At the South Window.

DAYS AND HOURS IN

A GARDEN.

BY

“E. V. B.”

NINTH EDITION.

LONDON:

Elliot Stock, 62, Paternoster Row, E.C.

1896.

NOS ET MEDITEMUR IN HORTO

TO

RICHARD CAVENDISH BOYLE.

WHOSE LOVE FOR NATURE AND FOR ART,

YEARS HAD NOT CHILLED

NOR TROUBLE CHANGED,

THESE RECORDS OF OUR GARDEN

WERE INSCRIBED BY

E. V. B.,

IN 1884.

[Pg ix]

PREFACE.

IF for a sixth reprint of Days and Hours in a Garden a new Preface was deemed advisable, still more so, perhaps, should there be something new prefixed to the Seventh Edition, although, indeed, it contains nothing that in any sense is new. Neither new words nor any new vignettes appear therein. Nevertheless we venture to hope that perhaps new readers may be found. Since the last edition was published some three years have come and gone, with their world-old roll of seasons and their burden of inevitable change. The garden has three times slept beneath the rains and the snows of winter, and has awakened in spring with the birds and the bees. Meanwhile, the shrubs are taller and larger, and the trees have extended their roots and stretched out their branches over lawns and gravel paths. And the summer shade, so coveted in other[Pg x] days, has broadened, while, on the other hand, it has become more hard to maintain in their wonted brilliancy our borders and flowerful closes. The axe and the pruning-knife have been busy during the winter months; and many a fine Laurel, in all its wealth of glossy green, has been laid low, and with Yew and the full-foliaged Phylleria, and more than one tall Deodara,—become a burnt sacrifice to “Apollo’s sunny ray.” For the south sunshine must be let in, no matter what the cost. In certain ways the garden may be said to suffer change; and chiefly when the grace and softly rounded loveliness of various evergreens which do not bear the shears—Cryptomeria Elegans, Red Cedar, and the like—after a course of years begins to wane. Even to the upward-pointing Cypress middle life in an English garden is not becoming. And as the larger trees increase in size, so the overshadowed lawns diminish. And thus the slower progress of some of our trees has given place to a rapid growth, which bids fair to overstep all bounds of such limited space as ours. The Douglas Fir and the branching Cedar of Lebanon keep growing into one another, while Excelsa touches them both, and wants to reach across to the clump of Yew and Laburnum. Their near neighbour the Sequoia already rises to the height of fifty[Pg xi] feet, and measures over nine feet round at some two feet from the ground. Nordmaniana alone (most beautiful of all), through having five times lost his leader, is forced to greater moderation. Still, although no future of green maturity can ever compensate the earlier, expectant delight of watching our young trees’ youth, all is not lost; for the pleasures carried away by Time, Time itself replaces by others to the full as sweet. It may be that favourite plants become established and yield a larger harvest of beauty, or that deep-laid plans ripen into bright perfection, while a thousand garden joys arise fresh each year, nay, well-nigh every day. As to the living frequenters of the garden, whose presence there for the most part enhances our enjoyment of it, the tomtits and nuthatches, are as busy with the cocoanuts which hang for their use all winter from the Rose-arches as the mice and the sparrows are with the crocuses; the white pigeons still circle in the air and settle upon the gables, or preen their feathers in the sunshine amongst the yellow stonecrop at the base of the old grey pillar in the parterr; the swallows return year by year to their nests within the porch; but the faithful satin-coated Collie lies still for ever under the turf by the ivied wall, and the earth lies heavy on his noble head. For these thirteen[Pg xii] summers past he had taken his pleasure in the garden—had chased marauding cats, or bounded after apples with any playfellow of the hour, while his glad bark rang again; or as in later days, had gravely followed the steps of his mistress about the walks, or rolled upon the grass, or watched with lazy but unfailing interest his friend the Gardener at work. Four words graven on a little white marble tablet that shines amidst the dark ivy-leaves on the wall record his name and character:—

CASSIO.

TENDER AND TRUE.

May, 1876.] [Nov., 1889.

Already the Snowdrops are giving way before impatient Hepaticas and Primroses, the bare Elms are thickening with purple, and we begin to count the Gentian buds. Everywhere Nature repairs herself in ceaseless round. Only in our human lives some vacant spots there may be, where the grass will not grow green again.

E. V. B.

Huntercombe Manor,

February, 1890

[Pg 1]

OCTOBER.

[Pg 2]

Fas est hic, Indulgere Genio.

[Pg 3]

OCTOBER 17, 1882.

Of Nuns and White Owls; Yews, Thrushes, and Nutcrackers.

THE GARDEN’S STORY. It is only eleven years old, though the place itself is an old place—an old place without a history, for scarce a record remains of it anywhere that we have ever found. Its name occurs on a headstone in the parish churchyard, and on one or two monuments within the chancel of the parish church. There is brief mention of it in Evelyn’s Diary. It is there described as “a very pretty seate in the forest, on a flat, with gardens exquisitely kept, tho’ large, and the house, a staunch good old building.” It seems George Evelyn (the author’s cousin) was amongst the many who have lived here once. At that time eighty acres of wood[Pg 4] surrounded the house, where now there lies a treeless stretch of flat cornfields. Quite near, across the road, are the ruins of an ancient nunnery. Our meadow under the high convent wall is called the Walk Meadow, because here the nuns used to walk. The great Walnut tree, which they might possibly have known, only died after we came. It was cut down for firewood, and its hollows were full of big chestnut-coloured “rat bats,” very fierce and strong. At that time also white owls lived in the ruins, and used to come floating over the lawn at twilight—until the days of gun licenses, since when, they have disappeared. Dim legends surround the place, but nothing clear or certain is known or even said, and there is not a ghost anywhere. All we know is, that since taking possession, wherever a hole is dug in the garden to plant a tree, the spade is sure to strike against some old brick foundation of such firm construction that they have to use the pick to break it up. Bones of large dogs also are found all about the place whenever the ground is broken—remains of the watch dogs, or hunting dogs,[Pg 5] of the olden time—also quaintly shaped tobacco-pipes. I know of nothing to support the tradition that monks abode here once. There were signs of an upstairs room having at some remote time been used as a chapel; a piscina in the wall and a narrow lancet window having been found and destroyed, when the house was in the builder’s hands eleven years ago. Broken arches, also, and mouldings in chalk and stone, were dug up out of the foundations of some outhouses at the same time. “They say” there is an underground passage between the Abbey and the house, but we do not believe it, and we do not believe in the murder of a monk for his money, said to have been committed by a nun in the upper room now a guest-chamber. Such vague traditions are sure to hang around old walls, like mists about a damp meadow. Very distinct, however, and carved in no vague characters, are certain initials and dates still visible on the stems of the trees in the Lime avenue. For in old times—

[Pg 6]

When the trees are bare and the western sky is bright, you can see them quite plainly—large capital letters, often a pair, enclosed in a large heart with the date. The dates run from 1668 on to late in 1700. Those old village lovers must have had sharp pen-knives, which cut deep! They and their names have long passed away and been forgotten; but, for so much as is traced in the living bark, these Limes have proved as good as any marble monument; much better than the long wooden “rails” which are still in fashion hereabouts. Since the place was ours this short avenue of twenty-four trees has been taken in from the public road; and now the Limes give us cool shade and fragrance and many midges in the hot summer days. I fear there is nothing more to be discovered about the past history of the House than we now already know. We must be content, and follow as we best may George Herbert’s concise admonition—

[Pg 7]

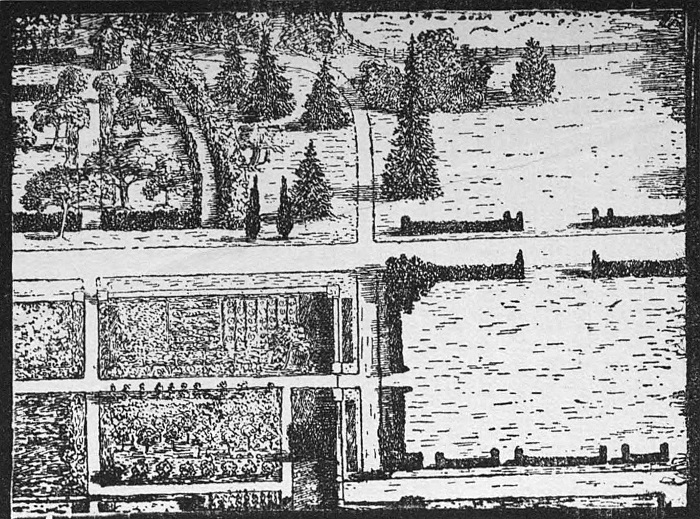

We have had the great pleasure of making the garden. The feature of the place was, and is, two symmetrically planted groups of magnificent Elms in the park field, in which every season we hope the rooks will build. There was everything to be done in the garden, to which these Elms form a background. We found hardly any flowers; a large square lawn laid out in beds, with unsatisfactory turf and shrubberies beyond, a long, broad terrace walk, old brick walls, with stone balls on the corners, two or three old wrought iron gates in the wrong places, dabs of kitchen garden and potato plots, stable-yard and carriage entrance occupying the whole south front, with a few pleasant trees, a young Wellingtonia, a Stone Pine, a Venetian Sumach (Rhus cotinus), and a very large red Chestnut (from a seed brought from Spain in the waistcoat pocket of one of our predecessors here, fifty years ago, and said to be the first of the kind raised in England). Such was our new playground in 1871. Here we brought a skilful Gardener, possessed of common sense and uncommon good taste—can one say much more in a few words?—and [Pg 8]aided by our own most unscientific but exceeding love for flowers and gardening, we set to work at once. These “gardens on a flat” are transformed.

