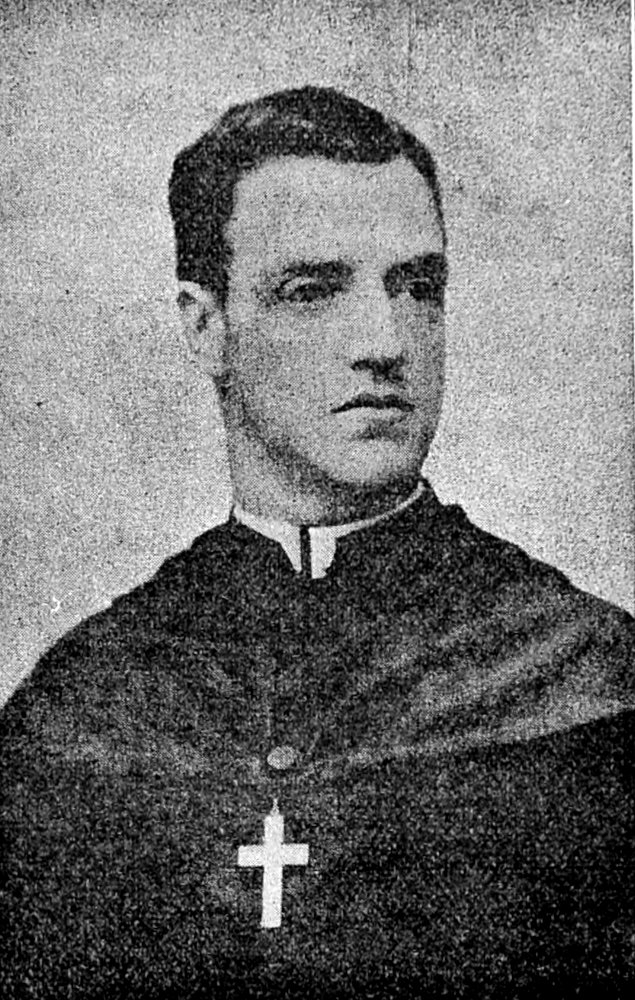

Photo. by Walery. Frontispiece.

Alice Hayes

The Project Gutenberg eBook of My leper friends, by Alice Hayes

Title: My leper friends

An account of personal work among lepers, and of their daily life in India

Author: Alice Hayes

Contributor: G. G. Maclaren

Release Date: March 16, 2023 [eBook #70301]

Language: English

Produced by: The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Photo. by Walery. Frontispiece.

Alice Hayes

MY LEPER FRIENDS.

AN ACCOUNT OF

PERSONAL WORK AMONG LEPERS, AND OF THEIR

DAILY LIFE IN INDIA.

By Mrs. M. H. HAYES.

WITH A CHAPTER ON LEPROSY,

By Surgeon-Major G. G. MACLAREN, M.D.

ILLUSTRATED.

LONDON:

W. Thacker and Co., 87, Newgate Street.

Calcutta: THACKER, SPINK AND CO.

Bombay: THACKER AND Co., Limited.

1891.

[Pg v]

The objects I had in view when writing this book were to interest the public in the white lepers who are homeless in India, and to obtain money for the “Leper Fund” which I raised, and which is now being administered by the Very Reverend Archdeacon Michell of Calcutta. My publishers, Messrs. Thacker & Co., 87, Newgate Street, E.C., have kindly consented to forward to this gentleman any profit that may accrue from the sale of the book, which, on this account, I trust will be large. I venture to think that, apart from the good intent, all classes of readers will find this small work worthy of perusal, in that it is a series of true pictures of a very sad phase of human misery, namely, the inner life of sufferers whom I have known so well and have cared for so much, that I can in all sincerity call them “My Leper Friends.”

[Pg vi]

I hear, with deep regret, that, since my departure from India, subscriptions to the “Leper Fund” have decreased. As it is the means of brightening the lives of the most wretched of all human beings, I would appeal to the generosity of the public to support it by sending contributions to Archdeacon Michell, Calcutta, who personally superintends the distribution of the fund. I may mention that aid is given without any distinction as to creed.

My best thanks are due to Dr. G. G. MacLaren for his sympathy in my labours, and for his kindness in writing a chapter on leprosy for this book. I, also, am glad of this opportunity of expressing my great indebtedness to “Brother John,” who was my fellow-worker among the lepers and in the hospitals of Calcutta.

I shall be happy to answer inquiries on this subject. My address is, care of Messrs. W. Thacker & Co., 87, Newgate Street, London, E.C.

Alice Hayes.

London, 3rd September, 1891.

[Pg vii]

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Settling in Calcutta—Our “Sporting News” | 1-4 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Brother John—Mr. McGuire—Government officials—The leper asylum—An Irish woman—The Jewess—Daisy and Bella—A death scene—Eurasian lepers | 5-23 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The account I wrote—Bridget—An official visit to the lepers | 24-33 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Newspaper criticism—“Truth” and Mr. Prinsep—“The Queen” | 34-38 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Efforts to comfort—Our subscription fund—Improvements | 39-47 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Miss O’Brien—Amateur actors—A performance in aid of our fund | 48-55[Pg viii] |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| White lepers—Dr. MacLaren—Heat and misery | 56-62 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Need for a home for European and Eurasian lepers—Our public meeting | 63-73 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Hope—Kate Reilly | 74-80 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Archdeacon Michell—Disposal of our fund—The leper cat—The idiot boy | 81-88 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| The nuns of Loretto Convent | 89-94 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Medicine—No warm baths—An ugly looking-glass—Christmas-day in the Leper Asylum—The leper boy—Mr. Bailey | 95-111 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Lepers in Bombay—A lecture at the Sorosis Club—Our departure from India | 112-119 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Remarks on Leprosy, by Surgeon-major G. G. MacLaren, M.D. | 120-127 |

[Pg 1]

In the early summer of 1888 my husband and I found ourselves enjoying a well-earned holiday in Japan. He, I may explain, writes books about horses, which have rendered his name widely known among English readers; and having a special talent for making these animals conform to his wishes, he conceived the idea of going on a tour, with the object of teaching all he knew about “breaking” to those interested in the subject. In England, horses, as a rule, are so well “made” that the equine instructor finds much difficulty in illustrating his lessons. But abroad the case is very different. In India he had, during the[Pg 2] year he was there, hundreds of buck-jumpers, man-eaters, jibbers, and other refractory creatures, the subjugation of which gained him great credit, as well as a goodly sum of money. Even in China, from which we had just come, there were plenty of examples among the sturdy Mongolian ponies to test his skill and patience. When a horse or pony, which previously would not allow anyone to mount him, was reduced to obedience in an hour or two, a side-saddle was usually put on him, and then I mounted him, took up the reins, put him through his paces, and jumped him over some improvised fences. Although our work “caught on” wherever we went, it proved somewhat monotonous, and I longed for a settled home after this continued round of hotel and steamer life. My husband wanted to go to California, and then on to New York, while I suggested India, where I had spent a pleasant time in the indulgence of my then hobby—theatricals. In those days I looked upon my dear old teachers—Mr. Hermann Vezin, Mr. John MacLean, and Miss Glyn Dallas—as the greatest of man and womankind, and thought more of a favourable notice in some obscure local print of my acting, than of the praise in[Pg 3] the Field and Graphic accorded to my riding, when my husband gave a performance at Neasden, near London, in aid of the funds for the “Home of Rest for Horses.” Knowing what a charm novelty had for my husband, and wishing to get back to India, I suggested the advisability of his going to Calcutta and starting there a sporting paper, which, with his name as editor, would be sure to draw! My counsel proved so acceptable that I had only barely time to pack up my boxes and get them on board the French mail, for which my husband had taken tickets. We arrived at Calcutta, started our paper, and, in a short time, settled down to our work as journalists. This came easy to my husband, as he had been connected with the press for many years, and not very difficult to me, as I was deeply interested in the success of our venture, and had been accustomed, during my travels, to write articles for various papers. My rôle on our Sporting News was that of dramatic and musical critic, as well as that of describing events of passing interest, with a certain dash of sporting flavour, from a lady’s point of view. The habit of observation which was forced on me probably sobered down my thoughts a good deal;[Pg 4] for I was gradually led to pay more and more attention to the sadder aspects of human life, which were but too common around me. In India, I found death was such an intimate acquaintance that his terrors, in the case of others, were too often regarded with callous indifference; and that the fact of the English residents being but temporary sojourners made them disinclined to support permanent charitable institutions, although they are extremely liberal, at the time, when personally appealed to, in the cause of suffering humanity. With the view of counteracting the apathy displayed by the local public towards its institutions for the good of the poor, and to furnish readable “copy” to our paper, I began a series of articles called “Calcutta Charities.” One day while I was writing, my husband came back from a visit to an old broken-down jockey, who used, many years ago, to ride for him, and who was then living in the Calcutta Almshouse. He told me all he had seen in this institution, and I became so interested in it that I resolved to call and see its female inmates.

