The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

In this version, the illustrations are placed differently on the page than in the original. This was done to keep them on the same page as the original.

Copyright, 1909

by

Armstrong Cork Company

PITTSBURGH

U. S. A.

1909

Armstrong Cork Company

of

Pittsburgh

U.S.A.

Few things in general use in the great world to-day have the hall-mark of approval of two thousand years set upon them. New materials, new processes, new commodities have followed the train of advancing civilization and the ensuing multiplication and alteration of man’s economic needs. Even where the demand for a certain material to fulfill a particular function has continued through the centuries, widening knowledge of natural resources coupled with modern invention has usually found some substitute cheaper, more efficient, and better adapted for the purpose in question. Not so with cork. Recognized by the ancients as peculiarly suited for certain uses, time has vindicated their verdict; nothing has yet been discovered to supplant it in its wide sphere of usefulness.

Theophrastus, Greek philosopher and writer on botany, who flourished in the fourth century before Christ, was evidently familiar with the material, for he mentions the cork tree as being a native of the Pyrenees. For decades before the time of Horace cork was used for stoppers for wine vessels. In fact, the poet tells one of his friends, about 25 B. C., that on the occasion of a coming anniversary banquet he expects to “remove the cork sealed with pitch” from a jar of the rare vintage of forty-six years previous, the first but not the last proceeding of this character of which history makes record.

[Pg 6]

It remained for the elder Pliny, however, in his wonderful work on natural history, written in the first century of the Christian era, to make the most remarkable reference to cork to be found in ancient literature: “The cork oak is but a very small tree and its acorns of the very[Pg 7] worst quality * * *; the bark is its only useful product, being remarkably thick, and if removed will grow again * * *.

This substance is employed more particularly attached as a buoy to the ropes of ships’ anchors and the drag-nets of fishermen; it is used also for the[Pg 8] bungs of casks and as a material for the winter shoes of women.” Cork jackets—life-preservers—are mentioned by Plutarch. Thus five of the principal functions which cork fills in the world to-day were recognized two thousand years ago. In the fifteenth century glass bottles were introduced, which gave such great impetus to its general use that the real beginning of the cork industry may properly be said to date from that period. Some conception of its importance to-day may be gathered from the fact that the importations of the United States of crude and manufactured cork now aggregate almost $5,000,000 in value annually.

The word cork is derived from the Latin cortex, meaning bark, and the study of its origin and manufacture leads at once to those romantic countries bordering[Pg 9] the Mediterranean Sea.

Spain and Portugal divide honors among the nations of the world so far as yield of raw material is concerned, with perhaps the advantage leaning slightly to the latter.

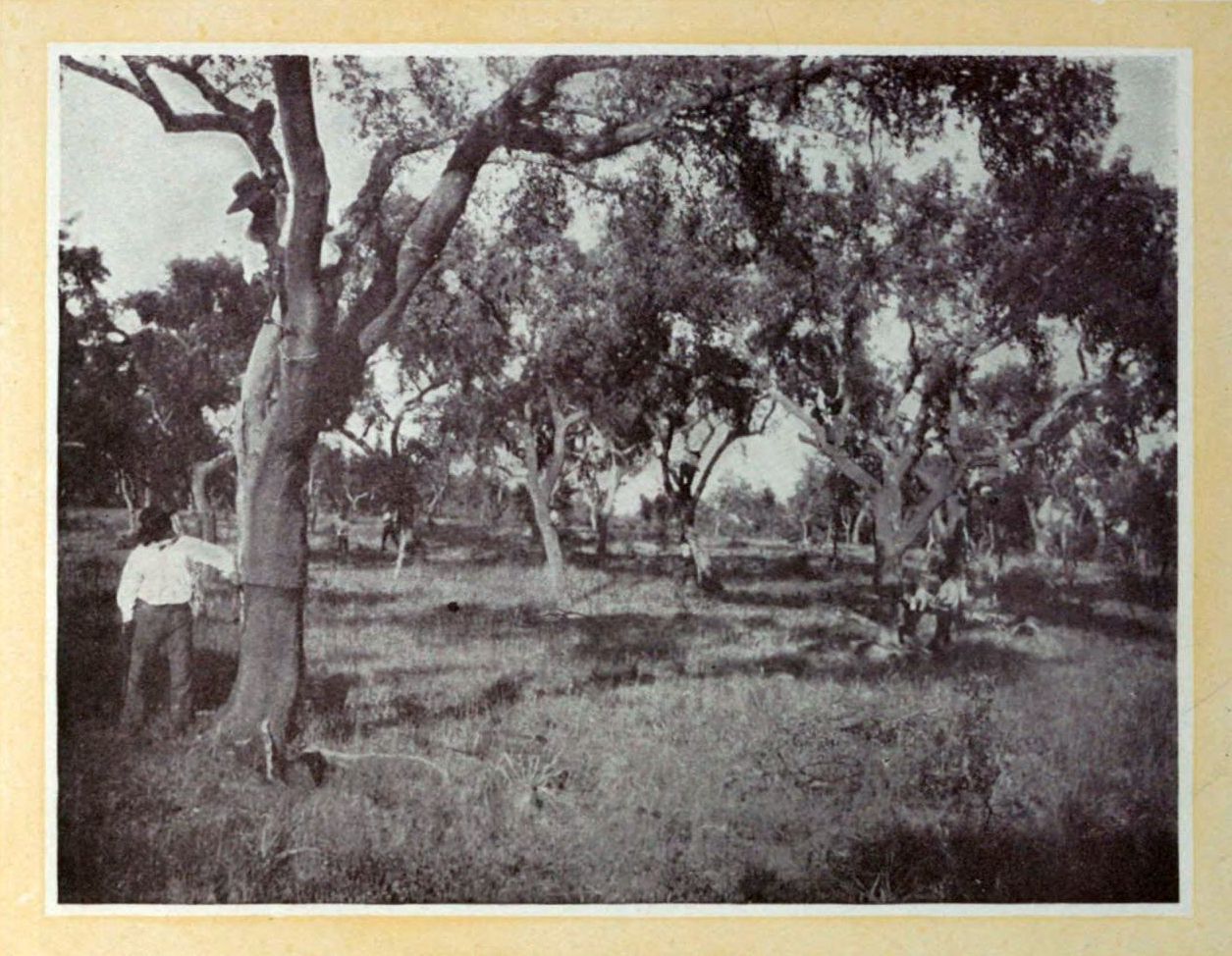

The cork-producing territory covers practically the whole of Portugal, sweeps toward the east through the southern districts of Spain known as Andalusia and Estremadura, thence northeast, embracing thousands[Pg 10] of acres of forests in Catalonia.

Algeria, with Tunis, ranks next in importance in yearly tribute of bark, southern France, including Corsica, following closely after. Italy, too, with the help of Sardinia and Sicily, continues to be quite a factor in meeting the demand for the crude material, while across the Strait of Gibraltar the sun-scorched forests of Morocco are as yet undeveloped. The total area covered by cork forests is estimated at from four to five million acres, while the annual production of bark is declared to be not far from fifty thousand tons. Although no official statistics are obtainable, these figures approximate the truth. In Portugal and Spain, particularly in Catalonia, which is probably the greatest cork manufacturing district in the world, a large portion of the corkwood produced[Pg 11] goes to supply domestic factories, where more and more machinery is being introduced every year. With these exceptions, however, the major part of the yield is exported to the United States, England, France, Germany, Austria, Russia, Denmark, or Sweden, to be turned into finished form.

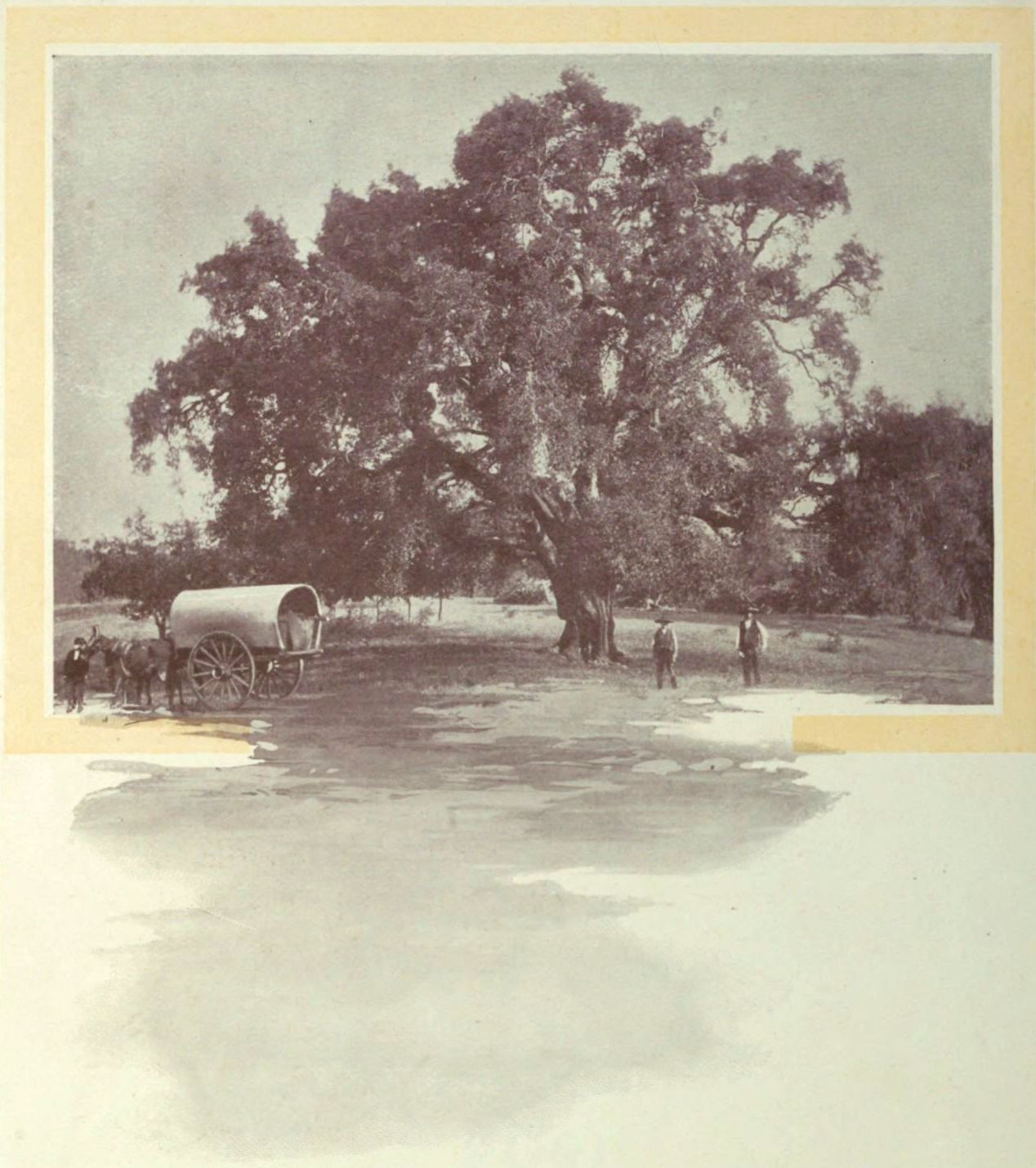

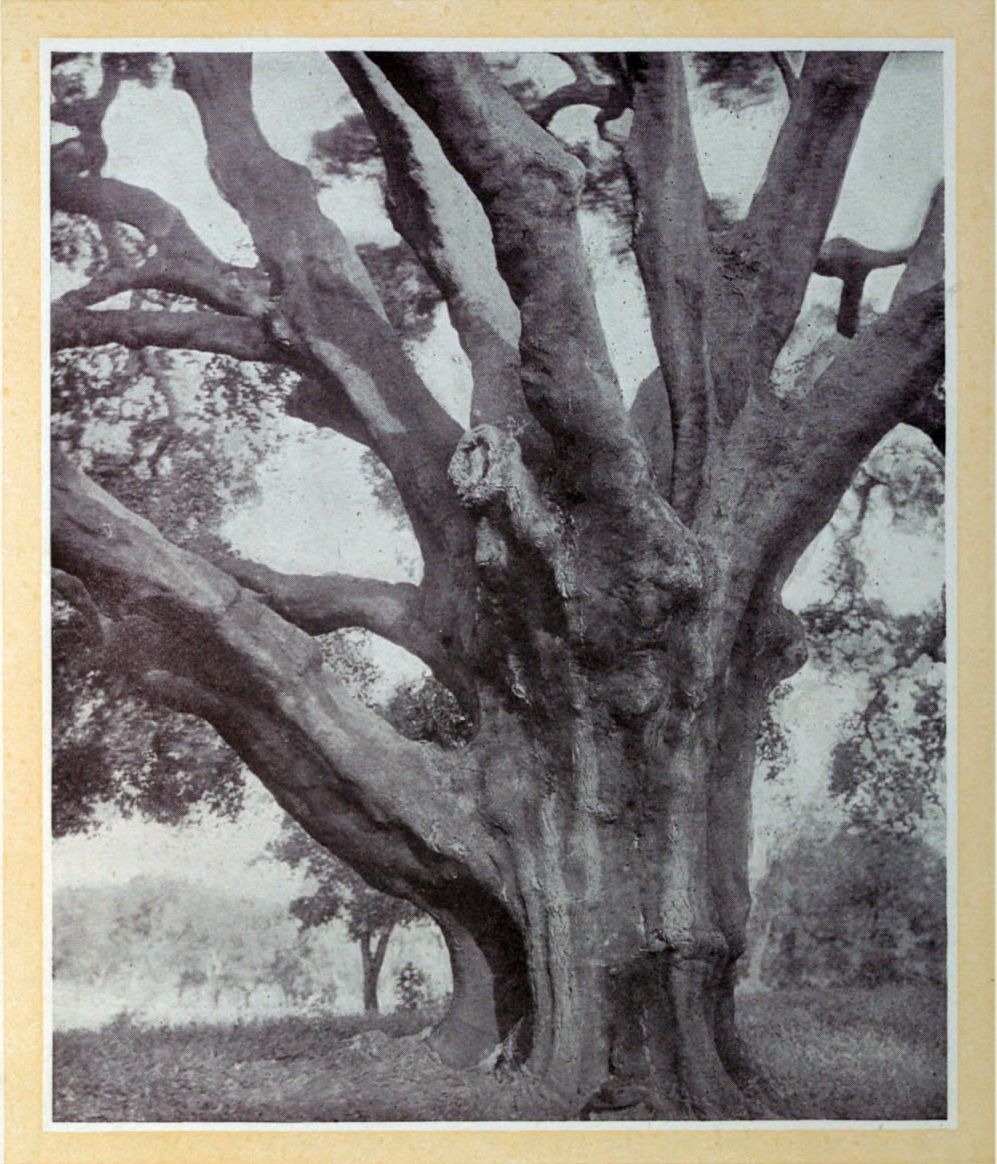

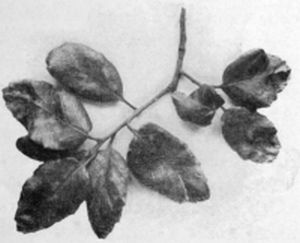

The cork oak, known botanically as Quercus suber, attains a height of from twenty to sixty feet and measures sometimes as much as four feet in diameter. Its wide-spreading branches are rather closely covered with small evergreen leaves, thick, glossy, slightly serrated, and downy underneath. In April or May flowers of a yellowish color appear, succeeded by acorns which ripen and fall to the ground in the late fall. Pliny evidently knew whereof he wrote, for the cork oak’s acorns are bitter and not[Pg 12] at all pleasant to the taste.

They form, however, one of the forests’ chief sources of revenue, since, fed to swine, they give a peculiarly piquant flavor to the meat, Spanish mountain hams being noted for their excellence. Unfortunately, the herds in foraging for food destroy the young trees and thus do serious and permanent injury by preventing new growth.

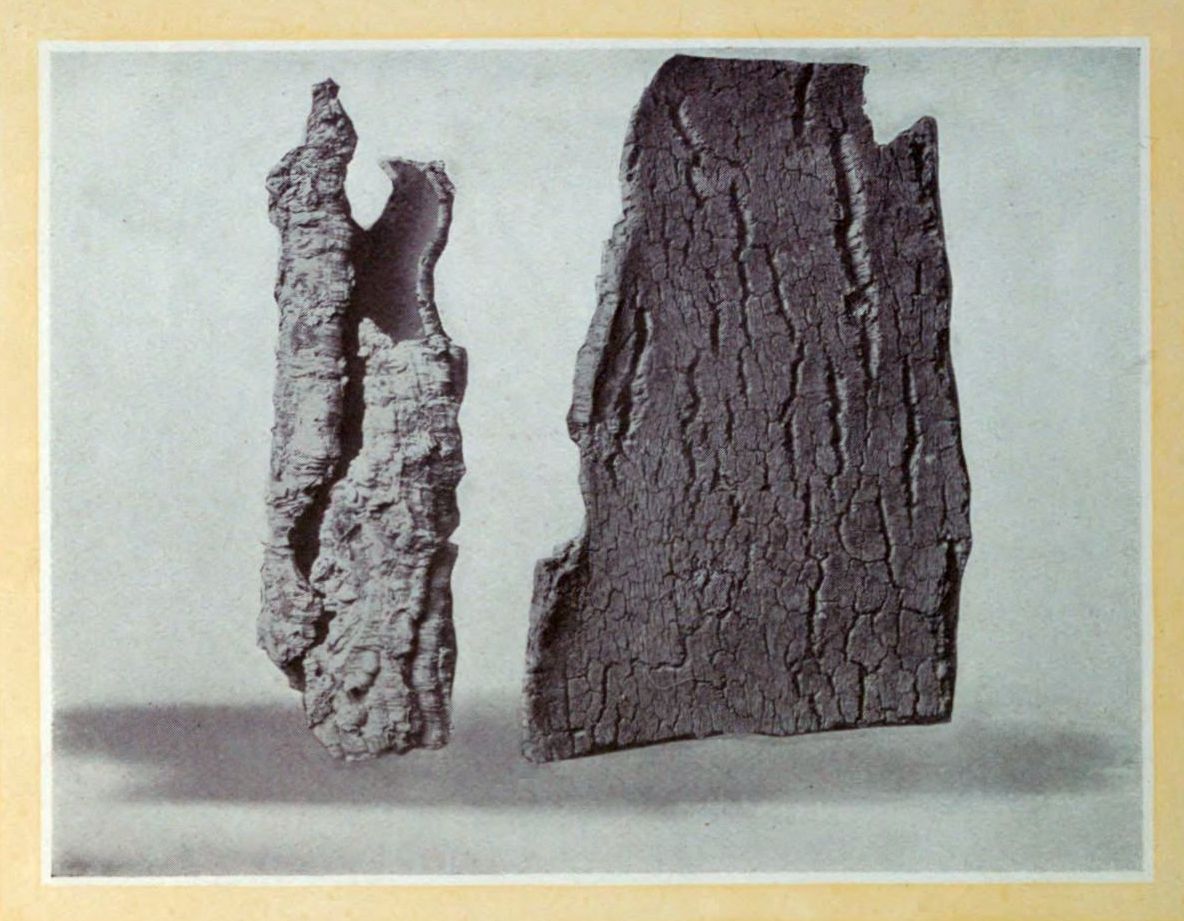

The “corkwood,” or cork of commerce, is the outer bark of the cork oak. When it has attained a diameter of approximately five inches, or, to be more exact, measures forty centimeters in circumference according to the Spanish governmental regulations, which the tree does usually by the time it is twenty years old, the virgin cork, as the first stripping of bark is called, is removed. This[Pg 13] virgin cork is so rough, coarse, and dense in texture that it is of very little commercial value.

