HOLLY

The Romance of a Southern Girl

BY

AUTHOR OF “A MAID IN ARCADY,” “KITTY

OF THE ROSES,” “AN ORCHARD

PRINCESS,” ETC.

With illustrations by

EDWIN F. BAYHA

Copyright, 1907

By The Curtis Publishing Company

Copyright, 1907

By J. B. Lippincott Company

Published October, 1907

Electrotyped and Printed by J. B. Lippincott Company

The Washington Square Press, Philadelphia, U. S. A.

TO

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

Holly’s eighteenth birthday was but a fortnight distant when the quiet stream of her life, which since her father’s death six years before had flowed placidly, with but few events to ripple its tranquil surface, was suddenly disturbed....

To the child of twelve years death, because of its unfamiliarity and mystery, is peculiarly terrible. At that age one has become too wise to find comfort in the vague and beautiful explanations of tearfully-smiling relatives—explanations in which Heaven is pictured as a material region just out of sight beyond the zenith; too selfishly engrossed with one’s own loneliness and terror to be pacified by the contemplation of the radiant peace and beatitude attained by the departed one in that ethereal[10] and invisible suburb. And at twelve one is as yet too lacking in wisdom to realize the beneficence of death.

Thus it was that when Captain Lamar Wayne died at Waynewood, in his fiftieth year, Holly, left quite alone in a suddenly empty world save for her father’s sister, Miss India Wayne, grieved passionately and rebelliously, giving way so abjectly to her sorrow that Aunt India, fearing gravely for her health, summoned the family physician.

“There is nothing physically wrong with her,” pronounced the Old Doctor, “nothing that I can remedy with my poisons. You must get her mind away from her sorrow, my dear Miss India. I would suggest that you take her away for a time; give her new scenes; interest her in new affairs. Meanwhile ... there is no harm....” The Old Doctor wrote a prescription with his trembling hand ... “a simple tonic ... nothing more.”

So Aunt India and Holly went away. At first the thought of deserting the new grave[11] in the little burying-ground within sight of the house moved Holly to a renewed madness of grief. But by the time Uncle Randall had put their trunk and bags into the old carriage interest in the journey had begun to assuage Holly’s sorrow. It was her first journey into the world. Save for visits to neighboring plantations and one memorable trip to Tallahassee while her father had served in the State Legislature, she had never been away from Corunna. And now she was actually going into another State! And not merely to Georgia, which would have been a comparatively small event since the Georgia line ran east[12] and west only a bare half-dozen miles up the Valdosta road, but away up to Kentucky, of which, since the Waynes had come from there in the first part of the century, Holly had heard much all her life.

As the carriage moved down the circling road Holly watched with trembling lips the little brick-walled enclosure on the knoll. Then came a sudden gush of tears and convulsive sobs, and when these had passed they were under the live-oaks at the depot, and the train of two cars and a rickety, asthmatic engine, which ran over the six-mile branch to the main line, was posing importantly in front of the weather-beaten station.

Holly’s pulses stirred with excitement, and when, a quarter of an hour later,—for Aunt India believed in being on time,—she kissed Uncle Ran good-bye, her eyes were quite dry.

That visit had lasted nearly three months, and for awhile Holly had been surfeited with new sights and new experiences against which no grief, no matter how poignant,[13] could have been wholly proof. When, on her return to Waynewood, she paid her first visit to her father’s grave, the former ecstasy of grief was absent. In its place was a tender, dim-eyed melancholy, something exaltedly sacred and almost sweet, a sentiment to be treasured and nourished in reverent devotion. And yet I think it was not so much the journey that accomplished this end as it was a realization which came to her during the first month of the visit.

In her first attempts at comforting the child, and many times since, Aunt India had reminded Holly that now that her father had reached Heaven he and her mother were together once more, and that since they had loved each other very dearly on earth they were beyond doubt very happy in Paradise. Aunt India assured her that it was a beautiful thought. But it had never impressed Holly as Miss India thought it should. Possibly she was too self-absorbed in her sorrow to consider it judicially. But one night she had a dream from which she awoke murmuring happily in the darkness. She could not remember very clearly what she had dreamed, although she strove hard to do so. But she knew that it was a beautiful dream, a dream in which her father and her mother,—the wonderful mother of whom she had no recollection,—had appeared to her hand in hand and had spoken loving, comforting words. For the first time she realized Aunt India’s meaning; realized how very, very happy her father and mother must be together[15] in Heaven, and how silly and selfish she had been to wish him back. All in the instant there, in the dim silence, the dull ache of loneliness which had oppressed her for months disappeared. She no longer seemed alone; somewhere,—near at hand,—was sympathy and love and heart-filling comradeship. Holly lay for awhile very quiet and happy in the great four-poster bed, and stared into the darkness with wide eyes that swam in grateful tears. Then she fell into a sound, calm sleep.

She did not tell Aunt India of her dream; not because there was any lack of sympathy between them, but because to have shared it would have robbed it of half its dearness. For a long, long time it was the most precious of her possessions, and she hugged it to her and smiled over it as a mother over her child. And so I think it was the dream that accomplished what the Old Doctor could not,—the dream that brought, as dreams so often do, Heaven very close to earth. Dreams are blessed things, be they day-dreams or dreams of the night; and[16] even the ugly ones are beneficent, since at waking they make by contrast reality more endurable.

If Aunt India never learned the cause she was at least quick to note the result. Holly’s thin little cheeks borrowed tints from the Duchess roses in the garden, and Aunt India graciously gave the credit to Kentucky air, even as she drew her white silk shawl more closely about her slender shoulders and shivered in the unaccustomed chill of a Kentucky autumn.

Then followed six tranquil years in which Holly grew from a small, long-legged, angular child to a very charming maiden of eighteen, dainty with the fragrant daintiness of a southern rosebud; small of stature, as her mother had been before her, yet possessed of a gracious dignity that added mythical inches to her height; no longer angular but gracefully symmetrical with the soft curves of womanhood; with a fair skin like the inner petal of a La France rose; with eyes warmly, deeply brown, darkened by large irises; a low, broad forehead[17] under a wealth of hair just failing of being black; a small, mobile mouth, with lips as freshly red as the blossoms of the pomegranate tree in the corner of the yard, and little firm hands and little arched feet as true to beauty as the needle to the pole. God sometimes fashions a perfect body, and when He does can any praise be too extravagant?

For the rest, Holly Wayne at eighteen—or, to be exact, a fortnight before—was perhaps as contradictory as most girls of her age. Warm-hearted and tender, she could be tyrannical if she chose; dignified at times, there were moments when she became a breath-taking madcap of a girl,—moments of which Aunt India strongly but patiently disapproved; affectionate and generous, she was capable of showing a very pretty temper which, like mingled flash of lightning and roar of thunder, was severe but brief; tractable, she was not pliant, and from her father she had inherited settled convictions on certain subjects, such for instance as Secession and Emancipation,[18] and an accompanying dash of contumacy for the protection of them.

She was fond of books, and had read every sombre-covered volume of the British Poets from fly-leaf to fly-leaf. She preferred poetry to prose, but when the first was wanting she put up cheerfully with the latter. The contents of her father’s modest library had been devoured with a fine catholicity before she was sixteen. Recent books were few at Corunna, and had Holly been asked to name her favorite volume of fiction she would have been forced to divide the honor between certain volumes of The Spectator, St. Elmo, and The Wide, Wide World. She was intensely fond of being out of doors; even in her crawling days her negro mammy had found it a difficult task to keep her within walls; and so her reading had ever been al fresco. Her favorite place was under the gnarled old fig-tree at the end of the porch, where, perched in a comfortable crotch of trunk and branch, or asway in a hammock, she spent many of her waking hours. When the weather kept[19] her indoors, she never thought of books at all. Those stood with her for filtered sunlight, green-leaf shadows, and the perfume-laden breezes.

Her education, begun lovingly and sternly by her father, had ended with a four-years’ course at a neighboring Academy, supplying her with as much knowledge as Captain Wayne would have considered proper for her. He had held to old-fashioned ideas in such matters, and had considered the ability to quote aptly from Pope or Dryden of more appropriate value to a young woman than a knowledge of Herbert Spencer’s absurdities or a bowing acquaintance with Differential Calculus. So Holly graduated very proudly from the Academy, looking her sweetest in white muslin and lavender ribbons, and was quite, quite satisfied with her erudition and contentedly ignorant of many of the things that fit into that puzzle which we are pleased to call Life.

