular rooms arranged with little regularity, and 7 circular kivas, belonging to the vaulted-roofed variety. It is a fine example of a composite pueblo of the pure type, in which there are several large kivas. Morley has pointed out a possible sequence in the addition of the different kivas to a preexisting tower and offers an explanation of the chronological steps by which he thinks the aggregation of rooms was brought about. Occasionally we find inserted in the walls of these houses large artificially worked or uncut flat stones, such as the author has mentioned as existing in the walls of the northwest corner of the court of Far View House. This Cyclopean form of masonry is [Pg 31] primitive and may be looked upon as a survival of a ruder and more archaic condition best shown in the Montezuma Mesa ruins farther west, a good example of which was described by Jackson.[29]

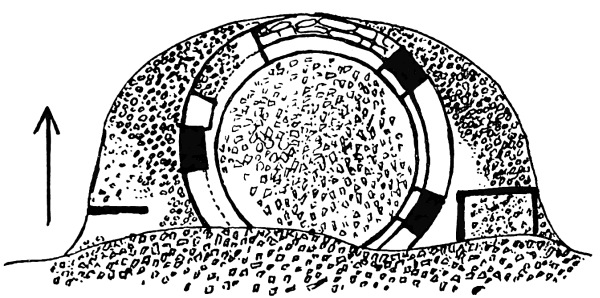

It has long been recognized that circular ruins in the Southwest differ from rectangular ruins, not only in shape but also in structural features, as relative position and character of kivas. The relation of the ceremonial chambers to the houses, no less than the external forms of the two, at first sight appear to separate them from the pure type.[30] They are more numerous and probably more ancient, as their relative abundance implies.

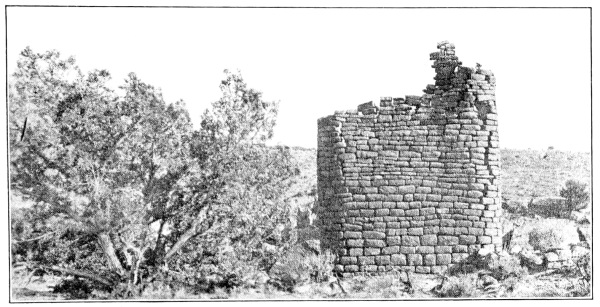

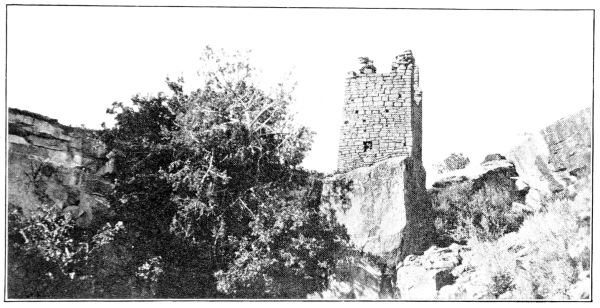

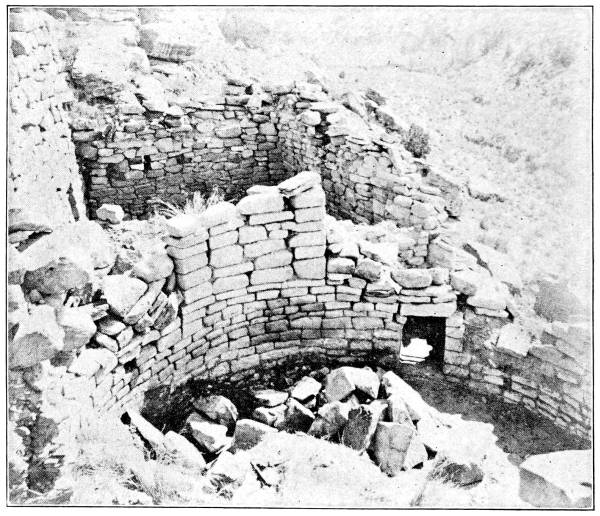

These circular ruins, in which group is included certain modifications where the curve of one side is replaced (generally on the south) by a straight wall or chord, have several concentric walls; again, they take the form of simple towers with one row of encircling compartments, or they may have a double wall with inclosed compartments.

