—Page 29

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Fuzzy-Wuzz, a little brown bear of the Sierras, by Allen Chaffee

Title: Fuzzy-Wuzz, a little brown bear of the Sierras

Author: Allen Chaffee

Illustrator: Peter Da Ru

Release Date: February 1, 2023 [eBook #69923]

Language: English

Produced by: Charlene Taylor, Krista Zaleski and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

—Page 29

A Little Brown Bear of the Sierras

By

ALLEN CHAFFEE

Author of “Unexplored,” “Lost River,” “Twinkly Eyes, the Little Black Bear,” “Trail and Tree Top,” etc.

Illustrated by

PETER DA RU

MILTON BRADLEY COMPANY

SPRINGFIELD - - - MASSACHUSETTS

Copyright, 1922

By MILTON BRADLEY COMPANY

Springfield, Massachusetts

All rights reserved

Bradley Quality Books

PRINTED IN UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

To

M. M. Soule

A LITTLE brown bear, no bigger than a house cat, that the Ranger found near drowning, is brought up with the orphaned fawn his children tamed, a rascally young burro, a ring-tailed cat, an owl, a tame canary, and a valiant yellow pup.

The scene is laid in the high Sierras, where trout-filled streams cascade down fragrant cedar slopes.

The author has turned natural science into story form. With the enterprising bear cub, we meet pine squirrels and painted chipmunks, the pika of the snow-clad peaks and the rattler of the sun-baked low-lands, the weasel and the wapiti, and have at least a glimpse of the cougar and the coyote.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | Mother Brown Bear | 1 |

| II | The Cinnamon Cub | 5 |

| III | The Young Screech Owl | 8 |

| IV | With the Ranger’s Children | 12 |

| V | Fuzzy Runs Away | 16 |

| VI | The Coyotes | 19 |

| VII | The Spotted Fawn | 22 |

| VIII | Wild Playmates | 27 |

| IX | The Hunter | 31 |

| X | Tiny Folk and Their Troubles | 34 |

| XI | Chuck and Chipper | 38 |

| XII | Mother Chipmunk’s Adventure | 43 |

| XIII | The Home Under the Rock | 46 |

| XIV | The Cache | 50 |

| XV | The Pine Nuts | 54 |

| XVI | Fuzzy-Wuzz Plays Fate | 58 |

| XVII | Bucky, the Burro | 62 |

| XVIII | “As Stubborn as a Mule” | 66 |

| XIX | The Pinto Pony | 70 |

| XX | The Pack-Horse Trip | 75 |

| XXI | When the World Turned White | 79 |

| XXII | The Ring-Tailed Cat | 83 |

| XXIII | The Baby Canary | 87 |

| XXIV | “Jest an Ornery Pup” | 92 |

| XXV | A Regular Dog | 97 |

| XXVI | Chums | 101 |

| XXVII | Pretty Paws, the Pine Squirrel | 105 |

| XXVIII | The Rattlesnake Den | 110 |

| XXIX | Mother Brown Bear and the Bull | 115 |

| XXX | Pika of the Peaks | 121 |

| XXXI | Fuzzy and the Weasel | 125 |

| XXXII | Wapiti | 129 |

| XXXIII | Dapple Disappears | 133 |

| XXXIV | Dapple’s Secret | 136 |

| XXXV | Old Friends | 139 |

MOTHER BROWN BEAR

THE stars, twinkling like diamonds on a black velvet sky, looked down that night on a tender sight. A huge brown bear lay in the mouth of her cave in the rocks above the falls, nuzzling her babies to sleep.

A crafty old coyote also watched, his yellow eyes gleaming murderously at the tiny balls of fur. Soon, he told himself, the mother would have to go in search of her own supper, leaving the cubs asleep in the den. He licked his chops at the thought.

The littlest cub looked so tender and helpless! His cinnamon-brown fur, that matched the red-brown soil and the red-brown trunks of the pines, was still as fuzzy as a kitten’s.

But it just happened that the cubs were[Pg 2] not left alone that night. As the last red flush had faded from the peak of Red Top, their mother had had an unexpected feast. A Forest Ranger, with his camp outfit on a burro, had stopped at the foot of the falls to cook a string of trout and other good things, and had then pushed on up the trail to the hot springs, where he had work to do.

The mother bear had scarcely waited till the man was out of sight before she had gobbled up the fish heads, the left-over flapjacks, the bacon rind, everything,—while the burro, hobbled with a rope about his heels, had snorted in alarm and browsed as far away as he could get.

Now she could stay at home, at least till daybreak,—for her clever nose had caught the message that the breeze carried her, from that sneaking little yellow wild dog, and no coyote was going to steal a march on her! Her teeth gleamed in a snarl as she thought of the danger to her unweaned cubs.

Had she seen more of men, she would have thought it strange that the Ranger should leave his burro and pack behind. But this was in the high Sierras, a steep mountainside[Pg 3] where few men passed, and she had seen little of the strange creatures who always walked on their hind legs and made mysterious fires.

In one way she was different from most bears. She had three cubs instead of only two. It was about all she could keep track of. Of course they were obedient youngsters. Wild babies have to be, if they are to survive.

When their mother took the trail to the river, they followed her in single file, the biggest cub first, wee Fuzzy-Wuzz at the end of the procession. If she heard something she did not understand, and rose to her hind legs to listen, the three little bears stood up the same way, pricking their ears and trying to hear what she heard. If she sniffed at a strange scent, they sniffed; and if she turned and ran, they turned and scrambled after her as fast as their fat legs could carry them.

As it happened, the Ranger returned to camp before the yellow moon had risen from behind the lacework of the pines, and, gathering an armful of springy fir boughs, made his bed by the river, which slapped rhythmically[Pg 4] against the rocks in the stealthy quiet.

It was just as he was watering the burro in the chill of sun-up that the shaggy one led her little family forth on an exploring expedition. Plodding along with her nose to the trail, she suddenly heard the sound of footsteps. Instantly, with a startled “Hoof!” she rose to her full height. Instantly three wee mimics rose to their hind legs behind her, breathing each his startled little “Hoof!”

[Pg 5]

THE CINNAMON CUB

HAD the man been nearer, mother brown bear would have fought to save her cubs. But there was time for escape. As quick as lightning she turned and went racing back to the den, her cubs following at her heels.

This region, so far up the glacier-polished slopes, was so smooth that a burro could hardly walk across it without slipping. As the man turned to stare at the unaccustomed motion in the landscape, the little family was just disappearing behind the bowlder that camouflaged the entrance to the den. All but Fuzzy-Wuzz! That fat, furry mite slipped on the smooth granite slope, his short hind legs slid out from under him, and before he could get his balance, he was rolling down, down, too surprised even to[Pg 6] call for help. Indeed, the breath was all knocked out of him and he couldn’t have squealed had he tried.

The river rolled at the foot of the slope, as green as the woods that bordered it, save where it churned in white foam over the upstanding bowlders. The next thing Fuzzy knew, splash! He was in deep water!

He struck out with all fours, like a pup, trying to run through the water. Of course he swam, as all young animals can when they have to. But the water was icy from the melting snows of the surrounding peaks. Worse, the current here above the falls was so strong that soon it was all he could do to keep his nose above water, to say nothing of paddling back to the bank.

Had he let out a frightened whimper now, his mother, with the two remaining cubs to lead safely into the depths of the cave, would not have heard him. The water whirled the wee brown mite this way and that. Choking and spluttering, he was soon too tired to paddle.

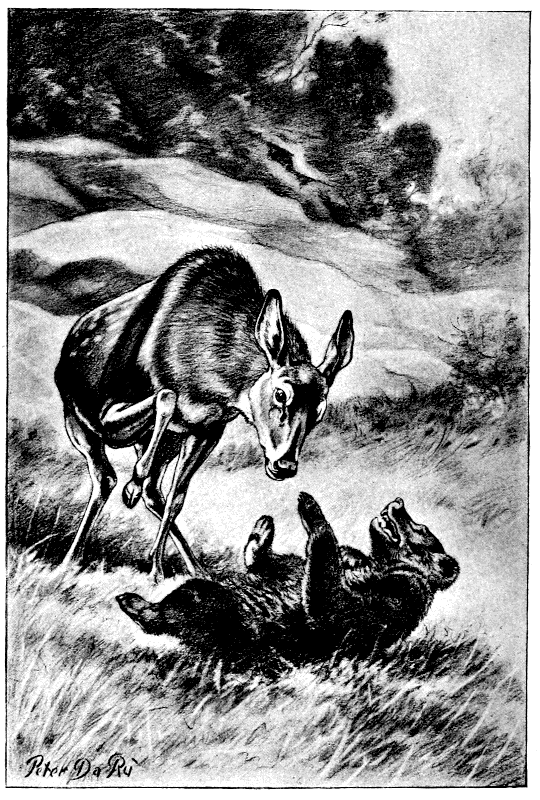

At that climactic moment, something solid went floating by his right fore paw, and[Pg 7] with all his feeble might he grabbed for it. It was a branch the Ranger had thrown in after him, and the branch was tied to a rope.

Clinging, chilled and strangled, to the raft so mysteriously flung to him, Fuzzy-Wuzz was towed to shore. Had the little bear been caught at any other time, he would have done effective work with his needle-sharp little teeth. But he was so nearly drowned that he could make no protest when the Ranger rubbed him down and fitted a leash to his neck.

