THE OCEAN WIRELESS BOYS OF THE ICEBERG PATROL

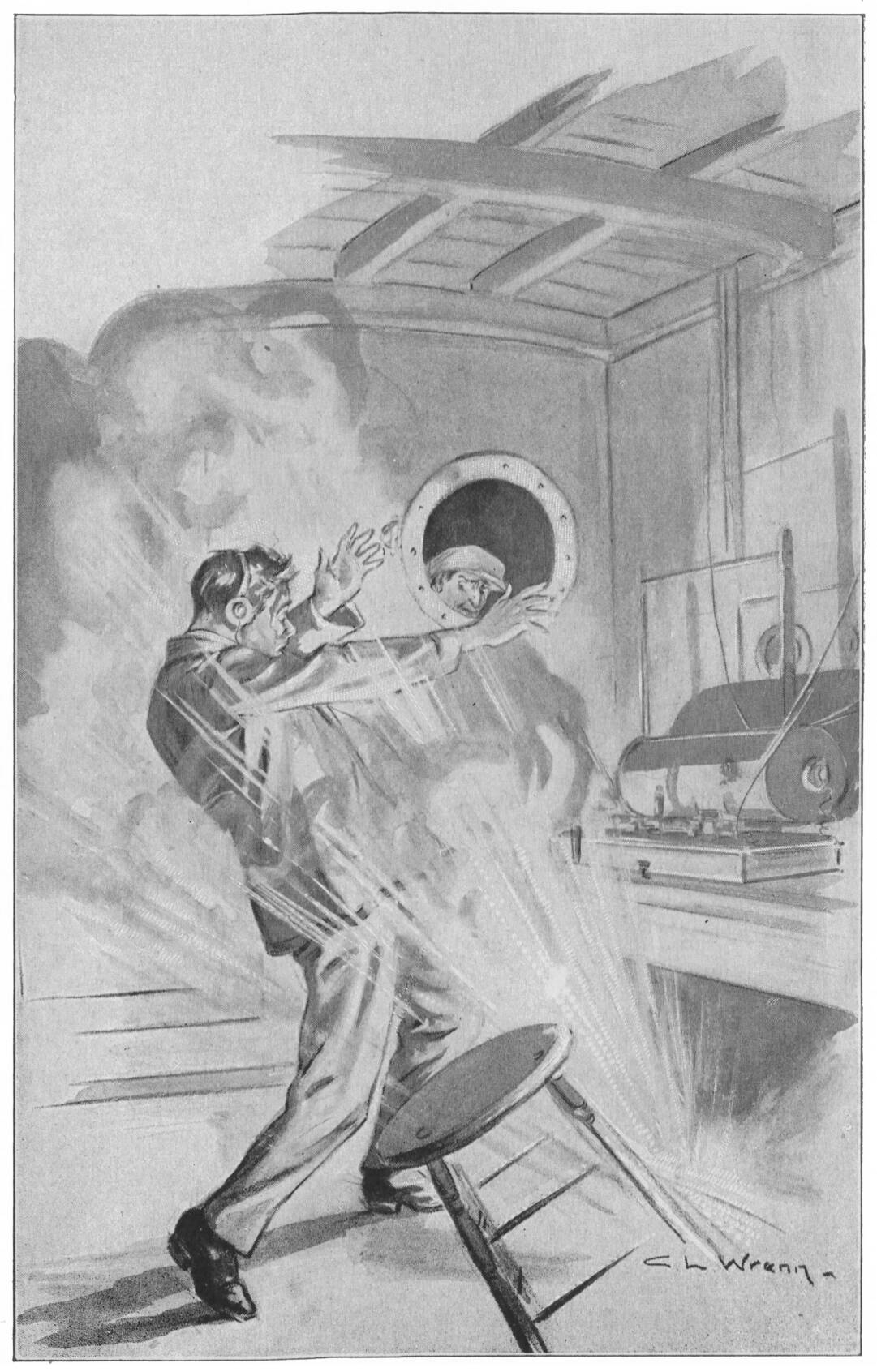

Amidst a glare of red flame and lurid smoke, the young operator staggered backward.

The Project Gutenberg eBook of The ocean wireless boys of the iceberg patrol, by Wilbur Lawton

Title: The ocean wireless boys of the iceberg patrol

Author: Wilbur Lawton

Illustrator: Charles L. Wrenn

Release Date: December 10, 2022 [eBook #69517]

Language: English

Produced by: Roger Frank and Sue Clark

Amidst a glare of red flame and lurid smoke, the young operator staggered backward.

| CONTENTS | |

| I. | ON THE OCEAN TRAIL |

| II. | ON THE LOOKOUT FOR ICE |

| III. | A NARROW ESCAPE |

| IV. | MAN OVERBOARD! |

| V. | IMPRISONED |

| VI. | MAROONED ON AN ICEBERG |

| VII. | JACK SAVES THE CAPTAIN |

| VIII. | ON BOARD THE “POLLY ANN” |

| IX. | A JOKE ON POMPEY |

| X. | PLANS TO ESCAPE |

| XI. | A FIENDISH PLOT |

| XII. | UNCLE TOBY IS OFF FOR TREASURE |

| XIII. | POMPEY MYSTIFIED |

| XIV. | TERROR CARSON’S NERVE |

| XV. | A WHALE IS ANNOYED |

| XVI. | LOCKED IN THE CABIN |

| XVII. | IN THE EYES OF THE SHIP |

| XVIII. | RAYNOR TO THE RESCUE |

| XIX. | SKULL ISLAND |

| XX. | JACK TRIES OUT HIS INVENTION |

| XXI. | THE WRECK OF THE “POLLY ANN” |

| XXII. | FOOTPRINTS ON THE SAND |

| XXIII. | AN UNEXPECTED MEETING |

| XXIV. | A FRIGHT IN THE NIGHT |

| XXV. | POMPEY LEARNS ABOUT WIRELESS |

| XXVI. | A JOYOUS MESSAGE |

| XXVII. | A CRASH IN THE FOG |

| XXVIII. | UNCLE TOBY IS SURPRISED |

| XXIX. | OFF FOR SKULL ISLAND |

| XXX. | JACK AND BILL MEET ONCE MORE |

| XXXI. | IN A BOILING SEA |

| XXXII. | CEDAR ISLAND AT LAST |

| XXXIII. | TERROR CARSON AGAIN |

| XXXIV. | A PERILOUS ADVENTURE |

| XXXV. | THE TREASURE |

The big, high-sided Cambodian, in ballast, that is, carrying no cargo, and outward bound from New York for Rotterdam, was shouldering through the green seas that came racing to meet her. The Cambodian was a brand new freighter of the big shipping combine controlled by Jacob Jukes, and as just then no better berth had been offered, Jack Ready found himself occupying her wireless room getting the newly installed radio apparatus in shape and tuned up for effective service.

As he worked over a refractory detector Jack, although normally of a cheerful disposition, felt a strong inclination to grumble at his present berth. He had been hoping for a chance at the wireless operator job on board the Empire State, the newest and greatest of the Jukes trans-Atlantic liners. But at the last moment he had been passed over and another operator appointed on the ground of seniority.

But Jack’s gloomy mood did not last long. As usual, the stimulus of work soon caused the clouds to dissolve, and by the time he had the detector adjusted, he was humming cheerfully. As he looked up from his completed job, a ruddy-faced, cheery-looking lad about two years older than Jack, who was eighteen, stuck his head in at the door of the wireless-room which, besides the apparatus, contained Jack’s bunk, a picture of the boy’s dead mother hanging at its head, and the desk at which he made out his reports.

“Hello there,” hailed Jack, as Billy Raynor appeared, “going off watch?”

“Well, don’t I look it, with this fine old coat of grime on my hide?” laughed Jack’s chum, now promoted to the post of second engineer on the new freighter.

“Thought when you got to be second you were just going to loll around with your hands in your pockets and give orders,” commented Jack.

“Um, so did I,” rejoined Raynor with a rather wry grin, “but, as you see, it didn’t just work out that way. By-the-way, I thought you were going to be the dandy, brass-buttoned wireless hero on a passenger packet this trip.”

It was Jack’s turn to give a rueful smile and he rejoined, “So did I.”

“Old Jukes was mighty nice about it though,” he explained. “I’m getting the same pay as I would on a liner and then, too, that check for that South American business came in mighty handy, so that, financially, I’m not kicking. But I do want to get ahead in my work.”

“Well, old Jukes ought to shove you right along,” declared Raynor, coming in and planting his overalled form in a chair by the desk. “You’ve sure done a lot for him, starting in by saving his daughter, and——”

“Say, shut up, will you!” sputtered Jack, turning red. “I don’t want any favoritism for anything I may or may not have done. That isn’t it. I just want to get right ahead in the wireless game.”

“And so you are, so far as I can see,” replied Raynor. “Incidentally, how’s the portable set coming along?”

He referred to Jack’s pet hobby, an invention over which he had worked during all his spare time, afloat and ashore, for months. It was a portable wireless set in which weight and complexity had been cut to the bone. Jack had managed to reduce the weight by degrees till at last he had produced what he believed would prove a practicable device for use in the field, which weighed a trifle under fifty pounds, and could be carried over the operator’s shoulder in a satchel.

In reply to young Raynor’s question, Jack opened a closet and produced a set of instruments of exquisite finish. Attached to them was a neat coil of copper wire and, strapped to the base that supported the whole, was a flat package of cloth and bamboo sticks.

“What’s that jigger underneath?” asked Raynor, referring to the latter bit of apparatus.

“That’s a box kite,” explained Jack.

“A box kite? What in the world do you want with that?”

“Well, you can’t send out or receive messages without aërials, can you?” parried Jack.

“No, but you could hitch your aërial wires to a tree or——”

“All right, Mr. Smarty, but just suppose that you are in a country where there are no trees.”

“Oh, I see,” exclaimed Raynor, “in that case you’d do a little kite flying.”

“That’s the idea exactly,” responded Jack.

“Have you tested it yet?” inquired Raynor.

“Up to 150 miles. It works splendidly. I’m going to gear up my hand-generator higher so as to produce a stronger alternating current, however. Then I think I’ll get better results.”

