Illustrated by Alfred

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Unknown Worlds April 1943.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Say, that is mighty white. I do not mind if I do, though I remembers the day when I would not of touched beer with a ten-foot pole. Weight. Jockeys has got to watch their weight like it is tombstones they is putting on instead of pounds.

Well, here's luck, mister. May all your double parlays give the bookies fits.

What's that? Yeah, sure I am a jockey. Was. There is not no point in giving you the old three and five. You look like a right guy. Why should I kid you? I have not been up on a horse for four years. Six months cold for a jock is a wide turn, but four years—say, four years is—what the devil, I am washed up cleaner than a choirboy's ears.

And this is not my fault. That is what gives me the burn. It is not my fault. When Lady Luck smiles in the racing game she has got a grin so broad you can count her back fillings, but, when she quits smiling, brother, she just quits and you might as well go wrap your head in a sweat blanket and forget it.

You know, you is going along good, not winning no Champagne Stakes nor nothing like that, but hitting the percentages and going along O.K., see, when all of a sudden you finds that things begin to happen. And they keeps right on happening and you can spit in the wind all you want to and chew four-leaf clovers and take a horseshoe to bed with you and it does not have no effect. Things just keeps right on happening until after a while the trainers puts the double O on you and you can not even get a leg up on a spavined brood mare and everybody takes to calling you "Jinx."

That is me, mister. Jinx Jackson.

Oh, I am not beefing none. I manages, what with one thing and another. But believe me, buddy, it is enough to give you the yelping wipes when you stands there by the fence with the sun beating down on you, and the crowd milling around excitedlike, and the bugles blowing, and the flags waving, and the horses walking past—nervous—and the colors up with their pants skintight and their shirts bellying out like silk balloons, and then they are wheeling the barrier in, and you look at the track and it is smooth and sweet and fast as a filly with bees in her ears, and everything gets still except the popcorn peddlers, and there is that awful minute when you is waiting and the shirt sticks to your back and you gets that old, familiar, tight feeling on the inside of your thighs, and your tongue is like a sponge bit between your teeth, and then that cry—like a rising wind—"THEY'RE OFF!"

That is when it hits you. Right here. As if somebody has yanked your stomach out and let it go wham back at you, like a pair of suspenders.

That—and when you see a snipe getting hisself boxed on a inside turn, or bearing out in the run through the stretch, or—aw, nuts with it. It gets you, that is all. It gets you.

Once you has got the feel of horses in your blood you is a goner. A gone goner. It is there, brother, and there is not no use fighting it. You cannot no more keep away from a paddock than you can stop blinking your eyes.

Jimmie Winkie used to say, "You can shake grief and sorrow, you can bury remorse—but you can't never lose the feel o' a horse."

Jimmie Winkie. Yeah, Wee Willie. That is the same.

Good! Man, he had the magic touch. Why, he could add twenty lengths to anything on four legs. Easy. Jimmie was tops. Why, I has seen him come from behind the hard way and spot them a extra advantage by pulling out and still win and there was not no photo finishes, neither. When he won, mister, he won.

He was a funny guy, he was. Had a kind of puckery face and big ears. Walked springy, like a banty rooster. Used to use a special bridle when he was up. Superstitious? It is not superstition exactly. It is just a kind of a feeling you get about certain things. Lots of us jocks are thataway. I know I would of had a hissy—four years ago—if I had of mislaid a old wore-out crop I always carried. Moe Prentice had a buckeye he would not of parted with for nobody. Jackie Watson had some sort of a medal on a silver chain. Cry Baby Noolan would not no more of thought of riding with his cap anyway but hind side to than he would of thought of riding without any clothes on. In fact, if he would of had to make a choice, I reckon he would of rode in his skin before he would of changed his cap proper. And, like I said, Jimmie has this here special bridle, though there is not much special about it except that it is goldish-looking if you hold it in the right light. But seems he takes a fancy to it and from the way he acts you would of thought it is made from the tanned hide of a Derby winner. But it is not no such thing, of course. It is just a bridle like any racing bridle only, like I said, it is goldish-looking in a unnoticeable manner.

He gets it one year when we is finishing up the circuit down in Tijuana. This is before he hits his stride. When he is going along, like me, not snaffling no tall money nor nothing but knocking off his percentages. He is plain Jimmie Winkie then. The newspapers has not tagged that there Wee Willie on to him yet and he is not endorsing no leather jackets, nor saying as how he likes Puffie Wuffies because they is superroasted and rolled on hoops.

Well, as I was saying, we is down in Tijuana and it is nighttime and we is walking down one of them crooked streets which is about as thick in Tijuana as saddle sores is in a riding academy. We is walking along with our hands in our pockets and not much else, being as how we has inadvertently got mixed up in a game knowed as faro, the same which is like being on the wrong end of a loco bronc, and which we would not of got into if Jimmie had not of wanted to increase a five-dollar bill into a ten-dollar bill so as to buy a real nice present for Ditsy. Anyhow, like I said, we is walking along minding our own business when there is—

Ditsy? Oh, Ditsy was Jimmie's sister. Name was Dorothy, but Jimmie called her Ditsy. He was crazy about her. Seemed like he had raised her since she was knee high to a feed box. Guess they had some muddy tracks, them two, and what with their not having nobody but theirselves and her being crippled, why, one way and another, he set a lot of store by her.

Anyway, we is walking along, Jimmie and me, and I am thinking about what we is going to eat for breakfast the next day, and lunch, and supper, and Jimmie is thinking about how is he going to buy Ditsy something when we hear a rumpus going on around a corner up ahead. It increases graduallike and when we gets to the corner we meets it, head-on you might say.

There is about a dozen people who is all personal acquaintances of John Barleycorn, and they is pestering a woman who looks like she is on her way to a masquerade at a insane asylum. She has got on a sheet all draped and wrapped every which way and her feet is laced up in sandals and there is a wreath on her hair, only now it is setting cockeyed on account of as how these here people has been chasing her, and she is carrying a bridle. In fact, if I had of spent my money on John Barleycorn instead of faro, I probably would of joined in on the side of these here people who is laughing theirselves sick and grabbing at this here sheet and having a big time, for which I cannot blame them any as this woman is sure a curious sight.

While I am thinking what a curious sight she is, Jimmie busts up the party. He does this with very little fuss, hitting merely one guy who goes down like a sack of wet oats and the rest takes to their heels as I am doubling up my fists preparing to wade in.

