The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Hans Holbein the Younger, Volume 2 (of 2), by Arthur B. Chamberlain

Title: Hans Holbein the Younger, Volume 2 (of 2)

Author: Arthur B. Chamberlain

Release Date: December 8, 2022 [eBook #69502]

Language: English

Produced by: Tim Lindell, Barry Abrahamsen, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Vol. II. Frontispiece

KING HENRY VIII

Earl Spencer’s Collection, Althorp

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| XVI. | THE MERCHANTS OF THE STEELYARD | 1 |

| XVII. | “THE TWO AMBASSADORS,” 1533 | 34 |

| XVIII. | PORTRAITS OF 1533-1536 | 54 |

| XIX. | “SERVANT OF THE KING’S MAJESTY” | 90 |

| XX. | THE DUCHESS OF MILAN | 114 |

| XXI. | THE VISIT TO “HIGH BURGONY” | 138 |

| XXII. | BASEL REVISITED | 156 |

| XXIII. | ANNE OF CLEVES: 1539 | 171 |

| XXIV. | THE LAST YEARS: 1540-1543 | 185 |

| XXV. | HOLBEIN AS A MINIATURE PAINTER | 217 |

| XXVI. | THE WINDSOR DRAWINGS AND OTHER STUDIES | 243 |

| XXVII. | DESIGNS FOR JEWELLERY AND THE DECORATIVE ARTS | 265 |

| XXVIII. | THE BARBER-SURGEONS’ PICTURE AND THE PAINTER’S DEATH | 289 |

| XXIX. | CONCLUSION | 312 |

| A. | Early Drawing by Holbein in the Maximilians Museum, Augsburg (Vol. i. p. 43) | 323 |

| B. | Designs for Painted Glass of the Lucerne Period (Vol. i. p. 79) | 323 |

| C. | Early Drawings for wall-paintings (Vol. i. p. 101) | 326 |

| D. | Glass Designs with the Coats of Arms of the Von Andlau and Von Hewen Families (Vol. i. p. 145) | 326 |

| The Glass Designs of “The Passion of Christ” (Vol. i. p. 156) | 327 | |

| E. | The Faesch Museum (Vol. i. pp. 88, 166-8, 180, and 239-41) | 328 |

| F. | Hans Holbein and Dr. Johann Fabri (Vol. i. p. 175) | 330 |

| G. | The Trade-Mark of Reinhold Wolfe (Vol. i. p. 202) | 332 |

| H. | Nicolas Bellin of Modena (Vol. i. pp. 282-4) | 333 |

| I. | The More Family Group (Vol. i. pp. 291-302) | 334 |

| The Portrait of Sir Thomas More (Vol. i. pp. 303-4) | 340 | |

| J. | Holbein’s Return to England in 1532 (Vol. i. p. 352) | 340 |

| K. | Lord Arundel and Rembrandt as Collectors of Holbein’s Pictures (Vol. ii. p. 66) | 341 |

| The Portraits of Sir Nicholas Poyntz (Vol. ii. p. 71-72) | 342 | |

| viL. | Holbein’s Visit to Joinville and Nancy in 1538 (Vol. ii. pp. 148-149) | 343 |

| M. | Holbein’s Studio in Whitehall (Vol. ii. p. 185) | 344 |

| The Barber-Surgeons’ Picture (Vol. ii. p. 294) | 346 |

| SUMMARY LIST OF HOLBEIN’S CHIEF PICTURES AND PORTRAITS | 347 |

| PICTURES BY AND ATTRIBUTED TO HOLBEIN, AND OF HIS SCHOOL AND PERIOD, EXHIBITED AT VARIOUS EXHIBITIONS BETWEEN 1846 AND 1912 | 359 |

| I. | The British Institution, 1846 | 359 |

| II. | Art Treasures of the United Kingdom Collected at Manchester in 1857 | 360 |

| III. | Special Exhibition of Works of Art, South Kensington Museum, June, 1862 | 361 |

| IV. | Special Exhibition of Portrait Miniatures on Loan at the South Kensington Museum, June, 1865 | 362 |

| V. | First Special Exhibition of National Portraits ending with the Reign of King James the Second on Loan to the South Kensington Museum, 1866 | 363 |

| VI. | Third and Concluding Exhibition of National Portraits on Loan to the South Kensington Museum, April, 1868 | 367 |

| VII. | Royal Academy of Arts, Winter Exhibitions of Works by the Old Masters, 1870-1912 | 368 |

| VIII. | Grosvenor Gallery, Winter Exhibition of Drawings by the Old Masters, 1878-79 | 374 |

| IX. | Exhibition of the Royal House of Tudor. New Gallery, 1890 | 374 |

| X. | Exhibition of the Royal House of Tudor. Corporation of Manchester Art Gallery, 1897 | 381 |

| XI. | New Gallery, Winter Exhibition, 1901-2. Monarchs of Great Britain and Ireland | 382 |

| XII. | Loan Collection of Portraits of English Historical Personages who died prior to the Year 1625. Oxford, 1904 | 383 |

| XIII. | Exhibition Illustrative of Early English Portraiture. Burlington Fine Arts Club, 1909 | 384 |

| XIV. | Pictures by or Attributed to Holbein, described by Dr. Waagen in his “Treasures of Art in Great Britain,” 1854 | 386 |

| A SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY | 390 | |

| INDEX | 401 |

| KING HENRY VIII Reproduced in colour, by kind permission of Earl Spencer, G.C.V.O. Althorp. |

Frontispiece | |

| 1. | GEORG GISZE (1532) Reproduced in colour. Kaiser Friedrich Museum, Berlin. |

4 |

| 2. | HANS OF ANTWERP (1532) Reproduced by gracious permission of H.M. the King. Windsor Castle. |

8 |

| 3. | HERMANN HILLEBRANDT WEDIG (1533) Reproduced in colour. Kaiser Friedrich Museum, Berlin. |

17 |

| 4. | (1) DERICH BORN (1533) Reproduced by gracious permission of H.M. the King. Windsor Castle. |

18 |

| (2) DERICH TYBIS (1533) Imperial Gallery, Vienna. |

18 | |

| 5. | DERICH BERCK (1536) Reproduced by kind permission of Lord Leconfield. Petworth, Sussex. |

22 |

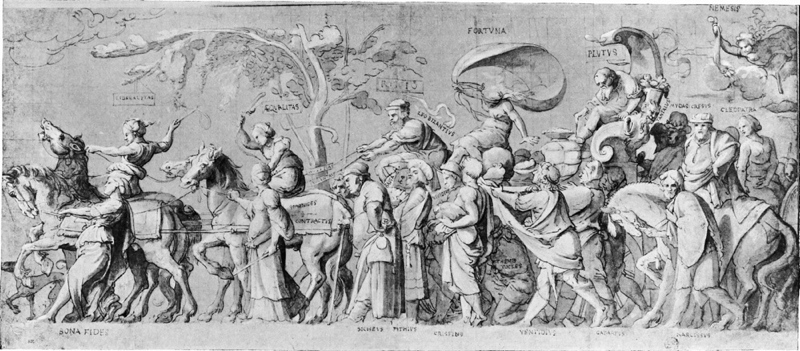

| 6. | THE TRIUMPH OF RICHES Design for the wall-decoration in the Guildhall of the London Steelyard Merchants. Pen-and-wash drawing heightened with white Louvre, Paris. |

26 |

| 7. | THE TRIUMPH OF POVERTY Seventeenth-century copy, by Jan de Bisschop, of the wall-decoration in the Guildhall of the London Steelyard Merchants. British Museum. |

27 |

| 8. | APOLLO AND THE MUSES Design for the decoration of the Steelyard on the occasion of the coronation of Anne Boleyn. Pen-and-wash drawing touched with green. Royal Print Room, Berlin. |

31 |

| 9. | THE TWO AMBASSADORS: JEAN DE DINTEVILLE AND GEORGE DESELVE (1533) Reproduced in colour. National Gallery, London. |

36 |

| viii10. | PORTRAIT OF A MUSICIAN Reproduced by kind permission of Sir John Ramsden, Bt. Bulstrode Park, Bucks. |

52 |

| 11. | ROBERT CHESEMAN (1533) Reproduced in colour. Royal Picture Gallery, Mauritshuis, The Hague. |

54 |

| 12. | CHARLES DE SOLIER, SIEUR DE MORETTE Royal Picture Gallery, Dresden. |

63 |

| 13. | TITLE-PAGE OF COVERDALE’S BIBLE (1535) Woodcut. From a copy in the British Museum. |

76 |

| 14. | SIR THOMAS WYAT Drawing in black and coloured chalks. Reproduced by gracious permission of H.M. the King. Windsor Castle. |

79 |

| 15. | PORTRAIT OF A LADY, PROBABLY MARGARET WYAT, LADY LEE Until recently in the collection of Major Charles Palmer, by whose kind permission it is reproduced. Mr. Benjamin Altman’s Collection, New York. |

82 |

| 16. | SIR RICHARD SOUTHWELL (1536) Reproduced in colour. Uffizi Gallery, Florence. |

84 |

| 17. | SIR NICHOLAS CAREW Drawing in black and coloured chalks. Reproduced in colour. Public Picture Collection, Basel. |

87 |

| 18. | HENRY VII AND HENRY VIII Cartoon for the Whitehall wall-painting. Reproduced by kind permission of the Duke of Devonshire, G.C.V.O. Chatsworth, formerly at Hardwick Hall. |

97 |

| 19. | HENRY VIII National Gallery, Rome. |

102 |

| 20. | QUEEN JANE SEYMOUR Reproduced in colour. Imperial Gallery, Vienna. |

111 |

| 21. | THE DUCHESS OF MILAN (1538) Reproduced in colour. National Gallery, London. |

