*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 69330 ***

LIFE

OF

SIR WALTER SCOTT.

LIFE OF

SIR WALTER SCOTT

BY

ROBERT CHAMBERS. LL.D.

WITH

ABBOTSFORD NOTANDA

BY

ROBERT CARRUTHERS, LL.D.

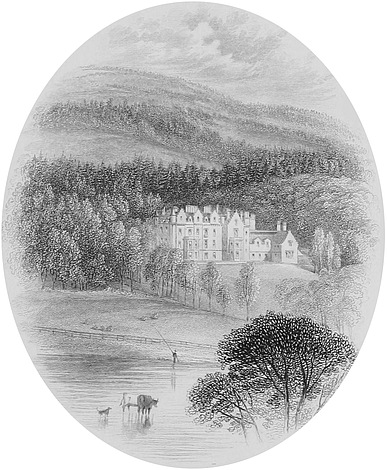

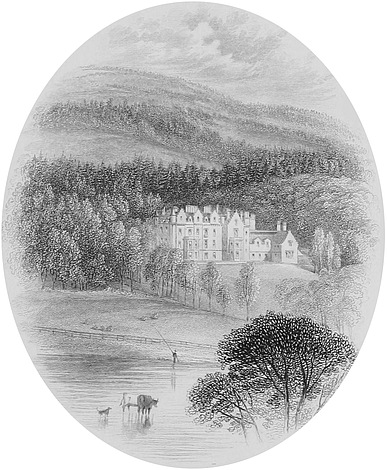

View of Abbotsford and grounds from the Tweed.

EDITED BY W. CHAMBERS.

W. & R. CHAMBERS,

EDINBURGH AND LONDON.

1871.

LIFE

OF

SIR WALTER SCOTT

By ROBERT CHAMBERS, LL.D.

WITH

ABBOTSFORD NOTANDA

By ROBERT CARRUTHERS, LL.D.

Edited by W. CHAMBERS

W. & R. CHAMBERS

LONDON AND EDINBURGH

1871

Edinburgh:

Printed by W. and R. Chambers.

PREFATORY NOTE.

The present Memoir of Sir Walter Scott was written

by my brother, the late Dr R. Chambers, immediately

after the decease of the great novelist, and having been

issued at a small price for popular reading, had what was

then considered a large circulation—180,000 copies. It

was subsequently republished, with some improvements.

The Memoir is now reproduced in somewhat better

style, as a small but fitting contribution in homage

of the great man, the centenary of whose birth, 15th

August 1871, is about to be very generally celebrated.

I have taken the liberty of adding only a few paragraphs,

distinguishable by being enclosed within brackets. The

principal of these insertions refers to the manner in

which my brother had the honour to become acquainted

with, and acquired the esteem of, Sir Walter Scott.

To the Memoir are now appropriately appended

certain ‘Abbotsford Notanda,’ descriptive of the friendly

intercourse which long subsisted between Sir Walter

and his factor and amanuensis, William Laidlaw, prepared

by one well qualified to write on the subject,

Dr R. Carruthers, Inverness.

W. C.

Edinburgh, June 1871.

CONTENTS.

| |

PAGE |

| PARENTAGE |

1 |

| BIRTH—BIRTHPLACE—EARLY SCENES |

8 |

| THE LAND OF SCOTT |

10 |

| SCHOOL-BOY DAYS |

16 |

| UNIVERSITY |

25 |

| PROFESSION |

28 |

| POLITICAL OPINIONS—SOLDIERING |

33 |

| VISIT TO PEEBLESSHIRE |

35 |

| MARRIAGE |

37 |

| POEMS |

42 |

| WAVERLEY NOVELS |

51 |

| SIR WALTER AND MR R. CHAMBERS |

64 |

| LATER NOVELS, AND LIFE OF NAPOLEON |

67 |

| PECUNIARY MISFORTUNES |

70 |

| LATER EXERTIONS |

82 |

| CONCLUDING YEARS—DECEASE |

87 |

| PERSONAL APPEARANCE |

97 |

| CHARACTER |

99 |

| CONCLUSION |

105 |

|

| ABBOTSFORD NOTANDA |

109 |

1

LIFE

OF

SIR WALTER SCOTT.

PARENTAGE.

Sir Walter Scott was one of the sons of

Walter Scott, Esq., Writer to the Signet, by Anne,

daughter of Dr John Rutherford, Professor of the

Practice of Medicine in the University of Edinburgh.

His paternal grandfather, Mr Robert Scott, farmer at

Sandyknow, in the vicinity of Smailholm Tower, in

Roxburghshire, was the son of Mr Walter Scott, a

younger son of Walter Scott of Raeburn, who in his

turn was third son of Sir William Scott of Harden, in

which family the chieftainship of the race of Scott is

now understood to reside. Sir Walter’s grandfather, Mr

Robert Scott, farmer at Sandyknow, as we learn from

the Border Antiquities, ‘though both descended from

and allied to several respectable Border families, was2

chiefly distinguished for the excellent good sense and

independent spirit which enabled him to lead the way

in agricultural improvement—then a pursuit abandoned

to persons of a very inferior description. His memory

was long preserved in Teviotdale, and still survives, as

that of an active and intelligent farmer, and the father

of a family all of whom were distinguished by talents,

probity, and remarkable success in the pursuits which

they adopted.’

Walter, the third son of Sir William Scott of Harden,

lived at the time of the Restoration, and embraced the

tenets of Quakerism, which at that period made their

way into Scotland. For this he endured a degree of

persecution for which it is now difficult to assign a

reason. The Scottish Privy-council, by an edict dated

June 20, 1665, directed his brother, the existing representative

of the Harden family, to take away his

three children, and educate them separately, so that

they might not become infected with the same heresy;

and, for doing so, he was to be entitled to sue his

brother for the maintenance of the children. By a

second edict, dated July 5, 1666, the Council directed

two thousand pounds Scots money to be paid by the

Laird of Raeburn for this purpose; and, as he was now

confined in the Tolbooth of Edinburgh, where he was

liable to be further tainted by converse with others of

the same sect there also imprisoned, the Council further

ordered him to be transported to the jail of Jedburgh,

where no one was to have access to him but such as

might be expected, to convert him from his present

principles.

Walter, the second son of this gentleman, and father

to the novelist’s grandfather, received a good education3

at Glasgow College, under the protection of his uncle.

He was a zealous Jacobite—a friend and correspondent

of Dr Pitcairn—and made a vow never to shave his

beard till the exiled House of Stuart should be restored;

whence he acquired the name of Beardie.

Dr John Rutherford, maternal grandfather to the

subject of this memoir, was one of four Scottish pupils

of Boerhaave, who, in the early part of the last century,

contributed to establish the high character of the Edinburgh

University as a school of medicine. He was

the first Professor of the Practice of Physic in the

university, to which office he was elected in 1727, and

which he resigned in 1766, in favour of the celebrated

Dr John Gregory. He was also the first person who

delivered lectures on Clinical Medicine in the Infirmary.

His son, Dr Daniel Rutherford, maternal uncle to the

novelist, was afterwards, for a long period, Professor of

Botany in the Edinburgh University, and further distinguished

by his great proficiency in chemistry. Dr

D. Rutherford was one of the cleverest scientific men

of his day; and, but for certain unimportant circumstances,

would have been preferred to the high honour

of succeeding Black in the chair of Chemistry. When

he took his degree in 1772, Pneumatic Chemistry was in

its infancy. Upon this occasion he published a thesis,

in which the doctrines respecting gaseous bodies are

laid down with great perspicuity, as far as they were

then known, and an account also given of a series

of experiments made by himself, which discover much

ingenuity and address. He was the first European

chemist who, if the expression may be used, discovered

nitrogen. Had he proceeded a single step farther, he

would have anticipated the discoveries of Priestley,4

Scheele, and Lavoisier, respecting oxygen, which have

rendered their names immortal. As it was, the experiments

and discoveries of Dr Rutherford made his name

respected all over Europe.

