RAGGETY

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Raggety, by Mary Josephine White

Title: Raggety

His life and adventures

Author: Mary Josephine White

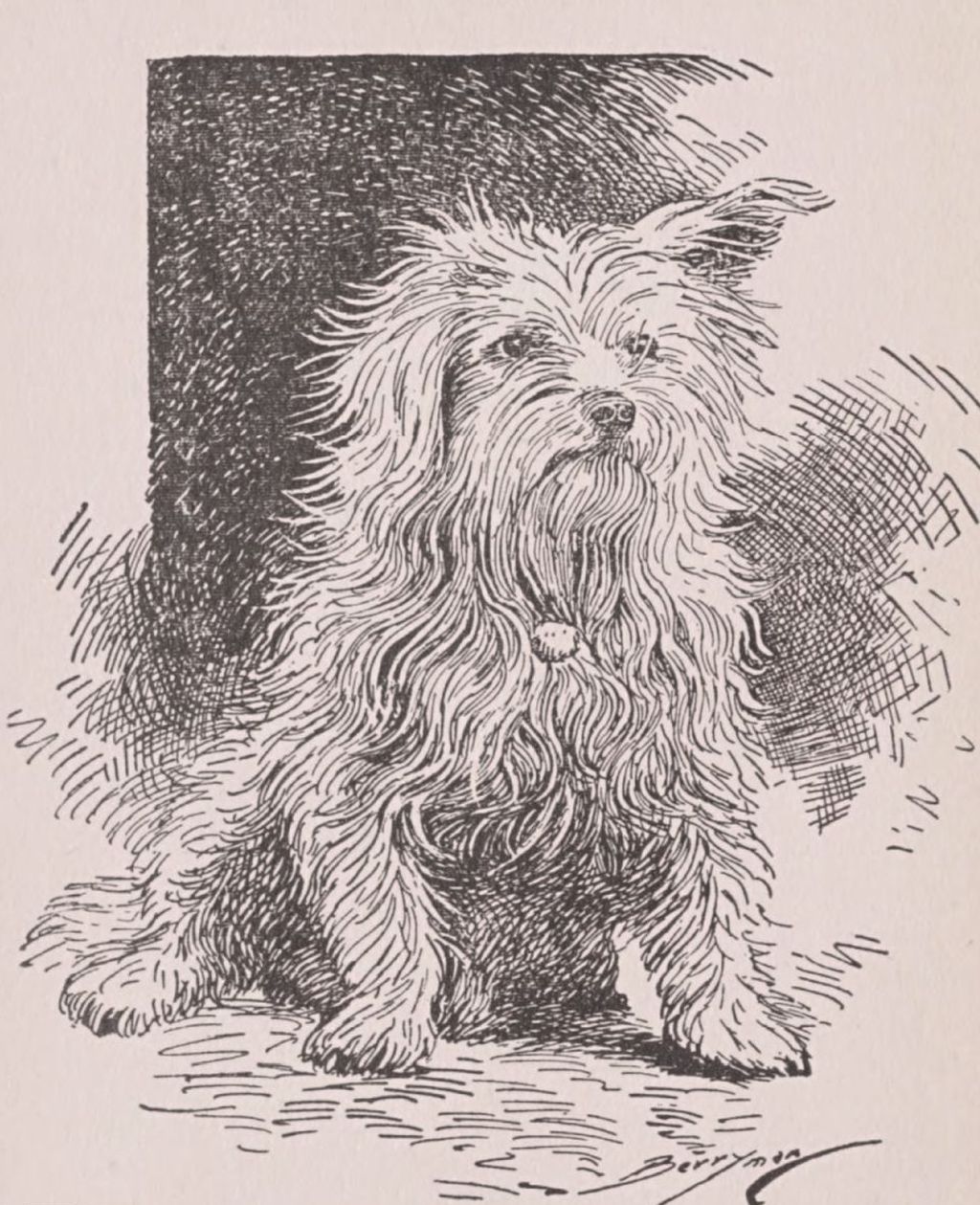

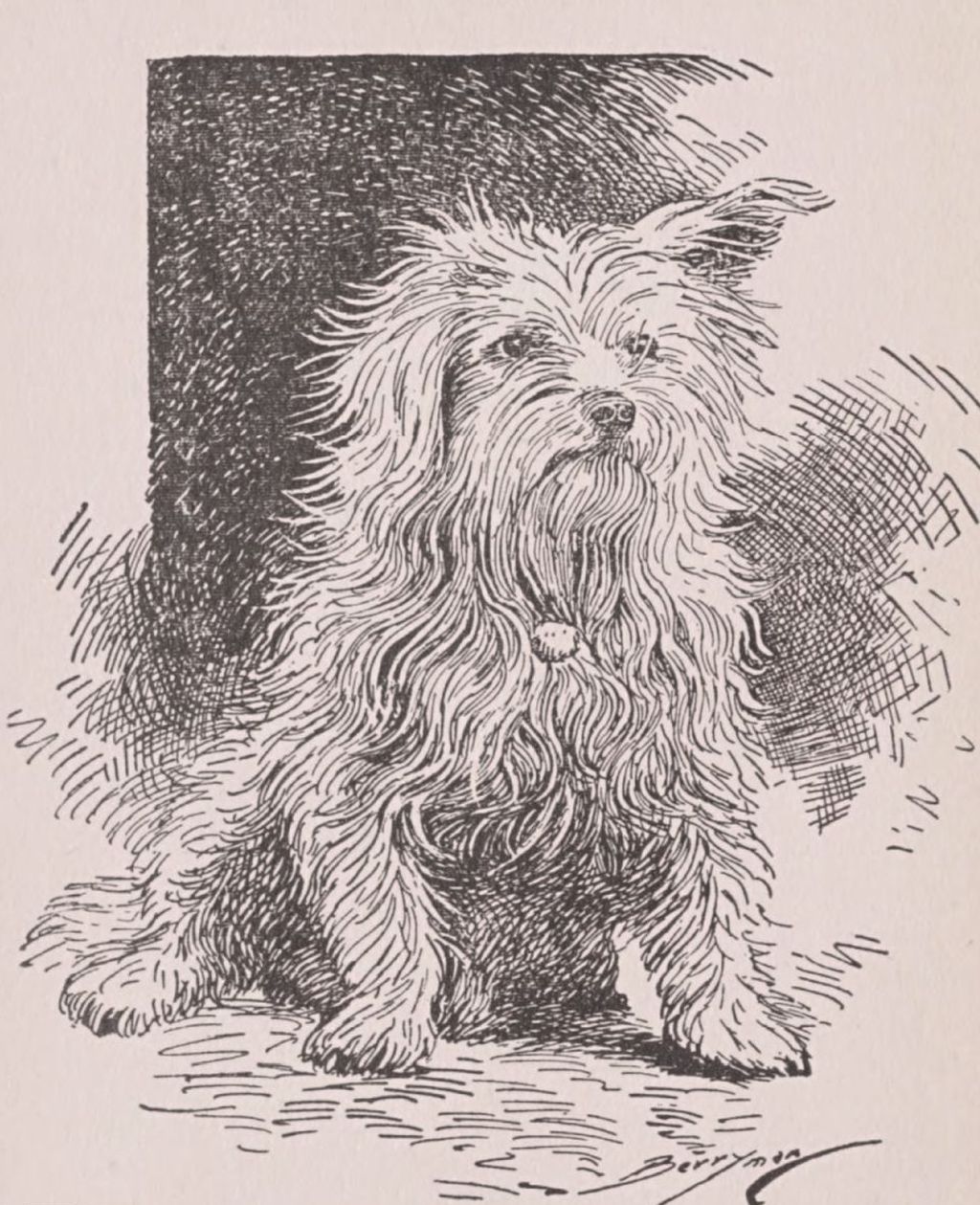

Illustrator: Clifford K. Berryman

Release Date: February 10, 2023 [eBook #70004]

Language: English

Produced by: Charlene Taylor, Carla Foust and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Raggety

RAGGETY

HIS LIFE AND

ADVENTURES

BY

MARY JOSEPHINE WHITE

WITH DRAWING BY

CLIFFORD K. BERRYMAN

PRIVATELY PRINTED FOR THE AUTHOR BY

H. L. & J. B. McQueen, Inc.

Washington, D. C.

1913

Copyright, 1913, by Mary Josephine White

Number ....

OF THIS EDITION THREE HUNDRED AND

FIFTEEN COPIES HAVE BEEN PRINTED FROM

CASLON TYPE AND THE TYPE DISTRIBUTED

To

The Lovely Lady

and

The Lovely Lady’s Husband

| 1 | The Arrival of Raggety | 13 |

| 2 | Raggety Chooses | 19 |

| 3 | Raggety’s Education | 22 |

| 4 | His Love of Travel | 25 |

| 5 | How Raggety Proved Himself a Real Dog | 28 |

| 6 | How He “Borned His Baby” | 32 |

| 7 | How Raggety Met His Lovely Lady | 35 |

| 8 | His Devotion to His Lovely Lady | 38 |

| 9 | How Raggety Bit The Great Man and How He Then Apologized | 41 |

| 10 | Raggety’s Ears | 45 |

| 11 | Raggety’s Tail | 49 |

| 12 | His Athletic Interests | 51 |

| 13 | Raggety’s Love Affairs | 55 |

| 14 | Raggety’s Friendships | 58 |

| 15 | Raggety and The Dear Man Who Passed | 61 |

| 16 | Me and Jeems | 63 |

| 17 | What The Lovely Lady Says | 67 |

| 18 | Raggety Trots Out of His Book | 71 |

RAGGETY IS A REAL DOG

