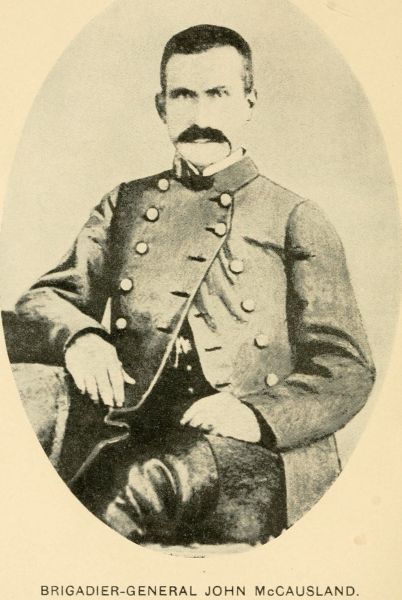

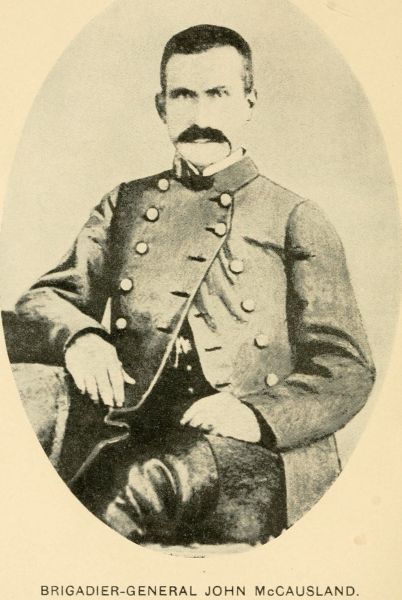

BRIGADIER-GENERAL JOHN McCAUSLAND.

FROM A PHOTOGRAPH TAKEN IN LYNCHBURG DURING THE WAR.

Campaign and Battle

of

Lynchburg, Va.

By CHARLES M. BLACKFORD,

OF THE LYNCHBURG BAR.

Delivered by Request of the Garland-Rodes Camp of Confederate Veterans of Lynchburg, Virginia,

JUNE 18th, 1901.

PRESS OF

J.P. BELL COMPANY,

LYNCHBURG, VA.

PREFACE.

During the winter of 1901, the Garland-Rodes Camp of Confederate Veterans of the City of Lynchburg passed a resolution requesting their comrade, Captain Chas. M. Blackford, of Company B, Second Virginia Cavalry, C.S.A., to prepare an address upon the Campaign and Battle of Lynchburg, which was to be delivered on June 18, 1901, the thirty-seventh anniversary of the events of which he was to speak.

Captain Blackford consented to do this work, and did it so much to the satisfaction of the Camp that it ordered his address to be printed as a valuable contribution to the history of the war and the traditions of our city. It is now presented to our citizens and to all who are interested in the details of our great struggle.

The Committee have also added, as a matter of local history, a roster of the various volunteer companies which left here when the war commenced. Many names were added afterwards, but it is to be regretted that the list cannot be perfected.

Jno. H. Lewis, Chairman,

N.J. Floyd,

R.H. Boatwright,

W. Barbour Jones,

H. Grey Latham,

Committee.

December 10, 1901.

The Campaign and Battle of Lynchburg.

The strategic importance of the city of Lynchburg was very little understood by those directing the military movements of the Federal armies during the Civil War, or, if understood, there was much lack of nerve in the endeavor to seize it.

It was the depot for the Army of Northern Virginia for all commissary and quartermaster stores gathered from the productive territory lying between it and Knoxville, Tennessee, and from all the country tributary to, and drained by, the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad. Here, also, were stored many of the scant medical supplies of the Confederacy, and here many hospitals gave accommodation to the sick and wounded from the martial lines north and east of it. Lynchburg was, in addition, the key to the inside line of communication which enabled the Confederate troops to be moved from our northern to our eastern lines of defence, without exciting the attention of the enemy.

Under these circumstances, it can well be understood that the Confederate authorities were ever on the alert to guard so important a post. They relied, however, on the facility with which its garrison could be reinforced, when threatened, and not on an army of occu[Pg 6]pation, for it could not afford to keep so many troops idle.

Though equally important to the success of the Northern armies, in their operations in Virginia, no serious effort was directed against it until the spring of 1864.

On the 6th of June, 1864, General Grant wrote from the lines around Richmond to General David Hunter, then commanding the Department of West Virginia, informing him that General Sheridan would leave the next day for Charlottesville for the purpose of destroying the Central (now the Chesapeake & Ohio) Railway. Having given this information, he directed General Hunter to operate with the same general end in view, adding that "the complete destruction of this road and of the canal on the James River is of great importance to us." He further says, "you [Hunter] are to proceed to Lynchburg and commence there. It would be of great value to us to get possession of Lynchburg for a single day."

According to this letter, Hunter, after reaching Staunton, was to move on Lynchburg, via Charlottesville, and thence along what Grant calls "the Lynchburg branch of the Central Road," meaning the Lynchburg extension of the Orange & Alexandria Railroad. Having captured Lynchburg and destroyed the bridges and vast stores there concentrated, he was to return by the same route, join Sheridan, and together they were to move east and unite with Grant, who then proposed to move his whole army south of the James[Pg 7] and make his attack on Lee at, and south of, Petersburg. (70 War of Rebellion, 598.)

Hunter was given some latitude as to how he should execute this order and as to the best mode of reaching Lynchburg. It seems he determined to move up the Valley, and to that end called on General William W. Averell to "suggest a plan of operations, the purpose of which was the capture of Lynchburg and the destruction of the railroads running from that place in five days." (Id. 146.)

During the first three years of the war, raids were made upon the line of the Virginia & Tennessee Railway (now Norfolk & Western) west of Lynchburg, for the purpose of destroying Lee's communications with the South and Southwest over that important conduit of supplies.

By these raids some damage was done by burning depots and overturning bridges, but none which caused any permanent injury or produced any serious delay in transportation over it. Except for local panics and the destruction of a small amount of property, these raids were, from a strategic point of view, a useless expenditure of military strength. They did, however, fortunately direct the attention of the Confederate authorities to the importance of this line and greatly increase their vigilance.

On the 9th of June, 1864, when Averell's plan was laid before Hunter, he approved and adopted it. He was then at Staunton, Virginia, in command of an army, the exact number of which is not disclosed by[Pg 8] the records. The official report for the month of May, 1864, for that department, discloses the fact that upon the 31st of that month there was in it an aggregate present for duty of 36,509. (70 Id. 571.) The published correspondence shows that during the month of May every possible effort was made to concentrate these forces, and it seems from the roster that every brigade and division in the department was represented at Staunton when the expedition started. Hence, making due allowance for heavy details on guard, provost and escort duty, it may well be claimed that when the start was made there were present for duty, of all arms, at least 25,000 men, fresh and well equipped. (Id. 103.)

Some of these troops, like their leader, were renegades from the traditions and instincts of their forefathers, and hence very little to be trusted, but far the greater proportion of the force was composed of high types of the soldier from Pennsylvania, Ohio and New York, and, under a proper leader, would have been very formidable. The want of such a leader, despite the efficient aid of able subordinates, made the campaign a fiasco with no historical parallel, except, perhaps, that of the famous King of France, who,

"With twenty thousand men,

Marched up the hill, and then marched down again."

Hunter's army consisted of four divisions, two of infantry, commanded respectively by Generals Sullivan and Crook, and two of cavalry, severally commanded by Generals Duffie and Averell. Each division con[Pg 9]sisted of three brigades, and they were accompanied by eight batteries of artillery, with an aggregate of thirty-two guns.