The wife of Dr John Rutherford, and maternal grandmother

of Sir Walter Scott, was Jean Swinton, daughter

of Swinton of Swinton, in Berwickshire, one of the

oldest families in Scotland, and at one period very

powerful. Sir Walter has introduced a chivalric representative

of this race into his drama of Halidon Hill.

The grandfather of Jean Swinton was Sir John Swinton,

the twentieth baron in lineal descent, and the son of

the celebrated Judge Swinton, to whom, along with Sir

William Lockhart of Lee, Cromwell intrusted the chief

management of civil affairs in Scotland during his

usurpation. Lord Swinton, as he was called, in virtue

of his judicial character, was seized, after the Restoration,

and brought down to Scotland for trial, in the

same vessel with the Marquis of Argyll. It was

generally expected that one who had played so conspicuous

a part in the late usurpation, would not elude

the vengeance of the new government. He escaped,

however, by suddenly adopting the tenets of the society

to which Walter Scott of Raeburn afterwards attached

himself. On being brought before the parliament for

trial, he rejected all means of legal defence; and his

simply penitent appearance and venerable aspect

wrought so far with his judges, that he was acquitted,

while less obnoxious men were condemned. It was

from this extraordinary person, and while confined

along with him in Edinburgh Castle, that Colonel David

Barclay, father of Robert Barclay, the eminent author of

the Apology for the Quakers, contracted those sentiments5

which afterwards shone forth with such remarkable

lustre in his son.

While the ancestry of Sir Walter Scott is thus

shewn to have been somewhat more than respectable,

it must be also stated, that, in his character as a man,

a citizen, or a professional agent, there could not be a

more worthy member of society than his immediate

parent. Mr Walter Scott, born in 1729, and admitted

as a Writer to the Signet in 1755, was by no means a

man of shining abilities. He was, however, a steady,

expert man of business, insomuch as to prosper considerably

in life; and nothing could exceed the gentleness,

sincerity, and benevolence of his character. For

many years, he held the honourable office of an elder

in the parish church of Old Greyfriars, while Dr

Robertson, the historian of America and Charles V.,

acted as one of the ministers. The other clergyman was

Dr John Erskine, much more distinguished as a divine,

and of whom Sir Walter has given an animated picture

in his novel of Guy Mannering. The latter person led

the more zealous party of the Church of Scotland, in

opposition to his colleague, Dr Robertson, who swayed

the moderate and predominating party; and it is

believed that, although a Jacobite, and employed mostly

by that party, the religious impressions of Mr Scott

were more akin to the doctrines maintained by Erskine,

than those professed by Robertson.

Mrs Scott, while she boasted a less prepossessing

exterior than her husband, was enabled, partly by the

more literary character of her connections and education,

and more perhaps by native powers of intellect,

to make a greater impression in conversation. It has

thus become a conceded point, that Sir Walter derived6

his abilities almost exclusively from this parent. Without

pretending to judge in a matter of such delicacy, it

may at least be allowed that the young poet was at

first greatly indebted to his mother for an introduction

to the literary society of which her father and brother

were such distinguished ornaments. It has somewhere

been alleged that Mrs Scott, who was an intimate

friend of Allan Ramsay, Blacklock, and other poetical

wits of the last century, wrote verses, like them, in the

vernacular language of Scotland. But this can be

denied, upon the testimony of her own son. The

mistake has probably arisen in consequence of a Mrs

Scott of Wauchope, whose maiden name was likewise

Rutherford, having published poetry of her own composition.

Mrs Walter Scott, who was altogether a woman

of the highest order of intellect and character, was, at

an early age, deemed worthy by her father to be intrusted

with the charge of his house, during his temporary

widowhood; and thus she possessed opportunities enjoyed

by few young ladies of her own age, and of the

period when she lived, of mixing in literary society. It

is unquestionable that this circumstance was likely to

have some effect in later life upon her son, with the

training of whose mind she must, in virtue of her

maternal character, have had more to do than her

husband. It may be further mentioned that Mrs Scott

had been principally educated by a reduced gentlewoman,

a Mrs Euphemia Sinclair (grand-daughter of Sir

Robert Sinclair of Longformacus), who kept a school

for young ladies in the now wretched precincts of

Blackfriars’ Wynd, in Edinburgh, and who had the

honour of educating many of the female nobility and

gentry of Scotland, some of whom were her own7

relations. Sir Walter’s own words respecting this

person are given in the work entitled Traditions of

Edinburgh: ‘To judge by the proficiency of her

scholars, although much of what is called accomplishment

might then be left untaught, she must have been

possessed of uncommon talents for education; for all

the ladies above mentioned’ [the list includes Mrs

Scott] ‘had well-cultivated minds, were fond of reading,

wrote and spelled admirably, were well acquainted with

history and with the belles-lettres, without neglecting

the more homely duties of the needle and accompt-book;

and, while two of them’ [meaning, as there is

reason to believe, Mrs Scott, and Mrs Murray Keith,

the Mrs Bethune Baliol of the Chronicles of the Canongate]

‘were women of extraordinary talents, all of them

were perfectly well bred in society.’ Sir Walter further

communicated that his mother, and many others of

Mrs Sinclair’s pupils, were sent, according to a fashion

then prevalent in good society, to be finished off by

the Honourable Mrs Ogilvie, lady of the Honourable

Patrick Ogilvie of Longmay, whose brother, the Earl

of Seafield, was so instrumental, as Chancellor of

Scotland, in carrying through the union with England.

Mrs Ogilvie trained her young friends to a style of

manners which would now be considered intolerably

stiff; for instance, no young lady, in sitting, was permitted

ever to touch the back of her chair. Such was

the effect of this early training upon the mind of Mrs

Scott, that even when she approached her eightieth

year, she took as much care to avoid touching her chair

with her back as if she had still been under the stern

eye of Mrs Ogilvie.

8

BIRTH—BIRTHPLACE—EARLY SCENES.

Sir Walter Scott was born at Edinburgh on the 15th

of August 1771, being the birthday of the great European

hero [Napoleon] whose deeds he was afterwards

to record. He was the third of a family consisting of

six sons and one daughter. The eldest son, John,

attained to a captaincy in an infantry regiment, but was

early obliged to retire from service on account of the

delicate state of his health. Another elder brother,

Daniel, was a sailor, but died in early life. Of him

Sir Walter has often been heard to assert, that he was

by far the cleverest and most interesting of the whole.

Thomas, the next brother to Sir Walter, followed the

father’s profession, and was for some years factor to the

Marquis of Abercorn, but eventually died in Canada in

1822, in the capacity of paymaster to the 70th Regiment.

Sir Walter himself entertained a fondly high

opinion of the talents of this brother; but it is not borne

out by the sense of his other friends. He possessed,

however, some burlesque humour, and an acquaintance

with Scottish manners and character—qualities which

were apt to impose a little, and even induced some

individuals to believe, for some time, that he, rather than

his more gifted brother, was the author of ‘The Novels.’

Existence opened upon the author of Waverley in one

of the duskiest parts of the ancient capital, which he has

been pleased to apostrophise in Marmion as his ‘own

romantic town.’ At the time of his birth, and for some

time after, his father lived at the head of the College

Wynd, a narrow alley leading from the Cowgate to the

gate of the college. The two lower flats of the house

were occupied by Mr Keith, W.S., grandfather of the9

Knight Marischal of Scotland, and Mr Walter Scott

lodged on the third floor, his part of the mansion being

accessible by a stair behind.

It was a house of what would now be considered

humble aspect, but at that time neither humble from its

individual appearance nor from its vicinage. As it

stood on the line necessary for the opening of a street

along the north skirt of the new university buildings, it

was destroyed on that occasion, and never rebuilt.

