|

NORTH BY NIGHT |

| BY PETER BURCHARD | |

| |

| COWARD-McCANN, INC. NEW YORK | |

Second Impression

© 1962 by Coward-McCann, Inc.

All rights reserved. This book, or parts therefor, may not

be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from

the publishers. Published simultaneously in the Dominion of

Canada by Longmans Canada Limited, Toronto.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 61-18609

Manufactured in the United States of America

To the memory of

Captain V. B. Chamberlain

Seventh Connecticut Volunteers

| Also by Peter Burchard | |

| JED: The Story of a Yankee Soldier and a Southern Boy. |

Author’s Note

This story opens on St. Helena Island in July 1863. It is fiction but the battle and prison experiences of Lieutenant Timothy Bradford are based on those of Captain V. B. Chamberlain of the Seventh Connecticut Volunteer Infantry.

The Seventh Connecticut was part of an expeditionary force which was sent to South Carolina in October 1861 to occupy the islands along the coast and establish a base for military operations against the city of Charleston.

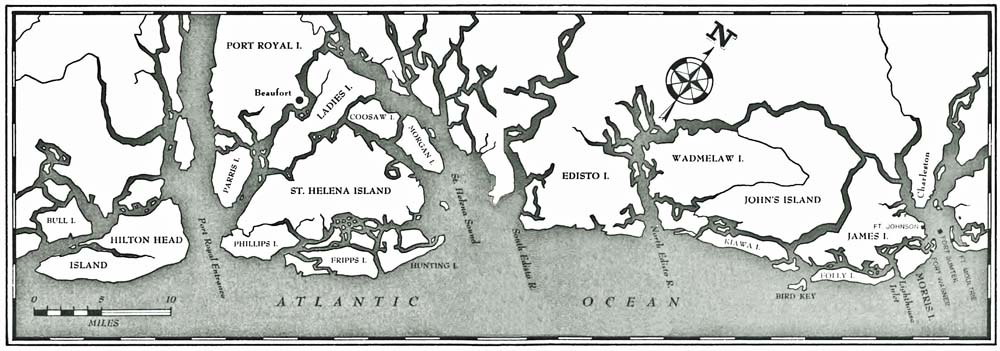

Union troops occupied the town of Beaufort on Port Royal Island and made their headquarters and their main base of supplies on the Island of Hilton Head.

The first charge on Fort Wagner (called Battery Wagner by the Confederates) is described in this book. Wagner was probably the strongest earthwork in the history of modern warfare.

A second charge on Wagner was mounted just one week after the first. This second attack was repulsed. Wagner was finally reduced by siege and occupied by Union troops in September 1863.

NORTH BY NIGHT

A big Negro was cleaning fish at the end of a spindly pier. He looked up as the two Yankee soldiers came toward him. He watched steadily as they approached but he showed no fear. The hot air shimmered as it rose from the sandy soil and the marsh grass whispered in a light breeze. The midday sun flashed on the water, making the white men draw their eyes into thin horizontal slits.

The taller soldier raised his hand in a casual greeting and stopped before his boots touched the gray, weathered boards of the pier. “Good catch?” he asked.

The Negro stood up slowly and hunched his massive shoulders and looked down at a half-cleaned fish. “Good enough,” he said. Then he raised his head. “I hear talk that most of you are leaving soon.”

The shorter soldier pulled at his red beard. “Soldiers are always on the move,” he said.

“Why must you sail away from here? You buy our vegetables and fish; you rent our boats. It’s good to have you here.”

The taller soldier smiled. “We have to fight.”

The fisherman lowered his head again. “If you must[12] fight, you need a swim before you go.” He pointed down the creek. “Take my boat and row across the inlet to the beach.”

The taller soldier reached into the pocket of his blouse, but the big man put up his hand. “No money today. Jus’ take the boat.”

The soldier stepped onto the pier, as if to shake the colored man’s hand. “Thank you,” he said. “My name is Lieutenant Bradford and this is my friend Lieutenant Kelly.”

The fisherman didn’t take the hand, but his mouth formed the hint of a smile. “Thank you,” he said. “My name is Sam.”

Red Kelly took the oars of the little boat and Tim Bradford sat on the sagging seat in the stern as they moved along the creek and into the inlet that separated St. Helena from the complex of smaller outer islands. These islands laced the coast of South Carolina from Georgetown to Hilton Head. The Atlantic Ocean washed their beaches, and their backs were honeycombed with deep creeks and rivers where shallow-draft Confederate blockade runners had once found it easy to move and hide.

Shortly after the start of the War the first expedition to these islands had been mapped by President Lincoln and his military planners. There had been good reasons for taking the War to South Carolina without delay. The state had been the first to secede, the first to fire on the flag, and there was need of a base of supplies for the ships of the North.

Now Federal forces held most of the outer islands from Savannah to Charleston. A base of supplies had been set up on Hilton Head, and the town of Beaufort on Port Royal Island was occupied by Yankee troops.

Sixty miles northeast was the proud port of Charleston,[13] heavily fortified, Fort Sumter at the mouth of its beautiful harbor, the place where the War had begun. Fast Confederate packets still ran into Charleston under cover of night, taking supplies to the Southern forces, but the Federal Navy had made it a dangerous game. Nowadays most of the packets headed for Cape Fear, about a hundred and thirty miles northeast of Charleston.

As Tim’s thoughts went back over the past two years, he was troubled by a familiar restlessness. He looked into the fish-smelling bottom of the little boat and across the inlet to the palmettos and scrub oaks that lined the shore of the outer island, and he flexed his hands.

Red Kelly, watching him with piercing blue eyes, read his thoughts. “We move tomorrow,” he said. “Be patient. God made this land and the sky above it. Live at peace this lazy day.”

“Do you think we can win this war?”

“We have many more men under arms than the Rebs and we’re backed by the might of our industry. But this is a big, far-ranging war. The good Lord knows how long it will last.”

Tim pushed back his cap and ran his hand through his stiff sandy hair. “The boys in the West are fighting a war that moves. We’re fighting a sitting war.”

“They’ve done their share of sitting in the West and in Virginia. Before this week is finished you’ll have your chance to fight again and a chance to die.”

Tim smiled. “I have no wish to die.”

Red’s face was flushed as he pulled at the oars. They moved across the inlet and glided into a tidal pool. They beached the boat, dragging it into the marsh grass. They moved through the heavy undergrowth, shielded from the sun by tall mop-headed palmetto trees. As they left the shadow of the trees the sun flashed pain into their eyes.

[14]The beach stretched away to the northeast, ending in a point of land where palmetto trees hung over the sand on great shelves, their roots stripped bare by stormy seas. The ocean was flat and vast, and on the horizon the masts of a sailing ship barely moved in a distant, ghostly mist. To the southwest a big steam frigate moved slowly into Port Royal Sound. When its ensign had disappeared behind the trees they stripped off their clothes and splashed into the water.

Red had never learned to swim, so he stuck close to the shallow places. Tim swam into deeper water and paddled just out of his depth, letting the current take him along the shore. Suddenly Red shouted, “Sharks!”

Tim saw two putty-colored fins sliding obliquely toward him. Terror struck at his chest and he wheeled and swam for shore. As he reached shallow water he leapt and dashed, the water dragging at his legs, pulling him back. At last his ankles broke free.

Red was white as plaster in the sun, his arms crooked tensely. “Saints preserve us,” he said, “that was a close one, indeed.”

Tim stood on the sand, his chest heaving, and scanned the water for signs of the sharks but the fins were gone.

Red said, “They gave it up as soon as you started to splash toward shore.”

“Thank God for that. I swam as if my feet were made of lead.”

The men pulled on their pants and sat on the sand. Red was quiet for a while and then he said, “I’m thinking of Nancy and Tommy back in New Haven, waiting for me to finish with the War. Tommy would be a little boy now, not a baby any more. I’ve never even seen his picture. I keep begging Nancy to send me a photograph of both of[15] them, but I suppose she doesn’t have the money to have one made.” He smiled. “You single men are a happy lot. No family worries. Devil may care, that’s what you are.”

Tim smiled. Then his face grew serious. “I have a girl,” he said. “We have an understanding, but I haven’t spoken to her father yet.”

“A girl is it? Well, you’re a fox, Timmy boy. I’ve lived and fought with you since we left the North and you’ve never so much as mentioned a girl.”

Red’s face took on a faraway look. “Nancy and I were thinking of moving away from New Haven after the war. Tell me, how is life in a country town?”

Tim squinted his eyes. The distant sailing ship had scarcely moved, but the mist had burned away. “The town is clean,” he said. “The yards of the houses are neat, and the village green is really green. The Connecticut River flows wide and deep below the houses. My girl’s name is Kate. She lives three miles down river. Her eyes are blue and her hair is dark. She’s full of life. Sometimes I worry that she’ll bust loose and go to New York or Boston and marry some tall, dark handsome man.”

