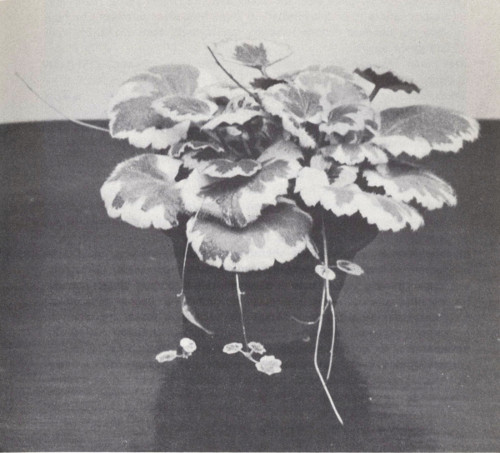

Miniature geraniums arranged in uniform rows

By the same author:

ALL ABOUT BEGONIAS

ALL ABOUT VINES AND HANGING PLANTS

BERNICE BRILMAYER

Sketches and Landscape Designs

by Fritz Schaefer

Additional Art Work

by Kathleen Bourke

DOUBLEDAY & COMPANY, INC., GARDEN CITY, NEW YORK

1963

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 63-18225

Copyright © 1963 by Doubleday & Company, Inc.

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition

[5]

| AUTHOR’S NOTE | 9 | |

| ACKNOWLEDGMENTS | 13 | |

| Chapter 1 | MINIATURE WINDOW GARDENS | 17 |

| Chapter 2 | MINIATURE GARDENS WITH ARTIFICIAL LIGHT | 23 |

| Chapter 3 | MINIATURE GARDENS IN CONTAINERS | 38 |

| Chapter 4 | MINIATURE GARDENS IN GLASS | 53 |

| Chapter 5 | MINIATURE GREENHOUSE GARDENS | 61 |

| Chapter 6 | MINIATURE HOUSE AND GREENHOUSE PLANTS | 74 |

| Chapter 7 | MINIATURE ROSES, INDOORS AND OUT | 137 |

| Chapter 8 | MINIATURE SINK GARDENS | 150 |

| Chapter 9 | MINIATURE PLANTS, BONSAI-STYLE | 159 |

| Chapter 10 | MINIATURE GARDENS IN THE LANDSCAPE | 177 |

| Chapter 11 | MINIATURE ROCK AND WALL GARDENS | 183 |

| Chapter 12 | MINIATURE POOLS AND WATER PLANTS | 199 |

| Chapter 13 | MINIATURE WOODLAND GARDENS AND PLANTS | 211 |

| Chapter 14 | MINIATURE TREES AND SHRUBS | 226 |

| Chapter 15 | MINIATURE PERENNIALS AND ROCK PLANTS | 251 |

| Chapter 16 | MINIATURE ANNUALS | 277 |

| Chapter 17 | MINIATURE GARDEN BULBS | 288 |

| EPILOGUE | 299 | |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 300 | |

| WHERE TO BUY MINIATURE PLANTS AND SUPPLIES | 301 | |

| INDEX | 307 |

[6]