"Now, sister," Jimmie says, rubbing his knuckles tenderlike, "if I was you I would vamoose. Tijuana is no place for a lady without as how she has got company to see that she gets where she has started out for."

Well, this woman straightens her wreath and breaks out in some kind of a foreign language which sounds like nothing I ever heard unless it is "Chopsticks" played on a piano which is out of tune and is minus some of the keys.

"Look, sister," Jimmie says, "vamoose while the vamoosing is favorable."

The woman makes some motions and spouts some more of this here talk and there is just one word I get and that is "grease." She says this over and over, "Grease, grease," meanwhile gesturing for all she is able.

"Grease?" Jimmie says, puzzled, and she nods violently and shakes the bridle she is carrying and does a act like she is putting it on a horse and then flaps her arms like she is flying.

"Grease," she says.

I begins to get uneasy. "Say," I says to Jimmie, sotto voice, "let's us get out of here—this gal has got bats in her belfry."

"I think she has lost a horse," Jimmie says slow.

"Horse!" I says. "How is she going to straddle a horse in that getup? She has lost her mind. Let's us get out of here. Loonies is not no picnic."

Jimmie does not pay no attention to me. He takes the bridle away from her—gentle—so as not to scare her and he does a act like he is putting it on a horse. "Horse?" he says.

This looney looks at him a minute, then her face kind of brightenslike. She points to the bridle Jimmie is holding and says, "Hippos."

"She has got the D. T.'s," I cheeps. "She is talking about a hippopotamus what flies or I will eat that there bridle. Come on," I says, "this is not no place for—" But I do not get no further because there is a faint whinny and this here woman shrieks joyfully and—without so much as a kiss-my-foot—lams in the direction of this here nickering which, judging from the sound, is a block or so to our rear—though we has not seen no sign of no horse when we is walking by thataway.

We stands there gawking after this dame while she disappears in the night and Jimmie, suddenlike, yells, "Hey, here is your bridle," and starts after her and me after Jimmie, because I has not got no wish to see Jimmie sucked in on something that is not kosher, and it is plain that there is something here that does not meet the eye right off.

I dope it that this here dame is a kind of a lead rein for some guys which is laying low in a alley or some place figuring to roll whoever she ropes in, and it is a unpleasant statistic that persons is often beat up severe when it is discovered they has not got no wherewith to make such a business profitable.

When we gets down the street a ways I catches up to Jimmie and stops him and I says, "Has you taken leave of your senses? This here is one of them cul-de-sacs or I am a ring-tailed—" But I do not say baboon, which I had intended, because somewhere I hears a noise like a lot of pigeons taking off—like they has been shooed—and from way up, like on a roof, I hears this woman laughing and it dwindles away and, then, it is quiet and a little white feather drifts down and lands in the gutter. It is all very weird and I do not like it.

"I would of swore a horse nickered down here a minute ago," Jimmie says.

"Shut up," I says, "and let's us get out of here before we is knifed in the back."

So we does and that is how Jimmie come by the bridle.

Well, say, I do not mind if I do. There is this about beer. You do not have to worry none the next morning about tying your shoes. Ever try sticking a hot knife in it? Many's the time I has seen my old man heat the poker until it is as red as the old Scratch hisself and then plunge it into the pail. That was when you could get all you wanted for a dime with boiled ham and cheese and bologna throwed in to boot and, like as not, a slice of liver for the cat.

Here's bumps, mister. And may you never tear up your ducats without looking twice.

Where was I? Oh, yeah, Tijuana. Well, here we is without a buffalo between us. Broke as a skillet of scrambled eggs and up in the fifth the next day, the same which dawns bright and early and finds me and Jimmie nearly splitting a girth trying to trade that there bridle for a plate of buckwheat cakes, but everybody gives us the zero gaze until I begins to wonder if we is coming down with smallpox. So we hunts up a dopester by the name of Stew Hatcher and he stakes us to a meal after which we hangs around until he has got up his sheet and then we rides out to the track with him and his girl. We asks Stew, just kidding, who he is picking in the fifth and Stew says it is not us and he is not kidding. For his money, he says, it is High Jinks, Admirella and Sky Eagle. One, two, three.

I am up on Black Boy and Jimmie he is up on Peajacket, so we thumbs our noses at Stew and gives him the buzz and says as how we is pleased to have met this girl he is with—which is a lie because she is very snooty—and we goes on in.

We gets into our colors and sets around with the fellows dishing out a lot of bull about what we done in Tijuana and Jimmie gives me the wink and says he has got hold of a nifty bridle he is willing to take a loss on. And he gets this here bridle out of his locker and says if anybody will give him a fin for it they can have it, though they will be rooking him on the deal.

Boy, does he get the laugh. Moe says he will give him a fin for it if Jimmie will throw in Peajacket and shine his boots for a week, too. And Cry Baby Noolan says if it is such a hot bridle why don't he bridle Peajacket with it. And everybody starts gaffing Jimmie and I acts real indignant and I says what is it worth to them if he does bridle Peajacket with it, them being such sports. Jimmie, seeing the lay of the land, plays up to me and says, "No," and everybody chimes in giving him the merry ha-ha and when there is three bucks up he will not do it, why, then Jimmie says O.K., he will do it, see.

Does a holler go up when they catches on to how they has been taken! But Jimmie says a bet is a bet and he is game enough to live up to his end of the bargain if they is. "Of course, if they isn't—" he says, inferring that anybody who reneges is a horse's patoot, so, naturally, nobody reneges, though there is some grousing.

I used to say to Jimmie, I would say, "Jimmie, remember the day at Tijuana when we nicked Moe and them for three bucks?" And Jimmie, he would say, "Yeah," and kind of draw in his breath like he was thinking about it—hard. Remembering how Peajacket upset the bookies' apple cart.

You see, Stew Hatcher is wrong. It is Peajacket, High Jinks and Admirella. One, two, three. And the owner of Peajacket—I forget his name, big loose-mouthed chap with a face like a side of beef—is fair to be hobbled because he has not bet on his own entry on account of as how it is a cinch to lose. It is a two-year-old he has picked up for seven and a quarter at a public sale and he is just feeling him out and damn if Jimmie does not bring in a win.

Me? Oh, I comes in with the tailbearers. I could of got in a lame fourth, but I am so whooper-jawed watching Jimmie go down the stretch like a lighted fuse that I lets this here Black Boy I am up on bear out—he was death on bearing out—and, of course, that puts the quietus on us. There is not no percentage in whipping a horse over for fourth place. A horse has got sense enough to know when you is making a fool out of him.

