Variable spelling and hyphenation have been retained. Minor punctuation inconsistencies have been silently repaired. A list of the changes made can be found at the end of the book.

INTERNATIONAL HUMOUR.

Edited by W. H. DIRCKS.

THE HUMOUR OF GERMANY.

THE

HUMOUR OF GERMANY

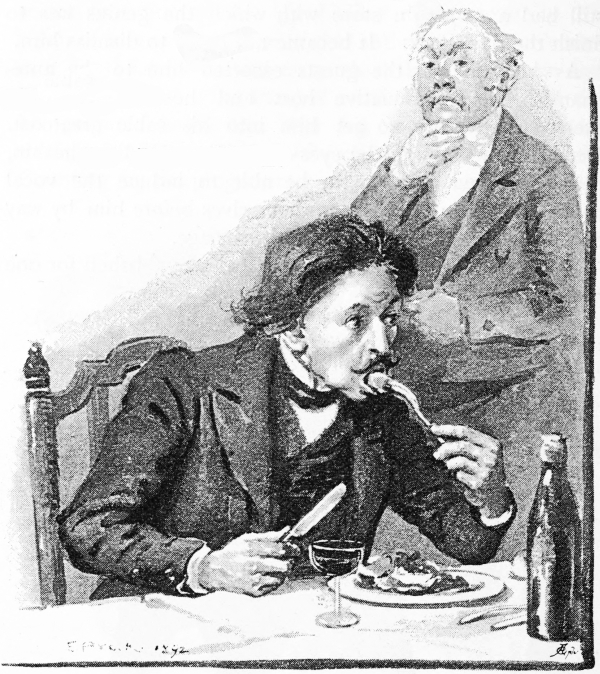

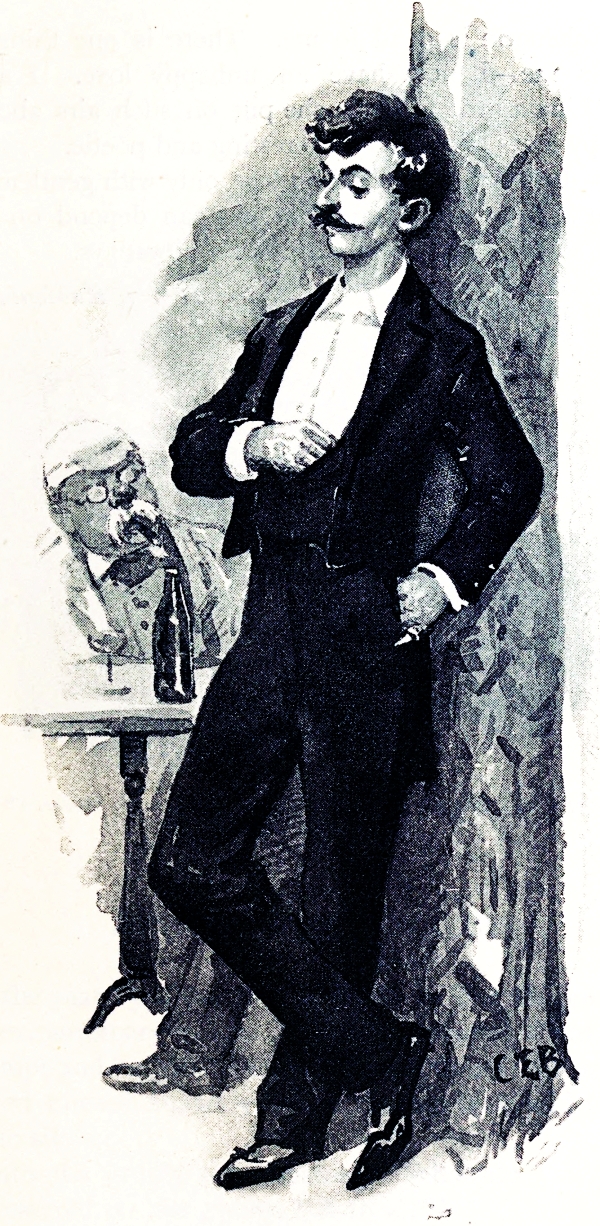

SELECTED AND TRANSLATED, WITH INTRODUCTION AND BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX, BY HANS MÜLLER-CASENOV: WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY C. E. BROCK.

LONDON

1892

WALTER SCOTT

LTD.

[vii]

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Introduction | xi |

| Master Fox, the Confessor—Hugo von Trimberg (1260-1309) | 1 |

| St. Peter’s Lesson—Hans Sachs (1494-1576) | 4 |

| A Raid on the Parson’s Kitchen—Christoffel von Grimmelshausen (1620-1676) | 6 |

| The Revolt in the Theatre—Ludwig Tieck (1773-1853) | 12 |

| The Unaccountable Stranger—Ludwig Tieck | 24 |

| Van der Kabel’s Last Will and Testament—Jean Paul Friedrich Richter (1763-1825) | 28 |

| Division of Labour in Matters Sentimental—Jean Paul Friedrich Richter | 35 |

| A Tender-Hearted Critic—Jean Paul Friedrich Richter | 37 |

| The Accident of the Distinguished Stranger—August von Kotzebue (1761-1819) | 38 |

| How the Vicar came Around—Heinrich Zschokke (1771-1848) | 49[viii] |

| The Man who Sold his Shadow—A. von Chamisso (1781-1838) | 62 |

| The Ghost of Dr. Ascher—Heinrich Heine (1799-1856) | 66 |

| Tourists at the Brocken—Heinrich Heine | 70 |

| My Appreciative Friend—Heinrich Heine | 72 |

| “Madam, Do you Know the old Play?”—Heinrich Heine | 73 |

| Verses from Heine | 100 |

| About Money—M. G. Saphir (1795-1858) | 105 |

| A Night in the Bremer Rathskeller—Wilhelm Hauff (1802-1827) | 107 |

| The Duel with the Devil—Wilhelm Hauff | 125 |

| Editorial Co-operation—Wilhelm Hauff | 130 |

| Mozart’s Journey to Prague—Edward Mörike (1804-1875) | 133 |

| A Rabid Philosopher (Auch Einer)—Friedrich Theodor v. Vischer (1807-1889) | 146 |