“But she writes you still?”

“Sure she writes, and she sounds as loving-hearted as she ever did.”

“Then put away your fears of tall, dark city men.” Red smiled. “Tell me more about the town. What do the men do for a living?”

“My father is the only doctor in town. I guess I told you that before. Then there’s the owner of the general store and the parson and the blacksmith. Most of the other men are farmers. It’s just like any country town.”

Tim reached for a handful of sand and let it trickle through his fingers. “My father worked so hard he never[16] had time for me or the twins. That grieved him sorely, I’m afraid.”

“That’s the way with doctors.”

The two men finished dressing and turned away from the stretch of peaceful beach and the limitless ocean.

They walked to the boat and dragged it through the slime. Red stepped in and sat in the stern. Tim took the oars.

Not a breath of air was stirring the trees. One of Tim’s oars smacked the water, and a white egret flapped suddenly into the air from a saffron-colored tidal pool, flickering white against the bluish Spanish moss that clung to the trees along the shore.

The moon came up above the cooking fires and shimmered behind the heat that was still held by the sands of St. Helena Island. Mosquitoes rose from the swamps and pools and sluggish rivers to the west.

The soldiers unstacked their rifles and cleaned them. They packed their gear and settled down by the cooking fires and boiled what might be their last hot meal for quite a while.

Tim and Red shared a tent with Captain Kautz and Dawson but tonight they sat at the table alone. Tim had set out a candle in a bright brass holder. A faint breeze stirred the tent flaps, and the light flickered on the tin cups and plates. Red’s beard glinted in the yellow light.

Most of the boys had already struck their tents, but Kautz liked to keep things set up until the very last so he could spread out maps and do his work. He was short and fierce and powerfully built. He would sit for hours before the company went into action, his blouse open and his head bent, studying the map. He would pull his beard and fuss and fidget and suddenly get to his feet with his[18] bristling chin thrust forward. “And that’s how it will go,” he would say and then smile frostily to himself. “If the Confederates will cooperate.”

Tonight Kautz was having supper with the colonel. Tim hadn’t seen Dawson since early morning. Everyone knew the regiment was to sail at dawn, and the camp hummed with talk of the fighting that lay ahead. The boys knew they were moving against Charleston, and most of them were eager to go.

The candle guttered as the two men finished their meal. Red cupped his hand around the flame and blew it out. In a nearby tent they heard a clatter of plates, and a shout went up. Tim leaned back so that he could see past the tent flap. A man was running wildly around a cooking fire, stripped to the waist. “It’s Corporal Steele,” Tim said. “Every company has a clown.”

Now Sergeant Fitch and some of the other boys joined the fun. They whooped and hollered and jigged. The firelight struck their bodies like a patchwork quilt. Tim smiled to himself.

A voice was suddenly raised above the din. A blond-haired man of middle height came into the light, with both fists clenched. “You men have work to do,” he screamed. “Clean your rifles and assemble your gear. Tomorrow we move up the coast.”

Tim said, “Dawson’s drunk as a lord.” He stood up and stepped outside the tent, moving toward the fire.

Dawson looked up, his chin trembling. “Lieutenant,” he said in a shaking voice, “are these your men?”

“Yes, Captain, they’re my men,” Tim said. “Their rifles are clean and they’re ready to go. They were just letting off a little steam.”

“Are you being insolent with me?”

Tim looked down at the captain’s sweat-streaked shirt.[19] He turned to Sergeant Fitch. “Sergeant,” he said, controlling the anger in his voice, “you men look over your gear and report back to me.”

“Captain.” He turned. “Can I help you to a cup of coffee?”

Dawson put his hands on his hips and swayed a little, focusing his watery eyes on Tim. “Mind your manners, Lieutenant,” he said and turned and walked unsteadily away.

As soon as he’d gone Red staggered out of the tent. He put his hands on his hips, swayed back and forth and crossed his eyes. “Were you bein’ inshulent wi’ me?”

Tim grinned, reached out a long arm and pushed Red so hard that he staggered back and fell on the grass.

It wasn’t long before Sergeant Fitch came back with his boys. “Our rifles are clean and our gear is packed,” he said.

Tim stood up and kicked some sand into the fire. “Are your buttons nice and shiny so the Rebs can see them in the dark?”

“Like diamonds, sir.”

Corporal Steele was hanging back, but Tim could see that he was smiling. “Why don’t you boys sit down for a while?”

Steele sat on an empty hardtack box and the others sprawled on the grass. Sergeant Fitch cleared his throat. “Lieutenant Kelly, I wonder would you sing us that Irish lullaby?”

“Now what would a strapping man like you be wanting with a lullaby?”

Red sang in his fine tenor voice.

As other soldiers gathered around, Tim stood up and left the group. He walked back to the tent. A warm breeze blew in from the ocean. He reached for his poncho and[20] spread it on the ground not far from the tent. He lay on his back with his hands behind his head.

Red’s voice came clear in the silence of the starlit night. Tim thought of Kate. The last time he’d written her he’d known in his heart he was writing the thoughts of a boy who had left home two long years before. If only he and Kate could meet and talk for a while.

He remembered the first time he’d danced with her, the light from the chandeliers striking the whirling figures in the white-painted room of the new Town Hall. As he drifted into sleep Tim thought about the dresses, pink and salmon and powder blue against the men’s black suits.

When reveille sounded Tim woke up and rolled over. Red lay on the sand a few feet away, groaning as he opened his eyes in the predawn light. “Last night when I curled up here,” he said in a rasping whisper, “I thought you had a good idea, sleeping on the ground.”

Tim felt his poncho and his clothes. They were soaked with dew.

Captain Kautz was already up, sitting on a keg outside the tent, straining his eyes to take in every detail of the waking camp, already thinking about the day that lay ahead. “We break camp now. The transport moves with the morning tide.” He stood up. “I suppose we have to set off a charge of powder by Dawson’s head to get him up.”

Dawson came out of the tent and stared, silent and hostile, at Kautz’s back. “Very funny, Captain,” he said, putting his hand to his head.

The four men ate their rations of salt pork and hardtack and bitter coffee. The companies formed in columns to march to the pier and board a ferry that would take them across to Hilton Head.

[21]As they crossed Port Royal Sound the sky in the east was touched by the light of dawn. A mist hung over the sea. The ferry coasted into the landing and the soldiers were silent, watching the shore or staring moodily at the deck, showing none of the spirit of the night before. The troops waited by the big, gray sheds, built when the islands had first been occupied. The men talked quietly and some of them realizing that there would be a wait, took off their cartridge boxes and canteens and stacked their rifles.

The pier crossed a narrow strip of beach and jutted more than a hundred yards into the water. A narrow-gauge railroad track ran out to the end of the pier where a T-shaped float broadened the docking space. Two large transports waited at the end of the pier, smoke trailing away from their single funnels. Just ahead of them a smaller vessel was being unloaded by half-a-dozen stevedores. Beyond the pier were the masts and funnels of a score of other ships, the farthest ones dim in the morning mist.

Tim went forward to speak to Kautz. The captain turned. “The colonel says dispense with roll call. No one will want to desert us here.” He motioned toward the waiting transports and gestured toward a column of men that waited on the pier. “We board the ship on the left,” he said. “Company K will occupy the forward deck. We will occupy the stern.”

Tim made his way back along the wall of one of the sheds. He found Red no more cheerful than anyone else. Tim said, “At least we’re heading north.”

“I suppose there should be comfort in that.”

Dawson stood close by. “North or south, it’s all the same to me,” he said. “I want to see the last of these flea-ridden islands. I’d like to be defending Beaufort. That’s the job for me. The boys in Beaufort sit on verandas and rock all day.”

[22]Red smiled. “A veranda in New Haven would look good to me.”

The branches of a spindly oak showed above the roof of the nearest shed. The place was colorless and barren in the early morning light.

Now the columns of soldiers began to move.

A couple of Navy men dashed past on their way to their ship, holding their little pie-shaped hats, their bell-bottomed trousers flopping foolishly around their ankles. A soldier raised a little cheer and the whole column took it up. One of the sailors blushed and quickened his pace.

Kautz and Dawson were waiting at the end of the pier. They motioned the soldiers forward and directed them to climb the gangplank.

As the men reached the deck they passed a solemn old sailor with a full white beard. He watched them closely as one by one they stepped to the deck, nodding to each in a silent gesture of mournfulness.

The transport moved through the anchored fleet and into the channel. She steamed east until she was well away from shore. When she was two miles out she swung northeast, and some of the soldiers sought shelter from the heat on the deck below or in the shadows of the boats.

Tim leaned against the rail with Red, watching the distant shore. Close by, the air seemed clear and the sun reflected on the water, but the distance was shrouded in haze.

Shortly after noon one of the lookouts gave a yell. A big, black-bearded gunner shouted to his men, and they struggled up from where they lounged with the soldiers on the deck.

