R. Westall R.A. del. Chaˢ. Heath fc.

BY

WILLIAM FALCONER

EMBELLISHED WITH ENGRAVINGS

FROM THE DESIGNS OF

RICHᴰ. WESTALL R.A.

R. Westall R.A. del. Chaˢ. Heath fc.

LONDON;

PRINTED FOR JOHN SHARPE, PICCADILLY.

1819.

THE

SHIPWRECK;

BY

WILLIAM FALCONER.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR JOHN SHARPE,

PICCADILLY,

BY C. WHITTINGHAM, CHISWICK.

M DCCC XV III.

The Shipwreck is one of those happy productions in which talent is seen in so exquisite adaptation to the nature of the subject, that it is difficult to determine whether the author is the most indebted to his subject, or the subject to the author. No one who had not passed through the circumstances which Falconer describes, could have painted them as he has done; and of the comparatively few who have had the opportunity of drinking in the fearful inspiration of such scenes, and survived to tell of them, Falconer is the first who appears to have possessed the genius requisite to retain and embody the impression, with the vigour of imagination and the fidelity of memory. It was not more necessary[6] that he should be a poet, than that he should be a seaman. He was eminently both; and the Poem is as perfect in every technical excellence, as it is in respect to the simplicity of its plan, the classical elegance of its composition, and the pathos of its narrative. It is altogether a unique production.

Falconer originally designed the Poem, (as appears from an advertisement prefixed to the second edition, published in 1764,) for the entertainment of “the gentlemen of the sea;” but he complains that they had not formed one tenth of the purchasers. He printed that edition in a cheaper form, expressly with a view to render it more acceptable to the inferior officers. Falconer was thoroughly the seaman; he was warmly attached to the profession, and prided himself more on his nautical science than on his literary talents. The author of the Shipwreck compiled a “Universal Dictionary of the Marine,” a work which cost him years of extraordinary[7] application. The Shipwreck is said to comprise within itself the rudiments of navigation, so as even to claim to be considered as a grammar of the nautical science. The correctness of the rules and maxims laid down in the Poem, for the conduct of a ship under circumstances of perilous emergency, render it extremely valuable to the seaman. The notes originally affixed to the Poem, in explanation of the technical terms, the frequent introduction and euphonous arrangement of which, form so striking a peculiarity of the composition, were thought necessary by the Author, on account of there being, at that time, no modern dictionaries to which he could refer the reader, without forfeiting, by his implied commendation of them, his claim to the professional character he had assumed,—a claim of which he professes himself to be much more tenacious, than of his reputation as a poet.

Fresh-water critics venture out of their element in entering upon a minute examination of such a[8] poem as this. The care with which it appears to have been elaborated, has, however, left little for the invidious notice of criticism. In a few instances, the hand of correction has been injudiciously applied in the editions of the Poem subsequent to its first appearance; it is conjectured, that some of the alterations in the third edition, which are of this nature, are to be attributed to his having left the final revision to his friend Mallet, who, although a poet, was not a seaman. If the style of the Poem is faulty in any respect, it is in that of the too ambitious phraseology, by which it seems to have been Falconer’s effort to sustain the epic dignity of the narrative. Into this fault the models of the day were adapted to seduce any young writer, and the versification he adopted, presents a constant temptation to artificial and inverted forms of expression. Thus, for instance, to weigh anchor, is paraphrased in the following line:—

The frequency of the classical allusions, by which also the Poet probably intended to render his work more secundum artem poetical, is justified by their local propriety. As suggested by the surrounding scenery, they seem perfectly natural, and they are introduced, generally, with considerable skill and effect. The most pleasing parts of the Poem, however, are those in which the narration is characterized by all the simplicity of the seaman, rather than by the embellishments of a half-learned taste.

Short and simple are the annals of poor Arion’s history. He was born at Edinburgh, about the year 1730. His father was a poor but industrious barber, who had to maintain a large family, under the distressing circumstance of all his children, with the single exception of William, being either deaf or dumb. Reading English, writing, and a little arithmetic, comprised the whole of Falconer’s education, although he afterwards acquired some knowledge of the French,[10] Spanish, and Italian languages, and, it is added, even of the German. When very young, he entered on board a merchant vessel at Leith, in which he served an apprenticeship. He was afterwards servant to Campbell, the author of Lexiphanes, when purser of a ship, who is stated to have taken considerable pains in improving the mind of the young seaman, and to have subsequently felt a pride in boasting of his scholar. At what time the calamitous event occurred, which furnished the subject of the Shipwreck, has not been ascertained: he was then, it appears, employed in the Levant trade. He continued in the merchant service till 1762. In that year, the Shipwreck made its first appearance, in quarto, dedicated to his Royal Highness Edward, Duke of York, who had hoisted his flag as rear-admiral of the blue, on board the Princess Amelia, of eighty guns, attached to the fleet under Sir Edward Hawke. The Poem immediately took with the public, and Falconer, having, as it is said, at the Duke’s recommendation, quitted the merchant[11] service for the royal navy, was soon after rated a midshipman on board the Royal George.

