The Project Gutenberg eBook of The story of Santa Klaus, by William S. Walsh

Title: The story of Santa Klaus

Told for children of all ages from six to sixty

Author: William S. Walsh

Illustrator: Thomas Nast

Illustrator: Raphael

Illustrator: Rubens

Illustrator: B. Plockhorst

Illustrator: Murillo

Illustrator: F. Defregger,

Illustrator: Annibale Caracci

Illustrator: John Leech

Illustrator: Diedrich Bouts

Illustrator: Hubert and Jan Van Eyck

Illustrator: J. Portaels

Illustrator: Sebastian Conea

Illustrator: Andrea del Sarto

Illustrator: Bernardo Luini

Illustrator: Fra Angelico

Illustrator: Veronese

Illustrator: E. Burne Jones

Illustrator: Kenny Meadows

Illustrator: A. F. Gorguet

Illustrator: Raymond Potter

Illustrator: J. R. Shaver

Illustrator: C. J. Taylor

Illustrator: Gavarni

Illustrator: Power O’Malley

Illustrator: Henry Hutt

Release Date: February 26, 2023 [eBook #70142]

Language: English

Produced by: Tim Lindell, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

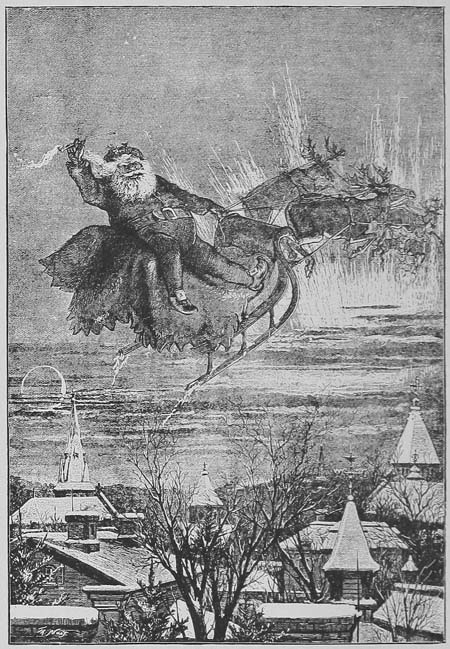

Merry Christmas to all!

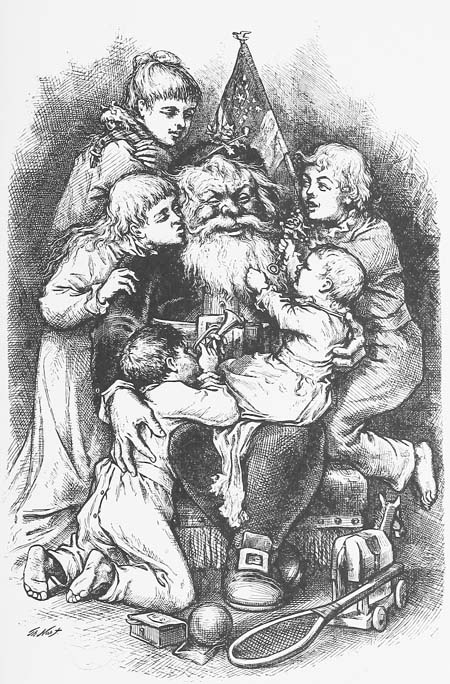

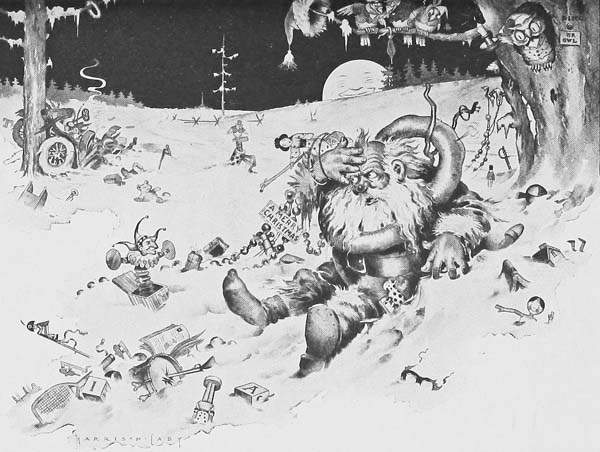

From Thomas Nast’s “Christmas Drawings for the Human Race.”

Copyright 1889 by Harper and Brothers.

