ORPHEUS

OR

The Music of the Future

BY

W. J. TURNER

Author of “The Seven Days of the Sun,” etc.

New York

E. P. DUTTON & COMPANY

681 Fifth Avenue

ORPHEUS

OR

The Music of the Future

BY

W. J. TURNER

Author of “The Seven Days of the Sun,” etc.

New York

E. P. DUTTON & COMPANY

681 Fifth Avenue

Copyright, 1926

By E. P. DUTTON & COMPANY

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States of America

[Pg v]

[Pg 1]

ORPHEUS

The dullest books on literature are the books which begin with a history of the alphabet. A good history has its uses; however, this book is not a history but a phantasy or, if you like, a philosophy. For if it be a good phantasy it will be a good philosophy since all philosophy is phantasy, or the imagination of love.

Amor che muove il mondo e l’altre stelle

We know, however, that philosophy degenerates from that love which moves the spheres into that love of moving in the tracks of the spheres which is called the love of knowledge, and philosophers are commonly men who[Pg 2] spend their lives describing the old tracks in which they are running, and teaching how you also may keep your feet in them. So, too, musician has come to mean a man who performs music—he plays over again Beethoven’s sonatas and Chopin’s studies;

partout il parcourit et parfournit

This performance of his is a tribute to our weakness and a sign of our imperfection, and, since we are weak and imperfect, is necessary; but I cannot state too clearly and decisively at the outset that music is not the playing or the hearing of symphonies and sonatas but the imagination of love.

If music is not the imagination of love, if it is not a spiritual act, what is it? The commonsense reply will be that it is an ordered arrangement of sounds. But two words of this definition[Pg 3] beg the question. What is meant by “ordered,” and what by “arrangement”? Order and arrangement imply meaning and significance. Can we have an order that is an end in itself, is intrinsically satisfying, or beautiful, or stimulating? But to whom? To man. But take away love from man, and what is he? What is left is meaningless, even indescribable, for in love all things exist and have their being. Music is the imagination of love in sound. It is what man imagines of his life, and his life is love. There are as many kinds of love as there are many kinds of life, and it is possible that they may not all be imaginable in sound. I say it is possible, I do not say it is probable. We do not know at present, and indeed we shall only know when the common instinct of mankind has abandoned sound as a means of expression. And[Pg 4] that may happen. There may be no unending future of music, only a limited future. Or the world of music may be like the universe of Einstein, “finite but unbounded.” And this indeed is my belief. It is a finite, a closed world.

Can you express the life of the vegetable world in music? The imagination of a plant? The tree that rises to the sun throws its shadow upon the mind of man; you may think you cannot throw that shadow in music but you can sound forth the shadow of that shadow, turn the impalpable ghost of light into a ghost of sound, transform those tremulous visual waves into auditory waves—not in the laboratory of the physicist but in the laboratory of the mind. The musician may do this. He may do in a bar of notes what the poet does in a line of verse—make a unique sensible[Pg 5] impression upon the mind. Debussy’s Prélude à l’Après-midi d’un Faune makes this impression of a vegetable world alive in quivering hot sunshine and Debussy’s music is full of the imagination of a special order of life, the life of trees, streams and lakes, the play of light upon water and on clouds, the murmur of plants drinking and feeding in the sunlight, and all that order of motion and movement which we are in the habit of calling physical, all that order of emotion which we describe as belonging to the five senses. I do not believe there is any sensation or feeling of which man is capable in the presence of the natural world which may not be expressed in music.

Music is the most concrete and physical of all the arts as it is probably the earliest and most primitive. Beasts which cannot draw or write can make[Pg 6] expressive sounds, and the earliest men undoubtedly communicated by sound before they learned to communicate by written or painted signs. But whether at the other end of the scale there is a limit to music’s power of expression no one can say. It is only possible at this stage in the history of mankind to affirm that up till now the highest, most spiritual powers of the human mind have been able to find expression in music. There is nothing in the world’s finest literature that surpasses what we may find in the world’s best music, although, as we shall see later, music may have a virtue that is entirely its own. But it will not surprise us to find ourselves limited to the work of a very few composers when we ask for music that is as highly organized as the finest poetry.

Music in this respect has been in the past nearer to painting and to sculpture[Pg 7] than to poetry. As with the plastic arts its swifter and stronger appeal to the senses is a source of weakness as of strength. It is a source of weakness because in every artist there is a natural tendency to slip into what comes easiest in his medium. In music it is easier to make sounds that merely gratify or stimulate the sense of hearing and the cruder emotions than to make sounds of a more complex character which will express the subtler and finer life of a more spiritual imagination. Infantile music is both easier to compose and easier to hear than mature music, so the public and the musician find themselves in a natural league in favour of the rawer kinds of music. Thus the song of obvious and commonplace sentiment and the jazz tune of blatant rhythm have universal popularity. Even an animal, one sometimes fancies might[Pg 8] be conscious of such music. Its combinations are so simple that they may certainly be understood by every human creature. “All Nature hears thy voice,” one might almost say of the saxophone, and possibly it is the sort of music to which the mountains would skip like rams could they but hear it.

All life moves in rhythm. We know to-day that the old distinctions between spirit and matter are superficial. When I was a student at the School of Mines at the age of seventeen, learning organic and inorganic chemistry, we were taught Mendeléeff’s Law which showed that all the elements were multiples of a common denominator, the atom; and since then it has been discovered that instead of the atom being the smallest possible bit of matter, finite and irreducible, it is a solar system—its sun and planets being[Pg 9] bits of positive and negative electricity. All that is left of the whole structure of nineteenth century materialism has crumbled away to that word “bits.” We cannot as yet imagine or think without resting somewhere on “bits.” Our minds like our feet need a solid something beneath them. It is paralysing to conceive that the floor we stand upon, the chair we sit upon, consist solely of rotating electrical forces, but when we think of “bits” welded together we feel safe again, although actually these “bits” are a pure mental fiction, and what we stand and sit upon is motion. If the motion stopped we should fall into the bottomless pit, the famous vacuum abhorred of Nature (alias Tophet in biblical language).

My chemistry teachers would have been as scandalized to think that at the bottom of their inorganic and[Pg 10] organic chemistry there was nothing but motion, as my music teachers would have been scandalized to think that at the bottom of the major and minor scales there was nothing but love. They imagined that these were two entirely different worlds with an infinite chasm between them. They thought that inorganic chemistry was absolutely different from organic chemistry, although of course they would have got into a hopeless muddle had they tried to prove their belief—but then only fools and geniuses try to prove their beliefs. Neither my chemistry nor my music teachers could ever explain anything. One was simply asked to swallow whole and regurgitate whole what was obviously mere unintelligible rigmarole. Those of us who had this parrot-like faculty became in our turn Professors of Chemistry and of Music.

[Pg 11]

The great creative scientists of this age have disintegrated those old hard ideas, and it now appears that the Universe is a miracle of rhythm, and that “matter,” just like man, is kept going, is maintained as a co-ordinated whole by some electrical urge or spiritual impulse—at bottom it is perhaps the same thing, although “thing” is a very inappropriate word. The conception of the “will to live” has a profounder meaning for us now, and we realize that if the “will to live” dies in a man the man himself dies. A recent anthropologist, the late Dr. W. H. R. Rivers, F.R.S., in a book on the decay of Melanesia, attributes the dying off of the population in certain islands, unaffected by disease and with an abundance of food, to life having become devoid of meaning to them after contact with an alien and unassimilable civilization. They had[Pg 12] lost faith in their old world of ideas without having the power to enter the completely new and strange white man’s world. With the decay of their ancient beliefs they took no pleasure in their ancient religious exercises. Joy and Ritual simultaneously faded. They lost the desire to live. Each one of us goes on living only so long as he desires to live, and the desire varies in degree.

