The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Chinese theater, by Adolf Eduard Zucker

Title: The Chinese theater

Author: Adolf Eduard Zucker

Release Date: December 4, 2022 [eBook #69475]

Language: English

Produced by: Tim Lindell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

THE CHINESE THEATER

Seven hundred and fifty copies

of The Chinese Theater have

been printed from type and the

type distributed. Of this Limited

Edition, seven hundred and

twenty copies are for sale, of

which this is

Number 16

A GENERAL

Chinese Character Type

THE

CHINESE THEATER

BY

A. E. ZUCKER

Professor of Comparative Literature, University of Maryland

Formerly, Assistant Professor of English,

Peking Union Medical College

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

BOSTON

LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY

MCMXXV

Copyright, 1925,

By Little, Brown, and Company.

All rights reserved

Published November, 1925

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

To

MY WIFE, LOIS MILES

The genial Reverend Arthur Smith in his “Village Life in China” says that the Chinese sometimes finds it hard to understand the Westerner. As an instance he cites the case of a tired traveler who stops at an inn for the night and is told that there will be theatricals in the evening. Instead of sharing the glee of the natives, he gathers his tired self together and hurries on to the next village that he may enjoy his sleep far away from sounding brass and clanging[1] cymbal. Possibly this explains why among all the books written on China comparatively few concern themselves with the theater. One might add too that the drama stands on a relatively lower level than some other Chinese arts, for example, landscape painting and lyric poetry. Yet though his dramas are poor the Chinese actor has at his command consummate skill to hold the mirror up to life; he is no less of an artist than his Occidental colleague.

Still, the subject has attracted a fair number of[viii] Occidental writers. Du Halde was the first; in his monumental description of China published in 1735 he printed a translation by a Jesuit missionary of the Yuan Dynasty drama, “The Orphan of the Chao Family.” It was this translation that inspired Voltaire’s “L’Orphelin de la Chine.” Other translations followed in the nineteenth century, together with some critical material and various descriptions of Chinese staging. In the last few years the interest in the Chinese stage has evidently become greater than ever, both in China and in Western lands. A history of the Chinese drama, however, has never been written; largely because the Chinese themselves have no such work. Only a few present-day innovators among Celestial scholars consider the drama as literature. Thus the information we possess on this vast subject is very meager, and much of it is also out of print. This book is an attempt to gather together what is known on the subject, as well as to present in a volume supplied with vivid illustrations the results of five years’ experience with the Peking theater by a student of comparative literature possessed of a modest knowledge of the Peking dialect.

Those who have so far written on the subject have always spoken of a decadence of the drama which set in immediately after the first period of bloom in the Yuan Dynasty (1280-1368). In the course of the revaluation of values now going on in China this opinion is being changed. Mr. Wang Kuo-wei[ix] has recently compiled a dramatical catalogue which shows that numerically, at least, there is no decrease in the production of dramas. A trenchant critic, Doctor Hu Shih, holds that only technically can the drama of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) be said to be inferior, because the compact and unified plays of the Yuan period become diffuse and of serpentine length; but that in the matter of characterization, poetic diction, and content they are far superior. Furthermore, modern Chinese criticism considers the very highest point of the drama to have been reached in two historical tragedies of the Ching Dynasty (1644-1911). As can readily be seen, there is an enormous amount of work to be done in this field; and if the gaps and errors in this book shall impel a competent scholar to write the long overdue history of the Chinese drama this work will have served its purpose.

In general the Chinese drama is like ours. It is divided into acts, often corresponding in number to our customary four or five. It is presented in a manner strikingly similar to that employed during our greatest period of the drama—Shakespeare’s day. It can be classified according to content into our usual divisions. Historical drama prevails perhaps; because of the great love of the Chinese for his long tradition contemporaries of the Romans or even earlier heroes are favorites on the stage. Family drama is extremely popular, with subdivisions such as the drama of the court room and[x] criminal drama. The magic or mythological drama, recalling perhaps “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”, is also very important; among this group the very best plays are those that treat superstitious beliefs satirically. Then there are dramas of character, among which can be found a good counterpart to “The Miser” of Plautus or Molière. Dramas of intrigue abound on every program. Even the monodrama can be found among modern innovations. And last, but by no means least, there is the religious drama in some ways analogous to our miracle and mystery plays.

The three chief religions of China have exerted their influence on the stage. Confucianism supplies the general moral background of the majority of plays. The veneration of the scholar rather than of the warrior makes the former the chief hero on the Chinese stage, while filial piety is the most outstanding virtue which the hero displays. Taoism, generally described as the religion of superstitions, is responsible for the many mythological and ghostly figures that fill Chinese plays. Rational Confucianism is not conducive to imaginative writing, but under the influence of Taoism the Chinese allowed his fancy to roam to the end that innumerable delightful fairy and ghost stories were invented. The keen sense of humor of the Chinese often comes to the fore in plays dealing with Buddhist monks. These monks are the exact counterpart of the lazy, ignorant, sensual, superstitious brethren who people[xi] the pages of Boccaccio, Chaucer, Hans Sachs, and many other tellers of droll tales. In fact when Père Prémave first came to China (around 1700) and saw the monasteries with the celibate monks, who abstained from meat, chanted offices, burned incense, shaved their heads, prayed with beads, and gathered money from the pious, he decided that this was an invention of the Evil One for the sole purpose of exasperating the Jesuits. With the exception of some satire on the migration of souls the doctrine of Sakyamouni has had little influence, but whenever chanting priests or monks are brought on the stage they are burlesqued. The Chinese are extremely tolerant in regard to religion and never fanatical; their attitude toward the supernatural has been aptly defined as “politeness toward possibilities.”

But the main theme of the Chinese drama, as of all drama, is the human side of life. The stage is naturally enough a mirror in which we can see the Chinese as they see themselves. They present themselves not as the wise men of the East that some idealizing travelers would like to make them, nor as the bloodthirsty monsters of the “Limehouse Nights” brand; but as human beings, neither white nor black. We see the corruption of officials, the callousness toward suffering, the selfishness of parents, the eagerness for compromise, and the lack of physical or moral courage; on the other hand the polite civilization with its long tradition, the respect for the past and for learning, the love of poetry and[xii] art, the general kindliness and honesty of the people, the love of humor, the extreme democracy in social relations, and the reasonableness and lack of fanaticism. He who would know the Chinese ought to know their stage; and furthermore, he who loves our Middle Ages will derive endless pleasure from its counterpart, the pageant of Chinese life.

In my years in the East I received helpful suggestions from many friends in the course of hundreds of visits to the theater. Professor Soong Tsung-faung first introduced me to this fascinating spectacle. Doctor Hu Shih discussed it illuminatingly in conversation and by correspondence. Lucius Porter, Professor of Chinese, Columbia University, 1922-1924, offered helpful suggestions on the manuscript, which he read in part, as did likewise Professor Ferdinand Lessing, formerly of the National University, Peking. Two of my students, Huang Ke-k’ung and Jung Tu-shan, who learned from me about Sophocles and Shakespeare, introduced me in turn to many fine things on the Chinese stage. And finally, I wish to express my appreciation to Mr. Chang Ziang-ling and the many other p’iao-yu (amateurs) for acquainting me with the nonprofessional stage. Thanks are due to the editors of La Revue de Littérature Comparée and of Asia for permission to reprint a number of chapters.

