SKEGBY VILLAGE.

Frontispiece.] [See p. vi.

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Elizabeth Hooton, by Emily Manners

Title: Elizabeth Hooton

First Quaker woman preacher (1600-1672)

Authors: Emily Manners

Norman Penney

Release Date: February 28, 2023 [eBook #70165]

Language: English

Produced by: Fay Dunn and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

SKEGBY VILLAGE.

Frontispiece.] [See p. vi.

FIRST QUAKER WOMAN PREACHER

(1600-1672)

BY

EMILY MANNERS

WITH NOTES, ETC., BY

NORMAN PENNEY, F.S.A., F.R.Hist.S.

London:

HEADLEY BROTHERS, Bishopsgate, E.C.

American Agents:

DAVID S. TABER, 144 East 20th Street, New York.

VINCENT D. NICHOLSON, Earlham College, Richmond, Ind.

GRACE W. BLAIR, Media, Pa.

1914.

This volume is issued

as Supplement 12 to

THE JOURNAL OF THE

FRIENDS HISTORICAL SOCIETY

The Notes collected by the late Mary Radley, of Warwick, for her contemplated “Life of Elizabeth Hooton” seem to indicate a work of much wider scope than I have attempted. Since her research commenced many notable works on the rise of the Society of Friends have been issued which cover the investigations made by her. I have therefore endeavoured to bring together in a collected form the scattered fragments of Elizabeth Hooton’s history, which are to be found up and down, together with many of her letters, or extracts from them, which I believe have never before been published.

Many kind friends have materially assisted in the work, and I desire gratefully to acknowledge their services here: to Norman Penney, F.S.A., and the staff at Devonshire House, London, without whose invaluable help I could not have compiled the little history; to Mrs. Dodsley of Skegby Hall, for her search of the Skegby Manor Rolls, and the Church Registers, also for the illustration of the village which she kindly lent for reproduction; to A. S. Buxton, Esq., for various notes connected with the history of the district and for his unfailing help and interest in the work; to Mrs. Mary G. Swift, of Millbrook, New York, for notes of various authorities; to my cousin, Ethel Barringer, for her sketch of Lincoln Castle Gateway; and to my daughter, Rachel L. Manners, for her photograph of Beckingham Church and her suggestions and advice generally.

For New England History I have drawn largely on Dr. Rufus M. Jones’s recent book, The Quakers in the American Colonies, and for the account of the Quaker persecution in that country my authority has been New England Judged, 1703 edition.

Emily Manners.

Edenbank,

Mansfield.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I.— | Early Service in England | 1 |

| II.— | First Visit to New England | 18 |

| III.— | Second Visit to New England | 35 |

| IV.— | Closing Years | 53 |

| Addenda: | ||

| The Husband of Elizabeth Hooton | 77 | |

| Noah Bullock | 78 | |

| Commitment to Lincoln Castle | 78 | |

| Unketty | 79 | |

| A Young Man out of the North of England | 79 | |

| Hooton Descendants: | ||

| Samuel Hooton | 80 | |

| Elizabeth Hooton, Jr. | 82 | |

| Oliver Hooton | 83 | |

| Martha Hooton | 84 | |

| Thomas Hooton | 84 | |

| John Hooton | 85 | |

| Josiah Hooton | 86 | |

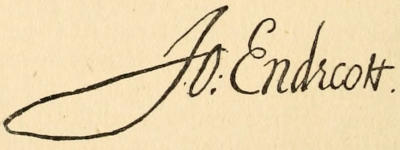

| Judge Endicott | 86 | |

| Bibliography | 87 | |

| Index | 91 |

| Skegby Village prior to 1897 | Frontispiece. |

| Photograph by the Sherwood Photographic Co., Mansfield. | |

| The tall house on the extreme left of the picture is standing to-day. It was the property of the Society of Friends until 1800, when it was sold, with the adjoining Burial Ground, now a garden, the proceeds going towards the re-building of the Meeting House at Mansfield. The house is considered by some to have been the home of Elizabeth Hooton. It is probably of seventeenth century construction. | |

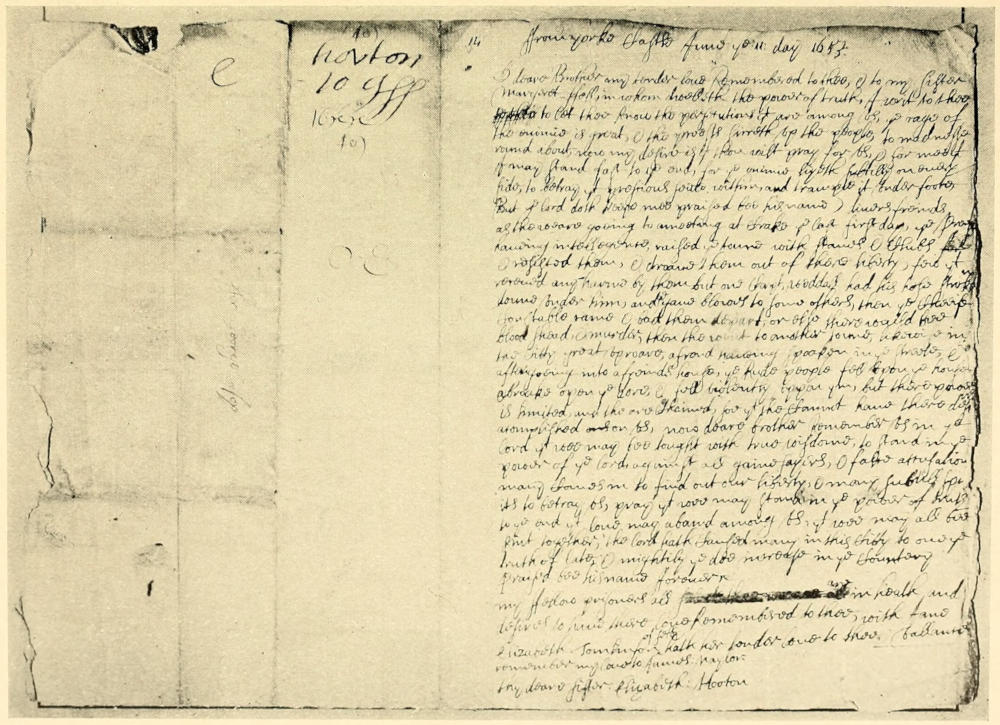

| Letter from Elizabeth Hooton to George Fox, 1653 [?] | 12 |

| Photograph by Henry G. Summerhayes. | |

| This is probably an autograph letter. It is endorsed by Fox: “e houton to gff 1655.” | |

| Beckingham Church | 14 |

| Photograph by Rachel L. Manners. | |

| The village of Beckingham is about five miles south of Newark-on-Trent. The church has a fine Norman porch and the churchyard is remarkable, being the shape of a coffin. | |

| Heading of the Tract “False Teachers,” etc. | 17 |

| Photograph by Humphrey L. Penney from the original. See p. 11. | |

| Signature of John Endicott | 34 |

| Photograph by Walter J. Hutchins from a facsimile in Annals of Salem.[vii] | |

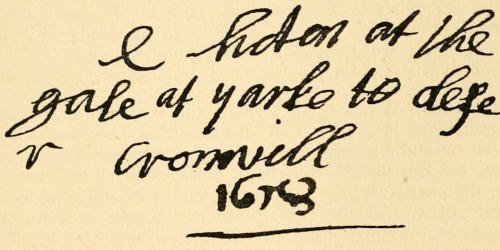

| Endorsement by George Fox | 52 |

| Photograph by W. J. Hutchins from an early copy of a letter from Elizabeth Hooton to Oliver Cromwell. See p. 10. | |

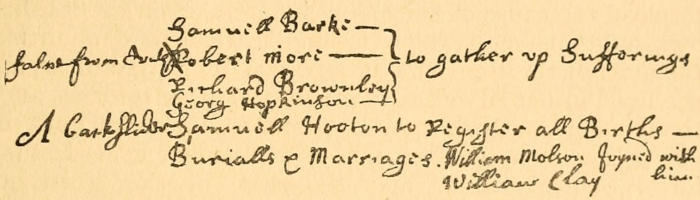

| A Portion of a Page of the Earliest Minute Book of Nottinghamshire Quarterly Meeting | 75 |

| Photograph by Sherwood Photographic Co., Mansfield, from the original. See p. 81. | |

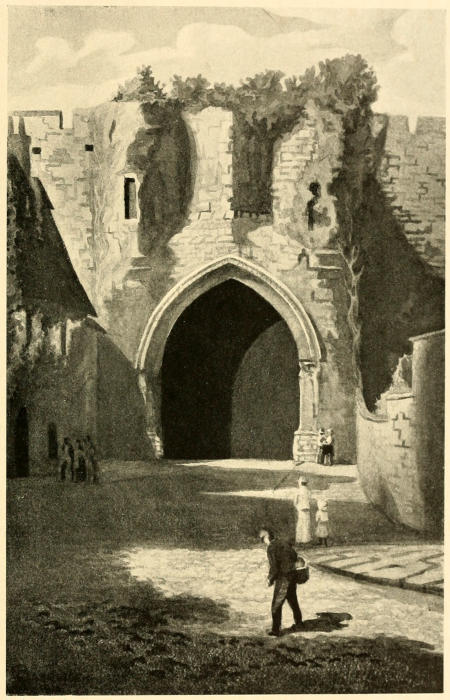

| Lincoln Castle Gateway | 78 |

| Original drawing by Ethel Barringer. | |

| This, with some fragments of the old wall, and a small, strongly-built structure, supposed to have been a dungeon and known as Cobb’s Hall, is all that remains of the old Castle. The area of the fortress is now occupied by the County Hall and a building now disused, which was the County Gaol. |

D. = The Friends’ Reference Library, at Devonshire House, 136, Bishopsgate, London, E.C.

A.R.B. MSS. = A collection of two hundred and fifty Letters of early Friends, 1654 to 1688, so named because worked over by Abram Rawlinson Barclay in 1841. In D.