Many representations of semicircular ruins were found in the region here considered, some of which are of considerable size. The simplest form is well illustrated by the D-shaped building, Horseshoe House, in Hackberry Canyon, a ruin which will be considered later in this article. Other examples occur in the Yellow Jacket, and there are several, as Butte Ruin, Emerson, and Escalante Ruins, in the neighborhood of Dolores.

In contrast to the village type consisting of a number of pueblos clustered together, but separated from each other, where the growth takes place mainly through the union of components, the circular ruin in enlarging its size apparently did so by the addition of new compartments peripherally or like additional rings in exogenous trees. Judging from their frequency, the center of distribution of the circular type lies somewhere in the San Juan culture area. This type does not occur in the Gila Valley or its tributaries, where we have an architectural zone denoting that a people somewhat different in culture from the Pueblos exists, but occurs throughout the “Central Zone,” so called, extending across New Mexico from Colorado as far south as Zuñi. Many additional observations remain to be made before we can adequately define the group known as the circular type and the extent of the area over which it is distributed.

The following examples of this type have been studied by the author: [Pg 32]

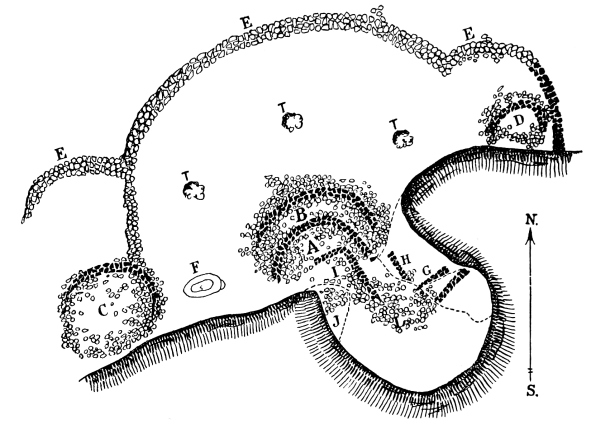

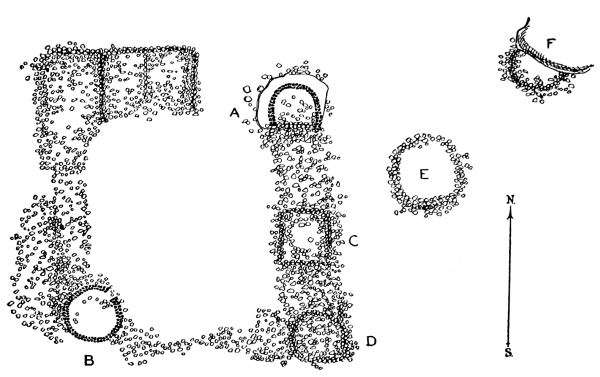

Reports were brought to the author of large ruins on the rim of Wood Canyon, about 4 miles south of Yellow Jacket post office, in October, 1918, when he had almost finished the season’s work. Two ruins of size were examined, one of which, situated in the open sagebrush clearing, belongs to the village type composed of large and small rectangular mounds. The other is composed of small circular or semicircular buildings with a surrounding wall. The form of this latter (fig. 2) would seem to place it in a subgroup or village type. Approach to the inclosed circular mounds was debarred by a high bluff of a canyon on one side and by a low defensive curved wall (E), some of the stones of which are large, almost megaliths, on the side of the mesa. From fragmentary sections of the buried walls of one of these circular mounds (A, B), which appear on the surface, it would seem that the buildings were like towers (C, D). This is one of the few known examples of circular buildings in an area protected by a curved wall. In the cliffs below Wood Canyon Ruin is a cliff-dwelling (G, H, J) remarkable mainly in its site.

