*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 69956 ***

The many sections of this volume are presented in order of the month and

day, regardless of the year, beginning with January 1.

The Contents lists the topics alphabetically, and refers to

a date (month and day) rather than a page number. These descriptions

do not necessarily exactly match the title of the sections verbatim,

and the same section occasionally appears twice, with different descriptions.

There is a more detailed index at the end of the volume, with page references.

To facilitate navigation, the dates in the Contents are linked

to the correct topics.

The few footnotes have been collected at the end of each section, and are

linked for ease of reference.

Basic information from the titlepage has been added to the blank green cover

and, so enhanced, is added to the public domain.

Minor errors, attributable to the printer, have been corrected. Please

see the transcriber’s note at the end of this text

for details regarding the handling of any issues encountered

during its preparation.

Any corrections are indicated using an underline

highlight. Placing the cursor over the correction will produce the

original text in a small popup.

Any corrections are indicated as hyperlinks, which will navigate the

reader to the corresponding entry in the corrections table in the

note at the end of the text.

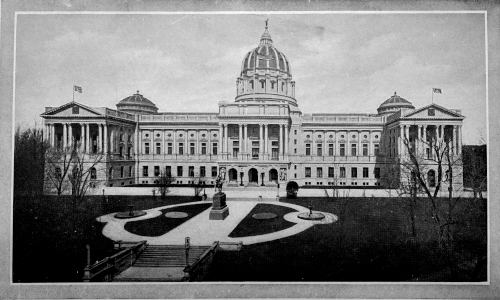

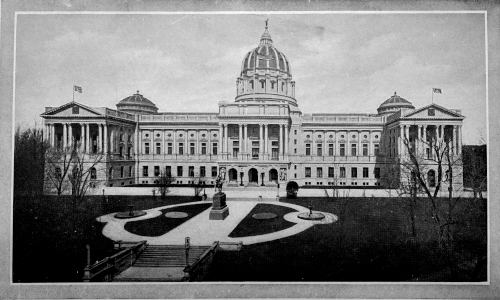

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE CAPITOL BUILDING

I

DAILY STORIES

OF

PENNSYLVANIA

Prepared for publication in the leading daily

newspapers of the State by

FREDERIC A. GODCHARLES

Milton, Pennsylvania

FORMER REPRESENTATIVE IN THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY, STATE

SENATOR, DEPUTY SECRETARY OF THE COMMONWEALTH,

MEMBER HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA,

HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF UNION COUNTY,

HISTORICAL SOCIETY LYCOMING COUNTY,

AND OTHERS

Author of Freemasonry in Northumberland

and Snyder Counties, Pennsylvania

Copyrighted 1924

BY

FREDERIC A. GODCHARLES

Printed in the United States of America

These Daily Stories of Pennsylvania

are dedicated to

MY MOTHER

THROUGH WHOM I AM DESCENDED FROM

SOME OF ITS EARLIEST PIONEERS AND

PATRIOTS AND FROM WHOM I INHERITED

MUCH LOVE FOR THE STORY OF MY NATIVE

STATE.

iv

PRINCIPAL SOURCES UTILIZED

- Archives of Pennsylvania.

- Colonial Records of Pennsylvania.

- Hazard’s Annals of Philadelphia.

- Egle’s History of Pennsylvania.

- Gordon’s History of Pennsylvania.

- Cornell’s History of Pennsylvania.

- Day’s Historical Collection.

- Shimmel’s Pennsylvania.

- Frontier Forts of Pennsylvania.

- Pennypacker’s Pennsylvania The Keystone.

- The Shippen Papers.

- Loudon’s Indian Narratives.

- Sachse’s German Pietists.

- Rupp’s County Histories.

- Magazine of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

- American Magazine of History.

- Egle’s Notes and Queries.

- Harvey’s Wilkes Barre.

- Miner’s History of Wyoming.

- Jenkin’s Pennsylvania Colonial and Federal.

- Scharf and Westcott’s History of Philadelphia.

- Lossing’s Field Book of the Revolution.

- On the Frontier with Colonel Antes.

- Meginness’ Otzinachson.

- Linn’s Annals of Buffalo Valley.

- Hassler’s Old Westmoreland.

- Fisher’s Making of Pennsylvania.

- McClure’s Old Time Notes.

- Parkman’s Works.

- Shoemaker’s Folklore, Legends and Mountain Stories.

- Jones’ Juniata Valley.

- Prowell’s York County.

- Smull’s Legislative Hand Book.

- Journal of Christopher Gist.

- Journal of William Maclay.

- Journal of Samuel Maclay.

- Journal of Rev. Charles Beatty.

- Scrap Books of Thirty Years’ Preparation.

- Annual Reports State Federation of Historical Societies.

- And others.

v

INTRODUCTION

The Daily Stories of Pennsylvania were published in the newspapers

under the title “Today’s Story in Pennsylvania

History,” and there has been a genuine demand for their publication

in book form.

During all his active life the author has been impressed

with the unparalleled influence of Pennsylvania in the development

of affairs which have resulted in the United States

of America.

Since youth he has carefully preserved dates and facts of historical

importance and has so arranged this data that it made possible these

stories, each of which appeared on the actual anniversary of the event or

person presented.

This idea seems to have been a new venture in journalism and the

enterprising editors of our great Commonwealth, contracted for and

published “Today’s Story in Pennsylvania History,” and their readers

have manifested a deep interest to these editors and to the author.

Soon as there developed a demand for the collection of stories in

book form, the author determined to add a story for the fifty-three

Sunday dates, which have not before been published, and to arrange the

entire collection according to the calendar, and not chronologically. In

this arrangement they can be more readily found when desired for quick

reference or study.

These stories have been prepared from many different sources, not

a few from original manuscripts, or from writings which have not been

heretofore used; many are rewritten from familiar publications, but too

frequent reference to such sources has been omitted as these would

encumber the foot of so many pages that the stories would require a

much larger book or a second volume, either of which would be objectionable

and unnecessary.

It is a hopeless task to acknowledge the many courtesies received,

but in some slight manner the author must recognize the friendship of

Prof. Hiram H. Shenk, custodian of records in the State Library, who

so generously placed him in touch with many valuable papers, books

and manuscripts, and in many ways assisted in much of the historical

data. The names of Dr. Thomas L. Montgomery, Librarian Historical

Society of Pennsylvania; Dr. George P. Donehoo, former State

Librarian; the late Julius Sachse; the late Dr. Hugh Hamilton; former

Governor Hon. Edwin S. Stuart and Colonel Henry W. Shoemaker,

each of whom contributed such assistance as was requested. The

valuable help extended by officers and assistants in the State Library,

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania, The Wyoming Historical and

Geological Society, The Historical Society of Dauphin County, The

Lycoming County Historical Society and other similar organizations

deserves particular mention and gratitude.

It is also a matter of intense satisfaction that the author acknowledges

the following progressive newspapers which carried the stories,

viand the editors of which so materially assisted by their personal

attention in making his work such an unusual success: Allentown

Chronicle and News, Altoona Mirror, Berwick Enterprise, Bethlehem

Globe, Bloomsburg Morning Press, Carlisle Sentinel, Chester Times,

Coatesville Record, Danville Morning News, Doylestown Democrat,

Du Bois Courier, Easton Free Press, Ellwood City Ledger, Erie Dispatch-Herald,

Farrell News, Greensburg Record, Greenville Advance

Argus, Harrisburg Evening News, Hazleton Standard-Sentinel, Indiana

Gazette, Johnstown Tribune, Lancaster Intelligencer, Lansford Evening

Record, Mauch Chunk Daily News, Meadville Tribune-Republican,

Milton Evening Standard, Mount Carmel Item, Norristown Times-Herald,

Philadelphia Public Ledger, Pittsburgh Chronicle-Telegraph,

Pittston Gazette, Pottsville Republican, Reading Herald-Telegram,

Ridgway Record, Scranton Republican, Shamokin Dispatch, Sharon

Herald, Shenandoah Herald, Stroudsburg Times-Democrat, Sunbury

Daily Item, Tamaqua Courier, Titusville Herald, Uniontown Herald,

Waynesboro Record-Herald, Wilkes Barre Times-Leader, Williamsport

Sun, and York Gazette.

Frederic A. Godcharles.