Camb. Jnl. = The Journal of George Fox, Cambridge ed., 1911.

D.N.B. = Dictionary of National Biography, 68 vols., 1885-1904.

F.P.T. = “The First Publishers of Truth,” being early Records (now first printed) of the Introduction of Quakerism into the Counties of England and Wales. Edited for the Friends Historical Society by Norman Penney, with Introduction by Thomas Hodgkin, D.C.L., D.Litt., 1907.

Jnl. F.H.S. = The quarterly Journal of the Friends Historical Society, commencing 1903.

Spence MSS. = A collection of seventeenth century MSS. belonging to Robert Spence, of London. 3 vols. Deposited in D.

Swarth. MSS. = A Collection of about fourteen hundred letters, papers, etc. of the seventeenth century. In D.

Travelling on through some parts of Leicestershire and into Nottinghamshire, I met with a tender people, and a very tender woman whose name was Elizabeth Hooton.

Journal of George Fox.

Such is our introduction to the earliest convert of George Fox: one who was destined to travel far in the service of Truth and whose steadfastness, determination, fearlessness and patience are unconsciously revealed in the numerous letters which she wrote. No insignificant place was hers in the long and bitter struggle for religious liberty, and her life’s story has left an indelible mark on the history of the beginnings of the Society of Friends.

Little is known of her early life. Crœse says:[1]

In this same Fiftieth Year, Elizabeth Hooton, born and living in Nottingham, a Woman pretty far advanced in Years, was the first of her Sex among the Quakers who attempted to imitate Men and Preach, which she now (in this year) commenced.

After her Example, many of her Sex had the confidence to undertake the same Office.

This woman afterwards went with George Fox into New-England, where she wholly devoted her self to this Work; and after having suffered many Affronts from that People, went into Jamaica, and there finished her Life.

An exhaustive examination of the Nottinghamshire Parish Registers shows that the name of Hooton is not an uncommon one and appears in many different places.[2] Ollerton, however, a village situated about eight miles north of Mansfield, seems to have been the home of the family, and here we find definite traces of Elizabeth Hooton. Amongst the names of the owners of Ollerton in 1612, given by Robert Thoroton,[2] an early Nottinghamshire historian, is Robert Hooton, and in 1631 the Parish Register shows that “Robert Hooton Paterfamilias” died. On 11th May, 1628, a certain Oliver Hooton married Elizabeth Carrier; it is uncertain whether this Elizabeth was the convert to Quakerism, for from further entries in the record of Baptisms and Burials it seems probable that there were two men of the same name living in the parish at that time, and in 1629 the wife of one whose name was Elizabeth died: it is clear, however, that later on an Oliver and Elizabeth Hooton were living in Ollerton, for there on 4th May, 1633, “Samuell s. of Oliver and Elizabeth Hooton” was baptized.

Hardly a trace of the seventeenth century village of Ollerton remains except the ancient churchyard; in 1797 Throsby[3] describes Ollerton as follows:

This lordship belongs to the hon. Lumley Savile of Rufford Abbey. It contains about 1,300 acres of land enclosed. Many hops are grown hereabouts. This place has a little market on Friday, and two fairs, one on May day, and the other the 26th of September for hops; in which month there is a kind of market or hop club every Tuesday. The town contains about 600 inhabitants. The bridge here like many others was thrown down (or blown up as it is called) in the flood of 1795. The church, or rather chapel, is small and is newly built, consequently no food there for the mind of the antiquary; but at the Hop-pole, near the church, I have more than once after journeying from village to village completely tired, found comfortable refreshment for the body.

The principal inn still bears the name of “The Hop-pole”—all that remains to tell of the vanished industry,[3] but the ancient forest still surrounds the village, and the quiet stream flows gently on as in the time long past.

Between the years 1633 and 1636 Oliver and Elizabeth Hooton appear to have migrated to Skegby, a village about four miles west of Mansfield. The Parish Registers there show that in 1636 “Thomas [?] yᵉ sonne of Olive Hooton and Elizabeth” was baptized, and in the years 1639 and 1641 the names of John and Josiah appear. There is no entry of the births of her two children, Oliver and Elizabeth, so possibly they were born at Ollerton between the years 1633 and 1636, when no entries appear in those Registers.

The owners of the village of Skegby in 1612 were stated by Thoroton to be “William Lyndley Gent: Lord of the Mannor, Roger Swinstone, Clark, Richard Tomlinson, William Butler, Francis Swinstone, Will. Osborne, James Cowper of Tibshelf, Thomas Jackson of Askham,” and as the name of Hooton does not appear on the Manor Rolls it is evident Oliver Hooton did not own the property on which he settled. In 1650 Thomas Lyndley of Skegby was appointed a Commissioner to assess the fines of confiscated Royalist estates. Thomas Lyndley applied for and received a licence for the holding of Divine service in part of his house. This particular building still remains (1914) and is now used as a laundry for Skegby Hall.

Francis Chapman, in his return made in accordance with the order issued by the Archbishop of Canterbury, July 1669, “to enquire after all Conventicles, or unlawful meetings under pretence of religion and the worship of God, by such as separate from the unitie and conformitie of the Church as by law established,”[4] says:

In reply to your worshipful Archdeacon’s letter, I know nothing but this: that in Mansfield Woodhouse we have no conventicle but one of Quakers, at the house of Robert Bingham (excommunicated for not comynge to church) but who they are who frequent it I cannot say. At Skegby, alsoe, there is a conventicle of Quakers at the house of Elizabeth Hatton [Hutton][4] widow; but I cannot learn who they are who frequent them, they being all of other towns. In the same town of Skegby, alsoe, there is another conventicle, reputed Anabaptists and fifth monarchy men, held at Mr. [Mrs.] Lyndley’s (excommunicate also) but I know neither their speakers or hearers.

Possibly it was with these last-named people Elizabeth Hooton associated before her meeting with George Fox, for it is evident from the following[5] that she had dissociated herself from the Church before that time and joined a Baptist community:

Oliver Hutton Saith

And my Mother Joyned with yᵉ Baptists but after some time finding them yᵗ they were not upright hearted to yᵉ Lord but did his work negligently and she haveing testifyed agᵗ their deceit Left yᵐ who in those parts soon after were scatered & gone: about the year 1647 George ffox Came amongst them in Nottinghamshire & then after he went into Lestershire where yᵉ mighty power of yᵉ Lord was manifest that startled their former separate meeting & some Came noe more but most yᵗ were Convinced of yᵉ truth stood of wᶜʰ my mother was one and Jmbraced itt:

Oliver Hutton writes in his hystry pag: 46:

Soe here you may see yᵗ they were Called Baptists and Separates not Children of yᵉ Light till after G: ff: had preached yᵉ Light of yᵉ Gospell to them & they Received itt.

The memorable meeting with George Fox in 1646-7 changed the whole tenour of her life. At first she met with opposition at home.

Her husband (says Fox in his Testimony concerning her)[6]

being Zealous for yᵉ Priests much opposed her, in soe much that they had like to have parted but at Last it pleased yᵉ[5] Lord to open his understanding that hee was Convinced alsoe & was faithfull untill Death.

But clearly her faithfulness had its reward, for he further adds:

She had Meetings at her house where yᵉ Lord by his power wrought many Myracles to yᵉ Astonishing of yᵉ world & Confirming People of yᵉ Truth wᶜʰ she there Received about 1646.

During these years Fox appears to have spent much time in Mansfield and the neighbourhood, and in his Journal at this period are noted some of his deepest religious experiences. Here was revealed to him that over the sorrow and suffering, the sin and pain, of the world,—“the ocean of darkness and death,” as he termed it, there for ever flowed the infinite ocean of God’s light and love; and this perception brought added strength, for he tells us, “I had great openings”; and who can doubt that this deeper spiritual experience and its resultant strength proved an inspiration to his early disciple?

