JANE AUSTEN’S SAILOR BROTHERS

Being the Adventures of Sir Francis Austen, G.C.B., Admiral of the Fleet and Rear-Admiral Charles Austen By J. H. Hubback and Edith C. Hubback

mdccccvi

London: John Lane

The Bodley Head, Vigo Street, W.

New York: John Lane Company

Printed by Ballantyne & Co. Limited

Tavistock Street, London

TO M. P. H.

“i have discovered a thing very little known, which is that in one’s whole life one can never have more than one mother. you may think this obvious. you are a green gosling!”

[Pg vii]

Perhaps some apology may be expected on behalf of a book about Jane Austen, having regard to the number which have already been put before the public in past years. My own membership of the family is my excuse for printing a book which contains little original matter, and which might be described as “a thing of shreds and patches,” if that phrase were not already over-worked. To me it seems improbable that others will take a wholly adverse view of what is so much inwoven with all the traditions of my life. When I recollect my childhood, spent chiefly in the house of my grandfather, Sir Francis, and all the interests which accompanied those early days, I find myself once more amongst those deep and tender distances. Surrounded by reminiscences of the opening years of the century, the Admiral always cherished the most affectionate remembrance of the sister who had so soon passed away, leaving[Pg viii] those six precious volumes to be a store of household words among the family.

How often I call to mind some question or answer, expressed quite naturally in terms of the novels; sometimes even a conversation would be carried on entirely appropriate to the matter under discussion, but the actual phrases were “Aunt Jane’s.” So well, too, do I recollect the sad news of the death of Admiral Charles Austen, after the capture, under his command, of Martaban and Rangoon, and while he was leading his squadron to further successes, fifty-six years having elapsed since his first sea-fight.

My daughter and I have made free use of the Letters of Jane Austen, published in 1884, by the late Lord Brabourne, and wish to acknowledge with gratitude the kind permission to quote these letters, given to us by their present possessor. In a letter of 1813, she speaks of two nephews who “amuse themselves very comfortably in the evening by netting; they are each about a rabbit-net, and sit as deedily to it, side by side, as any two Uncle Franks could do.” In his octogenarian days Sir Francis was still much interested in this same occupation of netting, to protect his Morello[Pg ix] cherries or currants. It was, in fact, only laid aside long after his grandsons had been taught to carry it on.

My most hearty thanks are also due to my cousins, who have helped to provide materials for our work; to Miss M. L. Austen for the loan of miniatures and silhouettes; to Miss Jane Austen for various letters and for illustrations; to Commander E. L. Austen for access to logs, and to official and other letters in large numbers; also to Miss Mary Austen for the picture of the Peterel in action, and to Mrs. Herbert Austen, and Captain and Mrs. Willan for excellent portraits of the Admirals, and to all these, and other members of the family, for much encouragement in our enterprise.

JOHN H. HUBBACK.

July 1905.

[Pg xi]

| [Pg xiii] CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | BROTHERS AND SISTERS | 1 |

| II. | TWO MIDSHIPMEN | 15 |

| III. | CHANGES AND CHANCES IN THE NAVY | 28 |

| IV. | PROMOTIONS | 41 |

| V. | THE “PETEREL” SLOOP | 56 |

| VI. | THE PATROL OF THE MEDITERRANEAN | 78 |

| VII. | AT HOME AND ABROAD | 94 |

| VIII. | BLOCKADING BOULOGNE | 111 |

| IX. | THE PURSUIT OF VILLENEUVE | 130 |

| X. | “A MELANCHOLY SITUATION” | 147 |

| XI. | ST. DOMINGO | 164 |

| XII. | THE CAPE AND ST. HELENA | 180 |

| XIII. | STARS AND STRIPES | 196 |

| XIV. | CHINESE MANDARINS | 212 |

| XV. | A LETTER FROM JANE | 227 |

| XVI. | ANOTHER LETTER FROM JANE | 243 |

| XVII. | THE END OF THE WAR | 260 |

| XVIII. | [Pg xii] TWO ADMIRALS | 274 |

| INDEX | 287 | |

| PAGE | |

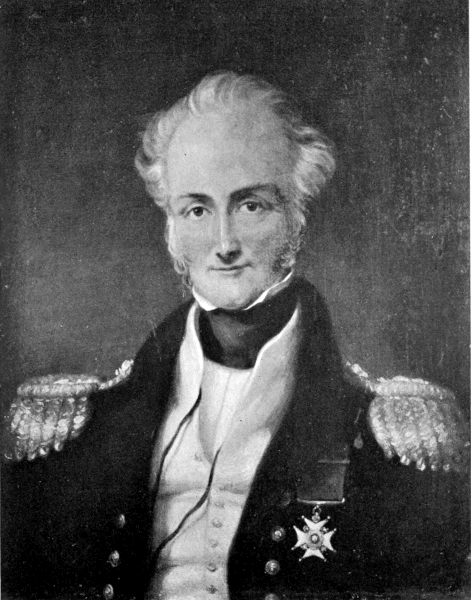

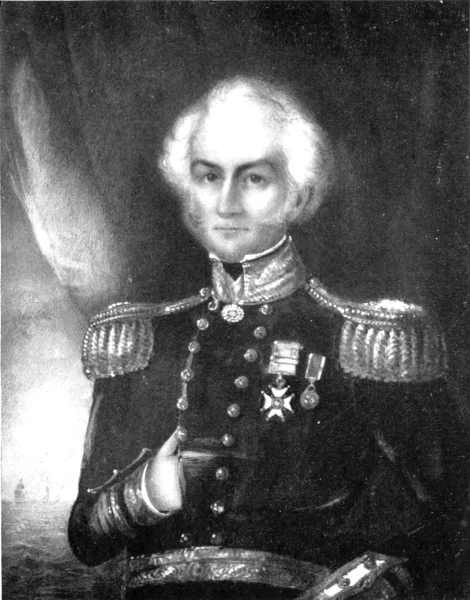

| Vice-Admiral Sir Francis Austen, K.C.B. (From a painting in the possession of Mrs. Herbert Austen) | Frontispiece |

| The Reverend George Austen, Rector of Steventon (From a miniature in the possession of Miss M. L. Austen) | 8 |

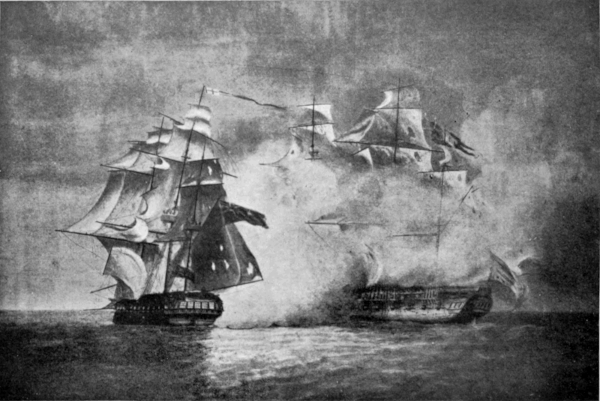

| Action between the English frigate Unicorn and the French frigate La Tribune, June 8, 1796 (From a painting in the possession of Captain Willan, R.N., and Mrs. Willan). By kind permission of Miss Hill | 22 |

| Francis Austen as Lieutenant (From a miniature) | 44 |

| Sloop of War and Frigate (From a pencil sketch by Captain Herbert Austen, R.N.) | 64 |

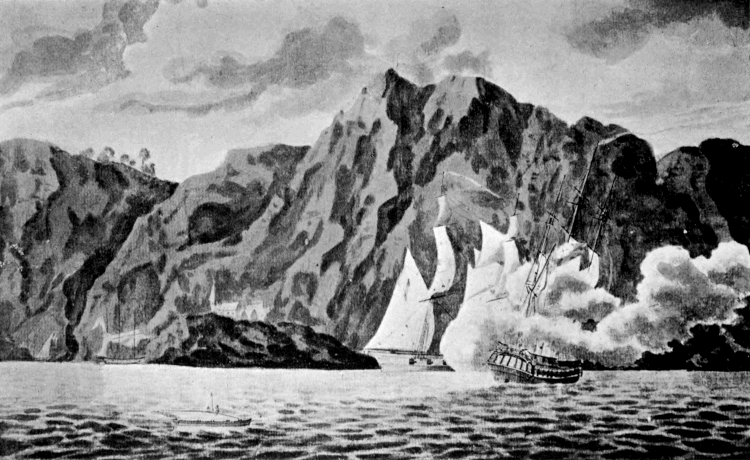

| Peterel in action with the French brig La Ligurienne after driving two others on the rocks near Marseilles, on March 21, 1800 (From a sketch by Captain Herbert Austen, R.N., in the possession of Miss Mary Austen) | 84 |

