THE NEW METHOD OF MAP DRAWING

[100 ILLUSTRATIONS]

WITH INTRODUCTION

AND

Suggestions on the Use of the Map

BY

IDA CASSA HEFFRON

(Late of the Cook County Normal School, Chicago, Ill. Lecturer

and Instructor in Pedagogics in Art, University Extension

Division, University of Chicago.)

EDUCATIONAL PUBLISHING COMPANY

BOSTON

New York Chicago San Francisco

Copyrighted

By EDUCATIONAL PUBLISHING COMPANY

1900

| PART I. Introduction. |

||

| 1. | Necessity for the Study of Structural Geography as Preparatory to the Drawing of Maps | 9 |

| 2. | Necessity for Field Lessons and Importance of Forming, in Connection with Them, the Habit of Modeling and Drawing | 13 |

| 3. | Importance of Learning to Interpret Pictures as an Aid to Imaging the Continent | 27 |

| 4. | Maps—of the Past and Present. The Chalk Modeled Map | 34 |

| PART II. Fifteen Lessons in Chalk Modeling. |

||

| Remarks | 52 | |

| I. | Representation of Surfaces with Hints on the Delineation of Distances. Land Sloping from the Observer. Light and Shade | 54 |

| II. | Land Sloping toward the Observer. Quality of Line. Relations and Proportions | 59 |

| III. | High and Low Water-partings, with Map Showing Divide | 63 |

| IV. | Meeting of Land and Water. Lakes. Springs. Islands. High and Low Tide | 66 |

| V. | Sketches Illustrative of Wind and Water Erosion | 69 |

| VI. | Scenes Typical of the Different Zones | 76 |

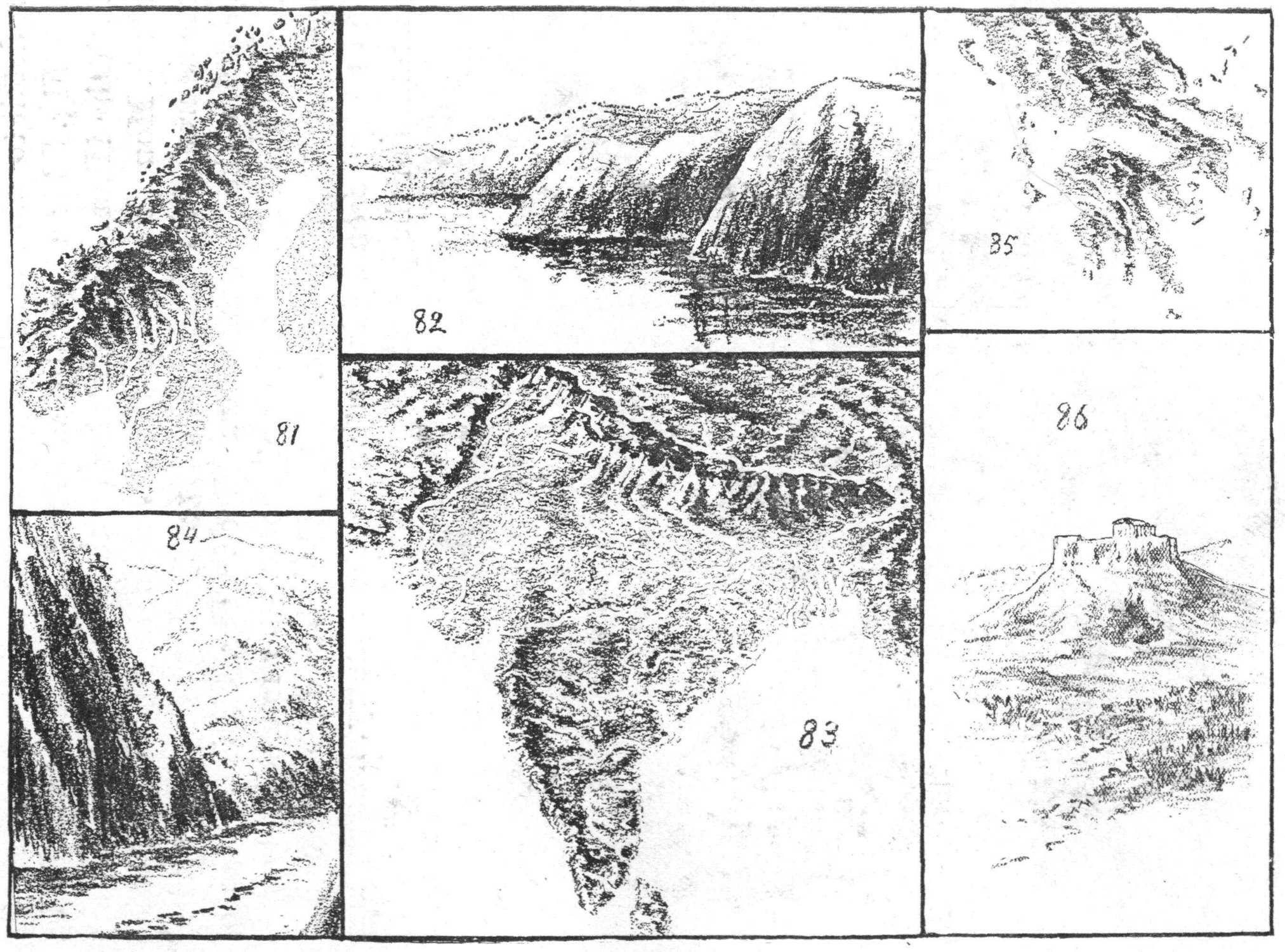

| VII. | River Basins. Coasts | 82 |

| VIII. | Suggestions on the Use of the Chalk Modeled Map of North America in Fourth and Fifth Grades | 87 |

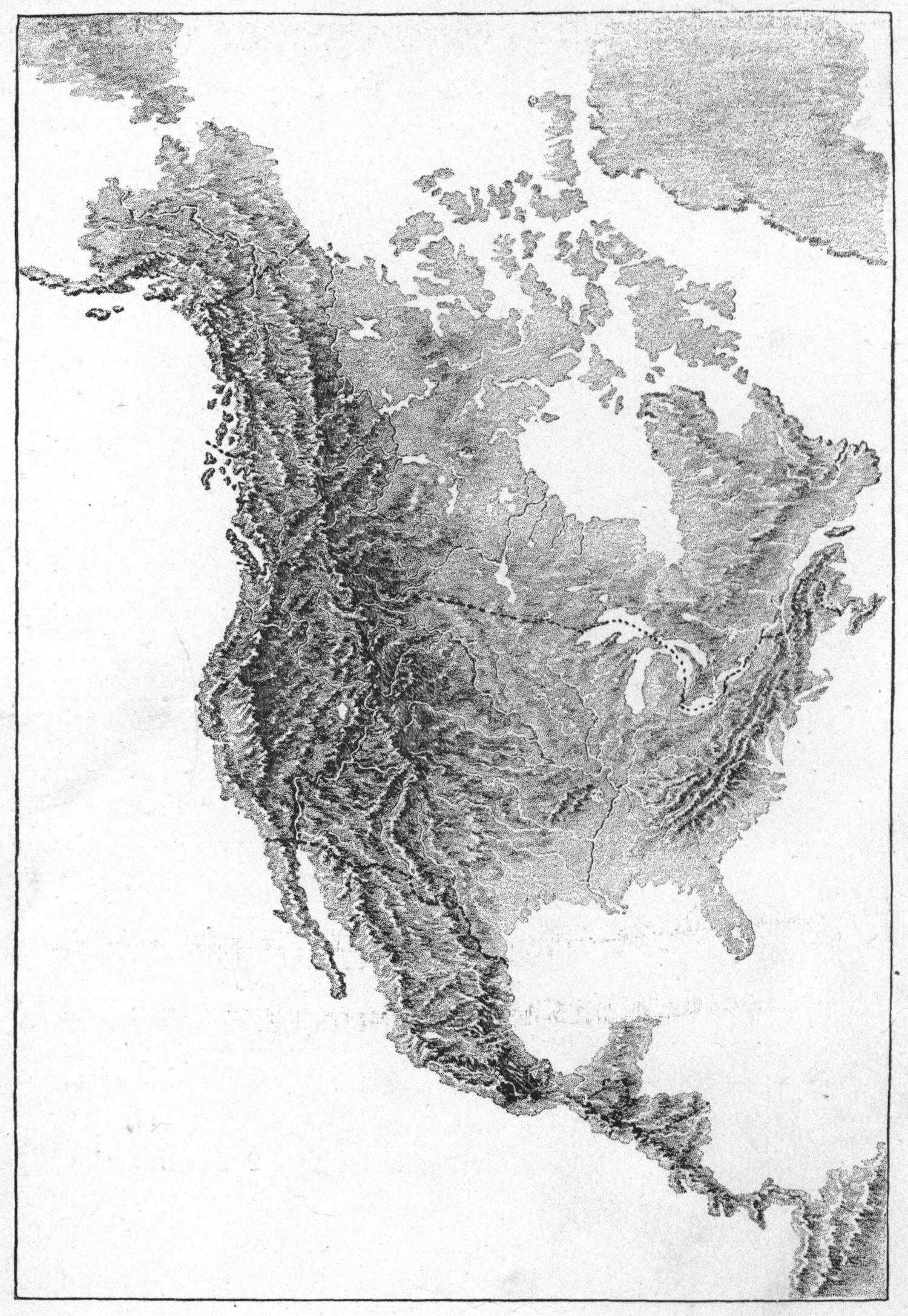

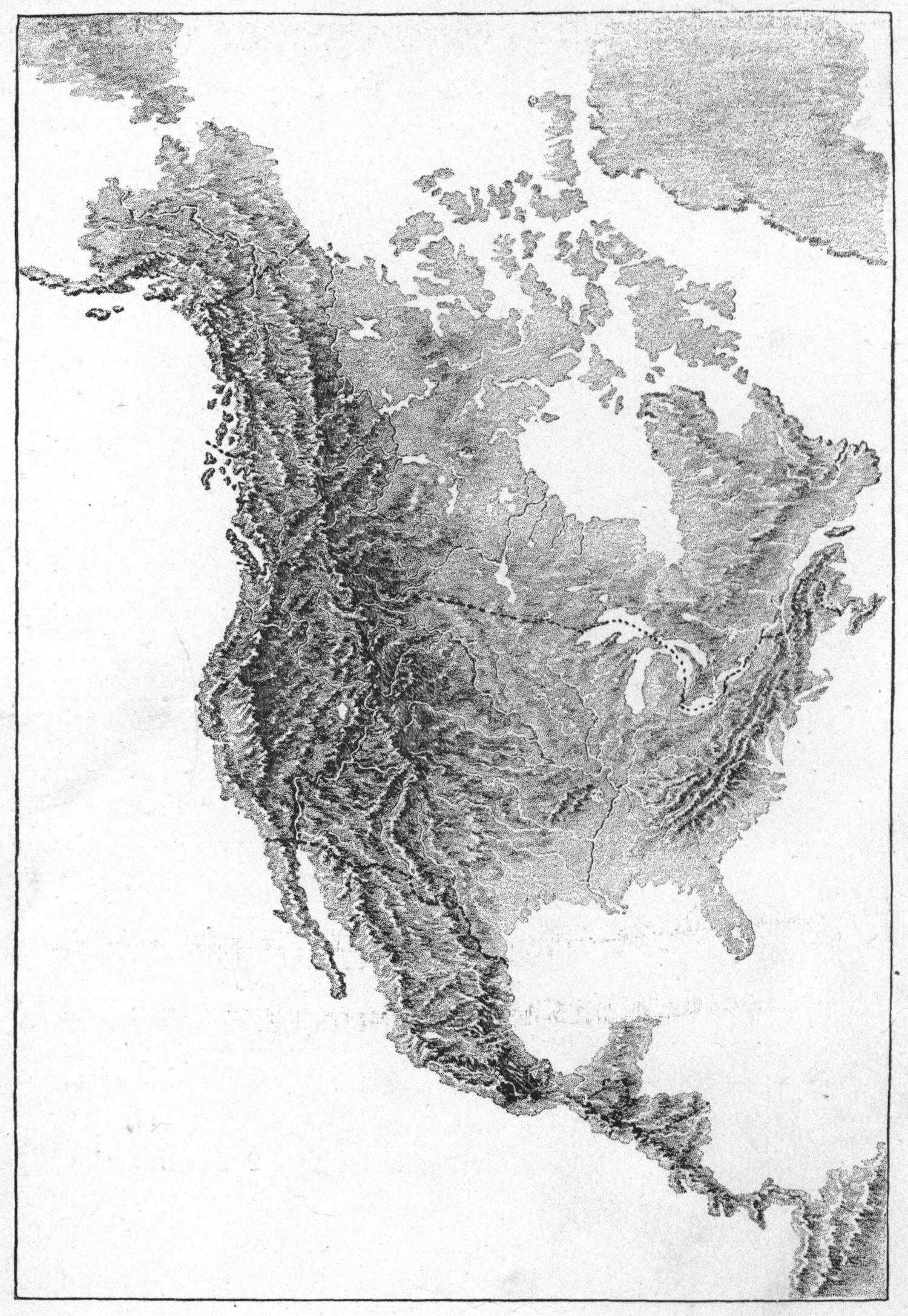

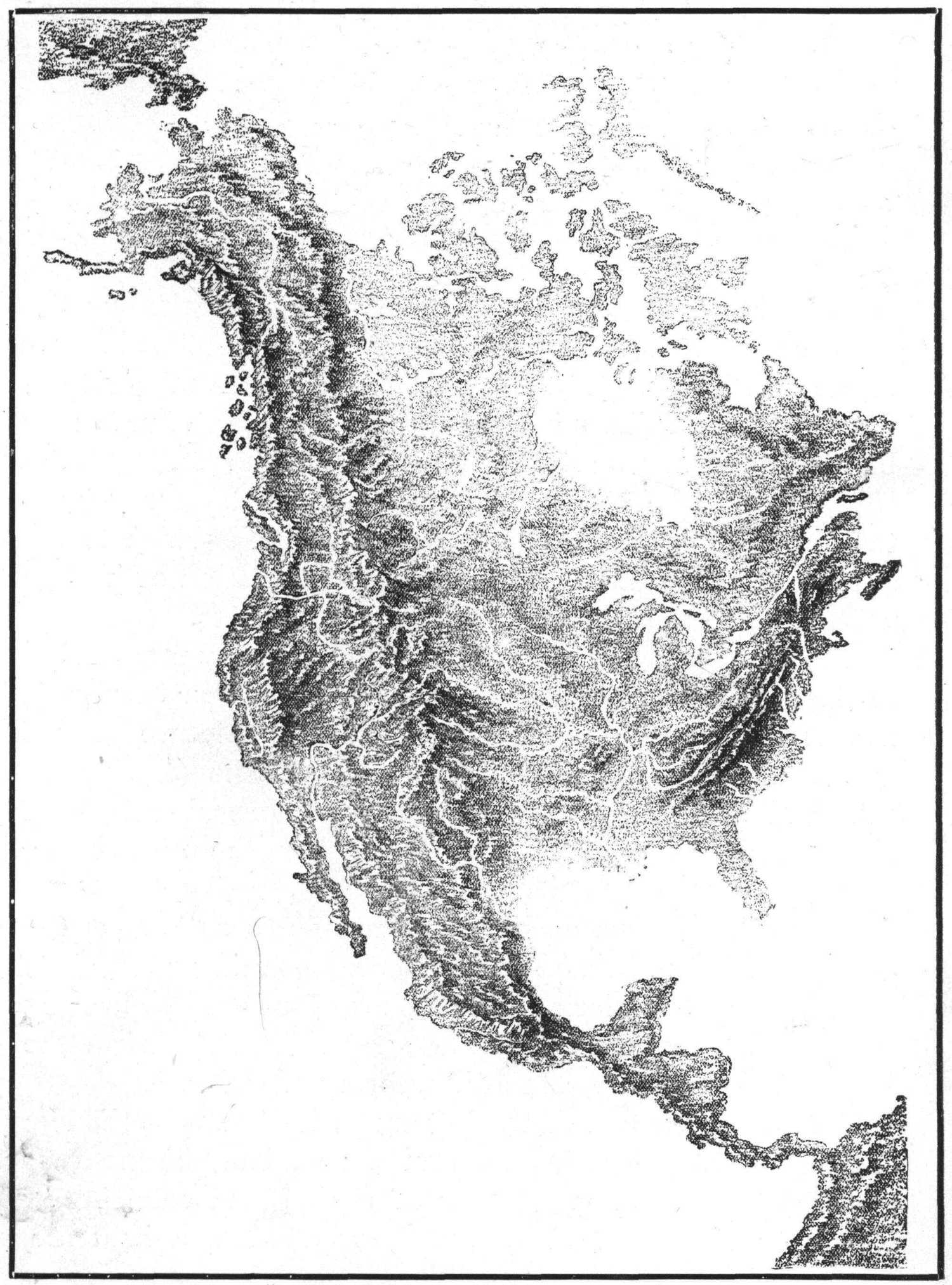

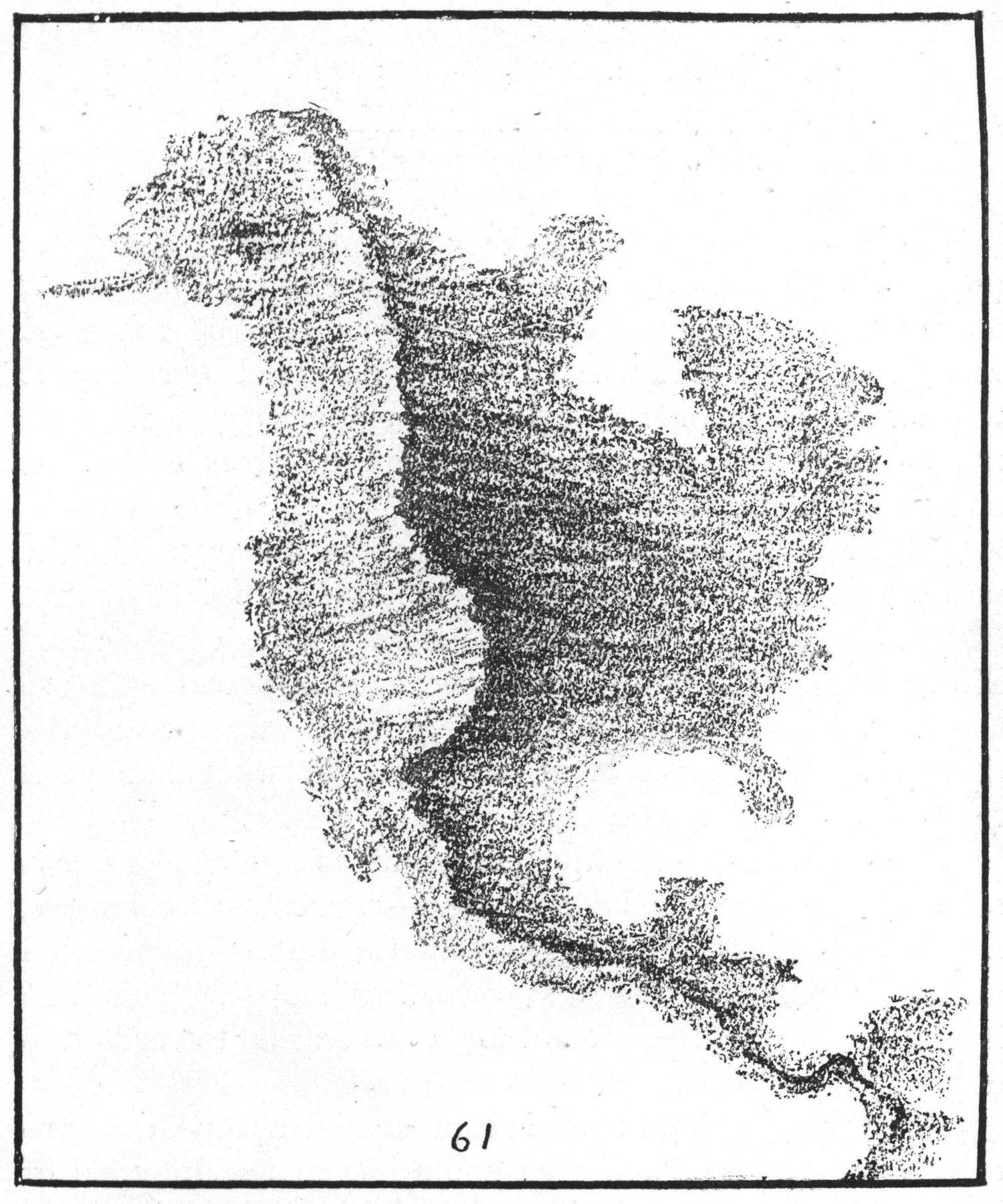

| IX. | Map of North America | 96 |

| X. | Natural Features of Interest in North America | 104 |

| XI. | Map of Mexico, with Suggestions for Teachers of Fifth and Sixth Grades | 108 |

| XII. | Map of Section of the United States of America for Use in Preparatory Lessons on the Civil War | 117 |