The rapid development of the Mansfield of to-day has brought many changes, and but little remains to remind one of the seventeenth century town. The “steeple house” mentioned by Fox has been restored but its interesting features have been preserved; near it there still stands on old house, a survival of the past in the midst of modern surroundings, which was undoubtedly in existence when he walked “by the steeple house side in Mansfield.” Hard by lived Elizabeth Heath, that benefactress to the town whose thoughtful charity has brightened the lives of so many aged pensioners. Though it does not appear that she ever openly joined the followers of Fox, she still held their honesty and probity in such high esteem that she appointed all the trustees of her charity from amongst them, and to-day the trust is still administered by members of the Society of Friends.[7]

In the year 1649 George Fox suffered imprisonment at Nottingham and in his “Short Journall”[8] we read: “There came a Woman to mee to the Prison & two wᵗʰ her and said yᵗ shee had been possessed two and thirty years.” He goes on to describe her symptoms and how “the Priests had kept her, and had kept fasting days about her, and could not do her any good.” After his release from prison he bade “friends have her to Mansfield.” Her conduct there was apparently so extraordinary that she

would set all friends in a heat and Sweat.... And so she affrighten’d the World from our meettings; and then they said if that were cast out of her while she were wᵗʰ us and were made well, Then They would say yᵗ wee were of God: this said The world.... And Then it was upon mee that wee should have a meetting at Skekbey at Elizabeth Huttons house, where wee had her there, and there were many friends almost overcome by her ... and yᵉ same day shee was worse then ever shee was.

Another meeting was held and a cure was effected. Then the narrative continues:

Wee kept her about a fortnight in yᵉ sight of yᵉ world, and she wrought and did Things and then wee sent her away to her friends. And Then the Worlds Professors Priests & Teachers never could call us any more false prophetts deceivers or witches after but it did a great deal of good in yᵉ Countrey among People in relac̄on to yᵉ Truth and to yᵉ stopping the mouths of yᵉ world & their Slandrous Aspersions.

Shortly after this time Elizabeth Hooton’s active ministry commenced and bonds and bitter persecutions awaited her. At Derby in 1651 she suffered imprisonment for “speaking to one of the Priests there, who so resented her Reproof that he applied to the Magistrate to punish her. For it is common with Men who most deserve Reprehension, to be most offended with those who administer it.”[9] Although 1651 is the date given,[7] there is preserved a letter from E. Hooton written from Derby gaol and bearing two endorsements, the first in the handwriting of George Fox: (1) “To the meir of darby from Elliz: hoton 1650.” (2) “This was sent to the meir of darby from Goodde hutton.” The letter consists entirely of religious exhortations, and is similar to many others bearing her signature. It concludes: “Would you have me put in beale wᶜʰ have not trensgresed your lawe nor mes be haved my selfe—Conseder is this the Good ould way that you was touth [taught?].” It is addressed to “noaH Bullocke of derby in the towne” and is chiefly interesting as the earliest letter of hers known to be in existence, addressed to a public official.[10]

There is no record of the length of her imprisonment at Derby but in 1652 she was committed to York Castle for speaking in the Steeple House at Rotherham and remained there for sixteen months. There are interesting allusions to Elizabeth Hooton and her husband in letters from Thomas Aldam[11] written from York Castle in the above year; he says:[12]

... We have great friendship and love from yᵉ governor of the Towne, and many of yᵉ Souldiers are very sollid & loveing. Oh his wonderful love and oh the exceeding riches of his grace held forth to vs. to him alone all glorie, honour, and praise, now & for ever; My Sister Elizebeth Hooten remembers her dear love vnto you in yᵉ lord, and my sister Mary ffisher[13] who was brought to prison from Selbie for speakeing to yᵉ preist in yᵉ Steeple house there, she was as servant with Richard Tomlingson of Selbie.

And again:[14]

... My sister Elizebeth Hooton & I did looke for noe Calling to goe before the Judge & Elizabeth husband in the flesh came to the Assize & went backe againe shortly: the Justices told him shee might not bee Called here but at their Sessions: but at the end of their Assizes they called vs all together to goe before them; ... an inward peace & rejoiceing was given mee in goeing up.... I was made to Cry out, Woe to the partiall Judge.... My sisters was made to speake in great bouldnes at the Bench against the deceite of their Corrupt Lawes & Governements & deceitfull Preists we are Kept all of vs in greate friedome in these outward bonds, & the Lord is p̄sent wᵗʰ vs in power; to him alone bee praises for ever & ever.... Your deare Brethren & Sisters in the Lord,

There are two letters signed by Elizabeth Hooton which were probably written at this period. The first is as follows:[17]

Deare Freind Cap: Stothers[18] & the wife: my deare and tender love to yᵘ both, my deare freinds I am moved to writ to you my brethren, yᵗ wee are well, the lord is pleased to recover me and shew me abundance of his mercy, makeing me acquainted with Satans wiles and Cuning devices, to trap the simple Seed, and to ensnare and bondage the people of god, with his subtil bayts Continually, O deare frends, when the lord hath set you free and brought you into joy, then you thinke you have over come all, but there is a daiely Crosse to bee taken vp, whilst yᵗ the fleshly will remaineth, if any of yᵗ stand vncrucified, the Serpent there getts hould and brings into death, & darkenesse, soe yᵗ there is a continuall Warfare for there is noe thing obtained but throug Death & Suferings, which is by the power of Faith, which Caryes through all troubles, keepeing Close to it the power of darkenes cannot hurt, but lookeing out to satisfie the will of the flesh, there doth the Serpent get in & tells the Creature of ease, & liberty in the flesh. and say thou needest to take vp the Crosse noe longer, for thou art now come to thy rest, thou may eate & drinke and bee merry & I will give thee joy enough, & thus many a pore soule is drowned and runs on in lightnes & wantonnes, tho become odious both in the sight of god and men, & cause Scandalls to arise against yᵉ Church, & soe through backesliders we are rendered odious to the world putting on yᵗ which was once put of, disobedience is the beginner of these things: O deare frends beeware & exort others, yᵗ wee may sit doune in the lowest roome, taking vp the Crosse dayely and foloweing Christ & yᵗ hee may goe before vs & leade vs at his one pleasure, I have experience of the wiles of Satan, the lord hath exercised mee, but there is noe way but sit doune and submitt to his will, & there is rest and peace.

farewell. my love to Richard Hatter & his wife & to Will: Tomlinson.

your frend Elizabeth Hooton

The second of the two letters is a plea on behalf of James Halliday,[19] of Northumberland, imprisoned in York Castle:[20]

Yoᵘ that sitt on the Bench doe Justice and Equity to those honest hearted people Called Quakers whome yoᵘ putt in prison and Call them to the Barr & sett them at Liberty for[10] they have done yoᵘ noe wrong nor hurt the cause is for worshiping of God as hee requires in Spᵗ & in Truth that they Suffer—James Holliday who hath Laine in Six Months being A North Country freind the Geoler hath very much Abused By Taking away his Victualls & Beateing of him till hee hath been black & Blew & his Skin broake & soe oʳ desire is that yoᵘ would sett this poore man at Liberty whome the Geoler keepeth for his fees

Elizabeth Hooton.

In a very vigorous and lengthy letter[21], endorsed by Fox: “e hoten at the gale at yorke to olefer Cromwell 1653,” in which she describes herself as a Prisoner of the Lord at York Castle, she reminds the Protector:

The Lord hath beene pleased to make [the] an Instruement of warr and Victorie; hee hath given the power over thy enemies & ours, hee hath given much into thy hand, & thou hast beene Looked vppon, & sett vpp wᵗʰ many, and wᵗʰ my selfe.

She denounces in no measured terms the corruptness of Judges, Magistrates, teachers and clergymen and all officers and gaolers and compares them to Herod and Pontius Pilate; and continues:

Your Judges Judge for reward, And at this Yorke many wᶜʰ Committed murder escaped throughe frends & money, & pore people for Lesser facts are put to death; many Lighe in prison for fees yet; they Called their Assize a generall Gaole Delivʳie, but many was but delivʳed from the p̄sence of the Judges in to the hands of two greate Tirantes vizᵗ. the Gaoler & the Clearcke of the Assize & these two keepes many pore Creatures still in prison for fees, the Gaoler hee must have Twenty shillinge four pence for his fee; & the Clearcke of the Assize hee must have fifteene shillinges eight pence, & this they will have of pore Creatures; or els they must starve in prison, They Lighe worse then doggs for want of strawe, Many beinge in greate want, that they have not to releeve them wᵗʰall; yet these Tirants keepe them in this pore Condic̄on The Judges & Magistrates they might as well have put them to death at the Assize as put them into the hands of these two tirants who keepes men for money starveing them in a hole till they be ruined [?] or starved to death.

She next complains of the way she and her fellow sufferers for the Truth are treated and tells the Protector: “Wee have not that Libertie that Paull had of the Heathenish Romans.” She then appeals to him as follows:

O man what dost thou there except thou stand for the truth which is trampled under foote Who knowes but thou was Called to deliver thy brethren out of bondage & slaverie, & that the Truth may bee set free to speake freely, wᵗʰout money or wᵗʰout Prize.... O frend thou must lighe downe in the dust & Cast thy Crowne at the feete of Jesus, how Can you beleeve that seeke honor one of another & seekes not the honor wᶜʰ is of god onely; Distribute to the pore, & Denie thy honor, & take up the Crosse & followe Jesus Christ.

Much more follows in the same strain, mingled with warnings of the woes that will come upon him and the nation generally if justice is not done. The whole is a very good example of the epistolary methods of the period, and at the same time throws an interesting light on the condition of prisoners, and the way Justice was administered—or rather not administered—during the Commonwealth.