We have to admit that we use these words “life” and “living” still without knowledge of what they mean, but it is not necessary, nor do I think it possible, to know what they mean. Knowledge is not important, it is life that is important, and we can feel life if we cannot know it. The only way in which we can know life is by creating it, and it will be my duty in a later chapter to discuss this.

In the meantime it is clear that the[Pg 13] line from Dante which I began by quoting:

Amor che muove il mondo e l’altre stelle

is no idle phantasy but a literal truth. The world about us seems to be material, but exists in rhythm. It is a living world, and it is kept alive by a spiritual force which we can best describe as love, and I end this chapter with the definition with which I began it. All art is the imagination of love, and music is the imagination of love in sound.

[Pg 14]

What is knowledge? And what is musical knowledge? The latter question is no doubt included in the former, but we shall see. We know by experience that it is possible to learn the alphabet of a language. The alphabet as such has no longer any meaning, that is why it is possible to use it with meaning—in that form we call language. But, at the beginning, these perfectly conventionalized, perfectly meaningless symbols, A, B, C, D, etc., had each a meaning and a very definite meaning. And those series of meanings (which have now shrivelled into the scentless, savourless, unembodied twenty-six ghosts of the[Pg 15] alphabet) precluded by their very vitality the possibility of all other meanings. Their life was death to all other life and not until they were dead could others live. This strange phenomenon is an element in the beautiful myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. Orpheus must not behold the face of Eurydice when he brings her up from the underworld where she disappeared, for in the physical vision he will be forever blinded to the spirit which is returning with him, who is not the Eurydice that was but the Eurydice that is to be. And the whole life of language is in this process of continuous dying. Words die by becoming abstract, then when they are completely dead they come to life again as members of a more complicated life, the life of the sentence. Sentences die and become idioms, idioms ideas, ideas theories, theories philosophies and[Pg 16] religions. Every page of prose is a harvest raised from corpses and under its flowering abundance dead bodies lie thickly buried. Then a time comes when these extremely complex systems break up and the words re-emerge in single units again, but with changed countenances and expressions, to begin a new series of death-and-life existence. But the letters themselves, of which all words are comprised, are finally and forever dead—which is another way of saying they are immortal; for they do not change as words change from one generation to another. The “o” in dog does not differ from the “o” in god because “o” has no longer individuality or meaning. What we call “knowledge” is that which has become fixed and immortal, that which has ceased to live and have being and is immutable. Obviously we cannot be said to know a thing which is susceptible[Pg 17] of change, which may differ to-morrow from what it is to-day. Therefore we can only know what is unknowable, because we only know what does not exist. This is no empty paradox. It is not a play on the word “exist.” We may say we know the letters A, B, C, D, etc., because they are the same for everybody; but they are only the same for everybody because they are nothing to anybody. If I ask you what A means to you it is impossible for you to tell me, since it means no more to you than to me. A in itself is nothing, you can neither think it nor feel it, you can only state it, and so it is, as I have said, a fact. There are in all our literature only twenty-six absolute facts. And they are facts merely because there is no life in them.

In music there are also facts, so there is a part of music which we can say we know. The modern European[Pg 18] knows a certain number of musical sounds which are the facts of music. They can be described in various ways, but as European musical facts they are twelve semi-tones repeated in series between two arbitrarily selected points which are the highest and the lowest notes comfortably audible to the human ear. Each of these semi-tones is an arbitrarily selected note or vibration number chosen out of all the masses of vibrations which we call noises by virtue of an inner unity, a mathematical symmetry which gives it form and makes it a musical sound. But even this mathematical symmetry is a fiction, a thing made by the human mind; and these sounds, like the letters of the alphabet, have no life or meaning in themselves.

But at this point a reservation must be made. For most, possibly for all, the letters of the alphabet have a varied[Pg 19] character, a character which derives (a) from their different shapes, (b) from their different sounds. The effect of their shape belongs to the world of graphic art, the effect of their sound belongs to the world of music. We may think of these impressions as the residuary fossils left by giantlike primitive emotions which have stalked through those other worlds. A certain artistic use can be made of them, and indeed we find that every new wave of artistic expression is preluded by a breakdown of the abstract combinations of symbols in which the symbols had become most completely devitalized, and a return to a sense of a meaning, a colour, a life in the symbol itself. This results in simplification, which ultimately gives place to a new complication. What is called progress in art consists mainly of this process. Whether there is another kind of[Pg 20] progress underlying this process must be considered in another chapter.

Now that we have become clear as to what facts are we can perceive what knowledge is. But I must prevent the danger of a mere logomachy between reader and writer by stating at once that I am giving here definitions of “knowledge” and “life” to which we must both adhere. If any reader likes to give the name of “true knowledge” to what I call life and says that what I call knowledge is not true knowledge at all, he is welcome to do so. But I am going to use my own terms, and I shall continue to use the term “life” instead of so idiotic a term as “true knowledge.”

The knowledge of music, then, is the knowledge of the facts, and the facts are, as we saw, the alphabet of music, the twelve artificial semi-tones of the tempered scale. If a musician knows[Pg 21] these and knows those combinations of them which are called intervals—as the combinations of letters are called words—he knows what the man knows who knows the letters of the alphabet and has a vocabulary of words. He may know them by sight, by sound, or by sight and sound. If only by sight he is in the position of a man who can read and write but not speak the words of a foreign language; if only by sound he is in the position of a man who can speak the words of a foreign language and understand them when spoken but cannot read or write them. The reader can make this analogy more precise by subdivisions which I shall not bother to make here. I will merely point out that the ordinary auditor, the music-lover who is no musician, knows the facts by sound only and may so know them with greater or less precision and depth of impression.[Pg 22] That he should not know them by sight is immaterial to his understanding what he hears, although it prevents his communicating what he hears to anyone else. He is therefore technically equipped to hear but not to compose music.

Such knowledge may extend beyond the knowledge of the vocabulary of words or chords to those more complicated combinations which have also died and become facts—sentences, idioms, ideas; or, in music, sequences, harmonies, melodies. All this knowledge represents so much dead life which can be incorporated into a page of music as it can be incorporated into a page of prose. When sentences, idioms and ideas (or sequences, harmonies and melodies) have been used over and over again so frequently as to have become immediately recognizable they cease to have meaning;[Pg 23] because, as I pointed out at the beginning of this chapter, having been used so often in so many different contexts they have shrivelled to that residuum or abstraction which fits the lot. Having shed all individuality they shed all expression, and what was once life becomes knowledge. For example, what was a feeling in Wagner becomes merely a major ninth in Vincent d’Indy. When the music of Debussy was first heard it was an emotional experience. Presently the intellect abstracted an element which it found commonly in that experience, and that element was the whole-tone scale. Then everybody by using the whole-tone scale could write music which superficially sounded like Debussy’s; but such music had no meaning or life, it was dead music, mere knowledge. And Debussy’s music itself tended to become a perceptive[Pg 24] and not an emotional experience. There is a universal tendency to this intellectual formalizing, stereotyping process which I have called knowledge or death; and contrasted with it everywhere is a complementary process, the process of creation or life. But the one is necessary to the other and all experience is the one becoming the other. Just as life uses death—as when we eat meat and transform it into living tissue—so art uses knowledge. Music, therefore, is experience becoming knowledge and knowledge breaking up and becoming experience, and its especial nature lies not in the experience but in the medium. Music is the experience of life and death in sound.

