The Project Gutenberg eBook of Tall tales of Cape Cod, by Marillis Bittinger

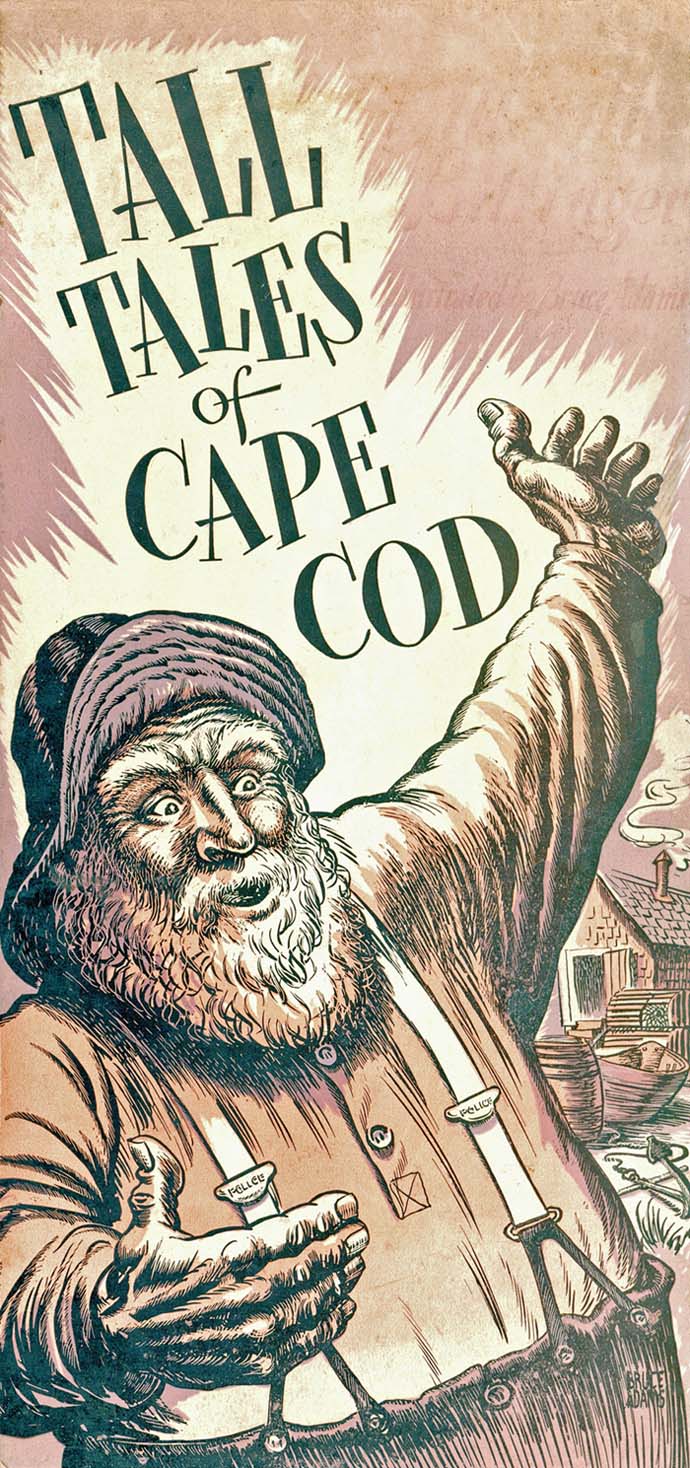

Title: Tall tales of Cape Cod

Author: Marillis Bittinger

Illustrator: Bruce Adams

Release Date: January 7, 2023 [eBook #69718]

Language: English

Produced by: Steve Mattern, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

It Pays to Keep the Sabbath Day

TALL TALES

OF CAPE COD

by

MARILLIS BITTINGER

With Illustrations by

Bruce Adams

THE MEMORIAL PRESS

PLYMOUTH · MASSACHUSETTS

1948

TALL TALES OF CAPE COD

Copyright, 1948, by

THE MEMORIAL PRESS

All rights in this book are reserved.

Designed and Printed by

THE MEMORIAL PRESS

PLYMOUTH, MASSACHUSETTS

To My Father, who Mother says

tells the tallest tales of them all,

and who helped me in the preparation

of this book.

There is not a part of the United States that does not have its share of fascinating folklore. From the coast of California and its legends of gold, to the hardy New England shores, rich with its stories of shrewd Yankee peddlers, personalities and fables march back from the past and implant themselves into the region as firmly and lastingly as the giant redwoods of California or the huge elm-arches of Yarmouth on Cape Cod. An integral part of sectionalized history, American folklore holds its own as a meter by which we may judge and understand those hardy men and women who took the new world in their hands and molded its character for the generations to come.

The title of this volume is perhaps misleading. Tall Tales of Cape Cod they are, yes, but in a broader sense that are the feel and the basis of a way of life. These fables and superstitions, personalities and adventures cannot be labeled merely Tall Tales, for they were such an important part of life on Cape Cod that to think of the narrow land without them would be impossible.

The stories I have presented here are, in a sense, true. Some of them are original, that is, products of my own imagination, fired by the Cape and its history. Others are as old as the Cape itself, and have been repeated time and again. Still others have been gleaned from conversation with Cape Cod folk and from the invaluable old books which I have been fortunate enough to have made available to me.

It would be impossible for me to state the credulity of the tales found in this volume, that is a matter entirely for the reader to decide. But this is Cape Cod, with its adventure and romance, mystery and humour, and I hope that the reader will find in them the true feel of a land that is incomparable in history, salty humour, and rock bound tradition.

Marillis Bittinger

Plymouth, Massachusetts

April 1, 1948

| No Kissing On Sunday | 1 |

| The Cape Cod Gold Rush | 3 |

| How Scargo Lake Got Its Name | 7 |

| The Curse of Old Mother Melt | 9 |

| Barney Gould | 12 |

| It Pays to Keep the Sabbath | 15 |

| Timmy Drew and The Bull Frogs | 17 |

| The Wrong Gulls | 28 |

| She Had the Last Word | 30 |

| The Singular Case of the Young Anatomist | 31 |

| The Mooncussers of Cape Cod | 38 |

| How the Fogs Came to the Cape | 40 |

| The Peddler’s Coffin | 45 |

| The Whale that Went to New York | 48 |

| The Snake Biting Indian | 50 |

| Johnny Blunt’s Courtship | 53 |

| The Trusting Maiden | 58 |

| Shipwrecked | 60 |

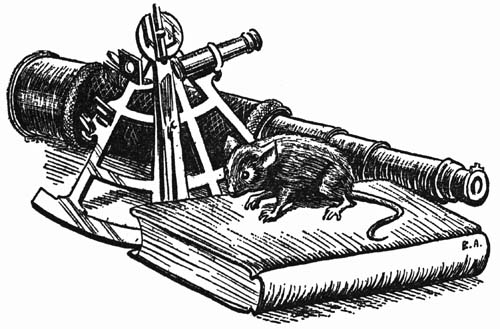

| The Enchanted Mouse | 65 |

| Ole Bill Hardy | 68 |

| How Sophie Got A Husband | 71 |

| The Orleans Lamplighter | 76 |

| The Giant of Longnook Valley | 77 |

| Cupid and the Tree Warden | 82 |

| The Singing Fish of Monomoy Point | 85 |

It isn’t unusual during the light-hearted days of Spring, or during any season for that matter, to see a boy and girl exchange a kiss. But back in the days when a kiss between any but married couples was a gross impropriety, any demonstration of affection on the Sabbath was against the law, even between married couples. There is no attempt to claim here that this law was never broken, but woe unto those hapless couples who were found out!

A Harwich great-great-great-ancestor, a red blooded sailing man, had been away on a long sea journey, and returned unexpectedly on one Sabbath afternoon. He strode down the street to his home, and at the gate, bellowed joyously for his wife. She rushed out the door and into his arms, and the captain’s natural inclination was of course to greet his wife with a hug and a kiss. They both, in the moment of meeting, quite forgot the law which forbade any such goings on. A prying neighbor—a frustrated old maid, no doubt—reported[2] the incident to the authorities, with the result that the affectionate captain was clapped into the stocks for two days to repent.

Not less than a month after this romance thwarting incident, another couple was hauled into court. It would seem from this story that it was not god-fearing folks who gathered garden fresh peas on the Sabbath. The husband had returned from the sea Sunday morning, and his loving wife, knowing that fresh peas were his favorite vegetable, had gone into her garden and gathered an apron-full for dinner. It is not known what punishment was levied on the couple, but it is recorded in the family records that “they received their just punishment with god-like mien.”

The lights in the cell block of the Charlestown State Prison shone forth in musty yellow streaks one mid-summer night in 1849. It was the hour when the prisoners were left to their own devices within their tiny cells before the final night lock-up.

The final lock-up bell clanged through the stone prison, the main lever was thrown, and the block was dark save for two lanterns at the end of the long corridor. The men settled down to sleep. But in the corner cell of Section 3, 2nd floor, there was no thought of sleep. The occupant of this cell was William Phelpes, sentenced to a long term after confessing to a startling $50,000 bank robbery at Wheeling. The[4] loot had never been found, and it had taken authorities a long time to catch up with Phelpes. But it was not thoughts of reclaiming the fortune upon being released from prison that kept Phelpes awake this night. He had no intention of waiting ten long years to return to the outside world, and tonight he was planning a way to beat this waiting. His was not a plan of violence or a foolhardy attempt at escape. Phelpes was not unintelligent, and although he had little formal education, he was nevertheless known to be shrewd, cagey, and quick-witted.