Fortunately its removal does not kill the tree, but, on the other hand, seems to promote further development, for the inner bark—the seat of the growing processes—undertakes at once the formation of a new covering of finer texture. Each year this, the real skin, with its life-giving sap, forms two layers of cells—one within, increasing the diameter of the trunk; the other without, adding thickness to the sheathing of bark. After eight or ten years this is also removed, and, while more valuable than the virgin cork, it is not as fine in quality as that of the third and subsequent strippings, which follow at regular intervals of about nine years. At the age of about forty years the oak begins to yield its[Pg 14] best bark, continuing productive as a rule for almost a century, although cork trees several hundred years old are not unknown.

Flourishing as it does in a hot, semi-arid climate, there seems to be no reason why this valuable tree should not be successfully introduced in the southern and southwestern sections of the United States; in fact, in the year 1858 the United States Government took certain steps in this direction, and even went so far as to distribute seedlings to interested persons in several states.

The[Pg 15] Civil War interfered, however, and the experiments were never fully carried out.

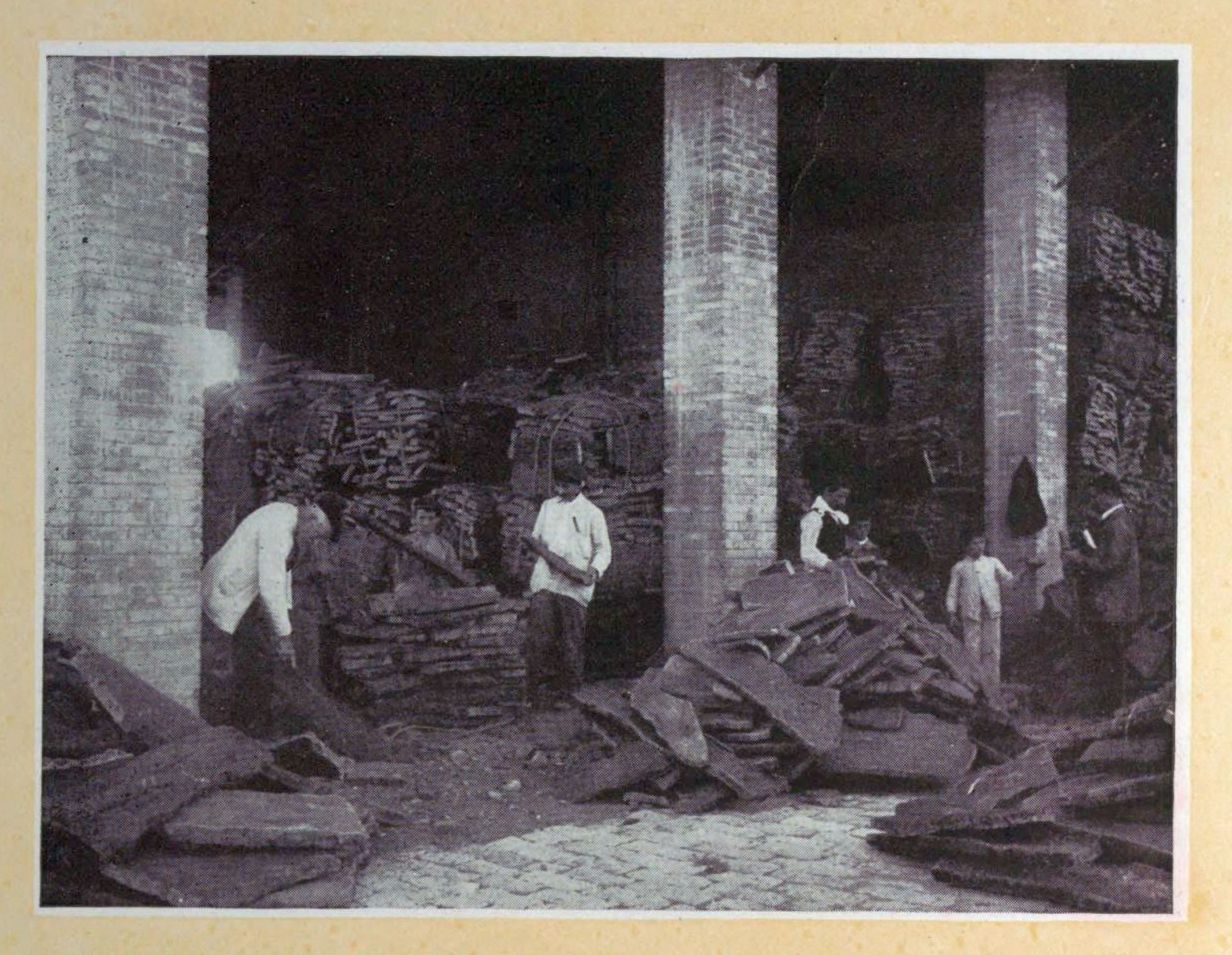

The stripping generally takes place during July and August, and is a process which demands skill and care if injury to the tree is to be avoided. In Algeria, the French strippers sometimes use crescent-shaped saws; but under the usual Spanish method a hatchet with a long handle, wedge-shaped at the end, is the only implement employed.

The bark is cut clear through around[Pg 16] the base of the tree and a similar incision is made around the trunk just below the spring of the main branches; the two incisions are then connected by one or two longitudinal cuts, following so far as possible the deepest of the natural cracks in the bark.

Inserting the wedge-shaped handle, the tree’s covering is then pried off, care being taken not to injure the inner skin at any stage of the process, for the life of the tree depends on its proper preservation; and if it is injured at any point, growth there ceases and the spot remains forever afterward scarred and uncovered.

The larger branches are stripped in the same manner, yielding thinner but[Pg 17] generally a finer grade of cork than that from the trunk.

The thickness of the bark is anywhere from one-half to two and a half inches, while the yield also varies greatly—from forty-five to five hundred pounds—depending on the size and age of the tree.

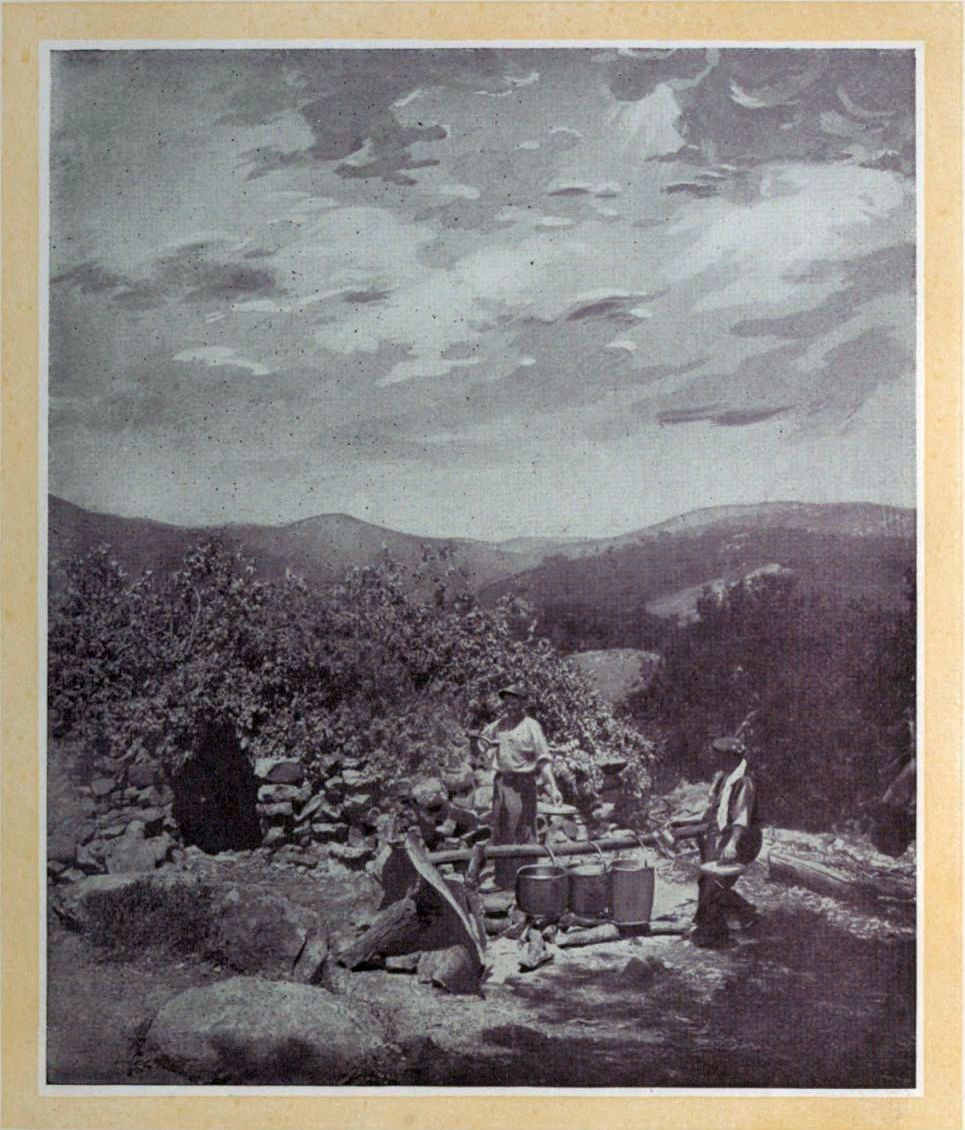

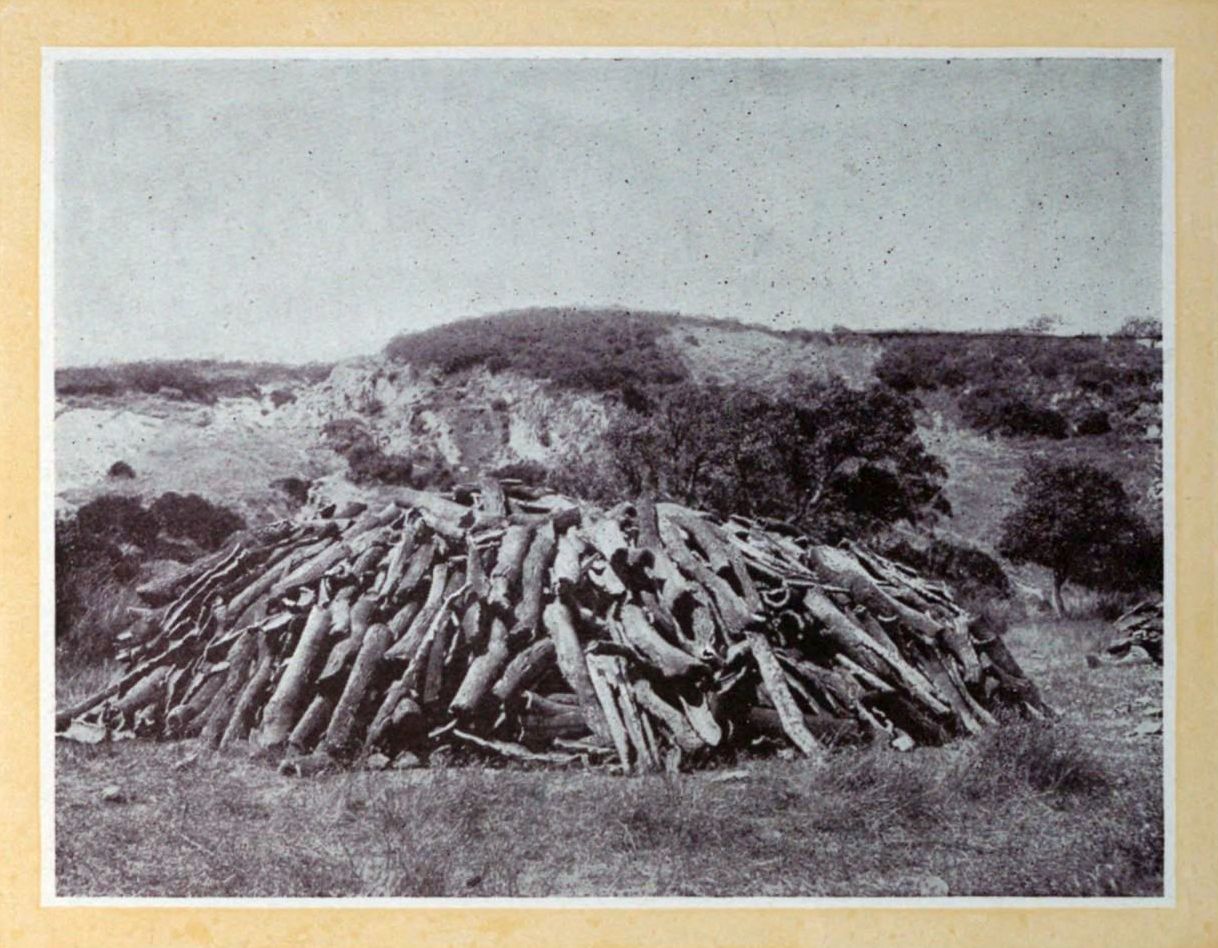

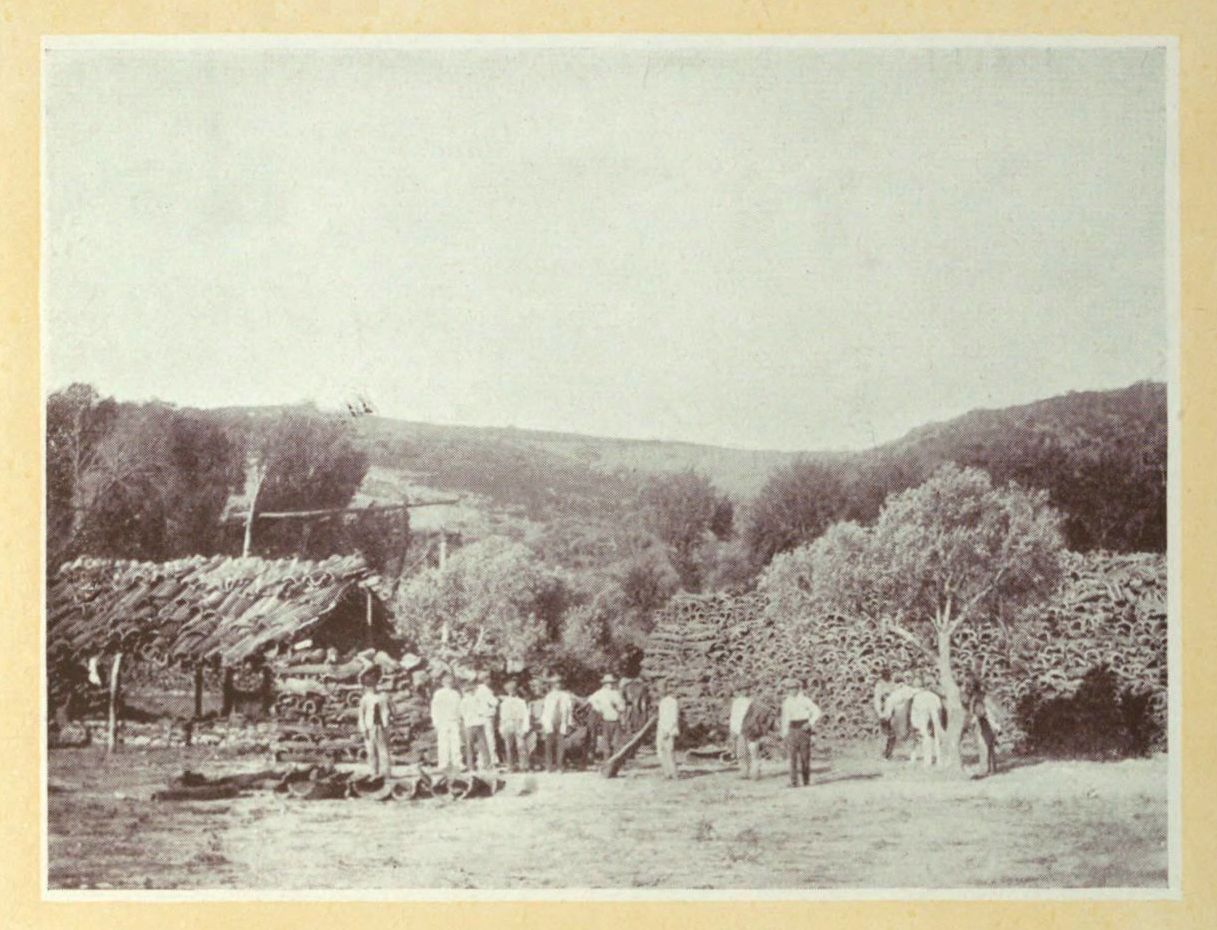

As the bark is removed it is gathered up in piles and left for a few days to dry. Having been weighed, it is next carried either in wagons or on the backs of burros to the boiling stations, where it is stacked and allowed to season for a[Pg 18] few weeks. It is then ready for the boiling process, which at times is postponed until the crude material reaches Seville or some other shipping point.

But if the forest is distant, the water supply adequate, and the quantity of bark ample to justify such procedure, the vats are erected at a convenient spot and this operation carried out on the ground.