No, I do not guess you will recollect Peajacket. He turns out to be a foozle, after all. He is entered a couple of more times, Saratoga, I thinks, and Empire City—Syl Patton up—but he does not do nothing but pick up a coupla pounds of mud.

But he sure is not no foozle that afternoon at Tijuana.

There is not no barrier. You just keeps back of the line as best you can. That is one way to lose a race before the gun. I has seen them do it on purpose. You know, too tight a rein, get your horse skittered, make him break three or four times, and, when the gun goes, hold him back just long enough to let him see that he is a cooked potato. Nine times out of ten you can whip him raw and he will run, but he will not run fast enough. But your nose is clean. The trainer cannot say as how you did not try.

Say, am I boring you with this? If I am—okke doke, any time you has had a sufficiency, say so.

Well, as I was saying, there is not no barrier. Outside of a little tail flicking and head tossing, Black Boy is as calm as a Jersey cow. High Jinks breaks once and Sky Eagle and some of the field prances around a bit, but Peajacket he acts like he has been fed hopped oats. In fact, there is some talk of it later on, but they cannot never prove nothing. Anyway, this here Peajacket is taking on for a fare-you-well with Jimmie trying to gentle him down and the starter getting mad and a jock, name of Happy Slauderwasser—that is a moniker for you, nice guy though—who is next to Peajacket swearing something fierce. Finally, Jimmie gets this here Peajacket backed in and he is lathered up like a ad for saddle soap, and the gun goes, and out of the tail of my eye as me and Black Boy takes off I sees Peajacket rearing up and I thinks, "Oh, Lordy," because it is a rule last one in has to pitch a buck in the kitty. And it is plain to see, in a field of fifteen, Jimmie is slated to be the last one in and then we will only have a buck apiece instead of a buck fifty.

I settles down and starts easing over to the inside track hoping for a pocket. High Jinks is up ahead and he is not anywheres near let out yet. There is three or four horses in between, then Admirella nosing up, Sky Eagle alongside, doing like me, playing a wait, and Jimmie and the rest of the field bunched in behind.

I am not thinking about Jimmie no more, though. I am concentrating on them three or four babies cutting off my view of High Jinks. I am not worried about them none, but when there is a opening I wants to be there instead of Sky Eagle. So I am concentrating, like I said, and I hear this horse coming. You do not actually hear them as much as you feel them. It is a mixture of both. It is like you got an alarm system inside of you and all of a sudden it is ringing like who popped Mollie and you know with a kind of a ... of a ... a kind of a awareness that you got heavy competition.

I remembers wondering who it could be. There is High Jinks and Admirella in plain sight. Sky Eagle and me practically pat-a-caking at each other, some of the field ahead, but they is giving by now and, so far as I know, what is left in tow is not capable of doing nothing but horse apples.

I do not take my mind off this here opening, though. It is getting ripe, I can see that, and I am bound I am going to be there when it is due before it closes in and strings out.

Then, I catches a glimpse of this here horse on the off side of Sky Eagle. A kind of consciousness it is of this here third horse and I am sort of cheered when I see it is not bothering none about no openings, nor no inside track, nor nothing like that. And, while I am being cheered and thinking what a smart guy I am, this here third horse pounds ahead past Sky Eagle, a shoulder, half a length, a length, and that opening I been hovering over swings wide as a barn door and Sky Eagle is through it because I am yawping at Jimmie Winkie with his ears skinned back crouched high on Peajacket, and if I had not of knowed better I would of swore he was scared green, and while I am yawping, Black Boy bears out so, as I said, that puts the quietus on us.

There has been better races run and bigger ones has been won by darker horses, but, off-hand, I cannot call any to mind that I got such a thrill out of. I do not know whether it is because I am so cocksure Jimmie is bringing up the rear, or because Moe Prentice—he is up on High Jinks—is took down a peg or two, or maybe because there is a certain something about the way that there horse runs with his nostrils red and wide, and his tail streaming out behind him like it has been starched, and his hoofs beating music out of that there track like a crazy drummer, and Jimmie pasted to him close as a surcingle and with a kind of a look about him like night wind sounds, if you know what I mean. A kind of a queer, wild, blowy look. But most of all I guess it is the horse.

Jimmie says it is the horse and he ought to of knowed being as how he was up on him. Jimmie says it is also a great surprise to him that Peajacket wins, but, naturally, he does not say this out—but just to me—as it is not a good policy to let on that you are surprised when you bring in a winner.

How does it feel to bring in a winner? Brother, you can have the greatest symphony that was ever wrote; I will take the thunder of a winner's hoofs coming down the straightaway. That is something, brother. That is really something. It is like a ... like a ... well, like I said, a kind of a awareness. Like you was conscious of the noise and the feel all at the same minute. Take that there Peajacket. I got it right away. The noise and the feel together, I mean. Like there was two horses running. One on top the other.

We bums a ride back after the seventh and gets out on the main drag and flips a coin to see whether we eats or buys Ditsy something. It comes out buying Ditsy something so we goes to one of these here shops that has a window full of everything from jewelry to tablecloths and we picks out a powder box that plays a tune when the lid is lifted off. A thin, tinkly, sort of plink, plink tune, but pretty. Reminds you of the way ladies used to rustle when they walked, if you know what I mean.

While the guy is wrapping it up, Jimmie goes over and picks up a vase which is setting on a shelf with a lot of other vases. This here vase he picks up is blue and has a lot of well-built dames on it holding garlands of flowers. Jimmie kind of whistles.

"Look at this here," he says.

I agrees it is nice, but points out that we has got exactly twenty-nine cents between us and the price is marked clear two fifty.

"This is a strange coincidence," he says, more to hisself than me, and I says it is not no coincidence it is a vase and if he is thinking about switching over, why, there is a vase on the shelf above which is better-looking on account of as how it has a scene painted on it and the price is twenty-five cents cheaper.

This guy comes up about this time and washes his hands in the air and asks if we are interested in a vase.

"No," I says.

"Yes," Jimmie says. "Who is this here middle dame on this here vase?"

"They represent the Muses," this guy says. "A marvelous buy for the money."

"This here middle dame is a Muse?" asks Jimmie.

"They are all Muses," this guy says, "goddesses of the arts and poetry and science. A very artistic vase. Only two fifty."