Milton, Penna., September 4, 1924.

vii

CONTENTS

| Adoption of Federal Constitution |

Sept. 17 |

| Allummapees, King of Delaware Indians |

Aug. 12 |

| American, John Penn, the |

Jan. 29 |

| Antes, Lt. Col. John Henry |

May 13 |

| Antes, Pious Henry |

Jan. 12 |

| Anti-Masonic Investigation |

Dec. 4 |

| Anti-Masonic Outbreak in Pennsylvania |

Aug. 18 |

| Anti-Masonic Period Terminates |

Dec. 4 |

| Armed Force to Forks of Ohio |

Feb. 17 |

| Armstrong, Captain John, Murdered |

April 9 |

| Armstrong Destroys Kittanning |

Sept. 8 |

| Arnold Arrested, General Benedict |

Feb. 3 |

| Asylum, the French Settlement |

Dec. 20 |

| Attempted Slaughter of Indians at Wichetunk |

Oct. 12 |

| Attempt to Navigate Susquehanna Fails |

April 27 |

| Baldwin, Matthias |

Jan. 8 |

| Bank, First in America |

Dec. 31 |

| Bank of North America |

Jan. 7 |

| Bard Family Captured by Indians |

April 13 |

| Bartram, John |

March 23 |

| Battle of Brandywine |

Sept. 11 |

| Battle of Bushy Run |

Aug. 6 |

| Battle of Fallen Timbers |

Aug. 20 |

| Battle of Germantown |

Oct. 4 |

| Battle of Gettysburg |

July 1 and 2 |

| Battle of the Kegs |

Jan. 5 |

| Battle of Lake Erie |

Sept. 10 |

| Battle of Minisinks |

July 22 |

| Battle of Monongahela |

July 9 |

| Battle of Muncy Hills |

Aug. 26 |

| Battle of Trenton |

Dec. 26 |

| Beatty, Rev. Charles, and Old Log College |

Jan. 22 |

| Bedford County Erected |

March 9 |

| Beissel, John Conrad |

July 6 |

| Bell for State House |

June 2 |

| Berks County Outrages |

Nov. 14 |

| Bethlehem as Base Hospital in Revolution |

March 27 |

| Bi-centennial |

Oct. 21 |

| Bills of Credit Put State on Paper Money Basis |

March 2 |

| Binns, John |

Nov. 16 |

| Binns, John |

June 24 |

| Binns, John, Fights Duel with Samuel Stewart |

Dec. 14 |

| Black Boys |

Nov. 26 |

| Bloody Saturday |

Aug. 14 |

| Bloody Election |

Oct. 1 |

| Boone, Daniel |

Oct. 22 |

| Border Troubles Reach Provincial Authorities |

May 14 |

| Border Troubles with Maryland |

May 25 |

| Border Troubles with Thomas Cresap |

Nov. 23 |

| Boundary Disputes Settled |

Nov. 5 |

| Boundary Dispute with Maryland |

May 10 |

| Boundary Dispute with Virginia |

Sept. 23 |

| Bounty for Indian Scalps |

April 14 |

| Bouquet Defeats Indians at Bushy Run |

Aug. 6 |

| Bouquet Relieves Fort Pitt |

Aug. 10 |

| Boyd, Captain John |

Feb. 22 |

| Boyd, Lieutenant Thomas Murdered |

Sept. 13 |

| Braddock’s Defeat |

July 9 |

| Braddock’s Road Begun |

May 6 |

| Braddock’s Troops Arrive |

Feb. 20 |

| Brady, Captain James, Killed |

Aug. 8 |

| Brady, Captain John |

April 11 |

| British and Indians Attack and Destroy Fort Freeland |

July 28 |

| British Destroy Indian Towns |

Aug. 25 |

| British Evacuate Philadelphia |

June 17 |

| British Invest Philadelphia |

Sept. 26 |

| Brodhead Arrives at Fort Pitt to Fight Indians |

Mar. 5 |

| Broadhead Destroys Coshocton |

April 20 |

| Brodhead Makes Indian Raid |

Aug. 11 |

| Brown, General Jacob |

Feb. 24 |

| Brulé, Etienne |

Oct. 24 |

| Buchanan, President James |

April 23 |

| Buck Shot War |

Dec. 5 |

| Bucks County Homes Headquarters for Washington and Staff |

Dec. 8 |

| Bull, Ole |

Feb. 5 |

| Bull, Gen John |

June 1; Aug. 9 |

| Cameron, Colonel James |

July 21 |

| Cameron Defeats Forney for Senate |

Jan. 13 |

| Cammerhoff, Bishop John Christopher |

Jan. 6 |

| Camp Curtin |

April 18 |

| Canal Lottery, Union |

April 17 |

| Canals Projected in Great Meeting |

Oct. 20 |

| Canal System Started |

Feb. 19 |

| Capitol, Burning of |

Feb. 2 |

| Capitol, New State |

Jan. 2 |

| viiiCapital, Removed to Harrisburg |

Feb. 21 |

| Capture of Timothy Pickering |

June 26 |

| Carlisle Indian School |

July 31 |

| Carlisle Raided by Rebels |

June 27 |

| Carey, Matthew |

Sept. 16 |

| Chambers-Rieger Duel |

May 11 |

| Chambersburg Sacked and Burned by Rebels |

July 30 |

| Charter for City of Pittsburgh |

Mar. 18 |

| Charter for Pennsylvania Received by William Penn |

Mar. 4 |

| Chester County, Deed for |

June 25 |

| Church West of Alleghenies, First |

June 20 |

| Civil Government Established in Pennsylvania |

Aug. 3 |

| Clapham Builds Fort Halifax |

June 7 |

| Clapham Family Murdered by Indians |

May 28 |

| Clark Drafts Troops for Detroit Expedition |

Mar. 3 |

| Coal First Burned in a Grate |

Feb. 11 |

| Cochran, Dr. John |

Sept. 1 |

| Cooke & Co. Fail, Jay |

Sept. 18 |

| Cooper Shop and Union Saloon Restaurants |

May 27 |

| Commissioners Appointed to Purchase Indian Lands |

Feb. 29 |

| Conestoga Indians Killed by Paxtang Boys |

Dec. 27 |

| Confederate Raids into Pennsylvania |

Oct. 10 |

| Congress Threatened by Mob of Soldiers |

June 21 |

| Constitutional Convention of 1790 |

Nov. 21 |

| Constitution of 1790 |

March 24; Sept. 2 |

| Constitution of United States Adopted |

Sept. 17 |

| Continental Congress First Meets in Philadelphia |

Sept. 5 |

| Conway Cabal |

Nov. 28 |

| Cornerstones Laid for Germantown Academy |

April 21 |

| Council of Censors |

Nov. 13 |

| Cornwallis Defeats Americans at Brandywine |

Sept. 11 |

| Counties, First Division into |

Feb. 1 |

| Counties of Pennsylvania Organized |

Mar. 10 |

| Courts, Early Records |

Jan. 11 |

| Court Moved from Upland to Kingsesse |

June 8 |

| Cruel Murder of Colonel William Crawford |

June 11 and 12 |

| Crawford Burned at Stake by Indians |

June 12 |

| Crawford Captured by Indians, Colonel William |

June 11 |

| Cresap’s Invasion |

Nov. 23 |

| Croghan, George, King of Traders |

May 7 |

| Crooked Billet Massacre |

May 1 |

| Curtin Inaugurated Governor |

Jan. 15 |

| |

|

|

| Darrah, Lydia |

Dec. 11 |

| Davy, the Lame Indian |

May 30 |

| Declaration of Independence |

July 4 |

| Deed for Chester County |

June 25 |

| Deed for Province Obtained by Penn |

Aug. 31 |

| Denny Succeeded by Governor Hamilton |

Oct. 9 |

| De Vries Arrives on Delaware |

Dec. 6 |

| Dickinson, John |

Nov. 10 |

| Disberry, Joseph, Thief |

Nov. 22 |

| Doan Brothers, Famous Outlaws |

Sept. 24 |

| Donation Lands |

Mar. 12 |

| Drake Brings in First Oil Well |

Aug. 28 |

| Duel, Binns-Stewart |

Dec. 14 |

| Duel in Which Capt. Stephen Chambers is Killed |

May 11 |

| Dutch Gain Control of Delaware |

Sept. 25 |

| |

|

|

| Easton, Indian Conference at |

Jan. 27; Aug. 7; Oct. 8 |

| Education Established, Public School |

Mar. 11 |

| End of Indian War |

Oct. 23 |

| Ephrata Society |

July 6 |

| Era of Indian Traders |

Aug. 12 |

| Erie County Settled |

Feb. 28 |

| Erie Riots |

Dec. 9 |

| Erie Triangle |

April 3 |

| Etymology of Counties |

Aug. 30 |

| Europeans Explore Waters of Pennsylvania |

Aug. 27 |

| Ewell Leads Raid on Carlisle |

June 27 |

| Excise Laws, First |

Mar. 17 |

| Expedition Against Indians |

Nov. 4; Nov. 8 |

| Exploits of David Lewis, the Robber |

March 25 and 26 |

| |

|

|

| Farmer’s Letters, Dickinson’s |

Nov. 10 |

| Federal Constitution Ratified by Pennsylvania |

Dec. 12 |

| Federal Party Broken Up |

Nov. 29 |

| Fell Successfully Burns Anthracite Coal |

Feb. 11 |

| Fires, Early, in Province |

Dec. 7 |

| First Bank in America |

Dec. 31 |

| First Bank in United States |

Jan. 7 |

| First Church in Province |

Sept. 4 |

| First Church West of Allegheny Mountains |

June 20 |

| First Continental Congress |

Sept. 5 |

| First Excise Laws |

Mar. 17 |

| First Fire Company in Province |

Dec. 7 |

| ixFirst Forty Settlers Arrive at Wyoming |

Feb. 8 |

| First Governor of Commonwealth |