THE STORY OF SANTA KLAUS

TOLD FOR CHILDREN OF ALL

AGES FROM SIX TO SIXTY

BY

WILLIAM S. WALSH

AND ILLUSTRATED BY ARTISTS OF ALL AGES

FROM FRA ANGELICO TO HENRY HUTT

NEW YORK

MOFFAT, YARD AND COMPANY

1909

Copyright, 1909, by

WILLIAM S. WALSH

New York

Published October, 1909

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Who is Santa Klaus | 13 |

| II. | Strange Adventures of the Saint’s Body | 39 |

| III. | Christ-kinkle and Christ-kindlein | 50 |

| IV. | The Evolution of Christmas | 58 |

| V. | Silenus, Saturn, Thor | 69 |

| VI. | A Terrible Christmas in Old France | 80 |

| VII. | The Christmas Tree in Legend | 90 |

| VIII. | The Christmas Tree in History | 99 |

| IX. | The Christmas Tree in Europe | 109 |

| X. | The Christmas Tree in England and America | 118 |

| XI. | The Story of the Three Kings | 124 |

| XII. | Some Twelfth Night Customs | 151 |

| XIII. | St. Nicholas in England | 158 |

| XIV. | Father Christmas and His Family | 165 |

| XV. | Pantomime in the Past and Present | 185 |

| XVI. | Saint Nicholas in Europe | 194 |

| XVII. | Saint Nicholas in America | 214 |

| PAGE | |

| Merry Christmas to all! | Frontispiece |

| St. Nicholas as the patron saint of children | 15 |

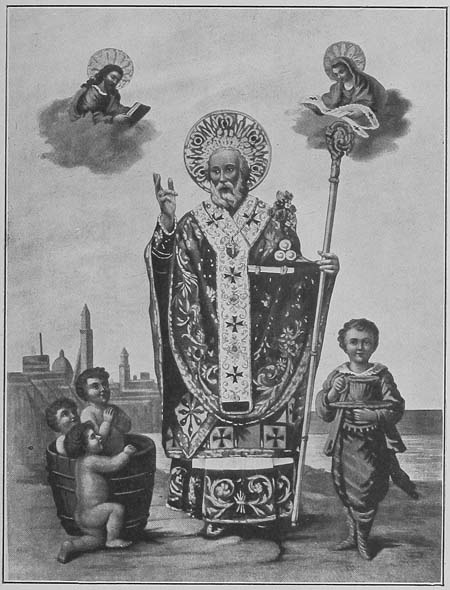

| The Consecration of St. Nicholas | 19 |

| St. Nicholas and the three maidens | 23 |

| St. Nicholas resuscitating the schoolboys | 27 |

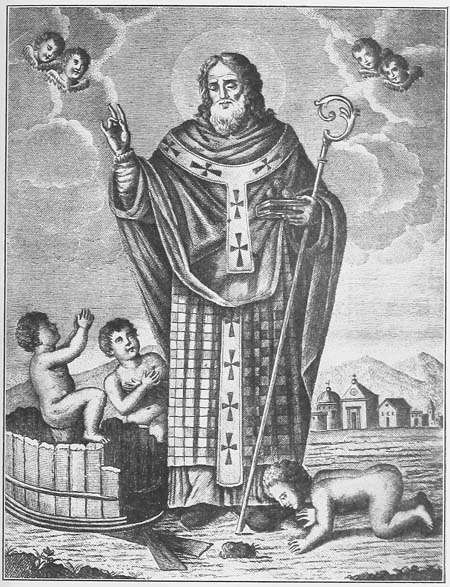

| Bishop Nicholas | 31 |

| St. Nicholas of Bari | 35 |

| Heads of the Christ-child | 41 |

| The Christ-child surrounded by angels | 47 |

| “Suffer little children to come unto me” | 51 |

| Christ the giver | 55 |

| Christmas presents | 59 |

| Saturn, the God of Time | 63 |

| Silenus and Fauns | 71 |

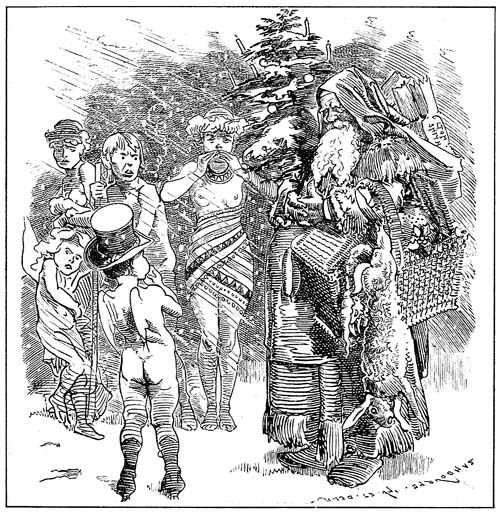

| Santa Claus and his young friends | 73 |

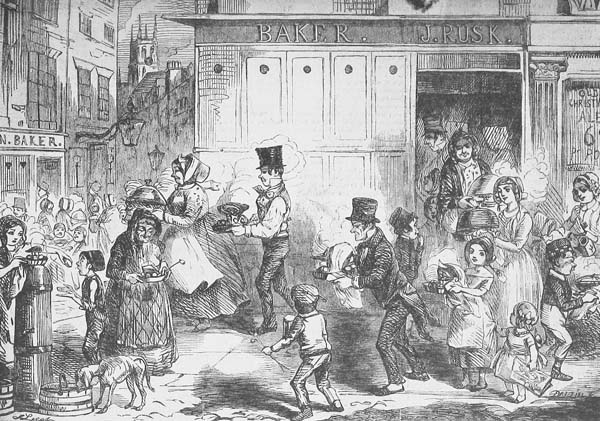

| Carrying home the Christmas dinner | 77 |

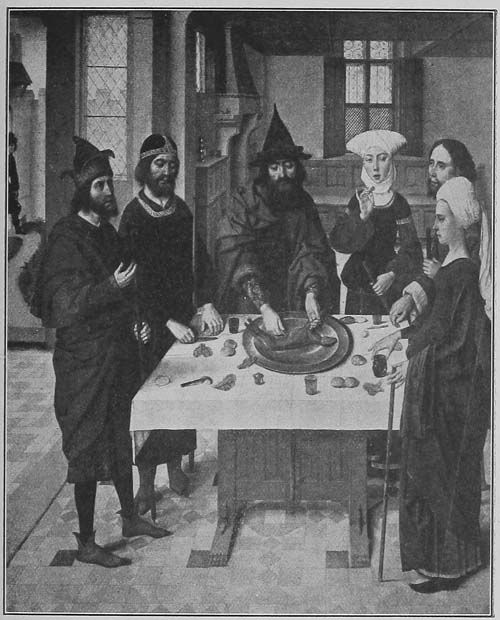

| The Feast of the Passover | 81 |

| The Adoration of the Lamb | 87 |

| Luther and the Christmas tree | 101 |

| Christmas tree of the English royal family | 111 |

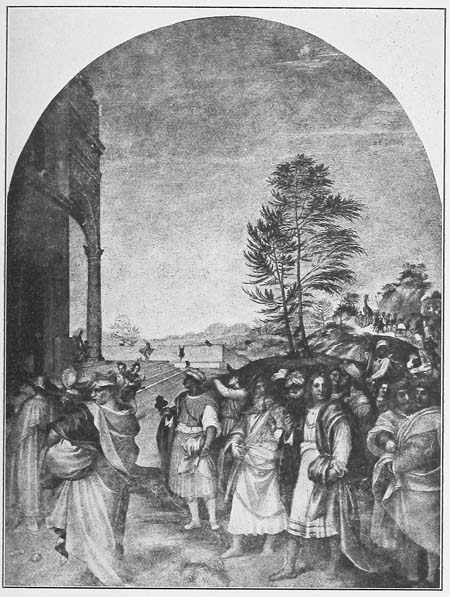

| On the way to Bethlehem | 125 |

| The Three Kings visit Herod | 129 |

| The Journey of the Three Kings | 133 |

| The Arrival of the Three Kings | 137 |

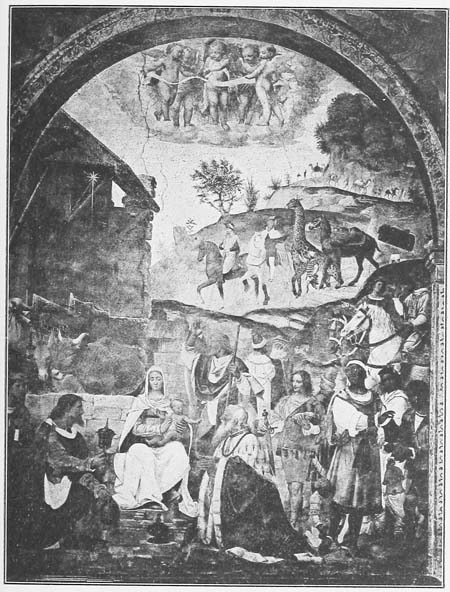

| The Adoration of the Magi (1) | 141 |

| The Adoration of the Magi (2) | 145 |

| The Adoration of the Three Kings | 149 |

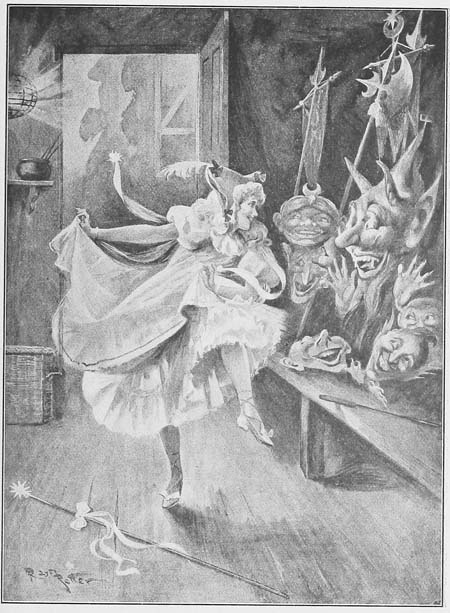

| The Child’s Twelfth Night Dream | 153 |

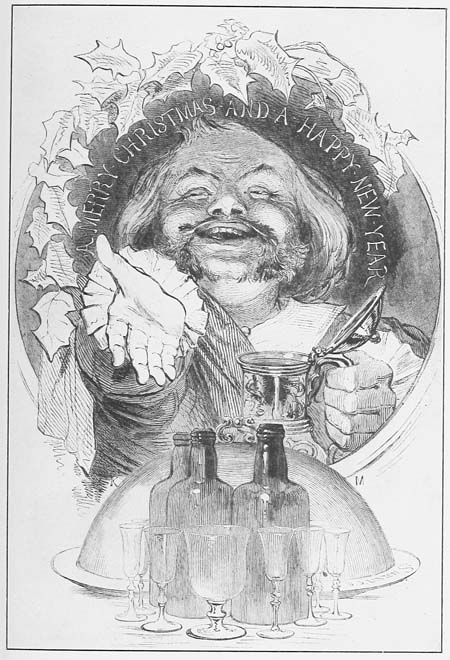

| Father Christmas | 167 |

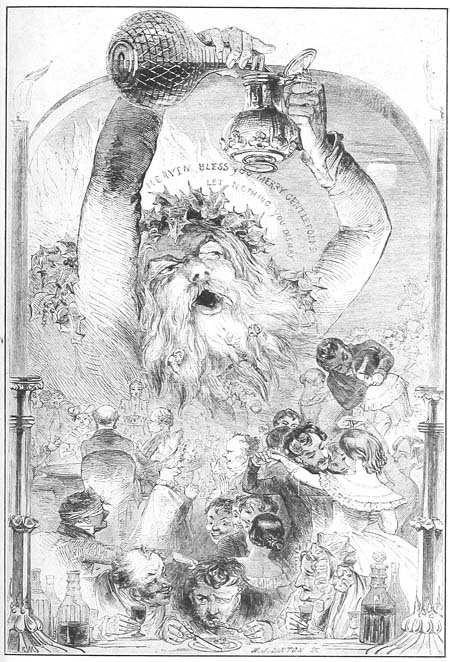

| Father Christmas (another conception) | 171 |

| The Old and the New Christmas | 175 |

| Bringing in Old Christmas | 179 |

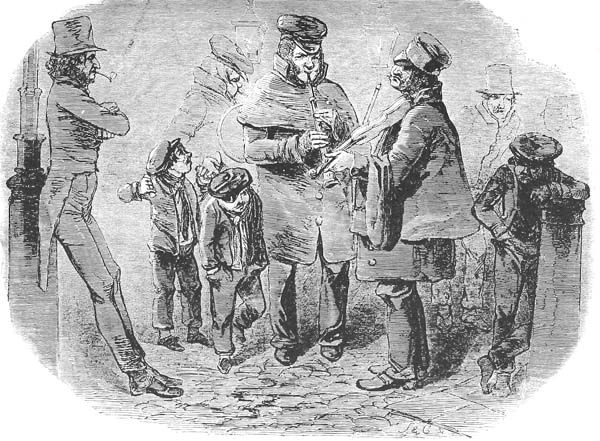

| The Christmas Waits | 183 |

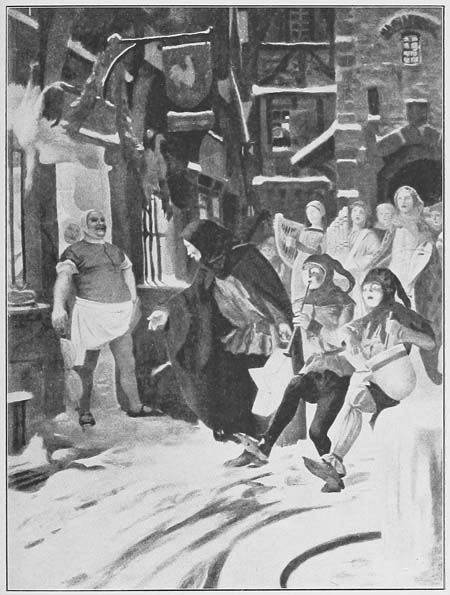

| Jongleurs announcing the birth of our Lord | 187 |

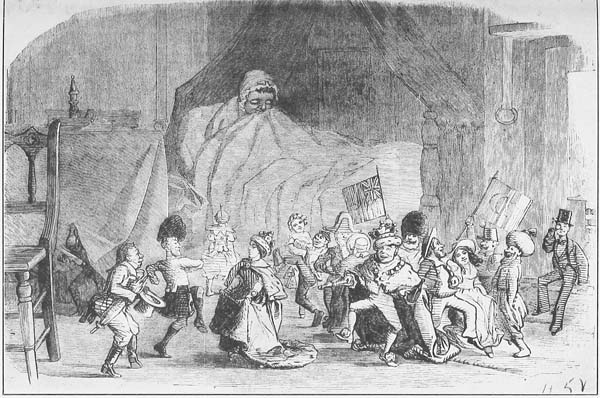

| Going to the Pantomime | 191 |

| Mute admiration | 195 |

| Santa Klaus comes to grief on an automobile | 199 |

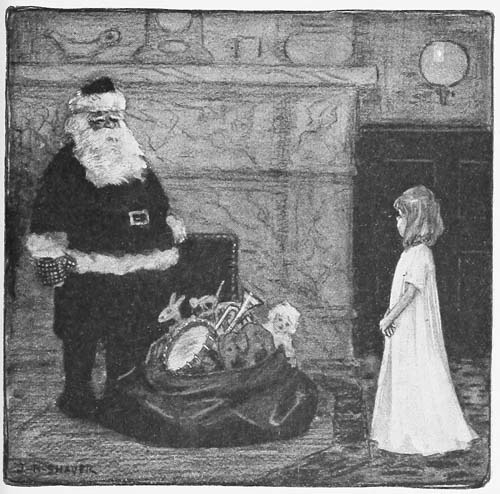

| “No, I don’t believe in you any more” | 203 |

| Santa Klaus | 207 |

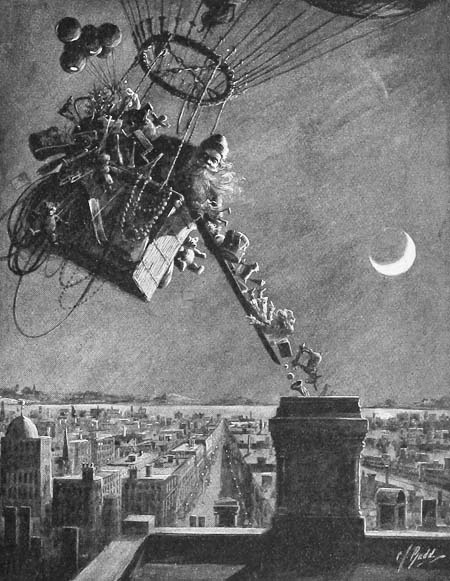

| Santa Klaus up in a balloon | 211 |

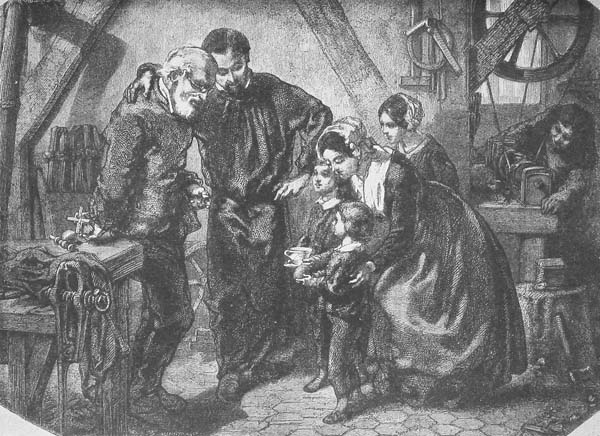

| New Year’s gifts in a French workingman’s family | 215 |

| French children gazing up the chimney for gifts | 219 |

| Silenus and Bacchus | 223 |

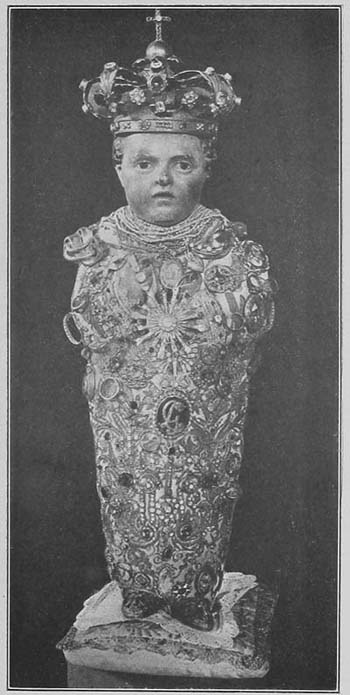

| The bambino | 225 |

| Santa Klaus on New Year’s eve | 227 |

| The investigating committee | 229 |

| St. Nicholas unveils | 231 |

[13]

