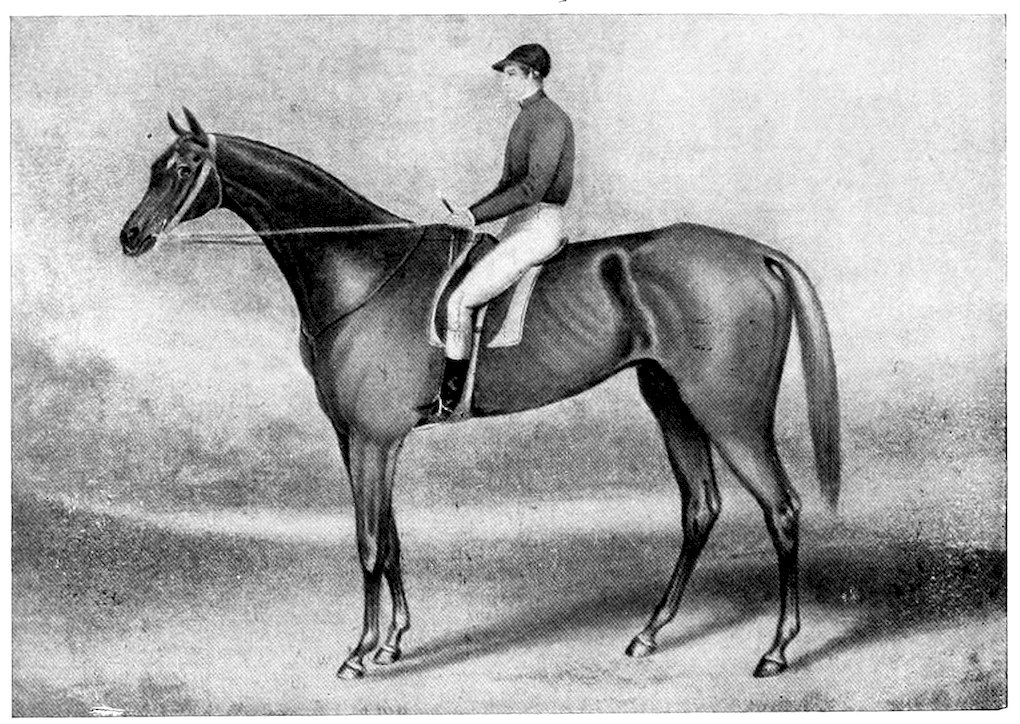

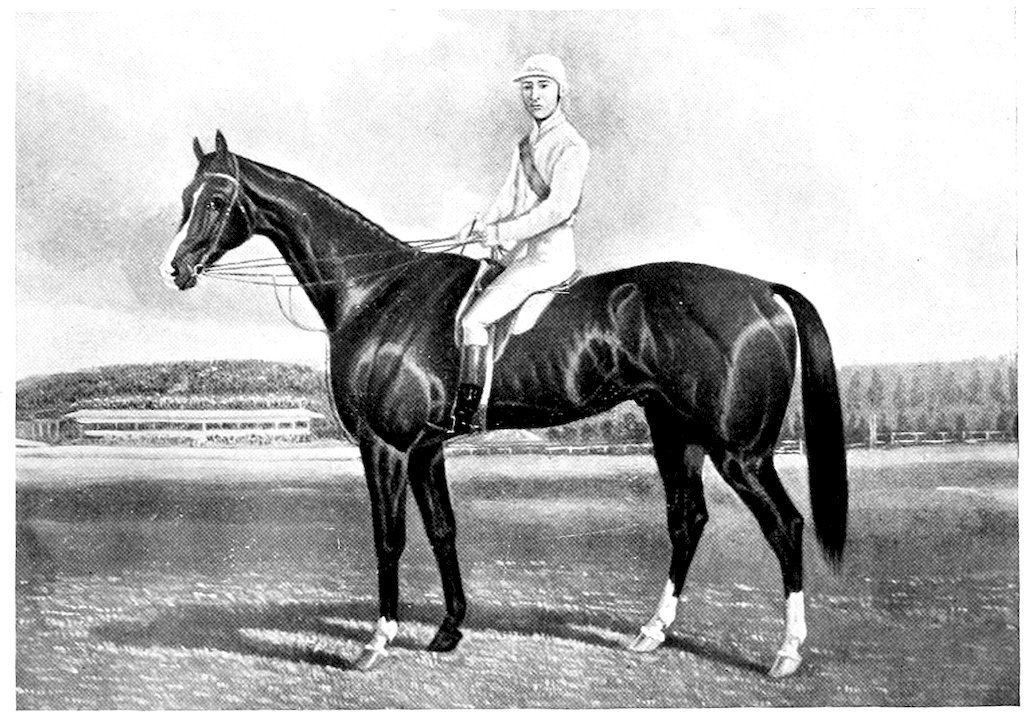

From an old painting

A change of horses never meant a change of whisky.

It was always then as now—JOHNNIE WALKER.

JOHN WALKER & SONS, LTD.

Scotch Whisky Distillers

KILMARNOCK, SCOTLAND.

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Racehorses in Australia, by W. H. Lang

Title: Racehorses in Australia

Editors: W. H. Lang

Ken Austin

Stewart McKay

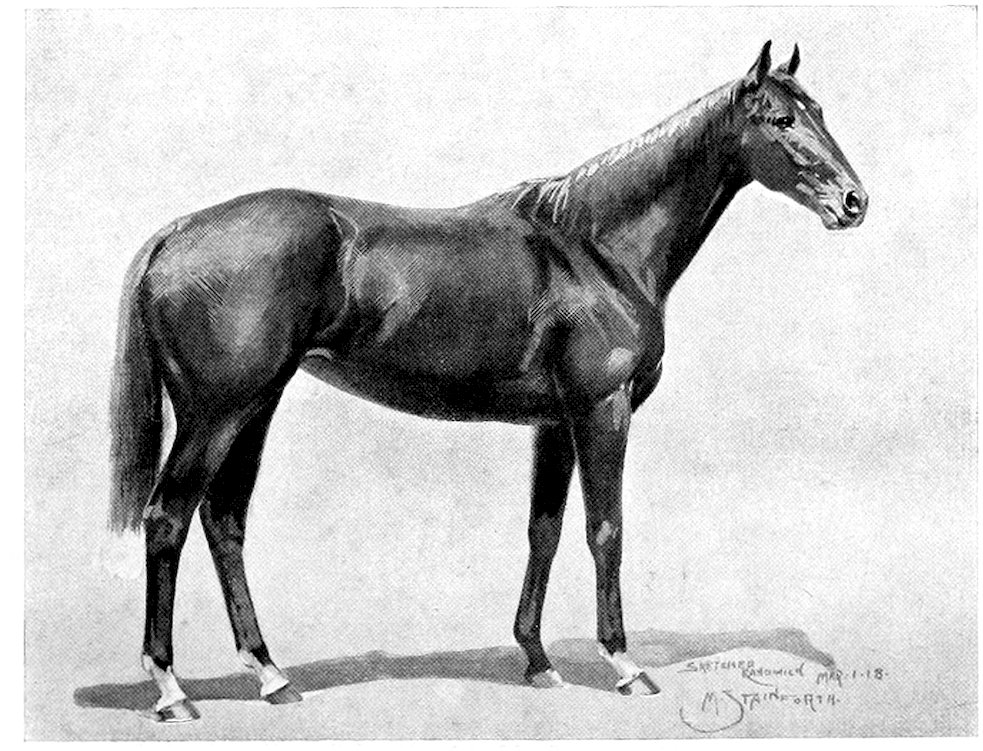

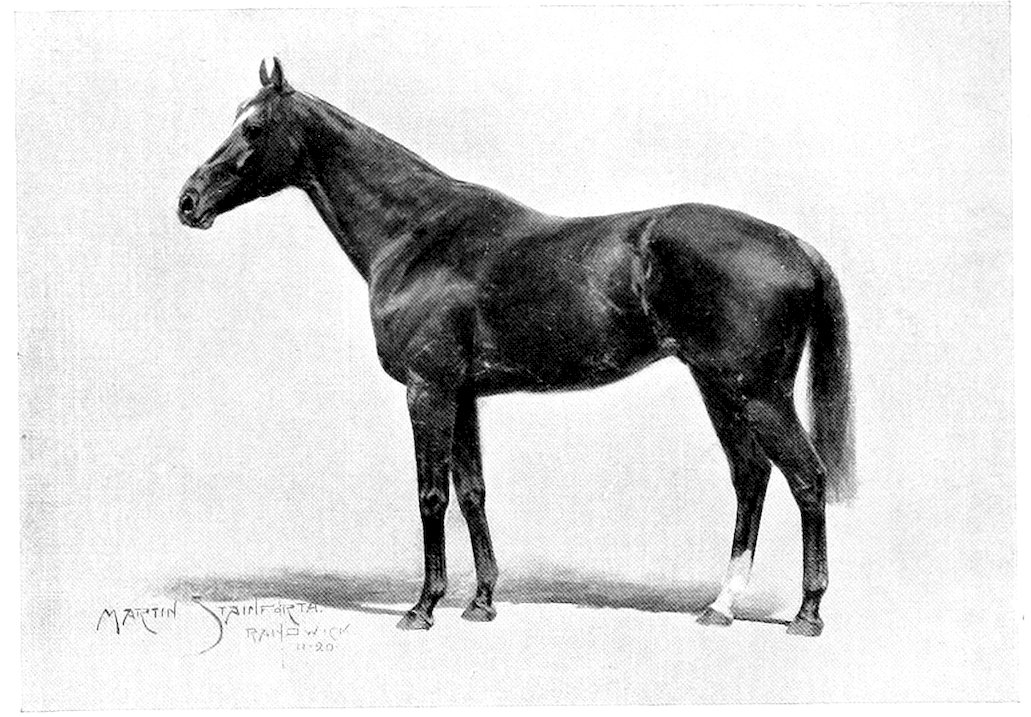

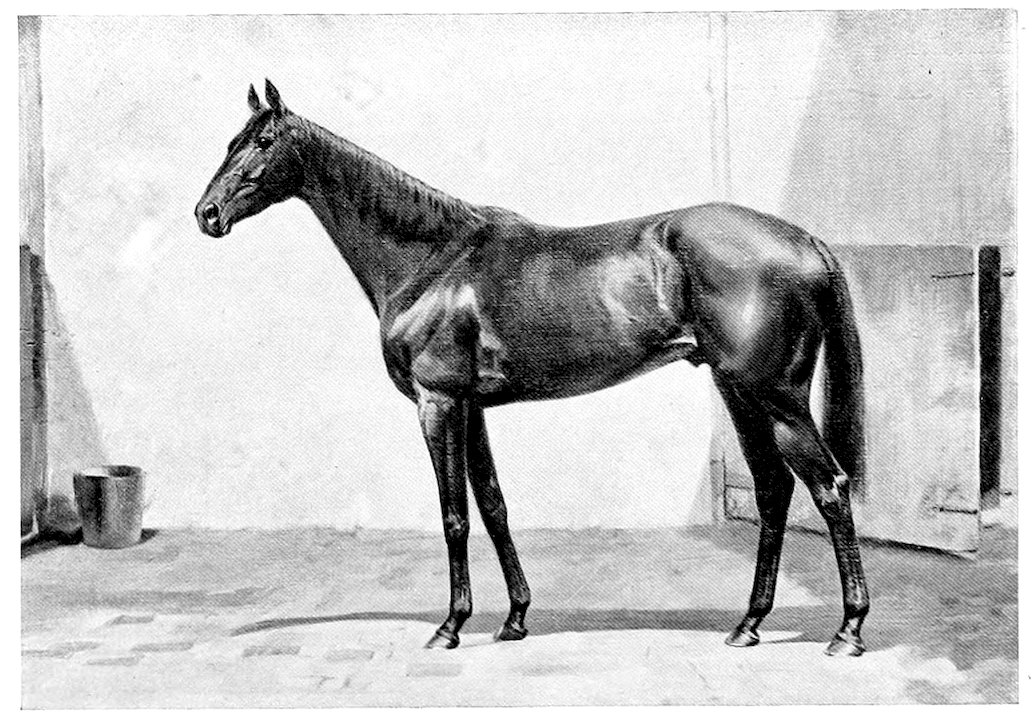

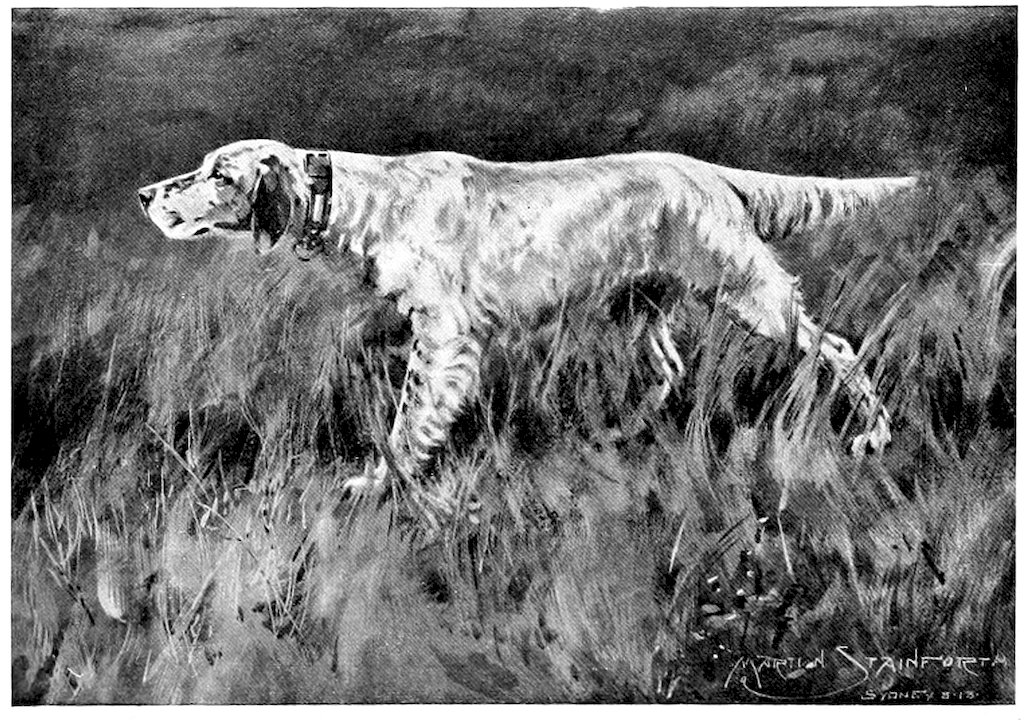

Illustrator: Martin Stainforth

Release Date: February 16, 2023 [eBook #70050]

Language: English

Produced by: Richard Tonsing and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

The blocks in this book were made by the Globe Engraving Co. and Messrs. Patterson Shugg Pty. Ltd. of Melbourne, and Messrs. Hartland & Hyde and Messrs. Bacon & Co. of Sydney.

Wholly set up and printed in Australia by Messrs. W. C. Penfold & Co. Ltd. of Hosking Place, Sydney, and published by Sydney Ure Smith at 24 Bond Street, Sydney, for Art in Australia Ltd.

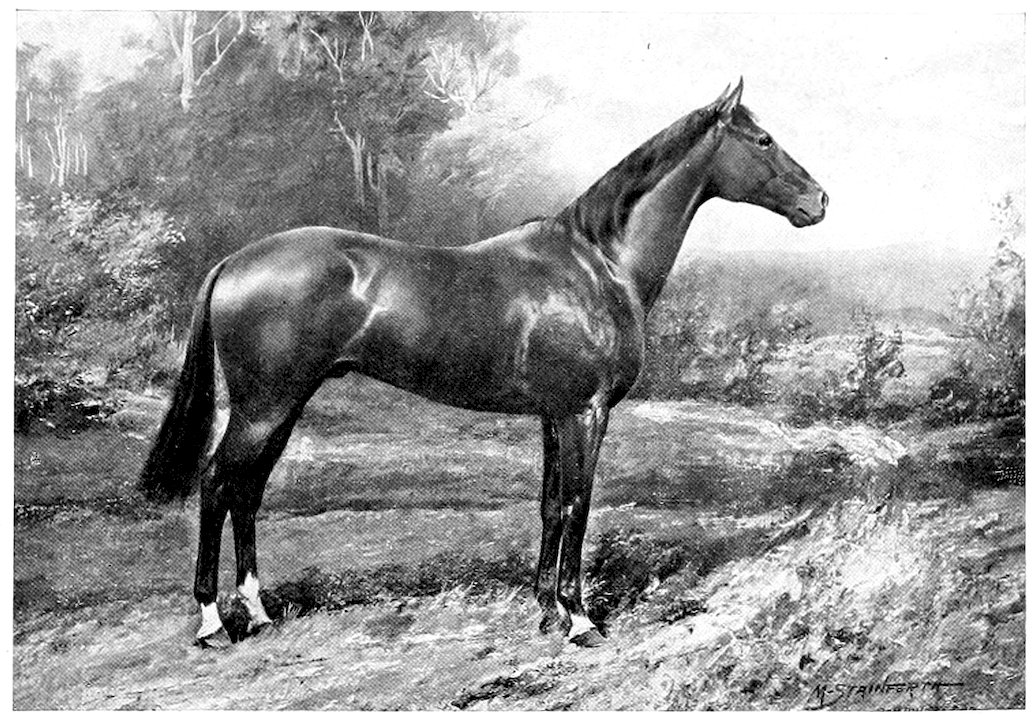

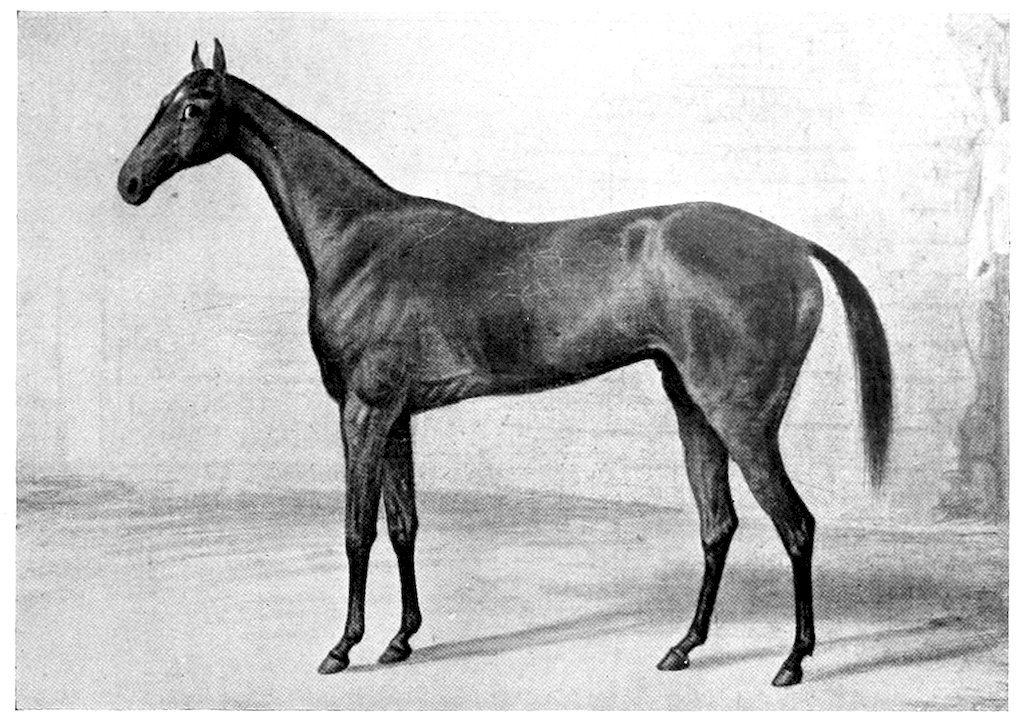

From an old painting

A change of horses never meant a change of whisky.