| His Serenity will build a Palace—Fritz Reuter (1810-1874) | 159 |

| His Serenity and the Thunder-storm—Fritz Reuter | 167 |

| The Lieutenant’s Dinner—Fritz Reuter | 177 |

| The Higher Altruism—Fritz Reuter | 181 |

| My Pictures—Fritz Reuter | 182 |

| Liszt expected at an Evening Party—E. Kossak (1814-1880) | 188 |

| A Prince in Disguise—Gottfried Keller (1815-1887) | 196[ix] |

| A Disreputable Saint—Gottfried Keller | 203 |

| Military Inspection—F. W. Hackländer (1816-1877) | 221 |

| The King of Maccaroonia—Professor Volkmann (1830-1891) | 225 |

| The Sad Tale of Seven Kisses—Professor Volkman | 232 |

| A Country Comedy—Heinrich Schaumberger (1843-1874) | 235 |

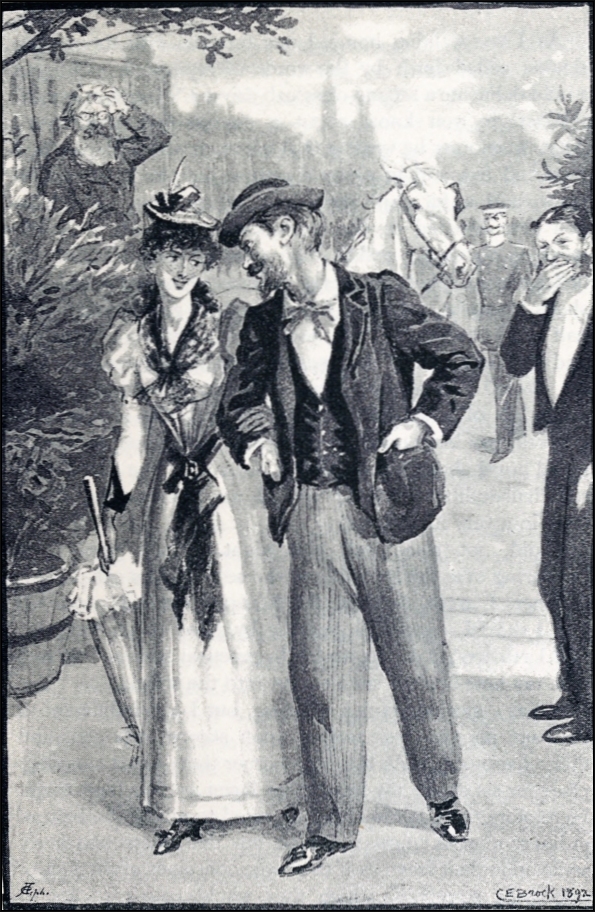

| How Blindschleicher went Courting—P. K. Rosegger | 249 |

| “Whom First we Love”—H. von Kahlenberg | 255 |

| Wooing the Gallows—W. H. Riehl | 261 |

| Elective Affinities—Franz von Schönthan | 274 |

| Hot Punch—Julius Stinde | 281 |

| Woman—Bogumil Golz (1801-1870) | 284 |

| A Christmas Tale—Eduard Pötzl | 288 |

| The Case of Minckwitz—Paul Lindau | 293 |

| Students’ Songs— | |

| Old Assyrian-Jonah—Joseph Victor Scheffel | 304 |

| Heinz von Stein | 305 |

| Brigand Song | 306 |

| A Farthing and a Sixpence—Count Albert von Schlippenbach | 307 |

| The Teutoburger Battle—J. V. Scheffel | 308 |

| [x]The Last Pair of Breeches—J. V. Scheffel | 311 |

| Enderle von Ketsch—J. V. Scheffel | 313 |

| God and the Lover—Old German | 316 |

| Unintentional Witticisms of the Absent-minded German Professor | 317 |

| The Incarceration of the Herr Professor—Ernst Eckstein | 320 |

| Our War-Correspondent—Julius Stettenheim | 335 |

| Schnorps’ Swallow-Tail—Fritz Brentano | 339 |

| The Man of Order—Johannes Scherr | 352 |

| The Luxury of Going about Incognito—Hans Arnold | 359 |

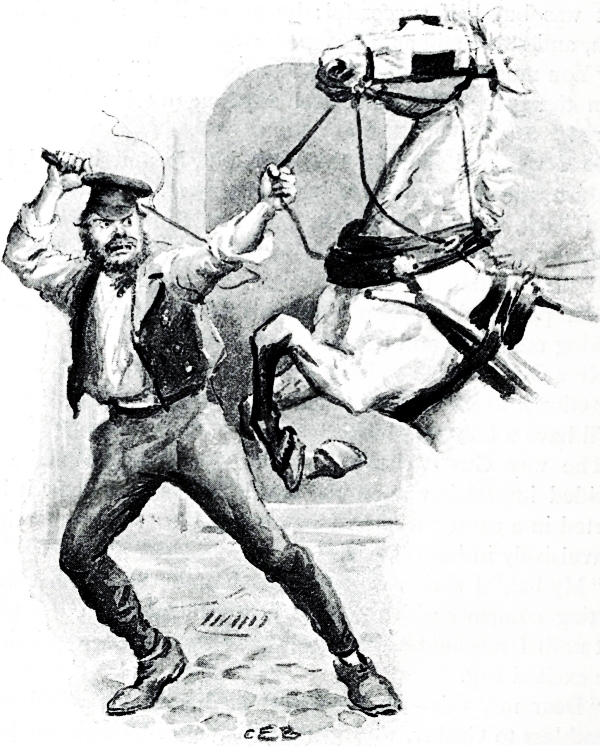

| The Inner Life of the Second-Class Cab-Driver—Ernst von Wildenbruch | 382 |

| Bon-Mots | 404 |

| The Early Days of a Genius—Wilhelm Raabe | 408 |

| Newspaper Humour | 423 |

| Biographical Index of Writers | 431 |

[xi]

In endeavouring to bring together examples of so significant and at the same time elusive a phase of national character—literary as well as psychological—as a nation’s humour, it were of course vain to seek to make each selection typical in itself—typical, that is, in the sense of referring to the broad basis of a nation’s individuality in respect of its humour as distinguished from other nations.

A general idea can only be obtained by scanning a broad field; here, as elsewhere, details have little meaning unless considered in their relation to the broader outlook. A constant interplay of varied influences has to be taken into account. The purely national aspect is obtruded upon by the individuality of each author, which nowhere expresses with such effect as in the literature of humour. The time of writing, considered historically, with its political tendencies, has also to be considered; its church dependence perhaps, and the peculiar trend of its social interests. It is intruded upon also by the time considered in its relation to literature as a whole, to the tendencies of form and style predominant at given periods.

Furthermore, there are strictly local peculiarities, subdividing Germany itself. It is more especially these that the student of literature, unless he be also a student of ethnological influences, is likely to wrongly estimate, while it is of the utmost importance that they be borne in mind to arrive at a just view of qualities that oversway minor differences, which are often the first to catch the eye. The more the Comic Muse is bound within the narrow limits of place, time, and personality, the more is she in her element. She of all muses is a painter[xii] of detail, versed in the art of reproducing punctiliously those petty traits which disengage her subject from all broader problems, and make it effective in proportion to its unimportance to the world’s general affairs.

Writers upon the theory of humour are apt to deplore the absence of just such local land-marks in Germany as are strongly characteristic and still recognisable to the foreigner. It would appear to me that they have done so with some injustice. The Volkscharacter of southern and northern Germany, of the lowlands, and the Franco-Bavarian and Suabian districts, even of the various centres of civilisation, the large towns, is abundant in those differentiating qualities which go to make up originality of manner. The modes of thought and feeling characterising the population of different districts bear a stamp so distinct that one is inclined to consider them more strongly marked by provincial locality than by nationality.

In these days dialect proper, having gained the prestige of comparative rarity, like a peasant’s national costume, or a bit of bric-à-brac, has been favoured by the humorist, although its reproduction in our literature has well-nigh insurmountable difficulties to cope with. The Low German, one of the most interesting of German dialects, because, historically, the most intact, and the most incapable of amalgamation with the language that has superseded it, had been left to grow rusty so far as literature was concerned, until Fritz Reuter rescued it from threatening oblivion, and made it the vehicle of a naïve and spontaneous genre of humour, to which it lent itself with singular charm and appropriateness.

The cause of the former neglect of Low German as a means of literary expression was very obvious, and there was no gainsaying the justice of it—viz., that it is used to-day only by the lower classes of Northern Germany, and that among readers there is but a very limited number to whom it is more comprehensible than a foreign language would be. It is this fact also which explains why Fritz Reuter, the most intimate and sympathetic of German humorists, although extensively read, has never attained the widest popularity.

Fundamentally, the German character appears to be averse to humour. Its mirth does not come to it spontaneously, a gift[xiii] of the gods, arising out of the mere exuberance of being. This nation shares the temperament of all northern races, it moves more to the minor strains of feeling, to the Adagio which Richard Wagner found so aptly expressive of its character. It is quick to respond to things mystic, and yearns over the vague grace of twilight moods. It worships at the shrine of the hapless Prince of Denmark.—I say fundamentally, for, looking at the life of the nation as it appears to-day, in those pleasures of the lower and middle classes which have their scene of action in the out-of-door world, there would appear to be in plenty a spirit of merry-making and pleasure-seeking inherent in the German character. The mere primitive love of a good time, however, is inseparably connected with those classes representing, in a manner, a child-like stage of intellectual development the world over, and is not characteristic in any special sense of the German people.

It is safe to admit that a certain lightness of disposition, which seems indispensable to the humorous attitude, is absent among those race-qualities which go to make up the German nature pure and simple. If the nation has developed within itself those germs which have blossomed into a sense of the humorous; if it has passed through all those early stages of perception and expression which have culminated in a humorous literature of sturdy strength; if it has found at length a humorous literature (with Gottfried Keller for its prophet, and F. T. Vischer for its critic and exponent), it is due probably to a complexity of influences somewhat difficult to determine.

However free in its purely literary aspect humour may be from all ulterior purpose and aim, the tale of its growth with us is largely interwoven with impulses received from outside sources and sources didactic and philosophical. Outwitting the devil, the theme that recurs again and again as the oldest form of farcical expression in mediæval Germany, meant dealing with the stresses of adverse circumstance. This was the first step taken on the road to humour in Germany. The Powers of Evil had all the brute force upon their side; there was no coping with them, except by sharpening one’s wits and irritating them by practical jokes until they might yield. The laugh that followed had all the hard ring of the victor’s triumphant[xiv] scorn. Early satirical writings were imbued with a like spirit. There was the lash to be swung at some enemy, and derision at his downfall was tempered by no kindlier emotion. There was a grim attitude of self-defence throughout it all. Indeed, it is only in going back painfully step by step that one is enabled to discern in this early literature the germs of humour at all.

The farces and puppet-shows at country fairs and the burlesques at the early theatre began to make room for the idea of retaliation. It became a question of clown against clown. The supremacy was never yielded long to one side. Laying aside all personal interest in the matter for the time being, there was an impartial shout of laughter at him who got the most kicks and cuffs. The popular mind began to rise above the situation, to put itself in the position of an unbiassed spectator, and to take delight in merely putting down whatever asserted itself. As an instance of this may be counted the practice of granting the devil, or a person disguised as such, a hearing in church on certain days of the year instead of the parish priest.

Then the sense of discrepancy between things great and small, things important and unimportant, the world of the senses and the world of the spirit, began to enter the popular perception, the impossibility of reconciliation, and, as a consequence, the pleasure of turning this world topsy-turvy, and so demonstrating the supremacy of the individual.

Side by side with this development, or partly perhaps based upon it, went the philosophic development. Thinkers, dreamers, and philosophers went on constructing a universe according to the laws of their individual minds, a universe containing nothing at all to be laughed at, and for many decades scholars were deeply buried in obstruse problems and finely-spun theories and systems, the lighter muse of poetry and art for the most part following but humbly and timorously from afar. But when philosophy and theology had spoken at large, and the mystery and fatal contradiction at the heart of things had not been unravelled, the pale brooding of some turned to melancholy, with others it turned to boisterous living and philosophic indifferentism.

[xv]

Then it was that irony, directed upon the inordinate intellectual ambitions of man, removed him half imperceptibly into the sphere of the ludicrous. Self-irony may be the result of misanthropy, but it is certainly the beginning of a cure. One finds oneself to be made up of two absurdly contradicting hemispheres, as well as the rest of the world; the sense of the universal incongruity seems to make the case less tragic. To pass through this stage into the clearer atmosphere of conscious reconciliation with the actuality of things, of placid acceptance of the ups and downs, the shortcomings inherent in things, and in human nature withal,—into the atmosphere of pure humour, unperturbed by the possibility of personal disappointment, is a long step, easy to some, to others impossible. And it would seem that German Humour—taking the term in its widest sense as signifying subjective apprehension on the one hand and artistic expression on the other—is less the result of a temperamental predisposition than the culmination of a development. With a turn for flaccid sentimentalism, and by nature inclined to take themselves very seriously, it was a reaction, a bankruptcy in metaphysical methods that inaugurated and established something of a humorous Weltanschauung. The often oppressively heavy Zeitgeist has borne along its own corrective in the literature of two centuries as on an ever-strengthening under-current. There have been silent forces at play working imperceptibly through the innate robustness of the national character. It was this undeniable robustness which could not for long brook the extravagancies of weak emotionalism. Revolt was opened upon it on the one hand by the spirit of exact science, on the other by the need of æsthetic equilibrium. These two tendencies, the æsthetic and the scientific, are still contending for the field with much ado and bustle in some quarters.

Though a nation counting Heine and Lichtenberg among its own, it is not in the spielende Urtheil, as Jean Paul has called inspired sallies of wit, that German humour specially distinguishes itself; now and again there it has its moods of riotous absurdity; but where it is most characteristic is in the telling of the humorous tale, lovingly handled in its details, the pathetic verging very near upon the comic, finally succumbing[xvi] in a ripple of good-natured laughter at somebody or other who is really not so very bad, but only very human, and for whose misfortunes—poor devil!—we may have a kindly feeling. Then we have a mastership in spectral stories, uncanny and imaginative, leaving the reader’s mind in a delightful condition of doubt as to their actual meaning and significance; and we have also the expression of the spirit of poetic adventure,—a determination to have fun at all hazards, either with the public or else at the public, if perchance it should prove too dull to be taken into partnership. There is much of this in Chamisso’s Peter Schlemihl, which, in the face of many dizzy structures of elucidation that have been based upon it, remains so truly humorous and so profoundly touching.