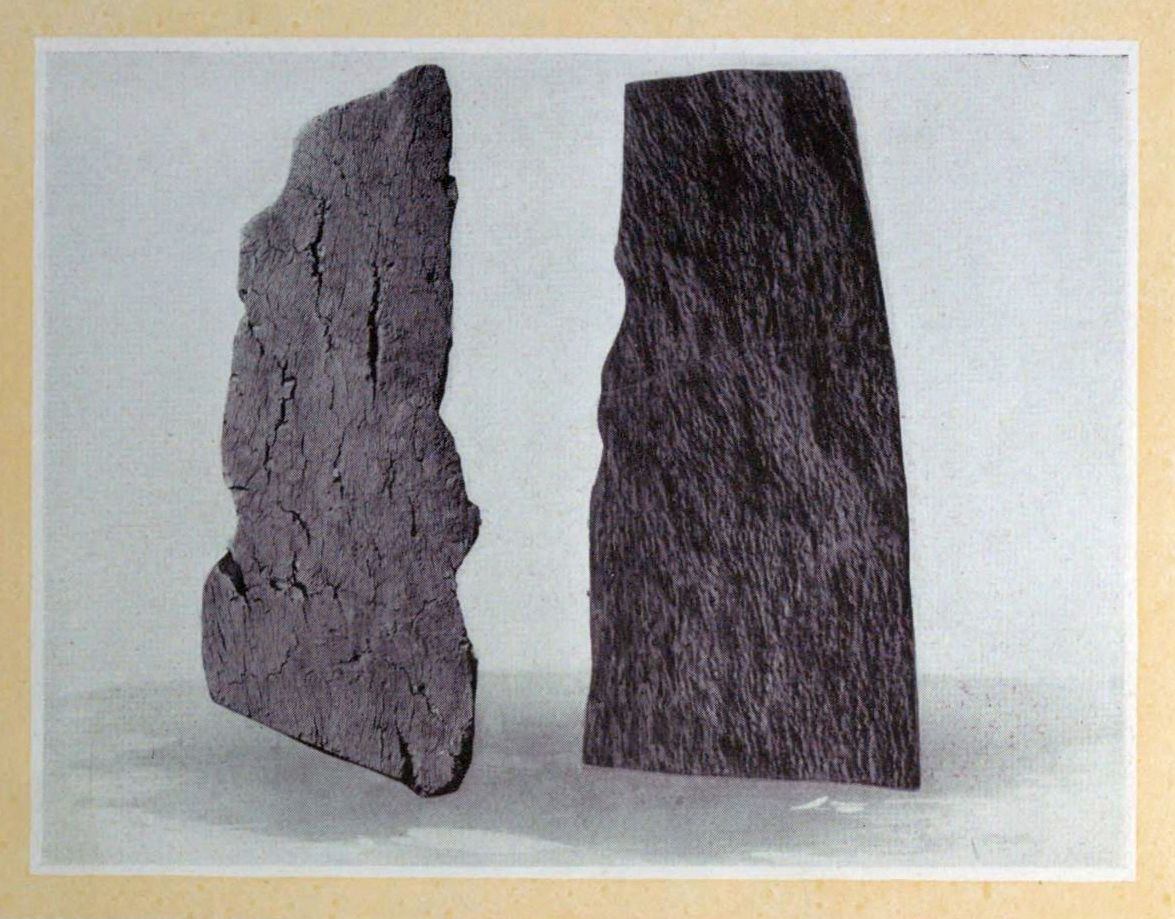

The outside of the bark in its natural[Pg 19] state is, as may well be imagined, rough and woody, owing to exposure to the weather. After boiling, this useless outer coating is readily scraped off, thereby reducing the weight of the material almost twenty per cent. The boiling process also serves to remove the tannic acid, increases the volume and elasticity of the bark, renders it soft and pliable, and flattens it out for convenient packing.

After being roughly sorted as to quality and thickness the bark is then ready for its first long journey, and, as the forests are generally located in hilly or even mountainous country, the faithful burro must again be called into service. Truly the Spaniard’s best friend, though the worst treated of all, these patient little animals present a most grotesque appearance when loaded from head to[Pg 20] hind quarters with a huge mass of the light bark.

Down from the hills they go in trains of thirty, forty, or even a hundred, threading the rocky bridle paths in single file and wending their way through the narrow streets of quaint villages, where traces of Moorish occupancy may still be seen, to the nearest railway station, or even to Seville itself.

Of course, if conditions permit, wagons are used, but since Spain is not a country famous for its good roads, it is probable that for many years to come the burro will play his part in supplying the cork markets of the world.[Pg 21]

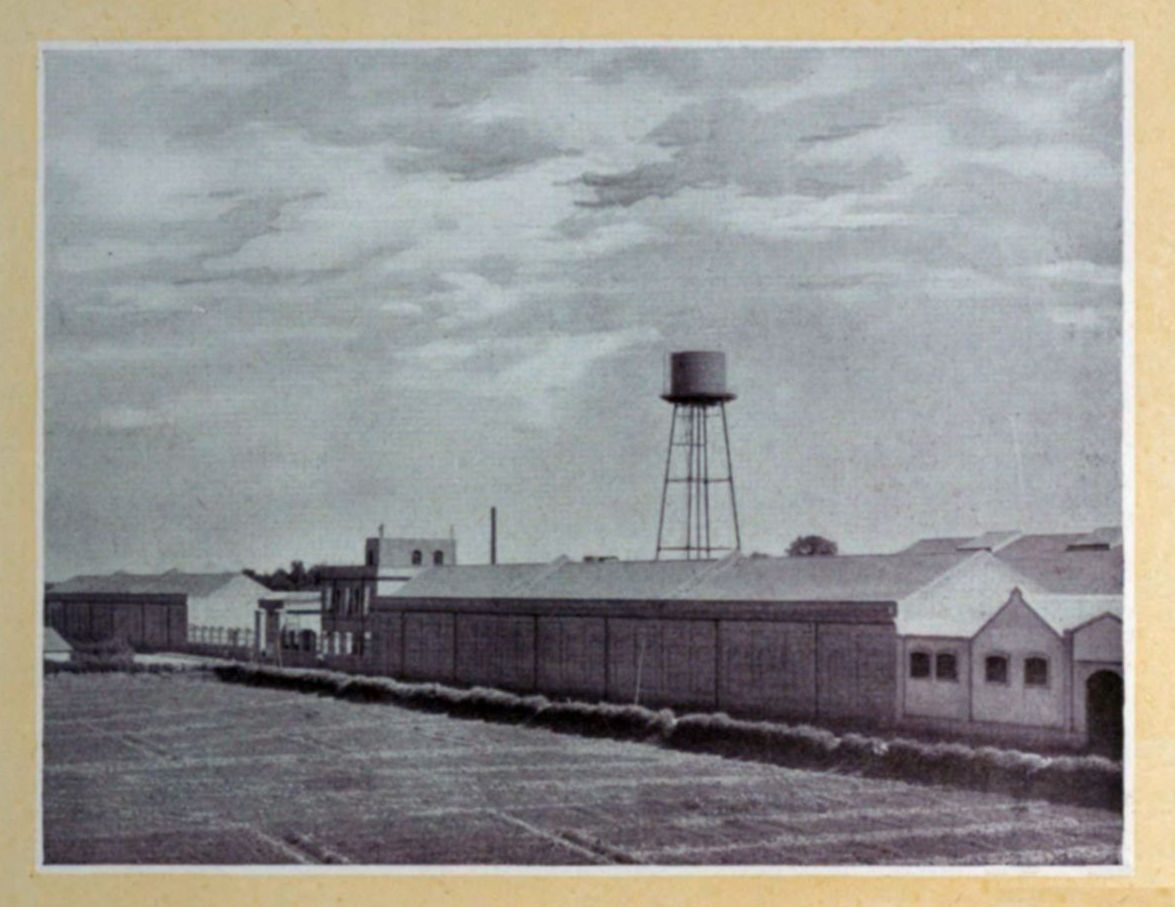

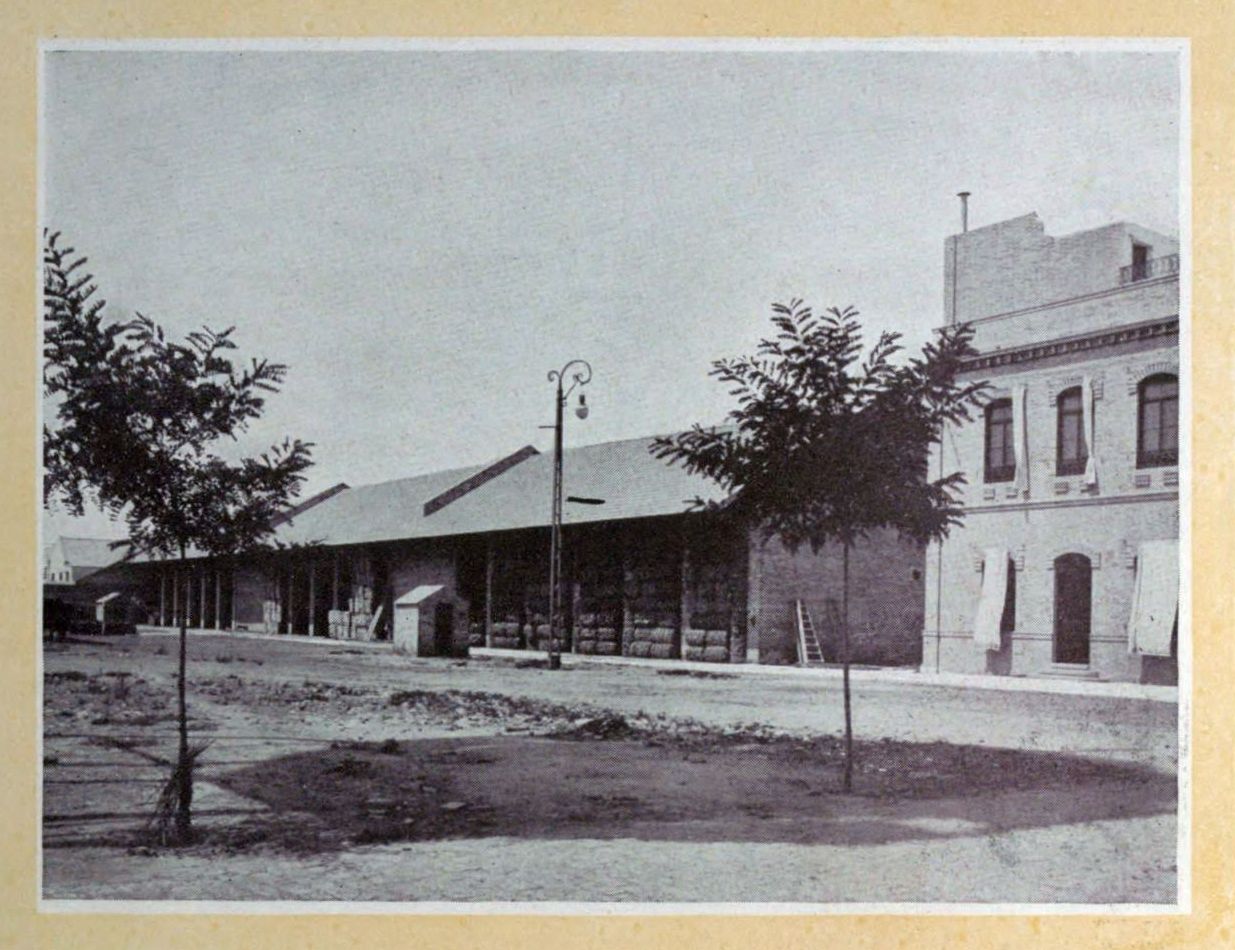

Although large supplies of raw material are drawn from Portugal, the principal foreign warehouse and Spanish factory of the Armstrong Cork Company are situated in Seville; hence it is to that historic city on the banks of the Guadalquivir that the bark from many hills and valleys finds its way during the summer months.

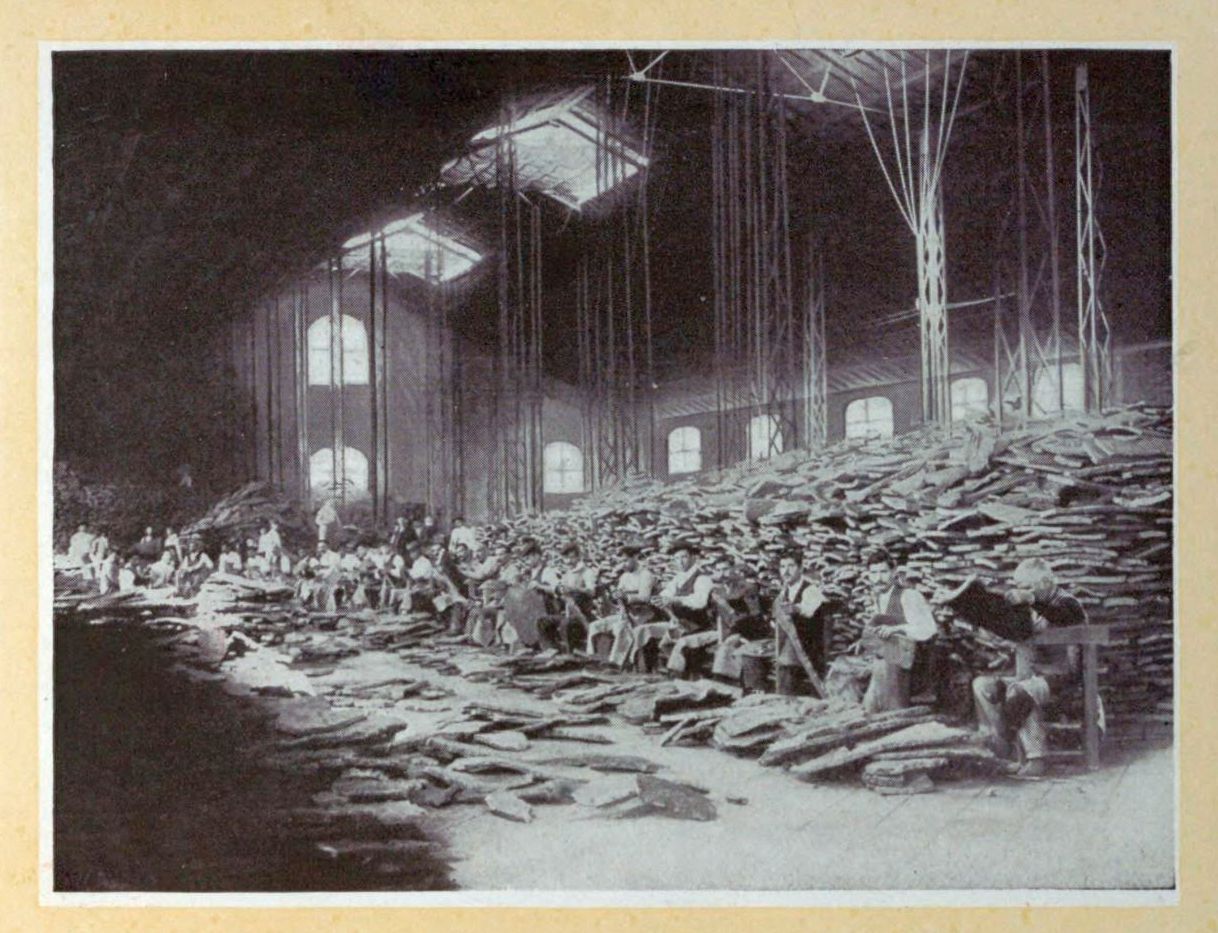

There the bales as they come from the country are opened, the bark boiled and scraped, if this has not already been done, and then, after the edges have been trimmed, is sorted into a dozen or more grades of different quality and thickness. The importance of this last mentioned operation cannot be overemphasized, as the[Pg 22] whole problem of the successful and economical manufacture of cork centers about it.

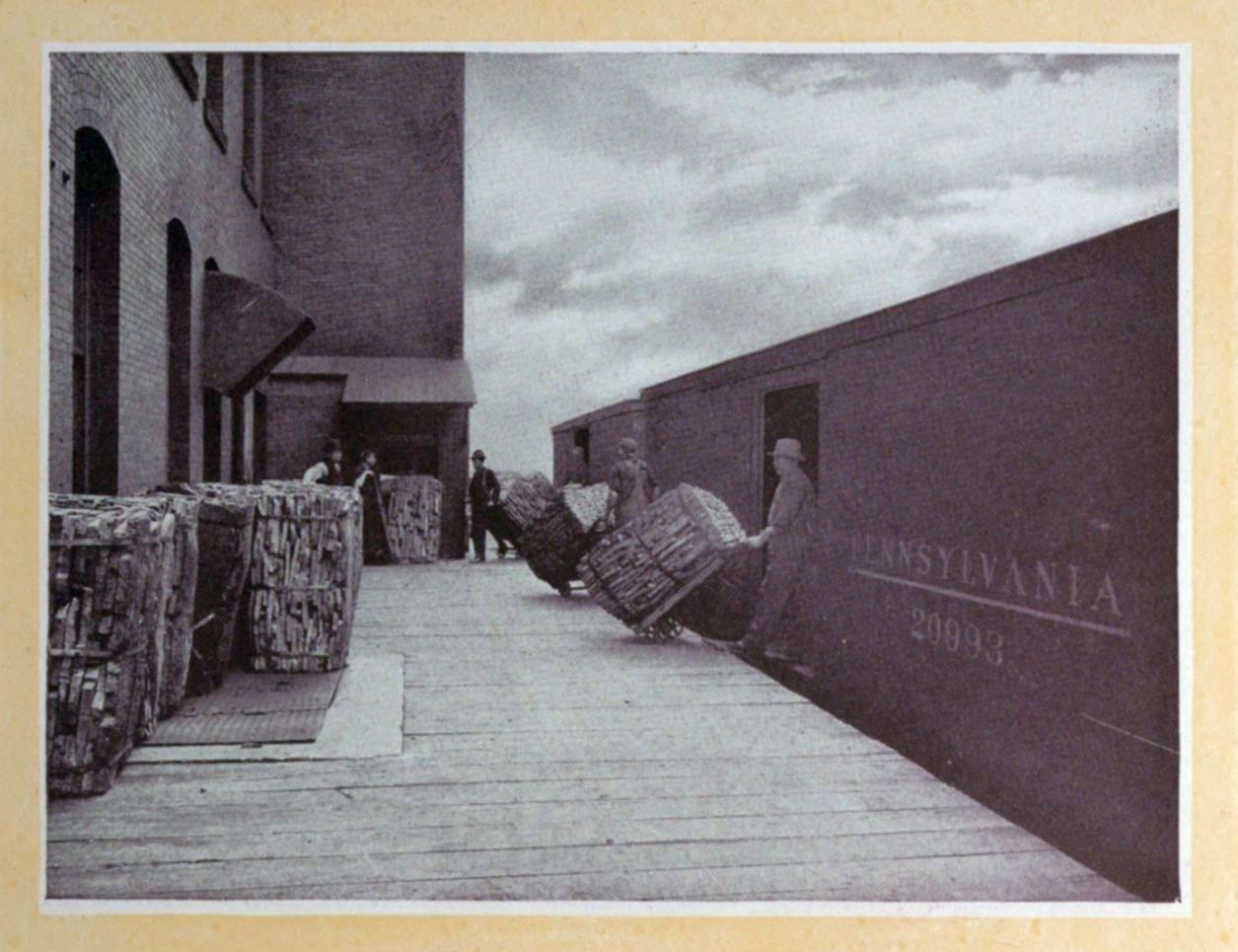

The expert Spanish sorters having finished their work, the bark is ready to be rebaled for shipment to America.