A pan of warm canned milk and water won his trust, though the Ranger had to dip his unaccustomed muzzle into the fluid before he saw that the thing to do was to plant both fore paws firmly in the pan and suck with a noise like a little pig.

The Ranger made him a bed on the top of the pack that the burro carried, and tied him so that he couldn’t get down,—and there he was shortly snoozing, while the June sun dried his fur, and the trail climbed higher and higher. Life had taken a new turn for young Fuzzy-Wuzz.

[Pg 8]

THE YOUNG SCREECH OWL

ALL that week the wee brown cub rode on the pack the burro carried.

Every few hours the Ranger stopped to give him a panful of warm milk, and at night, when the mountain air turned chill, he snuggled the little bear under the blankets, though he never took him off the leash.

Finally one day they came to a neat log cabin beside a singing creek, where the pines and cedars made spots of shade on the forest floor. The next thing Fuzzy knew, he was inside the cabin, and two delighted man cubs, a boy and a girl, were dancing around him. This was so alarming that he crept inside the Ranger’s coat, crying, “Mu-uh! Mu-uh!” in a frightened whimper.

The man cubs were told to keep very, very[Pg 9] still and watch. Then Fuzzy was set on the floor before his pan of milk, and after a few minutes, when nothing seemed to hurt him, he drank it thirstily.

After that he went on an exploring expedition. He looked exactly like the brown plush Teddy bear, only larger, for Fuzzy was nearly as large as the cat. The children watched with shining eyes as he poked into every corner of the room, now climbing half way up the screen door, now standing on his fat hind legs under a chair, with his fore paws on the rungs.

“Muh! Muh! M-m-mu-uh!” he wailed every now and again. But no great furry mother came, and at last he decided there was nothing in that den to harm him, not even the children.

Soon what fun they had! The children’s mother said he could have bread in his milk, and the children even used to give him bits of the gingerbread that they saved in their pockets. It didn’t take long for the fuzzy mite to learn where that gingerbread came from! He would climb all over them, sniffing, sniffing, sniffing, till he found[Pg 10] where it was hidden, then claw till he had found the way into the pocket. These days, he cared more for eating than anything else.

Had Fuzzy been the only pet at the Ranger’s cabin, all might have gone smoothly. But he had one rival in the children’s affections,—and life was not to be all peace and play for the newcomer.

One rainy day that spring, when the wind had blown a limb off the old pine by the corral, leaving the screech owl’s nest exposed to gaze, a wee, soft-feathered fledgling had fallen to the ground and lay there, nearly lifeless from his fall.

The Ranger’s son, a curly-pate of nine, had found this downy bird, and had taken him home to warm and feed him. Thus the owl had become a member of the family circle. Clickety-Clack they named him, from his habit of clicking his bill when angry.

Given full freedom of the cabin, he generally perched by day just over the chamber door, on a pair of antlers that hung there for a hat rack.

But when the dusk began to fall Clickety-Clack[Pg 11] would come floating down to the mantel shelf, soundless as a shadow on his soft-feathered gray wings. There he would claw at the toys and bits of sewing, the pipe and match box, everything he found there. He was a solemn-looking bird, with his great round eyes, but he liked to play, for all that. His great delight was to be given a sheet of paper to claw into bits.

He was used to much attention, was Clickety-Clack, riding around on the children’s shoulders and receiving the dainties offered him with a clawed foot that solemnly conveyed the morsel to his mouth.

For a time Fuzzy-Wuzz paid little attention to Clickety-Clack, as the owl generally slept all day and the cub all night. But one evening he made a sad, sad mistake, did the little bear. As the owl floated down to the hearth rug, Fuzzy made a playful pounce for him. He caught the owl between his fore paws. But as he opened his jaws to take a nip at the feathered back, he got an awful surprise.

[Pg 12]

WITH THE RANGER’S CHILDREN

FUZZY-WUZZ made a big mistake when he tried to grab that owl. For no sooner had he got a taste of the feathers than Clickety-Clack was after him with beak and claws. When they finally called it off, the hearth rug bore a souvenir of both fur and feathers.

After that the little bear made many a playful, puppy-like dash at his fellow pet, but if ever he came too near, he got as good as he gave. It was tit for tat between them.

True, there were other ways in which Fuzzy managed to have a good time. For instance, he was always on the look-out for a romp in the children’s bed, if he was the first one up of a morning. The children’s mother objected, until the Ranger suggested a tubbing for the young bear.

[Pg 13]

This surprising thing,—a tub bath,—happened when Fuzzy-Wuzz had been a member of the Ranger’s family for about a week. No sooner did he find himself in the washtubful of warm, soapy water than he struck out vigorously for shore and scrambled over the edge of the tub. This process was repeated till the Ranger took a hand.

In the end Fuzzy-Wuzz emerged as clean a cub as any one could wish, but he stayed clean just until he was put on his leash and allowed to have a run outside. The California dry season had begun, with its dust, and the roly-poly rascal liked nothing better than to roll on his back.

The great trouble with the Ranger’s backyard, from Fuzzy’s point of view, was that there were no trees to climb. The clothes pole only went so far, and it had no bark and was dreadfully hard to get one’s claws into; but Fuzzy used to scramble up and down that clothes pole for all he was worth, pausing each time at the top to sit looking down at the children.

As the weeks flew by and the little bear grew stronger, he longed more and more[Pg 14] for the freedom to climb and romp and race the way Mother Nature meant him to. It got to be mighty tiresome to live on the end of a chain or be cooped up in the cabin. He would gaze into the green woods behind the house, and whimper and beg to be let out, but it seemed as if no one understood.

The Ranger was afraid if he let the cub go some big animal would get him. There were great yellow cougars (California lions) in the mountains, and perhaps timber wolves. Besides, even a wildcat could have made way with such a tiny cub, and no telling but that even a pair of coyotes (slinking yellow wild dogs that they are) might harm him. These animals were all afraid to come too near the cabin, for they were cowardly where human beings were concerned. But once let Fuzzy-Wuzz spend a night in the woods and no telling if he would ever see the morning.

Sometimes they could hear the coyotes’ bark, or the lion’s cry. Then Fuzzy’s fur would rise along his spine, and he would[Pg 15] huddle closer to the children on the hearth rug. But he never thought of that when the sun shone through the forest and he longed for freedom.

[Pg 16]

FUZZY RUNS AWAY

ONE day it came,—the chance he had been longing for!

Fuzzy-Wuzz was now a four months’ cub and much larger than when the Ranger brought him home,—a bear as big as a house cat. He made an armful for the children. And where at first he had been frightened in a world where no great furry mother came to his whimper, he now began to feel as if he could look out for himself.

One day the kitchen door was left ajar. Fuzzy had longed often to go exploring in those green woods that stretched behind the cabin and up the mountainside. Now he simply ran, and ran, and ran, deep into the woods, climbing to the tops of the tallest trees and exploring here and there and everywhere. Here he nibbled at the green,[Pg 17] growing things he found on the moist meadows by the spring holes, and there he took tiny cat-naps, all curled up into a warm ball of brown fur.

Not once, all that glorious afternoon, did he think of the coyotes and timber wolves, the lions and the lynxes that might come out of their dens when night came, and hunt squirrels and rabbits, and perhaps stray cubs who were young enough to make tender eating.

Towards sun-down he had an adventure. He met a band of range cattle, and when the foremost cow saw the runaway racing about like a puppy, she took him for a dog and made for him with her horns. It was only by sheer luck that he escaped her lunge. For in his surprise he simply tumbled over backwards. Being near a clump of seedling pines, he rolled right into the thick of them, and the old cow’s horns could not reach him.

If any one had advised him what to do when chased by a cow, he could not have given better advice than to get in the midst of a clump of saplings.

[Pg 18]

His natural fondness for climbing prompted his next move, and again he did the wisest thing. He made straight for the nearest tree and scrambled out of reach. After that the cattle wandered on and left him in peace.

But now the yellow sun no longer gilded the fir trees, and the woods became cool and shadowy. The wind, that all day had blown up the canyon of the creek bed, now turned the other way and blew down into the valley, chilled from the snow-clad mountain peaks. Fuzzy shivered with the cold. A horned owl solemnly boomed “whoo-whoo, whoo-whoo!”

By the time the first stars peeped from the blackening sky, he began to shiver from fright as well. For down the canyon came the long-drawn cry of the great, tawny, man-size cat that Californians call the mountain lion.

[Pg 19]

THE COYOTES

YES, sir! Fuzzy was a mighty frightened bear cub as the cougar’s cry chilled the night. He waited in his tree top with straining ears. The cry had ceased, but he dare not climb down, for what might not lurk in the rustling darkness?

Colder and colder grew his airy perch. Fuzzy curled up tight in the crotch of the limb. The lion was away off on the mountainside, and after awhile, when nothing happened, the little bear fell asleep.

His dreams were broken by a weird, wailing, high-pitched howl. He sprang awake in the instant. Peering through the gray darkness of the starry night, he tried to see what was causing that sound.

On a rock ridge half way down the slope stood two animals that any one might have[Pg 20] taken for yellow dogs, or perhaps for small-sized wolves. As an actual fact, they were cousins to both dog and wolf. They were coyotes, in search of their supper,—and Fuzzy-Wuzz had not forgotten the old coyote that used to howl below his mother’s den.