[Pg 5]

I took with me, on the occasion of my visit to the almshouse, a friend, Brother John, of the Society of St. Paul, who was engaged in the work of the Calcutta Seamen’s Mission, under the direction of his superior, the Reverend Father Hopkins. I became acquainted with Brother John through Father Hopkins, who called and asked me to sing at one of his weekly concerts for sailors in Bentinck Street, arranging to send Brother John to take me to the place in a cab. Father Hopkins said, “You must not be shocked on finding the brother a rough sailor, who drops his ‘h’s’ and is afraid of women, never having been accustomed to[Pg 6] ladies’ society. You will find he has a good heart. The sailors all like Brother John.” On the evening appointed, the brother arrived with the cab for me. He was shown into our drawing-room, and was evidently keeping those refractory “h’s” of his well under control, for I could not get him to talk at all, and thought him rather stupid, as he sat nervously clutching his hat. Afterwards, when he knew me better, he told me that he suffered agonies on that evening, and begged Father Hopkins not to depute him to fetch me, but to send, instead, Brother Paul, who knew how to behave to ladies. Poor Brother John little knew me, if he thought that the mere fact of his being insufficiently educated would render me heedless of the many good traits in his fine character! I liked him as soon as he had overcome his nervousness enough to permit of his saying, “I hope you’ll excuse me if I’m not accustomed to ladies’ society. I’m only a rough sailor, and I don’t know how to speak or what to say to ladies. I get along all right with the sailors. I’ve never had any education, and I feel the want of it now badly.” This honest speech of his made me his friend at once, and I often went to the sailors’ concerts[Pg 7] after that night. He was one of nature’s gentlemen, who seemed always able to say and do the right thing instinctively, and whose quiet, simple manner would command the respect of his fellows. I used to like going with Brother John every week to visit the sick sailors in the Calcutta hospitals. On such occasions he would provide a good supply of plug tobacco (beloved of Jack) and newspapers. It was while going our weekly round one day that I mentioned my intended visit to the almshouse, and arranged with him to accompany me.

When we arrived at the place, we were shown into the office of a soldierly-looking man of about sixty years of age, who was evidently a thorough disciplinarian. He was obliging and communicative; and told me he had read with pleasure my articles on “Calcutta Charities” in our paper, and heartily endorsed every word I had written. He said a great deal more, and before I left the office showed me his discharge certificate from the Army, in which he had been a sergeant, and also his Mutiny medal. We went with him over the male ward of the almshouse. I need not describe the occupants; poor things! They all looked becomingly miserable. I think[Pg 8] there were some Eurasians among them, but the majority were pure Europeans. Mr. McGuire—for that was the superintendent’s name—asked us to stay and see them fed, as it was their dinner-hour. We saw stew being doled out of a big saucepan into small bowls and put on a table. Each bowl was taken by its owner to a long, bare table, with forms down each side, and the meal, after grace being said, commenced. I felt uneasy while watching the poor things eating as if they were animals, so made a move to the women’s quarters. As we walked up the stairs to the top of the building set apart for females, Mr. McGuire called out, “Mrs. Smith!” and the matron of the place, a woman of about forty, appeared. I spoke to her but little. She showed me the women working at a table, mending or making house linen, and also their rooms. The inmates themselves took small notice of me: they looked bored and sad, evidently remembering that visitors who give them no substantial help, but who beam on them with a patronizing smile, are in these parts as common as they are useless. I felt that I should have liked to have spoken to the poor women, and to have asked them if I could help them in little[Pg 9] presents of tea or other things; but Mr. McGuire seemed to have divined my wish, for he told me they live very comfortably, having everything they could reasonably wish for as paupers. The word “pauper” jarred on me, but I said nothing as I gazed sorrowfully on them. One old woman, evidently with bad sight, was trying to hem a quilt. She appeared to be working under such difficulties on account of her eye-sight that I thought a pair of spectacles might be got for her. However, she was a “pauper,” and paupers are not beings to be favoured with such luxuries! I asked if I might read to them once a week, but was referred to the committee of the District Charitable Society for permission, which I applied for, but received no answer to my letter. If I had been given the least encouragement, or even sanction to have done so, I could have provided these poor women with many little comforts; but I was not. Brother John said little, but was as much struck with the defensive attitude of the officials as I was; for he was the first to speak of it on our way home.

I must here explain that Indian institutions, like the one in question, are usually presided over by Government[Pg 10] officials, who have little time to spare from their routine work for the exhibition of sympathy and practical kindness. The climate, too, greatly militates against philanthropic efforts in the cause of unpaid duties. Hence, the tendency to shift the onus of superintendence on subordinates, whose actions their superiors have to support, or to burden themselves with a large amount of personal attendance. With such an alternative, the choice generally accepted can easily be guessed. As long as things go outwardly smoothly, the subordinate draws his salary, plays the vicarious part of big man, and no doubt enjoys the well understood perquisites of such offices. If a public exposé takes place, the high official gets worried and questioned about a subject with which he has failed to keep himself in touch; the subordinate sees with dismay the chances of his direct and indirect emoluments being snatched from his grasp. Hence, the entire staff bitterly resent any journalistic comments on their working that are not wholly laudatory. All such officials, therefore, act on the principle of L’état, c’est moi. “If” say they, “you have got anything to find fault with, report it to me; but don’t write to the[Pg 11] papers.” If the would-be reformer acts contrary to this dictum, he will make such officials his bitterest enemies. In such an ignoble category, men like Dr. MacLaren, superintendent of the Dehra Dun Asylum, and Mr. Ackworth and Dr. Weir, of Bombay, find no place; for their object is not to gain credit for charitable work they do not perform, but to relieve and comfort those under their kindly charge.

We were about to depart from the almshouse when I espied a number of low red-brick buildings enclosed in a small compound on the opposite side of the road. On inquiring the name of the place, I was told it was the Leper Asylum. “May I go over it?” I asked the superintendent of the almshouse. “Yes, if you are not afraid,” he replied; “I am also superintendent of the Leper Asylum; but I may tell you that I have never taken a lady over the place before.” I looked at Brother John, and asked him if he would prefer to wait for us outside, or go into the abode of leprosy. He said he would like to accompany us; so we all went. I had frequently seen and pitied lepers in the streets; but had never before been brought into communication with them.

[Pg 12]

The illustration facing this page will give my readers an idea of the leper, as he is to be seen in the Indian public thoroughfares. We throw the poor things a few coppers in passing; but, as there are no lepers in England, the majority of us know little about the horrible disease from which they suffer, and are therefore inclined to regard them as ordinary beggars. I had read “Life and Letters of Father Damien,” and from that little book, which was lent me by the nuns of the Loretto Convent in Calcutta, I learned something of leprosy; just enough perhaps to make me wish to know more and to see for myself what was the condition of the sufferers.

A Leper Beggar.

p. 12.

We were taken into an enclosure bounded by a high wall, and containing three long, one-storied, detached brick buildings, which, I was informed, were for the female lepers, and that there were three similar buildings on the other side of the compound, separated by a wall, for the men. As I walked up a few steps which raised the building from the level of the road, and entered the first ward, I was conscious of a “faint” smell (which is peculiar to the disease) emanating from it. We entered a long room with a stone floor, and rows of beds ranged down each side. Lying or sitting on these beds—for there was not a vestige of any other kind of furniture—were several native women, all more or less bandaged. They looked up at me with a pitifully sad expression on their faces. One woman tore off her bandages and exposed a few diseased stumps remaining from what had once been fingers. The smell in the place was very bad; the sheets on the beds were discoloured and dirty; the bandages covering the sores of these poor wretches were filthy. I would fain have spoken a few words of comfort to them, for my heart was sad within me; but knowing very little of the language, I could do no more than make a few friendly gestures. Brother John told them we should come again, and we were just turning to depart when the superintendent said, “You haven’t seen Bridget.” On saying this, he lifted a filthy sheet that was tied on to a stick placed across an opening at the further end of the building, which contained a small room, or alcove, and disclosed a white woman sleeping! I was horrified to find a European woman in the Leper Asylum, and with nothing more than a dirty sheet dividing her from[Pg 14] natives. The poor old thing, who had grey hair, was sleeping so peacefully that I begged the man not to disturb her. When we got outside I asked who she was, and found that she was an Irishwoman who had been an inmate of the asylum for many years.