Fig. 2.—Ground plan of Wood Canyon Ruin.

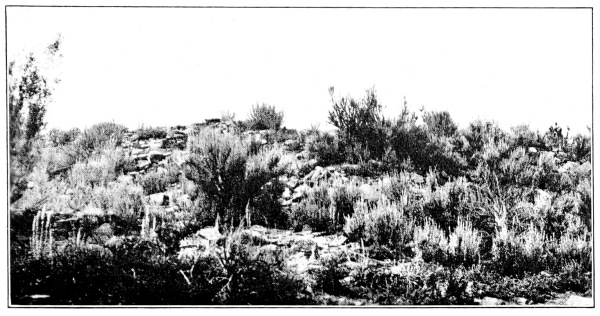

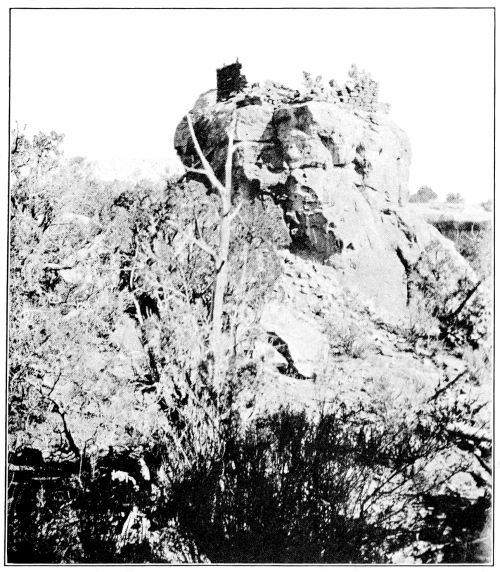

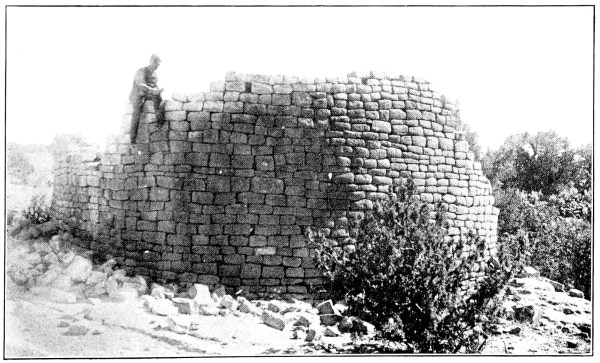

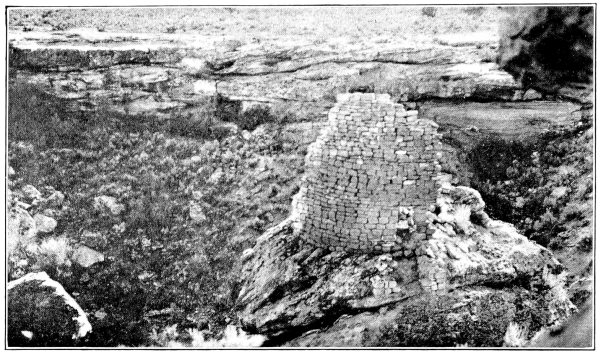

The so-called Butte Ruin, situated in Lost Canyon, 5 miles east of Dolores, belongs to the circular type. It crowns a low elevation, steep [Pg 33] on the west side, sloping more gradually on the east, and surrounded by cultivated fields. The view from its top looking toward Ute Mountain and the Mesa Verde plateau is particularly extensive. The butte is forested by a few spruces growing at the base and extending up the sides, which are replaced at the summit by a thick growth of sage and other bushes which cover the mound, rendering it difficult to make out the ground plan of the ruin on its top.

From what appears on the surface it would seem that this ruin was a circular or semicircular building about 60 feet in diameter, the walls rising about 10 feet high. Like other circular mounds it shows a well-marked depression in the middle, from which radiate walls or indications of walled compartments. Like the majority of the buildings of the circular form, the walls on one side have fallen, suggesting that a low straight wall, possibly with rectangular rooms, was annexed to this side.