These coyotes, as it happened, had a family of fourteen little ones hidden in a cave on the hillside. That meant that they had to bring home a great many mice and rabbits for their family, which was still too young to go hunting with them.

Had the Ranger known about them, he would have made an end to them; for many a time they had robbed his chicken house, or harried a new-born colt, for their meat was anything too young and helpless to escape their jaws.

Even had Mother Brown Bear not taught her cubs to keep still and hide when the coyote cried, Fuzzy would have been afraid, with that weird cry in his ears. As it was, he shivered into a still tighter ball of fur and wished he were back in the Ranger’s cabin.

[Pg 21]

The coyotes must have got his scent with their wonderful doggy noses, as the wind blew down over his tree top to them, for they came circling nearer, and stood howling right up at his hiding-place. But none of the dog family can climb, and the cub was safe.

After awhile they saw a rabbit and went loping after it with all the speed of their slender feet. Again Fuzzy fell asleep, and when he awoke, it was a bar of silver sunlight shining in his eyes that woke him.

The woods now looked as green and peaceful as they had the afternoon before, and it did not seem possible that he could have been so frightened in the night. But he was hungry.

[Pg 22]

THE SPOTTED FAWN

BACKING down the tree trunk, the runaway began looking about him for something to eat. It was the little bear’s first experience at fending for himself. Had he not been taken from his mother, he would have learned from her how to find the fat white grubs that hide under a fallen tree trunk. He might have learned how to dig out a hiding wood mouse, or where to look for roots and berries.

As it was, he sampled a mouthful of bark, but it was no good. He sniffed this way and that through the pine woods, wriggling his nose in the effort to find a breakfast. And he thought of the pan of warm milk that always awaited him after the morning’s milking.

The children were just sitting down to[Pg 23] their breakfast of oatmeal when a whine and a scratching of claws sounded faintly through the kitchen door. Now they had cried themselves to sleep the night before, thinking their pet was gone.

“It’s Fuzzy-Wuzz!” they shouted, tumbling over one another to let him in. My! What a hugging he got! He wriggled and squirmed to get away. Then the Ranger brought in the foaming milk pails, and the prodigal was soon planting both fat fore paws in his feed pan.

After that they never put him on a leash, and Fuzzy never stayed away after dark,—at least not while he was such a tiny cub.

One morning the Ranger found that a mountain lion had been down to the corral. From the footprints he judged that the cows had driven the great cat away with their horns. But there was soon to be a new calf, and he decided to spend that day in hunting the lion.

The California mountain lion is a great, tawny beast as long as a man is tall, and it is fortunate that he is such a coward that he runs when he sees a human being. For[Pg 24] he can fell a deer at one stroke of his great barbed paw.

But he kills sheep and calves every chance he gets, and Uncle Sam asks his Forest Rangers to kill every lion they find.

The Ranger took his gun and started following the footprints the giant cat had left in the dust of the trail as it led up the mountain side. Soon the animal had leapt aside where only a scratch of its claws on a rock here and there told the tale.

By and by the slim, pointed hoof prints of a doe crossed the trail. The Ranger hurried even faster now, for he did not want another deer killed.

A gentle-eyed young doe had sought hiding that morning in a leafy clump of deer brush,—for in the evergreen forests of the Sierras there is little of the thick under-growth that one finds among the oaks and elms and maples of the Eastern woodlands.

This doe had a reason for selecting a good hiding-place, for that very morning twin fawns were born to her, and she had known they must be hidden away where[Pg 25] neither lions nor coyotes could find the helpless things.

The fawns had dappled coats, with milk-white spots on their soft, rusty-colored fur; and the doe found a place where the sunlight danced in patches on the rusty-colored earth, and the fawns would not have been noticed had one looked at the very spot,—unless they moved.

Such innocent, soft-eyed babies as they were, these firstlings of the rust-red doe! Like their mother, they had long ears and white tails with black tips. Their long, slender legs were at first too fragile for them to stand, and they lay on the soft moss as she licked their fur, with her wild mother love in her great eyes.

Off on the mountain peak their father, a great, handsome buck with branching antlers, was in retreat, with half-a-dozen other deer, while their horns were in velvet, for this velvety fur that covers the new growth of horn is tender, and the deer brush of the lower slopes would hurt it.

But alas for the wild mother, who would[Pg 26] willingly die fighting for her little ones! At the very moment that she lay nuzzling them so happily, the giant cat was crouched along the limb of a fir tree watching, with yellow eyes blinking hungrily. The way the wind blew, no taint of the lion reached her nostrils, and she had no warning.

The mountain lion had been unsuccessful in his last night’s hunt; he had wandered miles in search of prey. Suddenly gathering all fours beneath him, he had made one powerful leap at the doe. At this moment the Ranger, hurrying along his trail, sighted the tawny form and sent a bullet through its heart.

But so powerful had been the great cat’s leap that it did not stop even then, but still clutching the doe, it went sliding and rolling down the hillside till it crashed over a ledge,—and one of the fawns with them.

It was too late to save the others, but the Ranger took the remaining fawn in his arms and carried it home to his children. Thus Dapple, the fawn, became a fellow member of Fuzzy’s household.

[Pg 27]

WILD PLAYMATES

HAD the bear cub and the fawn been older, they would never have been friends; but these were both such babies that the little bear much preferred his milk to venison, and the fawn did not know to be afraid.

Their strange friendship might not last, as they grew older, but for the time there was peace between them.

The fawn had to be brought up on a bottle, and the children loved it first for its very helplessness.

As Dapple grew stronger, her long, slim legs developed the most amazing ability to jump. She followed the children around like a pup, for they were the only parents she knew. And if they became separated,[Pg 28] she would go leaping after them with great, graceful leaps that carried her straight over the bushes.

They used to like to run and hide from her, just for the fun of seeing her come bounding after them. She could overtake them in a foot race, too. She enjoyed a game of tag as much as they did, and everywhere the children went, the fawn would follow after.

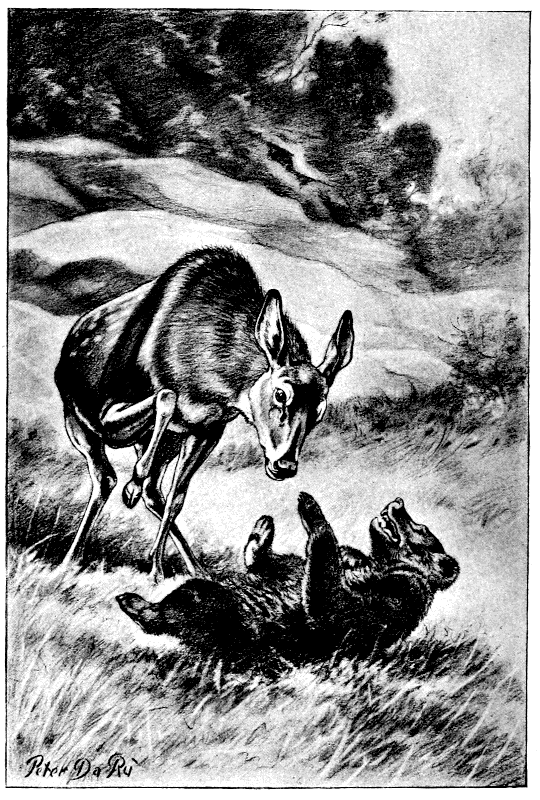

But though Fuzzy-Wuzz understood that Dapple was under the children’s protection, the young rascal loved to chase her. He never had the slightest chance of overtaking her, for his short, fat legs and round, flat feet were not built for speed. But sometimes he got her cornered and woofed at her, as a puppy would a calf.

At such times she learned to take refuge in the corral. Leaping lightly over the three-log fence, she would trip her way into the midst of the cattle, who would lower their horns the instant the little bear came near.

No matter if Dapple were lying down when Fuzzy-Wuzz grew mischievous, she[Pg 29] took her afternoon nap with all four feet under her, and when she made up her mind to go, she rose like a Jack-in-the-box, and away she leapt with a whistle, like a bit of thistle-down.

After a time Dapple found still another way to defend herself, when Fuzzy-Wuzz grew mischievous. Her slender hoofs were sharp as knives, and she would rear up on her hind legs and strike at him with her fore feet. He kept his distance.

Sometimes a deer will fight a snake that way.

Now Dapple learned to follow the children everywhere they went. Through the corral and into the woods, and even up the porch steps, would she trip after them. Once she even came into the cabin, and she would have every time, had the Ranger’s wife permitted.

She was like Mary’s little lamb. But there were no schools in this wilderness. The children’s mother taught them to read and figure, and their father told them about the trees and flowers and birds, the rocks and clouds, and read them books about the[Pg 30] great world outside their Sierras. That way, lessons were mostly play. Their playmates were the two wild children, Dapple and Fuzzy-Wuzz.

[Pg 31]

THE HUNTER

ONE morning a party of huntsmen stopped at the Ranger’s cabin. It was open season for deer, and they meant to make the most of those few weeks by shooting what the law allowed them.