At the peace of 1763, the Royal George was paid off, and Falconer, in the course of the same year, was appointed purser of the Glory frigate. Soon after this, he married a young lady of the name of Hicks, who survived him. From the Glory, he was, in 1767, appointed to the Swiftsure.

In 1764, he published a new edition of his Poem, in octavo, corrected and enlarged, and, in the following year, a political satire on Lord Chatham, Wilkes, and Churchill, of which it is enough to say, that had Falconer never written any thing but satire, his name would long since have been forgotten. His Universal Dictionary of the Marine, was published in 1769, at which period he was resident in the metropolis, supporting himself chiefly by his literary exertions. Among other resources, he is said to have received a pittance[12] from writing in the Critical Review, under his countryman Mallet. He had received, the preceding year, proposals from his friend Mr. Murray, to enter into company with him as a bookseller, on his taking Mr. Sandby’s business in Fleet-street; it does not appear from what cause he was led to decline the offer. While he was preparing to publish a third edition of the Shipwreck, he obtained the highly advantageous appointment of purser to the Aurora frigate, Captain Lee, which was ordered to carry out Mr. Vansittart and the other Commissioners to India, with the promise of being made their private secretary. The catastrophe is well known. The Aurora frigate sailed on the 30th of September, 1769, left the Cape on the 27th of December, and was heard of no more. It is the most probable opinion, that she foundered in the Mozambique channel, the dangers of which, the captain, in spite, as it is said, of remonstrances, was rash enough, although a stranger to its navigation, to encounter.

In 1773, a black was examined before the East India Directors, who affirmed that he was one of five persons who had been saved from the wreck of the Aurora, and that she had been cast away on a reef of rocks off Mocoa.

To these particulars, for which the public are chiefly indebted to the assiduous researches of the Rev. James Stanier Clarke, it may be added, on the same authority, that Falconer was, in his person, about five feet seven inches in height, of a thin light make, hard featured, and weather-beaten, of blunt and aukward manners, but cheerful, kind, and generous. He was, however, inclined to be satirical, and delighted in controversy: strange characteristics of a man who was a thorough seaman and a poet!

THE

SHIPWRECK.

INTRODUCTION.

DRAWN BY RICHARD WESTALL, R.A. ENGRAVED BY EDWARD PORTBURY.

PUBLISHED BY JOHN SHARPE, PICCADILLY,

OCT. 1, 1819.

THE SCENE OF WHICH LIES NEAR THE CITY OF CANDIA.

TIME,—ABOUT FOUR DAYS AND AN HALF.

I. Retrospect of the Voyage—Arrival at Candia—State of that Island—Season of the Year described.—II. Character of the Master and his Officers, Albert, Rodmond, and Arion—Palemon, Son to the Owner of the Ship—Attachment of Palemon to Anna, the Daughter of Albert.—III. Noon—Palemon’s History.—IV. Sunset—Midnight—Arion’s Dream—Unmoor by Moonlight—Morning—Sun’s Azimuth taken—Beautiful Appearance of the Ship, as seen by the Natives from the Shore.

THE

SHIPWRECK

CANTO I.

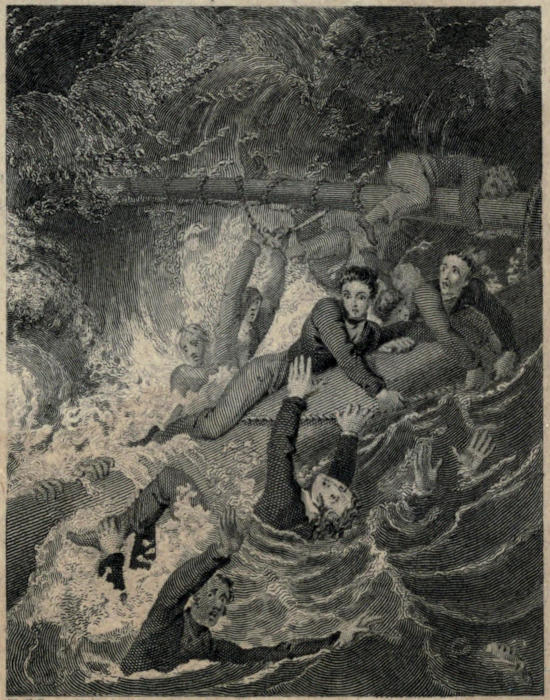

DRAWN BY RICHARD WESTALL, R.A. ENGRAVED BY WILLIAM FINDEN.

PUBLISHED BY JOHN SHARPE, PICCADILLY,

OCT. 1, 1819.

