The Project Gutenberg eBook of The story of chamber music, by Nicholas Kilburn

Title: The story of chamber music

Author: Nicholas Kilburn

Release Date: March 4, 2023 [eBook #70203]

Language: English

Produced by: Andrew Sly, MFR, Linda Cantoni, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

MUSIC-STORY

SERIES

CHAMBER MUSIC

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTES

The Music Story Series

Edited by

FREDERICK J. CROWEST.

The

Story of Chamber Music

The Music Story Series.

Already published in this Series.

THE STORY OF ORATORIO. By Annie Patterson, B.A., Mus. Doc. With Illustrations.

THE STORY OF NOTATION. By C.F. Abdy Williams, M.A., Mus. Bac. With Illustrations.

THE STORY OF THE ORGAN. By C.F. Abdy Williams, M.A., Mus. Bac. With Illustrations.

THE STORY OF CHAMBER MUSIC. By N. Kilburn, Mus. Bac. (Cantab). With Illustrations.

The next volume will be

THE STORY OF THE VIOLIN. By Paul Stoeving. With Illustrations.

This Series, in superior leather bindings, may be had

on application to the Publishers.

[ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.]

Sir E. Burne-Jones, pinx.

F. Hollyer, photo.

Chant d’Amour.

BY

N. Kilburn

Mus. Bac. (Cantab.)

Conductor of the Middlesbrough, Sunderland, and

Bishop Auckland Musical Societies.

London

The Walter Scott Publishing Co., Ltd.

New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons

1904

-v-

Berlioz, who, by the way, wrote no chamber music save a serenade for two flutes and harp (“L’Enfance du Christ”), in his imaginative fashion somewhere speculates as to which of his own works he would preserve if it were ordained that all except one should perish. In like manner, we may ask ourselves which of the great forms of musical composition we would plead for in case all the rest were doomed to destruction. Music for the orchestra, with its vivid colours, its strength and delicacy; the vast range of choral music; works for the organ, that huge modern plexus of pipe and reed;—these and others no doubt have strong claims on our musical affections. But, if forced to such a choice, it is certain that many a musician would, without hesitation, pledge himself to uphold the claims of Chamber music, for who can measure the almost infinite variety and charm which it affords, and that, too, with the slenderest means?

Probably no other form of music would wear so well as this, and to hardly any other could we turn, day by day, with such abiding satisfaction. Of course, in a-vi- matter of this kind unanimity is not to be expected, and some will no doubt take exception to the view here stated; but, all the same, it may be confidently asserted that the more this kind of music is cultivated, and the more thoroughly its literature is known and studied, the less divergent will opinion tend to become.

The term chamber music, excluding piano solos, which, strictly speaking, do not come under this head, embraces compositions in the form of duets, trios, quartetts, and other larger combinations, for strings (i.e. violins, violas, ’cellos, and double basses), and for wind instruments (chiefly wood wind and horns), both with and without the pianoforte.

Of all the musical forms, this of chamber music is the most adapted for home consumption, and its cultivation by any community may safely be taken as a strong proof of an advanced condition of musical taste.

As regards the present day tendency, no doubt many chamber works are written too much in orchestral style; and, in addition to this, there has arisen an inclination on the part of some composers to make this form express more than it seems naturally fitted to do. We allude to string quartetts such as Raff’s op. 192, “Die Schöne Müllerin,” and Smetana’s “Aus meinem Leben,” which introduce the programme idea into chamber music.

It should not, however, be overlooked that this tendency is by no means absent in the compositions of earlier times. Among others, Bach and Beethoven-vii- contributed towards it; and in a number of Haydn’s string quartetts we find a proneness towards realism, although the usual classical form is in no way violated; such, for example, as op. 33, No. 3, “The Bird”; op. 50, No. 6, “The Frog”; op. 64, No. 5, “The Lark”; op. 74, No. 3, “The Rider.” It is not to be taken that Haydn gave these names to the movements, but that the imitations, while artistically good, are too obvious to be overlooked, and have led up to the fancy titles which have grown round the compositions.

Even in the earliest forms of vocal music such realism may occasionally be found. Mr. Henderson, in his book, How Music Developed, tells of certain composers, about the year 1550, who tried to imitate natural sounds and movements. He names a work by one Jannequin, in which an attempt is made to portray the street life of Paris; and that, too, in a piece written for four voices, and entirely unaccompanied! As showing how, with a difference, history repeats itself, one can hardly help being reminded by this of an orchestral composition by a distinguished musician of our time which has for its purpose the portrayal, in vivid musical colours, of the street life of great London city. We allude, of course, to Dr. Elgar’s Cockaigne overture, “In London Town.”

It is also now the custom to perform chamber music in large concert halls. No doubt, so far as the public is concerned, this is convenient, and maybe it is, financially, essential. None the less it cannot but be regarded as a perversion, for such music is heard to the-viii- greatest advantage under what may be called domestic conditions. Richard Wagner said that he never knew what Beethoven’s sonatas really meant until he heard them played by Liszt, under the most sympathetic conditions, at Wahnfried, his (Wagner’s) residence in Bayreuth.

The String Quartett may be regarded as the prototype, on the instrumental side, of chamber music, and along with it must be placed the other like forms of Quintett, Sextett, etc.; also the Octett, and Double Quartett, which differs in its antiphonal style from the Octett.

All these imply the opportunity for perfect intonation. The use of the pianoforte, however, introduces another “atmosphere.” Perfect intonation is no longer possible, and the purity which the “strings” afford is of necessity somewhat marred.

It may no doubt be fairly urged that “all life is but a compromise,” and that the utility of the pianoforte and the splendid array of compositions which it has called forth condone its defects. This is unquestionably true, but none the less it must be said, in spite of the practical hindrances which exist, that the imperfect intonation of the tempered scale falls short of the artistic ideal.

The late Sir G.A. Macfarren, although an advocate of the tempered scale, acknowledges that “on the voice and on bowed instruments the smallest gradations of pitch are produceable, and so all notes, in all keys, can be justly tuned, which, among others, is one reason for-ix- the exceptional delight given by music that is represented by either of these means.”[1]

Those who are interested will find the matter fully argued in Perronet Thompson’s treatise on Just Intonation, in the preface of which work the case against the tempered scale is thus stated with characteristic fervour:—“Among the signs of progress in these times (1850!) is the growing discontent with the thing called temperament. Instead of being considered as the crowning exertion of musical skill, it begins to be viewed as a lazy attempt to save trouble, like nailing a telescope to one length for all eyes and distances, or making the fingers of a statue of one medium size. The belief also gains ground that all who are able, as for example singers and violinists, do without it, or more properly, perform in tune in spite of it.”

On the other side a high authority[2] says:—“An ideally tuned scale is as much a dream as the philosopher’s stone, and no one who clearly understands the meaning of Art wants it.” And farther on he adds:—“It will probably be a good many centuries before any new system is justified by such a mass of great artistic works as the one which the instincts of our ancestors have gradually evolved for our advantage.”

Thus we find that one view is based on the ideal principle that if, on instruments of the piano and organ type, one key can be put in perfect tune, the whole matter becomes only a question how practically to get-x- over the mechanical difficulty of modulation into other keys. The other view, of course, is that by the compromise of putting all keys a little out of tune you solve the difficulty most easily; that our present musical system, to which is due the wonders of our present-day music and its magnificent literature, is based on the tempered scale; and, above all, that it works well.

This question no doubt belongs, strictly speaking, to the science of Acoustics; but of all the forms of the art, chamber music is the one most affected by intonation, hence these few words on a deeply interesting matter, which may some day become one of the practical considerations in connection with music.

N.K.

May, 1904.

-xi-

THE BEGINNINGS OF CHAMBER MUSIC.

| PAGE | |

| How Chamber Music began — Early Chamber Music compositions — Musical position of England — Purcell — J.S. Bach — Great violin makers — Haydn and Mozart — Corelli and the compass of the violin — William Shield and 5/4 time | 1 |

CHAMBER MUSIC INSTITUTIONS AND CONCERTS.

| John Banister’s concerts — Thomas Britton, the musical coalman — Britton’s concerts — “Music Meetings” — Oxford Music School — Pepys’s Diary — Evelyn’s Diary — Frederick the Great — Bach and the Emperor — The Emperor Frederick’s compositions — Dando concerts — John Ella and The Musical Union — Analytical programmes and position of platform — Quartett Association — Dannreuther’s Musical Evenings — Sir Charles Hallé’s recitals — Monday Popular Concerts — Joachim — Various chamber music institutions — Japanese chamber music | 12 |

-xii-

HAYDN, P.E. BACH, DITTERSDORF, HANDEL.

| J.S. Bach — Joseph Haydn — Philipp E. Bach — Dittersdorf — Early quartetts of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven — Silence as an effect in music — Haydn’s quartetts — Haydn’s Kaiser Quartett — Haydn’s other chamber music — Handel | 37 |

MOZART.

| Mozart’s C major Quartett — Mozart’s string quartetts — The genius of Mozart — Mozart’s other chamber music — Wagner on Mozart — Mozart’s letter to his father | 59 |

BEETHOVEN.

| Beethoven as democrat — Rhythmic similarities — Beethoven’s first and last compositions — Musical humour — The distinction in Beethoven’s chamber music | 71 |

SCHUBERT, MENDELSSOHN, SCHUMANN, AND SPOHR.

| Schubert as song-writer — Schubert’s chamber music — Mendelssohn — Mendelssohn’s position in England — Mendelssohn’s character — Mendelssohn’s chamber music — Schumann — Schumann as absolute musician — The E♭ Piano Quintett — Piano trios — Spohr’s opinion of Beethoven’s work — Characteristics of his compositions | 82 |

-xiii-

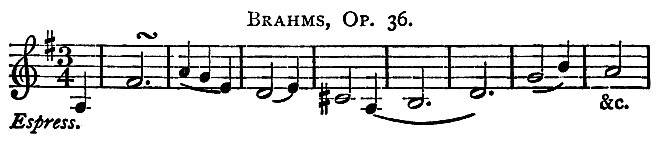

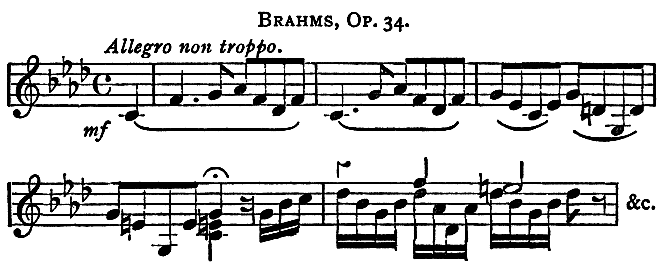

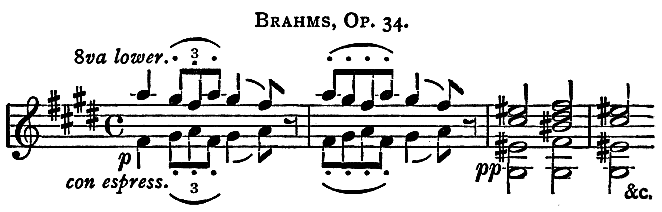

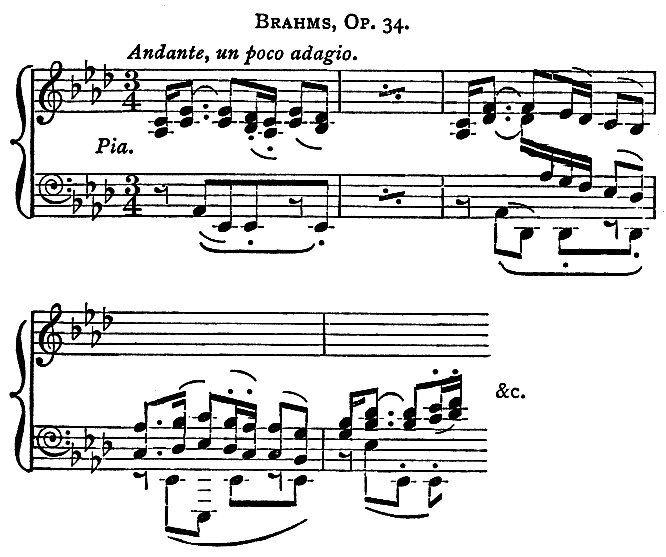

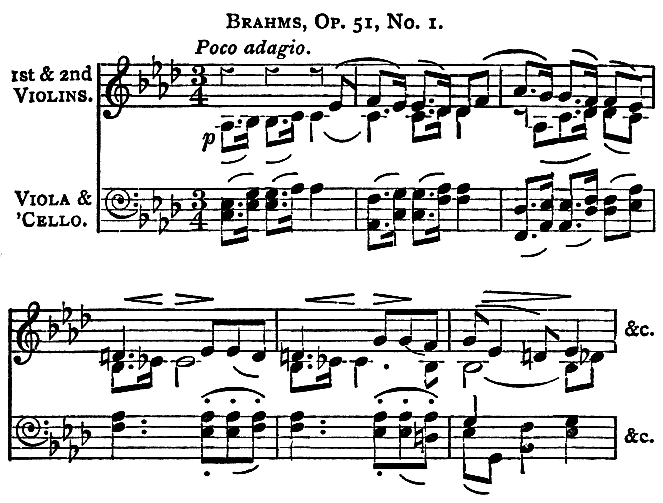

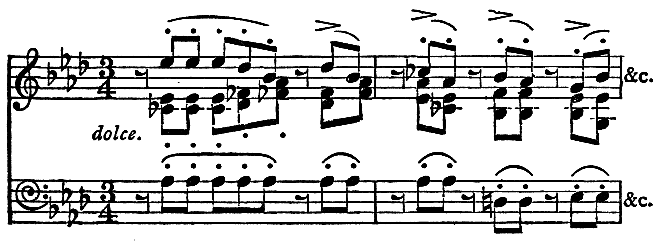

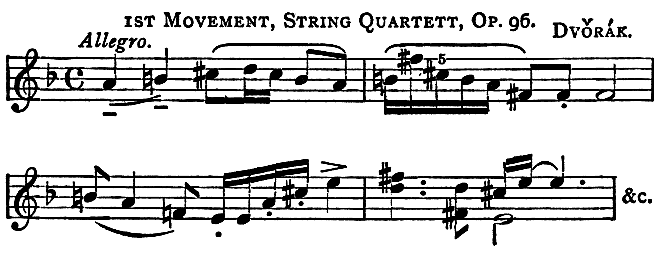

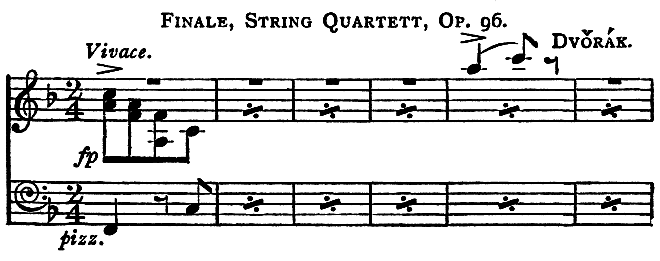

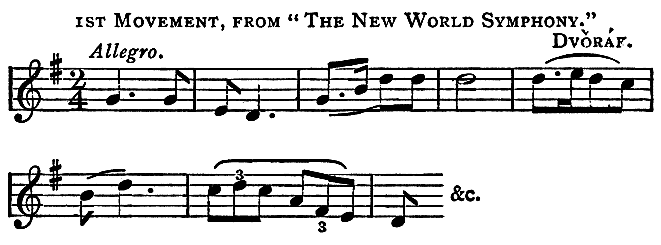

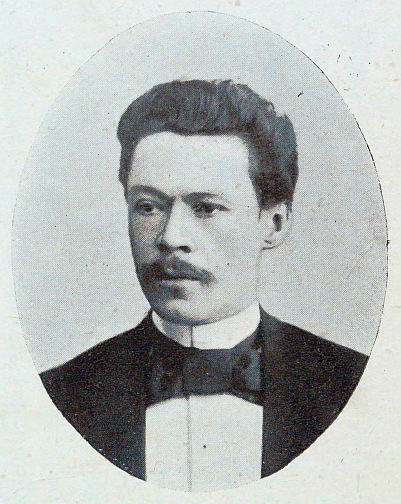

BRAHMS AND DVOŘÁK.

