[Pg 2]

Khama, the Christian Chief of the Bamangwato

Tribe.

[Pg 3]

THROUGH LANDS

THAT WERE DARK

Being a Record of a Year’s Missionary Journey

in Africa and Madagascar

BY

F. H. HAWKINS, LL.B.,

Foreign Secretary of the London Missionary Society for Africa, China

and Madagascar.

“To the Darkness and the Sorrow of the Night

Came the Wonder and the Glory of the Light”

LONDON MISSIONARY SOCIETY

16, New Bridge Street, London, E.C.

1914

[Pg 4]

This little Book is dedicated (without permission) to the Friend whose generosity made it possible for the journey herein recorded to be taken free of any expense to the London Missionary Society

[Pg 5]

[Pg 7]

[Pg 8]

I hear a clear voice calling, calling,

Calling out of the night,

O, you who live in the Light of Life,

Bring us the Light!

We are bound in the chains of darkness,

Our eyes received no sight,

O, you who have never been bound or blind,

Bring us the Light!

We live amid turmoil and horror,

Where might is the only right,

O, you to whom life is liberty,

Bring us the Light!

We stand in the ashes of ruins,

We are ready to fight the fight,

O, you whose feet are firm on the Rock,

Bring us the Light!

You cannot—you shall not forget us,

Out here in the darkest night,

We are drowning men, we are dying men,

Bring, O, bring us the Light!

John Oxenham.

[Pg 9]

This short record of a year’s missionary journey in Africa and Madagascar is written at the request of the Directors of the London Missionary Society, and is based upon a series of Journal Letters written to my family and friends while I have been on my travels. This fact must be my excuse for writing in the first person. This little book has been prepared in the midst of the pressure of Secretarial work.

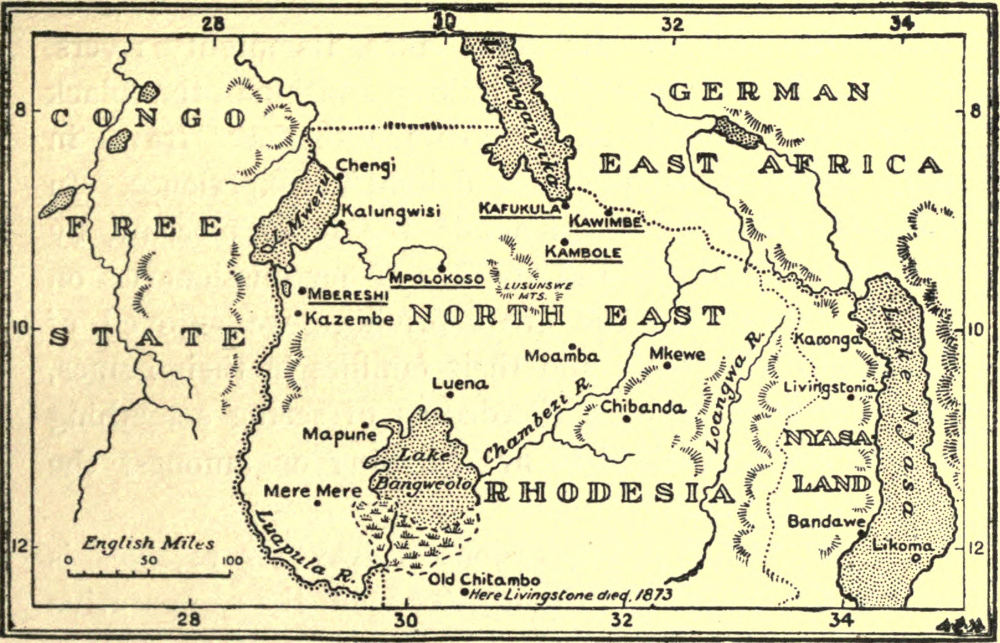

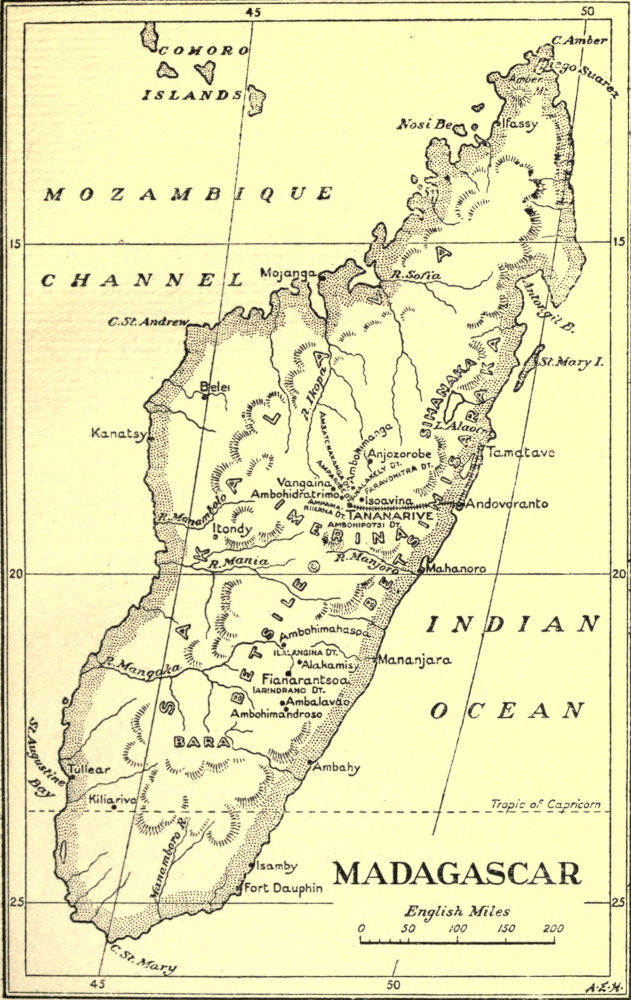

My visit to South Africa was a Secretarial visit. In Central Africa and Madagascar I formed one of a Deputation from the London Missionary Society. My colleague in Central Africa was the Rev. W. S. Houghton of Birmingham, and in Madagascar the other members of the Deputation were Mr. Houghton and Mr. Talbot E. B. Wilson of Sheffield.

It is not my purpose to attempt to give any description of the three Mission Fields which it has been my privilege to visit during the journey. Details with regard to the countries and the peoples will be found in three Handbooks published by the Society.[1]

[Pg 10]

Nor does the discussion of questions of missionary policy or any account of the details of the work in the various fields fall within the scope of this book. These matters have been dealt with in Reports prepared for the Directors of the Society. Further information with regard to all the fields can be obtained in the Society’s Annual Report. Some account of Madagascar and the missionary work there will be also found in a book just published, entitled “Madagascar for Christ,” being the Joint Report of the Simultaneous Deputations from the London Missionary Society, The Friends’ Foreign Mission Association, and the Paris Missionary Society, which have recently returned from Madagascar.[2]

The journey has been one of great fascination. From the point of view of the traveller it has been full of interest. From the point of view of a Secretary of a Missionary Society carrying on work in the lands visited, the outstanding impression has been that of the growing Christian Church. In Central Africa that Church is in its infancy, but it is an infancy full of promise. In South Africa and Madagascar the Native Church is nearly a century old. Its foundations have been well and truly laid, and it exhibits all the signs of healthy life and growth. As one travelled from station to station and came into contact with the Native Church in all stages of development and met the Native leaders of that Church, one looked into the future and saw a vision of a Church which would one day become not only self-supporting[Pg 11] and self-governing, but so possessed with the missionary spirit that it would be an instrument in God’s hands for evangelising the peoples amongst whom it is now set as a lamp in the night. One hundred years ago and less these lands were in gross darkness; to-day the curtains of the night are being lifted and long closed doors are wide open to the light. The darkness has turned to dawning and the growing Church is becoming “a burning and a shining light” in the lands which aforetime sat “in darkness and in the shadow of death.”

F. H. H.

31st January, 1914.

[Pg 12]

[1] “South Africa”: Rev. W. A. Elliott (price 6d., post free 8d.); “Central Africa”: Mrs. John May, B.A. (price 6d., post free 7¹⁄₂d.); “Madagascar”: Rev. James Sibree, D.D., F.R.G.S. (price 6d., post free 8d.). I am much indebted to the “Ten Years’ Review” of the Madagascar Mission, edited by Dr. Sibree (L.M.S., price 2s. 6d. net), for much information embodied in the Madagascar section of the book.

[2] Copies can be obtained at the L.M.S., 6d. net, post free 8d.

[Pg 13]

Through Lands That Were Dark

A land of lights and shadows intervolved,

A land of blazing sun and blackest night.

John Oxenham.

South Africa exercises a great charm over those who visit it. It is a land of sunshine. An unkind critic has described it as “a land of trees without shade, rivers without water, flowers without scent, and birds without song.” It is a land of vast distances and sparse population. The portion of the African Continent which is popularly referred to as “South Africa” is that part which lies south of the Zambesi. This great expanse of country is as large as Europe without Russia, Scandinavia and the British Isles, but its entire population is less than that of greater London.

I left England in the late autumn and arrived at Cape Town seventeen days later in the early summer. London[Pg 14] fog was exchanged for a land of lovely flowers and luscious fruits. Cape Town has been so often described that I will not dwell upon its beauties or attempt to draw a picture of Table Mountain, The Devil’s Peak, The Lion’s Head, or The Twelve Apostles.

My first impression—and it is a lasting one—was of the abounding kindness and hospitality of the Colonials wherever I went. On the day of my arrival I was entertained by the Executive Committee of the Congregational Union of South Africa. On the following day I was the guest of the Archbishop of Cape Town at his lovely home at Bishopscourt, where I met fourteen South African Bishops in full canonicals gathered together for their Annual Synod. Bishopscourt is a beautiful old Dutch House with a far-famed garden which surpassed in luxuriance of colour anything I had ever seen except in Japan. All through South and Central Africa I was often the guest of Government officials and European residents, and everywhere received, as the representative of the Society, a warm welcome and the utmost hospitality and kindness.