END OF THE FIRST CANTO.

THE SCENE LIES AT SEA, BETWEEN CAPE FRESCHIN, IN CANDIA, AND THE ISLAND OF FALCONERA, WHICH IS NEARLY TWELVE LEAGUES NORTHWARD OF CAPE SPADO.

TIME,—FROM NINE IN THE MORNING UNTIL ONE O’CLOCK OF THE NEXT DAY AT NOON.

I. Reflections on leaving Shore.—II. Favourable Breeze—Water-Spout—The dying Dolphin—Breeze freshens—Ship’s rapid progress along the Coast—Top-Sails reefed—Gale of Wind—Last appearance, bearing, and distance of Cape Spado—A Squall—Top-Sails double reefed—Main-Sail split—The Ship bears up; again hauls upon the Wind—Another Main-Sail bent, and set—Porpoises.—III. The Ship driven out of her course from Candia—Heavy Gale—Top-Sails furled—Top-gallant-yards lowered—Heavy Sea—Threatening Sunset—Difference of Opinion respecting the mode of taking in the Main-sail—Courses reefed—Four Seamen lost off the lee Main-yard-arm—Anxiety of the Master, and his Mates, on being near a Lee-shore—Mizen reefed.—IV. A tremendous Sea bursts over the Deck; its consequences—The Ship labours in great Distress—Guns thrown overboard—Dismal appearance of the Weather—Very high and dangerous Sea—Storm of Lightning—Severe fatigue of the Crew at the Pumps—Critical situation of the Ship near the Island Falconera—Consultation and resolution of the Officers—Speech and advice of Albert; his devout Address to Heaven—Order given to scud—The Fore Stay-sail hoisted and split—The Head Yards braced aback—The Mizen-Mast cut away.

THE

SHIPWRECK.

CANTO II.

DRAWN BY RICHARD WESTALL, R.A. ENGRAVED BY EDWARD FINDEN.

PUBLISHED BY JOHN SHARPE, PICCADILLY,

OCT. 1, 1819.

END OF THE SECOND CANTO.

THE SCENE IS EXTENDED FROM THAT PART OF THE ARCHIPELAGO WHICH LIES TEN MILES TO THE NORTHWARD OF FALCONERA, TO CAPE COLONNA IN ATTICA.

THE TIME ABOUT SEVEN HOURS,—FROM ONE, UNTIL EIGHT IN THE MORNING.

