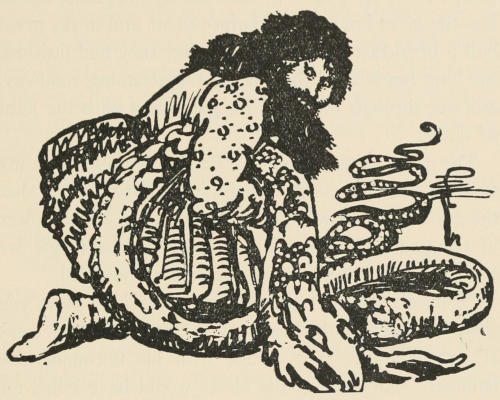

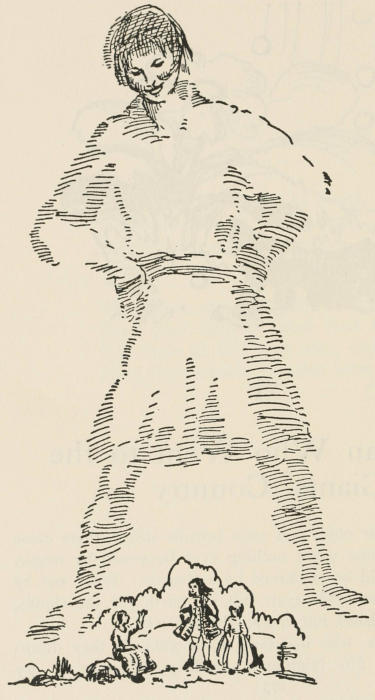

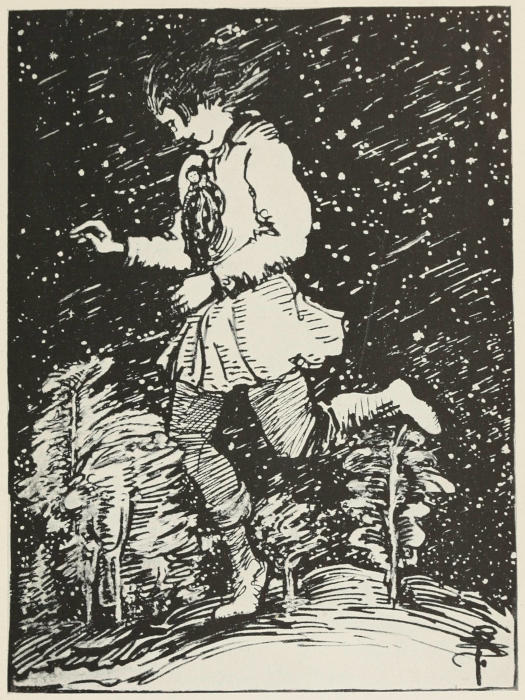

“Good-by,” he roared. “And don’t forget the giant Riverrath”

The Project Gutenberg eBook of The book of friendly giants, by Eunice Fuller

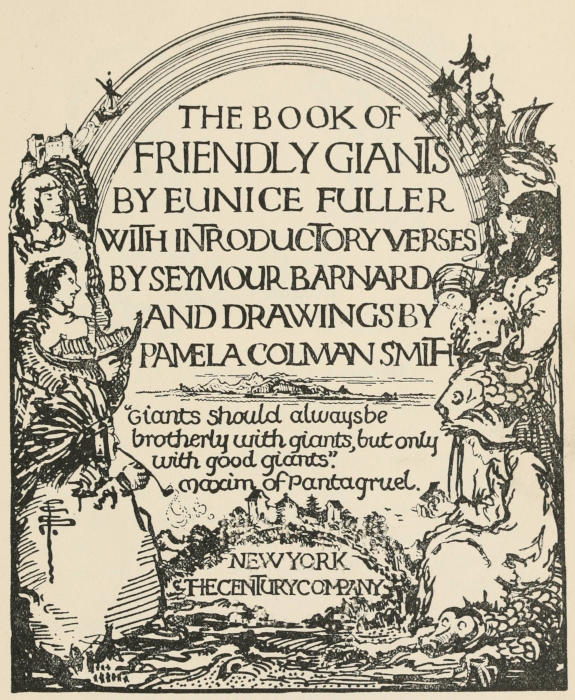

Title: The book of friendly giants

Authors: Eunice Fuller

Seymour Barnard

Illustrator: Pamela Colman Smith

Release Date: January 9, 2023 [eBook #69746]

Language: English

Produced by: ellinora and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

“Good-by,” he roared. “And don’t forget the giant Riverrath”

THE BOOK OF

FRIENDLY GIANTS

BY EUNICE FULLER

WITH INTRODUCTORY VERSES

BY SEYMOUR BARNARD

AND DRAWINGS BY

PAMELA COLMAN SMITH

“Giants should always be

brotherly with giants, but only

with good giants.”

Maxim of Pantagruel.

NEW YORK

THE CENTURY COMPANY

Copyright, 1914, by

The Century Co.

Published, October, 1914

PRINTED IN U. S. A.

Somehow or other, the giants seem to have got a bad name. No sooner is the word “giant” mentioned than some one is sure to shrug his shoulders and speak in a meaning tone of “Jack and the Beanstalk.” Now, this is not only unkind, but, on the giants’ part, quite undeserved. For, as everybody who is intimate with them knows, there are very few of the Beanstalk variety.

No self-respecting giant would any more think of threatening a little boy, or of grinding up people’s bones to make flour, than would a good fairy godmother. Giants’ dispositions are in proportion to the size of their bodies, and so when they are good, as most of them are, they are the kindest-hearted folk in the world, and like nothing better than helping human beings out of scrapes.

The trouble is that many of the stories were written by people who do not really know the giants at all, but are so afraid of them as to suppose that giants must be cruel just because they are big. Every one else has taken it for granted that the giants were big enough to take care of themselves, and so nobody has bothered to look into the facts of the case. Mr. Andrew Lang has given us a whole rainbow of books about the fairies, but no one seems ever to have written down the whole history of the giants.

This is a pity, particularly since a great many people have had a chance to know the giants intimately. For in the old days the giants used to live all over the world—in Germany, and Ireland, and Norway, and even here in our own country. And since they have moved back into a land of their own, they have sometimes come into other countries on a visit and a brave Englishman, as you will see, once went to visit them.

The history of the giants is as simple as their good-natured lives. All the giants came originally from one big giant family. And wherever they went, they kept the same giant ways, and enjoyed playing the same big, clumsy jokes on each other.