Fuzzy-Wuzz had to wear a red bow on his neck these days, so that the huntsmen would not mistake him for a wild bear. For it was open season all the year around for bears, and a hunter loves nothing better than to kill a cub and have bear steak for breakfast. But Dapple wore no collar, as it was against the law to kill fawns at any time of the year.

The children had been playing tag with Dapple in the woods when they fell asleep in the sunshine of an open hillside. Dapple,[Pg 32] too, took a nap nearby, but instead of lying right out in the open, as they did, her instinct told her it was safer under the dappled shade of a clump of bushes.

One of the huntsmen, peering over the brow of the hill, saw a little movement in Dapple’s clump of bushes, as Dapple awoke and began cropping the leaves. Thinking it was a porcupine that had set the bushes swaying (and not being sportsman enough to make sure), he fired.

Dapple gave a scream of pain, and went bounding away on three legs. The children, thus awakened, stared after her, then started to follow her dainty hoof prints. Soon they noticed drops of blood on the stones.

At the same time the huntsman, seeing the children, came on the run. “Oh, I say!” he called, “I hope I didn’t hurt any one?”

“You’ve killed Dapple,” sobbed the little girl.

“You’ve shot Dapple!” shouted the boy. And to his sister, “I’d like to shoot HIM in the leg, and see how HE likes it!”

[Pg 33]

“Who’s ‘Dapple’?” gasped the huntsman, alarmed.

“She’s our tame fawn!” yelled the boy angrily.

“I’m so sorry,” apologized the huntsman. “I thought it was a porcupine.”

“Oh, then you didn’t mean to do it,” forgave the little girl.

It was decided that the huntsman had better not go with the children lest he frighten the fawn still further away.

“Dapple! Come, Dapple!” they called gently, as they traced the staggering footprints. They came upon the little creature lying on her side. Tenderly the boy carried her home in his arms, and the Ranger removed the bullet and bound the wound up properly.

Such an appealing invalid as Dapple made, with her great, reproachful eyes, that Fuzzy felt himself neglected. The day came, though, when the wounded leg was well. That day Dapple was allowed to follow them into the cabin, and even Fuzzy-Wuzz gave her a lick with his warm, moist tongue.

[Pg 34]

TINY FOLK AND THEIR TROUBLES

ONE thing that always interested the little bear was the robin who used to bring her fat fledglings, nearly as big as herself, to the Ranger’s lawn.

She had made her big clay nest on a beam of the porch, where the young birds would be sheltered from wind and rain. The young robins would flop to the ground, when she urged them, then hop around after Mrs. Red-breast as she pulled grubs and worms from the ground for them. They soon learned to look for the crumbs the children threw them. Fuzzy would watch, and sometimes make a playful dash at them; but at such times they would suddenly find they could fly out of reach.

Another time a humming-bird flew in[Pg 35] through the open window and began sipping nectar from the bunch of wild flowers the children had brought for the dining-table. Tiniest of birds, he made as much noise as any airplane that size could have made. The children held as still as mice while they watched.

One day Fuzzy was put on his leash just as some one left a bunch of grapes on the porch rail, for the Ranger had ridden down to the valley settlement for supplies the day before, and brought home a basket of the luscious fruit. My, how he wanted those grapes! But he could not reach them. There was nothing left to do but to watch the young robins flying, for their tails had grown longer, and so they could keep their balance better in the air.

When he looked back at the grapes again, an orange-breasted oriole was plunging his beak thirstily into a grape. He only ate one this time, and flew away. But soon he was back again, eating another grape. Fuzzy watched anxiously. Again the oriole came, and the little bear watched the grapes disappear, one by one. When the children[Pg 36] finally let him off his leash, there was nothing left of those grapes but the stems.

Never mind, there were lizards and field mice all about the place. This afternoon, while the reddening sun still shone warm on the bowlders, the tiny gray lizards with beady eyes on the alert for flies darted hither and thither among the gray rocks. The instant they saw Fuzzy watching, they would freeze motionless, or rise on their crooked legs till their orange breasts showed, watch him till he came too near, then race into a crack between two stones.

Fuzzy spent much time chasing field mice, or digging them out of their tunnels. One night the family was just sitting down to supper when a clawing at the door announced that Fuzzy wanted to come in. Coming proudly straight to the little girl, Fuzzy laid his catch in her lap. It was a fat field mouse!

The young mouse had not been hurt by Fuzzy’s jaws, and the instant he found himself free, he leaped to the table and raced across it and away, and not even Fuzzy could find him after that. But the next[Pg 37] morning he was sitting trembling in the mouse trap in the pantry, which was one of these round wire affairs that has a hole on top that lets a mouse get in, but won’t let him out.

How he trembled when the little girl found him. Fuzzy watched to see if the prisoner would be given to him to dispose of. But no, the little girl took the trap out into the woods and there opened the door and let the mouse find a hiding-place in the woods where he belonged.

[Pg 38]

CHUCK AND CHIPPER

THE little brown bear spent much of his first summer chasing chipmunks, but these squirrel-like orange and black striped fellows were too quick for Fuzzy-Wuzz.

The pretty creatures lived along the rock ledges and manzanita bushes that surrounded the Ranger’s cabin. Chuck and Chipper were two young chipmunks who had been born that spring. Now their mother had a second brood and left them pretty much to themselves.

My, what fun they had playing tag and stuffing their cheeks with everything good to eat they could find! Their cheeks were built like pockets and extended away down the sides of their necks. All the long, sunny days they explored the interesting[Pg 39] world in which they found themselves,—a world of good things to eat.

So tiny and mouselike were they that Fuzzy would have liked a taste of them, even if there were plenty of green things to eat, but the awkward, flat-footed, four months’ cub could not catch them.

The children, too, tried to capture a chipmunk, just for the fun of holding it in their hands for a minute. The boy had a cracker box that he placed upside down on the ground, then propped it open a crack with a stick. To this stick he tied a long string. Strewing the ground under the box with peanuts, he waited behind a tree till a chipmunk came and began stuffing his cheeks with the nuts. Then he jerked the string, and the box came down and made a prisoner of him. It was Chuck, who went about all day with his cheerful “chuck, chuck, chuck!”

The boy, holding his cloth hat in readiness, lifted the box a crack and Chuck dashed from under, but only to find himself in the hat crown. The next thing he knew, the boy was stroking his back with[Pg 40] one finger. Did he bite? Not the least little bit in the world. Chuck never tries to fight any one. His safety lies in running away when danger threatens. He only cowered down, quaking, with fear, his warm, furry sides panting hotly.

Until he could make a cage, the boy tethered him out on a leash, on a string as long as the cabin kitchen, and left him with a handful of peanuts. But the prisoner was too frightened to eat. He was even more so when he was turned loose in the cracker box, across the open side of which the boy had tacked a piece of screen wire. He only crept to the darkest corner, under a lettuce leaf, and wondered if he were ever again to go racing through the green woods in the sunshine.

The boy did not mean to keep him a prisoner, but the little captive did not understand.

Curiously Chuck’s brother, Chipper, peered at him from the top of a stump. “I told you not to go into that box,” he chippered in a frightened chirp. “Now what[Pg 41] are you going to do?” Just then he saw the little girl coming, and he whisked away under a stone.

All would have been well, she would not even have looked his way, had he not lost his nerve at the very moment she was passing, and begun his frightened chippering. Quick as a flash she had thrown her sunbonnet over rocks and all, and the next thing he knew, she had put him in the box with Chuck.

“Well, at least there are two of us,” Chuck tried to find a bright spot in the situation. And he felt so much better that he began to eat and drink. Then the night grew chilly, and they wadded the paper with which the box was carpeted into a sort of hay stack of paper wads, and burrowed inside it, all cuddled together into a ball to keep warm.

But Chipper did not have the heart to eat. Three days later he was so feeble from lack of food and exercise that he could hardly crawl. The boy, seeing this, opened the cage door and let them out.[Pg 42] After all, he told his sister, they had not been half so much fun as when they had been racing mischievously all over the place.

[Pg 43]

MOTHER CHIPMUNK’S ADVENTURE

THE Ranger was leading his horse down a steep trail one day, the dust rising yellowly in the noon-day calm, when he came to an inviting bit of shade and took out his lunch. For a time he munched his cheese sandwiches with his mind on his work. His horse neighed thirstily, and he led him to the spring, which trickled from the hillside.

As he turned back, he saw a chipmunk nervously gathering up his crumbs. Standing so still that he hardly breathed, so as not to frighten her, he watched while she darted forward, stopped to study him with her beady eyes, then dared a few steps farther. At last she picked up a big cracker crumb, and taking it in her handlike fore paws, began nibbling as if she were starved.

[Pg 44]

A slight movement on the Ranger’s part sent her instantly to her hole, but in a few minutes she was back again, eating ravenously and stuffing her cheeks with crumbs to take home. But the crumbs had all been cracker. The Ranger now threw her a morsel of cheese. This she found delicious. Never in all her life had she tasted anything so good. And it seemed as if she never could get enough to eat these days, for she had a family of wee baby chipmunks that she nursed as a cat does her kittens.

Next the Ranger held a piece of cheese between his thumb and finger. She wriggled her nose longingly, and hesitated, darting forward a few inches, now stopping in affright at what she had done, then getting up courage for another step.

