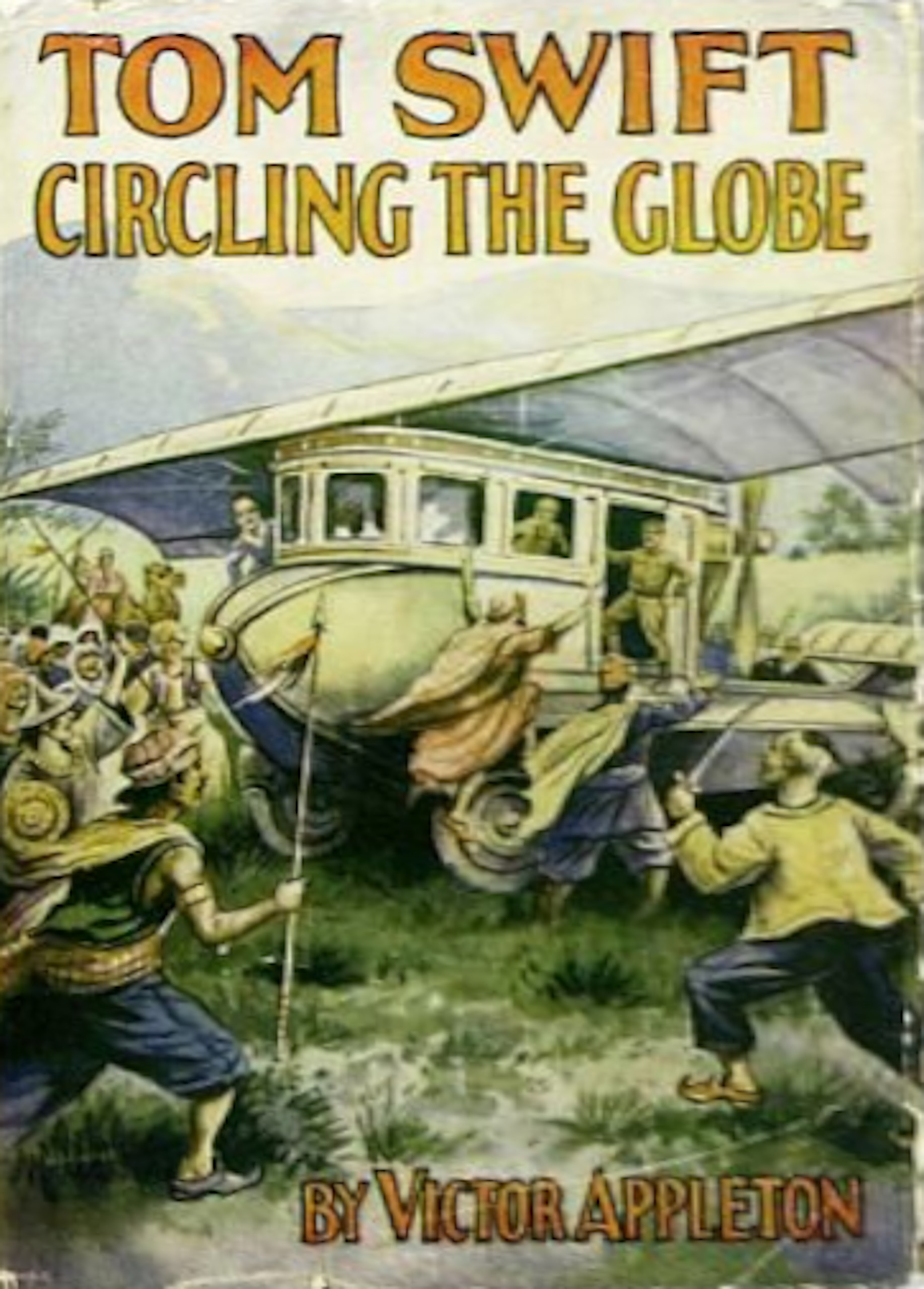

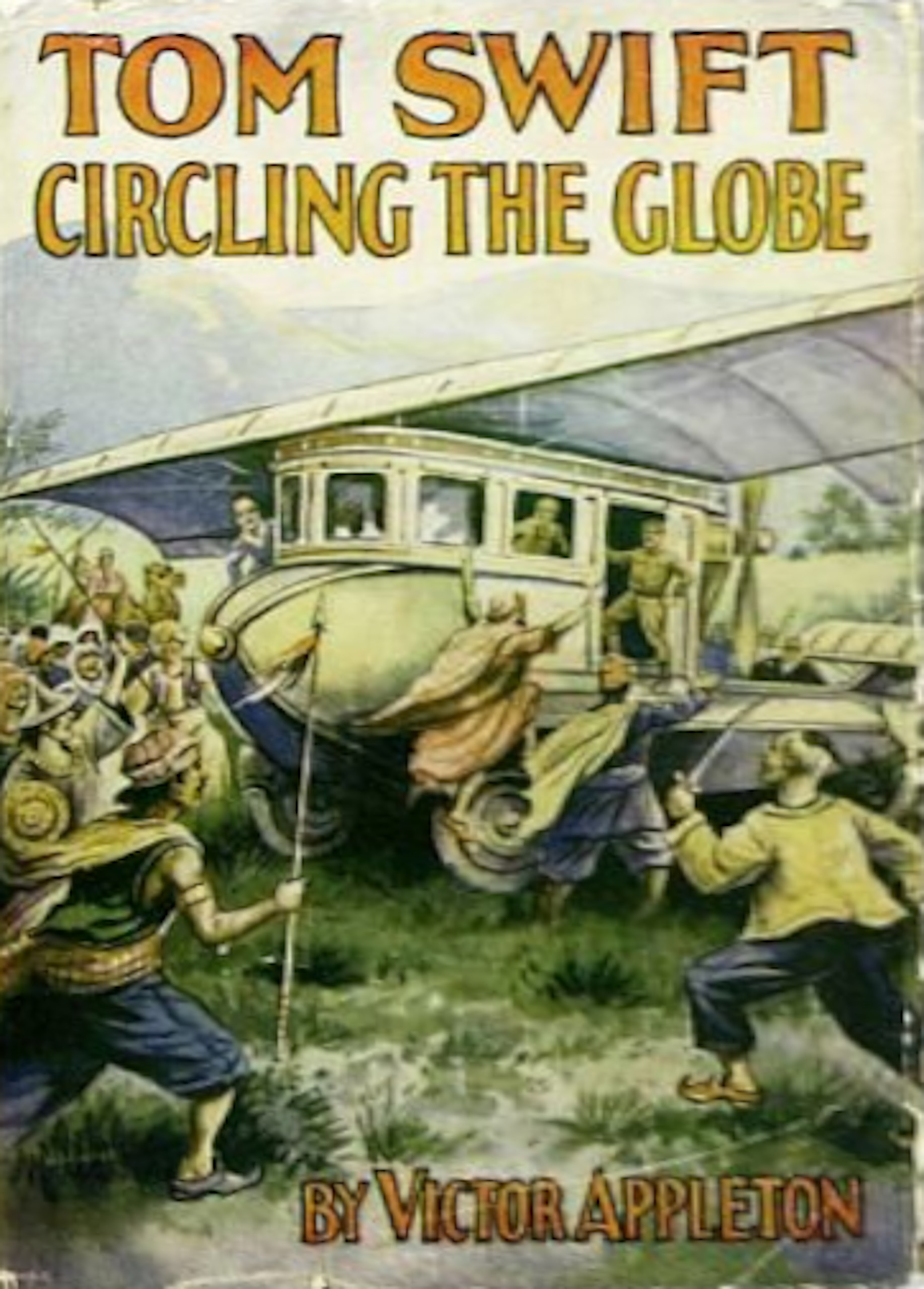

TOM SWIFT CIRCLING

THE GLOBE

OR

The Daring Cruise of the Air Monarch

By

VICTOR APPLETON

Author of

“Tom Swift and His Motorcycle”

“Tom Swift Among the Diamond Makers”

“Tom Swift and His Airline Express”

The Don Sturdy Series

Etc.

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

Made in the United States of America

| BOOKS FOR BOYS |

| By VICTOR APPLETON |

| 12mo. Cloth. Illustrated. |

| THE TOM SWIFT SERIES |

| TOM SWIFT AND HIS MOTORCYCLE |

| TOM SWIFT AND HIS MOTORBOAT |

| TOM SWIFT AND HIS AIRSHIP |

| TOM SWIFT AND HIS SUBMARINE BOAT |

| TOM SWIFT AND HIS ELECTRIC RUNABOUT |

| TOM SWIFT AND HIS WIRELESS MESSAGE |

| TOM SWIFT AMONG THE DIAMOND MAKERS |

| TOM SWIFT IN THE CAVES OF ICE |

| TOM SWIFT AND HIS SKY RACER |

| TOM SWIFT AND HIS ELECTRIC RIFLE |

| TOM SWIFT IN THE CITY OF GOLD |

| TOM SWIFT AND HIS AIR GLIDER |

| TOM SWIFT IN CAPTIVITY |

| TOM SWIFT AND HIS WIZARD CAMERA |

| TOM SWIFT AND HIS GREAT SEARCHLIGHT |

| TOM SWIFT AND HIS GIANT CANNON |

| TOM SWIFT AND HIS PHOTO TELEPHONE |

| TOM SWIFT AND HIS AERIAL WARSHIP |

| TOM SWIFT AND HIS BIG TUNNEL |

| TOM SWIFT IN THE LAND OF WONDERS |

| TOM SWIFT AND HIS WAR TANK |

| TOM SWIFT AND HIS AIR SCOUT |

| TOM SWIFT AND HIS UNDERSEA SEARCH |

| TOM SWIFT AMONG THE FIRE FIGHTERS |

| TOM SWIFT AND HIS ELECTRIC LOCOMOTIVE |

| TOM SWIFT AND HIS FLYING BOAT |

| TOM SWIFT AND HIS GREAT OIL GUSHER |

| TOM SWIFT AND HIS CHEST OF SECRETS |

| TOM SWIFT AND HIS AIRLINE EXPRESS |

| TOM SWIFT CIRCLING THE GLOBE |

| THE DON STURDY SERIES |

| DON STURDY ON THE DESERT OF MYSTERY |

| DON STURDY WITH THE BIG SNAKE HUNTERS |

| DON STURDY IN THE TOMBS OF GOLD |

| DON STURDY ACROSS THE NORTH POLE |

| DON STURDY IN THE LAND OF VOLCANOES |

| DON STURDY IN THE PORT OF LOST SHIPS |

| DON STURDY AMONG THE GORILLAS |

| Grosset & Dunlap, Publishers, New York. |

Copyright, 1927, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP, Inc.