A. E. Zucker

Riverdale, Maryland, December 7, 1924

| PAGE | |

| Preface | vii |

| CHAPTER | |

| 1 Early History | 3 |

| 2 Formal Development—Yuan Dynasty, 1206-1368 A.D. | 19 |

| 3 The Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644 A.D. The Pi-Pa-Chi | 43 |

| 4 The Drama under the Manchus and the Republic—1644 to the Present Day | 69 |

| 5 Modern Tendencies | 108 |

| 6 External Aspects of the Chinese Theater | 129 |

| 7 The Conventions | 161 |

| 8 Mei Lan-fang—China’s Greatest Actor | 171 |

| 9 Analogies Between East and West | 190 |

| Chronological Table | 221 |

| Bibliography | 223 |

| Index | 231 |

For the purpose of giving a vivid impression of the colorfulness of the Chinese stage, the publishers have imported from China four thousand paintings on silk, done by students of the Peking School of Fine Arts. They represent four of the standing character type of the Chinese stage, in their traditional make-ups.

| A General | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| A Scholar | 52 |

| A Demi-Mondaine | 152 |

| A Clown | 206 |

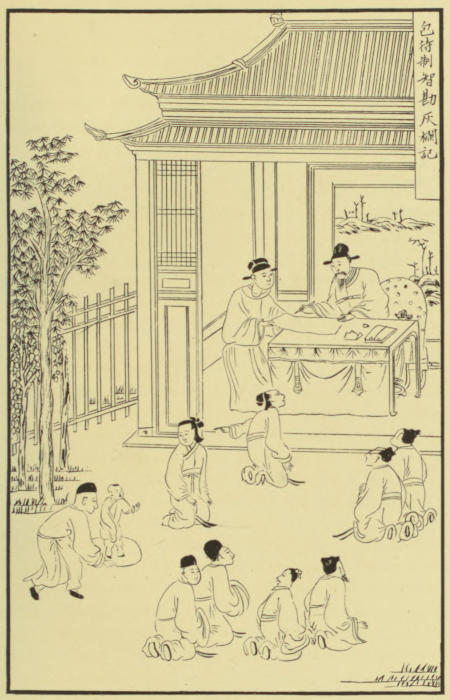

| Illustration by a Chinese artist for “The Chalk Circle” | 28 |

| Illustration by a Chinese artist for “The Chalk Circle” | 32 |

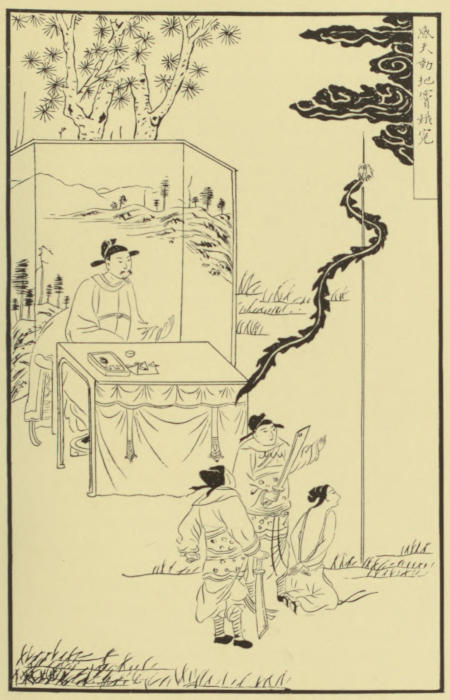

| Illustration by a Chinese artist. Tou-E before the judge | 38 |

| Illustration by a Chinese artist. Tou-E about to be beheaded | 40 |

| A Chinese artist’s conception of two pious souls | 48[xvi] |

| Warrior-acrobats | 80 |

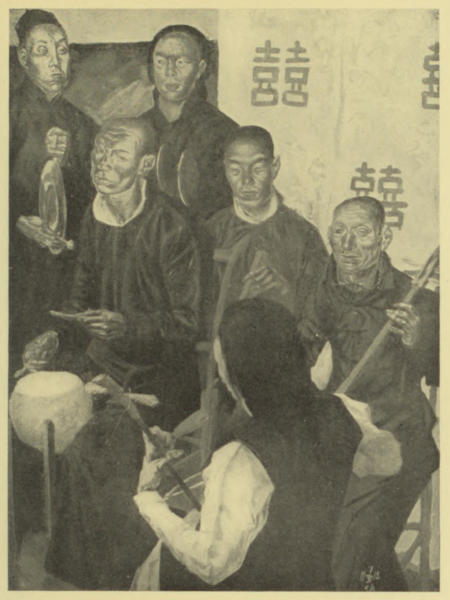

| Amateur actors in an old-style Chinese play | 110 |

| Hu Shih | 118 |

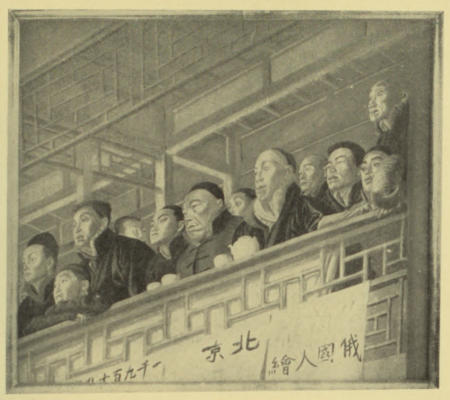

| A typical Peking audience with the inevitable teapots | 130 |

| Orchestral instruments | 146 |

| Orchestral instruments | 148 |

| The actress Kin Feng-Kui in a male rôle | 164 |

| Mei Lan-fang in European dress, and in parts | 176 |

| “Burying the Blossoms” | 180 |

| The Fortune Theater | 198 |

| A typical Peking theater | 198 |

| The orchestra seated in a corner of the stage | 202 |

“Students of the Pear Garden” (Li Yuan Tzu Ti) is the name by which actors in China are called in elegant literary style. This appellation was given them in memory of the traditional origin of the Chinese theater in the imperial palace gardens of a T’ang Dynasty emperor, Ming Huang (Yuen Tsung, 713-756 A.D.), who was a generous patron of the arts in his splendid capital Ch’ang An. This ruler established a college called the Pear Garden for the training in music and dramatics of young actors of both sexes. His plan for court entertainment the emperor had derived, according to legend, from a visit to the moon where he had seen a troupe of performers in the Jade Palace of the lunar emperor. In the annals of the T’ang Dynasty the following is told about the art-loving ruler:

“Ming Huang was not only passionately fond of music, but he also had a thorough knowledge of its essential principles. He established an academy of[4] music with three hundred students. Ming Huang himself gave them lessons in the Pear Garden; if any of the students sang in poor taste or incorrectly the emperor noted the fault immediately and corrected it sharply. The young girls of the harem, several hundred in number, were later also attached to the academy as students.... On the occasion of the emperor’s birthday the empress ordered them to perform some musical numbers in the Palace of Eternal Life.”

The French scholar Bazin in the introduction to his translation of four Chinese plays comments upon this as follows: “Surely it is a great thing that, at a time when the Chinese had as yet no idea of dramatic performances, a man who had founded the institution of the Han-Lin (literally ‘The Forest of Pencils’, i.e., The Imperial Academy of Scholars), and who could justly call himself ‘the teacher of his nation’, conceived and carried out single-handed a work of art, in which we find for the first time with all its marvelous charm the union of lyric poetry with the drama. This work, fitted to arouse in the souls of the spectators the sentiment of the sublime, could be the product only of a genius.”

In “The Chinese Drama”, William Stanton writes on the origin of the drama as follows:

The long reign of Yuen Tsung, styled the Illustrious Emperor (Ming Huang) owing to its splendid beginning and disastrous close, is one of the most remarkable in Chinese history.

On ascending the throne, the young emperor zealously strove to purge the empire of the extravagance and debauchery that was ruining it; and in his austerity went so far as to prohibit the wearing of the then fashionable costly apparel, and, as an example to his subjects, he made a large bonfire in his palace of an immense quantity of embroidered garments and jewellery. Under the wise administration of this stern ruler and his able ministers the state attained a great height of prosperity. But unexpectedly the emperor’s character underwent a change; he developed a love of sensuality and himself indulged in the luxuries he had formerly so strongly condemned.

In A.D. 734 he obtained a sight of his daughter-in-law, the beautiful Yang Kuei-fei, and became so violently enamoured with her that he took her into his own seraglio. She speedily obtained a complete ascendency over him and succeeded in getting raised to the highest position next the throne.

According to legendary stories the Herdsman and Spinning Damsel are two lovers who each inhabit a star separated by the Silver River (the Milky Way) and are unable to meet except on the seventh night of the seventh moon, when magpies from all parts of the world assemble, and with their linked bodies form a bridge to enable the damsel to cross to her lover. Consequently this is one of the great festive occasions of China. On the said evening of A.D. 735, Yuen Tsung and his celebrated consort stood gazing into the starlit sky. Remembering the occasion Yang Kuei-fei burst into protestations of affection and assured the monarch that she was more faithful than the Spinning Damsel, for that she would never leave him, but, inseparably with him, tread the spiritual walks of eternity. In order to reward such love the emperor sought to discover a novel amusement for her. After consideration he summoned his prime minister and commanded[6] him to select a number of young children, and, after carefully instructing and handsomely dressing them, to bring them before the beautiful Yang Kuei-fei, to recite for her delectation the heroic achievements of his ancestors. That was the origin of the drama in China. The first performances were generally held in a pavilion in the open air, among fruit trees, and Yuen Tsung subsequently established an Imperial Dramatic College in a pear garden, where hundreds of male and female performers were trained to afford him pleasure. From the site of the college the actors become known as the “Young Folks of the Pear Garden”, a title they claim to the present day.