Kitchen Garden, East Lawn, etc.

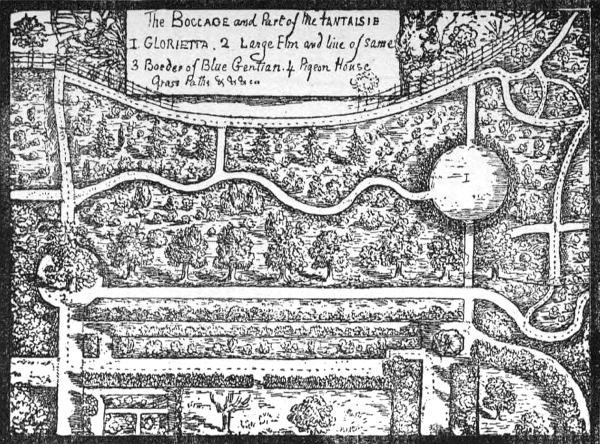

There now are close-trimmed Yew hedges, some of those first planted being 8 feet 6 inches high, and nearly 3 feet through, while others are kept low and square. There are Yews cut in pyramids and buttresses against the walls, and Yews in every stage of natural growth. I love the English Yew, with its “thousand years of gloom!” (an age that ours, however, have not yet attained). The Wellingtonia, planted in 1866, has shot up to over forty feet high, and far outgrown its youthful Jack-in-the-Green look. The Stone Pine, alas! has split in two, and been propped up; and although half killed since by frost, it yet bears a yearly harvest of fine cones, chiefly collected for use as fire revivers—though the seeds ripen for sowing, or eating. The borders are filled with the dearest old-fashioned plants; the main entrance is removed to the north side; the stable-yard is removed also, and instead thereof are turf and straight walks, and a sun-dial, and a [Pg 10]parterre for bedding-out things—the sole plot allowed here for scarlet Pelargoniums and the like. In this parterre occurs the only foliage plant we tolerate—a deep crimson velvet-leaved Coleus. The centre bed is a raised square of yellow Stonecrop and little white Harebells; with an old stone pedestal, found in a stonemason’s yard, bearing a leaden inscription—“to Deborah”—surmounted by a ball, on which the white pigeons picturesquely perch. There are green walks between Yew hedges and flower borders, Beech hedges, and a long green tunnel—the Allée Verte—so named in remembrance of a bower-walk in an old family place, no longer in existence. There are nooks and corners, and a grand, well-shaded tennis-lawn, and crown of all, there is the “Fantaisie”! This is a tiny plantation in the field—I mean the Park—date 1874, connected with the garden by a turf walk, with a breadth of flowers and young evergreen trees intermixed, on either hand. Here all my most favourite flowers grow in wild profusion. The turf walk is lost, after a break of Golden Yew, in a little wood—a few paces round—just large enough[Pg 11] for the birds to build in, and with room for half-a-dozen wild Hyacinths and a dozen Primroses under the trees; with moss, Wood Sorrel, and white and puce-coloured Periwinkles, and many a wild thing, meant to encourage the delusion of a savage wild! I am afraid I never can be quite serious about a garden; I always am inclined to find delight in fancies, and reminiscences of a child’s garden, and the desire to get everything into it if I could. This “Fantaisie” was a dream of delight during the past summer—from April, when a nightingale possessed in song the half-hidden entrance under low embowering Elm branches and Syringa—through all the fairy days and months, up to quite lately. Yes, even last week, it was fragrant with Mignonette and Ragged Jack (I mean that Alpine Pink Dianthus Plumarius), gay with yellow Zinnias and blue Salvia in rich luxuriance, with a host of smaller, less showy things—with bunches of crimson Roses, and pink La France, blooming out from a perfect mist of white and pinkish Japan Anemones, white Sweet Peas, and a few broad Sunflowers[Pg 12] towering at the back—their great stems coruscating all over with stars of gold; and here and there clusters of purple Clematis, leaning sadly down from a faggot of brown leaves and dead, wiry stalks,—or turning from their weak embrace of some red-brown Cryptomeria Elegans. Even last week the borders throughout the garden looked filled and cheerful—brilliant with scarlet Lobelia and tall deep red Phloxes, and bushes of blue-leaved starry Marguerites, and the three varieties of Japan Anemone, with strange orange Tigridias and Auratum Lilies and Ladies’ Pincushion (Scabious, the “Saudades” of the Portuguese language of Flowers), and every kind of late as well as summer Roses, the evening Primrose (Œnothera) making sunshine in each shady spot, with here and there the burning flame of a Tritoma; though these last have not done well this autumn.

Out near the carriage drive are Golden Rod and crimsoned patches of Azalea, and a second blow of late and self-sown Himalayan (so called) Poppies. In one narrow bit of south border one finds that pretty blue[Pg 13] daisy (Kaulfussia Amelloides)—such an odd, pretty little thing. I remember a bed of it in the garden of my childhood, and I possess a portrait of it, done for me by my mother; and then, never met with it again till a year or two ago, when unexpectedly it looked up at me, somewhere in a remote country churchyard. I am afraid our present stock comes from that very plant. Until now, the long border of many-coloured Verbenas was still rather gay, and the three east gables of the house were all aflame with Virginian Creeper. But two days of rain spoilt us entirely. The variegated Maple slipped its white garment all at once in the night, causing a melancholy gap. In the kitchen garden a bright red Rose or two remains, but along the east border the half-blown buds are rotted away. In the centre of one drenched pink bloom I saw a poor drone, drowned as he sat idly there. Small black-headed titmice are jerking about among the tallest Rose trees, insect hunting; and still tinier wrens flit here and there, bent on the same quest. Great spotted missel thrushes are now haunting the pillar Yews, beginning[Pg 14] to taste the luscious banquet just ready for them. While thus perched amongst the sweet scarlet Yew berries and dark foliage, the thrushes always bring to one’s mind a design in old tapestry.

And this reminds me of the good and abundant fruit-feast we have ourselves enjoyed this season. Strawberries and Raspberries were not much, but such Gooseberries, Apricots, and Nectarines! Peaches, plenty enough, but no flavour. Figs, enough to satisfy even our greediness,—though we have but one tree, on a west wall. Pears, especially Louise Bonne, first-rate and plenty. Apples, a small crop, but sufficient. Wood Strawberries have been ripening under the windows till within the last few days: I planted them there for the sake of the delicious smell of the leaves when decaying—a smell said to be perceptible only to the happy few. Nuts (Filberts and Kentish Cobs) were plentiful, but we were only allowed a very few dishes of them. A large number of nuthatches settled in the garden as soon as the nuts were ripe; they nipped them off, and, carrying them to the old[Pg 15] Acacia tree, which stands conveniently near, stuck them in the rough bark and cracked them at their ease (or rather punched holes in them). The Acacia’s trunk at one time quite bristled over with the empty nutshells, while the husks lay at the roots. The fun of watching these busy thieves at work more than made up for the loss of nuts. We had a great abundance of large green and yellow wall Plums, also a fair quantity of purple. Of sweet Cherries, unless gathered rather unripe, my dear blackbirds and starlings never leave us many. But there were a good lot of Morellos; they don’t care a bit for them. Whilst on the subject of fruit, let me say that never a shot is fired in the garden, unless to destroy weazels. Our “garden’s sacred round” is free to every bird that flies—the delight of seeing them, and of hearing their music, compensates to the full any ravages they may indulge in. Thanks to netting without stint, and our Gardener’s incomparable patience and longsuffering, I enjoy the garden and my birds in peace; and if they ever do any harm, we never know it; fruit and green[Pg 16] Peas never fail us!... Here is a sunny morning; and the cows are whisking their tails under the Elms, as if it were July. But indeed the last lingering trace of summer has vanished: the garden is in ruins, and already the redbreast is singing songs of triumph.