Phelpes waited until the prison was completely quiet and he could hear only the steady breathing from the cell next to his, and an occasional murmur from the lips of some uneasy sleeper. Then he sprang into action. He took his tin drinking cup in his hand, and rattled it across the bars of his cell, hollering loudly for the guard. The lights in the corridor lit up, and the guards came running down to his cell, where Phelpes demanded to see the warden, saying that he wished to tell of the whereabouts of the $50,000.

When the warden stumbled sleepy and red eyed from his room, his annoyance about being awakened was amazingly short-lived when he learned the reason. It was decided that the search for the loot was to start early the next morning. Phelpes had promised, under guarantee of a lightened sentence, to lead the warden and his assistants to the very spot in which he had hidden the $50,000. The buried treasure, said Phelpes, was at Cotuit on Cape Cod.

There were two men that did not sleep in the prison that night, for their heads were whirling with plans. These men were Warden Robinson and Prisoner Phelpes. A golden cloud of money and freedom from[5] the job of warden filled the mind of Warden Robinson, for his share of the reward promised for the return of the money would make it possible for him to retire and live pretty much as he chose. For Phelpes, the golden cloud meant only one thing—freedom, and already his mercurial thoughts were sliding from one fabulous plan to another—plans that could only be fulfilled by this freedom.

At 5 o’clock the next morning, Phelpes, Warden Robinson and the sheriff started out for Cape Cod and the $50,000. Phelpes, after the trio had arrived at Cotuit, and the general vicinity of the buried loot, pulled out a map, which he had carefully prepared the night before, and studied it intently. Elaborate steps were taken to follow the map to the letter. Warden Robinson’s hands shook as he held the map in his hands, and even the calm Phelpes seemed ruffled and excited.

The exact spot was finally found, and the digging began—digging that went on and on for what seemed like endless hours. It grew darker as evening began to turn into night when Phelpes sprang to his feet and shouted “We’s almost there!” Shovels tossed dirt furiously, and the exhilarated sheriff leaped into the hole for a closer look. The warden’s face, illuminated by the lantern which he held, was a mask of suppressed desire, and his eyes were holes of excitement and longing. He had no thought of anything but the money which lay so close within his grasp. But it was at this moment that Phelpes, forgotten both by the warden and the sheriff in this instant of near-wealth, put his ingenious plan into culminating action. As the warden leaned still closer into the hole where the sheriff was still frantically digging Phelpes lifted his[6] foot and booted the gullible warden into the hole on top of the sheriff. In the confusion that inevitably followed, Phelpes made a successful dash for freedom, and later made his way to the true spot where the $50,000 was hidden.

The handsome, stalwart young brave runner from a distant tribe looked just once at the proud and fiery Princess Scargo, beautiful daughter of Sagem, chief of the Bobusset tribe that once dwelt on the shore of Dennis, and lost his heart to her. And the Princess, who had given her heart to no man before, fell madly in love.

As token of his love and devotion, the young brave presented his beloved with a beautifully carved, hollowed-out pumpkin, filled with water in which were swimming four small silvery fish. The Princess adored her gift, and placed the small fish in a tiny pond which she hollowed out with her own hands. The beautiful Indian maiden spent long hours by her pond, for her lover had promised to return to her before the fish had grown to maturity. And so every day she watched the growth of her fish, for each change in size brought her closer to the young brave to whom she had pledged her love.

[8]But the summer was a long and dry one, and when Princess Scargo went to her pond one morning, she found it dry and three of her beloved fish dead. The Princess was mad with grief. She wept and wailed, and the tears of grief kept alive the one remaining fish, which she placed once more in the pumpkin.

Her indulgent father immediately called an important pow-wow. It was decided that a lake should be dug especially for Princess Scargo’s fish. The strongest and most skillful brave shot an arrow in four directions. Each time an arrow fell, it marked a boundary of the lake.

The work of digging the lake basin went on steadily. When Autumn’s bright hues painted the countryside, and the Fall rains came, the lake bed filled deep and clear.

Princess Scargo placed her fish in the man-made lake, and prepared to wait once more for her lover. He came as he had promised, and after their marriage, they lived in their lodges on the shores of Scargo Lake, where the descendants of the silvery fish, token of an Indian love, still swim.

No one knew her real name, or from where she came. She seemed as old as Time itself, and her cavernous eyes were fathomless pits of mystic wisdom. The villagers spoke of her in hushed tones, and they called her Old Mother Melt. They believed she was a witch.

Old Mother Melt lived in an ancient, ragged cottage on the outskirts of Provincetown, and the townspeople dared not venture near her cottage after dark. Many a youth, returning from an evening of courting in a neighboring town, and forced to pass by the cottage of Old Mother Melt on his way home, was scared out of his breeches by the strange noises and eerie lights that came from the windows. This fear came from years of inbred superstition and ignorance, for Mother Melt had never done any harm that could be proven. Nevertheless, she remained an avoided, fearsome character. Whenever disaster, illness or calamity befell someone in the village, there were many who murmured ominously about “one of Mother Melt’s[10] curses,” and the threat that “Old Mother Melt will get you” disciplined many an obstreperous child.

Whenever Mother Melt made one of her infrequent trips to the village for a few meagre staples, those on the streets slid quickly into doorways and shops, children scampered to their calling mothers, and all peered suspiciously at the grotesque old figure of Mother Melt as she picked her way slowly through the narrow streets.

The days of Old Mother Melt were the great days of fishing in Provincetown, and there was not a seaman in the village who would go near her cottage the week before he was to sail. But there was one whaling man, Capt. Samuel Collins, who scoffed at any mention of such things as witchcraft and curses, and it was to this man that Mother Melt spoke one day. Her request was a simple one. She knew that Capt. Collins was to leave shortly for a long whaling trip, and she asked that he take her son, a strong, intelligent lad of about fifteen, with him on his trip as cabin boy and apprentice. Captain Collins had no qualms about accepting, for he knew and liked the boy, and had often been impressed by his quickness. So Mother Melt’s dream of her boy off to sea, perhaps someday becoming master of his own ship, was realized.

But through some mix-up, when sailing time arrived, Mother Melt’s son was not to be found, and the captain could wait no longer for the boy. As the Collins’ ship sailed away, Mother Melt was at the wharf shrieking a curse upon the ship and all its hands.

Several weeks of steady winds and fair weather favored Captain Collins, but this run of good weather was shattered by a freak storm of sudden, fierce intensity. Monstrous waves and savage winds battered the[11] fishing ship. Several of the crew were washed overboard to their deaths, and valuable time was lost in repairing the damage. Captain Collins recalled then the curse of Mother Melt, and declared that she was responsible for the disaster, for he could see no other explanation for the weird freak storm which had arisen so unexpectedly and caused so much damage. He swore to kill Mother Melt when he returned to home port.

When the great fishing ship limped into Truro, Captain Collins wasted no time. He was the first to stride down the gangplank and made his way straight to the old cottage at the edge of Provincetown village. There he found Mother Melt, weak and spent from a long illness. But nothing halted him or his anger. Mother Melt pleaded so passionately for her life, however, that he gave up his determination for revenge and promised to spare her if she in turn promised to never again utter a curse.

Upon the death of Old Mother Melt, Captain Collins took her son under his wing, and the lad later became master of his own ship, which had a long and remarkable record of clear sailing, free from storms and disasters. It is said that Mother Melt watched over the ship as it sailed the seven seas.

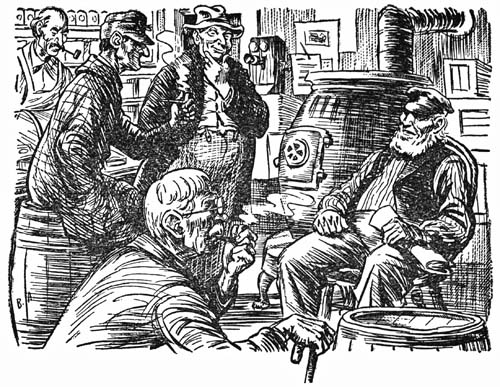

I happened into the Orleans General Store one drizzly afternoon, and found some old timers gathered round the potbellied stove, reminiscing about days gone by, and some of the personalities that colored those days. Perhaps the old cracker barrel, the wonderful, mixed smell of molasses and spices, and the kerosene lanterns were missing, but, in the midst of modern conveniences of a modern store, I travelled back into the past as I listened to the talk that flowed around the circle by the stove. Rain streaked down the window panes; a little puddle of rain water at the doorway widened as a few stragglers came in out of the storm, stamping their boots, and shaking off their slickers like ducks just out of water. The moods of the weather have a wonderful effect on conversation in such a setting,[13] and bring forth stories almost forgotten, stories oft-repeated, and tall tales that grew and grew with the years.

Seth Finlay had a ghost of a smile on his wrinkled face, and a reminiscent twinkle in his deep-sea eyes. I heard him chuckle deep down inside, and felt somehow that a good yarn or two was forthcoming. Seth caught me looking at him, and chuckled again. “’Spose you’re wondering what I’m lookin’ so pleased about, don’t you? Wal, I’ll tell ye. All these stories ’bout what you off-Capers would call ‘characters’ brings to mind old Barney Gould. I ain’t sayin’ all the stories you hear ’bout him air true, but he was quite a feller. A mite bit tetched, mebbee, but harmless.