Major-General David Hunter, the commander, was a Southerner by race and environment, and members of his family had often been honorably connected with the history of the State of Virginia. He had been an officer in the United States army, and on the breaking out of the war between the States, ignored the traditions of his race and took up arms against Virginia. It is not the custom of those of Virginian blood to be disloyal to their State, and it is her proud boast that the roll of those who have been false is very short. What moved Hunter to act as he did must be developed by his biographer; it is enough for the historian to record the fact of his apostasy. Most Southern officers in the old service disapproved the secession of the States, but on the breaking out of the war, with rare exceptions, they resisted the powerful temptations held out as inducements to stay and join the Northern army. They preferred poverty and the uncertainties of the approaching conflict to a military distinction which could only be won by shedding the blood of their brothers and friends. With this faith they joined in the defence of their several States whether they agreed with them in their political course or not. Such was the course of the Lees and the Johnsons, of Stuart and the Hugers, of the Maurys, and of hundreds of others who stood by their people, right or wrong. They believed it alike the path of duty and of honor to draw their[Pg 10] swords in defence of their native land, in the hour of its greatest need, and they turned a deaf ear to the whisper of that tempting thrift which is so often the reward of fawning.

When Hunter and his army were approaching Staunton, a part of his force, estimated at about eight thousand men, had a battle with a small, disorganized detachment under General Wm. E. Jones, at a place called Piedmont, near Port Republic. The troops under Jones were much worn, and were weary with hard work, sharp fighting and scant rations. Those of Hunter were fresh, vigorous and well equipped. Jones and his men fought well, but he was killed early in the action. His death had a bad effect on his command, and it gave way in much confusion and with heavy loss. Much good was done during the confusion by Lieutenant Carter Berkeley and his two ubiquitous guns, which afterwards did such good service in the lines around Lynchburg and upon Hunter's retreat.

After this disaster, Jones's command, under Vaughan, fell back first to Fishers ville and Waynesboro, and then towards Charlottesville. This left the Valley open as far as Buchanan, except for the small, but ever vigilant force of cavalry, so skillfully and manfully handled by Brigadier-General John McCausland, who had shortly before been transferred from the command of an infantry to a cavalry brigade.

Imboden, with a small body of cavalry, which had escaped from the battle of Piedmont, and which was[Pg 11] badly mounted and equipped, had crossed the Blue Ridge and was energetically attempting to defend the Orange & Alexandria Railroad (now the Southern), in Nelson and Amherst Counties, from a heavy detachment from the column of General Duffie, sent by Hunter to destroy that road for the purpose of cutting off reinforcements from Lynchburg.

After the death of General Jones and the defeat of his little army, Hunter blew his trumpets with boastful triumph. Staunton, of course, forthwith fell into his hands, which was the occasion for another blast. General Hunter, in his report of the battle of Piedmont, written on June 8, says, with pride, that his "combined force, now in fine spirits and condition, will move, day after to-morrow, toward the accomplishment of its mission," which was the capture of Lynchburg, and the destruction of its bridges and stores. (70 W, of R. 95).

The plan of campaign which General Averell had suggested and Hunter had adopted, was a movement up the Valley to Buchanan in four columns, each column composed of a division, commanded respectively by himself, Crook, Sullivan and Duffie. The last-named division was to march in the same direction on the western slope of the Blue Ridge, sending raiding parties through the gaps to destroy the Orange & Alexandria Railroad, and was finally to move through White's Gap to Amherst Courthouse, whence it was to march toward the James River, cross it below Lynchburg, cut the James River & Kanawha Canal, destroy the[Pg 12] Southside Railroad, and then move up the river and join in the attack upon the objective point of the campaign. (70 W. of R. 146).

For the purpose of carrying out this plan, General Hunter left Staunton on the 10th of June, with his army marching in four columns, as suggested by Averell. Drums were beating, flags were flying and triumphant bulletins flashed over the wires to announce to the Secretary of War the great deeds which were soon to astonish the nation.

On the day Hunter left Staunton with so much pomp and circumstance, the City of Lynchburg was resting quietly, guarded only by the convalescents from the hospitals, and the halt and the maimed who were there congregated in invalid camps. A gallant and appropriate leader was found for this anomalous force in General Francis T. Nicholls, who was in command of the post. He had left a leg and an arm, respectively, upon two different battle-fields, but he still managed to mount his horse and do heroic service. He heard of Hunter's movements as soon as a start was made, and commenced organizing his sick and wounded into an army of occupation. From his trenchant dispatches it seemed that he had determined to hold the town with his cripples against Hunter's whole force. (70 W. of R. 760).

The little remnant of the detachment which had been defeated under Jones at Piedmont was then along the line of the Orange & Alexandria Railroad, and[Pg 13] near Charlottesville, under General Vaughan, much demoralized and short of ammunition and supplies. It came by forced marches, however, to the aid of Lynchburg, where it was under the immediate orders of General John C. Breckinridge, the commander of the Confederate Department of Southwest Virginia. Unfortunately General Breckinridge, though in Lynchburg, was an invalid in bed, having been injured when his horse was shot under him at Cold Harbor. Some of the troops which had fought under him around Richmond were en route to the Valley, and, their destination being changed, they reached Lynchburg before Early's corps, or any part of it, came up.

There was also another small but efficient force which, by almost an accident, was added to the troops defending Lynchburg. The Botetourt Artillery, a battery of six guns, under Captain H.C. Douthat, had been operating in Southwestern Virginia. On the fifth of June it was ordered to the Valley, via Lynchburg, to the command of General W.E. Jones. It reached Lynchburg as soon after receiving the order as transportation could be afforded, and reported to General Jones by the wires. He directed the battery to remain in Lynchburg until further orders.

The battery was on the 11th of June ordered to Staunton, and it and its men, about one hundred in number, were at once put on a freight train on the Orange & Alexandria Railroad and started, despite rumors of raiding parties, on its proposed route.

At New Glasgow Station the conductor was notified[Pg 14] that a large raiding party was at Arrington Depot, and the smoke disclosed the fact that the depot buildings were being destroyed.

Captain Douthat at once pushed forward with the train, upon which there happened to be a car-load of muskets, with suitable ammunition. Douthat's object was to reach the Tye River bridge before the Federal troops and save it from destruction. This he did, and, breaking open the ordnance boxes, armed his men with muskets and forty rounds of ammunition, and then, at a double quick, crossed the Tye River, and got into position to defend the bridge.

When the Federal videttes came in contact with what seemed a heavy infantry picket they retired and reported a large infantry force on hand, and the whole raiding party at once withdrew and the bridge was saved. Had it been destroyed, Lynchburg must have fallen, as reinforcements could not have come up in time to protect it.

The sound judgment and prompt and bold action of Captain Douthat and the gallantry of his men on this occasion is worthy of all praise—yet, strange to say, as he was unattached at the time, there is no official report of this valuable service.

The battery, after this, was unable to continue its journey to Staunton, as the railroad had been much damaged, and it therefore fortunately returned to Lynchburg and took a very active part in the defence of the city. It aided in the repulse of Duffie's division on the Forest Road, one section of two guns being sta[Pg 15]tioned at the old soapstone quarry on that road, on the crest of the hill beyond the road to Tate's Spring. These two guns protected the railroad bridge over Ivy Creek and drove the Federal cavalry from it whenever they approached. The other four were on the other side of the road, supporting the brigade under Colonel Forsberg, and kept up a very heavy fire on the enemy during his stay. Our comrade and fellow-citizen, Mr. A.H. Plecker, was a gunner in this battery, and for his gallant services was tendered a commission. This he declined on the ground that he could do better service as a gunner, in the discharge of which duty he had won much reputation.

The arrival of these different detachments of troops gave much comfort to Nicholls, and they were at once placed in position. There were still, however, so few of the Confederates on the ground that they counted more as a picket than as a regular line of battle.

To add to the general confusion incident to this campaign which had been inaugurated in General Lee's rear, it must be remembered that General Sheridan, with a large body of well-equipped and well-mounted cavalry, had, on the 7th of June, crossed the Chickahominy, and on the 10th had struck the Virginia Central Railroad (now the Chesapeake & Ohio), with the intention of joining Hunter in his march on Lynchburg. He was met on the 11th and 12th of June at Trevilian's Depot, in Louisa County, by a Confederate force of cavalry, under General Wade Hampton, and was repulsed with such disorder that he hurried back[Pg 16] to the cover of Grant's lines in disorganized confusion, leaving the road open for the reinforcements which Lee was hurrying to the defence of Lynchburg.