Dec. 21 |

| First Jury Drawn in Province |

Nov. 12 |

| First Law to Educate Poor Children |

Mar. 1 |

| First Magazine in America |

Feb. 13 |

| First Massacre at Wyoming |

Oct. 15 |

| First Mint in United States |

April 2 |

| First Oil Well in America |

Aug. 28 |

| First Newspaper in Province |

Dec. 22 |

| First Newspaper West of Allegheny Mountains |

July 29 |

| First Northern Camp in Civil War |

April 18 |

| First Paper Mill in America |

Feb. 18 |

| First Permanent Settlement |

Sept. 4 |

| First Post Office |

Nov. 27 |

| First Protest Against Slavery |

Feb. 12 |

| First Settlement of Germantown |

Oct. 6 |

| First Theatrical Performances |

April 15 |

| First Troops to Reach Washington at Cambridge |

July 25 |

| First Union Officer Killed in Civil War |

July 21 |

| Flag, Story of |

June 14 |

| Flight of Tories from Fort Pitt |

Mar. 28 |

| Forbes Invests Fort Duquesne |

Nov. 25 |

| Forney Defeated for U. S. Senate by General Simon Cameron |

Jan. 13 |

| Forrest, Edwin |

April 7 |

| Forrest Home for Actors |

April 7 |

| Fort Augusta |

Mar. 29 |

| Fort Freeland Destroyed by British and Indians |

July 28 |

| Fort Granville Destroyed |

Aug. 1 |

| Fort Halifax |

June 7 |

| Fort Henry |

Jan. 25 |

| Fort Hunter |

Jan. 9 |

| Fort Laurens Attacked by Simon Girty |

Feb. 23 |

| Fort Mifflin Siege Begins |

Sept. 27 |

| Fort Montgomery |

Sept. 6 |

| Fort Patterson |

Oct. 2 |

| Fort Pitt First So Called |

Nov. 25 |

| Forts Built by Colonel Benjamin Franklin |

Dec. 29 |

| Fort Swatara |

Oct. 30 |

| Fort Wilson Attacked by Mob |

Oct. 5 |

| Frame of Government |

April 25 |

| Francis, Colonel Turbutt, Leads Troops to Wyoming |

June 22 |

| Franklin, Benjamin |

Jan. 17 |

| Franklin at Carlisle Conference |

Sept. 22 |

| Franklin at French Court |

Dec. 28 |

| Franklin Builds Chain of Forts |

Dec. 29 |

| Franklin County Erected |

Sept. 9 |

| Franklin Sails for England |

Nov. 8 |

| Free Society of Traders |

May 29 |

| French and Indians Destroy Fort Granville |

Aug. 1 |

| French and Indian War |

May 5 |

| French and Indian War Started |

Feb. 20 |

| French Defeat Major Grant at Fort Duquesne |

Sept. 14 |

| French Plant Leaden Plates |

June 15 |

| Frenchtown, or Asylum Founded by Refugees |

Dec. 20 |

| FrietchieFrietchie, Barbara |

#Dec. 18:c1218⑲ |

| Fries Rebellion |

Mar. 14 |

| Fulton, Robert |

Aug. 17 |

| |

|

|

| Gallatin, Albert |

Jan. 20 |

| Galloway, Joseph |

Aug. 29 |

| Garrison at Fort Pitt Relieved by Colonel Henry Bouquet |

Aug. 10 |

| German Pietists Organize Harmony Society |

Feb. 15 |

| Germantown Academy |

April 21 |

| Gettysburg Address, Lincoln’s |

Nov. 19 |

| Gnadenhutten Destroyed |

Nov. 24 |

| Gnadenhutten (Ohio) Destroyed |

Mar. 8 |

| Gibson’s Lambs |

July 16 |

| Gilbert Family in Indian Captivity |

Aug. 22 |

| Girard, Captain Stephen |

May 21 |

| Girty Attacks Fort Laurens |

Feb. 23 |

| Girty, Simon, Outlaw and Renegade |

Jan. 16 |

| Gordon, Governor Patrick |

Aug. 5 |

| Grant Leaves Philadelphia on World Tour |

Dec. 16 |

| Grant Suffers Defeat at Fort Duquesne |

Sept. 14 |

| Great Runaway |

July 5 |

| Groshong’s, Massacre at Jacob |

May 16 |

| |

|

|

| Hambright’s Expedition Against Great Island |

Nov. 4 |

| |

|

|

| Hamilton, James, Becomes Governor |

Oct. 9 |

| Hand, General Edward |

Sept. 3 |

| Hand’s Expedition Moves from Fort Pitt |

Oct. 19 |

| Hannastown Burned |

July 13 |

| Hannastown Jail Stormed by Mob |

Feb. 7 |

| Harmony Society |

Feb. 15 |

| Harris, John |

Oct. 25 |

| Hartley’s Expedition Against Indians |

Sept. 7 |

| Hiester, Governor Joseph |

Nov. 18 |

| Hiokatoo, Chief |

Nov. 20 |

| Hospital at Bethlehem, Base |

Mar. 27 |

| Hot Water War |

Mar. 14 |

| Howe Moves Against Philadelphia |

July 23 |

| x |

|

|

| Impeachment, Supreme Court Judges Yeates, Smith and Shippen |

Dec. 13 |

| Inland Waterways Meeting |

Oct. 20 |

| Inquisition on Free Masonry a Fiasco |

Dec. 19 |

| Inauguration of Governor Curtin |

Jan. 15 |

| Inauguration, Governor Thomas Mifflin |

Dec. 21 |

| Inauguration of Governor Packer |

Jan. 19 |

| Indian Conference at Easton |

Jan. 27; Aug. 7; Oct. 8 |

| Indian Conference at Harris Ferry |

April 1 |

| Indian Conference at Philadelphia |

June 30; Aug. 16 |

| Indian Conference at Lancaster |

Apr. 1 |

| Indian School at Carlisle |

July 31 |

| Indian Shoots at Washington |

Nov. 15 |

| Indian Traders, Era of |

Aug. 12 |

| Indian War Ends |

Oct. 23 |

| Indians Capture Assemblyman James McKnight |

April 26 |

| Indians Commit Outrages in Berks County |

Nov. 14 |

| Indians Defeated at Fallen Timbers |

Aug. 20 |

| Indians Destroy Widow Smith’s Mill |

July 8 |

| Indians Kill Major John Lee and Family |

Aug. 13 |

| Indians Murder Colonel William Clapham and Family |

May 28 |

| Indians Ravage McDowell Mill |

| Settlement |

Oct. 31 |

| Indians Slaughtered at Gnadenhutten, Ohio |

Mar. 8 |

| |

|

|

| Jail at Hannastown Stormed |

Feb. 7 |

| Jennison, Mary, Capture of |

April 5 |

| Johnstown Flood |

May 31 |

| Journey of Bishop Cammerhoff |

Jan. 6 |

| Judges Yeates, Shippin and Smith Impeached |

Dec. 13 |

| |

|

|

| Kegs, Battle of the |

Jan. 5 |

| Keith, Sir William |

Nov. 17 |

| Kelly, Colonel John |

April 8 |

| Kittanning Destroyed by Colonel John Armstrong |

Sept. 8 |

| Know Nothing Party and Pollock |

June 5 |

| |

|

|

| Labor Riots After Civil War |

Sept. 18 |

| Lacock, General Abner |

April 12 |

| Lafayette Retreats at Matson’s Ford |

May 20 |

| Leaning Tower, John Mason’s |

April 22 |

| Lee Family, Massacre of |

Aug. 13 |

| Lewis, David, The Robber |

March 25 and 26 |

| Lewistown Riot |

Sept. 12 |

| Liberty Bell Hung in State House |

June 2 |

| Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address |

Nov. 19 |

| Littlehales Murdered by Mollie Maguires |

March 15 |

| Lochry Musters Troops in Westmoreland County |

Aug. 2 |

| Locomotive, First Successful |

Jan. 8 |

| Logan, Hon. James |

Oct. 28 |

| Logan’s Family Slain, Chief |

May 24 |

| Log College, Old |

Jan. 22 |

| Lost Sister of Wyoming |

Nov. 2 |

| Lottery for Union Canal |

April 17 |

| Lower Counties in Turmoil |

Nov. 1 |

| Lumbermen’s War at Williamsport |

July 10 |

| Lycans, Andrew |

Mar. 7 |

| |

|

|

| Maclay, Samuel |

Jan. 4 |

| Maclay, Hon. William |

July 20 |

| Magazine, First in America |

Feb. 13 |

| Major Murdered by Mollie Maguires |

Nov. 3 |

| Maguires, Mollie |

Jan. 18; Feb. 1#; March 15; May 4; Aug. 14; Nov. 3; Dec. 2 |

| Mason & Dixon Boundary Line |

Dec. 30 |

| Mason, John, and His Leaning Tower |

April 22 |

| Massacre Along Juniata River |

Jan. 28 |

| Massacre at Conococheague Valley |

July 26 |

| Massacre at Crooked Billet |

May 1 |

| Massacre at French Jacob Groshong’s |

May 16 |

| Massacre at Mahanoy Creek |

Oct. 18 |

| Massacre at Patterson’s Fort |

Oct. 2 |

| Massacre at Penn’s Creek |

Oct. 16 |

| Massacre at Standing Stone |

June 19 |

| Massacre at Williamsport |

June 10 |

| Massacre at Wyoming |

July 3 |

| Massacre of Americans at Paoli |

Sept. 20 |

| McAllister, Colonel Richard |

Oct. 7 |

| McDowell’s Mills, Outrages at |

Oct. 31 |

| McFarlane, Andrew |

Feb. 25 |

| McKee, Captain Thomas |

Jan. 24 |

| McKnight, James, Captured by Indians |

April 26 |

| Meschianza |

May 18 |

| Mexican War |

Dec. 15 |

| Mifflin, General Thomas |

Jan. 21 |

| Mifflin, General Thomas, Inaugurated Governor |

Dec. 21 |

| Military Laws Repealed |