“One thing he was most set about. That was usin’ trains or enythin’ else besides the two legs that God gave him. He uster make regular trips up Boston and back, carryin’ packages and letters for folks. ’Twasn’t long before we wuz callin’ him ‘Barney Gould’s Express!’ And I swan efen one day, when Ben Howes wanted a dozen wood-end tooth rakes, he gave Barney a quarter and the durn fool walked all the way to Boston, got the rakes, and hiked all the way back with the rakes over his shoulder.

“Nuther funny thing ’bout Barney. He’d got the idee somewheres that he owned the roads. He’d stop everybody he met and ask ’em for two cents for his ‘road tax.’ I ’member one day he came up to me for the tax. All’s I had was a dime. He said that would pay my road tax for five years. If he’d lived fer that five years, he would’ve waited ’til then to ask me again; he never forgot who had paid and who hadn’t, and never hit up the same feller twice in the same year.

“Yu’ve heard tell about them long-distance walkers,[14] I calculate. Wal, Barney was one of ’em. Least aways that’s how the stories go. They tell one story ’bout that’s kinda hard t’ believe. Seems that Cap’n Joel Nickerson was startin’ off in his schooner for New Orleans. Barney was foolin’ ’round down the dock, helpin’ the crew cast off. Cap’n Nickerson hollered over to him—‘Say, Barney—meet us down New Orleans to help us tie up, will ye?’ You won’t believe me, but sure enough, when the old schooner hove ’long side at the New Orleans dock, there was Barney, waitin’ to help tie up. He’d walked all the way from P’town to New Orleans.

“An’ one time—bet you won’t believe this either—he thought he’d like t’ see the Wild West. Yep—walked all the way to ’Frisco and back. Took him near two years, but he said it was wuth it. ’Course, that was when he was young and strong. Yep—he sure had a pair of legs, did Barney Gould.”

Joe Crocker, down Wellfleet way, learned through bitter experience that it pays to keep the Sabbath.

Joe was always one to find a dollar, and when he did, he made the most of it. But he didn’t hanker after what most folks call real work. His financial status depended mostly on old Lady Luck. And she chose one Sunday to shine down on him.

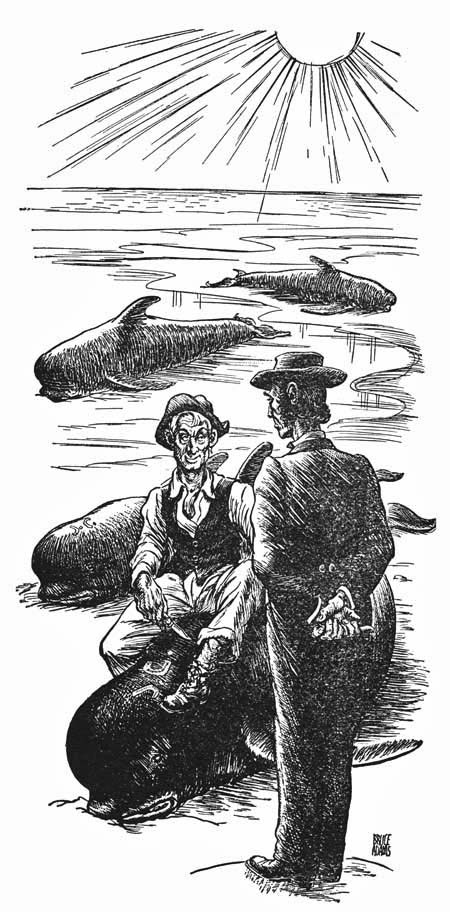

Joe was strolling down the beach one Sunday morning when God-fearing folks were in church, and he came across a school of blackfish flung up on the beach. Now a man who finds such a school of beached blackfish is a fortunate one indeed, for he is well paid for the “melons” that are found in the skulls of the fish.

Old Joe promptly set to work cutting his initials in the blackfish skulls as a claim to his ownership. He was busily engaged in this task when the Methodist[16] minister came by and caught him in the act, so to speak. He reprimanded him severely, and Joe just laughed. The minister said he could laugh then, but that he would get the devil’s own pay tomorrow, and strode on. I guess he knew it was useless to try and convert a melon-cutting heathen on the Sabbath.

Well, early next morning, Joe went down to sell his fish, but the market prices had taken a sudden weekend drop, and the sperm oil man wouldn’t buy. So there was Joe, left with a beach full of smelly blackfish. And you’ve never smelled such a stench as comes up from a beached school of blackfish when the wind is coming from the sea. The townspeople finally couldn’t stand it another minute, and a group of them came down to the beach to get rid of the school. And sure enough, there were Joe’s initials, carved in the skulls where he had put them on Sunday forenoon. Those initials J.C. were enough to convince every man jack of them that the whole smelly job was up to one man—the owner, and the owner was obviously Joe Crocker. He put up quite an argument, but he finally had to hire a half dozen fishermen to tow the blackfish back out to sea. The Methodist minister was heard to remark that some people had to learn the hard way that it pays “to keep the Sabbath day.” Joe didn’t have a thing to say, and he still didn’t come to Sunday meetin’, but no one ever saw him looking for easy work on the Sabbath again.

Once upon a time, it is said, there lived in Chatham on Cape Cod a little whipper-snapper of a fellow, named Timothy Drew. Timmy was not more than four-feet-eight, and that standing in his thick-soled boots. And so, as befalls so many unfortunates of Timmy’s stature, he was forced to accept heckling from his taller associates, among whom Timmy appeared a dwarf. But long-legged men held no fears for Timmy, for although small, he made up in spirit what he lacked in bulk, as is so often the case with small men. Timmy was all pluck and gristle, and no steel trap was smarter.

When Timmy refused to stand for the gibes that were thrown at him, he was chock full of fight. To be sure, he could hit his tormentors no higher than the belt-buckle, but his blows were so rapid and full of force that he beat the daylights out of many a ten-footer.[18] When Timmy was in his fiery youth, the words “If you say that ’ere again, I’ll knock you into the middle of next week!” were enough to quell any belligerent.

Timmy Drew was a natural born shoemaker. No man around could hammer out a piece of leather with such speed and accuracy. Timmy used his knee for a lap stone, and years of thumping made it hard and stiff as an iron hinge. Timmy’s shoe shop was near a pleasant valley on the edge of a pond. In the Spring, this pond was a fashionable gathering place for hundreds of bull frogs, that came there from all parts to spend the warm season. Several of these bull frogs were of extraordinary size, and as they became used to Timmy, who spent some time down near the pond’s edge feeding them, they would draw near to his shop, raise their heads, and swell out their throats like balloons until the area vibrated with their basso music. Timmy, keeping busily at his work to the accompaniment of this bull frog male chorus, beat time for them with his tooling hammer, and in this manner the hours passed away as pleasantly as the day is long.

Now Timmy was not one of those shoemakers who stick eternally to their bench like a ball of wax. In fact, Timmy made a habit of carrying his work to his customer’s house, partly for assurance of perfect fit and partly for company. Then, too, he always stopped at the tavern on his way home from work for sociability and to inquire about the day’s news. It was here especially that Timmy found his size unfortunate, for here gathered all the jokers and wags of the neighborhood, as well as the notoriously teasing and practical joking peddlers. Although Timmy felt as uncomfortable[19] as a short-tailed horse in fly time in this company, he loved to be there and reveled in the conversation and the stories that were told.

Unfortunately for Timmy, however, the peddlers took the keenest delight in imposing on his credulity as well as on his stature. They always seemed to have the most amazing conglomeration of tall stories at hand, but also seemed to have even more amazing ones when the gullible Timmy was present. They had learned long before that Timmy was not to be toyed with about his height, but still retained their practice of goading him on to believe their incredibly tall tales. And there was no one who can describe an incredible fact with more plausibility than a peddler. His profession alone had taught him to maintain an iron gravity when selling his wares, which, with very few exceptions, could certainly not sell themselves. Thus their tales, sufficient in themselves to embarrass any other narrator, carried great conviction.

But there was a joke which the peddlers played on Timmy that carried itself out far beyond any and all expectations. Many and diverse were the pranks played on Timmy the gullible, but never before one with such repercussions as this one, which, from the start, seemed made to order for him.

A fashionable tailor in the neighboring and larger village decided to advertise in Chatham, thereby bringing to himself trade from the small community and others like it. This tailor took it on himself to have a large and flaming advertisement made which was posted in the tavern which Timmy frequented on his way home from the shoe shop. The advertisement excited general interest, for the tailor asserted to have, at greatly reduced prices, a splendid assortment of[20] coats, pantaloons and waistcoats of all colors and fashions, as well as a great variety of trimmings such as tape, thread, buckram, ribbons, and—this last item was especially stressed—“frogs,” those cord material hooks in the shape of that deep-throated and squat reptile.

The next time Timmy appeared at the tavern, his associates and peddler hecklers pointed out to him the advertisement, with special stress on the “frogs.” They reminded him of the plenteous supply of these frogs to be found in his own neighboring Lily Pond.

“Why, Timmy,” they said, “this is the chance of a life time. If you were to give up shoemaking and take to frog catching, you would make your tarnal fortune!”

“How so?” asked Timmy.

“Why, lad,” spoke up one of the peddlers, “can’t you see by that poster that frogs are in great demand in fashionable tailoring?”

“Yes, Timmy,” spoke up still another conspirator in the joke, “you might bag a thousand in half a day, and folks say they will bring a dollar a thousand!”

It was obvious that these words had a great effect on Timmy, for he was carefully considering the suggestion, and could see the money pouring already into his outstretched hands.

“There’s frogs enough in Lily Pond,” he mused, “but it’s tarnation hard work to catch ’em. I swaggers! They’re plaguey slippery fellows!”