Tom Swift Circling the Globe

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | A Blast of Fire | 1 |

| II. | Tom Accepts | 10 |

| III. | Into a Nose Dive | 20 |

| IV. | Just in Time | 30 |

| V. | The Air Monarch | 37 |

| VI. | Kicked Out | 46 |

| VII. | Struck Down | 57 |

| VIII. | Midnight Prowlers | 67 |

| IX. | They’re Off! | 80 |

| X. | Across the Ocean | 91 |

| XI. | Forced Down | 97 |

| XII. | The Hurricane | 103 |

| XIII. | A Close Call | 112 |

| XIV. | Whizzing Bullets | 121 |

| XV. | Yellow Gypsies | 130 |

| XVI. | To the Rescue | 137 |

| XVII. | Kilborn’s Trick | 146 |

| XVIII. | Chinese Bandits | 154 |

| XIX. | The Typhoon | 162 |

| XX. | Malay Pirates | 172 |

| XXI. | Among the Head-Hunters | 178 |

| XXII. | The Raft | 188 |

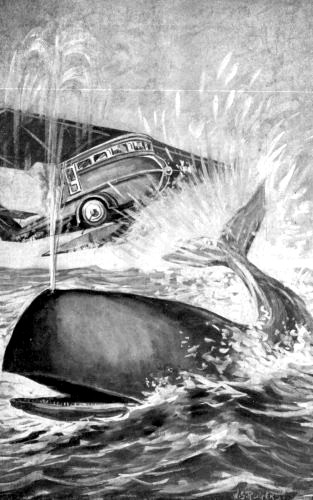

| XXIII. | There She Blows! | 196 |

| XXIV. | The Last Trick | 201 |

| XXV. | Across the Continent | 208 |

IT WAS A NARROW ESCAPE FROM THE WHALE.

TOM SWIFT CIRCLING

THE GLOBE

Tom Swift’s father folded up the newspaper he had been reading, made a sort of club with it, and banged it down on his desk with the report of a gun. At the same time the aged inventor exclaimed:

“I’ll wager ten thousand dollars my son Tom can do it! Yes, sir, Tom can do it! I’ve got ten thousand dollars that says he can!”

His face flushed because of the unusual excitement under which he was laboring, but his eyes never flinched as he looked at Thornton Burch, a retired manufacturer of automobiles, with whom Mr. Swift had just engaged in some spirited conversation.

“Do you want to take up that little wager, Thorn?” asked Mr. Swift, friendly enough but very determined.

“I’m not afraid to bet, Bart,” rejoined the other, with a tantalizing smile; “but I don’t want to rob you. That would be like taking candy from a baby!”

“You’re right!” chimed in Medwell Trace, who was associated with Mr. Burch in business. Both were old-time friends of Mr. Swift’s. “Better save your money, Bart!” he added, with a chuckle.

“Don’t worry about my money, Med!” snapped out Mr. Swift, who, in spite of his age, seemed to have plenty of pep. He went on: “Ten thousand dollars won’t break me if I lose it, but I’m not going to. I say Tom can do it, but my saying so doesn’t seem to make you believe it. They say money talks, so I’m going to let mine do a little conversing for me. I say again, I’ll wager you ten thousand dollars that Tom can do it!”

“Bless my fountain pen, but I agree with you, Bart!” exclaimed Wakefield Damon, an eccentric friend of Tom and his father. “If anybody can turn that trick it’s my friend Tom.”

“But be reasonable,” suggested Mr. Trace. “Granting that Tom Swift has some speedy machines and that he has made good with them in the past, he hasn’t a piece of apparatus now capable of speed enough and varied activities enough, to enable him to make that trip in the time you are claiming he can do it in, Bart. It’s impossible!”

“I say it isn’t impossible!” replied the aged Mr. Swift. “And to show I’m in earnest I’ll wager a second ten thousand dollars with you, Medwell Trace, that Tom can complete the journey inside of the time mentioned.”

“Better go slow, Bart,” advised Mr. Burch, with a smile. “I may hold you to the wager you made with me. I didn’t turn it down. Why do you go to betting with Med before you close with me?”

“I thought I had closed with you,” stated Mr. Swift, in some surprise. He had drawn some sheets of paper toward him on his desk and was taking the top off his fountain pen ready to write out a memo of the wager.

“What!” cried Mr. Burch. “Are you making a double bet? With Med and with me?”

“That’s what I’m doing!”

“For ten thousand dollars each?”

“That’s right!” and Mr. Swift seemed surprised that anybody should doubt his word.

“Twenty thousand dollars!” murmured Mr. Damon softly. “It’s a pile of money, Bart!”

“I know it is,” agreed Mr. Swift. “But I have more than twenty thousand dollars worth of faith in Tom. I know he can do it!”

“That’s right! He can!” burst out the eccentric visitor. “Bless my bald spot, but I’m almost willing to do some betting myself!”

“Leave this to me,” begged Mr. Swift. “You know Tom pretty well, for you’ve been on enough queer trips with him—more than I have, as a matter of fact. But I want to vindicate him and prove that I believe in him, and I’m willing to do it to the extent of twenty thousand dollars.”

“All right! All right!” exclaimed Mr. Trace, with a snapping of his fingers. “If you feel that way about it, Bart, put me down for ten thousand dollars. I can use that sum very nicely.”

“If you get it—which you won’t!” chuckled Mr. Swift grimly.

“Not if Tom can help it!” echoed Mr. Damon. “Bless my——”

But he got no chance to complete one of his odd expressions, for Mr. Swift interrupted with:

“Tom doesn’t know anything about it yet. I’ll have to call him in and tell him and urge him to get busy and invent a new aeroplane or something, for, frankly, I don’t believe he has just the proper piece of apparatus yet to do the trick!”

“Whew!” whistled Mr. Burch. “And yet you’re willing to bet that Tom can do it!”

“I know my boy,” said the aged inventor quietly.

“Now let’s get this straight,” suggested Mr. Trace, who had also taken out pen and paper. “You say, Swift, that the hero of Jules Verne’s story, who circled the globe in eighty days, was a piker. I agree with you about that as far as the time consumed is concerned. With the perfection of automobiles, oil burning steamers, and fast trains, the journey can be accomplished in much less time than Verne ever dreamed possible. But to say it can be done in twenty days flat is absurd!”

“Then twenty thousand dollars is absurd,” retorted Mr. Swift. “And it’s the first time I ever heard such a sum so designated.”

“Oh, we don’t despise the money!” chuckled Mr. Trace. “We’ll take it from you willingly enough, Bart, if you are mad enough to persist in this wager. If you had said thirty days you might be within the bounds of reason.”

“Considerably nearer the truth,” agreed Mr. Burch. “The trip has been made in about twenty-eight days, elapsed time, I believe. But twenty days, Bart——”

“I say Tom will circle the globe in twenty days flat—doing it actually within twenty days!” interrupted Mr. Swift. “The only stipulation I make is that he can use as many and as different means of locomotion as he pleases—that is to say, aeroplanes, seaplanes, motor boats, steamers, or trains.”

“That’s fair enough,” stated Mr. Trace. “I’ll just make a note of that. No use passing up ten thousand dollars,” he added with a smile at his friend. “I’ll never earn that sum any easier.”

“You mean I never shall,” said Mr. Swift.

“Then this seems to be the state of the case,” went on Mr. Burch, who had been busily writing. “I’ll just run over this and we can all sign it if it strikes you as being the terms of the wagers.”

The two friends, Mr. Burch and Mr. Trace, had called for a friendly visit with Mr. Swift one day in the early summer. Some time before, Tom and his father had turned out some machines for these two men in their big shops, and in this way a firm friendship had been started.

Mr. Damon, who lived in the neighboring town of Waterford, had been passing the Swift works and had stopped off for a chat. In some way the conversation had turned on a recent globe-circling event of some United States Naval airmen, who had made what was considered good time.

“But Tom can beat that!” Mr. Swift had said. “Tom can circle the globe in twenty days flat!”

“What in?” asked Mr. Burch incredulously. “There isn’t a machine made than can do it.”

“Tom’s working on a new machine now,” his father had said. “It’s a secret, but I don’t mind mentioning it to you old friends. I haven’t heard him say it is to be used in a globe-circling event, but from what he has told me of it I’m sure it will make fast time, and I’m willing to bet he can put a girdle around the earth, not quite as quickly as Puck, but in twenty days.”

“You mean that he will use the same machine all along the route?” asked Mr. Trace. “Why, that’s impossible!”

