Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

RECORDS

BY

ADMIRAL OF THE FLEET

LORD FISHER

HODDER AND STOUGHTON

LONDON NEW YORK TORONTO

MCMXIX

v

The main purpose of this second book is obvious from its title. It’s mostly a collection of “Records” confirming what has already been written, and relates almost exclusively to years after 1902. As Lord Rosebery has said so well, “The war period in a man’s life has its definite limits”; and that period is what interests the general reader, and for that reason all attempt at a biography has been discarded.

In our present distress wevi certainly want badly just now Nelson’s “Light from Heaven”! Nelson had what the Mystics describe as his “seasons of darkness and desertion.” His enfeebled body and his mind depressed used at times to cast a shade on his soul, such as we now feel as a Nation, but (if I remember right) it is Southey who says that the Sunshine which succeeded led Nelson to believe that it bore with it a prophetic glory, and that the light that led him on was “Light from Heaven.” We don’t see that “Light” as yet. But England never succumbs.

vii

Napoleon at St. Helena told us what all Englishmen have ever instinctively felt—that we should remain a purely Maritime Power; instead, we became in this War a Conscript Nation, sending Armies of Millions to the Continent. If we stuck to the Sea, said Napoleon, we could dictate to the World; so we could. Napoleon again said to the Captain of the British Battleship “Bellerophon”: “Had it not been for you English, I should have been Emperor of the East, but wherever there was water to float a ship, we were sure to find you in the way.” (Yes! we had ships only drawing two feet of water with six-inch guns, that went up the Tigris and won Bagdad. Others, similar, went so many thousand miles up the Yangtsze River in China that they sighted the Mountains of Thibet. Another British Ship of War so many thousand miles up the Amazon River that she sighted the Mountains of Peru, and there not being room to turn she came back stern first. In none of these cases had any War Vessel ever before been seen till these British Vessels investigated those waters and astounded the inhabitants.)

viii

Again, Napoleon praised our Blockades (Les Anglais bloquent très bien); but very justly of our Diplomacy he thought but ill. Yes, alas! What a Diplomacy it has been!!! If our Blockade had been permitted by the Diplomats to have been effective, it would have finished the War at once. Our Diplomats had Bulgaria in their hands and lost her. It was “Too Late” a year after to offer her the same terms as she had asked the year before. We “kow-towed” to the French when they rebuffed our request for the English Army to be on the Sea Flank and to advance along the Belgian Coast, supported by the British Fleet; and then there would have been no German Submarine War. At the very beginning of the War we deceived the German Ambassador in London and the German Nation by our vacillating Diplomacy. We wrecked the Russian Revolution and turned it into Bolshevism.

I mention these matters to prove the effete, apathetic, indecisive, vacillating Conduct of the War—the War eventually being won by an effective Blockade.

ix

| CHAPTER I | |

| PAGE | |

| Early Years | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Further Memories of King Edward and Others | 24 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The Bible, and other Reflections | 38 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Episodes | 50 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Democracy | 69 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Public Speeches | 79x |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| The Essentials of Sea Fighting | 88 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Jonah’s Gourd | 97 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Naval Problems | 127 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Naval Education | 156 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| Submarines | 173 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| Notes on Oil and Oil Engines | 189 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| The Big Gun | 204 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| Some Predictions | 211xi |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| The Baltic Project | 217 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| The Navy in the War | 225 |

| Postscript | 249 |

| APPENDIX I | |

| Lord Fisher’s Great Naval Reforms | 251 |

| APPENDIX II | |

| Synopsis of Lord Fisher’s Career | 259 |

| Index | 271 |

xiii

| 1882. Captain of H.M.S. “Inflexible” | Frontis piece |

| Facing page |

|

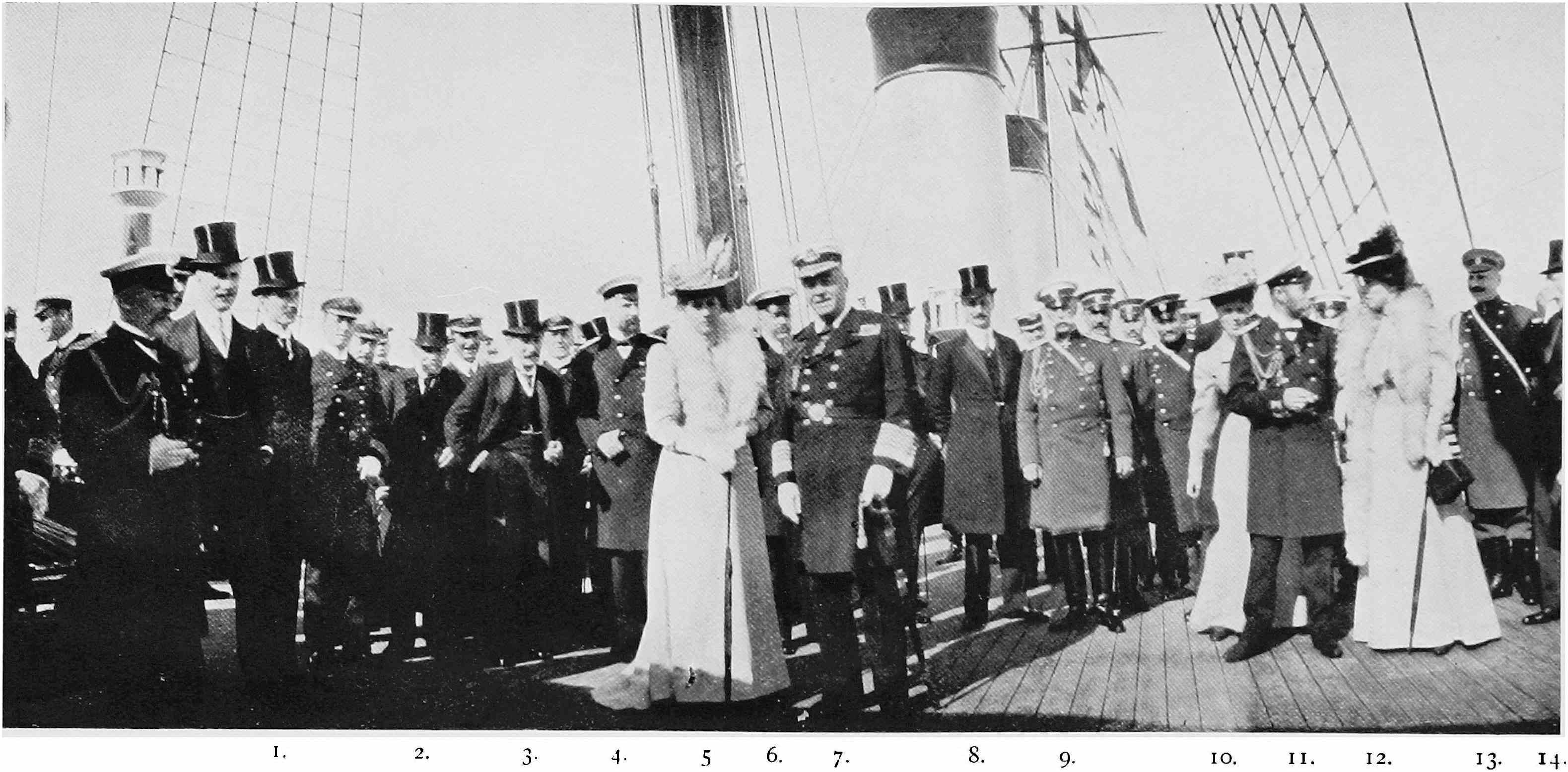

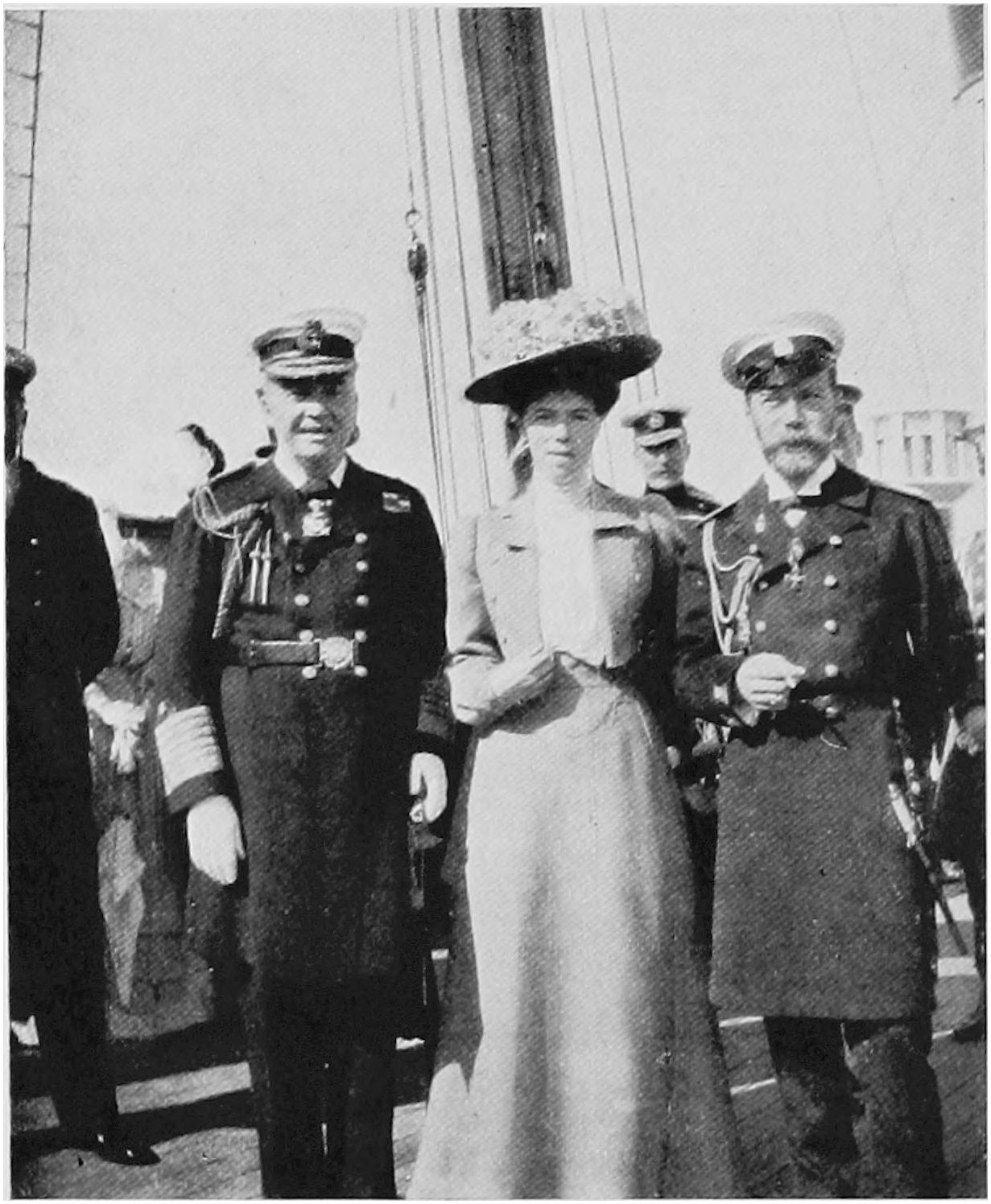

| King Edward VII. and the Czar, 1909 | 16 |

| Two Photographs of King Edward VII. and Sir John Fisher on Board H.M.S. “Dreadnought” on her First Cruise | 33 |