"Did any of them have a horse?" Jimmie asks.

"Horse?"

"Horse."

"I could not say. It is a very handsome vase, howinever, and I will make you a special price of two twenty-five, if you are interested."

"Where can I find out if any of them had a horse?"

"I could not say, unless it is the library. Two dollars even I will make it. Below that I cannot go."

"Very well," I chimes in, being tired of Jimmie ribbing this here guy about a horse, "we will take it in place of the powder box."

With that this guy freezes over like the outside of a mint julep and he says chillylike, "I have just remembered that this vase has been put aside for another party."

And I says, "That is very odd being as how you were so all fired set on us having it at reduced cost."

"Herman," this guys says.

And another guy with a neck like a Percheron, shoulders his way through a curtain in the back and stands there like as if he is itching for somebody to say "When." So we takes our package and we leaves.

I am in favor of hunting up a crap game and shooting our twenty-nine cents and Jimmie says that is a splendid idea and for me to do so and he will meet me at the pool parlor in a hour. I asks where is he going? And he says the library. And as he has never been inside a library in his life to my certain knowledge, I figure he is telling me in a nice way to mind my own business. Which I does. And in a hour I has run the twenty-nine cents into eight bits and a Masonic emblem.

I meets Jimmie like he said and I can see right away he is exceptional thoughtful. We go to a place called La Cucuracha where the second cup of coffee is free and you gets gravy with your potatoes, although Jimmie seems to have lost his appetite. He keeps transferring his food from one side of his plate to the other until I outs and asks him pointblank what is ailing him.

"Did you ever hear tell of a horse called Pegasus?" he says by way of answer.

"No," I says. "Who sired him?"

"He is out of Medusa by Neptune," says Jimmie.

"I never heard of them, neither," I says shoveling in a mouthful of potatoes and gravy. "What has this here Peg-whoit got to do with you?"

"I am not certain for sure," he says, "but I has got a idea,"

"Which is?"

"Could be he got blowed off his course," Jimmie says, "or got scared by another gadfly or some such, landed in Tijuana and this here Muse comes after him and—"

"Look," I says, "one of us has got a screw loose and it is not me. Begin over and repeat slow and there is apple pie with the dinner and if you do not want it I will eat your piece, if it is all the same to you. Now what was you saying?"

He shoves his plate back. "I am going to break the track record tomorrow," he says, and there is something about the way he says it, some quality in his voice that makes me sit up and take notice all of a sudden.

A kind of creepy sensation comes over me and I am reminded of when I am a kid and the grandfather's clock in the hall would strike during the night. It would go bong—bong—bong real slow and soft, but filling the house, howinever, and making the air vibrate. I would lie there and think, "It is just the grandfather's clock in the hall," but that did not make no difference. My feet would get cold and my eyes near bug out of my head, and I would not have no swallow and I would lie there thinking, "It is just the grandfather's clock in the hall."

I gives Jimmie one of them searching looks you read about, but it does not tell me nothing except that he is a mite tightened-uplike and is letting some fifty cents worth of food go to waste.

"Thanks for the tip," I says. "Who you planning on being up on? Man-o'-War?"

"Ditsy has always wanted a grand piano," he says, "since she was not bigger'n a boot-jack." And he says, "I will get her the best one money can buy."

It is obvious that he tightened up more than I think because there is not enough space in that two-room flat in Cleveland to hold both Ditsy and a grand piano at the same time.

"That will be dandy," I says, "but I am afraid there will not be no grand piano in it. Them things cost folding money."

"Folding money," he repeats and the words sounds like a three-inch sirloin the way he says them—thick and red and juicy. "You know what I am going to have," he says, "I am going to have a pair of handmade boots—them that laces at the ankle—and I am going to have a suit with buttonholes under the buttons on the sleeves. Not just thread sewed to look like buttonholes—real buttonholes I am going to have under the buttons and a yellow chamois bag."

"A yellow chamois bag under the buttons," I says and, recalling to mind a chap named Joe Hankins who fought a bunch of Comanches all one night in a psycopathic ward at a hospital in Louisville, I continues to smile pleasantly while I eases my chair back.

"Yeah," Jimmie says, "lined with flannel so as the bridle will not get scratched up none."

"Sure," I agrees, "flannel."

"Saratoga," says Jimmie, "Havre de Grace, Narragansett, Hialeah, Aqueduct."

"Hawthorne, Churchill Downs, Empire City, Belmont Park, Thistledown," I chimes in nodding like a Chinese laundryman who has lost your wash. I holds my breath and gets to my feet praying that I will be able to ease him out quiet.

"Through?" Jimmie says, cool as a cucumber. "What say we see if we can get a game of pool on the cuff?"

The next day he breaks the track record.

I has thought about it a great deal since then and do you know what I figure? I figure it like this. I figure that Jimmie had got on to a secret. There is a secret to doing everything. Like tight-rope walking, or shooting par golf consistent, or whizzing a ball over a tennis net so as it falls just so and dribbles off before it can be got up off the ground. There is a secret to juggling plates and a secret to pole vaulting higher than anybody else. The plates and the pole and the rope and the golf clubs and tennis racquet is all the same. What I mean is you could take half a dozen plates and throw them up in the air and they would land behind the eight ball. But take these here same identical plates and give them to a juggler and he will make them perform without so much as mussing his tie. Why? Because he knows the secret.

Well, then, why can it not be the same way with horses? I am not saying you can take a plow horse and make him win a race any more than that there juggler can juggle plates made out of pig iron. But I am saying, if you know the secret, you can take a race horse and make him win a race. And, like I said, I has thought about it a lot and I figure there is a secret and Jimmie has got on to it. I figure the secret comes to him in a flash like when you know, in a sort of a burst of knowing, that the dealer has aces back to back. Because from that day on he never rides a loser. Except one. I will get around to that in a second.

Saratoga and Hialeah and Havre de Grace and all of them is not no pipe dream. And neither is Ditsy's grand piano, though it is not in no two-room flat. It is in a living room as big as from here to there. One of them two-storied jobs that goes all the way up to the roof. One of them studio living rooms. And done real classy with drapes and hand-carved furniture and lamps with rose silk on the underneath parts of their shades, and them black-and-white, pen-and-ink-looking pictures on the walls, and a rug that feels like it will arch in the middle and purr if you rub it, it is that soft.