In the neighborhood of Butte Ruin there is another hill crowned with a pile of stones, probably a round building of smaller size and with more dilapidated walls. Old cedar beams project in places out of the mounds.

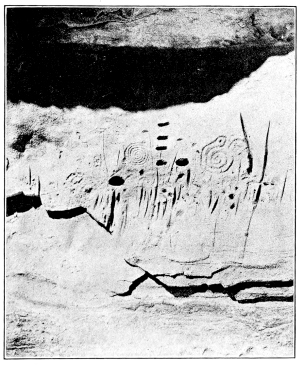

The cliff-houses below the largest of these mounds show well-made walls with a few rafters and beams. There are pictographs on the cliff a short distance away.

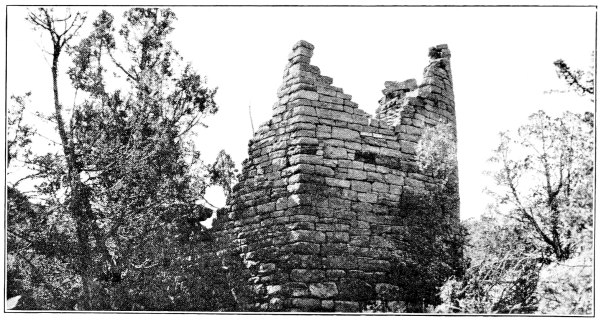

This ruin crowns a low hill about 3 miles south of Dolores (fig. 3). The form of the mound is semicircular with a depression in the middle around which can be traced radiating partitions suggesting compartments. Its outer wall on the south side, as in so many other examples of this type, has fallen, and the indications are that here the wall was straight, or like that on the south side of Horseshoe Ruin.

The author’s attention was first called to this ruin by Mr. Gordon Parker, supervisor of the Montezuma Forest Reserve, it having been discovered by Mr. J. W. Emerson, one of his rangers. The circular or semicircular form (fig. 4) of the mound indicates at once that it does not belong to the same type as Far View House; the central depression is surrounded by a series of compartments separated by radiating walls like the circular ruins in the pueblo region to the south. Mr. Emerson’s report, which follows, points out the main features of this remarkable ruin.[31]

[Pg 34]

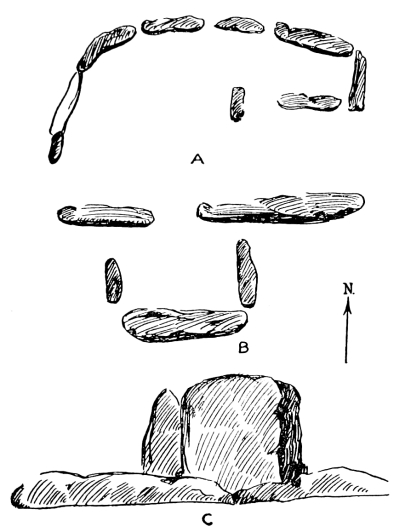

Fig. 3.—Metes and bounds of Emerson Ruin. (After Emerson.)

In August, 1916, I visited Mesa Verde National Park. While there Doctor Fewkes inquired in regard to ruins in the vicinity of the Big Bend of the Dolores River. He informed me that the log of two old Spanish explorers of 1775 described a ruin near the bend of the Dolores River as of great value.

Later, during October, 1916, I visited a number of ruins in this vicinity, including the one which (for the want of a better name) I have mapped and named Sun Dial Palace. Later, last fall, I again visited these ruins with Mr. R. W. Williamson, of Dolores, Colorado.

On July 5, 1917, I again visited these ruins, which I have designated as Reservoir Group and Sun Dial Palace.[32] For location and status of land on which they lie see map of sec. 17, T. 37 N., R. 15 W., N. M. P. M. (fig. 3).