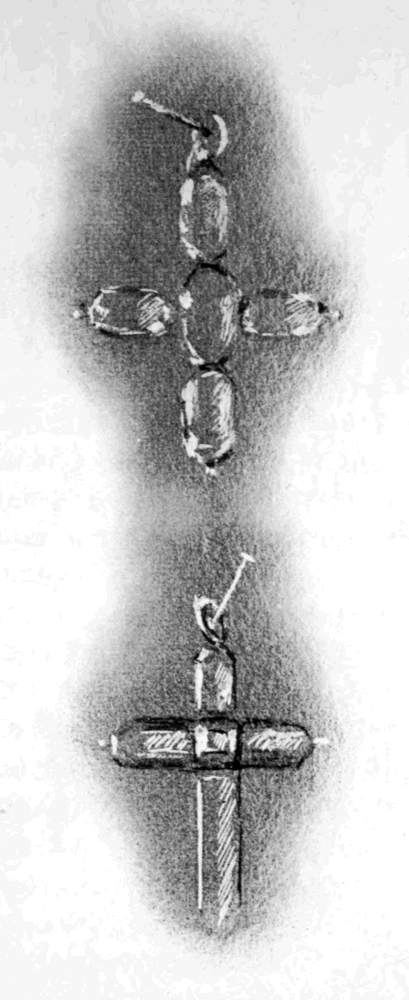

| Topaz Crosses given to Cassandra and Jane by Charles Austen (In the possession of Miss Jane Austen) | 92 |

| The Way to Church from Portsdown Lodge (From a pencil sketch by Catherine A. Austen) | 108 |

| Mrs. Austen (From a silhouette in the possession of Miss M. L. Austen) | 124 |

| Order of Battle and of Sailing, signed Nelson and Bronté, dated March 26, 1805 | [Pg xiv] 132 |

| Order of Battle and of Sailing, signed Nelson and Bronté, dated June 5, 1805 | 138 |

| Captain Francis William Austen (From a miniature of 1806, in the possession of Miss M. L. Austen. The Order of the C.B. has been painted in at a later date, probably when conferred in 1815) | 156 |

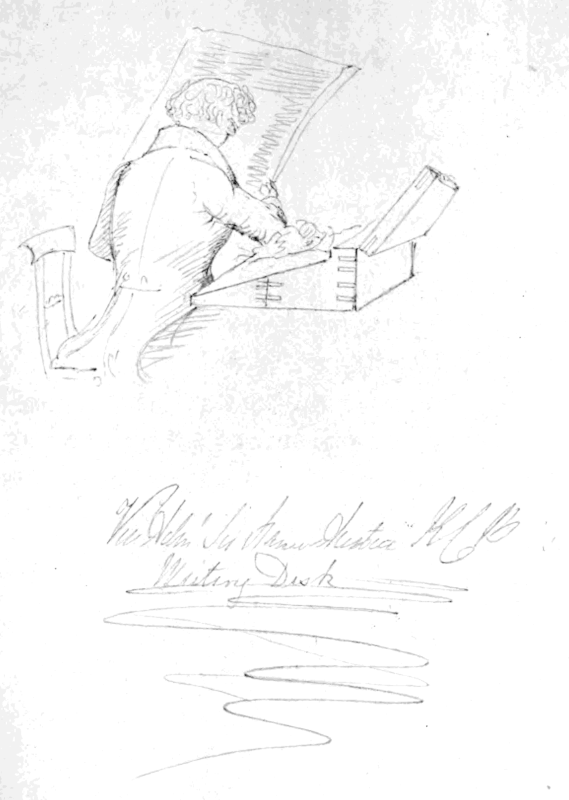

| “Vice-Admiral Sir Francis Austen, K.C.B.’s writing-desk” (From a caricature sketch by his daughter Cassandra, about 1840) | 174 |

| Cassandra Austen (From a silhouette in the possession of Miss M. L. Austen) | 184 |

| Portchester Castle. The French prisoners were interned in the neighbouring buildings after the Battle of Vimiera (From a sketch by Captain Herbert Austen, R.N.) | 200 |

| Captain Charles Austen (From a painting of 1809, in the possession of Miss Jane Austen) | 210 |

| Jane Austen, from a sketch by her sister Cassandra (In the possession of Miss Jane Austen) | 226 |

| Mrs. Charles Austen, née Fanny Palmer, daughter of the Attorney-General of Bermuda (From a painting in the possession of Miss Jane Austen) | 252 |

| Captain Charles Austen, C.B. (From a painting in the possession of Captain Willan, R.N., and Mrs. Willan) | 266 |

| Jane Austen’s work-box, with her last piece of work (In the possession of Miss Jane Austen) | 270 |

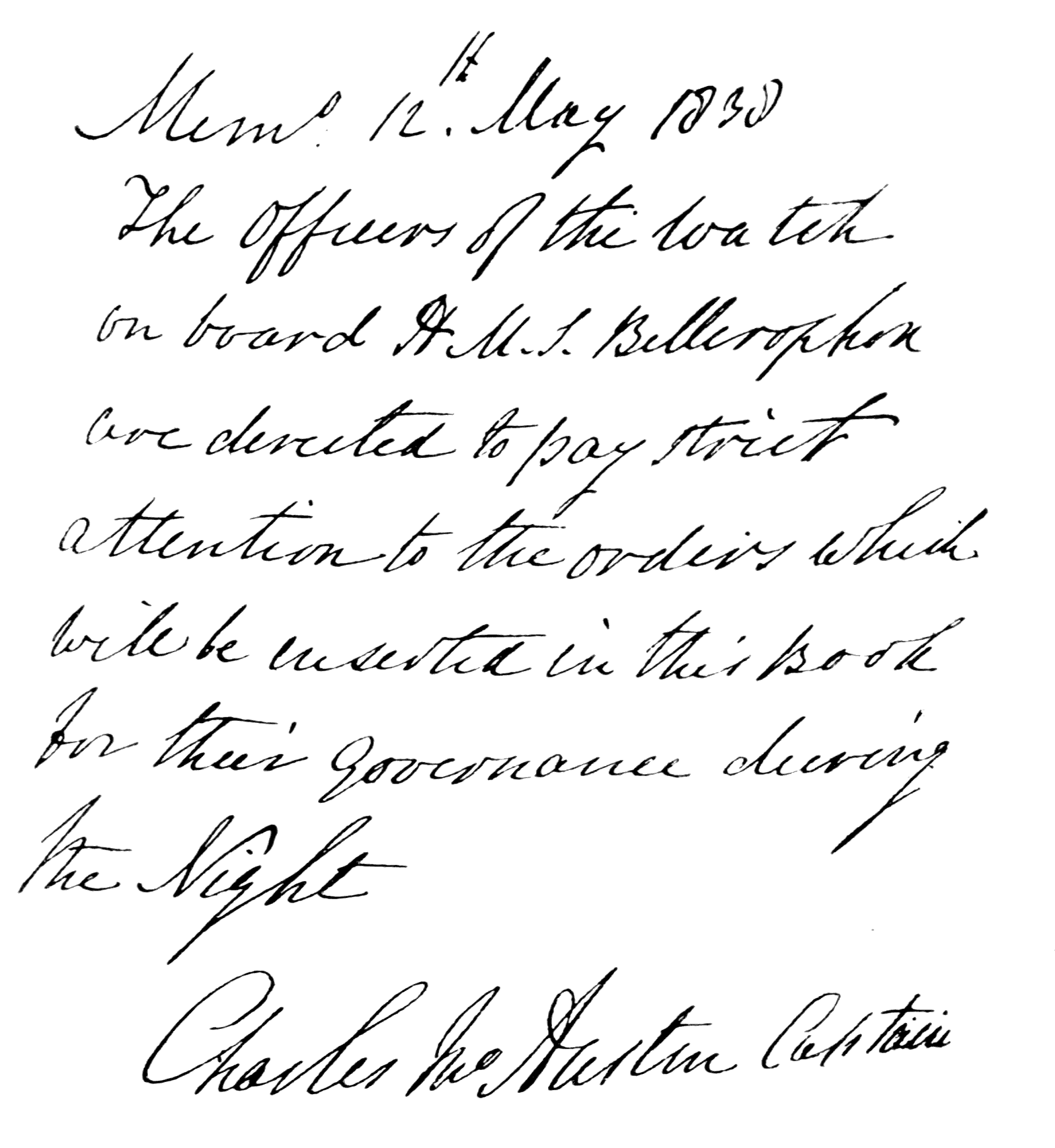

| Memorandum, dated May 12, 1838, signed by Charles Austen on taking command of the Bellerophon | 274 |

| Rear-Admiral Charles Austen, C.B. (From a miniature painted at Malta in 1846, in the possession of Miss Jane Austen) | 278 |

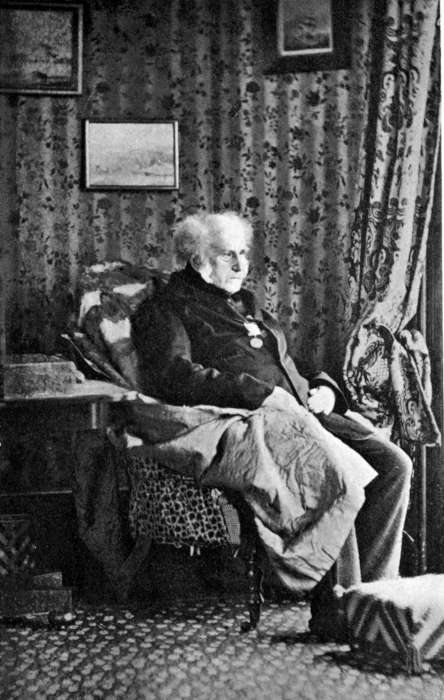

| Sir Francis Austen, G.C.B., Admiral of the Fleet, at the age of ninety | 284 |

JANE AUSTEN’S SAILOR BROTHERS

No one can read Jane Austen’s novels, her life, or her letters, without feeling that to her the ties of family were stronger and more engrossing than any others.