It is by no means always the funny element that predominates in German writings of a humorous tendency. Their office seems to be more to suggest the effect which these lighter moods of fancy have upon the serious affairs of life, and in studying the humour of Germany in a spirit of literary criticism it is indispensable to take these two aspects in their action and reaction upon each other. There is a psychical development of the individual which runs parallel to that of the nation. In confirmation of the theory of humorous development here faintly outlined, it may be said that in Germany, humorous perception is for the most part not the possession of youth. It is not until the need of a corrective to a habit of speculative brooding has been felt that imperceptibly and unconsciously healthful minds rise to those dispassionate heights whence the Occidental Brahmin gazes upon a motley world.

HANS MÜLLER-CASENOV.

[For Acknowledgments to Authors and Publishers, see page 430.]

[1]

THE HUMOUR OF GERMANY.

Hugo von Trimberg (1260-1309).

[4]

Hans Sachs (1494-1576).

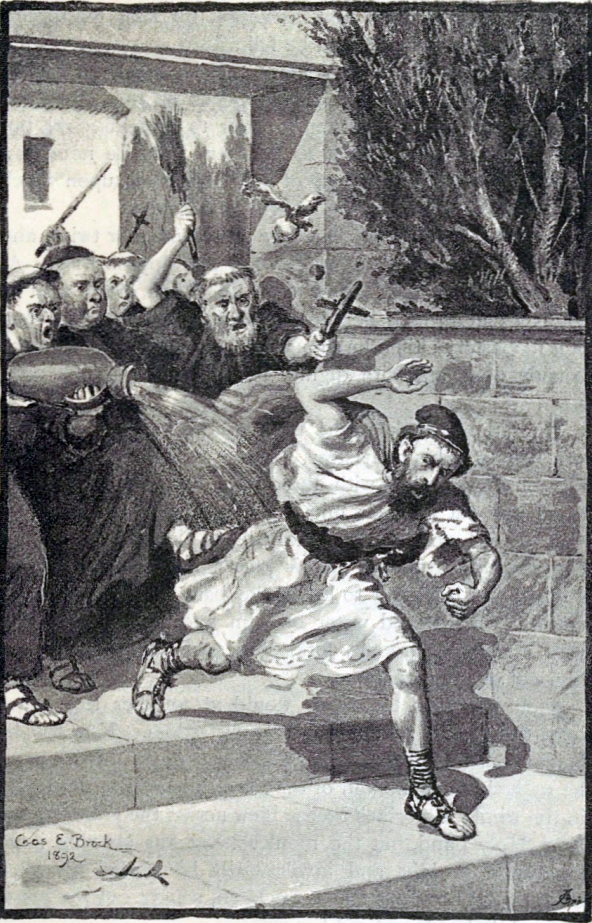

[6]

THE commandant at Soest looked at me with approval, and said, “Tut, little huntsman, you shall be my servant, and wait upon my horses.”

“Sir,” I replied, “I should prefer a master in whose service the horses wait upon me. As it is not likely I shall find such a one, I am going to be a soldier.”

“Hoity-toity,” he said, “you have no more hair on your lip than a tree-frog. You are too young.”

[7]

“Oh, no,” I replied, “I will venture to brave any man of eighty. The beard does not make a man, else the he-goats would be in high esteem.”

He said, “If you can show courage as well as you can wag your tongue, so be it.”

I answered, “The first opportunity shall furnish the proof.”

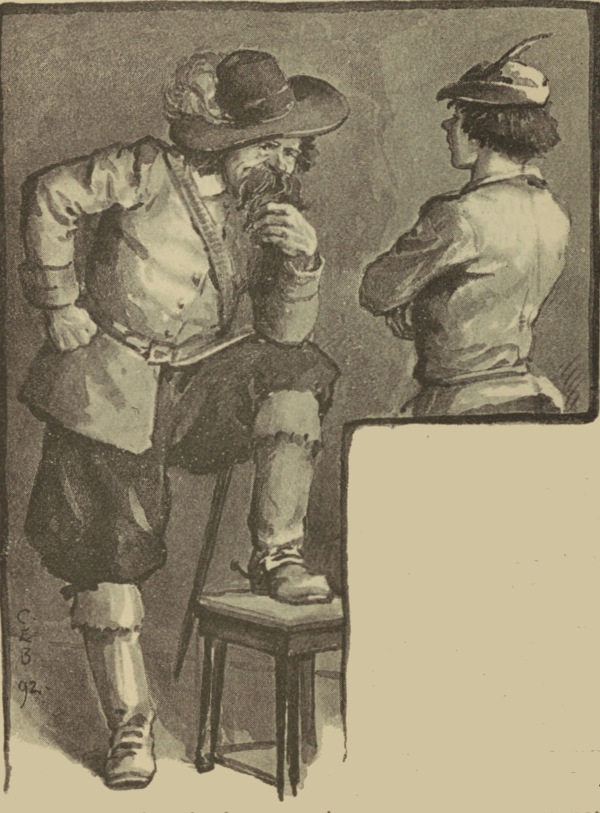

And so the commandant made over to me my dragoon’s old trousers, in which my master had sewed a goodly number of ducats. Out of their vitals I provided myself with a good horse and the best fire-arms I could get; I thereupon polished up my belongings to their utmost possibility of brightness. I got me a new suit of green, for I delighted in the name of “huntsman,” and gave my old garments to my boy, as they had grown too short and too tight for me. I sat on my horse like a young nobleman, and did not think small beer of myself. I took special delight in decorating my hat with a smart bunch of feathers like an officer. There were enough to envy me, and soon words and blows were the order of the day. But no sooner had I given proof to two of my enemies as to the nature of the thrusts I was skilled in, than I was left in peace, and my friendship was much sought for. In our raids upon the enemy I threw myself forward like bubbles in a boiling kettle, to be always the first in the fight. Whenever it was my good fortune to lay hands upon a desirable bit of pillage I shared it freely with the officers. The consequence was that I was allowed to plunder even in forbidden places, and could be secure of protection under all circumstances. So I was soon looked up to by friend and foe, and my purse grew as great as my name; even the peasants I managed to keep upon my side by fear and love, for I took vengeance upon those that tried to hinder me, and gave rich rewards to all who were helpful. I did not confine myself to large[8] schemes, and never despised small ones if there was praise and admiration to be won thereby.

At one time we had been vainly hoping for some waggons with provisions to come into our way at the Castle of Recklinkhausen, and the pangs of hunger were upon us. And when I and my comrade, a student just run away from school, were leaning out of one of the windows, and hungrily gazing out into the country, my companion sighed after the barley-soup of his dear mother, and said: “Ah, brother, isn’t it a shame to think that after having studied all the arts, I should not be able to supply food for myself? Brother, I know for certain, if I were only allowed to visit the parson in yonder village—you can see the church steeple just beyond the poplars—I should find a most excellent feast.”

After a short parley the captain gave us permission; I exchanged my clothes with those of another, and the student and I betook ourselves to the village on a very roundabout way. The reverend gentleman received us civilly. When my companion had greeted him in Latin, accompanying his words with a profound bow, and briskly conjuring up a fine array of lies how the soldiers had robbed him, a poor student, of all his provisions, the parson gave him bread and butter and a drink of beer. I passed myself off as a painter’s apprentice, and acting as if my companion and I had never met before, I told them both I should go down the village street to the inn for refreshment, and would then call for him, as we seemed to be going the same way. So I went away in search of anything that might be worth the trouble of coming for the following night, and I was so fortunate as to meet a peasant who was plastering up an earthen oven in which large loaves of brown bread were to lie and bake for twenty-four hours. I thought, “Go ahead; plaster away! I’ll find you a customer for these delicious viands.” I made but a short stay at the inn,[9] knowing this cheaper way of getting bread, and returned to my companion, who had eaten his fill, and had told the parson that I was on my way to Holland to perfect myself in my art. The parson asked me to go and see the church with him, as he would like to show me some paintings that were in need of restoration. As it would not do to spoil the game, I consented. He conducted us through the kitchen, and when he opened the night-lock on the strong oaken door which led to the churchyard, I saw a wonderful sight. From the black heavens of this kitchen violins, flutes, and cymbals were pendent—in reality they were hams, sausages, and slices of bacon. I looked at them with happy forebodings, and they seemed to smile irritatingly upon me. I wished them in the castle to my comrades, but in vain; they were obstinate, and remained hanging where they were. I mused on ways and means of bringing them under my plan regarding the peasant’s loaves of bread, but there were serious difficulties in the way, as the yard of the parsonage was surrounded by a stone wall, and all the windows were well protected with iron bars. Moreover, there were two large dogs in the yard that certainly would object to having that stolen the remnants of which was, in the course of time, to be the reward due to their watchfulness.

Once in church, it appeared that the parson generously intended to entrust me with the restoration of his old pictures. As I was exerting myself to find some plausible subterfuge, the sexton turned to me and said: “Fellow, you look more like a disreputable soldier-lad than like a painter.” I was no longer accustomed to such speeches, and yet there was nothing for it but to swallow the taunt. I shook my head softly and replied, “Oh, you knave! give me a brush and colours, and I will paint a fool in a twinkling who shall resemble you throughout.”

The parson made a joke of the matter, and reminded both[10] of us that it is not meet to tell each other unsavoury truths in so holy a spot. Then he gave us another drink, and we departed. But I left my heart with the sausages.

Returning to our people, I picked out six reliable fellows to help me carry home the bread. About midnight we entered the village and quietly took the bread out of the oven, and as we were about to pass the parsonage I could not bring myself to go on without the bacon. I stood still and looked up and down to discover some way into the parson’s kitchen, but there was no opening except the chimney. We stored our guns and our treasured booty of bread in the charnel-house of the churchyard, managed to get a ladder and rope out of the barn, and I and my crony Springinsfeld climbed up on the tiled roof. I twisted my long hair into a top-knot, and let myself down by the rope to the objects of my desire. Once there, I did not delay, and tied ham after ham, and sausage after sausage to the rope. Springinsfeld fished everything out skilfully from his post on the roof and handed it down to the others. But, alack-a-day! as I was just going to give myself a holiday and come out, the pole that I was standing on gave way, and poor Simplicisimus was suddenly precipitated, and found himself in as bad a fix as need be—in fact, it was like a regular man-trap. Springinsfeld tried to help me by letting down the rope, but that also broke. I said to myself, “Now, huntsman, you are in for a chase in which there will be small mercy for your hide.”

