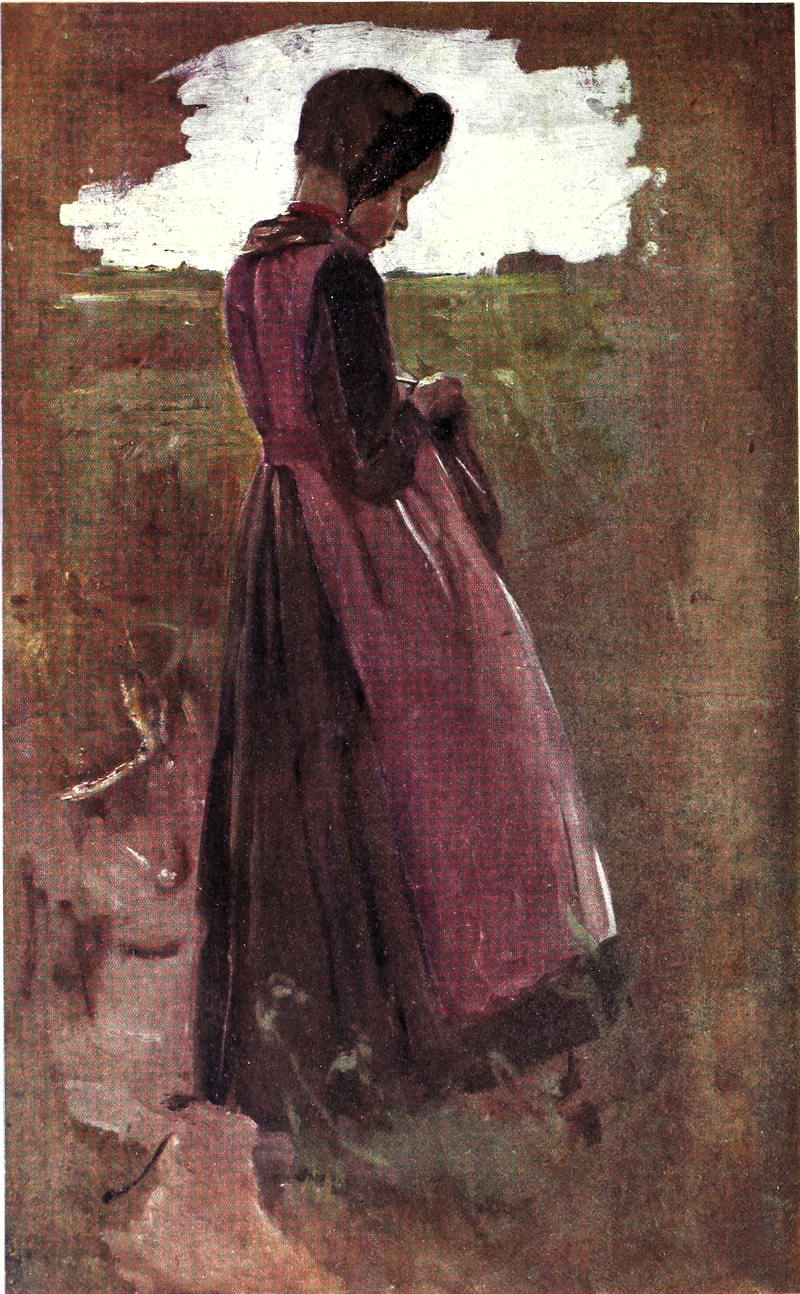

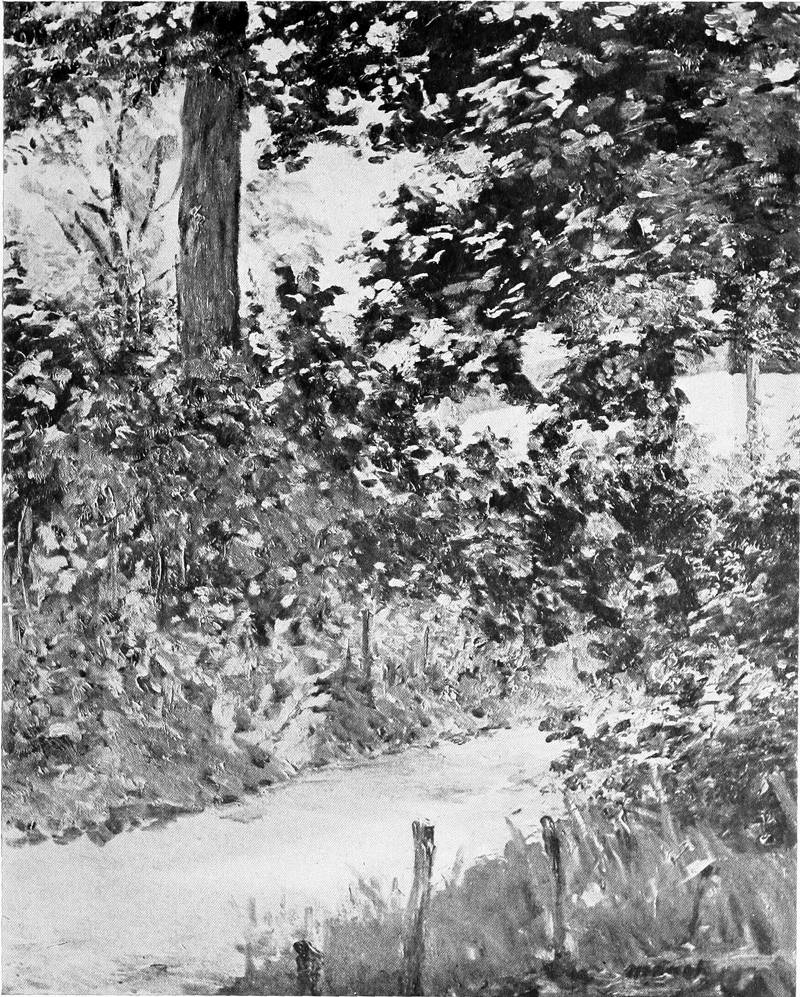

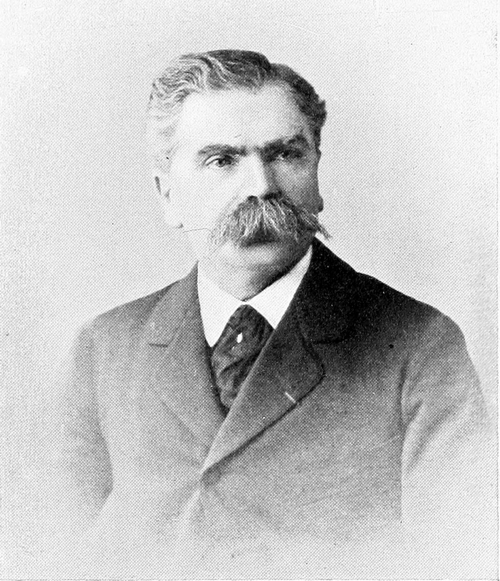

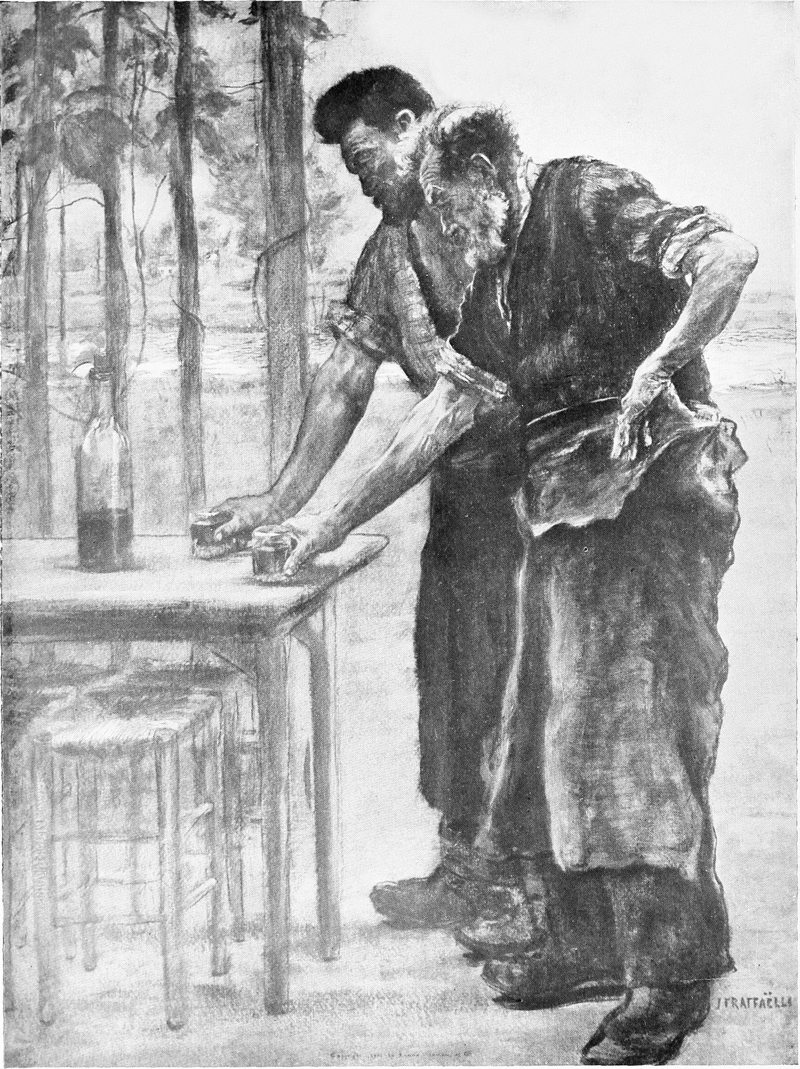

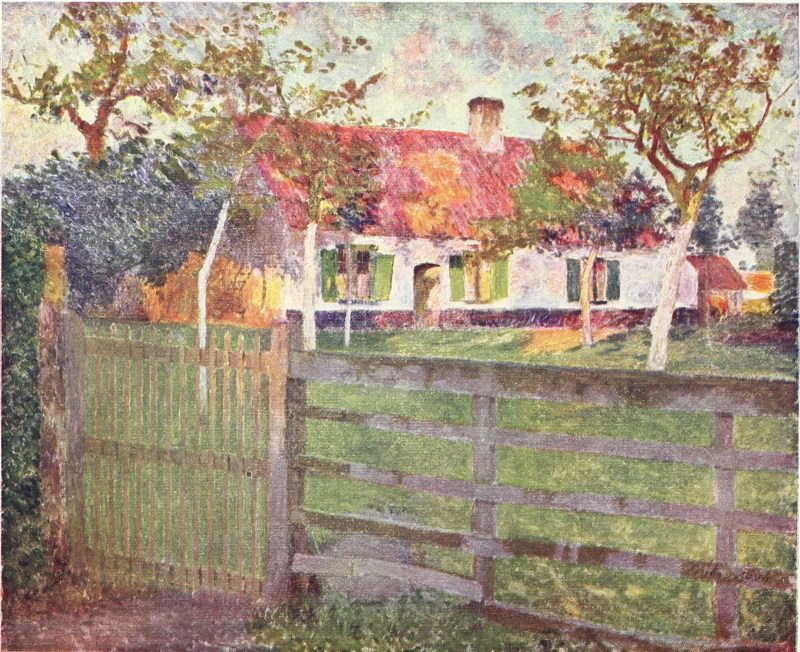

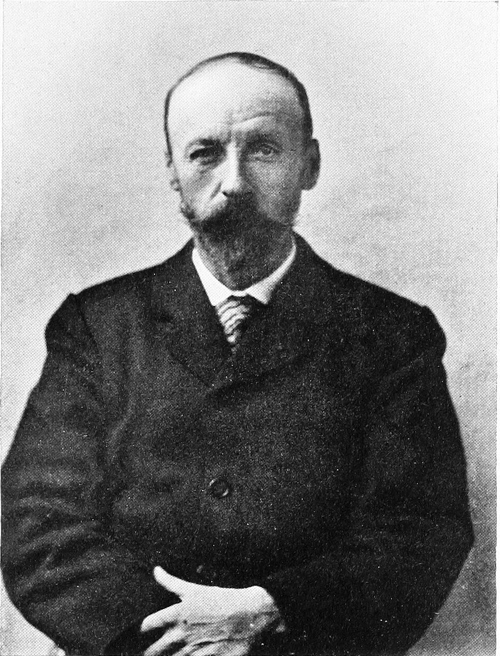

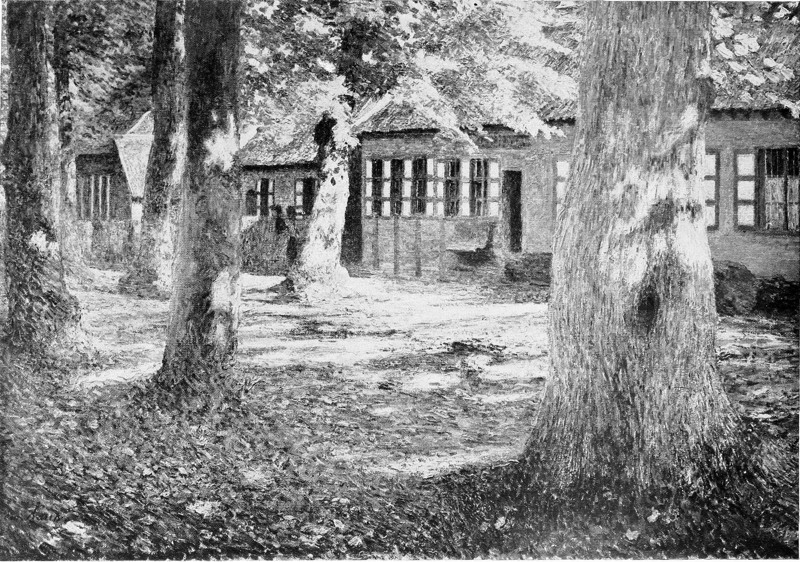

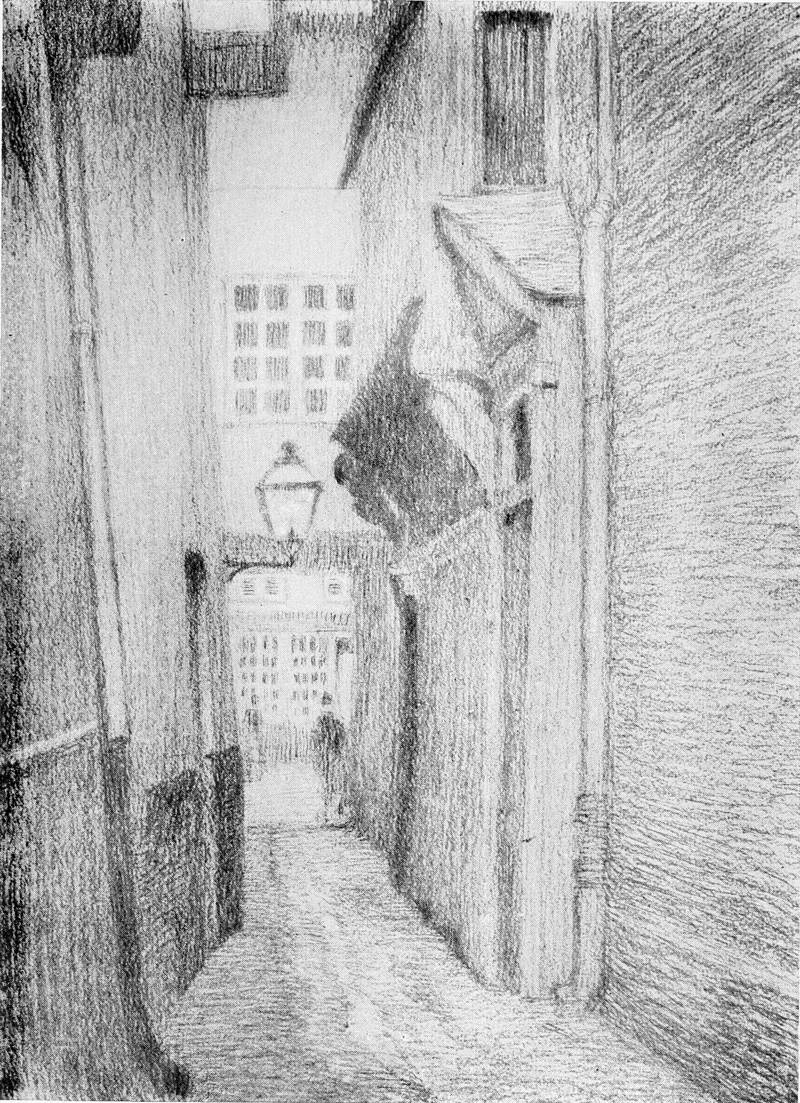

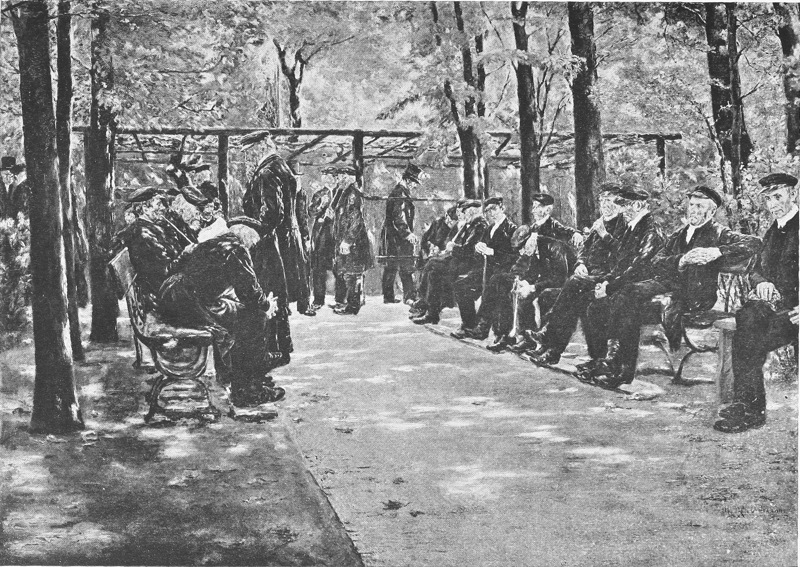

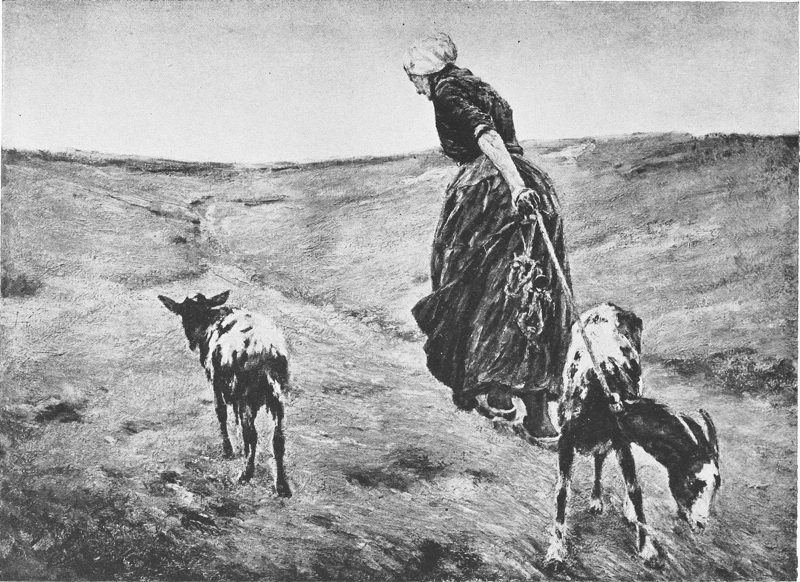

A STUDY · MAX LIEBERMANN

IT may perhaps be interesting to the readers of this book to give a short account of its origin. From the earliest days of my pupilage to art I had been instinctively drawn towards the paintings of Turner, Corot, Constable, Bonington, and Watts, with an intense admiration for their manner in viewing, and methods of recreating, nature upon their canvases; and in later years I had been fascinated by the works of more modern artists, such as La Thangue, George Clausen, Edward Stott, and Robert Meyerheim. In 1891, a student in Paris, I found myself face to face with a beautiful development of landscape painting, which was quite new to me. “Impressionism,” together with its numerous progeny of eccentric offshoots, was at the time causing a great furore in the schools. Curiously enough I had been charged with copying Monet’s style long before I had seen his actual work, so that my conversion into an enthusiastic Impressionist was short, in fact, an instantaneous process.

Since then I have endeavoured, by precept and by example, to preach the doctrine of Impressionism, particularly in England, where it is so little known and appreciated. It has always seemed to me astonishing that an art which has shown such magnificent proofs of virility, which has long been accepted at its true value on the Continent and in America, should be comparatively neglected in my own country. A stimulating propaganda being needed, I invaded for a short time the domain of the writer on art, a sphere of activity for which I feel myself none too well equipped. For years, as a hobby, I had collected all manner of documents bearing upon the subject of Impressionism, and the mass of material which thus accumulated formed the basis for several articles which have appeared under my name in the English magazines. To the Editors of the Pall Mall Magazine, the Artist, and the Studio, I must tender my best thanks for the leave, so courteously given, to incorporate the substance of the respective articles in this volume.