| COLOR By the author except as noted |

|

| BETWEEN PAGES | |

|---|---|

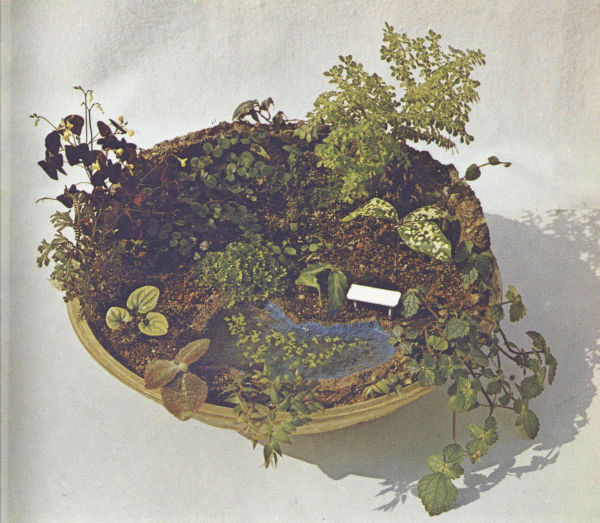

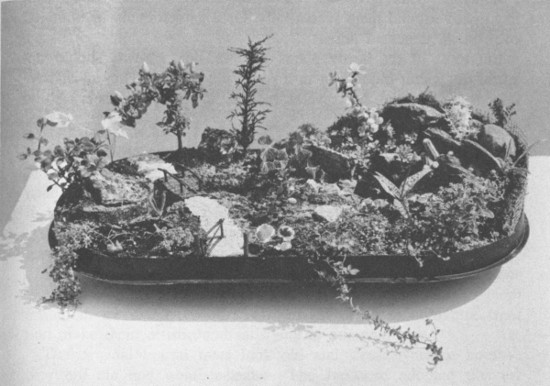

| Formal garden in a wash-boiler lid | 32–33 |

| Tiny tropical garden with pool | 64–65 |

| Achimenes, a beautiful gesneriad | 96–97 |

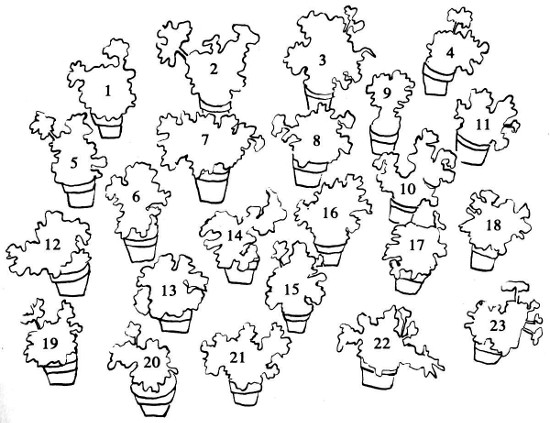

| Twenty-three varieties of miniature and dwarf geraniums | 128–129 |

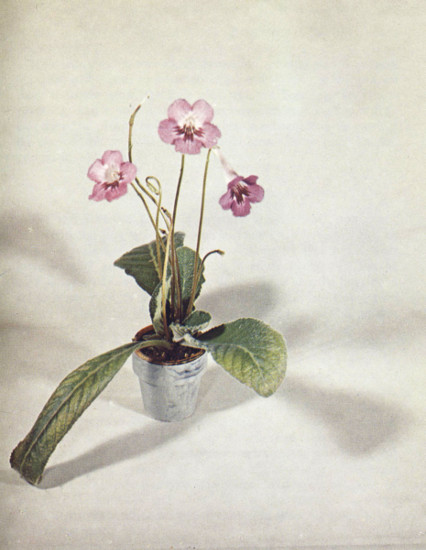

| Streptocarpus, Weismoor hybrid | 160–161 |

| Rose and miniature rose | 192–193 |

| Garden in the landscape | 224–225 |

| Rock garden effectively composed | 256–257 |

| BLACK AND WHITE By the author except as noted |

|

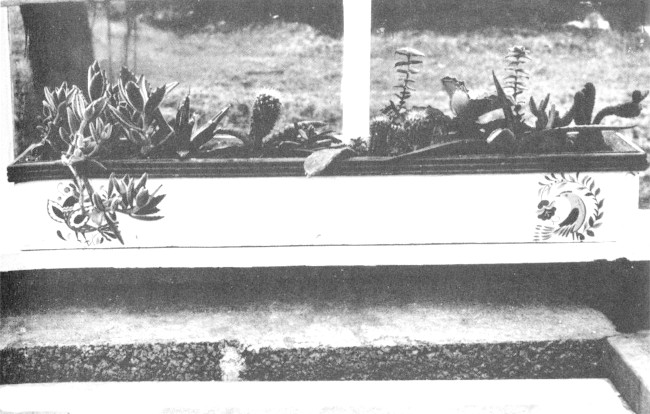

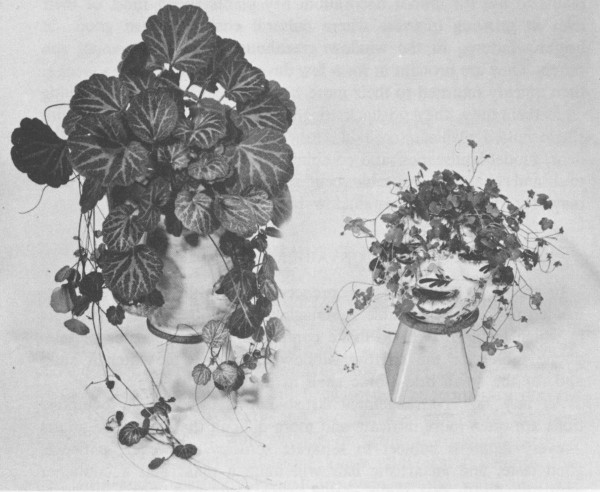

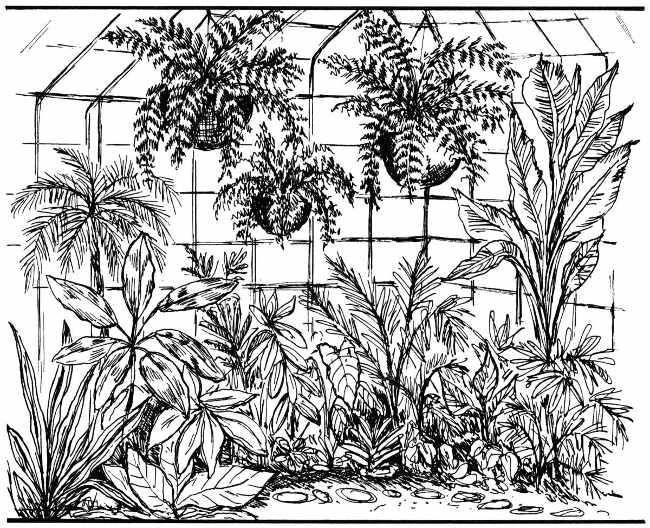

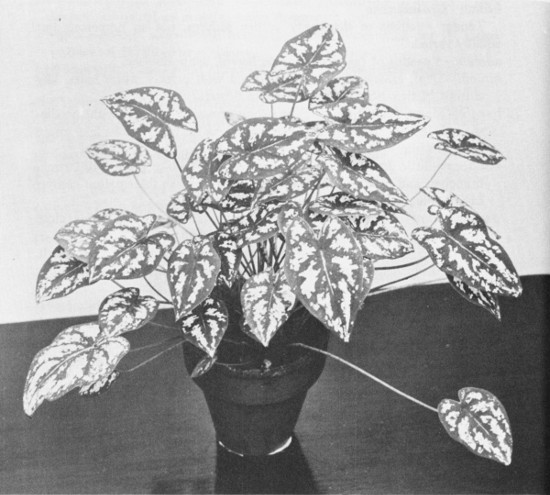

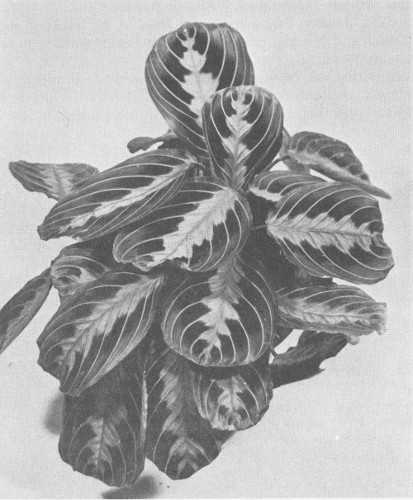

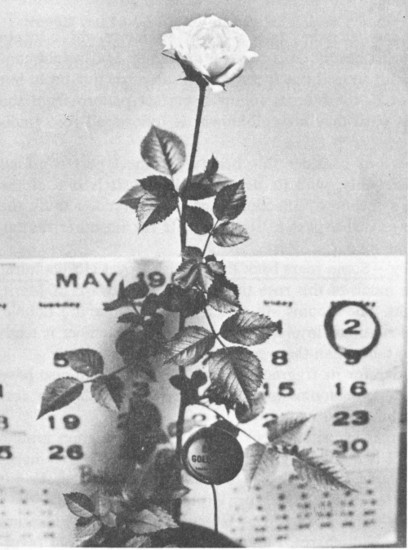

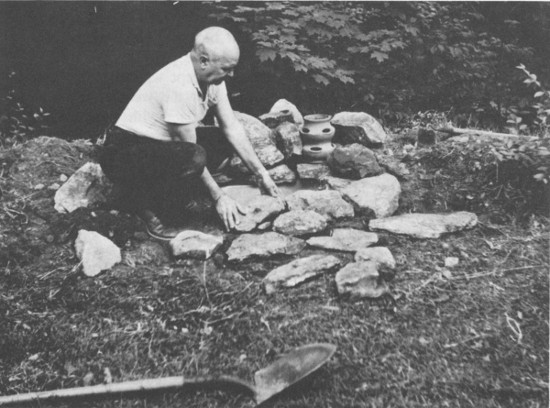

| Miniature geraniums in uniform rows | 20 |

| Mexican motif with cacti in window box | 21 |

| Child’s cactus garden over radiator | 21 |

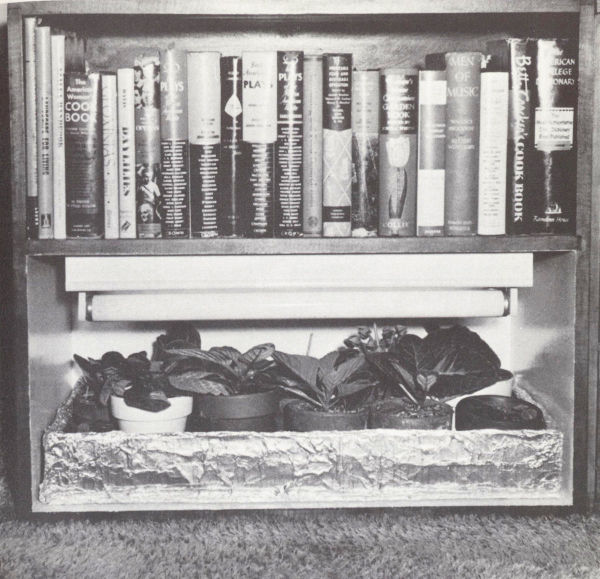

| Small plants in a lighted bookcase | 25 |

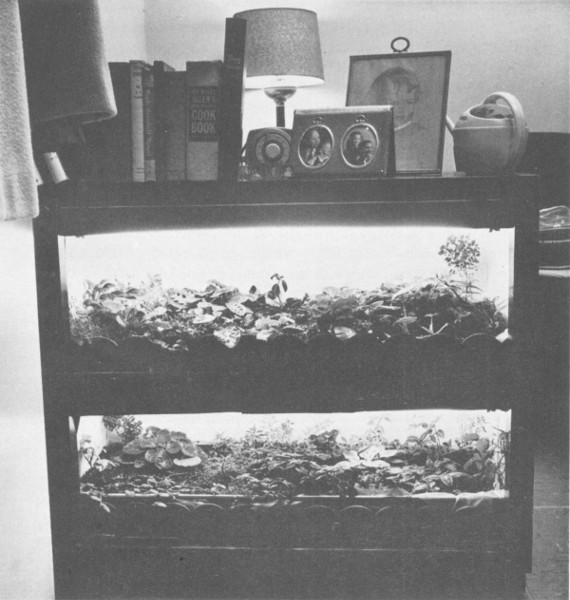

| An indoor “jungle garden” | 26 |

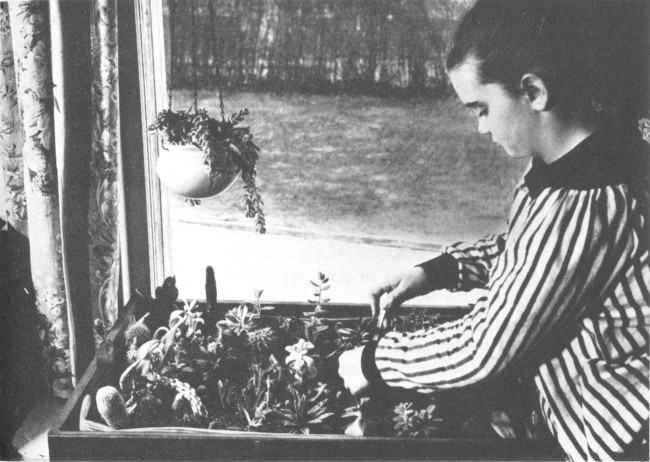

| Light-case planted with various small plants | 28 |

| Light shelves with begonias | 29 |

| Kenilworth ivy in gnome strawberry jar | 40 |

| Pawnbroker’s planter with ivy | 41 |

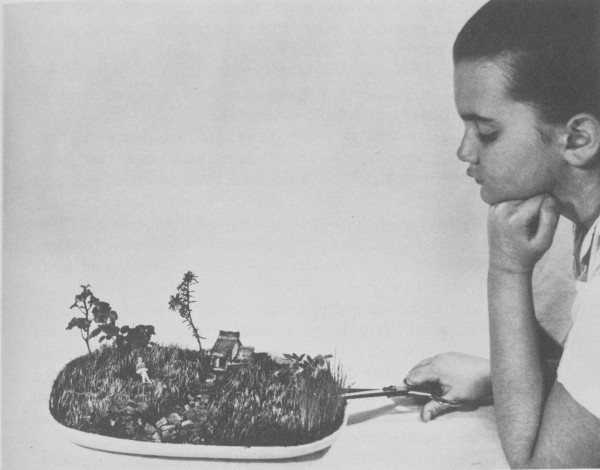

| Pruning a dish garden | 43 |

| Apple-tree root with pocket for plants | 45 |

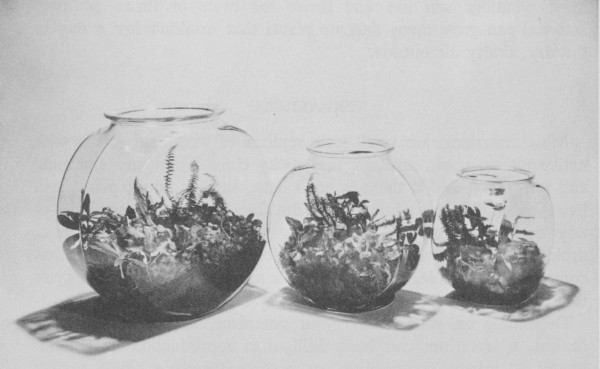

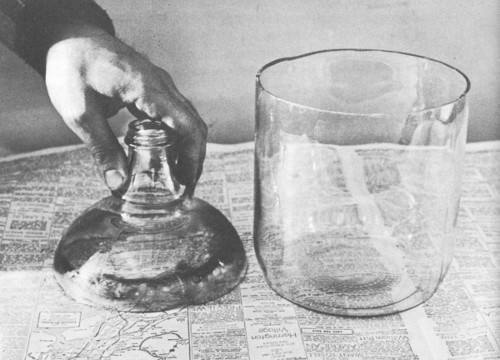

| Miniature plants in fish bowls (Industrial Photographic Specialists) |

54 |

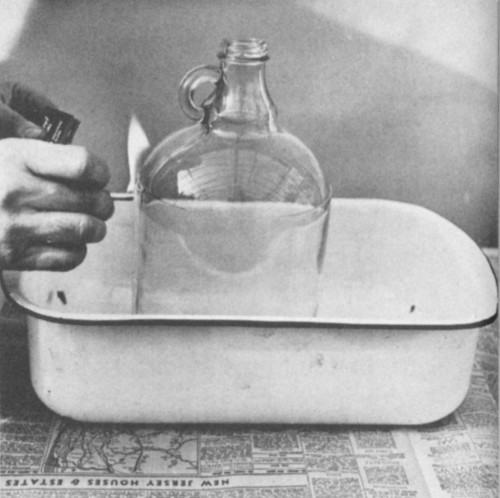

| Converting a cider jug into a terrarium | 56–57[7] |

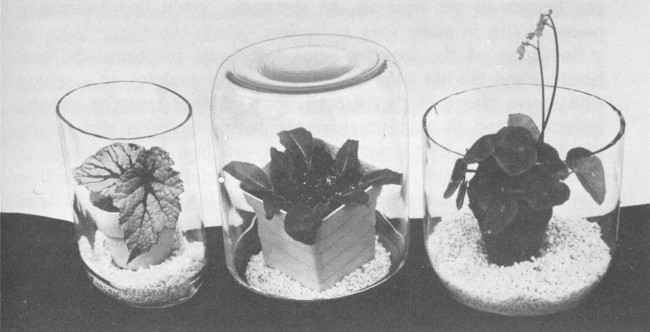

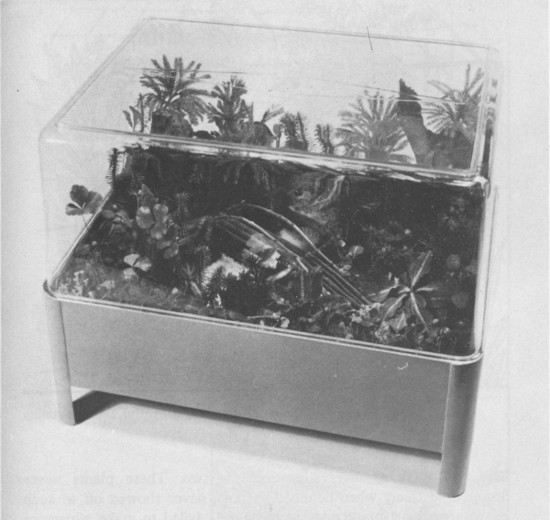

| Commercially produced terrarium (Russ Stone) | 65 |

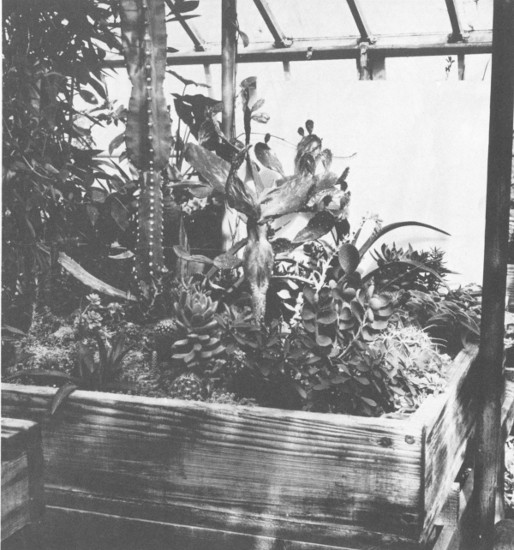

| Author’s succulent garden | 68 |

| Rampant greenhouse | 69 |

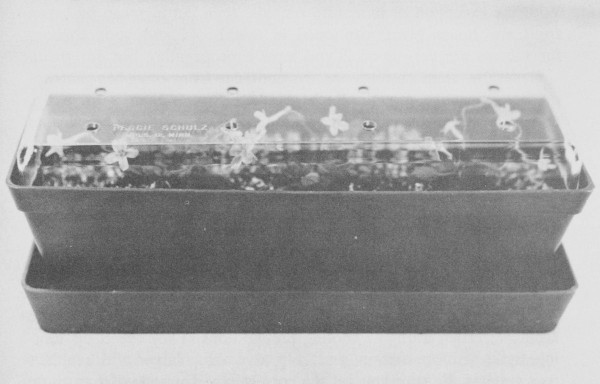

| Unusual propagation box | 87 |

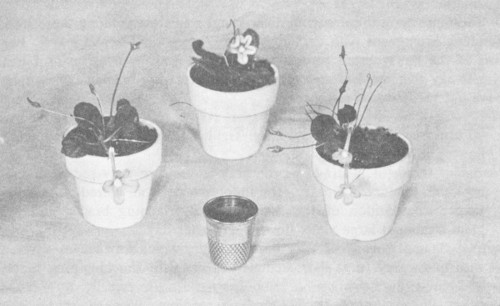

| Sprouted stem cuttings of dwarf geraniums | 88 |

| ‘Spaulding,’ bushy dwarf begonia | 98 |

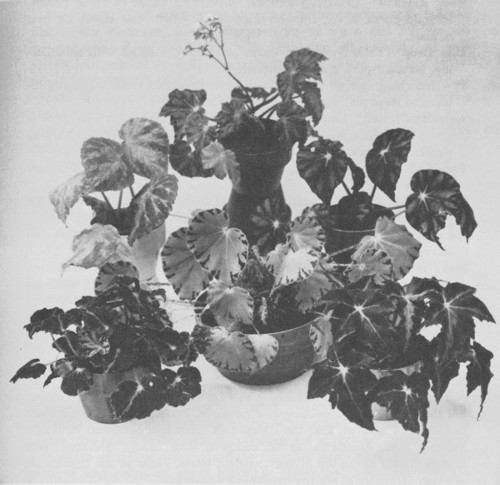

| Group of dwarf begonias | 99 |

| Caladium humboldti | 108 |

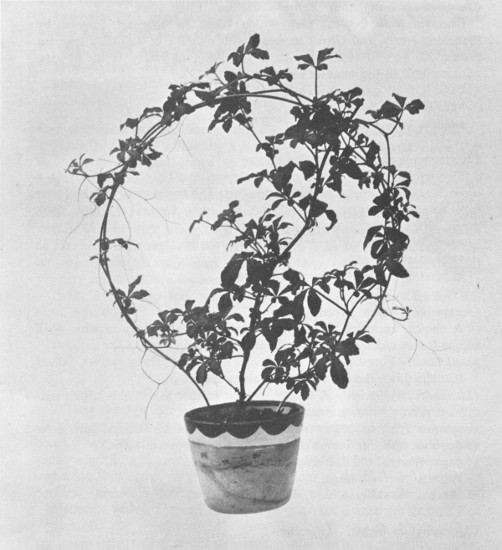

| Miniature climber, Cissus striata | 112 |

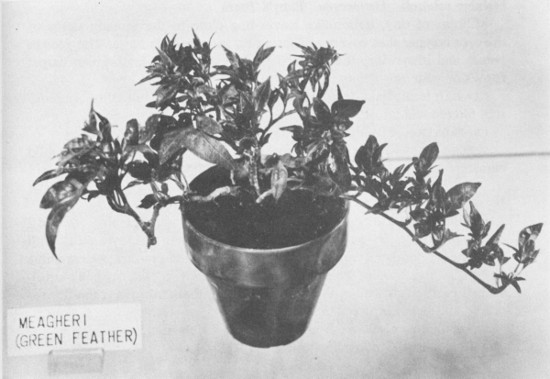

| Ivy meagheri | 119 |

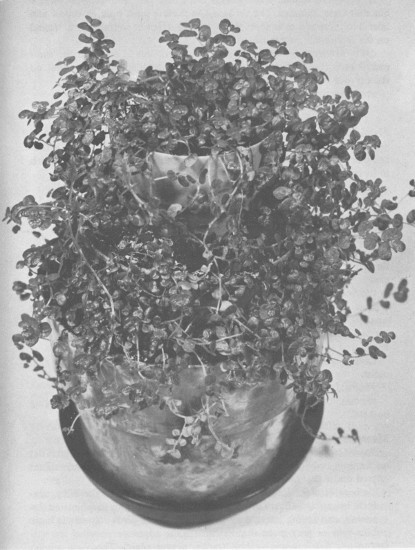

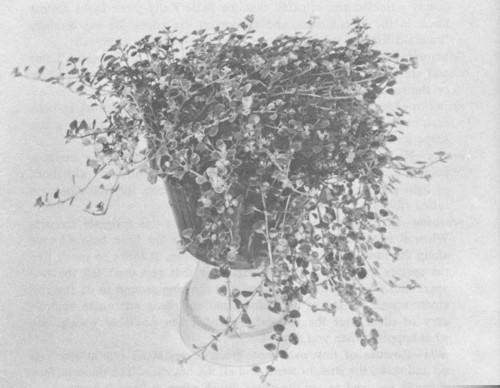

| Helxine soleiroli | 121 |

| Leuconeura massangeana | 123 |

| Oxalis hedysaroides rubra (Merry Gardens) | 125 |

| Three dwarf geraniums (Merry Gardens) | 127 |

| Dwarf geranium, ‘Robin Hood’ (Merry Gardens) | 127 |

| Creeping Pilea depressa | 130 |

| Hardy Saxifraga sarmentosa | 133 |

| Sinningia pusilla, miniature of miniatures | 135 |

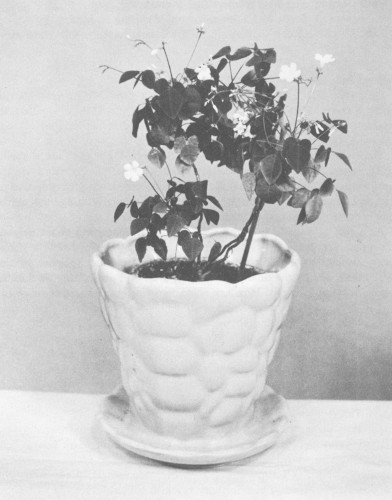

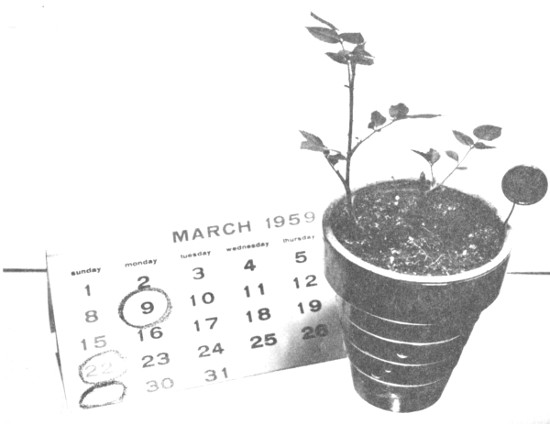

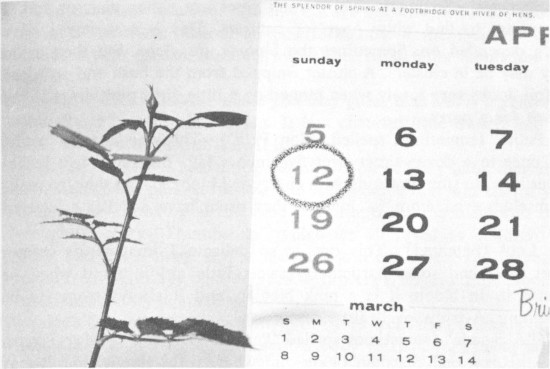

| A miniature rose grows | 146–147 |

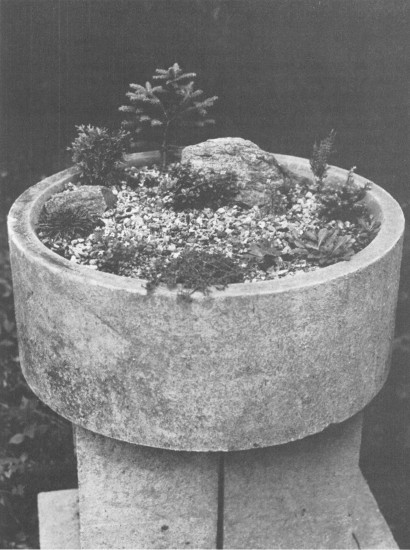

| Miniature garden of dwarf evergreens | 152 |

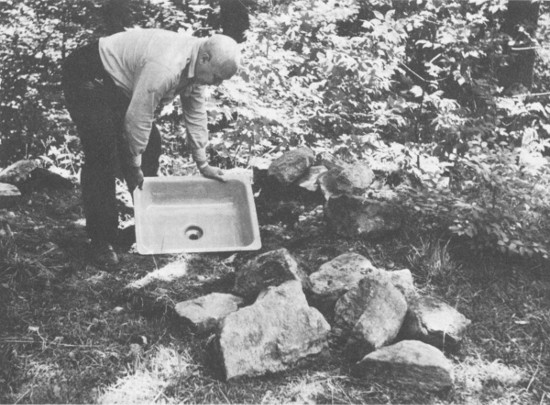

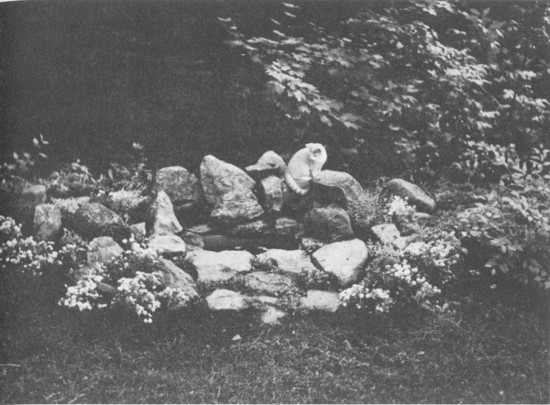

| Rock garden in a wash-boiler lid | 157 |

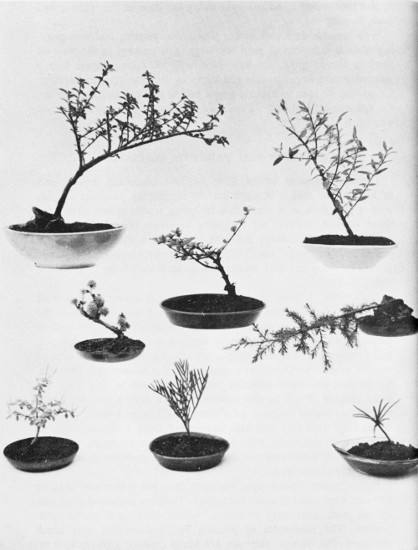

| Variety of bonsai trees | 162 |

| Bonsai in citrus | 163 |

| White poppies in a tiny garden | 178 |

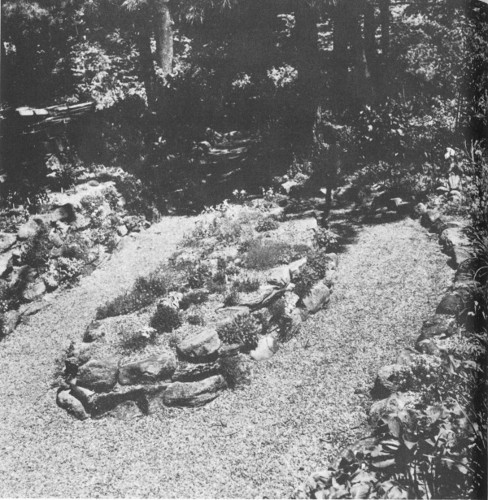

| Raised flower bed | 186 |

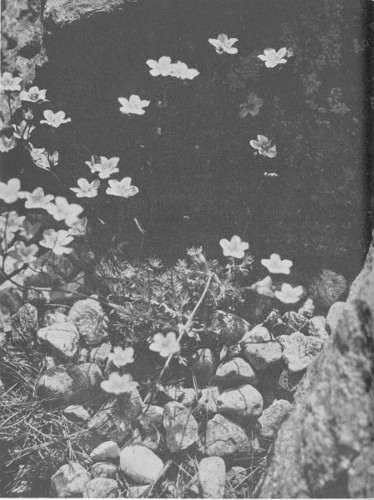

| Saxifraga seedlings | 188 |

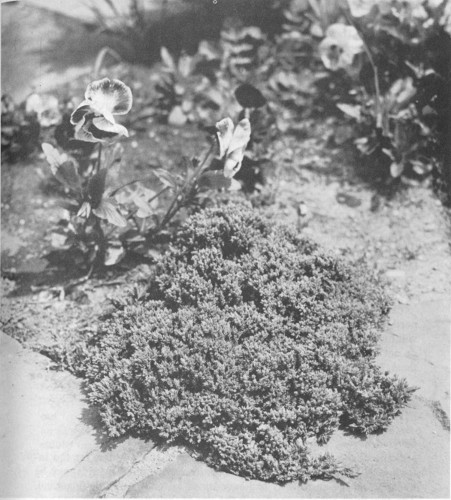

| Trimmed lemon thyme and ivy | 194 |

| Constructing a no-cost pool | 204–205 |

| Wild garden in New York City | 213 |

| Bloodroot | 214 |

| Juniper with pansies | 245 |

| Planted cold frame | 257 |

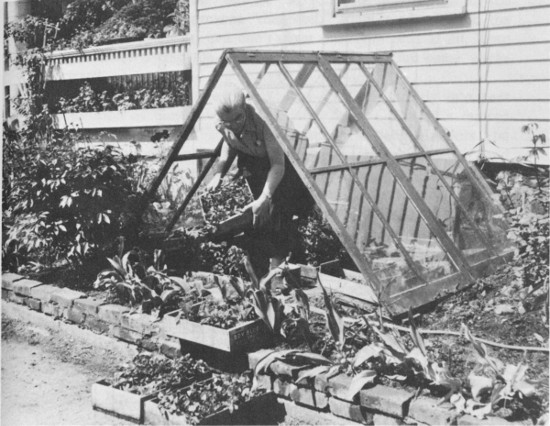

| Author in her $00.00 greenhouse | 279[8] |

| DRAWINGS | |

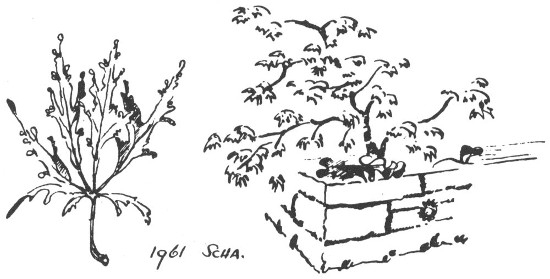

| Dream greenhouse (Kathleen Bourke) |

66 |

| A fancy to build on (Kathleen Bourke) |

67 |

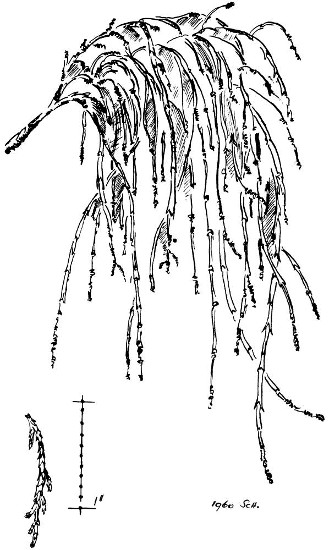

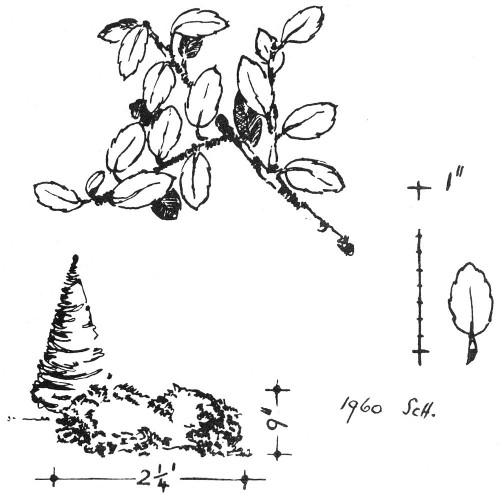

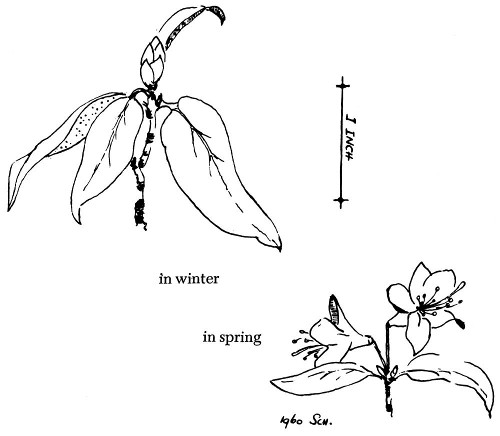

| Foliage details of five popular miniature trees and shrubs (Fritz Schaefer) |

237 |

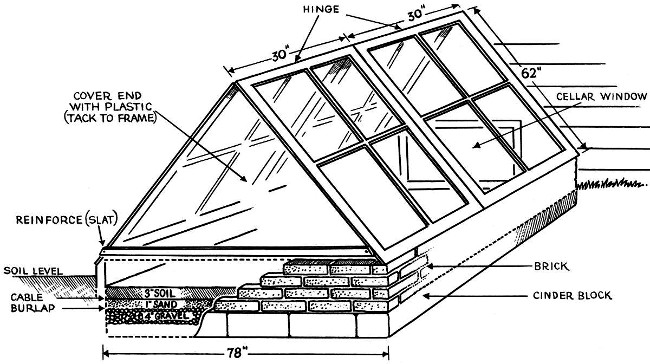

| Construction diagram for low-cost greenhouse (Hal Gearhardt) |

280 |

[9]

Naturally, the children’s welfare was the compelling reason for moving our family out of New York and into Connecticut. But we can’t deny that we also had visions of more expansive gardening. So we set out to find an old (meaning dilapidated—not antique), spacious, window-rich house with acres of neglected land where we could indulge our yen for flower borders with delphiniums by the dozens, sweeping green expanses of lawn, even obese bullfrogs on lily pads in a modest lake.