Clang-g-g-g-g-g-g-g!

A gong above Jack’s head sounded clamorously. This gong was another of the boy’s inventions. By means of a silicon detector ingeniously connected, a wireless wave striking the antenna of the Cambodian’s apparatus instantly sounded the gong. In this way Jack had done with a lot of tiresome waiting for calls with his receivers clamped to his head.

“Something doing?” asked Raynor, as Jack sprang from the chair he had been sitting on and seated himself in front of the wireless key.

“I guess it’s nothing much,” was the reply, “Siasconset maybe, or Race.”

But a moment later the expression of the young operator’s face grew concentrated. His hand reached out for a pencil and he began to scribble on his transcription pad the words that came pulsing against his ears like waves out of a vast sea of space.

“Steamer Athenia (Br.) reports,”—thus Jack wrote—“Along parallel of 45.06 saw ice as follows:—Grindstone, one mile of ice inshore. Scatari, close-packed ice inshore. Cape Ray, loose strings distant. Money Point, heavy close-packed ice inshore. Cape Race, several small strings loose ice drifting S. W.”

Raynor had been peering oyer Jack’s shoulder as the boy wrote. When he ceased, the young engineer was full of eager questions. Jack flashed out an answer to the Athenia and then “grounded” his instrument.

“Well, that’s to be expected in April,” was his comment. “I guess we’ll get a lot more of such reports before long.”

“Think we’ll run into any bergs?” asked Raynor rather anxiously.

“Don’t get nervous,” laughed Jack, “the iceberg patrol is on the lookout for those. I’m surprised they haven’t ‘tapped-in’ yet with some information. That’s the service for you, old man, the iceberg patrol. Think of the lives you have a chance to save and—and—but I’ve got to be off with this message to the old man.”

Jack hurried from the cabin, and forwarded his message to Captain Briggs on the bridge. Raynor followed with more deliberation and made for his own cabin and soap and water. As he removed the grime of the engine-room, he mused on the subject of icebergs. Not many weeks before a big liner had blundered at night into a huge floating continent of ice and had sunk, with a terrible toll of lives and suffering.

“If a big old liner like that couldn’t stand one wallop from an iceberg what chance would the Cambodian stand?” he wondered. “Still, as Jack said, since the accident they’ve had a regular iceberg patrol to send out warnings by wireless of any bergs that happen to be in the vicinity. I wouldn’t mind seeing a berg though, if it wasn’t at too close range. Wonder if I ever will?”

Had the young engineer possessed the gift of second sight, he would have been able to foresee that in the immediate future he was destined to come into closer contact with icebergs than he would have dreamed possible, and also that the entire current of his life was to be changed by a series of unlooked for and astonishing happenings.

With the dropping of the sun it fell bitter cold. The sea heaved in a leaden, lightless swell which the forefoot of the Cambodian, as she drove along, broke into spuming spray. The officers donned their heavy bridge coats. The crew, or that portion of it which had the watch on deck, wrapped up as warmly as they could in the scanty garments they possessed.

When Jack opened his cabin to go below to his evening meal, a slight flurry of snow struck him in the face.

“Goodness!” thought the boy, “here’s a change, and when we left New York folks were thinking about Coney Island and putting their winter coats in moth-balls.”

The captain was the only other occupant of the dining-room, from which opened the officer’s cabins, when Jack went below. The boy noticed that Captain Briggs’ face was rather flushed, and his eyes were very bright as he took his seat. The captain had finished eating but before he left the room he came to Jack’s side and, leaning over him, asked in a rather thick voice, if there had been any more reports on icebergs. Jack replied in the negative.

“Tha’s aw’ ri’ then,” said the captain in a loud, boastful voice, whose tones were thick. “Donner be ’fraid icebergs with Cap’n Briggs on board. I’m an old sea-going walrus, I am. I jes go ri’ through ’em, yes, sir, jes like knife goin’ thro’ cheese. Thas me.”

He swaggered out of the cabin with his scarlet face grinning. Jack’s eyes followed him as the captain rather staggeringly ascended the companionway.

“I don’t know much about such things,” thought the boy, while a serious look came over his face, “but it seems to me that Captain Briggs is under the influence of liquor. That’s a bad thing. Liquor is bad at all times but it’s more dangerous at sea than anywhere else.”

He finished his meal hastily and returned to his cabin to find his “wireless bell” ringing furiously. Jack lost no time in getting to work. He found that the U. S. revenue cutter Seneca, one of the craft detailed by Uncle Sam to the iceberg patrol, was flashing out signals of warning. Jack got the operator to repeat them when half a dozen or more other steamers had picked them up.

The Seneca’s operator was in a bad mood at this.

“Confound you fellows,” he flashed through space, “why don’t you pay attention and get the message from the jump?”

“I was eating supper,” Jack replied contritely.

“I haven’t had a chance to eat yet, and I’m so hungry I could gobble a boiler-plate pie,” growled the government man. “This is a dog’s life.”

“I’d trade you jobs,” flashed Jack, but the other ignored this and began thundering out his message concerning the white terrors of the north.

“Ready?” he flashed.

“Fire away!” sparked crackingly from Jack’s key. Far above him, in the night, the aërials flashed and snapped.

“Seneca, U.S. Iceberg Patrol. Str. Montrose reports from 50:47 on parallel 42, sighted three bergs, two growlers, April 6th, moving S.W. Barometer 30. Temperature 36. Overcast. Wind N.W. About 18 miles per hour.

“April 7th, 2:00 a. m., big berg, lat. 42.34, long. 48.15. Growler four miles north-west. Both moving south.”

“That’s all. Now I’ll get a chance to stow some grub—maybe,” grumpily concluded the report. Jack did not jot down these latter words.

As he made his way forward with his report, the young wireless man noticed that the fog was beginning to rise from the sea in long, wavering wreaths. They looked ghostlike under the stars. In the light breeze they danced a sort of witches’ dance. It looked as if the sea was a boiling expanse with whirling banners of steam rising from it. Even as Jack hurried forward he saw that the banners were closing in to form a solid web of mist.

The Cambodian was ploughing steadily forward. From her single big funnel, black with a broad white band, inky smoke was pouring out a volume that showed there was to be no niggardly saving of coal on the present voyage. In fact, before sailing, Jack had heard that she represented a new type of fast freighter, and that her maiden voyage would be utilized as an opportunity of trying her out thoroughly.

Above the young operator hung the spiderweb strands of the antenne. Practiced operator as he was, Jack had never quite lost his wonder at the often recurring thought that from those slender copper cables, seemingly inert, he could, by the pressure and release of a key, send out a message, in time of danger, that would bring a score of ships hastening to the stricken one. It was characteristic of the boy that close acquaintance with the wireless had not in the least dimmed his enthusiasm and reverence for its marvels.

On the bridge were three figures, shrouded in heavy coats. They were the captain, chief officer, and second officer. From one end of the bridge a seaman was constantly casting overboard a canvas bucket attached to a rope and hauling it in board again. Each time he brought the bucket to the group of officers, one of whom thrust a thermometer into it and then read off the temperature of the water.

“Dropped ten degrees, by Neptune!” Captain Briggs exclaimed thickly as Jack came up. He had just finished scrutinizing the thermometer under the light of a hooded lantern.

“Ten degrees, sir!” cried Mr. Mulliner, the first officer.

“That’s what. We ought to smell ice before long,” was the reply, with a loud, hilarious laugh.

“It’s too bad. The captain has certainly been drinking,” mused Jack to himself as he stood at attention and presented the dispatch he had just copied.

“What’s this?” demanded the captain, regarding him with bloodshot eyes that blinked suspiciously.

“Report from the Seneca, sir. Bergs in the vicinity,” spoke up Jack.

“Report from the Seneca, eh?” muttered Captain Briggs muzzily. “Well I know as well as they do there are bergs ahead. Let’s see what it’s all about.”

He took the message and scanned it under the light of the lantern by which he had been taking thermometer readings. His hand shook and he called first officer Mulliner to read the message to him. Mulliner repeated it in a grave voice.

“Hadn’t we better slow down, sir?” he asked.

“Slow down? What for?” blustered the flushed captain.

“Why, sir, the temperature of the water and then this dispatch all go to show that we are nearing ice-fields, maybe growlers and bergs. We are making fully eighteen knots now and——”

“We’ll continue to do so,” exclaimed the captain. “I’ve sailed these seas for a good many more years than you’ve been on earth, Mr. Mulliner.”

“That may all be, sir,” rejoined the young officer anxiously, “but at this speed——”

“At this speed we’ll head ’em off according to my calculations,” declared the captain. “If we slowed down we’d land in the middle of ’em. If we keep full speed ahead, we’ll pass to the south of ’em.”

“Then you mean to race them, sir?”

“That’s what. If that’s what you want to call it. Now get to your duty, Mr. Mulliner,” added the captain in sharp tones, as if he felt he had been too lenient even to argue with his subordinate. Mr. Mulliner, muttering something about “suicidal,” turned away.

“Any orders, sir?” asked Jack, when he was alone with the captain.

Captain Briggs shook his head. He was a seaman of the old school and did not place much faith in wireless.

“Just stick at your instruments,” he said, “but if there’s bergs about the look-out, bet my nose ull pick ’em up ahead of any fool wireless contraption.”

Jack made his way aft, burning with indignation. Here was a fine, new ship, being driven at top speed toward the greatest peril a seaman can encounter, at the whim of a man who had been drinking. But there was nothing to be done, as Jack reflected with a sense of speechless anger. Aboard ship the captain, no matter how insane his orders may appear, is absolute czar of the situation. His word is law. He can hang or imprison, for mutiny, anyone who dares to question his orders.

The young wireless operator paused, before he reentered his snug cabin with its shining instruments, to lean over the rail and gaze out into the night. The mist had thickened now. It struck at his face like clammy fingers. The night was quite silent but for the vague hum of the engines far below him, and the hiss and roar of the sea as the hulk of the Cambodian was driven through it.