Has sound in itself any meaning? I mean by this is there a quality, virtue, life—call it what you will—specifically in sounds and the combination of sounds which does not exist elsewhere—in[Pg 25] painting, in sculpture, in architecture, in mathematics? I think there is; but to go further into this would be to transgress the limits I have set for myself, for here we touch on perhaps the profoundest problem of philosophy. I shall be content to throw a little light upon it by analogy. Experience in sound has an individuality which separates it from experience in the other arts. This individuality in the arts is comparable to individuality in animal and vegetable life (the different and analysable virtues of an elephant, a butterfly, a lily and a violet) and to personality in human life. It is an implicit and unexplained factor in all that I shall have to say; but we have to remember that it is the combining, the making of a harmony of this character or idiosyncrasy with the composer’s imagination of love which makes music. It is then that musical[Pg 26] form is created. What we call musical genius is related to this individuality in some mysterious and as yet unfathomable way and it would seem that there are degrees of musical genius. But it is only when great musical genius is combined with great human personality that we get what we may call the great artist as distinct from the merely great musician.

[Pg 27]

It may be objected that my persuasion in Chapter I that music is the imagination of love in sound and in Chapter II that music is also the experience of life-and-death in sound are two conclusions not only extraordinary in themselves but different. It will be seen that they are not irreconcilable. My conception of the nature of music must, if true, be such as to include all music, the music of Sullivan, Puccini, Elgar and the Jazz-Kings as well as the music of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and Wagner; the songs of the folk, old and new, peasant and urban, as well as the songs of Schubert and Hugo Wolf. There is no difficulty in this.

[Pg 28]

We have seen that the development of music is analogous to the development of language. That this must be so is obvious when we understand that both music and language are mental structures contemporary with the human mind, reflecting its development and having their origin in the senses of sight and hearing. No arts have been founded on the sense of touch in its forms of taste and smell. The reason for this gives us a clue to the character of progress in general. The senses of smell and taste are too intimate, too physically diffused, too direct or primitive in effect to be controlled by the mind. We may say that the body now short-circuits in these sensations and that the mind is cut out. But when, in the past, the sense of touch developed into the more complicated organs of the eye and the[Pg 29] ear[1] which made touch at a distance possible, then what the mind sensed was more highly organized and less direct and amorphous. Smells and tastes may be compared with noises before the mind has organized them into musical sounds, or with sensations which have not yet passed through the imagination and become organized into emotions and ideas.

It would seem that the history of man is the history of this process of organization and that the organizations differ more from one another than do the senses from which they grew. A Chinaman, for instance, is much more like an Englishman in his body than in his language; he can have a child by an Englishwoman with whom he is unable to speak.[2]

[Pg 30]

What we think is understanding Chinese music when we hear it is merely recognition of that organization of vibration, which we call musical sounds, an organization common to the human ear in all mankind. The major part of popular music consists of stringing these sounds together for the mere pleasure of recognizing them—pleasure in their organization as contrasted with the unorganized mass of mere noise out of which they have been selected; also its use of them in simple combinations expressing simple emotions—sensations of rudimentary organization—which again are common to all mankind. It is because language is not an organization of the merely visual or auditory sensations[Pg 31] made by the physical eye and ear with which almost everybody is born (there are colour-blind and tone-deaf people) but a post-natal acquired and complicated mental construction that it is totally unintelligible until learnt. So Chinese music does not mean the same to us as to a Chinaman, nor does European music mean the same to him as to a European, because it is not merely a construction of the ear, but is also in some although in varying degree a construction of the mind. Just as it took a multitude of lives and deaths to evolve the human eye and ear—organs with which all men are now born—so it has taken many generations of that mental development we call culture and tradition to create a language that was more than onomatopoeia, and a music that was more than recognizable and, therefore, agreeable sounds.

[Pg 32]

There is, and I maintain there can be no absolute, universal, pure art immediately intelligible to all men. It was the false idea that music was purely sensual which led Pater to think that music was such an art and that all other arts should attain its perfection. The development of every art is a development farther and farther away from the mere sensations upon which it is founded, and these developments make a web of experience which is constantly being rewoven and renewed (probably without a single strand ever being lost or destroyed) and, without this, music would dissolve into meaningless sounds. We look upon the eye and the ear as beautiful complex creations of life. We think of them as physical entities because their creation is so far back in life that it belongs to the sub-human or animal epoch, and so they have become physical things,[Pg 33] if not material objects. But this power of becoming physical (life taking on flesh, the spirit achieving form) or material (electricity becoming molecules of hydrogen, lead, etc.) is the process which I have described as death; and as that necessary and important death, death the complement of life. But, as I have already shown, a third kind of death, other than the material and the physical, is that of intellectual structure—known variously as tradition, belief, dogma, logic, technique or, most comprehensively, as knowledge. Just as a multitude of deaths were necessary to the evolution of the eye and the ear so a multitude of deaths (an Encyclopædia is a mental cemetery) are necessary to the evolution of the mind. The past experience of music which every trained musician possesses is such knowledge. If he merely repeats it, copies out of the past stored in his[Pg 34] mind, in the mind of his generation, in the culture he and his generation have inherited, he is a mere academic musician and not a creative artist. But there are degrees in this as in everything else. It is not the possession of the tradition which makes a musician academic and lifeless, it is the failure to use the traditions to express himself; and this is a failure in musical life. A musical mind which is a mere body of musical tradition is like a detached ear or a plucked out eye—an ear which does not hear or an eye which does not see. The life of hearing is not in the organ, not in what has been heard—of which it is the physical representation, the death-shape—it is in creation, the hearing of a new thing. And creation is that movement from life to death, from soul to substance, from the spirit to the form which is[Pg 35] the imagining forth of love, for love alone is a creative motive.

And the forms of love vary from the flowering and seeding of plants to the music of Beethoven. It is not a progress from bad to good, it is not a retrogression from good to bad. It is rather a process which fills the Universe with death—death in myriads of lovely forms, from the form of the wood-violet to the form of the symphony. And this process is life. And life increasing the varieties of death is the general principle of progress. What is the purpose of this process? We do not know. But we can say that its purpose is delight. Ecstasy clothing Himself in a thousand Forms. The Universe delighting in itself preserves itself in death, for in death the imagination of the spirit is made immortal.

[1] How was this achieved? No biologist can tell us, but we shall not go far wrong in seeing here again the created organs of Desire.

[2] Here we can find a conclusive argument in proof of the superiority of sentiment to sense in sexual experience. Sentiment is non-existent among animals and it is very faint in the lower human types but in the highest European types it now almost completely controls the sexual sense.