[Pg 17]

NOVEMBER.

[Pg 18]

“The True Pleasure of a Garden.”—Bacon.

[Pg 19]

NOVEMBER, 1882.

Of Blossoms, Buds, and Bowers—Of May and June

and July Flowers.

November 3.—The ruin is complete! and cleared away, too.... Yet there is consolation, and something very comfortable, in the neatness of the dug borders, and the beds made up for the winter.

The symmetrically banked-up Celery—crested with the richest green, in the kitchen garden—rather takes my fancy; so also does the fine bit of colour in some huge heaps of dead leaves, that I see already stored in the rubbish yard. The dead leaves have to be swept away from lawn and garden walks—but I believe we do not consider[Pg 20] any except those of Beach and Oak to be of much service. It is my heresy, that leaves do not fall till the goodness of them has decayed. They are of use, however, when left to cover the ground above tender roots. In the Fantaisie the earthy bed can scarce be seen, so close lies this warm counterpane of leaves! The great Elms, on the greyest days, now make sunshine of their own. Their lofty breadths of yellow gold tower above the zone of garden trees. When the sun illumines them, and the light winds pass, it is a dream to watch the glittering fall of autumn leaves. The ancient times return, and Jove once more showers gold around some sleeping Danae! During the first days of the month, the parterr was done, Tulips put in, and a lot of Crocuses in double row. In a few beds the dwarf evergreens, which had been removed for the summer, are planted in again—just to make the parterr’s emptiness look less cheerless from the dining-room windows. Between these small evergreen bushes, in their season, will come up spikes of Hyacinths, of varied hue. I do not care for a whole bed of Hyacinths[Pg 21] or Tulips; they give me little real pleasure unless the colours be mixed. One chief charm of a garden, I think, depends on surprise. There is a kind of dulness in Tulips and Hyacinths, sorted, and coming up all one size and colour. I love to watch the close-folded Tulip bud, rising higher and higher daily—almost hourly—from its brown bed; and never to be quite certain of the colour that is to be, till one morning I find the rose, or golden, or ruby cup in all its finished beauty; perhaps not at all what was expected. And then, amid these splendours, will suddenly appear one shorter or taller than the rest, of the purest, rarest white. How that white Tulip, coming as it were by chance, is valued! And so, again this year a mixed lot are planted. There was a time when we had only one Tulip in all the garden. I used to look for it regularly in a certain shady border under a Laburnum tree; an old-fashioned, dull, purple and white-striped flower, but it never failed to show, at the very end of every season. I had a regard for that Tulip, and last summer it was a disappointment vainly[Pg 22] to wait for its appearance in the accustomed spot. Many there were of its kind, surpassing it in loveliness; but then they were not the same.

Hyacinth beds will be a new thing here, but I doubt if they will make us quite so happy as has hitherto the unexpected advent of some stray pyramid of small odorous bells, pink, blue, or creamy-white, in out-of-the-way places about the garden. After their flowering is over, the pot-bulbs are always turned out somewhere in the borders. When a plant has lived with us for a time under the same roof, or even in the green-house, giving out for us its whole self of sweetness or of beauty, it seems so cruel that it should at last be thrown away as if worthless and forgotten! Some Narcissus that have had their day have just been put into a round bed on the further lawn, mixed with the “Mrs. Sinkins” white Pink; and there is a rim all round of double lilac Primroses. I have long wished to have plenty of that dear old neglected Primrose; so now we have a number of healthy roots from an old garden in Derbyshire. In the[Pg 23] centre of this bed is a very tall dead Cupressus, one of our few failures in transplantation last spring. A Cobæa, which was to have grown up quick and made a “bonnie green gown” for the poor bare tree, proved failure number two. It absolutely refused to grow, or do anything but look stunted and miserable, till one day, late in October, there it was running up the tree as fast as possible, clothing every twig with leaves and tendrils, and large, deep, bell-like blossoms! Its day must be short, however, at the wrong end of the year, and even now its bells are chilled to a greenish hue. A fine red climbing Rose on one side, and one of the old Blairii on the other, will make a kinder and more beautiful summer garment.

We have made a new Lavender border, and now I hope to have enough for the bees, and afterwards enough, when dried, to lay within the drawers and wardrobes, and give us “all the perfume of summer, when summer is gone;” enough, too, for pot-pourri, though we do not always make this fresh each year. It takes time, and there is so little time in these days! and often the[Pg 24] Roses are too wet, and the Lavender too scarce. The recipe we use is an old one: the paper is yellow, and the ink faded. But our best pot-pourri of these days comes not near the undying fragrance of some Rose leaves—three generations old—that we still preserve in one or two old covered jars and bowls of Oriental porcelain. Along the south wall, an oblong bed is planted with dark purple Heartsease, and two more with yellow. There are six beds, and in the spring they will glow resplendently with a setting of Crocuses, white, yellow, and lilac; meanwhile a good layer of cocoanut fibre gives a look of comfort for the winter; and moreover, rather annoys the field-mice.

Under the Holly hedge, facing south, a narrow border has been made ready to receive a quantity of white Iris roots. The Holly hedge, planted for shelter and for pleasure, along a broad walk on one side of the carriage drive, is not in itself a success as yet. It was put in four years ago, but the trees were too old, I think; this year it is flushed all over with scarlet berries.

[Pg 25]

I am sorry to have to remove my beloved white Irises, but they have increased so enormously as to make some change necessary. Nearly twenty years ago I carried home from the south of France a few small roots in a green pitcher. For half that time they grew and multiplied on the sunny terraces of a sweet Somersetshire garden, and now for ten other years the same roots, transplanted here, have flourished, if possible, still more abundantly. It may be fancy only, but I think our white Irises might not have succeeded as they do, had they not been loved so well. Everybody has a favourite flower, I suppose—the white Iris is mine—the Fleur-de-lys of France—the lily of Florence. Nothing can be more refined and lovely than the thin, translucent petals. To see these flowers at their best, one must get up and go into the garden at five o’clock on some fine morning at the end of May. I did it once, and as I walked beside their shining rows in the clear daylight, I felt there were no such pearly shadows, nor any such strange purity in the whiteness of other flowers. We have[Pg 26] given away a great many, but I fear I am not altogether sorry that they do not seem always to succeed elsewhere as they do with us. I am trying to collect every different Iris I know of. We have now several which are very beautiful, and we should have more were it not that numbers die off after, perhaps, one short summer’s loveliness. They dwindle and become sickly, and then altogether disappear. Almost our whole stock of one well-established kind—an old inhabitant of the garden—was destroyed by mice two seasons ago. The flower is bronze-brown, with a golden blaze in the middle. La Marquise (Iris Lurida?), an old-fashioned dove-coloured sort, with purple frays on the falls, will grow anywhere. So will the large, broad-leaved, pale lilac kind, and the yellow Algerian. A little black wild Iris, that fringes the vineyard trenches about Florence, we have either lost or it will not flower. They call it here “La Vedova.” I brought home some roots once from Bellosguardo, and we put them in where all the warmest rays of the south sun would find them. But only the long, narrow,[Pg 27] wild onion-like leaves appear—or, I fancy, they are the Vedova’s leaves. Still I do not lose hope, but watch for it always when March comes round; and some day, somewhere, I think, my little “widow” is sure to surprise me. The wild yellow Italian Tulip, that came with the Iris, succeeds here well. The patch of pale gold never fails, by the first week in April, to enliven the sunny side of a Yew hedge. A few untidy yellow blooms, supported on slender limp stalks, live there, just the same as in their own dear Italy. I stoop down to gather one, and for a moment the English garden is not there.... Before me lies a grassy vineyard path—there are the great open farm-sheds, full of sunlight and sunlit shade—and the pair of grey long-horned oxen, calmly waiting for the yoke. Near them, with her knitting, stands a patient sad-eyed woman, while happy children run down the path at play, or tie up bunches of yellow Tulips under the fig-trees.... Then there is a tall, white flag Iris, whose place is not yet fairly fixed. It is a handsome thing, and quite unlike the Fleur-de-lys. I think of mixing[Pg 28] it in with the yellow Flags and Osmunda Regalis beside the little watercourse. Last July, to watch the slow blooming of some Japanese Iris in the kitchen garden gave me intense delight. They grew tall and straight, with curiously ribbed leaves. The single flower at the top of each stem opened out very flat, with rounded petals, rich purple in colour, and measuring nearly seven inches across. One saw at once it was the purple flower the Prince, in the German fairy tale, found on the mountains, and carried off to disenchant his love with, in the old witch’s cottage by the wood—only a large pearl lay in the centre of that flower. (There is no such thing as anachronism in fairy tales!)