To begin with, he is a really truly dog; not a dog in a picture, not a dog in a story, not a dog in a book, but a real dog. One that would come up and lick your hand with his warm little tongue if you spoke to him, and would jump up and down and wiggle all over if you asked him to go for a walk.

THE MINTIE

Once I was walking in the Fields of the Earth[A] and there I met a Mintie, with a head on before and a tail on behind, and inside the Mintie there lived a Growl. Now the Growl had neither head, body, nor legs, but it lived inside of the Mintie.

[A] Apologies to John Bunyan.

A SUGARED DESCRIPTION

He’s all made of lollipops stuck together with treacle, and then there was a high wind blowing and lots of sugar in the air. And the sugar stuck all over him and that’s the reason he’s fluffy.

Raggety

His Mark

[Pg 13]

He trotted into my life one sunshiny day in May over there in a town on the Hudson. He was trying to teach a hound puppy with very large dull paws how to play. The puppy was clumsy, he was slow, he panted abominably, but the little yellow dog went round and round him in flashing circles, the circles growing smaller and faster. The center of them all came and the fluff turned like down before the wind and flew away to rest. I laughed out loud with joy at the fun of that little yellow dog. As he rested he thrust his hind-legs out on either side, in a way peculiar to terriers, and from my window looked an animated doormat. “How slow and stupid that hound puppy is!” said every hair of the gay little yellow body.

[Pg 14]

Next morning I was sitting on the doorstep watching the robins busy among the rain of apple blossoms. I know I felt expectant: there was that delicious Spring hush of an awakening world, and one’s heart waited too.