It was always then as now—JOHNNIE WALKER.

JOHN WALKER & SONS, LTD.

Scotch Whisky Distillers

KILMARNOCK, SCOTLAND.

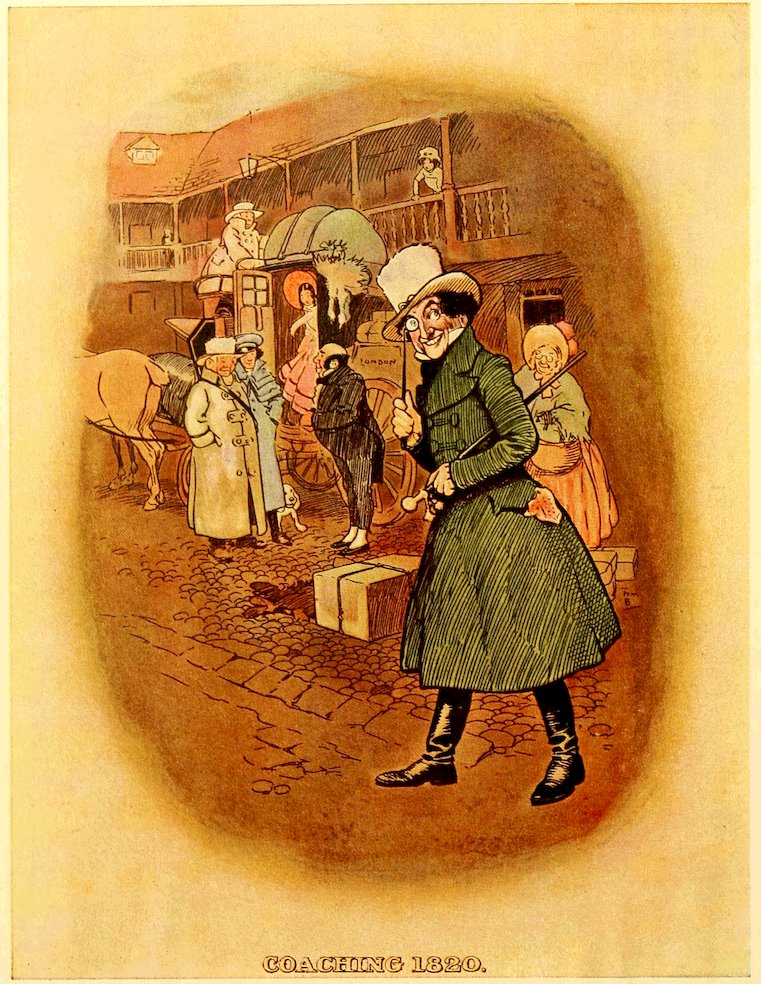

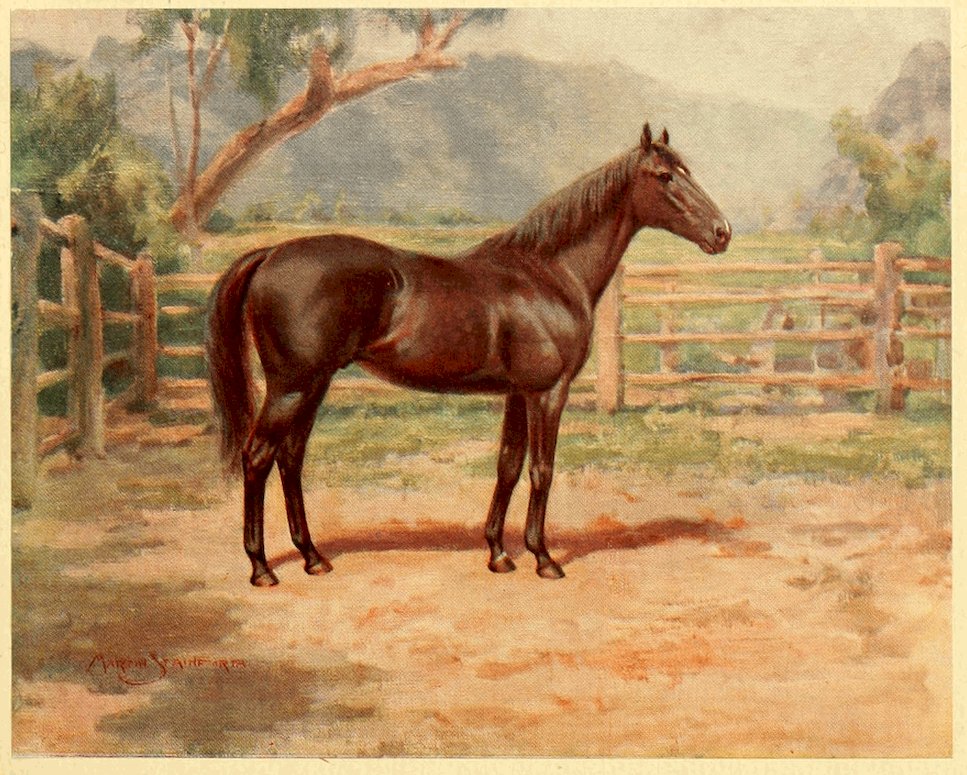

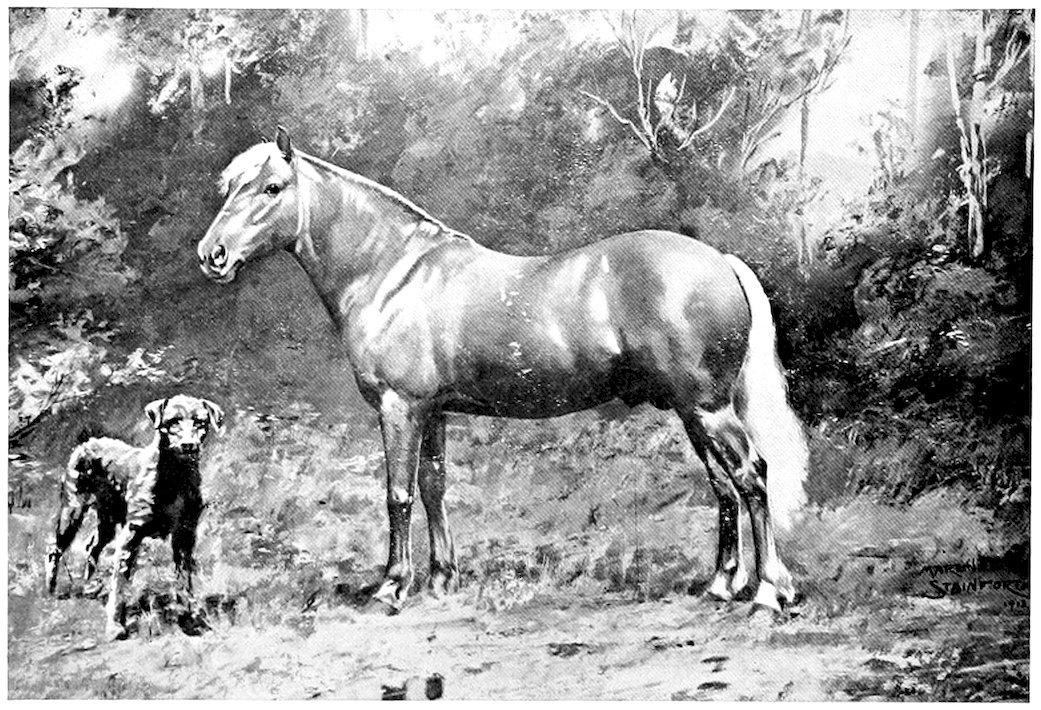

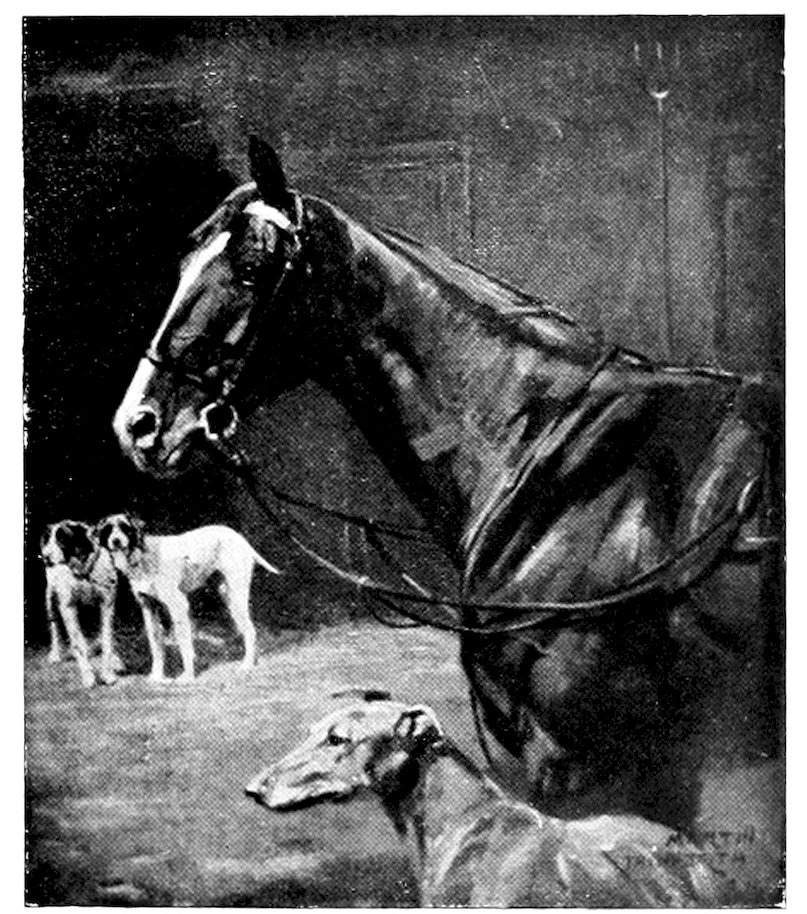

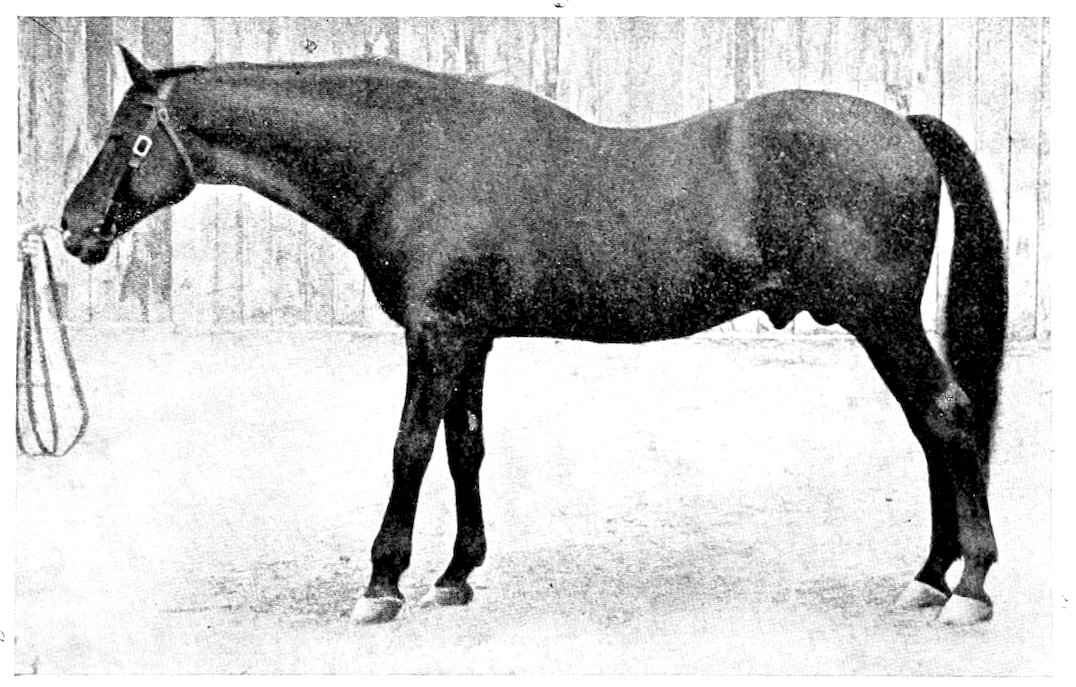

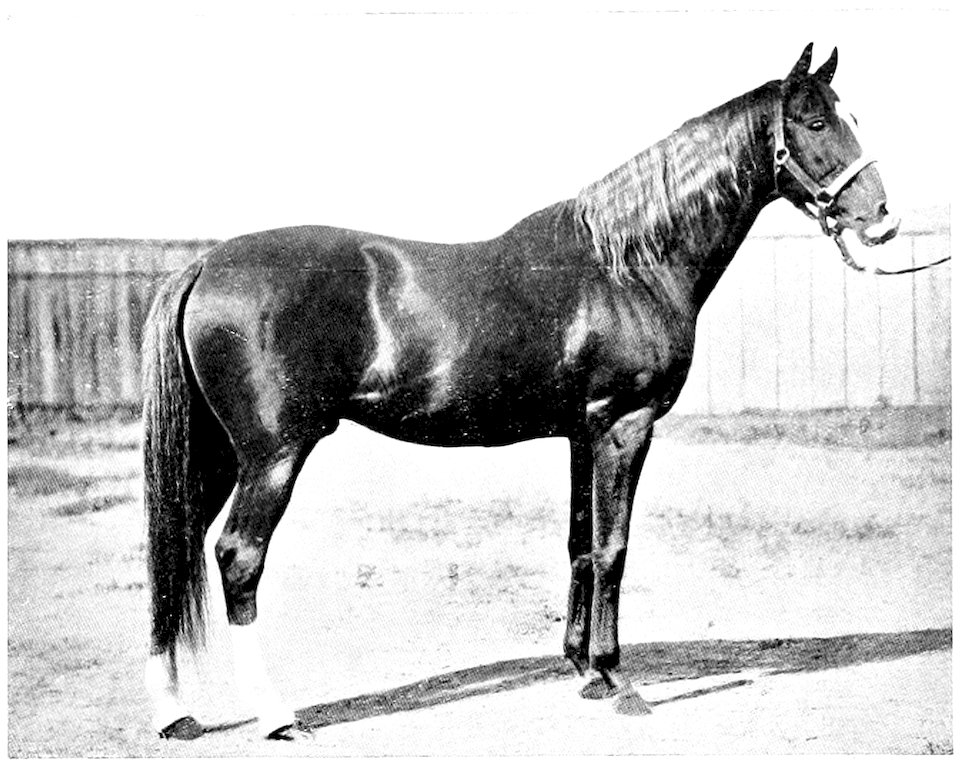

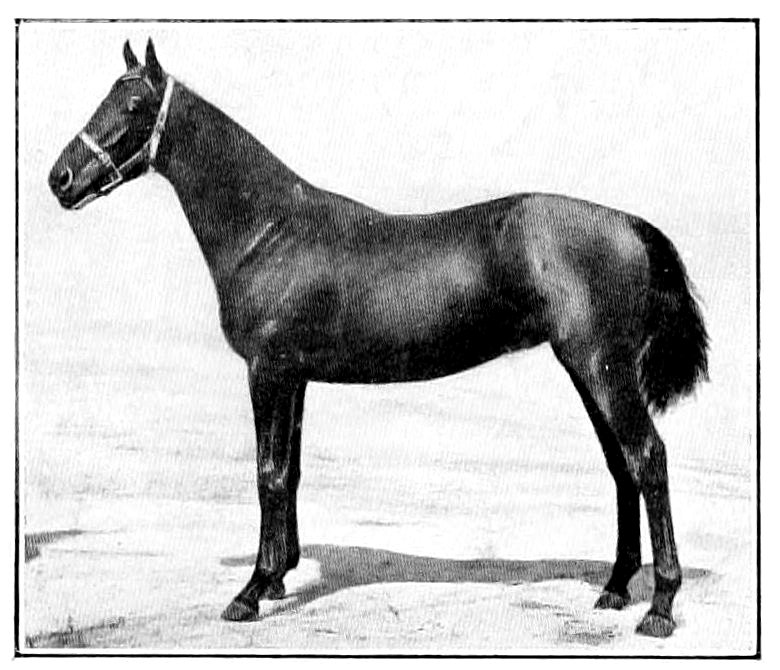

PLATE 1.