We have gathered in our harvest of winter decorations for the hall and corridors. There is Pampas-grass with its silken plumes, and soft tassels of all kinds of downy German grasses, and Everlastings of all lovely shades of orange and red. They have hung in bunches head downwards in the vinery to dry for weeks past, and they will last for the next twelve months as fresh as they are[Pg 29] now. I have been told of a great bouquet of Everlasting Flowers, in a Dutch gentleman’s drawing-room at the Cape, which was affirmed to be two hundred years old. We have sheaves of Honesty, also—“Money in your Pocket,” as the poor say—which are to gleam like flakes of mother-o’-pearl in the firelight of December’s dusky afternoons. We left plenty in the garden, however, where they will stand a good deal more of rough weather before they fall to pieces. Honesty is always handsome, in all stages of its growth; and like the people who take things easily, it thrives everywhere. With us it is quite at home in a damp north border, close under a line of Elms. All through June and July, the violet glow of a mass of it in full bloom made a brilliant effect; and now, in these November days, the ripe seed-vessels are transformed—their outer husk has shelled off, leaving only the silvery centre. The other day, in my early walk, just where the Allée Verte ends (no longer green, it is now a golden corridor, with, underfoot, crisp russet leaves), I seemed to come upon—not Wordsworth’s host of[Pg 30] dancing Daffodils, but a company of spirits! The slanting sunbeams fell upon a clump of Honesty, and touched with fire every one of the myriad little silver moons. Though no wind stirred, they seemed to quiver with ghostly life in a shimmer of opal lights.

*****

Nov. 18.—Winter is striding on, and every bit of colour in the garden becomes more precious than ever. Only a few days ago I made a nosegay of crimson summer Roses, a fine Auratum Lily, a Gladiolus, a Welsh Poppy, and a large red-rimmed annual Poppy, with a wonderful spray of Flexuosa Honeysuckle, that filled the room with its fragrance. A little while since, in one sheltered corner, Salvia Patens still held its own in unsullied blue. Marigolds were plenty; St. John’s Wort must have made a mistake in its dates, for it was all over polished yellow buds ready to unclose; Mignonette and a few Sweet Peas lingered still. Here and there one came upon a white Snap-dragon or a flash of rose-red Phlox (“Farewell Summers” they call them in the West). It was impossible not to[Pg 31] admire the vigour and beauty of Primroses and Polyanthus of every colour. One only hopes this abundant autumnal bloom may not interfere with their blossoming in the spring; it is certainly finer than I ever remember in former seasons. A rockwork of big flints was quite gay with Virginian Stock and Primroses. To-day the frost is most severe. The Marigolds look unlike themselves, with a white cap border of frost, quilled round their orange faces; the half-opened buds in a Tea Rose bed are like fancy Moss Roses; only the moss is white, and every leaf is fringed with little sharp-pointed crystals. The China Rose tree by the green door in the wall is covered with pink roses, which I forgot to gather yesterday for my flower-glasses. This morning the frost has curiously changed them. The delicate petals are stiffened all through, as if they were turned into wax models, though their lovely pink is not dimmed, and they smell as sweet as if nothing had happened. By this time our Irish Yews have resumed their wonted sadness. The berries are all carried off, and the blackbirds have fattened[Pg 32] so well on them, and on the bunches of grapes (left for their benefit on the house Vines), that they rise from the lawn quite heavily. I never saw such fat blackbirds! The seed of the Yew berries, which is believed to be the only poisonous part, is, I think, in most cases, left unswallowed; and in one little tree I found the remnants of an old nest filled with a compact mass of Yew seeds. The large blue titmouse carries off his berry to the Sumach tree, and there pecks off the pulp, holding it down with his foot. The larger thrushes are gone, I know not where; only one small bird, with richly spotted breast, is still seen about the grass, under the Stone Pine.

The Chrysanthemums in the greenhouse must have the last word. Nothing could be more beautiful than they are now, and have been for several weeks past. Some of the Japanese kinds are indescribably lovely; arrayed in tints that make one think of a sea-shell, or the clouds about an April sunrise. There is something, perhaps, in their delicious confusion of petals, that helps this wonderful effect of colour. The other sorts,[Pg 33] which are stiffer in arrangement, and more decided in colour, are to me somewhat less delightful. A tiny wren was among the Chrysanthemums this morning, noiselessly flitting in and out, like a little shade; evidently in a state of the highest enjoyment. No doubt I and the bird both took our pleasure with them—in different ways!

[Pg 35]

DECEMBER.

[Pg 36]

“Once a Dream did Weave a Shade.”...

“He who goeth into his garden to look for spiders and cobwebs will doubtless find them; but he who goes out to seek a flower may return to his house with one blooming in his bosom.”

[Pg 37]

DECEMBER.

Of Spiders’ Webs, Christmas Roses, King Arthur,

and the Tree I Love.

December 6.—Among the strange and beautiful sights of the garden during the hard hoar-frost that ushered in the first days of the month, not the least beautiful were the spiders’ webs. Passing along the Larch Walk, the oak palings that divide us on that side from the new road (the old road, made by Richard, King of the Romans, in the thirteenth century, is now within the grounds) were hung all over with white rags—or so it seemed at first sight. And then, just for one second, that curious momentary likeness of like to unlike chanced. I remembered the street of palaces at Genoa, the day when I saw[Pg 38] it last; the grand old walls covered with fluttering rags of advertisements—yes, advertisements in English: “Singer’s Sewing Machine.” The white rags on our palings were spiders’ webs both new and old, a marvellous number, thus crystallized, as it were, into existence by the frost, where scarcely one had been before. In open weather the webs are as good as invisible to human eyes; but now that frost had thickened the minutest threads to the size of Berlin wool—though in beauty of texture they resembled fine white velvet chenille—there was a sudden revelation of these wonderful works of art! One feels, if the nets show only half as large and thick to a fly’s eye, the spider’s trade must be a poor one. Here is a calculation that will probably interest nobody: 567 feet of pales over 5 feet high, and an average of 18 webs to every 9 feet. It may prove, however, something of the unsuspected multitude of spiders in a given area, though it is nothing to the acres of ploughed land that the level sun-ray of an autumn afternoon will show completely netted over with gossamer. Making the[Pg 39] most of a few minutes’ inspection—for I should myself have frozen had I watched much longer these frozen webs—I could see but two varieties of work—the cobweb which usurped the corners, and the beautiful wheel-within-wheel net. In them all one might observe once more that ever-recurring stern immutability of the thing called Instinct. Here, for instance, are two sets of spiders living close neighbours for years together. Each set makes its snares on an opposite plan; and although they cannot help seeing each other’s work continually, neither takes the least hint from the other. The plain cobweb is never made more intricate; the artist of the wheel never dreams that she might do her spinning to a simpler pattern. Happy people! They trouble not their heads about improvements; yet, on looking closer at the last-named webs, there seemed something of the faintest indication of a slight individuality; so far at least, that in a dozen nets there would be five or six worked within a square of four lines, while the remainder had five, tied rather carelessly in a knot below. Perhaps the variation[Pg 40] marks two distinct species; or it may be only accidental. Next day every visible trace of the strong beautiful webwork I had so admired was gone with the frost. The spider may have “spread her net abroad with cords” as usual, but there was no magician’s wand to touch it.

*****

The orchard ought to be very gay in the spring. Daffodils have been dropped in all over the turf, and a round patch dug round each Apple tree is to be filled with yellow Wallflowers. This is an experiment, and I do not feel sure that I shall like the flowers so well as the trees simply growing out of the grass. A change, however, is always pleasant; though, perhaps, one might hardly care to lay out the garden differently every year, as the Chinese are said to do. I had a dream, of the orchard grass enamelled with many-coloured Crocuses—in loving reminiscence of certain flowery Olive grounds I know; but after all, the imitation would have been as poor as a winter sky compared to the glowing blue of June. I am not without hope some day—that golden “some day”[Pg 41] which so seldom comes—to naturalize in our orchards the real enamelling of the Olive groves—that often-used phrase is too hard in sound and in its usual meaning to express the loveliness of those lilac star Anemones—with here and there a salmon-pink, or a fiery scarlet, blazing like a sun in the living green beneath the trees. I used to think nothing on this earth could come so near a vision of the star-strewn fields of Paradise.