Some description of Hampton's great cavalry battle at Trevilian's Depot would strictly be a part of any history of the siege and battle of Lynchburg, for had he failed, Lynchburg would necessarily have fallen into the hands of the enemy; but time will not permit so pleasant a digression. It is enough to say that it was one of the most brilliant and successful engagements in which our troops were involved during the war, and one which shed well-deserved renown not only on General Wade Hampton, who commanded, but on every officer and man under him. Conspicuous for their gallantry and valuable service in that battle was the Second Virginia Cavalry, under our distinguished fellow-citizen, General T.T. Munford. This great regiment was made up of companies from Lynchburg and the surrounding counties, and was therefore one of whose record we all have a right to be proud. On the day of that fight it was especially distinguished for its daring courage and for its achievements. It was in the front of the charging column which broke Custer's line and captured four out of the five caissons lost by Sheridan on that day. It captured Custer's headquarters, his sash and private wagon and papers. The wagon was used by General Munford until it was recaptured, a few days before Appomattox.

On the 12th of June General Lee, who had anxiously been watching the movements of the enemy in the[Pg 17] Valley, and who was perfectly informed of his designs, gave verbal orders to General Jubal A. Early to hold his corps (the Second, or Ewell's), with Nelson's and Braxton's artillery, in readiness to march to the Shenandoah Valley. After dark upon that day these orders were repeated in writing, and he was directed to move to the Valley that night at three o'clock via Louisa Courthouse, Charlottesville and Brown's Gap. He was further ordered to communicate with General Breckinridge at Lynchburg, with a view of a combined attack on Hunter. Breckinridge was to attack in front and Early in the rear.

The Second Corps was then at Gaines' Mill, near Richmond, numbering about eight thousand muskets. (Memoirs of J.A. Early, page 40.) It had been for the last forty days constantly fighting, and had taken a prominent part in the battles of the Wilderness, Spottsylvania Courthouse, Gaines' Mill and Cold Harbor, and had had no time or place for rest or reorganization. At Spottsylvania Courthouse it lost nearly a whole division. Its commander, Major-General Edward Johnson, had been wounded and captured. Four of its Brigadier-Generals had been killed during the campaign, four desperately wounded, and two more had been promoted to Major-Generals and removed to other commands. The troops therefore, though hardy and well-tried veterans, were in bad condition for so arduous an undertaking. Despite these facts, so well calculated to throw the command out of joint, it was on the march an hour before that fixed by General Lee in[Pg 18] his order! No one but Early knew where they were going, but all felt that if Lee ordered the march it was right and led to victory. When it started, Hunter was within fifty miles of Lynchburg, while Early, on his route by Charlottesville, had to move one hundred and sixty miles, of which a part of his troops had the aid of very poor railway transportation for sixty miles.

On the 16th of June Early had reached Charlottesville, and his corps was at the Rivanna bridge, four miles east of that place, having marched eighty miles in four days, well maintaining the reputation won under Jackson as "foot cavalry." Here Early received a dispatch from Breckinridge announcing that Hunter was at Liberty (now Bedford City), only distant twenty-five miles. The Orange & Alexandria Railroad had not been sufficiently repaired for transportation in cars. Every effort was made, however, to hurry the repairs and to secure trains to speedily forward the troops from Charlottesville to Lynchburg, for Early, when the perilous position of that city was known, was ordered to push on to save it from Hunter's advancing host. He could get only one engine and a few cars at first, but soon added to this limited transportation enough to enable him to move a part of his command. Duffie's attack upon the road between Charlottesville and Lynchburg had not been very serious either to the railroad or to the telegraph lines, and both were repaired in one or two days, hence at sunrise on the morning of the 17th, Early commenced to move his corps by rail. The transportation[Pg 19] was so limited that he could only get half of his infantry moved on that day. Ramseur's division, one brigade under Gordon and part of another, were placed upon the train, while Rodes' division and the residue of Gordon's were ordered to march along the county road, which runs parallel to the railroad, and to meet the train as it returned. The artillery and wagon trains were started over the county road the night before, but got no aid from the railway, and did not reach Lynchburg in time to take any part in the engagement at that point. Rodes demanded the right to be sent forward with his division ahead of Ramseur, on the ground that he should be called upon to defend his native city. This privilege, from some unaccountable reason, was denied him, a denial which led to high words between Early and himself.

General Early was on board the first train, but so indifferent was the motive power, and so bad the condition of the track, that he and the first half of his corps did not reach Lynchburg until the afternoon of the 17th, and the rest of his small army did not arrive until nearly night the next day—too late to take part in the engagement. Early found Breckinridge in bed suffering from the injury to which reference is made above, and as Breckinridge could not go out to reconnoitre, he had called upon General D.H. Hill, who happened to be in the city, to ascertain and define the best lines of defence. This duty was performed by General Hill, with the assistance of General Harry T. Hays, of Louisiana, who was also in town disabled by[Pg 20] a wound received at Spottsylvania Courthouse. Hill established the line close to the city in breastworks, which had been thrown up on College Hill. These were at once occupied by the disorganized infantry force which had been defeated at Piedmont under Jones, the Virginia Military Institute Cadets, and the invalid corps. To this was added Breckinridge's small command, when it arrived on the 16th, and Douthat's battery.

Early, on his arrival, thought this line too near the city for the main defence. He feared that in case of battle the shot and shell of the enemy would do damage to the property and the people of the town; consequently a new line, further out, was established, to which were taken the troops with Early, Breckinridge's men and the artillery.

When he reached the field on the afternoon of the 17th, Early found Imboden with his small remnant of cavalry, and McCausland with his little brigades, occupying the hill at the old Quaker Meeting House, on the Salem Turnpike. This cavalry, with their gallant leaders, was holding the enemy in check, which was a great achievement, and was one absolutely essential to the safety of the city. They were, however, very slowly driven back as the main body of Hunter's army advanced.

The small force under Ramseur, which arrived on the evening of the 17th, was at once thrown forward and occupied the new line established by Early, across the Salem Turnpike, about two miles from the city and[Pg 21] a mile and a half beyond Hill's line on College Hill. This force, with two guns of Breckinridge's command, in charge of Lieutenant Carter Berkeley, of Staunton, now Dr. Carter Berkeley, of Lynchburg, two guns of Lurty's battery, some of the guns of Floyd King's battalion and two of Douthat's battery, were placed in the redoubt near the toll-gate and stayed the advance of the enemy until dark closed the engagement for the day.

These guns of Lieutenant Berkeley had done good service in the Valley and rendered themselves and their young commander very famous. They reached Lynchburg by forced marches, through the upper part of Amherst County, on the evening of the 16th of June. On their arrival at the bridge across James River, they were urged forward, as it was supposed Hunter was even then in sight. The general direction in which the enemy was expected was pointed out to Berkeley, who was ignorant of Lynchburg and its topography. He was told to go directly out from the bridge to the hills west of the city, so he urged his weary horses up Ninth street, passed the old market house to the foot of Courthouse hill. There even his nerve was daunted, and he turned up Church street to Eighth. He halted a moment, wondering what sort of teams and conveyances they had in Lynchburg, but noticing that Eighth street was the nearest route to the enemy, he urged his horses up the steep declivity, putting several men at each wheel. One-third of the hill was thus surmounted, but there is a limit to human[Pg 22] and equine endurance, and the two guns and their caissons stalled hopelessly. Fortunately some of Imboden's cavalry were just passing at the foot of the hill on Church street. They saw the trouble, and knowing how important it was to get those useful guns into action, jumped from their horses, reinforced the storming party and soon had the guns at the top of the hill; thence, at a gallop, they moved forward into the line of battle.

The line then selected extended from a point some distance to the left of the turnpike through the toll-gate into what is now known as Langhorne's field. The residue of Early's command did not reach Lynchburg until late on the afternoon of the 18th, when it was hurried through the city at a double quick, much to the relief of the citizens, who cheered them on their pathway. During the night of the 17th a yard engine, with box cars attached, was run up and down the Southside Railroad, making as much noise as possible, and thus induced Hunter to believe and to report that Early was rapidly being reinforced.