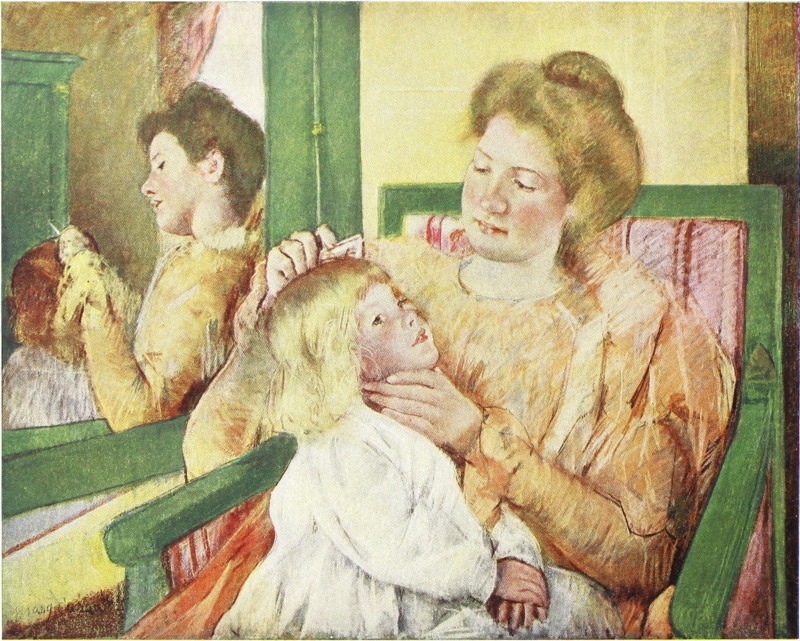

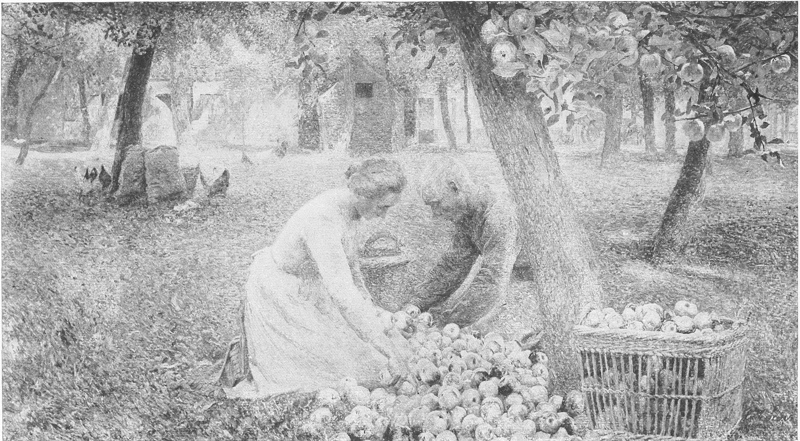

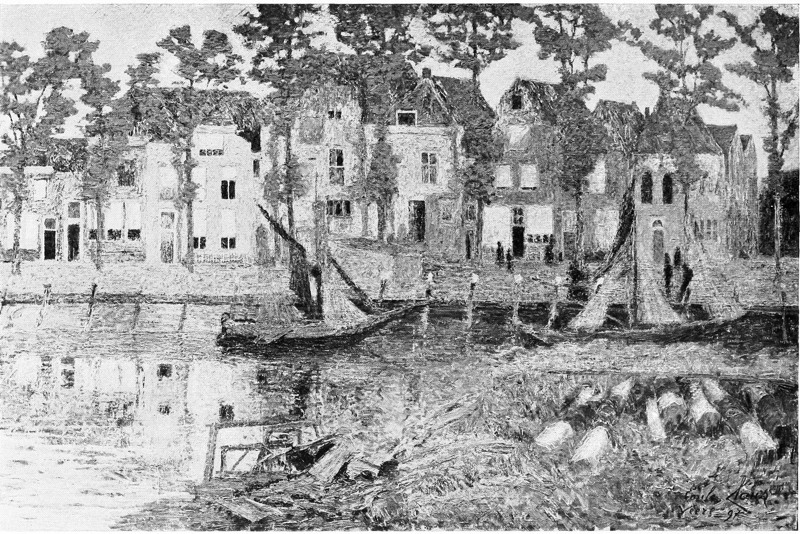

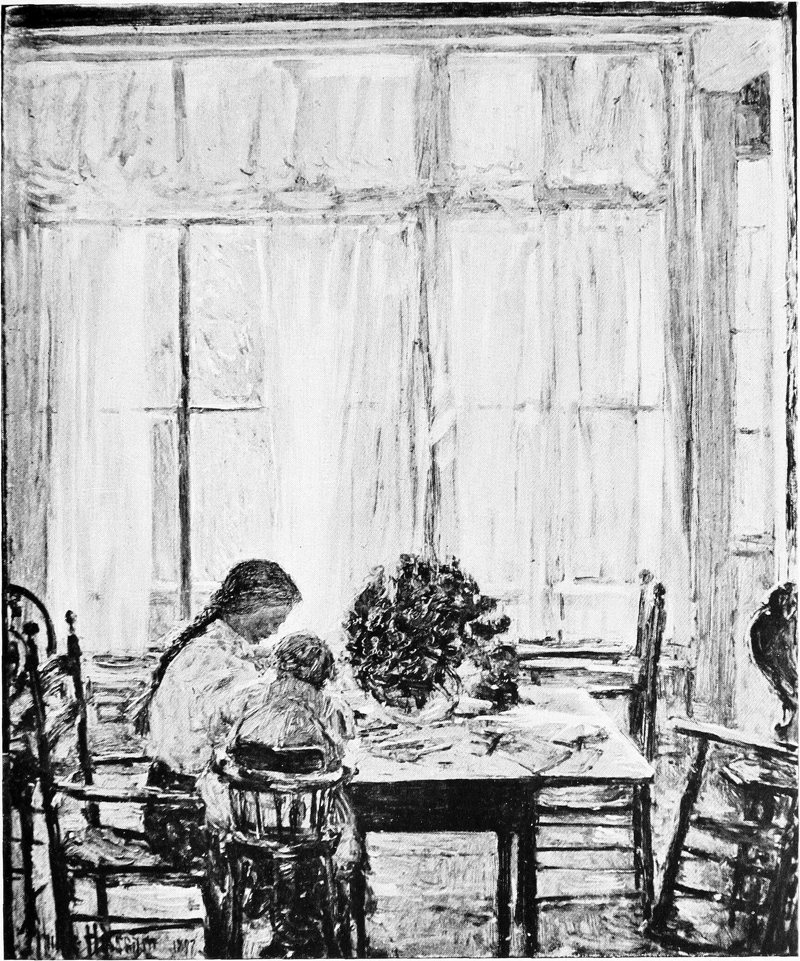

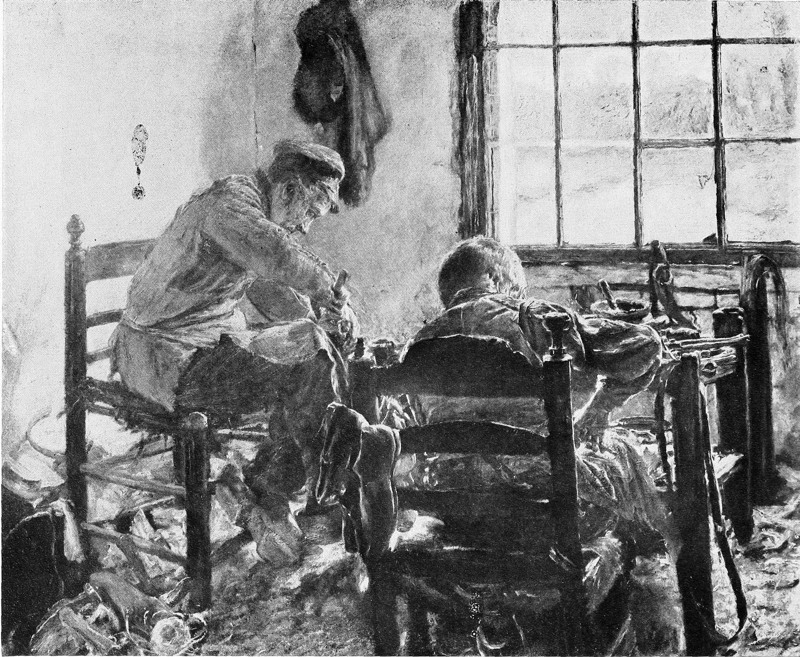

viiiMany of the pictures which illustrate these pages are unique, having been reproduced for the first time, the photographs not being for public sale. I have to acknowledge my sincere obligations to Miss Mary Cassatt, Messieurs Durand-Ruel (who have given me much personal assistance), George Petit, Bernheim jeune, Maxime Maufra, Alexander Harrison, Paul Chevallier, Lucien Sauphar, Emile Claus, Max Liebermann, and, indeed, to all the artists illustrated, for permission to use the photographs of their works. To Miss Mary Cassatt, and Messieurs Claude Monet, Emile Claus, and Max Liebermann I am also indebted for the loan of valuable pictures, and also for permission to reproduce them in colours. Without such aid it would have been impossible to produce satisfactorily any account of Impressionism. I trust that this volume may be of real service in the cause of art education, and that it may introduce to an extended circle of art-lovers the masterpieces of the great artists who founded and are continuing Impressionist Painting.