THE STORY OF SANTA

KLAUS

If you go to England you will find many people there who have never heard of Santa Klaus. Only the other day a leading London paper confessed that it could not understand why a magazine for children should be called St. Nicholas.

Now if you were asked the question which heads this chapter do you think you could answer it so as to make an Englishman understand who Santa Klaus is? Could you also explain what connection Saint Nicholas has with children?

Of course you might glibly reply:

“Santa Klaus is the Dutch diminutive (or pet name) for Saint Nicholas, and Saint Nicholas is the patron saint of boys and girls.”

But the Englishman might want to know more than this. Perhaps you yourself would be glad to know more. It is for the purpose of supplying you[14] with information that I have prepared this little book.

Let us begin with the legends which concern this holy man and see what help they will give us. I say let us begin with the legends, because history itself tells us little or nothing about the saint beyond the fact that he was Bishop of a town called Myra in Asia Minor and that he died about the year 342. Legend fills out these meagre details with many a pretty story which throws a kindly light upon the character of good Saint Nicholas.

You know what a legend is? It means a story which was not put into writing by historians at the time when the thing is said to have happened, but which has been handed down from father to son for hundreds and sometimes for thousands of years. It may or may not have had some basis of truth at the beginning. But after passing from mouth to mouth in this fashion it is very likely to lose what truth it once possessed. Still, even if the facts are not given in just the manner in which they happened there is nearly always some useful moral wrapped up in the fiction that has grown around the facts. That is why wise and learned men are glad to collect these legends from the lips of the peasants and other simple minded folk who have learned them at their mothers’ knee, and who believe that they are all true. These legends are called by the general name of folk-lore.

[15-16]

St. Nicholas as the patron of children.

Italian print.

[17]Two brothers of the name of Grimm once collected into a book the folk-lore of their native country, Germany. This book is known to you as Grimm’s Fairy Tales. Hans Christian Andersen also found among the legends of Denmark some of the prettiest and most fanciful of his tales.

Now stories concerning Saint Nicholas abound in almost every country of Europe, for almost every country except Great Britain is interested in his name and fame. He may, indeed, be called the busiest of all the saints. In the first place legend makes him the patron saint of children all over the world, no matter of what sex or color or station in life. Ever childlike and humble, so we are told by a quaint old author, “he keepeth the name of a child, for he chose to keep the virtues of meekness and simpleness. Thus he lived all his life in virtues with this child’s name, and therefore children do him worship before all other saints.”

One might think that to be a patron of the world’s children would keep one saint pretty busy, even if it did not exhaust his energies. Not so with Saint Nicholas. He occupies his spare moments as the protector of the weak against the strong, of the poor against the rich, of the servant and the slave against the master. Because he once calmed a storm he is the patron of travellers and sailors and of many seaport towns. Because he once converted a gang of robbers and made them restore their booty to the men they had robbed[18] he is still thought to retain a kindly interest in thieves.

Moreover he is the patron of the largest of all European countries, the empire of Russia.

Now we will make our promised examination of the legends which have gathered around this saint and given him a fame so widespread.

Saint Nicholas is said to have been born in a town called Potara in Asia Minor. To the great wonder of his nurses he stood up in a tub on the day of his birth with his hands clasped together and his eyes raised to heaven and gave thanks to God for having brought him into the world. It is added that on Wednesday and Fridays, (both fast days in the early Church) he would refuse to take milk until the going down of the sun.

His parents died when he was very young. As they were wealthy they left him well provided with the world’s goods. But he would not accept them for himself. Instead he used them for the good of the poor and of the Church.

When he was old enough he studied for the priesthood in the town of Myra and was ordained as soon as he had reached man’s estate. He at once set sail on a voyage to the Holy Land to visit the tomb of Jesus Christ in Jerusalem. On the way a dreadful storm arose. The winds howled and whistled, the great waves shook the vessel from stem to stern.

[19-20]

The consecration of St. Nicholas.

Old print.

[21]The captain and the sailors who had been used to bad weather pretty much all their lives declared that this was the worst storm they had ever known. Indeed they had given up all hope when the young Nicholas bade them be of good cheer.

His prayers soon calmed the wind and the waves, so that the ship reached Alexandria safe and sound. There the saint landed and made the greater part of the journey from Alexandria to Jerusalem on foot.

Returning by sea, he wished to go straight back to Myra. The captain, however, would not obey his orders and tried to make the port of Alexandria. Then Saint Nicholas prayed again and another great storm arose. And the captain was so frightened by this evidence of the saint’s powers that he gladly listened to his request and headed the ship towards Myra.

In the year 325 Nicholas, then still a young man, was elected Bishop of Myra. On the day of his consecration to that office a woman brought into the church a child which had fallen into the fire and been badly burned. Nicholas made the sign of the cross over the child and straightway restored it to health. That is the first of his miracles which showed the interest that he took in children.

Two other miracles which are still more famous are thought to foreshadow the fame he has won since his death as the patron of children and the bearer of gifts to them at the holy Christmas season.

[22]Among the members of his flock (so runs the first story) there was a certain nobleman who had three young daughters. From being rich he became poor,—so poor that he could not afford to support his daughters nor supply the dowry which would enable him to marry them off. For in those days, as even now in many countries in Europe, young men expected that a bride should bring with her a sum of money from her parents with which the young couple could start housekeeping. This is called the dowry.

Over and over the thought came into the nobleman’s mind to tell his daughters that they must go away from home and seek their own living as servants or in even meaner ways. Shame and sorrow alone held him dumb. Meanwhile the maidens wept continually, not knowing what to do, and having no bread to eat. So their father grew more and more desperate.

At last the matter came to the ears of Saint Nicholas. That kindly soul thought it a shame that such things should happen in a Christian country. So one night when the maidens were asleep and their father sat alone, watching and weeping, Saint Nicholas took a handful of gold and tying it up in a handkerchief, or as some say placing it in a purse, set out for the nobleman’s house.

[23-24]

St. Nicholas and the three maidens.

Fifteenth century painting.

[25]He considered how he might best bestow the money without making himself known. While he stood hesitating the moon came up from behind a cloud, and showed him an open window. He threw the purse containing the gold in through the window and it fell at the feet of the father.

Greatly rejoiced was the old gentleman when the money plumped down beside him. Picking up the purse he gave thanks to God and presented it to his eldest daughter as her dowry. Thus she was enabled to marry the young man whom she loved.

Not long afterwards Saint Nicholas collected together another purse of money and threw it into the nobleman’s house just as he had done before. Thus a dowry was provided for the second daughter.

And now the curiosity of the nobleman was excited. He greatly desired to know who it was that had come so generously to his aid. So he determined to watch. When the good saint came for a third time and made ready to throw in the third purse, he was discovered, for the nobleman seized him by the skirt of his robe and flung himself at his feet, crying:

“Oh, Nicholas, servant of God, why seek to hide thyself?”

And he kissed the holy man’s feet and hands. But Saint Nicholas made him promise that he would tell no one what had occurred.

The second legend is much more wonderful. It tells how Saint Nicholas was once travelling through his diocese at a time when the people had been driven[26] to the verge of starvation. One night he put up at an inn kept by a very cruel and very wicked man, though nobody in the neighborhood yet suspected his guilt.

This monster, finding that the famine had made beef and mutton extremely scarce and greatly raised their price, had conceived the idea of filling his pantry with the fat juicy corpses of children whom he kidnapped, killed and served up to his guests in all varieties of nicely cooked dishes and under all sorts of fancy names.

Nobody could guess how he alone of all the innkeepers in that neighborhood could maintain a table so well supplied with meats, boiled and roasted, and stews and hashes and nice tasty soups.

But no sooner had a dish of this human flesh been served up to the saint than he discovered the horrible truth.

Leaping to his feet he poured out his anger in bitter but righteous words. Vainly the landlord fawned and cringed and protested that he was innocent. Saint Nicholas simply walked over to the tub where the bodies of the children had been salted down. All he had to do was to make the sign of the cross over the tub, and lo! three little boys, who had been missing for days, arose alive and well, and, coming out of the tub, knelt at the feet of the saint.

[27-28]

St. Nicholas resuscitating the schoolboys.

Old Neapolitan print.

[29]All the other guests of the inn were struck dumb at the miracle. The children were restored to their mother, who was a widow. As to the landlord, he was taken out and stoned to death, as he richly deserved to be.

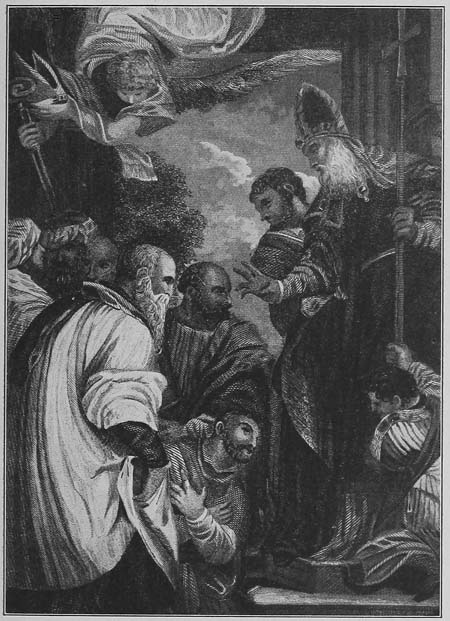

Another of St. Nicholas’ miracles shows that he had a kind heart for grown-ups as well as for the young folk. A revolt having broken out in Phrygia, Emperor Constantine sent a number of his tribunes to quell it. When they had reached Myra, the bishop invited them to his table so that they would not quarter themselves on poorer citizens, who might be ill able to afford their keep.