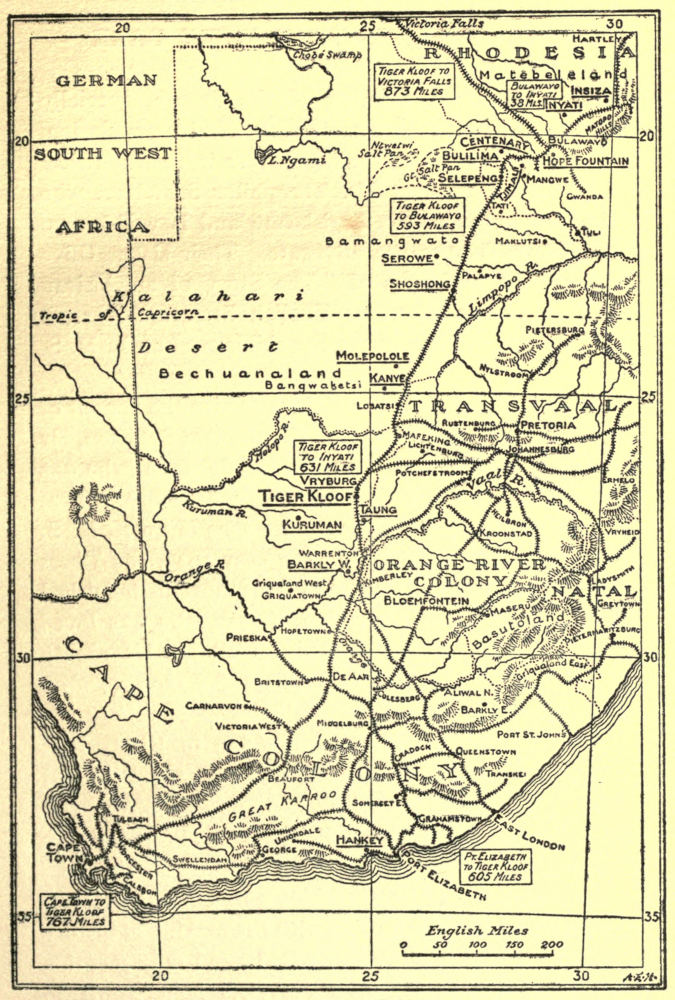

Map of South Africa, showing L.M.S. Mission

Stations.

My next impression was of the great contribution which the London Missionary Society has made to the public life and development of Cape Colony and South Africa generally, quite apart from the direct work which its missionaries have been able to accomplish. Evidences of the value of this contribution abounded everywhere I went. In Cape Town I had the pleasure of meeting the Hon. W. P. Schreiner, who was the Prime Minister of Cape Colony at the outbreak of the Boer War. Mr.[Pg 16] Schreiner is now a member of the Senate, specially chosen to represent the interests of the Native population. He is recognised as the leading lawyer in South Africa. I also met his brother, Mr. Theophilus Schreiner, who is also a member of the Legislature and is well-known as a leading Temperance advocate. Their sister, Olive Schreiner, the authoress of “The Story of an African Farm,” is known wherever English literature is read. This distinguished family are the children of an L. M. S. Missionary.

It is not often that three brothers receive the honour of knighthood for public services. Sir William Solomon, Sir Saul Solomon and the late Sir Richard Solomon (who was Agent-General for the Commonwealth of South Africa, and who died a few weeks ago) are sons of an L. M. S. Missionary. In its Review of the year 1913, the Times speaks of Sir Richard Solomon as “the most distinguished South African of his generation, a man who was loved by his intimates and respected by all for his ability and efficiency,” and of Sir William Solomon as “an eminent judge.”

Dr. Mackenzie, the leading physician in Kimberley; his brother, Dr. W. Douglas Mackenzie, the Principal of the Hartford Theological Seminary, U.S.A.; and another brother, at present Solicitor-General for Southern Rhodesia, are three sons of John Mackenzie, the missionary-statesman of South Africa and Lord Rosebery’s friend, who had so much to do with the making of history in South Africa thirty years ago. I need only mention other families whose names are household words in[Pg 17] South Africa, and whose representatives are to be found in many places—the Philips, the Moffats, the Kaysers, the Andersons, the Helms, the Rose-Innes, to show how large a part the L. M. S. has indirectly played in building up the Commonwealth of South Africa.

Throughout Cape Colony I found numerous Congregational Churches of coloured people at places which were formerly Mission Stations of the Society. Amongst others, Pacaltsdorp, Kruisfontein, Hankey, Port Elizabeth, King Williams Town, and Fort Beaufort were visited. The Society many years ago withdrew its missionaries and left these Churches to develop along their own lines into self-governing communities, supporting their own pastorate and carrying on their own work. Wherever one went, one found evidences of the great part which the Society had played in days gone by in planting churches which are now independent, thus contributing both to the civilisation and evangelization of the peoples of the land. Passing reference may be made to one of these Churches which I visited. In the Brownlee location at King Williams Town I found at work the Rev. John Harper, who nearly thirty years ago exchanged his position as a missionary of the Society for that of pastor of the Congregational Church. For forty-five years he has laboured there as the minister of the Kaffir Church in the Native Location and in charge of nineteen out-stations. This veteran not only ministers to the spiritual needs of a very large congregation, but acts both as doctor and lawyer to all the natives. In 1912 he treated 4,000 patients and[Pg 18] acted as guide, philosopher and friend to the members of his congregations, advising them in all their difficulties, drawing up their wills for them and ever looking after their temporal and spiritual interests. Many of these coloured Churches are now served by ministers of their own race, who have been trained for the pastorate.

From Cape Town I proceeded to Great Brak River and paid a short visit to Mr. Thomas Searle, who for some years has been the Society’s Agent for its properties at Hankey and Kruisfontein. The history of the Searle family at Great Brak River during the last fifty years affords a good example of the contribution to the development of the Colony which Christian families have been able to make.

On the 31st December, 1859, the late Mr. Charles Searle arrived at Great Brak River with his wife and four children to take up the position of toll-keeper at the Causeway carrying the main road over the river. The toll-house was the only habitation in the place. Mr. Searle erected a house for the accommodation of travellers, and afterwards a shop and a store. Four more children were born. He purchased a farm of 354 acres for £91, and spent some money in constructing water-furrows. A church was built. The business grew and subsequently a tannery and boot-and-shoe factory were started. Branch stores were afterwards established at George, Oudtshoorn, Heidelberg, Riversdale and a wholesale depot at Mossel Bay. Mr. Searle had three sons, Charles, William, and Thomas, who entered the business, and now direct the Limited Company, which[Pg 19] has been formed to carry it on. As the place grew the Searles successfully opposed all applications for a licence for the sale of intoxicating drinks, and to-day there is no licence between Mossel Bay, 16 miles to the west, and George, 18³⁄₄ miles to the east. The present population of Great Brak River exceeds 900, all of whom are in the employ of, or dependent on, the Searles, except the doctor, the post-master and the school-teacher. At first, all the employees were coloured people. Latterly, however, white people have also been employed, but they are treated exactly in the same way as the coloured people and receive the same wages as coloured people doing similar work. A very large new factory is now being built. Mr. Thomas Searle preaches regularly in the spacious church. Dutch is the language spoken. There is an excellent golf course. About six years ago old Mr. and Mrs. Charles Searle died. They and other members of the family are buried in the beautiful little private cemetery in Mr. Thomas Searle’s garden—the first of numerous garden burial places I saw in different places in the Colony. The three sons continue to reside in Great Brak River honoured and esteemed by the whole countryside.

While at Great Brak River I paid a visit to Pacaltsdorp, an old L. M. S. station founded 100 years ago, where the Rev. G. B. Anderson, whose father and grandfather were L. M. S. missionaries, is pastor. A massive stone Church was erected in 1824, and is a memorial to the Rev. Charles Pacalt, who devoted his salary to the building of the Church. In addition to being pastor,[Pg 20] Mr. Anderson is also schoolmaster, post-master, registrar of births, marriages and deaths and agent for the Society’s property known as Hansmoeskraal farm.

Mr. Searle kindly took me in his motor car to visit Kruisfontein and Hankey, where the Society still owns property. The South African roads are not constructed for motor car traffic. They defy description and I shall not soon forget this journey. The gradients are very bad, the surface execrable. The ruts, rocks, stones and especially the sand made rapid travel in a motor car a mixed pleasure. Rivers, and more often dry river-beds, had to be crossed. For the most part the roads were very narrow and were often over-hung with trees and prickly-pear, constantly blocked by great ox-waggons with teams of fourteen to eighteen oxen, or by goats, sheep, pigs, cows and more often than all by ostriches, which seemed to take a delight in trying to race the car. In spite of, or perhaps partly because of, these drawbacks, however, the journey was most enjoyable. Some parts were very wild and desolate, but others were scenes of sylvan beauty. There were mountain passes, ravines, funereal forests (in one of which wild elephants are still to be found), fairy glens and water-falls (often with very little water on account of the prolonged drought), and in turn one was reminded of the Pass of Glencoe, the Barmouth Estuary, the Precipice Walk, Dolgelley, the New Forest and the Highlands of Scotland.

Hankey is a name well known to all interested in the work of the L. M. S. in South Africa. Through the engineering skill of one of the missionaries applied to[Pg 21] the construction of a tunnel through a narrow mountain ridge, the waters of the Gamtoos River were made available for watering the Hankey valley, and ever since the desert has “blossomed as the rose.” Above this tunnel, near the top of the mountain, is a remarkable natural feature known as “The Window.” It is a large opening in the rocky ridge through which a beautiful landscape can be seen on both sides.

Another feature of Hankey which impresses a stranger from Europe is the frogs’ chorus every evening rising from an innumerable multitude of these amphibious reptiles which infest the fields and water-furrows. They are known as the canaries of South Africa, and reminded one of the music so characteristic of the rice fields of Central China.