Mar. 20 |

| Militia Organization |

Jan. 23 |

| Minisink Battle |

July 22 |

| Mint, First in United States |

April 2 |

| Minuit, Peter, Arrives |

Mar. 30 |

| Mob Attacks Court House at Lewistown |

Sept. 12 |

| xiMob Attacks Home of James Wilson |

Oct. 5 |

| Mob Threatens Congress |

June 21 |

| Monmouth, Battle of |

June 28 |

| Montour, Madame |

Sept. 15 |

| Moravian Church Established when Mob Assails Pastor |

July 27 |

| Moravian Indian Mission at Wyalusing |

May 23 |

| Moravians Massacred at Gnadenhutten |

Nov. 24 |

| Moravians Visit Great Island |

July 11 |

| More, Dr. Nicholas |

May 15 |

| Morris, Robert |

Jan. 31 |

| Mother Northumberland, Old |

Mar. 21 |

| Mott, Lucretia |

Jan. 3 |

| Murder of Sanger and Uren by Mollie Maguires |

Feb. 10 |

| Mutiny in Pennsylvania Line |

Jan. 1 |

| |

|

|

| Navy of Pennsylvania |

May 8 |

| Negro Boy Starts Race Riot in Philadelphia |

July 12 |

| Negro School at Nazareth Started by Whitefield |

May 3 |

| Neville, Captain John, Sent to Fort Pitt |

July 17 |

| News of Revolution Reaches Philadelphia |

April 24 |

| New Sweden, Governor Printz Arrives |

Feb. 16 |

| Northumberland County Erected |

Mar. 21 |

| |

|

|

| Oil Discovered at Titusville |

Aug. 28 |

| |

|

|

| Pack Trains Attacked at Fort Loudoun |

Mar. 6 |

| Paoli Massacre |

Sept. 20 |

| Paper Mill, First in America |

Feb. 18 |

| Paper Money Basis |

Mar. 2 |

| |

| Pastorius and Germans Settle at Germantown |

Oct. 6 |

| Patent for Province Given Duke of York |

June 29 |

| Patriotic Women Feed Soldiers in Civil War |

May 27 |

| Pattison to Burning of Capitol |

Feb. 2 |

| Paxtang Boys Kill Conestoga Indians |

Dec. 27 |

| Pence, Peter |

Mar. 22 |

| Penn, John |

Feb. 9 |

| Penn (John) Succeeds Richard Penn as Governor |

Feb. 4 |

| Penn, John, “The American” |

Jan. 29 |

| Penn Lands in His Province |

Oct. 29 |

| Penn Obtains Deed for Province |

Aug. 31 |

| Penn Receives Charter for Pennsylvania |

Mar. 4 |

| Penn Sails for England |

Nov. 1 |

| Penn, William |

Oct. 14 |

| Penn’s Creek Massacre |

Oct. 16 |

| Penn’s First Wife, John |

June 6 |

| Penn’s Frame of Government |

April 25 |

| Penn’s Second Visit to Province |

Dec. 1 |

| Penn’s Trip Through Pennsylvania |

April 6 |

| Pennamites Driven from Wyoming |

Aug. 15 |

| Pennsylvania in Battle of Monmouth |

June 28 |

| Pennsylvania Line, Mutiny in |

Jan. 1 |

| Pennsylvania Navy in Revolution |

May 8 |

| Pennsylvanian Proposes Railway to Pacific |

June 23 |

| Pennsylvania Railroad Organized |

Mar. 31 |

| Pennsylvania Ratifies Federal Constitution |

Dec. 12 |

| Pennsylvania Reserve Corps |

April 19 |

| Perry Wins Victory on Lake Erie |

Sept. 10 |

| Philadelphia Evacuated by British |

June 17 |

| Philadelphia Invested by British |

Sept. 26 |

| Philadelphia Riots |

July 7 |

| Pickering, Colonel Timothy |

June 26 |

| Pitcher, Molly |

Oct. 13 |

| Pittsburgh Gazette |

July 29 |

| Pittsburgh Receives City Charter |

Mar. 18 |

| Pittsburgh Railroads Fight for Entrance |

Jan. 14 |

| Plot to Kidnap Governor Snyder |

Nov. 9 |

| Pluck, Colonel John, Parades |

May 19 |

| Plunket Defeated by Yankees |

Dec. 25 |

| Plunket Defeats Yankees |

Sept. 28 |

| Plunket’s Expedition Against Yankees |

Dec. 24 |

| Pollock and Know Nothing Party |

June 5 |

| Pontiac’s Conspiracy |

May 17 |

| Post, Christian Frederic |

April 29 |

| Post Office, Pioneer |

Nov. 27 |

| Powder Exploit, Gibson’s |

July 16 |

| Powell, Morgan, Murdered by Mollie Maguires |

Dec. 2 |

| Presqu’ Isle Destroyed by Indians |

June 4 |

| Preston, Margaret Junkin |

Mar. 19 |

| Priestley, Dr. Joseph |

Feb. 6 |

| Printz, Johan |

Feb. 16 |

| Provincial Conference |

June 18 |

| Provincial Convention |

July 15 |

| Provincial Troops March Against Wyoming Settlements |

June 22 |

| Public Education Established |

Mar. 11 |

| Purchase Caused Boundary Dispute |

June 9 |

| |

|

|

| Quakers Protest vs. Slavery |

Feb. 12 |

| Quick, Tom |

July 19 |

| |

|

|

| Race Riot in Philadelphia |

July 12 |

| xiiRailroads Fight to Enter Pittsburgh |

Jan. 14 |

| Reading Railroad Organized |

April 4 |

| Rebels Raid on Carlisle |

June 27 |

| Rebels Sack and Burn Chambersburg |

July 30 |

| Records of Early Courts |

Jan. 11 |

| Reign of Mollie Maguire Terror Ended |

Jan. 18 |

| Riots at Philadelphia |

July 7 |

| Rittenhouse, William |

Feb. 18 |

| Ross, Betsy |

Jan. 30 |

| Ross, George |

July 14 |

| Ruffians Mob Pastor |

July 27 |

| Runaway, Great |

July 5 |

| |

|

|

| Sailors Cause Bloody Election |

Oct. 1 |

| Saturday Evening Post |

Aug. 4 |

| Sawdust War |

July 10 |

| School Law, First |

Mar. 1 |

| Schoolmaster and Pupils Murdered by Indians |

July 26 |

| Second Constitution for State |

Mar. 24 |

| Settlers Massacred at Lycoming Creek |

June 10 |

| Settlers Slay Chief Logan’s Family |

May 24 |

| Shawnee Indians Murder Conestoga Indians |

April 28 |

| Shikellamy, Chief |

Dec. 17 |

| Sholes, Christopher L., Inventor of typewriter |

Feb. 14 |

| Siege at Fort Mifflin Opens |

Sept. 27 |

| Slate Roof House |

Jan. 29 |

| Slavery, Quakers Protest Against |

Feb. 12 |

| Slocum, Francis, Indian Captive |

Nov. 2 |

| Smith, Captain James |

Nov. 26 |

| Smith, Captain John |

Sept. 29; July 24 |

| Smith, Colonel Matthew |

Mar. 13; [Oct. 10]. |

| Smith’s Mill, Widow |

July 8 |

| Snyder Calls for Troops in War of 1812 |

Aug. 24 |

| Snyder Escapes Kidnapping |

Nov. 9 |

| Springettsbury Manor |

June 16 |

| Squaw Campaign |

May 2 |

| Stamp Act |

Nov. 7 |

| Steamboat, Robert Fulton’s |

Aug. 17 |

| Steamboat “Susquehanna” Explodes |

April 27 |

| Stevens, Inquiry About Free Masonry |

Dec. 19 |

| Story of “Singed Cat” |

Aug. 4 |

| Stump, Frederick |

Jan. 10 |

| Sullivan’s Expedition Against Six Nations |

May 26 |

| Sunbury & Erie Railroad |

Oct. 17 |

| Susquehanna Company |

Feb. 8 |

| Susquehanna Company Organized |

July 18 |

| Swedes Come to Delaware River |

Mar. 30 |

| Swedes Make First Permanent Settlement |

Sept. 4 |

| |

|

|

| Tedyuskung Annoys Moravians at Bethlehem |

Aug. 21 |

| Tedyuskung at Easton Conference |

Oct. 8 |

| Tedyuskung Defends Himself at Easton Council |

Aug. 7 |

| Tedyuskung, King of Delaware Indians |

April 16 |

| Theatrical Performances, First |

April 15 |

| Thief Joseph Disberry |

Nov. 22 |

| Thompson’s Battalion of Riflemen, Colonel William |

July 25 |

| Threatened War with France |

Nov. 11 |

| Tories Flee from Fort Pitt |

Mar. 28 |

| Tories of Sinking Valley |

April 10 |

| Transit of Venus |

June 3 |

| Treaty of Albany |

Oct. 26 |

| Treaty Ratified by Congress, Wayne’s |

Dec. 3 |

| Trent, Captain William |

Feb. 17 |

| Trimble, James |

Jan. 26 |

| TulliallanTulliallan or Story of John Penn’s First Wife |

June 6 |

| Turmoil in Lower Counties |

Nov. 1 |

| Typewriter, Sholes Invents the |

Feb. 14 |

| |

|

|

| Unholy Alliance with Indians |

Sept. 21 |

| Upland Changed to Chester |

Oct. 29 |

| |

|

|

| Venus, Observation of Transit of |

June 3 |

| Veterans French and Indian War Organize |

April 30 |

| Vincent, Bishop John Heyl |

May 9 |

| Walking Purchase |

Sept. 19 |

| War of 1812 |

Aug. 24 |

| War of 1812 Begun |

May 12 |

| Washington and Whisky Insurrection |

Sept. 30 |

| Washington at Logstown |

Nov. 30 |

| Washington Leads Troops in Whisky Insurrections |

Oct. 3 |

| Washington Shot at by Indians |

Nov. 15 |

| Washington to Command Troops in War with France |

Nov. 11 |