Senator John W. Daniel, then a Major on Early's staff, though at the time disabled from duty by a very dangerous wound, describes the entrance of these troops upon the scene as follows:

"In this condition Tinsley, the bugler of the Stonewall Brigade, came trotting up the road sounding the advance, and behind him came the skirmishers of Ramseur's Division with rapid strides. Just then the artillerists saw through the smoke the broad white slouch hat of 'Old Jube,' who rode amongst them....

Poor Tinsley! His last bugle call, like the bagpipes at Lucknow, foretold the rescue of Lynchburg, but on that field he found, in a soldier's duty and with a soldier's glory, a soldier's death."

Up to that time Hunter's army was several times larger than that opposing him. The addition of Rodes' command and the residue of Gordon's to the Confederate forces the next night diminished the disparity, but made our army but little over one-half as large as that under Hunter. Yet Hunter did not make any serious demonstration on the 17th, nor until after two o'clock on the 18th. There was firing along the picket line and much cannonading, but no serious fight until that hour.

Half of the Second Corps and Breckinridge's command, with some fifteen guns, occupied the front line, while the cadets, the dismounted cavalry and the invalid corps occupied the inner line established by Hill.

On the 18th General Duffie's division of the enemy made some attack on Early's right. This attack by Duffie with his division of two brigades of cavalry and a battery of artillery is described by him in a report made in the field to General Hunter on June 18. He says:

"I have carried out your order in engaging the enemy on the extreme left. I attacked him at 12:30 and drove him into his fortifications. Have been fighting ever since. Two charges have been made and the enemy's strength fully developed in our front. His force is much superior to mine. All my force is engaged. The[Pg 24] enemy is now attempting to turn my right. I shall send a force to check him. I do not communicate with Averell on my left." (70 W. of R. 650.)

This force which Duffie describes as so superior to his consisted of two small brigades of infantry under General Gabe C. Wharton and the cavalry under General John McCausland. It is impossible that the whole force was half the size of Duffie's. Wharton's command was but a remnant left from Gaines' Mill and Cold Harbor, and McCausland's had been in one continuous fight for ten days, and was therefore much dismounted, worn and weary. Of the two so-called brigades under Wharton, one was commanded by our gallant comrade, Colonel Aug. Forsberg, and had, under his leadership, been more than decimated in the fights around Richmond during the four weeks immediately preceding.

Had Hunter made a vigorous assault on the line through Judge Daniel's Rivermont farm, he could have marched directly into Lynchburg and burned the railroad bridges without successful resistance, for Early could not have spared a man from his line to oppose him. Wharton's two brigades were both east of the Blackwater, and between that stream and James River there was only the skirmish line of McCausland's cavalry, and a few old men in the trenches across the Rivermont farm. These old citizens, however, though entirely "muster free" either from age or physical infirmity, did good service. They remained in the trenches, though without equipment or even the scant[Pg 25] comforts of the regular soldier, and were anxiously and gallantly awaiting the anticipated attack. Had it been made, they were ready to die in defence of their homes.

A reconnoissance was made by Averell on the 18th in the direction of the Campbell Courthouse Turnpike. It amounted to nothing, and he soon returned to the main lines. Beyond these two movements, picket firing and artillery duels, nothing was done until about 2:30 o'clock in the afternoon, when the infantry divisions of Sullivan and Crook commenced their advance upon Early's centre. This brought about for a short time a very active engagement. Our skirmish line was driven in upon the main body, as is usual in such cases, and the engagement was fairly general and, for a time, very sharp. The enemy soon fell back into a new line, and there each side rested on their arms apparently for the night.

Early scarcely felt himself strong enough, before Rodes arrived, to attack the enemy on ground selected by them, but was courting an attack all day. The enemy's forces showed no signs of weakness or timidity, but the indications were that its movements were lacking in well defined purpose, and there was obviously want of confidence on the part of the subordinate Brigadiers in the Major-General commanding. That this feeling prevailed amongst the division and brigade commanders is clearly observed on reading their official reports, in which they differ with him as to what was done and the causes of the failure to do more.

The report of General Crook, who was a very excel[Pg 26]lent officer, is particularly striking. After telling of his march and the occupation of his corps on the 17th, he says (70 W. of R. 121):

"Next morning I was sent to the right with my division to make a reconnoissance for the purpose of turning the enemy's left; found it impracticable after marching some three or four miles, and just returned with my division and got into position to support Sullivan's division when the enemy made an attack on our lines."

Having said this, and without further word of explanation or description of the result, he continues:

"On the retreat this evening my division brought up the rear. When I reached Liberty, I found General Averell had gone into camp on the edge of the town. The infantry were going into camp some mile and a half further on."

He sings no paean of victory, as did Hunter, but preserved a silence which is suggestive, if not eloquent.

General Sullivan made no report. All that General Averell says about the movements is an elaborate analysis of the causes of the failure, chief amongst which he asserts was General Hunter's delay at Lexington (70 W. of R. 148). Colonel Frost, who commanded a regiment in Crook's division, reports that on the 18th—

"His command marched three miles to the right, and on the afternoon was ordered again to the front of the enemy's works, and were afterwards formed in line on our left under a heavy fire of artillery. Our brigade charged the enemy and drove them back to his rifle-pits.

Here the right gave way, and our brigade being exposed to a close firing of musketry, grape and canister, we were obliged to retire about thirty paces to a new line of battle, which was held until orders were received to fall back. Marched all that night, and reached Liberty about 3 p.m. on the 9th." (70 W. of R. 135.)

Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes, afterwards President of the United States, in reporting the battle of the 18th, says:

"Pursued the retreating rebels and drove them from their rifle-pits to the protection of their main works. The works being too strong to be carried by the force then before them, the regiment retired in some disorder, but was promptly reformed before reaching our own lines. After leaving Lynchburg the officers and men of the First Brigade sustained themselves through the hardships and privation of the retreat like good soldiers." (70 W. of R. 123.)

Other quotations from other reports might be made to the same effect.

That these reports may have their true significance it is necessary that we note what General Hunter himself says of what took place on the 17th and 18th. It will be found difficult to understand where all the glory comes in. He writes:

"Early in the morning of the 17th orders were given for the troops to move, but the march was delayed for several hours at the Great Otter River, owing to the difficulty in crossing the artillery, and in consequence we did not overtake the enemy until four o'clock in the afternoon. At that hour Averell's advance came upon the enemy, strongly posted and intrenched at Diamond Hill, five miles from Lynchburg. He immediately attacked, and a sharp contest ensued. Crook's infantry arriving at the same time, made a brilliant advance upon the enemy, drove him from his works back upon the town, killing and wounding a number and capturing seventy men and one gun. It being too late to follow up this success, we encamped upon the battle-field. The best information to be obtained at this point of the enemy's forces and plans indicated that all the rebel forces heretofore operating in the Valley and West Virginia were concentrated in Lynchburg, under the command of General Breckinridge. This force was variously estimated at from ten thousand to fifteen thousand men, well supplied with artillery, and protected by strong works.