At Hankey there is a large Church of coloured people, representing an old mission station of the Society, and an Institution for the training of teachers now under the control of the South African Congregational Union. Through the sale of the Society’s property a considerable population of Europeans has been attracted to Hankey, and I had the honour during my visit of opening the new European Church.

From Hankey I proceeded to Port Elizabeth, where I was again hospitably entertained. I had an opportunity of meeting the Congregational ministers and the leading laymen at a Reception, and learnt much of the contribution of the L. M. S. to the development of this part of South Africa. The coloured Church there for so many years ministered to by the Rev. William[Pg 22] Dower, formerly a missionary of the Society, is another instance of a strong self-supporting and self-governing Church which has grown out of the missionary work of years gone by. On the occasion of my visit it was crowded from floor to ceiling with a congregation of coloured people, who are under the pastoral care of a young and able coloured minister.

After leaving Port Elizabeth I had the privilege of paying a visit to two of the greatest Native Institutions in South Africa. At Healdtown, near Fort Beaufort, the Wesleyans are carrying on a great work in the training of Native Teachers. There are 185 boy and 84 girl boarders. The results obtained in the Government examinations are the best in the Colony. The students come from all parts; most of them are Kaffirs. The medium of instruction is English. This great work is mainly the result of the blessing of God upon the labours of one man, Principal R. F. Hornabrook, who is in supreme control. The Institution is nominally in charge of a Committee which, however, has not met for ten years. When he commenced work there twenty-two years ago there were thirty-three students. Mr. Hornabrook is his own architect and builder. He is also a farmer and a doctor. The fees charged are £12 a year, and there is a large Government grant. Some small help is given by the Wesleyans in South Africa. Not a penny comes from England. The buildings are quite unambitious in character, and for the most part have been erected from the profits made from carrying on the Institution. The whole enterprise is a triumph[Pg 23] of organisation. There are four white men teachers, three white lady teachers, two matrons and several coloured teachers. The course is three years, and the students must have passed the sixth standard before they enter. All have a little manual labour to do, but there is no industrial department except so far as it is necessary to teach woodwork. All sorts of difficulties have had to be surmounted, the chief physical one being the water-supply, which is now satisfactorily provided by a windmill. The whole Institution is a monument of what can be done by one man with comparatively small funds. Mr. Hornabrook is doing great things for South Africa.

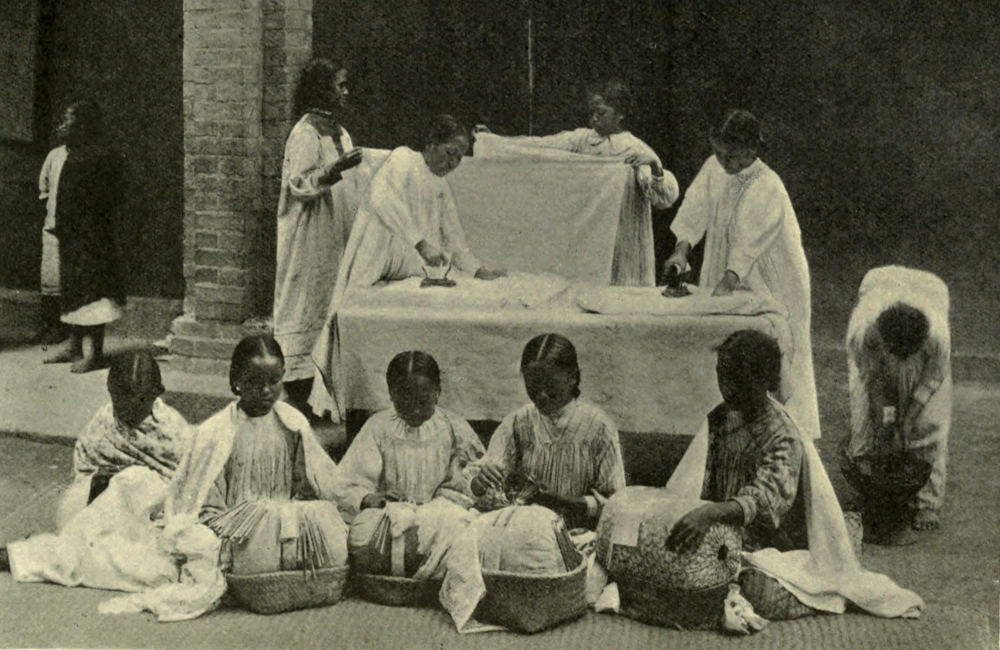

From Healdtown I journeyed to Lovedale, the centre of the world-famed labours of Dr. James Stewart, who will always be known as “Stewart of Lovedale.” This is an Institution carried on by the Free Church of Scotland. There are 550 boarders from all parts of South Africa, and of these 155 are girls. There is also a “practising school” with 210 children. The fees range from £12 to £16 a year. Since the Institution was commenced considerably over £100,000 has been received in fees. Preachers and teachers for the South African Churches and schools are trained here. The industrial work is widely known. The Natives are taught carpentry, waggon-making, smith’s work, printing, book-binding, boot and shoe making, office work, needle and laundry work, horticulture and many other industrial pursuits.

The present Principal is the Rev. James Henderson, formerly of the Nyasaland Mission. The Warden of the[Pg 24] Boys’ department is Dr. Moore Anderson, a son of Sir Robert Anderson, at one time Chief of the Metropolitan Police Force. On the staff there is the famous South African astronomer, Dr. Roberts. It was good to find the daughter of one of our present South African missionaries occupying a responsible position in the Girls’ department. Words fail me to describe the great work which is being done. The Institution is an enduring memorial to the ability and devotion of Dr. Stewart. Over the grave of this great and good man, which I visited, is the simple inscription, “James Stewart, Missionary.” On the hill-top is a huge stone monument erected to his memory.

On leaving Lovedale I journeyed via King Williams Town, Blaney Junction, and De Aar to Kimberley. The railway meanders in and out amongst the hills through picturesque scenery. Great rocks are much in evidence. On the latter part of the journey I passed numerous block-houses and stretches of galvanised wire fencing reminiscent of the Boer war. Here as elsewhere the country has an unfinished look about it. Most of the buildings are of galvanised iron. Long distances were traversed without any signs of human habitation, and where such signs appeared they were not always pleasing. The wretched huts of “red-blanket kaffirs,” and the abject poverty in which they live, showed that there is still much to be done to raise the native inhabitants out of their degradation and to teach them to live decent lives.

In order to see at first-hand the conditions under[Pg 25] which so many of the Bechuanaland Natives live in the Compounds of the great De Beers’ Diamond Mines, I visited Kimberley. Dr. Mackenzie kindly took me over the diamond mine workings and one of the Compounds. From these mines the bulk of the world’s supply of diamonds comes. I was very pleased with what I saw in the Compound I visited, where 4,762 natives were quartered. The annual death rate is only eight per thousand, about half that of London. Every provision is made for the comfort, health and well-being of the native workers. There is an admirable hospital and a well-organised store, where the necessaries of life are to be obtained at cost price. The fact that the natives are well cared for is evidenced by the popularity of the work in the Kimberley mines all over South Africa. Natives who have worked there return again and again for a further period. There can be no doubt that the restraint upon their liberty, to which they voluntarily submit while at work in the mines, is greatly to their advantage, and the facilities which exist for the remitting of wages to their families obviate, to a great extent, the risks they would run if they left the Compound with large sums of money in their possession. Nor are their spiritual needs neglected.

While at Kimberley I paid a visit to Barkly West, formerly a mission station of the Society for many years, associated with the name of William Ashton. From Kimberley I proceeded to Tiger Kloof. I shall refer to the great work which is being carried on there later in this narrative.

[Pg 26]

As one travelled through the Cape Province and visited many places, which were at one time stations of the Society in the charge of missionaries and entirely supported by funds from home, but are now independent Churches carrying on their own work, one realised the power of the growing Church in the lands which 100 years ago were in darkness. This province is still “A land of lights and shadows intervolved, a land of blazing sun and blackest night,” and some of its portals are still “barred against the light.” That light has for a century and more been beating up against “close-barred doors,” but the missionary traveller looking down “the future’s broadening way” sees many a sign that the time will surely come—

“When, like a swelling tide,

The Word shall leap the barriers, and The Light

Shall sweep the land; and Faith and Love and Hope

Shall win for Christ this stronghold of the night.”

[Pg 27]

Kingdoms wide that sit in darkness,

Grant them, Lord, Thy glorious light;

And from eastern coast to western,

May the morning chase the night.

William Williams.

Up to this stage the narrative of travel has taken us through districts in which the London Missionary Society has laboured in days gone by. We shall now visit the stations where it is carrying on work at the present day.