“Not impossible,” said Mr. Swift. “Tom’s new machine is going to be capable of traveling in the air, on the land, or in the water. I mean on the surface of the water, not a submarine. That would be a little too much. But when I say I’ll wager ten thousand dollars that Tom can circle the globe in twenty days, I don’t want to tie him down to this one machine. Something might happen to it. If you gentlemen take my bet, it is with the understanding that any machine or machines may be used. The one condition is that Tom, himself, personally, shall complete the girdle of the earth in twice ten days.”

“It can’t be done!” declared Mr. Burch.

“Never!” asserted his friend.

“If anybody can do it, bless my key ring, Tom’s the boy!” voiced Mr. Damon.

So the wagers had come to be laid. Mr. Swift had spoken at first rather rashly and in the heat of excitement. But he was not one to back down, and he listened to the reading of the simple agreement which Mr. Burch wrote out.

“Item,” droned the retired manufacturer as he scanned his paper, “a wager is entered into this third day of June to the effect that if Tom Swift can circle the globe inside of twenty days, actual time, in any machine or machines of his own or any make, then I, Thornton Burch, and I, Medwell Trace, agree that we will each and severally pay to Barton Swift the sum of ten thousand dollars. If, on the other hand, Tom Swift fails to circle the globe inside of twenty days flat time, then the said Barton Swift will pay each and severally to the said Burch and Trace the sum of ten thousand dollars.”

“Suits me!” exclaimed Mr. Trace, after a moment of thought.

“That’s my understanding of the wagers,” assented Mr. Swift.

“Then we’ll all sign this,” suggested Mr. Burch, “and Mr. Damon can put his name down as a witness and also keep this agreement. There is no need of putting up any money among gentlemen,” he added, and this was assented to.

“What about a time limit?” asked Mr. Damon. “I mean the trip ought to be undertaken and finished within a stipulated time.”

“We’ll say six months from now,” suggested Mr. Burch, and, there being no objection, this was written in.

One after another the four signed, Mr. Damon finally as a witness.

Hardly had the last of the fountain pens ceased scratching than there was reflected across Mr. Swift’s private office a flash of fire, followed by a dull, booming sound that seemed to shake the whole building.

“An explosion!” cried Mr. Damon, and from without, while the men looked anxiously at one another, a voice cried:

“The works are on fire! They’ve been blown up! The works are on fire!”

Pausing only long enough to lay aside the pens they had been using to sign the strange agreement, Mr. Swift and his friends rushed from the private office of the aged inventor where the talk had been going on.

Silence had settled over the great Swift plant following that booming explosion. But the silence was quickly broken by voices calling:

“Fire! Fire! Fire!”

“Bless my insurance policy, something has happened!” gasped Mr. Damon.

This was so obvious that no one took the trouble to agree with him.

“I hope nothing has happened to Tom!” exclaimed Mr. Swift.

As the four rushed out they were met by Eradicate, an old colored man, a sort of family retainer, who was limping along, trying to forget his rheumatism long enough to keep pace with a veritable giant of a man who, with Eradicate, was rushing to tell Mr. Swift the news.

“Master’s shop—him go boom!” roared Koku, the giant whom Tom had captured during one of his strange trips.

“I seen it same as he did!” cried Eradicate in his quavering cracked voice. “Massa Tom’s office done cotch fire!” he added.

“That’s bad!” Mr. Swift murmured, as he looked toward the part of the works where his son had his own private place for experiments and tests. A pall of smoke hung over it.

While Tom’s father and his friends are rushing to do what they can to rescue the young inventor, something about the hero of this story will be told to new readers of this series.

Tom Swift lived with his father in their beautiful home in Shopton, a town in one of our Eastern states. Tom’s mother had been dead some years, and Mrs. Baggert was the housekeeper, and a veritable second mother to the young inventor.

For Tom was an inventor, like his father, and in the first volume of this series, entitled “Tom Swift and His Motorcycle,” it is related how he bought Mr. Damon’s smashed machine, improved it, and turned it into one of the speediest things on the road.

Tom had many adventures while doing this, as he had while in his motor boat, his sky racer and other machines by which he ate up time and distance as set forth in the various volumes. It was on one of Tom’s journeys to unknown lands in a machine of the air that he had brought back Koku, one of a race of giants, and since then the big fellow had faithfully served Tom Swift.

Just before the present tale opens, Tom, as related in the volume just preceding this, entitled “Tom Swift and His Airline Express,” had perfected an aeroplane that could pick up a coach, something like a Pullman car, and bear it quickly through space. Tom established an airline service across the United States, dividing the journey into several laps, picking up different coaches in Chicago, Denver, and San Francisco.

He succeeded after battling with unscrupulous men who sought to hamper his efforts, and he also succeeded against a financial handicap. When almost doomed to failure, however, Tom saved a millionaire, Jason Jacks, from death in a runaway accident, and out of gratitude Mr. Jacks loaned Tom the money to complete and perfect his Airline Express.

The odd machine, an airship with a detachable car, met with favor, and from the proceeds of it Tom and his father gained large sums. Then, running true to form, the young inventor looked for a new world to conquer and turned his attention to a machine he hoped would move rapidly over the land, like a racing automobile, in the air, like an aeroplane, and on the water, like a motor boat.

Tom had practically completed his plans, and work on the new apparatus was well under way when the visit of Mr. Burch and Mr. Trace occurred, resulting in Mr. Swift’s rather rash wager.

“I guess I’m likely to lose before Tom even has a chance to try,” mused Mr. Swift as he hurried on toward his son’s private workshop. “If his place is blown up, he may be blown up with it!”

A pall of smoke hung over that part of the works, and it was impossible to see what really had taken place. Men were running from other parts of the plant, and the fire alarm was clanging.

Tom and his father had mapped out a plan for their own private fire company, since the city engine house in Shopton was too far away to be depended on and the Swift plant covered a large space of ground. In this plant many machines, not all of Tom’s invention or his father’s, were turned out and scores of men were employed.

Many of these, realizing the danger as soon as they heard the explosion and listened to the clanging of the fire bell, realized what portended and rushed to their stations. Some hurried toward Tom’s own particular part of the shop with chemical apparatus, others dragged lines of hose into which the water would soon be turned.

“I hope this is nothing serious,” voiced Mr. Trace.

“Bless my spectacles, it looks bad enough!” fairly shouted Mr. Damon, pointing to the thick pall of black smoke. “The whole place is gone, I guess!”

However, it was not quite so serious as that, and a moment later, when a puff of wind blew aside the dark vapor, it was seen that Tom’s small, private experimental building was standing intact. Smoke was pouring from several windows, however, and the shattered glass told its own story. But the smoke was lessening, and this seemed to indicate that the fire was not increasing.

As several of the workmen, bearing portable chemical extinguishers, hurried into the building, Mr. Damon pointed to a plot of grass beneath one of the windows that, Mr. Swift well knew, was the place where Tom had his desk.

“There’s your boy, now!” said the odd character.

Mr. Swift caught his breath sharply, for he beheld the prostrate form of Tom stretched motionless on the sod.

“That’s bad!” murmured Mr. Burch softly, and he had it in mind to tear up the wager agreement as soon as possible.

“Ho, Massa Tom!” yelled Eradicate in his high-pitched voice. “I save yo’!”

But Koku also had a desire to be of service to the master who had been so kind to him, and he likewise pressed forward.

There was a look of pain, grief, and anxiety on the face of Mr. Swift, and his friends were about to murmur some words of sympathy, for it looked as if Tom had been killed, when suddenly that young man stirred, put his hand to his head in a dazed fashion, and then sat up.

“Glory be!” shouted Eradicate. “He am alive!”

There was no doubt of it. Tom Swift was not only alive, but he did not seem to be hurt. There were black marks on his hands and face and his clothing was torn, also he was mud-stained where he had fallen into a soft spot on the turf. But he seemed not to be crippled or otherwise seriously injured.

His first glance, after he had looked toward his father and the advancing friends, was to his shop, and when he saw smoke pouring from several windows he leaped up with a cry of alarm.

But a moment later Garret Jackson, the shop manager, who had been among the first to enter the building, came running out to call:

“Fire’s out! Not much damage done!”

“Thank goodness for that!” murmured Mr. Burch.

“What happened, Tom?” asked Mr. Damon, with the freedom of an old friend. “Sounded as if the place went up.”

“It pretty nearly did,” answered the young inventor, looking at his smudged hands and then wiping his face, on one cheek of which appeared a small trickle of blood. “Have you got the fire under control?” he asked Mr. Jackson.

“Yes,” was the answer. “Don’t turn on the water!” he shouted as those in charge of a hose line were about to give a signal. “The chemicals are all we needed. The blaze didn’t amount to much.”

“I’m glad of that!” Tom was heard to say.

“Are you sure you’re all right, my boy?” asked his father.

“Positive!” was the quick answer. “Sound in wind and limb!” and Tom jumped about and executed a few side steps to show that he had not suffered. “I was mixing some chemicals,” he added, “when something went wrong and I saw a smoulder of fire that I knew would turn into an explosion in a few seconds more. So I stood not on the order of my going, but jumped out of the window instead of running to the door.”

“We were wondering why you were lying on that grass plot,” said Mr. Damon.

“I landed there when I jumped,” explained Tom. “And I wasn’t sure but what some of my clothing had caught fire, so I rolled over and lay on my face to protect myself. I couldn’t get up right away—sort of stunned I guess.”

“What were you working on, Tom—that new triple traveler?” asked his father, giving the name temporarily assigned to the strange machine that Tom hoped would go on land, in the air and in the water.

“Well, not directly on that,” said the young inventor as he walked toward his shop to ascertain the extent of the damage. “Yet it had to do with it. I was experimenting on a mixture to make gasoline more explosive. Not like ethyl gas, though,” he added, “for I want mine to be more powerful but not dangerous.”