| PAGE | ||

| I | THE GIANT AND THE HERDBOY | 3 |

| II | THE GIANTS’ SHIP | |

| PART ONE:—HOW THE GIANTS WENT EXPLORING | 31 | |

| PART TWO:—HOW THE GIANTS’ SHIP WAS STOLEN | 43 | |

| III | HOW THE GIANTS GOT THE BEST OF THOR | 63 |

| IV | THE CUNNING OF FIN’S WIFE | 87 |

| V | HOW JACK FOUND THE GIANT RIVERRATH | 109 |

| VI | THE GIANTS’ POT | 147 |

| VII | THE GIANT WHO RODE ON THE ARK | 171 |

| VIII | THE WIGWAM GIANTS | 191 |

| IX | THE GIANT WHO BECAME A SAINT | 215 |

| X | GARGANTUA | |

| PART ONE:—HOW GARGANTUA LEARNED HIS LATIN | 235 | |

| PART TWO:—HOW THE BAKERS WISHED THEY HADN’T | 251 | |

| XI | THE MAN WHO WENT TO THE GIANTS’ COUNTRY | 273 |

| XII | THE GIANT WHO CAME BACK | 305 |

| PAGE | |

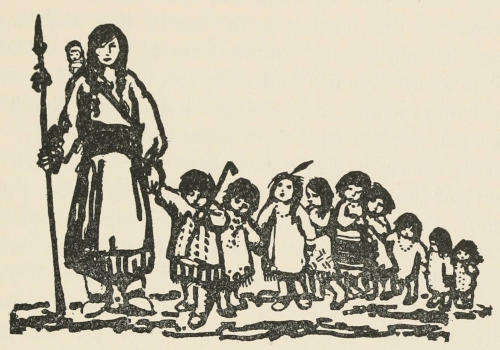

| “Good-by,” he roared. “And don’t forget the giant Riverrath” | Frontispiece |

| A fountain that shot up in a silver torrent | 11 |

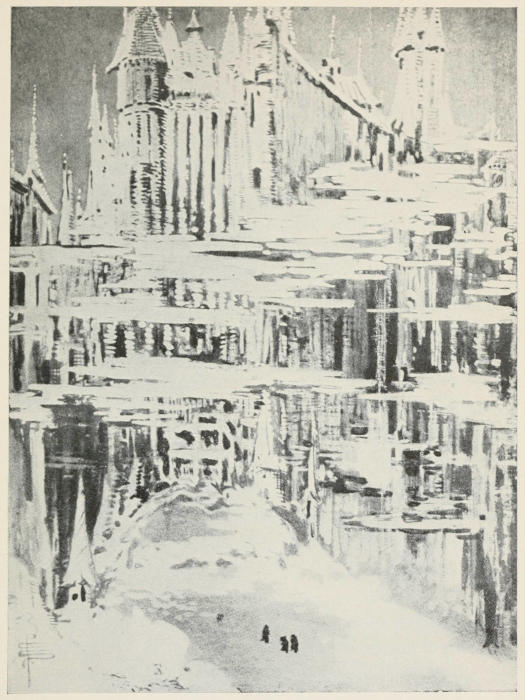

| A tremendous palace, all of ice | 71 |

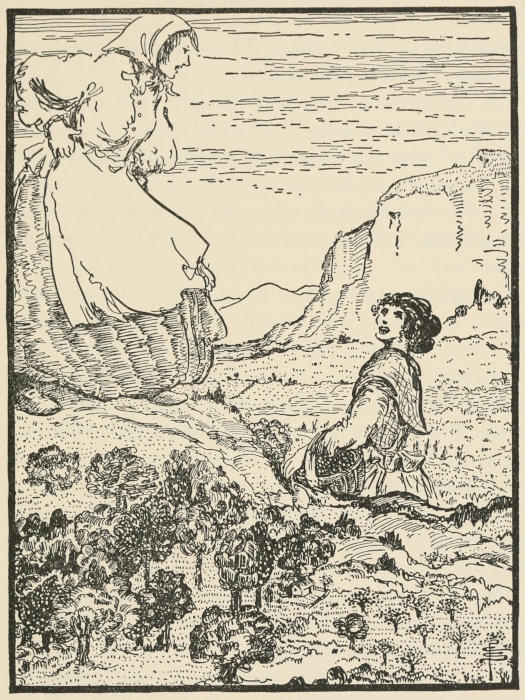

| “No,” said Granua, “I’m down in the valley, picking bilberries” | 93 |

| The giants in the market-place | 157 |

| The little man stood on the edge of the chimney | 181 |

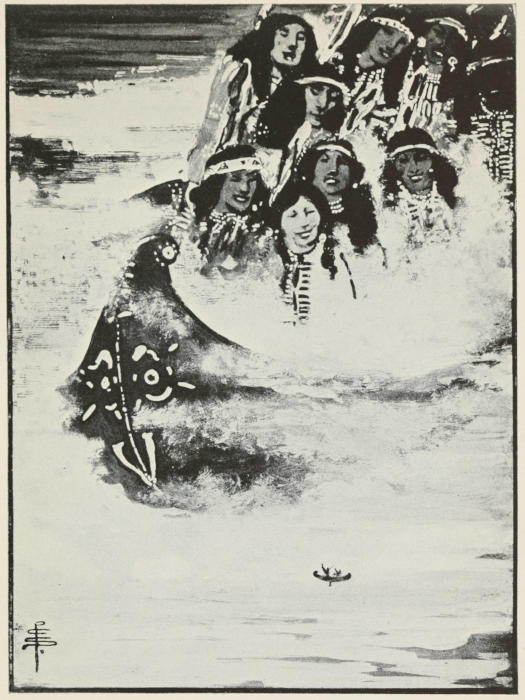

| A tremendous canoe as high as a cliff, and filled with men who seemed to touch the sky | 195 |

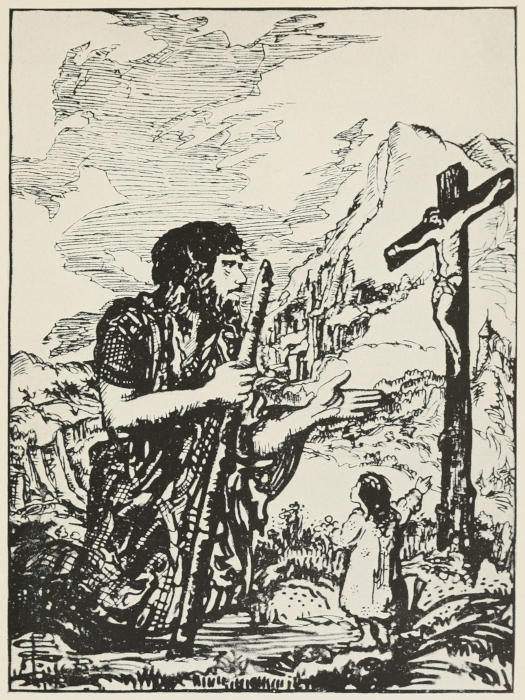

| “Good day,” said Offero. “Can you tell me the way to the king called Christ?” | 223 |

| He would make it trot or gallop | 239 |

| She could not dine without me | 289 |

| The trees brushed them | 321 |

Ivan, the herdboy, lay on the hillside watching the King’s sheep. It was growing dark, but he did not start for home. For in all the world he had no home to go to. There was no one who belonged to him,—neither father nor mother, nor brother nor sister, nor grandfather nor grandmother, nor so much as a stepmother. Even his best friends, the sheep, belonged to the King.

Ivan took good care of them nevertheless; and got his black bread and white cheese to eat in return. Day and night he stayed with his flock out in the open field; and only when the storm beat down very wet did he crawl into the little hut he had built at the edge of the forest.

It was not so very lonely after all. For there were ninety-nine sheep to keep out of bogs and briers. And besides, there were ever so many good games he could play by himself, vaulting over the bushes with his crook and playing little tunes on a reed.

It was only at the dead of night when he woke up to hear the wolves howling, howling in the dark, and the icy shivers began to chase each other along his back, that he couldn’t help wishing for a warm bed at home, with a stout father sleeping nearby.

But the queer part was that whenever he thought what kind of father he should like to have, he could think of nobody but the King himself mounted on his charger. And as for a mother, who could be better than the Queen with her nice, motherly arms that hugged the little Princess Anastasia? When it came to a sister, Ivan could imagine no one more satisfactory than the Princess herself with her whisking curls and her blue eyes that were roguish and friendly both at the same time. But that, of course, was out of the question. So he contented himself with naming the softest, whitest, curliest lamb Anastasia, and let it go at that.

But to-night as he lay on the hillside he couldn’t help thinking what fun it would be if the lamb Anastasia were really the Princess, and all the other sheep were[5] boys and girls so that they could play hide-and-seek together among the rocks and bushes in the moonlight. But the sheep had long since nestled down on the hill, and there was nothing for Ivan but to watch the moon as it came up and up behind the black mountain across the valley. His eyes began to blink, and he felt himself slipping, slipping off to sleep.

Ivan listened

A cry broke through the quiet pasture. Ivan started up. “Wolves!” said his heart. “Wolves! Wolves again!” But it was not a fierce sound after all. Again it came, loud like a roar of temper wailing off into a moan.

Ivan listened. “No sheep could bleat like that,” thought he. Nevertheless he looked. There in the moonlight the nine-and-ninety woolly shapes shone dimly, huddled safely against the hill.

Once more the sound came, fairly bursting through the air. Ivan held his breath. It was not the cry of animals but of men, of several men perhaps, shouting together. “A party of hunters,” thought Ivan, “lost in the forest!” And he breathed again.

Picking up his crook, he dashed off up the hill, along the edge of the wood. “I’m coming!” he shouted. “Coming!” But the hunters did not seem to hear. The same cry kept ringing through the trees ahead, louder at every step he ran. It seemed directly opposite him now, somewhere in the forest. He turned in, feeling his way with his crook among the black shadows of the branches.

There was a crashing and stirring. The trees before him trembled. Ivan stopped and looked up. Full in the moonlight, half way to the treetops, gleamed the gigantic shoulder of a man. His head was bent, and he seemed to be sitting down, gazing intently at something near the ground. As he moved his arm, the trees swayed and creaked.

Ivan crept nearer. Through an opening between the trees he could see the giant’s great hands fumbling over his foot. With a piece of fur he was trying to stop a small cataract of blood that was bursting out from it. Every now and then, in his clumsy efforts, he seemed to hurt himself more, for he would throw back[7] his head and give the same deafening howl Ivan had heard before.

Ivan shivered. In all his life he had never seen a giant; and terrified as he was, he must have a good look at this one. Crouching, he stole through the shadow to a little thicket at the giant’s side, and parting the twigs, leaned eagerly forward. But he had reckoned too much on the bushes. Under his weight they cracked and bent, and snapped altogether. His foot slipped, and losing his balance, he crashed through the brush at the giant’s very elbow.

With a swoop the giant grasped at him. But Ivan was too quick. He dodged just out of reach, and ran as he had never run before.

“Little creature! Little creature!” called the giant, “don’t run away. I won’t hurt you. Come back, do come back and help me. If you will bind up my foot for me, I will give you a reward.”

Ivan’s heart thumped. The giant could crush him in one of his great hands. But he was in pain, and he had a kindly face. It would be mean to leave him there alone.

“Oh, little creature,” moaned the giant again, “don’t leave me. I promise I won’t hurt you. Do come, do come.”

Ivan turned. Stanchly he walked over to the giant’s foot, and running his hand gently along the sole, picked the rocks and pebbles out of the great gash.

The giant sighed with relief. “Thank you!” he said. “I hurt it rooting up an oak-tree, and then I walked on it.”

Ivan pulled off his blouse, and tore it into long pieces. Knotting them together, he made a strip five or six yards long. He laid it against the wound, and the giant drew it over the top of the foot where it was hard for him to reach. Between them they made a neat, firm bandage of it, with all the knots on top.

The giant beamed. “That feels better,” he said. “And now, little herdboy, I will show you how a giant keeps his word. If you are not afraid to sit upon my shoulder, I will take you where no little creature has ever been: to see a giants’ merrymaking. We are holding a wedding-feast now, and there will be plenty of fun, you may be sure. Come, I will take good care of you.”

Ivan picked up his crook. This would be more fun than hide-and-seek on the hill. He was not in the least afraid, and he felt on good terms with the giant already. “I’d like to go,” he said.

“Good! Good!” cried the giant, chuckling with the noise of a happy waterfall. “Up with you, then. Lean[9] against my neck, and take tight hold of my long hair.” And with that, he picked Ivan gently up and tucked him snugly just below his right ear.

The giants danced

“Why, you’re too light! I can’t feel you at all!” he gurgled, as if it were the best joke in the world. “And I must fix it so that my brothers can’t see you. Here is a belt for you. Put it on, and you will be quite invisible.”

So he handed Ivan a long piece of gray gauze, so fine that in the moonlight he could hardly see it at all. Ivan tied it about his waist. And then although he pinched himself and knew quite well that he was all there, he couldn’t so much as see his own toes.

As for the giant, now that he could neither see Ivan nor feel his weight, he began to be a little nervous. “Once in a while,” he said, “I wish you’d stand up and shout my name ‘Costan’ into my ear, so that I’ll know you haven’t tumbled off. And now, are you ready? Hold tight, and we’ll go on.”

Costan raised himself, and strode off with a long, limping step through the forest. To Ivan it was like being on a great ship at sea, going up a long wave, and down. He felt that he might fall asleep if it were not such fun sitting there on Costan’s shoulder and watching the treetops glide past the moon.