| Opinions of Brahms — Weingartner — H.T. Finck — Bülow on Rubinstein — H. Davey — Schumann — W.J. Henderson — Philip Spitta — Sir Hubert Parry — W.H. Hadow — Piano Trio, op. 8: two versions — Horn Trio, op. 40 — String Sextett in B♭ — String Sextett in G major — Piano Quartett in G minor — Quintett in F minor — String Quartetts — Thematic resemblances — String Quintetts — Clarinet Quintett — Dvořák — Revival of Bohemian music — Birthplace and early career — Criticisms on his works — His symphonic poems for orchestra — An American national style of music — The Negro Quartett — String Quartetts — Piano Quartetts — Piano Trios — String Sextett — Other chamber music | 101 |

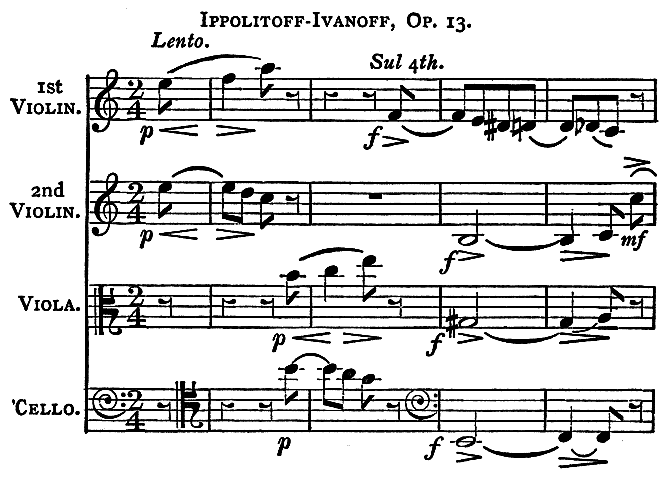

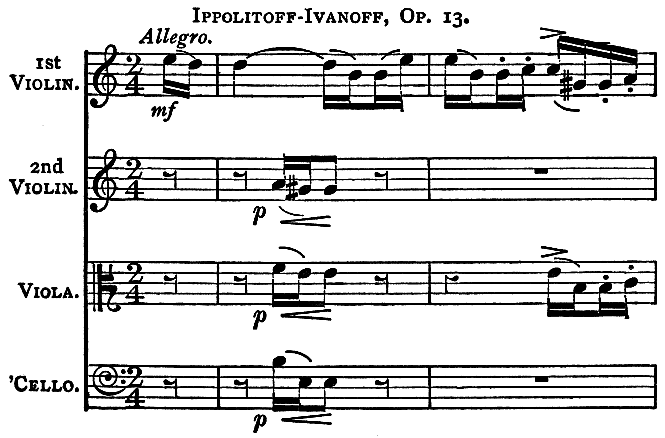

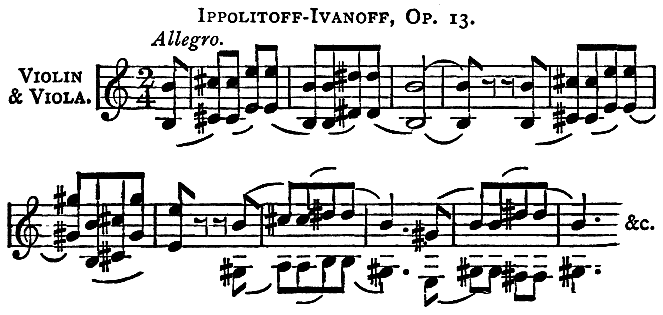

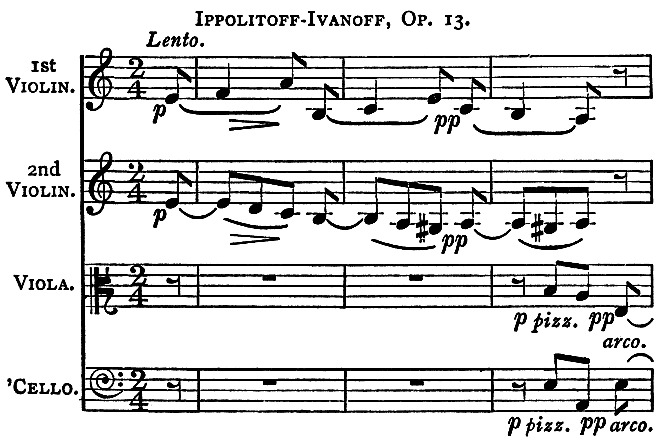

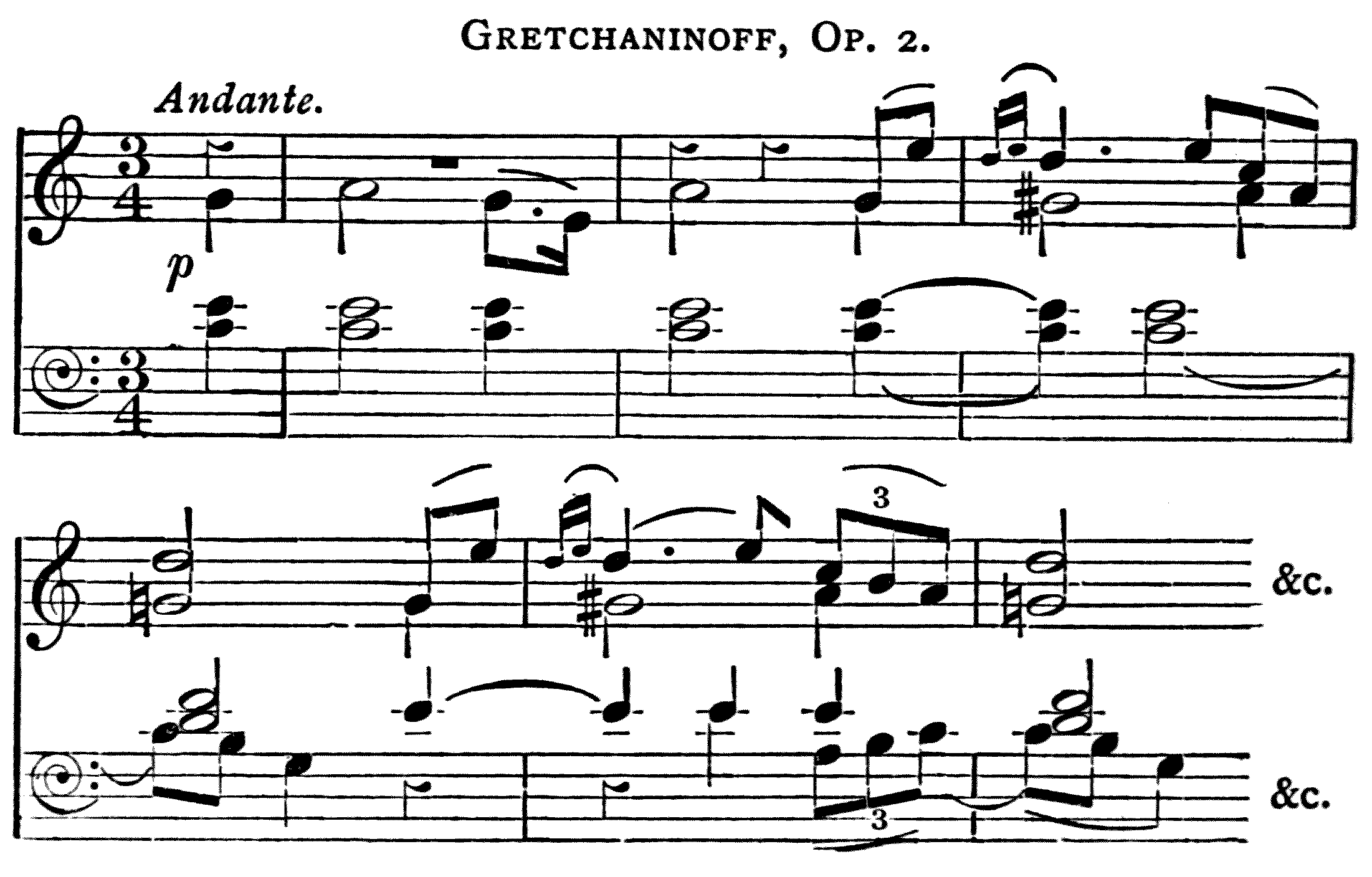

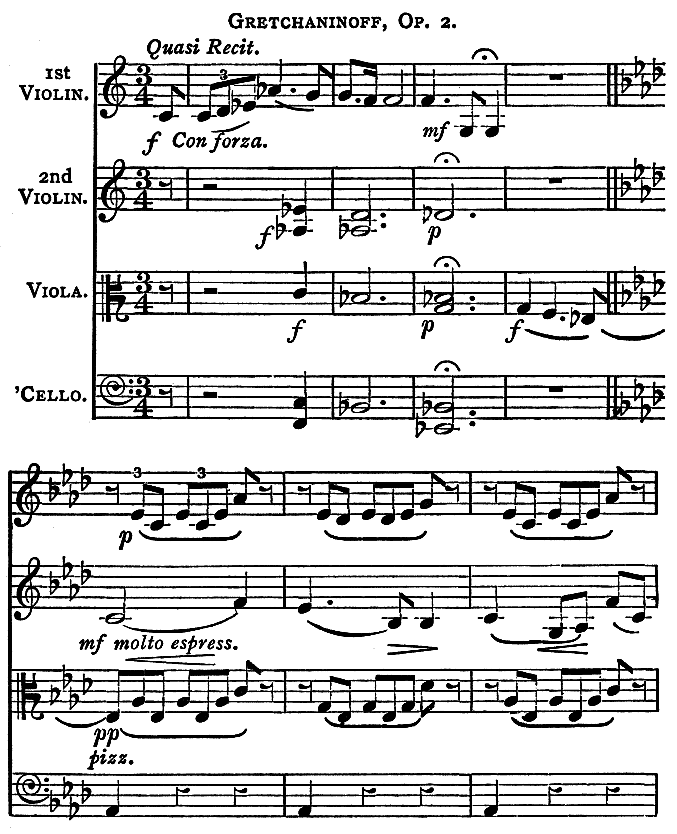

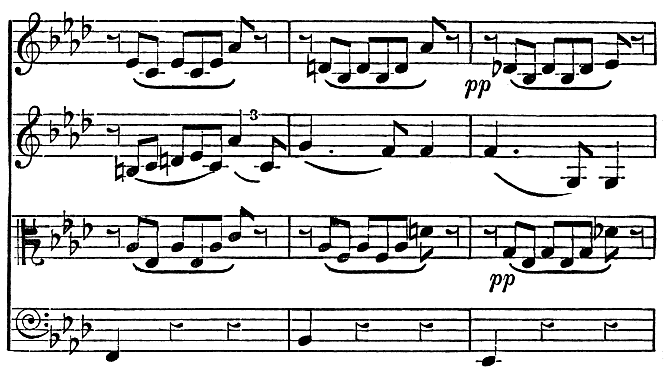

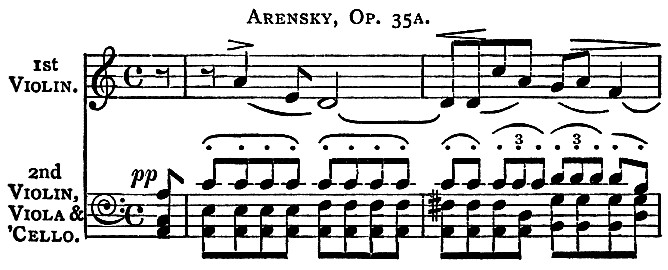

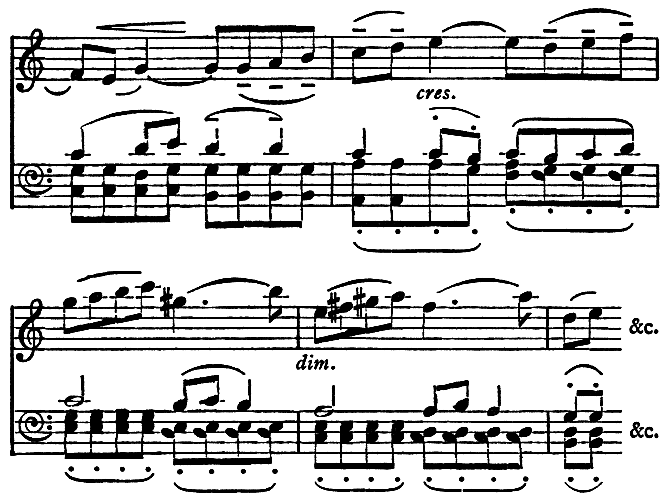

CHAMBER MUSIC OF THE RUSSIAN COMPOSERS.

| Russian chamber music — Glinka — Quartett by Ippolitoff-Ivanoff — Quartett by Gretchaninoff — Mozart on melody — Russian schools of musical thought — Belaieff — String Quartett on name Belaieff — Arensky — Trio in D minor: Arensky — Sokoloff — Tanyeëff — Kopyloff — Tschaïkovsky | 133 |

