Transcriber’s Note

Cover image created by Transcriber, using an illustration from the original book, and placed into the Public Domain.

To see larger, higher-resolution images, click “(Larger)” below the images. The two maps may be seen in a third, intermediate size by stretching them or right-clicking and opening in a new tab or window.

BEING THE NARRATIVE OF AN EXPEDITION FROM THE ATLANTIC TO THE PACIFIC,

UNDERTAKEN WITH THE VIEW OF EXPLORING A ROUTE ACROSS THE CONTINENT TO BRITISH COLUMBIA THROUGH BRITISH TERRITORY, BY ONE OF THE NORTHERN PASSES IN THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS.

BY

VISCOUNT MILTON, F.R.G.S., F.G.S., &c.,

AND

W. B. CHEADLE, M.A., M.D. Cantab., F.R.G.S.

Ros. Well, this is the Forest of Arden.

Touch. Ay, now I am in Arden; the more fool I; when I was at home, I was in a better place: but travellers must be content.

As You Like It.

LONDON:

CASSELL, PETTER, AND GALPIN,

LUDGATE HILL, E.C.

[THE RIGHT OF TRANSLATION IS RESERVED.]

TO

THE COUNTESS FITZWILLIAM

AND

MRS. CHEADLE,

WHO TOOK SO GREAT AN INTEREST IN THE SUCCESS OF THE TRAVELLERS, THIS ACCOUNT OF THEIR JOURNEY IS DEDICATED BY

THE AUTHORS.

4, Grosvenor Square,

1st June, 1865.