A grand banquet was served up to them. As host and guests were preparing to sit down, news was brought into the hall that the prefect of the city had condemned three men to death, on a false accusation that they were rebels. They had just been led to execution and the whole city was in a ferment of excitement over this terrible act of injustice.

Nicholas rose at once from the table. Followed by his guests he ran to the place of execution. There he found the three men kneeling on the ground, their eyes bound with bandages, and the executioner standing over them waving his bared sword in the air. Nicholas snatched the sword out of his hand. Then he ordered the men to be unbound. No one dared[30] to disobey him. Even the prefect fell upon his knees and humbly craved forgiveness, which was granted with some reluctance.

Meanwhile the tribunes, looking on at the scene, were filled with wonder and admiration. They, too, cast themselves at the feet of the holy man and besought his blessing. Then, having feasted their fill on the banquet that had been provided for them, the tribunes continued their journey to Phrygia.

They, too, it was decreed were to fall under the ban of a false accusation. During their absence from Constantinople, Constantine’s mind had been poisoned against them by their enemies. Immediately on their return he cast them into prison. They were tried and condemned to death as traitors. From the dungeon into which they had been cast to await the carrying out of this sentence they sent out a piteous prayer to St. Nicholas for assistance. Though he was hundreds of miles away, he heard them.

And that same night he appeared to Constantine in a dream, commanding him to release these men and to declare them innocent,—threatening him at the same time with the wrath of God if he refused. Constantine did not refuse. He took the saint’s word for their innocence, pardoned them, and set them free. Next morning he despatched them to Myra to thank Saint Nicholas in person for their happy deliverance. As a thank offering they bore him a copy of the gospels, written in letters of gold, and bound in a cover embossed with pearls and precious stones.

[31-32]

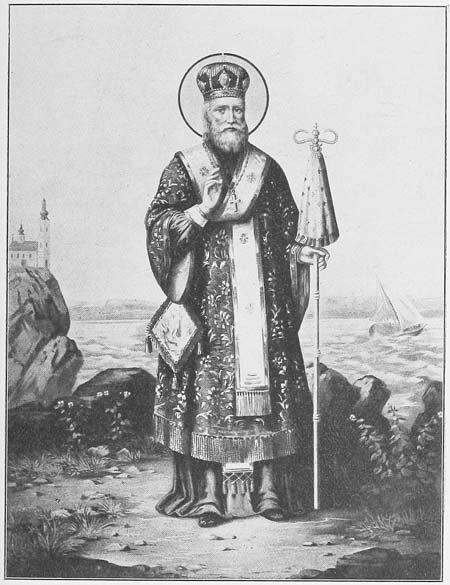

Bishop Nicholas.

From old Italian print.

[33]Nor did the saint’s miracles end with his life. Even after death he listened from his high place in heaven to the prayers of the humblest and gladly hastened to their assistance when they asked for help in the right spirit and at the right time.

Here are three legends which have been especially popular in literature and art.

A Jew of Calabria, hearing of the wonderful miracles which had been performed by Saint Nicholas, stole his image out of the parish church and bore it away to his home. There he placed it in his parlor. And when, next day, he had made ready to go out for the morning he commended all his treasures to the care of the saint, impudently threatening that his image would be soundly thrashed if he failed in his trust. No sooner was the Jew’s back turned, however, than robbers broke into the house and carried off all its treasures. Great was the Jew’s wrath when he returned. Bitter were the reproaches he hurled at the saint. Many and fierce were the whacks he bestowed upon the image.

That very night Saint Nicholas, all bruised and bleeding, appeared to the robbers, and commanded them immediately to restore what they had taken. Terrified at the vision they leaped to their feet, collected the plunder, and brought it back to the Jew’s[34] house. The Jew was so astonished at the miracle that he was easily converted to Christianity and baptized.

There was a wealthy man who, though married, had no son to inherit his estate. This man vowed that if Saint Nicholas would provide him with an heir he would present a cup of gold to the saint’s altar at Myra. Saint Nicholas heard the prayer and, through his intercession, God sent the childless man a son. At once the father ordered the cup of gold to be prepared. When it was finished, however, it seemed so beautiful in his eyes that he decided to keep it for himself and offer the saint a meaner one made of silver. When this, too, was finished, the merchant with his son set out to make the presentation. On the journey he stopped by a river to quench his thirst. Taking out the golden cup he bade the son fetch him some water. In obeying the child fell into the river and was drowned.

Weeping bitter tears of repentance the merchant appeared in the church of Saint Nicholas and there made his offering of the silver cup. But the cup would not stay where it was put. Once, twice, thrice, it fell off the altar.

While all the people stared with astonishment, behold the drowned boy appeared before them,—standing on the steps of the altar with the golden cup in his hand. Full of joy and gratitude, the father offered both the cups to the saint and bore his son home with thanksgivings to God and to His saint.

[35-36]

St. Nicholas of Bari.

Old Italian print.

[37]A certain rich merchant, himself a Christian, dwelt on the borders of a heathen country. He cultivated a special devotion to Saint Nicholas. One day his only son was taken captive by some of the wicked neighbors across the boundary line and sold into slavery. The lad finally became the property of the pagan king, and served him as his cup-bearer.

One day, while filling the royal cup at dinner he suddenly remembered that it was December 6, and the feast of Saint Nicholas. He burst into tears at the thought that his family were even then gathered around the dinner table in honor of their patron.

“Why weepest thou?” testily asked the king. “Seest thou not that thy tears fall into my cup and spoil my wine?”

And the boy answered through his sobs:

“This is the day when my parents and my kindred are met together in great joy to honor our good Saint Nicholas; and I, alas! am far away from them.”

Then the pagan blasphemer swore a good round oath and said:

“Great as is thy Saint Nicholas, he cannot save thee from my hand!”

Hardly were the words out of his mouth when a whirlwind shook the palace. A flash of lightning[38] was followed by a loud peal of thunder and lo! Saint Nicholas himself stood in the midst of the affrighted feasters. He caught the youth up by the hair of his head so suddenly that he had no time to drop the royal cup, and whirled him through the air at a prodigious speed until, a few moments later, he landed him in his home. The family were gathered in the dining room when saint and boy made their appearance,—the father being even then engaged in distributing the banquet to the poor, beseeching in return that they would offer up their prayers in behalf of his captive son.

St. Nicholas, as I have said, died in the year 342 and was buried with great honor in the cathedral at Myra.

Being the patron saint of such roving folk as sailors, merchants and travellers it was only natural that his body should have lain in perpetual peril from thievish hands. The relics of saints were highly prized because it was held that they performed miracles on behalf of the townsfolk and of the strangers who visited their shrines. Of course the relics of so great and popular a saint as Nicholas were especially coveted, and most so by the classes of whom he was the patron.

In those rude days it was believed that no saint was greatly troubled by the manner in which his body was procured. Even if it were stolen and reburied elsewhere by the robbers themselves the body worked miracles in its new abode as cheerfully as it had done in the old one. Moreover it drew trade and custom to any city in which it was enshrined and so brought wealth to the people of the entire neighborhood.

[40]In fact pilgrims from various parts of the world came in crowds to the shrine at Myra. As the fame of Saint Nicholas increased so did the value of his relics. At various times during the first six centuries after his burial attempts were made to carry off his body by force or by fraud.

None of these attempts was successful until, in the year 1084, certain merchants from the city of Bari, in southeastern Italy, landed at Myra to find that the entire countryside had been laid waste by an invasion of the Turks. All the men who could bear arms had gathered together and were now gone in pursuit of the invaders. Three monks only had been left behind to stand guard over the shrine of Saint Nicholas.

It was an easy task for the merchants of Bari to overpower these monks, break open the coffin which contained the body and bear it away with them to their own city.

Here it was received with great joy. A fine new church was built on the site of an old one which had been dedicated to Saint Stephen and which was now torn down to make room for its successor. This was to serve as a shrine for the stolen body. The new church is still standing and though it is now old it is still magnificent. In a crypt or vault under its high altar lies all that was mortal of the one-time Bishop of Myra. On the very day of the re-burial, so it is said, no less than thirty people who attended the ceremony were cured of their various ailments.

[41-42]

Heads of the Christ-child.

Selected from Raphael’s pictures.

[43]Such is the story that is generally accepted. But another story was and is told by the people of Venice. They, too, claim that they possess the body of Saint Nicholas, and insist that it was taken from Myra by Venetian merchants in the year 1100, and reburied in Venice by the citizens.

They do not accept the story told by the Bari merchants, but declare that the latter carried off from another spot the body of another saint, possibly of the same name, which they palmed off upon their fellow citizens as the body of the former Bishop of Myra.

The true body, they claim, is that which lies to-day, as it has lain for centuries, in the church of St. Nicholas on the Lido. The Lido is a bank of sand which projects, promontory fashion, out of the Grand Canal in Venice into the Adriatic Sea.

The fame of a holy man so closely connected with two great trading ports of the Middle Ages was sure to spread wider and wider among the nations of Europe. And, indeed, we find that everywhere sailors acknowledged him as their special guide and protector and sang his praises wherever they landed.

Both at Bari and at Venice the churches dedicated in his honor stand close to the mouth of the harbor. Venetian crews on their way out to sea would land at the Lido and proceed to the church of St. Nicholas,[44] there to ask for a blessing on their voyage. There also they would stop on their home-coming to give thanks for a safe return. Sailors of Bari would in the same way honor the shrine in which lay what they claimed was the true body of Saint Nicholas.

Many tales of miraculous escapes from shipwreck, due to the intercession of their patron, were related by seamen and travellers, not only at home, but at the various ports where they stopped, so that the name and fame of the good Saint Nicholas grew more resplendent every year. Churches erected in his honor abound in the fishing villages and harbors of Europe.

In England alone, before the Reformation, there were 376 churches which bore his name. The largest parish church in the entire land is that of St. Nicholas at Yarmouth, which was built in the twelfth century and retains that name to the present day. Some of the other churches were rebaptized by the Protestants.

The churches dedicated to Saint Nicholas in Catholic countries are especially dear to people who make their living out of the sea. Sailors and fishermen when ashore frequent them, and if they have just escaped from any of the perils of the deep they show gratitude to their patron by hanging up on the church walls what are known as votive pictures. These are either prints of the saint or sketches, rudely drawn by local artists, which represent the danger that the sailors[45] had run and the manner in which they had escaped. Often a figure of Saint Nicholas appears in the darkened heavens to calm the fears of the imperilled mariners.

It is fishermen and sailors also who take the chief part in the great festival in honor of Saint Nicholas that is celebrated at Bari on the fifth and sixth of December in every year.