While examining Sun Dial Palace I noted the “D-shaped construction, also that the south wall of the building ran due east and west.” Also please note the regularity of wall bearings from the approximate center of the elliptical center chamber. I also noted that a shadow cast by the sun apparently [Pg 35] coincides with some of these walls at different hours during the day. This last gave suggestion to the name. Also please note that the first tier of rooms around the middle chamber does not show a complete set of bearings but seems to suggest that these regular bearings were obtained from observation and study of a master builder. The result of his study was built as the next circular room tier was added. The two missing rooms on the western side of the building seem to suggest that this building was never completed, and also bear out my theory of an outward building of room tiers from the middle chamber.

On the ground this building is fully completed on the south side and forms a due east and west line. An error in mapping the elliptical middle chamber has given the south side an incomplete appearance.

I believe that the excavation and study of this ruin will recall something of value, as Father Escalante wrote in his log in 1775.

Respectfully submitted.

Fig. 4.—Schematic ground plan of Emerson Ruin. (After Emerson.)

A personal examination of the remains of this building leads the author to the conclusion that while it belongs to the circular group, with a ground plan resembling Horseshoe House, and while the central part had a wall completely circular, the outer concentric curved walls did not complete their course on the south side, but ended in straight walls comparable with the partitions separating compartments. The author identifies another ruin as that mentioned by the Catholic fathers in 1775. [Pg 36]

The name Escalante Ruin, given to the first ruin recorded by a white man in Colorado, is situated about 3 miles from Dolores on top of a low hill to the right of the Monticello Road, just beyond where it diverges from the road to Cortez. The outline of the pile of stones suggests a D-shaped or semicircular house with a central depression surrounded by rooms separated by radiating partitions. The wall on the south or east sides was probably straight, rendering the form not greatly unlike the other ruins on hilltops in the neighborhood of Dolores.

This is supposed to be the ruin to which reference is made in the following quotation from an article in Science:[33]

“There is in the Congressional Library, among the documents collected by Peter Force, a manuscript diary of early exploration in New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah, dated 1776, written by two Catholic priests, Father Silvester Velez Escalante and Father Francisco Atanacio Dominguez. This diary is valuable to students of archeology, as it contains the first reference to a prehistoric ruin in the confines of the present State of Colorado, although the mention is too brief for positive identification of the ruin.[34] While the context indicates its approximate site, there are at this place at least two large ruins, either of which might be that referred to. I have no doubt which one of these two ruins was indicated by these early explorers, but my interest in this ruin is both archeological and historical. Our knowledge of the structure of these ruins is at the present day almost as imperfect as it was a century and a half ago.

“The route followed by the writers of the diary was possibly an Indian pathway, and is now called the Old Spanish Trail. After entering Colorado it ran from near the present site of Mancos to the Dolores. On the fourteenth day from Santa Fe, we find the following entry: ‘En la vanda austral del Vio [Rio] sobre un alto, huvo anti-quam (te) una Poblacion pequeña, de la misma forma qᵉ las de los Indios el Nuevo Mexico, segun manifieran las Ruinas qᵉ de invento registramos.’

“By tracing the trip day by day, up to that time, it appears that the ruin referred to by these early fathers was situated somewhere near the bend of the Dolores River, or not far from the present town Dolores, Colo. The above quotation indicates that the ruin was a small settlement, and situated on a hill, on the south side of the river or trail, but it did not differ greatly from the ruined settlements of the Indians of New Mexico with which the writers were familiar, and had already described.” [Pg 37]