The Pear Garden origin of the Chinese drama is a fine legend and heroic history, but it is typical of Chinese who have come in touch with Occidental science that they should search for a more realistic, if less picturesque, account of the beginning of their theater. The first, and so far the only, systematic and scientific work on this subject is “The History of the Drama under the Sung and Yuan Dynasties”, by Mr. Wang Kuo-wei.[2] This author has taken great pains in collecting all evidences of pantomimes, dramatic dances, satirical buffoonery, or anything else to which the roots of a theater might be traced. While he is not yet able on the basis of his evidence to lead us back step by step to the genesis of the theater—as could for example a scholar dealing with the Greek drama—yet the evidence he adduces is most interesting.

About 2000 B.C. there were found mediums called wu when they were women or hsien when men, who performed dances and sang songs in the worship of the gods, to exorcise evil spirits, to induce the gods to send rain, or to act as mourners in times of calamity. It was believed that the gods descended to earth and communicated with men through these mysterious beings, especially in the course of violent dances. This form of worship designed for the pleasure of the gods was evidently much according to the taste of men, for we find it such a widespread form of popular amusement that I-Yin, famous minister of the Shang Dynasty (1766-1122 B.C.), issued an edict prohibiting it. “The late sovereign instituted punishments for the officers, and warned the men in authority, saying, ‘If you dare to have constant dancing in your mansions, and drunken singing in your houses, I call it wu-fashion’.”[3] During the classical Chou Dynasty, beginning 1122 B.C. with Wu Wang, everything in Chinese life was cast into the fetters of a strict ritual. There were regulations governing the dress to be worn, the speeches to be made, and the postures to be assumed on all possible occasions, whether at the court or in private life; in fact, these rules were the prototypes of most of the characteristic features governing Chinese public and social life down to the present day. It can be seen readily that the more or[8] less spontaneous and popular mimicry of the wu (mediums) would naturally enough be suppressed at this time; but in later dynasties we find again many references to the beauty, the splendid costumes, the singing and dancing, and in general the charm of these actors in popular religious ceremonies.

These performances of the early Chinese centered about the divine worship, as everything of æsthetic nature in the life of primitive man seems to do. Even to-day all of the theatrical performances in China outside the large cities are a form of divine worship, usually harvest festivals staged by way of thanksgiving for good crops. That there is in the minds of the Chinese a definite religious association with theatricals performed in the villages is shown by the fact that the Christian converts always receive a dispensation for their share of the sum demanded by the traveling company. Sometimes missionaries hear complaints from the village elders that some thrifty members of their flocks save the tax for theatricals and yet go to look on at the shows; however, thanks to the reasonable and unfanatic character of the Chinese such quarrels are usually easily adjusted.

Because of this close association of the theater with temple worship,[4] it seems reasonable to seek[9] for another possible origin of the drama in the early ancestor worship in which the deceased forefather of the family was impersonated by one of his descendants. A ceremony of honoring a revered ancestor could easily be expanded into a representation of his great deeds. It is also known that not only men but also gods were impersonated by the actors; as Mr. Wang puts it, they dressed in the attire of the gods and imitated their gestures. However, in regard to these representations of the gods our author feels that it is impossible to give any definite details. Yet in the verse of the time there are allusions to these performances referring to extravagance in dress and in articles of toilet, such as perfume; to a change in the style of music; to the employment of themes of love or of sadness in parting—all of which indicates the great popularity of these entertainments of singing or dancing. Hence our Chinese scholar believes that out of these beginnings the drama has grown.

In this connection it would seem proper to mention the work of the Cambridge University scholar, Professor William Ridgeway. He holds that Greek tragedy proper did not arise in the worship of the Thracian god Dionysus; but that it sprang out of the indigenous worship of the dead, especially dead[10] chiefs who in some cases are later deified.[5] In dramatic dances in honor of ancestors or deceased heroes in Asiatic countries Professor Ridgeway finds support for his theory of the origin of the Greek theater. Speaking of the Chinese theater, he says that already in the time of Confucius certain solemn dances were held in the ancestral temples; at the present time in the temples of local deities, who were once heroes or heroines of the immediate neighborhood, dramatic performances are held in which these deified heroes are supposed to take an interest for the reason that they are themselves frequently the object of the worship; and that these modern theatricals seem to be descended directly from the ancient cult practiced five hundred years before Christ. It would seem from the foregoing that Mr. Wang’s evidence gives support to Professor Ridgeway’s theories of the origin of tragedy out of the worship of deified heroes.

Doctor Berthold Laufer, curator of the Field Museum, Chicago, has stated to me that in his opinion a discussion of the origin of the Chinese drama ought to differentiate between the beginnings of the “military plays” and the “civil plays.” The latter are, as will be explained more fully in a later chapter, plays in our sense of the word, while the “military plays” consist of acrobatics that symbolize fighting. Doctor Laufer believes that these[11] last-named take their origin from ancient ceremonials in which the use of weapons was the chief feature. Doctor Laufer has had considerable experience with the Chinese theater, and his museum is the only one in the world, so far as I know, which possesses life-size figures of Chinese actors in correct costume.

So much for ancestor worship as the source of the drama with the wu or hsien. Mr. Wang adduces records also of other types of actors. As early as 1818 B.C., according to a none too reliable Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-221 A.D.) record, a ruler is said to have abolished the temple rites and ceremonies and to have collected about his court clowns, dwarfs, and actors to perform amusing plays. In the more historic period of “Spring and Autumn” (770-544 B.C.) there are records of dwarfs in rôles similar to those of our court fools. They attempted to gain the favor of the rulers by their witty sayings which were often full of satire. Confucius in his capacity of prime minister saw himself forced to put to death one of these wits[6] because of his disrespectful allusions to the ruler—an action, incidentally, that seems most characteristic of the noble sage, who with all his virtues certainly was not endowed with a sense of humor. The function of these dancing, singing, play-acting dwarfs was not a religious[12] one; “they were to amuse men, not to amuse the gods.”

In a review[7] of Mr. Wang’s “History of the Drama under the Sung and Yuan Dynasties” Professor Soong calls attention to the following interesting analogies between Orient and Occident:

The influence of the court fools was considerable, and on the whole salutary in China. Shih Huang-ti (255-206 B.C.), the builder of the Great Wall, was so addicted to great building enterprises that the people suffered in consequence. It was Yu Sze, the court fool, who caused the emperor to treat the people with more consideration. The successor of this mighty ruler conceived the plan of having the Great Wall painted—perhaps just a caprice on his part, perhaps in order to render the Wall less subject to the influence of the weather. Again Yu Sze dissuaded the emperor from carrying out such a costly and wasteful project. The history of Yu Meng is even more interesting. In the kingdom of Chou the family of Suen Lo Ngao had become extremely impoverished because the king had forgotten the merits of the chief of the house, a famous general. Yu Meng, the court fool, donned the armor of the defunct military leader and sang of his exploits before the royal palace; now the king could no longer refuse to recognize and recompense the merits of the family. This touching episode told by the historian in the “Biography of Court Fools” cannot but recall Will Sommer to whom “The King would ever grant what he would crave.”

During the Han Dynasty records show the existence of jugglers, magicians, rope-walkers, sword-swallowers,[13] and also of plays in which masked actors disguised as gods, fearful leopards, cruel tigers, white bears, and gray dragons had their parts. Dwarfs and giants were made to play together in humorous pieces. Singing girls in costumes of feathers executed artful dances. Some of these performances are said to have been so indecent that passers-by covered their eyes. However, such performances were sharply censored at the time, just as they would be in present-day China.