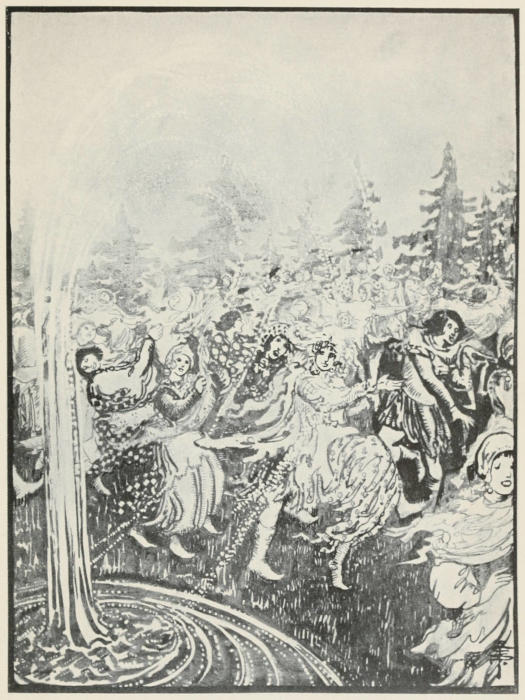

The trees grew fewer and fewer. Ivan swung around, and peered ahead, clinging to Costan’s hair. They were coming to a great open space in the midst of the forest, a meadow thronged with giants and giantesses. There seemed to be hundreds of them, dressed not like Costan in skins but in wonderful shimmering garments that blew about their shoulders like clouds of mist in the moonlight. In the center of them all was a huge fountain that shot up in a silver torrent far above their heads.

One of the giants came running to meet Costan. “Oh, here you are!” he cried. “We were afraid you weren’t coming.” And with that, he gave him a friendly pat on the shoulder that nearly sent Ivan spinning off a hundred feet or more to the ground.

Costan explained about his hurt foot. “I’ll just sit and look on for to-night,” he said, and chuckled to himself, thinking of Ivan.

A fountain that shot up in a silver torrent

And so Ivan, safely nestled on Costan’s shoulder, watched till his eyes stood out, as the giants danced and played giant games, chasing each other through the fountain, with a shower of spray like a whirling rainstorm. They wrestled, they leaped, they sang till all the trees trembled.

She pulled up a fir-tree

Just as the fun was at its liveliest, there was a mighty gurgle, and the fountain, which had been casting itself[14] so high into the air, sank suddenly into the earth. The oldest giantess of all gathered her great fluttering robes about her, and striding to the edge of the forest, pulled up a fir-tree with one wrench of her wrist.

“Midnight!” whispered Costan.

Silently the giants crowded about the uprooted tree.

“Este tennes!” cried the giantess.

They cut into the ground like huge knives

Instantly the giants seemed to flatten out. Their backs seemed to come forward, and their fronts to shrink back. Their arms, their legs, their heads, their bodies,[15] grew thin as cardboard. They stood there like great paper-dolls, taller than the trees. One by one, they stepped into the hole where the tree had been, and cut their way down into the ground like huge knives.

Costan bent his ear. “Are you there, little herdboy?” he whispered.

“Yes, Costan,” cried Ivan.

“Keep tight hold, then,” cautioned Costan, “and don’t be afraid. I’m going to take you with me underground.”

As the last giant vanished, Costan got up slowly and walked toward the hole. With every step, Ivan could feel him shrinking, until his shoulder was nothing but a long, thin edge.

There was a quick moment of darkness, and suddenly they were in a hall shining from floor to ceiling with gold, and so vast that Ivan could not see to the end of it. Down the center, around a long table sat the giants, all in their natural shapes again.

Costan slipped into the huge seat that was left for him, and the banquet went merrily on. To Ivan, who never in all his life had had anything but bread and cheese, with a little fruit sometimes and a sugar cake at Christmas, it seemed an impossible dream. There were grapes as big as the oranges above ground, pheasants[16] the size of eagles, and cakes and tarts and puddings as big around as the towers of the King’s palace.

But Costan sat silent and uneasy. Then Ivan realized what was the matter: Costan was not sure that Ivan was there. Steadying himself with his crook, Ivan scrambled up. Standing on tiptoe, he could almost reach the giant’s ear.

“Costan!” he whispered, as loud as he dared, “I’m here,—all safe.”

Costan beamed with relief, and fell to joking and eating with the rest. But every now and then he would poise a tiny piece of cake or meat carelessly above his right shoulder, where Ivan would make it disappear as completely as he had himself.

At last the oldest giantess rose in her place, to show that the banquet had come to an end. Amid all the jollity and confusion Costan leaned over and took from the table a giant roll, as big to Ivan as a whole loaf of bread.

“Here!” he whispered, below the scraping of the giant chairs. “Tuck this in your bag, little herdboy, as a reminder of a giant’s promise. And don’t forget Costan in the world up above.”

As he spoke, everything was suddenly lost in a whirl of darkness,—the giants, the hall and the feast, even[17] Costan himself. The shouts and laughter of the huge banqueters grew fainter and fainter till they faded away into silence.

A sudden bleat made Ivan open his eyes. He was lying on the hillside near his sheep, and the mountain across the valley glowed red in the sunrise.

“And so,” thought Ivan sadly, “it was a dream after all,—the giants, the fountain, the banquet, and dear Costan as well.”

He reached for his crook, and started back in amazement. For though he could feel the handle tightly grasped in his fingers, it seemed to his startled eyes that the crook suddenly rose up of itself and stood clearly outlined against the morning sky. As he stepped back, the crook sprang after him. When he walked forward, the crook bobbed along by his side. He could feel his hand upon it, but when he looked he could see plainly that there was no hand there.

Ivan rubbed his eyes. Was he still dreaming then? But no, everything was just as usual,—the sheep, the hillside and the morning sky. Was it he or the crook that was bewitched? He looked down at himself in alarm,—and saw nothing but the stones and grass of the pasture. There was no Ivan to be seen: no arms nor hands nor legs nor feet.

A sudden thought came over him. He felt of his waist. Sure enough! It was tied about with gauze.

“The invisible belt!” he cried, and pulled it off.

In a twinkling there he was, arms, legs, hands, feet, just the same as ever. He folded up the long, wispy sash and stuck it into his bag. Inside, his hand hit something hard and bulgy. It was the giant’s roll,—the great loaf Costan had given him.

It was past Ivan’s breakfast time, and the sight of the tempting white bread made him hungry. He tried to break off a piece, but the great roll would not so much as bend. He drew out his knife, but the harder he cut, the firmer and sounder the loaf seemed to be. He could not even dent it.

Provoked and impatient, he tried with his teeth. At the first bite, the hard crust yielded. Something cold and slippery struck his tongue and rolled out clinking on the ground.

Ivan stooped and stared. There at his feet lay a great round gold-piece as big as a peppermint-drop. In amazement he looked at the loaf in his hand. There was not a break anywhere. It was as smooth and whole as before. He bit again and again. Another gold-piece, and another, fell at his feet, as round and shining as the first. But the loaf remained unbroken.

Ivan’s eyes almost started from his head. In all his life he had never seen a gold-piece before; and whatever he should do with so many he had not the least idea. He might, of course, build a palace and live like a lord. But that would take him away from the sheep, and the King and Queen and Anastasia. On the whole, he decided he was much better as he was, where he could roll the gold-pieces down the hill and race after them to the bottom.

Then a splendid idea struck him. To-morrow was the Princess’ birthday. For a long time he had been wondering what he could give her. Here was just the thing! What could be better than a heap of the pretty gold-pieces to play with? He sat down at once, and bit and bit at the loaf till he had enough of them to fill his bag to overflowing. Bag, loaf, belt, and all, he hid in his hut at the edge of the forest. Then he ate his black bread and cheese and went back to his sheep, bounding over the boulders for sheer happiness.

As soon as the sheep were settled for the night, he ran to the hut again. Tying the magic belt about his waist, he took up the bag of gold-pieces and trudged off with them across the fields.

In the moonlight the palace towers rose straight and shining. Every window gleamed, darkly outlined.[20] Ivan did not hesitate. He knew quite well which one he wanted. It was the window of the Birthday Room, where once every year all the servants and the shepherds were allowed to come to see Anastasia’s presents. To-morrow, he thought, with a catch of his breath, would be the day.

The bulky form of a guard broke the bright wall of the palace ahead. For an instant Ivan shrank back. Then with a smothered laugh he dashed across the grass, underneath the man’s very nose. The guard turned sharply. But there was no one to be seen. Palace and park lay bright and still in the moonlight.

Ivan had gained the palace wall. Just as he had remembered, a stout vine with the trunk of a small tree ran up the side to the very window of the Birthday Room. He tried it with his foot. It would not have held a man, but it could bear Ivan even with a bag of gold. Breathless, he climbed,—so fast that the vine had barely time to tremble before he was at the top. At his shoulder the casement of the Birthday Room stood ajar. With one tug he swung it open, and leaned across the sill.

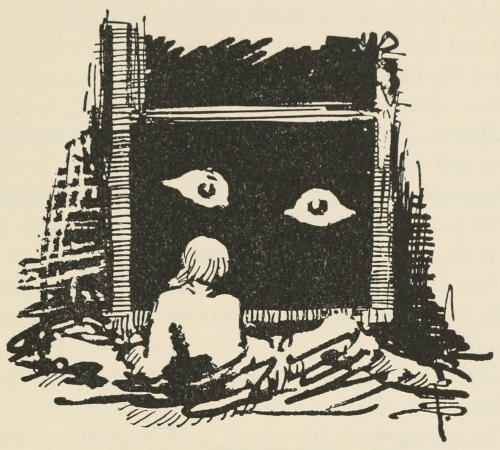

Ivan gazed. On broad chests all about the room glimmered jewels and toys for the Princess; and in the doorway stood a guard, erect and silent, watching over them.[21] Underneath the window, deep in shadow, was a low, cushioned seat.

Every window gleamed

Something jangled on the floor; and the guard stooped to pick up a knife fallen from his belt. Instantly, Ivan saw his chance. Holding his bag, bottom up, on the window seat, he loosened the strings, letting the gold fall in a heap in the black shadow. By the time the[22] guard had adjusted his belt again, Ivan was out of the window, climbing down the vine.

Next morning, everything was a-buzz at the palace. The servants and shepherds, filing around the Birthday Room, barely glanced at the gorgeous jewels. Every eye was fixed on a glittering pile of gold-pieces in a glass case. They were worth a king’s fortune, people said. The Princess could buy with them anything in the world her heart desired,—castles or coaches, jewels or gowns. And the mystery of it was, no one knew who had sent them. They had suddenly appeared in the middle of the night. The whole court was alive with conjectures.

Ivan, filing by with the others, said never a word; but his heart thumped with pride and happiness. Through a half-open door he could see Anastasia herself using four of the great round gold-pieces as dishes for her dolls. Ivan beamed. To-morrow, he decided, the Princess should have a birthday as well as to-day.