“Not dangerous!” exclaimed Mr. Damon. “Bless my accident policy, don’t you call a fire, an explosion, and having to jump through a window dangerous enough, Tom Swift?”

“Yes. But I haven’t got my new gasoline mixture perfected yet,” was the answer. “When I do there won’t be any fires or explosions. Why did you think I might be working on the triple traveler, Dad?” he asked his father.

By this time the fire in the young inventor’s private building was practically out and most of the smoke had blown away. Tom and his father and friends entered, and Tom pointed to the table where he had been working. Some shattered retorts and glass tubes testified as to the explosion’s power. Tom had been slightly cut by flying glass, but that was the extent of his injuries.

“Well, I had the triple traveler in mind, Tom,” said Mr. Swift, “because, just before you tried to blow yourself up, my friends and I were talking about round-the-world travel. And I guess I sort of made a foolish boast, Tom.”

“What was that, Dad?”

“Why, I said, Tom, that you could circle the globe in twenty days actual time—nothing taken out for stops or anything like that. In twenty days flat, Tom.”

“Well, I guess maybe it can be done when I get my new machine perfected,” the young inventor said, calmly enough.

“It’s got to be done, Tom, unless you want me to lose twenty thousand dollars!” said his father.

“Twenty thousand dollars! What do you mean?”

“He wagered us ten thousand dollars apiece,” said Mr. Burch, indicating his friend, “that you, Tom Swift, could circle the globe in twenty days. We say it can’t be done!”

For a moment Tom Swift did not answer. His eyes roved to the wall of his office where a world map hung. Quickly Tom’s eyes glanced along the fortieth parallel of latitude, the most logical course to follow on a race of this sort.

“It can be done,” said Tom quietly. “You may take on those bets, Dad! I’ll see that you win!” and there was a determined air about him. “I’ll circle the world in twenty days!” promised Tom.

“Bless my alarm clock, that’s the stuff!” cried Mr. Damon.

A moment later a girl’s voice out in the plant yard was heard excitedly asking for Tom Swift.

“What happened? Is Tom hurt? Let me go to him at once!” the voice exclaimed.

A smile came over Tom’s face.

“It’s Mary Nestor,” he murmured, and to the two visitors Mr. Damon explained in an aside:

“She and Tom are engaged.”

“Lucky boy!” murmured Mr. Burch as he caught sight of a pretty girl hurrying into the rather upset office. For the place was upset in spite of the comparatively small damage caused by the explosion and fire.

“Oh, Tom! are you hurt?” Mary cried, hastening toward him, totally oblivious of all the others in the disordered room. “I heard a rumor that your whole plant had burned and I came over as fast as I could.”

“Well, Mary,” went on the young inventor, with a smile, “I’m glad to say that, for once, rumor got ahead of itself. Nothing very much happened. Just a few chemicals went off unexpectedly.”

“But you’re cut!” Mary gasped, as she saw the blood on Tom’s cheek. “Oh!”

“Just a scratch from a broken test tube,” he explained.

Then Mr. Burch, with a fine sense of what was fitting, said:

“Mr. Trace, since we have concluded our business here and have made arrangements for separating our friend Bart from twenty thousand dollars, we might as well get out and——”

He did not say it, but the inference was obvious that he wanted to leave the two young people alone. Tom seemed to sense this for he said:

“Just a moment, please. I want to understand a little more about this wager.”

“You’ll understand it better when your dad has to take some of his big profits and hand over twenty thousand to us,” chimed in Mr. Trace. It was true that the Swift Company had been very profitable of late, thanks to some of Tom’s inventions.

“But still I don’t like the idea of losing twenty thousand, or even ten,” said Tom, with a smile. “And I don’t intend to lose it, either, gentlemen!” he concluded.

“I’m glad you are backing me up, Tom,” murmured his father. “How soon will the triple traveler be done?”

Tom looked at some plans on his desk, glanced at the world map and was about to answer when Mary broke in with:

“Is this a hold-up?” Her smile took any menace from the words.

“It’s just a little bet among three old friends,” said Mr. Burch, with a chuckle, “and our friend Tom is going to be the goat. I mean he is going to lose the race!” he concluded.

“Not much I’m not!” cried the young inventor, and when Mary looked a bit mystified Mr. Trace explained:

“We were discussing various means of travel, Miss Nestor, and the feat of Jules Verne’s hero in girdling the earth in eighty days. That time has been brought down to about thirty, but Tom’s father declared it could be done within twenty days.”

“That suits me!” cried Tom. “If you give me time to complete the making of my new machine I’ll prove my father to be right.”

“Good boy!” murmured the aged inventor.

“Then you will have a part in this wager,” suggested Mr. Trace.

“That suits me!” went on Tom. “Let me see—what can I do with my share of twenty thousand dollars?” he asked musingly, and with a smile. But the smile faded when he looked at Mary’s face and saw how distressed she was.

“Oh, Tom,” she murmured, “think how near death you were just now in the explosion! And now you are going to risk your life again in one of your strange machines!”

She bit her lips to keep back her tears, it seemed, and the young inventor, seeing that she was on the verge of a nervous alarm, quickly said:

“Don’t worry, Mary! There’s no danger at all. Wait until you take a look at my new triple traveler. Come on out and I’ll show it to you.”

Tom did not invite any of the others into that part of the works whither he led Mary Nestor, and Mr. Damon and his friends had common sense enough not to intrude where, obviously, they were not wanted. Tom did not stop to wash his hands or face of the grime of the explosion, and he only wiped away the blood, which had now almost ceased to flow from the slight cut.

He led the girl into a large building, the doors of which were carefully locked, and when Mary’s eyes had become accustomed to the gloom she saw a dim shape of something which seemed to have the elongated body of a boat, beneath which were sturdy wheels and above which were stretched big wings like those on an aeroplane, with two rear propellers.

“This is really only a working model,” Tom explained.

“A working model of what?” inquired Mary.

“Well, the triple traveler is all we call it at present,” Tom answered. “As you see——”

“I can’t see anything much!” interrupted Mary.

“Well you’ll see later,” went on Tom. “It’s a secret yet and I have the windows shrouded. That’s also why I keep the doors locked. No telling who of my enemies might try to sneak this new machine away from me. I’ve got to be careful. But when it’s finished it will be one of the best things I have ever made.”

“And are you really going to circle the earth in it, Tom?”

“I’m going to try. There’s no question but what I can do it. But whether I can do it inside of twenty days is another question.”

“You don’t mean to say you are going to try to win that foolish bet?”

“I don’t see how I can help myself,” replied Tom. “It may have been a bit rash of dad to make it, but, now that he has, I must do all I can to help him win it. I owe it to my own reputation. It isn’t so much a question of the money.”

“Oh, dear!” sighed Mary.

“What’s the matter?”

“I wish you weren’t always chasing off on these wild trips, Tom!”

“I don’t go very often. And they aren’t as wild as the ones I used to take at first—like those to the bottom of the sea, for instance. I haven’t been on any for a long while, either.”

“No! Not since last fall when you inaugurated the Airline Express,” said Mary, a bit sarcastically. “And look what a lot of danger you were in!”

“But I came out all right and I made a lot of money,” said Tom, defending himself.

“And now you’re going around the world. Oh, dear!” and Mary sighed dolefully.

Tom looked at her sharply. He saw that she was laboring under the reaction of fear after having heard the false report that his plant was blown up.

“Look here, Mary,” he said, “I’m afraid you’re losing your nerve! That will never do!”

“Losing my nerve?”

“Yes. I’ll wager right now any flavor of ice-cream you care to name that you don’t dare take an aeroplane ride with me!”

“I’ll take you up!” cried Mary, and she smiled. “I’ll show you!” and she tossed her head.

She often accompanied Tom on his trips in one of his smaller and less complicated aeroplanes, for Tom traveled this way on many occasions, to transact some business or to conduct experiments having to do with other machines.

“Then you’ll take a sky trip with me, Mary?”

“I surely will. I think it will do me good!”

“I’m sure of it,” said Tom, smiling.

They went out of the partially wrecked office, Tom giving orders to have it cleaned up and his gasoline experimental apparatus put aside for future use.

Tom next gave orders to have one of his speedy double planes run into the flying field while he went to the house to wash and get ready for the trip with Mary. Then he added his name to the signatures on the bet agreement, and said inside of six months from the present time he would start to circle the globe.

Mr. Swift, who had somewhat regretted his rash action, was all smiles now, for he had great faith in Tom.

“Of course twenty thousand dollars won’t break us, Tom,” he confided to his son as the latter was putting on his leather flying helmet and getting one ready for Mary, together with a leather jacket. “But, at the same time, I’d like to win it.”

“Same here, Dad,” echoed Tom. “And we will, too!”

In a short time the little plane, which would carry only two, was in readiness. The motor was tuned up and Tom and Mary took their places in the double cockpit, where the girl sat beside her sweetheart. It was a type of plane perfected by Tom.

“Where to, Mary?” asked Tom, as he looked over the controls.

“Oh, anywhere,” she answered. “I want to get away from everything for a while.”

“Then maybe you’d rather go up alone,” suggested the young man.

“I said everything—not everybody,” and Mary’s accent made the meaning clear, at which Tom laughed.

He turned on more gas, there was a roar from the motor, the plane taxied across the field, and a few seconds later was soaring up toward the blue.

“I suppose you’ll be traveling like this when you start on that—I can’t help saying it—foolish trip around the world, Tom,” said Mary.