v

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

| Sail for Quebec—A Rough Voyage—Our Fellow-Passengers—The Wreck—Off the Banks of Newfoundland—Quebec—Up the St. Lawrence—Niagara—The Captain and the Major—Westward Again—Sleeping Cars—The Red Indian—Steaming up the Mississippi—Lake Pippin—Indian Legend—St. Paul, Minnesota—The Great Pacific Railroad—Travelling by American Stage-Wagon—The Country—Our Dog Rover—The Massacre of the Settlers by the Sioux—Culpability of the United States Government—The Prairie—Shooting by the Way—Reach Georgetown | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Georgetown—Minnesota Volunteers—The Successful Hunters—An Indian Hag—Resolve to go to Fort Garry in Canoes—Rumours of a Sioux Outbreak—The Half-breeds refuse to Accompany us—Prepare to Start Alone—Our Canoes and Equipment—A Sioux War Party—The Half-breed’s Story—Down Red River—Strange Sights and Sounds—Our First Night Out—Effects of the Sun and Mosquitoes—Milton Disabled—Monotony of the Scenery—Leaky Canoes—Travelling by Night—The “Oven” Camp—Hunting Geese in Canoes—Meet the Steamer—Milton’s Narrow Escape—Treemiss and Cheadle follow Suit—Carried Down the Rapids—Vain Attempts to Ascend—A Hard Struggle—On Board at last—Start once more—Delays—Try a Night Voyage again—The “Riband Storm”—“In Thunder, Lightning, and in Rain”—Fearful Phenomena—Our Miserable Plight—No Escape—Steering in Utter Darkness—Snags and Rocks—A Long Night’s Watching—No Fire—A Drying Day—Another Terrible Storm—And Another—Camp of Disasters—Leave it at last—Marks of the Fury of the Storms—Provisions at an End—Fishing for Gold-eyes—A Day’s Fast—Slaughter of Wild-Fowl—Our Voracity—A Pleasant Awakening—Caught up by the Steamer—Pembina—Fort Garry—La Ronde—We go under Canvass | 18vi |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Fort Garry—Origin of the Red River Settlement—The First Settlers—Their Sufferings—The North-Westers—The Grasshoppers—The Blackbirds—The Flood—The Colony in 1862—King Company—Farming at Red River—Fertility of the Soil—Isolated Position of the Colony—Obstructive Policy of the Company—Their Just Dealing and Kindness to the Indians—Necessity for a proper Colonial Government—Value of the Country—French Canadians and Half-breeds—Their Idleness and Frivolity—Hunters and Voyageurs—Extraordinary Endurance—The English and Scotch Settlers—The Spring and Fall Hunt—Our Life at Fort Garry—Too Late to cross the Mountains before Winter—Our Plans—Men—Horses—Bucephalus—Our Equipment—Leave Fort Garry—The “Noce”—La Ronde’s Last Carouse—Delightful Travelling—A Night Alarm—Vital Deserts—Fort Ellice—Delays—Making Pemmican—Its Value to the Traveller—Swarms of Wild-Fowl—Good Shooting—The Indian Summer—A Salt Lake Country—Search for Water—A Horse’s Instinct—South Saskatchewan—Arrive at Carlton | 36 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Carlton—Buffalo close to the Fort—Fall of Snow—Decide to Winter near White Fish Lake—The Grisly Bears—Start for the Plains—The Dead Buffalo—The White Wolf—Running Buffalo Bulls—The Gathering of the Wolves—Treemiss Lost—How he Spent the Night—Indian Hospitality—Visit of the Crees—The Chief’s Speech—Admire our Horses—Suspicions—Stratagem to Elude the Crees—Watching Horses at Night—Suspicious Guests—The Cows not to be Found—More Running—Tidings of our Pursuers—Return to the Fort | 59 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| The Ball—Half-breed Finery—Voudrie and Zear return to Fort Garry—Treemiss starts for the Montagne du Bois—Leave Carlton for Winter Quarters—Shell River—La Belle Prairie—Riviere Crochet—The Indians of White Fish Lake—Kekekooarsis, or “Child of the Hawk,” and Keenamontiayoo, or “The Long Neck”—Their Jollification—Passionate Fondness for Rum—Excitement in the Camp—Indians flock in to Taste the Fire-water—Sitting out our Visitors—A Weary Day—Cache the Rum Keg by Night—Retreat to La Belle Prairie—Site of our House—La Ronde as Architect—How to Build a Log Hut—The Chimney—A Grand Crash—Our Dismay—Milton supersedes La Ronde—The Chimney Rises again—Our Indian Friends—The Frost sets in | 70 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Furnishing—Cheadle’s Visit to Carlton—Treemiss there—His Musical Evening with Atahk-akoohp—A very Cold Bath—State Visit of the Assiniboines—Their Message to Her Majesty—How they found out we had Rum—Fort Milton Completed—The Crees of the Woods—Contrast tovii the Crees of the Plains—Indian Children—Absence of Deformity—A “Moss-bag”—Kekekooarsis and his Domestic Troubles—The Winter begins in Earnest—Wariness of all Animals—Poisoning Wolves—Caution of the Foxes—La Ronde and Cheadle start for the Plains—Little Misquapamayoo—Milton’s Charwoman—On the Prairies—Stalking Buffalo—Belated—A Treacherous Blanket—A Cold Night Watch—More Hunting—Cheadle’s Wits go Wool-gathering—La Ronde’s Indignation—Lost all Night—Out in the Cold again—Our Camp Pillaged—Turn Homewards—Rough and Ready Travelling—Arrive at Fort Milton—Feasting | 79 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Trapping—The Fur-bearing Animals—Value of different Furs—The Trapper’s Start into the Forest—How to make a Marten Trap—Steel Traps for Wolves and Foxes—The Wolverine—The Way he Gets a Living—His Destructiveness and Persecution of the Trapper—His Cunning—His Behaviour when caught in a Trap—La Ronde’s Stories of the Carcajou—The Trapper’s Life—The Vast Forest in Winter—Sleeping Out—The Walk—Indians and Half-breeds—Their Instinct in the Woods—The Wolverine Demolishes our Traps—Attempts to Poison him—Treemiss’s Arrival—He relates his Adventures—A Scrimmage in the Dark—The Giant Tamboot—His Fight with Atahk-akoohp—Prowess of Tamboot—Decide to send our Men to Red River for Supplies—Delays | 99 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Milton visits Carlton—Fast Travelling—La Ronde and Bruneau set out for Fort Garry—Trapping with Misquapamayoo—Machinations against the Wolverine—The Animals’ Fishery—The Wolverine outwits us—Return Home—The Cree Language—How an Indian tells a Story—New Year’s Day among the Crees—To the Prairies again—The Cold—Travelling with Dog-sleighs—Out in the Snow—Our New Attendants—Prospect of Starvation—A Day of Expectation—A Rapid Retreat—The Journey Home—Indian Voracity—Res Augusta Domi—Cheadle’s Journey to the Fort—Perversity of his Companions—“The Hunter” yields to Temptation—Milton’s Visit to Kekekooarsis—A Medicine Feast—The New Song—Cheadle’s Journey Home—Isbister and his Dogs—Mahaygun, “The Wolf”—Pride and Starvation—Our Meeting at White Fish Lake | 113 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Our New Acquaintances—Taking it Quietly—Mahaygun Fraternises with Keenamontiayoo—The Carouse—Importunities for Rum—The Hunter asks for more—A Tiresome Evening—Keenamontiayoo Renounces us—His Night Adventure—Misquapamayoo’s Devotion—The Hunter returns Penitent—The Plains again—The Wolverine on our Track—The Last Band of Buffalo—Gaytchi Mohkamarn, “The Big Knife”—Theviii Cache Intact—Starving Indians—Story of Keenamontiayoo—Indian Gambling—The Hideous Philosopher—Dog Driving—Shushu’s Wonderful Sagacity—A Long March—Return to La Belle Prairie—Household Cares—Our Untidy Dwelling—Our Spring Cleaning—The Great Plum Pudding—Unprofitable Visitors—Rover’s Accomplishments Astonish the Indians—Famine Everywhere | 138 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| La Ronde’s Return—Letters from Home—A Feast—The Journey to Red River and back—Hardships—The Frozen Train—Three Extra Days—The Sioux at Fort Garry—Their Spoils of War—Late Visitors—Musk-Rats and their Houses—Rat-catching—Our Weather-glass—Moose Hunting in the Spring—Extreme Wariness of the Moose—His Stratagem to Guard against Surprise—Marching during the Thaw—Prepare to leave Winter Quarters—Search for the Horses—Their Fine Condition—Nutritious Pasturage—Leave La Belle Prairie—Carlton again—Good-bye to Treemiss and La Ronde—Baptiste Supernat—Start for Fort Pitt—Passage of Wild-Fowl—Baptiste’s Stories—Crossing Swollen Rivers—Addition to our Party—Shooting for a Living—The Prairie Bird’s Ball—Fort Pitt—Peace between the Crees and Blackfeet—Cree Full Dress—The Blackfeet—The Dress of their Women—Indian Solution of a Difficulty—Rumours of War—Hasty Retreat of the Blackfeet—Louis Battenotte, “The Assiniboine”—His Seductive Manners—Departure for Edmonton—A Night Watch—A Fertile Land—The Works of Beaver—Their Effect on the Country—Their Decline in Power—How we crossed the Saskatchewan—Up the Hill—Eggs and Chickens—Arrive at Edmonton | 161 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Edmonton—Grisly Bears—The Roman Catholic Mission at St. Alban’s—The Priest preaches a Crusade against the Grislies—Mr. Pembrun’s Story—The Gold Seekers—Perry, the Miner—Mr. Hardisty’s Story—The Cree in Training—Running for Life—Hunt for the Bears—Life at a Hudson’s Bay Fort—Indian Fortitude—Mr. O’B. introduces Himself—His Extensive Acquaintance—The Story of his Life—Wishes to Accompany us—His Dread of Wolves and Bears—He comes into the Doctor’s hands—He congratulates us upon his Accession to our Party—The Hudson’s Bay People attempt to dissuade us from trying the Leather Pass—Unknown Country on the West of the Mountains—The Emigrants—The other Passes—Explorations of Mr. Ross and Dr. Hector—Our Plans—Mr. O’B. objects to “The Assiniboine”—“The Assiniboine” protests against Mr. O’B.—Our Party and Preparations | 183 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Set out from Edmonton—Prophecies of Evil—Mr. O’B.’s Forebodings—Lake St. Ann’s—We enter the Forest—A Rough Trail—Mr. O’B., impressedix with the Difficulties which beset him, commences the study of Paley—Pembina River—The Coal-bed—Game—Curious Habit of the Willow Grouse—Mr. O’B. en route—Changes wrought by Beaver—The Assiniboine’s Adventure with the Grisly Bears—Mr. O’B. prepares to sell his Life dearly—Hunt for the Bears—Mr. O’B. Protects the Camp—The Bull-dogs—The Path through the Pine Forest—The Elbow of the McLeod—Baptiste becomes Discontented—Trout Fishing—Moose Hunting—Baptiste Deserts—Council—Resolve to Proceed—We lose the Trail—The Forest on Fire—Hot Quarters—Working for Life—Escape—Strike the Athabasca River—First View of the Rocky Mountains—Mr. O’B. spends a Restless Night—Over the Mountain—Magnificent Scenery—Jasper House—Wild Flowers—Hunting the “Mouton Gris” and the “Mouton Blanc” | 203 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Making a Raft—Mr. O’B. at Hard Labour—He admires our “Youthful Ardour”—News of Mr. Macaulay—A Visitor—Mr. O’B. Fords a River—Wait for Mr. Macaulay—The Shushwaps of the Rocky Mountains—Winter Famine at Jasper House—The Wolverine—The Miners before us—Start again—Cross the Athabasca—The Priest’s Rock—Site of the Old Fort, “Henry’s House”—The Valley of the Myette—Fording Rapids—Mr. O’B. on Horseback again—Swimming the Myette—Cross it for the Last Time—The Height of Land—The Streams run Westward—Buffalo-dung Lake—Strike the Fraser River—A Day’s Wading—Mr. O’B.’s Hair-breadth Escapes—Moose Lake—Rockingham Falls—More Travelling through Water—Mr. O’B. becomes disgusted with his Horse—Change in Vegetation—Mahomet’s Bridge—Change in the Rocks—Fork of the Fraser, or original Tête Jaune Cache—Magnificent Scenery—Robson’s Peak—Flood and Forest—Horses carried down the Fraser—The Pursuit—Intrepidity of The Assiniboine—He rescues Bucephalus—Loss of Gisquakarn—Mr. O’B.’s Reflections and Regrets—Sans Tea and Tobacco—The Extent of our Losses—Mr. O’B. and Mrs. Assiniboine—Arrive at The Cache | 236 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Tête Jaune Cache—Nature of the Country—Wonderful View—West of the Rocky Mountains—Rocky Mountains still—The “Poire,” or Service Berry—The Shushwaps of The Cache—The Three Miners—Gain but little Information about the Road—The Iroquois return to Jasper House—Loss of Mr. O’B.’s Horse—Leave The Cache—The Watersheds—Canoe River—Perilous Adventure with a Raft—Milton and the Woman—Extraordinary Behaviour of Mr. O’B.—The Rescue—The Watershed of the Thompson—Changes by Beaver—Mount Milton—Enormous Timber—Cross the River—Fork of the North Thompson—A Dilemma—No Road to be Found—Cross the North-west Branch—Mr. O’B.’s Presentiment of Evil—Lose the Trail again—Which Way shall we Turn?—Resolve to try and reach Kamloops—A Naturalx Bridge—We become Beasts of Burden—Mr. O’B. objects, but is overruled by The Assiniboine—“A Hard Road to Travel”—Miseries of driving Pack-horses—An Unwelcome Discovery—The Trail Ends—Lost in the Forest—Our Disheartening Condition—Council of War—Explorations of The Assiniboine, and his Report—A Feast on Bear’s Meat—How we had a Smoke, and were encouraged by The Assiniboine | 264 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| We commence to Cut our Way—The Pathless Primeval Forest—The Order of March—Trouble with our Horses: their Perversity—Continual Disasters—Our Daily Fare—Mount Cheadle—Country Improves only in Appearance—Futile Attempt to Escape out of the Valley—A Glimpse of Daylight—Wild Fruits—Mr. O’B. triumphantly Crosses the River—The Assiniboine Disabled—New Arrangements—Hopes of Finding Prairie-Land—Disappointment—Forest and Mountain Everywhere—False Hopes again—Provisions at an End—Council of War—The Assiniboine Hunts without Success—The Headless Indian—“Le Petit Noir” Condemned and Executed—Feast on Horse-flesh—Leave Black Horse Camp—Forest again—The Assiniboine becomes Disheartened—The Grand Rapid—A Dead Lock—Famishing Horses—The Barrier—Shall we get Past?—Mr. O’B. and Bucephalus—Extraordinary Escape of the Latter—More Accidents—La Porte d’Enfer—Step by Step—The Assiniboine Downcast and Disabled—Mrs. Assiniboine takes his Place—The Provisions give out again—A Dreary Beaver Swamp—The Assiniboine gives up in Despair—Mr. O’B. begins to Doubt, discards Paley, and prepares to become Insane—We kill another Horse—A Bird of Good Omen—The Crow speaks Truth—Fresher Sign—A Trail—The Road rapidly Improves—Out of the Forest at last! | 286 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| On a Trail Again—The Effect on Ourselves and the Horses—The Changed Aspect of the Country—Wild Fruits—Signs of Man Increase—Enthusiastic Greeting—Starving again—Mr. O’B. finds Caliban—His Affectionate Behaviour to him—The Indians’ Camp—Information about Kamloops—Bartering for Food—Clearwater River—Cross the Thompson—The Lily-berries—Mr. O’B. and The Assiniboine fall out—Mr. O’B. flees to the Woods—Accuses The Assiniboine of an attempt to Murder him—Trading for Potatoes—More Shushwaps—Coffee and Pipes—Curious Custom of the Tribe—Kamloops in Sight—Ho! for the Fort—Mr. O’B. takes to his Heels—Captain St. Paul—A Good Supper—Doubts as to our Reception—Our Forbidding Appearance—Our Troubles at an End—Rest | 311 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Kamloops—We discover True Happiness—The Fort and Surrounding Country—The Adventures of the Emigrants who preceded us—Catastrophe at the Grand Rapid—Horrible Fate of Three Canadians—Cannibalism—Practicability of a Road by the Yellow Head Pass—Variousxi Routes from Tête Jaune Cache—Advantages of the Yellow Head Pass, contrasted with those to the South—The Future Highway to the Pacific—Return of Mr. McKay—Mr. O’B. sets out alone—The Murderers—The Shushwaps of Kamloops—Contrast between them and the Indians East of the Rocky Mountains—Mortality—The Dead Unburied—Leave Kamloops—Strike the Wagon Road from the Mines—Astonishment of the Assiniboine Family—The remarkable Terraces of the Thompson and Fraser—Their Great Extent: contain Gold—Connection with the Bunch-grass—The Road along the Thompson—Cook’s Ferry—The Drowned Murderer—Rarity of Crime in the Colony—The most Wonderful Road in the World—The Old Trail—Pack-Indians—Indian Mode of catching Salmon—Gay Graves—The Grand Scenery of the Cañons—Probable Explanation of the Formation of the Terraces—Yale—Hope and Langley—New Westminster—Mr. O’B. turns up again—Mount Baker—The Islands of the Gulf of Georgia—Victoria, Vancouver Island | 322 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Victoria—The Rush there from California—Contrast to San Francisco under similar Circumstances—The Assiniboines see the Wonders of Victoria—Start for Cariboo—Mr. O’B. and The Assiniboine are Reconciled—The former re-establishes his Faith—Farewell to the Assiniboine Family—Salmon in Harrison River—The Lakes—Mr. O’B.’s Triumph—Lilloet—Miners’ Slang—The “Stage” to Soda Creek—Johnny the Driver—Pavilion Mountain—The “Rattlesnake Grade”—The Chasm—Way-side Houses on the Road to the Mines—We meet a Fortunate Miner—The Farming Land of the Colony—The Steamer—Frequent Cocktails—The Mouth of Quesnelle—The Trail to William’s Creek—A Hard Journey—Dead Horses—Cameron Town, William’s Creek | 351 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| William’s Creek, Cariboo—The Discoverers—The Position and Nature of the Gold Country—Geological Features—The Cariboo District—Hunting the Gold up the Fraser to Cariboo—Conjectured Position of the Auriferous Quartz Veins—Various kinds of Gold—Drawbacks to Mining in Cariboo—The Cause of its Uncertainty—Extraordinary Richness of the Diggings—“The Way the Money Goes”—Miners’ Eccentricities—Our Quarters at Cusheon’s—Price of Provisions—The Circulating Medium—Down in the Mines—Profits and Expenses—The “Judge”—Our Farewell Dinner—The Company—Dr. B——l waxes Eloquent—Dr. B——k’s Noble Sentiments—The Evening’s Entertainment—Dr. B——l retires, but is heard of again—General Confusion—The Party breaks up—Leave Cariboo—Boating down the Fraser—Camping Out—William’s Lake—Catastrophe on the River—The Express Wagon—Difficulties on the Way—The Express-man Prophesies his own Fate—The Road beyond Lytton—A Break-down—Furious Drive into Yale—Victoria once more | 364xii |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Nanaimo and San Juan—Resources of British Columbia and Vancouver Island—Minerals—Timber—Abundance of Fish—Different kinds of Salmon—The Hoolicans, and the Indian Method of Taking them—Pasturage—The Bunch-grass: its Peculiarities and Drawbacks—Scarcity of Farming Land—Different Localities—Land in Vancouver Island—Contrast between California and British Columbia—Gross Misrepresentations of the Latter—Necessity for the Saskatchewan as an Agricultural Supplement—Advantages of a Route across the Continent—The Americans before us—The Difficulties less by the British Route—Communication with China and Japan by this Line—The Shorter Distance—The Time now come for the Fall of the Last Great Monopoly—The North-West Passage by Sea, and that by Land—The Last News of Mr. O’B.—Conclusion | 385 |