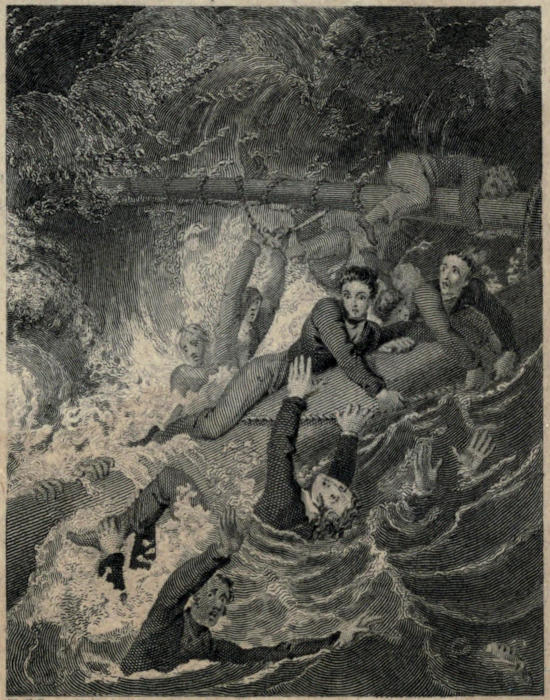

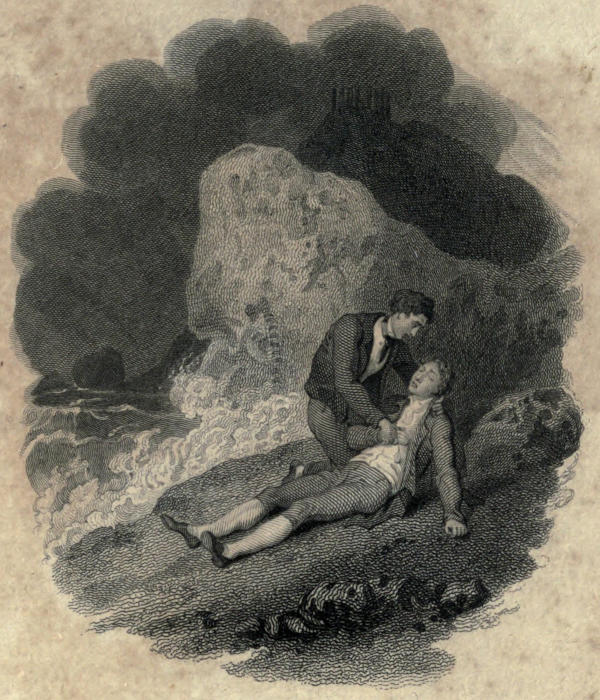

I. The beneficial influence of Poetry in the civilization of Mankind—Diffidence of the Author.—II. Wreck of the Mizen-mast cleared away—Ship put before the Wind—Labours much—Different stations of the Officers—Appearance of the Island of Falconera.—III. Excursion to the adjacent Nations of Greece renowned in Antiquity—Athens—Socrates—Plato—Aristides—Solon—Corinth—Its Architecture—Sparta—Leonidas—Invasion by Xerxes—Lycurgus—Epaminondas—Present state of the Spartans—Arcadia—Former happiness and fertility—Its present distress the effect of Slavery—Ithaca—Ulysses and Penelope—Argos and Mycæne—Agamemnon—Macronisi—Lemnos—Vulcan—Delos—Apollo and Diana—Troy—Sestos—Leander and Hero—Delphos—Temple of Apollo—Parnassus—The Muses.—IV. Subject resumed—Address to the Spirits of the Storm—A Tempest, accompanied with Rain, Hail, and Meteors—Darkness of the Night, Lightning and Thunder—Day-break—St. George’s Cliffs open upon them—The Ship, in great danger, passes the Island of St. George.—V. Land of Athens appears—Helmsman struck blind by Lightning—Ship laid broadside to the Shore—Bowsprit, Foremast, and Main Top-mast carried away—Albert, Rodmond, Arion, and Palemon strive to save themselves on the wreck of the Foremast—The Ship parts asunder—Death of Albert and Rodmond—Arion reaches the Shore—Finds Palemon expiring on the Beach—His dying Address to Arion, who is led away by the humane Natives.

THE

SHIPWRECK.

CANTO III.

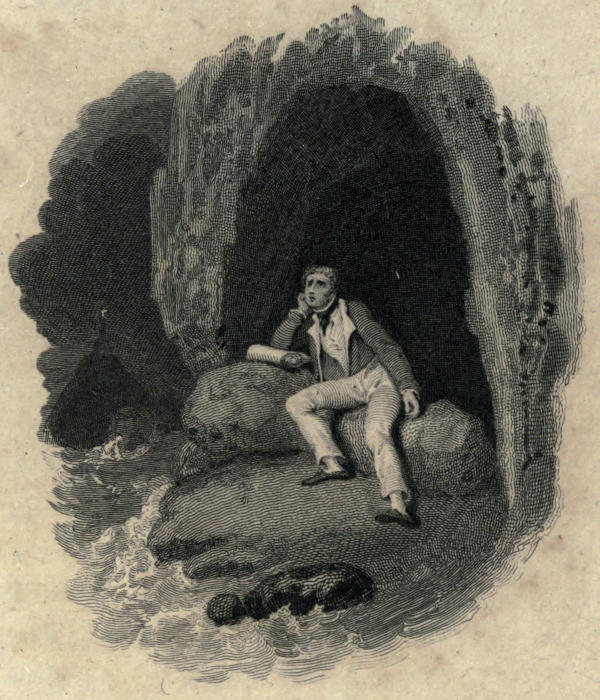

DRAWN BY RICHARD WESTALL, R.A. ENGRAVED BY F. ENGLEHEART.

PUBLISHED BY JOHN SHARPE, PICCADILLY,

OCT. 1, 1819.

THE

SHIPWRECK.

ELEGY.

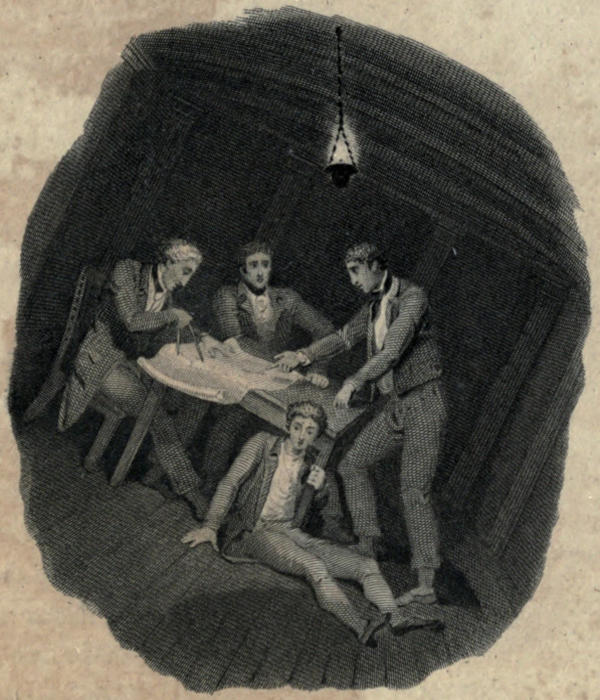

DRAWN BY RICHARD WESTALL, R.A. ENGRAVED BY F. ENGLEHEART.