[Pg 36]

In the history of the world as we know it we discover that not all forms of death are immortal. There are animals which are extinct, there are plants which have disappeared, there are flowers which bloom no more. In vain has life fixed their images in that immortality of automatic repetition which we call death. Even death, we seem to find, is occasionally an illusion and its sleep is not more eternal than a man’s dream. It is probable that all things as things are perishable; and we have no reason to believe that even the music of Beethoven will last for ever, or even for as long as man lasts. But there is the problem why some[Pg 37] things last longer than others, and this perhaps raises the question of value, of goodness. Here is a new element in the idea of progress. Is it possible to discover any principle in the history of music which explains why, already, Bach has outlasted Frohberger?

If we say that Frohberger is superfluous because Bach is the same as Frohberger, only better, we are saying something very difficult to understand, for how would it be possible to prove that two things can be the same and yet different, one of them being better—except by making goodness depend on quantity? But, obviously, to think that Bach is three Frohbergers is not the same as thinking he is three times as good as Frohberger. As the ordinary man speaks this is not at all what he means. We definitely do think Bach is better than Frohberger, not that he is Frohberger[Pg 38] plus a Frohberger fraction. I submit that we think so because we find all Frohberger in Bach plus something more which is not Frohberger. But this has a tremendous consequence for, if true, it means that Frohberger is not unique. He is included in Bach. And may we not think that the music which vanishes from human consciousness is the music which is not unique and that so long as a composer is unique his music will be heard? I believe so. It is reasonable to think that every act, everything created has value. Our minds cannot imagine a Universe in which that would not be true; but we can imagine complex organizations incorporating simpler organizations, which then cease to have a separate existence. Therefore it is possible that nothing goes out of the Universe, and the idea that a thing may be lost seems illusion. Our minds find it difficult to[Pg 39] imagine an exit from the Universe. Where? But the incorporation of the lesser within the greater remains, as stated, a mechanical idea. We can find no satisfaction in a mere increasing complexity of structure. “If that is all that makes Bach better than Frohberger”—we can imagine someone saying—“I never want to listen to music again.” The process, we feel, must have a purpose or a meaning. Well, we have forgotten one vital element. Delight. The Universe is the imagination of its delight. If the purpose of the Universe were merely to attain to an ever higher degree of complexity for its own sake it would not be littered with these innumerable shapes of death—the violet, the lily, the rose, the cedar, the oak, the pine, the butterfly, the tiger, the elephant, and all other lovely and curious structures. Even man has not supplanted the ape,[Pg 40] nor has the fugue of Bach annihilated the song of the shepherd boy. We may think all these things are unique and that is why they still persist. But what about Frohberger, was he not unique? Why has Frohberger vanished? For if Frohberger was not unique how did he come to appear? Not to be unique is not to exist. Yes, but his uniqueness may not have been in his music. Here at last we have it. And his music does not exist since there is no music which can be said to be his. This is a different kind of non-existence to that of the Dinosaur, the Dodo, the Great Auk. Although their death-shapes no longer repeat themselves upon the earth they have not completely vanished. Their images live in the imagination of man, vivid, individual, unique. We have no such image of Frohberger’s music. It is a shrivelled, meaningless ghost, a letter[Pg 41] in the alphabet of music, which has in itself no life. Frohberger’s music is not like the Great Auk, an isolated death-shape of the physical world, nor like the Centaur, an isolated death-shape of the intellectual world, its position in music is that of one of those intermediates which, like the “missing link,” can never be found because the mind works per saltum. Frohberger and the “missing link” are for ever lost in the gaps. All that is without residuary value, all that has been completely incorporated in a new structure disappears thus because it slips through the mesh of the mind—not because the mind is not fine enough to retain the most minute differences, but because it chooses not to perceive. This reconciles the pre-Bach existence of Frohberger’s music with its present non-existence and delivers us from the apparent contradiction;[Pg 42] for it allows us to make what is, philosophically, a necessary assumption, namely, that no two things are ever exactly the same, and consequently that Bach’s music does not contain Frohberger’s music absolutely. Therefore the equation is not:

Bach = B(ach) + F(rohberger)

but

Bach = B + (F-X)

X being that unknown quantity which is Frohberger’s uniqueness and which we to-day cannot perceive.

But although art feeds on knowledge as life feeds on death at the same time creating more knowledge, as life creates more death—Ecstasy clothing Himself in Forms—yet there remains much that is mysterious. Why there are different forms of art is a question which insistently recurs. A comparison of music with the other arts in order to[Pg 43] discover a value specific and exclusive to music is not likely to enlighten us. Painters talk of “pictorial construction” as the specifically painter’s element which in all good graphic art is wedded to the illustration, psychology, representation or whatever other content a picture may yield, be it ancient or modern. They point out that the spectator is not emotionally moved by the representation of tears but by the rhythm of lines and the recession of planes. The good writer knows that a description of a sad event is not in itself saddening, it may even be comic; but unlike the painter he has no technical term for this essential quality without which literature is mere verbiage—unless, indeed, we apply the word “poetic” to this quality, as we have every right to do. Painting which is without this vital element—call it “pictorial representation,”[Pg 44] “significant form,” or what you will—is not art but knowledge or science.[3] Literature which is without this “poetic” quality is, again, mere knowledge, mere fiction. We have no need to seek for examples. A dozen famous names leap to our minds. Rather have we to seek for that literature which is poetic. Similarly in music there is a specific, purely musical quality without which music also is mere science. This quality I will call melodic imagination.

And here an interesting fact emerges. In all three arts the valuable element, the element of life is linked with the imagination. In painting pictorial imagination, in literature verbal imagination, in music melodic imagination—imagination always is the magical[Pg 45] essence, the power referred to in the lines:

“In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God and the Word was God.”

And we may be sure that there can be no art unless the word is made flesh—in the forms of painting, literature, or music—and dwells among us. But when we ask ourselves why it should take the form of painting or of words, or of music, it is impossible to give an answer. We can only echo: Why the lily, the rose, the violet? Why the tiger, the elephant, the antelope? Why the Moon, Venus, and the Stars? Ecstasy clothing Himself in Forms.

And still we have failed to discover in music any principle of progress other than increasing complexity of organization and a multiplication of lovely deaths. A principle which does[Pg 46] not as yet satisfy our instincts since it seems quantitative rather than qualitative. But perhaps we are on the verge of a discovery.

[3] Such according to eminent critics is the work of the painter Sargent and, for my part, I have no difficulty in seeing that what they say is just.

[Pg 47]

It may appear fantastic to assert that art is the only sphere where absolute values appear, and that the function of art in the Universe is to create absolute values, but it may be true. It is impossible to avoid the insistent demand of the human instinct for absolute values. This exists, an insatiable craving which will not rest content with the good but demands the better. And yet it is impossible to discover values that are absolute in themselves. The very notion is a meaningless abstraction. I do not even believe we can prove that Beethoven’s music is better music than Mozart’s or that Shakespeare’s poetry is better than Milton’s, or vice versa, unless we[Pg 48] first of all limit the idea of music or poetry to something intellectually measurable. For example it would be difficult to convince all music-lovers that Bach’s counterpoint was better than Beethoven’s, or that Palestrina’s was better than Bach’s; for what is to determine “good” counterpoint? Very few musicians would accept any individual theorist’s rules—all rules being mere abstractions or generalizations from practice, and varying according to their historic date, so that even the academic theory of one age differs from that of another. Even in judging a fugue, one has ultimately to fall back upon expression, significance, or meaning, and who is to say—and on what universally acceptable principle is it to be said—that Bach’s “St. Anne” fugue is better than Beethoven’s “Grosse Fuge,” Op. 133?