xiii

| PAGE | |

| Our Party across the Mountains Frontispiece. | |

| Our Night Camp on Eagle River.—Expecting the Crees | 68 |

| Our Winter Hut.—La Belle Prairie | 76 |

| A Marten Trap | 102 |

| Swamp formed by Beaver, with Ancient Beaver House and Dam | 179 |

| Fort Edmonton, on the North Saskatchewan | 183 |

| The Forest on Fire | 225 |

| Over the Mountain, near Jasper House | 231 |

| View from the Hill opposite Jasper House.—the Upper Lake of the Athabasca River and Priest’s Rock | 232 |

| Crossing the Athabasca River, in the Rocky Mountains | 245 |

| The Assiniboine rescues Bucephalus | 259 |

| Our Misadventure with the Raft in crossing Canoe River | 271 |

| A View on the North Thompson, looking Eastward | 275 |

| The Trail at an End | 281 |

| Mr. O’B. triumphantly Crosses the River | 292 |

| The Headless Indian | 296 |

| The Terraces on the Fraser River | 338 |

| Yale, on the Fraser River | 345 |

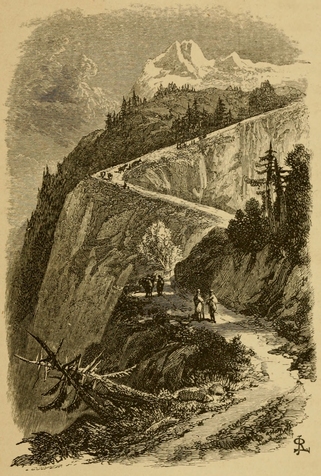

| The “Rattlesnake Grade.”—Pavillon Mountain, British Columbia; altitude, 4,000 feet | 356 |

| A Way-side House.—Arrival of Miners | 357 |

| A Way-side House at Midnight | 357 |

| Miners washing for Gold | 370 |

| The Cameron “Claim,” William’s Creek, Cariboo | 371 |

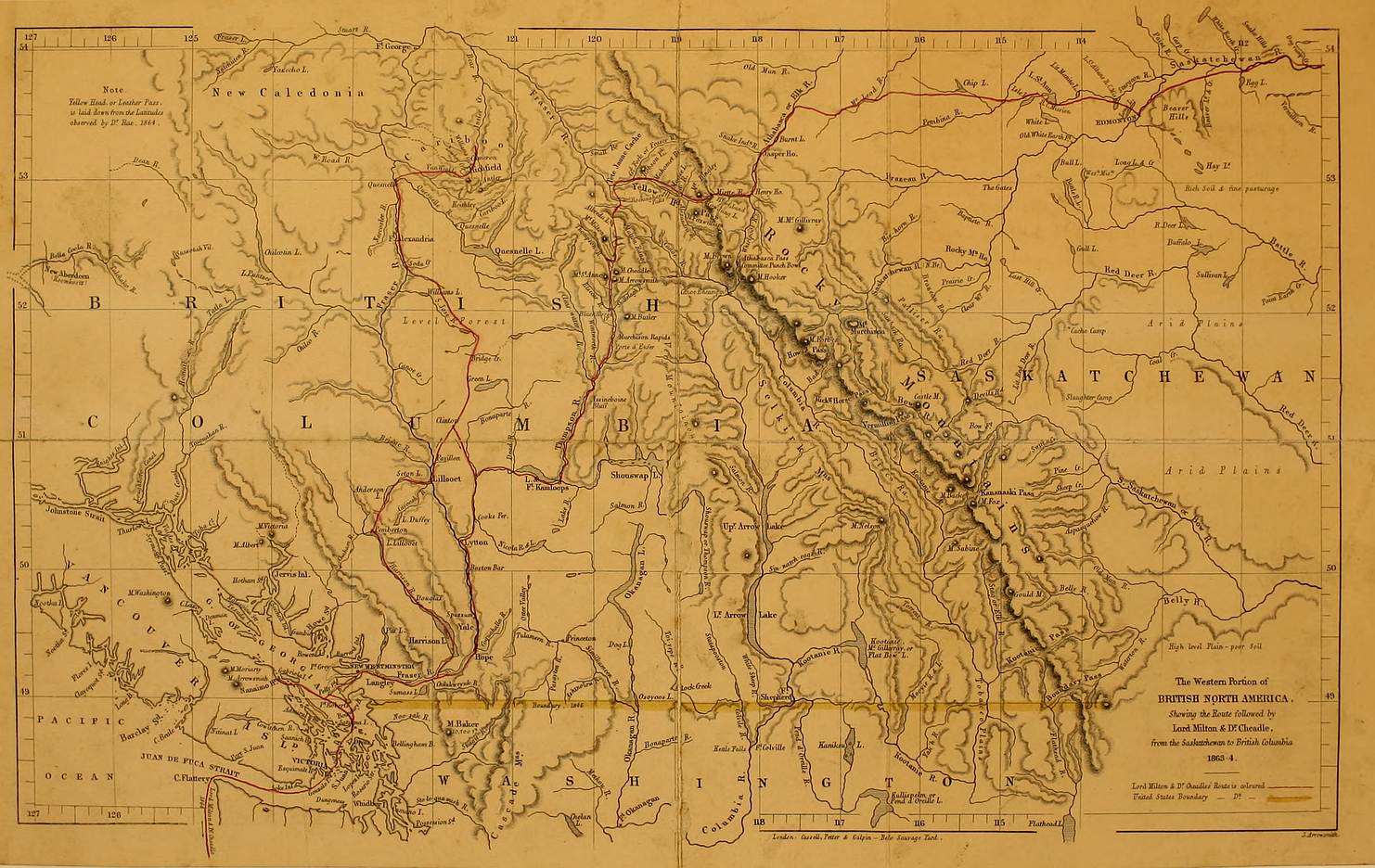

| General Map of British North America, showing the Authors’ Route across the Continent (Bound with Volume.) | |

| Map of the Western Portion of British North America, showing the Route across the Rocky Mountains by the Yellow Head, or, Leather Pass into British Columbia, on a larger scale. (In the Pocket.) |

xv

The following pages contain the narrative of an Expedition across the Continent of North America, through the Hudson’s Bay Territories, into British Columbia, by one of the northern passes in the Rocky Mountains. The expedition was undertaken with the design of discovering the most direct route through British territory to the gold regions of Cariboo, and exploring the unknown country on the western flank of the Rocky Mountains, in the neighbourhood of the sources of the north branch of the Thompson River.