| Washington Uses Bucks County Homes for Headquarters |

Dec. 8 |

| Washington, Lady Martha |

May 22 |

| Waters of State Explored by Europeans |

Aug. 27 |

| Watson, John Fanning |

Dec. 23 |

| Wayne Defeats Indians |

Dec. 3 |

| Wayne Defeats Indians at Fallen Timbers |

Aug. 20 |

| Weiser, Conrad |

June 13 |

| Westmoreland County Erected |

Feb. 26 |

| Whisky Insurrection in Pennsylvania |

Sept. 30 |

| Whitefield Starts Negro School at Nazareth |

May 3 |

| White Woman of Genesee |

April 5 |

| xiiiWiconisco Valley Suffers Indian Attack |

Mar. 7 |

| Wilmot, David |

Mar. 16 |

| Wilson, Alexander, The Ornithologist |

Aug. 23 |

| Wilson’s Indian Mission |

Oct. 27 |

| Witchcraft in Pennsylvania |

Feb. 27 |

| Wolf, Governor George and Public Education |

Mar. 11 |

| Wyalusing Indian Mission |

May 23 |

| Wyoming, First Massacre |

Oct. 15 |

| Wyoming Massacre |

July 3 |

| Yankees Drive Pennamites from Wyoming |

Aug. 15 |

| |

|

|

| Yankees Humiliatingly Defeat Colonel |

| Plunket |

Dec. 25 |

| Yellow Fever Scourges |

Nov. 6 |

| York County in Revolution |

Aug. 19 |

| York, Duke of |

June 29 |

| Yost Murdered by Mollie Maguires |

May 4 |

| |

|

|

| Zinzindorf, Count Nicholas |

Dec. 10 |

1

Mutiny Broke Out in Pennsylvania Line,

January 1, 1781

As the year 1780 drew to a close there were warm disputes in

the Pennsylvania regiments as to the terms on which the men

had been enlisted. This led to such a condition by New Year’s

Day, 1781, that there broke out in the encampment at Morristown,

N. J., a mutiny among the soldiers that required the

best efforts of Congress, the Government of Pennsylvania and

the officers of the army to subdue.

New Year’s Day being a day of customary festivity, an extra proportion

of rum was served to the soldiers. This, together with what

they were able to purchase, was sufficient to influence the minds of the

men, already predisposed by a mixture of real and imaginary injuries,

to break forth into outrage and disorder.

The Pennsylvania Line comprised 2500 troops, almost two-thirds of

the Continental Army, the soldiers from the other colonies having, in

the main, gone home. The officers maintained that at least a quarter

part of the soldiers had enlisted for three years and the war. This

seems to have been the fact, but the soldiers, distressed and disgusted for

want of pay and clothing, and seeing the large bounties paid to those

who re-enlisted, declared that the enlistment was for three years or the

war.

As the three years had now expired, they demanded their discharges.

They were refused, and on January 1, 1781, the whole line, 1300 in

number, broke out into open revolt. An officer attempting to restrain

them was killed and several others were wounded.

Under the leadership of a board of sergeants, the men marched

toward Princeton, with the avowed purpose of going to Philadelphia to

demand of Congress a fulfillment of their many promises.

General “Mad” Anthony Wayne was in command of these troops,

and was much beloved by them. By threats and persuasions he tried

to bring them back to duty until their real grievances could be redressed.

They would not listen to him; and when he cocked his pistol,

in a menacing manner, they presented their bayonets to his breast, saying:

“We respect and love you; you have often led us into the line of

battle; but we are no longer under your command. We warn you to

be on your guard. If you fire your pistol or attempt to enforce your

commands, we shall put you instantly to death.”

General Wayne appealed to their patriotism. They pointed to the

broken promises of Congress. He reminded them of the effect their

conduct would have on the enemy. They pointed to their tattered garments

and emaciated forms. They avowed their willingness to support

2the cause of independence if adequate provision could be made for their

comfort and they boldly reiterated their determination to march to Philadelphia,

at all hazards, to demand from Congress a redress of their

grievances.

General Wayne determined to accompany them to Philadelphia.

When they reached Princeton the soldiers presented the general with a

written list of their demands. These demands appeared so reasonable

that he had them laid before Congress. They consisted of six general

items of complaint and were signed by William Bearnell and the other

sergeants of the committee, William Bouzar, acting as secretary.

Joseph Reed, President of Pennsylvania, who had been authorized

by Congress to make propositions to the mutineers, advanced near Princeton

on January 6, when he wrote to General Wayne in which he expressed

some doubts as to going into the camp of the insurgents. The

general showed this letter to the sergeants and they immediately wrote

the President:

“Your Excellency need not be in the least afraid or apprehensive of

any irregularities or ill treatment.”

President Reed went into Princeton. His entry was greeted with the

whole line drawn up for his reception, and every mark of military honor

and respect was shown him.

Articles of agreement were finally assented to and confirmed on both

sides, January 7, 1781. These articles consisted of five sections and

related to the time of their enlistment, terms of payment, arrearages and

clothes. It was also agreed that the State of Pennsylvania should carry

out its part of their contract.

The agreement was signed by Joseph Reed and General James Potter.

General Arthur St. Clair, the distinguished Pennsylvanian, and General

Lafayette went voluntarily to Princeton and offered their services

in the settlement of the difficulty, especially as they had learned of the

attempt of the British to win the malcontents to their cause.

When Sir Henry Clinton heard of the revolt of the Pennsylvania

Line he misunderstood the spirit of the mutineers and dispatched two

emissaries—a British sergeant named John Mason and a New Jersey

Tory named James Ogden—to the insurgents, with a written offer that,

on laying down their arms and marching to New York, they should

receive their arrearages; be furnished with good clothes, have a free pardon

for all past offenses and be taken under the protection of the British

Government and that no military service should be required of them

unless voluntarily offered.

Sir Henry entirely misapprehended the temper of the Pennsylvanians.

They felt justified in using their power to obtain a redress of

grievances, but they looked with horror upon the armed oppressors of

their country; and they regarded the act and stain of treason under the

circumstances as worse than the infliction of death.

3Clinton’s proposals were rejected with disdain. “See, comrades,”

said one of them, “he takes us for traitors. Let us show him that the

American army can furnish but one Arnold, and that America has no

truer friends than we.”

They seized the two emissaries, and delivered them, with Clinton’s

papers, into the hands of General Wayne.

The court of inquiry sat January 10, 1781, at Somerset, N. J., with

the court composed of General Wayne, president, and General William

Irvine, Colonel Richard Butler, Colonel Walter Stewart and Major

Benjamin Fishbourne. The court found John Mason and James Ogden

guilty and condemned them to be hanged.

Lieutenant Colonel Harmar, Inspector General of the Pennsylvania

Line, was directed to carry the execution into effect. The prisoners

were taken to “cross roads from the upper ferry from Trenton to Philadelphia

at four lanes’ ends,” and executed.