And now, in the first week of November in the year 1898, the tranquil stream of her[20] existence was about to be disturbed. Although she could have no knowledge of it, as yet, Fate was already poising the stone which, once dropped into that stream, was destined to cause disquieting ripples, perplexing eddies, distracting swirls and, in the end, the formation of a new channel. And even now the messenger of Fate was limping along with the aid of his stout cane, coming nearer and nearer down the road from the village under the shade of the water-oaks, a limp and a tap for every beat of Holly’s unsuspecting heart.

Holly sat on the back porch, her slippered feet on the topmost step of the flight leading to the “bridge” and from thence to the yard. She wore a simple white dress and dangled a blue-and-white-checked sun-bonnet from the fingers of her right hand. Her left hand was very pleasantly occupied, since its pink palm cradled Holly’s chin. Above the chin Holly’s lips were softly parted, disclosing the tips of three tiny white teeth; above the mouth, Holly’s eyes gazed abstractedly away over the roofs of the buildings in the yard and the cabins behind them, over the tops of the Le Conte pear-trees in the back lot, over the fringe of pines beyond, to where, like a black speck, a buzzard circled and dropped and circled again above a distant hill. I doubt if Holly saw the buzzard. I doubt if she saw anything that you or I could[22] have seen from where she sat. I really don’t know what she did see, for Holly was day-dreaming, an occupation to which she had become somewhat addicted during the last few months.

The mid-morning sunlight shone warmly on the back of the house. Across the bridge, in the kitchen, Aunt Venus was moving slowly about in the preparation of dinner, singing a revival hymn in a clear, sweet falsetto:

To the right, in front of the disused office, a half-naked morsel of light brown humanity was seated in the dirt at the foot of the big sycamore, crooning a funny little accompaniment to his mother’s song, the while he munched happily at a baked sweet potato and played a wonderful game with two spools and a chicken leg. Otherwise the yard was empty of life save for the chickens and guineas and a white cat[23] asleep on the roof of the well-house. Save for Aunt Venus’s chant and Young Tom’s crooning (Young Tom to distinguish him from his father), the morning world was quite silent. The gulf breeze whispered in the trees and scattered the petals of the late roses. A red-bird sang a note from the edge of the grove and was still. Aunt Venus, fat and forty, waddled to the kitchen door, cast a stern glance at Young Tom and a softer one at Holly, and disappeared again, still singing:

Back of Holly the door stood wide open, and at the other end of the broad, cool hall the front portal was no less hospitably placed. And so it was that when the messenger of Fate limped and thumped his way up the steps, crossed the front porch and paused in the hall, Holly heard and leaped to her feet.

“Is anyone at home in this house?” called the messenger.

Holly sped to meet him.

“Good-morning, Uncle Major!”

Major Lucius Quintus Cass changed his cane to his left hand and shook hands with Holly, drawing her to him and placing a resounding kiss on one soft cheek.

“The privilege of old age, my dear,” he said; “one of the few things which reconcile me to gray hairs and rheumatism.” Still holding her hand, he drew back, his head on one side and his mouth pursed into a grimace of astonishment. “Dearie me,” he said ruefully, with a shake of his head, “where’s it going to stop, Holly? Every time I see you I find you’ve grown more radiant and lovely than before! ’Pears to me, my dear, you ought to have some pity for us poor men. Gad, if I was twenty years younger I’d be down on my knees this instant!”

Holly laughed softly and then drew her face into an expression of dejection.

“That’s always the way,” she sighed.[25] “All the real nice men are either married or think they’re too old to marry. I reckon I’ll just die an old maid, Uncle Major.”

“Rather than allow it,” the Major replied, gallantly, “I’ll dye my hair and marry you myself! But don’t you talk that way to me, young lady; I know what’s going on in the world. They tell me the Marysville road’s all worn out from the travel over it.”

Holly tossed her head.

“That’s only Cousin Julian,” she said.

“Humph! ‘Only Cousin Julian,’ eh? Well, Cousin Julian’s a fine-looking beau, my dear, and Doctor Thompson told me only last week that he’s doing splendidly, learning to poison folks off real natural and saw off their legs and arms so’s it’s a genuine pleasure to them. I reckon that in about a year or so Cousin Julian will be thinking of getting married. Eh? What say?”

“He may for all of me,” laughed Holly. But her cheeks wore a little deeper tint,[26] and the Major chuckled. Then he became suddenly grave.

“Is your Aunt at home?” he asked, in a low voice.

“She’s up-stairs,” answered Holly. “I’ll tell her you’re here, sir.”

“Just a moment,” said the Major, hurriedly. “I—oh, Lord!” He rubbed his chin slowly, and looked at Holly in comical despair. “Holly, pity the sorrows of a poor old man.”

“What have you been doing, Uncle Major?” asked Holly, sternly.

“Nothing, ’pon my word, my dear! That is—well, almost nothing. I thought it was all for the best, but now——” He stopped and shook his head. Then he threw back his shoulders, surrendered his hat and stick to the girl, and marched resolutely into the parlor. There he turned, pointed upward and nodded his head silently. Holly, smiling but perplexed, ran up-stairs.

Left alone in the big, square, white-walled room, dim and still, the Major unbuttoned[27] his long frock coat and threw the lapels aside with a gesture of bravado. But in another instant he was listening anxiously to the confused murmur of voices from the floor above and plucking nervously at the knees of his trousers. Presently a long-drawn sigh floated onto the silence, and—

“Godamighty!” whispered the Major; “I wish I’d never done it!”

The Major was short in stature and generous of build. Since the war, when a Northern bullet had almost terminated the usefulness of his right leg, he had been a partial cripple and the enforced quiescence had resulted in a portliness quite out of proportion to his height. He had a large round head, still well covered with silky iron-gray hair, a jovial face lit by restless, kindly eyes of pale blue, a large, flexible mouth, and an even more generous nose. The cheeks had become somewhat pendulous of late years and reminded one of the convenient sacks in which squirrels place nuts in temporary storage. The Major[28] shaved very closely over the whole expanse of face each morning and by noon was tinged an unpleasant ghastly blue by the undiscouraged bristles.

Although Holly called him “Uncle” he was in reality no relation. He had ever been, however, her father’s closest friend and on terms of greater intimacy than many near relations. Excepting only Holly, none had mourned more truly at Lamar Wayne’s death. The Captain had been the Major’s senior by only one year, but seeing them together one would have supposed the discrepancy in age much greater. The Major always treated the Captain like an older brother, accepting his decisions with unquestioning loyalty, and accorded him precedence in all things. It was David and Jonathan over again. Even after the war, in which the younger man had won higher promotion, the Major still considered the Captain his superior officer.

The Major pursued an uncertain law practice and had served for some time as[29] Circuit Judge. Among the negroes he was always “Major Jedge.” That he had never been able to secure more than the simplest comforts of life in the pursuit of his profession was largely due to an unpractical habit of summoning the opposing parties in litigation to his office and settling the case out of court. Add to this that fully three-fourths of his clients were negroes, and that “Major Jedge” was too soft-hearted to insist on payment for his services when the client was poorer than he, and you can readily understand that Major Lucius Quintus Cass’s fashion of wearing large patches on his immaculately-shining boots was not altogether a matter of choice.

The Major had not long to wait for an audience. As he adjusted his trouser-legs for the third time the sound of soft footfalls on the bare staircase reached him. He glanced apprehensively at the open door, puffed his cheeks out in a mighty exhalation of breath, and arose from his chair just as Miss India Wayne swept into[30] the room. I say swept advisedly, for in spite of the lady’s diminutive stature she was incapable of entering a room in any other manner. Where other women walked, Miss India swept; where others bowed, Miss India curtseyed; where others sat down, Miss India subsided. Hers were the manners and graces of a half-century ago. She was fifty-four years old, but many of those years had passed over her very lightly. Small, perfectly proportioned, with a delicate oval face surmounted by light brown hair, untouched as yet by frost and worn in a braided coronet, attired in a pale lavender gown of many ruffles, she was for all the world like a little Chelsea figurine. She smiled upon the Major a trifle anxiously as she shook hands and bowed graciously to his compliments. Then seating herself erectly on the sofa—for Miss India never lolled—she folded her hands in her lap and looked calmly expectant at the visitor. As the visitor exhibited no present intention of broaching the subject of his visit she took[31] command of the situation, just as she was capable of and accustomed to taking command of most situations.

“Holly has begged me not to be hard on you, Major,” she said, in her sweet, still youthful voice. “Pray what have you been doing now? You are not here, I trust, to plead guilty to another case of reprehensible philanthropy?”