Round the hedge that same little yellow dog trotted into my life. I called to him, “Raggety, Raggety, how do you do?” And he came straight to me, looked at me with sad questioning beautiful brown eyes, my eyes answered, and we knew each other. From that moment I belonged to him and he to me. He let me carry him to my room,—he was such a tiny thing, so little, so independent,—protesting with faint growls. I saw his neglected hair was matted, tangled, muddy, and that his nose was sore; his eyes alone preserved the beauty to which he had been born. Then I let him go but found from the gardener where he belonged. Where he came from no one[Pg 15] knows but he himself and he has never told me a word about it.

This is all I could find out. Down in the poor little settlement under the hill, which we called “The Cabbage Patch” in memory of Mrs. Wiggs, there lived The Junkman with his wife, many children big and little, and an old white horse. Every Monday the man hitched the white horse to his peddler’s cart and drove back among the hills and the tiny villages and scattered farms. The cart was always filled on Mondays with new bright jingling tins, pots, pails, pans, with here and there a japanned tea-caddy or a bright blue wash basin for a touch of color. When the cart came back to town towards the end of the week,—the better the trade, the sooner it came,—all its glory had departed. No more shining pans, but instead great dingy bags of rags, the clank of old iron, and perhaps on the top of the heap a dilapidated[Pg 16] baby-carriage, the cast-off things of life. The horse seemed older and wearier; the man more bent, more broken. Earlier that Spring, on his way down from the hills, The Junkman noticed a little dog trotting under the cart. Where he joined him he did not know, at what house he had seen him he could not remember, only that the little long-haired yellow dog had come down from the hill-farms with him, had followed the cart, did not leave him when he reached home, and had become a playmate to his children. Little tousled things the children were, tumbling over each other in the two rooms that were home to them. The little yellow dog shared their play, their food, their bed, until the day that he came up the hill to teach that stupid hound-puppy to run races.

Through the gardener’s helper I made a bargain with The Junkman. He was[Pg 17] glad of the little extra money, even though the children were sorry to lose their gay good-natured playmate, and the little yellow dog became mine.

I shall never forget that first arrival. The gardener’s man (I always feel that the larger part of the little bargain money went into his pocket) came leading him proudly, with a rope heavy enough to have dragged a cow to market about that active liberty-loving fluffy neck, and reproaches stared from those brown eyes.

Then began a series of struggles, heartrending for the little dog and for his new mistress. He had to be washed, not once, but twice and thrice, yea, unto the fourthly, to get him clean and sweet and habitable and uninhabited. We emerged from the bath room, he a glaring, fiercely protesting bundle in a bath towel, I with flaming cheeks, weary back, and collar awry.

He mourned the loss of his little jolly[Pg 18] tousled playmates, refused to eat, refused to be comforted. Then he persisted in returning to the Cabbage Patch at every opportunity, and this meant fees to the gardener’s helper, anxious waiting, and laborious cheerfulness when he, sulky and unwilling, returned.

[Pg 19]

This went on for four or five days. Then one morning I took him on my lap and said, “Raggety dear, I don’t want you to stay with me unless you want to. I want you for my pleasure, but if it isn’t your pleasure too, you must go back to the Cabbage Patch. Here you will have love and care, plenty to eat, and the baths which you hate. There you will have the little children to play with, scraps to eat, perhaps be cold, and surely will be dirty, with little sore eyes and nose. But I won’t try to keep you if you want to go, you must choose for yourself.” Those sad rebellious eyes looked into mine, and with aching heart I put him down and made no attempt at shutting the doors that day and off he went to his little playmates. I did not know whether I should[Pg 20] see him again. I waited through the day, but no Raggety. But quite late there came a gentle scratching at one of the long windows. You can imagine how I hastened to open it and in marched Master Raggety with a ridiculous air of possession, as much as to say, “Well, here I am, home again.” And the curious part of his choice was that it was final. He never again went back to the Patch, never even offered to go.

Of course, a very reasonable person, who does not understand dog nature, will say, “Why, The Junkman’s family drove him away, would not let him into the house, did not feed him; so after walking about for many hours, he decided to return to the place where he knew food and shelter waited for him.” But that does not, to my mind, explain why he never again wanted to return to The Junkman’s, why he seemed willing to leave his little playmates and a life of[Pg 21] unwashed freedom. I believe that he really chose me, that he understood my talk of the morning, knew my affection, and that his own little heart responded.

[Pg 22]

Where he had come from no one knew but himself. He had all the pretty ways of a pet dog when he came, loved to be petted, could sit on his haunches and beg, give paw, and had the ingratiating ways of a loved and loving comrade. What sort of a home had he left? Why did he leave it voluntarily to follow the Raggedy Man? Was his soul fettered and cramped and did he long for Adventure and the Open Road and,—dare it? When you see what a little dog he is, when you know his liberty-loving spirit, when you realize that he meets change and vicissitude with courage, you feel sure that he comes of good stock. Mary Cholmondley said in one of her books, “Good blood is never cowardly,” and Raggety has good blood.

Three humiliating and exasperating[Pg 23] new bonds he learned to endure with me. First, a collar, and a collar with an annoying bell which jingled as he walked and scampered. How he rolled and pushed his head about, and wriggled on his back to get rid of that abominable thing about his neck! Second, he had to learn to walk attached to a leash and that was terrible. I carefully fastened the clip of the leash into the ring of his collar and started, and he refused to use his legs. So for a few steps I dragged him on his little body but that looked and seemed cruel. Then I carried him for a few steps, set him down again, again no legs, and the little body dragged over the dirt of the road. Alas and alack, how long it took before he submitted!—was it days, was it weeks? I have forgotten, but just as he chose to return and stay with me, one fine day he decided that he would walk properly at the end of a leather strap. Now it has come to mean a walk, so he kisses it.