Then up spoke Joe Gawky, by far the most infamous practical jokester in the company. “Never mind, Timmy. Take a fish net and scoop ’em up. You must have ’em alive, and fresh.” And then, drawing Timmy aside, Joe whispered, “Tell you what I’ll do. I’ll go[21] you shares. Say nothing of it to anyone. Tomorrow night I’ll come up and help you catch a goodly batch, and we’ll divide the gain.”

Timmy was in raptures. But he was, as you will soon see, counting his frogs before they were caught.

As Timmy walked home that night, a cagy thought, upon which he inwardly prided himself, came into his head. Thought Timmy, “These ’ere frogs in a manner belong to me, since my shop stands near Lily Pond. Why should I make two bites at a cherry and divide profits with Joe Gawky? By gravy! I’ll get up early in the morning, and be off with a batch of them to the tailor’s before sunrise, and so keep the money all to myself!”

And so he did. Never before had there been such a stir among the placid frogs of Lily Pond. In fact, they were taken quite by surprise, and with no little difficulty. Timmy captured a huge bag of them and set off on his journey to the tailor’s.

Mr. Buckram, the fashionable tailor, was an elderly gentleman, and a nervous one, and, when disturbed, inclined to be peevish. Mr. Buckram was also very particular both about his own attire and that of his customers, and prided himself on the neat-as-a-pin appearance of his shop.

The unsuspecting Mr. Buckram was busily engaged in making a waistcoat for a Harwich gentleman when Timmy entered the shop. The sight of Timmy alone was enough to make anyone take notice, but Timmy, together with a large and curiously jumping bag slung over his shoulder was indeed a sight to see. Timmy wasted no time in preliminaries, perhaps under the impression that big business needed no introduction. Since the tailor had not noticed or seemingly did not[22] hear his entrance into the quiet shop, Timmy assumed that the elderly man was deaf. So, without further ado, Timmy leaned down, and, pressing his mouth near the old man’s head, bellowed at the top of his lungs, “Do you want any frogs today?”

The old gentleman dropped his shears and jumped clear off his stool in astonishment, viewing Timmy with a mixture of amazement and alarm. “Eh? Any frogs? What in tarnation for?”

“I’ve got a fine lot here,” persisted Timmy, thinking the tailor was being shrewd. “They are jest from the pond, and lively as grasshoppers!”

Mr. Buckram was plainly confused. “Don’t bellow in my ears,” he exclaimed. “I’m not deaf! Tell me what you want and then be off.”

“I want to sell you these frogs. You shall have them at a bargain. Only one dollar a hundred. I won’t take a cent less. Do you want them or not? If I can’t get satisfaction here, I shall go elsewhere, and you shall miss out on a great bargain!”

Mr. Buckram thought he was face to face with a miniature mad man, and attempted to rid himself of[23] the small nuisance with bravado. “No, I don’t want any frogs. Now get out of my shop, you young fool!”

“I say you do want ’em!” shouted Timmy, “but you’re playing offish-like to beat down my price. I won’t take a cent less, I tell you!”

The conversation went on like this for fully ten minutes, and finally Timmy, puzzled, mortified, and angry, slowly withdrew. “He won’t buy ’em,” thought Timmy “for what they are worth. And as for taking nothing for them, I won’t. And yet, I don’t want to lug them back to Lily Pond again. Curse the old man anyway. I’ll try him once more, and be durned if I’ll ever plague myself this way again!”

And once more he entered the tailor shop.

“Mr. Buckram, this is absolutely your last chance. Are you willing to give me anything for these frogs?”

The old man was goaded beyond endurance. He sprang from his work and took after Timmy with his long shears.

“Well, then” said Timmy bitterly, as he backed away, “Take ’em among ye for nothing,” and so saying, emptied the contents of the bag on the floor of the shop and marched indignantly away.

Well, you can imagine the confusion that followed. One hundred live bull frogs had a marvelous time jumping about the shop. Every nook and corner had a bull frog in it, and to make matters worse and add to the confusion, they set up a loud and indignant cacophony of chug-a-lums.

And thus dissolved the golden visions of Timmy the Frog Catcher.

After this affair, Timmy could not bear the thought, sight, sound, or mention of a frog. He never admitted that a joke had been played on him, but his associates[24] would not let him forget the incident. They referred constantly to the matter. He was rarely seen now at the tavern, and even the town children called after him on the street—“There goes the frog catcher.” You see the story had spread up and down the Cape, and Timmy had no peace.

The sound of frogs singing in the Lily Pond incensed Timmy to such a degree that he would run out of the shop and pelt the poor things with stones to stop their noise. It seemed after a while that their song, which he heard both day and night, had definite words in it, and contained his own name.

On one night in particular, Timmy was awakened from sound sleep by a tremendous bellowing directly under his window. It seemed as if all the frogs in the world were clearing their throats for a mass chug-a-lum. He listened with amazement, and could soon distinguish—

Timmy was certain no ordinary frogs could pipe out such a song at that rate. He leaped out of bed and rushed from the house. “I’ll teach those rascals to come around plaguing me,” he said. But no one could be seen. It was a clear bright night, all was solitary and still, save for an occasional rumble from the sleeping frogs. After throwing a few stones into the bushes, Timmy retired once more and fell into uneasy sleep.

The amazing concert continued night after night,[25] swelling on the evening breeze, and then sinking away into the distance. Again and again Timmy attempted to discover who were the perpetrators of the nightly serenading. They could not be found. He began to feel certain that he was to be forever haunted by the music. His friends sympathized with him, but Timmy was too upset to sense the mischief in the air.

The next time Timmy stopped at the tavern, he found all in earnest consultation.

“Here he comes,” said one, as soon as Timmy entered.

“Have you heard the news?” inquired the tavern keeper.

“No,” said Timmy with a groan.

“Joe Gawky ’as seen sech a critter in the pond! A monstrous large frog, as big as an ox, with eyes as large as a horse. I never heard of no such thing in all my born days!”

“Nor I,” said Sam Greening.

“Nor I,” said Josh Whiting.

“Nor I,” said Tom Bizbee.

“I have heard tell of sech a critter in Ohio,” said Eb Crawley. “Frogs have been seed there, as big as a suckling pig, but not in these ’ere parts.”

“Mrs. Timmings,” said Sam Greening, “feels quite melancholy about it. She guesses as how it’s a sign of some terrible thing that’s going to happen.”

“I was fishing for pickerel,” said Joe Gawky, who, by the way, was a tall, spindle-shanked fellow, with a white head, and who stooped in the chest like a crook-necked squash. “I was after pickerel, and had a frog’s leg for bait. There was a tarnation big pickerel just springing at the line, when out sailed this great he-devil from under the bank. By the living hokey! He[26] was as large as a small-sized man! Such a straddle-bug I never seed! I up line, and cleared out like a blue fish, I can tell you!”

Timmy searched anxiously the faces of all present for some sign of spoofing, but he could see only sober concern that credited the story. He began to feel very uneasy.

“That must be the critter I heard t’other night in the pond!” exclaimed Josh Whiting. “I swanny, he roared louder than a bull.”

This last statement aroused in Timmy divers emotions, all connected with the serenading that had been his for the past many nights. In vain, the company questioned him concerning his knowledge of the matter. He would not say a word.

After this introduction, the conversation took naturally to discussion of the supernatural. Each one had some story to tell of witches, ghosts and goblins. By degrees, the company dispersed, until Timmy Drew found himself quite alone. He found it difficult to get up and start home, for the conversation had impressed him more than he would admit at the time, and the walk home by the Lily Pond was nothing he cared to consider.

At length, he got up courage and started home. His course lay over a solitary road, darkened by over-shadowing trees. A tomb-like silence, heightened by his thoughts, prevailed, disturbed only by his echoing foot-steps. Timmy Drew marched straight ahead with a stealthy pace, not daring to look behind, yet dreading to proceed by Lily Pond. At last he reached the top of the hill at the foot of which were his house and Lily Pond. He had just about reached his door, when a sudden rustle of leaves by the pond brought his[27] heart dry and bitter to his mouth. At this moment, the moon slipped aside a cloud and seemed to focus on an object that turned Timmy to stone on the spot. An unearthly monster, in the shape of a mammoth bull frog, sat on its ugly haunches, glaring at him with eyes like burning coals. With a single leap, it was by Timmy’s side, and he felt one of his ankles caught in a cold wet grasp. Terror gave him strength. With a howl and a Herculean effort, he pulled himself away from the monster’s clutches and tore up the hill.

“By the living hokey!” said Joe Gawky, slowly rising from the ground and arranging his clothing. “Who’d uv guessed thet this ’ere old pumpkin head atop my shoulder with a candle a-burning in it would have set old Timmy’s stiff knees a-goin’ at that rate! I couldn’t see him travel for the dust his boots rose!”

It is hardly necessary to add that Cape Cod saw no more of the Frog Catcher from Chatham, Timothy Drew.

Cap’n Caleb Nickerson of Truro, master of a large ship which oftentimes took on young boys as apprentices and cabin boys, was sailing home to the Cape after a long journey. When the ship was almost to P’town, Cap’n Nick, bone-weary and worn from the long run, decided to turn the wheel over to young David, a youth who had shipped out with him to learn the fine art of seamanship.

“But, Cap’n Nickerson,” the boy demurred, “I don’t know much about navigation yet, and the compass is still strange to me.”

“Don’t worry, Lad,” said Caleb reassuringly. “See them gulls over there? Wal, just folly them right along, and they’ll take ye right home to port.”