Speaking of this house in a series of notes communicated

to a local antiquary in 1825, Sir Walter said: ‘It consisted

of two flats above Mr Keith’s, and belonged to

my father, Mr Walter Scott, Writer to the Signet; there

I had the chance to be born, 15th August 1771. My

father, soon after my birth, removed to George’s Square,

and let the house in the College Wynd, first to Mr

Dundas of Philipstoun, and afterwards to Mr William

Keith, father of Sir Alexander Keith. It was purchased

by the public, together with Mr Keith’s’ [the inferior

floors], ‘and pulled down to make way for the new

college.’

It appears, however, that, before Sir Walter could

receive any impressions from the romantic scenery of

the Old Town of Edinburgh, he was removed, on

account of the delicacy of his health, to the country,

and lived for a considerable period under the charge of

his paternal grandfather at Sandyknow. This farm is

situated upon high ground, near the bottom of Leader

Water, and overlooks a large part of the vale of Tweed.

In the immediate neighbourhood of the farm-house,

upon a rocky foundation, stood the Border fortlet

called Smailholm Tower, which possessed many features

to attract the attention of the young poet. It was his10

early residence at this romantic spot that imparted an

intense affection for the southern part of Scotland, to

which he finally adjourned. Some account of the district

which he so dearly loved may here properly be given.

THE LAND OF SCOTT.

The district which this mighty genius has appropriated

as his own, may be described as restricted in a great

measure to the counties of Roxburgh and Selkirk, the

former of which is the central part of the frontier or

Border of Scotland, noted of old for the warlike character

of its inhabitants, and even, till a comparatively

late period, for certain predatory habits, unlike anything

that obtained at the same time, at least in the southern

portion of Scotland. Though born in Edinburgh,

Walter Scott was descended from Roxburghshire families,

and was familiar in his early years with both the scenery

and the inhabitants, and the history and traditions,

of that romantic land. He was indeed fed with the

legendary lore of the Borders as with a mother’s milk;

and it was this, no doubt, which gave his mind so

remarkable a taste for the manners of the middle ages,

to the exclusion of all sympathy for either the ideas of

the ancient classics, or the literature of modern manners.

There was something additionally engaging to a mind

like his in the poetical associations which have so long

rendered this region the very Arcadia of Scotland. The

Tweed, flowing majestically from one end of it to the

other; the Teviot, a scarcely less noble tributary; with

all the lesser streams connected with these two—the

Jed, the Gala, the Ettrick, the Yarrow, and the Quair—had,

from the revival of Scottish poetry, been sung by11

unnumbered bards, many of whose names have perished,

like flowers, from the face of the earth which they

adorned. From all these associations mingled together,

did the mind of this transcendent genius draw its first

and its happiest inspiration.

The general character of this district of Scotland is

pastoral. Here and there, along the banks of the

streams, there are alluvial strips called haughs, all of

which are finely cultivated; and the plough, in many

places, has ascended the hill to a considerable height;

but the land in general is a succession of pastoral

eminences, which are either green to the top, or swathed

in dusky heath, unless where a patch of young and green

wood seeks to soften the climate and the soil. Much

of the land still belongs to the Duke of Buccleuch, and

other descendants of noted Border chiefs, and it annually

supplies much of what both clothes and feeds the British

population. Being little intruded upon by manufactures,

or any other thing calculated to introduce new ideas,

its population exhibit, in general, those primitive features

of character which are so invariably found to characterise

a pastoral people. Even where, in such cases

as Hawick and Galashiels, manufactures have established

an isolated seat, the people are hardly distinguishable,

in simplicity and homely virtues, from the tenants

of the hills.

Starting at Kelso upon an excursion over this country,

the traveller would soon reach Roxburgh, where the

Teviot and the Tweed are joined—a place noted in

early Scottish history for the importance of its town

and castle, now alike swept away. Pursuing upwards

the course of the Teviot, he would first be tempted

aside into the sylvan valley of the Jed, on the banks12

of which stands the ancient and picturesque town of

Jedburgh, and whose beauties have been rapturously

described by Thomson, who spent many of his youngest

and happiest years amidst its beautiful braes. Farther

up, the Teviot is joined by the Aill, and, farther up still,

by the Rule, a rivulet whose banks were once occupied

almost exclusively by the warlike clans of Turnbull and

Rutherford. Next is the Slitrig, and next the Borthwick;

after which, the accessories of this mountain

stream cease to be distinguished. Every stream has

its valley; every valley has its particular class of inhabitants—its

own tales, songs, and traditions; and when

the traveller contrasts its noble hills and clear trotting

burnies with the tame landscapes of ‘merry England,’

he is at no loss to see how the natives of a mountainous

region come to distinguish their own country so much

in poetical recollection, and behold it with such exclusive

love. When the Englishman is absent from his

home, he sees a scene not greatly different from what he

is accustomed to, and regards his absence with very

little feeling. But when a native of these secluded vales

visits another district, he finds an alien peculiarity in

every object; the hills are of a different height and

vesture; the streams are different in size, or run in a

different direction. Everything tells him that he is not

at home. And, when returning to his own glen, how

every distant hill-top comes out to his sight as a familiar

and companionable object! How every less prominent

feature reminds him of that place which, of all the earth,

he calls his own! Even when he crosses what is termed

the height of the country, and but sees the waters running

towards that cherished place, his heart is distended

with a sense of home and kindred, and he throws his13

very soul upon the stream, that it may be carried before

him to the spot where he has garnered up all his most

valued affections.

There is one part of Roxburghshire which does not

belong to the great vale of the Tweed, and yet is as

essentially as any a part of the Land of Scott. This

is Liddesdale, or the vale of the Liddel, a stream which

seeks the Solway, and forms part of the more westerly

border. Nothing out of Spain could be more wild or

lonely than this pastoral vale, which once harboured

the predatory clans of Elliot and Armstrong, but is now

occupied by a race of more than usually primitive sheep-farmers.

It is absolutely overrun with song and legend,

of which Sir Walter Scott reaped an ample harvest for

his Border Minstrelsy, including the fine old ballads of

Dick o’ the Cow and Jock o’ the Syde.

It may be said, indeed, that, of all places in the south

of Scotland, the attention of the great novelist was first

fixed upon Liddesdale. In his second literary effort—the

Lay of the Last Minstrel—he confined himself in

a great measure to Teviotdale, in the upper part of

which, about three miles above Hawick, stands Branxholm

Castle, the chief scene of the poem. The old

house has been much altered since the supposed era of

the Lay; but it has nevertheless more of an ancient

than a modern appearance, and does not much disappoint

a modern beholder. For a long time, the Buccleuch

family have left it to the occupancy of the

individuals who act as their agents or chamberlains on

this part of their extensive property; and it is at present

kept in the best order, and surrounded by some fine

woods of ancient and modern growth. Seated on a

lofty bank, it still overlooks that stream, and is14

overtopped by those hills, to which, it will be recollected,

‘the lady’ successively addressed her witching

incantations.

The small vale of Borthwick Water, which starts off

from the strath of the Teviot a little above Hawick, contains

a scene which cannot well be overlooked—namely,

Harden Castle, the original though now deserted seat

of the family of Scott of Harden, from which, through

the Raeburn branch, Sir Walter Scott was descended.

This, though neglected alike by its proprietor and by

tourists, is one of the most remarkable pieces of scenery

which we, who have travelled over nearly the whole of

Scotland, have yet seen within its shores. Conceive,

first, the lonely pastoral beauty of the vale of Borthwick;

next, a minor vale receding from its northern side,

full of old and emaciated, but still beautiful wood:

penetrating this recess for a little way, the traveller sees,

perched upon a lofty height in front, and beaming

perhaps in the sun, a house which, though not picturesque

in its outline, derives that quality in a high degree from

its situation and accompaniments. This is Harden

House or Castle; but, though apparently near it, the

wayfarer has yet to walk a long way around the height

before he can wind his way into its immediate presence.