There is exactly the same difficulty[Pg 49] in poetry. In an excellent and well-known book on the English Sonnet a definition is given of perfect sonnet form which is intellectually satisfactory. But we find that most of the greatest English sonnets are not written in this form, while thousands of mediocre sonnets observe it correctly. The same is true of Bach’s Fugues. You cannot value them according to their correctness.[4] What then becomes of our “perfect” sonnet and our “perfect” fugue? Each is apparently an unreal abstraction—like all other attempts at creating absolute value. But are these “absolute” ideas necessarily valueless in themselves? I do not think so, for they correspond to and are the formalization or death-shapes of desires ineradicably rooted in the human soul, those desires which[Pg 50] create all values, and that profounder urge which is satisfied with none.

What is important to recognize is the diversity of these desires and to understand that it is the diversity (in itself profoundly desired) which nullifies standards. We can say that this fugue is more perfect than that fugue—having made an abstract and definable conception of the fugue form and separated it from all life. Criticism is an application of such abstract conceptions—derived by analysis from the practice of artists—from all past works of art to one present work of art and, again, backwards, from all existent works of art to one past work of art. The former is historical criticism (when a composer is judged only on what preceded him) and the latter is, or should be, the absolute æsthetic criticism. But what prevents its being so is that it leaves out the future. The[Pg 51] work of art is judged by the present and the past but the future is unknown and the judgment is thereby vitiated and is not and cannot be an absolute judgment. But this does not mean that the future does not exist now, somewhere. To demonstrate this, however, would take me on too far-stretching a parabola. I would merely draw attention to this reservation, and say that its relevance will appear later.

My belief is that when I say, as I do emphatically say, that Beethoven is a greater composer than Bach and find my assertion difficult or impossible to prove I am judging by an instinctive but not yet intellectually formalized sense of value, or values, which will only emerge in the future to take a place among all the other principles and standards—the totality of life in its sum of death-shapes so far created. So we see there can be no such thing[Pg 52] as a perfect fugue-in-itself but only the idea of one. The actual fugue must have a meaning, it must be an expression of life; a fugue-in-itself without relation to life, perfect and completely, is an impossibility. Nevertheless a musician like Bach finds in himself the fugue-idea as well as the fugue-emotion, the fugue-form as well as the fugue-content, and there is a constant struggle between them to coincide exactly and to materialize in one indivisible unity. Sometimes the fugue idea prevails and sometimes the fugue-emotion prevails, and the result always is an imperfect fugue. But this imperfection in all its varying degrees is the musical reality. Absolute perfection, absolute unity is annihilation, the end of all things and the attainment of Nirvana. But even the fugue-idea is not a constant unchangeable abstraction or fixed shape. It is[Pg 53] modified by the actual fugues which are created, for it is an abstraction, a general principle from examples, an induction from particulars; and as fresh particulars arise, the induction must be modified. Again, I spoke of the content or fugue-emotion, but this fugue-emotion is not—except perhaps in the simplest and most feeble examples—single but, on the contrary, multiple. Who is to appraise or range in order of value these emotions? How is it to be done? The belief that any single judgment may do it—the mind of any one critic, expert or practitioner—is preposterous. But this does not suspend individual judgment or make it vain, since it is through the conflict or discord of all genuine individual judgments that new conceptions or attempts at concord emerge. This conflict arises from unsatisfied desire and, in the end, we think[Pg 54] Beethoven better than Bach only because Beethoven more profoundly satisfies our desire or satisfies a deeper desire than any satisfied by Bach. Just as new conceptions emerge or are induced from discordant or unrelated conceptions so new emotions and new desires are induced from the discordance or conflict of our desires. This process of organization would seem infinite—a conception which I, personally, find intolerable and incomprehensible—were it not for a strange phenomenon, and this phenomenon is that ultimately at the core of all men there seems to be the same desire.

The world is not really divided as to who are its greatest painters, sculptors, scientists, mathematicians, musicians and poets. We may not be able to prove to our own logical satisfaction that Beethoven is greater than Bach, that Bach is greater than Haydn,[Pg 55] that Palestrina is greater than Verdi, but we are all strangely certain that it is so. What are we to make of this? Evidently there is a unity somewhere in our diversity, and it is more than a lowest common factor—a far-away dim primitive element, never quite lost sight of but growing ever fainter, linking all men and all art. It is not that touch of nature making the whole world kin, for that—although it might enable us to have some sympathy with all things—would not enable us to range them in value. Such a minute dose of common kinship could not so vitally relate us. It is, on the contrary, by our very essence, by the most spiritual and intense of our desires that we are united. We are not unanimous about Scriabin, Puccini, Tchaikovsky, Liszt, Rimsky-Korsakov, Schumann, Chopin, Mendelssohn and Dvorak, just as we are not unanimous about[Pg 56] Aubrey Beardsley, Sargent, El Greco, or about Byron, Tennyson, and Conrad.

Apparently each of us carries within him a fundamental note which picks out all the notes struck upon us by nature and mankind and ranges them in a series. And it is this which gives to each one his values. The fundamental note which any individual carries may not be the fundamental note of mankind, or of the Universe, but it must have a more or less simple relationship with them. Thus the values of one individual are true for all others, within their limits. They are real values though not necessarily ultimate values; they can and will be related to all other values but can only be so related through a more fundamental note—hence the importance of such a note. It is my belief that the profoundest, most fundamental note in music, so far, has been[Pg 57] struck by Beethoven. There is nothing in the music of any other composer which his does not comprehend. But his, on the other hand, has a new foundation to which no other music reaches.

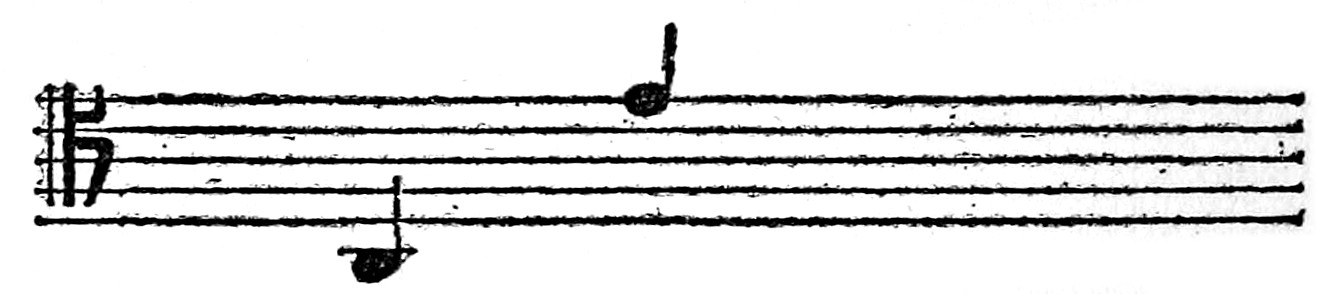

But this analogy of the fundamental note must be understood merely as an analogy, suggestive rather than explanatory. Of all the simpler musical intervals I find that of the seventeenth the most satisfying to my ear. I may wonder what is the secret of the purity of its concord—so much greater than that of the perfect fifth or the perfect fourth, which at first sight seem to be more intimate relationships. Then I discover that the ratio of the vibrations[Pg 58] of the two notes of the seventeenth is 1:5, whereas that of the perfect fifth is 2:3, of the perfect fourth 3:4. Stated thus this may not mean much to the non-mathematically minded reader but it denotes that the seventeenth is a perfect and not a syncopated interval. That is to say there is no syncopation of the vibrations of the two notes, but they beat together in a closer more united rhythm than that of a perfect fifth or perfect fourth.