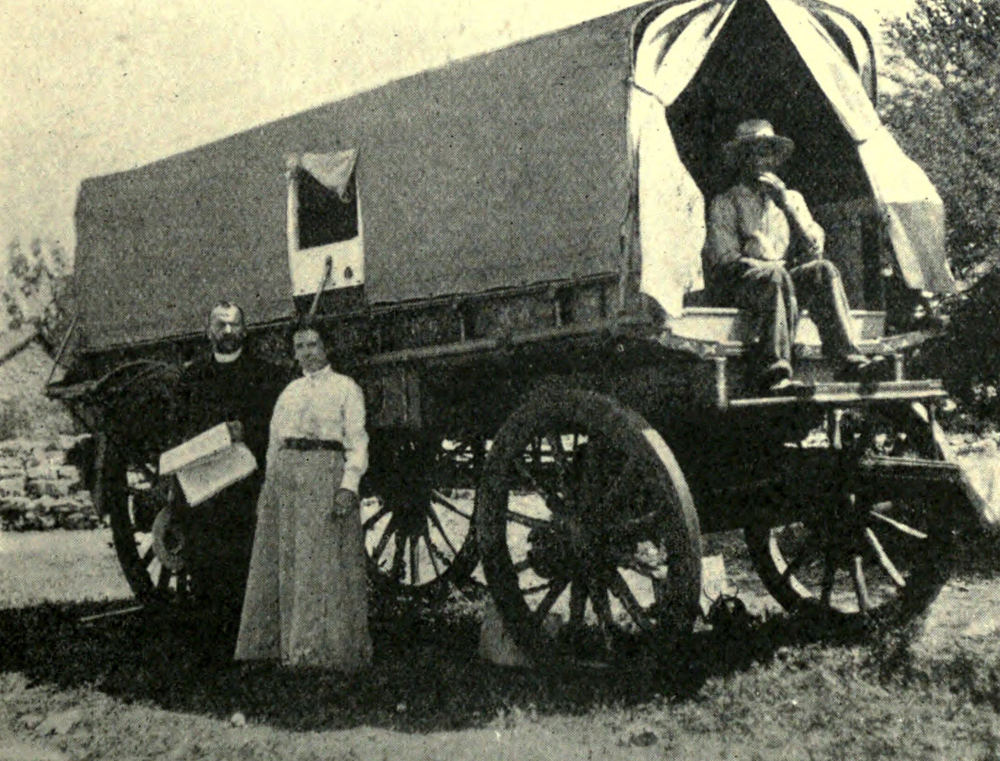

Until quite recently the South Africa Mission of the L. M. S. might be described, from the point of view of means of locomotion, as “an Ox-waggon Mission.” The days of the Ox-waggon are rapidly passing. This slow cumbersome means of conveyance, which was formerly almost universal throughout South Africa, is giving place to the Cape cart and the Railway. The change is symptomatic of the progress in the methods of work. Greater facilities of communication have revolutionized the conditions under which Missionary work is carried on. Missionaries are no longer isolated from their fellows as they were in the days of old. Until recently they were obliged to spend a considerable portion of their time in actual travel in the ox-waggon. Now they[Pg 28] can get about rapidly and are able to cover much more ground and visit many more out-stations in a given period of time. I was enabled to visit the Society’s stations in Bechuanaland and Matebeleland in one-fifth of the time which would have been necessary for such a visitation thirty years ago.

After a few days’ stay at Tiger Kloof, the first place I visited was Vryburg, where the Rev. A. J. Wookey, the missionary in charge of the numerous scattered Churches of the Baralong tribe, resides. Vryburg is not in a true sense a station of the Society, but the headquarters for an extensive out-station work. After a stay of two days there, I journeyed with Mr. Wookey in a Cape cart drawn by four horses to Ganyesa, forty miles to the north-west. The growth of the work in the lifetime of a single missionary is well illustrated by what has happened at this place. When Mr. Wookey first visited it, forty-three years ago, two or three people met with him for worship in a hut there. A man read the Scriptures, and a woman led in prayer and preached. Now there is a good stone Church with 120 Church members, and an Anglo-vernacular school with seventy children. Connected with it are three branch churches and schools.

A short description of the visit to Ganyesa will serve to illustrate one’s experience at many a country out-station in Bechuanaland and Matebeleland. I started from Vryburg at 7.10 and reached Ganyesa at 4.30, after out-spanning twice. We camped for the night on an open common, in the middle of a large Native Reserve, close to an ox-waggon which had brought two other[Pg 29] missionaries, Mr. Helm and Mr. Haydon Lewis, to the place. On all sides stretched the illimitable veldt. There were very few trees, but almost all around the sky-line was broken by the conical thatched roofs of the Native huts. Close at hand were to be seen emaciated oxen returning from the almost dry watering-places in charge of little black herd-boys, who were nearly naked, their bodies glistening like polished ebony, and having an appearance which suggested that they had recently been black-leaded, and presenting a great contrast with the white of their eyes and of their perfect teeth. After my arrival I was visited by the schoolmaster and the deacons, and afterwards attended a concert in the Church, organised to raise funds to help to send a teacher to Tiger Kloof. The price of a ticket for the concert was 6d. The night was hot, and the Church was packed. In spite of the almost overpowering heat the doors and windows were kept closed, in order that the crowd outside should not enjoy the music for which they had not paid! The atmosphere within was beyond description. Evening meetings are almost unknown in Bechuanaland. Some antique lamps had been requisitioned, and the air was laden with the pungent smell of the lamp oil. The “Bouquet d’Afrique” was also strongly in evidence. The audience afforded a picturesque scene in the dim lamp light. Most of the women wore highly coloured head-dresses, and with their numerous babies sat on the floor, which was made of a mixture of sand and cow-dung. The rest of their dress was remarkable for its colour and variety. Many[Pg 30] of the boys and men were in dilapidated European costume. There were 100 items on the programme, and the concert continued until the small hours of Sunday morning. I left before midnight, and slept on the ground underneath the bright penetrating stars. The darkness of the night was illuminated by flashes of summer lightning on the eastern horizon.

The following day, Sunday, will live in my memory. The service was announced to begin at eleven o’clock, but at ten o’clock the evangelist came to say that the chapel was already full, and forthwith the service commenced. The building was crowded to its utmost capacity, and there were large numbers of men, women and children sitting in the shade on the ground outside. I spoke to the people from a side-door in order that my words might be heard by the crowd inside and out. After the service I was visited by a large number of deacons and workers from the Churches for many miles round. Afterwards I went to see an old woman named Dipepeng in her kraal near by. She is over eighty years of age, and for a long time has not had the use of her legs. She sat in the entrance to her hut in the shadow of the over-hanging eaves, reading her Sechuana Bible. She told me she had been a servant to Dr. and Mrs. Moffat at Kuruman, and remembered David Livingstone courting Mary Moffat under the historic almond tree, and was present at their wedding. She described them, and spoke of an arbour in the garden where they used to sit. The old woman has been a Christian for sixty years, and is deeply interested in the Church at Ganyesa.

[Pg 31]

I visited the only European in the place, he being a store-keeper. In the afternoon there was a baptismal service, Sunday School, a sermon, and a crowded Communion Service conducted with great reverence. At the close the people all rose and sang, “God be with you till we meet again.” At day-break on the following morning there was a prayer meeting. This was followed by the wedding of five couples, and a visit to the school. Later in the morning Mr. Wookey and I started on our return journey to Vryburg in the Cape cart.

Later in the week I journeyed by rail and cart to Taungs where Mr. McGee is the resident missionary. The Society has carried on work there for forty-five years, and although the Church membership in connection with Taungs and its out-stations is the largest (1,184) connected with any L. M. S. Church in South Africa, the place was described quite recently by an experienced missionary as “a back-water of heathenism.” The signs of heathenism are certainly very apparent. The Native Chief is a bad specimen of a Bechuana. Some of his headmen make themselves particularly hideous by a plentiful application of the contents of the blue-bag to their faces and heads. There are many evidences of superstition and heathenism, and yet there is another side to the picture. On the Sunday the spacious Church—which has recently been built by the tribe, heathen and Christian alike contributing—was crowded both morning and afternoon. Twenty infants and thirty adults were baptised. The scene from[Pg 32] the platform was extremely picturesque. About half the congregation consisted of women, most of whom wore brilliantly coloured head-dresses, vivid yellows and startling pinks predominating. Many were clad in gaudy shawls. In the afternoon a solemn Communion Service was held, at which individual communion cups were used. The service was rendered the more impressive by the fact that a great thunderstorm broke before it closed. Looking through the great west doors of the Church at the beginning of the service one could see the wide-spreading veldt stretching away into the distance as far as the eye could reach, and looking dry and thirsty in the pitiless blaze of the afternoon sun. Then a kind of mist appeared on the horizon. It was a dust-storm approaching. The natives have a proverb which says that “God sweeps His land before He waters it.” The clouds of dust came nearer, until at last all the doors had to be shut. The Church became dark. Then came claps of thunder, which made speaking difficult, while the dim interior was from time to time lit up with brilliant flashes of lightning. Then followed a downpour of heavy rain upon the galvanised iron roof, making a terrific noise. The storm increased in intensity until there was a perfect artillery of thunder, while the lightning was continuous and most vivid. In spite of the storm the service was continued in an orderly fashion, and the crowded congregation seemed perfectly oblivious to the hurricane raging outside. The service concluded with thanksgiving for the rain, for which the people had long been praying.

[Pg 33]

Taungs is the centre of a widespread district, in which there are twenty-three outstations regularly visited by the missionary. I visited one of them, called Manthe, nine miles away. That visit was impressed upon my memory by one of the appalling contrasts which are so common in heathen lands. Under an extemporised roof at the back of the evangelist’s house I saw and talked with a bright Christian boy, the eldest son of the evangelist, by name Golekynie, who had been for seven years at Tiger Kloof. He was on the point of passing his third and final examination as a pupil-teacher, when, a month before, he had been compelled to return home in an advanced stage of consumption. He was lying on his bed in the open air. He spoke excellent English and had a refined face and manner, and was evidently an earnest Christian youth. He realised that he could not live long, and spoke with high appreciation of the happiness that had come into his life at Tiger Kloof. He told me that he was not afraid to die.

An hour afterwards I paid a visit to the Chief of the village, who was slowly dying of a loathsome disease in a wretched, evil-smelling native house. He lay on a dirty mattress with a coloured blanket over him. He was a heathen of a low type. Two of his wives and several children were on the verandah outside the open window. After Mr. McGee and I had left he sent to us to ask us to return to pray for him, the first time he had ever made a request for spiritual help.

From Taungs I proceeded to the historic station of Kuruman, accomplishing the journey of 143 miles by[Pg 34] cart, rail, motor-car and ox-waggon. The contrast in the modes of travel is illustrated by the fact that the first seventy-seven miles occupied five hours, and the remaining sixty-six miles—which were travelled by ox-waggon—occupied three nights and two days. This journey helped to bring home the sparseness of the population. On Christmas Eve I travelled from early morning till late at night in the ox-waggon without seeing a single human habitation, or a single human being, except those who were accompanying me, and this not in the recesses of Central Africa but in British Bechuanaland, which is part of the Cape Province. I travelled in a new waggon recently made by the boys at Lovedale for the Kuruman station. It was drawn by fourteen oxen, kindly provided by the Church at Kuruman, with two supernumeraries in reserve in case of accidents. As travelling by ox-waggon is rapidly becoming a thing of the past, it is worth while attempting a short description of the journey. The waggon in which I travelled, although a new one, had no springs. The road was of a most primitive description, although the main thoroughfare between two important centres of population. The jolting and bumping defy description. The speed is nearly two miles an hour if all goes well. The discomfort of travelling is somewhat mitigated by the “cartel”—a wooden frame hung within the waggon by very short chains of three links. Across the frame are stretched “rims” or strips of undressed ox-hide about a quarter of an inch broad. When the waggon is at rest this makes a very comfortable bed, far more so than some[Pg 35] of the beds of my experience in China, such as the boards of a Chinese chapel vestry, or the planks of a Chinese boat.