The next ward we visited was constructed on exactly the same lines. In this there were, I think, seven women. The superintendent had a deal to say of a girl called Bella, who, he told us, had been studying medicine at the Umritzar Medical Mission when the disease broke out in her. Poor Bella lay on a dirty bed, and smiled feebly as we approached. Her fingers and toes were in a terrible state. The former had been dressed with something black that looked like tar. She wore no bandages on them, and there were great holes in her poor fingers, as though some wild animal had been biting pieces of flesh from them. Bella was a Eurasian, so spoke English. I could have cried aloud as I stood gazing helplessly on this young girl, cut down in the very flower of her youth, and doomed to spend the remainder of her days in this horrible abode of disease and death. “Oh, can nothing be done for her?” I asked. “Nothing,” replied the[Pg 15] superintendent; “I will give her three years to live—three years at the outside.” I felt sorry that my question should have called forth such a reply; for poor Bella heard it in sad silence. I longed to comfort her, but I could think of nothing to say; it was all so horrible. I determined, however, that as no woman regularly visited the place, I would do so myself. I did not fear the disease; I only felt wretched on seeing its poor victims. I turned and spoke to another woman in European dress. She was a Polish Jewess, and was evidently afflicted with a different kind of leprosy, for her skin was the colour of indigo, and was much puffed and swollen, though no open sores were visible on her. She told me that she was married and the mother of a family. She could in no way account for her present state. When leprosy first showed itself on her, her husband cast her adrift, and refused to see or help her in any way. She had saved a little money and had been to doctors in Austria and Germany, and had tried all sorts of pretended cures, but without success. “Have you any money now?” I asked. “Yes,” she replied, “I have a hundred and fifty rupees [about ten guineas] in the bank; but I[Pg 16] would sooner starve than touch it. I am a pauper in this place; but after death I will be again a lady. The money is for my funeral; I will be buried in my own coffin, as a Jewess.” I asked them if they would like some books to read, but they shook their heads sadly, and said that their sight was going fast, and reading hurt their eyes too much. They tried to speak cheerfully; but it was all terribly sad. Brother John could hardly trust himself to speak to poor Bella, while she herself seemed ready to cry. I looked at the miserable bareness of the place, and at the native women squatting about on the floor, and inquired if they had no chairs or washstands, or any more furniture than what I saw. They shook their heads. The Jewess pointed to a little oil-stove that was worn out and full of holes, and asked me if I would try to get her a new one, as she had no stove to boil water for her tea. I found that they washed themselves at a tap in the enclosure, but had neither bath-tubs or washstands. The sheets on their beds were supposed to be changed once a week: it was evident from their colour that they could not have been washed oftener. I wish to lay particular stress on the need there was of clean bed-linen[Pg 17] and underclothing, both from the offensive nature of the disease and from the tropical heat of the climate. In the alcove attached to this ward we found another girl, called Daisy, whom the superintendent informed me was of Scotch parentage, but who had been suckled as an infant by a Madrassi nurse, who had afterwards turned out to be a leper. Her features were terribly distorted by the disease. Her fingers and toes were in much the same state as those of poor Bella, and she wore a green shade over her eyes. There were a couple of wicker chairs in her little room, also an accordion, with which the superintendent told me she used to accompany herself to songs; that she had a sweet voice, and often sang to the other lepers. “To whom do these women apply for their wants?” I asked. “To me,” said Mr. McGuire. “I come here once a week.” “But is there no woman to look after such things?” “No,” he said; “women don’t care to come to such places as these.” I passed sorrowfully out, telling Daisy and the others that I would soon return with fruit, flowers, etc., which they said they would like. They smiled sadly, as though doubting my word, having had, as I afterwards discovered, many[Pg 18] other promises of the kind which had not been kept. Poor Bella was tortured by flies, which surrounded her open sores in swarms. The smell, too, of the disease was so great that I was perforce obliged to walk with my handkerchief to my face the whole time. It was a very hot day, and I felt bitterly sorry for these poor sufferers, without fans, lavender water, or any little comforts whatever. I would fain have fled from this pestilent abode, and yet I lingered, wishing in my helplessness that I had the power of God behind me to enable me to say to these poor women, “I will, be thou clean.” As it was, I could only stand gazing sadly on them, wondering why God had so afflicted His creatures. I walked as one bewildered through another ward, wherein were nine miserable native women, all more or less terrible to behold. “Is there no English doctor to attend to the European women here?” I asked. “No,” replied the superintendent. “There is a native doctor, at a salary of twenty rupees a month.” “How many lepers are there?” “Seventy-six.” “But you have not half of the lepers in Calcutta in the asylum?” “Half! Why we only touch the fringe of leprosy.” “Has Government done nothing in the[Pg 19] matter?” “So far, no, though an inquiry is to be made some day with a view to providing accommodation for lepers.” “Are they allowed to go in and out of the asylum when they like?” “There is no law to prevent them,” he replied. “A leper falls fainting by the way-side, he is seized by the police, and conveyed in a third-class hackney carriage to the asylum. As soon as he has had his wounds dressed, has gained a little strength, and finds himself able to do so, he walks out into the streets again to beg. The Europeans do not go out.”

He then asked us if we would like to see the men, and, on our replying that we would, conducted us to the opposite side of the grounds, through a door labelled “Male Ward,” and into three buildings exactly similar to those we had just quitted. We walked down the first ward, filled with poor diseased specimens of humanity, in silence. The heat and smell of the place, and the filthy sheets and flies surrounding these poor lepers, were a sight that I shall never, never forget. One poor, half-naked creature was sitting in a corner trying to adjust a bandage round his legs, which, with only one or two stumps in the place of fingers, was to[Pg 20] him no easy task. My first impulse was to fix the dirty rag for him; but I suddenly remembered that contact with this terrible disease might possibly be fatal to me, so passed on. In the next ward, which was even in a dirtier state than any that I had previously visited, the native lepers were crowded together as thickly as possible. A horrible smell pervaded the place. Bits of dirty stained bandages hung here and there. On the floor, curled up on a piece of Indian matting, lay the form of a man in the last stage of leprosy. His back was turned to me, and, although I spoke a word to him, he made no sign, no movement. I stood and looked at him in his misery. His poor bones were almost protruding through his skin, which was drawn over his body like parchment. He groaned aloud, as if in agony, every now and then moistening his parched lips with his tongue. There was no friend or attendant near to give him a drop of water. All his fellow-sufferers in the wards seemed to be watching for the end. I asked if water could be given him, but was told that he had better be left to die in peace. He was a native, and men of his caste will not, I believe, accept a drink of water from a[Pg 21] European’s hands, or from a European water vessel: I know not whether the agonies he was enduring would have induced him to break his caste. Poor wretch, he carried our heartfelt sympathy with him on his journey into the unknown country, as well as our will to have helped him if we could have done so in any way. He died, I was told, a few hours after we left the asylum. About sixpence in coppers had been found on him, which sum was duly handed over to the authorities, who buried him according to the custom of his race.

There were three English-speaking Eurasian lepers in this ward. One man enlisted my sympathies on his behalf about some property which was confiscated to the State on the death of his mother, but which he asserts virtually belonged to him. He had made a struggle to retain possession of it, and had addressed a long petition to Lord Dufferin, who was then Viceroy of India; but, having failed to prove his legitimacy, was informed that nothing could possibly be done for him. I found him a refined, well-educated man, very fond of reading George Eliot’s works, and any well written novels.