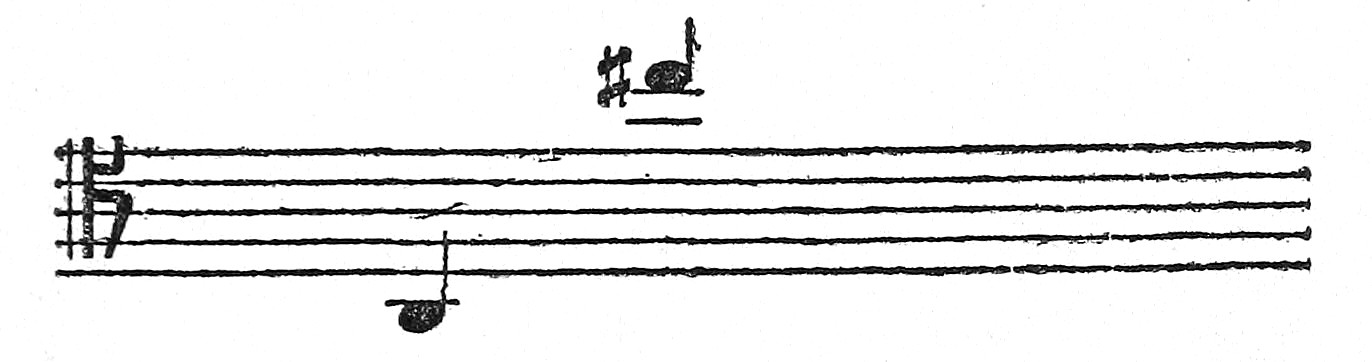

But the twelfth

(I use the tenor or C clef partly because it is more obscure and will annoy those who are only accustomed to the treble and bass clefs) has a ratio of 1:3 which also is not a syncopated interval but has the same kind of perfection as[Pg 59] that of the octave (1:2) and the seventeenth (1:5). Yet the twelfth is not so pleasing an interval as the seventeenth, and the octave is inferior to them both. Nevertheless the twelfth and octave are mathematically closer relationships than the seventeenth. Evidently there is another principle to be discovered, and I will call it the principle of affinity in unlikeness and illustrate it by an analogy which may seem far-fetched but which I believe to be illuminating and significant.

Let us imagine that the unison or note A represents oneself; that the relationship of the octave (1:2) represents that of father and daughter; the relationship of the perfect fifth (2:3) that of brother and sister; the relationship of the perfect fourth (3:4) that of two brothers; the relationship of the twelfth (1:3) that of male and female cousins—in which a new element[Pg 60] that of sexual affinity, is introduced, bringing with it a deeper reverberation although the blood relationship is more distant. And, finally, the relationship of the seventeenth, that of unrelated lovers which—although the most distant of all in blood—strikes a still profounder sympathy and beauty. It is now possible to understand more clearly why my analogy of the relation of Beethoven to the rest of music as that of a more fundamental note is not to be taken in its literal meaning. With Beethoven, a new element came into music, an element of such sublimity and beauty that its advent into the world of imagination is comparable in importance with that of sex in the physical world.

Sex as we know it did not always exist; it does not exist in the inorganic world, hardly in the vegetable world, but dimly in the animal world. It is[Pg 61] a human discovery, and upon that new more fundamental note (fundamental not in the vertical sense but in a focal sense) rises the whole wealth of man’s intellectual and physical harmony. But even in sex we have not touched an absolute. The presage of a still profounder intimacy trembles fitfully here and there in music throughout the historical European period. In the music of Palestrina, of Byrd, of all the rarer spirits up to Bach, Mozart and Wagner there are fitful gleams of a more central desire until, finally, a love that plumbs deeper than even the love of sex rings forth unmistakeably in the music of Beethoven and immediately creates for us a new hierarchy of values. And so here we find for the time being an Absolute. The world of art, we find, resembles both the world of the atom and the world of solar space. There are greater[Pg 62] and lesser planets and greater and lesser satellites. We can imagine that if there were inhabitants upon the Moon they might think the Earth was the primary fact of their being, since it was the focal point of their orbit, whereas the Sun would seem so eccentrically placed as to be an irregular and incomprehensible singularity; until by a process of more profound imagining they conceived the more fundamental though more distant relationship in which it stood to them.

Just as the Sun is the centre of the only system of the physical universe so far formulated—for no centre has been found to the innumerable suns of the stellar universe—so Beethoven is our temporary Absolute in the world of music. And just as the Sun is the source of all vegetable and animal life upon the earth, so I believe that in art[Pg 63] we find the vital spirit which animates our human life. Thus it would seem to be true—as I suggested we might discover—that the function of art in the world is to create absolute values in the imagination upon which the human species can continually re-create its intellectual, moral, and physical structures. And if this is so it means that in the values of art we approach most nearly to Truth.

[4] See Mr. Harvey Grace’s excellent book on the organ works of J. S. Bach.

[Pg 64]

A technical analysis of the art of music as practised in Europe during the past few hundred years would be interesting, but it lies outside the scope of this book. What is relevant is to consider the emotional and intellectual significance of the music composed during that period. Folksong, from which most great composers have consciously or unconsciously drawn, is the emotional substratum of all European music. At its best it is simple, sensuous and passionate—the heart-cry of men whose desires are frustrated by the accidents of life, whose joys are too short, or whose griefs are too enduring. Where it chiefly differs from similar, later, more sophisticated music is in the[Pg 65] simple intensity of the emotion. In a society more subject to extreme vicissitudes of fortune than later and more stable social states it was easier, and natural, to believe that mere irresponsible “accident” or mischance separated men from happiness.[5] In a beautiful old Neapolitan song collected by Madame Geni Sadero the singer bewails the loss of his love carried off by Moorish pirates in a raid on the Italian coast. Such a song has an extraordinary plasticity of melody, rivalling in expressiveness the melodic invention of the greatest composers. These melodies were modelled by an intense sincerity, of a kind inconceivable to men in a more complex environment, richly provided with compensations. Any attempt at such[Pg 66] sincerity would to-day be insincere.[6] Equally insincere would be any modern composer’s attempt to express the simple natural thrill of the Sardinian shepherd boy who greets the rising of the Sun in a wonderful song included in the Sadero collection. In our civilized society man knows that the sun will rise to-morrow as it did yesterday, and that next year or the year after he may love again. It is not Moorish pirates, or the accident of plague, or the malefic interference of an unfriendly God that will bear away his happiness. It is happiness itself that has flown away as he sits securely in the midst of his possessions and asks himself, what he used not to ask himself: “Why do I live?”