128 |

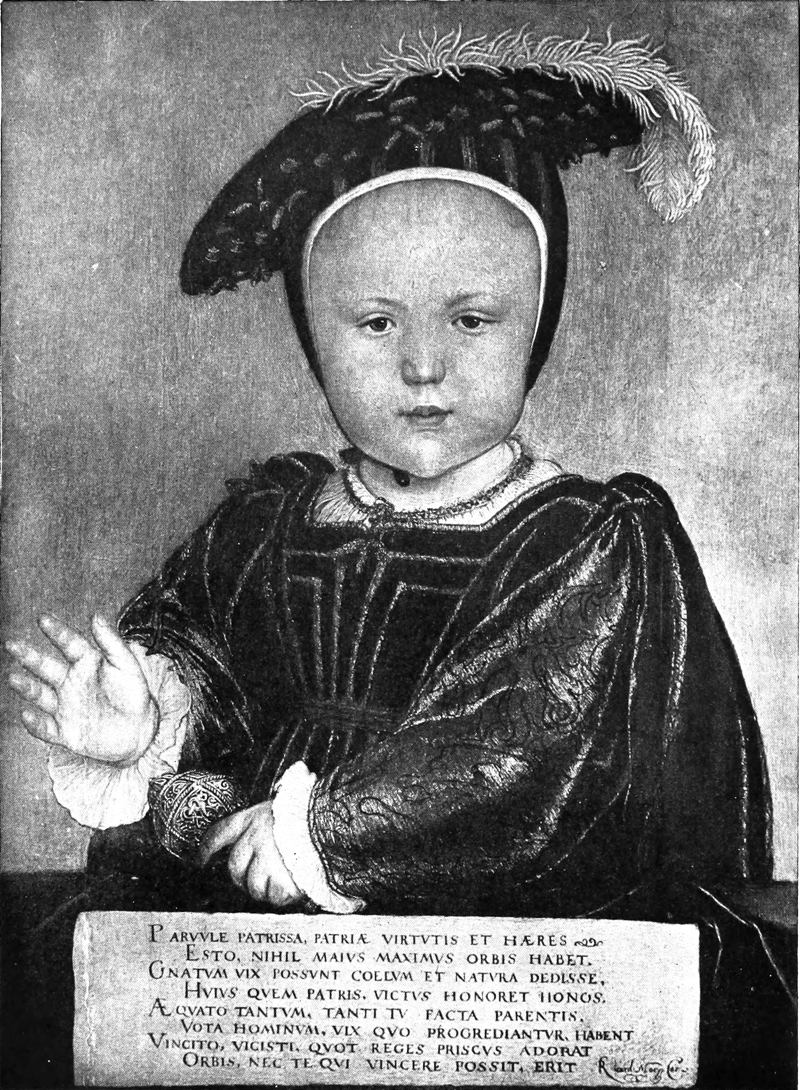

| 22. | EDWARD VI WHEN PRINCE OF WALES (1538-9) Reproduced by kind permission of the Earl of Yarborough. Earl of Yarborough’s Collection. |

165 |

| 23. | EDWARD VI, WHEN PRINCE OF WALES Drawing in black and coloured chalks. Reproduced by gracious permission of H.M. the King. Windsor Castle. |

167 |

| ix24. | QUEEN ANNE OF CLEVES (1539) Reproduced in colour. Louvre, Paris. |

181 |

| 25. | THOMAS HOWARD, DUKE OF NORFOLK Reproduced in colour, by gracious permission of H.M. the King. Windsor Castle. |

197 |

| 26. | HENRY HOWARD, EARL OF SURREY Drawing in black and coloured chalks. Reproduced by gracious permission of H.M. the King. Windsor Castle. |

200 |

| 27. | PORTRAIT OF AN UNKNOWN YOUNG MAN (1541) Reproduced in colour. Imperial Gallery, Vienna. |

202 |

| 28. | PORTRAIT OF AN UNKNOWN YOUNG MAN WITH A FALCON (1542) Reproduced in colour. Royal Picture Gallery, Mauritshuis, The Hague. |

203 |

| 29. | (1) PORTRAIT OF AN UNKNOWN ELDERLY MAN Kaiser Friedrich Museum, Berlin. |

205 |

| (2) PORTRAIT OF AN UNKNOWN ENGLISH LADY Imperial Gallery, Vienna. |

205 | |

| 30. | DR. JOHN CHAMBER Imperial Gallery, Vienna. |

208 |

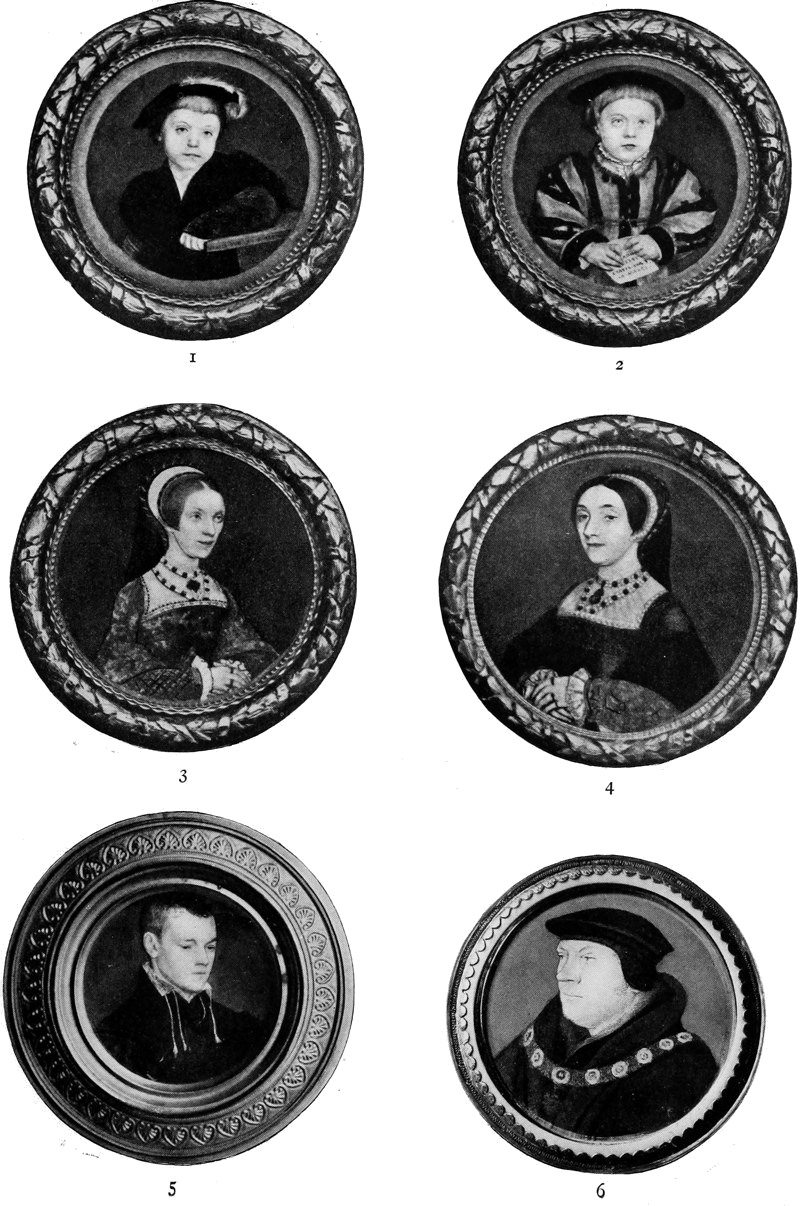

| 31. | MINIATURES (1) Henry Brandon. (2) Charles Brandon. (3) Lady Audley. (4) Queen Catherine Howard. Reproduced by gracious permission of H.M. the King. Windsor Castle. (5) Portrait of an Unknown Youth. Reproduced by gracious permission of H.M. the Queen of Holland. Royal Palace, The Hague. (6) Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex. Reproduced by kind permission of the late Mr. J. Pierpont Morgan. New York. |

222 |

| 32. | STUDY FOR THE PORTRAIT OF A FAMILY GROUP Indian-ink wash drawing with brush outline. British Museum. |

226 |

| 33. | MINIATURES (1) Mrs. Robert Pemberton. Reproduced by kind permission of the late Mr. J. Pierpont Morgan. New York. (2) Hans Holbein: Self-Portrait. Wallace Collection. |

228 |

| x34. | (1) UNKNOWN ENGLISHMAN. (2) WILLIAM PARR, MARQUIS OF NORTHAMPTON Drawings in black and coloured chalks. Reproduced by gracious permission of H.M. the King. Windsor Castle. |

(1) 256 (2) 256 |

| 35. | THOMAS, LORD VAUX Drawing in black and coloured chalks. Reproduced by gracious permission of H.M. the King. Windsor Castle. |

257 |

| 36. | (1) UNKNOWN MAN, SAID TO BE JEAN DE DINTEVILLE (2) MARY ZOUCH Drawings in black and coloured chalks. Reproduced by gracious permission of H.M. the King. Windsor Castle. |

(1) 257 (2) 257 |

| 37. | (1) LADY AUDLEY. (2) LADY MEUTAS Drawings in black and coloured chalks. Reproduced by gracious permission of H.M. the King. Windsor Castle. |

(1) 257 (2) 257 |

| 38. | “THE LADY HENEGHAM”: POSSIBLY MARGARET ROPER Drawing in black and coloured chalks. Reproduced by gracious permission of H.M. the King. Windsor Castle. |

258 |

| 39. | PORTRAIT OF AN UNKNOWN YOUNG MAN Drawing in black and coloured chalks. Reproduced in colour. Public Picture Collection, Basel. |

259 |

| 40. | THE QUEEN OF SHEBA’S VISIT TO KING SOLOMON Silver-point drawing washed with colour. Reproduced by gracious permission of H.M. the King. Windsor Castle. |

262 |

| 41. | QUEEN JANE SEYMOUR’S CUP Pen-and-ink drawing. British Museum. |

274 |

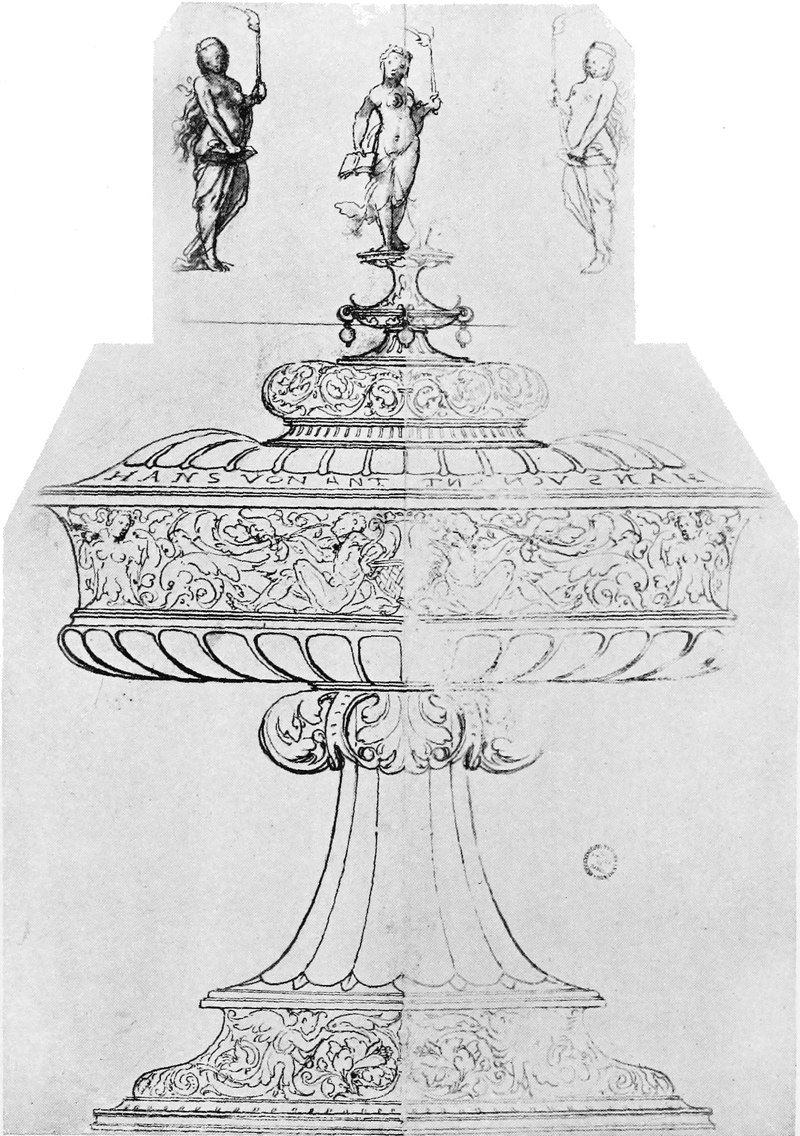

| 42. | HANS OF ANTWERP’S CUP Pen-and-wash drawing. Public Picture Collection, Basel. |