“A lot faster,” was his answer. “You see I’ve got to do twenty-five thousand miles in twenty days. That’s twelve hundred miles a day. Counting twelve hours to a day on the average, that’s a hundred miles an hour. But of course there will have to be stops, forced or others, and so practically I’ll have to double that rate and make it two hundred miles or more of flying every hour.”

“Can you go that fast, Tom?”

“Faster, I hope. I just read of a navy seaplane that did two hundred and fifty-six miles an hour. I’m going to better that record if I can. Just wait until I get the new triple traveler finished.”

“I hope it doesn’t finish you, Tom,” said Mary.

He leaned over toward her. By a new muffler attachment on the engine the roar of the exhaust was deadened and it was possible to talk without shouting. Love making can never be carried on in shouts, as you know well.

On and on flew Tom and Mary, the little plane gaining speed and height each minute. They were soon up above the clouds, flying fast.

“You’re a good traveler, Mary,” said Tom. “How’d you like to come along on the world-circling jaunt?”

“In some ways I’d like it—I could make sure you were safe,” she said with a smile. “But I’m afraid I can’t manage it,” she added, as Tom gave her hand a squeeze. To do this he had to release one of the levers he was manipulating, and when he again shifted it there was a peculiar sound.

“What’s that?” cried the girl.

Tom Swift did not answer, but began frantically manipulating the controls. The plane was acting in a peculiar manner—even Mary with her inexperience realized that.

“Is anything wrong?” she asked.

“I’m afraid there is,” Tom answered with a grim tightening of his jaws. “We seem to be going into a nose dive!”

Hardly had he spoken than the plane tilted forward and plunged toward the earth at frightful speed.

Tom Swift had been in dangerous situations before with aeroplanes and other machines of his invention. He had more than once been close to death, and he knew that the only way to get out of a tight corner was to keep his head. Now he did not so much fear for himself as for Mary.

“Is there any danger?” asked the girl, who had sense enough to sit quietly in her seat and not grab Tom’s arms or interfere in any way.

“Yes, there is danger,” the aviator answered quietly, as he kept at his task of trying to straighten out the plane. “If I can’t bring her up we’re likely to crash.”

Beyond a gasp of her breath and a look of terror in her eyes, Mary showed no signs of the fear that was within her. Yet she was terribly frightened, for Tom as much as for herself.

“Come up here!” cried the young inventor, speaking to the plane as he might to a horse. He adjusted the levers, pulled back on the one that tended to raise the forward edges of the plane to tilt her nose, and he tried to get the elevation rudder up. But in the end he had to admit that he was beaten.

“She won’t come up!” he gasped.

“Then we’ll have to crash!” murmured Mary.

Tom nodded hopelessly. He reached over and began loosening the buckle of the girl’s safety belt before unfastening his own.

“The only thing to do is to jump when I give the word.”

“Is there no chance of saving the plane, Tom?”

“I don’t believe so, Mary. But I’m not worrying about the machine. I can make another. It’s you!”

Tom put his arm around her and she leaned close to him. The machine was dashing downward now at terrific speed, and on a dangerous slant that meant the nose would strike the earth first, driving the engine back upon those in the cockpit. The motor had stopped, whether having been cut off by Tom or because of some defect Mary did not inquire.

“Leap clear when I tell you to,” said Tom, as he made one more fruitless effort to straighten the plane out so he could pancake down instead of hitting on the nose. “You go out on that side, Mary, and I’ll go on this.”

“If there was only some water for us to land in,” murmured the girl. “If we were only over Lake Carlopa instead of having to jump on the hard ground, it wouldn’t be so bad, Tom!”

“I’m heading for Jamison’s cranberry bog,” the aviator answered, pointing to a marshy place just ahead. “It will be a softer place to jump on than the fields or in the woods. I hope we can make it!”

Nearer and nearer the earth the plane was descending. In a few seconds more it would be all over, and the machine would crash itself into a mass of tangled wreckage, while the bodies of Tom and Mary—it was terrible to think of.

“Shall I jump now?” the girl asked as she leaned over the edge of the cockpit and saw how perilously close the earth was.

“Just a moment,” said Tom. “Wait!”

He made one last attempt to straighten the plane out, pulling on the lever with all his force. To his joy and surprise it yielded where before it had held firm. Back it came to the last notch and, with a suddenness that was like the quick stopping of a falling elevator, the plane flattened out on a level keel just as it started over the big cranberry bog, part of which was flooded with water.

“I leveled her out!” cried the young man. “There’s a chance now that we can make a three point landing and save ourselves.”

The plane, however, had acquired terrific speed during her dive, and was going much faster than would have been the case had she been driving along under the power of the motor and on a level. In this latter case Tom could have eased the machine down gently.

As it was, they were going to strike the ground while going at terrific speed. Though in their favor was the fact that they could now hit the earth at a long slant instead of at an acute angle.

“Shall I jump?” asked Mary, who was closely watching her lover.

“No!” he cried. “Sit tight! Maybe we can do it!”

He was making some adjustments to the wings and tail rudder. The controls had jammed just when they were most needed, but they had now suddenly loosened up in as strange a manner as they had tightened, and this gave Tom Swift his chance.

He looked down, picking out the best possible spot for a landing, since he could now steer the plane somewhat. The spot he picked was where the water was deepest over the cranberry bog. The plane was not fitted with pontoons for landing on water, and doubtless the under carriage was going to be greatly damaged in the fall. But, other things being equal, a fall into water in an aeroplane is less harmful to the occupants than a landing on the hard ground.

With steady hands and clear eyes that sought for the most advantageous spot, Tom guided the almost unruly craft. It was now within a few hundred feet of the earth, and a couple of seconds more would tell the tale.

Aside from the rushing of the wind past them, causing a roaring noise in spite of the helmets they wore over their ears, there was silence in the plane, for the motor was still dead. Amid the silence Tom heard some voices shouting below him.

He wondered dimly who could be calling, but guessed it was some autoists on the highway that bordered the cranberry bog.

“They’re going to see something they didn’t count on!” thought Tom grimly.

“Stand up, Mary, when I give the word!” said Tom to her as he leaned over the edge of the cockpit and looked down. His gaze took in a small automobile racing along the highway toward that part of the bog where he hoped to land.

“Stand up! What for?” asked the girl. “Shall I have to jump after all?”

“No, but by standing, instead of sitting, the shock of landing will be less,” Tom said. “Get ready now!”

His eyes were measuring the distance. In three seconds more, he calculated, the plane would crash into the bog of mud and water. But it would crash on a nearly level keel instead of on its nose, in which case nothing, in all likelihood, could have saved the occupants from death.

“Up!” cried Tom sharply, and he and Mary rose in their seats, clinging to each other.

An instant later the plane hit the ground with terrific force, but fortunately in the middle of a soft spot of mud and water which greatly reduced the shock. As it was, the jolt knocked Tom and Mary down, stunning them as they were crushed back into their seats, so that for a few seconds after the forced landing they did not realize what was happening.

Mary was the first to recover her senses. She struggled to a position where she could look over the side of the cockpit and at once cried:

“Tom! We’re sinking! We’re almost submerged!”

By this time the young inventor had aroused and, pulling himself to the edge of the cabin space, he glanced over.

“We’re in a bad hole!” he exclaimed.

He learned later that the plane had gone down in what was virtually a quicksand in the cranberry bog—a place shunned by all who knew its dangers.

“What’s to be done, Tom?” cried Mary. “We got out of the nose dive just in time, but if we’re going to sink in this bog it will be just as bad, though not so quick!”

She saw, in fancy, a slow, terrible death by suffocation in the mud and water.

“Let’s jump out and try to wade to solid ground!” she went on.

“No! No! Don’t do that!” yelled Tom. “It would be sure death! The plane will hold us up for a time—perhaps until help comes.”

“Where will help come from?” asked Mary. “No one knows we are here, Tom.”

Before he could answer there came the sound of shouting voices and the tooting of an automobile horn from somewhere in the distance.

“Maybe that’s help now,” Tom said. “But they’ve got to hurry,” he added grimly. “We’re sinking fast!”

Rapidly the small plane settled in the mud and water. It was down almost to the edge of the cockpit, and Tom was about to advise Mary to climb out and up on the upper surface of the wings, which he, likewise was going to do, when shouts over to the left attracted the attention of the two.

A couple of men—automobile mechanics to judge by their grease-soiled garments—stood on the edge of the bog, waving their hands.

“Hold fast!” the taller one urged. “We’ll get you in a minute!”

“You can’t come out here!” Tom shouted back. “It’s a regular quicksand. You’ll get in yourselves!”

“There’s some sort of a boat here,” said the other man. “We’re coming out in that!”

“A boat! Then they’ll save us!” gasped Mary.

“Maybe,” returned Tom grimly. He did not understand how a boat could be propelled through that bog which was more like thick, slimy mud than it was water.

The two men disappeared behind a screen of bushes, and Mary cried:

“Oh, they are leaving us!”

But the reassuring shout came back:

“We’ll be there with the boat in a minute!”

By this time the thick, muddy water (quicksand in solution it was) began seeping over the edge of the cockpit. Tom was helping Mary to climb up to a dry place, back on the fuselage of the machine, when out of the underbrush the two men emerged, pushing, by means of poles, a low, broad, flat-bottomed punt, which was so broad of beam that it did not sink in the swamp.

“We’ll have you off in a minute!” called the shorter of the two men encouragingly.

By dint of hard pushing they worked the punt to the side of the stranded and bogged aeroplane, and Tom and Mary lost little time in getting into the safer, if less picturesque, craft.

“Will it float with all four of us in it?” Tom asked anxiously.

“I guess so,” the tall stranger said. “But it will be slow work poling back to solid ground.”