Ahead it was almost impossible to see anything but a dense, black pall that might hide anything. Dimly through the mist curtains, Jack could make out the figure of the look-out in the crow’s nest. Occasionally he could catch his hoarse shout of “All’s well” and an answer, booming through the smother, from the bridge.

Suddenly the whistle began sounding. At regular half minute intervals it shrieked hoarsely.

Jack knew what they were doing. If bergs were in the vicinity, in the intervals of silence between blasts, an echo would be flung back.

“Pshaw, that’s a haphazard way of detecting bergs at best,” muttered Jack to himself.

But he found himself listening with strained ears to catch the slightest sound of an echo after each clamorous yammer of the big siren. He fell to musing of the night on the Ajax when the big berg had loomed up before them.

Details of that night were told in the first volume of the Ocean Wireless Series, which was called “The Ocean Wireless Boys on the Atlantic.” This volume introduced Jack, his strange dwelling place, and his odd relative, Cap’n Toby Ready, to our readers. We found Jack, pretty well disheartened in his ambition to become a wireless operator, on his way home among the shipping to the queer old derelict craft where he lived with his uncle Toby, the latter a purveyor of vegetable drugs and medicine, to old and superannuated skippers.

Seeing a crowd on a dock, Jack went to find out what was the matter. He soon discovered that the young daughter of Jacob Jukes, the millionaire head of the great shipping combine, had strayed from her father, who was visiting a great “oil-tanker” moored there, and had tumbled overboard.

Jack leaped from the dock, while the others stood paralyzed with helplessness, and saved the child in the nick of time. This won him Mr. Jukes’ extravagant gratitude. He wanted to give Jack money. But all Jack wanted was a job as wireless operator on the big “oil-tanker,” the Ajax. He got it. Mr. Jukes would have given him the ship had he asked for it. But the millionaire was autocratic. After Jack’s first voyage he wanted the lad to give up the sea and, at a big salary, become the friend and companion of the millionaire’s son, Tom, a sickly lad. This by no means suited Jack and he and the millionaire quarreled.

But Jack forged steadily ahead in his chosen profession. On his first voyage, by a clever wireless trick, he brought confusion on a gang of tobacco smugglers and set all their plans at naught. For this brave act he almost paid with his life. But all came out well, and on a homeward voyage from Antwerp he was able, once more with the aid of the wireless, to unite Mr. Jukes and his son, Tom, who had become separated when the millionaire’s yacht caught fire and burned to the water-line at sea.

In the next volume, which was called “The Ocean Wireless Boys and the Lost Liner,” Jack found himself the natty chief wireless man of the crack West Indian liner, Tropic Queen, one of the finest passenger craft plying those waters.

Jack and his assistant, a youth named Sam Smalley, found themselves involved in an intrigue almost at once. A mysterious wireless code and a plot to steal papers involving the Panama Canal formed its chief features.

In trying to fight the ring of rascals, against whom he found himself pitted, Jack was drugged in the Island of Jamaica and cast into an inaccessible dungeon—part of an old Spanish castle called The Lion’s Mouth. By wonderful ingenuity and pluck he escaped from the fate planned for him.

Later a safe was blown open on the Tropic Queen and the Panama papers were stolen.

But Jack’s quick work at the wireless key soon summoned Uncle Sam’s speediest battleships and cruisers to an ocean wide search for the yacht, on board which was the gang that had stolen the papers. They were recovered eventually by Jack and handed over to the rightful owner. But not long after the Tropic Queen was caught in a hurricane and cast on an island.

All seemed lost, for a huge tidal wave overwhelmed the wreck to which Jack and Sam had swum out, leaving the others ashore. But eventually the two boys reached land and rejoined the other castaways. The message that Jack had sent out before the convulsion of nature ended, the lost liner had reached other crafts, however, and all were rescued safely. Jack and Sam each received substantial rewards for their services.

Jack was turning out of the night to reënter his cabin when Raynor came along. He was going on watch again.

“What news?” he asked, as he paused near Jack.

“Nothing much, except that there is ice ahead.”

“Bergs?”

“Yes, and growlers too, and field ice maybe. The Seneca reports it.”

Raynor looked about him in a puzzled way.

“But we haven’t slowed down,” he said at length.

“That’s just it. Captain Briggs is a drinking man. He is drinking to-night and reckless. He means to keep right on this way.”

“Why, that’s madness. At any minute——”

“That’s just what Mr. Mulliner says. But what are we going to do? You know as well as I do that the skipper’s word is law at sea.”

Raynor perched himself on the rail, balancing there high above the water, a favorite position with him.

“I wish you’d brace your legs when you do that,” remarked Jack. “If there was a sudden lurch or anything you’d go right overboard, and nothing could save you. I’ve spoken to you a dozen times about it and——”

“I know you have, you croaking old land-lubber,” laughed Raynor, “it’s alright. As for danger, if you could see me lying in the crank-pit, with the big steel throws smashing round within half an inch of my nose I guess you’d be worried then.”

“No, I wouldn’t, because that’s your business and you know what you’re doing,” responded Jack, “but balancing like that’s just pure foolhardiness.”

“So there’s ice ahead?” said Raynor, ignoring Jack’s protest.

“That’s the report. They’re testing the temperature of the water on the bridge. It’s falling all the time.”

“Well, what does that amiable maniac Briggs think he’s going to do, knock a berg out of his way if he hits it?”

“No; he figures in his muddled brain that by keeping up full speed he can pass to the south of the path of the bergs. In other words, he’s racing them.”

“And if he loses the race there’ll be a most almighty smash-up.”

“That’s it. I—— What in the name of time is that?”

Jack broke off in an alarmed voice. Hoarsely, through the night, had come the frightened cry of the man in the crow’s nest.

“For the Lord’s sake back her!”

“What’s up?” was shouted from the bridge.

“It’s ice. Ice dead ahead! To the port to starboard!”

With startled eyes and drumming pulses Jack stared forward.

Ghostlike, gigantic and looming white in the darkness a monolithic tower overhung, as it seemed, the Cambodian’s bow.

“Full speed astern!” came the voice of Mulliner, shrill with alarm, and then the hoarse shout of Captain Briggs.

“No, confound you. Ahead! D’ye hear me—ahead!”

And then came a shout to the wheelman.

“Hard over! Hard over for your life!”

The Cambodian, at unreduced speed, swung off her course. A shivering shock ran through her steel frame as she grazed the giant berg and then—swung off, hardly scratched. Jack felt a quick bound of his heart. In spite of his dissipation, Captain Briggs had shown he knew how to handle the emergency. That quick order of full speed ahead, and the swift shifting of the wheel had enabled the Cambodian to save her life.

“Say, Raynor, old man!” cried the boy enthusiastically, while the shouldering form of the berg grew dim, a passed menace, and the raucous shouts of the crew rose up to him, “say Raynor, I’ll take back what I said about Captain Briggs. I——why don’t you answer?”

Jack turned swiftly. Then he stiffened with alarm. The place where his chum had been perched upon the rail was vacant. Raynor was gone. For a brief instant Jack was silent from the shock. Then his voice rang out in tones of vibrant fear.

“Man overboard!” he cried, running forward stumblingly, “man overboard!”

Simultaneously with the shivering shock of the impact with the iceberg, Billy Raynor felt himself lose his balance.

He grasped frantically at the air as he fell backward. But the next moment, too alarmed to cry out, he was himself tumbling through space. Then came the sharp shock and the icy sensation of his immersion as he struck the water.

He came to the surface, his lungs full of brine and his ears roaring as if an express train had been rushing past them. He gasped for breath and spat the salt water out. Far above him he saw for a flash the black, high hull of the Cambodian. He saw her lights. For a brief instant he could hear shouts.

And then the ship had passed by. An instant later she had vanished from the castaway lad’s sight.

“Help!” yelled Raynor, finding his voice at last. He sent the cry echoing and volleying across the dark water again and again. But there was no response.

A chill of deadly fear, not altogether born of the icy water, struck in at his heart. He was alone on the Atlantic. Nothing but his own efforts would keep him above the water very long. And weighted as he was by his water-soaked clothes, he felt his strength ebbing every moment.

“Great heavens,” he moaned to himself, “is this to be the end? Am I doomed to end my life here in the ocean with nobody to know of my fate?”

He cast his eyes upward. Then he almost gave a shout of relief. Towering above him was a mighty white wall.

It was the iceberg to which he owed his predicament.

It has been said that drowning men will clutch at straws. This may, or may not, be true, but certain it is that to Billy Raynor, almost exhausted by his long fight in the chilly water, the iceberg appeared a haven of refuge. Like most of such huge ice structures it was very irregular in shape.

Near him was a spot at which a narrow shelf stretched out close to the water’s edge. Raynor struck out for it and drew himself upon the ledge of ice. Then, for a time, he lay there supine, too weak to even move.

He was fearfully cold. His teeth chattered and he felt as if his flesh must be blue. But at least he had saved his life for the time being. He knew that ten minutes more in the water would have finished him. Raynor sat up and took stock of the situation.

He was afloat on an iceberg, a precarious enough situation surely. His momentary feeling of exultation at having found a safe refuge began to fade. He felt a wave of fear pass over him. He shouted with all his might, cupping his hands and casting his voice in the direction he thought the Cambodian had vanished. But had he known it he was sending his appeals in altogether the wrong quarter, for the iceberg was slowly revolving as it lumbered its way south.

“This won’t do. I mustn’t give way,” thought the lad, pluckily striving to overcome his depressing fears.

He felt in his pockets. The tin box in which he was carrying down his midnight lunch for consumption in the Cambodian’s engine room was still there.

“That’s lucky,” thought Raynor, and was still more pleased when he found that its contents, sandwiches and a piece of pie, were not much damaged by water. He began to eat ravenously, in the meantime turning his dilemma over and over in his mind.

“I’m in the steamer track anyhow,” he thought. “I’m bound to be sighted and picked up before long, even if the Cambodian isn’t standing by and waiting for morning.”

But then came the disquieting thought that the iceberg was drifting. He had no means of knowing how fast. But by daylight it might be far south of the steamer track, which is as well marked as any land road, and rarely deviated from by any vessels except sailing craft.