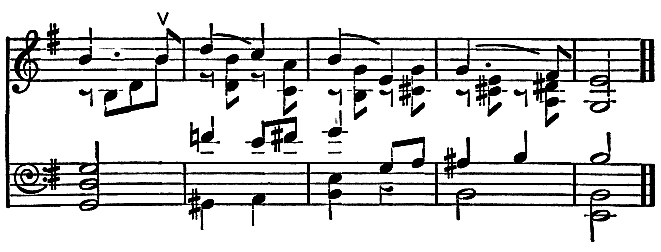

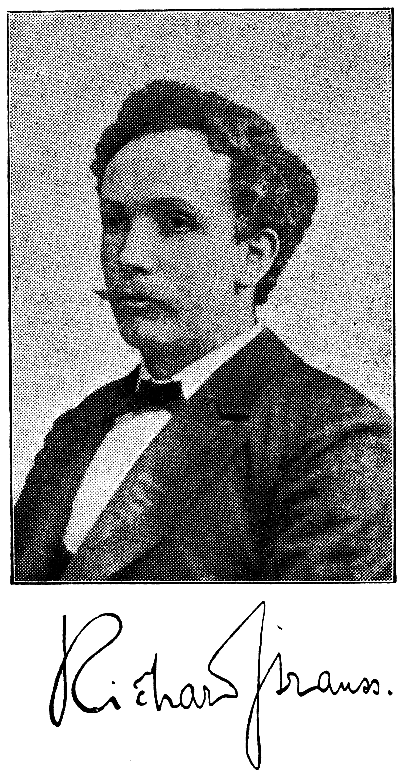

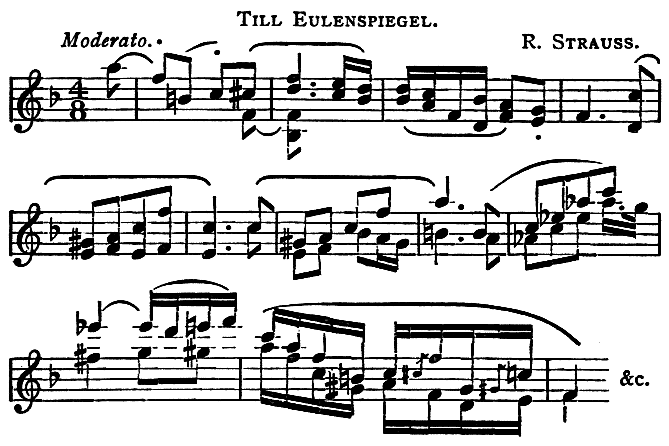

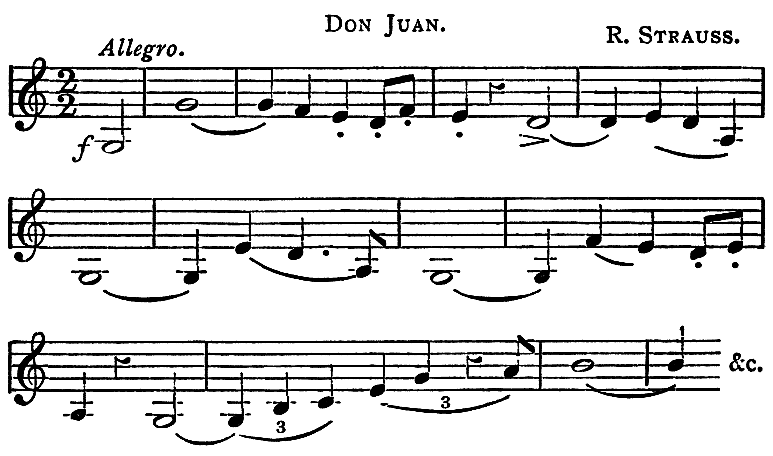

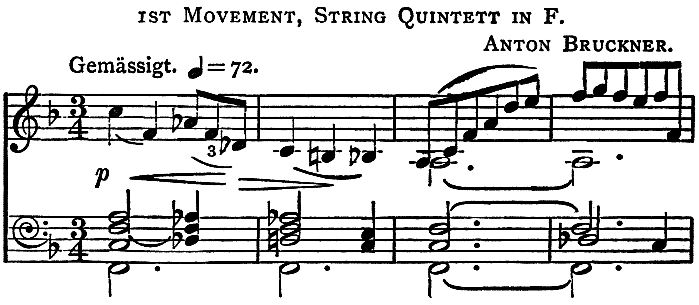

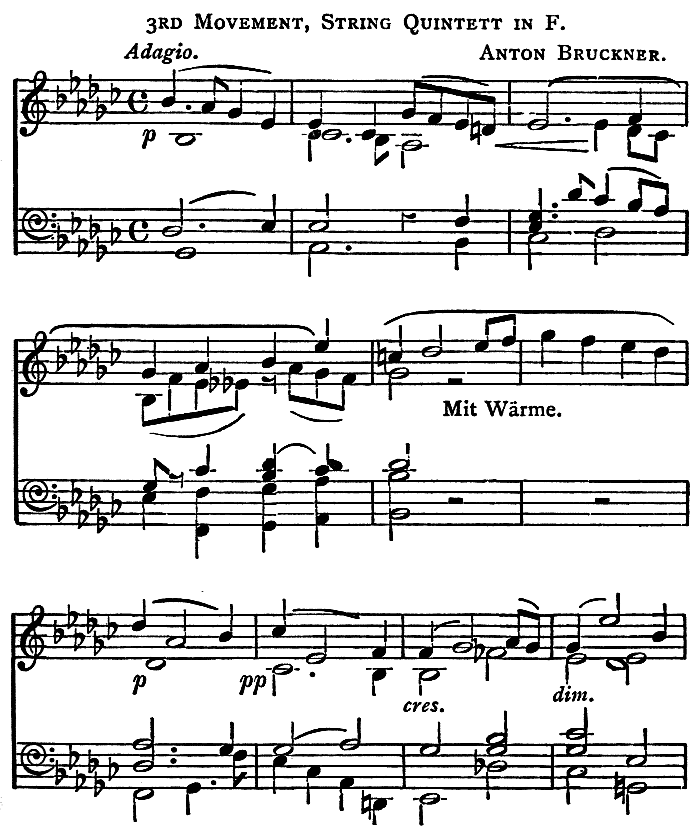

RICHARD STRAUSS AND ANTON BRUCKNER.

| Position with regard to classical form — Strauss’s chamber music — Bruckner’s character and individuality — Bruckner’s symphonies — String quintett in F major — Hanslick on Bruckner’s works — Krehbiel on Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony — Weingartner’s opinion | 177 |

-xiv-

CHAMBER MUSIC OF RECENT TIMES.

| Trio by E. Schütt — Trio by Kirchner — Raff’s C minor Trio — Balfe’s Trio in A major — Trio: C. Hubert Parry — Trio: Bargiel — Sterndale Bennett’s Trio, op. 26 — Trio, D minor: F.E. Bache — Trio, E flat: Nawratil — Trio: Goetz — Trio: Schmidt — Other Trios — String Trios — Quartett: Mackenzie — E flat Quartett: Rheinberger — Quartett: W. Rabl — Quartett: Prout — Quartett: Verdi — Quartett: Onslow — Quartett: W.H. Veit — Unusual combinations | 191 |

| Appendix A. — Chronological and Biographical | 209 |

| Appendix B. — Glossary of Terms | 244 |

| Index | 249 |

-xv-

| PAGE | |

| “Chant d’Amour”: Photogravure after Sir E. Burne-Jones’s Painting | Frontispiece |

| A Group of Musicians | 15 |

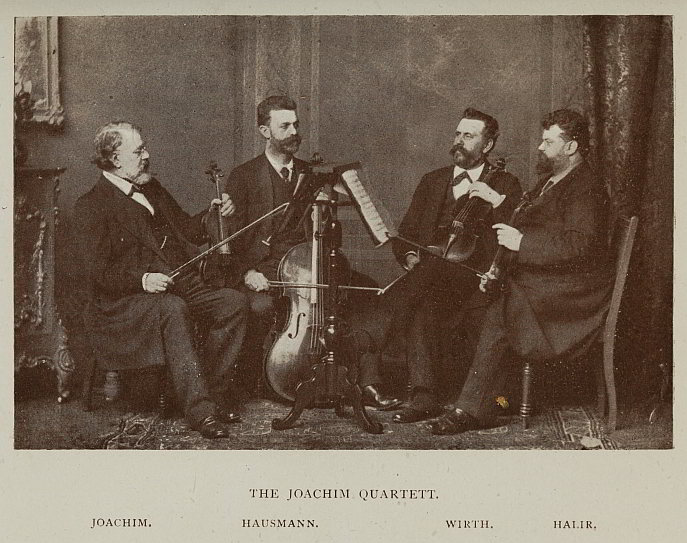

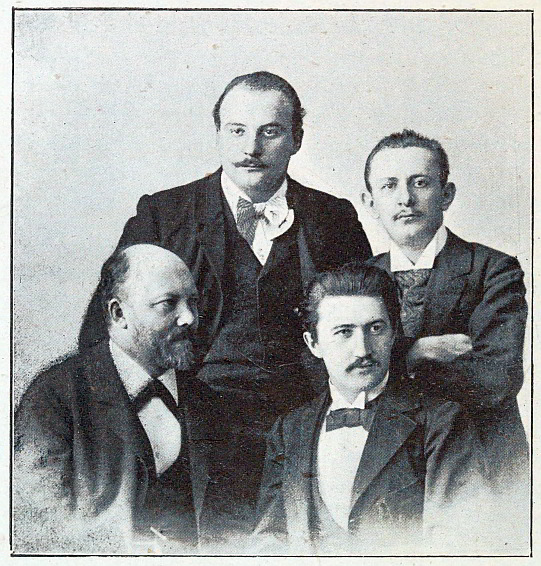

| The Joachim Quartett | Face 32 |

| Beethoven | Face 71 |

| Brahms | Face 101 |

| The Bohemian Quartett | Face 123 |

| Ippolitoff-Ivanoff and Arensky | Face 135 |

| Richard Strauss | 178 |

-1-

The

Story of Chamber Music.

THE BEGINNINGS OF CHAMBER MUSIC.

How Chamber Music began — Early Chamber Music compositions — Musical position of England — Purcell — J.S. Bach — Great violin makers — Haydn and Mozart — Corelli and the compass of the violin — William Shield and 5/4 time.

“In the time of the Frankish kings,” says Mr. H.E. Krehbiel,[3] “the word chamber was applied to the room in the royal palace in which the monarch’s private property was kept, and in which he looked after his private affairs. When royalty took up the cultivation of music it was as a private, not as a court function, and the concerts given for the entertainment of the royal family took place in the king’s chamber or private room. The musicians were nothing more nor less than-2- servants in the royal household. This relationship endured into the present century. Haydn was a Haus-officier of Prince Esterhazy. As vice-chapelmaster he had to appear every morning in the prince’s ante-room to receive orders concerning the dinner music and other entertainments of the day.”

This may be taken as one explanation of the origin of chamber music. Another is that near the end of the fifteenth century, madrigals and other pieces which no doubt were originally intended for singing began to be described as “madrigali et arie per sonare et cantare,” or, in the plain English of the time, “apt for voices and instruments,” by which is meant that the instruments joined with the voices probably at first to support them, both performing the same music.

About the same period and earlier it became customary to introduce instrumental music at the banquets of the wealthier classes, and what may be regarded as chamber music was used as a stimulus and a cover for conversation, a practice not even yet quite obsolete.

From some such sources it seems likely that this form of music made a beginning. Composers then began to turn their attention to the growing requirements of such performers, and we find that many works were issued chiefly in the form of Courantes,-3- Sarabandes, Gavottes, Gigues, and other dance forms. Music called Fancies, and sets of Ayres, and other pieces for lutes (a kind of guitar), and viols (the predecessor of the violin), also incidental music for masques, were much in vogue in England about this time, composed, among others, by Morley, Gibbons, John Dowland, Mace, Sympson, Jenkins, Lawes, and Locke. Hugh Aston, an instrumental composer of distinction, may also be mentioned. He left, among other works, a hornpipe which is remarkable. There is also a virginal book in the library at Cambridge that contains two or three hundred pieces for virginals, which instrument was a kind of harpsichord. In 1611 a collection of music for the same instrument was issued, the compositions of Byrd, Bull, and Gibbons. It was called “Parthenia.” Byrd’s “Variations on the Carman’s Whistle,” and Sellinger’s “Round,” are noteworthy works. John Jenkins published sonatas for two violins and a bass, with thorough bass for the organ and theorbo.

This was the great period of English music. Our position as compared with other nations was one of artistic supremacy, and we ought not to forget this as Continental writers are apt to do to-day.[4]

-4-

Later on compositions such as we have mentioned were followed both in England and on the Continent by works of a more highly organised character, and to some of them the titles Sonata and Concerto were applied. These must not, however, be confused with the music of like name of our day, for they were much simpler in construction, and contained little or nothing of what we call development.

Thus we find, to name but a few examples, that Reinken (1623-1722), a pupil of the celebrated Amsterdam composer, Sweelinck, wrote a notable Quartett, or Suite, for two violins, viola, and bass, which he called “Hortus Musicus.” Our own Henry Purcell (1658-95), whose compositions in many styles are so justly held in high esteem, left among others the so-called Golden Sonata, one of a fine set for stringed instruments. Corelli (1653-1713) too, a distinguished violinist and composer, of-5- Italian origin, published in 1685 (the year J.S. Bach was born), twelve chamber sonatas for two violins, ’cello, and harpsichord.

John Sebastian Bach (1685-1750), whose mighty influence pervades the art of music of our day, and seems likely to increase in the future, wrote in all styles, even that of the Humorous Cantata. We need, however, here only mention his clavier music, which alone extends to four goodly-sized volumes; his compositions for clavier and strings, and flute; and, especially as belonging more particularly to chamber music, the Sonata in C major for two violins and clavier; another in G major for flute, violin, and clavier; and also that in C minor for the same instruments, from the so-called “Musical Offering,” which was written for the Emperor Frederick the Great of Prussia, on a theme given to Bach by that monarch himself.

Among those more or less distinguished composers who contributed to the store of chamber music about this time, may be named Geminiani (1680-1762), Tartini (1692-1770), Giardini (1716-96), Pugnani (1731-98), and Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714-88), a son of John Sebastian. These lead up to, among others, Dittersdorf (1739-99), Boccherini (1743-1805), and-6- Haydn (1732-1809), whose first String Quartett was published in 1755.

It may not, however, be overlooked that the influence of the great violin makers, the families Amati, Guarneri, and Stradivari (1535-1745), contributed not a little to the advancement of chamber music, for these men were no mere artisans engaged in the manufacture of instruments from a commercial point of view. Rather were they true artists, and the product of their labours furnished both performers and composers the highest means of artistic expression. During the period in which they worked, the old viol was gradually changed into the violin, viola, and ’cello of our time, a change which has had a most important and far-reaching effect on the entire art of music.

With Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) we enter a new era, for before the time

of this master and of Mozart, says a high authority,[5] “such a form

(the string quartett) hardly existed, and their work with it was such

as almost to complete its artistic maturity in the course of one

generation.” The same writer also states that prior to the time of

these two great masters “the pleasure of the player-7- was more studied

than that of the auditor,” by composers of chamber music. In this

connection, technically considered, it is interesting to note that

Corelli, who has already been mentioned as a distinguished performer

on the violin as well as a composer, regarded the note D

as the upward limit of the violin’s compass, and he refused to entertain,

on the ground that it was impossible, any passage written higher than

this note.[6] Yet in Haydn’s Quartett op. 76, No. 5, which was written

not so very long after the time referred to, there is a violin passage

that reaches the note F♯ one octave and two notes higher than Corelli’s

limit; also in the finale of the same composer’s Quartett op. 77, No.

2, a passage reaching an octave higher, and in other of his quartetts,

the adjacent high notes C and B♭ are frequently written. Thus we see

that along with the growth of musical ideas there was a corresponding

expansion of technical means.

as the upward limit of the violin’s compass, and he refused to entertain,

on the ground that it was impossible, any passage written higher than

this note.[6] Yet in Haydn’s Quartett op. 76, No. 5, which was written

not so very long after the time referred to, there is a violin passage

that reaches the note F♯ one octave and two notes higher than Corelli’s

limit; also in the finale of the same composer’s Quartett op. 77, No.

2, a passage reaching an octave higher, and in other of his quartetts,

the adjacent high notes C and B♭ are frequently written. Thus we see

that along with the growth of musical ideas there was a corresponding

expansion of technical means.

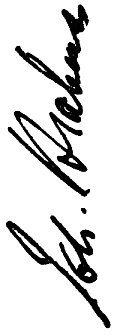

As regards the music of this particular period, even in features which are generally supposed to belong exclusively to modern music, it is interesting to find that the older composers have really set the pattern. For example, the popular idea is that the 5/4 movement-8- in Tschaïkovsky’s Pathetique Symphony is a rhythmic novelty. Yet in a set of six chamber trios published in 1790 by William Shield (1748-1829), Musician-in-Ordinary to his Majesty, may be found such a movement, and this is all the more curious seeing that it is marked “Alla Sclavonia,” thereby betokening some connection between Russian music and this unusual kind of time. Shield was a prolific writer of works both practical and theoretic. Some forty, now forgotten, operas are credited to him, but his songs remain among the best which England has produced, such for instance as “The Wolf,” “Old Towler,” “Arethusa,” and “The Thorn.”