| PAGE | ||

| DEDICATION | v | |

| PREFACE | vii | |

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | xi | |

| LIST OF PORTRAITS | xv | |

| CHAP. | ||

| I. | THE EVOLUTION OF THE IMPRESSIONISTIC IDEA | 1 |

| II. | JONGKIND, BOUDIN, AND CÉZANNE | 9 |

| III. | EDOUARD MANET (1832-1883) | 17 |

| IV. | THE IMPRESSIONIST GROUP, 1870-1886 | 31 |

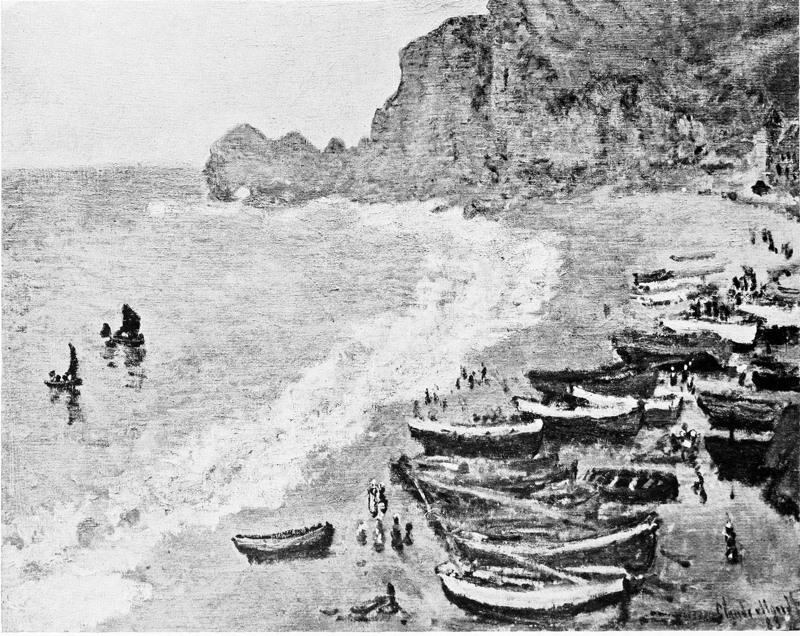

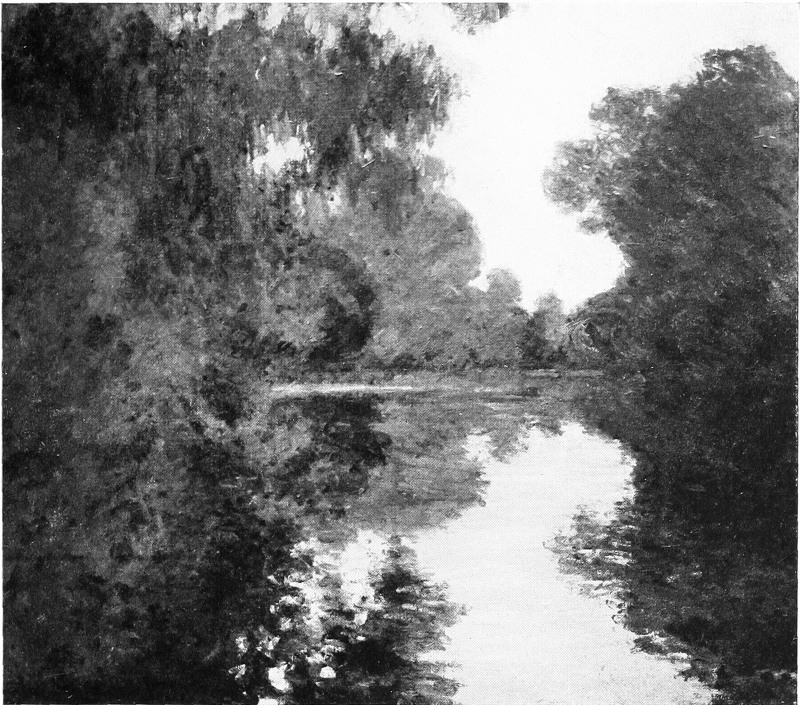

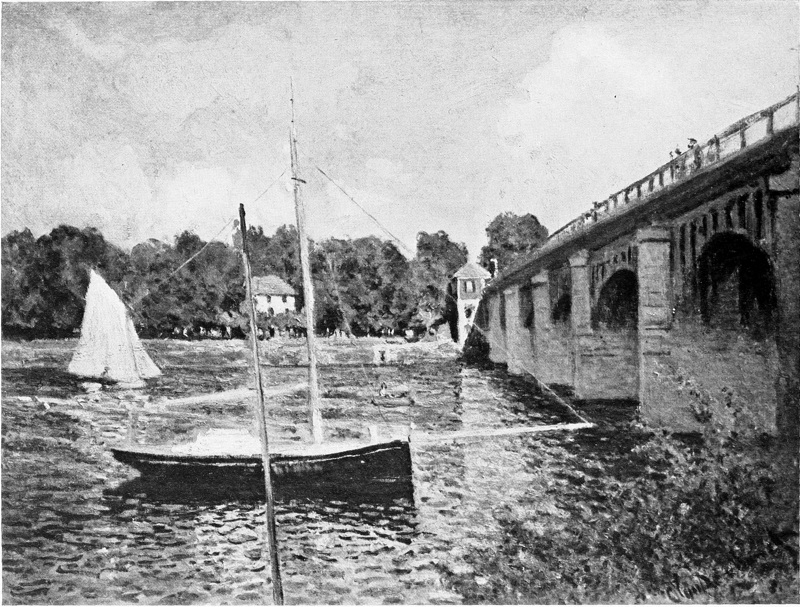

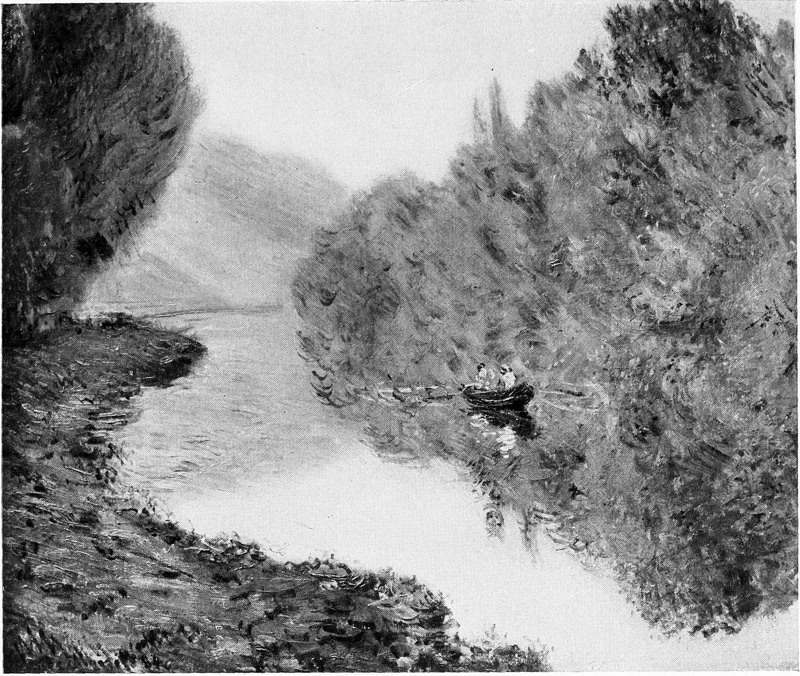

| V. | CLAUDE MONET | 37 |

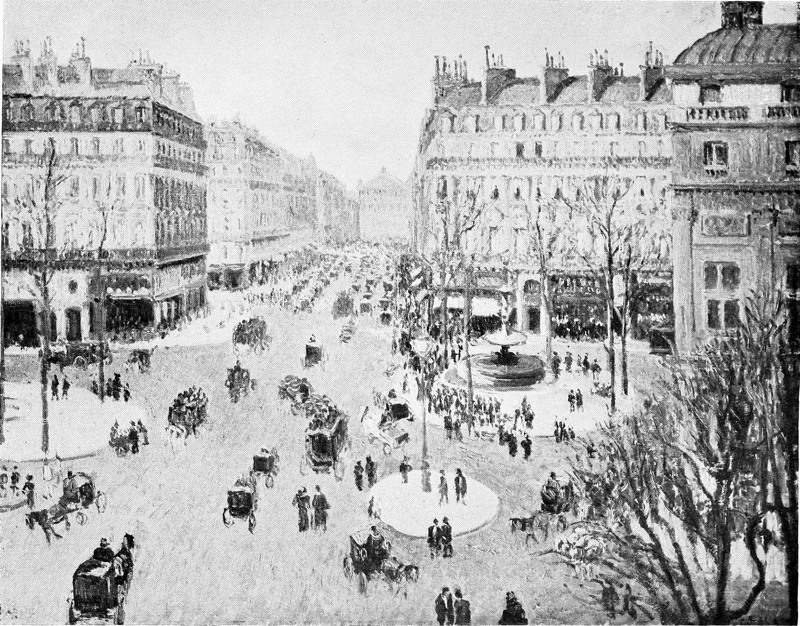

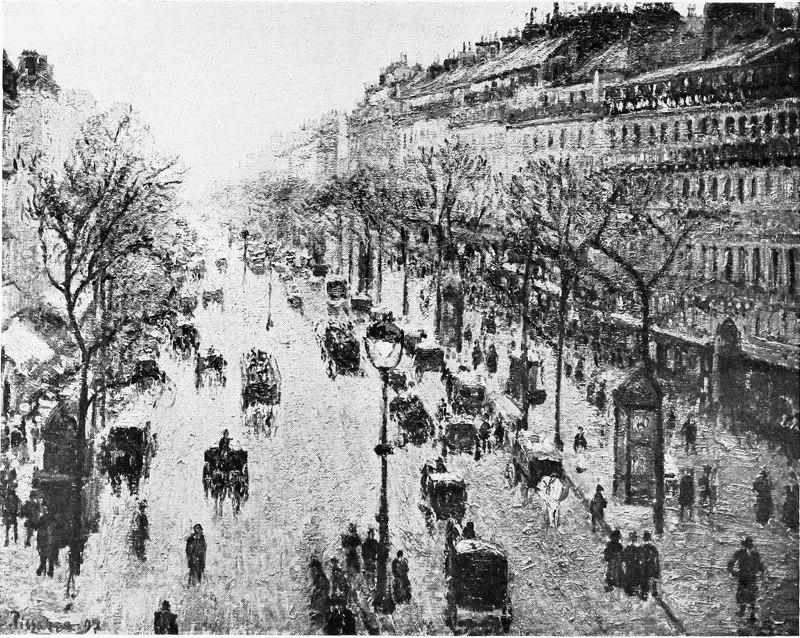

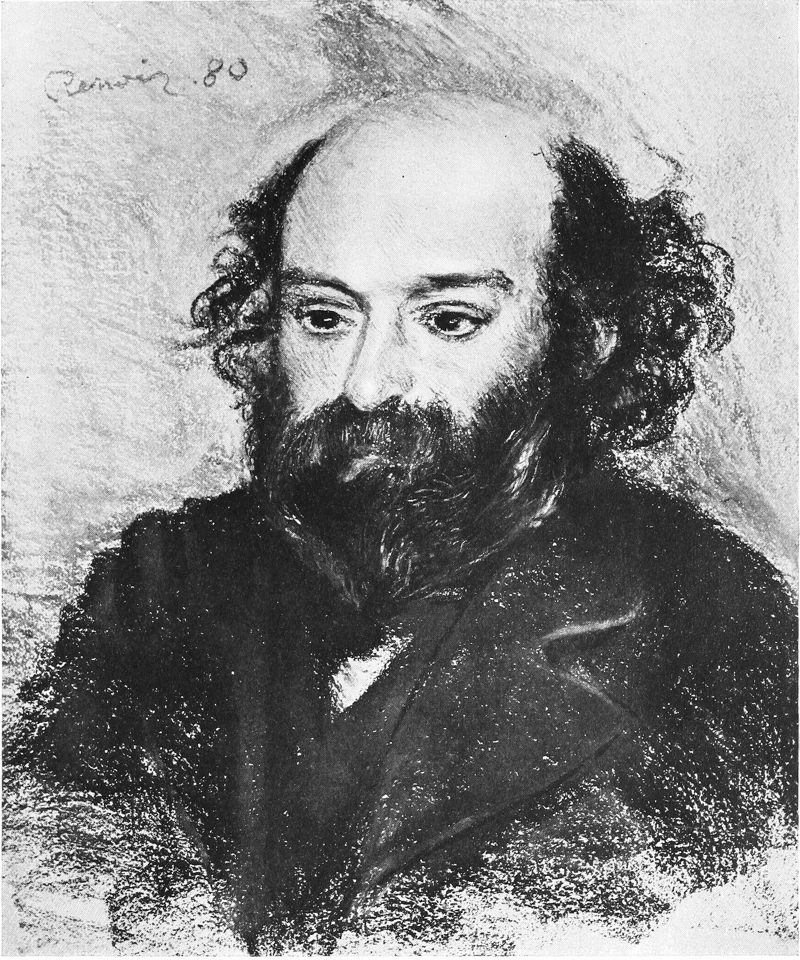

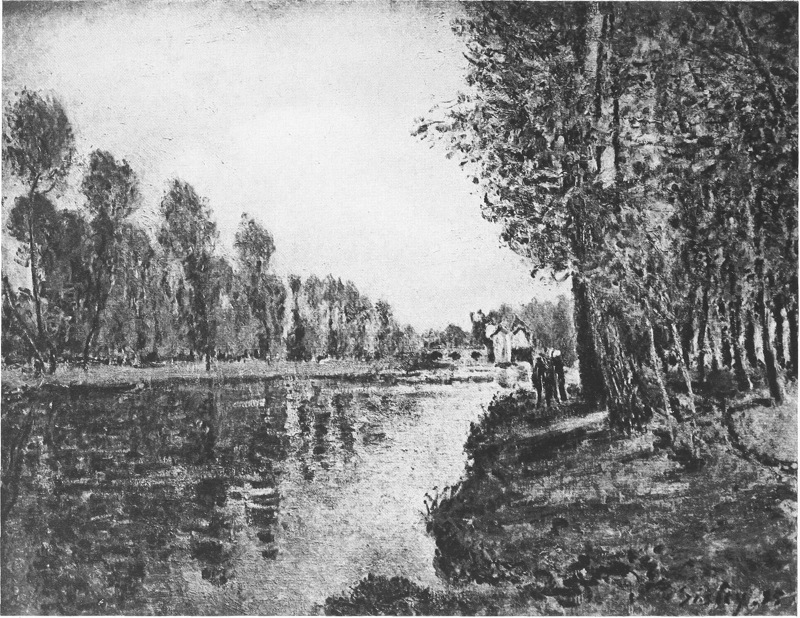

| VI. | PISSARRO, RENOIR, SISLEY | 49 |

| VII. | SOME YOUNGER IMPRESSIONISTS: CARRIÈRE, POINTELIN, MAUFRA | 57 |

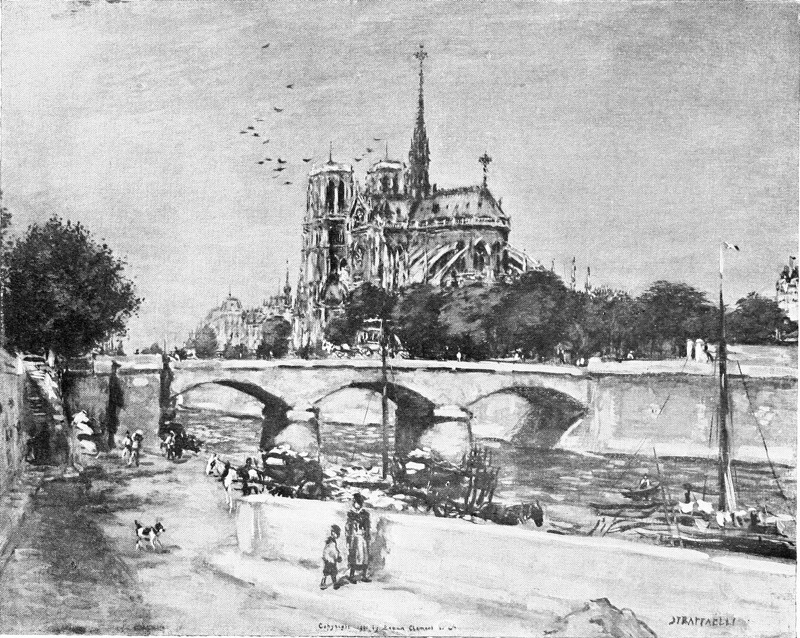

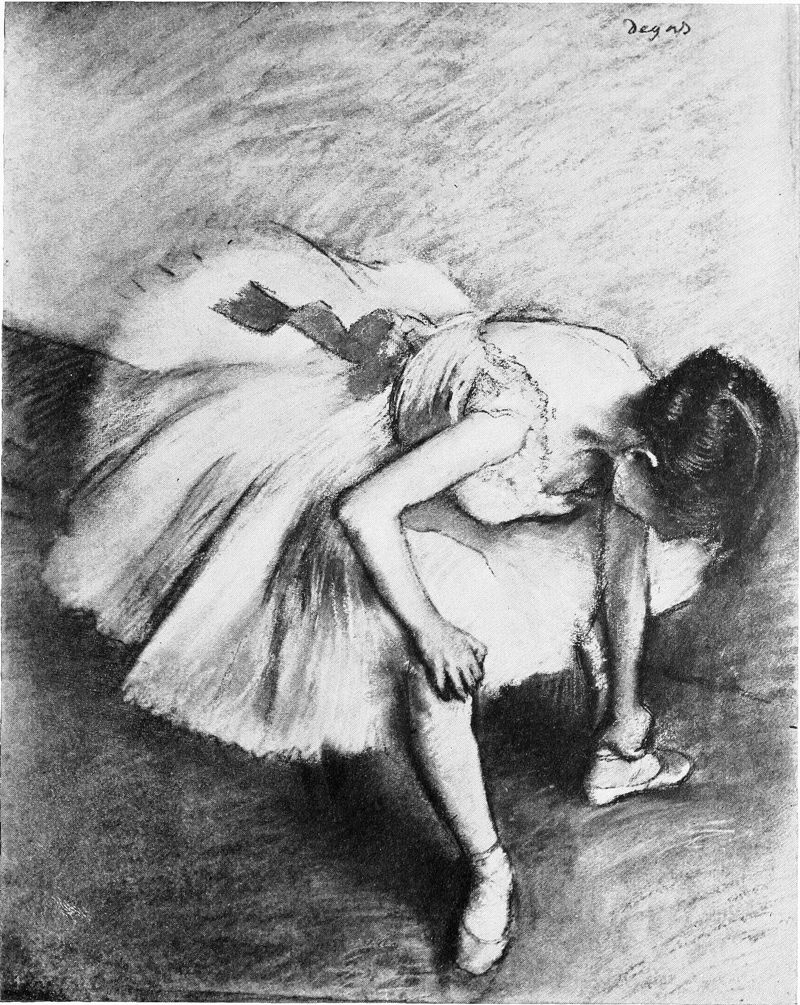

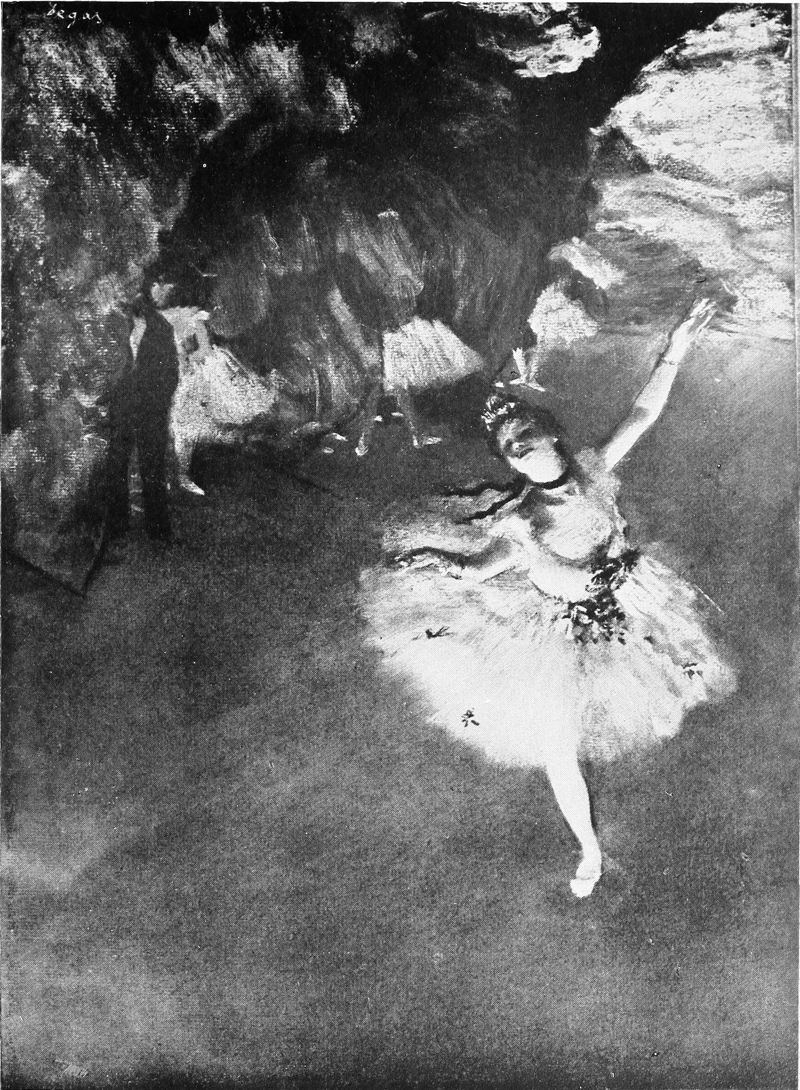

| VIII. | “REALISTS”: RAFFAËLLI, DEGAS, TOULOUSE-LAUTREC | 65 |

| IX. | THE “WOMEN-PAINTERS”: BERTHE MORISOT, MARY CASSATT, MARIE BRACQUEMOND, EVA GONZALÈS | 75 |

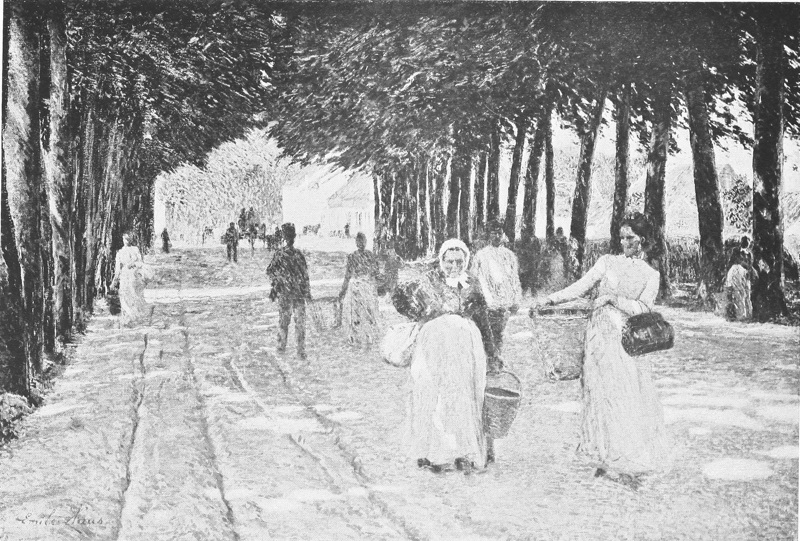

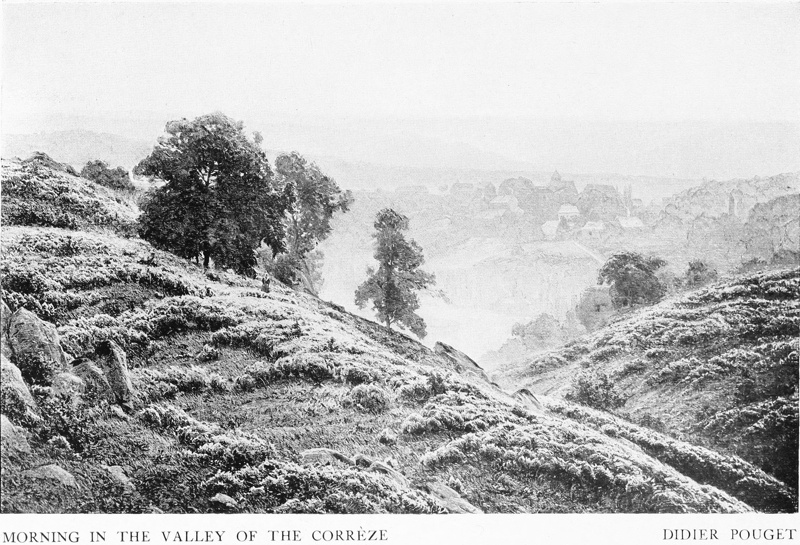

| X. | “LA PEINTURE CLAIRE”: CLAUS, LE SIDANER, BESNARD, DIDIER-POUGET | 79 |

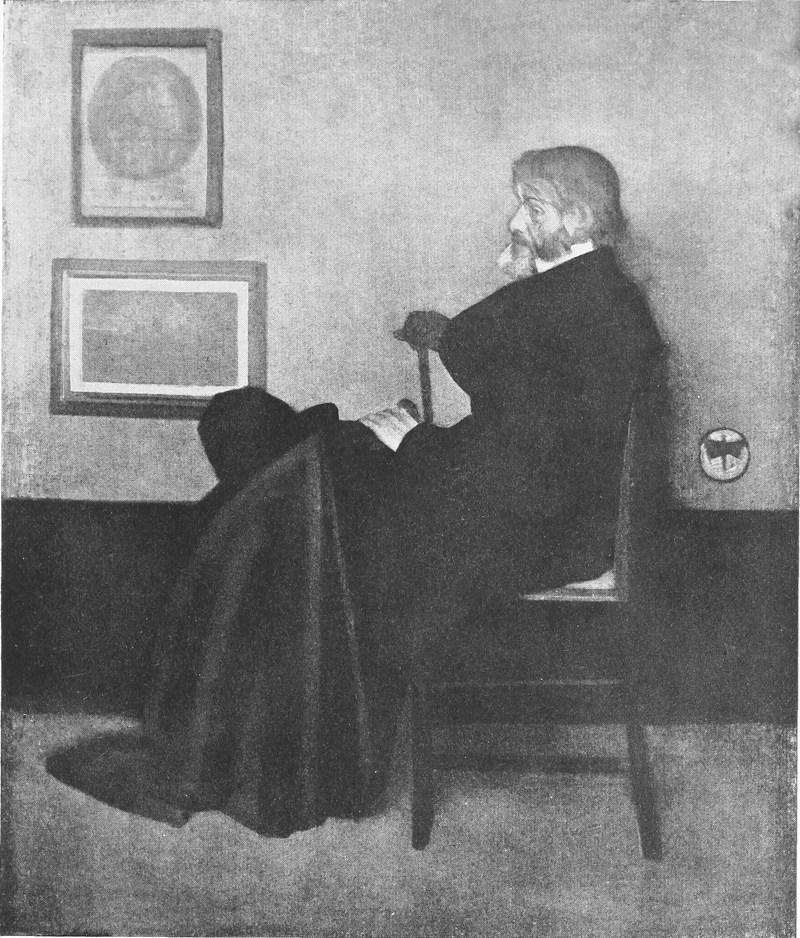

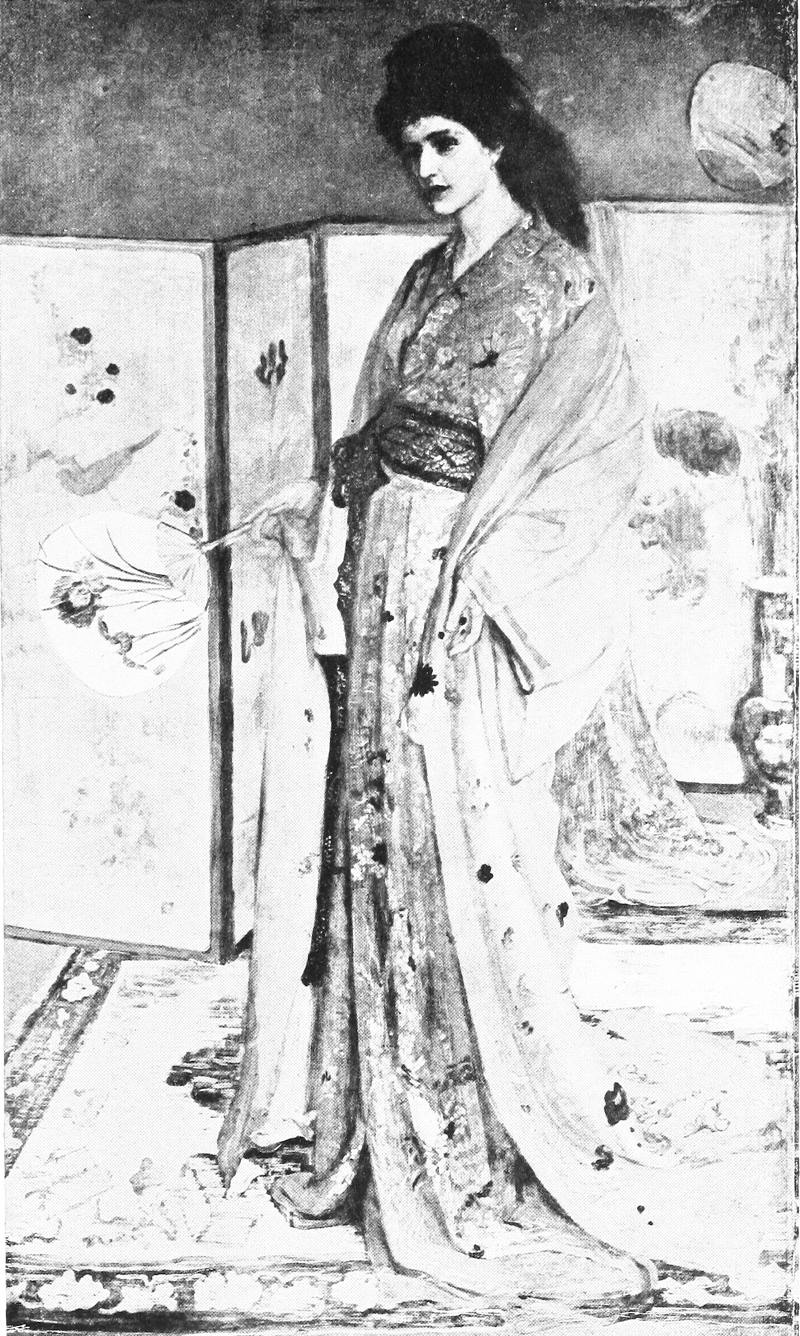

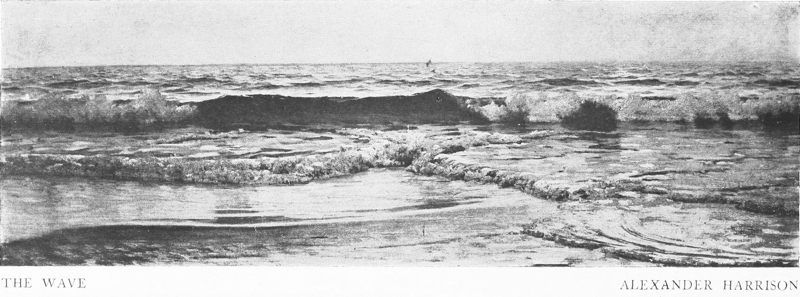

| XI. | AMERICAN IMPRESSIONISTS: WHISTLER, HARRISON, HASSAM | 89 |

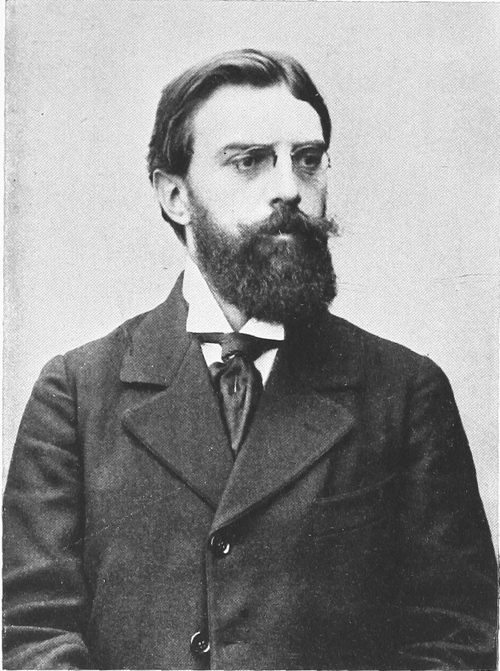

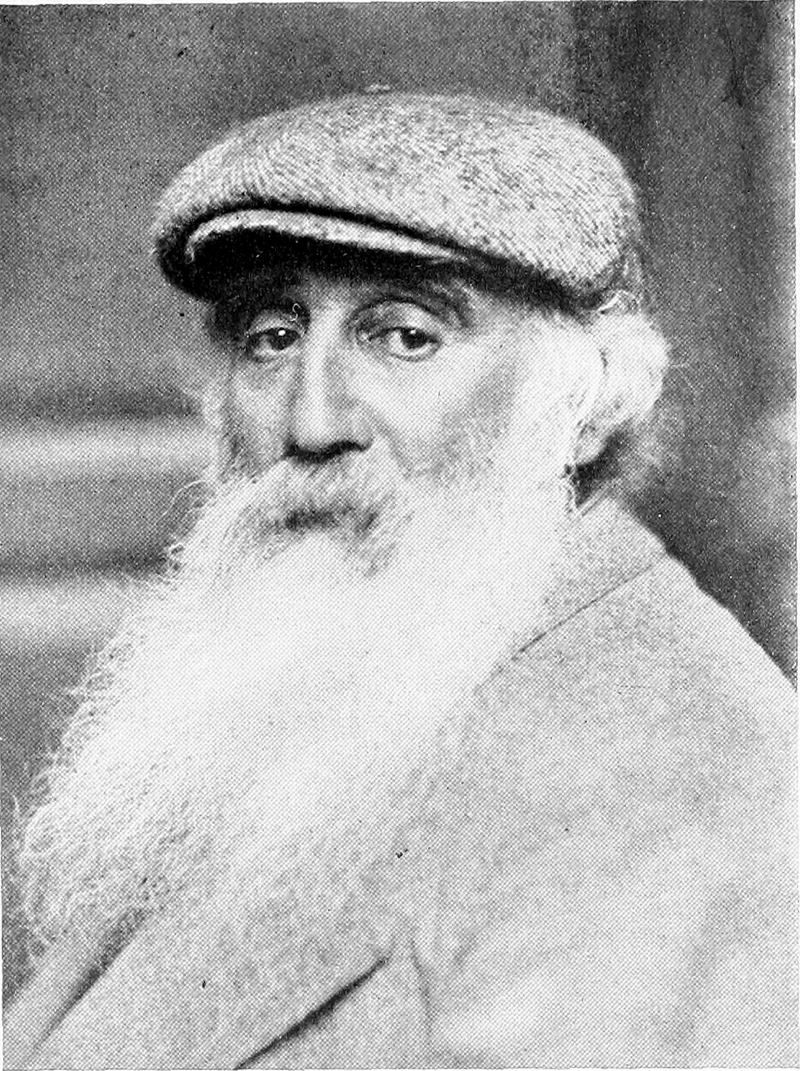

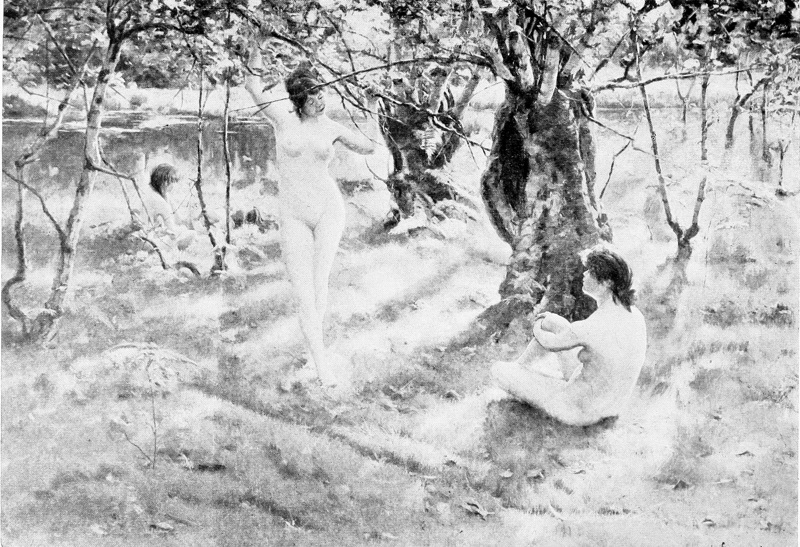

| XII. | A GERMAN IMPRESSIONIST, MAX LIEBERMANN | 95 |

| XIII. | INFLUENCES AND TENDENCIES | 101 |

| APPENDIX | 107 | |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 113 | |

| INDEX | 121 |

MODERN ITALY · J. M. W. TURNER

“L’IMPRESSIONISME, ELLE EST DIGNE DE NOTRE ADMIRATIVE ATTENTION, ET NOUS POUVONS RATIONNELLEMENT CROIRE QUE, AUX YEUX DES GÉNÉRATIONS FUTURES, ELLE JUSTIFIERA CETTE FIN DE SIÈCLE DANS L’HISTOIRE GÉNÉRALE DE L’ART”

GEORGES LECOMTE

ALTHOUGH the great revolution of 1793 changed the whole face of France both politically and socially, it failed to emancipate the twin arts of painting and literature. In each case one tradition was succeeded by another, and nearly forty years elapsed before the new spirit completely broke through the barriers set up by a past generation.

In literature the victory was complete. The reason is easy to discover. The smart dramatist and the young novelist are always more likely to catch the fickle taste of the uneducated public than the budding painter, who depends to a great extent for his appreciation upon the trained and generally prejudiced eye of a connoisseur. There is another reason for the success of the Romantic School in literature. The majority of its leaders lived to extreme old age, and were themselves able to correct their youthful extravagances. Hugo, Dumas, Gautier (to mention but three) went down to their graves in honour. They had outlived the antagonisms of their early days, and no man dared to raise his voice in protest against poets who had added fresh laurels to the glory of France.

The world of art was less fortunate. Many of the younger men barely lived through the first flush of youth. Destroying Death is the worst enemy to the arts. It is idle to imagine the changes which must have ensued had Géricault and Bonington reached the Psalmist’s allotted span. The unnatural union of Classical traditions with the yeast of Romanticism might not have taken place. Such artists as Delaroche and Couture would have dropped into the background, and there would have been less reason for the revolt of Edouard Manet. It is possible that Claude Monet might have been forestalled. Surely, Impressionism would have come to us in another shape from different easels. In any event it was bound to arrive, for a French artist had already struck the note nearly a century and a half before.

2The schools of painting which flourished under the last three Capet kings lacked many of the essentials of truly great art. But they possessed qualities, which the Classicalists despised, and the Romanticists never reached in exactly the same way. They possessed a strong sense of colour. Watteau, in particular, was the first to catch the sunlight. The painters of “les fêtes galantes” are artificial, unreal, dominated by mannerisms. But the cold inanities of David, Girodet, Gérard, and Gros are no more to be compared with them than the bituminous melodramatics of the lesser Romantic artists.

Watteau’s successors never entirely lost their master’s sense of light and colour. In a mild way Chardin attempted realism. Boucher, and, later, Fragonard were influenced by that Japanese art which was to take such a prominent place in the movement of a hundred years later. But the world altered. The stern, hard ideals of Rome and Greece were too severe for these poor triflers with the Orient. David reigned supreme. The Journal de l’Empire considered Boucher ridiculous. Unhappy, forgotten Fragonard, surely one of the most pathetic of figures, died in poverty whilst the drums of Austerlitz were still reverberating through the air.

Ingres, a pupil of David, taught his students that draughtsmanship was of more importance than colour. “A thing well drawn,” he said, “is always well enough painted.” Such teaching was bound to provoke dissent, and the germs of the coming revolution were to cross from England. Byron and Scott were the sources of the literary revolution which swept across Europe. British artists showed the way in the fight against tradition and form, which resulted in the School of Barbizon, and its great successor, the School of Impressionism.

Excluding the miniaturists, and such foreign masters as Holbein, Vandyck, Kneller, and Lely, English art could hardly boast one hundred consecutive years of history when its landscape artists first exhibited in the Paris Salon. The French School could not forget Italy and its own past. Even to this day the entrance to the École des Beaux-Arts is guarded by two colossal busts of Poujet and Poussin, and the supreme prize in its gift is the Prix de Rome. But English art has never been trammelled excessively by its own past, simply because it did not possess one, and, with insular pride, refused to accept that of the Continent.

Photo by W. A. Mansell & Co.

PETWORTH PARK · J. M. W. TURNER

Photo by W. A. Mansell & Co.

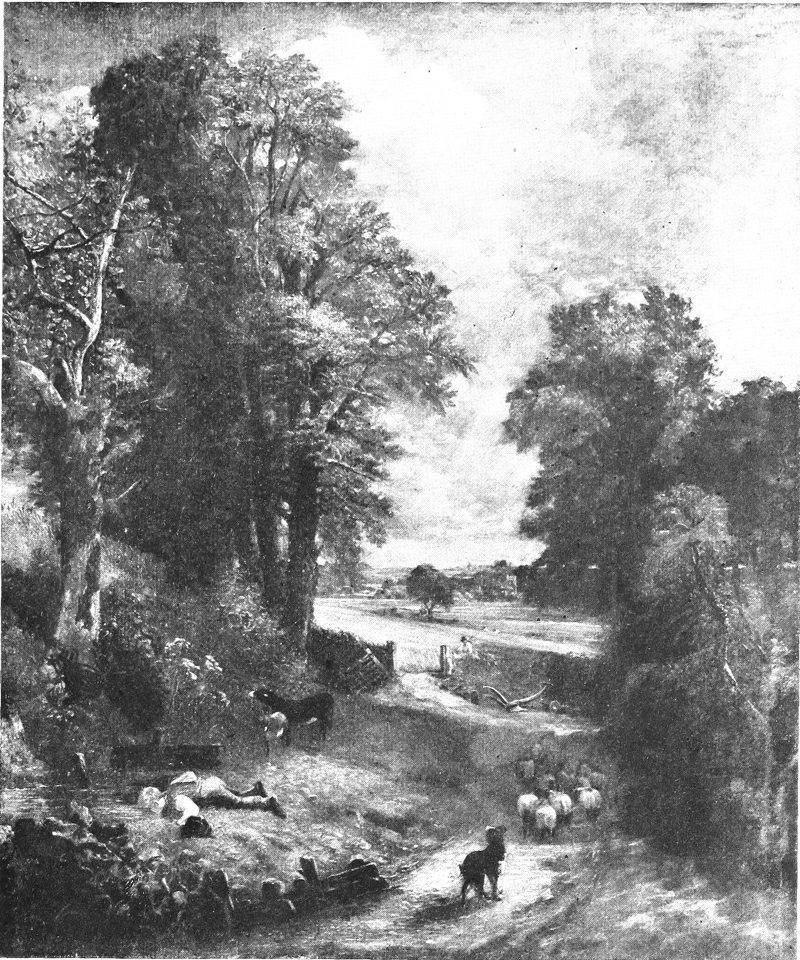

THE CORN FIELD · J. CONSTABLE