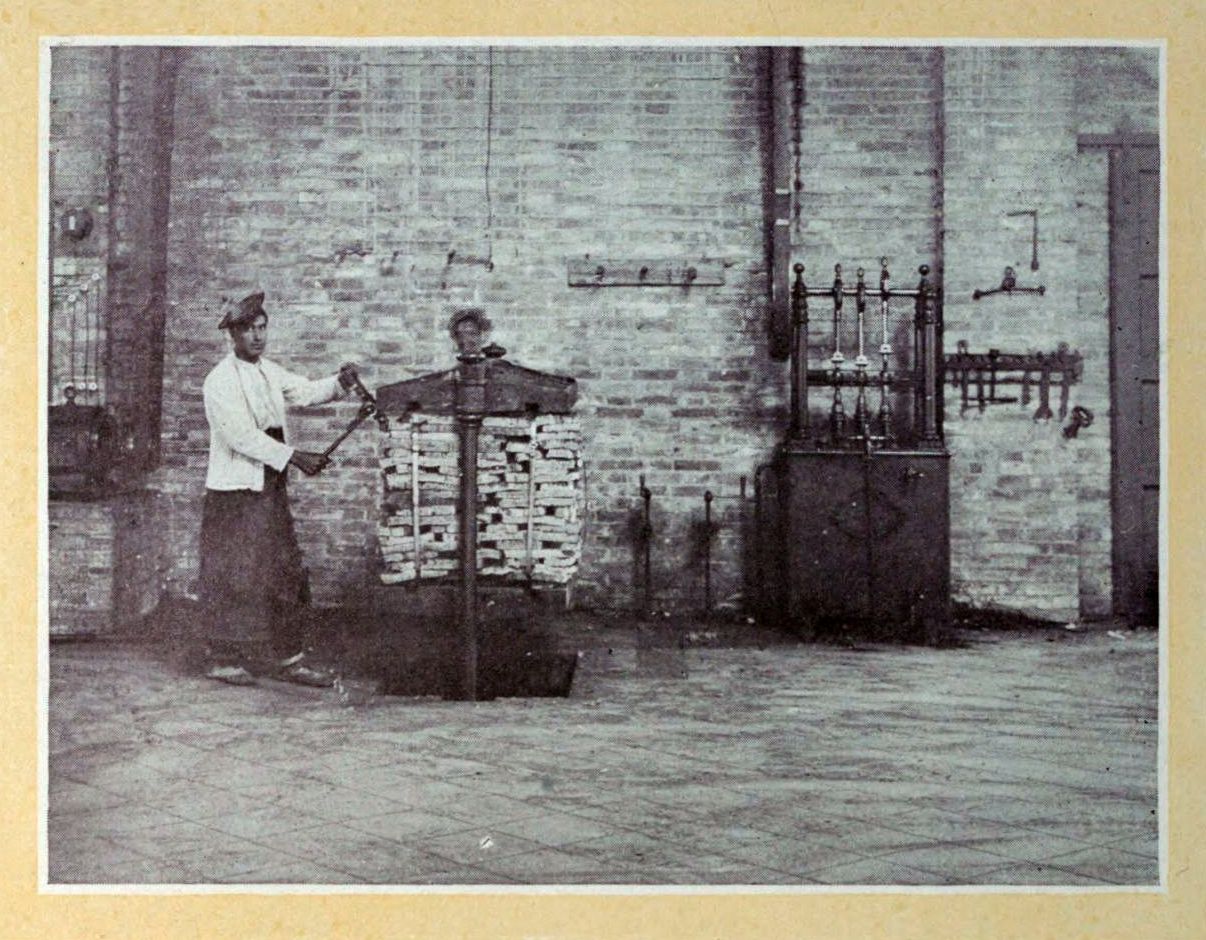

Broad sheets are placed in a baling box to form the bottom of the bale, and above them are laid smaller pieces, which are covered in turn with larger sections; then the whole mass is subjected to pressure to render it compact, afterward being bound up securely with steel hoops or wire.[Pg 23]

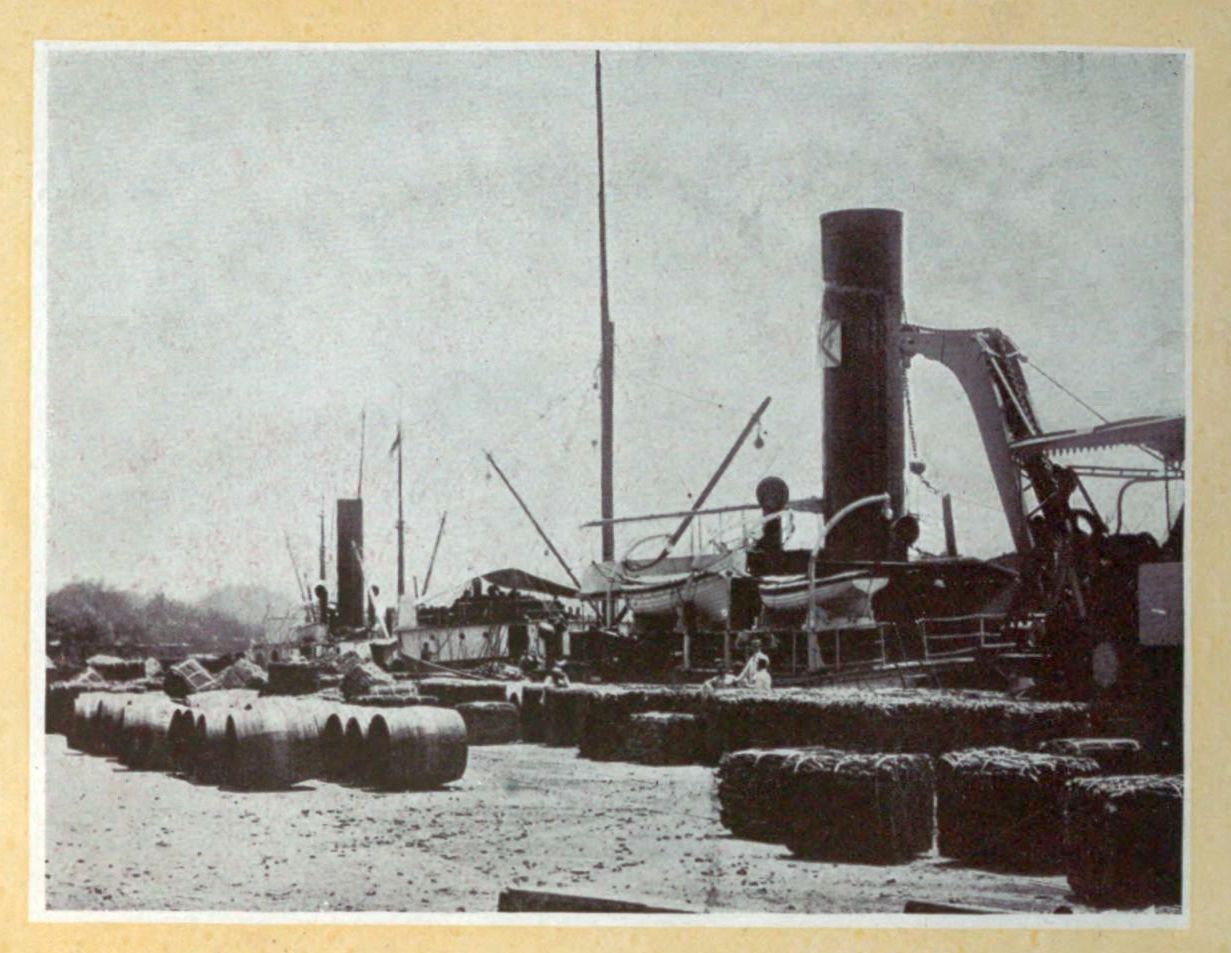

Each bale is carefully stenciled with marks indicating grade or quality. Loaded directly into ocean-going steamers alongside the Seville docks, not infrequently a whole ship’s cargo of cork at a time is transported to Philadelphia, New York, or Baltimore, and thence freighted to the Pittsburgh factory.

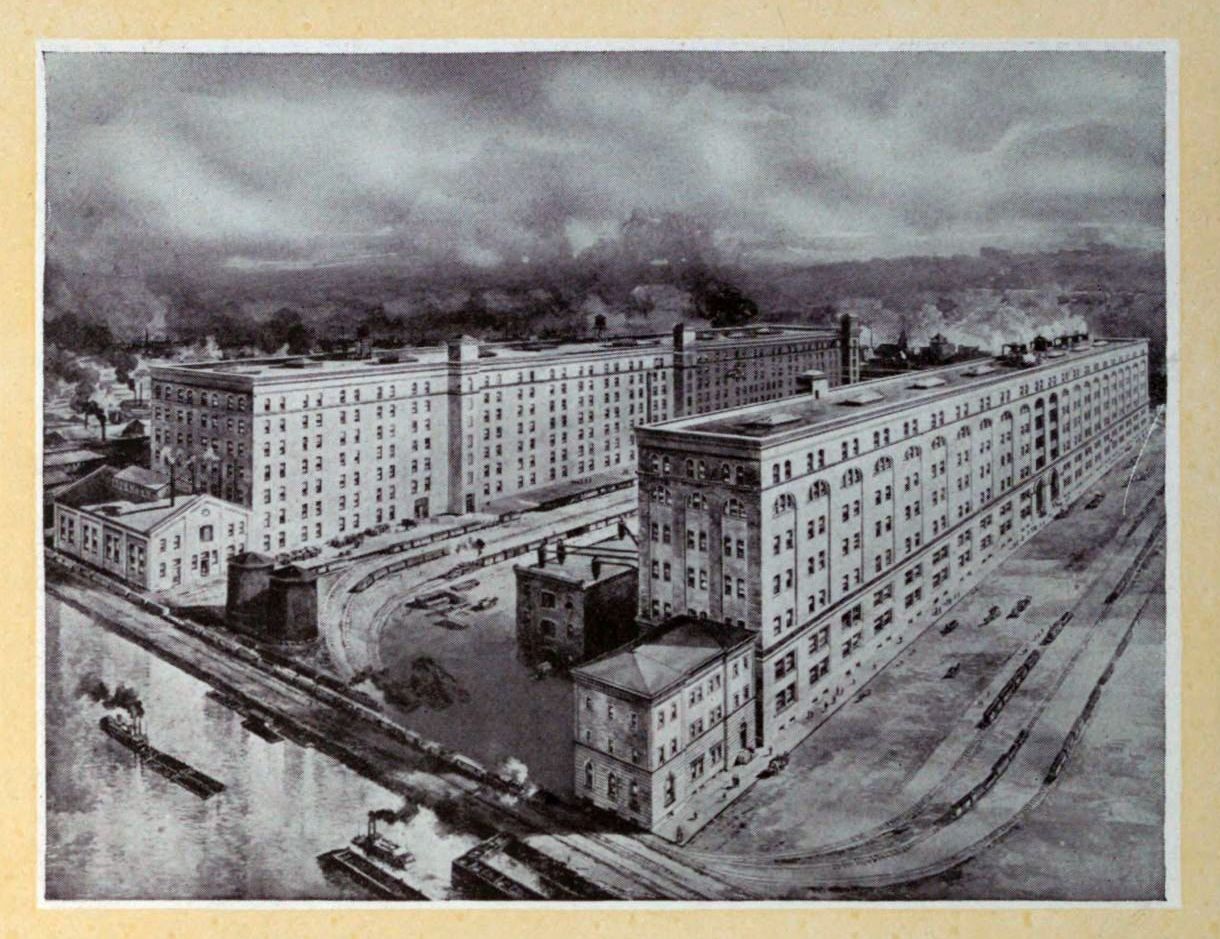

From the mountain of cork unloaded at its doors a host of different articles are produced by means of wonderfully ingenious machinery coupled with hundreds of keen brains, for the human element must always play a large part in cork[Pg 24] manufacture.

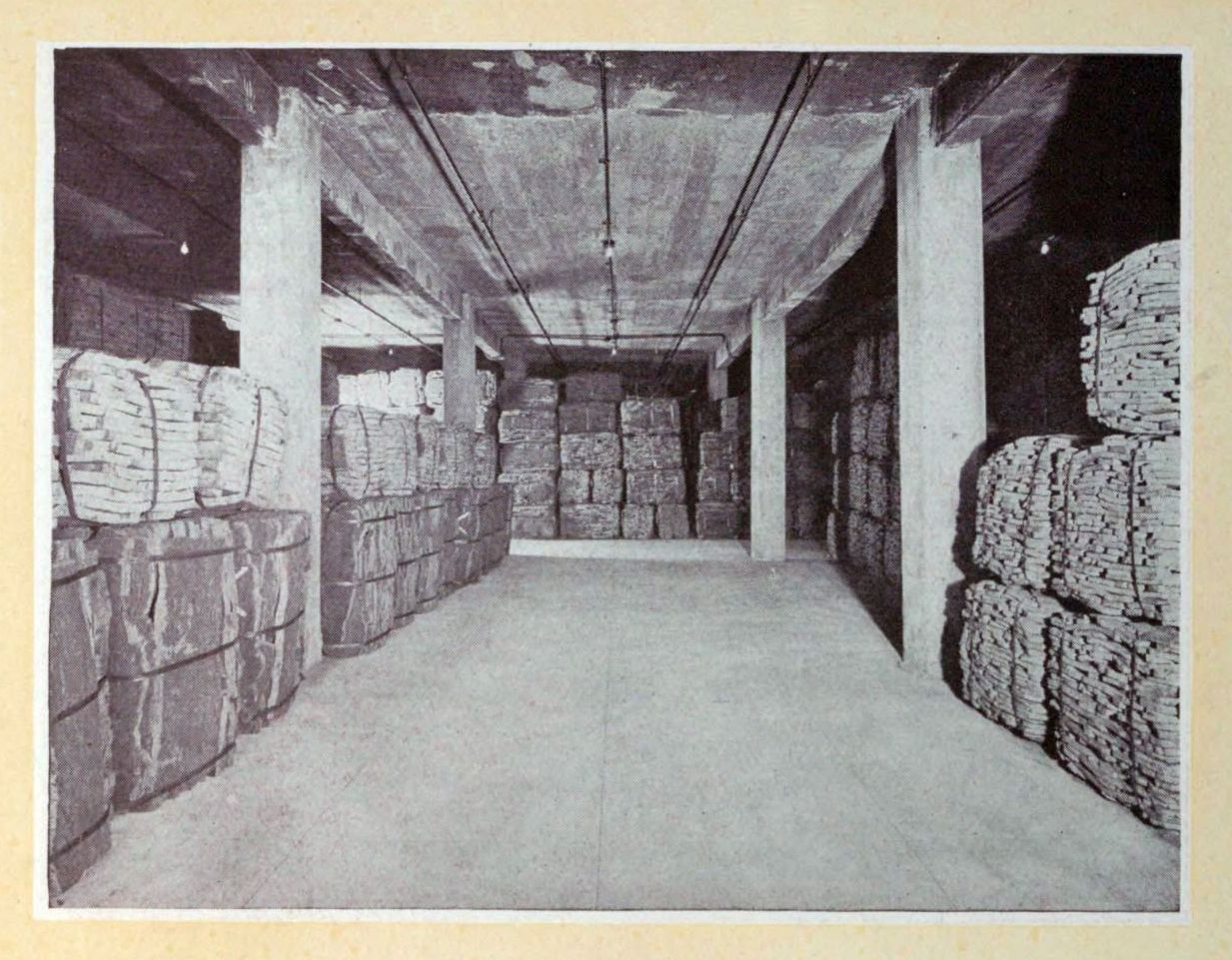

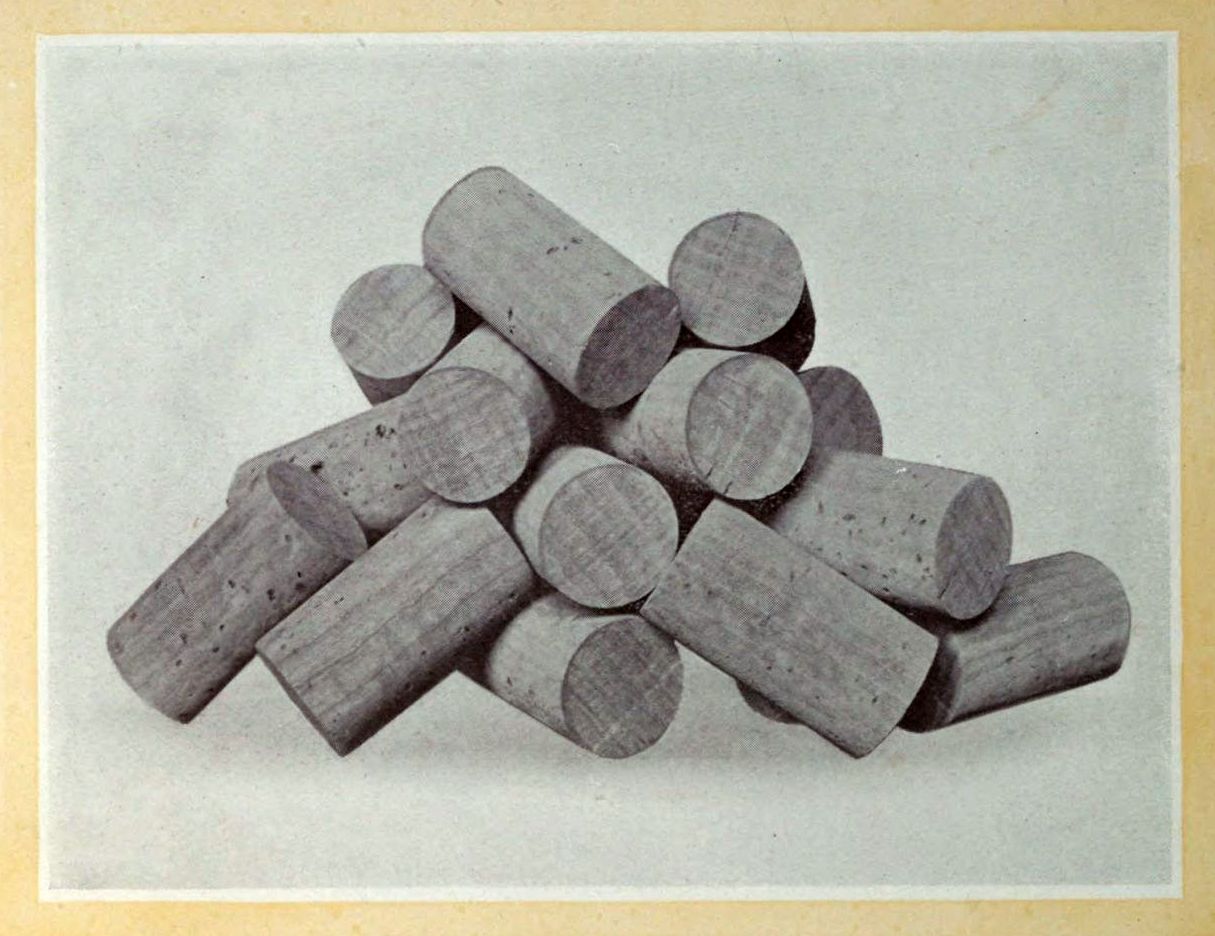

Among them corks rank first in importance; hence the greater part of the floor space of this factory, the largest of its kind in the world, is given over to their production.