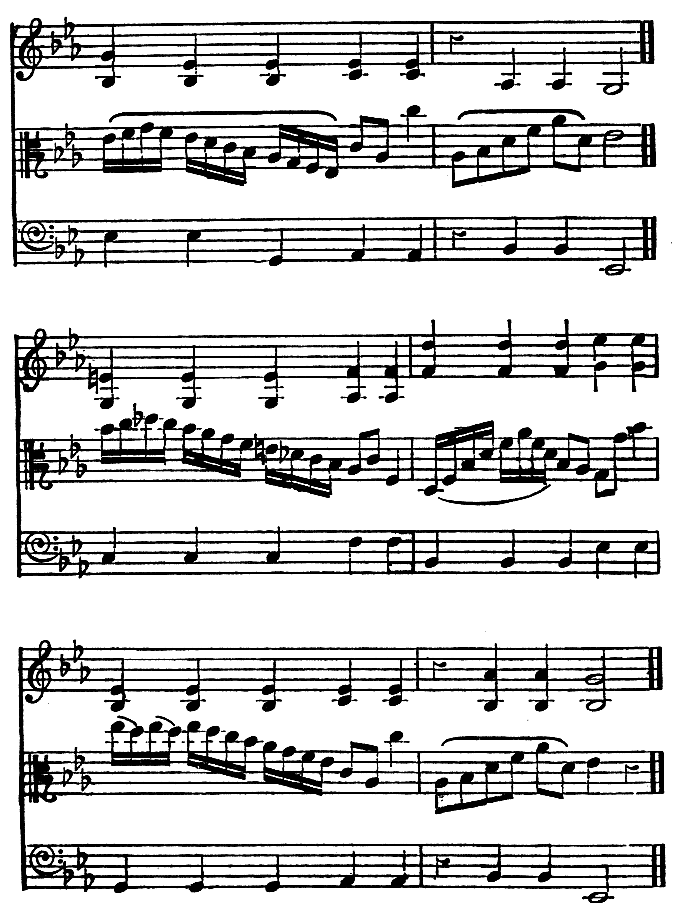

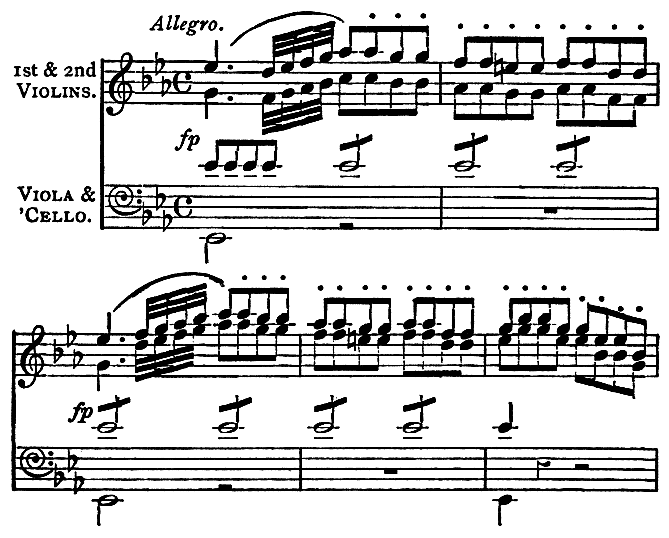

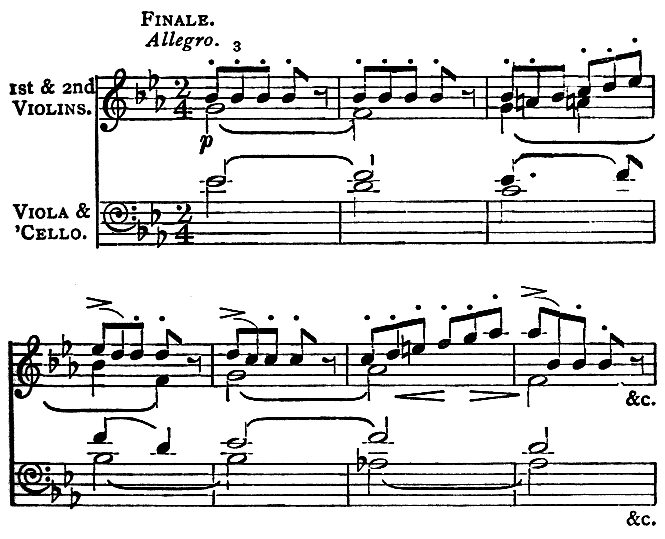

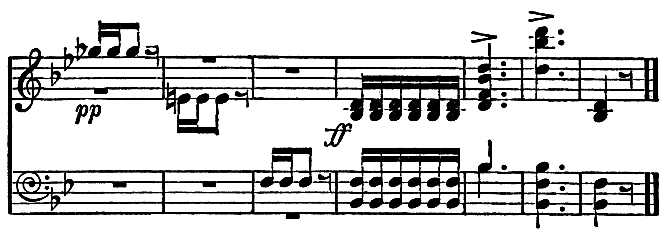

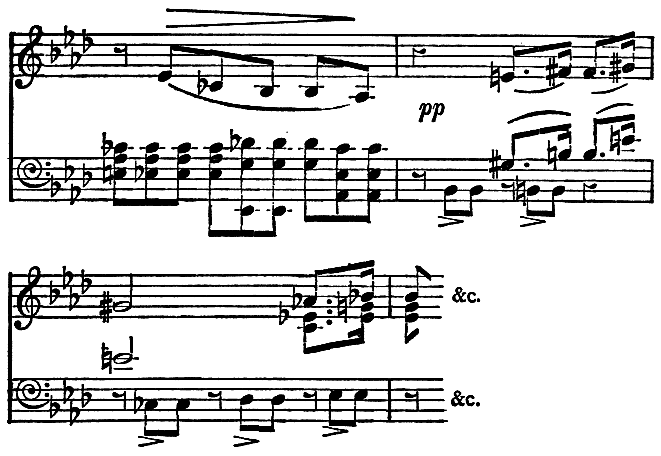

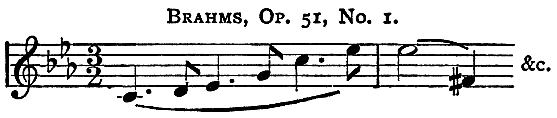

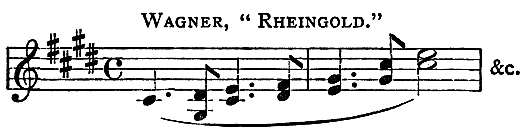

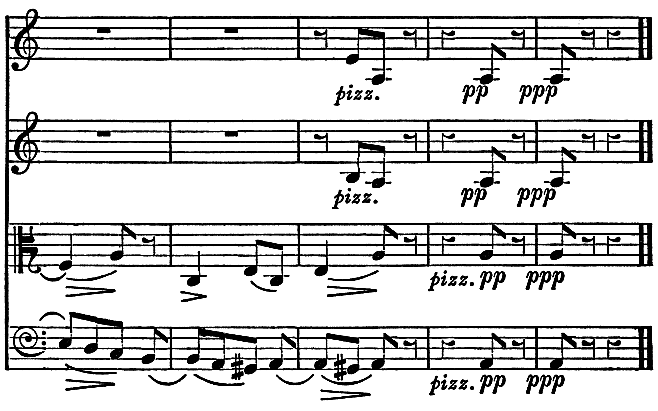

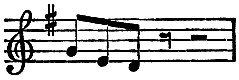

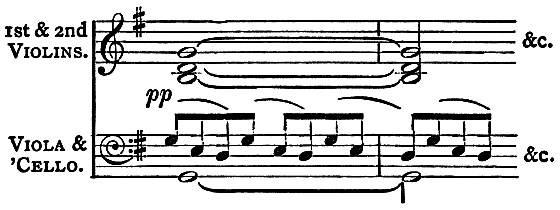

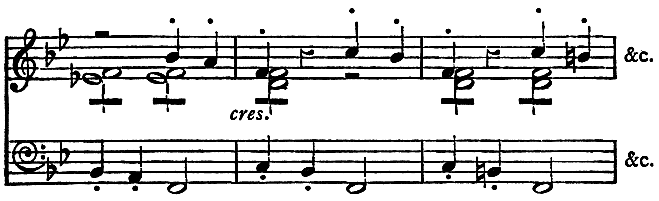

We quote a portion of the String Trio which has been mentioned:—

Giuoco: Alla sclavonia tempo straniere con variazione.

-11-

The 2nd variation has a syncopated figure in the first violin part.

The 3rd variation gives the solo part to the violoncello, and this leads to a coda concluding the movement with a repetition of the original theme.

-12-

CHAMBER MUSIC INSTITUTIONS AND CONCERTS.

John Banister’s concerts — Thomas Britton, the musical coalman — Britton’s concerts — “Music Meetings” — Oxford Music School — Pepys’s Diary — Evelyn’s Diary — Frederick the Great — Bach and the Emperor — The Emperor Frederick’s compositions — Dando concerts — John Ella and The Musical Union — Analytical programmes and position of platform — Quartett Association — Dannreuther’s Musical Evenings — Sir Charles Hallé’s recitals — Monday Popular Concerts — Joachim — Various chamber music institutions — Japanese chamber music.

With the general advancement which we thus see had taken place in instrumental music, there naturally arose a desire for its performance, and this led to the establishment of Concerts, both private and public.

Burney in his History of Music tells us that upon the decease of Baltzar the Lubecker, who was the first leader of King Charles the Second’s new Band of Twenty-four Violins, John Banister (1630-79), the first Englishman who seems to have distinguished himself on the violin, succeeded him. This musician was one of the first who established lucrative concerts in-13- London. These were advertised in the London Gazette, and in No. 742, for December 30th, 1672, there is the following advertisement:—“These are to give notice that at Mr. John Banister’s house, now called the Music School, over against the George Taverne in White Fryers, this present Monday will be music performed by excellent masters, beginning precisely at four of the clock in the afternoon, and every afternoon for the future, precisely at the same hour.”

There are a number of such advertisements, and in the Gazette of December 11th, 1676, Banister’s performance is announced to be held at the Academy in Little Lincoln’s Inn Fields, where it was to begin “with a parley of instruments composed by Mr. Banister, and performed by eminent masters.”

In Mr. North’s Memoirs of Music we have a more minute account of these performances:—“Banister having procured a large room in White Fryers near the Temple Back Gate, and erected an elevated box or gallery for the musicians, whose modesty required curtains, the rest of the room was fitted with seats and small tables, alehouse fashion. One shilling, which was the price of admission, entitled the audience to call for what they pleased! There was very good music, for Banister found means to procure the best hands in-14- London, and some voices, to assist him, and there wanted no variety, for Banister, besides playing on the violin, did wonders on the flageolet to a thro’ base, and several other masters likewise played solos.”

Banister had his first lessons from his father, who was one of the waits in the parish of St. Giles-in-the-Fields. He left behind him a son, John, who became an excellent performer on the violin, and was one of King William’s band, and also played first violin at Drury Lane when operas were first performed there.

In 1678, a year before the decease of the elder Banister, a club for the practice of chamber music, established by Thomas Britton, the celebrated small-coal man, had its beginning, and continued until 1714. Britton[7] (1651-1714) was born in Northamptonshire, and apprenticed to a London coal-dealer; he afterwards carried on business in Aylesbury Street, at the corner of Jerusalem Passage, Clerkenwell, as a small coal (probably charcoal) dealer. He seems to have been a man of progressive mind, and to have cultivated an extensive knowledge of many subjects, including both theoretical and practical music. His learning indeed seems to have led to his being regarded-15- with suspicion on the part of certain narrow-minded and superstitious people, who attributed to him even so strange a mixture as atheism, Jesuitry, and magic.

There does not, however, seem to be any foundation for the imputations which were made against him, for he appears to have been a sincere, plain man, but endowed with fine natural tastes, which raised him so far above his class that he had to pay the usual penalty for such superiority.

-16-

As a result of his study of music he established the club to which reference has been made. Here weekly concerts were held in a large room over his place of business in Clerkenwell, and these became exceedingly fashionable. The performers were drawn from among the most distinguished musicians, professional and amateur, such as Pepusch, Wollaston (the painter), John Banister, John Hughes (the poet), and Abel Whichello. It is also said that Handel frequently played the harpsichord, but the records do not entirely agree on this point. These concerts, which seem to have been due to Britton’s personal influence, together with the mutual love for bibliographical and other studies held by many of his audience, were at first free, but afterwards a subscription was levied. There appears to be no doubt that many learned and titled people, such as the Earls of Oxford, Pembroke, Winchelsea, and Sunderland, were subscribers, and that they fully appreciated and acknowledged the high conversational powers and book learning of the musical small-coal man.

Britton’s books were sold after his death, and the catalogue was issued as “The Library of Mr. Thomas Britton, small-coal man, deceased, who at his own charge kept up a consort of musick above forty years in his little cottage. Being a curious collection of-17- Books in Divinity, History, Physick, and Chimistry, in all volumes.”

His portrait by J. Wollaston, who was one of his supporters, hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in London. So recently as 1892 concerts called the Britton Concerts were given in his memory at the Hampden Club, Phœnix Street, St. Pancras, London.[8]

About the year 1680 the principal music-masters in London, perceiving an eagerness in the public for musical performances, caused a room to be erected in York Buildings and purposely fitted up for concerts, where the best compositions and performers of the time were to be heard. This was called the “music meeting,” and this room was for a long time the place where the lovers of music assembled at the benefit concerts of the most eminent professors of the art.

As regards the provinces, in 1665 a music school was founded at Oxford by the members of the old Oxford meetings which were suppressed during the Rebellion. Anthony Wood speaks of these meetings when King Charles was driven to Oxford. This new (1665) school, it is quaintly recorded, was furnished “with a number of instruments, including an organ of four stopps, and-18- seven desks to lay the books on, at two shillings each.” Subscription concerts were given, and these Oxford gatherings were the first of which any account is to be met with, indeed they seem to have been the only association of the kind in the kingdom. (Hawkins, History of Music.)

For the common and ordinary people there were entertainments suited to their notions of music; these consisted of concerts in unison, as they were called, of fiddles, hautboys, trumpets, etc., performed in booths at fairs held in and about London, but more frequently in certain places called music-houses, of which there were many in the time of King Charles II.

Among the first of this kind was one known by the sign of the Mitre near the west end of St. Paul’s Cathedral. This was about the year 1664. The name of the master of this house was Robert Hubert, alias Forges, who besides being a musician was a collector of natural curiosities.

Another well-known place of this kind was in Stepney, where there was an organ and a band of fiddles and hautboys, and here at times dancing was allowed.

As quaintly casting light on the musical condition of things during this period, the following extracts from Pepys’s Diary may be given:—

“Oct. 1, 1667. To White Hall: and there in the-19- Boarded Gallery did hear the musick with which the King is presented this night by Monsieur Grebus, the master of His musick; both instrumental (I think twenty-four viols.) and vocall; an English song upon Peace. But God forgive me! I never was so little pleased with a concert of musick in my life. The manner of setting words and repeating them out of order and that with a number of voices, makes me sick, the whole design of vocall musick being lost by it. Here was a great press of people, but I did not see many pleased with it, only the instrumental musick he had brought by practice to play very just.”