These naïve notions were quickly canceled by the orbital prices of Connecticut real estate. In order to achieve our principal purpose, we had to make concessions to the second. The house we settled for is small; its windows are few and runty; and it has less than an acre of cultivatable land. It is one hundred feet at its widest, nearly six hundred feet long, and less than a hundred feet level in any one expanse. In other words, we got split-level land instead of a split-level house. But it is charming. Neighbors with great expanses of gardens and lawns actually envy us for our “natural setting.”

Actually, my favorite landscape architect, who happens to be my husband, Bob, would be lost if given a perfectly flat piece of land of equal length and width. He would have no contours to follow and would probably go fishing. As it is, both of us have plenty of challenges and the fun of running up and down ridges in our plantings. The acreage is ample for two persons who have little more than so-called “spare” time.

From this quick summation of facts, it is obvious why we gave up our grandiose ideas of immense perennial beds, a half-acre vegetable plot, naturalized bulbs by the thousands. Instead, we’ve learned how to tuck little gardens into odd corners; to compensate for limited space with intimate miniature perfection; to hunt for and find the small plants that are in sympathy and in scale with our small house and landscape. Cramped growing quarters indoors have[10] even led us to collect miniature house plants. And when, some sweet day, we have our own personal greenhouse on the place, it’s bound to be in scale with the rest of it.

Fortunately, we are by no means a minority. More small homes than large are being built today, and on more small lots. Gardeners are intensifying their demands for small plants of all sorts; and hybridists and suppliers are working nobly at filling the need. We now have four-inch ‘Wee Willie’ sweet William, tiny Twinkle Phlox, other dwarf annuals and perennials. Some nurseries are beginning to feature dwarf trees and shrubs. Florists and greenhouses are giving us minuscule house plants such as Sinningia pusilla and orchids with one-inch flowers. The charm and intimacy of the miniature is replacing the magnificence (and oppressive maintenance) of the massive.

There you have the beginning of this book and the reason why it contains many quite new projects. They would be illustrated as “before and after,” except that the “after” is yet to be written. Regardless of how long miniature gardening has been practiced, we feel the greatest developments are yet to come. Small houses and small plots of land force us to this conclusion.

Admittedly many of our personal opinions are based on experience and observations in Northeastern gardens. However, whenever possible we have included reliable information for other climates. You will, of course, make your own interpretations and adaptations. This a reader must always do, no matter where an author lives and gardens. And there is always your county agent to consult or your local garden-supply florist with whom to discuss your particular situation. Always an added pleasure.

As the author, I have used two criteria for including or omitting plants at the time of writing. I am concerned with those that are readily available from florists, nurseries, and the suppliers listed in the Appendix; and those that in my opinion are suitable for miniature gardens.

Except for the specific art of bonsai, I have not included plants that are unnaturally dwarfed by pruning or other means. I have omitted plants that look like miniatures when they are young, grow slowly, but eventually get out of miniature proportions if given time. I have not attempted to differentiate between miniatures and dwarfs,[11] nor have I set up restrictive dimensions. Sizes vary with types of plants. A miniature orchid may be three inches high, a miniature shrub three feet or more.

This book has been written by an amateur gardener for other amateurs; and I have made it as readable and enjoyable as I could. But in the interests of clarity and accuracy, Latin botanical names are used in preference to the vernacular. This is the only way to be sure plants are correctly identified. Popular names are confusing. Kenilworth ivy, grape ivy, and English ivy certainly sound as if they were related in some way; but when you use botanical names (Cymbalaria muralis, Cissus striata, and Hedera helix, you know they are not. By using the botanical names you are more likely to find the ivy you want in a reference book or catalogue.