I do not lament this change as a disaster. I merely wish to point out[Pg 67] the difference and to show why the music of to-day must differ from the music of yesterday. Those who believe that music is a purely abstract art (mere negation this, which I have abundantly shown to be empty of reality) will be shocked at the dependence of music upon man’s life; but the great composers themselves knew better:

“The error in the art-genre of opera consists in the fact that a Means of Expression (Music) has been made the object, while the Object of Expression (the Drama) has been made a means.”

Those words of Wagner’s show clearly that to Wagner, as Mr. Newman aptly puts it:

“To invent a theme for its own abstract sake, to pare and shape it till it was ‘workable’ and then to weave it along with others of the[Pg 68] same kind into a pattern of which the main lines were predetermined for him by tradition—this was something he could not imagine himself doing, and that he scoffed at when he found the Conservatoire musicians engaged in.... Wagner always protested against the current fashion of performing Beethoven’s symphonies as if they were nothing more than agreeable or exciting musical patterns.”

My preceding chapters will have made it quite clear why Wagner’s instinct was right, although his mode of expression is so inexact as to be often confusing and misleading.[7] What Wagner means is that intellectual forms or death-shapes are given no significance by being manipulated,[Pg 69] dove-tailed, and re-arranged by the intelligence working from rules and examples. It is “life” that gives significance, a spiritual urge into creation, and where this is absent there is no artistic creation. We may perceive by his use of the word “drama” that Wagner’s conception of “life” was a limited one; but he could only express the life that was in him and his soundness lay in his recognizing this. But we shall not make the mistake of inventing an artificial and unilluminating distinction between Wagner as a dramatic or programmatic composer and, for example, Mozart or Bach as absolute composers. The difference between all these composers (including Beethoven) lies mainly in inner feeling, in spiritual life, in the individual psyche—not in their musical faculty as composers. It was natural to each one of them that his vital[Pg 70] activity should run into the form of sound-patterns. It is this idiosyncrasy which has made them all musicians and not poets, sculptors, or painters. But this peculiarity is only a physiological bias for—to quote Mr. Newman again, since he is a musician and what he says will be more appropriate here than the words of a poet or sculptor, besides being admirably clear—

“It is only the most superficial of psychologists and æstheticians who can regard any human faculty as wholly cut off from the rest. Our perceptions of sight, of taste, of touch, of hearing are inextricably interblended as is shown by our constantly expressing one set of sensations in terms of another, as when we speak of the colour of music, the height or depth or thickness or clarity or muddiness of musical tone. In every poet there is[Pg 71] something of the painter and the musician; in every musician something of the poet and the painter; in every painter something of the musician and the poet. The character of the man’s work will depend upon the strength or weakness of the tinge that is given to his own special art by the relative strength or weakness of the infusion of one or more of the other arts.”

Thus we can explain the sensuous individuality of an artist as being a result of the special and peculiar bias and intermixture of his senses. But this is only a part of his character or personality, and it is my argument that it is the minor (though essential and indispensable) and not the major or most important part. For besides this physical individuality he has a spiritual individuality. The former is the instrument, the latter is the “life,”[Pg 72] and, in the case of music, the physical expression, the communication, the tangible (eye and ear are “touch” at a distance) death-shape is the musical creation or form—a Bach fugue, a Beethoven symphony, a Mozart or Wagner opera, a Schubert song.

The importance of Beethoven—which Wagner was the first to understand—lay in that stupendous stream of “life” within him which burst through all the old academic forms, as the sap bursts through a tree into colour and blossom, and strewed the history of music with those gigantic skeletons of spiritual life which we know as his works. But we have yet to discover the meaning of these compositions. Their full meaning can only be felt, it cannot be re-stated—except when his works are adequately performed; but they have a characteristic to which I shall try to give a verbal[Pg 73] construction because I think it immensely important. It is not a quality for which there exists a word, or a phrase, or even a poem; but it is a particular kind of desire. “Like as a hart desireth the water-brooks so thirsteth my soul after the living God,” that—were it not for its association with the desires of Baptists, Methodists, Wesleyans, Anglicans, Catholics, Mohammedans, Buddhists, Christian Scientists, Mormons, and all those bodies of people known to-day as “religious”—would perhaps be suggestive. At any rate it would serve to distinguish the quality of this desire or passion from the passion which created Tristan und Isolde. And, magnificent and beautiful as that was, its magnificence compared with the magnificence of Beethoven’s passion is as the magnificence of a coloured duck to a black swan. The simile is[Pg 74] a totally unworthy one, for we have nothing to which we can compare Beethoven. We can easily find similes for Wagner, but Beethoven is a rara avis.

It is natural to the young to be idealists, an old idealist is generally either a rogue or a fool—unless he happens to be a Beethoven. The young find something stirring in their hearts when listening to Beethoven which they never find when listening to Bach, Mozart or Wagner, great as these composers are. Beethoven awakes a feeling so romantic, so idealistic, of so fine and exquisite a bloom that it is guarded by everyone who experiences it as a precious secret. What Beethoven imagined inevitably lures men away from the sensuous delights of Debussy and Strauss, from the fatiguing excitements of Stravinsky and Jazz, from the gaieties of Verdi and Rossini, from[Pg 75] the sentimental nostalgia of Brahms, from the solid satisfaction of Bach, from the sensitive melancholy of Mozart and from the lesser loves of Wagner; but why it does so we cannot tell.

“Had I been willing,” said Beethoven to Schindler in 1823, in the course of a conversation about the Countess Giulietta Guicciardi, “to surrender thus my vital power and my life what would have been left of the best and noblest in me?” What a different ring this plain statement has beside the rhetorical pæans to renunciation on the lips of Wagner, who was satisfied to accept what would never have satisfied Beethoven.

It is a peculiarity of Beethoven that he can use the words “best” and “noblest” without making an intelligent man laugh up his sleeve. If we do succeed in laughing it is with[Pg 76] the wrong side of our mouths. The very words “good,” “noble,” “spiritual,” “sublime,” have all become in our time synonymous with humbug. In Beethoven’s music they take on a new and tremendous significance and not all the corrosive acid of the most powerful intellect and the profoundest scepticism can burn through them into any leaden substratum. They are gold throughout. Am I wrong in thinking this an achievement without parallel in the modern world? Point to me in poetry, painting, sculpture, music, anywhere, one other artist who has recreated (not paid lip-service to) the meaning of good and left to us the imagination of a love transcending both the sacred and the profane. There is none.

We cannot live without values and at present we cannot conceive a state when men would not ask themselves:[Pg 77] “Why do I live?” “Is life worth living?” This is the theme which touches us to-day when we marry and settle down with our love, measure the spots on the Sun, and fear neither plagues, pirates, nor eclipses:

“Here I am an old man in a dry month,

Being read to by a boy, waiting for rain.

I was neither at the hot gates

Nor fought in the warm rain

Nor knee-deep in the salt marsh, heaving a cutlass,

Bitten by flies, fought.

My house is a decayed house,

And the jew squats on the window-sill, the owner,

Spawned in some estaminet of Antwerp,

Blistered in Brussels, patched and peeled in London.

The goat coughs at night in the field overhead;

Rocks, moss, stonecrop, iron, merds.

The woman keeps the kitchen, makes tea,

Sneezes at evening, poking the peevish gutter.

I am an old man,

A dull head among windy spaces.”

The bravest, the most intelligent, the most sensitive are oppressed with that profound sense of the futility of[Pg 78] life which Mr. Eliot expresses so admirably in the above lines. It is, indeed, the constant burden of the most characteristic of our modern poets:

“This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper.”