Hogarth is a case in point. His education was slight and desultory; he did not indulge in the Grand Tour; he professed a truly British scorn for foreigners, uttering “blasphemous expressions against the divinity even of Raphael, Correggio, and Michelangelo.” 3He took his subjects from the life which daily surged under his windows in Leicester Square, and when he attempted a classical composition he utterly failed, and was promptly told so by his numerous enemies. His canvases form historical records of the men and women of the early Georgian era, in much the same manner as Edouard Manet represents the “noceurs” and “cocottes” who wrecked the Second Empire and reappeared during the first decade of the Third Republic.

Hogarth was a colourist, and the early English School was always one of colour and animation, attempting to follow Nature as closely as possible. Some of the slighter portrait studies of Sir Joshua Reynolds have a strong affinity to the work of the French Impressionists. Richard Wilson was not altogether blind to the beautiful world around him, although he considered an English landscape always improved by a Grecian temple. Gainsborough was decidedly no formalist, and whilst the lifeless group, comprising Barry, West, Fuseli, and Northcote, was endeavouring to inculcate the classical idea, the English Water-colour School began to appear, the Norwich School was in the distance, Turner’s wonderful career had commenced, and Constable, the handsome boy from Suffolk, was studying atmospheric effects and the play of sunlight from the windows of his father’s mill at Bergholt. In 1819 Géricault, one of the leaders of the reaction in France against Classicalism, paid a visit to England. He does not seem to have been greatly influenced by English work, owing no doubt to his lamentably early death. But his visit resulted in Constable and Bonington becoming known in France.

For years English painters exhibited regularly at the Salon. In 1822, the year when Delacroix hung Dante’s Bark, Bonington exhibited the View of Lillebonne and a View of Havre, whilst other Englishmen exhibiting were Copley Fielding, John Varley, and Robson. In 1824 the Englishmen were still more prominent. John Constable received the Gold Medal from Charles X. for the Hay Wain (now in the London National Gallery), and exhibited in company with Bonington, Copley Fielding, Harding, Samuel Prout, and Varley. In 1827 Constable exhibited for the last time, and, curious omen for the future, between the frames of Constable and Bonington was hung a canvas by a young painter who had never been accepted by the Salon before. His name was Corot, and he was quite unknown.

The influence of these Englishmen upon French painting during the nineteenth century is one of the most striking episodes in the history of art. They were animated by a new spirit, the spirit 4of sincerity and truth. The French landscape group of 1830, which embraced such giants as Corot, Rousseau, and Daubigny, was the direct result of Constable’s power. The path was made ready for Manet, who, though not a “paysagiste,” became the head of the group which included Monet, Sisley, and Pissarro. Forty years later the younger men sought fresh inspiration in the works of an Englishman. Indirectly, Impressionism owes its birth to Constable; and its ultimate glory, the works of Claude Monet, is profoundly inspired by the genius of Turner.

When the principles which animated these epoch-making English artists are contrasted with those which ruled the Impressionists, their resemblance is found to be strong. “There is room enough for a natural painter,” wrote Constable to a friend after visiting an exhibition which had bored him. “Come and see sincere works,” wrote Manet in his catalogue. “Tone is the most seductive and inviting quality a picture can possess,” said Constable. It cannot be too clearly understood that the Impressionistic idea is of English birth. Originated by Constable, Turner, Bonington, and some members of the Norwich School, like most innovators they found their practice to be in advance of the age. British artists did not fully grasp the significance of their work, and failed to profit by their valuable discoveries.

It was not the first brilliant idea which, evolved in England, has had to cross the Channel for due appreciation, for appreciated it certainly was not in the country of its origin. As the genius of the dying Turner flickered out, English art reached its deepest degradation. The official art of the Great Exhibition of 1851 has become a byword and a reproach. In English minds it stands for everything that is insincere, unreal, tawdry, and trivial.

The group of pre-Raphaelites, brilliantly gifted as they undoubtedly were, worked upon a foundation of retrograde mediævalism. And, as the years followed each other, English art failed as a whole to recover its lost vitality. Domestic anecdote, according to the formulæ of Augustus Egg, Poole, or, slightly higher in the scale, Mulready and Maclise, formed the product of nearly every studio. The false Greco-Roman convention of Lord Leighton luckily had no following. Rejuvenescence came from France in the shape of Impressionism, and English art received back an idea she had, as it proved, but lent.

A STUDY · J. CONSTABLE

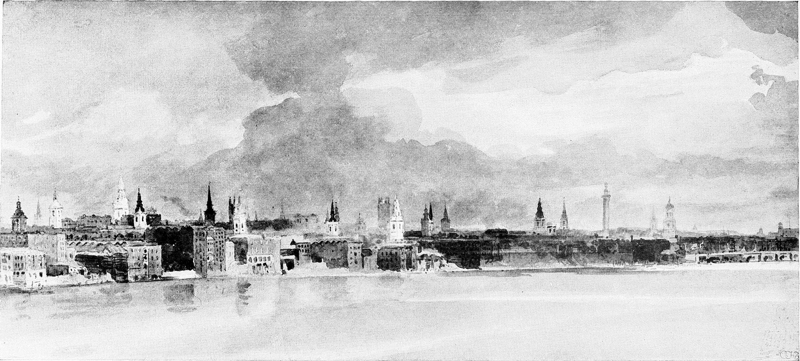

VIEW OF THE THAMES · THOMAS GIRTIN

Photo by W. A. Mansell & Co.

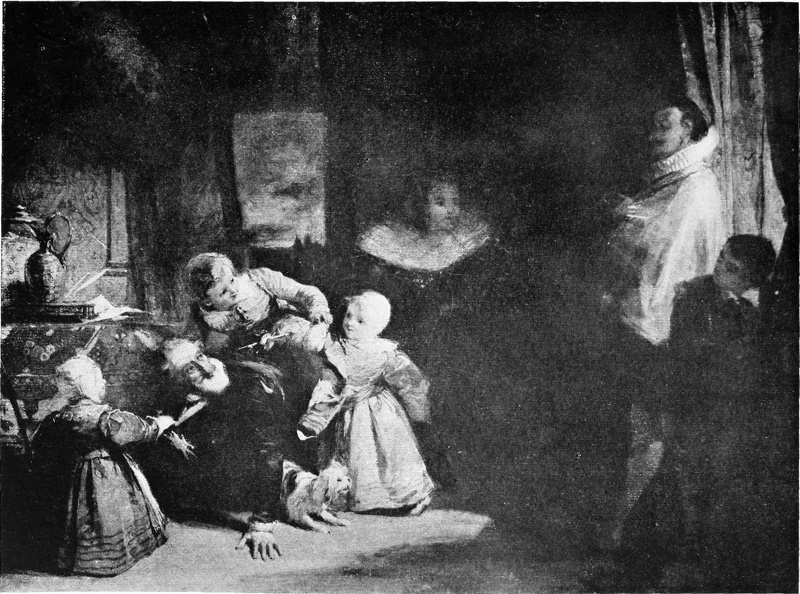

HENRI IV. AND THE SPANISH AMBASSADOR · R. P. BONINGTON

Those Englishmen who are taunted with following the methods of the French Impressionists, sneered at for imitating a foreign style, are in reality but practising their own, for the French artists simply 5developed a style which was British in its conception. Many things had assisted this development, some accidental, some natural. All the Englishmen had worked to a large extent in the open. Now the atmosphere of France lends itself admirably to Impressionistic painting “en plein air.” All landscapists notice that the light is purer, stronger, and less variable in France than in England.

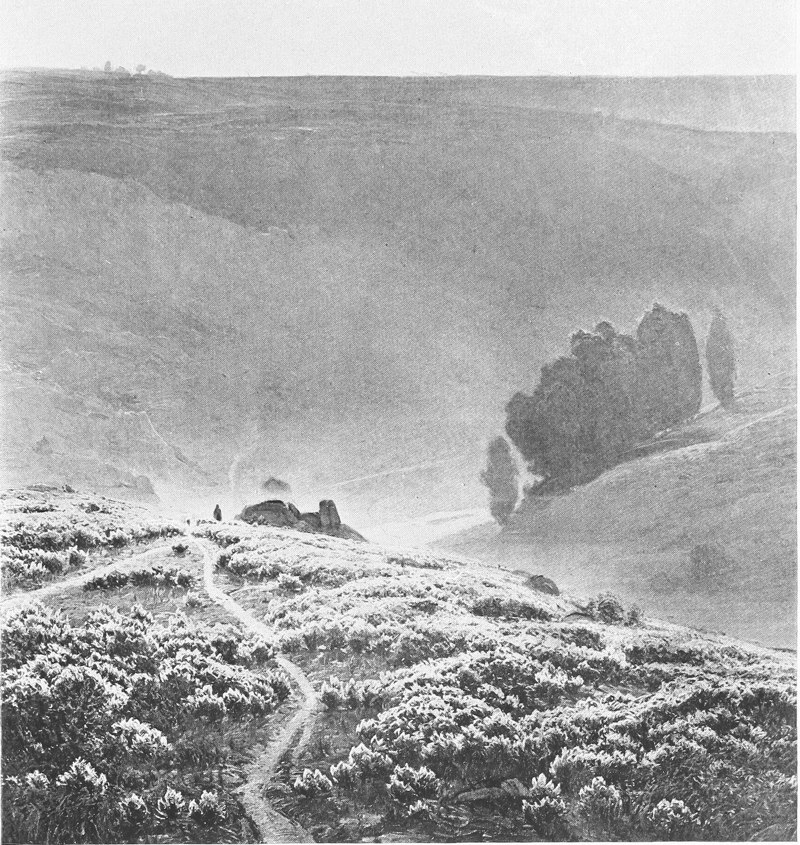

By thus working in the open both Constable and Turner, together with their French followers, were able to realise upon canvas a closer verisimilitude to the varying moods of nature than had been attempted before. By avoiding artificially darkened studios they were able to study the problems of light with an actuality impossible under a glass roof. They were in fact children of the sun, and through its worship they evolved an entirely new school of picture-making. The Modern Impressionist, too, is a worshipper of light, and is never happier than when attempting to fix upon his canvas some beautiful effect of sunshine, some exquisite gradation of atmosphere. Who better than Turner can teach the use and practice of value and tone? In triumph he fixed those fleeting mists upon his immortal canvases, immortal unhappily only so long as bitumen, mummy, and other pigment abominations will allow.