Sure enough, my fall had waked up the parson, and he called his cook and bade her strike a light. She appeared in night-attire, her petticoat around her shoulders, and stood close beside me. She seized a coal from the hearth, held her candle up close to it, and began to blow. At the same time I blew much stronger than she, which frightened the poor body so that she dropped both candle and coal, and retreated near her master. Now the parson himself struck a light, while the woman was telling him there was a horrible[11] two-headed ghost crouching in the kitchen; she had probably mistaken my top-knot for a second head. When I heard this I quickly rubbed my face and hands with ashes and soot, until I doubtless bore small resemblance to the angel I had figured for at the nunnery. And if the sexton could have seen me thus occupied, he would certainly have given me credit for being a rapid painter. Thereupon I began to make as much noise as I possibly could, throwing pans and kettles about. I hung the ring of the large kettle about my neck, and took the poker in my hand, to have a weapon in case of need. All this did not put out the pious parson, who approached as if he were heading a procession, his cook behind him, carrying two wax tapers and a stoup. He was attired in his surplice, and had a book in one hand and his holy-water sprinkle in the other. He read some ritual of exorcism aloud before me, and then asked me who I was, and what was my business here. Seeing that he was labouring under the impression that I was the Evil One, I thought it but fair that I should act in accordance with my new rôle, and I answered him as I had once answered the robbers in the woods, “I am the devil, and I have come to turn your neck, and your servant’s as well.” He thereupon tried his most potent charm, “All good spirits praise the Lord! I conjure thee, return from whither thou comest!” I replied that this was impossible, happy though I should be to comply with his request.

Meanwhile my boon-companion Springinsfeld was indulging in spectral revelries upon the roof. When he heard what was going on in the kitchen below, and how I was passing myself off for the devil, he began to hoot like an owl, then barking like a dog, neighing like a horse, bleating like a sheep, crying like a donkey, cackling down the chimney like a hen about to lay an egg, and then again giving forth unearthly music like a hundred serenading cats; for this fellow was clever in imitating the voices of animals, and[12] could howl as naturally as if a pack of wolves were standing about the house.

During the consternation of the parson and his charming feminine choir-boy I had time to look about me, and, to my joy, I made the discovery that the night-lock had not been put on the back door. Quick as a flash I pushed back the bolt, slipped out into the churchyard, where my companions were standing with triggers drawn, and left the parson to conjure devils as long as he pleased. And when Springinsfeld came down from the roof, bringing my hat along, and we had packed our spoils upon our shoulders, we returned to our party, not having anything more to do in the village, though I admit that we might have returned the borrowed ladder and rope.

Christoffel von Grimmelshausen (1620-1676).

(From Act I. of “A Topsy-Turvy World.”)

Scaramuccio.[1] Poet.

SCARAMUCCIO.

No, Sir Poet, say what you please, talk as you wish, make as many objections as you can possibly make, it shall in no wise alter my purpose, to listen to nothing, to consider nothing, to insist upon having my own way,—so there!

POET.

Dear Scaramuccio!

SCARAMUCCIO.

I listen to nothing. Look, Sir Poet, how I am stopping up my ears.

[13]

POET.

But the piece——

SCARAMUCCIO.

Nonsense! the piece! I am a piece too, and I have a perfect right to say my say. Or do you suppose I have no will of my own? Do you poets labour under the delusion that a gentleman actor is called upon to do just as you say? My dear sir, know you not that the times are changing?

POET.

But the spectators——

SCARAMUCCIO.

And because there are spectators in the world, would you make me unhappy? Nice principles those!

POET.

Friend, you must listen to me.

SCARAMUCCIO.

Very well then, if I must. Here I sit; now talk like a sensible man, if it is in your nature so to do. (Sits down on the ground.)

POET.

Most esteemed Sir Scaramuccio! Your Grace has been engaged at this theatre for a special rôle—in a word, to express myself briefly, you are the Scaramuccio. It is not to be denied that you have reached a degree of excellence in this your speciality, and there is no man in the world more willing than myself to do justice to your talents; but, my dear sir, for all that you are not possessed of the qualities fitting you for a tragedian; for all that you will never be able to play a lofty character.

SCARAMUCCIO.

The impudence of it! By my soul, I’ll play you a loftier character than you will be able to write. I take your[14] remark as a personal insult, and I challenge the whole world to out-do me in the high and lofty.

SCAEVOLA (one of the spectators).

Oh, Sir Scaramuccio, we’ll all take up your challenge.

SCARAMUCCIO.

How so? What now? I confess I am struck dumb by this insolence.

SCAEVOLA.

My dear sir, there is no cause for that. I am here for my money, Sir Scaramuccio, and I can think what I please.

SCARAMUCCIO.

You are free to think as you see best, but you are not allowed to speak here.

SCAEVOLA.

So long as you may speak, I don’t see why I shouldn’t.

SCARAMUCCIO.

Well, then, what have you done that was so noble?

SCAEVOLA.

The day before yesterday I helped my spendthrift of a nephew out of his debts.

SCARAMUCCIO.

And yesterday I saved the prompter from talking himself hoarse by leaving out a whole scene.

SCAEVOLA.

I was in a merry humour at table one day last week, and gave a whole shilling in charity.

SCARAMUCCIO.

The day before yesterday I quarrelled with my tailor, who came to dun me, and I had the last word.

[15]

SCAEVOLA.

A week ago I helped get a tipsy man home.

SCARAMUCCIO.

Sir, I was this tipsy man; but I had been drinking my sovereign’s health.

SCAEVOLA.

I confess myself vanquished.

(Enter Pierrot in a state of excitement.)

POET.

What’s the matter, Pierrot?

PIERROT.

What’s the matter? I will not play to-day. On no account will I play.

POET.

Why not?

PIERROT.

Why not? Because it’s high time for me to become a spectator. I’ve been a mime long enough.

(Enter Wagemann, the manager.)

POET.

You are just in time, Herr Wagemann. There is confusion abroad.

WAGEMANN.

How so?

POET.

Pierrot will not play to-day. He wants to be a spectator, and Scaramuccio insists upon taking the rôle of Apollo in my drama.

SCARAMUCCIO.

And am I not right, Herr Wagemann? I have played the fool long enough, and I should like to try my hand at the wise.

[16]

WAGEMANN.

You are too severe, Sir Poet. You must give the poor fellows a little more liberty. Let them have it their own way.

POET.

But the requirements of the drama, of art——

WAGEMANN.

Oh, all that will come right enough. Look you, my way of thinking is this—the spectators have paid their money, and with that the most important thing is regulated.

PIERROT.

Adieu, Sir Poet. I go to join the illustrious assembly of spectators. I will venture the bold leap over the footlights, to see if I can be cured of being a fool, and graduate to a spectator. (Sings.) Fare-thee-well, thou old love; a new life is dawning for me, and most sensible impulses are moving my heart. No footlight shall affright me, no prompter can hold me. Ah, I would taste the peaceful bliss of being an auditor. Receive me, wild waves; stage, fare-thee-well, my spirit yearns to be drawn beyond thy precincts. (Jumps into the parterre.) Where am I? Oh heavens! do I still breathe? Ah! is it possible I stand here below? The rays of the footlights shine over yonder. Ye gods, ye behold me surrounded by people. Who gave me this life, this better life?

THE AUDIENCE.

Monsieur Pierrot is one of us. A hearty welcome to thee, Spectator Pierrot. We greet thee, thou great man!

PIERROT.

Can it be, ye noble ones, that you will count me as your brother? Ah, my gratitude will last as long as there is breath within this bosom.

[17]

GRÜNHELM (one of the spectators).

Glorious, glorious! By my soul he speaks well! But as for me, I should like to take a part on the stage for a change; it would do my heart good. To be sure I tremble and stammer, and my wit is not of the quickest, but I am never so happy as when I am making a little joke. (He scrambles up on the stage.) And so, Sir Scaramuccio, leave your funny rôle to me, and then, for all I care, you may play the Apollo.

POET.

And what then is to become of my excellent drama?

AUDIENCE.

Scaramuccio shall play the Apollo. It is a unanimous decision.

POET.

’Tis well. I wash my hands of it. The audience may bear the responsibility. I am deeply miserable. Ah, yes, it is the fate of Art to be misunderstood and travestied, and it is only then that it finds its public. In vengeance for the judgment passed upon Marsyas, Poetry herself is flayed alive to-day. My sorrow is greater than I can endure. Herr Grünhelm, so you undertake to do the joking?

GRÜNHELM.

I do, Sir Poet, and I will hold my own against any rival.

POET.

How will you do it?

GRÜNHELM.

Sir, I have been one of those whose chief business it is to be amused long enough to know what will please. The people down there want to be entertained. At bottom that is the only reason they stand there so quietly and patiently. The good-will of the public is the principal thing, I know[18] that as well as you do. True art is to keep this good-will on the surface.

POET.

Yes, of course, but by what means do you propose——?

GRÜNHELM.

Let that be my care, Sir Poet. (Sings:)

AUDIENCE.

Bravo! bravo!

GRÜNHELM.

Are you pretty well amused, gentlemen?

AUDIENCE.

Excellently, most excellently!

GRÜNHELM.

Do you feel a longing for anything reasonable?

AUDIENCE.

No, no; but by-and-by we should like to have our feelings worked upon.

GRÜNHELM.

Patience, you can’t have all good things in a lump. Do you miss the genuine Apollo?

AUDIENCE.

Not in the least.

GRÜNHELM.

Well, Sir Poet, do you still object to granting the excellent Scaramuccio’s request?

POET.

Not in the least. I withdraw all my objections.

AUDIENCE.

But we don’t want him to give us nothing but nonsense.

[19]

SCARAMUCCIO.

Mercy on us! We would not be guilty of such a sinful thing. What kind of an Apollo were I if I should admit of that? No, gentlemen, there shall be an abundance of serious things—things to think about, things to train one’s intellectual faculties.

SCAEVOLA.

Is it to be a tragedy?

PIERROT.

No, gentlemen, we actors have all sworn that we will not die, so it won’t be a tragedy, whatever the poet may have in his mind.