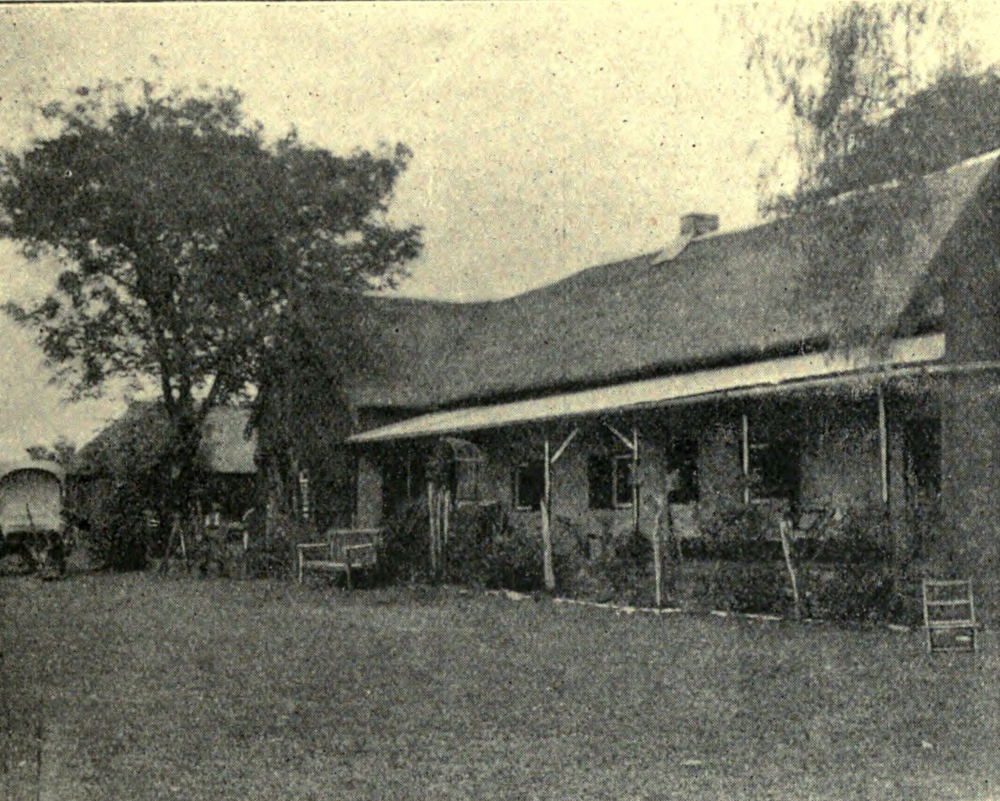

Photo by] [Mrs. Hawkins.

Kuruman Mission House, built by Moffat and Hamilton.

Photo by] [Neville Jones.

The New Kuruman Waggon, with Mr. and Mrs. J. Tom Brown.

The oxen are outspanned about three times a day at places where there is water, or where they are likely to find some grass. No reins are used in driving, but the oxen are controlled by a very long whip which is used with great dexterity either by the driver from the front of the waggon or by his assistant walking alongside the oxen. These two men also act as cooks. A Christmas Day spent in these conditions will live in the memory.

The stay at Kuruman was a delightful experience. This place is a veritable oasis in the desert with a perennial water supply from the Kuruman river, which issues from a place called “The Fountain” in the Kuruman township three miles away from the Mission station. Thence in summer and winter, in flood and in drought, flows 4,000,000 gallons of water a day. By means of water-furrows, constructed by the early missionaries, the dry and thirsty land is converted into a paradise of green. The trees in the garden are a constant delight.

I stayed in the Mission House built by Robert Moffat and Robert Hamilton eighty years ago. The whole place is rich with associations. It was here that David Livingstone courted Mary Moffat. The almond tree in the garden under which he proposed to her is still flourishing. Close by is the great Church, built by Moffat, and rich with many a memory. Next to it is the house where William Ashton lived for many years, which is now occupied by Mrs. Bevan Wookey, who is in charge of the excellent Mission School at Kuruman. Behind is[Pg 36] the school and the old printing office. The garden is most fertile; oranges, lemons, quinces, mulberries, pears, apples, plums, apricots, peaches, pomegranates, walnuts, melons and richly-laden vines, abounding. For more than a quarter of a century the Rev. J. Tom Brown has carried on Missionary work at this station.

The great fact of the growing Christian Church in South Africa was abundantly emphasised on the Sunday of my stay at Kuruman. From outstations far and near the Christians came in for the Communion Service on the last Sunday of the year and for the New Year’s meetings. In the morning some 1,500 gathered together for public worship, and three services were carried on simultaneously. Moffat’s long, and somewhat dark Church, with its great wooden beams, was filled with a Sechuana-speaking congregation. The dimness of the Church was relieved by the orange, yellow, pink and blue of the dresses of the women. In the spacious school there was a crowded service for the Dutch-speaking natives and coloured people. In the yard of Mrs. Wookey’s house there was a service, conducted by an evangelist, for the Damaras, a stalwart tribe of blackest hue. These people are refugees from German South-West Africa. In the afternoon all the Church members gathered together in the Church at a solemn Communion Service. A stranger will not soon forget the impressive quietness and reverence of the service as the bare-footed deacons moved noiselessly along the serried ranks of the great black crowd that was present.

The meetings on the following day were further evidence[Pg 37] of the growing Church. A large gathering of Church members was held at which discussions took place on several subjects quite familiar to the Home Churches, many Natives joining in with great intelligence and earnestness. The Native Pastor at Kuruman, the Rev. Maphakela Lekalaka, an eloquent preacher, a capable minister, and a master of metaphor—known as the “Joseph Parker of Bechuanaland”—superintended the work of the station with ability and success during the absence of the Missionary on furlough.

The journey back to Vryburg was made in an old ox-waggon drawn by fourteen oxen kindly lent by the Church at one of the Kuruman outstations. I travelled back via Motito, which has pathetic associations. In a tiny grave-yard there are buried two or three missionary children. There is also a grave which recalls a grim tragedy,—that of Jean Fredoux, a son-in-law of Dr. Moffat, and a missionary of the Paris Evangelical Missionary Society, which was formerly at work there. It was in 1865 that he met his death. A “depraved European” (to quote from the inscription on the gravestone) attacked his wife in his absence. The Native Christians defended her and made him prisoner, intending to send him to Kuruman for trial. Next day they were afraid they might get into trouble for arresting a white man and they let him go. He escaped in his waggon to the place where Mr. Fredoux was, and the Natives followed and told the latter what had happened. Mr. Fredoux went to speak to the man, who retreated inside his waggon. Then followed an explosion of gunpowder,[Pg 38] which blew the waggon, the “depraved European,” Mr. Fredoux and all the Natives to pieces.

At the conclusion of the journey from Kuruman I paid a short visit to Tiger Kloof and then proceeded north to visit the Matebeleland stations, in what is now known as Southern Rhodesia, taking three days’ holiday to see the wonderful Victoria Falls and places of interest in Bulawayo and the neighbourhood. Every Britisher naturally associates Rhodesia with the name and work of Cecil Rhodes. His statue stands in a commanding position in Bulawayo. His grave in the rocky fastness of the Matopo Hills is an impressive monument to his memory. All round are immense blocks of granite piled up in fantastic shapes. Four groups of these granite boulders almost completely enclose a rocky surface about 30 yards square, in the centre of which there is a large untrimmed block of granite lying on the ground. On the top of this is a sheet of bronze about 10 feet by 4 feet and 2 inches thick, on which are deeply cut these words:—

“HERE LIE THE

REMAINS OF

CECIL JOHN RHODES.”

There is no date. Close by on the slope of the hill there is a white marble rectangular monument, with bronze panels, commemorating Major Wilson and thirty-four men who laid down their lives in one of the Matebeleland wars. The inscription reads:

“TO BRAVE MEN.”

Few people, perhaps, realise what Rhodesia owes to[Pg 39] the lives and labours of L. M. S. Missionaries. When Cecil Rhodes was a youth of twenty Mr. Helm was establishing the Mission Station at Hope Fountain, 10 miles away from the present town of Bulawayo, which was then non-existent. Rhodes was always ready to acknowledge the value of the services rendered by Mr. Helm in his early pioneering days in the country which afterwards was named Southern Rhodesia. He was a constant visitor to Hope Fountain, and Mr. Helm often took part in his negotiations with Lobenguela, the blood-thirsty Matebele king. John Smith Moffat, the son of Dr. Moffat, at one time an L. M. S. Missionary, afterwards for many years a Government official, and always the friend of the Natives, played an important part in the establishment of British rule in Rhodesia. John Mackenzie, too, did a great work in this direction, and was ever a stalwart champion of the rights of the Natives.

Mr. Helm drove me from Bulawayo to Hope Fountain in a cart drawn by four mules, the two leaders rejoicing in the names of “Bella” and “Donna.” At Hope Fountain the Society holds for the benefit of the Natives a farm upon which some 500 people are living. In Southern Rhodesia, outside the towns, it is very difficult, if not impossible, to carry on missionary work except on such farms or in Native Reserves. Throughout the country farms are being rapidly taken up by white farmers, and the Natives are steadily and inevitably being driven off the lands which they previously occupied into the great Native Reserves provided for them by the Government.[Pg 40] Hope Fountain is the centre of some thirteen outstations, most of which are under the charge of resident evangelists. These men and many of the Native Christians came into the head-station to meet me. These small Churches form another example of the growing Native Christian Church of South Africa. The principles of self-support have been inculcated with such success that they raise for the support of their own Christian work a sum considerably in excess of that raised at any other station of the Society in the sub-continent.