With these words, Cap’n Nickerson went below to his quarters for a snooze. When he awoke a few hours later, he peered out of the porthole and was dumfounded to find himself still out in the open ocean, when the ship should have arrived in Provincetown[29] long before. Rushing madly topside, the cap’n grabbed poor Dave by the nape of the neck, and in a few choice mariner’s words, demanded what in tarnation he thought he was doing.

“But, Cap’n,” exclaimed the perplexed boy, “you told me to folly them gulls over there, and I’ve been right on their trail!”

Cap’n Nick grabbed the telescope, took one squint-eyed look at the gulls, and then bellowed, “Why you durn fool! Them’s Chatham gulls, not Truro gulls!”

A Cape Cod widow, whose married life had been far from peaceful and happy, refused to let the minister write a flowery tribute for her husband’s gravestone, as was the custom.

But propriety and convention of the times insisted that something appear carved on the headstone, and so the indomitable woman left the choice of verse entirely up to the local stone-cutter. He resorted to the stock phrase:

Convention thus being satisfied, no more was thought of the matter, but when friends and relatives paid their next visit to the grave, they were shocked and stunned to see, carved beneath the stone-cutter’s verse, these lines:

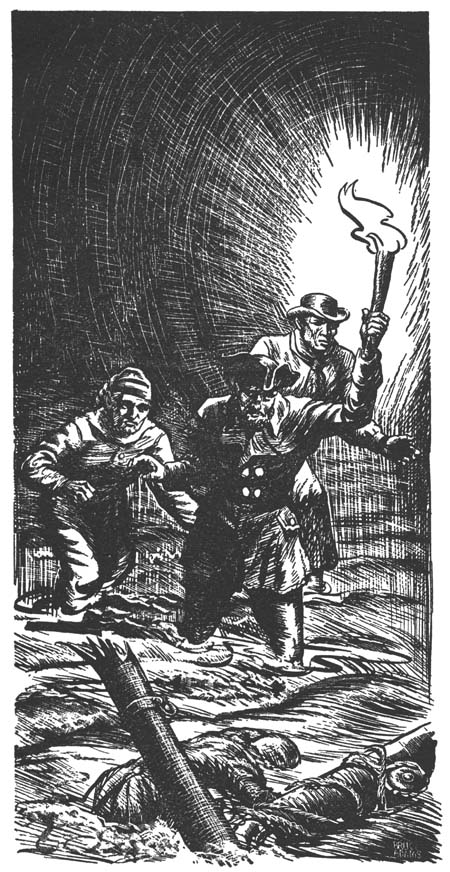

Fate, that capricious ruler of the tides that governs our lives, arranged a meeting on the wild, windswept Hill of Storms in Truro on Cape Cod; a meeting so strange that, for the sake of credulity, I must withhold the name of the earthly being who took part in it. For it was on a dark Fall night, long ago, that a Cape Cod boy, with nothing in his pockets but his dreams and a burning ambition, met and talked with a live skeleton, and, caught up on the crest of Fate’s precarious wave, was swept high to Fame and Fortune.

We will call him Tom, and nothing else, this young and ardent hero of our story, for if, in the telling of this strange tale, which I swear to be true, the real name of the young man were disclosed, you, gentle reader, would scoff and read no further.

A look at young Tom as this amazing story unfolds[32] would reveal a singularly insignificant youth, dreamy of eye and slight of form. Tom burned with that white flame of ambition thwarted by a financial standing about equal to that of a beachcomber, and a scanty country education. But youth has strange ways of overcoming such obstacles, and Tom’s energies, rather than diminishing, seemed to gather momentum and strength from the meagre stuff upon which they were fed. Why or how, cut off as he was from higher learning, Tom chose Anatomy as his field to conquer, no one knows, but chose it he did. He spent every waking hour and every dream yearning for the day when he would be able to buy for himself the text books that would pave his rocky road to Success. A penny here, and, a week later, a penny there—finally Tom was able to purchase a small text on Anatomy. In less than three weeks, he had memorized, with the correct Latin names thrown in for good measure, every word, every definition, every diagram in the text book. This subject was his life, and he wrapped himself so completely in his fierce desires that to shake hands with a man became not merely a gesture of friendship, but a good chance to feel the finger bones manipulate. But, happily, Tom was too intelligent not to know that this knowledge, although he could describe exactly the position, use, and articulation of every bone in the human body, did not make him an anatomist. For his descriptions were merely a repetition of the words in the small book which had become his bible. His burning desires now changed course to those of seeing and examining an actual skeleton, and these thoughts buzzed around in his mind like a swarm of angry bees.

A pensive, solitary figure, Tom sat one night by the huge fireplace in the local Inn, lost in thought and[33] dream. The flames in the fire before him took the shape of grinning, cavorting skeletons. He was so absorbed in his dream-world that the noisy animation and conversation about him pricked his consciousness no harder than a fly on an elephant’s hide. The men were talking, as they had for weeks, about old Cyrus Goodestone, a man always thought of as rich, but who had died without a trace of money to be found anywhere, much to the distress of his creditors.

But when, during one of those violent and sudden early Spring rain storms, the door of the Inn flew open, and a hooded and cloaked stranger strode into the room, even Tom took notice. For the stranger stood before the fire, his back to the company, and neither spoke nor turned when greeted. The storm stopped as suddenly as it had started, and when the moonlight shone once more through the window, the stranger heeled about, gathered his voluminous cloak more closely about him, and left. An eeler, sitting near Tom, spoke up:

“That be a queer chap. I’m a-goin’ to see what he’s about,” and with these words, he too left the Inn.

Less than five minutes later, he returned, white as a flounder’s belly. He made a beeline for the table, and gulped down a glass of rum. Then, gasping, partly from fright and partly from the raw drink of rum, he spoke.

“Udds hiddikins! Old chap just gone out—got no proper face like—only a Death’s head—looked me square in the face in the moonlight, he did, and I c’n tell ye, I waited to see no more!”

At this startling tale, Tom sprang from his lethargy like a man possessed, and clutching the terrified eeler by the coat lapels, he yelled, “You mean—he was a[34] skeleton?” When the answer was a startled “yes,” Tom shouted, “Which way did he go?”

“Why, down towards the graveyard, sure,” said the eeler. But Tom was out the door before the words had barely tickled the lips of the eeler.

No thought that the eeler might have been “seein’ things” entered Tom’s mind and he tore down the road toward the graveyard on Truro’s Hill of Storms. The wild wind, the scudding clouds that made the night a night of shadows, the bony-fingered branches that picked at his face as he ran through the shortcut in the woods—of these things Tom was unaware. For on the Hill of Storms, midst gravestones battered by sea winds and spray, was his heart’s desire!

Tom stood at the top of the hill, bracing himself against the sea wind. His heart thudded against his ribs like the heavy breakers that boomed against the rocks below. His wild eyes swept the graveyard, and then, in the split second when the clouds parted, and the moon shone through, Tom saw, still enveloped in the cloak, the figure from the Inn, gazing sorrowfully down at the new grave marker of Cyrus Goodestone. Then, in a sudden sweep of wind, the cloak billowed up, fell to the ground—and left, gleaming phosphorously in the misty moonlight, the unbelievable figure of a Skeleton!

“Thank my stars!” yelled Tom. “I have found my Skeleton at last!”

“Young man,” said the Skeleton in a hollow voice, clacking his hideous hinged jaws, “Attend!”

“How beautifully,” cried Tom, ignoring the command, “can I see the play of the lower maxilliary!”

“Attend, I say!” repeated the Skeleton, in a still more frightening voice. And then, turning, “Rash[35] boy, what are you about?” exclaimed the bony apparition. The fact is, our enthralled hero was busily running his fingers up and down the vertebrae of the Skeleton, counting them to see if they corresponded with the number given in his book, and muttering gleefully, “Seven cervical, twelve dorsal—just right!”

The Skeleton, angered and shocked speechless, raised his arm and shook his fist at the absorbed Tom, who, with his eyes fixed on the bony elbow, merely shouted joyfully, “The gingyloid movement is perfect!”

The Skeleton was plainly confused. Never before had he, accustomed to scaring the wits out of people, encountered any such attitude as this, for Tom stood before him completely unafraid. He was amazed at the scientific stand taken by our young anatomist. As a matter of fact, the skeleton began to feel a little wary himself, and moved away from Tom, darting in and out from behind the gravestones in an effort to get away. But Tom was not to be put off at this late date, and overtaking the Skeleton, grabbed on and held for all he was worth.

The ensuing conversation, however, was friendly, and the Skeleton explained that he was old Cyrus Goodestone himself. He had, he said, buried his money underground, and could not rest in peace until he had dug it up and paid off his creditors. This he asked Tom to do. Tom consented, upon one condition, which he laid in a very businesslike manner before the Skeleton.

“It will be some trouble,” he said, “and the affair is none of mine, but look ye—I’m willing to comply with your request, if, as a reward, you will allow me to come here and study you every night for the next[36] month. You may then retire to rest for as long a time as you please.”

“Agreed!” cried the Skeleton, and, recovering from his original alarm, shook hands with the exultant Tom to seal this strange bargain.

Tom found the money, just as the Skeleton had said, distributed it among the amazed creditors of Cyrus Goodestone, and passed every night for the next month in the graveyard on the Hill of Storms. There, amidst the gravestones, he studied his accommodating Skeleton, who, as it turned out, was a congenial and humorous fellow. The Skeleton tirelessly moved into any position or pose Tom requested, giving the young anatomist an opportunity no other had ever, or will ever have, that of watching the actual bone movement of a live Skeleton!