Long minutes the Ranger waited, with that inviting bit of cheese held out to her at arm’s-length. So timid was she that he dared not even turn his head. Closer, closer she crept, till at last she could just get a frightened nibble. My, how good it was! Closer still she came, till she was eating it out of his hand. She ate until he[Pg 45] could feel her warm, furry nose against his finger.

Making a sudden grab, he closed his hand around her. He hadn’t meant to, but the temptation had been too much. He wanted first to stroke her silky fur. Then he thought there could be no harm in taking her home in his pocket to show the children. For he had been away when they caught Chuck and Chipper. Of course he didn’t know about her babies.

Mother Chipmunk gave one shrill squeak of despair. Then she was buttoned fast in the Ranger’s pocket, and he was riding farther and farther away from those wee, helpless babes of hers in the hole under the rock.

[Pg 46]

THE HOME UNDER THE ROCK

BUT what of the babies left behind, when Mother Chipmunk rode away in the Ranger’s pocket?

From an entrance hole under a rock just large enough to let her in, and not large enough for a weasel, Mother Chipmunk had built a branching tunnel that led for many feet under the pine needles of the forest floor. Three feet under-ground was the nursery cave, as big around as a dinner plate, all softly lined with dry leaves and moss.

Out of the main tunnel opened a smaller cave in which refuse was placed. There were also three storage caves or pantries, where in winter Mother Chipmunk kept her nuts and berries, dried grasshoppers and[Pg 47] other delicacies for the long months when it is white and cold out of doors.

Just now the nursery cave was occupied by four of the most cunning baby chipmunks that ever were,—helpless at this age, without teeth. When Mother Chipmunk washed them, she would stand on her hind legs and take one up on her arms so that she could smooth its fur with her tongue.

Now these helpless babies would starve to death, she told herself. She must find a way to escape, if her life depended on it. And she must find it quickly, or she could never travel back all those miles the Ranger was taking her.

She struggled and struggled, there in the Ranger’s pocket. But he had fastened it shut. On they went, jogging slowly down the rocky trail. She couldn’t see a thing, but she felt the rhythmic jolting at each step of the horse. At last it seemed as if she must be standing on her head. The Ranger had leapt to the ground, and was stooping to drink at a spring. As he bent, the pocket came unbuttoned. Out she squeezed, straight into the icy water.

[Pg 48]

“Well, I never!” exclaimed the Ranger, as she struck out with all her might, swimming across the pool till she could scramble to shore. Hiding under a stone till she was sure he had gone, she started racing back along the way she had come. She reached home to find her babies crying for her.

Chipmunks are easy to tame, if one does not try to keep them prisoner. Before the summer was over, the children had Chuck and Chipper so that they came around every meal time for something good to eat, and if the window was left open, they would come right into the cabin for it. Once they nearly buried themselves by jumping into the cold ashes of the fireplace.

They used to drink from the water pail when it was full enough for them to reach the water from the rim. One day Chipper reached too far, fell in, and had to swim for it. But when he reached the side of the granite pail, it was too smooth for his claws and he could not get out. The children found him near drowning.

Now Fuzzy had a real grievance, for always before, anything the children had in[Pg 49] their pockets to eat was for him. Now Chuck and Chipper searched them first. Fuzzy was more eager than ever to catch the impudent rascals.

[Pg 50]

THE CACHE

CHUCK and Chipper were mighty busy chipmunks, filling their cache,—to use the Western term that rhymes with to-day, meaning a hiding-place for food supplies.

The season was short, here in the high Sierras. Ordinarily it snowed as late as May, and as early as October. By the last of August one expected frost to tint the mountain sides. Day followed perfect, sunny day, and night succeeded cool, star-strewn night without a hint of rain; but Chuck and Chipper knew that before the moon was full again, the snow would be silvering the pine trees,—promise of the fifteen-foot drifts to come.

They must have enough in their cache to live on till spring.

Chipmunks do not hibernate in the way[Pg 51] that bears do. They sleep a good deal, but they do not go into an all-winter sleep, and when they wake, there in their caves away under-ground where the cold cannot reach them, they must eat.

Everywhere among the brush and fallen timber and along the rock ledges they searched for food to store away for winter. Racing briskly forth each morning, as soon as the sun began to slant warmingly through the fir trees, Chuck and Chipper vied with each other to see which could harvest the most nuts. And Fuzzy-Wuzz vied with both to see if he could catch them.

Always they were too alert for him. Their black, beady eyes would spy him out, no matter how softly he came padding along, and then they would climb into the top of some bush he could not climb and scold him and mock at him with their bird-like chirp.

Wild gooseberries were one of their favorite foods,—as they were the little bear’s, for they could bite off the prickers, and Fuzzy didn’t mind them.

They also collected thistle seed in their[Pg 52] cheek pockets, to say nothing of thimble berries, dogwood seed, and other seeds and berries. But where Fuzzy envied them was when it came to pine nuts. Every pine cone, from the yellow pine that grew so tall, to the dwarfed nut pine that the Indians love, is full of seeds. But the cones are also covered with sharp thorns, and so long as the cones were green, the nuts were safe from the little bear. He would have to wait till they turned brown and opened of their own accord.

But Chuck and Chipper had no such trouble. They could nibble the cone apart and get at the sweet kernels as easily as anything. Fuzzy used to watch them enviously. Then an idea came to him. He watched narrowly as the chipmunks filled their cheeks and scuttled away to their under-ground store-rooms.

Sniffing and snuffing this way and that, along the way they had gone, his wonderful nose finally told him just where their cache was located. Digging down about three feet, he scratched the roof off it while Chipper[Pg 53] chucked wrathfully and Chuck chippered in his fright.

What a find for the bear cub! Fully a peck of the delicious pine nuts lay before him,—and how he did feast! How his little black eyes twinkled at thought that he had outwitted the impudent things!

But for Chuck and Chipper it meant that half their harvest work was gone for nothing, and winter now too near for them to gather more. Then Chipper had a big idea.

[Pg 54]

THE PINE NUTS

“IT is the queerest thing!” exclaimed the Ranger’s wife, “what can have become of those pine nuts I was saving for Christmas. I had fully a peck in that basket on the top shelf.” She looked doubtfully at Fuzzy-Wuzz.

“The cub never could have done it,” the Ranger said. “If he had climbed up there, he would have knocked down a lot of stuff.”

“No, but what can have become of the nuts? There isn’t a sign of mice, either. And we never have a human thief, away up here in the mountains. Besides, what a funny thing it would be for a thief just to take the pine nuts and nothing else.”

“The thief must be some one of our furry friends, some one who is especially fond of nuts,” suggested the Ranger.

[Pg 55]

“There is a tiny hole gnawed in the wall up there. I thought it might be a mouse, but they always leave some sign.”

“Let’s see, now, if there aren’t some footprints to tell the story,” and the Ranger climbed up on the window sill and began peering about with a lighted match. “Ho, ho!” he called.

For there, faintly outlined by the dust, was a footprint like that of a tiny squirrel,—the print of a long, hind foot, with its five delicate toe marks. And on the edge of the hole the Ranger’s sharp eyes had spied a hair,—a single hair of some one’s orange colored fur.

“It’s a chipmunk, and he must have sat up here on his hind legs to sample a nut before he stuffed his cheeks. But imagine how many trips he must have had to make to carry away all those nuts!”

“Perhaps there was more than one.”

“That’s right. But there are so many tracks running through the dust that this is the only clear one I see. Must have been made just this morning, for no dust has settled in it yet. Well, now, the nuts are gone.[Pg 56] And I don’t believe they’ll come for anything more. That frost last night will send them into winter quarters.”

The Ranger was right about the chipmunks. But he little dreamed what had driven them to it. Had Fuzzy-Wuzz not found and gobbled up the nuts they had gathered for themselves, Chuck and Chipper never would have gotten up the courage to come so often to the cabin, where Clickety-Clack, the owl, prowled about the dark corners looking for just such tid-bits as they would make for him.

As it was, Chuck and Chipper were going to have a well-stocked cache that winter.

“As an actual fact,” said the Ranger that evening, when they had told the children about it, “I don’t begrudge the little rascals what they have taken, they are such good foresters.”

“Foresters!” exclaimed the boy, dragging his father to the arm chair by the fire and snuggling against his knees, for he scented a story.

“You see,” his father told him, “they bury so many nuts that they often forget[Pg 57] where they put them, and these nuts that are planted that way grow into trees.”

“My!” exclaimed the boy, “wouldn’t a chipmunk be surprised if he knew he planted trees!”

“He doesn’t know it. It is just a part of Mother Nature’s wonderful plan for keeping this old world going.”

The children’s mother suddenly laughed. “What do you think I saw to-day?” she asked them. “Fuzzy-Wuzz curled up asleep under a tree and looking so much like a hump of earth that a chipmunk hopped off the trunk and landed square on his nose. I don’t know which was the more surprised, the cub or the chipmunk.”

[Pg 58]

FUZZY-WUZZ PLAYS FATE

FUZZY-WUZZ lay basking in the late September sunshine. The mountains had blossomed forth since the frost with patches of berries that gleamed handsomely against the evergreens.

He had followed the children to a sandy place among the granite ledges back of the cabin, where they found a colony of the giant black ants. The children had been having a lot of fun with these ants. First they laid a piece of leaf over the entrance to an ant hill. Promptly one of the inmates poked his head forth to see what had so suddenly shut off the light.