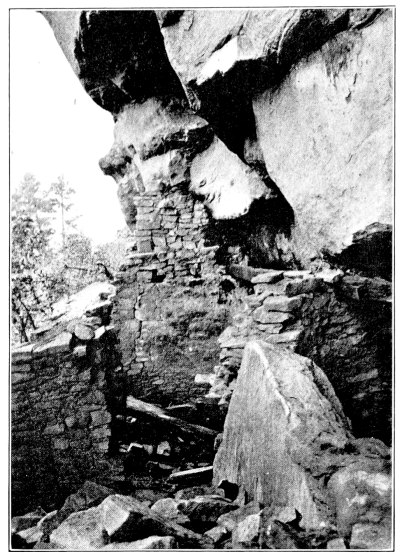

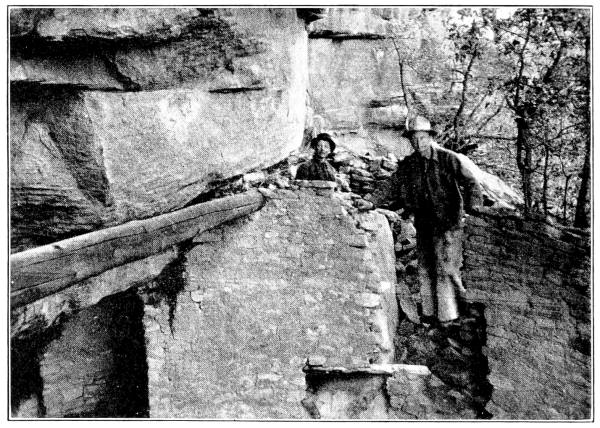

There are numerous cliff-houses in this district, but while, as a rule, they are much smaller than the magnificent examples in the Mesa Verde, they are built on the same architectural lines as their more pretentious relatives. Both large and small have circular subterranean kivas, similarly constructed to those of Spruce-tree House, and have mural pilasters (to support a vaulted roof, now destroyed), ventilators, and deflectors.

There are also many rooms in cliffs, possibly used for storage or for some other unknown purposes, but too small for habitations. It is significant that these are identical so far as their size is concerned with the “ledge houses,” near Spruce-tree House, indicating similar or identical uses.

The kivas of cliff-dwellings of size in the region considered have the same structural features as those of adjacent ruins, but very little resemblance, save in site, to those of cliff-dwellings in southern Arizona, as in the Sierra Ancha or Verde Valley, the structure of which resembles adjacent pueblos.

The absence in the McElmo region of very large cliff-houses is due partly but not wholly to geological conditions, the immense caves of the Mesa Verde not being duplicated in the tributaries of the McElmo; but wherever caverns do occur, as in Sand Canyon, we commonly find diminutive representatives. While differences in geological features may account for the size of these prehistoric buildings, the nature of the site or its size is not all important.[35]

Here and there one sees from the road through the McElmo Canyon a few small cliff-houses, and if he penetrates some of the tributaries, he finds many others. The canyon is dominated by the Ute Mountain on the south, but on the north are numerous eroded cliffs in which are many caves affording good opportunities for the construction of cliff-houses.

These buildings do not differ save in size from the cliff-houses of the Mesa Verde. Their kivas resemble the vaulted variety and the masonry is identical.

Although the existence of cliff-dwellings in the tributaries of the McElmo has long been known, the characteristic circular kivas which occur in the Mesa Verde had not been recognized previous to the present report.

The relative age of the pueblos and great towers and the same structures in caves can not be decided by the data at hand, but the indications are that they were contemporary.

On account of the similarity in structure of the McElmo cliff-dwellings [Pg 38] to those on Mesa Verde, only a few examples from the former region are here considered. It may be worthy of note that while McElmo cliff-dwellings are generally accompanied by large open-air pueblos and towers or great houses on the cliffs above, in the Mesa Verde open-air buildings[36] are generally situated some distance from the cliff-dwellings.