[Pg 24]

The third thing he had to learn with his new mistress and to which he never in all the years of our friendship has become reconciled is the weekly bath. “Any refuge in a storm,” he seeks the darkest closets and the deepest corners under beds as safe retreats and is only dislodged by coaxing most persuasive and long-continued. How he hates it!

[Pg 25]

Whether his instinctive love of adventure persists, or whether he has the confidence that where I go he too may go in safety, I do not know, but I do know that Raggety really loves to travel, to go, that the excitement of change rouses and amuses him. When bags and trunks are brought out he is very depressed for often they mean separation, a parting from one he loves, and once when a trunk, half-packed, was left standing open, in he got and curled down to sleep, saying quite plainly, “If this goes, pack me in it and take me along.” But when the time comes for departure and he finds he is to go too, his excitement is intense. Capering, jumping, barking, he expresses his joy and rapture.

When going for long visits he takes[Pg 26] his bed with him, an open dog-basket inherited from older generations of little pet dogs. He gets into this of his own accord, is lifted into the baggage car, his leash is attached to one of the handles and there he stays. Unless the kindly baggage-men find that he can sit up and “beg,” when he often has the freedom of the car. And the men always report at the end of the journey, “A very good dog, ma’am,” sometimes adding, “and a cute one.” His wide friendliness and gentle manners win him friends on street cars, trains, among any community where he lives. His traveling equipment is such as belongs to any gentlemanly dog. His bed, his mattress, his blanket,—for Royalty ever carry Their Own,—his comb and brush, his washcloth, his soap, his powder (for a chance and vulgar inhabiter), his collars, and his harness (now grown fat in later years, a collar slips over his head and is not safe in traveling).[Pg 27] This harness was also an inheritance from a dear little dead girl-dog, of whom you will hear again.

[Pg 28]

Most men like big dogs, hunting dogs, useful dogs, watch dogs. They don’t understand that idea of a little dog, a dog small enough to take up in your arms and cuddle. A dog that will get up on the lounge beside you, lay his tiny head in your lap, give a comfortable and comforting sigh, and settle himself for a delicious nap next to “Missie Nannie” while she reads or sews. Men don’t have that ache for something little in their arms the way we empty-armed women do. So they don’t care for and love little dogs. And my brother-in-law was one of the most men. Even during the courtship he ventured, when he ought to have been studying to make good impressions, to call Raggety “a silly dog,” “a lollypop.” I know Raggety resented this as much as[Pg 29] I did, for he soon showed Brother-in-Law that he was no “lollypop.”

They were tremendously in love, with that beautiful abandon and obliviousness of surroundings which is characteristic of the Divine Passion, and they went to walk that lovely summer afternoon by the ponds and never even saw that Raggety had gone along. He trotted demurely at their lagging heels until the pond was reached, then with a squeal of joy he chased a water-rat, dug deep into its watery hole, emerged panting, triumphant, the rat in his jaws, gloriously black-mud from nose to tail. The oblivious ones were forced to witness the triumph and a mild feeling of respect crept over Brother-in-Law’s indifference. The oblivious ones were also beautifully dressed in fresh and gay-colored clothing as becometh lovers. Having dispatched the rat, Raggety saw their awakened interest and pleasure and running gaily to them shook violently,[Pg 30] depositing all the black mud and water possible upon that gay clothing, and frisked about as much as to say, “Now, will you ever call me a silly dog again?”

Later, after the honeymoon, when earth had once more become their abode, Raggety visited the Brother-in-Law. He at once adopted him as a comrade, not that Brother-in-Law wanted to be so adopted, but that made no difference to Raggety’s enthusiasm. He insisted upon walking with him, and as there was deep snow that winter, my sister said she often would see her tall man approaching, followed by what looked like a yellow feather. Buried between the snow banks, only the tip of Raggety’s tail waved into sight. Then too he adopted Brother-in-Law’s favorite chair. Pushed out of it at first whenever its master wanted it, Raggety genially but continuously chose that special chair as his own place of repose and never offered to leave it voluntarily. Instead[Pg 31] he would raise polite beseeching eyes, and with a casual wave of his tail, question, “You don’t really want this chair, do you?” It was all so politely, so serenely accomplished that in the end Raggety won out and kept the chair. Ever since then Brother-in-Law has had respect for the “silly dog” and even inquires how he does with a reminiscent chuckle. He remembers the episodes of the mud-bath and the winner of the disputed property-rights in special chairs.

[Pg 32]

During one winter it was not possible for me to keep Raggety with me. I had to find him a home in the village near enough so that I could go and get him for a daily walk. His home was with the family of one of the undergardeners, where there was already one baby girl toddling about and hugging Raggety to her heart’s content. He adores children, no amount of pulling or patting or hugging by tiny hands and arms can upset his good-nature. If his hair becomes too much involved, a faint growl warns tiny fingers to be more gentle, but Raggety can always be trusted with children.

So Raggety lived and played with the Donahues and then a new baby came. Mrs. Margaret faintly told them that Raggety was under the bed, so down on[Pg 33] hands and knees got Mr. Donahue and the doctor, but no coaxing, no blandishments would dislodge the faithful little yellow dog who had mounted guard over his Margaret, who had been so good to him and was now in such mortal distress. Vicious snapping teeth and savage small glaring green eyes were the welcome given out-stretched hands which would have pulled him forth. There was much to be done otherwise, the attempted evictment was abandoned, the little dog-guardian was forgotten. So through the long night he waited without food, without water, without rest. In the dim light of early dawn, Mrs. Margaret lying quiet with a tiny baby on her right arm felt the gentle touch of a little dog’s paw on her shoulder. It was Raggety come to see her and the strange little bundle. She spoke his name, “Raggety,” he answered with a soft whimper of relief, sighed with pleasure and stretched himself on Margaret’s[Pg 34] other arm, across from the new baby. Margaret was his Margaret, the baby was his baby.