The reward which had been offered for the apprehension of the offenders

was tendered to the mutineers who seized them. They sealed

the pledge of patriotism by nobly refusing it, saying: “Necessity wrung

from us the act of demanding justice from Congress, but we desire no

reward for doing our duty to our bleeding country.”

The whole movement, when all the circumstances are taken into

account, should not be execrated as a military rebellion, for, if ever there

was a just cause for men to lift up their strength against authority, these

mutineers of the Pennsylvania Line possessed it. It must be acknowledged

that they conducted themselves in the business, culpable as it

was, with unexpected order and regularity.

A great part of the Pennsylvania Line was disbanded for the winter,

but was promptly filled by new recruits in the spring and many

of the old soldiers re-enlisted.

General Assembly Occupies New State

Capitol, January 2, 1822

The General Assembly of Pennsylvania met in the Dauphin

County courthouse for the last time December 21, 1821, and

then a joint resolution was adopted:

“Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives,

That when the Legislature meets at the new State Capitol, on

Wednesday, the 2d of January next, that it is highly proper,

before either house proceeds to business, they unite in prayer to the

Almighty God, imploring His blessing on their future deliberations,

and that the joint committee already appointed be authorized to make

the necessary arrangements for that purpose.”

4On Wednesday, January 2, 1822, on motion of Mr. Lehman and

Mr. Todd, the House proceeded to the building lately occupied by the

Legislature. There they joined the procession to the Capitol and attended

to the solemnities directed by the resolution of December 21,

relative to the ceremonies to be observed by the Legislature upon taking

possession of the State Capitol.

The Harrisburg Chronicle of January 3, 1822, printed an account

of the proceedings from which the following is taken:

“The members of both branches of the Legislature met in the morning

at 10 o’clock, at the old State House (court house) whence they

moved to the Capitol in the following

Order of Procession

The Architect and his Workmen, two and two.

Clergy.

Governor and Heads of Departments.

Officers of the Senate.

Speaker of the Senate.

Members of the Senate, two and two.

Officers of the House of Representatives.

Speaker of the House of Representatives.

Members, two and two.

Judges.

Civil Authorities of Harrisburg.

Citizens.

“In front of the Capitol the architect and his workmen opened into

two lines and admitted the procession to pass between them and the

Capitol.

“The service was opened by a pertinent and impressive prayer, by

Rev. Dr. A. Lochman, of Harrisburg. The prayer was followed by an

appropriate discourse, by Rev. D. Mason, principal of Dickinson College,

Carlisle, Pa., which concluded as follows:

“Sixty years have not elapsed since the sound of the first axe was

heard in the woods of Harrisburg. The wild beasts and wilder men

occupied the banks of the Susquehanna. Since that time, with the mildness

which has characterized the descendants of William Penn, and that

industry which has marked all the generations of Pennsylvania, the

forests have been subdued, the wild beasts driven away to parts more

congenial to their nature, and the wilder men have withdrawn to regions

where they hunt the deer and entrap the fish according to the mode

practiced by their ancestors.

“In the room of all these there has started up, in the course of a few

years, a town respectable for the number of its inhabitants, for its

progressive industry, for the seat of legislation in this powerful State.

“What remains to be accomplished of all our temporal wishes?

5What more have we to say? What more can be said, but go on and

prosper, carry the spirit of your improvements through till the sound of

the hammer, the whip of the wagoner, the busy hum of man, the voices

of innumerable children issuing from the places of instruction, the lofty

spires of worship, till richly endowed colleges of education, till all those

arts which embellish man shall gladden the banks of the Susquehanna

and the Delaware, and exact from admiring strangers that cheerful

and grateful tribute, this is the work of a Pennsylvania Legislature!”

The act to erect the State Capitol was passed March 18, 1816, and

carried an appropriation of $50,000. A supplement to this act was approved

February 27, 1819, when there was appropriated $70,000, with

the provision that the said Capitol should not cost more than $120,000.

But a further supplement was approved March 28, 1820, for “the

purpose of constructing columns and capitols there of hewn stone, and

to cover the roof of the dome, etc.,” there was appropriated $15,000.

At this time the total cost of all the public buildings was $275,000,

and consisted of the new Capitol, $135,000; executive offices on both

sides of the Capitol building, $93,000; Arsenal, $12,000, and public

grounds, its enclosure and embellishment, $35,000.

The cornerstone of this new Capitol was laid at 12 o’clock on Monday,

May 31, 1819, by Governor William Findlay, assisted by Stephen

Hills, the architect and contractor for the execution of the work; William

Smith, stone cutter, and Valentine Kergan and Samuel White,

masons, in the presence of the Commissioners and a large concourse of

citizens. The ceremony was followed by the firing of three volleys from

the public cannon.

The newspaper account of the event states that the above-mentioned

citizens then partook of a cold collation, provided on the public ground

by Mr. Rahn.

The Building Commissioners deposited in the cornerstone the following

documents:

Charter of Charles II to William Penn.

Declaration of Independence.

Constitution of Pennsylvania, 1776.

Articles of Confederation and perpetual union between the several

States.

Copy of so much of an act of the General Assembly of Pennsylvania,

by which indemnity was made to the heirs of William Penn for their

interest in Pennsylvania.

Treaty of peace and acknowledgment by Great Britain of the independence

of the United States.

Constitution of the United States, 1787.

Constitution of Pennsylvania, 1790.

Acts of the Legislature of Pennsylvania, by which the seat of

government was removed from Philadelphia to Lancaster and Harrisburg,

6and the building of a State Capitol at the latter place authorized.

A list of the names of the Commissioners, architects, stonecutter and

chief masons; likewise, a list of the then officers of the Government of

Pennsylvania, embracing the Speakers of the two Houses of the Legislature,

the Governor, the heads of departments, the Judges of the Supreme

Court and Attorney General, with the names of the President and

Vice President of the United States.

It was a singular oversight that this cornerstone was not marked as

such, and in after years it was not known at which corner of the building

the stone was situated.

An act providing for the furnishing of the State Capitol was approved

March 30, 1821: Section 1. The Governor, Auditor General,

State Treasurer, William Graydon, Jacob Bucher, Francis R. Shunk

and Joseph A. McGinsey were appointed Commissioners to superintend

the furnishing of the State Capitol. This able commission expended the

$15,000 appropriated, and the new Capitol was a credit to the Commonwealth

of Pennsylvania when the General Assembly formally occupied it

January 2, 1822.

Lucretia Mott, Celebrated Advocate of

Anti-Slavery, Born January 3, 1793

From the earliest settlement at Germantown, and especially

in the period following the Revolutionary War, there were

many thoughtful people in all walks of life who considered

slavery to be an evil which should be stopped. But the question

of actually freeing the slaves was first seriously brought

forward in 1831, by William Lloyd Garrison, in his excellent

paper, “The Liberator,” published in Boston.

Seventy-five delegates met in Philadelphia in 1833 to form a National

Anti-Slavery Society. It was unpopular in those stirring days to

be an abolitionist. John Greenleaf Whittier acted as one of the secretaries,

and four women, all Quakers, attended the convention.

When the platform of this new society was being discussed, one

of the four women rose to speak. A gentleman present afterward said:

“I had never before heard a woman speak at a public meeting. She

said only a few words, but these were spoken so modestly, in such sweet

tones and yet so decisively, that no one could fail to be pleased.” The

woman who spoke was Lucretia Mott.

Lucretia Coffin was born in Nantucket January 3, 1793. In 1804

her parents, who were Quakers, removed to Boston. She was soon

afterward sent to the Nine Partners’ Boarding School in Duchess

7County, N. Y., where her teacher (Deborah Willetts) lived until 1879.

Thence she went to Philadelphia, where her parents were residing.

At the age of eighteen years she married James Mott. In 1818 she

became a preacher among Friends, and all her long life she labored for

the good of her fellow creatures, especially for those who were in bonds

of any kind.

She was ever a most earnest advocate of temperance, pleaded for

the freedom of the slaves, and was one of the active founders of the

“American Anti-Slavery Society” in Philadelphia in 1833.

She was appointed a delegate to the World’s Anti-Slavery convention,

held in London in 1840, but was denied a seat in it on account of

her sex. She also was a very prominent advocate of the emancipation of

her sex from the disabilities to which law and custom subjected them.

When the Female Anti-Slavery Society was organized Lucretia

Mott was its first president and served in that office for many years.

The anti-slavery enthusiasts dedicated a building, Pennsylvania Hall,

in Philadelphia, May 14, 1838, which excited the rage of their enemies

and the mob burned the building three days later. The excited crowd

marched through the streets, threatening also to burn the houses of the

abolitionists.

The home of Mr. and Mrs. James Mott stood on Ninth Street

above Race. Lucretia Mott and her husband were warned of their danger,

but refused to leave their home. Their son ran in from the street,

crying, “They’re coming!”

The mob intended to burn the house, but a young man friendly to

the family assumed leadership and with the cry “On to Motts!” led

them past the place and the mob satisfied its thirst by burning a home

for colored orphans, and did not return.