Among the numbers of men and women who cheerfully sacrifice the claims of their family in order that they may be free to confer somewhat doubtful benefits on society, it is refreshing to find one who is the object of much love and gratitude from countless unknown readers, and who yet would have been the first to laugh at the notion that her writing was of more importance than her thought for her brothers and sister, or the various home duties which fell to her share. It is this sweetness and wholesomeness of thought, this clear conviction that her “mission” was to do her duty, that gives her books and letters their peculiar quality. Her theory of life is clear. Whatever troubles befall, people must go on doing their work and making the best of it; and we are not[Pg 2] allowed to feel respect, or even overmuch sympathy, for the characters in the novels who cannot bear this test. There is a matter-of-courseness about this view which, combined with all that we know of the other members of the family, gives one the idea that the children at Steventon had a strict bringing up. This, in fact, was the case, and a very rich reward was the result. In a family of seven all turned out well, two rose to the top of their profession, and one was—Jane Austen.

The fact of her intense devotion to her family could not but influence her writing. She loved them all so well that she could not help thinking of them even in the midst of her work; and the more we know of her surroundings, and the lives of those she loved, the more we understand of the small joyous touches in her books. She was far too good an artist, as well as too reticent in nature, to take whole characters from life; but small characteristics and failings, dwelt on with humorous partiality, can often be traced back to the natures of those she loved. Mary Crawford’s brilliant letters to Fanny Price remind one of Cassandra, who was the “finest comic writer of the present age.” Charles’ impetuous disposition is exaggerated in Bingley, who says, “Whatever I do is done in a hurry,” a remark which is severely reproved by Darcy (and not improbably by Francis Austen), as an “indirect boast.” Francis himself comes in[Pg 3] for his share of teasing on the opposite point of his extreme neatness, precision, and accuracy. “They are so neat and careful in all their ways,” says Mrs. Clay, in “Persuasion,” of the naval profession in general; and nothing could be more characteristic of Francis Austen and some of his descendants than the overpowering accuracy with which Edmund Bertram corrects Mary Crawford’s hasty estimate of the distance in the wood.

“‘I am really not tired, which I almost wonder at; for we must have walked at least a mile in this wood. Do not you think we have?’

“‘Not half a mile,’ was his sturdy answer; for he was not yet so much in love as to measure distance, or reckon time, with feminine lawlessness.

“‘Oh, you do not consider how much we have wound about. We have taken such a very serpentine course, and the wood itself must be half a mile long in a straight line, for we have never seen the end of it yet since we left the first great path.’

“‘But if you remember, before we left that first great path we saw directly to the end of it. We looked down the whole vista, and saw it closed by iron gates, and it could not have been more than a furlong in length.’

“‘Oh, I know nothing of your furlongs, but I am sure it is a very long wood; and that we have been winding in and out ever since we came into it; and therefore when I say that[Pg 4] we have walked a mile in it I must speak within compass.’

“‘We have been exactly a quarter of an hour here,’ said Edmund, taking out his watch. ‘Do you think we are walking four miles an hour?’

“‘Oh, do not attack me with your watch. A watch is always too fast or too slow. I cannot be dictated to by a watch.’

“A few steps farther brought them out at the bottom of the very walk they had been talking of.

“‘Now, Miss Crawford, if you will look up the walk, you will convince yourself that it cannot be half a mile long, or half half a mile.’

“‘It is an immense distance,’ said she; ‘I see that with a glance.’

“He still reasoned with her, but in vain. She would not calculate, she would not compare. She would only smile and assert. The greatest degree of rational consistency could not have been more engaging, and they talked with mutual satisfaction.”

It is in “Mansfield Park” and in “Persuasion” that the influence of her two sailor brothers, Francis and Charles, on Jane Austen’s work can be most easily traced. Unlike the majority of writers of all time, from Shakespeare with his “Seacoast of Bohemia” down to the author of a penny dreadful, Jane Austen never touched, even lightly, on a subject unless she had a real knowledge of its[Pg 5] details. Her pictures of the life of a country gentleman and of clergymen are accurate, if not always sympathetic. Perhaps it was all too near her own experience to have the charm of romance, but concerning sailors she is romantic. Their very faults are lovable in her eyes, and their lives packed with interest. When Admiral Croft, Captain Wentworth, or William Price appears on the scene, the other characters immediately take on a merely subsidiary interest, and this prominence is always that given by appreciation. The distinction awarded to Mr. Collins or Mrs. Elton, as the chief object of ridicule, is of a different nature. The only instance she cared to give us of a sailor who is not to be admired is Mary Crawford’s uncle, the Admiral, and even he is allowed to earn our esteem by disinterested kindness to William Price.

No doubt some of this enthusiasm was due to the spirit of the times, when, as Edward Ferrars says, “The navy had fashion on its side”; but that sisterly partiality was a stronger element there can be no question. Her place in the family was between these two brothers, Francis just a year older, and Charles some four years younger. Much has been said about her fondness for “pairs of sisters” in her novels, but no less striking are the “brother and sister” friendships which are an important factor in four out of her six books. The[Pg 6] love of Darcy for his sister Georgiana perhaps suggests the intimacy between James Austen and Jane, where the difference in their ages of ten years, their common love of books, the advice and encouragement that the elder brother was able to give his sister over her reading, are all points of resemblance. The equal terms of the affection of Francis and Jane are of another type.

Henry Tilney and his sister Eleanor, Mrs. Croft and Frederick Wentworth, give us good instances of firm friendships. In the case of the Tilneys, confidences are exchanged with ease and freedom; but in “Persuasion,” the feeling in this respect, as in all others, is more delicate, and only in the chapter which Jane Austen afterwards cancelled can we see the quickness of Mrs. Croft’s perceptions where her brother was concerned. For so long as she supposes him to be on the brink of marrying Louisa Musgrove, sympathy is no doubt somewhat difficult to force, but “prompt welcome” is given to Anne as Captain Wentworth’s chosen wife; and with some knowledge of Mrs. Croft we know that the “particularly friendly manner” hid a warmth of feeling which would fully satisfy even Frederick’s notions of the love which Anne deserved. But it is in “Mansfield Park” that “brothers and sisters” play the strongest part. No one can possibly doubt the very lively affection of Mary and Henry Crawford. Even when complaining of the[Pg 7] shortness of his letters, she says that Henry is “exactly what a brother should be, loves me, consults me, confides in me, and will talk to me by the hour together”—and the scene later on, where he tells of his devotion to Fanny Price, is as pretty an account of such a confidence as can be well imagined, where the worldliness of each is almost lost in the happiness of disinterested love, which both are feeling.

When Jane Austen comes to describing Fanny’s love for her brother William, her tenderness and her humour are in perfect accord. From the reality of the feelings over his arrival and promotion, to the quiet hit at the enthusiasm which his deserted chair and cold pork bones might be supposed to arouse in Fanny’s heart after their early breakfast, when he was off to London, the picture of sisterly love is perfect. We are told, too, that there was “an affection on his side as warm as her own, and much less encumbered by refinement and self-distrust. She was the first object of his love, but it was a love which his stronger spirits and bolder temper made it as natural for him to express as to feel.” So far this describes the love of William and Fanny, but a few lines further on comes a passage which has the ring of personal experience. In reading it, it is impossible not to picture a time which was always of great importance in the life at Steventon—the return on leave[Pg 8] for a few weeks or a few months of one or other of the sailor brothers, and all the walks and talks which filled up the pleasant days. “On the morrow they were walking about together with true enjoyment, and every succeeding morrow renewed the tête-à-tête. Fanny had never known so much felicity in her life as in this unchecked, equal, fearless intercourse with the brother and friend, who was opening all his heart to her, telling her all his hopes and fears, plans and solicitudes respecting that long thought of, dearly earned, and justly valued blessing of promotion—who was interested in all the comforts and all the little hardships of her home—and with whom (perhaps the dearest indulgence of the whole) all the evil and good of their earliest years could be gone over again, and every former united pain and pleasure retraced with the fondest recollection.”

Some slight record of the childhood of the Steventon family has been left to us. Most of the known facts have already been told by admirers of Jane Austen, but some extracts from an account written by Catherine Austen in the lifetime of her father, Sir Francis Austen, will at least have the merit of accuracy, for he would certainly have been merciless to even the simplest “embroidery.”

The father, Mr. George Austen, was the rector of Steventon. He was known in his young days, [Pg 9]before his marriage, as “the handsome tutor,” and he transmitted his good looks to at least three of his sons; Henry, Francis, and Charles were all exceptionally handsome men. Indeed, neither wit nor good looks were deficient in the Steventon family. Probably much of Jane’s simplicity about her writing arose from the fact that she saw nothing in it to be conceited about, being perfectly convinced that any of the others, with her leisure and inclination, could have done just as well. Her father had a gentleness of disposition combined with a firmness of principle which had great effect in forming the characters of his family. The mother’s maiden name was Cassandra Leigh. She was very lively and active, and strict with her children. It is not difficult to see whence Francis derived his ideas of discipline, or Jane her unswerving devotion to duty.

The elder members of the family were born at Deane, which was Mr. Austen’s first living, but in 1771 they moved to Steventon, where they lived for nearly thirty years.

The account of the house given by Catherine Austen shows the simplicity of the life.

“The parsonage consisted of three rooms in front on the ground floor, the best parlour, the common parlour, and the kitchen; behind there were Mr. Austen’s study, the back kitchen and the stairs; above them were seven bedrooms and[Pg 10] three attics. The rooms were low-pitched but not otherwise bad, and compared with the usual style of such buildings it might be considered a very good house.” An eulogy follows on the plainness and quietness of the family life—a characteristic specially due to the mother’s influence.