As soon as it was dark, he hurried to his hut, drew out the magic loaf from its hiding-place, and bit and bit till he had a bagful of gold-pieces again. Then he put on his invisible belt and ran to the palace. Everything happened almost as before; and he got away, down the vine, and back to his sheep before any one was the wiser.

On the window-seat next morning the Princess found the shining heap. And if the court had been excited before, now it was in an uproar of astonishment. Hereafter, the King ordered, two guards should stand hidden beside the window to discover who it was that brought the gold.

So night after night for a week Ivan left the gold-pieces. And morning after morning the guards reported to the King that no one had been there. The window, they said, had suddenly swung open; and a bag, jumping unaided from the sill, had emptied itself on the seat below, disappearing through the window as magically as it had come. At last the King, tired of the mystery, declared that he would watch himself.

The eighth night was dark and rainy, and Ivan slipped over the soggy ground. When he got to the entrance of the park, he realized with a dreadful sinking of his heart that he had forgotten to put on the magic belt. He turned to go back, but the thought of the dismal, stormy walk made him suddenly bold. The palace-guards, he reflected, would be keeping close to shelter, a night like this. He could easily escape them, and crawl up the vine unsuspected. Once at the window, he had only to watch his chance, pop in the gold, and fly back in the darkness to his sheep.

So Ivan kept on. He stole softly by the guard-house where the lazy soldier lounged half asleep, and crept stealthily up the dripping vine. The window swung open with a creak, and Ivan, frightened, crouched breathless beneath the sill. Minutes passed. There was a stir behind one of the great curtains. The guard was moving. Now perhaps would be the best time.

Ivan reached over and began emptying his bag. A heavy hand seized his collar and dragged him bodily into the room. By the light of a flickering lantern Ivan found himself face to face with—the King!

“Ivan!” exclaimed the King.

There was a pause, Ivan blushing like a culprit, with the empty bag trembling in his hands.

The King frowned. “To think that you,” he cried, “my best herdboy, whom I have trusted, should come to steal the gold which a good fairy brings the Princess! Well, you have given me good service before this, and I will not treat you harshly now. But go, go at once, and never let me see your face again.”

And with that, he led him down a staircase and thrust him out into the dark.

Choking and wretched, Ivan ran back to his hut. Gathering up his loaf and belt, he crammed them into his bag, and started off into the world.

“Good-by, my sheep!” he cried; and stooped to fondle the little lamb Anastasia.

“I suppose now,” he reflected miserably, “I shall have to be a great lord after all.”

By the time he got to the town, day was breaking. The rain had stopped, and rosy clouds floated across the eastern sky. A sunbeam slanted over the roof tops, and shone into Ivan’s face. He felt happier all of a sudden; and taking his loaf, he bit a dozen great gold-pieces out of it. Then wrapping it up in the magic belt so that no one could see it, he knocked at a cottage door. Inside, he found a warm breakfast, and dried himself off by the fire.

A dazzling scheme slowly unfolded in his mind. As soon as breakfast was done, he went to the coachmaker and ordered a great gold coach; to the tailor and ordered a golden suit; to the hatter for a hat with golden plumes. And when the tradespeople heard the clink of his gold-pieces, they were very glad to serve him, you may be sure.

Only the coachmaker demurred. “A gold coach is nothing,” said he, “without a coat-of-arms on the door.”

“But I haven’t any,” said Ivan.

“Never mind!” replied the coachmaker, “I will make you one. How did your good-luck begin?”

“From a loaf of bread,” said Ivan, “and a giant.”

So, the coachmaker painted and painted on the coach-door. When he had finished, there was as fine a coat-of-arms as you would wish to see,—a loaf of bread against a background of gold-pieces, and a giant standing up above.

Ivan’s coat-of-arms

Then six white horses with gold trappings were harnessed to the coach; and six servants in golden livery took their places,—two riding ahead, two riding behind, and two sitting up very straight on the box. Ivan stepped inside, all dressed in his golden suit and the hat with the golden plumes. Underneath his arm he carried the giant’s loaf wrapped up in the magic belt. (But of course nobody could see that.)

“Drive to the King’s palace!” cried Ivan.

So they drove; and all the people along the way were[27] so amazed at the magnificence of the coach that they ran and told the King that some great prince was coming to visit him. The King dashed to put on his crown; and just as the coach drew up at the palace gate, he got seated on his throne with all his court about him.

So they drove

Ivan walked up the great hall and bowed low. And all the courtiers bowed in return to the splendid young prince. Before the King could say a word, Ivan threw back his head and told the story of the gold-pieces from beginning to end.

For a moment the King was dumb with astonishment and remorse. Then he spoke. “Ivan,” said he, “I have done you a wrong. If there is anything I can do to make it right, you have only to tell me.”

Ivan beamed. “There is only one thing in all the[28] world I want,” he cried, “and that is to have you for my father, the Queen for my mother, and Anastasia for my sister!”

“Where is your real father?” asked the King.

“And where is your real mother?” asked the Queen.

“Where is your real sister?” cried Anastasia.

But to all these questions the herdboy gave a satisfactory answer. “I never had any,” he said.

“Very well then,” cried the King. “You are adopted! I will be your father; the Queen shall be your mother; Anastasia shall be your sister. What is more, in five years and a day, when you are quite grown-up, you shall marry the Princess!”

But by the time he got to that part Ivan and Anastasia were too much excited to hear. The minute he finished they bowed and curtsied as well-mannered children should, and ran into the courtyard to play tiddledywinks with the gold-pieces, over the bread.

Nevertheless, it turned out as the King had said, and in five years and a day, when they were quite grown-up, Ivan and the Princess were married. And ever after in the palace-treasury instead of heaps of gold-pieces for robbers to steal, there was nothing but a single loaf of bread.

—Based on a Hungarian Folk-tale.

After the earth was newly washed by the Flood, nearly all the land of Europe lay flat and green under the sun. Except in one far corner there was not a mountain nor a valley nor a hill nor a hollow, nor so much as a little stream. The soft young grass stretched away and away, in a wide meadow, as far as one could see.

But there was nobody there to look. For all the people there were, lived in the Up-and-Down Country, on a great forked point in the Far North. And that was a very different kind of place, with mountains that went up and valleys that went down, cliffs that rose and cascades that fell, and not so much flat land as a giant could cover with his pocket-handkerchief.

But the giant Wind-and-Weather, who lived there, did not mind that in the least. He sat quite placidly on[32] a mountain-top and looked through a kind of glass that he had, out over the sea. As for his wife, the giantess Sun-and-Sea, nothing bothered her. She sat on a cliff and wove on a kind of loom that she had, back and forth, back and forth, with a noise like the long ocean rollers on a fair day.

Playing Follow-the-Leader down the long row of peaks

When it came to the children, they never sat at all. Like the country, they were always going up or down,—sliding down the mountains, scrambling up the waterfalls, or playing Follow-the-Leader, hoppety-skip, skippety-hop, straight down the long row of peaks that made their home.

And when they all played together, it made rather a good game. For there were fourteen of them, sturdy youngsters, each over a mile high, and growing fifty[33] feet or so every day. Then too, they happened in the jolliest way, for they came in pairs so that every one had his twin. There were Handsig and Grandsig, Kildarg and Hildarg, Besseld and Hesseld, Holdwig and Voldwig, Grünweg and Brünweg, Bratzen and Gratzen, Mutzen and Putzen,—a boy and a girl, a boy and a girl, a boy and a girl, straight down through.

Now, one morning, with Handsig ahead and Putzen straggling somewhere behind, they were all playing Follow-the-Leader, rather harder than usual. Handsig had rolled down peaks, and wriggled up, hopped on one foot and jumped on two, turned somersaults and splashed through waterfalls. And the whole line of them had come rolling, wriggling, hopping, jumping, tumbling, splashing after. Being put to it for something[34] to do next, Handsig started on the dead run from peak to peak, straight along the mountain-tops.

All of a sudden he stopped short. Ahead of him were no more mountains, only a straight drop thousands of feet to the sea. He had come, before he knew it, to the end of the Up-and-Down Country. But that was not what made Handsig stop so quickly. He had been to the end of the land before. It was something beyond the water that attracted him,—another country so different from his that at first it did not seem to be land at all. There was no up or down in it. It stretched flat and green as far as he could see.

Handsig waved his arms and shouted, “Oh, Kildarg, Hildarg, Besseld, Hesseld, see the nice, green running-place!”

And all the other children, thinking it was still part of the game, waved their arms and shouted, “Oh, Kildarg, Hildarg, Besseld, Hesseld, see the nice, green running-place.”

By that time Handsig had no doubt any longer. Without another word he plunged headforemost into the sea, and swam with all his might straight for the wide meadow that was the rest of Europe.

Splash! Splash! Splash! The other children dived after, and puffing, blowing, kicking, raced across the[35] channel. Then hand in hand, fourteen in a row, they scampered pell-mell down across the plain where Germany is to-day.

But with swimming so hard and running so fast, poor Putzen was quite out of breath. It was so strange, too, to be going along on a level. It did not pitch one forward; it did not hold one back. It was just the same—just the same, step after step after step. The twenty-six legs beside Putzen did not stop for a minute; they beat along faster and faster. Putzen hung on to Mutzen as best she could, but her legs would not go and her breath would not come. And so, gasping and plunging, she sprawled headlong, pulling Mutzen after her.

Mutzen dragged down Gratzen, and Gratzen dragged down Bratzen; and so they all tumbled till the land for miles around was a mass of upturned turf and sprawling giant children. Then Bratzen wailed, and Gratzen wailed; and Mutzen and Putzen who were at the bottom of the whole pile, wailed loudest of all; and the air was so full of large sounds that it seemed likely to burst.

Now, Grandsig, who felt responsible as the oldest girl of the family, started to scramble up to quiet Mutzen and Putzen. As she did so, her hands dug into the soft, moist earth, and scratched up two good-sized hills.[36] A happy idea struck her. “Kildarg! Hildarg!” she cried. “Look!” And she burrowed into the earth again, scooping up handful after handful.

Kildarg sat up and wiped his eyes. Hildarg sat up and wiped her eyes. Then they both began to dig as if their lives depended on it. In a twinkling, there were no more giant children piled on top of Mutzen and Putzen; and twenty-eight giant hands were scooping out valleys and piling up mountains of earth.