275 |

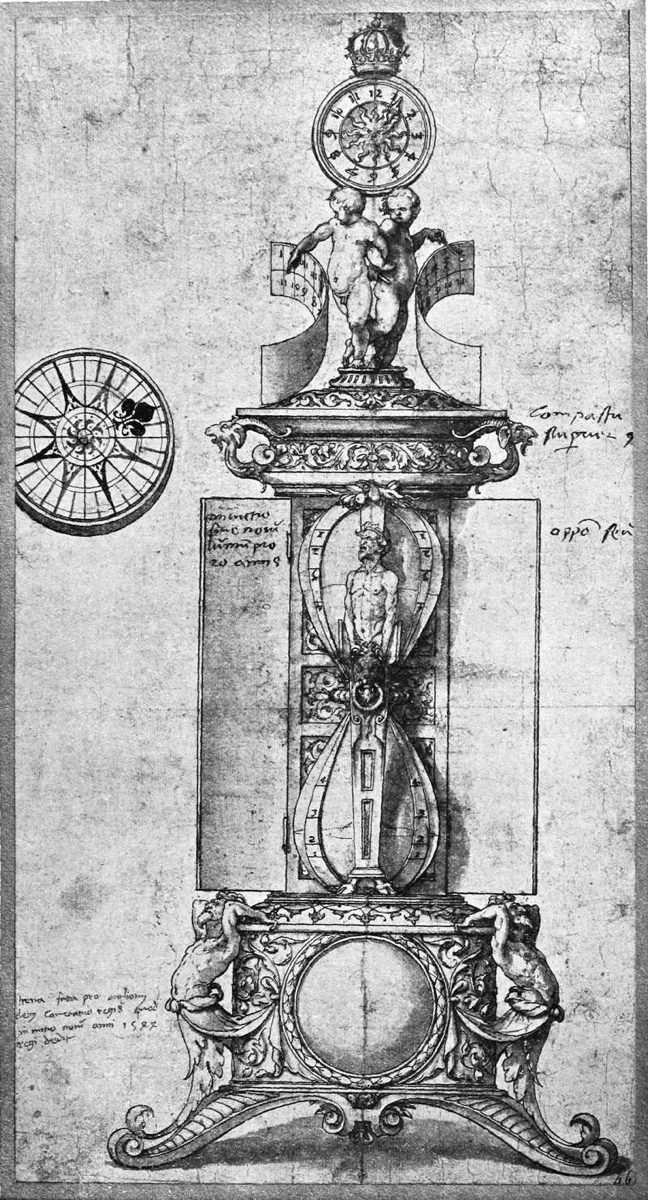

| 43. | SIR ANTHONY DENNY’S CLOCK Indian-ink wash and pen drawing. British Museum. |

276 |

| 44. | DESIGN FOR A DAGGER HILT AND SHEATH Pen-and-ink and Indian-ink wash drawing. British Museum. |

277 |

| xi45. | (1) DAGGER SHEATH WITH FOLIATED ORNAMENT (DATED 1529). (2) UPRIGHT BAND OF ORNAMENT: PIPER AND BEARS. (3) DAGGER SHEATH WITH THE “JUDGMENT OF PARIS” Public Picture Collection, Basel. |

278 |

| 46. | (1) DAGGER SHEATH WITH A DANCE OF DEATH. (2) DAGGER SHEATH WITH A ROMAN TRIUMPH. (3) DAGGER SHEATH WITH “JOSHUA’S PASSAGE OF THE JORDAN” Public Picture Collection, Basel. |

278 |

| 47. | FIVE DESIGNS FOR DAGGER HILTS British Museum. |

278 |

| 48. | EIGHT DESIGNS FOR PENDANTS AND ORNAMENTS British Museum. |

279 |

| 49. | NINE DESIGNS FOR PENDANTS British Museum. |

279 |

| 50. | NINE DESIGNS FOR MEDALLIONS OR ENSEIGNES British Museum. |

280 |

| 51. | (1) BAND OF ORNAMENT: CHILDREN AT PLAY. (2) BAND OF ORNAMENT: CHILDREN AND DOGS HUNTING A HARE Public Picture Collection, Basel. |

282 |

| (3) DESIGN FOR A COLLAR, WITH NYMPHS AND SATYRS. (4) DESIGN FOR A CHAIN. (5) DESIGN FOR A BRACELET OR COLLAR WITH DIAMONDS AND PEARLS. British Museum. |

282 | |

| 52. | DESIGNS FOR ARABESQUE ENAMEL ORNAMENTS British Museum. |

282 |

| 53. | DESIGNS FOR MEDALLIONS, &c. (1) Hagar and Ishmael. (2) The Last Judgment. (3) Icarus. (4) Diana and Actæon. (5) Cupid and Bees. (6) “I await the Hour.” (7) The Rape of Helen. Reproduced by kind permission of the Duke of Devonshire. Chatsworth. |

285 |

| 54. | HENRY VIII GRANTING A CHARTER TO THE BARBER-SURGEONS’ COMPANY Reproduced by kind permission of the Barber-Surgeons’ Company. Barber-Surgeons’ Hall, London. |

288 |

The German Steelyard in London, and Holbein’s connection with its members—Portraits of Georg Gisze—Hans of Antwerp—The Wedighs—Derich Born—Derich Tybis—Cyriacus Fallen—Derich Berck—“The Triumph of Riches”—“The Triumph of Poverty”—Triumphal arch designed by Holbein for the Steelyard on the occasion of Queen Anne Boleyn’s coronation.

THERE is no record to show in what part of London Holbein took up his residence upon his return to England. Possibly he may have settled in the house in the parish of St. Andrew Undershaft, in Aldgate Ward, in which he was residing in 1541; or there may be some truth in the tradition recorded by Walpole[1] that he lived for a time in a house on London Bridge, in close proximity to the Steelyard, where he was much occupied in painting various members of that colony of German merchants for the next year or two. There is nothing to indicate that he returned to Chelsea, for the purpose of finishing the More family picture, or that he received further commissions from Sir Thomas and his immediate circle of friends. During Holbein’s absence in Basel More had been made Lord Chancellor, but had resigned that office on May 16th, 1532, which was about the time of Holbein’s return to London. More, a generous man, had not amassed wealth in the public service, and on relinquishing office and the salary it carried with it, retired into private life on a modest income, not sufficient to permit a lavish patronage of art. Two other members of the More circle, and good friends to Holbein, Sir Henry Guldeford, and Archbishop Warham, died in the same year, the former in May and the latter in August, and thus the painter lost two other patrons immediately after his return. A certain John Wolf was the 2painter employed to provide the escutcheons, banners, and other decorations for Guldeford’s funeral.[2]

1. Anecdotes, &c., ed. Wornum, 1888, vol. i. 86, note.

2. C.L.P., v. 1064.

Whether Holbein’s appearance amid entirely new surroundings was due to these events is doubtful. It is natural to suppose that he would turn instinctively towards a society of fellow-countrymen, speaking the same language, and of similar habits and modes of thought, with whom he would feel most at home, men of comfortable fortunes, well able to afford the luxury of sitting for their portraits, and with the means also of finding him other remunerative work.

These merchants of the Hanseatic League in London formed a rich corporation of considerable numerical strength, whose beginnings went back to the very early days of English history. Some of its most valuable privileges and trading monopolies were granted it by Richard I and Edward III, in return for moneys lent, monopolies which hampered English trade for centuries afterwards. This colony had always occupied a part of the river bank above London Bridge, on the site of what is now the South-Eastern Railway Station in Cannon Street.[3] Their buildings were surrounded by a turreted wall, which stretched from the river northward to Thames Street, and from Allhallows Street on the east to Cosin (Cousins) Lane on the west, their property extending towards Dowgate. Entrance in the principal front in Thames Street was by three fortified gateways, above which the Imperial double-eagle floated, and within stood their old stone Guildhall, with a pleasant garden planted on one side with fruit trees and vines after the fashion of their fatherland, and, to the west of the main gate, vaults where Rhenish wine and other foreign delicacies were sold, a favourite place of resort for English citizens as well as foreigners. It has been generally supposed that its name, the Steelyard, or Stahlhof, arose from the great weighing-machine or steelyard 3which stood within its entrance.[4] The Guildhall and Council Chamber were situated in the western corner on Thames Street, and several passages, including Windgoose Alley, ran from that street to the river, giving access to the shops and small houses, the latter usually consisting of a bedroom and sitting-room for the merchant, and, at the back, stores and apartments for clerks and workmen. The corporation was a close one, and the rules by which its members were bound were as strict as those of a monastery. Within its precincts women were strictly forbidden; all married members had to live outside the walls, nor were guests allowed to lodge there unless also of the Hanseatic community. Each night at nine the gates were shut, and the Steelyard was then like a small walled German town in the midst of London. The breaking of its laws, or the practice of any bad habits, was followed by severe punishment. Its members, too, were obliged to take their share in the wider civic life of London. The Steelyard was represented by an Alderman and a Deputy, and, among other duties, each merchant had his allotted post in case of war, and was obliged to keep the necessary arms ready for the defence of the city.