HEAD OF TRAFALGAR, one of the most genuine stayers bred in Australia of recent years. From a painting of the horse, at the age of 7 years, in the possession of Dr. Stewart McKay.

| Page | ||

|---|---|---|

| Introduction | By Ken Austin | 1 |

| Racehorses in Australia | By Dr. W. H. Lang | 3 |

| Martin Stainforth—an appreciation | By Dr. Stewart McKay | 105 |

| The Secret of Staying Power | By Dr. Stewart McKay | 117 |

| The A.J.C. and Randwick | By Ken Austin | 124 |

| The V.R.C. and Flemington | By Dr. W. H. Lang | 130 |

| The Thoroughbred Homes of Australia | By Ken Austin | 137 |

| Famous Racehorses | By Frank Wilkinson (Martindale) | 147 |

| Racing in New South Wales | 159 |

| COLORED PLATES | |

| Plate | |

|---|---|

| Head of Trafalgar | 1 |

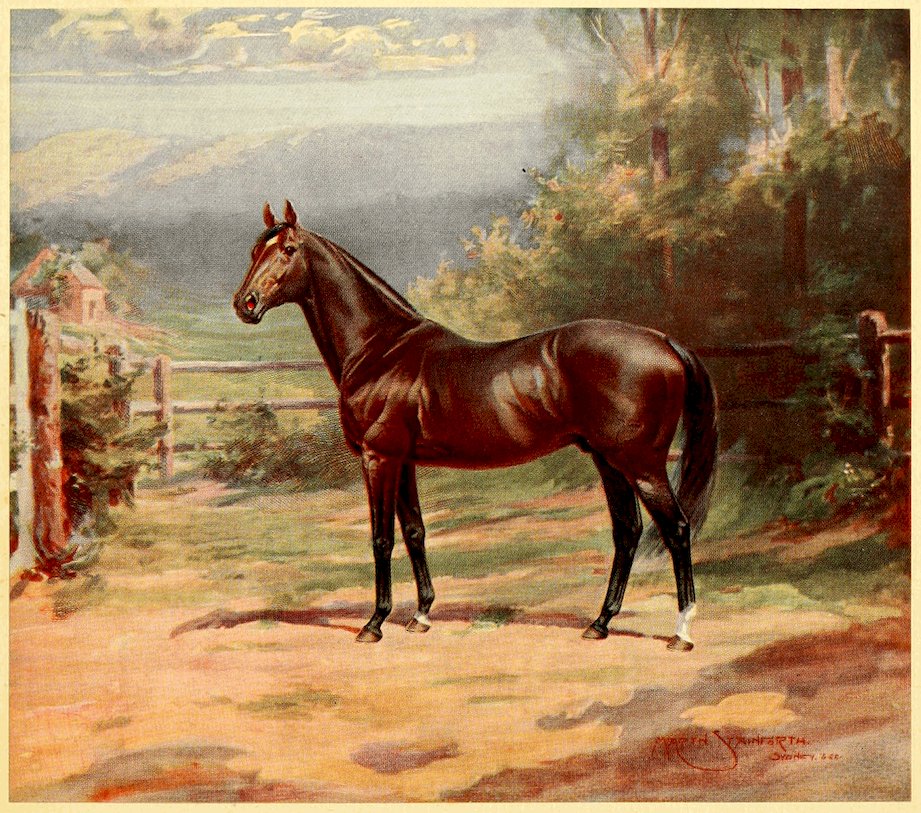

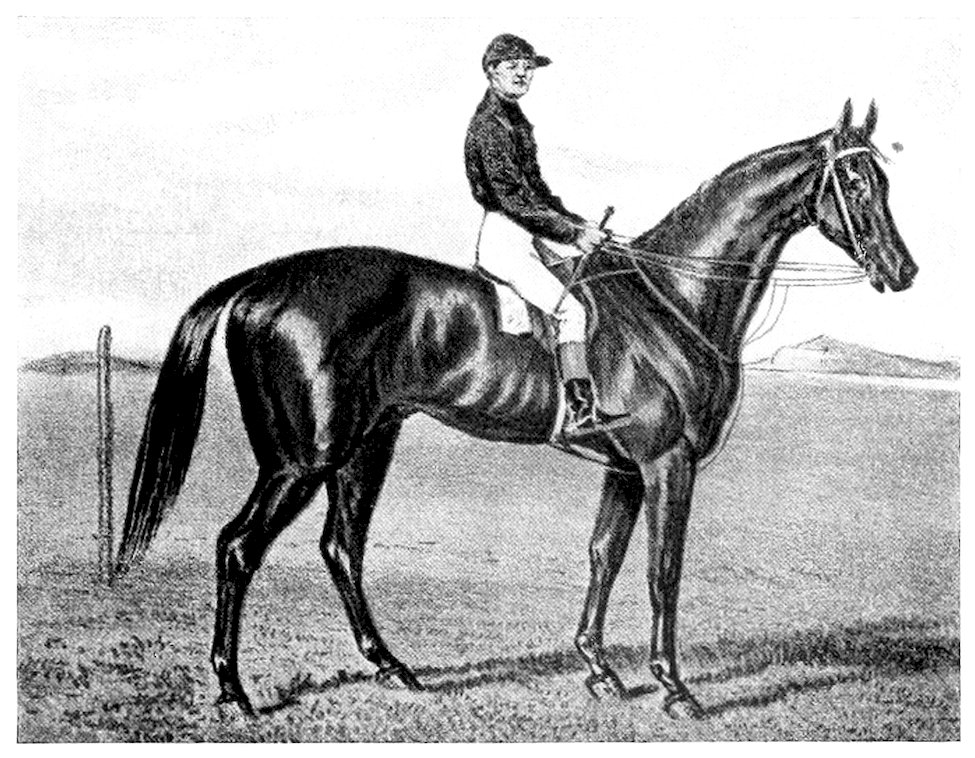

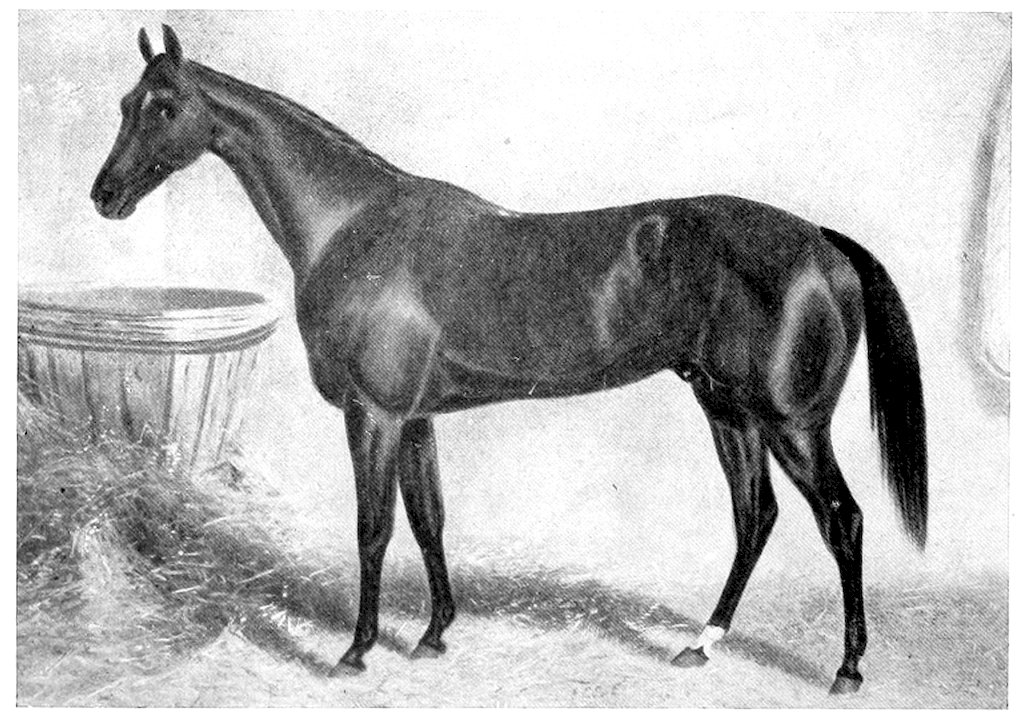

| Musket | 2 |

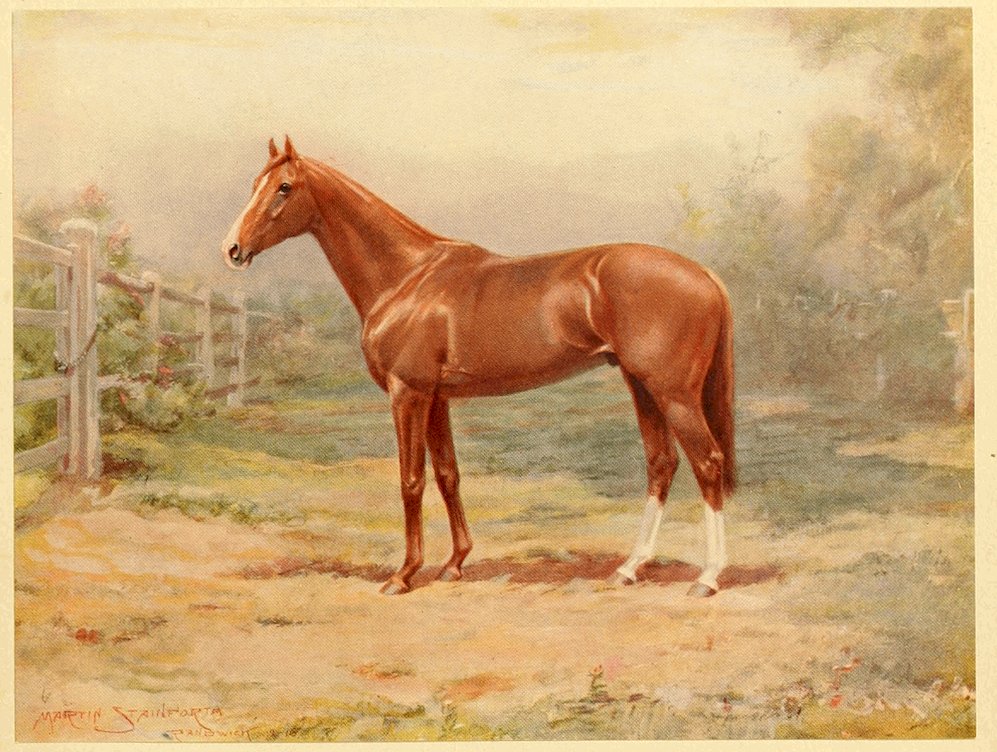

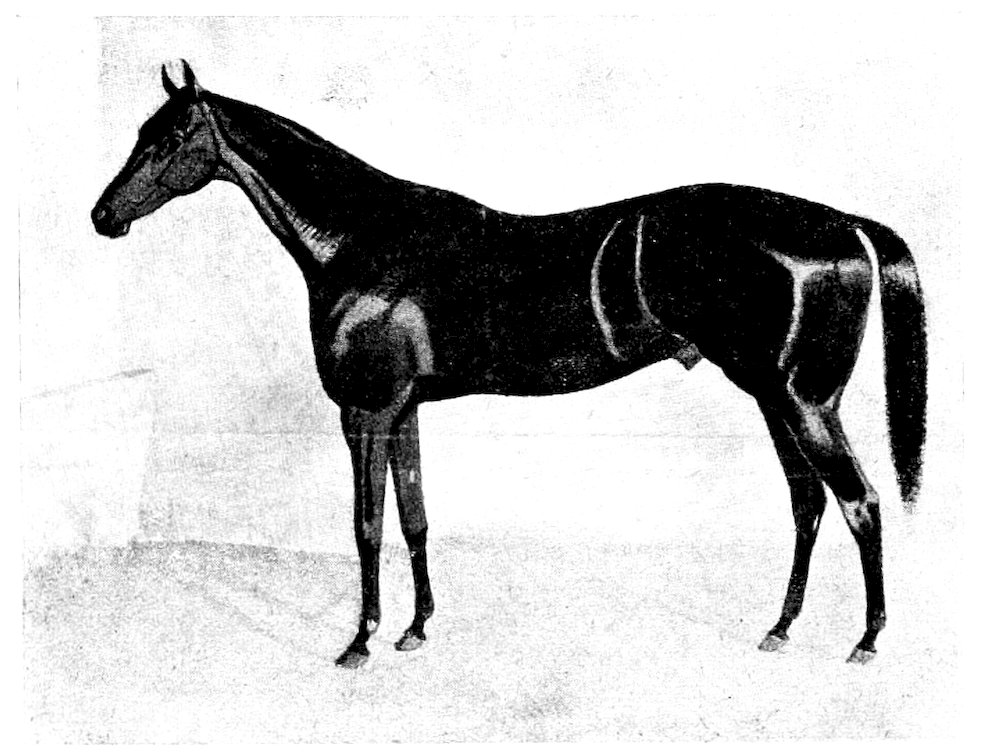

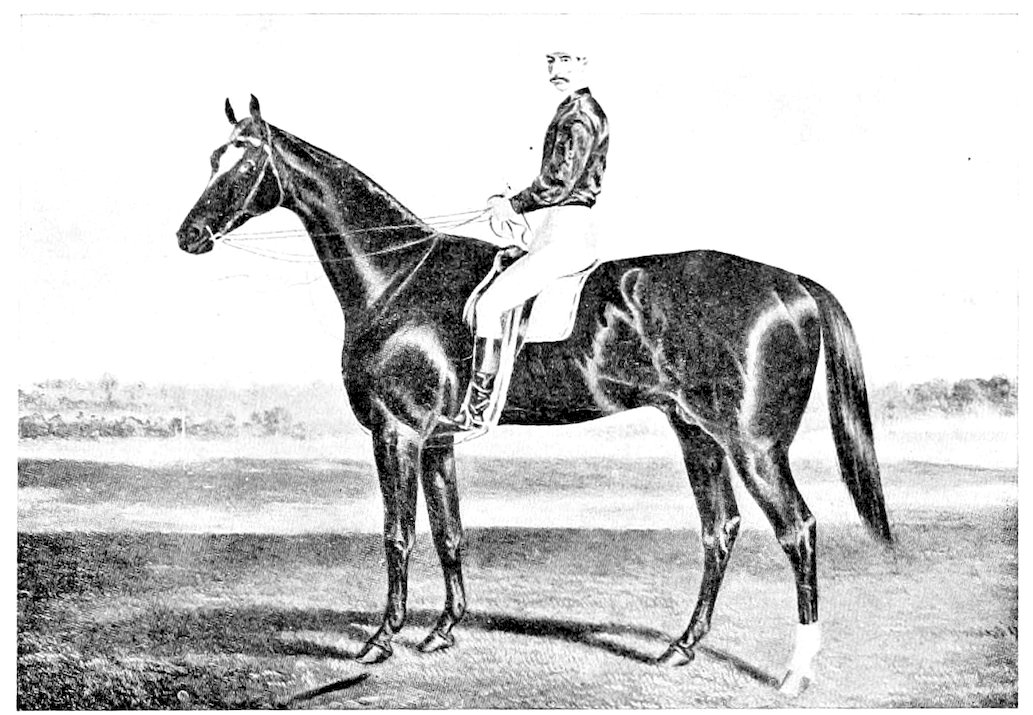

| Carbine | 3 |

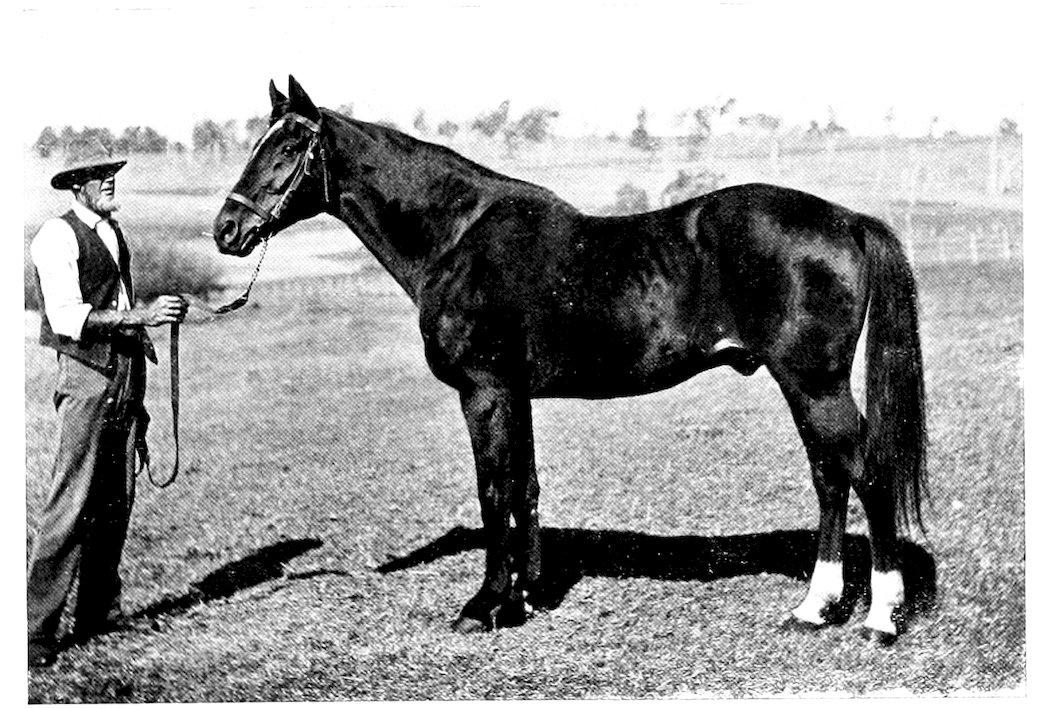

| Trenton | 4 |

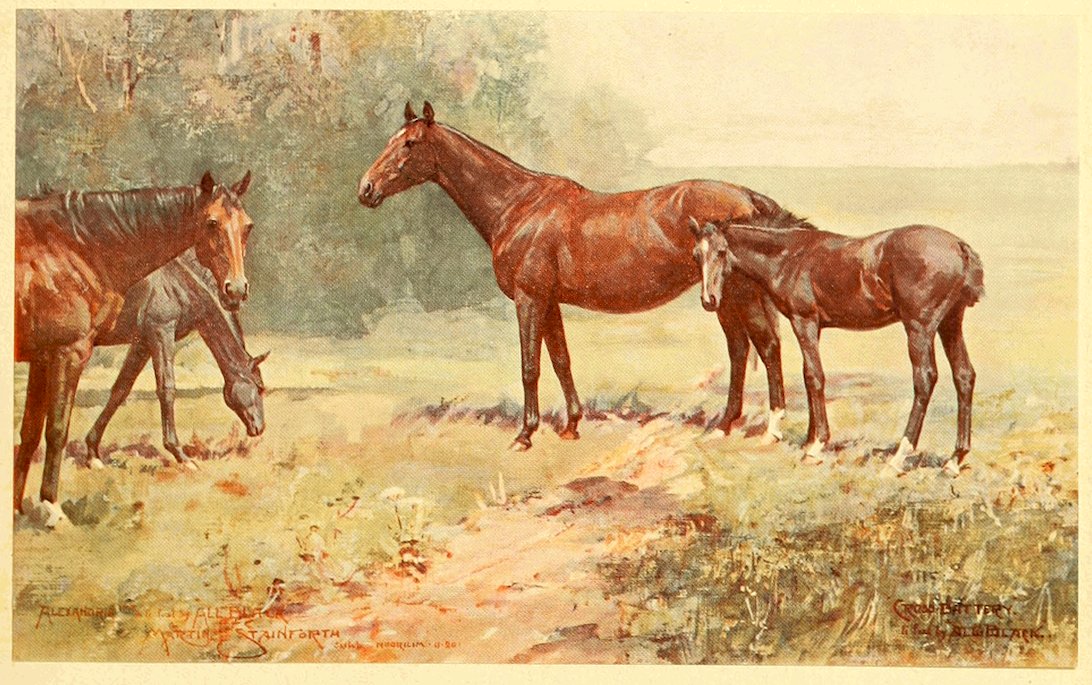

| Cross Battery | 5 |

| The Finish for the V.R.C. Flying Stakes, 1902 | 6 |

| Maltster | 7 |

| Wallace | 8 |

| Lanius | 9 |

| Linacre | 10 |

| Yippingale | 11 |

| Trafalgar | 12 |

| Brattle | 13 |

| Poitrel | 14 |

| Gloaming | 15 |

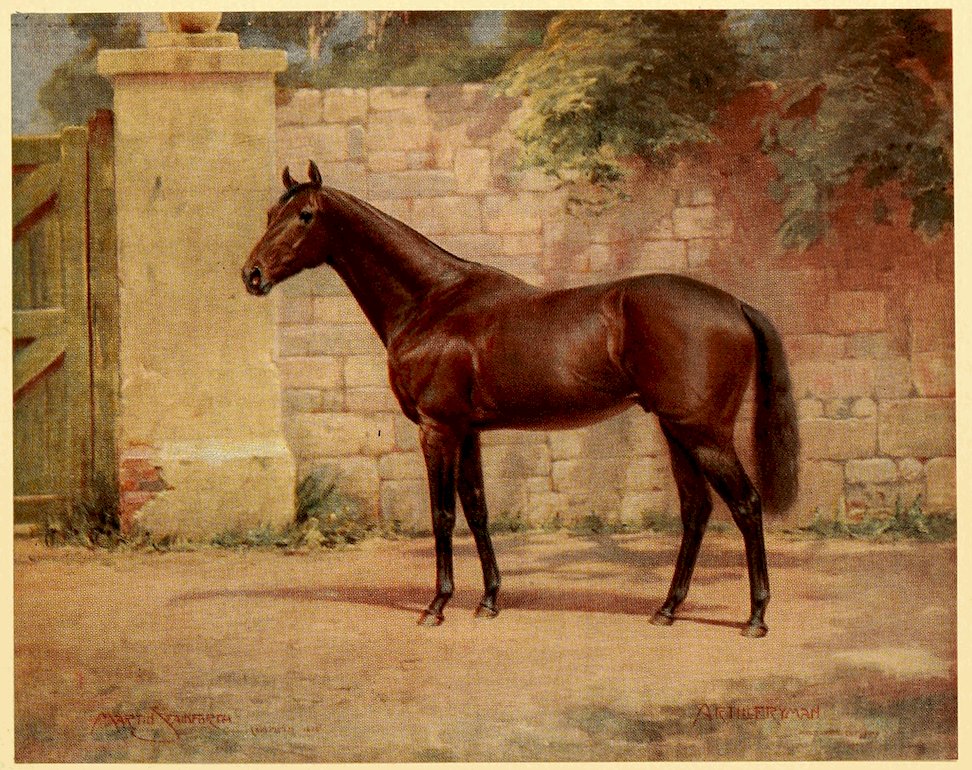

| Artilleryman | 16 |

| Triptych | 17 |

| Cetigne | 18 |

| Kennaquhair | 19 |

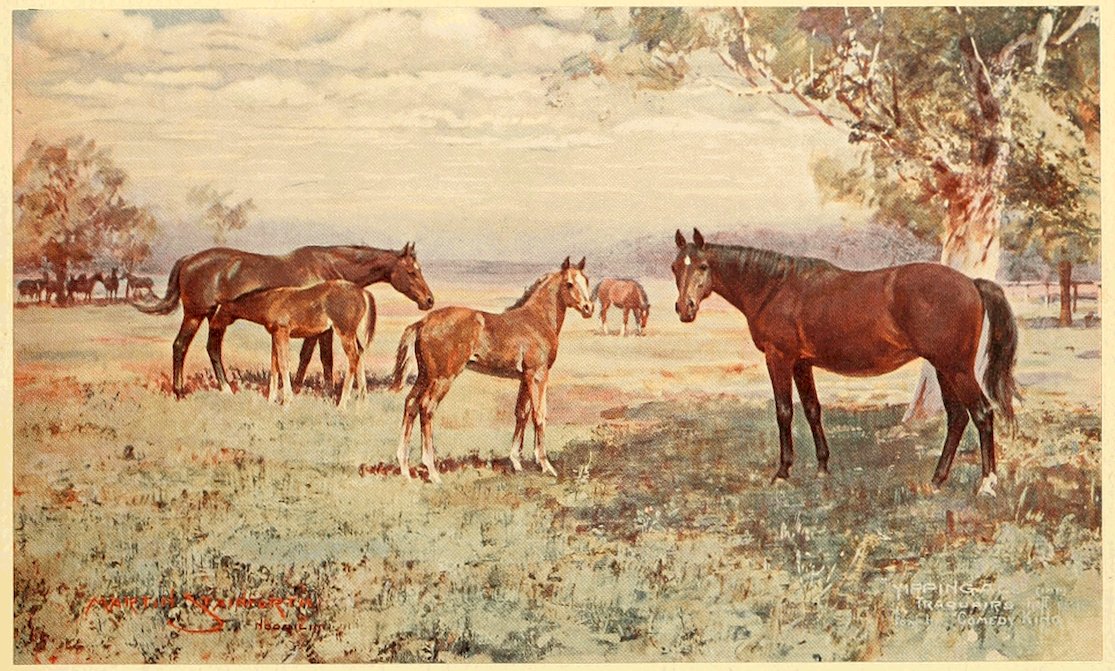

| Comedy King | 20 |

| Woorak | 21 |

| Panacre | 22 |

| Eurythmic | 23 |

| The Finish for the A.J.C. Craven Plate, 1918 | 24 |

| BLACK AND WHITE ILLUSTRATIONS | |

| Page | |

| Duke Foote | 107 |

| Desert Gold | 107 |

| Malt King | 108 |

| Biplane | 108 |

| The Welkin | 109 |

| Cagou | 109 |

| Greenstead | 110 |

| Beauford | 110 |

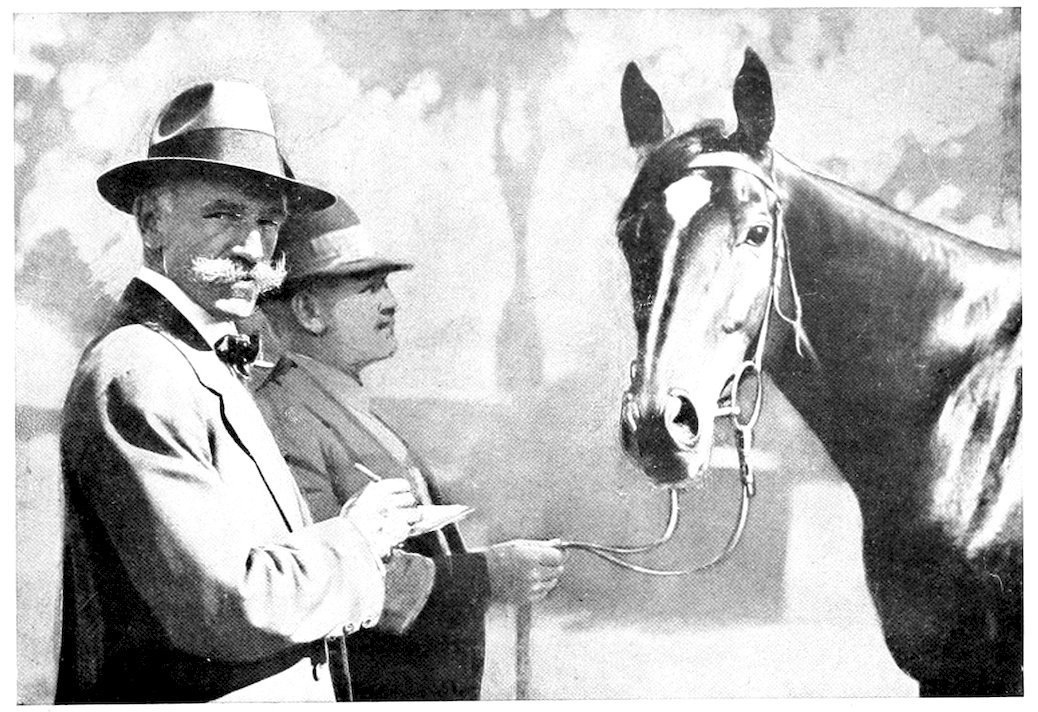

| Martin Stainforth | 111 |

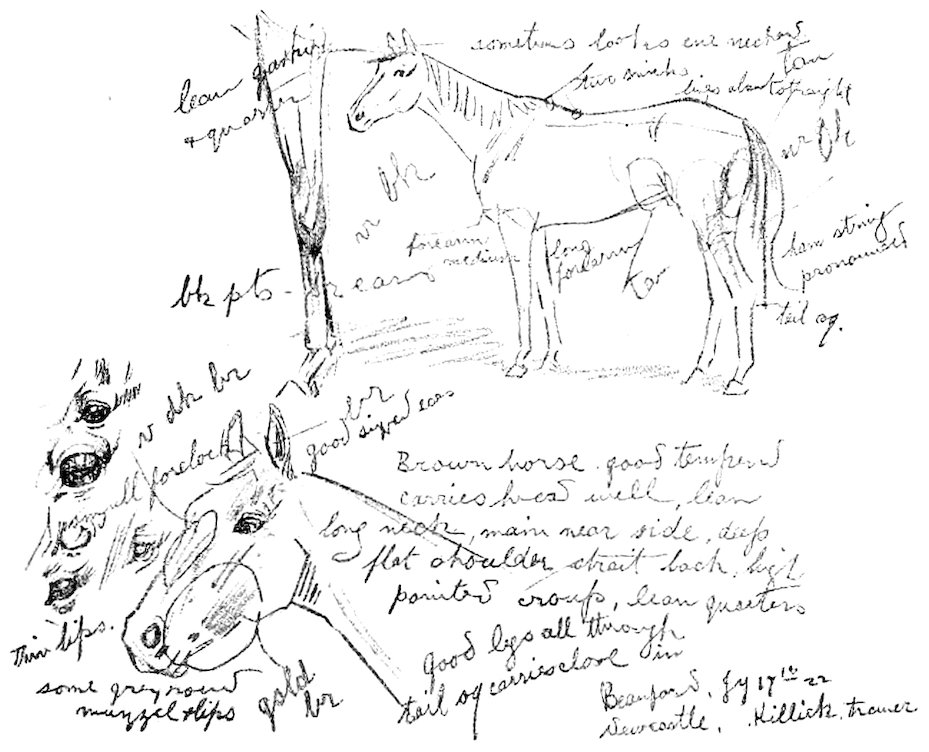

| Pencil Sketches | 111 |

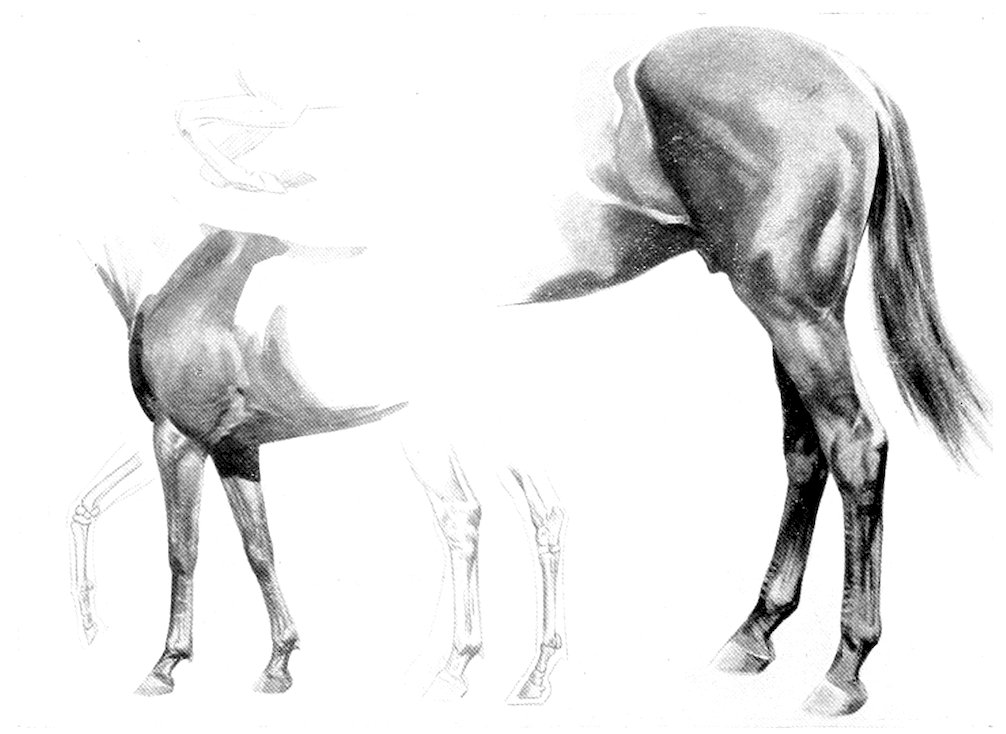

| Anatomical Study | 112 |

| Sketch of Pony | 112 |

| Artilleryman | 113 |

| Ready | 113 |

| Pal | 114 |

| Mallwyd Albert | 114 |

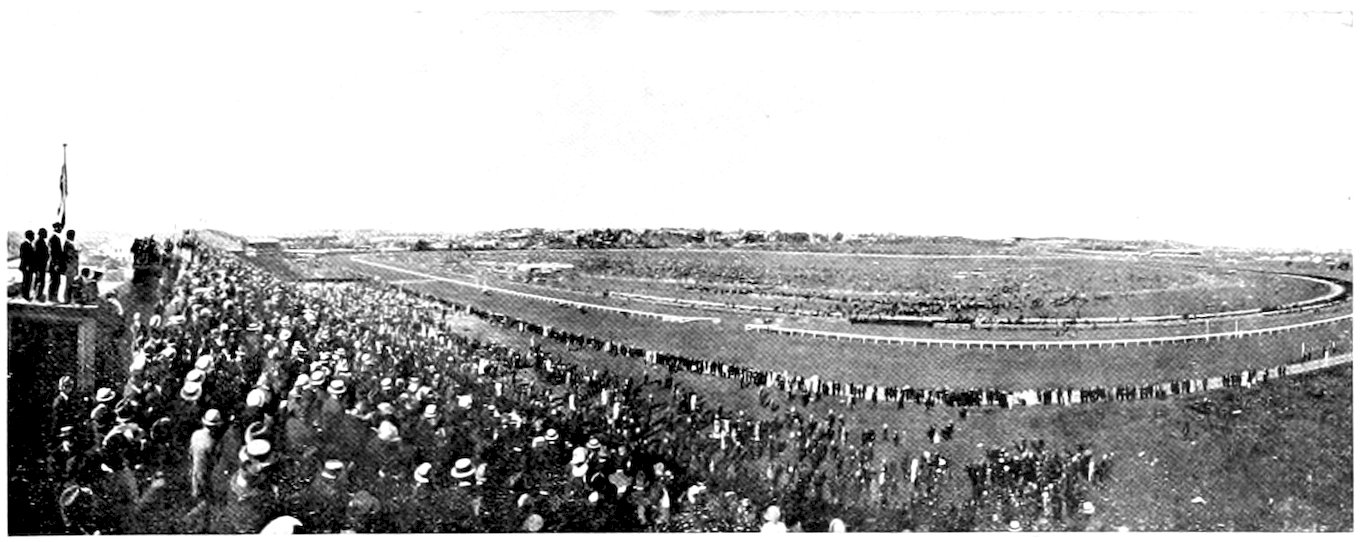

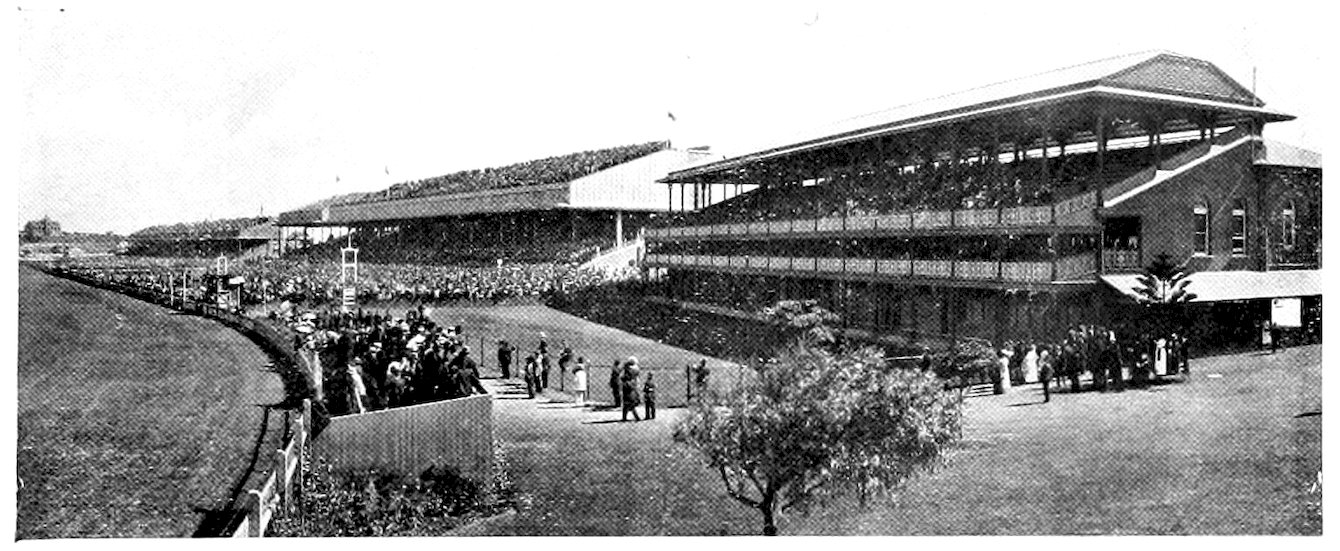

| Views of Randwick | 125 |

| Plan of Randwick | 126 |

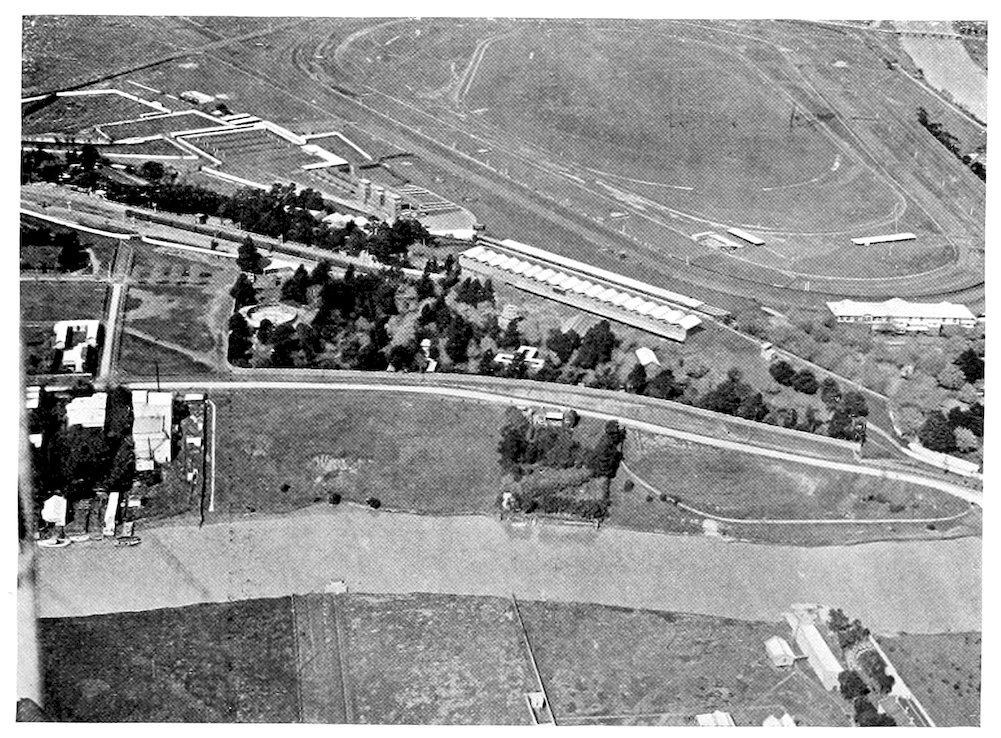

| Views of Flemington | 135 |

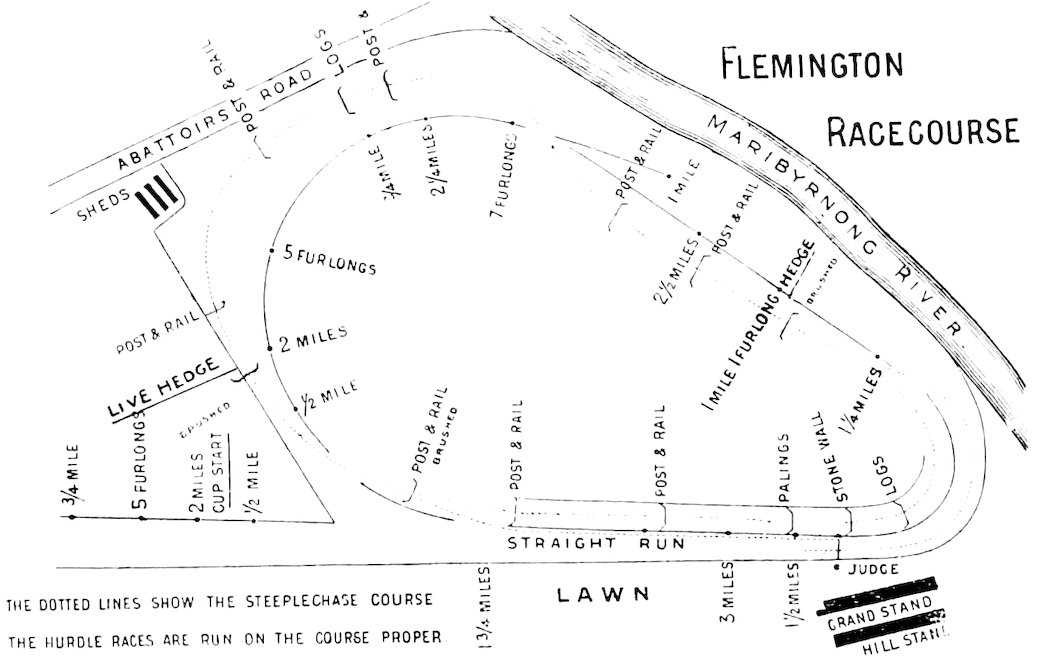

| Plans of Flemington | 136 |

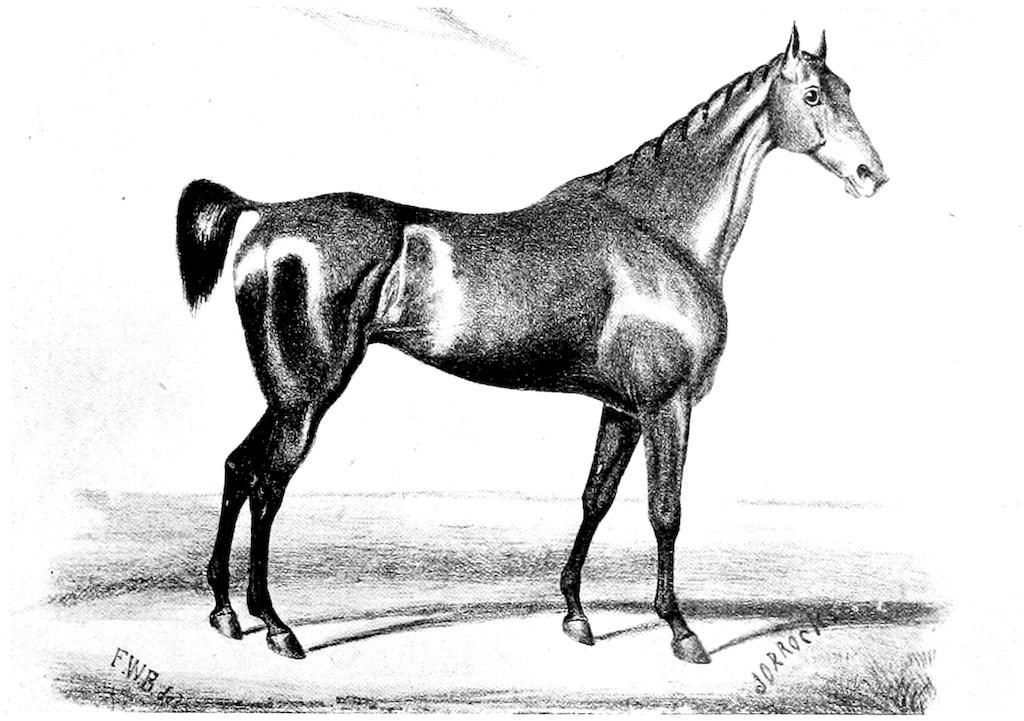

| Jorrocks | 147 |

| Veno | 148 |

| Fisherman | 148 |

| Flying Buck | 149 |

| Archer | 149 |

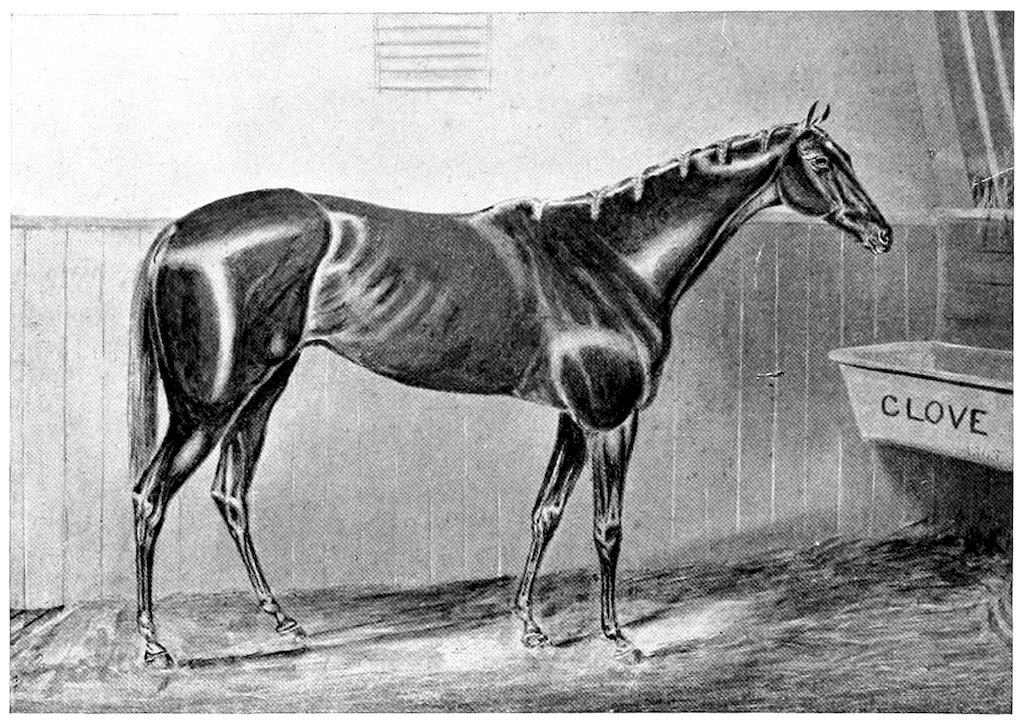

| Clove | 150 |

| Yattendon | 150 |

| Maribyrnong | 151 |

| The Barb | 151 |

| Tim Whiffler | 152 |

| Chester | 152 |

| First King | 153 |

| Robinson Crusoe | 153 |

| Goldsbrough | 154 |

| Grand Flaneur | 154 |

| Abercorn | 155 |

| Malua | 155 |

| Wakeful | 156 |

| La Carabine | 156 |

| Carlita | 157 |

| Tartan | 157 |

| Poseidon | 158 |

| Prince Foote | 158 |

This volume should have made its appearance towards the close of last year but the regrettable death of Bertram Stevens, who had the work in hand, practically suspended matters in connection with its publication. With characteristic energy Mr. Harry Julius took up the work, and it is due to his efforts that the book is now complete. The amount of detail work concerned in bringing out this publication has been very great, and can only be appreciated properly by those like myself who have been connected with Mr. Harry Julius during the time the book was in the press.