“That she had no taste for expensive show or finery, may be inferred from the fact being on record that for two years she actually never had a gown to wear. It was a prevalent custom for ladies to wear cloth habits, and she having one of red cloth found any other dress unnecessary. Imagine a beneficed clergyman’s wife in these days contenting herself with such a costume for two years! But the fact illustrates the retired style of living that contented her.” Even when she did find it necessary to provide herself with some other costume, the riding-habit was made to serve another useful purpose, for it was cut up into a first cloth suit for little Francis.

The following account of their upbringing closes this slight record:

“There is nothing in which modern manners differ much more from those of a century back than in the system pursued with regard to children. They were kept in the nursery, out of the way not only of visitors but of their parents; they were trusted to hired attendants; they were allowed a[Pg 11] great deal of air and exercise, were kept on plain food, forced to give way to the comfort of others, accustomed to be overlooked, slightly regarded, considered of trifling importance. No well-stocked libraries of varied lore to cheat them into learning awaited them; no scientific toys, no philosophic amusements enlarged their minds and wearied their attention.” One wonders what would have been the verdict of this writer of fifty years ago on education in 1905. She goes on to tell us of the particular system pursued with the boys in order to harden them for their future work in life. It was not considered either necessary or agreeable for a woman to be very strong. “Little Francis was at the age of ten months removed from the parsonage to a cottage in the village, and placed under the care of a worthy couple, whose simple style of living, homely dwelling, and out-of-door habits (for in the country the poor seldom close the door by day, except in bad weather), must have been very different from the heated nurseries and constrained existence of the clean, white-frocked little gentlemen who are now growing up around us. Across the brick floor of a cottage Francis learnt to walk, and perhaps it was here that he received the foundation of the excellent constitution which was so remarkable in after years. It must not, however, be supposed that he was neglected by his parents; he was[Pg 12] constantly visited by them both, and often taken to the parsonage.”

One cannot but admire the fortitude of parents who would forego the pleasure of seeing their children learn to walk and satisfy themselves with daily visits, for the sake of a plan of education of which the risks cannot have been otherwise than great.

The rough-and-tumble life which followed must have thoroughly suited the taste of any enterprising boy, and given him an independence of spirit, and a habit of making his own plans, which would be exactly what was wanted in the Navy of those days, when a man of twenty-five might be commander of a vessel manned by discontented, almost mutinous, sailors, with the chance of an enemy’s ship appearing at any time on the horizon.

Riding about the country after the hounds began for Francis at the age of seven; and, from what we hear of Catherine Morland’s childhood, we feel sure that Jane would not always have been contented to be left behind.

Catherine, at the age of ten, was “noisy and wild, hated confinement and cleanliness, and loved nothing so well in the world as rolling down the green slope at the back of the house.” When she was fourteen, we are told that she “preferred cricket, base-ball, riding on horseback, and[Pg 13] running about the country, to books—or, at least, books of information—for, provided that nothing like useful knowledge could be gained from them, provided they were all story and no reflection, she had never any objection to books at all!”

This, if not an accurate picture of the tastes of the children at Steventon, at least shows the sort of amusements which boys and girls brought up in a country parsonage had at their command.

Perhaps it was of some such recollections that Jane Austen was thinking when she praised that common tie of childish remembrances. “An advantage this, a strengthener of love, in which even the conjugal tie is beneath the fraternal. Children of the same family, the same blood, with the same first associations and habits, have some means of enjoyment in their power which no subsequent connection can supply, and it must be by a long and unnatural estrangement, by a divorce which no subsequent connection can justify, if such precious remains of the earliest attachments are ever entirely outlived. Too often, alas! it is so. Fraternal love, sometimes almost everything, is at others worse than nothing. But with William and Fanny Price it was still a sentiment in all its prime and freshness, wounded by no opposition of interest, cooled by no separate attachment, and[Pg 14] feeling the influence of time and absence only in its increase.” That it was never Jane’s lot to feel this cooling of affection on the part of any member of her family is due not only to their appreciation of their sister, but to the serenity and adaptability of her own sweet disposition.

[Pg 15]

Both Francis and Charles Austen were educated for their profession at the Royal Naval Academy, which was established in 1775 at Portsmouth, and was under the supreme direction of the Lords of the Admiralty. Boys were received there between the ages of 12 and 15. They were supposed to stay there for three years, but there was a system of sending them out to serve on ships as “Volunteers.” This was a valuable part of their training, as they were still under the direction of the College authorities, and had the double advantages of experience and of teaching. They did the work of seamen on board, but were allowed up on deck, and were specially under the eye of the captain, who was supposed to make them keep accurate journals, and draw the appearances of headlands and coasts. It is no doubt to this early training that we owe the careful private logs which Francis kept almost throughout his whole career.

[Pg 16]

Some of the rules of the Naval Academy show how ideas have altered in the last hundred and more years. There was a special law laid down that masters were to make no differences between the boys on account of rank or position, and no boy was to be allowed to keep a private servant, a rather superfluous regulation in these days.

Three weeks was the extent of the holiday, which it seems could be taken at any time in the year, the Academy being always open for the benefit of Volunteers, who were allowed to go there when their ships were in Portsmouth. Those who distinguished themselves could continue this privilege after their promotion. Francis left the Academy in 1788, and immediately went out to the East Indies on board the Perseverance as Volunteer.

There he stayed for four years, first as midshipman on the Crown, 64 guns, and afterwards on the Minerva, 38.

A very charming letter from his father to Francis is still in existence.

“Memorandum for the use of Mr. F. W. Austen on his going to the East Indies on board his Majesty’s ship Perseverance (Captain Smith).

“December, 1788.

“My dear Francis,—While you were at the Royal Academy the opportunities of writing to you[Pg 17] were so frequent that I gave you my opinion and advice as occasion arose, and it was sufficient to do so; but now you are going from us for so long a time, and to such a distance, that neither you can consult me or I reply but at long intervals, I think it necessary, therefore, before your departure, to give my sentiments on such general subjects as I conceive of the greatest importance to you, and must leave your conduct in particular cases to be directed by your own good sense and natural judgment of what is right.”

After some well-chosen and impressive injunctions on the subject of his son’s religious duties, Mr. Austen proceeds:

“Your behaviour, as a member of society, to the individuals around you may be also of great importance to your future well-doing, and certainly will to your present happiness and comfort. You may either by a contemptuous, unkind and selfish manner create disgust and dislike; or by affability, good humour and compliance, become the object of esteem and affection; which of these very opposite paths ’tis your interest to pursue I need not say.

“The little world, of which you are going to become an inhabitant, will occasionally have it in their power to contribute no little share to your pleasure or pain; to conciliate therefore their goodwill, by every honourable method, will be the part of a[Pg 18] prudent man. Your commander and officers will be most likely to become your friends by a respectful behaviour to themselves, and by an active and ready obedience to orders. Good humour, an inclination to oblige and the carefully avoiding every appearance of selfishness, will infallibly secure you the regards of your own mess and of all your equals. With your inferiors perhaps you will have but little intercourse, but when it does occur there is a sort of kindness they have a claim on you for, and which, you may believe me, will not be thrown away on them. Your conduct, as it respects yourself, chiefly comprehends sobriety and prudence. The former you know the importance of to your health, your morals and your fortune. I shall therefore say nothing more to enforce the observance of it. I thank God you have not at present the least disposition to deviate from it. Prudence extends to a variety of objects. Never any action of your life in which it will not be your interest to consider what she directs! She will teach you the proper disposal of your time and the careful management of your money,—two very important trusts for which you are accountable. She will teach you that the best chance of rising in life is to make yourself as useful as possible, by carefully studying everything that relates to your profession, and distinguishing yourself from those of your[Pg 19] own rank by a superior proficiency in nautical acquirements.

“As you have hitherto, my dear Francis, been extremely fortunate in making friends, I trust your future conduct will confirm their good opinion of you; and I have the more confidence in this expectation because the high character you acquired at the Academy for propriety of behaviour and diligence in your studies, when you were so much younger and had so much less experience, seems to promise that riper years and more knowledge of the world will strengthen your naturally good disposition. That this may be the case I sincerely pray, as you will readily believe when you are assured that your good mother, brothers, sisters and myself will all exult in your reputation and rejoice in your happiness.

“Thus far by way of general hints for your conduct. I shall now mention only a few particulars I wish your attention to. As you must be convinced it would be the highest satisfaction to us to hear as frequently as possible from you, you will of course neglect no opportunity of giving us that pleasure, and being very minute in what relates to yourself and your situation. On this account, and because unexpected occasions of writing to us may offer, ’twill be a good way always to have a letter in forwardness. You may depend on hearing from some of us at every opportunity.

[Pg 20]

“Whenever you draw on me for money, Captain Smith will endorse your bills, and I dare say will readily do it as often, and for what sums, he shall think necessary. At the same time you must not forget to send me the earliest possible notice of the amount of the draft, and the name of the person in whose favour it is drawn. On the subject of letter-writing, I cannot help mentioning how incumbent it is on you to write to Mr. Bayly, both because he desired it and because you have no other way of expressing the sense I know you entertain of his very great kindness and attention to you. Perhaps it would not be amiss if you were also to address one letter to your good friend the commissioner, to acknowledge how much you shall always think yourself obliged to him.

“Keep an exact account of all the money you receive or spend, lend none but where you are sure of an early repayment, and on no account whatever be persuaded to risk it by gaming.