Bari, it may be well to explain, is a very old and still a very important seaport on the eastern coast of southern Italy. It is situated on a small peninsula projecting into the Adriatic. From very early days the city has been the official seat of an archbishop and hence possesses a grand old cathedral.

Grand, however, as is this cathedral, it is eclipsed both in beauty and in popular regard by the church of Saint Nicholas which I have already mentioned as containing the bones of the saint. These repose in a sepulchre, or huge tomb, that stands in a magnificent crypt some twenty feet beneath the high altar. Water trickles out through the native rock which forms the tomb. It is collected by the priests on a sponge attached to a reed, is squeezed into bottles, and sold or given away under the name of “Manna of Saint Nicholas” as a cure for many ailments.

On the eve of Saint Nicholas’ Day, that is on the day before it (December 5th) the city of Bari is overrun by hosts of pilgrims from the neighboring[46] cities, as well as others from the furthest corners of Italy and even from Mediterranean France and Spain and Adriatic Austria. All Catholic mariners whose ships happen to be lying in port at the time are sure to join the throng.

The pilgrims carry staffs decorated with olive, palm or pine branches. From each staff depends a water bottle, which is to be filled with the manna of Saint Nicholas. Most of the pilgrims are barefoot. All are clad in the picturesque costumes in use in their native places on holiday occasions.

On entering the church the pilgrims may, if they choose, make a complete circuit of it, moving around on their knees with their foreheads pressed every now and then against the marble pavement. Often a little child leads them by means of a string or handkerchief, one end being held in the mouth of the pilgrim.

Next day, December 6th,—the actual feast of Saint Nicholas,—is celebrated by a procession of the seafaring men of Bari. Rising at daybreak they enter the church early in the morning. The priests, who have assembled to greet them, take down from the altar a wooden image of Saint Nicholas, clad in the robes of a bishop. This is handed over to the care of the paraders for the rest of the day. The priests may accompany the image only as far as the outer gate of the church. The procession, with the image in the hands of its leaders, files out into the street and, followed by the populace, visits the cathedral and other sacred or public places. Then the leaders take Saint Nicholas out to sea in a boat. Hundreds of other boats accommodate their fellow paraders, as also such of the citizens as can afford the luxury, and follow Saint Nicholas over the waves.

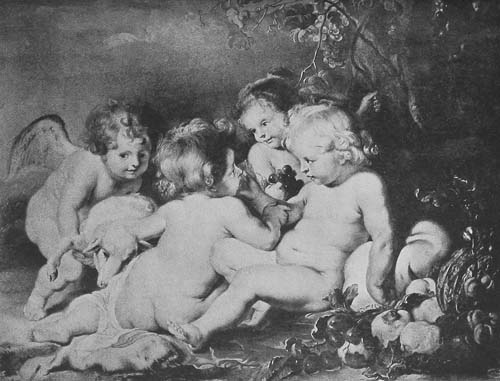

[47-48]

The Christ-child surrounded by angels.

Painting by Rubens.

[49]The shore meanwhile is lined with the bulk of the populace of Bari and the pilgrim visitors who eagerly await the return of the image at night-fall. Bonfires are then burned, rockets are shot off, everybody who possesses a candle or torch lights it and the people fall in line with the paraders to restore the sacred image to its guardians at the church.

I have now told you all that is known of the story of Saint Nicholas during his lifetime and even after his death. I think you will agree that we have not yet gone very far in identifying Santa Klaus, the modern Saint Nicholas, with the historic saint who was once Bishop of Myra.

It is true that some learned men have thought to find in the legend of the three maidens an answer to a couple of problems that bother the inquiring mind.

First they explain that the three purses of gold, which, in pictures by the old Italian masters, figure as three golden balls, and which were looked upon as the special symbol or sign of the charitable Saint Nicholas, are the origin of those three gilt balls which swing over a pawnbroker’s shop in token of that well-spring of human kindness which has earned for him the affectionate title of “uncle.”

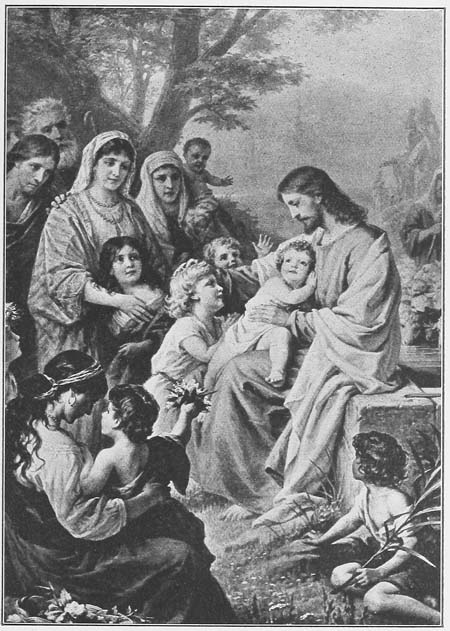

[51-52]

“Suffer little children to come unto me.”

Painting by B. Plockhorst.

[53]If you have a fine sense of humor you will see that the last sentence is sarcasm. And if you have small love for clever explanations that don’t explain, you will reject this theory of the origin of the pawnbroker’s sign and prefer to believe that it sprang from the gilt pills which adorned the shield of the great Medici family of Italy. Medici means doctors. Both the name and the shield were reminders that the family earned their first fame as physicians many years before they became the greatest princes and money changers of Europe.

But the other theory, what of that? The other theory is more to the point. It assumes that the Saint Nicholas who was Bishop of Myra is the Santa Klaus of modern Christmas, whom he pre-figured in the fact that he appeared in the night-time and secretly made valuable presents to the children of a certain household.

Here is some appearance of truth. In the first place there can be no doubt that Santa Klaus and Saint Nicholas are the same name. Indeed to this day our Christmas saint is known either as Santa Klaus or Saint Nicholas, Klaus in Dutch being “short and sweet” for Nicholaus, and, as such, the same as our Nick for Nicholas.

But, after all, there seems to be little likeness in other respects between the saint of the legend and the modern patron of the Christmas season. What connection is there between a single case of charity, performed at no particular time, with the splendid and widespread generosity of Santa Klaus, who every[54] Christmas eve loads himself down with presents for the little ones he loves, and finds means to distribute them all over the land in a single night?

As the answer is not apparent on the surface, let us turn to the other legend. We shall have to confess however that the story of the three schoolboys miraculously restored to life after they had been cut up and salted down, helps us even less than does the story of the three purses. It is simply one of a whole group of stories wherein Saint Nicholas appears as the friend and benefactor of children. In this respect only does he resemble our Santa Klaus.

In all the characteristics which modern painters and story tellers, in America, in Holland and in Germany, have bestowed upon the jolly saint of the Christmas season he differs entirely from the slender and even emaciated Nicholas, clad in the robes of a bishop, with a mitre on his head and a crozier in his hand, whom the early painters were fond of depicting.

So the legends of Saint Nicholas afford but a slight clew to the origin of Santa Klaus,—alike, indeed, in name but so unlike in all other respects.

Let us turn elsewhere. In Germany and to a certain extent in America the name Christ-Kinkle or Kriss-Kingle is looked upon as another name for Santa Klaus. But in fact history teaches us that is a far different Being, though the two have been welded into one in the popular imagination.

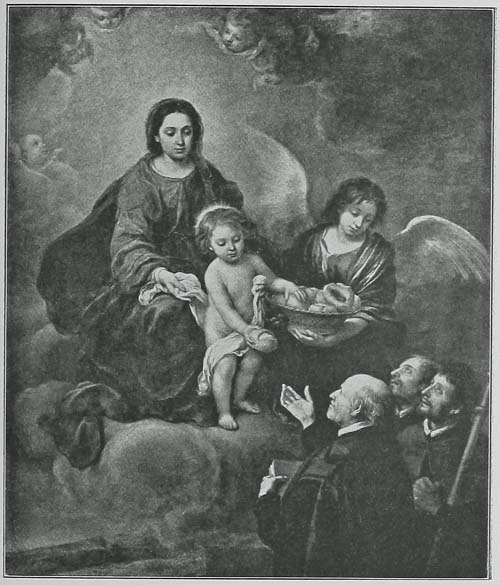

[55-56]

Christ the giver.

Painting by Murillo.

[57]

A very small knowledge of German reveals the fact that Christ-Kinkle is simply a “corruption” or mistaken pronunciation of the German word Christ-Kindlein which in English means Christ-child. Now the connection of the Christ-child with the gift-giving season is obvious enough. In the first place He is the hero of Christmas day itself. Born a human child He ever preserved a great love for young people.

“Suffer little children to come unto me,” He said, “for of such is the kingdom of Heaven.”

The old masters were fond of painting Him as a child among children. In nearly all the famous pictures which Raphael, the greatest of Italian artists, painted of the Holy Family or of the Madonna and Child, the infant Jesus is accompanied by the infant Saint John as friend and playmate.

Now I must own that at first sight it is difficult to explain how the Christ-child of the past—the Holy One whose birth is remembered and honored in that feast which we call Christmas, should gradually have been changed into the white-haired, white-bearded, merry-hearted and kindly old pagan whom we sometimes call Christ-Kinkle but more frequently Santa Klaus.

Yet at the very moment when we come face to face with this difficult problem we have reached the explanation which seemed impossible when we strove to understand the much less startling transformation of Saint Nicholas, Bishop of Myra, into Santa Klaus, patron of the Christmas season.

We remember that the Christmas festival of to-day is a gradual evolution from times that long antedated the Christian period. We remember that though it celebrates the mightiest event in the history of Christendom, it was overlaid upon heathen festivals, and many of its observances are only adaptations of pagan to Christian ceremonial.

[59-60]

Christmas presents.

Painting by F. Defregger.

[61]This was no mere accident. It was a necessary measure at a time when the new religion was forcing itself upon a deeply superstitious people. In order to reconcile fresh converts to the new faith, and to make the breaking of old ties as painless as possible, these relics of paganism were retained under modified forms, in the same way that antique columns, transferred from pagan temples, became parts of the new churches built by Christians in honor of their God and his saints.

Thus we find that when Pope Gregory sent Saint Augustine as a missionary to convert Anglo-Saxon England he directed that so far as possible the saint should accommodate the new and strange Christian rites to the heathen ones with which the natives had been familiar from their birth. For example, he advised Saint Augustine to allow his converts on certain festivals to eat and kill a great number of oxen to the glory of God the Father, as formerly they had done this in honor of the devil. All pagan gods, it should be explained, were looked upon as devils by the early Christians.

On the very Christmas after his arrival in England Saint Augustine baptized many thousands of converts and permitted their usual December celebration under the new name and with the new meaning. He forbade only the mingling together of Christians and pagans in the dances.

[62]From these early pagan-Christian ceremonies are derived many of the English holiday customs that have survived to our day.