3. The buildings of the Steelyard were finally pulled down in the autumn of 1863, and the ground was excavated immediately afterwards. The Cannon Street Railway Station covers approximately the whole site of the Steelyard except the strip on the north front cut off for the widening of Upper Thames Street. See Philip Norman, “Notes on the Later History of the Steelyard in London,” Archæologia, vol. lxi. pt. ii. (1909), pp. 389-426; Wykeham Archer, Once a Week, vol. v. (1861); J. E. Price, Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archæological Society, vol. iii. 67 (1870). See also for the whole history of the Steelyard, Lappenberg, Urkundliche Geschichte des Hansischen Stahlhofes zu London, Hamburg, 1851.

4. Dr. Norman, however, considers that it has nothing to do with a weighing-machine, but that it is an Anglicised form of the German “Stahlhof.” See his paper in Archæologia, quoted on the preceding page.

Their privileges were so great that they had always been unpopular, and this dislike grew in strength until the reign of Henry VIII, when the first attempts were made to break up their monopolies, which ended, some sixty years later, in their complete overthrow. When Holbein first came among them, however, they still occupied the foremost place in the commercial life of London, and were an exceedingly rich and prosperous community. They served the King and Court in more ways than one, for they were constantly made use of for the despatch of letters abroad and for the translation of communications received from foreign countries. They made arrangements with their agents in Europe for the payment of the diets and other expenses of Henry’s ambassadors and special messengers, and much confidential continental news was received through their business houses. Books, prints, and various rare and artistic objects were also forwarded to them for delivery to the English court. Thomas Cromwell, in particular, made much use of them in the sending and receiving of foreign correspondence. They also entertained all important visitors, 4artists, craftsmen, and others of their own countrymen who visited England.

Holbein, however, does not appear to have come into contact with them during his first visit to England; no portrait, at least, of a Steelyard merchant of that date has survived, though he painted Niklaus Kratzer, who must have known many of them intimately. Possibly his introduction to them in 1532 was due to his friendship with the German astronomer. In any case, between 1532 and 1536, he painted a considerable number of them, chiefly small half-length portraits, in which the sitter is shown in his own room or office, dressed in sober black, with the accessories of his work scattered round him, and with letters in front of him containing his name and his address at the Steelyard. These portraits were most probably painted for presentation by the sitters to the League of which they were leading members, to be hung on the walls of the Council Chamber of their Guildhall, rather than for the purpose of sending them to family relations abroad. This would account for the presence of several of them in England to-day, for when the Guild was finally broken up in 1598 and much of its property scattered far and wide, some of the portraits remained in this country while others found their way abroad.

Vol. II., Plate 1

GEORG GISZE

Kaiser Friedrich Museum, Berlin

The portrait of Georg Gisze, now in the Berlin Museum (No. 586) (Pl. 1),[5] was one of the first, if not the first, of these likenesses of Steelyard merchants to be painted by Holbein. This portrait is not only the most elaborate work of the whole series, but the sitter was also one of the most important members of the League then in London. His name is spelt in more than one way on the picture itself, and other versions of it are to be found in the English State Papers. In the letter from his brother, which he holds in his hand, he is addressed, according to the Berlin Catalogue, as Jerg Gisze. The full address is “Dem erszamen Jergen Gisze to lunden in engelant mynen broder to handen.” Below the motto on the wall, beneath the shelf on the left—“Nulla sine merore voluptas”—in the sitter’s own handwriting, is the signature G. Gisze or Gyze. It has been read both ways, for the second letter may be taken either as an i followed by a long s, or, as two connected strokes representing the letter y. On other letters from foreign correspondents, tucked behind the wall-rails on the right, his name is also spelt Gisse and Ghisse, while in the 5distich inscribed on a cartellino fastened to the wall over his head it appears in its Latinised form of Gysen. This distich, which also contains the date and the sitter’s age, runs as follows:—

5. Woltmann, 115. Reproduced by Davies, p. 140; Knackfuss, fig. 117; Berlin Catg., p. 176; Ganz, Holbein, p. 95; and in colour by the Medici Society.

In days when spelling was largely phonetic it is not surprising to find proper names spelt in a variety of ways, and the Hanse merchants, in particular, received letters from correspondents in all parts of the world, speaking a variety of languages and dialects. According to the Berlin Catalogue, Georg Gisze was born on 2nd April 1497, so that he was of Holbein’s own age, and died in February 1562, and was a member of a leading Danzig family. Woltmann regarded him as a Swiss, and states that there was a family called Gysin settled in the neighbourhood of Basel, and that the name is still to be seen on numerous sign-boards in the adjacent small town of Liestall.[6] Miss Hervey, on the other hand, suggests that, however the name may be spelt, it was probably a variation of that of Gueiss, which was one of the most distinguished in the annals of the Steelyard.[7] The family belonged to Cologne, and Albert von Gueiss was a representative of the Steelyard at the Conference held at Bruges in 1520. In at least one entry in the Steelyard records this name is spelt Gisse. She suggests, therefore, that Georg Gisze may have been a younger brother or a son of this Albert von Gueiss. In his book on Holbein’s “Ambassadors” picture, Mr. W. F. Dickes, who, in his anxiety to prove that Holbein was not in England in 1532, conveniently ignores the evidence of the letter which Gisze holds in his hand, addressed to him “in London,” conclusive proof that the portrait was produced in this country, is of opinion that it was painted in Basel.[8] Little is known of its history since it left the walls of the Guildhall in Thames Street. It was in the Orleans Collection in 1727, and was purchased at the sale of that collection by Christian von Mechel.[9] Various attempts to induce the 6Basel Library to buy it proved unavailing. It was afterwards for a time in Basel, and in 1821 was added to the Solly Collection, passing later into the Berlin Gallery.

6. Woltmann, i. 366.

7. Holbein’s Ambassadors, p. 240.

8. Holbein’s “Ambassadors” Unriddled, p. 2.

9. See Ganz, Holbein, p. 240. It was brought to England with the Orleans pictures in 1792, and in the Sale-Catalogue was described as “Portrait of Gysset.” It fetched 60 guineas. See Waagen, Treasures, &c., Vol. ii. p. 500.

The first time the name of Georg Gisze occurs in the English State Papers is in 1522,[10] when he was twenty-four years of age. The paper is an English translation of a protection, dated Lyon, 26 June 1522, granted by Francis I to Gerrard van Werden, George Hasse, Henry Melman, Geo. Gyse, Geo. Strowse, Elard Smetyng, Hans Colynbrowgh, and Perpoynt Deovanter, merchants of the Hanse, during the war between him, the Emperor, and England. They are forbidden to deal in wheat, salt, “ollrons,” harness, and weapons of war. Deovanter appears to have been one of the leading merchants. At this period he went as a representative of the Steelyard on several missions to Francis for the purpose of the recovery of goods taken from their ships by the Captain of Boulogne. During his absence he gave power of attorney in a suit of his against George Byrom, of Salford, to several friends and fellow-merchants, among them “George Guyse,” and, it is interesting to note, “Th. Crumwell, of London, gent.”[11]

10. C.L.P., vol. iii. pt. ii. 2350.

11. C.L.P., vol. iii. pt. ii. 2446, 2447, 2754.

The next reference to Gisze is at Michaelmas, 1533, in a letter from Thomas Houth to the Earl of Kildare in Ireland,[12] respecting the death of a certain John Wolff, in which, speaking of some bills, he says,—“I ascertained at the Steelyard that the handwriting was his, by the evidence of Geo. Gyes, the alderman’s deputy, and others.” This letter proves that Gisze held an important position in the Steelyard, as Deputy to the Alderman, who was probably Barthold Beckman, of Hamburg.[13] Possibly his appointment to this position occasioned the painting of his portrait.

12. C.L.P., vol. vi. 1170.

13. Lappenberg, Urkundliche Geschichte des Hansischen Stahlhofes zu London, p. 157; Miss Hervey, Holbein’s Ambassadors, p. 239.

The portrait is life-size, and half-length, the sitter being turned to the right, the face towards the spectator, and the eyes turned slightly to the left. He is wearing a flat black cap over his fair hair, which is cut straight across the forehead and covers the ears; and a dress of rose-coloured silk with a sleeveless overcoat of black, and a fine white linen shirt. He is seated behind a table covered with a cloth of Eastern design, and is in the act of opening his brother’s letter. By him, on the table, stands a tall vase of Venetian glass with twisted handles, 7filled with carnations, and scattered in front of him are various objects used in his business, a seal, inkstand, scissors, quill pens, a leather case with metal bands and clasps, and a box containing money. From the shelves on the walls hang scales for weighing gold, a seal attached to a long chain, and a metal ball for string, with a damascened design and a band with the words “HEER EN” repeated round it.[14] Books and a box are upon the shelves, and tucked within the narrow wooden bars which run round the walls are parchment tags for seals and several letters with addresses in High German. On these occur the dates 1528 and 1531, while the names of the correspondents with which they are endorsed can be more or less clearly discerned, as well as the word “England.” Woltmann reads the names as “Tomas Bandz,” “Jergen ze Basel,” and “Hans Stolten.” This last letter is marked with the writer’s particular device, which also occurs on a second letter, and is very similar to the device on the letter in the picture of Derich Tybis in Vienna. The walls of his room are painted in greyish green, the paint shown as rubbed and discoloured here and there, and along the bars and shelves, which have been worn by constant use.

14. In the inventory of the goods of John Wolff, attached to the letter mentioned above, a similar ball is included—“a round ball gilt for sealing thread to hang out of to seal withal.” C.L.P., vol. vi. 1170.

The painting of the numerous details is wonderful in its accurate realism, showing the closest observation and an evident delight in their perfect rendering. It has been suggested, as the picture contains many more accessories than in his other portraits of members of the Steelyard, that Holbein took particular pains with it as the first of a possible series, and that it was a kind of “show-piece,” in order that his clients might see of what he was capable. This superb portrait, which is in a better state of preservation than most of Holbein’s existing works, is finer in its clear, luminous colour and more delicate in its drawing than any other of his pictures of this period. It is almost Flemish in the minuteness and care of its finish and in its cool, clear tones. All the objects of still-life which surround the sitter, which are placed about him as naturally as though the artist had come upon him suddenly when engaged upon his daily business, and had there and then painted him, without arranging or posing, whether of silk, or linen, or gold, or steel, or glass, are painted with a fidelity to nature never excelled by the Dutchmen or Flemings of the following century, 8who devoted their whole career to the rendering of still-life. In Holbein’s portrait, however, all these carefully-wrought minor details, beautiful in themselves as they may be, in no way force themselves on the attention to the detriment of the portrait itself, which stands out as a vivid representation of the sitter’s personality, in which the essentials of his character have been seen with an unerring eye, and set down upon the panel with an unerring hand. We get here the young German merchant to the very life, precise, deliberate and orderly in the transaction of his affairs, with strongly-marked German features, long nose, and determined chin, a living presentment which only a master could have produced.