SCAEVOLA.

I am relieved to hear it, for I am possessed of a very soft heart.

PIERROT.

Hang it, sir, neither are we made of stone and iron. I have the honour of assuring you that my susceptibilities are uncommonly delicate. The devil take all inelegancies.

SCAEVOLA.

That is what I say. There is nothing above being a spectator. It is the highest thing one can be.

PIERROT.

Ay, that it is. Are we not more than all the emperors and princes that are but acted?

SCARAMUCCIO.

Thunder and lightning! Where, in the hangman’s name, is my Parnassus?

GRÜNHELM.

I will go and get it. (Exit.)

WAGEMANN.

Now all is in order. Adieu, Sir Scaramuccio.

[20]

SCARAMUCCIO.

Your humble servant. Beg you to express my respects to Madam, your wife. (The manager exit. Three attendants enter, carrying the Parnassus.) Put it down here,—a trifle further to this side, so that I can hear the prompter. (He climbs up and takes a seat.) A pleasant mount this. What revenues does it yield? Can any one tell me? Send for the treasurer.

(Enter the Treasurer.)

SCARAMUCCIO.

What does the mount bring me annually?

TREASURER.

Under your predecessor, the only profits derived were those from the Castalian Spring.

SCARAMUCCIO.

What sort of a spring? Was it a mineral spring; a sulphur spring, perhaps? Was there much demand for the waters? What was the price per bottle?

TREASURER.

What little there was wanted was given away. Few people liked the water. Your predecessor, the other Apollo, was fond of it.

SCARAMUCCIO.

I hope there are no mortgages on the mount?

TREASURER.

No, your majesty.

SCARAMUCCIO.

Is it insured?

TREASURER.

Oh, yes.

[21]

SCARAMUCCIO.

There is some security in that. I shall have a brewery and a bakery put up at the foot. The common pastures must be otherwise disposed of; Pegasus and the other beasts that belong to me must henceforth be fed in the stable.

TREASURER.

It shall be as you say.

SCARAMUCCIO.

Have the spectators paid for the play?

TREASURER.

Yes, your excellency.

SCARAMUCCIO.

I hereby decree that there shall be no complimentary tickets in future.

TREASURER.

These are innovations not at all in accordance with the institutions of Greece.

SCARAMUCCIO.

Hang Greece! Thank goodness we live in better times. This is an age of enlightenment, and I reign supreme. Send for the Muses. (Exit the Treasurer.)

(Enter the nine Muses, bowing profoundly.)

SCARAMUCCIO (lightly nodding to them).

Pleased to make your acquaintance, Mademoiselles. Hope we shall get on finely together. Henceforth you shall be my tenants on the Parnassus. Should you ever desire to change your residence, quarterly notice is required. What is your name, fair child?

MELPOMENE.

I am Melpomene.

[22]

SCARAMUCCIO.

You look so woe-begone.

MELPOMENE.

Oh, Herr Apollo! I am of a very good family. My father had a high position at court, and the thane gave me a matchless education. Ah, how happy I was in my parents’ house, and what a dutiful daughter did I strive to be! I also had a lover, but he jilted me, and my parents died of grief. Our family physician, a worthy man, took an interest in me; but he was too poor to marry me, so there was nothing for it but to join the Muses. Have I no right to be sad?

SCARAMUCCIO.

Yes indeed, my child; but I will be as a father to you.

SCAEVOLA (to another spectator).

Now see, for heaven’s sake, how the tears are flowing from my eyes.

THE OTHER.

Why, neighbour, save them for the fifth act.

SCARAMUCCIO.

And who are you, pretty maid?

THALIA.

Thank you kindly, sir, for asking; I was christened Thalia. I was a servant in the family of this excellent lady, and I could not bring myself to leave her in her distress, and followed her among the Muses.

SCARAMUCCIO.

When the last act comes your faithfulness will surely be rewarded. Where is my groom?

(Enter the Groom.)

[23]

SCARAMUCCIO.

Saddle my Pegasus. I wish to go riding.

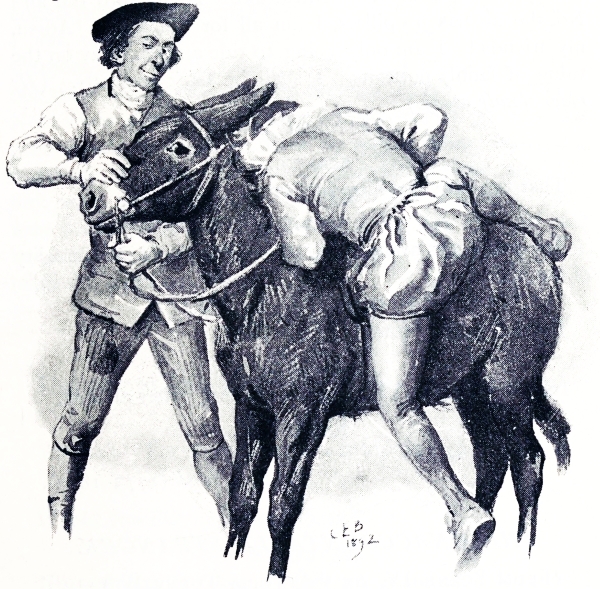

(Exit the Groom, coming back immediately with a bridled donkey.)

Help me. (He gets in the saddle.)

GROOM.

By what rules of quantity does your Honour choose to take his pleasure to-day?

SCARAMUCCIO.

Oh, fool! I will ride in plain, sensible prose. Do you suppose I wish to be jolted in Alcaic measures, or break my neck in Proceleusmatics? No, I am for sense and order.

[24]

GROOM.

Your predecessor was always flying in the air.

SCARAMUCCIO.

Don’t talk to me about the fellow. He must have been a very clown, a most eccentric ass. To fly into the air! No, the air has no pillars, I am all for the earth. Adieu, my friends! I am only going to ride a short essay on the value of family portraits. I shall be back presently. (He rides slowly away.)

(The curtain drops.)

SCAEVOLA.

That was only the introduction.

PIERROT.

The first act is always of great importance for the lucidity of the whole.

THE OTHER TO SCAEVOLA.

There is much morality in the piece.

SCAEVOLA.

Indeed there is; I feel myself growing better already.

PIERROT.

Music!

Ludwig Tieck (1773-1853).

(From Scene IV. of “A Topsy-Turvy World.”)

(The room of an Inn.)

INNKEEPER.

Few enough guests put up at my house nowadays. If this goes on I might as well take down my sign. Dear me, those were other times when there was scarce a piece performed but had a tavern and a host in it. I well remember in how many hundreds of pieces the foundations for the[25] finest plots were laid in this very room. Now it was a prince in disguise, who spent his money here; now it was a prime minister, or a wealthy count at the very least, who lay in ambush here for some conspiracy. Yes, even in things that were translated from the English, I always earned an honest penny. Some drawbacks to be sure there were, when I was required to be a disguised member of a band of sharpers, and then be smartly rated by the moral characters; but there was always healthy activity in it. But now!—Now when a wealthy stranger returns from a journey, he goes to stay with his relatives by way of doing something novel and original, and does not drop his disguise until the fifth act; others appear only upon the street, as if there were no respectable house for them to stay at. All this keeps the audience in a marvellous state of curiosity, but it takes the bread out of our mouth.

(Enter Anne.)

ANNE.

You seem to be in low spirits, father.

INNKEEPER.

Yes, child, I’m out of sorts about my calling.

ANNE.

Would you like to be something finer?

INNKEEPER.

No, not exactly; but it vexes me more than I can tell you that there is no more demand for my calling.

ANNE.

Surely in time all that will change for the better.

INNKEEPER.

No, dear daughter. The times do not tend that way. Oh, why was I not a Hofrath! You may look at any play-bill this day, it always says at the bottom: “The scene is[26] at the house of the Hofrath.” If things go on like this I’ll study for a gaoler, for prisons, you know, still occur in patriotic and mediæval pieces. But my son must see to it that he gets to be a Hofrath.

ANNE.

Be comforted, dear father, and do not yield to your melancholy.

INNKEEPER.

I’ve half a mind to turn poet myself, and invent a new art of poetry which shall supersede the Hofrath pieces, and in which the scene shall invariably play in a tavern.

ANNE.

Do so, dear father, and I will attend to the love-scenes.

INNKEEPER.

Hist! There is a diligence pulling up at the door. Indeed it seems to be an express. Kind heavens, where can the unsophisticated person come from who would put up at this house?

(Enter a Stranger.)

STRANGER.

Good morrow, mine host.

INNKEEPER.

Your servant, your servant, noble lord. Who in the world are you to travel incognito, and put up at my house? Surely you are of the old school, eh? A man of the good old times! Perhaps translated from the English!

STRANGER.

I am neither a noble lord nor do I travel incognito. Can I lodge here this day and night?

INNKEEPER.

My whole house is at your disposal. But really, is there no family in the vicinity you wish to make happy? Or do you wish to marry suddenly, or find a sister?

[27]

STRANGER.

No, good friend.

INNKEEPER.

So you are only journeying as a simple, ordinary traveller?

STRANGER.

Yes.

INNKEEPER.

Then you will have but little applause.

STRANGER.

The fellow must be crazy.

(Enter a Postillion.)

POSTILLION.

Here is your trunk, sir.

STRANGER.

And here is your fee.

POSTILLION.

Oh, that is very little. I drove down the hill so smartly!

STRANGER.

There.

POSTILLION.

Many thanks. (Exit.)

STRANGER.

Shall I succeed in finding her? Oh, how all my thoughts turn to my beloved native shore! How can I endure the sight, when once more I view it?—when the past, with all its joys and pains, passes before my inner vision? Ah, thou poor mortal! what callest thou the past? For thee there is no present. Between the times that are flown and the future thou clingest to a little moment, and joys flit past thee, and do not so much as touch thy heart.

[28]

INNKEEPER.

If I may be permitted to ask, I take it your grace is from some old worm-eaten drama that some unknown author has modernised a bit?

STRANGER.

What say you?

INNKEEPER.

I greatly doubt that you will have applause! I hope, at any rate, that you have money? Or is it a part of the plot that you should pretend to be poor?

STRANGER.

You are very inquisitive, good friend.

INNKEEPER.