The Authors have been anxious to give a faithful account of their travels and adventures amongst the prairies, forests, and mountains of the Far West, and have studiously endeavoured to preserve the greatest accuracy in describing countries previously little known. But one of the principal objects they havexvi had in view has been to draw attention to the vast importance of establishing a highway from the Atlantic to the Pacific through the British possessions; not only as establishing a connection between the different English colonies in North America, but also as affording a means of more rapid and direct communication with China and Japan. Another advantage which would follow—no less important than the preceding—would be the opening out and colonisation of the magnificent regions of the Red River and Saskatchewan, where 65,000 square miles of a country of unsurpassed fertility, and abounding in mineral wealth, lies isolated from the world, neglected, almost unknown, although destined, at no distant period perhaps, to become one of the most valuable possessions of the British Crown.

The idea of a route across the northern part of the Continent is not a new one. The project was entertained by the early French settlers in Canada, and led to the discovery of the Rocky Mountains. It has since been revived and ably advocated by Professor Hind and others, hitherto without success.

The favourite scheme of geographers in this country for the last three centuries has been thexvii discovery of a North-West Passage by sea, as the shortest route to the rich countries of the East. The discovery has been made, but in a commercial point of view it has proved valueless. We have attempted to show that the original idea of the French Canadians was the right one, and that the true North-West Passage is by land, along the fertile belt of the Saskatchewan, leading through British Columbia to the splendid harbour of Esquimalt, and the great coal-fields of Vancouver Island, which offer every advantage for the protection and supply of a merchant fleet trading thence to India, China, and Japan.

The Illustrations of this Work are taken almost entirely from photographs and sketches taken on the spot, and will, it is hoped, possess a certain value and interest, as depicting scenes never before drawn by any pencil, and many of which had never previously been visited by any white man, some of them not even by an Indian. Our most cordial thanks are due to Mr. R. P. Leitch, and Messrs. Cooper and Linton, for the admirable manner in which they have been executed; and to Mr. Arrowsmith, for the great care and labour he has bestowed on working out the geography of a district heretofore so imperfectly known. We also beg to acknowledge thexviii very great obligations under which we lie to Sir James Douglas, late Governor of British Columbia and Vancouver Island; Mr. Donald Fraser, of Victoria; and Mr. McKay, of Kamloops, for much valuable information concerning the two colonies, and who, with many others, showed us the greatest kindness during our stay in those countries.

4, Grosvenor Square,

June 1st, 1865.

The Western Portion of

BRITISH NORTH AMERICA.

Showing the Route followed by

Lord Milton & Dr. Cheadle.

from the Saskatchewan to British Columbia

1863–4.

Sail for Quebec—A Rough Voyage—Our Fellow-Passengers—The Wreck—Off the Banks of Newfoundland—Quebec—Up the St. Lawrence—Niagara—The Captain and the Major—Westward Again—Sleeping Cars—The Red Indian—Steaming up the Mississippi—Lake Pippin—Indian Legend—St. Paul, Minnesota—The Great Pacific Railroad—Travelling by American Stage-Wagon—The Country—Our Dog Rover—The Massacre of the Settlers by the Sioux—Culpability of the United States Government—The Prairie—Shooting by the Way—Reach Georgetown.

On the 19th of June, 1862, we embarked in the screw-steamer Anglo-Saxon, bound from Liverpool to Quebec. The day was dull and murky; and as the trader left the landing-stage, a drizzling rain began to fall. This served as an additional damper to our spirits, already sufficiently low at the prospect of leaving home for a long and indefinite period. Unpleasant anticipations of ennui, and still more bodily suffering, had risen up within the hearts of both of us—for we agree in detesting a sea-voyage, although not willing to go the length of endorsing the confession wrung from that light of the American2 Church—the Rev. Henry Ward Beecher—by the agonies of sea-sickness, that “those whom God hateth he sendeth to sea.”

We had a very rough passage, fighting against head winds nearly all the way; but rapidly getting our sea-legs, we suffered little from ennui, being diverted by our observations on a somewhat curious collection of fellow-passengers. Conspicuous amongst them were two Romish bishops of Canadian sees, on their return from Rome, where they had assisted at the canonisation of the Japanese martyrs, and each gloried in the possession of a handsome silver medal, presented to them by his Holiness the Pope for their eminent services on that occasion. These two dignitaries presented a striking contrast. One, very tall and emaciated, was the very picture of an ascetic, and passed the greater part of his time in the cabin reading his missal and holy books. His inner man he satisfied by a spare diet of soup and fish, gratifying to the full no carnal appetite except that for snuff, which he took in prodigious quantity, and avoiding all society except that of his brother bishop. The latter, “a round, fat, oily man of God,” of genial temper, and sociable disposition, despised not the good things of this world, and greatly affected a huge meerschaum pipe, from which he blew a cloud with great complacency. As an antidote to them, we had an old lady afflicted with Papophobia, who caused us much amusement by inveighing bitterly against the culpable weakness of which Her Majesty the Queen had been guilty, in accepting the present3 of a side-board from Pius IX. A Canadian colonel, dignified, majestic, and speaking as with authority, discoursed political wisdom to an admiring and obsequious audience. He lorded it over our little society for a brief season, and then suddenly disappeared. Awful groans and noises, significant of sickness and suffering, were heard proceeding from his cabin. But, at last, one day when the weather had moderated a little, we discovered the colonel once more on deck, but, alas! how changed. His white hat, formerly so trim, was now frightfully battered; his cravat negligently tied; his whole dress slovenly. He sat with his head between his hands, dejected, silent, and forlorn.

The purser, a jolly Irishman, came up at the moment, and cried, “Holloa, colonel! on deck? Glad to see you all right again.”

“All right, sir!” cried the colonel, fiercely; “all right, sir? I’m not all right. I’m frightfully ill, sir! I’ve suffered the tortures of the—condemned; horrible beyond expression; but it’s not the pain I complain of; that, sir, a soldier like myself knows how to endure. But I’m thoroughly ashamed of myself, and shall never hold up my head again!”

“My dear sir,” said the purser, soothingly, with a sly wink at us, “what on earth have you been doing? There is nothing, surely, in sea-sickness to be ashamed of.”

“I tell you, sir,” said the colonel, passionately, “that it’s most demoralising! Think of a man of my years, and of my standing and position, lying for4 hours prone on the floor, with his head over a basin, making a disgusting beast of himself in the face of the company! I’ve lost my self-respect, sir; and I shall never be able to hold up my head amongst my fellow-men again!”

As he finished speaking, he again dropped his head between his hands, and thus did not observe the malicious smile on the purser’s face, or notice the suppressed laughter of the circle of listeners attracted round him by the violence of his language.

The young lady of our society—for we had but one—was remarkable for her solitary habits and pensive taciturnity. When we arrived at Quebec harbour, a most extraordinary change came over her; and we watched her in amazement, as she darted restlessly up and down the landing-stage in a state of the greatest agitation, evidently looking for some one who could not be found. In vain she searched, and at last rushed off to the telegraph office in a state of frantic excitement. Later the same day we met her at the hotel, seated by the side of a young gentleman, and as placid as ever. It turned out that she had come over to be married, but her lover had arrived too late to meet her; he, however, had at last made his appearance, and honourably fulfilled his engagement. A wild Irishman, continually roaring with laughter, a Northern American, rabid against “rebels,” and twenty others, made up our list of cabin passengers. Out of these we beg to introduce, as Mr. Treemiss, a gentleman going out like ourselves, to hunt buffalo on the plains, and equally enthusiastic in his anticipations5 of a glorious life in the far West. We soon struck up an intimate acquaintance, and agreed to travel in company as far as might be agreeable to the plans of each.

Before we reached the banks of Newfoundland we fell in with numerous evidences of a recent storm; a quantity of broken spars floated past, and a dismasted schooner, battered and deserted by her crew. On her stern was the name Ruby, and the stumps of her masts bore the marks of having been recently cut away.

Off the “banks” we encountered a fog so dense that we could not see twenty yards ahead. The steam whistle was blown every five minutes, and the lead kept constantly going. The ship crashed through broken ice, and we all strained our eyes for the first sight of some iceberg looming through the mist. A steamer passed close to us, her proximity being betrayed only by the scream of her whistle. Horrible stories of ships lost with all hands on board, from running against an iceberg, or on the rock-bound coast, became the favourite topic of conversation amongst the passengers; the captain looked anxious, and every one uncomfortable.

After two days, however, we emerged in safety from the raw, chilling fogs into clear sunlight at the mouth of the St. Lawrence, and on the 2nd of July steamed up the river to Quebec. The city of Quebec, with its bright white houses, picked out with green, clinging to the sides of a commanding bluff, which appears to rise up in the middle of the great river so6 as to bar all passage, has a striking beauty beyond comparison. We stayed but to see the glorious plains of Abraham, and then hastened up the St. Lawrence by Montreal, through the lovely scenery of the “Thousand Islands,” and across Lake Ontario to Toronto.