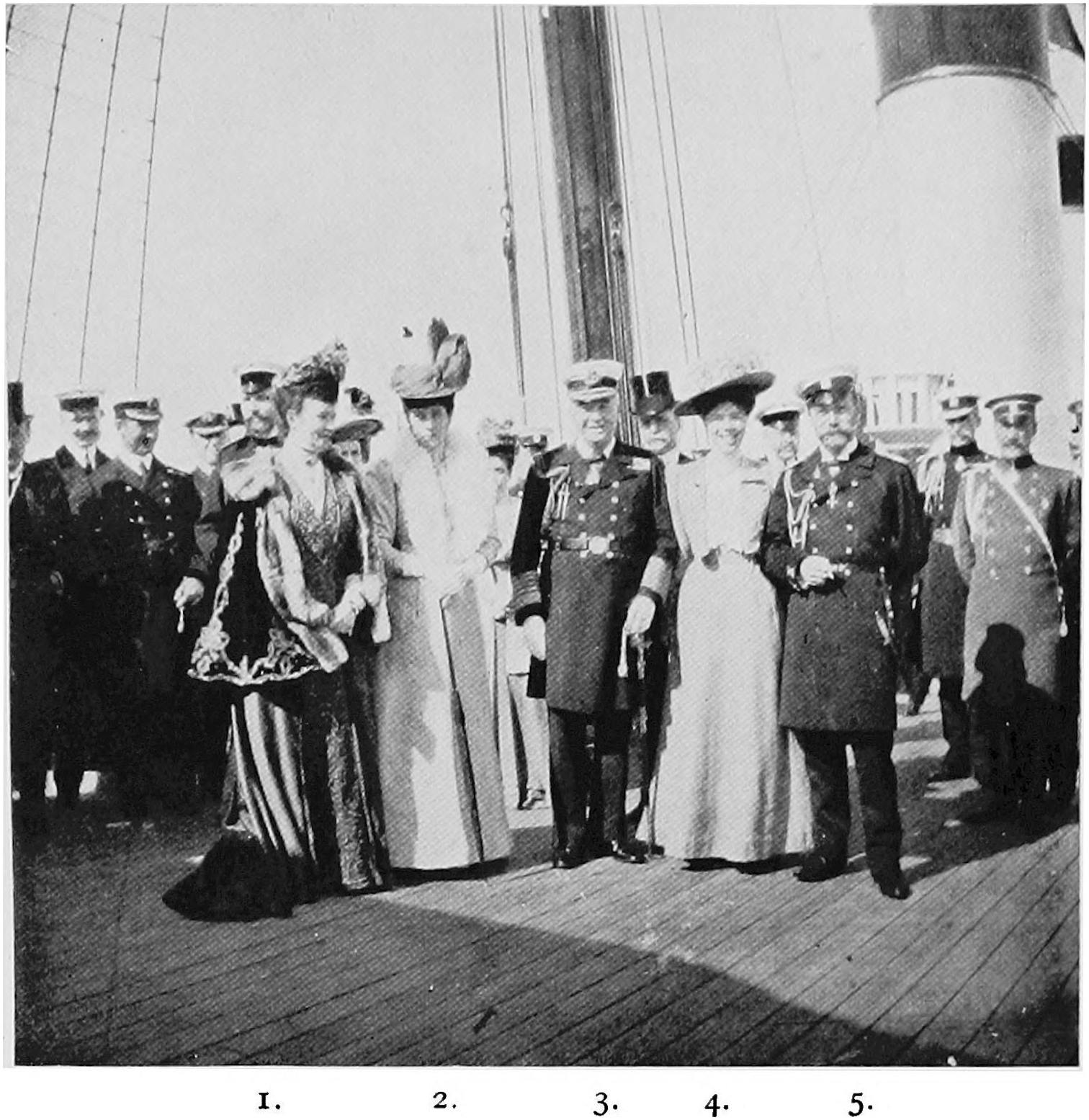

| Photograph, taken and sent to Sir John Fisher by the Empress Marie of Russia, of a Group on Board H.M.S. “Standard,” 1909 | 48 |

| A Group on Board H.M.S. “Standard,” 1909 | 65 |

| A Group on Board H.M.S. “Standard,” 1909 | 80 |

| A Group at Langham House. Photograph taken and sent to Sir John Fisher by the Empress Marie of Russia | 97 |