In the north, or entrance court, we have been busy transplanting some large Apple trees that had overgrown their place, and setting free the trimmed Yews between which they grew. The blackness of these formal, cut Yews shows well against the old walls, which are covered with very aged Greengages and golden Drops. On the turf between each of the pyramid Yews, broad oblong beds have been made; in April we hope to plant them with pink China Roses, which are to grow very dwarf, and to flower the whole year through! The border round the Roses may be blue Nemophila; or perhaps the lovely Santolina Fragrans, with the soft grey foliage.

[Pg 42]

I think the “going in” to one’s house should be as bright and cheerful as it is possible to make it. But how hard it is to brighten up a north aspect! ours has hitherto been far too gloomy. In the garden, the bed of Roman Roses is warmly matted over for the winter. This brave little red China Rose is one of my great favourites; it goes on flowering for ever! Even now, when the matting is raised a little bit, I can see buds and leaves and the red of opening blooms. I call it the Roman Rose chiefly because it grows at Florence; which is so very Irish, that I think there must have been some better reason now forgotten. The Rose hedges in the beautiful Boboli Gardens are crimsoned over with blossoms as early as the end of March; with us, however, it needs protection when planted in the open ground.

Under the east wall is our only Christmas Rose; it is a very large plant, and over it was built up, about a month ago, a little green bower of Spruce Fir branches. The shelter is to save the blooms from frost, which so often tarnishes their whiteness[Pg 43] with red. Almost daily, as I passed, I have peeped in to watch the cluster of white buds nestled snugly within. The buds have duly swelled and lifted one by one their heads, and now this morning our first bunch of perfect Christmas Roses has been gathered. This flower must, I think, be dear to every one with a heart for flowers. Its expression is so full of innocence and freshness—for it is not only human persons who have expression in their faces! and then the charm of its Myrtle-like stamens and clear-cut petals—snow-cold to the touch—and its pretty way of half-hiding among the dark leaves—always ready to be found when sought—and always with so many more blossoms than had been hoped for! To some, indeed, the associations bound up with the Christmas Rose—with even the sound of its name—may be dearer than all its outward loveliness; recalling, perhaps, the house and garden of their childhood, and happy Christmases of long ago; “the old familiar faces,” and tones of the voices that are gone. I must here make the confession that last year, in my anxiety for the whitest possible of blossoms,[Pg 44] I had glass placed over the plant; and in spite of warnings, put matting over that; all which ended at Christmas in a fine show of green Roses! In the pits there are several of the smaller kind coming on in pots, which will soon be ready to cut. These are easy enough in their ways. But the Christmas Rose out in the border is a difficult thing to grow; full of quirks and fancies, and like a woman, hard to please. Once, however, it settles down in any spot, it will thrive there; and then will sooner die than take to a new place.

Dec. 13.—Our second white frost has vanished, and the grass appears again with a moist and pleasant smell. The forest of the Fantaisie is thinned, and the encircling Laurels trimmed. The whole took just half a winter’s day to do. At the end of the turf walk, between the bushes and the golden Yews, peers out a Spindle tree, with its pink and scarlet fruit. The birds seem not to care for it, for the fruit is all there—untouched. I wonder if the name of Spindle comes from the unnatural thinness of the tree!

[Pg 45]

After these many years of working to a special end, we seem now to have almost reached it in one direction, for the garden looks well-nigh as green and furnished in winter as in summer—so far, at least, as the outline of verdure goes. The Yew hedges, and Pines, and perennial greens are at their best now, in mid-winter; they would even seem to have grown and thickened out since the summer died away. Watching the growth of these trees and hedges has been the delight and solace of many a troubled time, and one cannot but feel the most affectionate interest in them. In the centre of a triangular-shaped bit of lawn, surrounded by Conifers, we have placed a large stone vase on a square stone pedestal. The vase is old and grey, and had long stood in another place, where it made no show. The grey stone looks well against the warm greens that back it, and will look better when the season comes to fill it with bright summer flowers. The trees that stand around all wear a sort of charmed double life—at least to me—silently, fancifully.

It was at a time of sickness that the sleepless[Pg 46] hours of the long winter nights came to be passed in spirit with the trees in the garden, and especially with half-a-dozen or so of our beautiful straight young Pines. Dare I tell the secret? They all became knights and ladies of King Arthur’s Court! The great Wellingtonia standing a little apart is Arthur himself. The Nordmanniana, with its whorls of deepest green and strong upward shoot of fifteen inches in the year, is Sir Launcelot. The gold-green softly-feathered Douglas Fir, Sir Bedevere. The young Cedar of Lebanon, with fretted boughs of graceful downward sweep, Sir Agravaine. Sir Bors is a rounded solemn English Yew, of slow and steadfast growth. Sir Palomides—a fine pillar-shaped Thuia—towers between Sir Gawaine and Sir Gaheris, who are both clad in the wondrous green with almost metallic lustre of Cupressus Lawsoniana erecta viridis. These all stand round the triangular lawn, and amongst them comes, by some strange chance, St. Eulalie, a lovely Pine (Abies Amabilis), whose robe of grey-blue tufted foliage wraps her feet, and trails upon the grass.

[Pg 47]

Beyond, on the long lawn next “the par,” stands Sir Tristram, the fine young Pinsapo; he all but perished in the frost of 1879-80, but now he seems to have drawn new strength and vigorous green from that nearly fatal conflict with his terrible enemy. On the house lawn, the Deodara, is the fairy Morgan-le-faye. Near her stood Sir La Cote-mal-taille, an ill-formed Lawsoniana; but he is now transplanted elsewhere. King Mark is a rather wretched ill-grown Cedrus, in summer almost hidden by Laburnums. Dame Bragwaine is a curious Cryptomeria Elegans; she has so many names (seven, at least, that I know of), and she takes such odd diverse disguises! once, loaded with heavy snow, she had to be supported by a stake, and took the semblance of a bear leaning on a ragged staff. In summer she is green, and in winter she wears a dress of purple brown; in rain or heavy dew she is spangled all over with diamonds and pearls. Queen Guinevere was never represented; no tree was found to fit her character. But near King Arthur and Sir Tristram, the two great Pampas tufts, still waving wintry plumes,[Pg 48] are “La Beale Isoude” and “Isoude les Blaunch Mains.”

From our foolish garden-dreaming let us rest, and turn with a long look of revering love to the great Oak, that stands in his strength out in the park field, beyond the garden. On three sides round are lines of guardian Elms, in all their pride of delicate leafless intricacy; alone, amid the leafless ones, rises the Oak, wearing still his crown of brown, sere leaves. Smooth and straight grows up the giant stem, full twenty feet to the spring of the lowest branch. Two brother Oaks stand on either side. Their form is more rounded, more perfect; but high above them the great Oak uprears his head—unconcerned, and grandly branched, though shattered by every fierce west wind that blows. Every storm works some loss, but from the way each torn limb lies, you would say he had thrown it down in proud defiance. The wood-pigeons shelter among the summer leaves; the autumn ripens a rich store of acorns; and now, as I survey him from the terrace walk, or gaze upwards from the wet dead leaves beneath, through all the mystery[Pg 49] of his bare and spreading boughs, I think of Keats’ stanza—

The Oak is to my mind the tree of trees; and the destruction of its foliage, by insect ravages, that has year by year saddened so many parks and woods, has not come near us, I rejoice to say. Our few (there are but four or five) are safe as yet. I heard the gardener of one great place that had suffered much acknowledge as the cause the scarcity of birds.

[Pg 51]

JANUARY, 1883.

[Pg 52]

“To the Attentive Eye, each Moment of

the Year has its own Beauty.”—Emerson.[Pg 53]

JANUARY.

Of Field-Mice, and the Thorn of Joseph of Arimathea—Of “Poor Johnnys”—A Lilac Gem—and Greenhouse Flowers.

January 5, 1883.—A large body of the army of the small ones of the earth has attacked us, and it is no fault of theirs if we are not despoiled of the best of our spring delights. The field-mice have at length found out the Crocuses; we, on our side, have set traps in their way, and large numbers have fallen—quite flat, poor little things!—under the heavy bricks. We believe we should have slain many more, had not some clever creature made a practice of examining the traps during the night, devouring the cheese, and[Pg 54] in some way withdrawing the bit of stick, so as to let the brick fall harmless. Suspicion points towards one person especially—the old white fox-terrier, who lives in the stables, and is master (in his own opinion) of all that department, and whom neither gates nor bars can prevent going anywhere he chooses to go. “Impossible!” says he, with Mirabeau; “don’t mention that stupid word!” Up to this time field-mice have not troubled us much. In the days when there was always a hawk or two hovering over the ploughed land, or keeping watch over the green meadows, and when we used to hear the owls in the summer nights, and saw the white owl who lived somewhere near by sail silently in the grey of evening across the lawn—in those days we knew little of the plague of field-mice. But now we have changed all that; cheap gun licences have put a gun into every one’s hand, the vermin is ruthlessly shot, and the balance of Nature is destroyed.