That’s part of my trade, sir, as any schoolboy will tell you. Old people must be old; Telephus must be a beggar; the slave must chatter in keeping with his rôle. You can look it up in the Ars poetica, to which I too am subject in my office as host.

STRANGER.

Thank you for this graceful frenzy; I have not found so rare a curiosity for a long time. Show me to my room.

(Exeunt.)

Ludwig Tieck.

EVER since Haslan was a duke’s residence there was no record of anything having been looked forward to with such curiosity—excepting the birth of a hereditary prince—as the opening of Van der Kabel’s last will and testament. Van der Kabel might have been called the[29] Crœsus of Haslan, and his life a comedy of coins. Seven distant relatives of seven deceased distant relatives of Kabel’s indulged in some little hope of a place in the testament, the Crœsus having sworn to remember them there; but the hope was a faint one, as he seemed not greatly to be trusted, not only because he was in the habit of managing his affairs in a grimly moral and unselfish manner—in matters of morality the seven relatives were but beginners—but also because he handled things in so cynical a spirit, and with a heart so full of traps and snares that there was no depending upon him. The continuous smile about his temples and thick lips, and his shrill sneering voice, impaired the good impression which his nobly-formed features and a pair of large hands, dropping New Year’s gifts and benefits every day, might have made; therefore the swarms of birds declared this man, this living fruit-tree, which furnished them with food and nests, to be a secret snare, and would not see the visible berries for invisible nooses.

Between two strokes of paralysis he had dictated his testament, and entrusted it to the magistrate. When in a half-dying state he handed the receipt of deposit to the seven heirs-presumptive, he said, in his old tone, that he should greatly deplore it if this sign of his approaching decease would strike down sensible men, whom he liked to picture as laughing heirs rather than as weeping ones.

In due time the seven heirs put in an appearance at the Rathhaus with their receipt of deposit. There was the Right Reverend Glanz, the Police-inspector, the Court-agent Neupeter, the Court-attorney Knoll, the Bookseller Pasvogel, the Preacher Flachs, and Flitte from Elsass. They urged the magistrate to produce the charte of the deceased Kabel, and open the will with all the formalities of the law. The high executor of the same was the ruling burgomaster in person; the low executors were the town councillors. Without delay the charte and testament were[30] fetched out of the private closet and deposited in the court-room, passed around to the senators and heirs, that they might gaze upon the printed town-seal. The directions written upon the outside of the charte were read in a loud voice by the town-scribent to the seven heirs, who were therewith informed that the deceased had in truth deposited the said charte with the magistrate, and entrusted it to the same scrinio rei publicae, and that on the day when he had thus deposited it he had been in his right mind; last, the seven seals which he himself had placed thereon were examined and found intact. After the town-scribent had entered a registry of all these proceedings, the testament was opened in God’s name, and read aloud by the ruling burgomaster as follows:—

“I, Van der Kabel, herewith declare my last will and testament this 7th day of May 179—, here in my house in Haslan in the Hundgasse, without many millions of words, though I was once a German Notary Public and a Dutch dominé. But I believe I am still sufficiently conversant with the art of a notary to be enabled to act the part of a testator and bequeather in a proper and becoming manner.

“As for charitable legacies, so far as they are any concern of the lawyer’s, I declare that the poor of this town, 3000 in number, shall receive as many light florins, for which they may celebrate the anniversary day of my death next year by pitching a camp upon the public common; make a merry day of it, and then take the tents to make clothes out of them. To all schoolmasters of our dukedom I bequeath a Louis d’or apiece; and to the Jews of the place I bequeath my pew in church. As I desire to have my testament sub-divided into paragraphs, this may be considered as the first.

“Paragraph 2.—Declarations of inheritance and disinheritance are universally counted among the essentials of a testament. I therefore bequeath to the Right Reverend[31] Glanz, the Court-attorney Knoll, the Court-agent Peter Neupeter, the Police-inspector Harprecht, the Preacher Flachs, the Bookseller Pasvogel, and Herr Flitte, nothing for the present, not so much because the most distant relatives can lay no claim to a Trebellianica, nor because most of them have enough to pass on to future generations as it is, but mainly because I know from their own assurance that they esteem my humble person more than my large fortune, of which I must therefore dispose otherwise.”

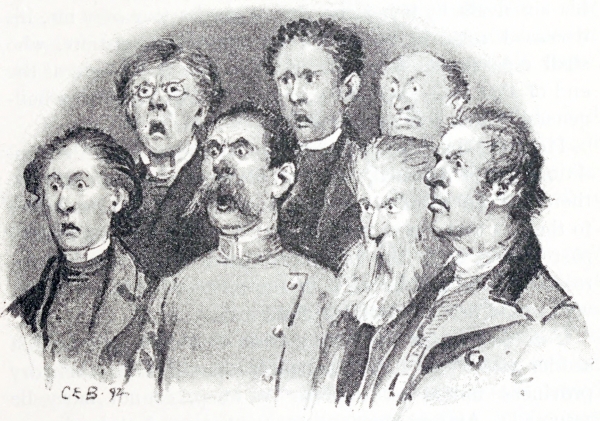

Seven elongated faces here started up. Especially did the Right Reverend Glanz, a young man noted throughout Germany for his spoken and printed sermons, feel himself keenly injured by such sneers. Flitte, from Elsass, permitted a whispered oath to escape his lips; and as for Flachs, the preacher, his chin grew longer and longer, and threatened to grow into a beard. Many a whispered ejaculation was overheard by the magistrate addressing the[32] late Herr Kabel by such appellatives as scoundrel, fool, antichrist. But the ruling burgomaster waved his hand, the court-attorney and the bookseller set all the elastic springs in their faces as in a trap once more, and the former continued reading albeit with affected seriousness.

“Paragraph 3.—Excepting my present residence in the Hundgasse, which, according to this third paragraph, I will leave, with all that pertains thereto, to that one of the afore-mentioned seven gentlemen who, in one half-hour (counting from the reading of the paragraph), shall outdo his six rivals by being the first to shed a tear over me, his deceased relative, before an honourable magistrate, who shall register the fact. Should there be a drought at the end of that time, then the property must accrue to my heir-general, whom I shall forthwith name.”

Here the burgomaster shut the will, remarking the conditions to be unusual, but not illegal, and in accordance therewith the court would now proceed to award the house to the first that wept; laid his watch, which pointed to half-past eleven, upon the table, and sat down silently to note, together with the lawyers, in his office of chief executor, who would first shed the required tears.

That so long as this world exists there has ever been a sadder and more ruffled assembly than this of seven dry provinces united as it were to weep, cannot fairly be assumed. At first precious moments were lost in dismay and smiling surprise; it was no easy matter to be transported so abruptly from cursing to weeping. Emotion pure and simple was not to be thought of, that was quite evident; but in twenty-six minutes something might be done by way of enforcing an April shower.

The merchant Neupeter asked if that was not a confounded affair and fool’s comedy for a respectable man to be concerned in, and would have nothing to do with it; but at the same time the thought that a house might be[33] washed into his purse on the bosom of a tear strangely moved his lachrymal glands.

The Court-attorney Knoll screwed up his face like a poor workman getting shaved and scratched by an apprentice on Saturday night by the light of a murky little lamp; he was greatly enraged at the misuse of testaments, and was not far removed from shedding tears of wrath.

The sly bookseller at once proceeded to apply himself assiduously to the matter in hand, and sent his memory on a stroll through all the sentimental subjects he was publishing or taking on commission; he looked much like a dog slowly licking off the emetic which the Paris doctor Demet had spread on his nose; some time must necessarily elapse before it could take effect.

Flitte, from Elsass, danced about the Session-room, looked at all the mourners with laughing eyes, and swore, though he was not the richest among them, he could not for the whole of Strasburg and Elsass weep when there was such a joke abroad.

At last the Police-inspector Harprecht looked at him very significantly, and remarked that if Monsieur hoped to extract the required drops from the well-known glands by means of laughter, and fraudulently profit thereby, he begged to remind him that he would gain as little as if he were to blow his nose, for it was well known that the ductus nasalis caused as many tears to take that direction as flow into a pew under the most affecting funeral sermon. But the Elsassian assured him that he was only laughing for fun without any serious intentions. The inspector on his part tried to bring something appropriate to the occasion into his eyes by opening them very wide and looking fixedly at one spot.

The preacher Flachs looked like a beggar on horseback, whose nag is running away with him; like the sun shining on a dismal day, his heart, which was piled about with the most suitable clouds of hardships at home and in church,[34] might easily have drawn water on the spot, but unfortunately the house swimming in on the high-tide proved too pleasant a sight, and repeatedly served as a dam.

The Right Reverend Glanz, who knew his nature from his experience in New Years’ and funeral sermons, and who was quite certain that he would be able to work upon his own feelings if only he were granted an opportunity of addressing himself in touching language to others, now arose and said with dignity that he was sure every one who had read his printed works would feel convinced that he had a heart in his bosom, and that it was rather to be expected of him to suppress such sacred symbols as tears, so as to deprive no human brother, than to extract them by force. “This heart has overflowed ere now, but it was in secret, for Kabel was my friend,” he said, and looked about him.

With satisfaction he saw that they were all sitting there as dry as so many sticks. As things stood now, crocodiles, stags, elephants, and witches could have wept more easily than the heirs, irritated and enraged by Glanz as they were. Only Flachs had a turn of good luck. He thought of Kabel’s good deeds and of the shabby dresses and grey locks of his congregation at early service, then in haste he gave a thought to Lazarus and his dogs and to his own lengthy coffin, then to all the people who have been beheaded at one time or other, the “Sorrows of Werther,” a battle-field; and last he gave a pitiful thought to himself, how young he was, and how he was working and slaving for a miserable paragraph in a testament. Another good heave with his pump-handle and it would fetch him water and a house.

“Oh, Kabel, my Kabel,” continued Glanz, almost weeping at the glad prospect of mournful tears, “when on some future day, beside thy precious bosom now covered with dust, my own lies mouldering——”

[35]

“I believe, gentlemen,” said Flachs, getting up sadly and overflowing with tears, “I am weeping.” Thereupon he sat down again and allowed them to run cheerfully down his cheeks; he was high and dry now; he had successfully angled the house away from Glanz, who was very much put out by his efforts, because he had talked away his appetite all to no purpose. Flachs’s emotion was duly registered, and the house in the Hundgasse was legally assigned to him. The burgomaster was gratified that the poor devil should have it. It was the first time in the dukedom of Haslan that the tears of a teacher and preacher, like those of the goddess Freya, had changed into gold. Glanz was profuse in his congratulations, and jocosely reminded Flachs that he himself had perhaps been instrumental in bringing about this happy consummation.