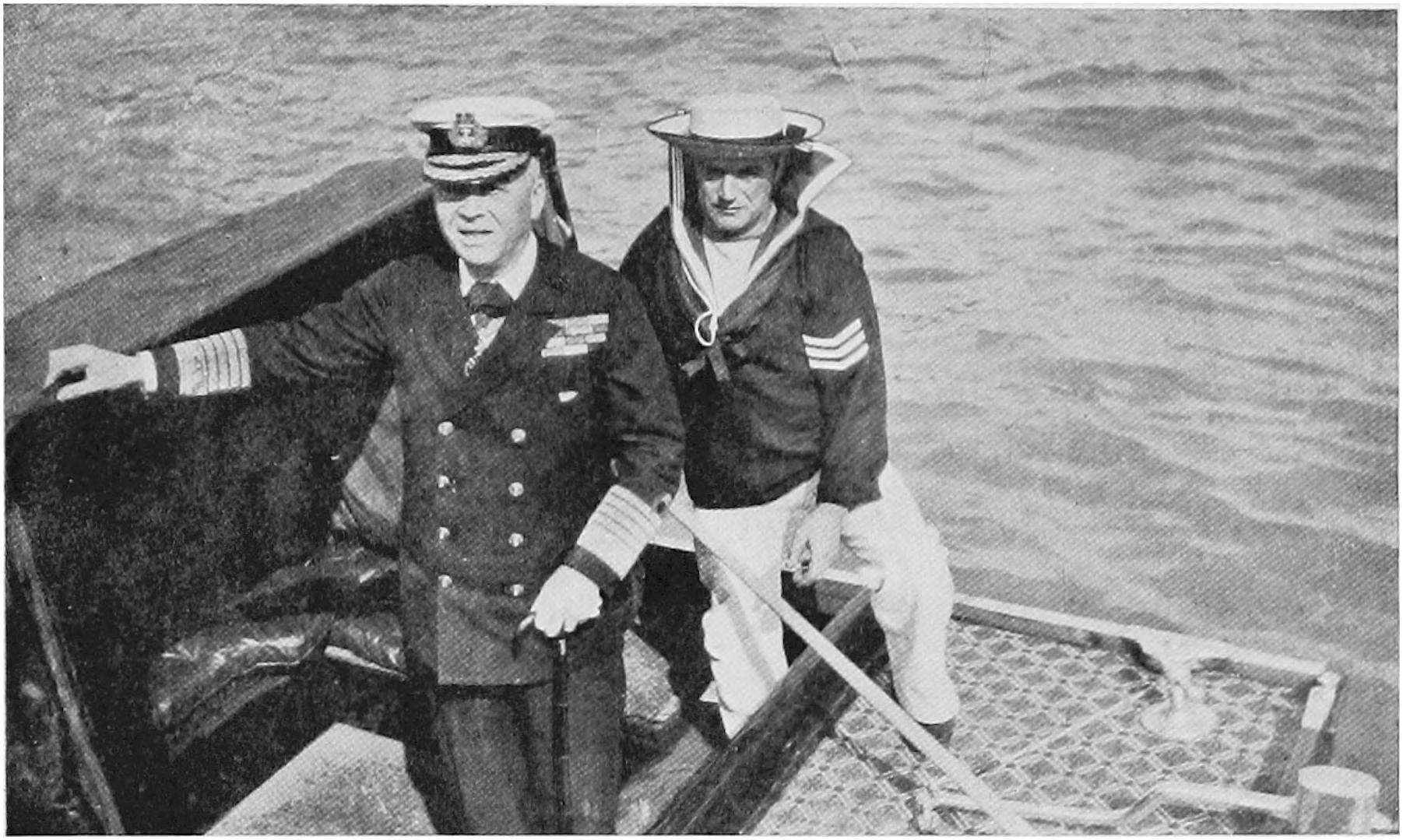

| Sir John Fisher going on Board the Royal Yacht | 112 |

| Sir John Fisher and Sir Colin Keppel (Captain of the Royal Yacht) | 129xiv |

| “The Dauntless Three,” Portsmouth, 1903 | 160 |

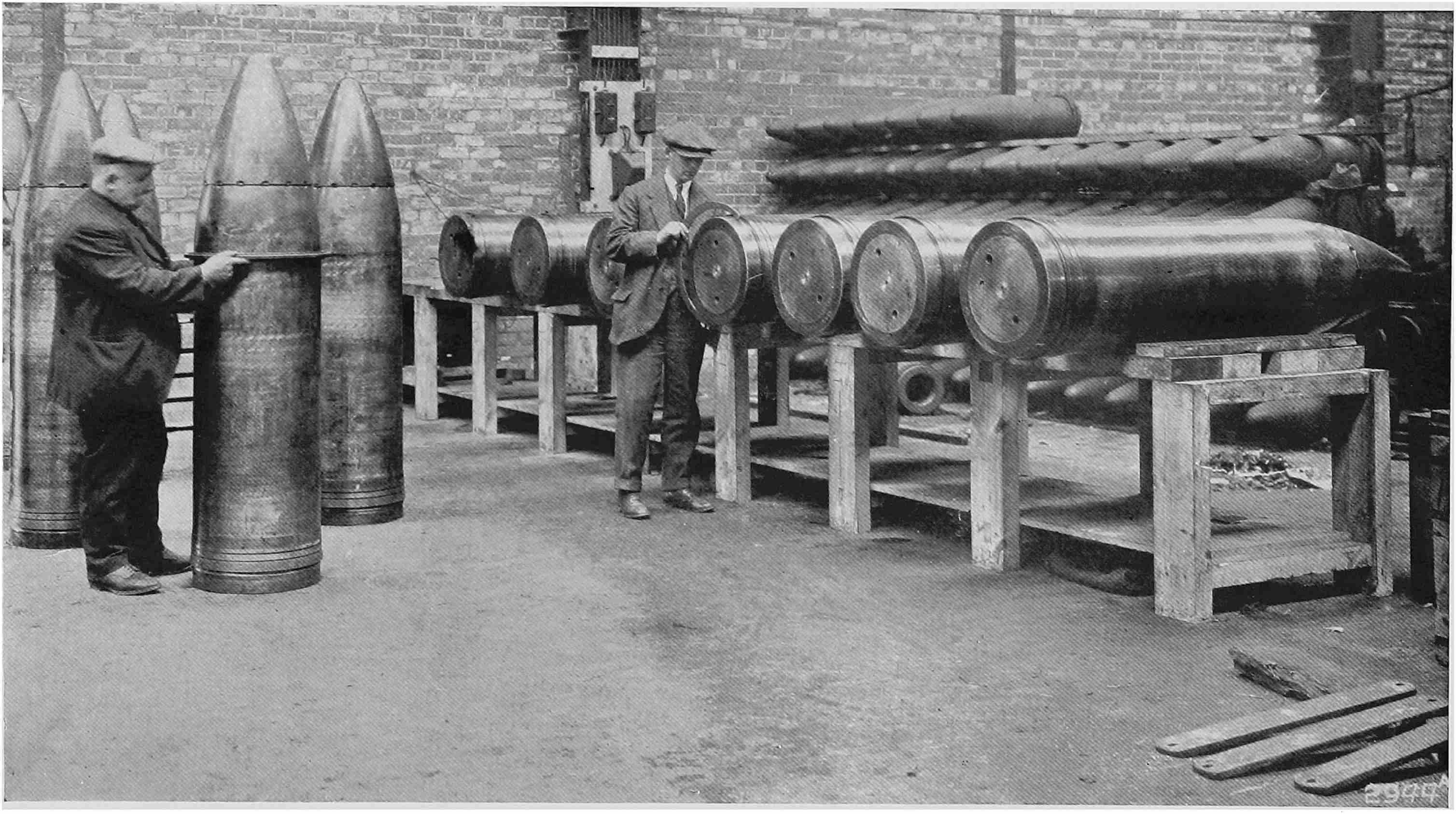

| Some Shells for 18-inch Guns | 177 |

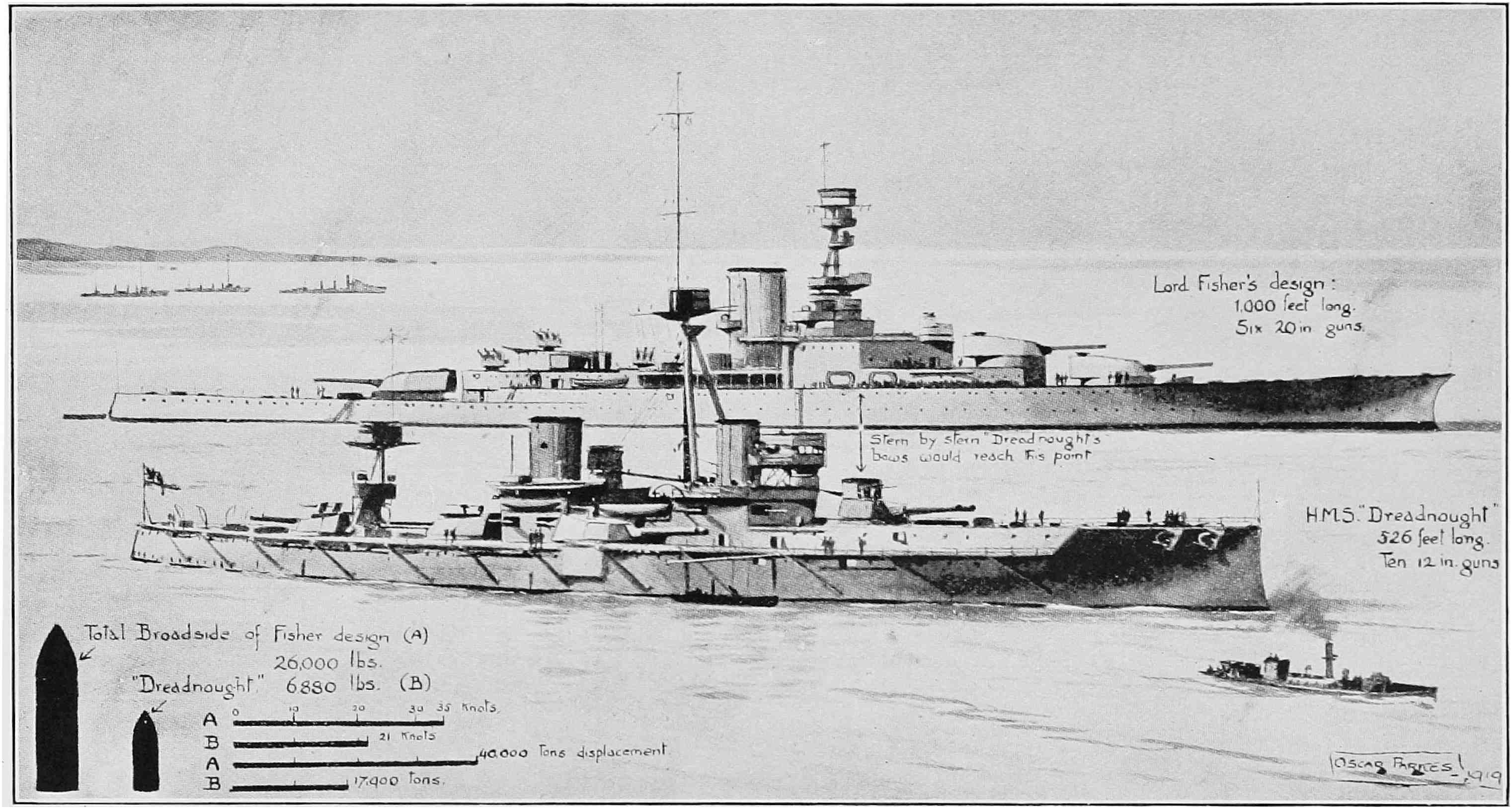

| Lord Fisher’s Proposed Ship, H.M.S. “Incomparable,” shown alongside H.M.S. “Dreadnought” | 208 |

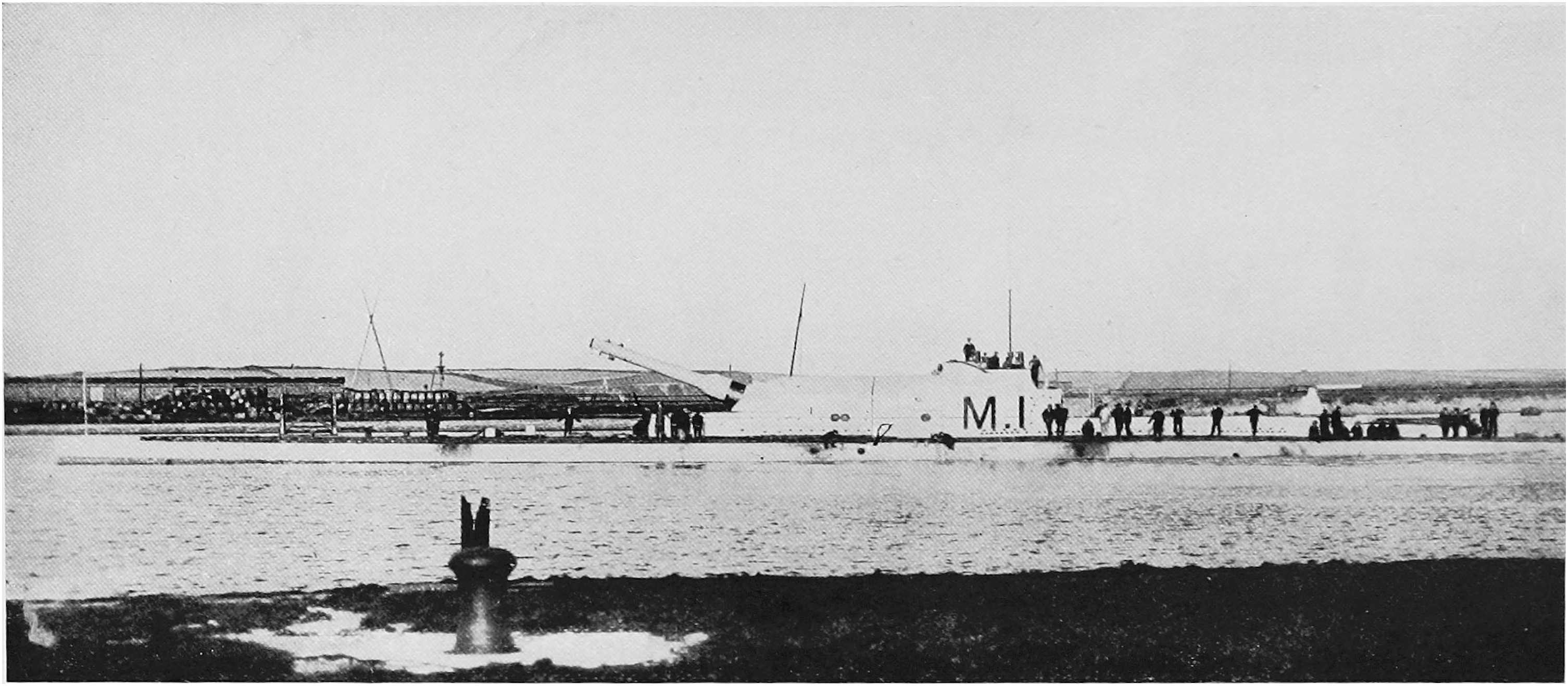

| The Submarine Monitor M 1 | 240 |

1

Of all the curious fables I’ve ever come across I quite think the idea that my mother was a Cingalese Princess of exalted rank is the oddest! One can’t see the foundation of it!

“The baseless fabric of a vision!”

My godfather, Major Thurlow (of the 90th Foot), was the “best man” at my mother’s wedding, and very full of her beauty then—she was very young—possibly it was the “Beauté du diable!” She had just emerged from the City of London, where she was born and had spent her life! One grandfather had been an officer under Nelson at Trafalgar, and the other a Lord Mayor! He was Boydell, the very celebrated engraver. He left his fortune to my grandmother, but an alien speculator (a scoundrel) robbed her of it. My mother’s father had, I believe, some vineyards in Portugal, of which the wine pleased William the Fourth, who, I was told, came to his counting house at 149, New Bond Street, to taste it! Next door Emma, Lady Hamilton, used to clean the door steps! She was housemaid there.

2

I don’t think the Fishers at all enjoyed my father (who was a Captain in the 78th Highlanders) marrying into the Lambes! The “City” was abhorred in those days, and the Fishers thought of the tombs of the Fishers in Packington Church, Warwickshire, going back to the dark ages! I, myself, possess the portrait of Sir Clement Fisher, who married Jane Lane, who assisted Charles the Second to escape by disguising his Majesty as her groom and riding behind him on a pillion to Bristol.

The Fishers’ Baronetcy lapsed, as my ancestor after Sir Clement Fisher’s death wouldn’t pay £500 in the nature of fees, I believe. I don’t think he had the money—so my uncle told me. This uncle, by name John Fisher, was over 60 years a fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford, and told me the story of an ancestor who built a wing of Balliol at Oxford, and they—the College Authorities—asked him whether they might place some inscription in his honour on the building! He replied:

“Fisher—non amplius,”

(but someone else told me it was:—

“Verbum non amplius Fisher!”)

My uncle explained that his ancestor only meant just to put his name, and that’s all.

But the College Authorities put it all on:

“Fisher! Not another blessed word is wanted.”

One of my ancestors changed his motto and took these words (I have them on a watch!):—

3

A Poacher, I suppose! or was there a “double entendre”?

I’m told in the old days you could change your motto and your crest as often as you liked, but not your coat of arms!

A succession of ancestors went and dwelt at Bodmin, in Cornwall—all clergymen down to my grandfather, who was Rector of Wavendon, in Bucks, where is a tablet to his brother, who was killed close to the Duke of Wellington at Waterloo, and who ordered his watch to be sent to my uncle’s relatives with the dent of the bullet that killed him, and that watch I now have.

My uncle was telling this story at a table d’hôte at Brussels a great many years afterwards, and said he had been unable to identify the spot, when an old white-haired gentleman at the table said he had helped to bury him, and next day he took him to the place.

I remember a Dean glancing at me in a Sermon on the Apostles, when he said the first four were all Fishers!

On the death of Sir Robert Fisher of Packington in 1739, a number of family portraits were transferred apparently to the Rev. John Fisher of Bodmin, born January 27th, 1708. The three principal portraits are a previous Sir Robert Fisher, his son Sir Clement Fisher, who died 1683, and Jane Lane, his wife. Another portrait is a second Sir Clement Fisher, son of the above and of Jane Lane. This Sir Clement Fisher died 1709, and was succeeded by his only brother, Sir Robert Fisher, who died A.D. 1739, one year before his niece, Mary Fisher, wife of Lord Aylesford. All these portraits were4 transmitted in direct inheritance to Sir John Fisher. The four generations of Reverend John Fishers of Bodmin, commencing with John Fisher born 1708, were none of them in a position to incur the heavy expenses involved for their assumption of the Baronetcy. They were descended from a brother of the Sir Robert Fisher who lived before the year A.D. 1600.

I was born in 1841, the same year as King Edward VII. There was never such a healthy couple as my father and mother. They never married for money—they married for love. They married very young, and I was their first child. All the physical advantages were in my favour, so I consider I was absolutely right, when I was nine months old, in refusing to be weaned.