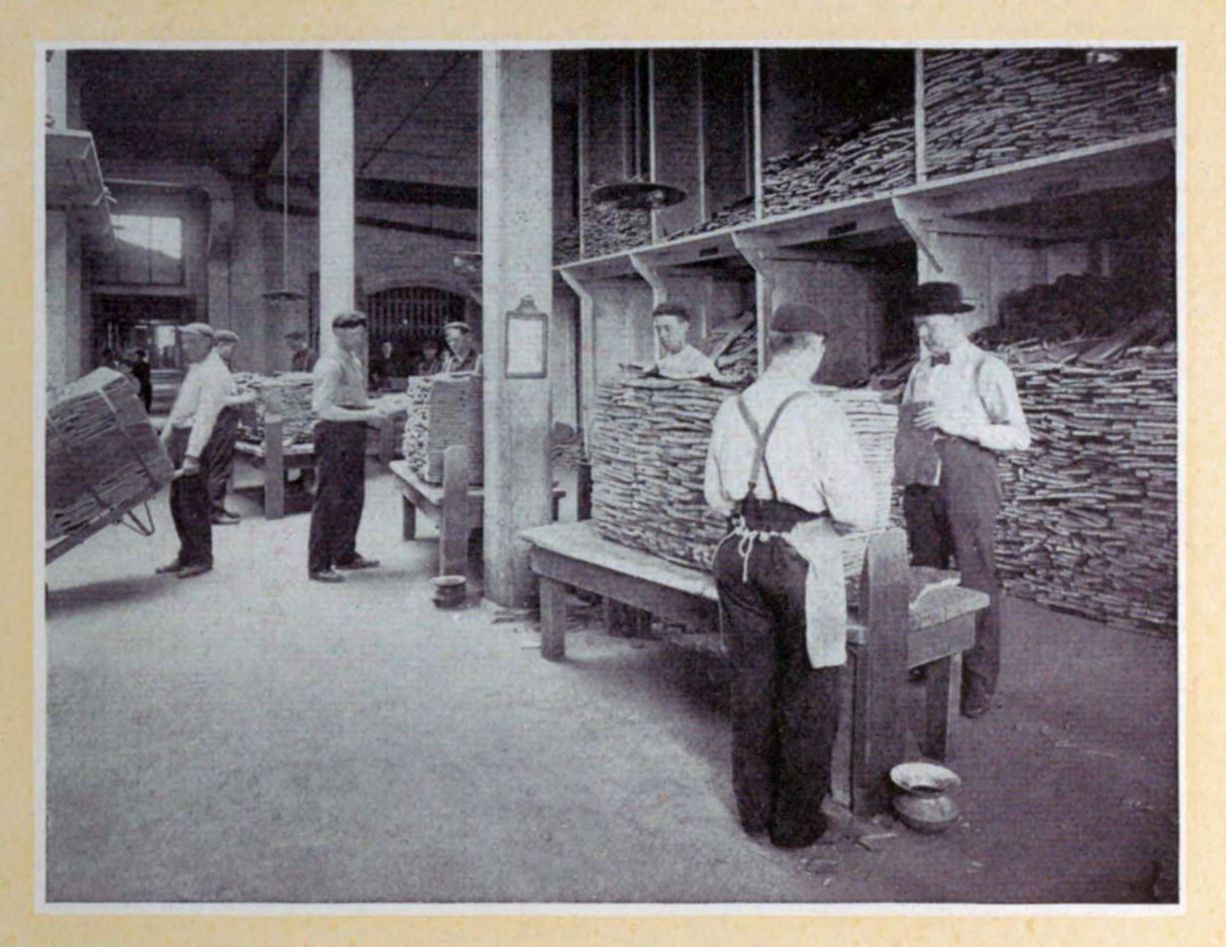

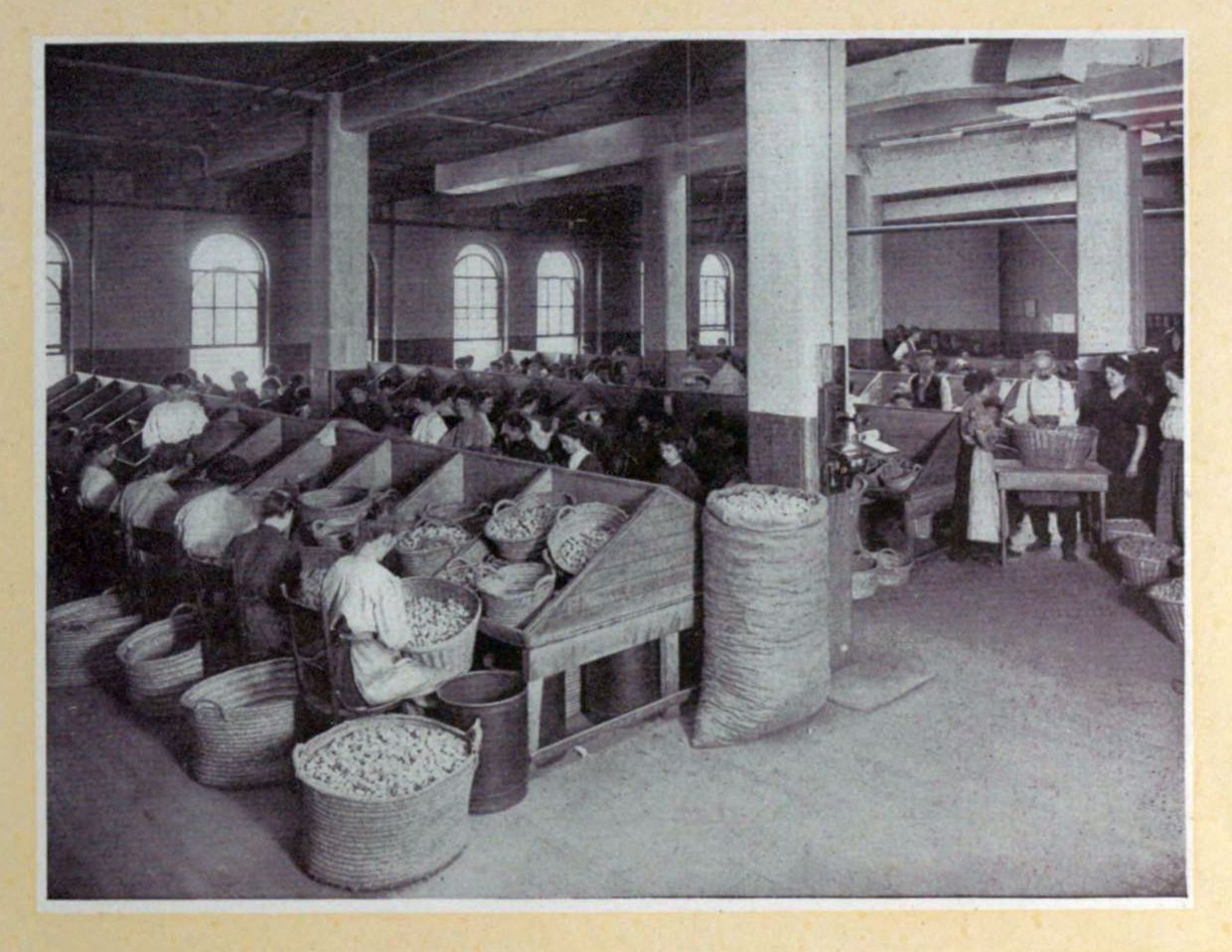

For whatever purpose it is to be used, all bark removed from the immense storage rooms is taken first to the sorting department, where, under skilled eyes, the twenty-five or more foreign grades are resorted into approximately one[Pg 25] hundred and fifty different classes, according to quality and thickness.

The speed and skill with which this work is done is astounding. So slight is the difference between some of the grades that to the inexperienced eye none can be seen whatever, and yet success hinges on the care and skill exercised in this and the other sortings that follow.

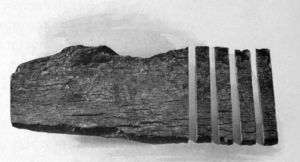

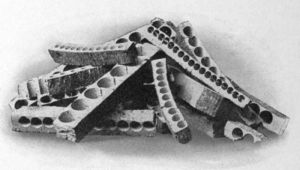

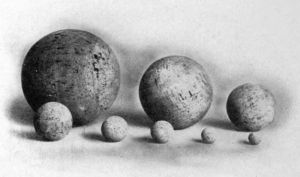

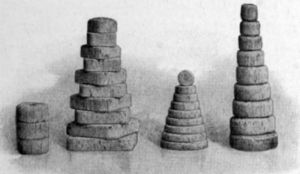

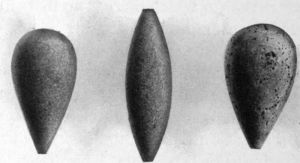

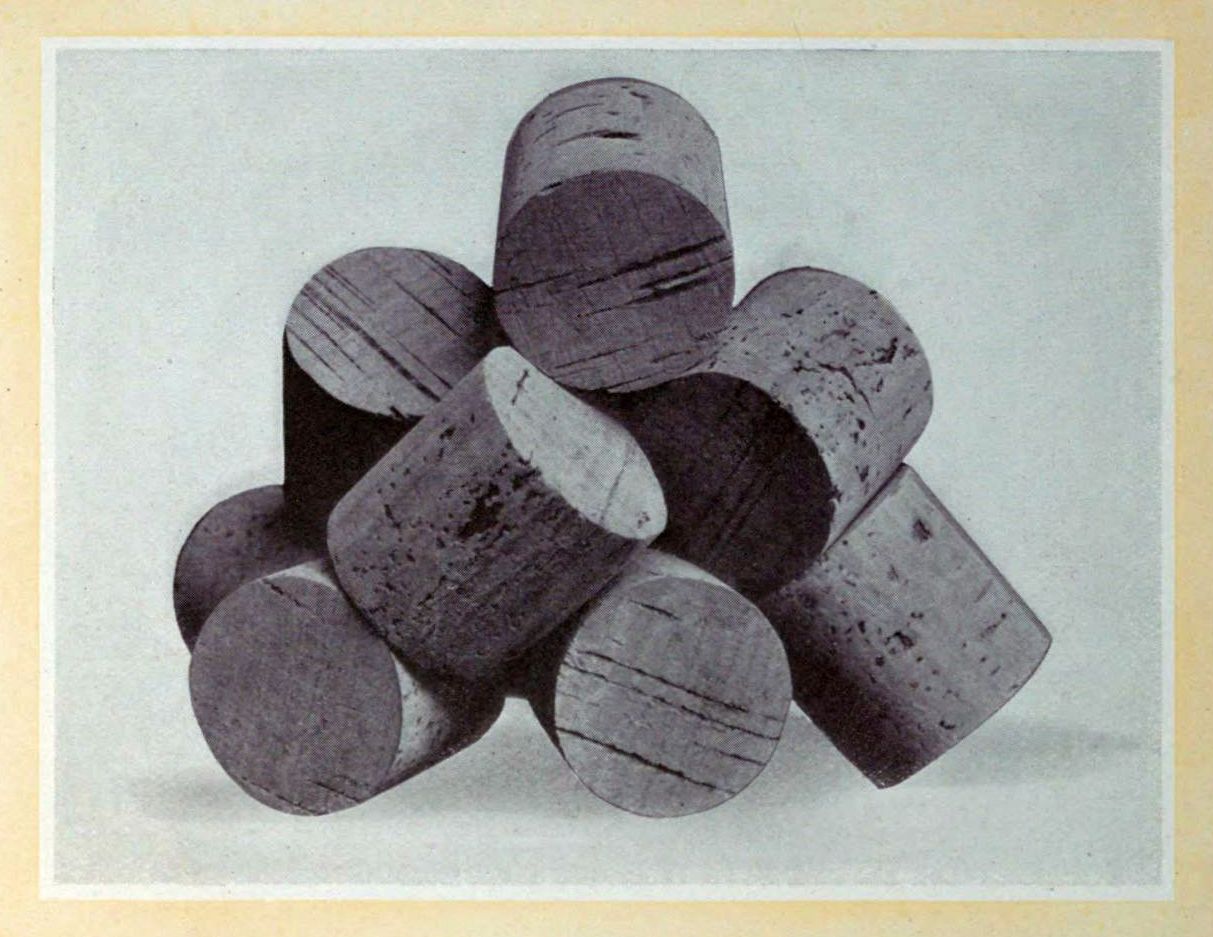

Corks punched from Strips

In manufacturing corks it must be understood in the first place that the thickness of a given piece of bark[Pg 26] determines the maximum diameter of the stopper which can be made from it, as the cutting is done across and not with the grain.

Leaving the sorting room the corkwood is softened by placing it in a warm vapor bath. This process increases its flexibility greatly, its bulk slightly, and prepares it to undergo the various mechanical operations which follow in rapid succession.

The keen edge of the slicer first confronts the sheets of bark, and it is at this point that the first mechanical obstacle in cork manufacture has to be overcome,[Pg 27] for the soft, light, elastic material is, withal, very difficult to cut, as may be determined by simple personal experiment.

But before the onslaught of a circular steel knife, revolving hundreds of revolutions every minute and kept at razor-like sharpness, even this difficulty disappears, and the sheets are readily cut into strips whose width is determined by the length of the cork desired.

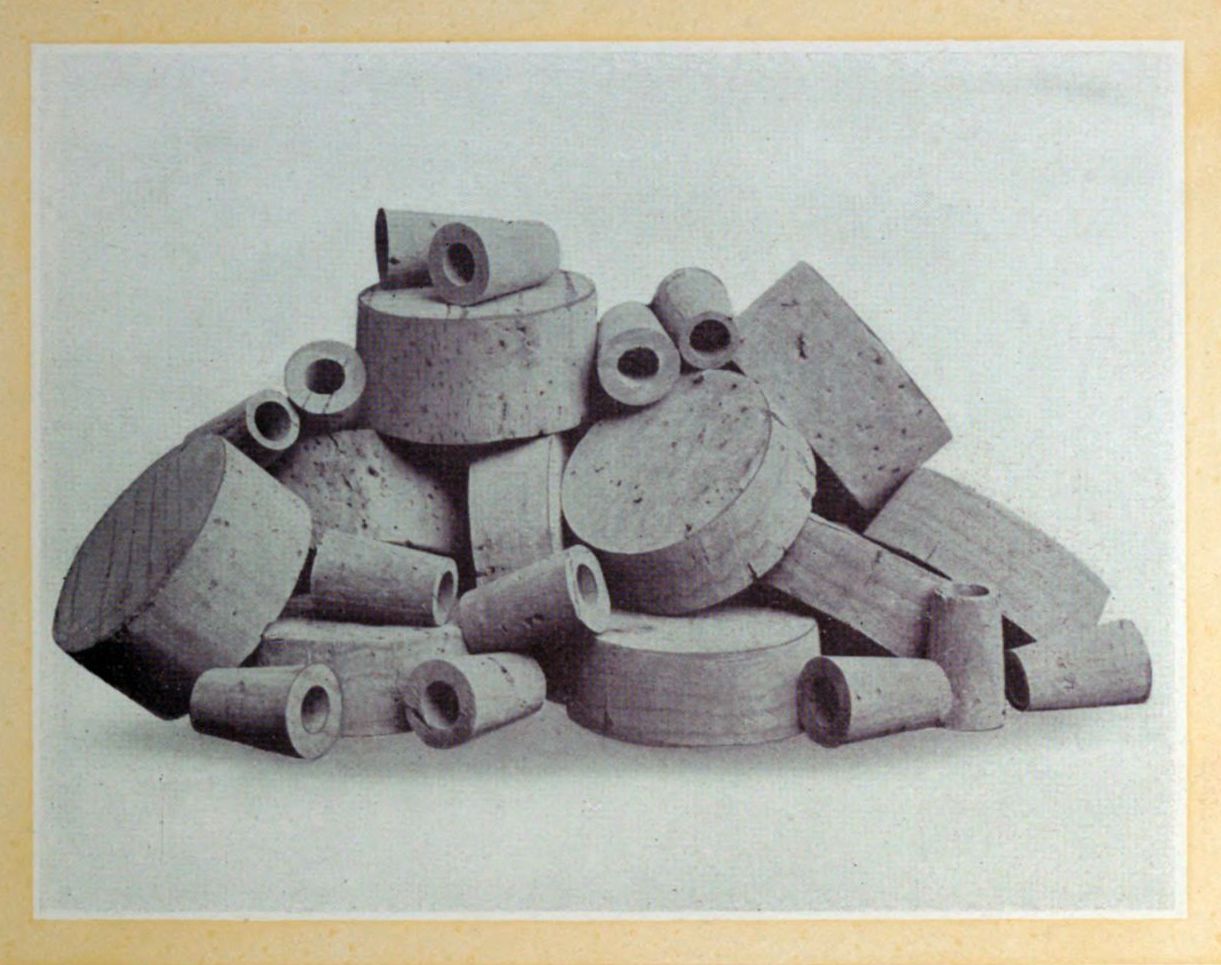

From the slicer the strips pass to the blocking machines, where, by means of a rapidly rotating tubular punch, cylindrical pieces are bored out and released with[Pg 28] almost incredible speed.

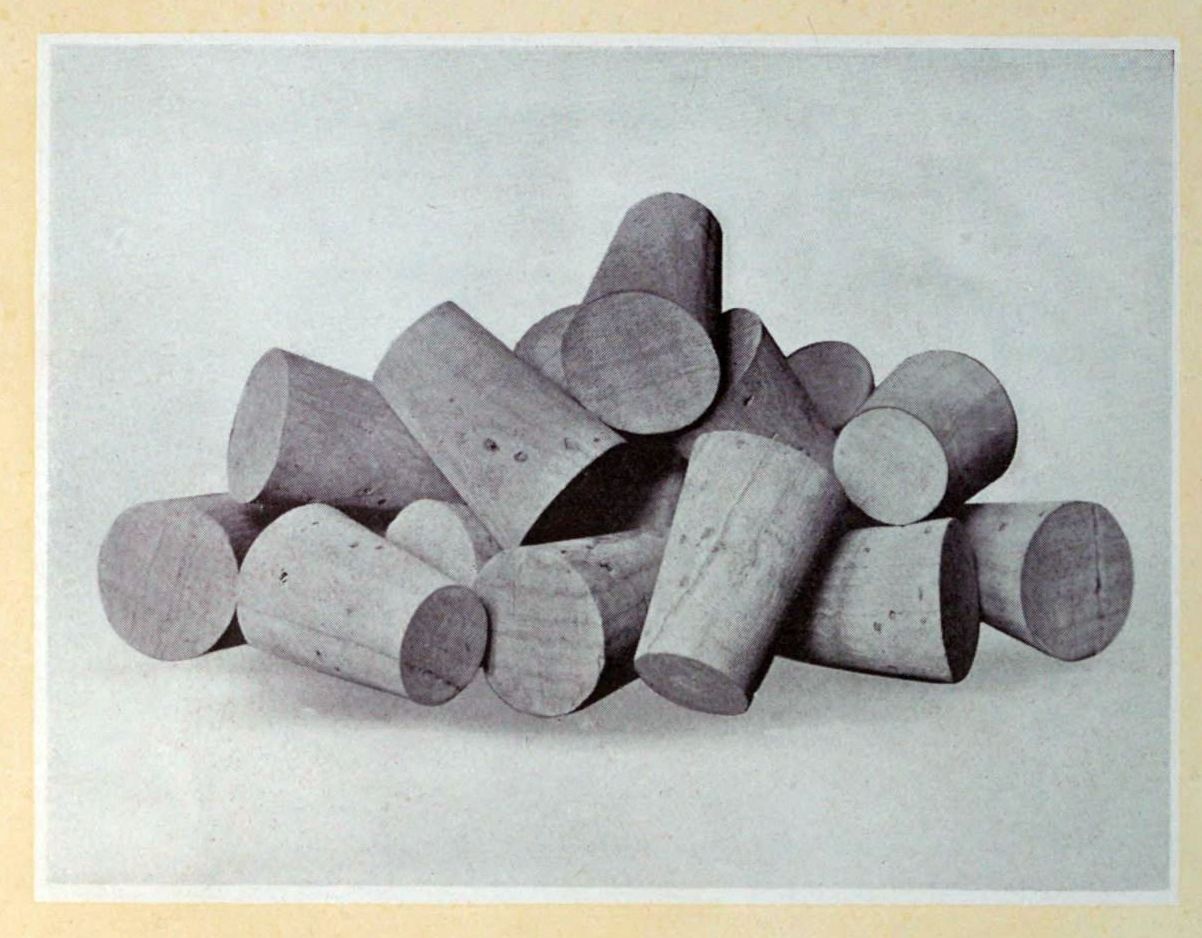

The operative, of course, must use care to avoid defective spots in the bark, and also to cut the corks out as closely together as possible so as to reduce waste to a minimum. The stoppers which come from these machines are round with parallel sides. If tapered corks are desired, larger at the upper end than at the lower, the cylindrical or “straight” pieces must be passed through another machine, which handles them deftly, holding them against the edge of another circular knife.