“I have nothing to add but my blessing and best prayers for your health and prosperity, and to beg you would never forget you have not upon earth a more disinterested and warm friend than,

“Your truly affectionate father,

“Geo. Austen.”

That this letter should have been found among the private papers of an old man who died at the[Pg 21] age of 91, after a life of constant activity and change, is proof enough that it was highly valued by the boy of fourteen to whom it was written. There is something in its gentleness of tone, and the way in which advice is offered rather than obedience demanded, which would make it very persuasive to the feelings of a young boy going out to a life which must consist mainly of the opposite duties of responsibility and discipline. Incidentally it all throws a pleasant light on the characters of both father and son.

The life of a Volunteer on board ship was by no means an easy one, but it no doubt inured the boys to hardships and privations, and gave them a sympathy with their men which would afterwards stand them in good stead.

The record of Charles as a midshipman is very much more stirring than Francis’ experiences. He served on board the Unicorn, under Captain Thomas Williams, at the time of the capture of the French frigate La Tribune, a notable single ship encounter, which brought Captain Williams the honour of knighthood.

On June 8, 1796, the Unicorn and the Santa Margarita, cruising off the Scilly Islands, sighted three strange ships, and gave chase. They proved to be two French frigates and a corvette, La Tribune, La Tamise, and La Legère. The French vessels continued all day to run[Pg 22] before the wind. The English ships as they gained on them were subjected to a well-directed fire, which kept them back so much that it was evening before La Tamise at last bore up and engaged one of the pursuers, the Santa Margarita. After a sharp action of about twenty minutes La Tamise struck her colours.

La Tribune crowded on all sail to make her escape, but the Unicorn, in spite of damage to masts and rigging, kept up the chase, and after a running fight of ten hours the Unicorn came alongside, taking the wind from the sails of the French ship. After a close action of thirty-five minutes there was a brief interval. As the smoke cleared away, La Tribune could be seen trying to get to the windward of her enemy. This manœuvre was instantly frustrated, and a few more broadsides brought down La Tribune’s masts, and ended the action. From start to finish of the chase the two vessels had run 210 miles. Not a man was killed or even hurt on board the Unicorn, and not a large proportion of the crew of La Tribune suffered. No doubt in a running fight of this sort much powder and shot would be expended with very little result.

When this encounter took place Charles Austen had been at sea for scarcely two years. Such an experience would have given the boy a great notion of the excitement and joys in store for him [Pg 23]in a seafaring life. Such, however, was not to be his luck. Very little important work fell to his share till at least twenty years later, and for one of his ardent temperament this was a somewhat hard trial. His day came at last, after years of routine, but when he was still young enough to enjoy a life of enterprise and of action. Even half a century later his characteristic energy was never more clearly shown than in his last enterprise as Admiral in command during the second Burmese War (1852), when he died at the front.

Francis, during the four years when he was a midshipman, had only one change of captain. After serving under Captain Smith in the Perseverance, he went to the Crown, under Captain the Honourable W. Cornwallis, and eventually followed him into the Minerva. Admiral Cornwallis was afterwards in command of the Channel Fleet, blockading Brest in the Trafalgar year.

Charles had an even better experience than Francis had, for he was under Captain Thomas Williams all the time he was midshipman, first in the Dædalus, then in the Unicorn, and last in the Endymion.

The fact that both brothers served for nearly all their times as midshipmen under the same captain shows that they earned good opinions. If[Pg 24] midshipmen were not satisfactory they were very speedily transferred, as we hear was the lot of poor Dick Musgrove.

“He had been several years at sea, and had in the course of those removals to which all midshipmen are liable, and especially such midshipmen as every captain wishes to get rid of, been six months on board Captain Frederick Wentworth’s frigate, the Laconia; and from the Laconia he had, under the influence of his captain, written the only two letters which his father and mother had ever received from him during the whole of his absence, that is to say the only two disinterested letters; all the rest had been mere applications for money. In each letter he had spoken well of his captain—mentioning him in strong, though not perfectly well-spelt praise, as ‘a fine dashing felow, only two perticular about the schoolmaster.’”

No doubt Dick’s journal and sketches of the coast line were neither accurate nor neatly executed.

William Price’s time as a midshipman is, one would think, a nearer approach to the careers of Francis and Charles. Certainly the account given of his talk seems to bear much resemblance to the stories Charles, especially, would have to tell on his return.

“William was often called on by his uncle to[Pg 25] be the talker. His recitals were amusing in themselves to Sir Thomas, but the chief object in seeking them was to understand the reciter, to know the young man by his histories, and he listened to his clear, simple, spirited details with full satisfaction—seeing in them the proof of good principles, professional knowledge, energy, courage and cheerfulness—everything that could deserve or promise well. Young as he was, William had already seen a great deal. He had been in the Mediterranean—in the West Indies—in the Mediterranean again—had been often taken on shore by favour of his captain, and in the course of seven years had known every variety of danger which sea and war together could offer. With such means in his power he had a right to be listened to; and though Mrs. Norris could fidget about the room, and disturb everybody in quest of two needlefuls of thread or a second-hand shirt button in the midst of her nephew’s account of a shipwreck or an engagement, everybody else was attentive; and even Lady Bertram could not hear of such horrors unmoved, or without sometimes lifting her eyes from her work to say, ‘Dear me! How disagreeable! I wonder anybody can ever go to sea.’

“To Henry Crawford they gave a different feeling. He longed to have been at sea, and seen and done and suffered as much. His heart was[Pg 26] warmed, his fancy fired, and he felt a great respect for a lad who, before he was twenty, had gone through such bodily hardships, and given such proofs of mind. The glory of heroism, of usefulness, of exertion, of endurance, made his own habits of selfish indulgence appear in shameful contrast; and he wished he had been a William Price, distinguishing himself and working his way to fortune and consequence with so much self-respect and happy ardour, instead of what he was!”

This gives a glowing account of the consequence of a midshipman on leave. That times were not always so good, that they had their share of feeling small and of no account, on shore as well as at sea, is only to be expected, and Fanny was not allowed to imagine anything else.

“‘This is the Assembly night,’ said William. ‘If I were at Portsmouth, I should be at it perhaps.’

“‘But you do not wish yourself at Portsmouth, William?’

“‘No, Fanny, that I do not. I shall have enough of Portsmouth, and of dancing too, when I cannot have you. And I do not know that there would be any good in going to the Assembly, for I might not get a partner. The Portsmouth girls turn up their noses at anybody who has not a commission. One might as well be nothing as a midshipman. One is nothing, indeed. You remember the[Pg 27] Gregorys; they are grown up amazing fine girls, but they will hardly speak to me, because Lucy is courted by a lieutenant.’

“‘Oh! Shame, shame! But never mind it, William (her own cheeks in a glow of indignation as she spoke). It is not worth minding. It is no reflection on you; it is no more than the greatest admirals have all experienced, more or less, in their time. You must think of that; you must try to make up your mind to it as one of the hardships which fall to every sailor’s share—like bad weather and hard living—only with this advantage, that there will be an end to it, that there will come a time when you will have nothing of that sort to endure. When you are a lieutenant!—only think, William, when you are a lieutenant, how little you will care for any nonsense of this kind.’”

[Pg 28]

Francis obtained his Lieutenant’s commission in 1792, serving for a year in the East Indies, and afterwards on the home station. Early promotions were frequent in those days of the Navy; and, in many ways, no doubt, this custom was a good one, as the younger men had the dash and assurance which was needed, when success lay mainly in the power of making rapid decisions. Very early advancement had nevertheless decided disadvantages, and it was among the causes that brought about the mutinies of 1797. There are four or five cases on record of boys being made captains before they were eighteen, and promotions often went so much by favour and so little by real merit that the discontent of the crews commanded by such inexperienced officers was not at all to be wondered at. There were many other long-standing abuses, not the least of which was the system of punishments, frightful in their severity. A few instances of these, taken[Pg 29] at haphazard from the logs of the various ships on which Francis Austen served as Lieutenant will illustrate this point.

Glory, December 8, 1795.—“Punished P. C. Smith forty-nine lashes for theft.”

January 14, 1796.—“Punished sixteen seamen with one dozen lashes each for neglect of duty in being off the deck in their watch.”

Punishments were made as public as possible. The following entry is typical:

Seahorse, December 9, 1797.—“Sent a boat to attend punishments round the fleet.”

In the log of the London, one of the ships of the line blockading Cadiz, just after the fearful mutinies of 1797, we find, as might be expected, that punishments were more severe than ever.

August 16, 1798.—“Marlborough made the signal for punishment. Sent three boats manned and armed to attend the punishment of Charles Moore (seaman belonging to the Marlborough), who was sentenced to receive one hundred lashes for insolence to his superior officer. Read the articles of war and sentence of Court-martial to the ship’s company. The prisoner received twenty-five lashes alongside this ship.”

In the case of a midshipman court-martialled for robbing a Portuguese boat, “the charges having been proved, he was sentenced to be turned before the mast, to have his uniform stripped off him on[Pg 30] the quarter-deck before all the ship’s company, to have his head shaved, and to be rendered for ever incapable of serving as a petty officer.”

No fewer than six executions are recorded in the log of the London as taking place among the ships of the fleet off Cadiz. Only one instance is mentioned where the offender was pardoned by the commander-in-chief on account of previous good conduct. Earl St. Vincent certainly deserved his reputation as a disciplinarian.