"During the night the trains on the different railroads were heard running without intermission, while repeated cheers and the beating of drums indicated the arrival of large bodies of troops in the town, yet up to the morning of the 18th I had no positive information as to whether General Lee had detached any considerable force for the relief of Lynchburg. To settle the question, on this morning, I advanced my skirmishers as far as the toll-gate on the Bedford Road, two miles from the town, and a brisk fire was opened between them and the enemy behind their works. This skirmishing with musketry, occasionally assisted by the artillery, was kept up during the whole of the forenoon. Their works consisted of strong redoubts on each of the main roads entering the town, about three miles apart, flanked on either side by rifle-pits protected by abatis. On these lines the enemy could be seen working diligently, as if to extend and strengthen them. I massed my two divisions of infantry in front of the works on the Bedford Road, ready to move to the right or left as required, the artillery in commanding positions, and Averell's cavalry division in reserve. Duffie was ordered to attack resolutely on the Forestville Road, our extreme left, while Averell sent two squadrons of cavalry to demonstrate against the Campbell Courthouse Road, on our extreme right. This detachment was subsequently strengthened by a brigade. Meanwhile I reconnoitred the lines, hoping to find a wreak interval through which I might push with my infantry, passing between the main redoubts, which appeared too strong for a direct assault. While the guns were sounding on the two flanks, the enemy, no doubt supposing my centre weakened by too great extension of my lines, and hoping to cut us in two, suddenly advanced in great force from his works, and commenced a most determined attack on my position on the Bedford Turnpike. Although his movement was so unexpected and rapid as almost to amount to a surprise, yet it was promptly and gallantly met by Sullivan's division, which held the enemy in check until Crook was enabled to get his troops up. After a fierce contest of half an hour's duration, the enemy's direct attack was repulsed; but he persistently renewed the fight, making repeated attempts to flank us on the left and push between my main body and Duffie's division. In his effort he was completely foiled, and at the end of an hour and twenty minutes was routed and driven back into his works in disorder and with heavy loss. In the eagerness of pursuit, one regiment (One Hundred[Pg 29] and Sixtieth Ohio) entered the works on the heels of the flying enemy, but being unsupported, fell back with trifling loss. Our whole loss in this action was comparatively light. The infantry behaved with the greatest steadiness, and the artillery, which materially assisted in repelling the attack, was served with remarkable rapidity and efficiency. This affair closed about two p.m. From prisoners captured we obtained positive information that a portion of Ewell's corps was engaged in the action, and that the whole corps, twenty thousand strong, under the command of Lieutenant General Early, was either already in Lynchburg or near at hand. The detachment sent by General Averell to operate on our right had returned, reporting that they had encountered a large body of rebel cavalry in that quarter, while Duffie, although holding his position, sent word that he was pressed by a superior force. It had now become sufficiently evident that the enemy had concentrated a force of at least double the numerical strength of mine, and what added to the gravity of the situation was the fact that my troops had scarcely enough of ammunition left to sustain another well-contested battle. I immediately ordered all the baggage and supply trains to retire by the Bedford turnpike, and made preparation to withdraw the army as soon as it should become sufficiently dark to conceal the movement from the enemy. Meanwhile, as there still remained five hours of daylight, they were ordered to maintain a firm front, and with skirmishers to press the enemy's lines at all points. I have since learned that Early's whole force was up in time to have made a general attack on the same afternoon (18th)—an attack which under the circumstances would probably have been fatal to us; but, rendered cautious by the bloody repulse of Breckinridge, and deceived by the firm attitude of my command, he devoted the afternoon to refreshment and repose, expecting to strike a decisive blow on the following morning. As soon as it became dark I quietly withdrew my whole force, leaving a line of pickets close to the enemy, with orders to remain until twelve o'clock (midnight), and then follow the main body. This was successfully accomplished without loss of men or material, excepting only a few wounded who were left in a temporary hospital by mistake."

By a critical examination and comparison of these reports it will be seen that the men who did the fight[Pg 30]ing say nothing of the Confederate force being "disgracefully routed," or of their "overwhelming numbers," and maintain a prudent silence as to the cause of Hunter's withdrawal. No one can read the whole correspondence without being satisfied that such men as Averell, Crook, Sullivan and Hayes, who seemed to have all been gallant soldiers, were much discouraged and had no faith in Hunter. They believed they could have forced their way through our lines and were anxious to do so, for they knew that they had force superior both in numbers and equipment. Believing this, they were chagrined that a retreat was ordered just as victory was apparently within their grasp.

Hunter claimed that he was overwhelmed by numbers, and that he was short of ammunition. That he was not outnumbered the official reports plainly show. He had two full divisions of infantry, each with three brigades, two of cavalry, composed in the aggregate of five brigades and thirty-two guns. Early, on the other hand, had only the small though very efficient force belonging to Breckinridge's department, McCausland's and Imboden's cavalry, the corps of cadets, the Silver Grays of the city, the invalids, and about one-half of Ewell's corps; the second half did not reach Lynchburg in time to take active part in the battle on the 18th. Opposed to Hunter's thirty-two guns, Early had none of the artillery attached to the second corps and only the guns under Major Floyd King belonging to Breckinridge's command, Douthat's battery, two of[Pg 31] Berkeley's and several of Lurty's, some fifteen or twenty all told. King had four companies of four guns each in his command, but Otey's battery was on duty elsewhere. The batteries with him were Chapman's, Bryant's and Lowry's. Doing good service in Lowry's company was our townsman M.H. Dudley, of the Glamorgan Works.

Early's cavalry, opposed to the elegant divisions of Averell and Duffie, consisted of Imboden's remnant, one-half of which was dismounted, and all of which, though it did good service, was disorganized by the defeat at Piedmont, and, in addition, the gallant little brigade so admirably handled by General McCausland.

If General Hunter did not know all this, it was his fault, for it was his duty to know, and he had ample opportunity to acquire the information. He had scouts on both railroads and the country was filled with the vigilant spies who prided themselves on their cleverness. They were famous under the name of "Jessie's Scouts"; a name assumed in honor of Mrs. General Fremont, who was a daughter of Senator Thomas H. Benton. He also had the aid of several notorious local traitors, who affected to keep him informed. The truth is he had all the necessary information, but lacked the nerve to act on it.

The other excuse made by General Hunter that his army was out of ammunition, is equally untenable. It cannot be believed that a corps was short of ammunition which had been organized but a few weeks, a part only of which had been engaged at Piedmont, and[Pg 32] which had fought no serious pitched battle, and the sheep, chickens, hogs and cattle they wantonly shot on their march could not have exhausted their supply. The corps would not have started had the ammunition been so scarce. It would have been against all precedent, and any thinking man must know that the Ordnance Department of the United States army, always full-handed, had well supplied ammunition to an army about to start on so important an undertaking. No brigade or division commander in his correspondence or in his report made any such complaint. It would have given them pleasure to have had some excuse for retreating. They undertook to give no excuse, and their silence is so logical that it points out with great effect the fact that they had no belief in Hunter's excuses, and laid the real blame of the ignominious failure upon the incompetence of Hunter himself.

The obvious cause of Hunter's failure was that he did not reach Lynchburg on the 16th, the day upon which, according to Averell's plan, he was due. Had he reached his destination on the 16th he could have occupied the town without opposition. General Breckinridge was there, an invalid, and his troops were there in small numbers, much wearied, and they, with a few Silver Gray home guards, and the boys from the Institute, constituted the sole garrison opposing his army of twenty-five thousand men. Why he did not come up is accounted for upon two grounds. The first of which was the unnecessary delay at Lexington.

He says in his report, after giving the detail of his performance there, "I delayed one day in Lexington" (70 W. of R. 97). Colonel Hayes says two days. (Id. 122.) Had he marched without delay he would have been in Lynchburg before Early or any part of his troops left Charlottesville, and the town would have surrendered without firing a gun. He delayed at Lexington that he might vent his personal ill-will upon the State of Virginia. He says in his report that he ordered the Virginia Military Institute, a college for the education of youth, to be burned, and that he also ordered the burning of the residence of Hon. John Letcher, formerly Governor of Virginia, alleging as his reason for this latter act of barbarity that the governor had urged the people to rise in arms to repel the invasion. In burning both places he gave no time for anything to be saved. The family of Governor Letcher barely escaped with the clothes upon their persons, and the torch was applied to the Institute without the opportunity to save its library, its philosophical apparatus, its furniture or its archives. All alike were consumed to appease his vindictive spite. The statue of the Father of his Country, belonging to the Institute, was stolen and sent to be erected upon the grounds at West Point. (Id. 640.) It was returned after the war.

General Early in his memoirs says:

"The scenes on Hunter's route to Lynchburg were truly heart-rending; houses had been burned, and helpless women and children left without shelter. The country had been stripped of provisions[Pg 34] and many families left without a morsel to eat. Furniture and bedding had been cut to pieces, and old men and women and children robbed of all the clothing they had except that on their backs. Ladies' trunks had been rifled and their dresses torn to pieces in mere wantonness; even the negro girls had lost their little finery.

"Hunter's deeds were those of a malignant and cowardly fanatic, who was better qualified to make war upon helpless women and children than upon armed soldiers. The time consumed in the perpetration of these deeds was the salvation of Lynchburg, with its stores, foundries and factories, which were so necessary to our army at Richmond."