“Febry. 27, 1668. With my wife to the King’s House to see The Virgin Martyr, the first time it hath been acted a great while; and it is mighty pleasant; not that the play is worth much, but it is freely acted by Beck Marshall. But that which did please me beyond anything in the whole world was the wind-musique when the angel comes down; which is so sweet that it ravished me and indeed, in a word, did wrap up my soul so that it made me really sick, just as I have been formerly when in love with my wife; that neither then nor all the evening going home and at home I was able to think of anything, but remained all night transported, so as I could not believe that ever any musique hath-20- that real command over the soul of a man as this did upon me; and makes me resolve to practice wind-musique, and to make my wife do the like.”

In Evelyn’s Diary of November 20th, 1679, we find the following:—“I dined with Mr. Slingsby, Master of the Mint, with my wife invited to hear musick which was exquisitely performed by foure of the most-renown’d masters: Du Prue, a Frenchman, on the Lute; Signor Bartholomeo, an Italian, on the Harpsichord; Nicolao, on the violin; but above all for its sweetnesse and novelty, the Viol d’amore of five wyre strings plaied on with a bow, being but an ordinary violin played on, lyre-way, by a German. There was also a Flute-douce, now in much request for accompanying the voice. Mr. Slingsby, whose sonn and daughter play’d skilfully, had these meetings frequently in his house.”

In Hawkins’s History under the date November 23rd, 1685, we find a copy of an advertisement of the publication of several sonatas “composed after the Italian way, for one and for two Bass Viols with a thorough Bass, by Mr. August Keenell,” and of their being performed at the Dancing School, Walbrook. Also at the school in York Buildings, some performances on an instrument called the Baritone by the same Mr. Keenell. Again on January 25th, 1693, it is stated that “at the-21- Concert room in York Buildings will be performed Mr. Purcell’s Song composed for St. Cecilia’s day in the year 1692, together with some other compositions of his, both instrumental and vocal, for the Entertainment of His Highness Prince Lewis of Baden.”

Other institutions such as the Academy of Ancient Music, established in 1710, The Anacreontic Society (about 1770), the Ancient Concerts (about 1776) did much for the cultivation of good music, but they were not specially concerned with chamber music.

Of foreign doings, Hawkins relates that in 1598 “upon the arrival of Margaret Queen of Austria at Ferrara to celebrate a double marriage, between herself and Philip III. of Spain, and between Archduke Albert and the Infanta Isabella, the King’s sister, at the monastery of St. Vite the nuns performed a concert in which were heard Lutes, Double Harps, Viols, and other kinds of instruments.” Also in an Italian work of this period called Il Desiderio there occurs a long dialogue on the concerts which were then the entertainment of persons of the first rank in the principal cities of Italy, particularly Venice and Ferrara. The Accademia degli Filarmonica, an important Italian institution, was begun at Vicenza, exactly when is not now known, but certainly before 1565, for in that year the Accademia degli Incantenati was incorporated with it.-22- To this “the nobility and gentry were used to resort once a week to entertain themselves with music.”

Brahms is reported to have said, “Be careful how you speak of the music of princes. One never knows who may have written it.” But even with this note of warning in mind, the story of the Emperor Frederick the Great of Prussia can hardly be passed over, seeing how influential must have been the support which he accorded to the art and to his musicians—Quantz, who composed so many works for the flute (the Emperor’s beloved instrument); C.H. Graun, the conductor; J.G. Graun, the violinist; and especially Philipp Emanuel Bach, a son of the great John Sebastian. The Emperor was accustomed to spend some £7000 a year on his Court music, which shows that it was an affair of considerable importance.

A pleasant and interesting account is recorded of the meeting of J.S. Bach with the Emperor. It was on a Sunday evening in the spring of 1747, as the Emperor was about to open his concert with a flute solo, the stranger’s list was brought to him. Having read it, flute in hand, he turned to the band and said excitedly, “Gentlemen, old Bach is come.” The flute was laid aside, and Bach was sent for at once, no time being allowed him even to change his travelling dress. The-23- elaborately formal greetings over, Bach was invited to try the numerous Silbermann pianos distributed through the palace, the band following from room to room as he tried each instrument. Frederick expressed a desire to hear a six-part fugue, which Bach then improvised with the utmost skill on a theme given to him by the King. Next day, wishing to hear him on his more congenial instrument, the King escorted Bach to all the organs in Potsdam.

One outcome of this visit was the so-called “Musical Offering” which Bach wrote on his return to Leipzig. It consists of an elaborate working out of the royal theme named above, and the work is dedicated to the Emperor.[9]

It is said that the Emperor’s chamber concerts were dominated by himself and his flute, for virtually the only music performed was that of Frederick himself and his master, Quantz. Artistically there does not seem much to commend in this, and indeed, if accurately recorded, it raises serious doubts of the Emperor’s musicianship. But nevertheless the compositions which this remarkable man left behind him are of a kind to make one pause before accepting such a view of the matter, for at the command of the present German Emperor, and under the editorship of such eminent-24- musical authorities as Spitta, Count Waldersee, and Barge, four volumes of these compositions have been published. They consist of twenty-five sonatas for flute and piano, and four concertos for flute and stringed orchestra.

“An examination of the King’s musical MSS., made at the instance of the Minister of Education, has shown that the compositions, written entirely by the King himself, are not only of historical interest, but exhibit command of artistic form and talent for musical invention; a healthy musical life breathes through them; the slow pieces frequently surprise us by their beautiful melodies full of warm feeling, and by their brilliant passages. Such fervour inspires them that the publication of these noble works, which solaced the monarch amid the troubles of his country and in his old age, in the loneliness of his high office, will present the personality of the great King in a new and important aspect. The notion that Frederick merely sought an agreeable pastime in flute-playing will be removed by this edition of his works; his admirers will learn to see in old Fritz a creative musician of deep feeling and noble simplicity.”[10]

-25-

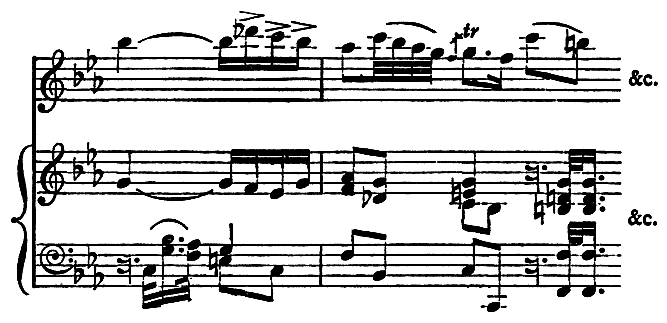

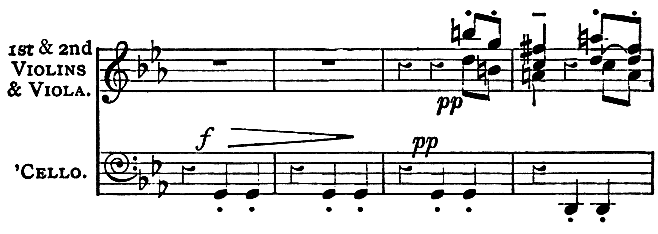

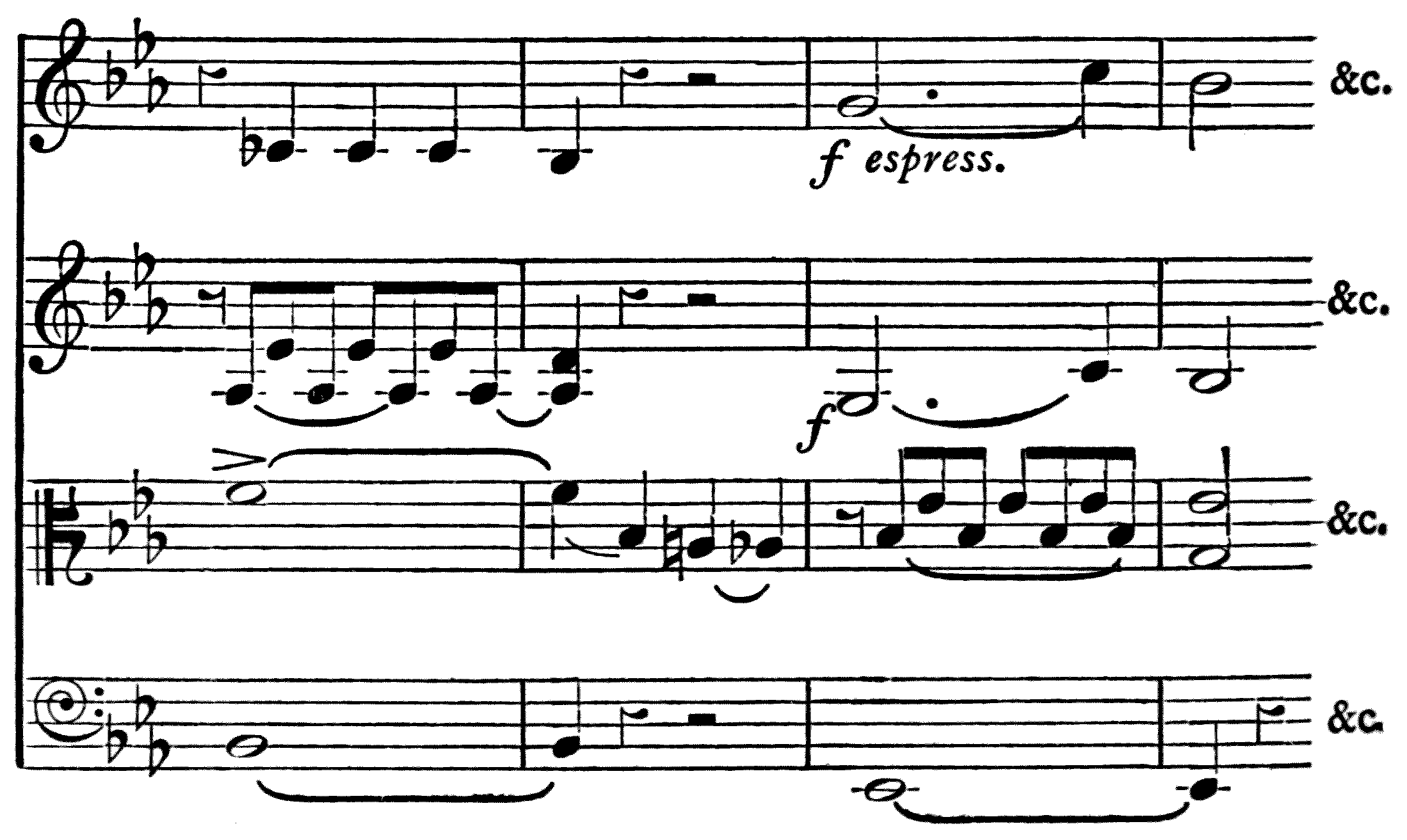

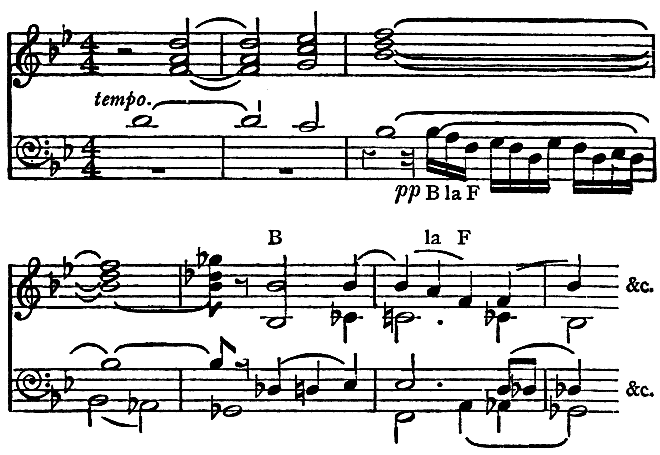

The following fragment, which is quoted from the slow movement (Grave) of the Emperor’s Third Concerto, will show better than any mere description the quality of his music, which certainly warrants the expressions given below from Professor Spitta’s preface to the edition referred to above:—

From the 3rd Concerto for Flute and Strings.

Frederick the Great.

-26-

“The form of the music is no doubt like that of his master Quantz, unoriginal and stereotyped, but his specialty lies in the simple musical thoughts, which flow freely and easily from him, as the natural adequate expression of inward emotions. Frederick’s musical personality is most clearly delineated in his Adagios. These compositions furnish the proof of the story that he often moved his hearers to tears by his adagio playing. They reveal a surprising tenderness of feeling, a soul which seeks its satisfaction in the sweet melancholy and tender, almost feminine, yet never effeminate plaintiveness. The lovely Siciliani of Sonatas 3, 16, and 25 charm like Watteau pictures, with their graceful figures and delicate colour harmony, at the same time not lacking German depth of feeling. More serious, darker feelings rise up in the Grave of the Third-27- Concerto.... Certain it is, and remains, that his music affords the hearer deep insight into a unique soul-life, and for this reason alone its publication would be justified.”

In the year 1836 a series of Quartett Concerts were organised by Joseph Dando, a London violin professor. These concerts, which were continued until 1842, were held in the Hanover Square Rooms, and the artists associated with Dando were Henry Blagrove, Henry Gattie, and Charles Lucas. Dando is said to have been the first to introduce public performances consisting altogether of instrumental quartetts in London.

In 1845 a series of Morning Concerts for chamber music, under the title of “The Musical Union,” were commenced in London by John Ella (1802-88), a Yorkshireman, who, originally intended for the legal profession, became a violinist, and established himself in the metropolis. These concerts continued for some thirty-three years. In the year 1850 Ella also started another series under the title of “Musical Winter Evenings,” and they went on until 1859. At these concerts the best chamber music was performed by the leading artists, both English and foreign.

The Musical Union is said to have had its origin-28- in chamber music meetings which were held at Mr. Ella’s residence in London, and it would be difficult to over-estimate the important influence which its doings have had on the taste for high-class music of this kind in England. To Mr. Ella is also due the introduction of analytical Programmes, which were unknown before. These were sent to the subscribers some days before the concerts, thus enabling all earnest students to acquaint themselves with the various points of interest in the works to be performed.

Another feature which is worthy of notice was that the Platform for the performers was placed in the centre of the concert hall (St. James’s Hall, Regent Street). It was a little raised from the floor, and the listeners sat in a circle around it. This custom has been recently (1901-2) revived at the concerts given by the Joachim Quartett, with, however, the somewhat serious difference that the platform is much too high, and this interferes with the comfort of those who are seated near to it. At the Musical Union Concerts of Mr. Ella the platform was much lower, and this worked well.

Another effort for the spread of a knowledge of chamber music was started in London in the year-29- 1852 by Messrs. Sainton, Cooper, Hill, and Piatti. It was called the Quartett Association. Six concerts each season were given, at which the most eminent artists performed. These were held at Willis’s Rooms, but after the third season they were abandoned for want of sufficient public support.

Among a number of other attempts of a like kind may be mentioned Mr. Edward Dannreuther’s Musical Evenings, which upheld a high ideal, for it is well known that Mr. Dannreuther, while an earnest apostle of the new school of music, is no less zealous for the old, as the range of the programmes which he set forth at these concerts, and his masterly interpretations of Bach and Beethoven, abundantly prove.

The late Sir Charles Hallé (then Mr. Hallé) began in 1861 his celebrated Chamber Music Recitals, the first eight concerts being taken up with a presentation of the whole of the Piano Sonatas of Beethoven. There can be no doubt that these recitals, along with Hallé’s musical work in other directions, have had a most beneficial effect on our national taste.