PUBLISHED BY JOHN SHARPE, PICCADILLY,

OCT. 1, 1819.

A bar is known, in hydrography, to be a mass of earth, or sand, that has been collected by the surge of the sea, at the entrance of a river, or haven, so as to render navigation difficult, and often dangerous. A shelf, or shelve, so called from the Saxon Schylf, is a name given to any dangerous shallows, sand-banks, or rocks, lying immediately under the surface of the water.

Alluding to the ever memorable siege of Candia, in 1669.

The windlass is a large cylindrical piece of timber used in merchant ships to heave up the anchors: it is furnished[148] with strong iron pauls to prevent it from turning back by the efforts of the cable, when charged with the weight of the anchor, or strained by the violent jerking of the ship in a tempestuous sea. As the windlass is heaved about in a vertical direction, it is evident that the effort of an equal number of men acting upon it will be much more powerful than on the capstan. It requires, however, some dexterity and address to manage the handspec, or lever, to the greatest advantage; and to perform this the sailors must all rise at once upon the windlass, and, fixing their bars therein, give a sudden jerk at the same instant; in which movement they are regulated by a sort of song pronounced by one of the number. The most dexterous managers of the handspec, in heaving at the windlass, are generally supposed to be the colliers of Northumberland; and of all European mariners, the Dutch are certainly the most awkward and sluggish in this manœuvre.

From the Saxon teohan. Towing is chiefly used, as in the present instance, when a ship for want of wind is forced toward the shore by the swell of the sea.

1. Stud, or studding-sails, called by the French Banettes en etui, are light sails, which are extended in moderate breezes beyond the skirts of the principal sails: where they appear as wings upon the yard-arms. 2. Stay-sail; though the form of sails is so extremely different, they may all be divided into sails which have either three or[149] four sides: a stay-sail comes under the first class, and receives its name from a large strong rope on which it is hoisted, called a stay, employed to support the mast, by being extended from its upper end towards the fore part of the ship, as the shrouds (a range of large ropes), are extended to the right and left of the mast, and behind it. The yards of a ship are said to be square, when they hang across the ship, at right angles, with the mast; and braced, when they form greater or lesser angles with the ship’s length.

The magnetical Azimuth, a term which astronomers have borrowed from the Arabians, is the apparent distance of the sun from the north or south point of the compass; and this is discovered, by observing with an azimuth compass, when the sun is ten or fifteen degrees above the horizon.

Before the art of coppering ships’ bottoms was discovered, they were painted white. The wales are the strong flanks which extend along a ship’s side, at different heights, throughout her whole length, and form the curves by which a vessel appears light and graceful on the water: they are usually distinguished into the main-wale, and the channel-wale.

In our largest merchantmen, the tops, or platforms,[150] which surround the heads of the lower mast, (for every ship’s mast, taken in its apparent length, consists of the lower mast, the top-mast, and top-gallant mast) are fenced on the aft, or hinder side, by a rail of about three feet high, stretching across, supported by stanchions; between which a netting is usually constructed, the outside of which was formerly covered with red baize, or canvass painted red, and was called the top armor; being a sort of blind against the enemy for the men who were there stationed. This name is now nearly lost, and the netting is always covered with black canvass.

The scud is a name given by seamen to the lowest and lightest clouds, which are swiftly driven along the atmosphere by the winds.

When the wind crosses a ship’s course, either directly or obliquely, that side of the ship upon which it acts is termed the weather side; and the opposite one, which is then pressed downwards, is termed the lee side; all on one side of her is accordingly called to windward, and all on the opposite side to leeward: hence also are derived the lee cannon, the lee braces, weather braces, &c.

Topsails, reef, blocks.

Topsails are large square sails, of the second magnitude and height; as the courses are of the first magnitude, and the lowest.—Reefs are certain divisions of the sail, which are taken in or let out in proportion to the increase or[152] diminution of the wind. Blocks are what landsmen would rather term, from the French word, (poulie) pullies.

Halyards—bow-lines—clue-lines—reef tackles—earings.

Halyards are those ropes by which sails are hoisted or lowered. Bow-lines are ropes fastened to the outer edge of square sails in three different places, that the windward edge of the sail may be bound tight forward on a side wind, in order to keep the sail from shivering. Clue-lines are fastened to the lower corners of the square sails, for the more easy furling of them. Reef-tackles are ropes fastened to the edge of the sail, just beneath the lowest reef; and being brought down to the deck by means of two blocks, are used to facilitate the operation of reefing. Earings are small ropes employed to fasten the upper corners of the principal sails, and the extremities of the reefs, to the respective yard-arms, particularly when any sail is to be close furled.