We determined to spend a day at Niagara, and, taking another steamer here, passed over to Lewiston, on the American side of the lake, at the mouth of the Niagara River. From Lewiston a railway runs to within a mile of the Falls, following the edge of the precipitous cliffs on the east side of the narrow ravine, through which the river rushes to pour itself into Lake Ontario. Glad to escape the eternal clanging of the engine bell warning people to get out of the way as the train steamed along the streets, we walked across the suspension bridge to the Canadian side of the river, and forward to the Clifton House. We heard the roar of the cataract soon after leaving the station, and caught glimpses of it from time to time along the road; but at last we came out into the open, near the hotel, and saw, in full view before us, the American wonder of the world. Our first impression was certainly one of disappointment. Hearing so much from earliest childhood of the great Falls of Niagara, one forms a most exaggerated conception of their magnitude and grandeur. But the scene rapidly began to exercise a charm over us, and as we stood on the edge of the Horseshoe Fall, on the very brink of the precipice over which the vast flood hurls itself, we confessed7 the sublimity of the spectacle. We returned continually to gaze on it, more and more fascinated, and in the bright clear moonlight of a beautiful summer’s night, viewed the grand cataract at its loveliest time. But newer subjects before us happily forbid any foolish attempt on our part to describe what so many have tried, but never succeeded, in painting either with pen or pencil. On the Lewiston steamer we had made the acquaintance of Captain ——, or, more properly speaking, he had made ours. The gallant captain was rather extensively got up, his face smooth shaven, with the exception of the upper lip, which was graced with a light, silky moustache. He wore a white hat, cocked knowingly on one side, and sported an elegant walking cane; the blandest of smiles perpetually beamed on his countenance, and he accosted us in the most affable and insinuating manner, with some remark about the heat of the weather. Dextrously improving the opening thus made, he placed himself in a few minutes on the most intimate terms. Regretting exceedingly that he had not a card, he drew our attention to the silver mounting on his cane, whereon was engraved, “Captain ——, of ——.” Without further inquiry as to who we were, he begged us to promise to come over and stay with him at his nice little place, and we should have some capital “cock shooting” next winter. The polite captain then insisted on treating us to mint-juleps at the bar, and there introduced us with great ceremony to a tall, angular man, as Major So-and-so, of the Canadian Rifles.

8

The major was attired in a very seedy military undress suit, too small and too short for him, and he carried, like Bardolph, a “lantern in the poop,” which shone distinct from the more lurid and darker redness of the rest of his universally inflamed features. His manner was rather misty, yet solemn and grand withal, and he comported himself with so much dignity, that far was it from us to smile at his peculiar personal appearance. We all three bowed and shook hands with him with an urbanity almost equal to that of our friend the captain.

Both our new acquaintances discovered that they were going to the same place as ourselves, and favoured us with their society assiduously until we reached the Clifton House.

After viewing the Falls, we had dinner; and then the captain and major entertained us with extraordinary stories.

The former related how he had lived at the Cape under Sir Harry Smith, ridden one hundred and fifty miles on the same horse in twenty-four hours, and various other feats, while the “major” obscurely hinted that he owed his present important command on the frontier to the necessity felt by the British Government that a man of known courage and talent should be responsible during the crisis of the Trent affair.

We returned to Toronto the next day, and lost no time in proceeding on our way to Red River, travelling as fast as possible by railway through Detroit and Chicago to La Crosse, in Wisconsin, on the banks of the Mississippi.

9

We found the sleeping-cars a wonderful advantage in our long journeys, and generally travelled by night. A “sleeping-car” is like an ordinary railway carriage, with a passage down the centre, after the American fashion, and on each side two tiers of berths, like those of a ship. You go “on board,” turn in minus coat and boots, go quietly to sleep, and are awakened in the morning by the attendant nigger, in time to get out at your destination. You have had a good night’s rest, find your boots ready blacked, and washing apparatus at one end of the car, and have the satisfaction of getting over two hundred or three hundred miles of a wearisome journey almost without knowing it. The part of the car appropriated to ladies is screened off from the gentlemen’s compartment by a curtain; but on one occasion, there being but two vacant berths in the latter, Treemiss was, by special favour, admitted to the ladies’ quarter, where ordinarily only married gentlemen are allowed—two ladies and a gentleman kindly squeezing into one large berth to accommodate him!

At one of the small stations in Wisconsin we met the first Red Indian we had seen in native dress. He wore leather shirt, leggings, and moccasins, a blanket thrown over his shoulders, and his bold-featured, handsome face was adorned with paint. He was leaning against a tree, smoking his pipe with great dignity, not deigning to move or betray the slightest interest as the train went past him. We could not help reflecting—as, perhaps, he was doing—with something of sadness upon the changes which had10 taken place since his ancestors were lords of the soil, hearing of the white men’s devices as a strange thing, from the stories of their greatest travellers, or some half-breed trapper who might occasionally visit them. And we could well imagine the disgust of these sons of silence and stealth at the noisy trains which rush through the forests, and the steamers which dart along lakes and rivers, once the favourite haunt of game, now driven far away. How bitterly in their hearts they must curse that steady, unfaltering, inevitable advance of the great army of whites, recruited from every corner of the earth, spreading over the land like locusts—too strong to resist, too cruel and unscrupulous to mingle with them in peace and friendship!

At La Crosse we took steamer up the Mississippi—in the Indian language, the “Great River,” but here a stream not more than 120 yards in width—for St. Paul, in Minnesota. The river was very low, and the steamer—a flat-bottomed, stern-wheel boat, drawing only a few inches of water—frequently stuck fast on the sand bars, giving us an opportunity of seeing how an American river-boat gets over shallows. Two or three men were immediately sent overboard, to fix a large pole. At the top was a pulley, and through this a stout rope was run, one end of which was attached to a cable passed under the boat, the other to her capstan. The latter was then manned, the vessel fairly lifted up, and the stern wheel being put in motion at the same time, she swung over the shoal into deep water.

11

The scenery was very pretty, the river flowing in several channels round wooded islets; along the banks were fine rounded hills, some heavily timbered, others bare and green. When we reached Lake Pippin, an expansion of the Mississippi, some seven or eight miles long, and perhaps a mile in width, we found a most delightful change from the sultry heat we had experienced when shut up in the narrow channel. Here the breeze blew freshly over the water, fish splashed about on every side, and could be seen from the boat, and we were in the midst of a beautiful landscape. Hills and woods surround the lake; and, about half way, a lofty cliff, called the “Maiden’s Rock,” stands out with bold face into the water. It has received its name from an old legend that an Indian maiden, preferring death to a hated suitor forced upon her by her relatives, leaped from the top, and was drowned in the lake below. Beyond Lake Pippin the river became more shallow and difficult, and we were so continually delayed by running aground that we did not reach St. Paul until several hours after dark.

St. Paul, the chief city of the State of Minnesota, is the great border town of the North Western States. Beyond, collections of houses called cities dwindle down to even a single hut—an outpost in the wilderness. One of these which we passed on the road, a solitary house, uninhabited, rejoiced in the name of “Breckenridge City;” and another, “Salem City,” was little better.

From St. Paul a railway runs westward to St.12 Anthony, six miles distant—the commencement of the Great Pacific Railroad, projected to run across to California, and already laid out far on to the plains. From St. Anthony a “stage” wagon runs through the out-settlements of Minnesota as far as Georgetown, on the Red River. There we expected to find a steamer which runs fortnightly to Fort Garry, in the Red River Settlement. The “stage,” a mere covered spring-wagon, was crowded and heavily laden. Inside were eight full-grown passengers and four children; outside six, in addition to the driver; on the roof an enormous quantity of luggage; and on the top of all were chained two huge dogs—a bloodhound and Newfoundland—belonging to Treemiss. Milton and Treemiss were fortunate enough to secure outside seats, where, although cramped and uncomfortable, they could still breathe the free air of heaven; but Cheadle was one of the unfortunate “insides,” and suffered tortures during the first day’s journey. The day was frightfully hot, and the passengers were packed so tightly, that it was only by the consent and assistance of his next neighbour that he could free an arm to wipe the perspiration from his agonised countenance. Mosquitoes swarmed and feasted with impunity on the helpless crowd, irritating the four wretched babies into an incessant squalling, which the persevering singing of their German mothers about Fatherland was quite ineffectual to assuage. Two female German Yankees kept up an incessant clack, “guessing” that the “Young Napoleon” would soon wipe out Jeff. Davis; in which opinion two male friends of the same race13 perfectly agreed. The dogs kept tumbling off their slippery perch, and hung dangling by their chains at either side, half strangled, until hauled back again with the help of a “leg up” from the people inside. This seventy mile drive to St. Cloud, where we stayed the first night, was the most disagreeable experience we had. There six of the passengers left us, but the two German women, with the four babies they owned between them, still remained. The babies were much more irritable than ever the next day, and their limbs and faces, red and swollen from the effects of mosquito bites, showed what good cause they had for their constant wailings.