It is rather a fearful pleasure that we take just now to mark the unwonted earliness of green things of all kinds. One cannot help[Pg 55] dreading that some great check will happen later on in the year; and yet it may be an omen for good that the birds’ full concert has only just begun, in these dark mornings, amongst the trees of the garden. The saying goes in Scotland, “If the birds pipe afore Christmas they’ll greet after;” and so far as I know, not a note was sung till December 30. The birds served our Hollies a good turn at Christmas. In November the Hollies were scarlet with berries, and one thought with a shudder of how they would have to suffer, when the time came for Christmas decorations; then occurred two short severe frosts, and, to my joy, the Holly trees were swept clear of every tempting spot of scarlet before Christmas, and thus were saved the customary reckless breaking and tearing of branches. Dear birds! Does any one ever think, I wonder, sitting in the summer shade near “some moist, bird-haunted English lawn,” how dull it would be without them—how much they enhance for us the grace and charm of the garden and the country? It is their gay light-heartedness that is so[Pg 56] delightful, and that we should miss so much if they were not there. Who ever saw a grave bird?—at least I mean a grave little one—the bigger the sadder it is, with them. Their very labours of nest-building, and of feeding their young ones, are done like a merry bit of child’s play! The birds’ never-failing interest in life is like a sort of tonic to those who love them. Michelet felt this when he called them “des êtres innocents, dont le mouvement, les voix, et les jeux, sont comme le sourire de la Création.”

I do not remember having seen before in mid-winter a Hawthorn hedge bursting out into leaf! At the end of last month, however, there were strong young shoots and fully formed leaves on some of the Quicks in a hedge planted last spring in our lane. I have known nothing like this, except the Glastonbury Thorn. There is one of these strange Thorns, a large tree, growing just within the park gates of Marston Bigot, in Somersetshire. It used to bloom with great regularity in mild winters about this time. Tufts of flowers came all over the branches, smelling as sweet as Hawthorn in May. I [Pg 58]have often cut a long spray all wreathed with pearly bloom, on New Year’s Eve, in former years. The flowers come with scarce a sign of leaf about them, and they are rather smaller than those of the common May. The emerald green of turf, thickly sprinkled with Daisies, seems also an unusual sight for January. The first green glow on the grass and the first Daisy we are surely used to hail as signs of approaching spring. On the lawn, too, a yellow Buttercup, careless of the heavy roller, has dared to hold up its head!

The Boccage and Part of the Fantaisie

1. Glorietta. 2 Large Elm and line of same

3 Border of Blue Gentian. 4. Pigeon House

Grass Paths & & &.... (click image to enlarge)

Jan. 8.—The weather has been for many weeks so dark and gloomy, that the rare sunshine which shone upon the land to-day was as welcome and nearly as unlooked for as May flowers in January. The house stood blocked out in sun and shadow. Magnolia Grandiflora, which covers the south-east gable, looked grand in this flood of radiance. Standing before it, the refrain of a wild canzonetta I once heard, chanted forth lazily in the little sun-steeped piazza of an old Italian town, came back to the mind’s ear—“Oh, splendid bella!” The eye, soon tired,[Pg 59] however, of so much dazzling brilliance in the polished foliage, each leaf reflecting back the sun, follows the ascending lines of beauty up above the pointed roofs, where the soft golden rust of the topmost leaves’ inner lining meets the deep blue, cloudless sky. Next the Magnolia, just under the painting-room window, is a Flexuosa Honeysuckle which has not lost a leaf this winter. New shoots and twists of brightest green, set with young leaves two and two, are springing all over it. One tender shoot, indeed, has had the heart to curl twice round a branch, sending out a length of spray beyond.

Hard by the Flexuosa flourished once a fine Gum Cistus. To my sorrow, it perished in the frost of two winters back. The aroma of its gummy foliage, under the noontide sun, would penetrate deliciously through the open windows. We lost that winter all but one of our Gum Cistus, and their destruction was so universal that there was a difficulty in replacing them. I like the Gum Cistus best when growing upon the lawn. The snow of fallen petals on the grass seems right, and gives no sense of untidiness, there.[Pg 60] The loss of the Cistus, however, made room for better growth to the old Maiden’s-blush Rose in the corner, by another window. She has hard work, anyhow, to hold her own against the flowery smothering of an Everlasting Pea, which persists in spreading beyond all bounds, notwithstanding the hints it yearly receives from knife and spade. Further on, still under the south front, a white Hepatica (Poor Johnny) is already shyly blooming. The root is sheltered by its own undecayed leaves; other plants of the same kind being quite bare. Hepaticas in England almost always look discontented, and this is no marvel to any who have seen them wild in their own place. I remember as clear as yesterday the joy of finding the blue Hepatica for the first time. It was in a narrow lovely valley at Mentone, on a mossy bank beside the little stony river. We were gathering Violets, which abound in that place; but on the edge of the bank, and over its steep side, intermingled with deep Moss and Ferns, there was another blue, which was not the blue of Violets. It was like the surprise[Pg 61] and wonder of a new world thus unawares to come upon such a flower—the beloved of childhood—in such rich profusion—a flower we had never seen before that happy day, save in rare scanty patches, in some damp garden border! About the same time I saw also both the pink and white Hepaticas, from the Pine woods on the slopes of the Alpes Maritimes. In a corner near the Hepaticas is a little patch of Violets with Bella Donna Lilies. The Lilies are sending up strong, healthy leaves, and that is about all they will ever do to please me. Fine, good roots were put in six years ago in this choice south corner, where I believed they could not but do well. But no; it is in vain I watch and hope!—not one of those exquisite “harmonies in ink” I so long to enjoy do they vouchsafe to give me. Possibly they may object to the society of the Violets!

Primroses have been with us more or less since September last, and now they are more abundant than ever—all colours—red, brown, yellow, white, sulphur: the garden is quite full of Primroses. Roses, also, we have scarcely been without all winter. Within[Pg 62] the walled garden there are real red Rosebuds, rather tightly closed up, but capable of opening any day. Many Rose-bushes have never lost their old leaves, and some are already putting forth new. On the top of the wall I perceived to-day a white spot—it was a Gloire de Dijon—looking very pale, but fully opened; and below it the Marcartney and an Apricot Tea Rose are in bud. A space of kitchen garden wall by the north iron gate is resplendent with Jasminum Nudiflorum, and close by, the bare branches of a Fig tree are already pointed with green, recalling in a dim way the Fig trees of the South, which in March glow like great branched candlesticks lighted up with flames of golden-green, in honour of the coming festa of spring. The Pyrus Japonica—a very old plant—has opened two coral cups. But the gem of the whole garden just now is a small, most delicately yet brilliantly tinted lilac Iris.[1] The contrast between it and the rich dark green of its reed-like leaves, amidst which the flower shines, is charming. It is only in the mildest of winters [Pg 63]that it ventures to appear. Last year the date of its blooming first was February 10. There are several tufts of foliage, but as yet only this one perfect flower, and we find rarely more than half-a-dozen in the season. In “the land of flowers,” however, which I believe to be its own, the paths of many a Cypress and Ilex-shaded garden must be lined with lilac and green, at this very time. I often think how little use is made of that most poetical of colours, lilac—“lalock,” as our grandmothers used to pronounce it. It was Schiller’s favourite colour; but I hardly know of any one else particularly caring for it. Perhaps one reason may be, because it is so hard to mix the most lovely shades of lilac in painting, or in manufactured stuffs; and then it is so evanescent. Even Nature herself does not make use of lilac so freely as of other colours—yellow being, I almost think, her favourite. She has, however, hit the mark indeed in the colouring of my lilac gem; there is a sharpness in the flavour—so to speak—which makes it perfect. The dear little winter Aconite—each bud of pure clean yellow surrounded with its green frill[Pg 64] of leaves—appears here and there among the damp dead leaves. Snowdrops are showing daily whiter and larger above the ground, and all sorts of green peaceful spears are piercing in their strength, up through the black mould everywhere.

[1] Iris Ensata.