Seeing the leaf, he went back and got help, and about a dozen ants came out and took hold of one edge of the leaf, and pulled, while the first ant stood on the stem and[Pg 59] directed operations. That way, they had their entrance clear again in no time.

The next thing, the children laid a bit of bark over their front door. This time they shoved the obstruction from underneath till they had turned it over, out of their way.

Then the children laid a pebble over the hole. That was almost too much for the little colony. At first they couldn’t even get out. Then they tunneled a way past the edge of the stone, and began studying the situation. Some clambered over the pebble while others walked around it, measuring. Then they tried pushing, but it was too heavy for them.

They tried pulling, but with no result. They tried getting underneath and shoving, but still they could not budge it. And at last the children got tired of waiting for them, and went away, deciding to come back later and take away the pebble if the ants had not succeeded in so doing.

Meantime Fuzzy-Wuzz had gone to sleep. His dreams were cut short by the awfullest pinching on the sensitive tip of his nose. The ants had finally tunneled a new opening[Pg 60] beside the pebble, though it had meant a long afternoon’s work for them. Seeing the cub asleep so near, they naturally decided that he must be responsible for all their trouble, and appointed a committee to drive him away.

But because of his thick fur, they couldn’t find a spot where they could reach him with their pincers except on the nose.

“Gee! I always get the worst of things!” rumbled the little brown bear, as he swept them off with one swipe of his furry paw, and would have shuffled away but for the sight that met his gaze.

Chuck, the chipmunk, stood there before him, paralyzed with fright. Coiled in front of him swayed an enormous bull snake, with red jaws open to swallow him.

If the snake had been stretched out full length, he would have been as long as the Ranger was tall. Just now he looked like a coil of thick rope, with his ugly head coming up out of the middle of the coil and pointing his forked red tongue straight at the young chipmunk.

He was a white snake, with brownish[Pg 61] stripes that seemed to mark his back in squares. As is true of most snakes, he was not a kind that would do any harm to a child, but he swallowed chipmunks whole, and poor Chuck knew it.

It seemed to Chuck as if his legs had frozen too stiff to run away, yet if he did not run, the snake would swallow him.

At that fateful moment, Fuzzy-Wuzz caught sight of them. One pounce and the fat cub had the snake writhing between his jaws. Then the snake had wriggled away and was making for his hole, the chipmunk forgotten.

“That certainly squares the matter of the pine nuts,” Chuck told his partner when he was safe back home. For the cinnamon cub had certainly played the rôle of Fate, though without realizing it. For him the snake had only meant a bit of sport.

[Pg 62]

BUCKY, THE BURRO

FUZZY-WUZZ had learned to ride a burro away back there when the Ranger had rescued him from drowning.

He had traveled on top of the pack as the Ranger went his rounds. After awhile he learned to leap to the little donkey’s back whenever he wanted to ride. The burro never minded.

She was mighty useful to the Ranger, was the donkey, for she could carry a pack over the narrowest mountain trail. No matter how rocky and dangerous it was, she never missed her footing. (A horse sometimes slipped and fell over the canyon wall.) She also possessed the ability to go without water when it was necessary. Her compact little hoofs were just built for rocky trails, and her ancestors had lived in Egypt and[Pg 63] the dry mountainous regions of Mexico, where a good drink every night after the day’s work is over, often has to suffice. That makes a burro especially useful during the long California dry season.

Then, too, a pack burro can live, and fatten on the dry grass and leaves she can find for herself during the months when no rain falls. That is more than a horse can do. The Ranger kept a couple of saddle horses, which he had to treat with especial care, but for the long trips into the back country, or down to the settlement and back for supplies, he relied on his burros.

Jack and Bucky, as he called them, had even carried the furniture of the cabin twenty miles on their backs. And so obedient were they that one day, when the Ranger wanted to send supplies home but could not leave the settlement himself for several days yet, he simply gave the shaggy little animals a slap and pointed their noses along the home trail, and they went back all alone.

But they had one fault. They were as stubborn as could be. If they made up[Pg 64] their minds to stop, no amount of urging, nor beating, even, could make them change their minds. If the Ranger accidentally put too heavy a pack on their backs, or one that didn’t fit comfortably, they would simply lie down, or else leap into the air with bowed backs and buck it off.

Now that spring a baby burro had been born in the corral. Young Bucky, they called the gray rascal. Such a cunning baby as he was, too, with his long, waggling ears, and almost hairless tail with just a tassel on the end of it.

At first he was so shy that every time Fuzzy-Wuzz came near, he would run for all he was worth. But gradually he got used to the fat brown cub.

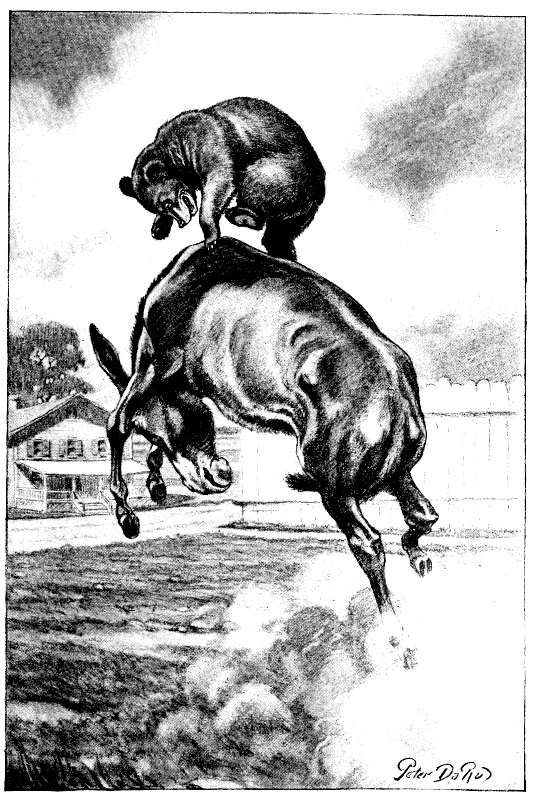

The pack burros were gone on a trip to the settlement when it occurred to Fuzzy-Wuzz that he would like to take a little ride around the corral. Seeing no one but young Bucky, he leapt to his back.

The next thing Fuzzy knew, he was sailing into the air, for Bucky, objecting to such a passenger, had simply given one big jump that sent the little bear flying off over[Pg 65] his head. Nor did he stop at that. Coming with all four of his neat hoofs together, his back bowed, he leapt again and again, shaking his head angrily and grunting with the effort he had made.

After that, if Fuzzy came too near, he simply struck out at him with his hind feet, and it was only luck on Fuzzy’s part that he did not get a good kick.

[Pg 66]

“AS STUBBORN AS A MULE”

“THERE is nothing like starting early,” said the Ranger one day, “when it comes to training animals and children. I am going to break young Bucky to the pack saddle.”

The little donkey was accordingly fitted with a pair of kyacks, almost empty to start with. So far, so good. But Bucky would not budge.

Meekly he stood there, his long ears pointed inquiringly at the Ranger and his eyes rolling till the whites showed. He made no protest, but neither could he be made to move. The Ranger did not believe in beating him. Besides, he knew from watching others that it would do no good. A burro will die under your blows, but he will not give in.

[Pg 67]

The Ranger tried coaxing, he tried commanding, he tried pulling on the halter rope and shoving from behind, but still that mite of a donkey stood with hoofs braced and refused to go one step with that pack saddle on his back.

It occurred to the Ranger that perhaps he had tried too heavy a load, for a burro knows better than any man what he can carry. He emptied the kyacks entirely. Sure enough, they had been too heavy,—light as they were.—Bucky now followed him with ears wagging peacefully, back and forth, back and forth, as is the way of burros.

He followed the Ranger, as docile as a puppy, planting his small hoofs carefully on the rocky trail. After perhaps half an hour he stopped. The Ranger coaxed him with a biscuit from his lunch, but the burro would not budge; he switched his heels, but Bucky would not move. He simply felt that it was time for a rest, and he used the one argument at his command. When he had rested long enough, he started on again of his own accord.

[Pg 68]

“‘He’s as stubborn as a mule,’” laughed the Ranger. “But I guess he knows better than I do when he’s had enough. I wouldn’t urge him beyond his strength for anything.”

Bucky certainly had a mind of his own. Fuzzy had been frog hunting down along the creek one day when the Ranger came along on horseback, with the big burros and young Bucky following after. He was on his way to bring in firewood from a clearing where he had chopped up a fallen tree, and though Bucky was not to carry more than one stick on each side, he thought it good training for him to go along and learn to follow a pack train.

They came to a corduroy bridge across the creek. Now burros are afraid of water. Their ancestors were desert animals, and every last donkey of them has to be taught to cross a bridge. It was no different with young Bucky.

Tripping daintily along behind his mother, he stopped when he came to the first log of that bridge, and planted his fore hoofs firmly against it.

[Pg 69]

The Ranger was prepared to offer him an apple, but Bucky would only stretch his neck toward the fruit and beg without being willing to come one inch nearer for it. Then the Ranger tried to pull him by his halter rope, but he tugged and he pulled till he was afraid he would pull the rascal’s head off, without being able to budge him.

The Ranger set his wits to work once more. He had heard of people actually lighting a fire under the stubborn animals, but though the flame singed their fur, they were more afraid of the bridge.