By the end of the month, Tom and his Skeleton were warm friends, for they had discussed many things, and had played cribbage by the grave of Cyrus Goodestone, upon many occasions when the night’s posing was done. They parted with regrets, and the Skeleton wished Tom success and happiness in his career.

Tom completely retained in his mind all he had observed in his amazing month’s study, and by that knowledge, laid the foundation of a profound anatomical science by which he was afterwards to become famous.

It is needless to state that the above is the early history of an obscure Cape Cod boy with a dream who became a famous anatomist, and that any and all other accounts are baseless fabrications.

[37] The Mooncussers

Remaining only in tradition as some of the most colorful characters in the unending novel of Cape Cod are the swashbuckling domestic pirates known politely as salvagers, romantically as mooncussers, and more authentically as bandits.

Fables and tradition say that a band of these men anciently infested the shores of Cape Cod. But they were not merely plunderers who swept down on unsuspecting victims; their business was a serious, planned and profitable one, flavored with a touch of the wildly romantic stuff of which pirate stories are made. Theirs was a dangerous game, and they played it well.

The whole band of them were mounted on horses when they began their nightly adventures. Up and down the beaches they rode, armed with large lanterns which they placed at strategically dangerous points along the shores. These decoy lanterns led ships astray on treacherous sandbars and shoals. This completed, they plundered them of everything, leaving the ships stripped and gutted.

A group of the mooncussers would divide, two of them tramping the beach in one direction, two in the other, a shingle held up to protect their eyes from the flying sand, and straining to pierce the darkness for a light from a ship in distress or for a glimpse of a hull on the bars off shore. Perhaps the first sign would be a spar flung up by the wild surf, the tattered remnants of a sail, or the still and battered form of a dead sailor. It is easy to see the origin of the word “mooncusser,” for moonlight nights held no profit for these men, and[39] the beauty of moonlight on still ocean was cursed and not admired.

The nights of the mooncussers were the nights of howling winds, thundering surf, and a wild and turbulent sea, for those were the nights when the work of the mooncussers were the most profitable. It was a wild setting for a wild play.

But the advent of the huge lighthouses, put up after much opposition, especially from the men of Eastham, put an end to mooncussing, for the great white eye of the light beacon could pierce the darkness of a night even brighter than the hated full moon.

For many, many moons, the great tribe of the Mattacheesits had lived in peace in their lodges near the clear blue waters of Cummaquid. It was a noble tribe, renowned for its beautiful young maidens, its fearless braves, and especially for its Great War Sachem, the Giant Manshope. But the heartbreaking mourning of the death dirge had many times wailed through the camp, for the Mattacheesits had a foe far more terrible than any fierce enemy tribe.

Twice each year since the beginning of Time—once[41] in the Moon of Bright Nights, and again in the Moon of Falling Leaves—the Great Devil Bird from over the Southern Sea spread wide his smothering wings and swept down on the tribe, capturing in his terrible talons the little papooses, and even some of the youngest braves who had just learned the art of the tomahawk. With a laughing shriek, he bore them away to his secret lair in the Region of the South Wind, where no man had ever ventured. They were never seen again.

On the eve of a triumphant victory over the Nausets, Great War Sachem Manshope returned, leading his braves in the ritual chant-dance of victory. But the battlecry was mingled with the wail of the death dirge, floating up towards the braves from the camp, and echoing sorrowfully through the stillness of the summer evening. The Giant Manshope found his faithful squaw with face gashed and breast torn, the ashes heaped on her head mingling with tears of anguish, for the Great Devil Bird had carried away her first-born, a strong young brave of just sixteen summers. The Devil Bird had carried him off to the Unknown Place before the sun had dropped from the edge of the world.

A fierce cry, filled with all the venom and hate and sorrow of many moons and many deaths, tore from the throat of Manshope. His people trembled with fear and pride as they watched him stand there, his face aglow with the call of battle, his eyes savage with hate and revenge, for they knew that their great leader would leave for the Unknown Place, stalking the Great Devil Bird.

His huge war tomahawk in his hand, Manshope strode away without a word from the camp, the wails[42] of the sorrowing squaws and the war shrieks of the braves echoing in his ears. The war drums beat their relentless rhythm of death for the Devil Bird. With giant strides that took him across the breadth of the Cape, Manshope plunged thigh deep through the deepest streams, pushed trees aside in forests he had no time to skirt, and came at length to the low treacherous swamplands that lay at the edge of the Southern Sea, the last barrier to the Unknown Place. In the misty half-light, Manshope saw, far in the distance, the Great Devil Bird, its human prey in its talons, winging its way swiftly towards its lair.

Many wondered, but none knew what lay in the Unknown Place across the Southern Sea, for no man had dared cross the churning waters to that island lair of the Devil Bird. But the Sachem’s eyes saw the turbulent waters not as danger, but as a bloody challenge. The Giant Manshope called out to the Great Spirit to give him the strength and cunning to follow the Devil Bird to its hiding place and slay him there. Then he strode boldly forth into the deep, treacherous waters.

Guided only by the stars, he came at length to the strange and feared Unknown Place, now Martha’s Vineyard. From the western end of the island, he saw majestically sheer cliffs which rose straight from the sea. At the narrowest end of the land, he saw something which made his heart sink, and his blood run cold in his veins, for there was a giant oak, its twisted exposed roots strewn with the white bleached bones of Indian children captured by the Devil Bird for countless years.

The Giant Manshope crept noiselessly towards the death tree. Under the enveloping shadows of its great[43] branches he looked up, and saw the dim silhouette of the Devil Bird sleeping in the uppermost branches. Its head was beneath its wing, its beak dripped blood, and its belly was distended with gluttonous human feasting.

Manshope glanced at the stone tomahawk in his hand, and saw it gleam in the half-light. He fastened it to his belt, and then swung himself soundlessly up through the branches towards the sleeping Devil Bird. At last he reached his goal at the top of the Death Tree, so close to the Bird that the night breeze ruffled its feathers across Manshope’s cheek.

There he paused, gazing down at the Bird, hate in his eyes, his heart beating wildly with the excitement of near victory and revenge. He raised his weapon high over his head and brought it down with a crushing thud on the neck of the Devil Bird. The Great Evil One fell to earth, never to rise again.

Panting with excitement and triumph, Manshope waited until he was sure the Devil Bird was dead before he left the hated Death Tree and its sorrowful remains. But his triumph had a bitter taste, and his heart was heavy, for although he had vanquished the Great Evil One, his soul cried out in anguish for his beloved son.

Lost in sorrowful meditation, Manshope rested for a while at the northern end of the island before returning to his camp on the mainland. He drew forth his pipe, but the tobacco was dampened by the waters through which he had plunged, and would not burn, so he gathered some poke weed, and, loading his pipe, sat quietly smoking. As he smoked, the rings and swirls from his pipe billowed and rose through the early morning air. It floated across the Southern Sea,[44] over the Cape moors and the lodges of the Indian camp, where his sorrowing squaw awaited his return.

Great was the rejoicing in the Indian lodges when Manshope’s people saw this smoke, for they knew that their Great Sachem would never linger to smoke his pipe while an enemy he was stalking was still alive.

The Great Devil Bird no longer ravaged and killed, and the Indians lived without fear once more. And when the sweet summer air drifted in from the woods, the mist lay low on the swamplands, and the fog bank from the sound curled in over the mainland just as the smoke from Giant Manshope’s pipe did on that morning—Indian mothers drew their children closer to the fire, and while the enveloping mists and fogs crept slowly in, they told them the legend of the Great Devil Bird, saying, “Here comes Old Manshope’s Smoke.”

The winter nights are long on Cape Cod. When the lonely winds howled ’round the house, and the naked branches tap-tapped against the windowpane, friends and neighbors gathered in the big, warm kitchen of the old Nickerson farmhouse down Rock Harbor Road in Orleans for an evening of story telling and popcorn or apple roasting.

Jonathan Snow, twelve years old, full of imagination and very impressionable, loved these story evenings. Jonathan would curl up in his favorite niche between the fireplace and the window, and there, munching on apples, would listen pop-eyed to the spooky stories. Here he was close enough to the bright, friendly fireplace to feel secure, but also close enough to the dark eye of the window and the wild, windy night to feel a delicious tingle of fear run up and down his spine.

One bleak and howling February night, when the stories had been especially hair-raising, a lull in the[46] conversation and a few yawns proclaimed that it was time for all to depart for their respective homes. Jonathan knew he should leave, but he felt chained to the fireside. He couldn’t stay, was too proud to voice his fears, and yet shuddered at the thought of leaving this warm kitchen for the dark and lonely walk home. But boy’s pride won. Jonathan buttoned up his greatcoat, pulled his wool cap down over his ears, and bidding the Nickersons a brave but reluctant good night, set off for home.

It was not far from the Nickerson to the Snow home, but the night was a wild one; a night of wind and floating mist, when familiar daylight objects assumed fantastic shapes, and the road was filled with shadowy forms. Jonathan held himself in admirable check for about 100 yards. He strolled along whistling casually, but when he glanced back and could see no more the winking lights of the Nickerson house, he was casual no longer, and tore at breakneck speed down the road.

Rounding the turn that meant the halfway mark to home, in the place where the road was flanked on one side by a high stone wall and on the other by a creek which ran parallel to it, Jonathan stood stock still, blood turning to slow ice in his veins. For there, not four yards before him, gleaming in a flickering pool of moonlight that filtered through the scudding clouds, was a coffin.