Seemingly motionless, the only outward indication of the speed with[Pg 29] which the keen blade is revolving is the delicate shaving which curls upward for an instant, only to be drawn away through pipes by powerful air-suction to the mill building a hundred yards distant, where all such waste is ground up, to be disposed of in the form of various by-products.

Both “straights” and “tapers” next journey to the washing rooms. There dumped in great vats, thousands at a time, they are carefully washed and then dried by being whirled about dizzily in great revolving cylinders of wire net located in heated chambers.

[Pg 30]

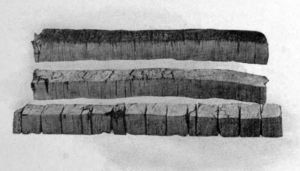

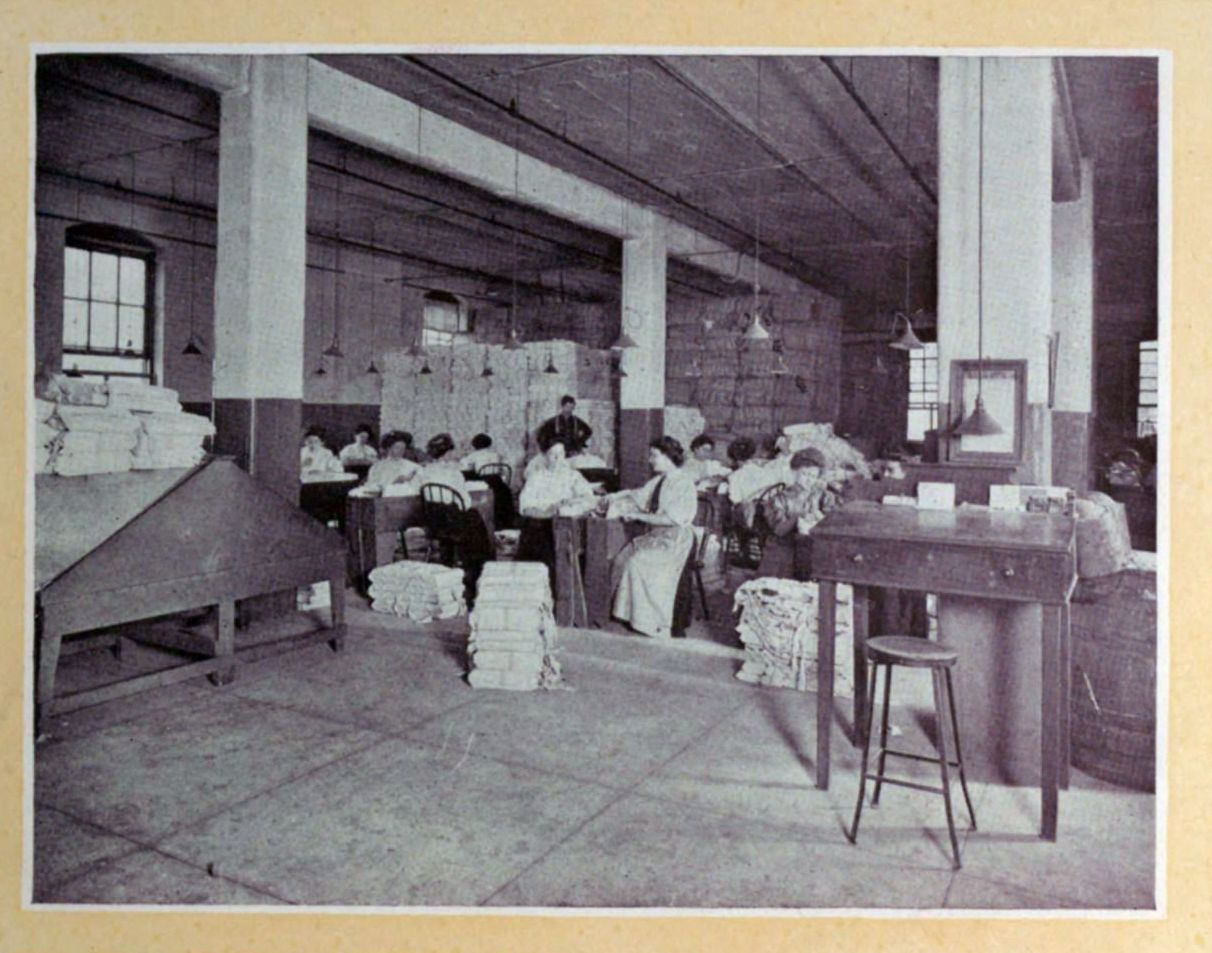

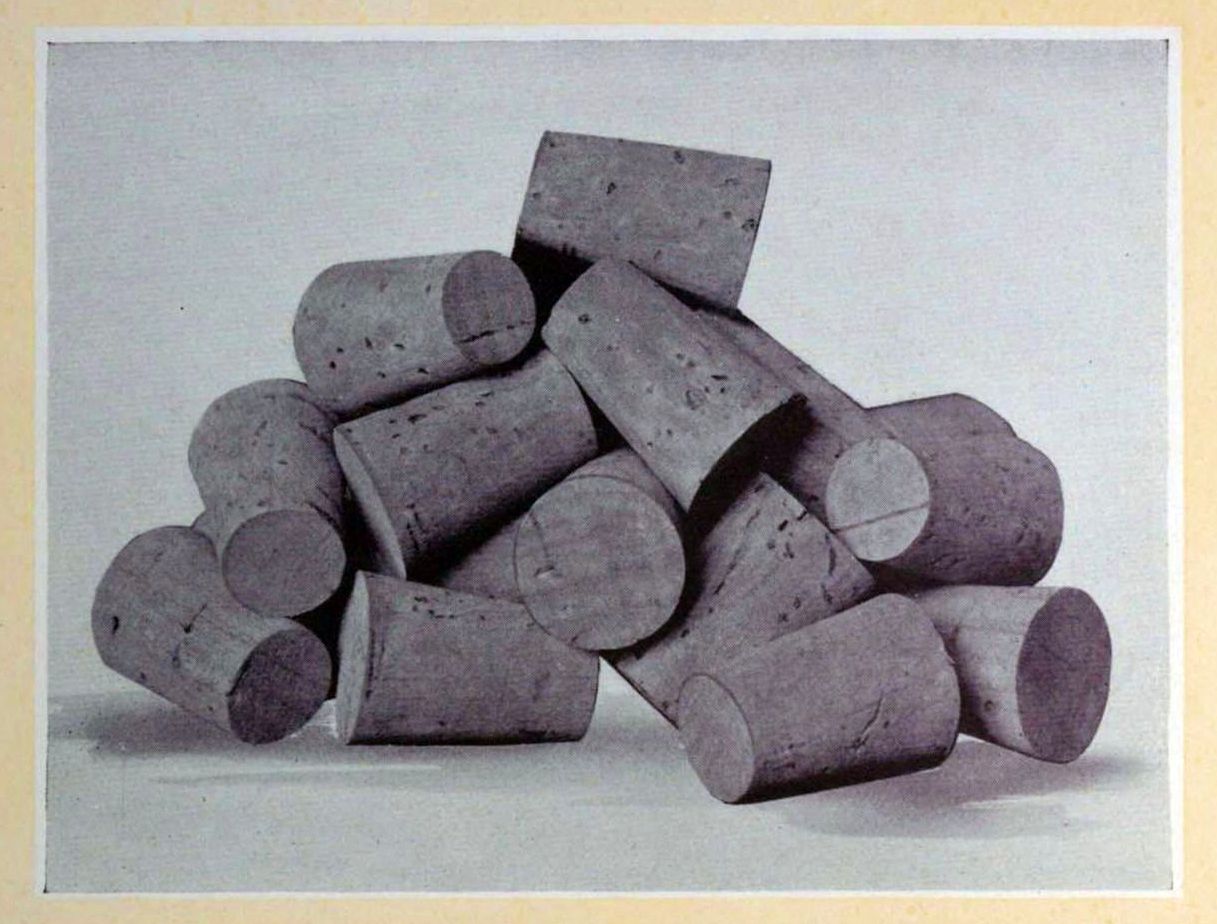

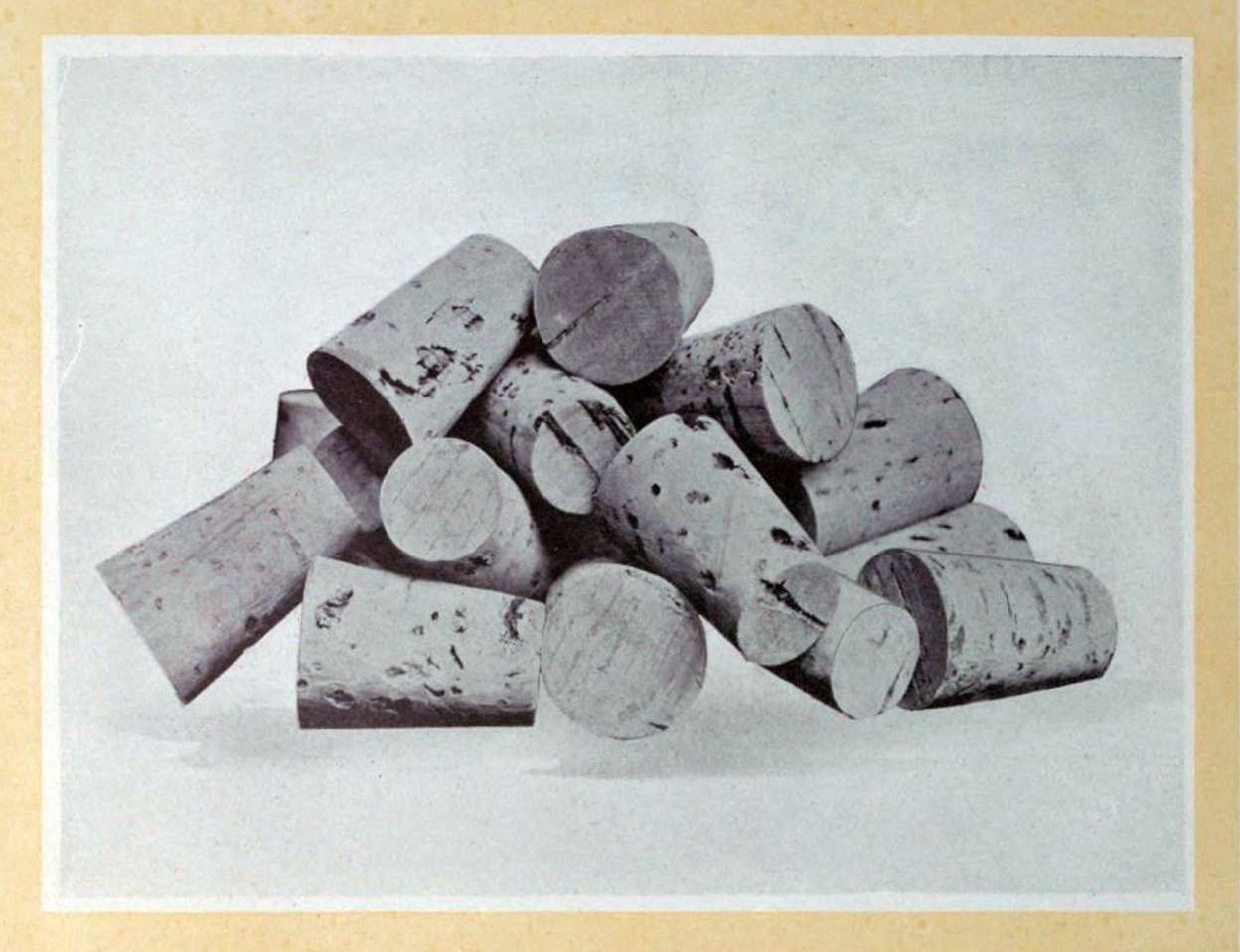

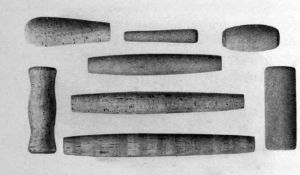

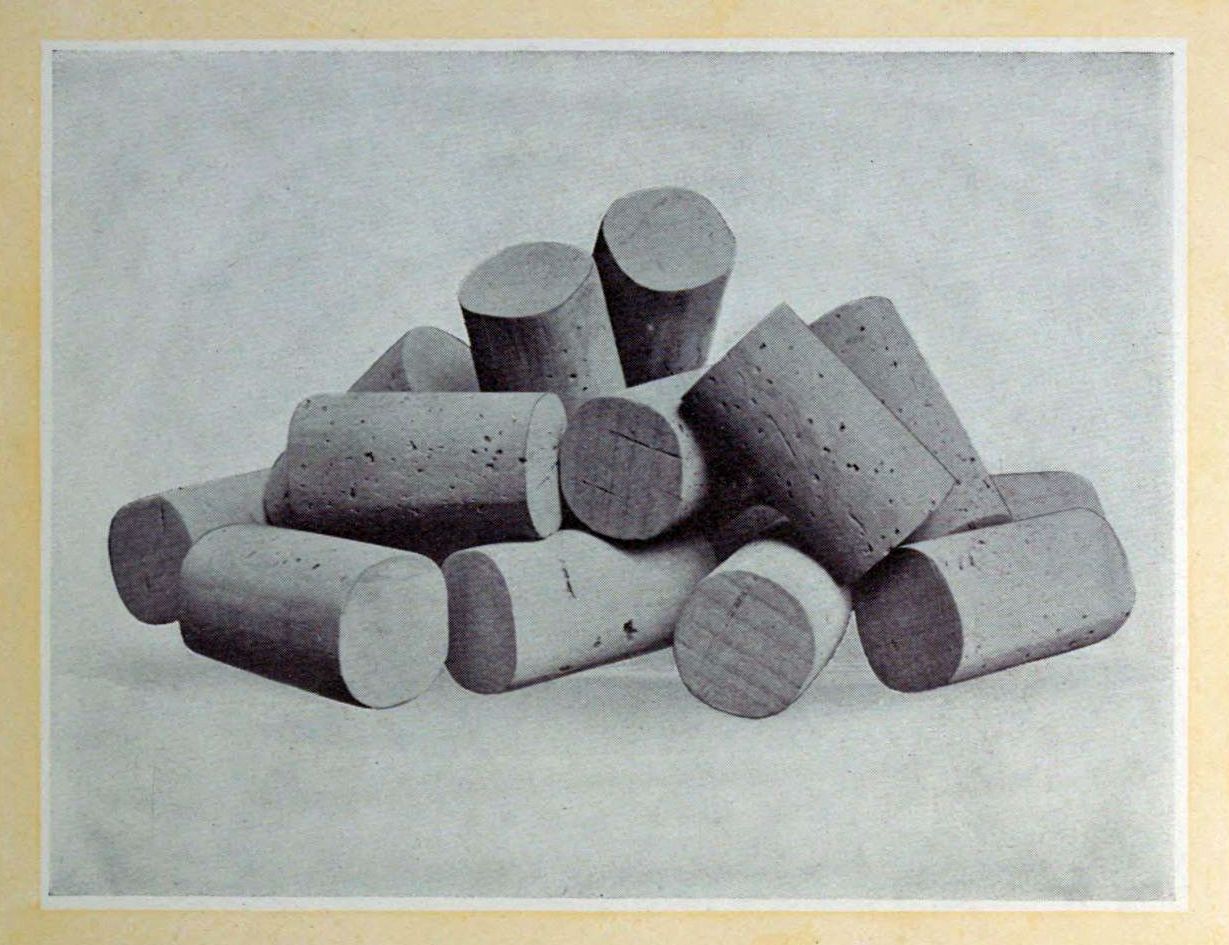

Not all of the bark, however, that is destined to be turned into corks follows the course that has just been described; for certain varieties a different process of manufacture, approximating in many respects the original Spanish method, is found more practicable.

The crude bark, after being sorted, is cut into strips on the slicing machines, the width as before depending on the length of the stopper to be made. To remove the rest of the hard back, or outer crust, much of which still remains despite the scraping before shipment to America, the[Pg 31] pieces are then passed beneath a revolving knife which shaves off the rough, uneven portion.

Free now from objectionable matter, the strips are cut into small rectangular blocks of the dimensions of the cork desired. In this process, just as in blocking, care must be taken to avoid defects in the bark, and at the same time to prevent waste. Passing to another department the rectangular pieces are rounded into proper shape.