The mizen is a large sail bent to the mizen mast, and is commonly reckoned one of the courses, which consist of the main-sail, fore-sail, and mizen. As the word brails is a general name given to all the ropes which are employed to haul up the bottoms, lower corners, and skirts of the great sails; so the drawing them together, for the more ready operation of furling, is called brailing them up. The effect which the operation of brailing up the mizen produces, is noticed in the last note of this Canto.

Clue-garnets are the same to the main-sail and fore-sail, which the clue-lines are to all other square-sails, and are hauled up when the sail is to be furled or brailed. Sheets: it is necessary in this place to remark, that the sheets, which are universally mistaken by our English poets for the sails, are in reality the ropes that are used to extend the clues, or lower corners of the sails, to which they are attached.

The reason for putting the helm a-weather, or to the side next the wind, is to make the ship veer before it when it blows so hard that she cannot bear her side to it any longer. Veering, or wearing, is the operation by which a ship, in changing her course from one board to the other, turns her stern to windward; the French term is, virer vent arriere.

The helmsman, from the French, timonnier.

Called with more propriety the fore top-mast stay-sail: it is of a triangular shape, and runs upon the fore top-mast stay, over the bowsprit: it consequently has an influence on the fore-part of the ship, as the mizen has on the hinder part; and, when thus used together, they may[154] be said to balance each other. See also the last note of this Canto.

The main-sail and fore-sail of a ship are furnished with a tack on each side, which is formed of a thick rope tapering to the end, having a knot wrought upon the largest extremity, by which it is firmly retained in the clue of the sail: by this means the tack is always fastened to windward, at the same time that the sheet extends the sail to leeward.

Bunt-lines are ropes fastened to the bottoms of the square sails to draw them up to the yards, when the sails are brailed or furled.

A yard is said to be braced, when it is turned about the mast horizontally, either to the right or left: the ropes employed in this service are called the larboard and starboard braces.

Brails, head-ropes, robands.

Brails: a general name given to all the ropes which are employed to haul up, or brail the bottoms, and lower corners of the great sails. A rope is always attached to the edges of the sails, to strengthen and prevent them[155] from rending: those parts of it which are on the perpendicular or sloping edges, are called leech ropes, that, at the bottom, the foot rope, and that on the top, or upper edge, the head-rope. Robands, or rope bands, are small pieces of rope, of a sufficient length to pass two or three times about the yards, in order to fix to them the upper edges of the respective great sails: the robands for this purpose are passed through the eyelet holes under the head-rope.

The braces are here slackened, because the lee-brace confining the yard, the tack could not come down until the braces were cast off. The chess tree, called by the French taquet d’amure, consists of a perpendicular piece of wood, fastened with iron bolts, on each side the ship: in the upper part of the chess-tree is a large hole, through which the tack is passed; and when the clue or lower corner of the sail comes down to it, the tack is said to be aboard. Taught, the roide of the French, and dicht of the Dutch sailors, implies the state of being extended, or stretched out. Tally, is a word applied to the operation of hauling the sheets aft, or toward the ship’s stern. To belay is to fasten.

The rolling tackle is an assemblage of blocks or pullies,[156] through which a rope is passed, until it becomes four-fold, in order to confine the yard close down to leeward when the sail is furled, that the yard may not gall the mast, from the rolling of the ship. Gaskets are platted ropes to wrap round the sails when furled.

Top-gallant-yards, travellers, back-stays, top-ropes, parrels, lifts, topped, booms.

Top-gallant-yards, which are the highest ones in a ship, are sent down at the approach of an heavy gale, to ease the mast-heads. Travellers are iron rings furnished with a piece of rope, one end of which encircles the ring to which it is spliced: they are principally intended to facilitate the hoisting or lowering of the top-gallant yards; for which purpose two of them are fixed on each back-stay; which are long ropes that reach on each side of the ship, from the top-masts (which are the second in point of height) to the chains. Top-ropes are employed to sway up or lower the top-masts, top-gallant-masts, and their respective yards. Parrels are those bands of rope, by which the yards are fastened to the masts, so as to slide up and down when requisite; and of these there are four different sorts. Lifts are ropes which reach from each mast-head to their respective yard-arms. A yard is said to be topped, when one end of the yard is raised higher than the other, in order to lower it on deck by means of the top-ropes. Booms are spare masts, or yards, which are placed in store on deck, between the main and foremast, immediately to supply the place of any that may be carried away, or injured, by stress of weather.

This is particularly mentioned, not because there was, or could be, any dispute at such a time between a master of a ship, and his chief mate, as the former can always command the latter; but to expose the obstinacy of a number of our veteran officers, who would rather risk any thing than forego their ancient rules, although many of them are in the highest degree equally absurd and dangerous. It is to the wonderful sagacity of these philosophers, that we owe the sea maxims of avoiding to whistle in a storm, because it will increase the wind; of whistling on the wind in a calm; of nailing horse-shoes on the mast to prevent the power of witches; of nailing a fair wind to the starboard cat-head, &c.