Ruskin’s glowing description of the picture is well known, but it is so true and so eloquent that a sentence from it may be quoted:—

“Every accessory is perfect with a fine perfection; the carnations in the glass by his side; the ball of gold, chased with blue enamel, suspended on the wall; the books, the steelyard, the papers on the table, the seal ring with its quartered bearings—all intensely there, and there in beauty of which no one could have dreamed that even flowers or gold were capable, far less parchment or steel. But every change of shade is felt, every rich and rubied line of petal followed, every subdued gleam in the soft blue of the enamel and bending of the gold touched with a hand whose patience of regard creates rather than paints. The jewel itself was not so precious as the rays of enduring light which form it, beneath that errorless hand. The man himself what he was—not more; but to all conceivable proof of sight, in all aspect of life or thought—not less. He sits alone in his accustomed room, his common work laid out before him; he is conscious of no presence, assumes no dignity, bears no sudden or superficial look of care or interest, lives only as he lived—but for ever. It is inexhaustible. Every detail of it wins, retains, rewards the attention with a continually increasing sense of wonderfulness. It is also wholly true. So far as it reaches, it contains the absolute facts of colour, form, and character, rendered with an unaccusable faithfulness.”[15]

15. Ruskin, “Sir Joshua and Holbein,” Cornhill Magazine, March 1860; reprinted in On the Old Road, vol. i. pt. i. pp. 221-236.

Vol. II., Plate 2

HANS OF ANTWERP

1532

Windsor Castle

The portrait of Hans of Antwerp, in Windsor Castle (Pl. 2),[16] 9belongs to the summer of the same year, 1532, and was one of the earliest of the Steelyard series. It is in oil on panel, and has darkened with age, and has suffered to some extent from repaintings. It represents the half-length figure of a middle-aged man, about three-quarters the size of life. He is turned to the right, seated at a table, upon which his elbows rest, and he is about to cut the string of a letter with a long knife. He has thick bushy hair and beard, brown in colour, and brown eyes, and is wearing a dark overcoat, which may have been originally dark green in colour, edged with a broad band of brown fur, and beneath it a brown dress and a white shirt with the collar embroidered with black Spanish work. On his head is a flat black cap. The table is covered with a dark green cloth, and upon it, in front of him, are placed a pad of paper with a quill pen resting on it, some coins and a seal engraved with the letter W. The head, strongly lightened, stands out against a background of grey-brown wall, with a strip of darker colour on the right-hand side of the panel. He wears a signet ring on the first finger of his left hand, and a smaller ring on the little finger of the right.

16. Woltmann, 265. Reproduced by Law, Holbein’s Pictures at Windsor Castle, Pl. ii.; Davies, p. 30; Knackfuss, fig. 119; Cust, Royal Collection of Paintings, Windsor Castle, 1906, Pl. 46; Ganz, Holbein, p. 96.

The letter which he holds in his hand has a superscription in crabbed Teutonic writing, which Woltmann, after careful examination, deciphered as follows:—

The parts in brackets are hidden in the original by the knife, and have been added conjecturally by him, so that the whole inscription would run in English: “To the honourable Hans of Antwerp in London, in the Steelyard, these to hand.” The words “ersamen” and “Stallhoff” are distinct, but the “Anwerpen” is less clear, and only the first letter of the Christian name is certain.

The brown under-dress the sitter is wearing certainly has some appearance of the leather apron worn by goldsmiths which Woltmann declared it to be;[17] and this, together with the gold coins on the table, such as goldsmiths were in the habit of exhibiting in their shops, he regarded as additional proof that the portrait represents the goldsmith, 10Hans of Antwerp, Holbein’s close friend and one of his executors.[18] There is considerable probability that this ascription is correct, though it is by no means absolutely certain. On the paper-pad lying on the table there is an inscription, evidently in the sitter’s handwriting, giving his age and the date. Even this inscription is not absolutely clear. Woltmann reads it:—

17. Woltmann, i. p. 368. An under-dress of similar fashion, however, is worn by nearly all Holbein’s Steelyard sitters.

18. It should be noted, however, that similar coins appear in the box on the table in the portrait of Georg Gisze.

The second “A.D.,” however, is evidently wrong. Mr. Law[19] reads it as a possible “Aug.” for August, and is doubtful about the word “Julii.” Both these writers fail to decipher the sitter’s age, but it appears to be “53,” or, perhaps, “33,” the latter agreeing better with the apparent age of the sitter.

19. Law, Holbein’s Pictures, &c., p. 5.

The W. on the seal affords some evidence against the portrait being that of John of Antwerp. Woltmann calls it “the device of his trading house,” and in this Mr. Law follows him. It is much more probable, however, that it is the initial of his surname. The seal is of a similar shape to those in the portraits of Georg Gisze and Derich Tybis. In the former the lettering is illegible, but in the latter it is plainly “D. T.” Before Hans of Antwerp’s surname was known, Woltmann’s suggestion was not out of place, but Mr. Lionel Cust[20] has recently discovered it to have been Van der Gow, which does not accord with the letter on the seal. Among the numerous references to John of Antwerp in the State Papers and elsewhere he is never once spoken of as belonging to the Steelyard, whereas the picture in question is in all probability a portrait of some merchant of the Hanseatic League. More than one German merchant of the Steelyard whose surname began with W is mentioned in the records, such as Gerard van Werden and Ulric Wise, while one of the leading jewellers of Henry’s reign was Morgan Wolf, though he was almost certainly a Welshman. However, until further evidence is forthcoming, the name Hans of Antwerp must stand as the sitter for this portrait, and it has much in its favour.

20. Burlington Magazine, vol. viii. No. XXXV. (Feb. 1906), pp. 356-60.

As the friend and witness and administrator of Holbein’s will, the question of the true portrait of John of Antwerp is of unusual interest. 11The two men appear to have been closely associated, and there is no doubt that Holbein supplied him with designs. One such design is well known—the drawing for a beautiful drinking-cup in the Basel Gallery upon which is inscribed the name “Hans Von Ant....” (Pl. 42).[21] Mr. Lionel Cust conjectures that the cup given by Cromwell to the King on New Year’s Day, 1539, made by John of Antwerp, was this identical cup; but it hardly appears probable that an object made for such a purpose would have the maker’s name placed upon it so prominently on a broad band running round its centre. It may be suggested that it is more likely to have been intended by the maker for presentation to the Hanseatic League to form part of the corporation plate of that body kept in the Guildhall of the Steelyard.

John of Antwerp’s name occurs frequently in the private accounts of Thomas Cromwell for the years 1537-39, and Mr. Lionel Cust has gathered together much interesting information about him. In a letter from Cromwell to the Goldsmiths’ Company we learn that he had been settled in London since 1515, but the first reference to him Mr. Cust finds is in March 1537, in the Privy Purse Expenses of the Princess Mary, which runs: “Item payed for goldsmythes workes for my ladies grace to John of Andwarpe iiij li, xvij s, vij d.” There is, however, an earlier reference, and one of considerable interest, in the State Papers, in a letter from one Richard Cavendish to the Duke of Suffolk, dated Norton, 5th June 1534, which shows that John Van Andwerp was at that time employed with a certain Hans De Fromont in searching for a gold mine at Norton. “They are,” says Cavendish, “applying themselves with diligence to find the mine. Here is the greatest diversity of earth and stones, for the stones in the gravel in most places appear to be very gold. Many assays have been made to prove it, but nothing found as yet, and it is believed the glitter ‘is but the scum of the metal which groweth beneath the ground.’ They have now begun to dig pits to get at the principal vein. The people are as glad as ever he saw to further the matter, for in old evidences the place is called Golden Norton, which proves that gold may be found there. He sees no great forwardness as yet, but prays God they may find some.”[22]

22. C.L.P., vol. vii. 800.

Cromwell employed him in a number of ways. In December 1537[23] 12he received 15s. for setting a great ruby, and 29s. for the gold in the ring. In November 1538[24] he was at work on the cup already mentioned for a New Year’s Gift to Henry, for which purpose he received 52 oz. of gold, and was paid nearly £20. Other work during these years consisted in making a George, setting stones in rings, making chains and trenchers, and repairing various Georges, Garters, and other jewellery belonging to the Lord Privy Seal, full details of which will be found in Mr. Cust’s paper, the last entry being dated 15th December 1539.[25]

23. C.L.P., vol. xiv. pt. ii. 782, ii. (p. 333).

24. C.L.P., vol. xiv. pt. ii. 782, ii. (p. 338).

25. Ibid., under various dates.

An entry in the Book of Payments of the Treasurer of the Chamber for April 1539[26] shows him in another capacity, one, as already noted, in which the foreign traders in England were frequently employed by the Court. He received one shilling from the King’s purse for forwarding letters of importance to Christopher Mount and Thomas Panell, “his gracis servauntes and oratours in Jarmayne.”[27]

26. C.L.P., vol. xiv. pt. ii. 781 (p. 309).

27. Mr. Cust suggests that this message was addressed to Holbein. He says: “At Lady Day, 1539, he (Holbein) seems to have been still absent (in Basel), though he was back in England before Midsummer.” (Burlington Magazine, February 1906, p. 359.) This, however, is not probable. Holbein was certainly back from Basel by December 1538, when he received £10 for his journey to Upper Burgundy, and he presented a portrait of Prince Edward to the King on New Year’s Day, 1539. He received no salary on Lady Day, 1539, because he had already received a year’s wages in advance at Midsummer, 1538, to date from the previous Lady Day, and not because he was out of England. At this period messages and money were being constantly sent to Christopher Mount, who was much abroad on missions to the German Protestant princes, and the question of the marriage with Cleves was only one of the many affairs, and one of the least important, upon which he was then engaged.

In 1537 Hans of Antwerp’s name occurs in the return for Subsidies of Aliens in England, among foreigners dwelling in the parish of St. Nicholas Acon, as “John Andwarpe, straunger, xxx li., xxx s.” In a similar list for the same parish in 1541 he is given for the first time his proper name: “John Vander Gow, alias John Andwerp, in goodes, xxx li., xxx s.” Mr. Cust suggests that his name may have been Van der Goes. This assessment of his goods at £30 and the tax on it of thirty shillings was the customary rate for foreigners. Nicholas Lyzarde, Elizabeth’s serjeant-painter,[28] was assessed to the same amount—but Holbein was taxed at the higher rate of £3 on his salary of £30, as it was the custom to tax “lands, fees and annuities” at double the rate of goods.