When arrived at the platform whereon the house stands,

he finds it degraded into a farm-house; its court forming

perhaps a temporary cattle-yard; every ornament disgraced;

every memorial of former grandeur seen through

a slough of plebeian utility and homeliness, or broken

into ruin. A pavement of black and white diced

marble is found in the vestibule, every square of which

is bruised to pieces, and the whole strewed with the

details of a dairy. The dining-room, a large apartment15

with a richly ornamented stucco roof, is now used as the

farmer’s kitchen. Other parts of the house, still bearing

the arms and initials of Walter Scott, Earl of Tarras,

great-grandfather of the late Mr Scott of Harden, and

of his second wife, Helen Hepburn, are sunk in a

scarcely less proportion. This nobleman was at first

married to Mary, Countess of Buccleuch, who died,

however, without issue, leaving the succession open to

her sister Anne, who became the wife of the unfortunate

Duke of Monmouth, eldest natural son of Charles II.

Through this family connection, the Earl of Tarras was

induced to join in the conspiracy which usually bears

the name of the Rye-house Plot, for which he was

attainted, only saving his life by giving evidence against

his more steadfast companion, Baillie of Jerviswood, the

great-grandfather of another Scottish proprietor, who

happened to be an immediate neighbour of Harden.

It may be asked why Mr Scott did not inherit the title

of his ancestor: the answer is, that it was only thought

necessary to invest the husband of the Countess of

Buccleuch with a title for his own life—which proves

that the hereditary character of the peerage has not

always been observed in our constitution. While all of

this scene that springs from art is degraded and wretched,

it is striking to see that its natural grandeur suffers no

defalcation. The wide-sweeping hills stretch off grandly

on all hands, and the celebrated den, from which the

place has taken its name, still retains the features which

have rendered it so remarkable a natural curiosity.

This is a large abyss in the earth, as it may be called,

immediately under the walls of the house, and altogether

unpervaded by running water—the banks clothed with

trees of all kinds, and one side opening to the vale,16

though the bottom is much beneath the level of the

surrounding ground. Old Wat of Harden—such is the

popular name of an aged marauder celebrated in the

Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border—used to keep the large

herds which he had draughted out of the northern

counties of England in this strange hollow; and it

seems to have been admirably adapted for the purpose.

It was this Border hero of whom the story is told

somewhere by his illustrious descendant, that, coming

once homeward with a goodly prey of cattle, and seeing

a large haystack standing in a farm-yard by the way,

he could not help saying, with some bitterness: ‘By my

saul, an ye had four feet, ye should gang too!’

SCHOOL-BOY DAYS.

It is understood that, at the ‘evening fire’ of Sandyknow,

Sir Walter learned much of that Border lore

which he afterwards wrought up in his fictions. To

what extent his residence there retarded his progress in

school instruction, is not discovered. After being at

Sandyknow, he was, for the sake of the mineral waters,

sent, in his fourth year, to Bath, where he attended

a dame’s school, and received his first lessons in

reading. Returning to Edinburgh, he made some

advances in the rudiments of learning at a private

school kept by a Mr Leechman in Hamilton’s Entry,

Bristo Street [now a small, decayed building, with a

tiled roof, occupied by a working blacksmith]. This

was his first school in Edinburgh. It is almost

certain that his attendance at school was rendered

irregular by his delicate health. He entered Fraser’s

class at the High School in the third year—that is to17

say, when that master had carried his class through one

half of the ordinary curriculum of the school; wherefore

it is clear that any earlier instruction he could have

received must have been in some inferior institution,

and very probably communicated in a hurried and

imperfect manner. It is at the commencement of the

school year in October 1779 that his name first appears

in the school register: he must have then been eight

years of age, which, it may be remarked, is an unusually

early period for a boy to enter the third year of

his classical course. What is further remarkable, his

elder brother attended the same class. It is therefore

to be suspected that his educational interests

were sacrificed, in some measure, to the circumstances

of the school, which were at that period in

such an unhappy arrangement as to teachers, that

parents often precipitated their children into a class

for which they were unfitted, in order to escape a

teacher whom they deemed unqualified for his duties,

and secure the instructions of one who bore a superior

character.

Although Mr Luke Fraser was one of the severest

flagellators even of the old school, he enjoyed the

reputation of being a sound scholar, so far as scholarship

was required for his duties, and also that of

a most conscientious and painstaking teacher. He

first caused his scholars to get by heart Ruddiman’s

Rudiments, and as soon as they were thoroughly

grounded in the declensions, the Vocabulary of the

same great grammarian was put into their hands, and

a small number of words prescribed to be repeated

every morning. They then read in succession the

Colloquies of Corderius, four or five lives of Cornelius18

Nepos, and the first four books of Cæsar’s Commentaries.

Ere this course was perfected, the greater part of

Ruddiman’s Grammatica Minora, in Latin, was got by

heart. Select passages from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the

Bucolics and the first Æneid of Virgil, concluded the

fourth year; after which the boys were turned over to

the rector, by whom they were instructed for two years

more; making the course in all six years. It must

also be understood, that every one of the three masters

besides Mr Fraser pursued the same system, bringing

forward a class from the first elements to the state in

which it was fitted for the attention of the rector; after

which he returned once more to take up a new set of

boys in the first class—and so forth for one lustrum

after another, so long as he was connected with the

school. If any teacher could have brought a boy over

such a difficulty as that which attended the commencement

of Sir Walter’s career at the High School, it

would have been Mr Fraser; for few of his profession

at that time were more anxious to explain away every

obstruction in the path of his pupils, or took so much

pains to ascertain that they were carrying the understandings

of the boys along with them through all the

successive stages. Apparently, however, neither the

care of the master nor the inborn genius of the pupil

availed much in this case, for it is said that the twenty-fifth

place was no uncommon situation in the class for

the future author of the Waverley Novels.

After two years of instruction, commenced under

these unfavourable circumstances, Sir Walter, in October

1781, entered the rector’s class, then taught by Dr

Alexander Adam, the author of many excellent elementary

books, and one of the most meritorious and19

most eminent teachers that Scotland has ever produced.

The authors read by Dr Adam’s class at this period,

and probably during the whole of his career, were Virgil,

Horace, Cicero, Sallust, Livy, and Terence; but it was

not in reading and translating alone that an education

under this eminent man consisted. Adam, who was an

indefatigable student, as the number and excellence of

his works testify, was a complete contrast to Mr Fraser.

The latter hardly ever introduced a single remark but

what was intended to illustrate the letter of the author;

whereas Dr Adam commented at great length upon

whatever occurred in the course of reading in the class,

whether it related to antiquities, customs, and manners,

or to history. He was of so communicative a disposition,

that whatever knowledge he had acquired in his

private studies, he took the first opportunity of imparting

to his class, paying little regard whether it was above

the comprehension of the greater number of his scholars

or not. He abounded in pleasant anecdote; and while

he never neglected the proper business of his class, it

is certain that he inspired a far higher love of knowledge

and of literary history into the minds of his pupils than

any other teacher of his day. At the same time, he

displayed a benevolence of character which won the

hearts of his pupils, and nothing ever gave him so much

pleasure as to hear of their success in after-life. To

this venerable person, Sir Walter was always ready to

acknowledge his obligations, and it is not improbable

that much of his literary character was moulded on that

of Dr Adam.

As a scholar, nevertheless, the subject of this memoir

never became remarkable for proficiency. There is his

own authority for saying, that, even in the exercise of20

metrical translation, he fell far short of some of his

companions; although others preserve a somewhat

different recollection, and state that this was a department

in which he always manifested a superiority. It

is, however, unquestionable, that in his exercises he was

remarkable, to no inconsiderable extent, for blundering

and incorrectness; his mind apparently not possessing

that aptitude for mastering small details, in which so

much of scholarship, in its earliest stages, consists.