Two thirty-pound cannon were mounted near the stern, one on either side. The gunner leaned on the starboard[23] cannon and shielded his eyes, looking into the mist that veiled the horizon.

Tim strained his eyes, then clutched Red’s arm and pointed across the crowded deck. “There she is!”

A small, gray packet ghosted through the mist, about two miles off their starboard bow. The transport swung to port and the soldiers were ordered to stand clear. The gun crew went to work. They sponged and rammed. The gunner grabbed a big pinch bar and crouched and moved the gun around its track. He adjusted the screw to suit his judgment. When the gun seemed ready the gunner sighted again along the barrel and gave another wrench with the bar. Then he stepped aside and shouted, “Fire!”

One of his gun crew jerked the lanyard, and the wooden deck trembled as the cannon thundered and recoiled, straining against the breeching tackle. The ball arched out of sight, and Tim imagined that he saw a fleck of white where it hit the water short of its mark.

Before the gunner could fire a second shot the packet had shown them her stern and was lost in the mist.

Red squinted into the distance. “She must have been a phantom surely. She could hardly expect to run into Charleston in the afternoon. It must be risky enough at night.”

“She was probably due to arrive last night. She must have been delayed somehow. She’s killing time until sundown.”

The gunner heard Tim and nodded his head. “And now we’ll be on the lookout for her.” He smiled. “But they’re slippery devils, sure enough.”

[24-25]

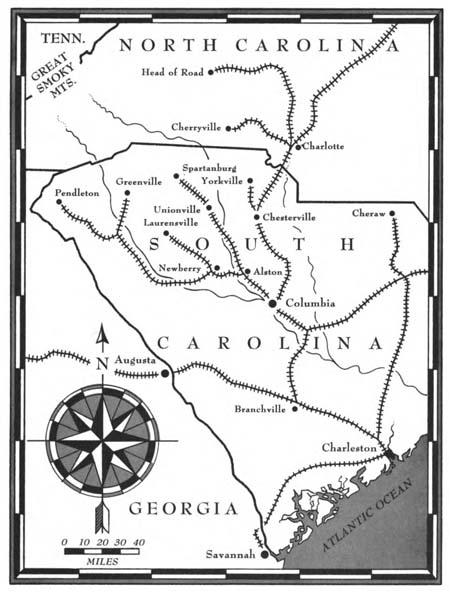

The South Carolina Coast from Hilton Head to Charleston, 1863

[26]As the transport approached Folly Island, Captain Kautz spread a map on the deck. It showed the coast from Savannah to Charleston. Tim’s eyes traced their course from Hilton Head past St. Helena, Edisto and Kiawa to Folly Island, Lighthouse Inlet and Morris Island, which lay at the entrance to Charleston Harbor.

“We bivouac at the southwest end of Folly tonight,” Kautz said, drawing a stubby finger across the map, “and tomorrow at dusk we march the length of the island to the shore of Lighthouse Inlet. We will launch our attack in small boats. Morris Island is a sparsely covered place.”

The captain had things figured one, two, three. He straightened up with his hands on his hips and looked toward Morris Island, as if he were going to take a bite out of it with his even white teeth. “It shouldn’t be more than one day’s work to clear the rifle pits and capture the batteries along the shore. By Saturday night we’ll be cleaning our rifles inside the fort.”

Tim studied the map. Morris Island was shaped like a big pork chop, the thin part curving north toward Fort Sumter. At the end of the thin part, on Cummings Point, stood Battery Gregg. Guarding this narrow neck of sand from land assault, Fort Wagner stretched from the ocean on the east to a tidal creek on the west.

As he and Red turned away from the map Tim said under his breath, “That fort is in a strong position. I wish I shared the captain’s confidence.”

Folly was a thin, sandy island stretching northeast like a crooked finger. It was already garrisoned by Union forces.

As the transport ran up Folly River the men could see the tops of Yankee tents above the undergrowth.

The troops disembarked at Pawnee Landing. They cut through a little wood on a well-worn path and made their bivouac in a barren place not far from the beach, close to another Yankee camp.

[27]They built no fires that night. Tim and Red, Dawson and Kautz sat together breaking out their rations, glad for a chance to rest. Captain Dawson turned to Kautz. “I wonder if the Rebels know what’s up?”

“It won’t be long before they do.”

Tim was impatient. “Why can’t we march tomorrow morning?”

“We can boil up our rations and clean our rifles,” Dawson said. “We can make good use of the extra time.”

Red laughed. “If the boys clean their rifles a couple more times they’ll wear the bores down smooth.”

Dawson didn’t feel like joking. “Sea air is death to firearms,” he said.

Kautz gave no sign of having heard. “We’ll have plenty of support for our initial attack. We have a hidden battery on the shore of Lighthouse Inlet. As soon as the enemy sees our boats our mortars will open fire.”

Just before sundown of the following day a corporal from General Strong’s brigade came around and handed out squares of white cotton cloth. The men were to sew them to the left sleeves of their blouses to prevent mistakes if they should be attacked while they marched.

At midnight came the sounds of quiet commands, the tinkle of buckles and the creak of leather as the men made ready for the march.

Tim’s men grouped around. Sergeant Fitch and Steele and the others leaned on their rifles.

“We don’t expect trouble tonight but we have to go quiet. General Strong’s brigade is on our left. We’ll travel close to the beach, with the Sixth Connecticut just behind.”

Tim found marching a pleasant relief from the heat and boredom of the day. The moon rose and traced its path across the sky. The breeze from the ocean riffled the marsh grass and cooled the sand. They reached the inlet well before dawn.

Tim turned to Sergeant Fitch. “Fall out and be silent,” he whispered. The boys sat around on the sand.

[29]Captain Kautz moved along the line. “Ten minutes to rest and then we embark,” he said. “We cross the inlet and wait near shore for a signal from Colonel Rodman’s boat. When we finally start for the beach, row fast.”

In the ghostly light the silhouetted figures fussed with the boats, setting the oarlocks and putting in the oars. The boatloads departed one by one.

The boats were made of rough milled pine primed over with lead and oil. Tim cautioned his men to step with care. “The bottom’s eggshell thin,” he said.

The men rowed silently across the inlet. Tim sat at the tiller in the stern.

They waited in the shelter of the grass-covered dunes, dipping their oars so that the boats wouldn’t drift. Aside from the occasional plop of a clumsy oar, there was barely a sound. Corporal Steele sat just across from Tim, rowing and watching the rippling grass. “There must be Rebels behind those dunes,” he whispered. “We’ll be sitting ducks if they catch us here.” As he spoke the flat of his right oar smacked the water.

Tim whispered fiercely, “You’re doing your best to give us away.”

The oarsmen rocked and dozed, dipping an occasional oar. Tim started to worry. Suppose they’d been seen by a random picket as they’d crossed the inlet, and suppose the picket had held his fire and reported the presence of Yankee boats? If that had happened, every boat in the inlet would be blown to bits in the first light of dawn.

Tim combed the shore for signs of life, but there were none. The lapping of the water against the boats and the distant whisper of the sea were broken just once in that early morning vigil when a lone gull rose with an urgent flapping, circled and rested again.

As the rising sun blazed fire across the sky, flooding the[30] sea with an orange light, the silhouettes of the boats took form and shape.

The silence was shattered by the opening shot. An eight-inch shell from the Federal battery arched overhead and dropped into the Rebel camp. The Confederates shouted and ran to their guns. The smoke from the discharged gun twisted lazily in the morning air. Tim gripped the side of his boat and watched through the haze for a sign from the colonel.

Now the water was churned by shot and shell. A near miss doused Tim’s boat, and the boys went pale. “Why the devil must we wait to move?” Tim said out loud.

A trickle of water ran down his cheek and into his mouth. He wanted to shout the command himself.

The Yankee battery fired again. The shell burst just behind a nearby sand hill. A mass of gulls rose against the sun in a speckled cloud and flew, squawking, toward the open sea.

Now one of the boats was hit. The man in the stern rose from his seat, swayed and toppled to the water in a trail of blood. Another was wounded, and his screaming echoed across the water above the sound of rifle fire and the yells of the Rebels on the shore. There was a throbbing in Tim’s head. He could feel his temper rise. Now at last the signal was given, the oarsmen bent to their work and the boats moved toward shore.

Kautz’s boat was one of the first to scrape the sand. He jumped out, ranging up and down the beach like a fighting cock, urging the men to move in fast.

Tim’s boat landed just behind Kautz’s, with other boats following closely. He jumped over the side and into the water and waded ashore in a hail of bullets.

Kautz said, “Hit the beach and start firing.” He knelt near Tim. “Half a minute to get your breath, then move[31] inland with your men and clear the rifle pits. If you keep moving, the rest of the company will follow right behind.”

The other boats swarmed in to shore and the soldiers started jumping out, holding their rifles high and dry.