The others are two Eurasian lads who are[Pg 22] cousins. One about 22, the other 10 years of age. I felt much sympathy for the poor child, cut off from everyone, and doomed to spend what should be his brightest days in this awful place. He is a nice-looking boy, with a bright face, and a sweet, kindly disposition; and is devoted to drawing and painting, which he can do remarkably well. He has often since drawn dogs, cows, and different animals, and laid them out on his bed for me to see and admire. Indeed, so well were some of these executed that I should have liked to have shown them to friends of mine, had it been safe to have handled them. Leprosy was only just asserting itself on him; no sores were visible, but his fingers were doubled up, and a few ominous spots were on his body. His cousin is a leper in a more advanced stage, so one would be led to infer from this that the disease has been transmitted by heredity. I do not know how he managed to do his drawing and painting so well as he did, for there was neither a chair or table in the ward, so he must have used the bed as a table, and worked in a kneeling position.

Brother John and I drove home from the leper asylum in silence, as our hearts were too full for[Pg 23] words. It seemed terrible that men and women should be living in the very midst of this crowded city as in a living tomb. Women, too, of my own caste and country, left alone to die without a friend in the world. One lady, Mrs. Grant, the matron of an institution known as the Military Orphan School, at Kidderpore, had visited them occasionally; but when I first went there four months had elapsed without their seeing her. This, I am certain, was no fault of hers; as she has many other duties to perform, and the Indian climate seldom allows one to continue well for any lengthened period. The men, poor things! had had no visitor to practically help them. Mr. Hall, the clergyman of the district, was in the habit of reading prayers in the little church attached to the Leper Asylum on certain Sundays; but the lepers did not appreciate mere words. His wife, Mrs. Hall, took to visiting the native leper women after I had published articles in our paper, and after I had raised a substantial fund for the cause I had at heart; but, though she would distribute flowers to the natives, she always refrained from giving any to the European and Eurasian women, who would have greatly appreciated such presents.

[Pg 24]

When I arrived home from the asylum, I went at once to find my husband, to tell him all that I had seen, and ask him to help me in doing something for the lepers. He was out, unfortunately, and, no one else being in the house, I tried to interest my little boy in the fate of the poor leper child whom I had just seen. His baby brain could not grasp the full extent of my meaning; but he understood enough to offer his scrap-book and promise me his musical-box and other things, all of which were duly handed over to the poor little leper next day.

I could do nothing all day but brood over what I had seen. In the evening, with the incidents fresh on[Pg 25] my mind, I sat down and wrote an account of them for our paper. This raised for me the anger of the officials in charge of the place, who had accepted the responsibility of caring for the lepers. I described exactly what I saw and smelt. If I had not written the truth, Brother John, who was with me, would have corrected my statements when appealed to in the matter, instead of publicly corroborating them, as he afterwards did. My husband thoroughly entered into, and appreciated, my wish to relieve the sufferers, and we presented ourselves next day at the asylum with offerings of fruit, flowers, fans, scent, biscuits, jam, clean linen for bandages, sheets, underclothing, and as many other things as I could think of. These things were tearfully received by the poor women, including Bridget, whom I now had an opportunity of seeing for the first time. Mr. McGuire was not pleased with me. He said they had all they required, and informed me, when I told the women I should try and get sufficient money to allow them a rupee a week each for extra washing, etc., that the Jewess had money in the bank, and that my money was not required. I happened to know about this money, and the use[Pg 26] for what it was being kept, so allowed his remarks to pass in silence. Bridget was a strange and weird sight when I first saw her. She wore a short black petticoat, reaching a little below her knees, and a soiled cotton jacket that had once been white. She had evidently gone without a bath for a long time, for her face and neck were dirty. Her bare feet were swollen, but there were no leprous sores on her, nor any distortion of her fingers or toes. As she stood towering above me, a tall, gaunt, starved-looking woman, I noticed a wild, restless look in her eyes which appeared to me to be a sort of challenge. On a table near her were some old loaves of bread from which all the crumb had been eaten, leaving nothing but the outside crust, that, from want of teeth, she had been unable to eat. There was also a little sour milk in a bowl. I inquired and found that her diet was bread, milk and a little coarse sugar, and that she begged scraps of curry, or dall (lentil) and rice from the inmates. It appears that at the Calcutta Leper Asylum there is a milk diet, on which Bridget was placed, and which consisted of twenty-two ounces of bread and a quart of milk daily, and a little sugar, and a meat diet;[Pg 27] the latter being sufficient for an adult, but the former was not. Bridget had her choice of the two diets, and, as she was loth to sacrifice her milk, which she would have to do if she chose the meat diet, elected to take the milk diet. The rules of the place were not sufficiently elastic to admit of a milk diet varied with meat. Bridget, therefore, in order to keep body and soul together, was obliged to beg food from the other inmates. She replied, when I asked her why she had not taken a bath, that there was no place in which she could bathe. Outside, there was a brick building that had evidently been constructed for the use of native women, and without reference to the requirements of Europeans. This building was divided into three small compartments, in each of which there was a tap for water and a drain for its outlet. There were no doors of any kind. I must here explain that the tap, rather than the more convenient bathing-tub, was selected in the interests of sanitation. The floor was of stone or concrete, and the wall in front, which shut off the bathing compartments from view, was open at both ends. My lady readers will understand how repugnant it is to[Pg 28] the feelings of white women to bathe in a place in which they are not entirely secure from observation, even from that of their own sex; a condition which is not obtainable at the Calcutta Leper Asylum. Bridget, having been brought up in Ireland with some ideas of decency, would not take a bath under these conditions; so went without.

After making this discovery, I could not rest until I had written a letter to Mr. Lambert, the Commissioner of Police, asking for an interview. He granted my request, and appointed a time for me to call at his office. I found him a typical official, the performance of whose routine duties allowed him but little scope for the exercise of personal sympathy. I told him of the state of the Leper Asylum exactly as I had found it. He gave me little satisfaction, but ended by remarking that he and Mr. Justice Prinsep, who was President of the District Charitable Society, were going down to the Leper Asylum on the following morning, and that he would be glad if I would then shew them the dirty sheets described in my article which had appeared in our paper. I was too much awed by Mr. Lambert’s official manner to point out to him the[Pg 29] futility of such a quest; for the most rigid believer in the artlessness of human nature would have known that the sheets destined to meet the forthcoming scrutiny, after all that had been written and read about their previous state, would be characterised, as far as possible, by scrupulous purity. However, being in a position to be thankful for the smallest mercy, I accepted Mr. Lambert’s offer, and drove down to the asylum, with my husband, on the following morning. Mr. Prinsep, who, I believe, had never been to the place before, appeared to be amused on seeing me, and was little inclined to treat the inquiry seriously. Owing to my article, no doubt, the asylum had undergone a thorough cleaning; the sheets were clean, and the place tidied up. Mr. Lambert, without a smile on his face, turned to us and said that he failed to see any cause for complaint, and that the place was clean. At that moment I saw a dying leper lying on a filthy bed, the sheets of which were covered with spots of blood and matter. I pointed this out to Mr. Lambert, who asked the man how often his sheets were changed. “We have a clean sheet every eight or nine days,” replied the[Pg 30] man in English. I had given the time as once a week in our paper, so it was even longer than I had stated. When we got outside, Mr. Prinsep joined us, and we went to Bridget’s room. I asked Mr. Prinsep if he considered 22 ounces of bread, a quart of thin milk, and 4 ounces of coarse sugar a day sufficient for her? He turned to me and said he certainly thought it plenty. I could not help looking at his portly and well-nourished form, and comparing it with that of the thin, starved-looking old Irishwoman, standing at the door and offering a bowl of well-watered milk for his inspection.