The technical methods of the French Impressionists and of the early English group vary but little. The modern method of placing side by side upon the canvas spots, streaks, or dabs of more or less pure colour, following certain defined scientific principles, was made habitual use of by Turner. Both Constable and Turner worked pure white in impasto throughout their canvases, high light and shadow equally, long before the advent of the Frenchmen.

An example of this was to be seen in a large painting by Constable hung in the Royal Academy Winter Exhibition of 1903. The Opening of Waterloo Bridge, exhibited in 1832, was declared by the artist’s enemies to have been painted with his palette-knife. Almost the whole of the canvas, especially the foreground, is dragged over by a full charged brush of pure white, which, catching the uneven surface of the underlying dry impasto work, produces a simple but successful illusion of brilliant vibrating light.

This work was not well received by the contemporary press and public. It was regarded as a bad joke, became celebrated as a snowstorm, compared with Berlin wool-work (a favourite simile which Mr. Henley has recently applied to Burne-Jones), and was derided as the product of a disordered brain. Seventy years have barely sufficed for its full appreciation.

By a curious coincidence Bonington’s Boulogne Fishmarket was 6hung almost exactly opposite in the same Winter Exhibition. This canvas must have had an enormous influence with Manet, its blond harmony and rich flat values within a distinct general tone being a distinguishing feature of the great Frenchman’s style.

The Impressionists, therefore, continued the methods of the English masters. But they added a strange and exotic ingredient. To the art of Corot and Constable they added the art of Japan, an art which had profoundly influenced French design one hundred years before. The opening of the Treaty ports flooded Europe with craft work from the islands. From Japanese colour-prints, and the gossamer sketches on silk and rice-paper, the Impressionists learnt the manner of painting scenes as observed from an altitude, with the curious perspective which results. They awoke to the multiplied gradation of values and to the use of pure colour in flat masses. This art was the source of the evolution to a system of simpler lines.

In colour they ultimately departed from the practice of the English and Barbizon Schools. The Impressionists purified the palette, discarding blacks, browns, ochres, and muddy colours generally, together with all bitumens and siccatives. These they replaced by new and brilliant combinations, the result of modern chemical research. Cadmium Pale, Violet de Cobalt, Garance rose doré, enabled them to attain a higher degree of luminosity than was before possible. Special care was given to the study and rendering of colour, and also to the reflections to be found in shadows.

So far as the term implies the position of teacher and pupils, the Impressionists did not form themselves into a school. On the contrary, they were independent co-workers, banded together by friendship, moved by the same sentiments, each one striving to solve the same æsthetic problem. At the same time it is possible to separate them into distinct personalities and groups.

Photo by W. A. Mansell & Co.

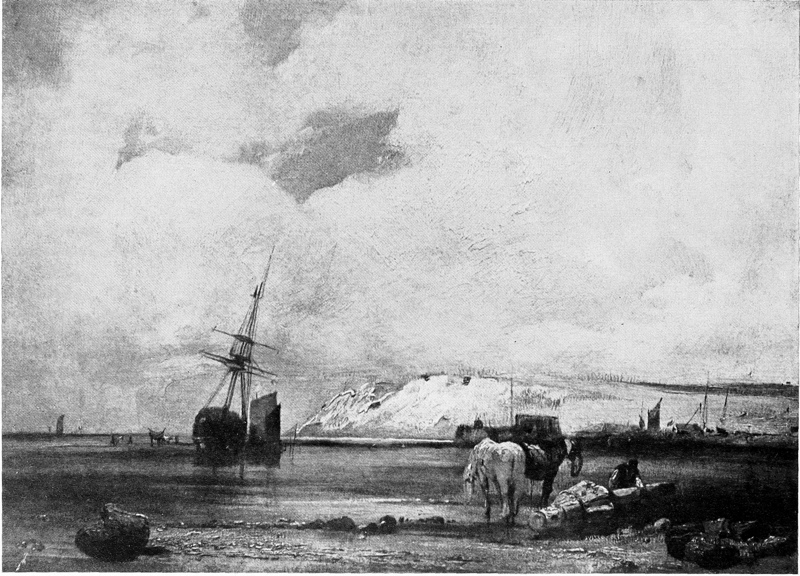

A COAST SCENE · R. P. BONINGTON

Photo by Fredk. Hollyer

TIME, DEATH, AND JUDGMENT · G. F. WATTS

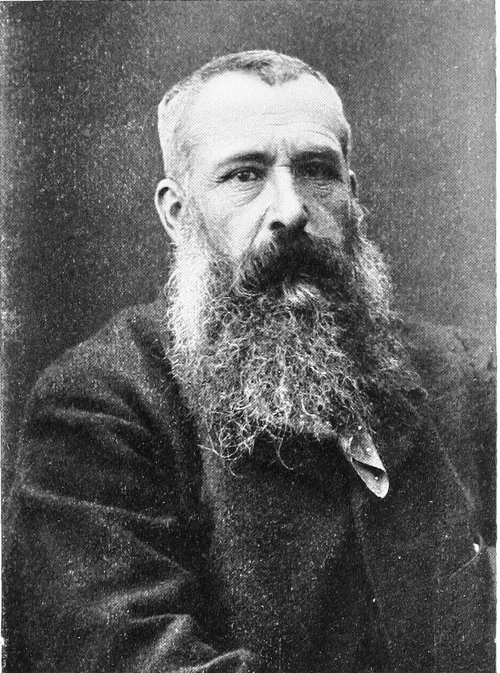

Edouard Manet occupies a position alone. His work can be separated into two periods, divided by the year 1870. His earlier work deeply influenced Claude Monet, who was a prominent member of the group which gathered round Manet at the Café Guerbois. After 1870 the position was slightly changed, for, although he retained the nominal leadership of the group which was now known under the title of Impressionists, Manet was influenced by the technique of Claude Monet. The question has yet to be decided whether Manet or Monet was the founder of the new school. Monsieur Camille Mauclair declares for the latter, stating that Manet’s pre-eminence was due to the attention he attracted by 7his excessive realism, and that Claude Monet was the true initiator. It may be admitted that Impressionism, as the phrase is now understood, did not really gather force until 1867. Claude Monet was greatly attracted by Manet’s work as early as 1863, and upon these new methods he seems to have based his own, widened though after his visit to London with Pissarro in 1870.

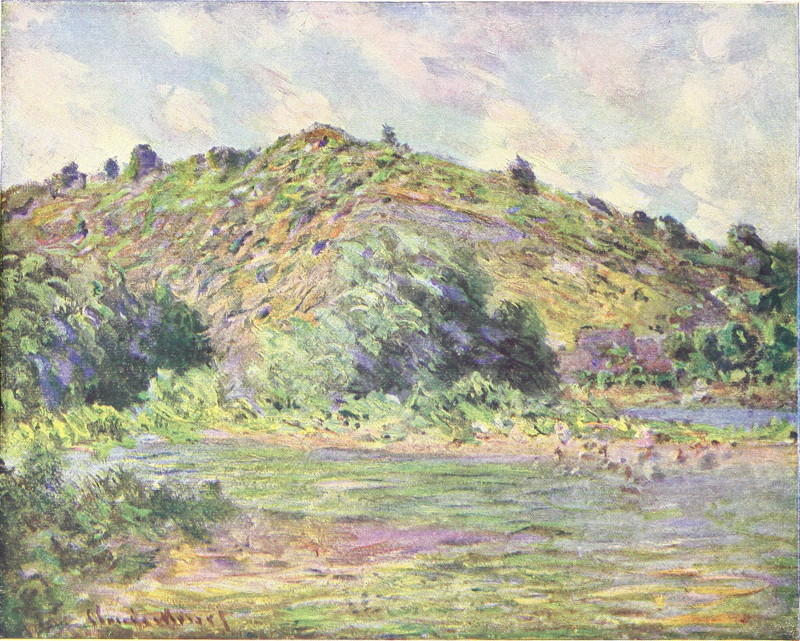

During his lifetime Manet was the recognised head, and around him was formed the famous circle of the Café Guerbois, which became known as the School of Batignolles. This included Monet, Pissarro, Sisley, Cézanne, Renoir, and Degas. If there is one man greater than the others it is Claude Monet. Only during comparatively recent years have his originality and strength been generally recognised. He now occupies the position held by Manet, although he cannot be said to be Manet’s successor. Manet painted the figure, seldom attempting landscape, a genre which is primarily Monet’s. Claude Monet is doubly indebted to English art. Profoundly moved by Turner, whose works he studied at first hand in England, he also traces an artistic descent through Jongkind and Boudin from Corot, who caught the methods of Constable and Bonington.

Jongkind and Boudin are two little masters not to be forgotten. Not altogether Impressionists themselves, they were in close affinity to the school upon which they had much influence. Men of uncommon character and earnestness of purpose, their art was sincere. In themselves they were interesting, for, richly endowed with natural talents, they were for the most part poor beyond belief in material wealth. Inspired by a genuine love for Nature in all her aspects they never reached the high technique of their English predecessors, and were far surpassed by Claude Monet and his group. Forerunners in the evolution of the school of “plein air” painting, a reference is necessary to them in order to follow the development of the school as a whole.

For the first time in the history of art women have taken an active part in founding a new school. Madame Berthe Morisot, Miss Mary Cassatt, and Madame Eva Gonzalès must be included amongst the early Impressionists.

Various movements based upon the Impressionistic idea have taken place in France and on the Continent generally. There are the Pointillistes for instance, and the Neo-Impressionists. Amongst foreign artists Whistler must be mentioned; a student at Gleyre’s he attended at the Café Guerbois, and embraced many of Manet’s ideas.

8The history of the early battles over Impressionism centres for the most part round one personality. In following the story of the failures and successes of Edouard Manet we follow the gradual rise of the entire school, for no man fought more bravely in defence of its principles.

Photo by Fredk. Hollyer

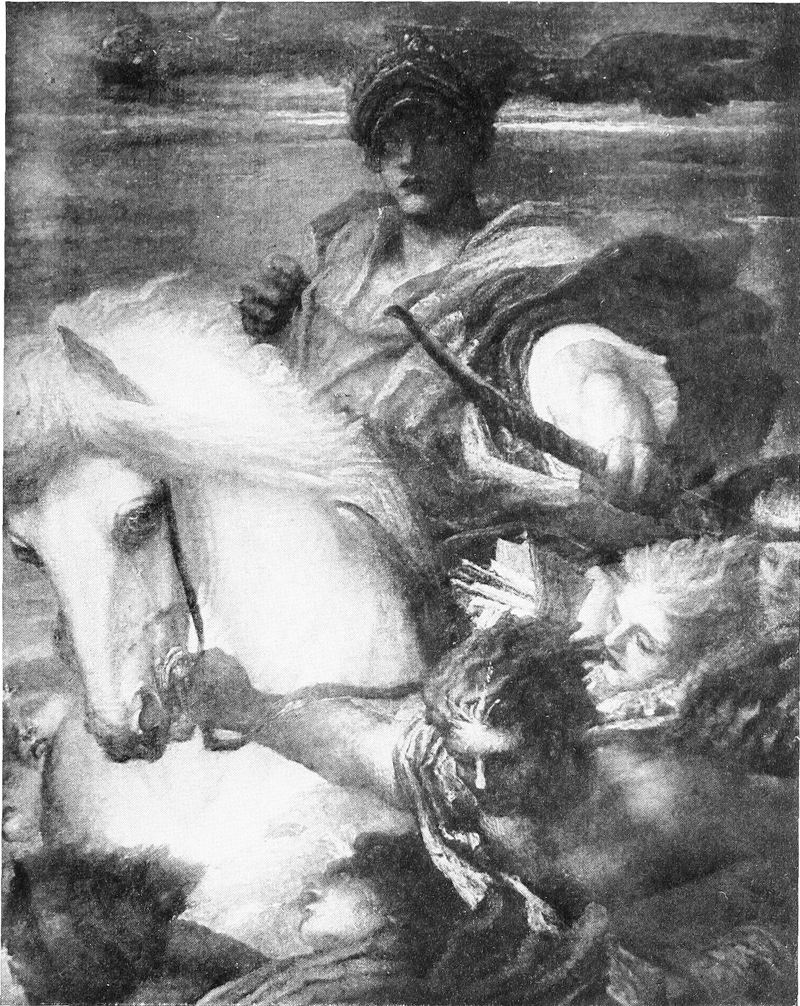

RIDER ON THE WHITE HORSE · G. F. WATTS

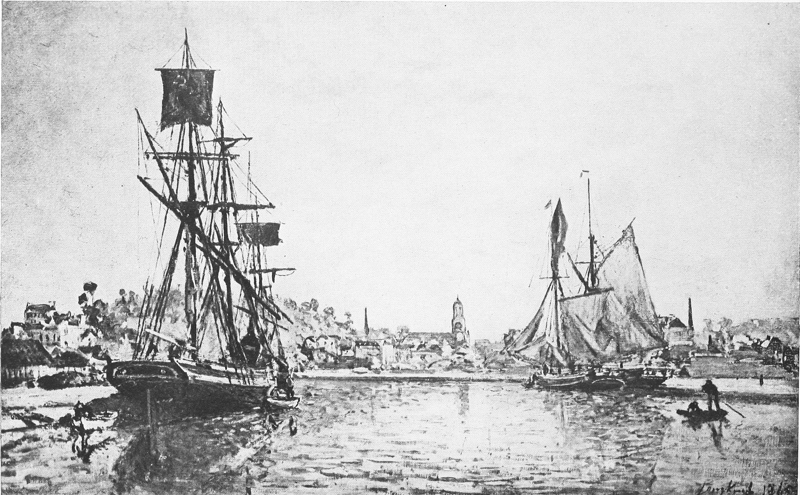

VIEW OF HONFLEUR · J. B. JONGKIND

“ILS PRENNENT LA NATURE ET ILS LA RENDENT, ILS LA RENDENT VUE À TRAVERS LEURS TEMPÉRAMENTS PARTICULIERS. CHAQUE ARTISTE VA NOUS DONNER AINSI UN MONDE DIFFÉRENT, ET J’ACCEPTERAI VOLONTIERS TOUS CES DIVERS MONDES”

ZOLA

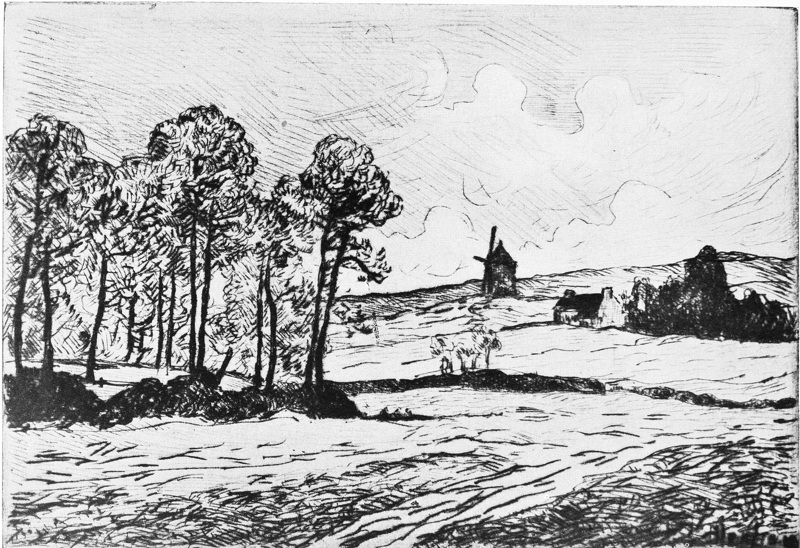

JONGKIND and Boudin are the links which connect the Barbizon men of 1830 to the Impressionist group of 1870. Although little public fame came to them during their lifetime, they had considerable influence upon the younger landscape-painters of their generation. Both were artists of great ability as well as of enormous industry; both suffered from continued misfortune and neglect. Yet no collection illustrating the history of Impressionism can exclude examples of the Dutch Jongkind, or of Boudin, a follower of Corot and master of Monet. Jongkind’s pictures are doubling, nay trebling, in value, and the records of the public sale-rooms are astounding evidences of the increasing appreciation of Boudin by modern collectors.

The biographies of Jongkind and Boudin form excellent texts over which one may moralise upon the uncertainties of art as a career. It is not often that the Fates compel two men to struggle for so long against such hopeless and wretched surroundings. The life of Jongkind was a life of continued misery. Towards its end he utterly gave way, and died a dipsomaniac. Boudin possessed a little more grit, although his surroundings were not more propitious. He lived almost unnoticed until a beneficent Minister awarded him the greatest prize a Frenchman can receive on this earth, the Cross of the Legion of Honour.

Johann Barthold Jongkind was born at Lathrop, near Rotterdam, in 1819. Dutch by birth, many years’ residence in France, together with a strong sympathy with Gallic ways, made him almost a citizen of his adopted country, and certainly a member of the French School of Painting. At first he was a pupil of Scheffont, and afterwards he worked under Isabey. At the Salon of 1852 he obtained a medal of the first class, and then for years in succession was rejected by the juries. Almost at the end of his life he was offered the long-coveted decoration, but he was never a popular artist, nor even well known 10amongst the art public. A few amateurs bought his works, his water-colours were lost in old portfolios, and the exhibition of his pictures previous to the sale after his death was a revelation alike to painters and critics. His life was a sad history of neglect, terrible privation, and want. All that we know of him is that he gave way to alcoholism, dying in Isère in 1891, alone, friendless, and forgotten.

Jongkind was one of the very first men in France to occupy himself with the enormous difficulties surrounding the study of atmospheric effects, the decomposition of luminous rays, the play of reflections, and the unceasing change crossing over the same natural form during the different hours of the day. His influence over several of the more prominent men of the Impressionist group was great. Edouard Manet was strongly impressed by his methods, and Claude Monet refers to him as a man of profound genius and originality of character, “le grand peintre.”

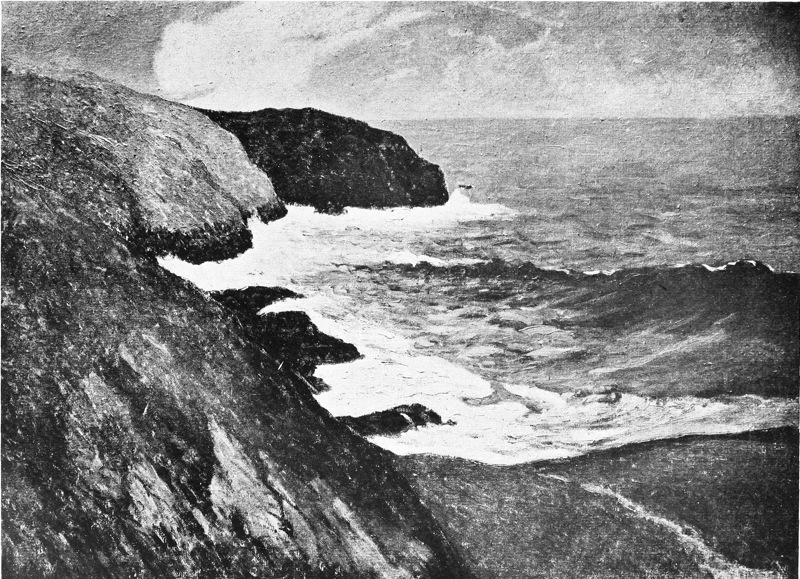

In the sale-rooms Jongkind’s water-colours and etchings are now reaching very high prices, although one cannot agree that they are his most remarkable creations. Works the artist was content to sell for £4 to £8 now change hands under the hammer at sums ranging from £160 to £800. The best canvases were painted towards the end of his life, especially those depicting the luminous atmosphere of the beautiful Dauphiné countryside. His large landscapes are extremely unequal, somewhat hard and dry in technique, and more or less stereotyped in the choice of subject. His pictures do not always convey the true feeling for atmospheric effect, and many are simply experiments which lack the great quality of charm. Without a doubt he possessed extraordinary ability, but he lacked the illuminating spark of genius. He pointed out a way he was not himself strong enough to follow.

MOONRISE · J. B. JONGKIND

Louis-Eugène Boudin, an old comrade and life-long friend of Jongkind, is the head of the group of “little masters” who reigned during the transitional period in French landscape art between 1830 and 1870. He was born in the Rue Bourdet, Honfleur, on July 12, 1824, and died within a few miles of his birthplace in 1898. He leaves a magnificent record of work accomplished, and the memory of a noble life devoted to a beautiful ideal. Pissarro, in a letter addressed to the writer, says that Boudin had much influence upon the advancement of the Impressionist idea, particularly through his studies direct from Nature. His father was a pilot on board the steamboat François of Havre, a bluff and hearty sailor, typical of the coast nearly a century ago. A good specimen is to be found in the 11burly guardian of the Musée Normand at Honfleur, who, by a coincidence not altogether strange in this world of coincidences, travelled round the world with old Boudin, and knew intimately “le petit Eugène.”