Sergeant Fitch and the other boys lay close to Tim, their faces streaming and their chests heaving. Tim fingered his pistol. “A couple more seconds, then we go.” He raised his hand. “Three yards apart. Keep me in sight. Move in low and give them a lively target.”

He moved fast to the crest of the nearest dune. The first line of rifle pits had been deserted. The enemy camp was deserted too. It was strewn with boots, canteens and other odds and ends. A cooking fire smoldered on the sand. Tim and his boys moved past the tents. The Rebel garrison must have been small.

A cannon on the right was standing alone. Red and a squad of his men moved in to swing it around. Tim ran forward to the second dune and crouched to see what lay beyond. There was a line of rifle pits a hundred yards or so away. Men peered anxiously over the sides. Tim signaled to his men. Rising up in full view of the pits, he gave a yell and ran a zigzag course, with Sergeant Fitch and Steele by his side. The other men yelled and followed close on their heels. Neither Yankees nor Rebels stopped to fire. The Rebels, outnumbered as they were, just jumped the pits and scurried for the rear.

One of the Rebels was very young. With youthful awkwardness he was trying all at once to put on his shirt, hold his blouse and rifle, and run for his life. As he ran his shirt streamed out behind. He dropped his rifle and when he stopped to pick it up he dropped his blouse. When the boy’s face turned toward his pursuers Tim raised his pistol as if to shoot. The boy deliberately picked up his[32] blouse and his rifle and turned his back; he moved a few steps closer to the shelter of a dune.

Tim signaled for his men to hold their fire. He lowered his pistol. They watched the lad as he cut loose and sprinted like a rabbit for the safety of the dune, his shirt still clinging to one of his arms and streaming out behind.

Tim looked back. The Federal force was moving forward in a solid line. He scrambled up a knob of sand. Beyond him, over a waste of dunes, a Rebel battery was just about to be deserted. Behind the cannon the ground was dotted with soldiers in full retreat.

The attackers paused to catch their breaths. Off to the right Red had taken prisoners. He was giving orders to three of his men who were acting as guards. He gestured and pointed toward the rear, then turned his back on his prisoners, looking over the ground ahead.

Tim and his boys moved forward again, this time so fast that they caught a gun crew off its guard. Tim dropped behind a crescent-shaped drift of sand, and edging forward, found himself staring straight into the muzzle of a cannon—a parrot rifle not fifty yards beyond. Five of the gun crew made themselves scarce, but two of the braver ones started to empty their powder barrels. One of the men saw Tim and grabbed for a rifle, but Tim brought up his pistol and fired. The Rebel winced and grabbed his shoulder, dropping to the sand as the other man scurried away.

The fleeing man paused in the cover of a little valley and brought up his rifle. Corporal Steele lay close to Tim, his rifle cradled easily in his hands. He squeezed the trigger and the man pitched forward and lay still on the sand. Then one of Steele’s hands left his rifle. He reached into a hollow in the sand and brought out a speckled sea-gull egg. Steele slipped the egg into his cartridge box and both men stood up and moved toward the gun.

[33]Tim spoke to the man he had shot. “You hurt bad?”

Blood had soaked through the man’s gray blouse. There were patience and sadness in his face. “The war is finished for me now,” he said.

Tim propped the man against the cannon and took up the chase again.

The sun traveled across the hard blue sky as the Yankees moved along the shore, taking gun after gun and turning them on men who had manned them minutes before.

About midday Tim paused with his men to drink from his canteen and eat some hardtack and a ration of pork.

As the Yankees closed on Wagner there was token resistance, but it was clear that the Rebels would make their stand inside the fort. By late afternoon the attackers had traversed the ridge and the last of the coastal guns was theirs. Tim watched Kautz as Red and his men swung a big seacoast howitzer around and discharged a shell that burst above the heads of the retreating cannoneers.

The advance was halted and Tim settled down for a rest. Captain Kautz sat down close by. From where they rested, part of the fort could be seen—a great sculptured mound of earth and sand.

Kautz pointed to a bastion close to the sea, then motioned to the left. “The other salient is just out of sight behind those little trees. We’re told the fort holds three hundred men. The parapets are bristling with artillery.”

As if to accent what he had said, a shell from the fort arched high across the sky and exploded short of its mark. The fire from the fort was fitful now. The enemy was saving its fury for the Yankee assault.

Kautz spoke again. “We’ll launch our attack at low tide. Just now the tide is high. The strip of sand between the tidal creek and the sea wouldn’t hold a company, much less a regiment.”

[34]Ships of the Federal Navy lay in a flat calm, just out of range of the Confederate shore batteries. The masts of the ships of the coastal blockade could be seen in the distance.

“Looks as if we’ll have Naval support,” Tim said.

“We’ll need support. As we sit here we’re well within range of the guns at Sumter and the batteries across the channel on Sullivan’s Island.” Kautz gestured toward the narrow neck of sand, the pathway to the fort. “That beach will be a hell on earth when all the batteries open fire.”

Sergeant Fitch came by. He smiled dryly and motioned toward the fort. “That place is bulging with angry men.” He put a hand on his hip. “But there’s one Rebel soldier who comes to my mind who might not find the heart to shoot at all.”

Blue uniforms covered the sand as far as the eye could see. Tim said, “If numbers counted, we could take the place without a fight.”

“That’s a pretty big ‘if,’ Lieutenant,” Fitch said. “Schoolboys with slingshots could hold that fort.”

“If we go in strong we’ll take the place,” Tim said. He turned away.

He found Red by a little stream on the westerly side of the neck of land. Red was stripped to the waist, dousing his hair and scrubbing his beard with a piece of soap.

Tim took him by surprise. “That beard would frighten the devil himself.”

Red straightened up, grinning.

A row of wounded lay on the sandy bank of the stream, waiting to be taken to the rear. Tim noticed three gray blouses at the end of the line. Two mounted officers rode along the crest of the hill above the stream. A ferry service must have been set up to bring the horses and wagons across from Folly.

[35]Red finished his washing and the two men moved up the hill. To their left the tower of Charleston’s St. Michael’s Church was a knife of fire in the light of the setting sun.

When his boys had cleaned their rifles and settled for the night Tim found a place close to the ocean, where he could be alone. A waning moon climbed the dark blue sky, and the phosphor-lighted waves that edged the mass of the open sea lapped gently against the shore below. The black outlines of the ships of the Navy—the monitors and gunboats—were etched against the hazy distance. He thought of a springtime more than two years ago when he and Kate had sat on Lookout Rock high above the river in the warmth and freshness of the sun, letting their eyes wander over the morning haze, finding patches of pine and green-gold willow trees. He remembered the sun striking the river and the trailing smoke from a distant train. When he had seen the train he had touched Kate’s hand. “Do you ever feel you’d like to bust loose and sprout wings and fly to the ends of the earth?”

Kate’s eyes had shone. “You make me feel that way.”

It was dark when Tim opened his eyes, and for a moment he couldn’t remember where he was. Then a passing horseman, giving orders, reminded him of their position. Tim was conscious of the silent lines of men stretching away to the rear, and he knew that sentries in the unseen fort waited quietly in the darkness, straining their eyes toward the Yankee pickets, wondering when the attack would come. Fear came to him, then ebbed away. He knew that the hours ahead must be lived a minute at a time. He got to his feet.

Muffled voices sounded on the left and Sergeant Fitch came out of the gloom. “General Strong and Colonel Rodman are up and about.”

“Did you get some sleep?”

“Not much. But most of the boys are dead to the world.”

“Fitch, do you think the men are fit?”

“Fit enough, I guess. But that new lad Greene, he worries me. He’s so confounded young.”

The colonel came along the line. “Turn the boys out.[37] We have a job on hand. We must have silence as we move to our picket line.”

In the ghostly light the voices of the sergeants brought the boys to life. Fitch’s voice came in a pleasant rumble. “Here, Steele, time to get up. Up now, Bailey. Come along, Campana. That’s it, Greene. Time to rise, lad, we have a job to do.”

And from farther away came other voices. “On your feet, grab your rifles, put on your boots.”

The colonel’s aide ordered quiet, and the sounds died down to a restless hum as the men clasped their belts around their waists, grabbed their cartridge boxes and fixed their bayonets.

Tim walked among his boys. Most of the faces were chestnut brown from two years in the southern sun, but one face stood out white as chalk. Tim stopped to talk to Private Greene. As he faced the boy he thought, He’s just as I probably was two years ago.

“Just keep moving,” Tim said in a quiet voice. “It’s dangerous to falter.”

They moved forward, keeping their line as straight as they could in the dark. Just as Tim fancied he could pick out the shape of the fort against the sky a Yankee picket stood in their path, raising his hand in silent greeting. The order came to halt and rest.