“Sorry we can’t save your bus, mister,” remarked the other.

“Don’t worry about the plane,” was Tom’s answer. “There are more where that came from. And I may be able to save it at that.”

“It would take a tank to yank that bus out,” said the short man.

“What do you know about tanks?” asked Tom, as he took up a pole from the bottom of the punt and helped the two rescuers push the craft toward the solid point of land whence the welcome hails had come.

“I used to manicure one on the other side when we had the Big Fuss,” was the answer, and Tom knew the man had been in one of the ponderous tank machines of the World War.

“I hate to leave that bus,” sighed the tall man, with a look back at the now almost submerged plane. “She’s pretty, but you had some trouble, didn’t you?” he asked. “Sounded to me like your motor died on you.”

“It did,” admitted Tom. “And I couldn’t straighten out.”

“She was nose diving when my buddy and me saw you as we were riding along in our machine,” went on the tall man.

“Nose diving is right,” conceded Tom. “But I got her straightened out just in time.”

“But not enough to zoom up,” went on the other, and Tom was sure the man knew whereof he spoke.

“You’ve run a bus?” asked Tom.

“In France,” was the sufficient answer.

By this time the punt had been poled through the mud, water, and quicksand of the cranberry bog far enough so that all danger was past. It was shoved against the point of land on which the two men had run out as they leaped from their auto, which they said they had left back on the highway.

“Well, I guess you’ll be all right now,” remarked the tall man as Tom and Mary got out of the punt.

“Yes, thanks to you,” said the young inventor.

“If we can drop you anywhere in our flivver,” went on the short man, “we’ll do it.”

“If you can take us to the Swift plant,” said Tom, “it will be a great accommodation.”

“We’ll do that,” said the short man, as his companion made the punt fast to a stump. “That Tom Swift is the big inventor, isn’t he! Do you know him?”

“Slightly,” was the answer, with a smile.

“This is Tom Swift!” exclaimed Mary, unable to resist the opportunity. She indicated Tom.

“You are?” gasped the short man.

“Gee!” exclaimed his tall companion.

“I happen to be,” replied Tom. “And if you will leave us at my plant and come in so that I can thank you properly for what you did——”

“Aw, forget it!” snapped out the short man. “We don’t want any thanks. You’d do the same, wouldn’t you?”

“Of course,” said Tom. “But——”

“Forget it!” said the other again.

“At least tell me who you are,” begged Tom, as the two led the way to where they had left their small touring car.

“I’m Joe Hartman,” said the tall man who had admitted he was an aviator in the World War.

“And when I hear anybody yell for Bill Brinkley then I come and get my chow!” added the short chap whimsically.

“This is my friend, Miss Mary Nestor,” introduced Tom, and the girl held out a hand each to the two mechanics.

“All oil and grease!” apologized Brinkley, putting his hand behind his back. “We work in a garage at Waterford,” he went on in explanation.

“And we’ll gum you all up if we shake hands!” added Joe Hartman bashfully.

“As if I cared!” exclaimed Mary, and she insisted on grasping their oil-begrimed palms in a warm pressure. “I want to thank you, too,” she said as she told where she lived, begging the two to call and see her father and mother.

“If you fellows work in Waterford, maybe you know Mr. Wakefield Damon?” Tom added.

“Guess not,” admitted the short man, while his companion shook his head in negation. “We haven’t worked there very long,” he went on. “Just now we had to deliver a repaired car in Shopton and we two went together. I drove this flivver,” he added with a kick at one of the tires, “so I could bring Joe back.”

“Well, it’s a good thing you happened to be where you were,” said Tom. “And I wish you’d come and see me some time,” he added as the little auto was headed for his plant.

“Maybe we will,” was all the two would promise when, a little later, they let Tom and Mary out at the office entrance and then drove on.

As the accident to the plane had happened several miles from Tom’s plant, neither his father, Mr. Damon, nor the two wagering friends, Medwell Trace and Thornton Burch, were aware of it. Not until Tom and Mary came in, somewhat spattered by mud, and told of their experience was anything known of it.

Tom sent Mary home in an automobile and dispatched some of his workmen with a big truck and long ropes to see if it was possible to get the little plane out of the swamp.

“And now,” said Tom, as he finished washing off some of the grime, “I’m going to get seriously to work and help dad win that twenty thousand dollars.”

Tom Swift had made a start on his new machine some time before. He had conceived the idea of a craft that was at once an automobile, a motor boat, and an aeroplane, and though his father had at first been doubtful and some of the mechanics who worked on it openly skeptical, Tom had persisted and now the craft was well on in the process of manufacture.

A model had been made, and though at first it would not work, Tom had kept improving it until it was perfect. The only thing that disappointed the young inventor was that it was not speedy enough, and he was looking for fast performances, not only in the air but on land and water.

“I’ve got to use a more powerful gasoline,” he decided and he was experimenting on this fluid when the explosion came. Luckily, little damage was done and three days after the fire Tom’s office had been repaired and he was hard at work again.

“What are you going to call it, Tom?” asked Ned Newton, the young former bank cashier who was a close friend of the young inventor and, of late, treasurer and one of the managing officials of the Swift Company. Ned was in Tom’s private workshop looking at the strange device.

“Well, I did think of calling it Monarch,” was the answer. “The Air Monarch might not be such a bad name, if it does what I think it will do.”

“When will you know?” Ned asked.

“In a few weeks. I’m going to rush work on it, now that dad has made his wagers. I’ve got to help him win that twenty thousand dollars.”

“Do you think you can?” asked Ned.

“I’m going to!” declared Tom, with conviction. “Take a look at the Air Monarch, Ned, and see what you think of her as far as I’ve gone.”

“Looks pretty good,” admitted the young treasurer. “What’s that for?” and he pointed to a small door in the rear of the machine, a door under the tail rudder.

“That’s where the propeller is concealed,” was Tom’s answer. “Look and you’ll see how it works!”

He pulled a lever, the door slid back, and in a tunnel-shaped compartment was a large, three-bladed, bronze propeller.

“That’s for use when running on the water,” the inventor explained.

“How does it run on land?” inquired Ned. “Like an automobile?”

“Not exactly,” Tom said. “The same propeller that sends the craft through the air sends it along on the ground. Just as an aeroplane taxies across the field before mounting, you know. By keeping the tail rudder depressed I prevent the machine from rising, and it moves over the ground, though of course not as fast as in the air.”

“There is no direct drive on these wheels then?” asked Ned, pointing to four strong wheels on which the machine rested and on which it would land after making a flight.

“Oh, yes, I can drive the car on the ground by gearing the motor directly to the wheels,” said Tom. “But I can’t get much speed that way, though I do get a lot of power. And in front here——”

But Tom suddenly stopped his explanations and looked toward the door of his private shop. The knob was turning in a stealthy manner.

“What’s the matter?” asked Ned Newton, who was very much interested in Tom’s new machine. Ned had gone on air trips with his chum before and, having heard of the wager and now seeing the Air Monarch, it is not at all unlikely that Ned had visions of another strange journey. “Anything wrong?” went on Ned, as Tom did not answer, but continued to stare at the door.

“There may be—I’m not sure,” was the answer in a low voice. “Wait a minute.”

Tom tiptoed softly to the door, opened it suddenly, and then uttered an exclamation of disappointment.

“What’s the matter?” asked Ned again.

“He skipped,” answered Tom.

“Who?”

“The fellow who was outside that door trying to overhear some of my secrets and find out about the Air Monarch,” was Tom’s answer.

“Spies?” exclaimed Ned.

“That’s about it. Ever since I first started on this new idea and began work on the model and the craft itself, I’ve had a sneaking idea that I’m being spied upon. I am sure of it now. Somebody was listening at the keyhole, but they heard me coming and skipped.”

“Who is it?” asked Ned.

“That’s what I’ve got to find out. Keep quiet about this, and I’ll set a trap.” Then the two friends went to a far corner of the room, out of all possible range of the door, and talked for a long time.

The next few days were busy ones in the shop of Tom Swift. Now that his father, by his rashness, had committed his son to the attempt to circle the earth in twenty days, the older inventor was as enthusiastic over the matter as was Tom himself.

“I’ll help you get the Air Monarch finished, Tom,” said the old man, “and then you can start. I’m not going to have Burch and Trace crowing over me!”

“They won’t crow, Dad,” said Tom, with a smile. “I’ll win that money for you!”

In order to hasten the completion of the Air Monarch, men who were in other shops controlled by Tom and his father were taken off their work and put to finishing the triple traveler. All who were admitted into the shop where the big new machine was housed were sworn to secrecy.

The new machine was like a large aeroplane, but with an enclosed cabin something like the European air line de luxe expresses. Built like a Pullman car, only lighter, the cabin of the Air Monarch afforded sleeping berths for five. When not in use the bunks folded up against the wall, thus making an observation room. There was a combined dining room and kitchen where meals could be served.

The motor of the craft was abaft the living quarters, thus keeping the sleeping compartment free of gasoline fumes. The Air Monarch was of the pusher and not the tractor type of plane. Extending over the cabin, and out on either side was the big top plane. There was another plane below this, and from the lower one extended the long tail which carried the rudders, one for directing the craft up or down and the other to impart a lateral motion.

The body of the craft was something like a seaplane, staunchly built to enable it to travel the surface of the ocean if need be. And, as already explained, there were four sturdy wheels on which the Air Monarch could roll along the ground. These wheels could be geared directly to the motor, as are the wheels of an automobile, or by using the air propeller the craft could be sent along as an aeroplane taxies across its starting field. The housed propeller for use in water has already been mentioned.

To such good advantage did Tom Swift set his men to work that four weeks after the laying of the wager the Air Monarch was completed except for the fitting up of her cabin and the taking aboard of supplies.