“No, Miss Indy, I assure you that you have absolutely reformed me, ma’am.”

Miss India smiled in polite incredulity, tapping one slender hand upon the other as she might in the old days at the White Sulphur have tapped him playfully, yet quite decorously, with her folded fan. The Major chose not to observe the incredulity and continued:

“The fact is, my dear Miss Indy, that I have come on a matter of more—ah—importance. You will recollect—pardon me, pray, if I recall unpleasant memories to mind—you will recollect that when your brother died it was found that he had unfortunately left very little behind him in[32] the way of worldly wealth. He passed onward, madam, rich in the love and respect of the community, but poor in earthly possessions.”

The Major paused and rubbed his bristly chin agitatedly. Miss India bowed silently.

“As his executor,” continued the Major, “it was my unpleasant duty to offer this magnificent estate for sale. It was purchased, as you will recollect, by Judge Linderman, of Georgia, a friend of your brother’s——”

“Pardon me, Major; an acquaintance.”

“Madam, all those so fortunate as to become acquainted with Captain Lamar Wayne were his friends.”

Miss India bowed again and waived the point.

“Judge Linderman, as he informed me at the time of the purchase, bought the property as a speculation. He was the owner of much real estate throughout the South. At his most urgent request you consented to continue your residence at[33] Waynewood, paying him rent for the property.”

“But nevertheless,” observed Miss India, a trifle bitterly, “being to a large extent an object of his charity. The sum paid as rent is absurd.”

“Nominal, madam, I grant you,” returned the Major. “Had our means allowed we should have insisted on paying more. But you are unjust to yourself when you speak of charity. As I pointed out—or, rather, as Judge Linderman pointed out to me, had you moved from Waynewood he would have been required to install a care-taker, which would have cost him several dollars a month, whereas under the arrangement made he drew a small but steady interest from the investment. I now come, my dear Miss Indy, to certain facts which are—with which you are, I think, unacquainted. That that is so is my fault, if fault there is. Believe me, I accept all responsibility in the matter and am prepared to bear your reproaches without a murmur, knowing that I have[34] acted for what I have believed to be the best.”

Miss India’s calm face showed a trace of agitation and her crossed hands trembled a little.

The Major paused as though deliberating.

“Pray continue, Major,” she said. “Whatever you have done has been done, I am certain, from motives of true friendship.”

The Major bowed gratefully.

“I thank you, madam. To resume, about four years ago Judge Linderman became bankrupt through speculation in cotton. That, I believe, you already knew. What you did not know was that in meeting his responsibilities he was obliged to part with all his real estate holdings, Waynewood amongst them.”

The Major paused, expectantly, but the only comment from his audience, if comment it might be called, was a quivering sigh of apprehension which sent the Major quickly on with his story.

“Waynewood fell into the hands of a[35] Mr. Gerald Potter, of New York, a broker, who——”

“A Northerner!” cried Miss India.

“A Northerner, my dear lady,” granted the Major, avoiding the lady’s horrified countenance, “but, as I have been creditably informed, a thorough gentleman and a representative of one of the foremost New York families.”

“A gentleman!” echoed Miss India, scornfully. “A Northern gentleman! And so I am to understand that for four years I and my niece have been subsisting on the charity of a Northerner! Is that what you have come to inform me, Major Cass?”

“The former arrangement was allowed to continue,” answered the Major, evenly, “being quite satisfactory to the new owner of the property. I regret, if you will pardon me, the use of the word charity, Miss India.”

“You may regret it to your soul’s content, Major Cass,” replied Miss India, with acerbity. “The fact remains—the horrible, dishonoring fact! I consider[36] your course almost—and I had never thought to use the word to you, sir—insulting!”

“It is indeed a harsh word, madam,” replied the Major, gently and sorrowfully. “I realize that I have been ill-advised in keeping the truth from you, but in a calmer moment you will, I am certain, exonerate me from all intentions unworthy of my love for your dead brother and of my respect for you.” There was a suggestive tremble in the Major’s voice.

Miss India dropped her eyes to the hands which were writhing agitatedly in her lap. Then:

“You are right, my dear friend,” she said, softly. “I was too hasty. You will forgive me, will you not? But—this news of yours—is so unexpected, so astounding——!”

“Pray say no more!” interposed the Major, warmly. “I quite understand your agitation. And since the subject is unpleasant to you I will conclude my explanation as quickly as possible.”

“There is more?” asked Miss India, anxiously.

“A little. Mr. Potter kept the property some three years and then—I learned these facts but a few hours since—then became involved in financial troubles and—pardon me—committed suicide. He was found at his desk in his office something over a year ago with a bullet in his brain.”

“Horrible!” ejaculated Miss India, but—and may I in turn be pardoned if I do the lady an injustice—there was something in her tone suggesting satisfaction with the manner in which a just Providence had dealt with a Northerner so presumptuous as to dishonor Waynewood with his ownership. “And now?” she asked.

“This morning I received a letter from a gentleman signing himself Robert Winthrop, a business partner of the late unfortunate owner of the property. In the letter he informs me that after arranging the firm’s affairs he finds himself in possession of Waynewood and is coming here to look it over and, if it is in condition to[38] allow of it, to spend some months here. He writes—let me see; I have his letter here. Ah, yes. H’m:

“‘My health went back on me after I had got affairs fixed up, and I have been dandling my heels about a sanitarium for three months. Now the physician advises quiet and a change of scene, and it occurs to me that I may find both in your town. So I am leaving almost at once for Florida. Naturally, I wish to see my new possessions, and if the house is habitable I shall occupy it for three or four months. When I arrive I shall take the liberty of calling on you and asking your assistance in the matter.’”

The Major folded the letter and returned it to the cavernous pocket of his coat.

“I gather that he is—ah—uninformed of the present arrangement,” he observed.

“That, I think, is of slight importance,” returned Miss India, “since by the time he arrives the house will be quite at his disposal.”

“You mean that you intend to move out?” asked the Major, anxiously.

“Most certainly! Do you think that I—that either Holly or I—would continue to[39] remain under this roof a moment longer than necessary now that we know it belongs to a—a Northerner?”

“But he writes—he expresses himself like a gentleman, my dear lady, and I feel certain that he would be only too proud to have you remain here——”

“I have never yet seen a Northern gentleman, Major,” replied Miss India, contemptuously, “and until I do I refuse to believe in the existence of such an anomaly.”

The Major raised his hands in a gesture of helpless protestation.

“Madam, I had the honor of fighting the Northerners, and I assure you that many of them are gentlemen. Their ways are not ours, I grant you, nor are their manners, but——”

“That is a subject upon which, I recollect, you and my brother were never able to agree.”

The Major nodded ruefully. The momentary silence was broken at last by Miss India.

“I do not pretend to pit my imperfect knowledge against yours, Major. There may be Northerners who have gentlemanly instincts. That, as may be, I refuse to be beholden to one of them. They were our enemies and they are still my enemies. They killed my brother John; they brought ruin to our land.”

“The killing, madam, was not all on their side, I take satisfaction in recalling. And if they brought distress to the South they have since very nobly assisted us to restore it.”

“My brother has said many times,” replied the lady, “that he might in time forgive the North for knocking us down but that he could never forgive it for helping us up. You have heard him say that, Major?”

“I have, my dear Miss India, I have. And yet I venture to say that had the Lord spared Lamar for another twenty years he would have modified his convictions.”

“Never,” said Miss India, sternly; “never!”

“You may be right, my dear lady, but there was something else I have often heard him say.”

“And pray what is that?”

“A couplet of Mr. Pope’s, madam:

“I reckon, however,” answered the lady, dryly, “that you never heard him connect that sentiment with the Yankees.”

The Major chuckled.

“Deftly countered, madam!” he said. And then, taking advantage of the little smile of gratification which he saw: “But this is a subject which you and I, Miss India, can no more agree upon than could your brother and myself. Let us pass it by. But grant me this favor. Remain at Waynewood until this Mr. Winthrop arrives. See him before you judge him, madam. Remember that if what he writes gives a fair exposition of the case, he is little better than an invalid and so must find sympathy in every woman’s heart.[42] There is time enough to go, if go you must, afterwards. It is scarcely likely that Mr. Winthrop could find better tenants. And no more likely that you and Holly could find so pleasant a home. Do this, ma’am.”

And Miss India surrendered; not at once, you must know, but after a stubborn defence, and then only when mutineers from her own lines made common cause with the enemy. Before the allied forces of the Major’s arguments and her own womanly sympathy she was forced to capitulate. And so when a few moments later Holly, after a sharp skirmish of her own in which she had been decisively beaten by Curiosity, appeared at the door, she found Aunt India and the Major amicably discussing village affairs.