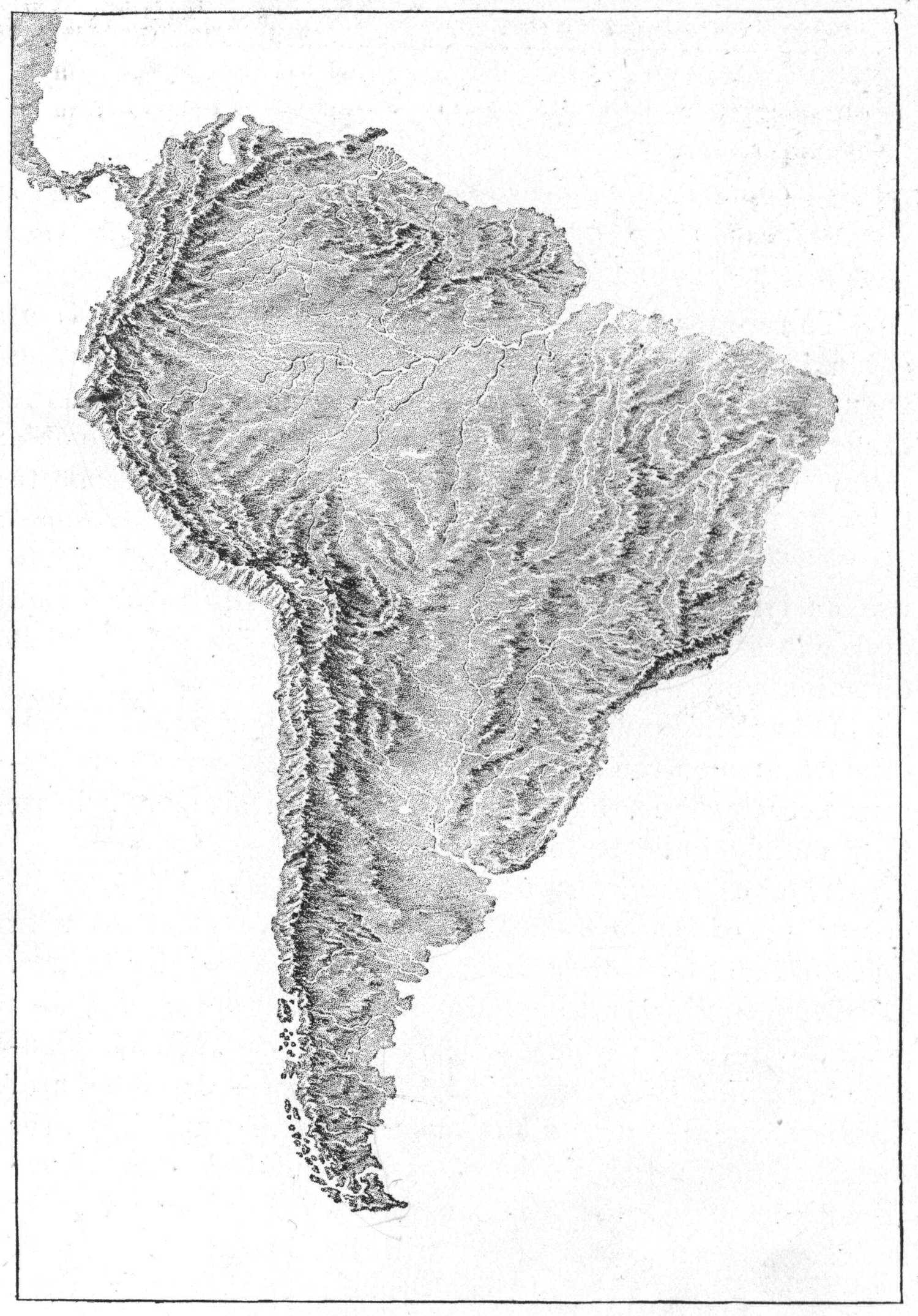

| XIII. | Map of South America | 123 |

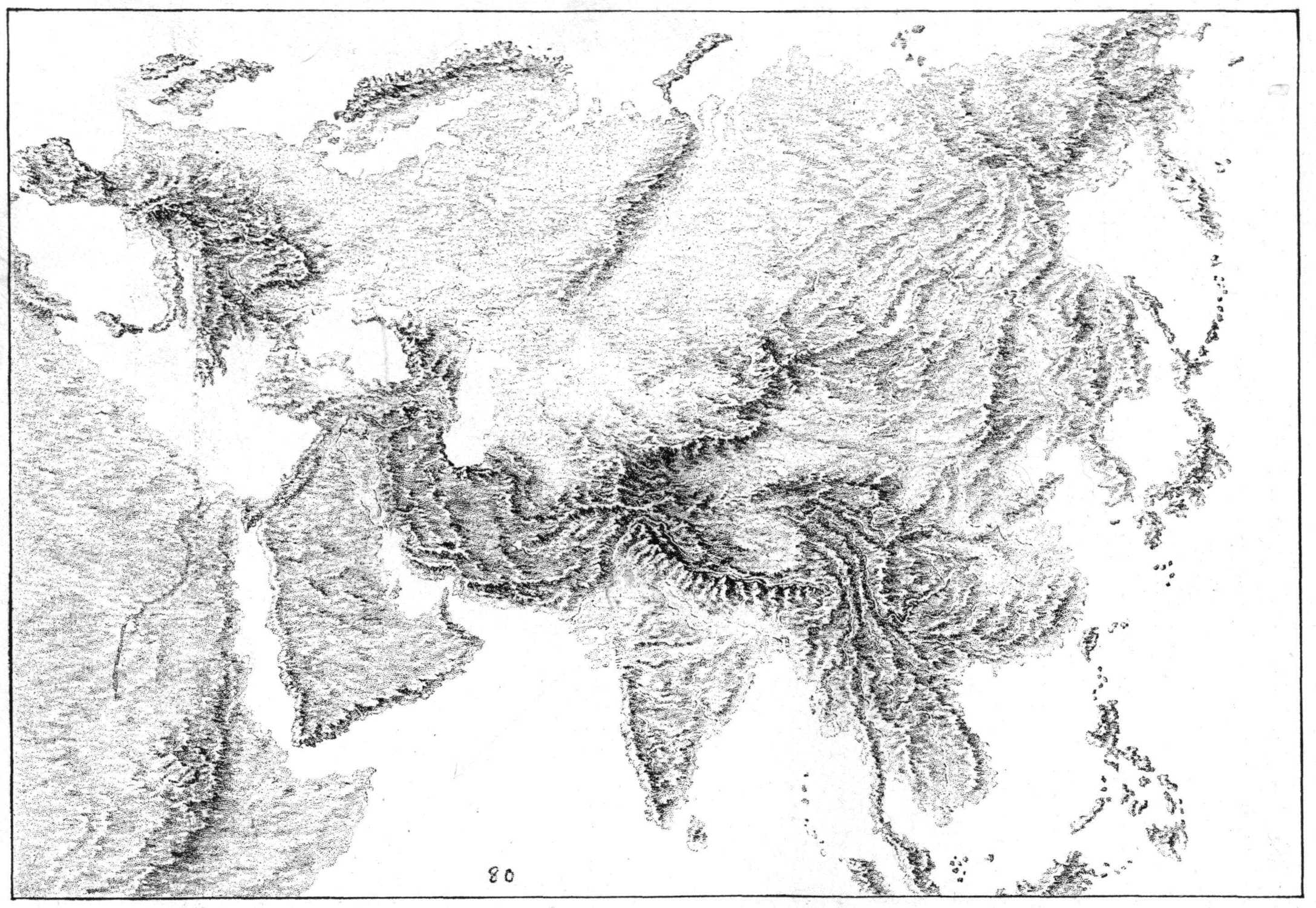

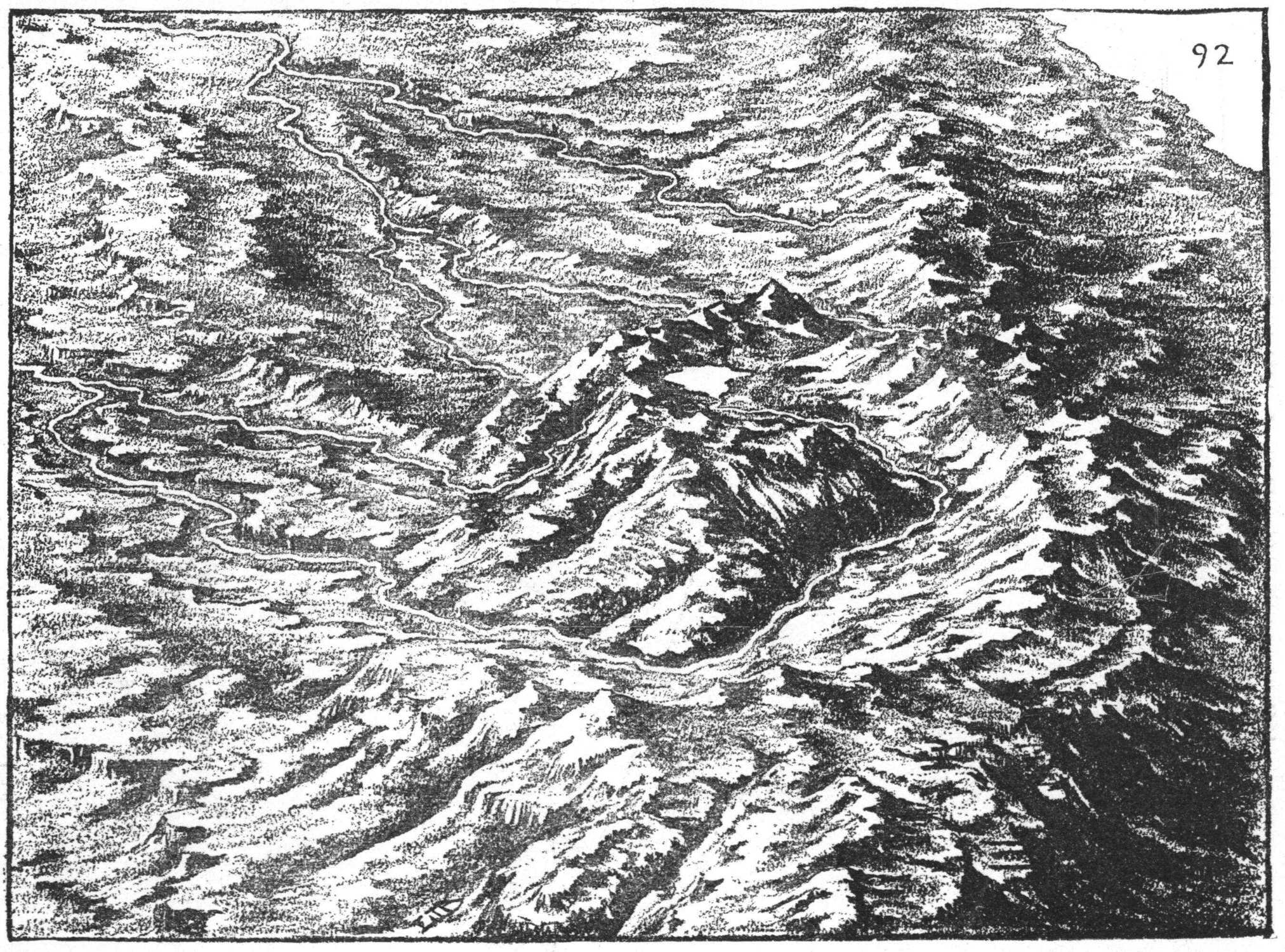

| XIV. | Map of Eurasia, with Sections in Detail | 127 |

| XV. | Maps of Africa and Australia. Summary of Instructions | 132 |

| Books of Reference | 137 | |

In preparing the following lessons, in answer to the demand of the public school teacher for such assistance, the aim has been to present them in such a manner that both teacher and pupil may, through the understanding and acceptance of the steps involved, become expert in the development and delineation of original maps showing surface structure in relief.

To this end, suggestions vital to the success of the would-be mapmaker will be found in the Introduction.

In Part II. it is aimed to show that, with a clear mental image of surface forms and areas, the expression of the same will be a simple and easy matter, and a valuable preparation for the mapping of large areas or continents.

For the illustrations a medium has been used, which, in many respects, closely resembles in its results on paper the texture of chalk on the blackboard.

The author desires to acknowledge her indebtedness to Francis W. Parker, the head of the Chicago Institute, late Principal of the Chicago City Normal School, for help derived from the study of his works, and for the rare educational privilege enjoyed while working as a member of his Faculty. Especially were the discussions under his leadership, at the ever-to-be-remembered weekly meetings, a continual source of inspiration.

Under the new light thrown upon the subject of geography, as presented by Colonel Parker, the impulse was first received which afterward bore fruit in the development of a new method of map drawing; a[6] method which it was desired should be an adequate expression of the solidity and continuity of the continental land mass.

The necessity for such a map Colonel Parker had himself realized for years and had sought its delineation. With a desire to meet the pupil’s needs in this respect, upon further study of structural geography the idea was conceived of drawing maps which would show mass without outline, and which would also represent relief.

This method of map drawing was called “Chalk Modeling,” and from the first crude effort in this direction by the author, in the year 1891, at the Cook County Normal School, the “Chalk Modeled Map” passed through many stages of development until it reached its present form.

Thus to Colonel Parker himself is primarily due whatever of educational value has resulted from the invention of the author or development by others of what is called “The Chalk Modeled Map.”

Acknowledgments are also due Miss Louise Barwick, for the zeal displayed in forwarding the development and delineation of the Maps of the Continents, and for valuable assistance rendered in the drawing of the same, as illustrations for this work.

I. C. H.

Chicago, Ill.

To the Teacher in General, and to the Members

of the C. C. N. S. Alumni Association in Particular,

Is this Book Respectfully Dedicated by

The Author.

The fundamental object in the study of Geography, as we understand it, is to acquire mental images of the present appearance of the earth’s surface; its structure, the rocky material of which it is composed, and the causes and effects of its changes, as a preparation for the home of organic life.

It is a study of the earth as a material basis for the evolution of man, and the development of civilization. It leads up to a search for the laws and workings of the creative forces—forces relating to our planet and to the sun, the central source of light and heat.

This study has a different meaning to different persons. To one it means the study of all that lies between the covers of a book, or memorizing other people’s sayings. To another it means “Connected information regarding the condition of man’s life on this planet”—again “Geography is a description of the earth’s surface, or anything that affects or is affected by it.” A more common definition is, “Geography is a description of the earth’s surface and its inhabitants.”

An ability to recognize in present environment that[10] which leads to an understanding of geographical conditions in general, is much to be desired and is the aim of the teacher of the present day. Geologists tell us that the same processes are going on now that have ever been in operation, in the fitting of the earth for the habitation of man. That these changes are taking place is implied in the very fact that we are studying the earth’s present appearance.

The study of the history of these changes, and of the nature of the earthy material as shown in rock and soil, and in vegetation, and of the influence of heat, light, air and moisture, means the study of all the natural sciences; not as special isolated studies, but bound together in one great whole. So closely are they related, merging into and impinging upon each other as they do, that there seems to be no place or line of separation between them.

The larger part of the surface of the earth (nearly three-fourths) is covered with water, and the action of this mighty agent, under the influence of that great dynamic force and life-giving energy, heat, opens an immense field for investigation.

These combined influences constitute the study of the environment of all organic life; and knowing these in a given case, we get an approximate idea of the stage of development. The development of man, the highest type of organic life, depends largely upon structural, climatic, vegetable and animal environment.

To know these is to understand his habits of life, his reasons for choice of homes, and to judge of his probable advancement in civilization.

The powerful influence which the physical features of[11] the earth’s surface have exerted in shaping the current of historical events, can hardly be realized, until thoughtful investigation of the subject has been made. The knowledge of geographical conditions, as climate, mountains, valleys, rivers and seas, with vegetable and animal life gives us the theatre of action for events in history.

As the mere existence of mountain range, desert, sea or river, may be essentially the influence which has led to the growth or downfall of empires, it is clearly seen that a sound knowledge of structural geography is absolutely necessary for all intelligent study of history; no general relation of important occurrences can be traced without it.

Nearly, if not equally necessary is it in the study of literature. In order to properly appreciate the works of our best writers, both of prose and poetry, an acquaintance with nature, a scientific and geographical knowledge, local and general, is very essential. It forms a basis for the correct understanding of books, since the best writers and thinkers of all ages have been students of nature. Their writings are filled with lessons and illustrations, as well as generalizations drawn from close observations of her methods. If, then, a knowledge of structural geography is requisite to the true understanding of man’s relation to man and the world around him, it becomes important that the subject be presented in such a manner as to attract and hold the interest of the pupil; and properly presented there can be nothing more interesting than the study of his immediate environment—that which touches him in his every day experience.

This study of his immediate environment is essential to the forming of mental images of areas and surface forms[12] outside and beyond his sense grasp and to a comprehension of the structure and surface contour of the world at large: such mental images being fundamentally a necessity to the delineation of adequate structural maps of the whole or any part of the earth’s surface.

The study of geography, which in the past consisted mainly in the memorizing of meaningless names with little or no exercise of the reasoning faculties, or opportunities for making generalizations through acts of comparison and inference, has been superseded by instruction of a more rational order.

We have learned that to memorize names and locations of mountains, rivers and lakes, without seeing their relation to a whole, or to make only superficial observations of extended areas of land, results merely in indefinite mental impressions, leaving out the very basis of all concise and clearly defined geographical knowledge.

To the end that definite mental images may be acquired, field excursions under the direction of competent leaders are now advocated, and when entered upon with an intelligent purpose are held to be indispensable factors in the correct study of geography.

Section of Stream Showing Rapids.

Under these conditions (the intelligent purpose and the competent leader), the pupil who visits a lake is likely to have a more adequate mental image of old ocean, than one who has never seen a lake or other large body of water. One who has seen low hills with their out-cropping rock, and the action of small streams upon them, will have a better idea of what mountains and rivers may be.

In the new education the pupils are thus in the field lesson brought face to face with nature. Through these lessons the powers of the imagination are quickened and strengthened by the continual observation of surface forms, the true basis for all attempts to image the structure of the earth.