“The motor’s the main thing, and that’s completed and installed,” said Tom to Ned one evening.

“Does it work?” asked the financial representative of the firm.

“It sure does!” was the enthusiastic answer. “Tried it on a brake test this afternoon and she did a little better than two thousand seven hundred R.P.M.”

“Hope that doesn’t mean ‘Rest In Peace',” chuckled Ned, who was not versed in mechanics.

“R.P.M. stands for revolutions per minute,” Tom explained. “And when I tell you my new motor did more than twenty-seven hundred it’s going some. That motor will rate better than six hundred and ninety horse power.”

“Yes?” asked Ned, politely enough.

“Yes, you big boob!” cried Tom with good-natured raillery. “Why, don’t you understand that the best performance a naval seaplane ever did was only twenty-seven hundred R.P.M., and they couldn’t get more than six hundred and eighty-five rated horse power out of their V-type motor? But at that they made two hundred and fifty-six miles an hour,” said Tom with respect.

“Who did?” asked Ned.

“The United States naval flyers,” Tom replied. “I’m ashamed of your ignorance,” he chuckled. “Think of it—two hundred and fifty-six miles an hour! If I can equal that record, and I think I can, I’ll win the twenty thousand dollars for dad with my hands down.”

“Let’s see,” said Ned musingly, and he began doing some mental arithmetic. He was good at this. “The distance around the earth, say at the fortieth parallel of latitude, is, roughly, twenty-five thousand miles. At the rate of two hundred and fifty-six miles an hour, or say two hundred and fifty to make it round numbers, it would take about a hundred hours, Tom. A hundred hours is, roughly, four days, and you’ve got twenty! Why, say——”

“Look here, you enthusiastic Indian!” yelled Tom, playfully mauling his chum’s hair. “You can’t fly one of these high-powered machines for a hundred hours straight! They’d burn up. You have to stop now and then to cool off, take on gas and oil, make adjustments, and so on.”

“I thought you were going to do continuous flying,” objected Ned.

“I’m going to do it as continuously as possible,” was Tom’s reply. “But I’ll need all of twenty days to circle the globe. There will be accidents. Storms may force us down, and you may want to stop and inquire into the financial system of the Malays.”

“Me?” queried Ned. “Am I going?”

“You sure are!” was the answer. “You’re going to be official score keeper. Dad needs that twenty thousand dollars. Yes, sir, you’re going and it’s about time we began to make serious preparations to start. You won’t back out, will you?”

“No, I guess not,” Ned said. “Who else is going? Mr. Damon?”

“Well, he wants to go,” said Tom; “but he’s afraid his wife won’t let him. Dad is too old, of course. But I’ll need three good mechanics, besides myself. With you that will make five—just enough to fill the cabin nicely. Come on out and take a look at the boat.”

“Going to take along plenty to eat?” asked Ned, as he and his chum went across the now dark shop yard toward the brick building that housed the newest creation of the young inventor.

“Oh, sure!” was the response. “But we won’t have to stock up very heavily. You see we’ll make several stops on the way.”

“Just what are your plans?” Ned wanted to know.

“Well, I thought of starting from around here, or, possibly, from the vicinity of New York,” Tom answered. “You see, there’s a possibility of a race.”

“A race to circle the earth?”

“Yes. The papers have got hold of this wager of dad’s—I think Mr. Damon, in his enthusiasm, spilled the beans—and there is some talk of a national aero club taking the matter up. A paper or two has mentioned that such a trip will greatly advance the science of flying, and there may be a big prize offered for the winner of the race—the one who makes the best actual time around the world.”

“Then you’re likely to win considerable money,” suggested Ned.

“If the plans are carried out, yes. But I’ll be satisfied to win that twenty thousand dollars for dad. It will just about make me come out with an even break.”

“An even break?”

“Yes. This machine will cost me around twenty thousand,” said Tom. “Of course, I’ll be out my expenses, but then dad got me into this thing unthinkingly and I’m going to see it through. But if some one offers a prize and I can win it, I’ll have that much velvet.”

“It’s a bigger thing than I thought,” Ned stated. “I hope you won’t be disappointed in your craft, Tom. I mean I hope it will work.”

“It will work—I’m sure of that,” said the young inventor. “Of course whether I can eat up the miles and actually get around the world in twenty days remains to be seen. But I’m going to try!”

The two were at the workshop now. It was shrouded in darkness, for the day’s labor was over.

“Stand still a minute until I turn on the lights,” Tom said, as he opened a little side door and stepped in, leaving Ned to follow. “It’s as dark as a pocket in here.”

Ned could hear Tom fumbling for the electric switch. Then, just as the light was turned on, there came, from the other side of the big shop and back of the Air Monarch, a clicking sound followed by a scream of pain.

“What’s that?” cried Ned.

“I think it’s my sneak trap!” answered Tom. “I hope I’ve caught him!”

In an instant the shop was flooded with light, and Ned followed Tom on the run around the big Air Monarch, which occupied most of the space. A moment later Ned saw Tom spring upon a man who was caught by one leg in a curious wooden trap, the smooth jaws of which had clamped around the intruder’s ankle.

“Help! Help!” screamed the man, for such he was—a burly, ugly, lowering chap dressed in the greasy clothes of a mechanic.

“You aren’t hurt!” said Tom, pausing in front of the captive and eyeing him. “I set that trap there to catch any one who came in here unauthorized. It isn’t meant to hurt—just to hold you fast. And I’ve got you, Cal Hussy! Got you good!”

“Let me out of here!” snarled the man, trying, without success, to free his foot.

“I will in a minute. But first I’ll find out if you have taken anything,” Tom said coolly. “Here, Ned, search him!” he called to his chum.

Then, while Tom deftly caught Hussy’s hands in a loop of rope drawn tight, Ned went through the intruder’s pockets. Aside from some personal effects, the search revealed nothing.

“You let me go!” snarled the man, with an evil scowl.

“I will if I make sure you haven’t damaged my machine,” went on Tom.

A quick inspection showed nothing wrong. The motor compartment of the Air Monarch was locked, and Tom knew the fellow had not been in it.

“Now I’ll let you go,” said the inventor to the fellow. “But I warn you the next time you step into my trap it will have teeth!”

Pulling on a lever, Tom opened the jaws of the trap and the man was free to step out. He limped slightly as he walked toward the window by which he had entered, for the spring of the trap was strong.

“Who is he?” asked Ned as the man started to crawl out. He had cut a pane of glass out of the window, sawed some of the iron protective bars, and gotten in that way. But in walking across the floor in the dark he had stepped into one of several traps Tom had set recently.

“That is Cal Hussy,” explained Tom, watching every movement of the man. “He works for the Red Arrow Aeroplane Company, one of my rivals. Evidently they have heard something of my new invention and are trying to find out its secret. But I’ve fooled them. I caught Hussy the first crack out of the box.”

“Yes, you caught me all right, Tom Swift!” snarled the man, turning when he was half way through the window. He scowled and shook his fist at the young inventor. “You caught me, but I’ll catch you next time!”

This threat seemed to enrage Tom. He rushed at the fellow just as Hussy cried again:

“It will be my turn next time!”

Tom raised his foot and planted a well directed and richly deserved kick on Hussy where it would do the most good. Like a football dropping over the crossbar, the intruder went tumbling over the window sill, to fall heavily to the ground below.

He grunted, uttered some strong language, and then, as he ran off down the road in the darkness, he called back:

“You’ll be sorry, some day, you did that, Tom Swift! You’ll be sorry!”

“I’m sorry now that I didn’t kick you twice!” cried the angry inventor.

“What’s the idea, Tom?” asked Ned when his chum had returned to the middle of the big, barnlike room where he stood in front of the Air Monarch, contemplating the powerful machine. “What’s the game?”

“A dirty game!” snapped out Tom Swift. “This Red Arrow gang has been trying to sneak around and discover some of my secrets for a long time. This is another attempt. Hussy has been here before. But I don’t think he’ll come again,” added the young inventor grimly.

“Are they trying to do you out of this new contrivance?” asked Ned.

“I don’t know that they are specifically after this,” stated Tom. “They’ll steal any new invention they can. But from the fact that Hussy was in here I judge they must have heard something about the Air Monarch and they want to get an idea of how she’s made. I suspected they might try something like this, and so I set several traps. Hussy happened to step into one,” and taking Ned to the various windows Tom showed other devices to nab intruders.

Going over the machine and making an examination of the workshop in company with Ned, convinced Tom that Hussy had been caught before he could do any damage.

“But from now on I’ll have to be doubly careful,” Tom declared. “And if I see Hussy around here again——” he did not finish, but it could easily be guessed what would happen.

From then on it became increasingly difficult for strangers to get near the Swift plant. Eradicate and Koku were kept on guard in the shop where the Air Monarch was housed and Mr. Swift, with a smile, said they at times even looked on him with suspicion.

But the days passed and the big machine was practically completed, and then came a trial flight which was successful. The giant craft took the air like a bird, and though its speed was not quite up to Tom’s expectations, he said that with some adjustments he thought it would beat any aircraft he had ever made.

On land the progress was necessarily slower, and in the water it was slower still. But even at that the Air Monarch did well, and it could do still better, Tom declared.

The machine was taken back to the shop for some final adjustments, and Tom was busy superintending these one day when Ned Newton burst into the building, waving a paper over his head and exclaiming:

“Look at this, Tom! Listen to this! You’ve got a chance to make a fortune!”

“I sure need it,” said the young inventor, with a smile. “This machine is costing a lot more than we’d figured on. But what’s the idea? Has some one left me a million?”