Robert Winthrop, laden with bag, overcoat and umbrella, left the sleeping-car in which he had spent most of the last eighteen hours and crossed the narrow platform of the junction to the train which was to convey him the last stage of his journey. It was almost three o’clock in the afternoon—for the Florida Limited, according to custom, had been two hours late—and Winthrop was both jaded and dirty; and I might add that, since this was his first experience with Southern travel, he was also somewhat out of patience.

Choosing the least soiled of the broken-springed, red-velveted seats in the white compartment of the single passenger car, he set his bag down and sank weariedly back. Through the small window beside him he saw the Limited take up its jolting progress once more, and watched the[44] station-agent deposit his trunk in the baggage-car ahead, which, with the single passenger-coach, comprised the Corunna train. Then followed five minutes during which nothing happened. Winthrop sighed resignedly and strove to find interest in the view. But there was little to see from where he sat; a corner of the station, a section of platform adorned with a few bales of cotton, a crate of live chickens, and a bag of raw peanuts, a glimpse of the forest which crept down to the very edge of the track, a wide expanse of cloudless blue sky. Through the open door and windows, borne on the lazy sun-warmed air, came the gentle wheezing of the engine ahead, the sudden discordant chatter of a bluejay, and the murmurous voices of two negro women in the other compartment. There was no hint of Winter in the air, although November was almost a week old; instead, it was warm, languorous, scented with the odors of the forest and tinged at times with the pleasantly acrid smell of burning pitch-pine from the engine.[45] It was strangely soft, that air, soft and soothing to tired nerves, and Winthrop felt its influence and sighed. But this time the sigh was not one of resignation; rather of surrender. He stretched his legs as well as he might in the narrow space afforded them, leaned his head back and closed his eyes. He hadn’t realized until this moment how tired he was! The engine sobbed and wheezed and the negroes beyond the closed door murmured on.

“Your ticket, sir, if you please.”

Winthrop opened his eyes and blinked. The train was swaying along between green, sunlit forest walls, and at his side the conductor was waiting with good-humored patience. Winthrop yielded the last scrap of his green strip and sat up. Suddenly the wood fell behind on either side, giving place to wide fields which rolled back from the railroad to disappear over tiny hills. They were fertile, promising-looking fields, chocolate-hued, covered with sere, brown cotton-plants to which here and there tufts of white still clung. Rail fences[46] zigzagged between them, and fire-blackened pine stumps marred their neatness. At intervals the engine emitted a doleful screech and a narrow road crossed the track to amble undecidedly away between the fields. At such moments Winthrop caught glimpses of an occasional log cabin with its tipsy, clay-chinked chimney and its invariable congress of lean chickens and leaner dogs. Now and then a commotion along the track drew his attention to a scurrying, squealing drove of pigs racing out of danger. Then for a time the woods closed in again, and presently the train slowed down before a small station. Winthrop reached tentatively toward his bag, but at that instant the sign came into sight, “Cowper,” he read, and settled back again.

Apparently none boarded the train and none got off, and presently the journey began once more. The conductor entered, glanced at Winthrop, decided that he didn’t look communicative and so sat himself down in the corner and leisurely bit the corner off a new plug of tobacco.

The fields came into sight again, and once a comfortable-looking residence gazed placidly down at the passing train from the crest of a nearby hill. But Winthrop saw without seeing. His thoughts were reviewing once more the chain of circumstances which had led link by link to the present moment. His thoughts went no further back than that painful morning nearly two years before when he had discovered Gerald Potter huddled over his desk, a revolver beside him on the floor, and his face horrible with the stains of blood and of ink from the overturned ink-stand. They had been friends ever since college days, Gerald and he, and the shock had never quite left him. During the subsequent work of disentangling the affairs[48] of the firm the thing haunted him like a nightmare, and when the last obligation had been discharged, Winthrop’s own small fortune going with the rest, he had broken down completely. Nervous prostration, the physician called it. Looking back at it now Winthrop had a better name for it, and that was, Hell. There had been moments when he feared he would die, and interminable nights when he feared he wouldn’t, when he had cried like a baby and begged to be put out of misery. There had been two months of that, and then they had bundled him off to a sanitarium in the Connecticut hills. There he, who a few months before had been a strong, capable man of thirty-eight, found himself a weak, helpless, emaciated thing with no will of his own, a mere sleeping and waking automaton, more interested in watching the purple veins on the backs of his thin hands than aught else in his limited world. At times he could have wept weakly from self-pity.

But that, too, had passed. One sparkling[49] September morning he lay stretched at length in a long chair on the uncovered veranda, a flood of inspiriting sunlight upon him, and a little breeze, brisk with the cool zest of Autumn, stirring his hair. And he had looked up from the white and purple hands and had seen a new world of green and gold and blue spread before him at his feet, a twelve-mile panorama of Nature’s finest work retouched and varnished overnight. He had feasted his eyes upon it and felt a glad stirring at his heart. And that day had marked the beginning of a new stage of recovery; he had asked, “How long?”

The last week in October had seen his release. He had returned to his long-vacant apartment in New York fully determined to start at once the work of rebuilding his fallen fortunes. But his physician had interposed. “I’ve done what I can for you,” he said, “and the rest is in your own hands. Get away from New York; it won’t supply what you need. Get into the country somewhere, away from cities and tickers. Hunt,[50] fish, spend your time out of doors. There’s nothing organically wrong with that heart of yours, but it’s pretty tired yet; nurse it awhile.”

“The programme sounds attractive,” Winthrop had replied, smilingly, “but it’s expensive. Practically I am penniless. Give me a year to gather the threads up again and get things a-going once more, and I’ll take your medicine gladly.”

The physician had shrugged his shoulders with a grim smile.

“I have never heard,” he replied, “that the hunting or fishing was especially good in the next world.”

“What do you mean?” asked Winthrop, frowning.

“Just this, sir. You say you can’t afford to take a vacation. I say you can’t afford not to take it. I’ve lived a good deal longer than you and I give you my word I never saw a poor man who wasn’t a whole lot better off than any dead one of my acquaintance. I don’t want to frighten you, but I tell you frankly that if you stay here[51] and buckle down to rebuilding your business you’ll be a damned poor risk for any insurance company inside of two weeks. It’s better to live poor than to die rich. Take your choice.”

Winthrop had taken it. After all, poverty is comparative, and he realized that he was still as well off as many a clerk who was contentedly keeping a family on his paltry twenty or thirty dollars a week. He sub-rented his apartment, paid what bills he owed out of the small balance standing to his name at the bank, and considered the question of destination. It was then that he had remembered the piece of property in Florida which he had taken over for the firm and which, having been the least desirable of the assets, had escaped the creditors. He went to the telephone and called up the physician.

“How would Florida do?” he had asked. “Good place to play invalid, isn’t it?”

“I don’t care where you go,” was the response, “so long as there’s pure air and sunshine there, and as long as you give[52] your whole attention to mending yourself.”

He had never been in Florida, but it appealed to him and he believed that, since he must live economically, there could be no better place; at least there would be no rent to pay. So he had written to Major Cass, whose name he had come across in looking over his partner’s papers, and had started South on the heels of his letter. The trip had been a hard one for him, but now the soft, fragrant air that blew against his face through the open car window was already soothing him with its caressing touch and whispering fair promises of strengthening days. A long blast of the whistle moved the conductor to a return of animation and Winthrop awoke from his thoughts. The train was slowing down with a grinding of hand-brakes. Through the window he caught glimpses of gardens and houses and finally of a broad, tree-lined street marching straight away from the railroad up a sloping hill to a gray stone building with a wooden cupola which[53] seemed to block its path. Then the station threw its shadow across him and the train, with many jerks and much rattling of coupling, came to a stop.

“Corunna,” drawled the conductor.

Outside, on the platform which ran in front of the station on a level with the car floors, Winthrop looked about him with mingled amusement and surprise. In most places, he thought, the arrival of the daily train was an event of sufficient importance to people the station platform with spectators. But here he counted just three persons beside himself and the train crew. These were the two negresses who had travelled with him and the station agent. There was no carriage in sight; not even a dray for his trunk. He applied to the agent.

“Take that street over yonder,” said the agent, “and it’ll fetch you right square to the Major’s office, sir. I’ll look after your bag until you send for it. You tell the nigger to ask me for it, sir.”