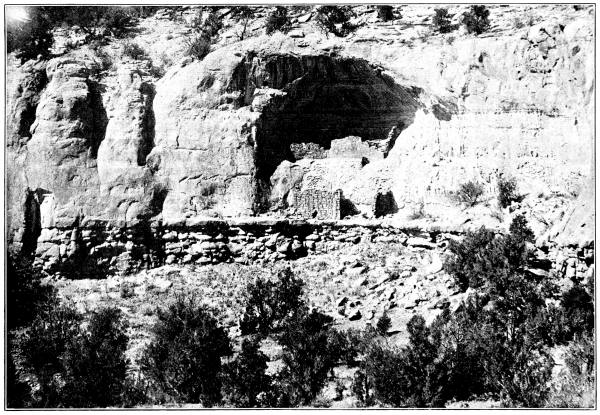

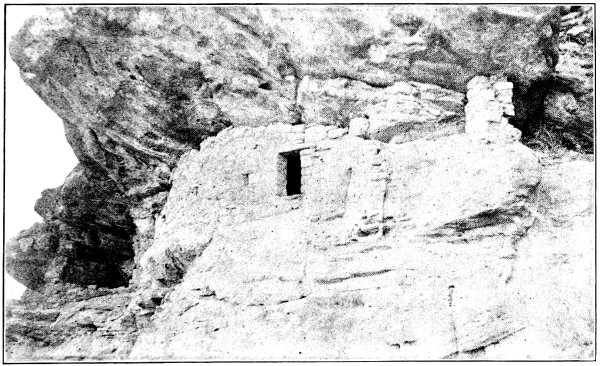

Several small cliff-houses occur in Sand Canyon, one of the northern tributaries of the McElmo. Stone Arch House, here figured (pl. 6, a), so-called from the eroded cliff (pl. 4, b) near by. It is situated in the cliff, about a mile from where the canyon enters the McElmo Canyon near Battle Rock. Abundant piñon trees and a few scrubby cedars grow in the low mounds of the talus below the ruin, near which, on top of a neighboring rock pinnacle, still stand the well-constructed walls of a small house (pl. 4, a).

The formerly unnamed cliff-house shown in plate 8[37] is one of the best preserved in Sand Canyon. It consists of an upper and a lower house, the former situated far back in the cave, the latter on a projecting terrace below. Unfortunately it is impossible to introduce an extended description of this building as it was not entered by the author’s party, but from a distance the walls exhibit fine masonry. It is unique in having double buildings on different levels, an arrangement not rare in a few examples of cliff-dwellings on the Mesa Verde. As shown in plate 8, the character of the rock on which the lower house stands is harder than that above in which the cave has been eroded. The upper house is wholly protected by the roof[38] of the cave and occupies its entire floor. The lower house shows from a distance at least two rooms, the front wall of one having fallen.

From a distance the walls of both the lower and the upper house seem to be well preserved, although many of the component stones have fallen to the base of the cliff.

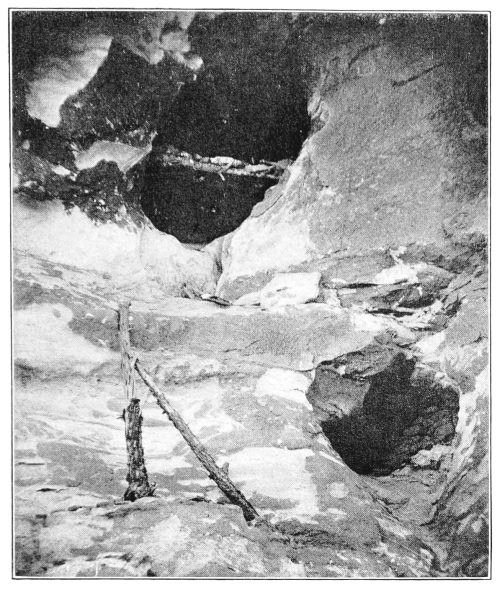

One of the cliffs bordering Sand Canyon has an inaccessible cave in which is an artificial platform or lookout shown in plate 7, a. Although this structure is not as well preserved as the scaffold in the neighborhood of Scaffold House in Laguna (Sosi) Canyon, on the Navaho [Pg 39] National Monument, it seems to have had a similar purpose. It is constructed of logs reaching from one side of the cave to the other supporting a floor of flat stones and adobe. Its elevated situation would necessitate for entrance either holes cut in the cliffs or ladders.