“No,” answered Ned. “But this paper, the New York Illustrated Star, offers a prize of one hundred thousand dollars for an international race around the world in the shortest time—actual time. Why, Tom, those are exactly the conditions under which your father wagered with Burch and Trace! Why don’t you go in for this?”

“Maybe I will,” said Tom. “Let’s have a look!”

Eagerly he read the story in the paper, setting forth the terms of the prize offer. They were simple enough.

At a date about a month off, any person who wished to contest must start from an aero field on Long Island. The first person to return to the starting point, after actually circling the globe, would be given a hundred thousand dollars.

There were no conditions except that all contestants must prove by documentary evidence, such as having signed statements from officials in various countries, that they had passed through or over them on certain dates. The world must be girdled on a circle of one of its great circumferences, that is the equator, or a parallel not too far above or below it. Or, if a contestant desired, he could circle around a longitudinal line. But as this would mean flying over the north and south poles, that was practically out of the question. It was assumed that those who took part would travel along about the fortieth parallel, as this would keep them over fairly civilized countries for the longest period.

Contestants could travel as they liked, in any sort of conveyance, motor car, steamer, train, airship, or submarine. They could change conveyances as often as they pleased. The sole requisite was that they must come back to the starting point, after traveling completely around the earth, and they must prove that they had done it.

“This suits me!” exclaimed Tom, as he read the conditions.

“Then you’ll enter for the hundred thousand dollars?” asked Ned.

“I certainly will, and I hope to win it. Now this race is going to be worth while. If I won the twenty thousand dollars for dad, I’d hardly break even. But if I win the prize—oh, boy!” and Tom patted the big machine into which his hopes were built.

Keyed up to a high pitch by the prospect, Tom hurried his mechanics and helpers to the limit. Not any too much time was left to enter the Illustrated Star’s contest, and within a few days Tom Swift’s entry had been formally sent in and acknowledged.

Each succeeding day’s issue of the paper gave Tom and Ned news of the event, and one day Tom pointed to an item in the general story.

“The Red Arrow people are going to try for the prize,” he said. “They’re going to fight me. That’s why Hussy was sneaking in here, I guess. They wanted to see if they could add anything to the aeroplane they are going to enter.”

“Are they going to try in an aeroplane?” asked Ned.

“So it says here. It doesn’t mention any boat or automobile auxiliary.”

Tom had been obliged to describe the method he proposed to follow in the world race, and of course it was publicly known now that he would try in a combined automobile, motor boat, and aeroplane. Aside from some hydroplanes, which of course can skim along on the surface of the water, as well as soar over land, Tom’s was the only machine of more than a single ability.

Many of the contestants, of which there seemed likely to be plenty, at least at the start, were going to make the attempt by special steamers or trains, for not a few wealthy globetrotters entered the contest for the big purse.

It lacked about a week of the time of the start of the international race when one morning Tom Swift received a telegram. It was signed by a name he did not at first recognize, that of Armenius Peltok, and read:

“If you are going to enter international world race I shall be honored if you will take me with you. I speak all civilized languages and some uncivilized, and am also an aircraft mechanic. Reference the National Aero club.”

“Another crank,” murmured Ned.

“I don’t know about that,” voiced Tom. “It’s worth looking up. See if you can get the Aero Club on the wire.”

When Ned had done so and had been told that Peltok, though little known in America, had a great reputation in Europe and was thoroughly reliable, a message was sent asking him to call at the Swift plant. Peltok had wired from New York. A day later he telephoned that he would be with Tom very shortly.

“We need another good man,” Tom said to Ned.

“How many are going?”

“Five.”

“Well, who are the other two besides you, Peltok, and me?”

“I haven’t decided yet, but I have my eye on a couple of young fellows. Now let’s see what we have next to do.”

“There’s plenty,” stated Ned, with truth.

The work went along. The Air Monarch was fully equipped for the race, and another trial flight showed big improvement as regarded her three speeds, on land, water, and in the air. Night and day men were on guard now, to keep Tom’s secret of his craft. Though in general its character was known, there were many things about it that the inventor did not want to reveal.

Meanwhile, the plan of an international world race was meeting with favor on all sides. Though one paper had offered the prize, the other journals gave plenty of space to the event and excitement was at a high pitch. Some wild and rash schemes were talked of, and not a few new and queer machines, both for land, air and water travel were entered. One man proposed to go in a motor car, hiring speedy, small steamers when land failed him, to transport his machine.

Peltok arrived and created a favorable impression on Tom and Ned. He was a quiet, reserved man, of great muscular strength, and he knew travel machines from end to end.

“And he can speak anything!” declared Ned. “He even talked to Koku in the giant’s own language.”

“No!” cried Tom.

“Fact! You ask Koku.”

Tom confirmed Ned’s statement. Peltok was a great linguist, and it was felt this accomplishment would be valuable should the Air Monarch have to land in uncivilized countries.

A few days before the Air Monarch was to leave for Long Island, Ned came to Tom with rather a serious face.

“We need more money, Tom, to complete the stocking of the ship and arranging for carrying on the business here while you are gone,” said the financial manager.

“Get it from the bank,” said Tom.

“We can’t. We’ve stretched our credit to the limit. We need ten thousand dollars in cash.”

For a moment Tom did not know what to do. Then he remembered his millionaire friend Jason Jacks, who had helped him on the Airline Express in a like emergency.

“Call Jacks,” Tom decided. When Ned did this, explaining Tom’s predicament, that eccentric, but kindly, character at once arranged the matter, sending, not ten, but fifteen thousand dollars to the credit of the Swift Company in the bank.

“And if you want more you can have it,” added Mr. Jacks. But Ned said that would do.

“Well, I go to New York to-morrow,” said Tom to Ned one evening, “to sign the final papers in the race contest. All contestants are to be present in the Illustrated Star office.”

“Where are you going now?” asked Ned, for his chum had on his hat and the electric runabout was at the door.

“Over to see Mary,” was the answer.

A little later Tom Swift was on his way. But for some reason or other, when he was within a quarter of a mile of the girl’s house, the electric machine suddenly went dead and stopped.

“That’s queer!” mused Tom, as he got out of the stalled car to have a look. “I thought the batteries were fully charged. Some one must have been running it without telling me. Well, I can walk, I suppose. It isn’t far.”

He tested the storage batteries, found that his surmise was correct—that they had exhausted themselves, though unaccountably—and then he started to walk.

But he had not gone far along the road, which was very lonely at this point, when a dark figure sprang suddenly from the bushes, leaped toward the young inventor, and uttered a smothered imprecation. There was a dull, thudding blow, and Tom was stricken down, sinking unconscious in the long grass at the side of the highway. Then the dark figure, with a sinister chuckle, fled amid the shadows of the night.

“Well, Mary,” remarked Mr. Nestor as he looked at the clock. “Tom is a bit late, isn’t he?”

“Oh, he’ll be here,” said the girl, with a smile. “He said he was coming to take me for a little ride in the electric runabout before he has to go to New York to-morrow to sign up in the world race. Tom will be here.”

“Yes, I never knew him to fail an engagement,” went on Mr. Nestor with another look at the clock. “Yet he’s a bit late. I’m going out and smoke a cigar. If I see him coming——”

“Now, Daddy!” laughed Mary, “you don’t need to tell Tom to hurry. He isn’t a child. What if he is late?”

“Oh, well, nothing. But I just thought I’d mention it,” and with that Mr. Nestor went out.

Though Mary would not admit to her father that Tom was later than usual, she was more honest with herself. And when nine o’clock came and Tom had not appeared, she became uneasy.

“If anything in the way of business had detained him he would have telephoned,” said the girl. “I wonder if anything could have happened? Highfield Lane is lonesome after dark, and he would come that way.”

She waited a bit longer, growing more nervous all the while, and then she came to a decision.

“I’m going to walk along toward the Lane and see if he’s coming,” she said.

Mary expected to see her father out in front, also peering down through the darkness for the approach of Tom’s headlights, for the young inventor and Mr. Nestor were firm friends. But the glow of two cigars on a side porch and the murmur of voices there told Mary that her father had met Mr. Goodrich, from next door, and the two were visiting.

“Where are you going, Mary?” her father called to her as he heard her go out the front gate.

“To look for Tom. He’ll be along pretty soon.”

Though the girl peered sharply all along the quarter of a mile that lay between her house and Highfield Lane, she did not see her lover. Then she turned into the lane proper and caught sight of the glowing lights of a car she knew, because of their peculiar position, to be on the runabout.

“Here he comes now!” Mary exclaimed. A moment later she was aware that the lights were not moving. The car was standing still. “He must have had a break down,” thought Mary. She knew, from often having ridden in it, that the car lights were hooked up to a separate battery from the powerful ones that operated the motor.

When the girl, wondering what had happened, hurried toward the machine, she stumbled over Tom’s body, prone on the ground. She recognized him by the light from the car lamps.

“Oh, Tom! what has happened?” she cried.

There was no answer, and when Mary put her hands to his head she felt a dampness that told of blood. But she was a girl of grit and spunk, and, exerting all her strength, she managed to half drag, half lift Tom into the machine. Mary knew how to operate the runabout, but when she turned on the current there was no response and she realized that the batteries were useless.

She hardly knew what to do, but was about to shout and summon help. Should this fail to bring assistance, she planned to hurry to the nearest house. But just as she was about to call she became aware of an approaching car.

For a moment she feared that it was Tom’s assailant returning to finish the cruel work, for that Tom had been attacked Mary at once guessed. But the car proved to contain a man whom Mary knew, and when he had stopped in response to her frantic hail he helped her lift the unconscious form into his car and took Tom to the Nestor home.