“And just think how little things can grow into big ones,” mused the lad, as he munched his scanty store. “Jack told me not to balance on the rail. If I’d taken his advice instead of laughing at it I wouldn’t be here. I’d be on board the Cambodian. Jove though—” he broke off suddenly, as a new thought struck him,—“maybe the Cambodian was badly ripped by the collision. She may have sunk—and Jack——”

He buried his face in his hands, too much unnerved by all that he had gone through to think any longer. By degrees he regained possession of his faculties, however. He fell once more to revolving his plight. He need not fear death from thirst for he had his knife and could chip off fragments of ice and let them melt in his mouth when he felt so inclined. Food, though, was another consideration. He resolutely set aside two sandwiches and half his wedge of pie for emergencies.

It was still dark and misty and he could see little but the blackly heaving water at his feet and the towering white walls of the berg above him. Suddenly, however, he became aware of a sound, a strange sound to hear in his present position.

It was the sound of a footfall, furtive and cautious!

The blood flew poundingly to the boy’s pulses. He sprang erect, knife in hand. What he might be called upon to face he did not know.

But he knew he was not alone on the iceberg.

His heart beat thick and hot and then seemed to stop. Advancing onward, from round a shoulder of ice which reached down to the shelf on which he had found refuge, was a tall white form.

It resembled nothing that the boy had ever seen. As if in a nightmare he stood there fixed as a graven image, staring at it with starting eyes as it slowly approached him.

Captain Briggs looked blankly at Jack as the frightened boy came forward by leaps and bounds to the bridge, shouting “Man overboard,” a cry which was speedily taken up and echoed from end to end of the ship.

“Whasser marrer?” demanded the captain, seizing the excited boy’s shoulder.

Jack pointed back into the obscurity. His voice was choked with emotion.

“It’s Raynor,—Billy Raynor, second assistant engineer, sir. He fell overboard when we bumped that berg.”

“He did, eh?” repeated the captain thickly, staring stupidly at Jack. “Well, he’s in Davy Jones locker by this time, you may depend upon that.”

For a moment Jack stood stupefied. Then he broke out angrily, utterly forgetting all discipline.

“Aren’t you lowering a boat? Why don’t you order one away? Raynor’s drowning back there.”

“Look here, my lad, you’re excited,” said the captain in more collected, sober tones, “I’m not going to lay my ship to among these icebergs on the chance,—it’s one in ten thousand,—of saving him. A boat couldn’t live among that field ice. It would be crushed in a jiffy.”

“Then you’re going to hold on your course without an effort to save him—? You’re going to abandon him like a coward?” shouted Jack, beside himself.

“Nuzzing to be done,” mumbled the captain, relapsing again, “on your course, Mr. Mulliner.”

But Jack was too far enraged to stand this. He sprang forward and grasped the first officer’s sleeve.

“Mr. Mulliner, sir, you won’t see this cowardly thing done? You won’t leave that poor lad back there without a chance for his life?”

“I can’t help it, my boy, captain’s orders, sorry,” and the officer stepped into the wheelhouse to give the steersman his orders.

“It’s murder,” shouted Jack, “I’ll see that you suffer for it, Captain Briggs. It’s a black crime, it’s the work of a coward, it’s——”

A heavy hand fell on his shoulder. It was Captain Briggs. His face was aflame with indignation.

“Wadderyer mean, you young jackanapes,” he roared, beside himself with anger and the potations he had drunk, “Jenks, Andrews!”

The seamen who had been heaving the bucket stepped up. They stood waiting.

“Bind this young turkey cock hand and foot and lock him in his cabin,” thundered Captain Briggs, “he’s guilty of mutiny on the high seas, by Neptune. To-morrow I’ll see if there’s not a pair of irons on board that will fit him.”

“Do you mean that I am under arrest, captain?” stammered Jack, completely taken aback.

“I do, yes, sir, and it may go hard with you if I don’t change my mind,” yelled the captain furiously. “Take him away, you men, and I’ll hold you responsible for him.”

Jack saw red for a minute. He made a leap for the captain but the two sailors caught him.

“Easy there, young feller, easy,” one of them whispered, “we’ve no more use for him than you have, but going on this way ain’t goin’ ter get yer anything. Better come quietly.”

With a sigh that was half a sob Jack submitted to be bound and then half carried, half dragged, to his cabin. He heard the key turned in the lock. He was a prisoner. A wild idea crossed his mind of flashing out by wireless an account of his plight and the captain’s drunkenness.

The next instant it dawned upon him that he was powerless. He was a prisoner, bound hand and foot like a criminal. And where was Raynor? Dead, beyond the possibility of a doubt. He could not have lived more than a few moments in that icy sea. Jack groaned aloud in anguish as he strained and writhed at his bonds. His plight was quite forgotten in his anxiety over Raynor’s fate.

“Hist!”

The sibilant sound of a man’s voice demanding attention broke in on Jack’s sad reverie at this juncture. It came from a circular grating, made for ventilation in the door of the cabin. Jack looked up and saw the face of one of the seamen looking in at him. The hard lines of the mariner’s countenance were illumined by the electric light within the cabin.

“Well, what’s the matter?” demanded Jack, rather petulantly.

The man, it was the one who had been addressed as Andrews by Captain Briggs, began speaking rapidly and cautiously.

“This here Captain Briggs,” he began, “we don’t like him no more than you do. I’ve sailed with him before. There’s a plot on foot to——”

The heavy footsteps of an officer approaching caused the face to vanish and the voice to cease. Outside, Jack recognized Mr. Mulliner’s voice giving an order.

“Andrews, you can get forward, you too, Jenks. There’s no need to stand on guard here. Give me the key.”

Jack listened and heard the men clump off in one direction. Then he heard the sound of Mr. Mulliner’s footsteps die out. He was left to his own reflections once more. His mind dwelt on the mysterious hint dropped by Andrews.

“There’s a plot on foot——” the man had said.

Jack wondered to himself if there was a mutiny brooding on board the Cambodian. There had been a seaman’s strike in New York when she sailed, and the crew was made up of all sorts of water-front riff-raff. Some of them were desperate-looking characters.

The young captive struggled with his ropes as these thoughts ran through his mind, But the knots had been tied by seamen, and try as he would he could not loosen them. The bonds began to impede his circulation and grow painful in the extreme.

“Well, I suppose I’ll have to reconcile myself to my fate till morning,” said Jack to himself resignedly. “Something tells me that this voyage is going to turn out to be not quite so tame as I thought. From what that fellow Andrews said, mutiny is afoot among the crew, and we are not yet forty-eight hours out of port.”

His reflections were startlingly interrupted.

The sharp crack of a revolver split the night from somewhere forward. Then came hoarse shouts and the sound of trampling feet.

“The trouble has started already!” exclaimed Jack, rising in his bunk despite the cruel pain the sudden movement gave his bound limbs.

“Am I going crazy?”

Raynor, marooned on the drifting berg, passed a hand across his eyes. The white form that had menaced him with he knew not what peril a minute before had vanished as suddenly as it had appeared. Badly overwrought, the lad stood staring at the place where he had seen it.

“This won’t do,” he said to himself, “I mustn’t lose my nerve and get to seeing things.”

With an effort he braced up his faculties. With infinite patience he waited for daylight. At last, after what seemed years, the east began to flush with the dawn. Soon a gray light was diffused over the sea, the fog had lifted and the horizon could be seen in every quarter.

Raynor gave a groan, despite his determination not to give way, as he gazed about him. The sea was empty. The berg, surrounded by a small belt of floating ice, was the only object on the surface of the waters. Not even a streak of smoke on the sky showed the vicinity of steamers.

“I must have drifted right off the ocean track in the night,” muttered Raynor. “It’s a million chances to one now if I ever get picked up.”

The thought overwhelmed even his sturdy determination to bear up. He sank down on the berg utterly unnerved. How long he sat there with his head between his hands in an attitude of abject despair he did not know.

But he was aroused by a sound of snuffling not far from him. He looked up and gave a shout of terror as he did so.

Eyeing him from a slight acclivity of the berg not a hundred feet away, was an immense polar bear!

Like a flash he realized that this was the mysterious visitant of the night, the other occupant of the drifting berg. The creature, as is not uncommonly the case, must have been trapped on the berg when it broke loose from the ice fields of the north.

The bear stood perfectly still except for a wagging motion of its long, narrow, almost snake-like, head. Had the circumstances been different Raynor could have found it in his mind to admire the snow white king of the polar regions. But now his emotions were very different. The bear was no doubt famished, and he was unarmed, except for his knife, which would not be much more use than a darning needle against such an antagonist.

Cold as it was the sweat broke out on the lad’s brow as he realized his position. He stood immovable, staring at the white bear. The great creature, too, appeared to be pondering its next move. Behind Raynor the berg rose to its summit in a series of ledges. Anxious to place as great a distance as possible between himself and the wild beast, the young engineer began to climb upward.

The bear did not follow till he had clambered some distance up the icy walls.

Then it extended its long neck, and opening its mouth emitted an appalling roar. Raynor’s blood ran cold as he saw it shuffle deliberately from the ledge where it had been eyeing him and begin to climb up after him.

“I’ve not a chance on earth,” he groaned.

He looked down at the white monster as it clumsily clambered up toward him. Its movements were quite deliberate, as though the creature knew that the lad could not escape by any possibility. Saliva dribbled from its red fangs as it mounted steadily and Raynor could glimpse its sharp white teeth.

He felt his scalp tighten with fear and kept back a shout of terror only by a supreme effort of will power. The distance that had at first separated the lad and his savage foe was now diminished from feet to inches. In a few seconds more they would be face to face and then——?

Raymond could almost feel its hot breath.

In a frenzy of alarm Raynor seized his tin lunch box from his pocket and hurled it with all his force in the face of the bear. One of the sharp corners struck it fairly on the nose and brought the blood. But it did not stop the creature’s progress.

On the contrary, it enraged it. Shaking its head from the pain, the bear emitted a thunderous roar of rage and scrambled up faster than ever. The scrape of its claws, like steel chisels, against the ice, was horribly suggestive. Raynor could almost feel its hot breath, when something entirely unexpected happened.