In the still, gray hours General Strong, with a yellow bandanna fluttering at his neck, mounted on a big, stamping horse, moved along the line. He paused near Sergeant Fitch and looked down at the men. “Don’t stop to fire. Trust in God and give them the bayonet.” Then he spurred his horse, and the man and the massive haunches of his charger and the beast’s switching, whipping tail were swallowed by the gloom.

Tim noticed that Private Greene stood close.

[38]“We move with caution till the enemy pickets open fire,” Tim said. “Then we go in double quick. The Maine and Pennsylvania boys will come in right behind.”

The sand gave way with every step, and a lump of impatience grew in Tim’s chest.

As the soldiers advanced the ones on the right flank fell back so that they wouldn’t be forced to walk in the ocean.

A Rebel picket sent up an earsplitting yell, there was a warning rifle shot, and the order came for the Yankees to charge. As Wagner’s batteries opened fire the ground in front of the advancing soldiers was churned by a stream of shot and shell.

Tim drew his sword and raced forward, motioning for his men to follow. The ground was covered with dead and dying, great shell holes loomed suddenly in their path, and some of the men pitched headlong into the yawning cavities.

The figures of the charging men were punched in black against the brilliance of enemy fire. As Tim moved into the choking, blinding haze a shell hit close. The familiar bulk of Sergeant Fitch spun around, suspended for a moment, then crumpled in a gesture of death. Fear cut into Tim like a knife of ice. His knees were numb but he moved in a crescendo of speed for the outer work, a soundless screaming tearing at his throat.

A dozen or so men had halted just behind the man-made ridge of sand.

“Don’t stop to fire!” Tim yelled.

In the light of the exploding shells he caught sight of Captain Dawson just to the left. Dawson was rocking a man in his arms, rocking and sobbing in a ghastly burlesque. Tim scrambled over to Dawson’s side. The light of a following shell showed him that the man Dawson was holding was dead. Tim wrenched the dead man free,[39] grasped the front of Dawson’s blouse and hit him full force in the face with the flat of his hand. “Move on,” he shouted.

Dawson shook his head in confusion and got to his feet.

With the shriek of shells splitting his ears Tim grasped his sword and dashed across the trembling sand toward the water of the moat where it reflected the flashes of cannon fire.

A wounded soldier lay at the water’s edge, struggling to rise. Tim grabbed the man’s blouse and dragged him clear so that he wouldn’t drown.

As Tim straightened up he saw a half-familiar figure dashing toward him.

“It’s Private Greene,” he said aloud.

Together he and Greene dashed into the moat. Tim heard a splash. Greene lay in the water, face down. Tim reached for the boy to pull him out but Greene jumped up. “I’m alive. I only tripped,” he screamed. “Alive, alive!”

Tim choked down a desperate laugh as he rushed for the massive, sloping bank of earth. Scrambling up the rutted parapet, he felt something sharp prick the seat of his pants. He swung around and looked into the dogged face of Private Greene.

“Private Greene,” he said. “Watch what you do with that bayonet.”

Daybreak was streaking the sky in the east. In the gathering light a scattering of Yankees had dug in just below the crest of the parapet, firing rapidly into the fort. The ground below the fort was peppered with rifle and cannon fire.

It was clear to Tim that the Federal ranks were threadbare. The supporting regiments had dropped to the ground behind the outer work. A shell hit a portion of[40] the work, spraying sand into the air, picking up men like jackstraws in a gale and sending them sprawling back to earth.

Tim whipped the air with his sword and shouted through the smoke and noise, rallying his men. He slipped and scrambled to the crest where the sandbags were stacked. He kept moving as he reached the crest, half sliding, half jumping into the fort. He was blinded for a moment by a thick cloud of acrid smoke that made him cough and choke. As the smoke blew away he saw a Rebel sergeant straight in front of him and cannoneers at either side. He lowered his sword.

Off to the right a big voice commanded the sergeant, “Hold your fire.” A Confederate lieutenant moved toward Tim, his pistol ready, a broken-toothed smile cracking his leathery face. “A prisoner, sir.”

Tim sheathed his sword.

“Your sword and pistol,” the lieutenant said.

Tim unbuckled his belt, slid off his bolstered pistol and held it toward the man. “I’ll surrender my sword to the officer who commands this battery,” he said.

The lieutenant nodded. “As you wish it, sir,” he said, raising his voice above the rattle of musket fire and pointing to a man who was stripped to the waist and covered with grime and sweat. “There’s Captain Chichester. Surrender your sword to him.”

The Confederate captain turned as Tim walked toward him. The Captain nodded respectfully. He reached for his pistol and handed it to a boy not more than twelve years old who stood by his side. “Guard this prisoner,” he said, “and mind you don’t shoot him by mistake.”

Tim walked with the boy to a place near a bombproof shelter where empty powder barrels were thrown helter-skelter on the sand. “I’ll sit on one of these,” he said to the boy. “I’m tired.”

The boy stood nearby, serious and manly, but frightened[42] too. He pointed the revolver at the ground and looked at it to be sure he knew how it worked. With his chin down he looked back at Tim.

Tim sat on the barrel, looking off through the smoke, the racket of battle in his ears, the screaming of soldiers, the thunder of cannon and the chatter of rifle fire. His spirit was chilled. Fitch was dead. He wondered whether Red and Kautz were lying lifeless in the moat, or were they prisoners too? He thought of the Rebel soldier he had wounded, was it yesterday? The man had said, “The war is finished for me now.” And now, Tim thought, the war is finished for me too.

A huge siege gun was fired close by, shaking the earth and sending a puff of acrid smoke rolling along the sandbags at the top of the parapet, making the gunners cough and choke. All at once the firing stopped, the last musket cracked. The smoke of the battle rose above the fort and thinned as it was blown away. The sun filtered through the gloom and there were voices in the silence, loud at first, then soft, like the voices of schoolboys when the teacher comes into the room.

Captain Chichester, his shirt draped loosely around his shoulders, walked toward Tim through the thinning smoke.

Tim stood up, reached for his sword and handed it to the captain. The man’s sand-colored hair and eyebrows were dusted with powder that ran in streaks down his tanned face. His blue eyes reflected a sleepless night and a morning of battle. “No cause for Yankee shame today,” he said.

The powder monkey stood by his captain now, handing him his pistol, looking up at his face.

Tim looked toward the big guns. “Captain,” he said,[43] “I wonder if I could see the field beyond the parapet?”

The captain lowered his eyes. “It’s a heartbreaking sight,” he said, and he raised his eyes and held Tim’s gaze, as if he wished he could say more.

The two men walked toward the parapet, the boy tagging along behind. The Rebel soldiers gawked, and one big sergeant spat hard on the blackened sand.

“Save your spit for the next assault,” the captain said with a look of towering disgust. As they reached the gun he turned to Tim. “There’s an armistice in effect,” he said, “to give your men a chance to carry off the wounded and bury the dead. The boy and I will stay back here. I’ve seen enough today.”

Tim moved up beside a gun and looked across the plain. The dusky, shadowy world of early morning had given way to a sunlit day. There were no shellbursts or knifelike tongues of flame—just silence and the litter of death, scattered in terrible profusion on the sand.

Under a flag of truce ambulances moved along the beach, hurrying to gather up the wounded before they were claimed by the incoming tide. A surgeon who was working at the edge of the moat signaled to a driver. “Here’s one alive,” he called. An ambulance creaked and rattled to where the man lay. The surgeon and the driver lifted the wounded man gently into the canvas-covered vehicle.

With sickening dread Tim’s eyes moved across the distance, studying the men who lay on the sand. He fancied he saw a red-haired officer lying in the distance with his feet to the sun, but he couldn’t be sure. Men lay at the base of the parapet, almost covered by the waters of the moat which was fed by the ocean tides. Tim suddenly wondered what had happened to Private Greene.

[44]He looked once more across the plain at the dead and broken and dying. Then he turned to the captain and the boy who stood by his side.

“There are other prisoners waiting by the sally port,” Chichester said. He looked down at the boy. “Billy Moore will show you the way.”

“Thank you for your courtesy, sir.”

“What is your name?”

“Lieutenant Bradford, Seventh Connecticut Volunteers.”

“Maybe we’ll meet again on a happier day,” the captain said. He turned and walked away with two swords swinging and rattling at his side.

As Tim followed the boy past the bombproof the boy spoke. “All Yankees aren’t bad,” he grinned, “but most are devils, sure enough.”

“You come from Charleston, lad?”

“I come from Beaufort, sir,” he said with a sudden frown. “It was the Yankees chased us away.”

They left the shadow of the bombproof and walked through the sally port, and there, guarded by half-a-dozen men, were forty or fifty Yankee captives. There was Dawson, hatless, with his corn-colored hair shining in the sun, his face like death. An ugly welt ran across his cheek.

One guard laughed when he saw the unarmed boy with the tall Yankee. “Big fish this time, little Billy,” he rasped. “Give him over to me.”

Tim nodded to the boy and went to Dawson. “Glad to see you still alive,” he said.