At Hope Fountain, as in so many places in the Mission Field, one is reminded of the great and good men who have given their lives to the work in days gone by. In the cemetery there David Carnegie is buried, and his white stone tomb can be seen from the Mission House across the valley. His widow and family live at a house on the road between Hope Fountain and Bulawayo.

The next week of my travel was devoted to exploring one of the great Native Reserves above referred to. Mr. Helm drove me from Bulawayo to Inyati, the most northern station of the Society in South Africa, a journey of forty-five miles. Thence, accompanied by Mr. Cullen Reed and Mr. R. Lanning, the Native Commissioner, I paid a visit to the Shangani Reserve, which comprises a large tract of country situated about midway between Bulawayo and the Zambesi. This Reserve has been set apart by the authorities for the accommodation of Natives who have been driven off the land by the gradual settlement of white farmers. The expedition involved[Pg 41] a cart journey over rough country of some 220 miles, some of it through virgin tropical forest across which the road consisted of little more than a track. For seven nights I slept on the ground near the great fires which were necessary to keep off lions and other beasts of prey. The experience was a delightful one in spite of a too abundant insect life which often proved troublesome. Mr. Lanning has a unique knowledge of the country and his experience of travel on the veldt added greatly to the comfort and the pleasure of the journey. Moreover, he is a keen hunter and kept the larder well supplied with fresh meat. The cart was drawn by six mules and we were accompanied by another cart which conveyed the Native servants, the luggage and the camp equipment. The interest of the journey was enhanced by meetings with Native chiefs and headmen at different places. They may be typified in the person of Tjakalisa, Lobenguela’s third son, a fine specimen of the human race, standing over six feet high and every inch of him an aristocrat.

Clad in a vest and a short leather apron and some wire bracelets, he looked like the son of a king. Years ago he was nearly burnt to death in a tree in which he had taken refuge from a bush fire. David Carnegie treated him and saved his life. On another occasion he was out hunting with his father. His cartridges were several sizes too small for his gun. As fast as he put them in at the breech they fell out at the muzzle. Lobenguela insisted that he was bewitched, and this opinion was apparently confirmed when, on his shooting[Pg 42] expedition, his horse took fright and threw him, breaking his leg into splinters. Mr. Helm came to the rescue and effected a complete cure.

Nowadays Tjakalisa has settled down in the Shangani as a farmer on a large scale. He has been known to realise as much as £600 at one time on the sale of his produce. He came to discuss with us the question of the settlement of a resident missionary. He was accompanied by a fine old chief, Sivalo, who still wears one of the old Matebele iron circlets on the top of his head. I shall not soon forget the long morning spent in the blazing sun—in “the splendour, shadowless and broad,” of a South African midsummer. Tjakalisa and Sivalo were attended by a score of headmen. They were eloquent in praise of their new country, which had not suffered from the terrible drought which has been afflicting so much of the sub-continent. They realise the benefits of elementary education and promised to support a school and to build a house for a teacher. They were filled with enthusiasm for the future of this promised land.

Later on the same night I was lying on my bed, consisting of leaves and grass and a rug, under the stars which were soon to be extinguished by the brilliant light of a South African full moon. A few yards away our black servants were sitting around the camp-fire. One of these was a Basuto who had passed some of his life in prison and was now a servant in the mission. Another was a black, curly-headed herd-boy from one of our mission stations. With them were some naked Matebele.[Pg 43] Before I slept I heard the strains of a hymn in the native language, sung to a well-known tune. It was:

Jesus, still lead on,

Till our rest be won;

And, although the way be cheerless,

We will follow, calm and fearless;

Guide us by Thy hand

To our Fatherland.

I fell asleep to dream of the African church of the future in this new fatherland of their race.

Already under the steady pressure of white settlement large numbers of Natives have been driven into this Reserve and month after month there are fresh arrivals. In the old days the L. M. S. was ever to the front as the pioneer Society in the evangelization of South Africa. In these days it is looking forward to establishing a new mission station in this Reserve, unless prevented by the great deficiency and the lukewarmness of the Home Churches.

From Shangani I returned to Inyati, the station where Mr. Bowen Rees has laboured so long and faithfully. He was away on furlough at the time of my visit. During my stay there I was reminded of some of the minor inconveniences—not to say dangers—of a missionary’s life. One evening while we were sitting on the verandah a snake paid us a visit, while the next day a cobra was caught in the woodstack close at hand.

I inspected the school and attended a large gathering in the Church of Christians from Inyati and its outstations. Most of the adults squatted on the floor with[Pg 44] their families around them. The naked babies tumbled over each other in their playful frolics, or slept on their mothers’ backs while I was trying to speak to their parents.

From Inyati Mr. Helm drove me to Insiza, formerly a station of the Society. On the following morning I left at 4 a.m. by train for Bulawayo, where I proceeded to Marula Tank Siding en route for the new Arthington station at Tjimali, where our Missionary, Mr. Whiteside, met me. A drive of twenty miles in the mule cart brought us to the Mission House, which is beautifully situated in the midst of granite kopjes which form the western spur of the Matopo Hills. The view is magnificent. The garden terminates in a forbidding precipice some hundreds of feet deep. On one side of the house is a lofty rocky hill which commands a wide stretch of mountainous country in all directions with intervening valleys, and plains and hills. There are, however, drawbacks to Tjimali as a residence. The baboons are very numerous in the immediate neighbourhood and go about in herds of forty or fifty and rob the gardens in the day time. The wild cats steal the chickens at night. The eagles carry off the lambs, and the insect life is super-abundant. Tjimali is the Society’s newest station in Matebeleland and the work is in its early stages. There are ten outstations, at each of which there is a native teacher who conducts school during the week and acts as pastor-evangelist on Sundays, preaching and holding classes for inquirers. The work is bright with promise and is reaching the miners who are settling in the outskirts of the district.

[Pg 45]

From Tjimali I journeyed by cart to Dombodema, a long day’s drive of fifty-eight miles. My experience that day illustrates one of the disadvantages of the new mode of travel in South Africa. I had been driven to the Marula Siding to catch the train for Plumtree, the station for Dombodema. On arrival there I found that on the previous day the time for the starting of the train had been put forward four hours without any notice whatever to the public or even the station master, and hence there was nothing for it but to drive the whole distance. On the way I was met by Mr. Cullen Reed, the Dombodema missionary, who has been at work there since the foundation of the station in 1895. Mr. Reed has to carry on his work in three languages and has to itinerate a parish of 3,000 square miles inhabited by 15,000 people. On each side of the Mission station are low picturesque kopjes. The day before I arrived Mr. Reed had killed a snake fifteen feet long in the garden.

Preachers, teachers and Christian workers had come in from the outstations for the meeting. Three of them had travelled all the way from Nekati, a distance of 150 miles. At this place Segkome Khama lives. He is the eldest son of Khama, the famous Chief of the Bamangwato tribe. For the Sunday service the Church was crowded, the congregation sitting on the floor, and some scores more finding seats under the shadow of a great fig tree outside the door. The Service was conducted in two languages. In the afternoon an impressive Communion Service was held.

[Pg 46]

On leaving Dombodema I proceeded south to Serowe, spending two days on the way at the British Residency, Francistown, as the guest of Major Daniel, the Assistant Commissioner for the Northern half of the Bechuanaland Protectorate. My visit to Serowe was one of my most interesting experiences in South Africa. Leaving Phalapye Road railway station at 3.20 a.m. in the faint light of the waning moon I started on the cart ride of thirty-five miles to Serowe. The cart was drawn by eight fine mules kindly put at my disposal by the Government. It was the dustiest ride I have ever experienced, in many places the road being several inches deep in sand and dust. The dust of the Plain of Chihli in North China makes an impression on the memory which it is not easy to forget, but the drive to Serowe was a more trying experience, because eight galloping mules travel much faster than the sorry beasts which draw the Peking carts of North China. About three miles from Serowe we saw a cloud of dust ahead and there emerged from it a company of horsemen whom Khama had sent to escort me. A mile further on the whole veldt seemed to be enveloped in a mighty dust-storm. When it reached us we stopped. Khama had come in person with some hundreds of horsemen. The old Chief sprang from his saddle like a man of 26 rather than a man of 76. He joined me in the cart and we renewed our drive. The horsemen galloped before and behind and on either side. The drivers thrashed their mules with two whips to force them to keep pace with the horsemen. A regular stampede ensued. Fresh detachments of Natives, all[Pg 47] mounted on fine steeds, joined the cavalcade every two or three minutes. The Chief thoroughly enjoyed the fun and laughed heartily as the horses of the various members of our escort kept cannonading against one another in the mad rush.

Serowe, the largest Native town in South Africa, contains about 26,000 inhabitants, and is picturesquely situated. Mr. Jennings, the L. M. S. missionary, has carried on work there for upwards of ten years. It is a typical Bechuana town, having no streets but consisting of numerous collections of native huts within fenced kraals. The position of the Mission House is particularly striking, lying as it does between three great piles of rocks.

The town owes much of its importance to the fact that it is Khama’s capital. This old Chief—the Jubilee of whose baptism was celebrated two years ago—is the most distinguished Native of South Africa. He is undoubtedly one of the busiest men in the world. He spends laborious days in the Kgotla—the great open-air meeting place of the tribe—dealing with all sorts of questions affecting his people, and acting as judge. Nothing concerning the life of the tribe is too minute for his careful attention. He knows all that happens and rules his people with a firm hand, exercising a benevolent despotism.