So Winthrop yielded the bag, coat and[54] umbrella and started forth. The station and the adjoining freight-shed stood, neutral-hued, under the wide-spreading branches of several magnificent live-oaks, in one of which, hidden somewhere in the thick greenery, a thrush was singing. This sound, with that of the panting of the tired engine, alone stirred the somnolent silence of mid-afternoon. A road, deep with white sand, ambled away beneath the trees in the direction of the wide street which Winthrop had seen from the car and to which he had been directed. It proved to be a well-kept thoroughfare lined with oaks and bordered by pleasant gardens in front of comfortable, always picturesque and sometimes handsome[55] houses. The sidewalks were high above the street, and gullies of red clay, washed deep by the heavy rains, divided the two. In front of the gates little bridges crossed the gullies. The gardens were still aflame with late flowers and the scent of roses was over all. Winthrop walked slowly, his senses alert and enravished. He drew in deep breaths of the fragrant air and sighed for very contentment.

“Heavens,” he said under his breath, “the place is just one big rest cure! If I can’t get fixed up here I might as well give up trying. I wonder,” he added a moment later, “if every one is asleep.”

There was not a soul in sight up the length of the street, but from one of the houses came the sound of a piano and, as he glanced toward its embowered porch, he thought he caught the white of a woman’s gown.

“Someone’s awake, anyhow,” he thought. “Maybe she’s a victim of insomnia.”

The street came to an end in a wide[56] space surrounded by one- and two-story stores and occupied in the centre by a stone building which he surmised to be the court-house. He bore to the right, his eyes searching the buildings for the shingle of Major Cass. A few teams were standing in front of the town hitching-rails, and perhaps a dozen persons, mostly negroes, were in view. He had decided to appeal for information when he caught sight of a modest sign on a corner building across the square. “L. Q. Cass, Counsellor at Law,” he read. The building was a two-story affair of crumbling red brick. The lower part was occupied by a general merchandise store, and the upper by offices. A flight of wooden steps led from the sidewalk along the outside of the building to the second floor. Winthrop ascended, entered an open door, and knocked at the first portal. But there was no reply to his demands, and, as the other rooms in sight were evidently untenanted, he returned to the street and addressed himself to a youth who sat on an empty box under the wooden[57] awning of the store below. The youth was in his shirt-sleeves and was eating sugar-cane, but at Winthrop’s greeting he rose to his feet, wiped his mouth with the back of his hand and answered courteously:

“Waynewood is about three-quarters of a mile, sir,” he replied to the stranger’s inquiry. “Right down this street, sir, until you cross the bridge over the branch. Then it’s the first place.”

He was evidently very curious about the questioner, but strove politely to restrain that curiosity until the other had moved away along the street.

The street upon which Winthrop now found himself ran at right angles with that up which he had proceeded from the station. Like that, it was shaded from side to side by water-oaks and bordered by gardens. But the gardens were larger, less flourishing, and the houses behind them smaller and less tidy. He concluded that this was an older part of the village. Several carriages passed him, and once he paused in the shade to watch the slow approach[58] and disappearance of a creaking two-wheeled cart, presided over by a white-haired old negro and drawn by a pair of ruminative oxen. It was in sight quite five minutes, during which time Winthrop leaned against the sturdy bole of an oak and marvelled smilingly.

“And in New York,” he said to himself, “we swear because it takes us twenty minutes to get to Wall Street on the elevated!”

He went on, glad of the rest, passing from sunlight to shadow along the uneven sidewalk and finally crossing the bridge, a tiny affair over a shallow stream of limpid water which trickled musically over its bed of white sand. Beyond the bridge the sidewalk ceased and he went on for a little distance over a red clay road, rutted by wheels and baked hard by the sun. Then a picket fence which showed evidence of having once been whitewashed met him and he felt a sudden stirring within him. This was Waynewood, doubtless, and it belonged to him. The thought was somehow a very pleasant one. He wondered why.[59] He had possessed far more valuable real estate in his time but he couldn’t recollect that he had ever thrilled before at the thought of ownership.

“Oh, there’s magic in this ridiculous air,” he told himself whimsically. “Even a toad would look romantic here, I dare say. I wonder if there is a gate to my domain.”

Behind the fence along which he made his way was an impenetrable mass of shrubbery and trees. Of what was beyond, there was no telling. But presently the gate was before him, sagging wide open on its rusted hinges. From it a straight path, narrow and shadowy, proceeded for some distance, crossed a blur of sunlight and continued to where a gleam of white seemed to indicate a building. The path was set between solid rows of oleander bushes whose lanceolate leaves whispered murmurously to Winthrop as he trod the firm, moss-edged path.

The blur of sunlight proved to be a break in the path where a driveway angled across[60] it, curving on toward the house and backward toward the road where, as Winthrop later discovered, it emerged through a gate beyond the one by which he had entered. He crossed the drive and plunged again into the gloom of the oleander path. But his journey was almost over, for a moment later the sentinel bushes dropped away from beside him and he found himself at the foot of a flower garden, across whose blossom-flecked width a white-pillared, double-galleried old house stared at him in dignified calm. The porches were untenanted and the wide-open door showed an empty hall. To reach that door Winthrop had to make a half circuit of the garden, for directly in front of him a great round bed of roses and box barred his way. In the middle of the bed a stained marble cupid twined garlands of roses about his naked body. Winthrop followed the path to the right and circled his way to the drive and the steps, the pleasure of possession kindling in his heart. With his foot on the lowest step he paused and glanced about[61] him. It was charming! Find his health here? Oh, beyond a doubt he would. Ponce de Leon had searched in this part of the world for the Fountain of Youth. Who knew but that he, Robert Winthrop, might not find it here, hidden away in this fragrant, shaded jungle? And just then his wandering glance fell on a sprawling fig-tree at the end of the porch, at a white figure[62] perched in its branches, at a girl’s fresh young face looking across at him with frank and smiling curiosity.

Winthrop took off his hat and moved toward the fig-tree.

The Major had accomplished his errand and had taken his departure, accompanied down the oleander path as far as the gate by Holly. He was very well satisfied with his measure of success. Miss India had consented to remain at Waynewood until the arrival of the new owner, and if the new owner proved to be the kind of man the Major hoped him to be, things would work out quite satisfactory. Of course a good deal depended on Robert Winthrop’s being as much of an invalid as the Major had pictured him to Miss India. Let him appear on the scene exhibiting a sound body and rugged health and all the Major’s plans would be upset; Miss India’s sympathy would vanish on the instant, and Waynewood would be promptly abandoned to the enemy.

The Major’s affection for Miss India[64] and Holly was deep and sincere, and the idea of their leaving Waynewood was intolerable to him. The thing mustn’t be, and he believed he could prevent it. Winthrop, on arrival, would of course call upon him at once. Then he would point out to him the advantage of retaining such admirable tenants, acquaint him with the terms of occupancy, and prevail upon him to renew the lease, which had expired some months before. It was not likely that Winthrop would remain in Corunna more than three months at the most, and during his stay he could pay Miss India for his board. Yes, the Major had schemed it all out between the moment of receiving that disquieting letter and the moment of his arrival at Waynewood. And his schemes looked beyond the present crisis. In another year or so Julian Wayne, Holly’s second cousin, would have finished his term with Doctor Thompson at Marysville and would be ready to begin practice for himself, settle down and marry Holly. Why shouldn’t Julian buy Waynewood?[65] To be sure, he possessed very little capital, but it was not likely that the present owner of Waynewood would demand a large price for the property. There could be a mortgage, and Julian was certain to make a success of his profession. In this way Waynewood would remain with the Waynes and Miss India and Holly could live their lives out in the place that had always been home to them. So plotted the Major, while Fate, outwardly inscrutable, doubtless chuckled in her sleeve.

At the gate the Major had shaken hands with Holly and made a request.

“My dear,” he had said, “when you return to the house your Aunt will have something to tell you. Be guided by her. Remember that there are two sides to[66] every question and that—ah—time alters all things.”

“But, Uncle Major, I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Holly had declared, laughing.

“I know you don’t, my dear; I know you don’t. And I haven’t time to tell you.” He had drawn his big silver watch from his vest and glanced at it apprehensively. “I promised to be at my office an hour ago. I really must hurry back. Good-bye, my dear.”

“Good-bye,” Holly had answered. “But I think you’re a most provoking, horrid old Uncle Major.”

But if the Major had feared mutiny on the part of Holly he might have spared himself the uneasiness. Holly had heard of the impending event from Aunt India at the dinner table with relish. Of course it was disgusting to learn that Waynewood was owned by a Northerner, but doubtless that was an injustice of Fate which would be remedied in good time. The exciting thing was that they were to have a visitor,[67] a stranger, someone from that fearsomely interesting and, if reports were to be credited, delightfully wicked place called New York; someone who could talk to her of other matters than the prospects of securing the new railroad.