Three thoughts scampered through the terrified Jonathan’s mind. He could jump the stone wall, splash through the creek, or leap over the coffin and make a dash for home and safety. And jump he did. Now a twelve-year-old Cape Cod boy can jump like a grasshopper, but Jonathan did not jump high enough.[47] Just as he thought he had cleared the coffin, and indeed, his feet were running before they touched the ground, his ankle was clutched by a bony hand, and he was pulled right into the terrible coffin!

Reflex action and young strength bounded together simultaneously. Using all his energy, Jonathan pushed out with his hands and heels and leaped from the coffin like fat from a hot skillet. Scared near out of his wits, Jonathan broke an all-time speed record to home. There he babbled out his story to puzzled parents, who, as hardy Cape Codders, scoffed at the idea of a coffin, but decided to go and investigate anyway. So Jonathan, armed with mother and father, returned to the fateful spot, only to find that the “coffin” was a two-bushel market basket which had rolled from a peddler’s cart, and which, in the dark night, Jonathan’s aroused imagination had turned into an occupied coffin. The resident of the coffin, which Jonathan believed had clutched his ankle, was only the high basket handle which he did not clear in his leap for life.

It all started when a seventy-ton whale washed ashore at Wellfleet. Now, seventy tons of whale is no easy thing to deal with, and the costs of towing the whale back out to sea were more than the town fathers felt the thin town treasury purse could afford. Many suggestions were offered, but two enterprising old sea captains hit on a plan to raise enough money for the project with perhaps money left over to add to the town funds.

Why not charge admission to see the whale? This seemed like an excellent scheme but the Board of Health had something to say about having a dead whale on the docks that squelched the plan before it got into motion. But the old seamen, undaunted, still thought it was a good plan.

Yankee ingenuity reached an all-time high when the captains decided to find out for themselves just how many people would pay fifty cents for the dubious privilege of seeing a seventy-ton dead whale. They decided to tow the monster to New York, paying all towing charges, which were by no means slight, themselves.[49] Their fellow townsmen scoffed at the idea, but the two captains answered that the whole project would undoubtedly reap a goodly financial harvest, and that the town could whistle for a part of the expected profits. But, sad to relate, the get-rich-quick scheme back-fired, for the two down-Capers found that the New York Board of Health was no more eager to have a month’s dead whale reposing in smelly grandeur on their docks than were the Wellfleet officials. And so the two captains, poorer but wiser, and by this time sick and tired of the whole business, dug deep into their pockets once more and made suitable arrangements for the disposal of the whale. When they returned home and were met with a cross-fire of questions, they had not a thing to say.

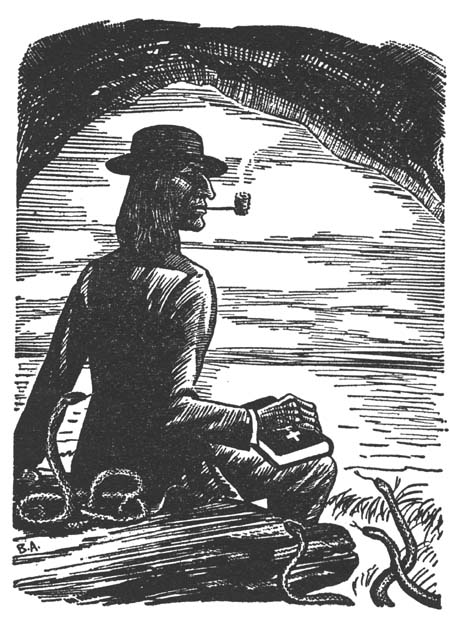

Tall, straight, and dark browed, Joseph Naughaught was a familiar figure as he made his way throughout the Cape, Bible tucked under his arm. Wherever his wandering feet brought him, he stopped to preach for Christianity, for he was a converted Indian. Pious, rum-hating Joseph was a self-made man both educationally and religiously, and was well known as a religiously, and at times, fanatically, sincere man—so well known for this, in fact, that he soon came to be called “The Deacon.”

When “The Deacon” was not evangelicaling, converting, or leading future converts in prayer, he could[51] be found, in all seasons, strolling leisurely through the woods and along the beaches.

One bright Fall day, when the Deacon was walking through the Truro Hills, he came to his favorite place of meditation, a rocky, cave-like shelter which was close to the ocean bluffs. There he sat for some time, quietly smoking and thinking, when his thoughts were arrested by a strange and ominous hissing.

The Deacon was trapped, for there directly before the mouth of the cave, was a huge circle of deadly black snakes. The Deacon was unarmed, and the snakes he knew, would close in on him faster than light at his slightest movement. He sat frozen with horror.

The minutes dragged by. The Deacon never took his eyes off the snakes, and they in turn were like frozen black ribbons, heads slightly raised, as they stared at him with eyes he could not see. The small gusts of occasional sea breeze were cold against the Deacon’s skin, for he was drenched with the sweat of fear.

The snakes crawled slowly towards him, with one of the black lines a little ahead of the others. When the reptiles reached his feet, they stopped once more. He could hear their soft hissing, and feel the weight of the lead snake across his foot. They moved again, like a soft, clinging wave, slithering and undulating towards him. Sluggishly and relentlessly they moved up his immobile form, until they had twined their dank bodies all around him. They clung to him like tenacious pieces of damp wool. The Deacon could see their wicked slit eyes, bright and expressionless, but deadly; he could hear their hissing breaths, and feel their hungry bodies in a horrid caress. Still he[52] did not move a hair, a muscle—he seemed not to breathe. The leader snake was wound around his neck, and was looking, his head raised, right at the Deacon, darting its flat head in and out at the Indian’s face.

On one of these thrusts, when the snake’s head came within an inch of his mouth, the Deacon opened wide his great jaws, and at the moment when the snake thrust its head inquiringly inside, the Deacon clamped shut his huge teeth, and bit the snake’s head off. This so frightened the rest of the snakes that they hurtled themselves from the Deacon’s body and fled. Some of the black reptiles were stunned from their fall, and the Deacon, master of the field, quickly killed them with a huge stone. The dead snakes he skinned, and brought their dried hides home as evidence of the terrible encounter.

After the sleigh ride last winter and the slippery tricks served by Patty Bean, nobody would suspect Johnny Blunt hankering after women again in a hurry. To hear him rave and take on, and rail out against the whole feminine gender, you would have taken it for granted that he would never look at one again, to all eternity.

Johnny did take an oath and swore if he ever meddled, or had any dealings with women again—in the sparking line, he meant—he might be hung or choked. But swearing off women, and then going into a meeting house chock full of gals, all shining and glistening in their Sunday clothes and clean faces, is like swearing off liquor and going into a grog shop—it’s all smoke.

Johnny held out pretty well for three whole Sundays but on the fourth there were strong symptoms of a change. A chap looking very much like Johnny, was[54] seen on his way to the meeting house, with a new patent hat on, his head hung by the ears upon a shirt-collar, his cravat had a pudding in it, and branched out in front into a double-bow-knot. He carried a straight back, and a stiff neck, as a man ought to when he has his best clothes on, and every time he spit, he sprung his body forward like a jack-in-the-box, in order to shoot clear of the ruffles.

Squire Jones’ pew was next but two to Johnny’s and when Johnny stood up he naturally looked straight at Sally Jones.

Now Sally had a face not to be grinned at in a fog. She was easy to look at and Johnny succumbed.

Squire Jones had got his evening fire on and set himself to read the great Bible, when he heard a rap at his door.

“Walk in. Well John, howder do? Git out Pompey!”

“Pretty well, I thank you Squire; and how do you do?”

“Why, so as to be crawling. Ye ugly beast, will ye hold yer yop! Haul up a chair and sit down, John.”

“How do you do, Mrs. Jones?”

“Oh, middlin’. How’s yer marm?”

“Don’t forget the mat there Mr. Blunt.”

This put Johnny in mind that he had been off soundings several times in the long muddy lane, and that his boots were in a sweet pickle.

It was now old Captain Jones’ turn, the grandfather. Being roused from a doze by the bustle and rattle, he opened both his eyes, at first with wonder and astonishment. At last, he began to halloo so loud that you could hear him a mile, for he took it for granted that everybody is just as exactly deaf as he is.

[55]“Who is it, I say? Who in the world is it?”

Mrs. Jones going close to his ear, screamed out, “It’s Johnny Blunt!”

“Ho, Johnny Blunt! I remember he was one summer at the siege of Boston.”

“No, no, father; bless your heart, that was his grandfather, that’s been dead and gone this twenty years!”

“Ho! But where does he come from?”

“Daown taown.”

“Ho! And what does he foller for a livin’?”

And he did not stop asking questions after this sort, till all the particulars of the Blunt family were published and proclaimed by Mrs. Jones’ screech. Then he sunk back into his doze again.

The dog stretched himself before one andiron, the cat squat down before the other. Silence came on by degrees, like a calm snowstorm, till nothing was heard but a cricket under the hearth, keeping time with a sappy yellow birch forestick. Sally sat up prim as if she were pinned to the chairback, her hands crossed genteelly upon her lap, and her eyes looking straight into the fire.

For Johnny’s part he sat looking very much like a fool. The more he tried to say something, the more his tongue stuck fast. He put his right leg over his left, and said “Hem!” Then he changed, and put the left over the right. It was no use, the silence kept coming thicker and thicker. Drops of sweat began to crawl all over him. He got his eye upon his hat, hanging on a peg by the door, and then he eyed the door. At this moment, the old Captain all at once sung out:

“Johnny Blunt!”

[56]It sounded like a clap of thunder and Johnny started right up on end.