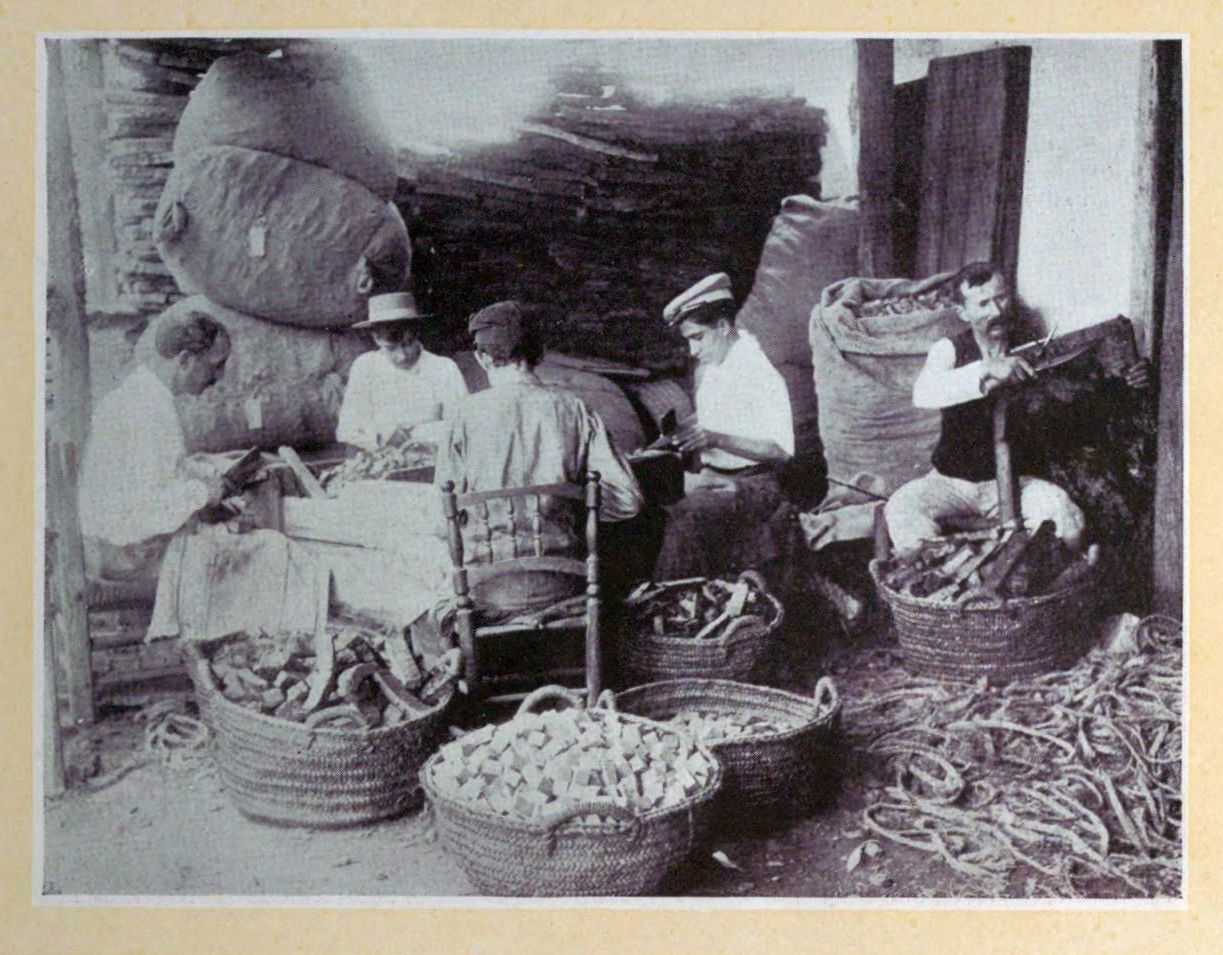

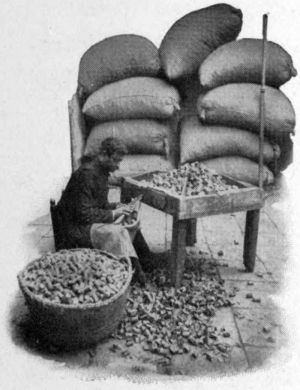

In Spain, before the days of large cork factories employing labor saving machinery, and even to a great extent at the[Pg 32] present time, all of these operations are carried out by hand.

Whole families participate, slicing the bark into strips, then into squares, and finally cutting the corks from the square blocks slowly and laboriously. This hand method of manufacture is gradually disappearing as more and more machinery comes into general use.

What are known as hand cut corks are stoppers which are not exactly round, but of a shape which might be appropriately described as a “square circle.” In the judgment of some, they are better suited for certain purposes than straights or tapers.

[Pg 33]

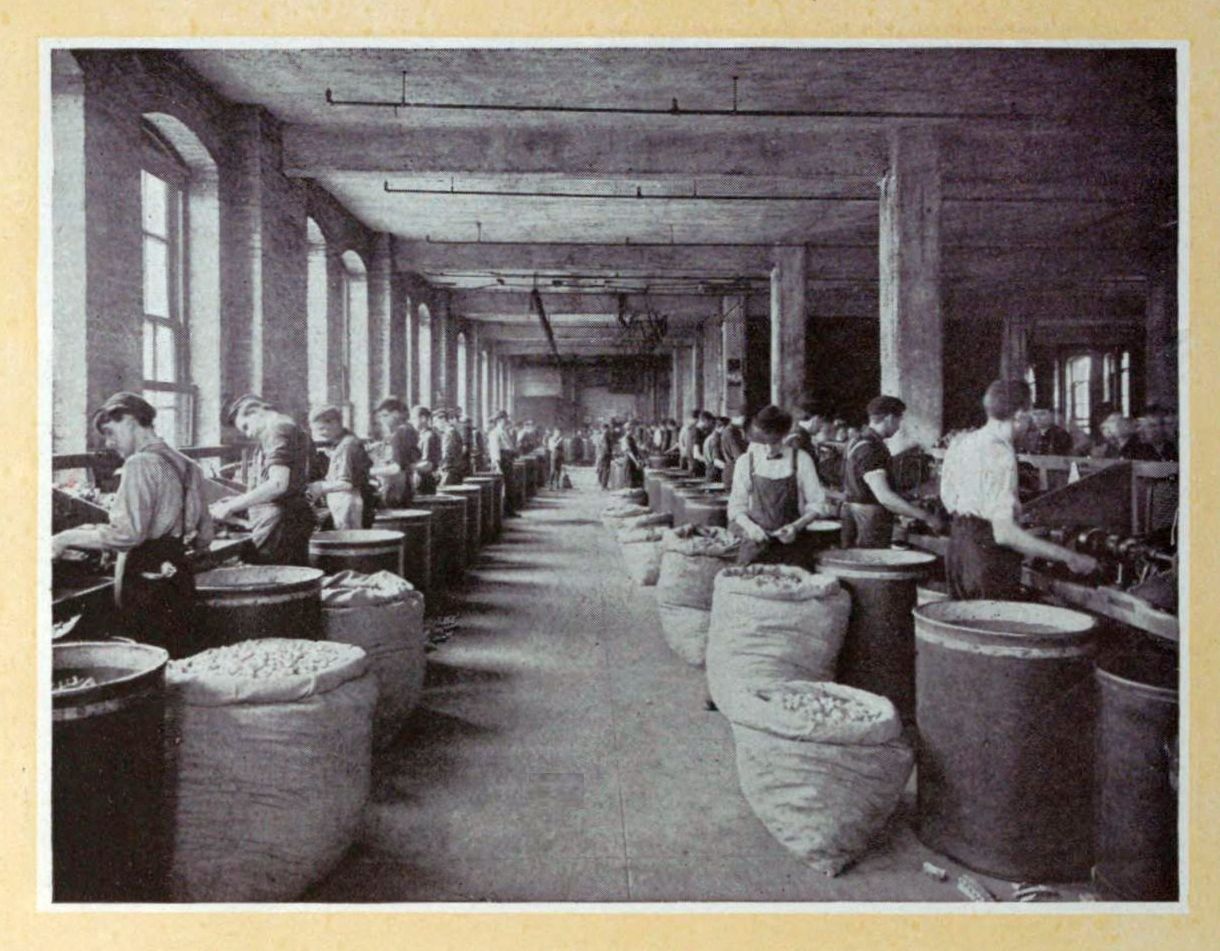

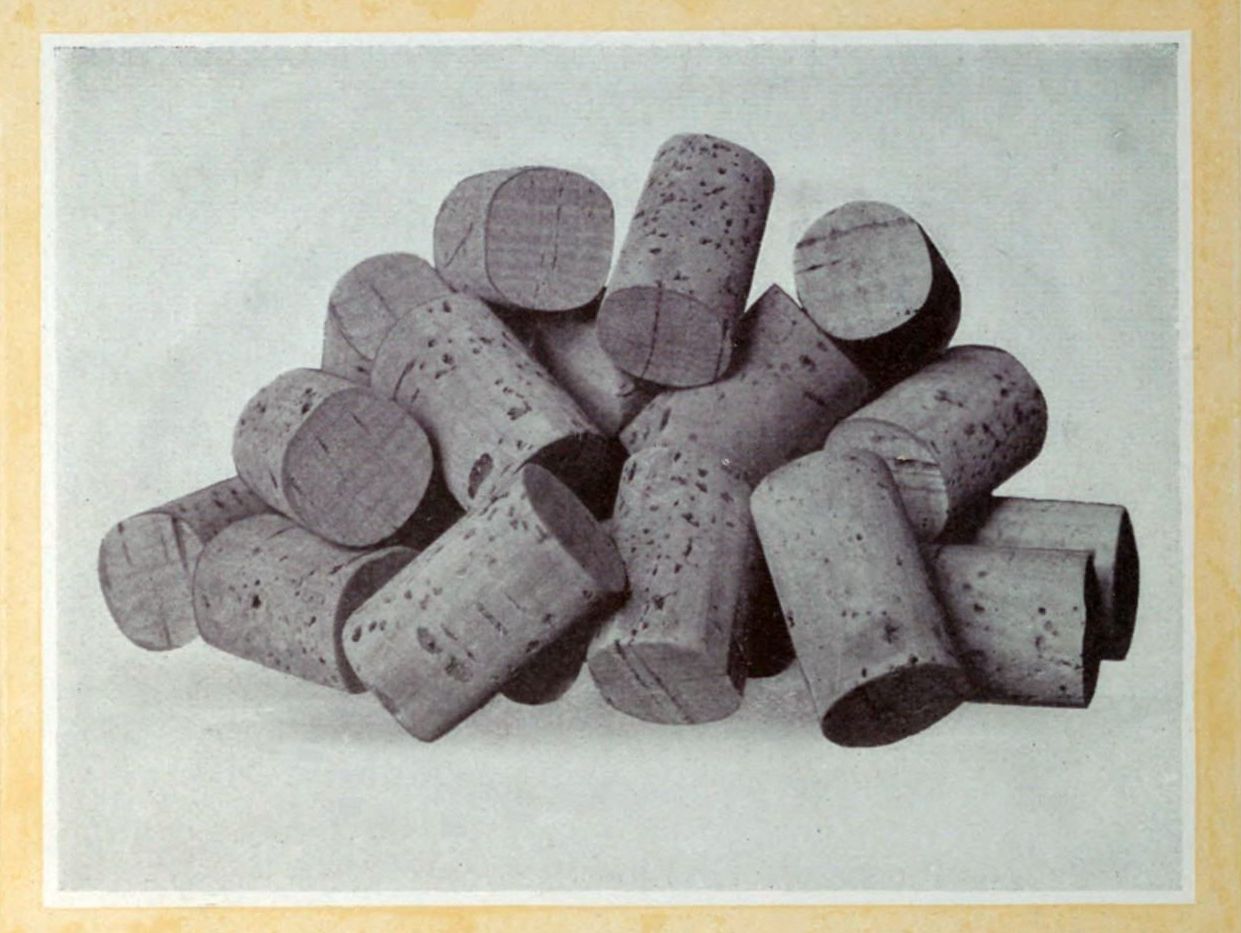

From the driers all corks are taken to the sorting rooms, where they are subjected to the last of the actual manufacturing processes, and, from many standpoints, the most interesting of all. Here, again, the importance of proper grading is paramount, and when one considers that almost five million corks pour into this department every working day, the magnitude of the task can be partly grasped.

When the further fact is known that this enormous output is to be sorted into about twenty regular besides numerous special grades, one can still further appreciate what the problem involves. The[Pg 34] work itself calls for such a peculiar combination of faculties that only one out of every five operatives who are given preliminary training in this department is found satisfactory; but so highly skilled do the regular workers become that the sorting of thirty-five thousand corks may be considered an average day’s labor.

Experts exercise careful supervision and actually test each lot of corks as they come from the operatives in order that uniform standards may be maintained from day to day and month to month.

When past the keen eye of the tester, the cork, after its long journey through the factory, passes either direct to the packing department or to the warehouses. This last point involves a problem which is often very puzzling and difficult of solution. Thousands of dollars’ worth of corks are placed in the warehouses every year to[Pg 35] remain there indefinitely.

An order for a quantity of corks of a certain size and quality also involves, of necessity, the manufacture of a great many corks of other grades. The reason for this is, of course, found in the fact that the raw material, no matter how carefully sorted at the outset, will not produce a finished product of uniform quality. Thus frequently it becomes necessary to work over a given lot of corks for which there is no demand into a smaller size for which orders are pouring in.

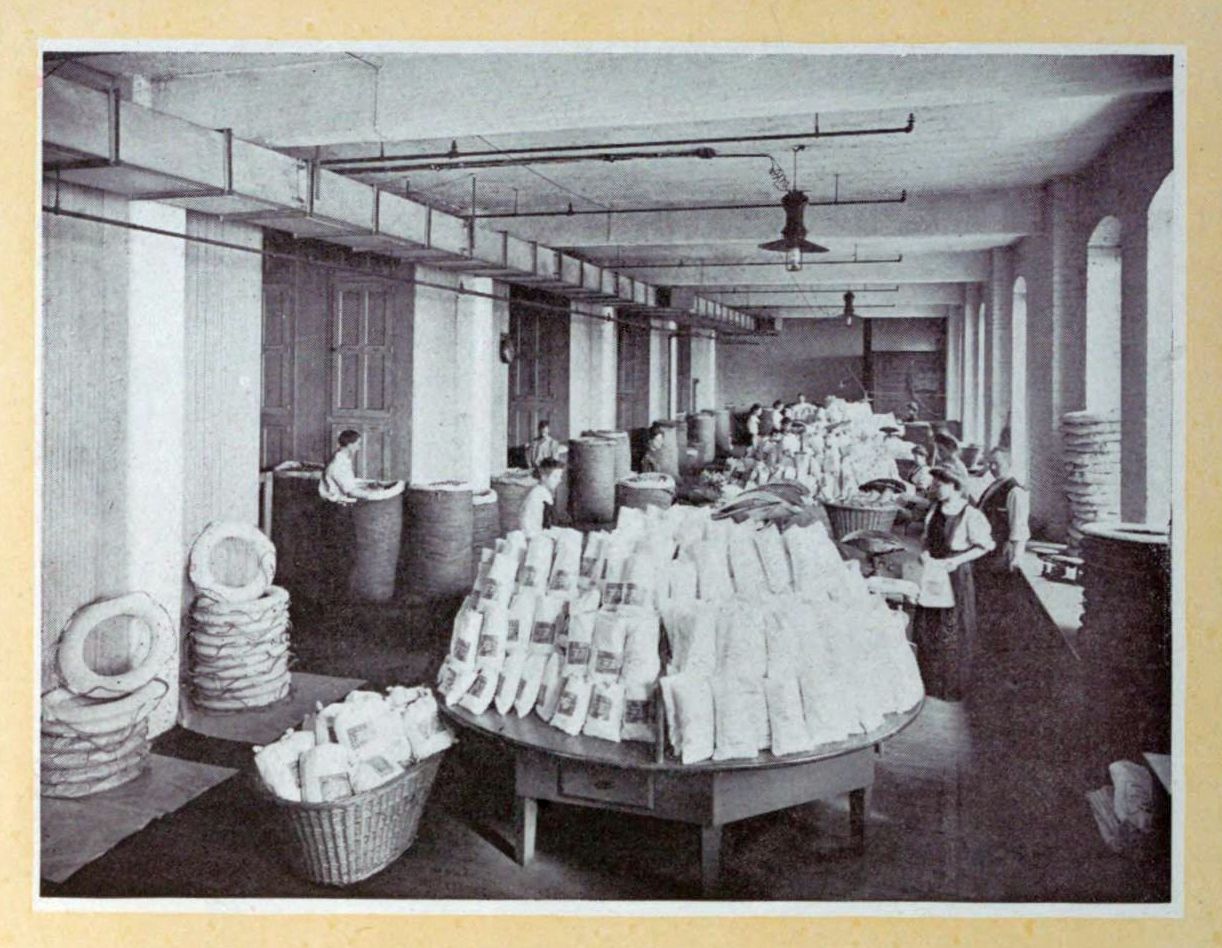

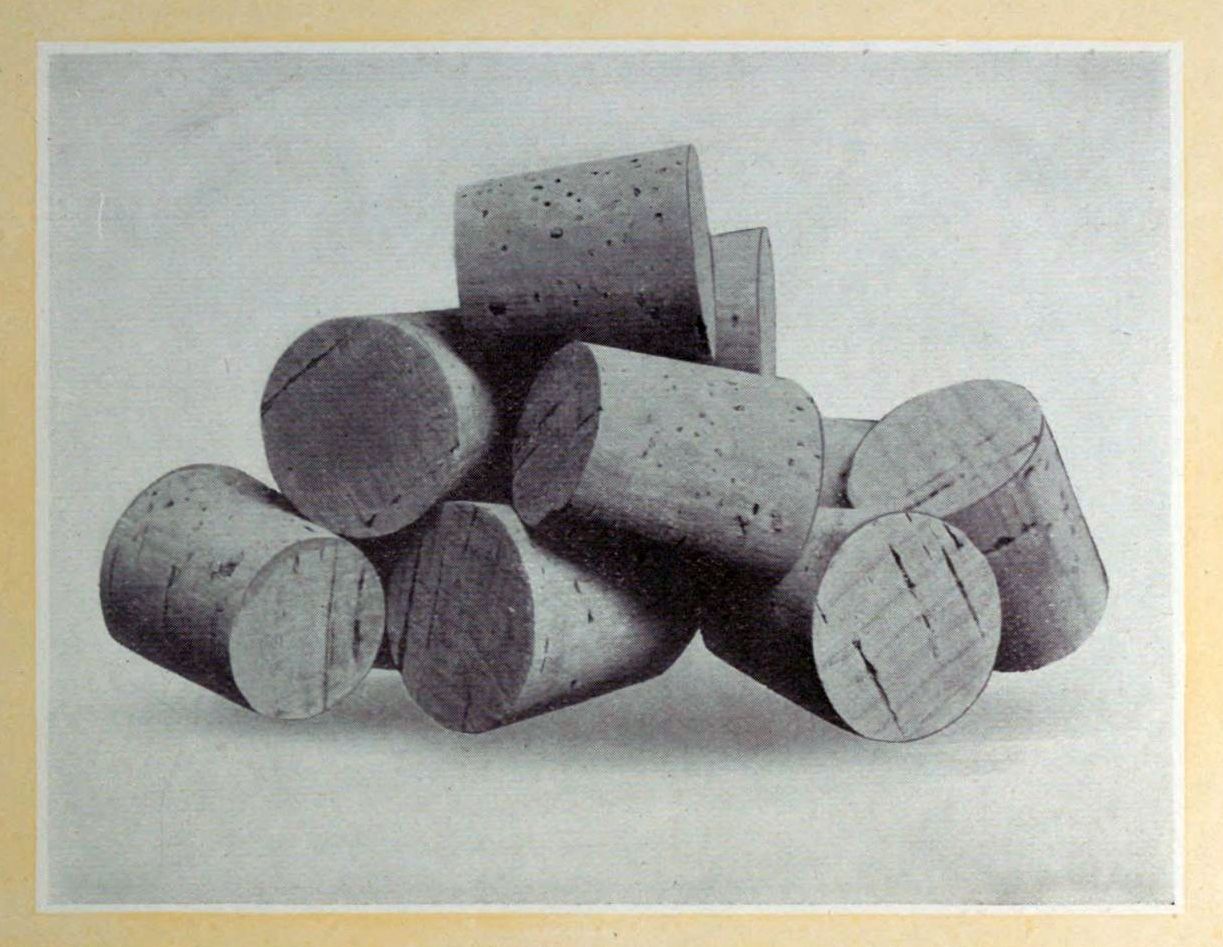

Into the packing department streams a bewildering array of corks of every conceivable shape, grade, and size. The tapers appear in a dozen qualities, at the head of which stand the peerless “Circle A” and “Circle B,” prescription corks found in every first-class pharmacy in the land. The straights have been separated into various[Pg 36] classes, running from the fine champagne corks down to the common soda water corks.