“Auntie, is he married?” she had asked, suddenly.

“My dear Holly, what has that to do with it?”

“Well, you see,” Holly had responded, demurely, “I’m not married myself, and when you put two people together who are not married, why, something may happen.”

“Holly!” protested Miss India, in horror.

“Oh, I was only in fun,” said Holly, with a laugh. “Do you reckon, Auntie dear, that I’d marry a Northerner?”

“I should certainly trust not,” replied Miss India, severely.

“Not if he had millions and millions of money and whole bushels of diamonds,” answered Holly, cheerfully. “But is he married, Auntie?”

“I’m sure I can’t say. The Major believes him to be a man of middle age, possibly fifty years old, and so it is quite likely that he has a wife.”

“And he is not bringing her with him?”

“He said nothing of it in his letter, my dear.”

“Then I think she’s a very funny kind of a wife,” replied Holly, with conviction. “If he is an invalid, I don’t see why she lets him come away down here all alone. I wouldn’t if I were she. I’d be afraid.”

“I don’t reckon he’s as much of an invalid as all that.”

“Oh, I wasn’t thinking about his health then,” answered Holly. “I’d be afraid he’d meet someone he liked better than me and I wouldn’t see him again.”

“Holly, where do you get such deplorable notions?” asked her Aunt severely. “It must be the books you read. You read altogether too much. At your age, my dear, I assure you I——”

“I shall be eighteen in just twelve days,” interrupted Holly. “And eighteen[69] is grown-up. Besides, you know very well that wives do lose their husbands sometimes. There was Cousin Maybird Fairleigh——”

“I decline to discuss such vulgar subjects,” said Miss India, decisively. “Under the circumstances I think it just as well to forget the relationship, which is of the very slightest, my dear.”

“But it wasn’t Cousin Maybird’s fault,” protested Holly. “She didn’t want to lose him, Aunt India. He was a very nice husband; very handsome and distinguished, you know. It was all the fault of that other woman, the one he married after the divorce.”

“Holly!”

“Yes?”

“We will drop the subject, if you please.”

“Yes, Auntie.”

Holly smiled at her plate. Presently:

“When is this Mr. Winthrop coming?” she asked.

“He didn’t announce the exact date of[70] arrival,” replied Miss India. “But probably within a day or two. I have ordered Phœbe to prepare the West Chamber for him. He will, of course, require a warm room and a good bed.”

“But, Auntie, the carpet is so awful in the West Room,” deplored Holly.

“That is his affair,” replied Aunt India, serenely, as she arose from the table. “It is his carpet.”

Holly looked surprised, then startled.

“Do you mean that everything here belongs to him?” she asked, incredulously. “The furniture and pictures and books and—and everything?”

“Waynewood was sold just as it stood at the time, my dear. Everything except what is our personal property belongs to Mr. Winthrop.”

“Then I shall hate him,” said Holly, with calm decision.

“You must do nothing of the sort, my dear. The place and the furnishings belong to him legally.”

“I don’t care, Auntie. He has no right[71] to them. I shall hate him. Why, he owns the very bed I sleep in and my maple bureau and——”

“You forget, Holly, that those things were bought after your father died and do not belong to his estate.”

“Then they’re really mine, after all? Very well, Auntie dear, I shan’t hate him, then; at least, not so much.”

“I trust you will not hate him at all,” responded Miss India, with a smile. “Being an invalid, as he is, we must——”

“Shucks!” exclaimed Holly. “I dare say he’s just making believe so we won’t put poison in his coffee!”

In the middle of the afternoon, what time Miss India composed herself to slumber and silence reigned over Waynewood, Holly found a book and sought the fig-tree. The book, for having been twice read, proved none too enthralling, and presently it had dropped unheeded to the ground and Holly, leaning comfortably back against the branches, was day-dreaming once more. The sound of footsteps on the garden path[72] roused her, and she peered forth just as the intruder began his half circuit of the rose-bed.

Afterwards Holly called herself stupid for not having guessed the identity of the intruder at once. And yet, it seems to me that she was very excusable. Robert Winthrop had been pictured to her as an invalid, and invalids in Holly’s judgment were persons who lay supinely in easy chairs, lived on chicken broth, guava jelly and calomel, and were alternately irritatingly resigned or maddeningly petulant. The expected invalid had also been described as middle-aged, a term capable of wide interpretation and one upon which the worst possible construction is usually placed. The Major had suggested fifty; Holly with unconscious pessimism imagined sixty. Add to this that Winthrop was not expected before the morrow, and that Holly’s acquaintance with the inhabitants of the country north of Mason and Dixon’s line was of the slightest and that not of the[73] sort to prepossess her in their favor, and I think she may be absolved from the charge of stupidity. For the stranger whose advent in the garden had aroused her from her dreams looked to be under forty, was far from matching Holly’s idea of an invalid, and looked quite unlike the one or two Northerners she had seen. To be sure the man in the garden walked slowly and a trifle languidly, but for that matter so did many of Holly’s townsfolk. And when he paused at last with one foot on the lower step his breath was coming a bit raggedly and his face was too pale for perfect health. But these facts Holly failed to observe.

What she did observe was that the stranger was rather tall, quite erect, broad of shoulder and deep of chest, somewhat too thin for the size of his frame, with a pleasant, lean face of which the conspicuous features were high cheek-bones, a straightly uncompromising nose and a pair of nice eyes of some shade neither dark nor light. He wore a brown mustache which, contrary[74] to the Southern custom, was trimmed quite short; and when he lifted his hat a moment later Holly saw that his hair, dark brown in color, had retreated well away from his forehead and was noticeably sprinkled with white at the temples. As for his attire, it was immaculate; black derby, black silk tie knotted in a four-in-hand and secured with a small pearl pin, well-cut grey sack suit and brown leather shoes. In a Southerner Holly would have thought such carefulness of dress foppish; in fact, as it was, she experienced a tiny contempt for it even as she acknowledged that the result was far from displeasing. Further observations and conclusions were cut short by the stranger, who advanced toward her with hat in hand and a puzzled smile.

“How do you do?” said Winthrop.

“Good evening,” answered Holly.

There was a flicker of surprise in Winthrop’s eyes ere he continued.

“I’m afraid I’m trespassing. The fact is, I was looking for a place called Waynewood[75] and from the directions I received in the village I thought I had found it. But I guess I’ve made a mistake?”

“Oh, no,” said Holly; “this is Waynewood.”

Winthrop was silent a moment, striving to reconcile the announcement with her presence: evidently there were complications ahead. At last:

“Oh!” he said, and again paused.

“Would you like to see my Aunt?” asked Holly.

“Er—I hardly know,” answered Winthrop, with a smile for his own predicament. “Would it sound impolite if I asked who your Aunt is?”

“Why, Miss India Wayne,” answered Holly. “And I am Holly Wayne. Perhaps you’ve got the wrong place, after all?”

“Oh, no,” was the reply. “You say this is Waynewood, and of course there can’t be two Waynewoods about here.”

Holly shook her head, observing him gravely and curiously. Winthrop frowned.[76] Apparently there were complications which he had not surmised.

“Will you come into the house?” suggested Holly. “I will tell Auntie you wish to see her.” She prepared to descend from the low branch upon which she was seated, and Winthrop reached a hand to her.

“May I?” he asked, courteously.

Holly placed her hand in his and leaped lightly to the ground, bending her head as she smoothed her skirt that he might not see the ridiculous little flush which had suddenly flooded her cheeks. Why, she wondered, should she have blushed. She had been helped in and out of trees and carriages, up and down steps, all her life, and couldn’t recollect that she had ever done such a silly thing before! As she led the way along the path which ran in front of the porch to the steps, she discovered that her heart was thumping with a most disconcerting violence. And with the discovery came a longing for flight. But with a fierce contempt for her weakness[77] she conquered the panic and kept her flushed face from the sight of the man behind her. But she was heartily glad when she had reached the comparative gloom of the hall. Laying aside her bonnet, she turned to find that her companion had seated himself in a chair on the porch.

“You won’t mind if I wait here?” he asked, smiling apologetically. “The fact is—the walk was——”

Had Holly not been anxious to avoid his eyes she would have seen that he was fighting for breath and quite exhausted. Instead she turned toward the stairs, only to pause ere she reached them to ask:

“What name shall I say, please?”