A Tract entitled, False Prophets and false Teachers described, signed by Thomas Aldam, Elizabeth Hooton, William Pears, Benjamin Nicholson,[22] Jane Holmes, and Mary Fisher; “Prisoners of the Lord at York Castle, 1652,” is an eloquent testimony to their unceasing activity in Truth’s service.[23]

Another detailed account of this imprisonment is given in a further letter, sealed and directed: “ffor Capt Stodard at his house in Long Aley in more fields this đ đ đ in London.” E. Hooton writes:[24]

Deare friends [paper torn] unto you Concerning yᵉ assise but we 3 sisters were not Called, but they keepe us still in prison, with the Rest of oure brethren, 3 of them was Called, but the corupt Judge sett fines vpon them, for Comeing wᵗʰ their hatts on, but they keepe yᵉ truth murdred, in a whole & will not suffered it to speake in shutting us vp, what yᵉ truth should be declared, Some of our brethren was bold & did speake freely to them, but my bro: Thomas [Aldam] they would not let him stay nor sufer him to speake, but we are maide to Rest in yᵉ will of god ... if we would submitt to their wills, then would they take of our fines, but we dare not deny yᵉ lord, for at yᵗ time yᵗ he hath apointed he will sett vs fre, from vnder yᵉ bondage of men, but our fredom is wᵗʰ yᵉ father & yᵉ sone, whom yᵉ sone hath maide fre is fre indeede.... O noble Captaine yᵉ lord hath manifested his love to the, & he hath maide the an instrument of good to his people, now it stands yᵉ vpon to stand vp for the leberty of yᵉ gospell, yᵗ them yᵗ hath frely Received it, may have fredome to preach itt, & hold it out to yᵉ world, yᵗ hierlings may be putt downe & have no more hier, for they through there deceits deceives yᵉ people & Raises vp yᵉ Magestraites for persecution, for they, yᵉ Clergy & yᵉ gentry, hath yᵉ lande betwixt them, & yᵉ people of god & yᵉ power doe they persecute & treade vnder feete, & those Corupt Magestraits wᶜʰ knowes noe true Justice, keepes yᵉ poore people in bondage & ꝑsecutes according to their own will, many of vs are put heare in prison, not ofending their owne way, Consider of these things and as thou art moved soe speake to yᵉ generall [Cromwell] yᵗ yᵉ truth may be sett fre, though we be willing to waite the lords laysure. I did sende some letters to yᵉ generall, & would know whether they ever was seene, or noe, & one to yᵉ Parlement, I would know wᵗ became of them, whether they were brought to light or noe, any of them.

Elizabeth Hooton,

A prisoner of yᵉ lord in Yorke Castle.

At what period her liberation from York Castle took place is as yet undetermined—on the 11th June, 1653, she wrote from the Castle to George Fox,[25] but when free, undeterred by this imprisonment, she went forward in her religious service. Here follow some glimpses of her further labour and suffering.

ELIZABETH HOOTON TO GEORGE FOX.

To face p. 12.] [See p. vi.

Margaret Killam[26], writing to George Fox, in 1653, says:[27]

I was moued of the lord to goe to Cambridge, & I went by Newarke side & was att a meetinge uppon the first day there, & I was moued to goe to the Steeplehouse & I was kept in Silence whilst their teacher had done, & hee gaue ouer in subtilty, a litle, & after began againe, thinkinge to haue ensnred mee, but in the wisdome of god I was p̄served, & did not speake untill hee was come downe out of the place.... His hearers were uery silent & attentiue to heare & did confesse itt was the truth wᶜʰ was spoken to them, & was troubled att their Teacher yᵗ hee fled away. Itt was the same wᶜʰ did Imprison Elizabeth Hooton, & did ensnare her by his craft, & hee had told them if any came & spoke in meeknesse hee would heare.

Besse has no record of the above-mentioned imprisonment of Elizabeth Hooton, so possibly it was not of long duration.

In the year 1654 George Fox says: “I came to Balby; from whence several Friends went with me into Lincolnshire; of whom some went to the steeple-houses and some to private meetings.”[28]

From the following interesting entry in an early Lincolnshire minute book[29] it appears likely that John Whitehead[30] and Elizabeth Hooton were of this company:

In the beginning of the Ninth Month in the yeare 1654 John Whitehead first came to preach the Light within, & for beareing Testimony in the High Place called the Minster in Lincoln that[14] it is the Light of the Glorious Gospell that Shines in Man’s heart & Discovers Sin, He was buffetted & most shamefully intreated, being often knocked down by the Rude & Barberous People, who were encouraged thereunto by Humphrey Walcott who then was in Commission to have kept the peace; but brake it by striking of the said John Whitehead with his owne hands, wᶜʰ so encouraged the Rude People, that so far as could be seene they had slaine the said John, but that God stirred some Souldiers to take him by fforce from amongst them.

Elizabeth Hooton was imprisoned in Lincoln Castle in the 9ᵗʰ month 1654 by the Procurement of Joseph Thurston, then Priest of Beckingham, for speaking to him in the Steeplehouse, she was kept Prisoner about 6 months. She was Imprisoned againe by procurement of the same priest at Lincoln Castle in Ninth Month 1655 for speaking to him after the Exercise was done, & at that time kept prisoner eleven or twelve weeks.

According to Besse, E. Hooton was the first sufferer for the Truth in Lincolnshire.[31]

BECKINGHAM CHURCH.

To face p. 14] [See p. vi.

There is an imperfect letter from Elizabeth Hooton in existence, which, though undated, appears to belong to this period and naturally finds a place here. It is endorsed: “E. H. Prisoner in Lincolne Castle, pleads to him in Authority to reforme the abuses of yᵉ Goal,” and contains a striking description of the state of the gaols of the Commonwealth and of the many abuses connected with their management.[32] Her protests against strong drink, her plea for the separation of the sexes and for the employment of the prisoners reads more like an appeal from Elizabeth Fry two centuries later.

O thou that artt sett in Authoryty to doe Justice and Judgmente, and to lett the oppressed goe free, thease things are required att thy hands, looke vpon the pore prissonors, heare is that hath not an[y] [al]lowance all though thear be a greatte sume of mony comes out of the country suffic[ien]tt to hellpe them all that is in want, booth theare dew alowance and to sett them aworke which would labor, And those that are sentt hether for deb[ts] that theare rates for beds, which is ten grots the weeke may be taken downe [paper torn] at to reasonable raites, And theare beare which is sould at such an vnreasonab[le] [paper torn] thear[15] meseuers being so extreame littell that itt may be amendid [paper torn] and equity, for many pore detters is sett in heare for a small dett and [paper torn] a great deale of the score fare more then thear dette. And it is [? a place of g]reate dissorder and of wickednes, so that for oppression and prophaines J neuer came in such a place, because a milignant woman keeps the gole.

Opprission in meat and in drinke and in feese, and in that which they call garnishes, and in many other thinges, And J my selfe am much abused, booth hir and hir prissonars, and hir houshould, so that J cannott walke quiatly abroade but be abused with those that belonge vnto hir. When a drunken preist comes to reade command praire, or to preach aftar his owne in vention or Jmmaginations, then thay locke me up, and all the rest are comanded to come forth to heare, and so is keptt in blindnes.

And so in drinking and profaines and wantonnes, men and women to gether many times partte of the night, which grefes the spiritt of god in me night and day. This is required of the o man, to reforme this place, as thy power and Authority doth alow, ether remove strong drinke out of this place or remove the Golar, seckondly that theare rates for theare beds may be taken dowen. That theare garnishes and theare greate fese may be taken of, and thease oppresed prissonors may come to some hearing, such as is wrongfuly prissoned, And that theare may be some beter order amongst the men and woman which is prissonars to keepe them assunder and sett them a worke, and sett them att libbirty that is not able to pay the feese, and to take out the dissordred person, which kipeth all in dissorder, in carding and dicinge, and many other vaine sportes, and so J leave itt to thy Concsence to redres the dissorders in this rewde place, and so have J discarged my Concsence [paper torn] much vpon me, that thou mightest know itt and itt redres.

Elizebeth Houton,

prisonr in linckoln Castell.

George Fox, after his missionary visit into Lincolnshire, accompanied by Robert Craven, the Sheriff of Lincoln (who had been convinced by his preaching) and by Thomas Aldam, passed into Derbyshire and thence into Nottinghamshire to Skegby, “where,” he records, “we had a great meeting of divers sorts of people: and the Lord’s power went over them and all was quiet. The people were turned to the spirit of God, by which many came to receive his power, and to sit under the teaching of Christ their Saviour. A great people the Lord hath in[16] these parts.”[33] No mention is made of Elizabeth Hooton, possibly she was in Lincolnshire at the time, but it may be that her fostering care of the infant Church and her unwavering steadfastness to the Truth which she had received had been mainly instrumental in raising up “a great people to the Lord.” In 1655 we know she was again in Lincolnshire, but the brief entry in the Lincoln Minute Book appears to be the only record of her labours in that county at this period. She was one of the first Quaker preachers to visit Oxfordshire as evidenced by an early Minute which runs: “Also Eliz Hutton, a good ould woman, came and vised us early.”[34]

In 1657 her husband, Oliver Hooton, died. The entry in the digest of Friends’ burial registers preserved at Nottingham reads:

Oliver Hooton died 30 4 1657 Seckbie, Mansfield Mo. Meeting Buried 30 4 1657. Seckbie.