Now get clearly into your head one very important fact. Although at the time when Augustine visited England the date of Christmas had been fixed upon as December 25 there is no biblical reason why this should be so. The gospels say nothing about the season of the year when Christ was born. On the other hand they do tell us that shepherds were then guarding their flocks in the open air. Hence many of the early fathers of the Church considered it most likely that the Nativity took place either in the late summer or the early fall. The point was of no great moment to them, as the early Church made more fuss over the death day of a great or holy person than over his birthday. The birthday is only the day when man is born into mortality, the death day chronicles his birth into immortality.

The important fact then which I have asked you to get clearly into your head is that the fixing of the date as December 25th was a compromise with paganism.

For countless centuries before the Christian era pagan Europe, through all its various tribes and peoples, had been accustomed to celebrate its chief festival at the time of the winter solstice, the turning point when winter, having reached its apogee, has also reached the point when it must begin to decline again towards spring.

[63-64]

Saturn, the God of Time.

Painting by Raphael.

[65]The last sentence requires further explanation. I shall try to put it into words as simple as possible.

You must be aware of the fact that the shortest day in the year is December 21st. Therefore that is the day when winter reaches its height.

It was on or about December 21st that the ancient Greeks celebrated what are known to us as the Bacchanalia or festivities in honor of Bacchus,[1] the god of wine. In these festivities the people gave themselves up to songs, dances and other revels which frequently passed the limits of decency and order.

In ancient Rome the Saturnalia, or festivals in honor of Saturn, the god of time, began on December 17th and continued for seven days. These also often ended in riot and disorder. Hence the words Bacchanalia and Saturnalia acquired an evil reputation in later times.

We are most interested in the festivals of the ancient Teutonic (or German) tribes because they are most closely linked with Christmas as we ourselves celebrate it.

The pagan feast of the Twelve Nights was religiously kept by them from December 25th to January[66] 6th, the latter day being known, as it is still known to their descendants, as Twelfth Night. The Teutonic mind personified the active forces of nature,—that is to say it pictured them as living beings.

The conflicts between these forces were represented as battles between gods and giants.

Winter, for example, was the Ice-giant,—cruel, boisterous, unruly, the destroyer of life, the enemy alike of gods and men. Riding on his steed, the all-stiffening North Wind, he built up for himself great castles of ice. Darkness and death followed in his wake.

But the Sun-god and the South Wind, symbols of light and life, gave battle to the Ice-giant. At last Thor, the god of the Thunderstorm, riding on the wings of the air, hurled his thunderbolt at the winter castle, and demolished it. Then Freija, the goddess of fruits and flowers, resumed her former sway. All of which is only a poetical way of saying that after the Ice-giant had conquered in winter he was in his turn overthrown by the Sun-god in spring.

Now the twenty-first day of December, the depth of winter, marked the period when the Ice-giant was in the full flush of his triumph and also marked the beginning of his overthrow. It was the turning point in the conflict of natural forces. The Sun-god having reached the goal of the winter solstice, now wheeled around his fiery steeds and became the sure[67] herald of the coming victory of light and life over darkness and death of spring over winter.

A thousand indications point to the fact that Christmas has incorporated into itself all these festivals, Greek, Roman and German, and given them a new meaning. The wild revels of the Bacchanalia, the Saturnalia and the Twelve Nights survive in a milder form in the merriment and jollity which mark the season of Christmas to-day.

Christmas gifts themselves remind us of the presents that were exchanged in Rome during the Saturnalia. In Rome, it might be added, the presents usually took the form of wax tapers and dolls,—the latter being in their turn a survival of the human sacrifices once offered to Saturn.

It is a queer thought that in our Christmas presents we are preserving under another form one of the most savage customs of our barbarian ancestors!

The shouts of “Bona Saturnalia!” which the Roman people exchanged among themselves are the precursors of our “Merry Christmas!” The decorations and illuminations of our Christian churches recall the temples of Saturn, radiant with burning tapers and resplendent with garlands. The masks and mummeries which still survive here and there, even in the America of to-day, and which were especially prominent in the Middle Ages, were prominent also in the Saturnalian revels.

[68]And a large number of the legends, superstitions and ceremonials which have crystallized around the Christian festival in Europe and America are more or less distorted reminiscences of the legends, superstitions and ceremonials of the Twelve Nights of ancient Germany.

And now you may be tempted to ask, “What bearing has all this stuff about the pagan festivals upon the question of the identity of our old friend Santa Klaus?”

I am coming to that. In every one of these festivals the leading figure was an old man, with a lot of white beard and white hair rimming his face.

In the Bacchanalia the representative god was not the young Bacchus, but the aged, cheery and decidedly disreputable Silenus, the chief of the Satyrs and the god of drunkards.

In the Saturnalia it was Saturn, a dignified and venerable old gentleman—the god of Time.

In the Germanic feasts it was Thor, a person of patriarchal aspect, and a warrior to boot.

Now, although the central figure of the Christian festival was the child-god—the Christ-Kindlein—none the less the influence of long pagan antecedents was too strong within the breast of the newly Christianized world to be readily dismissed. The tradition of hoary age as the true representative of the holiday[70] period, a tradition, it will be seen, in which all pagan nations agreed, still remained smouldering under the ashes of the past. It burst into flame again when the past was too far back to be looked upon with dislike or disquietude by the Church. No longer did there seem to be any danger of a relapse into the religious errors of that past.

At first the more dignified representative was chosen as more in keeping with a solemn season. Saturn was preferred to Silenus, and was almost unconsciously rebaptized as Saint Nicholas, the latter being the greatest saint whose festival was celebrated in December and the one who in other respects was most nearly in accord with the dim traditions of Saturn as the hero of the Saturnalia.

If you look at the pictures printed in this book you will see that in face and figure the Saint Nicholas of the early painters was not unlike the ancient idea of Saturn.

And it was many, many years before Saint Nicholas had ousted the Christ-child from the first place in the Christmas festivities. Indeed, as we shall see, he often accompanied his Master on His Christmas rounds. It may be added that he still does so in certain country places in Europe where the modern spirit has been least felt.

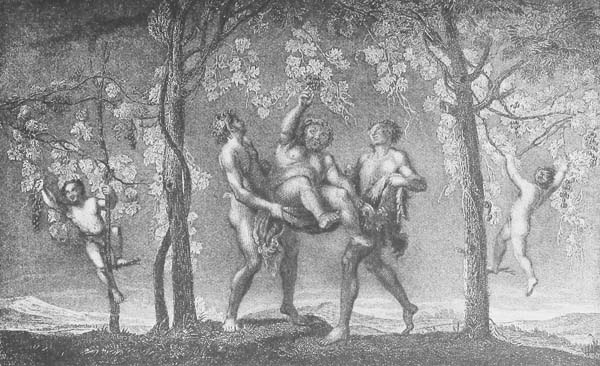

[71]

Silenus and Fauns.

Painting by Annibale Caracci.

In course of time, as the idea of worldly merriment at the Christmas season prevailed over that of prayer and thanksgiving, the name Saint Nicholas gradually merged into the affectionate diminutive of Santa Klaus. Under the new name the old saint lost all his austerity. He became ruddier, jollier, more rubicund in aspect, while the Christ-Kindlein faded more and more into the background, until at last the very name of the latter, under the slightly different form of Kris-Kinkle, was transferred to his successor.

And now compare the pictures of Santa Klaus which are scattered through this book with that of Silenus. Is it not evident that the one is a revival of the other, changed, indeed, in certain traits of character, sobered up, washed and purified, clad in warm garments that are more suited to the wintry season which he has made his own, but still the god of good fellows,—the representative of good health, good humor and good cheer?

Extremes meet once more. The most modern hero of the season of merriment is a return to the most ancient. The Santa Klaus of to-day is the Silenus of an unknown antiquity.

Let us learn a little more about Silenus. He was the tutor of Bacchus and seems to have had so much respect for his pupil that his life after the invention of wine was one long spree. It was a merry and good-natured spree, however. Silenus never became maudlin or quarrelsome in his cups. He was the most[72] jovial of tipplers. His outlook upon life was as rosy as his nose. A cheery laugh beamed over his large fat face, the light of humor twinkled in his beady eyes, his rotund stomach spoke of good cheer, his smile beamed assurance of an unruffled disposition.

Among all the brute creation he chose an ass, that caricature of the horse, as his favorite charger. He always appeared with a troupe of laughing fauns and satyrs around him, and his advent was everywhere the signal for quips and cranks and wreathèd smiles.

Now Saint Nicholas, also, in former times used to ride abroad on an ass, and still continues to do so in certain portions of Europe. In fact, as already noted, all the genial traits of Silenus, save only that of drunkenness, are reproduced in Santa Klaus,—the jolly pagan who is to-day the personification of Christmas.

But though a modernized pagan god holds this important position in our festival, everything that could be offensive in the old pagan way of celebrating it has been abolished.

[73-74]

Santa Claus and his young friends.

From Thomas Nast’s “Christmas Drawings for the Human Race.”

Copyright 1899 by Harper and Brothers.

[75]It was not always so. The Church which so wisely sought to retain the old heathen forms, found it often very hard, and sometimes impossible, to subdue the heathen spirit. In spite of the protests of priests and the anathemas of popes, in spite of the condemnation of all wise and good men, Christians in the early days frequently reproduced all the worst follies and vices of the Bacchanalia and the Saturnalia. Even the clergy were for a period whirled into the vortex. A special celebration, called the Feast of Fools, was instituted in their behalf with a view, said the doctors of the Church, that “the folly which is natural to and born with us might exhale at least once a year.” The intention was excellent. But in practice the liberty so accorded speedily degenerated into license.

Early in the history of the Church excesses were so great that a council of bishops held at Auxerre was moved to inquire into the matter. Gerson, the most noted theologian of the day, made an immense sensation by declaring that “if all the devils in hell had put their heads together to devise a feast that should utterly scandalize Christianity, they could not have improved upon this one.”

If even among the clergy heathen traditions survived so strenuously, what wonder that they survived among the laity? The wild revels, indeed, of the Christmas period in olden times almost stagger belief. No amount of drunkenness, no blasphemy, no obscenity was frowned upon. License was carried to the utmost limits of licentiousness. Even in the seventeenth century, when the revels had been slightly toned down, Master William Prynne discovered in them those vestiges of paganism which are apparent enough to the historian of to-day.

“If we compare,” he says in his Histrio-Mastix,[76] “our Bacchanalian Christmas and New Year’s tides with these Saturnalia and feasts of Janus, we shall find such near affinity between them, both in regard of time,—they being both in the end of December and the first of January—and in their manner of solemnizing—both being spent in revelling, epicurism, wantonness, idleness, dancing, drinking, stage-plays, masques and carnal pomp and jollity—that we must conclude the one to be but the ape, or issue, of the other.”