In April of the same year Van der Gow was anxious to obtain the 13freedom of the Goldsmiths’ Company as a step towards being admitted to the right of citizenship in London. Cromwell’s letter, recommending him to the Company “most hartely,” states that he had already lived twenty-six years in London, had married an Englishwoman, by whom he had many children, and purposed continuing in London for the rest of his life. This desire to become a naturalised Englishman might be taken as some evidence that he was not a member of the Steelyard confraternity.

From the register of the church of St. Nicholas Acon, in Lombard Street, where the goldsmiths have always congregated, we learn that he had a son, Augustine Anwarpe, baptized on 27th November 1542, and a second son, Roger, on 10th December 1547; that on three successive days in September 1543 three of his servants, John Ducheman, Jane, his maid, and Richard, were buried; that a fourth servant was buried on the 10th August 1548; and that his son Augustine was buried on 1st July 1550.[29] There can be little doubt that the three servants died of the plague which was raging in London in September 1543. Holbein was almost certainly another of its victims, and Mr. Cust suggests that he may very probably have caught the infection in John Van der Gow’s house.

29. These facts are taken from Mr. Cust’s paper.

The portrait, it is to be supposed, like Holbein’s other representations of Steelyard merchants, was very possibly presented to the Guild, and would remain hanging in their Guildhall until they were expelled by Elizabeth in 1598. “When in 1606,” says Woltmann, quoting from Lappenberg, “under James I, the Steelyard was given back to its possessors, the rooms were found in an evil condition, and all movables, such as tables, seats, bedsteads, and even panels and glass windows, were almost entirely stolen. That under such circumstances a sparing hand watched over the pictures is scarcely to be expected.”[30] The portrait of Hans of Antwerp, whatever its earlier adventures may have been, was in the collection of Charles I, in which it was No. 29, and is described in his catalogue as: “Done by Holbein. Item. Upon a cracked board, the picture of a merchant, in a black cap and habit having a letter with a knife in his hand cutting the seal thread of the letter; a seal lying by on a green table; bought by Sir Harry Vane and given to the King.” The crack in the panel is still plainly 14visible. It was valued by the Commonwealth Commissioners at £100, and sold for that sum. It reappears, however, in James II’s catalogue, No. 499: “By Holbein. A man’s head, in a black cap, with a letter and penknife in his hand.” It is possible that it is the picture by “Holbin” of “a Dutchman sealing a letter,” which was in the Duke of Buckingham’s collection at York House in 1635,[31] from which it may have passed into that of Charles I. The picture, though it has not the richness and transparency of colour of the “Gisze,” or its extreme delicacy of execution and luxuriance of detail, is a vigorous and life-like representation of a somewhat stolid German, painted with the truth and sincerity which Holbein brought to everything he touched.

30. Woltmann, i. p. 381. See also Norman, Archæologia, vol. lxi. pt. ii. p. 394.

31. See Randall Davies, “Inventory of the Duke of Buckingham’s Pictures,” &c., Burlington Magazine, March 1907, p. 382.

The two small roundels, which hitherto have always been regarded as likenesses of Holbein himself, undoubtedly represent, as Dr. Ganz has recently pointed out, the same individual as the sitter in the Windsor picture, who, until his identity is finally settled, it is most convenient to call Hans of Antwerp. The first is the beautiful little painting on oak in the Salting collection,[32] in which the sitter is shown in full-face, with a flat black cap, a gown lined with light-coloured fur, and a dark under-coat or vest, cut straight across the top, as in most of Holbein’s other Steelyard portraits. The left hand only is shown, with a ring on the first finger. On the background on either side of the head is the faded inscription “ETATIS SVÆ 35.” It was possibly painted a year or two later than the Windsor portrait, to which the likeness is very marked. If, however, the sitter really represents Hans of Antwerp, and he was painted a second time by Holbein about 1534-5, when 35 years of age, he must have been only a boy when he settled in London in 1515. The second roundel is in Lord Spencer’s collection at Althorp,[33] and this, too, has always been regarded as a portrait of Holbein by himself. Here again the likeness to the Windsor picture is a strong one, though the opposite side of the face is seen, as he is shown in three-quarters profile to the spectator’s left. There are slight variations in the dress, the undervest being lower, and disclosing more of the white shirt. Some critics 15regard it as a genuine work by Holbein, but Dr. Ganz places it among the doubtful and wrongly-attributed pictures. He suggests that it is probably one of the two roundels considered to be self-portraits by Holbein which C. van Mander saw in Amsterdam in 1604, and was engraved by A. Stock as such in 1612 and published by H. Hondius. There is a replica of it in the Provinzial Museum in Hanover.[34] All three works evidently represent the same man, and at about the same age.

32. Exhibited Burlington Fine Arts Club, 1909, Case D, No. 1, and reproduced in the Catalogue, Pl. xxxiv.; also by Ganz, Holbein, p. 114.

33. Reproduced by Ganz, Holbein, p. 226.

34. See Ganz, Holbein, p. 253.

In the same year, 1532, he painted another goldsmith, Hans von Zürich, but the picture has disappeared, and is now only known from the engraving Hollar made of it in 1647, when it was in the Arundel collection. In the engraving he is shown at half-length, full-face, the body turned slightly to the left, and is a thin man, with a pleasant expression. It is inscribed on the top: “Hans von Zürch, Goltshmidt. Hans Holbein, 1532,” and below, “W. Hollar fecit, 1647, ex collectione Arundeliana,” and has a dedication by the publisher, H. Vander Borcht, to Matthäus Merian.[35] The date indicates that Hans von Zürich must have been living in London at that time, though his name does not occur in the State Papers.

35. Reproduced by Ganz, Holbein, p. 197 (i.). Parthey, No. 1411.

One other portrait of a German merchant by Holbein was painted in the year 1532.[36] It is in the collection of Count von Schönborn in Vienna, and is one of a pair of portraits of brothers or near relations, members of the Wedigh family of Cologne.[37] They hung together until 1865, in which year the finer one of the two, dated 1533, was acquired by Herr B. Suermondt, of Aix-la-Chapelle, and is now in the Berlin Gallery, having been purchased in 1874, together with another fine portrait by Holbein of an unknown young man, from the Suermondt collection. The close relationship of the two sitters is proved by the exactly similar coat of arms on the enamelled ring each one is wearing. In the first edition of his book Woltmann gave it as his opinion that they were Englishmen, but afterwards came to the conclusion that both portraits represented German Steelyard merchants. The belief that they were Englishmen was afterwards strengthened by a communication to the Berlin authorities from Privy Councillor Dielitz, who, from the coat of arms on the rings, held that the pictures represented 16two members of the English family of Trelawney. This ascription, however, has been proved to be wrong, and it may be pointed out that the motto inscribed on the paper projecting from the book in the Vienna portrait,—“Veritas odium parit” (“Truth brings hatred”), is not the present motto of the Trelawney family. On the side of the same book, painted on the edges of the leaves, are the letters “H E R. W I D.,” and more recent research has established the fact that the two men were members of the Wedigh family. Members of this patrician family of Cologne had been connected with the London Steelyard since 1480. In this connection it is interesting to note that the seal in the so-called “Hans of Antwerp” picture is engraved with the letter “W,” which suggests some possibility that he, too, may have been a Wedigh.

36. Woltmann, 262. Reproduced by Knackfuss, fig. 118; Ganz, Holbein, p. 97.

37. Both portraits are mentioned in an inventory of 1746.

The 1532 picture in the Schönborn collection is a small half-length. The subject, who is seated at the back of a table, is turned to the right, with head almost full-front and looking at the spectator. His right arm rests on the table, and he holds his gloves in his left hand. His hair, cut straight across his forehead, covers his ears, and he is clean-shaven. He is wearing the usual dark overcoat with deep fur collar, and an inner collar or lining of lighter fur, opened sufficiently to show a part of his embroidered under-dress, the sleeves of which are of watered or patterned silk, and a white pleated shirt gathered round the neck in a small frill. The customary flat black cap is on his head. On the table to the left is a leather-bound book with two clasps, with the artist’s initials on the cover, and a piece of paper projecting from between the leaves on which is written the Latin motto already quoted. On the plain blue background is inscribed on either side of the head, “ANNO. 1532.” and “ÆTATIS.SVÆ. 29.” It is a sympathetic and simple rendering of a young man of serious expression, in which both the beardless face, of a somewhat reddish complexion, and the two hands are very finely painted. Woltmann conjectured that the Latin motto indicated that the book on the table might be one of those writings which the German reformers were at that time busily engaged in smuggling into England, the secret dissemination of which neither Wolsey or More could stay, in spite of the drastic methods they employed to stamp it out. Although possessing many privileges, the men of the Steelyard were by no means free from persecutions of this nature.

The companion picture, in the Berlin Gallery (No. 586B) (Pl. 3), 17represents Hermann Hillebrandt Wedigh.[38] Like that of his brother, it is a small half-length. He stands directly facing the spectator, the left hand holding his buff-coloured gloves, and the right half hidden by the heavy dark-brown cloak, with black velvet collar and velvet at the wrists, the folds of which are finely arranged and painted. This cloak lacks the customary fur collar. The white shirt, partly open and showing the bare chest beneath, is tied in the front by long strings passed through a white button, and the embroidered collar is almost hidden by his beard. A flat black cap is on his head, of the type worn by all the Steelyard merchants in Holbein’s portraits. The hair, beard, and long moustache are fair, the separate hairs being indicated with almost microscopic care. The eyes are brown, the left one being decidedly smaller than the right, and there is a corresponding difference in the development of the two sides of the face. There are no accessories of any kind, and upon the plain blue background, on either side of the head, is inscribed, in gold letters: “ANNO. 1533.” and “ÆTATIS SVÆ. 39.” The gold ring is enamelled in red, white and black, and in the circle round the coat of arms there are some letters now undecipherable. This is one of the finest and most sympathetic portraits ever painted by Holbein. The face, in spite of its slight irregularity, is one of great charm and much sweetness of expression. The drawing of the hands and mouth is particularly fine.[39]

38. Woltmann, 116. Reproduced by Dickes, p. 79; Knackfuss, fig. 121; Ganz, Holbein, p. 98; and in colour in Early German Painters, folio v.