[Pg 35]

He met His Lovely Lady long before I met her. And perhaps somewhere else she’ll tell you herself about their meeting, but this is what I know of it. I was going away for the summer to study and in a place where little dogs are not encouraged, so he had to stay behind, and Nellie Jones, who was in my Sunday School class and also my god-daughter, brought him to the train to say “Good-bye.” He was rather excited by the crowds and the train so I did not let him come out onto the platform but made Nellie stay in the waiting-room with him, and there I, with a sad heart, said good-bye for a little while. He wagged his tail encouragingly, his eyes fixed on mine waiting for that happy permission to go which I could not give; Nellie cried and clung about[Pg 36] my neck and I hurried away so that the parting, which must be, might be quickly accomplished. I turned at the door and saw the sad little group, Nellie with her scant little skirt and long legs dangling from the bench, and sitting next to her, with that world-old look of infinite patience and of things not understood but endured, sat that little yellow comrade I was leaving behind. “Good-bye, Raggety. Good-bye, dear faithful little friend.”

How many times have I said it through the long years, but as many times have I said in greeting as I said at our very first meeting, “Raggety, Raggety, how do you do?” I dare not think of that time when I must say, “Good-bye, Raggety. Good-bye, dear faithful little friend,” with no hopes of a greeting to follow.

There the Lovely Lady found them, Nellie and Raggety. And two years later I told her of my little dog, for did[Pg 37] not the Lovely Lady herself have precious tiny Balribbie of gentle memory. I told her of Raggety’s living at the Donahue’s, and how I missed his warm fluffiness. And then I spoke of one of the many homes Raggety and I have had together and she exclaimed with delight, “Why, I know Raggety!” And she’s going to tell you herself how they met.

[Pg 38]

First of all the Lovely Lady loves dogs and knows what they think about, and what they like to do, and what they want. Then she has the most enchanting way of talking to you if you are a dog and a little fluffy dog. She has a dance that fills you with pleasure, so that you caper about her in sheer ecstasy of joy. Best of all her possessions, besides her own lovely self, is “Jeems.” Jeems is a terrier too, young, rather rough, but good company for a walk, and since Raggety has licked him into shape by many instructions of what to do and what not to do, administered in the shape of growls, Jeems is really an all-round good dog. When Raggety came to live near to his Lovely Lady and Jeems, he found that of a morning a breakfast with these friends started[Pg 39] the day satisfactorily. So off he will start with never a thought of “Home and Mother,” when there is the prospect of a ’licious breakfast, to be followed by a walk in the woods.

His marked attentions to his Lovely Lady are witnessed and encouraged by me and by the Lovely Lady’s Husband. Neither of us could be even a tiny bit jealous of the Lovely Lady and her devoted little lover, Raggety. Only recently Raggety showed that it is indeed his Lovely Lady and no one else whom he follows. One unhappy day she packed her trunk and went away for a visit, and during all her absence neither the gambols of Jeems nor the blandishments of the Lovely Lady’s Husband had any effect on his faithful little heart. He simply would not, could not go to that empty house; he stayed away for many days.

And will you tell me how he learned[Pg 40] of the Lovely Lady’s return? He was fast asleep in his little bed at home at the late hour of her arrival. But bright and early the next morning he was at her door greeting her with barks of welcome, ready to go in and have breakfast with her. What or who told him that she was back again? Did some dog friend tell him early in the morning that she had come? Did the fragrance of her presence come to his keen sagacious nostrils? Did some occult sense, denied us human beings, tell him that his loneliness was over, and that his little heart again might beat with joy?

[Pg 41]

He had just come to live in the house of The Great Man, and as neither Raggety nor I were quite sure whether The Great Man would allow him to stay or not, it behooved us both to be exceedingly circumspect. It was therefore most unfortunate that The Great Man should have chosen to behave so strangely. They were playing Bridge that evening, The Great Man and the others, and Raggety politely put aside the curtains with his nose and advanced into the room to ask them how the game was going. He waited a moment, waving a propitiating tail, then advanced further. At this critical moment he came under observation and The Great Man ordered him from the room.

Now, between you and me, I do not[Pg 42] believe that Raggety had ever been ordered from a room. Let us plead in extenuation that he did not understand the order. At any rate, he did not go. So of course the order was more vehemently repeated. Stunned, astonished, surprised, Raggety remained passive. Then The Great Man came to him and took him by the collar to pull him ignominiously from the room. Now neither a well-bred dog nor man allows fingers to be inserted under his collar without protest. Raggety protested. He shook off the offending hand and taking the nearest finger, vigorously pinched it between his teeth. It was his way of saying quickly and positively, “None of that, please,—let go.” Then, to end the unpleasant scene, he left the room, while the others bound up the pinched finger,—no skin was broken, no blood flowed,—and soothed the wounded feelings of The Great Man.

[Pg 43]

And I hearing the tale trembled, fearing that Raggety’s protest meant banishment for him.

But there is a pleasant sequel to the tale.

A day or two later, while his fate was hanging in the balance, Raggety again nosed aside the curtains of the rooms of The Great Man. The latter tells the rest of it this way: “I had been drowsily reading the newspapers, probably took a cat-nap and woke with a consciousness of something breathing in the room. I looked about for our big cat but could not find him. Then on the floor, beside my chair, that little cock-eared dog was sitting up, quietly begging.” Mr. Great Man opened his eyes to find Raggety sitting up on his haunches, waving entreating paws. Nor would he get down until The Great Man stretched out a forgiving hand, took his paw, and there was peace between them. As The Great Man says, “When[Pg 44] one gentleman asks pardon of another whom he has hurt, what can the latter do but forgive him generously?” So The Great Man and Raggety have been firm friends ever since.