There was, however, another more potent influence which stayed Hunter's advance. General John McCausland had been operating against the enemy in Southwest Virginia with a body of cavalry. When Hunter reached Staunton he was ordered across the country to meet him. When near Staunton, McCausland was joined by a small brigade under the command of Colonel William E. Peters, now professor of Latin at the University of Virginia, who was then Colonel of the Twenty-first Virginia Cavalry. These two brigades, aggregating some sixteen hundred men, under McCausland's leadership, ably seconded by Peters, at once commenced to worry Hunter and to keep his whole force in a constant state of alarm. This force was so ubiquitous that it was estimated by the enemy as being five times its real size. Amongst the officers in the force under Colonel Peters was his nephew, and our fellow-citizen, Major Stephen P. Halsey, who did good service and distinguished himself for his active gallantry.

As Hunter moved from Staunton to Lynchburg these brigades were ever in his front, one hour fighting and the next falling back as the main column would appear, but ever causing delay and apprehension. The tireless little band performed deeds of gallantry as they hung upon Hunter's front which entitled every officer and man to a cross of honor.

When Hunter's army reached Buchanan, McCausland had been hovering in front of his vanguard for many miles. There was a bridge at this point across James River, over which Hunter expected to cross. McCausland sent his men over the bridge, and from the south side of the river they opened fire on the head of Hunter's column as it appeared in sight, and thus checked their advance. McCausland had caused hay to be piled on the bridge, much of which was wet with coal oil. He, with Captain St. Clair, of his command, had remained on the north side for the purpose of setting fire to the bridge. The Federal cavalry charged up very close to him before McCausland applied the match, as he was desirous that every man of his command should get safely over. As fire was opened on him he applied the torch to the hay, and the coal oil at once flashed up in a furious blaze.

Captain St. Clair ran up the river bank, and the enemy was so occupied in the effort to kill him that they did not see McCausland, who escaped in a small boat under the burning bridge, and was not again under their fire until he was climbing up the opposite bank of the river.

This thoughtful and gallant conduct of McCausland delayed Hunter's column for a whole day, thus giving Lynchburg a better chance for defence and rendering Hunter's raid ineffectual.

In Early's dispatch reporting the battle at Lynchburg an expression is used which implies a doubt as to whether the cavalry would do its duty. Never did cavalry do better service than did that under McCausland, both as Hunter advanced and as he retreated. Had McCausland had the full command of the cavalry on the retreat, Hunter's wagon train and artillery would have fallen into the hands of the Confederates; but for some reason, which it is now unnecessary to explain, great opportunities were permitted to pass without advantage being taken of them. McCausland at Hanging Rock with his force was in a position to have attacked the retreating column of the enemy and to have cut off his wagon train and many of his guns. He begged to be allowed to attack, but was told to await the arrival of the infantry. While he waited the enemy discovered his position and so far withdrew that when the inhibition was withdrawn the great opportunity was gone, though, despite the delay, a number of guns, wagons and supplies were captured by his force.

During the second day that Hunter was in the lines around Lynchburg McCausland made a raid around his rear and attacked his train at Forest Depot, driving a guard of one regiment of infantry and one of cavalry back to the Salem pike. This gave Hunter much apprehension and threw his force into confusion; how[Pg 37] much it contributed to his rapid flight that night can never be known. Due credit was not given McCausland for this, nor for many of his other valuable services.

Lynchburg owes much to Ramseur's division of the Second Corps and to the men who occupied the lines when Hunter arrived, but it was the skill of McCausland and Peters and the unflagging energy and courage of their officers and men, which so retarded Hunter's movements that when he did arrive there was force enough on our line to prevent his capturing the city. McCausland and his command were the real saviors of the city, and some lasting memorial of its gratitude should be erected to perpetuate their deeds.

McCausland proved himself a soldier of a high type. There were few officers in either army who, with such a force, could have accomplished as much. His little command had been in constant contact with the enemy for many days, had been continuously in the saddle and on exhausting marches, was badly mounted and badly equipped; everything about it was worn and weary but their dauntless spirit; that, under the example of their indomitable leaders, never flagged for an instant. The truth is, heroism was so common a quality amongst the "old Confeds" during that war that heroes were almost at a discount and heroic acts passed unnoticed, however great.

The services of this command were recognized at the time by a vote of thanks adopted by the City Council of Lynchburg on the 24th of June, 1864, "for their[Pg 38] gallantry in opposing for ten days the march of a greatly superior force, thereby retarding the advance of the enemy on our city until a proper force could be organized for its defence." The citizens of the town at the same time presented General John McCausland with a sword and a pair of silver spurs in token of their gratitude.

It is not fair to close this special notice of the service rendered the city by McCausland's command without referring especially to the gallant conduct of Captain E.E. Bouldin, of the Charlotte cavalry, who commanded its rear guard as it fell back before Hunter's army. The records show that the numberless charges of Captain Bouldin and his valiant band upon Hunter's vanguard were conspicuous, even amongst the men of a command where each proved himself a hero. Captain Bouldin still survives, and is a useful and modest citizen of Danville, Virginia, and a learned and efficient member of its bar.

What General McCausland did in this defence was not the only service he rendered the city. When Lee surrendered he rode off with his men toward the mountains of Southwest Virginia for the purpose of there disbanding. As he approached Lynchburg a committee from the civil authorities met him, and, after telling him that the place was being looted by lawless squads of disbanded soldiers from Lee's army, asked his aid. He at once sent in a squadron which cleared the streets and soon restored order. He continued to preserve order until the civil authorities organized a force sufficient to maintain it.

When Hunter commenced his advance from Staunton our townsman, Colonel J.W. Watts, of the Second Virginia Cavalry, was at his home near Liberty, recuperating from severe wounds. Despite his disabled condition, he mounted his horse, joined McCausland and rendered him valuable aid. To him was assigned the duty of blocking the road from Buchanan to the Peaks of Otter. He did this work very thoroughly, but he states that so complete was the equipment of Hunter's pioneers that they cleared the road in less time than it took him to blockade it. Nevertheless the blockade was one of the causes which materially delayed the advance of Hunter, and therefore was one of the causes which led to the relief of the city.

Major Robert C. Saunders, of Campbell, was at the time of the attack by Hunter a resident of the city, being in charge of the Quartermaster Department for the collection of the tax-in-kind for this Congressional District. He had been in the field as captain of an infantry company from Campbell County, and as soon as Hunter's approach was a certainty General Nicholls sent for him and sent him out to bring him definite information of Hunter's position. He started immediately and soon was among Hunter's vanguard, but, though much exposed, he wonderfully escaped under cover of the night and brought accurate information which was very valuable. He was sent out again, and was in the sharp battle fought by General McCausland at New London and by McCausland and Imboden at the Quaker Meeting House, and then, as Hunter re[Pg 40]treated, he was with McCausland and Peters and saw much hard service with those sturdy soldiers and their men. His manuscript account of what he saw is very interesting, and might properly be inserted in this paper but that it would make it too long for one evening's address.

Be the causes of General Hunter's failure what they may, the fact is he did fail, and failed disgracefully, where he should have succeeded, for he had every advantage of numbers, of guns and of equipment. There are many pages of reports of Federal officers about this campaign published in the Records of the War of the Rebellion by the United States Government, but the cotemporaneous literature on the part of Confederate officers is very scant; they fought better and longer than they wrote. As a specimen of the Confederate reports, that of General Early may fitly be taken. It contrasts strikingly with the ten-page document of General Hunter upon the same subject, found in the seventieth volume of the War of the Rebellion, page 94.

General Early's report is as follows:

"New London, June 19, 1864, 9:30 A.M.

"General:

"Last evening the enemy assaulted my line in front of Lynchburg and was repulsed by the part of my command which was up. On the arrival of the rest of the command I made arrangements to attack this morning at light, but it was discovered that the men were retreating, and I am now pursuing. The enemy is retreating in confusion, and, if the cavalry does its duty, we will destroy him.