It has been already remarked, that the tack is always fastened to windward; consequently, as soon as it is cast loose, and the clue-garnet is hauled up, the weather clue of the sail immediately mounts to the yard; and this operation must be carefully performed in a storm, to prevent the sail from splitting, or being torn to pieces by shivering.

To stand by any rope is, in the language of seamen, to take hold of it. Whenever the sheet is cast off, it is necessary to pull in the weather brace, to prevent the violent shaking of the sail.

The spilling lines, which are only used on particular occasions in tempestuous weather, are employed to draw together, and confine the belly of the sail, when inflated by the wind over the yard.

The violence of the gale forcing the yard much out, it could not easily have been lowered so as to reef the sail, without the application of a tackle, consisting of an assemblage of the pullies, to haul it down on the mast: this is afterwards converted into rolling tackle, which has been already described in a former note.

Jears, or geers, answer the same purpose to the main-sail, fore-sail, and mizen, as haliards do to all inferior sails. The tye, a sort of runner, or thick rope, is the upper part of the jears.

Reef-lines, shrouds, reef-band, outer and inner turns.

Reef-lines, are only used to reef the main-sail and fore-sail. Shrouds, so called from the Saxon scrud, consist of a range of thick ropes stretching downwards from the mast heads, to the right and left sides of a ship, in order to support the masts, and enable them to carry sail; they are also used as rope ladders, by which seamen ascend or[159] descend to execute whatever is wanting to be done about the sails and rigging. Reef-band, consists of a piece of canvass sewed across the sail, to strengthen it in the place where the eyelet-holes of the reefs are formed. The outer turns of the earing serve to extend the sail along its yard; the inner turns are employed to confine its head-rope close to its surface.

A sea is the general term given by sailors to an enormous wave; and hence, when such a wave bursts over the deck, the vessel is said to have shipped a sea.

To weather a shore is to pass to windward of it, which at this time was prevented by the violence of the gale. Drift is that motion and direction, by which a vessel is forced to leeward sideways, when she is unable any longer to carry sail; or, at least, is restrained to such a portion of sail, as may be necessary to keep her sufficiently inclined to one side, that she may not be dismasted by her violent labouring produced by the turbulence of the sea.

To try, is to lay the ship with her side nearly in the direction of the wind and sea, with her head somewhat inclined to windward; the helm being fastened close to the lee-side, or in the sea language, hard a-lee, to retain[160] her in that position. See a further illustration in the last note of this Canto.

Topping lift, knittle, throt.

A tackle, or assemblage of pullies, which tops the upper end of the mizen-yard. This line, and the six following, describe the operation of reefing and balancing the mizen. The knittle is a short line used to reef the sails by the bottom. The throt is that part of the mizen-yard which is close to the mast.

Companion, binacle.

The companion is a wooden porch placed over the ladder that leads down to the cabins of the officers. The binacle is a case, which is placed on deck before the helm, containing three divisions; the middle one for a lamp, or candle, and the two others for mariners’ compasses. There are always two binacles on the deck of a ship of war, one of which is placed before the master, at his appointed station. In all the old sea books it was called bittacle.

The well is an apartment in a ship’s hold, serving to inclose the pumps: it is sounded by dropping down a measured iron rod, which is connected with a long line—The brake is the pump-handle.

The waist is that part of a ship which is contained between the quarter deck and forecastle; or the middle of[161] that deck which is immediately below them. When the waist of a merchant ship is only one or two steps in descent from the quarter deck and forecastle, she is said to be galley built; but when it is considerably deeper, as with six or seven steps, she is then called frigate built.

The lee-way, or drift, in this passage are synonymous terms.—The true course and distance resulting from these traverses is discovered by collecting the difference of latitude, and departure of each course; and reducing the whole into one departure, and one difference of latitude, according to the known rules of trigonometry: this reduction will immediately ascertain the base and perpendicular; or, in other words, will give the difference of latitude and departure, to discover the course and distance.

The movement of scudding, from the Swedish word skutta, is never attempted in a contrary wind, unless, as in the present instance, the condition of a ship renders her incapable of sustaining any longer on her side, the mutual efforts of the winds and waves. The principal hazards, incident to scudding, are generally a pooping sea; the difficulty of steering, which exposes the vessel perpetually to the risk of broaching-to; and the want of sufficient sea-room: a sea striking the ship violently on the stern may dash it inwards, by which she must inevitably[162] founder; in broaching-to suddenly, she is threatened with being immediately overset; and, for want of sea-room, she is endangered with shipwreck on a lee-shore; a circumstance too dreadful to require explanation.