We have got through some rather important work within the past three weeks. A new Beech hedge has been planted on the open side of a green walk or close, already hedged in on one side. I once read somewhere of how it is reckoned good for the health to walk between Beech hedges, the air being purified and freshened by passing through the leaves. An old border, full of bulbs and Damask Roses, has been dug and rearranged. The Roses, which are old plants, will be refreshed and improved by the moving, and we shall add some day one or two York and Lancaster Roses. In this border the Grape Hyacinths have increased so rapidly that it is literally full of them, and we are planting them about in different places, some under the Deodara (Morgan-le-faye) on the lawn, with Snowdrops and Daffodils. The Deodara is in the[Pg 65] wrong place, and was spreading so much as to injure the effect of the Yew hedges. So, instead of cutting it down, it is trimmed up to eight feet or so from the grass; and for this act I have had to brave a perfect storm of adverse criticism! In a few months I hope the stem will be clothed with Virginia Creeper, which, when touched by Autumn’s fiery finger, will become a pillar of flame, while wreaths of white Clematis (Virgin’s Bower) are to light up the green in summer. Then we have been planting out four fine tree Pæonies on the turf by the entrance drive. In their season they will be as beautiful as great cabbage roses.

There have been two days of frost and bitter cold, and yet the impatient flowers are not discouraged. At the further end of the broad walk, down among the broken Fern and withered leaves, a sense of colour is felt in the border as one passes by. Omphalodes Verna (would that dear English names were possible!)[2] is wide awake, and little[Pg 66] eyes of cœrulean blue are looking upwards. The Rock Roses are full of bud, and small variegated-leaved Periwinkles, on a low wall, already begin to tip their hanging sprays with stars of misty grey. But the strangest effort of all is a Foxglove spire of buds, rising well up from its leaf-crowned root on an ancient stump of Wistaria.

[2] Since writing this, I learn that the English name is French Forget-me-not, and that it is a flower once beloved of Queen Marie Antoinette.

The mention of all these flowers would make it seem, I fear, as if our garden were even now a sort of flowery Paradise. The truth is a sad contrast to every such idea; for though the beautiful things are all in truth here, it would be difficult to describe the heavy gloom and damp of the whole place. And so one turns more often than usual to the greenhouse for consolation. Small as ours is—only about fifteen paces long—it is large enough for as much pleasure as I desire, under glass. To me the open garden is daily bread, the greenhouse “the honey that crowns the repast.” There happens at this time to be a chord of colour there, worth noting—ivory whiteness of Roman Hyacinths, green of all exquisite gradations, pale yellow of Meg Merrilies[Pg 67] Chrysanthemums; others of a warmer yellow, and pure white; fairest pink of Primulas, and a deep purple note, struck once or twice, of Pleroma. What a flower that is! how charming in its way of blooming sideways on its stalk, to let the sun shine through its violet translucence!

[Pg 69]

FEBRUARY.

[Pg 70]

With the Trees of the Garden.

[Pg 71]

FEBRUARY.

Land of Mandragora and the Serpent Flower.

February 13.—If the West Country farmer’s rhyme prove true this year, the “dry” will have a heavy debt to pay! Some of the gravel walks in the garden are quite green, along the sides where the almost ceaseless rain flows down. All our dressed stone—sun-dial, vases, steps—is discoloured and green, and will all have to be scrubbed with hot water and soap, like the rocks in[Pg 72] the great rockery once described in the Gardener’s Chronicle (vol. xviii., p. 747). A large part of the grounds has been under water nearly all through the winter; the “wet,” however, in which they sometimes stand ankle deep for weeks, seems not to do any harm to the evergreens here; whilst we get from the floods charming landscape effects. I could almost wish the glassy meres, with their clear reflections of tree or sky, to be permanent.

I have been looking over and making notes of our Fir trees—we have only about a dozen or so, I am afraid! I find that Pinus Austriaca thrives better than any other here; it is a regret to me that we did not plant numbers more of them, instead of wasting years in trying to make Scotch Fir succeed. Spruce never seems to do well in this part of the country; we have two or three old Spruce Firs which are mere poles, and some much younger, which must be cut down to relieve our eyes from that garden misery, a sickly tree. Only in the “Fantaisie” are our Spruce Firs successful, and there, from overcrowding—for there are at least ten—they are well-nigh[Pg 73] spoilt. This little spot has proved good for them, I imagine, because it was new ground, taken in from old unbroken pasture and well trenched. One or two others, full and healthy, of a few years’ growth, suddenly went off last summer; it was as if a blighting wind had scorched their branches, or lightning had seared them. I know no successful Spruce plantations anywhere in the neighbourhood. The soil is gravelly, with chalk and flint; and sometimes trees seem to strike their roots down into a subsoil—perhaps an intermittent layer of greensand—and then they go off. But this can scarcely be the only cause that so fatally affects our Firs. About 120 miles down west, there is a group of extremely fine Spruce Firs that I have known for the last thirty years, and when I visited them last year I found they had all gone off in the same way as ours here. Excelsa Grandis flourishes equally with Pinus Austriaca. One fine young plant in the “Fantaisie” was, as one says, “quite a picture” in the summer for the perfect symmetry of its form, and on the two topmost laterals were just two beautifully shaped upright green[Pg 74] cones, crested with amber-coloured gum! I rejoiced in this young tree during all the season, but there is a fear since then that it may suffer in its growth from the premature effort. The Balm of Gilead Firs, a few of which we put in along one side of the turf walk, have failed entirely. I meant each to become a little rounded beauty, like that one planted by my father, which I remember long years since as a wonder of aromatic greenery; but these are grey and stunted, and they all wear such a look of age and decay as I fear we cannot long endure to see. The crisp leaves, however, are as sweet when crumpled in the hand as they ought to be. With two or three of these piteous little trees, the branches show, without losing stiffness, a certain tendency to droop or turn downwards at the extremities. It is rather curious, this droop, affected by a few individuals in a Fir plantation! For they do not begin life with that intention; the young tree may be just like any other for years, when suddenly one branch will be observed turned down, then another and another, till finally the whole thing is decided, and the tree becomes a [Pg 76]“weeper,” as some call them. In a large plantation in Aberdeenshire, some years since, I knew one young Silver Fir out of all the others that grew itself into a drooping form, so that it seemed at last to draw down its branches close together as one would draw a cloak around one in the cold. It was then ten or twelve feet high, and now it must indeed be a remarkable object if it has grown and drooped at the same rate. Our Douglas Fir (Sir Bedivere) has known this temptation to droop, but evidently the feeling of the mass of his branches is dead against the idea, and it will come to nothing.

Fair Maids of February.

This accident or sport is common in other trees all over the world, I suppose, and one of the most ancient nomadic patterns of Persian rugs depicts, on either side the Tree of Life, the columnar Cypress and the drooping Cypress, beside a little tomb.

In various odd nooks and corners of the garden, I know where to find a few little old Cephalonian Pines, all that remain out of a number we once had. They are only about 4 or 5 feet high, yet they were grown[Pg 77] from seed over a quarter of a century ago. Like poor old useless retainers, they have followed the fortunes of the family, and we have become attached to one another. One amongst the original number became a fine specimen—and perished. The rest have never had a chance of growing up, for every spring their new buds are nipped, so they remain still the same, with a sort of look of old-young trees. I am especially interested in the welfare of one of the Cephalonians, who lives in an English Yew. Those two are certainly bosom friends! The Yew itself was only half a tree, spared, out of charity, on what seemed a bare chance of surviving. The Cephalonian stood near and shivered, and lost its buds every spring, while the Yew crept nearer and nearer, till at last its thick dark foliage reached the little Pine, and so grew on; and now the Yew fairly holds it within its warm, comfortable embrace. Some say, “What a mistake to leave them thus!” I say, “They shall not be parted;” so the two remain together, and grow quite happily in each other’s arms. Oddly enough, the Pine seems to be[Pg 78] assimilating itself in colour, and partly in form, with the Yew, so that it is not easy to distinguish them. But if the Cephalonian at last out-tops its benefactor, what will happen then? At times the space of ground over which we reign seems to be very much too small; and I incline to envy the possession of land, with room enough to plant; for there can be no more engrossing interest of its kind than to watch the growth of trees, their manners and customs. I would plant at once acres of Ilex Oak. What shelter they would make! And in a congenial soil they would not be too slow of growth. There should be broad bands of Beech and Oak, and long groves of Larch, delicious in spring for the fragrance of their green and pink-tipped tassels. And there should be plantations of Fir—Scotch Fir, for the delight of their healthy blue-green in youth, and for the glory of their great red stems in age; and Spruce Fir, with all their charm of deep mosses underneath, and the loveliness in spring of starry Winter-green (Trientalis Europæ) and “the rathe Primrose;” and for the music of the winds among their[Pg 79] branches, and the velvet darkness of their colour under summer skies. (Mem.—The Winter-green would have to be sent us from the North.)