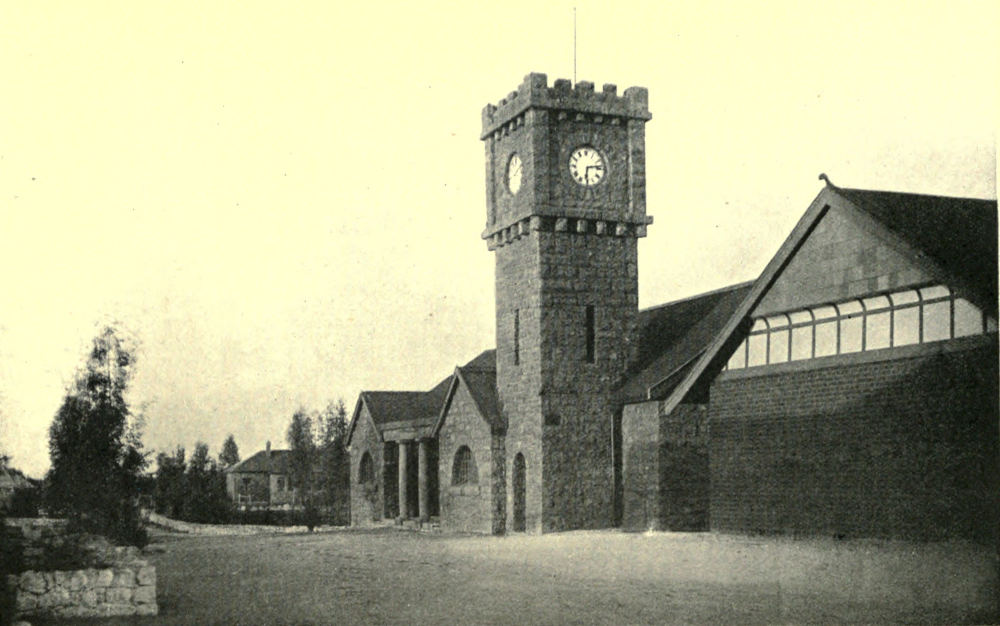

In a very true sense Khama is head of the Church as well as head of the State. He is most regular in his attendance at Sunday services and religious meetings. Under his leadership his people have just built a[Pg 48] magnificent stone Church, on the foundation stone of which are inscribed these words:—

“This Church was Erected to the Glory of God

by Chief Khama and the Bamangwato Tribe.”

Two great meetings in the Kgotla will live in my memory. At day-break on the morning after my arrival I attended a prayer meeting for rain. These meetings had been held for weeks. About 800 men and women were present in almost equal proportions. Most of the women sat upon the ground and the men on low chairs or stools which they brought with them. Khama sat on a deck chair under the shadow of a tree in the middle of one of the sides of the oval into which the people had grouped themselves. His young wife sat on his left hand. There was singing, reading and prayer. The Chief himself led the meeting in the final prayer, which lasted about five minutes. I am told he compared his country to a wilderness where there was no river, and his people to a lonely dog in the desert crying for water.

Another memorable meeting in the Kgotla was the Sunday morning service. Between 4,000 and 5,000 people assembled at 7 a.m., most of the men sitting on the right and the women on the left. The scene was a most picturesque one. The coloured head-dresses of the women were brilliant in the morning sunshine. Khama and his wife were present. A deacon with a fine voice led the singing, which was very hearty, and was unaccompanied by any instrument.

[Pg 49]

Many other gatherings were held during my visit to Serowe. I met deacons, Church members, catechumens, inquirers, Sunday School teachers, and other Christian workers. In several conversations with the Chief I found him to be deeply interested in Christian work in other parts of the world. He has the high spirits of a boy and told many yarns of hunting experiences. He had some interesting reminiscences of his meetings with David Livingstone to narrate. He told me that he remembered Livingstone visiting his father, Segkome, on three occasions. On the first and second of these visits Livingstone was riding on a hornless ox. On the third occasion he was travelling in an ox-waggon and came to Shoshong. “After that,” Khama added, “he went beyond the Zambesi, and I never saw him again.” Of his own accord he told me of Livingstone’s encounter with the lion, and described the damage to the arm and told me he remembered hearing of the incident at the time.

Khama has two houses, one a spacious and well-built native hut, where he lives with his wife, Semane, who was trained at the L. M. S. School, and is a fine specimen of a Native Christian woman. She takes great interest in the work and often visits the schools and is a regular attendant at the services in the Kgotla. Khama’s other residence is a European house, brick-built, with a verandah in front and containing four rooms. I visited him there, and was received in his sitting-room, which is about 18 feet square. The floor was covered with linoleum upon which was a Turkey carpet. There[Pg 50] were two tables—one a large old-fashioned drawing-room table, on which stood a photograph of Earl Selborne in a silver frame and two other photographs, and the other a light folding table on which was a richly framed autograph photograph of Queen Victoria, which she had given to the Chief when he was in England in 1895. On this table also stood a very large blue enamel milk-pail full of milk and a bottle of vinegar. In the corner was an Address from the Serowe Chamber of Commerce on the occasion of the Jubilee of his baptism. On the walls were portraits of the late King Edward, Queen Alexandra, King George and other Royalties. He showed me a gold hunter watch he was wearing, which contained an inscription recording that it was presented to him by the Duke and Duchess of Connaught. He was very interested in political matters and was most anxious about the future of his people, being apprehensive that the Protectorate might one day be incorporated in the South Africa Union, and keenly desirous of preventing the occurrence of anything in the nature of such a catastrophe, as he deems it would be.

Khama is a man of great physical strength. A week or two before I saw him he had ridden sixty miles to Shoshong on horse-back in a single day, and after a day or two’s stay had made the return journey in the same way. He exercises a tremendous influence over the tribe, and in recent years has put a stop to the manufacture and drinking of Native beer. The story is told of him that some time ago a man who had tried to bewitch him died of fright, when Khama reminded him[Pg 51] that he was the son of the greatest of witch doctors, Segkome, and that he could kill him if he wished to do so.

My week’s intercourse with Khama made two impressions on my mind. The first is that he is a Christian gentleman, and the second is that he is one of the most cautious and astute men I have ever met in my life. He has a remarkable mind, the working of which it is not always easy to understand, but of his desire to spread the light amongst the people over whom he rules with a rod of iron there cannot be a shadow of doubt.

Of the growing Church among the Bamangwato there are many manifest signs. Apart from the salaries of the missionaries and a small grant to keep the Mission House in repair, the work at Serowe is self-supporting. Moreover, the Church is a Missionary Church, and is seeking to pass on the light to others. For many years it has done much to sustain the work for God at Lake Ngami, which is the Mission field of the Bamangwato Church. It sends out its own missionaries. For twenty years Shomolekae has been the devoted and much loved evangelist of the far-away Lake Ngami district and has bravely held the fort in spite of loneliness and isolation and repeated attacks of fever. He has now been joined by Andrew Kgasi, who was trained at Tiger Kloof, and volunteered for service at the Lake.

From Serowe I travelled to Shoshong, being driven to Phalapye Road Station by the Acting-Magistrate in the Government mule cart. Proceeding south by railway to Mahalapye I was there met by Mr. Lloyd, the Shoshong[Pg 52] missionary, with his ox-waggon. We travelled all night and reached Shoshong at mid-day. This place in the old days was the capital of the Bamangwato tribe. It was here that Segkome, Khama’s father, ruled and Khama himself was baptised fifty-two years ago. Here David Livingstone preached and practised in the early forties, and later on John Mackenzie, Roger Price and J. D. Hepburn laboured. But its glory departed when in 1886 Khama moved his capital to Phalapye.

Shoshong is picturesquely situated in a wide plain with mountains on all sides, but there are few traces of its former greatness. The site of the old town is covered with bush. The present town consists of three large kraals under three local chiefs or head-men, one of whom is Khamane, Khama’s brother, and another Tshwene, Khama’s son-in-law. At the time of my visit Shoshong was experiencing the terrible effects of the prolonged drought. The only water supply was two miles away in the river bed, over one of the roughest paths I have ever traversed. Between the boulders over the stones and across the rocks the narrow serpentine track had been worn quite smooth by the long procession of women walking up and down day by day to fetch water from holes dug in the bed of the river. One of the vivid impressions of travel in these parts is that of a string of women carrying very heavy clay pots of water balanced on their heads, climbing over rocks and making their way through thorn bushes, and never spilling a drop of the water. These great pots are 18 inches across in the broadest part and one foot high, and when[Pg 53] filled are very heavy. I tried to lift one on to my head but entirely failed. The women help each other to hoist them and they do this very cleverly and quickly. A man attempted to help a woman to replace on her head the pot I had tried to lift. The woman said “No! you are no good, you are only a man! You cannot do it.” An old woman of sixty came to the rescue and between them they succeeded in replacing the pot upon the head of its bearer.

Shoshong is the centre of a large district comprising thirty-nine outstations, some of which, however, are little more than preaching stations. The missionary visits them from time to time. There are only seven schools in the district.

On my return journey to the railway I had an experience of travel which was much more common formerly, when the ox-waggon was the only means of conveyance, than to-day, when its place has been largely taken by carts and trains. We left Shoshong in the waggon at 10 p.m. The herd-boy had been unable to find two of the best oxen, and we started with a span of twelve, at least two of which were very poor specimens. In the first two miles we had to stop a score of times. Finally, one of the oxen laid down and refused to move. We left this creature and its fellow behind, and proceeded with ten oxen only. The heavy thunderstorm of the previous day had left water behind it on the road and our progress was slow. Between five and six on the following morning I was wakened by a tremendous banging and found one of the drivers standing[Pg 54] on the front seat of the waggon chopping off a branch of a tree which barred our way. Fifty yards further on, owing to careless driving and tired oxen, the wheels on one side of the waggon got lodged in a deep rut full of water and mud. I got up to find the waggon at an angle of forty-five degrees and in imminent danger of overturning. Dressing hurriedly and getting out of the waggon I found the boys had unyoked the oxen and fastened them on to the back in the vain hope that they might thus pull it out of the rut backwards. A futile effort was then made to dig out the two wheels, but it was impossible to move the waggon. The boy went off post-haste to Bonwapitse, two miles away, to borrow oxen and men from the Chief to extricate us. In two hours twenty men, including the Chief’s son, and ten of the most powerful oxen I have ever seen, came to our rescue. A chain was fastened round the back axle and in less time than it takes to describe the incident the waggon was dragged out of the rut. The new oxen, however, were not content with their performance, but rushed off, dragging the waggon backwards, and soon two considerable trees were levelled to the ground in the stampede. Fortunately, the oxen took a semi-circular course, and the great trees and dense bush checked them in their mad career, but not before some damage had been done and the interior of the waggon half-filled with broken branches of trees.