All of these performances were very much favored by the rulers, but they consisted mostly of singing and dancing, while there was very little that might be called drama. In the northern Ch’i Dynasty (550-570 A.D.) however, there arose what might be called a historical play based on an episode in the life of a heroic warrior, Duke Lan Lu. This warrior had a somewhat effeminate aspect, and therefore he wore a mask in battle to inspire fear in the hearts of his enemies. His story was dramatized and became a very popular play, probably similar to the present-day “military plays” in which the play with swords and spears forms the pièce de résistance. There is a record about the same time of a comedy also based on an actual occurrence, called “The Drunkard.” A certain man, Su Pao-pi (a name alluding to red spots on his nose) was a very heavy drinker and after each spree would beat his wife in the village street until she wept pitifully.[14] Two actors, one dressed as a woman and the other as a man, would amuse the people by a popular farce portraying this quarrel between husband and wife. The playlet must have been one of extraordinary vitality, for there are records of it in the Chi, Chou, and Sui dynasties—to be sure, three short dynasties that followed one closely upon the other. Music and dancing also played a part in these two early dramatic presentations, so that they were probably of the melodramatic (in the etymological sense of the term) variety, such as is most of the Chinese drama of to-day.

The dramas in China are classified according to the style of music they employ. Another play of the same, or perhaps a little earlier period, called “The Tiger,” is thought by Mr. Wang, because of the music of foreign tribes employed in it, to have been brought into China from “The Western Regions” (central Asia).[8] It is the story of a man who was killed by a tiger and whose son then set out on a search for the wild beast, fought with it and avenged his father by killing it in turn. Mr. Wang even hazards the suggestion that the two plays mentioned above, “The Mask” and “The Drunkard,” were in their music and manner of presentation imitations of “The Tiger,” in which case this form of drama[15] would be a borrowing from a foreign country and not indigenous to China.

Two other early plays which Mr. Wang mentions deal with historical episodes. From the Han dynasty (206 B.C.-221 A.D.) dates the story of an unjust mandarin who had “squeezed” as they say in China, ten thousand rolls of silk and was put in jail. Later on the emperor moderated this punishment, because of the mandarin’s great learning, into the following: the culprit had to appear at court dressed in a white robe while for the period of one year the court fools were at liberty to make sport of him. This became the basis of a play shown by a number of records to have been acted frequently before the T’ang Dynasty. The plot seems, indeed, to have been a comedy made to order for the court fools to display their wit. There is evidence to show that this play was enacted in the imperial palace in the middle of the eighth century. A group of actors from Chekiang in presenting this play were said to have had voices so loud that they penetrated to the clouds—a circumstance that would win the favor of the devotees of certain types of modern Chinese drama. The other historical play has for a hero Fan Kuai, a noble who saved the emperor’s life by his prompt action against rebels. It is said to have been written by the T’ang Dynasty emperor, Chao Tsung himself, and to have been acted in the imperial palace in Ch’ang An.

It was during the T’ang Dynasty especially that[16] a nonmusical type of drama flourished in the form of extemporized comedies. The plots hinged on local occurrences and differed with practically each presentation. However, much as in the Italian commedia dell’ arte, with its Arlecchino, Pantalone, Dottore, Scapino, etc., certain characters or character types seem to have arisen. The very same extortionate mandarin, mentioned above as the central figure of a play, became such a type who figured in almost all of these comedies—in fact he is a stock character on the Chinese stage even to-day—while opposite him there appeared as his regular companion a fool wearing a green cap. Thus dialogue between two actors—in other words rudimentary drama—became firmly established. Since the satirizing of current events and of local characters was the avowed purpose of these comedies, it will be readily understood by all familiar with life in the East that the dishonest official came in for his fair share.

A topical comedy with a purpose from the Sung Dynasty (960-1126 A.D.) played before the emperor attained all that might have been desired. Through the efforts of an unpopular official a system of coinage had been introduced in which the smallest coin had a value of ten cash. Naturally enough this caused great inconvenience to very many poor people. Therefore some actors called upon to play before the emperor in the course of a feast proceeded to give him a lesson in rudimentary economics. A[17] vendor of syrups appeared and shortly afterwards a thirsty customer. The latter paid one coin and demanded one drink. The merchant explained that he had no change for the coin and asked his patron therefore to take a number of drinks. The buyer does his best, but after the fifth or sixth cup taps his bulging stomach and exclaims, “Well, I’ve done it at last. But if the gentlemen in the government were to make us use hundred-cash coins I should surely burst!” The emperor was moved to gay laughter and smaller coins were at once issued. However, the efforts of these actors were not always so fortunate in outcome. The story is told, for example, of actors who had dressed up to represent Confucius, Mencius, and other sages for the purpose of giving the emperor some very pertinent advice on the division of land in the very words of the great moral teachers. The advice proved to be so inconvenient that the emperor had the actors whipped for their pains.

From the Sung Dynasty (960-1127 A.D.) Mr. Wang reports the names of 280 plays and from the Chin Dynasty (1115-1234 A.D.) 690 plays, but fails to state how many are extant. Of the so-called Ancient Drama it is known that a certain kind of free metrical form adapted to music (ch’ü) was employed; that as a rule only two actors appeared in each play; and that theatricals, though still very primitive, were quite popular, as they were presented both to the general public in shabby mat-sheds[18] and to the court at magnificent feasts. Our knowledge of the Ancient Drama is very meager to be sure, yet the work of Mr. Wang has made it possible to go beyond what Mr. Giles says in his “History of Chinese Literature”[9] after having mentioned the Pear Garden myth: “Nothing, however, which can be truly identified with the actor’s art seems to have been known until the thirteenth century, when suddenly the Drama, as seen in the modern Chinese stage play, sprang into being.” Owing to the great interest in Western drama in China at the present time it is very likely that other Chinese scholars will make researches in this interesting field and that more light will soon be shed on the origin of the Chinese drama.

The rise of the Chinese drama was due to a national disaster that broke the sway of the ruling literary class. In 1264 Kublai Khan with his Mongols fixed his capital at Peking and for the first time in their history the sons of Han passed under the rule of an alien sovereign. The barbarians naturally enough abolished the literary examinations for government posts, consisting of competitions in the writing of essays and poetry in the language of the classics, for they did not care to appoint as viceroys and justices members of the subject race. The Mongol language had absolutely no literature and, indeed, not even an alphabet until 1279, when a Tibetan priest constructed one by imperial order. Chinese scholars were thrust out of their high offices and could find employment only as writers of petitions or as lowly clerks. There was no longer any call for the exercise of their talents in[20] the writing of descriptive essays or lyrical poetry such as had been demanded in the examinations formerly leading to the highest offices; they found, however, a fruitful outlet for their literary powers in a genre previously greatly despised by the literati—the drama.

The cause of the scholar’s disdain for the drama and the novel was the great chasm that yawned between the classical language and the spoken language of the day in which, perforce, popular literature of entertainment or of the stage had to be written. For over a thousand years the literary language had been a dead language, so dead that a learned scholar could comprehend it only if he saw the text in black and white before his eyes—to hear it read did not by any means enable him to understand it. Everything that had been considered literature up to that time was composed in this language, and anything composed in the vulgar tongue was considered beneath the dignity of a scholar. Now, however, clever writers turned to the drama and the novel with the result that the written language was to a certain extent democratized in the works that appealed to the broad masses of readers or hearers. But let it be noted, to a certain extent only; for, as vanquished Greece in turn conquered Rome by her superior culture, so Chinese culture conquered the Mongols. After having been abolished for practically eighty years the literary examinations were reinstated and the drama too[21] was gradually caught in pedantic fetters of formalism. Yet in spite of the fact that the Yuan dramatists moved away from the spoken language to one presupposing considerable erudition on the part of the reader, there are many scholars even to-day who regard the novel and drama as beneath their notice, just as a medieval scholar would have despised any work not written in Latin.[10]

In fact these works have been recognized at their true worth only as late as 1917, when Hu Shih, Columbia University doctor of philosophy and professor at the National University in Peking, began to lecture on the Chinese drama as drama and to publish the best of the novels with historical introductions.[22] Professor Hu Shih finds in the language of these works a compromise which he hopes will be an aid in inducing the Chinese of to-day finally to adopt the vernacular as the language of science and belles-lettres. For, in spite of the concessions made to the firmly rooted conventions of the conservative class of scholars for the sake of lending dignity to their works and securing the approval of the literati, the novel and the drama, owing to their popular appeal, deviated largely from the dead language and approached the vernacular of the day.