[Pg 45]

I always wonder what people who do not own a dog do for general conversation. The very young, the uninteresting and uninterested alike, the dangerous, and the facetious can always be safely steered onto the discussion of dogs or the dog, if there happens to be a dog in the room. When you have not an idea, and your guest hasn’t an idea, when the man is treading on delicate ground or is approaching the barriers, if you just introduce Raggeties into the conversation the day is saved, the feelings are preserved, your own supremacy maintained. If politics and the market flavor the situation between men, dogs and dress savour the conversation with women. Take heed, if the woman has been driven to the dogs conversationally, you are losing headway and heart-way.[Pg 46] This is about Raggety’s ears. They always, sooner or later, come into the conversation.

The fact is Raggety’s ears are very interesting. Haven’t I told you about them before? He has one ear that stands up and one ear that flops down and never stands up. You can never remember whether it is the right ear that stands up and the left ear that lies down, or the left ear that stands up and the right ear that lies down. Which is it? Well, I myself after knowing Raggety intimately for many years do not feel quite sure!

Those ears cause an endless amount of surmise and conjecture. A person sits in my room enjoying stereotyped conversation and invariably says, “What do you suppose makes one of Raggety’s ears stand up and the other flop over?” Now here are the three theories with which I invariably entertain my questioner in stereotyped form. The first is my own[Pg 47] theory, which is that when Raggety was a baby-puppy, his mother or one of his baby-brothers bit him through the ear, just in play and broke the muscles. But when I once advanced this theory to a Doctor-friend of Raggety, he scoffed at it.

“Oh, no,” said Raggety’s Doctor-friend, “muscles don’t give out in that way. It is paralysis. The dog was kicked, probably in the head, once upon a time and that side is paralyzed and so he can not raise his ear.” This sounded professional and so thereafter I quoted this theory. But when I told this to a dog-trainer who observed and of course commented on the famous mismatched ears, again such theory was scorned as unprofessional.

“Why,” laughed the dog-trainer, “if the dog was kicked, his brain injured and paralysis occurred, he would have had all that side paralyzed, not just an ear. That isn’t it at all! That dog had a prick-eared[Pg 48] father and a lop-eared mother,—or the other way round,—and so he just took one ear from each. That’s no paralysis!”

So you can choose your theory after you look at Raggety’s picture. You see I do not know which is right—do you?

[Pg 49]

Yes, it’s a very sore subject with me, though Raggety is entirely indifferent. His tail is not pretty, indeed, it is rather ugly. It’s too long and it isn’t very fluffy and he carries it arching over his back, which makes it look twice as long as it is. Some rude boys once even pretended that they thought his name was Rag-tail, instead of Raggety! Yes, decidedly his tail is his weakest spot, a sort of Achilles’s heel. I never talk much about tails before him, for as I say his tail is a very sensitive subject.

Nevertheless, Raggety’s tail is beautifully responsive to suggestion! It is an emotional tail, reflecting the wearer’s innermost feelings. Indeed it seems as though sometimes it would wag itself off. And some of his girl friends say that it is[Pg 50] a “pinned-on tail” and does not belong to him, it is so ready and waggy whenever it has the least encouragement. But his tail is not beautiful, and were it not that this is a true story of a truly dog, I should not even mention Raggety’s tail.

He’s a molasses dog, with butter-scotch ears, chocolate-cream eyes, licorice nose, pink peppermint tongue, and teeth like the little candies that come in Christmas tree cornucopias. “But,” said one of the little girls, “isn’t his tail butter-scotch too?” “Oh, no,” I hurried to reply, “it’s molasses, only it’s darker because it is not pulled as much, for we never pull tails!”

[Pg 51]

Raggety is not built for an athlete. His general proportions are those of a very fat sausage mounted on four tooth-picks, “with a head on before and a tail on behind” (see rhapsody entitled “The Mintie”). Nevertheless like many a man of athletic instinct and corporate incapacity, he considers himself “an all-round one,” which perhaps is as true as it sounds!

First of all, he loves to walk. The mere fact that you are a biped and can walk wins Raggety’s interest. He even knows the word “walk” in a general conversation and the magic of it waves his tail. Oh, me! oh, my! what walks we have had together!

Then The Riding Lady once took him on horseback and from time to time since[Pg 52] he has ridden his horse. This is the way he rides with The Riding Lady: he sits on the saddle-bow (is that the right name? I hope it is for it sounds so nice and mediæval!) and puts a paw on each of her arms, and when the horse trots he gently bounces up and down and looks to right and left with a most knowing air.

One of his chiefest delights out-of-doors is swimming. Never can I forget the first time he showed me that he could swim. We were living in Portland, Maine, and below State Street Hill lie beautiful Deerings Oaks, earlier celebrated by the poet Longfellow. I took Raggety to walk in Deerings Oaks and he discovered the pond! Ducks swam in the pond and lived in a wonderful little house on a tiny island in the middle of the pond. He went down to the muddy bank, tasted the water, found it good, in went fore-legs, body, hind-legs, tail; just that yellow head and ears above the surface,[Pg 53] and how fast those four legs moved underneath! But that is not the worst of it! He saw the ducks and made towards them, off they started quacking furiously, fast the yellow head followed, barking. Round and round and round the pond they went, and my whistles and calls were utterly unavailing. Visions of duck-keepers, police, fines flitted through my head! He landed on the ducks’ island, inspected their house, roused to activity any sitting mother-ducks and having stirred the whole duckdom to hysterical agitation, came swimming over to me, emerging more like a drowned rat rather than a fluffy yellow dog! He rolled on the warm dry grass, then shook himself as who would say, “There, those old ducks needn’t think they own that pond!”