These lines were written by Lord Byron of my godmother, Lady Wilmot Horton, of Catton Hall, Burton-on-Trent. She was still a very beautiful old lady at 73 years of age when she died.

One of her great friends was Admiral Sir William Parker (the last of Nelson’s Captains), and he, at her request, gave me his nomination for entering the Navy. He had two to give away on becoming Port Admiral at Plymouth. He gave the other to Lord Nelson’s own niece, and she also filled in my name, so I was doubly nominated by the last of Nelson’s Captains, and my first5 ship was the “Victory” and it was my last! In the “Victory” log-book it is entered, “July 12th, 1854, joined Mr. John Arbuthnot Fisher,” and it is also entered that Sir John Fisher hauled down his flag on October 21st, 1904, on becoming First Sea Lord.

A friend of mine (a yellow Admiral) was taken prisoner in the old French War when he was a Midshipman ten years old, and was locked up in the fortress of Verdun. He so amused me in my young days by telling me that he gave his parole not to escape! as if it mattered what he did when he was only four foot nothing! And he did this, he told me, in order to learn French; and when he had learned French, to talk it fluently, he then cancelled his parole and was locked up again and then he escaped; alone he did it by filing through the iron bars of his prison window (the old historic method), and wended his way to England. I consider this instance a striking testimony to the inestimable benefit of sending little boys to sea when they are young! What splendid Nelsonic qualities were developed!

But it was quite common in those days of my old yellow Admiral for boys to go to sea even as young as seven years old. My present host’s grandfather went to sea as a Midshipman at seven years old! Afterwards he was Lord Nelson’s Signal Midshipman, his name was Hamilton, and his grandson was Midshipman with me in two ships. He is now the 13th Duke of Hamilton! It is interesting as a Nelsonic legend that the wife of the 6th Duke of Hamilton (she was one of the beautiful Miss Gunnings; she was the wife of two Dukes and the6 mother of four) peculiarly befriended Emma, Lady Hamilton, and recognised her, as so few did then (and, alas! still fewer now), as one of the noblest women who ever lived—one mass of sympathy she was!

The stories of what boys went through then at sea were appalling. I have a corroboration in lovely letters from a little Midshipman who was in the great blockade of Brest by Admiral Cornwallis in 1802. This little boy was afterwards killed just after Trafalgar. He describes seeing the body of Nelson on board ship on its way to Portsmouth. This little Midshipman was only eleven years old when he was killed! This is how he describes the Midshipman’s food: “We live on beef which has been ten or eleven years in a cask, and on biscuit which makes your throat cold in eating it owing to the maggots, which are very cold when you eat them! like calves-foot jelly or blomonge—being very fat indeed!” (It makes one shudder!) He goes on again: “We drink water the colour of the bark of a pear tree with plenty of little maggots and weevils in it, and wine, which is exactly like bullock’s blood and sawdust mixed together”; and he adds in his letter to his mother: “I hope I shall not learn to swear, and by God’s assistance I hope I shall not!” He tried to save the Captain of his Top (who had been at the “Weather earing”) from falling from aloft. This is his description: “The hands were hurried up to reef topsails, and my station is in the foretop. When the men began to lay in from the yards (after reefing the topsails) one of them laid hold of a slack rope, which gave way, and he fell out of the top on deck and was dashed to pieces7 and very near carried me out of the top along with him as I was attempting to lay hold of him to save him!!!” Our little friend the Midshipman was eight years old at this time! What a picture! this little boy trying to save the sailor huge and hairy! His description to his mother of Cornwallis’s Fleet is interesting: “We have on board Admiral Graves, who came in his ten-oared barge, and as soon as he put his foot on shipboard the drums and fifes began to play, and the Marines and all presented their arms. We are all prepared for action, all our guns being loaded with double shot. We have a fine sight, which is the Grand Channel Fleet, which consists of 95 sail of the line, each from 120 down to 64 guns.”

That is the Midshipman of the olden day, and one often has misgivings that the modern system of sending boys to sea much older is a bad one, when such magnificent results were produced by the old method, more especially as in the former days the Captain had a more paternal charge of those little boys coming on board one by one, as compared with the present crowd sent in batches of big hulking giants, some of them. However, there is more to learn now than formerly, and possibly it’s impossible (all the entrance examination I had to pass was to write out the Lord’s Prayer, do a rule of three sum and drink a glass of sherry!); but one would like to give it a trial of sending boys to sea at nine years old. Our little hero tried to save the life of the Captain of his Top when he was only eight years old! Still, the Osborne system of Naval education has its great merits; but it has been a grievous blow to it, departing8 from the original conception of entry at eleven years of age.

However, the lines of the modern Midshipman are laid in pleasant places; they get good food and a good night’s rest. Late as I came to sea in 1854, I had to keep either the First or Middle Watch every night and was always hungry! Devilled Pork rind was a luxury, and a Spanish Onion with a Sardine in the Middle Watch was Paradise!

In the first ship I was in we not only carried our fresh water in casks, but we had some rare old Ship’s Biscuit supplied in what were known as “bread-bags.” These bread-bags were not preservative; they were creative. A favourite amusement was to put a bit of this biscuit on the table and see how soon all of it would walk away. In fact one midshipman could gamble away his “tot” of rum with another midshipman by pitting one bit of biscuit against another. Anyhow, whenever you took a bit of biscuit to eat it you always tapped it edgeways on the table to let the “grown-ups” get away.

The Water was nearly as bad as the Biscuit. It was turgid—it was smelly—it was animally. I remember so well, in the Russian War (1854–5), being sent with the Watering Party to the Island of Nargen to get fresh water, as we were running short of it in this old Sailing Line of Battleship I was in (there was no Distilling Apparatus in those days). My youthful astonishment was how on earth the Lieutenant in charge of the Watering Party discovered the Water. There wasn’t a lake and there wasn’t a stream, but he went and dug a hole and there was the water! However, it may be that he carried out9 the same delightful plan as my delicious old Admiral in China. This Admiral’s survey of the China Seas is one of the most celebrated on record. He told me himself that this is how he did it. He used to anchor in some convenient place every few miles right up the Coast of China. He had a Chinese Interpreter on board. He sent this man to every Fishing Village and offered a dollar for every rock and shoal. No rock or shoal has ever been discovered since my beloved Admiral finished his survey. Perhaps the Lieutenant of the Watering Party gave Roubles!

I must mention here an instance of the Simple Genius of the Chinese. A sunken ship, that had defied all European efforts to raise her, was bought by a Chinaman for a mere song. He went and hired all the Chinamen from an adjacent Sponge Fishery and bought up several Bamboo Plantations where the bamboos were growing like grass. The way they catch sponges is this—The Chinaman has no diving dress—he holds his nose—a leaden weight attached to his feet takes him down to where the sponges are—he picks the sponges—evades the weight—and rises. They pull up the weight with a bit of string afterwards. The Chinese genius I speak of sent the men down with bamboos, and they stuck them into the sunk ship, and soon “up she came”; and the Chinaman said:

It’s a pity there’s no bamboo dodge for Sunk Reputations!

10

An uncle of mine had a snuff box made out of the Salt Beef, and it was french-polished! That was his beef—and ours was nearly as hard.

There were many brutalities when I first entered the Navy—now mercifully no more. For instance, the day I joined as a little boy I saw eight men flogged—and I fainted at the sight.

Not long ago I was sitting at luncheon next to a distinguished author, who told me I was “a very interesting person!” and wanted to know what my idea of life was, I replied that what made a life was not its mature years but the early portions when the seed was sown and the blossom so often blasted by the frost of unrecognition. It was then that the fruit of after years was pruned to something near the mark of success. “Your great career was when you were young,” said a dear friend to me the other day. I entered the Navy penniless, friendless and forlorn. While my mess-mates were having jam, I had to go without. While their stomachs were full, mine was often empty. I have always had to fight like hell, and fighting like hell has made me what I am. Hunger and thirst are the way to Heaven!

When I joined the Navy, in 1854, the last of Nelson’s Captains was the Admiral at Plymouth. The chief object in those days seemed to be, not to keep your vessel efficient for fighting, but to keep the deck as white as snow and all the ropes taut. We Midshipmen were allowed only a basin of water to wash in, and the basin was inside one’s sea-chest; and if anyone spilt a drop of water on the deck he was made to holy-stone it himself.11 And that reminds me, as I once told Lord Esher, when I was a young First Lieutenant, the First Sea Lord told me that he never washed when he went to sea, and he didn’t see “why the Devil the Midshipmen should want to wash now!” I remember one Captain named Lethbridge who had a passion for spotless decks; and it used to put him in a good temper for the whole day if he could discover a “swab-tail,” or fragment of the swabs with which the deck was cleaned, left about. One day he happened to catch sight of a Midshipman carefully arranging a few swab-tails on deck in order to gratify “old Leather-breeches’” lust for discovering them! And as for taut ropes, many of my readers will remember the old story of the lady (on the North American station) who congratulated the Captain of a “family” ship (officered by a set of fools) because “the ropes hung in such beautiful festoons!”

There was a fiddler to every ship, and when the anchor was being weighed, he used to sit on the capstan and play, so as to keep the men in step and in good heart. And on Sundays, everyone being in full dress, epaulettes and all, the fiddler walked round the decks playing in front of the Captain. I must add this happened in a Brig commanded by Captain Miller.

After the “Victory,” my next ship was the “Calcutta,” and I joined it under circumstances which Mr. A. G. Gardiner has narrated thus:—

“One day far back in the fifties of last century a sailing ship came round from Portsmouth into Plymouth Sound, where the fleet lay. Among the passengers was a little12 midshipman fresh from his apprenticeship in the ‘Victory.’ He scrambled aboard the Admiral’s ship, and with the assurance of thirteen marched up to a splendid figure in blue and gold, and said, handing him a letter: ‘Here, my man, give this to the Admiral.’ The man in blue and gold smiled, took the letter, and opened it. ‘Are you the Admiral?’ said the boy. ‘Yes, I’m the Admiral.’ He read the letter, and patting the boy on the head, said: ‘You must stay and have dinner with me.’ ‘I think,’ said the boy, ‘I should like to be getting on to my ship.’ He spoke as though the British Navy had fallen to his charge. The Admiral laughed, and took him down to dinner. That night the boy slept aboard the ‘Calcutta,’ a vessel of 84 guns, given to the British Navy by an Indian merchant at a cost of £84,000. It was the day of small things and of sailing-ships. The era of the ironclad and the ‘Dreadnought’ had not dawned.”

I think I must give the first place to one of the first of my Captains who was the seventh son of the last Vice-Chancellor of England, Sir Lancelot Shadwell. The Vice-Chancellor used to bathe in the Thames with his seven sons every morning. My Shadwell was about the greatest Saint on earth. The sailors called him, somewhat profanely, “Our Heavenly Father.” He was once heard to say, “Damn,” and the whole ship was upset. When, as Midshipmen, we punished one of our mess-mates for abstracting his cheese, he was extremely angry with us, and asked us all what right we had to interfere with his cheese. He always had the Midshipmen to breakfast with him, and when we were seasick he gave us champagne and ginger-bread nuts. As he went in mortal fear of his own steward, who bossed him utterly, he would say: “I think the13 aroma has rather gone out of this champagne. Give it to the young gentlemen.” The steward would reply: “Now you know very well, Sir, the aroma ain’t gone out of this ’ere champagne”; but all the same we got it. He always slept in a hammock, and I remember he kept his socks in the head clews ready to put on in case of a squall calling him suddenly on deck. I learned from him nearly all that I know. He taught me how to predict eclipses and occultations, and I suppose I took more lunar observations than any Midshipman ever did before.