Of course, it does not happen pronto. It starts out gradual with Jimmie's name in the papers—"Keep your eye on So-and-So up on So-and-So"—and then it takes a up curve with the sports writers pegging him with this here Wee Willie and first thing you know he is appearing regular Sundays in the rotogravure, him and Ditsy, holding a horseshoe or a shamrock or this here bridle or such as that, and persons are talking about the "Winkie Technique" and children is eating their weight in cereal because Wee Willie Winkie says as how it has got Vitamin Q and for six box tops or reasonable facsimiles thereof the cereal people will send you a handsome, autographed photograph of Wee Willie on Martinique or Little John or Fireflow or some such as them. And his stock is going up like a fever chart. And he is in the bucks. But I mean in, brother.

It changes him some. I do not mean he goes around putting out like he has hung the moon and painted the blue sky; if anything, he quietens down and kind of draws into hisself like. In fact, when he is congratulated on his ability, which he is every time he turns around, he acts like it is making him sick to his stomach. And when the write-ups come out about how modest he is and shy and retiring and how he always tries to give the credit for a win to the horse, why then he acts like he is even sicker and getting no better fast.

Naturally, while most of the publicity is along the lines of sweetness and light, there is some of it as squeezes out a few lemons. Like them that says as how Winkie rides a horse walleyed, and them as hints it is mighty peculiar he does not never lose and a pity, furthermore, because the odds on a horse what is toting Winkie is something to behold in a new all-time low.

Then there is the follow-up gang that always seems to heel to a celeb. Whether he gets to be a celeb by riding horses or eating goldfish or drinking thirty buckets of beer does not make no noticeable difference—they follows. It gets so Jimmie cannot go nowheres without getting the press took out of his pants and he is lucky if the pants is not also took out with the press.

People sends him alligators from Florida and salmon from Alaska. He gets lariats made out of tail hair plaited, and high-heeled boots with tooling. He gets silver spurs, and leather jackets, and saddles, and gloves, and sombreros. He gets blankets and pipes and racks for this and holders for that. He gets a sheep dog, a pair of love birds, a coon cat, a baby leopard, a bearskin rug with the teeth still in it, a stuffed owl, a collection of butterflies, and some twisty horns off a mountain goat all set and glued on a wooden thing to hang on the wall. He gets socks by the gross, handkerchiefs by carloads and one dame even sends him a box of pink silk underwear with his initials stitched in fancy in orchid embroidery.

To give you the idea, one day he appears in the papers cutting a piece out of one of them round coffee cakes and the next day there is nineteen round coffee cakes delivered to his address and he does not like round coffee cakes nor no kind of coffee cakes, but is cutting this here piece to please the press photographer who wants a homey touch.

But for everybody what is giving him something there is two wanting him to give them something. Jimmie used to say he got so he could tell right off who was a givee and who was a gimme. Not that he does not appreciate what is give him, even if he does not keep it, and not that he does not hand out to the gimmes—it is just that he does not want nothing off of nobody and does not want nobody to want nothing off of him.

But when you gets in the major brackets that is not the way things is. So, like I said, it changes him some. Some way, he reminds me of a kid what has eat a quarter's worth of jelly beans all one flavor.

It changes Ditsy, too. Her hair is not loose-like and fluffy no more. It is on the order of a cocker spaniel's, only precise, and her ears has got earbobs in them, and instead of wearing print housedresses she is all diked out in them dresses which is not referred to as dresses, but as "creations." She has got a new wheelchair which is streamlined and has more chrome on it than a limousine, and some bird with a Vandyke and a accent you can spread like marmalade is giving her some kind of underwater massage for her legs, so she should be very happy. She is not, though.

She puts on like she is happy and anybody what does not know her would say, "My, she is happy," and they would be ninety-nine and forty-four hundreds percent wrong because she is not happy by no means. She fools Jimmie because Jimmie is so anxious for her to be happy that, when she keeps saying she is happy, he believes she is happy and it does not occur to him that when you are happy you does not go around saying, "My, I am happy," like you was learning a lesson in memorizing.

When a woman is happy she sings and brushes her hair a lot and says stuff like, "I declare, it is four o'clock already, can you beat that?" and she looks smily even when she is not actually smiling. So it is obvious Ditsy is not happy because she is not doing none of them things. When she smiles it is more or less of a lip movement going on under her nose and not having nothing to do with the rest of her face, and she does not sing spontaneous, though when she is in that two-room flat the landlady has had to request her several times to pipe down. And, instead of saying, "I declare it is four o'clock already," she just says, "It is four o'clock," like you would say, "The dodo is now become extinct," or, "I see where there in a population of ninety-two in East Gleep, Nevada."

So, as I said, it changes Ditsy, too. And it is pathetic to watch them two, him and her, working so hard at being happy and pretending that life is a bowl of cherries when it is plain life is a onion poultice.

Some time passes and I am here, there, and yonder and word gets around that Jimmie Winkie is hitting the paint which occasions me to be surprised because Jimmie Winkie is never one to hit the paint even in a mild manner. So I am not paying any attention to these here remarks and I am once or twice very near smacking persons in the puss who say that it is a fact that Ditsy is turned into a red-hot momma.

What's that? Oh, that. Well, it seems that this here underwater massage is the stuff and she is able to get around some—not good, understand, but some.

What! Her! Say, listen here, bub—well, all right, no offense taken, but she is not that kind. O. K. O. K. Let it ride. Sure I will have another beer, only do not make no more remarks like that, see. O. K. O. K.

Maybe I do not make myself clear. I mean she has gone in for double-jointed cigarette holders and red fingernails and them long-haired guys what paints a picture of somebody so as they have one eye here and one here and clockwork springs for the top of their head and maybe a spare tire for one hand and a fiddle for the other with a bunch of carrots sprouting out of it.

Anyway, that is what I am hearing and—here's bumps, brother. You know I set and watched a glass of beer bubble from the bottom one night and it bubbled for three hours and a half 'fore it got flat. That was when Ditsy—But I will get around to that quick enough. Now and again I still catches myself trying not to think about it. And it has been a long time. A long time.

What was I saying? Oh, yeah, Jimmie hitting the paint. He is all right because I am setting in a place in Cleveland—having just got off the train—and some fellow comes in and I does not pay no attention until I see he is walking like a banty rooster which is sea-sick. And I yells, "Jimmie!" And he looks up and focuses on me and I see it is true he is hitting the paint and, if his present condition is a fair example, he is hitting it with a capital H.