39. Mr. Dickes, who does not hesitate to suggest that a date has been tampered with if it suits his argument to do so, regards this picture as “an unmistakable portrait of the second person” in the “Ambassadors” picture, such person being, in his opinion Philipp, Count Palatine. This picture, he says, “has a damaged date, catalogued as 1533, and a more clear “ætatis 34,” which is no doubt correct, for the moustache shows five years’ more growth” (i.e. than in the “Ambassadors”). “No one who compares the two faces can doubt the identity, or that if of Philipp—born November 12, 1503, as indicated in our picture—its correct date is 1538.” It requires a very vivid imagination to see a likeness between Wedigh and the portrait of the Bishop of Lavaur in the National Gallery group; but Mr. Dickes sees Philipp and Otto Henry in so many portraits scattered about Europe, having but the faintest resemblance to one another, and gives to Holbein so many pictures he never painted, and takes from him at least one of his finest works (the Morette in Dresden, which he calls Otto Henry and attributes to Amberger) that his attribution with regard to the Wedigh portrait is not worth serious consideration. The date upon it is plainly enough 1533. At the time he was writing his book the age of the sitter appeared to be “34,” but recent cleaning shows it to be “39.” (Dickes, Holbein’s “Ambassadors” Unriddled, p. 81.)

Three other portraits of Steelyard merchants bear the date 1533: Derich Born at Windsor, Derich Tybis at Vienna, and Cyriacus Fallen 18at Brunswick. The portrait of Derich Born (Pl. 4 (1)),[40] in the royal collection at Windsor Castle, painted when he was twenty-three, is, after the “Gisze” and “Hermann Wedigh” portraits, perhaps the most attractive of the Steelyard series. It is slightly under life-size, the figure shown nearly to the waist, turned to the right, and the head, upon which the light falls strongly from above on the right, nearly in full-face. His right elbow rests on a stone ledge or parapet which runs across the picture, the left hand placed across the right wrist, and a gold signet-ring with a coat of arms on his forefinger. He wears a flat black cap, black silk dress, and a white shirt with a collar of so-called Spanish work of black silk thread, very delicately painted. He is beardless, and has chestnut-brown hair, cut straight across the forehead and hiding the ears in the customary fashion.

40. Woltmann, 266. Reproduced by Law, Pl. 3; Davies, p. 154; Ganz, Holbein, p. 100; Cust, Royal Collection of Paintings, Windsor Castle, 1906, No. 45.

On the flat stonework below the ledge on which his arm rests is inscribed, in large Roman letters as though cut in the stone, the following Latin couplet:

(“If you were to add a voice this would be Derich, his very self; and you would doubt whether a painter or a parent had produced him.”)

Below this runs, in slightly smaller letters of the same type:

The background is of a dark greenish blue against which stand out some branches and leaves of a vine or fig tree. It is painted in cool and delicate tones, with flesh tints of a pale brown, in which it bears a close resemblance to the portrait of Georg Gisze. It is marked, too, by the same simplicity and restraint, and air of quiet and dignified repose, and searching truth and insight in the rendering of what must have been a very attractive nature, qualities which make Holbein’s portraiture so great.

Vol. II., Plate 3

HERMANN HILLEBRANDT WEDIG

Kaiser Friedrich Museum, Berlin

Vol. II., Plate 4a

DERICH BORN

1533

Windsor Castle

This is the only one of several portraits of the series without letters or papers bearing the name and address of the sitter which can be said with absolute certainty to represent one of the London Steelyard merchants. Mr. W. F. Dickes suggests that it represents the eldest son and successor of Theodorichus de Born, the printer, of Deventer 19and Nimeguen, who issued the Netherland New Testament in 1532, and he quotes a reference to a Theodorichus de Born de Novimagio acting as Secretary to the Faculty of Arts at Cologne University, and also to a Derichus de Born who had a licence to preach. “Remembering,” he says, “that Erasmus spent his schooldays at Deventer, and that Holbein owed to him several of his introductions, I think my suggestion deserves to be considered. At any rate, there is no necessity to assume, as is done without a tittle of evidence, that this young scholar was a member of the Stahlhof! Nor does the presence of this portrait at Windsor prove that it was painted in England.”[41]

41. Dickes, Holbein, &c., p. 6.

Mr. Dickes, whose chief object is to prove, for the purposes of his theory about the “Ambassadors,” that none of these Steelyard portraits was painted in England, starts by misquoting the inscription on the picture, which he gives as “Derichus si vocem addas de Born,” an extraordinary mixing of the first and third lines. There is no “de Born” in it, it is distinctly “Der. Born,” and though the young man depicted may have been a member of Theodorichus de Born’s family, as he suggests, he was certainly a member of the Steelyard, and known in London as Derich Born. In the Calendars of Letters and Papers, under the heading of “Ordnance,” a paper is printed which gives a list of “payments made by Erasmus Kyrkenar, the King’s armourer, by his Majesty’s command, from 15th Sept, to 13th Oct. 28 Hen. VIII” (1536), for wages of armourers, and the providing of armour, harness, &c., in connection with the Rebellion in the North. Among the items included in his account is the following:

“For various bundles of harness bought of Mr. Locke, merchant of London, and of Dyrycke Borne, merchant of the Steelyard,” &c.[42] This, though it does not actually prove him to have been in London in 1533, shows that he was most certainly here three years later as a member of the Steelyard. Evidence of his presence in London in the years 1542-49 is to be found in the Inventare hansischer Archive des 16. Jahrhunderts, I, quoted by Dr. Ganz,[43] who states that he was a merchant of Cologne.

42. C.L.P., vol. xi. 686.

43. Holbein, p. 240.

The picture is on oak, 1 ft. 11½ in. high by 1 ft. 7¼ in. wide. It was at one time in the Arundel collection, and is entered in the 1655 inventory as “Derichius a Born.” It is possible that the earl owned more than one of the Steelyard portraits, for there are two entries of 20portraits of men with black birettas. On the back is the brand of Charles I, “C.R.” crowned, though it is not described in his catalogue. There is a second portrait of Derich Born by Holbein, a small oval of about 3 in. high (9 × 8 mm.), on paper, in the Alte Pinakothek at Munich, giving the head and shoulders only.[44] It is painted in oil on paper, and has suffered somewhat from retouching, but is still an excellent example of the small portraits in oil on wood or paper, usually enclosed in a case of wood or ivory, which Holbein was fond of painting at this period, closely akin to his true miniatures of a rather later date. In the Munich version the position is reversed, the sitter being turned to the right, and the face not quite so fully to the front. The workmanship, more particularly of the collar, is as fine as in the larger Windsor portrait. His name and age and the date are given, but the last figures and letters have been cut away, probably when fitting it into the frame, so that all that is left of the inscription on the background, on either side of the head, now reads:

44. Woltmann, 220. Reproduced by Ganz, Holbein, p. 147.

There is every probability that the completed date was 1533, and that the little picture was produced at about the same time as the Windsor version, though the sitter looks slightly younger, and while the more important work was painted for a place on the walls of the Hanse Guildhall, the lesser one may well have been done for sending to the sitter’s relations abroad. The Munich catalogue states that it is from the Elector Palatine’s palace at Mannheim, but otherwise nothing is known of its history.

Vol. II., Plate 4b

DERICH TYBIS

1533

Imperial Gallery, Vienna

The half-length portrait of Derich Tybis, of Duisburg (Pl. 4 (2)), about half the size of life, in the Vienna Gallery (No. 1485), is of the same date, 1533.[45] It is a full-face representation of a young man, with dark brown eyes and hair, his double chin and upper lip being clean-shaven and tinged with blue. In his hands, which rest on a table in front of him, he is holding a letter which he is about to open. He wears the usual heavy, black, sleeveless cloak or overcoat, with a deep collar of fur, and a smaller inner collar of lighter fur. The fore-sleeves of his 21under-dress are of dark-brown velvet. The open fur collar allows a glimpse of a finely-pleated white shirt, with a neck-band of a conventional design of holly leaves worked in gold thread in place of the more usual black Spanish embroidery. He wears two rings on the forefinger of his left hand, one with an oval green stone in a claw setting. The table is covered with an olive-green cloth, and lying upon it are a second letter, a paper with an inscription, a seal, quill-pen, sealing-wax, and a circular inkstand in two divisions, with an ink-well in one half and some gold coins in the other.

45. Woltmann, 251. Reproduced by Knackfuss, fig. 120; Ganz, Holbein, p. 101; and in colour in Early German Painters, folio ii.

The picture has suffered some damage, more particularly in the colour. The ground, which was originally azure blue, has turned to a greenish tone, and the shadows of the flesh are now too grey; but the masterly draughtmanship is still there and the extraordinary insight into character. Here again the fine and expressive hands at once attract attention.

The letter he holds in his hands is from his father, and is addressed “Dem ersamen Deryck tybis von Duysburch alwyl London vff wi ... dgyss mynem lesten Sun....” (“To the honourable Derich Tybis of Duisburg, at the time in London, in Windgyss, my dear son”). This address shows that Tybis was living in Windgoose Alley, one of the passage-ways running through the Steelyard, with the houses and shops of the members on either side.

On the open paper lying on the table is inscribed, in imitation of the sitter’s handwriting:

“Da ick was 33 jar alt was ick Deryck Tybis to London dyser gestalt en hab dyser gelicken den mark gesch[rieben] myt myner eigenen Hant en was Holpein malt anno 1533. per my Deryck [device here] Tybis fan Drys[burch].”

(“When I was 33 years old, I, Deryck Tybis, in London, had this appearance, and I have marked this portrait with my device in my own hand, and it was painted by Holbein in the year 1533, by me Deryck (here stands the device) Tybis von Drys....”)

The device, a combination of crosses, is repeated on the seal on the table, with the letters D.T., reversed, on either side of it. There is a somewhat similar device on some of the letters in Georg Gisze’s portrait. The address on the second letter, lying in front of him, is now almost illegible. There is no inscription on the background. The writer has found no reference to Tybis in the English State Papers.

22The fourth Steelyard portrait of 1533, that of Cyriacus Fallen, in the Brunswick Gallery,[46] is also a half-length, about half the size of life. Like Derich Tybis, the sitter is shown full-face, looking at the spectator. His hair is cut in the customary Steelyard fashion, and he is clean-shaven. His black cap is set rather jauntily on one side, and his black overcoat has a very heavy fur collar, while his fore-sleeves are of brown silk with a pattern, as in the Wedigh portrait. The neck of his white embroidered shirt is just visible over the collar. In his hands he holds his gloves and two letters, superscribed with his name and address in London. These addresses are not very legible. Dr. Woltmann at first supposed the Christian name to be Ambrose, but further examination proved it to be Cyriacus. One of the inscriptions is: “Dem Ersamen syryacussfalen zu luden vp Stalhoff sy disser briff”; and the other: “Dem Ersamen f. ... syriakus fallenn in Lunde ... stalhuff sy dies....”