The scope of the volume as originally planned by the late Bertram Stevens was very much wider than the present book. It was found as the work progressed that the project was too ambitious and the field too large to cover in detail.

A general view of the development of Australian racing has been embodied, and the breeding of the racehorse in the Southern Hemisphere lightly touched on. The illustrations, which include some of the best performers of the present day, are devoted mainly to reproductions of pictures painted by Mr. Martin Stainforth. To make a comprehensive list of famous horses, Mr. Stainforth executed a number of paintings especially for the book. Pictures of other horses who have made their names famous on the racecourse or at the stud are also reproduced, and should serve as a valuable record to those interested in the thoroughbred.

Delays have been experienced in many cases with the colour reproductions. Many of the original blocks had to be discarded as they failed to accurately record the original colour and detail of line of Martin Stainforth’s pictures. To overcome this a great many of the colour plates were made again.

The publishers are indebted to a great many people for their helpful efforts—those who have loaned pictures for reproduction, and the officials of the Australian Jockey Club, Victoria Racing Club and the Rosehill Race Club—in connection with the publication of this book.

They have been particularly fortunate in having been able to secure Dr. W. H. Lang to write the bulk of the letterpress. No one is more conversant with the thoroughbred than Dr. Lang, and his literary style speaks for itself.

Dr. Stewart McKay has contributed a scientific article which opens up a new train of thought in connection with the racehorse, while others who have lent a helping hand are Messrs. Frank Wilkinson and Tom Willis.

Thanks are due to the trustees of the National Art Gallery of N.S.W., Sir Samuel Hordern, Dr. Stewart McKay, Messrs. McEvilly, R. De Mestre, W. A. Crowle, G. F. Rowe, A. J. Morton, Jas. Barden, F. G. White, Norman Falkiner, W. M. Borthwick, J. Campbell Wood, T. A. Stirton, Dr. Herbert Marks, Mrs. H. Gordon, Mrs. Flemmich, Mrs. F. Body, and Mrs. Herbert Marks, for permission to reproduce pictures in their possession.

The History of the Racehorse in Australia is such a short one that you might, with reason, imagine that the entire narrative could be condensed into a very small space when committed to print. But you would be utterly wrong. On the contrary, an historian, with his heart in the business, could reel off a number of fair-sized volumes, and still his work would not be fulfilled to his entire satisfaction. A little ancient history may be useful to us before we commence to study the subject. As you know, there was no trace of the genus horse on our island continent before the coming of the white man. In America, on the other hand, although there was no horse as we know him, before the advent of the Conqueror Cortez, in 1518, yet the fossilised remains of the Eohippus, the Protohippus and Hipparion are so numerous and well distributed on the great American continents that these wide lands seem to have been the most favoured home of the great race of equidae, in the far-off days before the ice.