"J.A. Early,

"Lieutenant General.

"General R.E. Lee."

This report is brief and to the point. It has been construed as ignoring the troops belonging to the command of Breckinridge, and as doing injustice to the cavalry of Imboden and McCausland. General Early should have been more careful in writing it, but it must be remembered that when it was written he was not informed of the great service which had been rendered by the cavalry, or of the faithful work which had been done by the troops, other than those belonging to the Second Corps.

In his memoirs (on page 44) General Early says that some time after midnight it was discovered that Hunter was moving, but, owing to the uncertainty as to whether he was merely changing front or retreating, nothing could be done until daylight, when, the retreat being ascertained, the pursuit commenced. Early's army moved in three columns, the Second Corps on the Salem Turnpike, Breckinridge's command, under Elzey, on the Forest Road, and the cavalry, placed by Early under General Robert Ransom, on the right of Elzey. The enemy's rear was overtaken at Liberty by Ramseur's division and was driven through that place at a brisk trot.

It is not within the scope of this paper to follow up the retreat of Hunter, nor to narrate the incidents of Early's campaign in Maryland and the scare he gave the Government at Washington. What a commotion his little army created can be easily understood by inspecting the 70th and 71st volumes of the War of the Rebellion, a large part of which is taken up by the[Pg 42] numberless orders and counter-orders, alarms and outcries incident to the fright then prevailing. General Grant seems to have been the only person in command on the other side who kept his equilibrium and acted with consistent courage and judicious poise.

But before we return to the scenes around Lynchburg incident to the attack, it may well be noted that Hunter, after reaching Salem, turned off to Lewisburg, West Virginia, and did not feel safe until he had placed his army far beyond the Alleghanies and upon the banks of the Ohio at Parkersburg. The effect of this remarkable line of retreat was that the Valley was left open, and Early seized the opportunity and at once commenced his march for the Potomac practically unmolested. On the 5th of July Hunter and his command were at Parkersburg, on the Ohio, while Early, whom he was to obstruct, was crossing the Potomac River into Maryland.

Poor Hunter! he seems to have had few friends, and it is almost cruel to recite his history, but men who undertake great enterprises must expect to be criticised when they fail. He got little comfort, and expected none, from the Confederate leaders, but he got even less from the Federal, except when it came in the form of such reports as that sent by Captain T.K. McCann to General Meigs, the Quartermaster-General, in which he says that "General Hunter fought four hours on the 17th; on the 18th the General ascertained that Rebel force at Lynchburg was fifty-thousand men, and from a prisoner taken it was reported that Lee was[Pg 43] evacuating Richmond and falling back on Lynchburg, and consequently General Hunter was obliged to fall back." (Id. 679.) General Grant, however, on the 21st of June, wrote General Meade to know where Hunter was, and said, "Tell him to save his army in the way he thinks best." (Id. 657.)

On the 17th of July Halleck wrote to Hunter, giving him some directions in regard to his future movements, saying that "General Grant directs, if compelled to fall back, you will retreat in front of the enemy towards the Potomac, so as to cover Washington and not be squeezed out to one side, so as to make it necessary to fall back into West Virginia to save your army." This order he disregarded most ignominiously.

In the same letter Halleck wrote Hunter that General Grant said that in the marching he does not want houses burned, but "that he wants your troops to eat out Virginia clear and clean as far as they can, so that crows flying over it for the balance of the year will have to carry their rations with them." (Id. 366.)

C.A. Dana, Assistant Secretary of War, wrote to Grant on the 15th of July (Id. 332): "Hunter appears to have been engaged in a pretty active campaign against the newspapers in West Virginia." And Halleck on the same day wrote to Grant that he thought "Hunter's command was badly used up in the Lynchburg expedition." (Id. 331.)

These assaults, and many others of a like nature, wounded General Hunter so greatly that he not only asked to be relieved, but wrote a letter to Grant, in[Pg 44] which, after speaking of the depressing effect upon him of these comments, he unstopped the vials of his wrath against his subordinates, upon whom he put the blame of his defeat.

In this letter he says that Sullivan, who commanded one of his divisions, was "not worth one cent; in fact very much in my way," and, again, he says: "I dashed on toward Lynchburg, and should certainly have taken it if it had not been for the stupidity and conceit of that fellow Averell, who unfortunately joined me at Staunton, and of whom I unfortunately had, at the time, a very high opinion, and trusted him when I should not have done so." (71 W. of R. 366.)

With these quotations from the correspondence of his associates, General Hunter may be left to the verdict which will be accorded him by the future historian of the stirring events in which he took part.

War is not a gentle occupation, and its customs are harsh. To make it effective, it is clearly within the rules of civilization to strip an enemy's country through which a hostile army is passing of everything which will sustain the life of either men or beasts. Hence Grant's historic order about the crow carrying his rations, while cruel, is within the line of legitimate warfare. But putting non-combatants to death, insults to women and children, the wanton destruction of household goods and clothes, the application of the torch to dwellings, factories and mills, or the destruction of public buildings, and especially of institutions of learning and their libraries, and works of art and[Pg 45] science, is a style of warfare long since relegated to the savage. The disgrace of reviving this barbaric strife in modern times was reserved for Hunter. General Crook, one of his division commanders, a soldier brave and true, felt constrained to note the conduct of the troops, and published an order in which he says he "regrets to learn of so many acts committed by our troops that are disgraceful to the command." Hunter knew all this, but there was no word of protest or repression from him.

It is to be regretted that later in this campaign, when we carried the war across the Potomac, some of our troops retaliated for these brutal acts, upon innocent parties. That Hunter had set the example was no good excuse, though it was pled. (See General Bradley T. Johnson's Report, 90 W. of R. 7.)

General Early has been severely criticised for permitting the escape of Hunter. It is always much easier to criticise than to accomplish; to point out how a thing should have been done, after we know the result of what was done, than to do it at the time. The facts heretofore stated can leave no doubt that all was done, as far as the prompt pursuit of Hunter is concerned, which could have been done. Early's line of defence, owing to the smallness of his force, was not only thin but was short; he had therefore to keep in such a condition that by changing front rapidly with the troops he had, he could supply the place of those he did not have. Hence, when he noticed Hunter moving away from his immediate front, he did not suppose[Pg 46] he was retiring, but merely withdrawing for the purpose of making his attack at another point, and prudence demanded that he should keep his troops in hand until the enemy's purpose was developed. To do this the delay until daylight was essential.

It is a subject of remark that with Hunter's army there were two men who very faithfully discharged their duties as soldiers and subsequently became Presidents of the United States—one Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes, who commanded a brigade, and the other Major William McKinley, who was a staff officer.

The loss on neither side was very heavy, but it was very much greater on that of the invader than upon ours. Hunter left his dead on the field to be buried by his enemy, and his wounded in a field hospital; facts which show how precipitously he departed.

The Federal line of battle was formed on the left, directly through the yard of the residence of the late C.H. Moorman, whose farm lay on both sides of Blackwater Creek, and occupied most of what is now called West Lynchburg. When it was known that Hunter was approaching, Mr. Moorman packed several wagons with provisions, and, with his negroes and stock, moved down toward the Staunton River, leaving his house in charge of his young, unmarried daughter, now Mrs. Hurt, his wife, an old negro man and several negro women. Before Mr. Moorman cleared his own plantation, which was large, he found it necessary to lighten his load, and to that end selected a spot and buried his supply of well-cured and much prized hams.[Pg 47] It turned out that the line of battle of Crook's division ran across the spot, and the buried treasure was discovered, much to the delight of the troops, who greatly enjoyed a very fine lot of old Virginia hams, always valuable, but especially so under such circumstances.