Dawson looked sullenly at Tim. “I’m tired,” he said with bitterness. “I’m glad to be out of it, if you want to know the truth.”

“Any word of Kelly or Captain Kautz?”

“None that I know of.”

[45]A big Rebel sergeant moved close to them with studied ease and snapped, “That’s enough talking. You’ll have plenty of time to talk in jail.”

Tim thought, If Red is dead I’ll visit his wife and child when I get home. But I pray to God he lives.

Off to the east thunderheads were piling up, and a stiff breeze sprang up.

A rusty steamer came puffing and wallowing across the choppy waters and made fast to the pier just to the west of the Confederate battery at Cummings Point.

As the prisoners clattered along the pier Tim wondered if the flimsy structure would hold them all. It creaked and groaned as one by one the men jumped to the heaving deck.

As Tim stood by the rail he caught sight of a familiar face. “Private Greene,” he said.

Greene turned a happy face and worked his way behind the crowd of men along the rail. Tim clasped the boy’s hand. “Glad to see you, lad.”

Greene just smiled.

“Have you seen Lieutenant Kelly or Captain Kautz?”

“No, Lieutenant.”

As the steamer moved away from the shelter of land it was lifted by swells that swept in from the open sea. The little ship rolled and tossed and smacked the waves, sending up sheets of spray and wetting the men who were wedged along the rails. It seemed to Tim she was carrying too many men.

“If we make it to Charleston I’ll be surprised.”

Greene smiled shyly. “Let’s mutiny,” he said, “and sail to Boston on the afternoon tide.”

Suddenly there was a commotion near them at the rail and one of the prisoners jumped over the side. Tim saw[46] the flash of a shirt then he saw a boy swimming and drifting swiftly astern. He said, “What chance does he think he has?”

A guard dashed out of the wheelhouse onto the shuddering deck. He raised his rifle and fired. Greene gritted his teeth and clenched his fists in a helpless fury as he watched the head of the struggling boy. “For the love of mercy, why don’t they give him a chance?”

Two shots followed the first, but the boy’s head still bobbed above the water. The fourth shot hit its mark. One of the swimmer’s hands thrashed weakly for a moment and he dipped below the surface, leaving a slick of blood to mark the place where he had disappeared.

Greene’s face was pale. He quivered with rage and fear. He stared transfixed and then, with a convulsive shudder, leaned over the rail and was sick. Tim put his hand on the boy’s shoulder and looked across the water at the stretch of beach that led to the mouth of the creek and the freedom of the Yankee lines.

The steamer made straight for Sumter. The fort stood like a block of granite in the harbor’s mouth, the sea dashing against the outer walls.

Now the sky was solid lead, washed across with moving clouds. The steamer nudged Fort Sumter’s wharf. The sailors looped the hawsers around the pilings, the sergeant of the guard leaped to the dock and was admitted to the fort. The steamer creaked and groaned against the pilings and Tim leaned on the rail with Greene beside him, looking up at the silent gray walls.

The sergeant walked back along the pier with his head down and his arms swinging at his sides.

As the steamer moved toward Charleston, leaving the silent gun ports in its wake, Tim noticed a flag at the top of the pole inside the fort. It snapped in the stiffening[47] breeze, its colors sharp against the flat, gray sky. I wonder, he thought, how long that flag will fly?

The harbor was dotted with the sails of fishing boats seeking shelter from the coming storm. The city of Charleston was strung across the horizon, her rose-brick and white-walled buildings like spots of color in a child’s painting, her church towers standing high above the piers and parks and the houses that lined the waterfront. Off to the right, masts and spars and a complex of shrouds marked the wharves on the eastern shore of the peninsula.

Greene’s voice barely rose above the thump of the paddle wheels. “Where are they taking us, do you suppose?”

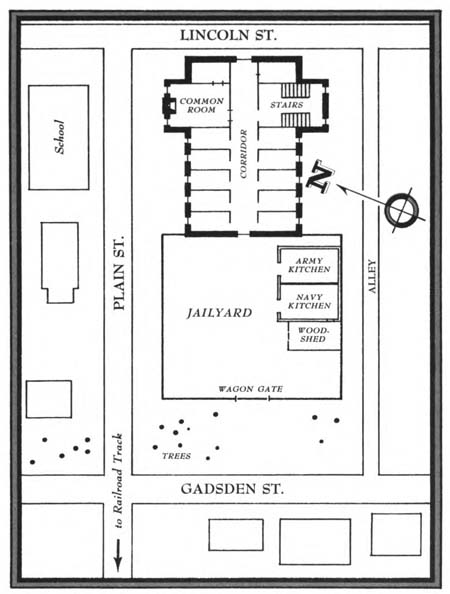

“There’s a jail in Charleston,” Tim said, “and others scattered throughout the South.”

“Are the stories of Rebel prisons true?”

“I’ve never been in a Rebel jail,” Tim said. “There’s always hope of being exchanged. The Confederacy can’t afford to have her soldiers wasting away in Northern prisons.”

Tim watched Greene’s face. “Promise me something, will you, Greene?”

“What would that be, Lieutenant?”

“Promise me if you try to escape you’ll pick a time when you have a fair chance.”

Greene spoke earnestly. “I wasn’t thinking of escape just yet. I’ll have to see the prison first. I’ll have to think on it a while.”

Tim laughed. “I’ll waste no more of my worry on you.”

The little steamer swung slowly around as it maneuvered to move toward one of Charleston’s piers. Now in the moment before the storm Tim saw a little island at the mouth of the river. Part of the island was struck by sunlight. On the sandy shore three men struggled to beach a boat, their figures distinct in the slice of light.

[48]There was a sudden gust of wind and the rain sluiced down, blotting out the little scene. It streaked down the faces of the prisoners and ran down their collars. At first it seemed a blessed thing, but as it drenched the men on the deck Tim stared across the flat, gray water whipped by rain, and a cold apprehension took root in his heart.

As the little steamer docked the rain stopped and the clouds blew away. The prisoners marched with their guards along the wharf, across a glistening cobbled street to a shedlike building that faced the waterfront. A short, sunny-faced woman came out and spoke to the sergeant of the guard. “We didn’t have much warning,” she said. “You’ll have to give us a minute or two.”

The sergeant frowned and mumbled something. Then the woman raised her chin and looked down the line of men, wet and disconsolate in their dirty uniforms. “Well, you’ll have to wait,” she said. Without pausing for an answer she went inside.

Tim stood on the cobbles and studied the row of fine brick houses that faced the river. This was the first time in months that he had stood on a street and looked at houses where people dined and slept, where children were born and raised.

The sunny-faced woman came out again, followed by others carrying trays of coffee and slices of buttered bread on squares of white paper. As the women moved among the men Greene straightened up and lowered his chin and brushed his cheek with the back of his hand.

“They’re just like the ladies of Philadelphia,” Tim said, “who served us goodies two years ago.”

One of the women, dark haired and young, turned to him. “Need is need, wherever it may be,” she said with a sweet, sad smile.

Tim noticed how graceful she was in her starched white[49] dress and pale blue shawl. She was so much like Kate that he felt his knees go weak. As she turned away he was filled with a yearning for home, a longing to sit on his horse and ride along the river road underneath the sunlit leaves until Kate’s house came into view.

When the women had disappeared into the building again the Rebel sergeant slapped the stock of his rifle. “Quiet,” he said. “Now we march to the railroad depot.”

They marched through the streets and alleys lined by houses, sometimes neat and tidy, sometimes deserted and forlorn. There were gardens filled with summer flowers still in bloom, palmetto trees along the sidewalk, dark green painted doors with knobs and knockers of polished brass. People leaned on their windowsills to watch the passing prisoners. Some of them hissed or spat. Others watched with expressions of compassion or concern. A scattering of ragged children ran ahead of the prisoners, spreading the word that they were on the way. They rounded a corner and walked along a wide cobbled street where most of the houses were of the “single style,” narrow at the front, with piazzas facing lawns and gardens at the sides.

People were gathering on the sidewalks, and as the prisoners approached St. Michael’s church the crowd grew thick, surged from under the portico and broke into catcalls and jeers. The soldiers of the Rebel guard flashed their bayonets and drove the people back. Most of the prisoners walked straight and proud. Tim set his jaw and stiffened his back but he couldn’t stop the trembling in his knees.

A gang of little boys dodged around the pillars of the church and one of them skittered through the crowd, made a face and flapped his hands like donkey ears. He reached into his pocket and brought out a tomato. Tim saw the[50] boy’s arm arch back as he took deliberate aim. The love apple caught the Rebel sergeant just over his ear. The sergeant moved to catch the boy.

“I was aiming at a Yank,” the little fellow screamed as he dashed behind the skirts and capes that lined the street.

People in the crowd began to laugh, the women first, and then the men. The sergeant’s face turned red, and even Yankee snickers turned to laughs. Then there was silence. The laughter of the Yanks had made the joke go sour.