No account of British chamber music would be complete without a notice of the Monday Popular-30- Concerts which were commenced in London in 1859. The first concerts were of a miscellaneous character, consisting of old ballads and well-known instrumental pieces. They had, however, but moderate success. The director, Mr. Arthur Chappell, in conference with Mr. J.W. Davison, the musical critic of The Times newspaper, then decided to try a series of good chamber music concerts. The first of these was announced as a Mendelssohn Night, and was, of course, made up entirely of chamber music by that composer; and afterwards a Mozart, Haydn, Weber, and a Beethoven night were severally tried. Still success did not follow, and the concerts were very nearly abandoned. Chiefly, however, owing to the determination of Mr. Chappell, a further series were tried, and as these produced a financial profit, the venture was continued, with the result that the concerts eventually became firmly established as the leading chamber music institution in England.

“The One-hundredth Popular Concert,” says Mr. Hueffer,[11] “was given on July 7th, 1862, when, according to The Times, more than one thousand persons were refused admission for the want of space—a statement in itself sufficient to show the broad popular basis-31- on which the concerts were by that time founded. In 1865 the Saturday Afternoon Concerts were added to those given on Monday evenings, and on May 15th of the same year one of the most important events in the history of this institution—the first appearance of Madame Schumann—took place. The programme on that occasion was devoted entirely to the works of her husband, which, in those days, were thought by the public and the press to be the abstruse effusions of the modern spirit, but which are now as generally, and almost as highly appreciated as those of Beethoven himself. Five years later, in 1870, Madame Norman-Neruda was added to the list of executants, and has remained one of the prime favourites of these and English audiences generally, ever since. In the season of 1873-74 more than common attention was paid to contemporary talent, the names of Saint-Saëns, Rubinstein, Rheinberger, Raff, and other then living composers playing a prominent part. The cause of this inroad upon established tradition is partly to be found in the appearance at the piano of Dr. Hans von Bülow, who, here as everywhere else, exercised a beneficial, but, so far as the popular concerts were concerned, a passing influence. There are few names of eminence absent-32- from the list of executants who have appeared on and off. The one-thousandth performance was given on April 4th, 1888.”

Among the other artists who constantly played at the “Monday Pops.” were Piatti, who for very many years occupied the position of leading ’cellist, and his brother-artist of world-wide repute, Dr. Joseph Joachim, the violinist. Although Joachim’s connection with the art of music is by no means limited to any one branch, yet it is in the realm of chamber music that we have chiefly felt his strong influence in Great Britain, and as an upholder of a high and pure standard of musical taste he obtains without doubt the grateful adhesion of all the serious musicians of our land. Were it for no other reason than his steadfast advocacy of the high claims of the works of Johannes Brahms, and for his presentation, under those conditions of a faultless rendering which they imperiously demand, of the later Quartetts of Beethoven, we, and the entire musical world, owe him a deep debt of gratitude.

Of course it is obvious that to call these concerts Monday Popular Concerts was, at the commencement, almost a jocose perversion of the facts, seeing that they were so badly attended; yet, as some one afterwards said, “Mr. Chappell (when the concerts at first-33- proved unpopular) took a bolder course than to alter his title; he altered the public taste instead,” and thus the name became an entirely appropriate one. That these concerts should, during recent years, have declined in public interest is a matter for regret, but no doubt a variety of causes has contributed to this result. Among these must be reckoned the competition of orchestral performances, for which there has grown up a strong public taste; the neglect in the Monday Popular programmes of the newer and novel compositions; and the death or absence of some of the most distinguished chamber music performers. At the same time it is hardly to be believed that chamber music concerts will be allowed to die out, and there is indeed already strong evidence of a revival in this direction in London, which shows that this, the purest form of abstract music, is still held in high esteem amongst us.

Other British chamber music institutions which should be mentioned are the Cambridge University Musical Society (1843), the Cambridge University Musical Club (1871), the Oxford University Musical Union (1884), the People’s Concert Society (1878), the concerts at South Place, Finsbury, where reigns a specially eclectic taste, and good annotated-34- programmes are provided; and the flourishing Oxford and Cambridge Universities Musical Club, established, largely by the untiring efforts of Dr. Horace Abel, during the year 1900 in the old Sir Joshua Reynolds’s House, Leicester Square, London; also the Schulz-Curtius Concerts.

During the season 1902-3 a new series of important chamber music concerts were inaugurated by Messrs. J. Broadwood & Sons, the well-known pianoforte makers, at St. James’s Hall, London. The original prospectus announced the following artistes, most of whom have appeared:—The Bohemian Quartett, the London Trio (Miss Amina Goodwin, Messrs. Simonetti and Whitehouse), the Wessely Quartett, Mr. Clinton’s Wind Instrument Quartett (Messrs. G.A. Clinton, W.M. Malsch, A. Borsdorf, and T. Wotton), the Grimson Quartett, the Brodsky Quartett (Messrs. Adolph Brodsky, R. Briggs, S. Speelman, and C. Fuchs), and the Gompertz Quartett (Messrs. Rd. Gompertz, C. Jacoby, E. Kreuz, and J. Renard). The Kneisel (American) Quartett and the Moscow Trio have also recently been heard at these concerts. Messrs. Broadwood have also organised another series of chamber music concerts in the city of Manchester.

The direction of the Monday Popular Concerts has-35- also been undertaken by Professor Johann Kruse, who was well known as a member of Dr. Joachim’s Berlin Quartett. The Joachim Chamber Concerts will also be continued, the artists, as before, being Messrs. Joachim, Halir, Wirth, and Hausmann. Mr. Willy Hess’s Quartett, the Newland Smith Trio, Messrs. Metzler’s concerts, the Mozart Society’s concerts, and those of Mr. Donald Tovey (which are of high importance), are among the Chamber Music Institutions that have recently come into notice.

In many of our provincial towns and cities, too, societies for the cultivation of chamber music are, in a quiet way, doing excellent work. These are too numerous to set forth in detail; but, as exemplifying the good influence which it, like many such institutions in other places, has for a long time exerted, the Chamber Music Society of Newcastle-on-Tyne may be mentioned. This Society a while ago set an example, which might well be followed by others, in commissioning our English composer, Villiers Stanford, to write a string Quartett (op. 44 in G major), which was performed at one of the Society’s concerts shortly after it appeared.

It has been stated by a writer,[12] who, by the way, is not afraid boldly to declare the truth “that the amateur is the backbone of a nation’s music”—that a Chamber-36- Music Society has been founded through the influence of an English amateur at Tokio, in Japan. He tells us that the violinist who leads at these concerts has been engaged by the Japanese Government to teach at the Tokio Conservatoire, and that he has already turned out some excellent Japanese pupils, at any rate so far as technique is concerned, one girl especially having become a really good viola player.

-37-

HAYDN, P.E. BACH, DITTERSDORF, HANDEL.

J.S. Bach — Joseph Haydn — Philipp E. Bach — Dittersdorf — Early quartetts of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven — Silence as an effect in music — Haydn’s quartetts — Haydn’s Kaiser Quartett — Haydn’s other chamber music — Handel.

Haydn (1732-1809) has been called the “Father of the Symphony,” and by some the origin of the Quartett (meaning, of course, that for strings) has been ascribed to him.

How far this is accurate can only be determined by an examination of what was being done by others about the same time; but it may be safely said that, in the absolute sense, no enduring art form has been the creation of one man. There has always been a growth, although it is no doubt true that at a certain stage of the process some one with genius has, as it were, put the top stone on the edifice. Robert Schumann, writing on this topic, uses the following characteristic words:—“The world is large. Be modest! You have not yet discovered and contrived what others before you have-38- not already imagined and found out;” the meaning of which doubtless is that of absolute originality there is very little at any time, and what stands in its place (and this will seem more or less according to our knowledge or ignorance of what has already been done) is really the fruition of many past influences, plus the genius of the man who assimilates and gives them fresh shape.

John Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) was probably the most original genius the art of music has known, but it would be idle to deny that he was deeply indebted to his predecessors, Frescobaldi, Buxtehude, Klemme, and Pachelbel.

Take, for example, the history of what now goes under the name of Programme Music. What Liszt aimed at in his Symphonic Poems, and what Richard Strauss’s remarkable creations—“Don Juan,” “Till Eulenspiegel,” “Ein Heldenleben,” and the rest, attempt to express, was already in the minds of composers a very long while ago.

Mr. Corder, in his article on this subject in Grove’s Dictionary, states that W. Byrd (1560) wrote a battle-piece for Virginals, and John Mundy, another English composer of that period, published a so-called “Fantasia on the Weather,” professing to depict fair weather, lightning, thunder, etc. Krieger (1667) gives us a four-part-39- vocal fugue entirely made up of an imitation of the mewing of cats! There is also the fairly well-known Cat’s Fugue by Domenico Scarlatti, suggested of course by his cat accidentally walking over the keys of his harpsichord. Bach, Handel, Haydn, and Beethoven are also among the great ones whose works occasionally tended in a like direction.

It is the same with any other distinctive feature in music, and therefore, while undoubtedly Haydn did very much for its expansion, the truth is that the form of the String Quartett was a gradual development, and not the creation of any single mind.

As to the vitality of the music of different composers, which is another matter, Boccherini, a contemporary of Haydn, wrote more quartetts than that master, and they were highly esteemed during his life-time; but, save the musical student, who knows or plays them to-day?

Haydn is known to have studied, early in life, the works of Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714-88), and there can be little doubt that he was thereby strongly influenced. Beethoven is said to have been quite familiar with the greater (John Sebastian) Bach’s compositions, even as a child, and an argument has been based on this that Haydn’s artistic position would to-day have been different had-40- he, too, studied the greater and not the lesser Bach.

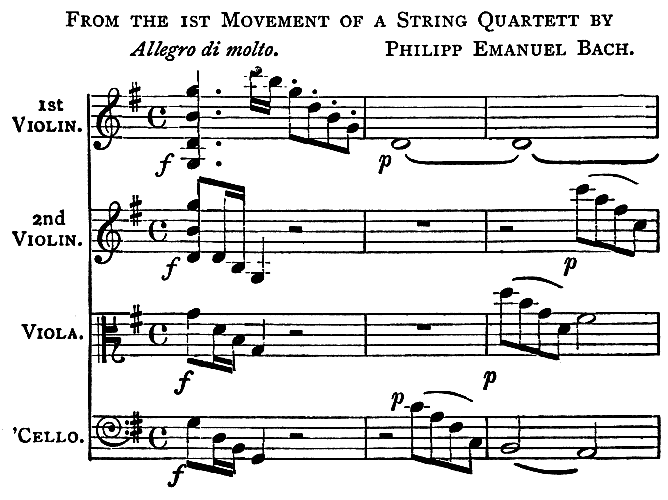

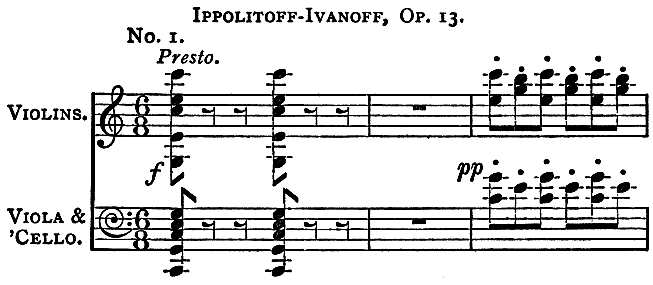

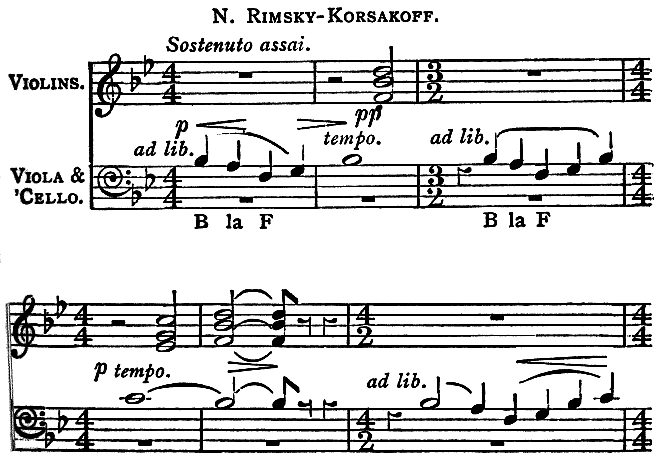

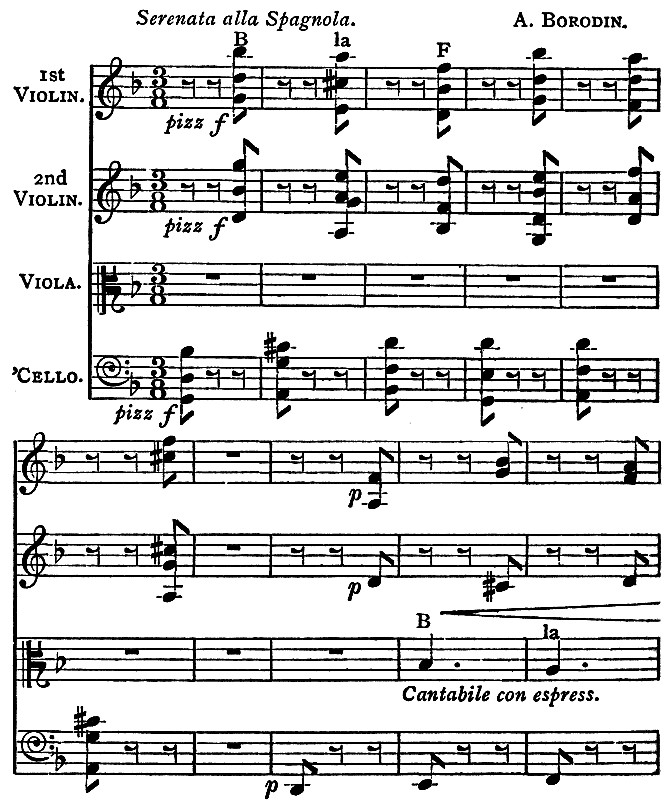

The following extracts from a String Quartett by this composer, P.E. Bach, which was found in the Library of the Thomas-Schule in Leipzig, will convey, perhaps better than any mere words, an idea of the style in which he wrote, and we will thereby see what it was that influenced Haydn.

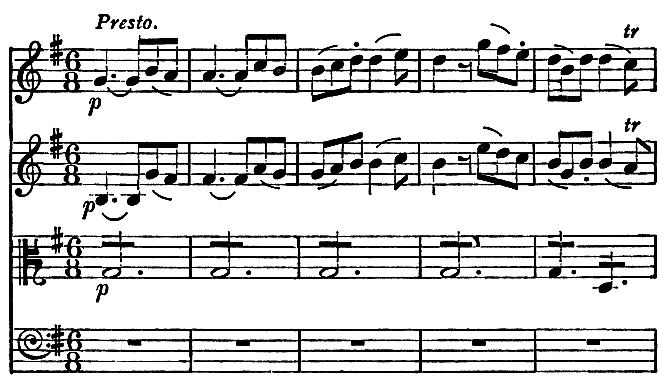

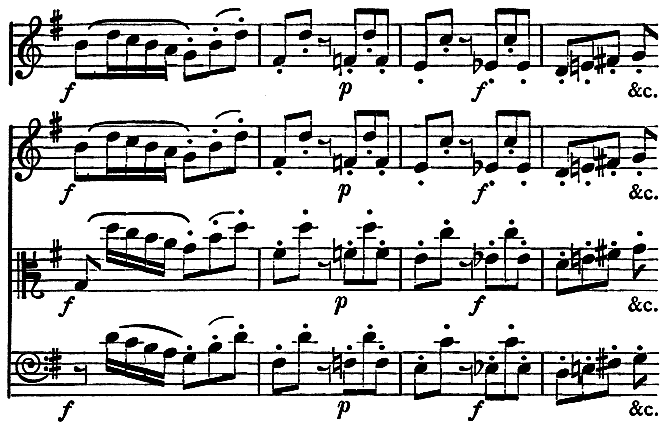

The Finale Presto may specially be noted, presenting as it does features remarkably like many such movements in Haydn’s Quartetts.