The country rapidly became more open and level—a succession of prairies, dotted with copses of wild poplar and scrub oak. The land appeared exceedingly fertile, and the horses and draught oxen most astonishingly fat. Sixty-five miles of similar country brought us, on the second night after leaving St. Paul, to the little settlement of Sauk Centre. As it still wanted half an hour to sundown when we arrived, we took our guns and strolled down to some marshes close at hand in search of ducks, but were obliged to return empty-handed, for although we shot several we could not get them out of the water without a dog, the mosquitoes being so rampant, that none of us felt inclined to strip and go in for them. We were very much disappointed, for we had set our hearts on having some for supper, as a relief to the eternal salt pork of wayside houses in the far West. On our return to the house where we were staying,14 we bewailed our ill-luck to our host, who remarked that had he known we were going out shooting, he would have lent us his own dog, a capital retriever. He introduced us forthwith to “Rover,” a dapper-looking, smooth-haired dog, in colour and make like a black and tan terrier, but the size of a beagle. When it is known from the sequel of this history how important a person Rover became, how faithfully he served us, how many meals he provided for us, and the endless amusement his various accomplishments afforded both to ourselves and the Indians we met with, we shall perhaps be forgiven for describing him with such particularity. Amongst our Indian friends he became as much beloved as he was hated by their dogs. These wolf-like animals he soon taught to fear and respect him by his courageous and dignified conduct; for although small of stature, he possessed indomitable pluck, and had a method of fighting quite opposed to their ideas and experience. Their manner was to show their teeth, rush in and snap, and then retreat; while he went in and grappled with his adversary in so determined a manner, that the biggest of them invariably turned tail before his vigorous onset. Yet Rover was by no means a quarrelsome dog. He walked about amongst the snarling curs with tail erect, as if not noticing their presence; and probably to this fearless demeanour he owed much of his immunity from attack. He appeared so exactly suited for the work we required, and so gained our hearts by his cleverness and docility, that next morning we made an offer of 25 dollars for him.

15

The man hesitated, said he was very unwilling to part with him, and, indeed, he thought his wife and sister would not hear of it. If, however, they could be brought to consent, he thought he could not afford to refuse so good an offer, for he was very short of money.

He went out to sound the two women on the subject, and they presently rushed into the room; one of them caught up Rover in her arms, and, both bursting into floods of tears, vehemently declared nothing would induce them to part with their favourite. We were fairly vanquished by such a scene, and slunk away, feeling quite guilty at having proposed to deprive these poor lonely women of one of the few creatures they had to lavish their wealth of feminine affection upon.

As we were on the point of starting, however, the man came up, leading poor Rover by a string, and begged us to take him, as he had at last persuaded the women to let him go. We demurred, but he urged it so strongly that we at length swallowed our scruples, and paid the money. As we drove off, the man said good-bye to him, as if parting with his dearest friend, and gave us many injunctions to “be kind to the little fellow.” This we most solemnly promised to do, and it is almost needless to state, we faithfully kept our word.

A fortnight afterwards, these kindly people—in common with nearly all the whites in that part of Minnesota—suffered a horrible death at the hands of the invading Sioux. This fearful massacre, accompanied16 as it was by all the brutalities of savage warfare, was certainly accounted for, if not excused, or even justified, by the great provocation they had received. The carelessness and injustice of the American Government, and the atrocities committed by the troops sent out for the protection of the frontier, exasperated the native tribes beyond control. Several thousand Indians—men, women, and children—assembled at Forts Snelling and Abercrombie, at a time appointed by the Government themselves, to receive the yearly subsidy guaranteed to them in payment for lands ceded to the United States. Year after year, either through the neglect of the officials at Washington, or the carelessness or dishonesty of their agents, the Indians were detained there for weeks, waiting to receive what was due to them. Able to bring but scanty provision with them—enough only for a few days—and far removed from the buffalo, their only means of subsistence, they were kept there in 1862 for nearly six weeks in fruitless expectation. Can it be a matter of surprise that, having been treated year by year in the same contemptuous manner, starving and destitute, the Sioux should have risen to avenge themselves on a race hated by all the Indians of the West?

Unconscious of the dangers gathering round, and little suspecting the dreadful scenes so shortly to be enacted in this region, we drove merrily along in the stage. As we went farther west, the prairies became more extensive, timber more scarce, and17 human habitations more rare. Prairie chickens and ducks were plentiful along the road, and the driver obligingly pulled up to allow us to have a shot whenever a chance occurred. On the third day we struck Red River, and stayed the night at Fort Abercrombie; and the following day, the 18th of July, arrived at Georgetown. The stage did not run beyond this point, and the steamer, by which we intended to proceed to Fort Garry, was not expected to come in for several days, so that we had every prospect of seeing more of Georgetown than we cared for.

18

Georgetown—Minnesota Volunteers—The Successful Hunters—An Indian Hag—Resolve to go to Fort Garry in Canoes—Rumours of a Sioux Outbreak—The Half-breeds refuse to Accompany us—Prepare to Start Alone—Our Canoes and Equipment—A Sioux War Party—The Half-breed’s Story—Down Red River—Strange Sights and Sounds—Our First Night Out—Effects of the Sun and Mosquitoes—Milton Disabled—Monotony of the Scenery—Leaky Canoes—Travelling by Night—The “Oven” Camp—Hunting Geese in Canoes—Meet the Steamer—Milton’s Narrow Escape—Treemiss and Cheadle follow Suit—Carried Down the Rapids—Vain Attempts to Ascend—A Hard Struggle—On Board at last—Start once more—Delays—Try a Night Voyage Again—The “Riband Storm”—“In Thunder, Lightning, and in Rain”—Fearful Phenomena—Our Miserable Plight—No Escape—Steering in Utter Darkness—Snags and Rocks—A Long Night’s Watching—No Fire—A Drying Day—Another Terrible Storm—And Another—Camp of Disasters—Leave it at last—Marks of the Fury of the Storms—Provisions at an End—Fishing for Gold-eyes—A Day’s Fast—Slaughter of Wild-Fowl—Our Voracity—A Pleasant Awakening—Caught up by the Steamer—Pembina—Fort Garry—La Ronde—We go under Canvass.

The little settlement of Georgetown is placed under cover of the belt of timber which clothes the banks of the river, while to the south and east endless prairie stretches away to the horizon. The place is merely a trading post of the Hudson’s Bay Company, round which a few straggling settlers have established themselves. A company of Minnesota Volunteers was stationed here for the protection of the settlement against the Sioux. They were principally Irish or19 German Yankees; i.e., emigrants, out-Heroding Herod in Yankeeism, yet betraying their origin plainly enough. These heroes, slovenly and unsoldier-like, yet full of swagger and braggadocio now, when the Sioux advanced to the attack on Port Abercrombie, a few weeks afterwards, took refuge under beds, and hid in holes and corners, from whence they had to be dragged by their officers, who drew them out to face the enemy by putting revolvers to their heads.

On the day of our arrival two half-breeds came in from a hunting expedition in which they had been very successful. They had found a band of twenty elk, out of which they killed four, desisting, according to their own account, from shooting more from a reluctance to waste life and provision!—a piece of consideration perfectly incomprehensible in a half-breed or Indian. We went down to their camp by the river, where they were living in an Indian “lodge,” or tent of skins stretched over a cone of poles. Squatted in front of it, engaged in cutting the meat for drying, was the most hideous old hag ever seen. Lean, dried-up, and withered, her parchment skin was seamed and wrinkled into folds and deep furrows, her eyes were bleared and blinking, and her long, iron-grey hair, matted and unkempt, hung over her shoulders. She kept constantly muttering, and showing her toothless gums, as she clawed the flesh before her with long, bony, unwashed fingers, breaking out occasionally into wild, angry exclamations, as she struck at the skeleton dogs which20 attempted to steal some of the delicate morsels strewn around.

Finding upon inquiry that, in consequence of the lowness of the water, it was very uncertain when the steamer would arrive, if she ever reached Georgetown at all, we decided to make the journey to Fort Garry in canoes. The distance is above five hundred miles by the river, which runs through a wild and unsettled country, inhabited only by wandering tribes of Sioux, Chippeways, and Assiniboines. After much bargaining, we managed to obtain two birch-bark canoes from some half-breeds. One of them was full of bullet holes, having been formerly the property of some Assiniboines, who were waylaid by a war party of Sioux whilst descending the river the previous summer, and mercilessly shot down from the bank, where their enemies lay in ambush. The other was battered and leaky, and both required a great deal of patching and caulking before they were rendered anything like water-tight. We endeavoured to engage a guide, half-breed or Indian, but none would go with us. The truth was that rumours were afloat of the intended outbreak of the Sioux, and these cowards were afraid. One man, indeed—a tall, savage-looking Iroquois, just recovering from the effects of a week’s debauch on corn whisky—expressed his readiness to go with us, but his demands were so exorbitant, that we refused them at once. We offered him one-half what he had asked, and he went off to consult his squaw, promising to give us an answer next day.

We did not take very large supplies of provisions21 with us, as we expected not to be more than eight or ten days on our voyage, and knew that we should meet with plenty of ducks along the river. We therefore contented ourselves with twenty pounds of flour, and the same of pemmican, with about half as much salt pork, some grease, tinder, and matches, a small quantity of tea, salt, and tobacco, and plenty of ammunition. A tin kettle and frying-pan, some blankets and a waterproof sheet, a small axe, and a gun and hunting-knife apiece, made up the rest of our equipment.