Inferences are made at every step of the way as to the history of the physical features observed, and the nature of the forces that have acted upon them to shape and distribute. Areas and forms of land are constantly being compared as to shape, size, width, length and height, and simple generalizations, formed from direct observations, are combined with other generalizations, to form those that are higher or more comprehensive. This is but a brief suggestion of the part the field lesson bears to education in general.

In the particular study of geography it must be borne in mind that no essential knowledge can be gained except through close observation of the earth’s surface forms. As the true teacher of science in his classes in botany or zoology leads his pupils to an individual study of plants and animals, and also to a study of these in their surroundings, their social relations, so also the student of geography goes directly to nature for all fundamental knowledge pertaining to the subject.

Field lessons, though conducted mainly as contributing to the student’s fund of knowledge, are also a source of[16] pleasure, and may be made the foundation of a more healthful love for and delightful companionship with nature. They are not alone a mine of knowledge but also a perfect well-spring of inspiration.

In every stream, plain and valley, new beauties of form and color are continually presenting themselves. Varying tints of landscape vistas, drifting cloud masses, softly rounding hills, majestic mountain forms, the play of sunlight and shadow; all make subtle appeal. Entering into harmony with creation we are led into harmony with its source.

Everything combined, all the wealth of color, warmth of sunlight, song of birds, hum of insects and breath of growing things, conspire to the unfoldment of the being on all the planes of life’s expression, for, the first and controlling impulse is toward expression; expression on the physical, mental and emotional planes—in fulfillment of the law of growth, for expression is a necessity to growth.

Expression. Geography has been said to be an analytical study of the earth’s surface, or the study of the separate landscape elements, such as form, color and organic structure.

Geography is emphatically a study of form, the forms of the earth’s surface features, each to be studied in relation to other and contrasting forms, as well as in relation to their environment.

Upon the pupils’ return from the field, the forms and areas observed may be modeled in sand, sketched on paper, or chalk modeled on the blackboard. Maps may be drawn of the areas studied and sketches may be made in color of stretches of different soils and verdure, together with the atmospheric effects observed. Tints of sea, sky and cloud,[17] color and shades of rock and foliage are all speaking in tones which the child may interpret and render intelligible to others, through the medium of brush and paints.

It is of great importance to his future growth that the student acquire the habit of freely expressing himself through the art modes of modeling, painting and drawing, since much of his mental power depends upon such expression; for by holding in mind, while in the act of expression, the images acquired through observation, more of the details of the object or scene as well as the generalities are recalled.

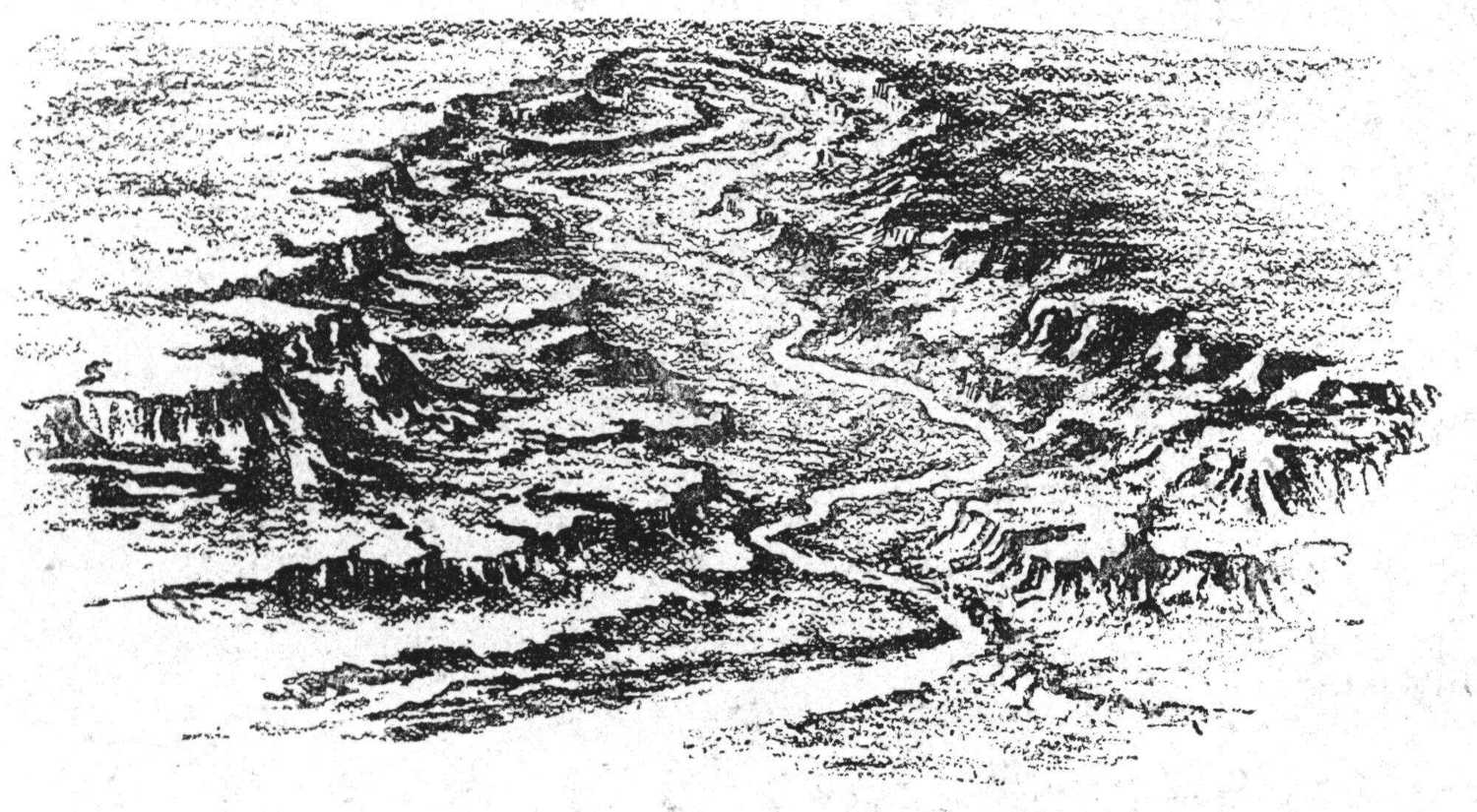

River Basin.

Expression thus reacts upon self, causing the mental picture to be intensified and expression to become more definite and complete. No other means are so adequate to this end: i.e., the forming of distinct images in the mind, unless it may be the giving of oral and written descriptions. These, of course, should be demanded of the pupil as well. By this demand the pupil sees the necessity of closer observation and investigation that he may give a[18] fuller and more truthful expression, and with careful leading he becomes a critic of his own thought and skill, which is a step pre-eminently educative.

Aim of Field Lesson. A direct purpose or aim of the field lesson in teaching geography should be to form a clear idea or mental picture of a river basin as a basis for imaging other river basins, and as a unit for the study of the continent, or of all land surface: and to know the river basin is to know its history; that is, the history of the river itself, its valley, and the story of its building and shaping.

It may not be possible for all students to make a study of the whole of a river or brook basin, yet it may be done by sections—getting a general idea of the slope of the river bed, water-parting, slope and valley. The action of the forces of nature may also be seen in the changes now going on in the different sections—the cutting back of the stream at its source, its eroding power, its carrying power, and its building or leveling power.

If it is not possible to take the children to the field for nature study, they may find fruitful sources of study without.

City Schools. Nearly every school-house has some surroundings that may be studied to advantage, except those in closely built city streets; but even in such cases there is always the work of rain, heat, frost, and wind to study, as well as insect life. The drifting of sand and snow, the frost on the window-panes, the forming of ice around doors and windows and the effect of heat in its melting, rain-drops, clouds, puddles of water in the slight depressions of sills and walks, with tiny streams flowing therefrom, are all to be observed.

Where did the dirt on the windows and sills come from, especially after some snow-storm? Tiny seeds in the corners where the winds have left them; insects in the spring;—where did they come from? Where were they all winter? These and many other hints might be given for such study.

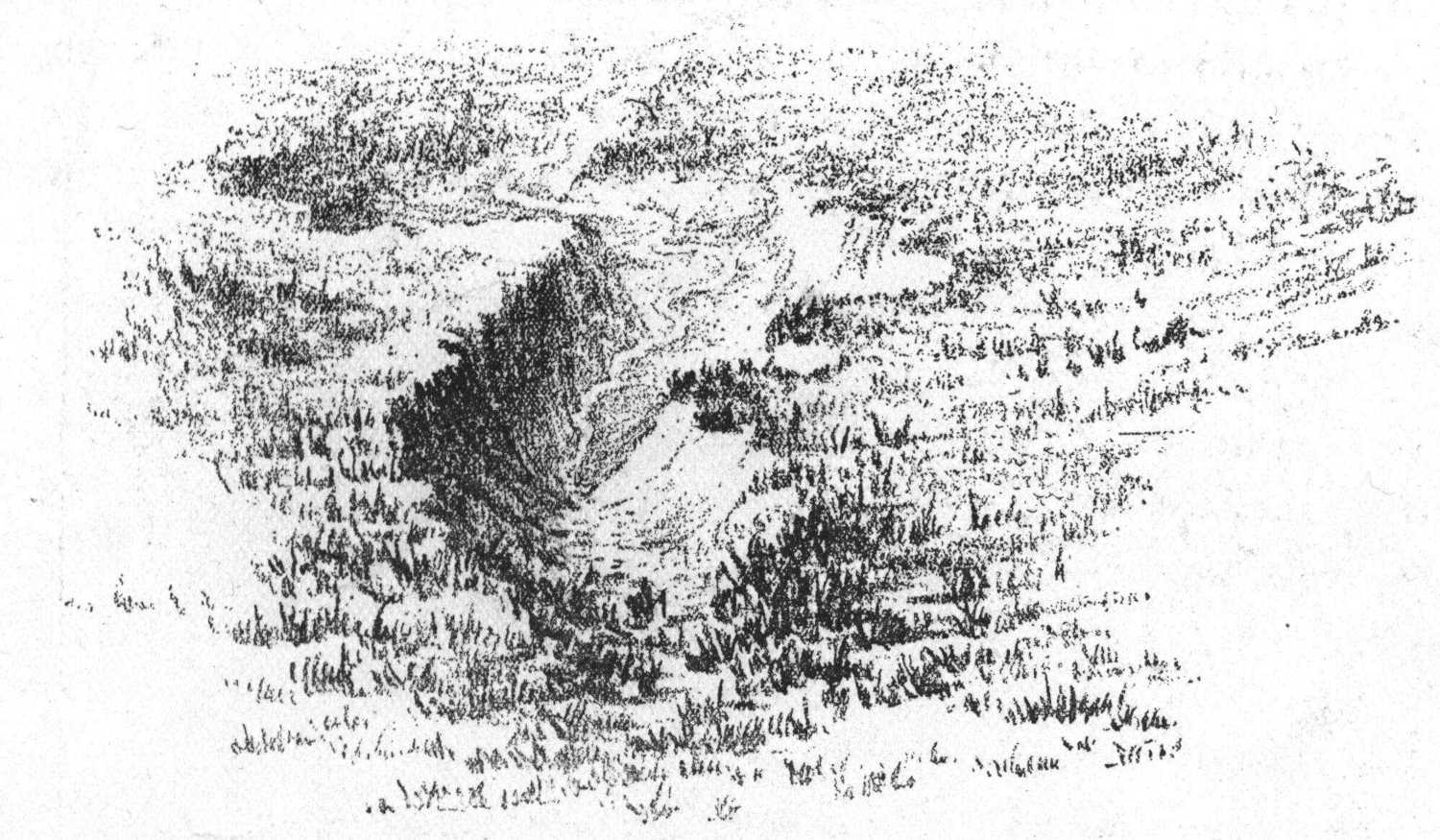

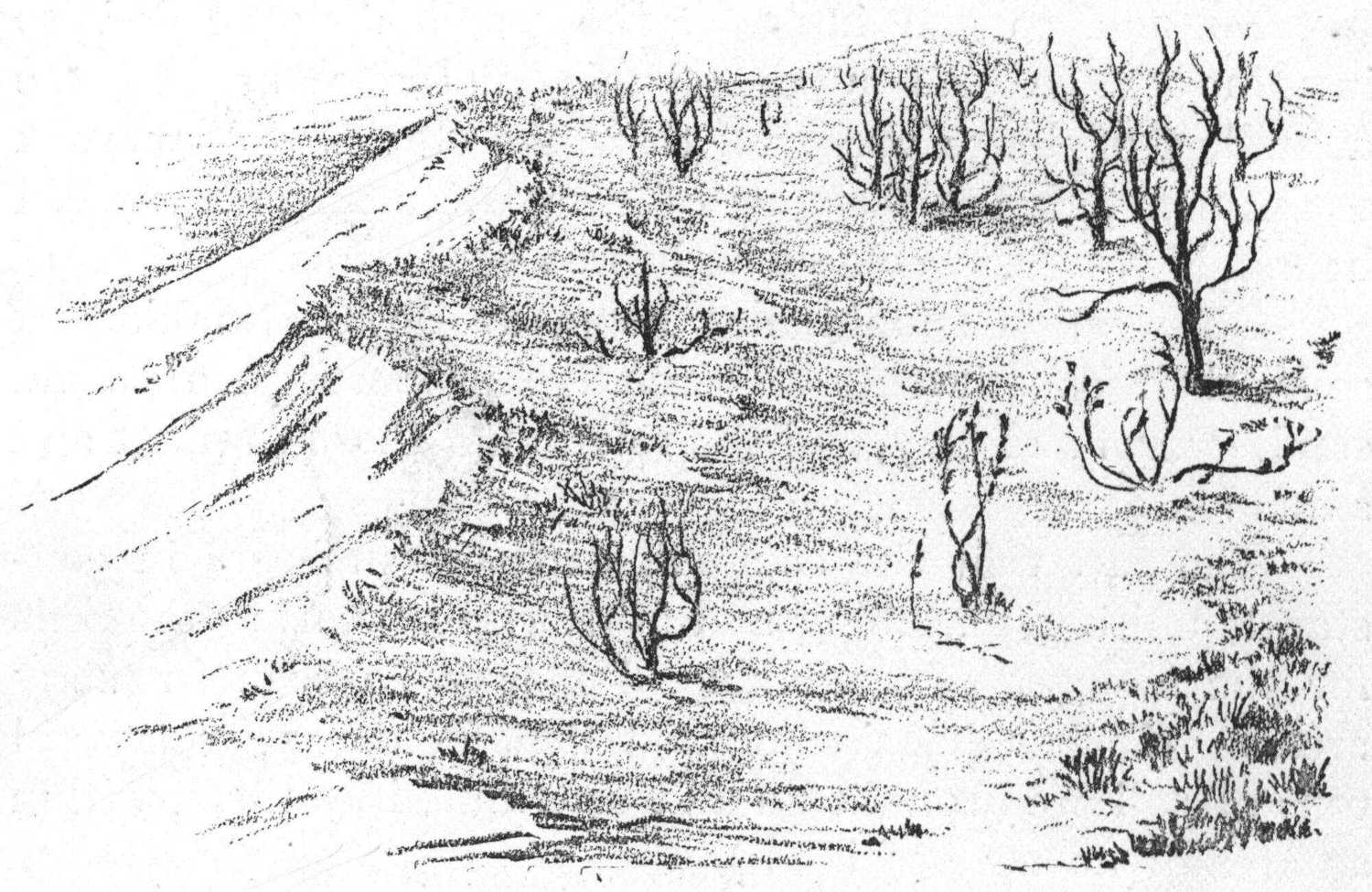

The Cutting Back of a Stream at Its Source.

The country furnishes a rich field for investigation. Around every building and in many localities that can be easily reached, most of the types of the earth’s surface forms may be found. Care must be taken that they are considered as types, or the pupil might answer the question, “How high are mountains?” as the child did who said in reply, “Two inches high.”

In the lower grades of school, much of the geography work should be the direct lesson in the field followed by lessons in school. The higher grades, also, should continue the frequent field excursions which are begun in the lower.

Source of Brook in Nearly Level Country.

Visits may be made to the hills, groves, lakes and ponds of the vicinity, and upon returning to the school-room, these and surrounding areas may be modeled in sand or clay, painted in water-color or drawn on the blackboard.

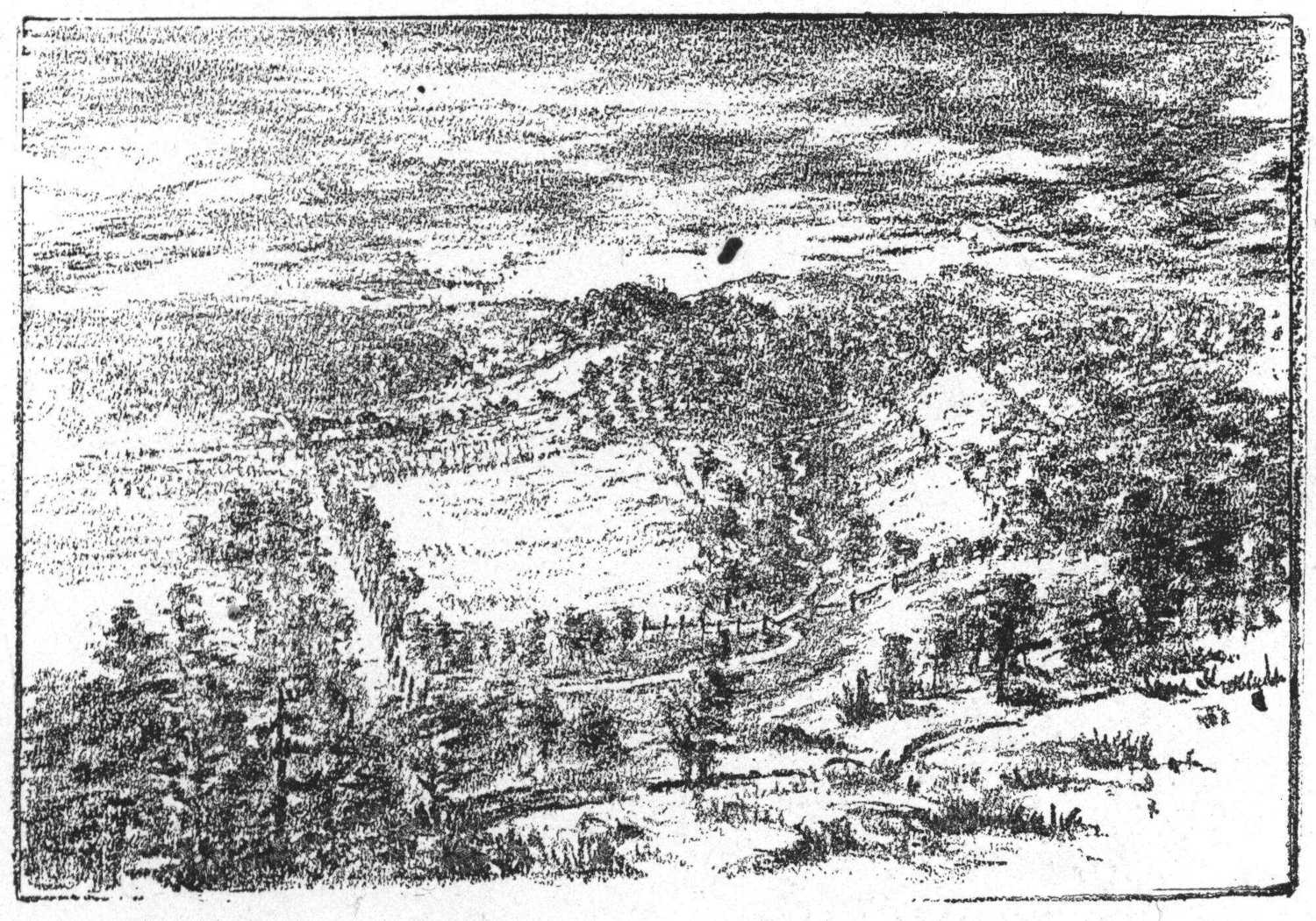

Farm in Central New York.