The whole species was then cut off, to a horse, possibly by an epidemic, or by the ravages, more probably, of some insect or microbe, and its history in that quarter of the globe recommenced with the Conquest. In vivid contrast the tale of our own Australian horse, and all our other domestic animals, begins as late as the 10th day of January, 1788. Governor Phillip brought with him from the Cape of Good Hope, where he had called to obtain supplies on his voyage hither with his first fleet of convicts, a stallion and three mares with foals at foot, a few cattle, and in all 500 head of live stock, but which consisted for the most part of poultry.

The new Colony had a good deal of bad luck at this time. The four-footed animals, owing to the negligence of a convict herdsman, strayed away, and although one has reason to believe that the horses were recovered, there is no certainty on that head. With the cattle there is a different story to tell, and on the very day upon which I am writing this, I read, in “The English Sporting Magazine” of 1797, the story of their loss and recovery. A boat’s crew sought a bay on the coast whilst searching for fresh water. At the spot where the men landed they fell in with a convict who had escaped five years before, and who had joined the blacks. This man showed them where the lost cattle had made their home, deep in some fertile valley, and in the course of their nine years of liberty they had increased in numbers to sixty-one head. It was a valuable find for the struggling colonists, who, from drought and flood, had lost a large portion of their property.

In the very early years of “the Colony” there was exceedingly little need for the assistance of light horses in the daily work of the place, whilst the desire to possess an animal more speedy than that owned by a neighbour had not yet arisen at all. You will, perhaps, recollect that, until the year 1813 or thereabouts, the only portion of our vast continent which was being made use of by white men was a little strip of soil between the Blue Mountains and the sea, some forty miles by eighty, and the few horses which had now been brought over from the Cape, or out from the Old Country, were simply beasts of burden, or, at the best, perhaps, hacks and harness horses.

It was on the 31st day of May of that year that Blaxland, Wentworth and Lawson burst their way through the hitherto impenetrable ranges and scrub into the limitless lands beyond, and it was upon that same day that the use for a swift and long-enduring saddle horse was discovered by the inhabitants 4who followed in the tracks of these explorers, and the first real need of the thoroughbred as a sire found its way into Australia.

Yet, though there seems to have been such a limited demand for the thoroughbred steed in these very early days, there were, at least, three importations before the transit of the Blue Mountains had been accomplished, and you cannot help wondering what was the inducement which tempted the importers to take the risk.

A mist floats over the particulars of these first arrivals. In the closing years of the eighteenth century there is on record that a blood horse, Rockingham by name, was shipped to Australia from the Cape of Good Hope. It was at the end of the seventeen nineties, and the only other authentic fact which I can ascertain concerning him is that he subsequently became known as “Young Rockingham.” There is no trace of anything which he may have left behind him in the way of progeny. He was probably by Rockingham, a stallion which was covering in England about this period, but not the Rockingham, of course, by Humphrey Clinker, who appears in the pedigree of Doncaster. The day of that sire had not yet dawned.