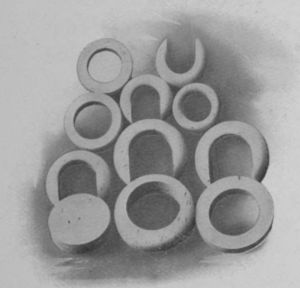

Besides, there are keg corks, hand cut corks, mustard and jar corks of large diameter, shell corks, perforated through the center, and glued corks made up of several layers, all of which must be put up in packages of suitable size, ready to be delivered to the shipping department for transportation to the consumer.

A host of other useful articles also find their way from the many manufacturing departments to the shipping rooms. Of insoles thousands of pairs are produced[Pg 37] annually.

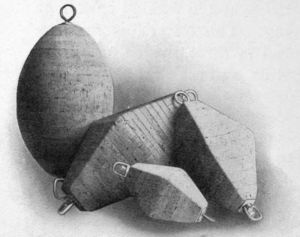

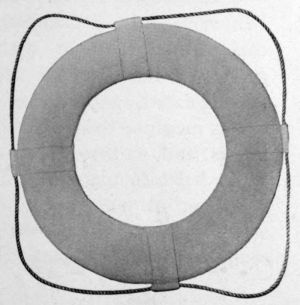

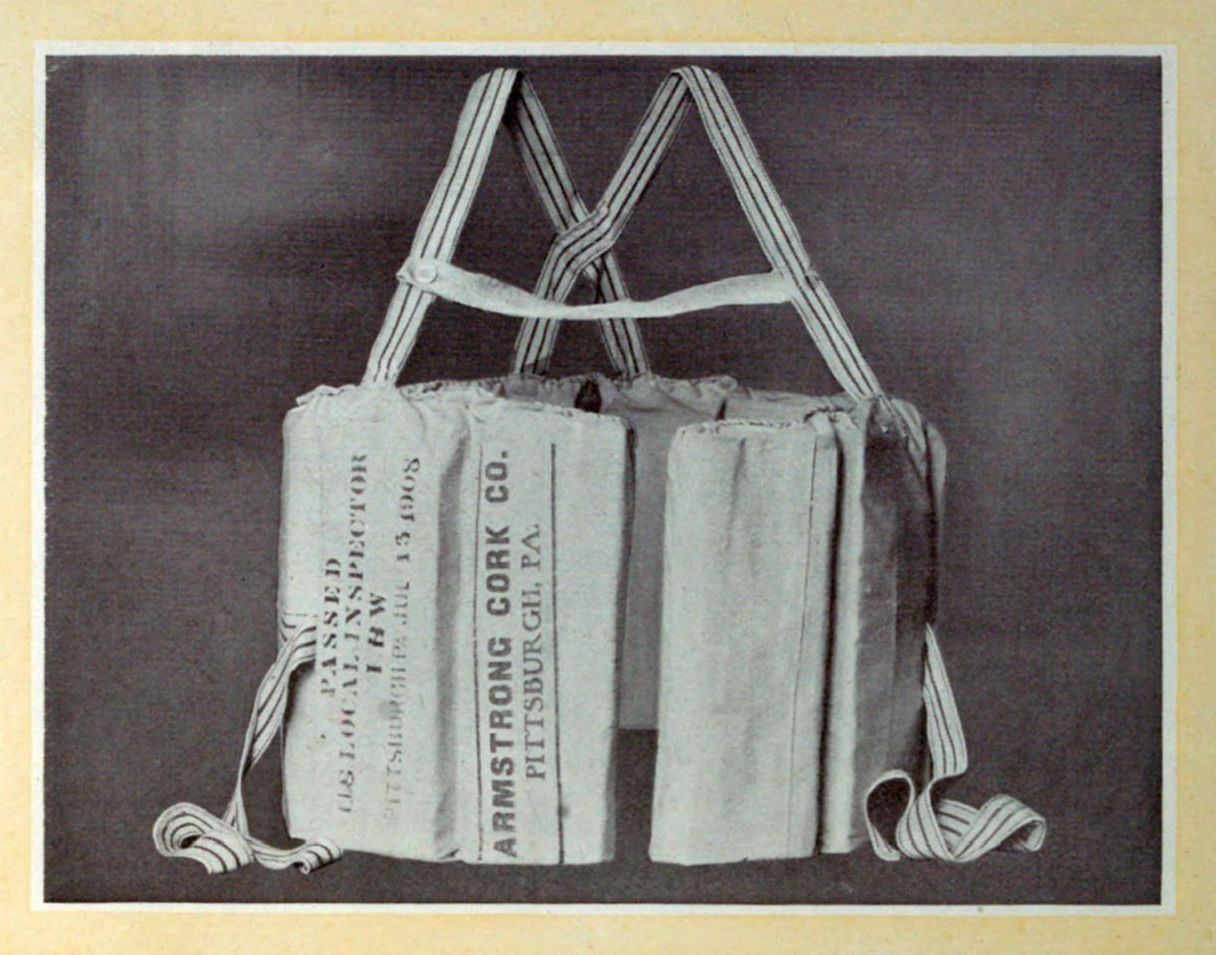

Discs and washers by the million are punched out for use in metal caps for bottles and jars, and as gaskets in lubricator cups. Life-preservers, ring buoys, yacht fenders, mooring and anchoring buoys are the specialties of one department, while another pays particular attention to the manufacture of seine and gill corks, and bobbers for fishing lines.

So varied, in fact, are the forms which cork assumes that the complete[Pg 38] cataloguing of the functions which it fills in the world to-day would be well-nigh impossible.

For instance, cork shapes may be found in animal heads on rugs and fur garments, and, covered with suitable material, are used as buttons on fur coats. Cork balls play their part in exhibiting cutlery and in various games; the automobilist finds cork carburetor floats indispensable; churn lids are made tight with cork gaskets; pen holders have cork tips; hats are lined with thin sheets of cork; friction clutches of cork are steadily growing in favor; the optician employs small cork strips in connection with eyeglasses; the plasterer uses cork floats; while the glass manufacturer knows no better medium for polishing his wares than cork wheels. The finest pieces of bark are made into cork paper, so thin that five hundred sheets measure but one inch in thickness. Sorted into[Pg 39] several different grades, this beautiful, velvety material is practically all used in making cigarette tips.

Fishing rod, whip, bicycle, trowel, and pyrographic instrument handles of cork are, of course, familiar to every one.

But the manufacture of corks and of all these other articles involves waste, and waste to an extent little dreamed of. In producing corks, for instance, fully sixty-five per cent of the raw material which started out on its journey through the factory may be found later in the form of scrap at the blocking and tapering machines; but even in this mutilated state the bark is still valuable, and after proper treatment in the[Pg 40] Pittsburgh plant, or one of the other factories of the Company, appears in the form of numerous by-products of great value and importance.

As a matter of fact, nothing is wasted; even the smallest particles are utilized. Large quantities of scrap are ground up, sifted, and made into composition cork with the aid of suitable binders.

From “Suberit,” as the finest variety of this material is termed—light, close grained, and tough, without the large pores of the natural cork—table mats to be placed under hot dishes, pin cushions, fishing line floats, polishing wheels, and instrument handles are[Pg 41] manufactured; while from “Acme,” a somewhat coarser grade, are made insoles, bath mats, washers, gaskets, and entomological cork—thin sheets for mounting insects.

Part of the waste is reduced to the form of cork shavings and used to stuff mattresses and boat cushions, for packing eggs and other fragile articles, and in making cork floor tiling.

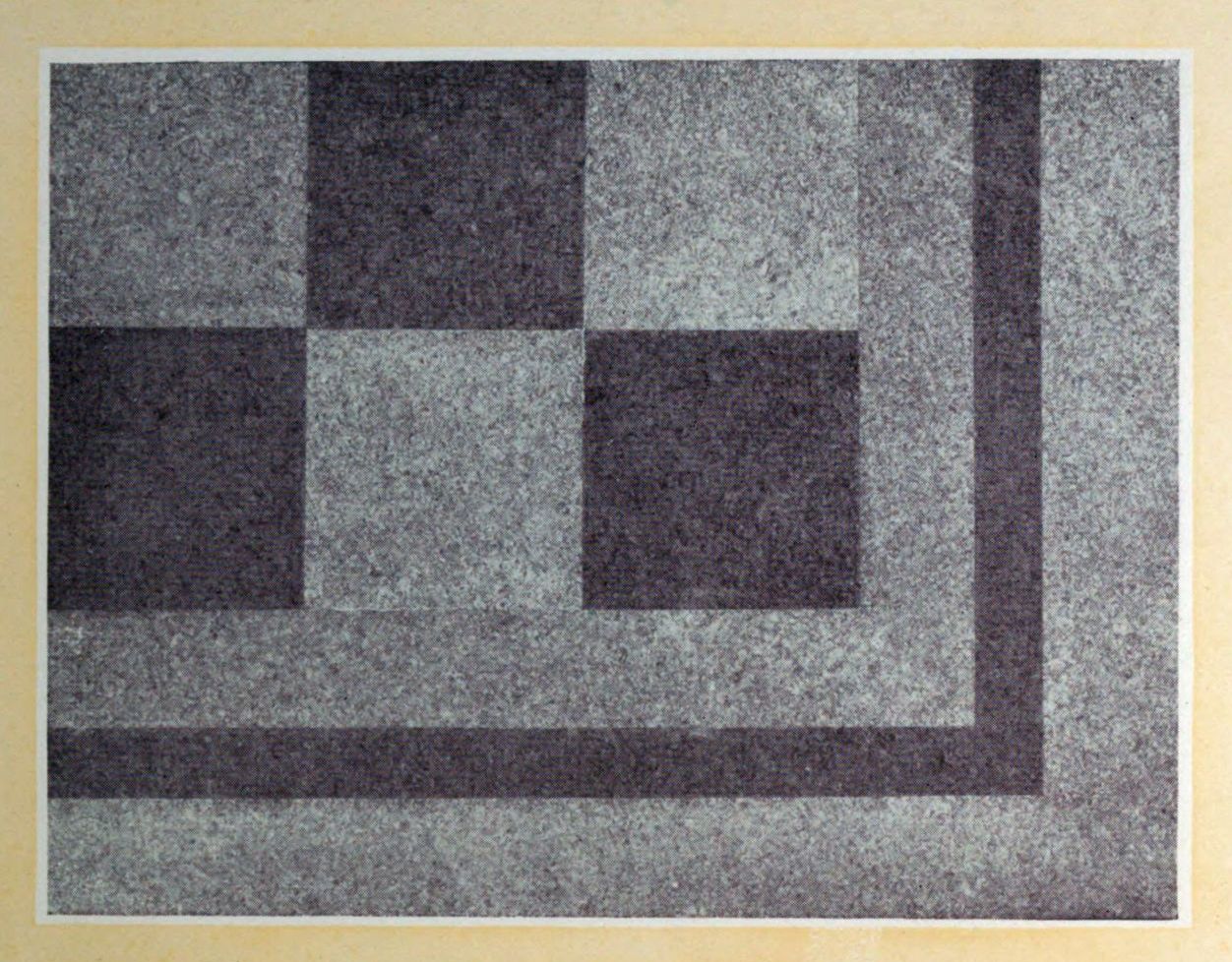

This material is manufactured in three shades of brown, and its warmth of tone and delicately mottled and veined appearance give it a distinctive charm peculiarly its own. Smooth and soft as velvet to the touch, cork tiling is nevertheless firm and[Pg 42] resilient and able to stand years of hard service.

Thousands of square feet have been installed in hotels, libraries, museums, clubs, and private residences.

Cork flour is another by-product, and is manufactured from the waste bark by much the same method as that employed in grinding wheat. This beautiful light brown dust is one of the chief constituents of high grade linoleum. In the Company’s plant at Lancaster, Pennsylvania, thousands of yards of this material are produced every day.

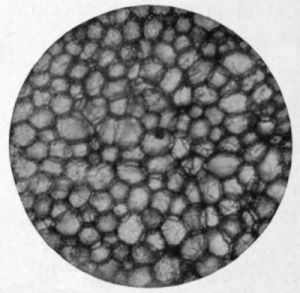

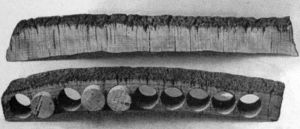

The many different grades of granulated[Pg 43] cork, made by grinding up cork waste, find a wide sphere of usefulness for packing and heat insulating purposes. In this last mentioned field, in fact, cork now ranks preeminent. Its peculiar structure, which may be seen under the microscope—myriads of sealed air cells, impervious to air and water—renders it not only a splendid nonconductor of heat, but also nonabsorbent of moisture.

For loose filling between the walls of ice boxes, water coolers, and cold storage rooms, and about the sides of freezing tanks in ice factories, hundreds of tons of[Pg 44] granulated cork are employed every year. Comparatively recently, however, an insulating material possessing permanency of form has been found desirable for many reasons.

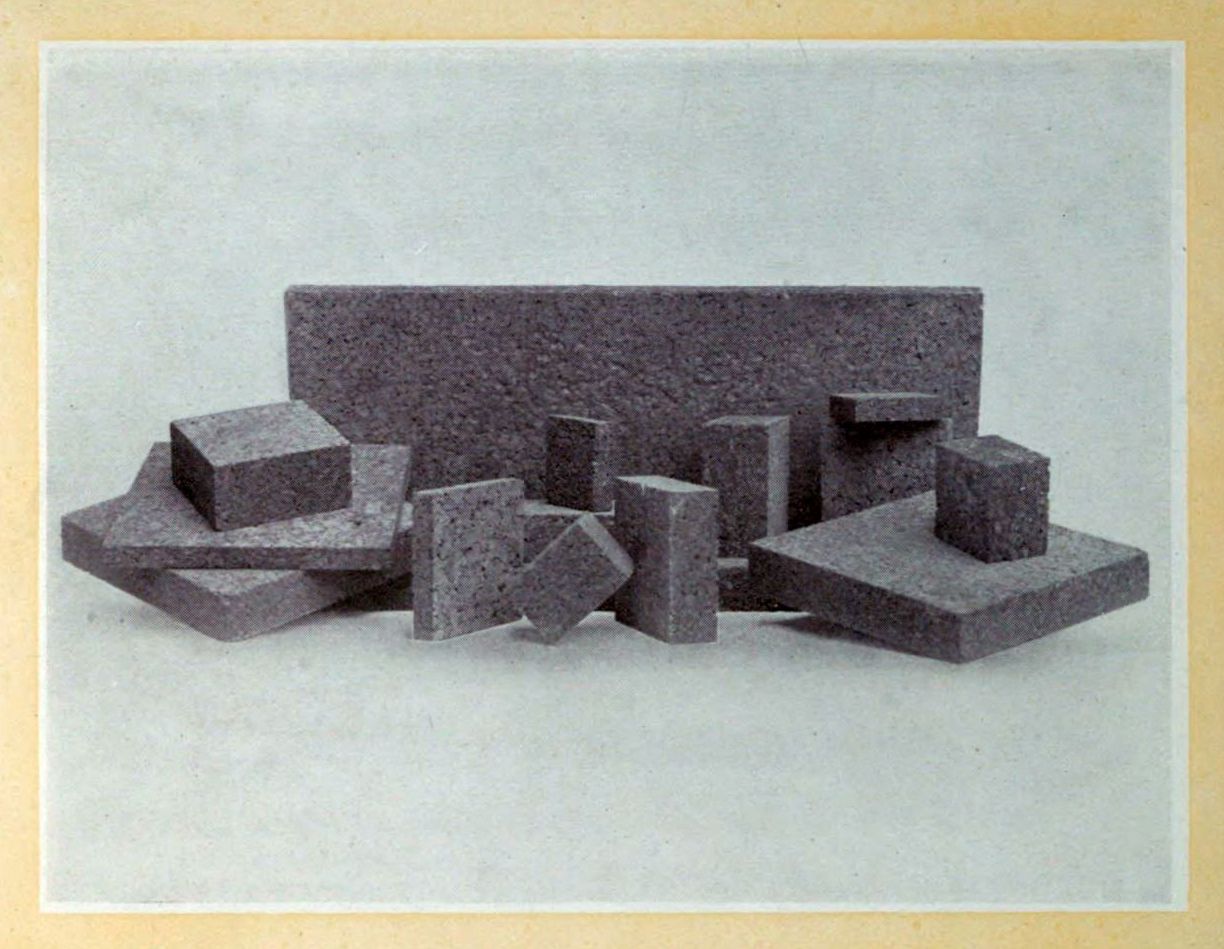

To meet this demand granulated cork is transformed into corkboard at the Company’s plants at Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, and Camden, New Jersey. Using the pure cork, either with or without an asphaltic binder, three grades of this material are made, known as Nonpareil, Impregnated, and Acme Corkboard, respectively. The sheets measure twelve by thirty-six inches, of various thicknesses, and, as they possess ample structural strength, may be nailed into place in buildings or rooms of frame construction, or put up with Portland cement against brick, stone, or concrete walls and ceilings. A plaster finish is readily applied. Owing to its freedom from progressive[Pg 45] deterioration, its constant efficiency, its slow burning and fire retarding properties, and its sanitary qualities, corkboard insulation is now recognized as the standard throughout the land, and may be found installed almost everywhere refrigeration is employed.

Hundreds of cold storage warehouses, abattoirs, fur storage vaults, breweries, ice plants, dairies, creameries, candy factories, and bakeries are insulated with it, not to mention refrigerated rooms in hotels, clubs, private residences, and aboard the ships of the United States, British, and Italian navies.

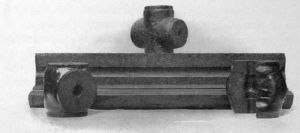

Another by-product, and the last one of importance, is cork pipe covering for insulating cold pipe lines. Made of pure granulated cork, slightly compressed and molded in sectional form to fit the many different sizes of pipe and kinds of fittings, it is a thoroughly durable covering[Pg 46] for brine and ammonia piping in refrigerating plants, and for ice water lines in office buildings, hotels, and industrial establishments.

In this rôle the cork bark, after its devious career in American factories, performs a service similar to that of its early days in Spain, when, sheathing trunk and branches, it prevented the sun’s rays and the parching winds from heating and drying up the cool, life-giving sap of its parent tree.

Rogers & Company

Chicago and New York

Minor punctuation errors have been changed without notice. All other inconsistencies are as in the original.