Jean Paul Friedrich Richter (1763-1825).

LOVE is the perihelion of women—ay, it is the transit of such a Venus through the sun of the ideal world. During this time of their highest refinement of soul they love whatever we love, even though it be Science, and the best world of beauty within us; and they despise whatever[36] we despise, even though it be dress and gossip. These nightingales sing up to the date of the summer solstice; their marriage-day is their longest day. The devil does not take it all at once, but piecemeal day by day. The firm bands of wedlock tie up the wings of poesy; to the free play of fancy marriage means imprisonment on bread and water. Many a time I have followed about one of these poor birds of paradise or peacocks or Psyches during their honeymoon, and picked up the moulted feathers that were strewn about; and when later the husband complained that he had taken unto himself a bald and unlovely bird, I would show him the wasted treasure. Why is this? Because marriage erects a crust of reality about the ideal world; it is much the same case as with the sphere we live on, which, according to Descartes, is a sun enveloped in an earthy shell. A woman lacks the power which a man has to protect the inner structures of air and fancy against the encroachments of the rough outside. Where shall she seek refuge? In her natural keeper. A man should ever stand guard with a spoon over the fluid silver of the feminine intellect, to remove the scum as it rises, that the regulus of the ideal may shine the brighter. But there are two kinds of men: the Arcadians or lyric poets of life, who love for ever, like Rousseau when his hair was grey—such are not to be comforted when the gilt-edged feminine anthology of wit shows no gold as they turn the leaves, as is apt to be the case in books bordered with gold; second, there are the boorish shepherds of to-day, the plebeian poetasters and practical men of business, who thank God when their enchantress, like other enchantresses, changes into a growling domestic cat, and keeps the house free from vermin.

No one suffers from greater ennui and anxiety than a fat, weighty, slouching, bass-voiced man of business, who, like the Roman elephants of former times, is called upon to dance upon the slender rope of love, and whose amorous[37] pantomimes always remind me of dormice, that seem to be at a loss about their every movement when sudden warmth interrupts their dormant state. Only with widows, who care less to be loved than to be married, can a heavy man of business begin his romance where the novelists end theirs—viz., at the steps of the altar. Such a man, constructed on the crudest style, would have a load off his mind if he could get some one to love his shepherdess in his name until there was nothing more to be done but to have the wedding; the taking upon myself of such crosses and burdens for another is just what I should feel a calling for. I have often thought of advertising it in public papers (had I not feared it might be taken for a joke), that I offer myself to serve as plenipotentiary to any man of business who has no time to properly make love to a girl. Provided only she be tolerable, I should be willing to swear platonic everlasting affection, make the necessary declarations of love, and, in short, substitute myself in the most disinterested manner, or escort her arm-in-arm through the ups and downs of the land of love, until on the border I could make her over to the prospective bridegroom in proper condition to be married. Instead of marriage by proxy we should thus have love by proxy.

Jean Paul Friedrich Richter.

HE composed reviews as others do prayers—only when in straits; it was like the carrying of water of the Athenian so that he might thus be free to devote himself to his favourite studies without hunger. But his satirical sting he would put in the sheath when writing reviews. “Petty authors,” he said, “are always bitter, and great ones are worse than their works. Why should I be less severe upon the genius for his moral faults, such as vanity, than upon[38] the dunce? On the contrary. Poverty and ugliness not self-incurred deserve no disdain; but neither do they deserve it when self-incurred, though Cicero be against me. For neither a moral fault nor its punishment can be increased by a physical consequence which may follow or may not follow. Is the spendthrift who is impoverished in consequence of his way of living more to be blamed than the spendthrift who goes free? On the contrary.”

Applying this to poor writers whose unconquerable self-conceit hides their worthlessness to themselves, upon whose innocent hearts the critic vents his just wrath over their guilty heads, it is certainly permissible to scoff bitterly at the type, but the individual should be more gently dealt with. Methinks it would be the gold-test of a morally immaculate scholar if he were called upon to review a poor but celebrated book.

Jean Paul Friedrich Richter.

(From Scene XII. of “Die Deutschen Kleinstädter.”)

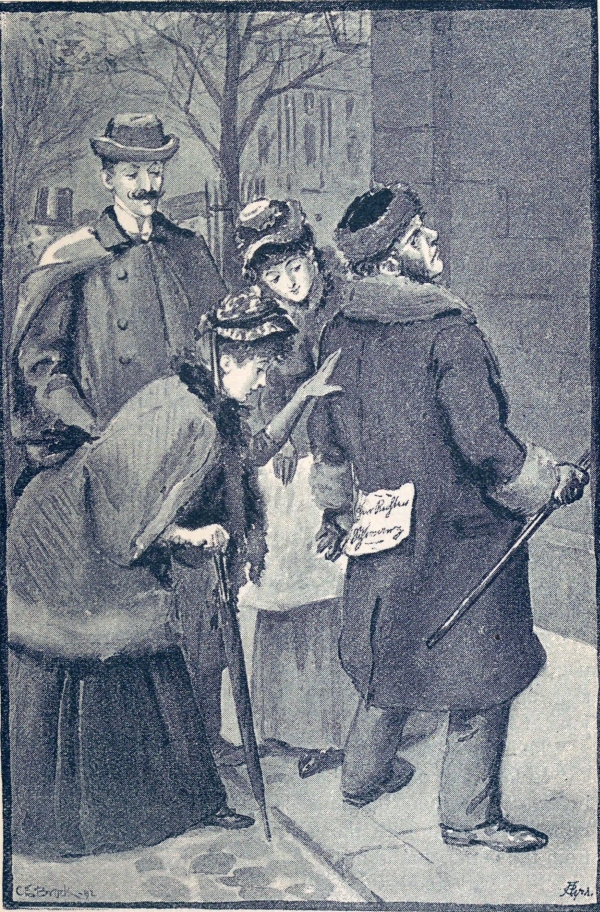

(Scene in the Burgomaster’s home in a small town. News has just been received of a traveller, whose carriage has met with an accident in a quarry just outside the town. Frau Staar, the Burgomaster’s mother, is all in a flutter as to the best way of doing honour to the distinguished stranger, and has sent for all of her female relatives, to obtain their advice in this difficult question.)

Frau Staar. Frau Brendel.

FRAU BRENDEL.

Here I am, most dear Dame Cousin. I ran so, I have no breath left. I was but just drinking my seventh cup of coffee, but I jumped up and left everything, at your message.

[39]

FRAU STAAR.

Greatly obliged, most esteemed Dame Cousin. Have you heard——

FRAU BRENDEL.

I know everything! My maid had gone to market, and the butcher told her his neighbour, the linen-draper, had heard how the bailiff had said to his daughter: Mickey, he said, out in the quarry there are a couple of counts lying, who have broken their arms and legs, and will be here in a minute. The watchman will blow a horn from the turret, the children will strew flowers on their path, the magistrate in corpore will go to meet them, and the bells will be rung.

FRAU STAAR.

It is only one, Dame Cousin; only one is lying in the quarry, probably a gentleman of quality. He is to be our guest. The Minister of State has written and has asked my son. Now you can fancy, Dame Cousin, the excitement in the house. And everything is on my shoulders! Everything rests upon me!

(Enter Frau Morgenroth.)

FRAU MORGENROTH.

Your servant, most esteemed Dame Cousin. Only see how my walk has heated me. I trust I am not too late? With your permission be it said, I had scarce a thing on me, was singing my morning hymn and combing my poodle-dog. At the third stanza your maid came rushing in. My God, I thought the house was on fire! Then and there I jumped up, the poodle-dog dropped from my lap, the hymnal fell in the coals where I was warming my coffee, the coffee was spilled, and two stanzas of the hymn, “Awake, my heart, and sing!” were burned up.

FRAU STAAR.

I regret it, exceedingly, worthy Dame Cousin——

[40]

FRAU MORGENROTH.

Oh, it’s of no consequence. I know all. Out in the quarry lie three or four princes; one is dead, the other is gasping a bit now and then. The coachman has broken his neck, the horses are lying stiff and stark. I met the Herr Assistant-Bailiff Balg on the street; his cook told him; she knows it from the wife of the Lottery Inspector; her husband’s barber told her all the details.

FRAU STAAR.

Tut, tut, it is not quite so bad as all that. A short time ago a peasant came here from Kabendorf——

FRAU BRENDEL.

I know, he got a solid thaler for a tip.

FRAU MORGENROTH.

Far from it, Dame Cousin, a Louis-d’or it was.

FRAU STAAR.

He had run as fast as he could run.

FRAU BRENDEL.

They say it gave him a pain in his side.

FRAU MORGENROTH.

His nose bled too.

FRAU STAAR.

A person of quality met with an accident.

FRAU BRENDEL.

A count——

FRAU MORGENROTH.

Several princes.

FRAU STAAR.

That we do not know. He must be of noble extraction, for he does not lodge in the “Golden Cat,” but at our house, at the express desire of his Honour the Minister of[41] State. Now, as my son, the Burgomaster and Chief Alderman, represents in his person the whole town as it were, you will, of course, understand that he must do honour to his position.

FRAU BRENDEL.

A banquet at the Town Hall——

FRAU MORGENROTH.

A dance at the archers’ guild——

FRAU STAAR.

To-morrow, as you know, is the great fête.

FRAU BRENDEL.

Oh yes, the woman that stole the cow nine years ago——

FRAU MORGENROTH.

To-morrow she goes to the pillory. I am looking forward to it with a great deal of pleasure.

FRAU BRENDEL.

I have had a brand-new robe made for the occasion.

FRAU STAAR.

There have been many arrangements made to fitly celebrate this event. But to-day the honour of the town is wholly in our hands; to-day we must show what we can do, and with the help of God we will. The tables shall bend under His blessings. My worthy cousins are herewith invited.

FRAU BRENDEL.

I look upon it as a great honour.

FRAU MORGENROTH.

Shall not fail.

FRAU STAAR.

Now, you see, I should like to make the distinguished stranger acquainted with our people of quality. So I have[42] sent for you to ask your advice as to the persons to be invited.