For most plants, Hortus Second has been used as the authority for identification and spelling of names; but in the interests of readability, the double ii ending has been reduced to a single i. For a number of plants that have become available since Hortus was last revised (1941), I have referred to Exotica II, by A. B. Graf.

Unless a plant name is complete (genus plus species—plus variety, if any), it is neither capitalized nor italicized. (The caladium is a favorite foliage plant.) Complete botanical names are italicized, but only the generic name has an initial capital letter, even when the specific name has been derived from the proper name of some person or place. (The diminutive Caladium humboldti needs humidity.) When you see a plant name in italics, you will know that this is a recognized botanical species or one of its varieties, and not a man-made hybrid.

The names of recognized hybrids, seedlings, and mutations of either or both are not italicized, but are capitalized and enclosed in single quotation marks (caladium ‘Little Rascal’). Common or popular names are set in regular type with initial capital letters only for proper nouns, when they appear in text. In separate listings each word is capitalized.

In order to make a gardening book completely accurate and understandable, it is almost mandatory to use some so-called[12] “scientific” terms which should really be as much a part of a gardener’s vocabulary as “annual” or “evergreen.” The following words are used in their technical sense:

Genus (plural, genera)—A group of plants related to each other by botanical characteristics. The name of the genus is like a human family’s surname, Smith, but it is written first instead of last. Oncidium is a genus of orchids.

Species (plural, species)—A plant that differs from others within a genus, usually occurring in a natural state and capable of reproducing itself in identical form. The name of a species is like a person’s first name, Alice, but is written last. Oncidium pusillum is one of several species in a genus of orchids.

Hybrid—Generally the result of fertilizing the flowers of one plant with the pollen of another; the resulting seedlings are hybrids.

Mutation or sport—A variation in any part of a plant that remains constant when that part is severed and propagated.

The word variety, however—although it has a strict botanical application—has been used more loosely and may often be defined here simply as “variation.”

[13]

I wonder if anyone ever wrote a book without being indebted to many persons for some sort of help or inspiration. Certainly, I couldn’t do it. Subtract the encouragement and time-consuming assistance of my family, friends, and horticultural acquaintances, and this would be less a book.

I am deeply grateful to: Fritz Schaefer for landscape designs and drawings of rare delicacy, and for letting me benefit by his wide horticultural training and talents; to Kari Berggrav for her enthusiastic contributions to the manuscript and for all sorts of help with plants and photographs; to Mrs. John Lee and to F. H. Michaud of Alpenglow Gardens for their help and the use of their artistic photographs; to Adolph Adukas of the Julius Roehrs Company for his talented arrangements of dish gardens; to Kathleen Bourke for her fanciful drawings and to Elvin McDonald of McDonald and Bourke for his assistance and advice; to Flower and Garden for allowing me to adapt material that had appeared in that magazine; to Mary Ellen Ross of Merry Gardens for her assistance and the photographs of miniature plants she allowed me to use; and to all the friends and tolerant gardeners who allowed me to put my camera tripod in the midst of their plants—Mr. and Mrs. H. Lincoln Foster, Mr. and Mrs. Alex O’Hare, Mr. and Mrs. Norman Cherry, and our neighbors, Mr. and Mrs. Henry Fuller. To Ernesta Ballard and Peggie Schulz, well-known garden writers, and Mrs. N. E. Dilliard of Tropical Gardens, my gratitude for your assistance. I thank my mother, Alice Gaines, and her keen eye for catching my witless errors.

[15]

ALL ABOUT

MINIATURE PLANTS AND GARDENS,

INDOORS AND OUT

[17]

In a living room so small that two dogs asleep before the fire must be roused to let you pass through, monstrous cut-leaf monstera would be out of place—literally and most certainly no asset. In our house, to be truthful, anything larger than a three-inch pot begins to get out of proportion. When we were buying the place, we called it “quaint” and “cozy.” But when we moved in our favorite house plants, it was just too crowded for words.

This was the origin of our intense interest in miniature house plants. But limited space is by no means the only reason why these little fellows are such cheerful and desirable indoor decorators.

First, of course, there’s the charm of the diminutive—the same lure that leads some people to collect figurines or doll’s furniture. But plants are alive and growing; you can pore over each leaf and flower as it matures to small-scale perfection.