The dramatists are as a rule men who are not otherwise famous as writers. Biographical material concerning the authors of the “One Hundred Yuan Dramas”, the collection of plays considered classical in China, is so meager that it does not seem worth while to mention names about whose bearers little more can be said than that they “flourished.” About five hundred plays were extant at the beginning of the Ming Dynasty, while to-day there exist but one hundred and sixteen. Modern Celestial scholars are proud of the fact that an overwhelming percentage of the authors were real Chinese, practically all from the territory now covered by the provinces of Chihli, Shantung and Shansi, about a third of them born in Peking (called Yenching at the time). Nine tenths of the authors lived in what is called the first period of the Yuan drama (1235-1280) with its center in Peking; while the much smaller Southern School developed later[23] (1280-1335) around Hangchow. Most of the authors were from among the common people, and only one among the whole ninety odd was a Tartar. Chinese critics regard Kuan Han-ching (the author of “The Sufferings of Tou-E”, a play discussed below) as the greatest of all these writers, because his manner is true and natural. Others are spoken of as having a style that is lofty and magnificent, or pure and beautiful, or biting and vigorous.

The historian of the Chinese drama, Mr. Wang Kuo-wei, quoted above, states that the Yuan drama is a natural growth out of the previously existing forms and the traditional plots. More than thirty Yuan plots, he points out, had been used before in plays of the Sung Dynasty. He finds the chief advance of the Yuan drama to consist in the employment of more flexible verse forms for the poetic sections and the use of more dialogue in the place of narration and description. Thus the essence of drama, action, takes the place of narration. Moreover, the drama rose to the dignity of an art. Previous to this the plays, generally dialogues by clowns, had been mostly interlarded in entertainments of acrobatics, dancing, and music. Such performances took place frequently at the royal court and are described also in the writings of the Italian Ma-Ke-Po-Lo (Marco Polo) when he tells about the feast of the Grand Khan: “When the repast is finished, and the tables have been removed, persons of various descriptions enter the hall and amongst these a troop[24] of comedians and performers on various instruments, as also tumblers and jugglers, who exhibit their skill in the presence of the Grand Khan to the high amusement and gratification of all the spectators.”[11]

As has been stated above, the dramas soon took on certain formal aspects. In general they have four acts, with a prologue, epilogue, or interlude, which makes them in appearance and length quite similar to our five-act plays. Some plays—analogous to our trilogies—have acts of a number that is a multiple of four and each group of four acts forms a unity by itself. For example, “The Western Chamber”, has twenty acts and forms really five plays. According to Chinese critics the drama is composed of three elements: (1) action; (2) speech; (3) singing. Speech may be divided into monologue and dialogue; the purpose of the latter is to advance the action and of the former to arouse emotions—a function that very properly invites comparison with the rôle of the chorus in the Greek drama. No longer are there only two characters in these plays, but we now find four chief rôles along with various minor parts. In very rigid manner only one character is made to sing in each act, which means that each of the four characters has one act in which he or she plays the main rôle. This arrangement has had its peculiar effect which can be[25] witnessed in present-day Peking, where plays of this type are staged, inasmuch as a famous actor who plays, let us say, the rôle of the lover, will not present entire dramas, but only such of the acts as give him the principal part. In the new plays of to-day, of course, a different practice is followed but the old repertoire of the average Chinese theater is so well known that it makes very little difference whether a drama is presented as a whole or in part. The character types of the Yuan drama, the Mei (male) and Tan (female), with their many variations, are in general quite similar to the types of present-day drama, a discussion of which is given in a later chapter. In the printed texts of the play characters are designated not by their names, but by the rôles which they play.

The classical drama of China offers many interesting parallels to different stages in the development of our drama, though it nowhere equals the plays of our great masters. Its greatest height reaches the level of perhaps the pre-Shakespearean drama in content, construction, and manner of presentation. The presentation of Chinese plays with the projecting platform stage, the lack of scenery and the emphasis on gorgeous costume, the playing of female parts by male actors, the extemporizing of clowns, and the use of music in “flourish” and “alarums” offers a strikingly close parallel to Elizabethan staging. But that is a chapter by itself.

In the consideration of Chinese drama a few facts[26] of Chinese life must be borne in mind. The beau ideal in the Middle Kingdom is not the warrior, but the scholar. There is no hereditary aristocracy, but wealth and power falls to him who distinguishes himself in the competitive examinations and thus becomes viceroy of a province or some other type of high official. The passing of the examination therefore serves as the deus ex machina in many plays, solving all knotty problems accumulated by the fifth act. Marriages are arranged by the parents, and the romance of courtship is a rare and forbidden fruit. The religious and ethical background consists chiefly of a respect for the minute moral precepts of Confucius, with some Buddhistic notions of reincarnation and some Taoist superstitions impartially admixed.

To examine a few of the acknowledged masterpieces of the Yuan drama is to invite fascinating comparisons. In “Chao Mei Hsiang” (Intrigue of a Lady’s Maid) we have a young servant girl uniting two lovers, a sort of Dorine of Molière’s “Tartuffe” in a Chinese setting. The destiny of the young man and the girl have been settled beforehand by their parents, much as Orgon in “Tartuffe” disposes of his daughter’s future:

The lovers in both plays revolt against parental authority, and in both cases a happy ending is[27] brought about indirectly through fortunate intervention on the part of the monarch himself. The meat contained in the Chinese play is about what “Tartuffe” would be with Tartuffe left out.

Two generals arrange, shortly before they die in battle, that their children are to marry. The son of the one, therefore, while on his journey to the capital to take his examination, visits at the home of the widow of his father’s friend. The widow invites him to take up his abode in a pleasant pavilion in the garden, but she meets with icy silence every reference on the part of the young man to marriage. This is because she wishes to observe the very strictest code of conduct, which ordains that when a girl has lost her father she dare not marry until three years afterward. The young people fall in love at first sight; the young man so desperately that the yearning for the girl he is not permitted to see after their first accidental meeting causes him to become violently ill. The quick-witted, impertinent maid sent to look after the wants of the patient carries messages between him and the young girl and finally arranges a meeting on a moonlit night. The lovers have exchanged but a few words when the mother discovers them. She punishes the maid and sends the young man away in disgrace. He goes to the capital and passes such a brilliant examination that he attracts the attention of the emperor. The latter becomes interested in the young man’s future and decides to carry out the wish of[28] his two faithful generals. The marriage is arranged by imperial command. Both lovers are in ignorance as to who their selected mates are to be, and at first are very much dejected; but when they meet as bride and groom their happiness is all the greater when they realize that the choice of their elders is also the choice of their hearts.

ILLUSTRATION BY A CHINESE ARTIST FOR “THE CHALK CIRCLE”

This, together with three similar illustrations, has been taken from the standard edition of the Yuan Dynasty classics

The play moves in an atmosphere of strictly prescribed etiquette of which the mother is a stony-eyed incarnation. The facetious little maid is a breaker of rules in the interest of more human considerations, and, like the servant in all our comedies from the time of Menander downward, she tells her mistress some frank home-truths. Not only is the young man a scholar, but the heroine with her maid-companion also have been ardent students of the classics. Quotations from Confucius, Mencius, Laotze, and the Buddhist writings lend their sparkle to the dialogue. The lovers exchange poems exhibiting that charming impressionism of delicately sketched moonlight on the lotus or snowfall on pine trees so characteristic of Chinese verse. Allusions to myths abound; for example, to the moonlit cloud that wooed the mother of Huang Ti as Jupiter did Io. As in the plays of Bernard Shaw and of his predecessor Shakespeare, the heroine takes the initiative by tossing into the room of the rather passive hero a bag embroidered with characters revealing her love. A wistful note is sounded by the young scholar when the wedding commanded by the emperor[29] is, as he believes, about to unite him to a woman other than the one he loves: “Musicians, please do not now play the air of the teals meeting in chaste pleasure who lament and yet feel no sorrow.” This speech gives the same blending of the emotions so often spoken of by our poets in analyzing the mystery of love, perhaps most strikingly in Goethe’s lines:

The play “Ho Lang Tan” (The Singing Girl) portrays the punishment of vice and the triumph of virtue. A rich merchant decides to take into his house a second wife, a certain singing girl. He finds himself desperately in love with this lady of easy virtue, while the girl herself is planning to get his money in order to run off with her real lover. There is a scene between husband and wife in which the latter bitterly resents the plan of bringing a concubine into the house and pronounces grave warnings of the evils that will befall her husband in consequence. But the merchant persists in his plan and brings the singing girl to salute his wife as mistress of the house. The former is required by etiquette[30] to make four bows, of which the last two must be returned by the wife. The wife refuses to greet the interloper, and after a short but violent quarrel she dies of anger. The next scene shows the singing girl stealing the merchant’s money and setting his house on fire. Her lover, disguised as a boatman, throws the husband into a stream and tries to strangle the latter’s son and his nurse. But passers-by prevent the cowardly murder, and one of the strangers buys from the nurse the seven-year-old boy for one ounce of silver. The poor nurse faces starvation and decides to adopt the profession of a singing girl. While traveling about in this capacity she meets the merchant who has had a miraculous escape from drowning and has sunk to the position of swineherd in a far country. His lowly state eloquently points the moral. At first he upbraids the nurse for having adopted her dishonorable calling, but afterward he accepts her invitation to quit his miserable post and to be supported by her. Thirteen years have passed and the young son has become a famous judge by virtue of having passed a brilliant examination. He happens to arrive in the same city where his relatives are and calls on the keeper of his inn to provide some singers for his entertainment. The host leads in his childhood nurse and his father. The young judge wipes his teacup with a piece of paper which he throws on the floor. As this paper happens to be the contract of his sale by the nurse to the kind-hearted stranger[31] who later made him his heir and as it happens to be picked up by the father, a recognition is effected. At the same time two thieves are brought before the judge, who turn out to be the erstwhile second wife and her scoundrel lover. They meet their just punishment; the judge puts them to death with his own hand as a pious offering to the spirit of his deceased mother. The father praises the justice of Heaven and asks his son to order a feast that they may celebrate in due form this remarkable meeting.

The chief interest of this clumsy play lies in the light it throws on Chinese life. The indignation and subsequent death of the wife show how even in countries where “they are used to it” women resent bitterly the advent of a concubine into the house. During my stay in Peking there occurred several weddings that were marred by violent quarrels between the first wife and the new bride. The husband in our play vainly exhorts his wife to be good, to observe the three obediences and the four virtues of a wife.[12]

Yet he cannot exile her, because she has borne him a son. All of the characters are drawn with great realism in their ignoble conduct. The sale of the child by the nurse is followed by a tearful monologue on the part of the sailor who had come to the[32] rescue: “Poor child, your lot is to be pitied. This woman who was just about to be strangled by the brigands finds herself reduced to the necessity of selling her child. Could one find a sadder and more heart-rending situation? Who would not shed tears of pity for her?”

The author sets out with a realistic portrayal of a phase of life, but he yields to the force of convention which required a moral and happy ending—an influence not unknown in the drama of Western countries.

Our plays, from “The Merchant of Venice” to “Madam X”, abound in court scenes, but the Chinese theater makes use of this effective device even more frequently. A play called “The Chalk Circle” presents in a trial scene a story almost identical with a Biblical one. Two women appearing before a judge with a child each claim it as their own. The judge orders the child placed in a circle drawn on the floor, while the women are to decide who is the mother by pulling at the child in a sort of tug-of-war. One woman refuses to hurt the child by pulling at his arm, and the judge decides with Solomonic wisdom that she must be the true mother. Very frequently these plays are satirical in character, making sport of the notoriously corrupt judges. In one of the naively primitive speeches of introduction, required by the theatrical convention of every character on entering the stage, a judge is made to say, “I am the governor of Ching-Chou. My name is Sou[33] Shen. Although I fulfill the functions of a judge, yet I do not know a single article of the code. I like only one thing and that is money. By means of the bright metal every plaintiff can always make sure the winning of his suit.”

ILLUSTRATION BY A CHINESE ARTIST FOR “THE CHALK CIRCLE”

“The Transmigration of You Hsin” is a play dealing with the popular superstitions regarding the reincarnation of souls in much the same spirit in which Voltaire in “Candide” treats the belief that this is the best of all possible worlds. As in Gogol’s “Revizor” the government sends an inspector to a certain village where the officials of the law court are said to be corrupt. The rumor of the coming inspection reaches town before the inspector; and most of the judges flee. Only You Hsin remains, together with the clerks and minor officials. One of these expresses his surprise at the fact that You Hsin is going to meet the inspector so calmly, especially since he had recently accepted a scandalously large bribe. You Hsin answers, “Yes, to be sure, I’ve accepted presents. But my friend, you certainly are simple! Isn’t it necessary that we fulfill our destiny? No one can die before his time has come. Have the courts ever prolonged by one minute the life of a man? If it were otherwise people would no longer believe in lucky and unlucky fates; they would no longer call Heaven and Earth the arbiters of life and death.” A famous anchorite appears prophesying that You Hsin will die within two hours. Then the inspector enters the village and[34] begins immediately his examination of the court records. However, since he is an extremely stupid and incapable man, the clerks succeed in persuading him that everything is in order. But You Hsin in his home has fallen ill. He implores his beautiful wife never to show her face in public and to remain a widow forever. He dies at the very hour the holy man had foretold—even though his death is not due to a sentence imposed on him because of his corrupt practices.

You Hsin’s soul appears before the judge of the lower world. As he had been very avaricious in life his punishment is to consist in having to gather coppers tossed into a deep kettle of boiling oil. But the holy man appears and obtains forgiveness for You Hsin, because he allows himself to be quickly converted to Taoism and makes the vows of poverty and chastity. The judge will even grant him the boon of a speedy return to earth. He cannot reënter his own body, because his wife has been a bit precipitate in cremating it; but he is allowed to enter that of a butcher who has just died, a blue-eyed, lame, and otherwise ugly man. The butcher’s parents, wife, and neighbors are engaged in mourning, when the dead man suddenly rises from his coffin. You Hsin wants, first of all, to see his pretty wife, but when he tries to walk he stumbles with his lame leg. As they hand him the crutch he reflects, “Ah, yes, in my former life I had a crooked conscience and in this life I have a crooked and useless leg. I[35] realize only too well the heavenly justice!” The butcher’s relatives follow him to his former home, where his wife had been happy to receive him after he had fully explained his miraculous return. A violent quarrel breaks out between the two women, each of whom claims her husband. The case is taken before the stupid imperial inspector, who is in great perplexity before the question as to whether the body or the soul constitutes the husband. The case and the play end when the anchorite arrives to remind You Hsin of his vows and to take him into the unworldly wilderness.

Plautus’ and Molière’s subject for a comedy of character, the miser, has been employed by a Chinese playwright with strong local color to his humor. One of the many scenes of his play describes how the miser comes to feel that he must have a son to pray at his grave and therefore decides to buy one from an unlucky scholar reduced by poverty to selling his children. He offers the parents one ounce of silver. The mother exclaims in her disappointment, “Why, for that sum you couldn’t buy a boy modeled in clay.” Perhaps this is a bit unmotherly in sentiment, but the retort is truly miserly, “Yes, but a boy of clay does not eat or cause other expenses.” When this sum is refused the miser instructs his servant to go once more to the man, to hold the silver high, very high, above his head and to say, “There, you poor scholar, His Excellency Lord Kou deigns to give you one precious ounce of[36] silver.” His servant replies that no matter how high he holds it an ounce will be only an ounce; and finally he pays the father more out of his own wages!

When the son has reached the age of twenty the miser scolds him one day because he seems to think that money is for the purpose of buying food and clothes! By way of instruction he tells how one can live economically:

“One day I felt inclined to eat roast duck and therefore I went to the market to that shop which you know. They were just roasting a fine duck and the delicious juice was running down. Under the pretext of bargaining I handled it and soaked my fingers thoroughly in the gravy. Then I went home without having bought it and called for a plate of boiled rice. With each spoonful of rice I sucked one finger. At the fourth spoonful I became tired and fell asleep. During my nap a treacherous dog came and licked my last finger. When on awakening I noticed this theft, I became so angry that I have been ill ever since.”

The house is in need of a picture of the god of luck, and the miser instructs his son to order the artist to paint a rear view, because to paint the face costs most. When he is about to die he orders his son to bury him not in a coffin of pine, nor even of willow wood, but to use the old watering trough standing in the back yard. The son objects that it is too short, but the father instructs him to chop[37] his body in two to make it fit. “And there is one more important thing I wish to say to you before I die; don’t use my good ax to cut me in two, but borrow one from the neighbor.”

“Since we have an ax, why should I bother the neighbor?”

“Perhaps you don’t know that my bones are extremely hard, and that if you’d use my good cutting edge you’d have to spend some coppers to get it resharpened.”