Yes, we are convinced. This is the way the world ends and we have no more faith in anything. Democracy, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, have all been added to the list of the Great Superstitions. Mussolini and Lenin have made moonshine of Socialism and Communism. God is a word used only in treatises on tribal magic, when it is spelt correctly as god. Love has been appropriated by the writers of silly magazine stories and even sillier novels. All honest men are reduced to silence before the daily avalanche of fraudulent lies from pulpit, printing[Pg 79] press, parliament and platform. Everywhere men speak with the tongues of serpents and the minds of manufacturers of chewing gum. And deep in all men’s hearts there is only one thought:

“I grow old—I grow old

I shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled.”

But in the midst of futility and inanity, in the midst of desperation and despair there sounds the music of Beethoven which says without bombast or credo: “This is not the way the world ends.” And says it in such a way that we are forced to listen. We listen to Beethoven when we would listen to nobody else because he is a man without any of the world’s illusions. How feeble and superficial seems the disillusionment of Mr. T. S. Eliot’s poems compared with the agony of the Cavatina in the B flat Quartet with its mysterious pause—as if the pulse of the whole[Pg 80] Universe were stopped and might not continue; of the Fugue in B flat Op. 133; and of the last Pianoforte Sonata which Beethoven wrote. In this last Sonata we feel the agony of a man whose imagination is grappling with some insupportable horror. Let us conceive the Captain of a ship standing on its bridge in a calm, unconscious sea. The boats are useless because land does not exist anywhere. From the deck come the cries, curses and weeping of the doomed crew, who are only his own embodied emotions, for he is really alone. Slowly they are going down into the unruffled water. The Captain does not shake his fist defiantly into the sky and deny that he is going down, but knowing that he is going down never to return sinks passionately into the sea. Such is the mind and temper of Beethoven. There is agony but no whimper, and if that[Pg 81] is not ending with a bang I don’t know what is. In the music of Beethoven there are no anodynes, no lullings of sense, no deceits of the intelligence, but pure virtus. And this virtus is thrilling absolutely, without reservations. After the tremendous drama of the first movement of the C minor Sonata, for example—a drama in which there is the whole ecstatic misery of life—we are not assuaged by a dream. The conflict does not cease. That wonderful Arietta—surely the most wonderful thing in all music—is no bringer of peace and resignation. In it something passes away but its passing away is an act of creation not of extinction. It is this which gives Beethoven’s music its peculiar significance, for Creation not Nirvana is the essence of Beethoven. It has its root therefore in human personality and may be most accurately described as the[Pg 82] supremest imagination of love in human art. But though beyond the conception of the Neapolitan fisherman mourning for his lost bride it does not lessen but enriches that ancient love-song, making it impossible for us to feel that it was meaningless.

And if anyone should say that the question: “Why do I live?” has not been answered, I reply that Beethoven has rendered it ridiculous.

[5] The ancient Greeks with characteristic intellectual power did not believe in mere irresponsible accident.

[6] Compare for example the feebleness of our contemporary love-songs and ballads.

[7] For example we can ask nothing more than that a composer should write “exciting musical patterns.” It all depends upon what is meant by “exciting.”

[Pg 83]

Music will not end with Beethoven. It is possible that the very problems that confronted him and still confront us will fade out of the imagination just as those political problems which occupied so much of the attention of the historical world from the Greek Republics to the British Empire are ceasing to exist before our very eyes. And when we think of the religious dissensions of Christendom and reflect on the questions which once divided father from son, sect from sect, church from church, it is with difficulty that we can give them a meaning intelligible to our minds, much less feel any shadow of the life that was once in them. In the memory of living men,[Pg 84] heartburning intellectual problems have become empty phrases. Darwin, Huxley, and the Anglican Bishops all seem as unreal as the waxworks of Madame Tussaud and are seen to be the complementary phenomena of an intellectual nightmare. No one to-day imagines that Truth wears the strange Victorian get-up of any of these gentlemen.

Similarly the sociological phantoms of the age of Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells, of Karl Marx and Lenin are cutting the last of their antithetical capers. Socialist and Anti-Socialist, Communist and Anti-Communist, Conservative and Revolutionary have suddenly caught sight of their own faces behind the masks of their opponents. Their passionate reality is seen to be no more than a Fancy Dress Ball—for all these figments, these fictions, these Ideas were never any more than[Pg 85] the Masks of false passions, passions which have never succeeded in begetting a progeny, since they are the mere nightmare passions of social indigestion.

In another five generations there will be no poverty, there may be no matrimony, there will certainly, if there is no poverty, be no patrimony. Children may take their mother’s name and then fathers will have not even a fifty-year royalty upon their creations. Men and women will look upon their children as artists look upon their works and will wish others to enjoy them. The world will be so changed that none of the problems which to-day set our newspapers printing and our politicians talking will even exist. Our present ideas on sex, morality, beauty and value will in those days appear as strange, as fantastic, as illusory as the ideas of our[Pg 86] ancestors who took Beecham’s pills to cure all ills.

Will the music of such a world differ from the music of to-day? Necessarily, since life without change is inconceivable to us and music that is alive must be changing. But the meaning of this change is not to be apprehended by the mind, for it is no less than life itself. A part of it, however, can be apprehended, for, although we feel instinctively that the more the world changes the more that it is the same[8] yet we cannot deny that it is the same with a difference. And it is the difference which matters and is matter—that which appears, is visible and audible—the death-shape of the spirit.

It would be boring and futile to[Pg 87] consider the methods which may be invented of distributing music or of making music heard. That a million persons listen to Beethoven by wireless or gramophone where, previously, a thousand listened in a concert hall is one of those statistical changes which it is beyond the wit of man to value.

Fortunately there is a period fixed to the possibilities of “progress” of this kind; and when every baby is born to Beethoven and to Freedom then culture and statistics of culture, education and measurements of education will have simultaneously ceased. There will be in those days no newspaper interviews with Neo-Edisons because there will be no newspapers; the people will have forgotten that it is interesting to know whether a celebrity drinks de-caffeined coffee or dehydrogened water because there will be no “people” and no celebrities.[Pg 88] The Age of Vulgarity will have passed.

What sort of music will be listened to in those days? The music of Orpheus, the music that comes out of darkness.

According to Plato when Orpheus descended into hell and succeeded by the strains of his mysterious music in softening the hearts of Pluto and Persephone—who themselves were phantoms, prisoners of the imagination, supernal beings chained to the bottom of Hades because they were imagined there and existed only in Imagination—he brought back with him but an Apparition. It was an Apparition that he gazed at so fondly, and which nevertheless vanished before his eyes. His music was that Apparition; those heavenly strains, mysterious, profound, issuing from his mouth took form, the form of Eurydice—the[Pg 89] imagination of light in darkness, of love in the midst of death.

The forms that music will take in the future are as yet unimagined; but these forms will always be the form of Eurydice plucked by Orpheus vainly out of Hell. And they will not be abstract forms but the apparition of a real love which, bitten by the serpent of life, descended into the kingdom of Pluto.

[8] The evolutionary theory will no longer be thought of as a continuous or a discontinuous ascent; biological species will be regarded as ripples on a pool; the Astronomical Universe will be conceived as stationary.

THE END