A blood horse called Washington is said to have been imported from America in 1802. The first volume of the “Australian Stud Book” simply mentions the fact, and adds that he was “said to have been a very handsome horse,” and there it ends. But Mr. T. Merry, in his book on the American horse, states that he was by Timoleon, and that he was not sent to Australia until 1825. The third importation before the transit was of one whose name is still alive, and that is “Old” Hector, or simply Hector. The exact year of his arrival here is uncertain. A correspondent in a weekly paper some months ago gives it with confidence as 1803, and states that the horse died in 1821. The first volume of the “Stud Book” quotes it as 1810, but refers to him as a “Persian.” Hector was a favourite name amongst horse-masters, and there were as many Hectors in Australia as there were King Harrys on the field of Shrewsbury. The thoroughbred Hector is described as “a very fine, commanding horse. The gameness of his stock proves that he was not an Indian horse.” The second volume corrects the dates, and believes that Hector was imported in 1806, whilst the seventh volume adds that Hector went to Tasmania from New South Wales in 1820. In a Tasmanian advertisement he is described as “by Hector, probably Hector by Trentham,” the property of the Iron Duke. All this is not only of interest, but it is of a certain value to studmasters, for the blood of Old Hector survives in some force to-day through the descendants of his daughter Old Betty. But, as that famous mare, the ancestress of such a very numerous and worthy family, was not foaled until 1829, we are left in a deep quagmire of doubt as to what her real pedigree can possibly have been. The “Stud Book,” however, accepts the mare as being by Hector.

And, to close these very early, almost prehistoric data, a bay stallion, named The Governor, was imported about 1817. He was by Walton from Enchantress, by Volunteer, from a mare by Mambrino, but I can find no mention whatsoever of this horse’s services, nor of his progeny. That, indeed, was inevitable, for until this period no race mare with a clean pedigree had ever come to our shores. Our country at that time was no land of promise, so hopelessly far away was it from the Old World, and from civilisation, over seas very dangerous, not only on account of the smallness of the vessels employed in transport, but also from the unceasing violence of the enemy.

But now, after Waterloo, with the seemingly interminable wars and tumults lulled into peace and calm at last, things were beginning to shape themselves in the Colony. Evans had explored the country a hundred miles or so farther out than that point to which Blaxland’s little company had penetrated, and he had discovered the Macquarie River, and named it. Oxley had already condemned as useless almost all the fertile land of the Southern Riverina, although, at any rate, he had thrown it open, and in 1824 Hamilton Hume had walked with his few followers, and with Hovell, an old ship’s captain with whom he continually fought, from Lake George to Port Phillip Bay. Cattle and sheep had increased enormously, the country over which they depastured seemed to be without end, but markets were few and far apart. Horses of stamina, and therefore of the best blood were urgently required in order to round up the mobs of bullocks and cows which roamed the unfenced plains, and to accomplish the long journeys to the distant towns.

And thus it was that our best early stallions, and some of our mares which still, through their descendants, carry on their lines, were brought to Australia. Steeltrap, in 1823, was the first of the successful stallions to land. His was valuable blood. He was by Scud, and Scud sired two Derby winners, the first, Sam, bred in 1815, the very year in which Steeltrap was foaled, and the second, Sailor, in 1817. The Oaks winner of 1819, Shoveler, was also a Scud filly, and therefore it is perfectly evident that Steeltrap came from the most fashionable blood of his day, and must have been worth a great deal of money. His dam was by Sorcerer out of Pamella, by Whiskey from Lais. He was a chestnut, and “sired very game horses.” Their gameness, no doubt, was exhibited during the long and tiring journeys after cattle, for contests must have been rare in which they could have had opportunities of proving their mettle on the racecourse. Steeltrap remains with us still in the persons of the descendants of “The Steeltrap mare.” There were several matrons identified by the same cognomen, but this particular representative of the clan was out of “a Government mare,” presumably clean bred, and she left two daughters, Beeswing and Marchioness, both by The Marquis, a son of Dover.

Zulu, the winner of the great Melbourne Cup in 1881, came from this line, as well as Bylong, Stanley, Sweetmeat and Tridentate, while around Wagga numbers of the same breed are still alive through the medium of the mares Lady Cameron, Lady Phoebe, Latona and Antonia.

In the same year, 1824, which brought us Steeltrap, there also came to our shores Bay Camerton, or Old Camerton, or simply Camerton. He was known by each and all of these names from time to time. He was by Camerton, from Waltonia, by Walton, and quickly ran out, on his dam’s side, to the very famous Burton Barb mare, which is now so readily identified as the tap-root of the exceptionally high qualitied No. 2 family. Bay Camerton survives through the line of Camilla, a daughter of his when mated with Old Betty. But now, in the following year, 1825, arrived the first of all the race mares that have made Australian Turf story. This was Manto. It was indeed a happy day for our Turf when she, then a three-year-old, landed in New South Wales. She was bred in England in 1822, was bought by Mr. Icely, Coombing Park, and imported to Australia in 1825. I can find no description of the colour of Manto, as, curiously, she does not appear in the “General Stud Book.” The omission came about probably in this manner: In 1780 the Duke of Cumberland, “the Butcher” of Culloden, bred a mare 6named Rose, by Sweet Briar out of Merliton, by Snap. She passed through several hands, but ultimately ended up in the ownership of old Dick Goodisson, an eccentric fellow, and the favourite jockey, as well as companion of the Marquis of Queensberry, better known as “old Q.,” and worse known in the lines of the Poet Wordsworth as “Degenerate Douglas.” Dick Goodisson bred a filly by Buzzard from Rose in 1800, a full brother to the same-named Lyncaeus, and two more sisters, one in 1802, and another in 1803. These mares were simply known, after the slack method of the time, as “sisters to Lyncaeus.” The last foal of one of these same sisters to Lyncaeus, by Soothsayer, the individual dropped in 1802, was this Manto of ours, and Mr. Wanklyn, the erudite keeper of the “New Zealand Stud Book,” and a prolific author in the matter of “Stud Book” lore, believes that it was the fact that she was the youngest born foal of her mother, and that she was sold as a youngster to go abroad, which accounted for the non-appearance of her name in the recognised official records of the day.

Before leaving England, Manto had been served by Young Grasshopper, by Grasshopper, who was by Windle, a son of Beningborough, by King Fergus, by Eclipse. Young Grasshopper’s dam was a daughter of Sorcerer, and as Manto was by Soothsayer, by Sorcerer, we have an early illustration of the value of close in-breeding. Manto dropped her foal a few days after setting her feet on Australian soil, and the little thing was christened Cornelia. Unfortunately, Mr. Icely, unappreciative of the excellence and value of his importations, failed to keep anything like accurate records of his stud. He did not even take a note of the colour of his foals. We do know, however, that Manto, subsequent to the birth of Cornelia, also foaled Chancellor, to Steeltrap, Lady Godiva to Rous’ Emigrant, Lycurgus to Whisker, and Emilius to Operator.

She also produced a colt named Jupiter, which was sent to South Australia, but he is returned without the name of his sire attached. It is to Cornelia that we must look for the tap-root from which nearly one thousand racehorses in Australia have traced their origin. She threw a colt named Emancipation, by Toss, a bold experiment in still more extensive in-breeding to Sorcerer—a filly, Lady Flora, by Whisker, a full sister to her, named Besom, a colt, Euclid, by Operator, a filly, Old Moonshine, by Rous’ Emigrant, and Flora McIvor, also by Emigrant. Moonshine’s name still crops up through Coquette, Speculation and Progress—Grand Flaneur’s understudy, but Flora McIvor had an enormous family. For Mr. Icely she threw the fillies Fatima, Florence, Faultless, Emily, Zoe, Flora and Chloe, and five colts, Figaro, Cossack, Nutwith, The Chevalier and Bay Middleton. Mr. Icely then disposed of the old mare to Mr. Redwood, of Nelson, New Zealand, and for him she produced at the age of 26 and 28, or possibly, for Mr. Icely’s lack of stud records causes much uncertainty, at 27 and 29. Io and Waimea, Flora McIvor’s pair of New Zealand children, and her children’s children, from these two famous mares, rose up and called her blessed. Io and Waimea were dropped in 1855 and ’57, and then, full of years and honours, and with no further offspring, the grand old mare died in 1861. The list of great racehorses which claim her for their ancestress is too long to quote, but the names of even a few of these will tell you what a very cornerstone of our pastime Flora McIvor has proved herself to be. There was Bloodshot. I can see him in the Cup chasing Newhaven home now, when my eyes are closed. And then there were Chicago, Churchill, Circe, Cissy, Cremorne, Cuirassier, Euroclydon, Frailty, The Gem, Havoc, Manuka, Newmaster, Niagara, Nonsense, Oudeis, Parthian, Progress, Siege Gun, Trenton, Wakatipu, Wild Rose, Zalinski, Beauford and Zoe, whilst the brood mares that trace to the same source run into hundreds.

There were very few clean bred horses imported to Australia between the arrival of Manto and the ’thirties of the last century. Such as they were, these are not only very interesting, but several of them proved themselves to be extremely valuable, and we have their representatives racing with credit on our courses to this day. Thus, in 1826, The Cressey Company brought to Tasmania the chestnut horse Buffalo, by Fyldener, a great grandson of Herod, from Roxana, a granddaughter, on both sides of the house, of the immortal Eclipse. It is a little surprising to find a commercial company in those far-off days selecting a stallion of such superlative blood lines for the purpose of producing utility horses in this distant land, for the racehorse can scarcely yet have entered into its calculations when the company made its purchases. We may be very certain that the managers had very wise heads upon their shoulders. By the same ship they also imported the stallion Bolivar, and the chestnut mare who became so famous in after days, Edella. The latter produced three chestnuts to her fellow traveller Buffalo, the colts Liberty and Fyldener, and the filly Curiosity. Edella was by Warrior, a great grandson of Herod, from Risk, a great, great, granddaughter of Herod from a Precipitate mare, and Precipitate was a granddaughter of Eclipse. You can thus see how tremendously closely our ancestors bred in and in to Herod and O’Kelly’s mighty nonpareil Eclipse. Curiosity, the in-bred daughter of Buffalo and Edella, was put to Peter Finn, a horse by Whalebone from a Delpini mare, brought to Tasmania in 1826, in the brig “Anne,” and the result was the bay filly Diana. This mare became the property of Mr. Field, of Tasmania, and his family has religiously cherished her descendants ever since. Mr. Field put Diana to Bay Middleton, a son of imported Jersey, who was by Buzzard, a son of Blacklock from Cobweb, the great Bay Middleton’s dam. The result of the union was the filly Resistance, who, when her time came, was sent to Peter Wilkins, a brown horse by The Flying Dutchman from Boarding School Miss. A daughter of hers was christened Edella, after her great-great-grand dam. One wishes that those forebears of ours had had more ingenuity in their choice of names. Edellas, Curiosities, Camillas, Violets and Cobwebs fly in clouds through the earlier stud books. However that may be, this particular Edella threw two great colts, Stockwell, by St. Albans, and Bagot, by the same sire. Stockwell, after showing that he was a first-class racehorse, unfortunately died, and Bagot, when his name had been changed to Malua, was the greatest horse of his day, and founder of his family. This history of the introduction of the horse into Australasia is an engrossing theme, but if we gave way to our desires and followed each and all of them up through the century we would run into many volumes. Skeleton was the only new arrival during 1827, and his name has, but for Woorak’s successes, nearly died out from our modern pedigrees. I, however, possess several letters from the Marquis of Sligo to Mr. W. Reilly, Skeleton’s importer, concerning him, and pointing out to Mr. Reilly the horse’s many qualities.

As a piece of contemporary history, one of these letters is worthy of reproduction in a history of the Racehorse in Australia:—

“In reply to your note requesting me to give my opinion of Skeleton, who formerly belonged to me, and whom you have sent to New South 8Wales, I have much pleasure in confirming the representation of my cousin, Captain Browne, relative to his performance and character; indeed, I can go much farther, in consequence of what has occurred since his statement was made. Every one of Skeleton’s brothers have since distinguished themselves in the highest degree, so much so that, when I wished to purchase another brother on account of my knowledge of the good qualities of two former ones, I was asked 500 guineas for him, though only a yearling. One of his brothers (not the same) was since sold for 700 guineas, a three-year-old, and that in Ireland, where money is scarce.

“My conviction is that, had he been fairly treated by my trainer, he would have found himself one of the best horses in England. Indeed, his public as well as his private trials warrant me in saying so. The proof of my opinion was my seeking to re-purchase his sire (Master Robert), and purchasing his brother.

“Were Skeleton now in this country, I would not hesitate to adopt him into my stud, which is pretty numerous and of some value, as may be proved by my selling last year a two-year-old, Fang, a relative, too, of Skeleton, for the enormous sum of 3,300 guineas money, and contingencies worth at market 500 more, making by £100 the greatest price ever given for a two-year-old. Mr. Western’s opinion of him is, I think, quite correct, and I know no stallion more likely to effect an important improvement in the breed of horses in Australia.”

You see what an alteration in values has taken place during the ninety years since the Marquis penned these lines. Three thousand guineas was an “enormous sum” for a horse, and seven hundred a great price for a three-year-old in Ireland, “where money is scarce.” Times have changed, indeed, with a vengeance. The Captain Browne mentioned in the letter was the father of our very familiar old friend, Rolf Boldrewood, and Skeleton has left behind him a deep mark in the Malvolio and Woorak family, through Madcap, Giovani, Lady Laurestina, and finally Latona, by Skeleton out of Miss Lane.

All told, there were forty-seven blood stallions imported into Australia between the beginning of things and the end of 1838, and, considering what state the world had been in, politically and socially, during a great part of that period, and remembering the weary length of the voyage, the risk of capture by the French, and all the dangers incident to a sea voyage of some twelve thousand miles in small vessels, ships which could only be described as cockleshells, we did not do so very badly after all. It is interesting, and valuable, too, to mark the chronological order of the advent of such of these as have left a name behind them, in spite of the great gulf of time and all the tremendous events which have taken place on the earth since their brief day.

9Blood Stallions of Note That Were Imported Between 1799 and 1838.

Emigrant was the king of them all. If ever you run out the pedigree of an Australian-bred horse of to-day, whose ancestors have dwelt for some generations in Australia, there crops up the name of Rous’ Emigrant. It forms a memorial, far more enduring than brass or iron, to that very gallant sailor and splendid judge of all things connected with the racehorse, the Hon. H. J. Rous, “The Admiral.”

Rous’ Emigrant was a black brown, according to one who actually saw him, although some authorities, including the General Stud Book, describe him as having been a bay. In my own eyes I always frame a mental picture of a rich, glowing, mahogany brown horse, with a bold, generous, manly head, a great full eye, a noble crest, deep, fine shoulders, a barrel as round as any cask, and a tremendous loin. “He carries his flag like a Russian duke” of the olden time, and his quarters and gaskins are immense, with hocks straight, flat and strong. Old Mr. Gosper, of Windsor, N.S.W., is reported to have given the following verdict concerning Emigrant, and in the vernacular, “I never seed an ’orse that I liked better than Rous’ Emigrant. ’Is ’oofs looked as though they war made o’ granite, and at eighteen there wasn’t a blemish of no sort on ’is legs.” A rare horse.

But if the tide of emigration had been a somewhat weak one up to 1839, something had evidently occurred in the history of the colony, or in the world’s politics, so as to entirely alter that state of affairs, and I am not quite sure what that something might have been. The prosperity of Australia about this period was not very startling. The price of cattle was low, the population was not increasing in a satisfactory manner, “boiling-down” had already been resorted to, and yet, between 1839 and the commencement of 1844, fifty-three blood stallions were brought into the country. And the bustle and boom of the gold rush was still in the womb of futurity.

We have examined the foundation stones of our thoroughbred horse, so far as the sires are concerned, and now it is necessary to look at that even more important element in the building up of our racing stock, the early brood mares. We have already noted the arrival of Manto and the birth of Cornelia, the most important events which ever occurred in the chronicles of our Australian turf. None of the mares that followed, between 1825 and the early ’forties of the last century, were nearly so potent for good, although the influence of one or two of these has been sufficiently great.

Here is a brief list of those worthy matrons:—

And then, during the ’forties, there came Falklandina, Quadroon, Paraguay, Nora Creina, Miss Lane, Splendora and the Giggler. A few others there were, but their sun has waned, their glory is faded, already they have slipped over the horizon of time, and are out of sight. Of the early arrivals, apart from Manto and Cornelia, Edella has handed down to us such horses as Caramut, Malua, Mozart, Rapidity, Glenloth, Sheet Anchor, and numerous matrons which may, at any moment, teem, once more, with winners as of old. Spaewife lives through David, a Debutant winner, Finland, Fishery, and all that Fishwife family which brings back so vividly the name of that excellent old sportsman, Mr. John Turnbull. Quambone, Fucile, Tim Whiffler and Troubadour spring from the same root. Whizgig is responsible for Blink Bonny, Coronet, Meteor, Prodigal, Ringwood, Rufus, Strop and Tim Swiveller.

Most of this little troupe came over to the mainland from Tasmania in order to earn their fame.

Lady Emily is the founder of the tribe of Beaumont, The Bohemian, Lady Betty, The Nun, Pardon, Picture and Reprieve, but Gulnare, who was imported in the same year as Lady Emily, has left a much more indelible mark on our records than any other of the pioneers, with the exception of Manto.

That very remarkable man, Captain John Macarthur, who, I believe, did more for young Australia than any other individual, imported this mare. She was a grey, but her colour character seems to have been lost during the gulf of years between us and them. Sappho retains her ghostly influence over 11her descendants much more markedly than does Gulnare. Yattendon was the great exponent of the family, but many good horses came from the same line, such as Camden, Cassandra, Dainty Ariel, Survivor, and so on, and there are a goodly number of mares still with us from one of which the ancient glories of the house may readily be revived. Merino, Fairy and Octavia are practically dead, but the Cape mare, through Moss Rose, had many good descendants in the early days, and she may yet again come to the front.

There is a very grave doubt, however, what the ultimate origin of this useful mare might have been, for the Cape mare was thirty years old when she is said to have dropped Moss Rose, and this is a very unusual, if not unprecedented, age at which a clean bred mare could drop a foal. Of those mares imported in the ’forties, Falklandina still exists. Ritualist, the sire of some useful jumpers of to-day, comes from her, and Maddelina, Torah, Terlinga and Monastery each claim her as their ancestress. It is a South Australian family. Quadroon was a live wire until of recent years, when she seems to have weakened considerably. Chuckster, Grey Gown, Hyacinth, Kit Nubbles, Metford, Oreillet, Riverton, Swiveller and Trenchant are amongst the best moderns who run back straight to this old dame.