The miser’s last words are inaudible, but he persists in holding up two fingers. All the relatives assembled in the death chamber are very much puzzled and try to please him by doing this or that, but the dying man’s discomfort increases. Finally his old servant enters and he understands. There are two candles burning where one might do; and after one of them has been extinguished the miser dies in peace.

Tragedy is not found in the Chinese drama. The plays abound in sad situations, but there is none that by its nobility or sublimity would deserve to be called tragic. The closest approach to it is found perhaps in “The Orphan of the Chao Family”,[13] made familiar to Western readers by Voltaire; or in “The Sorrows of Han.” This latter play, in the Chinese literally “Autumn in the House of Han”, is full of poetical touches. North of the Great Wall there is the Tartar Khan who sees in the weakness[38] of the Han emperor his opportunity for further conquest. This young emperor is addicted to a life of dissipation, and through his minister Mao he gathers beauties for his harem from the four corners of his realm. As a true Oriental, Mao demands a heavy bribe from the family of every girl whose portrait he submits to the emperor. But the family of the most beautiful girl of all is so poor as to be unable to pay a bribe, and therefore the minister causes the artist to distort the portrait. Naturally the emperor does not summon this lady into his presence. But one evening, when in a melancholy mood he walks in an unfrequented part of his palace grounds, he comes by chance upon this girl as she is singing to her lute. Her beauty enchants him. “The very lantern shines brighter in the presence of this maid,” he exclaims, and falls violently in love with her. Of course, he orders the grasping minister to be beheaded; but the latter flees to the Tartar Khan to show him a truthful picture of the favorite and to incite him to war against China.

The Khan sends an ultimatum: “Either give me this beauty for a wife or I will make war on China.” The emperor is aghast with fear of a Tartar invasion, but the princess is willing to be sacrificed. “In return for your bounties it is your handmaiden’s duty to brave death for you,” she says and adds that surpassing beauty has always been coupled with great sorrow, but that she will leave a name ever green in history. After a sad farewell she departs[39] for the country of the Tartars and meets the Khan on the banks of the Amur. She drinks a last cup of wine to her lover: “Emperor of Han, this life is ended. I await thee in the next.” With these words the princess casts herself into the swift current and drowns in spite of the Khan’s valiant effort to save her. He erects for her a tomb on the bank of the river, which tradition says is green both summer and winter. Moved by her noble character, the Tartar decides to live in peace with China.

ILLUSTRATION BY A CHINESE ARTIST. TOU-E BEFORE THE JUDGE

A play that is even to-day a favorite in Peking playhouses under the title of “Snow in June” was called by its Yuan dynasty author “The Sufferings of Tou-E.” It is the record of the endless sufferings at the hands of a pitch-black, wicked world of an innocent girl and her final vindication through a triple miracle from Heaven. In her childhood she was sold by her own father into a family where she became the son’s wife and the drudge of her mother-in-law. For thirteen years she was a dutiful wife and when her husband died she hoped to remain faithful to his memory, as every widow in China is expected to do. But two cowardly ruffians, father and son, force themselves into the house where she is living with her likewise widowed mother-in-law and demand that the women marry them, endowing them at the same time with all their worldly goods. The two women refuse to yield to these insolent demands. Then the younger intruder, or rather bandit, places some poison in a bowl of soup, intending[40] to murder the older woman, but his father drains the cup by mistake. Hereupon he tries once more to coerce the heroine into marriage by threatening to fasten the murder upon her. She feels quite secure in her innocence and dares him to bring the case to court, very certain in the belief that justice will prevail. But the wicked judge begins by having the accused tortured, and this so brutally that the girl is at last forced into a false confession merely to escape the unbearable pain. Upon this she is promptly condemned to death. As she is kneeling to be beheaded she announces that three things will prove her innocence; her blood will not fall on the ground but on a banner ten feet above her head; snow will fall although the season is summer; and there will be a drought of three years’ duration. All of this comes true as it had been foretold, and the strange tale is noised abroad in the land. Finally, a just judge—her very father who as a poor scholar had been forced to sell his child!—hears of the case and decides to investigate it. The spirit of his daughter comes to enlighten him in regard to the true state of affairs, and the real murderer is punished by being nailed to a wooden ass and cut into a hundred and twenty pieces.

ILLUSTRATION BY A CHINESE ARTIST. TOU-E ABOUT TO BE BEHEADED

This obtrusively moral ending is a sine qua non in Chinese plays; likewise the crude plot as well as the rôle played by accident rather mar one’s enjoyment of the play. Yet the courage of the girl in the face of her persecutors, her firm belief that justice[41] will prevail in the end, and her stoical manner of meeting death are elements not without their charm. The scene of the execution is rather impressive in its simplicity.

Tou-E: (sings) Ye clouds that float in the air on my account, make dark the sky! Ye winds that sigh because of my fate, come down in storms! Oh, that Heaven would make my three predictions come true!

Mother-in-law: Rest assured that snow will fall for six months, and that a drought will afflict the country for three years.

Now, Tou-E, let your soul reveal clearly the great injustice which is about to cause your death.

(The executioner strikes off Tou-E’s head).

The Judge (seized with terror): O Heavens! The snow is beginning to fall! This is surely a miracle!

Executioner: I behead criminals every day and their blood always flows on the ground, but the blood of Tou-E has spotted the two banners of white silk and not a drop has fallen on the ground. There is something supernatural about this catastrophe.

The Judge: This woman was truly innocent!

The plays discussed in this chapter are sufficient to show that in the thirteenth century the Chinese possessed a theater of fair merit. To be sure, the technique is extremely crude; characters on their first appearance on the stage tell the audience their names followed by a conscientious account of their past lives and the part to be played by them in the drama; the motivation of the actions is very poor; many plays seem to be dramatized narratives rather than real dramas; there is a great paucity of invention[42] as shown by the rather frequent repetition of dramatic devices and motives; the necessity of having a moral ending leads to numerous absurdities; and chance rules the playwright’s world from beginning to end, always in the interest of the good. Furthermore, there is lacking a real sense of the tragic; there are no sublime heroes overcome by the universal human limitations which they challenge, nor are there moral conflicts of an elevating nature in which poetic justice triumphs. The characters are in general types rather than individuals, and there is very little deep psychological insight displayed. And on the whole it must be said, the plays do not rise to a very high spiritual level. Yet there is great charm in this drama which brings on the stage characters of all sorts from emperors down to coolies, and displays in full the rich life in the Middle Kingdom of the days when Marco Polo described it.

The Yuan Dynasty of Mongol rulers was a very powerful one and extended the Chinese frontiers to include Korea, Yünnan, Annam, and Burma. The rulers proved themselves very tolerant of Chinese religions and institutions; the emperor Jen Tsung even reëstablished the Hanlin Academy and the official examinations. But though the government of these foreigners was fairly efficient yet it was by no means popular, and frequent rebellions occurred. Finally, the Chinese under the leadership of a former Buddhist monk, Chu Yuan-chang, drove the Mongols beyond the Great Wall and founded the Ming Dynasty. The ex-monk ascended the throne in 1368 and is known in history as Emperor Hung Wu.

The Ming Dynasty is known as a period of prosperity in which industry and commerce, as well as the arts of poetry and painting, flourished. It was also a great period for the drama. Over six hundred[44] Ming dramas are still extant or are at least known by title, and many of them were written by well-known authors of high literary standing and great scholarship. The drama was so much appreciated at this time that many high officials and wealthy families had private troupes of actors, a large number of the dramas being specially written for these troupes. Since the audiences were composed of the élite, the language of the dramas could be of a highly literary character.

A development took place at this time that altered considerably the form of the drama. Instead of the compact and unified three, four, or five-act plays of the Yuan period, playwrights began to produce dramas of thirty-two, forty, or even forty-eight acts. The name of this new form is ch’an ch’i (literally “novel”) in distinction to the tsa ch’i of the Yuan Dynasty. Doctor Hu Shih, writing to me about these two forms, suggests that one might call the former “play” and the latter “drama.” “Technically the new form seems to be a degradation,” he says, “but aside from the aspect of literary economy the Ming dramas were superior to the Yuan plays in many respects, viz. (1) profounder conception, (2) far better characterization, (3) more even distribution of parts among the characters. In the Yuan plays only one character had a ‘singing’ part and the others were completely subordinated; while in Ming dramas the rôles are more evenly balanced. In many cases the same theme was treated by Yuan[45] and Ming dramatists, and in most cases the Ming version is far better.”