From the 1st Movement of a String Quartett by Philipp Emanuel Bach.

-41-

The first movement of this work, which has also been called a Sinfonia, is connected with the second by modulation.

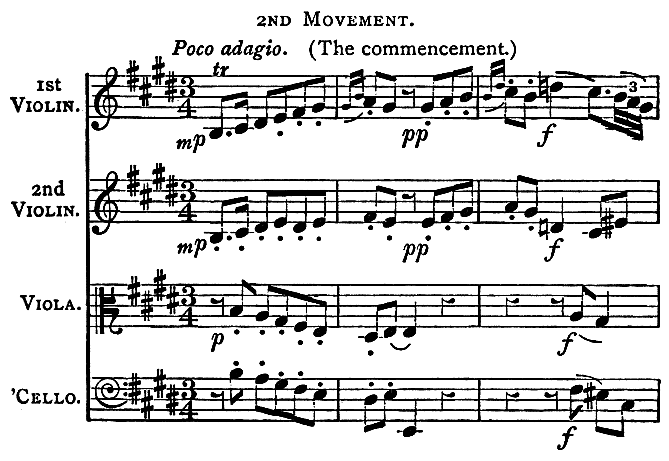

2nd Movement.

(The commencement.)

-42-

(The last 10 bars, leading to the Presto.)

-43-

-44-

The orchestral tendencies of this work and its symphonic feeling are, of course, quite evident; but Dr. Hugo Riemann, in his recently published edition, entitles it a String Quartett.

3rd Movement.

-45-

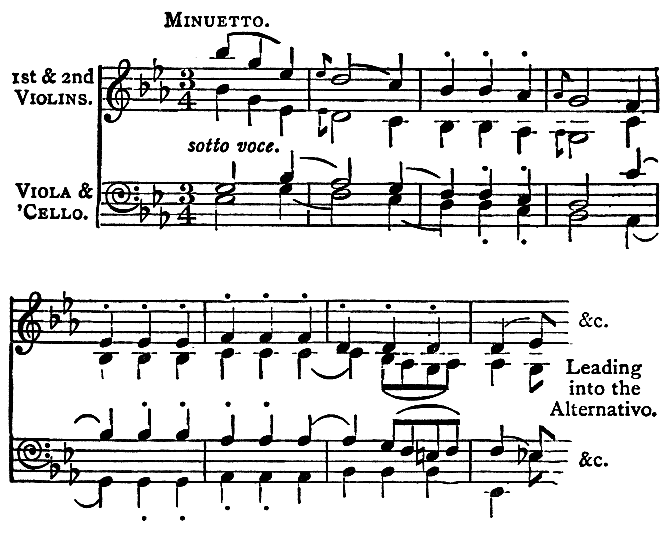

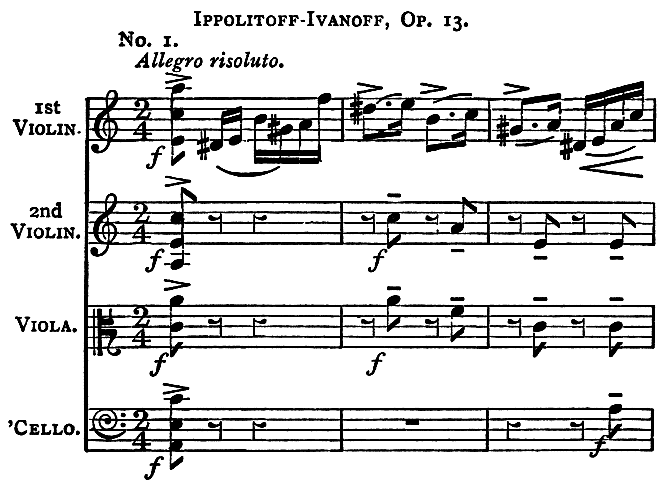

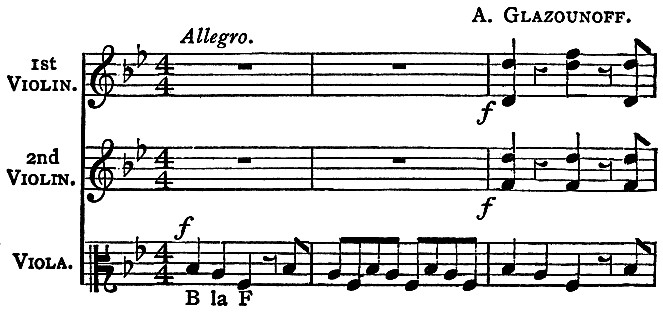

Dittersdorf (1739-99) is another chamber music composer of this period. His name is little known in England, but during his life-time he was regarded as a rival of Haydn, and although the verdict of time is against him, yet his compositions go far to justify the popular feeling in his favour. An opera of his, The Doctor and the Apothecary, still holds the stage in Germany, and his String Quartetts are yet occasionally heard. His twelve Orchestral Symphonies (most of them written to a programme), oratorios, and some twenty to thirty other operas are, however, now practically dead. The scores of six of his Quartetts, which are published in the Payne miniature-46- edition, are worthy of attention, especially that in E♭, from which the following quotations are made. Special attention may be directed to the minuet, which is followed by a trio or alternativo of a very charming and dainty character. The lively finale too reminds one of Haydn, and the effect of silence, which is mentioned elsewhere, is introduced in several places in this movement. While, however, the music is spontaneous and sincere in feeling, the absence of strong ideas and of contrapuntal skill soon shows itself, and the effect tends to become insipid.

From a String Quartett by Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf.

-47-

A noteworthy feature in the development portion of this movement is a sudden but effective modulation from E♭ to C major.

Minuetto.

Leading into the Alternativo.

-48-

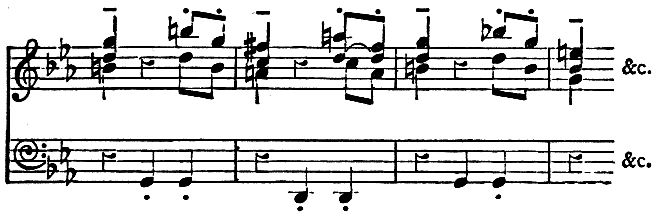

Alternativo.

Some editions of this quartett have three bars of the note G for the ’cello, after the double bar, instead of two, as here printed.

-49-

Finale.

Haydn wrote his first String Quartett about the year 1755. Mozart’s first appeared fifteen years later, in 1770. That of Beethoven (No. 1 in F, op. 18) in 1800;-50- so that a period of about forty-five years includes all three. A comparison of the three works can therefore hardly fail to be of interest. Haydn’s consists of five movements—viz., presto, minuet and trio, adagio, another minuet and trio, and presto. All the movements are in the key of B♭, except the adagio, which is in E♭. They are short and undeveloped, and there is little extraneous modulation. The music is fresh and spontaneous, but simple and of little importance—indeed, as compared with many of his other seventy-six Quartetts, it is trivial.

Mozart’s work is in G major. It has four movements—viz., adagio, allegro, minuet and trio, and rondo. Originally it had only three movements, the rondo being added later. All are, in accordance with the custom which prevailed up to about this time, in one key. The general character of the composition is stronger than that of Haydn, there is more counterpoint and independence in the parts, but not much modulation. It is an interesting, but by no means great work.

Beethoven’s is the well-known No. 1, op. 18, and has four movements—viz., allegro, adagio, scherzo and trio, and allegro. The introduction of the scherzo form will be observed here. Humour and jest had no doubt been attempted before in music, but Beethoven-51- made much more use of it than his predecessors, and in some of his works, notably the Fifth and Ninth Symphonies, employed it in a remarkable manner. In the C minor, the grim humour, with the strange touch of mysticism which occurs near to where the scherzo blends into the finale, are among the very great effects which Beethoven has left for us. All the movements of the quartett are in the key of F, save the adagio, which is in D minor. Both as to contrapuntal skill, modulation, individual use of each instrument, especially of the viola, and above all in poetic feeling, this work shows a great advance on the two of Haydn and Mozart. Beethoven no doubt had the great advantage of what Haydn and Mozart had already written, but for all this the gap between this first Quartett and theirs is remarkable. Unquestionably the best of Haydn’s and Mozart’s Quartetts are works of the highest genius, but in Beethoven the restraint of conventional form is less felt, and there is a richer and fuller poetic expression. Nor has Beethoven overlooked (we find it in bars 59 to 62 of the adagio) the use of a certain negative means which as a factor in musical expression is of great importance.-52- Just as it is well not to write continually in full four-part harmony, but to relieve what is apt to become monotonous, by reducing the score to three, two, or even at times one instrument, so the introduction of absolute silence may occasionally produce an excellent effect. Handel recognised this, and we find examples in “He rebuked the Red Sea” (Israel in Egypt), “Wretched Lovers” (Acis and Galatea), and at the close of the Amen Chorus (Messiah). Brahms makes use of the device in the allegretto of his Second Symphony, as does another master, Wagner, at the close of the prelude, Act 2 of Parsifal. The scherzo of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony also contains several examples, and Sir C. Villiers Stanford in the andante of his String Quartett, op. 45, produces a strikingly artistic effect, where after a full bar’s silence, the viola enters alone on a note unrelated to the previous tonality. Of course the use of a means of this kind obviously depends upon the character and feeling of the music, and its absence in no way implies imperfection, but it is curious to note that neither Schumann, Mendelssohn, nor Brahms introduces it into any of their String Quartetts.[13]

-53-

The bulk of Haydn’s Quartetts are so well known that any detailed reference to them would be superfluous. Op. 33, No. 3, in C major; op. 74, No. 1, in the same key; and op. 77, No. 2, in F major, may however be named as among the most interesting, and not perhaps so often played as, say, the so-called “Kaiser,” op. 76, No. 3, the op. 64, No. 5, and the op. 76, No. 1, which with some others are so justly held in high esteem wherever this style of music is cultivated.

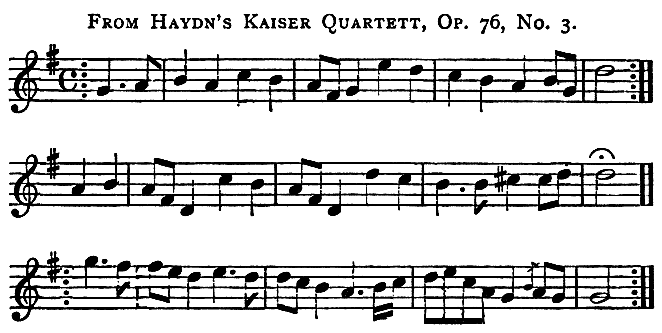

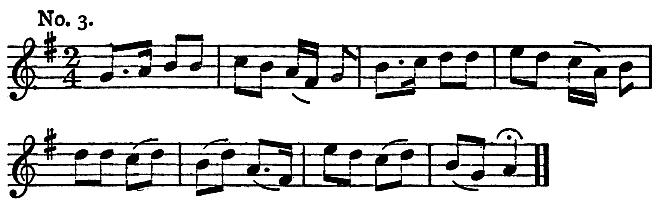

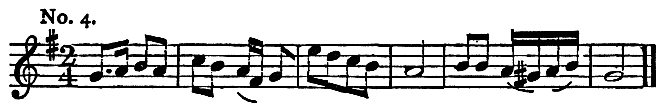

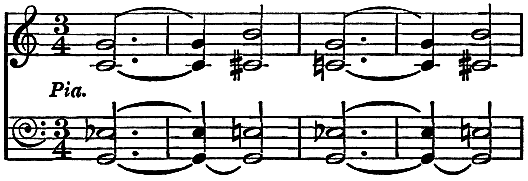

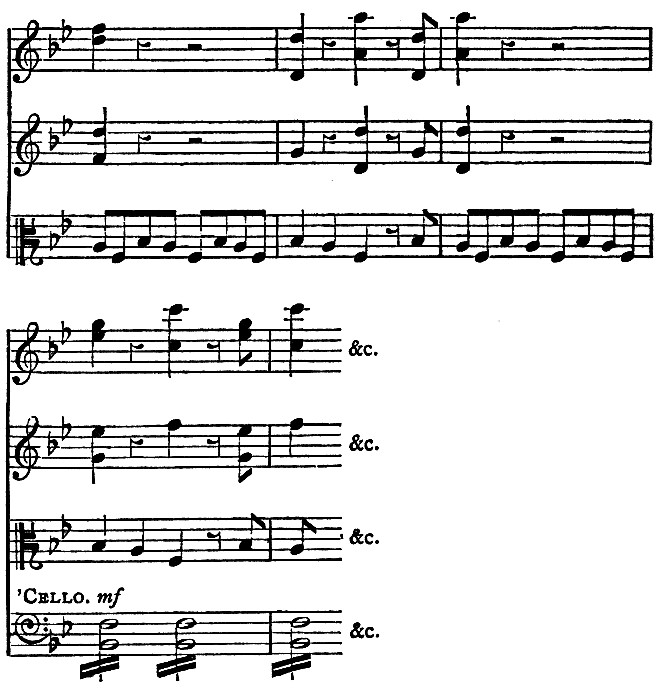

With regard to the slow movement of the “Kaiser,” a set of variations on the Austrian National Anthem, which Haydn is said to have composed because he envied the English their “God Save the King,” Mr. W.H. Hadow, in his book A Croatian Composer (which work may well be read, containing as it does a report of some very interesting investigations), gives a number of instances wherein the germ of symphonic and other of Haydn’s musical themes are traceable to Croatian folk-songs, and among them is this Austrian National Anthem. What Handel did with the works of Steffani and others is pretty well known by musicians, but this less known case is an equally interesting one.

Here is the familiar melody as it now stands in the Quartett (op. 76, No. 3) referred to. The five versions-54- of this melody which by the praiseworthy investigations of Mr. Hadow are now brought to light are quoted below. Each one presents the tune as it is found to-day in a certain district of Croatia. It will, as Mr. Hadow points out, be seen that in all these versions there is “apparent the same touch of inspiration, and the same weakness of development.” Haydn took advantage of-56- the inspiration and dignified the tune by a continuation worthy to make it take rank among the best national anthems of the world.

From Haydn’s Kaiser Quartett, Op. 76, No. 3.

No. 1

No. 2.

No. 3.

These three are of course very much alike, but the next two differ considerably from the others, and No. 5 has two bars more than No. 4.

No. 4.

No. 5.

Haydn’s compositions in the chamber music style embrace a large number of pieces which are now forgotten. Many of these were probably written to order for his patrons, and have little permanent value. Among them are some 32 Trios for strings and other combinations, 2 for 2 flutes and ’cello, 3 for piano, flute, and ’cello, and some 35 for piano, violin, and ’cello. As regards the last-named, some of which are still occasionally played, an examination of the twelve published in the Peters Edition, which may be regarded as favourable specimens, shows that many of them are hardly trios at all in the modern sense of that word. The ’cello part, generally speaking, either doubles the actual notes, or strengthens the harmony, of the left-hand piano part, and in some movements (e.g. the slow movement of No. 1 in G major) has not a single independent passage. There would, indeed, be little loss of effect if the music were played by the piano and violin.