Regarding his school-days, we may introduce an

extract from an original letter on the subject. ‘The

following lines were written by Walter Scott when he

was between ten and eleven years of age, and while

he was attending the High School, Edinburgh. His

master there had spoken of him as a remarkably stupid

boy, and his mother with grief acknowledged that they

spoke truly. She saw him one morning, in the midst of

a tremendous thunder-storm, standing still in the street,

and looking at the sky. She called to him repeatedly,

but he remained looking upwards without taking the

least notice of her. When he returned into the house,

she was very much displeased with him: “Mother,” he

said, “I could tell you the reason why I stood still, and

why I looked at the sky, if you would only give me a

pencil.” She gave him one, and, in less than five

minutes, he laid a bit of paper on her lap, with these

words written on it:

“Loud o’er my head what awful thunders roll,

What vivid lightnings flash from pole to pole,

It is thy voice, my God, that bids them fly,

Thy voice directs them through the vaulted sky;

Then let the good thy mighty power revere,

Let hardened sinners thy just judgments fear.”

21

The old lady repeated them to me herself, and the tears

were in her eyes: for I really believe, simple as they

are, that she values these lines, being the first effusion

of her son’s genius, more than any later beauties which

have so charmed all the world besides.’

Before quitting the High School, he, along with his

brothers, received the advantages of some tutorial training

under a Mr Mitchell, who afterwards became a minister

connected with the Scotch Church. Previous to entering

the university of Edinburgh, young Walter spent some

time with his aunt at Kelso. Here, in order that he

might be kept up in his classical studies, he attended

the grammar-school, at that time under the rectorship

of Mr Lancelot Whale, a worthy man and good scholar,

who possessed traits of character not unlike some of

those which have been depicted in Dominie Sampson.

It was while thus residing for a short time at Kelso,

about 1783, that Sir Walter made the acquaintance of

James Ballantyne, then a schoolboy of his own age, with

kindred literary tastes.

Sir Walter’s education being irregular from bad health,

he did not distinguish himself as a scholar, yet often

surprised his instructors by the miscellaneous knowledge

which he possessed, and now and then was acknowledged

to display a sense of the beauties of the Latin

authors such as is seldom seen in boys. In the rough

amusements which went on out of school, his spirit

enabled him to take a leading share, notwithstanding his

lameness. He would help to man the Cowgate Port in

a snow-ball match, and pass the Kittle Nine Steps on

the Castle Rock with the best of them. In the winter

evenings, when out-of-door exercise was not attractive, he

would gather his companions round him at the fireside,22

and entertain them with stories, real and imaginary, of

which he seemed to have an endless store. Unluckily,

his classical studies, neglected as they comparatively

were, experienced an interruption from bad health, just

as he was beginning to acquire some sense of their

value.

It would, nevertheless, be difficult to say whether

Scott was the worse or the better of the interruptions he

experienced in school learning. He lost a certain kind

of knowledge, it is true, but he gained another. The

vacant time at his disposal he gave to general reading.

History, travels, poetry, and prose fiction he devoured

without discrimination, unless it were that he preferred

imaginative literature to every other; and of all imaginative

writers, was fondest of such as Spenser, whose

knights and ladies, and dragons and giants, he was never

tired of contemplating. Any passage of a favourite poet

which pleased him particularly was sure to remain on his

memory, and thus he was able to astonish his friends

with his poetical recitations. At the same time, he

admits that solidly useful matters had a poor chance of

being remembered. His sober-minded parents and

other friends regarded these acquirements without pride

or satisfaction; they marvelled at the thirst for reading

and the powers of memory, but thought it all to little

good purpose, and only excused it in consideration of

the infirm health of the young prodigy. Scott himself

lived to lament the indifference he shewed to that

regular mental discipline which is to be acquired at

school. He says in his autobiography: ‘It is with

the deepest regret that I recollect in my manhood

the opportunities of study which I neglected in my

youth; through every part of my literary career, I have23

felt pinched and hampered by my own ignorance; and

I would at this moment give half the reputation I have

had the good-fortune to acquire, if by doing so I could

rest the remaining part upon a solid foundation of

learning and science.’

It is the tradition of the family—and the fact is

countenanced by this propensity to tales of chivalric

adventure—that Sir Walter wished at this period of his

life to become a soldier. The illness, however, which

had beset his early years rendered this wish bootless,

even although his parents had been inclined to gratify

it. His malady had had the effect of contracting his

right leg, so that he could hardly walk erect, even with

the toes of that foot upon the ground. It has been

related by a member of his family that, on this being

represented to him as an insuperable obstacle to his

entering the army, he left the room in an agony of

mortified feeling, and was found some time afterwards

suspended by the wrists from his bedroom window,

somewhat after the manner of the unfortunate Knight of

the Rueful Countenance, when beguiled by the treacherous

Maritornes at the inn. On being asked the cause

of this strange proceeding, he said he wished to prove

to them that, however unfitted by his limbs for the profession

of a soldier, he was at least strong enough in the

arms. He had actually remained in that uneasy and

trying posture for upwards of an hour.

His parents made many efforts to cure his lameness.

Edinburgh at this time boasted of an ingenious mechanist

in leather, the first person who extended the use of that

commodity beyond ordinary purposes; on which account

there is an elaborate memoir of him in Dodsley’s Annual

Register for 1793. His name was Gavin Wilson, and,24

being something of a humorist, he exhibited a sign-board

intended to burlesque the vanity of his brother-tradesmen—his

profession being thus indicated: ‘Leather leg-maker,

not to his Majesty.’ Honest Gavin, on the

application of his parents, did all he could for Sir

Walter, but in vain.

An attempt was made about the same time to give

him instructions in music, which used to be a branch of

ordinary education in Scotland. His preceptor was Mr

Alexander Campbell, then organist of an Episcopal

chapel in Edinburgh, but known in later life as the

editor of Albyn’s Anthology, and author of various other

publications. Mr Campbell’s efforts were entirely in

vain: he had to abandon his pupil in a short time, with

the declaration, that he was totally deficient in that

indispensable requisite to a musical education—an ear.

It may appear strange, that he who wrote so many

musical verses, should have wanted this natural gift;

but there are other cases to shew that a perception of

metrical quantities does not depend on any such

peculiarity. Dr Johnson is a splendid instance.

Throughout life, Sir Walter, however capable of enjoying

music, was incapable of producing two notes

consecutively that were either in tune or in time. He

used to be pressed, however, at an annual agricultural

dinner, to contribute his proper quota to the cantations

of the evening; on which occasions he would break

forth with the song of Tarry Woo, in a strain of

unmusical vehemence, which never failed, on the same

principle as Dick Tinto’s ill-painted sign, to put the

company into good-humour.

Sir Walter was placed in the University of Edinburgh,

October 1783. The usual course at this famed

seminary is, for the first year, to attend the classes of

Latin and Greek, to which, during the second, are added

Mathematics and Logic; the third and last year of the

course of a merely liberal education is spent in attending

the lectures on Moral and Natural Philosophy. It

would appear that Sir Walter did not proceed regularly

through this academical course. He was matriculated,

or booked, in 1783, at once for the Humanity or Latin

class under Professor Hill, and the Greek class under

Professor Dalyell; and for the latter, once more in

1784. But the only other class for which he seems to

have matriculated at the college was that of Logic,

under Professor Bruce, in 1785. Although he may

perhaps have attended other classes without matriculation,

there is reason to believe that his irregular health

produced a corresponding irregularity in his academical

studies. The result, it is to be feared, was, that he

entered life much in the condition of his illustrious

prototype, the Bard of Avon—that is, ‘with a little

Latin and less Greek.’