“Oh, I beg your pardon! Winthrop, please; Mr. Robert Winthrop, of New York.”

Holly wheeled about.

“Mr. Winthrop!” she exclaimed.

“If you please,” answered that gentleman, weakly.

“Why,” continued Holly, in amazement, “then you aren’t an invalid, after all!”[78] She had reached the door now and was looking down at him with bewilderment. Winthrop strove to turn his head toward her, gave up the effort and smiled strainedly at the marble Cupid, which had begun an erratic dance amongst the box and roses.

“Oh, no,” he replied in a whisper. “I’m not—an invalid—at all.”

Then he became suddenly very white and his head fell back over the side of the chair. Holly gave one look and, turning, flew like the wind up the broad stairway.

“Auntie!” she called. “Aunt India! Come quickly! He’s fainted!”

“Fainted? Who has fainted?” asked Miss India, from her doorway. “What are you saying, child?”

“Mr. Winthrop! He’s on the porch!” cried Holly, her own face almost as white as Winthrop’s.

“Mr. Winthrop! Here? Fainted? On the porch?” ejaculated Miss India, dismayedly. “Call Uncle Ran at once. I’ll get the ammonia. Tell Phœbe to bring some feathers. And get some water yourself, Holly.”

In a moment Miss India, the ammonia bottle in hand, was—I had almost said scuttling down the stairs. At least, she made the descent without wasting a moment.

“The poor man,” she murmured, as she looked down at the white face and inert[80] form of the stranger. “Holly! Phœbe! Oh, you’re here, are you? Give me the water. There! Now bathe his head, Holly. Mercy, child, how your hand shakes! Have you never seen any one faint before?”

“It was so sudden,” faltered Holly.

“Fainting usually is,” replied Miss India, as she dampened her tiny handkerchief with ammonia and held it under Winthrop’s nose. “Do not hold his head too high, Holly; that’s better. What do you say, Phœbe? Why, you’ll just stand there and hold them until I want them, I reckon. Dead? Of course he isn’t dead, you foolish girl. Not the least bit dead. There, his eyelids moved; didn’t you see them? He will be all right in a moment. You may take those feathers away, Phœbe, and tell Uncle Ran to come and carry Mr. Winthrop up to his room. And do you go up and start the fire and turn the bed down.”

Winthrop drew a long breath and opened his eyes.

“My dear lady,” he muttered, “I am so very sorry to bother you. I don’t——”

“Sit still a moment, sir,” commanded Miss India, gently. “Holly, I told you to hold his head. Don’t you see that he is weak and tired? I fear the journey was too much for you, sir.”

Winthrop closed his eyes for a moment, nodding his head assentingly. Then he sat up and smiled apologetically at the ladies.

“It was awfully stupid of me,” he said. “I have not been very well lately and I guess the walk from the station was longer than I thought.”

“You walked from the depot!” exclaimed Miss India, in horror. “It’s no wonder then, sir. Why, it’s a mile and a quarter if it’s a step! I never heard of anything so—so——!”

Miss India broke off and turned to the elderly negro, who had arrived hurriedly on the scene.

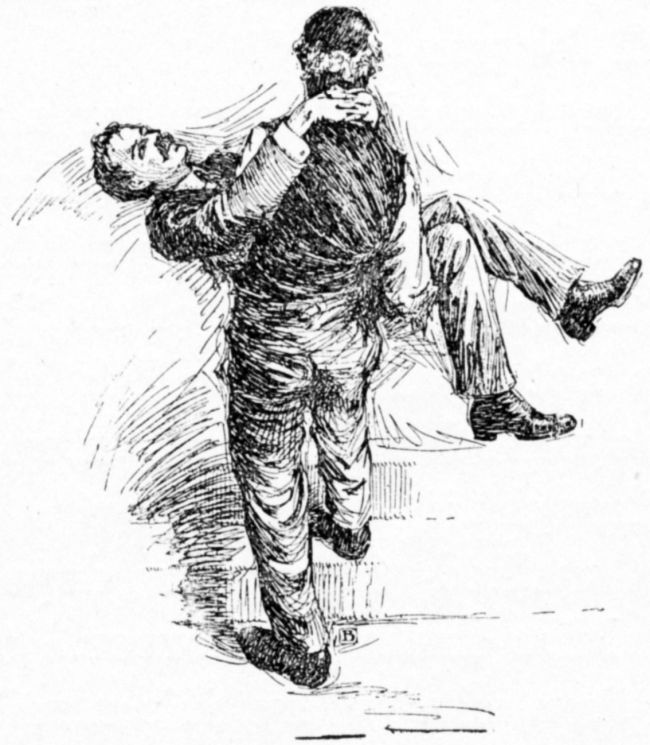

“Uncle Ran, carry Mr. Winthrop up to the West Chamber and help him to retire.”

“My dear lady,” Winthrop protested.[82] “I am quite able to walk. Besides, I have no intention of burdening you with——”

“Uncle Ran!”

“Yes’m.”

“You heard what I said?”

“Yes’m.”

Uncle Randall stooped over the chair.

“Jes’ you put yo’ ahms roun’ my neck, sir, an’ I’ll tote you mighty cahful an’ comfable, sir.”

“But, really, I’d rather walk,” protested Winthrop. “And with your permission, Miss—Miss Wayne, I’ll return to the village until——”

“Uncle Ran!”

“Yes, Miss Indy, ma’am, I heahs you. Hol’ on tight, sir.”

And in this ignoble fashion Winthrop took possession of Waynewood.

True to his promise, Uncle Ran bore Winthrop “careful and comfortable” up the wide stairs, around the turn and along the upper hall to the West Chamber, lowering him at last, as tenderly as a basket of eggs, into a chair. In spite of his boasts, Winthrop was in no condition to have walked up-stairs unaided. The fainting spell, the first one since he had left the sanitarium, had left him feeling limp and shaky. He was glad of the negro’s assistance and content to have him remove his shoes and help him off with his coat, the while he examined his quarters with lazy interest.

The room was very large, square, high-ceilinged. The walls were white and guiltless of both paper and pictures. Four large windows would have flooded the room with light had not the shades been carefully[85] drawn to within two feet of the sills. As it was, from the windows overlooking the garden and opening onto the gallery the afternoon sunlight slanted in, throwing long parallelograms of mellow gold across the worn and faded carpet. The bed was a massive affair of black walnut, the three chairs were old and comfortable, and the big mahogany-veneer table in the centre of the room was large enough to have served for a banquet. On it was a lamp, a plate of oranges whose fragrance was pleasantly perceptible, and a copy of Pilgrim’s Progress bound in the “keepsake” fashion of fifty years ago. The fire-place and hearth were of soft red bricks and a couple of oak logs were flaring brightly. A formidable wardrobe, bedecked with carved branches of grapes, matched the bed, as did a washstand backed by a white “splasher” bearing a design of cat-tails in red outline. The room seemed depressingly bare at first, but for all of that there was an air of large hospitality and plain comfort about it that was somewhat[86] of a relief after the over-furnished, over-decorated apartments with which Winthrop was familiar.

As his baggage had not come Miss India’s command could not be literally obeyed, and Uncle Ran had perforce to be satisfied with the removal of Winthrop’s outer apparel and his installation on the bed instead of in it.

“I’ll get yo’ trunk an’ valise right away, sir,” he said, “before they close the depot. Is there anything else I can do for you, Mr. Winthrop? Can I fetch you a lil’ glass of sherry, sir?”

“Nothing, thanks. Yes, though, you might open some of those windows before you go. And look in my vest pocket and toss me a cigarette case you’ll find there. I saw matches on the mantel, didn’t I? Thanks. That’s all. My compliments to Miss Wayne, and tell her I am feeling much better and that I will be down to dinner—that is, supper.”

“Don’t you pay no ’tention to the bell,” said Uncle Ran, soothingly. “Phœbe’ll[87] fetch yo’ supper up to you, sir. I’ll jes’ go ’long now and get yo’ trunk.”

Uncle Ran closed the door softly behind him and Winthrop was left alone. He pulled the spread over himself, gave a sigh of content, and lighted a cigarette with fingers that still trembled. Then, placing his hands beneath his head, he watched the smoke curl away toward the cracked and flaking ceiling and gave himself up to his thoughts.