A ship is said to be water-logged, when, having received through her leaks a great quantity of water into her hold, she has become so heavy and inactive on the sea, as to yield without resistance to the efforts of every wave that rushes over the deck. As in this dangerous situation the centre of gravity is no longer fixed, but fluctuates from place to place, the stability of the ship is utterly lost: she is therefore almost totally deprived of the use of her sails, which operate to overset her, or press the head under water: hence there is no resource for the crew, except to free her by the pumps, or to abandon her for the boats as soon as possible.

Hatches, lanyard.

Hatches, a term which seamen sometimes incorrectly use for gratings; a sort of open cover for the hatchways, formed by several small laths, or battens, which cross each other at right angles, leaving a square interval between: these gratings are not only of service to admit the air and light between decks, but also to let off the smoke of the great guns during action.

Lanyard, or laniard, is a short piece of line fastened to different things on board a ship, to preserve them in a particular place; such are the lanyards of the gun-ports, the lanyard of the buoy, the lanyard of the cat-hook, &c.; but the lanyards alluded to in the above line, were those[163] by means of which the shrouds were extended; or, as a sailor would express himself, taught.

The fore stay-sail being one of the sails which command the fore part of the ship, is for that reason hoisted at this time, to bear her fore-part round before the wind: for the same reason, after it is split, the foremast yards are braced aback; that is, so as to form right angles with the direction of the wind. For a further illustration of this, see the subsequent note.

“When a ship is forced by the violence of a contrary wind to furl all her sails, if the storm increases, and the sea continue to rise, she is often strained to so great a degree, that, to ease her, she must be made to run before their mutual direction; which, however, is rarely done but in cases of the last necessity: now, as she has no head-way, the helm is deprived of its governing power, as the latter effect is only produced in consequence of the former: it therefore necessarily requires an uncommon effort to wheel, or turn her, into any different position. It is an axiom in natural philosophy, that ‘Every body will persevere in its state of rest, or moving uniformly in a right line, unless it be compelled to change its state by forces impressed; and that the change of motion is proportional to the moving force impressed, and is made according to the right line in which that force acts.’

“By this principle it is easy to conceive how a ship is[164] compelled to turn into any direction, by the force of the wind acting upon her sails in lines parallel to the plane of the horizon: for the sails may be so set, as to receive the current of air either directly, or more or less obliquely; and the motion communicated to the ship must of necessity conspire with that of the wind. As therefore the ship lies in such a situation as to have the wind and sea directly on her side; and these increase to such an height, that she must either founder, or scud before the storm; the aftmost sails are first taken in, or so placed that the wind has very little power on them: and the head-sails, or fore-mast sails, are spread abroad, so that the whole force of the wind is exerted on the ship’s forepart, which must therefore of necessity yield to its impulse. The prow being thus put in motion, its motion must conspire with that of the wind, and will be pushed about so as to run immediately before it; for this reason, when no more sail can be carried, the fore-mast yards are braced aback; that is, in such a position as to receive all the current of air they can contain directly to perform the operation of head-sails; and the mizen-yard is lowered to produce the same effect as furling, or placing obliquely the aftmost sails; and this attempt being found insufficient, the mizen-mast is cut away, which must have been followed by the main-mast, if the expected effect had not taken place.”

The wind is said to enlarge, when it veers from the side towards the stern. To square the yards is, in this place, to haul them directly across the ship’s length.

Steady! is an order to steer the ship according to the line on which she then advances, without deviating to the right or left.

The left side of a ship is called port in steering, that the helmsmen may not mistake larboard for starboard. In all large ships, the tiller, (or long bar of timber, that is fixed horizontally to the upper end of the rudder), is guided by a wheel, which acts upon it with the powers of a crane or windlass.

Poop, bow.

Poop, from the Latin word puppis, is the hindmost and highest deck of a ship. The bow is the rounding part of[166] a ship’s side forward, beginning at the place where the planks arch inwards, and terminating where they close at the stem or prow.

On the beam, implies any distance from the ship on a line with the beams, or at right angles with the keel: thus, if the ship steers northward, any object lying east, or west, is said to be on her starboard or larboard beam.

The great difficulty of steering the ship at this time before the wind, is occasioned by its striking her on the quarter, when she makes the least angle on either side; which often forces her stern round, and brings her broadside to the wind and sea: this is an effect of the same cause which is explained in the last note of the second Canto.

The main top-mast stay comes to the fore-mast head, and consequently depends upon the fore-mast as its support. The cap is a strong thick block of wood, used to confine the upper and lower masts together, as the one is raised at the head of the other. The principal caps of a ship are those of the lower masts.

The sea at this time ran so high, that it was impossible to descend from the mast-head without being washed overboard.

FINIS.

Printed by C. Whittingham, Chiswick.