Brook basins may be studied as presenting many if not all of the features of the river basins. Maps may also be made of these areas, as well as detailed drawings of special features.

As has been said, the pupil should model and draw continually, in connection with or after every lesson in the field. It is the very best method by which to attain mental[22] growth, and should of course, be the genuine expression of his own mental images gained through observation. He should model and draw all surface features or areas seen in his excursions. He may model, in sand, putty or clay, maps of the areas of the school-yard, farms or parks in the vicinity; or chalk model them, then indicate upon them the boundaries of any sub-divisions they may have, such as fields, clumps of trees, houses or other buildings.

Map Showing Its Relation to the Brook and River.

Imaginary Areas. Let the pupil also sketch on the blackboard, imaginary scenes and typical features of other areas and countries under the same or contrasting climatic and other conditions; always questioning, as he draws his mental picture—if of a river, for instance—what is the[23] cause of its rapidity, what its probable depth and effect on the soil, why it cuts here or builds there, and why the slopes back of it are terraced as they are.

If he represents islands, he should ask himself the question why they are rocky or alluvial; i.e., what their origin; and never represent in any expression that which is contradictory and so untrue to nature.

Landscapes typical of the different zones of temperature, showing characteristic structure, vegetation, homes, habits and occupations of inhabitants may be drawn.

Maps, also, of these areas and those adjoining, may be chalk modeled. As the mind becomes stored with separate images acquired through actual observation of areas of the earth’s surface, gradually, by the combining and blending of these, a new mental image, a comprehensive picture is formed, corresponding in the main to the general features of the whole earth, with its uplifted masses and lower plains, its natural divisions of continents, seas and oceans, its atmospheric and climatic conditions.

If the habit has been formed of chalk modeling imaginary areas, as well as those within the sense grasp, it will be a comparatively easy matter to chalk model a map of the whole continent. On this the student may mark the boundaries of all political divisions as he studies them, and locate the important cities and places of interest.

Practical Suggestions. Before we leave the subject of field lessons, some practical suggestions in regard to them are here offered.

Actual observations may be made on the action and effects of rivers, underground water, rain, wind, heat and frost.

The effects of glacial action, and the eruptive forces of nature may also be seen in places.

To study river action it is not necessary to visit a river (if there be none near); any small stream of water, any tiny rivulet beside the roadway, tells its story of wearing and building, its vertical cutting and its swinging from side to side. It has its miniature valley, its basin and water-parting and possibly a delta at its mouth. It may also have its cascade or waterfall.

Rivulet Showing Fall of Water and Delta.

The wearing of rock, through the influence of rain, frost and heat, may be seen in any stone building, fence or pavement.

Effects of heat and moisture on vegetation, as influencing the growth of plants and trees, should be noticed. The growth of shrubs and trees during a dry season can be measured and compared with that of wet seasons.

The observer should mark the effect of vegetation in[25] the action of rain on a grassy slope—how the grass protects the soil, preventing it from being washed away, and how, by holding back the water so that it flows more slowly, it is less destructive in its action.

To add to the interest, the pupil may be led to imagine the effects upon climate and streams, of the denuding of large areas of their forests; also how rock sculpturing, in the forming of gorges, cañons, etc., would be modified by the volume and force of streams.

Observation should also be made on the making of soils, their constituents and relative proportions of loam, sand, gravel and clay, and the relation of these to plant and animal life.

The part that the common earth-worm bears in constantly uniting, enriching and otherwise preparing the soils for the support of vegetable life, may be seen in many areas. (It has been computed that in one year several tons of soil are brought up and distributed by them, within an area of an acre of land.)

A study made of the action of underground water, as shown in common and intermittent springs, would be full of interesting suggestions.

The effect of glaciers may be seen in part and their tremendous influence imagined, by the presence of the countless numbers of striated boulders, pieces of rock and pebbles, which are strewn all over our prairies hundreds of miles from any mountains which could have been their home.

It is not necessary to witness the devastation of a cyclone in order to study the effects of wind action. The piling of sand on the sea-shore, the drifting of snow or the whirling of dust in the street illustrate this. The observer[26] may notice where the dust blown from the street has choked and buried the grasses and weeds beside it, and imagine what might be the fate of forests in the path of encroaching sand-dunes.

Sand-Dune on the Shore of Lake Michigan.

Pupils may be told of the dunes which travel great distances: that one way by which this is known is by noting trees and houses that were once back of the traveling sand-hills and are now in front of them; also tell of the sites of ancient cities long buried and now being excavated and brought to light again.

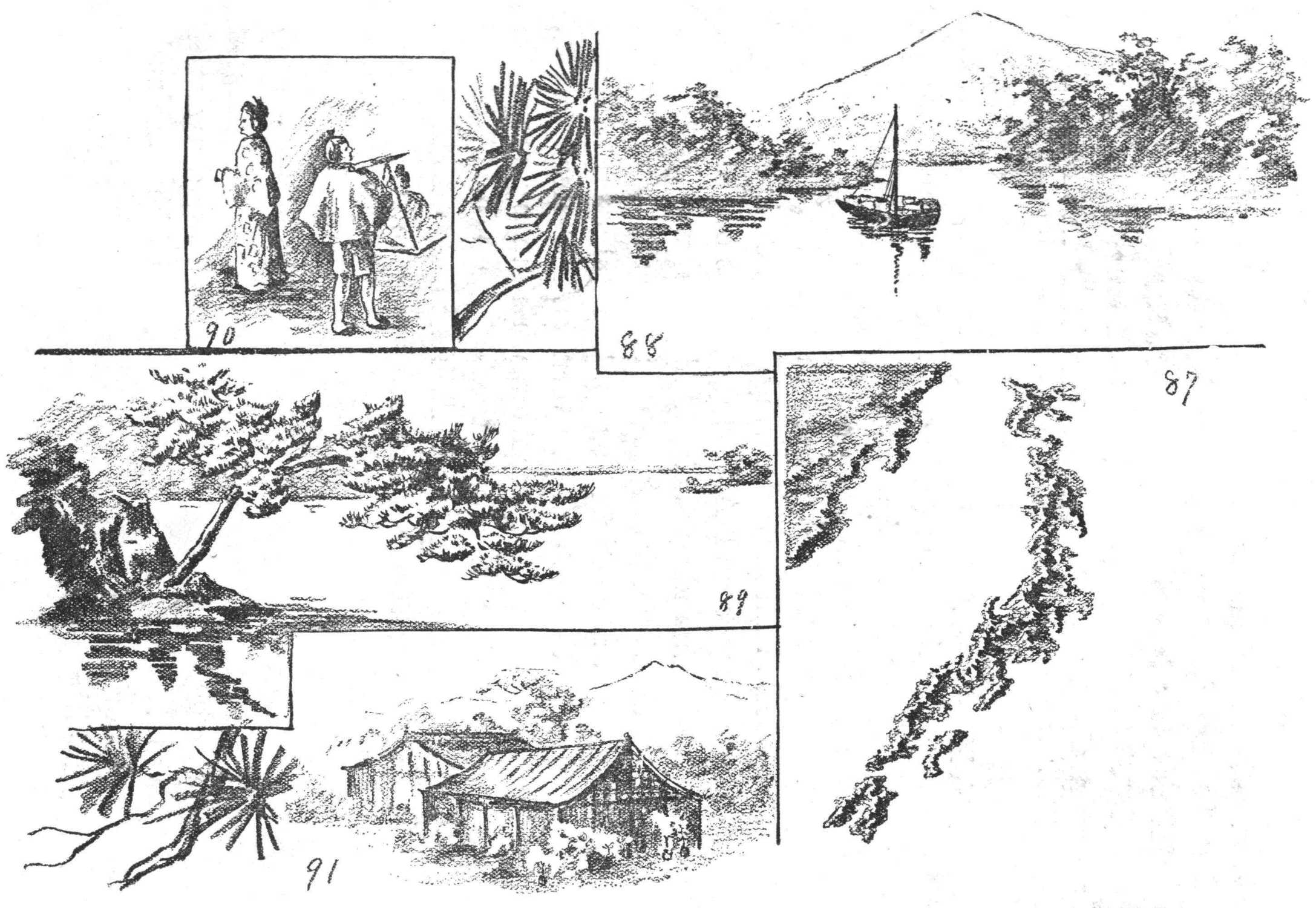

The ability to image the continent or any part of it, from the reading of pictures, is of great importance. It is an inexpressible aid to the imagination in the study of areas that lie outside of the sense grasp. Good pictures should be chosen: pictures showing several different views of the same section of a country; pictures that are a truthful representation of both detail and generalities. (Many wood cuts are as good as photographs for this purpose. Great care, however, should be taken that they are faithful transcripts.)

After a close study of them, questions may be asked the pupil as to climate, structure, nature of rock and soil; whether it may be supposed to be an arid or fertile region; whether the river basins are young or old; what agents were most active in shaping its features, and what its probable destiny: or the pupil may be led to give his own inferences as to conditions, without direct questioning.

In this way contrasting sections of country may be studied and compared, thus making the mental picture more vivid and complete.

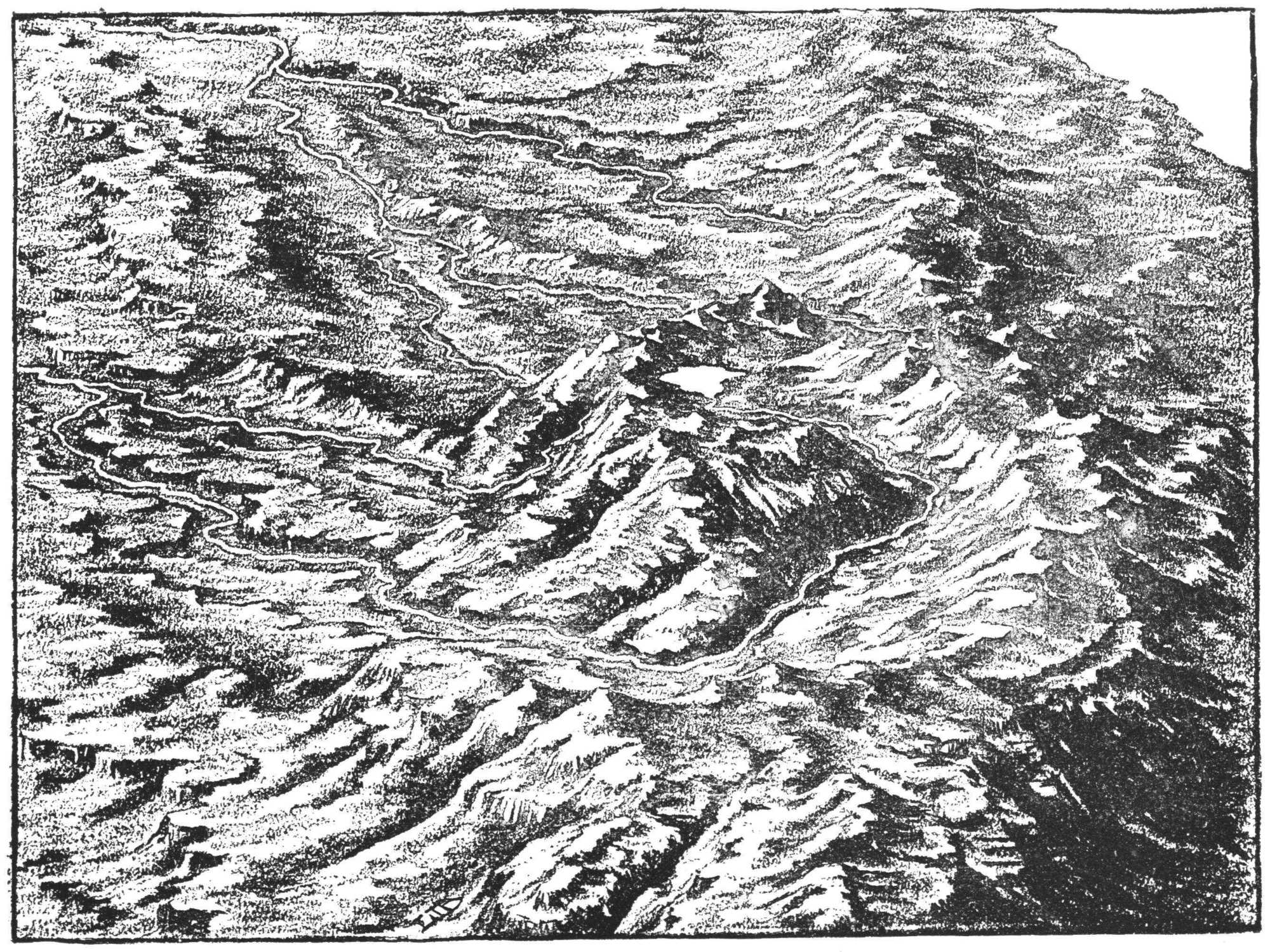

MAP OF ABYSSINIAN HIGHLAND.

(Drawn from information gained through interpretation of pictures and written description.)

It is understood that these mental images gained from such study of pictures, have as a basis, images acquired from actual observation of the earth’s surface. From this mental picture, supplemented by images gained by oral and written descriptions, maps may be chalk modeled which will contain all the essential features of structure.

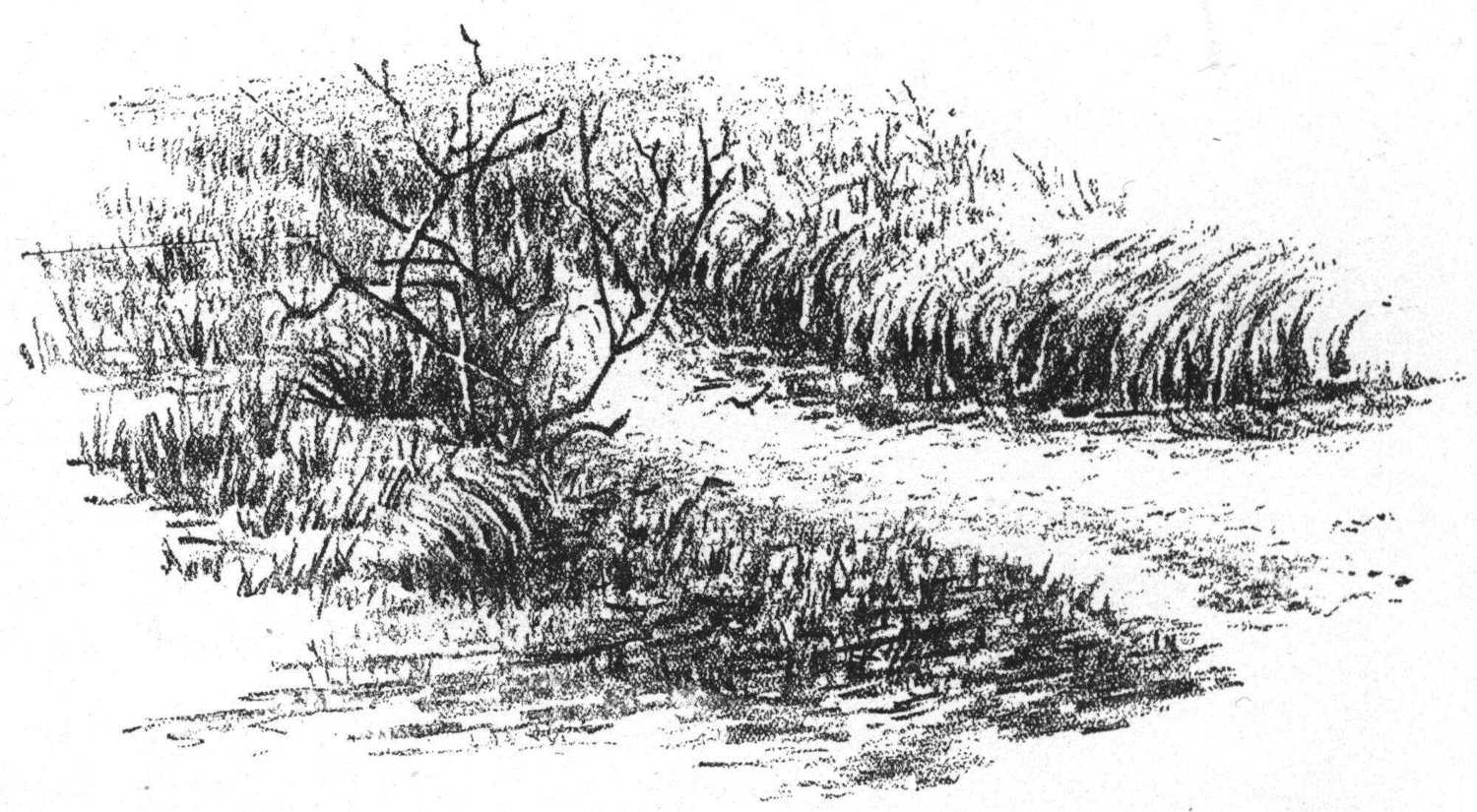

Young River Basin.

Valuable information for the making of maps has been gained in this way; indeed, adequate maps cannot be made without this means of acquiring the necessary knowledge, which the delineator has not been able to gain through travel and personal investigation.

Through this study or reading of pictures a natural interest is aroused in the mind of the pupil to see located on the map (that is, to see in relation to the whole) countries and places of special interest; such as natural[30] wonders of structure, and remarkable instances of man’s skill and power in overcoming obstacles and improving his environment.

Especially will this be the case if the teacher accompanies the descriptions with rapid illustrations on the blackboard.

Tepee or Wigwam of the Sioux Indians.

Necessity for skill in drawing on the part of the teacher, becomes very evident as the desirability of frequent illustrations is felt, and the fact is also realized that by it untold influence for good is exerted over the mind of the pupil. It is an aid to correct mental picturing, which the teacher cannot afford to omit.