“Johnny Blunt, you’ll never handle sich a drumstick as your father did, if you live to the age of Methuselah. He would toss up drumsticks, and while it was wheelin’ in the air, turn twice around, and then ketch it as it come down, without losin’ a stroke in the tune. What d’ye think of that, ha? But scull your chair round close alongside er me, so you can hear. Now what have you come arter?”

“I arter? Oh, jist takin’ a walk. Pleasant walkin’. I guess I mean, jist to see how ye all do.”

“Ho, that’s another lie! You’ve come a courtin, Johnny Blunt, and you’re a’ter our Sal. Say, now, do you want to marry, or only to court?”

This was a choker. Poor Sally made but one jump, and landed in the middle of the kitchen; and then she skulked in the dark corner, till the old man, after laughing himself breathless, was put to bed.

Then came apples and cider, and the ice being broke, plenty of chat with Mammy Jones about the minister and the “sarmon.”

At last, Mrs. Jones lighted t’other candle, and after charging Sally to look well to the fire, she led the way to bed, and the Squire gathered up his shoes and stockings and followed.

Sally and Johnny were left sitting a good yard apart. For fear of getting tongue-tied again, Johnny set right in with a steady stream of talk. He told her all the particulars about the weather that was past, and also made some pretty ’cute guesses at what it was like to be in the future. Johnny gave a gentle hitch to his chair until finally he planted himself fast by Sally’s side.

[57]“I swow, Sally, you looked so plaguy handsome today, that I wanted to eat you up!”

“Pshaw! Get along with you,” said she.

Johnny’s hand had crept along, somehow, upon its fingers, and began to scrape acquaintance with hers. She sent it home with a desperate jerk. Try it again—no better luck.

“Why, Miss Jones, you’re gettin’ upstroperlous; a little old maidish, I guess.”

“Hands off is fair play, Mr. Blunt.”

Johnny finally managed not only to get hold of Sally’s hand but managed to slip his arm around her waist. But not satisfied with this he began to go poking out his lips for a kiss. But he rued it for Sally fetched him a slap in the face, that made him see stars, and set his ears to ringing like a brass kettle, for a quarter of an hour.

“Ah, Sally, give me a kiss, and ha’ done with it, now?”

“I won’t, so there, nor tech to—”

“I’ll take it whether or no.”

“Do it, if you dare!”

How a bus will crack of a still, frosty night! Mrs. Jones was about halfway between asleep and awake.

“There goes my yeast bottle,” says she to herself, “Burst into twenty hundred pieces; and my bread is all dough again.”

The upshot of the matter is that Johnny fell in love with Sally Jones, head over ears. Every Sunday night, rain or shine, finds him rapping at Squire Jones’ door; and twenty times has he been within a hair’s breadth of popping the question. But now Johnny has made a final resolve. If he lives till next Sunday night, and doesn’t get choked in the trial, Sally Jones will hear thunder.

Margery Smith of Chathamport was thrilled and impressed when John Atwood, a respected widower, asked her to be his second wife. Nevertheless, being slightly younger than Widower Atwood, Margery demurred for quite some time before consenting to be his wife. Before she finally said yes, the widower carried on an extensive courtship and it was said that his promise of building a new house for his bride finally convinced her in his favour.

The trusting maiden waited until the knot had been tied before raising the question of the promised new house, only to be met with John’s reply of “Oh, that was jest courtin’ talk, Margy.” But although he shattered love’s young dream in that respect, he did build a small addition on to the old house. Margy spent the rest of her life in that hot ell of a kitchen, and never became mistress of a new house.

[59]

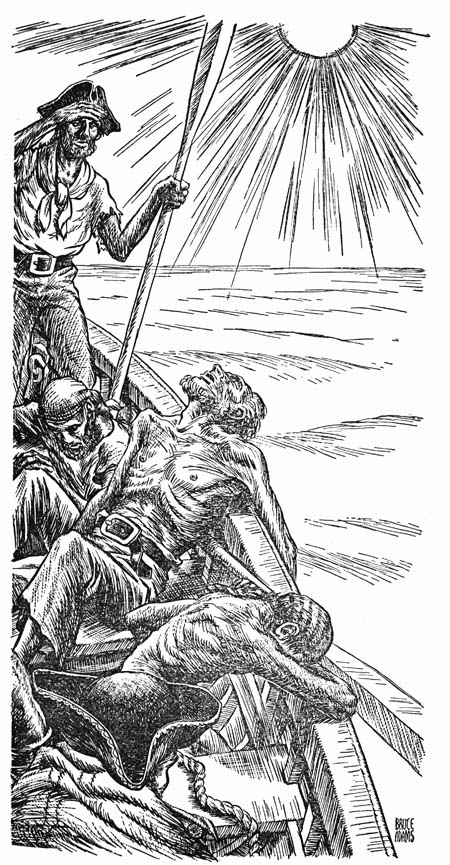

“We were conscious only of hunger, heat and thirst.”

[60]

On yellowed, tissue-thin paper, bound in leather, and entitled simply “Journal,” was found an entry which matches all the adventure stories of shipwrecked men ever told. Its authenticity can only be judged by the excerpt which follows:

Herein the reader, if there be any, will find the story of my most harrowing experience at sea. It is only by the Grace of God Almighty that I am alive this day to record it thus.

I was twenty years old when I shipped out from Boston on a journey to the East Indies. She was a good ship, my fellow crew members were capable, congenial men, many of whom I had sailed with in the past. Our captain had earned our respect even in the few short days we had been acquainted with him. All hands and officers were convinced that clear sailing and a profitable journey lay before all.

I cannot record here in a vivid enough manner, my impressions during the first three weeks of our sailing. The weather was fair and mild, good winds had prevailed constantly; the life aboard ship was especially pleasant. There was no need for any such feeling as I had found myself indulging in for several days. But it nevertheless prevailed. Perhaps all I can coherently say is that I had a vague unrest, a mind-plaguing thought constantly with me, like the shadow of some dark cloud over my being. This feeling brought with it the still, subconscious impression of disaster and imminent death which I could not, try as I would, shake off. I said nothing to my mates about this feeling. They would perhaps have scoffed at me—if not, my revealing of such an impression would only[61] serve to disturb the uncommonly smooth-running life of our close existence on the lonely seas.

It was on a calm, uneventful afternoon, while all hands were engaged in dilatory activities of repair and small duties, that this feeling reached its highest peak. I felt a strange compulsion to plunge into immediate intense activity, for my fears were mounting by the minute, and, in my youthful mind, I felt vaguely ashamed. I had just left my post by the starboard boat, where I had been engaged in lashing down some canvassing, when I glanced up to see the lookout in the crow’s nest peering intently out to sea. I knew somehow that my fear was about to materialize. And verily, a moment later, the call came from the nest, “Ship on far port horizon ho! She bears the Jolly Roger!”

The action over our entire ship was so instant in contrast to the almost sluggish movements of the minute before that it was as if a painting had suddenly sprung into life, each of its immobile figures leaping into definite motion. We clapped on every sail, but the pirate ship was on us before we could get up enough sail to escape. They sent a shot straight through our rigging.

The happenings of the next hour remain in my mind only as a confused jumble of shouts, clashing swords, and hand to hand combat. The pirate crew were a determined and bloodthirsty lot, not content to merely take over our monetary possessions. They outnumbered us and overpowered us, deliberately destroying and ravaging everything upon which they could lay their hands.

They seemed at last content with what damage they had wrought. The burly pirate captain ordered us to[62] abandon our ship, which he and his men then set afire. Before the fire had reached the hold, what few of our number were left managed to reach some supplies, and with those few essentials, we rowed away. I will never forget the frustrated agony in my soul as I watched our valiant ship, strewn with the bodies of our gallant captain and mates, burn to a charred skeleton, and sink slowly beneath the waters....

There were two lifeboats, lost and tiny as pea pods on a pond, drifting in lone aimlessness on the sea. There were eight of us, including myself, in one boat, and five in the other. We saw the other boat, which we could not reach because of the waves, drift farther and farther away. At last, after it had been hidden from our sight by a monstrous wave, we saw it again, capsized. We tried valiantly to reach those who were floundering in the sea. It was hopeless. One by one they sank beneath the surface, lost forever in the smothering embrace of the sea.

For a day and a night, the fierce winds and huge waves crashed against our small craft, and I cannot explain today why we did not meet the same fate as[63] had our unfortunate comrades in the other boat. Upon the second day, the rolling sea was changed to a flat, millpond surface, and the sun was unbearably hot. We had managed to bring with us only four bottles of water, enough to last but a few days. We did not live, we merely existed. I felt the gnawing, piercing pangs of thirst and hunger congest and constrict my being. Within fourteen days, four of our number had died of thirst, and there were three men besides myself left, starving.

My hands, when I reached up to touch my burned, bearded face, were trembling like a man beset with palsy. My eyes, I knew, were like my comrades’, empty, vacant, hopeless. I was conscious only of a searing ache over my entirety, and my mind was skipping and sliding over disjointed thoughts. We looked at each other, and still did not see; we were conscious only of hunger and heat and thirst. When we spoke, it was as if in a dream. Jackson had managed to hook a small fish, but had not the strength to pull it into the boat. I believe we realized the helplessness of our plight, and began at that moment of realization to get crazed. It was not long before we began to talk of drawing lots to see which of us should be killed to provide food for the others. The thought is horrible and distasteful now, as I sit with my belly full of good warm food, but then the thought meant only one thing—the lessening of the most terrible of pains—Hunger.

[64]We resisted this impulse as long as humanly possible. But at last the time came when we must destroy one of our number, or fall upon each other like crazed wolves. We cast lots, and it fell upon me to be the victim. I prepared to die so that others might live.