Between his twelfth and fifteenth year, young Scott

had a particularly favourite companion of his own age,

John Irvine, the mutual attraction being a love of

fictions of a chivalrous description, furnished by an

eminent circulating library, which had been founded in

Edinburgh by Allan Ramsay, and situated in the High

Street, a short way above the Tron Church, and then

belonged to Mr James Sibbald, a person of literary

tastes, who edited the Edinburgh Magazine, and a26

collection of Scottish poetry. This old-fashioned library,

the first of its kind, passed in time into the hands of

Mr Alexander Mackay; and was finally sold off in

1831. With a volume from this precious repository,

the two youths sometimes adjourned to the picturesque

sides of Arthur’s Seat, where, seated together so as to

read from the same page, they revelled in the adventures

of heroes and heroines of romance.

It will thus be observed that Sir Walter’s acquirements

in his early years did not lie nearly so much in

ordinary branches of education, as in a large stock of

miscellaneous reading, taken up at the dictation of his

own taste. His thirst for reading is perhaps not described

in sufficiently emphatic terms, even in the above narrative.

It amounted to an enthusiasm. He was at that

time very much in the house of his uncle, Dr Rutherford,

at foot of Hyndford’s Close, near the Netherbow,

and there, even at breakfast, he would constantly have a

book open by his side, to refer to while sipping his

coffee, like his own Oldbuck in the Antiquary. His

uncle frequently commanded him to lay aside his book

while eating, and Sir Walter would only ask permission

first to read out the paragraph in which he was engaged.

But no sooner was one paragraph ended than another

was begun, so that the doctor never could find that

his nephew finished a paragraph in his life. It may

be mentioned that Shakspeare was at this period frequently

in his hands, and that, of all the plays, the

Merchant of Venice was his principal favourite.

Another choice companion at this period was

young Adam Ferguson—afterwards known as Sir Adam

Ferguson—son of Dr Adam Ferguson, author of the

History of the Roman Republic, and who remained an27

intimate friend during life. The house of Dr Ferguson

was a villa situated on the east side of a southern

suburb of Edinburgh, called The Sciennes, from its

proximity to the remains of an ancient monastery,

dedicated to St Catherine of Sienna. Dr Ferguson’s

house is remarkable as that in which young Walter

Scott had an opportunity of being in the company of

Robert Burns. Scott had read Burns’s poetry, and he

ardently desired to see the poet. An opportunity was

at length furnished, when Burns, on visiting Edinburgh

in 1787, came by invitation to the residence of Dr

Ferguson. Of the meeting, Scott has communicated an

unaffected description to Mr Lockhart. Sir Adam

Ferguson favoured me with some particulars of the visit

of Burns to his father’s house on this occasion.

It was the custom of Dr Ferguson to have a conversazione

at his house in the Sciennes once a week,

for his principal literary friends. Dr Dugald Stewart,

on this occasion, offered to bring Burns, a proposal to

which Dr Ferguson readily assented. The poet found

himself amongst the most brilliant literary society which

Edinburgh then afforded. Sir Adam thought that Black,

Hutton, and John Home were among those present.

He had himself brought his young friend Walter Scott,

as yet unnoted by his seniors. Burns seemed at first

little inclined to mingle easily in the company; he went

about the room, looking at the pictures on the walls.

The print described by Scott, from a painting by

Bunbury, attracted his attention. It represented a sad

picture of the effects of war: a soldier lying stretched

dead on the snow, his dog sitting in misery on one

side, while on the other sat his widow, nursing a child

in her arms. The print was plain, yet touching;28

beneath were written the following lines, which Burns

read aloud:

‘Cold on Canadian hills or Minden’s plain,

Perhaps that parent mourned her soldier slain;

Bent o’er her babe, her eye dissolved in dew,

The big drops mingling with the milk he drew,

Gave the sad presage of his future years,

The child of misery baptised in tears.’

Before getting to the end of the lines, Burns’s voice

faltered, and his big black eye filled with tears. A little

after, he turned with much interest to the company,

pointed to the picture, and, with some eagerness, asked

if any one could tell him who had written these

affecting lines. The philosophers were silent—no one

knew; but, after a decent interval, the pale lame boy

near by said in a negligent manner: ‘They’re written

by one Langhorne.’ An explanation of the place where

they occur (poem of The Country Justice) followed, and

Burns fixed a look of half-serious interest on the youth,

while he said: ‘You’ll be a man yet, sir.’ Scott may

be said to have derived literary ordination from Burns.

Somewhat oddly, the name Langhorne is quoted at the

bottom of the lines, but in so small a character that the

poet might well fail to read it.1

PROFESSION.

About his sixteenth year, Sir Walter’s health experienced

a sudden but most decisive change for the better.

Though his lameness remained the same, his body29

became tall and robust, and he was thus enabled to

apply himself with the necessary degree of energy to his

studies for the bar. At the same time that he attended

the Lectures of Professor Dick on Civil Law in the

college, he performed the duties of a writer’s apprentice

under his father; that being the most approved method

by which a barrister could acquire a technical knowledge

of his profession, though it has never been uniformly

practised.

Respect for his parents and for the common duties

of life, was always a strong feeling in Scott; he therefore

applied himself without a murmur to the desk in

his father’s office, though he acknowledges that the

recess beneath was generally stuffed with his favourite

books, from which, at intervals, he would ‘snatch a

fearful joy.’ He even made his diligence in copying

law-papers a means of gratifying his intellectual passions,

often writing an unusual quantity, that with the result

he might purchase some book or object of virtù which

he wished to possess. It should be mentioned that the

little room assigned to him on the kitchen-floor of his

father’s house in George Square was already made a

kind of museum by his taste for curiosities, especially

those of an antiquarian nature. He never was heard

to grudge the years he had spent in his father’s painstaking

business; on the contrary, he recollected them

with pleasure, for it was always a matter of pride with

him to be a man of business as well as a man of letters.

The discipline of the office gave him a number of little

technical habits, which he never afterwards lost. He

was, for instance, much of a formalist in the folding and

disposal of papers. The writer of this narrative recollects

folding a paper in a wrong fashion in his presence,30

when he instantly undid it, and shewed, with a school-masterlike

nicety, but with great good-humour, the

proper way to perform this little piece of business.

While advancing to manhood, and during its first few

years, Scott, besides keeping up his desultory system of

reading, attended the meetings of a literary society

composed of such youths as himself. A selection of

these and of his early schoolfellows, became his ordinary

companions. Amongst them was William Clerk, son

of Mr Clerk of Eldin, and afterwards a distinguished

member of the Scottish bar. It was the pleasure of

this group of young men to take frequent rambles in the

country, visiting any ancient castle or other remarkable

object within their reach. Scott, notwithstanding

his limp, walked as stoutly, and sustained fatigue as

well, as any of them. Sometimes they would, according

to the general habits of those days, resort to taverns for

oysters and punch. Scott entered into such indulgences

without losing self-control; but he lived to think this

ill-spent time. As to other follies equally besetting to

youth, it is admitted by all his early friends that he was

in a singular degree pure and blameless. His genial

good-humour made him a favourite with his young

friends, and they could not deny his possessing much

out-of-the-way knowledge; yet it does not appear that

they saw in him any intellectual superiority, or reason

to expect the brilliant destiny which awaited him. The

tendency of all testimony from those who knew him at

this time is rather to set him down as one from whom

nothing extraordinary was to be looked for in mature

manhood.

We can easily see the grounds of this opinion. Scott

had not been a good scholar. He shewed none of the31

peculiarities of the young sonneteer, for poetry was not

yet developed in his nature. Any advantage he possessed

over others of his own standing lay in a kind of

learning which seemed useless. It is not, then, surprising

that he ranked only with ordinary youths, or perhaps a

little below them. It is asserted, however, by James

Ballantyne, that there was a certain firmness of understanding

in Scott, which enabled him to acquire an

ascendency over some of his companions; giving him

the power of allaying their quarrels by a few words, and

disposing them to submit to him on many other occasions.