A sudden shift to get further away from the bear resulted in the lad losing his footing on the steep and slippery surface of the berg.

Like a stone from a sling he shot down the glassy side with the speed of the wind. Ahead of him was green water but he was powerless to check himself.

Splash! The lad slid into the water, which closed over him in a flash. But in a second he was on the surface again and striking out. Not far from him was a large floe, one of the numerous ones that belted the big berg. With some difficulty he clambered upon this. He had hardly gained its surface when a roar made him look round. The polar bear was not going to be cheated of its prey in that way.

To his horror, Raynor saw the hunger-maddened creature leaping toward him across the ice floes. In a few minutes it would be upon him. Those cruel jaws would be crushing and tearing his flesh. The lad turned sick and faint and reeled as if about to fall. But he was brought sharply back to his senses.

Bang!

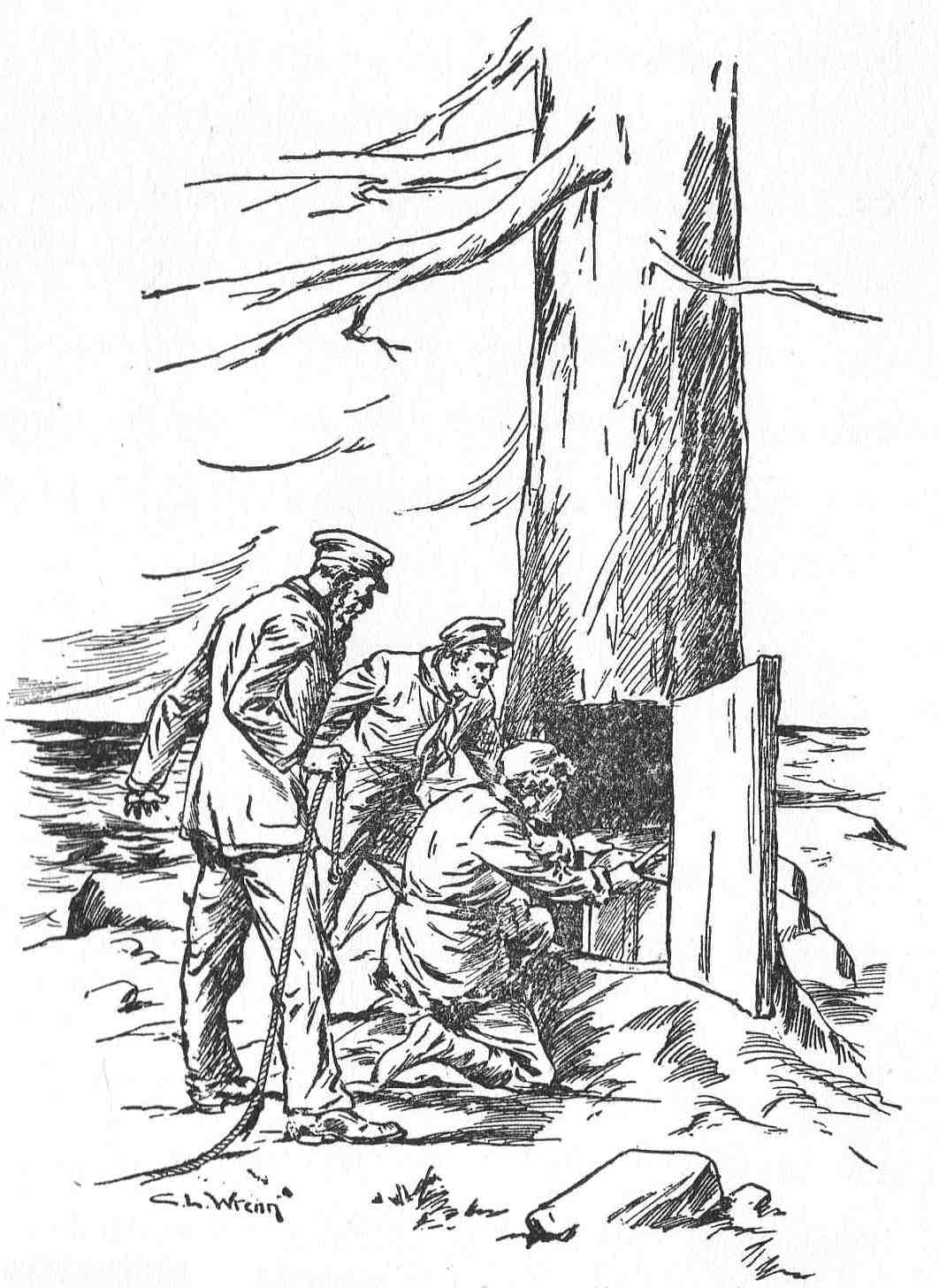

A rifle cracked and the bear, in a pool of crimson, sank on the floe it was about to leap from. The next instant the phenomenon was explained. Not far off lay a handsome, yacht-like looking schooner with her sails aback.

The rifle shot that had saved Raynor’s life had been fired from her deck. He could see the marksman, a tall, bearded fellow, lowering his rifle on which the light glinted.

Then Raynor saw a boat being lowered from the stern davits. Four oarsmen made the light craft fairly skim over the waves toward him. In the stern sheets of the boat the man who had fired the lucky shot stood up handling the tiller. The light gleamed in his great bronze beard and made it shine like copper. His huge build and his attitude at the helm made him look like a Viking of old.

But of all this Raynor, for the time being, had only a hazy impression. Vague lights swam and danced before his eyes in a mad merry-go-round and a sound like the roar of a thousand waterfalls drilled in his ears. Then everything went out in a great wave of darkness.

“Well, young man, I guess you won’t be sorry to get those ropes off.”

Jack looked up from the uneasy slumber into which he had fallen to find Chief Officer Mulliner looking down rather quizzically at him. His ankles and wrists felt as if they had been seared by hot irons. With the tide of his returning memory he recalled dropping off to sleep soon after the mysterious shot had been fired. And now here was Mulliner, knife in hand, and looking quite amiable, ready to set him free.

“You can cut the ropes as soon as you like Mr. Mulliner,” he said with alacrity, “but what has happened?”

“The captain has come to his senses again,” was the rejoinder in a rather uneasy tone, as Mr. Mulliner cut at the ropes, keeping at the work till Jack was free.

“I thought—that is I am sure I heard a shot in the night,” pursued Jack.

The officer’s reticence increased.

“That was nothing,” he said. “I wouldn’t be too curious. Just be glad that the captain has ordered you set at liberty.”

“He had no right to ever order me confined,” cried Jack hotly.

“That’s as it may be. On the high seas whatever he says goes. However, my advice is to keep quiet about this incident. I’m sure the skipper will.”

“I’ll not keep quiet about it,” protested Jack vigorously, “it was an outrage. I shall report it to the owners.”

“If you do you’ll only get a reputation as a trouble-maker, and that is a bad thing for a young man to have,” was the reply. “Captain Briggs is not regularly employed by the Jukes’ concern, and he would care little about anything you might say. He was just picked up, as you may say, to run the Cambodian to Rotterdam and back till one of their own captains gets off the sick list.”

This put things in a new light. Jack thought deeply as he sat on the edge of his bunk chafing his burning wrists to restore circulation. After delivering his advice, Mr. Mulliner had taken his departure.

“This is surely a strange ship and a strange voyage,” thought the boy, “and I’ve got a notion that the end isn’t yet, by a long way. There’s some mystery about that shot in the night too. I mean to find out what it was. Anyhow, I’m at liberty again and I suppose that, as Mulliner said, my best plan is not to cross the captain more than I can help, and wait my opportunity to get back at him for all he has made me suffer.”

Then came the thought of Raynor. Jack, although he was famished for food, sat down at the wireless key and sent out broadcast inquiries. But although he talked to a dozen ships, passenger vessels and freighters like the Cambodian, none reported picking up a castaway. It was with a heavy heart indeed that Jack turned away from his instruments.

His appetite was gone, but he told himself that he must eat. He made his way below. Breakfast was over but the German steward made him some hot coffee and got some rolls. While Jack ate, the man, who was a garrulous fellow, talked.

“Dot vos fine diddings vot vee haf py der nightdt ain’d idt?” he began.

“How do you mean?” asked Jack.

“Vot, you ain’t heard alretty. Vale der captain’s be py his bunk mit a bullet in his shoulder. He haf fights midt der man vot vos in der grows nest. Der captain say he haf him pudt in irons for not sighding der iceberg more quivicker. Der man get madt undt der captain try to shoodt him. In der struggle der pisdol goes off and hits der captain. Der man is a prisoner. He goes by chail ven ve gedt to Rotterdam.”

“How do the crew take it?” asked Jack, recollecting what the man Andrews had said in the night.

“Dey is very quiedt.”

“Nobody saying anything?”

“Nodt a vurd. Budt dey visper among demselves. Dot badt sign. Vunce pefore I vos on a ship vere der crew visper. Dere vos murder done pefore vee made port.”

“Oh, well, there’s nothing like that here,” said Jack with a breezy confidence he was far from feeling. “It’s true our crew is a mixed lot, but I don’t think there’ll be any serious trouble.”

He returned to the wireless room and spent the rest of the forenoon talking to various ships. The ice-patrol reports showed that the bergs had been left behind. The young operator carried his reports to Mr. Mulliner. Captain Briggs did not appear on the bridge till the next day. Then he carried his arm in a sling. From his friend, the steward, Jack learned that the wound was only a flesh one, the bullet having passed right through without lodging.

The remainder of the voyage to Rotterdam was without incident. The crew went about their tasks dutifully but without a word. A sullen silence was over them. Jack felt that, despite the apparent air of peace, a volcano was smoldering under their feet that was ready to break at any moment. He was glad when they tied up at Rotterdam and he was free for a run ashore. But the sight of the country saddened him. It reminded him of the time he and Raynor had spent such a happy time sight-seeing when on his first voyage the Ajax had docked at Antwerp.