My readers may imagine that in the face of so much opposition, I was beginning to lose heart. While these persons were inspecting the tank in which the lepers’ clothes were washed, I went into Daisy’s room, and gathering the three English-speaking lepers—Bella, Daisy, and the Jewess—around me, I begged of them to speak out and tell these gentlemen of their need of a female attendant, of washstands, and a place in which they could bathe in private, as well as of the bad food of which they had complained to me. The poor things said they would, but when the three stern men stood[Pg 31] before them, and Mr. Lambert asked, in his severest police tones, what complaints they had to make, the miserable leper women crouched down on the floor and were silent! What “complaints” dared they make? Did they not know that such men possessed the power of turning them, diseased and penniless as they were, into the streets at any moment? The horror and disgrace of a European leper woman begging in the streets was an idea that they could never have tolerated—anything rather than that. There is a certain amount of sympathy accorded to native lepers, but Europeans afflicted in like manner are regarded more as wild beasts than as human beings. Could they have uttered a word of complaint under the circumstances? Of course not. To me, as an Englishwoman, the sight of these three leper women, cowering before the very men who posed before the world as their friends and benefactors, was one that roused every feeling within me to rebellion! However, after all, I was only regarded as a meddlesome unit, whose blame or praise was a matter of utter indifference to persons of position and standing; though who knows but that a merciful God in Heaven, the Father of the[Pg 32] fatherless and afflicted, to whom all hearts are opened, did not see and pass judgment on one and all of us who stood before Him that day? It may have been this thought which caused me to bridle my tongue and refrain from giving utterance to strong words. Anyhow, I did manage to control my feelings sufficiently to enable me to speak calmly to Mr. Lambert, to point out to him the bathing-place, and to ask him, as a man who had daughters of his own, if he considered it a fitting bath-room for European women. Mr. Lambert, looking into the bathing-place, saw a native woman taking her bath, and retired in confusion. I commented on the unprotected state of the European women, who were obliged to bathe in this place, which was exposed in an enclosure where native male dressers, washermen, cooks and others were in the habit of walking, and suggested the desirability of having a door placed in one of the bathing partitions, which should be supplied with a bathing-tub, and reserved for the use of European women, who are unaccustomed to bathing like natives. I was informed that such additions were altogether superfluous, and that if the ends of the outer wall were rounded or curved in,[Pg 33] instead of being straight as they then were, all requirements as to the privacy and comfort of the bathing arrangements would then be met. This was done, but up to the time of writing, no door or bath-tub has been provided for the use of Daisy, Bella, or the Jewess, who have to make their daily ablutions under the tap as best they can. I may mention that there were no arrangements at all in this asylum for giving the patients a warm bath.

[Pg 34]

As I have already mentioned, the remarks I wrote about the Calcutta Leper Asylum made the honorary officials of that institution “mad” at being “shown up” (which was a necessary consequence of the appearance of a true account of that institution) as mere poseurs, and not as workers, as they fain would have appeared before the Government from whom they received pay, and expected preferment. Being the head of the institution, and never having visited it, to my knowledge, except on the occasion of the official visit I have described in the previous chapter, Mr. Prinsep was, of course, my bitterest opponent. Consequently[Pg 35] appeared the following extract in Truth of the 10th of July last year:—

On May 15th reference was made in Truth to a deplorable account of the Leper Asylum, Calcutta, given by Mrs. Alice Hayes, in a local paper called Hayes’ Sporting News. I have now received from Mr. Justice Prinsep, president of the District Charitable Society, which has the control of the Asylum in question, a letter in which the writer states that the statements in Hayes’ Sporting News “are absolutely without foundation, and are merely the careless and inaccurate reports of a hysterical, irresponsible woman seeking for notoriety.” Mr. Justice Prinsep does not deal with the whole of the statements specifically, but he states (1) that in only one of the six buildings “can it be pretended that there is any overcrowding at all;” (2) “that the medical attendance is appropriate;” (3) “that a person referred to by Mrs. Hayes as a native doctor is the ‘compounder;’” and (4) that he could, if it were worth while, “similarly refute all Mrs. Hayes’s statements.” He also sends me a copy of a letter addressed on behalf of the management to the local press; but I find here quite as much admission of the impeachment as denial. I find further that in subsequent articles in Hayes’ Sporting News, Mrs. Hayes adheres to her original statements, and points out that many of them are unanswered or unanswerable. It is impossible for me at this distance of time and space to go further into the matter, but the impression left on my mind is that Mr. Justice Prinsep’s abusive language of Mrs. Hayes is entirely unjustified, and that this Leper Asylum will probably be all the better for the light that has been turned on it.

Mr. Prinsep, being a lawyer (he was Judge in the Calcutta High Court), was well acquainted with the old legal maxim: “when you have got no case, abuse the other side.” Consequently his strong language—however[Pg 36] unbecoming it was in a man of his high official position, and addressed to a woman—was a convincing proof that the words I had written were true. His assertion that I made a mistake in the designation of the medical attendant, proves how sorely he was pressed to find something to refute; for the fact of a “compounder” being lower in grade than a “native doctor” made my case all the stronger.

I received not only a kindly pat on the back from Mr. Labouchere; but a most sympathetic article under the heading, “A Lady’s Work Among the Lepers,” appeared on the 22nd of the following November in The Queen, as follows:—

A Calcutta correspondent writes:—“Perhaps your readers may be interested to hear what a woman has done for the lepers in the Calcutta Leper Asylum. Mrs. Alice Hayes, lady correspondent of a local weekly entitled Hayes’ Sporting News, edited by her husband Captain Horace Hayes, lately commenced writing in her husband’s paper a series of articles on Calcutta Charities, visiting each one for this purpose, amongst them the Calcutta Leper Asylum. She found entombed there about seventy lepers—men and women, and one or two children. Amongst the inmates are some Eurasian and European men and women. The latter seem, from Mrs. Hayes’ accounts, to be badly furnished with the comforts of life. Two of the women had been students in some of our large public schools before the disease showed itself, and were hidden away here by parents and friends anxious to put such a[Pg 37] visitation from the world’s gaze. Mrs. Hayes was much touched at the sad loneliness of these poor creatures, and describes their condition most vividly in the paper before mentioned, inviting the help of the public to form a small fund to provide them with small creature comforts which the asylum had omitted to supply, such as sufficient clothes, sheets, washstands, fruit, jam, illustrated papers, &c., and proposing personally to visit the asylum weekly, and distribute amongst the afflicted people the small offerings. Her appeal has been very generously responded to, and money, clothing, etc., have been sent to her. Nobly too, does she, week after week fulfil her self-imposed mission, going among these poor outcasts, and cheering their loneliness with sprightly talk and news of the outside world, and leaving each time some memento of her kindly presence. Leprosy in our tropical climate assumes its most loathsome aspect, and many of the inhabitants of our Leper Asylum are in a very advanced stage of the disease. The sight, as described by others whom curiosity or pity perhaps has tempted there, is enough to appal any man. I hardly think a second visit is paid, however good the intention of doing so. Mrs. Hayes, on the contrary, as I have said before, has never failed a single Tuesday to visit her poor suffering fellow-creatures. We read with admiration of the deeds of Florence Nightingale, Sister Dora, Sister Gertrude, and I think we should add to this list the name of our brave young citizen, Mrs. Alice Hayes, whose kindness and courage are certainly unequalled in India.”

I had a great deal of criticism in the Indian papers. The Calcutta ones, which are largely dependent on the support of the local officials, chiefly backed up the principle that the king can do no wrong; while the journals that were free from Calcutta official influence, as a rule, took my side. The result, however, was[Pg 38] favourable; for subscriptions from all parts of India came to our fund, which, since our departure from the East, has, I am very sorry to say, decreased. As I can now no longer personally stimulate support, I am doing the next best thing by writing this book.