I am not one to stick my nose in other people's business. I am one who says other people's business is their own business and no business of mine, having found that a nose stuck in other people's business usually gets itself pinned up so as it does not look like a nose for quite a while after.

But this is different. First, it is Jimmie Winkie. Second, he is running a race the next day I have seen by the papers. Third, it will not put no shine on his shoes if somebody says, "Oh, look, is that not Wee Winkie and is he not skizzled?"

To make a long story short, I gets him out of there. I thinks about checking into a hotel, but there is those somebodies again, so there is not nothing to do but get a cab and take him home. The same which I does.

When I first sees Ditsy I also thinks it is true that she has turned into a red-hot momma. She has done something to her mouth so it looks like it has been swatted by a ripe plum, and she is wearing one of them "creations" that does not leave but very little to the imagination, and she is walking with two silver-headed canes, and her fingernails looks like they has been dipped in calves' liver while it is still in the calf.

She is quite a sight for sore eyes until you remembers it is Ditsy and, then your collar gets too tight and you say, "Hello, Ditsy," and she does not say nothing. She just looks at Jimmie until you thinks she does not know who it is and, then, she looks at me and her eyes is the color of a horse's flanks after a workout—dark and wet and velvety—and she says, "Bring him in, Jacks," and, some way, her voice sounds like it is bleeding. And, all at once, you know that underneath all this cover-up she has put on is the same old Ditsy. Worn finer, and kind of tired, but Ditsy.

She knows what to do, too. She does not put him to bed. She has me set him up in the bathroom with his head over the basin and she feeds him soapy water and as fast as one glass full comes up down goes another. And when he says he cannot do it no more, she wheedles him into doing it until his insides is as clean as a old maid's conscience, and his head is woozy but not boozy. Also, I am under the impression this is not the first time them two has underwent this here same procedure.

Soapy water? Best thing on earth. Makes you feel like you has been hollowed out and whittled thin, but it does not leave nothing in you that you would want to wake up with the next morning. Of course, it is not exactly a pleasant treatment while it is going on, but, after it is done, although you could not fight no mess of apes, you could give them a run for their money, if such become necessary.

After some time, Jimmie says in a washed-out voice, "O.K., go ahead. Tell me I am a louse."

Ditsy does not say nothing and I does not say nothing, neither, being busy examining my cuticles.

"I know I am a louse," he continues. "Go on. Get it over with. Go on, tell me I am a louse."

So I says, "You are a louse, period," and I leaves off examining my cuticles and takes up examining Jimmie like he is a rare specimen of garbage that has got in among us while we are occupied elsewhere.

"I was not asking you," Jimmie says, and he looks at Ditsy and Ditsy looks at him and Ditsy does not say nothing.

"I beg your pardon," I says, "I thought you was addressing the general public of which there are several that says you has lost hold of your senses."

"Shut up," Jimmie says. "SHUT UP. I did not ask you to butt in, did I? Why do you not go back where you come from?"

"Sure," I says, "I will be delighted. But when you is handing out your interviews tomorrow do not give the credit for the win to the horse—give it to Ditsy, here. If you win."

"What do you mean 'if'?" Jimmie says. "It is in the bag." He laughs. "Literal," he says. "You and Ditsy need not worry none."

"I am not worrying," Ditsy says toneless-like. "It does not matter either way. Nothing does not matter. Any more."

The way she tags that "any more" on to it is horrible to listen to. It has a dead, flat, hopeless sound and I keep thinking, if I look down, I will see it laying there on the bath mat spread out on its back with its eyes rolled up.

It gets Jimmie, too, because it is clear that if Ditsy had batted him on the bean with a lead sock he would not be more took back.

"What do you mean?" he says. "What do you mean?" like that, see, with a up on the end.

"I mean it is no good," Ditsy says. "I cannot stand it. You are not Jimmie Winkie any more. You are somebody else. Somebody else I do not know. Somebody else who I do not want to know. I hope you do lose tomorrow," she says and her words bump into each other and bunch up, like the field in a steeple-chase taking the first hedge. "I hope you lose tomorrow," she says, "and the next day, and the next and the next and next and next, and we can go back to that two-room flat and eat beef stew and take turns washing the dishes and put toothpicks in the windows to keep them from rattling, and play pinochle and watch the car lights come over the Freeway and, maybe, have a pint of ice cream for a treat and ... and ... be ... happy"—and her voice breaks in the middle and she puts her face in her hands and starts crying.

It is a awful experience to see a girl cry. It makes you feel like all your joints has swelled and your ears and feet belong to a two-humped camel.

Jimmie says, "You want me to lose?" like he is suffering from hallucinations.

Ditsy keeps on crying.

I gives her my handkerchief and wonders if I ought to pat at her or something.

"I cannot lose," Jimmie says.

"Look," I says, "I think I has had sufficient. I am going."

"I cannot lose," Jimmie says, "and, if I do, they will not call me Wee Willie no more. Guys like Moe Prentice will give me the laugh. I got to keep on winning. I cannot stop now."

"You has not got to do nothing but die," I says, "and if what guys like Moe Prentice says means more to you than Ditsy, here, I would go on off and die if I was you."

"What about your grand piano?" Jimmie says to Ditsy.

"I hate it," Ditsy says through her fingers. "I would like a c-c-canary b-b-bird."

"But I cannot lose," Jimmie says, shaking his fist. "I cannot—unless—" And he quits shaking his fist and uncloses it and looks at it like he expects to find it has varicose veins. And he looks at Ditsy setting there on the floor.

"You mean what you said?" he says.

Ditsy makes a kind of soft ooooooing noise like a stable hound what has been stepped on.

"O.K.," Jimmie says. "O.K." He gets up and sort of wavers a minute and then he goes out and Ditsy keeps on crying and I clears my throat once or twice and wishes she is a horse so as I could gentle her and then Jimmie comes back in and he is carting this here bridle.

"From me to you," he says, plunking it on the floor. And there is a long pause and then he adds, "Temporarily."

Ditsy looks at the bridle, hiccuping slightly like a baby what has been having colic.

"I do not get it," she says, hiccuping again.

Jimmie indicates the bridle. "Remember the time," he says, "that we was in the Home and you found a four-leaf clover in a book what belonged to Miss Watson? I had a toothache, so you snitched the four-leaf clover to put in my shoe so as it would go away—the toothache I mean. Only you said it was 'temporarily' because it was somebody else's four-leaf clover and might have repre ... repercussions being as how it does not actually belong to me. So I did—put it in my shoe I mean—and I got a blind abscess and it was—well, you know how it was."