In this chapter I am presenting an example of this new variety of drama, a 24-act piece called “Pi-Pa-Chi” (The Story of a Lute). Except for the fact that dialogue and stage directions are used the work might well be called a novel. Aside from the technical interest of the drama it is most significant as a presentation of Confucian ideals, a revival of which was typical likewise of the Ming Dynasty. Such ideals are embodied in the family system with the selfishness—as it appears to us—of old age. After reading about the adventures of the hero, Tsai Yung, the Westerner can understand why in Confucian writings along with widows and orphans there are enumerated “son-less fathers.” The conflict in the drama centers about the “higher” and the “lower” obedience—service to the state or to the family. But the problem is not a clear-cut one, as the son is to serve the state in the interest of the greater prosperity of his own family; nor can it be said that it is solved in any way. The drama, however, is full of Chinese moralizing along lines far removed from the thinking of the “practical” Westerner.

Indeed, much of the famous mystery of the East or the inscrutability of the Orientals might be less baffling to the average American if he were better acquainted with the literature of China. I have known, for example, a young Chinese politician who[46] was none too scrupulous in the manner in which he went about earning his living, who drank, supported a number of concubines, and in fact was what might be called by the vulgar a “rounder.” In the course of a dinner one evening he told me between the sharks’ fins and the Peking duck that he had been offered a post in Washington, but, lucrative though it was, he could not accept it because of “filial piety”—his very words. Now piety in any sense of the word was the last thing I associated with this youth, and therefore his statement seemed to me surprising. There was another Chinese, the owner of an excellent stable, with whom I went riding frequently in the Temple of Heaven. He was a vigorous young man, educated in Paris, very businesslike and progressive in all his ideas. One day I received an invitation to his wedding, and, on going, found a merry throng in the gaily decorated courtyard, with dancing in European fashion going on in full blast. I noted the groom among the dancers, congratulated him and remarked, “Well, I’m sure you’re very happy to-day!” But he shook his head and, as tears came into his eyes, he told me that the bride was not of his choice but had been selected and forced on him by his elder brother, the head of the family. Again, in speaking one day with a progressive young student who talked a great deal about reforms in politics and who participated eagerly in parades and other demonstrations staged for that end, I mentioned a certain official who had flagrantly stolen[47] funds collected for the famine sufferers. The student expressed perfunctory disapproval of the official’s conduct, but added, “Still, if I were in his position, I’d probably do the same.” Such is the manner in which the Chinese act and as such they show themselves in their literature.

“Pi Pa Chi” was written by an otherwise unknown author, Kao Tsi-ch’ing, about the end of the fourteenth century. The first performance of the play is known to have taken place in 1404, in the reign of Yung Loh, the ruler who, as every tourist knows, has the most prominent monument among the Tombs of the Ming Emperors north of Peking. The play is typically Chinese inasmuch as the hero is not a warrior or a prince, but a poor scholar who rises to fame through his knowledge of literature. It abounds in sad situations and is praised by Chinese critics because it makes the spectators or readers weep. Furthermore, it conforms to the demand made on all Chinese dramas by being strictly ethical in its tendency. The moral lesson inculcated is that of the chief virtue of the Chinese—veneration of parents. This is done with such devotion and force that the play might well be called the Song of Songs of Filial Piety.

The first scene introduces a young scholar, Tsai-yung, face to face with the alternatives of remaining in his village to take care of his aged parents or of going to the capital in search of honors and lucrative posts. His own wishes are to remain at home,[48] less for his parents’ sake than because of the beautiful wife whom he has married but two months ago. But his father urges him to go to Ch’ang An, to use his talents, and to gain fame and wealth. “At fifteen one must study, at thirty a man must act.” A friend of the family, an elderly gentleman called Chang, sides with the father against the mother, who wishes to keep her son at home. She tells the story of a young man who had left his family to take the examination at the capital, but who, when at last his learning had gained him a post as superintendent of an almshouse, found his parents as inmates in the very institution. The young wife takes no part in the discussion at all; in fact, the elderly gentlemen seem to consider affection for her an unmanly weakness on the son’s part. “He thinks of nothing but love and the sweet pleasures of the nuptial couch,” says his father. “Here it’s two months that he is married, and yet one cannot tear him away from this place.” This represents a very common attitude in China—I remember reading in a Peking paper in 1917 in an attack on the vice-president of Tsing Hua College that one of his faults was that he occasionally went walking with his wife! One of my students from Shansi told me one day that he had been married during the summer vacation. I asked whether his wife was with him in Peking, and when he answered in the negative, whether he was writing to her. “Oh, no,” he said shamefacedly, “I wouldn’t do such a thing.”

A CHINESE ARTIST’S CONCEPTION OF TWO PIOUS SOULS

The father calls on the son to state what he understands by filial piety. The son answers by quoting the “Book of Rites,” “It is the duty of the son to take every care that in summer as well as in winter his parents should enjoy all comforts of life. He must every evening himself arrange the bed on which they are to sleep; every morning at the first crowning of the cock he must inquire in affectionate terms about the state of their health; then, in the course of the day, he must ask repeatedly whether they are suffering from the cold or whether the heat incommodes them. The duty of the son is to watch over his parents wherever they go, to love those whom they love, honor those whom they honor; he must even love the horses and dogs whom his father loves.” And he adds from the “Sayings of Confucius”: “A son should not leave the home of his father and his mother so long as they are still living.”

To this the father retorts with a quotation from “The Book of Filial Piety”; “The first degree of filial piety consists in serving one’s parents; the second in serving one’s prince, and the third in seeking after honors.” The father persuades the son to go. His son will soon be a mandarin, he says, and then, “The three kinds of meat (beef, mutton and pork) and the rare foods which are offered up in the great sacrifices will be served to me three times a day in tripods of elegant form or in dishes of fine porcelain. That will be better than eating beans and drinking water.”

But the mother gives expression to her grief in a metaphor praised by Chinese commentators: “In a moment they will tear away the pearl I was holding in my hand.” Forebodings of evil fill her heart. “Go then, my son, but if during your absence your father and mother should die of hunger and cold, your honor will not therefore be smirched when you return in an embroidered robe.”

The second scene of the play transfers the action to Ch’ang An, the old capital. With the symmetry so characteristic of all Chinese art the action of the drama is divided almost equally between the scenes in Tsai-yung’s native village, and those in the imperial city. We are introduced into the palace of an imperial minister, a certain Niu, and here through the words of a maidservant we learn of the dull, tedious, joyless life in the women’s apartments. The author pictures the minister’s daughter, Niu-hsi, as the model young woman who prefers working at embroidery to playing in the open air. The servant girl on the other hand is sad because spring (used symbolically for love) is passing her by. In a beautiful allegory on spring and its manifestations she gives expression to her feelings, while her mistress cites in reply the ancient Chinese rule of conduct: “Women must not leave the interior apartments.” The scene seems to be a protest on the author’s part against this cruel stunting of the lives of his countrywomen.

Into Minister Niu’s house come two rival go-betweens[51] who make offers of marriage for Niu’s daughter in the interest of two fathers of distinguished sons. But Niu refuses; he will accept for his daughter none but the scholar who has won the very highest honors at the examinations. The two women begin to quarrel and are driven off with blows by Niu’s orders, because by fighting in his house they offend against the rites. A marriage arranged by such wrangling old hags between young people who meet for the first time on the day of their wedding certainly does not offer much in the way of romance. An even more depressing picture of the life of the young girl one gains from the manner in which Niu takes his daughter to task for having walked in the garden. “Don’t you know of what the principal merit of a young woman consists? I have told you before, men are looking for women who don’t like to leave the women’s apartments.” Everywhere the ghost of Confucius giving precepts for the regulation of the private life down to the minutest details!

The play returns to Tsai-yung, who is now on the road to the capital in the company of three other candidates for the examination. Each in turn tells of the purpose of his studies. Tsai-yung outlines his principles as follows:

“Here is the method I have adopted. When I was seated I read, when I walked I recited from memory what I had learned. I have studied thoroughly ten thousand chapters; I have carried on[52] difficult studies and researches. But as there are two things in life that one must never lose sight of—loyalty to the prince and filial piety—I have always tried to show myself grateful for the emperor’s benefits and to return with thankfulness the kindness of my parents.” This speech is applauded by the other scholars and they in turn give their answers, some of which are of rather satirical turn, especially the one of the student who explains that with him the essential is correct pronunciation and beautiful penmanship!