46. Woltmann, 126. Reproduced in The Masterpieces of Holbein (Gowan’s Art Books, No. 13), p. 34; Ganz, Holbein, p. 99. Reinach gives the surname as Kale, Répertoire des Peintures, Vol. ii. p. 518.

On the green background, on either side of the sitter’s head, is inscribed his motto, “Patient in all things,” his age, and the date:

Fallen has a broad face, and a somewhat stolid expression; like his fellow merchants, he has been placed upon the panel with absolute truth and precision, without a touch of flattery. The eyes, hands, and dress are still in excellent condition, but the head, unfortunately, has suffered greatly in the course of time, and has been much rubbed and overcleaned, and retouched in numerous places.[47]

47. Restored in 1892 by Hauser.

Vol. II., Plate 5

DERICH BERCK

1536

Lord Leconfield’s collection

Petworth

There is a gap of three years before the next and last of this series of portraits of Hanse merchants is reached, that of Derich Berck or Berg of Cologne, in Lord Leconfield’s collection at Petworth (#Pl. 5#),[48] which is dated 1536. He is represented life-size, at half-length, and full face, with brown hair and beard, and black dress and cap. Both hands are shown, and the left, resting on a table with a red cover, holds a letter addressed:—“Dem Ersame’ v[n]d fromen Derich berk i. London upt. Stalhoff,” together with the motto besad dz end (“Consider the 23end”), and the trade-mark of his business house. On the table is a slip of paper with the Latin motto, “Olim meminisse juvabit,” selected by Berck, says Dr. Ganz, to indicate that Holbein’s brush will secure him immortality.[49] In the top right-hand corner are the date and the sitter’s age, “AN. 1536. ÆTA: 30” twice over, a later inscription being painted over the faded original one. The background is blue, with a green curtain on the left.

48. Woltmann, 241. First published by Dr. Ganz in Burlington Magazine, October 1911, vol. xx. p. 33; Ganz, Holbein, p. 107.

49. See Burlington Magazine, vol. xx. p. 32.

The writer has not seen this picture, but it is described as follows by Dr. Ganz in the Burlington Magazine:—“The merchant’s cloth and cap are black, but not dark; the heavy silk reflects the light in a greenish colour finely observed. The background is blue, of the same blue as in the portrait of Richard Southwell at Florence executed in the same year. It is enriched by a green curtain with red strings, giving an opportunity for the artist—like the red cloth on the table—for introducing other tones into his composition, such as black, besides the main notes of blue and flesh colour. The brightest point in this profound harmony of colours, a part of the white shirt with black embroidery, is placed just under the face and makes the fresh and lively expression of it stronger. The light shines with a rare splendour over this man’s healthy face and is reflected in the grey-blue eyes, which look so frank and kindly.” This picture has suffered from over-painting, but it remains a splendid and virile example of Holbein’s portraiture. There is a poor copy of it in the Alte Pinakothek at Munich,[50] purchased in 1899 from a local picture-dealer. It had come originally from France, and was regarded as an unfinished portrait by Holbein of an unknown man. The Munich catalogue describes it as a school-replica.

50. Reproduced by Ganz, Holbein, p. 219.

To Holbein the Steelyard proved to be in all ways a fruitful source of income. Not only was he busily engaged for some years in painting individual members of the League, but he was also employed by them in their corporate capacity upon an important work of decoration for their Guildhall, and in at least one other direction. This decoration consisted of two large allegorical paintings in tempera representing “The Triumph of Riches” and “The Triumph of Poverty.” No record exists as to the date of this work, but it is reasonable to suppose that the commission was given him in 1532 or 1533, at the time when he was in constant attendance within the 24precincts of the Steelyard for the purpose of painting some of its leading members in the midst of their daily occupations.

These decorative paintings have long since disappeared, but the original design for “The Triumph of Riches” exists, as well as numerous copies of both compositions, so that it is possible to gain some idea of their beauty and importance. These allegories, which contained many life-size figures, were not painted on the walls, but on canvas, and so easily removable. They added greatly to the artist’s reputation in this country, and before the close of the sixteenth century they were celebrated throughout Europe among artists and connoisseurs of painting. Carel von Mander says that Federigo Zuccaro, about the year 1574, made two drawings from them, and declared them to be equal to anything accomplished by Raphael, and that after his return to Italy he told Goltzius the painter that they were even finer than any wall-paintings from Raphael’s brush.

The two pictures remained in the Guildhall of the Steelyard until 1598, when it was closed by Queen Elizabeth, who at the same time expelled the Germans from their houses. For some years the place remained desolate, and when, in 1606, under James I, the buildings were restored to the League, most of the property left behind was found to have been stolen or badly damaged. The glory and prosperity of the Steelyard, indeed, had completely vanished, never to be fully restored again, and when the affairs of the Company in London were finally wound up, the two pictures were presented by the League, through their representative, the house-master, Holtscho, on January 22nd, 1616 (old style) to Henry, Prince of Wales, like his brother, Charles I, a patron of the fine arts. Holtscho, in describing the event, says: “I cannot, also, leave it unnoticed, that although these works are old, and have lost their freshness, yet His Highness, as a lover of painting, and as the works of the master, specially this work, have been highly commended, has taken great pleasure in them, as I have myself perceived, and have also heard from himself.”[51] The researches of Dr. Lappenberg have placed these facts beyond doubt, thus disproving the old legend that the pictures were destroyed when still hanging on the walls of the banqueting-hall of the Easterlings during the Great Fire in 1666.

51. Woltmann, i. 381, quoting from Lappenberg, Urkundliche Geschichte des hansischen Stahlhofes zu London, 1851, pp. 82-87.

25It has been generally supposed that on the death of Prince Henry, two years after they were presented to him, the pictures passed into the possession of Charles I; and as they were not included among the pictures of that King’s collection sold by order of the Commonwealth in 1648-53, Dr. Lappenberg concluded that they must have remained at Whitehall until destroyed in the fire at that palace in 1698. Further evidence, however, appears to contradict this conclusion. In Van der Doort’s carefully-prepared catalogue of Charles I’s collection, although several less important works by Holbein are included, among them two miniatures, these two celebrated pictures are not mentioned. Again, Sandrart, in his autobiography, describes the two compositions in some detail, after seeing them in 1627 in the Earl of Arundel’s possession, in the long garden gallery in Arundel House. He does not say whether they were pictures or drawings, so that they may have been only the original designs; it is much more probable, however, that they were the large paintings, as Sandrart speaks of them first of all, as the chief of Holbein’s works belonging to the Earl, and afterwards describes three of his best known portraits, hanging in the same gallery, those of Erasmus, Sir Thomas More, and a “Princess of Lorraine” (the Duchess of Milan), which seems to indicate that Lord Arundel possessed the large works. It has been suggested that they may have been presented by Charles I to the Earl; but it is more likely that they were obtained by exchange with that monarch. Later on they were taken abroad with the rest of the collection by the Countess of Arundel, and were in Amsterdam at the time of her death in 1654. In the inventory then drawn up they are merely described as “Triumpho della Richezza” and “Triumpho della Poverta.” Probably they were among the pictures hastily sold by Lord Stafford in that town immediately after his mother’s decease.[52] The last trace of their history to be found is in a paragraph in Félibien’s Entretiens sur les Vies et sur les Ouvrages des plus excellents Peintres anciens et modernes, published in 1666, in which he speaks of them as having been brought from Flanders to Paris: “Il y avait encore dans la maison des Ostrelins, dans la salle du Convive, deux tableaux à détrempe, qu’on a veûs icy depuis quelques années, et qu’on avait envoyez de Flandres.”[53]

52. See Burlington Magazine, August 1911, vol. xix. pp. 282-6.

53. Quoted by Woltmann, i. p. 382.

26If Félibien is correct, the pictures had once more come into the possession of the Hanseatic League. They were, no doubt, purchased in Amsterdam by that body, and forwarded to Paris. No further record of them has been discovered, and as they were already in a damaged state when presented to the Prince of Wales, the probability is that they have perished.

Vol. II., Plate 6

THE TRIUMPH OF RICHES

Design for the wall-decoration in the Guildhall of the London Steelyard Merchants Pen-and-wash drawing heightened with white

Louvre, Paris

Holbein’s original sketch for “The Triumph of Riches,” a masterly pen drawing washed with Indian-ink, and touched with white in the high lights, is in the Louvre (#Pl. 6#).[54] A similar drawing in the British Museum, purchased in 1854, which at one time was attributed to Holbein himself, is said by Woltmann to be a tracing of the Louvre example; but it has no appearance of being traced, and is certainly a copy, perhaps by an Italian.[55] The heads and attributes are given a Raphaelesque air, strikingly different from the Flemish style of a second drawing in the Museum, of the second composition, “The Triumph of Poverty.”[56] This latter is in black and red chalks and pen, washed with Indian-ink, and heightened with white, on a blue background, and was acquired in 1894 from the Eastlake collection. Lady Eastlake possessed a similar drawing of the “Riches.” Both are in all probability by Lucas Vorsterman the younger, and were purchased by Sir Charles Eastlake from the Walpole sale in 1842 for sixteen guineas. They appear to be copies, as Vertue suggested, made for engraving purposes by Lucas Vorsterman from the drawings done by Zuccaro in 1574; or possibly from the original paintings when in Amsterdam. Vorsterman certainly engraved one, if not both subjects, though only his engraving of the “Poverty” is known. These drawings,[57] at one time in the Lely collection, were in Buckingham House, before it was purchased for a royal palace, and were sold as allegorical works by Van Dyck, and bought by Horace Walpole, who regarded the “Riches” as by Vorsterman, and the “Poverty” as by Zuccaro; but the latter, like the former, is decidedly Flemish in style.[58] 27Sandrart possessed copies, in all probability those made by Zuccaro, which were afterwards in the Crozat collection, and when that collection was sold passed into that of Privy Councillor Fleischmann, of Strasburg, and while in his possession were engraved for Von Mechel’s “œuvres de Jean Holbein,” and inscribed “Zuccari delin. 1574.” All further traces of these Zuccaro drawings have now been lost.

55. British Museum Catalogue of Drawings, &c., Binyon, ii. p. 342.

56. Ibid., p. 342.

57. The Vorsterman copies are reproduced in outline in Waagen’s edition of Kugler’s German, &c., Schools of Painting, from drawings made by Sir George Scharf when they were in the Eastlake collection.

58. Walpole, Anecdotes, &c., ed. Wornum, i. p. 89. Dr. Ganz, however, regards the “Poverty” as Zuccaro’s copy. See Holbein, p. 248.