Shadwell’s appearance on going into a fight I must describe. We went up a Chinese river to capture a pirate stronghold. Presently the pirates opened fire from a banana plantation on the river bank. We nipped ashore from the boats to the banana plantation. I remember I was armed to the teeth, like a Greek brigand, all swords and pistols, and was weighed down with my weapons. We took shelter in the banana plantation, but our Captain stood on the river bank. I shall never forget it. He was dressed in a pair of white trousers, yellow waistcoat and a blue tail coat with brass buttons and a tall white hat with a gold stripe up the side of it, and he was waving a white umbrella to encourage us to come out of the bananas and go for the enemy. He had no weapon of any sort. So (I think rather against our inclinations, as the gingall bullets were flying about pretty thick) we all had to come out and go for the Chinese.

Once the Chinese guns were firing at us, and as the shell whizzed over the boat we all ducked. “Lay on your oars,14 my men,” said Shadwell; and proceeded to explain very deliberately how ducking delayed the progress of the boat—apparently unaware that his lecture had stopped its progress altogether!

His sole desire for fame was to do good, and he requested for himself when he died that he should be buried under an apple tree, so that people might say: “God bless old Shadwell!” He never flogged a man in his life. When my Captain was severely wounded, I being with him as his Aide-de-Camp (we landed 1,100 strong, and 463 were killed or wounded), he asked me when being sent home what he could do for me. I asked him to give me a set of studs with his motto on them: “Loyal au mort,” and I have worn them daily for over sixty years. When this conversation took place, the Admiral (afterwards Sir James Hope, K.C.B.) came to say good-bye to him, and he asked my Captain what he could do for him. He turned his suffering body towards me and said to the Admiral: “Take care of that boy.” And so he did.

Admiral Hope was a great man, very stern and stately, the sort of man everybody was afraid of. His nickname was composed of the three ships he had commanded: “Terrible ... Firebrand ... Majestic.” He turned to me and said: “Go down in my boat”; and everyone in the Fleet saw this Midshipman going into the Admiral’s boat. He took me with him to the Flagship; and I got on very well with him because I wrote a very big hand which he could read without spectacles.

He promoted me to Lieutenant at the earliest possible15 date, and sent me on various services, which greatly helped me.

My first chance came when Admiral Hope sent me to command a vessel in Chinese waters on special service. His motto was “Favouritism is the secret of efficiency,” and though I was only nineteen he put me over the heads of many older men because he believed that I should do what I was told to do, and carry out the orders of the Admiral regardless of consequences. And so I did, although I made all sorts of mistakes and nearly lost the ship. When I came back everyone seemed to expect that I should be tried by Court-Martial; but the Admiral only cared that I had done what he wanted done; and then he gave me command of another vessel.

The Captain of the ship I came home in was another sea wonder, by name Oliver Jones. He was Satanic; yet I equally liked him, for, like Satan, he could disguise himself as an angel; and I believe I was the only officer he did not put under arrest. For some reason I got on with him, and he made me the Navigating Officer of the ship. He told me when I first came on board that he thought he had committed every crime under the sun except murder. I think he committed that crime while I was with him. He was a most fascinating man. He had such a charm, he was most accomplished, he was a splendid rider, a wonderful linguist, an expert navigator and a thorough seaman. He had the best cook, and the best wines ever afloat in the Navy, and was hospitable to an extreme. Almost daily he had a lot of us to dinner, but after dinner came hell! We dined with him in tail16 coat and epaulettes. After dinner he had sail drill, or preparing the ship for battle, and persecution then did its utmost.

Once, while I was serving with him, we were frozen in out of sight of land in the Gulf of Pechili in the North of China. And there were only Ship’s provisions, salt beef, salt pork, pea soup, flour, and raisins. Oliver Jones was our Captain, or we wouldn’t have been frozen in. The Authorities told him to get out of that Gulf and that’s why he stayed in. I never knew a man who so hated Authority. I forget how many degrees below zero the thermometer was, and it was only by an unprecedented thaw that we ever got out. And with this intense cold he would often begin at four o’clock in the morning to prepare for battle, and hand up every shot in the ship on to the Upper Deck, then he’d strike Lower Yards and Topmasts (which was rather a heavy business), and finish up with holystoning the Decks, which operation he requested all the Officers to honour with their presence. And when we went to Sea we weren’t quite sure where we would go to (I remember hearing a Marine Officer say that we’d got off the Chart altogether). Till that date I had never known what a delicacy a seagull was. We used to get inside an empty barrel on the ice to shoot them, and nothing was lost of them. The Doctor skinned them to make waistcoats of the skins—the insides were put on the ice to bait other seagulls, and a rare type of onion we had (that made your eyes water when you got within half a mile of them) made into stuffing got rid of the fishy taste.

17

On the way home he landed me on a desert island to make a survey. He was sparse in his praises; but he wrote of me: “As a sailor, an officer, a Navigator and a gentleman, I cannot praise him too highly.” Confronted with this uncommon expression of praise from Oliver Jones, the examiners never asked me a question. They gave me on the spot a first-class certificate.

This Captain Oliver Jones raised a regiment of cavalry for the Indian Mutiny and was its Colonel, and Sir Hope Grant, the great Cavalry General in the Indian Mutiny, said he had never met the equal of Oliver Jones as a cavalry leader. He broke his neck out hunting.

When I was sent to the Hythe School of Musketry as a young Lieutenant, I found myself in a small Squad of Officers, my right hand man was a General and my left hand man a full Colonel. The Colonel spent his time drawing pictures of the General. (The Colonel was really a wonderful Artist.) The General was splendid. He was a magnificent-looking man with a voice like a bull and his sole object was Mutiny! He hated General Hay, who was in Command of the Hythe School of Musketry. He hated him with a contemptuous disdain. In those days we commenced firing at the target only a few hundred yards off. The General never hit the target once! The Colonel made a beautiful picture of him addressing the Parade and General Hay: “Gentlemen! my unalterable conviction is that the bayonet is the true weapon of the British Soldier!” The beauty of the situation was that the General had been sent to Hythe to qualify as Inspector-General of Musketry.18 After some weeks of careful drill (without firing a shot) we had to snap caps (that was to get our nerves all right, I suppose!); the Sergeant Instructor walked along the front of the Squad and counted ten copper caps into each outstretched hand. At that critical moment General Hay appeared on the Parade. This gave the General his chance! With his bull-like voice he asked General Hay if it was believable after these weeks of incessant application that we were going (each of us) to be entrusted with ten copper caps! When we were examined vivâ voce we each had to stand up to answer a question (like the little boys at a Sunday School). The General was asked to explain the lock of the latest type of British Rifle. He got up and stated that as he was neither Maskelyne and Cooke nor the Davenport Brothers (who were the great conjurers of that time) he couldn’t do it. Certainly we had some appalling questions. One that I had was, “What do you pour the water into the barrel of the rifle with when you are cleaning it?” Both my answers were wrong. I said, “With a tin pannikin or the palm of the hand.” The right answer was “with care”! Another question in the written examination was, “What occurred about this time?” Only one paragraph in the text-book had those words in it “About this time there occurred, etc.”! All the same I had a lovely time there; the British Army was very kind to me and I loved it. The best shot in the British Army at that date was a confirmed drunkard who trembled like a leaf, but when he got his eye on the target he was a bit of marble and “bull’s eyes”19 every time! So, as the Scripture says, never judge by appearance. Keble, who wrote the “Christian Year,” was exceedingly ugly, but when he spoke Heaven shone through; so I was told by one who knew him.

It’s going rather backwards now to speak of the time when I was a Midshipman of the “Jolly Boat” in 1854, in an old Sailing Line of Battleship of eighty-four guns. I think I must have told of sailing into Harbour every morning to get the Ship’s Company’s beef (gale or no gale) from Spithead or Plymouth Sound or the Nore. We never went into harbour in those days, and it was very unpleasant work. I always felt there was a chance of being drowned. Once at the Nore in mid-winter all our cables parted in a gale and we ran into the Harbour and anchored with our hemp cable (our sole remaining joy); it seemed as big round as my small body was then, and it lay coiled like a huge gigantic serpent just before the Cockpit. Nelson must have looked at a similar hemp cable as he died in that corner of the Cockpit which was close to it. All Battleships were exactly alike. You could go ashore then for forty years and come on board again quite up to date. On our Quarter Deck were brass Cannonades that had fired at the French Fleet at Trafalgar. No one but the Master knew about Navigation. I remember when the Master was sick and the second Master was away and the Master’s Assistant had only just entered the Navy, we didn’t go to Sea till the Master got out of bed again. There was a wonderfully smart Commander in one of the other Battleships who had the utmost contempt for Science;20 he used to say that he didn’t believe in the new-fangled sighting of the guns, “Your Tangent Sights and Disparts!” What he found to be practically the best procedure was a cold veal pie and a bottle of rum to the first man that hit the target. We have these same “dears” with us now, but they are disguised in a clean white shirt and white kid gloves, but as for believing in Engineers—“Sack the Lot”!

It is very curious that we have no men now of great conceptions who stand out above their fellows in any profession, not even the Bishops, which reminds me of a super-excellent story I’ve been told in a letter. My correspondent met by appointment three Bishops for an expected attack. Before they got to the business of the meeting, he said, “Could their Lordships kindly tell him in the case of consecrated ground how deep the consecration went, as he specially wanted to know this for important business purposes.” They wrangled and he got off his “mauvais quart d’heure.” My correspondent explained to me that his old Aunt (a relation of Mr. Disraeli) said to him when he was young “Alfred, if you are going to have a row with anyone—always you begin!”

I come to another episode of comparatively early years.

Yesterday I heard from a gentleman whom I had not seen for thirty-eight years, and he reminded me of a visit to me when I was Captain of the “Inflexible.” I was regarded by the Admiral Superintendent of the Dockyard as the Incarnation of Revolution. (What upset him most was I had asked for more water-closets21 and got them.) This particular episode I’m going to relate was that I wanted the incandescent light. Lord Kelvin had taken me to dine with the President of the Royal Society, where for the first time his dining table was lighted with six incandescent lamps, provided by his friend Mr. Swan of Newcastle, the Inventor in this Country of the Incandescent light, as Mr. Edison was in America (it was precisely like the discovery of the Planet Neptune when Adams and Leverrier ran neck and neck in England and France). After this dinner I wrote to Mr. Swan to get these lamps for the “Inflexible,” and he sent down the friend who wrote me the letter I received yesterday (Mr. Henry Edmunds) and we had an exhibition to convert this old fossil of an Admiral Superintendent.

Here I’ll put in Mr. Henry Edmunds’s own words:—

At last we got our lamps to glow satisfactorily; and at that moment the Admiral was announced. Captain Fisher had warned me that I must be careful how I answered any questions, for the Admiral was of the stern old school, and prejudiced against all new-fangled notions. The Admiral appeared resplendent in gold lace, and accompanied by such a bevy of ladies that I was strongly reminded of the character in “H.M.S. Pinafore” “with his sisters, and his cousins, and his aunts.” The Admiral immediately asked if I had seen the “Inflexible.” I replied that I had. “Have you seen the powder magazine?” “Yes! I have been in it.” “What would happen to one of these little glass bubbles in the event of a broadside?” I did not think it would affect them. “How do you know? You’ve never been in a ship during a broadside!” I saw Captain Fisher’s eye fixed upon me; and a sailor was dispatched for some22 gun-cotton. Evidently everything had been ready prepared, for he quickly returned with a small tea tray about two feet long, upon which was a layer of gun-cotton, powdered over with black gun-powder. The Admiral asked if I was prepared to break one of the lamps over the tray. I replied that I could do so quite safely, for the glowing lamp would be cooled down by the time it fell amongst the gun-cotton. I took a cold chisel, smashed a lamp, and let it fall. The Company saw the light extinguished, and a few pieces of glass fall on the tray. There was no flash, and the gun-powder and gun-cotton remained as before. There was a short pause, while the Admiral gazed on the tray. Then he turned, and said to Lord Fisher, “We’ll have this light on the ‘Inflexible.’”