Because miniature plants occupy little space, you can grow more of them, and in greater variety. Three dwarf geraniums will bloom their heads off where a single large one might be crowded. Modern, narrow window sills are adequately spacious for a dozen or so two-inch pots of colorful cacti. One cattleya orchid can be replaced by several equally exotic, and much more personable, dwarf “botanical” orchids in delightful variety. Where full-sized narcissus and “daffy’s” that have been forced often seem to be just that, “forced,” miniatures fit in, add gaiety and color, along with naturalness.

Most important, miniature plants and gardens are thoroughly in tune with today’s decorating trends. They’re in scale with small rooms and low ceilings, in harmony with the spirit of suburban homes,[18] mobile enough to facilitate change and rearrangement, even functional because they’re more carefree. And they certainly go along as we leave last year’s stark, bare, uncluttered look behind and move toward the warmer, more personal décor that once more allows us to display snapshots of the children on the mantel.

Miniature plants are often less costly than large specimens, and require less care. They grow slowly, require fertilizing and repotting less frequently, don’t outgrow bounds, and seldom need to be renewed or replaced.

When I first started to collect miniature house plants, I had no idea how many were available, or in what delightful and wide varieties. There are miniatures in almost all of our best-known plant families, and there are some groups that have almost nothing but miniatures to offer. There are small-scale trailers, climbers, creepers; leaf rosettes or bushlets; tropical plants and mountain-dwellers; those with striking foliage, spectacular foliage, or both. Once you discover the wealth of Lilliputian plants you can grow in your home, I warn you, your will power had better be strong, else you never will stop following this fascinating hobby of raising the little fellows. It will run away with you before you know it.

The window is the place most naturally suited for a living garden. It is nearest to the fresh out of doors and brings the plants closer to the environment where they are at home. By creating a transition, the plants in turn seem to bring the outdoors inside. A window is often, also, the only place where indoor plants can get the daylight and sunlight they need to keep in good condition.

But a real window garden is not a motley assortment of plants in pots, haphazardly arranged (or not arranged at all) or lined up in precise, military rows. It is an artistic composition, a grouping of plants with some sound design in mind—an arrangement of plants and their containers for pretty and refreshing effect. The more natural the plants look, the less obvious or contrived the lines of the design, the more decorative the result. This principle is, of course, integral to all kinds of gardens, indoors and out; but it is particularly vital in a window where our eyes stray a dozen times a day.

With miniature plants I find it easier to achieve good composition—much easier than with large ones. There are more elements with which to work; there is more opportunity to rearrange, a wider[19] choice of colors, textures, and forms—the possibility of blending or playing them against each other. I recall a small window in an old country house, deeply recessed by the width of the thick stone wall. Three or four large or medium-sized plants might have stood on the two-foot-deep sill. But there were a dozen or so dwarfs and miniatures all blended and accented by two small baskets of miniature ivies. The display was so lovingly arranged and cared for, the effect was more of a garden than an obvious decoration.

(In a rich selection such as this one, there is a natural danger of “too-muchness.” Don’t crowd these plants. Just the addition of one extra pot can spoil the effect of a perfect garden. Miniatures are not meant to be massed. When crammed close together they can look like a weedy, unmown lawn. Give each plant enough space to set off its modest charm, then you’ll find each one doubly charming in its space.)

And so an assortment of small potted plants can be arranged as effectively in a window as perennials can be in a flower border. There should be a careful selection and placing of colors for both contrast and harmony; the interplay of foliage forms and textures; the blending of plants into one design with eye-catching accents where accent is needed. For a container, use a shallow galvanized metal tray made to fit the window sill and painted a matching white. It should hold about an inch of water with a layer of pebbles thick enough to keep the pots above the water. The evaporating moisture humidifies the air. Use miniature plants of several families but all needing approximately the same amount of light and sun. For color, there are the flowers of begonias and impatiens; for foliage contrast, peperomias; for accent, taller plants; with Ficus pumila ascending the window frame and small-leaved creepers dangling over the edge to soften harsh lines and blend the garden into the room.

There is equal charm in a collection of miniature plants of the same general type and of nearly the same size. Neat rows of cacti and other succulents in small pots look gay and colorful lined up on the sill and on glass shelves in the window above it—glass, of course, to permit all possible sun to reach the plants. Between the pots, at irregular intervals, set a collection of crystal wine glasses or figurines. Or line up impudent miniature geraniums as in the photograph. Here, the pleasure comes, not from the artistic composition, but rather in the uniformity of the rows of small-scale pots and plants.

[20]

Miniature geraniums arranged in uniform rows

For an indoor version of the outdoor window box, use a box made to fit on the sill, gaily painted and decorated in the Mexican spirit of the cacti growing in it. It should be deep enough (about four inches) for healthy root growth. The cacti are not potted, but planted in the sandy soil in the box. These indoor window boxes can be of all sizes and shapes—large enough to cover the sill of a big window plus the radiator under it; triangular, to fit in corner windows; suitable for the top of a child’s play table in a sunny bedroom or playroom.

All of these gardens are planned for windows with full sun, or nearly so. With less sun the choice of plants changes. For example, miniature gesneriads (African violets, streptocarpus, episcias) might be combined with ferns and other foliage plants; a selection of the widely varying types of peperomias would be effective where sun is very scarce indeed.

[21]

Mexican motif with cacti in a homemade window box

Child’s cactus garden over a radiator—fine for a playroom

[22]

Available light, or sunlight, is the first consideration in selecting plants for a window area, or in selecting the window for the plants you have or want. Light can be brighter (it even comes from overhead) inside a greenhouse that extends out from the window. You can buy these in all combinations of measurements, ready-made and assembled, or ready to be assembled. Or you can make them, or have them made, from the materials sold in most hardware stores for those who build their own screens and storm windows.

The greenhouse fits flush to the outside of the window frame and is sealed with a calking-gun after it has been screwed firmly in place. It may rest on the outside of the sill, or be supported by metal or wooden brackets on the underside. The top lifts open for ventilation, and the opening is covered with a screen. Glass shelves permit light to penetrate fully. A tray at the bottom holds moist vermiculite to humidify the air.

The window sash can be removed or not, as you wish. You can install an inexpensive, thermostat-controlled heater for extra warmth in winter.

If the light is right, and if humidity can be kept high enough, an installation such as this can contain not only all sorts of window-garden plants, but also many of those recommended for the greenhouse in Chapter 6.

A window greenhouse filled with growing, blooming plants is an attractive outdoor decoration on almost any house. Its effect indoors is always cheerful and refreshing. And it is especially suited for miniatures. Numerous small plants make a better decorative effect than a few large ones.

(For suitable plants, please refer to list at end of Chapter 6.)

[23]

The three tiny rooms of the Greenwich Village apartment possess a total of two narrow, old-fashioned windows; yet in its darkest corners bloom some of the most gorgeous gesneriads I’ve ever seen. In similar fourth-floor quarters on New York’s dreary 41st Street, miniature orchids and other tropicals make a flamboyant jungle. In an attic in Levittown, a cellar in Bayside, a heated garage in Westchester, plants make it look like July in January, living their life cycles over and over again without ever seeing the sun. The life they must have for existence is supplied by electricity.

Time was, when windows were the only place in the house where plants could be grown. But since government scientists first grew corn to maturity under artificial light at Beltsville, Maryland (back when I had more interest in boys and dating than in gardening), that picture has certainly changed. Now, all sorts of plants can flourish in the most unlikely places. Home decorators can use plants ornamentally wherever they look best, and create the conditions in which they grow best. The hobbyist who can’t afford a greenhouse can have a most satisfactory and inexpensive substitute in unused places in the house. And a greenhouse owner can double his growing space without adding another section of glass.

Naturally enough, scientific research in this field has been aimed at helping florists, farmers, and others to whom plants are a business; but amateurs have benefited, too. The principle of photoperiodism—that some plants set buds and flower only when nights are long, some others only when nights are short—led to delaying the flowering of commercial chrysanthemums by interrupting the long night with a period of light. Amateurs have used the same[24] principle to force tuberous begonias to flower in winter by lengthening the day with several hours of artificial light.

The discovery and isolation of a light-sensitive enzyme, photochrome, has been applied to cyclic lighting—a less costly method of regulating flowering by flashing lights on and off at intervals. Probing the mysteries of photochrome has also given orchid fanciers a better understanding of their plants’ blooming habits and has even made it possible, with some species, to have flowers twice or three times a year, rather than just once.

If I may be permitted a slight prejudice, it’s these amateur benefits that make me happiest. I love plants; and I think millions of other people do. From the windows of my commuting train I see New York tenement tenants wistfully watering morning glories that pathetically climb fire-escape trellises. More prosperous Manhattanites spend small fortunes on florists’ plants to bring the breath of green life into their sterile apartments; and their disappointment, if the plants die, is pitiable. Suburbanites have a yen to make a hobby of collecting plants. And now they can. I know, because I did.

In our roomy, old-fashioned cellar in Bayside we had triple-decker shelves fitted with fluorescent lights where we grew everything from begonias (finally, a collection of more than 350 varieties) to annuals for the gardens out of doors. That was some years ago. The information about lighting was sparse, inconclusive, and often confusing. Our light intensity was inadequate, and there were other deficiencies which we would correct were we setting up that cellar greenhouse today. But our successes were fascinating, our failures a challenge. And the hours we spent working with those plants in the cellar often were our only moments of refreshment and relaxation.

The hobbyist, with his dividends of fun, is not the only one who benefits from this new concept of light and plants. There is the home home-decorator, the woman of the house, who finds in plants the sort of ornament the entire family enjoys. She’d like the graceful lines of a vine tumbling down from the mantel, jewel-like flowering plants on the shelf of a corner cupboard, a garden of green atop the room divider between the living and dining areas. Frustratingly, she discovers that where the plants are most effective, too often they won’t grow and flourish. It is usually because there is insufficient light for their life processes. But now, she can set up a light on the mantel, install fluorescent tubes beneath cupboard shelves, or let ceiling lights flood the plants above the room dividers. Such[25] lighting has a double effect, it enables the plants to flourish, and it gives a dramatic accent to the décor of the house.

Interesting combination of bookcase and lights for African violets and begonias of several varieties

Artificial lighting is a help even for the casual grower—one who has only a few plants, whether by happenstance, for the fun of it, or simply because “a house is not a home” without a plant or two. Table, desk, and floor lamps can be used to supplement the natural light from windows. Too often windows are shielded by trees or the house next door, or perhaps it is winter and there isn’t enough light to keep most plants in a thriving condition. Just turning on a lamp so that the rays fall on a plant can lengthen the hours of light enough to bring out bloom that might otherwise be impossible.

[26]

Tropical plants with controlled light, heat, and moisture make a “jungle garden”

Miniature plants and gardens are, of course, shining prospects for growth under artificial light. They take so little space, and since there is a limit to the height, width, and depth a single installation will illuminate, you can make the most use of it if you are growing the little fellows.

Here’s how the “jungle garden” came to be our source of continual refreshment and pleasure. Our living and dining rooms, both rather small, are separated partially by deep shelves. The previous owners of the place, devout music-lovers, used the shelves for their hi-fi set and stacks of phonograph records. Our record player—pardon me, our stereophonic hi-fidelity music box—has its own cabinet, and that left a gap in the divider between the two rooms.[27] We naturally thought of plants, particularly the tender tropical miniatures I collect. Since we still hope to do extensive remodeling, the garden was not built permanently into the shelves, but was constructed as a separate case.

We are fortunate in having a generous friend who loves to work with fine wood, and can make cabinets with the precision of the real professional. The case he turned out is a beauty. It measures eighteen inches by twenty-four inches inside. The top rests on strong metal rods at the corners. Window glass slides horizontally in the grooves cut in the top and bottom, enabling us to open or close the case as need be. The inside of the top is painted white, thus reflecting the light from the lamps downward on the plants. We use both fluorescent and incandescent lights which are mounted on the underside of the top. The bottom of the cabinet is lined with the heaviest plastic we could find.

At first the case was used as an indoor greenhouse for many potted plants that need protective warmth and humidity. Several inches of vermiculite in the plastic lining were kept moist constantly, with the sides being opened or closed for ventilation.

Later, we filled the bottom with rich potting soil and put the plants’ roots right in it—climbers, creepers, tiny bush-shapes and trees. This turned out to be more of a “jungle” than we expected. Some notably delicate residents seeded themselves and started families. A dainty cissus strung itself langorously from one end to the other. The creeping fig nearly strangled the frail, whiskery bertolonia. But the planting was a source of delightful surprises—a bud here, a flower there, increasing colonies of some delicacies we hadn’t been able to grow at all, before.