Handsig and Grandsig made big mountains; Mutzen and Putzen made little ones. Every single giant child piled up a whole range higher than he was himself. Then, when all of them were done, there was such a patting and a pounding as never was heard before, as the valleys were smoothed, and the mountains molded into shape. There were sharp peaks and blunt peaks, smooth peaks and rough peaks, single peaks, double peaks, triple peaks. As for the valleys, they were of all sorts,—straight and crooked, wide and narrow, long and short.

Grandsig looked at it all, quite satisfied. “Oh, children,” she cried, “we have made an Up-and-Down Country!”

The other children looked. Sure enough! It was nothing but hills and hollows, hills and hollows, just as it was at home. And they all danced about and cried,[37] “Hooray! We have made an Up-and-Down Country.”

“There is your mast,” said Wind-and-Weather

“And now,” said Handsig, “let’s run!”

So all the children stepped out from between the mountains they had made, to run back again to the sea.

“But oh!” cried Kildarg, “where is our nice green running-place?”

The children gasped. Instead of their flat grass plot were miles and miles of mudholes, hardening in the sun.[38] As far as they could see, their green meadow was scarred with row after row of great black hollows,—the marks of their twenty-eight running feet.

That was too much for Putzen, and she sat down on one of her mountains and wept a whole lake into a valley. As for the other giantesses, they did very little better, and even Grandsig wept a few giant tears, as she tried to think what they could ever do to get their running-place back again.

“I know!” she cried at last. “We’ll go home and ask father to build us a ship; and then we’ll sail till we find another running-place.”

When a giantess starts to weep, she has so many tears and such large ones, that it is very hard to stop. So, although the children set off at once for home, it was some time before Putzen, Gratzen, and Brünweg, Hesseld, Hildarg and Voldwig were smiling again. And their tears, in a great torrent, flowed after them, over the hubbles, around among the hollows, and out toward the sea.

They cried, in fact, so hard and so much that even to-day their tears are still flowing,—for they gathered and gathered until they became the river Rhine. As for the mountains the giant children built, they too are still there. They hardened until they became quite firm and[39] rocky, so that nowadays in Switzerland people are continually climbing up and over them. And the place where the giant children made, so to speak, the first mud-pies, has been called the Playground of Europe ever since.

With as many trees as they could drag

When the children got home, there was old Wind-and-Weather sitting as usual on a mountain-top and looking through a kind of glass that he had, out to sea.

“Oh, father,” they cried, “we want a ship to sail the sea to find a running-place again.”

Old Wind-and-Weather was not disturbed in the least. He got up, put his glass into his pocket, and walked along the mountain-ridge. With one slow wrench, he pulled up by the roots a tree taller than he was himself.

“There is your mast,” said Wind-and-Weather.

Then, Handsig and Grandsig pulled up big trees for beams to make the sides and keel; Mutzen and Putzen[40] pulled up little trees for oars. And with as many trees as they could drag, they all trooped after their father down to the seashore.

Half-way down there was the giantess Sun-and-Sea, sitting as usual on a cliff and weaving on a kind of loom that she had.

“Oh, mother,” cried the children, “help us. We are building a ship to sail the sea to find a running-place again.”

Sun-and-Sea was not disturbed in the least. She got up and took out of her loom a sheet longer than she was herself.

“There is your sail,” said Sun-and-Sea.

Wind-and-Weather took the sail down to the shore, and the children began such a hacking and planing and pounding as no shipyard has ever heard. In just a few hours of giant time, there was the great ship with the mast set and the sail rigged, ready to be launched.

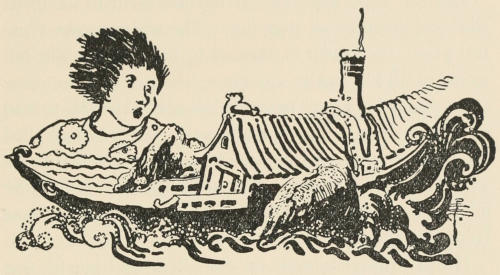

Mutzen and Putzen climbed in and took their oars; and the others pushed and pulled until the boat, slipping and grating, shot out into the water. Mutzen and Putzen, having nothing to christen it with, beat on the sides with their oars and cried, “We name you Mannigfual!”

“Mannigfual!” echoed the other children. “The giants’ good ship Mannigfual!”

The children climbed in and took the oars. Wind-and-Weather took the tiller. And there they were, skipping along over the sea. When the wind blew against them, the children rowed and sang. When the wind blew with them, they set the sail and strained their eyes to find a running-place ahead across the water. As for Wind-and-Weather, no matter which way the wind blew, he sat and steered.

Now, it must never be forgotten that giants’ time is as big as they are; and half a year to them was scarcely more than a day. Our night and day they did not bother about in the least, for their big eyes looked through the dark as well as the light. Sunrise and sunset were no more to them than the revolving of a lighthouse lamp to us. But the minute a half-year was up, the giants’ night began, and giant children felt then very much as ordinary children feel in the evening after eight o’clock has struck.

Mannigfual had not sailed many hundred miles when the giants’ night came on. Mutzen and Putzen knew that it was coming, because their heads and their arms and their legs began to feel so very much in the way. Soon they lost track of their oars altogether, their heads bumped, their mouths dropped open, and there they were,—fast asleep. Then Gratzen yawned, and Bratzen[42] yawned,—all the rest even up to Handsig and Grandsig. But somehow or other they managed to keep on rowing.

Wind-and-Weather took out his glass and scanned the sea ahead. In a little while they all saw what he was steering for. It was land. A few minutes more, and they had dropped overboard the great cliff they had brought for an anchor.

Wind-and-Weather picked up Mutzen and Putzen. With one against each shoulder, he stepped leisurely out and waded ashore. The children jumped after, splashing and rubbing their eyes. Straight ahead was a wide valley. Wind-and-Weather laid Mutzen and Putzen in that; and picking out a convenient hill for a pillow, stretched himself across the landscape.

“Well,” said Handsig, looking around, “I don’t think much of this as a running-place!”

And quite right he was. For there was nothing flat or broad about it. The whole country was broken up into little hills, little valleys, little fields, little forests. But Handsig might have spared his words, for there was nobody to listen. So he fitted himself neatly between two hills, and snored as loudly as the others.

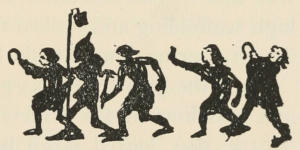

Now, it happened that the giants had landed in the North of England, which even in that early time was inhabited by the race of men. And although there was only wilderness in the part where the giants had stretched themselves, a few miles down the shore was the cave of the pirates, Dare-and-Do, Catch-and-Kill, Fear-and-Fly.

Dare-and-Do, Catch-and-Kill, Fear-and-Fly

The morning after the giants landed, Dare-and-Do was awakened unusually early. Somewhere outside the[44] dark of the cave, the air seemed full of rumblings and the noise of great waves beating on the beach. Dare-and-Do yawned irritably. He was wondering how their old long-boat was standing it, tied under the cliff. Drawing his dirk, he reached over and pricked his comrades awake, after the pleasant custom of the cave.

“Storm!” hissed Dare-and-Do.

Groping and growling, the three pirates got up to look after their boat, and stumbled out—into as fair and innocent a day as ever dawned off England. The thunderings kept on, but there was not a cloud in the sky. The waves still pounded, but they burst white and glittering into the sunlight.

Catch-and-Kill turned crossly. “The storm’s over,” he said.

But Fear-and-Fly stood where he was, pointing out to sea, and shaking from head to foot. “Sea-serpent!” he gasped.

The others looked. There, a mile or so out at sea, stretched a great monster, motionless and stiff. Was it after all a monster,—the long, high, level wall, hiding the horizon, the great column in the center, towering and towering until it was lost in the sky?

“Sea-serpent!” snorted Catch-and-Kill. “It’s an island, a magic island.”

Dare-and-Do peered, shading his eyes. Across that high column went a bar. “You’re both wrong!” he shouted. “It’s all a ship,—a great ship.”

Now, there was this to be said for Dare-and-Do. There was never a ship made that he was afraid of. No matter what the size, his one idea was always to capture it; and the bigger the better, for him. So, instead of cowering at the sight of the giants’ ship, he rushed back to the cave for his oars and a whole set of dirks and pikes.

“It will make our fortune,” he cried, “—our everlasting fortune!”

Catch-and-Kill headed off Fear-and-Fly, who was already making for the bushes, and dragged him down to untie the boat. Dare-and-Do took one oar, Catch-and-Kill the other; and, with Fear-and-Fly huddling astern, they set off at top speed. With every stroke of the oars the ship grew nearer and bigger. To Fear-and-Fly it seemed an unending stretch of wooden cliff ahead. As they drew toward it, he saw that the side was nothing less than a mountain, towering a thousand feet into the air. The sight made him dizzy. He threw himself down on the bottom and shut his eyes.

The others were rowing silently now. The boat slipped stealthily, stealthily, alongside the steep ship.[46] Dare-and-Do crept to the prow and thrust his pike into one of the ship’s enormous beams. It held. He passed a rope over, and the boat was tied.

Without a moment’s pause, he drew his knife, and began carving out footholds in the massive wood,—up, up, up the ship’s side. As he carved, he climbed, hand over hand, foot over foot, clinging like a fly to the precipice.

Catch-and-Kill did not hesitate. He fastened the boat’s stern, as Dare-and-Do had the prow. Stooping, he seized Fear-and-Fly by the collar, and dragged him forward along the bottom. With his free hand he pulled out his dirk and pointed with it, first at Dare-and-Do’s steps, then at the water. “Up?” he growled through his teeth. “Or down?”

Shaking and shrinking, Fear-and-Fly made the best of his way up the ship’s side. Catch-and-Kill followed at his heels, ready with a dirk to encourage him at the slightest hesitation.

Finally Dare-and-Do reached the top. Leaning against the side, he could look over into the great ship. Before him stretched, seemingly, a long, wide deck. He scanned it closely. As far as he could see there was not a single soul. He listened. Not a sound but Fear-and-Fly’s startled breathing below.

“Crew’s asleep,” muttered Dare-and-Do.

He turned to the others. “Quiet now,” he warned, “and follow me.”

With dirks drawn the pirates clambered over the side and tiptoed stealthily across the deck. Dare-and-Do headed for the stern. His idea was to make way with the crew before taking possession of the ship.