This is confirmed by the Parish Register at Skegby where he is described as the Elder, but there is a slight discrepancy as to day and month, the latter stating he was buried 24th July, 1657.[35]

At an early date Friends acquired a Burial Ground at Skegby where members of the Society from the district were interred. The entries in the Register show that many Mansfield Friends were buried there, for until Elizabeth Heath gave a piece of ground as a burial place in 1693, Friends of Mansfield had no place of sepulture there.

Quite recently, in the course of repairs to the house at Skegby, which up to 1800 was the property of Friends and was known as the Meeting House, and by some was believed to be the house in which Elizabeth Hooton lived, a stone used as a shelf in the pantry was found on which there were remains of an inscription and the date 1687. An old lady of Skegby, aged ninety-eight, states[17] that she fancies she can remember seeing some tombstones in the garden which covers the site of the old graveyard.

No record of Elizabeth Hooton’s ministry, or allusion to her, has been found in contemporary documents for the years 1658-1659, but in the early part of the year 1660 she was in Nottinghamshire, and Besse gives the following graphic description of an apparently unprovoked assault on her by Priest Jackson of Selston: “On the 2d of the Month called April, Elizabeth Hooton, passing quietly on the Road, was met by one Jackson, Priest of Selston, who abused her, beat her with many Blows, knockt her down, and afterward put her into the Water.”[36]

With this incident, the record of her early service in England ends. We next follow her in her perilous journeyings in a distant land.

Falſe Prophets and falſe Teachers deſcribed. 1652.

Longfellow, New England Tragedies, Prologue to “Endicott.”

We owe to their heroic devotion the most priceless of our treasures, our perfect liberty of thought and speech; and all who love our country’s freedom may well reverence the memory of those martyred Quakers, by whose death and agony the battle in New England has been won.

Brooke Adams, Emancipation of Massachusetts.

Fierce and cruel as was the persecution in England it was far exceeded by the tortures which awaited the first Quaker missionaries in the New World. Barely fifty years earlier the Pilgrim Fathers had left the homeland and gone forth into an unknown wilderness, there to establish freedom of worship; their descendants, by bitter persecution of the Quakers, demonstrated their failure—in spite of their own sufferings—to learn the lesson of religious toleration. The general attitude of those in authority in the Colonies is very well pourtrayed in the writings of the Rev. Mr. Ward, of Ipswich, Massachusetts, in 1645: “It is said that men ought to have liberty of conscience and that it is persecution to debar them of it. I can rather stand amazed than reply to this. It is an astonishment that the brains of a man should be[19] parboiled in such impious ignorance”; and, further, John Callender, writing in 1739, said that in 1637 “the true Grounds of Liberty of Conscience were not then known or embraced by any Sect or Party of Christians.”[37]

The early history of the New England Colony shows that, some years before the advent of the Quakers, religious differences had arisen amongst the Colonists, and a certain section of the community had not escaped persecution. Anne Hutchinson, a brave and intrepid woman, had boldly protested against what might almost be termed a purely theological religion and the extreme power which was of necessity vested in the priest, which was the basis of the Puritan faith. Dr. Rufus Jones states the differing points of view very clearly:[38]

The real issue, as I see it in the fragments that are preserved, was an issue between what we nowadays call “religion of the first-hand type,” and “religion of the second-hand type,” that is to say, a religion on the one hand which insists on “knowledge of acquaintance” through immediate experience, and a religion on the other hand which magnifies the importance and sufficiency of “knowledge about.”

Anne Hutchinson was arraigned before a General Court of all the ministers, held in Boston in 1637. She defended herself with great ability, but without avail, in fact it is very possible that such unusual temerity on the part of a woman may have been largely responsible for the severity of the sentence passed upon her, for she was condemned to banishment and declared excommunicate. As the exiled outcast woman passed sadly down the aisle, one Mary Dyer[39] joined her and went forth with her, thus taking the first step on that path of suffering which led, twenty-three years later, to the gallows on Boston[20] Common. Anne Hutchinson, after sentence of exile had been pronounced, joined her friends. She had a very considerable following in the new Colony of Aquiday, or Aquidneck, now called Rhode Island, which later became for the persecuted Quakers a veritable “little Zoar,”[40] for these early settlers learned the lesson of religious toleration which was reflected in their laws.[41]

The King’s Commissioners, who visited the Colony about 1664, reported that in Rhode Island “all who desire it are admitted freemen. Liberty of conscience and worship is allowed to all who live civilly. They admitted all religions, even Quakers and Generalists, and is generally hated by other Colonies.”[42]

Not only was Rhode Island a city of refuge for the persecuted Quakers, but their message was sympathetically received by many in the Colony. Anne Hutchinson did not live to witness the sufferings of the Quakers, as she and several members of her family were murdered by[21] the Indians in the autumn of 1643; her sister Katharine Scot,[43] however, early joined the new sect; she is described as “a Mother of many Children, one that had lived with her Husband, of an Unblameable Conversation, and a Grave, Sober, Ancient Woman, and of good Breeding, as to the Outward, as Men account.”[44] She came from Providence, Rhode Island, to Boston on hearing of the sentence passed on three young men who, for the crime of being Quakers, were condemned each to the loss of an ear; on account of her comments thereon she was cast into prison and received “Ten Cruel Stripes with a three-fold-corded-knotted-Whip,” and warned that “if she came thither again they were likely to have a law to hang her,” to which she replied: “If God call us, Wo be to us, if we come not; And I question not, but he whom we love, will make us not to count our Lives dear unto our selves for the sake of his Name.”[45] Truly she and her sister Anne Hutchinson came of heroic stock.

In 1656 the first Quaker preachers in the persons of Mary Fisher and Anne Austin[46] arrived at Boston. In consequence of the many wild rumours which had reached the Colony of the strange actions and teaching of the Quakers in England, they were detained on shipboard and their luggage searched for Quaker books or tracts. Several were found and these were ordered to be burned by the common executioner, and the women themselves were stripped and examined to see if they bore upon them marks which should prove them to be witches. They were detained in gaol for about five weeks and then deported again to Barbados. Their inhospitable reception did not in the least[22] quench the missionary zeal of the early Friends, and very shortly after, eight more arrived on the shores of New England, who, after two days’ examination, were sent back to England by the ship on which they came. The authorities of Boston then passed a law inflicting a fine of £100 on any shipmaster who knowingly conveyed a Quaker to the Colonies. This law failed as a deterrent, many Quakers obtaining an entrance to the Colonies, and still fiercer became the persecution. A strengthening of the law was deemed necessary and it was further decreed:

What Quaker so ever shall arrive from foreign Parts or Parts adjacent shall be forth with committed to the House of Correction; and at their entrance to be severely whipp’d, and by the master thereof to be kept constantly at Work, and none suffered to speak or converse with them.—If any Person shall knowingly Import any Quakers Books or Writings concerning their Devilish opinions, shall pay for every such Book or Writing the Sum of £5. who soever shall disperse or conceal any such Book or Writing and it be found with him or her shall forfeit or pay £5—and that if any Person within this Colony shall take upon them to defend the Heretical opinions of the said Quakers or any of their Books, &c., shall be fined for the first time 40/—If they shall persist in the same and again defend it the second time £4.—If they shall again so defend they shall be committed to the House of Correction till there be convenient Passage to send them out of the Land, being sentenced by the Court of Assistants to Banishment [1656].

This law was proclaimed by beat of drum before the house of Nicholas Upsall[47] who was rightly suspected of sympathy with the hated sect; he protested against the law and suffered banishment in consequence. In 1657 the law was again strengthened; and if a male Quaker, after he had once been banished, returned again to New England, he was to suffer the loss of one ear and to be kept in the House of Correction, and every woman was to be severely whipped and consigned to the same place. This law was to apply to “every Quaker arising from amongst ourselves” as well as to “Foreign Quakers.” Three men suffered the penalty of loss of their ears at Boston. Further laws were made and[23] penalties inflicted for meeting together to worship God after the manner of Friends. In 1658, in addition to the penalties already inflicted, any of the “Sect of Quakers,” after a trial by a special Jury and conviction by same, were to be sentenced to death.

In spite of, or rather because of these harsh laws and the inhumanity with which they were administered, the Quaker community rapidly increased; thus we are told[48] that

these Violent and Bloody Proceedings so affected the Inhabitants of Salem and so preached unto them, that divers of them could no longer partake with those who mingled Blood with their Sacrifices, but chusing rather Peace with God in their Consciences, whose Witness in them testified against such Worships, than to joyn with their persecutors, whatsoever they might therefore suffer, withdrew from the Publick Assemblies, and met together by themselves on the first Days of the Week, Quiet and Peaceable in one anothers Houses waiting on the Lord.