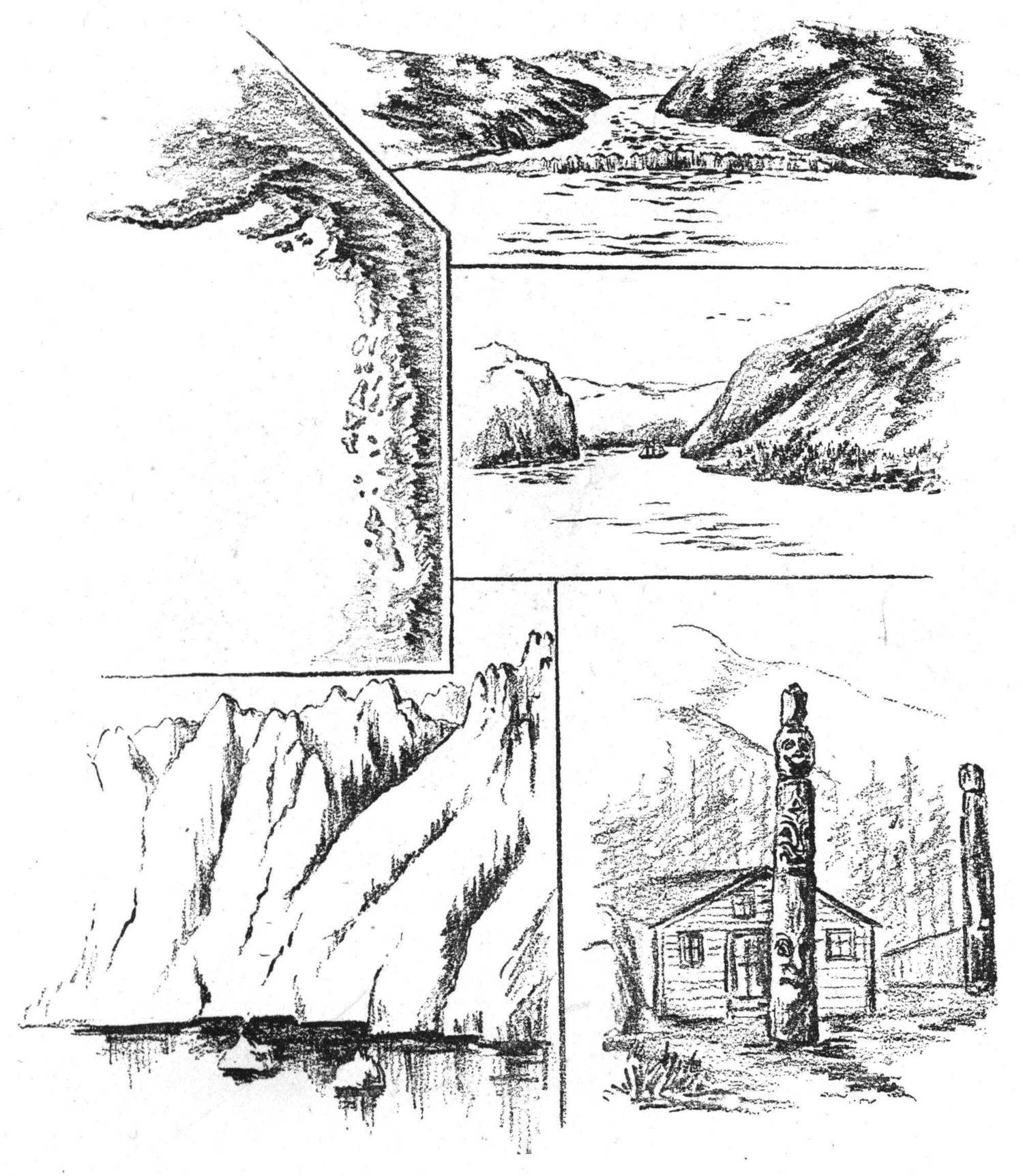

Coast of Alaska.

(Showing its drowned valleys caused by the gradual sinking of the land, also glaciers, Alaskan hut and totem pole.)

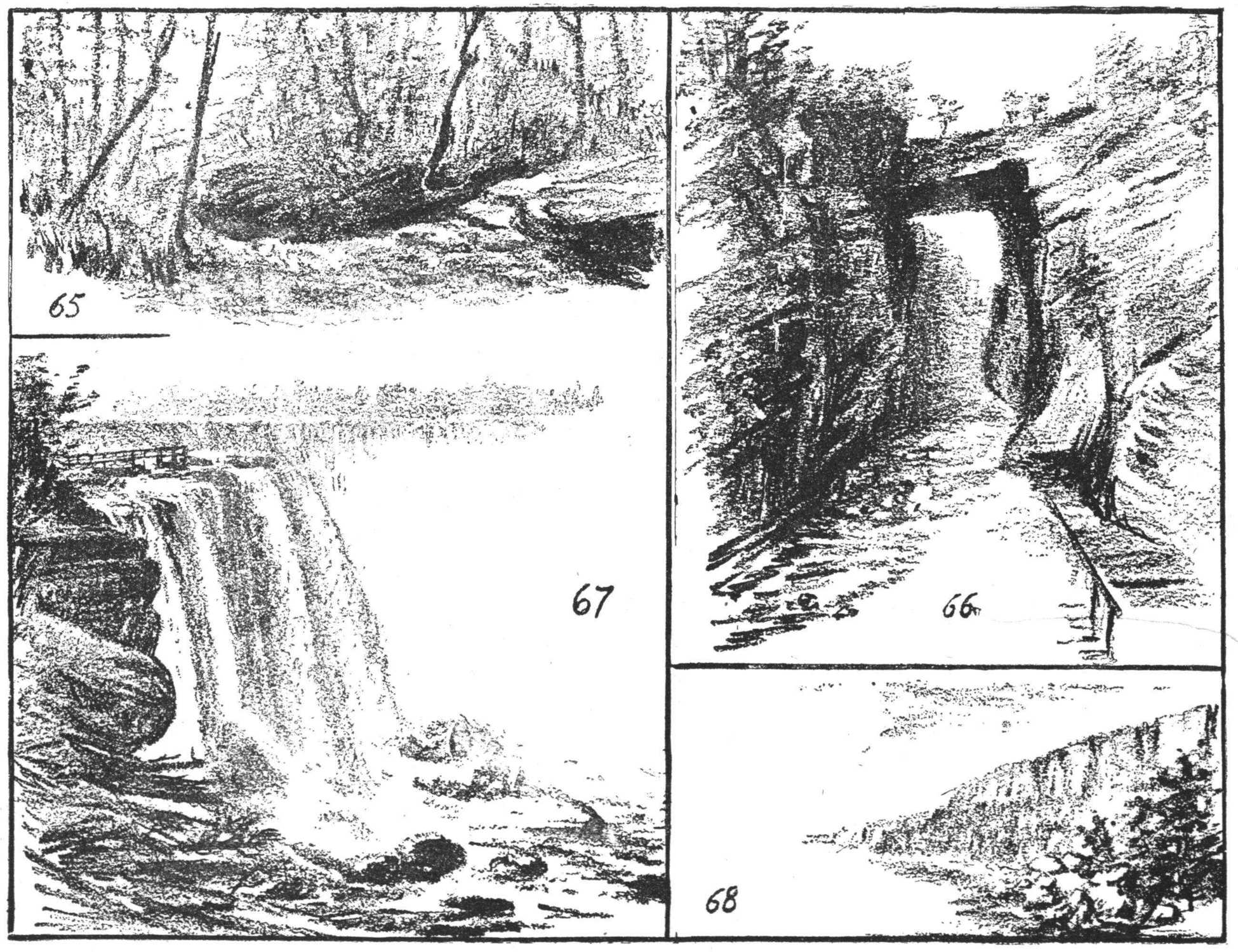

Special features are more readily understood when drawn in detail: as mountain peaks, stern or forbidding in outline, or lofty and grand in their mantles of snow and rivers of ice (Mt. Blanc); valleys with wooded slopes and streams of water; lakes, waterfalls (Niagara Falls); glaciers and icebergs, with typical scenes of Arctic regions, including inhabitants with their homes (Muir Glaciers), (Alaskan huts and totem-poles); deserts and oases, with typical trees and surrounding objects (palm trees, pyramids, camels); Indian homes and environment; dykes of Holland, Suez Canal, St. Gothard Tunnel, Great Wall of China, etc.

THE CHALK MODELED MAP.

As it is impossible to adequately teach the surface features of a country with only a vague idea of its structure, and with no aids in the form of pictures, drawing or modelings by which these surface features may be illustrated, there arises the necessity for maps.

These, to be of any real service, must be a representation of the form and character of the area which is the subject of study, and must indicate the relation of part to part, parts to the whole, and the whole to parts.

As symbols and more than symbols, they must bring to the mind vivid pictures of the real country or continent, not as too commonly taught; “A mental picture of the map, so clear and consistent ... that he (the pupil) can read the answers to all questions concerning it, from his mental map, as easily as he could from the printed one, if it were before him.”

This is to limit and cramp the mind’s action, as the pupil sees only the map and its corresponding concept of map, its size, boundaries and patches of colored paper. It gives no idea of relation or correspondence between the map and the actual world of life, form and color.

Aim of Teacher. In using maps it should be the aim of teachers to create in the mind a complete, harmonious picture; the blending together of the several concepts of structure, climate, drainage, soil, vegetation, animal life,[35] races of men, etc., corresponding to reality, or real life in the real world.

The flat political maps of the past made no attempt to show any structural features except those of horizontal or level plains, markings which show the locations of mountain ranges and volcanoes, and lines indicating rivers and outlines of continents or coasts.

These maps have had comparatively little meaning to the young pupil. There was in them no suggestion of solidity or mass; the contents to him seemed flat and thin, and confined between coasts which were sharply defined. Tent-like mountains crossed ghost-like surfaces, and thread-like rivers were made to zigzag along in an erratic and irresponsible way, showing to him no reason whatever for their being.

Many teachers or pupils have not known how to interpret maps. They have not realized that, where rivers rise in certain localities (especially if more than one rises in the same place), there is a reason for their rising just there and for their flowing in different directions; that their source is probably at an elevation or rise of land (called a divide or water-parting), that there is likely to be more rainfall on the side of the mountain range that has the more rivers, and that this has a close relation to the direction of the prevailing winds.

Natural Boundaries. In the past study of these maps, outlines of political divisions have been memorized. It was not realized that many of the boundaries of those areas were fixed in the beginning by the very nature of the surface structure, and that they are where they are, simply because they could not well be anywhere else. (See Mexico, India, Italy.)

Map of the Chicago Drainage Canal.

(With larger map showing its relation to Lake Michigan and the Mississippi River, also sections in detail.)

History. We have seen that the study of history cannot be successfully taught without a knowledge of structural geography on the part of teacher and pupil; so we may say the same of maps, that their use is of fundamental importance in that study, and the ability to read them understandingly is as indispensable as it is in the study of geography. To try to teach history otherwise would be a waste of time and effort.

The habit of locating the events recorded, of tracing upon the map the route of an army, or the line of an important road or canal, and observing the impediments or natural obstructions to be overcome, with the great advantages to be derived therefrom, together with inferences as to the time and labor required, has the effect of making the study of history of living interest, especially if the map used indicates such surface structure.

In the structural map the student readily sees the meaning to commerce of the cutting of a canal which would unite two large bodies of water, or the effect the building of roads and bridges across hitherto impassable regions would have upon the life and growth of a people in the opening up of new and extensive areas to civilization, and consequently the development of their own internal resources.

The importance of this habit of usage, or constant reference to the map, is also recognized when one realizes how it fixes in the memory not only the location of cities and boundaries of ancient empires, but the geographical structure and environment associated with their growth and with important historic events; making plain the reasons for, or causes why, certain events occurred at certain places, as the inevitable consequence of their environment.

Light dawns upon the pupil as he studies. He sees that environment has been an important factor in the development of the human race. He traces step by step in imagination the growth of civilization, from the time that man in his nomad stage first drove his herds into the valley in search of food and water. There, finding the soil productive, water unfailing in supply, and the valley protected from marauders by natural barriers, as desert or mountain walls, he fixes his home; in the course of time comfortable dwellings are constructed, land is cultivated and the place becomes a center of civilization.

In connection with this train of thought, the student by contrast notes the far different effects of environment as shown by life in the Arctic or other regions, and he turns to his map with renewed interest and eager inquiry.

Literature. The habit also of locating on the map every place, natural feature or country read about, should be cultivated, as it is of importance in obtaining a correct understanding of an author’s meaning.

If we did not have the knowledge of physical structure in mind as a stage on which the actors move, much of our literature would lose its value, becoming flat and uninteresting.

To know the great lake region adds to one’s interest in Longfellow’s “Hiawatha,” and the tales of the early explorers; and a knowledge of the Catskills and the geography of the Hudson River valley gives greater zest to the enjoyment of Irving’s “Rip Van Winkle” and “Sleepy Hollow.”

It is also necessary to the understanding of the stories of Holland (“Hans Brinker”) that we know the habits of[39] the Hollanders arising from the physical characteristics of their environment.

To read intelligently Scott, Dickens, George Elliot and others is to understand the peculiarities of climate and structure of the British Isles. The old Greek stories and the German Folk Lore as well, demand for their understanding and interpretation, that we place them not only in relation to the habits and thoughts of the people, but also to the physical foundation of the country itself.

Relief Map. The nearer a map corresponds in its inherent form and material, to the surface features of the earth which it is designed to represent, the more of reality does it recall to the mind. The most effective map of this kind and the one which corresponds most closely to the reality is the modeled map of putty or plaster, showing structure in relief.

These maps have been in use for years, and have been of incalculable interest and benefit to those whose stock of knowledge concerning geographical structure had been mainly gathered from the flat political map and old modes of teaching.

On seeing a relief map of one of the continents for the first time, there arises a sense of wonder and surprise, and as the realization dawns upon one of the continuity of the great mass of land represented, with its altitudes and depressions, and that it is one stupendous aggregation of soil, rock and vegetation, surrounded by a great expanse of water, a feeling of awe and astonishment is awakened.

As this new light comes to the student, he looks with interest and eagerness to see the plan of it all. We do not mean to say that he sees in the map before him an actual correspondence to the earth’s surface structure, that[40] is, forms that are reproductions in miniature of mountain range and valley, but he sees a representation of them calculated to arouse his imagination to a lively degree. He is enabled to picture to himself great slopes crowned by lofty mountain peaks, and the meeting of their lower edges where mighty rivers flow. He sees in imagination how these waters have cut deep channels into the great uplifted masses, how they have torn jagged gashes into their rugged sides as they leaped and tumbled through dark cañons, grinding off rocks that form sediment constantly to be deposited later on upon the plain below. He easily understands that they must act as a source of drainage for wet lands and as channels for the irrigation of dry areas.

In looking upon the great bodies of water, oceans, seas, lakes and gulfs, as represented on the maps, he questions the relation of these waters to the land, their depth and what place they fill in the economy of nature. Indeed, the relief map has an awakening effect, quickening the imagination and stimulating to mental effort—earnest thought.

They are invaluable in their place and have come to stay; yet on account of their weight and general unwieldiness they are not practically as useful as maps which are lighter and more easily handled.

The papier mache maps in relief, although much lighter in weight, are still very bulky if made large enough to be of much practical use as wall maps, since they cannot be folded or reduced in size to facilitate transportation, or removal from room to room.

The best of these, also, are modeled in such low relief that they are better adapted to the use of pupils in the higher than in the lower grades. Other maps of rather[41] recent date are the typographical map and the contoured map. The former shows general altitudes by the use of shades of color, and is of great value to one who can interpret it, but only a confused mass of signs and symbols to the young student, and thus not much more helpful to him than was the old reference map.

In the contoured map, the altitudes are scientifically represented by lines drawn to an exact scale, and such maps are most valuable to students of the higher grades.

A structural map suitable to all grades of pupils, the lower as well as the higher grades, seems highly essential; especially should it be one that is adapted to the teacher’s use while before the class—one to teach from. This should be entirely different from a reference map. It should plainly show the great facts of physical geography or surface structure, as well as some detail, and this in a simple form. For the lower grades there should be no lines to mark the political divisions, neither should there be any names of countries, states, or cities to designate localities.

Everything should be omitted that would have a tendency to divert the attention from the chief function of the map which is, to aid in the formation of a mental picture or image, corresponding to the structural features of the real country or continent.

The Chalk Modeled Map. These maps, following the use of the putty or plaster relief maps, should be the only ones placed before the pupils of the third and fourth grades, or even higher grades, until they have gained mental power to read and understand the signs and symbols of the map, and realize clearly the chief structural features of the whole globe.

The student should be enabled by the use of maps to[42] picture in his mind the configuration of the whole earth; the distribution and shape of land and water surfaces, the great structural division of continents, the slopes and counter-slopes with their crowned heights and level plains, the great land masses and river basins, peninsulas, gulfs and bays, islands and their relation to the mainland.

In fine, the whole world surface should become a reality to him if the map is rightly taught. This will be an easy matter for a teacher who is alive to the beauty of the world around us and who has a personal knowledge or clearly pictured concepts of the real country. Such an one will readily see the value of the maps as an aid to the pupil in gaining a comprehensive mental picture of the earth’s surface.

She will remember that the mere placing of the maps before the pupil is not enough, that they will be as unmeaning to him as the flat political map, unless he has already in mind the primary concepts acquired through observation of surface forms, and has made his inference as to cause from the effects seen.

Of what value will it be to him to know that certain lines indicate a mountain range or river, unless he has an approximate idea of what a mountain range or river is?

For the use of the more advanced pupils of the higher grades, who see the relation of structural environment to man in his development as a nation, the relation of natural structural divisions to political divisions, these maps should have lines drawn upon them to indicate the boundaries of such divisions. Names, also, of countries, mountain and river systems should be marked, and the large bodies of water of the interior. Later on, the smaller divisions of states and provinces, gulfs and bays, lakes and rivers, with[43] their tributaries, should be shown, and important cities may also be located; in the end, all the data needed as a reference map.

The map devised to fulfil these conditions, and now in considerable use in this country, is called the “Chalk Modeled Map.” It is drawn to represent surface structure in relief, giving much of the effect of an engraving or photograph of a relief map, yet intrinsically more truthful and artistic than any such representation could be.

There is an immense difference between this and a drawing from a relief map, or from a photograph of one. In this map the delineator expresses at first hand his own concept of the continental structure, as the artist or poet expresses in his work his own original ideas. We feel his thought in the very quality of line used. We read how the truths have appealed to his own consciousness. It stands where the relief map itself stands, as representing the delineator’s own mental image of such structure.

There are no lines drawn in this map that contradict or confuse the meaning; all is direct, truthful and clear in statement of fact. Each line has its own particular meaning. If represents direction. Applied to land surface, a vertical line means a perpendicular mountain or side wall of plateau, horizontal lines indicate level areas, and oblique lines a sloping surface.

Until recently, this map has not been available for general use, except as each teacher made his or her own. The latter, however, is the ideal way of teaching. To draw a map of a continent or section of it, as is required, in order to illustrate or emphasize any particular point before the class, adds intensely to the interest of the lesson and to the adequacy of concept gained by the pupil.

Too often, however, the opposite course is pursued. The teacher’s conceptions of earth structure are perhaps vague, or, teachers may not have been in the habit of representing by drawings that which they may be able to picture quite clearly in their own minds, even the desirability of so doing may not have been entertained by them.

In fact, there are comparatively few who have been persistent enough to make maps, for though there may be a good knowledge of geography, clear mental pictures of structure and the ability, also, to draw them, yet lack of time necessary for their proper delineation has doubtless often compelled the busy teacher to forego their execution.

Printed Wall Map. The Chalk Modeled map has recently been presented to us in a more durable and serviceable form for general use; a printed wall map, which combines the latest geographical knowledge together with the best available skill in delineation.

It does not embody all the desirable points of the original, yet it has an added one, that of durability.

The introduction of “Nature Study” into the public schools has contributed largely to the demand for such a map. Pupils brought into close relations with nature, naturally seek to relate the knowledge gained in this basic study of geography, to the map; as in connection with the field lessons, after actual observation of surface areas, the student is led to model or draw what he has seen. This he represents in pictorial form, as it appears to him, or he charts or maps it from actual measurements.

Sometimes he tries to combine these methods so as to show elevations as altitudes on his map or chart, but the results are often very crude; a mere representation of hills and mountains piled up on level ground.

He realizes that this is not a proper representation and is often discouraged. He knows that peaks are related to level ground by continuity of mass: that they are the corrugated tops of great uplifted masses or swells of land, and his failure to find this illustrated in the old maps has led him to lose much of his interest in them, and to greet the new one with ardor.

It appeals to his reason as a symbol more nearly corresponding to the features of the country represented. It is indeed the link needed to connect the political map with the putty relief map.