And that was the introduction of the incandescent light into the British Navy.

Talking about water-closets, I remember so well long ago that one of the joys on board a Man-of-War on Christmas Day was having what was called a “Free Tank,” that is to say, you could go and get as much fresh water as ever you liked, all other days you were restricted, so much for drinking and so much for washing. The other Christmas Joy was “Both sides of the ‘Head’ open”! What that meant was that right in the Bows or Head of the Ship were situated all the Bluejackets’ closets, and on Christmas Day all could be used! “all were free.” Usually only half were allowed to be open at a time. It was a quaint custom, and I always thought outrageous. “Nous avons changé tout cela.”

When I was out in the West Indies a French Frigate came into the Harbour with Yellow Fever on board. My Admiral asked the Captain of the English Man-of-War23 that happened to be there what kindness he had shown the French Frigate on arrival? He said he had sent them the keys of the Cemetery. This Captain always took his own champagne with him and put it under his chair. I took a passage with him once in his Ship, he had a Chart hanging up in his cabin like one of those recording barometers, which showed exactly how his wine was getting on. When he came to call on the Admiral at his house on shore, he always brought a small bundle with him, and after his Official visit he’d go behind a bush in the garden and change into plain clothes! All the same, this is the stuff that heroes are made of. Heroes are always quaint.

24

King Edward paid a visit to Admiralty House, Portsmouth, 19th February to 22nd February, 1904, while I was Commander-in-Chief there; and after he had left I received the following letter from Lord Knollys:—

Buckingham Palace,

22nd February, 1904.

My Dear Admiral,

I am desired by the King to write and thank you again for your hospitality.

His Majesty also desires me to express his great appreciation of all of the arrangements, which were excellent, and they reflect the greatest credit both on you and on those who worked under your orders.

I am very glad the visit was such a great success and went off so well. The King was evidently extremely pleased with and interested in everything.

Yours sincerely,

Knollys.

I can say that I never more enjoyed such a visit. The only thing was that I wasn’t Master in my own house, the King arranged who should come to dinner and25 himself arranged how everyone should sit at table; I never had a look in. Not only this, but he also had the Cook up in the morning. She was absolutely the best cook I’ve ever known. She was cheap at £100 a year. She was a remarkably lovely young woman. She died suddenly walking across a hay field. The King gave her some decoration, I can’t remember what it was. Some little time after the King had left—one night I said to the butler at dinner, “This soup was never made by Mrs. Baker; is she ill?” The butler replied, “No, Sir John, Mrs. Baker isn’t ill, she has been invited by His Majesty the King to stay at Buckingham Palace.” And that was the first I had heard of it. Mrs. Baker had two magnificent kitchenmaids of her own choosing and she thought she wouldn’t be missed. I had an interview with Mrs. Baker on her return from her Royal Visit, and she told me that the King had said to her one morning before he left Admiralty House, Portsmouth, that he thought she would enjoy seeing how a Great State Dinner was managed, and told her he would ask her to stay at Buckingham Palace or Windsor Castle to see one! Which is only one more exemplification of what I said of King Edward in my first book, that he had an astounding aptitude of appealing to the hearts of both High and Low.

My friends tell me I have done wrong in omitting countless other little episodes of his delightful nature.

“One touch of nature makes the whole world kin!”

This is a sweet little episode that occurred at Sandringham. The King was there alone and Lord26 Redesdale and myself were his only guests. The King was very fond of Redesdale, and rightly so. He was a most delightful man. He and I were sitting in the garden near dinner time, the King came up and said it was time to dress and he went up in the lift, leaving Redesdale in the garden. Redesdale had a letter to write and rushed up to his bedroom to write the letter behind a screen there was between him and the door; the door opened and in came the King, thinking he had left Redesdale in the garden, and went to the wash-hand-stand and felt the hot water-can to see if the water was hot and went out again. Perhaps his water had been cold, but anyhow he came to see if his guest’s was all right.

On another occasion I went down to Sandringham with a great party, I think it was for one of Blessed Queen Alexandra’s birthdays (I hope Her Majesty will forgive me for telling a lovely story presently about herself). As I was zero in this grand party, I slunk off to my room to write an important letter; then I took my coat off, got out my keys, unlocked my portmanteau and began unpacking. I had a boot in each hand; I heard somebody fumbling with the door handle and thinking it was the Footman whom Hawkins had allocated to me, I said “Come in, don’t go humbugging with that door handle!” and in walked King Edward, with a cigar about a yard long in his mouth. He said (I with a boot in each hand!) “What on earth are you doing?” “Unpacking, Sir.” “Where’s your servant?” “Haven’t got one, Sir.” “Where is he?” “Never had one, Sir; couldn’t afford27 it.” “Put those boots down; sit in that arm chair.” And he went and sat in the other on the other side of the fire. I thought to myself, “This is a rum state of affairs! Here’s the King of England sitting in my bedroom on one side of the fire and I’m in my shirt sleeves sitting in an armchair on the other side!”

“Well,” His Majesty said, “why didn’t you come and say, ‘How do you do’ when you arrived?” I said, “I had a letter to write, and with so many great people you were receiving I thought I had better come to my room.” Then he went on with a long conversation, until it was only about a quarter of an hour from dinner time, and I hadn’t unpacked! So I said to the King, “Sir, you’ll be angry if I’m late for dinner, and no doubt your Majesty has two or three gentlemen to dress you, but I have no one.” And he gave me a sweet smile and went off.

All the same, he could be extremely unpleasant; and one night I had to send a telegram for a special messenger to bring down some confounded Ribbon and Stars, which His Majesty expected me to wear. I’d forgotten the beastly things (I’m exactly like a Christmas Tree when I’m dressed up). One night when I got the King’s Nurse to dress me up, she put the Ribbon of something over the wrong shoulder, and the King harangued me as if I’d robbed a church. I didn’t like to say it was his Nurse’s fault. Some of these Ribbons you put over one shoulder and some of them you have to put over the other; it’s awfully puzzling. But the King was an Angel all the same, only he wasn’t always28 one. Personally I don’t like perfect angels, one doesn’t feel quite comfortable with them. One of Cecil Rhodes’s secretaries wrote his Life, and left out all his defects; it was a most unreal picture. The Good stands out all the more strikingly if there is a deep shadow. I think it’s called the Rembrandt Effect. Besides, it’s unnatural for a man not to have a Shadow, and the thought just occurs to me how beautiful it is—“The Shadow of Death”! There couldn’t be the Shadow unless there was a bright light! The Bright Light is Immortality! Which reminds me that yesterday I read Dean Inge’s address at the Church Congress the day before on Immortality. If I had anything to do with it, I’d make him Archbishop of Canterbury. I don’t know him, but I go to hear him preach whenever I can.

The Story about Queen Alexandra is this. My beloved friend Soveral, one of King Edward’s treasured friends, asked me to lunch on Queen Alexandra’s sixtieth birthday. After lunch all the people said something nice to Queen Alexandra, and it came to my turn, I said to Her Majesty, “Have you seen that halfpenny newspaper about your Majesty’s birthday?” She said she hadn’t, what was it? I said these were the words:—

Her Majesty said “Get me a copy of it!” (Such a thing didn’t exist!) About three weeks afterwards (Her Majesty has probably forgotten all about it now, but she hadn’t then) she said, “Where’s that halfpenny newspaper?”29 I was staggered for a moment, but recovered myself and said “Sold out, Ma’am; couldn’t get a copy!” (I think my second lie was better than my first!) But the lovely part of the story yet remains. A year afterwards she sent me a lovely postcard which I much treasure now. It was a picture of a little girl bowling a hoop, and Her Majesty’s own head stuck on, and underneath she had written:—

“May she live till she looks it!”

I treasure the remembrances of all her kindnesses to me as well as that of her dear Sister, the Dowager Empress of Russia. The trees they both planted at Kilverstone are both flourishing; but strange to say the tree King Edward planted began to fade away and died in May, 1910, when he died—though it had flourished luxuriantly up till then. Its roots remain untouched—and a large mass of “Forget-me-nots” flourishes gloriously over them.

For very many consecutive years after 1886 I went to Marienbad in Bohemia (eight hundred miles from London and two thousand feet above the sea and one mass of delicious pine woods) to take the waters there. It’s an ideal spot. The whole place is owned by a Colony of Monks, settled in a Monastery (close by) called Tepl, who very wisely have resisted all efforts to cut down the pine woods so as to put up more buildings.

I had a most serious illness after the Bombardment of30 Alexandria due to bad living, bad water, and great anxiety. The Admiral (Lord Alcester) had entrusted me (although I was one of the junior Captains in the Fleet) with the Command on shore after the Bombardment. Arabi Pasha, in command of the Rebel Egyptian Army, was entrenched only a few miles off, and I had but a few hundreds to garrison Alexandria. For the first time in modern history we organised an Armoured Train. Nowadays they are as common as Aeroplanes. Then it excited as much emotion as the Tanks did. There was a very learned essay in the Pall Mall Gazette.

I was invalided home and, as I relate in my “Memories,” received unprecedented kindness from Queen Victoria (who had me to stay at Osborne) and from Lord Northbrook (First Lord of the Admiralty), who gave me the best appointment in the Navy. I always have felt great gratitude also to his Private Secretary at that time (Admiral Sir Lewis Beaumont). For three years I had recurrence of Malarial Fever, and tried many watering places and many remedies all in vain. I went to Marienbad and was absolutely cured in three weeks, and never relapsed till two years ago, when I was ill again and no one has ever discovered what was the matter with me! Thanks be to God—I believe I am now as well as I ever was in all my whole life, and I can still waltz with joy and enjoy champagne when I can get it (friends, kindly note!).

At Marienbad I met some very celebrated men, and the place being so small I became great friends with them. If you are restricted to a Promenade only a31 few hundred yards long for two hours morning and evening, while you are drinking your water, you can’t help knowing each other quite well. How I wish I could remember all the splendid stories those men told me!

Campbell-Bannerman, Russell (afterwards Chief Justice), Hawkins (afterwards Lord Brampton), the first Lord Burnham, Labouchere (of Truth), Yates (of the World), Lord Shand (a Scottish Judge), General Gallifet (famous in the Franco-German War), Rumbold (Ambassador at Vienna), those were some of the original members. Also there were two Bevans (both delightful)—to distinguish them apart, they called the “Barclay Perkins” Bevan “poor” Bevan, as he was supposed to have only two millions sterling, while the other one was supposed to have half a dozen! (That was the story.) I almost think I knew Campbell-Bannerman the best. He was very delightful to talk to. I have no Politics. But in after years I did so admire his giving Freedom to the Boers. Had he lived, he would have done the same to Ireland without any doubt whatever. Fancy now 60,000 British soldiers quelling veiled Insurrection and a Military Dictator as Lord Lieutenant and Ireland never so prosperous! I have never been more moved than in listening to John Redmond’s brother, just back from the War in his Soldier’s uniform, making the most eloquent and touching appeal for the Freedom of Ireland! It came to nothing. I expect Lord Loreburn (who was Campbell-Bannerman’s bosom friend) will agree with me that had Campbell-Bannerman only known what a literally overwhelming majority he was going to obtain32 at the forthcoming Election, he would have formed a very different Government from what he did, and I don’t believe we should have had the War. King Edward liked him very much. They had a bond in their love of all things French. I don’t believe any Prime Minister was ever so loved by his followers as was Campbell-Bannerman.