“Up? Or down?”

“Dirks and daggers!” he exclaimed. Before him opened a yawning abyss. The deck had come abruptly to an end. Beyond the wide chasm began another deck, made, seemingly, of a single, tremendous board.

Dare-and-Do turned and ran toward the prow. Again the deck stopped before an abyss, beyond which another deck began. He understood now. There was[48] no true deck at all,—simply a succession of immense planks laid at intervals from side to side.

Fear-and-Fly groaned. “Oh! Oh! Oh!” he screamed hoarsely. “It’s a giants’ ship, a giants’ ship, and the decks are their rowing-seats.”

Catch-and-Kill scratched his dirk remindingly across Fear-and-Fly’s throat. “Silence!” he hissed.

But Dare-and-Do caught his hand. “Dirks and daggers!” he cried. “But the coward’s right. It’s a giants’ ship. Look at the mast; look at the sail; look at the tiller there, far above our heads! A giants’ ship, and not one of the crew aboard! They won’t be back either, if I know giants. They’ve landed somewhere for their six months’ sleep. Here’s luck, luck, luck at last. We don’t have to capture the ship. We’ve got her!”

Catch-and-Kill looked up at the mammoth rigging. “Great luck!” he sneered. “Great luck! A ship you can’t move! A ship you can’t steer! I suppose you’ll set the sail; I suppose you’ll turn the tiller; I suppose you’ll sail her to the Gold Lands!”

Dare-and-Do came a step nearer. “Who wants the Gold Lands most?” he asked meaningly.

Catch-and-Kill started. “You don’t mean the King?” he cried.

“Three hundred builders, three hundred sailors, two hundred days,” said Dare-and-Do calmly, “and there’ll be enough gold for us all and a little to spare; eh?”

“Daggers and dirks!” cried Catch-and-Kill, making for the ship’s side. “Let’s be off to ask him!”

Dare-and-Do dashed after, but Fear-and-Fly (who was as anxious to be off the ship as he was loth to climb on) was the first over the ship’s rail and down into their boat.

Waste-and-Want

Stroke! Stroke! Stroke! Their oars flew through the water. In just half the time it had taken them to come, the pirates went back to their beach. Without stopping for food they ran over hill and dale, field and fen, brook and bog, till they reached the King’s castle.

Now the king of the country at that time was a spendthrift named Waste-and-Want. Half his time he spent[50] in running into debt, the other half in imploring his councillors to get him out.

At last one day his councillors came to him. “Your Majesty,” said they politely, “we have the honor to report that the hundred and one means of escaping from debt which are recorded in history, have, in your case, been exhausted.”

“What!” roared the King. “You mean to say that you can’t get me out this time!”

“All methods,” replied the councillors delicately, “have been employed.”

Then the King was angry indeed. He vowed that the common people of his kingdom could help him better than that, and he issued a proclamation promising half his ships and half his kingdom to the person who should find a new way to free him from debt. All who wished to try had but to come to the castle and give the password, “Fortune favors Kings.” But any one who spoke the password and failed of his errand, was doomed to exile on the sea.

Now, exile of that kind did not frighten Dare-and-Do in the least. He shouted the password at the top of his lungs, and strode by the guard right into the King’s castle.

In the great hall the King sat on his throne, doing[51] problems in arithmetic. But the trouble with the examples was that they were all in subtraction.

Dare-and-Do bowed low. The King looked up and hastily put on his crown.

“Your Majesty,” said Dare-and-Do, “may I make bold to ask you one question: Why is it that no ship yet has reached the Gold Lands?”

Now, it happened that the King had been thinking of that very matter himself. So he answered right off, “Why, we’ve never had one long enough, we’ve never had one strong enough, to stand the storms.”

Dare-and-Do’s eyes gleamed. “Just so, Your Majesty,” he said.

Then he drew a step nearer the throne. “But what would you say,” he asked, “if I could give you a ship long enough and strong enough to stand any storm that ever blew?”

“What!” cried the King; and then: “Where?”

Dare-and-Do told him about the giants’ ship. Before he was half through, Waste-and-Want rushed down his throne-steps, bawling, “Guards! Guards! Guards! Call together all the builders. Call together all the sailors. Get all the beams and boards in the kingdom!” And when the King spoke in that voice, the guards were not slow in obeying.

By the next morning every sailor and every builder in the kingdom was in line on the sea-beach. As for the piles of beams and boards, they stretched for miles and miles. All day long every sailboat and rowboat on the coast plied back and forth, loaded down with beams and boards, sailors and builders. Then began a hammering and pounding, a planing and joining, that kept up five months and a day.

In the pulley-blocks were little rooms

When it was over, even Dare-and-Do opened his eyes wide. From one end of the ship to the other ran a smooth deck, bridging the great gaps between the rowing-seats. At the stern was a high platform on which a hundred men could stand abreast to turn the tiller. Up the mast ran a ladder; and in the pulley-blocks were carved out little[53] rooms where the sailors could rest from climbing, over night. To Dare-and-Do as captain, the King gave his fastest horse, which could do the distance down the deck from stern to prow in a few hours.

Finally everything was ready. The builders went ashore. The sailors ranged themselves on board. A hundred hacked in turn at the anchor-rope. A hundred began to set the sail. A hundred began to turn the tiller. Dare-and-Do galloped up and down the deck, shouting orders.

At last the anchor rope was cut. The sail flapped slowly out. The tiller creaked. The wind blew and the ship started forward. All the people shouted, and as for King Waste-and-Want, he made a bonfire of all his bills on the beach.

The ship moved along at a terrible rate. But had it not been for losing sight of the shore, not a sailor on board would have known that it was stirring at all. Dare-and-Do walked his horse. The crew, in three shifts, took turns eating dinner and holding the tiller. Catch-and-Kill and Fear-and-Fly began to plan how the gold should be divided. An open sea, and the wind behind,—what better luck could be desired?

“Land ahoy!” the lookout’s voice came down. And again, “Land ahoy!”

Dare-and-Do galloped forward. On both sides cliffs began to appear. Every minute they seemed to grow closer and closer together. Dare-and-Do measured with his eye the width of the passage ahead. Then he thought of his ship. A ghastly fright seized him. Suppose the ship should not get through! It was too late to turn around. The channel was already too narrow for that. But they must not go dashing on like this.

“Take in sail!” screamed Dare-and-Do. “Take in sail!”

Now, it had taken the crew a day and a night to set the sail; and although they raced to their posts when Dare-and-Do shouted his order, it was no easy task to pull the sail in. A hundred of them all together tugged and hauled with all their strength. Dare-and-Do drew a long breath. The ship’s prow was safely through the channel—

Smash! Shock! Shiver! Shake! The great ship stopped;—stuck fast between the cliffs that line the straits of Dover!

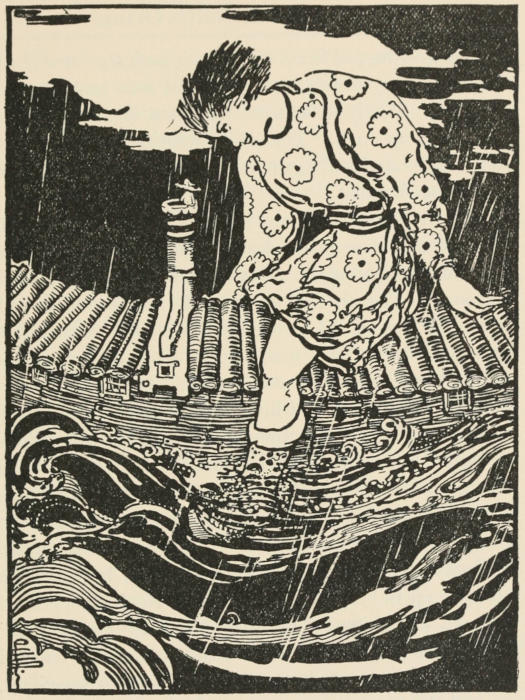

It happened that at the very moment when the ship was stopped so suddenly, the giant Wind-and-Weather awoke, a little early, from his six months’ sleep. He stretched his big arms and his big legs, and looked about him. Seeing his children still asleep, he got up softly;[55] and sitting down on a nearby hill, looked through a kind of glass that he had, down across England.

Looked through a kind of glass that he had, down across England

Just then there was a great stirring among the giant[56] children. They began to wake up and stretch the sleep out of their cramped bodies.

“Oh, father,” wailed Mutzen and Putzen.

“Oh, father,” wailed all the others. “Oh, father, our ship is gone!”

Old Wind-and-Weather was not disturbed in the least.

“Indeed?” he said.—“I see it.”

“Oh, where?” cried all the children.

“Over the little hills, over the little valleys, over the little fields, over the little forests,” said Wind-and-Weather, “I see the mast against the sky.”

“Oh, there!” cried Handsig, and “There!” cried Grandsig, and “There!” they all cried together.

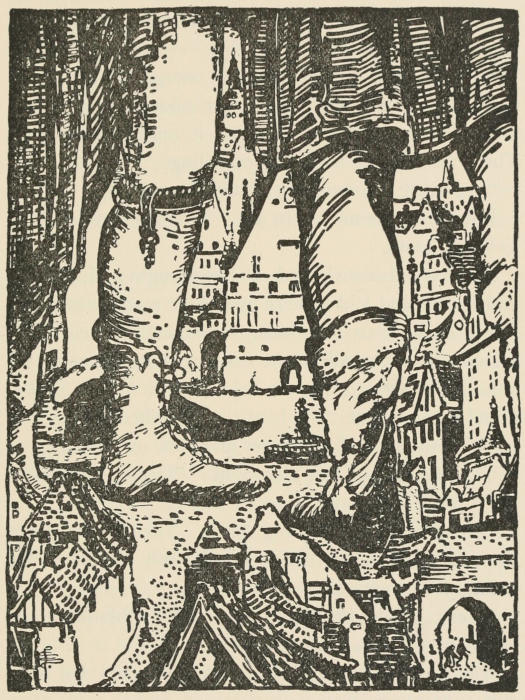

With one leap they started, plunging down across England. From hill to hill, from valley to valley, over field, farm, and forest they raced, stubbing their toes against towns and jumping over villages when they happened to see them. Wind-and-Weather strode along after them, a mile at a step; and was at the seashore as soon as they.