Mass Without Outline. Not only can we say that the Chalk Modeled map has been a great factor in the better understanding of the surface contour and conditions of the continental mass, thus advancing the true study of geography, but that it has also awakened some of the teachers of the public schools of the country, to the lack of interest and lifelessness in the teaching of drawing as it has prevailed in the schools in the past. It has been the means of revealing to them the beauty and desirability of delineating mass without a continuous hard outline. The artist when inspired with his subject masses his material in boldly and each stroke counts for the thing he wants to say—it tells of the direction of surface, or edge of mass, or detail.

In the new map, the representation of solidity and land continuity as mass, with no hard and fast limitations of land and water, such as the outlines so prominent in the old reference maps, is a noticeable feature.

It is a well-known fact that a general or approximate shape of the coasts of continents is all that can be known from the most careful surveys; for in reality with every[46] season there is more or less change in coast line, caused by wearing and building of ocean and river, as well as by the occasional rising or sinking of stretches of land along the coast. In course of time these changes become very apparent.

The omitting of outlines of continents, then, in the drawing of maps has been for a purpose. They have not been necessary to the showing of limitation of continental mass or the meeting of the surface plane of water with land surface; and as the direction of all lines used in delineating have their meaning, there can be truthfully none used to represent something lying between land and sea, as there is nothing there. Continental coast contours may be as accurately shown as the occasion demands without the use of any outline to confuse the eye or to contradict the direction of line used to delineate the structure of the land surface at the water’s edge. (See map illustrations in Part IV.)

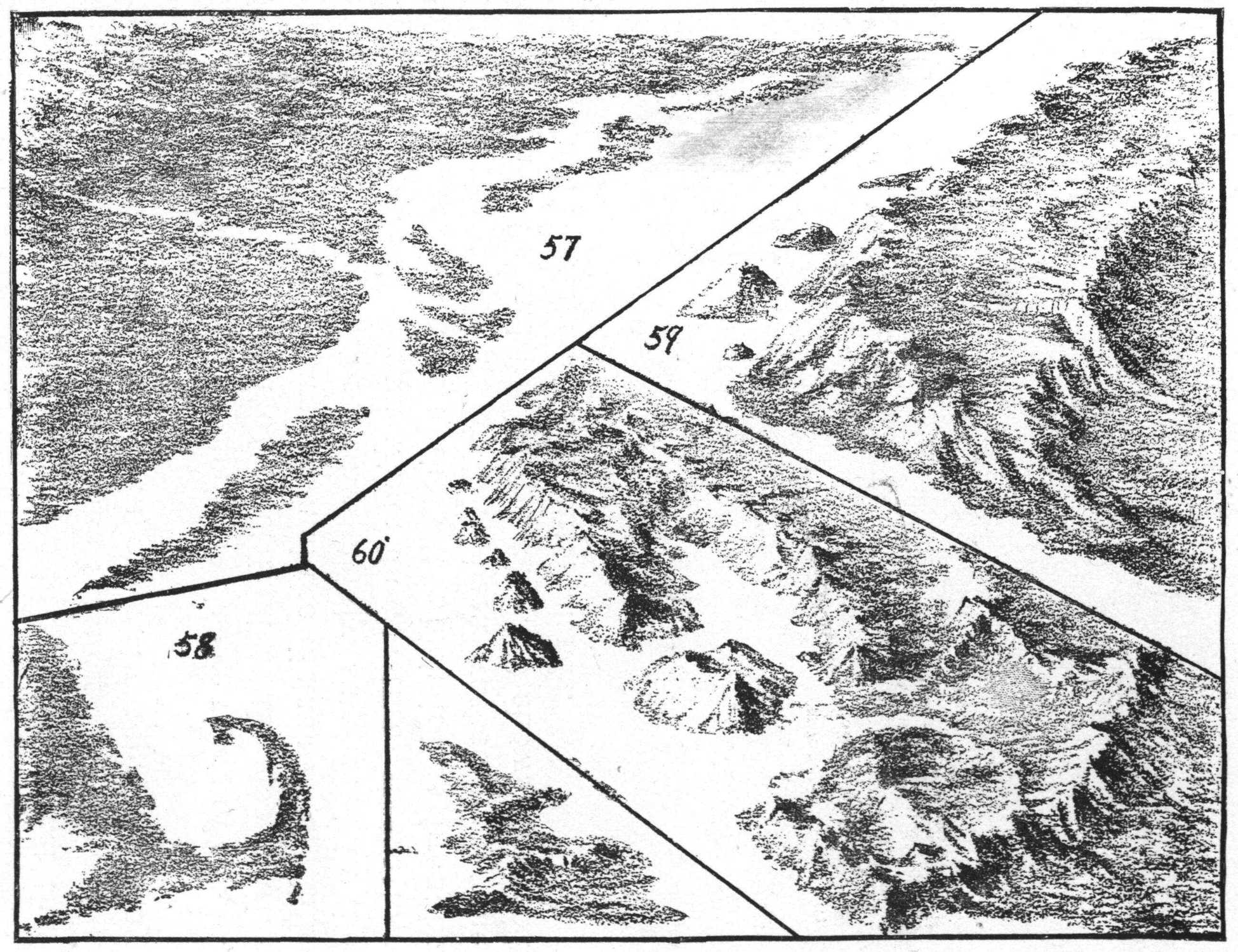

The most prominent feature of the new map is the representation of the relief of the earth’s surface; showing, as it does at a glance, the great back bone of the continent, with its ragged broken line of peaks dividing the waters of the two slopes; its great land masses, primary and secondary; and its area or line of greatest depressions. Its river basins also are plainly seen, and we infer the reason for the general course of the rivers and read their history from the sculpturing they have done.

We may note also the character of the mountain ranges; whether they are young or old; where new land is being made, and where areas are sinking. One can often determine what the prevailing wind of a section may be and the regions of greatest rainfall, and can judge of the[47] climate and vegetation; in short, very rational conclusions concerning the life and habits of a people may be formed from a study of the map alone, and the student can picture, in imagination, the growth or advancement of nations under the given conditions.

He will be enabled to see, as has been remarked in substance before, that the mighty influences bearing upon civilization have always been largely dependent upon the geographical structure of a country; the relation of natural divisions to existing political divisions will be noted, and the reasons for the locations of great centers of commerce, important cities, and military fortifications, will be understood.

Altitudes. In common with all relief maps, altitudes are shown in these, greatly exaggerated in comparison with the horizontal distances, but this is essential in order that the pupil may be able to grasp the general truths of the organization of the continent.

Relief maps in relatively exact proportions will not help to this, as the highest elevation would appear nearly on a plane with the ocean level, and would be of no better service for school use than the flat maps, from which no idea of the general organism can be acquired by the young student, if indeed it can be by one of riper years.

Also in all topographical surveys, and in the profile of vertical sections of country found in many geographies, we find the same exaggeration of height in relation to horizontal distances, used to illustrate elevations and slopes.

These, with photographs or pictures of relief maps are extensively used, as well as birds’-eye views, showing on the part of the map-makers, a recognition of the importance of the pupil’s gaining mental concepts of altitudes.[48] The latter, of course, must exercise his judgment in relating the heights, to the horizontal distances given, as he so continually does in every-day life in regard to other matters.

The horizontal map distances should be related to the other horizontal distances of the map, and the altitudes to other altitudes, and these with reference, also, to the tabulated lists found in every geography, of the heights of mountain peaks and lengths of rivers.

“All knowledge of external things comes through observation, comparison, and judgment.” To judge of great altitudes, one must have a knowledge of the heights within experience. To be able to gain a proper conception of immense distances, as the distance across a continent, comparison must be made with the distances one has already measured or traveled.

In the measurements of areas, size of fields and gardens, width of ponds, or heights of trees and hills, the pupil has numerical facts from which he judges of other forms and areas; as forests, marshes, plains, the width of rivers and lakes, the heights of mountains and cliffs, or length of rivers and mountain ranges.

Also in the measuring of the deposition of silt in small streams, he may judge of the quantity that large rivers like the Mississippi or Nile must carry; and from measuring the yearly growth of vegetation in his own climate, he judges what might be the growth in other climates. Thus through observations, inferences, and comparisons, he is enabled to read his map with some degree of power to judge its distances and altitudes.

The aim in the preceding pages has been to show the vital importance to the would-be delineator of Chalk[49] Modeled maps, of the thorough study of geography, in its truest sense, and that the foundation of such study lies in the field lesson, with its accompanying expression of the knowledge gained there, of surface forms, areas and structures.

The habit, also, of modeling and drawing in connection with the study of geography, is conducive to the wished-for end; i.e., an adequate knowledge and expression, of the surface contour of the continent.

The chalk modeling of maps is in itself the simplest of all modes of drawing. It may have been inferred from what has been said on the subject of maps, that drawing them consists merely in showing simple indications of slopes; short or long, abrupt or gentle, and summits; broken or rounded, river basins, character of water-partings, valleys, lakes, rivers and coasts either bold and rocky, or low and alluvial.

It would be as unnecessary for the purposes of geographical instruction, as it would be impossible, to draw absolutely correct maps of the earth’s surface.

Each mountain peak cannot be shown, nor every indentation of coast-line, but the general trend or direction of mountain ranges and rivers, and more or less of geological structure can be portrayed in a conventional manner.

It is not difficult to chalk model with reasonable accuracy. The ability to do this, however, with any degree of rapidity as well as accuracy, implies, as has just been said, an adequate knowledge of the subject to be represented. No mere imitation, or acquisition of technique, or copying of maps, is educational, nor has it any vital relation to the true study of geography. Like all[50] dead copies, it betrays in itself its lack of life, or of real knowledge on the part of the delineator.

An instructor whose eyes are open to truth, can generally tell from a pupil’s representation whether it is the result of his own individual thought, the expression of his own knowledge of the subject, or the reflex of another’s thought.

If it is an expression of his own, there will be much revealed in the touch and in the quality of line itself, that could not be depicted in form or put into words. The representation, also, will indicate to what degree the subject has interested and inspired the individual, and how, with a clear mental image, he has instinctively expressed himself in the simplest and most direct manner possible with the medium at hand.

In the following pages will be found suggestions as to the method of chalk modeling, given in the form of a series of lessons; the underlying principles in the lessons being those on which is based all expression of thought in every field of study and among all peoples.

The illustrations are not intended to be models for the teacher or pupils to copy, but are meant to be helps or encouragement to those who desire and have courage to attempt to express their own mental images.

Busy teachers need only to realize that comparatively little effort is necessary in order to acquire a certain amount of success, if they have their subject in hand, that is, if they have an adequate mental image of the object to be sketched.

It is hoped that such success will prove a strong inducement to a deep study of the subject of art, and especially to the psychology of expression.

Chalk Modeling of surface forms is the easiest and simplest method of geographical drawing, and one of the best ways of beginning art work in the school-room, for absolute definiteness of form and detail is not required, and we know that generalities are represented much more easily than details—large masses more easily than small objects.

No one need hesitate to try to draw who can write or gesture: this last we are all doing continually, either consciously or unconsciously.

Watch the friend while telling some interesting story, or while giving a description of some object or landscape. Note the gestures unconsciously employed and how truthful to the subject they are. Also notice that the more intense the desire to make you understand, the more adequate is the gesture.

No conscious thought is required as to what motion to make, for the very desire to express brings with it both the required word and action. This is spontaneity, and if a pencil or crayon were in the hand of the narrator, with paper or a blackboard near, a sketch might be the result, and one quite adequate to its purpose.

If you are in earnest and truly desire to express your thought by drawing or chalk modeling, you will forget[53] yourself in your effort to be understood. You will find a way to accomplish your object, choosing and using the right direction of line and giving the right accentuation or emphasis without any special attention as to the method of working.

Drawings may be made on the blackboard with common blackboard crayon of medium softness, or with charcoal or crayon upon paper. The blackboard is much the more serviceable, as upon that you can draw with great freedom, without fear of wasting paper or of spoiling your work. Swing the arm out freely from the shoulder as you work, give out that which you have to give, without fear, generously. If it is but a line to indicate the edge of a table, draw that line as though you were glad to draw it. Express your thought boldly regarding the fact or object you wish to make your statement about—fear not.

The most convenient length of crayon to use, is a piece about an inch and a half or two inches long, yet we may often profitably use the whole side or length of the crayon. If we wish to represent broad surfaces, we will naturally use the side of the crayon, as a child does. To show narrower widths of surface press more upon the end of the crayon, also use a long edge to represent the edges or the meeting of surface planes. This manner of using the crayon seems the most natural for the purpose, and it certainly economizes time.

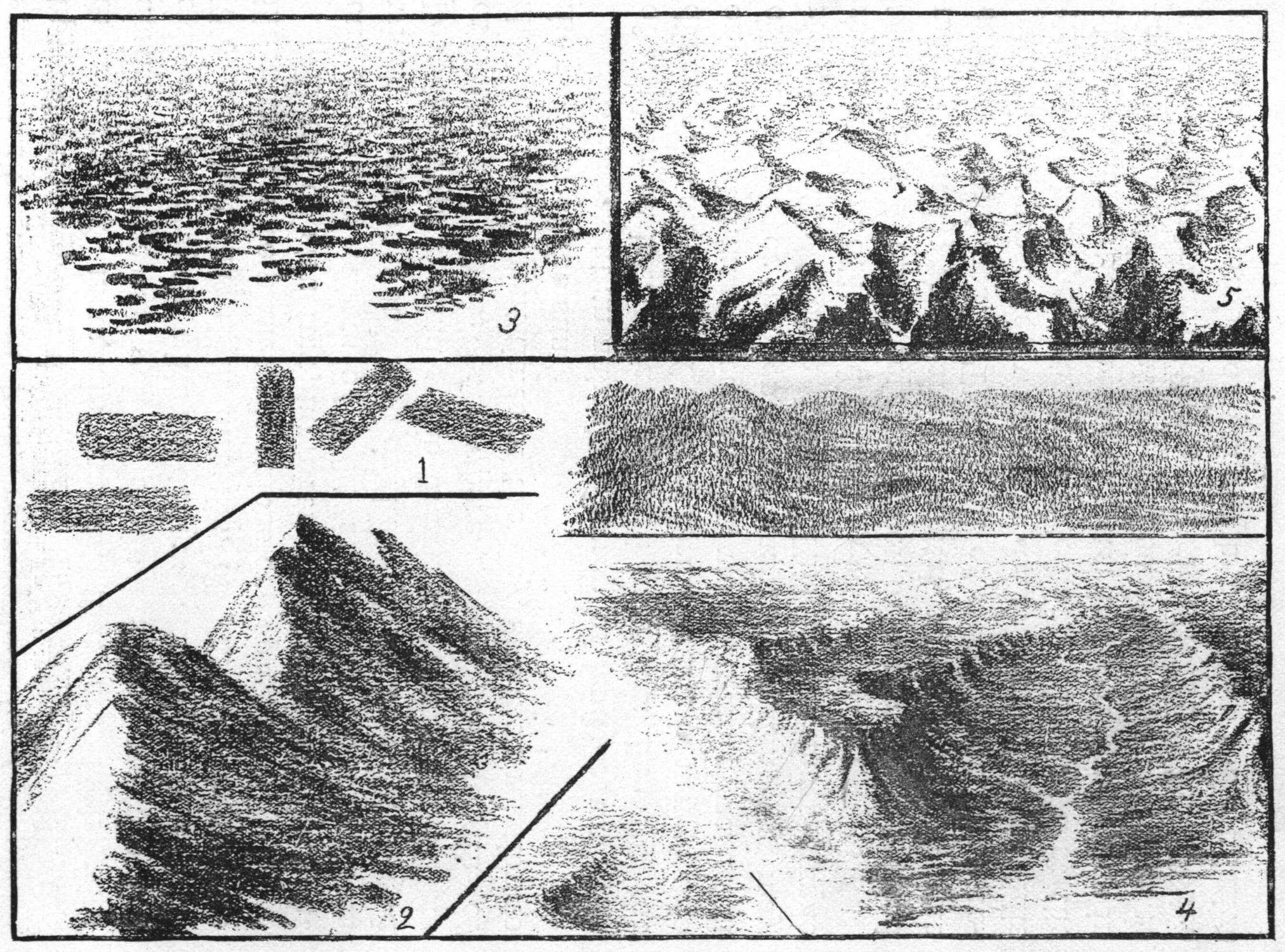

Line represents direction. When applied to surface we understand it to indicate horizontal, vertical, oblique, and curved surface directions. Try it and see if it is not true that lines in one direction never indicate any other direction; the vertical can never be mistaken for the horizontal, or the reverse. For the representation of a level plain, make simple strokes in the horizontal direction with the side of the crayon, and to represent a vertical surface as a cliff, make a stroke in the vertical direction with the same broad side of the crayon. Oblique surfaces, as slopes, are to be drawn with oblique strokes, and curved surfaces like rounded hills, represented by continuous upward and downward strokes. (See Fig. 1.) In the delineation of mountain masses, that are high with abrupt declivities as well as gradual slopes, we use the side of the crayon with an oblique stroke as in Fig. 2. We see then that right direction of lines of themselves illustrate surface planes, elevations or depressions.

1 2 3 4 5

Detail of structure, however, cannot be well brought out except by effects of light and shade. Choose from which direction your map or sketch is to be lighted, and keep it always in mind while drawing. Study the effects of light and shade everywhere. Note the length of shadows at different times of the day, and their relation to the position of the sun.

To represent an unbroken sweep of land or water, as of a plain or lake, draw a broad unbroken line for the distance, as all detail of surface forms seems to merge into one horizontal mass; nearer to us, we perceive more detail of landscape or broken land surface, which we may represent with broken lines. This is the most simple representation of level distance. (Note Fig. 3.)

In Fig. 4, or the representation of a plateau (upraised mass of land), there are horizontal, vertical, and oblique surfaces combined. The detail of structure in the foreground is represented with some definiteness of line, while the mountain slopes are quite indefinite. Notice that the oblique and vertical lines are shorter in the distance than in the foreground, and that the land seems to rise as it recedes from us. Look out of doors and see if it is not so. Notice rows of trees, houses, or telegraph poles, in their relative[57] height, also in their relation to the ground on which they stand.

In the delineation of a valley between parallel mountain ranges, keep in mind the proportionate height of mountains to width of valley; for example, think of the apparent width of street or railroad track at the farther end, in comparison with the width of the same close by you, and also notice that it decreases in definiteness as it recedes into the distance. Note the width of the valley in Fig. 4.

Fig. 5 represents land sloping from us as it recedes. Note the more definite lines in the foreground, indicating some detail of structure, and the indefiniteness, or less distinct lines that indicate the distant hills, these lines becoming more and more indistinct as the hills recede.