[Pg 39]

I managed, after a deal of trouble, to give each of the leper women a small tin-enamelled washstand; but much opposition was brought to bear on me by the officials in my efforts to alleviate their sufferings in any way. Daisy, who spoke to me about the bath-room, says she hangs up a towel in front of the doorway and so secures privacy in that way; but it is a wretched makeshift at the best. Seeing that no female attendant was provided to attend to the personal requirements of these poor women, whose disease renders them miserably helpless, we thought out a project by which a native woman could be got to wait on them.[Pg 40] By this time my article, which, as I explained, had been written when the scene presented to me on my first visit to the Leper Asylum was fresh and vivid in my recollection, had been published in our paper and had been productive of good results. Parcels of linen, books, soap, tea, and various things were sent me, together with subscriptions amounting to over Rs. 800. Out of this we sent a cheque for Rs. 192 to the committee of the District Charitable Society, with the request that a female attendant be provided for the female European and Eurasian inmates of the Leper Asylum, at a salary of Rs. 8 a-month, for two years. This money was, I am glad to say, accepted by the committee, and the attendant procured. We read an account in a local paper of Dr. Unna’s new medicine for leprosy, which had been highly recommended by Dr. Milton, senior surgeon of St. John’s Hospital for Diseases of the Skin, London, and at once forwarded to the committee of the D. C. S., from our Leper Fund, a cheque for Rs. 250, with the request that the money be used in procuring the medicine from England and giving it a fair trial in the Calcutta Leper Asylum, together with a promise of a further[Pg 41] remittance of Rs. 250 for this object should it be required. This money was, after some discussion, accepted, and an order for the medicine sent to England. I must not forget to mention that we pointed out in our letter to the Committee the advisability of having the new medicine tried here by an English doctor. I had secured the confidence of the public, who sympathised with me in my work, and sent me various sums of money from time to time. Monthly subscriptions to our Leper Fund amounted to Rs. 40. With this sum I was able to spend Rs. 10 weekly on comforts for the white female lepers. I gave the four of them a rupee each, and spent the remaining six rupees on jam, fruit, biscuits, lavender water, flowers, etc., always reserving a few rupees, which I exchanged into coppers, and gave each native leper woman as many as I could afford. My weekly visits to the Leper Asylum were always paid in company with Brother John, who arranged to go with me every Tuesday, and who was my most staunch and sincere helper in this work. We had at first to encounter much opposition from the officials; were not allowed to visit the asylum without sending for the superintendent,[Pg 42] nor permitted to give anything to the lepers without first having our gifts pass through his hands. I found this arrangement most unpleasant, for among my gifts to these poor friendless women were things that are not generally allowed to pass through the hands of a man, and, besides, I often wanted to speak to the women alone, and the presence of the superintendent was in no way desirable. Being utterly powerless to move the men on the Committee, who regarded me as an enemy to be thwarted at every turn, and held up to scorn and ridicule, I appealed to the public through our paper, with the result that several indignant letters from sympathisers appeared in the local daily papers. This caused a change of front. Mrs. Smith, the matron at the almshouse, opposite the asylum, was told to attend me in my visits, and distribute the gifts I took to the lepers. I noticed, also, that some improvements had been made in the asylum. Bridget’s room had been cut off entirely from the native ward by a wooden partition; a bath-room, constructed of matting and bamboos, for her special use, had been fitted up in the small verandah at the back of her room. The food of the[Pg 43] lepers had also been undergoing a change, and Bridget was given a little curry and rice, in addition to her bread and milk. The people who are always ready to put an entirely false construction on the motives of others had been busy with their tongues, and had told Bridget and the others that I had only taken them up as a “fad,” to drop as quickly when I got tired of them. This was all duly repeated to me by the lepers themselves, who had begun to put by their weekly rupee against the time when supplies would be stopped. Of course, I was hurt and grieved to think that people could be so ungenerous as to say such things to the poor lepers, and tried to impress on Bridget that so long as I remained in Calcutta, with health and strength, I would let nothing prevent me from paying my weekly visit to them, and that when I was unable to do so, failing any lady, Brother John had promised to take up the work. This satisfied the old woman somewhat. She considered for a time, and then said, “Yes, I think you are telling the truth, because you have always kept your promises. I asked Mrs. —— to bring me some red herrings, and she said she would; but they never came.[Pg 44] When I asked you, you brought them. Besides, a young clergyman came here once—only once—and promised to send me some picture-books, but he never sent them; so you see we haven’t much faith in people now: we only believe them when we see them keep their promises.” I often used to find Daisy, the Jewess, and Bella together in Daisy’s little room, talking of their affliction. Suffering and sorrow have bound at least two of these women together in the holiest ties of friendship and love. One day I found them much depressed. I know not what had happened: I think there had been trouble with the officials. Whatever it was, they were afraid to tell me more than that they had been forbidden to speak about their feeding and treatment, as I had been publishing articles on their state in our paper. When I told them that money had been sent to England for the newly-recommended medicine for them, they were delighted; asked me many questions as to what it was like, when it would arrive, whether I thought it would do them any good, and many others that I was unable to answer.

Brother John.

p. 41.

To show the horrible neglect, as far as medical[Pg 45] attention was concerned, that existed in this Leper Asylum, I may mention that the patients were in charge of a native “compounder” (see Mr. Prinsep’s remark on page 35). Although Bridget, the old Irishwoman, was regarded by the officials of the Asylum as a leper, my husband and I doubted the accuracy of their judgment in this case; for it seemed impossible that she could be in such fair health, as she was, had she been thus afflicted for a dozen or more years, as they asserted. Her features were as regular and clean cut, as they would be in any woman of her age; and were free, as far as we could see, from any tubercles or nodules peculiar to leprosy, especially when it is of long standing. There was no distortion of her fingers or toes (she generally went about barefoot), and there was no staining of the skin of the uncovered parts of her body. Her feet and lower parts of her legs were somewhat swollen, which condition might very easily have been induced by debility brought on by the insufficiency of the food she was allowed, by the effects of the enervating climate, by want of proper exercise, and by age. She suffered from no leprous pains, the acuteness of her senses were in no way diminished, and[Pg 46] she was affected with no special lassitude. The only symptom which in her was at all diagnostic (if I may be pardoned for using a medical term which exactly conveys my meaning) of leprosy was a feeling of numbness which she had. My husband, who is a Fellow of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, and who has studied the nature of disease both in the lower animals and in man, tells me that this feeling of numbness is not peculiar to leprosy, but that it might have arisen, in Bridget, from another and not very dissimilar disease, which Bridget, according to the Leper Asylum officials, had contracted many years ago. I may also mention that this poor Irishwoman was entirely free from the peculiar odour which Dr. MacLaren (than whom there is no more experienced authority) regards (see page 116) as diagnostic of leprosy. Besides, Mrs. Grant, who had taken an interest in Bridget for many years, told us that Dr. Kenneth Stewart, who was formerly in practice in Calcutta, and who had examined Bridget, had told her that the Irishwoman was not a leper. As we had only the unprofessional opinion of the Asylum people against our contention, and as we thought it horrible[Pg 47] that on such slight evidence this poor creature should be stowed away in a native leper asylum, we applied and received permission to have her examined by Dr. Crombie, superintendent of the Calcutta General Hospital. This was done, and Dr. Crombie gave it his opinion that she was a leper, because of the numbness or anæsthesia (see page 116) from which she suffered.

[Pg 48]