The boy’s mother was stewardess on board the boat her husband piloted, and the artist commenced life in the humble and not altogether enviable capacity of cabin-boy. In that position he remained until his fourteenth year, travelling from French and English ports as far as the Antilles. At that age an irresistible desire came over his soul. He wished to quit seafaring life and devote himself to the brush. He had already made many sketches in bitumen, some having attracted attention from passengers. Those which have been preserved display wonderful proficiency, considering the many difficulties the boy had to labour under. Chance helped the youth; for his father, tiring of his endless struggle with the elements, retired from his post and opened a little stationery shop on the Grand Quai at Havre. The cabin-boy became shop-boy.

This new mode of life gave him far greater time to follow his inclinations. All untaught he applied himself assiduously to draughtsmanship, painting on the quays, in the streets, devoting Sundays and fête-days to long excursions amongst the hills round about Havre. One day Troyon brought a canvas for framing to the elder Boudin’s shop. In the corner he noticed some curious little pastels of the shipping and harbour. Eugène made his first artistic friendship. Troyon, who was living in great poverty, only too pleased to sell a picture for twenty-five francs, was of great assistance to the lad. Another customer helped young Boudin. Norman by birth, son of a seaman, Jean-François Millet met the boy in Havre and was attracted by his evident skill. Millet was in the same quandary as Troyon; stranded in semi-starvation, he was executing portraits at thirty francs per head, diligently canvassing the retired ebony merchants, the harbour officials, the sailors and their sweethearts. Alphonse Karr and Courbet, whilst wandering through Normandy, became acquainted with Boudin’s sketches, and sought out the young artist.

Eugène Boudin’s career was now determined. The advice of friends was vain. They pointed out that if Corot with his immense talent was unable to earn an independence at the age of fifty, an untrained shop-boy had still less chance. No man could tell a more bitter story of the artist’s life than Millet, and he attempted to persuade the boy to keep to the shop. All efforts were fruitless. Couture and a few other associates obtained a small student’s allowance 12from the Havre Town Council, and Boudin set out for Paris. The bursary of one pound weekly soon came to an end, and left the artist without resources or friends. He paid for his washing with a picture valued at the sum of forty francs. The laundress immediately sold the work to cover her bill, and the canvas has recently changed hands for four thousand francs. His “marchand de vin” exchanged wine for pictures which have lately passed through the sale-rooms at forty times their original agreed values. By these means, together with a few portrait commissions, Boudin managed to eke out a most precarious existence.

From 1856 dates the foundation of the “Ecole Saint Simeon,” (so called from the rustic inn and farmhouse on the road from Honfleur to Villerville, halfway up the hill overlooking Havre and the mouth of the Seine), in which Boudin took a prominent part. In 1857 the artist exhibited ten pictures at the local Havre exhibition, which he followed with a sale by auction, his idea being to raise enough money to pay his expenses back to Paris. Claude Monet had been sending several pressing letters of invitation, holding out fair prospects of business with several art dealers. The sale was a complete failure, producing a net sum of £20. Boudin gave up his hopes of Paris and returned to the farmhouse of Saint Simeon saddened and discouraged. Roused by “la mère Toutain,” he opened an academy of painting, and the old inn of Saint Simeon may be called the cradle of French Impressionism.

For twenty-five years it formed the resting-place, from time to time, of all the most celebrated men of the group. The list is a long one—Millet, Troyon, Courbet, Lepine, Diaz, Harpignies, Jongkind, Cals, Isabye, Daubigny, Monet, and many others. Boudin always regretted that there was no history written of the place, no record of the scenes which took place there. One has the same regret over many other famous sketching grounds and artistic inns in France. What stories can be told of the joyous life, of the good fellowship, the games and escapades, the brilliant jokes of many a world-renowned genius in playful mood, happy little bands of men with the spirit and souls of children!

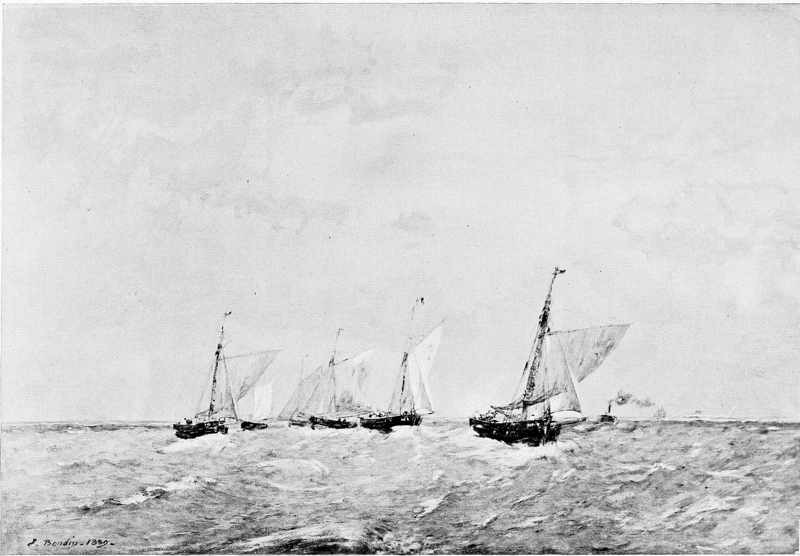

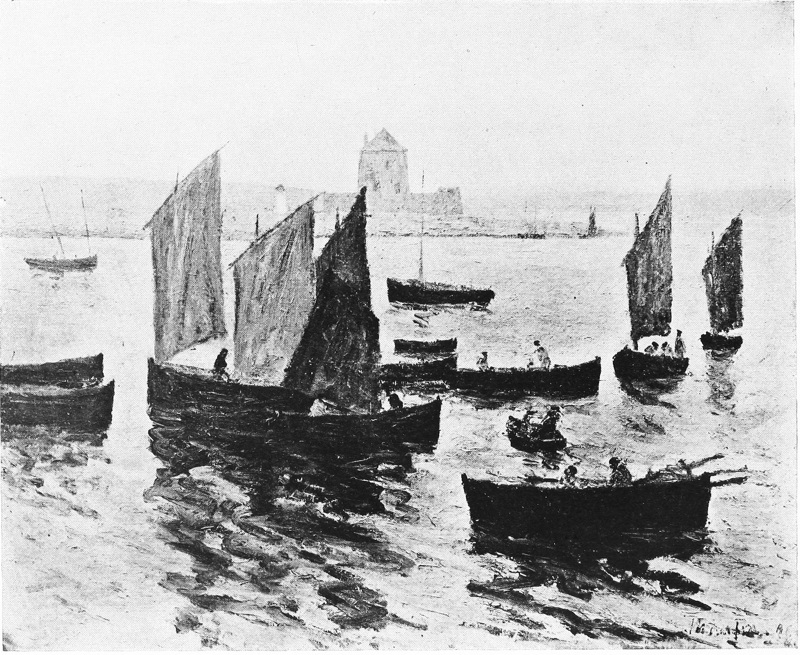

RETURN OF THE FISHING SMACKS · EUGENE BOUDIN

The hostesses are of a type apart, and no other country but France produces them in such numbers. “Mères des artistes,” they are full of pride with their anecdotes of celebrated lodgers. Peasants of the best class, admired and respected by all who come into contact with them, they are remembered with affection. The peaceful holidays spent in these lovely villages represent much of the brighter side of the art-student’s career, and memories mix with regrets as 13one recalls a youth spent in that beloved country of art—la belle France.

Boudin’s academy of painting at the inn was no great success, and he changed his habitat to Trouville, twenty miles down the coast, at the invitation of Isabey and the Duc de Morny. They suggested that he should paint “scènes de plage” of that gay and fashionable watering-place, the bathers, the frequenters of the Casino and the racecourse, the regattas, the “landscapes of the sea” as Courbet called them. “It is prodigious, my dear fellow; truly you are one of the seraphim, for you alone understand the heavens,” cried Courbet one day in excitement as he watched Boudin at work. Boudin was at last becoming famous. Alexandre Dumas addressed him as, “You who are master of the skies, ‘par excellence,’” and above all came the testimony of Corot, who described him as “le roi des ciels.”

Unfortunately, the public did not buy Boudin’s pictures, and he remained in poverty. In 1864 he married, his wife receiving a “dot” of 2000 francs, and a home was made up four flights of rickety stairs in a mean street in Honfleur, the rental of the garret being thirty-five shillings per annum. Amongst their visitors the saddest was Jongkind, the man of failure, a reproach to the blindness of his generation, and a warning to those who seek fortune by the brush. It was only by the combination of courage, energy, and robust health that Boudin was able to fight his way through actual periods of starvation in order to live to see his work justified by public appreciation.

Four years later the little household was moved to Havre. Boudin was reduced to such absolute poverty that he was not able to provide himself with sufficient decent clothing to visit a rich tradesman of the town, who had commissioned some decorative panels. The commission was lost, and the fight for bread was keener than before. During the winter furniture was converted into firewood, and the artist worked as an ordinary labourer. Boudin hated Paris, but at the urgent solicitation of artists, who promised him work, he left Havre for the metropolis. Ill luck still dogged his steps. No sooner had he settled with his wife in the new quarters than the war broke out with all the unendurable misfortunes of “l’année terrible” in its train.

Hopes of commissions were at an end, the art colony being scattered far and wide. Boudin fled first to Deauville, then to Brussels. Crowded with French refugees, the struggle for life entered its bitterest stage. For the second time Boudin became a day-labourer. At last, by a most trifling chance, his wretched position 14was altered for the better. By hazard Madame Boudin met a picture-dealer whilst marketing, and his appreciation and encouragement enabled the artist to return to his easel. The artist’s progress was, however, extremely slow. Nine years later he held an auction sale of his pictures, at which four paintings realised £21. A friend who had joined in the sale was more unfortunate, for he sold nothing. “You see,” he wrote to Boudin, “that nothing succeeds with me. I don’t know how it will all finish. What upsets me most in the midst of all this worry is the fear that I should lose all love for painting.” This phrase must have represented Boudin’s thoughts during the long years of disheartening struggle.

In 1881, after twenty-three years of almost annual exhibition in the Paris Salons, Boudin obtained a medal in the third class. Nowadays this award is usually made to the young man who exhibits for the first time. Three years later Boudin received a medal of the second class, which exempted his work from judgment by the jury, and places its recipient “hors concours.” He commenced, at the age of fifty, to sell his pictures more regularly, but at prices extremely low and out of proportion to their present value. At the Hôtel Drouot, Paris, in 1888, one hundred canvases by Boudin fetched the grand total of £280. It is difficult to estimate what sum such a lot would reach at the present day.

The tide had changed, for the Government bought a large painting, Une Corvette Russe dans le Bassin de l’Eure au Havre for the Luxembourg. In 1889, public honour was marred by the most mournful blow. To his inconsolable grief his wife died, after twenty-five years of the happiest companionship. Amongst the letters of sympathy were many acknowledgments of the artist’s genius, notably from Claude Monet, “in recognition of the advice which has made me what I am”—a striking and flattering phrase from the head of the Impressionist group. In this same year Boudin was awarded the gold medal at the Salon. In 1896 the Government purchased his Rade de Villefranche for the Luxembourg, and the old artist received from the hands of Puvis de Chavannes, at the recommendation of the Minister Léon Bourgeois, the ribbon and cross of the Legion of Honour.

THE REPAIRING DOCKS AT DUNKIRK · EUGENE BOUDIN

Boudin’s health, weakened by the long privations, had at last broken up. After several futile journeys he returned to his native Normandy, and, whilst working at his easel in his châlet near Deauville in 1898, died almost without warning. By his will he left a rich legacy of pictures to the gallery of his native town, Honfleur. Over one hundred of Boudin’s sketches can now be 15seen in the public gallery of Havre. Boudin’s connection with modern Impressionism is chiefly the influence generated by a strong enthusiasm for working “en plein air” and a deep love of Nature. His dominant colour, almost to the end of his life, was grey—a grey beautiful in its range and truthful in its effect. Personally Boudin had the head of an old pilot, with healthy ruddy complexion, white beard, and keen blue eyes. He spoke slowly in low monotonous tones, was doggedly tenacious of an idea, had strong artistic convictions. He was modest to a degree, and when he sought honours they were for brother artists, never for himself. His highest ambition was reached when the Town Council of Honfleur named a street “Rue Eugène-Boudin.” This street, long, narrow, hilly, with many rough places and occasional pitfalls, typifies the artist’s own life. After his death the town went further. Aided by M. Gustave Cahen, president of the “Société des Amis des Arts,” Honfleur erected a fine statue of its talented son by the jetty, where he had so often painted his favourite scenes of sea and shipping.

Boudin has left a name which will be honoured in the annals of French art. He lived a long life, produced many works of which not one falls below his own high standard. His position, midway between two great schools, is perhaps one reason why he has not loomed more strongly in the public appreciation. Upon their merits his pictures cannot easily be forgotten. When it is remembered that he links Corot to Monet, was in fact the true master of the latter, it will be seen what an important niche he occupies in any history devoted to Modern French Impressionism.

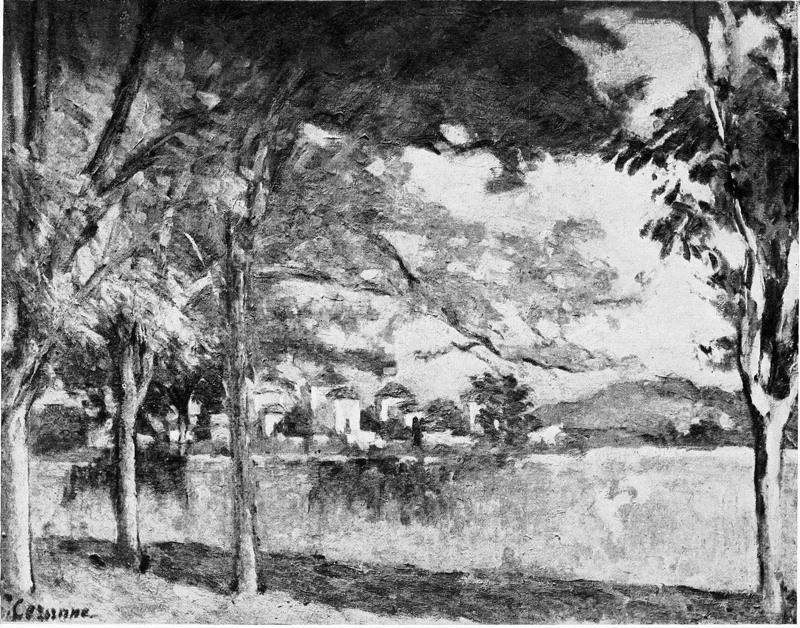

From Boudin is an easy step to Cézanne, one of the pioneers of the movement before 1870. Paul Cézanne and Zola were schoolboys together in Aix. They left Provence to conquer Paris, and whilst Zola was a clerk in Hachette’s publishing office Cézanne was working out in his studio the early theories of Manet, of whom he was an enthusiastic admirer. Both men frequented the Café Guerbois, and there is little doubt that in the remarkable series of articles contributed to De Villemessant’s paper “L’Événement,” Zola was assisted by Cézanne, who had introduced the journalist to the artists he had championed. When the criticisms were republished in 1866, in a volume entitled “Mes Haines,” Zola dedicated the book in affectionate terms, “A mon ami Paul Cézanne,” recalling ten years of friendship. The writer went still further, for the character of Claude Lantier, hero of “L’Œuvre,” a novel dealing largely with artistic life and Impressionism, is generally supposed to have been suggested by the personality of Paul Cézanne.

16For years Cézanne seldom exhibited, and his pictures are not known amongst the public. As to their merits, opinion is curiously divided. He has painted landscapes, figure compositions, and studies of still-life. His landscapes are crude and hazy, weak in colour, and many admirers of Impressionism find them entirely uninteresting. His figure compositions have been called “clumsy and brutal.” Probably his best work is to be found in his studies of still-life, yet even in this direction one cannot help noting that his draughtsmanship is defective. It is probable that the incorrect drawing of Cézanne is responsible for a reproach often directed against Impressionists as a body—a general charge of carelessness in one of the first essentials of artistic technique. Apart from this defect, Cézanne’s paintings of still-life have a brilliancy of colour not to be found in his landscapes.

In his student-days this artist had a great admiration for Veronese, Rubens, and Delacroix, three masters who had some influence upon Manet. Some of his latter methods showed a strong sympathy with the Primitives. The modern symbolists are his descendants, and Van Gogh, Emile Bernard, and Gauguin owe much to his example. Personally he unites a curiously shy nature with a temperament half-savage, half-cynical. Cézanne’s work is remarkable for its evident sincerity, and the painter’s aim has been to attain an absolute truth to nature. These ambitions are the keynotes of Impressionist art.

LA ROUTE · PAUL CÉZANNE

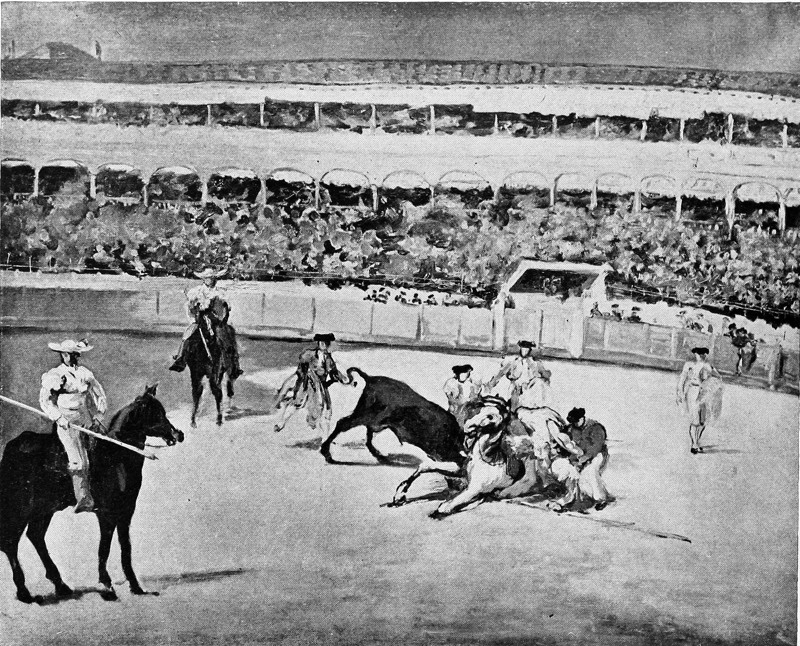

THE BULLFIGHT · EDOUARD MANET

“CE QUI ME FRAPPE D’ABORD DANS CES TABLEAUX, C’EST UNE JUSTESSE TRÈS DÉLICATE DANS LES RAPPORTS DES TOUS ENTRE EUX.

“TOUTE LA PERSONNALITÉ DE L’ARTISTE CONSISTE DANS LA MANIÈRE DONT SON ŒIL EST ORGANISÉ: IL VOIT BLOND, ET IL VOIT PAR MASSES”

ZOLA

FOR over twenty years the technique and methods of Edouard Manet were a subject for the most virulent debate. His art, in fact, became the scene of a battle in which every painter in Europe had a hand. Officialdom found no place for him in its heart, no matter whether the State was Imperial or Republican. The Empress Eugénie once asked that his pictures might be removed from public exhibition; President Grévy demurred when the artist’s name was placed on the list for the Legion of Honour. Clearly this man was no supporter of the established order of things. Refused recognition as an artist by the school of tradition, disowned by his own teacher, a source of hilarity to the public, Edouard Manet caught but a glimpse of the long-wished-for land of success which he was fated never to enjoy fully.

The battle is not quite finished, and the rout of the old school continues to the present day. One result remains. Manet has had a greater influence upon the art of the last forty years than any other master during that period, and the standard which he raised has become a rallying-point for the greatest painters of the present age.

Edouard Manet was born in Paris on January 23, 1832, at No. 5, Rue des Petits Augustins. Thirty-six years previously Corot was born round the corner, in the Rue du Bac. To-day the Rue des Petits Augustins is a long street running through the Latin Quarter, southwards from the Seine and the Louvre, known as the Rue Bonaparte. It has become the chief mart for commerce in artists’ materials, photographs, pictures, and all the odds and ends which fill up a studio. With a quaint appropriateness, the birthplace of Manet faces the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts.

The boy was the eldest of three brothers. His father was a judge attached to the tribunal of the Seine, and the family had been connected with the magistrature for generations. First a pupil at 18Vaugirard, under the Abbé Poiloup, Manet then entered the Collège Rollin, took his baccalaureate in letters, and grew into an elegant man of the world. But his inclinations clashed with his duties, and his uncle, amateur artist and colonel in the artillery, taught him how to sketch in pen and ink. M. Antonin Proust describes the result in a recent magazine article.