When, in addition to the system of punishment, it is further considered that the food was almost always rough and very often uneatable, that most of the crews were pressed men, who would rather have been at any other work, and that the seamen’s share in any possible prizes was ludicrously small, one wonders, not at the mutinies, but at the splendid loyalty shown when meeting the enemy.

It is a noticeable fact that discontent was rife during long times of inaction (whilst blockading Cadiz is the notable instance), but when it came to fighting for their country men and officers alike managed to forget their grievances.

On May 29, the log of the London is as follows:

“The Marlborough anchored in the middle of the line. At seven the Marlborough made the signal for punishment. Sent our launch, barge and cutter, manned and armed, to attend the execution of Peter Anderson, belonging to the[Pg 31] Marlborough, who was sentenced to suffer death for mutiny. Read the sentence of the court-martial, and the articles of war to the ship’s company. At nine the execution took place.” This is a record of an eye-witness of the historic scene which put a stop to organised mutiny in the Cadiz fleet.

The narrative has been often told. Lord St. Vincent’s order to the crew of the Marlborough that they alone should execute their comrade, the leader of the mutiny—the ship moored at a central point, and surrounded by all the men-of-war’s boats armed with carronades under the charge of expert gunners—the Marlborough’s own guns housed and secured, and ports lowered—every precaution adopted in case of resistance to the Admiral’s orders—and the result, in the words of the commander-in-chief: “Discipline is preserved.”

Perhaps the relief felt in the fleet was expressed in some measure by the salute of seventeen guns recorded on the same day, “being the anniversary of King Charles’ restoration.”

Gradually matters were righted. Very early promotions were abolished, and throughout the Navy efforts were made on the part of the officers to make their men more comfortable, and especially to give them better and more wholesome food—but reforms must always be slow if they are[Pg 32] to do good and not harm, and, necessarily, the lightening of punishments which seem to us barbarous was the slowest of all.

The work of the press-gang is always a subject of some interest and romance. It is difficult to realise that it was a properly authorised Government measure. There were certain limits in which it might work, certain laws to be obeyed. The most useful men, those who were already at sea, but not in the King’s service, could not legally be impressed, unless they were free from all former obligations, and the same rule applied to apprentices. These rules were not, however, strictly kept, and much trouble was often caused by the wrong men being impressed, or by false statements being used to get others off. The following letter, written much later in his career by Francis Austen when he was Captain of the Leopard in 1804, gives a typical case of this kind.

Leopard, Dungeness, August 10, 1804.

“Sir,—I have to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of the 17th inst., with the enclosure, relative to Harris Walker, said to be chief mate of the Fanny, and in reply thereto have the honour to inform you that the said Harris Walker was impressed from on board the brig Fanny, off Dungeness, by Lieutenant Taylor of his Majesty’s ship under my command, on the evening of the[Pg 33] 7th inst., because no documents proving him to be actually chief mate of the brig were produced, and because the account he gave of himself was unsatisfactory and contradictory. On examining him the following day he at first confessed to me that he had entered on board the Fanny only three days before she sailed from Tobago, in consequence of the captain (a relation of his) being taken ill, and shortly afterwards he asserted that the whole of the cargo had been taken on board and stowed under his direction. The master of the Fanny told Lieutenant Taylor that his cargo had been shipped more than a fortnight before he sailed, having been detained for want of a copy of the ship’s register, she being a prize purchased and fitted at Tobago. From these very contradictory accounts—from the man’s having no affidavit to produce of his being actual chief mate of the brig, from his not having signed any articles as such—and from his handwriting totally disagreeing with the Log-Book (said to have been kept by himself) I felt myself perfectly justified in detaining him for his Majesty’s service.

“I return the enclosure, and have the honour to be,

“Sir, your obedient humble servant,

“Francis Wm. Austen.

“Thomas Louis, Esq.,

“Rear-Admiral of the Blue.”

[Pg 34]

The reason assigned, that the reports Harris Walker gave of himself were “unsatisfactory and contradictory,” seems to us a bad one for “detaining him for his Majesty’s service,” but it shows clearly how great were the difficulties in keeping up the supply of men. Captain Austen had not heard the last of this man, as the belief seems to have been strong that he was not legally impressed. Harris Walker, however, settled the matter by deserting on October 5.

An entry in the log of the newly built frigate Triton, under Captain Gore, gives an instance of wholesale, and one would think entirely illegal action.

November 25, 1796, in the Thames (Long Reach).

“Sent all the boats to impress the crew of the Britannia East India ship. The boats returned with thirty-nine men, the remainder having armed themselves and barricaded the bread room.”

“26th, the remainder of the Britannia crew surrendered, being twenty-three. Brought them on board.”

So great was the necessity of getting more men, and a better stamp of men, into the Navy, and of making them fairly content when there, that in 1800 a Royal Proclamation was issued encouraging men to enlist, and promising them a bounty.

[Pg 35]

This bounty, though it worked well in many cases, was of course open to various forms of abuse. Some who were entitled to it did not get it, and many put in a claim whose right was at least doubtful. An instance appears in the letters of the Leopard of a certain George Rivers, who had been entered as a “prest man,” and applied successfully to be considered as a Volunteer, thereby to procure the bounty. He evidently wanted to make the best of his position.

The case of Thomas Roberts, given in another letter from the Leopard, is an example of inducements offered to enter the service.

Thomas Roberts “appears to have been received as a Volunteer from H.M.S. Ceres, and received thirty shillings bounty. He says he was apprenticed to his father about three years ago, and that, sometime last October, he was enticed to a public-house by two men, who afterwards took him on board the receiving ship off the Tower, where he was persuaded to enter the service.”

The difficulty of getting an adequate crew seems to have led in some cases to sharp practice among the officers themselves, if we are to believe that Admiral Croft had real cause for complaint.

“‘If you look across the street,’ he says to Anne Elliot, ‘you will see Admiral Brand coming down, and his brother. Shabby fellows, both of them! I am glad they are not on this side of the[Pg 36] way. Sophy cannot bear them. They played me a pitiful trick once; got away some of my best men. I will tell you the whole story another time.’” But “another time” never comes, so we are reduced to imagining the “pitiful trick.”

The unpopularity of the Navy, and the consequent shorthandedness in time of war, had one very bad result in bringing into it all sorts of undesirable foreigners, who stirred up strife among the better disposed men, and altogether aggravated the evils of the service.

Undoubtedly the care of the officers for their men was doing its gradual work in lessening all these evils. To instance this, we find, as we read on in the letters and official reports of Francis Austen, that the entry, “the man named in the margin did run from his Majesty’s ship under my command,” comes with less and less frequency; and we have on record that the Aurora, under the command of Captain Charles Austen, did not lose a single man by sickness or desertion during the years 1826-1828, whilst he was in command. Even when some allowance is made for his undoubted charm of personality, this is a strong evidence of the real improvements which had been worked in the Navy during thirty years.

With such constant difficulties and discomforts to contend with, it seems in some ways remarkable that the Navy should have been so popular as[Pg 37] a profession among the classes from which officers were drawn. Some of this popularity, and no doubt a large share, was the effect of a strong feeling of patriotism, and some was due to the fact that the Navy was a profession in which it was possible to get on very fast. A man of moderate luck and enterprise was sure to make some sort of mark, and if to this he added any “interest” his success was assured. Success, in those days of the Navy, meant money. It is difficult for us to realise the large part played by “prizes” in the ordinary routine work of the smallest sloop. In the case of Captain Wentworth, a very fair average instance, we know that when he engaged himself to Anne Elliot, he had “nothing but himself to recommend him, no hopes of attaining influence, but in the chances of a most uncertain profession, and no connexions to secure even his farther rise in that profession,” yet we find that his hopes for his own advancement were fully justified. Jane Austen would have been very sure to have heard of it from Francis if not from Charles, if she had made Captain Wentworth’s success much more remarkable than that of the ordinary run of men in such circumstances.

We are clearly told what those circumstances were.

“Captain Wentworth had no fortune. He had been lucky in his profession; but spending freely[Pg 38] what had come freely had realised nothing. But he was confident that he would soon be rich; full of life and ardour, he knew that he would soon have a ship, and soon be on a station that would lead to everything he wanted. He had always been lucky; he knew he should be so still.” Later, “all his sanguine expectations, all his confidence had been justified. His genius and ardour had seemed to foresee and to command his prosperous path. He had, very soon after their engagement ceased, got employ; and all that he had told her would follow had taken place. He had distinguished himself, and early gained the other step in rank, and must now, by successive captures, have made a handsome fortune. She had only Navy Lists and newspapers for her authority, but she could not doubt his being rich.”

Such were some of the inducements. That “Jack ashore” was a much beloved person may also have had its influence. Anne Elliot speaks for the greater part of the nation when she says, “the Navy, I think, who have done so much for us, have at least an equal claim with any other set of men, for all the comforts and all the privileges which any home can give. Sailors work hard enough for their comforts we must allow.”

That Sir Walter Elliot represents another large section of the community is, however, not to be[Pg 39] denied, but his opinions are not of the sort to act as a deterrent to any young man bent on following a gallant profession.

“Sir Walter’s remark was: ‘The profession has its utility, but I should be sorry to see any friend of mine belonging to it.’

“‘Indeed!’ was the reply, and with a look of surprise.