Whilst we were completing our preparations, another half-breed came in, in a great state of excitement, with the news that a war party of Sioux were lurking in the neighbourhood. He had been out looking for elk, when he suddenly observed several Indians skulking in the brushwood; from their paint and equipment he knew them to be Sioux on the war-path. They did not appear to have perceived him, and he turned and fled, escaping to the settlement unpursued. We did not place much reliance on his story, or the various reports we had heard, and set out the next day alone. How fearfully true these rumours of the hostility of the Sioux, which we treated so lightly at the time, turned out to be, is already known to the reader. As we got ready to start, the Iroquois sat on the bank, smoking sullenly, and showing neither by word nor sign any intention of accepting our offer of the previous day. Milton and Rover occupied the smaller canoe, while Treemiss and Cheadle navigated the larger one. At first we experienced22 some little difficulty in steering, and were rather awkward in the management of a paddle. A birch-bark canoe sits so lightly on the water, that a puff of wind drives it about like a walnut-shell; and with the wind dead ahead, paddling is very slow and laborious. But we got on famously after a short time, Milton being an old hand at the work, and the others accustomed to light and crank craft on the Isis and the Cam. We glided along pleasantly enough, lazily paddling or floating quietly down the sluggish stream. The day was hot and bright, and we courted the graceful shade of the trees which overhung the bank on either side. The stillness of the woods was broken by the dip of our paddles, the occasional splash of a fish, or the cry of various birds. The squirrel played and chirruped among the branches of the trees, the spotted woodpecker tapped on the hollow trunk, while, perched high on the topmost bough of some withered giant of the forest, the eagle and the hawk uttered their harsh and discordant screams. Here and there along the banks swarms of black and golden orioles clustered on the bushes, the gaily-plumed kingfisher flitted past, ducks and geese floated on the water, and the long-tailed American pigeon darted like an arrow high over the tree-tops. As night approached, a hundred owls hooted round us; the whip-poor-will startled us with its rapid, reiterated call; and the loon—the most melancholy of birds—sent forth her wild lamentations from some adjoining lake. Thoroughly did we enjoy these wild scenes and sounds, and the23 strange sensation of freedom and independence which possessed us.

Having shot as many ducks as we required, we put ashore at sundown, and drawing our canoes out of the water into the bushes which fringed the river-bank, safe from the eye of any wandering or hostile Indian, we encamped for the night on the edge of the prairie. It became quite dark before we had half completed our preparations, and we were dreadfully bothered, in our raw inexperience, to find dry wood for the fire, and do the cooking. However, we managed at last to pluck and split open the ducks into “spread-eagles,” roasting them on sticks, Indian fashion, and these, with some tea and “dampers,” or cakes of unleavened bread, furnished a capital meal. We then turned into our blankets, sub Jove—for we had no tent;—but the tales we had heard of prowling Sioux produced some effect, and a half-wakeful watchfulness replaced our usual sound slumbers.

We often recalled afterwards how one or other of us suddenly sat up in bed and peered into the darkness at any unusual sound, or got up to investigate the cause of the creakings and rustlings frequently heard in the forest at night, but which might have betrayed the stealthy approach of an Indian enemy. Mosquitoes swarmed and added to our restlessness. In the morning we all three presented an abnormal appearance, Milton’s arms being tremendously blistered, red, and swollen, from paddling with them bare in the scorching sun; and Treemiss and Cheadle exhibiting faces it was impossible to recognise, so24 wofully were they changed by the swelling of mosquito bites.

Milton was quite unable to use a paddle for several days, and his canoe was towed along by Treemiss and Cheadle. This, of course, delayed us considerably, and the delight we had experienced during the first few days’ journey gradually gave place to a desire for change.

Red River, flowing almost entirely through prairie land, has hollowed out for itself a deep channel in the level plains, the sloping sides of which are covered with timber almost to the water’s edge. The unvarying sameness of the river, and the limited prospect shut in by rising banks on either side, gave a monotony to our daily journey; and the routine of cooking, chopping, loading and unloading canoes, paddling, and shooting, amusing enough at first, began to grow rather tiresome.

The continual leaking of our rickety canoes obliged us to pull up so frequently to empty them, and often spend hours in attempting to stop the seams, that we made very slow progress towards completing the five hundred miles before us. We therefore thoroughly overhauled them, and having succeeded in making them tolerably water-tight, resolved to make an extra stage, and travel all night. The weather was beautifully fine, and, although there was no moon, we were able to steer well enough by the clear starlight.

The night seemed to pass very slowly, and we nodded wearily over our paddles before the first appearance of daylight gave us an excuse for landing, which25 we did at the first practicable place. The banks were knee-deep in mud, but we were too tired and sleepy to search further, and carried our things to drier ground higher up, where a land-slip from a steep cliff had formed a small level space a few yards square. The face of the cliff was semi-circular, and its aspect due south; not a breath of air was stirring, and as we slept with nothing to shade us from the fiery rays of the mid-day sun, we awoke half baked. Some ducks which we had killed the evening before were already stinking and half putrid, and had to be thrown away as unfit for food. We found the position unbearable, and, reluctantly re-loading our canoes, took to the river again, and paddled languidly along until evening. This camp, which we called “The Oven,” was by far the warmest place we ever found, with the exception of the town of Acapulco, in Mexico, which stands in a very similar situation.

A week after we left Georgetown our provisions fell short, for the pemmican proved worthless, and fell to the lot of Rover, and we supplied ourselves entirely by shooting the wild-fowl, which were tolerably plentiful. The young geese, although almost full-grown and feathered, were not yet able to fly, but afforded capital sport. When hotly pursued they dived as we came near in the canoes, and, if too hardly pushed, took to the shore. This was generally a fatal mistake; Milton immediately landed with Rover, who quickly discovered them lying with merely their heads hidden in the grass or bushes, and they were then captured.

26

When engaged in this exciting amusement one day, Milton went ahead down stream in chase of a wounded bird, while Treemiss and Cheadle remained behind to look after some others which had taken to the land. The former was paddling away merrily after his prey, when, at a sudden turn of the river, he came upon the steamer warping up a shallow rapid. Eager to get on board and taste the good things we had lately lacked, he swept down the current alongside the overhanging deck of the steamer. The stream was rough and very strong, and its force was increased by the effect of the stern-wheel of the steamer in rapid motion in the narrow channel. The canoe was drawn under the projecting deck, but Milton clung tightly to it, and the friendly hands of some of the crew seized and hauled him and his canoe safely on board. The others following shortly afterwards, and observing the steamer in like manner, were equally delighted, and dashed away down stream in order to get on board as quickly as possible.

The stern-wheel was now stopped, but as they neared the side it was suddenly put in motion again, and the canoe carried at a fearful pace past the side of the boat, sucked in by the whirlpool of the wheel. By the most frantic exertions, the two saved themselves from being drawn under, but were borne down the rapid about a quarter of a mile. Rover attempting a similar feat, was carried down after them, struggling vainly against the powerful current. Great was the wrath of Cheadle and Treemiss against the captain for the trick he had served them, and they squabbled27 no little with each other also, as they vainly strove to re-ascend the rapid. Three times they made the attempt, but were as often swept back, and had to commence afresh. By paddling with all their might they succeeded in getting within a hundred yards of the steamer; but at this point, where the stream narrowed and shot with double force round a sharp turn in the channel, the head of the canoe was swept round in spite of all their efforts, and down they went again.

When they were on the eve of giving up in despair, the other canoe appeared darting down towards them, manned by two men whose masterly use of the paddle proclaimed them to be old voyageurs. Coming alongside, one of them exchanged places with Cheadle, and thus, each having a skilful assistant, by dint of hugging the bank, and warily avoiding the strength of the current, they easily reached the critical point for the fourth time. Here again was a fierce struggle. Swept back repeatedly for a few yards, but returning instantly to the attack, they at last gained the side of the steamer. The captain kindly stopped half an hour to allow us to have a good dinner. Finding the steamer would probably be a week before she returned, we obtained a fresh stock of flour and salt pork, and went on our way again. Presently we found Rover, who had got to land a long way down the stream, and took him on board again.

After a few days’ slow and monotonous voyaging, being again frequently obliged to stop in order to repair our leaky craft, we decided to try a night journey once more. The night was clear and starlight, but in28 the course of an hour or two ominous clouds began to roll up from the west, and the darkness increased. We went on, however, hoping that there would be no storm. But before long, suddenly, as it seemed to us, the darkness became complete; then, without previous warning, a dazzling flash of lightning lit up for a moment the wild scene around us, and almost instantaneously a tremendous clap of thunder, an explosion like the bursting of a magazine, caused us to stop paddling, and sit silent and appalled. A fierce blast of wind swept over the river, snapping great trees like twigs on every side; the rain poured down in floods, and soaked us through and through; flash followed flash in quick succession, with its accompanying roar of thunder; whilst at intervals between, a dim, flickering light, faint and blue, like the flame of a spirit lamp, or the “Will-o’-the-wisp,” hovered over the surface of the water, but failed to light up the dense blackness of the night. With this came an ominous hissing, like the blast of a steam pipe, varying with the wind, now sounding near as the flame approached, now more distant as it wandered away.

We were in the very focus of the storm; the whole air was charged with electricity, and the changing currents of the electric fluid, or the shifting winds, lifted and played with our hair in passing. The smell of ozone was so pungent that it fairly made us snort again, and forced itself on our notice amongst the other more fearful phenomena of the storm. We made an attempt to land at once, but the darkness was so intense that we could not see to avoid the29 snags and fallen timber which beset the steep, slippery bank; and the force of the stream bumped us against them in a manner which warned us to desist, if we would avoid being swamped or knocking holes in the paper sides of our frail craft. We had little chance of escape in that case, for the river was deep, and it would be almost impossible to clamber up the slippery face of the bank, even if we succeeded in finding it, through the utter darkness in which we were enveloped. There was nothing else for it but to face it out till daylight, and we therefore fastened the two canoes together, and again gave ourselves up to the fury of the storm. We had some difficulty in bringing the two canoes alongside, but by calling out to one another, and by the momentary glimpses obtained during the flashes of lightning, we at last effected it. Treemiss, crouching in the bows, kept a sharp look-out, while we, seated in the stern, steered by his direction. As each flash illuminated the river before us for an instant, he was able to discern the rocks and snags ahead, and a vigorous stroke of our paddles carried us clear during the interval of darkness.