Where was Raynor now? Curiously enough Jack could not bring himself to the belief that his shipmate and chum was dead. But he thought of him almost constantly. He bought lots of postcards and mailed them home and received some mail, too. Among the latter, which had come by fast mail steamer and reached port three days ahead of the Cambodian, was a letter from Uncle Toby that puzzled Jack considerably.

“Deer buoy”—it read,—“here’s hopping yew will sune be hoam. Strainge things have been hapning. Capun Walters has gone to glory but—lef me die-and-gram and much infumachun erbout sum berried trezer. Leastwayz itz not berried but hidun. If I kan find it we will be rich, so hurry back, your affeckshonite unkil Toby.”

“Now, what wonderful scheme is this?” said Jack to himself, with a half smile, and speedily forgot the matter, for Uncle Toby was prolific of fortune making plans and usually had a fresh one to broach to Jack after every voyage. Jack would have liked to go to Antwerp to visit the good friends that he and Raynor had made there as a sequel to a surprising night adventure, the details of which were related in the first volume of this series. But he felt that he could not face them with the story of the young engineer’s loss; for even Jack was beginning to lose hope by this time.

There was little to do while the ship was in port, and Jack devoted a good deal of time to putting the finishing touches on his portable wireless set. Captain Briggs was ashore most of the time, coming back to the ship usually late at night and walking none too steadily. His wound had long since healed and the man who had inflicted it had been tried. But owing to some peculiarity of foreign law, he was acquitted. Jack was not sorry when he heard this, for he had come to regard the captain as a coarse, brutal bully, whose excesses only made him the more truculent. As to Jack’s imprisonment, it had not been referred to by the captain and Jack felt inclined to take the chief officer’s advice when his wrath cooled and let “sleeping dogs lie.”

Thus matters stood one evening when Jack, who had been into the town to a moving picture show, was making his way back to the ship. The docks were dark, forbidding places at night. Here and there a sputtering arc light hung from a gloomy warehouse. But these lights only made little islands of light, outside which the shadows lay blacker and thicker than ever.

Brawls were of frequent occurrence among the foreign sailors, and altogether the place bore a bad reputation. As Jack came out of a narrow alley between two warehouses he became aware of a figure skulking along ahead of him.

There was something indescribably furtive and suspicious in the way in which this man crept along, hugging the wall and gazing straight ahead of him. A filtering ray of light struck his head for an instant and Jack saw that in the man’s ears were earrings such as Spanish sailors wear.

The next instant he saw another figure still further in advance. As it passed under a light he recognized the stocky form and unsteady gait of Captain Briggs. At the same instant it flashed across him that the man with the earrings was Baden Alvarez, the sailor who had had the tussle with the captain in which the latter was shot.

“Is he after revenge or what?” Jack wondered as he drew into a slight recess in the wall as Alvarez turned a corner and still skulked on like some wild beast stalking its prey.

“It sure looks as if there was going to be trouble,” the boy said to himself. “Guess I’ll just follow along and be handy in case of mischief. Confound it, I wish I’d brought a gun, as this Alvarez is said to be an ugly customer.”

But, after all, like most healthy American boys, Jack had no love for firearms. He preferred to use his fists when the occasion arose and he knew that at the end of each of his stout arms he had a formidable weapon.

Along the dark docks the strange trio strung their way. In the lead Captain Briggs rolled along, sometimes bawling out snatches of sea songs, behind him, and creeping closer all the time, came Alvarez and, last of all, Jack, his every muscle and sense tensed for the climax that he felt must come now at almost any instant.

Suddenly, like a wild cat, the Spaniard darted forward. He flung his lithe form on the stout captain, taking him utterly by surprise. Jack, in the little light there was, caught the gleam of an upraised knife as he dashed toward the spot where Captain Briggs was struggling with his foe.

“Help!” roared the captain, but the cry was choked back in his windpipe as the Spaniard’s long, muscular fingers closed on the seaman’s throat.

“There ees no help for you,” snarled Alvarez, “for put me in preeson I keel you. I am Catalonian; we never for-geeve or forget.”

He raised his knife high, but the next instant a violent blow caught him under the chin and gave him the impression he had been struck by a pile driver. The knife went whirling out of his hand and fell, with a metallic ring, on a cement string piece some distance away.

“Caramba!” howled the Spaniard, holding his jaw.

Captain Briggs still lay sprawling on the dock. He was still only half aware of what was going on.

“Come, get up, captain,” said Jack, extending a hand. As he did so Alvarez made a rush for the young operator who had put his plans of revenge to rout. But again Jack was prepared for him. In his pocket he had a small nickel plated wrench. He held this like a pistol and pointed it straight at Alvarez, who had produced another knife.

“Stand where you are!” exclaimed the boy, “or take the consequences.”

The Spaniard stopped.

“Now, then, hands up,” ordered Jack, and then turned to the captain. “Captain, I see some rope over there. Will you borrow it and tie that rascal up while I keep him covered.”

The captain rose to his feet blinking, but he managed to get through his muddled intellect what Jack wanted him to do. In five minutes Alvarez was tied securely.

“Now, then, quick march,” said Jack, getting behind him.

“Where you teek me?” sputtered the Spaniard.

“To the ship. In the morning you will be lodged in jail, I hope.”

As they advanced to the ship, which lay two piers away, Jack explained to the captain the narrow escape he had had. The captain thanked him with maudlin tears, which rather disgusted Jack. When the ship was reached the captain reeled off to bed while Jack placed Alvarez forward under the guard of two men.

“He’ll be all right till morning,” he said to himself, but when morning came, Alvarez was gone.

The ropes that had bound him had been cut. They lay on the deck with cleanly severed ends.

Jack cross-examined the two sailors, set to guard him, severely. Both protested vigorously they had not taken their eyes off him all night. But Jack, of course, knew better. He knew, too, that among the superstitious sailors Alvarez, on account of certain claims he made to being a wizard, had much influence. It was certain he had escaped with the connivance of the crew.

“Well, good riddance of bad rubbish,” commented Jack to himself, little dreaming that he was destined to encounter Alvarez again.

When Raynor opened his eyes again he found himself lying on a bunk in a small cabin. Across the single port-hole which lighted it was a red calico curtain. Rough beams crossed the ceiling, from which swung a ship’s lantern, unlighted, of course, at that time of day.

He was on board a ship and a ship that was under way, for he could feel the rise and heave of her hull as she took the seas. With keen curiosity, he sat up. The furniture enumerated was all that he could see in the cabin. There was not even a strip of carpet on the floor, which was of well scrubbed planking.

He looked out of the port. All about him were tumbling green waves through which the schooner,—for he had long since guessed he was on board the craft that rescued him,—was driving smartly. He felt slightly dizzy and sat down on the bunk for an instant before he rose to open the door and find his rescuers and thank them. When he did so he experienced a shock.

The door was locked!

The briefest of investigations proved that it was locked from the outside, showing that he had been deliberately shut in, though for what purpose he could not imagine. He knocked impatiently at the door, hoping to attract the attention of somebody who could explain the mystery but nobody came. Raynor sat down on the bunk, again listening for any sign of movement without.

But none came for a long time. There was a great trampling to and fro of feet on deck and the timbers of the schooner complained as though she was being forced through the water, but this, and the constant rush of water along her sides, were the only sounds.

“Bother it all,” muttered Raynor, “this is a fine way to treat a rescued castaway. Anyone would think I was a prisoner.”

But at last there sounded steps outside and the rattling of a key in the lock and the door was flung open. The yellow-bearded man stood in the doorway, almost filling its frame with his huge bulk. He looked down at Raynor with a rather amused smile.

“I suppose you have been thinking that we don’t treat our guests very well on the Polly Ann?” he said in a deep, gruff voice.

“Well, I don’t see why I was locked in,” rejoined Raynor in a rather aggrieved tone.

“Maybe it didn’t occur to you that we might have private matters on board that we don’t want strangers peering into,” was the calm reply. “You know you were not invited on board.”

Raynor felt a sudden twinge of remorse. After all, he owed his life to this man. He began to thank him but the other silenced him with the wave of a hand.

“That was nothing. Anyhow, I got a fine bear pelt out of it. One of the finest I ever saw. But to get down to business. Have you any idea where you are?”

“On board the schooner Polly Ann,” rejoined Raynor, with an oddly uncomfortable feeling.

“True enough, but do you know anything about her?”

Raynor shook his head.

“Well, she’s Terror Carson’s craft. I’m Terror Carson. If you’d ever been in the northern seas, where we are bound, you’d have heard of me.”

The man uttered his sinister name with some pride. He squared his huge shoulders and stroked his glowing beard with evident satisfaction. Raynor felt his heart sink. There was something wrong about this schooner and this man.

“You are going north trading?” he asked, intending to demand being put aboard the first steamer or other vessel bound for the states that they encountered.

Terror Carson burst into a mighty laugh that seemed to shake the cabin timbers.

“Yes, we’re going trading. Trading in our own line,” he said, and then he beckoned to Raynor to come out into the main cabin from which six smaller ones, similar to the one the young engineer had occupied, opened.

“See those?” he asked, and pointed to three bright brass cannons that were ranged at the stern inside closed ports. “We use those in our trading. You see we are what the courts of law and the international boundary authorities call: ‘seal poachers.’”

“Seal poachers!” Raynor shrank back. He had heard of these wild, lawless men of the north who defied the international boundary rules and even war-ships sent to enforce them. Not a few of them, as he knew, had been captured after hard chases and sentenced to long terms of imprisonment. He could hardly bring himself to speak his next words.

“But of course you will put me on board the first vessel we sight,” he said, “you see, Captain Carson, I——”

“Oh, no, we can’t lose you now,” chuckled the yellow-bearded man, “you know too much. We need an assistant cook and I think you are just the man for the job.”

“Do you mean to say that, against my will, and against the law——” began Raynor, but Terror Carson checked him.

“You forget we know no law,” he said.

“Well, then, against my will you mean to enroll me as one of this lawless crew.”

“That’s about the idea,” drawled Carson amiably.

“But if we are caught by some British cruiser, I shall be imprisoned as one of you!” burst out Raynor frantically.