The authorities quickly noticed these abstentions from public worship and warrants were issued under a law of 1646, the offenders being fined for non-attendance 5s. a week; and on a second examination, after the Clerk of the Court had perverted their explanation as to their belief in the doctrine of the Inward Light, three of their number—Lawrence and Cassandra Southwick, with Josiah their son[49] (“all of a Family to terrifie the rest”) were sent to Boston, and there in the House of Correction were “caused to be Whipp’d in the coldest Season of the Year with Cords, as those afore, tho’ two of them were Aged People.”[50]

Many examples of the ferocity with which the Quakers were treated in the New England Colonies might be cited, yet so inspired were these early pioneers with the deep significance and importance of their message that they were compelled to brave the untried wilderness paths and surmount difficulties which we in these days might be tempted to deem insurmountable, in order to deliver it; women with their babes at the breast would[24] not hesitate to undertake “a very sore Journey, and (according to Man) hardly accomplishable, through a Wilderness above Sixty Miles,” knowing that it led inevitably to stripes and bondage and possible death; yet in spite of all, we are told of one such that she was enabled to kneel down and pray in the spirit of the Master for the forgiveness of her cruel persecutors. This “so reached upon a Woman that stood by, and wrought upon her, that she gave Glory to God, and said that surely she could not have done that thing, if it had not been by the Spirit of the Lord.”[51]

The Quakers still continued boldly to preach, and persecution waxed fiercer and fiercer. The Chronicler says: “Their lives (as men) became worse than Death and as living Burials.” The offences for which Friends suffered so severely were of a most trivial character, such as non-attendance at Public Worship for which they had been previously fined, and for not removing their hats. In the event of their refusal to pay any fines which might be imposed they became liable under a law made on accounts of debts, by which it was permissible to sell those persons who refused or were unable to pay their fines “to any of the English Nations as Virginia or Barbadoes to Answer the said Fines.”

Worse was to follow—in June, 1659, William Robinson, of London, Merchant, and Marmaduke Stevenson, a country-man from East Yorkshire, under a religious concern, passed from Rhode Island to Boston, where with an aged man named Nicholas Davis[52] they were speedily imprisoned, Mary Dyer, who came from Rhode Island, sharing the same fate; there they remained until the sitting of the Court of Assistants, when they were sentenced to banishment, and should they be found within the Jurisdiction of the Court after the 14th of September following they were condemned to death. They were kept prisoners till the 12th of September. Mary Dyer and Nicholas Davis “found freedom to depart” out of the Province; but William Robinson and Marmaduke Stevenson “were constrained in the love and power of God not to depart,” so they passed out[25] of prison to Salem and remained there and at Piscataway and the parts thereabouts in the service of the Lord. On the 13th of October they returned to Boston “that metropolis of Blood” as it was styled, and with them Alice Cowland, “who came to bring Linnen to wrap the dead bodies of them who were to suffer.” Several other Friends joined them and the Chronicler tells us: “These all came together in the Moving and Power of the Lord as one, to look your Bloody Laws in the Face,” and to accompany those who should suffer by them. Mary Dyer had returned also and on the 19th of the same month she, with William Robinson and Marmaduke Stevenson, was condemned to death. On the 28th of the same month they were led forth to execution, by the back way, we are told, for the authorities were afraid “of the fore way lest it should affect the people too much.” Drums, too, were beaten, so that no words from the prisoners might be heard; we are told that they came “to the place of Execution Hand in Hand, all three of them as to a Weding-day, with great Chearfulness of Heart.” The two men were hanged, but Mary Dyer was reprieved at the last moment, by petition of her son, only to suffer the death penalty a few months later.

Yet another martyr was to seal his testimony with his blood—William Leddra, described as of Barbados but a native of Cornwall, was executed at Boston the 14th of March, 1660/61, under the law of banishment, who, before his final trial, had suffered much persecution and grievous cruelty. His beautiful and saintly nature is revealed in a letter written by him “To the Society of the little Flock of Christ,” dated from Boston prison the day before his execution; therein is no fierce denunciation of his persecutors, but words of consolation and hope to his sorrowing friends.[53]

A contemporary letter, printed in New England Judged, is extremely interesting as showing the unbiassed opinion given by an entire stranger of the sentence passed upon this saintly man. So moved was he by the scene at the execution that he was impelled to remonstrate with those in authority. The letter is from Thomas Wilkie to his friend, George Lad, “Master of the America, of Dartmouth, now[26] at Barbados,” dated Boston, 26th of March, 1661. It is as follows:[54]

On the 14th of this Instant, here was one William Leddra, which was put to Death. The People of the Town told me, He might go away if he would: But when I made further Enquiry I heard the Marshal say, That he was Chained in Prison, from the time he was condemned, to the Day of his Execution. I am not of his Opinion: But yet Truly me thought the Lord did mightily appear in the Man.

I went to one of the Magistrates of Cambridge who had been of the Jury that condemned him (as he told me himself) and I asked him by what Rule he did it? He answered me, That he was a Rogue, a very Rogue. But what is this to the Question (I said) where is your Rule? He said, He had abused Authority. Then I goes after the Man [William Leddra], and asked him, Whether he did not look on it as a Breach of Rule, to slight and undervalue Authority? And I said, That Paul gave Festus the Title of Honour tho’ he was a Heathen (I do not say these Magistrates are Heathens) I said then, when the Man was on the Ladder, He looked on me, and called me Friend, and said, Know, that this Day I am willing to offer up my Life, for the Witness of JESUS. Then I desired leave of the Officers to speak, and said, Gentlemen, I am a Stranger, both to your Persons and Country, and yet a Friend to both: And I cried aloud, For the Lord’s sake, take not away the Man’s Life; but remember Gamaliel’s Counsel to the Jews, If this be of Man, it will come to nought; but if it be of God, ye cannot Overthrow it; But be careful ye be not found Fighters against God. And the Captain said, Why had you not come to the Prison? The Reason was, Because I heard, the Man might go if he would; and therefore I called him down from the Tree and said, Come down, William, you may go away if you will. Then Captain Oliver said, It was no such matter; And asked, What I had to do with it? And besides, Bad me be gone. And I told them, I was willing; for I cannot endure to see this, I said. And when I was in the Town, some did seem to Sympathise with me in my Grief. But I told them, That they had no Warrant from the Word of God, nor President from our Country; nor Power from his Majesty, to Hang the Man. I rest,

Your Friend,

Thomas Wilkie.

A bold protest, boldly made; the Chronicler, to our regret, is silent as to the fate of the protester.

Soon after the Restoration, Charles II., “judging it necessary that so many remote Colonies should be brought under uniform inspection for their future regulation, security and improvement,” signed a Commission appointing thirty-five members of Privy Council, the nobility, gentry and merchants, a Council for Foreign Plantations. (Calendar of State Papers Colonial). Wide powers were vested in this Council, any five members were empowered to “inform themselves of the condition of Plantations and of the Commissions by which they were governed as well as to require from any Governor an exact account of the constitution of his laws and government, number of inhabitants and any information he was able to give.” The Commissioners were also “to provide learned and orthodox ministers to reform debaucheries of planters and servants and instruct natives and slaves in the Christian faith.” The first meeting was held 7th of January, 1661, when Committees were appointed for the several Plantations; attention was first directed to the New England Colonies, and information, petitions and relations of those who had been sufferers were laid before the Council. At a subsequent meeting held on 11th of March, 1661, Captain Thomas Breedon, who had returned from New England in 1660, appeared and reported as to conditions in Massachusetts Colony. He presented a book of the Laws of the Colony which were stated to be by patent from the King, but he had never seen the patent and did not know whether they acted in accordance with the same. “Distinctions between freemen and non-freemen, members and non-members, is as famous as Cavaliers and Roundheads was in England, and will shortly become as odious. The grievances of the non-members who are really for the King, and also some of the members, are very many.”

In Breedon’s report, too, we have symptoms of discontent and disaffection—heralds of the storm which a hundred years later broke, and severed for ever the American Colonies from the mother-land. He continues:

They look on themselves as a free state, they sat in Council December last, a week before they could agree in writing to His Majesty, there being so many against owning the king or having any dependence on England. Has not seen their petition but[28] questions their allegiance to the King, because they have not proclaimed him, they do not act in his name, and they do not give the act [? oath] of allegiance, but force an oath of fidelity to themselves and their Governor as in the Book of Laws.

That there was considerable doubt in the minds of those in authority in New England as to the manner in which the news of their high-handed and ferocious persecution of the Quakers would be received by the Home Government is evident from a letter written by Captain John Leverett, London Agent for Massachusetts, to Governor Endicott and the General Court, 13th of September, 1660. After some discourse on other matters he continues:

Yᵉ Quakers I hear have been with yᵉ King concerning your putting to death those of theyr Frᵈˢ executed at Boston. Yᵉ general vogue of people is yᵗ a Govʳ will be sent over. Other rumours yʳᵉ are concerning you, but I omit yᵐ, not knowing how to move & appeare at Court on your behalf. I spoke to Lᵈ Say & Sele to yᵉ Eˡ of Manchester &c.

Yʳˢ in all faithfulness to serve you,

John Leverett.

Some Quakers say yᵗ they are promised to have order for yᵉ liberty of being with you.