Now, the three hundred sailors aboard the giants’ ship were hardly over their fright at having their big craft stuck between the cliffs when they were thrown into a much greater panic at hearing the giants’ footsteps beating down across England. They huddled in[57] the stern; they hid behind the mast; they scuttled this way and that. They tussled and scrambled and scrimmaged and scratched, each one trying to get behind his neighbor. Finally, as they saw Wind-and-Weather’s huge form bearing down upon them, every mother’s son of them took a wild leap and plunged recklessly into the sea.

Dare-and-Do and Catch-and-Kill did not jump. They had been in plenty of panics before, and it was always their policy to stay by the ship. So, they sat, one on Fear-and-Fly’s head, the other on his feet, and waited the coming of the giants.

They plunged into the sea

Wind-and-Weather’s great eyes made them out at once. He picked them all up with one scoop of his big hand and stuffed them into his pocket. Then he stepped into the ship. With a single[58] kick he sent the platform under the tiller flying a hundred miles across Europe. With a stamp of his foot he smashed the decks between the rowing seats, one after the other.

“But oh!” cried Mutzen; and “Oh!” cried Putzen; “our ship is stuck between the rocks! How shall we ever get it out again?”

“I know!” cried Grandsig. And putting her hands into her apron-pockets, she drew out two immense cakes of soap, which she had brought to wash the children’s faces.

She took one. Handsig took the other. And they went to work with a will, soaping Mannigfual’s sides. Then Wind-and-Weather pulled and all the children pushed. The ship creaked and scratched; then slipped and slid straight out into the English Channel. But the soap, which they put on rather thick, came off on the rocks, and that is why the cliffs of Dover have ever since been white.

With a good wind it did not take long, I can tell you, for the giant children to sail up around the British Isles, back to the Up-and-Down Country. There sat Sun-and-Sea just as usual, weaving on a kind of loom that she had.

“Oh, mother, mother!” cried the children. “See what father has brought you.”

Wind-and-Weather held out the little men on the palm of his hand.

“They are just what I need,” said Sun-and-Sea, “to keep my threads straight.” So she took the bold pirates Dare-and-Do and Catch-and-Kill, and set them on her loom.

Wind-and-Weather put Fear-and-Fly back into his pocket. “For,” he said, “he can polish my glass for me and keep it bright.”

Whether the giant children ever found another running-place I cannot say. But I fear not. For, years afterward, the great-limbed men who followed the giants in the Up-and-Down Country, were still sailing the seas in search of new lands.

—Based on Norse legends.

The cliffs of Dover have ever since been white

In the misty time when the gods walked about the earth, Thor, the strongest of them all, set out one day for Giantland. In his hand he carried his hammer which could batter down mountains; and around his waist he wore his magic belt which made him twice as strong as before. For he was going to humble the giants.

In spite of his wonderful strength, Thor was but little larger than a man; and the giants, by their very size, annoyed him. When he hurled his hammer through the clouds, the sky rocked, the sea shook, but the giants did not tremble. And when his chariot-wheels struck out swift streaks of fire across the sky, they only smiled in their big way as if it were some game of fireflies. Now he was bound to show them that however big the giants might be, Thor was stronger, and that a little trembling now and then might not be out of place.

With Thor went the hungry god Loki, and the swift runner Thialfi. All day long they walked together through sunny mists across the bare, green uplands, and just at nightfall they came to a wide moor. As far as they could see, there was not a house, nor a shed, nor any kind of shelter. Not even a tree broke the soft horizon. Thialfi ran ahead; and Loki, who was ravenous, walked furiously. Only Thor did not notice. He was planning how he would put the giants in their place.

It grew darker and darker. The mist which had played about them all day in gentle clouds, rose in a damp, gray fog. It filled their throats and their eyes. They lost sight of Thialfi altogether. Loki stepped back, groping to make sure that Thor was there behind him; and plunged on again, sullen and dripping.

Somewhere through the fog there came a shout. It was Thialfi far ahead. “Halloo!” he cried. “Halloo-oo-oo! Shelter!”

Thor and Loki answered, walking faster. Thialfi’s voice was louder now, and plainer. “Here!” he cried. “Here! Here!”

It seemed as if they must be close upon him. But the fog ahead grew no brighter. “Where is the house?” shouted Loki. “Hasn’t it a light?”

With Thor went hungry Loki and swift Thialfi

But even as he spoke, they stumbled across a wide threshold. Above them through the thick grayness they could make out a low ceiling. They put out their hands, groping for the door-arch, and met only empty air. There seemed to be no doorway at all; or rather, there was nothing but doorway,—a great entrance, like the mouth of a cave, as wide as the building itself.

Thor struck his hammer on the floor. “Who’s here?” he thundered. But there was no reply,—only soft echoes, “Here—here—here!”

Thialfi found them. “There is no one here,” he said. “I’ve shouted before. It’s a ruined palace, I think, with all one side gone. This part is a great hall; and[66] beyond, there are five narrow wings. Come, I’ll show you.”

But Thor and Loki yawned, tired out with their day’s journey. And throwing themselves down on the floor, they all three fell fast asleep.

About midnight Thor started up. The floor trembled, and the whole palace quaked. The wide roof above them shook till it seemed ready to fall. Thor roused the others. “Run into one of the wings,” he cried. And picking up his hammer, he himself went to sit in the great doorway to guard the house.

All night long the strange rumblings continued. There would be a great heaving sound, a silence, and then another sound louder than before. Thor clutched his hammer and waited.

At dawn the noises suddenly ceased. The fog thinned, and Thor looked out across the country. In the distance he could make out a bright hill, and amid the shrubbery on the side, two lakes gleaming through the morning mists. He started to walk toward them when all at once the whole hill stirred.

Thor stopped, motionless with surprise. For a moment he could hardly realize that what he had taken for a hill was a giant’s head, and that the lakes fringed with shrubbery were his eyes gleaming beneath his bushy[67] brows. Even the rumblings were explained, for they were the giant’s snores.

When the giant spied Thor, he laughed. “Well, well, my little fellow, you’re an early riser!” he cried. “And perhaps you’ve seen something of my glove. I had it yesterday, and I must have dropped it about here last night. Oho! There it is now!” And with that, he stooped and picked up the palace.

“Take care!” cried Thor, gasping. “Take care! People inside!”

He was just in time. Very gently, the giant took the glove by the fingers and shook Loki and Thialfi out into his tremendous hand.

When the giant heard how they had mistaken his glove for a ruined palace, and the finger places for wings, he roared till the ground rocked, and Thor had to skip about to keep his balance.

“Ho! Ho! Ho!” gasped the giant, wiping his eyes. “This is a rare meeting indeed. And now what do you say to some breakfast with the giant Skrymir?”

Setting Loki and Thialfi carefully on the ground, he untied a huge wallet which he had slung over his shoulder, and laid out small hills of bread and cheese in a wide semi-circle about him. The gods sat down opposite and opened their lunch-bag. A very merry breakfast[68] they had of it. For between his tremendous mouthfuls, Skrymir told the biggest jokes in the world.

Finally he got up, and shaking out of his lap three or four crumbs, the size of an ordinary loaf, said that he was ready to start along. “And where are you bound?” he asked.

Thor told him a little sheepishly.

“That’s my direction too,” said Skrymir good-naturedly. “Come along with me; I’ll show you the road and carry your bag.”

And picking up their wallet with his thumb and forefinger he tucked it into a corner of his big one, which he tied up securely and slung again over his shoulder.

So they set off, Skrymir walking as slowly as he could, and the gods running like terriers at his great heels in a desperate effort to keep up with him.

At nightfall they stopped under a towering oak-tree, and Skrymir seeming suddenly tired out, stretched himself full length upon the ground. But Loki, who since breakfast had thought of nothing but supper, cried out to him that he had their bag.

Sleepily, he took his big wallet from his back and laid it on the ground beside them. “Take anything from it you wish,” said he; and, with that, fell fast asleep.

In a minute Loki had climbed to the top of the sack[69] and begun to tug at the huge ropes that bound it. Thialfi sprang after him. But the harder they pulled, and the redder and hotter they grew, the more firmly the knots seemed to stay in place. Then Thor, tightening his magic belt, leaped up and pulled too. But the knots remained as securely tied as before.

“Skrymir! Skrymir!” shouted Loki.

A huge snore that nearly shook them off the sack was the only answer. By that time the gods were desperate with hunger, and Thor, who had never before failed in a trial of strength, was bursting with rage. Dashing down off the wallet, he took up his hammer and hurled it with terrific force at the giant’s forehead.

Skrymir turned a little in his sleep. “Did a leaf fall?” he murmured drowsily. “I thought I felt something on my head.” In another minute he was snoring again more loudly than ever.

Thor shrank back, astounded. Never before had his hammer failed to kill. Trembling and exhausted, he lay down beside Loki and Thialfi on the ground. But it was no more possible to sleep than it had been to get something to eat. The oak-tree rocked as in a wild hurricane; the leaves dashed together, and the ground quaked with the giant’s snores. It sounded as if a hundred vast trumpets were blaring at once.

By midnight Thor could stand it no longer. He sprang up, determined to put an end to Skrymir once and for all. Tightening his magic belt three times, he swung his hammer about his head and dashed it straight and sure into the giant’s temple.

Skrymir’s eyelashes flickered. “How troublesome!” he grumbled, raising his head. “These acorns dropping on my face!”

Thor held his breath. Minute after minute passed, and Skrymir did not begin again to snore. Would he never go to sleep? Thor clenched his fist till his fingernails bit deep into his hand. Somehow he must get one more chance with his hammer. It was maddening, unbelievable, that there was a giant who could withstand it.

Finally, just at dawn, Skrymir’s wide bosom began to move up and down, up and down, like the high waves at sea. At the first snore Thor was ready. He gripped his hammer with both his mighty hands, and hurled it with a force to kill a hundred men. With a thundering crash it sank deep into the giant’s forehead.

Thor ran exultingly to drag it out. But Skrymir, brushing his hand drowsily across his brow, swept it gently to the ground.

A tremendous palace, all of ice

“Just as I got to sleep!” he growled. “To have a twig drop on me! There must be birds building a nest in the branches above here. Are you awake, my little gods? Well, Thor, you are up early! What do you say to starting on?”

And with that, Skrymir stretched his great arms and sprang up as if nothing had happened. As for his forehead, it was as sound and firm as ever.

Thor leaned back weakly against the oak. “Yes,” he gasped, “let us be going.”