At last, in disgust, he simply took the young burro on his back by getting under him and drawing his fore legs over his shoulders, and carried him across.

Fuzzy, watching, enjoyed it hugely.

[Pg 70]

THE PINTO PONY

FUZZY-WUZZ, like all bears, old or young, was fond of trout, and these autumn days it was his great delight to fish the creek.

Earlier in the year the stream had been so high that he could not have done this, but now it came no more than neck high along the banks, as he stood with barbed paw outspread, ready to spear the first fingerling that came along.

He was there fishing the day that Bucky, the young burro, got his first swimming lesson. Where the bridge crossed the creek it was deeper. It was where the children came to swim. This time Bucky protested as he had before when they came to the bridge. Then he got the surprise of his life. The Ranger simply picked the little[Pg 71] gray beast up in his arms and flung him overboard into the pool.

You never in all your life saw such a surprised animal as young Bucky. But did he drown? Not a bit of it. Every animal—except the human—can swim if it has to, and Bucky simply struck out for shore with all fours.

Always thereafter he crossed the bridge willingly enough.

(How it did make Fuzzy’s little black eyes twinkle. For he had not forgotten when Bucky bucked him off.)

Another thing interested him, too. (For there is nothing in all the woods so curious as a bear cub). That was when the Ranger taught the pinto pony to walk a log.

Away off there in the high Sierras, it is often necessary for a man’s horse to make his way up and down steep slopes, over fallen tree trunks and over streams where there is no bridge. Sometimes a horse can swim, but where there is a log across a stream, those mountain-bred ponies are taught to cross the log.

First the Ranger found a log that had[Pg 72] fallen on a bit of level ground,—a big log that would have been wide enough for two ponies to walk abreast upon. Over this he led Pinto,—as he had named the pony from the large white patches on his brown coat. That log did not seem alarming.

Next the Ranger laid a log across a shallow arm of the creek where, if Pinto had fallen off, he would not have wetted more than his ankles. That was all right, too, thought Pinto.

As the final stage in his training, the Ranger led him along a log that crossed one end of the old swimming hole, where it was really deep. But Pinto had by this time learned to trust both his master and the logs, and he crossed unafraid.

Now Fuzzy-Wuzz had followed the creek up-stream till he was so high up the mountain side that the stony creek bed was all dry except for a mere trickle, and an occasional pool. He now proceeded to explore down-stream.

Here the rocks were all hollowed out in smooth, round bowls, some of them as big as wash tubs, some only the size of finger[Pg 73] bowls, and a few as large around as a dining-table.

When the snows melted in the spring, bringing with them a flood of rushing water and grinding stones, the stones had been swirled around and around till they had ground out these rock basins. The swimming hole was just a huge rock basin.

As Fuzzy came to deeper water, he met every here and there a make-believe waterfall. Sometimes he plunged over it head foremost, and sometimes his feet slipped out from under him before he was ready, and over the falls he went, landing in the pool beneath, and being swirled around in the rushing waters till he was half drowned.

But even a small cub is a good swimmer, and most of the time he really enjoyed the excitement.

These autumn days, however, he was to learn a new way of swimming. Now that the worst danger of forest fires was over and the Ranger had more leisure, he took two weeks off and the whole family went on a camping trip to a grove of Big Trees, and Fuzzy-Wuzz went with them.

[Pg 74]

Dapple was left to browse with the cattle, and Clickety-Clack was given the freedom of the barn; while the Ranger, his wife and boy rode horseback, and the little girl behind her father. The brown bear cub was placed on top of the pack Bucky’s mother carried. Young Bucky followed after.

[Pg 75]

THE PACK-HORSE TRIP

EVERY one enjoyed the camping trip, from the Ranger’s little girl, whose first long trip it was on horseback, to Fuzzy-Wuzz, whose natural love of exploring made it a real treat to ride all day atop the burro’s pack.

The sun felt good on one’s fur in the crisp autumn weather, as they threaded the clean aisles of pine and fir,—and my what appetites they had! Then the starlit evenings around the bon-fire, when the little bear was allowed to snooze on the saddle blankets!

He got himself in bad one night, though, by helping himself to a plate of flapjacks before the family had had their share. If it hadn’t been for that—but wait!

Bucky, the young burro, was also fond of flapjacks. In fact, he was fond of anything that could be eaten, and he was everlastingly[Pg 76] fond of eating. The Ranger used to say there was no bottom to his stomach,—the more he put into it, the more he wanted. But then, he was growing fast.

That little gray donkey would eat anything from a thistle to a piece of paper smeared with bacon grease. As each night two or three cans of vegetables were opened, he would eat the paper off the cans for the flour paste with which they had been pasted on.

He chewed the Ranger’s shoe, one night, just to sample the flavor. He loved potato parings, and raised his voice and sang for the bacon rinds.

Oh, what a voice he had! “Hee-haw, hee-haw, hee-haw!” he would bray till some one came to feed him. “It’s worth while giving him something to eat, just to keep him quiet,” declared the Ranger’s wife.

On the trail young Bucky, like his parents, expressed most of his feelings with his ears. When all was going well, their long ears swayed forward and backward, forward and backward, with each step they took. If something startled them, forward[Pg 77] would prick those great, listening ears till their curiosity had been satisfied. But if they got stubborn, back they would lay their ears as flat as they could plaster them.

One night every one was extra tired, and they all forgot and left the flour bag open. It was the night they arrived at the Big Trees, and they were too filled with awe and wonder to think of anything practical. The next morning Fuzzy happened to wake early, and went off on an exploring expedition of his own. That wonderful nose of his had told him that there was a nest of field mice somewhere about there, and he meant to dig them out.

Meantime the family arose, bathed in the river, and started breakfast preparations. While the boy brought in wood for the fire the little girl carried water from the spring, and the Ranger rounded up the stock,—as they say out West when they go to drive back the horses, who often stray in the night,—his wife made ready to bake biscuit.

She looked for the big twenty-five-pound flour sack. It was half empty, and flour was strewn all over the ground!

[Pg 78]

The two big burros were always hobbled, like the horses, over night, so that they could browse in the little mountain meadows without wandering too far. Young Bucky was left free. Just now he was nowhere in sight.

“Children,” called their mother sharply, “see what that bear of yours has done!” And Fuzzy, returning at that moment, wondered why every one scolded.

When the Ranger came in with the pack train, young Bucky’s muzzle was white with flour and his sides puffed out amazingly. “Here’s the culprit,” he sang out. “Trust a burro for raiding camp every chance he gets. Nothing but a donkey could pull through after a spree like what he’s been on.”

“Then Fuzzy didn’t do a thing,” and the boy flung his arms around the brown cub.

“Perhaps not this time, but if he hadn’t stolen those flapjacks, he wouldn’t have been misjudged.”

[Pg 79]

WHEN THE WORLD TURNED WHITE

IT certainly was hard, thought Fuzzy-Wuzz, for a cub bear to keep out of trouble.

Back from the camping trip, the Ranger’s children spent much time in the great log barn, and Fuzzy with them. How he did love to turn somersaults in the haymow! Like a furry clown, he would tumble about as if he hadn’t a bone in his body.

Sometimes the hens did not lay in their boxes, and the children used to be sent to hunt eggs, which they would find here and there in the hay. Fuzzy, too, learned to hunt for eggs, though those he found were never seen again, save for the smears of egg yolk on his jaws.

He soon found it was great sport to chase the hens and send them squawking, feathers[Pg 80] flying as he caught a mouthful of tail plumage.

He also delighted in coming around at milking time. At first the cows were so uneasy with the little bear around that they would kick their pails over and lower their horns at him. So the Ranger tried to drive him away by milking a stream of milk at him as one would turn on the hose.

Was Fuzzy driven away? On the contrary, he just opened his mouth wide and drank it down. After that he used to come and beg to have them milk into his mouth.

But Fuzzy was finally banished from the barn. The mischievous young rascal caught a pig one day and hugged him till the pig squealed as if he were being killed. A little more and he would have been, for a bear has a powerful hug. It certainly was hard for a fun-loving little bear to keep out of trouble.

At last Fuzzy disappeared. The children searched and searched, but they could find him nowhere. They set all his favorite dainties out on the back porch for him,—bacon, and honey, and wild gooseberries,—everything[Pg 81] they could think of that he especially loved.

They called him, they searched the woods for some trace of his footprints in the soft ground left by the early rains, but nowhere could they find hide nor hair of him.

“Do you suppose a lion’s got him?” they worried.

“No,” laughed the Ranger. “I shouldn’t be the least bit surprised if he had gone to hibernating. You know a bear always sleeps the winter away. He can’t find anything more to eat, with the snow deep on the ground, and he can’t keep warm unless he eats, so he just creeps off into some hole and curls up into a ball, with his toes inside, and sleeps till spring.”

“Fuzzy didn’t need to. We would have fed him.”

“Yes, but you see, bears have had to hibernate for so many, many years that it has become their nature to. I guess he couldn’t help himself: he just got to feeling so sleepy that nothing else mattered.”

“But where is he hibernating? I just wish we knew where he was.”

[Pg 82]

“Oh, probably in some cave in the hillside, or under a big bowlder where he would be sheltered from the wind; or perhaps he has just crawled under some fallen tree, where the snow will bank around him and make a cave, and keep the cold wind off him, and his breath will melt an air-hole.”