"I still do not get it," Ditsy says looking at the bridle like she is expecting it to turn into a four-leaf clover.

"It is like this," Jimmie says. "That there"—he points to the bridle—"is the same as the four-leaf clover. Maybe you got a toothache now, but, if I lose, it might turn out to be a blind abscess. So it is only temporary. I am not giving it to you. I am only letting you keep it for me."

"I still do not get it," Ditsy says, blowing her nose in my handkerchief.

"I do," I says. "He is saying you thinks you wants a canary bird when what you really wants is a grand piano, which you have already got."

"You stay out of this," Jimmie says.

"Lay off Jacks," Ditsy says to Jimmie. "He is all right."

"Jacks is a old lady," Jimmie says to Ditsy.

"I am going," I says. Which I does.

No. No more beer. I am not half through with this one. I do not like to crowd them. And, speaking of crowding, that is what I think happens to Jimmie.

Lose? I reckon he does. He does not even get away from the post.

What I mean about crowding, I figure this here horse Jimmie is up on gets crowded quick. There is some crows slow, some easy, some quick. Jimmie happens to be up on Beeknight and, the way I figure, I figure Beeknight crowds quick. You know how it is, out of the barrier, everybody trying for a inside track, some pushing maybe, though this is not noticeable unless you is up. Now them that crowds slow gets out and tries, and them that crowds easy falls in, but them that crowds quick rears up and starts doing the Highland fling. There is not many. But there is some. And, like I said, the way I figure, Beeknight is one of the some.

After it is all over, there is plenty who say there is something fishy because Beeknight is never one to crowd slow, easy, or quick. Jimmie has been up on Beeknight before and Beeknight has always came in home free. In fact, before this here episode I am getting ready to tell you about, Beeknight is being touted for the Jockey Gold Cup, so there is plenty who say the atmosphere smells highly of cod.

Jimmie pull him? You mean on account of Ditsy saying what she said? Maybe. I thought about that angle, but I am almost sure for certain that is not the case. I seen him right after it is over and, if he is putting on a show, I am a snub-tailed bloodhound.

No, I figure horses like I figure human beings. They is subject to change. This here Beeknight might of slept restless, he might of been overtrained, he might of been scary, he might of had gas, he might of sensed Jimmie was not in no mood. Them things affects a horse. So I say there is nothing off-color, but that this here Beeknight has underwent a change and happens to crowd quick.

It is like this, see. I avoided Jimmie like he has got the plague and this is reciprocated on his part. I see he is jittery and keyed up, but this is no mud on my boots, so I leave him be. Not that he is left be, because there is many who do not think he has got the plague. It is very sickening to watch.

I wonder if Ditsy is in the stands, but I do not wonder long as somebody asks him if his sister is in the stands and he says, "No, she is home." And somebody says, "Don't she like horse races?" And he says, "No." And somebody says, "Well, that is odd. Your own sister." And he says, "How would you like to go bag your ears," which shows that he is keyed up to a considerable degree.

He is up in the first, again in the third, and again in the fourth. I am not up at all until the next day. In fact, I am only there because I cannot stay away, so I goes out and hangs over the veranda rail to watch the first.

It is a swell day. One of them high, blue ones. There is music coming out of the announcing system and people is walking around and everything is kind of stirred up like—like it is before the start. It is a fast track and pretty to look at and Happy Slauderwasser comes out and says, "Move over," and we both hangs over the veranda rail and just look at how everything looks, if you know what I mean.

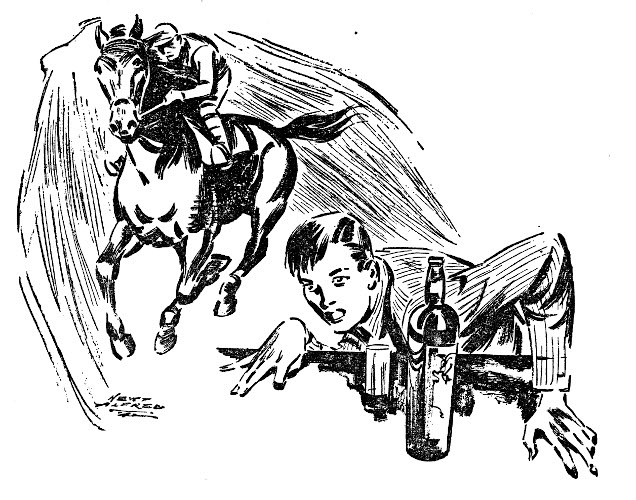

Then the horses is mincing past, Jimmie about as big as a good-sized pea, and then the barrier is in, and it is Beeknight in No. 6, and everything gets quiet with a little murmur running through it like a breeze with a lid on it, and you can hear the popcorn peddlers real plain, and then there is that swelling cry, "THEY'RE OFF!" But it chokes in the middle and there is a surge for the fence and the stands rise up and cranes their necks and Happy says, "My God!" and I near falls over the veranda rail because Beeknight is pawing the air and kicking and acting in general like he is a prize exhibition at a rodeo and for all them shenanigans he does not go nowheres. It is like he is trying to kick his way through a wall or something. Jimmie is stuck closer than a plaster, but not for long. Beeknight gives a lunge and Jimmie goes over, and a sort of a soft, gusty sound goes up from the crowd like a thousand breaths has been let out at once.

By the time Jimmie has hit the ground, they is taking Beeknight out and do you know that confounded horse is as calm as a June morning? Jimmie gets out under his own power.

Yeah. You see it coming, kick loose and roll with the fall and it does not no more than scrape off the top fuzz.

It seems like a hour at least has gone past, but it cannot be no more than a handful of seconds because it is all clear when the field moves into the stretch.

Happy and me look at each other.

Happy says, "Wow."

I says, "It looks like somebody is going to get a bird."

"Yeah," Happy says, "a Bronx one."

"No," I says, "a yellow one with feathers what sings," and I go on down to stand on the edge of the crowd what is surrounding Jimmie and listen to what is being said.

What is being said is all the same color and cut equal. Howinever, I am positive that Jimmie did not do no pull. He is white as death and keeps shaking his head like there is lead shot in it and he is listening to it rattle. He keeps saying, "I cannot understand it, I cannot understand it," over and over. No, he did not do no pull. Spencer Tracy cannot act that good and Jimmie Winkie is not no Spencer Tracy.