Such incidents failed to daunt the spirit of Lucretia Mott, and her

husband, who approved the part she took.

A meeting of the Anti-Slavery Society in New York City was

broken up by roughs, and several of the speakers, as they left the hall,

were beaten by the mob. Lucretia Mott was being escorted from the

hall by a gentleman.

When she noticed some of the other ladies were frightened, she

asked her friend to leave her and take care of the others. “Who will

look after you?” he asked. Lucretia laid her hand on the arm of one of

the roughest in the mob, saying: “This man will see me safely through

the crowd.” Pleased by the mark of confidence, the rioter did as she

asked and took her to safety.

The home of the Motts was always open for the relief of poor

colored persons, and they helped in sending fugitive slaves to places of

refuge. On one occasion the Motts heard the noise of an approaching

mob. Mr. Mott rushed to the door and found a poor colored man, pursued

by the mob, rushing toward the friendly Mott house. He entered

8and escaped by the rear door. A brick hurled at Mr. Mott fortunately

missed him, but broke the door directly over his head.

A sequel to the riot at Christiana, Lancaster County, September 11,

1851, which occurred on the farm then owned by Levi Powell, was the

arrest of Castner Hanway and Elijah Lewis, two Quakers of the

neighborhood, and nearly fifty others, mostly Negroes, on the charge of

high treason for levying war against the Government of the United

States.

The trial began in the United States Court at Philadelphia, before

Judges Green and Kane, November 24. It was one of the most exciting

ever held in the State. Thaddeus Stevens, John M. Read, Theodore

C. Cuyler, and Joseph J. Lewis, conducted the defense, while District

Attorney John W. Ashmead was assisted by the Attorney General of

Maryland, and by James Cooper, then a Whig United States Senator

from Pennsylvania.

Lucretia Mott attended the trial personally every day, and after the

elaborate argument of counsel, Judge Green delivered his charge. The

jury returned a verdict, in ten minutes, of “not guilty.”

A colored man named Dangerfield was seized on a farm near Harrisburg

on a charge of being a fugitive slave. He was manacled and taken

to Philadelphia for trial.

The abolitionists engaged a lawyer to defend the Negro. Lucretia

Mott sat by the side of the prisoner during the trial. Largely through

her presence and influence Dangerfield was released. The mob outside

the court awaited Dangerfield to deliver him over to his former master,

but a band of young Quakers deceived the crowd by accompanying

another Negro to a carriage and Dangerfield walked off in another

direction.

Lucretia Mott and her friends were rejoiced to see the Negroes all

free. There was still much to be done after the Civil War. This noble

woman remained a hard worker for their cause all through her life.

Lucretia Mott died in Philadelphia, November 21, 1881, at the age

of nearly ninety years. Thousands attended her funeral, the proceedings

were mostly in silence. At last some one said, “Will no one speak?”

The answer came back: “Who can speak now? The preacher is dead.”

Her motto in life had been “Truth for authority, not authority for

truth.”

Lucretia Mott’s influence still lives. Tuskegee Institute in Alabama,

Hampton Institute in Virginia, and Lincoln University in Chester

County, Pennsylvania, are institutions made possible by such as she, and

in them young colored persons are taught occupations and professions in

which they can render the best service to themselves and to their

country.

9

Samuel Maclay Resigned From United

States Senate January 4, 1809

A monument was unveiled in memory of Samuel Maclay, a

great Pennsylvanian, October 16, 1908. The scene of these

impressive ceremonies was a beautiful little cemetery close by

the old Dreisbach Church, a few miles west of Lewisburg in

the picturesque Buffalo Valley, Union County.

Samuel Maclay was the eighth United States Senator from

Pennsylvania and had the proud distinction of being the brother of William

Maclay, one of the first United States Senators from Pennsylvania.

The Maclays are the only brothers to ever sit in the highest legislative

body of this country. The third brother, John, was also prominent and

served in the Senate of Pennsylvania.

The imposing shaft was erected by Pennsylvania at a cost of only

$1000, which included the contract for the marble shaft and the reinterment

of the Senator’s body.

Miss Helen Argyl Maclay, of Belleville, a great-great-granddaughter

of Samuel Maclay, unveiled the monument assisted by her two

brothers, Ralph and Robert Maclay. Rev. A. A. Stapleton, D. D., delivered

the principal address. Other speakers included Frank L. Dersham,

then the Representative in the General Assembly from Union

County, who introduced the bill for this memorial; Alfred Hayes, now

deceased, also a former member of the Assembly, who represented the

Union County Historical Society; Captain Samuel R. Maclay, of Mineral

Point, Mo., a grandson of Senator Samuel Maclay.

Lieutenant Governor Robert Murphy attended the ceremony, as did

many distinguished citizens from this and other States, school children

and military, civic, historical and patriotic societies. There were thirty-five

representatives of the Maclay family in attendance.

Perhaps the strangest emotion during the preparation of this shaft

and its unveiling was caused by the seeming lack of knowledge of this

statesman, farmer, frontiersman, soldier, surveyor, citizen, who was an

officer in the Continental Army during the Revolution, who was a foremost

actor in the actual development of the interior of the State to commerce,

one who sat in the highest legislative councils of this Commonwealth

and presided over its Senate, who represented his State in Congress

and later in the United States Senate, and so serving was the compeer

of men whose names are radiant with luster on the pages of American

history.

Yet, strange to say, the memory of this man had so completely faded

from public view that college professors, members of the General Assembly

10and men who held some claim to be styled historians asked in

wonder, when the bill was before the Legislature, “Who was this man?”

The ancestors of Senator Maclay came from Scotland, where the

clan Maclay inhabited the mountains of County Boss in the northlands.

When the darkest chapter of Scotch-Irish history was written in

tears and blood, emigration was the only alternative to starvation, and

among the 30,000 exiles who left for these shores were two Maclays.

These two exiles were sons of Charles Maclay, of County Antrim

and titular Baron of Finga. Their names were Charles, born in 1703,

and John, born in 1707. They set sail for America May 30, 1734.

Upon arrival they first settled in Chester County, Pennsylvania,

where they remained nearly seven years, when they removed to what is

now Lurgan Township, Franklin County, on an estate, which is still

in possession of their descendants.

Here John, son of Charles, the immigrant, built a mill in 1755,

which, with modern improvements and alterations, is still operated by

the third succeeding generation. This mill was stockaded during the

French and Indian War, as it was located on the well-traveled highway

leading from McAllister’s Gap to Shippensburg.

During the Revolution every male member of the Maclay family, of

military age, was in the service, and every one an officer.

John Maclay, the younger of the immigrant brothers, married Jane

MacDonald in 1747. To this union were born three sons and one

daughter; John born 1748, a soldier of the Revolution, died 1800;

Charles, born 1750, a captain in the Continental Army, who fell in the

action at Crooked Billet, 1778; Samuel, born 1751, also an officer, fell

at Bunker Hill; Elizabeth, wife of Colonel Samuel Culbertson, of the

Revolution.

Charles Maclay, the elder immigrant brother, died in 1753. His

wife, Eleanore, whom he had married in Ireland, died in 1789. To

them were born four sons and one daughter: John, born in Ireland,

1734, for many years a magistrate, and in 1776 he was a delegate to

convention in Carpenters’ Hall, Philadelphia. He also served in the

General Assembly, 1790–1792 and 1794; William, born in Chester

County, July 20, 1737, whose sketch appears in another story; Charles,

also born in Chester County, in 1739, was a soldier of the Revolution,

died in 1834 at Maclays Mills; Samuel, the subject of our sketch, was

born June 17, 1741.

Samuel Maclay was educated in the classical school conducted by

Dr. J. Allison, of Middle Spring. He also mastered the science of surveying,

which he followed for years. In 1769 he was engaged with his

brother William and Surveyor General Lukens in surveying the officers’

tracts on the West Branch of the Susquehanna, which had been awarded

to the officers of First Battalion in Bouquet’s expedition.

A coincident fact is that the remains of this distinguished patriot lie

11buried on the allotment awarded Captain John Brady, who drew the

third choice, and which was surveyed for him by Maclay.

Samuel Maclay, November 10, 1773, married Elizabeth, daughter

of Colonel William Plunket, then President Judge of Northumberland

County, and commandant of the garrison at Fort Augusta. They took

up their residence on the Brady tract in Buffalo Valley. To this union

six sons and three daughters were born.

From the moment Samuel Maclay became a resident of what is now

Union County until his death he was identified with the important history

of the valley.

Samuel Maclay was one of the commissioners to survey the headwaters

of the Schuylkill, Susquehanna and Allegheny Rivers. The

others were Timothy Matlack, of Philadelphia, and John Adlum, of

York. They were commissioned April 9, 1789. These eminent men

were skilled hydrographical and topographical engineers and completed

the first great survey of Pennsylvania.

The journal kept by Maclay is interesting and valuable and relates

many thrilling experiences quite foreign to those of present-day surveyors.