There is more interest and vitality in No. 6 in D major, but even in this the continual doubling of the parts, and want of independence between the instruments,-57- becomes at last somewhat wearisome. It ought, however, to be remembered that some of these Trios were published as Sonatas for the piano with an accompaniment for violin and ’cello, and that this kind of composition was common during the period of which we speak. It has also been stated that Haydn wrote these Trios for a wealthy and enthusiastic patron, who unfortunately was a poor ’cello player, and hence that part was written in the simplest form.

Haydn also wrote about 175 works for an instrument called the baryton, a kind of viol da gamba. They were written for Prince Esterhazy, who played that instrument, but they are now practically forgotten. Some unpublished MSS. of Haydn’s are to be found in the library of the British Museum.[14] There are also, among his published works, four Sonatas for violin and clavier, and six Duets for violin and viola, as well as a number of other chamber music compositions, which, however, have no great musical value.

The following is a list of the chief chamber music works of Handel (1685-1759):—

The Sonata in A major for violin and piano (harpsichord) is of course familiar, as are others of the fifteen named above. The Trios are also of high interest, some of the slow movements being distinguished by that fine pathos which is associated with the best work of the composer of The Messiah. This music deserves more attention than has hitherto been accorded to it.

-59-

MOZART.

Mozart’s C major Quartett — Mozart’s string quartetts — The genius of Mozart — Mozart’s other chamber music — Wagner on Mozart — Mozart’s letter to his father.

“I declare to you before God, as a man of honour, that your son is the greatest composer that I know either personally or by reputation; he has taste, and, beyond that, the most consummate knowledge of the art of composition.”

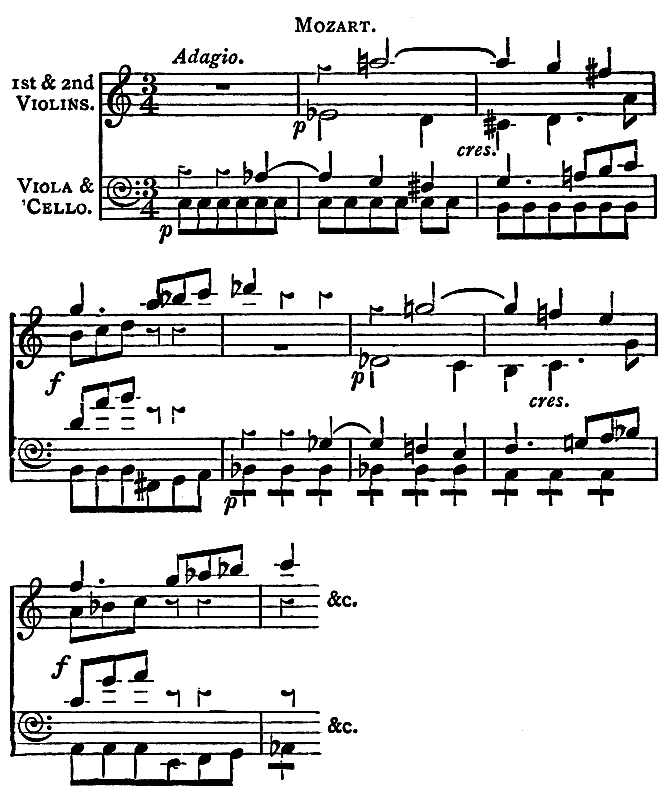

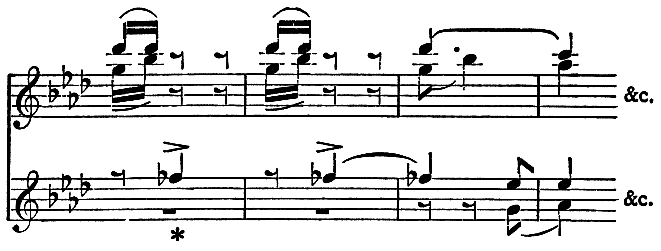

Such are the remarkable words of Haydn, spoken to Mozart’s father. The compositions played on the occasion when this was said were the String Quartetts numbers 458, 464, and 465 of the Köchel Thematic Catalogue of Mozart’s works, the last-named in C major, being that whose introductory passage is said to have given much offence to the purists of that time, on account of the following unusual harmony, which even to-day sounds (like some of Bach’s) quite modern:—

-60-

Mozart.

The celebrated Italian musician, Sarti, the master of Cherubini, said of this passage, “Can more be done to put the players out of tune?” and some, even of-61- Mozart’s admirers, after his death, proposed to alter and, as they considered it, rectify the passage. As regards Sarti, there can be no doubt that his word carried great weight at that time, and although his views may now be lightly regarded, Mozart evidently had a high opinion of him, for, in a letter written from Vienna in June 1784, we find him writing, “To-morrow there is to be a concert at Herr Players, at Döbling, in the country. Mdlle. Babette will play my new Concerto, I shall play in the Quintett, and together we shall give the Grand Sonata for two pianos. If the Maestro Sarti had not been obliged to leave for Russia this very day, he would also have come with me. Sarti is a fine fellow, an excellent fellow! I played a great deal with him, and finished with some variations on an air of his own, which gave him great pleasure.”

Mozart afterwards dedicated a set of String Quartetts, comprising that cited above and other five, to Haydn, and they remain until now amongst the most renowned works in this style.

Mozart (1756-91), who was, of course, contemporary with Haydn (1732-1809), was by nature a musical genius of the very highest order, but, all the same, he was only in a small degree a reformer, for he was guided more by the spontaneous creative powers with-62- which he was naturally endowed than by any mere intellectual or philosophical theorisings concerning art. The quotation from the Quartett given above must, no doubt, have alarmed the average musician of that time, but there is no reason to think that it was written in connection with any scheme for the reform or expansion of musical resources, for Mozart’s works display the utmost transparency of harmony and of style. No doubt he occasionally produces remarkable effects by means of unusual and sudden modulations (for example, the transition from G into E♭, near the close of the finale of the G minor Piano Quartett), but, as a general thing, his works do not furnish very many instances of this kind.

His acceptance of unsatisfactory operatic libretti also points in the same direction, and it has been jokingly said that he could have set beautiful music even to newspaper advertisements.

Another theory is that, unlike Haydn, and in a degree Beethoven, he had no wealthy patron who safeguarded him and his art, and that the want of easier circumstances affected the quality of-63- his work, as well as shortened his life. In any case, it may be taken as certain that his highly-strung organisation unfitted him for the hardships which fell to his lot, and that the sympathy and protection of some one possessed of worldly power and influence would, in his case, have been especially valuable. It is impossible, for example, to read without indignation of the manner in which he was treated by the Archbishop of Salzburg.

But apart from all this, there can be no doubt that his works are a priceless treasure, for whose good influence humanity, past and present, is deeply his debtor.

Of String Quartetts Mozart wrote fewer in number by far than Haydn, but none the less his work in this direction is such as to overshadow that of Haydn. It has been well said that “next in importance after his (Mozart’s) Symphonies come his Quartetts. In this form Haydn was again the pioneer, but it fell to Mozart to produce the first really great and perfect examples. This refined and delicate form of art had come into prominence rather suddenly. It was cultivated with some success by other composers besides Mozart and Haydn, such as Boccherini and Dittersdorf. But the quartetts which Mozart produced in 1782, and dedicated-64- to Haydn, are still among the select few of highest value in existence. In a form in which the actual possibilities are so limited, and in which the responsibilities towards each individual solo instrument are so great, where the handling requires to be so delicate and so neatly adjusted in every detail, Mozart’s artistic skill stood him in good stead. The great difficulty was the exact ascertainment of the style of treatment best suited to the group of four solo instruments. It was easy to write contrapuntal movements of the old kind for them, but in the new harmonic style, and in the form of a sonata order, it was extremely difficult to adjust the balance between one instrument and another so that subordination should not subside into blank dulness, nor independence of inner parts become obtrusive. Mozart, among his many gifts, had a great sense of fitness, and he adapted himself completely to the necessities of the situation, without adopting a polyphonic manner, and without sacrificing the independence of his instruments.”[15]

The wonderful power of Mozart as a composer is never more clearly revealed than in the production of that strangely mysterious effect which, unaided by any mere external text or programme, is here and-65- there to be found in the works of all the really great composers. It may be illustrated by even so familiar an example as the fifth bar of Beethoven’s No. 3 Leonora Overture, where the downward C major scale ends on F♯, and is followed by the unexpected and weird harmony of that note. Other instances may be found in the scherzo of the Fifth Symphony of Beethoven, and in Schubert’s Lebens-stürme, op. 144, where the chorale-like subject enters. Wagner, too, has many examples in the instrumental portions of his works; for instance, the commencement of Scene 4, Act ii., of Die Walküre.

The opening of Mozart’s Quartett No. 6 in C major, which has already been quoted on page 60, has sometimes been referred to as illustrating this mysterious kind of effect; but, while the passage is unquestionably peculiar, there are others which better exemplify what is meant by this atmosphere of “other worldness,” as it has been called. Take, for instance, the passage beginning at the forty-second bar of the first movement of Quartett No. 2 in D minor of the set dedicated to Haydn, and mark the subtle effect in bars 4 and 5, especially the sudden change from forte to piano at bar 4, and the double piano which follows:—

-66-

Mozart.

Of course it must by no means be overlooked that it is only by a perfect rendering of the music that ideal effects of this kind can be revealed as they first arose in the mind of the composer.

As illustrating another and quite different kind of-67- effect, we have in the andante of No. 8 Quartett in D major, dedicated to the King of Prussia, an example of pure and simple melody, which, without subtlety or mysticism, flows on in calm, unclouded beauty.

Mozart.

-68-

The earlier String Quartetts of Mozart are not of equal merit with those which he composed some nine years later. Of these the six dedicated to Haydn are quite remarkable, as are also the three dedicated to the King of Prussia. In these three the ’cello (the King’s favourite instrument) is more than usually prominent.

The Quartetts for flute and strings and those for oboe and strings are unimportant, but that for clarionet and strings is a more worthy work. Of the String Quintetts those in C, G minor, and E♭ are the best, especially the G minor, which is truly great. Mozart doubles the viola in these Quintetts. It was the custom of his contemporary Boccherini, to whom reference has been made, to double the ’cello.

There is also a Quintett for horn and strings, and one in C minor for the curious combination flute, oboe, viola, ’cello, and glass harmonica.[16] The Quintett in E♭, a special favourite of its author, for piano, oboe, clarionet, horn, and bassoon, is a fine work, as are the two piano and string Quartetts in G minor and in E♭.

Of Trios, the Divertimento in E♭ for violin, viola, and ’cello is remarkable; also that for clarinet, viola, and-69- piano, in the same key, an unusual but effective combination.

The seven Trios for piano, violin, and ’cello do not, as a whole, rank among Mozart’s most exalted efforts, but some of them, and especially certain movements, are excellent; that, for example, in E major, and the slow movement of No. 496 Köchel, in G major. For the piano and violin Mozart wrote forty-two Sonatas, an Allegro in B♭, and two sets of variations, which are said to have been generally written for his lady pupils. “They are neither deep nor learned, but interesting from their abundant melody and modulation.”[17]

This concludes the list of the more important of the chamber music works of this great master.

In the words of Richard Wagner: “The life of Mozart was one of continuous struggle for a peacefully-assured existence against the most unequal odds. Caressed as a child by the half of Europe, as youth he finds all satisfaction of his sharpened longings made doubly difficult, and from manhood onwards he miserably sickens towards an early grave.... His loveliest works were sketched between the elation of one hour and the anguish of the next.”[18]

-70-

But while this was so, it is pathetically interesting to read what he writes to his father when he first heard of his illness, for it shows clearly that amid the hardships and trials which beset him, Mozart never, at heart, repined, but sustained himself with a deep and far-reaching philosophy of human life. “As death,” he says, “strictly speaking, is the true end and aim of our lives, I have for the last two years made myself so well acquainted with this true, best friend of mankind that his image no longer terrifies, but calms and consoles me. And I thank God for giving me the opportunity of learning to look upon death as the key which unlocks the gate of true bliss. I never lie down to rest without thinking that, young as I am, before the dawn of another day I may be no more; and yet nobody who knows me would call me morose or discontented. For this blessing I thank my Creator every day, and wish from my heart that I could share it with all my fellow-men.”

-71-

BEETHOVEN.

Beethoven as democrat — Rhythmic similarities — Beethoven’s first and last compositions — Musical humour — The distinction in Beethoven’s chamber music.

The genius of this remarkable man has left us a heritage of undying beauty in every department of the art, and especially in that of chamber music.

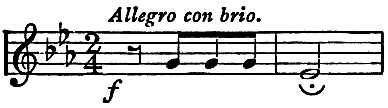

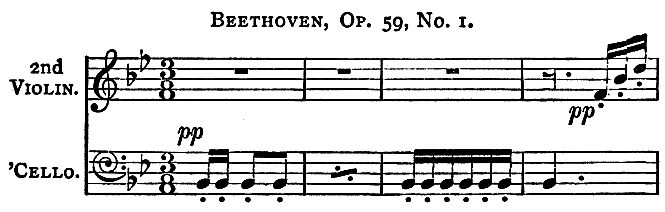

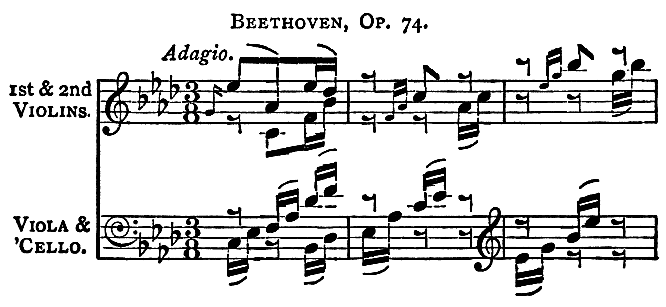

“Beethoven[19] (1770-1827) was the first great democrat among musicians. He would have none of the shackles which his predecessors wore, and he compelled the aristocracy of birth to bow to the aristocracy of genius. But such was his reverence for the style of music which had grown up in the chambers of the great, that he devoted the last three years of his life almost exclusively to its composition; the peroration of his proclamation to mankind consists of his last Quartetts—the holiest of holy things to the chamber musicians of to-day.” With regard to these works it has been-72- said with, at any rate a certain degree of truth, that the musical ideas contained in them are too large for the means of expression, just as we find some movements of Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas to be orchestral in feeling, and beyond the powers of the piano adequately to express. Some critics have ventured to regard the later Quartetts as loose and rhapsodical in form. This is, however, merely the penalty which conventionality seeks to impose on creative genius, and may be passed by as harmless.

Among the many notable features to be found in Beethoven’s compositions, it has, more than once, been pointed out that there is a curious rhythmic likeness in certain works written by him about same time, and this is confirmed (as to the time of composition) by the sketches to be found in his note-books. The opening of the well-known Fifth Symphony, op. 67, composed about 1804, for example:—

may be compared with the Piano Sonata, op. 57, in F minor, written about 1805, and the Piano Concerto, op. 58, written about 1806. Another noteworthy instance-73- is found in the String Quartett, op. 74, written in 1809.[20] The third movement of which opens thus:—