“From earliest years,” he writes, “Manet drew by instinct, with a firmness of touch and vigour unexcelled even in his latest works. His family was intensely proud of the boy’s uncommon gift, and his artistically-inclined uncle, Colonel Fournier, supported him against his father, who—despite his admiration—had other views as to his son’s career.”

“One should never thwart a child in the choice of his career,” said Colonel Fournier.

“If,” replied the father, “the boy is not inclined towards the ‘Palais,’ let him follow your example and become a soldier; but go in for painting—never!”

A studio-stool tempted the boy far more than a probable seat on the Bench. If he had to waste time, it should not be in the Salle des Pas Perdus.

His parents sent him, towards the close of his school-days, upon a voyage to Rio de Janeiro, hoping that travel might distract his mind from thoughts of an artistic life. It is said that they contemplated a naval career. Charles Méryon, it may be remembered, made the voyage round the world in a French corvette before he took up the etcher’s needle. Like Méryon, Manet improved his draughtsmanship, although a sailor. He sketched incessantly. One day the captain asked him to get out his paints and touch up a cargo of Dutch cheeses, which had become discoloured by the sea. “Conscientiously, with a brush,” says Manet, “I freshened up these têtes de mort, which reappeared in their beautiful tints of violet and red. It was my first piece of painting.”

His voyage in the Guadeloupe ended, he returned home with unaltered determination. After some protest his father relented, and in 1850 Manet entered the studio of Thomas Couture.

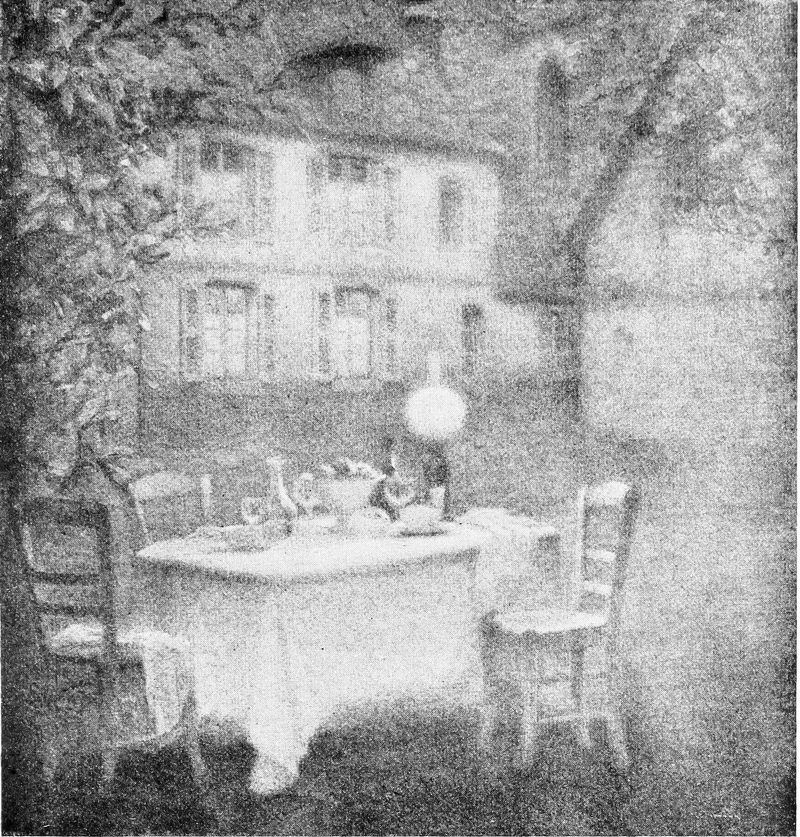

THE GARDEN · EDOUARD MANET

Couture occupied a leading position in that group sometimes called the “juste milieu.” Between the Romanticists and the Classicalists his preferences perhaps were for the latter. Of extreme irritability in temper, with a deep contempt for those in authority, he combined a keen desire for success both popular and financial. His picture, The Romans of the Decadence, in the Salon of 1847, brought both, and for a few years he remained one of the most celebrated 19artists in France. Then he criticised Delaroche, with the usual result when one painter puts another right: he offended King Louis-Philippe, he insulted the Emperor Napoleon III. Kings must be taken at their own valuation, if one wishes to enjoy their good graces. It was not surprising that Couture ultimately became a disappointed and forgotten man.

He has been called an Apostle of Classicalism. Taught first by Baron Gros, who vacillated from one school to the other, and afterwards by Delaroche, who endeavoured to reconcile the opposing parties, Couture could hardly have taken any other position in the art world of the ’forties. “He was apart among the painters of the day, as far removed from the cold academic school as from the new art just then making its way, with Delacroix at its head. The famous quarrel between the Classical and Romantic camps left him indifferent. He was of too independent a nature to follow any chief, however great.” This is the testimony of an American artist, Mr. P. A. Healy, who studied under Couture about the time Manet was in the atelier, and shows that the future Impressionist worked under a man by no means curbed by tradition. According to his pupil, Couture’s great precept was, “Look at Nature; copy Nature.” Manet’s doctrine was couched in almost the same words, “Do nothing without consulting Nature.”

We know that during the time Manet remained in Couture’s studio, master and pupil quarrelled incessantly. The reason usually given is that Manet would not respect tradition. But neither would Couture. “That in the captain’s but a choleric word, which in the soldier is flat blasphemy.” One was there to teach, the other to be taught. The temperaments of the two men were fundamentally different. The thick-set, scowling Couture, of shoemaker descent, would naturally rub against the grain of the rather dandified young scion of the magistrature. Couture hated the middle classes, and Manet belonged to the “haute bourgeoisie.” Manet’s family was legal to the bone, and Couture detested lawyers even more than he disliked doctors. With all these drawbacks Couture was admittedly the best teacher in Paris. Manet evidently recognised the advantage, for he remained in the studio for six years, until he was twenty-five years of age, although quite able to sever the connection had he wished.

Then came the “wanderjahre,” which commenced in 1856. Manet visited Germany, Holland, and Italy. In the Low Countries, Franz Hals exerted a great and permanent influence over the student; Rembrandt was copied in Germany; in Italy, Titian and Tintoretto 20received his homage. Dresden, Prague, Vienna, Munich, Venice and Florence were visited. Upon his return to Paris he copied assiduously in the Louvre, and it was in this wonderful gallery that he so thoroughly mastered all that a young painter could learn from the Spanish School. He did not visit Madrid until 1865. His Spanish subjects before that date were the result of a careful study of Velazquez and Goya in the National Collection and the visit of an Iberian troupe of players to Paris. In the Louvre he copied paintings by Velazquez, Titian, and Tintoretto.

Of living artists Courbet considerably influenced the first period of Manet’s activity. Ever on the fringe of Impressionism, although never in the group, Courbet was a romantically inclined realist who taught the younger men to turn to everyday life for their subjects. His canvases were full of colour; although they have sadly toned down in the course of time, owing to the curious and unsuccessful experiments he made in trying to combine his practice with his theories.

In 1859 Manet sent his work for the first time to the Salon. The Absinthe Drinker, strong, but reminiscent of Courbet, was rejected. The Salon was held every two years, and in 1861 both his contributions were accepted, one being a double portrait of his father and mother, the other a Spanish study called the Guitarero. For this Manet was awarded Honourable Mention, his first and almost his final official distinction, for he received no other until the year before his death, twenty-one years later. Working with tremendous energy in his studio in the Rue Lavoisier, Manet became the centre of a circle of friends which included Legros, Bracquemond, Jongkind, Monet, Degas, Fantin-Latour, Harpignies, and Whistler. The Guitar-player was an undoubted success. “Caramba,” writes genial Theo. Gautier, “Velazquez would greet this fellow with a friendly little wink, and Goya would hand him a pipe for his papelito.” Upon the jury it is said that Ingres himself was flattering, and the mention honorable was ascribed to the lead of Delacroix. Couture’s sneer that Manet would become merely the Daumier of 1860 did not seem likely to be justified.

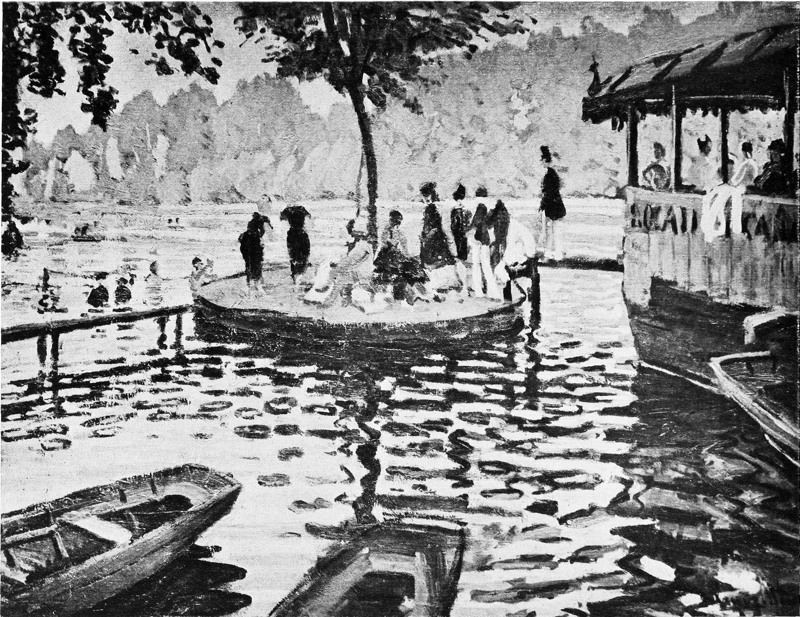

Manet was now engaged upon several pictures which must not be ignored. Music at the Tuileries (1861), refused at the Salon, was, as its name implies, an open-air study of the fashionable crowds gathered round the bandstand in the lovely gardens by the palace. The Street Singer is the earliest of the almost realistic renderings of everyday life which the Impressionists delighted in. A sad-faced 21girl (a well-known character of the day) standing with a guitar at a street corner; the type is the same to this hour both in London and Paris, one of the thousand wretched beings superfluous to a great city, at once its pleasure and its sport.

The Boy with a Sword, now in the Metropolitan Museum of New York, also belongs to this period. The picture is masterly. Inspired from Spain, it is, like most great paintings, full of simplicity, full of strength. The Old Musician is also extremely Spanish, with a haunting reminiscence of Los Borrachos by Velazquez (although Manet had not yet directly seen this canvas). A small group watches an old man about to play his fiddle. Some boys, a little girl with a doll (a figure very dear to Manet), a man drinking, a native of the Orient in a turban and a long robe, these form a straggling composition. The picture is a fantasy of a nation the painter loved but had never yet seen.

Two personal matters affected the life of Manet about this time. His father died, leaving him a considerable private fortune, thus making the artist financially independent of dealers and the ups and downs of public exhibition. In 1863 he married Mlle. Suzanne Leenhoff, a Dutch lady of great musical talent. From one point of view 1863 was disastrous, from another triumphant. Hitherto a man of promise, Manet now developed into a man of notoriety.

The little “one-man show” at the gallery of M. Martinet, Boulevard des Italiens, presaged the coming storm. Manet exhibited the Spanish Ballet, Music at the Tuileries, Lola de Valence, and nearly the whole of his other work up to that date. Baudelaire was enthusiastic. Verses on Lola de Valence are enshrined in “Fleurs de Mal.” Other critics were not so kind. M. Paul Mantz did not restrain his pen and referred to “a struggle between noisy, plastery tones, and black,” with a result “hard, sinister, and deadly,” the whole summed up as “a caricature of colour.”

The Salon of 1863, which followed, has become famous not through what it accepted, but by reason of what it refused. In a contemporary chronicle the most notable pictures of the exhibition are La Prière au Désert by Gustave Guillaumet, a Sainte Famille by Bouguereau, La Déroute by Gustave Boulanger, La Bataille de Solférino by Meissonier, and the Chasse au Renard by Courbet. With the exception of Courbet it is an academical list, although it is extraordinary how Courbet crept in.

The list of rejected artists is amazing. Like Herod’s soldiers, the jury seems to have been chiefly occupied in stamping out youth. Bracquemond, Cals, Cazin, Fantin-Latour, Harpignies, Jongkind, 22J. P. Laurens, Legros, Manet, Pissarro, Vallon, Whistler, these and many others were thrown out. The work was too vigorously performed, and Napoleon III. authorised the opening of another gallery in the same building as the old Salon, known as the Salon des Refusés. The most striking canvas in this room was Manet’s first great work, the Déjeuner sur l’Herbe (Breakfast on the Grass), sometimes called Le Bain.

The painting challenged opposition on two separate grounds. The first was its subject; the second its technique. Between two young men stretched on the grass, wearing the black frock-coats of a latter-day civilisation, sits a nude woman drying her legs with a towel. In the background another woman “en chemise” is paddling in the stream. In defence of such a subject it is usual to refer to the painters of the Renaissance, who, without exciting angry comment, mixed draped and undraped figures in their compositions. There is a celebrated Giorgione at the Louvre to which none objected. Other times, other manners. Infanticide is not encouraged in England although it is the practice in China. Many social practices of the Renaissance, innocent enough in the eyes of that golden age, are distinctly discouraged by the criminal code of to-day. Forty years have elapsed since the Déjeuner sur l’Herbe was first exhibited, and Mrs. Grundy is not the power she was. But if any English painter hung a representation of two dressmaker’s assistants bathing in the Serpentine under exactly the same conditions as Manet depicted the little party at Saint-Ouen, there would be some sharp criticism.

It is far more pleasing to discuss Manet’s manner of painting. In a period when work was sombre in tone and Nature rapidly losing her place in art, Manet with his Déjeuner sur l’Herbe, Olympia, and Le Fifre de la Garde, changed the current with startling directness.

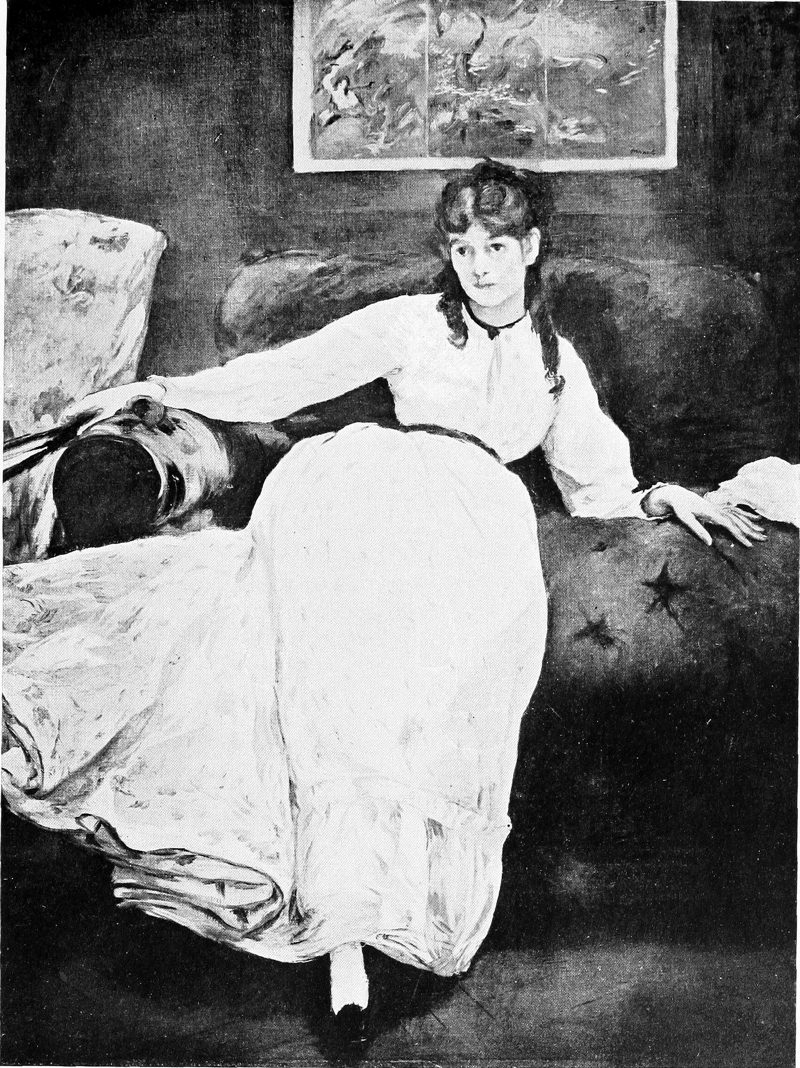

PORTRAIT OF BERTHE MORISOT · EDOUARD MANET

In these and other canvases there was not a shadow, the surface being from end to end clear and highly coloured. Where a Classicalist would have rendered a shadow in the usual burnt umber, Manet made his tones a little less clear, but always coloured and always in value. His method of working was to discard all blacks and preparations of blacks. This was directly antagonistic to the teaching of Couture, who painted on a black canvas. Manet drew straight away on a white canvas with the end of his brush. Then, after having endeavoured to render with a single tone all the pale parts, he carried the lights right into the shadows, of which he studied the slightest nuance. The result was novel to the vision, and strange to the public. The Déjeuner sur l’Herbe was a masterly rendering of 23white flesh against black clothes, which was not appreciated because it was so foreign to the eye.

is an excellent motto for painters who wish to achieve popular renown, but it was never the motto of Manet and the Impressionists.

To a certain extent the Salon des Refusés was successful. The jury of the old Salon had received a fright, and in 1865 they opened their doors very widely. Making a virtue of necessity, they reversed their policy and welcomed the whole artistic world, in order to obviate the necessity of a second Salon des Refusés.

Olympia was far in advance of anything the artist had yet attempted. In composition it recalls Velazquez, Goya, and Titian. A girl, anæmic and decidedly unprepossessing, quite nude, is stretched upon a couch covered with an Indian shawl of yellowish tint. Behind is a negress, with a bouquet of flowers. At the foot of the bed a black cat strikes a sharp note of colour against the white linen.

Gautier and Barbey D’Aurevilly—both men of exotic genius—received the painting with great favour. They found themselves alone in their opinions. Again the subject displeased the crowd, whilst the extraordinary technique exasperated the art world. Even Courbet, reformer as he was, repudiated it. “It is flat and lacks modelling. It looks like the queen of spades coming out of a bath.” Manet retorted: “He bores us with his modelling. Courbet’s idea of rotundity is a billiard-ball.” The general verdict, however, was one in which ridicule and mockery were equally mixed. A religious picture, Christ reviled by the Soldiers, received no greater encouragement, and in the next Salon Manet was rejected without mercy. Le Fifre de la Garde and The Tragic Actor were both refused. He had provoked such fierce animosity that he was even excluded from the representative exhibition of French art included in the Universal Exhibition of 1867.

Luckily, no longer dependent for money on his art, Manet was able to exhibit under more favourable circumstances. Like Rodin a few years ago, Manet opened a large gallery in the Avenue de l’Alma, which he shared with Courbet. Here he collected fifty works, including the Boy with the Sword, several Spanish subjects, seascapes, portraits, studies of still life, aquafortes, even copies. A catalogue was issued containing a short introduction. “The artist does not say to you to-day, Come and see flawless works, but, Come and see 24sincere works.” Another sentence shares with a title of Claude Monet’s the origin of the generic phrase, “Impressionism.” “It is the effect of sincerity to give to a painter’s works a character that makes them resemble a protest, whereas the painter has only thought of rendering his impression.” Manet never considered himself as a man in revolt.

The artist had now a considerable following, and was supported by several vigorous pens in the press, notably that wielded by Emile Zola, who had been introduced to Manet by an old school friend become artist, Cézanne. Zola’s campaign in 1866, following upon the rejection by the Salon of the Fifre de la Garde, saw some hard fights. Zola saluted Manet as the greatest artist of the age, and incidentally overturned a few pedestals in the Academy. Animosity directed against the artist was transferred to the journalist, and Zola was soon ejected from his position under M. de Villemessant as art critic to the Figaro (then famous as l’Événement). Artists of the old school used to buy copies of this journal containing the offending articles, seek out Zola or Manet on the boulevards, and then destroy the paper under their eyes with every manifestation of scorn.

About this time the gatherings in the Café Guerbois, in the Rue Guyot, behind the Parc Monceau, were held twice a week regularly, and the School of Batignolles became an established fact. The group was mixed, and held together more through comradeship than through identical aims. It included Whistler, Legros, Fantin-Latour, Monet, Degas (a young man fresh from the Ecole des Beaux Arts), Duranty, Zola, Vignaux, sometimes Proust, Henner, and Alfred Stevens. To these names should be added Pissarro, Sisley, Renoir, Bazille, and Cézanne. Monet had been attracted by Manet since the little exhibition at Monsieur Martinet’s in 1863, although they did not meet until 1866, the year that Camille Pissarro joined the camp. Fantin-Latour was an old chum, the friendship commencing in 1857, and he commemorated these gatherings in a picture of the members of the group, which attracted much attention in the Salon of 1870.