So Skrymir shouldered his great wallet again, and set off whistling across the field, with the gods following limply after. At the meadow’s edge Skrymir stopped and waited. Beyond a line of trees stretched a hard, bright road, gleaming like a sea of white marble in the sun.

Skrymir pointed along it. “This road,” said he kindly, “takes you to the palace of the giant king. My way lies over the hills so I must be saying good-by. Many thanks for your pleasant company, my little friends. You will be well received in Giantland. Only remember your size, and don’t get to boasting, my tiny gods. Here’s your wallet now; and good luck go with you.”

As he spoke, Skrymir took his great sack from his back and plucked it open with one pull at the huge knot. Picking out the wallet of the gods, he laid it on the ground; and flourishing his enormous cap about his[74] head, by way of good-by, he went leaping off toward the hills. The gods watched him, speechless, till he was out of sight. One moment his huge form rose clear against the blue sky as he jumped over a mountain range; the next, it was lost to view on the other side.

Loki turned trembling to the other gods. “Let us turn back,” he cried. “I am not going on to be laughed at in Giantland.” Then his eye caught the wallet. Diving for it, he tore it open, and the starving gods fell to. There was only a mouthful apiece, but it gave them new courage.

Thor brandished his hammer. “Go back? Never!” he cried. “On we travel to Giantland. They shall yet learn to know the great god Thor!”

Thialfi sprinted ahead along the marvelous white road, and Loki, more ravenous than ever, pelted after.

Suddenly, the road turned sharply upward. The gods climbed, panting. There in the distance, beyond the hill-top, gleamed a tremendous palace, all of ice. Immense icicles made its pillars, and its frosty pinnacles glittered above the clouds. In the sunlight it shone with a thousand rainbows.

Thialfi stopped. Straight before him flashed the palace gate, each great icicle-bar blazing back the sun. For a moment he paused, dazzled. Then he saw that wide[75] as the huge bars were, wider still were the spaces between them. He walked through, arms outstretched, without touching on either side. Thor and Loki followed along the glittering ice-roadway to the palace.

Up and down in front paced two giant sentinels, their heads erect and their great eyes peering out through the upper air. The tiny gods slipped unnoticed by their very feet, and into the great hall of the giant king.

Around the sides sat giant nobles on benches as high as hills, and at the end the king himself on his towering throne. Blinding light flashed from the floor, the ceiling, the walls. But the gods did not quail. Proud and straight, they passed unremarked down the center of the hall.

Before the throne Thor stopped, and dashed his hammer on the floor. The vast hall resounded and the giants rose to look.

Thor drew himself up. “I am the great god Thor,” he cried, “whose hammer cleaves the clouds and shakes the sky. I come to demand the homage of the giants.”

Like a burst from a hundred volcanoes at once, the giants’ laughter came booming down the hall.

The giant king smiled. “The giants welcome the gods,” he said kindly, “but we can bow only before proofs of greater power than our own.”

At that, Loki who was nearly starving, could stand it no longer. “Greater power!” he shouted. “Greater power! Let any one here eat food faster than I!”

The giants clapped their hands with a noise like waves smiting the beach. “Hear! Hear!” they roared.

“Have my cook Logi bring a trough of meat,” called the giant king.

Setting the trough before the throne, Logi sat down at one end, and Loki at the other.

“Ready!—Start!” cried the king.

Click-clack! Loki’s little jaws were at it before Logi got his great mouth open. Click-clack, click-clack, they kept on while Logi’s great tongue swept down the trough. Squarely in the middle, their heads bumped, Loki’s little head against Logi’s big one.

“A tie!” cried Thor. And so it seemed. But while Loki had eaten every morsel of meat from the bones, Logi had devoured meat, bones, trough and all.

Thialfi stepped forward, flushing at Loki’s defeat. “Who will race with me?” he cried.

“Hugi! Hugi!” shouted a dozen giant voices.

Hugi walked out, a slender young giant, and led Thialfi to a race-course covered with marble-dust, just behind the palace.

The giant king gave the signal, and off they dashed.[77] Thialfi smaller and quicker, was off first; but Hugi, with his long legs, covered an immense distance at a single bound. Before the course was half finished, Thialfi was running like a tiny hound at the heels of a deer. As they drew nearer the goal, Hugi with a sudden urge, sped forward and crossed the line before Thialfi was three-quarters of the way around.

The contest between Loki and Logi

“Bravo, Hugi! Well run, Thialfi!” cried the giants kindly.

But Thor blazed with wrath from head to foot. His muscles quivered and his throat was dry. “Bring out your largest drinking-horn,” he thundered, “and see how Thor will empty it.”

The giants trooped back into the hall, and Logi brought a horn as deep as a well, filled with mead.

“With us, Thor,” said the king, “a giant is thought a good drinker if he can empty the horn at a single draught; a moderate drinker does it in two, and any giant can do it in three.”

Thor gave his magic belt a quick twist. Instantly his little form began to expand; and he stood before them, a god of majestic size, half as big as the giants themselves, and with muscles greater than their own. Taking the horn in one of his mighty hands, he breathed with all his force and drank till it seemed as if the vessel must have been emptied twice over. Triumphantly he raised his head and looked within. But the mead still brimmed to the horn’s edge.

Astonished and angry, he bent his lips again and drank till he thought he should burst. But again the horn seemed as full as when he had begun. With a last desperate straining, he lifted it a third time and[79] buried his face in its vast depth. He stopped, breathless and choking. The mead had sunk below the rim, but the horn was still more than half full.

A great silence came over the hall. Loki and Thialfi cast down their eyes. But Thor threw back his head, unbaffled. “Give me any weight,” he cried, “and I will lift it. You shall yet see the matchless strength of Thor.”

A gray cat larger than an elephant rubbed itself against the steps of the throne. “Perhaps then, Thor,” said the giant king, “you will lift my cat for me.”

Snorting with scorn, Thor took a swift step forward, and put one immense arm around it. But the cat seemed bound to the floor with iron chains. Thor tugged again. But the harder he pulled, the higher the cat arched its back; and the best he could do was to make it lift one paw from the floor.

Thor roared with rage. “Let me wrestle,” he cried. “I defy any giant of you all to match his strength against mine. Let any one try to bring Thor low, in fair and single combat!”

“Ask my old nurse Elli to come in,” ordered the giant king.

Thor’s eyes flashed. “Do not mock me,” he thundered. “At your risk you taunt the great god Thor.”

“No offense is offered you,” said the giant king kindly. “Elli is no mean opponent. Many a bold champion before now she has brought to his knees.”

As he spoke, there hobbled into the room a hag so bent, so wrinkled, so infirm, that Thor drew back in anger and dismay.

“Elli,” said the giant king, “will you wrestle with the god Thor?”

The old dame nodded her head, and tottering up to the god, cackled tauntingly in his face. “Throw me!” she quavered. “Throw me!”

Enraged beyond endurance, Thor seized her about the waist, meaning to lay her gently upon the floor. But the harder he gripped her, the steadier she stood. Bracing all his muscles Thor took a new hold, but the hag had grasped him in her turn. Something in her slow embrace seemed to sink into his very limbs. His arms loosened. His legs weakened. Before he knew it, he dropped kneeling before her.

“Enough, Elli!” cried the giant king. “Let Thor go. We must give him better entertainment. Come, minstrels. Come, cooks; deck out our board and feast our guests like gods.”

In a twinkling a magnificent repast was spread, and giant jokes sped about the hall. The minstrels played[81] great, sounding tunes upon their mammoth harps, and the giants did their best to make their guests forget the outcome of all their boasting. But the gods, humbled and downcast, took little part in the merrymaking. Even Thor, who had resumed his natural size, had no more pride left in him. They sat silent and dejected, and went off early to bed.

The cat was none other than the terrible serpent

Next morning they rose before daybreak, hoping to[82] escape from the palace without seeing the giants again. But the giant king was up before them, and in the great hall a breakfast stood ready. After they had finished, the king himself led them down the gleaming roadway, and out through the great ice gate, rosy with the light of dawn.

The giant king paused. “Before I leave you, my small friends,” he said, “I must in honesty tell you that the giants admire while they do not yield to the power of the gods. For had it not been for the magic we used, we, and not you, would have been humbled.

“I myself was that giant Skrymir in whose glove you slept. I tied up the wallet with the enchanted rope. It was I whom Thor struck with his unconquerable hammer. Any one of the blows would have killed me had I not each time brought a mountain in between. There in the distance you can see in the peak the three great clefts his hammer made.

“Yesterday Loki could not win his eating wager. But it was because he was matched against Logi who is none other than Fire itself, which could devour meat, bones, trough and all. Thialfi lost his race. But we giants marveled at his speed, for he ran against Hugi who is Thought, the swiftest thing in the world.

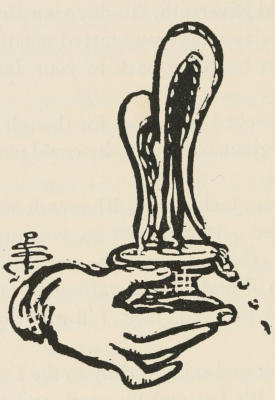

“When Thor drank, then indeed we wondered; for[83] his drinking-horn was connected with the ocean, and his great draughts made the waters ebb from shore to shore. My cat which he tried to lift was none other than the terrible serpent which lies around the world with its tail in its mouth. When Thor tugged, he lifted it up till its back arched against the sky, and it seemed likely to slip altogether out of the sea.

“When he wrestled with my nurse Elli, we saw the greatest marvel of all. For she is Old Age, whom no one has ever withstood.

“But strong as you are, do not boast again, my tiny gods. For remember, the giants’ magic is as great as the giants themselves, and can never be conquered.”

Overcome with rage, Thor raised his hammer to shatter the giant and his palace forever. But a sudden mist blinded his eyes. When it cleared, he found himself, with Loki and Thialfi, alone on a wide moor glowing in the sunrise.

—From a Norse myth.

The giants were building a causeway

The giants were building a causeway from Ireland over to Scotland. A great bridge it was to be: thousands of piles sunk in the sea, and over them such a road as would take ten giants abreast. All the giants in Ulster were working to make it, and Fin M’Coul was the head of them all. Whack, whack, whack! went their sledges pounding the piles; and roar, roar, roar! came Fin’s big voice telling how to place them.