As they moved along the middle of the street, carriages and wagons pulled aside to let them pass. The drivers turned hostile faces on the men in blue.

Tim brushed past the bright red wheels of a gleaming carriage and for a moment he looked into the face of a woman in the back seat. She was about his mother’s age and dressed in black. Her face was beautiful and filled with sadness.

Now the urchins who followed the prisoners were joined by others led by a dark-haired older boy. They screamed and taunted. They threw pebbles as they surged along the sidewalks and into the street ahead of the prisoners’ line of march. The sergeant of the guard was flushed with anger. When the leader of the gang began to taunt the prisoners the sergeant grasped the boy’s collar, tearing the shirt right off his back. “Next time I’ll give you the bayonet,” the sergeant said.

The boy grabbed his shredded shirt from the dirty stones and ran ahead with his gang behind him to the shelter of a narrow street. The sergeant and the other guards watched as they passed the street. All at once the boys appeared again and pelted the column with stones. A mean-faced Rebel corporal was hit in the leg, and he[51] and the sergeant, with another guard, dashed after the boys as they scattered like quicksilver into the alleys and doorways of the dingy street.

Greene’s face showed his excitement as the column was left with just one guard. Tim grabbed Greene’s arm. “This is no time to think of escape. Charleston is a cul-de-sac. They could seal off this peninsula easier than closing a cracker box.”

Greene relaxed. “Never even crossed my mind,” he said with a smile.

The prisoners were shouted to a halt beside a two-story depot with a turreted top and moss-covered walls. An old man poked his head out of one of the upper windows and glared at the sergeant through steel-rimmed spectacles. “Sit them down,” he squawked. “The train won’t be here for quite a spell. Just got it over the telegraph.”

“Where’s the Home Guard, granddaddy? We want to get back to the barracks for dinner.”

“They’re with the train,” the old man said and shut the window.

In front of the building three Negro women had set up shop. They sat on the steps, their bright cotton dresses, straw hats and shawls gleaming in the sun, oranges and yams and figs and shrimp in baskets and wooden bowls ranged around their feet. “Gentlemen, buy here!” one of them called. “Fruits and vegetables, molasses cakes. We still have tobacco and a few cigars.”

The Rebel sergeant loosened his collar and slung his rifle over his shoulder. “Buy if you have money,” he said to the prisoners, “but stay on the platform. We’ll shoot[53] the first man who wanders. We’ve had enough running for today.”

The sergeant walked past the colored women, up the steps and through the depot door.

Greene looked at the food. “I could eat it all,” he gulped.

“We’d better buy what we can and save what we can,” Tim said. “We may have to make it last a while.”

The prisoners clustered around the women. Tim noticed Dawson eating and stuffing his pockets with food. The woman in the center was big and fat. She was wreathed in smiles. “We give you good exchange,” she said, “five Confederate dollars to one greenback for Yankee gentlemen.”

Tim bought some yams and molasses cakes, and Greene cradled five big oranges in the crook of his arm.

The mean-faced Confederate corporal yelled, “Fall in at the center of the platform where I can keep my eyes on you.”

The prisoners drifted away from the bright little island of smiling, brown-skinned women and did as they were told.

Greene fumbled for his money and paid for his oranges. As he slipped his wallet into his pocket one of the oranges fell to the platform and rolled toward the track. He chased the orange, clutching the others against his blouse. Tim had pocketed his food and he started toward the orange as it rolled to the edge of the platform. The Confederate corporal watched the orange with cold indifference as it bumped onto the track. Greene scrambled after it. Suddenly the corporal swung his rifle around and caught Greene in the side with the point of his bayonet.

The wounded boy cried out in pain, the other oranges[54] dropped from his grasp and bumped and rolled onto the roadbed, bright spots against the stones.

Greene crumpled to the ground, holding his side, gasping and sucking for breath.

Tim’s eyes blazed fury. “Why, you damned fool,” he said. He turned his back to the corporal and knelt beside Greene.

The sergeant appeared from the shadow of the doorway. “Corporal,” he rasped, “we’ve had enough trouble today without you doing a thing like that.”

The color drained from the corporal’s face. “Just doing what you told us,” he choked, “getting the Yankees back in line.”

The fat woman dropped to her knees and wailed, “Lord have mercy on us all. That boy didn’t mean no harm.”

The sergeant turned on the woman. “Shut your face. You better do your selling some place else.”

Tim loosened the boy’s clothing, exposing the white flesh and the ugly mouth-shaped wound.

The sergeant squatted. “That’s nothing to worry about.” He reached into his haversack. “We’ll bandage it and they’ll dress it proper when you get to your jail.”

“Where are we going, Sergeant?” Tim asked.

“I’m not supposed to say.”

“How long a ride is it?” Tim asked evenly.

“Three or four hours I guess.”

Tim stood up slowly. “This man needs a doctor now.”

“My commanding officer would give me the devil if he knew about this.”

Tim clenched his fists. “Greene needs care. He needs it now.”

The sergeant wavered. “The train ...” he said.

“The train be damned, Sergeant. Stabbing this boy was an act of cruelty. If you send him to a prison in the shape[55] he’s in, I’ll find a way to let your commanding general know.”

Greene was breathing heavily. He had lost a lot of blood. It had soaked his trousers and formed a little pool on the ground. “Don’t bother, Lieutenant,” he whispered. “I can make the trip.”

Tim looked coldly into the Sergeant’s eyes. “Well, Sergeant?”

The sergeant turned to the corporal. “Leave your rifle with me,” he said. “Bring a baggage wagon around from the back. You can drive the Yankee to the hospital. If he dies, it’s on your head.”

“But ...” the Rebel corporal whined.

“But nothing. I’ve had enough of you.”

Greene looked up at Tim. “I’d rather stay with you, Lieutenant.”

“You can’t do that. You’ll be better off in a hospital. If your wound had been higher, you might have been killed, but it’s just in the flesh of the hip. If it’s properly dressed, you’ll be well in a week or two.”

The colored women were gathering up their bowls and baskets and getting ready to move away. The prisoners watched in silent anger as the corporal brought the wagon around and reined the horse to a stop.

Tim and the sergeant lifted Greene gently to the wagon floor, and Tim touched the boy’s sleeve. “You’re a brave lad, Greene,” he said quietly. Greene smiled and turned his face away.

As the wagon squeaked and rattled off, the sergeant turned to Tim. “Gather up the boy’s oranges, if you’re a mind to,” he said.

Tim stepped off the platform and leaned down to pick up the oranges. The other prisoners sat along the wall of the building. Tim stuffed the oranges into the bulging[56] pockets of his blouse and settled himself on the heavy, splintering planks of the baggage platform. He watched the wagon disappear into the dusty distance and then stared down at the backs of his hands, tanned and moist and heavily veined.

He thought of Greene and his other men. With a flash of fear he thought of Red. He studied the row of prisoners, looking for a familiar face, and there—turning toward him as if at a signal—was Dawson’s. The eyes of the two men met and Dawson turned away.

Tim looked along the length of track. The ribbons of steel reflected the blinding sun as they converged in the shimmering distance. He nodded sleepily but his ear caught a sound. A column of men moved along the street, thinly veiled by a cloud of dust. As they came closer Tim could see that their clothes were in tatters and they were pitifully thin. Some of them wore slouch hats and some of them straws. On poles that rested on their shoulders they carried their belongings: rusty pots and pans and bits of clothing, a three-legged chair and a couple of homemade tables. When the column halted Tim looked closely. He was shocked to see that two of the scarecrows wore dark blue forage caps and that a barefooted man had a tattered Federal blouse tucked into his belt at the back. They must be Yankee soldiers captured many months ago.

Their faces were sunken and vacant. They put down their rattling, tinkling poles and settled against the wall near the far corner of the building.

Tim felt a little sick. He turned his eyes away and rested his head in the flats of his hands and went to sleep.

The shriek of a whistle brought Tim to his senses. He was steeped in sweat and he shook his head and blinked at the train as it backed slowly toward him, its bell clanging, its wheels singing and screeching.

Six freight cars and a caboose made up the train. Up forward the stack of the engine stood high above the cars, belching smoke and sparks. Along the tops of the cars the ragged men and boys of the Home Guard stood with their muskets held loosely in their hands. On the platform at the back of the caboose stood a grisled old man with a pistol thrust into his belt. Beside him was a man, apparently young, in a soiled Confederate uniform, a slouch hat shading his face. As the train stopped, Tim could see that the young Confederate’s face was nothing but an expressionless scar.

It wasn’t long before another column of men came into sight. They were all in Yankee uniform, and as they marched out of the shadow Tim’s heart skipped a beat. At the head of the column, hatless and with his blouse thrown open, marched Red. There was life in his stride. His hair[58] blazed in the sun and he held his bearded chin at a jaunty angle. Alongside Red walked Kautz with a snappy military air.