All this time I was doing little or nothing for the male lepers. My monthly subscriptions were not sufficient to allow of my extending any gifts to them, much as I should have liked to have done so. Brother John undertook to provide them with tobacco, but he could do no more; for his salary amounted to but Rs. 50 (about £3 10s.) a month, out of which he had to keep himself and to feed many hungry sailors who found their way to his rooms. The native women, too, in the other wards were asking me to bring them fruit. Feeling myself cramped from want of funds, I took counsel with a dear friend of mine, Miss O’Brien,[Pg 49] who lived opposite our house, and who had assisted me in many ways with my work. She was the eldest of a large family, who were left almost penniless on the death of their father. Instead of asking alms of friends and acquaintances, she opened a school for young children, and by dint of hard and constant work, managed to support and assist the whole family until they were able to work for themselves. Another sister is the possessor of a fine soprano voice, which was trained in England by Signor Visetti. She is now one of the most popular singing-mistresses in Calcutta, and is able to assist her elder sister in keeping their old mother in comfort. These two admirable girls became greatly interested in my work among the lepers. The elder one read my articles to the school children. Over a hundred scholars were told of Bella and Daisy in the Leper Asylum. They raised a subscription among themselves, and sent me various small sums from time to time. The school-mistress, being cleverer than I am at book-keeping, took charge of my subscription-book and fund-money, giving me what I required every week for the lepers. She would have liked to have accompanied me on one of my visits[Pg 50] to the asylum, but her mother forbad her doing so, which, considering her position as head of a large school, was perhaps wise. Finding our Leper Fund getting low, and myself unable to do anything for the male lepers, my friends and I put our heads together one Sunday afternoon, and wrote out an appeal for more money, which we had printed and distributed round Calcutta. We also thought out a programme for an entertainment to be given in aid of the Leper Fund, to which we would all contribute help. I suggested that a lady pianiste should play a solo, my friend should sing something, we would ask a couple of gentlemen friends to sing also, the school children could wind up the first part with the pretty Highland schottische they had danced in the theatre on their last prize distribution day, and that I would arrange for the acting of “Our Bitterest Foe,” a pretty little play for three actors, which would fill the second part of the programme. Alas! the getting up of any performance is not at all so easy as it seems. Mrs. De Montmorency Smith will not promise to take part in any concert without first having had the names of the other performers submitted for her approval.[Pg 51] Then Miss de Courcy Jones will not perform unless she can choose her own place on the programme. The men, I must say, generally behave better. Having promised their help in the good cause of charity, they do not often worry one with petty tricks. Our proposed play was a difficult one to cast. Those of my readers who have seen it performed in England will remember that each of the three characters requires a deal of sound, strong acting. I had helpers in plenty; for amateur actors of a sort are not scarce in India; but they were not the right kind. Strange it is that almost every amateur actor is a low-comedy man! Our first rehearsal was altogether ridiculous. The man who essayed the part of the dignified Prussian General, Von Rosenberg, considered it the correct thing to sit in the presence of a lady with his feet on a chair! I had arranged my drawing-room as a stage, and had put each chair in its place, so, of course, could not allow the General to upset everything. When I told him of it, he answered stiffly, “That he wanted to make the part as natural as possible, and that men, when taking their ease, do sit in that position.” Knowing that a play cannot succeed,[Pg 52] if each actor is allowed to adopt what “business” he pleases, I told him that Mr. John McLean had taught me his way of playing the piece, and that I should prefer it done according to his instructions. My General removed his feet from the chair with an angry grunt. I discovered that he stammered on occasions of excitement, and when he looked at me and commenced his first speech, saying, “You are s-s-s-s-s-s—ad, Mademoiselle?” my other actor, who was to play the part of Henri de la Fere, and who was listening behind a screen, burst into such a fit of laughter that we were unable to proceed for some time. On hearing this, the General got up from his chair and walked up and down the stage in long strides, calling out to Henri to come and play the part himself, if he could do it better. He cooled down after a time and we were able to resume. When he came to the lines, “I am a Prussian, Mademoiselle,” he emphasized the word “Prussian” by banging his fist down on the table with so much violence, that I, who was sitting on the opposite side following his speeches with the book, was startled and dropped it. This provoked repeated roars of laughter from[Pg 53] Henri, which so incensed the General that he refused to say another word. I did not press him to do so; for I saw that his acting would not pass muster; so we partook of afternoon tea and passed things off pleasantly with some music. When the amateurs had gone, I decided to abandon my idea of a play and have a concert only, and to engage the Calcutta Town Hall for the occasion.

I found I had many kind friends to help me in getting up my concert. Besides the performers, who gladly offered their services free of all charge, was Mr. George, a clever artist, who was at that time engaged on an illustrated paper called The Empress, and who designed the programmes for me; Messrs. Thacker, Spink and Co., who provided and printed them free of charge; the Great Eastern Hotel Company, who sent their workmen with flags and drapery to decorate the Town Hall; and a number of other good people who all helped to make the evening a success. The Volunteer band, under Herr Kuhlmey, played during the interval, and also after the concert. Brother John and I had a hard day’s work before us in arranging the stage and decorating it with flowers and fairy lamps.[Pg 54] He procured a quantity of evergreens, and between us we managed to make the stage look very well. He had a large model of a ship that had been made by the sailors, and of which he was justly proud, arranged among the flags and flowers in the centre of the stage where the audience could see and admire it to their heart’s content. Brother John and my husband took the tickets and showed the people into their seats. The concert was a success in every way. Mrs. Bushby, a silver medalist, and one of the best pianists in India, played the accompaniments. The soloists were Miss O’Brien, Miss Stuart, Mrs. Turnbull, Mr. Eastly, Mr. Hartland, and Father Hopkins, all well-known amateurs of Calcutta. I recited two pieces, and received a very hearty greeting from the crowded audience when I went on the stage. I thought that after all the hostilities we had encountered in connection with this leper question, that I should have a small house; but though none of the officials connected with the Leper Asylum or their friends were present at our concert, so many other people came that we had to provide more chairs to meet them all, and the Town Hall was quite full. I plucked up courage on[Pg 55] seeing this, and recited in my very best style, gaining a hearty encore from my audience, who seemed to be thoroughly pleased with what I did. Miss O’Brien was, of course, the prima donna of the evening, and all the other performers were most successful with their songs.

[Pg 56]

Since my first visit to the Asylum two other men had been admitted, both Europeans. One man is English and was employed on the railway. He managed with the weekly rupee I was able to give him, to obtain some special kind of medicine which, he says, is doing him a deal of good. He showed me some in a small tin box. It looked like tobacco leaves and has a peculiar smell. He makes it into pills and takes several every day. There are many hundreds of different quack medicines which are advertised as “cures” for leprosy, but I have little faith in any of them. This English leper is entirely destitute, and is at the moment of writing sharing a[Pg 57] common ward with natives. His sole furniture consists of the bed on which he lies; not even a chair being provided for him to sit on. He has no washstand, nor any other furniture. In the next bed to him is a man of French extraction; a very bad case. Leprosy has obtained such a hold of him that I doubt whether he will live very long. He was formerly employed in the Calcutta water-works and several letters had appeared in the daily papers written by different persons who had seen him, commenting on the danger of allowing a leper to occupy this position. He was discharged shortly after the appearance of these letters, a pension being allowed him for the support of his family. I heard that he had transmitted the disease to his wife. Notwithstanding that two pure Europeans had been admitted into the male ward, not the slightest thing has been done towards making them comfortable. How differently Dr. MacLaren treats his European patients! This admirable gentleman started in 1879 a leper asylum for natives at Dehra Dun, in the north of India, where he was in practice. This institution has been supported entirely by voluntary contributions, and Dr. MacLaren has[Pg 58] devoted as much of his time as possible to trying to master this horrible disease with the aid of all that medical science can accomplish. In this year’s report of the Dehra Dun Asylum, we read, “During this year a European—the first—has been admitted to the Asylum. As, however, he does not belong to this district, and was admitted on his own urgent request, I may here make a short statement regarding him. Mr. C. W. J., who is in his forty-sixth year, was at one time in a good situation in a Government Office; but about nineteen years ago a blotch appeared on his body which in the course of a few years developed into disfiguring sores. He visited England on furlough to get what benefit he could from home treatment. After staying and receiving treatment for some time he had to return without having received the benefit which he had so confidently hoped for. Shortly after that, he was invalided out of the Service with only a gratuity; but on appealing to Government he ultimately succeeded in having a pension granted him. In July he first made application for admission; but as there was nothing in the way of accommodation for a European in the institution, I could not[Pg 59] give him much encouragement. Ultimately, the local Government and the Superintendent of the Dun, Mr. Nujent, magnanimously provided funds wherewith suitable accommodation and furniture was provided. A small cottage, consisting of a room, bedroom, closet, and verandah in a corner of the garden, was altered, and given up for his use, and Mr. J. came here in October.” My readers may learn from this that Dr. MacLaren did consider the requirements of a European as being entirely separate and distinct from those of natives, and arranged for suitable accommodation for the one under his charge, previous to his reception. In Calcutta this is not done, and up to the time of writing, Europeans are herding with natives in a ward entirely devoid of furniture, except a bed each. This is not from necessity or want of funds; for the District Charitable Society is one of the richest in Calcutta. I may here explain to those of my readers who have not lived abroad that, however poor and miserably afflicted a European man or woman may be, the one possession to which they cling, and on which they hang their last shred of personal pride when everything else[Pg 60] in the world has left them, is their nationality. Hence, they bitterly resent in their hearts, even when they are too stricken down to give vent to their feelings in words, any attempt to class them on a common footing with natives. The same commendable spirit animated St. Paul when he claimed that he was a Roman.