News of the sufferings of Friends in New England had indeed reached their Friends in the old country; Edward Burrough[55] had obtained audience of the King and represented in powerful though simple language the story of their inhuman treatment. His appeal resulted in the issue of a Mandamus by the King, dated Whitehall, 9th day of September, 1661, to John Endicott, and the Governors of the other Colonies,[56] commanding that all Quakers condemned to death or imprisoned should be sent to England for trial; Edward Burrough urged that this order should be sent with all speed, but the King objected, in his usual spirit of procrastination, that he had “no occasion at present to send a ship thither.” Burrough, however, was given permission to send the Mandamus by the hand of a messenger of his own choosing;[29] he at once decided that Samuel Shattuck,[57] of Salem, a Quaker exile from the Colony, should return as the bearer of the King’s message. English Friends at once chartered a vessel belonging to Ralph Goldsmith,[58] himself a Quaker. After a tempestuous voyage of six weeks the vessel reached the American shore. As she lay anchored in Boston Harbour one Sunday morning in October, 1661, Captain Oliver,[59] a Boston official, boarded her, and on his return to the town it is said he reported: “There is Shattock and the Devil and all.” The Mandamus was delivered in person by Samuel Shattuck to Governor Endicott and the immediate result was that, shortly after, many Quaker prisoners were set at liberty.[60] Whittier, in his poem, The King’s Missive, gives us a beautiful word picture of the incident and its setting; one can imagine how the weary prisoners “paused on their way to look on the martyr graves by the Common side,” and how surpassingly lovely the landscape seemed to[30] eyes so long accustomed to the gloom of the prison-house for

and

And with awe and deep humility we can enter in some faint degree into their silent yet fervent thanksgiving for “the great deliverance God had wrought,” and ah! how vividly we can picture how

Into the heat of this persecution Elizabeth Hooton with her companion, Joan Brocksopp,[61] had ventured. They suffered imprisonment in Boston prison on account of visiting Friends confined there, and were liberated with twenty-five others, after the receipt of John Leverett’s warning letter to Governor Endicott and the General Court.

But we will let Elizabeth Hooton give the story of her call to the service, her journeyings and the hardships she endured on the American Continent, in her own words:[62]

This is to lay before freinds or all where it may come of the sufferings & persecutions which we suffered in newe England J Elizabeth Hooton have tasted on by the prefessours of Boston & Cambridge, who call themselves Jndependants who fled from the bishops formerly, which have behaved themselves, worse then the bishops did to them by many degries, making the people of God to suffer much more then ever they did by the bishops which causeth their name to stink all over the world becaus of cruelty.

Jn yᵉ year 1661 it was upon me from the Lord & my freind Joan Broksopp [paper rubbed at crease and writing illegible] for God & his people to those people in the heate of persecution, & if God required us to lay down our lives for the testimony of Jesus & in love to their soules, not knowing but what they might heare & so be saved yᵗ they might be left without excuse & God might have his glory & we cleare of their bloud if they would not heare: ane old woman above three score yeares old when J went thither & my companion, but they had made a lawe of a hunder pounds fine to evry ship yᵗ caried a quaker & to cary them back againe, so yᵗ no ship would cary us from England thither, but we took ship to Virginia, & when we came there many ships denied us, & therfore we knew nothing but to goe by land which was a dangerous voyage, yet God was pleased to order us a way by a Katch to carie us a part of the way, & so we went the rest by land.[63]

When we came to Boston after a hard passage then there was no house to receive us as we knewe of by reason of their fines, yet did we venture in the night to a woman friends house where when we were gotten in, it pleased the Lord yᵗ we stayed yᵉ night by reason yᵗ the tyde did rise so speedily as we could not get a way, & so we went away in the morning to prison to visit freinds; but the Jaylour & his wife being filled full of cruelty, they would not let us come neare to the prison to see our freinds, but haled us away & he went to the Governour Jndicot & brought us before him, & many questions he asked us, to which the Lord inabled us to answer, but a mittimus he made to cary us to the Goale; for if any called quakers came into yᵗ country yᵗ was crime enough to commit us to prison without any just offence of lawe, & four of our freinds was hanged upon yᵗ same act of their own making for if they shall[32] ask if they be quaker, & if they own it then yᵗ was crime enough to hange them: One of them called William Leathry [Leddra] was hanged since the king came to England & he saide yᵗ he would appeale to the Lawes of Old England, he was hanged; & another[64] he did appeale to the generall Court of Boston he was reprieved though once condemned with the other yᵗ was hanged:

Allso they put 29 of us into prison at Boston till the generall Court did sit there, & when they sat in their Court they did call severall Juries upon us, wherby some were condemned to be hanged, some to be whipt at the carts taille, & some to be kept into prison, till they should resolve how to dispose of us; but another Jury after yᵗ was called which did condemne us to be banished to the French Jland, but yᵗ did not hold & after yᵗ they called another Jury which condemned us all to be driven out of their Jurisdiction by men & horses armed with swords & staffes & weapons of warre who went alonge with us neire two dayes journey in the willdernes, & there they left us towards the night amongst the great rivers & many wild beasts yᵗ useth to devoure & yᵗ night we lay in the woods without any victualls, but a fewe biskets yᵗ we brought with us which we soaked in the water, so did the Lord help & deliver us & one caried another through the waters & we escaped their hands.

And their lawes were broken, & yᵗ which they intendet against us it may fall upon themselves, & was a deliverance never to be forgotten praises be to the Lord for ever & ever & now their Lawes being broken & we delivered, for the terrour of the Lord did so seise upon them when we were in prison at the time of the Court, they were distressed both night & day as Caen was when he had Slaine his brother & they raised up all their souldiers about in the country to defend themselves against us that intended them no hurt, so did we come to Providence & Rhod Jland where was appointed by freinds a generall meeting[65] for New England where we were abundantly refreshed one with another for the space of a week, so yᵗ the persecutors of Boston & professors there were tormented because of innocent blood which they had shed they thought ane army was comming against them wᶜʰ was no other then yᵉ feare yᵗ surprised yᵉ hypocrite, yᵉ wrath of yᵉ Lord exceedingly seised upon them while we were kept in prison.

So we tooke shipping & went to Barbados & afterwards was moved to returne to New Englᵈ againe, through much of this country we went amonst ffriends & then was moved[33] to goe to Boston againe & cry through yᵉ towne, after yᵉ Lawe was broken, & then yᵉ Constable tooke hold of us to carry me to yᵉ ship & yᵉ wicked officer said it was their delight & could rejoice to follow us to yᵉ execution as much as ever they did, in wᶜʰ ship we did both of us Returne to England. & yᵉ bloud-thirsty men stopped in their desires blessed be yᵉ Lord for ever & for ever.

Two contemporary letters to Margaret Fell[66] give us a glimpse of the travellers in Barbados. Joan Brocksopp, writing from that island, 9th of August, 1661, says:[67] “We came here about A week since. We expect to Returne thether [Boston] agayne. Elizabeth Houtton dearly saluts thee.”

Ann Clayton,[68] writing also from Barbados under the same date, says:[69]

I shall pas towards New England as soon as Conuenient opertunity p̄sents, and Jeane Brocksopp hath thoughts of going with mee, for she sayth shee is not yet Cleare of that Place, & its like Elizabeth Houton may Returne againe alsoe. Theyer Law is bad, but yᵉ Powre of yᵉ Lord is sufisient, hee alone p̄serue vs in it to trust that hee may haue yᵉ whole prayes of his owne worke, and be sanctified in all our Harts Amen.

A. C.

An account of Elizabeth Hooton and her companion’s sufferings and the perils they passed through is given in New England Judged, but this account somewhat lacks the vivid touches of the autobiographical narrative given above. In the following words the travellers conclude the record of their experiences:[70]

Now ffriends as yᵉ Lord hath delivʳed us from yᵉ first sore travell that yᵉ hands of those bloud thirsty men could not prevaile to take away oʳ lives, but we came home againe unlookt for of[34] many yᵗ we should ever returne so safelie because yᵉ heate of persecution ranged over yᵉ Nations, & an ill savour & example they set forth wᶜʰ strengthned yᵉ hands of yᵉ wicked in all those Countries as Virginia & Mariland, & over all yᵉ Dutch plantations, thinking to have rooted out yᵉ Truth & its Children.

Joan Brocksopp, too, adds her testimony, and in her Lamentation for New England writes:[71]

Oh how doth my Soul pity you, ye Rulers of Boston, that ever ye should be so ignorant of your own Salvation, to turn the truth of our God into a ly, and put his Servants to death when he sent them among you to warn you.... Oh ye Rulers of Boston, my heart is made sad when I remember your condition and your state, how you are found out of the ways of God against your own soules.... And say not but that you were warned in your Life time by one who is a true Lover of the Seed of God, known unto the World by the Name of

Jone Brooksop

The 4 Month 1662.

And so at length after many hairbreadth escapes, “Elizabeth,” in the words of the old Chronicler, “having also suffered for her Testimony to the Truth returned to old England and abode some space of time at her own Habitation.”[72]

A perilous journey for two women, neither of them young, to undertake, and one marvels at the high courage and faith, and the deep sense of the guiding hand of God, which sent them forth “looking death in the face” to deliver the message of their Lord.

It is easy for us, at this comfortable distance, in an ordered society in which one believes what he wants to believe—or peradventure believes nothing at all—to say that these Friends walked of their own accord into the lion’s den.... That is undoubtedly true, but it indicates a superficial acquaintance with the spirit of these Quakers.... They would have preferred the life of comfort to the hard prison and the gallows rope if they could have taken the line of least resistance with inward peace, but that was impossible to them.... They had learned to obey the visions which they believed were heavenly, and they had grown accustomed to go straight ahead where the Voice which they believed to be Divine called them.