“That’s something you will have to take your chances of. You shouldn’t have fallen overboard from the Cambodian and then this wouldn’t have happened. You see I know some of your story and have guessed the rest.

“While you were asleep I took the liberty of reading your papers. Here they are,” and with all the grace in the world, Terror Carson handed the bewildered young engineer a package and a wallet which had been abstracted from his inner pocket.

“Now we will go on deck,” said Terror Carson, “and I’ll show you the scene of your future labors. You will berth and have your meals in the cabin and not with the men.”

Raynor felt grateful for this at least, for he judged the crew of a craft like the Polly Ann could be little better than a lot of desperadoes. But he was not prepared for the array of villainous, hard-bitten countenances he saw when they reached the deck. The schooner was under full sail and racing northward like a swift sea bird.

Except for the man at the helm, and a short, stocky man who was standing by him and gazing up at the rigging, the men were all lounging about, some squatting under the weather bulwarks. The short, stocky man proved to be the mate, Mr. Wiggins, a real “down-east bucko,” Terror Carson described him as being. The midship decks were piled with lashed down dories and from the stern davits hung a smart whale boat.

Aft of the foremast was a squat, white house with an iron pipe projecting from it. Terror Carson led the way there with Raynor at his heels. The men’s eyes followed them, some with scowls and some with curiosity.

From the door of the galley, or ship’s kitchen, for that is what the white structure was, there issued a cloud of steam as they approached. Suddenly, in the midst of the volume of vapor, there appeared the round, good-natured, freckled face of a lad of about Raynor’s own age. His head, of bright red hair, was uncovered, and he wore a very dirty apron about his waist.

“Noddy Nipper,” said Terror Carson, nodding toward Raynor, “here’s our assistant cook. Make him work, and if there’s any nonsense report him to me. That’s all.”

With an upward look at the sails, he turned on the heel of his big sea-boots and strode off aft, leaving the half-stupefied Raynor staring at the red-headed youth.

“So, youse is de guy what was floating about on a chunk uv ice tryin’ ter be pals wid a poley bear?” said Noddy, with an accent that betrayed him at once as being from the Bowery, or near it.

Raynor smiled faintly.

“Well, I got bounced off my ship on to that iceberg and came nearly being a meal for the bear if it hadn’t been for your captain, Terror Carson, as he calls himself.”

“An’ he’s a Terror, all right, all right, take dat right frum yer Uncle Dudley,” said Noddy, sinking his voice mysteriously. “I feel kind er sorry fer youse, fer youse ain’t ther sort as belongs aboard this wind-jammer. But take it frum me, kid, if yer follers my advice you’ll git along all right. An’ now let’s put youse ter woik.

“I see old Terror lookin’ this way. Jes’ trim them murphies uv their packets an’ then I’ll think up suthin’ else fer yer ter do. Gee! I’m reg’lar Fi’t Averner style all right, wid me valley an’ all.”

Raynor determined to make the best of a bad job. At least Noddy, as he was called, seemed to be friendly and kind-hearted under his odd exterior. The young engineer turned up his sleeves and went valiantly to work. In a few moments Noddy, who had been busy over a big pan of “scouse,” came to inspect his handiwork.

“Gee!” he exclaimed with scorn, “youse has got a lot ter learn erbout peelin’ spuds. Youse cut off more pertater than yer do skin. Do it dis way. Watch me.”

Raynor did better after this lesson, and before long had a big bucket-full of peeled potatoes that passed even Noddy’s critical examination.

“We’s ull put ’em on ter cook now,” said Noddy, “one bell has jus gone and ther old man wants the gang ter git their scoff by five er clock.”

At this juncture an aged colored man entered the galley. He wore a white cook’s cap on his head, on which he had scrawled, with ink, Pompey James, Chief Cook of the Polly Ann. Noddy introduced him with a flourish.

“Pompey, old top,” he exclaimed, “this is der new deputy assistant bottle washer.”

“Ah’m glad ter meet yer,” said Pompey ceremoniously, “ah hopes yo all is mo’ circumambulatory in yo’ ways dan dis yar raid haided boy. Gollyumptions, he shuh do make dis chile’s life bud’ensome at times.”

Noddy winked and grinned at Raynor. Then he turned suddenly and looked at Pompey with what appeared to be consternation.

“Gee! what’s dat you got in yer wool, Jupe?” he exclaimed, for the cook had taken his white cap off so as not to get it dirty during his culinary operations.

“In mah hair, Noddy?” asked Pompey.

“Yes, sir, in your hair. It’s big and white and round.”

Pompey investigated his wooly poll, scratching it carefully all over. Of course he found nothing.

“Guess yo’ all am tryin’ ter fool dis chile,” he said, with a good-natured grin, which showed a double set of white teeth.

“No, I ain’t. On the level, look!” The Bowery boy reached for the negro’s head and drew from it an egg. It was a simple sleight of hand trick.

But Pompey stared in amazement at the egg as it lay in Noddy’s palm.

“Land ob Goshen! How dat get dere?” he cried in great astonishment.

“Blessed if I know. Maybe you’re turning into an incubator.”

“Gollyumption!” gasped the negro, “I don’ want ter be no inky beater, whateber dat may be.”

“Well, take this ege and make a pudding with it, see,” said the red-headed Bowery youth, holding out the egg in his closed fist. But when he opened his fingers the egg was gone. Instead there lay a bright dime on Noddy’s palm.

“Gee whaitakers. Don’t dat beat de Dutch,” exclaimed Noddy, in apparent astonishment, “queer things seem to be going on here all the time.”

“Good land ob Beulah! Dis yah galley am voodooed!” yelled Pompey. “No, sah, I don’ wan’ner touch dat money under no circumstantials. Dat am witch money, dat am.”

“Oh, very well,” exclaimed Noddy, spinning the coin in the air and catching it, “I kin use it, Pompey. Gee, it’s great ter be pals wid de witches.”

“Is yo’ all a witch docto’?” asked Pompey with great awe.

“Sure I am. I’m a regular witch hazel from Witchville. Say,” he broke off suddenly, “what’s that growing out of this potato?”

He picked up a rotten one that Raynor had cast aside.

“Ain’t nuffin dat I kin see,” mumbled the colored man, much mystified but refusing to be trapped.

“Well, what d’yer call dis?” and the Bowery lad pulled another dime out of the tuber. “My goodness, Pompey, youse have got money scattered everywhere. Here, take this dime. Youse’ll be a rich guy if youse keeps on.”

Pompey took the dime. He turned it over thoughtfully, bit it and then said:

“Dat am good money fo’ sho. But ah don’ know but what it’ll turn inter rats er mice befo’ long.”

Just at that moment Pompey was summoned aft by the captain’s orders, who wanted to give some directions about his dinner. Noddy turned to Raynor with a grin.

“I’ve got him fooled to the queen’s taste,” he chuckled. “After I’ve played a few more tricks on him I’ll have him eating out’n my hand.”

“But what’s the use of scaring him that way?” asked Raynor.

Noddy stared at him. Then he whistled as if in astonishment and executed a sort of double shuffle.

“Say,” he said in low tone as he concluded, “don’t yer see my game? Dat old coon is the only friend we’ve got on this boat, and when the time comes for a getaway we’ll need him.”

“A getaway?” echoed Raynor, “then you want to escape?”

“Do I, say, kid, how’d you like to be tapped on the head in New York and shanghied on board a craft like dis?”

“You mean you were kidnapped on board?” asked Raynor, staring at the red-headed youth with whom he now felt a bond of sympathy.

“Surest t’ing you know. Write it in yo’ little book. But I mean ter get away first chance, you bet. Are you wid me?”

“I certainly am. This schooner is little better than a floating inferno.”

“All right. Tip us yer mitt. When de time comes dat smoke ull be de guy ter help us. He ain’t got no more use fer Terrer Carson dan I have, so fur as I’ve bin able to figger it out.”

The two allies shook hands, but further conversation was barred just then for Pompey reentered the galley.

Raynor found that his duties, besides his kitchen work, included waiting on the table in the cabin. He managed to acquit himself at this without getting into serious trouble, although Terror Carson gave him several gruff reproofs during the evening. When supper was over the duty of washing the dishes fell to the two boys. Pompey retired forward for a smoke and they had the galley to themselves.

The breeze, which had been steady all the afternoon, was beginning to increase. The schooner began to leap and strain as the waves grew bigger. Raynor found some difficulty in keeping his feet.

“Say, it’s coming on to blow,” observed Raynor.

“Yes, and that’s too bad,” rejoined Noddy. “I’d got it framed up fer a getaway ter night.”

“To-night?” gasped Raynor.

“Yep, Pompey is to have the wheel to-night. He has that duty every two weeks. At midnight he’ll be alone on deck and if we fix up like ghosts it would be dead easy to scare him and get at the boat on the stern davits and make our fare-you-well.”

The boldness of the plan almost overcame Raynor.

“Here’s de proposition,” went on Noddy. “If we don’t do it to-night we won’t have a show ter take a crack at it fer annudder two weeks—see. By dat time de men say we’ll be up among der ice where der seals are, an’ it wouldn’t do us no good if we did escape, fer deres mighty few craft up dere.”

“Well, I’m game,” said Raynor.

“Good for you,” and Noddy dropped his voice and began whispering the details of his plan. By the time they had finished their work the schooner was pitching and tossing wildly and they knew that the storm was on the increase. “But dat don’t make no never mind,” declared the Bowery boy. “I’ve heard de men say dat de whale boat ’ud live in seas dat would sink de schooner.”

They parted, Noddy to go forward to his bunk in a storeroom, where sails, paint, etc., were stored, and Raynor to his cabin. Terror Carson and his mate sat at the table. They took no notice of the lad. In his cabin Raynor did not take his clothes off. He could not have slept. The excitement of the projected escape would have prohibited that. Midnight was the hour agreed upon, and he listened to the ship’s bell sounding the slowly passing hours, and half hours, with great impatience. At last the growl of voices in the cabin ceased and then two doors banged and Raynor knew the captain and mate had turned in. Just then the bell struck seven times. It was eleven-thirty.