Paraguay, with a very limited list of foalings to her name, will probably live for ever in Australian turf lore, as, of her two sons, Whalebone and Sir Hercules, the latter has made a very deep mark in the honour list. Miss Lane we have seen as the founder of the Madcap clan. She was incestuously bred, her sire, Rector, a son of Muley, having produced her from a Muley mare. The Giggler was at one time full of promise, but with the failure of Menschikoff at the stud she seems to be fading into oblivion. And the last of the 1840 to 1850 immigrants which we will mention here is Nora Creina. Our reason for paying particular attention to her is that we have authentic notes concerning her journey hither, and as one voyage is not unlike another, we may, from this one example, receive a general idea of the difficulties and pleasures of transportation at that time from the Old Country. Mr. William Pomeroy Green, in the year 1842, chartered a ship from Plymouth, and brought his whole family, and all his household goods, along with him to this new land. I do not know whether the vessel was a brig, a barque, or a ship—most probably a barque—but, at all events, she was only of 500 tons register.

Into this little thing was squeezed a family consisting of the father and mother, six sons, one daughter, a governess, a butler, a carpenter, with his family, the head groom, a second groom, a herdsman, a “useful boy,” a gardener, a laundress, a man cook, with his wife, a housemaid, and a nurse, a young and inexperienced surgeon, two young friends of the family named Richard Singleton and James Ellis, Mr. Walker, a Sydney merchant and his sister, a Mr. Wray from Devonshire—an invalid—Mr. William Stawell, afterwards famous as Sir William Stawell, Chief Justice of Victoria, as well as all the crew and live stock.

The latter consisted of two thoroughbreds, Rory O’More, by Birdcatcher out of Nora Creina’s dam, Nora Creina herself, by Sir Edward Codrington from a mare by Drone, her dam Mary Anne, by Waxy Pope out of Witch, by Sorcerer; a hunter named Pickwick; a favourite mare of Mr. Green’s Taglioni; a Durham cow christened “Sarah”—and Mr. Stawell took out two bulls.

Here was prospective romance for you, and as much of it as you please. Mr. Stawell, of course, married Miss Green, and their sons are amongst the best-known, most trusted and well-liked of all Victorians of the present day. 12The patriarchs of old, the Swiss Family Robinson of our childhood, were never in it for the enterprise and romance of the whole affair. They sailed on August 8th, 1842. The ship “Sarah” was not very seaworthy—indeed, she was lost on the return voyage—but although there were several gales experienced on the passage, and parts of the bulwarks were washed away, they all arrived in safety at Port Phillip on the first day of December. “Mr. Stawell swam his bulls ashore, but our horses were taken in a horse box on a launch.”

In his diary, Mr. Green, under a September entry, says:—“My horses are doing well. I take them to the main hatch every day that is fine, and give them the height of grooming and salt water washing.” Mr. Green was a man of method, and he kept accurate records of his stud doings. There is no lack of particulars with regard to Norah Creina’s foalings, and the only thing about it which we can complain of is, that he put her to her near relative, Rory O’More, for all the first seven seasons. She had slipped a foal, however, on board the “Sarah,” to an English horse. I have no doubt he could not well do otherwise, there probably being no other available stallion within reach. The old mare had fourteen foals. Of these, the most famous were Tricolor (V.R.C. Derby), Oriflamme (Derby and Leger), Royal Irishman (Adelaide Leger), Norma (Australian and Adelaide Cups), Dolphin (Adelaide Cup), Pollio (Australia Cup), Quality (V.R.C. Oaks), Spark (the Hobart and Launceston Cups), and Garryowen, a lesser light. Such races, no doubt, were easier to win then than they are now, but it was a creditable record.

Taglioni, the “favourite mare,” although with no given pedigree, has rendered herself more or less immortal, in that Explosion, an Ascot Vale winner, Pegasus, a Hawkes Bay Guineas winner, Volume (New Zealand St. Leger), and some others trace to her.

So now we have taken a rapid and somewhat bird’s-eye view of the thoroughbred arrivals in the Colony down to the beginning of the fifties of the nineteenth century, and we shall now endeavour to take a like bird’s-eye photograph of what these same horses came out to do, and what racing was like in their day.

Horse racing in Sydney, of course, commenced some years earlier than it did in the Port Phillip division of the Colony, settlement in the north there having an advantage of nearly forty years over the south. I find in a copy of the first Melbourne “Argus” ever printed, on June 2nd, 1846, the entries for a race meeting at Homebush. Amongst these appear the names of Alice Hawthorn and Gulnare. They are somewhat puzzling at that date, as Macarthur’s Gulnare was three and twenty years old in ’46, whilst her daughter, also named Gulnare, was still breeding in ’83, a fact which apparently puts her also out of court. The name seems to have been a popular one, for some reason or another. There was also a mob of Alice Hawthorns, and this particular individual was most probably the mare by Operator from Lorina (imp.), a bay foaled about 1840.

But it is Victorian racing to which we are for the most part going to direct our attention at present. In January, 1803, a survey party had examined 13the site of the present Melbourne. Collins had formed a convict settlement during the same year at Sorrento, down close to the Heads, but had quickly abandoned the enterprise. Hume, as we have seen, had reached the neighbourhood of Geelong in ’24; Captain Wishart, in his cutter, “Fairy,” had entered and named Port Fairy after his little craft in ’27; Dutton, on a sealing expedition, had built a house at Portland in 1829, and Mr. Henty had made a permanent settlement there in ’34. In May, ’35, Batman entered Port Phillip Bay in a schooner from Tasmania, and Fawkner’s schooner “Enterprise” navigated the lower reaches of the Yarra in August of that year. He was the son of a convict who had been in Collins’ Sorrento picnic party, and was attracted back by his favourable recollections of the place.

In 1836 the blacks came down from the Goulburn and committed murder, somewhere near to the Werribee. In ’37 Messrs. Gellibrand and Hesse, exploring beyond Geelong, were lost, and killed by the aborigines, and life was very unsettled and wild. But now mobs of cattle had commenced to be driven over from Botany Bay to the new settlement, and white men, with the restlessness and energy of our race, were arriving with frequency, for reports concerning the place were distinctly good, and in 1838, so numerous were the inhabitants of Port Phillip, that they decided that the time was ripe in which to inaugurate a race meeting. We are a strange nation; a peculiar people. March 6th was the great day, just eighty-three years ago. There were five hundred spectators present, and four races took place for their edification. Two were won by a mare named Mountain Maid, and two by a gelding, Postboy. Four starters constituted the largest field of the day. The course was right handed, one mile round the she-oak clad Batman’s Hill, a rising ground between the present Spencer Street Railway Station and the gasworks. The starting post was at the site of the North Melbourne Railway Station. As you enter the city from Sydney, you can, if you care to, recall the scene. The scrub was thick between the hill and the surrounding country. It was cut by winding, deeply-indented waggon tracks, for the ground was soft and boggy. Two carts, sheltered from the sun by old sails, performed the functions of publicans’ booths.

It was a two-days’ meeting, but the second helping, like so many second helpings of other things than race days, was a failure, or even, indeed, an utter fiasco. In 1839 there was again a two-days’ gathering on the slopes of Batman’s Hill. The racing was poor, Postboy and Mountain Maid again being strongly in evidence, but the attendance was so large that it was generally agreed that the population must have doubled since the previous year. But now the turf world fairly began to hum, and Batman’s Hill was no longer considered suitable for the purposes of racing. The experienced eye of someone had “spotted” the flats by the Salt Water River as being made to order for the sport, and on the 3rd of March, 1840, the first race meeting at Flemington was successfully carried through. It was a three-days’ affair, and for the first time in Port Phillip the riders sported colours. The quality of the competitors must have been very poor, for, if you look up the arrivals, in their chronological order on a previous page, you will see that few, if any, of their stock can have been taking part in the contests, and, therefore, most of them must have been nothing better than half-bred hacks. But the spirit of emulation had now caught fire, and all through the country owners were making matches one with another, and metropolitan racing was booming to such an extent that a ruling body called “The Port Phillip Turf Club” was called into existence. To the deliberations of this body, and their resulting actions, we owe the fact that horses in Victoria now take their ages from the first day of August in each year.

14And now the course itself, at Flemington, became firmly and thoroughly established when, in 1844, plans were submitted to the Town Council, and that body approving of them, the place was declared to be a reserve for the purposes of racing. Five trustees were appointed, in whose name the ground was held, these including the Crown Commissioner of the day, the Surveyor-in-Charge, Mr. J. C. Riddel, Mr. Dalmahoy Campbell and Mr. William J. Stawell. Shortly afterwards the Superintendent of Port Phillip declared this transaction not to be legal, and a new grant was completed on October 22nd, 1847. The land included those portions of the Parish of Doutta Galla from 23 to 28 inclusive, beside the Saltwater or Maribyrnong River, the trustees being Mr. Riddel, Mr. Stawell, Mr. Dalmahoy Campbell again, and Mr. Colin Campbell. The term of years was subsequently increased from ten to twenty-one, which, on the latest renewal of the compact, was finally extended to ninety-nine, at the rent of one peppercorn per annum. The spot was then known to the inhabitants as “The Racecourse,” but a little village now began to grow up in the neighbourhood, and this was soon christened “Flemington,” in honour of a genial butcher who supplied meat to the hamlet, and whose name was Bob Fleming. In those early days everyone went to the races, and the route to and from the course was either by river-steamer or by road. The boats left the wharves at eleven o’clock and returned at sunset, and you may be sure there were hot times in the town o’ nights after the races. Bands and Christy minstrels enlivened the voyage by water. Passengers on the trip home not infrequently toppled overboard, and one or two were actually drowned. Accidents by road were common. At one meeting alone three men were killed, two being run over by vehicles, and one by a runaway horse. Assaults were common, and fighting very popular. Mr. O’Shanassy—who afterwards became Sir John—was attacked whilst taking a meditative canter round the course, and struck over the head very viciously by a ruffian armed with a heavy hunting crop. It was proved to have been a premeditated crime. Not being disabled by his injuries, and being a man of much determination and courage, O’Shanassy turned upon his assailant, pursued and captured him, and had the satisfaction of seeing him receive a sentence of six months’ imprisonment.

The winning post stood alongside the river bank somewhere between the present mile and seven furlong barriers. It was a handy spot at which the steamers could tie up to gum trees on the banks, and could disembark their passengers, but it had the disadvantage of being a considerable distance from the top of the steep, rising ground which soon became known as Picnic Hill. It was not, however, until the sport had been in existence for some twenty years that it was found advisable to change the winning post to its present site, thus converting the Hill into a permanent, convenient and commodious stand. By the year 1846 racing had taken a very firm hold of the light-hearted community, and already a public idol had been discovered and worshipped, spoken about and written about, much in the same way as the public and the press magnify our idols the Carbines, the Poitrels, the Artillerymen, and the Eurythmics of our own times. This golden image which the folk had set up on the Flemington Flats was a dark chestnut horse called Petrel. The reports concerning his paternity and his adventures before he became a racehorse varied considerably. By some he was considered to be by Rous’ Emigrant, whilst a sporting writer of the period maintained that he was “by Operator or Theorem from a Steeltrap mare.” The most authentic story concerning his origin seems to have been that, in 1841, an overlander between Sydney and Adelaide arrived at a station near the Grampians, bringing along with him 15two well-bred looking mares. Both were heavy in foal, and it was believed that they had been stolen. The overlander found employment on the station of a Mr. Riley, and here the foals, both of them colts, were dropped. One of these was Petrel.

At two years old the colts were sold to the overseer of a Dr. Martin for thirty-six pounds the pair, and the future champion commenced his education as a stock horse. Mr. Colin Campbell soon heard that Petrel had shown wonderful speed after cattle and emus, and you may be pretty sure that the stockmen had also discovered on their homeward way of an evening, that “the big chestnut beggar could gallop like fun.” Mr. Campbell swopped a mare worth twenty pounds for him, and his racing career then began. He was the undoubted champion of Victoria, and was then despatched, per sailing ship, to Botany Bay, to “take the Sydney-siders down.” But the voyage over was long and rough, he had no time before the races in which to recover himself, and he was very well beaten. The excitement in Sydney was tremendous, and the description of the event reminds one somewhat of a latter day happening when the Victorian, Artilleryman, was unexpectedly defeated by the New South Wales representative, Millieme, in the St. Leger.

It is pleasant to know that the old champion ultimately fell into the hands of Mr. James Austin, in whose possession he lived a life of ease, “roaming the flats by the homestead creek,” until, at the ripe age of twenty-five, he passed in his checks.

And during the Petrel fever days, one is glad to notice that at length the winners in the metropolitan areas were beginning to come from horses which were eligible for, and ultimately were entered in the Stud Books of Australia, and were now repaying their enterprising owners for their extensive outlay and boldness. Thus, when Petrel was carrying off the champion prizes at Flemington, Garryowen, the second living son of our old friend Nora Creina, was winning Town Plates and Publicans’ Purses, whilst Paul Jones, a colonial-bred colt, foaled in ’41, by imported Besborough out of imported Octavia, threw down his Van Diemonian gauntlet to Petrel, and on one occasion, to the wild delight of the Tasmanians present, actually finished ahead of him in a heat. But while these exciting happenings were taking place in the centres of population, racing was also catching a hold on the dwellers in the wild bush. Thus you will find, if you read the works of the late Revd. John Dunmore Lang, that in 1846 this distinguished divine made the overland journey from Sydney to Port Phillip, during which he kept an extensive diary of events.

On his arrival at Albury, he relates how he discovered the inhabitants of the town and neighbourhood, “on the Christian Sabbath Day,” indulging in the excitement of their annual races. So shocked was the minister that he broke into the Latin tongue:

which, in the words of “Young Lochinvar,” he aptly and freely translates as:

“The respectable publican of the place, one Brown, told me that he was, with great reluctance, compelled to serve out rum in pailfuls to his customers who were attending the races.” And all over the huge colony of New South Wales we find at this time, and during the succeeding few years, that racing was becoming the favourite pastime of the people. There was a meeting at Maitland in ’46, where Jorrocks beat Emerald, and the event was considered so important that it is immortalised in the calendar for 1867 printed in the 16first Australasian Turf Register. There was a two day gathering at Yass in ’47, a Geelong Steeplechase in ’45, a Colac Hurdle in ’46, a Launceston Derby and Town Plate in ’43, a Mount Gambier Town Plate in ’48, a Brighton Derby and St. Kilda Cup in ’49, and a meeting even at far-off Portland in ’48. Yes! We are a peculiar, a very peculiar, people!

Of course, there was no Turf Register in these very far-off days, and for some time the newspapers of Port Phillip were very few and far between. Just a couple of months prior to the running of that first race around Batman’s Hill, John Pascoe Fawkner had published “a rag,” a veritable “rag,” “The Port Phillip Advertiser.” It was in manuscript, and its “days were few, and full of woe.” Indeed, it was all but stillborn. There are no race records contained in its thin leaves. From January, 1838, until 1846 there was a succession of news sheets, “Port Phillip Gazettes,” “Patriots,” “Heralds,” “Figaros,” and what not, all of them weekly and weakly, squabbling, screaming, quarrelsome, puny infants, finding early deaths. The “Argus” was founded in 1846, and on June 2nd of that year its first number was printed. The racing news reported during the early years of its existence was meagre in the extreme, and was occasionally printed under the heading of “Domestic Intelligence.” But so mushroom-like was the growth of population in the later ’forties—and very much more so in the early ’fifties—that not only had a daily paper become a very flourishing concern, but the want of a weekly publication, of a purely sporting character, became so urgent that Bell’s “Life in Victoria” was established somewhere about 1855, and continued to exist until, in 1866, “The Australasian” came along with its sails bellying before a favourable breeze, and swept it out of sight. From 1860 until its disappearance, “Bell” had brought forth a little annual volume containing a list of all the principal race meetings of the past year, and “The Australasian” continued the publication under the title of “The Australasian Turf Register.” This was a thin little volume bound in red cloth, but nearly double the size of its diminutive predecessor. It has continued in an unbroken succession ever since.

The production of 1866–67 ran to two hundred and twenty-three pages. The stout, good-looking, substantial volume of 1920, with its blue boards and letters of gold, contains twelve hundred and thirty. And so, in proportion, has our racing and our horse flesh waxed mightily and increased in volume. Has the quality of our sport, and the excellence of our racehorse, grown during the fleeting years to as marked an extent? We will talk about that ere we wind up the clue of the argument.

But now the gold rush was affecting every portion of inhabited Australia, and the entire country was in a fever. People were too busy endeavouring to become rich quick to trouble very much about the importation of fresh blood stock, so that the list of arrivals between 1850 and 1860 was not nearly so extensive an one as might have been thought or desired. For 1851 was the “annus mirabilis” of Victoria. A Golden Age had dawned. On February 12th of that year Hargraves had washed his first shovelful of dirt near Bathurst, and had found gold in extremely payable quantities. The discovery had stimulated the early prospectors of Port Phillip, and the metal was soon 17being extracted from the earth by the ton at Clunes, Buninyong, Warrenheip and Ballarat. In September Her Majesty Queen Victoria had signified her assent to the Bill which granted separation of Port Phillip from New South Wales, and the province had now entered upon her career as a separate State. The only skeleton at the feast was the recollection of that dreadful day at the commencement of the year, when the world seemed to be on fire, and the end of all things might possibly be at hand. Black Thursday, February 6th, was a day ever to be remembered.