The very excesses of the Christmas period proved their own eventual cure. In England the Puritans revolted so bitterly that they for a period put an end to Christmas altogether. In Europe the revolution was more gradual. But everywhere a change of manners and of morals has purified the festival over which Santa Klaus presides, and Santa Klaus himself, even if we look upon him as a revival of the pagan Silenus, is a Silenus freed from all the offensive features of paganism, a Silenus who with his new baptismal name has taken on a new character.

[77-78]

Carrying home the Christmas dinner.

Drawing by John Leech.

[79]It must be remembered, however, that Santa Klaus does not rule all over the Christian world. There is even a wide difference between our Santa Klaus and the Saint Nicholas of Southern France and Germany. The latter, grave, sedate, severe, preserves more of the Saturn than the Silenus type. He is Saturn christianized and dignified with episcopal robes. He distributes gifts like our Santa Klaus, but in addition to gifts for good little boys and girls, he carries a birch-rod for bad ones. In the more primitive sections, such as certain parts of Lorraine, the Tyrol, Bohemia and so on, he is attended by an evil spirit called Ruprecht who looks after bad boys and girls.

It is also frequently the custom on Christmas Day for a couple or more of maskers to dress themselves up as Saint Nicholas and Ruprecht, and other attendants, such as the Christ-child or St. Peter or who not,—these additional characters varying with the locality. They go from house to house rewarding the good children and punishing the bad.

More of this, however, in a future chapter.

Forever memorable as an illustration of the manners of the French court in the fourteenth century stands a terrible accident that happened in Paris on the Christmas eve of 1393. All through the Christmas ceremonies of the preceding week riot had run unchecked. The wildest spirits of the French court had been given a free rein. One mad prank had followed another, until it might seem that imagination had been exhausted in the effort at inventing new follies.

But this would have been reckoning without Sir Hugonin de Guisay. Sir Hugonin was known as the maddest of the mad. The reckless and the ungodly loved and admired him as much as the sober and the godly hated and despised him. From his height as a nobleman of the French court he looked down with contempt on “the common people,”—tradesmen, mechanics, laborers and servants. He found a cruel pleasure in accosting harmless folk of this sort in the public streets, pricking them with his spurs, lashing them with his whip, and ordering them to creep on their hands and feet in the gutters.

[81-82]

The Feast of the Passover.

Painting by Diedrich Bouts.

[83]“Bark, dog, bark!” he would cry as he cracked his whip in the air.

To please him the victims had to bow-wow and growl like curs ere this polite and pleasant gentleman would allow them to rise from their degraded position.

On this particular Christmas Eve Sir Hugonin had a proposal to make. He suggested that, in order to continue the festivities, a mock marriage should be celebrated between a gentleman and a lady of the court. The proposal was accepted with shouts of joy. A young couple were chosen to stand up before a pretended priest, and to go through the form of the wedding service.

Just as the ceremony was nearing its end Sir Hugonin asked the king and four of his courtiers,—madcaps all of them and all of them members of the proudest families in France,—to withdraw with him for a moment. He had a fresh proposal to make. It happened that at this time all Paris had gone wild over the dancing bears brought into the capital by strolling performers. Hugonin’s plan was that he and the king, and the four courtiers, should disguise themselves as dancing bears. A pot of tar and a quantity of tow were ready at hand to transform them into fair imitations of the bears in the players’ booths. Then the five courtiers were to be bound[84] together with a silk rope. The king himself would lead them into the hall.

“Excellent!” cried the king and all the courtiers, save only Sir Evan de Foix.

Sir Evan seems to have been the one man of the party who had preserved a glimmer of common sense. He pointed out that they were about to rush into a room full of lights. Being all bound together, no one could say what disaster might not befall.

“Sire,” he pleaded, “it is certain that if one of us catches fire, the whole number, including your Majesty, will be as so many roast chestnuts.”

Then up spoke the reckless Sir Hugonin. “Who is to set us on fire?” he asked. “Where is there the traitor that would not be careful when the safety of the king is at stake?”

Sir Evan’s fears could not be set at rest. But when he found that the counsels of Sir Hugonin were bound to prevail he suggested that at least all due precautions should be taken.

“Let His Majesty be prevailed upon at least to give orders that nobody bearing a torch shall approach us.”

“That shall be done at once,” said Charles. Instantly sending for the chief officer in charge of the hall he gave instructions that all the torchbearers should be collected together on one side of the room, and that under no pretence should any of them approach[85] a party of savage men who were about to enter and perform a dance. These orders having been given the dancers entered.

They were greeted with a roar of laughter and cheers. The mimic bears followed their leader around the hall saluting the ladies as they passed them, and leaping and dancing for the amusement of the crowd.

“Who are they?” cried the spectators, eager to penetrate the disguise.

Now just at this moment it unfortunately happened that the Duke of Orleans made his appearance at the doors of the hall. He knew nothing of what had been going on behind the scenes. He was attended by six torchbearers, who in obedience to orders, should not have been admitted into the dance-hall. But the Duke of Orleans was the king’s brother. It was hard to dictate to the first prince of the blood. He could scarcely be included in any general order. So he was allowed to pass in with his companions.

“Who are they?” he exclaimed, taking up the cry that was ringing around the hall. “Well, we shall soon find out.”

Snatching a brand from one of his torchbearers he peered into the faces of the dancers, seeking to identify them. Coming at last to Sir Evan de Foix, he shouted out his name, and caught him by the arm. Sir Evan tried to shake himself free. But the Duke would not loosen his hold. Just then some one jostled[86] his elbows and the torch he held in his hand was brought into sudden contact with the tarry tow that did duty as a bearskin. In one moment Sir Evan was blazing from head to foot. In another moment the whole group of knights were aflame. Their frantic struggles served only to draw them more closely together within the silken rope that bound them.

Luckily for the king he had detached himself from the group, having stopped on his rounds to talk to the Duchess de Berri. When first the alarm was given he would have rushed to help his companions, but the duchess, guessing it was the king under this disguise, threw her arms around him and forcibly detained him.

“Sire,” she said, “do you not see that your companions are burning to death, and that nothing could save you if you went near them in that dress?”

Meanwhile, one of the maskers had wrenched himself free from his companions. This was the young Lord of Nantouillet, famous for strength, agility and presence of mind, possessed, moreover, of a powerful jaw and a splendid set of teeth. He bit through the silken rope that enmeshed him, wrenched it off, and then rushed through the hall and flung himself, like a blazing comet, through a window that opened into the yard below. Luckily he had remembered that underneath the window stood a cistern full of water. Plunging headlong into this impromptu bathtub he emerged, black, burnt and sizzling, but saved.

[87-88]

The Adoration of the Lamb.

Painting by Hubert and Jan Van Eyck.

[89]As for his companions, they were now whirling hither and thither through a horrified mob of spectators, who trampled over each other in their eagerness to escape contact with the blaze. Shrieking, praying, cursing, the doomed four fought with the flames and with one another. Women fainted; men who had never faltered in the fiercest battle sickened at the frightful spectacle. Eager as they would have been to assist their friends, the men knew only too well that no human arm could offer assistance.

All Paris had been aroused by the tumult and now crowded around the palace gates. At last the flames burned out. The four maskers lay, a charred and writhing heap, upon the floor of the dance-hall. One was a mere cinder. Another survived until daybreak. Still another died at noon the next day. The fourth lived on through three days of agony. This was Sir Hugonin himself.

Small pity did he get from the mechanics and tradesmen of Paris!

“Bark, dog, bark!” was the cry with which they greeted the charred and mangled corpse when it was borne through the streets to its final resting place in the cemetery.

We have seen that most of the ceremonies that have attended or still attend the season of Christmas may be traced back to a period long before the birth of Christ.

The Christmas tree is no exception to this rule. It is pagan, not Christian in its origin, though it has been adapted to Christian uses. It came down to us from the pagan Teutons and Scandinavians, and on the way it was Christianized in Germany and Holland, in Sweden, Norway and Denmark, long before it had been made holy in the same manner among the English-speaking peoples.

Myth and history have both busied themselves with guesses at its origin. Let us begin with myth.

A very old legend makes Saint Winfred the inventor of the Christmas tree. Winfred (please note that this is the masculine form of which Winifred is the feminine) was one of the early missionaries to Norway who helped to wean the ancient Scandinavians from their pagan beliefs and practices.

[91]He found that their priests, the Druids, had taught them to worship trees as if they were living gods. So he set himself the task of showing to his Christian converts that the objects of their former worship were not gods but trees,—trees and nothing more. On Christmas eve, therefore, he hewed down a mighty oak in presence of a great crowd of men, women and children.

A miracle indeed followed. But it was a Christian miracle, and as such was all the more convincing to these simple people that their old-time faiths had been misplaced.

This is how the miracle is described by an ancient historian:

“As the bright blade circled around Winfred’s head, and the flakes of wood flew from the deepening gash in the body of the tree, a whirling wind passed over the forest. It gripped the oak from its foundations. Backward it fell like a tower, groaning as it split asunder in four pieces. But just behind it and unharmed by the ruin, stood a young fir tree pointing a green spire towards the stars.

“Winfred let the axe drop and turned to speak to the people.

“‘This little tree, a young child of the forest, shall be your holy tree to-night. It is the wood of peace, for your houses are built of the fir. It is a sign of[92] endless life, for its leaves are ever green. See how it points upward to heaven. Let this be called the tree of the Christ-child; gather about it, not in the wildwood, but in your own homes; there it will shelter no deeds of blood, but loving gifts and rites of kindness.’”

There is another old legend that is told by the people around Strassburg, a famous old city on the Rhine. Half way between this city and the neighboring town of Drusenheim there are still to be seen the ruins of an old castle. It probably dates back to the seventh century. Its chief feature is a massive gate. Deep sunk in the stone arch above this gate, and as clearly and sharply defined as if it had been carved only yesterday, is the impress of a small and delicate hand. And this is the story that is told to account for the presence of the hand.

One of the early lords of the castle was Count Otto von Gorgas, a handsome and dashing youth, whose great delight was hunting big game. So devoted, indeed, was he to the shooting of deer and the spearing of wild boars that love could find no entrance into his heart. In vain did the fairest maidens in the land sigh for a soft speech or a tender glance from this wild huntsman. Mothers on both banks of the river Rhine had abandoned in despair all hope of securing him as a match for their daughters, while[93] the daughters themselves had spitefully given him the name of Stony-heart, by which he had become generally known throughout the country side.

But Count Otto only laughed at the anger of the ladies, and continued to kill with his own hand such large quantities of game that new servants would not come into his employ, unless he had first agreed to give them venison or wild boar steaks not oftener than four days in the week.

One Christmas Eve Count Otto ordered that a battue or monster hunt should take place in the forest surrounding his castle. So exciting was the sport that he was led deep into the thickets and at night-fall found himself separated from all his friends and followers. He reined up beside a far-away spring, clear and deep, known to the country people as the Fairy’s Well. His hands being stained with the blood of the wild animals he had slain, he dismounted from his horse to wash them in the spring.