“This is a bad night to leave the ship,” mused Raynor, as he sat waiting for the chiming of eight bells.

The schooner appeared to be under a press of canvas, for her hull was heeled over at a steep angle. At times she appeared to rush skyward and then hurtle down into a bottomless abyss. Raynor hoped the whaleboat was as seaworthy as such a type of boat is reputed to be. The thought of abandoning the enterprise, however, did not, enter his head. As Noddy had pointed out, it might be their only chance of escape, and Raynor longed for nothing more than to get free of the Polly Ann. It was his paramount ambition and it would have taken more than a stormy night to stop him.

As eight bells struck, Raynor rose and cautiously opened the door of his cabin a crack.

The swinging lamp outside was turned low and the main cabin empty. He stole cautiously out and then ascended the companionway to the deck.

Luckily, the companionway entrance was below a break in the stern so that the man at the wheel—Pompey—could not see him as, crouched almost double, he crept forward to the small deck house where Noddy had his berth. It was a wild night. Big seas, their white tops luminous, raced by, towering above the schooner’s rail. The speedy little vessel was heeled over almost on her beam ends at times, but she appeared remarkably seaworthy.

Not a soul could be seen on deck except Pompey’s dark form at the wheel, revealed by the faint glow-worm light of the binnacle lamp. At last Raynor, with infinite caution, reached Noddy’s sleeping place. He rapped three times, as they had agreed, and the door was opened.

Raynor almost uttered a cry of alarm as the portal was pulled back by Noddy. He saw what appeared to be a human face enveloped in pale green fire, out of which shone two luminous eyes.

“Swell ghost, eh?” chuckled Noddy, pulling him inside. “I made de stuff out’n match heads. Come on, here’s some fer you. Rub it on yer face an’ den I’ll give you yer shroud.”

He held up a shapeless-looking garment of white sail cloth that he had made, and at the same time cautiously turned up the flame of a lantern that stood in a corner so that Raynor could see.

“I don’t believe we can get away to-night in a small boat,” declared Raynor as he daubed on the phosphorescent solution under Noddy’s directions.

“Why not?” asked the Bowery lad.

“It’s too rough. Feel how the schooner is pitching. It’ll make the small boat dance about worse.”

“Well, we gotter take our chances on dat,” decided Noddy, “we’ll take a look when we git outside.”

At last the ghosts were ready. Raynor’s heart beat rather faster than was comfortable as they crept out upon the heaving, tossing decks. If their plan failed, and Terror Carson discovered it, a terrible fate might be in store for them. A strong wind whistled about them and a dash of rain beat in their faces.

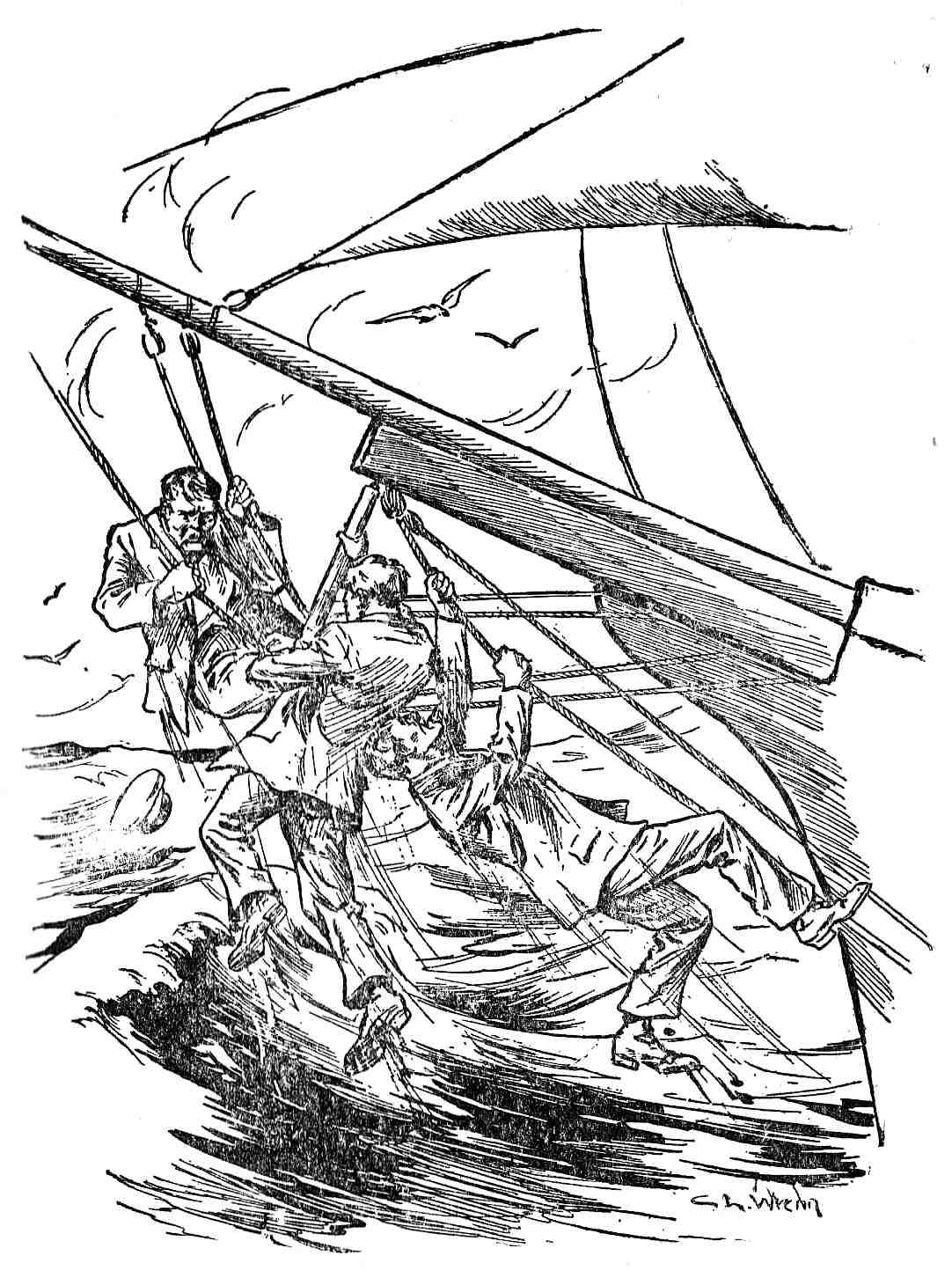

“Gee! It is pretty bad, fer a fact,” declared Noddy. “Well, let’s get along to the stern.” They proceeded cautiously, doubled up under the shadow of the bulwark till they reached the break in the stern. Then, with an appalling yell, Noddy dashed up the steps leading on to the raised poop where the helmsman stood. Raynor was close behind him. Noddy’s shriek was echoed by a shout of alarm from Pompey.

“Gollyumptions! Ghostesses! De good lawd hab mussey on mah soul! Oh, Massa, ghostesses don’ hurt me! Wow!”

A wild yell of fear came from the trembling Pompey as Noddy raised a flaming hand and pointed straight at him. Pompey dropped the spokes of the wheel and dashed forward, leaping the break of the poop in one jump. At the same instant the schooner “broached to” as her helm was deserted. The canvas flapped wildly and she rolled in the trough of the seas. A giant wave broke over her bow with a sound like thunder.

At the same instant, from below, came a stentorian shout like the roar of an angry bull.

“On deck, there! What in the name of Davy Jones is the matter?”

“That’s Terror Carson!” cried Noddy. “Come on, let’s get forward. No escape for us to-night.”

The two boys rushed toward the bow just in time to avoid Carson, who came rushing on deck followed by his mate. They bolted into Noddy’s sanctum in time to avoid the crew, who came tumbling up the fore-hatchway, and hastily removed their shrouds and washed off the phosphorus. Then they ran out and mingled with the crowd on deck as if they had just been aroused by the confusion.

It was a wild scene on the deck of the Polly Ann. Carson himself had seized the tiller and was holding the craft on her course, but two sails had been ripped and a lot of water shipped over the bow. The boys came out just in time to see some sailors dragging Pompey aft from the galley, where he had taken refuge from what he thought were supernatural visitors.

The black was beside himself with fear of Terror Carson and alarm at what he had seen. He stammered out incoherent explanations about being scared from the wheel by “ghostesses.” Carson roared savagely at him. He declared he had a good mind to have him flogged. But finally he commuted the sentence to two days in irons. The boys felt conscience-stricken at having involved poor Pompey in such a quandary, yet they could not have made explanations without making matters worse.

Fortunately for them, the confusion and crowd on deck were so great that nobody noticed from what direction they came when they appeared, and it was taken for granted by all concerned that both had rushed from their bunks when the general alarm that followed the “broaching to” of the schooner took place.

And so ended their first attempt to escape from the seal poacher Polly Ann. Both lads were bitterly disappointed at the way Fate had turned her face against them, but both determined to try again at the first opportunity. Meantime, the Polly Ann forged northward, and destiny was weaving strange threads which were fated to form an important part in the fabrics of their lives.

Captain Briggs, in a sheepish sort of way, tried to make friends with Jack following the episode on the dock. But Jack had little use for the man and kept on with his own devices, paying little attention to Captain Briggs, except in the line of duty.

On the night before which they were to sail for America again, Jack had been uptown to post some cards and letters and did not return to the ship till about nine o’clock at night. As he made his way to his cabin, he was startled to see what he thought was a human figure gliding among the boats and life-rafts on the deck outside, for the wireless-room of the Cambodian, like most such structures, was perched upon the boat deck.

“Now, who could that be?” thought the boy. “Guess I’ll take a look around. These docks are infested with thieves, and although there’s a watchman on duty, somebody may have sneaked on board.”

But although he made what was quite a thorough search, he could find no trace of the man he thought he had seen dodging among the boats as if seeking a hiding place. He was forced to conclude at length that, in the uncertain light, he must have mistaken the swaying shadow of a rope or part of the rigging, for a human form.

“Well, I guess I’ll turn in,” decided Jack, as he opened his cabin door. “We sail early to-morrow and I’ll have to be on the job.”