Still, this must have looked like a quality of the

common world, and especially unconnected with literary

genius.

When Scott’s apprenticeship expired, the father was

willing to introduce him at once into a business which

would have yielded a tolerable income; but the youth,

stirred by ambition, preferred advancing to the bar, for

which his service in a writer’s office was the reverse of

a disqualification. Having therefore passed through

the usual studies, he was admitted of the Faculty of

Advocates, July 1792. This is a profession in which

a young man usually spends a few years to little

purpose, unless peculiar advantages in the way of

patronage help him on. Scott does not appear to have

done more for some sessions than pass creditably

enough through certain routine duties which his father

and others imposed upon him, and for which only

moderate remuneration was made. He wanted the

ready fluent address which is required for pleading, and

his knowledge of law was not such as to attract business

to him as a consulting counsel. While lingering out

the first few idle years of professional life, he studied32

the German language and some of its modern writers.

He also continued the same kind of antiquarian reading

for which he had already become remarkable.

Amongst other things giving a character to his mind,

were certain annual journeys he made into the pastoral

district of Liddesdale, where the castles of the old

Border chiefs, and the legends of their exploits, were

still rife. On these occasions, he was accompanied by

an intelligent friend, Mr Robert Shortreed, long after

sheriff-substitute at Jedburgh. No inns, and hardly any

roads, were then in Liddesdale. The farmers were a

simple race, knowing nothing of the outward world.

So much was this the case, that one honest fellow, at

whose house the travellers alighted to spend a night,

was actually frightened at the idea of meeting an

Edinburgh advocate. Willie o’ Milburn, as this hero

was called, at length took a careful survey of Scott

round a corner of the stable, and getting somewhat

reassured from the sight, said to Mr Shortreed: ‘Weel,

de’il ha’e me if I’s be a bit feared for him now; he’s

just a chield like ourselves, I think.’ On these excursions,

Scott took down from old people anecdotes of

the old rough times, and copies of the ballads in which

the adventures of the Elliots and Armstrongs were

recorded. Thus were laid the foundations of the

collection which became in time the Minstrelsy of the

Scottish Border. The friendship of Mr Edmonstone of

Newton led him, in like manner, to visit those districts

of Stirlingshire and lower Perthshire where he afterwards

localised his Lady of the Lake. There he learned much

of the more recent rough times of the Highlands, and

even conversed with one gentleman who had had to

do with Rob Roy. These things constituted the real33

education of Scott’s mind, as far as his character as a

literary man is concerned.

POLITICAL OPINIONS—SOLDIERING.

From his earliest years, Sir Walter’s political leanings

were towards Conservatism, or that principle

which disposes men to wish for the preservation of

existing institutions, and the continuance of power in

the hands which have heretofore possessed it. ‘As

for politics,’ says Shenstone in his Letters, ‘I think

poets are Tories by nature, supposing them to be by

nature poets. The love of an individual person or

family that has worn a crown for many successions, is

an inclination greatly adapted to the fanciful tribe.

On the other hand, mathematicians, abstract reasoners,

of no manner of attachment to persons, at least to the

visible part of them, but prodigiously devoted to the

ideas of virtue, liberty, and so forth, are generally

Whigs.’ There is much in this passage that hits the

particular case of Sir Walter Scott. But moods of

political feeling are not confined to individuals—they

sometimes become nearly general over entire nations.

At the time when Sir Walter entered public life, almost

all the respectable part of the community were replete

with a Tory species of feeling in behalf of the British

constitution, as threatened by France; and numerous

bodies of volunteer militia were consequently formed,

for the purpose of local defence against invasion from

that country. In the beginning of the year 1797, it

was judged necessary by the gentlemen of Mid-Lothian

to imitate the example already set by several counties,

by embodying themselves in a cavalry corps. This34

association assumed the name of the Royal Mid-Lothian

Regiment of Cavalry; and Mr Walter Scott

had the honour to be appointed its adjutant, for which

office his lameness was considered no bar, especially as

he happened to be a remarkably graceful equestrian.

He was a signally zealous officer, and very popular in

the regiment, on account of his extreme good-humour

and powers of social entertainment. His appointment

partly resulted from, and partly led to, an intimacy with

the most considerable man of his name, Henry, Duke

of Buccleuch, who had taken a great interest in the

embodying of the corps. It was also perhaps the

means, to a certain extent, of making him known to Mr

Henry Dundas, who was now one of His Majesty’s

Secretaries of State, and a lively promoter of the

scheme of national defence in Scotland. Adjutant

Scott composed a war-song, as he called it, for the Mid-Lothian

Cavalry, which he afterwards published in the

Border Minstrelsy. It is an animated poem, and might,

as a person is now apt to suppose, have commanded

attention, by whomsoever written, or wherever presented

to notice. Yet, to shew how apt men are to judge of

literary compositions upon general principles, and not

with a direct reference to the particular merits of the

article, it may be mentioned that the war-song was only

a subject of ridicule to many individuals of the troop.

The individual, in particular, who communicated this

information, remembered a large party of the officers

dining together at Musselburgh, where the chief amusement,

at a certain period of the night, was to repeat

the initial line, ‘To horse, to horse!’ with burlesque

expression, and laugh at ‘this attempt of Scott’s’ as a

piece of supreme absurdity.

35

[VISIT TO PEEBLESSHIRE.

In the autumn of 1797, Walter Scott, accompanied

by his brother John, and Adam Ferguson, made an

excursion to the borders of Cumberland, taking in their

way the mansion of Hallyards, in the parish of Manor,

Peeblesshire, where Dr Adam Ferguson was now temporarily

settled with his family. Here Scott resided for a

few days, visiting Barns and other places in the neighbourhood.

In a small cottage on the property of

Woodhouse resided a poor and singular recluse, dwarfed

and decrepit, by name David Ritchie, who was visited

as one of the curiosities of the district; and it was

doubtless on this occasion that Scott received those

impressions which afterwards figured in the character of

the ‘Black Dwarf.’

Ritchie, with all his oddities, had a deep veneration

for learning; and as he was told that Scott was a young

advocate, he invested him with extraordinary interest.

Ferguson gave an amusing account of the interview.

He and his companion were accommodated with seats in

the lowly and dingy hut. After grinning upon Scott for

a moment with a smile less bitter than his wont, the

dwarf passed to the door, double-locked it, and then,

coming up to the stranger, seized him by the wrist with

one of his hands, and said: ‘Man, hae ye ony poo’er?’

By this he meant magical power, to which he had

himself some vague pretensions, or which, at least, he

had studied and reflected upon till it had become with

him a kind of monomania. Scott disavowed the possession

of any gifts of this kind, evidently to the great

disappointment of the inquirer, who then turned round

and gave a signal to a huge black cat, hitherto36

unobserved, which immediately jumped up to a shelf,

where it perched itself, and seemed to the excited

senses of the visitors as if it had really been the familiar

spirit of the mansion. ‘He has poo’er,’ said the dwarf,

in a voice which made the flesh of the hearers thrill,

and Scott, in particular, looked as if he conceived himself

to have actually got into the den of one of those

magicians with whom his studies had rendered him

familiar. ‘Ay, he has poo’er,’ repeated the recluse, and

then going to his usual seat, he sat for some minutes

grinning horribly, as if enjoying the impression he had

made; while not a word escaped from any of the party.

Mr Ferguson at length plucked up his spirits, and called

to David to open the door, as they must now be going.

The dwarf slowly obeyed; and when they had got out,

Mr Ferguson observed that his friend was as pale as

ashes, while his person was agitated in every limb.

Under such striking circumstances was this extraordinary

being first presented to the real magician, who

was afterwards to give him such a deathless celebrity.