Rufus M. Jones, Quakers in the American Colonies, p. 80.

To one of Elizabeth Hooton’s temperament it was obviously impossible that there should be any long period of rest after her arduous journeyings, and we soon find her dauntlessly remonstrating with magistrates, visiting prisoners, and appearing before King Charles II. About this period she rented a farm near Syston or Sileby in Leicestershire, which was worked for her by her son Samuel, its assessable value being £5. In 1662 we find that Samuel was “taken at a meeting” possibly at that place and thrown into Leicester prison, and from him were taken “three mares with geares.” This distraint is the subject of many letters to the King, the Lord Chamberlain, and various other people. On reading these epistles one is frequently reminded of the unjust judge and the importunate widow; it is not at all clear that she received reparation, though her numberless[36] appeals, one would have thought, might have proved sufficiently wearisome.

The following is E. Hooton’s own account of one interview with the King, perhaps the first:[73]

ffreinds,

My goeing to London hath not beene for my owne ends, but in obedience to the will of god, for it was layed before me, when J were on the sea, and in great danger of my life, that J should goe before the King to witnesse for god, whether he would heare or noe, and to lay downe my life as J did at Boston if it bee required, and the Lord hath giuen me peace in my Journey, and god hath soe ordered that the takeing away of my Cattle hath beene very seruiceable, for by that meanes haue J had great priuiledge to speake to the faces of the great men, they had noe wayes to Couer their deceits, nor send me to prison whatsoeuer J said, because the oppression was layed before them, and there waited J for Justice, and Judgement, and equity, from day to day, soe did this oppression Ring ouer all the Court, and among the souldiers, and many of the Citisens, and Countrey men and water men that were at the Whitehall and J laboured amonge them both from morning till night, both great men and priests and all sorts of people that there were.

J followed the King with this Cry J waite for Justice of thee o King, for in the Countrey, J can haue noe Justice among the Magistrates, nor Shreiffes, nor Baylyes, for they haue taken away my goods contrary to the Law, soe did J open the grieuances of our freinds all ouer the Nation, the Cry of the Jnnocent is great, for they haue made Lawes to persecute Conscience, and J followed the King wheresoeuer he went with this Cry, the Cry of the innocent regard, J followed him twice to the Tenace Court, and spoke to him when he went vp into his Coach, after he had beene at his sport, and some of them read my Letters openly amongst the rest, the Kings Coachman read one of my Letters aloud, and in some the witnesse of god was raised, to beare witnesse against the scoffers with boldnesse and Courage, and confounded one of the guard that did laugh, and stop the mouthes of the gainesayers, and they Cry they were my disciples, and soe great seruice there were for the lord in these things.

J waited vpon the King which way soeuer he went, J mett him in the Parke, and gaue him two letters, which he tooke at my hand, but the people murmured because J did not Kneele, but J went along by the King and spoke as J went, but J could[37] gett noe answer of my Letters, soe J waited for an answer many dayes, and watch for his goeing vp into the Coach in the Court, and some souldiers began to be fauourable to me, and soe let me speake to the King, and soe the power of the lord was raised in me, and J spoke freely to the King and Counsell, that J waited for Justice, and looked for an answer of what J had giuen into his hand, and the power of the lord was risen in me, and the witnesse of god rose in many that did answer me, and some wicked ones said that it was of the deuill and some present made answer and said they wish they had that spirit, and then they said they were my disiples, because they answered on truths behalfe, and the power of the lord was ouer them all, and J had pretty time to speake what the Lord gaue me to speake, till a souldier Came and tooke me away, and said it was the Kings Court, and J might not preach there, but J declared through both Courts as J went along and they put me forth at the gates, and it Came vpon me to gett a Coat of sackecloath, and it was plaine to me how J should haue it, soe we made that Coat, and the next morning J were moued to goe amongst them againe at Whitehall in sackecloath and ashes, and the people was much strucken, both great men and women was strucken into silence, the witnesse of god was raised in many, and a fine time J had amongst them, till a souldier pulled me away, and said J should not preach there, but J was moued to speak all the way J went vp to Westminster hall, and through the pallace yard, a great way of it, declareing against the Lawyers, that were vniust in their places, and warneing all people to repent, soe are they left without excuse, if they had neuer more spoken to them, but the Lord is fitting others for the same purpose, but he made me an instrument to make way, that some others may follow in the same exercise, and as they are filling vp the measure of pride and Costlynesse, and wantonnesse, persecution, lasciuiousnesse, with all manner of sin filling vp their measures, soe is the lord now filling vp his violls of wrath to poure out vpon the throne of the beast, soe that all freinds to be faithfull and bold and valliant to the measure, which god hath manifested to you, for a Crowne of life is laid vp for all that abide faithfull.

Elizabeth Hutton.

London the 17ᵗʰ of the 8ᵗʰ Month 1662.

This letter gives sufficient evidence of her determination and the fearlessness of her methods of procedure; an account which reads strangely to-day, when one considers the difficulty of access to the Sovereign and the forces and formalities which guard and hedge him about.

Another letter, undated, addressed “To you yᵗ are Judges or Magistrates in yᵉ Court,” possibly belongs to this period. Elizabeth, in very plain language, calls attention to the licentiousness of the times.[74]

... Take heed what you doe Least yᵉ Lord Arise in yᵉ feircenesse of his anger, and find you Beating yoʳ fellow servants, and shamefully abuseing them which doe well, and lett yᵉ wicked goe free. You haue sett yᵉ wicked a worke to spoyle vs of our goodes, and putt vs in prison for worshipping god, and turne yoʳ sword backward, which yᵉ higher power cannot doe, soe you make yoʳselues rediculouse to all people who haue sence and reason ... god will not be mocked, for such as you sowe such must you reape: for yᵉ cry of yᵉ Jnnocent will arise in yᵉ eares of yᵉ Lord, and he will terriblely shake yᵉ wicked: then will yoʳ dayes of pleasure be turned into mourning, & weepeing and howleing. Oh yᵗ you would consider this betimes, before it be too late, and instead of pulling downe yᵉ houses of gods people, pull downe whore houses and play houses, which keepes yᵉ people in vanitie and wickedneess. Every wicked worke is now att Libertie; and vertue Rightiousnesse & holynesse you sett yoʳ selues against with all yoʳ force. Oh what a nation would this be if you might haue yoʳ wills. Goe into Smythfeild & you shall see what store of play houses there is; and what abundance of wicked company resorts to them; which greiues the spirit of yᵉ Lord in yᵉ hearts of his people, to see yᵉ wickednesse of this citty.

After more in the same strain the letter concludes:

J am a Louer of yoʳ soules yᵗ am sent to warne you.

Elisabeth Hooton.

Although Charles II. had by his Mandamus issued in 1661 obtained some remission of the cruelties practised against the Quakers in Massachusetts, he appears to have quickly repented his clemency, for in an Order in Council, issued 28th of June, 1662, after acknowledging the receipt of an Address from that Colony and confirming the Patent and Charter granted by his father, he continues:

And as the principal end of their Charter was liberty of conscience His Majesty requires that those who desire to perform their devotions according to the Book of Common Prayer be not[39] denied the exercise thereof nor undergo any predjudice thereby and that all persons of good and honest lives be admitted to the Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper according to the Book of Common Prayer and their children to Baptism. We cannot be understood hereby to direct or wish that any indulgence should be granted to those persons commonly called Quakers, whose principles being inconsistent with any kind of Government, we have found it necessary, by the advice of our Parliament, here to make a sharp Law against them and are well contented that you do the like there.

Undeterred by the prospect of further persecution and the improbability of the King again intervening on behalf of the Quakers, Elizabeth Hooton once more believed herself called of the Lord to visit New England. This time she carried with her a licence from the King “to purchase land in any of his plantations beyond the seas.” One cannot help suspecting that King Charles, wearied with her importunities, had hit upon this method of ridding himself of the necessity of an enquiry into the high-handed proceedings of the Leicestershire magistrates, of which she had so vigourously complained, and that it would be a matter of perfect indifference to him whether she succeeded in making good the purchase in the Boston Courts, or not. Fortunately, again, the account of her journey and her sufferings can be given in her own words. She says:[75]

Afterwards was J moved of yᵉ Lord & called by his spᵗ to goe to New England againe, & tooke wᵗʰ me my Daughter to beare there my 2ᵈ Testimony, where when yᵉ persecutoʳˢ understood J was come they would have fined yᵉ ships Mʳ 100ˡⁱ, but yᵗ he told them J had been wᵗʰ yᵉ King & thither was J come to buy an house so stopped them from seizing on his goods, when J had been a while in yᵉ Country among ffriends, then came J up to Boston to buy an house & went to their Courts 4 times but they denied it me in open Court by James Oliver, who was one of their chief a persecutor, so J told yᵐ yᵗ if they denyed me an house yᵉ King having promised us libertie in any of his plantaçons beyond yᵉ Sea then might J goe to England & lay it before yᵉ King if God was pleased.