Tim could feel the thumping of his heart. He got to his feet, dizzy with sleep and fatigue. He jumped off the platform and waved to Red. Red broke ranks as the column halted. “Timmy,” he said, “I knew you were alive but I didn’t know when we’d meet again.”

Captain Kautz smiled and held out his hand. “Good to see you, Lieutenant,” he said.

The platform was crowded with prisoners. The guards began to shout, “Form ranks, get back in line” but the men just stood and talked.

A shout like the bellow of a bull broke through the talk. There was sudden quiet, and with a broken-toothed smile showing through his snow-white beard the old man on the back platform of the caboose said, “Bluebellies, you’re in my charge now.” He took off his gray slouch hat and bowed his white head in mock respect. “When a prisoner steps out of line my men will shoot to kill. My sergeant here will stand by one car at a time and count thirty men into each. Now get to your feet.”

The old man jumped to the platform and strode down the line until he saw the derelict prisoners with their pots and pans and furniture. Some of them were leaning against the wall and others were lying on the platform in the sun. He bellowed again and the derelicts stared like sick rats at a ravening dog. Slowly they got to their feet. “Proud Yankee bucks,” the old man sneered.

The emaciated prisoners reached for the poles that held their belongings.

“What the hell is this?” the old man screamed, frightening one of his charges so that he dropped the end of a pole,[59] letting his belongings clatter to the stones. “You can’t take your junk on the train.”

The men stood silent and timid in the sun. In a treacly voice that could barely be heard the old man said, “Just leave your stuff here and bring up the rear.”

“Filthy, bullying pig,” Tim said between his teeth.

Then his anger waned and he turned to Red. “I thought I’d never see you alive again.”

Red kept his voice low as the old man passed close to them. “A Confederate captain told us you were still alive.”

Red moved closer to Tim. “Captain Kautz has a plan of escape,” he whispered. “It was just to be the two of us. I imagine you’ll want to be coming too.”

Tim raised his brows. “That’s why you marched in here happy as a raw recruit.”

The old man stood on the platform, his pistol in his hand. “No talking in the ranks,” he ordered. “Move forward and be counted in.”

“Stick together from now on,” said Kautz in a tight-lipped whisper. He looked sharply at Tim. “We jump from the train. I give the sign.”

They were the last to be counted into the car ahead of the caboose. As they approached the door Tim held his breath as the scar-faced sergeant counted, “Twenty-six, twenty-seven....” And Red was twenty-eight.

The guards kept their places on the tops of the cars. All the doors on the opposite side of the train were shut and probably locked.

As the prisoners climbed into the car the smell of cow dung and urine struck them full in the face. The last ones in sat near the open door.

Tim’s head ached and he was stiff in every joint, but as he leaned against the boards of the cattle car with Kautz[60] on his right and Red on his left he smiled to himself. Friends, that’s what a man needs, he thought. It’s going it alone that makes it tough.

Kautz turned to Tim. “I’ve studied maps,” he whispered, slapping a slight bulge in the lower part of his blouse. “I thought about capture before we attacked the fort.”

Tim glanced at Kautz and for a moment he couldn’t believe his ears. Kautz had never shown the slightest doubt that they would take the fort.

“On this train,” he heard Kautz say, “we will probably head for Columbia. If so, we jump south of the city. We might branch west toward central Georgia. If we do that, I’m for jumping as soon as we see our chance. In either case, our objective would be Eastern Tennessee. If we should head south along the coast, we jump near Beaufort.”

Kautz looked around the car and leaned close to Tim. “The giving of the signal will depend on the position of the guards, the degree of darkness and other things.” His whisper became a hiss. “We will be taking great risks, in any case. I will go first, then Kelly, then you.”

The sergeant looked into the car. His skin was mottled purple and pink and white, scarred so badly that his face could express no emotion. When he talked the glistening skin crinkled dryly around his mouth. His voice came soft and deep. “We have to put three more men in here,” he said with something that sounded like regret, “but I’ll keep the door open if you behave yourselves. In this country,” he said, “escape is foolish. Don’t forget that.” He clamped his jaw shut and moved along to inspect the other cars.

Three of the derelicts crawled into the car and collapsed like half-empty sacks of meal.

[61]While Kautz had been talking Red had sagged and fallen asleep. “I’ve had a little sleep,” Tim said to Kautz, “you sleep now and I’ll stand watch for an hour or so.”

“Fine,” Kautz said. He rested his beard on his chest and went to sleep.

Tim smiled to himself. He even sleeps efficiently, he thought. As he smiled his eye was caught by the gaze of one of the derelicts. The man stared into Tim’s face with vacant, luminous eyes. Tim took three of Greene’s oranges out of the pocket of his blouse and held them toward the man. “You’re hungry,” he said. “One of these for each of you might help.”

The man’s emaciated hands shot out, grasped two of the oranges and clutched them to his body. He reached for the other with something in his pitiful face that made Tim draw the third orange back. “One to each,” he said.

The man’s lower lip quivered. He grasped the oranges and turned his back and started to claw at one of them. Another derelict saw his chance, plucked the other orange from the man and tore at the skin with his teeth. He sucked and bit as the juice ran down his tattered shirt.

The train whistle gave a sudden, piercing shriek and the cars bumped together with violent jerks. The third Yankee derelict, a boy still in his teens, opened his eyes. Tim leaned over and handed him the third orange. He took it silently, turned it around and around as if it were a ball of gold—as if spending the wealth would take some thought. He put up his knees to make a shield, and with his thumb and forefinger gently peeled off the first strip of skin ... and the second ... and the third. When the orange was peeled he quartered it and ate deliberately, gasps of pleasure punctuating every gulp.

Now the shouts of the guards and the roaring, cracking[62] voice of the captain rang along the platform, and the train moved slowly forward. The door on the right was left half open.

Tim watched the shadow of the train as it moved along beside the tracks. It must be past noon. Was it this morning they’d attacked the fort?

The train jerked and stopped. With a squeaking and clanking of tortured couplings it started again and gathered speed. Warehouses and sheds flicked by in a blur, like bits of faded glass in a kaleidoscope.

As the train left the city by the sea the landscape was flat, dotted with brown-leaved little trees and tall pines with trunks which reached high and bare before they branched into thickly needled clusters. Once when the train slowed down for a moment the face of one of the guards hung upside down from the roof of the car, then disappeared again.

As they rattled through the countryside Tim was the only one in the car who stayed awake. The train swayed and rocked across huge swamps filled with trees with swollen roots, their branches dripping with Spanish moss. The pungent odor of stagnant water and rotting wood mixed with the smell in the cattle cars.

Tim’s senses dimmed. His head dipped and came up again. He pinched himself, stood up and steadied himself against the door frame of the car.

Kautz’s head snapped up. “Have we changed direction?”

Tim sat down. “No,” he said. “I judge by the sun that we’re still going roughly northwest.”

“How long have we been on the road?”

“About half an hour.”

“No chance for Beaufort now,” Kautz said. “They’re taking us to Georgia or Columbia. There’s a place called[63] Branchville just ahead. If we fork right, it will be Columbia. I hope that’s what we do. My maps don’t cover much of Georgia. Then there’s the matter of getting help. We can’t get to our lines without some help. They say there are Unionists in North Carolina and Tennessee.”

“Then we go north, no matter what.”

“It looks that way,” Kautz said. “Get some rest, Lieutenant. I’ve had enough sleep.”

The train jerked to a stop, and after a spasm or two was still. Tim groaned and opened his eyes, got up, and stretched and poked his head into the blinding light outside the car. The crack of a pistol sounded in his ears. A bullet sang past his head and dug into the side of the wooden car. He ducked back into the car, feeling the blood drain away from his face. Slowly he sat down again on the floor of the car.

“Damned maniacs!” said Kautz.

The old man’s voice sounded just outside the car. “Another word like that and I’ll shoot every bluebelly on this train.” He pointed his pistol at Kautz’s head. “And I’ll start with you, Yankee Captain.”

Red looked up sleepily. “Who was doing the shooting?”

“The captain of the guard,” Tim said. “He nearly hit me in the head.”

They stared out at the settlement beside the tracks. A skinny horse was tethered to a lone pine tree. There were one or two white wooden houses and a chicken shed. A pig ran into view, going in circles, pursued by a boy of nine[65] or ten. The animal moved with great speed. He and the boy dropped from sight and appeared again, this time farther away. The boy dove at the pig and they tumbled in a cloud of dust. He got up, holding the animal, and took him, wiggling and squirming, to his pen.

When the train left Branchville it was clear that they were heading for Columbia. They were going north. The countryside was hilly now. The swamps gave way to meadows and copses, small farmhouses and cotton fields. They passed through a stand of trees, and in the blur of foliage Tim thought, If a man jumped here, he’d be sliced to ribbons by the trees.