Sir Charles Russell, afterwards Chief Justice, was equally delightful. We were so amused one day (when he first came to Marienbad) by the Head Waiter whispering to us that he was a cardsharper! The Head Waiter told us he had seen him take a pack of cards out of his pocket, look at them carefully, and then put them back! Which reminds me of a lovely incident in my own career. I had asked the Roman Catholic Archbishop to dinner; he was a great Saint—we played cards after dinner. We sat down to play—(one of my guests was a wonderful conjurer). “Hullo!” I said, “Where are the cards gone to?” The conjurer said, “It doesn’t matter: the Archbishop will let us have the pack of cards he always carries about in his pocket”! The Holy Man furtively put his hand in his pocket (thinking my friend was only joking!) and dash it! there they were! I never saw such a look in a man’s face! (He thought Satan was crawling about somewhere.)

Lord Burnham was ever my great Friend, he was also a splendid man. I should like to publish his letters. I have spoken of Labouchere elsewhere. As Yates, of the World, Labouchere, and Lord Burnham (those three) walked up and down the Promenade together33 (Lord Burnham being stout), Russell called them “The World, the Flesh, and the Devil.” I don’t know if it was original wit, but it was to me.

Old Gallifet also was splendid company; he had a silver plate over part of his stomach and wounds all over him. I heard weird stories of how he shot down the Communists.

Sir Henry Hawkins I dined with at some Legal Assemblage, and as we walked up the Hall arm in arm all the Law Students struck up a lovely song I’d never heard before: “Mrs. ’enry ’awkins,” which he greatly enjoyed. On one occasion he told me that when he was still a Barrister, he came late into Court and asked what was the name of the Barrister associated with him in the Case? The Usher or someone told him it was Mr. Swan and he had just gone out of the Court. (I suppose he ought to have waited for Sir Henry.) Anyhow Sir Henry observed that he didn’t like him “taking liberties with his Leda.” I expect the Usher, not being up in Lemprière’s Dictionary, didn’t see the joke!

Dear Shand, who was very small of stature, was known as the “Epitome of all that was good in Man.” He reeked with good stories and never told them twice. Queen Victoria fell in love with him at first sight (notwithstanding that she preferred big men) and had him made a Lord. She asked after his wife as “Lady Shand”; and, being a Scottish Law Lord, he replied that “Mrs. Shand was quite well.” There are all sorts of ways of becoming a Lord.

Rumbold knocked the man down who asked him34 for his ticket! He wasn’t going to have an Ambassador treated like that (as if he had travelled without a ticket!)

As the Czechs hate the Germans, I look forward to going back to my beloved Marienbad once more every year. The celebrated Queen of Bohemia was the daughter of an English King; her name was Elizabeth. The English Ambassador to the Doge of Venice, Sir Henry Wootton, wrote some imperishable lines in her praise and accordingly I worshipped at Wootton’s grave in Venice. The lines in his Poem that I love are:—

In dictating the Chapter on “Some Personalities,” that appears in my “Memories,” I certainly should not have overlooked my very good friend Masterton-Smith (Sir J. E. Masterton-Smith, K.C.B.). I can only say here (as he knows quite well) that never was he more appreciated by anyone in his life than by me. Numberless times he was simply invaluable, and had his advice been always taken, events would have been so different in May 1915!

I have related in “Memories” how malignancy went to the extent not only of declaring that I had sold my country to the Germans (so beautifully denied by Sir Julian Corbett), but also that I had formed “Syndicates” and “Rings” for my own financial advantage, using my official knowledge and power to further my nefarious schemes for making myself quickly rich! I have denied this by the Income Tax Returns—and I have also explained35 I am still poor—very poor—because one-third of my pension goes in income tax and the remaining two-thirds is really only one-third because of depreciation of the pound sterling and appreciation of food prices!

But let that pass. However, I’ve been told I ought to mention I had another very brilliant opportunity of becoming a millionaire in A.D. 1910, but declined. And also it has been requested of me to state the fact that never in all my life have I belonged to any company of any sort beyond possessing shares, or had any place of profit outside the Navy. That is sufficiently definite, I think, to d——n my enemies and satisfy my friends.

My finances have always been at a low ebb (even when a Commander-in-Chief), as I went on the principle of “whatever you do, do it with all your might,” and there is nothing less conducive to “the fighting efficiency of a Fleet and its instant readiness for war” than a Stingy Admiral! The applications for subscriptions which were rained upon me I countered with this inestimable memorandum in reply, invented by my sympathetic Secretary:—“The Admiral deeply regrets being unable to comply with your request, and he deplores the reason—but his Expenditure is in excess of his Receipts.” I always got sympathy in return, more especially as the Local Applicants were largely responsible for the excess of expenditure.

At an early period of my career I certainly did manage on very little, and it is wonderful what a lot you can get for your money if you think it over. I got breakfast for tenpence, lunch for a shilling and dinner for eighteen36 pence and barley water for nothing and a bed for three and sixpence (but my bedroom had not a Southern aspect). The man I hired a bedroom from was like a Father to me, and I have never had such a polish on my shoes. (I remember saying to a German Boots, pointing to my badly-cleaned shoes, “Spiegel!”—looking-glass; he took away the shoes and brought them back shining like a dollar. Hardly anyone will see the joke!) But what I am most proud of is that, financial necessity once forcing me to go to Marienbad quite alone, I did a three weeks’ cure there, including the railway fare and every expense, for twenty-five pounds. I don’t believe any Economist has ever beaten this. I preserve to this day the details of every day’s expenditure, which I kept in a little pocket-book, and read it all over only a couple of days ago, without any wish for past days.

I recall with delight first meeting my beloved old friend, Sir Henry Lucy; he had with him Sir F. C. Gould, who never did a better service to his country than when he portrayed me as an able seaman asking the Conscriptionists (in the person of Lord Roberts) whether there was no British Navy. The cartoon was reproduced in my “Memories” (p. 48). In my speech at the Lord Mayor’s Banquet in 1907 (see Chapter VI of this volume) I had spoken of Sir Henry Lucy as “gulled by some Midshipman Easy of the Channel Fleet” (Sir Henry had been for a cruise in the Fleet), who stuffed him up that the German Army embarking in the German Fleet was going to invade England! And in the flippant manner that seems so to annoy people,37 I observed that Sir Henry might as well talk of embarking St. Paul’s Cathedral on board a penny steamer as of embarking the German Army in the German Fleet! He and Gould came up to me at a séance on board the “Dreadnought,” and had a cup of tea as if I had been a lamb!

On the occasion of that same speech, a Bishop looked very sternly at me, because in my speech, to show how if you keep on talking about war and always looking at it and thinking of it you bring it on, I instanced Eve, who kept on looking at the apple and at last she plucked it; and in the innocence of my heart I observed that had she not done so we should not have been now bothered with clothes. When I said this in my speech I was following the advice of one of the Sheriffs of the City of London, sitting next me at dinner, who told me to fix my eyes, while I was speaking, on the corner of the Ladies’ Gallery, as then everyone in the Guildhall could hear what I said. And such a lovely girl was in that corner, I never took my eyes off her, all the time, and that brought Eve into my mind!

38

I have just been listening to another very eloquent sermon from Dr. Hugh Black, whom I mention elsewhere in this book (see Chapter V). Nearly all these Presbyterians are eloquent, because they don’t write their sermons.

The one slip our eloquent friend made in his sermon was in saying that the A.D. 1611 edition of the Bible (the Authorised Version) was a better version of the Bible than the Great Bible of A.D. 1539, which according to the front page is stated to be as follows:—

“The byble in English that is to say the content of all the Holy Scripture both of the old and new testament truly translated after the verity of the Hebrew and Greek texts by the diligent study of diverse excellent learned men expert in the aforesaid tongues.

“Printed by Richard Grafton and Edward Whitchurch. Cum privilegio ad imprimendum solum.

1539.”

It is true, as the preacher said, that the 1611 edition, the Authorised Version, is more the literal translation of39 the two, but those “diverse excellent learned men” translated according to the spirit and not the letter of the original; and our dear brother (the preacher) this morning in his address had to acknowledge that in the text he had chosen from the 27th Psalm and the last verse thereof, the pith and marrow which he rightly seized on—being the words “Wait on the Lord”—were more beautifully rendered in the great Bible from which (the Lord be thanked!) the English Prayer Book takes its Psalms, and which renders the original Hebrew not in the literal words, “Wait on the Lord,” but “Tarry thou the Lord’s leisure,” and goes on also in far better words than the Authorised Version with the rest of the verse: “Be strong and He shall comfort thine heart.”

When we remonstrated with the Rev. Hugh Black after his sermon, he again gainsaid, and increased his heinousness by telling us that the word “Comfort,” which doesn’t appear in the 1611 version, was in its ancient signification a synonym for “Fortitude”; and the delightful outcome of it is that that is really the one and only proper prayer—to ask for Fortitude or Endurance. You have no right to pray for rain for your turnips, when it will ruin somebody else’s wheat. You have no right to ask the Almighty—in fact, He can’t do it—to make two and two into five. The only prayer to pray is for Endurance, or Fortitude. The most saintly man I know, daily ended his prayers with the words of that wonderful hymn:

40

It must not be assumed that I am a Saint in any way in making these remarks, but only a finger-post pointing the way. The finger-post doesn’t go to Heaven itself, yet it shows the way. All I want to do is to stick up for those holy men who were not hide-bound with a dictionary, and gave us the spirit of the Holy Word and not the Dictionary meaning.

Here I feel constrained to mention a far more beautiful illustration of the value of those pious men of old.

In Brother Black’s 1611 version, the most famous of the Saviour’s words: “Come unto me all ye that labour and are heavy laden and I will give you rest,” is, in the 1539 version, “I will refresh you!” There is no rest this side of Heaven. Job (iii, 17) explains Heaven as “Where the wicked cease from troubling and where the weary be at rest.” The fact is—the central point is reached by the Saviour when He exemplifies the Day of Perfection by saying: “In that day ye shall ask me nothing.”

I have been told by a great scientist that for the tide to move a pebble on the beach a millionth of an inch further would necessitate an alteration in the whole Creation. And then we go and pray for rain, or to beat our enemies!

Again, I say—The only thing to pray for is Endurance.

Some people in sore straits try to strike bargains with God, if only He will keep them safe or relieve them in the present necessity. It’s a good story of the soldier who, with all the shells exploding round him was heard to pray: “O Lord, if You’ll only get me out of this d—d mess I will be good, I will be good!”

41

I am reminded of what I call the “Pith and Marrow” which the pious men put at the head of every chapter of the Bible, and which, alas! has been expunged in the literary exactitudes of the Revised Version. Regard Chapter xxvi, for instance, of Proverbs—how it is all summed up by those “diverse excellent learned men.” They wrote at the top of the chapter “Observations about Fools.” Matthew xxii: the Saviour “Poseth the Pharisees.” Isaiah xxi: “The set time.” Isaiah xxvii (so true and pithy of the Chapter!): “Chastisements differ from Judgments”; and in Mark xv: “The Clamour of the Common People”—descriptive of what’s in the chapter. All these headings, in my opinion, as regards those ancient translators, are for them a “Crown of Glory and a Diadem of Beauty”; and I have a feeling that, when they finished their wondrous studies, it was with them as Solomon said, “The desire accomplished is sweet to the Soul.”

March 27th, 1918.

Dear Friend,

When I was at Bath I read in the local paper a beautiful letter aptly alluding to the Mount Fiesole of Bath and quoting what has been termed that mysterious verse of David’s:

“I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills——.”

Well! the other day a great friend of that wonderful Hebrew scholar, Dr. Ginsburg—he died long since at Capri—told me that Ginsburg had said to him that all the Revisers and Translators had missed a peculiar42 Hebraism which quite alters the signification of this opening verse of the 121st Psalm: It should read:

“Shall I lift up mine eyes to those hills? DOTH my help come from thence?”