Then one afternoon, when the sun had been blotted out by the big white flakes of their first real, lasting snow, the boy was pitching hay from the mow for the horses when something round and furry tumbled out and into a horse stall. It was wee Fuzzy-Wuzz, who had been pried from the warm corner he had selected for his winter’s sleep.

He blinked and yawned a few times. Then he disappeared again, and it was not till the following spring that they found him snoozing away in the far corner of the haymow.

[Pg 83]

THE RING-TAILED CAT

THE children missed Fuzzy-Wuzz these days, the more so as Dapple, the fawn, had to spend the winter in the barn with the cows. They could not have her indoors, of course.

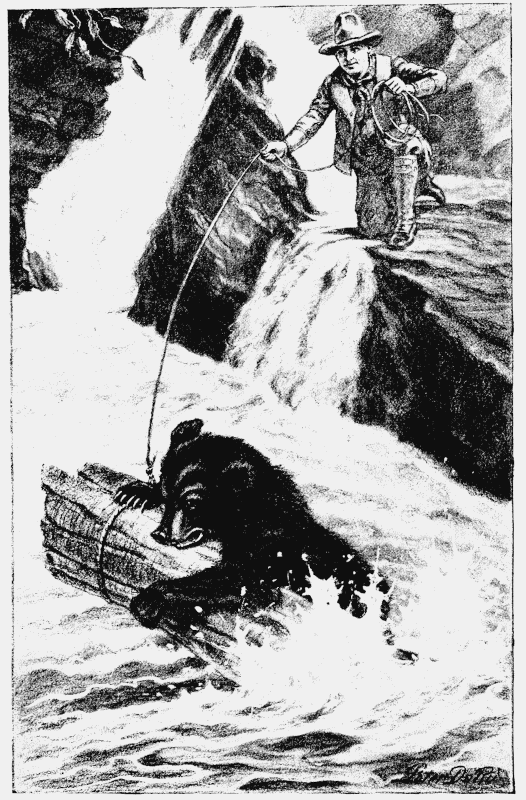

The Ranger found a litter of ring-tailed kittens. The kits are generally born in June, and this was October, so that they were half grown. Their mother and the two larger kittens ran away as the Ranger reached into their den in the hollow tree, but the littlest one was not quick enough.

Now the Ranger remembered his grandfather telling of the days of Forty-nine, when he joined the gold rush to California. He had had a ring-tailed cat for a pet.

Building his rude log cabin somewhere about these very mountains while he washed[Pg 84] the precious metal out of the gravel of the creek beds, he noticed that his supplies were being pilfered, and thinking it must be a fox, he set a trap.

He was awakened in the middle of the night by the most curious sound,—half the bark a small dog makes, and half yowl. Looking to see what he had in his trap, that he could put it out of its misery, he found an animal that he at first took to be a house cat. Then he noticed that it was longer, and had a much longer tail, and shorter legs. The most curious part of it was that the tail was striped black and white, like a ’coon’s. Its face, too, was pointed like that of a raccoon. Instead of the mischievous eyes peering from a black mask that a ’coon seems to have, this animal had large, gentle looking eyes and looked scared to death.

He learned later that it was a ’coon cat, or civet, more commonly called the ring-tail cat.

“There, there, pussy,” he soothed her, as he released her from the trap and carried her into his cabin. “You just come on in here and have some fish, and we’ll bury the[Pg 85] hatchet. I need a cat to keep the field mice out of my grub,” and he straightway adopted her.

She was easy to tame. She generally slept all day and chased mice all night,—of which an abundance were attracted by his pantry shelf. She also showed her likeness to the raccoon by her fondness for fruit and sugar.

The Ranger, remembering this pet his grandfather used to tell about, decided to take the ring-tail cat home to the children. And my, how pleased they were! At first they had to keep her in a cage, or she would have run away. And when they placed food before her, she would cower to the furthest corner as if terrified.

After a couple of days of this, the Ranger told his boy that if he really meant to tame her, he would have to make her eat from his hand. After that, though she had a pan of drinking water in her cage, she got no food till she was willing to eat it out of his hand.

For several days she refused to touch what he offered her. Then the tempting[Pg 86] odor of a piece of wild goose liver held between the boy’s fingers proved too much for her and she came up and ate it while he held it. A few days more and they could let her out of her cage.

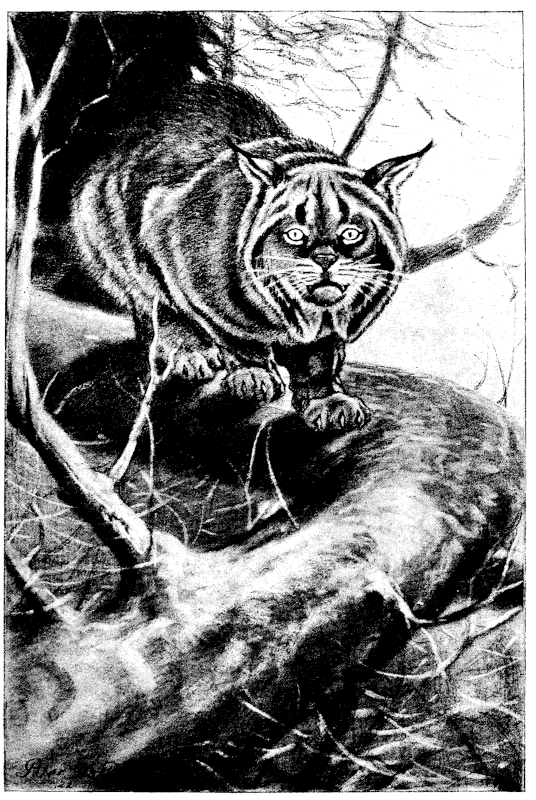

Ring-tail, as he named her, soon became the pet of the household,—to Clickety-Clack’s disgust, for the owl liked attention too. She would play like any other kitten, and she ate all kinds of table scraps, figs and prunes being her especial fondness.

She was no end graceful, was Ring-tail, with her long, plumy tail and her pointed face. And she responded to all the old kitten tricks, from chasing her tail to wrestling with one’s hand, tooth and claw. She craved affection, too, like any house cat.

There was just one trouble. They could not trust her in the same room with the canary.

Fuzzy-Wuzz had never bothered the bird, for though he could climb, he was too clumsy to reach into the cage as it hung there above the window box. But with Ring-tail it was different.

[Pg 87]

THE BABY CANARY

A WAY back last spring, before the Ranger found the little bear, the canaries had started a nest of five pretty eggs, and there the mother bird had sat, keeping them warm, while her mate sang to her.

By and by the children noticed a movement under the mother bird’s wing. Then a tiny yellow head came poking out through her feathers. When she got off the next day to eat, they noticed a hole no bigger than a pin head in the shell of one of the remaining eggs, then a yellow bill was thrust through, and withdrawn again. After that there was a pecking and a struggling inside the shell, and the next thing they knew, out came the funniest baby they had ever seen, with pieces of the shell still sticking to him.

[Pg 88]

Naked he was, with eyes not yet open, and a head so large for his slender neck that he could hardly hold it up. His legs sprawled weakly from beneath him, and his toes were so fragile that it seemed as if they must break if he tried to stand on them.

The bird hatched the day before was the same. The next day came another, and the day after that, another. The fifth egg did not hatch, and the mother bird shoved it out of the nest with her foot.

My, how busy those four fledglings did keep their parents for the next two weeks! Opening their wide mouths till one could see right down their throats, they would just sit there in the nest all day long eating what their parents brought them,—chopped egg and cracker, and baby bird seed, which the big birds first cracked for them in their own bills. It seemed as if there was no getting those young canaries filled. Every time one got a mouthful, he would flap his pin-feathery wings and cry “tweet-tweet-tweet-tweet,” till one wondered how so much voice could issue from such a tiny bird.

[Pg 89]

By the time the little ones were able to stand on the roost in a row, there were only three, for one had lost his balance as he stood on the edge of the nest, and all the flapping of his nearly naked wings had not served to break his fall.

Chirping their high-pitched food call, the remaining birdlings would flap wings that just began to show a row of teeny, pale yellow feathers along the edges.

Then a dreadful thing happened. A great brown butcher bird lived in a thorn bush not far away. This horrid creature lived on mice and little birds, and like the witch of the fairy tale, hung his victims on the thorns till he was ready to eat them.

One day the children thought the canaries would like to be out of doors, and hung the cage in a pine tree. An hour later that butcher bird had reached in through the bars of the cage and bitten the heads off the whole canary family save one little one. He had been in the nest out of reach.

The little girl cried her heart out. But they decided they would do their best to bring that fledgling up by hand. By this[Pg 90] time he was just about big enough to have gone to bed in a teaspoon. His wings were fringed with pale yellow, and he would perch on a fore finger and open his mouth for them to feed him, chirping shrilly and flapping his wings with all his might to keep from falling off.

The boy gave him just the tiniest bits at a time on the end of a flattened twig. Soon he was able to eat for himself. At night he had to be snuggled into a warm nest made of an old piece of flannel, and every day his cage was set in the sunshine and he was given a saucer of clean, warm water to bathe in. My, how he did love to splash.