At sunrise on the morning of the 17th, Miss Moorman went out on a hill near her house to reconnoitre the military situation. She saw a column of Federal troops moving on the Salem Turnpike, and was looking at them very anxiously when she was shocked to see a line of blue coats crossing the field close to her home. She at once ran back, sheltering herself behind the fence, but the officer in command was at the door before she was, and very politely advised her to stay in the house while the fight was going on. The family were not molested during the two days that the troops were there. With exceptional visits to the front yard, she obeyed the officer's instructions very carefully. She heard the constant cannonading and the picket firing without cessation all of the 17th and until the evening of the 18th, when the sounds changed and indicated that a real battle was going on close at hand. She was naturally in a fever of excitement, but could hear nothing of the result. About midnight of the 18th, or more probably on the morning of the 19th, she heard the rumbling of wagons and artillery on the Salem Turnpike, and found the lines around her house were being withdrawn, but it was some time before she discovered that the Federal troops were retreating. It was then nearly daylight, and she slipped out of the[Pg 48] house and ran down to the ford across Blackwater Creek and notified the cavalry at that point what she had seen. A company was at once sent off in pursuit to verify her statement. After they had gone, and as she returned home, she met a solitary Federal soldier on foot, who asked her what had become of his command. She told him they had been whipped and had retreated, and informed him that he was her prisoner. He stated he had fallen asleep and had been left, and at once surrendered to her.

On reaching her home, although it was not yet sunrise, she started over on foot to the point where the heaviest fighting had taken place, that she might learn the fate of her brother, Major Marcellus N. Moorman, who commanded a battalion of artillery in the Second Corps. He had not been in the fight, as the battalion had not reached Lynchburg until during the night of the 18th. His command had started in the pursuit when she left home on her mission, but she met him on the battle-field going to tell his mother good-bye. Thus another son of Lynchburg was in line to battle for her defence.

On the extreme right of the Confederate lines, and on a part of what is now the farm of Senator Daniel, was stationed the brigade in command of Colonel Aug. Forsberg, then a stranger in the city, and here merely by the accident of war. On the right of his brigade was the Thirtieth battalion of Virginia infantry, under the command of Captain, now Judge, Stephen Adams, who, on the breaking out of the war, was a practicing[Pg 49] attorney of West Virginia. He had married Miss Emma Saunders, of Lynchburg, but was then a stranger thrown into the line of defence of the city by the like accident. Captain Adams, after he became a citizen of Lynchburg, purchased the very land on which his men were that day formed in line of battle, and has often dug up pieces of shell and bullets which were fired at him. He now preserves them as pleasant reminders of the past. Both Captain Adams and Colonel Forsberg are now valued citizens of Lynchburg, and we owe them a debt of gratitude for their gallant efforts in its defence.

It is not generally known that a few of the Federal shells were thrown into the city, but such was the case. The writer has in his possession a part of a three-inch percussion shell, shot from a rifle cannon, which fell in what was then known as "Meem's Garden," near the spot where the Catholic Church of the Holy Cross is now situated. His mother lived in the immediate vicinity of the place where it exploded, and, when the sound was heard, one of the servants ran over and picked it up, and it was thus preserved in the family.

The blood-stained and battle-torn little command of Breckinridge reached Lynchburg on the 16th of June. Up to that moment no one in the city had hoped that the place could be saved from Hunter's vandalism by the cordon of boys, cripples and irregular troops which surrounded it, and there was an anxiety which cannot be described; its depth may be imagined, but the pen cannot paint it.

The arrival of this small force brought hope back to[Pg 50] the hearts of the old men and helpless women and children who constituted the population of the city, and as the hardy old veterans moved up Main and then up Fifth streets they were cheered by joyous crowds of excited women, jubilant convalescents and hopeful old men. The troops had made a two-days' forced march from the headwaters of Rockfish River and were in bad physical condition, but in high spirits. They much enjoyed their cordial reception. This is shown by a little incident preserved out of the many of the same character by a person who was one of the girls present on the occasion.

In the column of troops, as they swung along in a double-quick to meet the advancing foe, was one red-haired soldier who had lost both hat and shoes, but was advancing with the same alacrity as his comrades who had been more fortunate in preserving these valuable articles of dress. Miss Sally Scruggs, then a young lady, radiant with the enthusiasm of the occasion, was standing upon the wall of the front yard of what was then the residence of Mr. H.I. Brown, at the south corner of Fifth and Church streets, together with a great many other ladies. She was wearing a Confederate broad-brimmed straw hat of her own make, trimmed with all the colors which could be raked from the discarded finery of the past. Seeing the gallant fellow passing without a hat, she tore her own from her head and threw it to him. He caught it, tied it over his auburn locks, raised his musket to a present arms, and the brigade cheered as long as they were in sight.

The writer has taken much pains to gather from eyewitnesses incidents of these eventful days in the history of our city, but with little success. It is astonishing how few people took note, or, if they did, can narrate the small incidents which would be so interesting to the present generation. The main and patent facts they remember well, but the official reports and newspapers preserve them to us very accurately. What is wanted, and what was the prime aim of this paper, is the preservation of those traditional facts which give a reality to history which historic papers cannot impart. Little aid has been rendered in this respect, though many letters have been written asking it, and many personal applications made to those who might, with a little trouble, have reproduced from memory many of those incidents so essential to the personal interest of such a sketch as this.

Among the facts which have been preserved, it is pleasant to tell of another soldier whose subsequent career was one in which every citizen took pride. Young W.C. Folkes, the son of our late much respected member of the Legislature from this city, Ed. J. Folkes, was at home disabled by a wound which had carried away one of his legs. Though far from recovered, he seized his crutch and a musket and started out to the lines, taking with him our townsman, Mr. E.C. Hamner, then not sixteen years old. The two marched out to the furthermost line, and there did a soldier's duty under fire all day. Young Folkes, after the war, studied law at the University of Virginia and then[Pg 52] moved to Memphis, Tennessee, where he soon rose to the front rank in his profession, and, while yet a young man, was elevated to the Supreme bench of the State, where, after a few years of distinguished usefulness, he died, beloved and respected in his adopted as well as his native State.

The last incident shows the spirit of the boys. But the old men on that day were boys also. Mr. Mike O'Connell was over eighty years of age. He went out with the Silver Grays. His company was placed on the inner line, but with his long rifle he marched out to the skirmish line and kept up a constant fire on the enemy all day, though himself under a heavy fire.

The writer of this sketch was, he regrets to say, in another part of the Army of Northern Virginia at this time, and therefore can give nothing from his own experience. He was, however, in constant correspondence with his wife, who wrote him very full accounts of all that happened. Unfortunately all her letters on this subject, but one, have been lost; one extract from that may be worth inserting. It is dated Tuesday, June 21, 1864:

"I received three letters from you, for all of which you must accept my thanks. It was amusing to me in reading those of the 17th and 19th to see how little idea you had of the stirring times through which we were passing at Lynchburg.

"On Monday, the 13th, we begun to fear that Hunter would make Lynchburg his point of attack, but it was not a definite fear until we heard of his being in Lexington, and that he was turning this way. On Thursday, the 16th, we heard of his being at Liberty, marching in this direction, and then all was excitement and apprehension.

"General Breckinridge, with some troops, got here on Wednesday night, and as we saw them passing out West street, it was a most reassuring sight, and never were a lot of bronzed and dirty looking veterans, many of them barefooted, more heartily welcomed. The streets were lined with women, waving their handkerchiefs and cheering them on as they moved out to a line on the hills west of the city. We were made more hopeful also by the knowledge that General Early, with several brigades, was at Charlottesville, en route to reinforce the small command of Breckinridge. He arrived with some of his troops on the evening of Friday, the 17th, but could do little more than get what he had into position. On Saturday, the 18th, more of Early's men came, and it was a delightful sound to hear their cheers as they passed out to the lines. Eugene was among them, and seemed to delight in the chance of making a fight right at home.

"Saturday, the 18th, was a day we will not soon forget. There was no general engagement until about three o'clock, but a constant cannonade and heavy skirmishing went on all day. Our lines were out near and in Spring Hill Cemetery; the enemy's further out. Their skirmish line was in Mr. John B. Lee's yard, where a number were killed by our cannon. I went out on College Hill and watched the fighting much of the time. It was very exciting to see the cannon fire from both sides and the explosion of the shells on the opposite side. It was fascinating beyond description. I could see our troops moving and taking new positions, and could see the Yankee batteries doing the same thing, and then the fearful reality of the scene was forced upon me by the line of ambulances which were kept busy bringing our wounded into town.