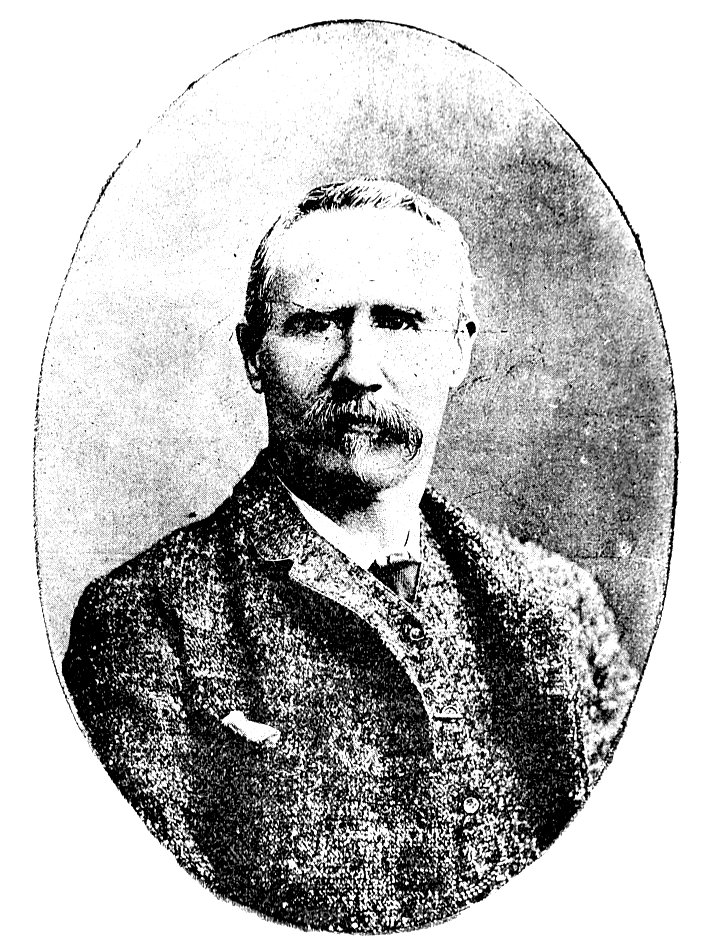

Dr. G. G. MacLaren.

p. 57.

At this time the weather in Calcutta was intensely hot. One Tuesday, as I drove down to the Asylum, my pony, evidently overcome by the heat, staggered and seemed unable to proceed. Seeing some cabmen bathing their horses’ temples with wet rags at a watering place in the road, I stopped my pony and got my native groom to do likewise to him. It revived him and we reached safely at the Asylum without further mishap. On taking up the Statesman newspaper next day, I read that five tramway horses had died of sunstroke about the very time that my pony became affected by the heat. The lepers at the Asylum were feeling it very much, and the smell of the disease was quite overpowering. I forwarded a gallon of phenyle for use in the Leper Asylum; but Mr. Lambert (the Commissioner of Police, who has charge of this institution)[Pg 61] wrote across my note: “return this to Mrs. Hayes, with thanks,” and the phenyle came back to me. Although some months had passed, during which time these officials were able to see for themselves that I was trying to do my best for the good of the lepers and working quietly; still they chose to maintain their hostile attitude towards me and to do their utmost to wound and annoy me in every way. Even Mr. McGuire must have felt that I was hardly treated; for, as he returned my phenyle and put it in the carriage, he showed me Mr. Lambert’s letter, and assured me that he was acting under orders. Just then I heard a roar as of a number of wild animals fighting. I proceeded to the native female ward from whence it came, and saw a number of leper women all rushing at the bed on which I had placed the coppers I had counted out for each of them, and trying to get possession of the whole, tearing and going at each other like so many tigers. Mrs. Smith was able to restore order after a while; but the sight of these loathsome-looking diseased women enveloped in dirty rags and bandages trying to hurt each other for a few coppers, was one that I shall never forget. The heat was overpowering; things[Pg 62] were all going wrong; the phenyle that Daisy had repeatedly asked for was not allowed to be given, and I returned home that day sick and wretched.

[Pg 63]

Dr. Wallace, a friend who came to lunch, on talking things over with me, proposed that instead of labouring away every week at the Government Leper Asylum under many vexatious restrictions, it would be better to try and open a Home for European and Eurasian lepers where they could find shelter and comfort, and be away from natives similarly afflicted. I entered gladly into the spirit of the proposition, but felt doubtful as to whether sufficient money would be forthcoming to carry on such an institution. We did not want it to rest on the shoulders of any one man or woman; but desired it to be properly managed[Pg 64] by a competent committee appointed for the purpose. I was in favour of putting the proposed Home in charge of Sisters of Charity, who, the Reverend Mother Matilda of the Loretto Convent, told me, would come out from England if we could insure them a home and food, and that they would devote their lives to this holy cause. This idea was not generally approved of by my Protestant friends, who said that Catholics would be certain to want to proselytise the persons under their charge, and that, although the Sisters would devote their whole time to the care of the lepers, my subscriptions would fall off directly I placed them under any special religious body. Besides, there exists a deal of suspicious distrust of Catholics in India, which has arisen, I think, from jealousy; for it is generally, if reluctantly, conceded that Catholics manage their public charitable institutions far better than do persons of other denominations. We decided that it would be best to put Dr. Wallace’s proposal to the test of public opinion, and to call a meeting at the Dalhousie Institute, which has a hall that is used for such purposes. We intended to put forward two resolutions at this meeting. The first[Pg 65] was to show the need of such a home; for although the Government Asylum gave shelter to European and Eurasian lepers, it placed them under conditions which few of them, however sorely pressed they might be by their misery, would accept. Dr. Wallace promised to speak on this point, and to tell the audience, as he had already informed us, that he knew, from his own personal experience, of from twenty to thirty of these hapless ones who were living in their own homes in Calcutta to the danger of their friends and of the general public. Besides this score or so in the metropolis, there must be hundreds of European and Eurasian lepers scattered throughout the length and breadth of India. Only a very small proportion of these cases come before the notice of the English residents; for the relations of such lepers naturally make every possible effort to prevent the fact of the existence of the disease in their family becoming known on account of the awful ban it would lay on all the other members. I need hardly say that no one, in his or her senses, would knowingly marry into a family affected with the hereditary taint of leprosy, nor even associate on intimate terms with such comparative outcasts. Owing to the[Pg 66] perverseness of human nature, such instances do sometimes occur. One was of a young gentleman, good-looking, well connected, charming in his manners, of great natural abilities and of irreproachable conduct, who fell in love with a young lady whose family had a trace of native blood in it, and laboured under the whispered stigma of leprosy. The young gentleman’s relations used every means in their power to prevent their union, and told him distinctly that if it took place they would know him no more. Their entreaties and threats were in vain; the marriage took place; some children were born; a few years passed happily despite the alienation of his friends, and then the effects of the dire malady broke out in the young wife. The husband tried, with rare heroism, to keep a bright face on the sorrow he endeavoured to hide, and obtained the best medical advice in the world, but all in vain; for the disease went steadily on to its end in its uncheckable course. Among others in Calcutta, we knew one who regularly attended church and sat beside his fellow worshippers; a second went to meetings of the local Salvation Army and used to shake hands with the members of his religious sect; a third lived with[Pg 67] his parents, brothers and sisters, none of whom had developed the malady; a fourth lived with his wife and family (the woman and children being apparently healthy) and eked out a precarious living by begging. We had heard of a planter, who, while we were in Calcutta, brought a brother of his, that was afflicted with leprosy, down to Calcutta with the object of placing him in the Leper Asylum; but, on seeing that it was altogether unsuitable to the requirements of a white man, he took him back with him to his own home. My husband knew an officer in the Indian Army, who was quartered in the same station with him, and who became a leper. When his condition could be no longer concealed, in the event of his going out in public, he was virtually made a prisoner of, in his house, by his friends, who screened him off from outside gaze till he died. My husband also knew of an equally sad case of a gentleman in Government employment in India, who contracted leprosy, and whose brother (his only relation in that country), as soon as he became aware of the fact, would no longer come to see him or hold any intercourse with him. Although some of his indigo planting friends, with[Pg 68] the kindness of heart which characterises all Indian planters, used to visit him from time to time and try to cheer him up, he had to live and die with only his Native servants near him. We know of two other cases of leprosy among acquaintances of our own in India; but these are only in their first stages, and are not sufficiently advanced to prevent the sufferers from appearing in public. I may mention that the Lancet of the 18th July of this year (1891) reports a case of leprosy at Lisburn (Ireland) in a man who had contracted the disease at Rangoon (Burma), where he had resided ten years. There have been many other instances of Europeans contracting the disease abroad. Any destitute white man who became a leper in India would have to remain there; as the Government, very rightly, would not send him home.

Female Lepers.

p. 65.