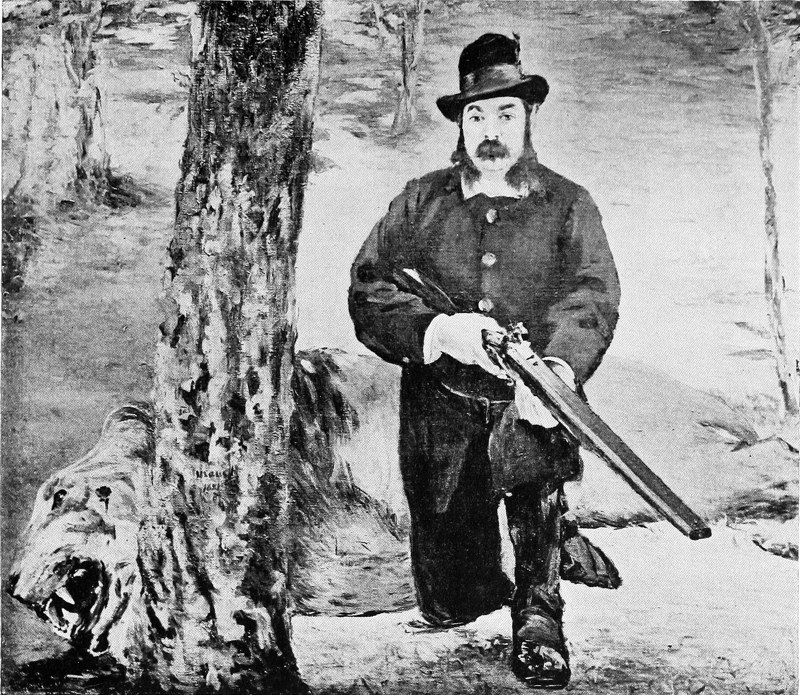

PORTRAIT OF M. P——, THE LION-HUNTER · EDOUARD MANET

The home life of Edouard Manet was strangely different from what one would expect of such an artist, so notorious in the Paris of the Empire that when he entered a café its frequenters turned to stare at the incomer. Manet lived with his wife and his mother in the Rue St. Pétersbourg. The old lady, faithful to her remembrance of the age of Charles X. and the Citizen King, lived amidst souvenirs of the past. Modernity was entirely absent from the little household, and those who anticipated evidences of the spirit of 25revolution which characterised Manet in the world of the boulevards here discovered the atmosphere, even the decoration and furniture, of the Louis-Philippe period. Romance had also entered into the hitherto prosaic Manet family. Mlle. Berthe Morisot, a clever young artist from Bourges, had married Manet’s brother Eugène, and became an ardent follower of her brother-in-law’s artistic doctrines, whom she aided frequently.

A famous work of this period is The Execution of the Emperor Maximilian, the subject representing a file of dark-hued Mexicans shooting the unfortunate monarch. It is a vast canvas, slightly inconsistent with many of the artist’s theories. Not lacking in actuality (it was commenced within a few months of the event), it was of historical genre and painted in a studio from models, the face of the Emperor being copied from a photograph. Rarely, if ever before, seen in London, this magnificent painting was received enthusiastically when exhibited at the first collection made by the International Society in 1898.

In France the authorities forbade the public exhibition of the Execution, the tragedy having had too intimate a relation with French politics; but at the Salon of 1869 Manet was represented by The Balcony, which provoked considerable derision from critics and public.

The famous duel with Duranty took place early in the following year. Duranty, an old friend and journalistic supporter of the movement, of great literary reputation in the ’sixties and ’seventies, but quite forgotten now, suddenly published a newspaper article in which the artist was violently attacked. There was no palpable reason for such a strange outbreak, and at the next gathering at the Café Guerbois, Manet requested explanations. In his anger the artist struck the writer across the face. Manet had for seconds Zola and Vigniaux, and his adversary was slightly wounded in the breast. Within a few years Manet stretched out his hand in friendship, and the quarrel was made up and forgotten by both parties.

The tremendous upheaval of the year 1870 had its effect upon Manet’s art, as it had upon the whole national and intellectual life of France. It marks the end of his first period, for after the war Manet paid more attention to the question of lighting, and gathered closer to the little group of “Luminarists” of which Claude Monet was the most significant figure. Early in 1870 the artist, when painting near Paris, in the park of his friend De Nittis, for the first time woke up to the prime importance of working “en plein air.” The war intervened, and Manet served with the colours. After the 26campaign he returned to his easel, but no longer an exclusive follower of the Spanish School and the Romanticists of the type of Courbet.

At the call of their country, artists and authors alike followed the flag. One can still remember how short-sighted Alphonse Daudet kept sentry-go during the first awful winter, and how, almost at the end of the siege of Paris, the brilliant Henri Regnault was shot down in a sortie. Bastien-Lepage was in the field, and one of the group of the Café Guerbois, Bazille, was killed in action. Manet enlisted in the Garde Nationale, and, for some reason which is not obvious, was at once promoted to the Staff. Unfortunately, Meissonier was nominated Colonel of the same regiment, which shows that the État-Major was quite ignorant of the state of contemporary art. Meissonier, a man of strong opinions, the recognised head of his profession, member of the Institute, was covered with official honour. Manet, with equally forcible convictions, the hero of the Salon des Refusés, was pariah to the Academy. It was not likely that two such men could get on well together.

Some years afterwards Manet displayed his feelings. He was gazing in a public gallery at a Charge of Cuirassiers, recently painted by Meissonier. A crowd gathered round. His criticism was short. “It’s good, really good. Everything is in steel except the cuirasses.” The mot travelled round the town, and duly reached the ears of the venerable artist at Passy. Manet saw active service. He was under fire at the Battle of Champigny, and also took part in the suppression of the Commune. A vivid little sketch by Manet shows a Parisian street, after some sharp fighting with the insurgents. It may be found reproduced in Duret’s monograph. Broken down in health, Manet joined his mother and sister at their retreat in the Pyrenees, and at Oléron painted the Battle of the “Kearsage” and “Alabama,” a wonderful piece of sea-painting, although executed far from the actual scene of the engagement.

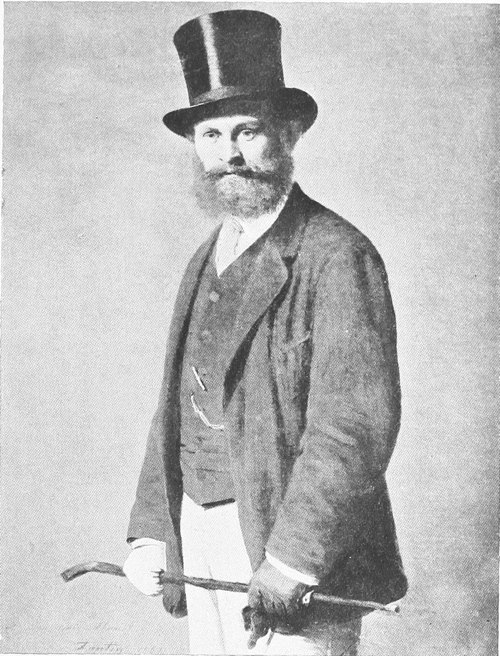

EDOUARD MANET

Manet had exhausted the paternal inheritance and was living on the fruits of his labour. The Impressionist School, as we now know it, was at the height of its activity, but by no means at the summit of its success. It assumed as its title the designation which had been applied to it as a nickname. The origin of this title is obscure. As already mentioned, Manet used the term in his introduction to the catalogue of 1867. Claude Monet named one of his pictures, a sunset, exhibited in the Salon des Refusés, “Impressions.” Ruskin though had used the same term years before in describing a canvas by Turner. Many of the members of the 27group were in the most abject poverty until the celebrated dealer, M. Durand-Ruel, came to their assistance. Manet had better sales than the rest of his brethren, for several collectors began to buy from his easel, viz. Gérard, Faure (of the Opera), Hecht, Ephrussi, Bernstein, May, and De Bellis. It is characteristic of the man that in his own studio he exhibited the works of his friends in order that the wealthy buyers he was beginning to attract should also invest in the productions of the less fortunate Impressionists.

In 1873 Manet contributed to the Salon a portrait of the engraver Belot seated in the Café Guerbois. Known as Le Bon Bock, it was his most popular success both with public and critics. Over eighty sittings were given before the canvas was completed. Manet had departed far from the technique of the Dutch portrait-painters, but Le Bon Bock strongly suggests the manner of Hals, although ranking on its own merits as an independent triumph. To the year of Le Bon Bock succeeded a long period of public indifference and artistic warfare. The Impressionists held their first collective exhibition, which was bitterly disappointing in its results. The public had changed but little. The Opera Ball and The Lady with Fans (about 1873), the Railway, painted wholly in the open air, and Polichinelle (exhibited at the Salon of 1874), The Artist and L’Argenteuil of 1875, all were received with disfavour.

It is extremely curious to note how canvases which appear to-day perfectly normal in their methods and aims positively outraged the feelings of critics thirty years ago. L’Artiste, a magnificent portrait of the engraver Desboutins, was refused by the Salon together with Le Linge. L’Argenteuil, a simple representation of two life-sized figures by the borders of the Seine, would be received with acclamation instead of disdain. Manet and his group were undoubtedly educating the public, but progress was very slow. There was an outburst of opinion in favour of the artist when the Salon refused L’Artiste and Le Linge. One sentence of criticism summed up the general feeling of those who were not entirely prejudiced against the new spirit. “The jury is at liberty to say that it does not like Manet. But it is not at liberty to cry ‘Down with Manet! To the doors with Manet!’”

Reaction on the part of the jury followed, exactly as it had followed in previous years. After the success of the Salon des Refusés Manet was accepted. Then, being rejected, he opened the gallery of the Avenue d’Alma, and was hung by the jury at the ensuing Salon. Rejected in 1876, the outcry in the press surprised the jury, who accepted his works in 1877. These extraordinary ups and downs culminated in 1878, when the jury of the Exposition 28Universelle, held in that year, definitely refused to hang any of his canvases. In the opinion of this jury the painter of Le Bon Bock was not a representative French artist. Ten years had changed the official art world but little, for the same thing had happened in 1867. This was almost the last insult Manet had to endure. In 1881 he received a second medal at the Salon. The discussion in the Committee had been acrimonious, but seventeen members of the jury were found to support the award. Amongst the names of the majority are those of Carolus-Duran, Cazin, Henner, Lalanne, de Neuville, and Roll.

One cannot deny that Manet’s work greatly varied. The portrait of M. Faure, in the character of Hamlet, was to a certain extent conventional studio-painting, and could offend nobody. The subject would not provoke the most susceptible. M. Faure was celebrated on the stage of the Grand Opera, possessed considerable wealth, and was one of Manet’s most devoted friends. Nana, sent to the Salon together with the portrait of M. Faure, was rejected. The technique was brilliant, but the subject, although harmless enough, suggested Zola’s heroine. Zola’s book was not published until 1879, but the name designated a class apart.

In 1880 Manet exhibited a wonderful portrait of M. Antonin Proust, and in the December of the following year his old friend, now Directeur des Beaux-Arts, was able to give to his life-long companion the Cross of the Legion of Honour. Had Manet no friends at Court, he would certainly not have received this coveted decoration. President Grévy objected when he saw the painter’s name, and would have struck out Manet from the list had not Gambetta exerted some little pressure.

But the struggle was nearly ended. Manet was dying. “This war to the knife has done me much harm,” he is reported to have told Antonin Proust. “I have suffered from it greatly, but it has whipped me up.... I would not wish that any artist should be praised and covered with adulation at the outset, for that means the annihilation of his personality.”

On New Year’s Day, 1882, he received the Cross, and at the Salon exhibited Un Bar aux Folies-Bergères, a barmaid enshrined amidst her glasses at a Paris music-hall, and a portrait, Jeanne. Since 1879 paralysis had been slowly sapping his powers. Edouard Manet died near Paris on April 30, 1883, at the early age of fifty-one. Disappointment, injured pride, lack of appreciation, continued and strong hostility, each had had its effect upon a physique always sensitive and never too strong. The artist had died for his art.

A GARDEN IN RUEIL · EDOUARD MANET

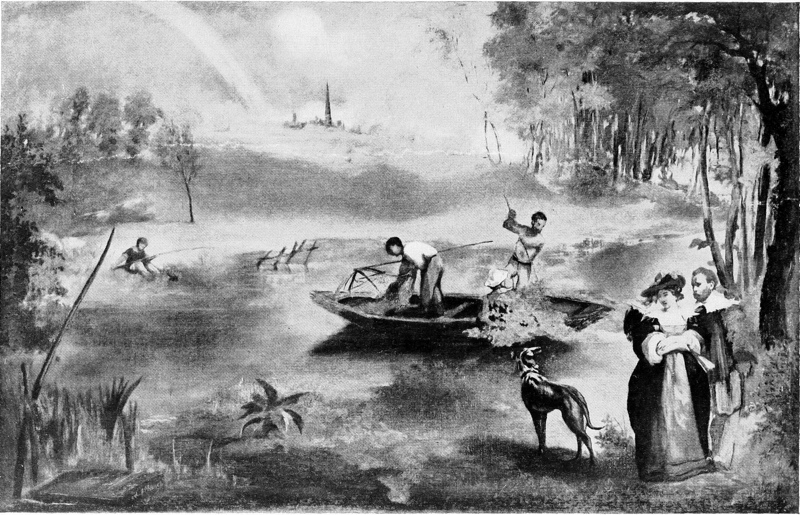

FISHING · EDOUARD MANET

29The secret of Manet’s power is sincerity and individuality; his main effort was a rendering of fact; his deepest interest the truthful juxtaposition of values, the broad and simple treatment of planes, combined with a constant search for the character of the person or object portrayed.

The influences which guided Manet during the earlier portion of his career have been noticed at length. He travelled extensively, and his works bear many souvenirs of foreign masters. But sufficient stress is not always laid upon the influences at work around Manet in Paris, namely, the influences of Delacroix, Corot, and the men of 1830, who carried but one stage farther the methods and tradition of the English masters, Constable, Bonington, Girtin and Turner.

Apart from sources of inspiration Manet was personally gifted. He possessed (as M. Duret so well points out) the faculty of sight, a gift from Nature which cannot be acquired by will or work. Technique he had obtained after six years’ hard study in the most severe atelier in Paris. But technique is a subsidiary equipment, for a complete command over one’s materials does not always imply the possession of genius.

“The fools!” said Manet with bitterness to Proust. “They were for ever telling me my work was unequal. That was the highest praise they could bestow. Yet it was always my ambition to rise—not to remain on a certain level, not to remake one day what I had made the day before, but to be inspired again and again by a new aspect of things, to strike frequently a fresh note.”

“Ah! I’m before my time. A hundred years hence people will be happier, for their sight will be clearer than ours to-day.”

Ambition to rise, never to remain on the same level! That is the whole doctrine of art, and the supreme epitaph for Edouard Manet, pioneer and master.

GEORGES D’ESPAGNAT

“L’ADMIRATION DE LA FOULE EST TOUJOURS EN RAISON INDIRECTE DU GÉNIE INDIVIDUEL. VOUS ÊTES D’AUTANT PLUS ADMIRÉ ET COMPRIS, QUE VOUS ÊTES PLUS ORDINAIRE”

ZOLA

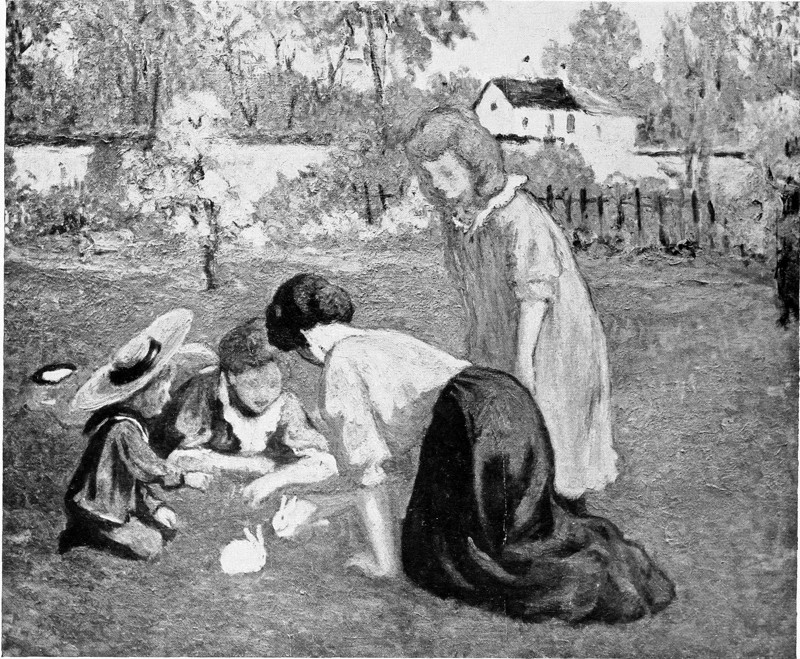

THE outbreak of the Franco-German War in 1870 scattered far and wide the little group that congregated at the Café Guerbois, and had a curious effect upon the evolution of their methods of painting. Several of the leading members of the circle crossed to England, and the studies they pursued in London formed the basis for the unconventional departures which have produced the masterpieces of Modern Impressionism. Practically all the later developments of their art date from the above-named year, and if a place of genesis be sought for it will be found in the London National Gallery.

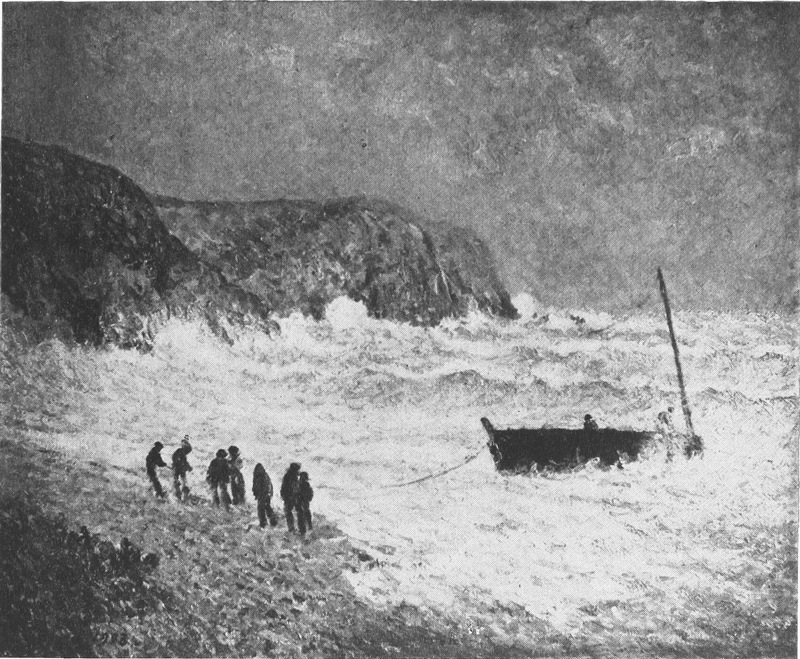

As related in a previous chapter, Edouard Manet, the acknowledged head at the Café Guerbois gatherings, became a captain in the Garde Nationale, with Meissonier as his colonel. Boudin and Jongkind fled to Belgium, and became labourers. Monet, Pissarro, Bonvin, Daubigny, and some friends, braved the horrors of “La Manche” and settled in London. They arrived almost penniless, thoroughly disheartened by the terrible events which were threatening their motherland with disaster. The journey, momentous to the unhappy passengers, was the opening of a new epoch in art.

The following letter from Pissarro, to the author, written in November 1902, gives an interesting account of their doings in London. He says: “In 1870 I found myself in London with Monet, and we met Daubigny and Bonvin. Monet and I were very enthusiastic over the London landscapes. Monet worked in the parks, whilst I, living at Lower Norwood, at that time a charming suburb, studied the effects of fog, snow, and springtime. We worked from Nature, and later on Monet painted in London some superb studies of mist. We also visited the museums. The water-colours and paintings of Turner and of Constable, the canvases of Old Crome, have certainly had influence upon us. We admired Gainsborough, Lawrence, Reynolds, &c., but we were struck chiefly by the landscape-painters, 32who shared more in our aim with regard to “plein air,” light, and fugitive effects. Watts, Rossetti, strongly interested us amongst the modern men. About this time we had the idea of sending our studies to the exhibition of the Royal Academy. Naturally we were rejected.”

“Naturally we were rejected!” These poor exiles were offering to the conservative Academy canvases painted in a method that Constable could not get accepted forty years before.

Their admiration of Turner and Constable was a repetition of the experiences of another great Frenchman nearly fifty years earlier. In his published journal, Delacroix has written: “Constable and Turner are true reformers.” At the Salon of 1824 the pictures of Constable so profoundly impressed him that he completely repainted his large canvas, the Massacre of Scio, then hanging in the same exhibition. The next year he visited London in order that he might more closely study Constable’s work. He returned to Paris marvelling at the hitherto unsuspected splendour of Turner, Wilkie, Lawrence, and Constable. Immediately he began to profit by their examples. Delacroix chronicles that he noticed that Constable, instead of painting in the usual flat tones, composed his picture of innumerable touches of different colours juxtaposed, and, at a certain distance, recomposing in a more powerful and more atmospheric natural effect. He adds that he considers this new method far superior to the old-fashioned one.