“‘Yes, it is in two points offensive to me; I have two strong grounds of objection to it. First, as being the means of bringing persons of obscure birth into undue distinction, and raising men to honours which their fathers and grandfathers never dreamt of; and, secondly, as it cuts up a man’s youth and vigour most horribly; a sailor grows old sooner than any other man. I have observed it all my life. A man is in greater danger in the Navy of being insulted by the rise of one whose father his father might have disdained to speak to, and of becoming prematurely an object of disgust to himself, than in any other line. One day last spring in town I was in company with two men, striking instances of what I am talking of: Lord St. Ives, whose father we all know to have been a country curate, without bread to eat: I was to give place to Lord St. Ives, and a certain Admiral Baldwin, the most deplorable-looking personage you can imagine; his face the colour of mahogany, rough and rugged to the last[Pg 40] degree; all lines and wrinkles, nine grey hairs of a side, and nothing but a dab of powder at top.’

“‘In the name of heaven, who is that old fellow?’ said I to a friend of mine who was standing near (Sir Basil Morley), ‘Old fellow!’ cried Sir Basil, ‘it is Admiral Baldwin.’

“‘What do you take his age to be?’

“‘Sixty,’ said I, ‘or perhaps sixty-two.’

“‘Forty,’ replied Sir Basil, ‘forty, and no more.’

“‘Picture to yourselves my amazement. I shall not easily forget Admiral Baldwin. I never saw quite so wretched an example of what a seafaring life can do; they all are knocked about, and exposed to every climate and every weather till they are not fit to be seen. It is a pity they are not knocked on the head at once, before they reach Admiral Baldwin’s age.’”

[Pg 41]

As Lieutenant, Francis Austen had very different experience and surroundings to those of his days as a midshipman. For three years and more he was in various ships on the home station, which meant a constant round of dull routine work, enlivened only by chances of getting home for a few days. While serving in the Lark sloop, he accompanied to Cuxhaven the squadron told off to bring to England Princess Caroline of Brunswick, soon to become Princess of Wales. The voyage out seems to have been arctic in its severity. This bad weather, combined with dense fogs, caused the Lark to get separated from the rest of the squadron, and from March 6 till the 11th nothing was seen or heard of the sloop. On March 18 the Princess came on board the Jupiter, the flagship of the squadron, and arrived in England on April 5 after a fair passage, but a voyage about as long as that to the Cape of Good Hope nowadays.

[Pg 42]

Francis notes in the log of the Glory, that while cruising, “the Rattler cutter joined company, and informed us she yesterday spoke H.M.S. Dædalus”—a matter of some interest to him, as Charles was then on board the Dædalus as midshipman, under Captain Thomas Williams. Captain Williams had married Jane Cooper, a cousin of Jane Austen, who was inclined to tease him about his having “no taste in names.” The following extract from one of her letters to Cassandra touches on nearly all these facts:

“Sunday, January 10, 1796.

“By not returning till the 19th, you will exactly contrive to miss seeing the Coopers, which I suppose it is your wish to do. We have heard nothing from Charles for some time. One would suppose they must have sailed by this time, as the wind is so favourable. What a funny name Tom has got for his vessel! But he has no taste in names, as we well know, and I dare say he christened it himself.”

Tom seems to have been a great favourite with his wife’s cousins. Only a few days later Jane writes:

“How impertinent you are to write to me about Tom, as if I had not opportunities of hearing from him myself. The last letter I received from him[Pg 43] was dated on Friday the 8th, and he told me that if the wind should be favourable on Sunday, which it proved to be, they were to sail from Falmouth on that day. By this time, therefore, they are at Barbadoes, I suppose.”

Having the two brothers constantly backwards and forwards must have been very pleasant at Steventon. Almost every letter has some reference to one or the other.

“Edward and Frank are both gone forth to seek their fortunes; the latter is to return soon and help us to seek ours.”

Later from Rowling, Edward Austen’s home, she writes:

“If this scheme holds, I shall hardly be at Steventon before the middle of the month; but if you cannot do without me I could return, I suppose, with Frank, if he ever goes back. He enjoys himself here very much, for he has just learnt to turn, and is so delighted with the employment that he is at it all day long.... What a fine fellow Charles is, to deceive us into writing two letters to him at Cork! I admire his ingenuity extremely, especially as he is so great a gainer by it.... Frank has turned a very nice little butter-churn for Fanny.... We walked Frank last night to (church at) Crixhall Ruff, and he appeared much edified. So his Royal Highness Sir Thomas Williams has at length sailed; the papers say ‘on a cruise.’[Pg 44] But I hope they are gone to Cork, or I shall have written in vain.... Edward and Fly (short for Frank) went out yesterday very early in a couple of shooting-jackets, and came home like a couple of bad shots, for they killed nothing at all.

“They are out again to-day, and are not yet returned. Delightful sport! They are just come home—Edward with his two brace, Frank with his two and a half. What amiable young men!”

About the middle of September 1796 Frank was appointed to the Triton, which event is announced to Cassandra in these terms:

“This morning has been spent in doubt and deliberation, forming plans and removing difficulties, for it ushered in the day with an event which I had not intended should take place so soon by a week. Frank has received his appointment on board the Captain John Gore, commanded by the Triton, and will therefore be obliged to be in town on Wednesday; and though I have every disposition in the world to accompany him on that day, I cannot go on the uncertainty of the Pearsons being at home.

“The Triton is a new 32-frigate, just launched at Deptford. Frank is much pleased with the prospect of having Captain Gore under his command.”

Francis stayed on board the Triton for about eighteen months. He then spent six months in [Pg 45]the Seahorse before his appointment to the London off Cadiz, in February 1798. On April 30 following is recorded in the log of the London the arrival of H.M.S. Vanguard, carrying Rear-Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson’s flag, and on May 3 the Vanguard proceeded to Gibraltar. On May 24 the “detached squadron” sailed as follows: Culloden (Captain Troubridge), Bellerophon, Defence, Theseus, Goliath, Zealous, Minotaur, Majestic, and Swiftsure.

These three entries foreshadow the Battle of the Nile, on August 1. The account of this victory was read to the crew of the London on September 27, and on October 24 they “saw eleven sail in the south-west—the Orion and the French line of battleships, prizes to Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson’s fleet.”

Now and then the London went as far as Ceuta or Gibraltar, and the log notes, “Cape Trafalgar East 7 leagues.”

It is curious to think that “Trafalgar” conveyed nothing remarkable to the writer. One wonders too what view would have been expressed as to the plan of making Gibraltar a naval command, obviously advantageous in twentieth-century conditions, but probably open to many objections in those days.

Charles, in December 1797, was promoted to be a Lieutenant, serving in the Scorpion. There[Pg 46] is something in the account of William Price’s joy over his promotion which irresistibly calls up the picture of Charles in the same circumstances. Francis would always have carried his honours with decorum, but Charles’ bubbling enthusiasm would have been more difficult to restrain.

“William had obtained a ten days’ leave of absence, to be given to Northamptonshire, and was coming to show his happiness and describe his uniform. He came, and he would have been delighted to show his uniform there too, had not cruel custom prohibited its appearance except on duty. So the uniform remained at Portsmouth, and Edmund conjectured that before Fanny had any chance of seeing it, all its own freshness, and all the freshness of its wearer’s feelings, must be worn away. It would be sunk into a badge of disgrace; for what can be more unbecoming or more worthless than the uniform of a lieutenant who has been a lieutenant a year or two, and sees others made commanders before him? So reasoned Edmund, till his father made him the confidant of a scheme which placed Fanny’s chance of seeing the Second Lieutenant of H.M.S. Thrush in all his glory, in another light. This scheme was that she should accompany her brother back to Portsmouth, and spend a little time with her own family. William was almost as happy in the plan as his sister. It would be[Pg 47] the greatest pleasure to him to have her there to the last moment before he sailed, and perhaps find her there still when he came in from his first cruise. And, besides, he wanted her so very much to see the Thrush before she went out of harbour (the Thrush was certainly the finest sloop in the service). And there were several improvements in the dockyard, too, which he quite longed to show her.... Of pleasant talk between the brother and sister there was no end. Everything supplied an amusement to the high glee of William’s mind, and he was full of frolic and joke in the intervals of their high-toned subjects, all of which ended, if they did not begin, in praise of the Thrush—conjectures how she would be employed, schemes for an action with some superior force, which (supposing the first lieutenant out of the way—and William was not very merciful to the first lieutenant) was to give himself the next step as soon as possible, or speculations upon prize-money, which was to be generously distributed at home with only the reservation of enough to make the little cottage comfortable in which he and Fanny were to pass all their middle and later life together.”

Charles’s year in the Scorpion was spent under the command of Captain John Tremayne Rodd. The chief event was the capture of the Courier, a Dutch brig carrying six guns. Undoubtedly the[Pg 48] life was dull on a small brig, and Charles as midshipman had not been used to be dull. He evidently soon began to be restless, and to agitate for removal, which he got just about the same time as that of Francis’s promotion.

In December 1798 Francis was made Commander of the Peterel sloop, and Charles, still as Lieutenant, was moved from the Scorpion to the frigate Tamar, and eventually to the Endymion, commanded by his old friend and captain, Sir Thomas Williams.