Several years ago a bookcase which I set up in my office as a garden was the object of considerable attention—how much I never realized until I dismantled it and gave away the plants. Then, I was bombarded with questions—and even some complaints that I had taken away this spot of greenery. From the night watchman up to the president of the company, people missed those plants. Some even thought I must have been fired.

There is a little house in Levittown, one which I always enjoyed visiting. The second floor has two finished rooms, one of which then was the office-den of the hard-working Elvin McDonald of Flower and Garden. (He has since moved to Kansas City.) His tiered plant table with fluorescent lights was there for a functional reason, but it had a decorative value as well. In other homes I’ve[28] seen plants growing by hundreds under lights in unused bedrooms, single specimens displayed in shadow boxes with circular fluorescent tubes, decorative gardens thriving in all sorts of dark corners. With artificial lighting taking care of the space problem, just about anyone can grow plants.

The author’s New York office light-case planted with gesneriads, begonias, and other plants

However, before your enthusiasm flies too high, consider this sobering caution. Like anything else, artificial lighting works best only when it is properly planned and executed. Light must have the[29] quality, intensity, and timing that plants need. Specific, accurate, up-to-date information is not always easy to find. Despite many fascinating discoveries and developments, this is still a relatively new horticultural principle, and there is still much more to be learned. Before he begins, the newcomer should locate the very latest and most reliable information; and the experienced grower should keep posted on the constantly changing rules. It has been my pleasant discovery that the big power-and-light companies, ever alert to develop new outlets for their product, are keenly aware of the possibilities of artificial-light plant propagation. Many of them are setting up departments to help horticulturalists. If you are puzzled, try your light company for information. It may take a few phone calls and letters, but eventually I know you will find some likeable chap wanting to help you.

Light shelves of medium height with begonias of many sizes and varieties (note miniatures down front center)

[30]

Although it is not necessary to become a botanist, I feel it is urgent to have a clear conception of how plants grow, and particularly how they use light. While we can’t all be electrical engineers, it is also helpful to have some basic facts about electric lights and how they relate to plant growth. But if it were possible, I think I’d consider writing the facts I have with invisible ink. Who knows but what today’s list of rules will be obsolete, and outmoded by new discoveries, before this book can be published?

Botanical Principles

For normal growth and flowering, plants must have light of the proper sort, intensity, and duration. Thus the leaves can perform their function of making starch, then sugar—the mysterious process called photosynthesis. Besides normal growth, plants require an extra supply of sugar and starch for producing flowers. True, plants need light, but they also need dark to convert food into energy and growth. And this means complete dark. It has been shown that if light falls on so much as a single leaf, the entire plant continues to operate as if it were day.

For normal growth and flowers, plants require a certain balance of the red and blue rays of the spectrum. In general terms, blue rays are especially effective in developing leaves, stems, and other vegetative growth, and often in greater proportions for seedlings as compared with mature plants. In general, the red rays keep plant growth sturdy, regulate the development of buds and flowers, affect the germination of seeds and the rooting of cuttings.

For normal growth and flowers, different sorts of plants need light of different intensities—depending usually on available light in their natural habitat. Again in a general sense, light of more intensity is needed for flowering as contrasted with the needs for healthy foliage. But light intensity requirements vary with various types of plants.

For normal growth, and flowers, some plants need dark periods of greater duration. This is the principle called photoperiodism. By now a good many plants have been classified as to this requirement, but there are many others whose needs are yet to be determined. Chrysanthemums, poinsettias, and Christmas cactus, for example, will set buds and flowers only when there are more hours of dark and fewer hours of light. These are called long-night plants. Tuberous begonias, and other summer-flowering types, come into flower when nights are of short duration, and are called short-night plants. Those plants that don’t seem to care one way or another are called day-neutral. For the sake of consistency you might even call them night-neutral. It is[31] also thought that there is some relation between the duration of light and dark periods and temperature. Thus it can be seen how much research is yet to be done. A challenge of course, but that is what makes our scientists great.

Electrical Principles

Artificial light is not the same as daylight—it doesn’t have to be. It needs only to supply the right kind of light (blue and red rays) of suitable duration and intensity. Because it is constant, and consistent, the intensity (as measured in foot-candles) does not have to equal the brightness of a sunny day at high noon. Daylight waxes and wanes from dawn to dark every day, and may be very dim on cloudy and rainy days. Artificial light, coming from generators, is not dimmed by clouds or other external conditions. Duration is controlled by a light switch, or a time clock.

Incandescent bulbs are an adequate source of red rays for plants, but give little blue. They get burning hot, are comparatively expensive, and actually are inefficient to operate. Incandescents are also a source of far-red rays that delay flowering on long-night plants and operate in reverse for short-night plants. According to U. S. Department of Agriculture scientists, incandescent light used as a supplement to fluorescent light “improves the growth habits of many kinds of plants, but is seemingly not required by others.”

Until the introduction of the new Gro-Lux tubes in 1961, fluorescent lamps have given light with more blue than red, and in varying proportions according to the types of lamps. Fluorescent tubes do not get burning hot, and they are comparatively inexpensive to operate, and also efficient. In using the older types, those created especially for illumination, it is important to come as close as possible to the proper balance of the red and blue rays needed by plants. For some plants it has been sufficient to use only fluorescent tubes. For some of the other types many growers use 10 per cent of the wattage in incandescent bulbs.

But the new Gro-Lux fluorescent tubes, developed by Sylvania Electric Products, Inc., are especially for plants and not for illumination. They give a lavender-looking light made up of red and blue rays which are carefully balanced to suit plant needs. Growers who have used them report a spectacular improvement in plant appearance, in plant health, in faster rooting of cuttings, and in increased flowering. If demand warrants it, no doubt other electrical manufacturers will introduce their own brands of fluorescent tubes for plants.

[32]

Obviously, in growing plants under artificial light there are so many variable elements it is impossible—and extremely unwise—to set down hard-and-fast rules. The types of plants to be grown, whether the installation is primarily decorative or functional, and the possibility of continuing research outdating your work, all should be taken into consideration when any installation is set up and put into operation.

Again, I must write in general terms. I have neither the knowledge nor the experience to explain the intricacies of wiring, ballasts, circuits, and the like. This technical information is available from your electrical supplier and from equipment manufacturers, and often is on the cartons in which the parts are packed. Our installation was so outrageously large we had to hunt up a friendly contractor for help. He was a sympathetic man who loved plants and was fascinated by the idea of growing them under lights. Also, he was a cautious person, mindful of the fact that our electrical system was about twenty-five years old. And that stamped it as being an antique (as your light-and-power men will tell you). Since our basement floor was likely to be damp at times, heavy waterproof cables with special plugs and outlets were used, and grounded to prevent shocks, etc. Be careful about your electrical system, especially if you are going to go into anything as elaborate as our first enthusiasms. Don’t build a firetrap for yourself. It’s hard on the plants, not to mention the old homestead.

Whether your plants are to be grown in a garden, or in pots on benches, on shelves, or in a greenhouse-like case, the lineal proportions will be determined pretty much by the space that is available in your house, basement, greenhouse, or perhaps, as was in my case, your office. In small decorative planters twenty-five-watt fluorescent tubes (two feet long) are used most frequently. However, it is important to use enough of them, lined up closely to each other, to give a light of sufficient intensity. In fluorescent tubes the light is most intense in the middle and tapers off sharply at the ends. Since short tubes have more end—and less middle—they give off less light. The “shorties” are less efficient, as your plants will tell you.

Miniature roses, begonias, a birdbath, and ground cover made this charming little formal garden.

The distance between the tubes and your plants also affects intensity. The closer they are, the stronger the light. If possible, hang[33] your fixtures on chains so that they can be raised or lowered. Adjust them to accommodate the taller plants and then raise your “little fellers” on upended pots, bricks, or boards so they will not be cheated of their share of light. Please remember, the greater the distance between light and plant, the more tubes you will need. Distance determines the number of tubes!

For greater intensity, and efficiency, forty-watt tubes (four feet long), or even larger, are usually recommended. If these are to be hung from the top of a case or cabinet, the simple strip fixtures are sufficient. If there is to be no “ceiling” directly above the lights, or if it is a decorative arrangement where glare might hurt the eyes of those who see it, use the industrial fixtures with shield-like reflectors. (In planning your light-garden, please don’t forget that the fixtures are a few inches longer than the actual tubes.)

If the case which you may be planning can be enclosed, at least on three sides, it will be easier to maintain the needed humidity. If the enclosing sides are opaque, they—and the “ceiling” above the lights—should be treated so the light rays are bounced back and the plants receive the extra benefit. In our cabinets we usually applied several coats of flat white paint on the inner surfaces. But once, under the blandishments of the aluminum industry, I lined a cabinet with their foil. It was plain foil, not the crinkled sort, so I did my own crinkling. Then I smoothed it out and fastened it in place with a staple gun. Plain foil, like high-gloss white enamel, seems to reflect the light every place except where it should be, on the plants.

In one of the installations we had at our place on Long Island I found it impossible to put in enough fluorescent tubes for the plants we wished to grow. Since they were day-neutral varieties, we made up for the lack of intensity by increasing the length of time the lights were used. Up to a point, increasing the light-hours will help to compensate for the lack of intensity—just to a point, however, and then the old law of diminishing returns takes over. Plants must not be under light so long that they fail to get their necessary periods of darkness. It is as essential as sleep is to a human being—perhaps more so.

In planning a light installation try to squeeze out a few extra dollars for an automatic timer. It will help to guarantee success for the operation. You’ll have a certain peace of mind if you tend[34] to be absent-minded. No more will you fret through a P.T.A. meeting, a movie, or a concert wondering if you turned off the lights on your plants. The timer will have done it for you. If you happen to have an enclosed case—one tight enough to conserve the humidity—you can very easily go away on a short trip (a day or two at most) and feel confident your pets will not suffer. If you have postponed buying a timer—actually, they are not expensive—and have to leave your plants for a day or so, it is better to turn off the lights completely. They’ll suffer less than if the lights are going full blast. But for peace of mind, particularly that of the plants, we’ve always used automatic timers. At one time we had three of them. When I was ordering one from a mail-order company, my husband was buying me one as a birthday gift. And at the very same time the electrical contractor who redid out light system donated one in the interests of our begonias. We had them popping on and off at all hours of the day and night. We even hooked a percolator into one for the morning coffee.

As I look back over our experiments of a few years ago, I find there are more plants which are day-neutral (night-neutral if you prefer) than plants which are short-night or long-night. For these day-neutrals, fourteen to sixteen hours of fluorescent light (of sufficient intensity) every day, all year round, will keep them happy and thriving. They won’t know the difference between winter and summer, spring and autumn, Florida or Long Island. That has been our experience, but now I find opinions vary on whether hours of light should be lengthened or shortened in spring and autumn for these seasonal changes. (There is still plenty of room for experimentation. For instance, the light requirements for many plants are still to be worked out—even for closely related plants within various types.)

Some growers, those who specialize in plants for which they know the light requirements, turn on the lights at dawn and turn them off at nightfall. This is a year-around schedule. Others who have plants of assorted types, or of undetermined light requirements, maintain a constant fourteen-hour growing day. And they are often surprised by even second, or third, bursts of bloom. A nice surprise, if you ask me.

[35]

Here again we find the needs of plants vary and fluorescent-light setups vary accordingly. If possible, measure the light in your growing area. The readings of a photographic light meter—the same instrument you employ in your photography—can be translated into foot-candles. Or you can get a meter that registers foot-candles. For advice, consult your camera dealer, or check with your local power-and-light company. Here in Redding we find the Connecticut Power and Light Company vitally interested in artificial-light plant propagation.

Again “in general,” house plants that require “full sun” when grown in a window need 1200 to 1500 foot-candles of artificial light, and for fourteen hours a day. Foliage plants will get by with 500 to 600 foot-candles. At about 1000 to 1200 foot-candles many plants, and I’m thinking of begonias and gesneriads in particular, will be robust and floriferous.

Should you find it difficult to figure light intensity as suggested above, you might follow the formula worked out by an old friend on Long Island, Elaine Cherry (Mrs. Norman Cherry, the wife of one of our engineering friends). Her formula is easy to follow. “A single forty-watt tube will serve a space approximately four feet long by six inches wide.” Small plants that need intense light can be set up close to the tubes.