Before quitting the district, Scott had an opportunity

of visiting the old inn and posting establishment of

Miss Ritchie in Peebles, then, and for ten or twelve

years later, the principal place of accommodation for

travellers. Miss Ritchie, an elderly lady, was somewhat

of an original in manner, and there can be little doubt

that her peculiarities furnished such recollections as were

afterwards matured in the character of ‘Meg Dods of

the Cleikum Inn, St Ronans.’ Proceeding southwards,

the tourists at length reached Carlisle, and extended

their excursion to Penrith and other places of interest

in Cumberland, where an incident occurred that requires

more than a casual notice.]

Two children, a boy and girl, named Charpentier,

of French parentage, fell by circumstances under the

guardianship of the Marquis of Downshire. In time,

the boy received a lucrative appointment in India; on

his naturalisation as a British subject, changing his

name to Carpenter. Miss Carpenter was placed under

the charge of a governess, Miss Nicholson, and, requiring

a change of scene, was, through the kindness of

Lord Downshire, sent with her governess to Cumberland,

where she was to live in such pleasant rural spot

as might be found by the Rev. Mr Burd, Dean of

Carlisle. The two ladies arrived unexpectedly, when

Mrs Burd was setting out for the sake of her health to

Gilsland. This was at the end of the month of August

or beginning of September 1797.

Having duly arrived at Gilsland, which is situated

near the borders of Scotland, they took up their residence

at the inn, where, according to the custom of

such places, they were placed, as the latest guests, at

the bottom of the table. It chanced that three young

Scottish gentlemen had arrived the same afternoon,

and being also placed at the bottom of the table,

one of them happened accidentally to come into close

contact with the party of Mr Burd. Enough of conversation

took place during dinner to let the latter individuals

understand that the gentleman was a Scotchman,

and this was in itself the cause of the acquaintance

being protracted. Mrs Burd was intimate with a Scotch

military gentleman, a Major Riddell, whose regiment

was then in Scotland; and as there had been a collision

between the military and the people at Tranent, on38

account of the Militia Act, she was anxious to know if

her friend had been among those present, or if he had

received any hurt. After dinner, therefore, as they

were rising from table, Mrs Burd requested her husband

to ask the Scotch gentleman if he knew anything of the

late riots, and particularly if a Major Riddell had been

concerned in suppressing them. On these questions

being put, it was found that the stranger knew Major

Riddell intimately, and he was able to assure them, in

very courteous terms, that his friend was quite well.

From a desire to prolong the conversation on this point,

the Burds invited their informant to drink tea with

them in their own room, to which he very readily consented,

notwithstanding that he had previously ordered

his horse to be brought to the door in order to proceed

upon his journey. At tea, their common acquaintance

with Major Riddell furnished much pleasant conversation,

and the parties became so agreeable to each other,

that, in a subsequent walk to the Wells, the stranger

still accompanied Mr Burd’s party. He had now

ordered his horse back to the stable, and talked no

more of continuing his journey. It may be easily

imagined that a desire of discussing the major was not

now the sole bond of union between the parties. Mr

Scott—for so he gave his name—had been impressed,

during the earlier part of the evening, with the elegant

and fascinating appearance of Miss Carpenter, and it

was on her account that he was lingering at Gilsland.

Of this young lady, it will be observed, he could have

previously known nothing: she was hardly known even

to the respectable persons under whose protection she

appeared to be living. She was simply a lovely woman,

and a young poet was struck with her charms.

39

Next day Mr Scott was still found at the Wells—and

the next—and the next—in short, every day for a

fortnight. He was as much in the company of Mr Burd

and his family as the equivocal foundation of their

acquaintance would allow; and by affecting an intention

of speedily visiting the Lakes, he even contrived to

obtain an invitation to the dean’s country house in

that part of England. In the course of this fortnight,

the impression made upon his heart by the young

Frenchwoman was gradually deepened; and it is not

improbable that the effect was already in some degree

reciprocal. He only tore himself away, in consequence

of a call to attend certain imperative matters of business

at Edinburgh.

It was not long ere he made his appearance at Mr

Burd’s house, where, though the dean had only contemplated

a passing visit, as from a tourist, he contrived to

enjoy another fortnight of Miss Carpenter’s society. In

order to give a plausible appearance to his intercourse

with the young lady, he was perpetually talking to her

in French, for the ostensible purpose of perfecting his

pronunciation of that language under the instructions of

one to whom it was a vernacular. Though delighted

with the lively conversation of the young Scotchman,

Mr and Mrs Burd could not now help feeling uneasy

about his proceedings, being apprehensive as to the

construction which Lord Downshire would put upon

them, as well as upon their own conduct in admitting a

person of whom they knew so little to the acquaintance

of his ward. Miss Nicholson’s sentiments were, if

possible, of a still more painful kind, as, indeed, her

responsibility was more onerous and delicate. In this

dilemma, it was resolved by Mrs Burd to write to a40

friend in Edinburgh, in order to learn something of

the character and status of their guest. The answer

returned was to the effect that Mr Scott was a respectable

young man, and rising at the bar. It chanced at

the same time that one of Mr Scott’s female friends,

who did not, however, entertain this respectful notion

of him, hearing of some love adventure in which he

had been entangled at Gilsland, wrote to this very Mrs

Burd, with whom she was acquainted, inquiring if she

had heard of such a thing, and ‘what kind of a young

lady was it, who was going to take Watty Scott?’ The

poet soon after found means to conciliate Lord Downshire

to his views in reference to Miss Carpenter, and

the marriage took place at Carlisle within four months

of the first acquaintance of the parties. The match,

made up under such extraordinary circumstances, was a

happy one; a kind and gentle nature resided in the

bosoms of both parties, and they lived accordingly in

the utmost peace and amity.

Scott now commenced house-keeping in Edinburgh,

where he had hitherto lived in the paternal mansion.

We now see him as a young married man, spending the

winter in the bosom of a frugal but elegant society in

Edinburgh, and the summer months in a retired cottage

on the beautiful banks of the Esk at Lasswade; cultivating,

as before, literary tastes, and storing his mind with

his favourite kind of learning, but not as yet conscious

of his active literary powers, or thinking of aught but

the duties of his profession and the claims of his little

family. As an advocate, he had perhaps some little

employment at the provincial sittings of the criminal

court, and occasionally acted in unimportant causes as

a junior counsel; but he neither obtained, nor seemed41

qualified to obtain, a sufficient share of general business

to insure an independence. The truth is, his

mind was not yet emancipated from that enthusiastic

pursuit of knowledge which had distinguished

his youth. His necessities, with only himself to provide

for, and a sure retreat behind him in the comfortable

circumstances of his native home, were not so

great as to make an exclusive application to his profession

imperative; and he therefore seemed destined

to join what a sarcastic barrister has termed ‘the ranks

of the gentlemen who are not anxious for business.’

Although he could speak readily and fluently at the bar,

his intellect was not at all of a forensic cast. He

appeared to be too much of the abstract and unworldly

scholar, to assume readily the habits of an adroit

pleader; and even although he had been perfectly

competent to the duties, it is a question if his external

aspect and general reputation would have permitted the

generality of agents to intrust them to his hands.

Nevertheless, on more than one occasion, he made a

considerable impression on his hearers. Once, in

particular, when acting as counsel for a culprit before

the High Court of Justiciary, he exerted such powers of

persuasive oratory as excited the admiration of the

court. It happened that there was some informality in

the verdict of the jury, which at that time was always

given in writing. This afforded a still more favourable

opportunity for displaying his rhetorical powers than

what had occurred in the course of the trial, and the

sensation which he produced was long remembered by

those who witnessed it. The panel, as the accused

person is termed in Scotland, was acquitted.

Simple and manly in habits, good-humoured, and42

averse to disputation, full of delightful information,

kind and obliging to all who came near him, yet