Charles had evidently written to his sister Cassandra to complain of his hard lot. Cassandra was away at the time, staying with Edward Austen at Godmersham, but she sent the letter home, and on December 18 Jane writes in answer:

“I am sorry our dear Charles begins to feel the dignity of ill-usage. My father will write to Admiral Gambier” (who was then one of the Lords of the Admiralty). “He must have already received so much satisfaction from his acquaintance and patronage of Frank, that he will be delighted, I dare say, to have another of the family introduced to him. I think it would be very right in Charles to address Sir Thomas on the occasion, though I cannot approve of your scheme of writing to him (which you communicated to me a few nights ago) to request him to come home and convey you to Steventon. To do you justice,[Pg 49] you had some doubts of the propriety of such a measure yourself. The letter to Gambier goes to-day.”

This is followed, on December 24, by a letter which must have been as delightful to write as to receive.

“I have got some pleasant news for you which I am eager to communicate, and therefore begin my letter sooner, though I shall not send it sooner than usual. Admiral Gambier, in reply to my father’s application, writes as follows: ‘As it is usual to keep young officers’ (Charles was then only nineteen) ‘in small vessels, it being most proper on account of their inexperience, and it being also a situation where they are more in the way of learning their duty, your son has been continued in the Scorpion; but I have mentioned to the Board of Admiralty his wish to be in a frigate, and when a proper opportunity offers, and it is judged that he has taken his turn in a small ship, I hope he will be removed. With regard to your son now in the London, I am glad I can give you the assurance that his promotion is likely to take place very soon, as Lord Spencer has been so good as to say he would include him in an arrangement that he proposes making in a short time relative to some promotions in that quarter.’

“There! I may now finish my letter and go[Pg 50] and hang myself, for I am sure I can neither write nor do anything which will not appear insipid to you after this. Now I really think he will soon be made, and only wish we could communicate our foreknowledge of the event to him whom it principally concerns. My father has written to Daysh to desire that he will inform us, if he can, when the commission is sent. Your chief wish is now ready to be accomplished, and could Lord Spencer give happiness to Martha at the same time, what a joyful heart he would make of yours!”

It is quite clear from this, and many other of the letters of Jane to Cassandra, that both sisters were anxious to bring off a match between Frank and their great friend, Martha Lloyd, whose younger sister was the wife of James Austen. Martha Lloyd eventually became Frank’s second wife nearly thirty years after the date of this letter.

Jane continues her letter by saying:

“I have sent the same extract of the sweets of Gambier to Charles, who, poor fellow! though he sinks into nothing but an humble attendant on the hero of the piece, will, I hope, be contented with the prospect held out to him. By what the Admiral says, it appears as if he had been designedly kept in the Scorpion. But I will not torment myself with conjectures and suppositions. Facts[Pg 51] shall satisfy me. Frank had not heard from any of us for ten weeks, when he wrote to me on November 12, in consequence of Lord St. Vincent being removed to Gibraltar. When his commission is sent, however, it will not be so long on its road as our letters, because all the Government despatches are forwarded by land to his lordship from Lisbon with great regularity. The lords of the Admiralty will have enough of our applications at present, for I hear from Charles that he has written to Lord Spencer himself to be removed. I am afraid his Serene Highness will be in a passion, and order some of our heads to be cut off.”

The next letter, of December 28, is the culminating-point:

“Frank is made. He was yesterday raised to the rank of Commander, and appointed to the Peterel sloop, now at Gibraltar. A letter from Daysh has just announced this, and as it is confirmed by a very friendly one from Mr. Matthew to the same effect, transcribing one from Admiral Gambier to the General, we have no reason to suspect the truth of it.

“As soon as you have cried a little for joy, you may go on, and learn farther that the India House have taken Captain Austen’s petition into consideration—this comes from Daysh—and likewise that Lieutenant Charles John Austen is[Pg 52] removed to the Tamar frigate—this comes from the Admiral. We cannot find out where the Tamar is, but I hope we shall now see Charles here at all events.

“This letter is to be dedicated entirely to good news. If you will send my father an account of your washing and letter expenses, &c., he will send you a draft for the amount of it, as well as for your next quarter, and for Edward’s rent. If you don’t buy a muslin gown on the strength of this money and Frank’s promotion I shall never forgive you.

“Mrs. Lefroy has just sent me word that Lady Dorchester meant to invite me to her ball on January 8, which, though an humble blessing compared with what the last page records, I do not consider any calamity. I cannot write any more now, but I have written enough to make you very happy, and therefore may safely conclude.”

Jane was in great hopes that Charles would get home in time for this ball at Kempshot, but he “could not get superceded in time,” and so did not arrive until some days later. On January 21 we find him going off to join his ship, not very well pleased with existing arrangements.

“Charles leaves us to-night. The Tamar is in the Downs, and Mr. Daysh advises him to join her there directly, as there is no chance of her going to the westward. Charles does not approve[Pg 53] of this at all, and will not be much grieved if he should be too late for her before she sails, as he may then hope to get a better station. He attempted to go to town last night, and got as far on his road thither as Dean Gate; but both the coaches were full, and we had the pleasure of seeing him back again. He will call on Daysh to-morrow, to know whether the Tamar has sailed or not, and if she is still at the Downs he will proceed in one of the night coaches to Deal.

“I want to go with him, that I may explain the country properly to him between Canterbury and Rowling, but the unpleasantness of returning by myself deters me. I should like to go as far as Ospringe with him very much indeed, that I might surprise you at Godmersham.”

Charles evidently did get off this time, for we read a few days later that he had written from the Downs, and was pleased to find himself Second Lieutenant on board the Tamar.

The Endymion was also in the Downs, a further cause of satisfaction. It was only three weeks later that Charles was reappointed to the Endymion as Lieutenant, in which frigate he saw much service, chiefly off Algeciras, under his old friend “Tom.” One is inclined to wonder how far this accidental meeting in the Downs influenced the appointment. Charles appears on many occasions to have had a quite remarkable gift for getting what he wanted.[Pg 54] His charm of manner, handsome face, and affectionate disposition, combined with untiring enthusiasm, must have made him very hard to resist, and he evidently had no scruple about making his wants clear to all whom it might concern. The exact value of interest in these matters is always difficult to gauge, but there is no doubt that a well-timed application was nearly always necessary for advancement. The account of the way in which Henry Crawford secured promotion for William Price is no doubt an excellent example of how things were done.

Henry takes William to dinner with the Admiral, and encourages him to talk. The Admiral takes a fancy to the young man, and speaks to some friends about him with a view to his promotion. The result is contained in the letters which Henry so joyfully hands over to Fanny to read.

“Fanny could not speak, but he did not want her to speak. To see the expression of her eyes, the change of her complexion, the progress of her feelings—their doubt, confusion and felicity—was enough. She took the letters as he gave them. The first was from the Admiral to inform his nephew, in a few words, of his having succeeded in the object he had undertaken (the promotion of young Price), and enclosing two more—one from the secretary of the First Lord to a friend, whom the Admiral had set to work in the business;[Pg 55] the other from that friend to himself, by which it appeared that his lordship had the very great happiness of attending to the recommendation of Sir Charles; that Sir Charles was much delighted in having such an opportunity of proving his regard for Admiral Crawford, and that the circumstances of Mr. William Price’s commission as Second Lieutenant of H.M. sloop Thrush being made out, was spreading general joy through a wide circle of great people.”

[Pg 56]

It will, perhaps, be as well to recall some of the principal events of the war, during the few years before Francis took up his command of the Peterel, in order that his work may be better understood.

Spain had allied herself with France in 1796, and early in the following year matters looked most unpromising for England. The British fleet had been obliged to leave the Mediterranean. Bonaparte was gaining successes against Austria on land. The peace negotiations, which had been begun by France, had been peremptorily stopped, while the French expedition to Ireland obviously owed its failure to bad weather, and not in the least to any effective interference on the part of the British Navy. Altogether the horizon was dark, and every one in England was expecting to hear of crushing disaster dealt out by the combined fleets of France and Spain, and all lived in fear of invasion. Very different was the[Pg 57] news that arrived in London early in March. Sir John Jervis, with Nelson and Collingwood, met the Spanish fleet off Cape St. Vincent on Valentine’s Day, and we all know the result. As Jervis said on the morning of the fight, “A victory was essential to England at this moment.” The confidence of the nation returned, and was not lost again through the hard struggle of the following years. An extract from the log of Lieutenant F. W. Austen, on board the frigate Seahorse, in the Hamoaze, October 6, 1797, reads as follows: “Came into harbour the San Josef, Salvador del Mundo, San Nicolai, and San Isidore, Spanish line-of-battle ships, captured by the fleet under Lord St. Vincent on the 14th February.”

After their defeat, the remainder of the Spanish fleet entered the port of Cadiz, and were for the next two years blockaded by Admiral Jervis, now Earl St. Vincent. In this blockade, Francis Austen took part, serving in the London.

During this time of comparative inaction, the fearful mutinies, described in a former chapter, seemed to be sapping the strength of the Navy. The greater number of the British ships were concentrated in the Channel under Lord Bridport, and were employed in watching the harbour of Brest, in order to prevent the French fleet from escaping, with what success we shall presently tell. Our flag was scarcely to be seen inside the[Pg 58] Mediterranean except on a few sloops of war. Each side was waiting for some movement of aggression from the other. Now was Bonaparte’s chance to get to the East. His plans were quietly and secretly formed. An armament was prepared at Toulon almost unknown to the British, and at the same time all possible measures to avert suspicion were taken. The Spanish fleet in Cadiz formed up as if for departure, and so kept Lord St. Vincent on the watch, while Bonaparte himself stayed in Paris until the expedition was quite ready to start, in order to give the idea that the invasion of England was intended. Still it was not practicable to keep the preparations entirely secret for any length of time.