Here is a tip—ever notice how your television picture is dim but brightens appreciably when you take a dust rag to the surface of the glass? The same is true of your light fixtures. Wipe them off now and then. Clean tubes give more light than dusty ones, and new tubes give more light than old ones. When a tube darkens at the ends, that means it has seen better days and should be replaced. According to Mrs. Cherry, it is a good policy to replace tubes after five thousand hours of service and not wait for the dwindling light to curtail the rays your plants need. While you are at it, it’s smart to insert new starters.

Until the introduction of the Gro-Lux lamps, we had to choose types designed primarily for illumination. And there were as many choices and combinations as there were tube types. In a private[36] and somewhat limited survey, I’ve found that when only one type of tube was used, cool white was to be preferred. In combinations of equal or two-to-one proportions, some growers use daylight and natural tubes; others prefer daylight and de-luxe warm white. And there are those who go for cool white and de-luxe warm white. Those who supplement their lights with 10 per cent incandescent light seem to favor all daylight fluorescent tubes.

The object of all these different combinations is to get the most favorable balance of red and blue rays. If you are a hobbyist who grows plants for the love of them, and not necessarily for their value in interior decoration, the new Gro-Lux tubes are less complex and less troublesome. You don’t have to be a light expert to get results and have fun with your light-garden.

Temperature, humidity, soil, fertilizing, potting—almost without exception, plants growing under artificial light need the same care as window-garden plants. But since the light is an artificial substitute for natural sun and light, watch for signs that the plants are not entirely satisfied with it. When they stretch out, get long and lanky, or the foliage has a weak, wan color, set the plant up closer to the tubes, or over toward the center where the light is strongest. You might do well to make room by shifting some of the plants that have been in the center. Sometimes when a plant has too much light it will become stunted. Until a more exact rule book is written, you will have to use your own good common sense.

Here is the big worry many growers have; the failure of their pets to flower. More often than not that means insufficient light, insufficient red light, or perhaps both.

As of this date it is probably ten years since we first started toying with plants under artificial lights. I say “toying” because it was just that—purely for fun. We kept no records. When frost was in the air we dug up flowers and brought them indoors. My husband even brought in eleven goldfish which he feared would be glacéed in an outdoor pool. We put everything under lights with the fish in terrariums. Eventually he spent thirty dollars for a pool in an untidy corner of the living room. Thirty dollars, not counting the electric bill, I felt was a little expensive for a dollar’s worth of goldfish. I sold twenty dollars worth of photographs of that pool and then included one of them in my book All About Vines and Hanging[37] Plants. Eventually he allowed me, very grudgingly, to place episcias around the pool. Mites moved in on them. He sprayed for the mites and killed all of the fish. He replaced the fish with eleven others. Thus the cycle continued.

All the time we had those indoor plantings our neighbors kept asking us what plants were good for lights and what lights were good for plants. Frankly, we couldn’t answer. Ten years ago that book hadn’t been written.

We tried just about everything less than five feet tall. We had wonderful results with African violets, begonias, orchids, and gesneriads. We even had a morning glory which singed itself on a steam pipe. All of them loved the kilowatts.

(In Chapter 6 I have indicated certain plants which are suitable for propagation under artificial lights.)

[38]

House plants are usually considered more or less lasting indoor decorations. But they can also be used the same as cut flowers for temporary and changeable displays, and then, like cut flowers, can be discarded when they begin to fade. They cost less and last much longer than bouquets, but because they’re temporary decorations, they cause less worry and require less care than the permanent inhabitants of window sills or artificially lighted gardens.

That sounds rather heartless, I know. But it’s a defense I’ve built up—and a perfectly logical one—against the wails of those who take beautiful florists’ plants, place them on dark mantels, or in other thoroughly unsuitable growing areas, neglect them wholeheartedly, and then “can’t make them grow.” How many people do you know who buy lovely Christmas begonias, poinsettias, or cyclamen for the holidays and expect them to bloom the following season?

Honestly, I can’t see any reason why plants must be immortal, why they can’t refresh and beautify the home as long as they remain healthy and attractive, and not one minute longer, and then be discarded. I do object to stringy, leafless stems of expiring philodendron, dried-up dish gardens, or any plant or combination of plants that has become undecorative because it is dying. Actually, some florists’ plants, such as greenhouse primulas and calceolarias, are annuals that come into full bloom only once, and having had their big moment are supposed to die peacefully afterward.

Do I treat my plants in the house so very cruelly? Well, no ... not exactly. My budget includes no allotment for florists’ fripperies. I have a different system, and I have a constant supply of healthy[39] plants to use for indoor decoration. My plants spend most of their lives in growing quarters where cultural conditions are good—in bright windows, in the window greenhouse, or on our small sun porch. They are brought in for a few days (never more than a week), then quickly returned to their more healthy, healthful homes. Having done their duty, they go back to grow and prosper. I do this with single potted plants, placed in attractive containers, with dish gardens, model landscapes, and combinations of plants. They are beautiful and charming as table centerpieces, mantel ornaments, displays for the coffee table, shadow box, or bookcase shelf.

In the past few years my preoccupation with miniature plants has led to some pleasurable rummaging and shopping for containers in which to place them to make compositions for a bedside or telephone table, for the narrow window sill above the kitchen sink, and for the small bric-a-brac shelf in the foyer.

As any flower-arrangement artist knows, small-scale compositions are often more intricate and more difficult than full-scale affairs—every detail is subject to separate scrutiny. However, patience, good taste, and an artistic flair will unite a plant and a container with an affinity that looks casual, even accidental, but actually is cunningly contrived. Container and plant become one picture—neither outshining the other—the container setting off the plant, and not sacrificing its own importance.

People who are intrigued with these miniature compositions usually collect containers in wide variety. Some of them are even made for the express purpose of holding plants—from wood, bronze, copper, all sorts of chinaware, glass, and ceramics. But the containers that give the most fun are those made for entirely different purposes. I’ve seen tiny bird cages, little woven baskets, glass lamp shades, odd-ball ash trays, punch cups, unusual tea or coffee cups, soup tureens, and even an ancient Buick hub cap which a little girl “borrowed” from her father’s collection of automobile antiquities. Some gourds are just the right size and shape, and with a nice wartiness, to lend enchantment for growing plants. Our cat keeps us well supplied with the tins in which his food is sold—spray them with paint and they are ideal for many plants. Some cocktail or champagne crystal looks precious with miniature vines drooping over the side.

[40]

Strawberry jar resembling gnome, planted with Kenilworth ivy

Once for our P.T.A. fair I collected a dozen or so unmatched liquor glasses, put a half-inch of soil in the bottoms, and planted tiny Sinningia pusilla. They sold immediately, with people wanting more. A plant sale at such an affair is a rather convincing test of popularity, and whether you have created a good arrangement.

Another favorite I have discovered for unusual containers is Cymbalaria muralis, the nostalgic Kenilworth ivy. I planted some in a small strawberry jar. Look at the jar from the right angle and it resembles a round-cheeked dwarf with a sparse green wig. I wish I could remember where I bought that jar—so many friends have wanted one. The “pawnbroker’s” planter cost five cents in a local junk shop. I also planted it with ivy.

Inexpensive hanging containers and wall brackets for miniatures are available in a wide variety at five-and-dime stores. But hanging baskets are not so easy to handle, as they must be suspended from[41] wire or screwed to the wall. I’ve seen a doll’s hat used delightfully, and also some nice little woven baskets. Or try anything of metal or ceramic if it has a lip to hold a wire or chain—or a two-handled consommé bowl; or a soup ladle with its handle fastened to the wall. You can easily punch holes in most plastic containers—and without cracking—by using a red-hot awl or old-fashioned ice pick.

Pawnbroker’s planter set with ivy

Occasionally I have seen props or accessories used in these miniature plant-and-container compositions that were successful, but only occasionally were they in perfect scale and harmony. More frequently, the silk, wood, or ceramic butterfly, bee, or bird is an unnatural and disturbing intrusion.

Be careful when you water plants in decorative containers. If possible keep the plant in its original pot so it can be lifted from the container and taken to the sink, where excess water will drain away. Otherwise, hold off on your watering until you are positive[42] the plant won’t wait any longer; then stop before the soil gets soggy and wet. Excess water, trapped by a container, can cause roots to rot, in fact will promote rot in most cases.

Be daring, be creative, be artistic when planning container projects and arrangements. If a fat little fern looks right for a teacup, let the cup be squat and fat; or let it be fluted gracefully and flared up to the delicate frond-fans. If a miniature orchid looks like a gem without a case, set it on pebbles in a clear crystal bowl; or perhaps invert a dome-shaped watch glass over it. If a succulent makes you think of a tough little gnome, for goodness sake don’t plant it in one of those grotesqueries which is the hump of a camel’s back or a cavity along the spinal column of a ceramic cat. (Remember how ridiculous a Venus stomach clock looks.) Use a little imagination. Perhaps you have something at hand—a droll bucket, a miniature fishing creel, a butter tub. Interesting containers make interesting compositions if you use good taste and imagination. Try to achieve the quality and feeling that the plant and container were “made for each other.”

A dish garden is the combination of a group of living plants and the container holding them. It should be designed and planted with artistry and originality, but without artificiality. Each dish garden should look distinctive—certainly without any resemblance to the ones which florists seem to make by formula. It should be neither crowded with too many plants, nor cluttered with accessories or small ornaments. It should be eye-catching but not brazen, harmonious but not dull, unusual in some manner and yet comfortably natural.

Like cut-flower compositions, dish gardens are arranged so that plant and container together complete an artistic design. And like any artistic design, these gardens follow (or have a good reason for not following) certain basic principles:

Plants and container blend into one pleasing picture.

Elements of the design interlock, overlap, or otherwise hang together.

The number of elements is limited by restraint and good taste.

All parts of the design are in pleasing relative proportion.

There is one focal point, or center of interest.

[43]

Pruning a dish garden to keep elements in size and proportion

If the design has formal balance, the focal point is in the center, with elements of equal weight at the sides.

For informal balance, the focal point is off-center, with heavier elements to balance it.

A design becomes fluid, rhythmic, with the dynamic use of line, and with pleasing contrast of colors, textures, and structural forms.

Of first importance, of course, is the container. It should be of proper size, shape, texture, color, and mood for the plants that will fill it. Rustic pottery is suitable for desert cacti and other succulents; glazed white, or lightly tinted, pottery for dainty flowering plants; copper, pewter, wooden bowls for an arrangement of heavy, masculine-looking foliage plants.

Containers can be of any shape—round, square, rectangle, triangle, ellipse, irregular. If possible they should be at least three inches deep so there is space in which to pack the roots of your[44] plants. And they should not make themselves conspicuous with bold ornament, texture, or color. Plain design and subdued colors bring out the beauty of the plants.

Very few artificial accessories look well in a dish garden; but natural garden or landscape features such as interesting rocks or bits of old wood are often quite successful.

Before you begin to plant a dish garden, set the plants (in their pots) in the container, and then shift them around until they begin to look right. This will give you a rough idea of how an arrangement will turn out. For formal balance, set the tallest or most striking plant in the center, with some low ones nestled around its base. For informal balance, set the accent plant in one corner of a rectangle and let a large expanse of unadorned sand, gravel, or ground cover spread out toward the diagonal corner.

Turn a sharply curved leaf or branch so it falls against a straight up-and-down plant. Play rough foliage against smooth; feathery against solid; bright colors against dull; pattern against plain leaf. Try lifting out one plant to see if the effect is cleaner. To blend plants with the container, let a creeping or hanging plant fall down over the edges. These beforehand experiments will help you avoid having to shift plants later, during the actual planting.

Although not strictly dish gardens, there are some attractive variations that can be composed without benefit of soil, or of a dish to hold it. In the pockets of a small piece of smooth, silky old root, or driftwood, tuck osmunda fiber (orchid-potting material) for the roots of epiphytic (air growing) plants—most are bromeliads. Terrestrial (soil growing) plants, such as the miniature begonia, are best in sphagnum moss. Or try tiny orchids; some will creep slowly over the surface of the wood. Fasten the plants firmly in place with inconspicuous fine florists’ wire. This will hold the plants until their roots penetrate the fiber and attach themselves to the soft wood. If you supply liquid fertilizer at regular intervals, the plants will grow normally. Water by dunking plants and log in a pan or the sink. Feed by adding soluble fertilizer to the water.