After a short period of blind suspense, the next flash showed us that we had avoided one danger to discover another a few yards in front. Hour after hour passed by, but the storm raged as furiously, and the rain came down as fast as ever. We looked anxiously for the first gleam of daylight, but the night seemed as if it would never come to an end. The canoes were gradually filling with water, which had crept up nearly to our waists, and the gunwales30 were barely above the surface. It became very doubtful whether they would float till daybreak.

The night air was raw and cold, and as we sat in our involuntary hip-bath, with the rain beating upon us, we shivered from head to foot; our teeth chattered, and our hands became so benumbed that we could scarcely grasp the paddles. But we dared not take a moment’s rest from our exciting work, in watching and steering clear of the snags and rocks, although we were almost tempted to give up, and resign ourselves to chance.

Never will any of us forget the misery of that night, or the intense feeling of relief we experienced when we first observed rather a lessening of the darkness than any positive appearance of light. Shortly before this, the storm began sensibly to abate; but the rain poured down as fast as ever when we hastily landed in the grey morning on a muddy bank, the first practicable place we came to. Drawing our canoes high on shore, that they might not be swept off by the rising flood, we wrapped ourselves in our dripping blankets, and, utterly weary and worn out, slept long and soundly.1

31

When we awoke, the sun was already high, shining brightly, and undimmed by a single cloud, and our blankets were already half dry. We therefore turned out, spread our things on the bushes, and made an attempt to light a fire. All our matches and tinder were wet, and we wasted a long time in fruitless endeavours to get a light by firing pieces of dried rag out of a gun. Whilst we were thus engaged, another adventurer appeared, coming down the river in a “dug-out,” or small canoe hollowed out of a log. We called out to him as he passed, and he came ashore, and supplied us with some dry matches. He had camped in a sheltered place before sundown, on the preceding evening, and made everything secure from the rain before the storm came on. We soon had a roaring fire, and spent the rest of the day in drying our property and patching our canoes, which we did caulk most effectually this time, by plastering strips of our pocket-handkerchiefs over the seams with pine-gum. But our misfortunes were yet far from an end. We broke the axe and the handle of the frying-pan, and were driven to cut our fire-wood with our hunting-knives, and manipulate the cooking utensil by means of a cleft stick.

Our expectations of having a good night’s rest were disappointed. About two hours before daylight we were awakened by the rumbling of distant thunder, and immediately jumped up and made everything as secure as possible. Before very long, a storm almost as terrible as the one of the night before burst over us. Our waterproof sheets were too small to keep out32 the deluge of water which flooded the ground, and rushed into our blankets. But we managed to keep our matches dry, and lighted a fire when the rain ceased. Meantime, about noon, nearly everything we had was soaked again, and we had to spend the rest of the day in drying clothes and blankets as before.

On the third day after our arrival in this camp of disasters, just as we were nearly ready to start, we were again visited by a terrible thunder-storm, and once more reduced to our former wretched plight. Again we set to work to wring out trousers, shirts, and blankets, and clean our guns, sulkily enough, almost despairing of ever getting away from the place where we had encountered so many troubles.

But the fourth day brought no thunder-storm, nor did we experience any bad weather for the rest of the voyage.

We paddled joyfully away from our dismal camp, and along the river-side saw numerous marks of the fury of the storm; great trees blown down, or trunks snapped short off, others torn and splintered by lightning. The storm had evidently been what is called a “riband storm,” which had followed the course of the river pretty closely. The riband storm passes over only a narrow line, but within these limits is exceedingly violent and destructive.

We had by this time finished all the provisions we brought with us, and lived for some days on ducks and fish. A large pike, of some ten or twelve pounds, served us for a couple of days, and we occasionally caught a quantity of gold-eyes, a fish resembling the33 dace. Having unfortunately broken our last hook, we caught them by the contrivance of two needles fastened together by passing the line through the eyes, and threading them head first through the bait. One night found us with nothing but a couple of gold-eyes for supper, and we were roused very early next morning by the gnawing of our stomachs. We paddled nearly the whole day in the hot sun, languid and weary, and most fearfully hungry. Neither ducks nor geese were to be seen, and the gold-eyes resisted all our allurements. We knew that we must be at least 150 miles from our journey’s end, and our only hope of escaping semi-starvation seemed to be the speedy arrival of the steamer. For be it remembered, that for the whole distance of 450 miles between Georgetown and Pembina, sixty miles above Fort Garry, there are no inhabitants except chance parties of Indians. We were sorely tempted to stop and rest during the heat of the day, but were urged on by the hope of finding something edible before nightfall.

Our perseverance was duly rewarded, for shortly before sundown we came upon a flock of geese, and a most exciting chase ensued. Faintness and languor were forgotten, and we paddled furiously after them, encouraged by the prospect of a substantial supper. We killed three geese, and soon after met with a number of ducks, out of which we shot seven. Before we could find a place at which to camp, we killed two more geese, and were well supplied for a couple of days. We speedily lit a fire, plucked and spitted our game,34 and before they were half cooked, devoured them, far more greedily than if they had been canvass-backs at Delmonico’s, or the Maison Dorée. The total consumption at this memorable meal consisted of two geese and four ducks; but then, as a Yankee would express it, they were geese and ducks “straight”—i.e., without anything else whatever. We slept very soundly and happily that night, and at daybreak were awakened by the puffing of the steamer; and running to the edge of the river, there, sure enough, was the International. The captain had already caught sight of us, and stopped alongside; and in a few minutes we were on board, and engaged in discussing what seemed to us a most delicious meal of salt pork, bread, and molasses. We had been sixteen days since leaving Georgetown, and were not sorry that our canoeing was over. On the following day we reached Pembina, a half-breed settlement on the boundary-line between British and American territory; and the next, being the 7th of August, arrived at Fort Garry. Directly we came to anchor opposite the Fort, a number of people came on board, principally half-breeds, and amongst them La Ronde, who had been out with Milton on his previous visit to the plains. He indulged in the most extravagant demonstrations of delight at seeing him again, and expressed his readiness to go with him to the end of the world, if required.

He informed us that our arrival was expected. Two men, who had left Georgetown after our departure from that place, had arrived at Fort Garry some days35 before by land, and from the unusually long time we had been out, serious apprehensions were entertained for our safety. Indeed, La Ronde had made preparations to start immediately in search of us, in case we did not arrive by the steamer. We pitched our tent near his house, in preference to the unsatisfactory accommodation of the so-called hotel, and had no cause to regret having at once commenced life under canvass.

36

Fort Garry—Origin of the Red River Settlement—The First Settlers—Their Sufferings—The North-Westers—The Grasshoppers—The Blackbirds—The Flood—The Colony in 1862—King Company—Farming at Red River—Fertility of the Soil—Isolated Position of the Colony—Obstructive Policy of the Company—Their Just Dealing and Kindness to the Indians—Necessity for a proper Colonial Government—Value of the Country—French Canadians and Half-breeds—Their Idleness and Frivolity—Hunters and Voyageurs—Extraordinary Endurance—The English and Scotch Settlers—The Spring and Fall Hunt—Our Life at Fort Garry—Too late to cross the Mountains before Winter—Our Plans—Men—Horses—Bucephalus—Our Equipment—Leave Fort Garry—The “Noce”—La Ronde’s last Carouse—Delightful Travelling—A Night Alarm—Vital Deserts—Fort Ellice—Delays—Making Pemmican—Its Value to the Traveller—Swarms of Wild-Fowl—Good Shooting—The Indian Summer—A Salt Lake Country—Search for Water—A Horse’s Instinct—South Saskatchewan—Arrive at Carlton.

Fort Garry—by which we mean the building itself, for the name of the Fort is frequently used for the settlement generally—is situated on the north bank of the Assiniboine river, a few hundred yards above its junction with Red River. It consists of a square enclosure of high stone walls, flanked at each angle by round towers. Within this are several substantial wooden buildings—the Governor’s residence, the gaol, and the storehouses for the Company’s furs and goods. The shop, where articles of every description are sold, is thronged from morning till night by a crowd of37 settlers and half-breeds, who meet there to gossip and treat each other to rum and brandy, as well as to make their purchases.

The Red River settlement extends beyond Fort Garry for about twenty miles to the northward along the banks of Red River, and about fifty to the westward along its tributary, the Assiniboine. The wealthier inhabitants live in large, well-built wooden houses, and the poorer half-breeds in rough log huts, or even Indian “lodges.” There are several Protestant churches, a Romish cathedral and nunnery, and schools of various denominations. The neighbouring country is principally open, level prairie, the timber being confined, with a few exceptions, to the banks of the streams. The settlement dates from the year 1811, when the Earl of Selkirk purchased from the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Cree and Sauteux Indians a large tract of land stretching along both banks of the Red River and the Assiniboine. The country was at that time inhabited only by wandering tribes of Indians, and visited occasionally by the employés of the North-West and Hudson’s Bay Companies, who had trading posts in the neighbourhood. Vast herds of buffalo, now driven far to the west of Red River, then ranged over its prairies, and frequented the rich feeding grounds of the present State of Minnesota, as far as the Mississippi.