One instinct born in every terrier’s blood is a love of the chase. Naturally small game is appropriate, so mice, rats, moles, squirrels, or a stray rabbit fill[Pg 54] Raggety’s hunting soul with joy. To-day he is too fat, too much petted, too old to have the ardor of his earlier years, but recently I saw him dig a mole, seize it, crack its neck with a celerity and dexterity which made me more than glad I was not a mole burrowing under Raggety’s path. Squirrels are an endless source of interest. You never catch one. I do not know whether secretly you ever hope to catch one, but like the pursuit of virtue it shows off your style to interested onlookers, and stirs your system to a healthy vigor. And you can always trot back and say, “My! But he’s a swift one! I did my best and you see how well I look in action.” Not alone the attainment, but the pursuit of virtue ennobles!

[Pg 55]

Raggety’s bachelorhood has always been an anxiety to me. Limited environment and force of circumstance have prevented my suing for the paw of some gentle little terrier Miss, and setting Raggety and his mate up in domesticity. Many times through the years simple and frank women have said to me, “How adorable Raggety’s puppies would be!”

Yes, indeed, if they could all be Raggeties. But genius does not always reproduce itself, and I’ve been fearful that the puppies might have two stupid prick-ears, or worse still, two dull lop-ears. But the hearts of dogs and men are not bound exclusively to domestic felicity. Therefore Raggety has had his loves, and, like the Greatest of Frenchmen, his love affairs show catholicity and wide range of imagination.

[Pg 56]

When this imagination is upon him he is ardent and progressive, fights with lordly rivals, and returns bloody but triumphant. Once he eluded a whole band of rivals, crept through a broken pane of glass far too small for the rest, and dropped eight feet below to the floor of the cellar where the adorable Belle had been secreted by cruel guardians. You may imagine the guardians’ surprise on the following morning when they came to feed the imprisoned Belle! Raggety greeted them with a cordiality and friendliness which exhibited his new and intimate relation to the family and—Belle.

Jeems, on the other hand, leads a guarded life and knows that virtue also has its rewards. I can only hope that Raggety has never communicated to Jeems’s innocent mind the joys of nature and the love of the sex. True follower of nature’s supreme law, how Raggety’s independence and disregard of[Pg 57] conventionalities would have delighted the liberty-loving heart of the ardent Jean-Jacques!

[Pg 58]

Along with an ardent temperament, a love of liberty, and a wide sympathy goes a democratic tendency. Quite true to the type, Raggety of unknown pedigree shows his aristocratic stock. No recent upstart can choose his friends as he elects. Only the true aristocrat can be absolutely democratic. If you have a social position to make or maintain, you must be careful that your associates are useful and important in the structure of society; if you are absolutely sure of your own position, your heart may reach up and down and round about and say, “Thou art mine, for I am yours.” And it is thus that Raggety elects his friends.

The Donahues, The Great Man, His Lovely Lady, Belle, Black Henry, the four Brooklyn Aunties of those delicious[Pg 59] chocolate crackers, Jeems, Brother-in-Law, all have place in his heart without reference to their place in the social edifice. Happy Raggety, to be free to choose and to refuse! For he will not accept those whom he does not desire. No amount of caressing or blandishment can fix his affections. I have discovered, however, that food and an interest in outdoor exercise attract him, but there must be some personal quality beyond to make this attraction permanent. I have seen both fail; why, I can not explain.

If you should ask Raggety about Black Henry, I know he would reply, “He is my invaluable friend.” Think of being invaluable to some one! Isn’t it what we mortals are all striving to attain? To be valued when present, to be missed when absent is the face-value of the note of friendship. This is the bond between Henry and Raggety.

The first rattle of the coal which Henry[Pg 60] brings to renew the fire in the early morning awakes Raggety to the joy of the day. Henry’s arrival means a breath of fresh air and breakfast to follow. Oh! and if one only investigates the glorious mysterious pockets of Henry’s white linen coat! Such tid-bits, shares of Henry’s own breakfasts and luncheons and dinners! Then Henry walks to the post-office when every other stupid person stays at home, so that on rainy days you can get in a walk with him when all others fail.

Often have I seen Raggety kiss the hem of Henry’s trousers in enthusiastic appreciation of some pleasant suggestion about walk or food. Coming in of an evening one finds Henry seated on the hall bench with Raggety beside him,—Henry the silent, the smiling, the serviceable friend. Raggety lifts a forepaw and puts it lovingly on Henry’s knee, saying, “What is race, what is rank between hearts that love? This is my invaluable friend Henry.”

[Pg 61]

Of one of his friendships I must make special mention, because the mortal part of it is no more. The Dear Man lived among Books, and about his Book House stood tall oaks inhabited by bands of quite tame squirrels. They were tame because they were loved by The Man and fed from his hands. I have seen Raggety sit in twitching self-control watching the squirrels feed, divided painfully between his desire to pursue those virtuous squirrels and his love of The Dear Man whose heart he could not grieve by the vain pursuit. When The Book Man wrote his noble tribute to The Dear Man, Raggety appropriately ran into the pages.

The Dear Man went away one summer and never returned, and the squirrels have[Pg 62] grown wild and fearful, for the hands that fed them feed them no more.

Almost the last message from The Dear Man before He Passed was to Raggety. I give it to you as it stands to-day, and on the reverse of the card is a colored picture of the blooming orchards of Montana.

Master Raggety:

I’m thinking of a far-away dog, a companion even as he seeks companionship, who has a mind of his own, interests of his own, an independence of his own, but who gives his little heart away to those whom it elects, and who look upon him to love him.

He who writes this begs that he will stand before the two friends who are with him and thus be the messenger to them of this friend’s love.

1 July, 1911.

[Pg 63]

(Raggety speaks)

Jeems is bigger than Me, but much, much younger and not half so clever; but that is partly due to his bringing-up, which of course he can not help, poor Pup!