It was Sunday morning. On reaching Bonwapitse we held a Service under the trees, which was attended by the Chief and his wife and about 100 people. This was[Pg 55] one of the many open-air services which will live in the memory. The trees afforded little shade. The almost vertical rays of the South Africa summer sun beat down with merciless severity upon the people gathered together as they joined in singing their hymns and listened with great attention to the words spoken to them, and took part with great devoutness in the prayers which were offered.

I proceeded by railway to Gaberones, arriving there between two and three in the morning. Alighting from the train I waited in the darkness until two men appeared with a lantern to conduct me to the Government waggon which Mr. Ellenberger had kindly sent. We in-spanned early in the morning and I was taken to the Residency three miles away, where a warm welcome awaited me. Mr. Ellenberger is the Assistant Commissioner for the Southern portion of the Protectorate. He is the son of a missionary of the Paris Missionary Society who laboured in Basutoland, and his wife is the daughter of the well-known Dr. Casalis of the same Society. I experienced from them the same kindness which was always extended to me by the Government officials, and my two days’ stay at the Residency was altogether delightful. They kindly drove me in the Government cart to Khumakwane, where we found the waggon which had conveyed my luggage on the previous day, awaiting us. Mr. Haydon Lewis, the missionary from Molepolole, met us there with his waggon. Afterwards another open-air service was held under a great tree, in the course of which Mr. Ellenberger spoke to the[Pg 56] people in Sechuana, and a business interview followed with the neighbouring Chief, at whose village the Mission Chapel had been burnt some time before at the instigation of a “false prophet.”

Mr. Ellenberger drove us to Kolobeng, where we saw the ruins of the house which Livingstone had built seventy years before, and which was destroyed during his absence by the Boers. The outline of the house was quite distinct, and on one side the walls are still standing about 7 feet high. The bricks were of the roughest description, and the marvel is that they have stood the storms of seventy years without disappearing altogether. In Livingstone’s day there was a large town here, but now not a hut is to be seen owing to tribal migration. The Kolobeng river itself has almost disappeared, but its course is clearly marked by a great line of reeds and rushes.

I met two old men who remembered Livingstone, and gave me some details of his personal appearance. One of them as a boy was doctored by him, the other still cultivates Livingstone’s garden—a small patch near the ruins, where mealies are grown. Close by are the remains of an old Dispensary, and a little further off are two nameless graves. It was a scene of desolation, nature having completely re-asserted herself, and obliterated all traces of the former town. But from the site there was a fine view of undulating veldt and valley and mountain, and one thought with gratitude of the great man who had “passed like light across the darkened land”—

[Pg 57]

“To lift the sombre fringes of the Night

To open lands long darkened to the Light,

To heal grim wounds, to give the blind new sight,

Right mightily wrought he.”

Next day I left for Molepolole with Mr. Haydon Lewis. This town, where missionary work has been carried on since 1866, is the capital of the Bakwena tribe. In the afternoon there was a great gathering of school children for their annual sports. Just after I had distributed the prizes a youth galloped up on a bare-backed horse, scattering the children in all directions. He was the Chief’s son and has the reputation of being a graceless young rascal, constantly under the influence of drink and a veritable vagabond in the tribe. He rejoices in the name of Ralph Wardlaw Thompson Sebele, having been born about the time when Dr. Thompson was last in Molepolole, and receiving at baptism the honoured name to which he is anything but a credit.

During my visit I inspected the schools and met the Church members and congregation, and was present at a crowded lantern service in the Church. In spite of great difficulties the evangelistic work is being carried on with success by means of twenty-eight native preachers trained on the station. This tribe has set an example to the other Bechuanaland tribes by levying a school tax of 2/-per annum upon all tax-payers, thus providing ample funds for educational purposes. Except for the salary of the missionaries and an annual grant for itineration the work at this station is self-supporting, and the Church is realising the duties of providing for its[Pg 58] own work, of governing itself and of spreading the Gospel in the outlying parts. Its Mission field is the North central part of the Khalahari Desert which adjoins the territory of the tribe on the west. At Molepolole, as well as at other stations, the missionary is also the doctor. A considerable portion of each morning, when he is at home, is spent in examining patients and dispensing medicines. He is ably seconded by his wife, who was a trained nurse. Thus the light is spread not only by the preaching of the Gospel and the teaching in the schools, but also by the healing of the sick. So our missionaries are found following in the footsteps of the Great Physician.

From Molepolole I travelled south in the ox-waggon to Mahatelo on my way to Kanye. Early next morning I was met at Gamoshupa by a cart and four mules, kindly sent for me by Seapapico, the Chief of the Bangwaketsi tribe. After a drive through beautiful scenery I reached Kanye, a town of 10,000 inhabitants, and the capital of the tribe, in the afternoon. I spent the greater part of a week at this station, where missionary work has been carried on under the superintendence of a resident missionary for forty years, and where Mr. and Mrs. Howard Williams were labouring. While this book is passing through the press a cablegram has been received, conveying the sad news that Mr. Williams has been called to the higher service, after a devoted missionary life of well-nigh thirty years. The increasing activities of a growing Church of nearly 700 members were apparent in the town itself and in[Pg 59] the numerous outstations in the district. On the Sunday the spacious Church, which was provided by the tribe and cost £3,000 apart from the bricks, and contains a fine organ, the gift of the late Chief Bathoen, was packed to its utmost capacity, many having come in from the outstations. The women’s head-dresses, which were of all the colours of the rainbow, were in striking contrast to the black heads of the men. After the service thirty-four adults were baptised, and in the afternoon a Communion Service was held, at which 550 Church members gathered round the table of our Lord. On the following days I attended meetings of Church members and Christian workers and of women, inspected the schools, and had interviews with some of the leading men.

The present Chief, Seapapico, is a young man of twenty-six, and the son of Bathoen, who accompanied Khama to England in 1895. The young man was educated at Lovedale, and speaks English well, and was a great support to the missionary, Mr. Howard Williams. His mother, Bathoen’s widow, is a fine Christian woman and gives great assistance to Mrs. Williams in her work amongst the women of the tribe. She was the favourite daughter of Sechele, the old Chief of the Bakwena tribe. When she was a girl she had a quarrel with a friend and destroyed her eyesight with a thorn. Sechele had one of his daughter’s eyes put out, on the principle of “an eye for an eye,” and she bears the mark of this parental correction to this day.

From Kanye I was driven in the Chief’s cart to the railway at Lobatsi, whence on the following day I was[Pg 60] escorted by the native ordained minister, Roger K. Mokadi, to his station at Maanwane, over the Transvaal border. After a service in the Church and a visit to Roger’s kraal, a hot tramp under a fierce sun brought us at Mabotsa to the ruins of the old Mission house built by Livingstone and Edwards. Some of the walls were standing seven or eight feet high, but the interior was overgrown with bush. Close by is the hill where Livingstone had his famous encounter with the lion, and near at hand an old native Christian lives who was with Livingstone at the time. A drive through Linokani, where the German Lutherans are carrying on a fine piece of missionary work, brought me to Zeerust and next day by means of the train I reached Johannesburg. It does not fall within the scope of this book to describe this wonderful city, the creation of the last twenty-five years. It is by far the largest business town in South Africa and is the centre of the greatest gold producing mines in the world. Here I experienced the utmost kindness from members of the Congregational Church and met my colleague, Mr. Houghton, with whom I was to travel for the next nine months. Nor must I stay to refer to a deeply interesting visit to Pretoria. At these great centres the evidence of the appalling racial conflict, which constitutes the greatest problem confronting the Christian Church in South Africa to-day, was abundantly apparent.

A few days later I travelled to Mafeking, for ever immortalised for its heroic defence during the Boer war, to see Colonel Panzera, the Resident Commissioner for[Pg 61] the Bechuanaland Protectorate, and thence proceeded to Tiger Kloof to meet all the Society’s South African missionaries for consultation upon the work and its problems.

Throughout my journeys amongst the Churches in Bechuanaland and Matebeleland there were many signs of the growing power and promise of the Native South African Church. That Church, planted first by Moffat and his colleagues at Kuruman, and carried north by Livingstone and his successors until it has well-nigh reached the Zambesi, has had a chequered career, but its progress has been unmistakably onward and upward. It has been tried and purified by the struggles of the past, and to-day its “far-flung battle line” is making a steady advance against the forces of superstition and heathenism with which it is confronted.

“Climbing through darkness up to God,” the members of that Church are bravely carrying “the wonder and the glory of the light” into “the darkness and the sorrow of the night” in which so many of their fellow-countrymen are still enshrouded. Through the open doors “the true Light, which lighteth every man coming into the world,” is pouring its ever-brightening rays.

[Pg 62]

From North, and South, and East, and West

They come.

John Oxenham.

The crown of the work of the L. M. S. in South Africa is the Tiger Kloof Native Institution. Ten years ago the site on which its buildings now stand was bare veldt. To-day it is a centre of light for all the L. M. S. work in South Africa. Situated on the Cape-to-Cairo Railway, 767 miles north of Cape Town, the Institution buildings, which challenge the attention of every passing traveller, are a monument to the princely munificence of that great missionary-hearted man Robert Arthington of Leeds, to the energy, ability, devotion and far-seeing statesmanship of the Rev. W. C. Willoughby, and to what can be accomplished by the South African boys trained in the Institution, who have erected most of the buildings which are now so notable a feature of the landscape.[3]

[Pg 63]