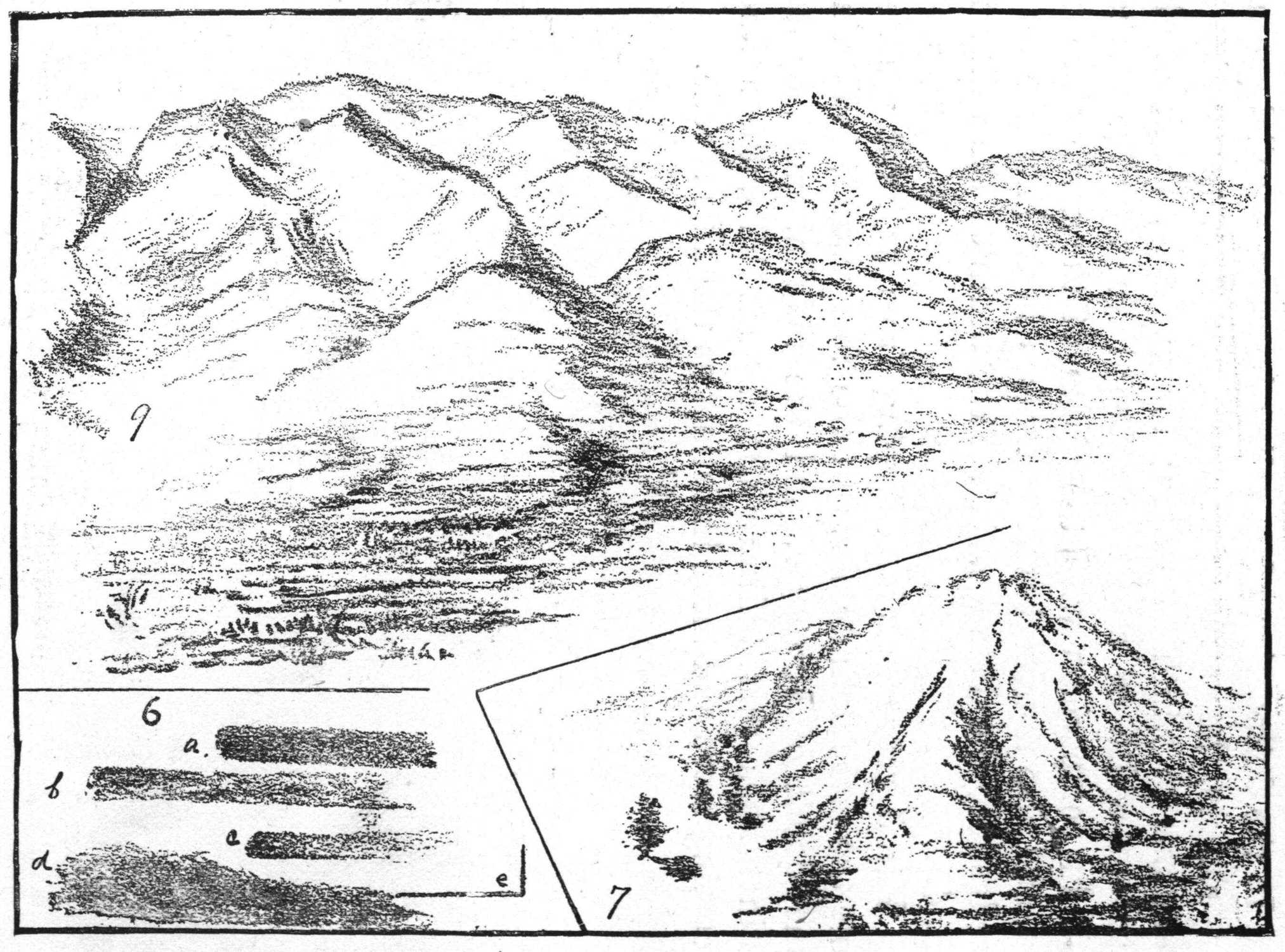

6 7 9

Each line drawn has its own characteristic meaning—its own individuality, so to speak. It not only represents direction, but carries with it a certain quality of effort or mentality, as indecision, fear, courage, certainty. (See Fig. 6, a. b. c.) We also see in it the habitual mental attitude of the delineator. This is plainly seen in the quality of line used by the timid, contrasted with that of the fearless—by the unstable or changeable mind in contrast to one who is clear in his thought (who “knows his own mind”) and positive in his expression. (d. c. e.)

It follows, then, that to draw a firm line with ease and rapidity, one must have a positive knowledge of what one desires to express, just the length of the line and its relation to all other lines; that is, one must see things or objects in their right relations. All things in the universe are related to each other—nothing stands alone. The mountain is closely related to the valley, it has given of its substance to build and enrich the latter, and its streams have carried nourishment to help swell the river at its base.

In its delineation, therefore, one must keep in mind the relation of its height to the width of the valley, and to the plateau on which it may stand; the declivity of its slopes, and their relation to the vertical direction, which may be seen as an imaginary line drawn from the center of the base to the zenith.

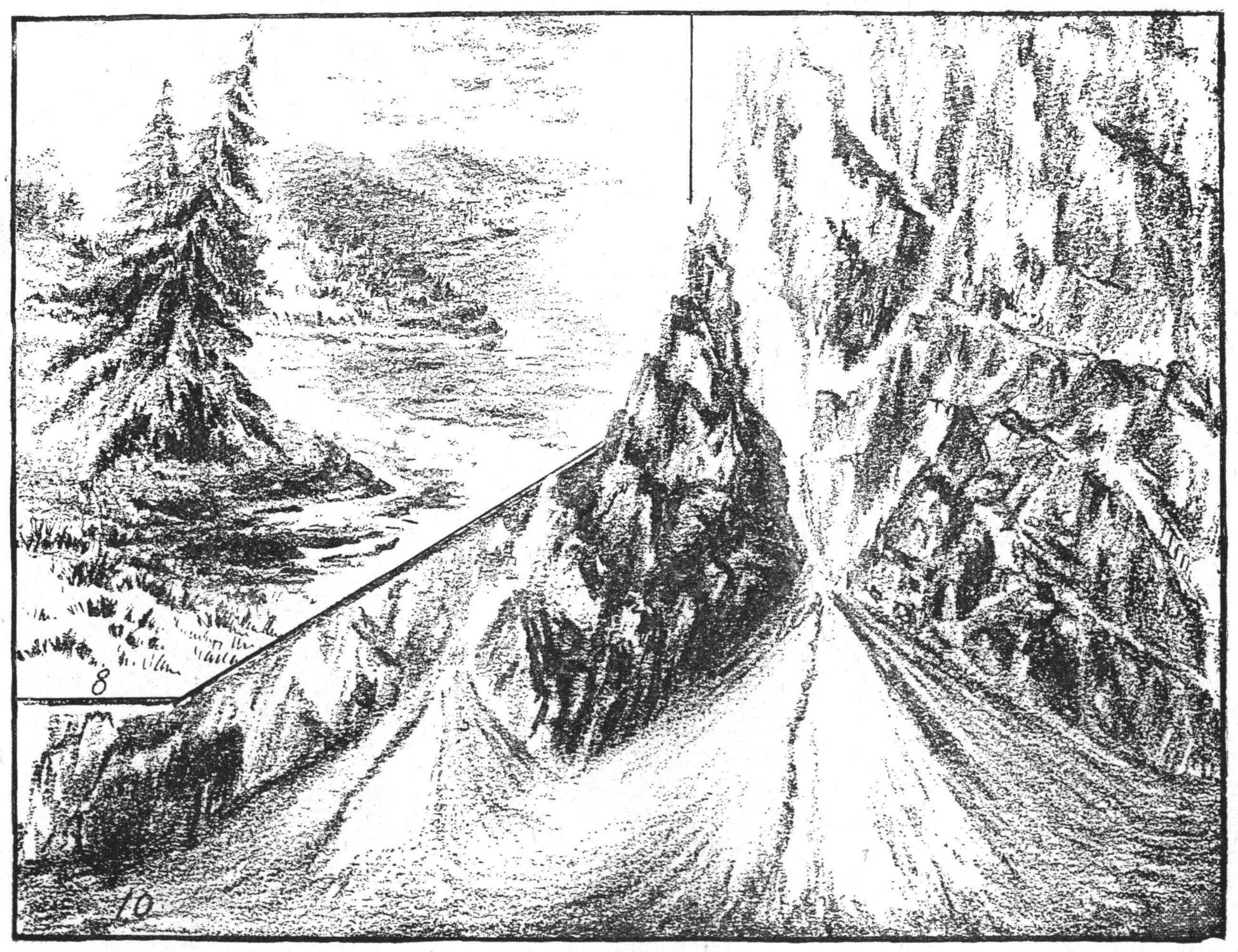

8 10

The trees beside the hill in Fig. 7 show the latter to be very high. In Fig. 8 the hill becomes low because of the relation of its altitude to the height of the trees in the foreground.

The delineation of more or less detail also helps to determine altitudes; as, to draw grasses, boulders or out-cropping rocks on the hill side, would show that we were near enough to the hill or knoll to see them in detail. Hills in the far distance would be represented without much detail, for they are too far away naturally for us to observe it.

To represent land sloping towards us as in Figs. 7, 9, and 10, the foreground must be broken up, that is, represented in more or less of structure detail. Fig. 9 shows low hills at the foot of the mountain range sloping toward the level land in the immediate foreground. Fig. 10 a steep alluvial fan indicating the nature and character of its structure by the direction and quality of line used. The crumbling sandstone rock, showing the effects of weathering, is indicated by short nearly vertical strokes, with the thought of stratification also in mind. The flowing sand is represented by vertical and oblique lines drawn in the direction in which sand would naturally flow. We have here three examples of land sloping towards us. One represented by nearly horizontal lines, the others by vertical or oblique lines. Grasses grow many blades from one root. Their tendency may be vertical but many influences combine to turn them from that direction. Use an edge of the chalk with an upward or downward motion. Knolls of any contour may be represented by drawing grasses in the direction of the slopes as in Fig. 8.

11 12 13 14

If your subject “possesses” you, there will be no need of giving special thought to effects or results; these will follow naturally from the state or quality of feeling engendered in your mind by its contemplation; that is, if one part of the surface to be represented is hard and rocky, and another soft and yielding, and you have observed this fact in relation to the whole, you will naturally show it in the quality of line you use. No other hints can be given that will help you so readily to the artistic touch as this, together with the hints given in our last lesson as to the necessity of an adequate knowledge of form and of relationships or proportions. Fig. 11. A water-parting high and mountainous. It shows its rocky structure in the harsh and “liney” quality of the work as well as in the surface contour. The paper is left white for the streams of water. On the blackboard, when drawing maps with chalk, use charcoal for the rivers, as in the rapid delineation of such maps it takes too much time to save spaces for them; and at the best it is such an exaggeration of the width of streams, that it misleads the pupil.

Fig. 12 represents a low water-parting. Notice the texture of line, soft and yielding, produced by thinking, knowing and feeling that the surface was not rocky, but a somewhat sandy soil, mixed with a little loam.

Perspective is shown by less of detail in the distance than in the foreground; the trees in the latter being more accurately drawn, as well as taller. The poplars at the right of the picture also show that the ground is a little uneven, as the distant ones seem to be partially below a slight rise in the surface. Fig. 13 is a map or bird’s eye view of a height of land worn down by streams running in different directions, leaving the water-parting sharply defined.

A little sketch of the sea shore (Fig. 14) illustrates another quality of “touch.” In depicting water rolling irresistibly on, a mighty force dashing against the shore and breaking into showers of spray, you will naturally use a steady, forceful but light touch in indicating its curves and masses. “Feeling” and “touch” are something to be experienced and not taught mechanically.

15 16 17 18 19

The artistic appeals to the higher or finer qualities of our nature, and to be artistic is to show forth or make visible these qualities. Work which is truly artistic can only be produced when we are in such harmony with our subject that these qualities predominate. These truths are so important that I ask you to experiment and discover them for yourselves. How will you get the “atmospheric” effect unless you realize that a certain volume of atmosphere is between you and the distant object? How will you keep true values unless you see truly (correctly)? In all drawing of any special subject it should be the aim to keep everything subordinated to the main point of interest, just as in writing you make every word or sentence bear upon the main point of your theme or your argument.

The meeting of land and water can never be represented by a continuous line; as line indicates direction of surface, and as the surface planes of both land and water are continually changing, the direction of line is changing or being broken, even if on the same general plane. Fig. 15 (a lake among the hills) shows the horizontal plane of water surface meeting the oblique surface of land. Where the water falls over the rock, the oblique and curved lines used are broken, to represent the nature of the rock underneath. Notice that the depth of each little fall corresponds with the stratification of rock. The water, as it recedes, lies level, also. You will have no difficulty in drawing ponds and lakes, if you think of the farther shores as less distinct, and the waves, although rough and broken in the foreground, as merged and blended together in the distance.

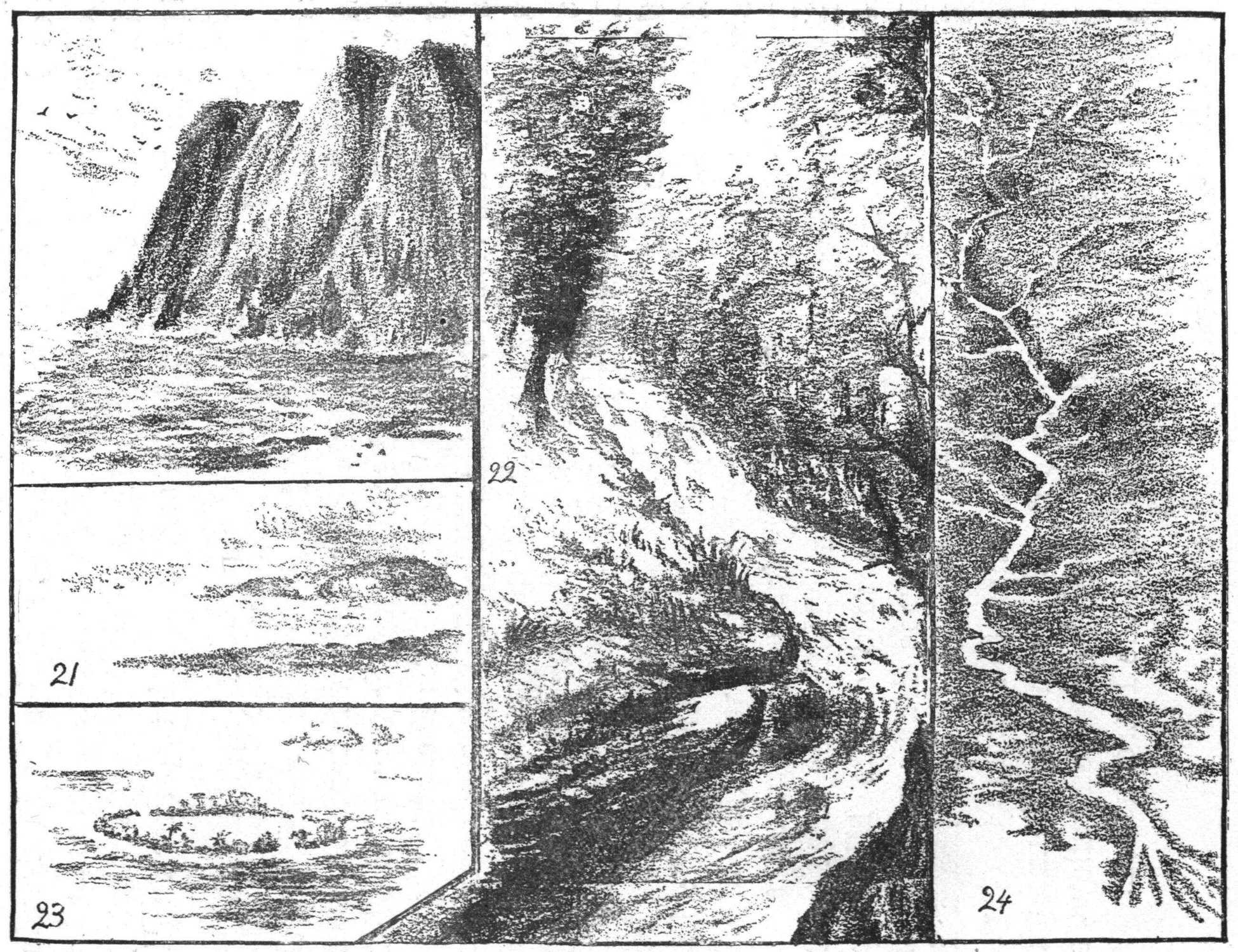

20 21 22 23 24

Figs. 16 and 17 are high and low tide on the Piscataqua River. (The ocean tides flow in for miles up the river.) These illustrations show the broken, or short, nearly horizontal lines used to indicate the tops of the little waves and ripples in the foreground. As the water lowers a little in the river, the island (Fig. 16) is seen, connected with the mainland by an isthmus, or narrow neck of land; and in Fig. 17 it is seen as a part of the mainland. Figs. 18 and 19 are springs flowing out from hillsides. Notice the relation the grasses and rock bear to the water. Fig. 20 represents North Cape; Fig. 23, a coral island: both show water in active motion, compared with that in Fig. 15, and with Fig. 21 (a rocky island). Fig. 22 shows rapids in a New England stream. Notice the velocity and volume of water. Fig. 24 is a map of the Mississippi River. The upper part of the map is drawn without any lines between river and land. The lower half has a line drawn close to the edge of the water, to indicate the levees, which are necessary in that region, to prevent inundation. For a map of continental islands and drowned valleys, see map of the fiord coast of Alaska, in the Introduction.

All who will may learn to draw. It is that which we most earnestly desire to do, that is accomplished in every department of effort. All lesser interests will give place to that which we consider of the greatest importance. Therefore if we as teachers recognize the value of the habit of sketching before our classes and greatly desire to be able to draw with ease and rapidity, we will put ourselves into right relationship to the work, and will undoubtedly acquire the desired skill.

We have been observing all our lives; we have made careful observations of many details of form and color, perhaps, and close investigation of structure, but we have not analyzed them into terms of drawing. We have not been looking for the planes of surface, or the relative proportions of parts, or for distance or foreground. Now, however, with the desire to be able to sketch readily, we will observe the object or landscape for that special purpose. One sketch will represent only what has been observed by looking in one direction without turning the head. The most interesting point of the view will be that at which one looks directly, and consequently it will be the most important part of the sketch with every other part subordinated to it.

25 26 27 28 29

In out of door sketching it will be necessary to eliminate much that is seen, only drawing that which is chosen to be the vital or interesting part of the picture, with that which modifies, or is necessary to show it in its completeness. Select your point of view, standing at such a distance that all you care to study may be comprehended in a glance.

30

Note the relation of earth to sky, and of trees to hills, streams, or other objects to be included in the sketch. As a help to find the true direction compare the surface planes and edges with that which you know is vertical. Study the light and shade, choose the simple broad tones which will best express distance, middle ground and near details. Work simply and easily, not straining after certain preconceived effects. It is this particular truth or fact which now appeals to you, which you are to express, and do not hesitate to express it freely and boldly. Sketch everything, anything, no matter how complicated it may seem to be,[72] and sketch often. The child does that, and learns to draw by drawing.