And this is the explanation:

Those hills alluded to were the hills in which were the Groves planted in honour of the idols towards which Israel had strayed. So in the second verse the inspired tongue says:

“No! My help cometh from the Lord! He who hath made Heaven and Earth! (not these idols).”

I have had an admiration for Ginsburg ever since he shut up the two Atheists in the Athenæum Club, Huxley and Herbert Spencer, who were reviling Holy Writ in Ginsburg’s presence and flouting him. So he asked the two of them to produce anything anywhere in literature comparable to the 23rd Psalm as translated by Wyclif, Tyndale, and Coverdale. He gave them a week to examine, and at the end of it they confessed that they could not.

One of them (I could not find out which it was) wrote:

“I won’t argue about nor admit the Inspiration claimed, but I say this—that those saintly men whom Cromwell formed as the company to produce the Great Bible of 1539 were inspired, for never has the spirit of the original Hebrew been more beautifully transformed from the original harshness into such spiritual wealth.”

Those are not the exact words, I have not got them by me, but that was the sense.

The English language in A.D. 1539 was at its very maximum. Hence the beauty of the Psalms which come from the Great Bible as produced by that holy company of pious men, who one writer says: “Did not wish their names to be ever known.” I send you the title page.

Yours, etc.,

(Signed) Fisher.

27/3/18.

43

I enclosed with this letter the front page of the first edition of the Great Bible, A.D. 1539, often known as Cranmer’s Bible, but Archbishop Cranmer had nothing whatever to do with it except writing a preface to it; it was solely due to Cromwell, Secretary of State to Henry VIII., who cut off Cromwell’s head in July, 1540. Cranmer wrote a preface for the edition after April, 1540. Cranmer was burnt at the stake in Mary’s reign. Tyndale was strangled and burnt, Coverdale, Bishop of Exeter, died of hunger. Coverdale headed the company that produced the Great Bible, and Tyndale’s translation was taken as the basis. (So those who had to do with the Bible had a rough time of it!)

John Wyclif, in A.D. 1380, began the translation of the Bible into English. This was before the age of printing, so it was in manuscript. Before he died, in A.D. 1384, he had the joy of seeing the Bible in the hands of his countrymen in their own tongue.

Wyclif’s translation was quaint and homely, and so idiomatic as to have become out of date when, more than one hundred years afterwards, John Tyndale, walking over the fields in Wiltshire, determined so to translate the Bible into English “that a boy that driveth the plough should know more of the Scriptures than the Pope,” and Tyndale gloriously succeeded! But for doing so, the Papists, under orders from the Pope of Rome, half strangled him and then burnt him at the stake. Like St. Paul, he was shipwrecked! (Just as he had finished the Book of Jonah, which is curious, but44 there was no whale handy, and so he was cast ashore in Holland, nearly dead!)

Our present Bible, of A.D. 1611, is almost word for word the Bible of Tyndale, of round A.D. 1530, but in A.D. 1534, Miles Coverdale, Bishop of Exeter, was authorised by Archbishop Cranmer and Thomas Cromwell (who was Secretary of State to Henry VIII.) to publish his fresh translation, and he certainly beautified in many places Tyndale’s original!

In 1539, “Diverse excellent learned men expert in the ‘foresaid tongues’” (Hebrew and Greek), under Cromwell’s orders made a true translation of the whole Bible, which was issued in 1539–40 in four editions, and remained supreme till A.D. 1568, when the Bishops tried to improve it, and made a heavenly mess of it! And then the present Authorised Version, issued in A.D. 1611, became the Bible of the Land, and still holds its own against the recent pedantic Revised Version of A.D. 1884. No one likes it. It is literal, but it is not spiritual!

In the opinion of Great and Holy men, Cranmer’s Bible (as it is called), or “the Great Bible”—the Bible of 1539 to 1568—holds the field for beauty of its English and its emotional rendering of the Holy Spirit!

Alas! we don’t know their names; we only know of them as “Diverse excellent learned men!” It is said they did not wish to go down to Fame!

“It is the greatest achievement in letters! The Beauty of the translation of these unknown men excels (far excels) the real and the so-called originals! All nations45 and tongues of Christendom have come to admit reluctantly that no other version of the Book in the English or any other tongue offers so noble a setting for the Divine Message. Read the Prayer Book Psalms! They are from this noble Version—English at its zenith! The English of the Great Bible is even more stately, sublime, and pure than the English of Shakespeare and Elizabeth.”

“Ye men of Galilee! Why stand ye gazing up into Heaven?” (Acts, Chapter i., verse 11.)

The moral of this one great central episode of the whole Christian faith (which, if a man don’t believe with his utmost heart he is as a beast that perisheth, so Saint Paul teaches in I. Corinthians, Chapter xv.), the moral of it is that however intense at any moment of our lives may be the immediate tension that is straining our mental fibre to the limit, yet we are to “get on!” and not stand stock still “gazing up into Heaven!” Inaction must be no part of our life, and we must “get on” with our journey as the Apostles did—“to our own City of Jerusalem!”

It is curious that Thursday (Ascension Day) was not made the Christian Sabbath. No scientific agnostic could possibly explain the Ascension by any such theories as those that try to get over the fact of the Resurrection by cataleptic happenings or an inconceivable trance! The agnostic can’t explain away that He was seen by the Apostles to be carried up into Heaven when in the46 act of lifting up His hands upon them to bless them “and a cloud received Him out of their sight!”

Vide the Collect for the Sunday after Ascension Day!

The prophet Zechariah says in Chapter xiv., verse 7:

And I conclude that in the last stage of life, as pointed out so very decisively by Dr. Weir Mitchell (that great American), “the brain becomes its best,” and so we rearrange our hearts and minds to the great advantage of our own Heaven and the avoidance of Hell to others! “Resentment” I find to fade away, and it merges into the feeling of Commiseration! (“Poor idiots!” one says instead of “D—n ’em!”) But I can’t arrive as yet at St. Paul, who deliberately writes that he’s quite ready to go to Hell so as to let his enemy go to Heaven! You’ve got really to be a real Christian to say that! I’ve not the least doubt, however, that John Wesley, Bishop Jeremy Taylor and Robertson of Brighton felt it surely! Isn’t it odd that those three great saints (fit to be numbered “with these three men, Noah, Daniel and Job,” Ezekiel, Chapter xiv., verse 14) each of them should have a “nagging” wife!

Their Home was Hell!

And I’ve searched in vain for any one of the three saying a word to the detriment of the other sex! They might all have been Suffragettes! (St. Paul does indeed47 say that he preferred being single! But Peter was married!)

But this “Resentment” section hinges entirely on “Charity” as defined and exemplified by Mr. Robertson, of Brighton, in one of the best of his wonderful Trinity Chapel Sermons.

I heard the Dean of St. Paul’s (Dr. Inge) preach in Westminster Abbey on the 17th Chapter of St. Matthew, verse 19: “Then came the disciples to Jesus apart, and said, ‘Why could not we cast him out?’”

The sermon was really splendiferous!

The Saviour had just cast out a devil that had been too much for the disciples, and He told them their inability to do so was due to their want of Faith, and added: “Howbeit this kind goeth not out but by prayer.” The Dean explained to us that some ascetic annotator 400 years afterwards had shoved in at the end of these two additional words—“and fasting.” That, of course, was meant by the Dean as “one in the eye” for those who fast like the Pharisees and for a pretence make long prayers! Then the Dean was just too lovely as to “Prayer!” He said he was so sick of people praying for victory in the great War! And speaking generally he was utterly sick of people praying for what they wanted! (as if that was Prayer!) No! the Dean divinely said, “Prayer was the exaltation of the Spirit of a Man to dwell with God and say in the Saviour’s48 words, ‘Not my will but Thine be done.’” “Get right thus with God,” said the Dean, “and then go and make Guns and Munitions with the utmost fury. That (said the Dean) was the way to get Victory, and not by silly vain petitions as if you were asking your Mamma for a bit of barley sugar.” (I don’t mean to say the Dean used these exact words!) Then he said an interesting thing that “this event of the disciples ignominiously failing to cast out the devil” happened to these chief of His apostles just after their coming down from the Mount of Transfiguration, where they had been immensely uplifted by the Heavenly Vision of the Saviour talking with Moses and Elijah. The Dean said “that it was really a curious fact of large experience that when you were thus lifted up in a Heavenly Spirit it was a sure precursor of a fierce temptation by the Devil!” These highly-favoured disciples, after such a communion with God, thought that they themselves, by themselves, could do anything! Pride had a fall! They could not cast out that devil! They trusted in themselves and did not give God the praise! And so it was that Moses didn’t go over Jordan, for he struck the rock and said, “How now, ye rebels!” (I’ll show you who I am!)

The Dean also observed that it was the Drains that had to be put right when there was an Epidemic of Typhoid Fever! “Prayer” wasn’t the Antidote!

The holy man Saint Francis summed up all religion and the Christian life in his famous line:

“How we are in the sight of God!—That is the only thing that matters!”

Photograph, taken and sent to Sir John Fisher by the Empress Marie of Russia, of a group on board H.M.S. “Standard,” 1909.

1. Lord Hamilton of Dalzell. 2. The Chevalier de Martino. 3. Sir Arthur Nicholson. 4. M. Stolypin, Russian Prime Minister. 5. The Czarina. 6. M. Isvolsky, Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs. 7. Sir John Fisher. 8. Sir Charles Hardinge. 9. Baron Fredericks. 10. The Grand Duchess Olga. 11. The Czar. 12. The Princess Victoria. 13. The Grand Duke Michael. 14. Count Benckendorff, Russian Ambassador.

It fortuned this morning that I read Joseph’s interview with his Brethren just after the death of their Father Jacob. They, having done their best to murder Joseph quite naturally thought that he would now be even with them, so they told a lie. They said that Jacob their Father had very kindly left word with them that he hoped Joseph would be very nice with his brethren after he died. Jacob said no such thing. Jacob knew his Joseph. But it gave Joseph a magnificent opportunity for reading one of Mr. Robertson’s, of Brighton, Sermons—he said to them, “Am I in the place of God?” Meaning thereby that no bread and water that he might put them on, and no torturing thumbscrews, would in any way approach the unquenchable fire and the undying worm that the Almighty so righteously reserves for the blackguards of this life. Which reminds me of the best Sermon I ever heard by the present Dean of Salisbury, Dr. Page-Roberts. He said: “There is no Bankruptcy Act in Heaven. No 10s. in the £1 there. Every moral, debt has got to be paid in full,” and consequently Page-Roberts, though an extremely broad-minded man, was the same as the extreme Calvinist of the unspeakable Hell and the Roman Catholic’s Purgatory. How curious it is how extremes do meet!

50

I was Controller of the Navy when Lord Spencer was First Lord of the Admiralty and Sir Frederck Richards was First Sea Lord. Mr. Gladstone, then Prime Minister, was at the end of his career. I have never read Morley’s “Life of Gladstone,” but I understand that the incident I am about to relate is stated to have been the cause of Mr. Gladstone resigning—and for the last time. I was the particular Superintending Lord at the Board of Admiralty, who, as Controller of the Navy, was specially responsible for the state and condition of the Navy; and it was my province, when new vessels were required, to replace those getting obsolete or worn out. Sir Frederick Richards and myself were on the very greatest terms of intimacy. He had a stubborn will, an unerring judgment, and an astounding disregard of all arguments. When anyone, seeking a compromise with him, offered him an alternative, he always took the alternative as well as the original proposal, and asked for both. Once bit, twice shy; no one ever offered him an alternative a second time.

51