Jeems belongs to The Lovely Lady and as Hers I thoroughly love and respect him. Of course I too belong in a kind of way to The Lovely Lady, for I love Her and she loves Me. Jeems came to take the place of dear gentle Balribbie who died. I never saw pretty Balribbie; perhaps if she had not died before I came to live here, our Mistresses might have let us marry and there would have been little Raggeties and tiny Balribbies. But pshaw! These are the Dream Puppies of an old bachelor dog!

(Don’t be surprised that I know about[Pg 64] dear Charles Lamb, for I live in a literary atmosphere and there is much writing going on all about Me!)

Jeems is anything but a dream!—except of course in looks, for he is very handsome and his tail is all right,—though Mistress would rather I did not mention tails. Funnily enough, mine never bothers me the way it does her. Well, Jeems is a bouncing barking breathless brother. But he’s being trained to be awful particular, more’s the pity, for he’s a true democrat at heart.

This in-breeding training of his makes him a bit slow. When we both sit up and beg for those good sweet crackers at afternoon-tea, I always get his share too, for he’s slow at finding. Of course his Mistress always sees that he gets enough, but he’s never had to fend for himself and I have, and it makes a dog or a man mighty sharp, doesn’t it? Jeems has had milk and chicken in painted saucers ever[Pg 65] since he was born. I’ve told him how especially good very old chicken bones out of a garbage pail are, but his tastes remain simple. I can’t get up his enthusiasm!

Jeems never goes out alone as I do. And he is always cleaned and combed so that The Lovely Lady doesn’t like him to get muddy in water-rat holes or stuck up with burrs. But with The Lovely Lady as companion and guide, Me and Jeems have elegant walks! Of course occasionally I have to break through and lie in a mud-puddle just to get the Nature-feel, but I know that Jeems and The Lovely Lady are both helpful to me, as they are refined and particular. It is not good for even a dog always to lead a dog’s life.

Best of all, Jeems speaks my language—doggerel, does one call it? Even when humans are dear and good and kind, one’s native tongue is sweet in the ears. So when Jeems and I dash down the hall[Pg 66] together and he shouts, “Hurrah, here goes for a run!” I shout back as sharp and loud as I can, “Hi, Jeems, off we are!” The Lovely Lady laughs, even while she holds on to her ears, for she almost knows the doggerel language herself since we, Me and Jeems, took up her education doggedly.

“Hi, Jeems Pitbladdo, there’s a squirrel on that oak! See who’ll get there first!” And off we go.

[Pg 67]

It was quite by accident that years ago I met a warm devoted bit of life called Raggety. He has since become a near neighbor and an intimate and devoted friend.

First in my memory, I see a bundle of wet yellow fur carried up a stairway in a northern city by the sea, and when I interestedly inquired who it was, received the reply, “Don’t you know Raggety?”

But the really truly introduction came in a railroad station one fine June morning, how long after our first meeting I do not know. I was unhappy. I had said good-bye for a whole Summer to my precious pet Balribbie, and left my bit of Blue Skye happiness behind me. It was no use, the tears would come when[Pg 68] I thought of that little bunch of affection with its soft yellow head sitting in the farmhouse window,—waiting, watching for her truant mistress.

Raggety’s little paw touched me and his cold wet black nose nuzzled into my hand with the wonderful sympathy of discovering a friend. Raggety’s lovely brown eyes were also filled with tears. He was in trouble and pining for the Mistress who had just left him. Every one was going away and he gasped at the loneliness of life.

We sat side by side on the hard station bench and had ten minutes of affection and bliss. All I could do was to say softly, “Wait a minute, wait a minute! Suddenly Time goes by and Mistresses reappear, tails wave round, and long happy walks begin again for little doggies!”

My train came and there was another tear at Raggety’s heart strings. The casual stranger of a few minutes before[Pg 69] had become endeared forever by her knowledge of the comforting scratching places of little beasties.

Summers in Europe went and came; Time slipped by and one day he took little dog Balribbie with him, and hurly-burly Jeems begged to take her place. Then as accidentally as Raggety and I had met in that distant railroad station, so Time brought Raggety and his Mistress and Jeems and his Mistress to live in a pretty southern village and we four became a dog club or show!

And here Raggety is to-day making friends as he needs them, or dropping them when he yearns for quiet; always ready for a walk with an agreeable companion, or a fight with Al Kelly’s dog up the road; a swim in the cold creek; a tid-bit (if it’s the same to you!); a scurry through the brush after Molly Cottontail or a plunge into the deep wet meadow where the frogs sing and the violets[Pg 70] bloom. Even a great pig does not fright him until he sees the snout bear down upon his little paws, to lift him up and off and away!

This is why Raggety is loved. He was born a little trusting dog and he has made himself the companion of scholars and sages.

You, dear Raggety, are one of the Dog-stars in my firmament of loves. Along with Balribbie and Teddy and Jeems, you will greet your slower, earth-plodding Mistresses in some far-off Heaven. We shall see you wagging your long tail of welcome and tinkling your little silver bell, ushering us into that Kingdom of Love.

[Pg 71]

Raggety trotted into my life and heart long years ago; he has trotted into the lives and hearts of many people since; he has trotted into your life too! It is good to love even a fluffy little yellow dog and have him love you. See, his tail is wagging! Will you say to him as I did, “Raggety, Raggety, how do you do?”

Minor punctuation errors have been changed without notice. The following Printer errors have been changed.

| CHANGED | FROM | TO |

| Page 13: | “thrust his hind legs” | “thrust his hind-legs” |

| Page 38: | “Devotion to His Lovely Laay” | “Devotion to His Lovely Lady” |

Other inconsistencies are as in the original.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.