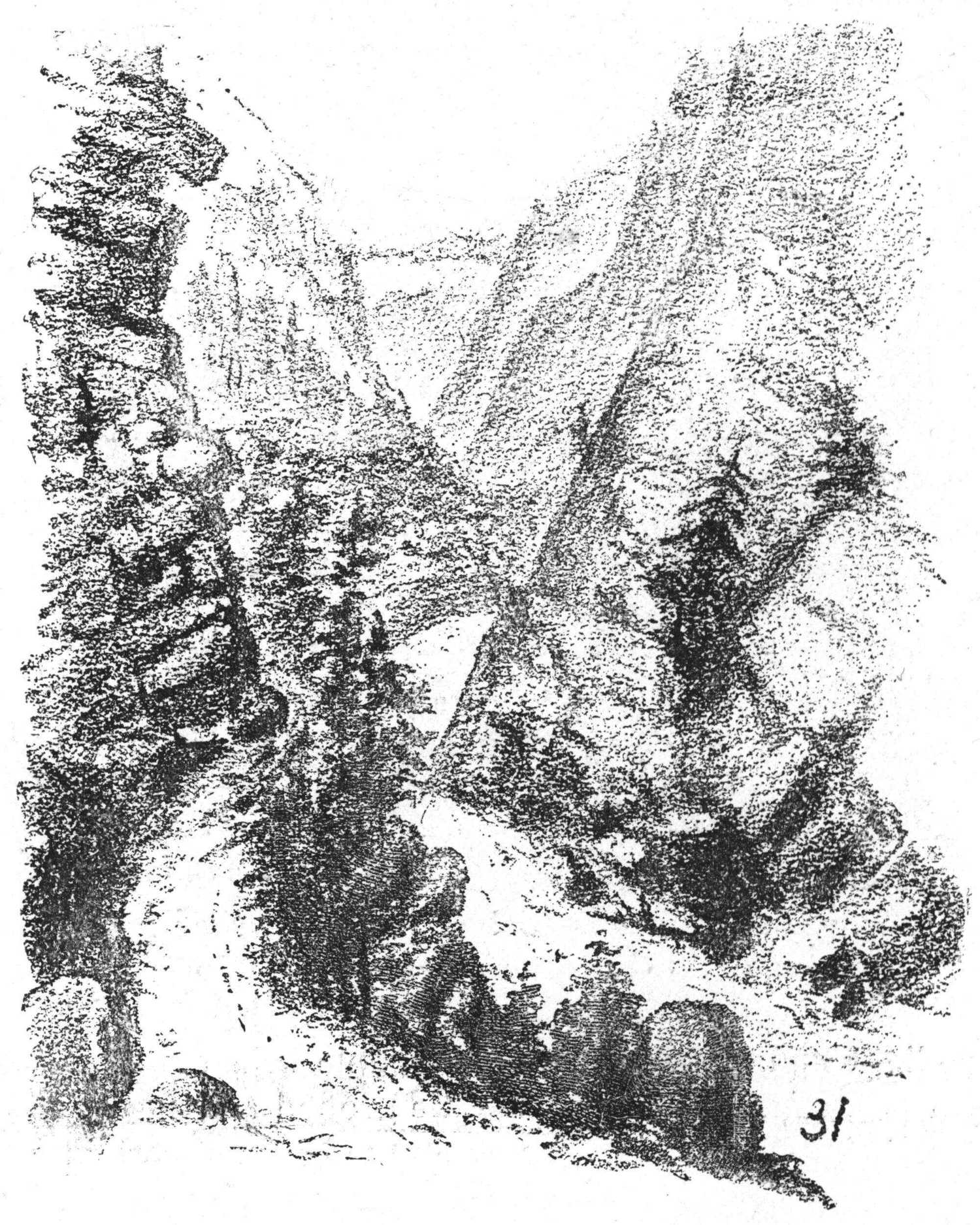

31

Fig. 25 shows the edge of a desert in Wyoming Territory, where the only vegetation is sage brush. The rains have worn a little gully in the general sandy level.[73] Notice the steep slant of the sandy sides. Fig. 26 is a sketch of a hole in the sandy soil of a farm, on the banks of the Au Sable River, New York. It was first worn by the rains as a little gully on the upper edge of the bank, and with every rain-storm more sand was washed out and carried down into the river. A part of this is deposited lower down the river, below the bank on the right, in the sketch Fig. 30.

32

Use horizontal lines for the sandy level, and curved lines to indicate the slow current in the water. Fig. 27[74] also shows the result of rain and wind erosion of the bank behind the stump of the tree. Fig. 28 represents a section of Yellowstone cañon, and Fig. 29 is a sketch from Monument Park, Colorado. In both the latter are seen examples of rain and wind erosion, more particularly in Fig. 29. Notice the hard layers of rock that cap and protect the softer sandstone beneath, and the hard pinnacles that jut out from among the sliding sands in Fig. 28.

33

The effects of river erosion, together with the weathering of rocks are seen in Fig. 31, which is a sketch of a section of Wilmington Pass, in the Adirondacks. The precipitous sides of rock, are shown with evergreens growing wherever they can find a foothold in the soil made by the disintegration of the rocks above. Boulders and trees have been brought down by the loosening of masses of rock, through the action of frost, heat, and melted snow, causing obstructions in the stream, over and between which the waters tumble and roll. Fig. 32 is a view taken from the beach of Arch Rock, at Mackinac Island. It is a mass of calcareous rock, showing the result of lake erosion and weathering. The rock in Fig. 33 shows signs of disintegration from the action of wind and rain.

34 36 37 38 39 40

Take the children into your confidence: that is, cause them to feel that you are not sketching for their amusement or for their admiration, but are trying to help them to a better understanding of the subject. They will appreciate your motive and be stimulated to increase their own efforts. With every attempt to sketch on your part, additional skill will be acquired, for it is only by repeated attempts that progress is made. By such continued efforts you not only gain the power to express the knowledge you have, but are led to see wherein you are deficient and require closer study of your subject. When we try to express our knowledge of a subject by drawing, we are often greatly surprised to find how little we know of it. It is the same with writing or speaking. Our knowledge or ideas of a subject should be arranged in orderly sequence, so logical and clearly defined, that we shall not be obliged to go back and modify or correct any part of our expression. Such corrections in connection with drawing destroy that pleasing quality which marks a sketch as “artistic.” The teacher who appreciates the importance of forming correct mental habits, will encourage in his pupils the practice of accurate and thorough study of a subject, before any attempts at expression are made.

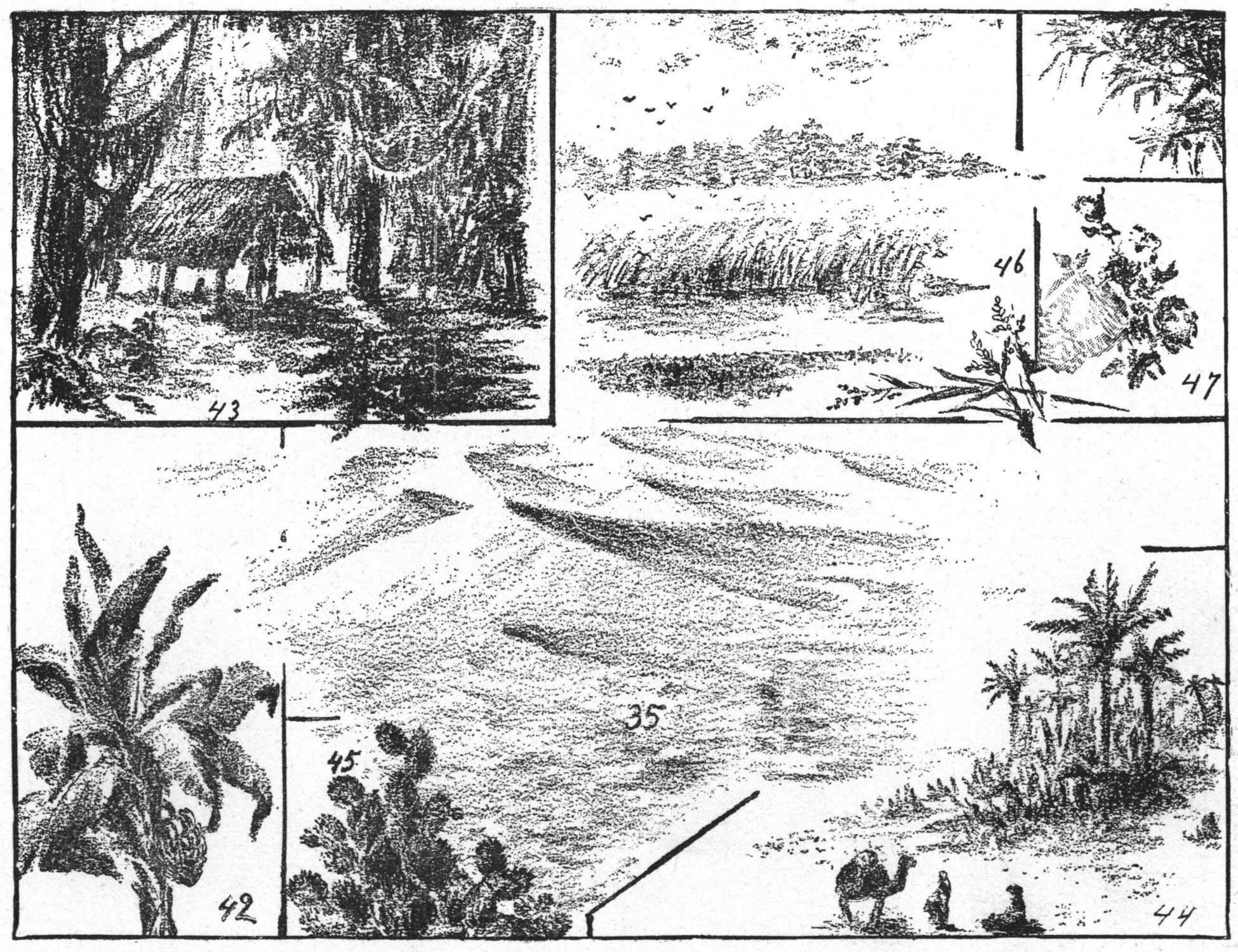

35 42 43 44 45 46 47

In drawing from your imaginary picture, look at it closely and carefully. Clear it up, classify its component parts into primary and secondary, that is, decide which is the most important and interesting part of the whole, and to what degree the other parts are to be subordinated to that, then analyze it into terms of drawing, i.e., vertical, horizontal, etc.

In the scenes given in this lesson as typical of the different zones of climate, some of the primary features were gained through observation, some through pictures supplemented by reading. Many of the sketches illustrating the other lessons, as well as those in the Introduction, will also give suggestions for this lesson, such as the illustrations on Alaska, India, and the continents. These need not be duplicated here.

In the scene from Siberia (Fig. 34), and in that of the dunes in the Sahara desert (Fig. 35), notice the form of both snow and sand drifts—their sharp edges and short and long slopes. The corn-field in northern New York (Fig. 36), illustrates the law of receding parallel lines—that they appear to converge as they recede, and if extended far enough, would seem to meet at a point on the horizon (the “point of sight”), a point immediately opposite the eye. A line drawn from the top and one from the bottom of each stalk in the front row, to the point of sight, will show this. Notice how the stalks in the foreground are brought out with more prominence than those farther away and outside of the direct line of vision.

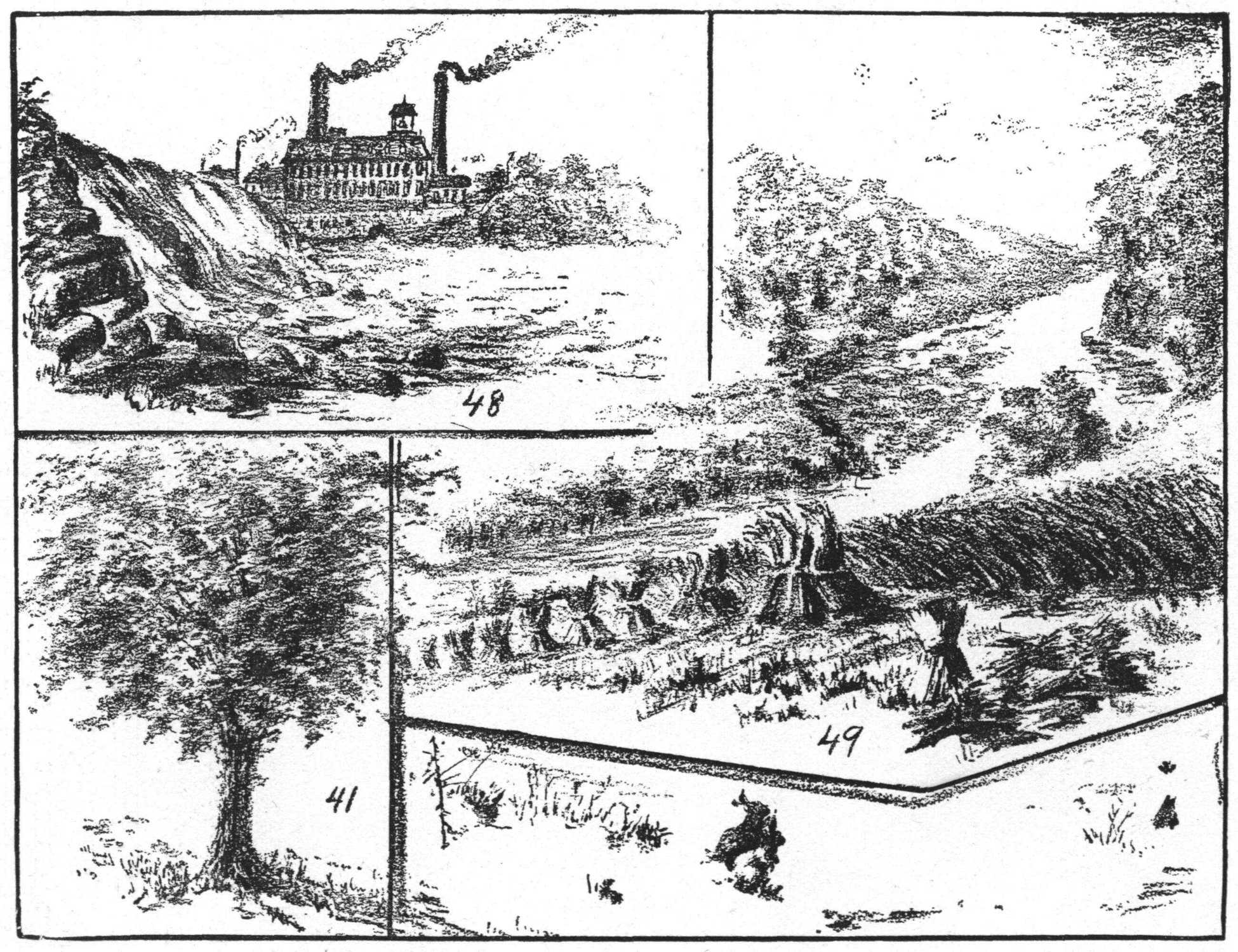

41 48 49

Figs. 37 to 40, inclusive, tell the stories of a lumber camp (Northern Michigan); logs of cotton-wood floating out into the Au Sable River (Adirondacks); a scarred and storm-worn pine tree, also one gashed by the axe of the wood-cutter. In contrast to the pine, notice the graceful elm of New England, in Fig. 41, and in Fig. 42, the banana tree of hot climates. Fig. 43 is a scene typical of the hot belt (the Amazon region, where there is abundant rainfall), and Figs. 44 and 45 show an oasis in the desert, also cactus, as another typical form of vegetation. Fig. 46 represents a rice-field, and Fig. 47 cotton balls and flowers.

Figs. 48 and 49, showing a factory or “mill” in New England, and the New York State harvest scene, are typical of the cool belt, or temperate zone.

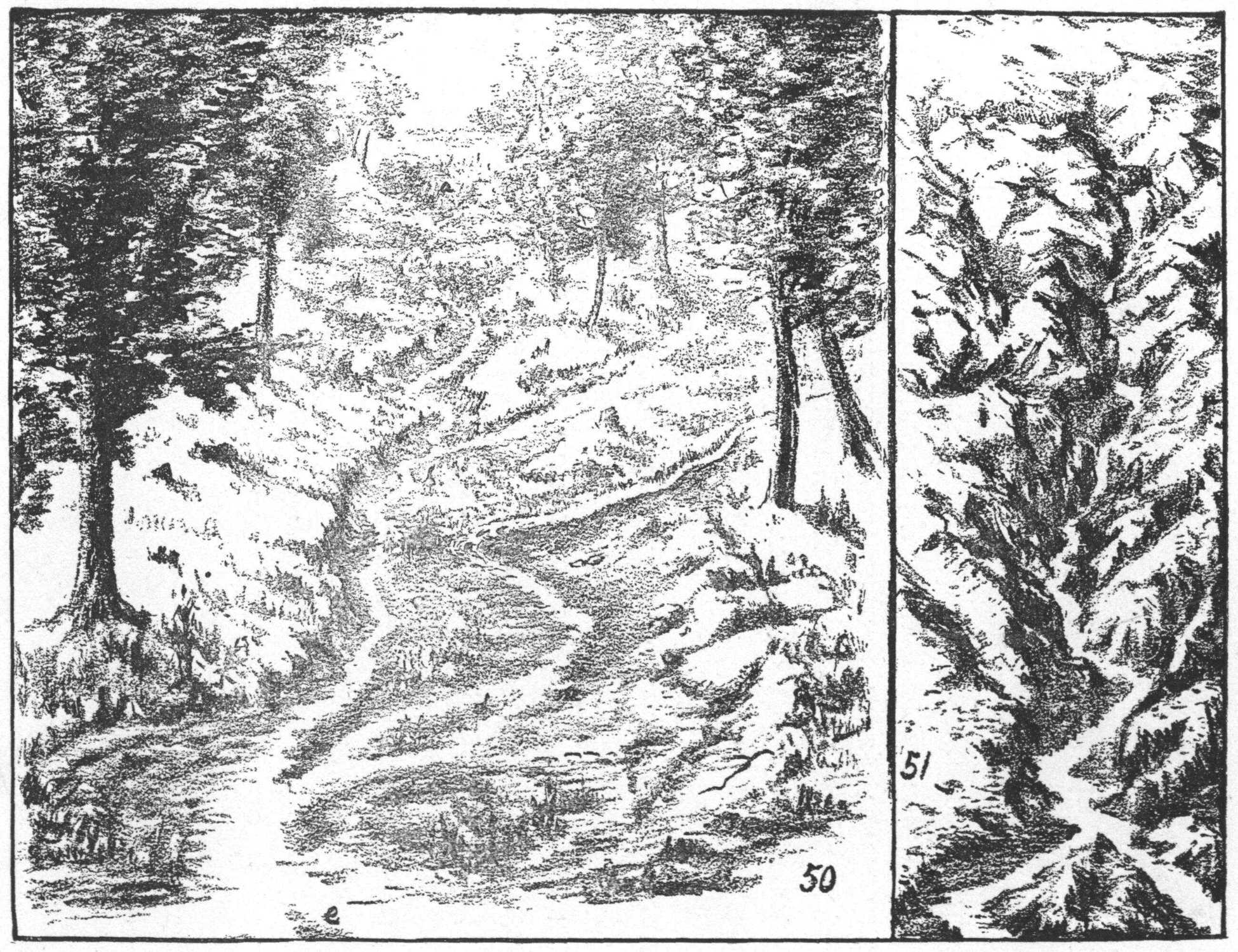

50 51

Do not copy the sketches given in these lessons. They are but suggestions to you, who will be able to express your own thoughts and represent your own mental pictures better than you can another’s. They are given to show you that simple sketches will help a child to a clearer understanding of the subject under consideration. As has been said elsewhere, all such illustrations should be drawn as they are needed to illustrate a given point in the development of a lesson; for they carry more weight than if sketched beforehand, that is, outside of the class exercise.

To merely locate in your sketch a house, spring, tree or man, will often be of great value to the pupil, though you may feel timid about trying to draw it, or think you have not the time. The experience of many teachers in this respect may be illustrated by supposing a case.

A sketch is to be drawn, including the figure of a man, animal or any object which has been considered difficult and therefore somewhat avoided.

The teacher, by one or two rapid strokes in the right direction, indicates the location and movement of this figure, and proceeds with the lesson without any hesitation or laborious attempts to really sketch it. The next time it is necessary to represent it (perhaps in the second or third lesson), sufficient confidence and skill have been gained to encourage additional strokes in the development of form, and every succeeding attempt has resulted in the addition of details of structure, until almost without knowing it, the necessary skill has been acquired to make an adequate sketch. How? By doing, the teacher has been forced to form the mental picture, which, once acquired, can be represented, though it may be more or less crudely at first.

52 53 54 55 56