Plants will often grow from cavities and crevices in rocks. If the rock is “limy,” stick to lime-tolerant plants. Tufa, if you can find it, is especially malleable for gardens like these. It is soft and porous, easily cut and shaped, and with ready-made cavities to hold roots and small amounts of soil or moss. It is perfectly acceptable to acid-loving plants.

Conch shells, and another large shell of a similar type which[45] we used to find on the beach—the sort kiddies hold to their ears when playing the game of “listening-to-the-sea”—offer interesting possibilities. Pack the cavity with moist sphagnum moss and plant with several smallish plants. Water with extreme care, and fertilize only slightly. Almost any moisture-compatible foliage plant that is available will live and grow this way for months.

Root from an apple tree, with a pocket for osmunda and a bromeliad

Although these indoor gardens also follow the rules of good design, the result is a different effect. Montague Free once called them “an idealization in miniature of an outdoor scene.” They are not arranged to give an artistic impression, but to re-create some part of the out-of-doors on a small scale. Their charm lies in their diminutiveness, intricate detail and, often, in their whimsy.

The elements are: container; tiny plants (for the purist, all must be living) to represent trees, shrubs, grass, and flowers; and props Or accessories such as miniature pools, fences, and other landscape or architectural features. I suppose rocks would be called accessories, too.

[46]

Each garden should have a theme, and all elements should be in harmony with the theme and help to carry it out. For example, it’s difficult to combine buoyant hybrid pansies with shy wild flowers. A contemporary garden is best in a container with clean lines, but an old-fashioned garden is fine in a platter with high fluted edges. A desert scene calls for a container that’s bare and stark. A white plastic trellis doesn’t belong in a woodland scene. And please, no green bath towels for grass.

Visualize your garden first—sketch the plan on paper. If you can draw it to scale, it will help in the selection of container, plants, and props. It is crucial that each element should be in proper proportion to all others. One element not in scale can ruin the entire effect.

In some gardens a plant or small group of plants will be the object of interest; in others it may be a particularly charming and important feature such as a rustic bridge or a shrine. In gardens of moderate size or less, one feature is usually sufficient, and not more than two in larger ones. Select your main feature first, place it, and make sure all other elements are in scale. For example, a fence should not be more than one and a half inches high under a tree of six inches.

The variety of plants, props, and containers from which you can select can be as wide as your enthusiasm and ingenuity want to make it. Here are a few suggestions.

Tree

Upright plant with a single stem-trunk, foliage at the top, usually taller than it is wide. If the tree is to be the object of interest, look for plants with character rather than symmetry—bent, twisted, gnarled trunk; interesting, lopsided shape; especially lacy foliage; tipsy tendency to lean. There are a number of useful house and greenhouse plants, and more to be found in the woods and fields. For deciduous trees, it is often permissible to use twiggy branches stuck in the soil. I find leafless pieces of mountain laurel very effective.

Shrubs

Upright plants of bushy habit and branching. You’ll find many suitable house plants and some in the wild.

Hedge

Tiny-leaved, bushy plants that can be set close together and clipped to shape. The tiniest boxwoods will also do if they are carefully thinned and each extra leaf is removed separately.

[47]

Flowering and Foliage Plants

Miniature house plants are best for these indoor gardens, although you can achieve temporary success with some annuals like alyssum.

Climbing and Trailing Plants

These are needed for training over walls, but even more necessary for planting at the container’s edge so they will fall over and softly blend the garden and the container.

Ground Cover

A cover for bare spots in the garden—get sheet moss from the woods. Or plant grass seed and keep it mowed with sharp scissors. Use your own ingenuity. You may very likely come up with something more appropriate.

Urns

Use thimbles, thumb-pots, miniature vases.

Pools

These can be built with Sakrete or plaster of Paris. Or sink a sardine can—painted blue-green—an ash tray, soap dish, or plastic cheese container.

Paths

A path should always be going somewhere, preferably to the point of interest. Make paths with sand, fine gravel, small pebbles, perlite. If your garden is a formal one, make cement sidewalks with Sakrete. (Please, we have no financial interest in Sakrete—don’t even know who makes it—but have always found it a most useful material around our gardens for patching, fixing, and repairing.)

Bridges, Fences, and Gates

Here is another chance for your personal ingenuity—and the more ingenuity you use the greater will be your pride when the job is done. Use matchsticks, toothpicks, balsa wood (it is available in hobby shops, but you can very likely snitch a few pieces from some model airplane the kiddies are making). In my office I get coffee from the corner drugstore, each container having a stirring stick. I save those sticks. It is wonderful what one can do with them—picket fences and the like. A little whittling is all that is necessary.

Rocks

Please, don’t use chunks of broken concrete. Hunt around for smooth, interesting specimens, eroded and rounded stones of the correct size. If you happen to come upon one with a lichen, you have a real prize.

There are as many themes for these gardens in miniature as there are outdoor scenes—cultivated or natural—in the world. The only[48] necessity is, once you have decided on a plan, stay with it. See that every plant and prop you use is in harmony. See that every plant has the same cultural requirements—especially if your garden is to be a lasting thing. Here are some general ideas:

Formal Garden

This is probably the easiest to execute, chiefly because it is based on perfectly mathematical balance. The plan is basically geometric—a rectangle with a birdbath in the exact center; walks straight and precise; pairs or quadruplets of plants that are identical in size and shape; hedges that are neatly trimmed. How about trying something different?—an Old World herb garden; perhaps a scene from Colonial Williamsburg; or something from the Elizabethan age.

Informal Garden

Re-create your own garden, or something you hope to have around your house and grounds. It will help you to visualize it in advance. Get a container the shape and proportions of your lot—do a planting with the lawn you want, build up patios and terraces. Build a model of your house and duplicate the plantings you want on a miniature scale. This sort of garden will give you a real thrill.

Old-fashioned Garden

I wonder if you ever had a wonderful grandfather and grandmother—I wonder if they had a trim house with a picket fence—white of course. If you did, how about trying to duplicate it. If you didn’t, do a little dreaming. Dream about what you would like to see—picket fence, billows of bloom from flower beds, climbing things on the walls and fences. Please, let yourself go and improvise à la dream. Next to your own home, I can think of nothing more satisfying than trying to duplicate an old-fashioned garden in the manner of that wonderful past generation. Use your imagination. You’ll be happy that you did.

Contemporary Garden

The central figure could be a miniature vase, to represent an urn, at the edge of a square or rectangular pool. Small boxes can be made like redwood planters. To be purely functional, use gravel or paving instead of grass. Plant sparsely and with an eye for modern design.

Oriental Garden

Here is a garden that can fool you with its simplicity. It calls for fewer plants, more minutely perfect props, figurines, stones, and moss. It may be built around a pool with a Japanese bridge. Outwardly, it looks so easy and simple, but it isn’t. Just get one feature out of proportion and you will be unhappy.[49] Remember, the Oriental artist is a person of great perfection, one with thousands of years of artistry behind him. Before attempting an Oriental garden, better get some good photographs or drawings. It will help you achieve a good picture and you will have a lasting satisfaction. Good luck.

Tropical Garden

This one should be lush with tropical creepers and climbing tropical trees, as pictured in the color section of this book. The container is a bowl from an overhead light fixture—the sort that used to hang above the dining-room table. (It cost ten cents in a junk shop.) The back is a masonry wall, made of pebbles and Sakrete, as is the irregular pool. Paint your pool blue-green. Since your plants will very likely require acid soil, separate the construction material from the soil by strong plastic.

Desert Garden

Little but cacti and kindred succulents can grow here, and sparsely at that. Sedum multiceps, little Joshua tree, has a picturesque tree-like character. Use a suitable soil mixture completely covered with a layer of desert sand, or very fine gravel. Build a dune perhaps. Or make an oasis with a few palms around a pool—an irregularly shaped pool like one might see in a mirage. How about a few strands of grass—maybe not quite in tune with the setting but it might be considered as bamboo. A little faking is permissible.

Rock Garden

This usually calls for building up a rocky slope supported by hardware cloth in the rear and lined with moss to keep the soil from falling through. Follow good rock-gardening rules—rocks of the same kind but of varying shapes, with their layers, or strata, running horizontal. At the base of the slope you might contrive a small pool overflowing into a plastic-limed stream. Make a rustic gate and bridges with evergreen twigs wired and glued together.

Woodland Garden

Naturalistic arrangements of woodsy plants, rocks, moss, fallen logs. Seedling evergreens are fine. Artificial props are out.

Meadow Garden

A gate might open through a split-rail fence to a winding, foot-trodden path through a field of waving grass and flowers. At the back leafy trees line the edge of the imagined cow pasture.

[50]

Most containers for dish gardens and model landscapes are watertight. That is wonderful for any furniture on which they might be placed, but not so good for the plants. There is that eternal danger of overwatering. Roots rot when they stand in mud or water. In tight-bottomed containers it is wise to start with a thick drainage layer—pieces of broken flower pots, pebbles, brick, coarse sand, or even small pieces of charcoal. That gives the excess water a place to go. Cover this bottom layer with burlap or moss to keep the soil from sifting down.

The soil mixture should be suitable for the type of plant which is going to live in it—acid or alkaline, sandy or humus-rich—and should be moist—not muddy—at planting time. One at a time take your plants from their individual pots, set them in place, and make the soil firm enough to support them. Add dangling-edgers and ground cover last. Mist the finished garden with a fine spray of water, thus washing off any dirt and refreshing the foliage. Set the garden in a shaded, protected spot until the plants have recovered from transplanting shock.

Watering these gardens can be tricky. The soil may feel dry on the surface and yet be boggy underneath. Find a small bare spot where you can insert the handle of a spoon or a fork. Dig down to the bottom to make sure that water is really needed. And water with the greatest of care—enough to moisten the soil, but not enough to leave water standing in the bottom. No puddles, please.

Now supposing your hand has slipped—the hand holding the watering-pot—and you have overdone it. If the planting will allow, put the container on its side for a half-hour or so. But, please be careful—actually, I shudder to give you this piece of advice. I’m afraid you might find your creation out of its container and a muddy mess in the kitchen sink. All right, here is something else you can do; dig a hole in a bare spot—a small hole the size of a pencil and in the deepest part of your garden. Suck up the extra moisture with a pipette until the hole is dry. What, no pipette in your garden kit, then try a medicine dropper. No medicine dropper either—try a soda straw, but you had better be nimble or you will get a taste of dish garden. They don’t taste as good as they look.

If your garden is only a temporary decoration, you have given it your all and that is all the care it needs. But I feel you are going to[51] love it so much you’ll want to keep it growing as long as possible. That changes the rules considerably. Place it, not on the coffee table, but in a window where it will get the light and sun the plants need, and where the temperature and humidity are to their liking. (Specific recommendations and plant preferences will be given in Chapters 6 and 16.) Hardy outdoor plants should be kept as cool as possible. You might set them in a cool room, or on an unheated porch, at night and bring them in only for the day. Fertilizing is usually not necessary, except when roots are severely crowded or you are trying to force a plant to bloom.

Keep the garden immaculately clean and neat. Remove faded flowers and tired leaves. Trim those plants that have a tendency to grow too large or straggly. It might be smart to remove any that refuse to stay within proper size. Train your climbers and creepers as you want them to grow. Keep your pools filled with clean fresh water. Mist foliage daily to keep it fresh and dust-free.

The dish gardens and model landscapes you plant this way are easy to care for, but those ones from a florist may present some problems. Now let’s be fair to florists—their gardens and landscapes are turned out on a commercial basis in order that they may make money. (Outside of a few fancy floral outfits, none of them gets rich, particularly when one considers the long hard hours they spend on the job.) In the interest of economy they often combine plants of complete cultural incompatibility—dry-growing succulents with moisture-loving aroids; African violets that need sun for flowering with ferns that scorch in it. Too often these dish gardens are crammed with too many plants for the amount of soil; and the roots have been bruised and broken in handling. The florist knows that two-thirds of the customers who buy his product are going to abuse it anyhow. So he takes a “what-the-dickens” attitude. Make it pretty for the moment, for tomorrow it is going to die anyhow. One more word in praise of my many florist friends—just let the man with the green paper, the ribbons, and the carnations sense that you love plants, understand them, and care for them, and he will go to bat for you. He will help you in every possible way. I’ve never known it to fail. Actually, they are a soft-hearted profession.