I mosey on off and am popping my knuckles and thinking when it comes over the announcing system that Winkie is not hurt none and will be up in the third as scheduled.

But this does not take place, as before the third, Gus Wever comes up to me and he is pale and his Adam's apple is riding up and down on his collar and he says, "Jacks, I got something for you to do."

"Shoot," I says.

"I want you should break the news to Winkie."

"What news?" I says. "They is not going to disqualify him for falling off a horse, I hopes."

"No," Gus says. "Word has just came that his sister has met with a accident."

I says, "Ditsy," or I tries to, but it sticks in my throat and, some way, I finds I am grabbing hold of Gus and there is guys endeavoring to pull us apart thinking we is having a altercation.

"Leave go," Gus says, shrugging them off—he is a big guy—"I am asking Jacks, peaceful, if he will tell Winkie his sister has met with a fatal accident. He is a friend of Winkie and if your sister is dead, it is better it comes from a friend. That is all I am asking. I, myself, cannot do it."

So I does it.

When we gets there everything is confusion. There is people everywhere and a important-acting guy is asking the maid questions, only this does not do no good as she is setting in a chair having hysterics. And there is other men down on their knees examining the floor and blowing powder on the doorknobs and there is a doctor putting his stuff away in a little black bag.

And there is Ditsy.

It does not look like Ditsy. It does not look human even. It is just a smashed-in, crumpled-up thing what is wearing Ditsy's clothes, and it has blood all over.

It reminds me of the way Tod Beemis looks when he is drug out and laid on a shutter after he is caught in a stall with a crazy stallion. Kind of ... kind of ... trampled-looking. It makes me feel kind of numblike, like maybe I has got a scream in me that has froze solid before it can get out.

The important-acting guy, by now, has saw us and advances forward.

"The maid, here," he says, "says she left Miss Winkie setting by the window and holding a bridle in her lap. Mooning over it kind of, she says. She goes downstairs, the maid does, and she has not no more'n got good and down when she hears a racket and she runs back up fast as she can and it is like this. We has not touched nothing. This," he, says pointing to a scruffed-looking place on the rug, "I guess is where she fell down and got up again, and this"—pointing to a spot where the plaster has been gouged out of the wall—"this here is where whoever done it must of swung and missed—and, from the evidence, whoever must of done it was strong as a horse. And this here is the bridle she was holding, which looks as if it was tore out of her hands and—" He pauses and squints at Jimmie. "Hey," he says, "you do not look like no coroner, who are you?"

"He is her brother," I says, and my voice seems to come from some far-off place and does not seem to belong to me at all.

"Oh," the man says embarrassed. "I am sorry, buddy. I did not know about you being related to the deceased. I am mighty sorry."

Jimmie does not answer. He is looking at the bridle like it is Lazarus arose from the dead and it is plain he is going to keel over.

He puts out his hand, as if he is in a trance, and takes the bridle from the man.

"It is all right," I says, "it is his bridle. Leave him have it. I will take him out of here." Which I do as they bring in a wicker basket and set it down by this thing on the floor around which they draws a white chalk mark before ... before they—

Guess I must be coming down with a cold. Yeah. Sure I will have another one. Just to wet my whistle. I seems to be kind of dried up like. Talking too much, I guess. There is times, though, when you has got to get it out of your system—the cold, I mean. Yeah. Well, here's to nothing, mister. If you got nothing, you got nothing to lose and, even if you does, it stands to advantage.

What did who win after what? Oh, Winkie. He does not win no more. And does not lose no more. Because he does not ride no more. No, I mean no more. Never. You see, he ... he bumped hisself off. I took it for granted you knew.

Yeah. Yeah. It was one of them things. After Ditsy—why, he kind of went haywire. I tried talking to him. Thought if he got to riding again it would take his mind off what it was brooding on. No, no, they never did catch whoever done it. I wish they had of. If I could of got just within reaching distance—

No, Jimmie would not pay no attention to me. He would just set there staring straight ahead and sometimes he would look at me like he could see clean through my backbone and out the other side.

"Do not bother none, Jacks," he would say. "You do not understand. It was my fault. I should of knowed."

And I would say, "Do not be like that. Them ... them kind of accidents is figured out statistical. You could not of knowed in a million years."

"I was wrong. I was the one who had the blind abscess. Not Ditsy," he would say. Morose, see. Only I thought he would snap out of it, eventual. But he does not. When he snaps, he snaps the other way.

I remember the night that he done it. I set up with him until midnight talking up Parvalu, which Colonel Crandall wanted him to ride in the Bay Shore. I says, "Look here, Jimmie, if you will just get out and mix around some, you will be O. K." And I says, "Do not forget what you always said: 'You can shake grief or sorrow, you can bury remorse—but you can't never lose the feel o' a horse.'"

"Yeah," he says, and he looks at me for the first time like he really sees me. "Yeah," he says, straightening up, "you can shake grief or sorrow, you can bury remorse ... bury remorse—"

"But you can't never lose the feel o' a horse," I finishes for him.

"Yeah," he says—slow. "Yeah, that is it."

So I goes home brightened up, thinking I has at last got him squared around and the next morning—it is in the papers.

They was two thoroughbreds, them two was. Yessir, two thoroughbreds that, some way, got boxed on a inside turn.

What's that? Bridle? Oh, that. I had it buried with Jimmie. He had made a will leaving everything he possessed to me. Can you beat it? That is the kind of guy he was. Yeah. Oh, I could of kept it if I had of had a mind to, but bridles is cheap and he had set such a store by that one that it did not seem right to keep it. Besides, I could not ever of used it and kept my mind on what I was doing. He ... he hung hisself with it, see. He was out of his head with grief, that is all. He did not think. Jimmie was not no coward to take the easy way out. I know that. But I could not of had it around me just the same. So I buried it with him. Holding the reins in his hand. I think he would of liked it if he could of knowed.

Well, bottoms up. I got to be going.

Thanks, brother, and the same to you. It has been a pleasure. No, I do not reckon you will be seeing me in no papers, unless it is the funny papers. Did I not tell you? Horses has got a habit of slowing down when I am up on them. Like they has got a dead weight swinging on the bridle holding them back. They calls me Jinx. Yeah. Jinx Jackson.

Well, so long, buddy.

THE END.