What an ass he had made of himself! And what a trump the little lady had been! He smiled as he recalled the manner in which she had bossed him around. But who the deuce was she? And who was the young girl with the big brown eyes? What were they doing here at Waynewood, in his house? He wished he had not taken things for granted as he had, wished he had made inquiries before launching himself southward. He must get hold of that Major Cass and learn his bearings. Perhaps, after all, there was some mistake and the place didn’t belong to him at all! If that was[88] the case he had made a pretty fool of himself by walking in and fainting on the front porch in that casual manner! But he hoped mightily that there was no mistake, for he had fallen in love at first sight with the place. If it was his he would fix it up. Then he sighed as he recollected that until he got firmly on his feet again such a thing was quite out of the question.

The cigarette had burned itself down and he tossed it onto the hearth. The light was fading in the room. Through the open windows, borne on the soft evening air, came the faint tinkling of distant cow-bells. For the rest the silence held profoundly save for the gentle singing of the fire. Winthrop turned on to his side, pillowed his head in his hand and dropped to sleep. So soundly he slept that when Uncle Ran tiptoed in with his trunk and bag he never stirred. The old negro nodded approvingly from the foot of the bed, unstrapped the trunk, laid a fresh log on the fire, and tiptoed out again. When Winthrop finally awoke he found a neat colored girl lighting[89] the lamp, while beside it on the table a well-filled tray was laid.

“I fetched your supper, Mr. Winthrop,” said Phœbe.

“Thank you, but I really meant to go down. I—I think I fell asleep.”

“Yes, sir. Miss Indy say good-night, and she hopes you’ll sleep comfable, sir.”

“Much obliged,” muttered Winthrop.

“I’ll be back after awhile to fetch away the tray, sir.”

“All right.”

When he was once more alone he arose and laughed softly.

“Confound the woman! She’s a regular tyrant. I wonder if she’ll let me get up to-morrow. Oh, well, maybe she’s right. I don’t feel much like making conversation. Hello! there’s my trunk; I must have slept soundly, and that’s a fact!”

Unlocking the trunk, he rummaged through it until he found his dressing-gown and slippers. With those on he drew a chair to the table and began his supper.

“Nice diet for an invalid,” he thought, amusedly, as he uncovered the hot biscuits.

But he didn’t object to them, for he found himself very hungry; spread with the white, crumbly unsalted butter which the repast provided he found them extremely satisfactory. There was cold chicken, besides, and egg soufflé, fig preserve and marble cake, and a glass of milk. Winthrop’s gaze lingered on the milk.

“No coffee, eh?” he muttered. “Not suitable for invalids, I suppose; milk much better.”

But when he had finished his meal the glass of milk still remained untouched and he observed it thoughtfully. “I fancy Miss Wayne will see this tray when it goes down and she’ll feel hurt because I haven’t drunk that infernal stuff.” His gaze wandered around the room until it encountered the washstand. “Ah!” he said, as he arose. When he returned to the table the glass was quite empty. Digging his pipe and pouch from his bag he filled the former and was soon puffing enjoyably,[91] leaning back in the easy-chair and watching the smouldering fire.

“Even if I have to get out of here,” he reflected, “I dare say there’s a hotel or boarding-house in the village where I could put up. I’m not going back North yet awhile, and that’s certain. But if there’s anything wrong with my title to Waynewood why shouldn’t they let me stay here now that I’m established? That’s a good idea, by Jove! I’ll get my trunk unpacked right away; possession is nine points, they say. I dare say these folks aren’t so well off but what they’d be willing to take a respectable gentleman to board.”

A fluttering at his heart warned him and he laid aside his half-smoked pipe regretfully and began to unpack his trunk and bag. In the midst of the task Phœbe appeared to rearrange his bed and bear away the tray, bidding him good-night in her soft voice as she went.

By half-past seven his things were in place and, taking up one of the books which he had brought with him, he settled[92] himself to read. But voices in the hall below distracted his attention, and presently footsteps sounded on the stairway, there was a tap at his door and Phœbe appeared again.

“Excuse me, sir,” said Phœbe, “but Major Cass say can he see you——”

“Phœbe!” called the Major from below.

“Yes, sir?”

“You tell Mr. Winthrop that if he’s feeling too tired to see me to-night I’ll call again to-morrow morning.”

“Yes, sir.” Phœbe turned to Winthrop. “The Major say——”

“All right. Ask the Major to come up,” interrupted Winthrop, tossing aside his book and exchanging dressing-gown for coat and waistcoat. A moment later the Major’s halting tread sounded outside the open door and Winthrop went forward to meet him.

“I’m honored to make your acquaintance, Mr. Winthrop,” said the Major, as they shook hands.

“Glad to know you, Major,” replied[93] Winthrop. “Come in, please; try the arm-chair.”

The Major bowed his thanks, laid his cane across the table and accepted the chair which Winthrop pushed forward. Winthrop drew a second chair to the other side of the fire-place.

“A fire, Mr. Winthrop,” observed the Major, “is very acceptable these cool evenings.”

“Well, I haven’t felt the need of it myself,” replied Winthrop, “but it was here and it seemed a shame to waste it. I’ll close the windows if you like.”

“Not at all, not at all; I like fresh air. I couldn’t have too much of it, sir, if it wasn’t for this confounded rheumatism of mine. With your permission, sir.” The Major leaned forward and laid a fresh log on the fire. Winthrop arose and quietly closed the windows.

“Do you smoke, Major? I have some cigars here somewhere.”

“Thank you, sir, if they’re right handy.” He accepted one, held it to his[94] nose and inhaled the aroma, smiled approvingly and tucked it into a corner of his mouth. “You’ll pardon me if I don’t light it,” he said.

“Certainly,” replied Winthrop.

“I never learned to smoke, Mr. Winthrop,” explained the Major, “and I reckon I’m too old to begin now. But when I was a boy, and afterwards, during the war, I got a lot of comfort out of chewing, sir. But it’s a dirty habit, sir, and I had to give it up. The only way I use tobacco now, sir, is in this way. It’s a compromise, sir.” And he rolled the cigar around enjoyably.

“I see,” replied Winthrop.

“I trust you are feeling recovered from the effects of your arduous journey?” inquired the Major.

“Quite, thank you. I dare say Miss Wayne told you what an ass I made of myself when I arrived?”

“You refer to your—ah—momentary indisposition? Yes, Miss India informed me, and I was very pleased to learn of it.”[95] Winthrop stared in surprise. “You are feeling better now, sir?”

“Oh, yes; quite fit, thank you.”

“I’m very glad to hear it. I must apologize for not being at the station to welcome you, sir, but I gathered from your letter that you would not reach Corunna before to-morrow, and I thought that perhaps you would telegraph me again. I was obliged to drive into the country this afternoon on business, and only learned of your visit to my office when I returned. I then took the liberty of calling at the earliest moment.”

“And I’m very glad you did,” answered Winthrop, heartily. “There’s a good deal I want to talk to you about.”

“I am quite at your service, sir.”

“Thanks, Major. Now, in the first place, where am I?”

“Your pardon, Mr. Winthrop?” asked the Major, startledly.

“I mean,” answered the other, with a smile, “is this Waynewood and does it belong to me?”

“This is certainly Waynewood, sir, and I have gathered from your letter that you had come into possession of it.”

“All right. Then who, if I may ask the question without seeming impertinent, who are the ladies down-stairs?”

“Ah, Mr. Winthrop, I understand your question now,” returned the Major. “Allow me to explain. I would have done so before had there been opportunity, but your letter said that you were leaving New York at once and I presumed that there would be no time for an answer to reach you.”

“Quite right, Major.”

“The ladies are Miss India Wayne and her niece, Miss Holly Wayne, sister and daughter respectively of my very dear and much lamented friend Captain Lamar Wayne, whose home this was for many years. At his death I found myself the executor of his will, sir. He left this estate and very little else but debts. I did the best I could, Mr. Winthrop, but Waynewood had to go. It was sold to a Judge[97] Linderman of Georgia, a very estimable gentleman and a shining light of the State Bar. As he had no intention of living here I made an arrangement with him whereby Miss India and her niece might remain here in their home, sir, paying a—a nominal rent for the place.”

“A very convenient arrangement, Major.”

“I am glad to hear you say so,” replied the Major, almost eagerly. “Judge Linderman, however, was a consarned fool, sir, and couldn’t let speculation alone. He was caught in a cotton panic and absolutely ruined. Waynewood then passed to your late partner, Mr. Potter. The arrangement in force before was extended with his consent, and the ladies have continued to reside here. They are paying”—(the Major paused and spat voluminously into the fire)—“they are paying, Mr. Winthrop, the sum of five dollars a month rent.”

“A fair figure, I presume, as rents go hereabouts,” observed Winthrop, subduing a smile.

The Major cleared his throat. Then he leaned across and laid a large hand on Winthrop’s knee.