FRAU BRENDEL (meditating).

Ah, well, I think——

FRAU MORGENROTH.

You might perhaps——

FRAU BRENDEL.

Invite the Herr Convoy-and-Land-Excise-Commissary Kropt——

FRAU STAAR.

No, Dame Cousin, he gave a banquet the other day on his mother’s birthday, and did not ask us.

FRAU BRENDEL.

Ah, indeed!

FRAU MORGENROTH.

Perhaps the Herr Board-of-Revenue-Supernumerary-Secretary Wittmann?

FRAU BRENDEL.

No, Dame Cousin; my husband, the late Herr Brendel, had a law-suit with him about his drains.

FRAU MORGENROTH.

That alters the matter.

FRAU STAAR.

I thought of the Herr Post-Luggage-Inspector-General Holbein?

FRAU MORGENROTH.

For heaven’s sake, Dame Cousin! he has a most insufferable wife! There’s hardly a Sunday passes but she has a new dress, and the way she goes rustling past my pew——

FRAU BRENDEL.

She carries her head higher than need be——

[43]

FRAU MORGENROTH.

And we all remember her so well——

FRAU BRENDEL.

Yes, when she wore a grey spencer with a green apron.

FRAU MORGENROTH.

There are strange rumours where she takes it from.

FRAU BRENDEL.

No, I would rather suggest the Herr County-Tavern-Harvest-and-Quarter-Tax-and-Impost-Controller Kunkel.

FRAU STAAR.

Don’t mention him, worthy Cousin; he is a rude fellow, who has no manners! Would you believe it, he did not so much as call upon us in a decent and proper manner, the pert addle-head! He left his card, fancy! One might sooner ask the Herr Penal-Raft-Commander Weidenbaum.

FRAU BRENDEL.

No, Dame Cousin, for heaven’s sake, no! You remember how the wicked fellow was seen to talk to my brother-in-law’s step-daughter three times, and how consequently he intended to marry her? Now he holds himself aloof, and has made the poor girl the talk of the town.

FRAU STAAR.

Goodness me, is there any one we can ask then?

FRAU MORGENROTH.

There comes Cousin Sperling.

(Enter Sperling, with a large bouquet.)

SPERLING.

Frau Under-Tax-Receiver, Frau Chief-Raft-and-Fishery Master, Frau Town-Excise-Treasury-Secretary, your humble servant! I was in my garden—the Herr Vice-Church-Superintendent sent for me—I ran like a sunbeam![44] Scarce did I take the time to cull these children of the spring.

THE THREE LADIES.

Do you know already?

SPERLING.

I know all. A celebrated professor—carriage smashed up—nose ditto—letter of recommendation from the Minister of State.

FRAU STAAR.

A professor, you say?

FRAU BRENDEL.

Only a professor?

FRAU MORGENROTH.

Oh, my delicious coffee that was spilled in the fire!

FRAU STAAR.

Never believe it, Dame Cousin. All my life I have heard that ministers take little interest in professors. No, no, there is some misunderstanding.

SPERLING.

Nay, but I will stand up for my opinion that the man who has had his nose smashed is a learned professor, on his way from Egypt or Weimar, where he has either been measuring the pillar of Pompey, or else seen Wieland put his head out of the window. In short, there is no time to be lost. Here are the flowers. Now get me some children. Children I must have! Then he may come and see what the town of Krähwinkel can do!

FRAU STAAR.

Gently, gently; they shall be here at once.

(Exit.)

(SPERLING turns aside and mutely practises the pantomimes of reception.)

[45]

FRAU MORGENROTH.

Have you noticed, worthy cousin, what ridiculous airs the old lady is putting on?

FRAU BRENDEL.

Yes, indeed, Dame Cousin; she puffs herself up like dough in the oven.

FRAU MORGENROTH.

Goodness me! Her husband was only Under-Tax-Receiver.

FRAU BRENDEL.

When he died he left a debt to the Treasury.

FRAU MORGENROTH.

Dear me, and I wonder what the banquet will be like? Do you remember that joint eight weeks ago? It was horribly burned.

FRAU BRENDEL.

And how she looks! what will she put on?

FRAU MORGENROTH.

Not much choice. She has but three gowns.

FRAU BRENDEL.

To be sure, the brown one——

FRAU MORGENROTH.

And the white one——

FRAU BRENDEL.

And her stuff gown.

FRAU MORGENROTH.

She had that made for the first christening at the burgomaster’s.

FRAU BRENDEL.

Begging your pardon, Dame Cousin, it was made when the Vice-Church-Superintendent married his second wife.

[46]

FRAU MORGENROTH.

Who was another such fool.

FRAU BRENDEL.

You’re right there, quite right there.

(Enter Frau Staar with two children, the latter eating enormous slices of bread and butter.)

FRAU STAAR.

There are the children.

SPERLING.

Come along then!

FRAU STAAR.

Drop a curtsey to your dear Dame Cousin first, there’s a good child! Now shake hands; that’s right!

[47]

FRAU BRENDEL (wiping the butter from her fingers).

Enchanting little creatures. God bless them!

FRAU MORGENROTH.

The very pictures of our dear Dame Cousin.

FRAU BRENDEL.

I trust they have had the pox!

FRAU STAAR.

Not yet. My son wished to have them inoculated, but I will never give my consent. I would not forestall the Almighty.

SPERLING.

Children, lay your bread and butter aside.

CHILDREN.

No, no.

SPERLING.

Well, then, take the flowers in the other hand.

(Enter Herr Staar and the Burgomaster.)

HERR STAAR (hastily).

They are just driving in through the gate. The street is full of boys. They are running along by the carriage, and yelling at the top of their voice.

BURGOMASTER (hastily).

He comes, he comes! The watchman is standing ready with his trumpet.

SPERLING.

Goodness gracious! The children are so awkward——

HERR STAAR.

All you have to do is to strew your flowers and fling them in his face.

(The blast of a trumpet very much out of tune.)

[48]

BURGOMASTER.

Quick, quick! All go to meet him!

HERR STAAR.

The children lead the way!

SPERLING (snatches the bread and butter out of their hands and throws it on the table).

Leave your bread and butter here.

HERR STAAR (urging the children toward the door).

Quick, quick!

CHILDREN (crying).

I want my bread and butter! My bread and butter!

BURGOMASTER (following them).

Will you hold your tongues?

FRAU STAAR.

Frau Chief-Raft-and-Fishery-Master, you will have the kindness to precede me.

FRAU BRENDEL.

Never, Frau Town-Excise-Treasury-Secretary. I most urgently beg you——

FRAU MORGENROTH.

Frau Under-Tax-Receiver, the honour is due to you.

FRAU STAAR.

The heavens preserve me! I am at home in this house.

FRAU BRENDEL.

I know my place——

FRAU MORGENROTH.

I will not stir a step.

(The three begin to bow and curtsey, and all talk at the same time.)

(THE CURTAIN DROPS.)

August von Kotzebue (1761-1819).

[49]

THE Frau Obersteuerrätin was “auntie” to the whole world; and indeed she deserved the name, for she was a motherly friend, counsellor, and helper to all who came within her domain; she was the best and most charitable of women, judging mildly of the weaknesses of others so long as her own little weaknesses were respected. She over-looked the eccentricities of her clerical brother, which he committed in a state of absent-mindedness, and she did not raise any objections to Susie’s marvellous naïveté, though often enough it caused her bitter dilemmas.

It was a warm May day on which the Vicar entered the room with his usual greeting: “Good morning, Auntie—good morning, Susie.”

Auntie nodded pleasantly. Susie, who was sitting by her on the sofa, knitting a white stocking, arose, dropped a little familiar curtsey, and said: “Votre servante, Uncle.”

“But, Heaven preserve us, what is the matter with you to-day, Vicar?” said Aunt Rosmarin.

“How so?” queried the Vicar, putting his hands in all of his pockets in a vain search for a handkerchief with which to wipe the perspiration from his brow.

“It’s very likely you have your wig in your pocket,” said Auntie, “for your handkerchief is on your head.”

“On my head,” exclaimed the Vicar in surprise, and putting his hand there he found it. “I shouldn’t be greatly surprised if you were right, Auntie; it’s a hot, hot day; the sun was burning, my back was burning; I came from town, so I took off my wig to cool my head, spread my handkerchief over the latter, and lay down in a corn-field.”

Again he began to search his pockets, while Susie made room for him on the sofa, and went out to get him a refreshing drink of water and raspberry syrup.

[50]

“What are you looking for, Vicar?” asked Auntie.

“If I mistake not, I brought a letter for you from town; but what has become of it is more than I can tell. I think it is from the Burgomaster. Seek and ye shall find.”

“But, Vicar, first of all, put on your wig—this is very indecent. It is an insult to your congregation to walk about bald-headed.”

“I should hope not. But in that case I trust that there would be bears to obey me, like the prophet Elisha, and devour all bad boys who would make bold to have a laugh at me. But, ad vocem, my wig, Auntie; what did you do with it?”

“What did I do with it? You did not entrust it to my keeping. Perhaps you lost it on the way!”

“Heaven preserve us! It was my best wig. You are right, Auntie; it is lying in the grass, together with the Burgomaster’s letter, precisely on the spot where I myself lay a quarter of an hour ago, in the shadow of the corn.”

Auntie seized her bell. The maid appeared; the Inspector was called, and ordered to send for the wig and the letter—as quick as possible. Auntie was quite as impatient to hide the Vicar’s baldness as to read the Burgomaster’s letter. The shape of the wig, as well as colour and address of the letter, were explicitly described to the Inspector, and he forthwith sent two grooms, four threshers, and one dairy-boy out upon all roads, footpaths, and byways that run between Nieder-Fahren and Waiblingen. He stationed himself upon the hill by the wind-mill and reconnoitred the field of action through a telescope. Such excellent arrangements could not fail to bring about the desired result. In half-an-hour the seven messengers returned to the house led by the wig, the letter, and the Inspector.

Sure enough the letter was from the Burgomaster. It contained nothing less than a formal invitation to the Frau Obersteuerrätin, together with her brother and Fräulein[51] Susie and the Inspector Säblein, to the wedding of the Burgomaster’s eldest daughter.

Although Auntie felt very much flattered by this attention of the Burgomaster, with whom she was but slightly acquainted, there were some difficulties in the way which must needs be talked over in a family council.