He was lieutenant colonel of the First Battalion, Northumberland

County Militia, organized at Derr’s Mills, now Lewisburg, September

12, 1775.

In 1787 Samuel Maclay was elected to Pennsylvania Assembly and

served until 1791, when he became Associate Justice of Northumberland

County. In 1794 he was elected to Congress. Three years later

he was elected to Pennsylvania Senate, where he served six years. He

was elected Speaker in 1802 and he served in this capacity until March

16, 1802, when he took his seat in the United States Senate, where he

continued until January 4, 1809, resigning on account of broken health.

He died October 5, 1811, at the age of seventy years. His wife,

Elizabeth Plunket Maclay, survived her distinguished husband until

1835.

12

Amusing and Memorable “Battle of the

Kegs,” January 5, 1778

In January, 1778, while the British were in possession of

Philadelphia, some Americans had formed a project of sending

down by the ebb tide a number of kegs, or machines that resembled

kegs as they were floating, charged with gunpowder

and furnished with machinery, so constructed that on the least

touch of anything obstructing their free passage they would immediately

explode with great force.

The plan was to injure the British shipping, which lay at anchor

opposite the city in such great numbers that the kegs could not pass

without encountering some of them. But on January 4, the very evening

in which these kegs were sent down, the first hard frost came on

and the vessels were hauled into the docks to avoid the ice which was

forming, and the entire scheme failed.

One of the kegs, however, happened to explode near the town. This

gave a general alarm in the city, and soon the wharves were filled with

troops, and the greater part of the following day was spent in firing at

every chip or stick that was seen floating in the river. The kegs were

under water, nothing appearing on the surface but a small buoy.

This circumstance gave occasion for many stories of this incident to

be published in the papers of that day. The following account is taken

from a letter dated Philadelphia, January 9, 1778:

“This city hath lately been entertained with a most astonishing instance

of activity, bravery and military skill of the royal army and navy

of Great Britain. The affair is somewhat particular and deserves your

notice. Some time last week a keg of singular construction was observed

floating in the river. The crew of a barge attempting to take it

up, it suddenly exploded, killed four of the hands and wounded the rest.

“On Monday last some of the kegs of a singular construction made

their appearance. The alarm was immediately given. Various reports

prevailed in the city, filling the royal troops with unspeakable consternation.

Some asserted that these kegs were filled with rebels, who were

to issue forth in the dead of night, as the Grecians did of old from the

wooden horse at the siege of Troy, and take the city by surprise. Some

declared they had seen the points of bayonets sticking out of the bung-holes

of the kegs. Others said they were filled with inflammable combustibles

which would set the Delaware in flames and consume all the

shipping in the harbor. Others conjectured that they were machines

constructed by art magic and expected to see them mount the wharves

and roll, all flaming with infernal fire, through the streets of the city.

13“I say nothing as to these reports and apprehensions, but certain it

is, the ships of war were immediately manned and the wharves crowded

with chosen men. Hostilities were commenced without much ceremony

and it was surprising to behold the incessant firing that was poured

upon the enemy’s kegs. Both officers and men exhibited unparalleled

skill and prowess on the occasion, whilst the citizens stood gaping as

solemn witnesses of this dreadful scene.

“In truth, not a chip, stick or drift log passed by without experiencing

the vigor of the British arms. The action began about sunrise

and would have terminated in favor of the British by noon had not

an old market woman, in crossing the river with provisions, unfortunately

let a keg of butter fall overboard, which as it was then ebb tide,

floated down to the scene of battle. At sight of this unexpected re-enforcement

of the enemy the attack was renewed with fresh forces, and

the firing from the marine and land troops was beyond imagination and

so continued until night closed the conflict.

“The rebel kegs were either totally demolished or obliged to fly, as

none of them have shown their heads since. It is said that His Excellency,

Lord Howe, has dispatched a swift sailing packet with an account

of this signal victory to the Court of London. In short, Monday,

January 5, 1778, will be memorable in history for the renowned

battle of the kegs.”

The entire transaction was laughable in the extreme and furnished

the theme for unnumbered sallies of wit from the Whig press, while the

distinguished author of “Hail Columbia,” Joseph H. Hopkinson, paraphrased

it in a ballad which was immensely popular at the time.

This ballad is worthy of reproduction and is given almost in full:

The Battle of The Kegs

By Joseph H. Hopkinson

Gallants attend and hear a friend,

Trill forth harmonious ditty,

Strange things I‘ll tell which late befell

In Philadelphia City.

‘Twas early day, as poets say,

Just when the sun was rising,

A soldier stood on a log of wood

And saw a thing surprising.

As in a maze he stood to gaze,

The truth can’t be denied, sir,

He spied a score of kegs or more,

Come floating down the tide, sir.

14A sailor too in jerkin blue,

This strange appearance viewing,

First d—d his eyes, in great surprise,

Then said “some mischief’s brewing.

“These kegs, I‘m told, the rebels bold

Pack up like pickl’d herring;

And they’re come down t’attack the town

In this new way of ferry’ng.”

The soldier flew, the sailor too,

And scar’d almost to death, sir,

Wore out their shoes, to spread the news,

And ran till out of breath, sir.

Now up and down throughout the town,

Most frantic scenes were acted;

And some ran here, and others there,

Like men almost distracted.

Some fire cry’d, which some denied,

But said the earth had quaked;

And girls and boys, with hideous noise

Ran thro‘ the streets half naked.

“The motley crew, in vessels new,

With Satan for their guide, sir,

Pack’d up in bags, or wooden kegs,

Come driving down the tide, sir.

“Therefore prepare for bloody war,

These kegs must all be routed,

Or surely despis’d we shall be

And British courage doubted.”

The cannons roar from shore to shore,

The small arms loud did rattle,

Since wars began I‘m sure no man

E‘er saw so strange a battle.

The rebel dales, the rebel vales,

With rebel trees surrounded;

The distant woods, the hills and floods,

With rebel echoes sounded.

The fish below swam to and fro,

Attack’d from ev’ry quarter;

Why sure, thought they, the devil’s to pay,

‘Mongst folks above the water.

15The kegs, ’tis said, tho’ strongly made

Of rebel staves and hoops, sir,

Could not oppose their powerful foes,

The conqr’ing British troops, sir.

From morn to night these men of might,

Display’d amazing courage—

And when the sun was fairly down,

Retir’d to sup their porrage.

A hundred men with each a pen,

Or more upon my word, sir,

It is most true would be too few,

Their valor to record, sir.

Such feats did they perform that day,

Against these wicked kegs, sir,

That years to come, if they get home

They’ll make their boasts and brags, sir.

Bishop Cammerhoff Started Journey Among

Indians on January 6, 1748

John Christopher Cammerhoff was a Moravian

missionary who undertook several hazardous trips to the Indians

along the Susquehanna and to Onondaga, and of whom

there is an interesting story to be told.

He came to America in the summer of 1747, in company

with Baron John de Watteville, a bishop of the Moravian

Church, and son-in-law and principal assistant of Count Zinzindorf.

They were also accompanied on the voyage by the Reverend John Martin

Mack and the Reverend David Zeisberger, the latter also an interpreter,

and each of these figured very prominently in the early history

among the Indians of the great Susquehanna Valleys.

Cammerhoff was born near Magdeburg, Germany, July 28, 1721;

died at Bethlehem, Pa., April 28, 1751. He was educated at Jena and

at the age of twenty-five was consecrated Bishop in London and came

to America.

His greatest success was among the Indians of Pennsylvania and

New York. The Iroquois adopted him into the Turtle Tribe of the

Oneida Nation, and gave him the name of Gallichwio or “A Good

Message.”

Accompanied only by Joseph Powell, he set out from Bethlehem

for Shamokin on the afternoon of January 6, 1748, and reached Macungy,

now Emaus, by night. The next day they traveled through deep

16snow, sleeping that night at the home of Moses Starr, a Quaker. Early

next morning the Schuylkill was reached, which was partly frozen over.

A crossing was effected with great risk over the thin ice, leading their

horses, which broke through and nearly drowned. They passed through

Heidelberg, Berks County, and reached Tulpehocken, where they slept

at Michael Schaeffer’s.

Next morning they arrived at George Loesch’s and here determined

to leave the mountain road via the Great Swatara Gap and Mahanoy

Mountains, and to travel along the Indian path leading from Harris’

Ferry, which they were to meet at the river.

They got as far as Henry Zender’s, where they spent the night, and

next morning set out for Harris’ Ferry, a long day’s journey along the

Great Swatara, which they reached at noon. Seven miles from Harris’

they got lost in the woods, but the missionaries arrived at Harris’ at 7

o’clock and found there a great company of traders.

Next morning, January 11, they proceeded toward Shamokin, following

the path made by some Indians who the previous day had

traveled from Shamokin to Harris’ Ferry. They passed by Chambers’

Mill, at the mouth of Fishing Creek, seven miles above the ferry. They

proceeded, after a sumptuous noonday meal, and in a few hours struck

the base of the mountain, which marked the northern limit of Proprietaries’

land. They passed over Peter’s Mountain, then forded Powell’s