Though the weather was cold and a white frost covered the dead leaves, Count Otto found to his surprise that the water of the well was warm and pleasant. A delightful feeling ran through his veins. Plunging his arms deeper into the well, he fancied that he felt his right hand grasped by another hand softer and smaller than his own, which gently drew from his finger a gold ring that he was accustomed to wear.

[94]Sure enough, when he pulled his hand out of the water the ring was gone!

Though annoyed by his loss, the count decided that the ring had accidentally slipped from his finger. There was no opportunity for any further search that day, for the well was very deep and the sun had already set.

So Otto remounted his horse and rode back to the castle, resolving that in the morning he would have the Fairy’s Well emptied out by his servants. Little doubt had he but that the ring would easily be found at the bottom.

As a rule Count Otto was a good sleeper. That night, however, he tried in vain to close his eyes. Lying restlessly awake he listened feverishly to the hoarse baying of the watch-dog in the court-yard until near midnight. Suddenly he raised himself on his elbows. What was that unusual noise he heard outside?

He strained his ears. Distinctly he again heard the creaking of the drawbridge as it was being lowered. A few minutes later there followed sounds as of the pattering of many feet up the stone stairs and into the chamber next to his own. Then a wild strain of music came floating on the air, shooting a sweet mysterious thrill even into his “stony” heart.

Rising softly from his bed, Otto hastily dressed himself. A little bell sounded. His chamber door was suddenly flung open. He accepted what seemed[95] like a wordless invitation. Crossing the threshold into the next room, he found himself in the midst of an assemblage of rather small but very lovely looking strangers of both sexes, who laughed, chatted, danced and sang without seeming in the least to notice him.

In the middle of the room stood a splendid Christmas tree from which a great number of many-colored lamps shed a flood of light throughout the apartment.

Now this was the first Christmas tree that had ever been seen in those parts, or indeed by any mortal folk in any portion of the world. And it was a Christmas tree of a sort that never again has been seen by any mortal folk in any portion of the world.

For surely never again has a Christmas tree borne such fruits. Instead of toys and candies the branches were hung with diamond stars and crosses, pearl necklaces, aigrettes of rubies and sapphires, baldricks embroidered with Oriental pearls, and daggers mounted in gold and studded with the rarest gems.

Lost in wonder at a scene he could not understand, the count gazed without the power of uttering a single word. There was a sudden movement at the end of the hall. The company stopped dancing and fell back to make way for a newcomer. Then in the bright rays of the Christmas lights, a dazzling vision stood in front of Count Otto.

[96]It was a princess of astonishing beauty. Though only a girl in size, she was a woman in age. Though small, her body was exquisitely formed. There she stood, magnificently dressed as for a ball. A diadem sparkled amid her raven black locks, rich point lace only half veiled her snowy bosom, and her dress of rose-colored silk sat close to her slender figure, falling in folds just so low as to reveal the neatest feet and ankles in the world, while her sleeves were short enough to display beautiful arms of dazzling whiteness.

The charming stranger showed no awkward timidity. On the contrary, after a short pause she walked straight up to the count, caught him by both hands, and said, in the sweetest of voices:

“Dear Otto, I am come to return your call.”

At the same time she raised her right hand to his lips. Forgetting all his old coldness towards the female sex he gallantly kissed it without making any other reply. Indeed, he felt fascinated, spellbound. He gladly let the beautiful stranger draw him to a couch where she sat herself down besides him. Her lips met his and before he could think about kissing them, he had done so.

“My dear friend,” whispered the lady into his ear, “I am the fairy Ernestine. I have brought you a Christmas present. That which you lost and hardly hoped to find again, see! I fetch it back to you.”

[97]And, drawing from her bosom a little casket set with diamonds, she placed it in the hands of the count. He eagerly opened it. Not entirely unexpectedly (for had not her words forewarned him?) he found within it the ring that he had lost in the forest well.

Carried away by a feeling as strange as it was irresistible, Count Otto pressed the casket and then the lovely Ernestine to his breast.

“Delightful,” murmured the maiden, who as you may see, was not so coy as are many maidens of the everyday world.

In brief the two had fallen in love with each other at first sight. Before they parted for the night, Otto had won the fairy’s consent to become his wife.

One thing only she demanded of him. He must never make use of the word “death” in her presence. Fairies are immortal; she did not wish to be reminded that she was bound to a mortal husband.

It was easy enough for him to make this promise, and no doubt he thought it would be easy to keep it. Next day Count Otto von Gorgas and Ernestine, the Queen of the Fairies, were married with great pomp and ceremony. They lived happily together for some years in the grand old castle.

One day it chanced that the young couple were to assist at a great tourney in the neighborhood. The Lady Ernestine’s horse stood in waiting for her at the castle gate. Being greatly occupied in adjusting a[98] new headdress which her milliner had just brought home, she kept her husband waiting until his patience was worn out.

“Fair dame,” he pettishly exclaimed when she at last appeared in the great hall where for half an hour he had been striding up and down in his uncomfortable armor, “you are so long making ready, you would be a good messenger to send for Death.”

Scarcely had he uttered the fatal word than with a wild scream the lady disappeared. She left no trace behind her, except the print of her little hand above the castle gate. Every Christmas eve, however, she returns and flits about the ruins with loud lamentations, crying at intervals:

“Death! Death! Death!”

As to Count Otto he went the way of all flesh and was gathered to his fathers not long after he had lost his spouse. But every Christmas Eve, while his life lasted, he would set up a lighted tree in the hall where he had first met the lady Ernestine,—in the vain hope of wooing her back to his arms. And this, it is said in Strasburg and its neighborhood, was the origin of the Christmas tree.[2]

The stories I have just told you are pretty enough and may amuse an idle half hour. But we must now pass from the region of myth into that of history and science.

My sexagenarian readers will not need to be introduced to the science called comparative mythology. But for the sake of the six year olds it may be well to explain, as simply as I can in a few words, that comparative mythology is a branch of human knowledge which compares the myths and legends of one age and one people with the myths and legends of another age and another people, the object being to show how the later myths descend from the earlier ones, or how all the myths go back to some parent germ in the far-away past.

By the aid, then, of the science of comparative mythology let us seek to study the historical growth of the idea that is now embodied in the Christmas tree. Here, indeed, we are in a whirl of problems. Comparative mythology is one of the most interesting and also one of the most difficult of sciences. In[100] the present case it must take account of the fact that we English-speaking peoples of the present day, and especially we Americans, are a hodge-podge mixture of many races and many religions. Somewhere in our brains we preserve dim memories of a thousand conflicting myths of the past which without knowing it we have inherited from our ancestors. In other parts of our brain we retain the facts and fictions which have been told to us by our elders, or which we have learned from books.

Now in all times and in all countries we find records of the worship, at some former period, of a tree as a divinity,—in other words as a god.

Greatest and most famous of all these sacred trees was a quite imaginary one which the Scandinavians called the ash-tree Yggdrasil. Nobody had ever seen it, but everybody among these imaginative people believed in its existence.

It was supposed to be a tree so big that you could not possibly picture it to your fancy, which encompassed the entire universe of sun and moon and stars and earth. And it had three roots, one in heaven, one in hell and one on earth.

The serpent who gnaws the roots of Yggdrasil was of course a heathen idea. Yet you cannot help seeing in him some likeness to the serpent of Genesis who is held to be a symbol of Satan, or the devil. Like Satan he seeks the destruction of the universe. When the roots of Yggdrasil are eaten through the tree will fall over and the end of all things will have arrived.

[101-102]

Luther and the Christmas tree.

[103]Now among the Anglo-Saxons or early inhabitants of England, who were in part descended from the Scandinavians, Yggdrasil survived in the Yule log, which they used to burn on Christmas Eve, as it is still burned in many an English home to-day.

And this is how the pagan tree was transformed into the Christian Yule log:—

The missionaries to the Anglo-Saxons denounced the Yggdrasil superstition. They made their converts hack to pieces all carved figures representing the idolatrous symbol, and then cast the pieces into the flames as a token that the Christ-child had destroyed heathenism.

Among the Germans and the Norsemen, however, the sanctity of the Yggdrasil myth could not be destroyed. It had to be transformed, and transferred to Christian uses by identifying it with some Christian or Jewish symbol like the tree of life in Genesis or the cross of Christ in the New Testament.

Compare the great tree Yggdrasil and its three roots with the description which a certain writer of the early middle ages, called Alcima, gives of the Tree of Life.

“It’s position,” says Alcima, “is such that the upper[104] portion touches the earth, the root reaches to hell, and the branches extend to all parts of the earth.”

Evidently Alcima had been influenced by Scandinavian legend as well as by biblical lore. Of course you will understand that he was speaking not of the actual cross, but of the cross as a symbol of Christianity.

Let us extend our researches a little further into the region of comparative mythology.

You will find Adam and Eve commemorated in old calendars under date of December 24th. This is the eve of Christmas. The symbol of our first parents is the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Christmas itself is the day of Christ, whose symbol is the tree of life or the cross. It is easy to see that when the minds of men were escaping from paganism into Christianity the tree of the old mythology grew to be associated with the birthday of Christ and thus with the cross. So the lights of the Chanuckah Festival of the Hebrews were borrowed to adorn the sacred tree, and the seven-branched candlestick, as a figure of that tree, was even introduced into the churches.

The representation—so common among the early painters and especially the painters of Italy—of the serpent squatting at the foot of the cross had of course its Christian meaning, but its adoption into Christian[105] art was in great degree influenced by the fact that the cross had become popularly identified with the serpent tree of the old pagan myth.

Scandinavia was not the only place that had its sacred tree. Egypt, for instance, had one in the palm, which puts forth a shoot every month. A spray of this tree with twelve shoots on it was used in ancient Egypt at the time of the winter solstice as a symbol of the twelvemonth or completed year.

From Egypt the custom reached Rome, where it was added to the other ceremonies of the Saturnalia. But as palm trees do not grow in Italy other trees were used in its stead. A small fir tree, or the crest of a large one was found to be the most suitable, because it is shaped like a cone or a pyramid. This was decorated with twelve burning tapers lit in honor of the god of Time. At the very tip of the pyramid blazed the representation of a radiant sun placed there in honor of Apollo, the sun-god, to whom the three last days of December were dedicated. These days were called the sigillaria, or seal-days, because presents were then made of impressions stamped on wax.

In further honor of Apollo, who was a shepherd in his youth, images of sheep were shown pasturing under the tree. Apollo himself sometimes took charge of the herd, or taught the shepherds the use of the musical pipe. All these customs were skilfully adapted by the priests of the early Church to Christian[106] uses. Shepherd and sheep were retained as symbols of Christ and his flock. As you know, our Lord is frequently alluded to as the good shepherd and is so represented in religious paintings. The sigillaria of the old Romans were also turned to a new use, the wax being now stamped with figures of saints and other holy persons.