Our great work of last month has been an alteration at the east end of the garden. A Quickset hedge, forty or fifty years old, is moved back, so as to take in from “the park” a bit of waste ground; the gravel path that ran under the hedge is widened, and a block of Laurels cut through. By this means a turf way, leading north and south, is made to enter the improved walk, whose chief attraction is the border of old damask Roses. Plum trees and Pears stand along the border amongst the Roses, and a large perennial yellow Lupin, in which thrushes have been known to make their nests. In the middle of the hedge grew a fine young Elder. I had long promised that Elder it should never be cut down, so when the Hawthorns were removed the tree remained, arching across the path to meet a Plum tree on the other side. An Elder in full bloom is such a beautiful thing that it is painful to feel obliged to destroy it; but Elders have such[Pg 80] an unfortunate knack of appearing where they are not wanted! The birds sow Elder seeds in the clefts of trees, in chinks of walls, flower borders—all sorts of inconvenient places—now that the berries are no longer requisitioned to make Elder wine. In old-fashioned days it was worth having a cold, to enjoy a night-cap of Elder wine from the saucepan on the hob! So this one tree is preserved in honour, as compensation for those others which are no more. I am not in the least superstitious, but it is rather uncanny to cut down an old Elder! Eldritch legends and spells have clung to the tree in days of yore, and have even come down to our own times. I used to listen at my mother’s knee, and beg again and again for the story of the fairy changeling. The interest of the story never failed, and the rhyme never tired, about the enchanted hare, who ran—

According to custom, I was rather on the look-out for treasures when the old hedge[Pg 81] was dug up, but nothing appeared excepting a huge yellow bone and a gigantic root of White Briony. The uncouth thing bore a strange resemblance to some organized being with arms and legs—something like an octopus in full swim, only twenty times as big, and yet also with a sort of human aspect! I was told it was a Mandrake (though it did not shriek on being pulled up), and so I desired it should be carefully buried, in order that the household might not be disturbed by its groans at night. In India the sounds emitted by a Mandrake in the dark night are said to be sometimes heartrending. And so the witch, in the Masque of Queens—

I wonder if White Briony is really the true Mandrake, about which there must seriously be something mysterious. I find in the dictionary, “Mandragora (Mandrake), a powerful soporific. Mandrage, a plant said to be so called because it points out that a cave is near.” I know no more, besides the wild traditions, and this vision the other day,[Pg 82] in the twilight, of a white misshapen figure lying on the earth. There are, however, few things more exquisitely graceful than the Black and White Brionies. Black Briony is rare in our part of Buckinghamshire. In this garden three White Brionies have leave to dwell. All winter, the mystic root lies hidden, awaiting the appointed time. On a day in spring or early summer, suddenly up-springs a group of delicate pale green stalks, and they, as soon as they have seen the sun in heaven, delay not to put forth all the strength stored under the earth in the big ugly root; and before many days the green stalks have grown into a beautiful leafy plant, mantling over whatever is nearest of tree or bush, with leaves of most fanciful cut, and a thousand ringlets of circling, sensitive tendrils. By-and-by there will be a whole firmament of little star-like flowers, greenish-white in colour—all either male or female, according to the plant. In October an unhappy collapse sets in. Life ebbs fast from the flaccid stalks and tendrils, dying away, sinking down, down into the buried root, till nothing remains but a dry colourless shroud,[Pg 83] clinging close over the supporting shrub, which scarce can breathe, till a friendly hand in due course clears the whole thing off.

I think I never saw a finer show of white Arums than we have just now. There is the grandest luxuriance of foliage, with thick tall stems, crowned by spathes in spiral lines of perfect grace. The rich texture of these flowers is marvellous; white as the drifted snow, with a lemon scent. Our success is perhaps due, not only to good management, but to what one may call imported bulbs. Four years ago they were thrown out of a garden at Cannes, as worthless rubbish, on to the road-side. I passed that way one day, while a little peasant girl was collecting some of these bulbs in her pinafore. I asked her what they were. “Des lis!” she said. So I immediately gathered up some for myself, and they were done up in newspapers and packed in our trunks and brought home. In grim contrast to these joyous flowers of light is the Serpent Flower, a tropical member of the Arum family. I saw it, once only, eleven years ago, in the beautiful garden of[Pg 84] Palazzo Orenga, at Mortola, near Ventimiglia. It grew on the edge of a ravine, under the deep shade of a low stone wall. Right up from a cluster of black-spotted leaves the centre spiral rose to about ten or twelve inches, bending over at the top into a sort of hood, like the hooded head of a cobra. The creature—flower I cannot say—took the attitude exactly of a snake preparing to spring, the body marked and spotted the same as a snake, with the hood greyish-brown. The whole thing seemed something more than a good imitation only of the reptile whose name it bears. The first glance gave a sort of shock, as if on a sudden one had become aware of the actual presence at one’s feet of a deadly serpent; and yet the terrifying object is, I believe, used by the Indians as an antidote to snake-bite.

All over the Olive grounds of the same country where the Serpent Arum is acclimatized, about this time or early in March, appear the little brown “Sporacci”—tiny hooded Arums of quaint form, little odd monks with yellow tongues hanging out (Arum Arisarum). My window is full of Paper[Pg 85] Narcissus—Narcissus is Remembrance; and for the sake of past days, I love it—they succeed a set of blue Roman Hyacinths, dear also from association, and beautiful in their full tones of blue and green. The perfume of both flowers brings back vividly the sweet South, where I knew them wild. I must end with a little bit out of a letter sent me from that southern land which has the power to create lovers of Nature:—

“I am longing for sunshine, to bring to life all the flowers I am watching for near the torrent beds. My ignorance of flowers has this advantage, that each leaf is a mystery to me, and I know not what flower it frames, so each will be a surprise as it appears.”

[Pg 87]

MARCH.

[Pg 88]

[Pg 89]

MARCH.

Of Rooks, and the Close of Day—Of Fairy Garlands, Snowdrops, and Wild Ivy.

March 9.—We are rejoicing in the fulfilment of a long-felt wish, and at last we possess a rookery! There are the nests, seven of them, in the Elms, in full view of our east windows. The grand old trees have always seemed to us a most tempting position for the rooks, who themselves have half thought so too. But it has taken them long to come to a decision. On many a spring morning for these eleven years past have we observed them settling upon the trees in hundreds. But after a short interval[Pg 90] of noise and clamour, they would rise and depart. They were only coquetting a little with us, or bent on kindling delusive hopes. “Ill blows the wind that profits nobody,” however; so the storm of April 29 last year, which uprooted some of our best trees, laid low also part of a neighbouring rookery. The shock seems to have decided the rooks, and to have won their confidence in our noble 300-year-old Elms. The seven nests were begun and nearly built in about as many days. How busy the old rooks are! And how, with no hands and only one beak, they can make up those neat bundles of moss and dry grass, just like potatoes, that we see them carrying to line the nests with, is difficult to understand. During the rough snowy weather no work was done; but a rook or two sat all day just above the nests on the very topmost twigs, swaying in the wind, as if to watch and test their security. One evening at dusk, after the rooks had gone off for the night, an inquisitive starling came peeping about. He flew up from his own lower range, visiting every nest; made a minute inspection inside and out, and then[Pg 91] decamped in a great hurry, afraid of being found out.

Near the great Elms, but far below the new black colony, is the dovecote. Beautiful white fantail pigeons, varied by two or three purple-necked greys, here live joyous lives. On the steep, heather-thatched roof they preen, and coo, and make love together, or rise with sudden dash into the air, and wheel in circling flight over the lawns and flower-beds. On sunny days, when they pass and repass the house, swift gleams flash along the rooms within; brown oak panellings reflecting back the sunshine from their silver plumes. Often, through long summer afternoons, will these bright shadows come and go upon the walls, like visions of happy ghosts upon the wing. It is not all poetry, however, with our fantails, I am afraid; for the handsomest of them all choked himself with too greedily swallowing a slug one day, and was found stretched dead upon the lawn. Sometimes a poor tailless fugitive, escaped from the nearest public-house shooting-match, will take refuge with our pigeons and feed shyly with them for a day or[Pg 92] so; but only one ever remained, and she went to live with the bantam cock, whose pert little wife had deserted him.