But when the first outburst of the gold fever had somewhat subsided, racing soon began to be more popular than ever before. With quantities of money and loose nuggets to fling about, with a well-developed and constantly indulged in itch for gambling, and with a natural sporting instinct, the diggers soon made things hum in the horse racing line. And now it was that there grew up the absolute necessity for keeping stud records. We have already noticed how inefficiently the stud careers of great mares such as Manto, Cornelia and others had been noted, and how, at this particular period in the history of the turf, it was more urgent than ever that a system should be adopted for preserving all information concerning each brood mare and her progeny, and of maintaining the breed as pure as it was possible to do under the peculiar conditions inseparable from a new country. For things were still what we, in our modern parlance, would call “pretty mixed.” The horse was the main means of progression, railways were short in their mileage, and their branches were scattered and few. The stage coach, buggies and horseback were practically the only means by which the country was traversed, and stock were of necessity still to be driven immense distances to market. With horses in profusion, with paddocks extremely large, with population scattered over a tremendous breadth of lonely country, horse “duffing” was a very tempting proposition to those people whose notions of “meum and tuum” were inclined to be careless and slack. To pick up a good-looking brood mare, in foal or with foal at foot, for nothing, was a temptation impossible to be resisted by many with such a weakness, as they travelled on horseback through the wild, outback places, behind their mobs of cattle and droves of sheep. The bushrangers, those unfortunate “gentlemen of the road,” too, required a constant supply of horse flesh, and the better looking, and the better bred, their cattle were, so much the more advantageous it was for them.

Troubadour, Mr. C. M. Lloyd’s well-known racing stallion, is reported to have been stolen by Ben Hall on three separate occasions, but was always recaptured. So many skirmishes had the old horse been in when ridden by Hall that, on the death of the horse, a post mortem was held, when seven bullets were discovered in various portions of his frame. Everyone has read Rolf Boldrewood’s inimitable book “Robbery Under Arms.” The story of horse stealing and cattle duffings is splendidly told in its pages, and the description of the stock concealed in “The Hollow” by Starlight and his gang is well calculated to make the mouths of all thoroughbred enthusiasts water, and almost to cause the best of us to covet our neighbour’s horse. Sappho, the greatest and most successful colonial-born brood mare that has ever been seen, was “lifted,” I have been informed, on at least three occasions, and Mr. George Lee had many long, weary rides whilst tracking the footprints of those that led her captive. Some of the most distinguished matrons of our stud book were either stolen or strayed mares whose owners never recovered them, and whose new masters, as a matter of course, dared not acknowledge their pedigrees, even if they had them. There was “Black Swan, by Yattendon from Maid of the Lake (bred by Captain Russell, of Ravensworth, but whose 18pedigree cannot be ascertained).” Her stock, inasmuch as they can win at all distances, at weight-for-age, and can stay, are palpably from no half-bred strain. There was Dinah, bought, it is believed, out of a travelling mob by the late Mr. James Wilson, of Victoria, and certainly as clean bred as Eclipse. Her descendants include, in a long list, Musidora, Newhaven, G’naroo and Briseis. There was Mr. C. Smith’s Gipsy, said to have been by Rous’ Emigrant, but whose dam was never identified. There was Lilla, whose granddam was a mare by Toss, “bred by the Rev. W. Walker, near Bathurst,” and there was Sappho herself, “by Marquis, her dam a grey mare by Zohrab, granddam a brown mare of unknown pedigree.” And then, too, there was Old Betty. Breeders would give untold sums of money to discover, with no possibility of error, the blood lines of these famous mares. It is to be feared, however, that it is an impossibility in each of these cases cited here, and every year that glides past adds to the apparently insurmountable difficulties which lie in the way. But it was to prevent such occurrences in the future that the first volumes of the Victorian, the New South Wales and the New Zealand Stud Books were compiled. Mr. William Levy essayed the task in Victoria in 1859. In N.S.W. the first production saw daylight at about the same time, and in New Zealand, breeders followed suit.

Mr. Levy’s volume ran to 40 pages, all told. There were one hundred and thirteen mares whose produce he recorded, and of these twenty-eight were owned, or partly owned, by Mr. Hector Norman Simson, of Tatong, near Benalla.

The second volume of the Victorian Stud Book, also edited by Mr. Levy, was published in 1865, and was even more meagre in its information than its predecessor, but volume three, compiled by William Yuille, junior, in 1871, was a much more ambitious effort, and volume four, the last of the series, was also edited by him. After this the need of an Australian Stud Book, apart from a mere provincial work, was so apparent, that Mr. William C. Yuille, the father of the Editor of the third and fourth Victorian records, and who had, unfortunately, died in the meantime, took over the great task. This first volume represents an enormous amount of work and of research. It is peculiarly interesting to the student of breeding, and is only surpassed in value by the second volume of 1882, a huge tome for those days, of over five hundred pages, a work which was undertaken by Mr. Archibald Yuille, assisted by his friend Mr. Francis F. Dakin. It was a splendid achievement. Thereafter, volume after volume was produced at fairly regular intervals, for many years, by these two enthusiastic experts, and after Mr. Dakin’s sudden death, in Sydney, by Mr. Archibald Yuille and his brother Albert. In 1913, however, the tenth volume was “compiled and published under the direction of the Australian Jockey Club, and the Victorian Racing Club.” It is a great work. The twelfth volume, published in 1919, runs to over nine hundred pages, and the information contained therein is complete and entirely satisfactory. The present Keeper of the Stud Book is Mr. Leslie Rouse, a member of a very old house which has been intimately connected with Australian racing and horse breeding, with all its traditions, ever since the beginning. Nothing has been left undone in order to place the Australian Stud Book on the same high pedestal of completeness and accuracy which distinguishes its great prototype, “The General Stud Book.”

Racing, always a peculiarly popular sport the world over, but more particularly so in Australia, was fairly on its legs in the new country by the time that Stud Books and Turf Registers had been established. A little snowball had been formed, and from this time onwards it continued to accumulate in bulk, until to-day, the quantity of racing, in proportion to the population, is simply extraordinary, and the snowball has grown to be an avalanche.

Between 1850 and 1864 the destinies of the Victorian Turf were guided by two sporting bodies, the Victoria Jockey Club and the Victoria Turf Club. Both associations held their races over Flemington, and although each was managed by a high-class Committee and Stewards, they were ever at war one with the other, so, naturally, the house divided against itself came to the usual termination, and neither of them could stand. In 1864 it was found that neither the Victoria Jockey Club nor the Victoria Turf Club were sound financially, and that racing was not progressing under their management as it ought to have been doing. A meeting of those interested was therefore held, and this conference resulted in the formation of the Victoria Racing Club, which newly risen body declared itself willing to take on the liabilities of the others, provided that they, in their turn, were willing to dissolve. This was agreed to, and the V.R.C. has, from that moment, governed all Victorian racing, and ruled it extremely well. Mr. Henry Creswick was its first chairman. Immediately after its inauguration a Secretary was appointed at a salary of One hundred and fifty pounds per annum, and Mr. R. C. Bagot was chosen to fill the position. The Club has been miraculously lucky, in that, from 1864 until this year of grace, 1921, there has only once been a change of hand at the wheel. Mr. Bagot worked strenuously, enthusiastically, and with knowledge, until his death in 1881, when Mr. Byron Moore succeeded him, and he is still working with all the old fire which distinguished his efforts of forty years ago. The fact that he applied for the position at all seems to have been one of those freaks of fortune, or dispensations of Providence, which sometimes work out for the greatest good. Mr. Byron Moore was not a racing man. He knew little about the sport, and cared less. But he had known Mr. Bagot, and was well aware of his aspirations in connection with the Club. When Mr. Bagot died, his widow urged upon Mr. Moore the advisability of his applying for the position, and, more to please her than for any other reason, he hastily wrote an application, briefly submitting his name as a candidate, but sending no credentials, and giving the matter no further thought. Indeed, the circumstance had passed from his mind until, meeting the Ranger of the Course, the well-known and faithful Jonathan, in the street one day, that official stopped him and immediately gave him the information—“Well, they’ve guv it ye.” “Guv what?” “The Secretaryship.” And Mr. Byron Moore has been installed there ever since. Here, there, and everywhere, never absent from his post, always courteous, bland, obliging, yet inflexibly business-like and punctilious, he has been, and is “the most precise of business men.” And so the Victorian Racing Club has had, probably, the unique advantage of having been managed by only a couple of Secretaries during nearly sixty years.

So soon as Mr. Bagot undertook the management of its affairs, so soon as the two contending bodies agreed to cease operations, so soon, too, did the affairs of the Victorian Turf enter into a period of wonderful prosperity and vigorous growth. Indeed, with the exception of short intervals, now 20and again, during which the whole prosperity of the country, or of the world, has been depressed, the story of the Turf, not only of Victoria, but of Australia, has been one of continuous growth and advance, and that upon the most solid lines.

The Melbourne Cup itself, one of the most famous races contested in the world to-day, is a barometer of the financial welfare and general prosperity of the community at large.

It was a very small affair for the first few years after it had been launched upon the sea of time. The race was run under the auspices of the Victoria Turf Club, the Derby and Oaks under the aegis of the Victoria Jockey Club.

The stake for the great Cup was of the value of two hundred pounds, and it was won, for the first couple of years after its inception, in 1861, by Mr. E. De Mestre’s Archer. This was a fine horse by William Tell (imported), a bay son of Touchstone from Miss Bowe, by Catton from Tranby’s dam, by Orville. There seems to be some doubt about Archer’s dam, but Mr. Wanklyn states that she descended through Bonnie Lass (by Bachelor (imp.)), to Cutty Sark, whilst the first and second volumes of the Stud Book give his dam as Maid of the Oaks, by Vagabond from Mr. Charles Smith’s mare by Zohrab. In 1869 the stake was increased to £300. In 1876 the value had mounted to £500, a sum which had already been far surpassed by the Tasmanians as a prize for their championship at Launceston. This was already worth one thousand. The thousand limit in the Cup was reached in ’83 for the first time, Martini Henry being the winner for the Hon. Mr. James White. After this prize-money ascended in leaps. In ’86 there was £2,000 of added money; it jumped to £2,500 in the following year; £3,000 in ’88; £5,000 in ’89; and £10,000 in 1890. It was the summit, the “suprema dies,” the grand climax of all things. This year compressed all the bests on record imaginable into its calendar.

There was a record sum of money added to the race, a record field (thirty-nine starters), a record weight was carried by the winner (ten stone five), and the time for the race (3 minutes 28¼ seconds) was another best ever seen up to that time. That has since, however, been far surpassed, Artilleryman, in 1919, having smashed up a great collection of good horses in most decisive fashion by very many lengths in 3.24½. And the winner of 1890 was undoubtedly a record horse—the brave, consistent, staying, immortal Carbine.

In the three following Cups, Malvolio, Glenloth and Tarcoola each swept in ten thousand sovereigns for their owners, but in Auraria’s year, and when Gaulus, Newhaven and The Grafter won, racing affairs had met with “an air pocket,” and had consequently suffered a heavy “bump.” The added money fell to three thousand pounds. The depression, however, during the seasons following the collapse of the land boom, did not last long, and ere the war drums boomed across a horrified world in 1914, the prize had once more risen to upwards of seven thousand pounds. Even whilst the struggle for life and death was progressing, the V.R.C. and the A.J.C. both strove nobly to maintain racing on the highest possible plane in every way, and the value of the great Cup never fell much short of five thousand pounds. And this, too, in face of the fact that the Committee of the V.R.C. presented to the numerous Patriotic War Funds the magnificent sum of over one hundred and two thousand pounds.

Since the early days of the V.R.C. other clubs have arisen in great numbers. For many years, all through the country districts, no township was too small to hold a race meeting. Even country public houses far outback could manage to give away sums of money, and gather a crowd of people for 21the benefit of boniface under the pretence of a day’s horse racing. But now, under the wise hands of the ruling body, “sport” of that nature is severely restricted, and the formation of District Associations, working under the V.R.C. is doing immense good in improving the whole thing, and in seeing to it that racing is carried on in the cleanest and fairest manner possible. There are many excellent up-country gatherings throughout the State. Warrnambool, with its annual Steeplechase, is splendid. Wangaratta and Benalla, where they have raced since before the flood, both provide capital sport. Ballarat, once second only in importance to metropolitan headquarters, is perhaps not the force that it used to be in the old days when mining was flourishing, and was one of the most prosperous industries in the country. But it is once more on the up-grade, and is well managed. Bendigo has always maintained a high standard. Camperdown is good, as is Colac, while Geelong, after suffering a partial eclipse, is also again climbing the ladder. And in the metropolitan area there are several clubs that have done, and are doing, a great deal for the sport. The Victorian Amateur Turf Club is in the foremost rank, and is only second to the V.R.C. in influence and importance. The Caulfield Cup has been in existence since 1879, when two hundred sovereigns was the amount of its prize-money. In 1920 this was represented by £6,500, and a gold cup valued at £100.

The V.A.T.C. was originally formed in 1876 by a number of enthusiastic riders and owners, whose opportunities for amateur jockeyship were too restricted for their vaulting ambitions. The promoters were the Messrs. Hector, Norman and Arthur Wilson, J. O. Inglis, Herbert and Robert Power, and others, and so well have their affairs prospered on that beautiful course at Caulfield that the original object of the Club has been entirely lost sight of long ago. It is a splendid institution.

Then there is the seaside racecourse at Williamstown, which has had a long and creditable history. The course is a fine one, and is being improved yearly and the annual Cup is now worth between two and three thousand pounds. Moonee Valley is possibly the most popular of all the suburban turf resorts. Its affairs are splendidly administered by Mr. A. V. Hiskins and an influential Committee. It is so close to the General Post Office that anyone now finds it an easy journey to the entrance gates. The course is a good one, well kept, and the prizes are liberal throughout the year. The Committee is entirely up to date, and this Club, like the V.A.T.C. and Williamstown, are not only steadily increasing their prize-monies, but each and all of them gave with ready and overflowing hands to the patriotic funds. There are other and numerous—too numerous—courses within reach of the metropolis. Epsom, situated close to Mordialloc, is also a club, and its affairs are ably controlled, but Mentone, Aspendale and Sandown Park are of the nature of proprietary concerns whose surplus funds revert to the pockets of the promoters, and no doubt pay ample dividends. But with these, so far as the actual history and welfare of the Racehorse in Australia is concerned, we have nothing to do.

And now that we have these accurate records to our hands of all our turf history since 1865, and with the Stud Book giving us the family tree of our thoroughbreds, so far as it can be obtained, from the present day back to the times of King Charles the Second, we can so easily, from that high perch of knowledge, take a quick, bird’s-eye view of the happenings of our own brief days in Australia. Shortly before this era of historical accuracy dawned upon our thoroughbred history, certain importations of blood stock took place which have left a deeper mark upon our annals than any other events since the arrival of the mare Manto.

It was in 1860 that Mr. Hurtle Fisher procured, from England, a stallion and several brood mares, and formed a breeding establishment at Maribyrnong. This is an estate composed of flats and rising ground, hill and dale, on the banks of the Saltwater River, within an easy morning’s ride from the main streets of the Victorian capital. Here Mr. Fisher built, high up upon a convenient and commanding eminence, excellent stabling for his valuable imported stud, and a house for his manager. It was an ideal spot, beautifully laid out, and so substantial that the main buildings stand to-day with every appearance of having only been erected yesterday. The mares which Mr. Fisher imported were from the bluest blood of the day, carefully chosen, with the soundest judgment, and regardless of expense. His stallion was one of the best-known horses in England, a mighty winner, a great stayer. This was Fisherman, a brown horse, by Heron out of Mainbrace, by Sheet Anchor out of a Bay Middleton mare. He had won upwards of sixty races, most of them over a distance of ground, and although, when you trace his blood lines carefully out, you might be led to believe that they are scarcely those of a stayer, yet he undoubtedly did possess that quality in a marked degree, and so, too, did the stock which he left behind him.

The names of the mares which accompanied Fisherman on his long voyage conjure up to every turfite a vision of romance, recall the time when our best turf traditions were in the making, and bring back to the memory hundreds of races lost and won. Gildermire, Marchioness, Juliet, her daughter Chrysolite (foaled after landing), Rose de Florence, Coquette, Cerva, Nightlight, Gaslight, Omen and Sweetheart formed the kernel of the stud. The lastnamed mare, by the way, was dropped in Victoria, her dam, Melesina, having been imported by Mr. Rawdon Green, who sold her to Mr. Fisher. She was but a short time in the possession of the latter, but it was whilst the mare was at Maribyrnong that she produced Mermaid to Fisherman, and Mermaid was the dam of Melody, the dam of Melodious, the mother of the immortal Wallace. Unfortunately, times then became bad for Mr. Hurtle and his brother, Mr. C. B. Fisher. Many people were speculating heavily in land during the ’sixties, and, as is usual in all booms, the few who were lucky became rich very quickly, whilst the great majority whom fortune did not favour went to the wall.

The entire Maribyrnong Stud came to the hammer on April 10th, 1866, the sale realising nearly £28,000. Prices were considered high, but were such lots with the same reputation put up to auction to-day, say, by the Messrs. Tattersall at Newmarket, England, probably a couple of them alone would bring in that sum. As it was, the two-year-old Fishhook fell for three thousand six hundred guineas, Seagull for nineteen hundred, and Lady Heron for 23fourteen hundred. But prior to the great sale the name of Fisher had, in conjunction with one or two others, dominated the turf.

And we find during the five decades or so that have elapsed since then, that but a few owners, a few breeds of horses, stand in the limelight during each period, and leave their influence for good or ill for all time.

Contemporary with the Fishers, however, there was quite an abundance of sportsmen whose names, even after the lapse of all those years, seem to be as familiar to us as are those of the magnates of their day in the Old Country, the Merrys, Graftons, Albemarles, Falmouths, Hastings, Westminsters, Portlands, Bowes and Peels. Listen to them as they are told, and see if they do not stir a chord within you, awakening afresh dear and stirring memories of the olden time, of those days gone by in which we fondly believe that there were many giants.

Andrew Town, John Lee and his brothers, C. Baldwin, John Tait (“Honest John”), the Rouse family, T. Ivory, E. De Mestre, P. Dowling, Hector Norman Simson, James Wilson, William Pearson, W. C. Yuille, H. J. Bowler, Rawdon Greene, F. Tozer, and George Watson. What teams the Fishers had, as well as old John Tait!

From Maribyrnong’s massive gateway there used to emerge each morning to their work, a string containing Angler, Fishhook, Rose of Denmark, The Sign, Lady Heron, Kerosene, Smuggler, Sea Gull, Bude Light, Sour Grapes, Ragpicker, The Fly, and for a brief day only, the beautiful Maribyrnong.

This colt, who afterwards took his sire’s place, fractured his near foreleg in the Derby, his only contest. His life was spared, however, and he made an enduring name at the stud.